Echoes of home

Echoes of home

Rediscovering Nantes’ Landscape through Movement

Graduation Project

Vincent Lulzac | 2024

Master in Landscape Architecture

2024 Academy of Architecture | Amsterdam University of the Arts

Commission members

Thijs de Zeeuw | Lada Hršak | Erik A. de Jong

The project is the culmination of a research journey that began in 2019, driven by a deep dissatisfaction with the current state of landscape architecture, which I found increasingly misaligned with my personal and ethical values. Over the years, through my professional experience and exposure to various projects and practitioners in the field, I began to see troubling inconsistencies. The vision I had once held, a vision of landscape architecture contributing to a more ethical and sustainable future, began to unravel. What I once believed to be a meaningful practice turned out, like so much else today, to be hollow—an instrument of a capitalist system entrenched in superficiality. The reality of our profession often reduces us to producing aesthetically pleasing designs that meet lofty sustainability goals on impossibly tight budgets. This, in turn, results in standardised, low-quality outcomes, ironically perpetuating the very unsustainable practices we are supposed to be moving away from.

One of the first landscape architects to influence my thinking was Gilles Clément, a figure who identified more as a gardener than a designer. His sensitive approach, grounded in the rhythms and forces of nature, offered a refreshing perspective. He redefined garden aesthetics, highlighting the beauty of wild nature and the gardener’s role in bringing that beauty to light. His concept of the “Garden in Motion” was not just a professional endeavour but a personal exploration—one that considered both his own relationship with the garden and the other living elements within it. Over time, his philosophy gained recognition and popularity, both within the landscape architecture community and beyond.

I find deep inspiration in Clément’s work, not only for his environmental approach but for the broader impact his ideas have had on people and society. If we, as landscape architects, are constrained by the limitations of a profit-driven system that hampers meaningful environmental change, perhaps our greatest contribution lies in inspiring others. We can empower people, offering them new ways to engage with their surroundings and encouraging them to take active roles in shaping their environments. Just as Gilles Clément inspired me, I hope to inspire others. This project marks my first step in exploring my own path and practice within this broader context.

* Green: Decolonising landscape architecture toolbox (Result of my research)

This booklet is the culmination of my final project for the Master’s in Landscape Architecture. It presents and explains the landscape design project, “Echoes of Home,” which I developed and presented for my final exam. Additionally, it encompasses the results of my research on decolonizing landscape architecture, which was conducted alongside the design project. This research served both as a case study for my academic inquiry and as a guiding philosophy for my design work. An earlier text I wrote on decolonizing landscape architecture, including an analysis of the work of Salima Naji, was also an important part of my journey. (accessible via the QR code below)

For those interested in understanding my journey through the decolonial movement, I recommend starting with the paper via the following QR code . This section provides insight into how I became acquainted with this movement, highlighting a specific project and architect in Morocco. It offers a clear example of the dynamics at play in (landscape) architecture, the significance of decolonizing the practice, and practical examples of how it is being done and can be done. The Moroccan Sub-Saharan oases ecosystem serves as an excellent case study, as the impacts and dynamics of colonial practices are easily identifiable and comprehensible.

The Moroccan project was a valuable starting point, enhancing my understanding of these processes. For my graduation project, however, I aimed to explore how these processes manifest in a European context, specifically in my hometown of Nantes, France. Decolonizing begins with self-reflection and critical self-assessment.

Thus, I embarked on identifying and understanding what decolonizing landscape architecture would entail in the context of a mid-sized French city. This research revealed various points where colonial practices persist and how they can be addressed. The insights gained from this research provided a toolbox that informed my design. These insights are interspersed throughout the text and are highlighted on green pages. I hope this will aid readers in understanding my design choices and enhance their comprehension of the project.

https://issuu.com/vincentlulzac/docs/decolonising_landscape_architecture_and_the_work_o

