Mission Moments

50 Years of Rebuilding Lives One Moment at a Time

50 Years of Rebuilding Lives One Moment at a Time

In the heart of healing, hope’s embrace, Shepherd’s mission finds its place. To mend the broken, both strong and weak, With courage and dignity, that they seek.

Through trials of injury, and disease’s test, They guide their way to a future blessed. With independence as their guiding star, They foster dreams that will take them far.

In every struggle, and every fight, They champion inclusion, day and night. They advocate for a world that’s safe and sound, Where every soul finds solid ground.

Rebuilding lives with strength anew, A tapestry of resilience woven through. With hope as the compass, that leads the way, For a brighter tomorrow, come what may.

To give quality care with precision Will always be My Shepherd Mission.

—By Rickie Bauer

Rickie Bauer works in Shepherd Center’s Acquired Brain Injury Rehabilitation Program. He has written poetry since childhood, though this is his first published work.

50 Years of Rebuilding Lives

One Moment at a Time

Copyright © 2025 Shepherd Center

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Shepherd Center.

Shepherd Center

2020 Peachtree Road NW Atlanta, GA 30309-1465 shepherdcenter.org

Editor Jo Tapper

Authors

Gayle C. White

Teresa K. Weaver

Content Manager

Martina Mays

Shepherd Editorial Team

Jessica Calloway

Heather Hercher

Erin Kenney

Kerry Ludlam

Ruth Underwood

BOOK DEVELOPMENT

Bookhouse Group, Inc.

Editorial Director

Rob Levin

Cover and Book Design

Amy Thomann

New Photography

Bita Honarvar

Contributing Photographers

Eley

Erica Aitken

Jenni Girtman

William Twitty

Project Manager

Stacy Moser

Archival Management

Renee Peyton Covington, Georgia www.bookhouse.net

History

2 Chapter One

‘Raw Hope and Brazen Determination’

Meeting Critical Needs Since 1975

The Moments

22 Chapter Two

We Are Shepherd

Supporting Patients and Families

42 Chapter Three

Innovative Spirits

Never Slowing, Never Letting Up

60 Chapter Four

Phenomenal Outcomes

Leading with Customized Care

90 Chapter Five

Part Philosophy, Part Attitude

Infusing Everything with Heart

118 Chapter Six

Generous Support

Believing in the Shepherd Story

Future

144 Chapter Seven

The Road Ahead

Building a Legacy

151 Appendix

Chapter One

Early in the year leading to the 50th anniversary of Shepherd Center, traffic in the main hallway is steady and varied—wheelchairs, crutches, a stretcher.

A man pushing a walker tells his visitor about the friends he has made. Incoming CEO Jamie Shepherd, MBA, MHA, FACHE, strides by, sharing hellos as he goes. His sister, Julie Shepherd, CCM, LMSW, CLCP,

Shepherd Center co-founders James and Alana Shepherd review construction plans with physician Dr. Herndon Murray, who has been with Shepherd Center since it opened in 1975 as its medical director of orthopedics and first head of Shepherd’s Adolescent Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Program.

director of founding family relations and canine therapy lead, draws smiles directed to her companions, facility dogs Lanza and Beta.

This hospital, ranked among the country’s top rehabilitation centers, is populated by people whose plans and goals have been upended by unexpected events. But instead of gloom, the atmosphere is upbeat, even cheerful. Positive messages are everywhere. Elevator doors display life-size photos of people who have reclaimed their lives.

Shepherd Center is built on "raw hope and brazen determination. This is hope when things are dark. It's tough love. It is fierce."

—Sarah Batts

The late James Shepherd, co-founder and longtime board chairman, set the tone years ago with his famous quote: “Shepherd Center is the bridge between ‘I can’t’ and ‘I can.’”

Nonagenarian Alana Shepherd, chairman of the board and 50-year volunteer, is in the middle of it all. She frequently uses a scooter, but this morning she is leaning only slightly on her sparkly cane as she makes her way to her office. Patients and staff greet her almost reverentially. If she is regarded as royalty, there’s a reason: The hospital has been her domain since 1975, when it consisted of six beds in a rented space in a now-defunct Atlanta hospital. To emphasize her significance, the staff insisted one Halloween that she dress up as Queen Elizabeth II, complete with toy Corgi. With trademark humor, Alana consented.

Alana is here today, as she is almost every day, to tend to hospital business and make her rounds buoying up patients and their families. She and her late husband, Harold, late son, James, and founding medical director David Apple, M.D., are responsible for what supporters call the “culture” of Shepherd Center—a commitment to infusing extraordinary care and compassion into every interaction, every treatment, and every outcome, so that patients and families can begin again.

