DISPLACED DISPLACED

an architectural approach on the impacts imposed by extractivism in rural areas

“o teu chão é chão sagrado, é o lugar onde eu nasci, podem dar-me o mundo todo (ai Barroso), ninguém me arranca de aqui”

“Exploração” by Carlos Libo Resident in Covas do Barroso

Luís Miguel Marques Garcia

Academie van Bouwkunst - University of Arts

Amsterdam, December 2024

Graduation Committee: Susana Constantino (mentor), Martin Probst and Marina Otero

| Prologue | Place | Displace | Placed varanda eira alpendre pátio | Emplaced | Bibliography and sources | Acknowledgments

1 PROLOGUE 1 PROLOGUE

On my first trip to Covas do Barroso in October 2022, I drove through valleys and mountains, following roads that seemed to dissolve into the landscape. As I am approaching the village, small hints began to tell a story — one of resistance and unease. On the backs of road signs, the walls of empty bus stops, and tarps rippling in the wind, the same message echoed over and over: “No to mines.”

These words weren’t just protests; they were a quiet, urgent reminder of a looming end. They hinted at the fragile balance between a community, its land, and the forces threatening to reshape them both.

This graduation project is born from that journey, driven by a desire to understand the weight of those words and the space they occupy in our architectural and cultural landscapes.

“No

to mines” - On the way to Covas do Barroso - October 2022

As I delved deeper into this research, I came to the conclusion that, while this project tells the story of Covas do Barroso, it is, in essence, the same story shared by countless other indigenous and rural communities all around the world.

Atacama Desert, Chile

Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia

Jujuy, Argentina

Sonora, Mexico

Kiruna, Sweden

Garzweiler, Germany

Wolfsber, Austria

Saskatchewan, Canada

San Miguel Ixtahuacán, Guatemala

Sámi people, Finland/Norway/Sweden

Anishinaabe people, Ontario, USA

Nevada/Oregon, USA

San José Valdeflores, Cáceres, Spain

Masvingo Province, Zimbabwe

Svalbard Archipelago, Norway

Kola peninsula, Russia

Jadar Valley, Serbia

Deva Muncel, Romania

Putu, Chile

Salar Coipasa, Chile and Bolivia

Punu, Peru

Laguna de Guayatayoc, Argentina

Halkidiki, Greece

Efemçukuru, Turkey

Mathiatis, Cyprus

Salar del Hombre Muerto, Argentina

Istranca/Yildiz, Turkey

Ada Tepe, Bulgaria

Tres quebradas, Argentina

Las Cruces, Sevilla, Spain

Catamarca, Argentina

Villeranges Gold Mine, France

San Luis, Argentina

Hualapai Nation, USA

Ávila, Spain

La Loutre, Quebec, Canada

Abitibi, Quebec, Canada

Trstenik, Serbia

Baita Craciunesti Teascu, Romania

Nauru, Canada

Sichuan, China

Manono, Democratic Republic of Congo

Serra d’Arga, Portugal

Monte Galineiro, Galicia, Spain

Kolontar-Devecser, Hungary

North Mara, Tanzania

Dead Sea area, West Bank

Lege Dembi, Ethiopia

Montalegre, Portugal

Kwa Zulu Natal, South Africa

Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia

Ambohitsy Haut, Madagascar

Nueva Vizcaya, Philippines

Ghaghoo, Botswana

Rovina, Romania

Nimmalapadu village, India

Isua, Greenland

Bumbuna, Sierra Leone

South Taranaki Bight, New Zealand

Banjima people, Australia

Vättern, Sweden

Imider, Morocco

Sabodala, Senegal

Left to right - top to bottom: Atacama, Ramón Morales©; India, businesstoday©; Chile, SusiMaresca©; Mexico, Santiago Navarro©; Guatemala, Johan Ordone©; Canada, ItzaFineDay©; Sweden, GretaThunberg©; Canada, Emma McIntosh©; USA, Jason Beanrgj©

In recent years, lithium has emerged as a cornerstone of the global energy transition. As the world pivots away from fossil fuels, lithium-ion batteries power everything from electric vehicles to renewable energy storage systems. This surge in demand has transformed lithium into a strategic resource, essential for achieving carbon-neutral goals and driving the green transition.

For the European Union, the urgency to secure lithium supplies stems not only from environmental imperatives but also from geopolitical and economic pressures. Currently, the global lithium market is dominated by a handful of players, with China controlling the majority of processing and supply chains, and significant reserves concentrated in the United States and Oceania. Recognizing this dependence as a strategic vulnerability, the EU has adopted policies aimed at reducing reliance on external sources.

The European Critical Raw Materials Act and the European Green Deal underscore the bloc’s ambition to establish domestic supply chains for critical materials, including lithium. Portugal, with its significant lithium reserves—particularly in the Barroso region—has been thrust into the spotlight as Europe’s potential gateway to lithium independence.

However, this vision of a self-sufficient and sustainable Europe comes at a cost. The extraction of lithium brings with it environmental degradation, disruption of ecosystems, and profound social consequences. Rural communities, like those in Covas do Barroso, stand at the frontlines of this conflict. For these regions, the promise of “green energy” does not resonate as progress but rather as an existential threat to their land, traditions, and way of life.

2 DISPLACED 2 DISPLACED

A specific location or position in space; a point of reference or meaning.

