COPYRIGHT 2006 © BYTHE JEWISH FEDERATIONOF GREATER ATLANTA

All rights reserved.No part ofthis book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,electronic or mechanical,including photocopying,recording,or by any information storage and retrieval system,without permission in writing from the Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta.

JEWISH FEDERATIONOF GREATER ATLANTA

The Selig Center

1440 Spring Street,NW Atlanta,Georgia 30309

404-873-1661 www.ShalomAtlanta.org

BOOK DEVELOPMENTBY

Bookhouse Group,Inc. 818 Marietta Street

Atlanta,Georgia 30318

404-885-9515

www.bookhouse.net

ROB LEVIN, Editorial Director

SARAH FEDOTA, Managing Editor and Project Director

RENEE PEYTON, ChiefOperating Officer

LAURIE PORTER, Design

MURIEL DIGUETTE, Office Manager

DAC AUSTIN,BRIGHTHOUSE, Design Concept

VICKIE BERDANIS, Prepress

JILL DIBLE, Press Preflight

BOB LAND, Copyediting and Indexing

Bookhouse Group,Inc.would like to thank the following editorial reviewers for their insight and assistance: Ellen Arnovitz; Sandra Berman,Archivist,William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum; Henry Birnbrey; Sherry Frank; Jack Halpern; Jerry Horowitz; Barbara Babbit Kaufman; Jane Leavey,Executive Director,William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum; Steven Rakitt,Executive Director,Jewish Federation ofGreater Atlanta; Milton Saul; Virginia Saul; and Erwin Zaban.

American Jewish Committee,120(b),127(b);Anti-Defamation League,160(a);Associated Press,160(b),163(c);Atlanta Journal-Constitution/ Dwight Ross,169;Atlanta Scholars Kollel,158(b),Betsy Babbit,158(a);Emory University,20(a),22(c);Renee Feldman,163(a),The Georgia Aquarium,162(b);Israel Bonds,154(c);The Jimmy Carter Library and Museum,122(a)(b);Fred Katz,154(b);Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center,14(a),16(c),17(a),20(c),24(a),26(a),35(b),47(c),48(a),57(b),57(c),58(b),81(c);Marcus Jewish Community Center ofAtlanta,170(a);Photofest,120(c);Bill Sommerfield,46(b).All other photos courtesy ofthe William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum and the Jewish Federation ofGreater Atlanta.

Manufactured in Manitoba,Canada

In 1906,Atlanta’s Central European Jewish leaders established a coordinating body for Jewish philanthropic endeavors known as the Federation ofJewish Charities.That modest undertaking has grown and blossomed over the course ofa century into an institution that has helped make Atlanta Jewry one ofthe premier Jewish communities in the United States.

During its first two decades,the Federation transformed itselfto meet the pressing needs ofthe community,first extending its umbrella to include the charities ofthe Eastern European Jewish immigrants and later developing an impressive network ofprofessional social service agencies.In 1936, a separate organization,the Atlanta Jewish Welfare Fund,was created to serve as a community fund-raising agency and to also allow Atlanta to participate in the national campaigns that supported Jewish causes.Then,after World War II,a Jewish Community Relations Council was founded to help represent Atlanta Jewry to the non-Jewish world,and to help create a process ofcommunity planning. In 1967,these three central agencies—the Federation,the Welfare Fund,and the Community Council— all merged to form the Atlanta Jewish Federation.A final step in the organization’s history was to change its name to the Jewish Federation ofGreater Atlanta,a move that reflected its enlarged role during the recent era ofunprecedented growth for Atlanta and its Jews.

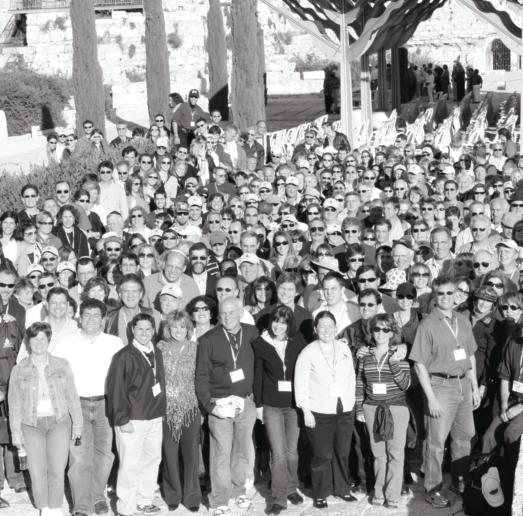

Since the Federation has never been a self-contained organization,but has always supported the multiple facets ofJewish community life in Atlanta,this volume celebrates its centennial by focusing broadly on the entire Jewish experience in Atlanta since the arrival ofthe first Jewish settlers in 1845. More than simply a photographic history,the book unites images ofJewish community life in Atlanta with the voices ofpeople who have been the lifeblood ofthat community.We have culled hundreds of photographs from the collections ofthe William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum’s Joseph and Ida

Pearle Cuba Jewish Community Archives,as well as from some other local repositories.Alongside these photographs,readers will find quotations from more than one hundred oral history interviews,quotations that help to narrate and bring to life the visual record.Most ofthese interviews with Jewish Atlantans from all walks oflife were conducted over the last three decades,first as a project ofthe American Jewish Committee and then as part ofthe Breman Museum’s Esther and Herbert Taylor Oral History Project. A few additional interviews were either drawn from the collections ofthe Atlanta History Center or conducted especially for this volume.

