knowledge in motion beyond the yurt

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

mentor Alexey Boev

committee member

Anastassia Smirnova-Berlin

committee member

Jop Voorn

knowledge in motion beyond the yurt

Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

mentor Alexey Boev

committee member

Anastassia Smirnova-Berlin

committee member

Jop Voorn

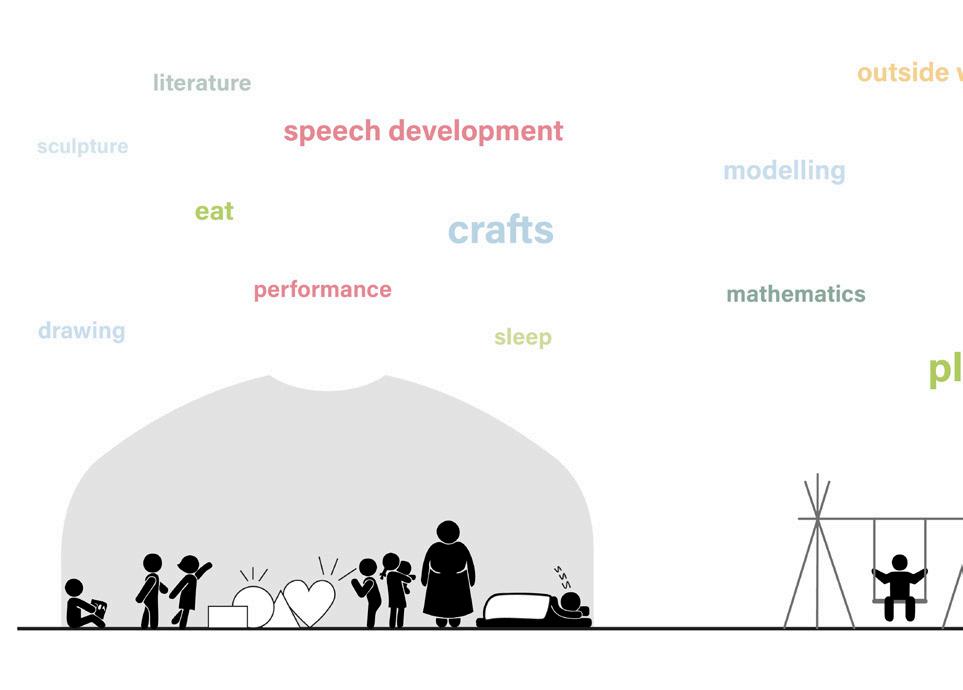

the nomads nomads of today today’s horse power sustainable nomadic dwelling characteristics of Kyrgyz yurt evolution of the yurt sacred and functional space floor is the foundation layered comfort amongst semi-nomads day in life of semi-nomadic family Jailoo Preschool - playground of knowledge new typology Jailoo Child Development Center operating hours challenges on the way

new routine for little semi-nomads

division of program

ergonomy

modularity

ergonomy

nature

filling-in the gaps

sourcing

traditional craftsmanship digital fabrication materials logistics the significance of place tracing nomadic path first stop - Pervoye Ozerko where wheather shapes learning classrooms in motion second stop - Chon Ak-Suu Gorge where wheather shapes learning learning within the nature landscape becomes classroom third stop - Kyrchyn

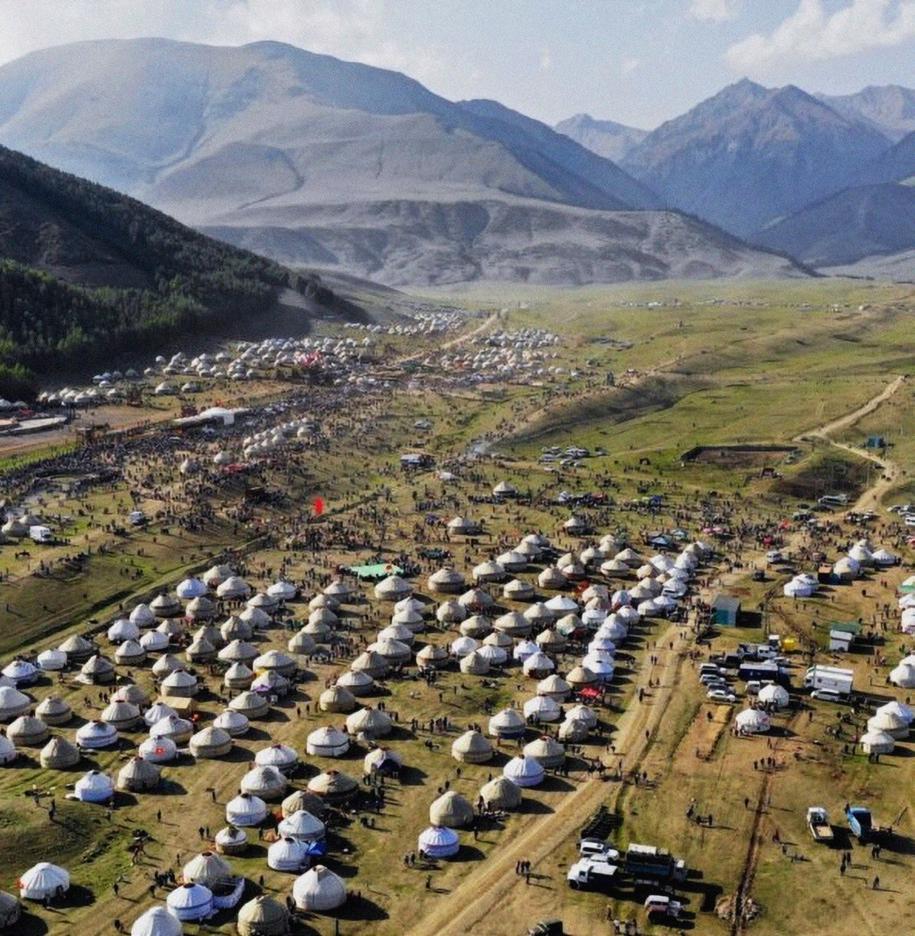

World Nomad Games where wheather shapes learning playscape expanding play conclusion

prototype’s prospects acknowledgements bibliography & sources

“...gone to a distant city beyond the mountains, beyond the lake, and beyond the mountains again.”

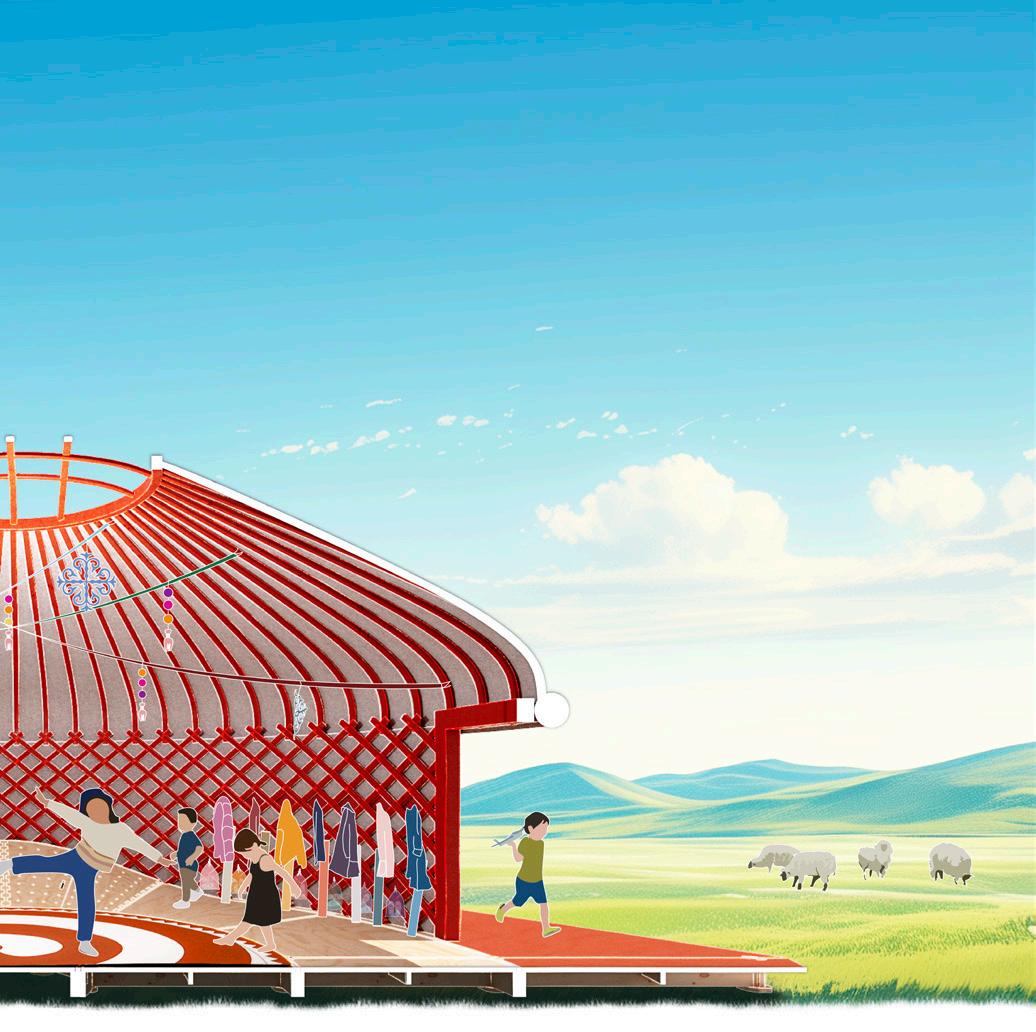

This research explores the intersection of nomadic traditions and early childhood education through the development of Jailoo Preschool, a mobile learning environment designed for semi-nomadic children in Kyrgyzstan. By integrating education into the migratory patterns of these communities, the project ensures that children can continue their cultural way of life without compromising access to learning.

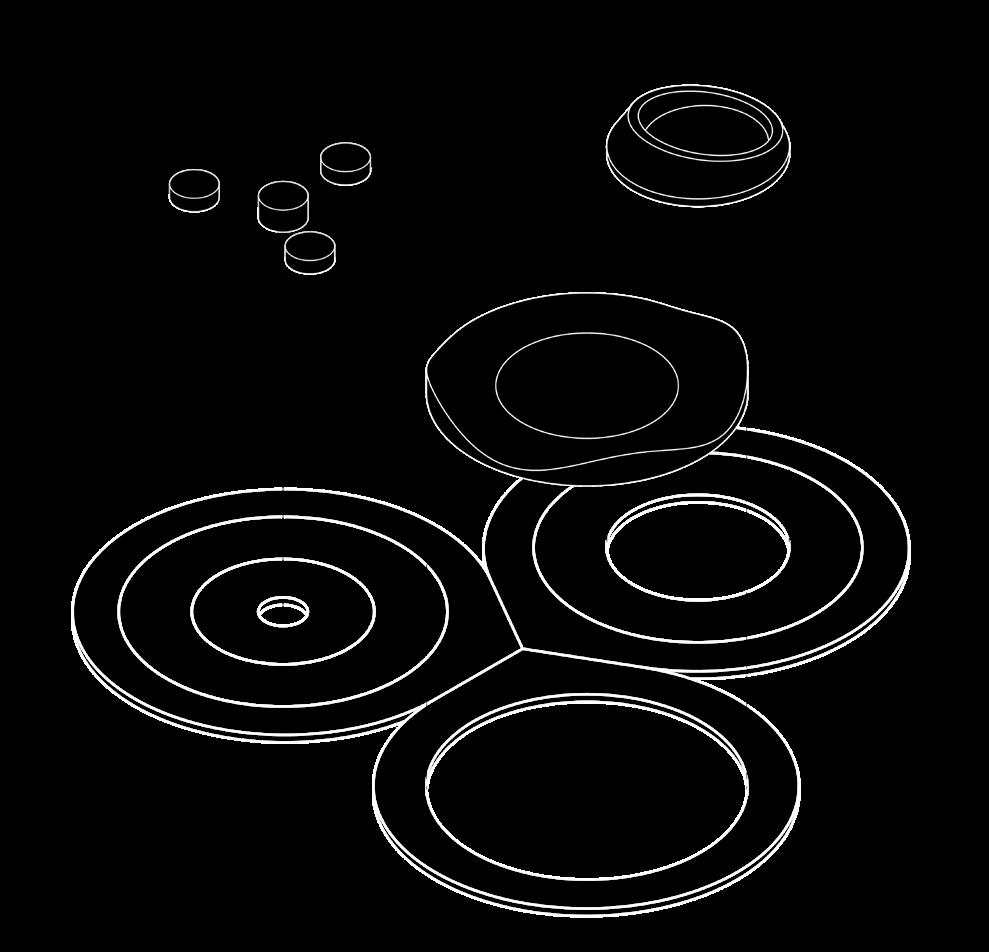

The design consists of three modular platforms, inspired by the Kyrgyz landscape - hills, rocks, and mountains—which reflect the nomadic environment. These platforms serve a dual purpose: when covered by yurts, they function as classrooms, and when disassembled, they transform into a dynamic playground. By blending the traditional craftsmanship of the yurt with digital fabrication techniques used in the newly designed platforms, the project balances cultural authenticity with modern efficiency. This fusion allows for scalable and adaptable construction, making the model applicable across all semi-nomadic communities in Kyrgyzstan.

Beyond its architectural function, the project introduces an innovative approach to education—knowledge in motion, where learning is fluid, interactive, and deeply connected to the environment. The design fosters both cognitive and motor skill development by integrating indoor and outdoor learning experiences. By reinterpreting the traditional yurt and cultural elements, the project preserves Kyrgyz heritage while addressing contemporary educational needs.

This research is grounded in case studies, interviews, and personal observations, ensuring that the proposed solution is practical, responsive, and culturally relevant. More than just a school, Jailoo Preschool serves as a prototype for mobile education, aiming to inspire similar initiatives in other nomadic communities and contribute to the global discourse on accessible education in remote regions around the world.

my childhood 12 interest & context 30

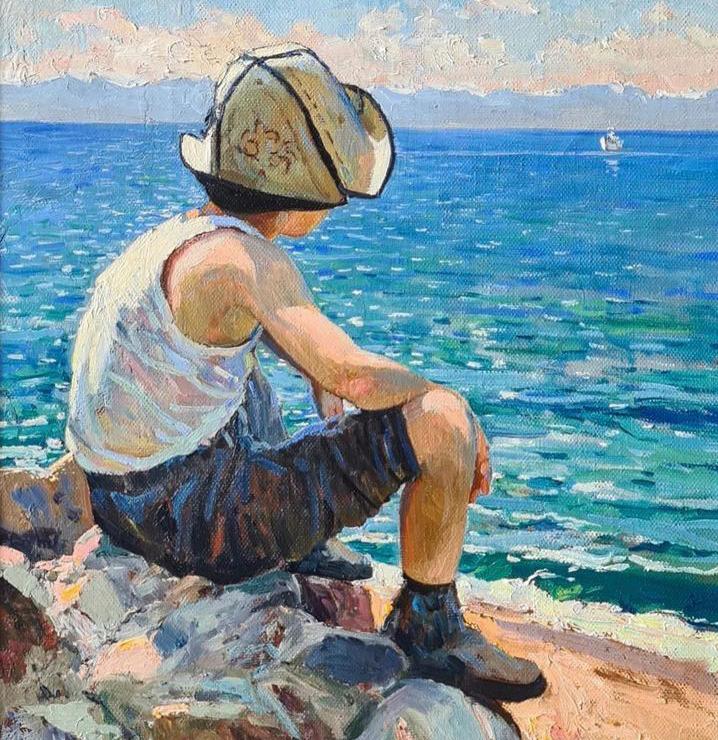

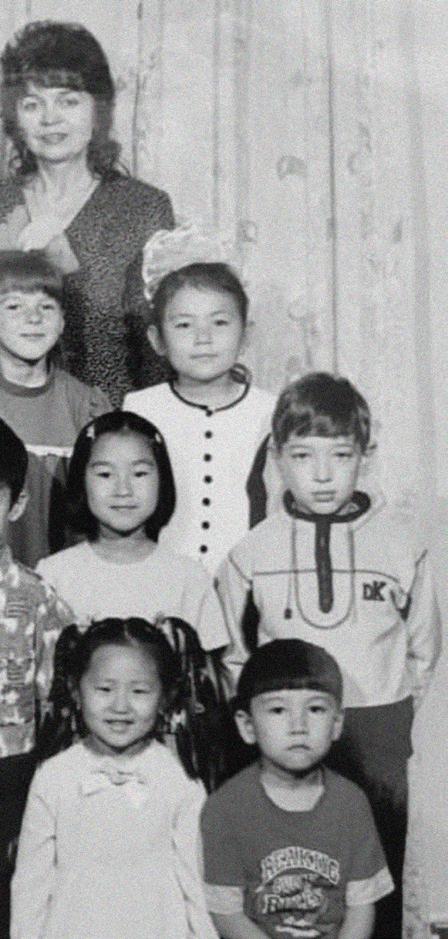

Growing up in Bishkek, my childhood was defined by a sense of exploration and play, rooted in both the structured urban environment and the natural landscapes around the city. The city’s concrete and metal playgrounds were my primary spaces of recreation. These playgrounds, though simple, were designed to serve a practical purpose, offering children a place to socialise and burn off energy. The structures themselves were often a mix of rusty swings, climbing frames, and seesaws, worn down by time but still sturdy enough for endless hours of fun. We, as children, made the most of these basic amenities, inventing games, creating imaginary worlds, and bonding with friends. Despite their utilitarian design, these spaces were where I learned to navigate relationships, test my physical limits, and develop a sense of independence.

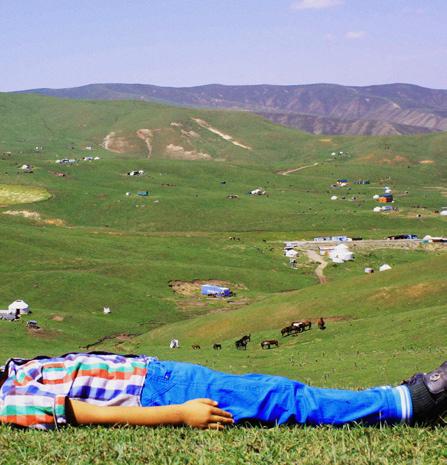

However, when visiting my relatives in rural areas, a different world emerged. In contrast to the organised playgrounds of the city, rural

spaces had no such defined recreational areas. Instead, we turned the open fields, riversides, and forests into our playgrounds. The freedom of nature offered a different kind of joy—no boundaries, no rules, just the vast expanse of the outdoors. We climbed trees, built makeshift forts, and ran across the open landscape, our imaginations turning the rural environment into endless possibilities. This contrast between the city’s structured urban play and the boundless rural landscape gave me a unique perspective on how children’s play can be influenced by their surroundings.

Both experiences - playing in the urban playgrounds of Bishkek and in the natural landscapes of the countryside - helped shape my understanding of space and environment. While the city offered defined, man-made spaces for recreation, the countryside offered an organic connection to nature, teaching me the importance of both the built environment and the natural world in shaping childhood experiences.

Bishkek, as the capital city of Kyrgyzstan, was deeply influenced by Soviet-era urban planning. Although I was born and raised in a time following the collapse of the Soviet Union, much of the city’s architecture and urban structure remained unchanged. The influence of the Soviet era was still visible in the public spaces, educational institutions, and overall urban design. My parents, who had moved to Bishkek years

earlier for education, chose to stay and raise me in the city, where life continued to reflect a blend of the old Soviet systems with the emerging post-Soviet changes. Despite this, the city remained a place where many elements from the past still shaped daily life, offering a unique glimpse into the intersection of history, culture, and urban development.

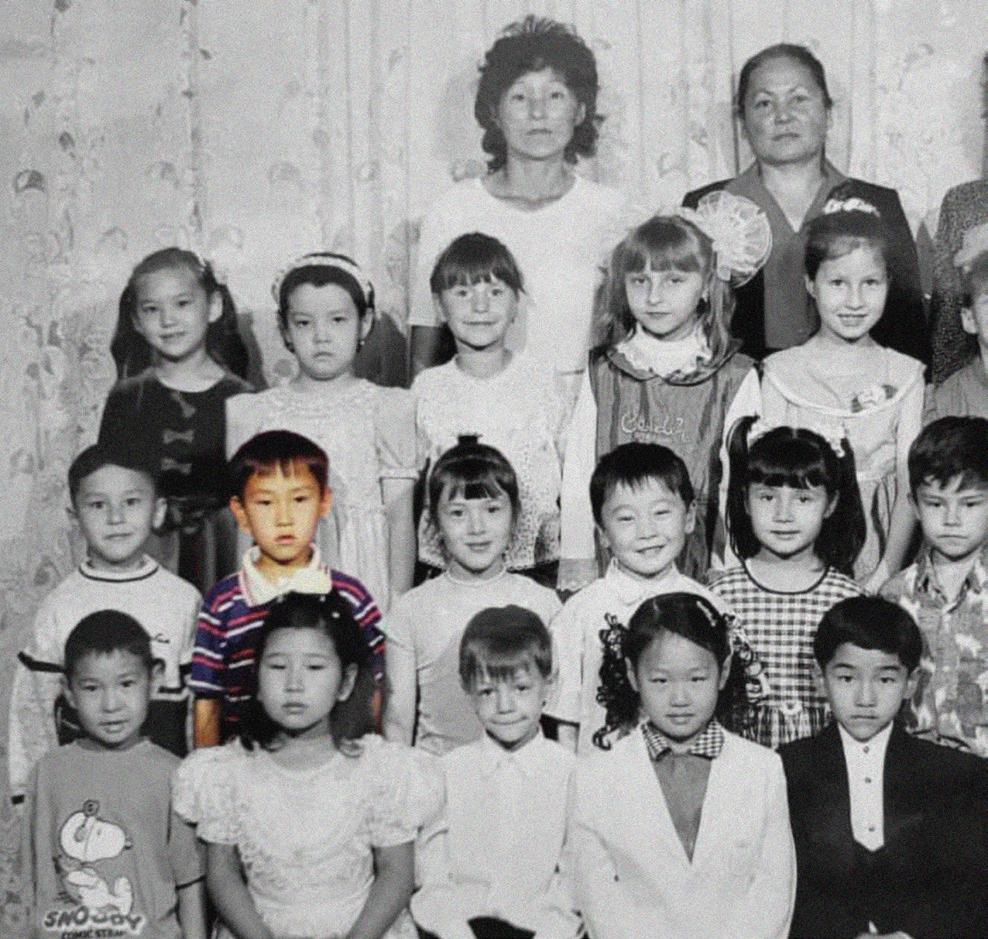

My first experience with education began at three years old when I started kindergarten. It was a familiar place for many children in the neighborhood - a concrete block building with bright classrooms divided by age groups. In my group of 25 kids, under the guidance of one teacher, every day was filled with new discoveries. Our classroom had small wooden chairs and tables, where we learned through songs, stories, and play.

At the back of the building, there was modest courtyard where all the groups could meet and play together. In the summer, I loved spending time in the sandpit, building castles and digging tunnels. In the winter, the same space transformed into a snowy playground where we built snowmen and had playful snowball fights.

Looking back, kindergarten was not just my first step into education but also a place where I built friendships, developed curiosity, and experienced the joy of shared learning - both in the classroom and out in the open.

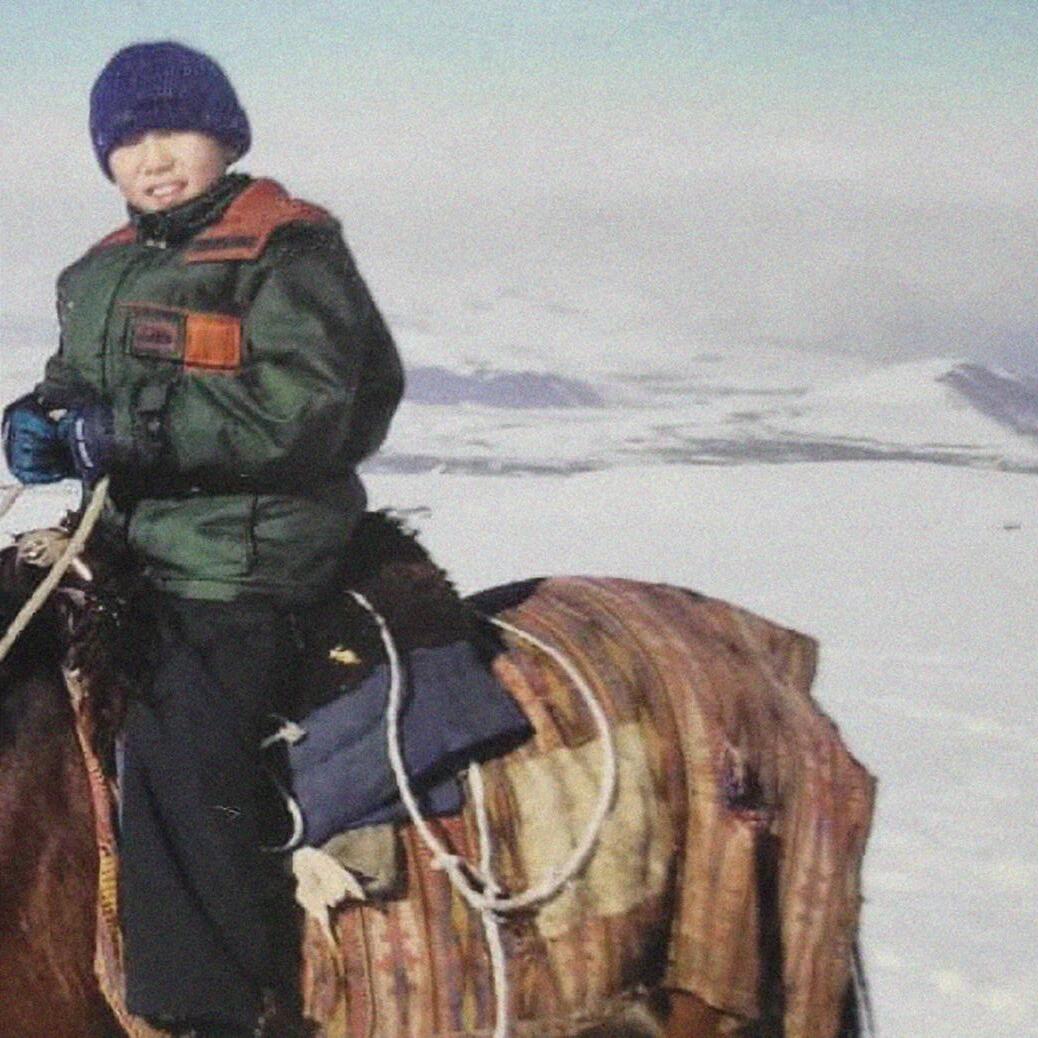

Although raised in the urban environment of Bishkek, big part of my childhood was shaped by the time spent in nature, a vital element of Kyrgyz heritage. Traveling across the country with my family, I encountered communities that led lives radically different from the urban way of life. Among these encounters were the nomadic children of local herders. During the pasture seasons, they traveled alongside their

families, moving through the vast landscapes of Kyrgyzstan. This nomadic lifestyle, while rich in traditions, also meant these children were disconnected from education and many aspects of modern life. This early exposure to their way of life left a lasting impression, influencing my understanding of the complexities of rural life in Kyrgyzstan.

Education should be accessible to all kids everywhere.

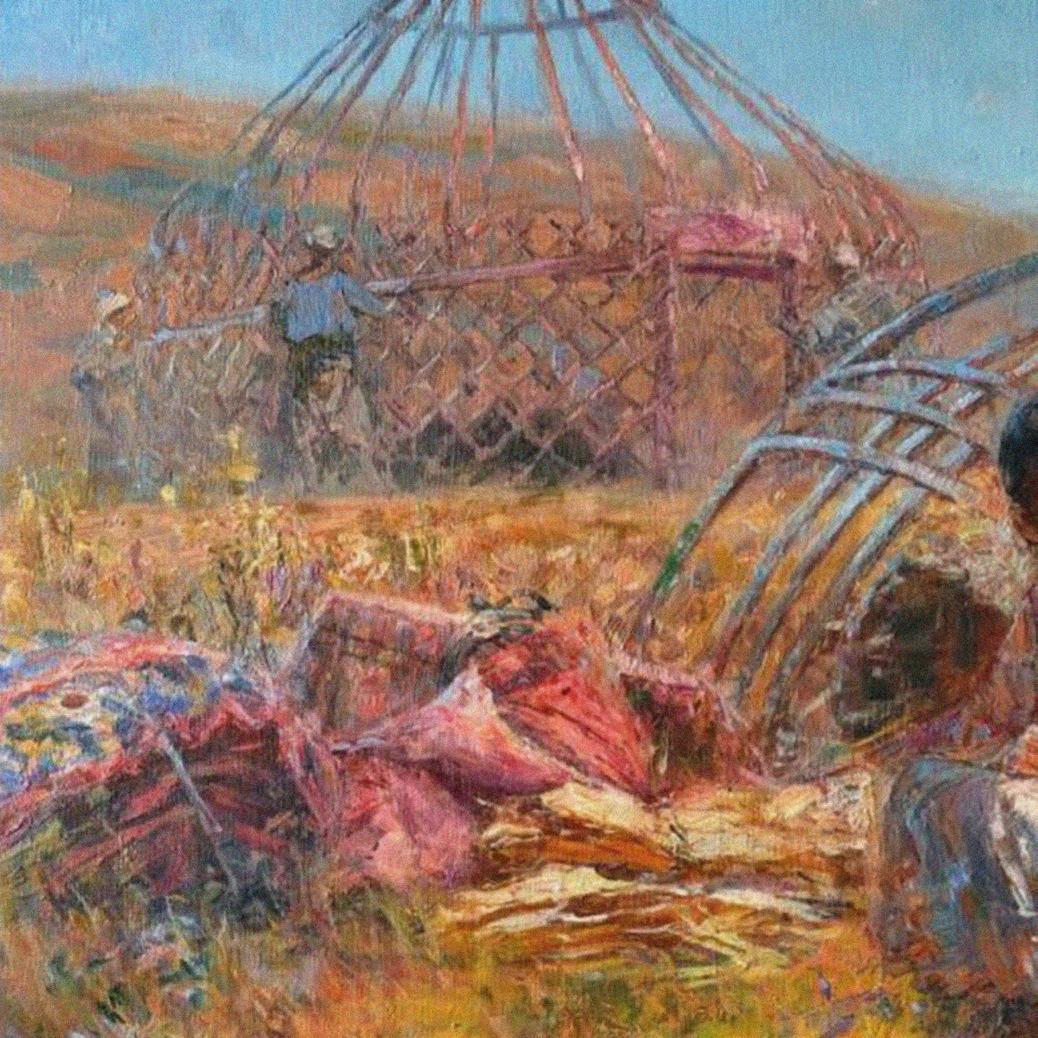

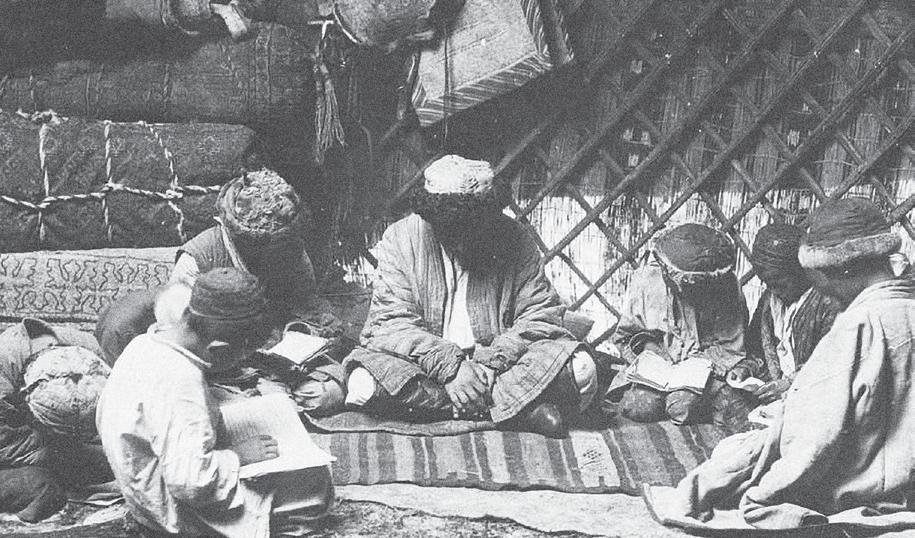

Education in Kyrgyzstan has evolved through significant historical shifts, shaped by both internal traditions and external influences.

In ancient times, Kyrgyz nomads passed down knowledge through oral traditions and craftsmanship. Between the 7th and 12th centuries, they developed their own alphabet, but later, Arabic influence led to the adoption of a new script and the introduction of Islam. Madrasahs (Islamic schools) played a crucial role in education, significantly increasing literacy. However, the Mongol invasion in the 13th century devastated educational institutions, causing a major setback. Despite these hardships, efforts to document history and preserve knowledge continued. By the late 18th century, after regaining stability, Kyrgyzstan saw a resurgence in education, with many new madrasahs being established.

With Kyrgyzstan’s incorporation into the Russian Empire in the late 19th century, education became a tool for cultural assimilation. The first Russian school opened in Tokmok in 1870, followed by institutions in Karakol and Bishkek. These schools taught Russian language, history, and geography, gradually phasing out religious education. Though classes were initially in Kyrgyz, Cyrillic script was introduced in 1876, and Russian became the primary language of instruction. Local teachers were supervised by Russian authorities, and preparatory schools were established to help Kyrgyz children integrate into the system. By 1917, Kyrgyzstan had 17 schools with 800 students, and evening classes were introduced for adults to combat illiteracy.

Upon joining the Soviet Union in 1936, Kyrgyzstan underwent rapid educational reforms. Efforts to eliminate illiteracy led to widespread literacy programs for adults. Schools expanded, and by the late 20th century, Kyrgyz secondary education had an 86.6% graduation rate. The Latin alphabet was briefly introduced in 1928 before being replaced again with Cyrillic in 1940. The Soviet period saw a 15-fold increase in schools, a 114-fold rise in students, and a 230fold growth in teachers. Higher education institutions, including Kyrgyz State University, med-

ical schools, and agricultural colleges, played a vital role in professional development.

However, Soviet education was heavily regulated, limiting foreign educational influences and enforcing communist ideology. The widespread use of Russian in schools contributed to the decline of the Kyrgyz language and cultural heritage. Despite these challenges, the Soviet era laid the foundation for a structured and extensive education system in Kyrgyzstan, which continues to shape the country’s academic landscape today.

Historically, education in Kyrgyzstan was deeply rooted in cultural traditions and adapted to the nomadic way of life. Knowledge was passed down orally through storytelling, craftsmanship, and mentorship within communities. This system prioritised practical skills, moral values, and philosophical teachings essential for survival. With the influence of Islam, madrasahs became centres of learning, integrating religious and academic studies. However, despite these institutions, education remained largely informal, shaped by the needs of Kyrgyz society rather than structured institutional models.

With the Soviet era came a centralised, standardised education system that aimed to modernise and unify learning. Schools were built to provide structured, state-controlled education, heavily influenced by Russian pedagogy. The focus shifted towards literacy, science, and ideological training, replacing traditional Kyrgyz methods. However, the Soviet system often overlooked local cultural needs, imposing foreign teaching methodologies that did not always align with Kyrgyz traditions. Additionally, the infrastructure of educational institutions in the city was not designed to accommodate future growth, leading to overcrowded classrooms and inadequate learning environments.

places 44 indigenous people 56 vernacular architecture 84 target group 108 case study 116

“Younger

What role does architecture play in designing sustainable preschools for semi-nomads, that can adapt to the cultural and climatic conditions of remote Kyrgyzstan?

The role of architecture in designing sustainable preschools for semi-nomadic communities in remote Kyrgyzstan is crucial in ensuring accessibility, cultural relevance, and environmental adaptability. Given the country’s diverse landscapes, harsh climatic conditions, and deeply rooted nomadic traditions, educational spaces must be thoughtfully designed to serve the needs of both children and their communities.

A key challenge is creating preschool environments that are not only functional but also flexible enough to accommodate semi-nomadic lifestyles. Architecture must balance mobility with permanence, allowing for seasonal movements while providing stable, high-quality learning conditions. This raises questions about the use of locally available materials, modular construction techniques, and energy-efficient solutions.

Moreover, the design of these preschools should reflect and respect Kyrgyz cultural val-

ues. Traditional nomadic dwellings, such as the yurt, emphasise communal learning and adaptable spaces, which can inspire contemporary architectural solutions. Integrating elements of vernacular architecture can foster a sense of identity and belonging, making early education more engaging and relevant for children from semi-nomadic backgrounds.

Ultimately, this research seeks to explore how architecture can create sustainable, adaptable, and culturally sensitive preschool environments. The proposed design serves as a prototype, intended not only for Kyrgyzstan but also for other nomadic and semi-nomadic communities worldwide. By addressing both practical and social dimensions, the goal is to develop innovative models that support early childhood education in remote regions, ensuring that learning spaces are both resilient and deeply connected to the way of life of the communities they serve.

