el cambio climático es una realidad. Año a año, instituciones internacionales logran acuerdos que buscan la carbono neutralidad, pero pese a grandes esfuerzos de los líderes mundiales, la meta de emisión de carbono a nivel global no ha sido cumplida. Sabemos que estamos en un momento crítico y que aún falta mucho por hacer para llegar a la huella de carbono 0.

Sin embargo, ¿esto justifica la acción de diversos activistas en contra de las obras que son clásicos de la historia del arte? La respuesta no deja de ser compleja, es la vida del mundo entero, versus la creación y la innovación de movimientos artísticos que nos recuerdan nuestros avances como civilización; pero, ¿qué sería de nosotros sin la memoria y la visualidad de lo que fuimos, de lo que somos?

Las obras de arte deben seguir en los museos. Retirarlas no logrará que los activistas dejen de lanzar frutas o pintura sobre ellas; sólo tendrá un efecto permanente en aquellos que viajan miles de kilómetros para verlas; y será perjudicial para los investigadores que ahora no podrán estudiarlas en exposición. Reforzar las medidas de seguridad, cumplir con más resguardos y dialogar con activistas para ver de qué forma los museos pueden ayudarlos a visibilizar las problemáticas, podrían ser soluciones atractivas para que dejen de vandalizar estos espacios.

Ahora, esta época del año no solamente se trata de los museos. El arte contemporáneo se abraza del mundo con la celebración de la Bienal de Venecia. Queremos destacar al pabellón chileno, el que a través de la obra de Valeria Monti Colque y la curaduría de Andrea Pacheco González, nos recuerdan la historia y vida en el exilio de aquellos chilenos que crecieron desarraigados de sus raíces, pero que lograron mantener costumbres e imaginarios latentes en sus memorias.

Por otro lado, la feria de arte Art Basel, se realizará nuevamente, convocando a cientos de agentes del arte que recorrerán las calles de la ciudad y las ferias satélites, para conocer, recomendar y visibilizar lo mejor del arte contemporáneo a nivel internacional.

Como revista, nuevamente estaremos presente en estos espacios, exhibiendo en nuestras redes sociales los imperdibles de estos grandes eventos; y promocionando la pronta apertura del Museo AAL.

climate change is a reality. Year after year, international institutions reach agreements aimed at carbon neutrality, but despite the great efforts of world leaders, the global carbon emission goal has not been met. We know this is a critical time and there is plenty left to do to reach a carbon zero footprint.

However, does this justify the actions of activists against some of the classic works in art history? The answer is complex. It is about the life of the whole world, versus the creation and innovation in artistic movements that remind us of our progress as a civilization. But what would become of us without memory, without displays of what we were and what we are?

Artwork must remain in museums. Removing them will not stop activists from throwing fruit or paint on them; this will only have a lasting effect on those who travel thousands of miles to see them or on the researchers who won’t be able to study them in the exhibits. Reinforcing security measures, setting greater safeguards and talking to activists to find ways museums can help further their cause are some appalling solutions to try and deter vandalism in these spaces.

Now, this time of year is not all about museums. The world embraces contemporary art with the celebration of the Venice Biennale. We would like to uplift the Chilean pavilion where, through the work of Valeria Monti Colque and the curatorship by Andrea Pacheco González, we are reminded of the life stories of exiled Chileans who were torn from their roots but managed to keep traditions and imageries alive in their memories.

In addition, the Art Basel fair will be held once again, summoning hundreds of art agents who will walk the streets of the city and satellite fairs to learn about, recommend and showcase the best of contemporary art at the international level.

Arte Al Límite’s magazine will be there one more, posting some of the must-sees of these great events on social media, and promoting the upcoming opening of our museum.

18th — 22nd September 2024

La Habana–Madrid

Proyectos Monclova

Mexico City

193 Gallery

Paris–Venice

Galería Elvira Moreno

Bogota Continua

San Gimignano, Beijing, Habana, Rome, São Paulo, Paris

Mayoral

Barcelona–Paris

Wizard Gallery

Milano–London

Romero Paprocki Paris

Albarran Bourdais Madrid

Christian Berst Art Brut Paris

DIRECTORES

Ana María Matthei

Ricardo Duch Marquez

DIRECTOR COMERCIAL

Cristóbal Duch Matthei

DIRECTORA DE ARTE Y EDITORIAL LIBROS

Catalina Papic

PROYECTOS CULTURALES

Camila Duch Matthei

EDITORA

Elisa Massardo

DISEÑO GRÁFICO

María Nestler

CORRECCIÓN DE TEXTOS

Javiera Fernández

ASESORES

Benjamín Duch Matthei

Ricardo Duch Matthei

Milagros Duch Matthei

Felipe Duch Matthei

REPRESENTANTES INTERNACIONALES

Julio Sapollnik (Argentina)

REPRESENTANTE LEGAL

Orlando Calderón

TRADUCCIÓN

Adriana Cruz

SUSCRIPCIONES

info@arteallimite.com

IMPRESIÓN

A Impresores

DIRECCIONES

Chile / Francisco Noguera 217 oficina 30, Providencia, Santiago de Chile. www.arteallimite.com

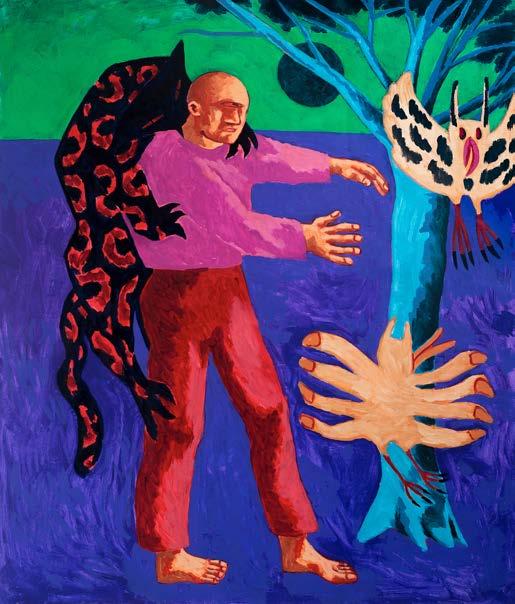

PORTADA

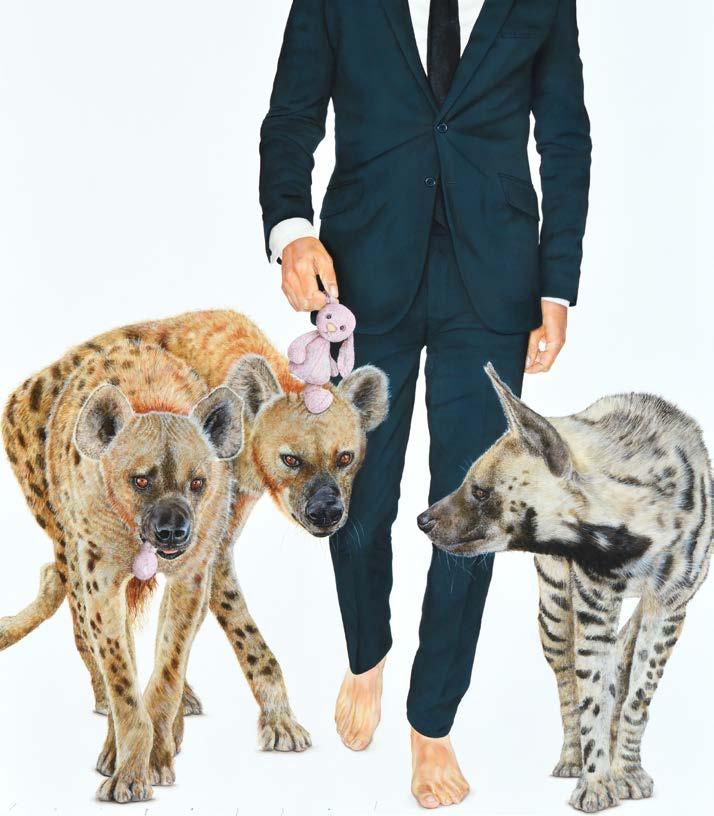

Ariel Vargassal, Feeding the pride, 2021, acrílico sobre tela, 152 x 122 cm.

VENTA PUBLICIDAD

+56 9 99911933. info@arteallimite.com marketing@arteallimite.com

Derechos reservados

Publicaciones Arte Al Límite Ltda.

Por Ivón Figueroa Taucán. Socióloga (Chile)

Imágenes cortesía del artista.

México

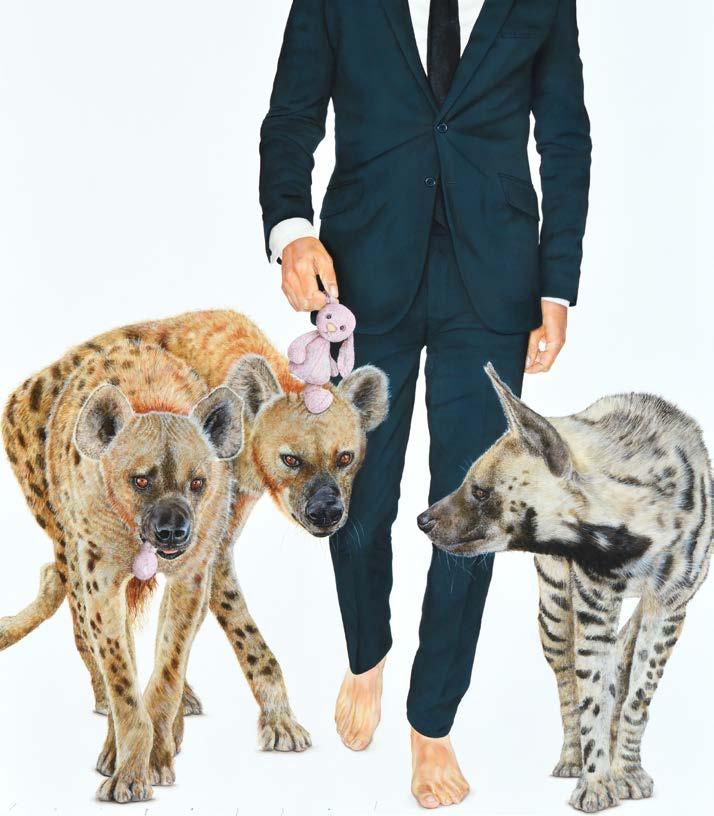

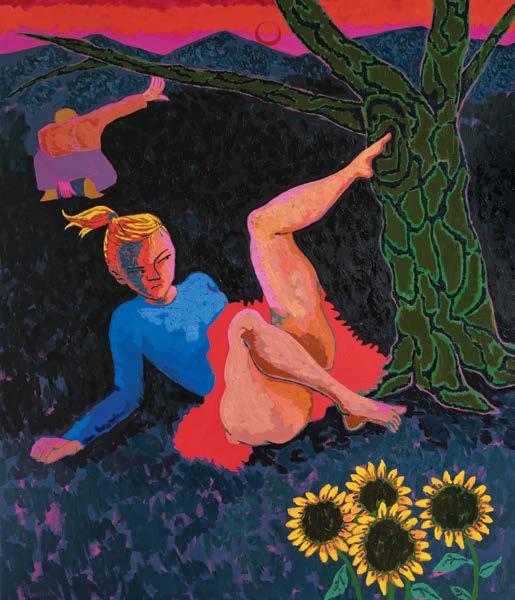

Dive to the win , 2024, acrílico sobre tela, 91 x 122 cm.

Dive to the win , 2024, acrílico sobre tela, 91 x 122 cm.

