Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts

Kauffman

Center for the Performing Arts

Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts

Kauffman

Julia Irene Kauffman

The concept of the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts began with my mother, Muriel Kauffman. It was her vision that launched this incredible journey. She shared that vision with a few of us, and its pursuit has grown to involve many dedicated people.

Growing up in Toronto, I regularly attended the opera, the symphony, and the ballet. We went on school trips to the Stratford Shakespeare Festival, heard performances by the New York Metropolitan Opera, and took in previews of top Broadway shows. The arts were an essential part of everyday life and a point of emphasis in education, from elementary school through university.

When we came to Kansas City, the needs of the arts community were apparent. Mother forged ahead and soon became an active supporter of and participant in many arts organizations. This was ultimately the motivation for the Muriel McBrien Kauffman Foundation and its mission to enhance the performing arts in Kansas City. The focus of my mother’s energy was to achieve true excellence in the performing arts, and in 1994, she put the impetus of her foundation behind the concept of a performing arts center. She revealed her aspirations to us, but, sadly, she did not live beyond giving us those first imaginative instructions. In her loving memory, I have carefully carried forward her idea. Over a decade of planning and design has brought clarity to what we believe was her forethought for the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts. The level of excitement surrounding this project has surpassed anything she could have hoped for.

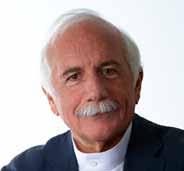

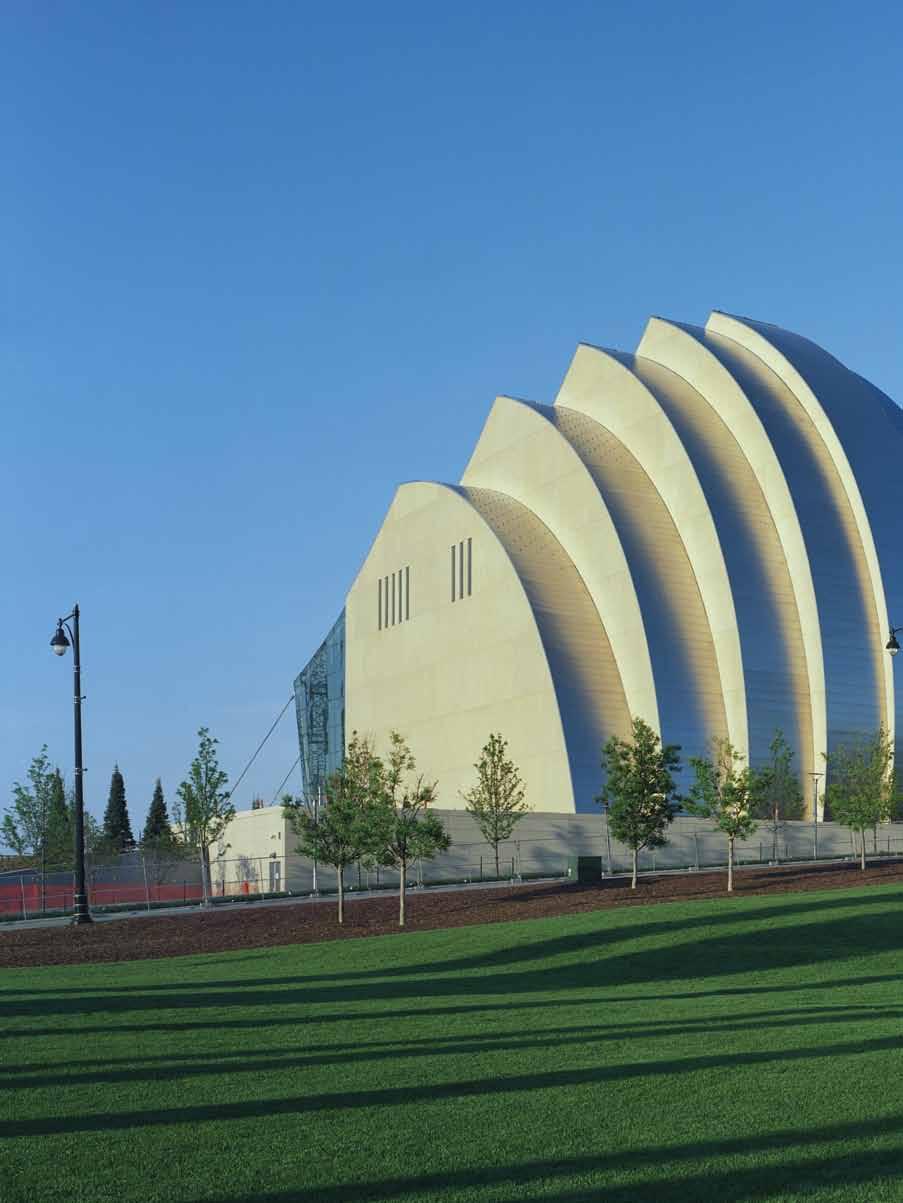

We considered a range of architects before deciding on the brilliant Moshe Safdie. He immediately recognized the demonstrable effect a project like the Kauffman Center would have on the city, and was bursting with ideas on how to integrate a multiuse, technically advanced center with Kansas City’s existing urban core. Moshe’s designs anticipate and incorporate the daily life that his buildings will embrace and the specific conditions to which they will respond. The Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts creates an extraordinarily striking visual impact, in both its outward physical form and interior. This is the tangible realm of Moshe’s architecture, allowing one to perceive and appreciate, on a universal level, the qualities of light and space. His goal of achieving timelessness has been borne out in every phase of design and construction.

