Exhibition texts

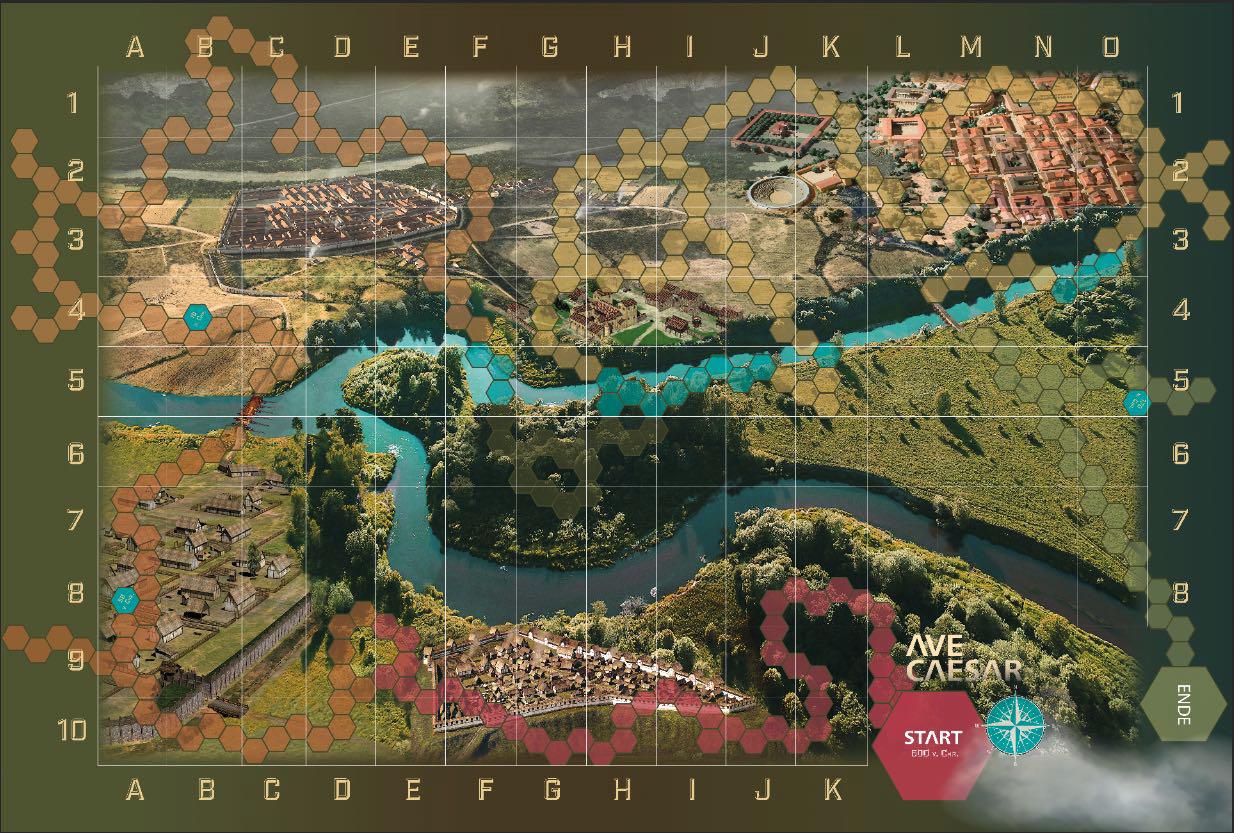

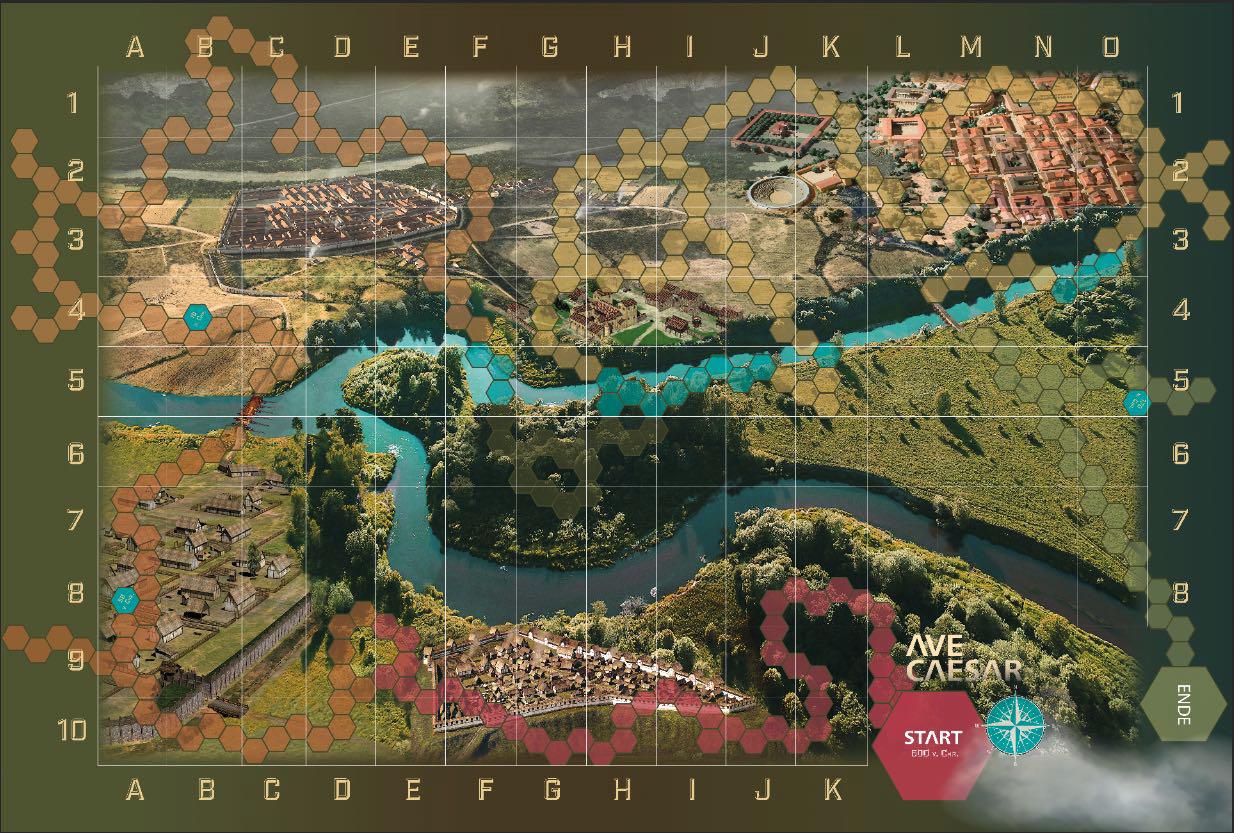

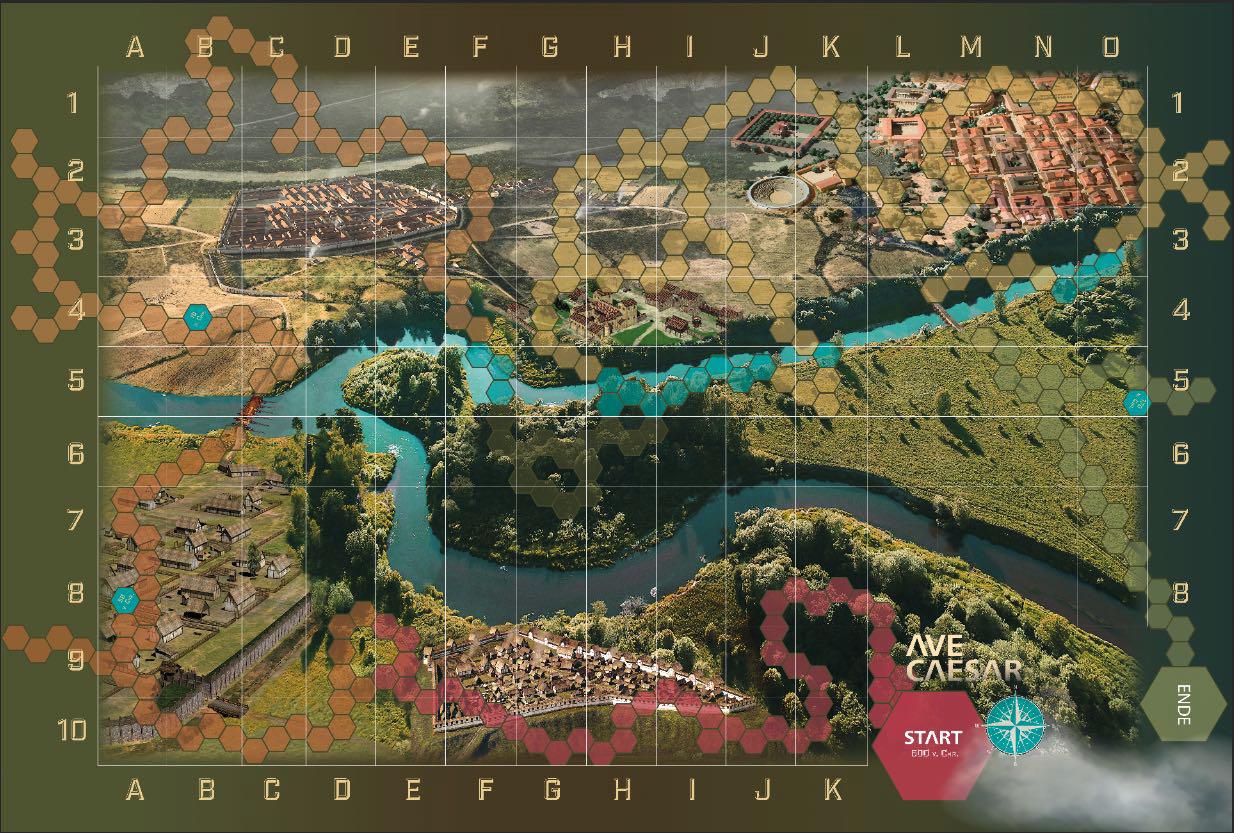

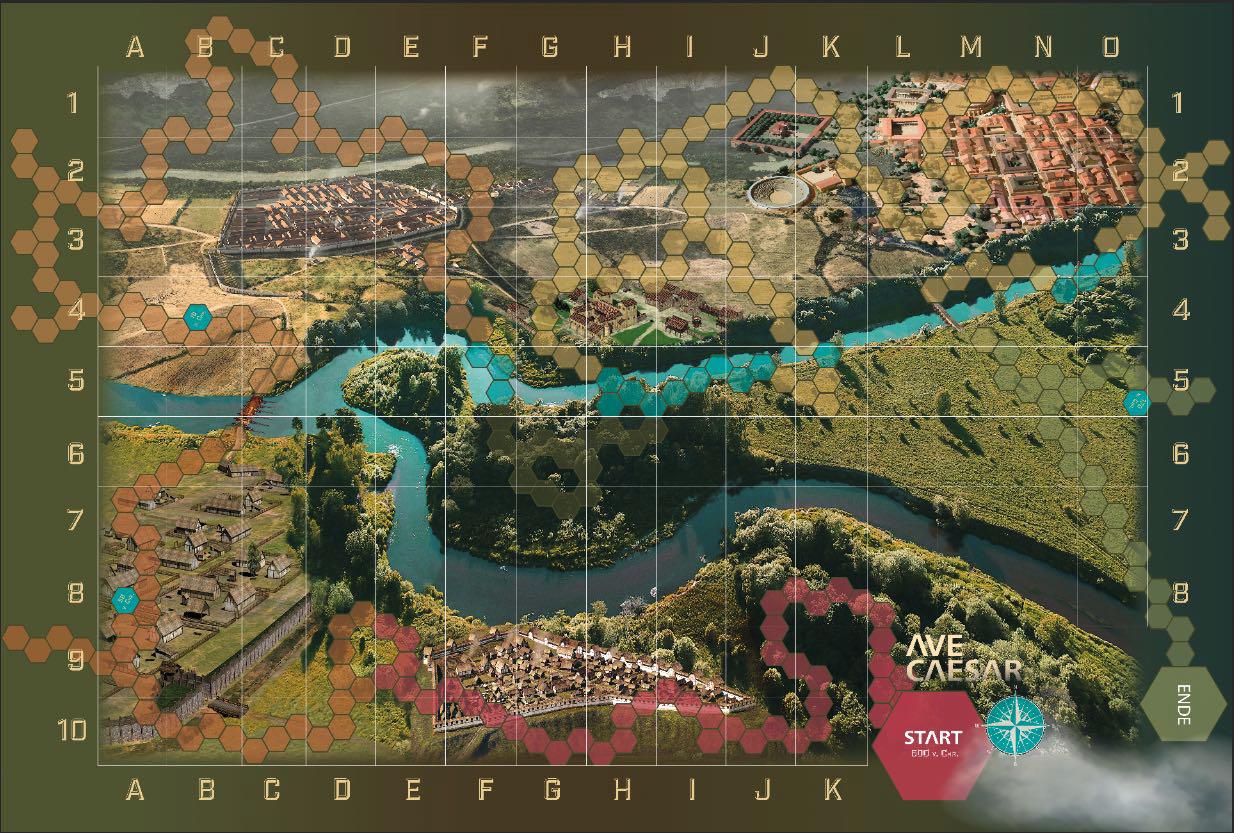

In Antiquity, the Rhine was a major communications artery stretching right across Europe, allowing trade, contacts, and cultural exchange between different regions. Then as now, the river was of immense importance strategically for controlling trade routes and sources of raw materials. On the “gameboard” of the Rhine’s history, indigenous and Mediterranean cultures met, fought, and influenced each other, with the river playing different roles: sometimes a communications axis, sometimes a battlefield, sometimes a border. Join in the game and discover its history!