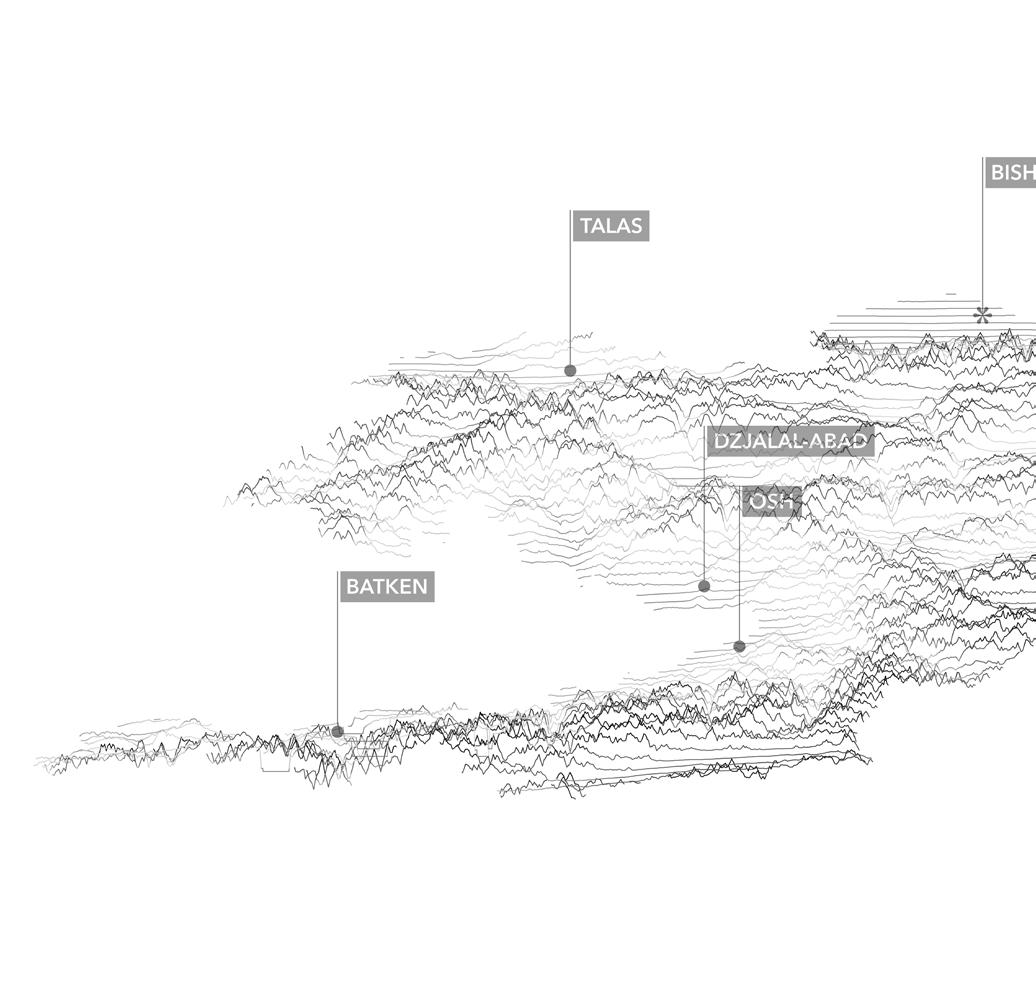

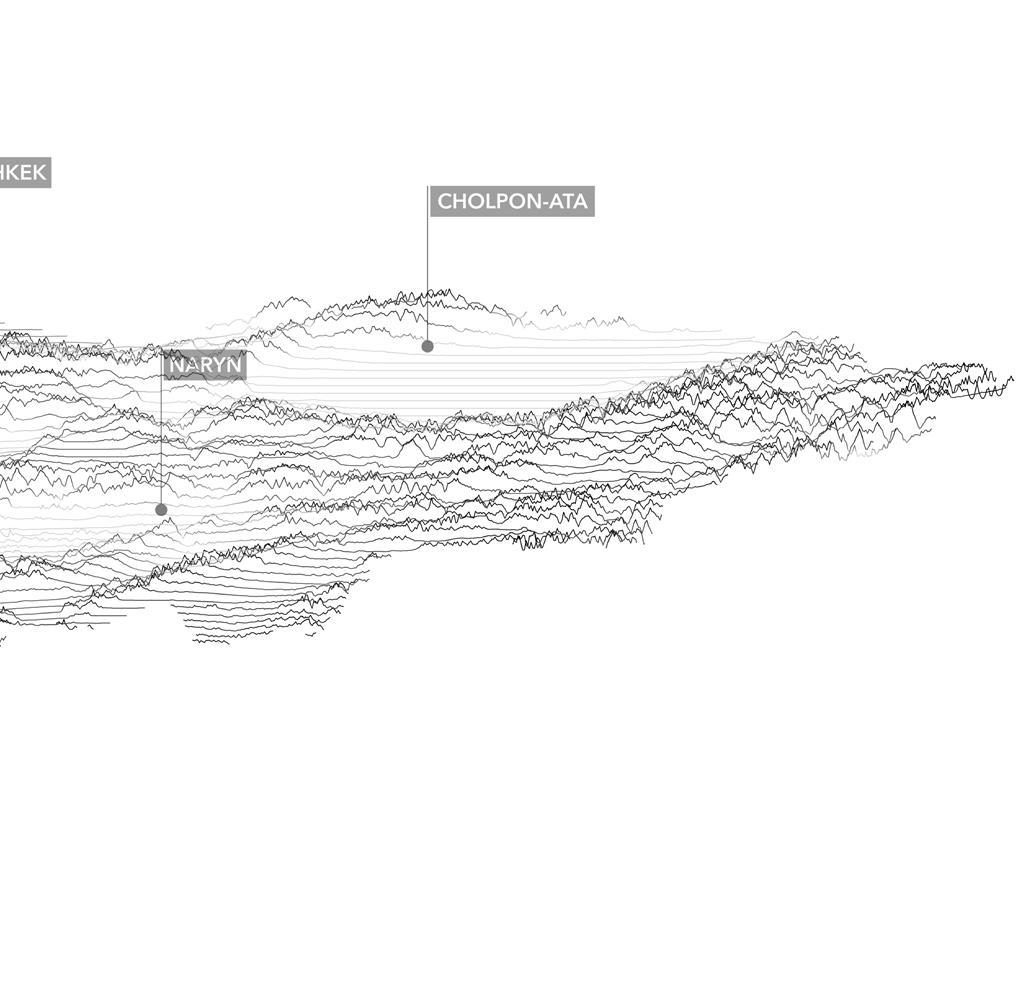

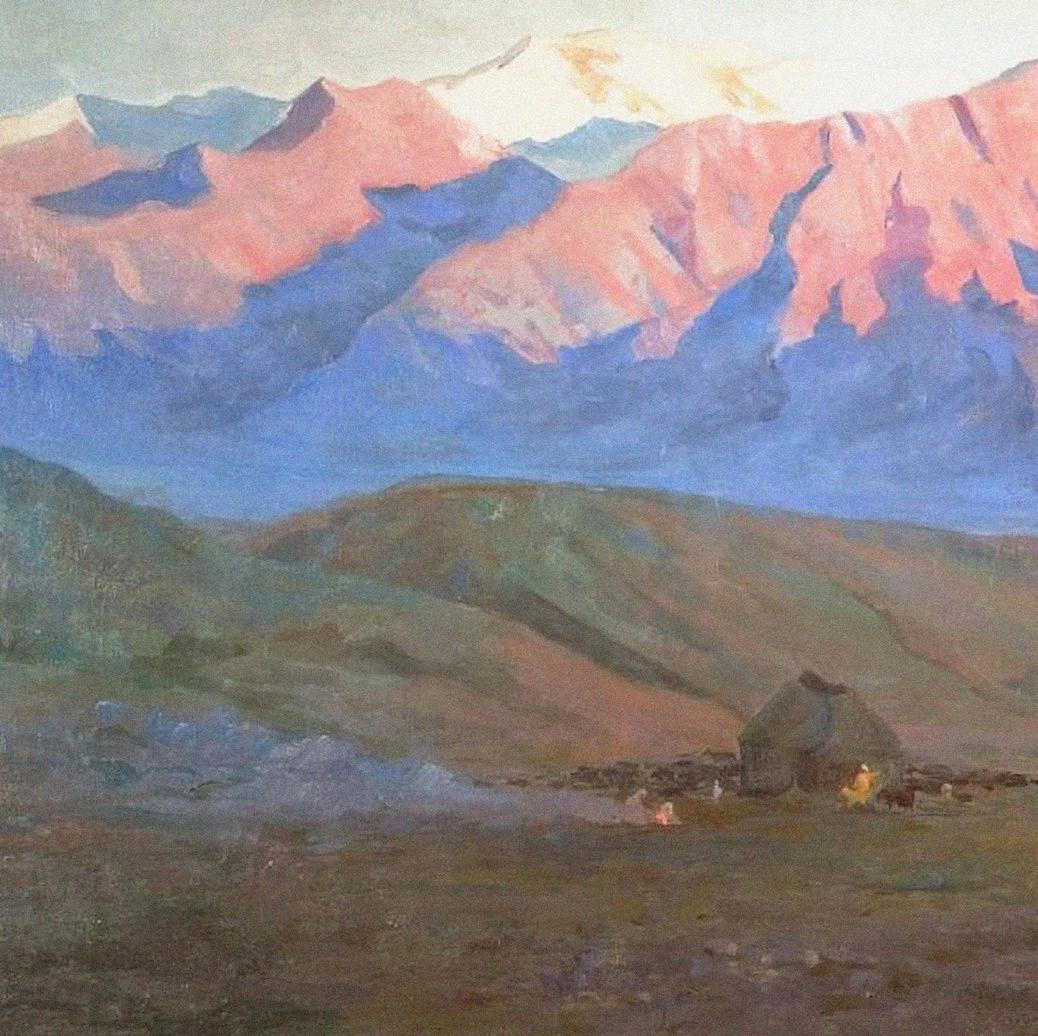

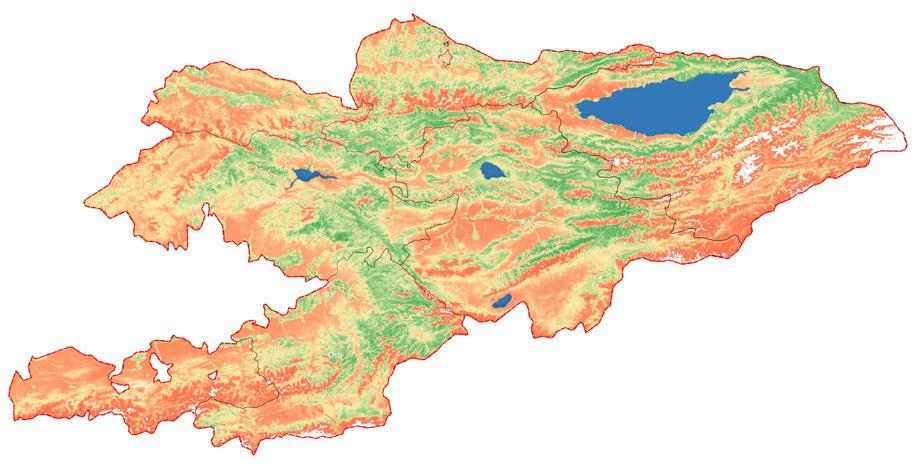

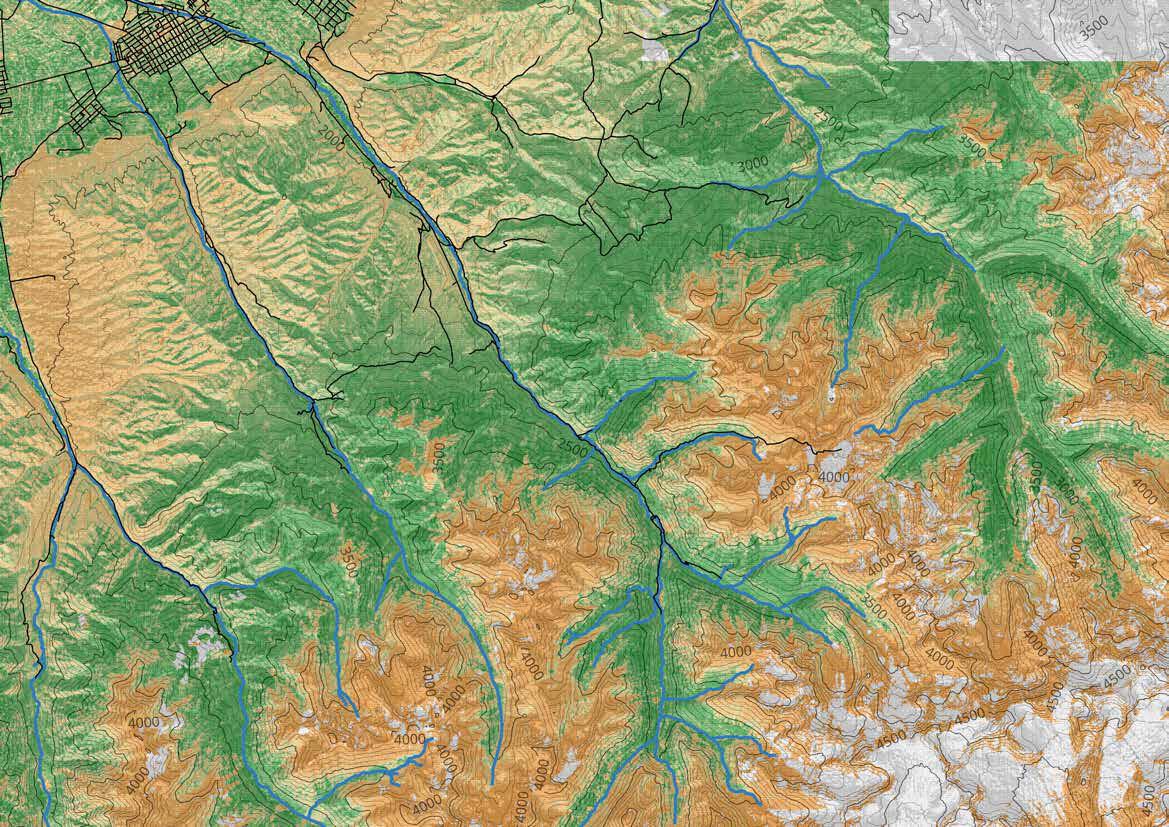

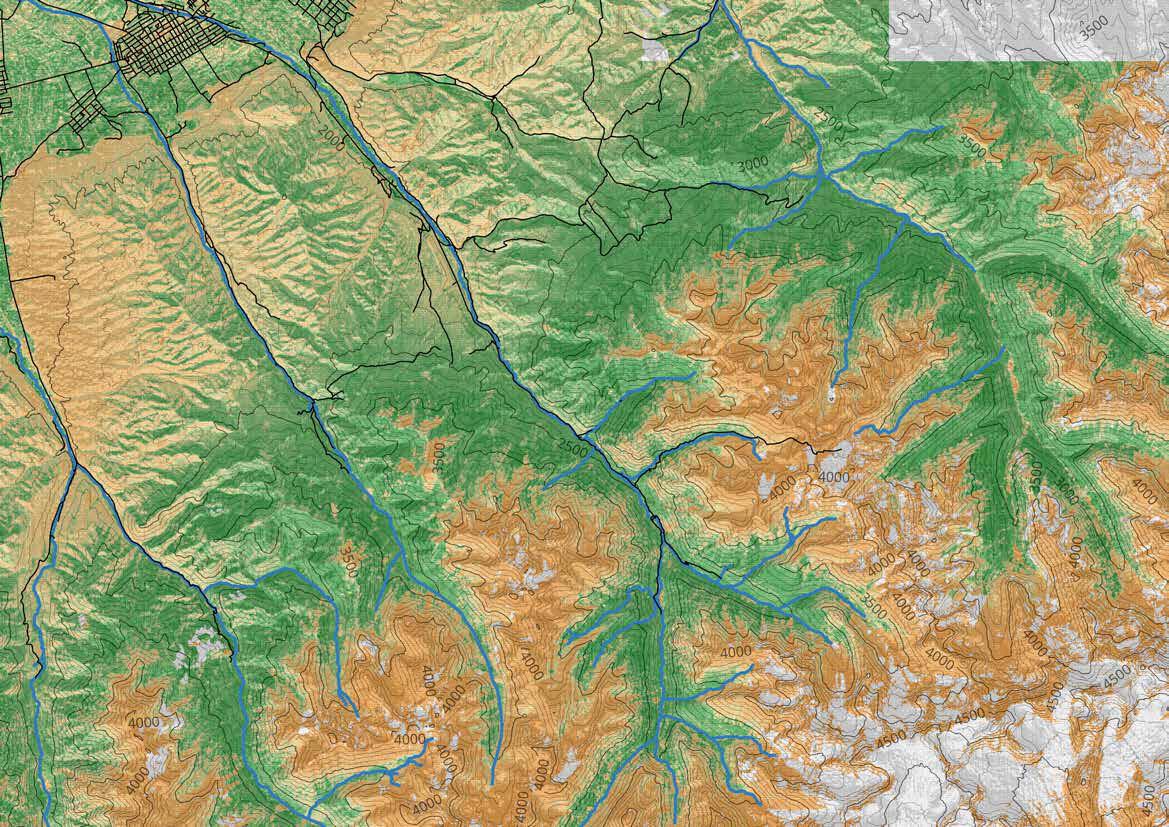

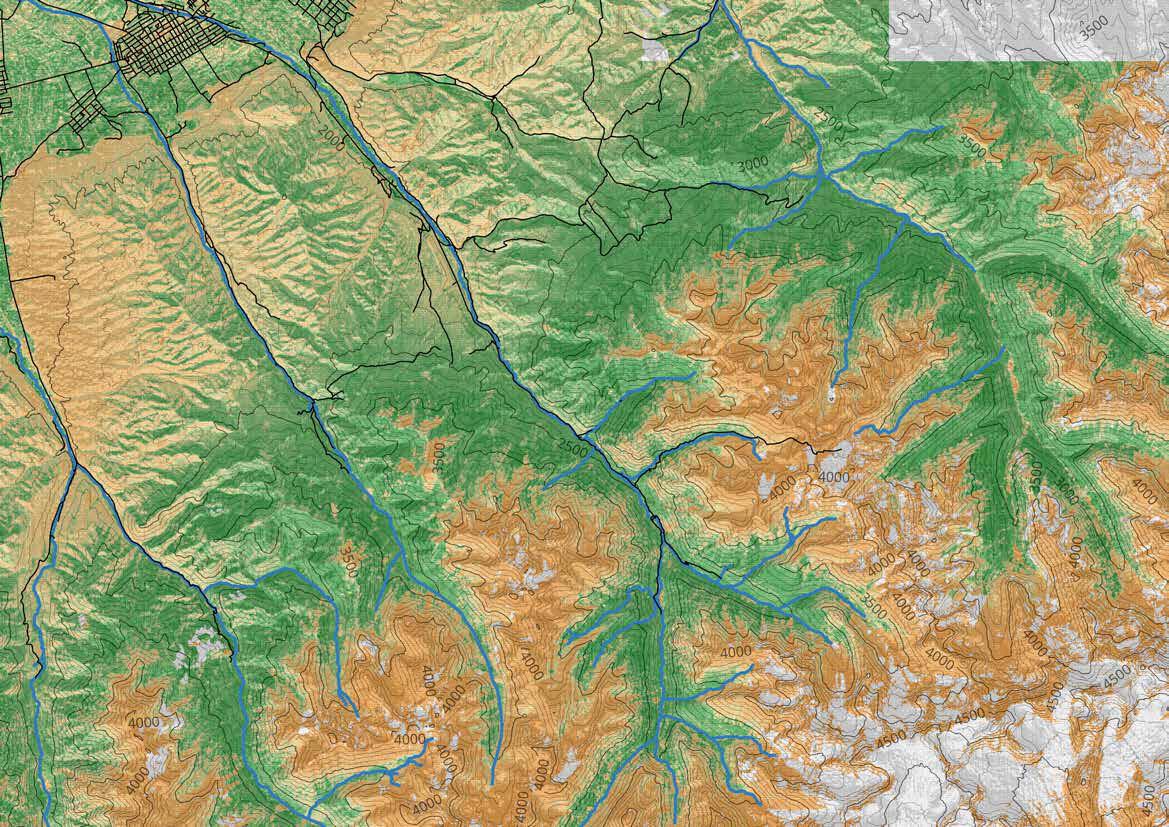

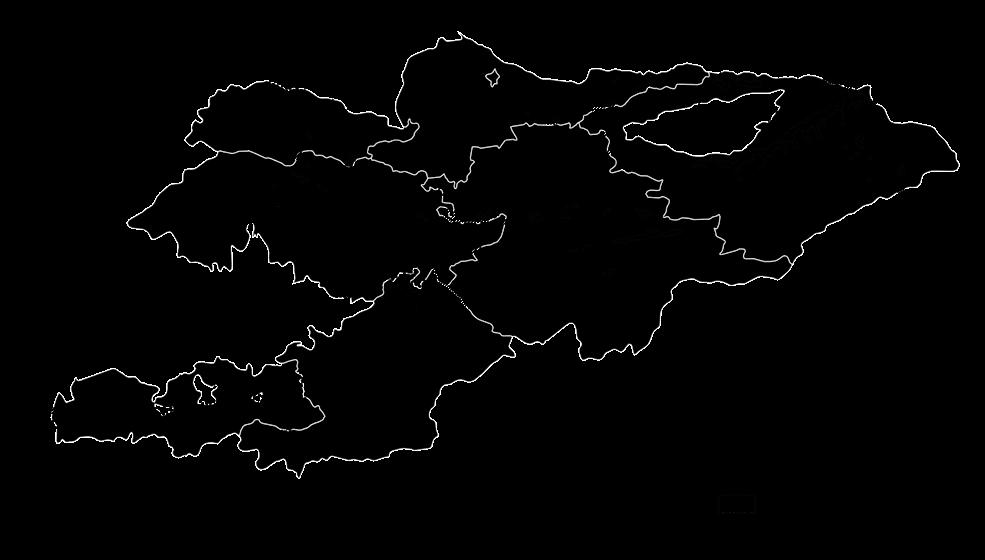

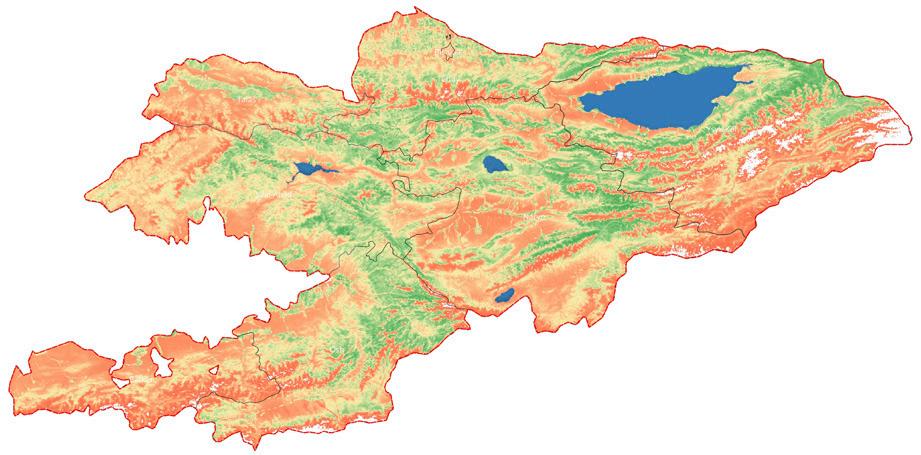

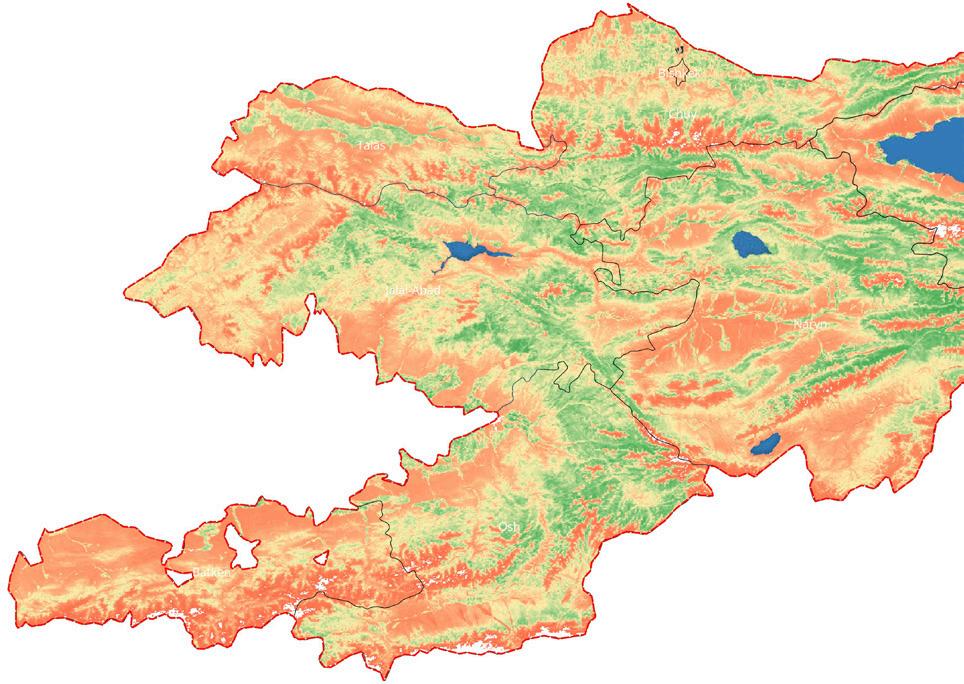

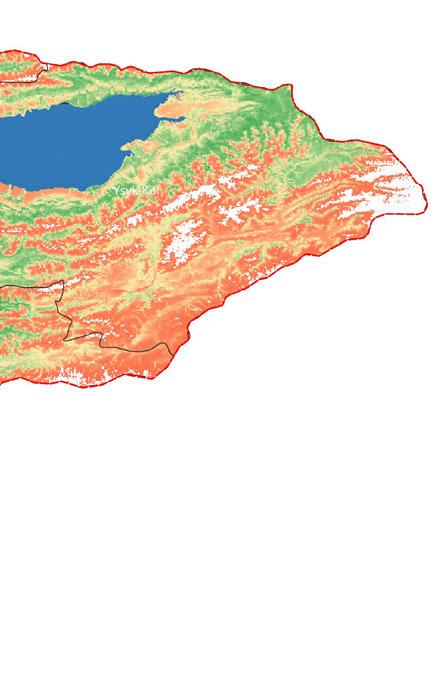

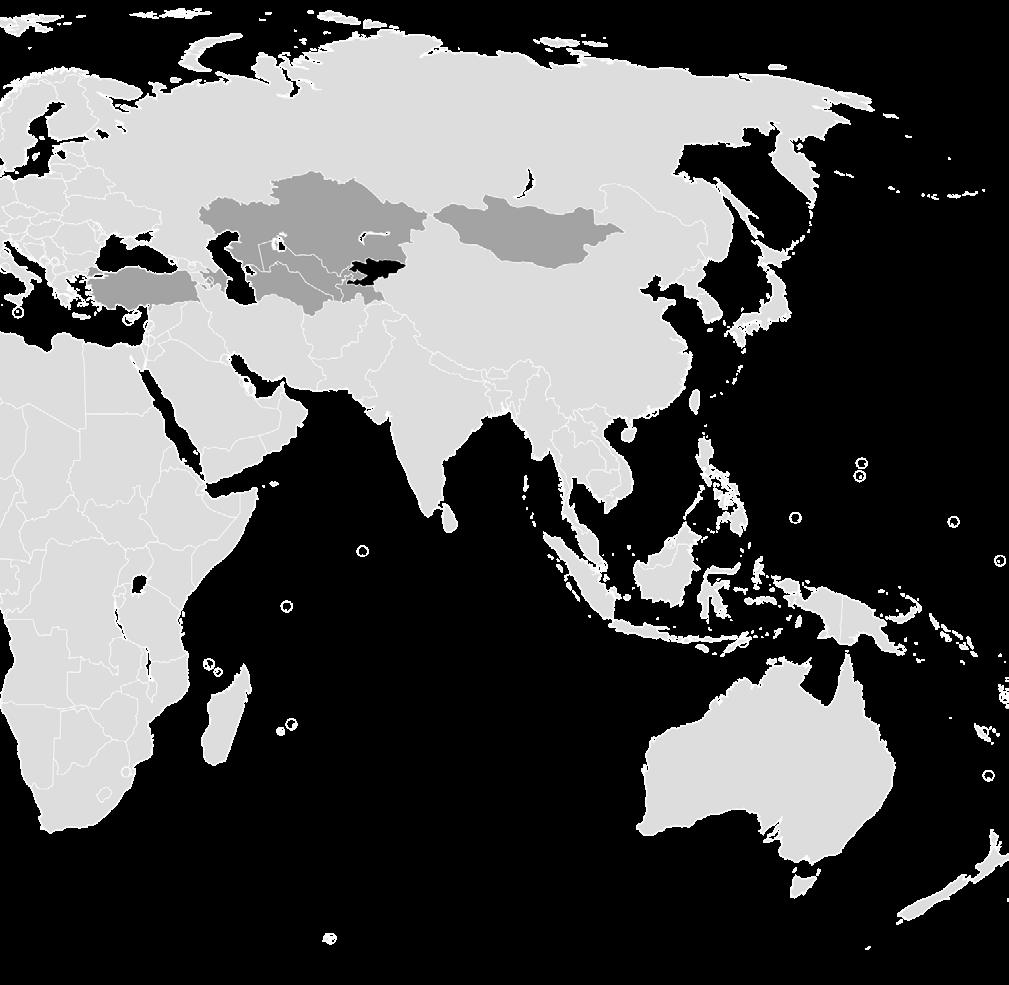

Kyrgyzstan is a landlocked country characterised by its dramatic mountainous landscape, which plays a significant role in shaping the distribution of its population. Around 86% of the country is covered by mountains, particularly the Tien Shan range, which stretches across much of the country. The rugged terrain and high altitudes create natural divisions that influence how people live and work.

The urban population, accounting for 35%, is concentrated in cities and towns nestled in the valleys and foothills of these mountain ranges, where the land is more accessible for agriculture and infrastructure development. Bishkek,

the capital, is located in the Chui Valley, offering a more stable and developed environment for those seeking employment, education, and modern services.

The majority of Kyrgyz people, about 55%, live in rural areas, often in small villages and settlements spread across the lower foothills or along rivers. These regions are more suitable for farming, with arable land supporting a predominantly agricultural lifestyle. Despite being less developed than the cities, rural areas are home to traditional Kyrgyz culture, where families live in close-knit communities and often practice livestock farming.

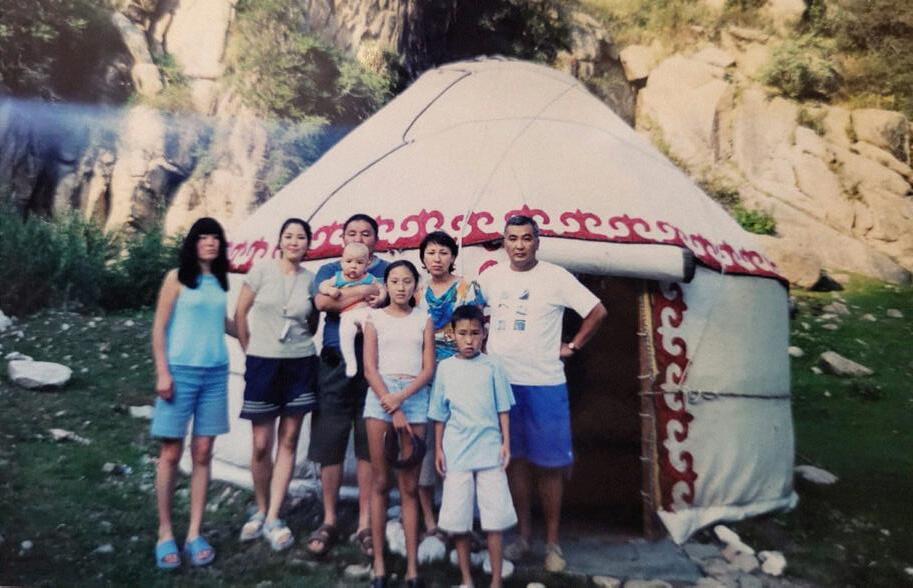

A unique aspect of Kyrgyzstan is the approximately 10% of the population that lives in remote pasture areas, often referred to “summer pastures” (“jailoo” in kyrgyz). These semi-nomadic communities inhabit high-altitude areas, where they move their livestock seasonally in response to the harsh climate. During the warmer months, families live in yurts, migrating with their herds to higher pastures, while in the winter, they return to the rural areas.

In recent years, Kyrgyzstan has undergone significant urbanisation, as many people from ru-

ral areas and remote pastures are increasingly migrating to larger cities in search of better opportunities and a more comfortable lifestyle. As cities like Bishkek continue to grow, the pull of urban centres for work, education, and access to modern amenities becomes stronger. This shift towards urbanisation is reshaping the country’s demographic landscape, as younger generations, in particular, seek to leave behind the hardships of rural and remote living in favour of a more modern, convenient existence. It also brings new challenges, such as overcrowding and the strain on infrastructure.

The vast mountains of Kyrgyzstan not only define the physical landscape but also influence social structures, cultural practices, and the way communities adapt to their environment. The varying altitudes and isolation of different regions contribute to a population that is spread across urban, rural, and remote areas, each shaped by the unique challenges and opportunities the mountainous terrain provides.

