Amsterdam Academy of Architecture Annual Review

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture Annual Review

TAKING STOCK

On 25 and 26 April, the fourth Deans’ Summit of the European Association for Architectural Education (EAAE) took place at the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture under the title ‘Transformation: New Directions in Education’. More than 70 deans and directors from architecture schools all over Europe had registered to meet and discuss an important and urgent question: How do we deal with our institutional responsibility towards the climate crisis? Addressing the environmental, social and political quandaries of this century will require changing fundamental theoretical and practical assumptions about what architectural design is and does. The climate crisis demands a radical change in the way we build and think about buildings. But how?

We are in a rapidly evolving situation of worsening scientific indicators and sweeping and contradictory policy proposals from different points on the political spectrum. What should designers do and how can they do it? How must the practice and education of architecture, urbanism and landscape architecture change?

In 2021, at the first Deans’ Summit in Oslo, the deans and directors wrote the ‘EAAE Pledge for Climate Crisis and Sustainable Future’, which implicitly referenced the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). At the fourth Deans’ Summit, we came together to reflect on what had changed in the schools since we wrote that pledge. After all, we’d made a promise to ourselves, to each other, to the students and to the faculty to promote a livable and just future on the planet. Here is what the Oslo Pledge says: ‘We recognize the climate crisis as the most significant issue within our lifetimes, and we recognize our institutional responsibility to promote conditions that support quality of life and dignity for future generations and our planet. We promise to incorporate the current concerns into common values and to choose the right measures in aligning our curricula and research to confront these wicked problems with the urgency, leadership and prominence they demand.’

That’s what we wrote then. It’s currently 2024. Where are we now?

Things are getting better in a number of areas, thanks to people who have been at the forefront of the climate and environmental movement. Some scientists, activists, journalists, writers and lawyers have made a big difference. But we can also make a difference in schools with the education we provide. As educators, we have a responsibility. Education is a work in progress, especially in this time of transformation: the world around us is changing constantly and at a rapid pace. The challenges of climate change, resource scarcity, energy transition, social inequality, biodiversity loss and more are complex and urgent. They all have spatial implications to which answers must be sought now in order to maintain the perspective of a sustainable and inclusive future.

According to the latest IPCC reports, rapid and profound changes in all parts of society are needed to limit global warming, as agreed in Paris. Dutch author Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer concluded his Huizinga Lecture in December 2023 with these words: ‘We cannot reverse disastrous global warming with a few stopgap measures without challenging the system of unbridled growth per se, but without the model of infinite growth, the bottom falls out from under capitalism. It is, as Albert Einstein puts it, impossible to solve problems within the system that created them. A paradigm shift is needed. But for that to happen, we must start boldly imagining a totally new society that can replace the stalled current system. What is needed for this is creativity. Only creativity can save the world.’ Change requires a certain chaos; we’re all looking for new directions and frameworks in education. Are we training students for the practice as it is now, or are we training them for a practice as it should be, given all the big issues? Can we imagine what that practice can and should be like in the future? How important is it to invite other disciplines into education, other forms of knowledge, in relation to the challenges of the climate crisis?

During the fourth Deans’ Summit in Amsterdam, deans and directors reflected on the pledge and discussed how curricula have changed and need to change further. What do our times demand and how can we help the new generation of designers to work in a regenerative way? And what can we learn from the students? In times of change, we have to rely on each other. Students learn from teachers and teachers learn from students. We all need courage and imagination: ‘The creativity and imagination to design a sustainable future and the courage to take a step forward,’ as Floris Alkemade, former chief architect of the Netherlands, concluded his keynote address at the start of the fourth Deans’ Summit.

This Annual Review shows that students and faculty at the academy have plenty of courage and imagination when it comes to addressing climate challenges. Many design and research courses offer climate-related assignments, and the results are a testament to the creativity and constructive approach that are needed. One thing is clear: spatial designers can’t do this alone. They need the expertise of other professions.

Let’s take a step forward together! ←

Text MADELEINE MAASKANT, DIRECTOR OF THE AMSTERDAM ACADEMY OF ARCHITECTURE

THE BEAUTY OF A BROKEN WORLD

In April, the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture hosted the fourth Deans’ Summit of the European Association for Architectural Education. The opening lecture was delivered by Floris Alkemade, chief government architect of the Netherlands from 2015 to 2021 and professor at the research group Tabula Scripta at the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture from 2014 to 2019. This is an edited version of his lecture.

Text FLORIS ALKEMADE

Thanks for the invitation to give a lecture about what I believe to be the most important task for current and future generations of designers. The main point of my lecture is that spatial designers are specialists in change, and so should be the schools that educate them. Not ‘change’ for the sake of it, but the kind of change that redefines our responsibilities.

If we want to take stock of the situation we’re currently in, all we need to do is go to bol.com, a big web shop in the Netherlands. This web shop currently offers its customers a choice of over 400 models of hand blenders. Please let that sink in for a moment. In total, it has 22 million products for sale. Amazon, which also operates on the Dutch market, offers a total of 600 million products. These staggering numbers are a reflection of humanity today. With all our knowledge and scientific, technical and political ingenuity, this is what we’ve achieved. Every possible product that anyone might desire can be ordered, and – to those who can afford it – delivered the next day. Its Chinese counterpart, Alibaba, operates on an even larger scale. On one of its busiest days last year, it sold 583,000 products – more than half a million products – every second. That’s the magnitude at which we’re using the planet’s resources. All of this production and logistics are used to satisfy our desire to consume. At the same time, humanity faces huge and disruptive challenges: climate change, biodiversity loss, economic crises, wars, migration, infectious diseases and the delusions of conspiracy theorists. Each of these seven challenges has the potential to change everything we know, everything we have built and everything we take for granted. And they’re all interconnected. Many of these challenges have spatial implications. To stick with the example of excess shopping: since the arrival of web shops, 2.5 per cent of the total built-up area in the Netherlands has been taken up by logistics warehouses. That’s where the hand blenders wait for their consumers. Paradoxically, all this variety of choice leads to more blandness. Cars, for instance, increasingly look alike. The same goes for architecture and public space around the world. The logic of the market economy seems to lead to a loss of creativity, as if all questions have only one answer, and that is ‘more’. Apart from the problems we create with this excess, we also create boredom. That’s something that we should take seriously as designers. And that, of course, is what culture is all about.

The shift from production to consumption has led to vast cultural changes over the last few decades. Today, we are experiencing a shift from the real world to the virtual world. On average, people are awake 1,000 minutes a day. Currently, an average American adult has 640 minutes of screen time per day, including time spent watching tv and interacting with computers, laptops, tablets and smartphones. Elsewhere in the world, that number is lower, but not by much. Worldwide, about half of the 1,000 minutes that people are awake are spent looking at a screen. In some ways, this is great. We have a wealth of information and social interaction at our fingertips. But the digital world is not the real world.

A lack of social interaction in the real world can lead to serious problems. Writers and filmmakers often have a very keen eye for what is happening in society. One of them is Michel Houellebecq, one of the writers I admire and I fear, because his view of the world is really dystopian. But he has a clear point. He says that the law of increasing entropy – an ever growing state of disorder – is not only a law of physics, it’s also a social law. That’s what we’re seeing today.

Currently, 40 per cent of all households in the Netherlands are single-person households. In cities like Amsterdam or Rotterdam, it’s half of all households. That means fragmentation and atomization. At the same time, the population is getting older. This aging will increase over time. Many problems are surmountable: people face and solve problems all the time. But when they are not, some people choose to close their eyes to the consequences. It’s not that hard. After all, we’ve got all this prosperity and things look great on our doorstep. People who choose to keep their eyes open will see that on a global scale things look frightening. The Netherlands is home to shipyards that build the most luxurious private yachts in the world. The opulence is unimaginable. When these ships are transported from the shipyard to the sea, there’s always a big uproar: they barely fit in the canals, bridges have to be dismantled to let them pass, and they tower over the buildings on the quays. These private yachts offer a clear picture of the utter inequality of this world. As they pass by, you see and feel the injustice.

