SPRING 2023

GOODBYE, PRESIDENT BEILOCK

A tribute to her tenure

SUZANNE VEGA ’81 ON PERFORMING PHILIP GLASS

MARISSA TREMBLAY ’12 EXPLORES ANTARCTICA

PHANÉSIA PHAREL ’21 MAKES ‘BLACK GIRL JOY’

SUZANNE VEGA ’81 ON PERFORMING PHILIP GLASS

MARISSA TREMBLAY ’12 EXPLORES ANTARCTICA

PHANÉSIA PHAREL ’21 MAKES ‘BLACK GIRL JOY’

A tribute to her tenure

SUZANNE VEGA ’81 ON PERFORMING PHILIP GLASS

MARISSA TREMBLAY ’12 EXPLORES ANTARCTICA

PHANÉSIA PHAREL ’21 MAKES ‘BLACK GIRL JOY’

SUZANNE VEGA ’81 ON PERFORMING PHILIP GLASS

MARISSA TREMBLAY ’12 EXPLORES ANTARCTICA

PHANÉSIA PHAREL ’21 MAKES ‘BLACK GIRL JOY’

2 Views & Voices

3 From President Beilock

4 From the Editor-in-Chief

5 Dispatches

Sian by the Numbers: An Infographic

A visual look at President Beilock’s many accomplishments (including a special appearance by Rosie the Cavapoo)

A Story in Stones

Geochemist Marissa

Tremblay ’12 analyzes Antarctic rocks to unravel Earth’s climate chronology and predict the planet’s future environment

Headlines | Q&A with President-elect Laura A. Rosenbury; Meet Dr. Sarah Ann Anderson-Burnett; Beyond Barnard at 5; An Alum at the Supreme Court; Columbia Women’s Basketball; Water Conference; Toddler Center at 50

11 Discourses

Faculty Focus | Tara Well

Read Watch Listen | Books by Barnard Authors; Zora Neale Hurston (Class of 1928); Jean Lichty ’81 and Phanésia Pharel ’21; Suzanne Vega ’81

37 Noteworthy

Passion Project | Khadijah Abdul Nabi ’08

Q&Author | Linda Elovitz Marshall ’71

AABC Pages | From the AABC President; A One-of-aKind Pandemic Presidency; URL to IRL

Class Notes

Alumna Profile | Jenn Pamela Chowdhury ’06

Crossword

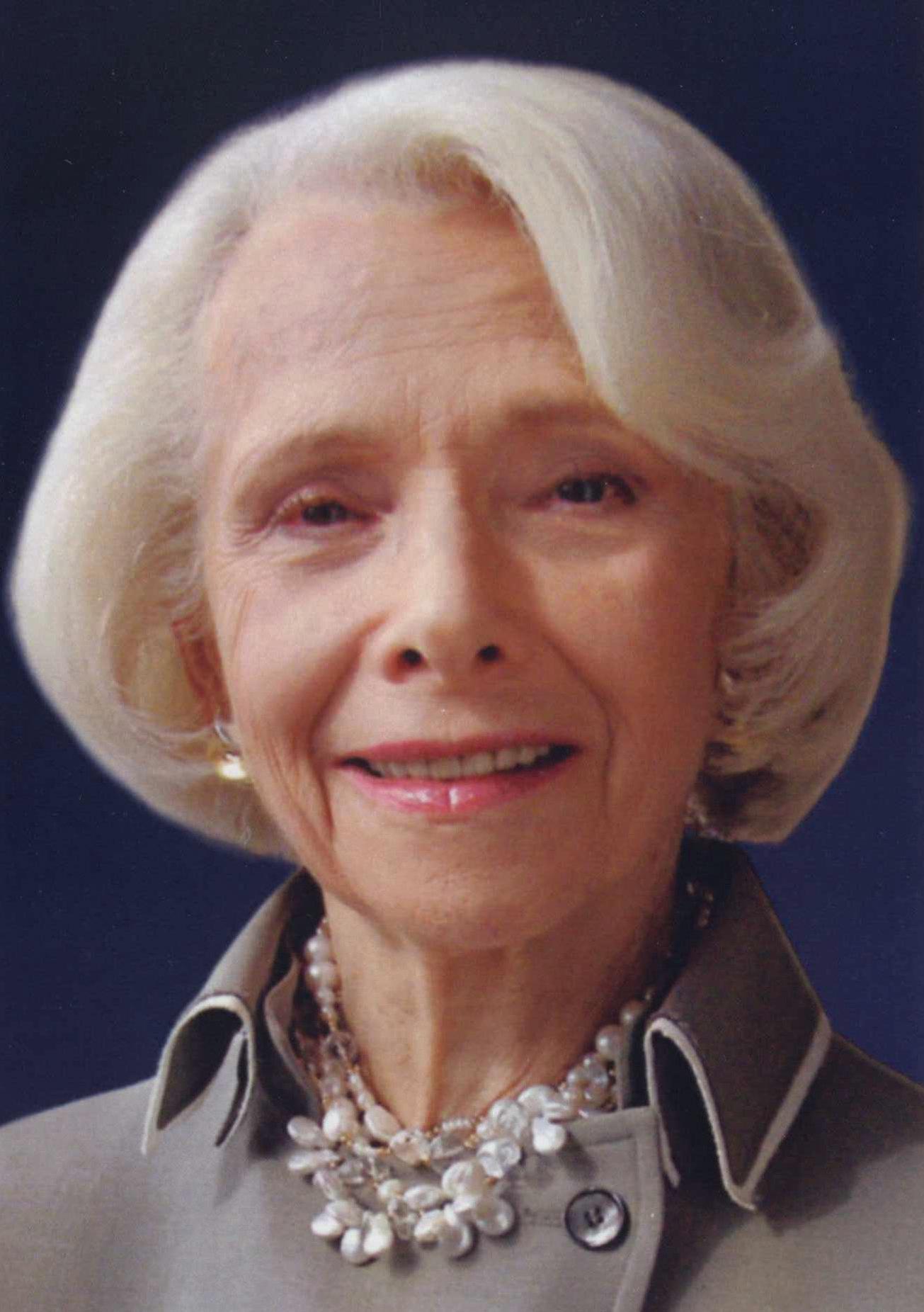

Obituaries | Helene Lois Kaplan ’53; Debra Tillinger ’04

In Memoriam

Last Word | Audrey Roofeh ’00

On the Cover and opposite page

Photos by Victoria Cohen

Back Cover

Photo of Riverside Park by Tom StoelkerRCTICA

Learn about alums shaping the New York City food scene in “Serving Community.” barnardbold.net/serving-community Read

Take a trip to the floral studio of Molly Oliver Culver ’03 in a video that complemented our feature “Breaking Ground in Sustainable Floristry.” barnardbold.net/sustainable-floristry

We hope you enjoy indulging in this deep dive into digital. We plan to bolster our digital offerings going forward, particularly for the online-only summer issue. Be sure to check out Barnard.edu/magazine for more photos, slideshows, and videos from Reunion 2023!

As always, we’d like to hear from you. More specifically, what are your thoughts on the change of administration? What do you think President-elect Rosenbury should know about Barnard? What would you like to ask her? Let us know at magazine@barnard.edu

EDITORIAL

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Nicole Anderson ’12JRN

CREATIVE DIRECTOR David Hopson

MANAGING EDITOR Tom Stoelker ’10JRN

COPY EDITOR Molly Frances

PRODUCTION DIRECTOR Lisa Buonaiuto

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS N. Jamiyla Chisholm, Kira Goldenberg ’07

WRITERS Marie DeNoia Aronsohn, Mary Cunningham, Preetica Pooni

STUDENT INTERNS Zuyu Shen ’24, Tara Terranova ’25

ALUMNAE ASSOCIATION OF BARNARD COLLEGE

PRESIDENT & ALUMNAE TRUSTEE Amy Veltman ’89

ALUMNAE RELATIONS

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Karen A. Sendler

ENROLLMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS

VICE PRESIDENT FOR ENROLLMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS

Jennifer G. Fondiller ’88, P’19

ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT FOR EXTERNAL RELATIONS AND LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT Emma Wolfe ’01 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Quenta P. Vettel, APR

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, DEVELOPMENT AND ALUMNAE RELATIONS Lisa Yeh P’19

PRESIDENT, BARNARD COLLEGE

Sian Leah Beilock

Spring 2023, Vol. CXII, No. 2

Barnard Magazine (ISSN 1071-6513) is published quarterly by the Communications Department of Barnard College.

Periodicals postage paid at New York, NY, and additional mailing offices.

Postmaster: Send change of address form to: Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598

EDITORIAL OFFICE

Barnard Magazine, Barnard College, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598 | Phone: 212-854-0085

Email: magazine@barnard.edu

Opinions expressed are those of contributors or the editor and do not represent official positions of Barnard College or the Alumnae Association of Barnard College. Letters to the editor (200 words maximum) and unsolicited articles and/or photographs will be published at the discretion of the editor and will be edited for length and clarity.

The contact information listed in Class Notes is for the exclusive purpose of providing information for the Magazine and may not be used for any other purpose.

For alumnae-related inquiries, call Alumnae Relations at 212-854-2005 or email alumnaerelations@barnard.edu.