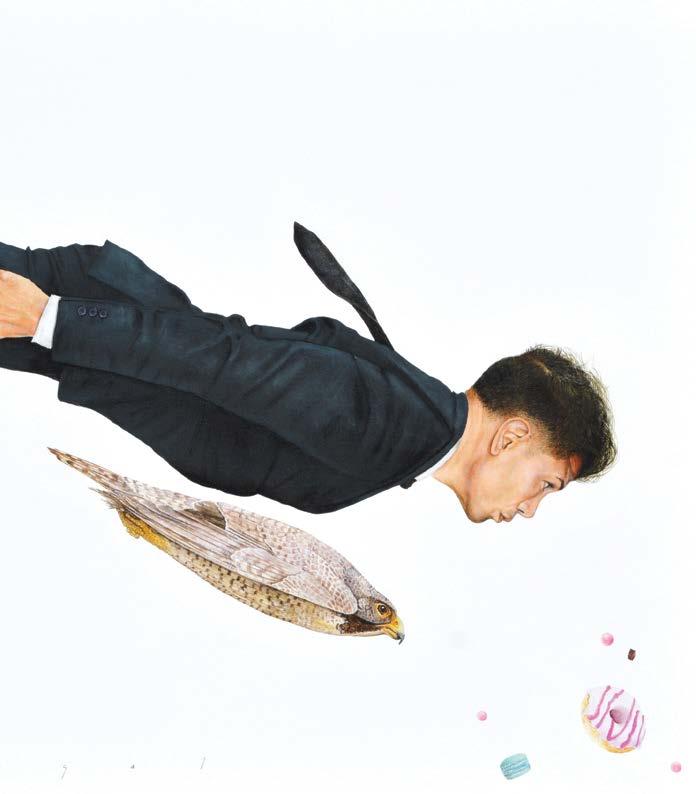

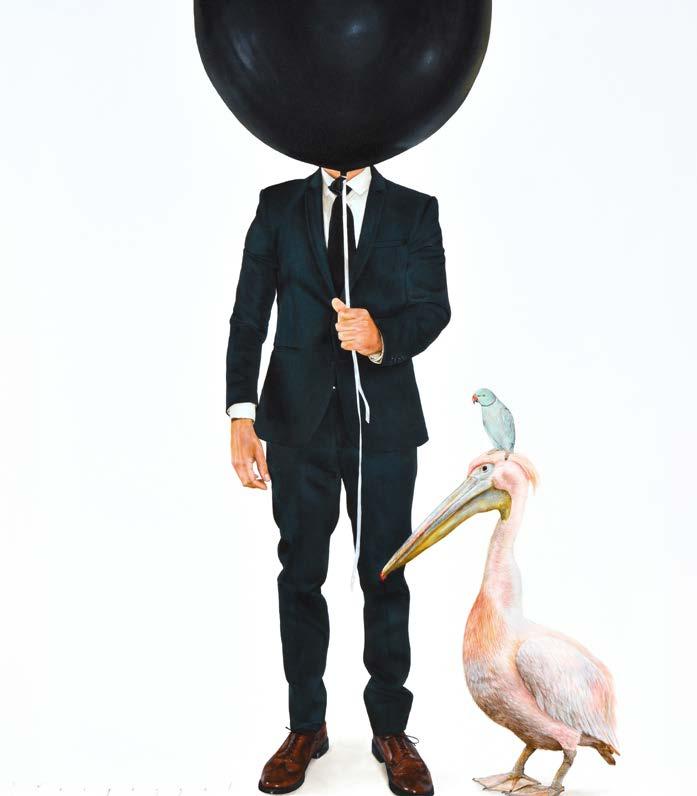

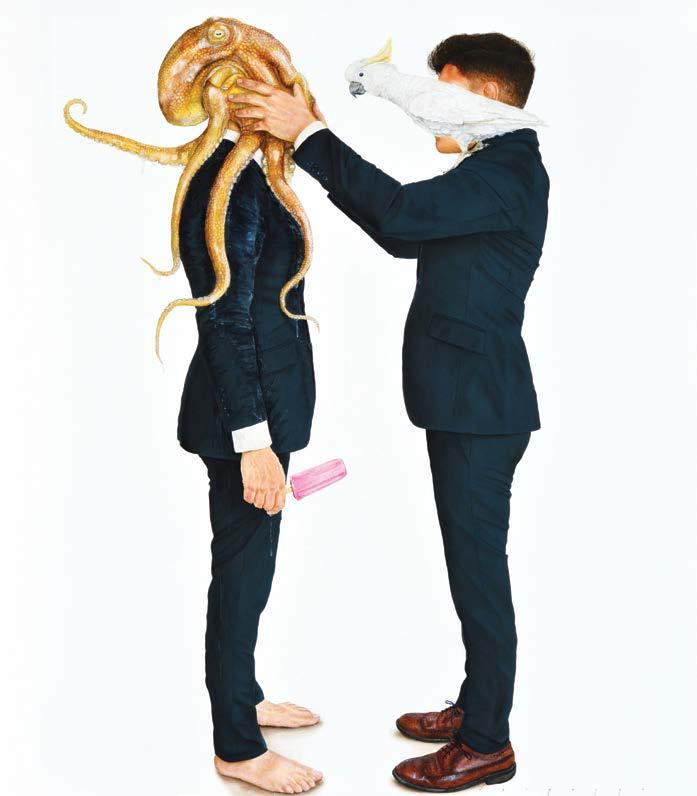

u n hombre vestido en traje de oficina vuela con aves de rapiña, pasea tranquilamente junto a una manada de hienas, salta con lémures, carga una oveja negra, tiene una cabeza de pulpo y festeja un cumpleaños con un oso pardo. Está descalzo mientras habita un espacio blanco y vacío, como una galería de artes visuales. Entre los cuerpos se vislumbran paletas de helado, chupetes, gorros de fiesta infantil, donuts y galletas de colores. Y, a pesar de la particularidad de cada elemento, las imágenes son minimalistas, elegantes, sencillas y juguetonas. Estamos ante In the Mirror, la serie de pinturas más recientes de Ariel Vargassal.

Durante sus estudios en la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, conoció referentes tradicionales de la pintura y el muralismo local como Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo y Francisco Toledo, cuyas visualidades se convirtieron en una zona de confort para él. Estas influencias fueron tan grandes e innatas, que en la escuela pintaba muy parecido a estos artistas, sin embargo, en 2011 decidió migrar a Los Ángeles por la necesidad de experimentar con la pintura y conocer nuevas formas de expresarse a través de ella, al margen de la estética que caracteriza internacionalmente a las artes visuales mexicanas.

Para Ariel es muy importante abordar fenómenos sociales complejos, como el racismo, las inequidades de género, la depresión y el suicidio, pero con una impronta que no sea oscura ni remita inmediatamente al campo temático en cuestión. Utiliza el sentido del humor junto a imágenes ligeras y disímiles a la situación que quiere proyectar, para generar preguntas en los espectadores. Así, se propuso consolidar un estilo propio: “llamo a mi estilo esencialismo, no en base al concepto filosófico griego de la esencia del ser y del alma, sino como un estudio de lo esencial y lo necesario para una narrativa. No me gusta el exceso en la pintura, quiero quitarle ese concepto a la composición y dejar solamente una línea muy clara.

aman dressed in a suit flies alongside birds of prey, leisurely roams around with a pack of hyenas, jumps with lemurs, carries a black sheep, has an octopus head, and celebrates a birthday with a grizzly bear. He is barefoot while inhabiting the blank and empty space, similar to an art gallery. Among the bodies we see colorful popsicles, lollipops, children’s party hats, donuts and cookies. Despite the peculiarity of each element, images are minimalist, elegant, simple and playful. This is In the Mirror, Ariel Vargassal’s latest series of paintings.

Throughout his studies at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, he learned about traditional painting and mural art referents such as Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo and Francisco Toledo, whose style became his comfort zone. These influences were so great and innate, he painted similarly to these artists. However, in 2011, he decided to migrate to Los Angeles seeking new ways of experimenting with painting and expressing himself through it, outside the aesthetics that internationally distinguish Mexican visual arts.

For Ariel, it is very important to address complex social phenomena like racism, gender inequalities, depression and suicide, but in a way that is not dark or immediately referring to the topic at hand. He uses humor and light-hearted images that contrast the situations he wants to convey in order to make viewers wonder. Thus, he set out to consolidate his own style: “I call my style ‘essentialism’, not based on the Greek philosophical concept of the essence of the self and the soul, but rather as a study of the essential and necessary for a narrative. I don’t like excess in painting, so I strip compositions from it and just leave clean-cut lines. I cannot call myself a minimalist because

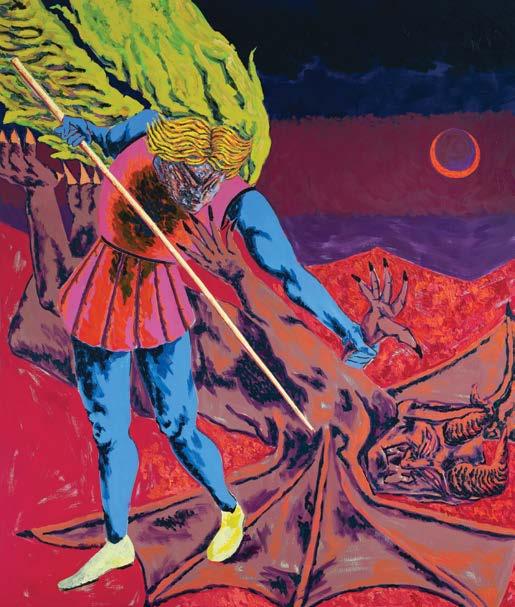

Instructions to flight, 2018, acrílico sobre tela, 152 x 122 cm.

Instructions to flight, 2018, acrílico sobre tela, 152 x 122 cm.

No me puedo llamar minimalista, porque mi obra es muy detallada y realista, tiene mucho detalle. Le llamo esencialismo, porque solo pinto los elementos que son necesarios para dar una narrativa y dejo fuera de la composición los que no son necesarios”.

Hace tres años, inmediatamente después de la pandemia, inició In the Mirror como un ejercicio de introspección, dejando de lado los conceptos universales que trabajó en series anteriores y poniéndose a sí mismo en el centro de una práctica cotidiana para mirarse al espejo. Esta serie fue impulsada por la necesidad de sanar: “fui diagnosticado con leucemia y pasé un proceso fuerte de quimioterapia. Al principio no sabía lo que tenía ni por qué estaba enfermo. Entonces tuve una necesidad de entenderme y de ver al mundo desde diferentes perspectivas, de encontrarme con otro yo. Por eso la llamé In the Mirror, porque empecé a descubrir que dentro de mí había otro punto de vista que encontré por un choque de salud”.

En estas obras hay tres elementos transversales: el autorretrato, los animales y los objetos de infancia. Ariel otorga a los animales el rol de las emociones humanas, antropomorfizándolos y caracterizándolos como seres que existen dentro del yo. Son una voz interna que sale a decir algo, o bien el desarrollo de un ego exterior que se convierte en conciencia. Por otra parte, los objetos de infancia, como los juguetes, las golosinas y los chupetes, son elementos de nostalgia y memoria, que lamentablemente el mundo de los adultos ha restringido a espacios y momentos muy específicos de la vida. Entonces, el ejercicio que él propone es imaginar que estos objetos trasciendan límites, posibilitando experiencias de inocencia y comodidad: “los objetos y los animales se convierten en parte de un diálogo y en parte de una metaforización de lo que ocurre dentro de mi voz. Se convierten en palabras visuales”.

my work is highly thorough and realist; it is very detailed. I call it essentialism because I just paint the elements necessary to craft the narrative, and I leave anything unnecessary away from the composition.”

Three years ago, immediately after the pandemic, he started In the Mirror as an introspective exercise, setting aside the universal concepts that he has addressed in prior artwork and positioning himself at the center of a daily mirror-reflection sort of practice. The series was prompted by the need to heal: “I was diagnosed with leukemia and I went through intense chemotherapy. In the beginning I didn’t know what I had or why I was sick. Then, I felt the need to understand myself and see the world differently, to find another me. That is why I titled it In the Mirror, as I found that within me there was another point of view that I discovered from a health scare.”