Cambridge University has studied the number of days per year that – at any given place in the world – the average daily temperature will exceed 25°C in the coming years.1 In many places, this will be the case on over 200 out of 365 days a year. In some places that are even worse off, this will be the case on every day of the year. This means that large parts of the world will become uninhabitable due to climate change. Soon, people will no longer be able to live there. Currently, about 2.3 billion people live in these places. They are the poorest people in the poorest countries, paying the price for the wealth accumulated in the richest parts of the world. Of course, this suffering is less visible than the private yachts we see passing by. How can we, as architects and teachers, take responsibility for questions that simply seem to be too big to answer? →

Heracles fighting the Lernaean Hydra, the ancient serpent-like infernal water beast. The British Museum, print made by Michel Dorigny after an engraving by Simon Vouet, 1651.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) employs some of the best scientists in the world. They don’t just monitor what’s happening to the climate, they also advise on what needs to be done to deal with the resulting problems. This is what is called ‘transformative change’. This is one level up from structural change. Transformative change is fundamental change that addresses social, technological and economic issues simultaneously. It’s nothing short of a revolution. In this case, it’s not the people who are demanding a revolution, but top-notch scientists. That’s good news: it’s a recipe against boredom. All that is needed is to take the right steps. But there’s a complication: we need politicians for that. It’s not a given that the current set of world leaders will take the right steps. It’s a real problem. There’s so much at stake and so much to organize, but somehow many politicians seem to be preoccupied with other things.

The New York Times fact-checkers reviewed a speech that then-president Donald Trump gave at a rally in Wisconsin in 2020, and they found that he made 131 false or inaccurate statements over the course of 90 minutes.2 How is it possible that a president of the United States can get away with this? This is, of course, a byproduct of the virtual world. He’s not the only politician who does this. These are the people who are in power and therefore ought to take responsibility for bringing about the transformative change that’s needed.

Trump is all about money, but some of the most aggressive entrepreneurs show that making money and transformative change are not necessarily incompatible. Larry Fink is the CEO of the biggest investment company of the world, BlackRock. This guy is here on this planet to make money, and he does it really well. In 2020, he shocked the financial world when he wrote his annual letter to all the CEOs of the companies he invests in.3 Titled ‘A Fundamental Reshaping of Finance’, the gist of his letter was: ‘As of now, sustainability is the new standard.’ The financial sector was flabbergasted. Asked by a journalist why he had done this, he replied: ‘Don’t worry, this is not idealism. I’m an investor. I need to know what the value of my companies is and if they have any financial liabilities, such as a possible tax for their CO2-emissions. In other words: it’s business.’ He’s only there to make more money, and that means he wants to protect his investments. The world is shaped by two major forces: politics and the market. Despite their power, both tend towards greenwashing. They’re not about transformative change; they add a bit of green to what they’re already doing. I have nothing against green façades, but they’re just that: the outer layer. They don’t change anything that’s behind them. But there’s also a third force: the force of imagination. That is where education, architecture, urban design and landscape architecture come into play. Both science and design are creative domains that have the capacity to bring about transformative change. Of course, there has always been change, and in many ways change is transformative by default. There are many examples. I will give one. People in the Netherlands – which in this case is probably more or less representative of Europe as a whole – on average spent 70 per cent of their income on food in 1850, and their average life expectancy in that year was 37 years. In 1950, they spent 39 per cent of their income on food, but their average life expectancy had risen to 67. In 2020, the Dutch spent just 11 per cent of their income on food. By that year, their average life expectancy had risen to 81. That is transformative change. What this example also shows is that transformative change is not always good by default. The way we produce and consume food today contributes to the loss of biodiversity in many ways, including the huge amounts of fertilizer that are used and the long distances over which food is transported. The huge feed silos that dot the landscape have changed the countryside: there’s no longer a direct link between the animals and the surrounding area because the silos contain soy from Latin America.

Another example of transformative change is the disappearance of religion from society. I live in a village in the south of the Netherlands. In this village and its surroundings, many churches are no longer in use. Culture that took millennia to build up, defining every aspect of our society, just evaporated.

A transformative change that could occur in the coming centuries is the consequence of rising sea levels. If sea level rise is within the range currently predicted, two-thirds of the Netherlands could be under water by 2300. This is particularly poignant when you realize that 80 per cent of the world’s metropolitan regions are located in coastal areas. The fundamental questions raised by this fact are all about transformative change. Perhaps one of the biggest changes mankind will have to face has to do with birth control. The introduction of the birth control pill in 1962 led to declining birth rates in societies that adopted the pill. As the standard of living rose, the birth rate fell. A New York Times →

Many churches in the Netherlands are no longer in use. Culture that took millennia to build up, defining every aspect of our society, just evaporated. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, painting by Bartholomeus Johannes van Hove, 1844.

article in 2023 pointed out that most people now live in places where the fertility rate is below the replacement level.4 Europe crossed the threshold in 1975, China in the early 1990s and Brazil in the early 2000s. India crossed below the replacement fertility in its most recent population census. Only African countries will continue to grow in the coming decades. In 2022, the total world population was about 8 billion people.

The world population is expected to peak around 2085 at about 10 billion people . I have always imagined or assumed that the world population would plateau after that, but current demographic insights show that in the twenty-second or twenty-third century, the population decline will be just as steep as its current rise.

Of course, the exact numbers may turn out to be different. The aforementioned New York Times article puts the world’s population peak at around 2085, the United Nations expects it will be in 2067, and the Club of Rome predicted it will happen in 2046. But that’s not the point. The point is that population decline will be one of the major stories of the coming century. Some people might be tempted to say: ‘Great, this decline will solve all of our housing and environmental problems at once, all by itself.’ But that’s not how it works. It’s not the number of people, it’s their wealth that counts when you look at the way they produce goods. And also, of course, the fact that by that time maybe half the world will be uninhabitable because of climate change. The problem is that almost all societies are based on organizing growth.

Organizing decline is a completely different ball game and requires an entirely new way of thinking, which we still have to learn. Decline has many side effects that growth doesn’t. Just to give an example: South Korea has a replication rate of 0.7, which means that in a few generations only a fraction of the population will be left. What does that mean in military terms, for example, given that it borders North Korea? Transformative change changes the rules of the game.

A very famous example is the Kodak photography company. Before smartphones were invented, if you wanted to take a picture, you needed a camera, and Kodak made the film for those cameras. Kodak employed 145,000 people. Kodak actually invented the digital camera in 1975, but decided not to produce it for a fear of losing its main business model. Then another company introduced the first digital camera on the market, and in 2012 Kodak went bankrupt. That same year, Instagram was sold to Facebook for $1 billion. At the time it employed only 13 people. This is the face of transformative change. If you see change coming, you’d better step forward. Otherwise, you’ll be gone. And that is true of many aspects of the change we now face. The answers to these questions are not easy to give because the rules of the game are changing, too. Normally, when most people want to get from A to B, they tend to do so in a straight line, if possible. But other cultures go about this very differently.

The Japanese art of kintsukuroi implies the understanding that broken pottery that has been repaired with attention and patience is more beautiful for having been broken. Photo by Steenaire, 2019.