The founders considered every aspect of the ambience. Paintings on the walls of the long hallways give patients and their families something to look at, Alana says. Employees across all disciplines are expected to make eye contact and smile. And what other hospital includes “the appropriate use of humor” as a criterion on staff evaluations?

Each feature of Shepherd Center culture is rooted in the Shepherd family’s own experience, the life change that began when Alana and Harold got what she describes as the “call from hell.” Son James, on a post-college graduation trip to Brazil, had been paralyzed in a bodysurfing accident.

As Alana switches from her cane to her red scooter for her rounds, she is determined to give patients and their families the reassurance her family so desperately needed when James was injured. After all these years, she is still a mother on a mission.

Alana travels from floor to floor, smoothly backing into elevators, maneuvering between pieces of therapy equipment, and, all along the way, greeting staff, patients, and family members by name. She has already met the newest arrival, a woman named Tiffany who came in by ambulance a couple of hours earlier.

Alana’s first visit of the day is Christopher Peixoto, an honor student and soccer player at Cobb County’s Lassiter High School, who was severely injured in a car crash. Alana greets him warmly, as if she has known him since his childhood.

“Hi, Chris,” she says. “Remember yesterday I came to see you? Oh, look at you! Your neck’s even moving better today. I’m so pleased!” Because he can’t yet speak, she asks him to raise his thumb to answer “yes” to her questions. “Did you like your therapist today?” A thumb moves up slightly off the arm of his wheelchair.

“We’ve had a very good morning,” his mother, Flavia Rocha, tells Alana. “It’s amazing how he’s changed. I’m so grateful to be here.

I can feel the peace and true love!” As Alana starts to leave, Flavia wants to take a picture with her.

Riding through a therapy gym, Alana stops to say to a patient, “You got your hair cut. It looks good!”

“How far did you walk?” she asks another.

And to yet another, “How long is your brace on? A neck brace in hot weather is no fun.”

She stops for a longer conversation with a man who is about to undergo electrical stimulation to help him move his hand

muscles. He is Svetolik Djurkovic, M.D., a physician at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Washington, DC, who is originally from Slovenia. She asks whether he misses his home country. “Right now, I am the happiest person in the world that I’m here,” he replies. As his therapist starts the stimulation, Alana jokes that it will make his hair curly. “I always wanted curly hair,” Dr. Djurkovic replies, going along with the gag.

Heading back to her office, Alana passes Shepherd’s Wheelchair Seating & Mobility Clinic, where Sondra Anthony is trying out equipment. Sondra is not a hospital patient, but her arthritis is becoming more debilitating, and she has come to see which wheelchair or scooter will best suit her needs.

Alana Shepherd visits patient Jeffrey Campbell on her daily rounds of greeting patients, staff, and family members.

Alana talks to her about cushions and back support and urges her to put the word out about the clinic, which is open to the public.

“Ma’am, I’m sort of new to this Shepherd Center,” Sondra says. “Are you the founder?”

“One of them,” Alana says.

“And you come in every day?”

“Every day. But I’m the chairman of the board, so I have to know what’s going on.”

Ask friends, family members, and Shepherd Center employees about Alana Smith Shepherd and the reply may be, “She’s a force to be reckoned with,” or, “You don’t say ‘no’ to Alana.”

Her father, an Iowa veterinarian, moved his family to Atlanta when she was 13. She was in high school when she met Atlanta native Harold Shepherd. They married in 1949.

The same year, Harold, the youngest of six children, opened Shepherd Construction Co. with two brothers. They built thousands of miles of highways and streets, and at one time managed 15 asphalt plants across Georgia and the Carolinas. James and his twin sister, Dana, were born to Alana and Harold in 1951; their brother, Tommy, five years later.

The telephone call that changed everything came on Oct. 21, 1973, a Sunday morning. James was traveling the world with friends after graduating from the University of Georgia. That morning, his friends called to tell the Shepherds that a wave had slammed James into the ocean floor while he was body surfing in Brazil. He was in critical condition, with a broken neck and pneumonia.

Harold and Alana rushed to Brazil, where they stayed for five weeks. Once they got James back to Atlanta, he spent three months at

Recruiting Dr. David Apple as co-founder and medical director was the first order of business when the Shepherd family decided to open a hospital.

Piedmont Hospital. They kept him alive, but no institution in the Southeast could provide the medical care and rehabilitative therapy he needed for recovery. And so, still on a ventilator, his parents took him to Craig Hospital in Denver for five months. As a result of the specialized care James received, his hard work, and his family’s support, James walked out with only a leg brace and a crutch.