An endeavor such as this could not have been completed without the help ofmany people.First,I give thanks to Barbara Babbit Kaufman and Ellen Arnovitz,who first envisioned this project and gave me the opportunity to help bring it about.They have also organized the supplement to this book,where photographs sent in by individuals have been included in a “family album”ofJewish Atlanta.Joey Reiman and the staffat BrightHouse helped us refine the initial concept and provided insight on organization and design.As I delved into the process ofchoosing photographs and selecting oral history quotations,the staffofthe Breman Museum—Jane Leavey,Sandy Berman,and Ruth Einstein— provided invaluable assistance and feedback.This book could never have been completed without them. Rob Levin,Sarah Fedota,and the rest ofthe staffat Bookhouse Group have provided helpful guidance throughout the writing and publishing process.

We particularly acknowledge our corporate sponsors,Wachovia Bank,Northside Hospital,and Piedmont Hospital,and the two hundred centennial sponsor families who provided generous funding. Chairs ofthe Centennial Year Celebration,Sid Kirschner and Joanie Shubin,have also provided critical support.

ONE TAKING ROOT IN SOUTHERN SOIL, 1845–1915

In an 1879 editorial in the short-lived newspaper The Jewish South,Atlanta rabbi Edward M.B.Browne compared Judaism to a deep-rooted tree,which over the centuries had been able to stand firmly in all weather and adapt to any climate.Judaism had found particularly fertile soil in the United States,argued Browne,but the American South above all regions had “succeeded in producing the loftiest fruits ofthe greatest beauty and grandeur.”1

Few ofBrowne’s Atlanta congregants would have contradicted his glowing assessment ofJewish life in the South. In the period after the Civil War,Atlanta recovered in an astonishingly short time from the damage that General Sherman’s army had inflicted,earning the nickname “Phoenix city.”2 The postwar prosperity attracted a stream of Jewish businessmen and their families,whom the local population often welcomed as industrious citizens and harbingers offurther economic growth.By 1880,Atlanta’s Jews included some ofthe city’s most well-known merchants and manufacturers,such as Morris Rich,Elias Haiman,and Jacob Elsas.3

Although Atlanta’s Jews experienced a heyday in the post–Civil War period,their presence in the city actually stretched back to 1845,just two years after the small railroad terminus—formerly known as Marthasville—was incorporated.That year,German-born Jacob Haas and Henry Levi moved their general merchandise store to Atlanta from nearby Decatur,Georgia.Several more Jewish families followed Haas and Levi;by 1850,twenty-six Jews,mainly recent immigrants from Central Europe,resided in Atlanta.Although they made up only 1 percent ofthe city’s population,the clothing and dry goods stores they opened along Whitehall Street represented about 10 percent of local business enterprises.4 Within ten years,the number ofJews had grown sufficiently to necessitate the founding ofa Hebrew Benevolent Society,which provided financial assistance to struggling immigrants and acquired six plots for Jews in the city’s main burial ground,Oakland Cemetery.Religious services had been held intermittently since the early 1850s, but in 1862 they were formalized with the founding ofthe Hebrew Benevolent Congregation.5

While Atlanta’s importance as a developing railroad center was a central factor in the emergence ofits Jewish community,the Civil War and the dramatic transformation it brought proved far more decisive to the community’s growth.The war itselfhad an uneven impact on the city’s Jews.Atlanta’s importance as a manufacturing and supply center for the Confederacy attracted many new Jew ish settlers,and some felt so passionately about the opportunities the South had offered them that they supported the Confederate cause by taking up arms or serving as supply agents. Others,however,left Atlanta during the war,fearing conscription and the advance ofNorthern troops.The future seemed dim after Sherman’s forces destroyed much ofthe city in 1864,but over the next few years,as the city’s infrastructure was rebuilt and Atlanta became the budding center ofthe “New South,”it attracted merchants and industrialists able to supply the needs ofthe reborn city.6 The scene was set for the great success and prosperity enjoyed by Atlanta’s Jews beginning in the 1870s.

The postwar years were not just auspicious times for Jewish economic advancement but for Judaism and Jewish community development as well.The Hebrew Benevolent Congregation,which had disbanded during the mid-1860s, was reconstituted shortly after the war.Its vitality was reflected in the imposing Moorish-style temple dedicated in 1877 on the corner ofForsyth and Garnett streets.In addition,other Jewish institutions emerged,including a Ladies’ Aid Society,several debating and literary clubs,a B’nai B’r ith lodge and a number ofother Jewish fraternal organizations,not to mention Browne’s Jewish newspaper.Moreover,Atlanta’s accepting environment during these years gave rapidly acculturating Jews entrée into the social and cultural circles ofthe larger society without requiring them to significantly attenuate their Jewish commitments.Southerners’ongoing tendency to view African Americans as the primary outsider group and to see Jews as an integral part ofthe white population helped prevent anti-Semitism.Jews were welcomed in Masonic lodges and civic organizations and even participated in local government.At the same time,local non-Jews showed their admiration and respect for Jewish undertakings by joining the Jewish-dominated Concordia Association,a social club that featured dances and German-style dramatic,musical,and literary events.7

During the 1880s,Atlanta won national praise as an exemplar ofthe New South creed,which envisioned a progressive society built on business and industry rising out ofthe ashes ofthe antebellum slave system.But the faltering ofthe southern economy in the early 1890s soon led to a lack ofself-confidence in many segments ofsouthern society. Growing doubts about the processes ofindustrialization and urbanization that were transforming the South helped alter popular attitudes toward Jews.While the most optimistic southerners often continued to laud them as the embodiment ofprogressive citizenship,there was an increasing tendency during the 1890s to label Jews as “Rothschilds”and exploiters ofsouthern workers and farmers.Although social discrimination against Jews in Atlanta never matched the expressions ofanti-Jewish prejudice found in northern cities,it became increasingly common for them to be barred from non-Jewish organizations that once welcomed them and to be denied the degree of participation in political and civic affairs they had enjoyed in previous decades.8

