The Range of the Electric Range: Womanhood, Race and Citizenship During the Early Years of the Cold War

Ayushi Mavuduru

ARCH 4315: Design and Society

Professor Marisa Gomez Nordyke

May 8th 2024

Abstract

In 1959, President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s debate on the merits of their respective socio-political structures in an American model home in Moscow confirmed the relevance of the postwar kitchen as a cultural battleground. The evolution of the electric range during the 1950s is representative of the period's broader cultural and political dilemmas in the Cold War context. Though the association of White domesticity with cleanliness and efficiency has its roots in the Progressive Era, the use of the kitchen as an instrument to uphold societal order took on new postwar significance in response to anxieties around the threat of communism, collapse of binary gender roles, and an emerging Civil Rights movement. Print advertising and intersectional social commentary from the period illustrate the cultural imperative amidst the Cold War to reaffirm the prospect of upward mobility and assimilate minorities and working-class women into previously inaccessible domestic ideals of the suburban housewife. Paradoxically, as women were encouraged to return to the domestic sphere, the range became a vehicle for subversion of racial status quos and a site for cultural experimentation among women of color and White women, respectively.

Introduction

In 1959, a set of sunshine yellow General Electric appliances became the focal point of a spirited debate between United States President Richard Nixon and Soviet Union Premier Nikita Khrushchev. 1 The two leaders were touring a prefabricated model home, part of the American National Exhibition on the outskirts of Moscow, when President Nixon asserted that the domestic technologies on display brought ease to the life of the American housewife and were a testament to the success of a capitalist economic system (Figure 1). 2 Khrushchev argued that these technologies were not unique to the United States, rather, Americans had to achieve such a standard of living through their income, while Soviets were entitled to it simply through their citizenship. 3 For Nixon’s defense of the American economic system at Moscow, and the United States’ parallel efforts to communicate its socioeconomic supremacy during the 1950s, to remain intact, the rhetoric surrounding the kitchen reached beyond surface-level technological comparisons and into the realm of what kitchen appliances signified in the lives of ordinary Americans.

The prospect of social mobility through perpetual consumption of newer and better household appliances, as well as the image of prosperity embodied in the devoted housewife of a

1 Regina Blaszczyk, The Color Revolution, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 241.

2 Regina Blaszczyk, The Color Revolution, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 241; Thomas Hine, "Just Push the Button," in Populuxe (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2007), 129.

3 Rebecca Devers, “You Don’t Prepare Breakfast... You Launch It Like a Missile’: The Cold War Kitchen and Technology’s Displacement of the Home,” Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture, 1900 to Present 13, no. 1 (2014): 7.

single-income household, were integral to the capitalistic ethos Nixon exalted during the kitchen debates. 4 Though the major technological advances resulting in the oven, refrigerator, dishwasher, and cooking range were in place by the 1930s, such appliances were charged with new nationalist significations during the Post-War era. 5 Coupled with ongoing New Deal initiatives like the Tennessee Valley Authority that had gradually brought electricity to rural households, the transition from defense to domestic production made electric appliances readily available to the American masses. 6 A cultural push to encourage women – especially affluent White women – to return to the home following a period of wartime employment further informed the marketing rhetoric highlighting the safety and convenience of appliances like the cooking range. 7 The electric cooking range calls for special attention due to its centrality to cooking, as well as the intensity of function within the kitchen it represented. The prosperous ‘long decade’ of the 1950s was pivotal for the range specifically due to increased diversification

4 Rebecca Devers, “You Don’t Prepare Breakfast... You Launch It Like a Missile’: The Cold War Kitchen and Technology’s Displacement of the Home,” Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture, 1900 to Present 13, no. 1 (2014): 7.

5 Thomas Hine, "Just Push the Button," in Populuxe (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2007), 123.

6 Shelly P. Nickles, “Preserving Women’: Refrigerator Design as a Social Process in the 1930s,” Technology and Culture 43 no. 4 (2002): 724.

7 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 195.

in styling, finishes, configurations, and auxiliary functions offered. 8 Notably, the introduction of color in major kitchen appliances like the range in the 1950s held far-reaching implications for existing race and class-based conceptualizations of taste and “good design” in the home. 9

The ideal image of American domesticity was unequivocally linked to Whiteness by the early twentieth century, when hygienic reforms re-shaped the kitchens of the Progressive Era. 10 Cleanliness and efficiency were therefore well-established as racialized lexicon in kitchen and appliance marketing discourse by the 1950s, while principles of Taylorism and Fordism were amplified to justify perpetual mass consumption. 11 The ideal of a traditional mother and homemaker, which “reached critical density” in the 1950s, retained an underlying continuity of

8 Historians identify the postwar “long decade” as a cohesive cultural period beginning in 1946 with the end of World War II and ending in 1963 with Betty Freidan’s book The Feminine Mystique signaling the arrival of a new feminist movement. Carlie Seigal, “The Ideal Woman: The Changing Female Labor Force and the Image of Femininity in American Society in the 1940s and 1950s,” (honor’s thesis, Union College, 2012), 17.

9 Regina Blaszczyk, The Color Revolution, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 256.

10 Jessamyn, Neuhaus, “Cooking at Home: The Cultural Construction of American ‘Home Cooking’ in Popular Discourse,” in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Food and Popular Culture, edited by Kathleen Lebesco and Peter Naccarato, (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018), 97.

11 Carlie Seigal, “The Ideal Woman: The Changing Female Labor Force and the Image of Femininity in American Society in the 1940s and 1950s,” (honor’s thesis, Union College, 2012),

44; Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 13.

White normativity, as exhibited in the design and marketing of the electric range. 12 Nevertheless, the anxieties of the Cold War brought with them need to project a promise of opportunity and upward mobility for all Americans, resulting in messaging promoting the “hegemonic kitchen” to marginalized women. 13

Historians use the term “containment culture” to describe the interplay between military advances, international diplomacy, and modernization of the domestic sphere in the postwar era. At a time when the United States sought to project itself as a land of personal freedom, the prerogative of containment culture was to “encapsulate” rather than eliminate nonconformities and threats to established status quos to prevent their “contaminating” influence from spreading. 14 Cold War containment rhetoric sought to prevent the destabilizing influence of external ideologies – like communism – as well as marginalized identities, like African Americans, women, and homosexuals, from undermining a broader projection of American

12 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 8.

13 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 8.

14 Jennifer Roberts. “Lubrications on the Lava Lamp,” in American Artifacts: Essays in Material Culture, ed Jules David Prown and Kenneth Haltman (Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 183.

cultural superiority. 15 Representations of the oven and range combination in the postwar period in a plethora of print media like newspaper advertising, recipe books, and magazine articles provide insight into the “schizophrenic” nature of containment culture. 16 The design evolutions of the electric cooking range in its many iterations attest to three key postwar anxieties. Firstly, was the fear of communism overtaking the country if the promise of opportunity under capitalism was not adequately reinforced. 17 Second, was the threat to the nuclear family and binary gender roles due to unprecedented female employment during World War II. 18 Lastly,

15 Wini Brienes, “Postwar White Girls Dark Others,” in The Other Fifties: Interrogating Midcentury Icons, ed. Joel Foreman (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 58.

16 Paul Boyer, “The United States, 1941-1963: A Historical Overview,” in Vital Forms: American Art and Design in the Atomic Age 1940-1960, ed. by Brooke K Rapaport and Kevin L. Stayton (New York: Harry N Abrams, 2001), 39.