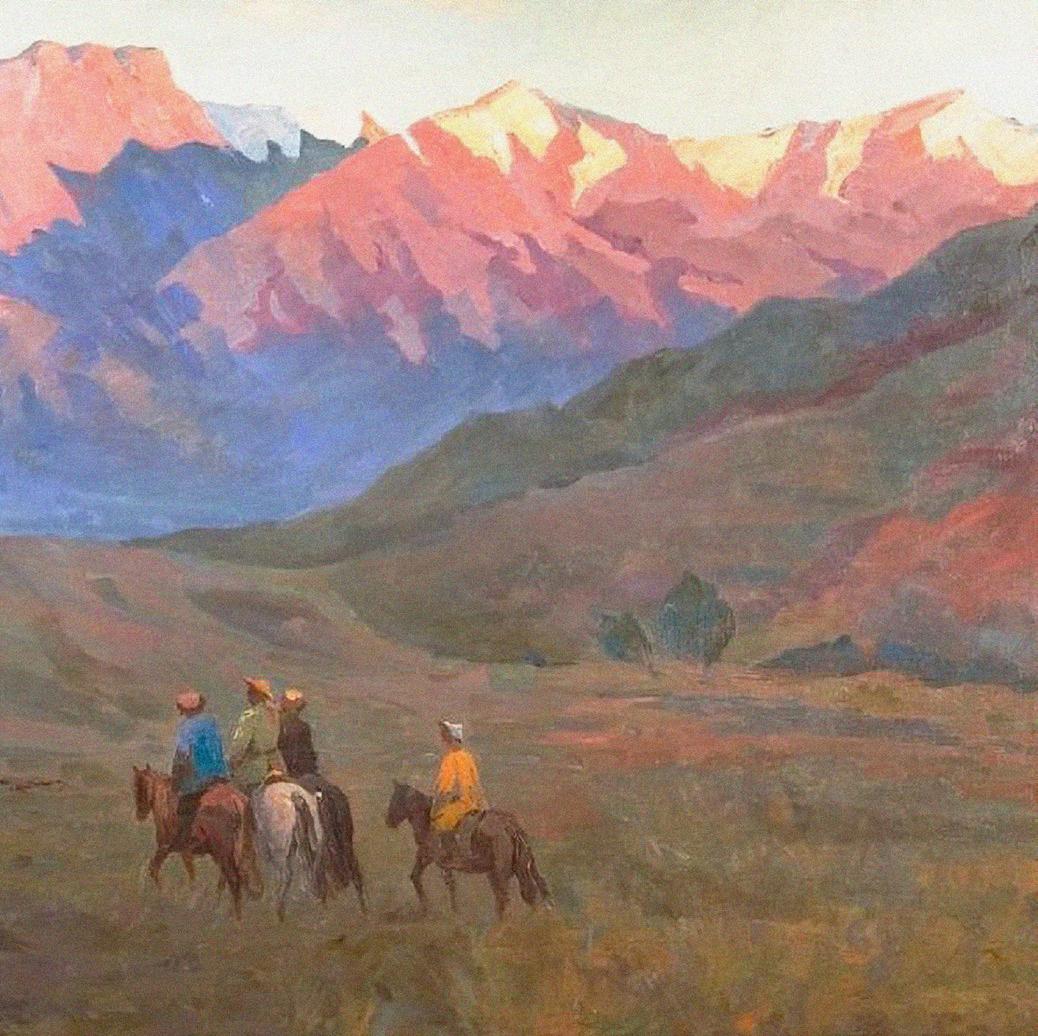

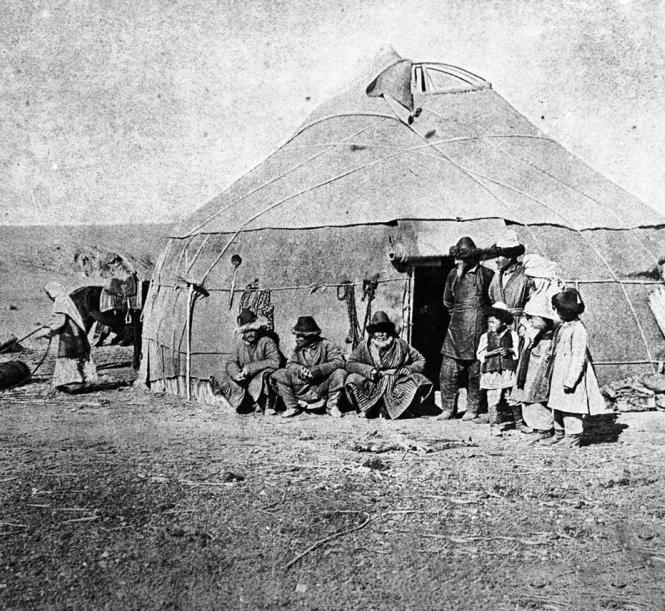

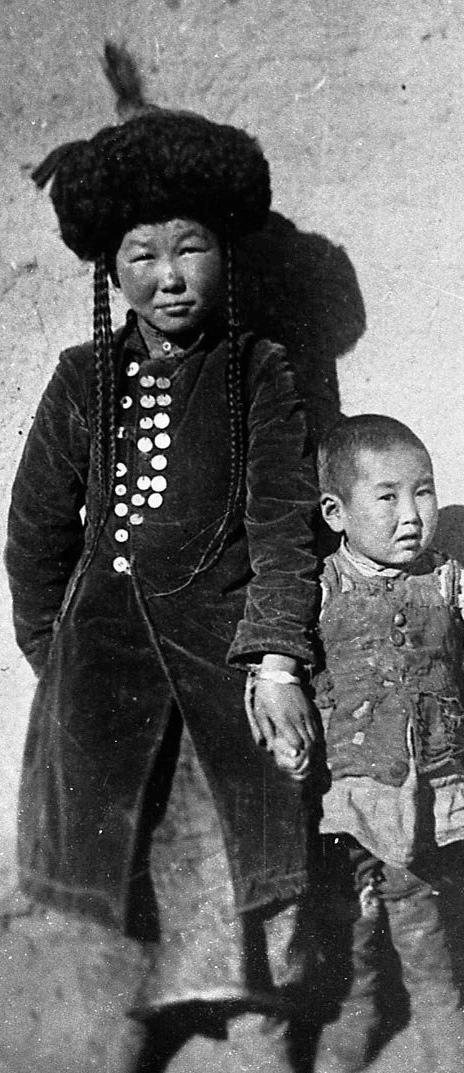

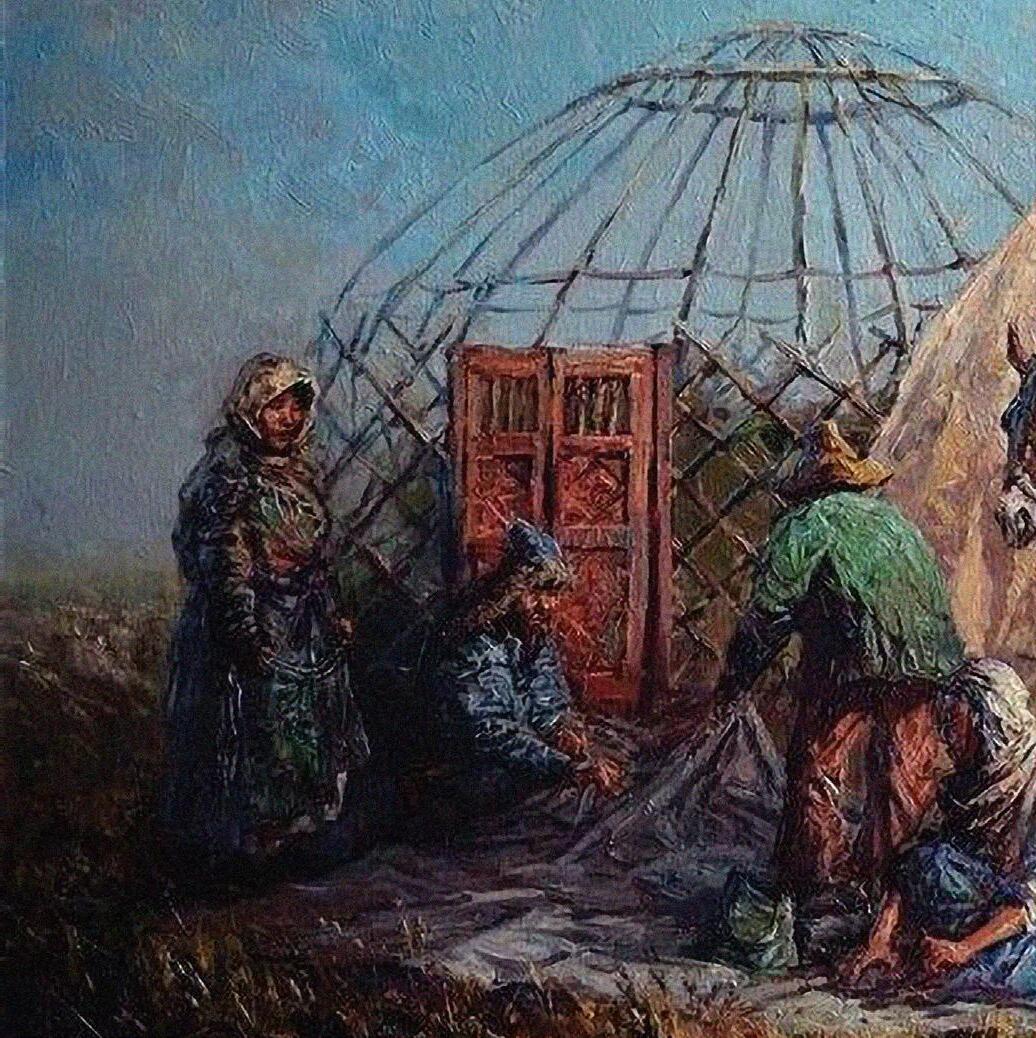

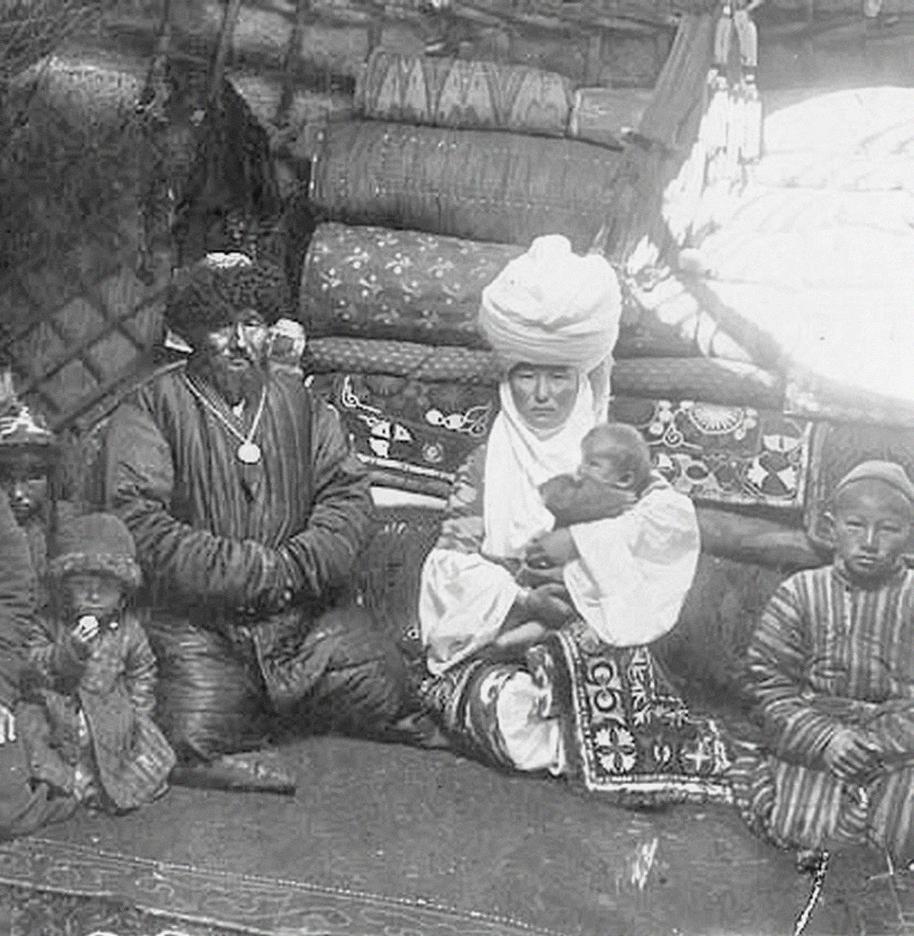

The original Kyrgyz nomads are a historically significant group of people who have lived in the mountainous regions of Central Asia for centuries. Their way of life is deeply tied to the vast, rugged landscapes of Kyrgyzstan, where they practiced seasonal migration with their herds of livestock. The Kyrgyz nomads traditionally lived in yurts, portable tents that allowed them to move easily with their animals between summer and winter pastures. Their lifestyle was centred around herding livestock, such as sheep, goats, cattle, and horses, and they relied on the natural resources of the land to sustain their communities.

Though many Kyrgyz people now live in rural and urban areas, the nomadic heritage continues to shape the cultural fabric of the country, with certain communities still practicing semi-nomadic lifestyles. The Kyrgyz nomads’ deep connection to the land and their resilience in adapting to the harsh environment remains an important aspect of their legacy.

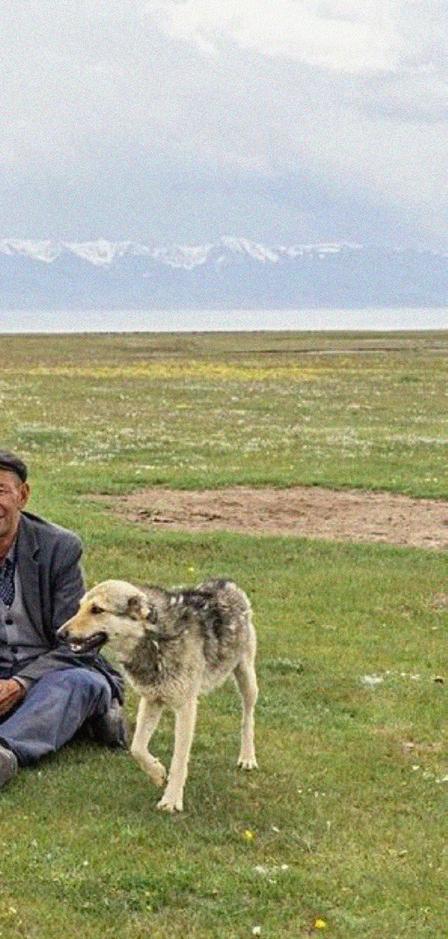

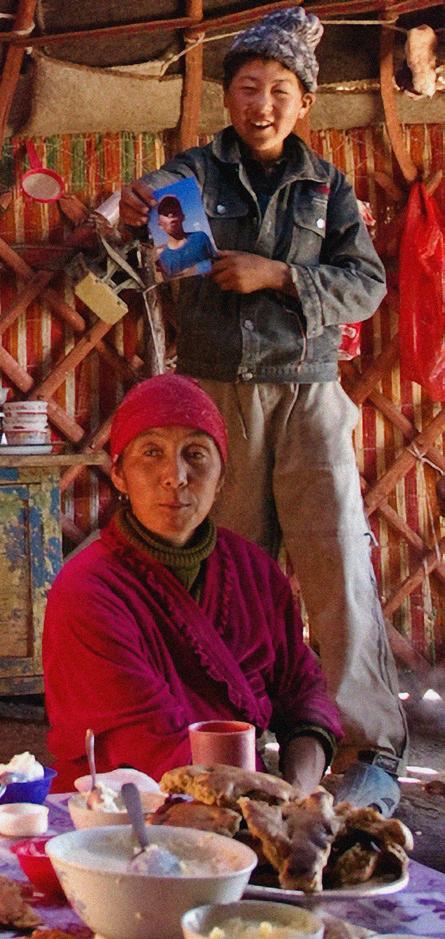

Kyrgyz semi-nomads are a unique group whose way of life is derived from the original nomadic traditions but adapted to modern realities. They continue to live according to the natural cycles of the land, moving seasonally between high mountain pastures and rural settlements. Semi-nomads are mostly families with children, where older members are occupied with daily duties such as herding, milking, and preparing

food, while the younger generation enjoys the freedom of nature, playing in the open landscapes and learning traditional skills from their elders. This semi-nomadic lifestyle is deeply influenced by the harsh climate and geography of Kyrgyzstan, where the extreme temperatures of winter and summer require a flexible and adaptive approach to living.

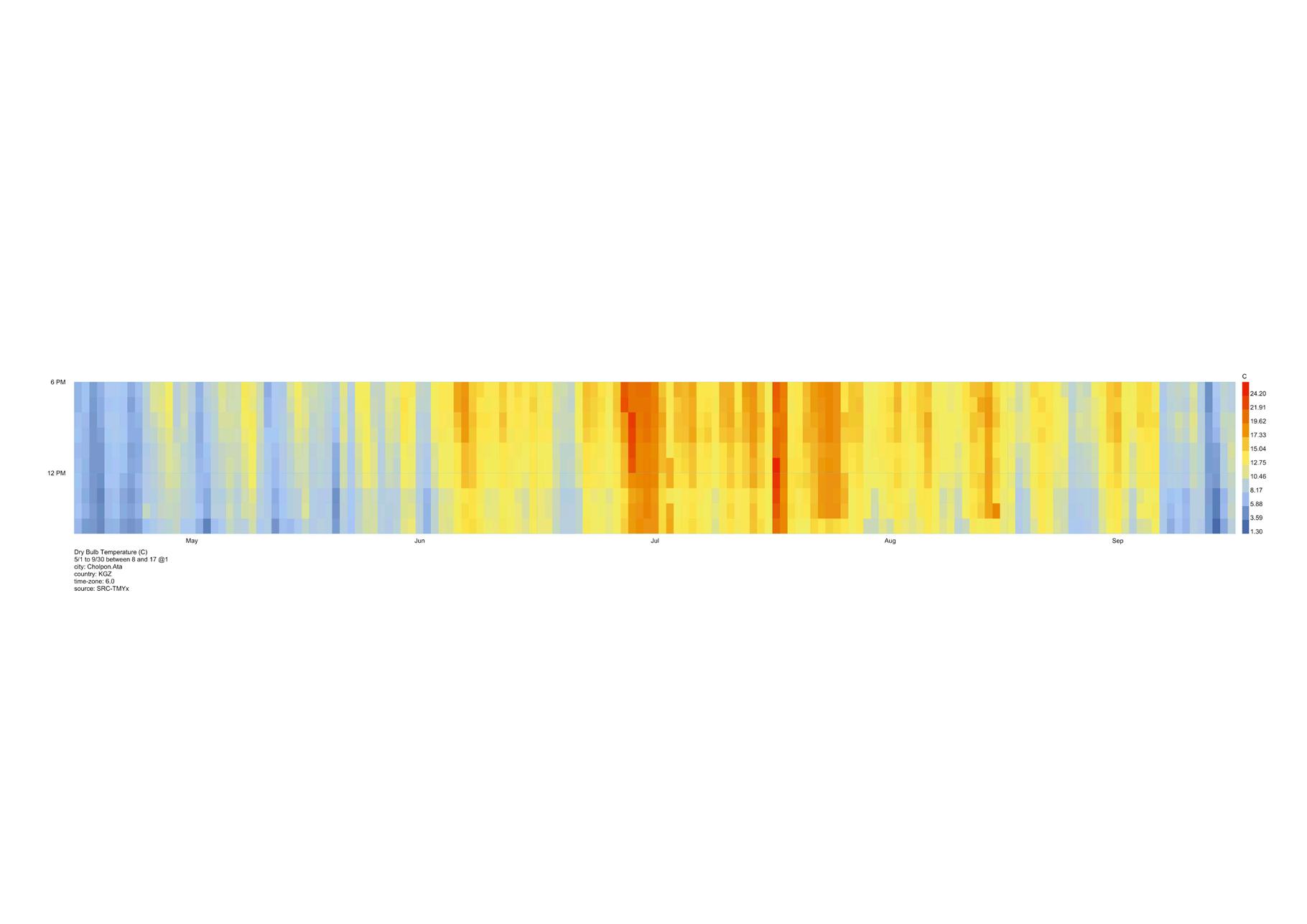

Issyk-Kul region

When the temperature drops and the harsh winter conditions set in, usually around October, the semi-nomadic families return to rural areas in the valleys and foothills, where they spend the colder months. These areas are more sheltered from the extreme winter weather, and while the families maintain a rural lifestyle, they are still connected to their nomadic roots. In these rural settlements, they rely on agriculture, small-scale farming, and the resources of the land to sustain themselves until the arrival of the warmer spring months.

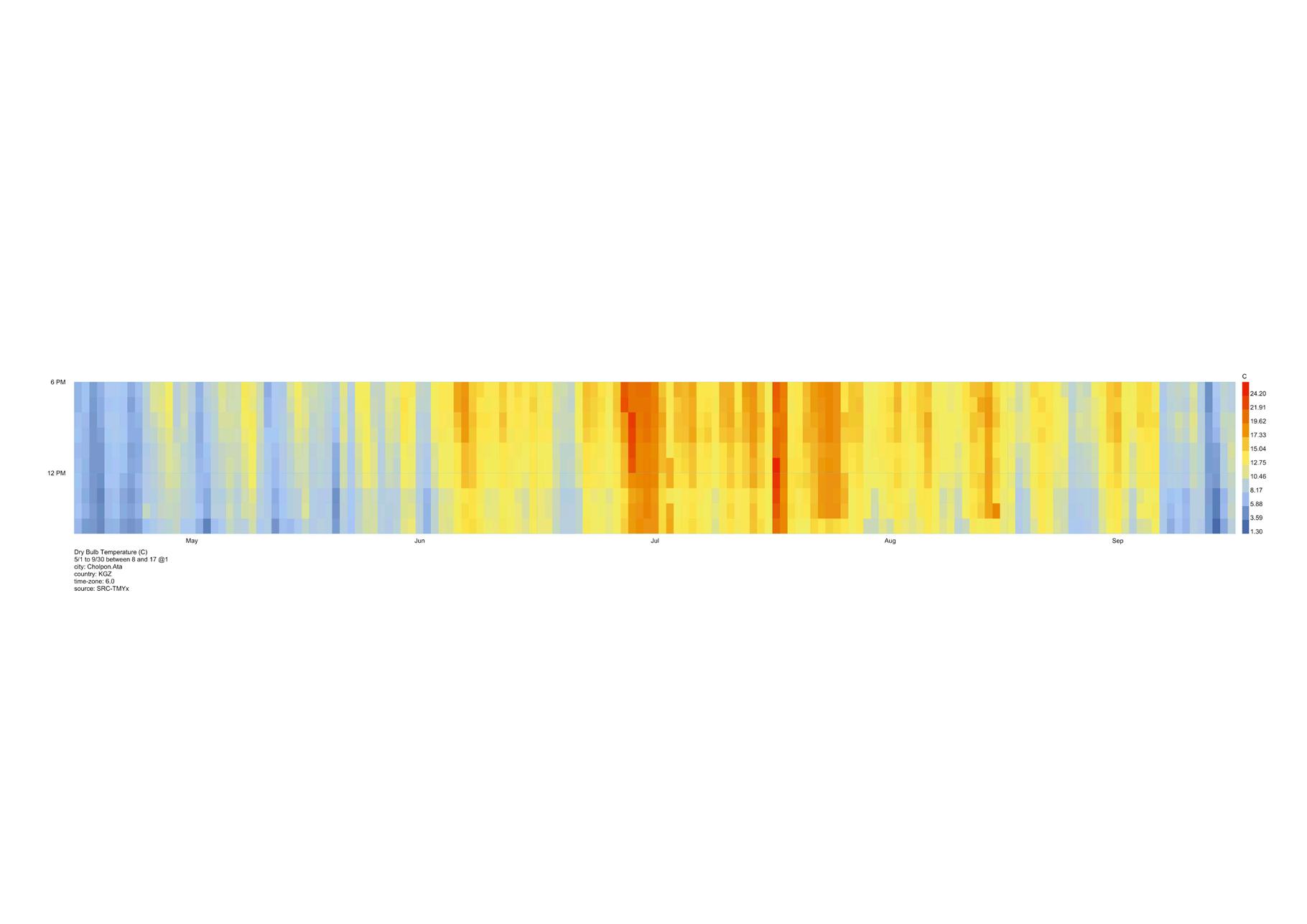

From May to October, the semi-nomadic families move with their livestock to the jailoo, the high-altitude summer pastures. The jailoo is a vital seasonal grazing ground, located in the mountains, where the herds can graze on fresh grass while the families live in traditional yurts. This period is crucial for livestock care, as the animals thrive in the cooler temperatures and lush vegetation of the higher elevations. The semi-nomads use this time to care for their animals, harvest milk, and prepare for the coming winter.

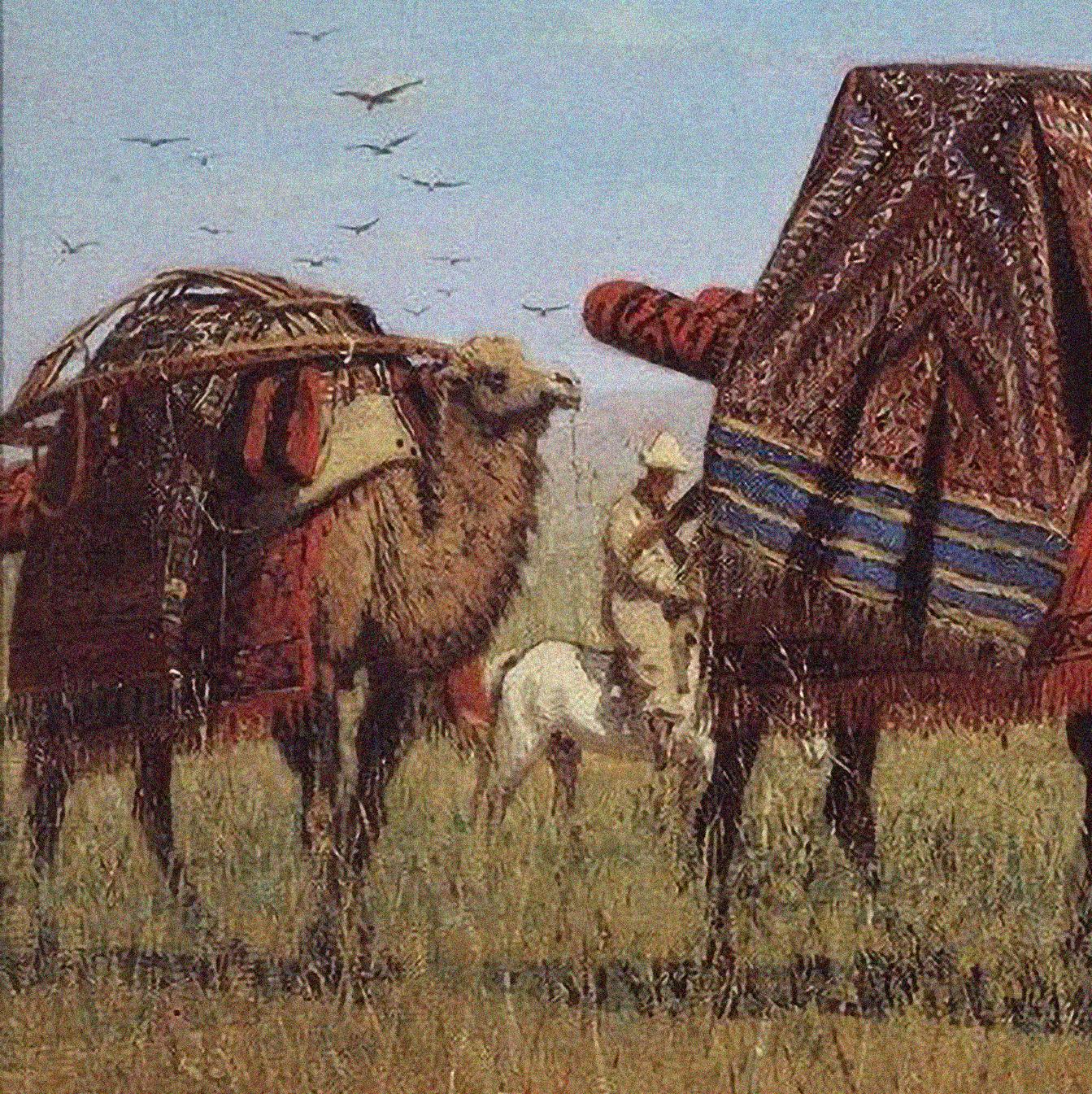

today’s horse power

Modern Kyrgyz semi-nomads have adapted their way of life to contemporary realities, including changes in transportation. Unlike traditional nomads who moved between pastures on horseback or with camel caravans, today’s semi-nomads rely on vehicles to travel between their seasonal destinations. This shift allows for faster and more efficient movement, making migration more manageable in the face of modern challenges.

When moving to the jailoo (high-altitude summer pastures) in May, semi-nomads load their

yurts and household supplies into trucks or trailers, reducing the physical strain and time required for relocation. These vehicles also enable families to transport larger amounts of goods, including food, fuel, and modern amenities that were previously unavailable in remote areas.

While horses still play a crucial role in daily herding activities, vehicles have become essential for long-distance travel and transporting heavy loads, marking a significant evolution in the Kyrgyz semi-nomadic lifestyle.

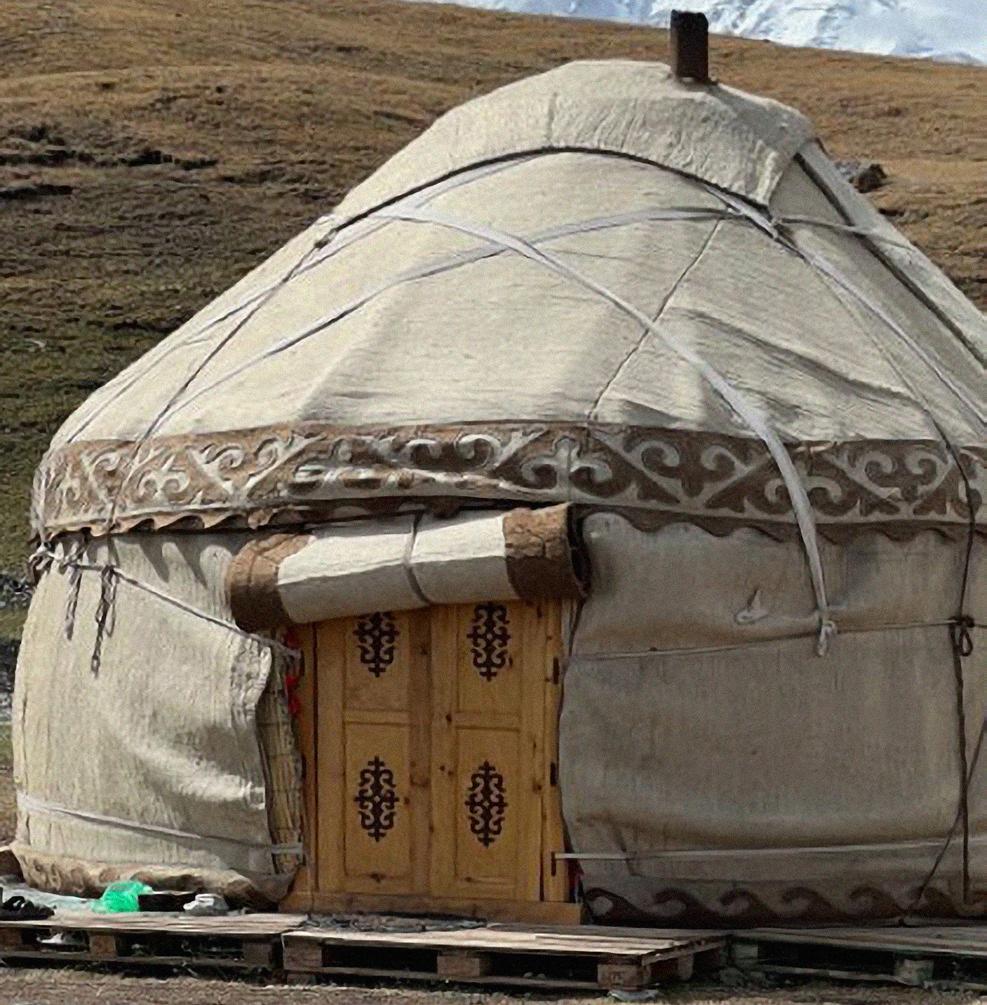

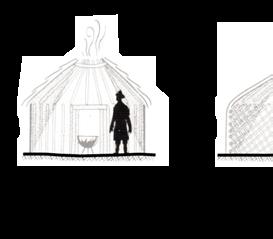

The yurt is an iconic symbol of nomadic life, representing both the resilience and adaptability of Central Asian cultures. Used for centuries by various nomadic nations, yurts serve as portable homes that provide shelter in the vast steppes and mountainous regions. These circular, tent-like structures are designed to be easily assembled, dismantled, and transported, making them ideal for communities that migrate with the seasons. While yurts are widely used across Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and other nomadic regions, the Kyrgyz yurt stands out as uniquely adapted to the rugged landscapes and extreme climates of Kyrgyzstan.

Unlike the yurts of other nomadic nations, the Kyrgyz yurt (called “Boz Üy” in Kyrgyz, meaning “Grey House”) has distinct structural and aesthetic features. While Mongolian yurts tend to have heavier, more rigid walls, and Kazakh yurts are often decorated with bright geometric patterns, the Kyrgyz yurt is designed for greater mobility, flexibility, and climate resilience. It is typically larger in size, with a more pronounced dome-shaped roof, allowing for better air circulation and insulation. Additionally, Kyrgyz yurts are known for their intricate wooden framework and symbolic decorations, which reflect the country’s deep cultural heritage.

assembled

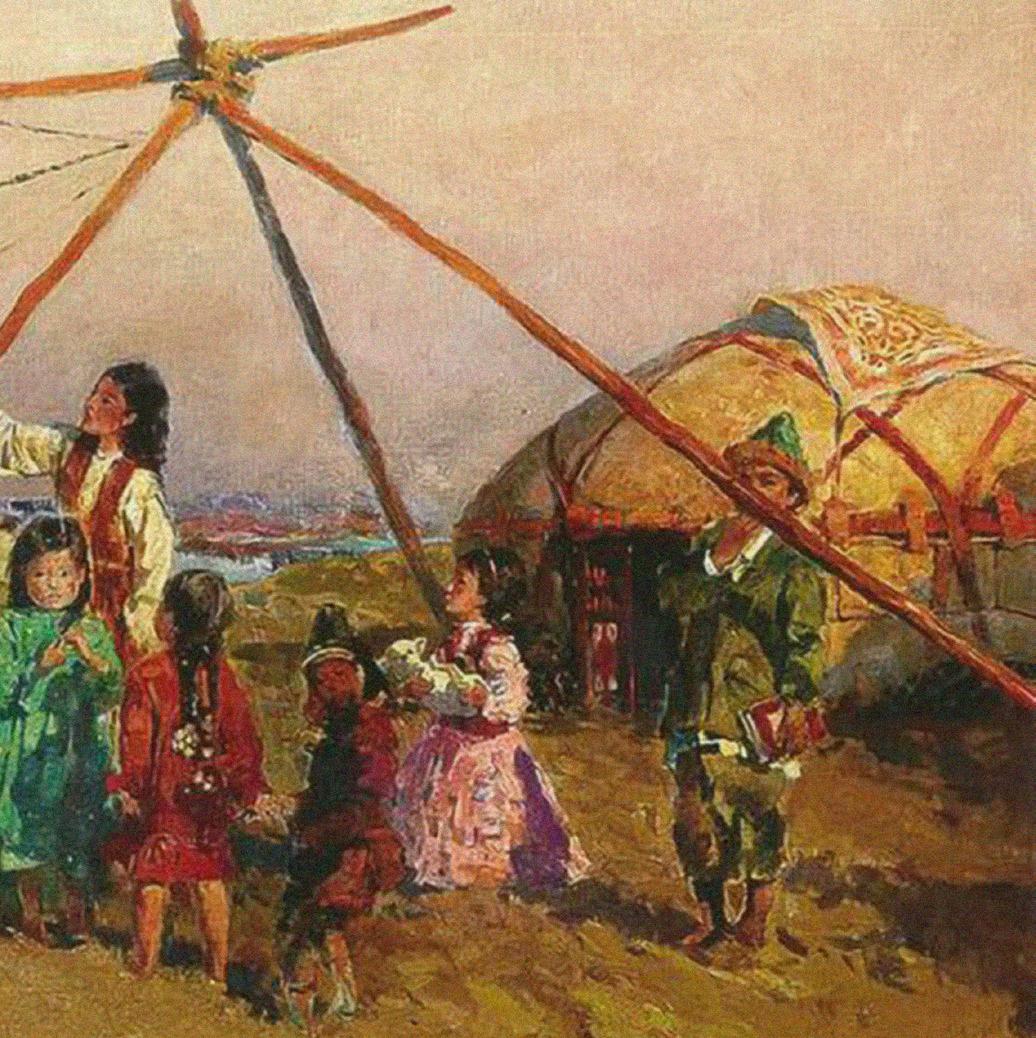

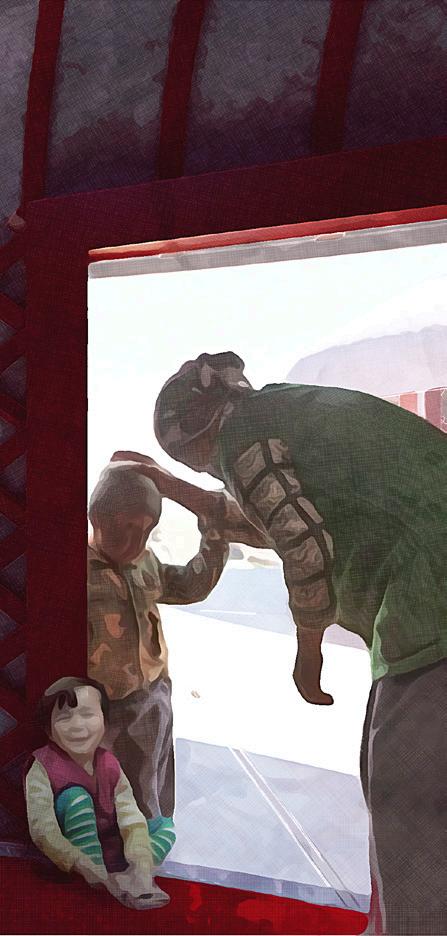

The Kyrgyz yurt is designed for quick assembly and disassembly, making it an essential home for semi-nomadic families who move seasonally between pastures. The structure consists of a lightweight yet sturdy wooden frame made from willow, which is held together without nails or screws, allowing for a flexible yet durable design. The entire yurt can be packed on two horses or, in modern times, transported by vehicle.

A crucial aspect of the Kyrgyz yurt is its harmony with nature. Since it is constructed entirely from natural materials - wood for the frame, felt made from sheep’s wool for insulation, and ropes woven from horsehair - the yurt leaves no permanent footprint on the land. When dismantled, it leaves the ground untouched, allowing

nature to recover quickly. This sustainable design aligns with the traditional Kyrgyz respect for the environment and the nomadic principle of living lightly on the land.

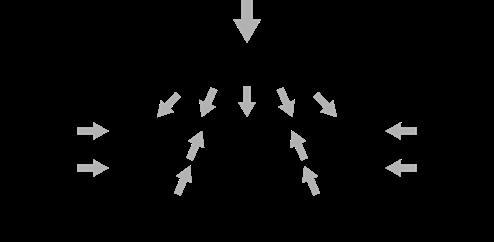

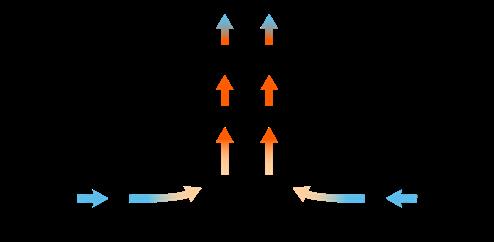

Kyrgyz yurts have evolved over centuries to withstand the country’s diverse and often harsh climate. In summer, the felt coverings can be lifted to allow airflow, keeping the interior cool, while in winter, thick layers of felt provide insulation against the extreme cold of the high-altitude pastures. The circular shape of the yurt also helps it withstand strong winds, distributing pressure evenly across the structure. The central opening at the top, called the “tunduk,” functions as both a ventilation and a source of light, allowing warmth to be efficiently distributed throughout the space.

downward pressure from weight of roof

by venturi effect (better with old-style raised tono)

The origins of the yurt date back to at least 3,000 years ago, with evidence of early nomadic dwellings found in the steppes of Central Asia. These early structures were developed out of necessity by nomadic tribes who followed their herds across vast landscapes in search of fresh pastures. The first yurts were likely simple and constructed directly in the ground, using lightweight wooden frames covered with animal hides or felted wool. These shelters provided quick and effective protection from the harsh elements, yet their close contact with the soil made them vulnerable to moisture, cold, and pests.