The increasing arrival ofJewish immigrants from Eastern Europe added significantly to the pressures faced by the acculturated Jewish community.Jews from Russia,Poland,and other Eastern European locales had been arriving in small numbers in the city since the onset ofanti-Jew ish pogroms in 1881,but a growing influx in the 1890s led established Jews to fear that the immigrants’foreign appearance,low economic status,religious orthodoxy,and frequent devotion to Zionism would further set them apart.The tendency ofthe Eastern Europeans to open stores and saloons that catered to African Americans and settle in black sections oftown was a further reason for concern in a society increasingly insistent on racial division.While Jewish community leaders did much to aid the Eastern European immigrants,their general coolness toward the newcomers reflected the animosity many harbored.9

In response to increasing social ostracism,Jews already established in Atlanta redoubled their efforts to demonstrate their integral place in southern society.First,they took immediate steps to refashion their own Judaism.In 1895 the Temple—as the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation was now often called—hired its first American-born rabbi,Dr. David Marx,who led his flock toward classical Reform Judaism.Marx banished almost all Hebrew from the service, did away with rites such as bar mitzvah,eliminated head covering for men,and discarded the second day ofall festival observances.To mirror Christian practice,he instituted a Sunday service alongside the traditional Friday night and Saturday worship.10 Second,although they could no longer move with ease in non-Jewish social circles,the established Jews ofCentral European origin created their own social world,one that paralleled the rituals ofelite society. Nowhere were these practices more evident than at the Standard Club,a social and recreational institution that was founded in 1905 to replace the declining Concordia Association.Significantly,the Standard Club barred all Eastern European Jews from membership as a means ofunderscoring the “high class”nature ofits clientele.11

Despite an unwelcoming climate,Eastern European immigrants found Atlanta to be an ideal setting to raise their families and embark on the road to economic mobility.Although they often faced greater economic challenges than Central European immigrants had a generation earlier,Eastern European Jews in Atlanta did not have to contend with the dank sweatshops and overcrowded tenement houses that plagued their northern cousins.Most were able to launch themselves in business more quickly than Jews living in Chicago or New York,and the immigrants were able to establish an elaborate array ofreligious and social institutions oftheir own.In 1887,the first Eastern European synagogue,Congregation Ahavath Achim,was founded,and was followed by several others,the most enduring of which were Shearith Israel (1904) and Anshi S’fard (1913).Like their Central European predecessors,the immigrants also established their own social,cultural,and charitable organizations,not to mention the Zionist societies that were an anathema to most old-line Jews.Many ofthese groups met at the Jewish Educational Alliance,a settlement house and community center built on Capitol Avenue in 1911.12

By 1913,Atlanta Jewry was hardly the united,well-integrated,middle-class community it had been in 1879.Adding to its diverse makeup was the arrival in the early twentieth century ofa third group—Jews from Turkey,Rhodes,and other parts ofthe Levant.Differing from both the Central and Eastern Europeans in their religious,cultural,and linguistic heritage,they formed their own congregation,Or VeShalom,created in 1914 by the merger ofRhodian and Turkish minyanim.13 Yet,despite the dramatic changes that had occurred over nearly three and a halfdecades and the general decline in the social status ofthe city’s Jews,members ofall three groups ofimmigrants had undoubtedly benefited from the opportunities afforded them by the Atlanta environment.Echoing the claim ofRabbi Browne, each group had demonstrated in its own way the efficacy ofsouthern soil for the sinking ofJewish roots.

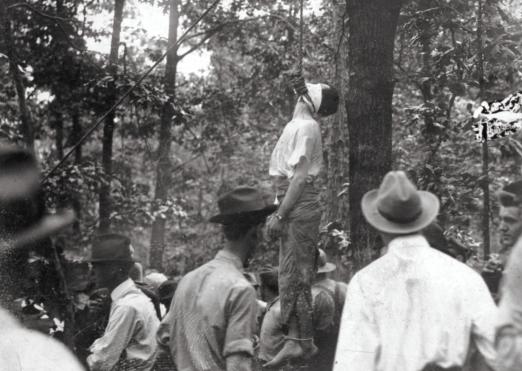

Atlanta Jews ofall backgrounds were shocked,therefore,when Leo Frank,a member ofthe city’s Eastern European Jewish elite and the superintendent ofthe National Pencil Company,was arrested and charged with the murder ofone ofhis employees,thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan,in the spring of1913.Frank’s trial,which was based on conflicting evidence and was carried on under the threat ofmob violence,ushered in a wave ofanti-Jewish hostility in Atlanta. Although inspired by the same social and economic tensions that had fueled discrimination against local Jews since the 1890s,the anti-Semitism that emerged from the Frank case was much more virulent.Ultimately,Frank was convicted and sentenced to death,but he remained in prison for two years while his lawyers unsuccessfully pressed his appeal in the courts.As both Jews and non-Jews across the country took up his cause,he was attacked vociferously by Georgia journalist and populist leader Tom Watson,who denounced Frank in the press as a Jewish “pervert.”After an agonizing review ofthe case,Governor John Slaton finally commuted Frank’s sentence to life imprisonment.Then, on August 17,1915,several men—some quite prominent in Georgia’s public life—wrested Frank from his cell at the state prison in Milledgeville and brought him to Mary Phagan’s hometown ofMarietta,where he was lynched.14 The Frank case shook the very foundation ofJewish life in Atlanta.Having established themselves successfully over the course ofsix decades,Atlanta’s Jews now looked toward the future with a growing sense ofinsecurity. (a)(b)

(a) Levi Cohen, c. 1860, arrived in Atlanta during the Civil War and was one of the founders and early presidents of the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation. He also served as Atlanta’s first mohel (ritual circumciser).

(b) In 1896, Jacobs’ Pharmacy and Harry Silverman’s cigar emporium were prominently situated at Five Points, the city’s largest crossroads. Jacobs’ Pharmacy was the first to serve Coca-Cola at its soda fountain in 1886.

