Università Iuav di Venezia

W.A.Ve. 2022 WORKSHOP

ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

Coordinamento / Coordination

Andrea Iorio con Lucilla Calogero

Staff / Staff

Susanna Campeotto, Elena Cavallin, Mattia Cocozza, Vincenzo d’Abramo, Martina Dussin, Marco Felicioni, Claretta Mazzonetto, Elena Sofia Moretti, Alessia Sala

Staff amministrativo / Administrative staff

Lucia Basile, Federico Ferruzzi, Irene Segalla

Identità visiva / Visual identity

Leonardo Sonnoli, Irene Bacchi

Web, Social, Exhibit graphic design

Damiano Fraccaro

Riprese audiovisive / Audiovisual footage

Beppe Ferrari, Martina Dussin, Luca Pilot, Servizio fotografico e immagini Iuav

Collaborazioni / Collaborations

Iuav Abroad – Iuav Alumni R3B – Rebiennale

Ringraziamenti speciali / Special thanks

Marco Ballarin, Michel Carlana, Vittorio De Battisti Besi, Alberto Ferlenga, Jacopo Galli, Marco Marino, Daniela Ruggeri

Pubblicazione a cura di / Publication edited by Andrea Iorio, Lucilla Calogero

Progetto grafico / Graphic design

Damiano Fraccaro

Pubblicato da / Published by Anteferma Edizioni, Conegliano (TV) 979-12-5953-047-9

Università Iuav di Venezia, Venezia 978-88-3124-165-6

Stampato da / Printed by Grafiche Antiga per / for Anteferma Edizioni

Prima edizione / First Edition Marzo / March 2024

Referenze iconografiche

/ Iconographic references Tutte le foto delle esposizioni finali, escluso quando riportato diversamente, sono del Servizio fotografico e immagini Iuav

/ All photos of the final exhibitions, unless stated otherwise, are from the Servizio forografico e immagini Iuav

Le mappature alle pp. 42-51 sono a cura di / The mappings on pp. 42-51 are edited by Susanna Campeotto, Mattia Cocozza, Vincenzo d'Abramo, Marco Felicioni, Claretta Mazzonetto, Elena Sofia Moretti

Questo lavoro è distribuito sotto Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Condividi allo Stesso Modo 4.0 Internazionale

W.A.VE. 2022 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

A cura di / Edited by

Andrea Iorio

Lucilla Calogero

INDICE / CONTENTS

VERSO IL CAMPUS FUTURO

/ TOWARDS THE FUTURE CAMPUS

UN NUOVO CAMPUS PER LA CITTÀ

/ A NEW CAMPUS FOR THE CITY BENNO ALBRECHT

VENEZIA CAMPUS FUTURO

/ VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS ANDREA IORIO

DELL’INTEGRAZIONE INSOFFERENTE

/ ON IMPATIENT INTEGRATION FRANCESCO ZUDDAS

IDEA DI ARCHITETTURA. SPAZIO DELLA DIDATTICA

/ IDEA OF ARCHITECTURE. THE EDUCATIONAL SPACE TOMMASO BRIGHENTI

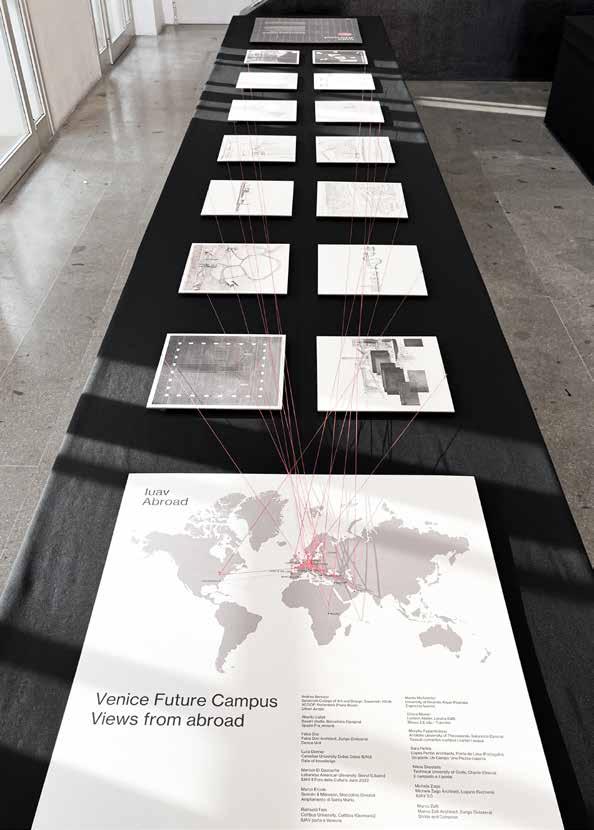

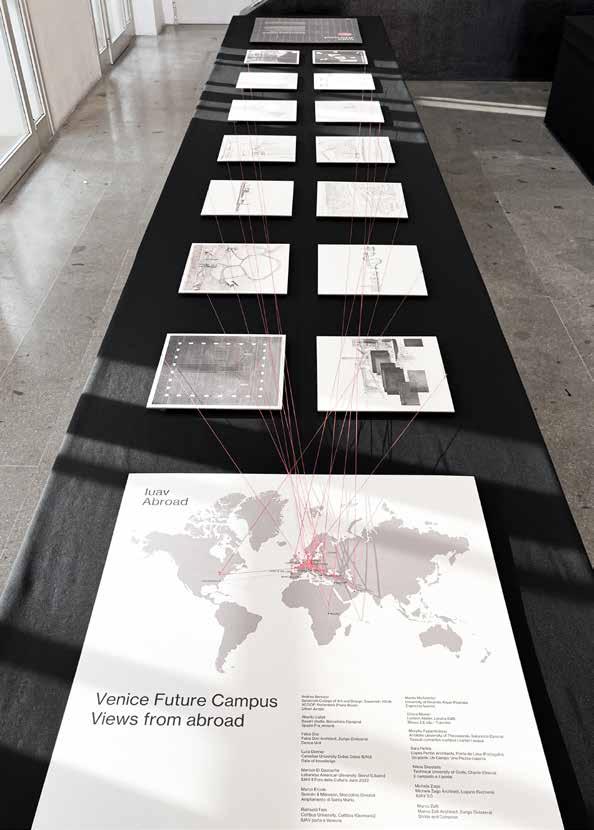

VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS. VIEWS FROM ABROAD

EMANUELA SORBO, ELISA BRUSEGAN, GIANLUCA SPIRONELLI, SOFIA TONELLO, MARCO TOSATO

OCCASIONI PER IL CAMPUS FUTURO

/ OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE CAMPUS

TEMI E AREE

/ THEMES AND AREAS

IL CAMPUS E LA CITTÀ

/ THE CAMPUS AND THE CITY

IL SISTEMA SANTA MARTA

/ THE SANTA MARTA SYSTEM

AREE

PUNTUALI

PUNCTUAL

8 10

34 38 40 48 50

/

AREAS

12 16 24 32

WS1

TIZIANO AGLIERI RINELLA

WS2

ROBERTA ALBIERO

+ ARABELLA GUIDOTTO

WS3

ALDO AYMONINO + GIUSEPPE CALDAROLA

WS4

BERGMEISTERWOLF GERD BERGMEISTER +

WS5

ANDREA

WS6

RICCARDA

WS7

FERNANDA DE MAIO +

WS8

PEDRO DOMINGOS

WS9

FABIO DON + MARCO ZELLI

WS10

ECKERT NEGWER SUSELBEEK ARCHITEKTEN WOUTER SUSELBEEK

WS11

FRES ARCHITECTES

LAURENT GRAVIER + SARA MARTÍN

PER IL CAMPUS FUTURO / VISIONS FOR THE FUTURE CAMPUS

VISIONI

MICHAELA WOLF

BERTASSI

CANTARELLI

DANIELA

RUGGERI

54 56 66 76 86 96 106 116 126 136 146 156

CÁMARA

WS12

WS13

WS14

WS15

WS16

WS17

WS18

WS19

WS20

TONI GIRONÈS

CRISTIÁN IZQUIERDO LEHMANN + NICOLÒ LEWANSKI

SARA MARINI

METRO ARQUITETOS GUSTAVO CEDRONI

ENRICO MOLTENI

MONOBLOCK ALEXIS SCHÄCHTER

GUIDO MORPURGO

RODRIGO PERÉZ DE ARCE

TALLER CAPITAL JOSÉ PABLO AMBROSI + LORETA CASTRO REGUERA

MARGHERITA VANORE

JORGE VIDAL + GUILLEM PONS + BIEL SUSANNA PREMI / AWARDS 166 176 186 196 206 216 226 236 246 256 266 276

WS21

WS22

VERSO IL CAMPUS FUTURO / TOWARDS THE FUTURE CAMPUS

8 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

UN NUOVO CAMPUS PER LA CITTÀ

/ A NEW CAMPUS FOR THE CITY BENNO ALBRECHT

VENEZIA CAMPUS FUTURO

/ VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS ANDREA IORIO

DELL’INTEGRAZIONE INSOFFERENTE

/ ON IMPATIENT INTEGRATION FRANCESCO ZUDDAS

IDEA DI ARCHITETTURA. SPAZIO DELLA DIDATTICA

/ IDEA OF ARCHITECTURE. THE EDUCATIONAL SPACE TOMMASO BRIGHENTI

VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS. VIEWS FROM ABROAD

EMANUELA SORBO, ELISA BRUSEGAN, GIANLUCA SPIRONELLI, SOFIA TONELLO, MARCO TOSATO

9 VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

UN NUOVO CAMPUS PER LA CITTÀ BENNO ALBRECHT

W.A.Ve. è giunto alla ventunesima edizione. Nato nel 2001 come Workshop di Architettura a Venezia, W.A.Ve. si è da subito distinto per la sua forma innovativa di fare e insegnare architettura nel mondo contemporaneo: ogni estate, per tre settimane, tra venti e trenta architetti e docenti di fama internazionale sono invitati a lavorare fianco a fianco con oltre mille giovani studenti dell’Università Iuav di Venezia, in una dimensione laboratoriale e collettiva che non ha eguali. Il lungo percorso intrapreso e i numeri di eccezionale rilevanza – circa 25.000 gli studenti coinvolti complessivamente, oltre 500 gli architetti e i docenti invitati, tra i quali tre Pritzker prize – ne hanno fatto un’esperienza unica nel suo genere, sicuramente il più grande workshop di architettura al mondo.