In these pieces, there are three cross-cutting elements: self-portraits, animals and childhood objects. Ariel assigns the animals the role of human emotions, making them anthropomorphic and beings that exist within the self . They represent the inner voice that speak to us or the development of the external ego that becomes the conscious. In turn, childhood objects such as toys, candy and lollipops are nostalgic elements that adulthood has unfortunately restricted to very limited spaces and moments in life. Thus, the exercise he proposes is to imagine the objects transcending the barriers, allowing for experiences of comfort and innocence: “The objects and animals become part dialog and part metaphor of what happens within my voice. They become visual words.”

Curiosity of my other self, 2021, acrílico sobre tela, 152 x 122 cm.

Curiosity of my other self, 2021, acrílico sobre tela, 152 x 122 cm.

Sugar heist, 2022, acrílico sobre tela, 152 x 122 cm.

Sugar heist, 2022, acrílico sobre tela, 152 x 122 cm.

Su trabajo ha sido muy bien recibido en el extranjero, exhibiendo en ciudades de Estados Unidos y Europa. Le interesa participar de espacios donde las personas puedan acceder a sus obras y le generen ingresos para seguir pintando, sin importar si son exposiciones temporales o colecciones, tanto públicas como privadas. A pesar de que considera al arte latinoamericano como una práctica muy diversa y de la que se siente parte, afirma que en Estados Unidos se ha construido un estereotipo de cómo debería ser. Ha recibido comentarios que lo acusan de no pintar como mexicano, llevándolo a cuestionarse cómo y por qué debería pintar como latinoamericano: “si alguien de Latinoamérica migró a los Estados Unidos, es probable que tenga la necesidad de reconectarse con sus raíces, convirtiendo al arte latinoamericano en un reflejo de esa necesidad cultural. Parece ser que ese arte lleva al público estadounidense a pensar que las obras latinoamericanas deben estar muy relacionadas y atadas a ciertas influencias culturales. Nos estigmatizan, imponiendo a qué se tienen que parecer nuestras creaciones y qué estructuras deben tener. Pero cuando te sales de esa caja y experimentas con otras cosas, les rompes el esquema”.

Ahora que está fuera de México, el interés por su obra se ha incrementado. No obstante, se ha encontrado con que hay coleccionistas de América Latina que perpetúan prejuicios tradicionalistas en torno al arte creado por artistas del Cono Sur, especialmente en la pintura: “me ha tomado años desarrollar mi estilo y tener la fuerza de decir las cosas como las quiero decir, visualmente. No quiero comprometer lo que hago con las expectativas de las instituciones del arte. Si en este momento empiezo a hacer obra para satisfacer esas necesidades, va a perder su identidad”. Ariel advierte que hay agentes del medio artístico mexicano que no entienden por qué está pintando de esa forma. Por ello, ha decidido mantenerse al margen de esas expectativas del mercado, buscando nuevos horizontes para el arte latinoamericano.

His work has been very well received abroad, managing to hold exhibits in the US and Europe. He is interested in participating in spaces where people can access his work and to make a living so he can keep painting, whether that be in private or public temporary exhibitions and collections. Despite regarding Latin American art as a very diverse practice he feels part of, he states that in the US he developed preconceptions on what that meant. He has been accusingly told he does not paint as a Mexican , making him question how and why he should paint as a Latin American : “If a Latin American migrates to the US, it is very likely that they feel the need to reconnect with their roots, making Latin American art a reflection of that cultural need. It seems that the American public believes Latin American artwork must be very tied to certain cultural influences. We are stigmatized, imposed what our creations must look like and what structures they must have. But when you step out of that box and experiment, you break their mold.”

Now that he is out of Mexico, interest for his work has increased. However, he has found that many Latin American collectors still perpetuate traditional prejudice surrounding art created in the Southern Cone, particularly for painting: “It has taken me years to develop my style and having the strength to say things my way visually. I don’t want to compromise what I do due to the expectations of art institutions. If I start conforming to that now to create artwork that meet those needs, it will lose its identity.” He has noticed Mexican art agents do not understand why he is painting the way he does. For this reason, he has decided to steer clear of such market expectations, seeking new horizons for Latin American art.

Between Lamb and Wolf , 2018, acrílico sobre tela, 152 x 122 cm.

Between Lamb and Wolf , 2018, acrílico sobre tela, 152 x 122 cm.

Imágenes cortesía del artista. Chile

Por Lucía Rey. Académica e investigadora independiente (Chile)

Representado por Spacio Nomade.

De la serie

álbum Negro de humo , 2015, humo sobre papel, 35 × 45 cm.

De la serie

álbum Negro de humo , 2015, humo sobre papel, 35 × 45 cm.

Entre el velo de la memoria y la negrura de lo no revelable

Between the veil of memory and the blackness of the undisclosable

el humo como índice habla de la presencia del fuego y en sus múltiples sentidos nos transporta al invierno, a escenas láricas, al calor que reúne circularmente, a la acción ritual de sahumar, pero también nos puede hablar de situaciones trágicas, traumáticas y memorables, como momentos decisivos en la vida. A través de la diversidad de estas coordenadas desplegadas en el tiempo, Danilo ingresa en la poética del humo, cuya marca en los espacios es tanto presencia como ausencia. Desarrolla un modo de crear imágenes a través del humo en la búsqueda de rostros y escenas, que parecieran huir de la memoria. Así, elabora una poética simbólica del humo, que apunta con sentido histórico y político al pueblo mapuche. El uso del humo contrasta con las técnicas contemporáneas del arte que apuntan muy frecuentemente, mediante su intensa precisión, a la literalización de la imagen. Valor estético y simbólico no menor en una cultura que pareciera querer olvidar el oscuro mundo análogo, para rendirse ante la automatización luminosa de la existencia. Este elemento será coherente con el contenido buscado y elaborado en su obra, pues habla de un cosmos, en donde la vida se presenta sin gran mediación tecnológica, sino de forma directa y misteriosa.

Trabajando desde mucho antes en desarrollar esta técnica, desde el 2008, Danilo presenta en sus obras el humo relacionado con el mundo mapuche y su cosmovisión, en donde está viva la práctica de rituales periódicos en los que se usa el fuego. Así, la presencia silenciosa del humo existe como indicador de actividad social, ya sea espiritual-comunitario, como también, en lo más íntimo y casero, pues la ruka (hogar) cuenta con la presencia de un kütral (fogón central) al interior. El humo, con el mülpun (hollín), deja su marca gráfica en las paredes, en los objetos y como un elemento etéreo, liviano, impreciso, también deja una marca olfativa. Como se sabe, las marcas de este tipo han sido objeto de discriminación social hacia el pueblo mapuche en las zonas urbanas de este país, relacionándose el olor a humo con el uso del mapudungun y de sus costumbres, ya que debido a las complejas condiciones de vida se han producido varias migraciones a la ciudad.

s moke adverts the presence of fire and, in its plurality of meanings, it transports us to winter, homey scenes, heat gathering people in circles, and incense burning rites. However, it also refers to tragic, traumatic and memorable situations, such as decisive moments in life. Through the diversity of this code that has developed over time, Danilo enters into the poetry of smoke, which leaves a trace in spaces from both its presence and absence. He has developed an image-creating method through smoke, seeking out faces and scenes that seem to elude memory. Thus, he has crafted a symbolic poetry around smoke that references the history and politics of the Mapuche people. The use of smoke contrasts with contemporary art techniques that tend to make images excessively literal due to their high-level precision. The aesthetic and symbolic value of his artwork is of note in our culture, which seemingly wants to forget the darkness of the analog world and submit to the brightness of automating existence. This theme is consistent with the content he sets out to and manages to convey in his artwork, as it addresses a universe where life is portrayed with little technological intervention in a direct and mysterious manner.

Having worked on the development of this technique for a long time –since 2008–, Danilo presents smoke in connection to the Mapuche people and their world view, which has kept alive the tradition of regular fire-related rituals. Thus, the silent presence of smoke serves as a signal of social activities, whether these be spiritual-communal or intimate and homey, since ruka (home) has a kütral (central fire pit) within. Smoke, along with mülpun (soot), leaves visible marks on walls and objects. As an ethereal, light and imprecise element, it also leaves a scent behind. Marks of this type, as it is well-known, have been the object of social discrimination against the Mapuche people in the urban areas of this country, as the smell of smoke is related to the use of Mapudungun and Mapuche customs, and complex living conditions have caused them to migrate to the city.

De la serie

álbum de Elena Mercado

Marileo , 2015, humo sobre papel, 70 x 100 cm.

De la serie

álbum de Elena Mercado

Marileo , 2015, humo sobre papel, 70 x 100 cm.

Álbum familiar Ramos Huina, 2017, humo sobre papel, 100 × 70 cm.

Álbum familiar Ramos Huina, 2017, humo sobre papel, 100 × 70 cm.

Las marcas de humo, entonces, nos hablarán tanto de tragedias, como de la quema abrupta de libros, archivos, fotografías, en la violenta invisibilización, aculturación, desaparición y borradura de memorias y conocimientos. De manera que las marcas de humo se presentan como veladura de la realidad y, en este sentido además, el autor las relaciona con los detenidos desaparecidos durante la dictadura militar en Chile; como también, al sentido de lo íntimo y del calor familiar, en el ámbito de los espacios donde se traspasan oralmente sabidurías y conocimientos no escritos.

En lo técnico, se destaca una etapa transversal en la creación de las obras. De forma análoga aplica herramientas del grabado (esténcil) que, según indica: “consiste en la impregnación de hollín sobre el papel usando plantillas caladas en el sector en que las fotografías tienen sus sombras”, ampliando las nociones tanto del dibujo y del grabado tradicional, en una articulación estética que las profundiza y poetiza. Las imágenes fotográficas aportan elementos formales, figurativos, tramas compositivas que parecen abstraerse entre las imprecisas marcas del humo. En este sentido el autor se configura, perseverantemente, como un investigador de la técnica y de la poética material, en la creación artística sensible a los contenidos mnémicos y simbólicos del dolor del otro y de los propios. Danilo trabaja transdisciplinariamente, en el sentido de que sus búsquedas y procedimientos técnicos que atraviesan diversas dimensiones de la realidad y disciplinas del saber, razón que le lleva a convocar diferentes áreas (historia, antropología, estética) para exponer su trabajo.

Aquí contamos con una selección de series de obras pertenecientes a tres contundentes proyectos: Negro de Humo, Ñamen. Desaparecer, venir en olvido y Técnica Seca (2021). Considerando que el artista llevaba a lo menos 15 años en la experimentación y elaboración de una técnica antes de hacerlas decantar en estas obras, las dos primeras series mencionadas están unidas por el contenido enfocado en el trauma que ha vivido el pueblo mapuche, en tanto imágenes que se van diluyendo en el mar de la memoria y hollín, de un grito que pareciera no tener eco en Chile.

The markings of smoke also speak on tragedy, such as abruptly burning books, archives, and photographs, in a violent obliteration, acculturation, forced disappearance and erasure of memories and wisdom. Therefore, smoke represents glazes of reality, which the artist threads to the people that were detained or who disappeared during the military dictatorship of Chile, as well as intimacy and family warmth in spaces where non-written knowledge and wisdom are transmitted orally.

In terms of technique, there is a stage that is common to the creation of all his artwork. He employs analog etching stencil tools that, as he states: “Consist of coating paper with soot using perforated stencils in the shadows of the photographs.” This way, he builds on the notions of drawing and traditional etching in an aesthetic construction that deepens and poeticizes them. Photographs contribute formal and figurative elements, compositional weaves that seem to abstract among the imprecise curls of smoke. In this sense, the author perseveringly configures himself as a researcher of technique and material poetry in artistic creation, sensitive to memories and symbolic contents of the pain of others, as well as his own. Danilo works transdisciplinary, in the sense that his research and technical procedures involve different dimensions of reality and fields of knowledge, which is why he calls on different areas (history, anthropology, aesthetics) to explore his work.