As nomadic cultures evolved, so did their dwellings. Over centuries, the structure of the yurt became more sophisticated and efficient, adapting to the environmental challenges of wind, snow, and extreme temperatures. The once simple tent transformed into an intricate, self-supporting wooden frame, featuring a circular lattice wall (kerege), flexible roof poles (uuk), and a central wooden crown (tunduk) that allowed smoke to escape while maintaining stability. This engineering advancement eliminated the need for ground stakes, making the yurt freestanding and durable.

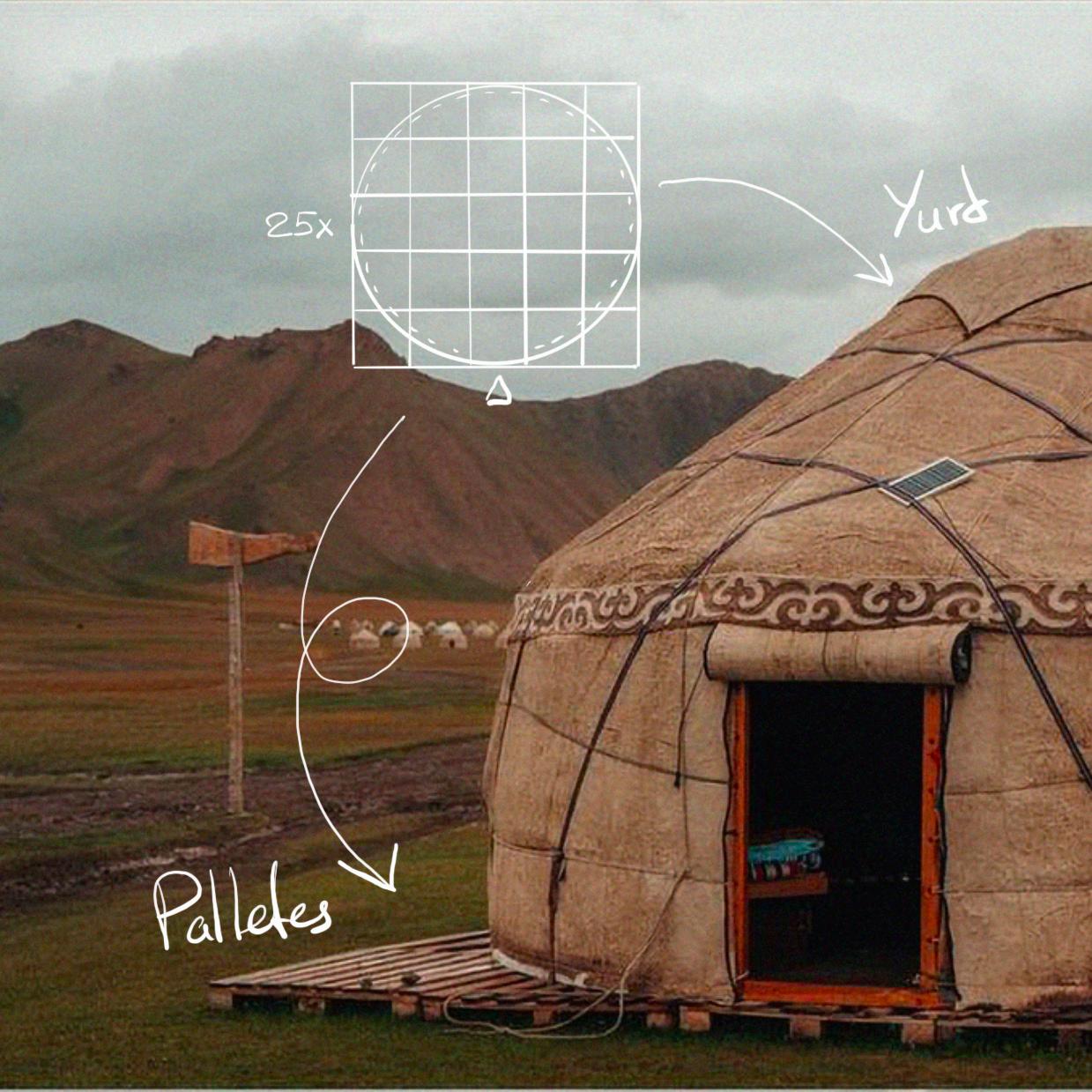

avoiding cold and moist ground

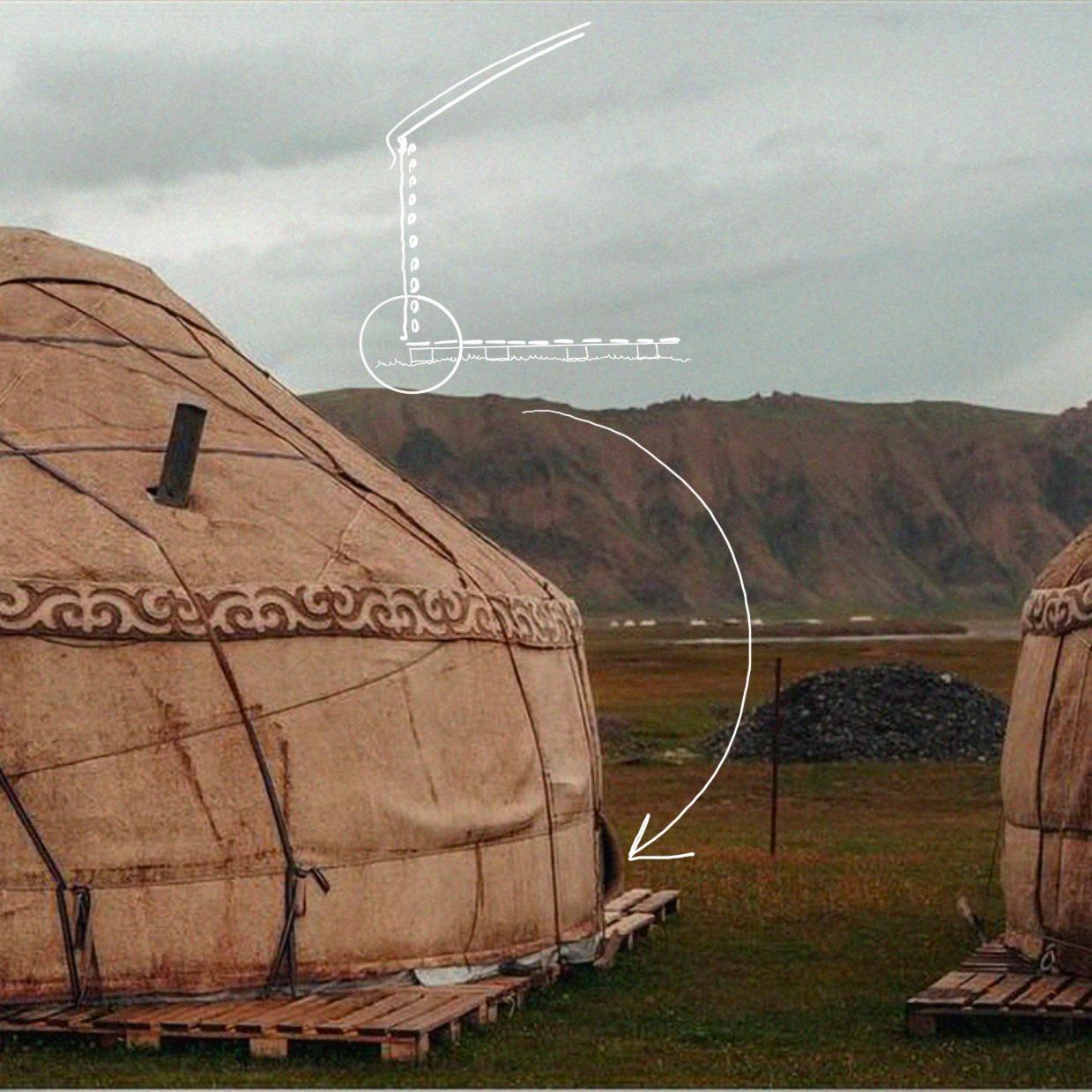

Even today, the Kyrgyz yurt continues to evolve, as modern users seek greater comfort, durability, and efficiency while maintaining the traditional essence of this nomadic dwelling. One of the most significant improvements has been the raising of the yurt off the ground, typically by placing it on a wooden pallets. This adaptation helps to reduce moisture buildup, preventing dampness and mould while making the interior warmer and drier during the seasons.

Additionally, semi-nomadic families have introduced insulated flooring, additional layers of thicker felt, and weatherproof outer coverings to enhance the yurt’s protection against the natural elements.

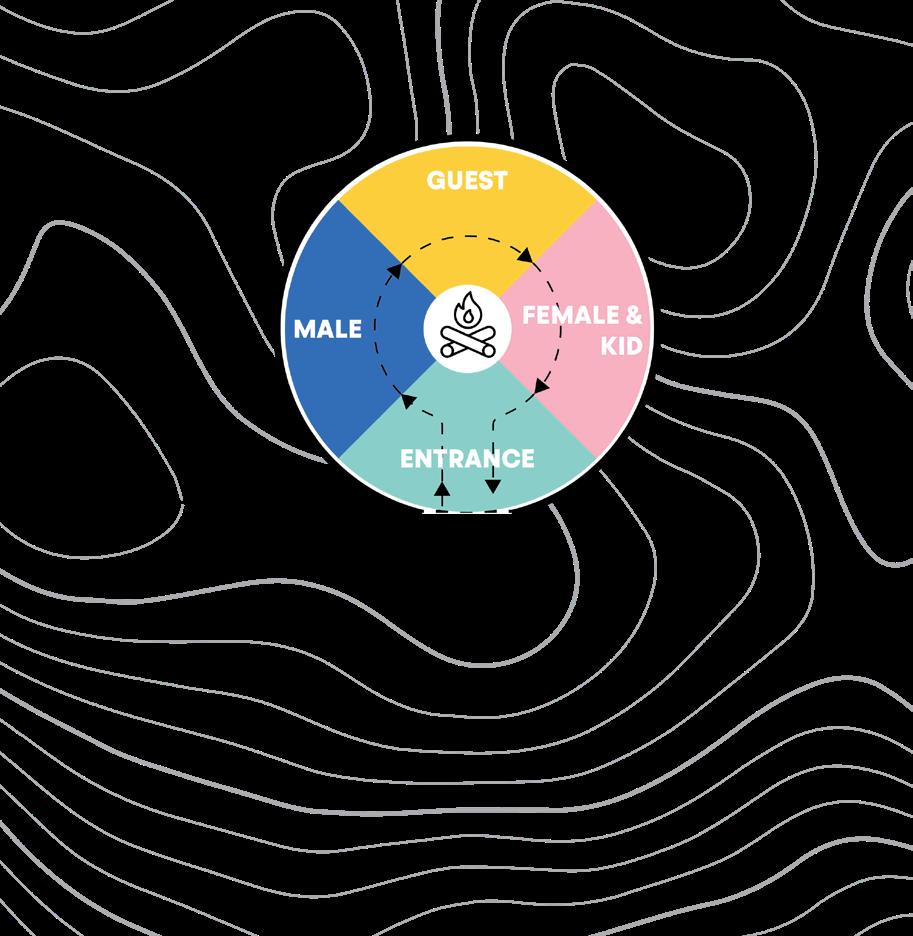

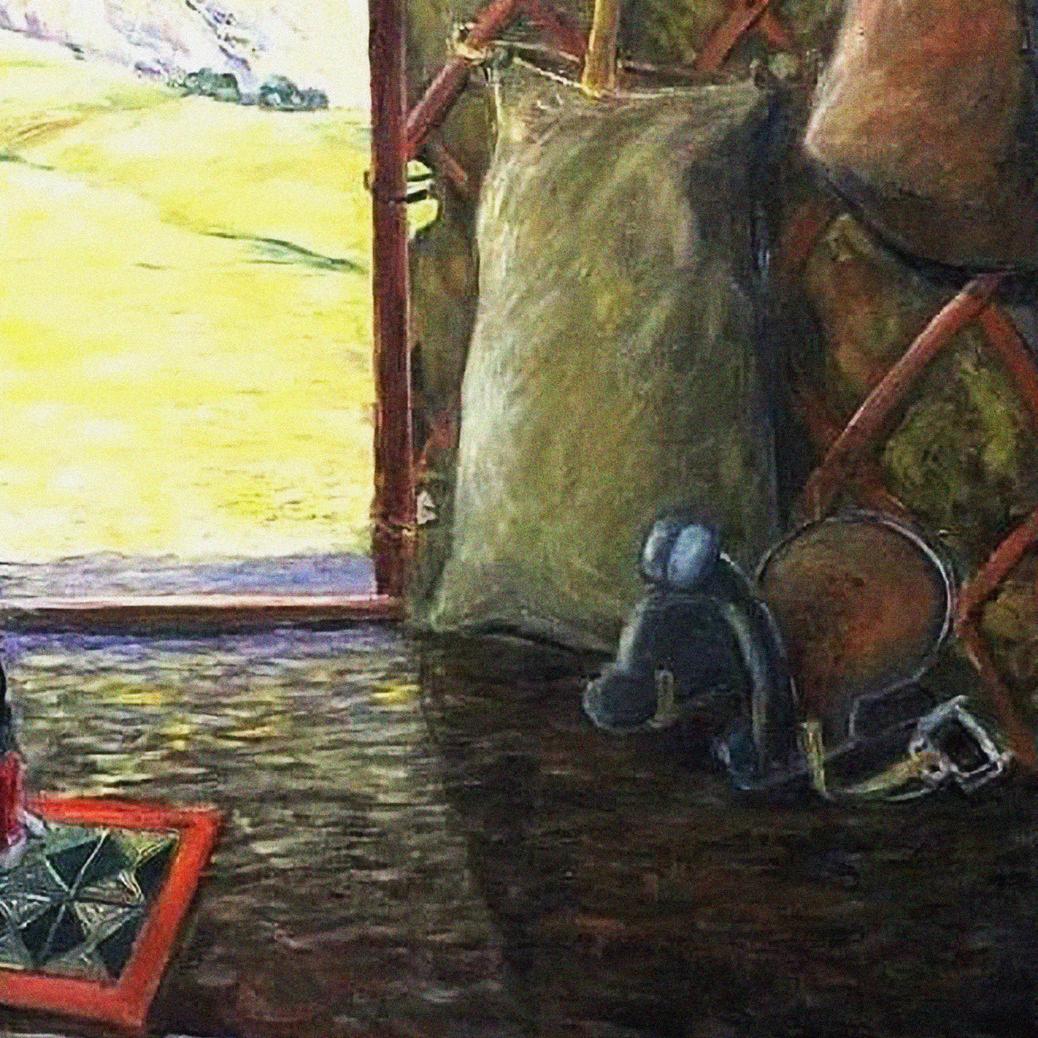

The interior of the Kyrgyz yurt is a carefully organised space, designed to be both functional and symbolic. Though compact, the yurt’s circular shape creates a harmonious and efficient living environment, where every item has a designated place. Traditionally, the interior is divided according to cultural customs and hierarchy, ensuring a well-structured and balanced way of life.

Upon entering the yurt, the space is typically divided into four main parts. The right side is considered the women’s area, where cooking utensils, food supplies, and storage chests are kept. This is also the place where women carry out daily household activities, such as preparing meals and weaving. The left side is designated as the men’s area, where tools, saddles, hunting equipment, and sometimes musical instruments are stored. The back of the yurt,

directly opposite the entrance, is the most honourable section, known as the tor (head of the house). This is where elders, guests, and respected members of the family sit. It is also where important possessions such as family heirlooms, religious artefacts, and decorative textiles are displayed. The central space, serves as the heart of the yurt, providing warmth, light, and a place for together activities.

Despite its well-organised interior, the yurt primarily serves as a private, family-oriented space. All communal and public activities traditionally take place outdoors, in the surrounding landscape. Gatherings such as weddings, feasts, storytelling, and games are held outside, taking advantage of the open steppe, mountains, and pastures. This reinforces the Kyrgyz people’s deep bond with nature, as the land itself becomes an extension of their home.

Male side is closer to the entrance on order to load and offload the armory/ hunting gear.

Honoured guests are always seat infront of the entrance.

Female & kids side is in opposite location from male part to resemble balance.

Public and communal activities took place outside. This separation of private and public spaces allowed the yurt to maintain its domestic environment.

The floor of the yurt holds deep cultural, spiritual, and practical significance in Kyrgyz traditions. Unlike Western homes, where furniture such as chairs, tables, and beds create layers of separation from the ground, the Kyrgyz way of life is closely connected to the floor, reinforcing a unique sense of unity between people and their environment. The yurt’s floor is more than just a surface - it is a place of gathering, rest, and tradition, forming the foundation of daily life.

The floor of a Kyrgyz yurt is a multipurpose space, transforming throughout the day to ac-

commodate different activities. In the morning, it serves as a place for family meals, where food is arranged on a dastorkon (a cloth spread on the ground). During the day, it becomes an area for crafts and daily chores, while at night, the same space is converted into a sleeping area by laying out soft bedding mats known as töshök.

The absence of furniture allows for flexibility in how the space is used. This adaptive use of the floor is not only practical but also deeply rooted in nomadic customs, where minimalism and efficiency are key to ever-changing landscapes.

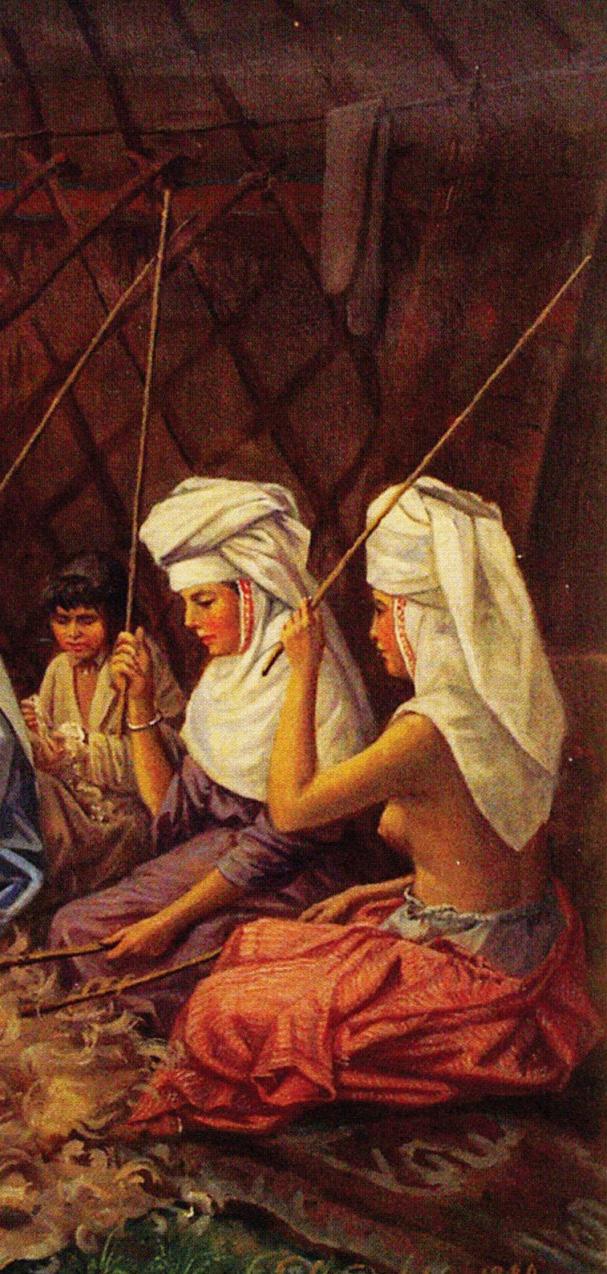

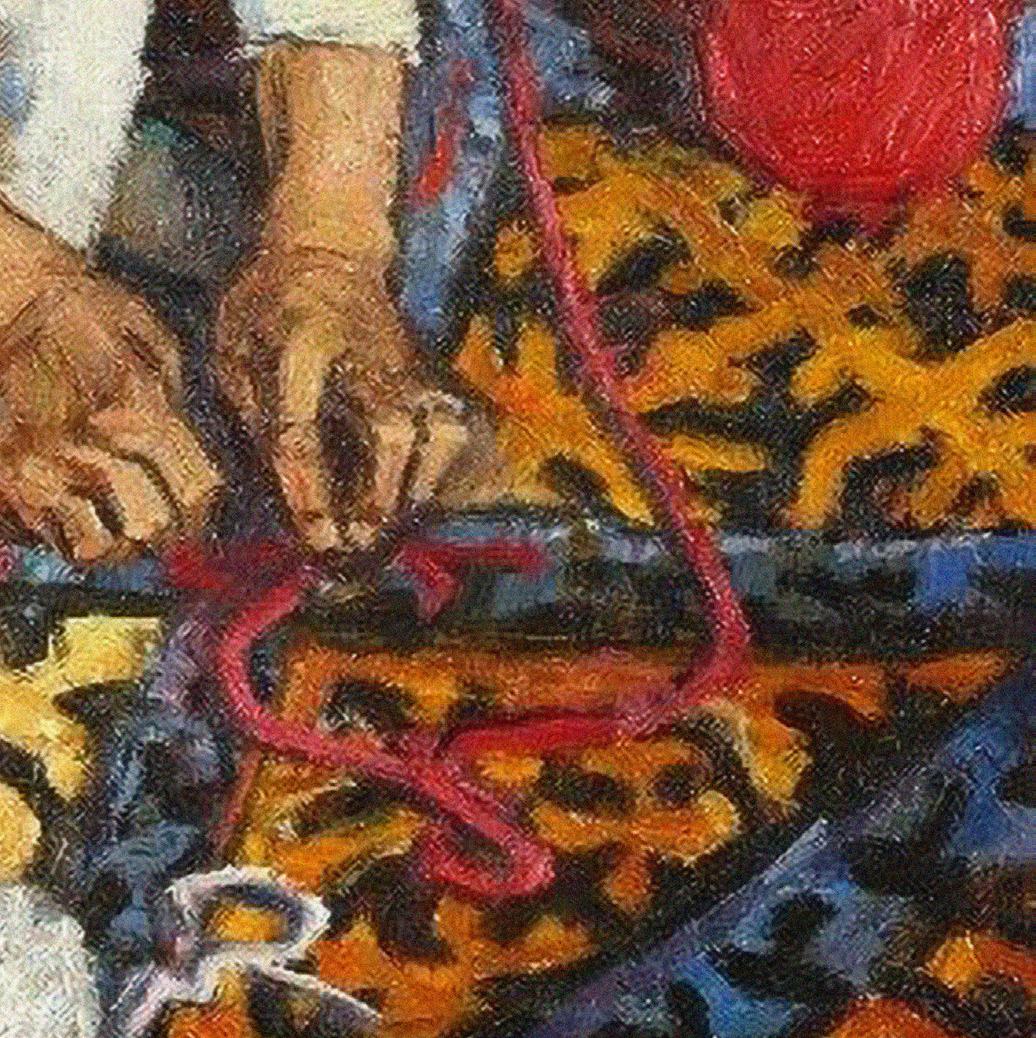

To make the floor comfortable and warm, layered felt carpets (shyrdak and ala-kyiz) are spread throughout the yurt. These carpets are made from compressed wool, which provides excellent insulation, protecting the interior from the cold ground and retaining heat within the yurt. The thickness and quality of the felt also offer a soft and cushioned surface, making it easier to sit, sleep, and move around.

Each carpet is more than just a functional piece—it is also a work of art and heritage. Traditional Kyrgyz patterns and motifs woven into the felt tell stories of family history, nature, and spirituality. These textiles are often handmade by women, passed down through generations as treasured family heirlooms.

The floor of the Kyrgyz yurt is a sacred foundation, symbolising respect, tradition, and harmony with the earth.

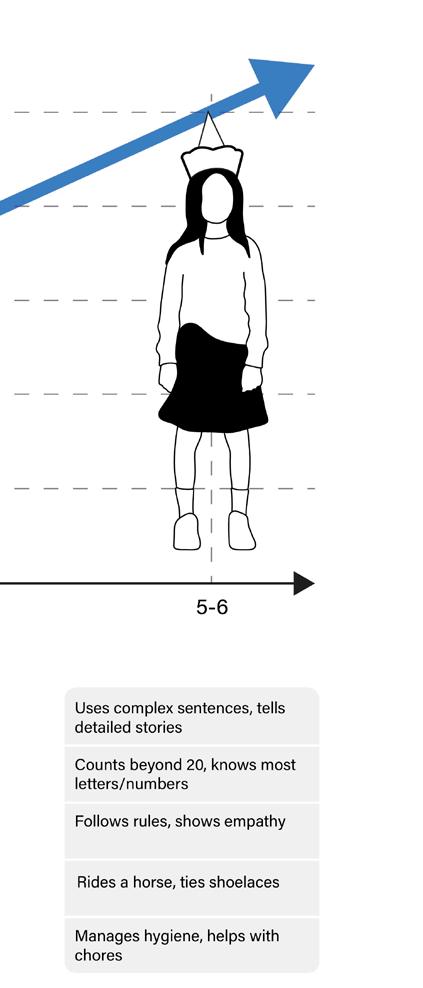

A typical semi-nomadic family in Kyrgyzstan consists of around 6 to 8 people, usually including the parents, their children, and sometimes extended family members such as grandparents. The whole family - including even the youngest children - travels together, which is an essential part of the nomadic lifestyle. There are no exceptions, as the success of the migration depends on the collective effort of every family member. As a result, children of all ages learn from their parents and siblings as they participate in the journey, even if their duties are small and manageable. This practice creates an environment where intergenerational learning thrives, as the younger ones absorb skills and knowledge that they will need as they grow into adulthood.

From an early age, children are taught to contribute to the family chores, helping with tasks like tending to animals, gathering firewood, or assisting in meal preparation. As they grow older, their responsibilities gradually increase, and by the time they are teenagers, they take on more specialised tasks such as herding livestock or managing more complex duties around the house. This hands-on learning ensures that children grow up understanding the demands of semi-nomadic life, and they take pride in being able to help provide for the family.

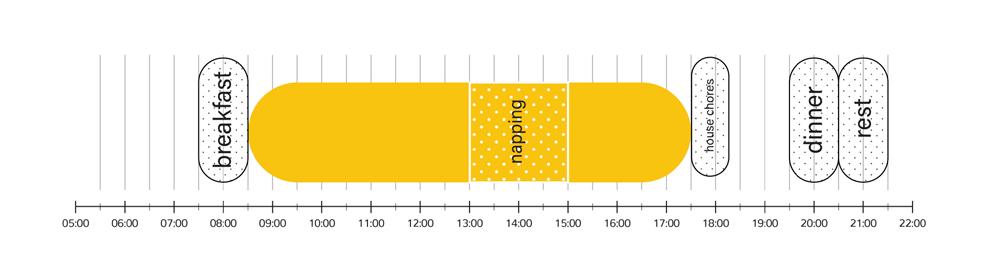

For children, the summer months coincide with the school holidays, allowing them to spend their days outdoors, exploring the environment and learning through experience. However, children under six years old, who are not yet in school but prechool, are still involved in family nomadic life, but they often spend their days wandering near the yurt, being unattended or looking for attention.

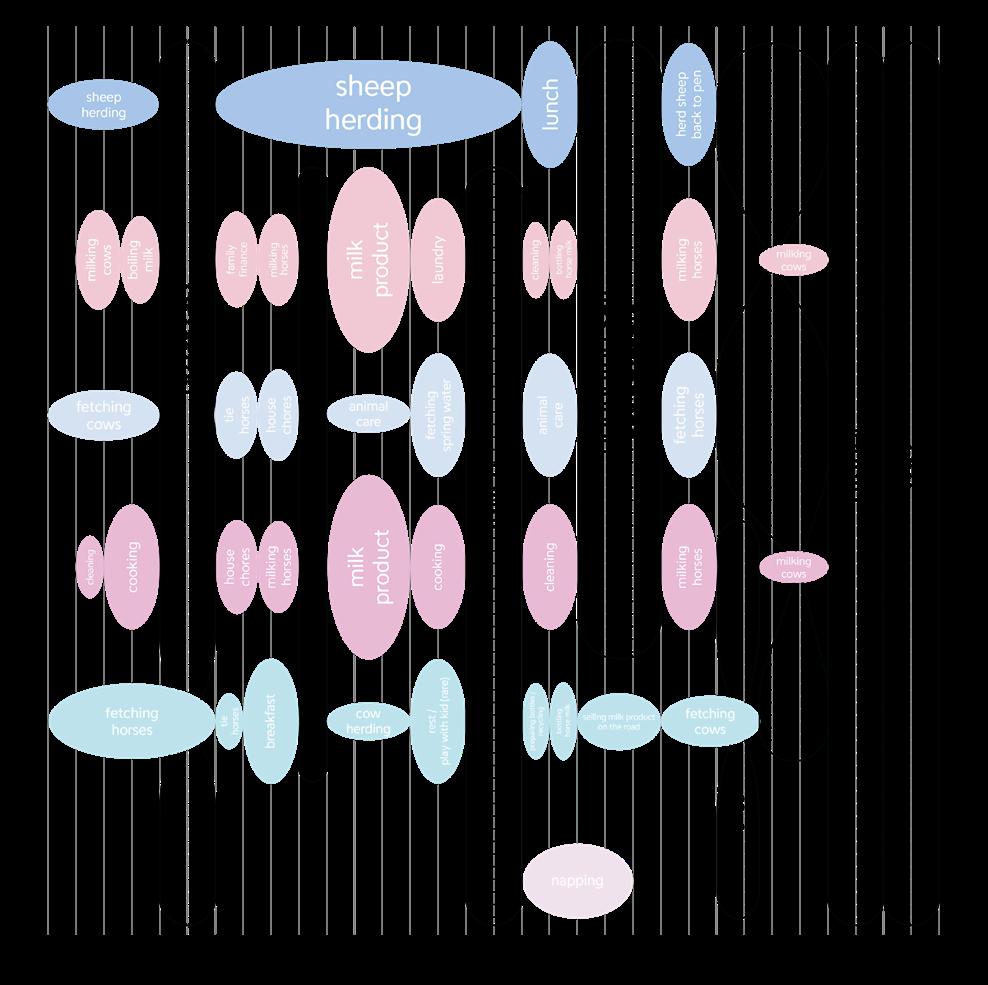

morning afternoon night

This age group faces a significant challenge: they are separated from education and often left alone without structured learning or supervision. Instead of engaging in early childhood education, these young children often roam the camps or are cared by older relatives. This highlights a gap in educational access for young children in remote areas. The lack of educational facilities and structured early childhood programs means that many children miss out on the critical developmental stage of their early years. Instead of educating and socialising, they are left to learn through observation and wandering, which can limit their exposure to structured learning and play that supports cognitive and emotional growth.

On the contrary, there can be a dedicated space where young children are engaged in studying and playing with their peers throughout the day, allowing the rest of the family to carry out their daily duties. While parents and older family members focus on their work, the children would benefit from both educational activities and social play, fostering their cognitive, emotional, and social development. Such a facility ensures that children are not left behind in their early years, providing them with the opportunity to learn in a way that is both structured and community-oriented, preserving their connection to their semi-nomadic lifestyle.

Issyk-Kul region

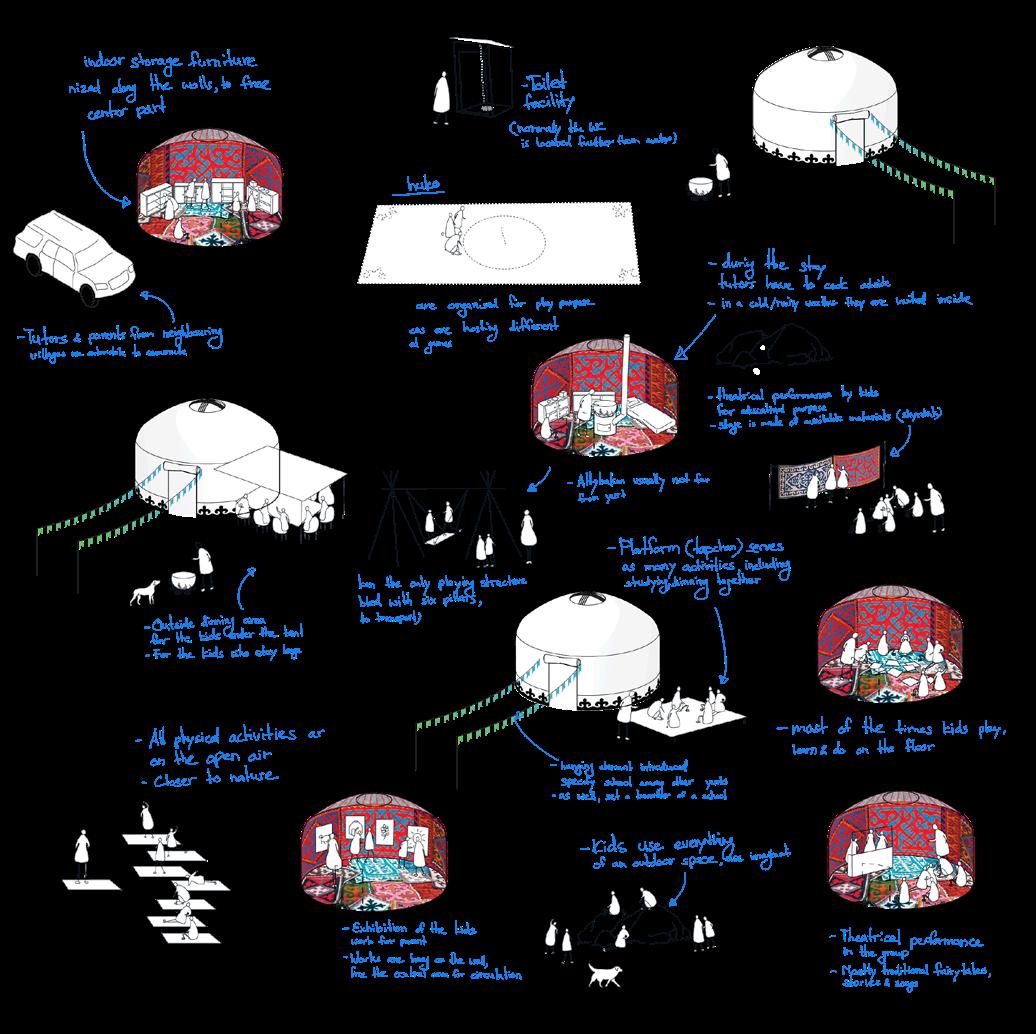

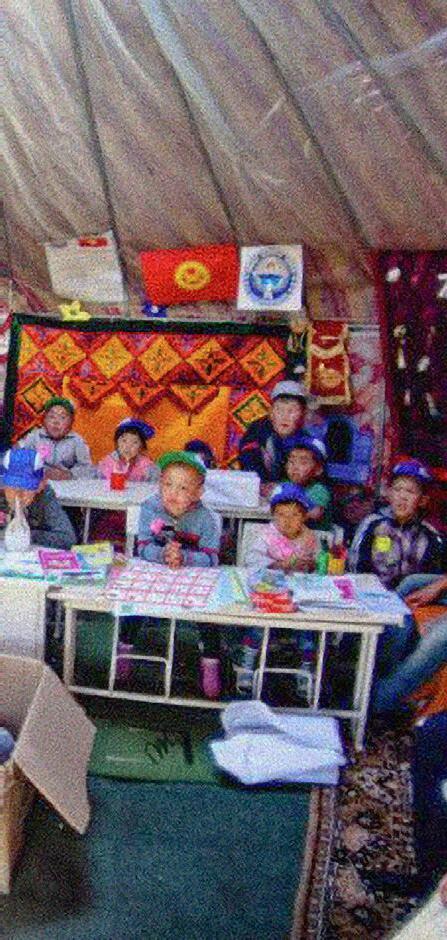

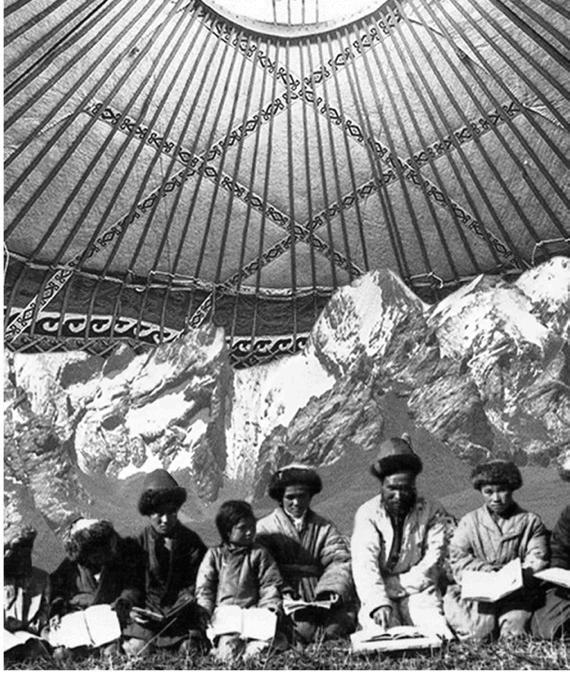

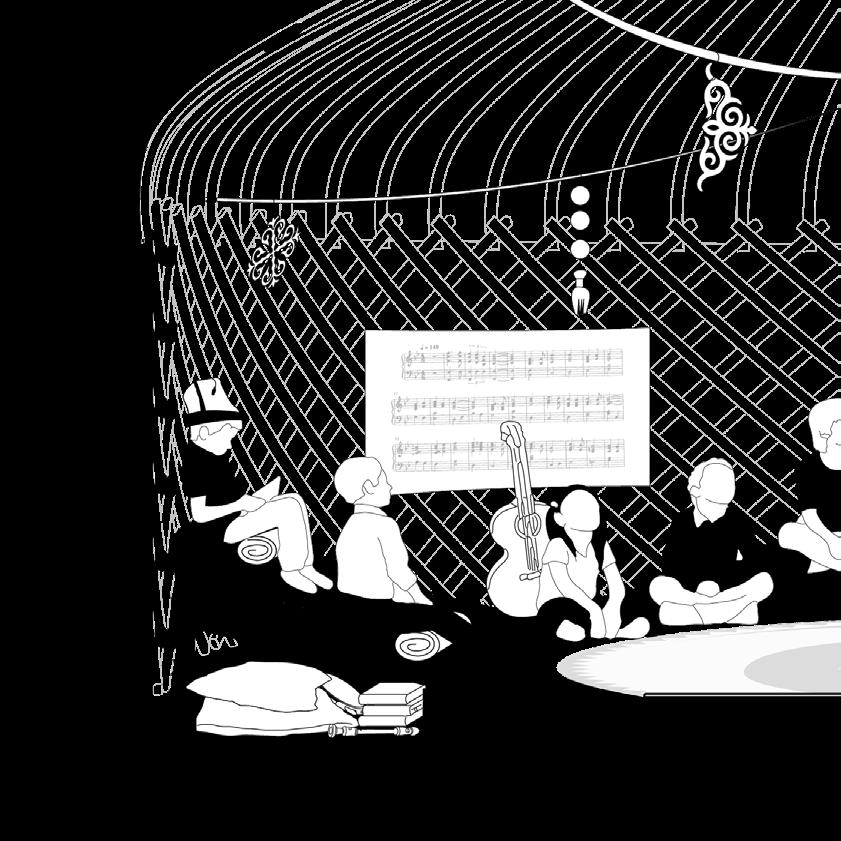

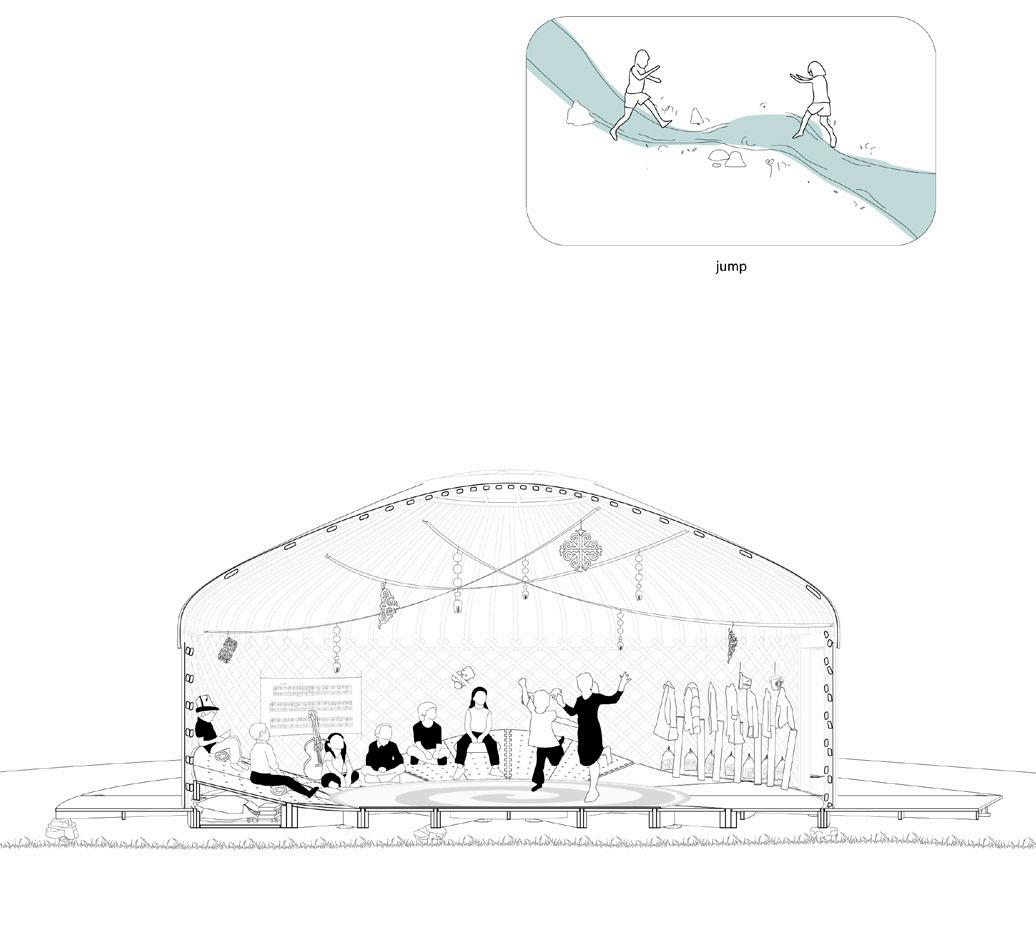

The “Jailoo Child Development” program is a remarkable initiative launched by the Roza Otunbaeva Foundation aimed to support early childhood development for kids 3 - 6 years old in remote areas of Kyrgyzstan. The initiative addresses a critical gap in the education system, particularly for young children who live in areas that lack educational institutions. The program operates in several regions across Kyrgyzstan, particularly in remote areas (jailoo) and semi-nomadic communities, where children traditionally have no access to education during the summer months. The number of operational sites for this initiative is steadily growing, as the foundation aims to expand the reach of the program.