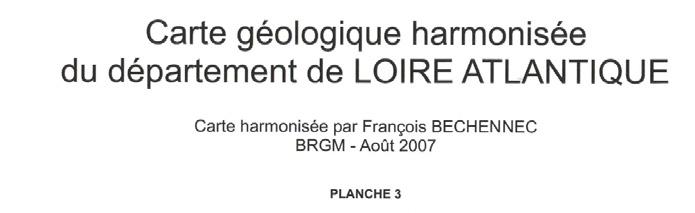

Echoes of Home: Rediscovering Nantes’ Landscape through Movement is a cultural garden project in which Nantes’ inhabitants and visitors are invited to interact and connect with the geological, hydrological and anthropological forces that lay the foundations of the city of Nantes. The 7 ha project site lies at the crossing of a 300 km vertical geological fault and a 1000 km horizontal river “Loire”, dividing the greater landscape of Nantes. These landscapes include river plateaux, wine-growing plateaux, marshlands, and the riverbed. Unfortunately, these landscapes’ richness and associated cultural heritage are not present in the city landscape.

Due to its strategic geographical position, Nantes played a significant role in the transatlantic slave trade, leading to rapid urbanization during the “Golden Age” and subsequent industrialization at crane distance of the river. It also influenced the city’s landscape and identity by fostering colonial architecture, displaying natural and anthropological riches in museums and parks, and incorporating customs and products from the colonies into the city’s heritage. In the 20th century, the maritime industry shifted closer to the sea, leaving empty quays and an industrial wasteland. To maintain the city’s attractiveness a strategic decision was made to channel investments into cultural initiatives, taking advantage of the colonial heritage. The consequence of this approach is evident today—a city that thrives on nostalgic aspirations yet struggles to anchor itself deeply within its local ethos.

Rooted in a personal quest to decolonize the practice of landscape architecture, this project tries to reclaim Nantes’ cultural and natural heritage while encouraging a deeper connection between visitors and the land. This project seeks to emancipate itself, both in its narrative and execution, from the extractive colonial practices by which the city landscape is shaped. Through design decisions and suggested scores, visitors are invited to engage with the space, both visually and physically. The design has been approached as a choreography in a collaborative sense with the natural forces in the site, where visitors and elements are part of a dance.

Divided into four quadrants and a central intervention, the garden invites visitors to reflect on Nantes’ history while exploring its natural features.

The northwest quadrant is an existing garden inspired by Jules Verne’s stories, showcasing exotic plants from the city’s collection, prompting visitors to contemplate the city’s past and present.

The northeast quadrant, “Dances of Granite,” integrates movement by lifting concrete slabs and allowing vegetation to emerge, immersing visitors in the dynamic landscape of the quarry.

The southeast quadrant “River breath”, faces the river. It features an intervention that reconnects the pavement to the riverbank, providing access to the water and creating intimate spaces for visitors to encounter the river’s presence.

The south-west quadrant, “Terra nullius” recreates flood plains and invites visitors to reflect on land ownership, while offering them the chance to get involved in the maintenance of a territory shared with the river.