Mother believed that Kansas City was a major-league city. She recognized its musical heritage and the fact that a new venue was overdue. Citizens across the metropolitan area have seized the moment and embraced what will become her ongoing legacy. The opening of the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts is a defining moment in Kansas City’s cultural history and economic development. People from all walks of life will be drawn to the building, not only for the caliber of its performances, but also for its architecture and stunning beauty. Together, we exceeded the challenge to understand and respond to our community’s needs and desires. Mother’s dream has been fulfilled, and the Center, the result of her initial vision, now beckons us to experience and enjoy the performing arts at unparalleled levels of excellence, today and into the future.

Moshe Safdie

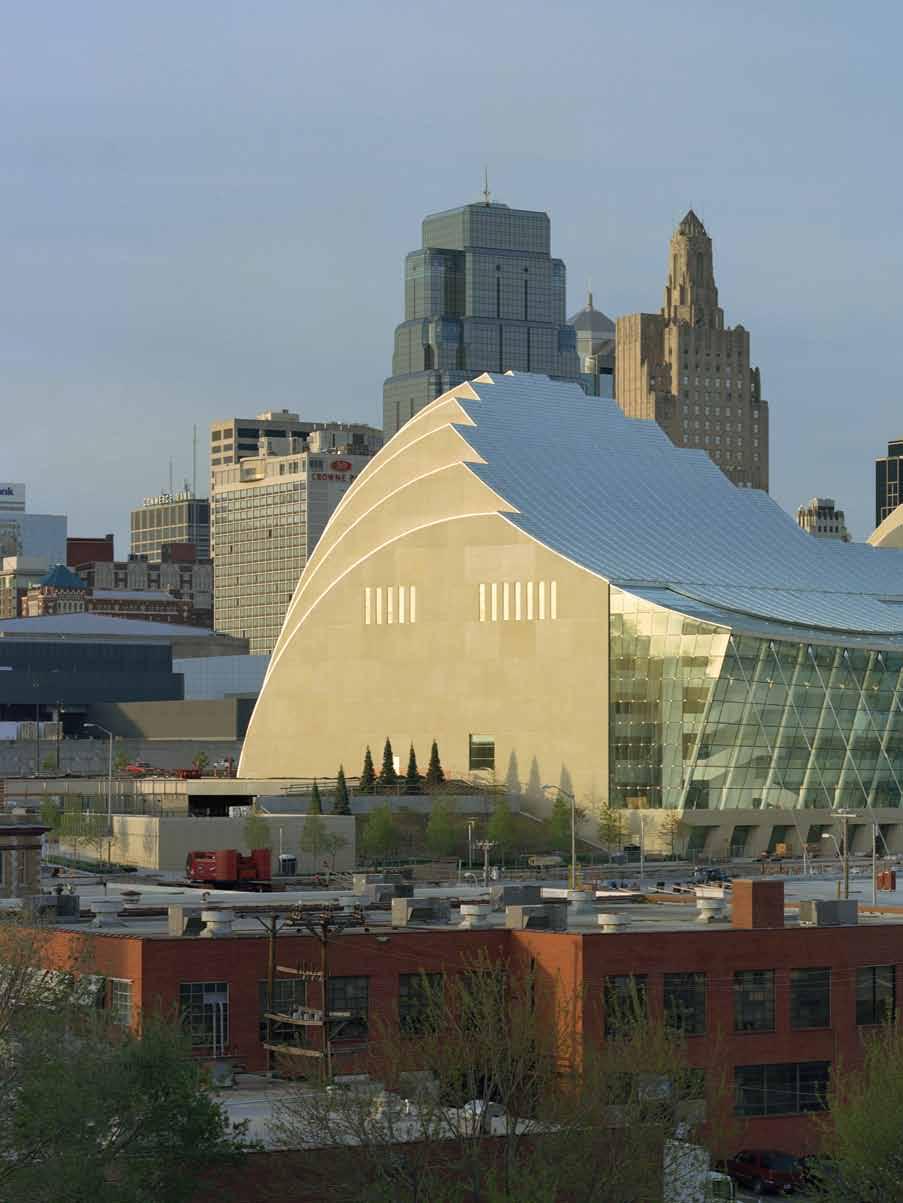

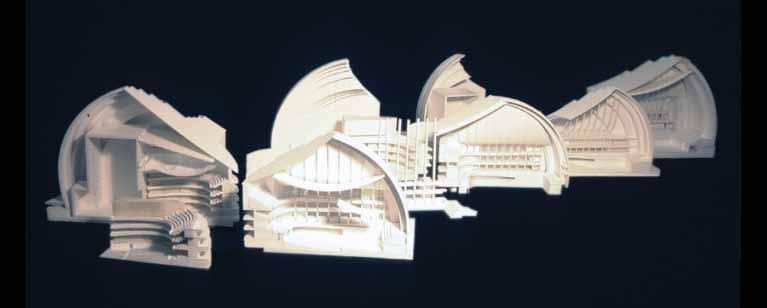

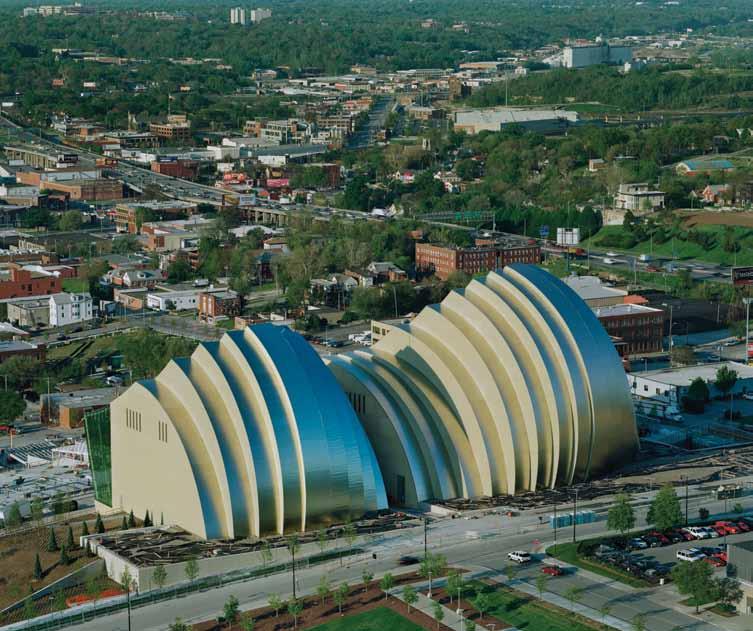

Two significant decisions preceded the arrival of the design team for the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts. The first was the selection of an extraordinary site crowning the escarpment overlooking the old warehouse district and the new entertainment district, with a 270-degree-view of the horizon. The other was to construct two, and ultimately three, dedicated halls for symphony, ballet, opera, and theater. It is these decisions that provided the opportunity for a world-class performing arts center.