Family discussions about the need to provide treatment closer to home began with, “Why doesn’t somebody . . . ?” but soon turned to, “How can we . . . ?” The family started to raise money and build a team. Harold’s family and business connections were vital to the effort. “Without those connections and his relationships, Shepherd Center might not be here,” Jamie Shepherd says.

First on the to-do list was finding a medical director. The Shepherds immediately approached David Apple, M.D., a West Virginia native who was raised in Kentucky. While in medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, he had an internship at Grady Hospital in Atlanta. In the region’s foremost trauma center, he saw the results of devastating falls, car crashes, gunshot wounds, pedestrian accidents, and other serious incidents.

“It was a very hands-on learning experience,” he says.

Dr. Apple completed his residency in orthopedic surgery. “You could see a problem, diagnose it, and do something about it,” he says. “I was bewitched by instant gratification.” But he also did a fellowship in rehabilitation orthopedics—a not-so-immediate form of treatment.

In 1973, he was affiliated with Piedmont Hospital but was involved only peripherally with James Shepherd’s care. Nonetheless, he formed a bond with the family. When the Shepherds approached him about joining their effort, a colleague warned him that pursuing the Shepherd Center dream would ruin his career. Dr. Apple was willing to help make that dream a reality.

With a co-founding physician on board, the next order of business was finding a home for the hospital. Dr. Apple proved his worth by connecting the Shepherds with West Paces Ferry Hospital, a forprofit facility on the north side of Atlanta that was planning to add a nursing home. Officials agreed to lease the space to Shepherd instead.

On August 19, 1975—667 days after James’s accident—the first incarnation of Shepherd Center, then called Shepherd Spinal Center, was ready to accept patients. A few days later, Tammy King, MSN, ET, CRRN, CCM, started work there while still in nursing school at Georgia State University.

“You walked in the door and stepped over people on the floor, because they were doing therapy on a mat in the lobby area,” Tammy recalls. “But, even in the earliest days, the culture and the

caring, it was always there. So, when I graduated, I naturally stayed on as a nurse.” She stayed for 47 years, becoming the chief nursing officer in 2008 before retiring in 2023, starting many of Shepherd’s hallmark programs, and earning local and national recognition for nursing leadership.

Tammy King, who came to Shepherd Center as a student nurse and rose to the rank of chief nursing officer, celebrates her retirement in 2023 after 47 years.

Within two weeks of opening, the hospital had a waiting list. A second physician, Herndon Murray, M.D., came on quickly. Like his friend Dr. Apple, he had held a fellowship for spinal care in California at Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center. Although the Shepherd family wanted Dr. Murray on staff, the hospital had no money in the budget to hire him.

“I got over there and Dr. Apple said, ‘We’ll be glad to have you here as the second doctor, but they’re not going to pay you anything,’”

Dr. Murray says. “Sometimes we got paid and sometimes we didn’t, but that was secondary at that point.”

Dr. Murray has interacted with hundreds of patients, many of them adolescents. He treated Woody Morgan after a diving accident in 2008. “The big thing at Shepherd when I was a patient was you don’t say, ‘I can’t,’” Woody says. “It was always, ‘I can’t yet.’”

Dr. Murray was there to make the “can’t yet” become “can.”

In 2023, Woody Morgan, M.D., returned to Shepherd as a physician, one of dozens of former patients and family members of patients so inspired that they wanted careers at Shepherd.

Also in 2023, Dr. Murray, still at Shepherd after 48 years, was recognized by the Georgia Hospital Association as a “physician hero” for tirelessly giving time, talent, and expertise to improve the hospital and the world.

As Shepherd Center got up and running, Harold Shepherd continued to run the family construction company with his brothers, but he began using his vast connections to garner support for the hospital. James, who was president of one of the divisions of the construction company, also served as chairman of the hospital’s board. For Alana, the hospital became a full-time mission.

Both the demand for, and the extent of, Shepherd’s services grew like kudzu. Dr. Apple himself funded the first recreational therapist

in 1979. “I felt that if I could get patients back to being involved in what they enjoyed before, we were going to have better outcomes,” he says. “We went swimming. We went boating. I have a farm up in North Georgia and I had them come up there and spend time outdoors. They could see what was possible.”

By its fourth anniversary, the hospital employed 60 full-time staff members. As Shepherd’s patient population grew, it leased more space. But there was a philosophical gulf between Shepherd and its landlord, Dr. Apple says. “They were interested in profit. We were interested in service,” he says. “That got to be a problem.”

Shepherd Center had enough patients to justify building a hospital, but raising the money was not easy, Dr. Apple says. “Who is going

to donate to a concept? We relied on friends and board members to back the initial fund.”