17 Paul Boyer, “The United States, 1941-1963: A Historical Overview,” in Vital Forms: American Art and Design in the Atomic Age 1940-1960, ed. by Brooke K Rapaport and Kevin L. Stayton (New York: Harry N Abrams, 2001), 50.

18 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 10.

19

shifts in the marketing of the electric range respond to fears of racial unrest stemming from Civil Rights legislation and a small but significant growth of a racialized middle class.

The development of color-coded, automatic, and push-button burners expresses a militarization of the kitchen that incentivized women to return to a safer, efficient kitchen in which they could reap the benefits of American technological and military advances without leaving the domestic sphere. Similarly, the emphasis on serving the family elaborate meals through energy-, cost-, and time-saving strategies with the use of oven and range combinations indicates an expansion of White-normative domestic ideals as attainable for working class, immigrant, and minority women. For marginalized women, purchase of an electric range signified assimilation into a nationalistic ideal of womanhood, a process which was dually restrictive in defining their role as women and empowering in terms of improving their standard of living and access to leisure time. Though working class, rural, Black, and immigrant women were inducted into the housewife ideal through cooking range, the same qualities of the appliance made it a controlled avenue of self-expression and cultural transgression for suburban White women. 20 Ultimately, the electric range of the 1950s embodies a delicate balance in empowering women with opportunities for creative freedom and fulfillment, while confining

19 Paul Boyer, “The United States, 1941-1963: A Historical Overview,” in Vital Forms: American Art and Design in the Atomic Age 1940-1960, ed. by Brooke K Rapaport and Kevin L. Stayton (New York: Harry N Abrams, 2001), 62.

20 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 175.

their advancement and self-expression within racialized and patriarchal conventions of appropriate womanhood.

The Burner and Militarization of the Kitchen

The marketing of electric ranges equipped with push-button technology characterized the cooking process of the 1950s as automatic, high speed, and precise. The design of pushbuttons, color-coded burners, and marketing materials of the electric range are physical embodiments of the militarization of domestic labor. Newspaper advertisements used the instantaneous, precise nature of the pushbutton as a key selling point for the electric range, as seen in a 1954 advertisement describing the range as “ready to go the instant you flip a switch” and urging consumers to “go electric- now!”(Figure 2). 21 Likewise, General Electric’s 1958 advertisement demonstrates a similar overlap in the language used to convey military strength and domestic efficiency, referring to its range design as “the leader” among all brands with “fingertip pushbutton control” and “extra high-speed units.” 22 Before its use in the cooking range, pushbutton imagery was associated with guided missiles in World War II, and thus carrying daunting implication of a near-automatic process devoid of human intervention 23 The centrality

21 Central Power and Light Company, Advertisement, Verdad (Corpus Christi, TX), Nov. 19, 1954, 2.

22 Ed Byrne Home and Auto Supply, “Advertisement,” Notas de Kingsville (Kingsville, TX) Oct. 16, 1958, 4.

23 Thomas Hine, "Just Push the Button," in Populuxe (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2007), 128.

of the push-button as a novel feature in electric range design represents advancement and ease of use in the domestic sphere, providing a positive, non-threatening parallel to the intimidating technological developments of modern warfare.

Precise linework, spiral motifs, and color-coding pervaded the electric cooktop's design and its marketing materials. Hotpoint’s electric range burners provided 5 color-coded precision heat settings, as well as distinct lighting patterns on each burner to reflect the same (Figure 3). 24

Concentric circles and spirals were a recurring motif in the graphic depiction of the modern kitchen, as seen not only in cookbooks like Hotpoint’s guide extolling the benefits of the range, but also illustrations like Donald Higgins’s work in the satirical magazine article “My Kitchen Hates Me” (Figure 4) 25 The visually engaging design of instructional materials and cookbooks featuring the electric range alludes to technological advances of the period (Figure 5).

Black-and-and white imagery and linework are accented by bold red lines and boxes on the pages of Thermador’s kitchen planning guide, a design choice that reconciles images of domestic abundance with cutting-edge computer-based imaging and tracking technologies used in national defense (Figure 6). 26

Companion instructional materials accompanying the electric range further highlight a militarized and technical approach to cooking during the 1950s. Many recipe books and

24 Virginia Francis. Let’s get acquainted with your Hotpoint electric range: instruction and recipe book (Chicago: Hotpoint Home Economic Institute, 1955), 6.

25 Sylvia Wright, “My Kitchen Hates Me,” Harper’s Magazine, August 1953, 93.

26 Plan a carefree kitchen with Thermador: the original bilt-in electric range (New York: Thermador Electrical Manufacturing Co, 1950), 4.

instructional guides came with a schedule: a table of prescriptive cooking and boiling times for various foods based on extensive testing of a specific cooktop model. Hotpoint’s “Surface Cooking” chart spans two pages and provides additional space for housewives to make note of their own optimal cooking times for a plethora of fresh and frozen produce (Figure 7). 27 The emphasis placed on meticulous planning, precision, and calculation in the cooking process reflects efforts to elevate domestic labor as a respectable duty for women, one that was just as significant to national strength as technological advances in warfare. 28 Messaging that a modernized cooking process, though user-friendly and efficient, required time-intensive planning and calculation, conveyed to women that domestic labor necessitated their undivided attention.

Projecting an image of modernity, convenience, and technological sophistication through the electric range was not only a means to convey national superiority of the United States to the Soviet Union amidst the Cold War. This same image was instrumental in elevating the perception of domestic labor to facilitate the return of women to the role of the housewife following a period of increased wartime employment. Through the promotion of the pushbutton, user-friendly color-coded ranges, and prescriptive, numbers-based cooking practices, there is a direct influence of wartime design motifs into the domestic realm. Much of these design characteristics were informed by previously established discourse on efficiency and cleanliness

27 Virginia Francis. Let’s get acquainted with your Hotpoint electric range: instruction and recipe book (Chicago: Hotpoint Home Economic Institute, 1955), 14-15.

28 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 10.

in the kitchen that were rooted in the White supremacy of Progressive Era hygiene and efficiency movements but were repackaged as symbols of national power due to the tensions of the Cold War. The marketing message of the modern kitchen as a bulwark of efficiency, safety, and userfriendliness was therefore aimed at “sanitizing the drudgery” of the kitchen for White womenfor whom pre-war employment was far less common or desirable – at a time when single-income households became more feasible and relevant as a symbol of prosperity. 29

The Oven and Preservation of Family Values

The many iterations of the electric oven maximized diverse functionalities out of a single appliance. Advertising and prescriptive literature related to the oven of the 1950s idealizes the White suburban housewife who cooks elaborate meals for her family. Westinghouse’s 1950 “Look to Your Laurels, Mom” advertisement exemplifies how marketing of the electric range sold the vision of an ideal, White suburban family to consumers (Figure 8). The new “miracle oven” component of Westinghouse’s freestanding Champion range is celebrated in the advertisement as “the biggest news of all.”

30 A woman is shown preparing a full meal with the help of the miracle oven- she holds up a cherry pie, while a meat pie and full roast brown in the oven next to her. The visible happiness of the woman’s mother and husband communicate the

29 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 195.

30 Westinghouse, “Look to your Laurels, Mom,” Newsweek (New York, NY), May 1, 1950, 42.

31

message to American housewives that cooking in such a manner is easier than ever, and the key to being a source of stability and happiness in their role as mothers and wives.