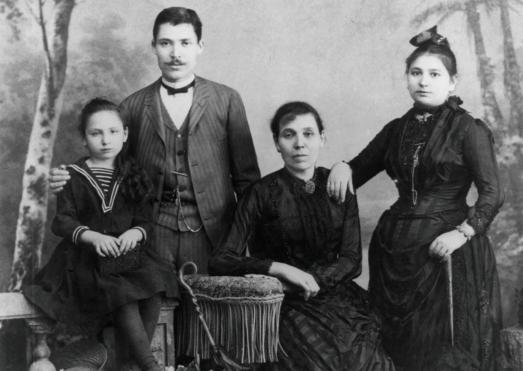

(c) Eastern European immigrants Max and Leah Yudelson (seated), along with their children (standing, left to right) Gertrude, Sol, Sarah, and Israel, c. 1900.

My Atlanta roots go back to 1848,when a man named Aaron Alexander came to Atlanta from Charleston.The city at that point was about twelve hundred people.Then his sons—one ofthem who had served in the Confederacy—came back to Atlanta after the war,and they started a hardware business.Aaron Alexander went north after he had done very well here as a druggist,and he got in debt and ended up in debtor’s prison in Philadelphia.He came back here and he started a rolling mill and did very well,and overcame all ofhis indebtedness.But no Alexander ever did venture north of Marietta since. —CECIL ALEXANDER,1980

My great-grandparents came to Atlanta with a good many children,and there were no public schools in Atlanta.It was in the late 1850s or middle 1850s,and they could not afford a tutor,so they moved to Newnan,Georgia,because Newnan had a school.They couldn’t make a living in Newnan,so they moved back to Atlanta,and at the outbreak ofthe Civil War my great-grandparents moved to Philadelphia and stayed there until after the Civil War.My grandfather,Isaac Guthman,had stayed in Atlanta all that time and was in the Confederate Army,and my family has been here ever since. It certainly must have been something,because they had nine children. —HELEN BAUER GORTATOWSKY,1987

In Atlanta,interestingly enough,there were several Jews who occupied rather prominent positions at that time.Aaron Haas was a member ofthe City Council.My grandfather was chairman ofthe Parks Committee when they commissioned the people to paint the Cyclorama for the park.He was also very interested in public works.There was a man here by the name ofDavid Mayer,the ancestor ofHenry Bauer on the mother’s side.David Mayer was [an officer ofthe] schools here at one time back in the early days.There was a story that David Mayer once had the job offiring a school superintendent.The man was a sort offlowery-talking fellow and said,“I’m so very disappointed.I hoped to make my living here,and I came here because Atlanta is the Gate City ofthe South.”Mr.Mayer said,“Well,this is the Gate City,[and] the gates are open to come in and to go out.” —JACOB HAAS,1994

(a) Aaron Alexander, one of Atlanta’s earliest Jewish residents, built this house for his family at 163 Peachtree Street in 1849, one year after his arrival in the city.

(b) In 1860, Bavarian native David Mayer headed Atlanta’s first Jewish organization, the Hebrew Benevolent Society. Nine years later he helped found the city’s board of education.

(c) Caroline Haas, c. 1862, was reputed to have been one of the first children born in Atlanta in 1845.

(d) Aaron Haas, a nephew of the Jewish pioneer Jacob Haas, was elected to the Atlanta City Council in 1873 and two years later served as mayor pro tem. In 1887, he was one of the founding members of the Gentleman’s Driving Club (later known as the Piedmont Driving Club). By the 1890s, increasing social discrimination made it difficult for Atlanta Jews to seize such roles in the larger community.

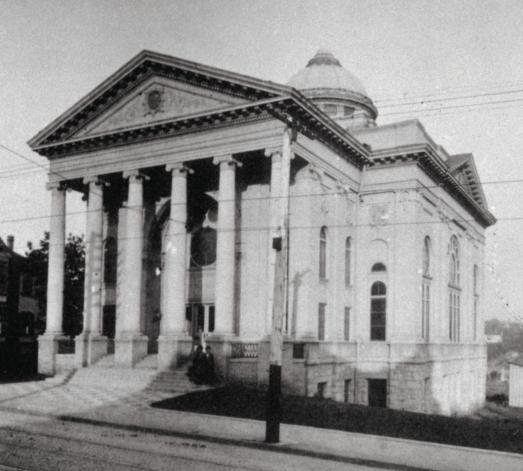

(a) The Hebrew Benevolent Congregation was organized by thirty families in 1862. This imposing synagogue building was dedicated in 1877 on the corner of Forsyth and Garnett streets.

(b) During the Civil War, Jewish religious activity in Atlanta lapsed but was revived in 1867 at the urging of Rev. Isaac Leeser of Philadelphia. Rev. Leeser came to Atlanta to officiate at the wedding of Emilie Baer and Abraham Rosenfeld, pictured c. 1870.

(c) Rabbi E. M. B. “Alphabet” Browne, c. 1880, was one of the early religious leaders of the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation and the first publisher of a Jewish newspaper in Atlanta.

My parents belonged to the Temple.As a matter offact,my grandfather and my great-grandfather were among the founding members,and we lived what I think was a routine Reform Jewish life in Atlanta. My parents went to weekly services,and I remember my mother wouldn’t let me cut out paper dolls or sew on Saturday,but we did not observe many ofthe home ceremonies that are today routine with my children and with almost all ofus.But religion always played an important part in our life.My mother told me that although the congregation was a Reform temple,the backgrounds ofall the founders were such that they still observed many rules that have since passed away with everybody except really Orthodox Jews.She said that,for instance,they went to Temple services on Saturday and then they went to Oakland Cemetery to visit their mother’s grave,and that they always had to walk because they weren’t allowed to ride on Saturday.