To change your address, write to: Alumnae Records, Barnard College, Box AS, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027-6598

Phone: 646-745-8344 | Email: alumrecords@barnard.edu

Nearly six years ago, I stood in front of you at Riverside Church and laid out a new path forward — one I believed was worthy of this incredible institution. I spoke about making science a foundational part of the liberal arts, extending our classroom into New York City and beyond, strengthening the College’s mission to be diverse and inclusive, and empowering students to focus on and nourish their well-being so that they can succeed long after they have left Morningside Heights. I told you on that day I like to move fast, that I had grown up wanting to be a jockey, and patience was not exactly my calling card. But I also knew my first job was to listen, learn, and understand the culture that is singularly Barnard.

I look back on those early months as the secret to everything. I sat in faculty offices and gained insight into their research. I met with students in Diana to hear about their day-to-day experiences, challenges, and dreams for the future. I chatted with alums and parents on the lawn (now known as Futter Field). It was in those moments that we wrote Barnard’s future together. No president’s tenure is predictable. Mine has been no exception. From a global pandemic to an overdue nationwide reckoning with systemic injustice, there have been challenges. But here is what I believe deeply: We have met this moment. And what we have achieved, we have achieved together.

The examples are endless. I think about the conversations with students who spoke candidly about how their well-being outside of the classroom — whether mental, physical, or financial — was shaping academic performance. Out of those conversations came our Feel Well, Do Well campaign and the Francine A. LeFrak Foundation Center for Well-Being. Or one of my coffee chats with students, when a first-generation student mentioned how difficult it was to secure the funding needed to present her research in New Mexico. I told her the school had a program for exactly that purpose — but she correctly pointed out how complex and bureaucratic it was to access that kind of support. That moment launched Access Barnard: the first-ever program to directly reach international, first-generation, and low-income students and make their transition easier.

I leave Barnard with endless gratitude to every community member who has pushed us forward. We have much to celebrate. Welcoming the most diverse class in Barnard’s history. Seeing more than 40% of our students go into math and sciences. Growing our endowment by nine figures.

And more than anything, I will miss this community. My goal as a cognitive scientist and leader has always been to better understand the way people perform, to foster learning and collaboration and create a special alchemy where we become more than the sum of our parts. At Barnard, that magic exists. I have seen it too many times to count.

Thank you all, from the bottom of my heart, for making Barnard the extraordinary place it is. I know I leave you in the best of hands. I cannot wait to see what comes next. B

In January, just as we started to lay the groundwork for the Spring issue, we received an email from Marissa Tremblay ’12, an assistant professor in Purdue University’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences. She had recently returned from doing fieldwork in Antarctica, where she had led an all-women team to study the earth’s past climate. She asked if we might be interested in sharing her story in the Magazine. The decision was, well, a no-brainer. Not only is Professor Tremblay’s research timely and relevant, but it also speaks to the kind of groundbreaking leadership that is nurtured by and thrives at Barnard — the very kind of leadership we’ve been so fortunate to experience the past six years under President Sian Leah Beilock.

Our cover story, “A Triumphant Presidency,” reflects on President Beilock’s many achievements and the indelible legacy she has left the College. One accomplishment that has particularly made a mark on the Magazine has been her focus on strengthening and supporting STEM at Barnard, which in turn has given us the opportunity to tell some pretty fascinating stories, from our exceptional student- and faculty-led research to our alumnae who are leading the way in fields from artificial intelligence to environmental science.