Downtown Kansas City sits on a plateau that extends south toward an escarpment. From this point it descends, opening to a view of the horizon accentuated by the flat prairie landscape. In the foreground are Crown Center and Union Station; the historic Plaza shopping area and the suburbs stretch out to the south. Looking north, we see the dramatic view of the downtown skyline, with the city’s street grid abutting the site and the Kansas City Convention Center’s Bartle Hall just beyond.

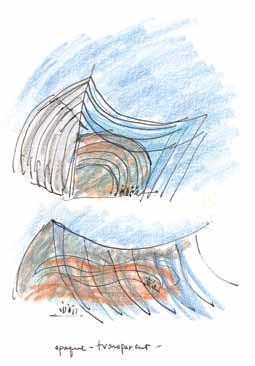

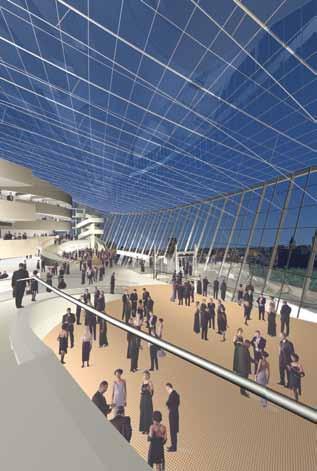

I believe that the site always holds the secret to a project’s design concept. Deciphering it provides clues to the building’s parti. Walking around, I was compelled by the dramatic vistas to the south. Thus, I placed the two performance halls facing those distant views, integrated and connected by a single grand foyer, an expansive glazed porch contained by a glass, tentlike structure. The drop in the land toward the south created yet other opportunities: a new road serves as the ceremonial vehicular drop-off to the Center, connecting to a large underground parking garage, on top of which is a rolling park. From the parking garage and the drop-off, the public ascends by grand stair or elevator to the foyer, named Brandmeyer Great Hall, which holds reception and refreshment areas and leads to Muriel Kauffman Theatre and Helzberg Hall on either side. Recognizing the significance of downtown as an additional access point, directly on the axis of Central Street, a north entrance penetrates the structure, as if along a canyon, into the grand foyer.