The Hadza are some of the last hunter-gatherers in the world living more or less authentically. They live in northern Tanzania. In a scientific experiment published in 2013 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers recruited 44 members of the Hadza tribe to wear GPS units and examined their bouts of foraging.5 The question was how these highly skilled foragers would search the terrain for food. The research project showed that the Hadza perform Lévy walks when foraging for food. A Lévy walk is a random pattern in which mostly short one-directional walks are combined with rarer, longer one-directional walks. This is a pattern often found in nature. Whales follow this pattern when they swim in the oceans. Birds follow it when they fly in the skies. Even Internet search engines use it. The essence of the pattern is that when you don’t know the terrain, you take a random direction, but as soon as you change your position, you have a new insight and you change your direction. That’s the art of adaptation. Going straight from A to B is a very valid strategy, but only if you know where B is. If you don’t know where B is, going straight can be a deadly strategy. That’s what we can learn from the Hadza and from nature in general.

In 1985, the artist Jenny Holzer projected a beautiful quote on a large screen on Times Square. It read: ‘Protect me from what I want.’ This is exactly what designers should do in the coming decades. We are trained to give people what they ask for, what they want, but we’ll need to do the opposite. This requires a different way of thinking.

During my time at OMA, where I worked for 18 years and became one of the partners, we founded AMO. It served as OMA’s think tank and was about liberating architectural thinking from architectural practice. AMO conducted research on organization, identity and culture. This didn’t mean that we thought that the way we designed buildings had lost its validity. Of course, architecture, urban design and landscape architecture are about aesthetics, detailing, the use of materials. These topics are all very important to the profession of architecture. But it’s only half of the story. The other half touches all these other domains. In many ways, especially when you look at the current global threats that we face, we are the Hadza. We’re well-trained and have a lot of knowledge that we can apply when confronted with a new domain. This domain may seem scary and full of dangers that are hard to grasp. But that’s what education is about. Education is not about fear but about creativity, change and taking responsibility. Those are the qualities that we have to train our students in.

Change can be very gradual and not always immediately visible from the outside. You can see this by looking at how the iPhone design has changed over time. From the outside, the changes seem very limited, but appearances can be deceiving. The current iPhone is already worlds apart from its first iteration in 2007. What we see is a byproduct of other, more important mechanisms at play. Studying those underlying mechanisms makes the profession much more profound, logical and intense, and much more difficult and creative. Collaborating with other professions is not only fun, it’s very necessary if we’re going to change those underlying mechanisms.

As chief government architect, I organized competitions for designers in which collaborating with other professions was an important condition. One of these competitions was called Bread & Games and one of the winning entries was titled Productief Peppelland. Half of this team were architects and the other half were farmers. That’s not an obvious combination these days, but their collaboration was very fruitful. Their topic was farmland, and the area they were working in is very suitable for poplars, trees commonly used in the paper industry. But now poplars can also be used to make cross-laminated timber. This gives farmers the opportunity to create new business models that improve, rather than degrade, soil conditions. This is an example of taking responsibility and redefining it. I also asked teams to work on post-war neighbourhoods by densifying them with about 25 per cent more dwellings while at the same time increasing the green areas. Those teams proved that this is perfectly possible using biobased materials, prefabrication and light-weight structures on top of existing buildings. Born out of the necessity to become more sustainable, an exciting, much more agile urbanity is possible. If you were to draw a graph of sustainability over time, this century should first show a gradual dip and then a steeper rise. We’re now just past the lowest point and that’s the most beautiful point in the graph. We still feel the downward gravity of the dip, but we are defining our way up. This has to be the story when future generations look back at our generation.

That’s what the book Rewriting Architecture is about. With this book, we concluded the research group Tabula Scripta. It’s about sustainability as a creative process. We worked on it with a lot of students and conducted many interviews with specialists from a wide range of backgrounds. The recurring question was: ‘How can we change the role of the contemporary architect in the current power dynamics?’ We defined ten actions plus one. One of those actions is ‘eliminate’: designing not by adding, but by removing things. It’s a beautiful domain of thinking. Another is titled →

‘continue’: rewrite on that which is already written, in the same way that James Joyce corrected his own longhand manuscripts. The eleventh action is ‘abstain’: do nothing. Sometimes as an architect, you have to say ‘no’. This is something we still need to learn. Architecture should not only be a product of imagination, but also of courage. In the past, many generations thought that the trials and tribulations they had to endure were more extensive than those of their predecessors. Today there’s the same tendency. In fact, humans have faced life-threatening challenges many times before and risen to the occasion. All that’s needed is a future-oriented attitude. As author Saul Bellow wrote to literature critic Lionel Trilling in 1952: ‘We may not be strong enough to live in the present. But to be disappointed in it! To identify oneself with a better past! No, no!’ We need to long for the future, not the past. Longing for the future is about storytelling, imagination and education. That’s what we can learn from history. When you face difficult circumstances, don’t be Kodak and step back. Be Heracles and step forward, as he did when he encountered a many-headed monster at the lake of Lerna. That’s courage. Courage is also a design tool: not stepping back when you meet opposition or other difficulties. Go for it. It won’t make life easier, but it will definitely make it more relevant and fun.

In her book La Vieillesse (The Coming of Age) from 1970, Simone de Beauvoir wrote: ‘By the way in which a society behaves towards the elderly, it unequivocally reveals the truth – often carefully concealed – of its principles and its ends.’ That still holds true in our time and age. We have a population with a lot of elderly people who are very vulnerable. We have an influx of immigrants who also need help. The way we deal with people who need help shows who we are.

Some people have placed all their bets on technical advance, which may solve many of the problems we’re facing, from elderly care to sea level rise. It’s amazing what technology can do and it’s full of promise. At the same time, it can also be a trap. These days, we can make anything. Self-driving cars, online healthcare, automated check-in: technology has the tendency to eliminate both human labour and social relations. With all the knowledge and possibilities we have, is this the best we can do? Where is the fantasy? Where is the imagination?

In an interview in Dutch national newspaper NRC Wim Sinke, a scientist who worked his entire career on the development of solar panels, said about solar-cell efficiency: ‘Current silicon panels are heading towards 25 per cent efficiency. That approaches the physical maximum achievable with a single material. A breakthrough will come from making tandems, two layers of solar cells of different materials on top of each other. With stacks of more layers, 40 per cent efficiency will eventually be possible.’6 He also said: ‘A lot of things have worked out that I didn’t think could.’ In other words: what counts is knowing what you want. What you consider possible is of secondary importance. I will end with the Japanese art of kintsukuroi, which means ‘to repair with gold’. It implies the understanding that broken pottery that has been repaired with attention and patience is more beautiful for having been broken. The fact that it was broken is part of its identity, aesthetics, beauty and essence. This is a metaphor for where we are at this moment in time. Things that we took for granted have broken. They’re no longer sustainable. The question is: How can we repair them? Taking kintsukuroi to heart, we should make the fact that they’re broken part of our identity and our beauty. History teaches us that it’s never the crises that determine who we are. It’s the way we react to those crises. We’re in control. Thank you. ←

1 Cambridge Global Risk Index, ‘New Approaches to Help Businesses Tackle Climate Change’, Cambridge University, 26 February 2020. https://www. cam.ac.uk/research/news/new-approaches-to-helpbusinesses-tackle-climate-change.

2. Linda Qiu and Michael D. Shear, ‘Rallies are the Core of Trump’s Campaign, and a Font of Lies and Misinformation’, New York Times, 26 October 2020. https://www. nytimes.com/2020/10/26/us/politics/trump-rallies.html.

3 Larry Fink, ‘A Fundamental Reshaping of Finance’, 2020. https://www.blackrock.com/americas-offshore/en/larry-fink-ceo-letter.

4 Dean Spears, ‘The World’s Population May Peak in Your Lifetime. What Happens Next?’, New York Times, 18 September 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/ interactive/2023/09/18/opinion/human-population-global-growth.html.