The selection of art series here belongs to three powerful projects: Negro de Humo, Ñamen. Desaparecer, venir en olvido and Técnica Seca (2021). The artist has been experimenting and perfecting a technique for at least 15 years before channeling them into these pieces. The first two are linked by themes of the trauma experienced by the Mapuche people in images that dilute in the sea of memories and soot, shouting for something that does not seem to echo in Chile.

De la serie

álbum de Elena Mercado Marileo , 2015, humo sobre papel, 70 x 100 cm.

De la serie

álbum de Elena Mercado Marileo , 2015, humo sobre papel, 70 x 100 cm.

Para el proyecto Ñamen, las imágenes fotográficas son reproducciones de otras originales que muestran personas desaparecidas, otorgadas por sus familiares, a través de un largo proceso de acercamiento e indagación, donde tuvo acceso a relatos asociados a la violencia contra el pueblo mapuche, días después del golpe de Estado en Chile. Esta obra cuenta con la elaboración poética de acciones, videos-performances e imágenes trabajadas a partir de las fotografías reproducidas. Dentro de Ñamen, homónimas a la serie, hay un conjunto de obras organizadas grupalmente mediante amarres de hilos, en donde, manteniendo el tamaño original de las fotografías, el artista realiza una analogía estética del álbum familiar ahumado, dando cuerpo artístico a las narrativas íntimas pudiendo, prácticamente, visualizar el momento en que las fotografías fueron recogidas tras el desastre y atadas con la fuerza simbólica de un hilo rojo.

En la tercera serie, Técnica Seca, el autor se inspira en la experiencia práctica y sensible de su obra anterior, para ahora enfocar su propia vida en una investigación estética auto-etnográfica. En estas obras las imágenes elaboradas son expuestas tras estructuras metálicas similares al diseño de las rejas de ventanas de su infancia, transportando al espectador hacia algún hogar de antaño, tal vez hacia una propia ventana interior.

Es llamativa la persistente trama y retícula de las imágenes que consta de finísimas líneas horizontales, que nos hacen proyectar un horizonte imaginario; y otras verticales, más anchas, que como marcas dan cuenta del gesto mnémico del doblado del papel para guardarlas. Todo esto dentro del marco expandido que las pone a levitar dentro de un marco ausente. Estas particularidades estéticas que tiene la técnica desarrollada por el autor nos llevan a un estado de ensueño, como si la imagen no estuviera impresa, sino que fueran los mismos personajes etéreos mirándonos hacia dentro, en algún recuerdo.

For Ñamen , the photographs reproduce pictures of some of the people who disappeared, which were donated by their families. Through a long process of outreach and research, he accessed stories of violence against the Mapuche people, days after the Chilean coup d’état. The work creates poetry through action, video-performances and images of photographic reproductions. Within the series Ñamen, there is a set of homonymous pieces where the artist arranges original-size photographic reproductions in groups and bounds them together with thread to create a smoked family album. In doing so, he builds intimate narratives, allowing us to virtually visualize the moment the original photographs were rescued after the disaster and bound symbolically with red thread.

In the third series, Técnica Seca , the artist draws inspiration from the practical and emotional lessons learned in his prior work to now turn his own life into an auto-ethnographic aesthetic exploration. These images are shown from behind metal structures similar to the window grille in his childhood, transporting viewers to homes of yesteryear, or perhaps windows to our inner selves.

This eye-catching and recurrent grid on the images is made up of very fine horizontal lines that refer us to an imaginary horizon, and thicker vertical lines reminiscent of the markings we make upon folding a piece of paper to store it. All this happens within an expanded frame that makes the images seem to levitate on another missing frame. These aesthetic features of the technique the author has developed take us to a dream-like state, as if images were not printed, but as though the ethereal beings themselves were looking inside us, reminiscing.

De la serie

álbum de Joel Huaiquiñir, 2017, humo sobre papel, 100 x 70 cm.

De la serie

álbum de Joel Huaiquiñir, 2017, humo sobre papel, 100 x 70 cm.

Por Ivón Figueroa Taucán. Socióloga (Chile) Imágenes de Rafael Guillén, cedidas por el artista.

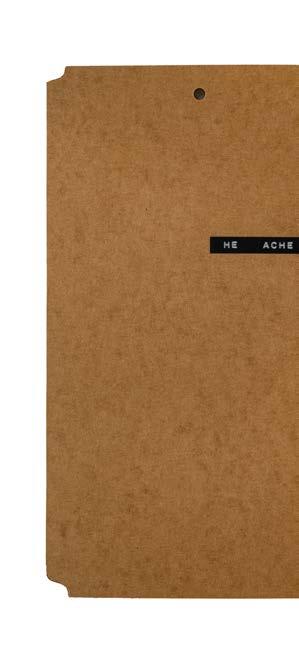

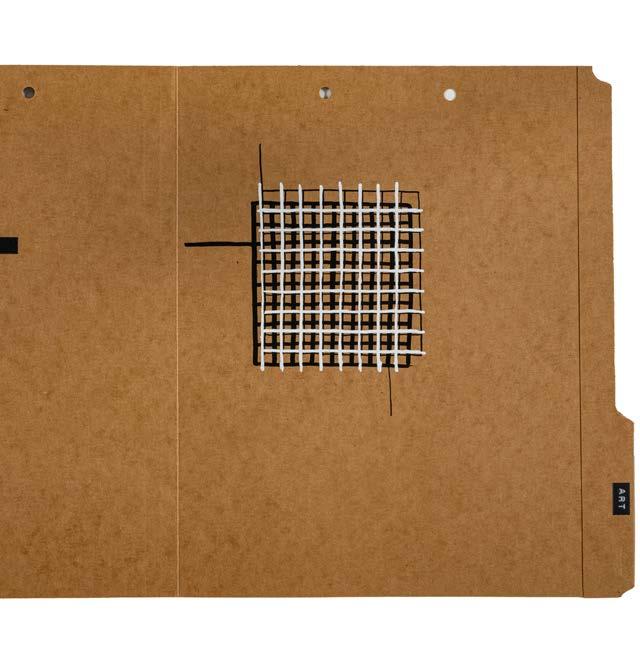

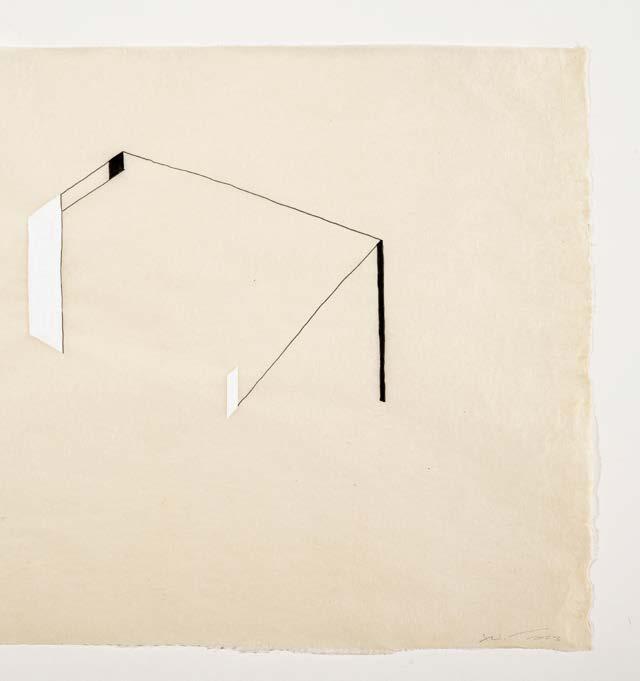

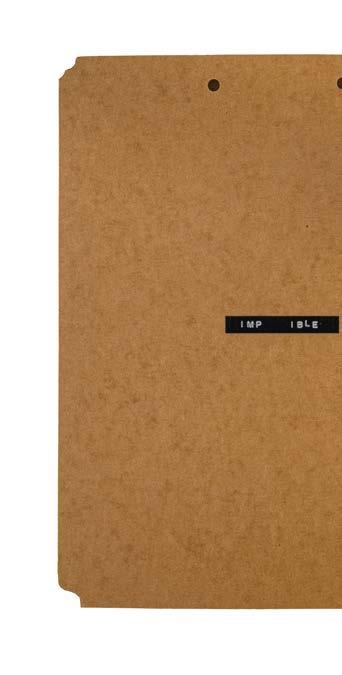

De la serie Men-Art-Work, “He ache”, 2014, tinta negra, tippex líquido, dymo negro en carpeta, 29.21 x 49.53 cm.

De la serie Men-Art-Work, “He ache”, 2014, tinta negra, tippex líquido, dymo negro en carpeta, 29.21 x 49.53 cm.

en medio de su jornada laboral, Andrés Michelena se da un espacio para conversar extendidamente sobre su obra. Se encuentra en la sala de exhibición de la Juan Carlos Maldonado Collection, localizada en el Design District de Miami, una colección de arte contemporáneo enfocada en la abstracción geométrica, de la cual es director.

Nació en Caracas en 1963, en el seno de una familia muy relacionada con el arte en sus diferentes vertientes. Realizó estudios de arquitectura en la Universidad Central de Venezuela, los cuales abandonó al cuarto año para dedicarse por completo al arte. El año 2000 decidió migrar a los Estados Unidos, donde desplazó su producción artística desde la pintura hacia el video y la videoinstalación.

Ahí empezó a tener contacto con el budismo Zen. Si bien no es budista, se considera practicante del Zazen —la meditación Zen—, una disciplina que transformó sustancialmente sus creaciones, poniendo la idea del vacío como eje de acción. Andrés ha construido modos sutiles, frágiles y delicados para -al vacío- presente en sus obras, ante la imposibilidad de trabajar directamente con él: “compongo imágenes que tienen un cierto grado de inconcluso, de algo que no está totalmente resuelto. Y son, de alguna manera, pistas de estrategias que he implementado en mi trabajo para sugerir ese vacío”.

in the middle of his work day, Andrés Michelena gifts us a moment to talk about his artwork. He is in the exhibition hall of the geometric-abstraction focused contemporary art collection he directs in the Juan Carlos Maldonado Collection, located in the Design District, Miami.

He was born in Caracas in 1963, in the bosom of a family closely related to the different branches of art. The pursued architecture studies at Universidad Central de Venezuela, which he abandoned in his fourth year to completely devote himself to art. In 2000, he decided to migrate to the United States, where his art production shifted from panting to video and video installation.

There, he also started engaging with Zen Buddhism. Though not a Buddhist himself, he practices zazen –zen meditation–, a discipline that substantially transformed his creation and positioned the concept of emptiness as the main axis of his work. Andrés has built subtle, fragile and delicate ways of representing emptiness in his work, as it is impossible to work with it directly: “I compose images that are somewhat unfinished quality, a quality of something that hasn’t been fully resolved. Somehow, they hint to the strategies I have implemented in my work to allude to that emptiness.”

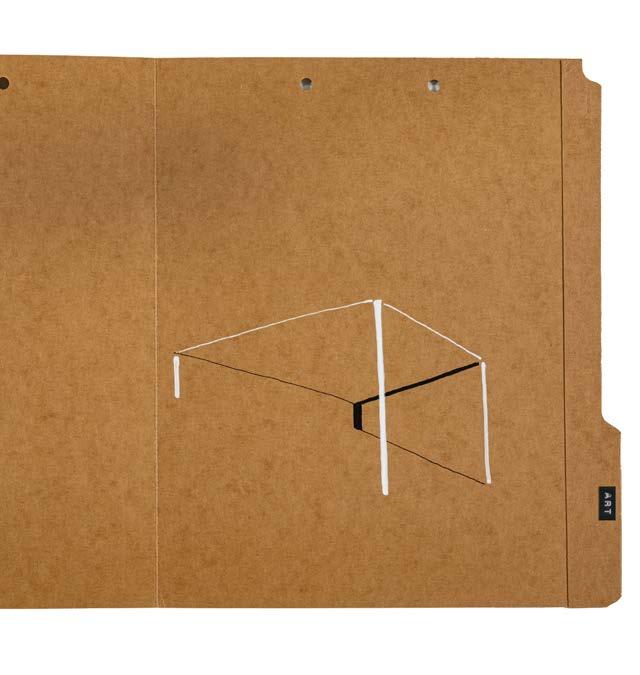

Untitled “9” , 2023, acrílico, tinta de archivo en papel yamagampi, 45.72 x 59.69 cm.