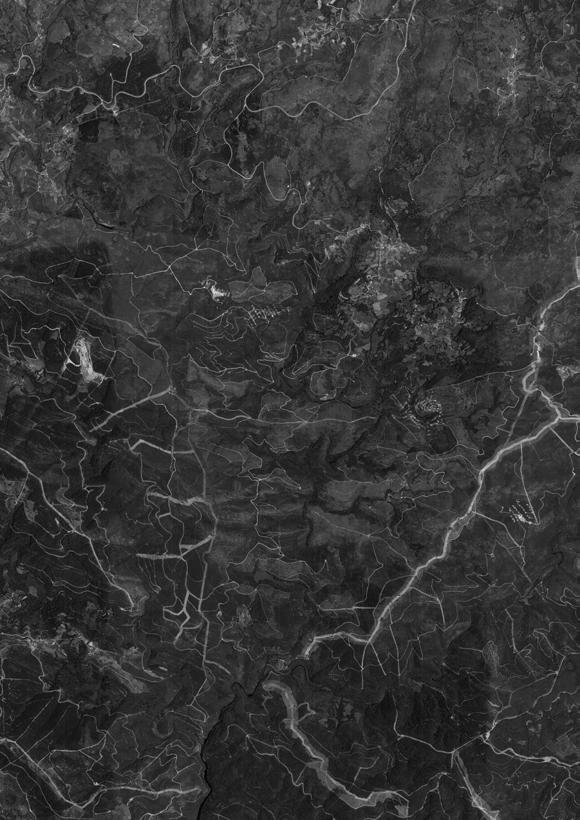

Barroso region

The Barroso region sits on the North of Portugal, on the border with Spain. It is defined by its natural and geographical isolation, a land shaped by plateaus, steep mountains, and deep valleys that carve out a mosaic of microclimates. Here, the rivers Tâmega and Cávado wind through lush, green slopes, their waters nourishing the fertile valleys below and adding life to a landscape as beautiful as it is unforgiving.

Winters in Barroso are long and relentless, with snow blanketing the higher altitudes. Summers, by contrast, are searingly hot but fleeting, a contrast so stark that locals sum it up with a popular saying:

“In Barroso, there are nine months of winter and three months of hell.”

These harsh conditions, however, have forged a region where livestock farming thrives. The land’s rugged nature makes it a sanctuary for sheep and cows, whose presence is as enduring as its people.

Average temperatures summer winter

Precipitation

<600mm

600 - 800mm

800 - 1500mm

>1500mm

Height >900 meter

Barroso communitarian villages

The communities of the Barroso region are shaped by collective systems of regulation and management that have sustained them through time. Portuguese communitarian villages are regulated in function of the traditional collective property that serves as basis of their economies. In the social life, the common good is placed above the individual interests.

But this model is far more than informal neighborly cooperation. It is grounded in the agro-pastoral system, where the community collectively manages the natural resources with shared responsibility. This approach fosters a social structure that is horizontal rather than hierarchical, ensuring an equitable distribution of resources such as land and goods.

Communitarianism is not just about shared resources or structured management. It is about the way people live and interact. Cooperation among inhabitants is the lifeblood of these villages and is essential for their survival.

Interactions shaped by communitarian values

Luís Polanah, a portuguese anthropologist, identifies four key forms of interaction that have underpinned the enduring success of this model.

The first is related with the exchange of services. This interaction would happen in times where the agricultural labor was more demanding and families needed additional manpower, since agriculture machinery was still not existent or widely available. Examples of this is the potato harvesting, also known locally as “malhada”.

The second is the “Vezeiras”. It entails all the activities that would take turns around the inhabitants. A clear example of this, that still takes place today, is the cattle grazing, where inhabitants take turns shepherding through the mountains.

The third entails all the works that are carried out for the community and its infrastructure. These are decided and mandated by the “neighbors council”. All the inhabitants, no matter their social group, must contribute equally to these tasks. The cooperation in the maintenance of the spaces and equipments of the population generated awareness and confidence on the community’s structure amongst the inhabitants.

The fourth is the regulation of the private interests in favor of the interests of the community. This relates to the private resources that were shared as a mean to ensure stable production and the community’s safety. This resulted in the development of common infrastructure like the oven, land and water irrigation systems in the agricultural fields.

This pragmatic approach to coexistence is reflected in the organization of the village and its productive landscape. It is visible today in agricultural practices, shared infrastructure like mills, ovens, and even local courts, and in communal resources such as water and land that continue to be managed collectively.

The spirit of this system, engraved into the land and lives of Barroso’s people, remains a testament to their resilience and unity.

Exchange of services

Neighbours council

Commonly used private infrastructure

Communal infrastructure

Communities in the Barroso region have long relied on shared infrastructure for their survival. These communal structures are deeply tied to the productive landscape and the stewardship of natural resources. Interestingly, this shared infrastructure often extends into the boundaries of individual homes, where certain private spaces are also used collectively, blurring the lines between personal and communal life.

“People’s

Oven” (Forno do Povo)

One of the most distinctive infrastructures that differs the Barroso region from the rest of the Rural areas in Portugal is the presence of the “People’s oven” and its community regime use. These structures date back to the 19th century, but it is believed that the tradition may be older than that.

These ovens are closely associated with a subsistence economy in isolated territories. In a time where not all the houses in the village had an oven, the use of a common oven allowed families and individuals without ovens at home to cook bread and other foods.

The oven is generally placed in the centre of the village, next to the chapel or church. This was to facilitate for an easier use and transferring of supplies (wood for the fire and flower for the bread). This structure could also serve as shelter for pilgrims, the poor, gypsies, travelling artists and artisans.

“People’s land” (Baldios)

One of the defining features of rural territory management in the Barroso region is the presence of baldios—a unique form of communal land owned and managed by local communities. For centuries, these lands have been integral to the lives and livelihoods of Barroso’s agro-pastoral populations. Spanning vast areas, often exceeding 1,000 hectares, baldios support a range of activities: grazing sheep, goats, and cattle; harvesting firewood for the stoves and fireplaces central to village life; and cutting weeds used for cattle bedding, which is later turned into manure.

Certain portions of these lands, known as cavadas, were also made available for individual use by the poorest villagers, many of whom had no other land to cultivate. This practice ensured a basic level of subsistence for the most vulnerable families, highlighting the communal ethos of the region.

The boundaries of baldios are not determined by modern administrative divisions but by traditional customs and practices that predate them. Management and ownership typically fall under the purview of Parish Councils, acting on behalf of the local population.

Beyond their functional role, baldios have also become a critical source of income for villages. Communities may lease grazing rights to outside shepherds or sell the resources the land produces.

Irrigation system (Regadio)

In a region like Barroso, where the contrast between summer and winter is striking, managing water from a collective perspective has become essential. This communal approach remains a defining feature of the villages today.

During the summer months, the lack of rainfall and the resulting stagnation of water sources, combined with runoff from the slopes, creates a water deficit. To address this, irrigation systems were built to capture water from either permanent streams or springs. These systems channel the collected water from the mountain peaks over several kilometers, directing it to the agricultural fields below.