Finding affordable land in a good location was another challenge. Shepherd officials discovered the ideal solution in a 4.5-acre parking lot next to Piedmont Hospital. By serendipity or providence, the land was owned by real estate developer Scott Hudgens, who had leaned on Harold for advice when his granddaughter was injured not long after James’s accident. Hudgens agreed to sell it at a deeply discounted price.

In October 1980, the founders broke ground at 2020 Peachtree Road; and, on May 13, 1982, a handful of patients boarded a van to move to the new building. One person was transported by ambulance. Greg Delay, the first patient to cross the threshold, popped the cork on a bottle of champagne.

Just seven years after its humble start, Shepherd Center was in a brand-new 93,000-square-foot building with 40 beds and a therapy gym roughly the size of the entire previous space. Soon afterward, an intensive care unit opened, providing highly sought-after care in weaning people from ventilators and starting the rehabilitation process as soon as possible. About the same time, the hospital was designated one of a handful of Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research, then a program through the U.S. Department of Education. The recognition came with a $246,000 grant.

Shepherd Center officially added research to its mission in 1985. Expansion of staff and space also allowed the development of some of the programs that differentiate Shepherd, such as peer support, vocational services, and advocacy.

As the reputation of the hospital grew, so did the realization throughout the country of the role it played in filling a gap in the healthcare spectrum. Less than two years after the move, Shepherd was granted approval to build out the shell of the third

(L-R) Fred Alias, James Shepherd, Bernie Marcus, and architect Henry Howard Smith II break ground in 1988 for an expansion that doubled Shepherd Center’s size.

floor, making space for an additional 40 beds. The expansion made Shepherd Center the country’s largest hospital for the comprehensive treatment of spinal cord injuries in both patient capacity and overall size.

Five years into the new facility, Shepherd reported that it served patients from 20 states and three countries beyond the United States. Another five years and the hospital doubled in size again with the Billi Marcus Building, named by her husband, the late The Home Depot co-founder Bernie Marcus, in honor of her birthday. Funding for the building was one of many generous donations from the Marcus family and foundation.

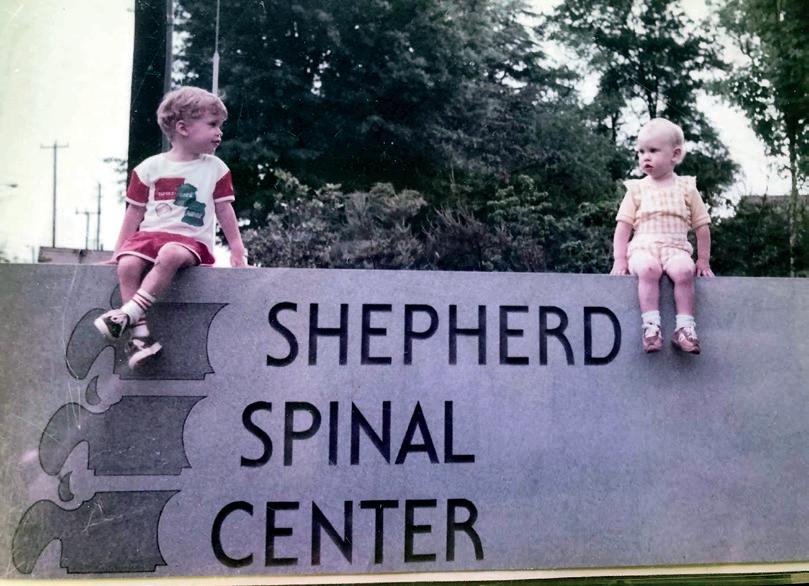

By then, a third generation of Shepherds was on the scene. James’s children, Jamie and Julie, would sometimes come with their father to the hospital. They confess to playing with wheelchairs and even getting caught racing them in the tunnel that connects Shepherd Center to Piedmont Hospital. “There were security cameras,” Jamie says, “and the security guards came and got us.”

Shepherd Center was no longer only serving people with spinal cord injuries. The Andrew C. Carlos Multiple Sclerosis Institute opened in 1991; a third specialty, acquired brain injury, came on board in 1995. Shepherd was already treating brain injuries in patients who had damage to their spinal cords. Now, the hospital would treat those who had only brain injuries, including strokes. The expansion in services led to a name change, and the Shepherd Spinal Center became Shepherd Center: A Catastrophic Care Hospital.

In 2008, Shepherd expanded again with the opening of the Jane Woodruff Pavilion and the expanded Billi Marcus Building, providing space for more beds and outpatient and day programs. The Virginia C. Crawford Nutrition Center added a full cafeteria for the first time.