Untitled “9” , 2023, acrílico, tinta de archivo en papel yamagampi, 45.72 x 59.69 cm.

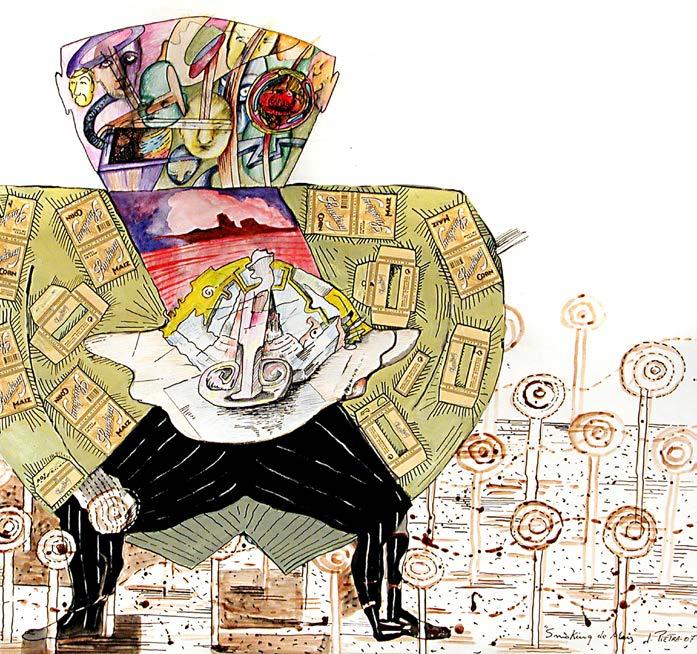

No espera tener los materiales ni las condiciones ideales. Gran parte del tiempo lo dedica a su empleo en el Design District, circunstancia que aprovecha para robustecer su cuerpo de obra. La colección que dirige está rodeada por tiendas de alta categoría que generan basura con el potencial de ser reutilizada en el diseño de una estética con componentes laborales: “una de las primeras obras que generé bajo esa actitud, fue trabajando como asistente para una galería que existió aquí en Wynwood, que fue una zona muy famosa de galerías en Miami. Sobre un bloc de notas, agarré la engrapadora de la galería. En un borde puse once grapas y en el otro borde puse cinco grapas, porque ese era mi horario. Yo trabajaba de once de la mañana a cinco de la tarde”.

Men Art Work es el título de una serie de obras en el que juega conceptualmente con las frases “hombres trabajando” y “obra de arte de los hombres”, ambas en inglés. En ella utiliza carpetas de cartón que presentan tres elementos. Por una parte, tienen un dibujo hecho con materiales propios de una oficina, como tinta negra y correctores de texto con tinta blanca. Esos dibujos proponen un reto visual, la obra no está totalmente resuelta en ellos. Al estar trazados sobre carpetas, cambian su estatus de contenedor a contenido, bajo la convención de que el dibujo es una de las formas más reconocibles del arte. Luego, en cada carpeta hay dos situaciones lingüísticas que hacen uso del vacío: “cuando la abres, en tu mano derecha vas a tener el dibujo y en tu mano izquierda vas a tener este enigma verbal que se resuelve con un pequeño detalle que está en la solapa: la palabra arte. Entonces, cuando agregas esa partícula dentro

He does not expect to have the ideal materials or conditions. Most of his time is spent on his job at Design District, which nurtures his body of work. The collection he directs is surrounded by high-end shops whose waste has the potential of being reused in the design of an aesthetic with work-related components: “One of the first pieces I created under this concept happened when I was working as an assistant for a gallery here in Wynwood, which was a very famous area for its galleries here in Miami. I grabbed the gallery’s stapler and I placed eleven staples on one of the edges of a notepad and 5 staples on another. That was my schedule, I worked from eleven to five.”

Men Art Work is the title of one of his series, a play on words of “men at work” and “men’s artwork.” In the series, he uses cardboard folders featuring three different elements. First, drawings made with office supplies such as black ink, and white liquid paper. These drawings pose a visual challenge; the pieces are not totally resolved with them. Since they are drawn on folders, their status changes from container to content, under the convention that drawing is the most recognizable form of art. Then, every folder contains two linguistic puzzles that use the empty space: “When you open the folder, the drawing is located to the right and that verbal enigma is to the left, which can be solved with the tiny detail in the tab: the word art. Then, when that particle is added to the

iculation”,

la serie

De Men-Art-Work, “Dis 2014, tinta negra, tippex líquido, dymo negro en carpeta, 29.21 x 49.53 cm.de la palabra que está al lado izquierdo del dibujo, se completa”. Las palabras tienen un rol importante en algunos de sus procesos creativos, estableciendo una conexión directa con el arte conceptual.

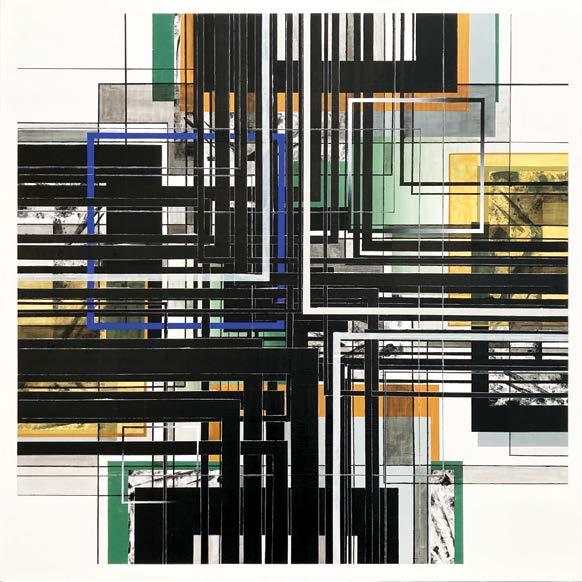

Siente una relación emotiva con la estética japonesa, especialmente el Mono-Ha, un movimiento iniciado en la década de los sesenta cuando los artistas reinterpretaron el minimalismo de forma más naturalista, dándole cabida al error y posicionándose críticamente ante el avance de la industrialización: “me gusta mucho la combinación de sobriedad con profundidad, incluso con poesía. Ellos han creado la posibilidad de algo muy poderoso a partir de lo débil, de lo frágil. La relación con ese tipo de manifestaciones creo que se puede notar en mi trabajo”.

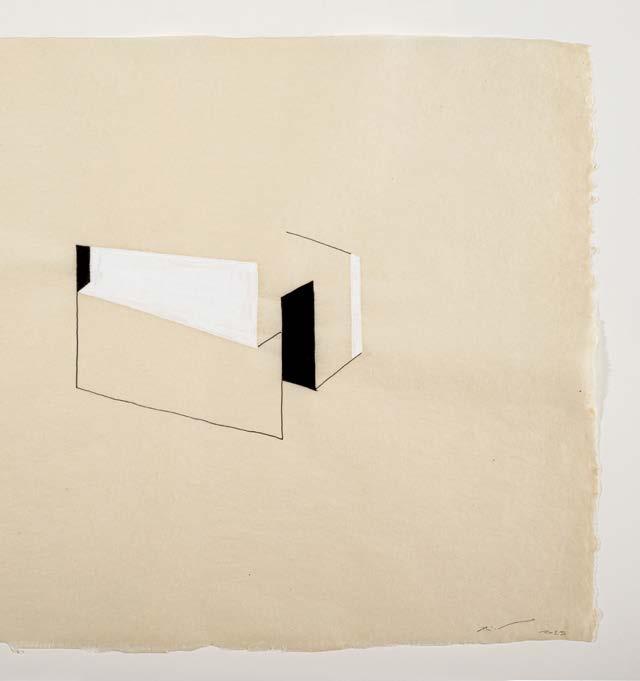

Ejemplo de ello es una serie de obras sin título creadas en 2023, que pertenecen a la serie Incoherencias. Fueron nueve dibujos con influencias de la arquitectura, construidos a partir de líneas sin pretensiones de perfección y abiertas en términos de su interpretación: “la idea era hablar de cómo los seres humanos hemos abordado el progreso. Hemos crecido, avanzado, progresado, pero, en muchos casos, hemos debilitado la base de los que nos mantiene unidos como sociedad y es parte de nuestras incoherencias en este mundo”. Los dibujos están hechos sobre papel Yamagampi, un material japonés hecho a mano que impide corregir los trazos , revelando la fragilidad del pulso y de la ejecución.

word to the left of the drawing, it becomes complete.” Words have an important role in some creative processes, establishing a direct connection to conceptual art.

The artist feels emotionally linked to Japanese aesthetics, especially Mono-ha , a 60s movement led by artist who interpreted minimalism the naturalist way, allowing for mistakes and criticizing the advent of industrialization: “I like the combination of austerity and depth, even in poetry. These create the possibility of something very powerful through something weak, fragile. I think the relationship with this sort of manifestation is noticeable in my work.”

An example of this is a set of untitled works created in 2023 from the series Incoherencias (Incoherences). These are nine drawings inspired by architecture, built through lines with no claims of perfection, open in terms of their interpretation: “The idea was to speak on how human beings have address progress. We have grown, advanced and progressed but, in many cases, we have weakened the foundation that keeps us united as a society, and that is part of the incoherence in this world.”

The drawings are made on Yamagampi paper, a handmade Japanese material that prevents stroke correction, thus evincing the fragility of the pulse and execution.

Untitled “6” , 2023, acrílico, tinta de archivo en papel yamagampi, 45.72 x 59.69 cm.

Untitled “6” , 2023, acrílico, tinta de archivo en papel yamagampi, 45.72 x 59.69 cm.

Andrés afirma que, con el paso del tiempo, su obra se ha ido colando en el medio artístico de Miami. Cuando decidió migrar, había tenido algunas exposiciones individuales en galerías de renombre y tenía el reconocimiento público de algunos artistas de su generación, pero no era ampliamente reconocido en Venezuela, su país natal. En los Estados Unidos empezó desde cero, lo que valora positivamente; la falta de éxito y reconocimiento en sus inicios le otorgó la libertad de seguir ejecutando sus ideas en un ritmo propio y de generar cambios en el camino: “muchas veces ocurre que hay artistas que se terminan convirtiendo en esclavos del mercado. Una vez que tienes un éxito muy grande y empiezas a ser reconocido por un cierto tipo de obra, el mercado empieza a reclamar ese estilo de piezas y muchas veces se termina esclavizando a una expresión única. Ese es el tipo de cosas que maneja el mundo del arte de una manera muy peculiar. Ese matrimonio con estéticas, con producciones exitosas, muchas veces crean una cárcel donde el principal guardián termina siendo el propio artista”.

Antes de terminar la videollamada, reafirma, con una sonrisa en el rostro, que el éxito no es sinónimo de reconocimiento público, sino que está en la oportunidad de continuar creando y viviendo procesos creativos en los que pueda modificar sus piezas al margen de lo que el mercado artístico espere de él.

Andrés states that, in time, his work has penetrated the Miami art scene. When he decided to migrate, he had had solo exhibitions in renowned galleries and was publicly praised by some artists of his generation, but was not widely acclaimed in Venezuela, his native country. In the United States, he started from scratch, which he regards as a positive thing. The lack of success and recognition in his early days granted him the freedom to continue developing his ideas at his own pace and to make changes along the way: “Many times, artists end up becoming slaves to the market. Once you are very successful and begin to be celebrated for a specific type of artwork, the market starts demanding those sorts of pieces and that single expression enslaves them. That is the kind of thing that the art world handles in a very peculiar manner. That being committed to a single style, successful productions, oftentimes creates a prison in which the main guardian are artists themselves.”