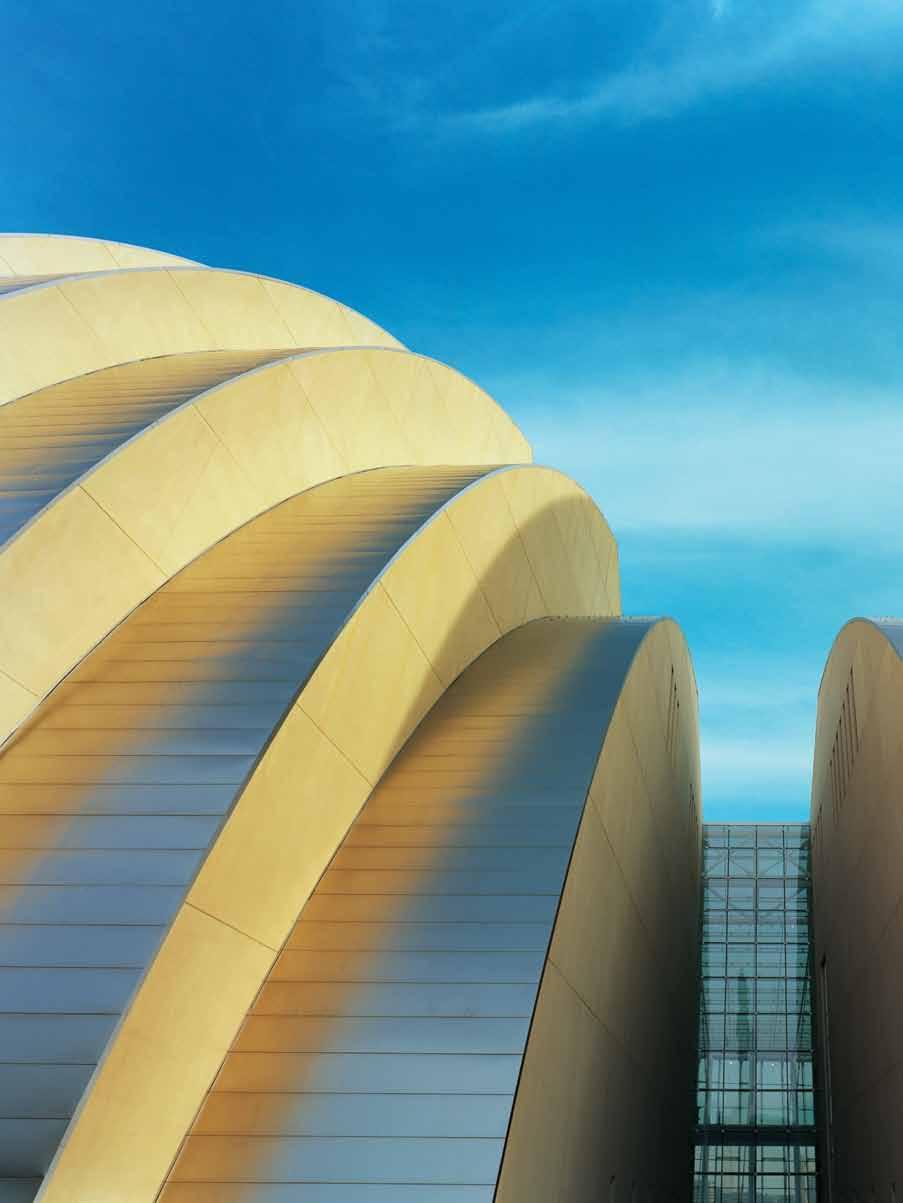

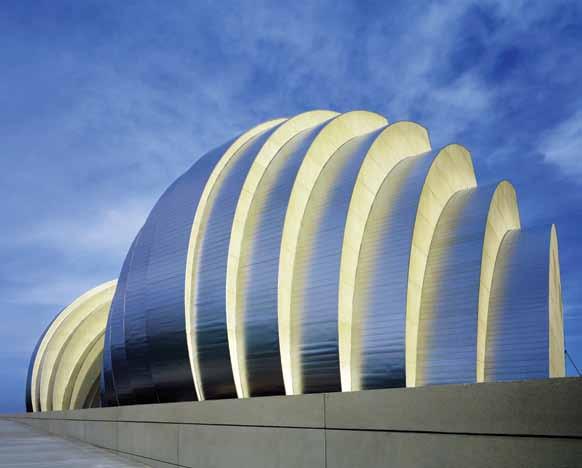

Each performance space reads as a distinct volume, metaphorically evoking a musical instrument, visible through the glass container. As the light changes, so does the building’s transparency. During the day, the Center reflects its surroundings and reveals only hints of its interior, while at night, it becomes totally transparent, displaying the activity within to the surrounding city.

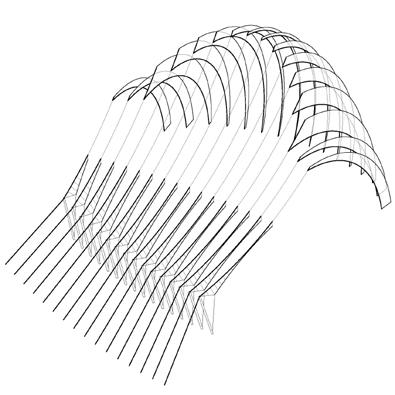

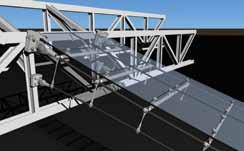

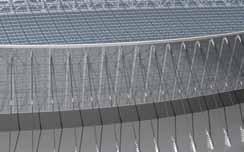

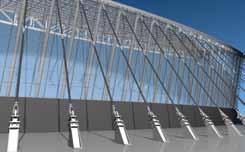

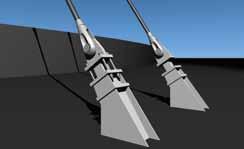

One of the features of the complex is a tensile structure, which is anchored in the building’s roof on one side and supported by a series of masts and cables on the other, enclosing the public spaces of the complex. The structure leans forward, glass inclined as in an airport control tower, shielding the interior from the sun and opening to the view. The cables supporting the glass roof descend to anchors deep in the bedrock. The fanlike array of cables hovers over the drop-off roadway, creating a canopy-like enclosure and evoking the imagery of a stringed instrument such as a harp or sitar.

Orienting the two halls and positioning the foyer and main entrance toward the south was a radical move, unexpected and unanticipated by previous site studies. The natural impulse had always been to face and position the entrance toward the downtown, to the north. The payoff of the southern orientation was the extraordinary view of the city and horizon. The resulting challenge was that the traditional rear of the theater, which accommodates the stage tower and back-of-house facilities, now faced downtown. The risk was a building that turned its back on the city.

We wanted to create a complex that has no front or back, and instead provides a rich and inviting face in all directions. Toward that end, we evolved a structural enclosure surrounding the stage tower of Muriel Kauffman Theatre and the organ wall of Helzberg Hall. The enclosure consists of a series of steel trusses, each of a similar radius, which rotate in relation to each other and ascend toward the sky as they contain the building’s bulk. These arclike elements form a fan shape, with the vertical faces clad in limestone-colored precast concrete and the curved surfaces clad in stainless steel. The play of light and shadow culminates in a stepped silhouette across the skyline. The two volumes, the theater and the concert hall, split apart, forming a deep cavity on the axis of Central Street. The public arriving from downtown gently descends through the passage, landing in the foyer overlooking the city to the south.