In Antiquity, rivers were the most convenient method of transport into the interior. The river system of the Rhône connected the Mediterranean with central Europe. The Rhine extended this trade route as far as the North Sea, while its tributaries provided yet more routes west and east.

Greek and Etruscan traders were interested in metals, salt, furs, and slaves from the north – the land of the Celts. In return, they supplied merchandise like wine and luxury goods.

Control of the trade routes guaranteed power and wealth. On the Rhine, too, a local Celtic elite developed and major centres of power grew up along the river.

The Celtic princes emphasised their social position by importing luxury goods from the Mediterranean region. Cultural influences travelled from the south as well; people began to use coins and settlements became increasingly urbanised.

Luxury tableware from Greece and the Greek cities of southern Italy has been discovered at Celtic princely seats.

1 Fragment of a vessel for mixing wine from Athens. It was found on the Münsterberg at Breisach, once the seat of a Celtic prince, from where trade along the Rhine could be controlled.

Pottery, c. 510 BC, Archäologisches Landesmuseum BadenWürttemberg

2 Wine-mixing vessel from Athens.

Pottery, c. 510 BC, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

3 Fragment of a bowl from Campania, also from the Celtic princely seat at Breisach.

Pottery, c. 300 BC, Archäologisches Landesmuseum BadenWürttemberg

4 Bowl from Campania.

Pottery, c. 300 BC, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

Around 450 BC, major social and cultural changes took place in the Celtic world. In the 4th century BC, Celts began to make military incur sions into the Mediterranean region. They also fought as mercenaries in wars between various Mediterranean powers and were well-known to the Greeks and Romans as courageous warriors. But we also hear about Helicon, a Helvetian who worked in Rome as a blacksmith and brought natural Mediterranean products back to his homeland.

Fighting Celt from a Greek victory monument. Plaster cast of an original from the 2nd century BC, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

The Etruscans, who ruled central Italy, also conducted a lively trade with the Celts. Their goods reached the Rhine via the Rhône River system and the Alpine passes.

1 Etruscan vessel in the form of a woman’s head, thought to have been found in Besançon.

Bronze, 3 rd-2nd century BC, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

2

Etruscan storage vessel from a Celtic princely grave near Weiskirchen (district of Merzig-Wadern).

Bronze, 6th-5th century BC, LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn

3 Etruscan beaked flagon from a Celtic grave near Urmitz (district of Mayen-Koblenz).

Bronze, c. 450 BC, LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn

The seat of a Celtic ruler Heuneburg on the Danube (c. 600 BC) – the seat of a Celtic ruler © Landesamt für Denkmalpflege im Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart/ Faber Courtial

The first major settlement on the left bank of the Rhine at Basel (known today as the “Basel Gasfabrik” site) appeared around 150 BC. It was aban doned around 80 BC because of the turbulent political situation. Settle ment activity was transferred to the fortified settlement on the Münster hügel.

Both sites reveal evidence of lively contacts with the south. As well as imported goods, there are also signs of cultural influence, not least in the way the settlements were organised.

1 Italian wine amphora from the Basel-Gasfabrik settlement. Pottery, late 2nd century BC, Archäologische Bodenforschung BaselStadt

The Celts minted their own coins, copying those of their trading partners.

2 Coin portraying King Philip II of Macedonia. Gold, 330/320 BC, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

3 Coin minted by the Celtic Helvetii, based on Greek examples. Gold, 2nd century BC, Historisches Museum Basel

Around 600 BC, the Greeks founded a settlement at Massalia/Marseilles. This was the starting point for the trade route leading via the Rivers Rhône, Saône, and Doubs to the Rhine.

4 Coin from the Greek city of Marseilles. Silver, c. 250 BC, Historisches Museum Basel

5 Celtic coin from northern Italy, based on coins from Marseilles. Silver, 2nd century BC, Historisches Museum Basel

From the 2nd century BC onwards, the influence of a new political power – Rome – began to make itself increasingly felt in trade with the Celts, with Roman coins now also serving as models for Celtic coinage.

6 Roman coin. Silver, after 211 BC, Historisches Museum Basel

7 Precision scales from the settlement of Basel-Münsterhügel. These were used to weigh coins and precious metals. Bronze, 1 st century BC/1 st century AD, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

Although the Celts had no written culture, they occasionally used the script of their Greek trading partners.