—HELEN BAUER GORTATOWSKY,1987On my maternal grandmother’s side the family name was Browne.Her father was a rabbi who came from Hungary,and that’s how they got to the South to start with.He was rabbi ofthe Temple in Atlanta from 1877 to 1881.He also had a newspaper while he was here,the Jewish South,and he was quite controversial.They called him Alphabet Browne.His name was Edward Benjamin Morris Browne,but he had I don’t know how many degrees from his education in the old country.He had all these initials before his name and afterwards he put all the initials ofthe degrees—it was M.D.,L.L.D., and so forth.He was really quite a character.

—JANICE ROTHSCHILD BLUMBERG,1989My mother was Eleanor Rosenfeld.Her father came here in 1866.When he got to Atlanta,it was still smoking from Sherman.He peddled behind Sherman’s army into Atlanta.I used to tease my mother that we were the only aristocratic Jews in Atlanta because Grandpa stole a mule and rode in,and the rest ofthe poor guys went walking.Anyway,he sent back to Chicago for my grandmother.They wanted to get married.There was a minyan in Atlanta,but no rabbi.So they had to send to Philadelphia for the rabbi,and the rabbi came here and married my grandfather and my grandmother.And at that time,and on that night,he founded the congregation,which my father became the rabbi ofin 1895.

—DAVID MARX JR.,1978

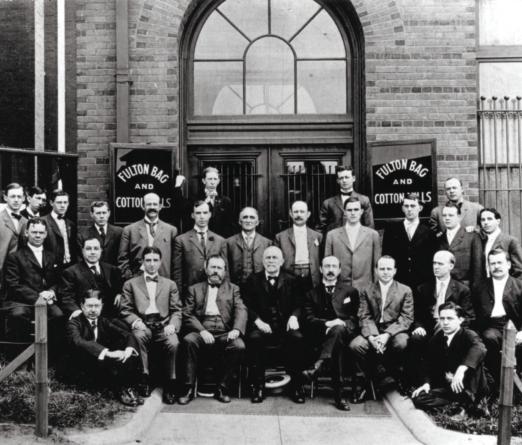

My grandfather probably had what would be a grammar school,maybe a middle school education. He was born in Germany in Ludwigsberg.The family had originally been in textile manufacturing in Ludwigsberg,so he concluded that the opportunity to manufacture was greater than the opportunities he saw in trading.He founded the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills,which was on Boulevard,right across from Oakland Cemetery.The business developed branches in New Orleans and St.Louis and even in Brooklyn,but the nucleus was here.My recollection ofthe executive office was a series ofabout six rolltop desks,one right behind the other.They were in a fairly long room,and Grandpa’s desk was the first one.Ifhe wanted a meeting ofhis executive committee,he’d just say,“I want to talk about something,” and all ofthem would pop out from behind their desks,and there was a long enough space that they could conduct business.One ofthe things I remember about him was that there was a great debate once on how an addition to the mill should be built.He had started the mill out ofbrick,brick actually made on the site.And there was a great debate as to what would be used in this new addition.They debated and debated and Governor [John] Slaton [who was a member ofthe board] was taking the minutes— this was a formal meeting ofthe board ofdirectors.After the discussion was all over and there was a vote,there had been some completely different material that was voted on.Grandpa turned to Governor Slaton and said,“We’ll build it out ofbricks.”He was very dominant. —HERBERT ELSAS,1990

(a) An early leader in clothing and dry goods, Morris Rich, who founded M. Rich Dry Goods in 1867, later expanded his operation by taking on two of his older brothers as partners. By the turn of the century, Rich’s Department Store, at 54-56 Whitehall Street, was one of Atlanta’s largest retail stores.

(b) Regenstein’s Wholesale and Retail Millinery, 74-78 Whitehall Street, c. 1885.

(c) Jacob Elsas arrived in Atlanta in 1869 and was involved in a number of business ventures before heading one of the city’s largest industrial enterprises, Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills. Elsas (front center) poses with his employees, c. 1910.

(a) Central European Jews in Atlanta were bound together by an extensive web of family and business networks, ties that enriched their social lives and also furthered their economic interests. Members of the Silverman family gathered for this portrait in 1887.

(b) Female members of the Steinheimer family and their children sit on the steps of their Washington Street home, c. 1910.

(c) Morris and Rosalind Montag Rich pose in 1910 with their grandson, Richard Rich, who later took over the family business.

I think I was about seven years old when we moved on Fourteenth Street,between Peachtree and West Peachtree.We lived in two houses on a hill—my father and his brother.My two grandmothers lived with us.Grandma Menko lived with us,and Grandma Joel lived next door with the other brother’s family.My mother had a big family.I don’t know how in the world she handled it.There was my mother and father and the three children,and Auntie,who took care ofGrandma until Grandma died. And my father came home for lunch in the middle ofthe day.My mother had to have three meals a day for seven people.As far as I was concerned,it was very pleasant.Grandma Menko was a darling,sweet old lady.She was a young girl when she came over from Germany.She always spoke with an accent; both grandmothers did.They spoke English perfectly okay,but they had a slight accent.And Grandma Menko taught my brothers and me songs to sing—German songs—and she would play the piano.Her hands were stiffwith rheumatism,and she would still bang,bang,bang on the piano,and we would sing songs that she taught us.Grandma had her breakfast in bed every morning,and before we went to school,we would go in and say,“Good morning,Grandmother,”and she would say,“Good morning, mein kind.”I think I had a very happy childhood. —JOSEPHINE JOEL HEYMAN,1989