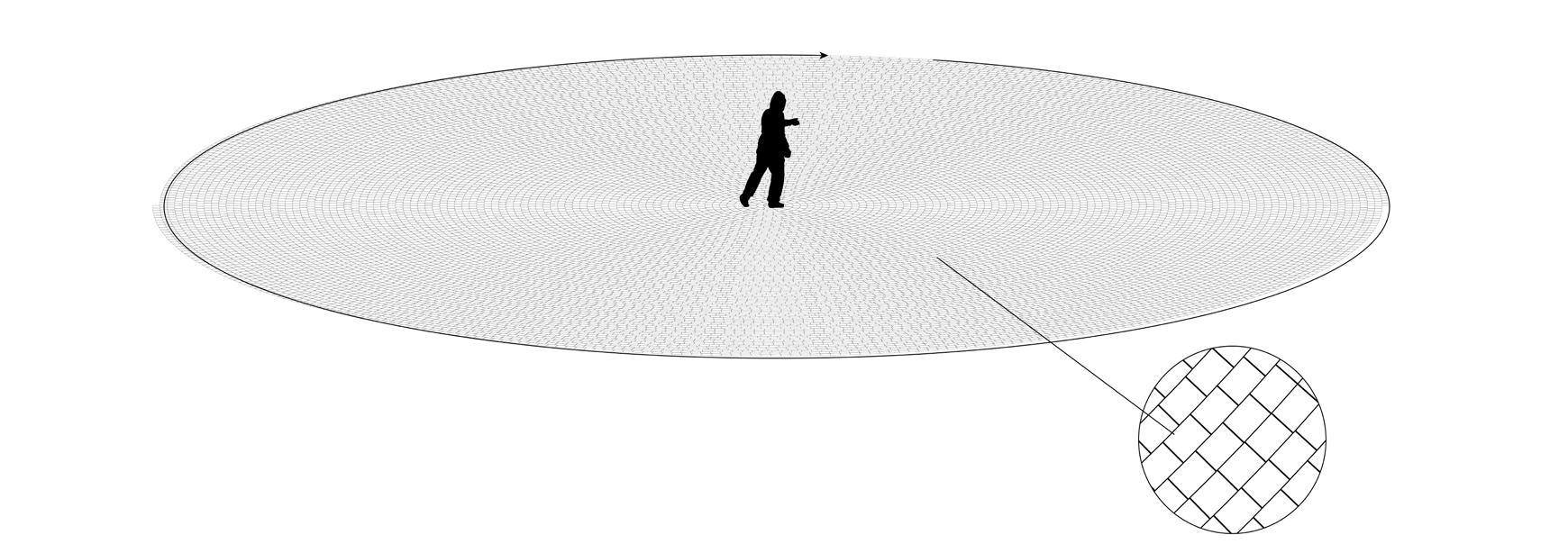

The central intervention is a polished circular surface made of recycled granite bricks, suggesting a place where all the forces of the sites meet and can be heard, it provides a space for visitors to transform this information in performative practices, like movement or sound.

Echoes of Home offers a transformative experience where visitors can actively engage and reconnect with Nantes’ landscape cultural and natural heritage.

Nantes is a city of medium size, boasting around 650,000 inhabitants. Its geographical and strategic significance prompted the establishment of a settlement in this location. Positioned near the Atlantic coast and intersected by numerous rivers, including the Loire, the largest river in France, Nantes flourished during several key periods in its history. One of the most noteworthy epochs is commonly referred to as the Golden Age, spanning from the 17th to the 19th century. During this era, the city experienced remarkable growth, owing largely to its strategic location near the Atlantic coast and its connectivity to the rest of France and Europe through a network of rivers and canals. Nantes served as France’s largest port during the colonial period, particularly during the transatlantic slave trade, when over 1,700 ships departed its ports bound for African and Caribbean shores, laden with enslaved individuals destined for colonial labor, and returned with produced goods.

Even after the abolition of the slave trade, Nantes maintained commercial ties with the rest of the world and its former colonies. The legacy of its colonial history profoundly influenced Nantes’ architectural and industrial landscape, with the development of industrial zones along the banks of the Loire and the construction of affluent residential areas for families who prospered from colonial economies. This period also left its mark on Nantes’ botanical and cultural identity, as interactions with the wider world influenced the city’s image. In the 18th century, ships often returned from voyages laden not only with treasures but also with botanical specimens, contributing to the city’s botanical diversity.

Today, this influence remains palpable in Nantes’ cultural institutions and parks. The Museum of Natural History and the Castle Museum exhibit numerous objects from the city’s colonial collections, including botanical specimens found in the city’s parks. It was during this period that Jules Verne grew up in Nantes, residing along the quayside. Witnessing the arrival of exotic goods on ships inspired his passion for travel and exoticism, themes prevalent in his works, which continue to shape the city’s identity. Many of Nantes’ cultural attractions are linked to Jules Verne’s universe, embodying the exoticism of his tales.

While the economic activities of the colonial era have ceased, their legacy persists in Nantes, evident in the city’s collective imagination and cultural landscape. Numerous attractions related to Jules Verne’s universe reflect this legacy, as does the city’s marketing and representation. It appears that Nantes continues to inhabit the remnants of a bygone era, where the aspiration to be globally connected was once its greatest strength but now exists solely in narratives.