8 Stylus (?) from the Basel-Gasfabrik settlement. Iron, late 2nd/ early 1 st century BC, Archäologische Bodenforschung Basel-Stadt

Inlaid finger-ring from the Basel-Gasfabrik settlement. It is of southern origin and proves that people needed to seal written documents, possibly in connection with trading contracts. Iron and glass, late 2nd/early 1 st century BC , Archäologische Boden forschung Basel-Stadt

Oxygen- and strontium isotope analyses suggest that some of the people who lived in the Basel-Gasfabrik settlement grew up a long way from the Rhine. This tooth belonged to a man who probably came either from Brittany or from the Mediterranean coast of southern France.

Tooth, 2nd century BC, Archäologische Bodenforschung Basel-Stadt

Between 58 and 52 BC, Caesar exploited quarrels between the Celtic tribes to expand Roman rule as far as the Rhine: the river became the frontier of the Roman territory. In Gaul as a whole, the Roman conquest cost up to a million lives.

Caesar stationed small garrisons along the Rhine, one of them on Basel’s Münsterhügel. The immediate presence of the Romans gave an even greater boost to trade with the south.

In his reports, Caesar described the Rhine as the border between Celtic and Germanic tribes. This is a great oversimplification, however: the river was by no means a cultural divide.

In 55 and 53 BC, Caesar crossed the Rhine north of Coblenz on wooden bridges which his soldiers erected in just a few days – a demonstration of the logistical prowess of his army.

Column plinth from Mainz showing Roman soldiers fighting. Limestone, 2nd half of the 1 st century AD, GDKE Direktion Landes museum Mainz

Baggage label belonging to the Roman soldier Titus Torius (or Titus from the unit of Torius), from the Basel-Münsterhügel settlement. He is the earliest inhabitant of Basel whose name we know. Horn, 20 BC – AD 20, Archäologische Bodenforschung Basel-Stadt

The Celtic settlement on the Donnersberg (Pfalz), 2nd/1 st centuries BC

© Ideal 3D computer reconstruction: Roland Seidel (archaeoflug)

1 Head of a dead barbarian from Avenches. According to sources from Antiquity, Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul cost up to a million lives. Bronze, 2nd century AD. Site et musée romains d’Avenches

2 Roman coin (denarius) with a portrait of Gaius Julius Caesar. It was struck at an army mint in Gaul. Silver, 43 BC, Historisches Museum Basel

3 Roman coin (denarius) of Gaius Julius Caesar. It was discovered in 1999 when the Antikenmuseum Basel was being extended. Silver, 49 BC, Archäologische Bodenforschung Basel-Stadt

4 Roman coin (aureus) of Lucius Munatius Plancus. In 44/43 BC, he founded a colony at Lyon and the Colonia Raurica. This second colony was probably sited on Basel’s Münsterhügel but has not left any confirmed archaeological traces. It was not until the reign of Emperor Augustus that the colony of Augusta Raurica was founded on the Rhine.

Gold, 45 BC, Historisches Museum Basel

5 Fragment of a Roman sword scabbard from the Münsterhügel in Basel. Caesar stationed a small garrison here to guard the new frontier on the Rhine.

Bronze, late 1 st century BC, Historisches Museum Basel

6 Hobnail from a Roman soldier’s boot from the Basel-Münsterhügel settlement.

Iron, 50/40 BC, Archäologische Bodenforschung Basel-Stadt

7 Axe belonging to a Roman army sapper, found at the BaselMünsterhügel settlement. Iron, late 1 st century BC – early 1 st century AD, Historisches Museum Basel

15

Portrait of the Roman politician and general Gaius Julius Caesar (100–44 BC) from a legionary camp near Nijmegen. Marble, end of the 1 st century BC, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden

Ten thousand Roman officers and soldiers, all with money to spend, were stationed on the Rhine, boosting the local economy and trade.

The Romans built numerous military bases on the left bank of the Rhine to secure their conquered territories. These also served as bases for military campaigns against the Germanic tribes on the right bank of the Rhine.

As far as possible, the Romans made use of existing social structures. If they agreed to enter Roman service, the local elites were allowed to keep their positions of power.

The Romans expanded the infrastructure along the Rhine, building a modern road system to ensure that the frontier was supplied with troops and provisions.

Portrait of Tiberius, Roman Emperor from AD 14 to 37. In 15 BC, under his predecessor, Augustus, Tiberius marched along the High Rhine: the Romans were expanding their control as far as the Danube. As commander-in-chief on the Rhine, he fought the Germanic tribes on the right bank of the river. Marble, 1 st half of the 1 st century AD, on loan

Portrait of Nero Claudius, called Germanicus. From AD 14 to 16 he led several campaigns against the Germanic tribes on the right bank of the Rhine, earning himself the victory title “Germanicus”. However, he failed to occupy the region. In AD 16, Emperor Tiberius called off attempts to expand the empire to the Elbe: the Rhine remained the frontier.