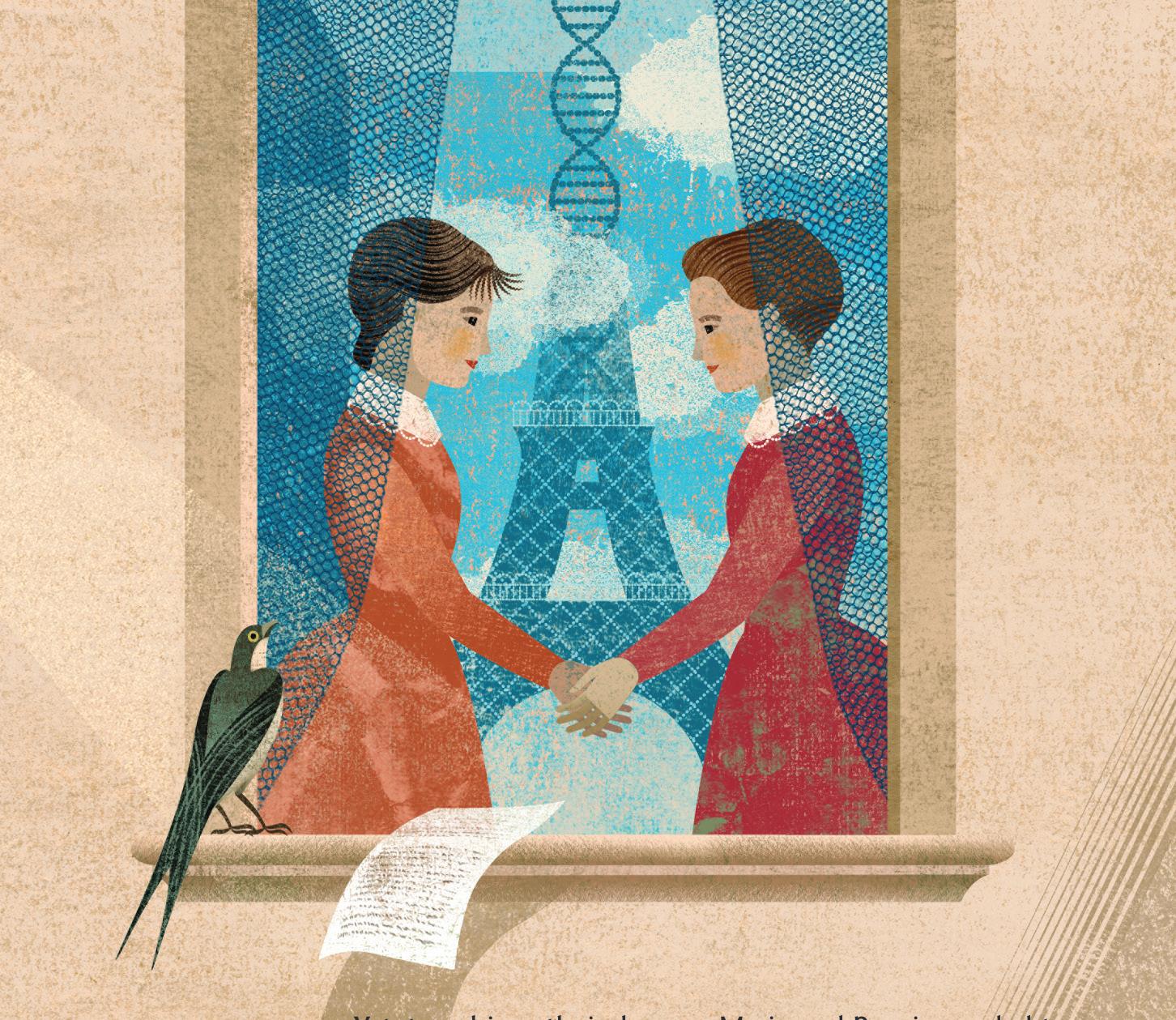

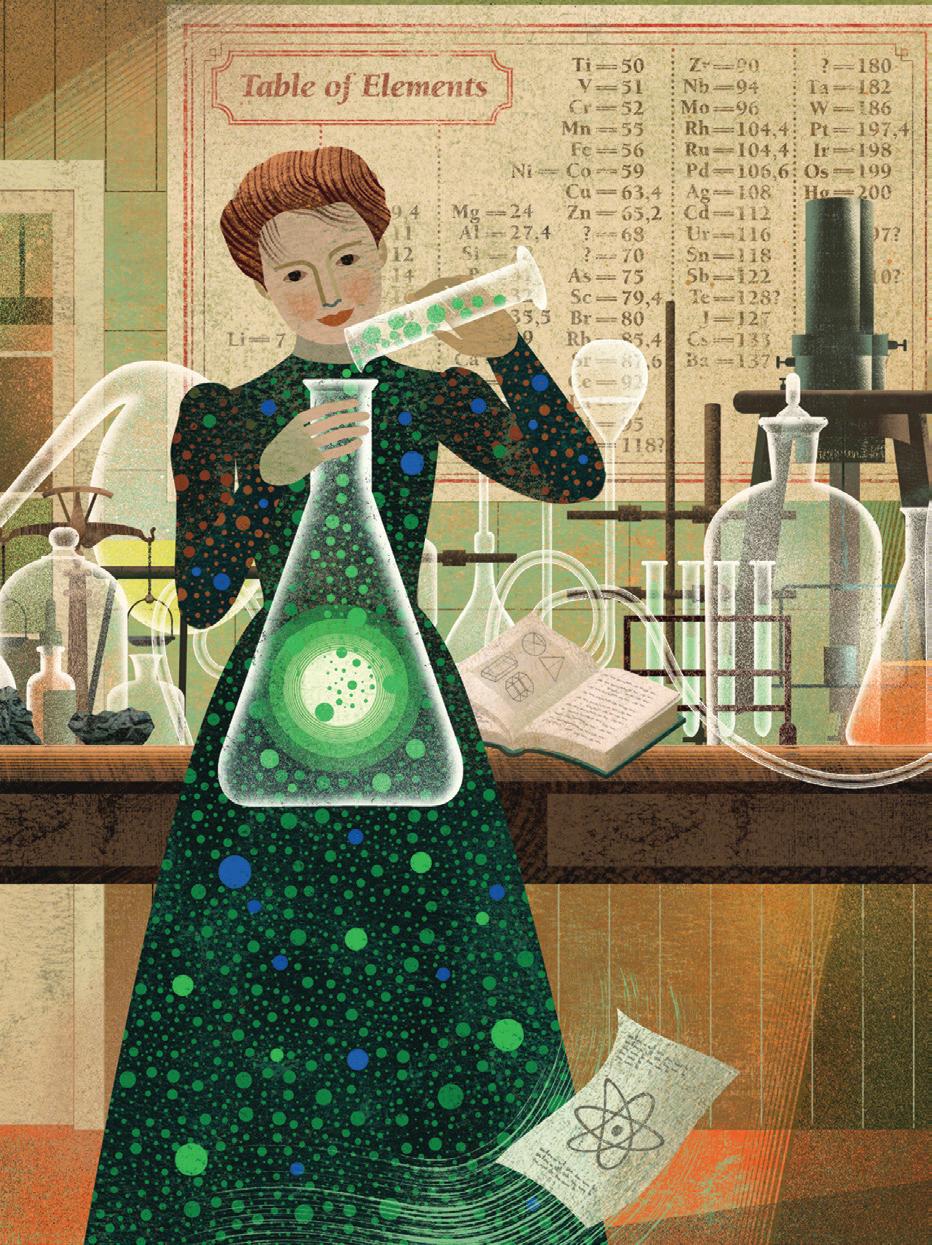

But above all, what President Beilock has taught us is that the sciences and the liberal arts are not siloed; in fact, there is an important, symbiotic relationship between the two. And it is this very thinking that continues to guide our storytelling in the Spring edition. In “Tara Well: Through the Looking-Glass,” you’ll read about how associate professor of psychology Well weaves together neuroscience and psychological research to promote self-awareness and empathy through her practice of mirror meditation. And in a Q&A with Linda Elovitz Marshall ’71, you’ll learn about the author’s latest children’s book, Sisters in Science, which provides a fun narrative of the relationship between the first woman Nobel Prize-winning scientist, Marie Curie, and her sister, Bronia Dłuska. And our “Passion Project” spotlights Khadijah Abdul Nabi ’08, whose switch from engineering to Middle Eastern studies and anthropology at Barnard set her on a career trajectory that eventually led her to establish a women-run design studio in Iraq. (All of these stories were written by our talented colleague Marie DeNoia Aronsohn.)

If anything, this issue is really about female leadership and taking risks — in the sciences and the liberal arts. And this brings us to our insightful conversation with President-elect Laura A. Rosenbury, in which we learn more about her vision, upbringing, interests — and, most importantly, her favorite karaoke song. We are excited for the many compelling stories that will emerge under her stewardship.

On a more personal note, in February — halfway through the Spring issue’s production — I had my son, Colum, and have been on maternity leave since then. To close out this letter, I want to say a big thank you to the Magazine team and my department for all their hard work and creativity in putting together this issue.

Nicole Anderson ’12JRN, Editor-in-Chief

Nicole Anderson ’12JRN, Editor-in-Chief

From the importance of a women’s college to her favorite song to sing at karaoke, the incoming president sat down with Barnard Magazine to answer a few questions.

What is the importance of a liberal arts education in today’s climate?

From the humanities to the social sciences to the arts and STEM, it’s important to be able to look at issues and problems from all perspectives. There is no significant challenge facing us today that only one discipline can fix or can be handled at the level of policy.

And the value of a college devoted to empowering young women?

There are many examples of the ways gender still mediates interactions and positions of power and

privilege. Being part of a community that grapples with that, and examines it, as opposed to pretending it doesn’t exist, is important. This past summer, we saw that what many people see as fundamental women’s rights are still up for negotiation and still contested. I’m excited to be joining a community that is concerned about that and wants to continue to ensure that young women have access to a great education that empowers them to go out and change the world.

You’ll be transitioning from a graduate school of law to an undergraduate liberal arts institution. Why the shift?

Undergraduate education is so important at this moment in time, as many are losing faith in a lot of our institutions, in our democracy, and in our ability to connect across differences. In a world that’s being transformed by technology, it is on our college campuses and universities where we can create the conditions for dialogue and prepare young people for engaging in an increasingly complex society.

What excites you most about working with Barnard undergraduates in particular?

Barnard undergraduates have so much energy and passion for making a difference. It’s that passion, that commitment, and that energy that motivates me to ensure our students have the best possible community in which to grow and thrive, while also benefiting from the opportunities created by partnering with an amazing research institution like Columbia. I’m eager to join a college that has such a long history of educating leaders and being a part of this vibrant city.

What excites you about working with the faculty?

Barnard faculty have a rich tradition of being teacher-scholars, embracing the teaching mission while also doing cutting-edge research on a wide variety of issues, engaging with the most pressing problems of our time. They are absolutely central to the academic excellence of Barnard and to mentoring our students to have a positive impact. I’m excited to get to know more of the faculty, to learn more about their research and how that research informs their pedagogy and their interaction with students.

You’ve often credited your high school adviser, Mr. Sweeney, for pushing you to go to Harvard, and later, other mentors helped you navigate academia. What have those relationships taught you about the value of one-on-one relationships in running a large organization like Barnard?

Mr. Sweeney taught me that people can often do more than they think they can, particularly young people. When I’m teaching, I have very high expectations for my students. I believe many of them can rise to the challenge and can do way more than they ever thought possible. Whenever possible, I try to connect individually, even if it’s for five or 10 minutes, because one conversation can have a big impact, more than you can ever imagine. [Harvard Law professor] Martha Minow and, later, Kent Syverud [president of Syracuse University] taught me how to translate that when it’s advocating for an institution in large groups. I try to make a personal connection with groups of students, potential employers, and alums. I’m excited to become that voice for Barnard and galvanize support to make sure everyone knows how amazing our students and alums are.

How has your Midwest background informed your ethics and values today?

It’s hard to separate out my Midwest background

from farming and agriculture. My passion for gardening is very much rooted in the family farm and seeing the gardens that my grandmother and mother planted and tended. So I think a lot in terms of the metaphor of planting seeds. When you’re planting a seed, you have no idea when it might take root. With a student, you plant the seed of an idea, and it might take root that week, it might happen later that semester, or it might be years down the road. But that doesn’t mean the teaching is futile. Instead, it means that all you can do as a professor is to plant those seeds and cultivate them. Then it’s up to each student and their circumstances that determines how those seeds grow.

Sometimes I tend to get a little impatient, and thinking about gardening helps me with that too. One of my favorite sayings is “We can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” We must acknowledge that there’s constant evolution. I think that’s true of organizations as well, even though sometimes change or innovation can be a long process. Thinking about the possibilities and what might happen if we experiment is rooted in the garden and my Midwest upbringing as well.

Fundamentally, how do you approach “the work”? I love to hear what’s on people’s minds and to think about ways that I can empower them to do even more than they’re currently doing. I have a very collaborative, open door policy. I thrive on working as part of a team, figuring out what any given department, student group, or faculty member needs, then providing them with the resources to be empowered to continue on their chosen path.

So ... what’s on your nightstand now?

A book by Mick Herron, a British mystery and thriller novelist. He wrote the “Slow Horses” series.

What are you watching?

I just finished Daisy Jones and the Six.

What are you listening to?

Thelonious Monk.

Favorite dish to cook? Rhubarb peach pie.

Favorite vacation destination? Rome.

Favorite song to sing at karaoke? “Dancing Queen.” B

The physician brings her passion for health equity and reproductive justice to Barnard

by Mary Cunningham

by Mary Cunningham

Growing up, Sarah Ann Anderson-Burnett remembers watching her mom, a nurse, take care of a relative with AIDS. At the time, people with the disease were completely written off by society, she recalls. Witnessing her mom’s empathy toward him and other patients is what made her want to go into medicine.

This past fall, Dr. Anderson-Burnett brought a wealth of experiences to Barnard’s campus to serve as the Director of Clinical Services and Quality Improvement. In her new role, she will focus on improving care and wellness for the community and be one of the brains behind the Francine A. LeFrak Foundation Center for WellBeing, set to open its new home on campus next school year.

“I want people to feel whole. I want to make sure that they know that I value them as a human,” she says of lessons learned from her mom. “As a Black woman, I have experienced healthcare at its worst — and also, ironically, at its best, because I’ve had advocates who stepped in on my behalf.”

This empathy-centered approach to care became a value she carried throughout her medical training and career. After receiving her M.D. from Columbia University’s Icahn School of Medicine Mount Sinai, Anderson-Burnett went on to pursue a Ph.D. in addiction neuroscience, looking at how those with depression have a higher proclivity for opioid addiction.

It was at this time that she started to see the fault lines in the healthcare system more clearly. Why is so much money being spent on adult care instead of preventive care? she wondered. This was a “pivotal time” in her life, she says, that directed her toward a residency in pediatrics. “I think for me, medicine has always been about

‘How do I help the most vulnerable populations, the most marginalized populations?’”