That same year, Shepherd reinforced its commitment to patients and families when it opened the Irene and George Woodruff

Family Residence Center with 84 wheelchair-accessible apartments and community space, which it offered to families at no cost during their loved one's time at Shepherd. This facility and ongoing support from donors helped address three major concerns for families—ensuring their ability to support their loved one emotionally during the rehabilitation process, learning alongside them so they could assist when they return home, and relieving the financial burden of being far from home.

In a parallel universe, Harold and Alana Shepherd, Dr. Apple, and other members of Shepherd Center’s board and staff were preparing for the 1996 Paralympics. A headline in The Atlanta Constitution

Jane Woodruff and Alana Shepherd celebrate breaking ground for the Jane Woodruff Pavillion in August 2004.

Alana Shepherd hoists the Paralympic torch as it comes to Atlanta in 1996 from the 1992 Barcelona Games. The Atlanta Constitution dubbed her the “godmother of Atlanta’s Paralympic effort.”

summed it up: “Shepherd Center Brings Games to Atlanta.” When the Atlanta Olympic Committee declined to bid on the Paralympic Games, Shepherd Center stepped up. A tiny office in the hospital basement became the headquarters for the Atlanta Paralympic Organizing Committee. At the close of the 1992 Paralympics in Barcelona, Alana Shepherd was one of a two-person escort to bring the Games’ flag to Atlanta.

Some naysayers predicted that the Atlanta contingent would find it “close to impossible” to match Barcelona’s Paralympics. But they didn’t know the Shepherd family. Four years later, the tone was different. The Atlanta 1996 Paralympic Games were the first to attract worldwide corporate sponsorship, and the first to be

televised in the U.S. The Atlanta Constitution called Alana the “godmother of Atlanta’s Paralympic effort.” Her efforts also led the International Olympic Committee to decree that all cities seeking to be the site of future Olympic Games must include plans and proposed financing for the Paralympics, as well as access to the same sites and facilities.

The Games were part of a larger effort by the Shepherd network to make Atlanta more accessible. James led the advocacy efforts that resulted in adding ADA-compliant wheelchair lifts to the MARTA system and making Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport one of the most accessible in the country.

Another Shepherd Center impact beyond its walls was Dr. Apple’s role in founding a national organization to improve care, education, and research in the area of spinal injuries. Besides Shepherd and

Craig in Denver, a handful of other spinal centers are scattered across the country. “We were all doing the same work,” Dr. Apple says. “So, we got together and founded the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA). It’s set up to advance the field.”

With the Atlanta Paralympics behind them, Shepherd leaders opened Shepherd Pathways in 1997. Headquartered in nearby Decatur, Pathways provides outpatient and residential rehabilitation therapy as post-acute treatment for brain injuries. The program added another level to Shepherd’s Acquired Brain Injury Program, which, similar to the spinal program, earned the designation as a Traumatic Brain Injury Model System by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research.

Shepherd Pathways, in Decatur, is an outpatient and day rehabilitation program for people recovering from brain injury.

As a new millennium dawned, Shepherd celebrated its silver anniversary. In 25 years, it had grown into a world-renowned center that continued to expand in size and scope. In 2000, the hospital added the Dean Stroud Spine and Pain Institute to treat people with chronic pain caused by disease or injury.

Five years later, after 30 years of full-time (and more) work at Shepherd, Dr. Apple retired as medical director. He was succeeded by Donald Peck Leslie, M.D., who had been director of the Acquired Brain Injury Program. Dr. Leslie’s first experience with Shepherd was a three-month rotation during a clinical residency while at Emory University School of Medicine. “I came to a revelation then

Shepherd Center has had only three medical directors in its 50 years: (L-R) Dr. Donald Leslie; Dr. David Apple, founding director; and Dr. Michael Yochelson, current chief medical officer.

that this is where I wanted to spend the rest of my practice life,” he says. Having had a residency in internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Leslie brought a new expertise to the hospital.

One reason Shepherd is so successful, Dr. Leslie says, is its team approach to patient care. “I was taught that I was at the top of the pyramid,” he says. “That’s not the case at Shepherd. Yes, the physicians examine the patients and admit them to the hospital, but everybody has an important and integral part of the treatment plan.”

Starting in 2005, the hospital evolved to provide even more services. It established Shepherd Center Foundation to assume

responsibility for major fundraising and development. Within five years, Shepherd had launched Beyond Therapy®, an activity-based program for patients with neurological damage to improve their lifelong health, minimize secondary complications, and get the most out of new neural links to their muscles, and the SHARE Military Initiative for post-9/11 service members and veterans (later expanded to first responders) with traumatic brain injuries and mental health concerns, funded by the Marcus Foundation and supported by an independent group called Shepherd’s Men.