Prehistorical times

Celtic / guaulois Roman occupation (Rezé) With somme invasions Pirates / Saxons / Germanic / Francs / Inner revolts Francs

Tin and copper Quarries

bronze

Francs Divide in multiple Seingeurerie. Nantes in the middle of multiple wars between brittany and multiple Lords Brittany (independant)

Brittany join France

Quai de la Fosse (1517)

Nantes - Main periods

Supported by French Monarchy, Nantes engage in the trade of Slave Ancient

Christopher Columbus 'discovery' of the New World of the Americas

Saint Christophe, Martinique, Guadeloupe Enslave people arrive in the Caribbean Louis XIV signed the 'Code Noir' that define black people as objects

Plantes and seeds arrive in Nantes

1srt French Colony (Quebec)

Creation of the apothicarie's garden

Nantes, largest slave port of France

Legalisation of wax printed textiles production in francev

Contemporary times

Shutting down of Brewerie

Shutting down of Shipyard

End of Slavery in France

1st Abolition of slavery in all French colonies Napoleon Bonaparte re-establish slavery Independance of Haiti, 455 000 enslaved people are set free

Birth of Jules Verne Opening of the Jardin des Plantes

Museum of Natural History

Nantes St Nazaire Development

Jardin extraordinaire

The spirit of the site

Graslin District

Abolition of Slavery in France

First Train tracks

Manufacture Tabacco

Beghin Say

Housing Project Dervaliere

Housing Project Malakoff

Filling of the Loire

Shema 2000

Bigeon

SCOT Metropole Nantes-St Nazaire Hangar a Bananes

Voyage a Nantes

LaLoireisFrance’slongestriver, Nantesislocatedwhitintheestuairyoftheriveratabout80kmfromtherivermouth. Eventhotheriverisaverylargeandimportantfeatureintheheartofcity,itseemsthatithasbeendesertedofany humanactivity.Lettingitsilentlyflowinbetweenit’swellreiforcedbanksawayforthecity’sdynamism.

La Loire

JardindesVoyages

Locatedonthesiteoftheformershipyard,theJardindesVoyages,likemanyothergardensandparksinNantes,boasts awealthofexoticvegetation.Thevegetationcollectedintheapothecary’sgardenhasbeenmultipliedandusedinmany gardensandparks,givingthecityitsexoticcharacter.

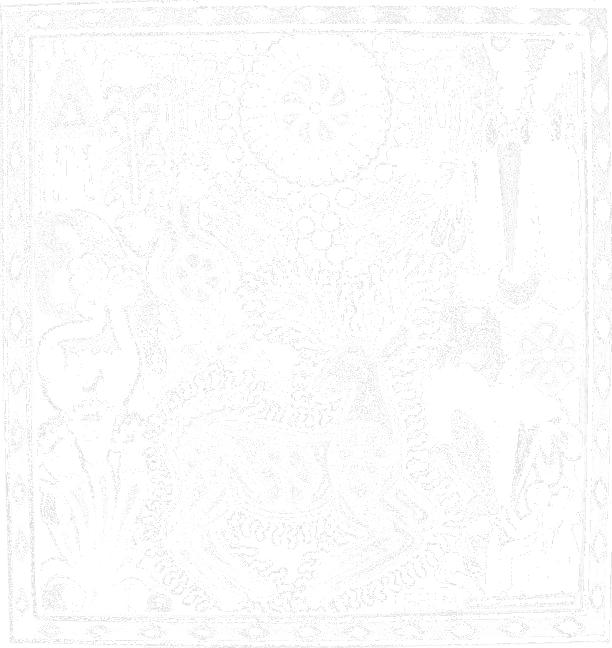

QuaiPrésidentWilson -Gateddesertedindustriallandscapes -Thisquayhasbeenbareandabandonnedfordecades now,theatreofyearlyillegalravepartyonthe21thofJuneforthe“Fetedelamusique”thesitewasclosedin2019after thedeathofayoungraverduringapoliceopertationaimingtostopthefestivities.Thissitecarriesalotintermof reclamationoflandbyinhabitantandrepression/landcontroleleadingtobridgingabigggergapbetweenthecitizens andtheircityandtheriver.