Marble, early 1 st century AD, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig Column plinth from Mainz showing Roman soldiers marching. Limestone, 2nd half of the 1 st century AD, GDKE Direktion Landesmuse um Mainz

Fragment of a relief showing Roman military standards. Marble, 2nd century AD, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

Funerary stele of Niger, son of Aeto. A member of the Germanic Nemetes tribe, he served in the Roman cavalry for 25 years, in the squadron of Pomponianus. He died at the age of 50 in Bonn. The Roman army was an important instrument of integration between local inhabitants and Romans. It guaranteed the possibility of social advancement and transmitted Roman values. Limestone, 1 st half of the 1 st century AD, LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn

1 Antefix of the 11th Legion showing a defeated Germanic warrior. From the legionary camp of Vindonissa Pottery, 2nd half of the 1 st century AD, Kantonsarchäologie Aargau

2 Roman dagger, found in the Rhine near Mainz. Iron with brass and enamel inlay, 2nd third of the 1 st century AD, GDKE Direktion Landesmuseum Mainz

3 Finger-ring with a cameo from Vindonissa. Did it belong to a Roman officer stationed there?

Gold and glass, late 1 st century BC – early 1 st century AD, Kantonsarchäologie Aargau

4 Helmet belonging to legionary soldier Sollionius Super of the 30 th Legion. His name betrays his Gaulish-Germanic ancestry. By serving in the Roman army, local men could earn themselves Roman citizenship while at the same time learning about Roman ideals. Iron, end of the 2nd – beginning of the 3 rd century AD, LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn

23

Numerous Roman emperors had personal memories of the Rhine.

1 Portrait of Emperor Caligula, who reigned from AD 37 to 41. As a small child, he spent a few years on the Rhine frontier with his father, the famous general Germanicus. In AD 39/40, as emperor, he led campaigns against the Germanic tribes on the right bank of the Rhine.

Bronze, AD 37-41, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

2 Equestrian statue of an emperor, probably Trajan, who reigned from AD 98 to 117. Just before ascending the throne, he was provincial governor in Mainz.

Lead, early 2nd century AD, on loan

3 The emperor addresses his troops. This could be Emperor Galba, who reigned briefly in AD 69. From AD 39 to 43 he had commanded the army in Upper Germania.

Bronze, c. AD 69, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

Relief showing a pile of weapons.

Marble, c. AD 100, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

Statuette of Victoria, the Roman goddess of victory, from the Roman colony of Augusta Raurica. Colonies were mostly settled by Roman army veterans, strengthening the Roman presence in the conquered territories.

Bronze, c. AD 200, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

The Roman legionary camp of Vindonissa in the 1 st century AD © ikonaut / Kantonsarchäologie Aargau

Portrait of Hadrian, who reigned from AD 117 to 138. In AD 97, he travelled from Rome to the Rhine to inform Trajan that he had been appointed as emperor. He went on to serve in Mainz as military tribune of the 22nd Legion.

Marble, AD 130/135, on loan Dice, gaming tokens and a spinning top from the Roman legionary camp of Vindonissa.

Bone / glass / wood, 1 st century AD, Kantonsarchäologie Aargau

More Roman settlements were founded on the Rhine. From around AD 85, the conquered territories became regular Roman provinces (Germania Inferior and Germania Superior). On the Upper Rhine, the Romans also controlled the right bank of the river, so that in this area the river itself was no longer the frontier.

The Rhine was the main transport axis for the new provinces. Agriculture and animal husbandry were improved and provided more food for the growing population.

The local elite adopted aspects of the Roman lifestyle as a way of demonstrating their status and continuing power, although it was now in the service of the Romans.

Grapes and Mediterranean fruit varieties were introduced to the Rhine region; improvements to infrastructure pressed ahead.

Statue of the wine god Bacchus from Trier. The Rhine River system was also used to transport stone from Mediterranean quarries, like the marble used for this statue and for decorating grand public buildings in the Roman style.

Marble, mid-2nd century AD, Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier –Generaldirektion Kulturelles Erbe Rheinland-Pfalz

Flat-bottomed Rhine barge, scale model 1:22.5. The original was discovered in 1997 in Vleuten-De Meern (NL). The oak timber used to build it was felled in AD 148 (+/- 6 years). The barge remained in use for many years until it met with an accident around AD 190/200, probably during a docking manoeuvre.