The overall result is a building that is ever changing as the public moves around and sees it from different vantage points. The glass, porchlike structure, with its taut cables, gives way to the fanlike stainless-steel surfaces, which reflect and transform the sky and city views throughout the day and evening.

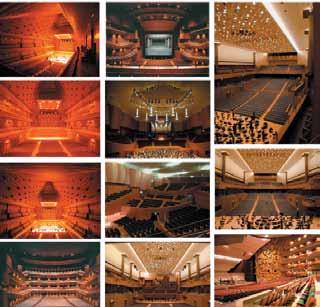

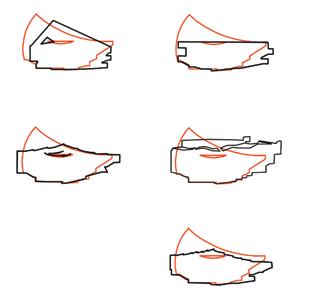

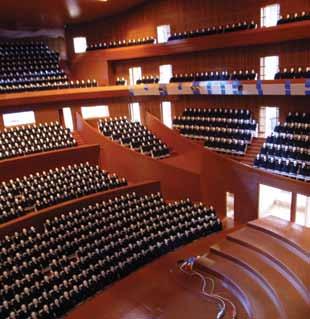

If the site was the design generator of the complex as a whole, acoustic strategy determined the design of Helzberg Hall. Working hand in hand with Yasuhisa Toyota of Nagata Acoustics, we evolved a volumetric and geometric concept for the hall. From the outset, we envisioned an intimate hall that would engage the public with the musicians and create a feeling of being contained. Rather than the traditional frontal relationship of stage to audience—as in Boston’s Symphony Hall, for example—we sought to surround the music makers with the public, an idea inspired by Hans Scharoun’s seminal Berliner Philharmonie and echoed in Walt Disney Concert Hall, in Los Angeles, and Sapporo Concert Hall, in Japan. Yet we wanted to go further. With 1,600 seats affording great intimacy, we strove to allow the entire audience to experience the music without a balcony or ceiling above. Each spectator would be within the principal volume of the space.

We also wanted the spatial experience inside the hall to evoke the exterior design of the building. (Too often, the interior spaces of concert halls are disconnected from their exterior envelopes.) Thus, the fanning geometry of the northern facade is echoed within the interior, highlighting the sculptural arrangement of the organ; as it reaches toward the ceiling, it splits apart, forming skylights that allow the daylight and sun to penetrate and reflect upon the organ below. The convex interior surface of the roof, ideal acoustically, likewise descends toward the upper tiers of seating. A sound-reflective canopy is suspended above the stage. The hall is clad in Douglas fir and its stage is Alaskan yellow cedar, both chosen for their natural acoustic properties. Sound reflectivity in the hall can be varied, depending on the mode of music and acoustic requirements, by adding absorptive fabric, both above the canopy and concealed within the walls.

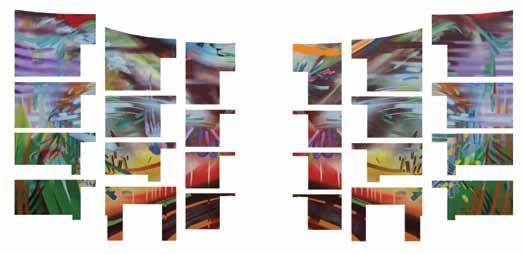

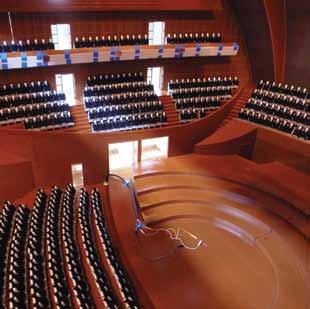

In comparison to the warm intimacy of Helzberg Hall, Muriel Kauffman Theatre—the setting for ballet, opera, and theater— is festive and exuberant. Three balconies contain the hall in a horseshoe-shaped enclosure. Each one is broken down into a series of steps descending from the center-rear balcony to the individual boxes on either side of the stage. The stepping enhances sightlines and provides a sense of greater connection with the action on stage. The ceiling of the hall is an inverted dome contained by a series of petal-like vaulted surfaces. The balcony balustrades are a contemporary interpretation of the gilded, glittering, candlelit balconies of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century theaters. Enclosing the balustrades is a cast resin that resembles glass and contains behind it crumpled Mylar and dimmable LED lights. The lights glow through the resin to form an ever-changing chandelier-like surface.