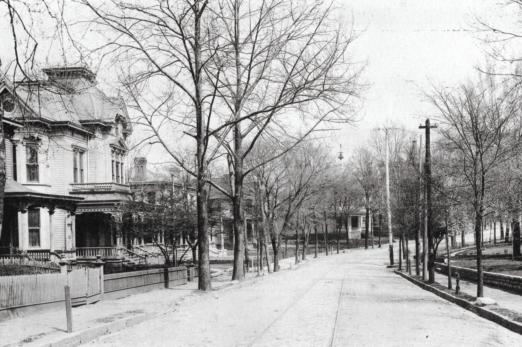

We had a great childhood.We could ride our bicycles; we could do everything we wanted to up and down Washington Street.It was practically a Jewish neighborhood.I could go on and on telling you about Jewish families that lived on Washington Street.They were all German Jews.The Orthodox Jews [from Eastern Europe] didn’t come until they had those fierce pogroms in Russia,and they settled mostly on Gilmer Street,Capitol Avenue,in that section oftown.Now after the German Jews moved away from Washington Street and came to the other side oftown,those people moved onto Washington Street.But originally,when the Orthodox Jews first settled here,none ofthem settled on Washington Street. —DAVID MARX JR.,1978

The Orphans’Home was,in retrospect,a very good place for a child to grow up in that it was well administered.They saw to it that you learned cleanliness.They saw to it that you studied.They saw to it that you had any opportunity in school,even to the extent that,in the afternoons,those who wanted to could take typing and shorthand by a teacher who was brought in from one ofthe public schools.Life was not a bowl ofcherries,but we played,we had a playground.We got along alright.The Home was actually founded by the German Jewry who had preceded the wave ofRussian Jewry and had become a little bit more established,particularly financially.It accepted children from what was known as the fifth B’nai B’rith district,which encompassed Alabama,Georgia,North Carolina,South Carolina, Virginia,on up to Washington. —ALFRED E.GARBER,1989

(a) During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Atlanta’s Central European Jews lived in several residential clusters, the largest of which was on Washington Street, pictured in 1895.

(b) The home of Dr. Julius and Clara Sommerfield, pictured around the turn of the century, was located at 370 Whitehall Street, close to the city’s principal Jewish business district.

(c) The Gate City Lodge of B’nai B’rith convinced the fraternal order’s Grand District Lodge No. 5 to locate its Hebrew Orphans’ Home in Atlanta in 1889 by raising more money for the project than competitors in Richmond or Washington, DC. Several hundred orphans from all over the Southeast were housed in the Venetian-style building on Washington Street, pictured c. 1903, until it closed its doors as a residential facility in 1930.

(a) The social acceptance that Atlanta’s Jews enjoyed following the Civil War was reflected in the activities of the Concordia Association, which focused on German culture and had both Jewish and non-Jewish members. As social discrimination became more prevalent at century’s end, however, Jews began to socialize among themselves, and the Standard Club, founded in 1905, replaced the Concordia. The Concordia Association is shown as it appeared c. 1880, next door to the Kimball Opera House at the corner of Marietta and Forsyth streets.

The Standard Club still says “Founded in [1866].”Actually,it was the Concordia Club,which was a music appreciation group,Jew and non-Jew,ofGerman descent.The building which housed the Concordia Club still stands on Forsyth Street.The building is a red brick building,and it has the music symbol,the harp,over the door.When the Concordia Club became the Standard Club it moved to Washington Street.The building was an old mansion that the club bought.As I recall,it had a large ballroom,a bowling alley,and card rooms,and a dining room. —JACOB HAAS,1994

In those days,we had dances in people’s homes.They would take up the rugs and turn on the Victrola, and we would dance.And then sometimes,[on] great occasions,we had parties at the old Standard Club.We went in crowds.Most ofmy crowd was the Sunday school class.Charles Heyman was just one year older,and he was the best dancer in our crowd. He was very popular,and I was amazed years later that he married my cousin.I thought she was very smart to be able to catch Charles Heyman.

—JOSEPHINE JOEL HEYMAN,1989

Morris Srochi came originally to New York and [then] to Atlanta in the early 1890s.The family story is that he had been a baker as a young boy in Poland.He saw an ad in a Yiddish-language paper in New York for a position as a baker,and he could make more money in Atlanta.He was making three dollars a week in New York.He came to Atlanta for three dollars and fifty cents.So Srochi came south for fifty cents.It went a long way in those days.

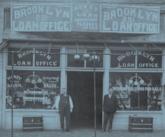

—STANLEY M.SROCHI,2001Decatur Street merchants I remember [were] Mr.Shukoff,Mr.Glustrom,Harry Pfeffer,and Mr.Adair. [Decatur Street] also had the wholesale people in the clothing business: Mr.Yalovitz was wholesale men’s shoes and work clothes; Hyman Mendel,who was not on Decatur Street but Gilmer Street,had anything you needed like pants,socks,pillowcases,household wares,and so forth.As well as I can remember,they were friendly to each other.When any ofthese men would pass a store,they would yell,“Hello,Isaac,”and then in Yiddish,“How are you? Is everything alright?”As a kid I understood them very well.These stores mainly sold clothing and shoes,used hats also.It was common among the merchants to have a black person take home a pair ofshoes on a Saturday night,wear it to church, [and] bring them back Monday morning.Black people in those days were not able to pay the prices for new shoes.Many ofthem worked as common laborers on a farm [or as] domestic help,and when they would come in,they would be shown shoes with the scuffed bottoms.In those days,halfofthe population that came on Decatur Street were blacks and also farmers,as on other streets like Edgewood Avenue,Peters Street,[and] Stuart Avenue. —MIKE BOCK,1992

(a) Galician immigrant David Zaban, who made his living as a furniture merchant, was an early president of the Ahavath Achim congregation and, in 1904, an incorporator of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association. Zaban is pictured with his family, c. 1902.