LeQuaidesAntillesetleHangaràbananes - Renovatedin2005

LeHangaràbananes -Fromindustrialtocultural

JulesVerne’sseamonstercarousel

L’Eléphantdel’îledeNantes-Themachine(inspiredbyJulesVerne)

Landscape architecture, as a practice, is deeply rooted in Western philosophical traditions that place humans above nature, granting them dominion over the natural world. This an-thropocentric viewpoint has shaped the field’s education and practice, combined with globalisation has led to a generalisation of the profession at the expense of local knowledge and ethos, raising questions about ethics, and sustainability.

In landscape architecture lies a narrative deeply entwined with the complex history of coloniality. The etymology of the term “landscape architecture” reveals an inherent division between human and nature, and it subtly reflects a power dynamic. The word “landscape” originates from the Dutch “landschap,” which referred to land shaped or controlled by human hands, implying a distinction between the natural world and human influence. The term “architecture,” derived from the Greek “arkhitekton” (chief builder), suggests mastery and authority over construction and design. When combined, “landscape architecture” conveys the idea of humans as architects or controllers of the natural environment, reinforcing a hierarchy where human design and intervention take precedence over nature’s innate state.

Throughout Western history, designed landscapes have often served as reflections of human needs, desires, and egos. From the manicured gardens of European aristocracy to expansive agricultural fields, landscapes have been shaped to extract resources, produce wealth, and display power. They have been used to showcase status, soothe aesthetic and leisure desires, and reinforce social hierarchies. Landscape architecture embodies the imposition of human will upon nature, mirroring the colonial mindset of extraction, exploitation, and control. It represents a legacy of domination where nature is subdued and reshaped to serve human purposes, often at the expense of ecological balance.

Moreover, The practices of landscape architecture marginalises indigenous knowledge, often disregarding the deep, place-based understandings that indigenous communities have cultivated over generations. As landscape architecture becomes increasingly globalised, the rich diversity of local traditions and ecological practices is frequently overlooked in favour of designs that align with Western aesthetics and capitalistic values. This global standardisation of landscapes not only homogenised the visual and cultural experience of spaces but also erodes the unique relationships that communities have with their land. By prioritising profit-driven models and universal design trends, contemporary landscape architecture risks further entrenching systems of exploitation and alienation from the natural world, sidelining indigenous wisdom and reinforcing the commodification of land.

Confronting this legacy requires a shift towards collaboration and stewardship, privileging diverse voices and embracing ecological justice.

Decolonization entails recognizing landscapes’ inherent value beyond human utility. Through humility and respect, we can cultivate landscapes rooted in reciprocity and sustainability. In reflection, we find an opportunity for transformation—a chance to forge relationships with the land grounded in equity and inclusion, essential for a just and sustainable future.

To contextualise and illustrate this analysis we will wind up Nantes’ botanical history. As botany and the use of plants is a central element of landscape architecture. It is interesting to understand the relationship between botany and the colonial side of landscape architecture.

In France, plant classification was initially managed by scientific figures such as physicians and apothecaries appointed by the monarchy, with a primary focus on cultivating and studying medicinal plants. By the 17th century, French cities began creating their own apothecary gardens, with Nantes establishing its garden in 1687. This garden was closely linked to medicinal schools, serving as a centre for education and research on plants and medicine. CRITICALRELFECTION

Unloadingtheexoticplantsfromtheship intheportofNantes

The 18th and 19th centuries saw a surge in botanical research, fueled by the transatlantic slave trade. Plants collected during explorations were brought to Nantes’ botanical garden, where they were studied, propagated, and distributed. Over time, this educational garden evolved into a popular attraction, showcasing a diverse array of exotic species. Nantes became renowned for introducing these plants, which spread throughout the city’s public and private gardens, contributing to its distinctive exotic character. The Magnolia grandiflora, an American species, is a notable example of this trend and has become a symbol of the city.

However, the introduction of these exotic plants came with significant costs. Uprooted from their native environments, these plants lost the cultural and ecological knowledge that indigenous communities had associated with them. They were reduced to mere objects of study and aesthetic appeal, highlighting the curiosity for novelty and the achievements of French scientists, while local knowledge of native flora and traditional practices was lost.