5 David A. Raichlen et al., ‘Evidence of Lévy Walk Foraging Patterns in Human Hunter–Hatherers’, PNAS 111 (2013) 2, pp. 728-733. https://doi.org/10.1073/ pnas.1318616111.

6 Laura Wismans, ‘Zonne-energie kan een hoeksteen zijn’, NRC, 27 June 2022.

ARCHIPRIX NOMINATIONS

The Amsterdam Academy of Architecture nominated two Architecture projects and two Landscape Architecture projects for the annual Archiprix Netherlands competition.

At the close of the Graduation Show 2023, director Madeleine Maaskant announced the four nominations for the Archiprix Netherlands. The nominated graduation projects were: Average Place by Maria Khozina (architecture), The Eyes are the Windows to the Soul by Gavin Fraser (architecture), Garden and Gardener of the Peelrandbreuk by Roy Damen (landscape architecture) and Burnt by Jacob Heydorn Gorski (landscape architecture). Additionally, both the Engagement Award and the Audience Award were awarded to Shelter by Alice Dicker Quintino (architecture) and the Research Award was awarded to Water Driven by Rex van Beijsterveldt (landscape architecture).

Archiprix Netherlands 2024 had four first prizes. Two of those first prizes went to graduates of the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture: Jacob Heydorn Gorski and Gavin Fraser.

BURNT –A TALE OF THREE FIRES

Community-driven maintenance creates a more wildfire-resilient landscape.

Burnt: A Tale of Three Fires investigates how embracing wildfire can restore resiliency and create new cultural connections between a landscape and its inhabitants. It draws from the designer’s childhood fascination with landscape and fire and takes inspiration from a Dutch attitude towards another natural threat: water. The project focuses on the mountain town of Red Feather Lakes in the American state of Colorado to question dominant narratives of wildfire and offer a new path forward. The project takes inspiration from local ecology to develop three new strategies for wildfire: defensive, resilient and resistant. Each strategy kickstarts a process based on community involvement and site-derived materials to let fire tell a different story about the landscape. In the first site, fire breaks shape how a forest burns, allowing recreants to experience the ‘terrible sublime’ of the postfire landscape. In the second site, a stream is transformed into a naturally managed defensive buffer that mitigates the effects of post-fire flooding. In the last site, a community comes together to restore a severely burnt forest. Together, these three strategies reshape and restore the ecosystem and use fire to create new landscape experiences and community exchange. While site-specific, the interventions here offer a model for other landscapes in the American West for a possible future with fire. To quote Dante, we have found ourselves ‘within a forest dark, for the straightforward pathway had been lost’. This project offers a new path ahead, one lit by the light of fire.

Cultural burning is a chance for exchange and education.

Model.

The burnt forest becomes a patchwork landscape.

Giving room back to wildfire.

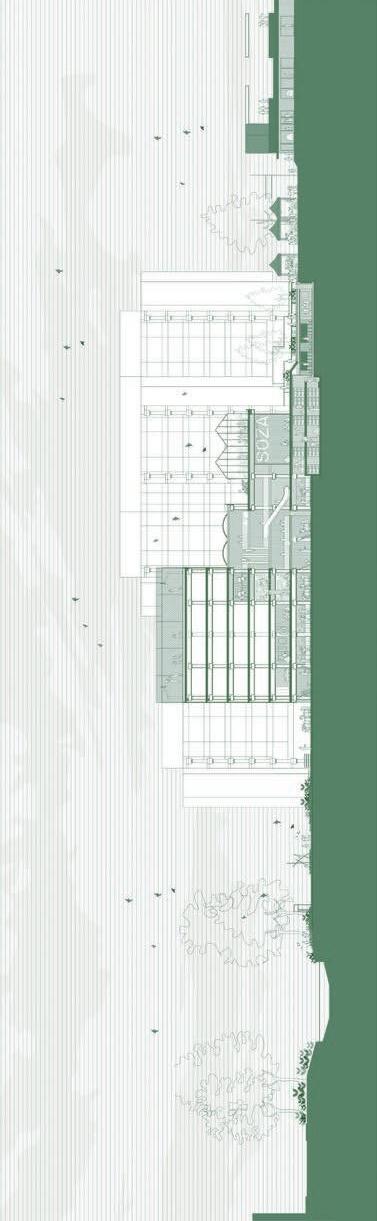

THE EYES ARE THE WINDOWS TO THE SOUL

manifested through several architectural interventions: spaces for physical therapy and education in a semi-private environment, coupled with highly public spaces for dialogue, exhibition, performance and social interaction within the wider community. In keeping with the eye hospital’s relative introversion, the social programme is the public face of the overall plan. This social foundation is designed to encourage a sense of self, accomplishment and purpose. One facet of this is the exposure of the visually impaired community to the wider public and the creation of valuable opportunities for education and financial independence.

These fall into two primary categories. The first is a direct consequence of diagnostics, testing, treatment, and oppressive clinical architecture. The second relates to a more expansive social sphere where visually impaired people suffer from social isolation, loss of purpose, loss of income, the inability to perform basic tasks and loss of self. This project addresses these current shortcomings by proposing a new combination of clinical and social responses. Through a new hospital architecture, the patient’s mental wellbeing is considered equal to the clinical aspects of care. To do so, this project redefines the traditional architecture of the eye hospital by incorporating spaces for escape, reflection, socialization and grief in the context of an accessible and communal village. This new hospital will establish new approaches to managing the challenges we face today in treatment, testing, diagnosis and clinical architecture. In parallel, a new social centre is created to supplement the new clinical approach. This new centre is an experimental ecosystem of alternative and physical forms of therapy; through the provision of therapies focusing on art, music, horticulture and movement, several social issues associated with visual impairment can be addressed. These activities are

Situated on the water’s edge of Greenock, Scotland, this project challenges the prescribed notions of care architecture for the visually impaired through the reuse of an abandoned complex of sugar warehouses and harbours in a city scarred by high rates of visually impaired people, caused by the long-lost sugar industry. Approximately 253 million people worldwide suffer from visual impairment. Currently, care for the visually impaired focuses exclusively on the physical visual condition of the individual. This leaves much to be desired when it comes to the litany of mental health issues associated with visual impairment.

STUDENT

DATE 05 October 2022

MENTOR Elsbeth Falk

MEMBERS Jeanne Tan and Jo Barnett

ADDITIONAL

MEMBERS Machiel Spaan and René Bouman ARCHIPRIX First prize ex aequo

Floor plan of the new eye hospital.

Axonometric drawing of the total master plan.

A view of a ‘sensory walkway’.

section of the eye hospital.

A view of a ‘sensory walkway’.

A view of a rest space and courtyard in the new eye hospital.

Interior image of the existing building showing the new intervention.

Axonometric drawing of the added programme in the existing sugar warehouse.

Perspective section of the existing building with new social programme additions.

GARDEN AND GARDENER

The project starts with my childhood in the village of Liessel in North Brabant, a village between arid and wet landscapes, between dry forests and the peat bog of De Peel. Separated by a geological fault, almost invisible on the surface, but 350 million years old: the Peelrandbreuk. Using the garden as a framework of thought and a spatial phenomenon in which man shapes nature, the gardener literally and figuratively searches for the fault line. The design of the garden forms a future story consisting of four garden rooms in the landscape, based on natural and social themes around the fault line: peat, wijst, groundwater and desire. Within these garden rooms, the gardener makes invisible processes visible and anchors us as humans in the deep time scales of the Peelrandbreuk. The garden of Peelrandbreuk is a spatial narrative consisting of four chapters in the spatial area of the fault line. The chapters form points or moments in the landscape where geological history and cultural history intersect. The garden’s boundary is formed by the thoughts of a person in the area and their handling of the soil. Through the hand of the gardener, man learns to know the fault again. Working on this project has allowed me to build a new relationship with the fault and the place I come from. You could say that I am the gardener in the story and my role as a landscape architect comes to life in the garden. By delving into the underground and rediscovering the fault line, I took a position within the project of awakening something rather than making it, giving it time and space, moving along with it and literally bringing people into the story of the landscape.