(b) Eastern European Jews who began arriving in the Atlanta area after 1881 found that the region offered great opportunities for economic advancement. While Jewish immigrants in the North often started their careers in the sweatshop, Teddy Blumenthal, c. 1910, started out as a peddler in north Georgia.

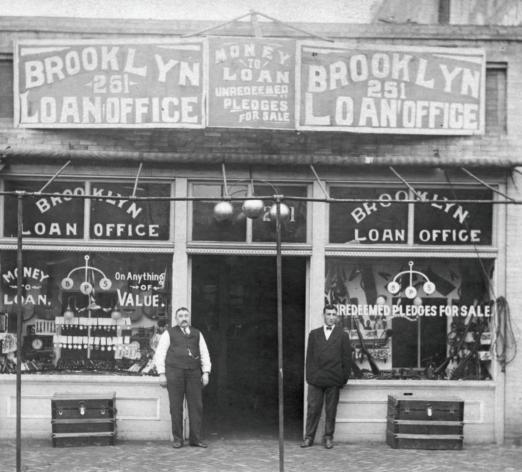

(c) With fewer financial resources than their Central European predecessors, Eastern European Jewish immigrants in Atlanta often began modestly in the business world and frequently served an African American clientele. Mike Greenblatt (right) and Joseph Bach, c. 1909, owned the Brooklyn Loan Office at 251 Marietta Street.

(a) Congregation Ahavath Achim, known to local Jews as the “AA,” was founded in 1887 by the city’s initial group of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. Rabbi Jacob Simonhoff, a native of Kovno, Lithuania, served as rabbi of the congregation from 1896 to 1902.

(b) Solomon Lev Zion, who served the Eastern European community as a shochet (kosher slaughterer), posed with his wife Faggie, c. 1910.

(c) The interior of Ahavath Achim’s first building at Piedmont Avenue and Gilmer Street, as it appeared for the wedding of Rosa Goldstein and Joseph Friedman in 1913.

My father was the first secretary ofAA in 1887.They had twelve members.They had a little place over on Gilmer Street,just a room.And ofcourse they had to have a shochet,so he sent over to Russia and brought a shochet to Atlanta.Jews at that time were poor,including us.They didn’t have much meat, so they raised their own chickens.And then they had to have a synagogue.On holidays,he went to shul and stayed there all day like all the good Orthodox Jews would do.We kids would slip offwhenever we could.He didn’t pay too much attention to us because he had too hard a job making a living without worrying about a couple ofkids,whether they went to synagogue or not.He was disappointed.That was that. —HERBERT TAYLOR,1987

A new rabbi came to town somewhere around 1907,and he apparently was so influential.His name was [Julius M.] Levin,and I detested him because he made my father more Orthodox than he had ever been.He was Orthodox,but he became very rigid,and he made our lives miserable.And we had to take two days out each time [for holidays],and ofcourse that was very hard on us at school.I remember he had a pew not far from the bimah.And when I was very young,on the holiday,I would just go and sit with him.And all the men around frowned to see a girl on the first floor,because all the women,of course,were up above. —BESSIE ZABAN JONES,1990

My grandfather died in 1922,fairly young,but by that time he had become prominent as a major leader ofthe [Eastern European Jewish] community.[He] helped found the Jewish Educational Alliance,which later became the Jewish Community Center,and was one ofthe original signators on the Ahavath Achim synagogue.My grandmother was one ofthe founders ofthe Montefiore [Relief Association],which was the welfare group which eventually became the Federation here,and was one of the founders ofthe predecessor to the Jewish Home.So both my grandfather and my grandmother were very active in the community.In 1907,my father founded a group called the Don’t Worry Club,and he was the first president.In fact,I’ve got his gavel somewhere around the house.Boys got together to form this club,and eventually there must have been about twenty,twenty-five boys.They used to debate and orate and play sports and socialize.My father was a very well-known debater and orator.He was called upon at ceremonies to speak.In those days,you did those sorts ofthings. —LEON EPLAN,1993

(a) Although Eastern European Jewish immigrants clung more closely to tradition than their Central European predecessors, their children adapted to American ways with zeal. The Joy Seekers’ Club lived up to its name at this 1912 gathering.

(b) In 1914, an Americanized young couple, Sam Sugarman and Ida Meyers, celebrated their wedding surrounded by friends and family.

(c) Members of the Don’t Worry Club, shown in 1914, hold their annual dinner at the Jewish Educational Alliance beneath symbols of American patriotism and a portrait of Zionist leader Theodor Herzl.

(a) In 1895, twenty-three-year-old David Marx, a native of New Orleans and a graduate of Hebrew Union College, became the rabbi of the Temple, as the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation had come to be known. At a time when the Jewish establishment in Atlanta worried about its social standing, he led the congregation toward increasing reforms and forged close ties with local Christian clergy.

(b) In 1902, the Temple built this new structure on Richardson and Pryor streets to be closer to its residentially mobile membership.

(c) Minnie Cuba, a daughter of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, holds her diploma and a celebratory bouquet of flowers upon her graduation from Commercial High School, c. 1910.