Today, landscape architecture in Nantes and beyond remains influenced by these exotic plants. Although they symbolise scientific and exploratory achievements, their presence has caused notable ecological damage, as non-native species often outcompete local flora and disrupt ecosystems. This awareness has sparked a strong movement toward prioritising native species in landscape design, aiming to restore local ecosystems and support native biodiversity. While the trend toward using native plants is gaining traction among landscape designers, achieving widespread acceptance is challenging. Public preference for exotic plants, driven by their novelty and visual appeal, requires significant educational efforts to shift attitudes. Moreover, this focus on native species highlights the broader issue of lost local knowledge about traditional plant uses and cultural significance. The shift towards native plants not only aims to address ecological imbalances but also serves as a reckoning with colonial legacies of extraction and exploitation, seeking to heal both the environment and the cultural connections severed by historical practices.

The Site

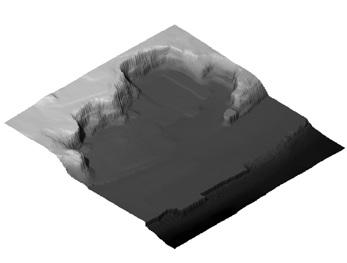

The site is situated along the banks of the Loire River, with part of the riverbank bordered by old quays that are no longer in use. Between these quays and the road are two vacant industrial buildings. One of them, CAP 44, a former industrial flour mill, holds significant architectural value as one of the first buildings constructed using reinforced concrete. This building is slated for transformation into the Jules Verne Museum and the City of Imaginations. Between CAP 44 and the quarry lies a busy road, with six lanes of traffic.

The quarry, dating back to the 16th century, was once a granite quarry used to produce cobblestones and foundation stones. Today, the quarry is divided in two: one half has been turned into a garden dedicated to recreating landscapes described in Jules Verne’s stories, while the other half remains undeveloped, reserved for a large cultural and tourist project—a 35-meter-tall iron tree.

Nantes-LacarrieredegranitdeMisery

Destructionofthevegetation fortheconstructionoftheexoticgarden

L’ Arbre aux Hérons - @ Les Machines de l’île

The relationship between coloniality, modernity, and the development of capitalism is central to understanding the need for critical reflection in landscape architecture. Drawing on Walter Mignolo’s approach, coloniality and modernity are not separate but co-constitutive processes. Modernity, with its ideals of growth, progress, and development, has historically been justified through the exploitation and domination of colonized regions. The capitalist drive for economic expansion, fueled by colonial extraction, has shaped not only global economic systems but also the ways in which land and space are conceptualized and designed. Landscape architecture, like many fields, has been influenced by the Western-centric ideals of modernity, which often prioritize economic growth over ecological balance and social justice.

Decolonizing landscape architecture requires a critical examination of the intents behind projects. Mignolo’s critique of modernity urges practitioners to question whether a project can truly be ethical or sustainable if its primary motivation is economic growth or aligned with personal or political interests. Often, large-scale urban development projects are driven by the intersecting interests of political elites, developers, and private stakeholders, which may compromise ethical considerations. When the primary goal is to serve economic or political agendas, such projects tend to prioritize profit, visibility, or political gain over the well-being of local communities and ecosystems. This raises the question: can a project be genuinely ethical or sustainable if it is primarily motivated by personal, political, or economic interests?

These issues are particularly evident in the context of urban expansion, where landscape architecture is often used to create spaces that cater to affluent demographics, a phenomenon commonly referred to as gentrification. Gentrification, driven by market forces and political interests, often leads to the displacement of marginalized communities. The aesthetic and economic upgrading of urban areas frequently results in the exclusion of lower-income populations, pushing them to the peripheries of the city. This process not only disrupts the social fabric of communities but also reinforces historical patterns of coloniality by reproducing power dynamics that privilege certain groups over others. The physical transformation of neighborhoods often disguises deeper forms of marginalization, where the cultural and social identities of local communities are erased in favor of market-driven redevelopment.