The title of the advertisement, “Look to Your Laurels,” further speaks to a public need for continuity of established values amidst the tensions of the Cold War. 32 This phrase refers to the daughter telling her mother that she is easily able to emulate the elaborate cooking of past generations, but it is also significant to Westinghouse’s position as a reputable brand. 33 Here, “Look to Your Laurels” also implies that Westinghouse is projecting an image of reliability and in the face of newer competitors, and by providing a high-quality range, can be trusted in its safeguarding of traditional “American” values. The roast is symbolic of continued family-centric traditions, as well as a symbol of material abundance appealing to Americans after decades of hardship due to the Depression and wartime rationing.

34 Like in Westinghouse’s advertisement, the roast makes repeated appearances inside built-in wall ovens in Thermador’s guide to planning an electric kitchen, providing an intelligible symbol of tradition and abundance next to sleek metal built-in appliances (Figure 9).

35 Thermador’s guide on “Planning a Carefree” kitchen

31 Westinghouse, “Look to your Laurels, Mom,” Newsweek (New York, NY), May 1, 1950, 42.

32 Westinghouse, “Look to your Laurels, Mom,” Newsweek (New York, NY), May 1, 1950, 42.

33 Thomas Hine, "Just Push the Button," in Populuxe (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2007), 128.

34 Shelly P. Nickles, “Preserving Women’: Refrigerator Design as a Social Process in the 1930s,” Technology and Culture 43 no. 4 (2002): 720.

35 Plan a carefree kitchen with Thermador: the original bilt-in electric range (New York: Thermador Electrical Manufacturing Co, 1950), 8.

further illuminates the relationship between family values, Whiteness, and upgrading one’s standard of living. This visually rich guide displays built-in electrical appliances of nearly infinite sizes and configurations that could “meet the needs of any size family or kitchen arrangement” 36 Opportunities for customization, personalization, and upgrading for to suit family needs in this way were consistent with the post-war American promise of opportunity. However glorified the custom-made, built-in kitchen was in popular media of the 1950s, it remained an aspirational ideal for those other than upper-middle-class Whites due to discriminatory barriers to home ownership.

37 The built form and marketing materials for the electric oven and range set, make suggestions of which practices –like making a Sunday roast –the appliances facilitated or negated. The marketing of the range obscured non-White cultural practices and assimilate minorities into the single-income, White and vaguely Christian family considered the default occupant of the modernized kitchen.

38 Even as text or diagrams in marketing materials alluded to smaller residences and limited family budgets, customized

36 Plan a carefree kitchen with Thermador: the original bilt-in electric range (New York: Thermador Electrical Manufacturing Co, 1950), 3.

37 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 7.

38 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 45.

kitchens belonging to well-dressed White women preparing an elaborate multicourse meal take visual precedence in marketing guides like those of Hotpoint and Thermador. 39

The electric oven’s promise of abundance, variety, and perfection in home-cooked meals created non-negotiable standards for women of all backgrounds in serving their families. 40 A 1959 advertisement from a local Hispanic newspaper, - Las Notas De Kingsville, - highlights the possibility of “Work ‘til 5:30, dinner at 6:00,” thanks to the electric oven. The advertisement is accompanied by a dinner recipe for a main course of baked pork chops and two sides – candied sweet potatoes and spinach. 41 Advertisements like this were especially prevalent in Black and Latina circles – as socioeconomic inequalities often precluded the single-income household –and assert that availability of the electric oven will allow these women to fulfill their role in cooking for the family despite having outside employment. 42 The rhetoric of establishing

39 Virginia Francis. Let’s get acquainted with your Hotpoint electric range: instruction and recipe book (Chicago: Hotpoint Home Economic Institute, 1955), 3; Plan a carefree kitchen with Thermador: the original bilt-in electric range (New York: Thermador Electrical Manufacturing Co, 1950), 4.

40 Carlie Seigal, “The Ideal Woman: The Changing Female Labor Force and the Image of Femininity in American Society in the 1940s and 1950s,” (honor’s thesis, Union College, 2012), 52.

41 Central Power and Light Company, “Cook the Automatic Electric Way,” La Notas De Kingsville (Kingsville, TX), Mar 5, 1959, 6.

42 Maire Simington, “Chasing the American Dream Post World War II: Perspectives from Literature and Advertising,” (PhD diss., Arizona State University, 2003) 271.

traditional gender roles through the kitchen espoused in advertising made significant inroads into Black gender discourse by the end of the decade. A 1963 article published in Ebony attests to the relevance of the housewife ideal, with artist Priscilla Mills “only stopping to prepare dinner for her husband,” while housewife Gwendolyn Williams describes “keeping your husband and children happy” as a “challenging and fulfilling” duty. 43 For Black women, who had historically been employed in domestic labor in White households, being able to perform the role of a housewife in their own home represented unprecedented freedom that historians term “the double triumph.” 44

The popular perception of domestic abundance readily available through purchase of the electric oven demonstrates a correlation between family values and the narrative of superiority of the American consumer society that characterizes containment culture. Marketing that seeks to assimilate working class and minority women into previously unattainable standards of a perfect housewife reaffirms the prospect of advancement through social classes for all Americans, and effectively softens the appearance of social inequalities that could undermine the capitalistic ethos of the United States during the Cold War. Efficiency, Cleanliness, and Frugality as Vehicles of Assimilation

The marketing and design innovations of the electric range in the 1950s reflect a desire to assimilate working class, immigrant, and non-White women into White normative constructions of a perfect domesticity. Changing messaging surrounding the value of thrift and adaptability

43 Lerone Bennet Jr, “The Negro Woman,” Ebony, September 1963, 91-93.

44 Maire Simington, “Chasing the American Dream Post World War II: Perspectives from Literature and Advertising,” (PhD diss., Arizona State University, 2003) 271.

embedded into the design of the range speak to the ways marginalized women found space for non-normative cooking and kitchen labor practices as a by-product of the novelty and product diversification that characterized American consumer society in the 1950s.

In comparison to earlier counterparts, electric ranges of the 1950s were routinely marketed – especially among immigrant and working-class communities – as easy-to-clean. The Hispanic publication La Prensa advertised Mirasol Homes, a public housing community in San Antonio, by highlighting the improved standard-of-living a white enamel “easy-to-keep-clean" kitchen would bring residents. 45 In their guide for first-time buyers of an electric range, the Tennessee Valley Authority similarly encouraged consumers to look for a “porcelain enamel finish” on ranges, as well as rounded corners and seams within ovens as they facilitated effective cleaning.

46 The stain-resistant qualities of white porcelain and enamel finishes were especially marketable to racial minorities and working class because they represented an ease of assimilation into wealth and Whiteness through cleanliness, which would “erase the damaging traces of an immigrant, ethnic, or nonwhite past.”

47 In his 1951 poem Deferred, Langston Hughes linked dreams of a “white enamel stove” to the realization of the American Dream, and a

45 Mirasol Homes, “Modern Public Housing,” La Prensa (San Antonio, TX), Dec. 12, 1954, 12.

46 Selecting Your Electric Range” (Knoxville, TN: Tennessee University College of Home Economics, 1954), 14-15.

47 Selecting Your Electric Range” (Knoxville, TN: Tennessee University College of Home Economics, 1954), 14-15.

life of privilege unknown to him as an African American in the 1950s. 48 Thus, the exaltation of the white porcelain kitchen to racial minorities and working-class groups historically regarded as inherently unclean, represents White-normative standards of cleanliness made attainable through consumption of new electrical appliances.