These gravity-fed irrigation systems are vital to the survival of the community. In each village, every household has a right to access this water—used in winter to nourish meadows for pasture and hay, and in summer to irrigate crops like potatoes, maize, and vegetables.

Water usage is carefully regulated, with irrigation periods strictly scheduled. The amount of water allocated to each household depends on the area of land they need to irrigate, and the rotation system is determined by the natural flow of water, guided by the land’s topography. In return for their access, every user is responsible for maintaining the infrastructure that sustains this shared system.

Water canal and dam next to the common oven - October 2022

Covas do Barroso

Covas do Barroso is a place that feels like it was carved out of the earth itself. Its name, rooted in the word “cova”— a hollow/ depression in the land — reflects its geography: a small village tucked into a valley, embraced by the rugged mountains and green slopes of the Barroso region.

Within this parish lie three settlements: Covas do Barroso, Romainho, and Muro. Together, they hold the stories of 191 people (data from 2021), with nearly half of them over 65.

Commonly owned land, known as “baldios”.

Commonly owned infrastructure such as mills, ovens and a common house.

Covas do Barroso and its people

These rugged lands are not just a backdrop, they are a vital resource that sustains the lives of those who call Covas do Barroso home. The mountains, valleys, and rivers provide everything from fertile soil to grazing pastures, shaping the rhythms of life in the village. In Covas, the landscape is more than a resource. The landscape is a partner in survival, deeply embedded in the practices and traditions of those who live here.

To gain an in-depth understanding of this community, I embedded myself within the village and its daily life. My research was inspired by the experiences of four key actors in the landscape: Lúcia, Aida, João, and Daniel. By observing and following their day-to-day activities, I was able to track and map how they interact with and utilize their territory, uncovering the intricate ways their lives are shaped by the land and the communal systems that sustain them.

Lúcia

Lúcia was born and raised in Covas do Barroso, where she later married a local man. Like many others in the 1960s and 1970s, she and her husband emigrated to France in search of better opportunities. She spent most of her adult life there, raising four children. Today, only one of them—her son Nélson—remains in Covas do Barroso. The others have settled abroad, two in France and one in the United States. Despite her years away, Lúcia returned to Covas, where she has resettled into the rhythms of the village.

I met Lúcia during my first visit to Covas do Barroso. I had planned to set up a tent and camp, but seeing the cold and rain, Lúcia kindly offered me a room in her house, even though I was a stranger. Her hospitality reflected a common saying in Covas: “When a stranger comes, first he sits and eats, then we ask his name.” This moment became my introduction to the warmth and generosity of the community.

Though Lúcia is retired, she remains active. While she no longer farms or grazes livestock directly, she helps her son Nélson with his agricultural work when needed.

She also plays a central role in the religious life of the village, actively participating in weekly masses and the annual procession. Lúcia is involved in organizing these events, from baking bread to preparing traditional clothes for celebrations. These activities not only sustain local traditions but also bring the community together.

Her home is central to her daily life, especially her balcony. The balcony serves as a place where she handles household tasks, interacts with neighbors, and stays connected to the landscape. From there, she pointed out the village boundaries, the fields she once farmed with her late husband, and the areas where Nélson’s animals were grazing.

Lúcia in her balcony where she spends most of her time. The balcony faces south, to maximize sun exposure and provind a clear view of the entire landscape.

L1 - October 2022

On the top of this montain there is a view point, that local call by “Olhar do guerreiro” meaning “warrier’s sight”

This is Romainho.

Lúcia’s balcony is where she does most of her house chores, like cleaning and laundry and at the same time can see who is passing on her street. You will most likely find her in the balcony chatting with her neighbour.

L2 - October 2022

This plot belongs to Aida and Nélson (Lúcia’s son)

The view to the south.

The view from Lúcia’s smoking workshop. This space sits on the groundfloor of her house, beneath her balcony. It is here where she makes sausages and smokes ham.

L3 - April 2024

Lúcia in her slippers collecting sausages that were hanging in the smoking workshop, after a few days of smoking.

L4 - April 2024

The sticks she uses to hand the sausages and ham.

The interior of the common oven in Covas do Barroso, a place that Lúcia uses to bake bread with other ladies of the village.

As she says, before everyone had their own oven this common facility would be used daily.

Now it’s used on celebrations or when someone needs to bake a big batch.

L5 - April 2024

Common oven.

This is part of the village’s irrigation system.

A series of damns and gates controls which plots receive water at a certain time.

Aida was born in Romainho, a neighboring village, but her life took root in Covas do Barroso after she married Nélson, Lúcia’s son. Together, they built their home gradually, a testament to their resourcefulness and patience, with much of the construction done by themselves and family members.

Life for Aida revolves around the land and her animals. She and Nélson maintain plots for growing seasonal fruits, olives, and vegetables, primarily for their own consumption. However, their main livelihood is cattle grazing. Each day, Aida ventures into the mountains and valleys with her cows and shepherd dog, joyfully navigating a patchwork of their own land and neighbors’ plots.

Aida was one of the first people I met in the village. Always busy, I often found her in her shed beside the Eira, a traditional threshing floor. The eira is essential for family life, used to dry corn, process grass for the cows, and clean olives after harvest. It is in this space that Aida fulfills many of her daily tasks.

When I gave Aida a disposable camera to document her life, her pride in her cows and shepherd dog shone through in the images she captured. The bond she shares with them is palpable, reflecting her deep connection to her role as a caretaker of animals and the land.

Beyond her household, Aida plays a vital role as leader of the Common Land Association, overseeing the management and preservation of shared resources. She organizes monthly meetings to address issues, plan maintenance, and coordinate communal work, ensuring the well-being of both the land and the community.

Aida’s life reflects the resilience and interconnectedness of Covas do Barroso. Whether caring for her cows, managing the common land, or working tirelessly in her eira, she embodies the dedication and pride that define the people of this region.

Aida standing in the eira, a threshing floor where, traditionally, grains are processed. Surrounded by open skies and rugged terrain.

A1 - October 2022

Eduardo Martins©

Lúcia, lives just being this slope.

A3 - July 2024

A4 - July 2024

A water canal, part of the village’s irrigation system. This picture was probably taken after Aida open the gate to allow the stream of water.

A5 - August 2024

Aida’s shepherd dog. Always next to Aida whenever she leaves with the cows to the mountains.

Aida and Nélson own 27 cows. Going out with all the cows is a daily task, no matter the weather outside. Aida usually goes to West and North of her house and her barn.

A6 - May 2024

A7 - August 2024

A8 - July 2024

João

I’ve met João during my second visit to the Barroso region when I spent three weeks in Romainho. I was looking for a shepherd to give a disposable camera to, much like I did with Aida, and asked around the village for the best photographer. The unanimous answer was João, and he lived up to the expectations.

The day after I handed him the camera, we crossed paths in the mountains as he was grazing his sheep. With a proud smile, he pointed to the small purse he carried and said “I already have the camera with me. I’ll take some snaps!”

Photography became the bridge that connected us. In the afternoons, we often met by the chapel in Romainho to chat about the pictures he had taken. Although the photos were yet to be developed, João described what he captured: his sheep, the valley, the baldios, and even his mother, who lives with him.

These conversations grew into something more personal as João opened up about his life and family. He has lived his entire life in Romainho, a place that defines and shapes him. Like many in the region, his family has deep ties to grazing. Despite his heart condition and medical advice to stop shepherding, João continues to care for his herd, although its size has reduced from 50 to 20 sheep.

The community is central to João’s life. Tasks like sheep shearing are done collectively, a practice that reinforces the strong bonds among the villagers. João often spoke with gratitude about the people who helped him or shared responsibilities, reflecting his deep connection to those around him.

Every time we met, he welcomed me onto his porch, a space filled with his tools and stories. It’s a humble yet meaningful place where his daily life intersects with the heritage of his craft.

João’s porch.

Concrete columns and a wood substructure with typical north portuguese roof tiling.

J1 - June 2024

Lúcia’s house.

J2 - April 2024

Covas do Barroso disused primary school. Since a few years, kids started attending primary school in Boticas (40 minutes bus drive).

This plot is privately owned but João comes here regularly while shepherding to maintain the plot. It is called “sistema de vezeiras” - “turn system”.

J3 - April 2024

João’s happiest sheep as he describes.

João’s shed where he keeps his tools but also his sheep overnight. It is located 8 minutes walking from his house.

J4 - April 2024

This is a route that João does in a regular basis, going south of Romainho into the common land “baldios” to maintain and safekeep the plots.

J5 - April 2024

In Penedo direito. The highest accessible point where the water stream that provides Romainho with most of its water for the collective irrigation system comes from.

J6 - April 2024

This process usually occurs in Paulo’s shed, that has the best conditions to conduct the shearing of all the sheep.

Shearing the sheep’s wool before the summer.

In order to do this process, all the shepherds in Romainho schedule a single day in which all the sheep of the villaged will be sheared.

J7 - June 2024

This is Paulo.

Another shepherd in Romainho with the biggest herd of Romainho and Covas do Barroso.

First walk after getting sheared.

J8 - June 2024

J9 - June 2024

J10 - April 2024

Daniel

My last visit to Romainho was just before Easter. The April weather was relentless, rainy and unforgiving. But that didn’t stop me from hiking around the valleys. One afternoon, as I returned to the village, I heard the faint sound of cowbells hidden among the trees. Following the sound, I found Daniel, clad in boots and a black jacket, balancing an umbrella in one hand and a hoe tool in the other. He was wrapping up his day, giving his 25 cows a final graze before heading home.

I introduced myself and, after a short chat, asked if I could join him the next day to see how he maintained the irrigation system and grazed his cows. He immediately agreed, though I sensed a mix of curiosity and surprise at my request. The next morning, I met Daniel and his daughter, Anabela, both of whom, over the following days, became important guides to life in Romainho. They walked me through their daily routines, showing me their sheds, the feed they prepare for their cows, and the water streams and system that irrigate their plots.

Daniel’s hospitality extended far beyond the fields. He and his wife, Maria, welcomed me into their home as if I were family. It became clear that this couple plays a central role in Romainho’s community. Maria, for instance, as Lúcia, is deeply involved in the care and use of the village’s communal oven, baking bread alongside other women in the village.

Daniel’s patio, which serves as the gateway to his home, is a remarkable space of activity and tradition. It’s where he stores his vast collection of tools, processes agricultural products, and, on occasion, transforms into a space for celebration, like his recent 65th birthday gathering. He also uses the patio for traditional practices like distilling aguardente (distilled spirit) and geropiga (a sweet liqueur) and preserving pork in his smoking workshop.

His patio is more than just a workspace, it’s a meeting place. The door, as they say, is always open.

Daniel in his enclosed Pátio, holding the bottles of liquor that we both produced during my site visit to Romainho.

D1 - November 2024

The “enchada” (Hoe tool). It is almost as a continuation of a shepherd’s body.

Daniel in his morning routine, after feeding the cows, he goes around the village to clean and maintain the water streams and cannals.

D2 - April 2024

The water streams that Daniel maintains and walks trough daily.

D3 - April 2024

Behind this wall there is a gate to control the water flow.

Shrubs harvested to lay on the bottom of the barn for the cows to lay on. This is in Daniel’s shed. Roughly 10 minutes walking from his house.

D4 - April 2024

On the way to “Sangrinhal”. This is a plot owned by Daniel to the South of Romainho. Daniel visits this place with his cows every month. The trip, while shepherding, can take up to 2 hours.

D5 - April 2024

Daniel’s cows in Sangrinhal.

D6 - April 2024

kitchen.

D7 - April 2024

This room is a workshop around Daniel’s patio. It is his distillery room. Here he produces strong liquor. After the grape harvest, after summer, the leftovers are kept in order to produce aguardente.

D8 - April 2024

- October 2023

Daniel’s potatoes crop for the year.

D10 - October 2023

Another of Daniel’s workshops around his patio. His smoke house.

D11 - April 2024

D12 - April 2024

On the horizon, Covas.

3 DISPLACED 3 DISPLACED

To take over the place, position, or role of.

The displacement actors

The region of Barroso is no strange to extractivism. Since early, small granite quarries as well as Quartz mine were common to find for ceramics and other realted products.

In 2006, Saibrais S.A., made a contract contract with the Portuguese government to create a Quartz mine to the west of Covas do Barroso. In 2010, these same rights were sold to another Ceramics company with the intention to boost the production of quartz in the region.

In 2016, the Portuguese government created a taskforce to “identify and caracterize the lithium deposits in Portugal” to “assess the possibility of production of Lithium.”

Right after, in 2017, Savannah Resources, a company quoted in the UK stock exchange, acquired all the extraction rights that belonged to Saibrais S.A. After this, Savannah led a prospection effort resulting in 135 holes and the destruction and disruption of the landscape to the south of Covas do Barroso.

Since then, there have been successful efforts by Savannah to expand the concession area from 120 to 550 ha.

Savannah Resources is a mining company “focused on the exploration and development of mineral resources, particularly those critical to the energy transition, such as lithium”, although it lacks previous proven experience in this field. The company’s flagship project is the Barroso Mine.

In 2020, the company officially opened offices in the village of Covas do Barroso and Boticas.

In May 2023, the Portuguese Environmental Agency issued the approval of the project with the Environmental Impact Declaration (DIA).

In November 2023, a political crisis erupted after police searches uncovered potential misconduct related to the lithium sector, particularly the licensing of lithium mines in the Barroso region. The scandal, implicated several high-ranking officials, including ministers. The investigation, which began in 2019, focused on illegal activities related to the lithium mining business, hydrogen projects, and a data center. Although the government fell, the controversial mining projects continued despite increasing public opposition and legal challenges.

Samples retrived from the mountains in Covas do Barroso displayed in Savannah Resources office in Boticas - October 2022

“Grandão”, as called by Savannah, one of the four open pits in the project - April 2024

“NOA”, land already owned by Savannah, serving now as a construction site and storage facility - April 2024

Documents, documents and documents

Researching the mining project was a challenging yet crucial process in understanding the full scope of its impact on the landscape and the community. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report, a monumental document spanning approximately 6,000 pages, presented significant obstacles: its language was highly technical, the data on specific elements often lacked clarity, and inconsistencies emerged between different sections of the report.

Through the use of architectural tools (diagrams, models and maps), I was able to spatialize and contextualize the project’s impacts, translating the dense and fragmented information from the reports into tangible, comprehensible elements. These tools provided means to not only visualize the spatial and environmental transformations but also to critically assess how the proposed infrastructure and interventions would alter the landscape.

Previous research

I began my research on the Barroso mine in September 2022 as part of a project at the Academy van Bouwkunst, focusing on the broader topic of lithium extraction. The Barroso mine served as a central case study, providing an opportunity to delve into the impacts of such projects on landscapes and communities. My aim was to make these impacts more accessible and comprehensible by translating the complex and often overwhelming information into visual forms. Using tools such as models, diagrams, and maps, I sought to unravel the layers of the project, spatializing its environmental and social implications. This approach not only highlighted the scale of the transformations but also offered a clear and critical lens through which to understand the profound changes the mine would impose on the region and the everyday lives of its inhabitants.

Scale - December 2022

Morphology - December 2022

Barroso lithium mine

“Geographical and Administrative Framework”, developed by Savannah Resources - March 2023

The open pits

The Mina do Barroso is characterized by the open-pit mining method, known as “cortas” (cuts). This approach involves large-scale excavation to access valuable mineral deposits, resulting in prominent and expansive pits.

In the latest report, Savannah presented four open pits. The first to be initiated in year one are named “Pinheiro” and “Grandão.” The name “Pinheiro” reflects the site where it is located, while “Grandão,” meaning “big” in Portuguese, is named for its considerable size, making it the largest pit of the concession Grandão spans a radius of 700 meters and reaches a depth of 250 meters.

Section through open pits, part of the Preliminary Study of the Environmental Impact Study made developed by Savannah Resources - March 2023

The landfills

The project includes four landfills, one of which is temporary, where waste material will be used to fill the pits after mining operations are completed.

Preparing the foundations for the landfills requires the removal of topsoil and weathered rock (up to 10 cm deep, known as Pargas). The landfills will serve as storage areas for inert waste removed from the pits during mining, originating from blasting, drilling, and general material excavation activities.

On landfill 1 and 2 (ESC 1 and ESC2), Savannah projects changing the topography of the land by increasing it to an average of 50-60 meters throughout 8 years. This means on average 7-8 meter per year.

Topography impacts of the landfills, part of the Preliminary Study of the Environmental Impact Study made developed by Savannah Resources - March 2023

The water management

The Water Management Structures are designed to control and manage runoff from disturbed and undisturbed watersheds within the project area. These include Water Reservoirs (RA), Clean Water Diversion Channels (CD), and Diversion Ditches (VD).

There are five Clean Water Diversion Channels aimed at reducing the volume of surface runoff disturbed by mining activities and directing clean water to designated reservoirs.

The Water Reservoirs, which have higher storage capacity, are intended to mitigate inflows coming from water streams or rainfalls. These reservoirs and channels the Pinheiro pit (RA1) and the Grandão pit (RA2 and RA3).

There are other water structures focused on the environmental control and treatment of runoffs from the pits. These are the Environmental Control Reservoir (RCA) and Sediment Control Reservoirs (RCS1 and RCS2). The later is to allow sediment particles to settle before discharge or reuse.

Other considerations

Pargas

“Pargas” are storage areas for topsoil removed during the clearing phase. This soil will be allocated to designated areas for use in the recovery of pits and landfills as restoration progresses.

Road Infrastructure

To support operations at Mina do Barroso, a new external access road (“Acesso Norte”) will be constructed, spanning 11.6 km and connecting the processing plant (Lavaria) to the national road).

Internally, the longest access road connects the Reservatório and NOA pits to the processing plant, approximately 6 km long. This includes the construction of a single-lane bridge for dump trucks over the Covas River, with a span of 25 meter and a width of 16 meter.

Fence

Fencing will be installed around workshops, processing plant and mining zones, as well as in areas with high wildlife activity to reduce the risk of animal collisions. The proposed fences will be 1.80 meter steel mesh. Barbed wire will not be used anywhere in the fencing.

Workshops and Offices

The processing of extracted rock and separation of spodumene from host rock will take place at the processing plant (Lavaria), located northeast of the Pinheiro pit. Adjacent to the Lavaria, the workshop will support maintenance and repairs of heavy mining equipment such as dumpers, graders, bulldozers, and excavators.

The Lavaria is located between the Grandão and Pinheiro pits. These areas will undergo through soil banking processes to create a flat area suitable operational activities.

Workers

During the construction phase, the workforce is expected to reach between 300 and 350 workers. In the mining operation phase, labor requirements will vary, with estimates ranging from 200 to 245 workers depending on activity levels.

Offices and workshops

Timeline

According to the proposed mining and recovery plan, the project is phased into five main components: mining operations (Mining Plan), modeling (Waste Management Plan), landscape recovery (Landscape Recovery Plan), environmental monitoring (Monitoring Plan), and decommissioning (Decommissioning Plan), as detailed in Table VIII.1.

The timeline indicates that all mining operations will be completed by the end of 14 years, with recovery and decommissioning activities finalized by the 17th year of the project. Following this phase, maintenance and inspections related to landscape recovery and waste facility monitoring will continue for an additional 2 years. In total, all activities within the mining area will cease by the end of 17 years, encompassing 2 years of installation, 12 years of operation, and 3 years of recovery.

In Portuguese legislation, mining concessions are typically granted for an initial period of up to 90 years, depending on the specific contractual conditions. In this specific case, the mining license can be extended for 20 years.

Planning timeline, part of the Preliminary Study of the Environmental Impact Study made developed by Savannah Resources - March 2023

Other case studies

To gain an in-depth and better understanding of the mining operations in Portugal, I selected several case studies that were compared based on their timeline, type of extraction and type of mineral.

Mina da Panasqueira

Mined mineral: Tungsten

Status: active

Extraction method: underground mining

Timeline:

1896: Commencement of mineral exploration in the Panasqueira region with the discovery of tungsten and tin deposits.

1906: The mining concession is granted to the “Beralt Tin & Wolfram Company Limited,” a British company.

1940s: During World War II, the Panasqueira Mine reaches its peak production, becoming a crucial source of tungsten for the Allies.

1955: The “Beralt Tin & Wolfram” company is acquired by the Portuguese “Sociedade Mineira e Metalúrgica da Panasqueira” (SMMMP).

1977: The mine comes under state control with the nationalization of the mining sector in Portugal.

1992: The mine is privatized and acquired by the Australian group “Wolf Minerals Limited.”

Mina de Aljustrel

Mined mineral:Zinc

Status: semi-active

Extraction method: underground mining

Timeline:

1901: The Aljustrel Mine is officially inaugurated, marking the beginning of systematic mining operations.

World War II: The demand for copper increases during the war, leading to heightened production at the Aljustrel Mine.

1970s-1980s: The mine experiences expansion and modernization efforts, with advancements in mining technology and infrastructure.

1990s: Temporary closure in the late 1990s.

Early 2000s: The Aljustrel Mine undergoes revitalization, with new investment and efforts to resume mining activities.

2007: Lundin Mining Corporation acquires the Aljustrel Mine, continuing efforts to modernize and expand operations.

Present: The Aljustrel Mine is one of the largest polymetallic mines in Portugal, producing copper, zinc, and lead concentrates.

Mina de São Domingos

Mined mineral: Gold, Silver, Tin and Lead

Status: inactive

Extraction method: open pit

Timeline:

1834: Commencement of mining activities in São Domingos, driven by the discovery of pyrite deposits.

1854: The mine undergoes significant expansion with the construction of a smelting facility, becoming a major center for metal production.

Late 19th Century: São Domingos experiences a period of prosperity, becoming one of the largest pyrite and copper mines in Europe.

Early 20th Century: The mine faces economic challenges due to a decrease in demand for pyrite and copper.

1960s: Closure of mining activities due to economic issues.

1990s: The site is designated as a National Monument, recognizing its historical and archaeological significance.

Mina do Mondego Sul

Mined mineral: Uranium

Status: inactive and redeveloped

Extraction method: open pit

Timeline:

1987: Commencement of mining activities in Mondego Sul.

1991: Closure of the mine.

2020: Commencement of the works to recover the landscape “The Recovery Project for the Former Uranium Mines of Mondego Sul aims for the longterm elimination of risk factors that pose a threat to the health and safety of the population. Additionally, it seeks to promote economic, cultural, and scientific development in the rehabilitated areas.”

Mina da Urgeiriça

Mined mineral: Uranium

Status: inactive and repurposed

Extraction method: undergrond mining

Timeline:

1913: Mining operations commence in Urgeiriça for the extraction of tungsten, a strategic metal.

1950s: With the growing strategic importance of uranium during the Cold War, exploration for uranium deposits begins in Urgeiriça.

1960s: Uranium mining operations intensify to meet the increasing demand for nuclear energy production.

1970s-1980s: Urgeiriça becomes a significant uranium mining area, contributing to the global supply of uranium ore.

1980: Closure of uranium mining operations due to environmental concerns and changes in the uranium market.

1990s: Designation of the site as a National Monument, recognizing its historical and geological value.

Mined mineral: Lithium

Status: approved

Extraction method: open pit

Conclusions on the case studies

The history of mining in Portugal reveals a pattern of significant environmental, social, and economic disruption. These minig developments are predominantly located in the central and southern regions, leaving northern Portugal, where Mina do Barroso is planned, largely untouched by such large-scale operations.

The case studies reveal that mining often leaves a lasting environmental and social impact. Mondego Sul, for example, closed shortly after opening in 1991, with meaningful rehabilitation efforts only beginning decades later.

The economic promises of mining, often central to justifying such projects, have also proven fragile. São Domingos, once a thriving center of pyrite and copper extraction, declined rapidly when the demand for its resources faltered, leaving a very vurnerable local economy.

Mining has often conditioned local ways of life. The historical mining sites in Portugal, such as Urgeiriça and São Domingos, have been rebranded as heritage sites, but only after they irrevocably altered the landscapes and communities they once sustained.

Mina do Mondego Sul

Mina da Panasqueira

Mina de Aljustrel

Mina de São Domingos

The current situation

The local community has initiated legal action against the Portuguese Environment Agency and the Ministry of Environment and Climate Action, challenging the approval of the Environmental Impact Declaration (DIA) for the project. The legal process, however, has been slow, with the Public Prosecutor already raising concerns about the legality of the DIA and its failure to adequately address the potential environmental and social consequences of the mine’s expansion.

The Public Prosecutor’s report highlighted several critical issues, including the risk that the mining project could disrupt the region’s Agro-Pastoral System, which is an important part of the region’s cultural and agricultural heritage. The report argues that the mine would threaten the status of the Barroso area as an Important Agricultural Heritage System (SIPAM), violating international commitments made by Portugal to the UN’s FAO and European agricultural policies.

There are also concerns regarding the mine’s impact on the local ecosystem, including the potential for harm to endangered species such as the Iberian wolf, water contamination, and the destruction of important natural resources.

Despite these legal challenges, Savannah Resources has resumed exploration activities, citing approval from the Portuguese authorities.

In response to the company’s actions, the community has taken direct action, with local residents organizing shifts to prevent the company’s workers from accessing the land.

The conflict has escalated into daily confrontations, with the community blocking the entry of machinery onto what they describe as being “baldio” common land.

The community’s commitment to resisting the project has brought daily anxiety and emotional strain in the village.

The preparation work initiated by the mining company was halted by the community. Photographed by Aida – September 2024.

4 DISPLACED 4 DISPLACED

Set in a particular position; assigned or arranged within a specific context.

Starting points of the “Placed” strategy

Human and Land. Human and Animal. Human and Community: the people of Barroso embody a deep and enduring harmony with their surroundings. Their way of life reflects a balance between human and land, human and animal, and human and community. This interconnectedness forms the backbone of their existence, where every element of life is intrinsically tied to the rhythms of the landscape and its resources.

People in Barroso will never give up: even in the face of external pressures, such as the proposed mining project, the people of Barroso exhibit resilience and a profound sense of land ownership. This connection to their territory transcends physical possession; it is rooted in cultural identity and an unyielding determination to protect their way of life.

Locals give and take to the Land: Barroso’s communities thrive on a system of give and take with the land. People and animals are integral parts of a circular system, where the landscape not only sustains their livelihoods but is also shaped and nurtured by their actions. The reciprocal relationship between the community and its environment ensures the continuation of traditions that have lasted for generations.

Locals do not orient themselves through North, South, East, West: orientation in Barroso isn’t dictated by cardinal directions like north, south, east, or west. Instead, people navigate their world through the names of specific places—lugares—a practice that underscores their intimate knowledge of the terrain and its features. Each lugar holds meaning and memory, forming a mental map that ties them to their surroundings in a deeply personal way.

Miners are just doing their job: it is important to recognize that those who work for the mining company are also members of this community. Their role as employees reflects their need to support themselves and their families, rather than a rejection of the values held by the region. This nuance adds complexity to the narrative, showing that even within conflict, there is a shared humanity.

The “Placed” strategy

“Placed” offers a sense of permanence within an ever-changing landscape.

It reclaims mining infrastructures for the community, transforming them into spaces that support villagers’ daily lives in a future shaped by mining activity.

The four interventions are strategically situated throughout the landscape, drawing inspiration from familiar elements found in the village. This connection imbues the landscape and these lugares with new meaning and function, ensuring they are not perceived as foreign objects but as integral, recognizable parts of the community’s identity.

They are designed within a time frame, emerging with the mine’s timeline, these interventions adapt and integrate into the ever-evolving terrain.

“Placed” updated timeline

Existing situation

During mining situation

“PLACED” situation

VARANDA VARANDA

ESC2 - Landfill 2

year -1

Inspired by the way Lúcia uses her balcony as a space of work, observation and connection with her surroundings, the “varanda” intervention is situated on the location of a future landfill (ESC2).

Initially a tower, it will eventually be covered by soil extracted from the surrounding open pits, blending into the landscape over time.

The purpose of the “varanda” is to elevate the community’s presence, providing a place where they can oversee the mining process throughout the years. It is a refuge for shepherds, villagers and volunteers, used for reflection and oversight.

Year -1

EIRA EIRA

RA2 - Water reservoir 2

Inspired by Aida’s leadership and her active role in the community’s resistance against the mine, the “Eira” reclaims the space of a water reservoir, transforming it into a space for dialogue.

Traditionally used in vernacular architecture for agricultural purposes, an Eira is a circular space where people come, chat and work together.

This Eira will serve as a meeting point between the leaders of the community and the mining company. In this case, its architecture is as negotiating with the environment as the people are negotiating between themselves.

ALPRENDRE ALPRENDRE

RA3 - Water reservoir 3

Inspired by João’s conversations, experience in his porch and our hikes with his sheep, the “Porch” intervention creates a new safe haven for shepherds

Just as João’s own porch serves as a gathering space at his home, this new structure will provide a place for workers to rest during their hikes, store their tools, and store and process agricultural products.

The porch reflects João’s deep connection to his animals, his surroundings, and the resources he relies on. It emphasizes the experience of the shepherd, offering a space where the relationship between the land and the cattle can be honored.

PÁTIO PÁTIO

year 4

The “Pátio” embodies the essence of a communal courtyard, a space shaped by the workshops that surround it. In this case, these workshops are the heart of the community.

Located at the center of the village, the Pátio becomes a vibrant gathering point where residents can meet, interact, and connect during their breaks.

Such like Daniel uses his Patio, this intervention can be used as a celebration area, providing a formal public space that can be used for traditional and religious celebrations.

5 EMPLACED 5 EMPLACED

Firmly established in a particular site with intention and purpose.

Emplaced approach

It is crucial to rethink how these projects are judged, planned, and reported. Throughout this research, I encountered numerous environmental impact assessments spanning hundreds of pages, each chapter confined to a specific discipline.

While thorough and necessary, these reports often fail to capture the intangible, unquantifiable aspects of human existence and community life.

What is missing from these documents is a population-centered perspective—one that moves beyond data and technical analysis. They overlook the profound emotional bonds people share with their landscapes, traditions, and one another. These connections may not be measurable, but they are fundamental to the identity and resilience of communities affected by such projects.

Design must be the foundation of these discussions, not an afterthought or a tool for aesthetic mitigation. It should serve as a critical lens through which we understand and preserve the human and cultural fabric of a place.

An Emplaced approach has the potential to illuminate and prioritize the emotional, ancestral, and communal ties that bind people to their land, animals, and history. It reveals what numbers and graphs cannot. It has the power to show the weight of memories, the continuity of traditions, and the deep sense of belonging that anchors people to their environment.

As we move forward globally, we must demand a multidisciplinary approach to assessment—one that integrates insights from sociology, anthropology, architecture, and other human-centered disciplines alongside the hard sciences. This acknowledges that the impact of mining and development is not only about altered landscapes and disrupted ecosystems but also about fractured relationships between people, their land, and their way of life.

This is not just a call for more inclusive methodologies but for a more humane, empathetic approach to development. If progress is truly meant to serve people, it must also respect and nurture the intangible connections that give life its meaning.

Bibliography and sources

EUROPEAN COMMISSION - “Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards Greater Security and Sustainability”. 2020. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/42849

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT - “Social and environmental impacts of mining activities in the EU”. 2022. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/729156/IPOL_STU(2022)729156_EN.pdf

GRAULAU, Jesus - “Lithium mining and indigenous land rights: Perspectives from South America”. Resources Policy, 74, 102312, 2021. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102312

SAVANNAH RESOURCES - “Environmental Impact Assessment for the Barroso Lithium Project”. 2021. Available at: https://www.savannahresources.com

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME (UNEP) - “Sustainability and the Green Energy Transition: The Role of Critical Minerals”. 2020.

WORLD BANK - “The Growing Role of Minerals for a Low Carbon Future”. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2020. Available at: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/ documentdetail/207371500386458722/the-growing-role-of-minerals-and-metals-for-a-low-carbon-future

POLITICAL PANDORA - “Indigenous Lives & Lithium Mines of Argentina”. Available at: https://www. politicalpandora.com/post/indigenous-lives-lithium-mines-of-argentina

NRDC - “Lithium Mining Leaving Chile’s Indigenous Communities High and Dry—Literally”. Available at: https:// www.nrdc.org/stories/lithium-mining-leaving-chiles-indigenous-communities-high-and-dry-literally

RIBEIRO, Orlando - “Portugal: o Mediterrâneo e o Atlântico”. Lisbon, 1993. MOUTINHO, Mário - “A Arquitetura Popular Portuguesa”. Lisbon, 1979.

DOMINGUES, Álvaro - “Vida no Campo”. Lisbon, 1981.

FONTES, António - “O comunitarismo de Barroso”. Etnografia transmontana, Volume II. Lisbon, 2016.

POLANAH, Luís - “Função da Vizinhança entre os camponeses de Tourém”. Antropologia Portuguesa, 1989.

DIAS, Jorge - “Rio de Onor: Comunitarismo agro-pastoril”. 1983.

OLGA, Teresa - “Barroso - 9 de Inverno, 3 de Inferno, Boi Eterno”. RTP, 1981. Available at: https://arquivos.rtp.pt/ conteudos/barroso-9-de-inverno-3-de-inferno-boi-eterno/

DIAS, Manuel - “Montalegre, Terras de Barroso”. Montalegre: Câmara Municipal de Montalegre, 2002.

VIEIRA, José - “Os lameiros e a sustentabilidade dos sistemas de produção agro-pecuários de montanha em Trás-osMontes”. Açores, 2000.

GUIMARÃES, Rui Dias - “O falar de Barroso - o Homem e a Linguagem”. Edited by João Azevedo. Viseu, 2002.

JÚNIOR, J. R. dos Santos - “Malha do Centeio em Lavradas (Barroso)”. Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto, 1962.

JÚNIOR, J. R. dos Santos - “A vezeira da Cabrada do Couto Dornelas (e outras vezeiras)”. Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto, 1962.

JÚNIOR, J. R. dos Santos - “Dois ‘fornos do povo’ em Trás-os-Montes”. Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto, 1962.

DE LA CADENA, Marisol - Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice across Andean Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

FRY, Tony - Defuturing: A New Design Philosophy. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020.

HAN, Byung-Chul - The Burnout Society. Trans. Erik Butler. Stanford, CA: Stanford Briefs, 2015.

PEREIRA, Godofredo - “Towards an Environmental Architecture.” e-flux Architecture Positions, 2018. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/positions/205375/towards-an-environmental-architecture/

DÍAZ, Francisco; KUBRAK, Anastasia; OTERO VERZIER, Marina (eds.) - Lithium: States of Exhaustion. Rotterdam: Het Nieuwe Instituut; Santiago: Ediciones ARQ, 2021.

RIOFRANCOS, Thea - “Shifting Mining From the Global South Misses the Point of Climate Justice.” Foreign Policy, February 7, 2022. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/02/07/renewable-energy-transition-critical-mineralsmining-onshoring-lithium-evs-climate-justice/

HET NIEUWE INSTITUUT - “Lithium.” Available at: https://lithium.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en

LITHIUM TRIANGLE RESEARCH STUDIO, RCA. Available at: https://ea-lithiumtriangle.com/Extraction

DUNLAP, Xander - The System is Killing Us: Land Grabbing, the Green Economy, and Ecological Conflict. London: Pluto Press, 2024.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to everyone who contributed to the completion of this graduation project.

To my thesis committee, Susana Constantino, Martin Probst, and Marina Otero, for their invaluable guidance and support throughout this journey.

To my parents, brother, and sister, for their unwavering support, encouragement, and sacrifice.

To my colleagues and friends from the academy, particularly Josje, Livia, Fabia, and Vincent, for their companionship and encouragement throughout this project, specially in the last strecht.

I am also deeply grateful to my current and past colleagues at Moke Architecten, with special regard to Ahmed, Rada, Pietro, Andre, Hanna, and Noemi, for the conversations, support, and impressive gluing skills.

To Joel and Inês, for lending me the drone that helped bring closer the beautiful landscape of Covas do Barroso. To Rúben, for his help in assembling the fragment models.

To all the people I crossed paths with in the streets, valleys, and mountains in and around Covas do Barroso and Romainho—thank you for sharing your time, stories, and kindness.

To Lúcia, Aida, Cunha, and Daniel—thank you for opening your doors to me the first time we met, allowing me to see through your eyes and feel the emotions carried throughout the last seven years. Thank you for showing me that it is always worth fighting, even when our voices are nearly gone.

My deepest, deepest thank you.

“Não às minas, sim à vida.”

Luís Miguel Marques Garcia Amsterdam, December 2024