DATE 13 December 2022

Paul de Kort and Erik de Jong

Maike van Stiphout and Remco van

De Peelrandbreuk subtly visible in the landscape.

Biography of a deep past in three chapters.

Chapter 1: Untamed Land, Untamed People.

Chapter 2: Soil with rest awakens points to life.

Chapter 4: Monuments of desire.

Chapter 3: Feeding with groundwater.

Four rooms in the garden tell its story.

A garden border signifies an imbal ance between man and nature.

Four garden rooms in the Peelrandbreuk landscape.

This project investigates an architect’s role and architecture’s language in an authoritarian state. How can architects use their skills and knowledge to contribute to social change, and what role can architecture play in the political agenda? While Average Place is a political issue, it also has personal consequences and implications. It’s about grief, the lost feeling of home and belonging. It’s about a loss of understanding of one’s role as an architect and citizen in their homeland. Through this project, the architect wants to explore how they can engender positive change by using their craft and professional role. This work is not just about traditional design methods; it’s about finding a different language of architecture that can be used to explore the possible roles of architecture and to define my role as an architect. This project began with an exploration of new relationships between architecture and power in authoritarian states. The project’s overarching goal was to explore the potential of architecture to interact with people, examining how architectural tools can engage users in interaction and deepen the comprehension of their experience. By integrating elements from the plastic arts, the utilitarian nature of architecture and the constraints faced by architects, the Architectural Machine, a formal embodiment of a social issue, was conceived. The project was not only about the physical embodiment of architecture, but also about asking questions and finding the right words to describe the current state and possibilities of architecture. Simplistic perceptions can lead to homogeneity and limit healthy development. The project aimed to promote diversity and expand awareness of reality, even if formal results were not yet known.

Machine of expression.

Machine of superiority.

Machine of self-will.

Machine of different perspectives.

Machine of expression. Structural principle.

Machine of expression. Façade and floor plan.

of self-will. Adaptability.

of different perspectives. Models 1:2 and 1:20.

Variability of machines.

Machine

Machine

The result is a low-dynamic, breathing landscape that gives and takes, driven by an innovative water mechanism. This vision encompasses a series of water basins within the river polders, each with its own function, land use and beauty.

Spatial carriers: structures, land use and waterworks.

Land use determined by soil and water conditions.

Rivers such as the Rhine and the Maas are vital lifelines for both humans and nature. However, with ongoing climate change and the detrimental effects of river and landscape cultivation, we’re reaching a new breaking point. This design research argues for a transformative approach to the Dutch river region. The river area is a stark example of the extreme ramifications of climate change. Both severe droughts and increased flood risks are putting a significant strain on this landscape, especially in the low-lying river polder regions along the riverbanks. These vulnerable zones are crucial in developing a comprehensive strategy to mitigate the effects of climate change on the Dutch river landscape. Such a strategy not only offers hope for nature and farmers, but also demonstrates the potential when water and soil are managed. It addresses the negative effects of climate change and an over-cultivated landscape, but also supports extensive nature restoration and introduces innovative forms of land use in these new conditions. Rain and river water can be stored and used later during droughts through an extensive and intelligent water management system.

Saline Verhoeven and Gerwin de Vries

Ziega van den Berk and Roel van

OF ARCHITECTURE Research Award

A witness to the new land use.

Land shaped by clay.

Land of Maas and Waal.

TO HOST WOMEN

The different types of housing are designed to accommodate the varying family configurations of women in need of shelter. Each unit offers the opportunity to open up and share experiences with a community, or to have moments of introspection in one’s own private space.

The design approach is inspired by the traditional Dutch ‘hofje’. Centrally located in the urban context and surrounded by the urban built structure, the hofje encloses a fascinating protected inner world with its own character and atmosphere, organized around a communal garden. Inspired by this tradition, the inner block of the site is transformed to accommodate women victims of domestic violence in a protected environment, while still allowing them to be part of society and city life. The paradoxical relationships between seclusion and inclusion, privacy and collectivity are key concepts in the design of a shelter, as observed in the various interviews conducted during the research phase. The proposed design creates spaces where a process of recovery can take place, where shared experiences are encouraged, while individuality and privacy are maintained. From arrival to departure, a domestic environment is imagined around a sequence of enclosed gardens that provide a secluded orientation to reality in terms of time and place. The gardens play an important role in shaping the transitional sequences between city and shelter, essential to enabling the unique atmos

phere of the block’s inner world, a place to feel protected and to recover.

According to the World Health Organization, ‘violence against women is a major human rights violation and a global public health concern of pandemic proportions’. The statistics show that one-third of women worldwide are subjected to violence at least once in their lives. The high majority of these violence cases relate to a former or current intimate partner, which is classified as domestic violence. When experiencing it, women are in need of support, often of a place to stay, to feel sheltered and to heal, where legal and psychological support is available. Women’s shelters have existed in the Netherlands since the 1970s, shaped by available resources, opportunities and the development of an approach that has continued to evolve over the past five decades. This graduation project consists of rethinking women’s shelters from an architectural perspective, in the firm belief that spatial design decisions can make a significant contribution to the recovery process that women victims of domestic violence go through. Situated on the edge of Amsterdam’s historical centre, the chosen site consists of an existing city block surrounded by a variety of urban atmospheres. Each of the three programmatic sections of a shelter on this siteinstitutional, residential and healthcarecan find its own ideal relationship to the city.

Ground floor plan.

Model of the project embedded in the urban context.

Fragmentary models of the wall surrounding the project with different levels of permeability linked to the private or collective character of the spaces enclosed by it.

Longitudinal and transverse sections illustrating the main accesses to the shelter and the sequence of arrival and daily life.

The main access through the institutional tower, followed by the transitional arrival square that embraces an existing tree and the guests arriving for the first time.

The emergency beds and the collective courtyard, both gardens of paradise where

collective life of the shelter takes place in different moments of one’s stay.

Daily entrance in a transformed existing base, lending access to the shelter in a small-scale, domestic, normalized manner.

Private outside spaces organized around the gardens of contemplation where one may observe the passage of time through the seasonal transformations of a centrally positioned fruit tree and the play of light and shadow on the façade’s relief.

Access to one’s temporary home through the collective garden; the double orientation of the housing units enables both communal and private life.

MOVING BEYOND ‘PROBLLEM SOLVING’

The graduation projects presented at the 2023 Graduation Weekend excelled at addressing big and complex questions, such as environmental and social issues. Guest critic Aric Chen reflects on what he saw during the show.

Text JOHN BEZOLD Photo MARWAN MAGROUN

Aric Chen is the director of Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam and was a guest critic at the 2023 Graduation Weekend at the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture. He and I spoke about his experience of reviewing the graduation projects, to identify commonalties. Rigorous research, personal narratives and histories, combined with meticulously crafted yet graphically playful presentations were common themes woven into the intellectual foundations of the projects.

Before we focus on student work, could you talk a bit about some of the changes in the Dutch architecture scene over the past 25 years, and how they might have found their way into architecture education?

‘The shifting of priorities and agendas we’re witnessing in architecture are prompting a complete rethinking of research and methodology. This is happening because the goals are evolving or at least changing in emphasis. Research, always integral to the process of making and doing architecture, is now changing in nature and definition. Back in the 1990s, a student would spend all their time with software and algorithms. Today, however, they engage in research that includes collaboration across multiple and diverse forms of expertise, whether or not that involves the communities they are designing for or with. The emphasis on the architect as a solitary artist-hero-genius is diminishing, leading to greater shared authorship. Currently, there’s a growing belief that the power of architecture lies in humility, a significant shift from just a decade ago. One issue that the previous generation perhaps didn’t convincingly resolve was the contradiction between the autonomy of architecture and its social-political relevance. We are still navigating the legacy of this contradiction, but now with a strong drive to address societal and ecological issues.’

So then, to zoom into the work that you’ve seen here so far today, what was your initial impression of the dominant approach of students, right now?

‘I definitely see the explicit agenda to take on environmental and social concerns. The two are always linked, of course, to more questions. I think it was also interesting to be reminded that the projects that we saw here today were done by students who were doing their work in the context of the COVID lockdowns. You can also see how through these projects there’s a trend towards thinking on much more local levels. So many of the projects were coming from a very personal place.’

I noticed that as well.

‘There were many projects that address sites, questions or issues in places where the students had personally lived. Lots of hometowns, for instance. Quite a lot of hometowns. Many focused on personal recollections, situations and experiences. Personal histories. I think that that’s also indicative of, in some ways, a less top-down mentality at the academy, in that it’s acknowledging the sort of agency of the individual and, by extension, instilling a greater sense of empathy in architects.

This approach is more empathetic and truly remarkable. As someone with considerable experience in the field, I’ve noticed a significant shift. For a long time, during reviews, students predominantly aspired to design museums and opera houses. However, in recent years, there’s been a discernible pivot towards socially oriented practices. Many proposals now involve working with marginalized or underrepresented groups. But when asked if they had engaged with these groups, the common response used to be a blank stare. It’s rather encouraging to see how much more sophisticated the research process has become, aligning with the evolving notions of research.’

Beyond many of the projects being local, could you identify some other common themes, like subjects or concerns among the projects as a whole – as in, the ones that stuck out to you?

‘I am finding that, more and more, one sees a disproportionate number of projects coming out of landscape architecture. They are especially compelling. I think partly because the questions and problems that were asked are so big and complex that in some ways, landscape architecture now has a broader scope than architecture on its own. It also has to do with the broadening of education and topics in general. ’

Can you talk about some of the presentations that stuck out to you on a visual level? Were there any that struck you as impressive in how they were presented?

‘For one thing, I think all of us were really impressed by the drawings. One student from Colorado designed his landscape project on fire mitigation. His proposal was basically a cooperation with nature, which includes migratory birds and beavers and so on, but also fire, which itself is also a generative part of the natural cycle of regeneration. And his illustrations! We were all admiring how great they were, in terms of extracting the sense of fear out of fire, meaning the fire was rendered in almost a sort of childlike, friendly way, though not cartoonish. In general, I find that there’s an incredible rigour here towards really thinking through processes and methodologies in very precise terms. You find that in a lot of the ways that the students have described their projects, there’s a lot of emphasis on statement of principles, a lot of self-reflection. But what I found less of, is texts talking about the actual project. And so I think that’s something to really work on.’

Is there something you would have liked to see more of within the project presentations?

‘It would have been nice to see broader framing, more experimental projects. Experimental, there you go. Longer missions and time frames. Generational projects. The prevalence of a very narrative-driven, personal approach was methodologically sound, but very short-term focused, due to their personal approach. However, I’m happy to notice that architects, as a profession, are moving beyond design and architecture as, ‘quote-unquote’, problem-solving.’ ←

MATERIAL- IZING THE INVISIBLE

Every year, an Amsterdam Academy of Architecture alumnus gives a Kromhout lecture, named after one of the founders of the academy. This year, Lesia Topolnyk was the speaker. She talked about her professional journey so far and the personal motivations for her work.

Text DAVID KEUNING Photo LESIA TOPOLNYK

Lesia Topolnyk graduated from the Academy of Architecture in 2018. For her graduation project she designed a counterpart to the United Nations headquarters in New York: The Un-United Nations headquarters on the Crimean Peninsula, which was annexed in 2014. The starting point of her design: politics by definition imply potential conflict. Realizing the impossibility of political stability and the inevitability of potential conflict, Topolnyk assumed a perpetual instability, a constantly renegotiated temporariness. She designed Un-United Nations as a neutral arena for disagreement, providing ground for a discussion about the morality of opposed political systems.

For the graduation project she chose the archaeological site of Chersonesus, an ancient city founded by Greeks and currently located near military facilities. The Greek city grid exemplifies a democratic ideal and Topolnyk proposed to excavate it, revealing different historical layers and political regimes in its exposed walls. Over the existing city grid she placed a 600 m-long structure, reflecting one of the public streets and creating a building consisting of only corridors as informal decision-making places instead of chambers where decisions are prearranged. The building seems to serve as a dividing wall, but simultaneously acts as a gate due to its elevated position over the landscape, offering relationships between the Eastern and Western worlds. Not only did the project win her a shared first prize at Archiprix Netherlands in 2019, she was also one of seven winners of Archiprix International in the same year. Additionally, she won a first prize in the Tamayouz International Award in Jordan. In 2022, she went on to win the Prix de Rome with No Innocent Landscape, in which she linked the shooting down of the MH17 flight in eastern Ukraine in 2014 to environmental problems in that same area.

In the Kromhout lecture, Topolnyk discussed the links between politics and her work as an architect and artist. Pointing out the biological, climatic, chemical and geological challenges of our time, she argued that architecture is slowly losing its relevance as a profession if it’s only concerned with adding new buildings to the existing stock. Buildings and landscapes are indeed shaped by designers, she argued, but only to a very limited extent. Much more important, and often overlooked, are abstract forces, such as financial

markets, political systems, artificial intelligence, energy production means, algorithms and racial divisions, which all produce physical environments but are also produced by the physical environment. Therefore, she said, designers should become a mediator and guide between the physical environment and invisible processes.

Giving examples from Ukraine, Topolnyk showed how political power was exercised through architectural and landscape design in the past. The pared-back design of Hotel Ukraine, built in 1962 as ‘Hotel Moscow’, was heavily influenced by a 1955 decree by Khrushchev, banning Stalin-era decorative features such as colonnades, sculptures and pilasters. And in 1946, almost 80,000 Ukrainians (including Lesia’s great-grandparents) were stripped of their assets and forcibly deported to Siberia in a large-scale landuse planning effort in the tradition of the Soviet Union’s five-year plans. With its central Maidan location, Hotel Ukraine was the backdrop for both the 20042005 Orange Revolution and the 2013-2014 Revolution of Dignity.

2013 was also the year in which Topolnyk started her architecture studies at the academy. ‘It was a difficult year for me,’ she said. She witnessed the events from a distance: first another revolution in Ukraine, then the Crimea annexation and the downing of the MH17 plane in war-torn Donetsk. Being outside rather than within the course of events allowed her to reflect on them.

Given the world’s perpetual instability, the design assignments she was given at the academy sometimes didn’t feel that relevant to her.

After the Un-United Nations headquarters and No Innocent Landscape projects, Topolnyk is now conducting further research into the transformative power of design. She strives to apply her thinking as an architect to multiple domains, linking a site-specific approach to urgent global issues. In doing so, she touches on themes such as landscapes of trauma, neocolonialism, cultural and historical heritage, and the relation between psychology and space. The common thread running through those topics is the way that invisible structures determine our physical surroundings, and how design can be a tool to expose those relationships. International relations and large-scale conflicts have a huge backlash on a local level, and that’s the context that architects have to operate within. ‘Why not turn this around and have architectural and landscape design play a role in those relations,’ she asked. ‘People who say that they’re not interested in politics and that they have no part in events that happen far away deny the fact that everything they do is interconnected with geopolitical events.’ In her work, Topolnyk tries to offer people ways to relate to those events, professionals as well as the general public. In the Prix de Rome project, she involved her own family members, making the project into a healing ground.

Most recently, Topolnyk worked with local NGOs in Morocco on a project about the influence of the European energy transition on the African continent. In the Netherlands she developed a future vision for the Defence Line 1629 in Den Bosch, commemorating the 400th anniversary of the city’s siege during the Eighty Years’ War. Questioning what we will celebrate for the 400 years to come, instead of reconstructing the defence line she proposed a curatorial framework with site-specific interventions redefining our historical and future connection with the landscape. She also made a proposal for the historical Aa-kerk in Groningen, which resulted in a new pavilion and an interior design that exposes past and future narratives. The Aa-kerk is a church that takes its name from the River Aa. In Topolnyk’s intervention the River Aa serves as a storyline, recounting the history of the church, its province and highlighting the urgency of climate issues. It flows through the church like a river, shaping its landscape into an auditorium and extending into the pavilion.

While all of these projects are very consistent with her other work from a methodological point of view, they seem to take very different shapes. Her projects are driven by ideas and not by a preconceived design style. ‘People like to put you in a box,’ she said after the lecture. ‘After the Prix de Rome project, the implicit expectation is yet another installation. But I don’t want to be pinned down. I want to be versatile and keep being open to exploration and experiment. My work is a manifestation of my life and the questions that are bothering me. I’m driven by a very personal inner quest.’ ←

Topolnyk made a proposal for the historical Aa-kerk in Groningen, which resulted in a new pavilion and an interior design that exposes past and future narratives.

ARTISTS IN THE MAKING

In the 2023 edition of the Start Workshop, students had a go at dancing, sound experiments and storytelling.

Text DAVID KEUNING Photos GREG JENNIE

During the Start Workshop, students acquaint themselves with each other, some of the staff and the city of Amsterdam. This year’s edition, which spanned two days, was organized by Stephanie Ete and Jacopo Grilli. Having graduated from the academy themselves, they appreciate being involved with students. ‘I enjoy the learning and teaching environment at the academy,’ says Ete. ‘It’s essential to the designer you eventually become.’

Ete and Grilli aimed to familiarize the students with Amsterdam beyond the city centre. They visited the outlying areas of the city: Nieuw West, Southeast and North. After an introduction at the academy, they first went to the Kröller-Müllerpark – not the famous one on the Veluwe, but the much smaller one near the Sloterplas. The park boasts some interesting buildings, such as apartments built in former water purification drums made of concrete. ‘We wanted the students to experience the city intuitively,’ says Ete, ‘not by looking at the architecture, but by experiencing it through their bodies.’ To help students get started, they invited dancers from the Rorschach Collective to demonstrate how to do so.

After lunch at the Sloterplas, the whole group moved to the Shebang art space in Southeast, where sound performer Oscar van Leest demonstrated how to experience a space through sound. After the performance, the students themselves were invited to perform. The day concluded with dinner at the academy.

On the second day, the students gathered at the Gele Pomp, a disused petrol station on the edge of the Noorderpark in Amsterdam Noord. Here they were met by writers Alina Hinterberger and Massih Hutak, who taught them about storytelling in relation to the city. ‘They talked about the differences between expats and immigrants, the meaning of belonging, and how to improve neighbourhoods without resorting to gentrification,’ says Ete. ‘It was an eye-opener, not only for the students but also for me.’

The afternoon was spent at the academy, where the students met with study advisers, a student coach, and the professional experience coordinator. The two-day programme ended with performances by the students, demonstrating what they had learned throughout the programme. ‘The output was very varied,’ says Ete. ‘They made physical models, created sounds and told stories in the form of poems. Our expectations were exceeded. The students gave it their all.’ ←

The two-day programme ended with performances by the students, demonstrating what they had learned throughout the programme.

CEREMONY OF THE SENSES

This year’s Winter School, which took place from 11 to 19 January 2024, was led by artist-in-residence Theun Karelse. He was invited by Joost Emmerik, head of the master’s programme in Landscape Architecture. Theun and Joost look back on a successful and happy week, which was all about ceremony.

Text DAVID KEUNING Photos GREG JENNIE

Theun Karelse and Joost Emmerik named the programme they put together for the Winter School 2024 ‘Cult of the Earth’. It was based on ten themes, each supervised by a lecturer or a team of lecturers. They presented the themes in performances during an opening evening at De Duif, an impressive nineteenth-century church building on the Prinsengracht. Three guest performers also attended the opening. Artist Ibelisse Ferragutti kicked off the Winter School with a ritual welcome to the four winds. Frank Heckman from the Embassy of the Earth spoke about the role of the sacred space in his work on socioecological regeneration, while Johan Roeland was interviewed about his research on theology and religious practices. Over the following week, students explored the ten themes, culminating in a celebration on Friday afternoon, when their explorations came together in a final ceremony in the academy’s gallery around the courtyard. Visitors could join in circles around three artificial fires, time was made tangible, there was a procession in which students represented ancestors and students worked with choreographies in the courtyard. The atmosphere was lively and elated; it was a successful finale of a great week. A few weeks later, Karelse and Emmerik look back on the event.

Theun, what did you like most about the Winter School? THEUN What I liked most was the freedom the students felt to express themselves. This grew throughout the week.

How could you tell?

TH They were cautious at first, which is understandable, as this Winter School focused on working methods that were very different from those used in everyday practice. I was running in and out of the classrooms, so I had a bit of an overview, but the students and lecturers did not. At first, they only noticed their own group going off the beaten track, but as the week progressed the teams began to work more and more in the gallery. Its cyclical shape lends itself well to rituals. The space is roughly aligned with the four directions of the wind and can be used for all kinds of cycles: that of a human life, a season, a day. As the teams saw that others were also doing unusual things, they became more confident. Over the last two days, that confidence took flight.

Apparently, when people go off the beaten track, they need reassurance that it’s okay to do so.

TH Some weren’t bothered by that at all. The theme of the Winter School was different from previous years, and so was the form, ending with a ceremonial feast. We set the bar quite high. We were working towards an experience, not a performance for an audience. The aim was for people to learn from what they experienced.

JOOST The students didn’t touch their computers all week. That’s what I found special about the final ceremony: it was all sensory experiences, with smells, movement, visual things, but also auditory. It felt like a kind of festival, with different things happening in different places. But what I liked most was that the students came out of their comfort zones. Many of them felt safe enough to walk around in unusual costumes, to make noise and dance.

TH I saw the academy becoming a place where people could show something of themselves that they wouldn’t normally display. Perhaps the festive atmosphere was a result of this.

JO This was in keeping with the nature of the Winter School. It’s a place of experimentation and it has a clear connection with the Amsterdam University of the Arts. The students were singing a different tune from the rest of the curriculum. That’s valuable.

Joost, it was up to you this time to invite the artist-in-residence. How did you find Theun?

JO I was inspired by a quote from one of my favourite authors – Ton Lemaire – and I wanted to do something with a cult of the Earth. In the rest of the curriculum I also try to confront students with a different relationship with nature. I spoke to several people and a couple of them mentioned Theun. I hadn’t heard of him at the time. Everyone said: ‘Theun is not only a good artist, but also a pleasure to work with.’ That got me interested: the importance of creating a good atmosphere is often overlooked. When I teach, I try to have fun with the students, first. You have to be comfortable with the group, and from that safety you can say a lot to each other. I made a suggestion to Theun, which he accepted and then completely transformed. I also wanted a joint conclusion at the end, with lots of sensory experiences.

Theun, how did you find the lecturers you invited?

TH I wondered who, given the unusual ambitions, best matched the intended format. I wanted to make sure that all the senses were represented. I also wanted to put together a team consisting of people with different levels of experience of working with students. If you only have people with a lot of experience, you might lean too much on what you already know. If there are a few people with less experience, then it gets exciting for everyone. And when it gets exciting, more is going to happen. Because there’s room for it.

In order to get everyone on the same page, Joost and I created a Winter School Reader. It included a glossary in which we tried to answer questions like: What is the purpose of rituals? What does transmutation mean? One of the key concepts is holism. By this we often mean the way human beings impact the environment. But while making the Reader, I realized that it is important to turn that around as well. What impacts us?

Can you give an example?

TH Adriana Knouf, one of the guest lecturers, is really engaged with the universe. She says: ‘The sky used to speak to us.’ In our everyday lives, we tend to think of the sky dome as something separate from our lives on Earth. The stars don’t really have anything to do with the academy building. Why is that? Is that justified? When you think about the damage our activities on this planet cause, it might be a good idea to reconnect with things we’ve lost touch with, like the sun, the moon and the sea. So, I started looking for →

guest lecturers whose artistry had a connection with this topic. Adriana’s universe was a perfect fit. It was the same with the others.

JO Theun was really open during the process. The initial idea for the closing feast on Friday afternoon was a kind of dinner, something with several courses. But in the groups, all sorts of other ideas came up. One group wanted to make an object while another wanted to work with movement. We did have fixed locations, which we started calling ‘tents’.

TH We used three metaphors: tents, processions and wanderers. The ideas the groups worked on all fit those metaphors. Everything else was open-ended.

Didn’t you find that exciting? It could go either way. After the opening in De Duif I thought: ‘I’m curious for the end result.’

JO We all thought that!

TH I was confident, though. There were some pretty impressive people in the teaching team. The exact shape the closing ceremony would take was up in the air the longest. That was only decided on Thursday evening. We agreed: there’s a starting point, there’s an end point, we have a kind of map of the locations of the tents, and we have a fixed order for the processions. As a teaching team, we can just decide on the pace during the ritual. That worked really well. The energy and action were instant.

Were any of the students sceptical about the topic and the approach?

TH I was initially worried that students might not see its relevance to their practice. We tried to address that question in the Reader. But at some point, I was sure that it wasn’t going to be an issue. After all, students understand why it’s important to experience something and not just reason about it. During this Winter School, students were not presenting while they stood next to a model or a drawing pinned up on a wall, but as they stood in the middle of their research.

JO In general, students are quite good at engaging their intellect. They all study hard and have responsible jobs, so they need to be excellent at planning and have their affairs in order. They’re very much in their heads. The Winter School offered them the opportunity to do physical things.

You brought a drum to the opening in De Duif. After some hesitation, the students started playing it quite enthusiastically. At the academy, too, I regularly heard its beat resonate through the building during the Winter School. What was the purpose of this?

TH I was so glad I decided to take it with me. Sometimes you get tired and less inspired. But if you can play the drum for a while, you always feel like doing something again at some point.

JO We don’t usually work with sound or music at the academy. But the moment you give people a drum, they start telling stories. One of the students said he used to play the drums a lot. Another student started drumming a particular rhythm that’s specific to the region she comes from. When you bring something new to the school, you see that it appeals to some students but not to others. That’s also fine.

TH It’s partly culture specific as well. At the start, someone from India and someone from Turkey were sitting at the drum. They were talking about the rituals in their cultures in which drums are used, and how they are used.

JO That’s what the Winter School is all about. You bring something to the table – a particular object or a specific way of thinking – and then it’s up to the students to engage with it. Some get really excited, while others

The ten groups were:

Universe: The Xenophysics of the Cosmos by Adriana Knouf

Guilty Air by Frank Bloem

Experiencing Time through Taste by The Centre for Genomic Gastronomy (Cat Kramer and Zackery Denfeld)

Glitter by De Onkruidenier (Jonmar van Vlijmen, Rosanne van Wijk and Ronald Boer)

Too Far, too Slow, too Small by Marit Mihklepp

Sensing Spirit: Sound and Listening as Portal into the ‘Spirit World’ by Robbi Meertens

Weaving Tribe by Teun Castelijn

Decolonization and Ancestors: Be(yond) them System: Personal and Collective Transformation & the Need for New Gods by Anne de Andrade

Bodies of Movement by Emma Hoette

Fire by Anna Maria Fink and Elza Berzina

need more time to warm up. Some ideas don’t connect with everyone, and that’s okay too. That’s why the Winter School is so much fun. We bring in things that many students don’t normally come into contact with. The result is like a miracle: all those ideas and objects!

TH From very extravagant things to small, unimposing objects. I should mention that the drums also had another function. We needed to transform the gallery into a ceremonial space. How do you do that in a building that the students already know inside out? I thought about hanging garlands, completely clearing the space, or creating an open fire. The latter wasn’t going to happen. So, I thought about using sound to create a ceremonial atmosphere.

JO Anna Maria Fink and Elza Berzina’s group, whose topic was fire, spent the whole week trying to make a fire in a building where fire is not allowed. They found out that what matters is the pain stimulus, and that the pain of heat is similar to the pain of cold. So, they had a container of ice water in which you had to immerse your hand for as long as possible.

Were there any other interesting outcomes?

TH Anne de Andrade did an exercise that she normally does with native elders and youngsters. There weren’t any elders there, so she asked half the group to imagine they were ancient beings with lots of wisdom and that they were having a conversation with a student. That worked well. We can actually do that, even without practising! It’s amazing what we’re capable of as human beings, without perhaps knowing it ourselves. I saw some interesting things in the other groups too. It’s clear that this is a pretty unusual study week. I hope this freedom of expression will stick around for a while.

JO I was very proud. People had dressed up, people were dancing, there were smells and sounds, it was really an apotheosis. Everything came together.

TH For me, the most important result of this week was the community itself. Beforehand, I thought we were going to connect with the sun, the moon and the universe. But what actually happened was that we connected with each other. ←

A film of the Winter School 2024 can be viewed at: bouwkunst.ahk.nl/ opleidingen2/onderwijsprojecten/winter-school/winter-school-2024/

PAVING THE WAY

Anna

Gasco took over from Markus Appenzeller as the head of the Master’s programme in Urbanism on the same night that the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture celebrated its 115th anniversary.

Text DAVID KEUNING Photos JONATHAN ANDREW

After six years at the head of the Urbanism Master’s programme, Markus Appenzeller handed over the helm to Anna Gasco on 5 October 2023. That day also marked the 115th anniversary of the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture. Director Madeleine Maaskant reminded the audience in the Hoge Zaal of how the course began on 5 October 1908. ‘The first lesson was taught by architect Cuypers and was titled “Natuursteen, de steensnede” [Natural stone, stone-cutting],’ she recalled. ‘On the second evening, 6 October, “Bakstenen en andere materialen” [Brick and other materials] followed, and on the third evening, architect Kromhout took over with “Dragende bouwdelen” [Loadbearing structures]. Cuypers and Kromhout, together with Berlage, dreamt about the school of the future, and they established this Academy of Architecture. We’ll never know if it became the school they had in mind. But the guiding principles on which their educational model was based, are still going strong.’

After this brief historical exposé, Maaskant turned to Appenzeller, who had been at the helm of the Urbanism Master’s programme for two terms, totalling six years. ‘It’s your directness and positive attitude that make working with you such a pleasure,’ said Maaskant. She praised his international network and his commitment to teaching at the Academy. ‘Many times on Friday mornings, you entered the meetings of the Board of Studies straight from Schiphol. You were known as the man with the suitcase.’ As well as inviting people from all over the world to teach at the Academy, he also organized many design studios abroad.