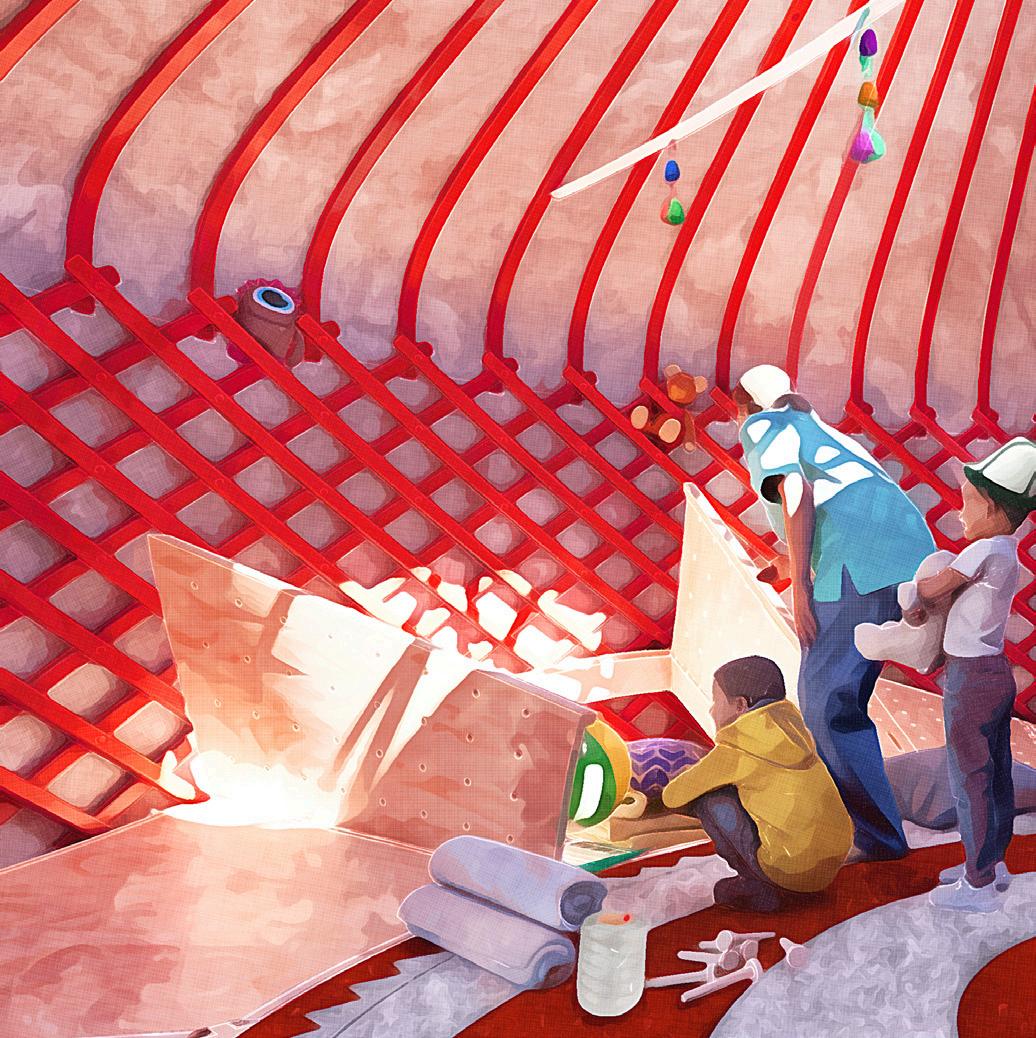

The program works by collaborating with local communities, who provide the necessary space for educational activities. This space that they can offer is usually a yurt. The use of it is not only aligns with the culture but also offers a practical solution in terms of accessibility, as these structures are familiar and already present in many nomadic families.

Once the community provides the yurt, the Roza Otunbaeva Foundation takes responsibility for the rest, including the provision of qualified teachers, learning materials, and necessary resources to facilitate early childhood education.

donation yurt

26 kids (3-6 years old)

This support ensures that the children receive a structured learning experience, even while living in remote locations. The program typically includes activities that encourage social and language development, basic cognitive skills, as well as activities that reflect the local culture and traditions of Kyrgyzstan.

The initiative also focuses on play-based learning, recognising the importance of play in early childhood development. Through games, storytelling, and hands-on activities, the children are able to develop their emotional intelligence, problem-solving abilities, and social skills in a supportive and engaging environment.

Jailoo Child Development program is helping to bridge the gap in access to early education for those living in remote areas of Kyrgyzstan. This project is a clear example of how community-based, culturally relevant solutions can improve early childhood education and ensure that children in even the most remote corners of Kyrgyzstan can have access to the tools they need for future development.

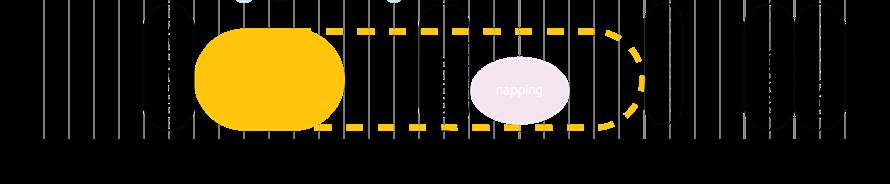

play & study

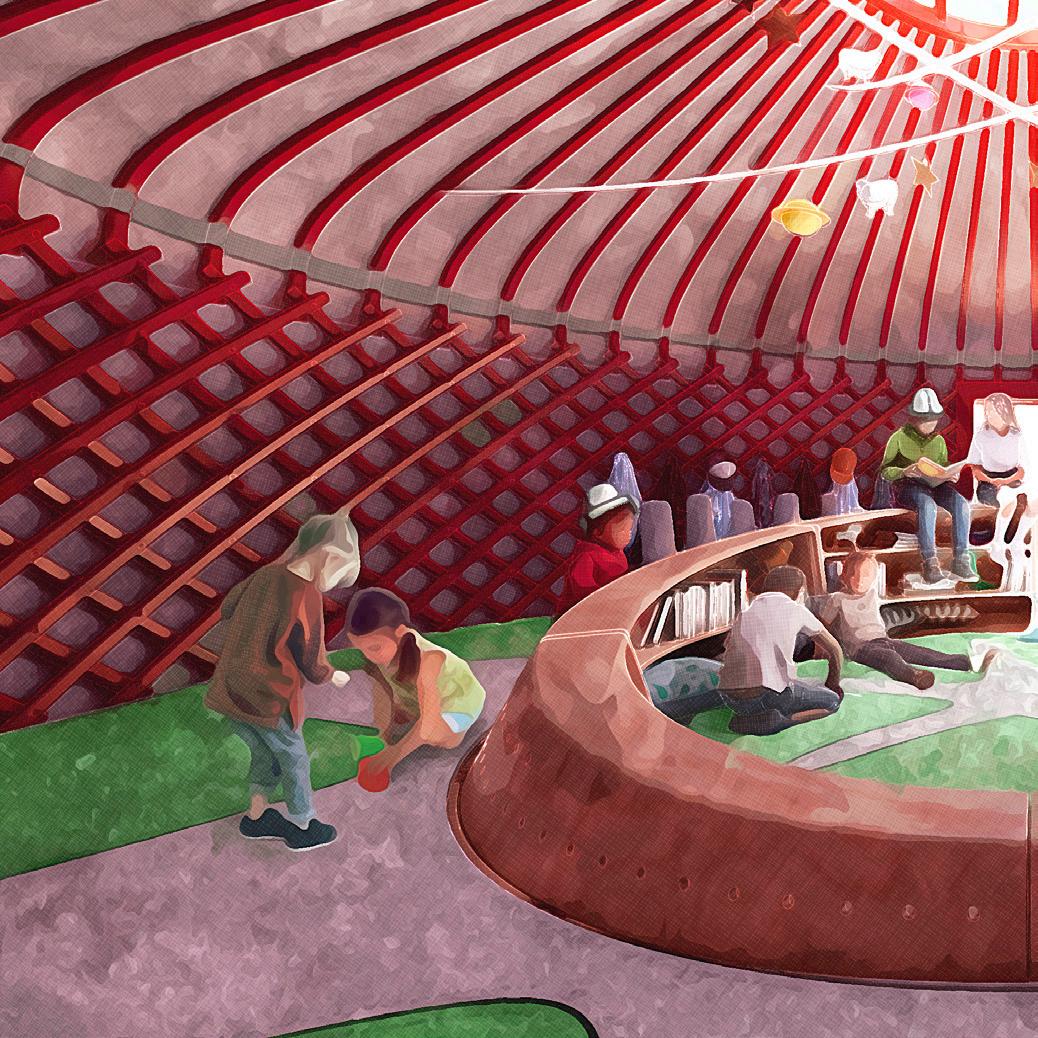

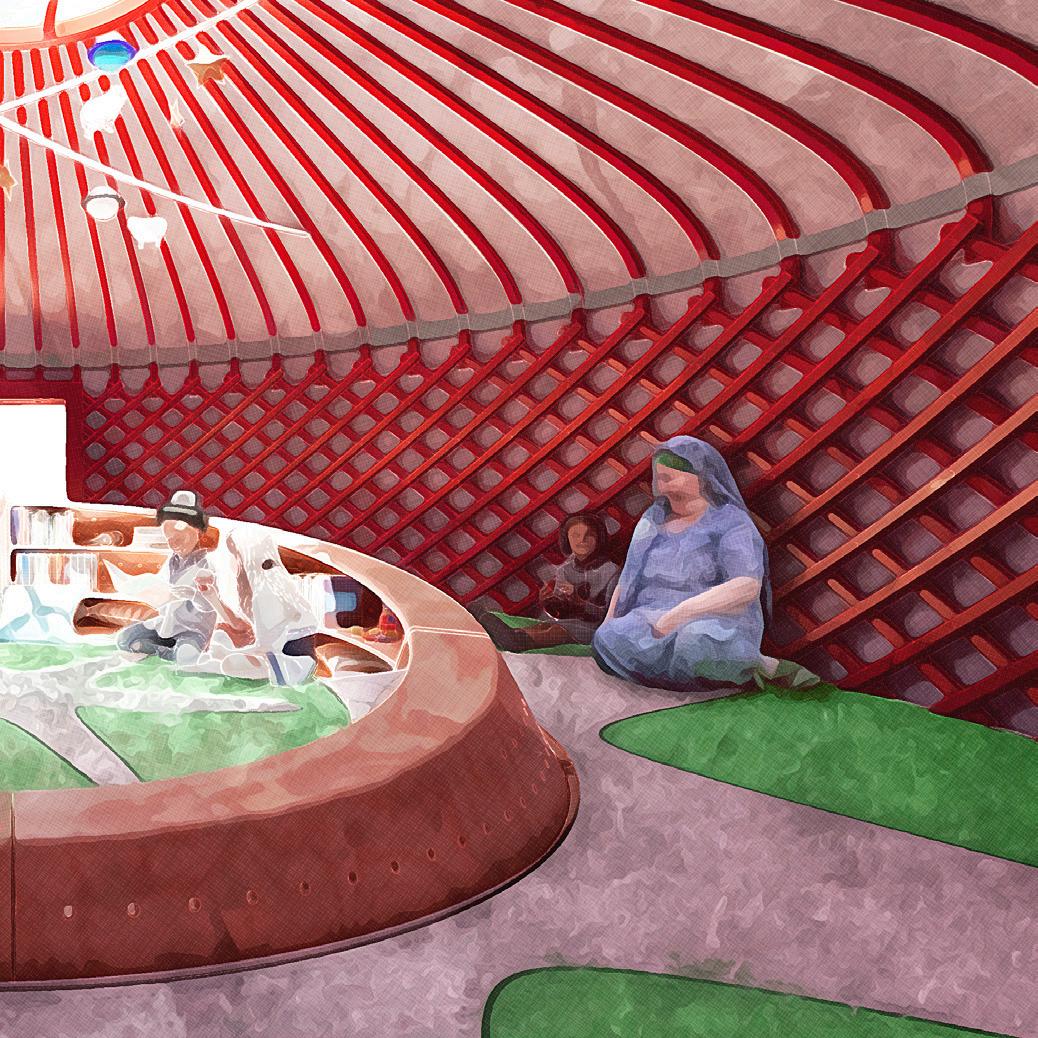

The Jailoo Child Development Centers are organised to maximise the use of a single, unified space for multiple activities, both indoors and outdoors. The flexibility of these spaces allows children to engage in structured learning inside the yurt while also participating in interactive outdoor activities that connect them to their natural surroundings. The program includes a mix of reading, singing, hands-on crafts, and group play, ensuring a well-rounded educational experience.

Currently, the child centres operate for only three hours a day. This limited schedule is due to the lack of facilities required for a full-day

program, such as designated spaces for napping and lunchtime. Without these accommodations, it is challenging to extend the learning hours while ensuring the children’s well-being and comfort throughout the day.

Despite the short duration, the program effectively supports early childhood development by providing young children with educational material, social interaction, and supervision. Potentially expanding the program to a full-day schedule would require additional spaces, such as rest and eating area, allowing the centres to accommodate children for longer periods and further enhance their learning experience.

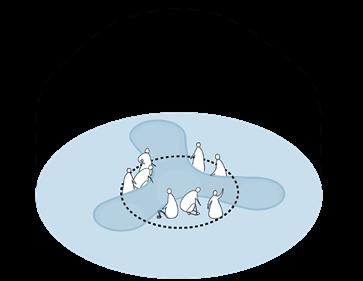

While the Jailoo Child Development Centers aim to provide early education to children in remote areas, the current approach raises significant challenges, particularly in the use of space and the impact on nomadic mobility.

The program attempts to apply a conventional, city-based learning model to a traditional yurt environment, which is primarily used as a living space. Its circular layout, program divisions, and flexibility are integral to nomadic life. While introducing a new function, space has to be reinterpreted accordingly. In the Jailoo Child Development Centers, these aspects are often overlooked.

colorful domestic interior and distractive patterns

challenging with traditional school furniture

limits to accommodate the group of 26 children

Instead, the space is used similarly to an urban classroom with furniture like chairs, desks and shelves, as well as structured seating that do not fully embrace the organic and nature of the yurt.

This rigid classroom setup conflicts with the traditional flexibility of the yurt and does not take full advantage of the open, interactive, and experience-based learning that could better align with the semi-nomadic lifestyle. Rather than adapting the education model to the space, the organisation has forced a conventional system into an environment that functions differently, limiting the effectiveness of the program.

Another fundamental challenge of the Jailoo Child Development Centers is their stationary nature, which contradicts the nomadic way of life. Traditionally, semi-nomadic families move between pastures based on seasonal cycles, spending May to October in high-altitude pastures (jailoo) and returning to lower-altitude rural settlements in the colder months. However, the Jailoo Child Development Centers are fixed in one location, typically closer to urban areas to make it easier for teachers to commute daily from the city rather than relocating with the families.

The

traditional yurt priorities

domestic comfort but may not fully support children’s education, development, and social interaction.

This lack of mobility creates a major issue for semi-nomadic families, who must now choose between staying in one place so their children can attend school or continuing their traditional migratory patterns for their livelihood. Since livestock grazing and nomadic movement are essential for economic survival, many families are forced to prioritise work over education, leaving young children without learning opportunities. The immobility of the school limits access for many families who travel further into the mountains for better pastureland, effectively making the program inaccessible to a large portion of the population it aims to serve.

The solution emphasises education and adaptability, designed for easy transport and setup to support nomadic freedom.

kindergarten

r = 4km

concept 138 program 152 performance classroom 160 crafts classroom 182 reading classroom 206 details for little 226 construction & logistics 250 journey 262 nomads of the world 320

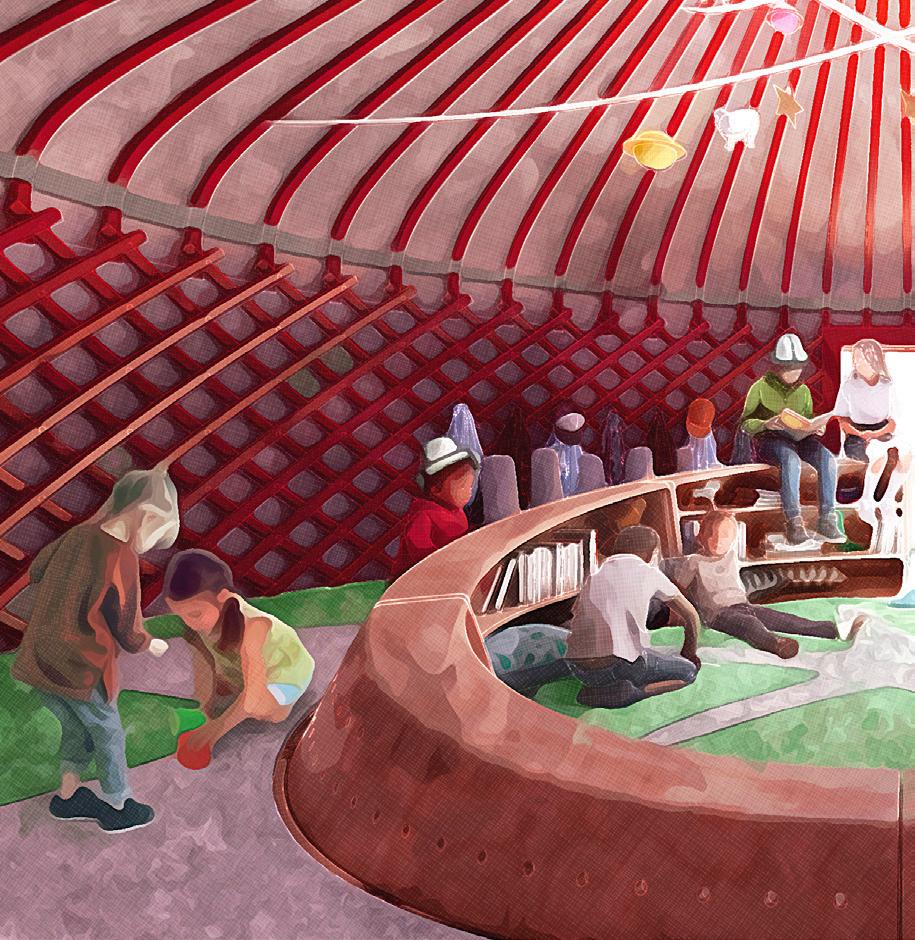

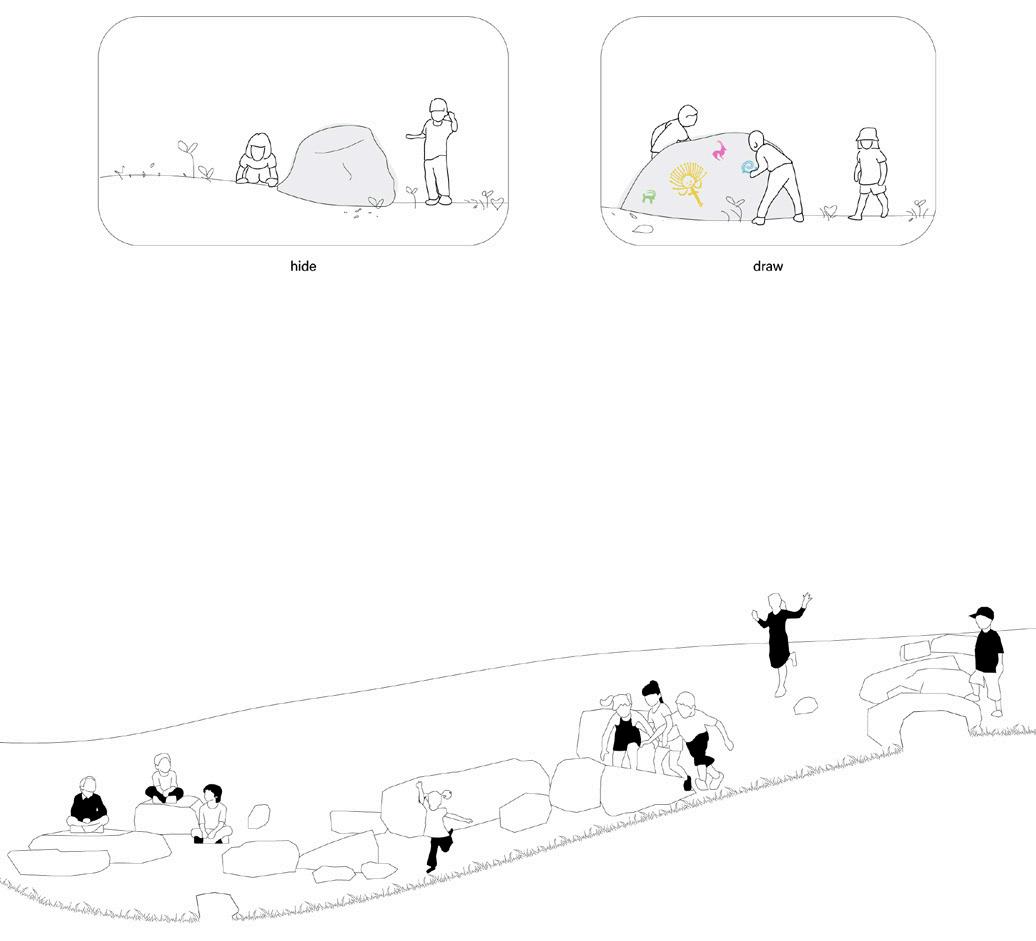

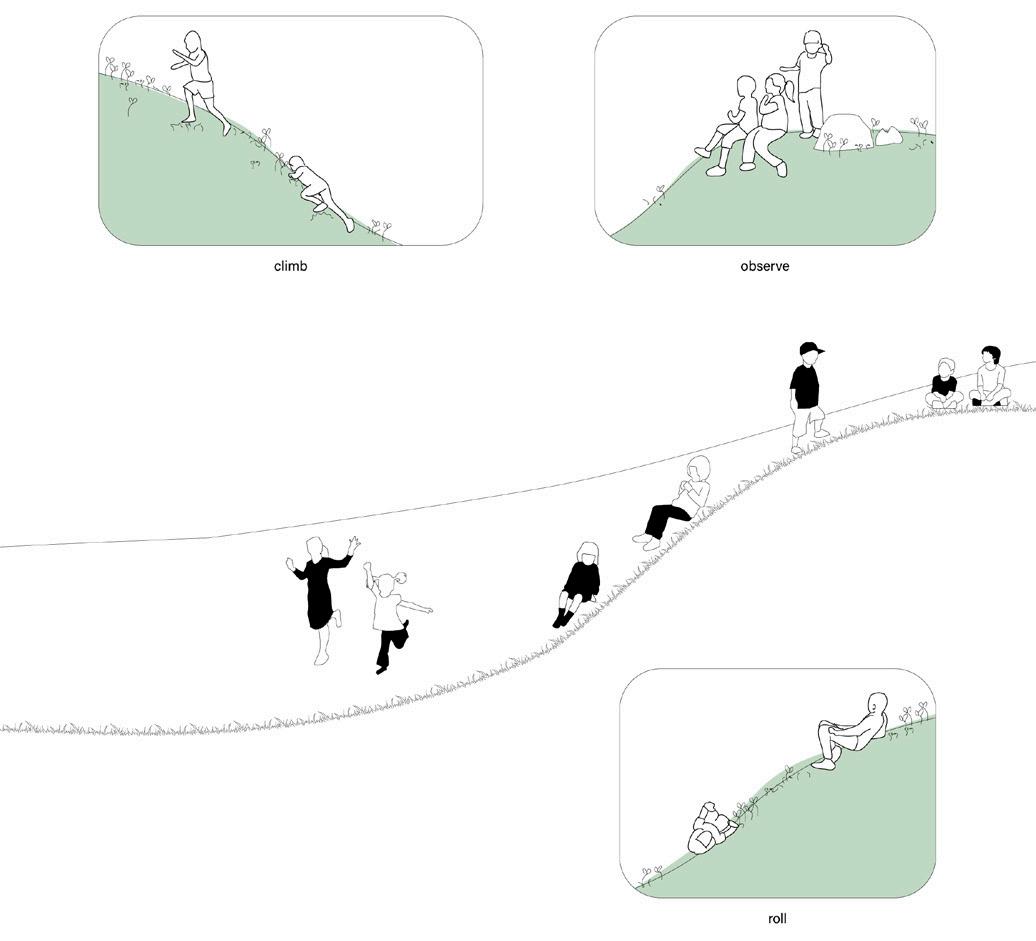

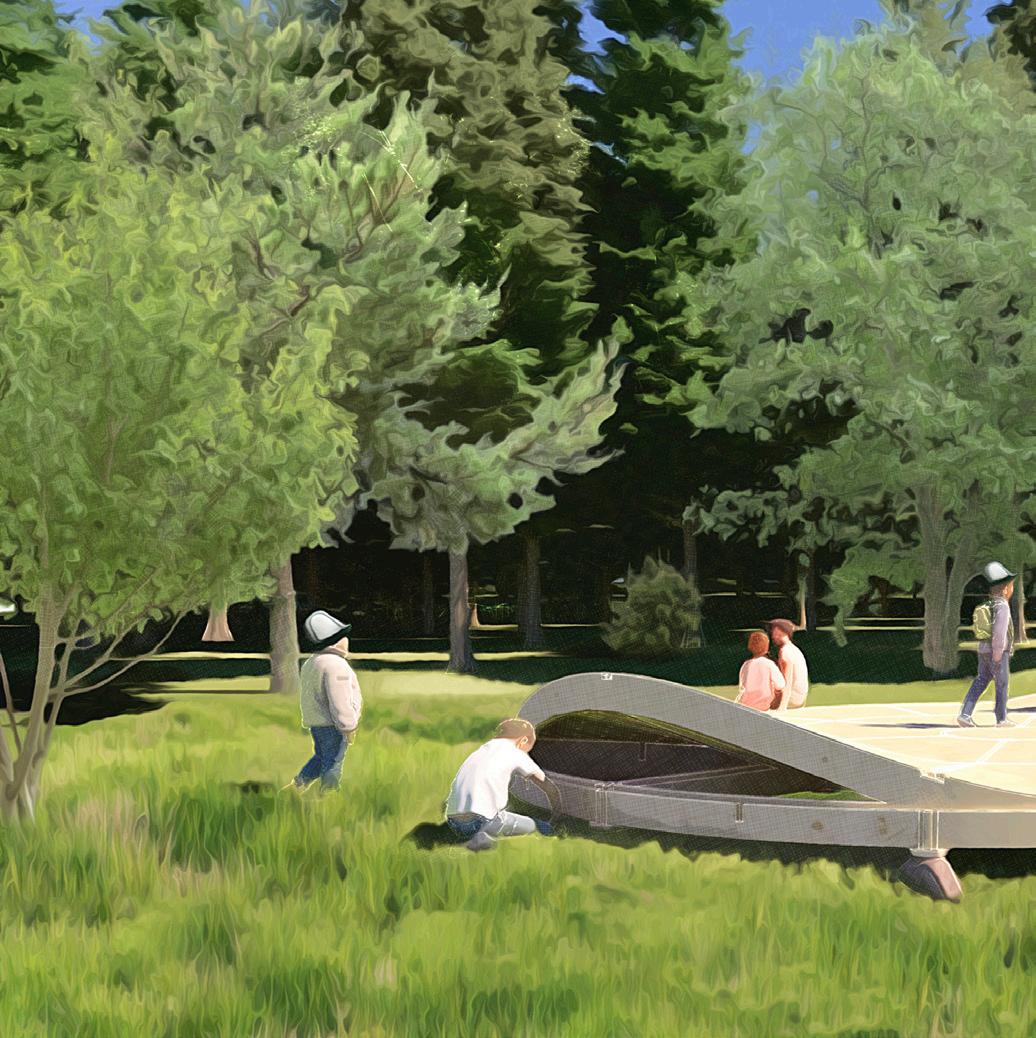

For semi-nomadic children, education must reflect their fluid and dynamic lifestyle, where movement, exploration, and nature are integral to their daily life. This concept envisions an adaptable, interactive learning environment that seamlessly merges education with play, tradition with modernity, and indoor with outdoor spaces. Space that encourages learning through movement and hands-on activities, with a dynamic surface where children can sit, play, and engage freely. Drawing inspiration from nature, the design incorporates rolling hills, climbing elements, and soft surfaces that foster both physical and cognitive growth.

The educational space is designed for mobility and flexibility, mirroring the semi-nomadic lifestyle where families frequently move between pastures. Unlike traditional schools that are

fixed in one location, this educational space is portable, using modular yurts and easily assembled learning elements that can function across various locations. This adaptability ensures that the preschool remains accessible to families throughout the season, enabling children to continue their education while staying connected to their nomadic way of life. This educational approach not only addresses the needs of the children but also preserves cultural heritage by incorporating local materials and Kyrgyz traditions, reinforcing the children’s connection to their identity and ensuring their education is deeply rooted in their way of life.

The project redefines education for semi-nomadic children, making it intuitive, engaging, and relevant, while embracing modern adaptability without disconnecting from tradition.

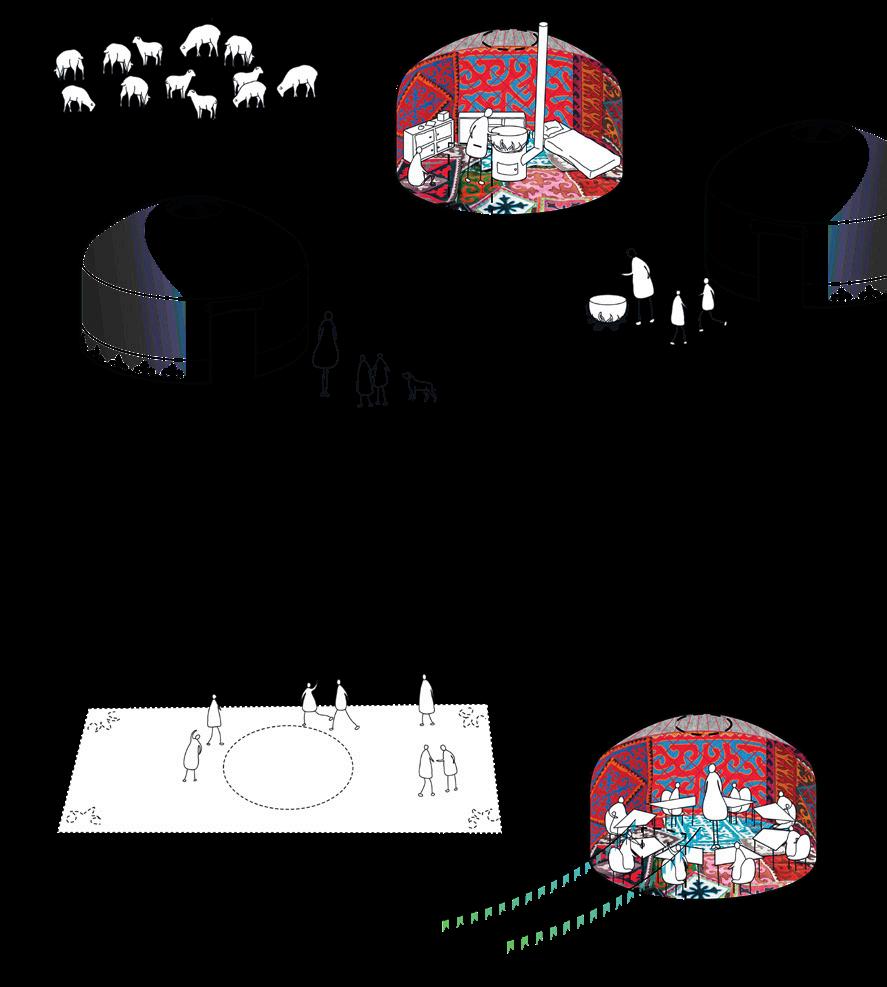

For nomadic people, the landscape is the foundation of their social and cultural life. Vast open spaces, pastures, and natural features shape how communities interact, work, and play. Traditionally, communal gatherings and children’s activities took place outdoors, reinforcing the deep connection between people and their environment.

The yurt, once solely a private dwelling, is now being redefined as a dynamic space that fosters social interaction, education, and collective experiences. This transformation blurs the boundaries between shelter and nature, creating a multifunctional hub where learning, play, and community life coexist.

By integrating landscape elements into the interior, the yurt evolves into a flexible environment that accommodates the changing needs of semi-nomadic families.

This architectural concept preserves cultural traditions while adapting to modern necessities,

ensuring that education and social engagement remain deeply connected to the natural world. The result is a new typology of the yurt - one that transforms the well-known space into a living, breathing extension of nomadic life, where the outdoors is seamlessly woven into the built environment.

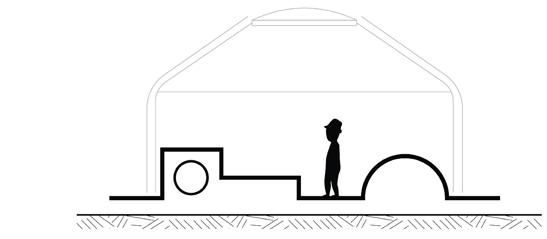

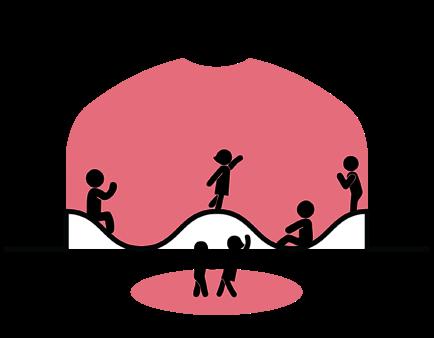

A key element of this concept is reclaiming the floor as an active, central component of the educational space. Traditionally, Kyrgyz culture has always emphasised the significance of the floor, where family and community members sit, eat, and socialise together. In this educational environment, instead of adhering to rigid classroom structures with desks and chairs, the design encourages a return to the traditional way of engaging with the space - sitting and learning on the floor.

This approach is not only culturally significant but also provides greater flexibility, allowing children to move freely and engage in a more organic, collaborative learning process. The floor becomes a multifunctional space, used for sitting, playing, learning, and socialising, all within a communal setting that reinforces Kyrgyz values of equality and shared experience.

typology: living

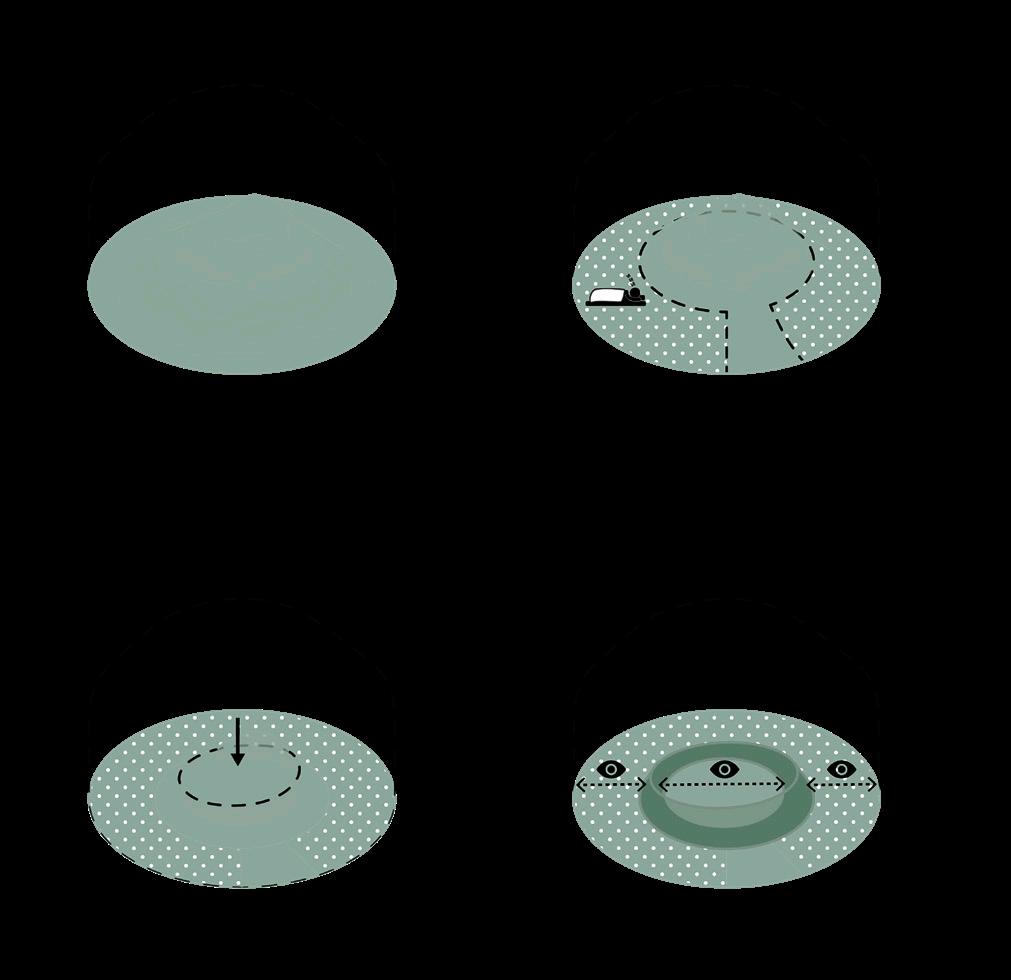

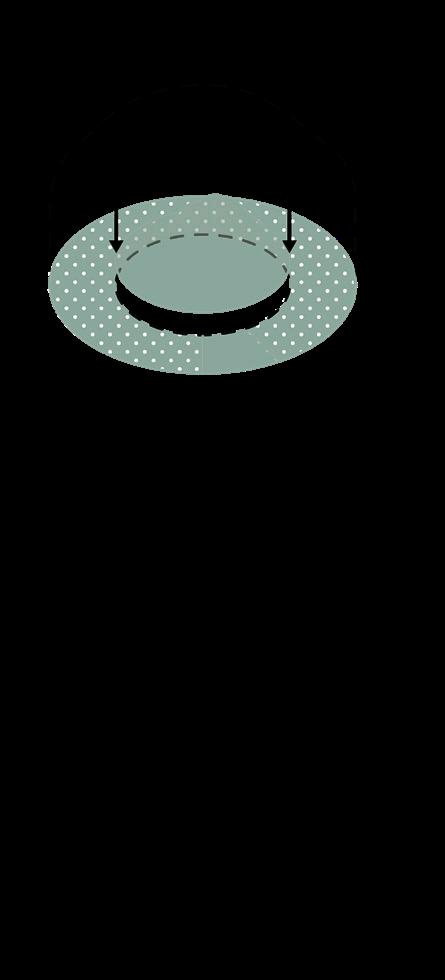

The floor of the yurt has continuously evolved, adapting to the needs of nomadic life. Originally, it was simply the bare ground, shaped and compacted for comfort. Over time, as people sought better insulation and protection from moisture, they began elevating the floor, transforming it into a surface that stands above the ground. Today, this evolution continues as new solutions are explored to enhance mostly comfort.

new typology: education

While the yurt’s structural framework has long proven itself as an ideal shelter, the changing needs of semi-nomadic communities, particularly for children’s education, have brought new focus to the floor. In shaping an educational environment within the yurt, the floor becomes more than just a surface - it defines how children engage with their surroundings.

Inspired by the landscape, the floor takes on new forms, reflecting the natural terrain to create a dynamic learning space. No longer just a static platform, it becomes an interactive element that supports movement, play, and exploration. This evolving foundation transforms the yurt into a new typology for education - one that embraces tradition while adapting to the needs of modern semi-nomadic children.

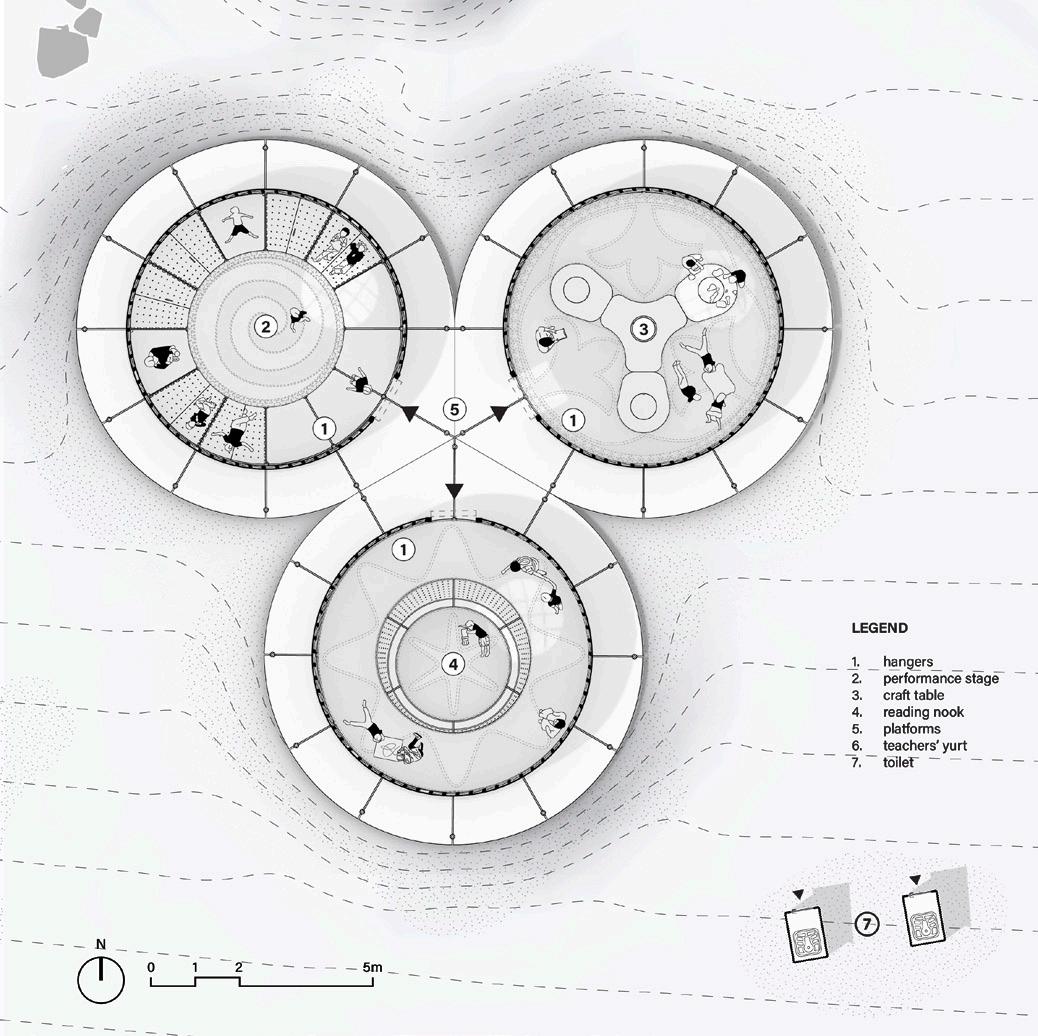

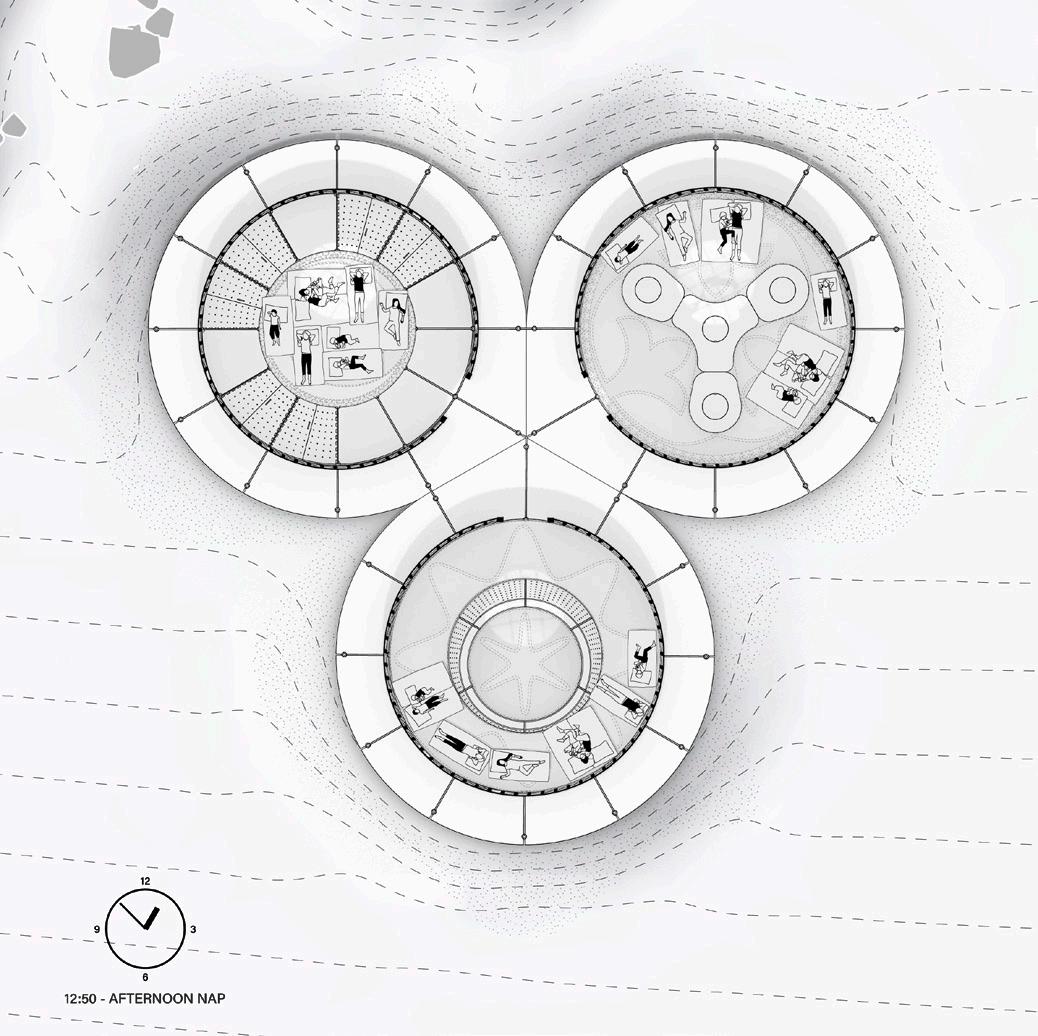

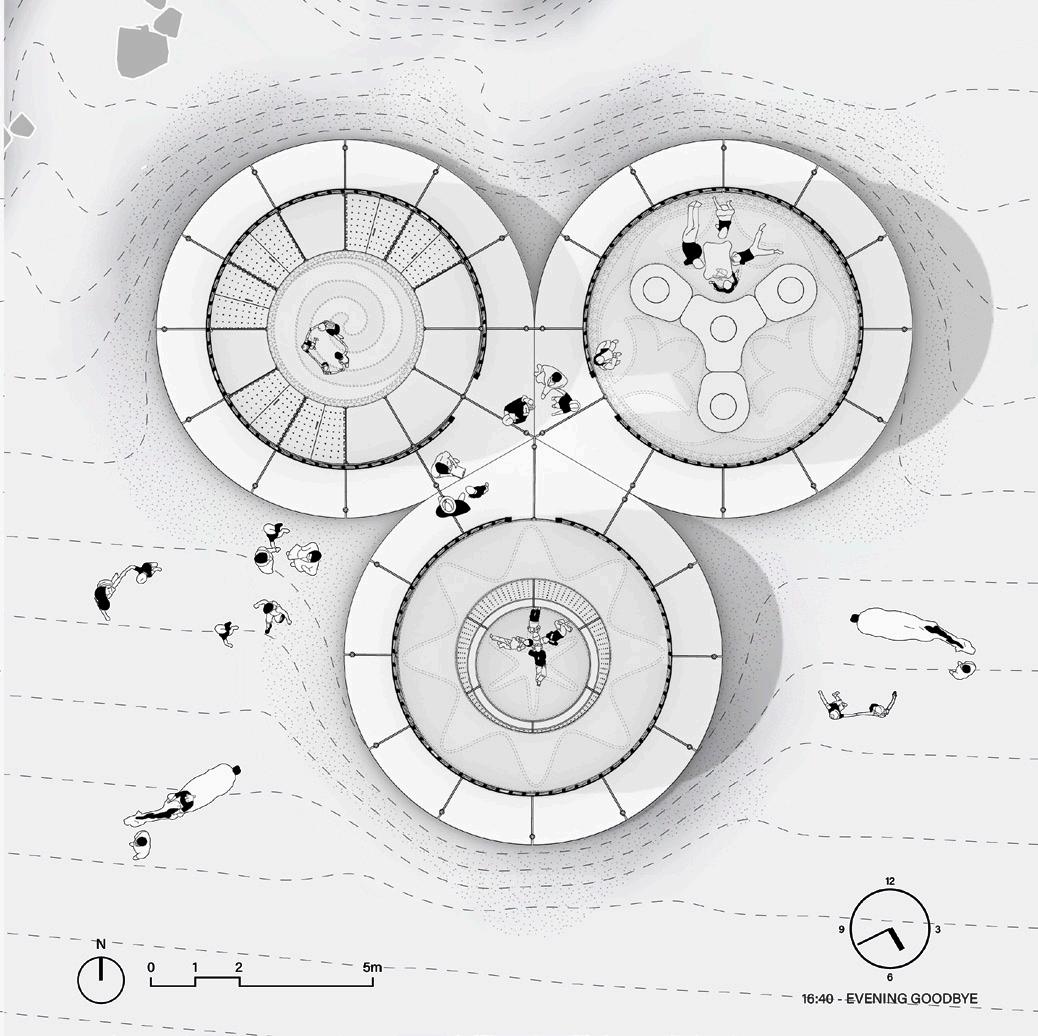

The existing 10 hour educational program is designed to provide a full day of structured activities, ensuring that children are engaged and cared for while their parents focus on their daily responsibilities. By extending learning and play throughout the entire day, the program offers a balanced routine that supports cognitive, social, and physical development.

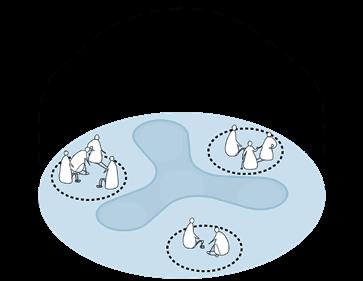

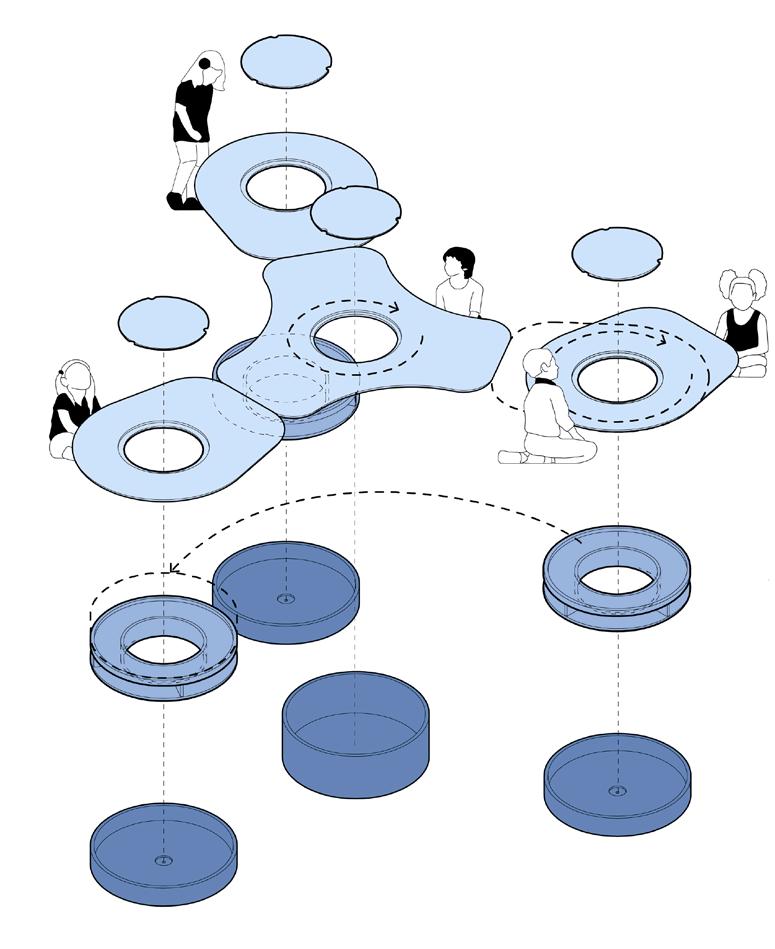

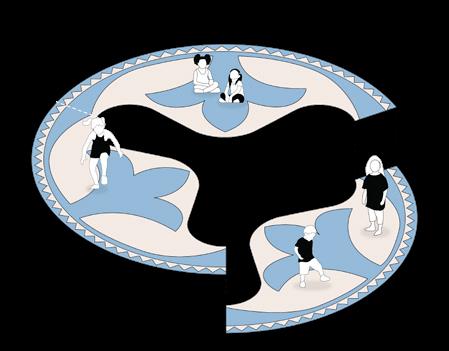

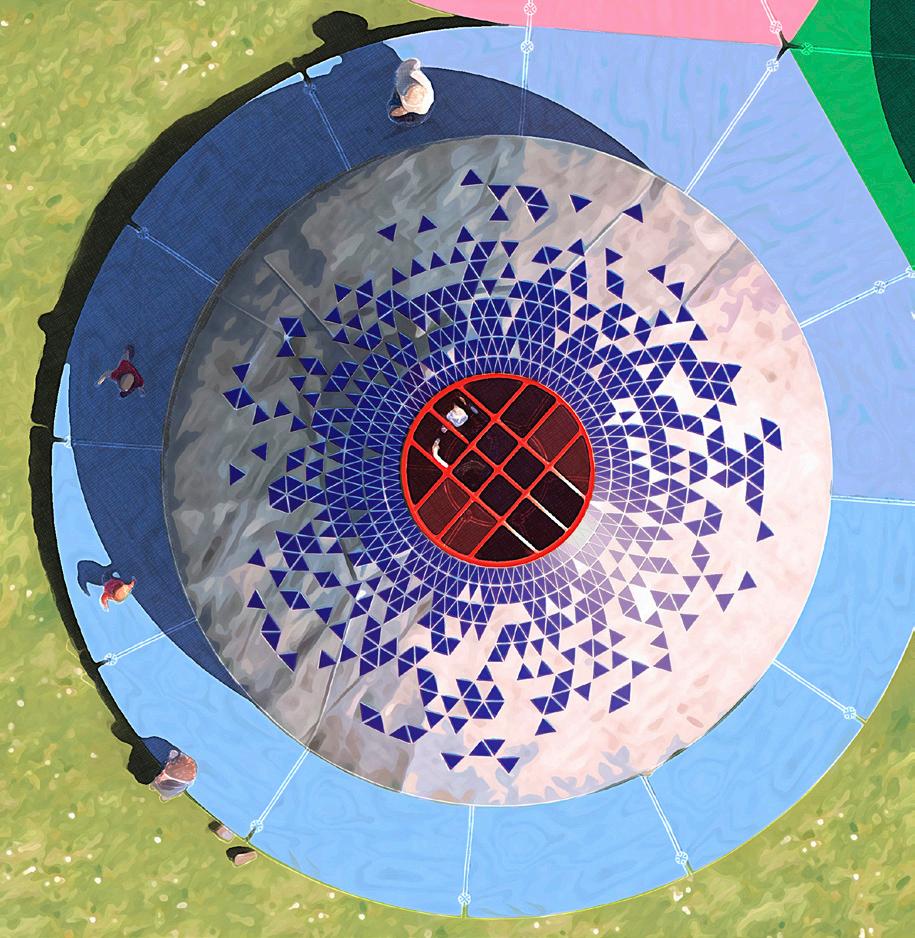

Jailoo Preschool is designed for children aged 3 to 6 years old, with a capacity of approximately 26 children based on case study findings. Each child is provided with 3.5 square meters of space, including an area for napping, which results in the need for three yurts to create a well-structured and comfortable learning environment.

new routine for little semi-nomads

Dedicated areas for sleeping and eating are incorporated, making it possible for children to stay in the space throughout the day without disruption.

This approach not only supports a full-day learning experience but also creates an environment where children can interact with peers of the same age. Growing and learning together, they develop essential social skills while being immersed in an educational setting that feels both familiar and dynamic. By integrating proper space requirements with an adaptable daily schedule, the program fosters a supportive and enriching environment for semi-nomadic children.

Children between the ages of 3 to 6 undergo significant developmental changes, making it essential to tailor their educational experiences accordingly. As they progress through these formative years, their cognitive, social, and motor skills evolve at different rates, requiring an environment that supports their specific needs.

To accommodate these developmental differences, the proposed three yurt Jailoo Preschool provides distinct spaces for each age group. A well-structured learning environment ensures that younger children engage in sensory exploration and foundational social interactions, while older children are introduced to more structured learning experiences that prepare them for future education.

By creating separate yet interconnected spaces, the preschool fosters age-appropriate growth while maintaining a sense of community among all children.

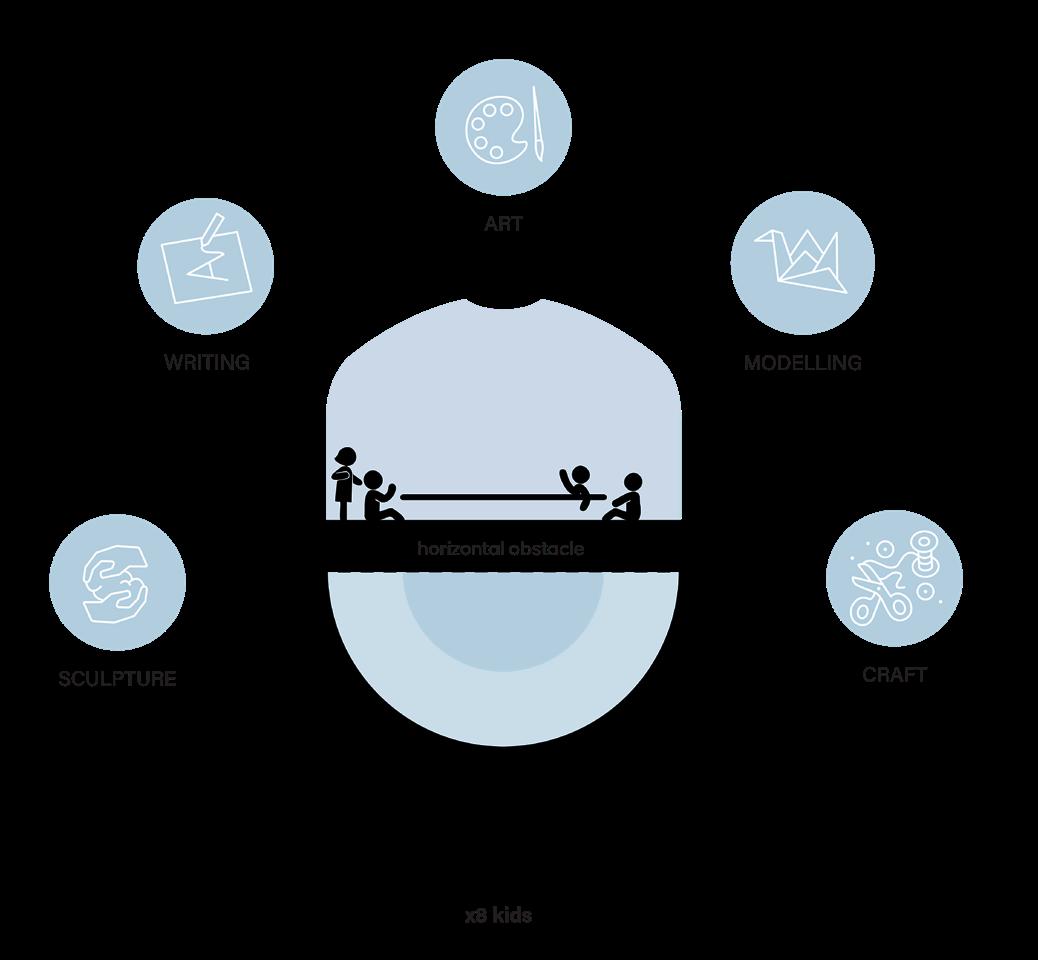

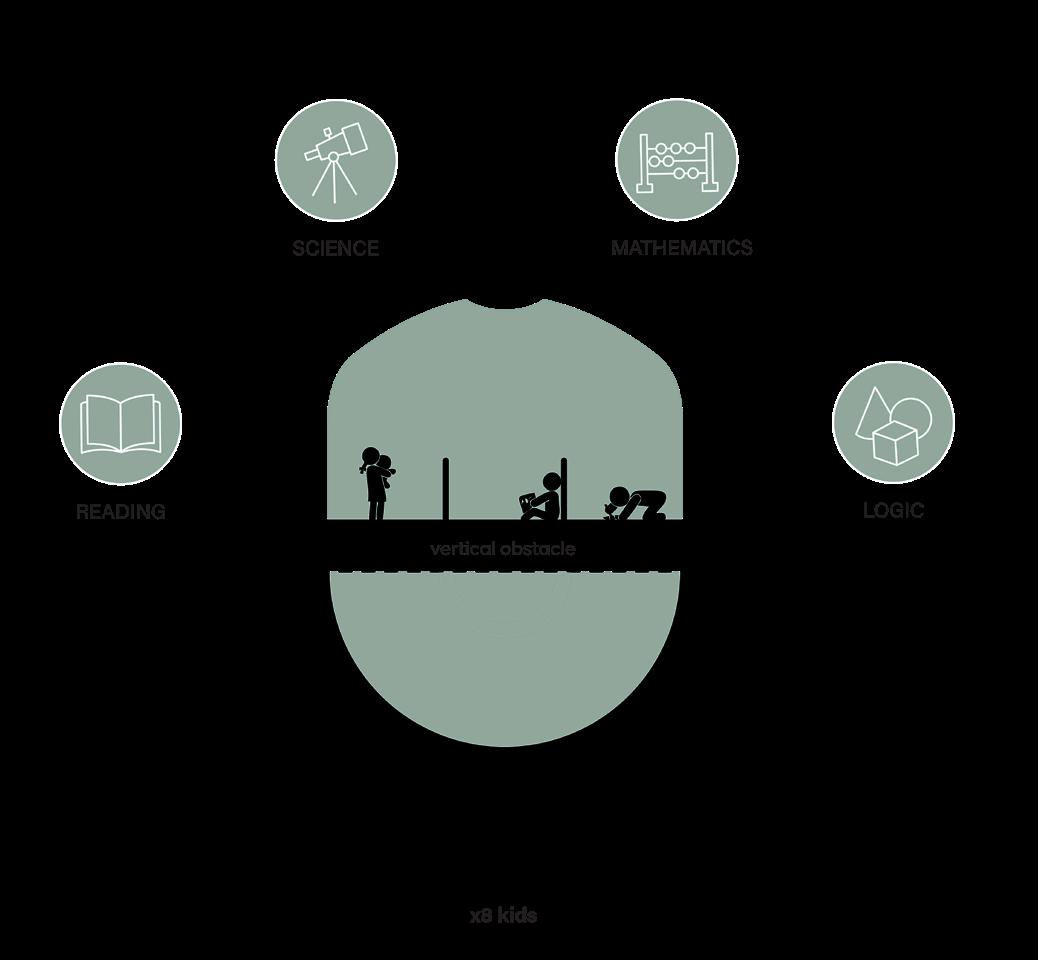

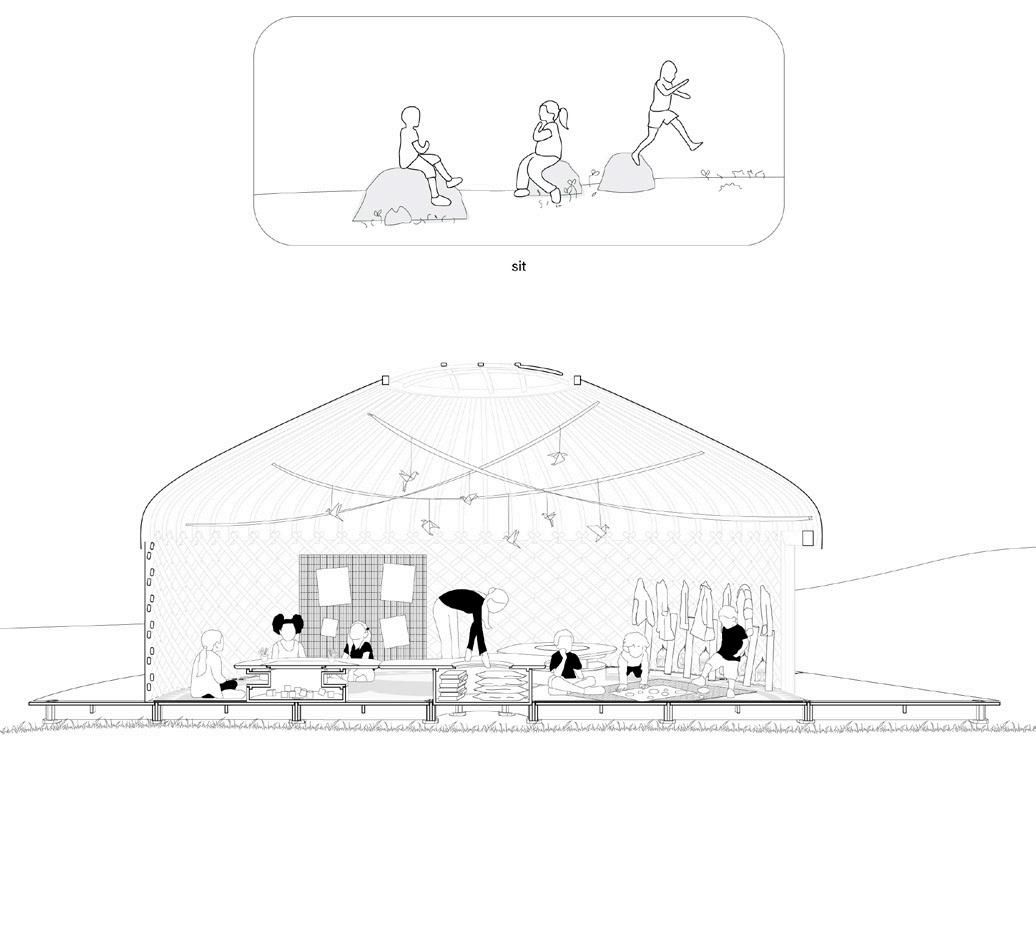

The extensive educational program is structured across three yurts, each designed to accommodate the number and age range of the children. To create an effective learning environment, the program is categorised into distinct activity groups, with each yurt dedicated to a specific focus area.

One yurt serves as a space for performance-based activities, allowing children to engage in movement, music, and storytelling. Another yurt is dedicated to crafts, where hands-on creative work helps develop fine motor skills and artistic expression. The third yurt functions as a reading and quiet space, providing an environment for literacy development and focused learning.

This distribution of activities ensures a dynamic and engaging educational experience, where children move between yurts daily, participating in a variety of learning methods. By organizing the space according to activity types, the design supports a well-rounded curriculum that nurtures cognitive, social, and creative development within a setting tailored to the needs of semi-nomadic children.

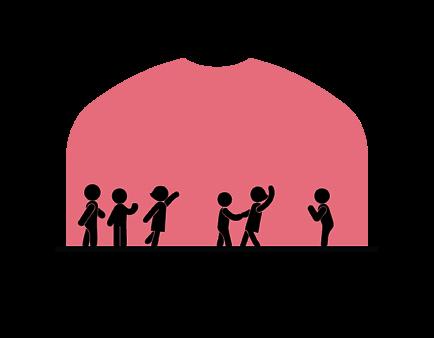

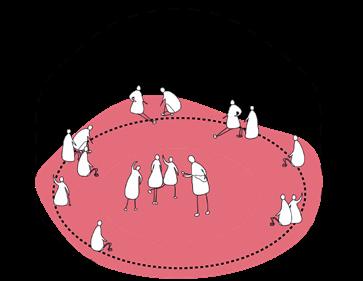

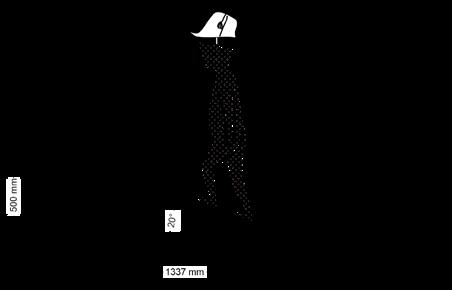

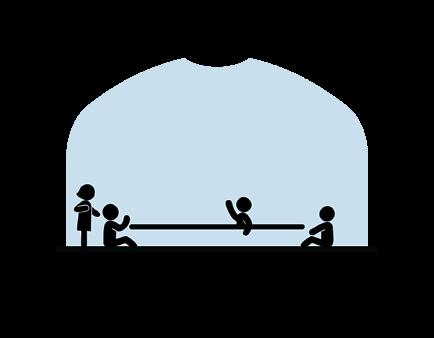

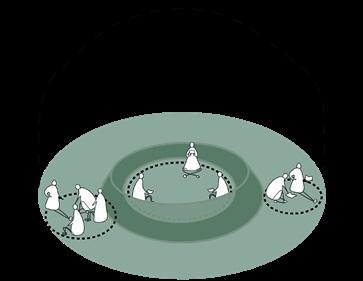

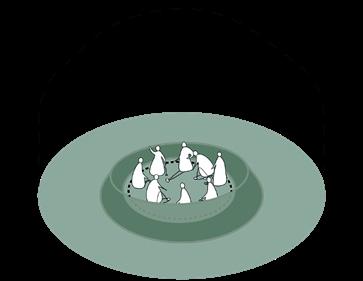

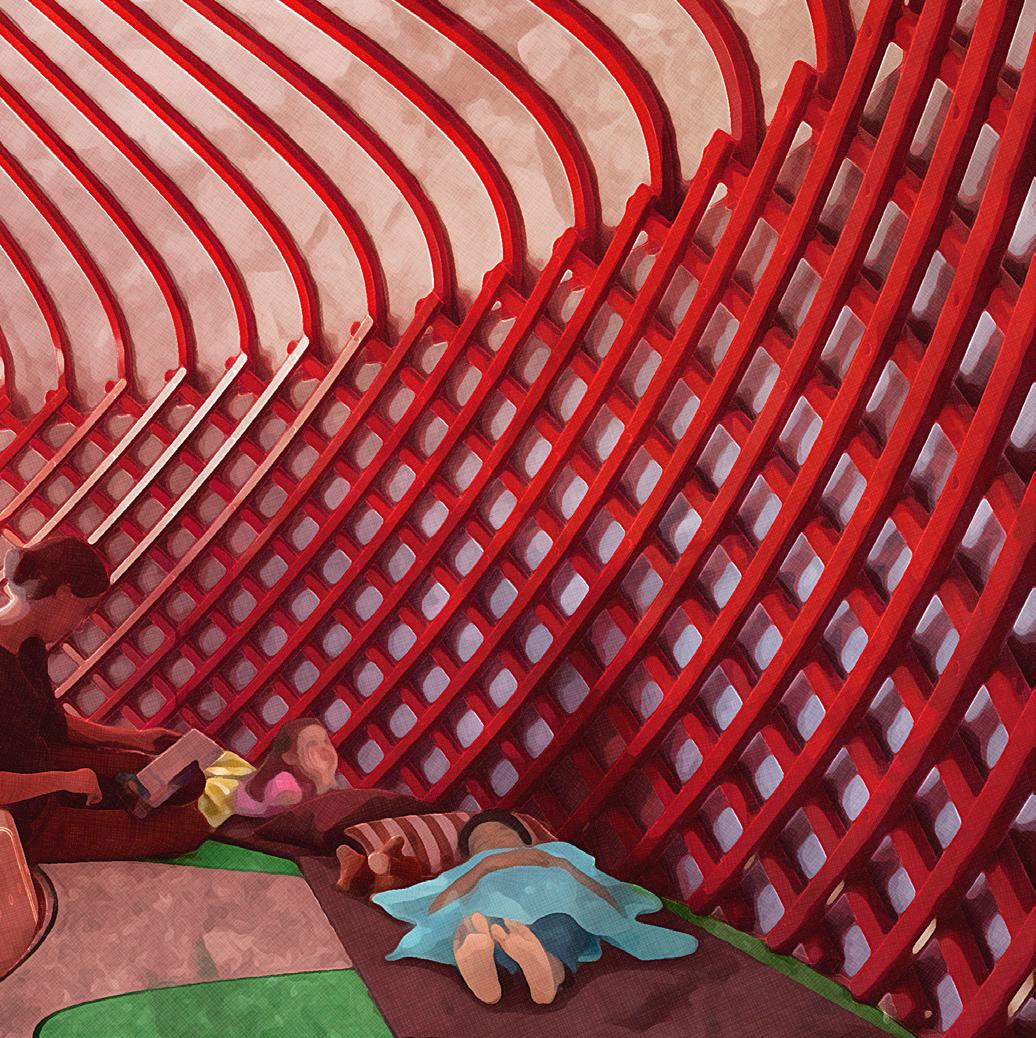

When setting up a stage in the open landscape, observers naturally prefer sitting on higher ground or an elevated surface to ensure an unobstructed view. This principle is the foundation of the design for the performance classroom, which draws inspiration from the surrounding hills. The elevated space provides clear sightline, enhancing the audience’s engagement with the performance.

The performance classroom is designed to accommodate various group activities, including

speech, music, and theatre. Each of these disciplines requires flexibility in space and seating, making the hill-inspired design an ideal choice. By integrating natural elements and prioritising the observer’s experience, the space becomes a dynamic environment where children can engage in creative expression and learning. The design not only reflects the natural landscape but also serves the educational purpose of fostering group activities in a functional and inspiring way.

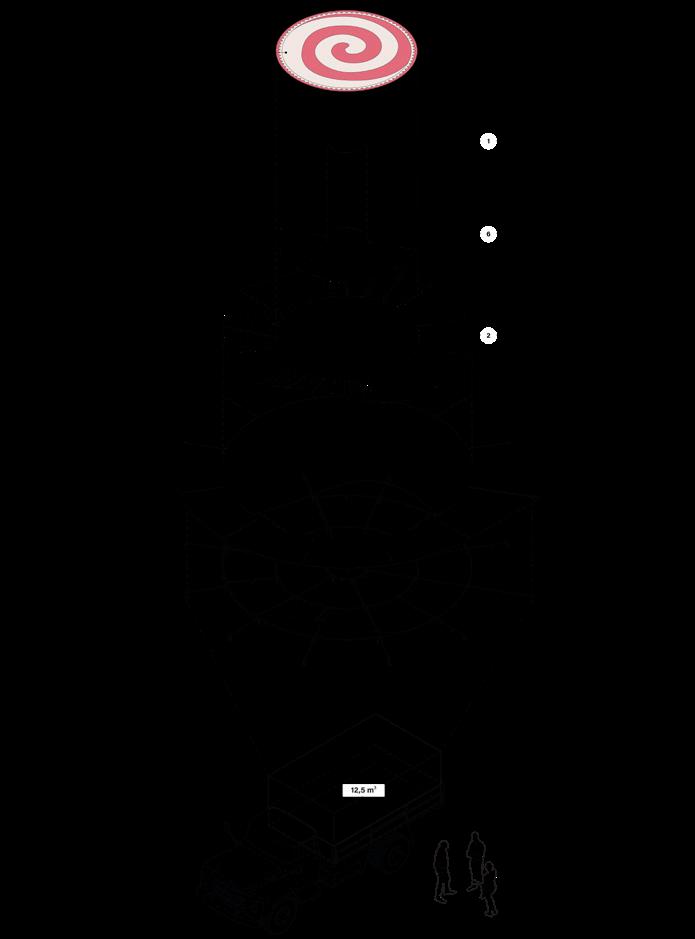

According to the concept of the performance classroom, elements of a hilly terrain (1) are incorporated within the domain of the yurt, creating a space that looks like the natural landscape while enhancing the educational environment. By outlining the entrance area and positioning the flexible sleeping zone (2) in the center of the classroom, the space remains open and adaptable to different activities. Observation points, shaped like gentle hills, are strategically placed along the edges (3), ensuring clear sightline and a continuous visual connection (4) throughout the entire space.

This design fosters an interactive and immersive learning experience, where children can engage in speech, music, and theatrical activities without physical or visual barriers. The

unobstructed layout allows for a fluid transition between different modes of learning, from structured lessons to free play. The integration of hilly elements not only enhances seating but also provides opportunities for movement, social interaction, and spatial awareness.

The carefully planned positioning of these elements ensures that children can navigate the space freely, and teachers can easily oversee the entire classroom, maintaining engagement and participation. By drawing inspiration from the surrounding landscape and incorporating it into the educational setting, the design of the performance classroom redefines the traditional learning space, making it more intuitive and flexible.

This design allows for versatile use of space, accommodating various group configurations for activities, whether for larger groups or smaller, more focused sessions. The hills within the performance classroom not only serve as elevated observation points, providing a unique spot for viewing performances or big group activities, but they also act as natural dividers. These hills can be used to create smaller, more intimate spaces for group work, fostering a sense of personal space while still maintaining a connection to the larger classroom environment. This flexibility ensures that the classroom can adapt to different needs throughout the day, supporting both collaborative and individual learning experiences.

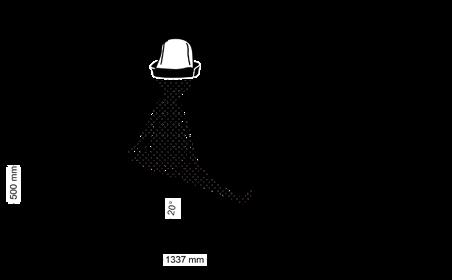

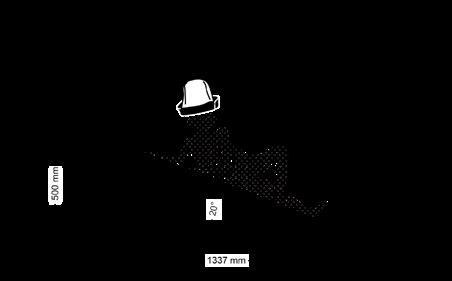

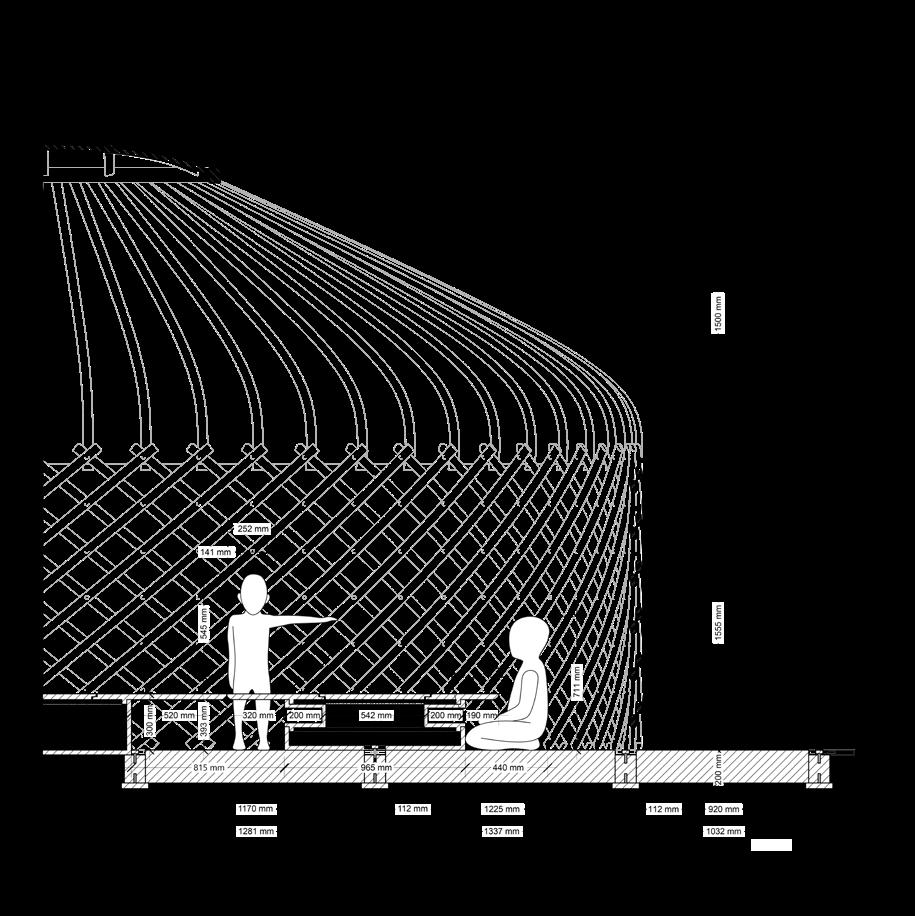

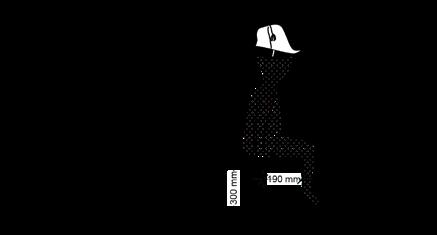

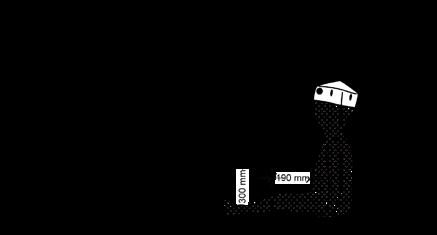

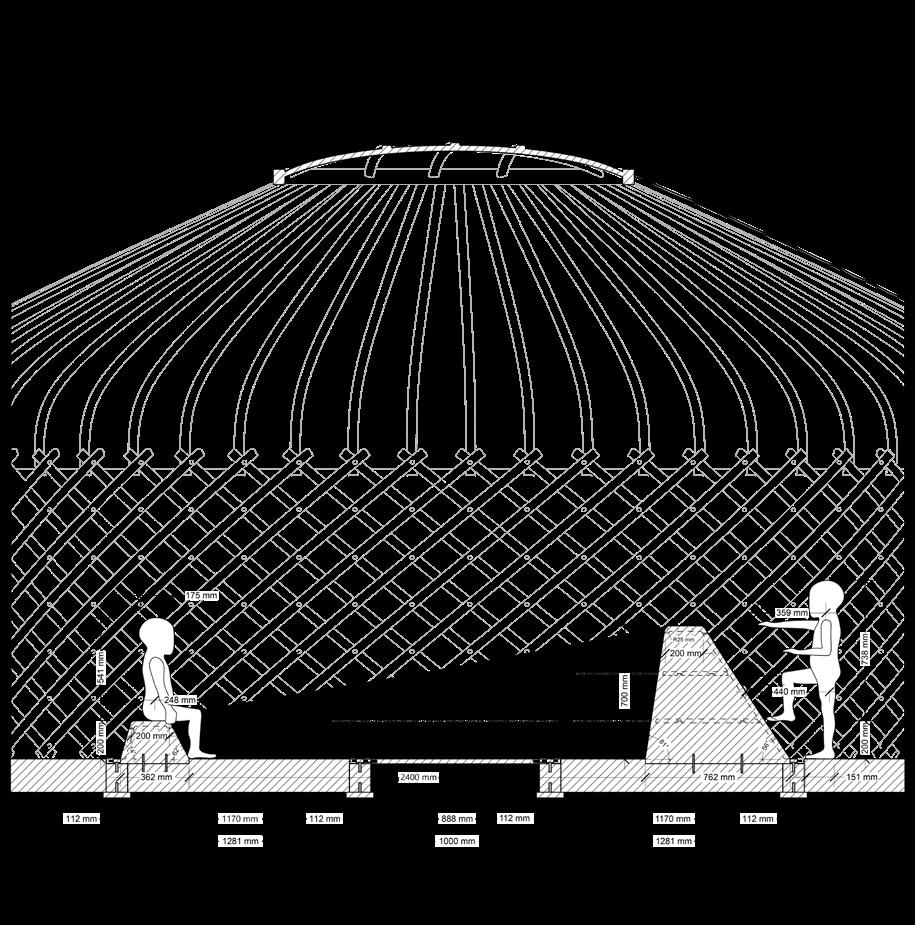

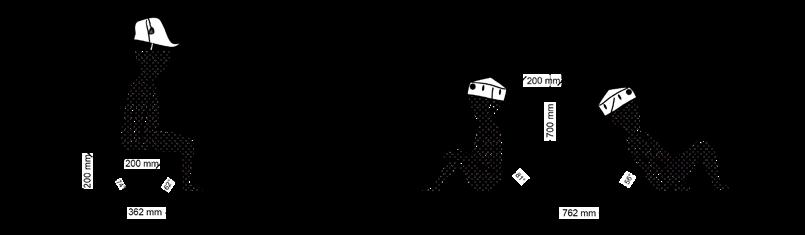

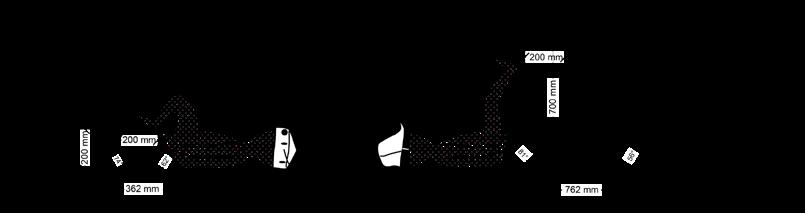

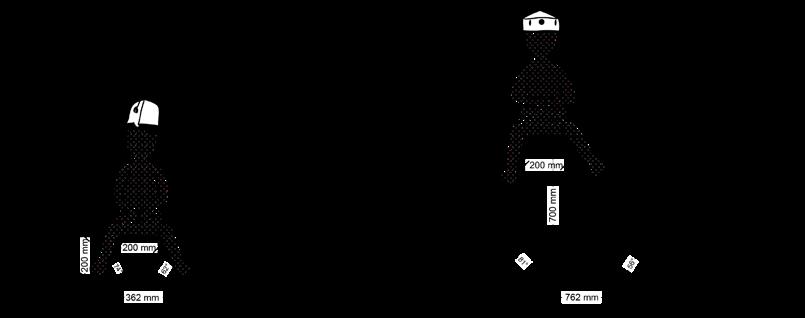

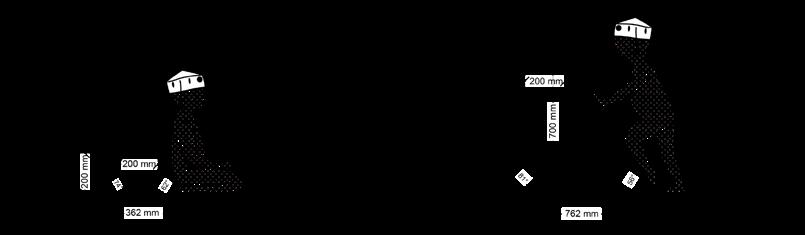

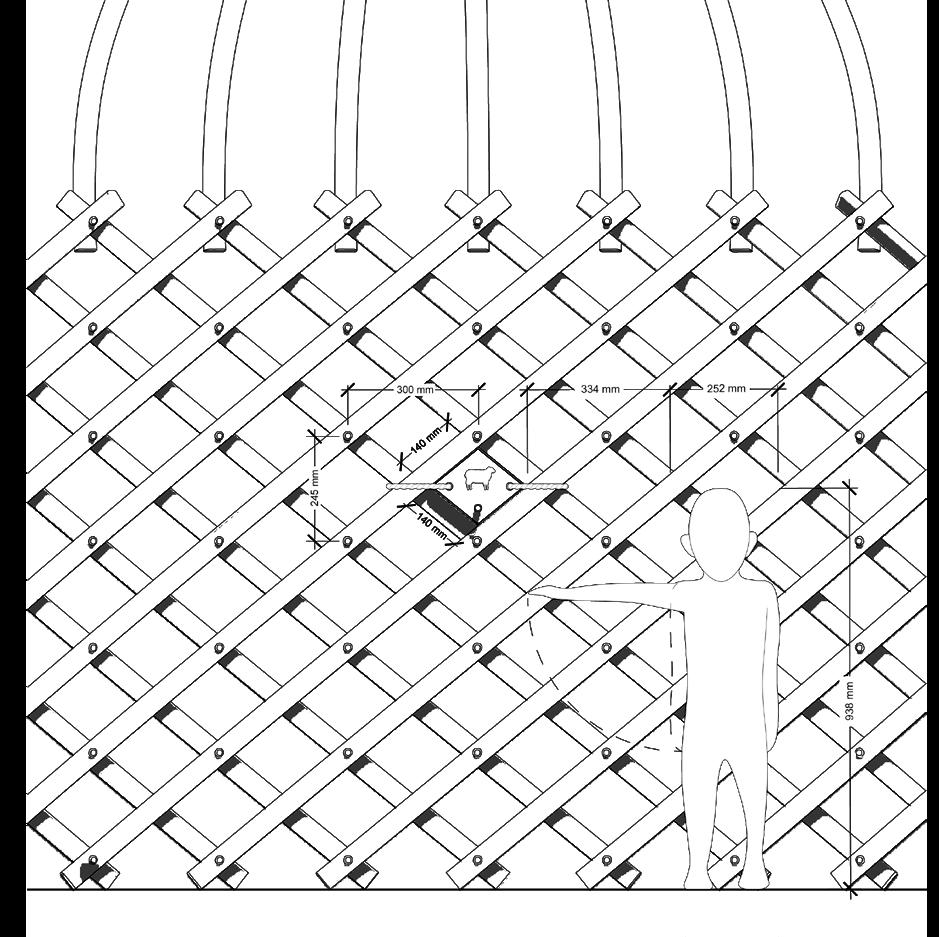

ergonomy of the element

The height and angle of the hills are carefully designed to accommodate the size and physical needs of young Kyrgyz children (92 - 120 cm), ensuring comfort, engagement and functionality. The gentle slope allows children to sit for 15-minute class segments without experiencing strain, while the incline supports an ergonomic posture that keeps them engaged in lessons. To further enhance seating comfort, the inclined floor features a perforated system that enables the attachment of rolled mats, blankets, or pillows. This flexible seating option provides additional cushioning, allowing children to remain seated at ease during longer sessions.

Beyond serving as seating, the hills are intentionally designed to encourage movement and playful interaction. Their gentle inclines make it easy for children to navigate between them

with minimal effort, fostering an active learning environment that integrates movement with education. This freedom of mobility supports both structured activities and unstructured play, allowing children to transition seamlessly between different modes of learning throughout the day.

The height of the hills, set at 500mm, is specifically chosen to prevent children from reaching or grabbing the yurt’s roof structure, enhancing safety. Additionally, it allows to organise built-in storage underneath. This hidden storage solution maximises the use of space, providing designated areas for educational materials, toys, and other classroom essentials. By keeping resources neatly stored yet easily accessible, the design maintains a clutter-free environment.

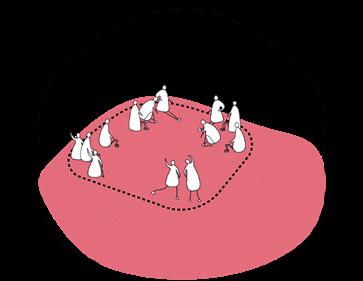

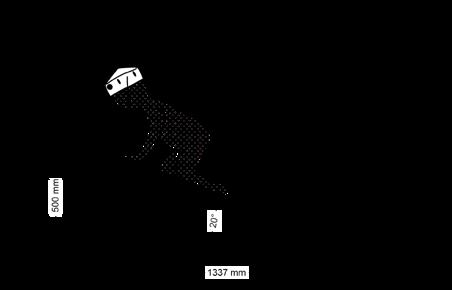

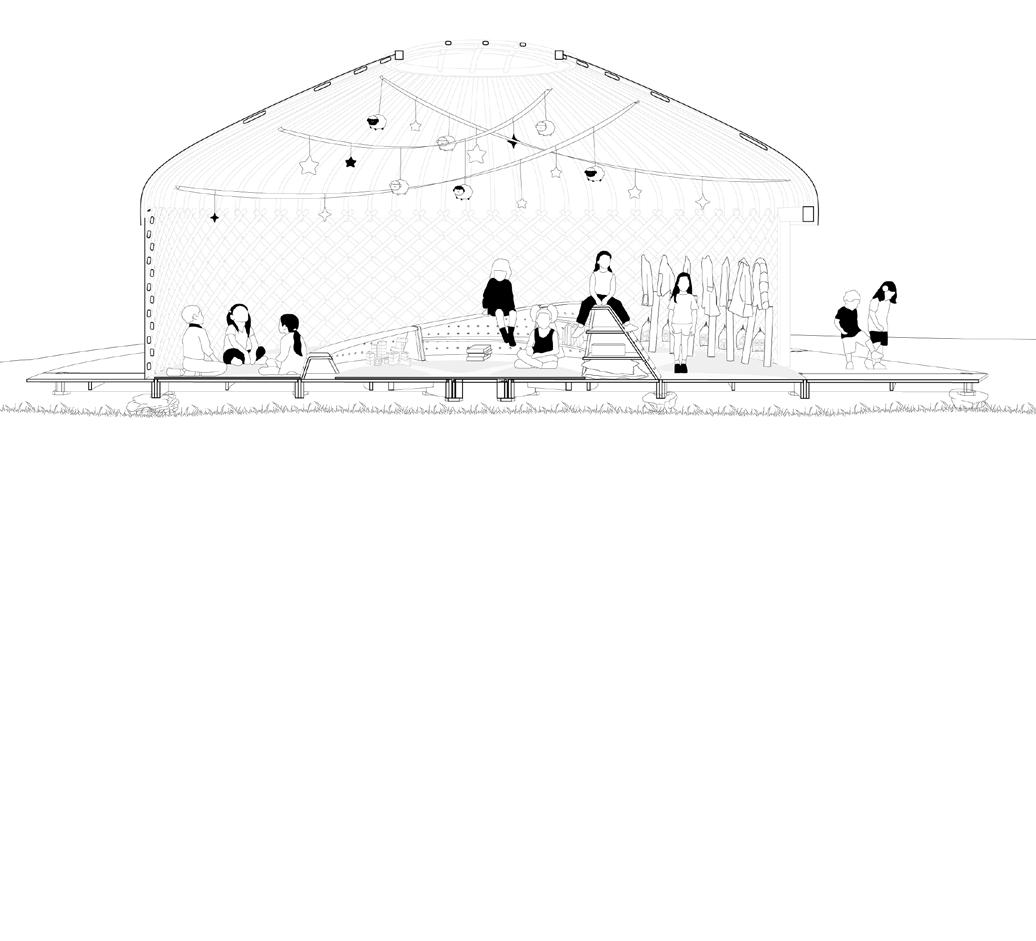

In the vast landscapes of Kyrgyzstan, stones and rocks naturally serve as surfaces for placing objects, informal seating, and subtle dividers in social settings. This organic relationship with the environment has inspired the design of the crafts classroom, where learning and creativity emerge from a space deeply connected to the surrounding landscape.

Drawing from the scattered stones and rock formations found throughout Kyrgyzstan, the classroom reinterprets these natural elements into modular seating and work surfaces that provide both functionality and a sense of place. Their arrangement fosters an intuitive spatial flow, creating distinct yet interconnected zones for various creative activities.

Designed for hands-on learning, the crafts classroom supports sculpture, writing, art, modeling, and traditional crafts. The rock-like formations serve as flexible workstations, with possibility of varying heights that encourage

a range of working positions - whether sitting, kneeling, or standing- allowing children to engage with their projects naturally and comfortably.

Beyond their functional role, these rock-inspired structures influence the spatial dynamics of the classroom. Just as stones in nature subtly mark boundaries, they create gentle separations within the space without forming rigid barriers. This ensures an open, fluid environment where children can move freely while still having areas for focused work.

By embracing the natural presence of stones in Kyrgyz culture, the crafts classroom extends beyond a conventional learning space - it becomes an evolving landscape for exploration, creativity, and connection to tradition. The design fosters an educational experience that is both rooted in heritage and adaptable to new interpretations.

scape (1) into the interior, drawing inspiration from the scattered stones and rock formations of Kyrgyzstan. These elements establish the foundation of the space, bringing the essence corporated. Unlike the performance classroom, where this zone is centrally positioned, in the crafts classroom, it is clustered into specific areas. Stone-like formations serve as subtle

taining openness and flow. To create functional yet adaptable workstations, some of the uneven

rock-like bases were levelled (3) and covered with modular surface (4). These provide versatile area for group activities such as sculpture, writing, and modeling, supporting various creative processes while preserving the organic feel of the space. The final design consists of a structured yet fluid horizontal landscape, where modular stone-like elements define zones without rigid barriers (5). These formations function as both workstations and subtle spatial dividers, ensuring a flexible, engaging environment that fosters creativity and movement within a space inspired by the natural surroundings.

The dynamic edges of the modular tables and surfaces allow for versatile configurations, enabling children to collaborate on large projects in groups, work individually, or engage with shared projects from opposite sides. This adaptability accommodates different learning styles and fosters both independent exploration and teamwork.

Additionally, the tables act as subtle spatial dividers, naturally organising the classroom into defined zones. Whether working directly at the surfaces or gathering on the floor, children can intuitively navigate between open collaboration and focused activities. This thoughtful design encourages movement, engagement, and creativity while maintaining a structured yet dynamic learning environment.

Beyond serving as a workspace, the table also functions as a communal dining area, designed to seat all 26 children at once. Mealtime becomes an integral part of the learning environment, reinforcing a sense of community and social interaction.

traditional straw mats

In traditional Kyrgyz culture, straw mats serve as essential work surfaces for crafting ala-kiyiz, a handmade felt textile created through a process of layering and pressing dyed wool. These mats provide a stable and breathable base, allowing artisans to manipulate the wool with ease while ensuring even pressure during felting.

Inspired by this tradition, the same straw mats are incorporated into the learning environment, offering children a flexible way to define their workspace on the floor. By placing the mats in designated areas, kids can create personal zones for various hands-on activities, including traditional crafts, felting, and other artistic projects. This approach not only fosters a sense of individual space within the shared classroom but also strengthens cultural connections by immersing children in the tactile and material traditions of their heritage.

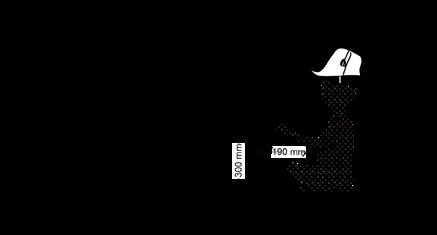

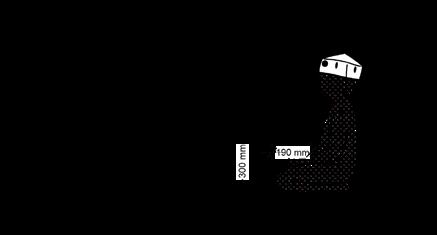

The ergonomic design of this element is carefully tailored to meet the needs of young children aged 3 to 6 years old, ensuring both comfort and accessibility. Height was a key consideration in making the design element functional and inviting, allowing children to engage with their activities with ease.

With a height of 300mm, the element is designed to accommodate a child’s natural posture, enabling them to sit comfortably while working on various tasks such as drawing, crafting, or modeling as well as eating the meal.

This proportion allows them to reach the surface effortlessly without straining their arms or backs, promoting a more relaxed and focused learning experience.

Beyond comfort, the thoughtful height selection fosters independence, encouraging children to move freely and interact naturally with their environment. By aligning the design with their scale and physical needs, the space supports intuitive engagement, making learning and creative exploration more fluid and enjoyable.

The modularity of the design elements creates a flexible and dynamic learning environment. The stackable shelf system allows for various configurations by placing units on top of one another, forming lower or higher surfaces that accommodate different working positions— whether sitting on the floor, kneeling, or standing. Additionally, the rotatable work surface can be pivoted to create more private group sessions, offering adaptability for different learning scenarios.

This flexibility ensures that children can engage with their activities in a way that feels natural and comfortable. The nature of the design not only enhances ergonomic comfort but also fosters an interactive and ever-changing space that responds to the needs of the children throughout the day.

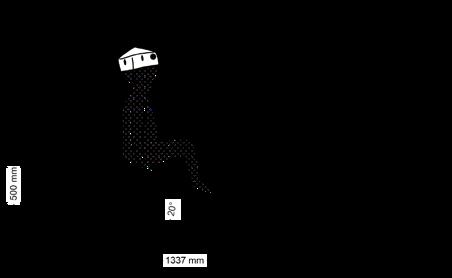

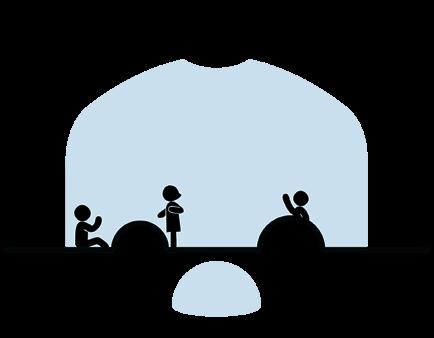

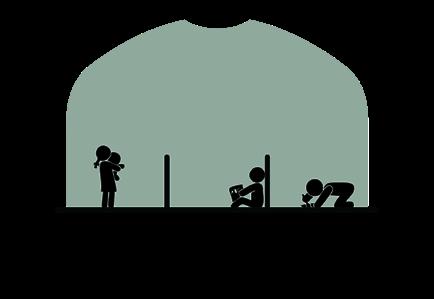

The landscape of Kyrgyzstan is defined by its vast mountain ranges, whose towering formations naturally divide the land, shaping the movement and settlement patterns of its people. These mountains create distinct separations between cities, villages, and pastures, influencing both the physical and cultural landscape of the region. Inspired by this ever-present terrain, the reading classroom integrates vertical elements to establish a learning environment that reflects the spatial organisation and sense of shelter found in the mountains.

Unlike the open and flexible design of other classrooms, the reading space is intentionally structured to foster enclosure, intimacy, and focused learning. The vertical structures, reminiscent of mountain ridges, act as gentle spatial dividers, creating cozy nooks where children can immerse themselves in reading. These partitions form quiet pockets within the classroom, offering privacy and seclusion while maintaining a sense of connection to the larger space.

The reading classroom draws inspiration from corporating its verticality and natural divisions into the yurt’s interior (1). The design centre around a high, mountain-like peak is the focal element, establishing a strong spatial identity. ing zone mirror foothills as natural resting spots (2), creating a smooth transition into the space (3). To maximise spatial efficiency, a cave-like nook is carved into the mountain peak, offer-

ing a quiet retreat for reading or small-group activities (4). The interplay of height and depth encourages exploration while balancing open and enclosed areas. The final design introduces a dynamic and playful vertical element that naturally divides the classroom (5). These mountain-like structures function as spatial organisers, fostering an engaging and immersive learning environment.

The reading space is designed as a multifunctional environment that supports both individual and group activities requiring focus and concentration. It fosters a calm and immersive atmosphere where children can engage with books and storytelling in a natural and comfortable setting.

A central element acts as a spatial divider, shaping movement while maintaining openness. It creates intimate nooks for quiet reading, offering a sense of security without complete isolation.

Groups naturally form in and around the cavelike space. A larger group can gather in the central area, inside for better focus, away from the entrance and external distractions. Smaller groups or individuals can use the sections divided by the mountain walls independent reading or small peer interactions. This layered spatial organisation ensures flexibility, allowing children to engage in various ways based on their needs and comfort.

Designed at two different heights, it serve distinct functions. The taller elements rise just enough to define separate zones while maintaining children’s visual connection across the space, preserving a sense of openness. The lower height ensures easy access for both children and senior teachers while maintaining spatial organisation. This height variation en-

hances functionality without disrupting the fluidity of the space.

Beyond the structural role, the element invites playful interactions. Children can engage with them in multiple ways - climbing mountain peaks, sitting on a horse like a true nomads, or using them as comfortable perches for reading.

(in kyrgyz “ala” meaning multicolored and “kiyiz” meaning felt)

Ala-Kiyiz holds deep cultural significance in the lives of Kyrgyz children, as it is often the first surface they step on when learning to walk. This traditional felt rug crafted through an ancient process of pressing and layering wool, is more than just a household item - it is a symbol of warmth, comfort, and connection to heritage.

For generations, Kyrgyz families have used Ala-Kiyiz in their yurts, providing a soft and insulating layer that protects from the cold ground. The rich, colourful patterns of Ala-Kiyiz also carry symbolic meanings, telling stories of nature, family, and the nomadic way of life.

• open communication

• inspire creativity

• increase productivity

• boost energy

• stire up conversation

• inspire movement

• improve memory

• increase focus

• help to relax

Beyond its practical function, Ala-Kiyiz plays an essential role in a child’s early development. It defines a safe space for play, learning, and creativity, fostering a sense of belonging and cultural identity from the very beginning. As children grow, they continue to engage with this felted landscape - whether through traditional crafts, games, or daily routines - further strengthening their bond with their nomadic heritage.

The design thoughtfully incorporates traditionally made Ala-Kiyiz, preserving its cultural essence while adapting it to enhance the learning environment. To reduce visual distraction during class activities, the traditional patterns have been upscaled, creating a more subtle yet meaningful presence. Additionally, each classroom is distinguished by a unique colour scheme, reinforcing its function and fostering a supportive atmosphere for study and creativity.

All three classrooms feature patterns inspired by the “Umai Ene” ornament, regarded as the origin of all Kyrgyz motifs. Symbolising protection and motherhood, this sacred design reflects the nurturing nature of the preschool, creating a space where children feel connected to their heritage while immersed in a stimulating and comforting environment. By blending tradition with thoughtful design, the classrooms honor cultural identity while supporting modern educational needs.

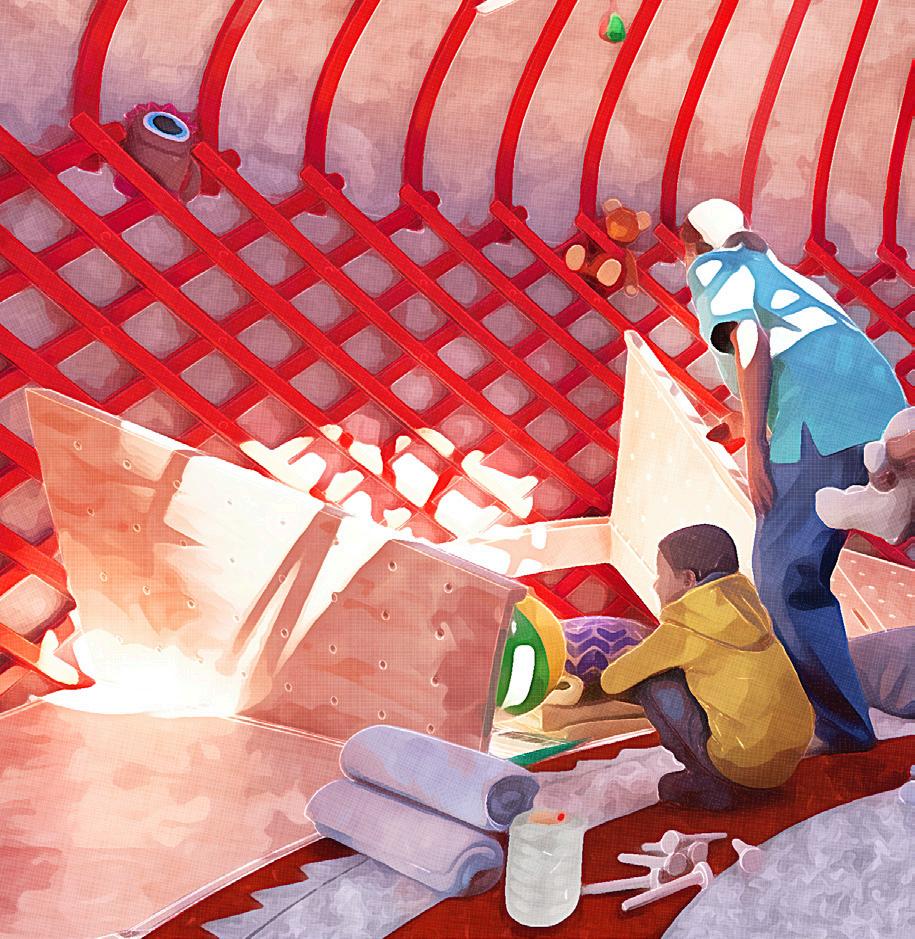

In Kyrgyz tradition, the wooden framework of the yurt, particularly the kerege (wall lattice) and uuk (roof poles), is often painted red, a colour deeply rooted in cultural symbolism and natural craftsmanship.

Red represents strength, protection, and vitality, embodying the warmth and resilience of nomadic life. This distinctive red colour is traditionally derived from madder root (Rubia tinctorum), a plant known for its deep, earthy red pigment. The roots are harvested, dried, and ground into a fine powder before being mixed with natural binders to create a durable paint. Beyond its aesthetic and symbolic significance, this natural dye also serves a practical purpose, helping to preserve the wood against environmental wear.

To make it easily recognisable among the many identical yurts scattered across the landscape, Jailoo Educational Centres used colourful flags as markers.

Building on this concept, the new Jailoo Preschool design incorporates vibrantly coloured platforms, ensuring the yurts stand out while adding a playful element to the environment. These platforms not only serve as visual identifiers but also enhance the learning space, making it more engaging for children. Natural pigments, traditionally used to dye yurts, are applied to maintain cultural authenticity while ensuring an eco-friendly approach. This integration of colour transforms the educational setting into a welcoming and stimulating space, where children can easily recognise their centre.

To accommodate the needs of arriving children, an additional element was introduced at the entrance of the preschool, providing a designated space for hanging clothes and storing shoes. Since children frequently transition between indoor and outdoor activities, it was essential to create an organised yet unobtrusive storage solution that blends seamlessly with the space.

The design integrates hangers directly into the existing lattice walls of the yurt. Utilising the natural gaps between the wooden framework, this built-in solution maintains the traditional aesthetic while enhancing functionality. This approach keeps the floor open and uncluttered, ensuring a harmonious and fluid interior.

Beyond practicality, this feature encourages independence, allowing children to manage their belongings with ease. Thoughtfully designed to complement the yurt’s structure, the addition enhances usability while preserving the lightness in transportation.

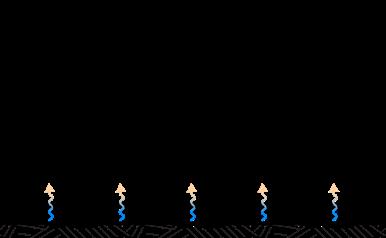

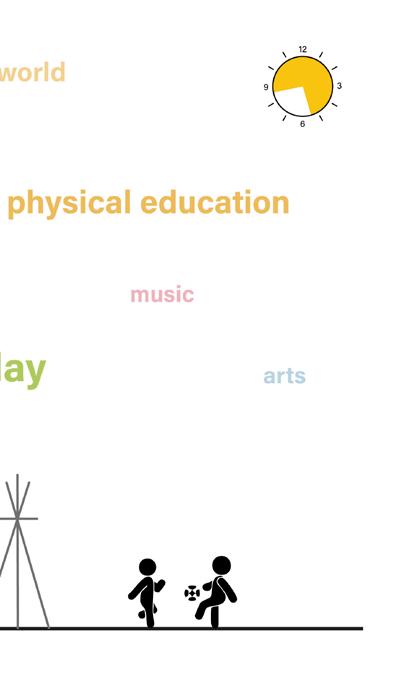

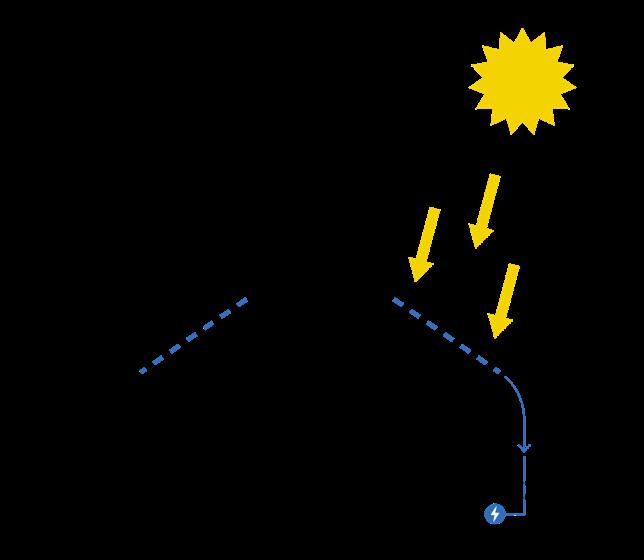

Modern semi-nomadic communities have long relied on small and transportable solar panels to generate electricity while moving between seasonal pastures. These lightweight systems provide essential power for lighting and small appliances, ensuring a more self-sufficient lifestyle in remote areas.

To address this, the new design seamlessly incorporates a triangulated mesh of solar panels into the fabric of the yurt itself. Unlike conventional rigid panels, this innovative system embeds photovoltaic cells within a rollable, textile-like structure, allowing the yurt to retain its flexibility while harnessing renewable energy. The solar mesh is lightweight, adaptable, and easily transportable, ensuring that the energy source moves with preschool without requiring

separate installations.

This approach not only enhances the practicality of solar energy for semi-nomadic kids and educational environment but also enhance the traditional aesthetics and portability of the preschool. The result is a solution that supports both cultural preservation and environmental sustainability, making it an ideal energy innovation for mobile communities.

The Kyrgyz yurt is a remarkable testament to centuries-old craftsmanship, embodying both the practicality and artistry required for nomadic life. Designed for portability, durability, and adaptability, it reflects a deep understanding of the natural environment and the needs of a mobile lifestyle. Each component is meticulously handcrafted using local materials, ensuring that the yurt remains lightweight yet resilient against the harsh climatic conditions of the Kyrgyz steppes and mountains.

The construction process is an intricate practice passed down through generations, preserving not just a building method but a cultural legacy. The wooden framework, traditionally made from willow, is carefully shaped and bent using steam-heating techniques, allowing it to be both flexible and strong. The lattice walls (kerege), the roof poles (uuk), and the central crown (tunduk) come together to create a self-supporting structure, requiring no nails or artificial fasteners. This structural ingenuity ensures stability in strong winds while allowing for easy assembly and disassembly, a crucial feature for nomadic families who relocate seasonally.

In the new design, this traditional craft is complemented by digital fabrication techniques, enhancing both efficiency and complexity in form. The platforms for the preschool introduced within the yurt utilise computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) and CNC milling, enabling the creation of intricate, organic shapes that would be challenging to achieve through traditional methods alone. This approach minimises material waste, ensures precise assembly, and allows for customised design solutions.

By merging digital precision with traditional artistry, the design respects heritage while embracing innovation. The platforms, inspired by Kyrgyzstan’s natural landscapes, maintain aesthetic while benefiting from modern fabrication techniques that improve durability, adaptability, and ease of assembly.

* construction detailed instructions can be found in additional booklet

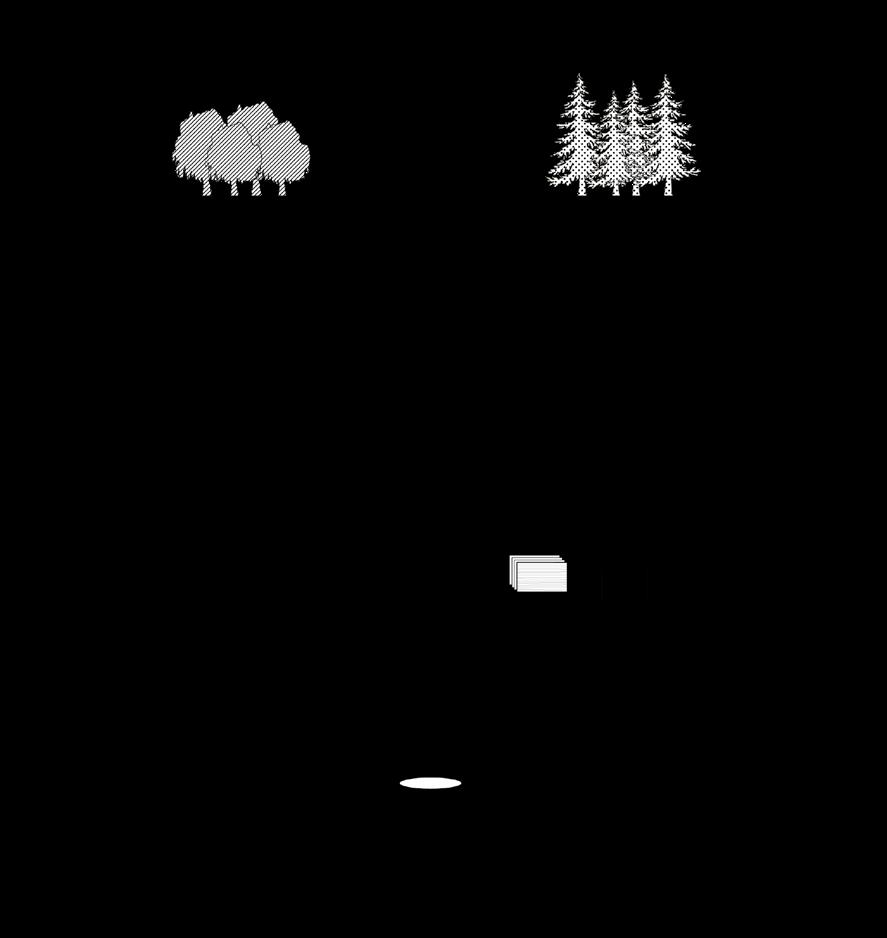

Forest type distribution

Willow

Walnut

Broad-leaved

Juniperus (Juniperus horizontalls)

Spruce, Silver Fir (Abies)

Pistachio, Almond trees

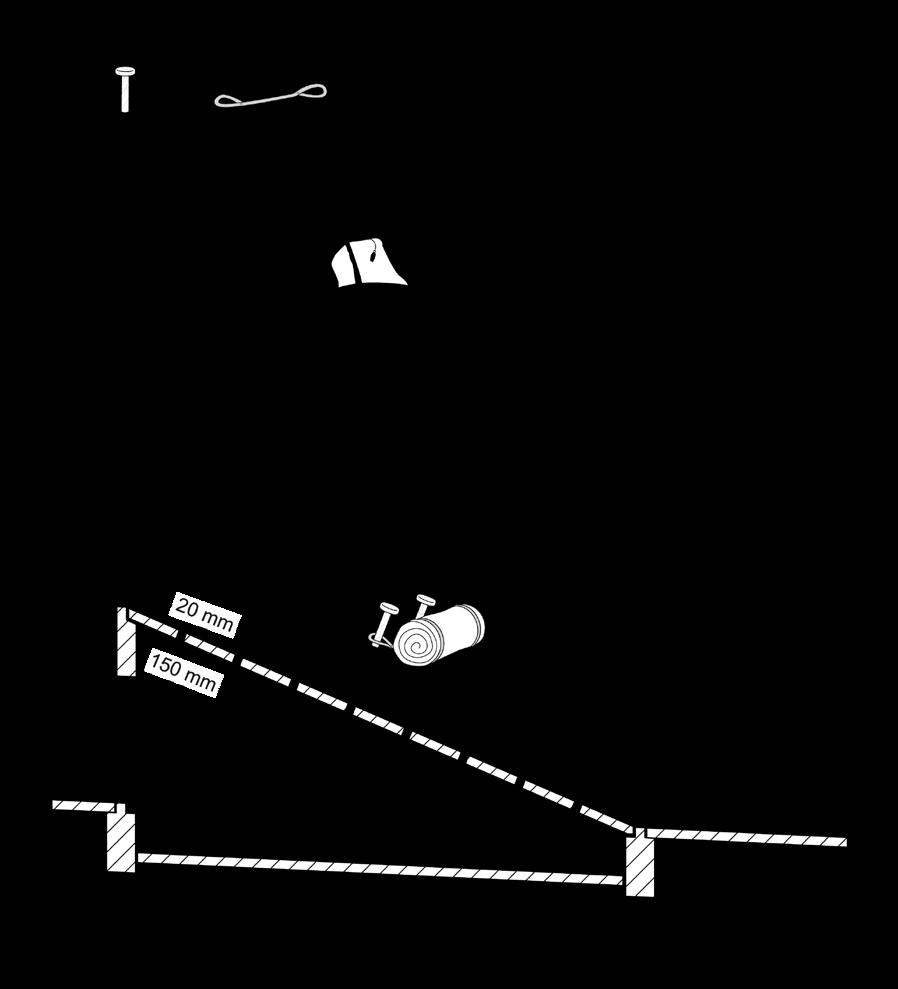

As for the new design, local spruce wood is introduced as the primary material for the beams of the platforms and flooring. Rich spruce forests in Kyrgyzstan provide a sustainable and durable resource well-suited for this purpose. Spruce is known for being lightweight yet strong, making it ideal for flooring elements that need to withstand daily use while remaining portable and easy to assemble.

Additionally, spruce plywood is used due to its flexibility and ability to be pressed and curved, allowing for the creation of organic, flowing forms that enhance the spatial experience inside the yurt. This adaptability enables the construction of seamless, ergonomic platforms that blend with the natural landscape while maintaining structural integrity.

One of the most commonly used trucks for this purpose is the ZIL-130, a durable and reliable Soviet-era vehicle that remains widely used in rural Kyrgyzstan. This truck has the capacity to transport up to three traditional yurts at once, including their wooden framework, felt coverings, and household belongings.

With the introduction of the newly designed platforms, logistics remain practical and feasible. Due to their size and form complexity, each platform requires one full truck for transportation. While this means fewer units per truck compared to traditional yurts, the modular construction and efficient assembly ensure that the platforms can be quickly set up upon arrival (min. 3 people required). Their pre-fabricated components allow for easy stacking and loading, making transportation streamlined and adaptable to nomadic lifestyles.

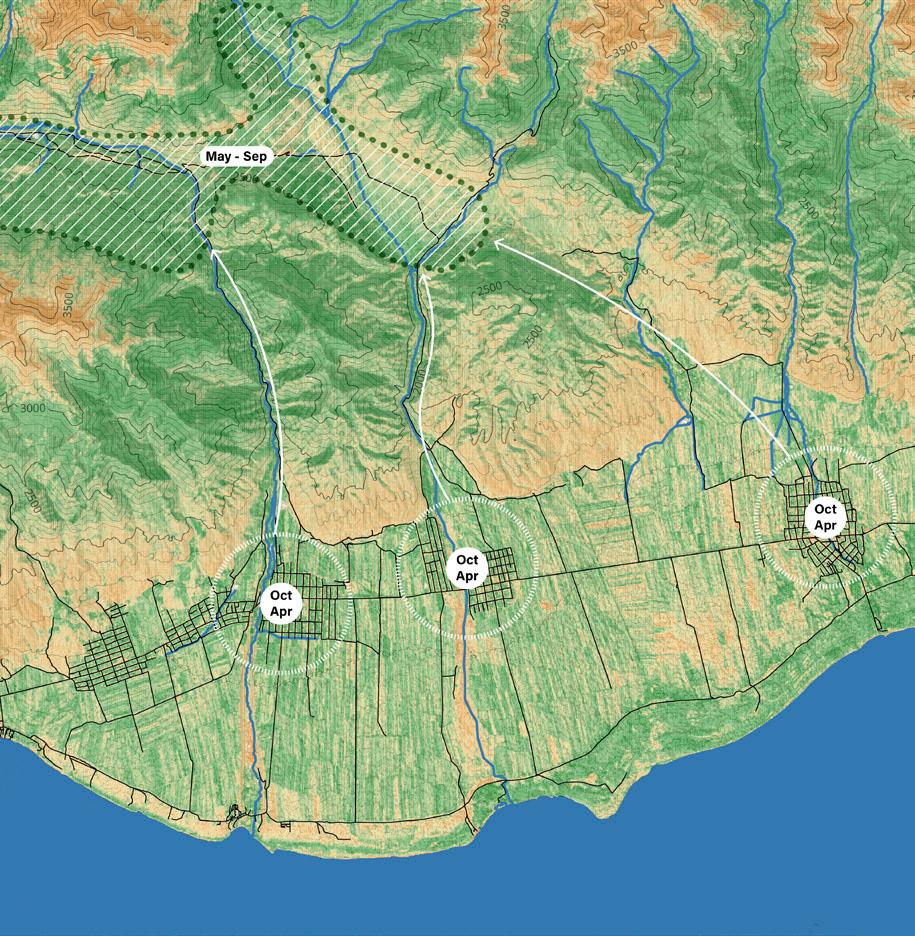

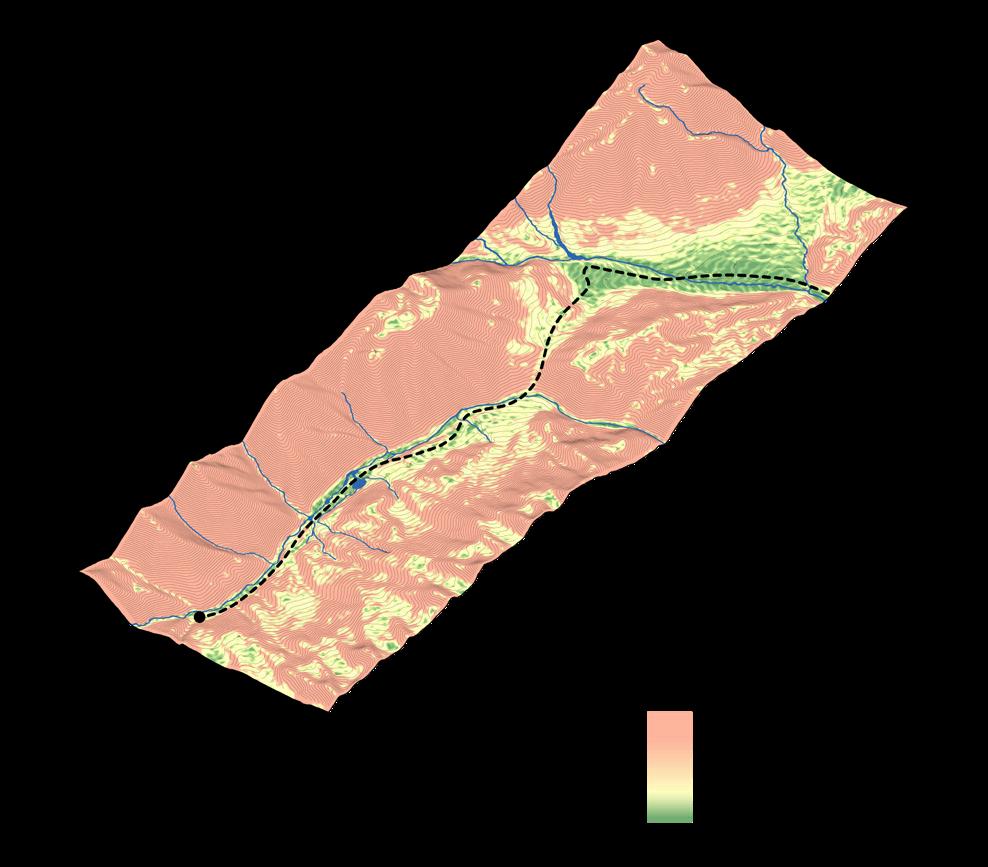

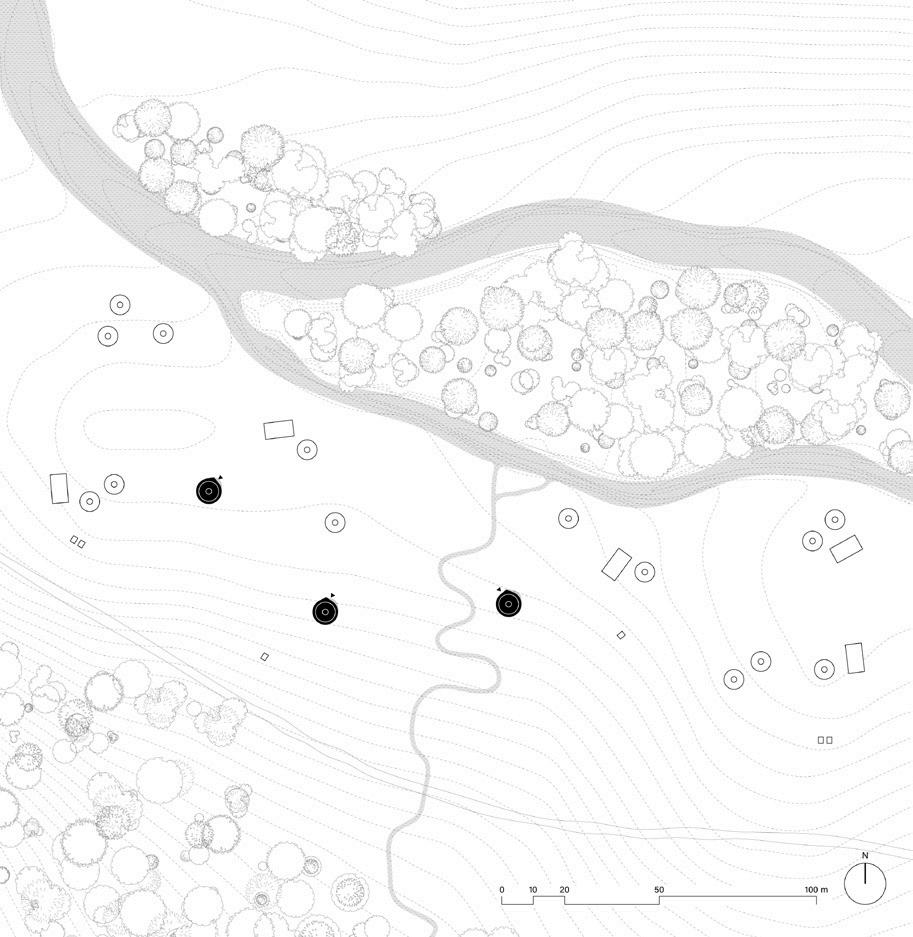

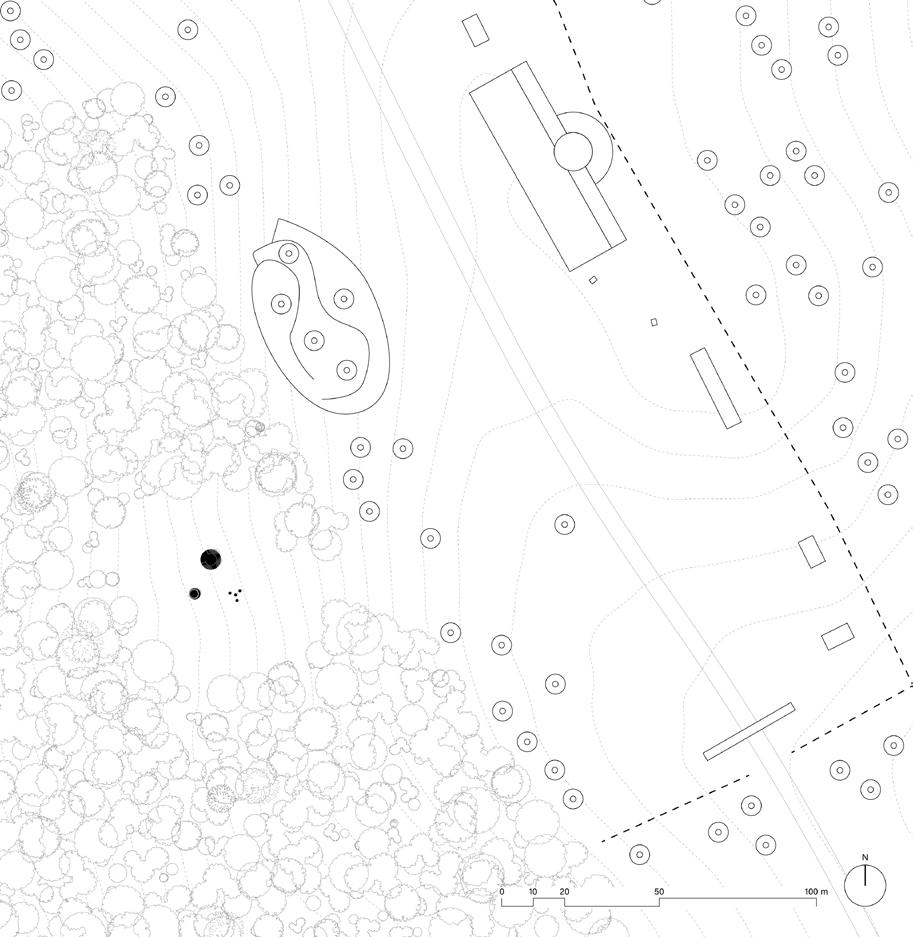

The proposed design is a prototype that can be adapted and implemented in various locations, providing flexibility to accommodate different landscapes and the needs of semi-nomadic communities. However, this specific site was carefully chosen as a reference due to its profound historical, cultural, and geographical significance.

Situated along one of the most well-known nomadic routes, the selected area lies in the Issyk-Kul region, on the northern shore of the lake. This place has long been a key passage for nomadic herders, serving as a crucial link be -

tween seasonal pastures and settlements. The dramatic landscape, shaped by mountains and open valleys, has supported the movement of people, livestock, and traditions for generations. Beyond its function as a migration corridor, this valley holds symbolic and contemporary importance as the host of the World Nomad Games - an international event dedicated to preserving and celebrating nomadic traditions.

By integrating the prototype within this historically rich and culturally vibrant setting, the design aligns itself with the enduring spirit of nomadic identity, resilience, and adaptability.

approx. 20km

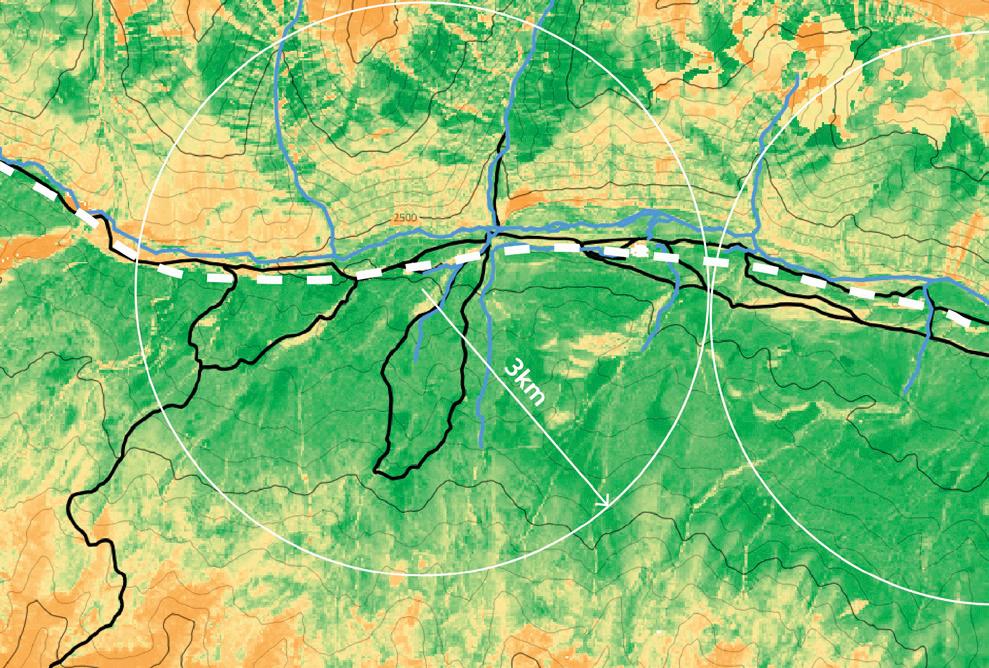

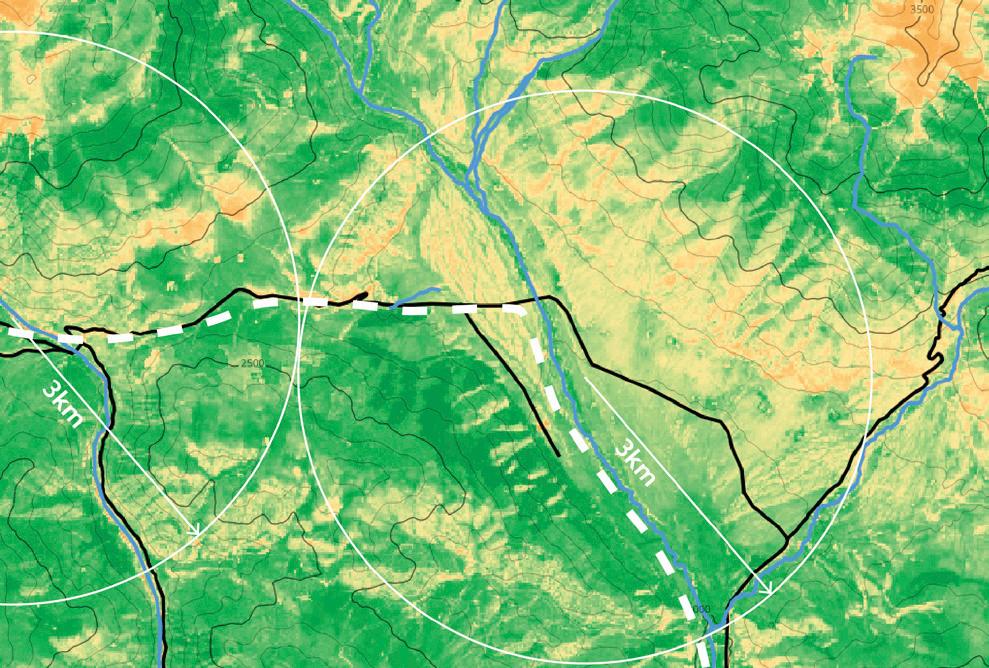

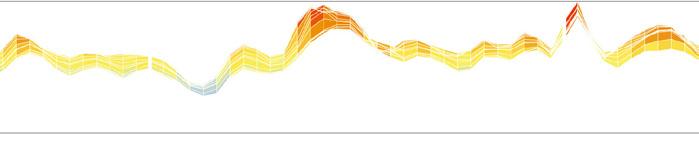

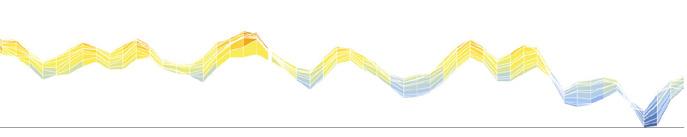

Semi-nomadic communities migrate through pastures in response to seasonal changes, ensuring the well-being of their livestock and sustaining their way of life. Typically, they relocate two to three times per season, covering around 20 kilometres in total. This movement follows a natural rhythm, beginning in higher-altitude pastures when temperatures are cooler and gradually descending to lower elevations as the season progresses.

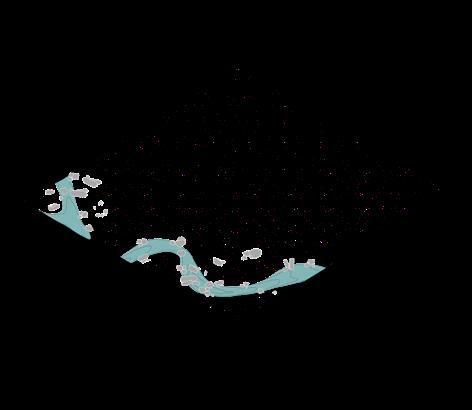

Flat terrain is a crucial factor in site selection, as it provides the necessary stability for setting up yurts and carrying out daily activities. Uneven ground can make it difficult to construct se -

cure living spaces and organise area efficiently. Access to water is equally essential, as rivers, streams, and lakes provide for both human consumption and livestock needs. These water sources also support vegetation, ensuring sufficient grazing land.

This cyclical migration reflects a deep understanding of the environment, balancing community needs with seasonal shifts in climate and resources. By adapting to these natural patterns, semi-nomads maintain a sustainable way of life, preserving traditions that have guided them for generations.

By understanding these environmental conditions and movement patterns, it becomes possible to determine an approximate location for a preschool that serves nomadic children throughout the season. Considering factors such as flat terrain for stability, access to water sources, and the natural migration routes, the preschool can be placed to align with the needs of semi-nomadic communities while remaining functional and accessible.

Additionally, proximity plays a key role in ensuring children’s ability to attend. Positioning the preschool within a 3-kilometre radius (max.) allows young learners to reach it comfortably, whether on foot or horseback, without disrupting their families’ daily routines. This thoughtful placement ensures that education is seamlessly integrated into their way of life, providing stability and learning opportunities within their nomadic journey.

first stop - Pervoye Ozerko

The analysis reveals that semi-nomadic communities make their seasonal stop near “Pervoye Ozerko,” a small lake nestled in a valley between mountain ranges. This stop is not random but rather a well-established waypoint shaped by generations of nomadic movement. The location is carefully chosen for its access to the water, fertile pastures, and natural barrier against strong winds provided by the surrounding mountains and greenery. Additionally, the terrain provides a relatively flat and stable surface for setting up yurts and temporary settlements. These elements make it an ideal resting point, offering essential resources for both people and livestock before continuing their seasonal journey.

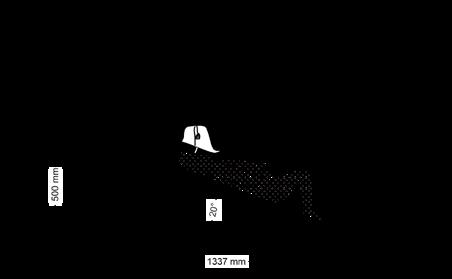

In the early season, during May, temperatures in the mountains remain cold, creating a challenging environment for outdoor activities. Given these conditions, the new design allows for three platforms to be placed together, forming a cohesive learning space where classrooms are positioned in close proximity to one another. This strategic arrangement minimizes the time children spend outside in the cold when moving between classes, ensuring their comfort and well-being.

During the colder periods, the focus of learning naturally shifts toward activities that can be conducted indoors. The enclosed classroom environment provides a warm and sheltered space where children can concentrate on developing fine motor skills through activities such as writing, crafting, and modeling, organising indoor performances, or reading a books.

3. assemble platforms

The first step in the setup process is selecting a suitable location (1) based on the terrain conditions. If necessary, the terrain can be slightly levelled (2) to create an even foundation for the platforms, preventing any imbalance that might affect the structural integrity of the classrooms. Once the site is prepared, the platforms are assembled (3). During this stage, the platforms themselves can serve as a temporary playground, allowing children to explore and engage with the space before the full setup is completed. With the platforms securely in place, the yurts are then set up on top of them

(4), transforming the space into fully functional classrooms. The elevated foundation not only provides insulation from the cold ground but also helps create a cohesive learning environment, bringing the different classrooms together in an organised and accessible manner.

When it is time for the semi-nomadic community move to a new seasonal location, the entire setup can be efficiently dismantled. The yurts are taken down first, followed by the disassembly of the platforms, which are then packed onto a truck for transport leaving zero footprint (5).

The second stop along the semi-nomadic migration route is the Chon Ak-Suu Gorge area, a diverse and dynamic landscape shaped by its varying terrain, striking stone formations, and the powerful river that flows through it. This region offers a distinct contrast to the first stop, providing new environmental conditions that influence the way nomadic families set up their temporary settlements.

The rugged topography, with its mix of rocky outcrops and open spaces, requires careful selection of a stable, relatively flat site for setting up yurts and educational platforms. The presence of the river adds both opportunities and