Con l’edizione 2022 W.A.Ve. ha assunto un valore e un ruolo nuovi all’interno di un ateneo in procinto di intraprendere un profondo rinnovamento, intenzionato a ridisegnare il proprio futuro come centro di riferimento per la ricerca e la didattica del progetto, ma anche la propria posizione all’interno dello straordinario contesto urbano. A partire dalla presentazione del Progetto Iuav 2021-27, ha preso avvio un processo di trasformazione che sta coinvolgendo l’intera comunità universitaria e gli spazi entro cui vive e lavora. Con l’obiettivo di rendere disponibili strutture, servizi e possibilità di relazioni sempre migliori e sempre più competitive, la visione strategica complessiva ha individuato un nodo di particolare rilevanza nel ripensamento delle strutture fisiche del campus universitario all’interno della città di Venezia. L’Università Iuav consolida così il proprio posto al centro delle grandi trasformazioni che riguarderanno le aree di Santa Marta e del porto, dove l’ateneo è uno dei principali stakeholder, partecipando attivamente alla rigenerazione delle aree periferiche della città storica.

La scelta di proporre il grande e impegnativo processo di trasformazione del campus come tema dell’edizione 2022 ha dimostrato che W.A.Ve. può essere uno straordinario strumento di esplorazione, capace di mettere in campo un forte potenziale operativo. Gli esiti prodotti, che sono presentati in questo volume, testimoniano il valore del lavoro svolto: l’ampiezza e la varietà delle visioni proposte riescono a tessere inedite trame di relazioni in una città che ha forte bisogno di ripensare le attività culturali e produttive al suo interno; le numerose declinazioni che i progetti sperimentano sono un importante bagaglio di possibili futuri, nati dalla condivisione con gli studenti, una componente fondamentale della popolazione universitaria attuale e futura; la diversità e la molteplicità dei punti di vista, infine, costituiscono un arricchimento necessario per riuscire a portare a compimento il processo. W.A.Ve. 2022 Venezia campus futuro ha rappresentato un importante passo avanti nel percorso intrapreso e rimarrà un significativo riferimento per la strada ancora da percorrere.

10 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

A NEW CAMPUS FOR THE CITY BENNO ALBRECHT

W.A.Ve. has reached its twenty-first edition. Born in 2001 as Workshop of Architeture in Venice, W.A.Ve. immediately stood out for its innovative way of doing and teaching architecture in the contemporary world: every summer, for three weeks, between twenty and thirty internationally renowned architects and teachers are invited to work side by side with over a thousand young students of Università Iuav di Venezia, in a laboratory and collective dimension that has no equals. The long path undertaken and the exceptionality of the numbers – around 25,000 students involved in total, over 500 architects and teachers invited, including three Pritzker prize winners – have made it a unique experience: certainly the largest architectural workshop in the world.

With the 2022 edition W.A.Ve. has taken on a new value and role within a university about to undertake a profound renewal, with the intent of redesigning its future as a reference center for design research and teaching, but also its position within its extraordinary urban context. Starting from the presentation of Progetto Iuav 2021-27, a transformation process has begun that is involving the entire university community and the spaces in which it lives and works. With the aim of making structures and services increasingly better and construct larger networks of relationships, the overall strategic vision has identified a particularly important node in the rethinking of the physical structures of the university campus within the city of Venice. Università Iuav di Venezia thus consolidates its place at the center of the major transformations that will affect the areas of Santa Marta and the port, where the university is one of the main stakeholders, actively participating in the regeneration of the peripheral areas of the historic city.

The choice to propose the large and challenging process of transformation of the campus as the theme of the 2022 edition demonstrated how W.A.Ve. could be an extraordinary exploration tool, capable of unleashing strong operational potential. The results produced, which are presented in this volume, testify to the value of the work carried out: the breadth and variety of the visions proposed manage to weave new patterns of relationships in a city that has a strong need to rethink its cultural and productive activities; the numerous variations that the projects experiment with are an important showcase of possible futures, born from the continuous sharing with students, the fundamental component of the university; finally, the diversity and multiplicity of points of view constitute a necessary enrichment to be able to complete the process. W.A.Ve. 2022 Venice Future Campus represented an important step forward in the path undertaken and will remain a significant reference for the road still to be traveled.

11 VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

VENEZIA CAMPUS FUTURO ANDREA IORIO

In vent’anni W.A.Ve. ha percorso un lungo cammino, ha toccato molteplici temi e altrettanti luoghi, incrociando approcci ed esplorando differenti scenari. Di volta in volta, le questioni poste dallo sviluppo contemporaneo di città e territori hanno offerto lo spunto di riflessione. Ma sempre, gli strumenti del progetto sono stati la modalità attraverso cui comprendere e migliorare il mondo in cui viviamo, favorendo i confronti tra approcci differenti, mescolando le scale, lavorando sul mondo fisico e sugli immaginari.

Nella sua ventunesima edizione, W.A.Ve. 2022 fa ritorno a casa, nel campus universitario in cui ha sede. È questo un ritorno che può contare su occhi allenati altrove e che, ancora una volta, è arricchito da una molteplicità di punti di vista, interni ed esterni, portatori di un ampio bagaglio di esperienze vicine e lontane. Perché è nel dialogo tra le posizioni che W.A.Ve. ha sempre offerto gli esiti migliori.

W.A.Ve. 2022 è dedicato al futuro del campus universitario Iuav a Venezia. Ragioni interne, legate al riassetto della presenza universitarie nella città, hanno dato lo spunto per il tema d’anno. La necessità di una riorganizzazione generale delle sedi ha visto l’avvio di un processo volto alla deframmentazione e all’efficientamento dei rapporti tra edifici, collocazioni e funzioni. Tale processo, però, non si esaurisce in se stesso: al contrario, rappresenta una straordinaria occasione per interrogarsi sull’identità e sulla struttura intima del campus a venire. La questione, cioè, non è solo contingente: trasferire funzioni o riempire contenitori. Piuttosto si tratta di gettare le basi – in questo caso, architettoniche e spaziali – per potenziare e sviluppare le attività presenti. Ma anche, e soprattutto, per scoprire opportunità latenti nel patrimonio edilizio attuale, esplorare l’introduzione di nuovi programmi e di nuovi spazi a questi dedicati, mettere alla prova inedite relazioni tra le parti. Il termine campus, allora, richiama un’idea di ‘campo’, come quello elettromagnetico, fatto di molteplici presenze, anche composite, e mutue interazioni, a contatto o a distanza, visibili o no. La sua attivazione – meglio, la sua intensificazione – costituisce irrinunciabile condizione di ricchezza per la vita universitaria.

Il particolare contesto in cui ha sede la parte più consistente del campus, l’area di Santa Marta, è un luogo piuttosto particolare, a partire dal quale poter innescare un più ampio ragionamento sulla stessa Venezia. Santa Marta, infatti, sebbene si trovi in diretta continuità con il tessuto urbano storico e sia ugualmente caratterizzata da un rapporto multiforme con l’acqua, rimane allo stesso tempo una parte atipica della città, riconoscibilmente distinta. L’eredità che deriva dalla sua storia particolare, legata allo sviluppo industriale di questo lembo estremo della città, ci chiede oggi di confrontarci con grandi manufatti, in parte già usati dalle università, in parte dismessi, e grandi vuoti. Sono questi altrettante straordinarie occasioni di progetto, altrimenti impensabili nella città più densa e consolidata.