Wood, loaned by D. Usher

Roman villa

The Roman country estate at Marnheim (Rheinland-Pfalz)

© Roland Seidel (archaeoflug)

The growing demand for luxury goods led to still greater expansion of trade with the south. Roman officers and the well-to-do upper classes even enjoyed costly spices from India.

1 Peppercorn from Biesheim (Alsace). 1 st century AD, Musée Gallo-Romain de Biesheim

2 “Fresh pepper” goods label from Trier, found in the River Mosel. Lead, 2nd century AD, Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier – General direktion Kulturelles Erbe Rheinland-Pfalz

Vertebrae of an approximately 40 cm long Mediterranean mackerel from Biesheim (Alsace). Traces of cut-marks show that it was made into a steak.

1 st 2nd centuries AD, Musée Gallo-Romain de Biesheim

Relief of a river god. The fact that it was found in Bonn and the presence of the two horns (probably a reference to the two main branches of the Rhine delta) suggest that it is a personification of the River Rhine.

Limestone, 2nd century AD, LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn

Portrait of a young man from Prilly (VD).

The portrait could be that of a Helvetian nobleman who chose to be portrayed in the Roman medium of the bronze statue. The work would thus refer both to his local origins and to his position in Roman society.

Bronze, second half of the 1 st century AD, Bernisches Historisches Museum

The Romans cultivated new fruit varieties in the Rhine region, including apples, pears, cherries, and grapes. In Kaiseraugst, in a latrine shaft filled with sediment, mineralised botanical remains were discovered in an excellent state of preservation.

1 Apple seeds from Kaiseraugst.

Late 1 st – early 2nd century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

2 Grape pips from Kaiseraugst.

Late 1 st – early 2nd century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

3 Coriander seeds from Kaiseraugst.

Late 1 st – early 2nd century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

4 Fig seeds from Kaiseraugst. It is not clear whether figs were actually grown here or whether dried figs were imported from the south.

Late 1 st – early 2nd century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

Many natural products still had to be imported from the south:

5

Charred pine-kernels from Vindonissa. They were burnt as part of a religious ritual.

2nd century AD, Kantonsarchäologie Aargau

6 Charred pomegranate seeds from Vindonissa. They come from a grave and had a symbolic significance in the burial ritual. Early 1 st century AD, Kantonsarchäologie Aargau

Some of the eating habits of the Roman troops were different from those of the native population. The soldiers in Kaiseraugst, for example, ate mostly goat and chicken, suggesting they may have come from Spain or southern France.

7 Goat bones with knife marks from the military camp at Kaiseraugst. Early 1 st century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

8 Chicken bones from the military camp at Kaiseraugst. Early 1 st century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

9 Finial in the shape of a mule. The Romans also introduced new animal species to the Rhine region, including donkeys and mules. Bronze, 1 st century AD, Stiftung “In Memoriam Adolf und Margreth Im Hof-Schoch”

Before new Roman towns could be built on the Rhine, the infrastructure had to be improved. The new settlements speeded up interactions between indigenous and Roman culture.

10 Wax tablet with the official insignia of the Roman colony Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (Cologne). From Vindonissa. Wood, 2nd half of the 1 st century AD, Kantonsarchäologie Aargau

11 Roman water faucet. Larger towns required a sophisticated water supply system and efficient sewers.

Bronze, 1 st century AD, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

12 Fragments of an amphora for fish sauce from southern Spain with a painted label, found in Augusta Raurica. Delivery for a slave of Emperor Caligula (AD 37-41): ---]HYMI . C(ai) . CAES(aris) [---. Found along with remains of luxurious Mediterranean cuisine. It is quite possible that a member of the familia Caesaris was in Augusta Raurica around AD 40; historical sources record a campaign by Caligula east of the Upper Rhine. Pottery, c. AD 40, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

Water fountain shaped like a dolphin from the Roman villa of Munzach near Liestal. Providing water was one of the most important logistical responsibilities of Roman architects in the newly conquered territories. A water supply was essential for a newly founded urban settlement.

Bronze, late 1 st – early 2nd century AD, Archäologie und Museum Baselland, Liestal Carrara marble fountain head from the Roman villa of Munzach near Liestal.

Marble, 2nd half of the 1 st century AD, Archäologie und Museum Basel land, Liestal

Statue of the wine god Bacchus from Avenches. Viticulture was also introduced to the Rhine region during Roman times, not only to satisfy demand from Roman soldiers, officials and veterans living in the region but also from the local population.

Bronze, c. AD 130/140, Site et musée romains d’Avenches

The economy on the Rhine boomed, thanks to increasing urbanisation and the fact that the whole Roman empire used a single currency.