The electric range created behavioral restrictions and imposed what Rebecca Devers characterizes as a “modernizing habitus” in reference to sociologist Pierre Bourdieu's definition of a “habitus” as “widely accepted rules” in this case, like maintaining a clean, white kitchen free of odors or stains. 49 In some ways, the functionalities and surrounding expectations of how to care for the electric range effectively restricted the cooking practices of immigrant groups.

Dianne Harris refers to these consequences of the electric range in the context of a 1954 study of Chinese immigrants in Wisconsin, whose cooking was restricted by the low power of electric ranges compared to gas, as well as the lack of adequate exhaust and ventilation needed to cook traditional dishes. 50 Eventually, these Chinese Americans, aiming to conform to the ideal of a

48 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 3.

49 Rebecca Devers, “You Don’t Prepare Breakfast... You Launch It Like a Missile’: The Cold War Kitchen and Technology’s Displacement of the Home,” Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture, 1900 to Present 13, no. 1 (2014): 3.

50 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 55.

clean, odor free main kitchen, began setting up auxiliary kitchens in their garages or laundry rooms.

In a break from range design of previous decades, novel and highly marketable features of the electric range –a such as griddles, deep well cookers and fryers – were repurposed and adapted to use in culturally specific cooking practices. Dianne Harris recalls the phenomena of adapting electrical appliances for use in “ethnic” cooking practices through memories of her Jewish grandmother repurposing a griddle on her built-in electric range to make matzo brei and latkes, although it was designed and marketed for cooking pancakes. 51 Examples of cultural repurposing situate the electric range squarely in the paradoxes of containment culture. 52 A mutual exchange thus occurred between electric range designers, who made space for, but still restricted and effectively diluted, the cooking practices of women at the margins of a White, suburban housewife ideal.

The prevalence of multifunctional, deep-well cookers and fryers illustrate a necessary expansion amidst the Cold War from exclusionary to pluralistic conceptualizations of home cooking. Hotpoint’s electric range models of many sizes and costs came equipped with a deepwell “Thrift cooker” designed for a range of techniques from steaming, pickling, braising, and, when paired with the “Calrod Golden Fryer” accessory, safe and temperature precise frying

51 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 45.

52 Shelley Nickles, “More Is Better: Mass Consumption, Gender, and Class Identity in Postwar America,” American Quarterly 54, no. 4 (2002): 605.

(Figure 10). 53 Deep wells were a staple feature in the 1950s for electric ranges of all sizes and price brackets and were marketed based on economical deep-fat frying due to the ease of recycling lard. 54 Frying was especially characteristic of southern, rural, and working-class cooking, thus the innovation of the deep well reflects a deliberate effort to capture emerging markets. 1954, La Prensa shared Mirasol Homes resident Maria Huerta’s use of her bulky, white electrical range to make a “Tortas de Camaron” recipe that safely deep-fried shrimp in her small, clean apartment (Figure 11). 55 Range design and marketing guides acknowledge a growing divergence from “bland, New England cuisine,” typically marketed in relation to kitchen appliances Hotpoint’s instruction manual includes recipes like “Seafood Croquettes” similar to Mrs. Huerta’s excerpt, as well as other “ethnic” and rural recipes like “Turkish Pilaf,” “Hungarian Goulash,” and “Corn Fritters” to provide guidance on how the “Thrift Cooker” and companion “Calrod Golden Fryer” were to be used. 56

The language of deep-well user guides and advertising demonstrates a reconceptualization of “thrift” as the driving force that softened racist constructions of non-white home cooking. After decades of food scarcity during the Depression and through wartime rationing, immigrants were seen as making “intelligent” choices in food practices that involved

53 Virginia Francis. Let’s get acquainted with your Hotpoint electric range: instruction and recipe book (Chicago: Hotpoint Home Economic Institute, 1955), 32.

54 “Selecting Your Electric Range” (Knoxville, TN: Tennessee University College of Home Economics, 1954), 7.

55 Maria Huerta, “Tortas de Camaron,” La Prensa (San Antonio, TX), Dec. 12, 1954, 15.

56 Virginia Francis. Let’s get acquainted with your Hotpoint electric range: instruction and recipe book (Chicago: Hotpoint Home Economic Institute, 1955), 33.

recycling fats and stocks that saved money and met nutritional needs. 57 When subsequently appraised amidst the rhetoric of preserving individual family values amidst the Cold War, nonnormative cooking practices like those of immigrants or rural households were quietly facilitated by mainstream range design.

The two-way exchange between appliance designers seeking to capture emerging markets, and the women adapting the electric range for their own uses resulted in a design ethos in the kitchen characterized by highlighting, rather than concealing, the intense functionalities of the electric range. The advertising of features that saved space, regulated temperatures, and overall positioned the range as a highly functional centerpiece of an adaptable, habitable kitchen space is indicative of the extent to which marginalized woman found empowerment in emulating the efficient, devoted, housewife ideal in the postwar era. The Latino newspaper Las Notas De Kingsville has a Uvalde resident, Mrs. K.W. Moore, attest to the value of an electric range in keeping a compact kitchen cool (Figure 12). 58 Rather than solely idealizing a spacious, custombuilt kitchen, The Tennessee Valley Authority guide to selecting an electric range, and a Westinghouse newspaper advertisement represent range models with “tuck away space,”

57 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 145.

58 Central Power and Light Company, “Advertisement”, Notas de Kingsville (Kingsville, TX), Apr. 9, 1953, 4.

60

allowing for a stool or storage to be placed within the kitchen (Figure 13). 59 Due to newly acquired wealth, working class and minority women

By the 1950s, design experts like the Modern Museum of Art had excused themselves from discourse on what constituted “good design” in relation to the electric stove, citing the futility of the task due to the dominance of market forces and functional requirements of the appliance. 61 Taste and style, as the MoMA dictated in the realm of furniture, were largely irrelevant to the concerns of the newly prosperous women in the 1950s. Because investment into the kitchen was tied to advancing standards of living, working-class women preferred bulky appliances that conveyed security and permanence. 62 Functionality and time saving were also of greater importance than style to women who did not fit the ideal of a suburban White housewife.

When interviewed by Ebony in 1963, Black lawyer Romae L Turner, married to an optometrist, speaks to her experience cooking for her family while balancing her career. She describes “not having time for frivolities,” and needed to make every moment of her kitchen

59 “Selecting Your Electric Range” (Knoxville, TN: Tennessee University College of Home Economics, 1954), 1; Westinghouse, “Look to your Laurels, Mom,” Newsweek (New York, NY), May 1, 1950, 42.

60 Shelley Nickles, “More Is Better: Mass Consumption, Gender, and Class Identity in Postwar America,” American Quarterly 54, no. 4 (2002): 600.