Allo stesso tempo, l’orizzonte di senso entro cui concepire il destino del campus interseca questioni più ampie e di più lunga prospettiva temporale. Tra i vari eventi occorsi negli ultimi anni, vari sono gli indizi di un prossimo inevitabile cambiamento per luoghi come questo: dalla pandemia che ha messo in discussione le forme della

12 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

vita collettiva – e, con particolare intensità, quelle della vita scolastica – fino ai più recenti piani nazionali di contrasto alla crisi economica, che prevedono nuovi investimenti nello sviluppo delle infrastrutture universitarie. Il termine futuro, in questo senso, dischiude almeno due possibili direttrici. Da un lato, prende corpo come difficile eredità: quella lasciata da un lungo e non ancora del tutto chiuso stato di emergenza, che ci obbliga a immaginare un futuro inevitabilmente diverso rispetto alle tradizionali modalità didattiche e della ricerca, con necessarie ricadute anche sugli assetti spaziali. Dall’altro, nel dischiudere nuove prospettive di sviluppo per le sedi universitarie, è necessario affrontare alcuni aspetti strutturali del futuro campus. Tra questi, alcuni hanno rilevanza, potremmo dire, interna, come per esempio il sistema dei collegamenti o la distribuzione degli spazi per le attività collaterali alla didattica (come laboratori, spazi per il lavoro collettivo, spazi espositivi e per eventi). Altri aspetti, invece, riguardano il generale ripensamento delle relazioni tra università e intorno. Sarebbe possibile individuare molteplici soglie tra ciò che succede all’interno degli edifici e gli spazi aperti circostanti: oggi questi spazi esterni sono tanto ampi quanto poco attrezzati per ospitare la vita universitaria (dalla vita quotidiana degli studenti, alla possibilità di utilizzo per eventi). In questo senso, anche il lavoro su luoghi puntuali può rivelarsi strategico quando riesce a traboccare dal proprio perimetro abituale per fuoriuscire a coinvolgere l’intorno, rinegoziando o articolando quelle soglie. In questo quadro, il progetto degli spazi esterni, oggi spesso di risulta, costituisce peraltro uno straordinario banco di prova per ripensare i luoghi relazionali post pandemia.

Un aspetto di particolare rilievo, infine, è occupato dal tema dei rapporti tra campus e città intera. O meglio, i rapporti tra un’università dedicata alle culture del progetto (dall’architettura al design, dalla pianificazione alla moda) e una città che da tempo manca di progetti sul suo futuro, sul ruolo che le attività ancora presenti possono avere nella vita urbana. Questi rapporti sono oggi fragili, poco sistematici e raramente attraggono una componente culturale già presente, altrove, in città. In questo senso, il ruolo che il campus futuro potrà svolgere sta a metà strada tra la progettazione di spazi capaci di attrarre e accogliere e il loro inserimento entro più ampie sequenze urbane (prima tra tutte il rapporto con il fronte sul canale della Giudecca). Il futuro del campus urbano è allo stesso tempo radicato e aperto, punti e rete.

La sfida proposta da W.A.Ve. 2022, allora, sottintende due quesiti fondamentali: il primo riguarda le possibilità, per il progetto di architettura, di svolgere ancora un ruolo trainante, o di innesco, nei processi di trasformazione urbana; il secondo, se e come l’occasione del campus urbano potrà contribuire a delineare il futuro di Venezia.

13 VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS ANDREA IORIO

Across the last twenty years, W.A.Ve. has traveled a long road, dealing with multiple themes and as many places, crossing different approaches and exploring multiple scenarios. From time to time, the issues posed by the contemporary development of cities and territories have triggered its discussions, offering food for thought. Nevertheless, the tools of the project have always been the mode through which to understand and improve the world we live in, fostering comparisons between different approaches, mixing scales, working both on the physical world and on imaginaries.

In its 21st edition, W.A.Ve. 2022 returns home, to the university campus where it is based. And such a return can count on eyes trained elsewhere and, once again, be enriched by a multiplicity of viewpoints, both internal and external, carrying a wide range of experiences from nearby and far away. For it is in the dialogue between positions that W.A.Ve. has always offered its best outcomes.

W.A.Ve. 2022 is dedicated to the future of the Iuav university campus in Venice. Internal reasons, related to the reassessment of the presence of the university in the city, pushed toward this year’s theme. The need for a general reorganization of the school’s venues prompted a process of defragmentation aimed at a more efficient relationships between buildings, locations and functions. This process, however, does not end in itself: on the contrary, it represents an extraordinary opportunity to question the identity and intimate structure of the campus to come. The matter, in fact, is not merely contingent, nor limited to the transferring of functions or the filling of containers. Rather, it also implies laying the foundations – in this case, architectural and spatial – for enhancing and developing present activities. But also, and above all, to discover latent opportunities in the current building stock, to explore the introduction of new programs and new spaces dedicated to them, to test unprecedented relationships between the parts. The term campus, then, recalls an idea of ‘field’, like an electromagnetic one, made up of multiple presences, even composite, and mutual interactions, in contact or from a distance, visible or not. Its activation –better, its intensification – constitutes an indispensable condition of richness for the university life.

The context in which the largest part of the campus is located, the Santa Marta area, is a rather peculiar place, from which a broader reasoning about Venice itself can be triggered. Santa Marta, in fact, although in direct continuity with the historic urban fabric and equally characterized by a multifaceted relationship with water, remains at the same time an atypical part of the city, recognizably distinct. The legacy coming from its particular history, linked to the industrial development of this extreme edge of the city, asks us today to confront large artifacts, partly already used by the universities, partly disused, and large voids. These all represent extraordinary design opportunities, otherwise unthinkable in the denser, more established city.

At the same time the boundaries of meaning, within which the future of the campus must be conceived, intersect broader issues of longer time perspective. Among the various events occurred in recent years, many indicators hint at an inevitable change for places such as this: on one side, the pandemic has challenged the

14 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

forms of collective life and, with particular intensity, those of the school life; on the other, the most recent national plans to counter the economic crisis have envisioned new investments in the development of university infrastructures. The term future, in this sense, discloses at least two possible directions. On the one hand, it embodies a difficult legacy, left by a long and not yet completely closed state of emergency, which forces us to imagine a future that inevitably differs from the traditional modes of teaching and research, bearing necessary repercussions on spatial arrangements as well. On the other hand, in unveiling new development prospects for the university’s venues, it is necessary to address some structural issues connected to the future campus. Among these, some bear more internal relevance, such as the system of connections or the distribution of spaces for other activities collateral to teaching (such as laboratories, spaces for collective work, exhibition and event spaces). Other aspects, besides, concern the general rethinking of the relationship between the university and its surroundings. Multiple thresholds could be possibly identified between what happens inside the buildings and the surrounding open areas: today these outdoor spaces are as large as they are poorly equipped to accommodate university life (from the daily life of students, to the possibility of use for events). In this sense, working on punctual places can also prove strategic if it manages to overcome its usual perimeter and encompass the surroundings, renegotiating or articulating those thresholds. In this framework, the design of outdoor spaces, now often considered as a left-over, represents an extraordinary test for rethinking post-pandemic relational places.

Finally, the relationships between the campus and the whole city frames a meaningful issue that must be addressed. Or rather, the relationships between a university dedicated to the culture of the project (from architecture to design, from planning to fashion) and a city that has long lacked plans for its future, for the role that the activities still present can play in its urban life. Today these relationships denote fragility, lack a systematic approach and rarely attract that cultural component already present, elsewhere, in the city. In this sense, the role the future campus can play lies somewhere between the design of spaces – capable of attracting or welcoming – and their insertion within broader urban sequences (first and foremost the relationship with the canale della Giudecca front). The future of the urban campus, then, is both rooted and open. It embodies both points and networks.

Thus, the challenge proposed by W.A.Ve. 2022 implies two fundamental questions: the first one concerns the possibilities for architectural design to still play a driving, or triggering, role in processes of urban transformation; the second one enquires whether and how the occasion of an urban campus will contribute to shaping the future of Venice.

15 VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

DELL’INTEGRAZIONE INSOFFERENTE FRANCESCO ZUDDAS

Nel 2016 l’associazione Young Architects Competitions promosse un concorso di idee per l’insediamento di un “campus universitario da sogno” a Poveglia, un’isola della laguna veneziana in stato di abbandono da circa cinquant’anni dopo un passato come stazione di quarantena.1 Sotto due aspetti il concorso si inseriva sul solco della storia degli insediamenti universitari, due aspetti che si intrecciano e la cui rilevanza si rinnova alla luce di attuali considerazioni che informano la coscienza collettiva e la politica. Il primo, proponendo il riuso di vecchi edifici, è l’idea che un’università si costruisce attraverso la riappropriazione e trasformazione di qualcosa che già esiste. Il secondo, sfruttando l’idea di isola, predica che l’università sia un fatto a sé, elemento che, in definitiva, sfugge all’integrazione nella società e nella città.

Come non demolire un edificio

Andiamo per ordine. Mentre scrivo queste note ricevo un’email di invito a una lezione aperta dello studio belga 51N4E. La lezione, organizzata dall’Architecture Foundation a Londra, si intitola How to not demolish a building. Non vi è titolo che più ci si dovrebbe aspettare in un tempo in cui le coscienze individuali e istituzionali sono scosse dal cambiamento climatico: l’era dell’Antropocene, quando la razza umana si accorge che i Limits to Growth proclamati cinquant’anni fa dal Club di Roma sono diventati un futuro non più prorogabile e, tra gli altri, chiama sul banco degli imputati architettura, architetti, e studenti di architettura a espiare una irrefrenabile sete di risorse. Sempre più raro è diventato assistere oggi a una presentazione di progetti studenteschi in cui non figuri la domanda, formulata più come accusa che dubbio, riguardo all’eventualità di distruggere e ricominciare. E finalmente, viene da aggiungere.