A decolonial approach to landscape architecture seeks to challenge these dynamics by shifting away from top-down, economically and politically driven methodologies. Instead, it promotes bottom-up, community-centered practices that prioritize the needs and aspirations of the people directly affected by these projects. Decolonizing landscape architecture involves working collaboratively with local communities, ensuring their active participation in decision-making processes. This approach emphasizes the importance of designing with, rather than for, communities, fostering spaces that are inclusive, reflective of local identities, and resistant to the forces of gentrification.

In my case study, this interplay between personal, political, and economic interests becomes particularly evident. The site in question is an old granite quarry along the Loire River in Nantes, close to the city center. Part of the site has already been transformed into an extraordinary botanical garden inspired by the stories of Jules Verne, while the other side was earmarked for the construction of a majestic 35-meter-high metallic tree with giant animal and insect machines. Visitors were to be invited to climb this fairy-tale installation, observing the river and the quarry from above. On the surface, this seems like an imaginative cultural project aimed at creating an engaging public space. However, a deeper look reveals that the project was commissioned to the company La Machine and Le Voyage à Nantes, two of the city’s major cultural institutions, which are frequently awarded large cultural development contracts by the local government.

The story behind Le Voyage à Nantes (2011) adds another layer to the analysis. This institution was created as an extension of a previous initiative, Estuaire created in early 2007, which aimed to reconnect

the cities of Nantes and Saint-Nazaire, located about 50 kilometers apart along the Loire River. However, this reconnection was not just cultural; it was also a part of a broader agenda to redevelop the industrial landscape of the region (SCOT de la Métropole Nantes-Saint-Nazaire 2003). As such, cultural strategies are being employed as tools for economic development and growth, blending the arts with broader market-driven objectives. The transformation of the granite quarry site is situated within a larger urban development plan called Les Bas de Chantenay, which envisions the construction of large housing complexes along the river, replacing the historical industrial harbor. This illustrates how cultural projects can act as entry points for gentrification and urban expansion that ultimately serve economic interests, often at the expense of local communities, local ecology and the preservation of local heritage.

A truly decolonial approach to this project would involve critically questioning the intentions behind it. Rather than aligning with cultural and economic institutions that prioritize growth and visibility, a decolonial project would focus on working with and for local communities, ensuring that the transformation of the quarry reflects their needs and values. This would involve bottom-up methodologies, where local stakeholders, including residents and community groups, co-design the space. Prioritizing public funds over private investment would allow the project to serve communal rather than commercial interests. Moreover, a decolonial project could aim to preserve the industrial character of the site, celebrating its historical significance while adapting it for community use in a way that avoids the gentrification process and the marginalisation of existing residents. In this way, landscape architecture becomes a tool not for the expansion of economic interests but for fostering social justice, environmental stewardship, and community resilience.

Arbre aux herons - @ Les Machines de l’île

Marais Audubon

LaLoire

Geomorphology

GondwanaVariscanRange

REASSESSDESIGNAPPROACHES:

Landscape architecture today often operates within an anthropocentric framework, heavily influenced by rational, scientific approaches that prioritize human needs and control over nature. This problem-solution mindset, similar to engineering, often disregards the ecological and cultural complexities of landscapes. A prime example is water management in the Netherlands, where the environment is manipulated for flood control through massive engineering projects. While technically impressive, such approaches reflect a colonial ideology of domination over nature, valuing efficiency and growth over ecological balance and community needs.

Decolonizing landscape architecture requires a shift in research and design methodologies by integrating diverse epistemic knowledge—ways of knowing that extend beyond the Western scientific tradition. This includes Indigenous practices, local traditions, and artistic approaches, all of which offer alternative perspectives that challenge the dominance of rationalist frameworks. By broadening our epistemic horizons, we create space for more inclusive, just, and sustainable approaches to landscape design. Art practice, in particular, provides a unique lens for engaging with the emotional, cultural, and spiritual dimensions of landscapes, aspects often overlooked in conventional, utilitarian approaches. By recognizing art as a form of epistemic knowledge, we enrich our understanding of landscapes and develop more holistic designs that reflect the interconnectedness of human and non-human experiences. This epistemic shift honours diverse ways of knowing, helping us move towards a more equitable and inclusive landscape architecture practice.

