R E V I E W S

Brenna Youngblood Roberts Projects By Eve Wood

How we balance our individual experiences within the larger scope of our lives in many ways determines who we are, and how we understand and relate to the world around us. Reflecting on the dense and often traumatic events of the past year, which included a global pandemic and a re-awakening to racial injustice, Brenna Youngblood, in her inaugural exhibition at Roberts Projects, mediates her personal associations to these very public events as all of the works in the exhibition comprise a space for both reflection and determined response. Blurring the boundaries between figuration and abstraction, and speaking directly to the title of the exhibition as a whole, “The LIGHT and the DARK,” i.e., the balance between light and dark,

with commerce. Youngblood’s use of everyday materials, including a pair of her own worn out shoes and an assortment of colorful buttons, constitute a grouping of assembled collage works that allow her to imagine a new-fangled topographical facade which she then enhances through a variety of processes including thick impastos, transparent washes and variously loose and smooth brushstrokes. Hourglass (2021) employs hundreds of black buttons pushed to the very top of the picture plane like small circular creatures, jostling each other to and fro, and desperately trying to come up for air. Metaphorically, this work specifically speaks to notions of disparity, prejudice and social inequality, and one has the sense that these buttons would rather be anywhere else than variously collected in this tightly claustrophobic mélange of darkness. A strange and hapless cloud floats beneath them, and one can’t be sure if the buttons are trying to escape it or are seeking reentry.

Stephen Neidich Wilding Cran Gallery by John David O’Brien

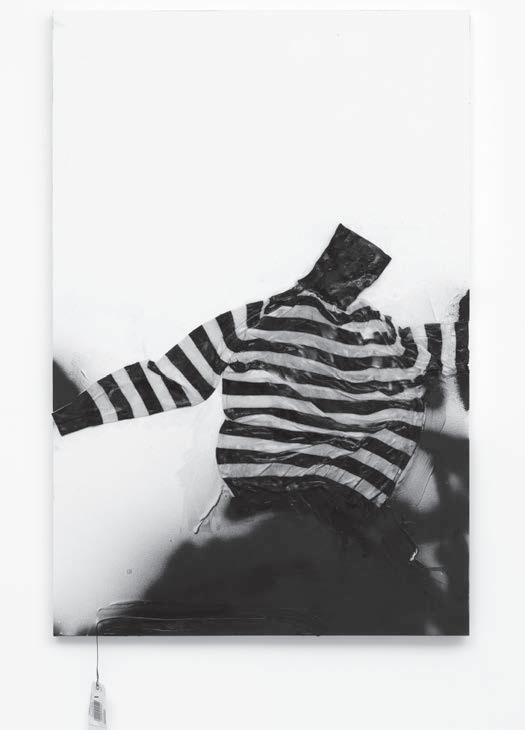

Brenna Youngblood, INCARCERATION,2020, courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects,Los Angeles, photo by Alan Shaffer.

works like INCARCERATION (2020), imply human culpability through the empty hull of a black-and-white striped sweater, the pattern of which is reminiscent of prison uniforms that date back to the 1820s. In this system, prisoners had to remain silent, walk in “lock step” and wear the distinguishing black-and-white stripes, which were meant to suggest the prison bars they lived behind. In Youngblood’s rendition of mixed media, the sweater appears to be trapped within its own incessantly theatricalized and poignant gestural sweep across the canvas, and yet it also appears strangely frozen in space, which further suggests the idea of opposites: of balancing the light with the dark, the good with the bad, the pain with the rapture. The fact that the price tag dangles from the bottom left of the frame in a gesture reminiscent of Rauchenberg’s dirty pillow in his seminal work Canyon (1959), further aligns the idea of prejudice and injustice

Upon entering Stephen Neidich’s solo show, “five more minutes please,” everything is stock still, until the clattering begins. It immediately becomes clear that one’s movements cause the Venetian blinds—hanging from the ceiling or against the gallery walls—to raise or lower themselves. Lamps are housed in the topmost part of the sculptures and vaguely ominous carmine red or neon blue lights pour down from the upper slats of the blinds, becoming darker as they fall, reminiscent of a nocturnal interior from an old film noir. Each blind is a separate work that represents a “window,” made from a series of giant steel belts, which incorporate both slippages and errors into the process. In a corner of the gallery, But they should never be buildings (2021) splatters acidic blue reflections up and down the moving slats with the machinery of the cranks more or less visible as it opens and closes. The oversized nature of this set of gears and motors are almost monstrous, and the coils of chain and power boxes are splayed out on the floor in disarray. The gallery is entirely dark except for the light coming from the (real) windows and from the moving blinds on the walls. All of the hanging sculptures appear to be moving in rotation, so that once the viewer has set off the sensor they just keep churning away. There are moments in Stephen Neidich, But They Should Never Be Buildings, which the individual me- 2021, courtesy Wilding Cran Gallery, photo by Ruben Diaz. chanics seem to catch and the metal has to be snapped back out of its arrested position. This stuttering performance heightens the decrepit and dystopian atmosphere. The question arises of what exactly is being evoked? More than the creation of a dysfunctional landscape, there appears to be an