As she continued her training, other fissures in the system began to present themselves, such as how long-acting reproductive contraception was disproportionately marketed to Black and Brown youth, raising the question “Who is fit for reproduction, and who is not?” Patient-centered contraceptive counseling is now central to her work. “Really talking to the patient, understanding them, and [encouraging] shared decision-making that centers their voice first is important to me,” she says.

While she tackles the big-picture initiatives, Anderson-Burnett will also be on hand to meet students’ everyday clinical needs by providing vaccines, lab assessments, prescriptions, and more. Only a few months into her new position — she started in November 2022 — Anderson-Burnett has already begun to make strides. Among her first moves was to expand the medications Barnard offers in its 24/7 vending machine in Brooks Hall.

“What really struck me on my day when I interviewed here was that there’s Plan B for $8 in the vending machine. That is a phenomenal innovation,” she says. After starting, Anderson-Burnett wanted to enhance the vending machine with student needs in mind. If they are looking at screens all day for class, eye drops could be a good addition, she contended. And with Plan B already available, pregnancy tests should also be offered, she thought. So AndersonBurnett and her team added the two items, along with others, such as urinary tract infection tests and hydrocortisone cream.

Anderson-Burnett has also honed her clinical expertise to shape the Primary Care Health Service’s approach to trauma-informed care. “Trauma-informed care really turns the paradigm from ‘What’s wrong with you?’ to ‘What happened to you?’” she says. The PCHS staff works closely with students to ease discomfort during visits that incorporate sensitive examinations by offering aromatherapy, calm music, stress balls, and heat packs.

Anderson-Burnett looks forward to having a “true hub on campus” for students, faculty, and staff with the opening of the Francine LeFrak Center. It will be a place where a wide range of issues — including food poverty, menstrual poverty, and financial well-being — can all be addressed under one roof, she says.

Her lifelong passion and advocacy for health justice have prepared her for Barnard. “[My experience] set me up for this opportunity now,” she says, “to really make a difference and add to the amazing work that’s being done here.”

After celebrating five years, the Beyond Barnard team is charting a new path forward. The career advising office has created a new strategic plan with goals to expand access to opportunities, guarantee access to funding for one internship or research experience to all Barnard students, deepen connections with partners, and bolster mentorship opportunities.

“Beyond Barnard spent its first five years working to become a deeply ingrained part of the Barnard experience,” said A-J Aronstein, assistant vice president of lifelong success and senior advisor to the provost. “As we build on those foundations in the next five years, we have to ensure that we continue to emphasize equity in access to life-changing opportunities that the College facilitates.”

As part of this effort to expand access, Beyond Barnard will liaise closely with offices and departments across campus, including Access Barnard. Beyond Barnard’s commitment to funding internships and research opportunities will mean increased collaboration with external partners. In just one example of deepening partnership ties and bolstering mentorship opportunities, the New Pathways Bridgewater Scholars Program, which will continue to unfold over the next four years, provides access to a range of mentorship opportunities for Barnard students from backgrounds that are underrepresented in the financial services industry. Likewise, funding from GRoW @ Annenberg will continue to provide financial and programmatic support for students completing summer internships at arts organizations.

On March 21, 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court reached a unanimous decision in favor of a deaf student in Michigan who was allegedly pushed through the public school system with insufficient support for his disability.

Despite repeated reassurances from the administration to his family that he was doing just fine, it wasn’t until graduation neared that Miguel Luna Perez’s parents were told that he would be receiving only a certificate, not a diploma. It would later be alleged that one of his tutors did not know sign language and left him alone for hours during the school day.

Barnard alumna Ellen Marjorie Saideman ’79 served as counsel for the Perez family, along with their representative, Roman Martinez of Latham & Watkins. Initially, the family settled their claim under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which allowed Perez to get extra schooling and sign language instruction for him and his family. But when they tried to sue for monetary damages under the Americans with Disabilities Act, lower courts ruled that Perez couldn’t pursue the claims because of language in the IDEA.

In response, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in the court’s decision, “We clarify that nothing in that [IDEA] provision bars his way.” The ruling, he wrote, “holds consequences not just for Mr. Perez but for a great many children with disabilities and their parents.”

For New York Water Week (March 18-24), Barnard connected three continents — Africa, Europe, and South America — in an interactive dialogue addressing issues of water impact, management, and sustainability.

The March 21 hybrid event — “Water We Waiting For?” — was organized by Brian Mailloux, co-chair of the Environmental Science Department and professor of environmental science, in partnership with the Netherlands’ Delft University of Technology

The participating water hubs — members of academic and research centers speaking from Delft, Nairobi, Kenya, and São Paulo, Brazil — discussed water security challenges and clean-energy technology solutions.

The U.N. 2023 Water Conference is the first of its kind in 50 years, and the Barnard sessions mobilized each water hub to commit to actionable targets that will contribute to the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) as well as shape the Water Action Agenda.

“In the U.S., we might not hear much about the SDG in the media or other places, but they are critical for achieving a sustainable future and used to guide resources and action worldwide,” says Mailloux. While the rippling effects of the global water crisis — drought, food insecurity, and displacement — have shaped the theme of “accelerating change” for this year’s World Water Day (March 22), a message of resilience resonated.

“The fact that you have come together, here [at Barnard], as research communities to look at practical solutions to make differences in people’s lives, is incredibly meaningful,” says Kitty van der Heijden (below, center), director-general for international cooperation at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Netherlands. “Change happens on the ground — we need practitioners on the ground.”

On March 1, when the Barnard Center for Toddler Development team celebrated the Center’s 50th year with a grand-opening reception and ribbon-cutting ceremony, they did so with a singular approach to studying early childhood development, in a brand-new, toddler-tested space in Milbank Hall.

“The Toddler Center [through the Department of Psychology] really wrote the playbook for this kind of program,” said Tovah Klein, the Center’s current longtime director. “There’s an emotionally and socially-emotionally based way of having a program for toddlers and also one where the adults can stand back and the toddlers can be led by their own curiosities.”

What began with seven children has blossomed into a vibrant facility that now hosts 50 toddlers each year. And at the opening reception, past and presently participating parents, grandparents, trustees, and neighborhood community members encountered a toddler’s dream space.

“In my final semester as Barnard’s president, it’s immensely satisfying to see another long-term goal come to fruition with the grand opening of our Toddler Center’s new home,” said President Sian Leah Beilock.

Klein, who is affectionately known as the “Toddler Whisperer,” partnered with architects and play consultant Cas Holman to design the Center. Included is a large playroom consisting of a calming, nature-inspired green-and-white color palette, observation areas, classrooms, spaces for parents, and research facilities to enable top-quality data collection, coding, analysis, and neuro-brain research.

Already, Klein has observed new developmental changes with this year’s toddler cohort, as a result of watching how they — and the student-teachers — react to the space. “What’s exciting about the new Center is that I can see the joy of the children as they work through lots of emotions,” she said. “Equally, I’m seeing that in our students: their excitement, their enjoyment, their learning. After all, that’s what Barnard is here for — our college students.”

The Barnard associate professor of psychology and author teaches the world how and where to find themselves

by Marie DeNoia AronsohnWhen she was a little girl growing up in Cleveland, Ohio, Tara Well got an early glimpse of her future by peering at a toaster. The shiny chrome surface was a first mirror, and her fascination with her reflection was a sign of big things to come. She would become an acclaimed personality psychologist with a particular focus on self-reflection. Her latest book, Mirror Meditation: The Power of Neuroscience and Self-Reflection to Overcome Self-Criticism, Gain Confidence, and See Yourself With Compassion, speaks to the power of facing yourself in the mirror.

Since its release in June 2022, the book has helped to further elevate the media profile of the Barnard associate professor of psychology. Well has a blog with 2 million readers and a TEDx talk with nearly 200,000 views, and she appeared on The Daily Show With Trevor Noah last year in a mock-documentary-style segment on the importance of small talk.

“It was fun. I mean, I knew I was just going to be the straight woman for that,”

says Well. She also presented her observations on the importance of small talk and how the pandemic has eroded society’s social skills at a Barnard College staff event in February, part of a series called Pro Tips.

Why the focus on small talk? As Well explained it, talking with others, face-to-face, is another important reflective experience: “Being reflected occurs naturally during face-to-face conversations. We need these reflections from others to affirm our sense of self, help us regulate our emotions, and be in social coordination with others.” In the book, Well demonstrates how facing ourselves in actual mirrors is a powerful way to better know and accept ourselves.

The impetus to include mirror work in her studies started with a serendipitous moment — a glance at her own reflection. She was taken aback by what she found: sorrow.

“I was looking really sad and kind of distressed,” she says. “I hadn’t realized I felt that way. So I started to meditate with a mirror mainly to help me get more in touch with my emotions because I felt that there was a gap between what I was feeling inside and what was showing on my face. The impact was powerful. I decided to do some mirror-gazing experiments where I had other people do it and

report to me what they discovered.”

Many of Well’s research subjects discovered deeper levels of self-awareness, and from that came self-compassion. Looking at your own face when your self-talk is negative, or even cruel, can spark a realization of the pain you’re inflicting on yourself.

Why are we so self-critical? In her book, Well explains that “negativity is an attention magnet.” The human mind is hard-wired to look for problems because we need to devote more attention and cognitive resources to potential problems. Our minds are predisposed to look for problems because they can indicate threats and possible danger.

“Due to a combination of evolution and socialization, our criticisms of the image we see in the mirror usually pertain to the three main topics: old, fat, ugly,” she writes. In a society that celebrates young, slender beauty, these assessments can cut deeply and distort self-perception. Well’s approach — facing one’s worst critic in the mirror — seeks to heal the psychological wound and foster self-kindness and self-knowledge.

Well’s path from her childhood home in Cleveland to Barnard was very much a work of claiming her identity despite external perceptions. As the adopted child of parents who did not attend college, she ran up against limiting expectations.

“I didn’t know places like Barnard even existed, frankly. I grew up being told that I wasn’t smart enough to go to college and I should go ahead and get a job while learning some kind of skill, like being a hairdresser or working in a hospitality field. Going to college and then continuing on and getting a Ph.D. was like an act of rebellion against my roots,” says Well.

She became fascinated with psychology and was driven to learn more and more, which led her to the study of personality. But in a twist of fate, self-discovery, and

scientific insight, she later went on to find her birth parents. Turns out, they were both college professors. Her birth father, now retired, was a psychology professor. Her own journey closely paralleled the professional lives of her biological parents.

“It’s interesting because I saw so many similarities,” she says. “I’ve been studying and teaching personality psychology at Barnard for the past 25 years. And one of the core questions is always looking at the contribution of environmental factors and learning factors and how they shape personality and then genetic factors and how they shape personality too. So it was a very interesting experiment.”

Well urges her students, readers, and listeners to conduct their own experiments, and she outlines specific steps to forming a mirror meditation practice to confront and heal self-criticism, selfie and social media addictions, and anxiety.

“I believe the mirror is one of the most valuable tools we have today,” Well says near the close of her TEDx talk. “Taking a few minutes to gaze into your own eyes can calm you and awaken your kindness. Imagine what the world would be like if we took the time to see ourselves and each other with unwavering clarity and compassion.” B

FICTION

Take What You Need

by Idra Novey ’00In this exhilarating novel set in the Allegheny Mountains of Appalachia, Leah traces the life and artwork of her stepmother after her death, discovering how much she had missed out on and forging a new self in the process. Take What You Need probes the perennial mystery of the people we love most and illuminates what can be built from what has been discarded.

In the Orchard

by Eliza Minot ’91Minot’s novel takes a deeply personal and moving dive into womanhood and maternal life through a day in the life of Maisie, a young wife and mother. Through Maisie, who dreams at night of a life without mortgages and credit-card debt but wakes to the usual real-world problems and responsibilities, Minot offers a perceptive and heartfelt exploration of motherhood, childhood, and love.

Hang the Moon

by Jeannette Walls ’84This novel depicts an indomitable young woman, Sallie Kincaid, in Virginia during Prohibition, who strives to reclaim her place in the family nine years after an accident resulted in her being cast out by her father. This actionpacked book describes how Sallie comes into her own in the family business — bootlegging — revealing her sharp-witted, unflinching, and humorous character.

In a dystopian New York City, a powerful government machine known as ReInception is used to correct human behavior and prevent crime. When a Columbia University student is propelled into an anti-government rebel group, an underworld of corruption is exposed to her. While set 100 years in the future, Straus’ first novel explores relevant social and political issues in answering the question of whether peace is worth the price of lies.

The Half Moon

by Mary Beth Keane ’99Keane, author of the bestselling Ask Again, Yes, centers her new work around

Malcolm and Jess, a couple navigating the future as youth begins to feel like a distant memory. The tension between Jess’ desire to become a mother and Malcolm’s dream to own a bar confront the couple, raising questions about their love for each another amid blame, anger, and fading desire.

Keane paints an intimate portrait that explores the disappointments and unexpected consolations of midlife.

The Trees of the Cross

by Gregory C. Bryda, professor of

by Gregory C. Bryda, professor of

art history

Bryda’s latest, lavishly illustrated book explores the significance of wood and greenery within the religious art of late medieval Germany. His research into the local environment, culture, and economy and discussion of the influential artists Matthias Grünewald, known for the Isenheim Altarpiece, and renowned sculptor Tilman Riemenschneider offers a extensive examination of how wood — an object of religious devotion itself — functioned in art to bridge the spiritual and natural worlds.

In this unconventional memoir, novelist Benedict writes of her cancer diagnosis and hypochondria with exceptional storytelling skills, levity, and wisdom. The seasoned author recalls her initial fear of her illness and subsequent indulgence in such “natural

remedies” as Tibetan mantras, shots of wheatgrass, and chocolate babka in prose both somber and funny by turns. Benedict investigates existential questions and, post-diagnosis, wonders “which fear is worse: the fear of knowing or the reality of knowing?”

Homeless Advocacy

by Laura Riley ’04A social justice attorney and director of the Clinical Program at Berkeley Law, Riley offers an extensively researched history of homelessness in the U.S. She discusses the obstacles that have disproportionately affected the unhoused population and perpetuated the poverty cycle. By including perspectives from both legal professionals and people who have experienced homelessness, this book functions as a valuable resource for encouraging advocacy.

The Loud Librarian

by Jenna Beatrice ’07

by Jenna Beatrice ’07

In her debut picture book, former lawyer and space camp counselor Beatrice tells the story of Penelope, an aspiring, friendly, and helpful studentlibrarian who has only one snag: a big voice. Instead of conforming, the librarian finds a way to stay true to herself and prove she’s perfect for the job. Mixedmedia and collage illustrations by Erika Lynne Jones bring to life prominently diverse characters for a playful reading experience.

Four in Hand

by Alicia Mountain ’10In her second book of verse, Mountain weaves together relevant social issues — identity politics, environmental degradation, late-stage capitalism — across four heroic crowns of sonnets featuring both traditional and experimental writing styles. Mountain’s writing doesn’t shy away from desire and the difficulties of personhood in a world saturated with injustice and pain. B

By the time Zora Neale Hurston became Barnard’s first Black graduate, she already had a lengthy history of chasing her dreams against overwhelming odds. This tenacity, which propelled Hurston from rural Florida to global acclaim, is chronicled in Zora Neale Hurston: Claiming a Space, which first aired on PBS in January and is now available to stream online in its entirety. The documentary follows her quest to research her own culture from within — at the time, a groundbreaking anthropological approach. She heads to Florida in a two-seater with a pistol at her side, initially conducting her research in “carefully accented Barnardese,” until she realizes that doesn’t endear her to her former neighbors. Unlike nearly all anthropologists of the day, she wasn’t there to study “the other.” After she joins in on the folkloric singing and religious rituals, they open up, providing her with unparalleled access to the Black South of the day. The documentary doubles as a critique of the discipline, particularly as it was developing at Columbia University under her mentor and sometimes champion, Franz Boas, “the father of modern anthropology.” It follows her ill-fated pursuit of a Ph.D. alongside contemporaries like Margaret Mead, who find unmitigated encouragement from Boas. Hurston’s work receives tepid support in comparison. But by putting her methods and her voice front and center, the documentary depicts a force of nature who believed in her own brilliance well before the academy belatedly followed suit.

Kira Goldenberg ’07It was December 2020 — that first bleak, isolated pandemic winter — when Phanésia Pharel ’21, then a senior at Barnard, initially crossed paths with Jean Lichty ’81.

Lichty’s La Femme Theatre Productions — which is dedicated to exploring and uplifting women’s experience — was staging a streamed performance of Tennessee Williams’ The Night of the Iguana, and she wanted Barnard interns involved in the process. She put out a call through Beyond Barnard, and Pharel applied.

“We had a Zoom call, and I fell in love with her,” says Lichty, who calls Pharel “my ersatz daughter.” Though the logistics did not ultimately pan out, when they crossed paths again at a 2021 Reunion event, the reconnection forged a mentorship and a partnership that is bringing Pharel’s playwriting prowess from Barnard to offBroadway.

Pharel, currently an MFA student at University of California, San Diego, is the author of Black Girl Joy, a play she began to write during college. It has already been performed at a workshopped reading in April 2022, directed by accomplished actress and playwright Regina Taylor, and it’s slated for an Actors’ Equity reading on June 15 before heading into full production in the 2024-25 theatre season.

“We are as excited about Black Girl Joy as we are about Night of the Iguana — that’s the truth,” Lichty says, during a conversation in which the two women regularly digress into exclamations of mutual respect and fondness.

Black Girl Joy was inspired by Pharel’s experiences of grief and loss as a young Black woman raised in Miami.

“I wanted to write a play about grief and sisterhood and really asking the question — the hashtag was everywhere, #BlackGirlJoy — what does ‘Black girl joy’ really mean?” Pharel says.

In the aftermath of the 2020 murder of George Floyd, the #BlackGirlJoy trend on social media moved her. For Pharel, it represented a determination to retain hope at a time of deep mourning triggered by police violence toward Black people, to say nothing of the pandemic that was disproportionately killing people of color.

Pharel describes the play — about a group of young women and nonbinary friends, also in Miami, grappling with a death — as a “coming-of-age through grief.” Beyond its narrative throughline, the play also explores these themes by incorporating poetry and art. At the April 2022 reading, Lichty says, the inclusion of a beatboxer amplified the play’s emotional resonance.

In addition to reacting to a societal reckoning, Black Girl Joy pulls from Pharel’s personal experiences of grief. Her family lost their home to a fire when she was 13, leading to years of harrowing housing insecurity, which she coped with through writing — initially stand-up routines and then, with encouragement from a high school drama teacher, playwriting. She also grappled with multiple gun deaths of young acquaintances in her childhood community.

These losses were compounded at Barnard when two beloved mentors, legendary playwright Ntozake Shange ’70 and Deputy Dean Alicia Lawrence, passed away during her time on campus.

“Here I am at college, and now I’ve lost two women who are really important to me,” Pharel says. “We never make space for grief, particularly for young Black girls. When I go back to the ‘about’ of this play and I’m circling around it, that’s really what I want to access and parse out.”

Lichty describes Black Girl Joy as imbued with the “soul of Phanésia. I found that the play really revealed a lot about her,” Lichty says. “As Sondheim said, personal is universal. There is something that was very universal about her, about her writing.”

Pharel’s eyes fill with tears, and she takes a deep breath.

“That means the world,” she says. “The last three years, Jean has mentored me and has taught me. Jean is someone I’ve learned how to take space and be yourself from.

“This is a lifelong relationship,” Pharel says. “You never know how long you have somebody, but I’m very grateful.”

by Kira Goldenberg ’07

by Kira Goldenberg ’07

Suzanne Vega ’81 is busier than ever.

“I did not find the COVID era to be terribly inspiring; I found it to be terrifying,” she says. “I need to make up for lost time.”

Vega is currently touring the U.S. and Europe — with a spate of East Coast tour dates in April — playing “An Intimate Evening of Songs and Stories.” She’s performing a grab bag of her biggest hits alongside lesser-known gems — “a really nice mixture of old and new,” she says — accompanied onstage by former David Bowie guitarist Gerry Leonard.

She also recently finished the latest run of the Philip Glass opera Einstein on the Beach, an ongoing collaboration with contemporary music ensemble Ictus and the vocal group Collegium Vocale Gent, both based in Belgium. Vega played all the speaking roles in a three-and-a-half-hour concert version of the five-hour opus. Her participation is the latest iteration of a connection to Philip Glass and his work that stretches back decades. The two have been collaborating since the 1980s, when Glass chose two of Vega’s songs for his Songs from Liquid Days album. She subsequently sang “Ignorant Sky” in Glass’ score for the 1995 Brazilian film The Interview

“We’re friends. I find him fascinating, and I love his work. I think he’s a very funny, very spiritual man,” Vega says.

The Ictus ensemble first approached Vega about the project because of her deep

familiarity with Glass’ work. “I had read the final monologue of Einstein on the Beach at Phil’s request at a benefit that he had done out in Brooklyn sometime in the early 2000s,” Vega says. “He asked me to read that final one about the two lovers sitting on a park bench and gave me some direction as to how to do it, and it was great fun. I loved it.” With this experience in Vega’s back pocket, Ictus members were thrilled when she agreed to participate.

The abstract work lacks a plot or much in the way of conventional logic. But its characters’ speech is mesmerizing, akin to reading the work of Gertrude Stein aloud.

“I try to differentiate between the different voices that I have to do: I vary the pitch, I vary the tone, I vary the speed with which I read,” Vega says.

“Sometimes it’s very fast and almost muttered — almost like texture more than text — but other times I have to really sort of pontificate.” She also dons various hats and glasses depending on the character. It’s unsurprising, given Vega’s foundational Barnard education, that she is drawn to this type of genrebending work.

“I think I have a sense of adventure, and that leads me back to my days there,” Vega says. “One of my happiest memories is minoring in theatre at the Minor Latham Playhouse. I majored in English literature, but I had enough theatre credits to minor in theatre, and what I learned there never left me.”

There have been a number of Einstein on the Beach performances since 2017; the most recent run was an eight-city European tour this past November. The Hamburg performance was recorded, and the whole three-plus hours can be watched at barnardbold. net/vega-video. Those who saw it in person were encouraged to come and go as needed during the performance, Vega says, and fans online can replicate the experience.

“You can approach the performance the same way,” Vega says. “You can have it on in the background and just enjoy it for its texture.” For listeners interested in experiencing the work more closely, Vega recommends learning about the different movements for more of a sense of the musical journey Einstein on the Beach entails.

Though there are no future performance dates scheduled, a reprise is not off the table. But as of now, Vega remains focused on completing her current tour and diving back into songwriting.

“I need to make a new album. This is my priority,” she says. “I need to write a bunch of new songs. I’ve started. I think I have two, and I need to write a ton more. I need to write, write, write, write, write.”

B

President Sian Leah Beilock is a deep believer in multiple selves. In her case, she says, there’s “my mom self, my research self, and my president self.” At the heart of all of Beilock’s identities, though, is a drive for excellence. “My goal is to get everyone, in addition to myself, to perform at a level where one plus one equals three,” she says, “where the whole is more than the sum of the parts.”

In service of this goal, six years ago, Beilock took on the role of eighth president of Barnard College. Now, it has likewise motivated her decision to become the first woman president of Dartmouth. “I’m sad to leave Barnard,” she says. “But I hope people see this as another legacy of Barnard helping women to go break barriers and change the world.”

Beilock took office at Barnard shortly after the 2016 presidential election. Her term encompassed years of unprecedented national and international upheaval: the COVID-19 pandemic, refugee and immigration crises, climate disasters, the Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements, mass shootings, reckonings over the influence of social media and fake news on society, and much more. The future, meanwhile, seems poised to become only more tumultuous and uncertain.

As a scientist, Beilock feels strongly that one way to meet the challenges we face now and on the horizon is to nurture the next generation of talented scientists, engineers, and technologists. “As a society, we need more people focused on critical issues in STEM,” she says — and especially “more women.”

From the beginning, Beilock set out to raise the eminence of Barnard’s math, science, and technology programs to parallel that of its renowned arts and humanities programs. She created new five-year undergraduate and master’s degree programs with Columbia University in engineering, quantitative social science, public health, and more. She also added new undergraduate majors, including in cognitive science and computer science, and launched Barnard’s Department of Neuroscience & Behavior. More than 40% of Barnard students are now math and science majors, up from 34% when Beilock became president in 2017.

She credits much of that success to providing students with both opportunities and faculty role models in STEM.

“We know when students don’t see themselves in a particular field, they’re less likely to go into it even if they are interested,” she says. “My goal is to really help every student pursue their passion.”

For Beilock, that passion means “helping people’s great ideas get traction,” whether in a classroom or

Sian Leah Beilock set and met ambitious goals amid challenging times

at an entire institution. In her own lab, which she moved to Barnard from the University of Chicago, she continued to mentor undergraduate students and a postdoctoral scholar. As a cognitive scientist, her research focuses on how children and adults learn and perform at their best, especially in high-stress environments.

Beilock herself has mastered the art of performing under such circumstances; on a recent afternoon, and within the span of just a couple hours, she prepped for her last Barnard board meeting, flashed relaxed smiles for a photo shoot for this magazine, took an urgent phone call from her mother, and then gave an on-point interview for this story. The interview was cut short by 20 minutes, but she didn’t “choke” — which, incidentally, was the title of her first book on the subject. Rather, she clearly articulated, in the condensed time she had, her reflections on the meaningfulness of her time at Barnard. Beilock also knows from her science that success, whether academic, professional, or personal, can occur only if people are given the right tools. Wellbeing is one of the most important such tools. Beilock manages her own well-being through morning runs and great food, both on the town at restaurants and in the kitchen at home (where she especially enjoys her 11-year-old daughter’s latest baking creations).

Beilock has already blazed a successful career for herself, though, which is not the case for Barnard students who now face a mixed bag of excitement and anxiety at having to make their own way in the world. This pressure can and does take a toll. Even before the pandemic, Beilock knew through her research that young people — especially young women — were suffering record-breaking levels of depression and anxiety.

In a recent study published in Science Advances,

Beilock and her colleagues found that AP calculus students who are anxious about math tend to avoid doing difficult practice problems prior to a test and that their grades suffer as a result. While this avoidance is understandable — who wants to do something that makes them feel uncomfortable? — it does suggest how to improve performance: find ways to help support students so they can face and overcome the things that make them anxious rather than avoid them and suffer as a result.

With all this in mind, Beilock set out at Barnard “to really normalize the fact that we all need help sometimes,” she says. The culmination of this effort will be the Francine A. LeFrak Foundation Center for Well-Being, construction on which began in February. Once complete, Barnard students, faculty, and staff will be able to come to the center for everything from meditation and financial literacy classes to guidance for promoting mental health for themselves and others. The ultimate goal, she adds, is “to weave wellbeing into everything we do.”

Financial security and a sense of belonging are other crucial elements of well-being. Conversations with students about these topics caused Beilock to seriously consider the financial barriers faced by many students — disproportionately young women of color — navigating academia. To ease that burden, Beilock stepped up financial aid availability and created Access Barnard, a center that provides both information and community for low-income, firstgeneration, and international students throughout their college career. “I believe very strongly that you don’t get the best ideas and knowledge unless you have diverse people with different lived experiences around the table,” she says. “Part of that is reducing barriers to entry.”

Beilock wanted to ensure, too, that the education, community, and life lessons students gain at Barnard extend well beyond the few years they spend enrolled there. To that end, she helped to create Beyond Barnard, a one-stop shop for career services, graduate fellowships, internships, and jobs. Beyond Barnard exists as both a website and a physical office and offers such resources as career advice, workshops, and networking opportunities to both students and alumnae.

As Beilock moves beyond Barnard, she says her connection to the College will endure. “I know it will be lifelong,” she says. She stresses, too, that the value she has brought to Barnard goes both ways. “It’s certainly changed my life,” she says of her experience serving as president. “I’ve learned so much, and I’m honored to be part of this community.”—Rachel

Nuwer“My goal is to get everyone, in addition to myself, to perform at a level where one plus one equals three,” she says, “where the whole is more than the sum of the parts.”

6 years of President Sian Leah Beilock’s leadership

338% increase in total dollars raised on Giving Day (2017/2023)

2.7M views of President Beilock’s 2017 TED Talk on how to avoid choking under pressure

140 slices of Mama’s TOO! pizza eaten by President Beilock since July 2017

6.5% admit rate (down from 15% six years ago); 55% increase in applications since 2017

6 consecutive years Barnard has been a “Top Producer” of Fulbright U.S. Student Program recipients

280 current full-time faculty members, up from 240 in 2019

6,600 miles run in Riverside Park by President Beilock since July 2017

52% increase in STEM graduates from Class of 2017 to Class of 2023

41% increase in Barnard’s endowment since 2017

1,246

Barnard-days that President Beilock vowed she would not get a dog

944

Barnard-days since President Beilock brought home Rosie the Cavapoo

16% increase in those identifying as students of color from Class of 2021 to Class of 2027

91% of Class of 2022 graduates used Beyond Barnard

23 recipients of the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program award since 2018

On February 9, 2018, in the grandeur of Riverside Church and with the formality an inauguration merits, President Sian Leah Beilock made clear the hopes and aspirations for her time at Barnard, not the least of which was to raise the College’s eminence in math, science, and technology to parallel its renown in the arts and humanities. “I am a scientist, by training and by nature, and that colors how I approach everything. I crave data; I crave trials; and I crave testing, evidence, and examination,” she said. Later, in a nod to Barnard’s fundamental ties to the liberal arts, she added, “It is this link, between our renown in the liberal arts and our bold moves toward new modes of thinking, that will serve our students well into the future.” Five years later, many of the goals she put forth have been realized — in bricks and mortar as well as in ideas.

In her inaugural address, President Beilock set out a precise vision — and then made it happen

In her remarks, Beilock said that she wasn’t the first president to emphasize the importance of fostering women in science; that credit goes to Barnard’s second president, Rosemary Park. Park advocated for the College to have a science lab of its own in the early 1960s.

Today, nearly 100,000 square feet of programmable space is under construction at the Roy and Diana Vagelos Science Center; Beilock has metaphorically and literally laid the foundation for growing STEM disciplines. Also known as the R&D Science Center, the renovated space will be the physical manifestation of aspiring with perspective.

Rather than tearing down an old building and replacing it with a new one, the plan is a massive exercise in “circularity,” transforming 45,000 square feet of programmable space at Altschul Hall to provide additional space for the Biology, Chemistry, Environmental Science, and Physics & Astronomy departments as well as establish new space for the Neuroscience & Behavior and Computer Science departments. And rather than turning its back on its neighbors, the building includes a pronounced glass entrance on Claremont Avenue that will activate the quiet street with young scientists on their way to class.

Much of the effort was made possible in large part by a $55 million gift, the College’s largest, from Roy and Diana Vagelos. They were joined in the fundraising effort by Daphne Recanati Kaplan and Thomas S. Kaplan P’24, Cheryl Glicker Milstein ’82 P’14 and Philip Milstein CC’71 P’14, and many generous others who together raised more than $240 million to make the project a reality.

“We cannot look forward without looking back or build a future without understanding the past. It is hard to aspire without perspective.”

In the years since her inaugural address, the sciences have indeed expanded. The Department of Neuroscience & Behavior, one of the College’s most popular programs, has grown by 50% to more than 100 majors since 2019. The College has also increasingly incorporated STEM curricula and programming into its liberal arts education, providing students with interdisciplinary knowledge and skill sets that they can carry beyond Barnard.

Young women interested in the sciences are choosing Barnard more than ever before in the College’s 132-year history — 35% of the Class of 2022 were STEM majors, compared with about 26% nationally. Among Black, Latinx, and Indigenous scholars from the same class year, who are significantly underrepresented in the field, 26% majored in STEM at Barnard. These statistics exemplify the College’s commitment to establishing itself as a leading educational institution in both STEM and the arts.

The mission continues to be to help students develop the intellectual drive required to excel, with an eye toward the emergence of new fields, new ideas, and new technologies. In the fall of 2021, Beilock announced the Barnard Year of Science, an initiative to celebrate all things related to STEM at the College. That same year, Beilock recruited BJ Casey, a world leader in the field of developmental neuroscience and now the College’s Christina L. Williams Professor of Neuroscience. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jhumpa Lahiri ’89 joined the faculty in the fall of 2022 as the Millicent C. McIntosh Professor of English and director of the Creative Writing Program, underscoring the College’s ongoing commitment to the arts as well as the sciences.

“Our size and research prowess mean that we can be nimble and multifaceted in our approach to building a strong presence in the fast-moving sciences.”

“Simply put, a diversity of lived experiences and viewpoints, in an environment that allows for open dialogue and understanding, is vital to our scholarship. … I want to be sure that our students are ready not just for doing well here — that’s the baseline — but for what happens after Barnard.”

President Beilock made clear from the start that making a Barnard education an inclusive experience and positioning every student for post-graduate success would be top priorities. In service of those goals, Beilock employed an ethos of unification to key initiatives, reframing College resources, integrating various services for easier access, and exploring ways to best leverage Barnard’s relationship with Columbia University.

The results have become a meaningful, powerful aspect of the Barnard College experience. Specifically, Beilock developed Access Barnard, Beyond Barnard, and the 4+1 Accelerated Pathways graduate degree program. Access Barnard, which launched in fall 2020, was designed to better serve underrepresented firstgeneration, low-income, and international students by bringing together various programming, including the Higher Education Opportunity Program (HEOP) and the Collegiate Science and Technology Entry Program (CSTEP), under one conceptual roof.

Beyond Barnard, which began in 2018, integrated Career Services, career development, student employment services, fellowship and pre-health-career advising, and funding for internships to create a comprehensive “one stop” resource. These initiatives have charted significant success. Ninety-one percent of the classes of 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022 were placed in a job or graduate program six months after graduation.

The 4+1 Accelerated Pathways program combines an undergraduate liberal arts degree at Barnard with a master’s degree at Columbia in five disciplines: engineering, public health, social sciences, public and international service, and Russian, Eurasian, and Eastern European studies.

Even as Beilock leaves Barnard, construction crews continue to move onto campus to realize her aspirations. During her inauguration speech, Beilock mentioned her research on women and girls, which she would later cite as the basis of her understanding of the direct link between wellness and success.

The Feel Well, Do Well @ Barnard campaign that Beilock launched in 2019 didn’t just promote physical and mental wellness but financial literacy as well. Literature about the initiative at the time recognized “disparities across campus for students, especially those having nondominant identities.” A culturally sensitive approach meant that top-down advocacy for health wouldn’t do.

Instead, in yet another unification process, the Beilock administration combined Barnard’s 36-year-old peer education program with Well Woman, a wellness initiative established in 1993. Combined, the two groups provided trained peer support for students during drop-in hours at a small room in Reid Hall.

But it was clear that the combined programs needed their own dedicated space. Thus, the linchpin of the effort will be the Francine A. LeFrak Foundation Center for Well-Being, which began construction this past winter, providing state-of-the-art spaces for financial fluency and wellness programs, a fitness center, and dance spaces. Under one roof in the lower level of Barnard Hall, initiatives addressing physical, mental, and financial wellness will offer students holistic support intended to propel success inside and outside the classroom.

“Barnard students have brought incredible talent and determination to this campus, and ... it is my job, our job, to see that they leave here ready to go, no matter what their next step in life might be.”

In the concluding remarks of her first important speech to the community that cold February day, President Beilock underscored how important Barnard’s relationship is to the city it calls home. “Barnard is of the city,” not just in it, she said.

To that end, Beilock launched STEAM in the City. With the support of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, the College offers a training fellowship to Harlem grade-school educators facilitated by Barnard scholars in STEAM fields (science, technology, engineering, arts/architecture, and mathematics). Using the city’s parks as classrooms, the effort trains teachers in how to teach their students outdoors and in concert with nature. There, they learn how to interact with local ecosystems and do science in innovative ways, such as beekeeping. They face challenges of how to solve problems in parks, such as Morningside Park, from measuring carbon dioxide levels to identifying trees. In addition, teachers meet up at a makerspace, which holds state-of-the-art tools for design exploration. The effort doesn’t stop at the weeklong program; the College also follows up with the teachers to make sure they have the materials needed to carry out what they created in the studio.

“Barnard College is not just in the City of New York, it is of the City.”

“When she arrived at Barnard, Sian promised to raise the College’s eminence in STEM fields, and she has delivered. As a renowned scientist herself, she has always understood the importance of the sciences, and she enthusiastically embraced efforts to improve every Barnard student’s scientific literacy — from increasing research opportunities and creating a special ‘Year of Science’ to leading the revitalization of the College’s facilities. We are confident that more young women than ever before now view Barnard as a premier destination for a world-class education in the sciences. That is Sian’s thrilling and remarkable legacy, and it has been a pleasure to work with her to help turn her promise into an extraordinary reality.”