My father was a disciple ofIsaac Mayer Wise.He attended the Hebrew Union College which Dr.Wise founded.Isaac Mayer Wise was the founder ofReform Judaism in this country,and my father and the other young men who absorbed his teaching went all over the country preaching the battle ofReform Judaism.At that time,the Jewish population was virtually all Orthodox,and it was a Herculean task for them to try and convert these people over into Reform.He had the support,eventually,ofhis congregation,and he was very much in the view ofthe non-Jewish population because he represented the Jews to the non-Jews.I’m very proud to be his son.I don’t think any Jewish man in the city of Atlanta has ever had the status that my father had.He was accepted everywhere,and he didn’t hide behind anything.They knew he was Jewish and they knew what he stood for,and there was never any equivocation. —DAVID MARX JR.,1978

I think there was somewhat ofan embarrassment on the part ofthe Reform community generally toward this group ofimmigrants that came from Eastern Europe.The Reform Jews were here very early—1840s,1850s—and by the time this immigration began to flow into the United States in the 1880s,the Reform Jews had become successful businesspeople and were respected in the community. And along came these people who claimed they were Jews,and I think there was a large amount of embarrassment.That was a separation that lasted for decades.My grandfather was one ofthe spokesmen for the [Eastern European] community,and he and Rabbi Marx were bitter enemies.There are stories oftheir conflicts.My grandfather was very large,and Rabbi Marx was very small.One time the story is that Rabbi Marx came into the Alliance and began to harangue my grandfather,who was leading a meeting.My grandfather went down and picked up Rabbi Marx and escorted him out and said,“Do not come back to this Alliance again.”

—LEON EPLAN,1993

My mother’s family had been on the Isle ofRhodes for many generations.My grandfather [in Rhodes] was the rabbi of la kehillah grande,which means the large synagogue.He taught almost all ofthe elders that were [later] here in Atlanta when I was growing up.It was a wonderful experience for me,because they would all tell me,“I learned with your grandfather.”They spoke ofhim in such a reverent fashion. He must have been a wonderful person.I never knew a grandparent,and that’s a terrible thing.That’s the sad part about leaving a country when you’re young.You mean to go back,but you never do.It wasn’t like today,[when] you can go in a week’s time by boat or in a day by air.They left their parents and their brothers and their sisters,and they never saw them again.My father’s godmother was the first ofthe Sephardic women that we know that actually lived here in Atlanta,and her name was Rebecca Amiel.She was such a beautiful lady.She had come from Cairo,Egypt.She knew some Spanish,but she spoke Italian,French,and Greek mostly.I guess that’s what they had spoken there.When all ofour young men brought their brides here to this country,they were all taken to Mrs.Amiel’s home.She was sort oflike the mother to all ofthe young women that would come here.The language was so hard for them,and she would open up her home to all ofthem.A lot ofthem came here with no family,and they would have to stay somewhere until the wedding.So she would say,“There’s room.Let them stay here until the time.”She lived next door to one ofthe synagogues on Gilmer Street,when the AA was there. There were about fourteen young men that were living here that were Sephardic Jews.There was no synagogue,so she wanted to have a service for them.And she had become so close to one ofthe rabbis at the AA,he actually let her bring a Torah to her home so that these young men could have a service.They wanted to have it the way that they knew,the way that they read,because the Sephardic and the Ashkenazic pronunciation were so different.So she asked,and the rabbi said,“Ofcourse.”

—REGINA ROUSSO TOURIAL,1989

(a) Sephardic Jews from Rhodes and the Levant began to arrive in Atlanta about 1906, forming a small community where they could speak their dialect of Spanish and perpetuate their distinctive customs. One of the first Sephardic families to arrive was the Amiels, pictured c. 1910.

(b) A member of the Amiel family poses in traditional Sephardic costume, c. 1910.

When I was about three,we moved to 209 Washington Street.My earliest recollections ofresidence there are the days ofthe Leo Frank trial.Our residence was so close to the State Capitol and the Fulton County Courthouse that we could hear all the rumblings ofthe mobs during that trying time.Uncle Herbert Haas,a lawyer,defended Leo Frank.The Haas family and his relatives were under constant police guards at night.I remember vividly the time that Mr.Frank was attacked in prison in Milledgeville,[when] some ofthe inmates cut his throat.The reason I remember is that my uncle Leo Strauss,my uncle Dr.Herbert Rosenberg,and Mr.Julian Boehm drove [to] Milledgeville to attend to Frank,to see that he would get the proper medical attention.Also,I remember my father taking me to the Fulton County [jail].They called it the Tower in those days.We took Frank his Sunday midday meal several times. —JACOB HAAS,1994

I remember that everybody was terribly depressed by [the Frank case].My mother used to buy apples from a peddler.She loved apples,and we used to buy them all the time from these farmers who would come around.I remember one farmer that made some remarks that Frank was guilty.[This] made my mother angry,and she wouldn’t buy apples from him.It was a very gloomy time for Atlanta Jews.

—BESSIE ZABAN JONES,1990

There had always been anti-Semitism,but the Frank case brought everything to the surface.I was eleven years old when that happened,and I can remember my father and Herbert Haas going down to the jail to see Leo Frank,and the whole Jewish community was up in arms about how terrible it was. Everybody felt that he had been framed,but they were more or less powerless to do anything about it.I can remember just certain instances that stand out.Leo Frank was sentenced to die,and [Governor John] Slaton commuted that sentence.A mob formed at the Capitol,and I remember my father with some other Jewish men going down to the pawnshops on Decatur Street and coming home with shotguns, rifles,ammunition.The reason for this? They felt that ifthe mob came out to Washington Street to attack the Jews,they had made up their minds to defend themselves.Fortunately,the mob was angrier at Governor Slaton for commuting Frank’s sentence than they were that particular night at the Jews on Washington Street.

—DAVID MARX JR.,1978

(a) Leo Frank came to Atlanta from Brooklyn, New York, to manage a pencil factory owned by his uncle. He married the daughter of a prominent Atlanta Jewish family (Lucille Selig, pictured with Frank, c. 1909), and became the president of the local B’nai B’rith lodge. Local Jews were shocked when Frank was put on trial for the murder of one of his employees, thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan, in 1913.

(b) On August 17, 1915, after Governor John Slaton commuted his sentence to life in prison, Leo Frank was lynched by a group of men that included prominent Georgia citizens. Almost seventy years later, in 1982, an eyewitness came forward to testify that Frank was innocent.