In 2017, SHARE moved to 80 Peachtree Park, a building funded by the Marcus Foundation. The Complex Concussion Clinic

Through virtual reality and studying balance and sway, the Bertec machine helps clients and patients at the SHARE Military Initiative and Complex Concussion Clinic return to their communities to more safely navigate streets, parks, uneven terrain, and more.

joined SHARE there. The Eula C. and Andrew C. Carlos Multiple Sclerosis Rehabilitation and Wellness Program, originally housed with SHARE, later moved to the main campus, which continued to expand. A 2007 addition to the Billi Marcus Building, the Jane Woodruff Pavilion, increased the number of beds from 100 to 120 and added more room for therapy and treatment. Capacity increased again, to 152, in 2010.

In keeping with Shepherd’s focus on the importance of family— both the family’s support for patients and the hospital’s support for families—the Irene and George Woodruff Family Residence Center opened in 2008, with 84 accessible apartments. Family members could stay up to 30 days at no charge if the family and patient live more than 60 miles from the hospital. In 2024, the Arthur M. Blank Family Residences opened with 165 additional units, so that families can stay for the full duration of their loved ones’ rehabilitation.

While accommodating present needs, Shepherd conducted research that would have an impact in the future, both at Shepherd and around the globe. Shepherd established the Virginia C. Crawford Research Institute in 1985. A large gift from its namesake and the Spinal Cord Injury Model System grant were the centerpieces. As the model system continued, annual grants increased from $250,000 to $500,000 per year.

Shepherd’s Center for Assistive Technology provided another avenue for research and innovation. Shepherd Center researchers conduct clinical studies in collaboration with leading experts and institutions from around the world. Whether studying a new device, testing a new medication, or developing new treatment methods, research at Shepherd Center is conducted daily in the clinics and translates directly into improved care and quality of life for Shepherd patients. Shepherd Center’s research falls into five areas: spinal cord injury research, brain injury research, multiple sclerosis research, user experience, accessibility, and usability research, and clinical trials. With Georgia Tech, Shepherd launched

“Superman” actor Christopher Reeve, who was injured in a horseback-riding accident in 1995, chats with then-Shepherd CEO Dr. Gary Ulicny on a trip to Atlanta. The Reeve Foundation has partnered with Shepherd on many educational tools for people living with paralysis.

the Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center, which attracted millions in research funding.

Around 2017, Shepherd Center conducted a different kind of study, based on a White House initiative called Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. Shepherd had always encouraged friendships among patients, according to Pete Anziano, manager of peer support. “Early on, it was all very casual and comfortable,” he says. With new funding through the initiative, Shepherd officials decided to look more closely at the impact of peer relationships on patient outcomes. They found that patients with spinal cord injuries were more attentive and less likely to be re-hospitalized when they were learning from others who had conquered challenges similar to their own.

Based on the findings, Shepherd expanded the peer support model, offering opportunities for patients to learn from other patients via video, and bringing in patients with brain injuries and their caregivers in keeping with Shepherd’s focus on families.

Board member Jim Caswell commissioned artist Ed Dwight’s bronze sculpture of a wheelchair javelin-thrower to mark Shepherd’s entrance. The sculpture honors Terry Lee, a former Shepherd Center patient and a true pioneer in wheelchair athletics. It symbolizes hope, resilience, and the belief that anything is possible.

Deborah Backus, PT, Ph.D., FACRM, vice president of research and innovation, describes Shepherd as “a unicorn” because it is involved in so much research but is not a major teaching hospital. “Our clinical questions drive what we’re doing in research,” she says, “and we try very hard to translate what’s effective into clinical care.”

Shepherd Center leaders are quick to say that they don’t want to keep their advances secret. They share details about any innovation that improves care and outcomes so that other people around the world can benefit.

As Shepherd Center president and CEO from 1994 until he retired in 2017, Gary Ulicny, Ph.D., oversaw the hospital’s expansions and achievements. For his leadership of all the hospital’s accomplishments, in 2014, he was presented the Lifetime Achievement Award in Healthcare by the Atlanta Business Chronicle.

During Dr. Ulicny’s tenure, Shepherd Center was ranked by U.S. News & World Report as one of the best rehabilitation hospitals in the nation 16 times, and it was named one of Atlanta’s best employers by the Atlanta Business Chronicle and Atlanta magazine.

“Gary has been forward-looking throughout his entire career at Shepherd Center,” the late James Shepherd said upon Ulicny’s retirement. “He’s always been very clear that he wanted to leave Shepherd Center in a better place than he found it. He’s been very successful at that.”