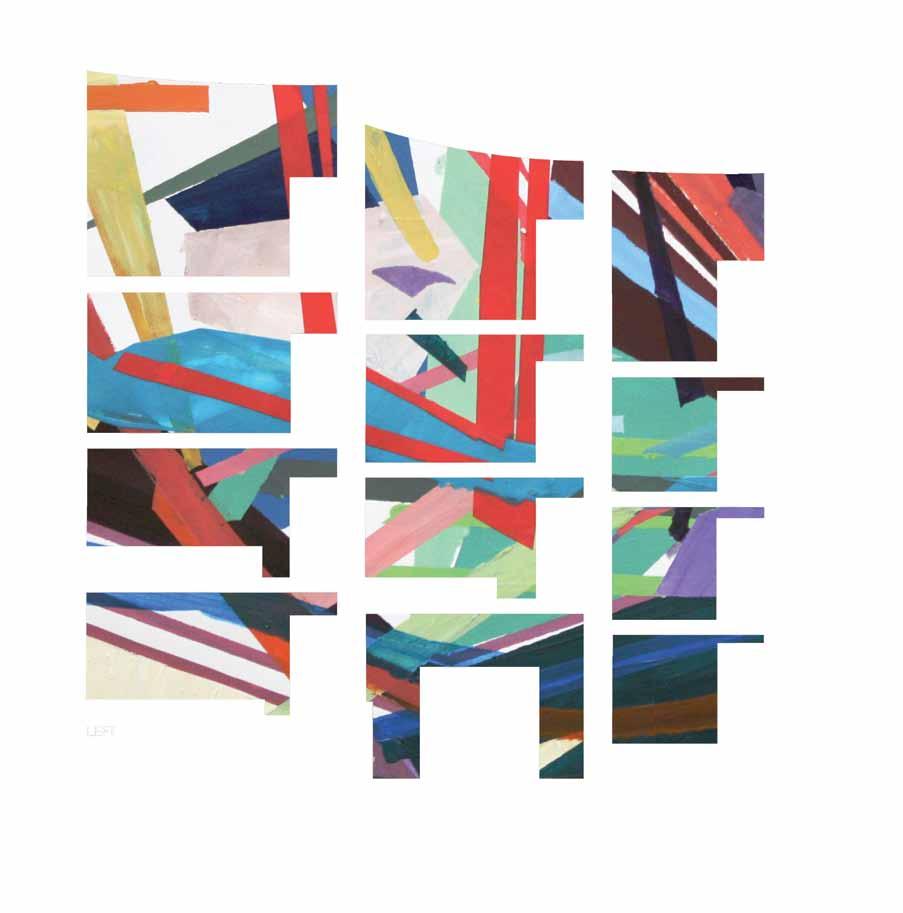

The hall has undulating walls that provide its acoustic enclosure. Collaborating again with Toyota, we shaped the walls like vertical stacked barrels for optimal sound reflection and then integrated these shapes into the whole with a screenlike series of slats. Illuminated behind the slats, directly on the barrels, are murals conceived and designed by students of the Kansas City Art Institute. The overall effect is that of a dynamic painting, rich in reds, greens, blues, and yellows, fused into the geometry of the room. The seat upholstery in the hall, a trilogy of reds, oranges, and maroons randomly mixed, further complements the murals.

A series of balconies fronting on the grand foyer serves both Helzberg Hall and Muriel Kauffman Theatre. The balconies form two conical stacked rings of white plaster. Before and after performances and during intermissions, the hundreds of audience members are theatrically visible to one another— some on the balconies facing the grand foyer, some within the foyer itself, and some on the jutting, boatlike terraces that project between the two theaters and accommodate the bars. Thus, Brandmeyer Great Hall and its surrounding balconies form a counterpoint to the theaters within; this is the theater of the public realm, where the celebrating patrons are visible to the city beyond.

Richard Pilbrow

For many centuries, enjoyment of music, drama, opera, and dance meant audiences being in the same space as performers. With the arrival of electronic media, so much began to change. Yet live performance—live actors surrounded by a live audience—remains a unique form of expression. You, the spectator, are in the same physical space as the performer. Your reaction plays a part in the performance. This is not like watching television. Actors, dancers, singers, and musicians are profoundly affected by the audience.

Kansas City, under the determined leadership of Julia Irene Kauffman, decided to build a performing arts center. Not, as had been fashionable for decades across the United States, a single, multipurpose hall serving all the arts of performance, but instead something very special—a complex with two main halls, one for music and one for theater, that sought to avoid compromise and aimed for the highest levels of international quality. By coincidence, Kansas City was blessed in its timing. For the past thirty years, there has been a revolution in the design of rooms for live performance. This city came quite late to the well-trodden path toward a new arts center. Now, it can reap the benefits of many other communities’ experiences.

In the mid-twentieth century, new theaters and concert halls imitated cinemas. Architects, directed to accomodate bigger audiences, often built overlarge auditoriums, placing rows of seats in serried ranks facing an ever more distant stage. Only in the 1980s did people begin to wonder if something valuable was being lost in the pursuit of so many “modern” spaces. Theaters of the more distant past, before the advent of electricity and amplification, were by nature intimate, and their architecture promoted a sense of community. From Shakespeare’s Globe to the footlights of Broadway, it was not enough for audiences to see and hear a performance; they had to be viscerally involved. This was achieved by bringing performer and audience into close physical proximity and by making every spectator feel part of a living whole. Today’s theaters aim to re-create this intimate experience, with elements such as multiple balconies, which bring more people closer to the stage, and side boxes of seating, which enwrap the room with lively humanity. Such venues, employing a rediscovered respect for the traditions of our ancestors, have excited performers and audiences around the world.

The stages of the Kauffman Center are exemplars of this revival. The design of Muriel Kauffman Theatre draws inspiration from the great opera houses of Europe, which have endured and prospered for generations. And Helzberg Hall deploys another successful form, only recently rediscovered: an arena-type space that places the musicians at the very heart of the room. Both Muriel Kauffman Theatre and Helzberg Hall combine outstanding acoustics, fine and spacious stages, and state-of-the-art performance technology while creating unparalleled intimacy. Each will foster an unrivaled sense of participation, to move, uplift, inspire, and entertain audiences long into the future.