61 Thomas Hine, "Design and Styling," in Populuxe (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2007), 65.

62 Shelley Nickles, “More Is Better: Mass Consumption, Gender, and Class Identity in Postwar America,” American Quarterly 54, no. 4 (2002): 588.

labor count. 63 For a Black woman like Turner, the ability to cook for her own family while working outside the home – and not in the service of White households – was an empowering act made feasible by the advances of the electric range. Due to pride associated with maintaining the kitchen as a safe, empowering domestic space separate from the inequities of American society, range design interventions marketable towards employed, lower income and minority women

The presence of design interventions in the electric range like ease of cleaning, space saving, and resource conservation speak to the paradoxical nature of containment culture for women at the margins of the traditional suburban housewife ideal. On one hand, messaging surrounding the cleanliness of the electric range reflects an imposition of White standards of domestic labor onto racialized women. On the other hand, a push for novelty and capturing new consumer markets for the electric range through innovations like the deep well created space for diverse culinary practices. The creation of space for such practices as an “expansion of the hegemonical kitchen” made the prospect of upgrading one's standard of living tangible for immigrants and racial minorities. 64 The concessions in design rhetoric surrounding the electric range made permissible the working class and lower income lifestyles where the kitchen could still be a symbol of modernity and prosperity. Such shifts in messaging were critical to retaining faith in an American consumer society considering the Cold War, yet the continued relevance of

63 Lerone Bennet Jr, “The Negro Woman,” Ebony, September 1963, 94.

64 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 8.

the American Dream they provided for minority women created additional opportunities for assimilation, control, and sanitization of cultural cooking practices.

The Range as a Means of Social Transgression Among White Women

Suburban White women embodied a place of privilege in Cold War constructions of ideal womanhood, yet their experience with containment culture through the electric range was fraught with contradictions. In terms of both the design and culinary output of the electric range, the sterility and efficiency of prewar kitchens became obsolete in terms of communicating suburban affluence. 65 To this effect, the configuration of the White American kitchen saw the most significant formal and stylistic redevelopments in the postwar period. The discourse surrounding styling and use of the electric range among suburban White women communicated dual efforts to assert their personhood while grappling with emerging threats – like racial unrest – to their position of relative privilege in American society. As technological improvements in the electric range made quality home cooking more affordable and attainable for the masses, including the working class and racial minorities, suburban constructions of an ideal kitchen would evolve further to retain the privileged position of White womanhood. 66 White anxieties surrounding the implications diversifying range design on preexisting constructions of Whiteness

65 Marilyn Mercer, “The Gourmets Get out of Hand,” Harper’s Magazine, February 1957, 37.

66 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 133.

67

in the kitchen is evident in the silence of high design institutions like the Museum of Modern Art on the matter of kitchen appliance design.

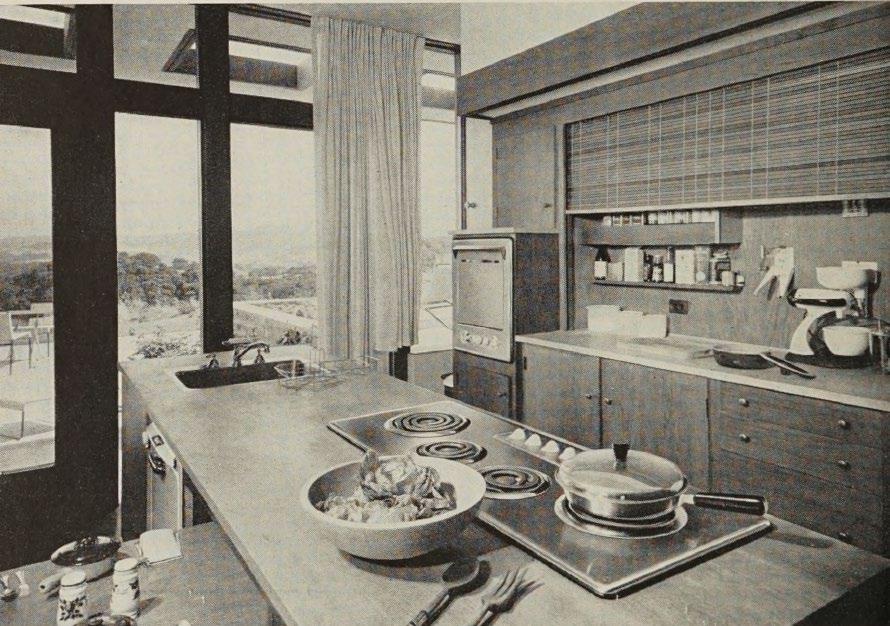

For suburban White women to keep their sense of womanhood invested in the domestic sphere, the portrayal of kitchen labor had to shift from one of drudgery into a professionalized, sophisticated, and knowledge-based pursuit. To this effect, the electric range was divided into its functional components as an oven and cooktop, and assimilated into the luxurious, stylized form of the suburban kitchen. In Thermador’s guide to “Planning a Carefree Kitchen,” the integration of a sleek, gleaming built- in oven and the disappearance of the cooktop into a stretch of cabinetry demonstrates the desire to divorce oneself from the labor and intense functionalities of kitchen appliances (Figure 14).

68

The built-in oven was instrumental in promoting a dignified understanding of homemaking for White women, as it eliminated “stooping, bending, or sweating while at work in the home.”

69 The dainty, feminine appearance of well dressed, high-heeled women depicted in built-in range advertising reinforces the messaging that through the acquisition of custom builtins, White women could be freed from the strain of demanding labor and thus preserve their

67 Thomas Hine, "Design and Styling," in Populuxe (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2007), 65.

68 Plan a carefree kitchen with Thermador: the original bilt-in electric range (New York: Thermador Electrical Manufacturing Co, 1950), 3.

69 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 205.

femininity and beauty (Figure 15).

70 Built-in range features became more feasible and marketable due to rising incomes post-war, yet it was disproportionately suburban homeowners, most of whom were White, who could realize this kitchen design ideal, and by extension, the notion of a perfect, delicate womanhood that came with it. 71

Built in electric range components were also marketed in the context of creating more storage space within the kitchen. Due to postwar patterns of suburbanization, acquisition of storage space to contain and display an increasing number of material possessions became linked to affluence, family stability, and Whiteness.

72 Thermador’s “Planning a Carefree Kitchen,” underscores expanded storage space as a primary selling point for its built-in and custom design services, asserting that built-ins resulted in “more space to store utensils.”

73 Where functionality became obsolete as a marker of Whiteness and affluence, the presence of the range was minimized to make space for the domestic items that remained relevant as signifiers of status in

70 Central Power and Light Company, “Built-in convenience,” La Verdad (Corpus Christi, TX), Mar. 9, 1956, 3.

71 “Improving the Kitchen,” New York Times (New York, NY), Feb 27, 1955, 48; Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 7.

72 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 1.

73 Plan a carefree kitchen with Thermador: the original bilt-in electric range (New York: Thermador Electrical Manufacturing Co, 1950), 6.

the kitchen: utensils and furniture. 74 The need to maintain “a place for everything” through orderly storage units became correlated to the middle-class White constructions of the kitchen, rooted in elevating domestic tasks to a professional level, displaying household objects of good taste, and freeing housewives from physically demanding and degrading tasks. 75 As innovations for maximum functionality in the electric range became widely accessible to the socially marginalized, White suburbanites turned to minimizing the presence of the range in their kitchens, establishing new design norms to gatekeep their privileged identity in response to fears of growing consumer power amongst the working class and racial minorities. 76

Amidst the debates of personal freedom during the Cold War, characterized by experimentation, self-expression, and transgressions against design conventions established in previous decades all characterized White privilege in the kitchen. In her satirical Harper’s magazine article “My Kitchen Hates Me,” Sylvia Wright is critical of the “bleak, closed off” and prescriptive effect storage units had on the modern kitchen. 77 While immigrants and women of color – deemed inherently unclean themselves – sought to embody the cleanliness and assimilation into Whiteness that a freestanding White enamel range signified, from the

74 Thomas Hine, "Design and Styling," in Populuxe (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2007), 75.

75 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 206.