New leadership took the helm at Shepherd Center in 2017. Sarah Morrison, PT, MBA, MHA, became president and CEO. And with the retirement of Dr. Leslie, Michael Yochelson, M.D., MBA, was named chief medical officer.

Sarah joined the staff as a therapist in 1984 and served in various roles before being tapped for the CEO role. Dr. Yochelson came to Shepherd from Washington, DC, where he was vice president

of medical affairs and chief medical officer at MedStar National Rehabilitation Network. He is board-certified as both a neurologist and a physiatrist. Entering Shepherd for the first time, he says, he knew immediately that he wanted to work there.

“The culture is palpable,” he says. “You can feel it from the minute you come in the door. You can see it in the patients’ faces and in the attitude of the staff.” As a U.S. Navy veteran, he was especially drawn to the SHARE Military Initiative, and, even as the hospital’s medical director, he is the primary physician for one of the SHARE teams.

All was going well as Sarah and Dr. Yochelson started to put their own stamp on the hospital. Support and honors flowed in. A donor, WIlton Looney, funded a CT scanner, saving untold hours of staff time that had been required to move patients next door to Piedmont for scans. Shepherd received its largest research grant to date—$5.7 million over four years—for the study of exercise in people with multiple sclerosis. And the hospital acquired land to expand family housing.

But there were huge losses, too. Harold Shepherd died on Dec. 10, 2018; James followed a year later, on Dec. 21, 2019. Harold had continued to participate in the hospital as an active board member, fundraiser, adviser, and member of the investment committee. In his later years, as he gradually drew away from the construction company, he spent more time at the hospital.

“He wanted to be here, talk to people, to be around the hospital and watch it as it grows,” his granddaughter, Julie, says. “He often talked about how proud he was of Shepherd Center. His construction career was rewarding in one way, but he was even prouder of what they did at the hospital and the lives they changed.”

Just before Harold’s 90th birthday in 2018, the Georgia General Assembly unanimously approved a resolution to name a section of Peachtree Road in Buckhead in his honor. The portion of Peachtree Road from Peachtree Battle Avenue to Brookwood Station—the

Harold Shepherd celebrates the renaming of the portion of Peachtree Road from Peachtree Battle Avenue to Brookwood Station—the very same slice of road that is home to Shepherd Center—to J. Harold Shepherd Parkway.

slice of road that is home to Shepherd Center—was designated J. Harold Shepherd Parkway.

Like his parents, James Shepherd “was a forward thinker—always with the staff, patients, and their families in mind,” says Dr. Apple, medical director emeritus. “James had a sense of humor, which endeared him to staff and friends. He was the epitome of one who turned tragedy into triumph.”

Along with Sarah Morrison, he was instrumental in launching Vision 2025, a comprehensive blueprint for the future that included increased bed capacity, outpatient clinics, and family housing, as well as capability for more research and innovation, and creation of the Innovation Institute and the Institute for Higher Learning, all while keeping Shepherd Center’s culture. That vision is coming to

fruition, piece by piece, making Shepherd even more effective and extending its reach to more people.

“James was committed to doing everything in his power to rebuild the lives of the people in our care, both inside Shepherd Center and out in the world,” Sarah Morrison says. “There wasn’t a day that went by that you could not feel and see his influence.”

One of the awards that James, a fervent Bulldog fan, valued most was the honorary doctorate he received along with Alana and Harold presented by the University of Georgia in 2011, when he also gave the commencement address. “The story of our lives is not what happens to us,” he told the graduating class. “It’s what we do about it.”

Upon James’s death, Alana succeeded him as chairman of the board.

As Shepherd marked 45 years in 2020, Sarah Morrison and Dr. Yochelson were faced with a hospital full of vulnerable patients, many of whom needed respiratory support, and a raging COVID epidemic. “Getting us through COVID was definitely one of the things I’m proudest of,” Sarah says. “That was unprecedented, so we had to kind of figure it out as we went. Whenever anybody asked me how I was sleeping, I would say, ‘Like a baby. I wake up every two hours and cry.’”

The hospital closed most outpatient services in the early days of COVID, losing the income they generated. Then, on April 3, 2020, the leadership team decided to shut hospital doors to visitors.

Keeping family members out “goes against our culture,” Dr. Yochelson says. “Family members and patients were not pleased, but we knew COVID was deadly, and we couldn’t take the risk with our patients.”

He especially remembers the parents of a 19-year-old in the intensive care unit. “I had a very difficult discussion with them,” he says.

(L-R) Dr. David Apple, Alana Shepherd, Arthur Blank, and Sarah Morrison hold shovels ready to launch Pursuing Possible, a $400 million campaign to expand programs and facilities, including construction of the Arthur M. Blank Family Residences.