Yasuhisa Toyota

The journey of planning and building the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts began almost ten years ago, but the real voyage starts with our experience of music performed by the Kansas City Symphony in this magnificent building. As the resident orchestra of the Center’s Helzberg Hall, the symphony was our most important collaborator while designing the acoustics. Now, its musicians will collaborate with the concert hall itself, since without the orchestra—without music— the acoustics cannot exist.

The finest concert halls in the world—in Boston, Vienna, Amsterdam, Berlin, and Los Angeles—all have world-class resident orchestras. This is not by coincidence, because over time, an orchestra and its hall form a kind of symbiosis, each supporting and nurturing the other. A concert hall can only reflect the quality of the musicians who play in it. In Los Angeles, we’ve had the pleasure of seeing the city’s philharmonic grow with the Walt Disney Concert Hall over the past eight years. The artistic development of the orchestra happened at an amazing pace, making it a completely different ensemble today than it was when Disney Hall opened in 2003. We hope that we have also made for Kansas City a concert hall that will cultivate its orchestra and, in the process, welcome more people into the warm embrace of live performance.

Acoustics has been called a mysterious thing, but its mystery depends on music. Without music, there would be no need of space for an orchestra and an audience. Since acoustics is dedicated to perfecting spaces for performance, we can only evaluate the results of our labor when music is played. And music itself contains its own mystery: Who can explain the power it holds over us, what draws us to it? Acoustics and music combined enact a kind of alchemy. Together, as individuals and as a community, we can now explore this magical phenomenon through the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts and the Kansas City Symphony, the proud partner of this new acoustic space.

0 25 50’ Site and main lobby-level plan

Paul Horsley

In the beginning was the idea. The idea of having a major performing arts center in the heart of Kansas City, one that would host local organizations, bring major events from around the world, and become a center for educational activities and community development. And with that idea came others. The idea of crafting an architectural landmark that would become an international destination, a primary reason for traveling to Kansas City—and a new icon on the city’s skyline. The idea of building a luxurious center with state-of-the-art facilities to take local arts organizations into the twenty-first century and beyond. And behind these ideas, an underlying truth: The Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts was born not of extravagance but of necessity. Because in the last half-century, something amazing has happened in Kansas City. The city’s arts scene has grown to worldclass levels, approaching that of much larger cities and showing no sign of slowing. The sheer excellence of opera and dance, symphonic and popular music, and presenters and artistic entrepreneurs has quite simply outgrown the physical spaces in which these groups are housed.

A great city needs a great performing-arts ecosystem, great presentations of the finest the world has to offer—and from the widest range of genres. And these presentations need great spaces. For more than 100 years, Kansas City has lacked venues that were user-friendly, acoustically favorable, and equipped with modern amenities. True, some downtown venues had been carefully adapted for the performing arts over the years, but they could never measure up to spaces built specifically, from the ground up, with top-level arts groups in mind.

For years, the Kauffman Center planned with great diligence. While some criticized that the project seemed to be taking too long, I pointed out that other performing arts centers around the country had taken much longer, languishing in financial crises or lack of community support. From its developmental stages to opening night, Los Angeles’s Walt Disney Concert Hall took some sixteen years to build—and that was just a single hall, only half the size of the Kauffman Center’s ambitions. In a sense, the Kauffman Center has beaten the odds by going from land purchase to opening night in just twelve years.

How well I remember the early phases, when the Kauffman Center board was interviewing arts leaders and city planners, and musicians, dancers, and other artists toward finding out their specific needs in a performing arts center. How much storage room does a contrabass require? How much fly space must a dancer have to exit gracefully—and safely—from a series of grand jetés? How much backstage area allows for the technologically complex sets of a modern Broadway musical? Richard Pilbrow, founder of Theatre Projects, had the answers, and developed a brief that fulfilled the needs of the companies and the community. Ready to move forward with master architect Moshe Safdie on board, the Kauffman Center could be assured of a design that would feature dazzling visuals but also respond on every level to the demands of the modern performer.

At the same time, the Center was examining in meticulous detail the needs of a place whose goal was to be not just an architectural or community landmark but an optimum acoustic landmark as well. Enter Yasuhisa Toyota, whose acoustic design for Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall is acclaimed as having resulted in one of the best-sounding spaces in the world. I know this, in fact, to be true, because I’ve heard it with my own ears in performances by the Los Angeles Philharmonic. The acoustics are indeed spectacular and consistent throughout the hall. And the enormously favorable responses to the building from the public and international critics alike had the effect of reflecting back on the Los Angeles Philharmonic itself, which began drawing renewed attention as one of America’s finest orchestras—a classic example of how a performance venue can help build the renown and prestige of its resident organizations.

The same methods that went into honing the acoustic design of Disney Hall—triedand-true science perfected over the years by Nagata Acoustics—have found fruition in the Kauffman Center. One sunny afternoon in Los Angeles, sitting in the gardens surrounding the hall, I asked Toyota if this meant Kansas City was destined for acoustics on a level of those of Disney Hall. “With each project, we learn new things,” he replied, with a twinkle in his eye, suggesting that Kansas City has a treat in store.

Artists are human, and they respond to physical space just as they respond to cold, humidity, and light. Musicians perform better when they feel comfortable and when they feel that a space lends warmth and intimacy. This is one of the reasons artists love Carnegie Hall: Standing on its stage, you have an odd, ineffable sensation you’re in someone’s living room and that the eager faces right in front of you are waiting to experience something wonderful. Both Helzberg Hall and the Muriel Kauffman Theatre have been designed with utmost intimacy in mind, and this will have an immeasurable impact on the level of performance we can expect. When orchestra members or singers can hear themselves and each other, and when they can see audience members reacting in the moment, they are inspired to give their all.