76 Paul Boyer, “The United States, 1941-1963: A Historical Overview,” in Vital Forms: American Art and Design in the Atomic Age 1940-1960, ed. by Brooke K Rapaport and Kevin L. Stayton (New York: Harry N Abrams, 2001), 62.

77 Sylvia Wright, “My Kitchen Hates Me,” Harper’s Magazine, August 1953, 93.

perspective of upwardly mobile suburban White women, “modern kitchens evidently got too clean.” 78 The desire for “warmth” and "authenticity" in the post-war suburban kitchen increased the marketability of colored models of the cooking range. 79 An interest in expressive, unconventional colored range models can be situated in the postwar trend of experimentation and transgression of societal conventions in the safety and privacy of the home. 80 Colored cooking ranges were most popular amongst, young, White suburban housewives who wanted to be “unlike their homebody mothers and grandmothers,” reflecting inclinations to exercise agency amidst patriarchal conditioning that relegated them to the domestic sphere. 81

The introduction of color into the electric range was one way in which women like Frigidaire’s all-female design group “Damsels of Detroit” sought to take decision making away from men. 82 Women’s use of color to reclaim their power from male experts in industrial design and home science exemplifies the paradoxes of containment culture. In 1954, Frigidaire put forth a full ensemble of colored electric appliances, taking a new approach to style obsolescence by encouraging households to incrementally purchase a “full ensemble,” as monochromatic

78 Sylvia Wright, “My Kitchen Hates Me,” Harper’s Magazine, August 1953, 91.

79 Sylvia Wright, “My Kitchen Hates Me,” Harper’s Magazine, August 1953, 92; Wini Brienes, “Postwar White Girls Dark Others,” in The Other Fifties: Interrogating Midcentury Icons, ed. Joel Foreman (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 54.

80 Sylvia Wright, “My Kitchen Hates Me,” Harper’s Magazine, August 1953, 93.

81 Regina Blaszczyk, The Color Revolution, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 18.

82 Regina Blaszczyk, The Color Revolution, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 249.

schemes were coveted amongst circles that could afford them. 83 Commitment to a color scheme by selecting a colored cooking range required an added financial investment and sense of “permanent stability” typically only afforded to White homeowners. 84 The consequences of purchasing a colored electric range were further complicated by home valuation liabilities due to variation in color preferences. 85 As a result, expressions of self through the purchase of a colored electric range remained rooted in the patriarchal limitations imposed on women and the individualistic consumer culture of the United States amidst the early years of the Cold War.

Given that the energy-efficient, high-speed functionality of the electric range was making routine home cooking easier for the masses, suburban White housewives sought to assert their social status by showcasing their cultural knowledge, creativity, free time as a “valued commodity.”

86 In 1957, The American Home Book of Kitchen Ideas: How to Give your Kitchen the ‘57 look introduced the ‘oriental’ kitchen as a playful and experimental style. 87 As design shifts like the built-in electric range removed suburban White women from the physical drudgery

83 Regina Blaszczyk, The Color Revolution, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 259; “Improving the Kitchen,” New York Times (New York, NY), Feb 27, 1955, 48.

84 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 1.

85 Regina Blaszczyk, The Color Revolution, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 257.

86 Marilyn Mercer, “The Gourmets Get out of Hand,” Harper’s Magazine, February 1957, 35.

87 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 133.

of the cooking process, interest in international cuisine emerged as a “creative outlet” as Marilyn Mercer notes in her 1957 Harper’s magazine article, “The Gourmets Get Out of Hand.” 88

Towards the end of the 1950s when exotic” ingredients like “sesame, coriander, and dried bonito fish” made their way into “even the most ordinary family kitchen.” 89 White women's postwar efforts to redefine their relationship to kitchen labor as one that was intellectually sophisticated rather than physically demanding thus displayed a divergence from prior aversions to “ethnic” cuisines.

Underlying race-related anxieties amidst the Cold War inform this cultural shift amongst White women that resulted in an acceptance of international food in home cooking. Amid “concerns that the United States was perceived as more racist than the Soviet Union,” an onus was placed on White mothers to “raise more cosmopolitan children.” 90 Food subsequently became the site of performative acceptance of the racialized “other” among an emerging educated White suburbia. However, the extent to which home cooking signified a reduction in racial difference was limited. Whitewashed home cooking like a “Mexican' chowder,” and a “sukiyaki” recipe that was simply steak strips with the addition of “oriental” ingredients like bamboo shoots and mushrooms provided in Hotpoint’s electric range guide highlight the use of

88 Marilyn Mercer, “The Gourmets Get out of Hand,” Harper’s Magazine, February 1957, 36.

89 Marilyn Mercer, “The Gourmets Get out of Hand,” Harper’s Magazine, February 1957, 35.

90 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 9.

the appliance to engage with the ethnic “other” in a hegemonic, sanitized manner. 91 The safety, precision, and projected modernity of the electric range thus created opportunities for upwardly mobile suburban White housewives to be creative and experimental in their cooking, while also participating in a “safe and palatable antiracism” that sought to preserve a progressive, democratic national image. 92

The occurrence of an “International Electric Cooking Competition,” reaffirms the reductive and performative, but highly publicized campaign that used the electric range to commodify minorities and promote a hegemonical construction of international cooking. A Chicago-based Mexican cooking competition described by Vida Latina in 1956 characterizes Mexican immigrants by their “billowing sequin splanged skirts and fresh peasant blouses” cooking enchiladas for the first time with an electric range. 93 The article asserts that alongside her experience in cooking for her many grandchildren in Monterrey, it was the “modern convenience” of the electric range that allowed winner Irene Jaramilla to cook her winning

91 Virginia Francis. Let’s get acquainted with your Hotpoint electric range: instruction and recipe book (Chicago: Hotpoint Home Economic Institute, 1955), 31; aura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 137.

92 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 175.

93 “Cooking Contest,” Vida Latina (Chicago, IL), Aug. 21, 1956, 27.

enchilada recipe with “time to prepare a tantalizing salad platter.” 94 The article notes the scheduling of similar competitions for a host of nationalities including Iran, Lithuania, Armenia, Sweden, Czechoslovakia, Italy, and a “Jewish” ethnic category, which would culminate in a final competition for preparing an American recipe – lemon meringue pie. 95

Overall, through expanding design and culinary expectations, the electric range embodies White women's negotiations of power in the face of gender-based marginalization and anxieties surrounding racial conflict. As time, cost, and energy saving functionalities of the range became available to the masses, White women sought to project an elevated status of their kitchen endeavors. Built-in designs that minimized the physical functionalities of the range and privileged styling through display of utensils and decor emerged as a new expression of prosperity and Whiteness in the kitchen. The use of pastel, monochromatic color schemes were another vehicle for White women to define their relationship to the kitchen as one of creativity and self-expression rather than the tiring, prescriptive labor of previous generations and their more marginalized counterparts. The creation of localized opportunities to communicate good taste, sophistication, and creativity within the kitchen allowed a continued pattern of marking status through consumption of appliances like the range, while providing a “compensatory discourse” in which women could enjoy the freedom and advancement of American society from

94 “Cooking Contest,” Vida Latina (Chicago, IL), Aug. 21, 1956, 28.