Three years later, the patient’s mother thanked him “for keeping our son safe.” In the early days of the severest form of the virus, Shepherd did not have a single case of COVID, he says.

After about three months, restrictions started to ease. Family members could visit but couldn’t leave the patients’ rooms. “They were essentially locked in,” Sarah says.

When it was all over, she had been able to stick to a promise she made to the staff that there would be no layoffs, no furloughs, and no change in salaries or benefits.

One positive offshoot of coping with COVID was the expedited launch of a system of telehealth, telepsychology, and telerehabilitation. Shepherd was recognized by the Georgia Hospital Association in 2021 with an award for use of telehealth and received a grant from the Wounded Warrior Project to study telehealth and hybrid programming for SHARE clients.

Heading from 45 to 50 years old, Shepherd Center continued to live its values of family, innovation, expertise, heart, and support. Pursuing Possible: The Campaign for Shepherd Center, the most ambitious fundraising effort in the hospital’s history, would support the plans outlined in Vision 2025 to expand beds, outpatient clinics, and services not covered by insurance, add more family housing and “smart room” technology, and create the Innovation Institute and the Institute for Higher Learning.

The expansion is part of a continuum that began around the Shepherd family kitchen table half a century ago. Just as James’s injury became a catalyst for a world-class rehabilitation center, bumps in the road along the way have turned into opportunities, always with the patients and their families in mind.

“When you think about this type of care, there’s nothing that compares to it,” says Sarah Batts, senior vice president of advancement and executive director of Shepherd Foundation. “It’s an expensive model of care, but everything from integrating mental health to recreational therapy, to housing, to outstanding food, to free parking—all those details add up.”

Shepherd Center is built on “raw hope and brazen determination,” she says. “I say ‘raw’ hope because when people think of hope, it’s usually the greeting-card kind of hope. But this is hope when things are dark. It’s tough love. It is fierce.”

When Sarah Morrison retired in 2024, Jamie Shepherd was named CEO. He had joined the hospital board in 2012 and started work at Shepherd in 2015 after 12 years in the construction business. “I thought my maximum involvement would be boards and events and that type of thing,” he says. But when Harold learned that Jamie was leaving construction, he had his own plans for his grandson. Within a year, Jamie was at the hospital.

Julie, whose background is in social work, came on staff in 2010, starting as a case manager after working elsewhere, most recently for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Part of that job was visiting the three multiple sclerosis centers in Georgia, including Shepherd. “Eventually, it just felt like it was time to try to come here,” she says.

CEO Jamie Shepherd and his predecessor, Sarah Morrison, look to a bright future as they implement the Vision 2025 strategic plan, including new buildings, beds, and programs.

Making her rounds, Alana Shepherd, chairman of the board (and Halloween queen) witnesses the work of half a century of grit, faith, and passion. She has lost her husband and her three children, including James, but has lived to see the third generation of her family helping to run the hospital she loves.

Both grandchildren are well-suited to their roles, she says. Julie “is so good with patients and families, and she knows so many people.”

As for Jamie, with Shepherd Center’s perpetual expansion, his experience in construction, along with master’s degrees in business and public health, makes him the ideal leader for the hospital, even if he weren’t part of the family, Alana says. “Anybody that we would bring in from around the country would not have the passion that he has because of the experiences he had growing up with his dad. He’s a perfect choice.”

By watching his father channel his resolve to overcome a spinal cord injury into his life’s work on behalf of others, Jamie developed his own determination to continue the tradition of the Shepherd Center and all it means.

In her 15 years at Shepherd Center, she has found her own way to serve the family legacy. “I think the biggest advantage I have in life is that I grew up here at Shepherd Center,” she says. “I always knew that people with disabilities are just people. You have to treat everybody the way you would want your family to be taken care of. If I can help every staff member understand that, I’ll be super successful.”

Julie’s position as head of founding family relations is new. “We’re lucky to have a lot of the same donors that we had when we were founded,” she says. “My role is reconnecting with the newer generations of those families, those companies.”

“I’m a numbers guy by education,” he says, “but this place is not about numbers. This place is about improving and healing people’s lives. And so that comes first. We’ll go the extra mile to make a difference in the patients’ lives. And we’ll worry about the money on the back end.”

Since the first conversations among Alana, Harold, and James, the Shepherd “family” has expanded to include employees—from behind-the-scenes staff to physicians, nurses, and therapists, former and current patients, their families and friends, donors, partners, and researchers.

Fifty years in, Alana looks to the future with optimism. “The culture of the family goes on,” she says.