I believe the Kauffman Center will have a transformative effect on Kansas City’s cultural life, through ways that we can barely imagine. Night after night, denizens of the arts will gather on the inviting lawn and in the glittering, glass-enclosed Brandmeyer Great Hall, snacking and socializing before moving into Muriel Kauffman Theatre or Helzberg Hall to partake of the best that the performing arts have to offer. Inside, we will hear every note, see every pirouette, experience every gesture in the most intense detail. We will be the envy of other cities, and we will watch our resident organizations—the Kansas City Ballet, the Kansas City Symphony, and the Lyric Opera of Kansas City—grow in steadily measurable ways. Fasten your seatbelts, Kansas City and America, you’re in for the ride of a lifetime.

Jane Chu

The opening of the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts marks the debut of a significant building and a historic occasion in the life of our city. The arts give us opportunities to express ourselves in ways that bring meaning to our lives. Thanks to our generous donors, the Kauffman Center will not only bring us together to affirm what artists can do but also create an essential hub for the community by providing comfortable, accessible, and diverse experiences.

The value of having a performing arts center extends beyond the arts world. Performing arts centers have been touted as a tool for revitalizing communities. Cultural programs are now positioned as key players in the urban economy, serving as catalysts to stimulate other activity in the region. Regardless of whether people live in the suburbs or the urban core, downtown areas are being recognized once again as nexuses of activity—as not only marketplaces for productivity but also places for social engagement and cultural exchange. Revitalization is not just about creating a template of activities downtown; it is about how culture can play a role in making a city unique. The Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts will contribute to Kansas City’s distinctiveness.

With its stages now ready, the Center will host a wide range of diverse artists and performances from around the world, including classical, jazz, and pop music, ballet and contemporary dance, musicals, speaker series, and more. The Kauffman Center will serve as the performance home of three of the region’s leading performing arts organizations—the Kansas City Ballet, Kansas City Symphony, and Lyric Opera of Kansas City. And programming under the umbrella of The Kauffman Center Presents will showcase artists and ensembles that represent the variety of outstanding performance in the twenty-first century: the American Legends series features artists who have been instrumental in defining American culture; the Vanguard series recognizes performers who have pushed boundaries and redefined their art forms; the Destinations series introduces audiences to high-quality performance from around the world; and the Contemporary & Diverse series highlights a variety of genres and genre hybrids.

All the series in The Kauffman Center Presents represent artistic excellence, boldness of vision, diversity, and accessibility. Together with the robust programming of the Kansas City Ballet, Kansas City Symphony, Lyric Opera of Kansas City, and community arts presentations, the Center will provide a connection to audiences that reflect the community as a whole. With this in mind, the Kauffman Center wants to fling wide its doors to young people in the region to ensure that they have regular and meaningful access to high-quality performing arts experiences. To implement this philosophy, we developed a fundraising program to encourage arts education. Support is now being sought to reach at least 30,000 young people annually through the creation of three separate funds—one to transport students to see performances, one for reduced ticket prices for underserved children and their families, and one that supports creativity by providing an opportunity for youth to perform on the Kauffman Center stages.

Muriel McBrien Kauffman’s vision for a performing arts center in Kansas City is realized through the energy and commitment of her daughter, Julia Irene Kauffman. As chairman of the Muriel McBrien Kauffman Foundation, Julia has led the project from conception to sketch, from groundbreaking to placing steel and installing finishes, and now, from grand opening to the ongoing connection of artists and audiences. We also have you to thank for your enthusiasm and munificence. The opening of the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts is both a culmination and a commencement of your generosity and belief that this iconic building will influence the cultural fabric of Kansas City, increase and enhance our city’s renown, and create a new cultural cornerstone in our vibrant arts community. Thank you for your support.

Published on the occasion of the opening of the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, September 16–18, 2011.

Authors

Jane Chu is the president and chief executive officer of the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts.

Paul Horsley is a musicologist, author, and the performing arts editor of The Independent in Kansas City.

Julia Irene Kauffman is the chairman of the Muriel McBrien Kauffman Foundation.

Richard Pilbrow is the founder of Theatre Projects.

Moshe Safdie is the principal designer on all projects undertaken by Safdie Architects. Yasuhisa Toyota is the president of Nagata Acoustics America, Inc.

Editors

Diana Murphy and Anne Thompson

Design

Beena Ramaswami, BNIM Architects

Coordinator

Sarah Lindenfeld, Safdie Architects

Building Photography

Timothy Hursley

Copyright © 2011 Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise (except that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers or the public press) without written permission from the publisher.

Illustration Credits

Isaac Franco: 45 right top and bottom; Paul Horsley: 46; Timothy Hursley, copyright © 2011: 2–3, 6–7, 14–25, 28, 30–33, 36–39, 45 left, 47–49, 52–53; Kansas City Art Institute: 13 middle, 26–27; Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts: 4, 5, 51; Nagata Acoustics America, Inc.: 34, 35; Novum Structures LLC, www.novumstructures.com: 44; Safdie Architects: 1, 8–12, 13 top and bottom, 40–43; Strauss Peyton Photography: 50; Theatre Projects Consultants: 29

Printed by Colormark, Kansas City, Missouri, on Appleton Coated Utopia U1X:Green, which is manufactured by Appleton Coated, Combined Locks, Wisconsin. U1X is FSC-certified, made from a minimum of 20 percent postconsumer recovered fiber (PCRF), and manufactured with Elemental Chlorine Free (ECF) green power.