Before hanging up from our video call, he states, with a smile on his face, that success is not synonymous with public acknowledgment, but it rather lies in the possibility to keep creating and experiences creative processes that allow for shifts in his work, regardless of what the art market expects from him.

De la serie Men-Art-Work, “Imp ible”, 2014, tinta negra, tippex líquido, dymo negro en carpeta, 29.21 x 49.53 cm.

De la serie Men-Art-Work, “Imp ible”, 2014, tinta negra, tippex líquido, dymo negro en carpeta, 29.21 x 49.53 cm.

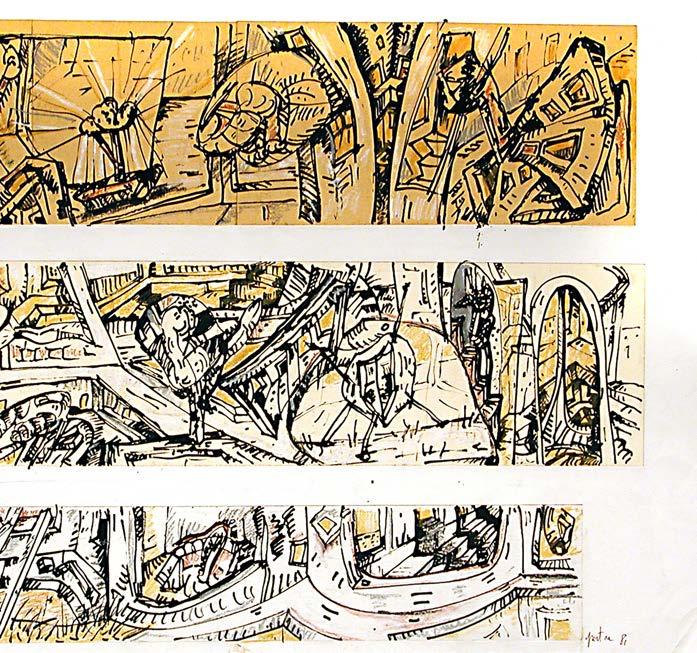

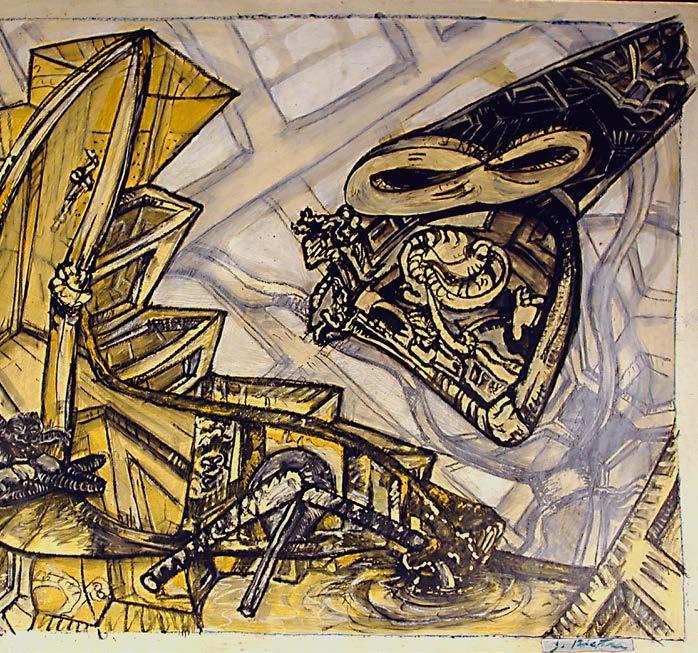

Por Julio Sapollnik. Crítico de Arte (Argentina) Imágenes cortesía del artista.

El retorno de la tristeza, 2023, fotografía color, foto performance lumínica, sublimación sobre seda, 140 × 160 cm.

la entrada de Arturo Aguiar al arte fue por la pintura. Esto nos recuerda los inicios de la fotografía. Los primeros fotógrafos fueron pintores. Al realizar un retrato, el elevado tiempo de exposición requería de grandes habilidades técnicas para efectuar los retoques necesarios.

La búsqueda estética de Arturo está en consonancia con el pictorialismo, un movimiento fotográfico que, partiendo de las teorías románticas del siglo XIX, destacaba la jerarquía de la sensibilidad asociada a la inspiración. La imagen adquirió un nuevo valor, superó la mera técnica y se alejó de la esencia instantánea y documental que se le otorgaba a la fotografía en aquella época.

Arturo cursó estudios para la Licenciatura en Ciencias Físicas en la Universidad de Buenos Aires. Al leer un artículo de Umberto Eco donde reflexionaba sobre la “creación del propio saber”, comenzó a pintar y a experimentar con la práctica fotográfica. El primer desafío fue desarrollar como tema el autorretrato. De su estudio universitario lo que más lo cautivó fue la representación del tiempo y el espacio. Así unió en la imagen esos dos conceptos, sumando la luz.

Al abordar el autorretrato comenzó a jugar delante de la cámara, moviéndose e iluminando con un dispositivo experimental, mientras mantenía abierto el obturador de la cámara. Ese módulo que controla el tiempo en que llega la luz a la película o al sensor digital, le permitió descubrir una propia performance.

A partir de sus lecturas sobre teoría del conocimiento, Aguiar aprendió que solo “vemos lo que podemos nombrar”. Fue el punto de partida para ir en

arturo Aguiar’s introduction to art was through painting. This reminds us of the early days of photography, as the first photographers were painters. To produce a portrait, low shutter speeds required photographers to possess great technical skill to make the necessary retouches.

Arturo’s artistic quest aligns with pictorialism, a photography movement inspired by romanticized 19th century theories that emphasized the hierarchy of sensitivity related to inspiration. The image gained new value, surpassing the quality of mere technique and moving away from the instant and documentary nature of photography at the time.

Arturo pursued studies in Physical Sciences at Universidad de Buenos Aires. When he read an article by Umberto Eco in which he reflected on “creating one’s own knowledge”, Arturo resolved to start painting and experiment with photography. The first challenge he encountered was to build on self-portraits as the main theme. Representations of time and space were the most fascinating things for him during his years at university. Thus, he merged both concepts, after which he also added lighting.

Through his work with self-portraits, he started to play in front of the camera, moving around and lighting the scenes with an experimental device, while he kept the camera shutter open. This component that controls how long the film or digital sensor is exposed to light helped him discover his very own sort of performance.

From reading about theories of knowledge, Aguiar learned that we only “see what we can name”. This was the starting point for him to set out on

La fin du monde, 2023, fotografía color, foto performance lumínica, sublimación sobre seda, 140 × 210 cm.

busca de lo inefable. Comenzó a desarrollar una estética propia, donde la representación de un punto de luz inquieta e interroga al espectador. Su fotografía provoca una sensación de extrañamiento, la mirada recorre la imagen buscando el Big Bang, el momento donde todo comenzó.

Puede fotografiar un paisaje nocturno que al iluminarlo aquí y allá activa la mirada del contemplador, buscando una definición para entender porqué la visión de lo fotografiado se intuye aterradora.

En 2023, Arturo Aguiar realizó una muestra en el Centro Cultural Ricardo Rojas de la Universidad de Buenos Aires. La tituló Luces y sombras de lo humano, y por medio de la inteligencia artificial basada en la arquitectura GPT3.5, creó a Gala Pandora Torrent, una exquisita y dedicada curadora especializada en artes plásticas. El lugar virtual de su existencia era la computadora personal de Arturo. Gala se transformó en su asistente personal, generando diálogos sobre su obra y la de otros artistas. Este juego virtual buscaba desenmascarar el uso de palabras vacías en la relación entre técnica y sentido. Una expresión científica del capitalismo avanzado que aleja al ser de su conciencia humanista. ¡Es increíble, pero la esencia creativa de nuestro artista le permite divertirse ampliando fronteras mentales!

En el desarrollo de su obra la fotografía iluminada a mano le permitió encontrar una técnica singular que combina precisión y sensibilidad, pero también acepta el error como aporte creativo. O la mancha, como un medio que incorpora una naturaleza impensable e imprevisible. La imagen

a quest for the ineffable. He started developing his own style, where the representation of a beam of light unsettles and questions the viewer. His photography causes a sensation of strangeness; the eye travels through the image looking for the Big Bang, the moment where it all began.

He can shoot nightscapes and, with strategic lighting, he manages to direct the viewers’ eye, looking for a way to understand why the sight of the photographs seems terrifying.

In 2023, Arturo Aguiar showed a sample at the Ricardo Rojas Cultural Center from Universidad de Buenos Aires, which he entitled Luces y sombras de lo humano. In it, he used a GPT3.5-based language model to create Gala Pandora Torrent, an exquisite and devoted IA curator specializing in visual arts. Her virtual existence resided in Arturo’s personal computer. Gala became his personal assistant, and together they discussed his and other artists’ work. This virtual game aimed to unmask the use of empty works related to technique and meaning, a scientific expression of the rampant capitalism that distances us from our humanist conscious. It is truly remarkable, but our artist’s creative essence allows him to have fun by expanding mental boundaries!

Manually lighting his photographs unlocked the discovery of a one-ofthe-kind technique that combines precision and sensitivity, but that also allows for errors to contribute to the creative process and splotching to consolidate an unthinkable and unpredictable nature. Images become

Venus, 2024, fotografía color, foto performance lumínica, sublimación sobre seda, 140 × 210 cm.

se convierte en una inimaginable fuente de creación, atraviesa un camino errático e indeterminado en su aproximación a lo real. En cada nueva toma alcanza una expresión personal, no porque capturó lo que está frente a la cámara, sino por la emoción que le imprime al momento de crearla.

A diferencia de la iluminación tradicional, Arturo creó un nuevo lenguaje que le permitió el control sobre la luz, alcanzando imágenes vivas de mayor naturaleza orgánica. La interacción entre la luz y la sombra comenzó a adquirir una importancia crucial, descubriendo contrastes intrigantes, sorprendentes y de gran profundidad visual.

La fotografía de Aguiar ofrece una versatilidad incomparable. Desde sus retratos íntimos, pasando por interiores o paisajes, captura la mirada por lo impredecible. Sus trabajos se destacan por una definida singularidad y una especial sofisticación. Cada fotografía es el resultado de una cuidadosa planificación, reflejando el compromiso del fotógrafo con su arte.

Arturo se alejó de la luz natural como fuente omnipresente que concentra lo visual sobre un ambiente realista. Desde la titilación que emite la luz dirigida manualmente, consigue fijar emociones gozosas o dramáticas, porque nacen desde la dinámica de lo que el artista quiere descubrir.

En su serie titulada Formas de luz, investigó sobre la creación de imágenes abstractas que enaltecen las propiedades de la luz y el color. La técnica creada que denominó “fotoperformance lumínica”, nació por el empleo de

an unimaginable source of creation through their erratic and undefined path towards their approach to reality. Every new shot attains a personal expression, not because he captures what is in front of the camera, but due to the emotion he captures.

Unlike traditional lighting, this technique establishes a new language that enables control over light, producing lively images with a greater organic nature. The interaction of light and shadow started thus to acquire crucial importance, discovering intriguing, surprising and visually complex contrasts.

Aguiar’s photography offers an unparalleled versatility: from intimate portraits to indoor scenes or landscapes, he captures people’s attention due to the pieces’ unpredictability. His artwork stands out for its sharp singularity and a special sophistication. Every photograph is the result of careful planning and execution, reflecting the photographer’s commitment to his art.

Arturo moved away from natural lighting as the omnipresent source highlights visuals in an organic and realist environment. Thanks to the flickering of the manually controlled lighting, he is able to capture joyful or dramatic emotions, because they are born from the dynamics of what the artist wants to discover.