The Romans introduced their own system of administration but to a large extent respected local social structures.

Roman soldiers from every province of the empire and new settlers moving to the colonies brought with them their own cultural experiences, which melded with local traditions that were still very much alive.

Towns developed on the Mediterranean pattern, with stone structures, public buildings, and an efficient water supply.

Roman plumb bob from Augusta Raurica. The Romans built the first stone structures on the Rhine, including monumental public buildings.

Bronze, 1 st 2nd century AD, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

Bust of the Roman goddess Minerva from Augusta Raurica.

Bronze, late 2nd – early 3 rd century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

Statue of Hercules from the Grienmatt sanctuary in Augusta Raurica. In this sacred precinct, local and Roman religious ideas were both represented.

Limestone, 2nd century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

1

Set of Roman coins of Emperor Trajan. The unified Roman currency was valid in every province of the empire, from Portugal to Syria and from the Rhine to Egypt.

Gold, silver and bronze, AD 98-117, Historisches Museum Basel

2 Inscription in honour of Lucius Octavius, probably a relative of Emperor Augustus, commemorating the re-founding of the colony in the late 1 st century BC.

Bronze, late 1 st century BC, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

3 Key to the Roman Schönbühl temple in Augst. Bronze and iron, 1 st half of the 1 st century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

4 Letter from the dedicatory inscription of the temple in the forum of Augusta Raurica. Here people worshipped the emperor and the goddess Roma, thus demonstrating their loyalty to the new political power.

Gilded bronze, 1 st century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

Appliqué decoration in the shape of a theatrical mask. In the Roman towns on the Rhine, public buildings in the Graeco-Roman tradition appeared – for example, theatres.

Bronze, 1 st-2nd century AD, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig Roman compass. It was used by workers like stone masons or architects for taking or transferring measurements.

Bronze, 1 st-3 rd century AD, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

The Roman colony of Augusta Raurica c. AD 230 © Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

Votive inscription to Mercurius Augustus from Augusta Raurica. The donor was of local descent: Lucius Giltius Cossus, son of Celtillus. He was a member of the town’s priestly college for the Imperial Cult – a prestigious position that was open to freed slaves, who were not permitted to hold political office in the town.

Limestone, AD 50-150, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

Gravestone showing a married couple. The man, wearing military costume, was an officer in the Roman Army. In AD 212, Emperor Caracalla decided to confer Roman citizenship on all free inhabitants of the Roman empire.

Sandstone, c. AD 210/220, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

1

Statuette of the local god Sucellus from Augusta Raurica. He is portrayed in the style of Roman gods. Bronze, 2nd century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

2 Sheaf of lightning bolts from Womrath (district of Simmern), which belonged to an over life-sized statue of Jupiter. Bronze, 1 st century AD, LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn

3 Statuette of the god Mercury. Caesar reported that Mercury was the most important god in Gaul. Bronze, 1 st-2nd century AD, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

4

Statuette of the god Attis from the Mosel. Even Eastern deities found their way into the Rhine region, brought by Roman soldiers. Bronze, 2nd century AD, Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier – General direktion Kulturelles Erbe Rheinland-Pfalz

Written culture also spread to the Rhine region with the Romans. Probably 10% to 20% of the population could read and write.

5 Inkwell from Augusta Raurica. Pottery, 2nd century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

During the Roman period, many artisanal products from the Rhine region were of remarkable quality.

6 Two finger-rings from Augusta Raurica. Gold, silver and glass paste, 2nd-3 rd century AD, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

7 Drinking vessel from Cologne. Glass, 4th century AD, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwi

Stylus from the Münsterhügel in Basel. Bone, 1 st century AD, Archäologische Bodenforschung Basel-Stadt

Altar with a votive inscription dedicated to the gods Jupiter and Mars. The name ‘Magianus’ also appears. This could either be the Celtic byname of Mars or the name of the altar’s local donor. Soapstone, 3 rd century AD, Römerstadt Augusta Raurica

Portrait of a Roman officer. The first evidence of Germanic incursions west of the Rhine dates from as early as AD 162. From then on, the situation became increasingly critical. In the Upper Rhine region, the frontier was withdrawn to the river around the middle of the 3rd century AD. Marble, c. AD 160, on loan

Portrait of Lucius Verus, Roman Emperor from AD 161 to 169. A serious epidemic spread through the globalised Roman world in AD 165 and raged for over 20 years. The Rhine region was also affected: the repercussions of the epidemic contributed to the general crisis of the 3rd century AD. Marble, AD 161-169, on loan

The exhibition was made possible by:

Media partners: