HOW TO CO-CREATE WITH NATURE

Bavarian State Minister for Economic Affairs, Regional Development and Energy

Design is a powerful driver of sustainable change, and it also drives our competitiveness as a prime business location in the future. It is a key success factor for our companies across all sectors of industry, from family-run organizations and SMEs to global players. With this in mind, this year the Free State of Bavaria is again pleased to support the munich creative business week (mcbw), Germany’s leading design fair. The ideal opportunity to experience the world of design at its powerfully innovative best. And the central theme of this year’s mcbw, exploring the relationship between design and nature, heralds exciting insights and future-facing perspectives. I am confident that in 2024, the mcbw will once again be a source of powerful impetus for a sustainable future, and we look forward to its top-level program of events with keen anticipation.

Mayor of the City of Munich

As the English Garden and the Olympic Park show, the capital of Bavaria is a past master at using groundbreaking design to devise successful ways for humans and nature to coexist in harmony. So I am delighted to welcome the munich creative business week back to our city in 2024, under the future-facing motto of “How to co-create with nature.” A theme that is of paramount importance, particularly for our urban spaces – such as New European Bauhaus, our flagship project for future living and housing in Munich Neuperlach. I wish all attendees an enjoyable and exciting visit, with inspiring opportunities for sharing ideas!

Chair of bayern design forum e.V. Managing Director DURABLE Hunke & Jochheim GmbH & Co. KG

As an entrepreneur, I know from my own experience that design is a critical factor in establishing a position on the market and tackling the challenges of our time. The munich creative business week (mcbw) is the premier occasion for encountering the full scope of design, spanning discussions, encounters and events. This time, the mcbw has embraced nature. And what a rewarding experience it is! We seek to show how designers can learn from nature and its processes, and to reveal the potential created when nature is incorporated into our development of new products and services from the outset. Come and join us!

Dear mcbw explorers and design enthusiasts,

Our current era, given the scientific name of Anthropocene, is dominated and shaped by humanity’s relentless drive to create. We are increasingly coming to the realization that progress comes at a price and is endangering the very foundations of our existence. Now we need to harness our creative drive to address behaviors, processes and viewpoints, while reinforcing holistic perspectives. We must (re-)learn how to work with nature, accept nature as a co-creator, and live and grow alongside it without seeking to regulate it. In short: not domination, but collaboration. To provide clear orientation for this idea, we have chosen the theme of “How to co-create with nature” for the 2024 mcbw.

Our standard of living is primarily based on our ability to continuously advance technologies. But now it is time to bring “how” to the fore: How can we learn how to develop more efficient, more effective methods by drawing on natural processes? How can we pierce the boundaries between technology and nature once again and interweave both these areas into new experiences?

These questions are explored at the 2024 munich creative business week. We aim to throw open the space for inspiring insights, visions and approaches. For everyone who feels this topic speaks to them – designers, companies, students, design enthusiasts. We have worked with our partners to draw up a varied program of exhibitions, events and talks that address our motto of “How to co-create with nature” and unlock surprising perspectives. This magazine presents a sample.

We have also invited Stefano Boeri to be our mcbw Creative Explorer. The internationally renowned architect focuses his work on reframing the relationship between humanity and nature. See our magazine for a taster of his conceptual thought.

Join us over nine exciting days as we explore the interaction between design and nature throughout the city of Munich. Let’s go!

Nadine Vicentini and the bayern design Team

Nine vibrant days packed with inspiration, discussion and networking – that’s the munich creative business week (mcbw). With some 150 partners, 200 events and up to 60,000 visitors, it is Germany’s largest design event, and an international window onto Bavaria’s creative and design industry. Launched by bayern design in 2012, the mcbw is an annual meeting-point for creative minds in the fields of design, architecture and business in Bavaria’s capital of Munich, sending the whole city into a veritable frenzy of design.

The mcbw is where we create a place for dialogue, where professionals, designers, companies, students and the interested public come together to connect

and debate about ideas and trends. The mcbw is where we make design come alive, in a wide-ranging program of events taking place throughout the city and extending into its environs, from exhibitions and panel discussions to guided design walks: www.mcbw.de

The mcbw is where we express our beliefs. Presenting recurring themes of social relevance, the mcbw confronts urgent challenges head-on and provides a platform for discussion and debate. As a new annual feature launched in 2023, we invite a figure from the international design and architecture scene to Munich as our Creative Explorer, tasked with identifying inspiring fields of action.

The mcbw offers a platform for all, from global players to hidden champions and start-ups, from agencies and offices to solo freelancers. Active participation is open to anyone with an affinity for design. Incidentally, many of the events have free entry and are open to the public.

The bayern design team at our Munich office is the driving force behind the mcbw. We are a compact, interdisciplinary team of designers and experts united by common passions for design and for Munich. Our team in Nuremberg provides hands-on support.

During the 2024 mcbw, our head office will be in the Ruffinihaus on Rindermarkt. Drop by and see us there – we look forward to meeting you!

Have we moved too far away from nature? These strategies could bring humanity and the environment back together.

In 2020, scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel calculated the total weight of all anthropogenic mass – comprising all human-made materials and structures such as steel, concrete, plastic and glass – at 1.1 teratonnes. Their findings marked 2020 as a tipping-point for the planet, the first time that its anthropogenic mass equalled its biomass. However, while the volume of biomass remains largely stable, anthropogenic mass has continued to grow exponentially and now significantly exceeds the weight of all flora, fauna, bacteria, etc. Researchers speak of a new age: the Anthropocene.

Nature is generally defined as everything that is “already there” without being created by humans: rocks, rivers, flora and fauna. A definition with a fundamentally material focus. Other opinions claim that humans have at least had a hand in creating, say, the ocean in its present form (with its acidification, its fish stocks and coral reefs, the changing Gulf Stream and its currents), or forests and mountain slopes. In turn, nature can likewise be said to have a creative power and force: all organisms actively contribute toward shaping their environment. Even “dead materials” (sand, rocks, stones) play a role in shaping the natural world and result in cultural landscapes that can vary as widely as the valleys of the Alps and the Sahara desert

Collaboration, not domination

It is thus high time for a more holistic view in which humans and nature are engaged

in a reciprocal relationship, a mutual balancing act with indistinct borders. It takes us to the threshold of a new era, where we must (re-)learn how to work with nature, accept nature as a co-creator, and live and grow alongside it without seeking to regulate it. We must learn to understand nature in a host of different roles: as teacher, as beneficiary, but equally as co-creator and even result of a design process. In the future, we will need to design fewer objects or spaces and more behaviors and processes, while framing viewpoints that make our world into a future-facing place worth living in for all – humans, flora and fauna alike.

How can we learn how to develop more efficient and more effective methods by drawing on natural processes? How can we devise solutions to protect nature (and humans) so that they also represent an

Design solutions based on nature as a role model. More from page 16

Design solutions that benefit nature and humanity. More from page 24

Design solutions in collaboration withnature. More from page 70

Design solutions that interweave nature and technology. More from page 102

attractive business model, and thus broaden their impact? How can we use the formative power of nature in collaborative innovations that benefit “both sides”? How can we pierce the boundaries between technology and nature and interweave both these areas into new experiences? To reflect these core issues, we have drawn up a list of focus topics.

These focus topics form the four main themes of this magazine, in which designers, artists, architects, entrepreneurs, engineers, digital experts, sociologists and many other professionals present their considerations of how we can design behaviors, processes and viewpoints that encourage a majority to perceive nature as a worthwhile – and, fundamentally, as the only relevant – goal. Our creative explorer Stefano Boeri gets the ball rolling.

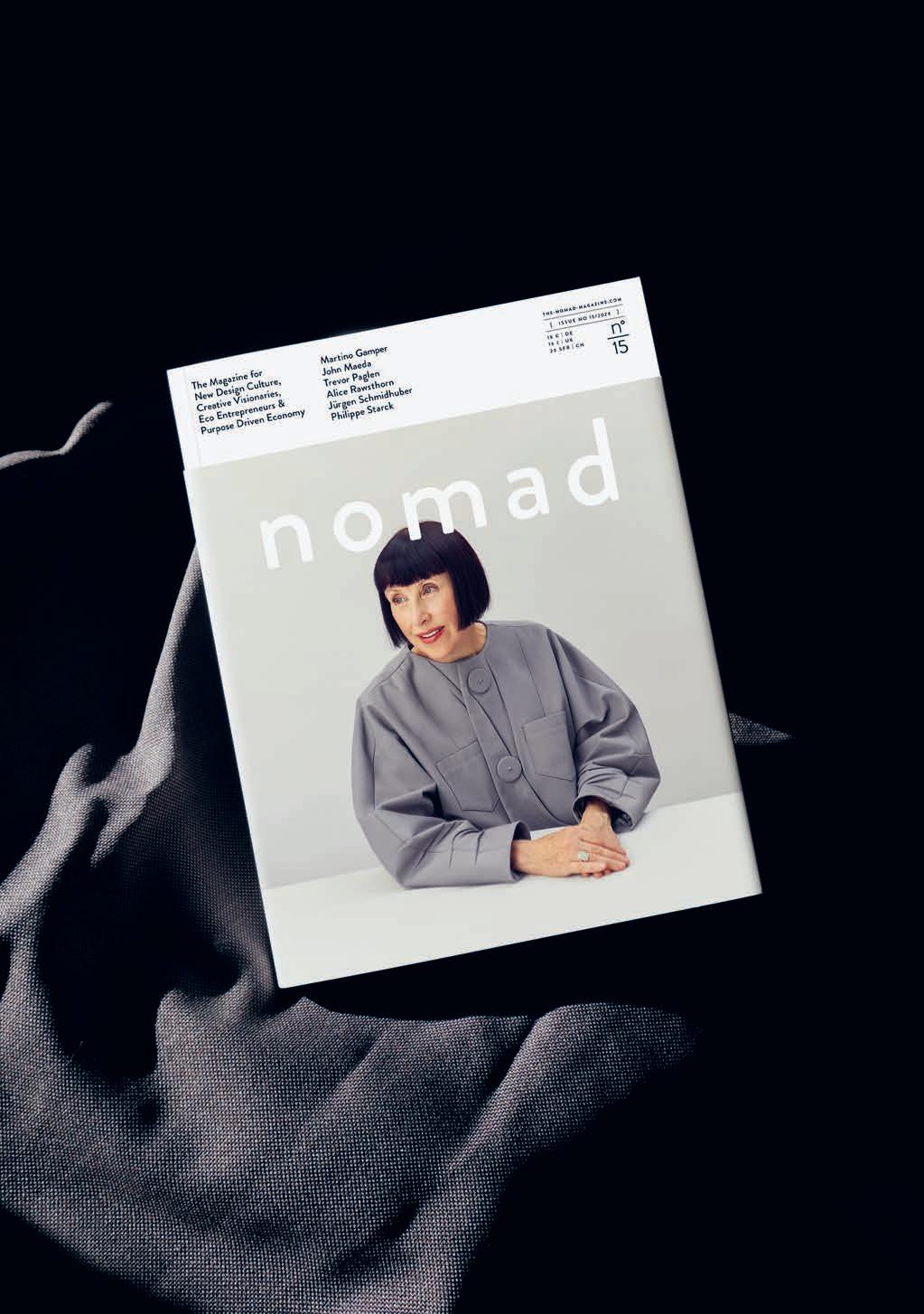

Professor Stefano Boeri explains why nature enriches our cities.

Stefano Boeri is mcbw’s Creative Explorer for 2024. Every year we seek out pioneers that embody our lead topic in their dedication and commitment, and take our society forward. Boeri is one of those pioneers. The multiple award-winning architect and urban planner is one of the world’s foremost visionaries in sustainable building. He directs his gaze at creating a new balance between the built and natural environment.

OLIVER HERWIG

It seems like yesterday. But the Bosco Verticale was actually completed ten years ago. It changed something. Was it a kind of revolution in the field of architecture that you started back then?

STEFANO BOERI

I don’t know if it was a revolution. It was an attempt to consider leaving nature as an essential component of architecture and not simply as an ornamental decoration. And to face with the intersection between living nature and artificial buildings, not only from an aesthetic point of view, but also considering the possible advantages of the cooperation of the two spheres, living nature and artificial buildings.

OH

The green curtain you created has several advantages.

SB

Sure. In terms of capacity to absorb CO 2 , reducing heat, saving energy and capturing fine dust, implementing biodiversity, collecting water and also promoting substantial physical and mental health.

The vertical forest in Milan was a prototype, an experiment and we are still studying ecosystems to adopt them to different cli -

mate conditions as they consist of different living species: not only humans, but also trees, birds and ... We consider this experiment the starting moment of several other experiments that we are developing, a group of buildings very different from each other.

OH

You have constantly developed the original concept further. Are there already some conclusions that you can draw from the line of development?

SB

We have built 12 vertical forests in different parts of the world, in China, Holland, Belgium and Italy. There are nine in construction, and we have designed more than 40 vertical forests for different parts of the world. New versions show also new combinations of living nature and artificial buildings. Such variations allow us to relate the vertical forest to the specific climatic conditions that prevail in different parts of the planet.

OH

What is your starting point when you design a vertical forest?

SB

The first step is to consider the climatic conditions, the second step is to select the plants, especially indigenous plants. Only at that very moment we start to

design the buildings considering the space that every tree, every plant, every bush should have in order to grow. It is a sequence of steps that produce very different results in terms of architecture. We have tried to make this typology more efficient. And more affordable, which was the main challenge, reducing the cost of construction. Thanks to prefabrication, the vertical forest is now fit even for social housing. Compared to the Milan prototype, we have reduced the construction costs by half. Another aim was to make these buildings more sustainable considering the consumption of energy. So, we are trying to enlarge the surfaces with photovoltaic panels and work with geothermal energy as often as possible. The organic facade actually reduces the heat on the façade in summer by some 30 to 45 degrees. The microclimate created by the trees and the plants is quite important. We also introduce wood in the construction process and use the prefabrication of wooden panels to reduce CO 2 emissions and speed up the construction process. We also spend a lot of time reusing water and using rainwater. Water management is becoming crucial.

OH

You have planted around 900 trees in Milan, which must be very well looked after. Do people really look after their trees?

SB

To be honest, I initially thought it was important to involve tenants in the protection and maintenance of these green spaces, as not everyone has the ability or sensitivity to respect plants and provide them with good living conditions. So everywhere we proposed a centralized maintenance with sensors distributed over the balconies. So far we have not had a problem at all, not even with plant mortality. Initially, we thought about replacing a certain percentage of the plants, but that didn’t happen. In Milan, we had to replace just five or six plants.

OH

Sounds very efficient, but can’t you expect people to get together and form a community to take care of their trees?

SB

I totally agree. But when you have invested so much in the idea

and in the construction process, there comes a certain moment when you have to leave b ecause the building has an autonomous life. Sometimes, you are not even allowed to contact the tenants or to interact with the property. In Eindhoven, for example, we have very good relations with many of the tenants, young tenants, and we know that some of them are introducing new plants, sometimes even marijuana plants.

OH

I was wondering if you were ever inspired by, say, etchings of Roman ruins overgrown with trees ...

SB Absolutely. When nature comes back it is capable of recolonizing artificial environments. It produces a combination that is quite similar to what we try to do, introducing a new environment and a new landscape. There is a

tower in Lucca that was an important inspiration for me, the Torre Guinigi, an amazing tower from the 13th century, made of bricks with a bunch of trees on the top. It was very important to us that we didn’t invent something impossible. There were also other inspirations from different fields, like Joseph Beuys suggesting that the metamorphosis between artificial and organic could become political. That kind of provocation was very important. There was also Italo Calvino and his “Baron in the Trees.” For me, the tree was very personal, very important and very influential. Just like Saint Francis and his Canticle of Creatures 800 years ago. Or Buddha proposing the same kind of intersection between living nature and the human sphere. Well, we are not doing anything new. We are simply trying to bring back nature to what we have done. The fact that we only made our habitat out of minerals was probably a serious mistake. We have understood

that. And now we are trying to return to a different state between the two spheres.

OH

Do you also question modernism and its idea of progress without any regard for nature and ecology?

SB

It’s true, I think that’s what modernism is all about. But it’s so difficult to correct this concept of a kind of binary between nature and the artificial, between nature and culture, between nature and cities and forests and cities. We have done our best to expel nature from our bodies, homes, houses and cities. And, well, at a certain moment, we understood that this was not the right solution. We just learned from Covid that a tiny microorganism is able to change our lives. In the future, we must consider coexistence and coexistence with other living beings, no matter how challenging this may be.

OH

How would you describe your personal relationship with nature?

SB

As quite normal. Ever since I was a child, I’ve had an obsession with trees, not with nature in general. Trees are amazing. They are a universe of individualities. In a forest every plant, every tree has its family, its roots in the past, its individuality, its intelligence and sensitiveness. A forest makes up a universe of varieties. From that point of view, this is a parallel between us humans and trees. Now we have to learn how to bring trees to our cities.

OH

It’s very interesting that you compare trees with people. Would you also compare trees and architecture and a forest with a city?

SB

Absolutely, because when we see a city, we see it as a compo -

sition of a variety of buildings and cultures of inhabitants, and there is the possibility of creating a community that belongs to the same environment. And that is more or less what you see in a forest. You see the variation of colours and proportion. Sometimes trees grow vertically, sometimes they expand their branch horizontally. Then you sense that this is a universe with common conditions, that we all have the same meteorological and physical conditions. So I think the analogy is absolutely fruitful.

OH

In one of your interviews, you stated: “Cities are among the most important protagonists of global warming.” Do we have to change the way we build, the way we develop spaces in order to respect the nature surrounding us?

SB

Since I started advocating reforestation and afforestation measures 20 years ago, I have been convinced that this is the most efficient, cost-effective and comprehensive way to combat global warming. This is not just about vertical forests. We also need to develop real forests. We need to change the way we eat and consume energy and water. Another very important issue is the question of heat. Shade has

become a scarce resource and almost a privilege.

OH So, this year’s motto “How to co-create with nature” is quite relevant for your work.

SB Yes, co-creation is important. We need to discuss how we can reduce anthropocentrism in our interaction with the environment. That’s an important step that we need to take, not in the sense of giving up our role as, let’s say, a prominent and powerful species on the planet. But to straighten out that role and change our approach. What we should try to do is to acquire the point of view of the other living species, considering their needs, considering their trouble, their concerns and needs. This will help us to safeguard and take care of the entire ecosystem. We cannot simply delegate this to other species. We have to stay on the pedestal because that is where we stand and we are responsible for improving our ability to consider the perspective of others. Co-creation is a result of a process of empathy. Only when we co-create will we be able to put ourselves in the eyes and minds of other species.

OH

Would you call this a spiritual turn in design and architecture?

SB

No, but there are so many thinkers in our field that were considering this notion of empathy – like Patrick Geddes, biologist and architect, promoting the idea of cohabitation between nature and cities, between trees and humans. He was less famous than Corbusier, but not less relevant in terms of producing a new focus on our environment. This spiritual dimension is very well rooted in rationalism.

OH

Are you still an optimist when it comes to our future as a species?

SB

I am optimistic when I see the young generation and their awareness of what we should do. And I am totally pessimistic when I see political decisions related to global warming. I believe that for the future we have to try to look at climate change and social polarization together, because that will be the main issue of the future: inequalities are simply the other side of global warming and the climate environment.

OH

Professor Boeri, thank you very much for this interview.

SB Very much appreciated it. I’m looking forward to being in Munich.

Bioinspired design solutions

Icarus tried to fly – and plunged to his death. Otto Lilienthal completed some 2,000 successful experiments in flights, but eventually he too crashed to earth. Seems that humans can’t turn into birds after all, even when they strap wings to their arms. But as the persistence of the myth shows, engineers have always looked to nature for inspiration. Technical solutions with minimal energy consumption are now more sought after than ever before. Bioinspired design that takes nature as a template means drawing on the biggest real-life laboratory on the planet, which has tested and rejected thousands and thousands of variants over the millennia. The fruits of evolution are rightly regarded as benchmarks. One of the best-known examples is probably the lotus effect. But while the plant’s self-cleaning surface proved ideal for sanitary facilities and kitchens, the solution itself was far from obvious: the self-cleaning effect came not from ultra-

smooth surfaces, but from surface microstructures with superhydrophobic characteristics.

Natural designs are very far from technical blueprints and cannot be adopted one to one. But their underlying methods can. When the disciplines of biology, physics and design come together, they create bionics. Named from a portmanteau of “biology” and “electronics,” the field systematically analyzes “phenomena found in nature” and explores how they can be applied to technical problems of today New bioinspired technologies can be created in a top-down process, where researchers systematically search for analogies in the natural world. One example can be found in tire design; engineers noticed that a running cheetah’s paws spread when they hit the ground,

enlarging the animal’s contact surface. They came up with biomimetic tires based on the same principle. But the design process can also be bottom-up, when general biomechanical principles inspire technical structures and processes. For example, significantly enhanced stability can be introduced to piping by basing its design on the natural structures of a plant stem.

In both these cases, nature is the source of inspiration, and bionics adopts the best tricks from her wealth of ideas. The cross-disciplinary science can be applied to create outstanding products that are both ultra-light and ultra-strong. Bionics “seeks to signpost the path toward the integration of technology and nature, taking aspects into consideration such as the possibility of saving energy and materials. Using natural growth criteria as a basis for ecological design of technological components is no longer a utopian dream,” as zoologist Werner Nachtigall and scientific journalist Kurt Blüchel explained in their 2003 standard work “Das große Buch der Bionik.” Much progress has been made since then. Computer simulations now allow us to visualize the evolution of materials and designs and identify promising variations more rapidly.

Bionic mindsets are becoming increasingly important in architecture and design. Nature is super-efficient, and unceasingly saves energy and materials. A tree only adds material to its branches at the points where external forces could break them. This phenomenon can be precisely calculated. Professor Andreas Mühlenberend, Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, applies natural principles to develop ideal forms – or rather, ideal structures – for objects. The SKO (soft kill option) is used to simulate formative processes, often with astonishing results; a loading hook swells and bulges, a ladder suddenly becomes as bow-legged as a cowboy. Things grow in order to “find more advanced, lighter, more stable and lower-carbon solutions.” But designers did not stop there. Their input perfected co-evolution by introducing formative structural ideas that gave the objects their visual form. The goal remained the same: fewer materials and resources, longer product life. Designers have been sparring over lean solutions like these for over fifteen years; they include Joris Laarman’s “Bone Chair” (one of twelve from the 2007 edition was auctioned at Sotheby’s with a reserve of USD 500,000) and “Gradation and Cube Air Vases” by

Torafu Architects in laser-cut paper, as well as ultra-light pavilion structures which imitate plants without resorting to simply copying them.

Ecological footprint

The “livMats Pavilion” in the University of Freiburg’s Botanic Garden features a bioinspired design. The networks of interwoven fiber structures found in the saguaro and prickly pear cacti are echoed here by a load-bearing structure of robotically woven flax fibers. Flax has similar mechanical properties to fiberglass; a robot places fiber bundles on a winding frame, allowing the building elements to grow with virtually no waste or offcuts. The only concession is a waterproof polycarbonate skin to protect the fibers from moisture and UV radiation. Structures like these combine and consolidate knowledge from a whole array of branches. In fact, the “livMats Pavilion” was designed as a collaboration between the ITECH master’s program at the Cluster of Excellence Integrative Computational Design and Construction for Architecture (IntCDC) at the University of Stuttgart and biologists from the Cluster of Excellence Living, Adaptive and Energy-autonomous Material Systems (livMatS) at the Univer-

sity of Freiburg. The winding process they devised delivers both material savings and high load-bearing capacity. With an area of 46 square meters, the whole pavilion weighs just one and a half tonnes, less than a midsize car.

The world of design is undergoing a fundamental shift towards lighter, yet more stable construction. However, despite all the optimism, bionics is still far from being a sure-fire success. It requires designers to have in-depth knowledge of statics and biology and is thus better served by interdisciplinary teams; in addition, many of its developments are immediately patented. Andreas Mühlenberend is one voice highlighting the opportunity for societal leverage alongside the goal of product optimization. He identifies six “completely indisputable things that will help us progress in ecological terms, namely sustainable energy sources, sustainable materials, durability, repairability, reusability, and sharing.” Thus, what we need are new forms of cooperative economy and social solidarity. If we aim to reduce our ecological footprint permanently and become truly climate-neutral, we will be forced to adopt bioinspired design solutions in the future. Otherwise, like Icarus, we may be doomed to fall.

CONDUCTS RESEARCH AT THE FRAUNHOFER IAO’S PIONIERHUB IN WERKSVIERTEL, MUNICH, FOCUSING ON SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS FOR FUTURE-FACING URBAN DEVELOPMENT

Nature has had millions of years to perfect its design. What can we learn from it?

Nature provides us with a host of strategies for future-facing urban planning that serve as inspiration for our research. In its complex ecosystems, all materials are resources for other organisms. But ecosystems and interconnections can be established in cities, too, by embracing the goals of recycling, repair and return of waste products to the material cycle.

What are the biggest challenges in this approach?

Collaborating with artists in one of our projects, we realized that areas such as urban food production call for society to adopt a new way of thinking with new processes, technologies and resources, but also give rise to new design requirements. If urban districts are to be self-sufficient in food production, we need to devise creative farming methods. What about, say, hydroponic workplaces, where the desks are surrounded by plants?

So if we really want to learn from nature, do we need to change?

Learning requires a change of perspective as a matter of principle. If we want to integrate natural principles into our technologies and designs, we need to be open to new approaches and reassess traditional ways of thinking. With this in mind, we contribute creative projects to the Fraunhofer Network Science, Art and Design (WKD) with the purpose of developing innovative solutions and debating with the public in participatory projects. We look forward to showcasing numerous projects at the PionierHUB in the Werksviertel district during this summer’s mcbw, and meeting as many visitors as possible to gain new impetus for our research.

MANAGING DIRECTOR

BHB

UNTERNEHMENSGRUPPE

Where do you draw inspiration from nature?

I find inspiration in the genius loci – the natural environment that surrounds our projects and the cultural landscapes, in forests, moors and herb gardens. I’m fascinated by the wealth of variety in nature; I turn my focus on endangered species like bees, butterflies and glowworms, and marvel at their survival skills. The impressions I take away are then incorporated into my construction projects, including DAS KLEINOD in Munich Riem and FVTVRIA, a local project in Garching, where we are creating biophilic habitats for all: flora, fauna and humans alike.

What can we learn in general from nature?

Nature is our finest teacher of holistic and regenerative design. Sustainability, circular economy, simplicity and authenticity are all things we can learn from nature. For me, that means paying attention to ecology, health, art and social aspects in my planning. More than a house to live in, a habitat needs to be a habitArt, taking nature as a template and based on an overarching socio-ecological concept. Like DAS KLEINOD, our integrated living project in the Riem district of Munich. It has apartments for families, singles and couples in lush natural surroundings that encourages residents to explore, experience and take care of them.

If we really want to learn from nature, do we need to change?

From my perspective as a woman and an urban planner, I believe it’s time to expand our perspectives and focus on the constantly changing natural environment, to understand buildings as adaptable organisms. A building needs to enter a symbiotic relationship with its natural surroundings and its inhabitants, take different lived realities into consideration and develop sustainable concepts for a future-facing way of life. Our pilot project for Building E in Mooritz adopts this innovative approach, which not only aims to transform the construction industry but also, and primarily, seeks to conserve resources.

Design solutions that benefit nature (and humanity)

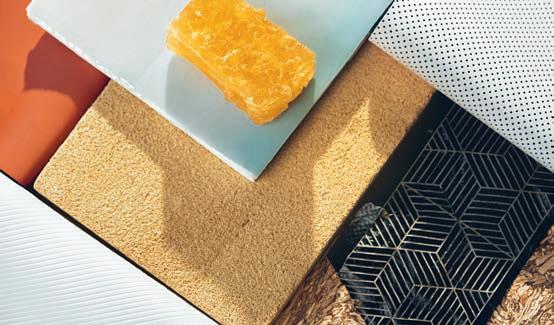

On the way to planet-centered design: new materials, old technologies.

Of course we’re materialists – or most of us are, anyway. We can’t stop ourselves picking things up, handling them and experiencing them for ourselves in our attempts to understand them. So wouldn’t it be good to be certain we hadn’t just ingested some microplastics or been exposed to pesticides or environmental toxins? This is the dark side of our modern age and all its indisputable successes, which has revolutionized the world and enslaved humanity. The Anthropocene reveals its true face in more than abstract figures and carbon concentrations. There is danger in streams that become torrents, glaciers that melt and microplastics that infiltrate the food chain. So what do design solutions that benefit nature (and humanity) look like? The question is far from naïve; it is directed at how we will manufacture in the future, and thus how we will live. Twentieth-century modernism has led us down a blind alley. We

need to rethink materials and processes, introducing material flow cycles and renewable energies.

But leaving aside the latest buzzwords like “circular economy,” which is currently replacing “ecology” in popularity, how will that work? One fascinating option is to combine traditional knowledge of sustainability and natural materials with cutting-edge manufacturing processes. A (suitably modified) 3D printer can easily handle clay, a traditional material with superb spatial properties. So why not print clay bricks for interior use? mused students at the Canadian University of Waterloo, and produced “Hive” from 175 hexagonal clay bricks. The beginnings of the project were far from straightfor-

ward. Basic research was called for. What kinds of material mixtures are printable, and how must the design and production equipment be adapted to them? A not insignificant goal was to find out whether digital processing of those materials could be cost-effective. 3D printing scored points for its ability to reproduce complex geometries, resulting in a curious phenomenon where digital craftsmanship tapped into millennia-old knowledge and applied robotically controlled precision to create completely new applications, entirely natural and toxin-free. The Canadian interior design project had built a bridge that others could now cross, particularly given that 3D printing had advanced from a niche technology to the heart of production operations. As the most recent Sculpteo survey on the status quo of 3D printing (2022) showed, rapid prototyping was now used by 18 percent of manufacturers for mass production, and by 28 percent for producing consumer goods.

Last November the University of Maine went one step further: its Advanced Structures and Composites Center ( A SCC) used printed wood fiber and bioresin to build a house with around 56 square meters of living space. Known as BioHome3D, it is thus 100 percent natural and fully recyclable. The highly insulated biohouse, created using the world’s largest polymer 3D printer, is hoped to be a medium-term solution to housing shortages; according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, there is a shortage of around seven million affordable homes in the USA alone. The prototype BioHome3D is equipped with sensors that monitor heat, environmental and structural factors. Data from last winter will help to improve the biohome and perhaps enable series production to launch soon.

But the team of 3D printing and biomaterials offers potential that goes beyond human habitation. Last year, strange, otherworldly structures began to appear in the Hildesheim Amphibian Biotope: delicate, intricate towers and slender buildings on a miniature scale, reminiscent of alien cities. Research project Symbiotic Spaces explores ways of enhancing the urban coexistence of humans and non-humans, and came up with habitats for insects and endangered fauna like the crested newt and yellow-bellied toad, 3D-printed from alumina. The brainchild of designer Joana Schmitz, it was supported by biologists from Hildesheim’s nature conservancy organization and schools biology center. It could soon catch on, setting a precedent for the benefit of humanity and nature.

The shift to planet-centered design (see article about Munich University of Applied Sciences) is going strong. Underlying this movement of change is the realization that we can only survive by abandoning our reductive view of the world around us as a mere source of raw materials, home for infrastructure and garbage tip. The new mindset starts with circular production and ends with new economic concepts that benefit humanity as a whole. And it is spearheaded by a largely intangible, incorporeal object: a search engine. Berlin-based search engine Ecosia is a mere ant in comparison with the Californian elephant that is its counterpart. But what’s so special about Ecosia is that 100 percent of its profits are ploughed into forestation projects around the world, and into renewable energy for its servers. In this way, over 20 million

users have planted around 185,000,000 trees. Virtually, of course; nobody actually picks up a shovel. Ecosia’s advertising highlights its protection of privacy, transparent business operations and climate-neutral production. With these advantages, the start-up is a blueprint for the often-hailed “new economy,” directed at the common good, participatory, transparent, sustainable – and sounding almost too good to be true. But Ecosia homes in on our need for convenience. Changing from our usual search engine couldn’t be simpler or more straightforward. One click, and it’s done. Surfing with a clear conscience, every click a seedling. This is where we can experience the transformation of our economy and our treatment of the planet and its human inhabitants.

If we genuinely want to become climate-neutral by 2045, that goal will not be a single finishing line, a single tape to breast. It will be more like a marathon, like the eternal consequences of mining: if we switch off the pumps in Germany’s Ruhr region, its cities will drown in the rising groundwater. Yet the transformation is already in full swing. So much so, in fact, that it is occasionally overlooked. “Based on the technologies of today, the annual energy consumption of all battery factories planned worldwide will reach 130,000 gigawatt hours by 2040. That’s roughly equal to the annual energy consumption of the country of Sweden.” Peter Carlsson, CEO of Northvolt, was referring to “the biggest industrial transition of our lifetime” and described the winners as the ones who attract the necessary capital, recruit the best people and have the best plan. Seeing the big picture is part of this. Because transformation is a task for the whole of society – indeed, for the whole of the planet. A task for idealists and materialists alike.

Alexander Stotz, CEO of Ströer Media, presents the digital city of the future. It is diverse but, most of all, sustainable.

Alexander Stotz, CEO Ströer Media

OLIVER HERWIG

Why are you an mcbw partner?

ALEXANDER STOTZ

Because we accept responsibility for the public space that we help to shape. Our goal is to align our design to reflect the city and the architecture where it is located, but also the wishes of the people that live there.

OH

So design is part of your process from the outset?

AS

Yes, because we are privileged to occupy valuable space in public places. With this in mind, we align our street furniture closely to its environments. We have always commissioned public t ransit shelters in modern

designs by Hadi Teherani and many others, because design needs to be unobtrusive, if only because of its repeated presence.

OH Does that apply to the content, too?

AS

Posters are still the basis of everything we do. When static images succeed in compressing information into the dimensions of a poster and inspiring images in the minds of the viewers, they express the supreme art of creativity.

OH

You provide advertising for around 1800 public transit shelters in Munich alone. Many moving images are pretty conspicuous.

AS

Moving images are all about persuasion. We launched digital out-of-home advertising in Munich twenty years ago, as global pioneers in the field. Nobody wanted the city to become a Las Vegas, and we were wise to wait for a while before introducing digital advertising to the streets. Only the technologies we now have today can comply with heritage protection requirements and integrate appropriately into their environment. The “bright lights” are no longer so bright, which is also good for energy efficiency.

OH

On that subject, how do the carbon footprints of, say, posters and screens compare?

AS

Let’s take the example of a poster lightbox in 9-m² format. It has a carbon footprint of around 55 grams of CO 2 per 1000 contacts, which is very good. Cost per thousand, or cost per mille, is the standard unit of calculation in the advertising industry. So a daily newspaper has the highest carbon footprint, with over 9000 grams. Online advertising has emissions ranging from 13 to 284 grams of CO 2 , depending on the format. TV has 828 grams of CO 2 , but radio has only 69 grams. And digital out-of-home advertising operated on green electricity has a carbon footprint per thousand contacts of just 5 to 6 grams of CO 2 .

OH

How does that work?

AS

It works because we’re not a broadcasting station, but we have many, many contacts –400,000 contacts per day at Munich’s central railway station, for example. This optimizes the energy efficiency per contact. In addition, we spent five years developing our own energy reduc -

tion methods, and succeeded in significantly cutting our consumption.

OH

And you did this by …

AS

... working on the ion control software that selects the colors in the advertisements. White uses the most power, up to the max. It took many, many small steps to achieve this energy saving. We also use green energy.

OH

What does sustainability mean to you?

AS

We celebrated our centenary last year. So our business model is pretty sustainable. We were already seeking to maximize our screens’ lifespan and proportion of recycled material years ago. The 2023 GreenTech Festival saw the debut of our new bus shelters, which filter particulates from the air, can absorb around 50 liters of rainwater, and create little oases of nature in heavily built-up areas. 40,000 bus and train shelters and advertising pillars can be greened. We have already started the process in Munich.

OH

Is there more that can be done?

AS

Sure. We install solar panels on the roofs to provide 100 percent of the power needed. And we collect driftwood from the Baltic Sea to use for the seating; there’s a small factory that manufactures it.

OH

So transit shelters become energy-autonomous?

AS

Or preferably, generate more than they need, so people can charge their phones or e-scoot -

ers wirelessly. We need to constantly be on the look-out for new connections. Sustainability primarily focuses on ecology, but it also involves social aspects. We aim to become a communication platform that can serve others. To this end, we provide a host of NGOs with their own sustainability window in our program, to inspire people to join in.

Are smartphones in competition with your advertising, or are they opening new doors?

AS

Both. There’s certainly plenty of competition for attention, particularly in the metro – or the subway, if you prefer. But passengers waiting for a train are grateful for the distraction. Alongside classic out-of-home advertising, we are also Germany’s largest online marketing company, so we are closely bound up with the development of the medium.

OH

Visual behaviors are changing.

AS

It’s a generational thing. Five years ago, we might have been asked whether ten seconds weren’t rather short. But look at Instagram today, and ten seconds suddenly seem like a whole movie. We have to be far quicker at capturing viewers’ full attention, especially where young people are concerned, otherwise they’ve already gone on to the next film.

OH

What about digitalization of public spaces? Are we moving in the direction of a virtual world?

AS

Screens can connect the digital and the real world. And those connections are what counts. Advertisers are moving away

from classic product campaigns and addressing topics of social relevance. When that happens in real time, we experience a new dimension of communication that makes the company and its values more accessible. That goes for products and services, but also for recruiting.

OH

Does artificial intelligence (AI) already play a role in your work?

AS

Yes, a big role where it comes to generating neighborhood content – in other words, scanning the Internet. AI eases the workload of people engaged in creativity. And it checks content for, say, religious or political extremism or propaganda.

OH

That could be pretty sensitive. What does the future have in store for us? Will advertisements address us directly by name?

AS

No, but things will become increasingly localized. For example, the restaurant on the corner

could book a screen on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 10 to 12 to advertise its lunch specials, and

quickly take the ad down when it’s sold out. That’s very efficient, including cost-wise. And creative YouTubers can naturally also use the neighborhood in the same way.

OH

And in five years’ time?

AS

Probably half of all media will be digital. I can imagine that in ten years there will only be digital media because by that time, transreflecting displays will have reached acceptable image quality. They only need energy when they switch images, so that they offer continuous communication in real time.

Digitale Außenwerbung ist Information, Plakat, Film, Banner und Soziales Medium in einem. Bundesweit oder hyperlokal, online-gesteuert, extrem skalierbar und vielleicht das letzte Massenmedium. Weil es die Mitte der Gesellschaft in Sekunden erreicht.

How Designworks is combining tomorrow’s mobility with sustainability.

As the water taxi accelerates, a plume of spray rises and the hull lifts out of the water. It glides over the water on three slim foils, which create far less wake than conventional vessels and generate uplift in a similar way to aircraft wings. Named The Icon, this is the first electrically powered water vessel to feature the hydrofoiling principle, which has long been in use on sailing yachts and some passenger boats.

The future-facing solution for water mobility is proof of what can happen when inventors think outside the box and carry innovations from one area over to a completely different one. But that is Designworks’ hallmark.

The 100-percent subsidiary of BMW was founded half a century ago in California and has further offices in Munich and Shanghai. Designworks’ design brief is extremely broad, from lifestyle products to aircraft interiors, digital user experiences and all forms of mobility – including car design for the BMW Group. The company’s three studios are hotbeds of completely new concepts, including hydrogen-powered electric vertical take off and landing vehicles. No ideas are off limits. Quite the opposite, in fact; BMW sends its best designers over to encourage them to develop new perspectives. Holger Hampf, President of Designworks since 2017, has the goal of uniting high-tech

Holger Hampf, President Designworks

and sustainability to benefit humans and nature alike. Mobility is no longer restricted to four wheels and a driver’s seat. It can now be an app, or part of a logistics system moving goods from A to B. “There’s so much service design behind it, so much systemic thinking.”

Los Angeles, Shanghai and Munich are ideally distributed around the world. But not only that: the locations and their extremely different cultures also bounce inspiration, ideas and market changes back to Munich. Adrian van Hooydonk, Vice President Design der BMW Group, once described Designworks as BMW’s eyes and ears onto the world. In this role, Designworks

need not strive for perpetual growth, but must primarily focus on developing an understanding of the markets and of exciting technologies –in other words, function as an agent for change and a think tank in a rapidly evolving world.

A huge dark panel stands in the conference room at the Munich office, used as a board for jotting down ideas. Holger Hampf grabs a piece of chalk and sketches out two axes of a graph, a timeline and an innovation trajectory. A vector soars upwards at a 45-degree angle, heading directly for a point of maximum innovation in the not-too-distant future –say, around 2035. The aim of all the designers is now to translate this vision into feasible steps that lead straight to that point. The team always keeps these milestones in view. After all, Designworks has the aim of combining technological and esthetically functional ideas with issues of sustainability, “from designing the façade of Africa’s most sustainable building to developing the Sirius Jet, a hydrogen-powered vertical take-off vehicle, or battery-powered maritime vessels with foiling technology,” says Holger Hampf. All this high tech needs technical expertise and a clear eye for the big picture. “We seek not to view nature as a partner, but to perceive ourselves as part of nature. We believe a paradigm shift will be necessary for humanity to be able to advance.”

One possible solution is modular design, in which objects are no longer created as inseparable units, but are separable and repairable. “Modularity offers the opportunity for new and different ways of thinking, particularly in the case of highly com -

plex integrated products.” The building block or kit concept already enables BMW to recycle over 90 percent of its parts and components. The knack is to incorporate design and sustainability goals into the product development process as early as possible, and the earlier the better. From initial vision to brand strategy, and beyond that to industrial production. In Hampf’s view, Europe draws on a trove of big brands, none of which would likely have emerged without the will to embrace rigorous design: “Design needs to understand contexts and take a holistic view.” Hampf thinks in terms of the emotional worlds that surround us, focusing on the “choreography of different experiences or functions.” The task of design is to bring everything together. Climate change shows that holistic thinking no longer stops with the product. The goal is “to design in harmony with the planet and the needs of our environment from the outset,” says Hampf. “Our considerations must address the needs of our environment and of the planet just as much as those of individual users.”

No wonder many projects relate directly to ecology issues – like the maritime vessel mentioned above, which has taken off by using foiling technology to cut around 80 percent of previous energy consumption. Another approach in response to a different task was the electric outboard motor designed for Mercury, where the goal was not to maximize range, but to power low-noise, emission-free shortrange travel on rivers and lakes. Even here, the e-motor represents a genuine alternative to

combustion engines. The boat can be charged while moored, or the battery can be removed for charging at home and reinstalled the next day. Many of Designworks’ ideas and technologies work along similar lines. Teams roam from cars to aircraft and back to other forms of mobility, taking in electric wingsuits on the way. Projects in widely diverse areas throw open unexpected perspectives, occasionally also short cuts. The “hybrid designers” working at Designworks do more than create products; they think beyond their boundaries, looking out at the world and identifying points of connection. Wherever modern

mobility is the focus, trains, aircraft and boats must also be part of the picture in order to design, say, an optimized car interior.

One of the most recent Designworks projects concerns “light productivity” on business class flights, when passengers are relaxing and watching movies or listening to music, but may still want to read through papers and answer mails. Knowledge like this can be important in the design of an autonomous vehicle, as can the ability to transfer questions and solutions from one area of operations to another. Hampf says, “We look at everything. It’s not about one single charging point,

one well-designed payment app or isolated product ideas. The goal is to bring everything together into a whole in order to create positive and universal user experiences.” He notes that long product lifespan is still the holy grail of sustainability, citing leather as an example, which even develops an attractive patina over time. However, Hampf warns the material is used too widely and sourcing plant-based alternatives has become vital. Here too, the essential ingredients are technical expertise, an appreciation of tactile quality and, of course, the flashes of inspiration sparked by Designworks’ three very diverse locations.

LEAD UX DESIGNER ERGOSIGN

UX DIRECTOR, HEAD OF SITE ERGOSIGN

Is “circular” the new “sustainable”?

“Circular” describes only one aspect of sustainability. At Ergosign, our goal is to design digital experiences that conserve resources, but also have a positive impact on society and company development. We integrate environmental, social and economic factors to create products and services that deliver continuous value added. To do this, we apply a collaborative approach to development that is deeply embedded in our DNA.

Do we need to question companies’ attitudes more closely?

Yes, definitely. Part of our responsibility as user experience professionals is to scrutinize companies’ attitudes to design, technology and sustainability. It’s our duty to foster ethical practices and transparency and to encourage companies to reflect on the impacts of their products and decisions on society and the environment. We achieve this by engaging in non-judgmental critical scrutiny and by visualizing ideas and their implementation in practice.

How does Ergosign overcome pushback against sustainability?

The majority of companies welcome sustainable leadership. Of course, some want to hold onto what’s familiar or long for “the way things used to be,” but others embrace rapid progress. Active listening, conducting surveys and offering co-determination are all ways of reducing concerns, enhancing motivation and encouraging people to come along on the journey. One of our design principles for sustainable development is “Act collaboratively and individually.” A culture of openness creates a framework where like-minded people can come together and proactively generate a huge surge of energy.

The Design Faculty at Hochschule München University of Applied Science (HM) focuses on design research and shaping the coexistence of humans and nature.

A key topic for the dci: how can cultural patterns be developed to provide impetus for social, ecological, technological or entrepreneurial futures?

Cultural patterns for social innovation are a research topic at the new Design Cultures Institute for Applied Design Research at Hochschule München.

Design research has experienced an upswing in recent years. At the head of the field in Bavaria is the Design Faculty at Hochschule München University of Applied Science (HM). But what kind of research takes place at HM’s Design Cultures Institute for Applied Design Research (dci), part of Bavaria’s state-funded Hightech Agenda scheme? “Cultural patterns make up our main theme,” explains the institute’s director, Prof. Markus Frenzl. “We use design to research cultures of perception, knowledge, action and innovation and company cultures. Our findings then serve as a catalyst for developing new ideas against the backdrop of social transformation.”

The scope is deliberately broad, encompassing perspectives on environmental, economic and social transformation in equal measure. The new institute’s activities will be wide-ranging to reflect the fact that design permeates our entire lives.

Markus Frenzl describes design as “practice that fosters identity and culture with its own culture of knowledge and research.”

Pointing out that culture is not something that can be prescribed, he explains that the institute does not itself drive cultural change; instead it focuses on the phenomena of such change, on the cultural patterns that, when further developed, are rendered “able to make cultural connections and thus lead to new ways of life, manufactur-

ing technologies and ways of understanding.”

Research starts from three main focal areas. The topic of “Participation, Co-Creation and Futures Literacy in the Context of Social Transformation,” for example, links to a master’s project which identified research drivers for the HM: UniverCity project “Creating NEBourhoods Together.” In the project, master’s students surveyed residents in the Neuperlach district of Munich to find out about their living conditions and their desires, with the goal of “working together to design attractive, ecological and future-facing neighborhoods.”

A further research topic, “LESS – Principles, Potential and Problems of Product Avoidance,” explores the role that sufficiency can play in architecture and design. Finally, “Areas of Potential in Bavarian Craft Cultures” seeks to research vanishing craft techniques and expertise in materials and workmanship. Because old methods and traditions have always embraced circular economy principles, they may reveal answers for the world of tomorrow. Bavaria’s history and self-image is thus throwing open fresh new perspectives for products, companies and services of the future.

An undogmatic, direct approach that involves individuals and communicates with founders and institutions offers enormous potential for design research

and beyond. Taking familiar cultural patterns as a starting-point, the dci thus provides “impetus for social, ecological, technological or entrepreneurial futures.” Alongside Prof. Markus Frenzl, the core team at dci is made up of Prof. Dr. Eileen Mandir, HTA Professor of Systemic Design in the Context of Social Change and Transformative Processes, and two research associates.

The institute has an ambitious goal: “We aim to create a vibrant space for thought that will provide a home for discursive practice at the Design Faculty here at HM,” says Markus Frenzl. The new step by HM will thus not only strengthen its design research; it will create space for an element that has always been intrinsic to design: the ability to identify perspectives for the future.

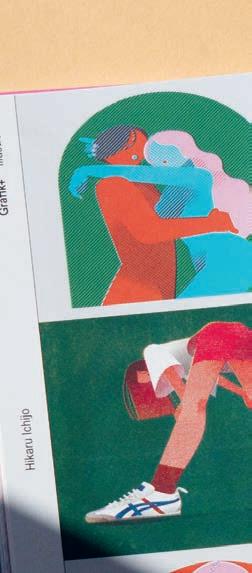

Do living beings need to be useful to justify their right to live?

(project: Angela Stellmacher)

How does design work in times of dwindling resources and soaring temperatures?

A seminar at Hochschule München sets out to explore the i ssue.

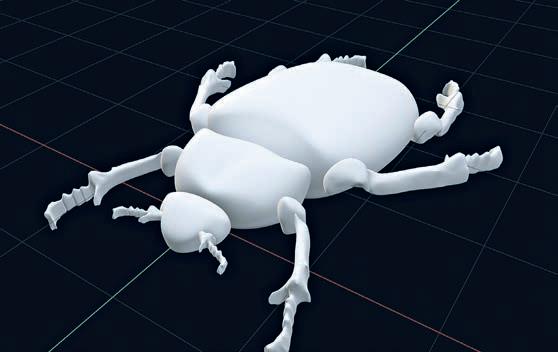

“We’re now firmly in the Anthropocene, an age in which humans are significantly influencing the changes occurring on our planet and profoundly impacting the earth by their actions,” explain Matthias Edler-Golla and Florian Petri. Both are professors at Hochschule München University of Applied Science (HM), one specializing in interaction design and sustainability, the other offering a perspective rooted in technical industrial design. Both have years of experience in teaching sustainability-focused projects. “Next Nature Design” is not their first joint course – but may well be their most crucial. It delves into the big picture, asking what purpose design can pursue in the Anthropocene. Can we, should we even continue producing in the way we have been doing? The seminar and subsequent exhibition will ad -

dress sustainability in all its many facets. No question is too offthe-wall, no project too fantastic.

Edler-Golla and Petri challenge their students to push the boundaries of human-centered design. They postulate “planet-centered design, which requires us to embrace new ways of thinking, new collaborations, the willingness to work with other living beings in a co-creative relationship, and the boldness to unite culture, technology and nature.” This big picture could hardly be any bigger. Given this, the professors firmly believe in direct dialogue as the seminar process. However, first of all the students themselves need to become experts. Each team investigates different issues. The 30 photographers and product, graphic and interaction designers work, discuss and design together.

The seminar aims to unlock spaces for creative thought that go beyond considerations of commerce. As Matthias Edler-Golla points out, “We’re not an agency, or an extended workbench for industry. We provide impetus for new ideas in a rapidly changing world.” That is precisely one of the tasks confronting the designers of the future: the need to assess projects accurately and turn them down if necessary, to reach out to people and bring meaning to the processes they design. Matthias Edler-Golla and Florian Petri are well aware that there is no single correct solution; instead, there is a web of mutually reinforcing impetuses. Many different paths are

unlocked in this way. Even lack of knowledge can prove to be a strength when it provokes a questioning mindset.

“Cohabitation” is the name for the new coexistence of humans and nature. Ultimately, there are “only positive visions.” But there is method behind this apparently unrealistic, even naïve notion. The professors explain that anyone can pen a dystopia, but our present age needs new ways forward. Instead of perfect products, which – as they point out – do not exist, they are seeking something more like perfect prototypes, which only unfold their perfection when put to use by real-life humans and the natu -

Who is the hermit beetle? Why are hermit beetles so unknown, and almost extinct?

(project: Angelika Bals and Finja Beck)

ral environment around them. Suddenly, space is opened up for new careers – a carpenter-designer, say, who allows users to try out a range of variations. The role of the designer is currently in flux. In the age of modernism, that role primarily revolved around striking a pose as heroes of progress, many engaged in creating ever-sleeker variations of tomorrow, right down to arrow-swift pencil-sharpeners. But styling alone is no concern of serious designers. They seek more. They seek, as far as their abilities allow, to make the world better – or at least preserve it. To ensure that the “age of the human” does not become the “age of human extinction.”

Kai Langer, Head of BMW i Design, takes nature’s efficiency as his benchmark.

Kai Langer, Head of BMW i Design

From fall 2027, the BMW Group’s historic location in Munich’s Milbertshofen district will switch all of its production over to battery-powered vehicles. This shift in drive systems marks a turning point, and a transformation. But what form should this new future take? If anybody can answer that question, it must surely be Kai Langer, Head of BMW i Design since July 2019. The industrial designer has accompanied the brand’s progress since the earliest stages. Langer has been part of the company for over two decades. A successful designer for BMW for many years, he was already responsible for BMW Group Advanced Design before taking over at the helm of BMW i five years ago.

Kai Langer – dark hair, jeans, black shirt – studied in Pforz-

heim, an elite cradle of German automotive design. Unsurprisingly, he loves to draw. But instead of sketching a few lines on paper, he prefers to map out the large-scale outlines of the future. In Langer’s view, the transformation to sustainable e-mobility extends far beyond mere questions of contours or dimensions. He sees it as a holistic task, a universal concept that starts by throwing everything into question that the automotive industry has spent decades building up: “We need to invent all-new structures, processes, tools and technologies,” he affirms. As an example, he mentions BMW’s radical switch to green energy to power the BMW i3 production operations at its Leipzig plant, the first company to do so. Alongside constructing production halls, BMW set up wind turbines to generate power – at a time where few had any inkling of what that would mean for the existing infrastructure. In addition, a new material, carbon, was introduced together with changes in production processes. The sustainability philosophy that underpins the BMW i3 starts with questions: “How can we supply the production line with green energy? What materials

can we use? We had to work hard to gain people’s acceptance,” recalls Langer. “But the challenge was welcomed by the whole team and the company because it enabled us to define the direction we would be heading in the future.”

Langer has long since made his peace with the fact that he no longer gets to design a vehicle from start to finish. In fact, as he points out, that isn’t even a possibility any more. “When I look at some of the things done by young members of our team, I have no idea how they do it,” says the Head of BMW i Design in a remarkably laid-back tone. “I still enjoy going back to the drawing-board; after all, it isn’t what I do today, but it’s what I originally trained in. But fortunately, we discuss designs in a group to reach the best solution, and that’s my job today. I let myself be inspired by my team, I welcome that inspiration, and I make a decision on that basis.” Langer compares the growth of sustainability with a tree planted by the company and now flourishing,

putting out more and more branches and twigs. Circularity is the key: “We need to significantly shrink our carbon footprint,” says the designer. “Actually, that’s what the whole world has to do. And once we actively accept the responsibility, the company needs to identify the biggest point of leverage.” Closed material cycles comprise one major point. Langer notes that renewable raw materials are already pretty good, but points out it is much more effective to keep everything within a loop, like the well-known glass bottle deposit system. To establish circularity, familiar vehicle designs need to be scrutinized and questioned down to the last screw: “How do I need to separate out the parts to ensure they can be made from material that goes back into the cycle?” Adhesive bonding is a thing of the past. Now the goal is unmixed materials and smart disassembly, approached in gradual steps. With this in mind, Langer waxes enthusiastic about traditional Japanese houses made from wood without a single nail. “Pretty cool! I couldn’t stop examining every single joint of the beams and panels. Crazy! It’s incredible to realize the wealth of ideas,

TRANSFORMATION ISN ’ T

A PROCESS THAT’S OVER AND DONE WITH ONE OF THESE DAYS, IT’S ONGOING

premium-quality craftsmanship and intellectual luxury that are involved.”

Today’s automobiles have to be 95 percent recyclable. Yet the proportion of secondary material – that is, materials that can be repeatedly returned to the materials cycle – is still relatively low. There is definitely more that can be done, says Langer; as a father, he is aware of his responsibility to the coming generations. The bigger the challenge, the better. “Be it sustainability or efficiency, we’re never done; we’re permanently moving towards improvement. Transformation isn’t a process that’s over and done with one of these days. It’s ongoing.” No wonder some solutions to problems feel as insurmountable as a moon land -

ing. At least until the next challenge comes along. And then there’s a whole new moon landing. And a new challenge.

But if everything is in flux, doesn’t that change our view of the world? Our view of what premium quality should look like, feels like? Up to now, perfection has meant that parts which failed a visual conformity test have been scrapped. But Langer takes that as a fresh challenge. He points out that people expect quality to be consistent, “and we want to replicate cars so that every one looks exactly like its neighbor. But that may clash with our sus -

tainability goal of never throwing anything away.” A whole new esthetic can’t be summoned up at the wave of a hand. But what about individual vehicles, in materials that may show unique surface or pattern variations? Like the “Vivid Blue Rubber” tire from a current study? Marble-effect surfaces, say, could create a warm, welcoming feel and inspire emotional connections. In that situation, every part would suddenly be absolutely perfect just as it came off the machine. “It has individuality. Design can make a virtue out of what appears to be a necessity.” Langer’s thoughts take flight. He proposes fully sustainable fabrics for clothing, ultra-comfortable, fun to wear and great-looking, and notes that thinking in production cycles is a return to nature. “We have materials, visionary materials, some of which we can even actually grow, and they look brilliant.” Langer talks about the structure of a snowflake, about the Fibonacci sequence. “In the future, we’ll also be able to create beautifully

esthetic designs from sustainable materials. That’s exactly where development is currently heading.”

Materials that grow? Yes, that’s right. High tech has moved to drawing on nature for its inspiration, because nature works at maximum efficiency. “Up to now, we’ve limited our production technologies to precisely accurate reproduction,” says Langer and enthuses about the 3D printers of the future that will do nothing else than make things grow. “In this way, we’ll progress towards higher efficiency, step by step. For example, we need more advanced printers that run on green energy.” It may soon be possible to print an entire car side panel in secondary aluminum. And instead of shipping spare parts halfway around the world, all that’s needed will be to transmit highly accurate specifications to printers in different continents. It’s like the seed of a tree that floats across the Atlantic, and then finds the perfect spot to start growing.

STRATEGIC PRODUCT MANAGER

KISKA MUNICH

MANAGING PARTNER

KISKA MUNICH

What’s your definition of sustainability?

We equate sustainability with long life and minimum impact. To reflect this, we develop strategies and creative solutions for products and brands that are here to stay. Up to 80 percent of a product’s environmental footprint is decided in the earliest design phase, so that’s where we start. Our aim is to make an impact by reducing impact. And long-lasting, high-quality products in timeless, distinctively brand-specific designs are the core of every strong brand.

Is “circular” the new “sustainable”?

It’s returning to the fore in considerations of strategy, product design and product development, and that can only be a good thing. Circularity is an important element of sustainability, but it isn’t the new “sustainable.” “Circular” means that as much as possible is put back into the cycle. This concept encourages brands to develop solutions for their products’ end of life right at the start. But there are many aspects to sustainability, and circular innovations need to be tailored to individual customers.

How is KISKA overcoming pushback against sustainability, both within and outside the company?

With strong strategies and creativity. Good ideas are pretty much invincible. Sustainability isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s a must-have. But unfortunately, it often carries negative associations such as high costs, unfamiliar processes, new materials or strict conditions under the European Green Deal. We remain determined in our quest to signal concrete ways in which sustainability can generate added value for brands and products – while also being cost-effective.

Fabian Mottl, Brand Communications Manager at Steelcase, on sustainable processes and products that benefit people and the planet.

OLIVER HERWIG

Last year, Steelcase launched the Karman office chair. The name alone is an indication that you have chosen to push the boundaries

Yes, indeed. The Kármán line is the boundary between the Earth’s atmosphere and outer space. And the Steelcase Karman also pushes the boundaries. It showcases what can be achieved by steadfastly sustainable design – from development and production to use and beyond. At Steelcase, we pursue a global sustainability strategy that spans product design and manufacture, DEI (diversity, equality and inclusion) and continuing training. We’ve been pioneers of sustainable product design for decades. Our 2023 Steelcase Impact Report details the status quo of our strategies and projects, and outlines our medium- and long-term sustainability goals and targets for the future.

OH

So what does that mean for your products?

FM

Our strategy is embodied in our product families. Our Gesture, Think, Please and Steelcase Series 1 and 2 chairs, the Trivio table, the Island Collection system and the WorkValet locker system are already available with Climate Impact Partners’ CarbonNeutral ® product certification. The most recent of our innovative Steelcase products, the Karman ergonomic office chair, is manufactured from sustainable materials using the absolute minimum of components and resources. This enables us to minimize carbon emissions and pollution.

OH

Where does design reach its limits in our striving to bring humanity and nature into alignment?

FM

At Steelcase, our international team at various locations develops workspace solutions that support millions of people around the world in their day-today working lives. But we can’t succeed in this mission alone, So we work with a host of international suppliers and manufacturers and maintain partnerships to realize our sustainable product designs. To fulfil our sustainability pledge to people and the planet, we focus on six significant areas of impact: Help Communities Thrive, Foster Inclusion, Act with Integrity, Reduce our Carbon Footprint, Design for Circularity, and Choose + Use Materials Responsibly.

OH

On the other hand, where are the limits for your customers? What additional costs are you willing to shoulder in order to benefit the environment?

FM

We firmly believe that all companies and organizations have the responsibility to build the principles of sustainable action into the design and implementation of forward-thinking, equitable workplaces. To achieve this, we use processes that help us to identify people’s various needs and translate them into inclusion strategies while also fulfilling our customers’ requirements.

Perseverance is essential for us to reach our sustainability goals and targets without raising costs or impacting production. Every day we make decisions to keep pushing forward to achieve success. In addition, we launched the “Better is Possible” speaker

1 HELP COMMUNITIES THRIVE

Our Better Futures Community develops innovative social programs to build equitable access to opportunity and provides financial support.

2 FOSTER INCLUSION

We design spaces, tools and experiences that support our employees, partners and customers in feeling seen, heard and valued.

3 ACT WITH INTEGRITY

We give all our employees the opportunity to represent their values, and are rigorous in how we implement policies that live up to our own ethics and goals.

4 DESIGN FOR CIRCULARITY

We implement impactful reuse, recycling and remanufacturing strategies across our entire product design and delivery process.

5 REDUCE OUR CARBON FOOTPRINT

We work toward and meet more ambitious carbon reduction goals at a greater global scale than anyone in our industry.

6 CHOOSE + USE MATERIALS RESPONSIBLY

We source and select materials that are healthier for people and the planet, and manage resources such as water and energy wisely.

series, where experts share innovative approaches to taking climate action, combating inequities and boosting equality. These talks are extremely popular and also provide our customers with transparent insights into our approach.

OH

Transformation and material circularity are currently cutting-edge themes. Where is Steelcase in this process?

FM

Our philosophy can be summed up as “Designing for Circularity”. This means that from the earliest idea and product development stages, we plan to create a product that factors in the potential for circularity or already draws on material cycles as sources. Like our partnership with Danish textile manufacturer Gabriel, where Steelcase supplies Gabriel with textile offcuts from our Sarrebourg production facility as the basis for sustainable textile production. Gabriel spins the fabric offcuts into new yarn, which thus comprises 100 percent scrap fabric. These environmentally friendly yarns comply with the same quality standards as all other Gabriel textiles. The partnership between Steelcase and Gabriel demonstrates that even waste is a

valuable and recyclable resource that can continuously be put back into the production cycle.

OH

What is your vision for the manufacturing industry of the future, operating production in alignment with nature?

FM

We aim to support people in giving their best at the workplace. How? By designing the best workplace for them. As a twenty-first century company, we need to ask ourselves how we and our products can contribute towards a better future for people and the planet. And our philosophy for the future is “Better is possible”. To achieve this goal, we’re building a Better Futures Community, bringing together our people with international partner organizations to help address the root causes of inequities around the world.

HEAD OF MARKETING & PR KÖNIGLICHE PORZELLAN MANUFAKTUR NYMPHENBURG

How does the Porzellan Manufaktur Nymphenburg define “sustainability”?

Instead of a constant stream of new products, we should continue to use what we have, particularly if no quality concerns stand in the way. Many inherited pieces of Nymphenburg porcelain are now gathering dust in cupboards instead of bringing pleasure in daily use. This inspired us to launch Generation T. The idea for this initiative came from the desire to breathe new life into plates, cups and bowls that had fallen out of fashion but were nonetheless of superlative quality.

Is “circular” the new “sustainable”?

It should be. Unfortunately, people are too afraid to use our porcelain. The finer and higher-quality the pieces, the less likely they are to see everyday use. And that’s a shame! In Generation T, inherited or second-hand items of Nymphenburg porcelain can be painted with designs by Hella Jongerius. Their desirability restored, they can once again return to their original function as tableware.

What kind of materials have a future?