Nulla si crea, nulla si distrugge, tutto si trasforma Meccanicamente ripetuta come un mantra da milioni di studenti, oggi più che mai questa frase offre una definizione dell’architettura. Se si vogliono trovare esempi da cui imparare come mettere in atto il portato creativo dell’enunciato di Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier, la storia dell’università, compresa quella delle università in Italia, offre un punto di partenza. Per rimanere in tempi non troppo passati e, indubbiamente, peccare di ovvietà, tornano alla mente gli interventi di Giancarlo De Carlo per le Università di Urbino e Pavia.2 Inserendo classi, docenti e studenti all’interno di vecchi muri, sia quelli istituzionali dei conventi (la facoltà di Magistero a Urbino), sia quelli popolari di vecchie strutture rurali (i poli universitari periferici proposti per Pavia), De Carlo agiva da destabilizzatore. Ciò che destabilizzava era un dibattito architettonico e urbanistico che, tra gli anni ’60 e ’70 e su scala internazionale, era principalmente impegnato a commentare gli innumerevoli nuovi insediamenti universitari, spesso celebrandoli come città di fondazione per il mondo occidentale e opportunità di crescita (si legga colonizzazione) per i paesi in via di sviluppo.3 Oltre a essere specchio del proprio tempo, e spesso agendo d’anticipo, i progetti di De Carlo mettevano in luce una caratteristica originale,

16 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

cioè attinente a un momento di origine, dell’università: il non nascere dal nulla ma essere, invece, mutazione di istituzioni precedenti.

La conoscenza, è stato scritto, si è reincarnata varie volte nel corso della storia, ogni volta creando istituzioni che reagivano a quelle precedenti, ma al contempo ne portavano in traccia alcune caratteristiche.4 L’università è solo una di tante reincarnazioni, si dice nata in epoca medievale dal precedente più prossimo del monastero, la sua origine. Ogni reincarnazione, come ogni nuova generazione, cerca di ridefinire le sue origini, e così l’università fu fin da principio orientata a essere, in confronto al precedente monastico, istituzione più aperta e diversificata. Ma il tentativo poteva solo essere vano perché, come nota Giorgio Agamben riflettendo sul significato interconnesso di opera, principio e comando, «l’inizio non è un semplice esordio, che poi scompare in ciò che segue; al contrario, l’origine non cessa mai di iniziare, cioè di comandare e governare ciò che ha posto in essere».5 Il monastero, quindi, non poteva che sopravvivere come comando nell’università.

È vero che dalle origini medievali l’università si è a sua volta reinventata nel tempo al punto di essere trasfigurata e, sostanzialmente, ricreata in epoca moderna come istituzione di “ricerca” (l’università di Berlino di inizio Ottocento), grande macchina burocratica (la Multiversity di cui scriveva nei primi anni ’60 il rettore della University of California, Clark Kerr6), e fabbrica della conoscenza (appellativo di ovvio stampo marxista proposto dai critici della deriva di mercato dell’università in epoca di capitalismo neoliberale7). Una contraddizione di fondo, tuttavia, permane come costante nel tempo. Nell’introdurre una raccolta di saggi ormai diventata un classico sul tema del rapporto tra università e città, Thomas Bender riassumeva così questa costante:

Then as now, it was difficult to balance the ideals of disinterested pursuit of ideas with the material facts of life surrounding academics in cities. There is a constant danger of corruption, of succumbing to the lures of power and wealth. But mostly it has been a creative tension.8

Crisi

Riassunto in ambito anglosassone col sintagma “town and gown”, il rapporto conflittuale tra università e città è forse il mito che più ha alimentato storie e controstorie, progetti e controprogetti per una delle istituzioni più difficili da definire in maniera univoca. Come tutti i miti, accertarne la veridicità è impossibile, se non inutile. Ciò a cui rimanda è la constatazione che un accordo su cosa sia un’università è raggiungibile quanto una chimera. Si può dire infatti che, almeno dal Conflitto delle facoltà con cui Kant al tramonto del Settecento discuteva la riorganizzazione della conoscenza per categorie – le discipline – l’università è un’istituzione in crisi, intendendo per crisi un momento di scelta, di decisione. Il rapporto dell’università con il campo largo a cui risponde e in cui si colloca – la città ne è solo una piccola parte – è sempre in bilico, sempre sull’orlo del tracollo. Così è stato e così dovrà essere fino all’eventuale fine dell’università. La richiamata lettura secondo cui la conoscenza si reincarna temporaneamente in nuove istituzioni che, a loro volta, la riorganizzano, porta alla logica conclusione che anche l’università non sia immortale, nonostante la constatazione di Bender che «no institution in the West, save the Roman Catholic church, has persisted longer».9

E in effetti, da tempo si attende, si teme, anche si spera, nella morte dell’università. È dai tempi dei progetti di De Carlo prima richiamati, intorno al 1968, che si dibatte questo momento di passaggio, con una crescente ansia per una istituzione dichiarata in rovina,10 forse defunta, sempre meno critica.11 Proprio nel ’68 un altro architetto italiano, Guido Canella, aveva scritto che lo stato di crisi dell’università si ritrova nel suo rapporto spaziale di frontalità nei confronti del suo alter ego, la città. L’essere una “anti-città”, per Canella, era un altro modo di nominare quella tensione creativa definita da Bender; una costante storica, aggiungeva l’architetto, tanto valida nelle università urbane di matrice europea quanto in quelle suburbane di matrice americana.12 Canella aiutava a escludere il mito del campus americano,

17 VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

nato e definitosi tra il XVII e il XVIII secolo, come momento di rottura di un ipotetico paradiso scomparso in cui fosse esistito, nel passato e in ambito europeo, un rapporto di maggiore integrazione tra città e università. L’università, ovunque si trovi, è un luogo insofferente alla troppa integrazione.

Iceberg

L’anti-città universitaria di Canella, e in certa misura i progetti di De Carlo, erano motivati dallo spirito contestatorio del ’68 per cui tutto ciò che rappresentava lo stato corrente doveva essere sottoposto a giudizio. L’università si doveva aprire alla società, si diceva, ma pur mantenendo una distanza di sicurezza, si direbbe critica, dai risultati non voluti dell’appiattimento e della neutralizzazione delle contraddizioni. Su questo ancora oggi ci si interroga: come creare una situazione che si distacchi dalla realtà pur appartenendovi a pieno?

Osservando un progetto recente, l’espansione della Columbia University in un nuovo campus a Harlem, Reinhold Martin (docente nella stessa università) letteralmente scava sottoterra per trovare prove che contraddicano le apparenti e dichiarate ambizioni di trasparenza e permeabilità del progetto elaborato da Renzo Piano Building Workshop con Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. Puntando l’arco del linguaggio verso il bersaglio del consenso, il progetto scomoda il foro di romana memoria per promuovere un’immagine di università in cui molteplici pubblici attraversano liberamente un campus proclamato privo di barriere e cancelli. Muovendo lo sguardo nei sotterranei, Martin mostra come ciò che emerge sia la punta di un iceberg la cui base sommersa è un edificio unico che, ancor più del celebrato campus che McKim Mead and White progettarono per la Columbia sul finire dell’Ottocento, sembra rispettare la griglia stradale per, in realtà, colonizzarla molto più a fondo. Sul suolo, in risposta all’affermata assenza di cancelli e barriere, Martin nota come una coppia di condotti di aerazione, già firma high-tech fin dai tempi del Centre Pompidou, creino un’allegoria di ingresso, «as if the campus gate must be reproduced and even commemorated».13

Si potrebbe dire che qui si pecca di troppa ingenuità. Il sodalizio tra chi, come Piano, spesso viene visto e sfruttato come esportatore di italianità (si pensi, tra i tanti, al progetto per Central Saint Giles in centro a Londra, discusso per la sua capacità di offrire una piazza alla città), lo studio corporate americano per eccellenza che tanto ha inciso anche in ambito di progettazione di spazi universitari (SOM), e una delle maggiori istituzioni accademiche al mondo che si è costruita la propria fama anche grazie alle proprie mosse sul mercato immobiliare, non può infatti che essere intriso di slogan mirati a placare le ansie e le rabbie dei tanti residenti dispossessati dalla costruzione di un nuovo grande campus universitario. Ciò che resta è l’ulteriore prova di quell’imminente pericolo di corruzione che Bender diagnosticava come costante nella storia dell’università.

Isola

Arriviamo così alla seconda considerazione introdotta in apertura – l’università come fatto a sé – che ci riporta al concorso per Poveglia dove la decisione più estrema sembra sia stata presa: creare un’università-isola. Riflettendo sul tempo corrente di crisi climatica e rinnovati fervori nazionalisti, Jill Stoner ha osservato come l’idea di isola sia orma obsoleta. Lo è in quanto luogo dell’utopia, come natura immacolata che variamente ha dato forma all’immaginario di scrittori e registi; ed è obsoleta come luogo della distopia nazionalista, in un «political ecosystem in which lies are disguised as truth»14 e le proposte di nuovi muri fisici (Messico/USA) e ideologici (Brexit) per tenere fuori l’indesiderato e conservare il mito dell’identità nazionale si scontrano con l’incontrovertibile realtà dell’interdipendenza globale.