In his series entitled Formas de Luz , he delved into abstract images that highlight light and color properties. The technique, which he called “light photoperformance”, was the result of using an exper -

Retrato de familia, 2023, fotografía color, foto performance lumínica, sublimación sobre seda, 110 × 140 cm.

un dispositivo experimental que le permitió representar composiciones abstractas, fotografiadas en tomas de larga duración. El tiempo de exposición, la superposición de las formas en el espacio y la exacerbación de los planos cromático-luminosos proporcionan una unidad creativa que recuerda aquella búsqueda iniciática donde todo comenzó. Así lo podemos observar en la indumentaria. Al imprimir sobre seda diseñó una vestimenta informal que se incorpora a la vida cotidiana. Recordemos a Octavio Paz cuando escribió: “La contemplación estética se terminó porque el arte se disuelve en la vida social”.

Al proponer un mundo que a simple vista no se puede ver, la fotografía de Arturo comenzó un derrotero internacional que, partiendo de sus exhibiciones en Argentina, continuó por Francia, España. Portugal, México, Estados Unidos, Costa Rica, Colombia, Bélgica y Alemania.

El impacto de la imagen nace por la acumulación de la luz en los objetos que llegan al ojo. Al introducir iluminaciones performáticas, nacidas de la intuición del artista, Aguiar interviene sobre la imprimación de la imagen. Las escenas fotografiadas revelan un universo oculto, una nueva manera de ver que sorprende e interroga.

La obra de Arturo Aguiar tiene un grado de perfección caravagesca. A partir del trabajo dinámico de la luz consigue que cada elemento se perciba de modo diferente. Nada queda unificado. Las texturas visuales resaltan su individualidad al igual que las personas se diferencian en la vida.

imental device that allowed for abstract compositions to be shot in long exposures. The shutter speed, the overlapping of shapes in the space and the heightened color-light planes provide a creative unity reminiscent of that initial quest where it all began. This is also the case for his fashion design. He has designed informal garments for daily life by printing on silk. This reminds us of Octavio Paz as he wrote: “Aesthetic contemplation is over because art dissolves into social life.”

By proposing a world that cannot be seen with the naked eye, Arturo’s photography began an international journey that started with exhibitions in Argentina and continued in France, Spain, Portugal, Mexico, United States, Costa Rica, Colombia, Belgium and Germany.

The impact of his images stems from the concentration of light on the objects that meet the eye. By introducing performative lighting led by the artist’s intuition, Aguiar influences the way images are captured. His photographed scenes reveal a hidden universe, a new way of perceiving that surprises and challenges.

Arturo Aguiar’s work features a certain degree of Caravaggist perfection. Through his dynamic work with light, he manages to make all the elements be perceived differently. Nothing is unified. Visual textures signal their individuality just like people are different in life.

MUSEO AAL TE INVITA A EXPLORAR EL PODER DEL ARTE CONTEMPORÁNEO.

AAL MUSEUM INVITES YOU TO EXPLORE THE POWER OF CONTEMPORARY ART.

PANQUEHUE, REGIÓN DE VALPARAÍSO, CHILE

Por Elisa Massardo. Lic. en Historia y Estética (Chile) Imágenes cortesía de Alfonso Yunge.

Representada por Factoría Santa Rosa.

¡¡¡¡¿¿¿¿ Quién puso la mesa !!!!!???? , 2023, collage tridimensional, madera, porcelana, metal, 65 x 18 x 15 cm. aprox. Foto: Alfonso Yunge.

De la serie

Revelar la incomodidad de la violencia

para generar incomodidad se necesita romper la armonía. Tanto en la pintura como en la escultura, donde los griegos y muchas culturas han buscado una matemática perfecta, la compensación visual, el cruce de líneas que permita dar equilibrio a la visualidad; es donde varios artistas, también, han encontrado el punto de quiebre: romper estas formas que generan armonía, para que el espectador se sienta incómodo y logre comprender que en la vida, no todo es color de rosa

“Busco enfrentar al espectador a escenas de desequilibrio y situaciones de violencia para mirar desde fuera y, en algunos casos, desde la ironía”, señala María Angélica Echavarri sobre su última serie de obras, donde la violencia en todas sus formas es el tema central. Según explica, son “situaciones que de tan comunes, ya no nos llaman la atención. Así, a través de la descontextualización logro que la gente se detenga y mire con la esperanza de ver lo que les estoy mostrando”.

Loza, sillas, una mesa, penden de unos hilos sobre una figura inestable; o se encuentran desarmados y desparramados encima de una superficie que puede ser la cubierta de un mueble de cocina o de una mesa, pero que en realidad es una tabla de picar o una bandeja de plata, ¿por qué lo íntimo se hace relevante en la obra de María Angélica Echavarri?, ¿qué busca enseñar y demostrar o revelar a través de estas instalaciones escultóricas?

La mesa es el elemento estable; aquel lugar de encuentros familiares, de trabajo, de amistad, del debate cotidiano, de lo íntimo y lo colectivo, que

to cause discomfort, you need to disrupt harmony. In both painting and sculpture –disciplines where the Greeks and many cultures have sought out perfect math, visual counterbalancing, intersections of lines providing harmony to visuals–, many artists have found a breaking point: disrupting the shapes that create balance so that viewers feel uncomfortable and understand that in life, not everything is rosy

“I aim to confront viewers with unbalanced scenes and violent situations so they can look from the outside and, sometimes, with irony,” María Angélica Echavarri says about her latest series, where violence in all its forms is the main topic. As she explains, the pieces are “situations so common, they no longer capture our attention. By decontextualizing them, I get people to stop and look, in the hopes they actually see what I’m showing them.”

Dishes, chairs and a table hang from threads and balance atop an unstable figure; or they are disassembled and scattered on top of a surface that may seem like a kitchen counter or tabletop, but is actually a chopping board or a silver tray. Why is the intimate so relevant in María Angélica Echavarri’s work? What is she trying to teach, show, or reveal through her sculpture installations?

Tables are stable elements, a place for where family, coworkers and friends gather, a place for day-to-day, intimate and collective discussions. Tables

“¿Le gustaría servirse este platito?”, 2023, collage tridimensional, mármol, porcelana, juguetes, 18 x 20 x 30 cm. aprox. Foto: Alfonso Yunge.

De la serie

puede representar aquel espacio donde se conversa la violencia social, pero se ejerce la psicológica a través de la familia. “La temática se afirma en una pata de esa mesa, bastante inestable, por decir lo menos. Los juegos de vectores se realizan a través de estas dimensiones exageradas”, así todo queda inseguro, incierto, propenso a la fractura y a la caída.

En Chile se comenta constantemente que hay un aumento de violencia, ¿qué piensas de ello?

No solo las estadísticas muestran que ha aumentado la violencia. Se ve en las reacciones de las personas en la calle, entre los alumnos en los colegios, en la cantidad y forma de los asaltos y crímenes. El terrorismo en el Sur de Chile. Violencia en la frontera del Norte, en algunas ciudades más que en otras. Las guerras en el mundo. Es bastante violento el ambiente en general. El temor ha cambiado nuestros hábitos, nuestros horarios. Es algo muy palpable. Se siente, se nota.

¿Por qué decides abocarte a la violencia doméstica?

No solo hablo de violencia doméstica; más bien la expongo en paralelo a la pública. Quiero que pensemos cómo ambas provocan una gran inestabilidad en diferentes ámbitos de nuestra sociedad.

De todas formas, ¿cómo definirías la violencia doméstica, que parece implícita en tu obra?

La violencia doméstica para mí es la más difícil y cruel porque es la que se calla. La que se oculta. De la que no se habla. El daño es profundo

can also represent the space where social violence is discussed, but psychological violence is exerted by family. “The subject matter stands on a leg of that table, quite shaky, to say the least. The interplay of the vectors is done through these exaggerated dimensions,” and thus everything remains uncomfortable, uncertain, vulnerable to breakage and falling.

In Chile, people are constantly talking about violence increasing. What do you think about this?

It is not only statistics that show that violence has increased. We can see it in people’s reactions on the street, among schoolchildren, in the amount and the way that muggings and crimes happen. In the terrorism in the south of Chile. Violence in the northern border, though in some cities more than others. Wars around the world. Our surroundings have become very violent overall. Fear has changed our habits and our schedules. It is very palpable. You can sense it; you can notice it.

Why did you decide to focus on domestic violence?

I don’t just speak about domestic violence, but rather I show it parallel to public violence. I want us to think how both of them cause great instability in different domains of our society.

In any case, how would you define the domestic violence implied in your work?

For me, domestic violence is the most difficult and cruel form, as it is the one that is kept quiet. The one that is hidden. The one we do not speak about. The damage it

De la serie “ En una Pata” , 2023, ensambles de madera, 170 x 80 x 70 cm. apróx. Foto: Alfonso Yunge.

De la serie “ En una Pata” , 2023, ensambles de madera, 170 x 80 x 70 cm. apróx. Foto: Alfonso Yunge.

¡¡¡¡¿¿¿¿ Quién puso la mesa !!!!!???? , 2023, collage tridimensional, madera, 70 x 15 x 18 cm. aprox. Foto: Alfonso Yunge.

De la serie

De la serie “ ¿Le gustaría servirse este platito?” , 2023, collage tridimensional, metal plateado, encendedores, madera, juguetes, 20 33 x 30 cm. aprox. Foto: Alfonso Yunge.

y crece por dentro de cada persona. Puede ser física o psicológica y al acumularla es natural que en algún momento la expreses en la intimidad de tu entorno o experimentes una catarsis en lo colectivo.

¿Por qué consideras importante trabajar con la violencia de manera metafórica?

Porque como artista, a través de la escultura y la tridimensión, quiero que pensemos que hay muchas formas de violencia. Que dentro de ella hay apariencias que la intentan “camuflar” como “bromas”, “cuidados”, “cariños”, entre otras maneras. Es una gran ironía y la uso en muchas de las obras de esta serie. La exposición se llama Peligro inminente, la serie de tablas de queso y fuentes de plaqué se llama “¿Le gustaría servirse este platito?”, porque, ¿te comerías esas escenas? ¿por qué no? A través de mis obras podrás pensar por qué no te las comerías y qué responsabilidad puedes tener frente a estas situaciones. Las escenas de mesas en plena caída sobre una pata de mesa o silla, se llama “!!!!????Quién puso la mesa ????!!!!” Porque todo está mal y nadie se hace cargo. Todo se cae y todos miramos sin hacer nada. La violencia no soluciona los problemas, solo te quiebra en mil pedazos y puedes encontrar esos pedazos que quedan de ti, puedes intentar pegarlos pero nunca quedarás igual. Y me refiero a las consecuencias que provocan en nosotros todos los tipos de violencia.

¿Hay una perspectiva feminista en tu trabajo?

El feminismo sin ideología política. Feminista por el hecho de ser mujer y sentir que todavía dentro de la sociedad somos vulnerables, exigidas y pasadas a llevar siendo nosotras las que generalmente seguimos tra-

causes is deep and grows within each person. It can be physical or psychological and when we kept it in, it is only natural that it comes out and that we express it in the intimacy of our surroundings or we experience a catharsis in a collective space.

Why do you think it is important to work with violence metaphorically?

Because as an artist, through sculpture and three-dimensions, I want us to understand violence takes on many shapes. That within it, appearances try to “camouflage”, regard it as “jokes”, “caring” or “love”, among other things. It is a huge irony and I use this in many pieces of this series.

The exhibition is called Peligro inminente (Imminent danger). The series of cheese boards and silver platters is entitled “¿Le gustaría servirse este platito?” (Would you like to help yourself to this dish?) because, who would eat those scenes up? Why wouldn’t we? Through my work, people will reflect on why they wouldn’t and what their blame might be in those situations. The scenes of tables mid-fall on a table leg or chair are called “!!!!????Quién puso la mesa ????!!!!” (Who set the table!!!??), as everything is wrong and no one takes any responsibility. As things collapse, we just watch and do nothing. Violence does not solve issues, they just shatter you to pieces and, although you can try to put them back together, you will never be the same. With this, I’m talking about the consequences of all kinds of violence.