95 “Cooking Contest,” Vida Latina (Chicago, IL), Aug. 21, 1956, 29.

the confinement of the domestic sphere. 96 An unprecedented interest in “ethnic” cooking also afforded middle class White women similar opportunities to exercise their creativity, but also carry out a nationalistic duty to promote a performative notion of cultural acceptance through their prescribed role as housewives. The freedom from physical drudgery to focus on creative expression afforded to middle class White women in the kitchen embodies the dichotomies of containment culture. These women were provided opportunities to diverge from prior constructions of Whiteness and propriety, but these freedoms were localized to the kitchen in ways that benefitted American consumer capitalism and postwar political agendas.

Conclusion

In its many design iterations over the course of a decade, the electric range of the 1950s was a physical manifestation of Cold War rhetoric, and the appliance shaped conceptions of empowerment, assimilation, and gendered citizenship among American women. Through the design of features like pushbuttons, and advertising the speed, automation, and efficiency of the electric range, kitchen labor underwent a process of militarization during the early years of the Cold War. Through prescriptive marketing messages, print literature from the period portrays cooking with the help of the electric range as a highly mathematical, intellectually stimulating responsibility that necessitated deference to technical experts. The marketing of the electric range as a precise, reliable, and technologically advanced appliance was part of a broader

96 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 14.

sociopolitical objective of the postwar era to elevate the perception of domestic labor. 97 Thus, the range functioned as a means of persuasion for women, who had taken up wartime employment, to return to the domestic sphere while still benefitting from postwar prosperity and technological progress.

On the international stage, kitchen appliances like the electric range became a means for the United States to assert national supremacy amidst the Cold War. The family-oriented, gendered, and stratified marketing messages surrounding various features of the electric range like the oven, deep well, built-ins, and colored finishes indicate that the appliance held cultural and political significance that reached beyond mere technological superiority. Rather, the electric range embodies the “schizophrenic” character of the postwar era rooted in cultural dilemmas of legitimizing the American promise of freedom, individuality, and upward mobility through consumerism amidst cultural anxieties and threats to established social norms. 98 Divergences seen in the design and marketing of the electric range in the 1950s were informed by the desire to legitimize a capitalistic ethos amidst the looming threat of Communism, contain women in a prescribed role of the housewife, and neutralize underlying anxieties surrounding racial unrest or integration.

97 Carlie Seigal, “The Ideal Woman: The Changing Female Labor Force and the Image of Femininity in American Society in the 1940s and 1950s,” (honor’s thesis, Union College, 2012), 1.

98 Paul Boyer, “The United States, 1941-1963: A Historical Overview,” in Vital Forms: American Art and Design in the Atomic Age 1940-1960, ed. by Brooke K Rapaport and Kevin L. Stayton (New York: Harry N Abrams, 2001), 39.

The availability of electric range models at various price points, sizes, and functionalities allowed women at the margins of the White suburban housewife ideal – such as rural, working class, and minority women – to assimilate into a White normative, patriarchal construction of women's citizenship exalted as an expression of American prosperity during the early years of the Cold War. The messaging towards marginalized women focused on the functionality and cleanliness of the electric range, imposing ideals historically linked to White womanhood onto their cooking practices. Nevertheless, the mass availability of auxiliary features like the deep well, griddle, and fryer –novelties intended to facilitate perpetual consumption- created space for minority, rural, and working-class women to carry forth adapted, often diluted, versions of their cultural cooking.

99

In response to threats of political division or unrest amidst the Cold War, previously xenophobic perceptions of acceptable home cooking softened to permit the “ethnic,” and experimental in the kitchen. Criticisms of the United States as intolerant and xenophobic compared to the Soviet Union resulted in White women being encouraged to experiment with bringing international, and particularly “oriental” food and styling into their kitchens. 100 The marketing of the electric range through recipe books and print discourse amongst White women was a key facilitator of this cultural shift. Sanitization and distortion of “ethnic” cuisine through

99 Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 45.

100 Laura Scott Holliday, “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign,” (doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000), 9.

home cooking from the precision and safety of the electric range is emblematic of the “containment” of non-White people and culture within the norms of the nuclear family and a culture of consumption

As basic functionalities of the electric range made routine home cooking more accessible for a wider population of women, wealthier, suburban White women found new ways to communicate privilege and status through their kitchens. Along with skill intensive, international recipes that indicated an increase in intellectual effort in the kitchen, the physical presence of the cooktop and oven were minimized in affluent kitchens with the advent of built-in appliances and storage units. While racial and ethnic minorities were marketed freestanding, white enamel ranges that signified induction into dominant constructions of cleanliness and prosperity achieved through hard work, for wealthier White women, the safeguarding of freedom during the Cold War manifested as controlled opportunities for self-expression and nonconformity. Ample storage to display decor and utensils, experimental styling using color, and novel recipes thus became dual agents of signaling status, and of keeping suburban, White women’s decisionmaking confined to the kitchen. Ultimately, the design diversification and wider availability of the electric range provided American women in the 1950s with a facade of agency and empowerment, one that effectively limited constructions of female citizenship to the domestic sphere to serve the broader sociopolitical goals of Cold War containment culture.

Newspaper advertisement highlighting the benefits of an electric range. 1954. La Verdad

6. Page design from Thermador’s Kitchen Planning Guide. 1950. Thermador Electrical Manufacturing Co.

Figure 7. Surface cooking chart provides space for users to add personalized optimal cooking times. 1955. Hotpoint Home Economics Institute.

8. Illustration of potential culinary output from Westinghouse electric range. 1950. Newsweek.

9.

of woman preparing a roast inside an electric oven. 1950. Thermador Electrical Manufacturing Co.

Figure 10. Introductory page with photograph and illustration of Calrod Golden Fryer. 1955. Hotpoint Home Economics Institute.

Figure 13. Photograph of Westinghouse’s Rancho Range with “tuck away” space. 1950. Newsweek.

14. Photograph of custom-built kitchen ensemble furnished with Thermador appliances. 1950. Thermador Electrical Co.

Bibliography

Aiken, Walter. “Menu, Seating Arrangements, etc.” Atlanta, GA: Keenan Research Center, 1959. https://www-aac-amdigital-couk.ezproxy.uta.edu/Documents/Images/ahc_MSS_0468_0003_0010_0001_0001/9

“Appliance ‘Countdown’ Cuts Service.” Latin Times (East Chicago, IN), Aug. 18, 1961.

Bean, Ruth. All-in-one Oven Meals. New York: M Barrows & Company, 1952.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112085296876&seq=36

Bennet, Lerone. “The Negro Woman.” Ebony, September 1963. https://www-aac-amdigital-couk.ezproxy.uta.edu/Documents/Images/UIC_BHC_0001_0001/43

Berkman, Dave. “Advertising in ‘Ebony’ and ‘Life’: Negro Aspirations vs Reality.” Journalism Quarterly 40, no 1. (1963): 53-64. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769906304000107

Blaszczyk, Regina. The Color Revolution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2012.

Boyer, Paul. “The United States, 1941-1963: A Historical Overview.” in Vital Forms: American Art and Design in the Atomic Age 1940-1960, edited by Brooke K Rapaport and Kevin L. Stayton, 38-75. New York: Harry N Abrams, 2001. 38-75.