Irrompe di nuovo Giancarlo De Carlo, che cinquant’anni fa scriveva della nascente università di massa come non «più un’isola di guarigione culturale, [piuttosto] una trama specifica ma non necessariamente emergente di una tessitura più generale che coinvolge tutti gli aspetti e i momenti della vita associata».15 Osservando di nuovo i suoi progetti per un’università che fosse della città, che contribuisse cioè a

18 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

1. YAC website. https://www. youngarchitectscompetitions. com/it/past-competitions/ university-island (ultimo accesso: 10 maggio 2023).

2. Francesco Zuddas, “Pretentious Equivalence: De Carlo, Woods and MatBuilding”, FA Magazine, 34 (2015): 45-65.

3. Stefan Muthesius, The Postwar University: Utopianist Campus and College. New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 2000; Francesco Zuddas, The University as Settlement Principle: Territorialising Knowledge in Late 1960s Italy. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2020.

dare anima alla vita associata dentro e fuori i suoi muri specializzati, che si disperdesse in un territorio urbano (dove anche la campagna era ormai parte dell’urbano), ci si trova di fronte alla crisi, a quel momento di decisione di cui si accennava prima. L’università come scelta, non in grado di offrire certezze, non ingenuamente aperta e permeabile, e sicuramente non ingannevolmente trasparente come dichiarato da tanta della più recente architettura universitaria. Senza imprescindibilmente tessere le lodi di un architetto che, come tutti, sarà dovuto scendere a patti e solcare il limite di quella corruzione morale sempre dietro l’angolo, soprattutto quando il cliente è al contempo così potente ma anche così fragile da cedere alle tentazioni mondane, quei progetti puntualizzano come un’università che sia parte di città sia lungi dall’essere il frutto di una gentile operazione senza dolore, semplice inserzione di programma. Il limite ultimo dell’integrazione rimane all’orizzonte, e lì deve rimanere come obiettivo ideale, forse non raggiungibile, ma il cui vero scopo è persistere come traguardo che risvegli le anime quando cadono nel torpore di una retorica troppo romantica o nell’eccessiva sete di potere.

L’integrazione tra università e città può esistere solo nella misura di accettare un dato di fatto che è intrinseco al fare architettura, che è l’architettura. Il fatto di operare sempre attraverso il dissenso, in qualche misura, nei confronti di ciò che si trasforma. Non tutto si accetta per ciò che è, ogni materiale si guarda con sospetto per ipotizzarne una nuova ragione d’essere. Usare l’università per attuare una tale trasformazione ha ovvie tinte simboliche che rimandano al ruolo di un’istituzione ricreata, in epoca moderna, come ragione critica della società, luogo di giudizio di conoscenze assodate e di creazione di nuovi miti. Un’istituzione sempre sull’orlo del tracollo, destinata forse a essere surclassata da qualcos’altro che la contraddirà pur mantenendone alcune delle caratteristiche. E speriamo, a pena della scomparsa di ogni ragione critica, siano le caratteristiche che oggi più stimolano il disaccordo su questa istituzione fondamentale.

4. Ian F. McNeely and Lisa Wolverton, Reinventing Knowledge: From Alexandria to the Internet. New York: W.W. Norton, 2008.

5. Giorgio Agamben, Creazione e anarchia: L’opera nell’età della religione capitalista. Vicenza: Neri Pozza, 2017: 93.

6. Clark Kerr, The Uses of the University. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963.

7. The Edu-factory Collective, Toward a Global Autonomous University, New York: Autonomedia, 2009; Gerald Raunig, Factories of Knowledge: Industries of Creativity. Los Angeles: Semiotext, 2013.

8. Thomas Bender, “Introduction”. In Thomas Bender (a cura di), The University and the City: From Medieval Origins to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988: 5.

9. Ibid.: 4.

10. Bill Readings, The University in Ruins. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

11. Douglas Spencer, The Architecture of Neoliberalism: How Contemporary Architecture Became an Instrument of Control and Compliance. New York: Bloomsbury, 2016.

12. Guido Canella, “Passé et avenir de l’anti-ville universitaire”, L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, 137 (1968): 16-19.

13. Reinhold Martin, “Made in Manhattanville”. In Caitlin Blanchfield (a cura di), Columbia in Manhattanville New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2016: 130.

14. Jill Stoner, “The End of the Idea of Island: On the Extinction of True Isolation”. Literary Hub Daily, 27 September 2021. https://lithub.com/the-endof-the-idea-of-island-on-theextinction-of-true-isolation/ (ultimo accesso: 10 maggio 2023).

15. Giancarlo De Carlo (a cura di), Pianificazione e disegno delle università. Roma: Edizioni universitarie italiane, 1968: 13.

19 VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

ON IMPATIENT INTEGRATION FRANCESCO ZUDDAS

In 2016, Young Architects Competitions launched an ideas competition to settle a “dream university campus” in Poveglia, an island in the Venetian lagoon that has laid in ruins for over fifty years after a past life as a quarantine station.1 In two ways the competition brief linked to the history of university settlements; two ways that intersect and whose relevance is renewed in the light of current preoccupations that have collective and political significance. Firstly, by proposing to reuse existing built structures a reminder was sent as to how a university gets built by re-appropriating something that already exists. Secondly, by leveraging on the idea of an island the brief claimed a university to be a thing onto itself; an element that ultimately escapes integration in society and in the city.

How to not demolish a building

Let’s start with an anecdote. As I write these notes my email inbox receives an invitation to a public lecture by the Belgian office 51N4E. Organised by the Architecture Foundation in London, the lecture’s heading is How to not demolish a building. Arguably no title should be more expected in times when climate change stirs individual and collective conscience; the times of the Anthropocene, when the Limits to Growth declared by the Club of Rome fifty years ago have become a no longer deferrable future. Sitting in the dock, architecture, architects, and architecture students plead to expiate their insatiable thirst for natural resources, and it has today become increasingly common in reviews of students’ work to hear the question – to be sure, more of an accusation than the expression of a doubt – about the legitimacy of razing down to start again. Finally, we can add.

Nothing is created, nothing is destroyed, everything is changed Repeated as a mantra by million students through the years, Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier’s principle offers today a most fitting definition of architecture. If lessons are sought as to how to put in practice the creative potential of the sentence one should look no further than the history of universities, with those in Italy offering an effective vantage point. To stay within not too remote times and, admittedly, fall prey of truism, the projects by Giancarlo De Carlo for the universities in Urbino and Pavia inevitably come to mind.2 Through the insertion of classrooms, teachers, and students within old walls spanning from the institutional ones of convents (i.e. the School of Education in Urbino) to the vernacular ones of rural buildings (i.e. the peripheral poles proposed for Pavia), De Carlo enacted a subversion. What he subverted was the international architectural and urbanistic discourse of the 1960s and 1970s and its celebration of numerous new university settlements as either the new towns for the postwar Western world or development opportunities (read colonisation) for underdeveloped countries.3 Emblematic of their times, and often capable of anticipating future trends, De Carlo’s projects shed light on an original (meaning proper of an originating moment) characteristic of universities: namely, their being born not out of nothing but through the mutation of some earlier institutions.

20 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

It has been said that knowledge has cyclically reincarnated, each time creating new institutions that reacted to yet also carried the traces of those that preceded them. 4 The university is only one of many reincarnations, notoriously born in medieval times and bearing the traces of one of its precedents: the monastery. Acting like any new generation set to redefine its own origins, the university aimed from the outset to be a more open and diverse institution in comparison to its monastic precedent. The aim, however, could only be a vain dream because, following Giorgio Agamben’s elaborations on the interlinked meanings of work, principle and command, «the beginning is not merely debut; it is not something that disappears in what comes after it. Instead, the origin never stops beginning, that is, it never stops commanding and governing what it has originated».5 The monastery could therefore only survive as command in the university.

There is no doubt that the university has reinvented itself multiple times since its medieval origins to the point of transfiguration. Firstly, as a research institution for the modern age (the 19th century University of Berlin); then, as gigantic bureaucratic machinery (the Multiversity advocated by the University of California President, Clark Kerr, in the early 1960s6); and more recently as a factory of knowledge (to use marxist-flavoured nomenclature to critique the marketisation of the university in the neoliberal age7). A fundamental contradiction, however, remains as a constant through time. This constant was summarised by Thomas Bender in his introduction to a collection of essays that has become a classic textbook on the relations between universities and cities:

Then as now, it was difficult to balance the ideals of disinterested pursuit of ideas with the material facts of life surrounding academics in cities. There is a constant danger of corruption, of succumbing to the lures of power and wealth. But mostly it has been a creative tension.8

Crisis

Summarised with the phrase “town and gown”, the conflictive relation between university and city is arguably the myth that most widely has sparked narratives and counter-narratives, projects and counter-projects for an institution that is among the most difficult to define. As for any myth, ascertaining its truthfulness is impossible if not pointless. It can be argued that, at least since Kant’s Conflict of the Faculties at the turn of the 18th century critiqued the re-organisation of knowledge into a set of categories – the disciplines – the university is defined as an institution in crisis. This is true if the etymology of crisis is considered, as the index of a moment of choice. The relation of the university with its vast outer condition, including but not limited to the city, is constantly set on a divide; always on the brink of collapse. This is how it has been in the past, and this is how it will be until, that is, the eventual end of the university. The mentioned idea that knowledge temporarily reincarnates in new institutions that, in turn, reorganise it, leads to the logical conclusion that the university is not immortal. This is true despite Bender’s acknowledgment that «no institution in the West, save the Roman Catholic church, has persisted longer».9

As a matter of fact, the death of the university has been waited, feared, but also longed for by some for a long time. At least since around 1968, the time of those projects by De Carlo that were mentioned before, debate about its ultimate transfiguration into something else has been matched with growing anxiety towards an institution that is variously commented upon as being in ruins,10 perhaps already defunct, surely less critical than ever.11 And it was precisely in 1968 that another Italian architect, Guido Canella, wrote about how the crisis of the university finds its mirror image in the confrontational relation it entertains with its alter ego, the city. For Canella, the university was an “anti-city”, which is another name for that constant creative tension mentioned by Bender and, in the Italian architect’s opinion, one that was recurring as much in the older urban universities of European origins as in their American suburban counterparts of later origin.12 Canella critiqued the reading

21 VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

of the American campus, born and grown to maturity between the 17th and 18th century, as a sudden rupture of some mythical previous integrity between university and city that existed in a European context. He helped understand that, wherever located, the university gets irritated from too much integration.

Iceberg

Canella’s university anti-city and, to some extent, De Carlo’s projects found their ethos in the protests of 1968, a time when every pixel of the status quo was meant to be critiqued. It was said at that time that the university needed opening up to society while managing to keep some safety, or better critical distance from unwanted levelling down and neutralisation of contradictions. This is still an open question today: how to give shape to a situation that is detached from reality and yet also fully belonging to it?

Reflecting on Manhattanville, the new campus of Columbia University in Harlem, Reinhold Martin (a professor at that very institution) literally digs underground in search of evidence to contradict the self-declared ambitions of transparency and permeability of the project authored by Renzo Piano Building Workshop in collaboration with Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. Pointing the terminological bow and arrows towards a target of consensus, the project advocates the Roman Forum to promote the image of a university that allows multiple publics to freely cross a campus that is presented as devoid of barriers and gates. By moving the attention to the underground of the campus, Martin demonstrates how what emerges is but the tip of an iceberg whose submerged base is, in fact, a single large building. Even more clearly than the earlier and celebrated Columbia campus designed by McKim, Mead and White at the end of the 19th century, Manhattanville deceitfully appears to be respectful of the street grid while in reality colonising the city in a much deeper way. As a response to the claimed absence of gates and barriers, Martin notices a pair of ventilation shafts of a similar type to those first popularised as part of high-tech vocabulary by the Centre Pompidou and now placed on the New York campus grounds to offer an allegory of a gate, «as if the campus gate must be reproduced and even commemorated».13

Some could say that I might be erring on the side of the naïve here. A partnership between someone like Piano who has amply been presented and used as bearer of Italian urban values (for one, think of his Central Saint Giles project in Central London, discussed for its capacity to offer a piazza for the city); the corporate American office par excellence that much has left a mark on the history of campus design; and one of the most powerful academic institutions that built its prestige also through real estate operations – such a partnership knows possibly no escape from giving shape to discourse soaked in slogans to appease the anxiety and anger of many residents that are being dispossessed of their neighbourhood by the construction of the new campus. What remains from this story of academia in the city is further proof of that impending risk of corruption defined by Bender as a constant in the history of universities.

Island

We have thus arrived at the second topic mentioned at the start: the university as a thing onto itself. This takes us back to the competition for Poveglia where the most radical decision seems to be taken, namely the creation of a university-island. Reflecting on the current times marked by climate crisis and a renovated nationalist spirit across the globe, Jill Stoner has noticed the obsolescence of the idea of an island. The island is an obsolete idea as a place for utopia; as immaculate nature that has variously inspired the imagination of writers and movie directors. But it is also obsolete, she notices, if understood as the place for nationalist dystopias in a «political ecosystem in which lies are disguised as truth»14 and the proposals for new walls, both physical (i.e. Mexico/US border) and ideological (i.e. Brexit), that are meant to keep the undesired away and protect the myth of national identity, crash on the unquestionable reality of global interdependency.

22 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

1. YAC website. https://www. youngarchitectscompetitions. com/it/past-competitions/ university-island (last accessed: 10 May 2023).

2. Francesco Zuddas, “Pretentious Equivalence: De Carlo, Woods and MatBuilding”, FA Magazine, 34 (2015): 45-65.

3. Stefan Muthesius, The Postwar University: Utopianist Campus and College. New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 2000; Francesco Zuddas, The University as Settlement Principle: Territorialising Knowledge in Late 1960s Italy. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2020.

Giancarlo De Carlo bursts into the picture again. It was him who fifty years ago wrote about the nascent mass university as «no longer an island for cultural healing, but a specific yet not necessarily emergent texture part of a wider weave that involves all aspects and times of associative life».15 Looking back at his projects for a university of the city; one that could animate collective life both inside and outside its specialist walls; and one that would ultimately dissipate in a vast urban territory that extended from city to countryside; looking back at those projects we are confronted with crisis, with that moment of choice that I previously mentioned. It is the university as a choice, something not capable of offering certainties, not naively open and permeable, and surely also not deceitfully transparent like a large part of current university architecture claims to be. Without proposing a wholesale celebration of an architect that, like any other, will indubitably have had to accept negotiation and walk the line separating from the ever-present risk of moral corruption, particularly when the client is concomitantly so powerful and so fragile to easily fall in the trap of mundane temptations, those projects underline how a university intended as a part of city is far from being the product of a painless process; far from being mere insertion of academic programme inside existing containers. Integration always lays on the horizon, and there is where it belongs as an ideal target, one that is perhaps unachievable. Its real aim is to persist in its role as a finish line that can arouse us each time we lean on the side of overly romantic rhetoric or excessive thirst for power. Integration between university and city can exist only to the extent of accepting a fact that is intrinsic to architecture; a fact that is architecture itself. It is the fact of operating always by means of some degree of dissent towards what is being transformed. Not everything is accepted for what it is, and every material is looked at with reasonable suspicion in order to find for it a new reason to exist. Using the university to put in place such type of transformation has obvious symbolic significance that touches on the role of an institution that was recreated in modern times to be society’s critical reason and a vantage point to assess consolidated knowledge and create new myths. The university is an institution always on the brink of collapse and possibly destined to be replaced by something else that will contradict it while keeping some of its characteristics. To exorcise the disappearance of any leftover critical reason, let’s hope that those that will be kept are the characteristics that today most stimulate disagreement on this fundamental institution.

4. Ian F. McNeely and Lisa Wolverton, Reinventing Knowledge: From Alexandria to the Internet. New York: W.W. Norton, 2008.

5. Giorgio Agamben, Creazione e anarchia: L’opera nell’età della religione capitalista. Vicenza: Neri Pozza, 2017: 93. My translation.

6. Clark Kerr, The Uses of the University. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963.

7. The Edu-factory Collective, Toward a Global Autonomous University, New York: Autonomedia, 2009; Gerald Raunig, Factories of Knowledge: Industries of Creativity. Los Angeles: Semiotext, 2013.

8. Thomas Bender, “Introduction”. In Thomas Bender (edited by), The University and the City: From Medieval Origins to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988: 5.

9. Ibid.: 4.

10. Bill Readings, The University in Ruins. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

11. Douglas Spencer, The Architecture of Neoliberalism: How Contemporary Architecture Became an Instrument of Control and Compliance. New York: Bloomsbury, 2016.

12. Guido Canella, “Passé et avenir de l’anti-ville universitaire”, L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, 137 (1968): 16-19.

13. Reinhold Martin, “Made in Manhattanville”. In Caitlin Blanchfield (edited by), Columbia in Manhattanville New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2016: 130.

14. Jill Stoner, “The End of the Idea of Island: On the Extinction of True Isolation”. Literary Hub Daily, 27 September 2021.

https://lithub.com/the-endof-the-idea-of-island-on-theextinction-of-true-isolation/ (last accessed: 10 May 2023).

15. Giancarlo De Carlo (edited by), Pianificazione e disegno delle università. Roma: Edizioni universitarie italiane, 1968: 13. My translation.

23 VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

IDEA DI ARCHITETTURA. SPAZIO DELLA DIDATTICA

TOMMASO BRIGHENTI

La forma dello spazio architettonico è capace di portare un proprio contributo alle metodologie didattiche e non costituisce uno sfondo neutrale ma è essa stessa portatrice di una propria autonomia interpretativa, dove l’arte diventa base per l’educazione. Compito arduo da argomentare compiutamente in così poche battute, piuttosto è utile richiamare alcuni riferimenti che possono indicare traiettorie in grado di chiarire quella duplice relazione tra lo spazio fisico dell’insegnamento e l’idea di architettura maturata per mezzo di un progetto culturale che una scuola di architettura può e deve, necessariamente, avere.

Tra i progetti più conosciuti ma necessariamente menzionabili è importante partire dall’edificio della Cooper Union di New York.1 Nel 1964 un giovane John Hejduk, chiamato a insegnare alla Cooper, divenne da lì a poco uno dei principali architetti teorici del panorama mondiale. Nei suoi esercizi avviene una narrazione dello spazio che riparte dai primi concetti basilari come l’esistenza di un pilastro in rapporto tra due pilastri, tra sei pilastri e via via, affrontando il tema della relazione tra i corpi e lo spazio attraverso un carattere topologico. Accompagnare il disegno dello spazio con una narrazione significa interpretarne il senso e la sua struttura interna dal punto di vista disciplinare, tramite una serie di metafore, piuttosto che attraverso una impostazione schematica. Il discorso favolistico o analogico aiuta ad arrivare alle stesse nozioni in modo più poetico e creativo attraverso un percorso personale che stimola la sensibilità al significato delle forme e della loro vita. Nel 1974 Hejduk, chiamato a occuparsi del progetto di restauro dell’edificio ottocentesco, proporrà un “dispositivo pedagogico” progettato sulla base di uno dei suoi esercizi fondamentali, il Nine square grid problem, una applicazione quasi letterale dell’insegnare per “osmosi” attraverso una narrazione. Hejduk manterrà l’involucro esterno, il guscio, la maschera, per poi ricostruirne completamente gli interni per arrivare a dire di progettare anche quegli spazi impercettibili che stanno tra il guscio e la struttura, quella membrana che si trova tra la pelle e lo scheletro. Nell’edificio della Cooper, vengono richiamati altri pensieri architettonici che trovano posto dietro al guscio come per esempio le lecorbuseriane Villa Savoie e Villa Stein che Hejduk stesso commenterà nel suo celebre libro Mask of Medusa affermando che esse «dialogano tra loro attraverso lo spazio assiale della biblioteca [come] due piccoli edifici dentro un edificio che è dentro un edificio». Questa dimensione poetica, racchiusa in questo progetto, sarà fondamentale per Hejduk per promuovere una conoscenza ricettiva di sentimenti e sensazioni che non sono fatti razionali, ma emozioni educatrici.

È proprio dal rapporto tra poesia e architettura che – in un altro contesto –quello latinoamericano, nascerà la scuola di Valparaíso in Cile.2 Questa esperienza pedagogica e il luogo in cui viene messa in pratica possono essere considerati tra i più originali rispetto alla didattica dell’architettura e al suo spazio di insegnamento. Una scuola fondata dalla collaborazione tra il poeta argentino Godofredo Iommi e l’architetto cileno Alberto Cruz dove la poesia diventa strumento di apertura verso il mondo. La poesia, come strumento cosciente per essere consapevoli del luogo in cui si vive, un continente splendido, quello del Sud America che, come loro stessi scrivono nel loro famoso poema Amereida, è ancora tutto da scoprire e una fede

24 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

nell’architettura, che si pone in antitesi all’insegnamento accademico e all’architettura intesa come professione, in cui l’attività artistica, la creatività, devono insorgere alle formule e alle regole tradizionali reinventando tutto ogni volta a partire dall’esperienza concreta.

Nel 1970 i docenti della scuola acquisteranno un lembo di terra a nord di Valparaíso, a Ritoque, poi denominato Ciudad Abierta, iniziando a costruire, assieme ai loro studenti, delle architetture dove lo spazio della scuola è inteso in una dimensione di arte totale e i principi pedagogici sperimentali trasmessi trovano un riscontro fisico. Un’esperienza caratterizzata da un progetto culturale fondato su un impegno di ricerca totalizzante che presuppone la collaborazione costante tra la poesia e le altre arti. In questa scuola, verrà intrapreso un percorso di maturazione in cui la ricerca di una identità latinoamericana caratterizzerà lo spazio fisico dove studenti e docenti lavorano, studiano e vivono praticando la costruzione come azione di gruppo per mezzo di risorse naturali e materiali poveri. Queste architetture diventano la prova di un’esperienza gratuita realizzata con spirito di comunità e non sono solo momento di trasmissione di una tecnica, ma assumono un valore attribuito alla pratica di un’azione disinteressata in cui l’agire cancella l’antinomia tra forma e contenuto, tra oggetto e programma al punto che quasi non esistono disegni di progetto degli edifici della Ciudad Abierta o delle piccole opere di Traversia, perché queste vengono realizzate en ronda, sul posto. Questa azione, chiamata atto e assunta come momento decisivo della loro didattica, è ciò che proviene dall’esperienza e nasce dall’osservazione per giungere alla forma come risultato espressivo di un approccio conoscitivo.

Atteggiamento identitario che in altri paesi latinoamericani ebbe una certa difficoltà a emergere, se non in casi eccezionali come, ad esempio, quello della FAU-USP l’opera di Villanova Artigas a San Paolo in Brasile.3 Questo edificio è l’espressione concreta del progetto pedagogico di Artigas, che fu anche direttore della FAU per diversi anni, dove la scuola di architettura diventa un grande laboratorio attraverso il quale la formazione di uno studente deriva da una libera commistione di arti e discipline umanistiche nel quale l’architettura, il pensiero pedagogico e l’ideologia sociale raggiungono una sintesi perfetta, espressione della chiara speranza e fiducia per un mondo migliore: «un’arma per trasformare il mondo» sosterrà lo stesso Artigas.

La FAU non ha porte e il passaggio dall’esterno verso l’interno è continuo, delimitato solo da una massiccia struttura in cemento armato che sorregge la copertura. Lo spazio pubblico entra nell’edificio e il percorso esterno si trasforma in una rampa interna, intorno alla quale si sviluppano diverse funzioni tra cui le aule, la biblioteca, la falegnameria, i laboratori e il grande salone centrale. Questa grande aula diventa una piazza al coperto per incontri, assemblee e manifestazioni pubbliche, celebre è la foto di questo spazio gremito di studenti durante una manifestazione che oltre a occupare lo spazio centrale al piano terra, si affacciano dalla rampa e dai ballatoi come in un grande teatro. La capienza di questa cavità illuminata dall’alto che nega ogni confine con l’ambiente circostante è la dimostrazione di come lo spazio diventa promotore di relazioni umane ed espressione di democrazia. «La città è una casa. La casa è una città», soleva ripetere Artigas.

Tornando in Europa, non si può non citare la facoltà di Architettura della Universidade do Porto progettata da Álvaro Siza4 in cui l’architettura è ancora considerata come arte, servizio e prodotto di carattere culturale, dove l’esercizio progettuale costituisce l’insegnamento erede di una lunga storia di tradizione di maestri in cui si insegna l’architettura partendo dai suoi esiti e il progetto, spina dorsale dell’attività didattica, diventa il punto di partenza del dibattito e motore del progetto architettonico dello spazio dell’insegnamento da cui emerge una precisa idea di architettura rispetto a un mondo implicito e condiviso di forme e figure, di riferimenti, di un retroterra artistico e letterario e in particolare di un modo di esprimersi attraverso il progetto e il disegno. Trasmissione che parte proprio dallo spazio fisico della scuola di architettura, che diventa spunto e riferimento per tutti i suoi studenti grazie al suo impianto perché l’architettura, dice Siza, è rivelazione di un «desiderio collettivo nebulosamente latente» che non può sicuramente essere insegnato, ma che è possibile «imparare a desiderarlo».

25 VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

Infine, due casi italiani, due progetti non realizzati di Guido Canella e Luciano Semerani, architetti che sono stati in grado di costruire all’interno della scuola un luogo di produzione di conoscenza. Lavori riconducibili a una presa di posizione che ha posto costantemente la città e le sue forme al centro della riflessione

Nel progetto per il nuovo insediamento del Politecnico di Milano alla Bovisa,5 presentato alla mostra Le città immaginate. Un viaggio in Italia. Nove progetti per nove città della XVII Triennale di Milano del 1987, sotto la direzione di Pierluigi Nicolin, Canella insiste sulla necessità di un’architettura finalizzata a individuare nuovi modelli di organizzazione del comportamento di una società che si vuole sviluppare, individuando i fattori che possono costruire questa trasformazione attraverso un nuovo ruolo dell’architettura per risolvere problemi sociali e politici mantenendo un rapporto inscindibile con la storia, con la città e con il suo contesto. Per Canella il programma anticipa l’oggetto e, ancora più precisamente, l’outil si sviluppa dalle potenzialità interne di un programma territoriale. Un’eredità che viene in parte da Samonà, che legava l’invenzione dell’organismo edilizio alla lettura strutturale del territorio, e in parte dal legame con la tradizione rogersiana.

La città e più precisamente la sua periferia è vista come «un organismo vivo dove azioni e reazioni risultano sempre concatenate» nella quale lo spazio dell’insegnamento universitario prende forma attraverso un’idea di architettura vista come volontà di trasformazione. Canella, immaginando di consolidare il rapporto tra città e periferia, si alimenta di molteplici riferimenti che evocano una figurazione che si lega al contesto milanese, «elementare eppure cosmica», che dal turrito incastellamento filaretiano, risale verso le ripide ed esaltanti profezie di Sant’Elia e i malinconici paesaggi di Sironi: figurazione che, come scritto nella relazione di progetto, è «tesa nell’insieme a scandire tempi improrogabili e a orientare scelte irrinunciabili pena lo scadimento di rango».

Per tornare a Venezia e concludere, nel 1998 Semerani con alcuni dei suoi collaboratori progetterà la nuova sede Iuav nell’area dei magazzini frigoriferi a San Basilio a Venezia6. In questo progetto, la forma mistilinea del perimetro nascerà principalmente dallo studio e dalla conoscenza della città di Venezia, ma anche dai sentimenti e dall’anima, ponendosi dichiaratamente in contrasto con chi sostiene che la forma deriva dalle ragioni pratiche, tecnologiche e funzionali. Semerani assume come oggetto di analisi la città, il senso della sua forma, della sua coerenza interna, la sua autenticità, ricercandone i segni che costituiscono il discorso e quelle figure che, come le parole dentro la scrittura, diventano linguaggio. Angoli acuti e ottusi prevalgono rispetto a un’ortogonalità mai presente in una città come Venezia di impianto medievale e gotico, generando forme complesse riproposte anche nella copertura che, sostenuta da pilastri di geometria esagonale, dà luce al grande vuoto centrale e alla piccola cavana che permette l’accesso dal mare.

Una ricerca, quella di Semerani, prima di tutto di carattere linguistico dove l’architettura non è più documento di una razionalità o di una tipizzazione astratta ma la ricerca di «una genesi della forma di Venezia, per attribuirne un senso» e in grado, attraverso l’efficacia del linguaggio, di trasmettere una personale visione del mondo, quel senso delle forme che si tramutano in insegnamento assumendo quel valore pedagogico che l’architettura progettata è in grado di trasmettere a chi si trova a studiare e praticare il progetto al suo interno.

26 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

1. John Hejduk, Mask of Medusa. Works 1947-1983. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1989; Giuseppina Scavuzzo, “John Hejduk o la passione di imparare”. In Lamberto Amistadi, Ildebrando Clemente (a cura di), John Hejduk. Soundings 0/I, Firenze: Aión, 2015: 7-21; Tommaso Brighenti, “La ricerca di uno spazio narrativo”. In Id., Pedagogie architettoniche. Scuole, didattica, progetto Torino: Accademia University Press, 2018: 76-123.

2. Alberto Cruz, “Cooperativa Amereida, Chile”, Zodiac, 8 (1992): 188-199; Massimo Alfieri, La Ciudad Abierta. Una comunità di architetti. Roma: Dedalo, 2000; Rodrigo Pérez de Arce, Fernando Pérez Oyarzun, Valparaíso School. Open City Group. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2003; Tommaso Brighenti, “La Scuola di Valparaíso. L’osservazione, l’atto e la forma”. In Id. Pedagogie architettoniche. Scuole, didattica, progetto. Torino: Accademia University Press, 2018: 24-75

3. Marcelo Carvalho Ferraz (a cura di), Vilanova Artigas: Arquitetos Brasileiros. San Paolo: Instituto Lina Bo e P. M. Bardi, 1997; Rosa Correira de Lira, José Tavares (a cura di), Vilanova Artigas, Caminhos da arquitectura. San Paolo: Cosac Naify, 2004; Carlo Gandolfi, “Note sull’architettura brasiliana e la scuola paulista. Da Vilanova Artigas a Mendes da Rocha”. In Id., Matter of Space. Città e architettura in Paulo Mendes da Rocha. Torino: Accademia University Press, 2018: 81-105.

4. Álvaro Siza, “Il progetto come esperienza”, Domus, 746 (1993): 17; Álvaro Siza, “Sulla pedagogia”. In Id., Scritti di architettura. Milano: Skira, 1997: 28-31; AA.VV., Álvaro Siza. Tutte le opere. Milano: Electa, 1999.

5. Guido Canella, “Progetto per l’area di Bovisa a Milano, XVII Triennale di Milano”, Zodiac, 7 (1992): 200-211; Enrico Bordogna, Guido Canella. Opere e progetti Milano: Electa, 2002: 138143; Enrico Bordogna, La Scuola di Architettura Civile a Bovisa e il disegno della città. Santarcangelo di Romagna: Maggioli, 2019; Giorgio Fiorese, Aura di Bovisa. Santarcangelo di Romagna: Maggioli, 2022.

6. Luciano Semerani, “Concorso per una nuova sede Iuav nell’area dei magazzini frigoriferi a San Basilio, Venezia, 1998”, Zodiac, 20 (1999): 174-181; Luciano Semerani, Antonella Gallo, Giovanni Marras, “Concorso per una nuova sede Iuav nell’area dei magazzini frigoriferi di San Basilio, Venezia, 1998”. In Luca Molinari (a cura di), Semerani e Tamaro. Architetture e progetti Milano: Skira, 2000: 44-47.

27 VENICE FUTURE CAMPUS

IDEA OF ARCHITECTURE. THE EDUCATIONAL SPACE TOMMASO BRIGHENTI

The form of architectural space can bring its own contribution to teaching methodologies and does not constitute a neutral background but is itself the bearer of its own interpretative autonomy, where art becomes the basis for education. In such a few lines, this is an arduous task, and one that can perhaps only be achieved by listing and briefly describing some potential references, which may indicate trajectories that could clarify the dual relationship between the physical space of teaching and the idea of architecture as developed through a cultural project that a school of architecture necessarily can and must adopt.

Among the better known projects that are necessarily worth mentioning, it is especially relevant to start with the Cooper Union building in New York.1 Invited to teach at Cooper in 1964, John Hejduk soon became one of the world's leading theoretical architects. In his exercises, a narrative of space takes place, starting from the first basic concepts such as the existence of one pillar in relation between two pillars, six pillars and so on, addressing the topic of the relationship between bodies and space through topological character. Accompanying the drawing of space with a narrative means interpreting its meaning and internal structure from a disciplinary point of view, through a series of metaphors, rather than through a schematic approach. The fable-like or analogical discourse helps to arrive at the same notions in a more poetic and creative way through a personal journey that stimulates sensitivity to the meaning of forms and their life. Called in to take charge of the restoration project of the 19th century building in 1974, Hejduk proposed a “pedagogical device” designed on the basis of one of his core exercises, the Nine square grid problem, an almost literal application of teaching by “osmosis” through narration. Hejduk will maintain the outer shell, the mask, and then completely rebuild the interior in order to even design those undetectable spaces that lie between the shell and the structure, or the membrane that is found between the skin and the skeleton. In the Cooper building, other architectural thoughts are recalled behind the shell, such as the lecorbuserians Villa Savoie and Villa Stein, which Hejduk himself commented on in his famous book Mask of Medusa, stating that they «converse with each other through the axial space of the library [like] two small buildings within a building that is within a building». Embedded in this building, this poetic dimension will be crucial for Hejduk in fostering a receptive knowledge of feelings and sensations that are not just merely rational facts but rather an emotional education.

It is precisely because of the relationship between poetry and architecture that the Valparaíso School of Architecture in Chile2 will be born in another context – that of Latin America. This pedagogical experience as well as the place where it is implemented can be considered as one of the most original in terms of architecture didactics and its teaching space. Combining poetry as a tool for opening up to the world, this School was founded by the collaboration between the Argentine poet Godofredo Iommi and the Chilean architect Alberto Cruz. Poetry, as a conscious tool to be aware of the place where one lives, a splendid continent, that of South America, which, as they themselves write in their famous poem Amereida, is yet to be discovered, and a faith in architecture, which stands in antithesis to academic

28 WORKSHOP ARCHITETTURA VENEZIA

teaching and architecture understood as a profession, in which artistic activity, creativity, must rise to the formulas and traditional rules, reinventing everything each time starting from concrete experience.

In 1970, the school’s teachers bought a strip of land north of Valparaiso, in Ritoque, later named Ciudad Abierta, and began to build, with their students, architectures where the school Space is conceived in a total art dimension and the experimental pedagogical principles conveyed are physically reflected. This experience is marked by a cultural project founded on a commitment to all-embracing research that presupposes constant collaboration between poetry and the arts. The school will engage in a maturing pathway where the search for a Latin American identity will characterise the physical space in which students and teachers will work, study and live, practising construction as a collective action using natural resources and poor materials. These architectures become the evidence of a freely given experience that is realised in a spirit of community, and not only a moment of transmission of a technique. They take on a value given to the practice of selfless action in which action overcomes the antinomy of form and content, and of object and programme to the extent that there are hardly any design drawings of the Ciudad Abierta buildings or the small Traverias works, because these are made en ronda, on site. Such action, named act and assumed as the most crucial element of learning experience, comes from experience and arises from observation to form as the expressive result of a cognitive approach.

This identitarian approach had some difficulty emerging in other Latin American countries, except in exceptional cases such as the FAU-USP’s Villanova Artigas in São Paulo, Brazil.3 This building is the concrete expression of Artigas’s pedagogical project, who was also director of the FAU for several years, whereby the school of architecture becomes a great laboratory through which the formation of a student comes from a free mingling of arts and humanities, and where architecture, pedagogical thought and societal ideology reach a perfect synthesis, an expression of clear hope and confidence for a better world: «a weapon to transform the world», Artigas himself claimed.

FAU has no doors and the passage from outside to inside is continuous, only delimited by a massive concrete structure supporting the roof. The public space enters the building, and the outside pavement is transformed into an internal ramp, around which are developed several functions including classrooms, library, carpentry, laboratories and the large central hall. This large hall becomes an indoor square for meetings, assemblies and public events. Famous is the photograph of this space packed with students during a rally, who not only occupy the central space on the ground floor, but also look out from the ramp and galleries as if in a large theatre. The capacity of this top-lit cavity that denies any boundary with its surroundings is a demonstration of how space becomes both a source of human relations and an expression of democracy. «The city is a home. The house is a city», Artigas used to repeat.