Is there a feminist perspective in your work?

Feminism but without a political ideology. It is feminist due to the fact that I’m a woman and I still feel that we are vulnerable, sanctioned and overlooked in society. This while we

De la serie “ ¿Le gustaría servisrse este platito?”, 2023, collage tridimensional, metal plateado, encendedores, madera, juguetes, 20 33 x 30 cm. aprox. Foto: Alfonso Yunge.

bajando dentro y fuera de la casa. Con menores sueldos, por ejemplo; o teniendo que dejar el trabajo porque por ser mujer eres quien tiene que cuidar al enfermo/a o al anciano/a de la familia. Eso es abuso y el abuso es violencia.

En estas microescenas que planteas a través de las esculturas-collage, se lee una referencia al trabajo de Liliana Porter, ¿cómo ves este diálogo?

La verdad es que si me llevas a un paralelo entre nuestros trabajos, claramente hay similitudes. Llevar situaciones cotidianas a lugares insólitos. No tengo interés en la proporción, en la escala real; hay interés en la intensidad de la escena. Ella usa el mismo recurso. Trabajo con el humor y la ironía para dar énfasis a lo que quiero decir. Todo eso en los collages tridimensionales, porque en las esculturas de madera no hay humor ni ironía, hay una preocupación escultórica solamente, que hace notar la inestabilidad que provoca la violencia.

¿De qué manera esta obra dialoga con tus trabajos anteriores?

Dialoga desde el punto de vista de la metodología de investigación, de la observación. Tu sabes que yo disfruto el proceso y en cada caso son diferentes materiales y técnicas que se van adecuando a lo que quiero decir. Que dan forma al respaldo teórico de lo que muestro. En ese sentido el cuerpo de obra ha sido siempre diferente y, en este caso, además agregué una buena cuota de ironía, porque la violencia tiene ese tono festivo; pareciera ser que quien la ejerce la disfruta y hace que la violencia sea exponencialmente aún más fuerte.

continue working within and outside the home, with lower salaries, or we are forced to quit work, as women are the one who take care of sick and old family members. That is abuse and abuse is violence.

In these micro-scenes you present through sculpture-collages, there is a reference to Liliana Porter’s work. How do you regard this connection? In truth, if you try to draw parallels between our work, there are certainly similarities, like extrapolating daily situations to unusual places. I have no interest in proportion or real scales; I’m more interested in the intensity of the scene. She uses the same resource. I work with humor and irony to highlight what I want to say. To do so, I use three-dimensional collages, because there is no humor or irony in wooden sculptures. There is only a sculptural concern, which highlights the instability caused by violence.

How do these pieces relate to your prior artwork?

In the sense that their research methodology and observation phase are the same. You know that I enjoy the process and materials and techniques vary to adjust to what I want to convey. These shape the theoretical framework of what I exhibit.

Therefore, this body of work has always been different and, particularly in this case, I added a good modicum of irony since violence has a festive tone, it seems that the people that exert violence enjoy it, and this makes the violence exponentially more powerful.

Argentina

Por Ricardo Rojas Behm. Escritor y Crítico (Chile) Imágenes cortesía del artista. Representado por Building Bridges Art Exchange.

The Noaide, 2023, performance y video con traje realizado en tela y lana, Serlachius Museum, Finlandia. Foto: UTUH Studio.

The Noaide, 2023, performance y video con traje realizado en tela y lana, Serlachius Museum, Finlandia. Foto: UTUH Studio.

tal como afirma Byuing-Chul Han: “La crisis existencial de la modernidad, como crisis de la narración, se debe a que ambas van cada uno por su lado”. No obstante, en el artista visual Tadeo Muleiro, que vive y trabaja en Buenos Aires, ese escollo no es del todo insalvable, dado que ha sabido articular un lenguaje en cuya fenomenología se inscribe una narración visual surgida del inconsciente, cobijado por una técnica llamada in media res, que permite que la trama de la historia se revele mediante recuerdos y escenas retrospectivas.

Lo sorprendente es que rara vez nos encontramos con un artista con capacidad para amalgamar los saberes de una espiritualidad ancestral con la cultura mainstream. Y no deja de ser estimulante que, si bien experimenta con la óptica del chamán o del hechicero, también puede ser simplemente Tadeo. En ese contexto, cada escena da para pensar, ya que vemos cómo las fronteras se desvanecen, producto de un rito ceremonial que es un acto de reparación y recogimiento, con el cual Muleiro devela las fisuras de los pueblos originarios.

Estos agrietamientos terminan en una singular representación, la cual supone despojarse de la subjetividad, no así de ciertos referentes autobiográficos, lo que se afianza a través del simbolismo histórico, con los que se enfrenta a: “la institucionalidad de lo real”. Así, lo atávico se mezcla con lo vernáculo, retomando los vínculos con el imaginario de diversas culturas ancestrales, con ecos venidos del norte argentino y Latinoamérica, como en el video La Salamanquera, imprimiéndole una perspectiva más contemporánea a la leyenda de la Salamanca del norte y sur de Argentina. Además, recurre a referentes de Asia y África e incluso de su imaginario más interno -entre y más allá de lo que se pueda expresar con palabras- evocando relatos mitológicos sudamericanos contados por su padre (también escultor), muchos remitidos a su infancia, con trajes de monstruos creados por su madre, quien además le enseñó a coser. Criaturas invocadas y emuladas como inolvidables seres, encarnados en grandes piezas escultóricas textiles, donde tanto el molde, el hilván y la costura es realizada por el mismísimo Muleiro.

as Byung-Chul Han states: “Modernity’s existential crisis –a crisis of narration– is caused by the splitting of life and narrative.” However, for visual artist Tadeo Muleiro, born and based in Buenos Aires, this obstacle is not entirely insurmountable. He has been able to articulate a language whose phenomenology contains a visual narrative that stems from the subconscious, using a technique called in media res, which allows the plot of the story to unfold through memories and retrospective scenes.

The surprising thing is we can rarely find an artist who can manage to combine the knowledge of ancestral spirituality with mainstream culture. What is even more stimulating is that, although he experiments with the point of view of shamans and sorcerers, he can also just simply be Tadeo. In this context, every scene makes us think as we witness frontiers vanish following a ceremonial rite that serves as an act of reparation and remembrance with which Muleiro reveals the cracks in native peoples.

These fissures end up composing a unique representation that involves shedding subjectivity, but not all autobiographical aspects, strengthened through historical symbolism to confront: “the institutionalization of reality.” Thus, the atavistic merges with the vernacular, revisiting connections with the imagery of various ancestral cultures, with echoes coming from the north of Argentina and Latin America. Such is the case of the video La Salamanquera, which imbues the legend of La Salamanca in northern and southern Argentina. He also turns to references in Asia and Africa, as well as his innermost personal imagery –beyond what words can express–, to evoke South American mythological stories his father told him (also a sculptor) during his childhood, dressed in monster costumes made by his mother, who taught him how to sew. These creatures are summoned and emulated as unforgettable beings, incarnated in large textile sculptural pieces, where both the mold, the thread and the sewing are done by Muleiro himself.

Collective Tótem , 2023, pintura sobre escultura textil y piezas de papel entelado intervenidas por la comunidad de Charlotte NC,

500 x 250 x 150 cm.

MCCOLL Center, EE.UU.

Foto: Tadeo Muleiro.

Collective Tótem , 2023, pintura sobre escultura textil y piezas de papel entelado intervenidas por la comunidad de Charlotte NC,

500 x 250 x 150 cm.

MCCOLL Center, EE.UU.

Foto: Tadeo Muleiro.

Vertientes multidisciplinares, a través de las cuales alimenta sus propios mitos, los que como es lógico, devienen en un rito que supera la malignidad, no así una ferocidad determinada por una “insurgencia cromática”, que desde ya lo hacen ver no sólo ungido de misterio, sino también de exuberancias que están en constante transformación. Tal como describe en La eficacia del arte José Luis Tuñón: “Aquellos rostros fieros del terror se convierten, entonces, en una mezcla rara - como corresponde al arte - de juguete y vestido disponible. No es difícil proyectarse en ellos y arroparse en la amable compañía de unas serpientes milenarias. Podemos estar seguros de evocar el asombro de lo sagrado ante la vista de estas criaturas, pero también de que allí hay lugar para nosotros y nada puede hacernos daño”.

Pero no todo es inocuo, y Tadeo Muleiro lo experimentó cuando su padre fue asesinado en 2014; luego de esto vino un incendio que lo llevó a realizar la obra El Padre, donde asume la pérdida y el duelo, vistiendo un traje cubierto de espejos, con el que deambula largamente sobre los cimientos del hogar convertido en cenizas. Una foto familiar y un conjunto de piezas escultóricas realizadas por su padre son los justos testigos que cierran este rito fúnebre, y que lo conectan intrínsecamente con otras obras que también abordan su faceta más emotiva, como Papá y mamá, El hijo, La casita, Los hermanos, El abuelo

Aunque sus propuestas artísticas lo hacen ver como el portavoz de una historia inconclusa entre lo ancestral y lo real, lo vemos agregar colorido a una opaca vida citadina, presa de su obsecuente pasividad, propiciando el desborde con todo un despliegue de simbolismos y una sensación atemporal, sustentada en una práctica revestida de una insurgencia conceptual que va de la provocación a la reflexión, y en cuya dialéctica subyacen una serie de vibrantes acciones: con videos y performance donde el traje es una escultura habitual-habitable que lo eleva a la categoría de performer, permitiéndole encarnar un atuendo con el que devela distintas historias que unen el pasado más primigenio con su universo autobiográfico, y donde cada personaje de este ámbito mitológico construye nuevas alteridades y alegorías que se constatan en sus últimos proyectos del 2023 como

He nurtures his own myths with multi-disciplinary sources which, as is logical, become a rite that overcomes evil, but not the ferocity resulting from a “chromatic insurgence” that makes it appear not only anointed with mystery, but also with exuberances that are in constant transformation. As José Luis Tuñón described in La eficacia del arte: “Those fierce faces of terror become, then, a rare mixture - as befits art - a toy and available costume. It is not difficult to project oneself onto them and tuck oneself in the kind company of millenarian snakes. We can be sure to evoke the awe of the sacred at the sight of these creatures, but also that there is room for us there and nothing can harm us.”

However, not everything is harmless. Tadeo Muleiro experienced this when his father was murdered in 2014, followed by a fire that led him to create El Padre (The Father), where he grieves his loss dress in a mirror-covered garment and long roams among the foundations of his home turned to ashes. A family picture and a set of sculptured made by his father are the only witnesses to this mournful ritual, also connecting it intrinsically with other pieces that address his most emotional side such as Papá y mamá, El hijo, La casita, Los hermanos, and El abuelo.

Even though his art proposals make him the spokesperson of an unfinished story between the ancestral and real, the artist adds color to the opaqueness of city life, a prisoner of its obedient passivity. This leads to an overflow with a whole array of symbolism and a timeless nature, sustained by a conceptually insurgent practice ranging from provocation to reflection. Underlying his dialectic is a series of vibrant actions: videos and performances in which costumes are inhabitable sculptures that elevate him to the category of performer, allowing him to incarnate an outfit that unveils different stories, merging the most primitive past with his autobiographical universe. In these mythological environments, he builds new allegories and feelings of otherness. This can be seen in

The Noaide, 2023, performance y video con traje realizado en tela y lana, Serlachius Museum, Finlandia.

Foto: UTUH Studio.

The Noaide, 2023, performance y video con traje realizado en tela y lana, Serlachius Museum, Finlandia.

Foto: UTUH Studio.

La Salamanquera, 2014, video, 07:01 min, Argentina.

Foto: Martina Matusevich.

La Salamanquera, 2014, video, 07:01 min, Argentina.

Foto: Martina Matusevich.