“Since the day President Beilock arrived on campus, she has been relentless in supporting our students and bringing Barnard’s story to the world. Look back at President Beilock’s four priorities and you will see she achieved exactly what she came here to do: We have the most diverse Barnard community in history, along with new levels of support to make sure all students can access the extraordinary education we provide. For the first time ever, over 40% of Barnard students are math and science majors, as our STEM reputation increasingly matches our excellence in the arts and humanities. With investments like the state-of-the-art Francine LeFrak Center, we are reaching the whole student — supporting their physical, mental, and financial well-being outside of the classroom. Finally, we are sending our students into the world wellequipped to succeed, with a new support network in Beyond Barnard that lasts a lifetime. As Board Chair, I couldn’t be more excited about Barnard’s position in this moment. We are grateful for President Beilock’s vision and determination and cannot wait to keep building on this foundation.”

“One afternoon in 2019, Sian and I had a meeting at the Ford Foundation, where we ran into alum Lisa Kim ’96, curator of the Ford Foundation Gallery, who said she had an idea: Would Barnard be interested in a loan of the I Am Queen Mary statue they had commissioned? Sian said yes immediately, as she saw the potential of installing the statue of a Black Caribbean woman who rebelled against unjust labor conditions in the aftermath of slavery and colonization. She saw how it could inaugurate a new set of conversations about race, representation, belonging, and art as activism. Sian integrates issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion into everything that she does, proven by her fulfillment of all the Diversity Task Force recommendations that she inherited when she became our president. But it was that afternoon at the Ford Foundation that I knew that Sian truly ‘got it.’ She looked at I Am Queen Mary and saw a Black woman righteously causing trouble and decided not to turn away.”

Campbell Family Director of Intercollegiate Athletics and Physical Education, Columbia University

“Sian’s incredible support for the Columbia-Barnard Athletic Consortium has meant the world to the young women who compete in the athletics program. Because of her leadership and partnership, the Consortium has never been stronger, with more Barnard women competing than ever before. And many of our women’s teams are achieving new levels of excellence both in and out of the competitive arena — led by our recently crowned Ivy League Women’s Basketball Champions. In addition, her scholarly research into performance under pressure is not only fascinating but can teach our student-athletes much about themselves in their pursuit of their goals. Sian, we will definitely miss having you part of the team.”

“Sian made wellness a priority from the beginning of her incredible tenure as president, and I was happy to support her vision with the creation of a new wellness center on campus — the first of its kind to include the three pillars of wellness: mental, physical, and financial. As a cognitive scientist, she knew that a focus on comprehensive well-being is crucial for today’s students and alumnae, and the pandemic only proved how right she was to emphasize a holistic approach to education. Because of her leadership, the College has emerged from a historically challenging period as a better, stronger community.”

Druckenmiller Professor of Computer Science, Director of the Vagelos Computational Science Center

“As a leader and a colleague, Sian is energetic, enthusiastic, and approachable. She deftly weaves her research and her educational values together, and her commitment to empowering women to become leaders and to succeed has been steadfast. At Barnard, she was instrumental in the creation of Barnard’s academic program in computer science and the development of the very popular 4+1 Pathways for accelerated graduate study at Columbia’s School of Engineering and Applied Science. Computer science has already become one of the largest majors at Barnard and is still growing, with many of our students going on to graduate study.”

Senior Representative to the Board of Trustees for the Student Government Association

“As a history major, I have always been drawn to learning about Barnard’s past. This exploration has taught me a lot. Did you know students once had to wear hats on campus? But I have walked away from my research with one prominent conclusion: Barnard’s past emphasizes how profoundly President Beilock shifted the direction of the College. Being the president of Barnard is a unique job — you have to consider the needs of students alongside the long-term success of the College, and yet President Beilock struck the right balance. While my time as a Barnard student has ended, I will continue to be inspired by her work to establish the College as a place I will forever be proud to call my alma mater.”

A geologic field excursion to Death Valley during spring break her first year at Barnard set Marissa Tremblay ’12 on course to becoming a scientist. She entered college intending to pursue a law degree, but stepping foot on that vast, desolate desert landscape marked with sand dunes ignited a curiosity to uncover the stories in stones.

“I ended up falling in love with geology on that trip,” says Tremblay. “I’d never been to a desert environment with basically no vegetation. You could see lots and lots of rocks for miles and miles, and I was captivated thinking about how to go about interpreting what you see in terms of the history of that place over lengthy timescales.”

Nicholas Christie-Blick, professor of earth and environmental sciences at Columbia, led the trip. Tremblay recalls being the only student who was awake, peppering the professor with questions, as the group drove around in the van. Christie-Blick became a mentor of Tremblay’s as she focused her studies in environmental science.

That summer, she interned at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory under Sidney Hemming, a geochemist and professor of earth and environmental sciences.

“Having Sidney Hemming as a role model early on was hugely influential in helping me figure out what I wanted to do and the path I would take,” Tremblay says. “She’s one of the few women senior scientists working in our field. It wasn’t always obvious that I would set up a similar lab to hers, but I’m pretty happy I ended up following in her footsteps.”

by Kat BrazNow an assistant professor of earth, atmospheric, and planetary sciences at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, Tremblay studies rock samples to measure the temperature history of continental surfaces. She uses a novel method she developed during her Ph.D. research at University of California, Berkeley, which measures historic temperatures using noble gases trapped in minerals. With this technique, scientists can determine how warm the planet was during a certain period of history.

Most of her research projects could stretch back only a few tens of thousands of years — until now.

Marissa Tremblay ’12 analyzes Antarctic rocks to unravel Earth’s climate chronology and predict the planet’s future environment

Last fall, in search of rocks that could tell a story from millions of years ago, Tremblay led an all-women scientific team on a six-week expedition to Antarctica to collect samples from the McMurdo Dry Valleys — a place nearly untouched by time. The McMurdo Dry Valleys are remote, even for Antarctica. It’s a one-hour flight via helicopter from McMurdo Station — the continent’s largest research facility — to reach some of the field sites. The team camped for about a week in the western Olympus Range to allow for more time collecting samples and installing instruments. The rock samples were shipped to Purdue in a cold-storage vessel, arriving in May — six months after the team departed Antarctica. Weather in the valleys can be bitterly cold, averaging between 5 degrees and minus 22 degrees Fahrenheit. And while Antarctica’s frigid temperatures boggle the mind, it’s global temperatures that shock as they continue to rise — 2022 was one of the hottest years on record.

Understanding how climate change will affect the polar regions in the future can influence policy changes implemented today. How warm was Antarctica when the ice sheets last melted? How many degrees would it take for the oceans to rise to catastrophic levels? By studying the stones, Tremblay hopes to find out.

The two enormous ice sheets that blanket much of Antarctica contain about 70% of all the freshwater on Earth. They are vulnerable to ongoing climate change; a significant increase in temperature could cause them to melt, contributing to a substantial rise in sea levels. But how fast and how soon that might occur has been difficult to determine. To help answer questions about the effects of a warming planet on Antarctica’s ice sheets, Tremblay sought to examine the geologic record during the mid-Pliocene Warm Period, about 3 to 3.3 million years ago, when sea levels were about 50 feet higher — the height of a five-story building.

“This period in time is of particular interest because it’s the last time carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere were similar to today’s,” Tremblay says. “It’s a good analog for understanding where our planet is heading in the next few centuries.”

Antarctic ice core records date back only 800,000 years, and historic ocean records don’t necessarily tell us how warm temperatures were on land. But the rocks in the McMurdo Dry Valleys — which is one of the driest and most remote places on Earth and not covered by ice sheets — have been sitting at the surface eroding at unfathomably slow rates for millions of years. They also contain the noble gases Tremblay uses to study past temperatures. The team identified six sites across the valleys to collect rock samples and set up weather stations to measure present-day temperatures.

“Developing a deeper understanding in general of the climate system is helping us make better predictions for what’s going to happen in the future,” Tremblay says. “In many ways, our research on the past climate of Antarctica is only just beginning. It will take many months to years studying their chemistry to unlock their climate secrets.” B

“In other parts of the world, things at the surface erode much faster. But in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, the processes acting on the landscape are so slow that these rocks are just sitting there, bearing witness to the changing climate.“ -Marissa Tremblay

There’s a sentence on the Ya Khadijah design studio website that has raised eyebrows. It reads: “Habibti [rough translation: “My darling”], we help you get your shit together.” The owner of the studio, Khadijah Abdul-Nabi ’08, stands by every word.

“It’s a little tongue-in-cheek,” says Abdul-Nabi, who established the business in 2017. “This consultant from Deloitte wrote to me and was like, ‘You know, I really love your studio and everything, but you have to understand [the sentence] is not professional.’ [But] the biggest paying clients I’ve had have always started with ‘Khadijah, so great to meet you. I love that line on your website.’ So it resonates with the people that I want.”

Bold, brash, Bronx-born-and-raised Abdul-Nabi believes in the power of knowing her audience. She is driven by intellectual curiosity and an iron will, which led her to establish Ya Khadijah, a women-led design studio in Iraq, despite daunting obstacles and a circuitous path.

When Abdul-Nabi came to Barnard in 2004, she was planning to pursue engineering or pre-med. But as she began her studies, she had a calling that caused her to change course.