Brienes, Wini. “Postwar White Girls Dark Others.” In The Other Fifties: Interrogating Midcentury Icons, edited by Joel Foreman, 53-72. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Budweiser. “Advertisement.” Ebony, September 1963.

Calvo-Quirós, William A. “THE POLITICS OF COLOR (RE)SIGNIFICATIONS:

Chromophobia, Chromo-Eugenics, and the Epistemologies of Taste.” Chicana/Latina Studies 13, no. 1 (2013): 76–116. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43941382

Central Power and Light Company. “Advertisement”. Notas de Kingsville (Kingsville, TX), Apr. 9, 1953.

Central Power and Light Company. “Advertisement”. Verdad (Corpus Christi, TX), Nov. 19, 1954.

Central Power and Light Company. “Built-in convenience.” La Verdad (Corpus Christi, TX), Mar. 9, 1956.

Central Power and Light Company. “Advertisement.” La Verdad (Corpus Christi, TX), Mar. 15, 1957.

Central Power and Light Company. “Advertisement.” La Verdad (Corpus Christi, TX) Oct. 30, 1959.

Central Power and Light Company. “Cook the Automatic Electric Way.” Notas De Kingsville (Kingsville, TX), Mar 5, 1959.

“Cooking Contest.” Vida Latina (Chicago, IL), Aug. 21, 1956.

Dacre, Douglas. “The Great Chinese Food Hoax.” Macleans, October 1955. https://login.ezproxy.uta.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/greatchinese-food-hoax/docview/1437754395/se-2?accountid=7117

Devers, Rebecca. “‘You Don’t Prepare Breakfast... You Launch It Like a Missile’: The Cold War Kitchen and Technology’s Displacement of the Home.” Americana: The Journal of

American Popular Culture, 1900 to Present 13, no. 1 (2014): 1-12.

https://login.ezproxy.uta.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarlyjournals/you-dont-prepare-breakfast-launch-like-missile/docview/1647734887/se2?accountid=7117

Ed Byrne Home and Auto Supply. “Advertisement.” Notas de Kingsville (Kingsville, TX) Oct. 16, 1958.

Flato’s Downtown Store, “Advertisement,” La Verdad (Corpus Christi, TX), Sept. 5, 1958.

Francis, Virginia. Let’s get acquainted with your Hotpoint electric range: instruction and recipe book. Chicago: Hotpoint Home Economic Institute, 1955.

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d022566223

Greenidge, Kaitlyn. “Interview with Louise B. Boyd,” interview transcript and recording, 2011

Weeksville Oral History Series, Weeksville Heritage Center, African American Communities, Adam Matthews Digital Database. https://www-aac-amdigital-couk.ezproxy.uta.edu/Documents/Details/whc_oralhistory_louisskookiebrown#transcript

Gustafson, Philip. “The Fight for Sales Changes Marketing Methods.” The Nation’s Business 48, no. 7 (1960): 38-52.

https://login.ezproxy.uta.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/fight-saleschanges-marketing-methods/docview/231625758/se-2?accountid=7117

Harris, Dianne. Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Hine, Thomas. “Design and Styling.” In Populuxe, 66-81. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2007.

Hine, Thomas. “Just Push the Button.” In Populuxe, 123-138. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2007.

Holliday, Laura Scott. “The Frying Pan and the Fire: Gendered Citizenship and the American Kitchen from the Postwar Era to the Family Values Campaign.” Doctoral Dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara, 2000. https://login.ezproxy.uta.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertationstheses/frying-pan-fire-gendered-citizenship-american/docview/250138827/se2?accountid=7117

Huerta, Maria. “Tortas de Camaron.” La Prensa (San Antonio, TX), Dec. 12, 1954.

“Improving the Kitchen.” New York Times (New York, NY), Feb 27, 1955, 48. https://login.ezproxy.uta.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historicalnewspapers/improving-kitchen/docview/113228582/se-2?accountid=7117

Kwamogi Okello, Wilson and Tiless Alesha Turnquest. “Standing in the kitchen’: race gender, history, and the promise of performativity.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 35 no. 2. (2022): 228-243. https://doiorg.ezproxy.uta.edu/10.1080/09518398.2020.1828653

Maffei, Nicolas. “Selling Gleam: Making Steel Modern in Postwar America.” Journal of Design History 26 no. 3 (2013): 304-320.

Mclean, Beth. Modern Homemaker’s Cookbook. New York: M Barrows & Company, 1950.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924003578691&seq=27

Mercer, Marilyn. “The Gourmets Get out of Hand.” Harper’s Magazine, February 1957.

https://login.ezproxy.uta.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/gourmetsget-out-hand/docview/1301532424/se-2?accountid=7117

Mesa-Bains, Amalia. “Domesticana: The Sensibility of Chicana Rasquache.” Aztlan 24, no. 2. (1999):157-67. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uta.edu/10.1525/azt.1999.24.2.157

Mirasol Homes. “Modern Public Housing” La Prensa (San Antonio, TX), Dec. 12, 1954.

Neuhaus, Jessamyn. “Cooking at Home: The Cultural Construction of American ‘Home Cooking’ in Popular Discourse.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Food and Popular Culture, edited by Kathleen Lebesco and Peter Naccarato, PP to PP. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

Nickles, Shelley. “More Is Better: Mass Consumption, Gender, and Class Identity in Postwar America.” American Quarterly 54, no. 4 (2002): 581-622. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30041943

Nickles, Shelley. “Preserving Women’: Refrigerator Design as a Social Process in the 1930s.”

Technology and Culture 43 no. 4 (2002): 693-727.

Plan a carefree kitchen with Thermador: the original bilt-in electric range. New York: Thermador Electrical Manufacturing Co, 1950.

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nnc2.ark:/13960/t0vr2js0t

Roberts, Jennifer. “Lubrications on the Lava Lamp.” In American Artifacts: Essays in Material Culture, edited by Jules David Prown and Kenneth Haltman, 167-189. Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 2000.

“Selecting Your Electric Range.” Knoxville, TN: Tennessee University College of Home Economics, 1954. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/inu.30000111995555

“September is Better Breakfast Month.” La Verdad (Corpus Christi, TX), Sept. 5, 1958.

Seigal, Carlie. “The Ideal Woman: The Changing Female Labor Force and the Image of Femininity in American Society in the 1940s and 1950s.” Honor’s Thesis, Union College, 2012.

https://digitalworks.union.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1940&context=theses

Shaun’s Hardware and Furniture, “Advertisement,” Notas de Kingsville (Kingsville, TX) Oct. 16, 1958.

Simington, Maire. “Chasing the American Dream Post World War II: Perspectives from Literature and Advertising.” Doctoral Dissertation, Arizona State University, 2003.

https://login.ezproxy.uta.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertationstheses/chasing-american-dream-post-world-war-ii/docview/305340098/se2?accountid=7117

Westinghouse. “Look to your Laurels, Mom.” Newsweek (New York, NY), May 1, 1950.

Wright, Sylvia. “My Kitchen Hates Me.” Harper’s Magazine, August 1953.

https://login.ezproxy.uta.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/mykitchen-hates-me/docview/1301533759/se-2?accountid=7117

Young, Whitney. “The Role of the Middle Class Negro.” Ebony, September 1963. https://wwwaac-amdigital-co-uk.ezproxy.uta.edu/Documents/Images/UIC_BHC_0001_0001/33