The old granite quarry and industrial quays along the river Loire in Nantes exemplify how landscapes were historically exploited for human enrichment. The site was transformed through resource extraction and industrial development, leading to habitat destruction and reshaping the land for economic gain. This reflects a colonial mentality of domination and exploitation of natural resources. A decolonial approach to this site involves shifting away from a focus on its future potential for development. Instead, it requires critically examining the land’s history and exploring how pre-colonial cultures may have interacted with it. However, in Nantes, there is limited information about Indigenous knowledge or traditions due to the lack of pre-colonial historical records.

In the absence of such information, we must turn to non-conventional forms of knowledge. Artistic practices can help us reconnect with the landscape by offering alternative ways of engaging with its emotional, cultural, and spiritual dimensions. Art, as an epistemic tool, allows for a deeper, more holistic understanding that goes beyond utilitarian or economic perspectives.

This approach transforms the site into more than a resource for future development. By using artistic and epistemic practices, we can re-explore its historical and cultural layers, fostering new connections with the land that honour its past and present complexities. the richness and complexity of the world around us.

Kauyumari,theBlueDeer,spiritoftheWixarikaMexico-UnlearningriutalAHK

Unlearningschool-UnlearningriutalAHK

to Dance

Line to the Video: https://youtu.be/1gm8JEn9eZw

In landscape architecture today, the design process is often top-down, driven by the desires of investors, clients, and those funding the projects. These stakeholders typically prioritize political or economic interests, often overshadowing the needs of the communities that will use the space. Architects, influenced by these pressures—and sometimes by their own egos—may focus on creating signature works that fulfill investor visions rather than addressing the real needs of the environment and local populations. This creates a disconnect between design and the communities affected, reinforcing a hierarchical approach.

Decolonizing landscape architecture requires a shift toward participatory processes where communities are involved from the outset. To be ethical and sustainable, designs must reflect local knowledge and the aspirations of those most impacted. This approach ensures that the process is inclusive, fostering equitable and resilient spaces that genuinely meet community needs.

Genuine engagement goes beyond tokenism; it involves building trust, fostering dialogue, and empowering communities to shape their environments. Architects must set aside ego-driven ambitions and listen to diverse perspectives, working collaboratively to co-create spaces that reflect the identities and aspirations of the people involved.

By embracing participatory, iterative design processes, landscape architects can move away from topdown, investor-driven practices and ego-centred designs, creating spaces that are both culturally meaningful and environmentally sustainable while fostering a sense of ownership and belonging within the community.

In the context of the old granite quarry along the river Loire in Nantes, a participatory, iterative design process would take shape by engaging not only the neighbouring communities but also the informal group of actors who have been using the site for years. Although no one lives directly on the site, nearby communities and individuals who have claimed the space for events, gardening, and architectural explorations have developed a unique connection to the land. Their experiences and the knowledge they’ve cultivated through their use of the site provide invaluable insight into its potential future.

By collaborating with these groups, landscape architects can understand what the site means to its current users and what practices and knowledge have emerged through their interactions with the quarry. Involving these groups ensures that their experiences are respected and integrated into the design, while also fostering a sense of continuity. By doing so, we create a space that not only serves the broader public but also ensures that the communities who have used the site continue to feel connected and included, even after the transformation. This ongoing engagement with the existing users also helps maintain a vibrant community presence on the site, rather than displacing them or rendering their activities obsolete.

Moreover, involving these communities in the design process helps ensure the long-term sustainability and maintenance of the site. When users are invested in the space and see their contributions reflected in the design, they are more likely to take responsibility for its upkeep and continued use. This fosters a sense of ownership that extends beyond the initial design phase, ensuring that the transformed site remains a living, active part of the community.

“Les trucs royal deluxe en bord de Loire, La géante et la girafe vers la piscine gloriette.”

“C'EST UNE VILLE DE PROVINCE COMME UNE AUTRE PAS TRÈS LOIN DE LA MER.”

“Si je pouvais ajouter des éléments à la Loire: Des parcs en bord de Loire. Dans un monde idéal, un en- droit où l'on pourrait se baigner”

“C'est mon fLeuve, si je devais choisir un FLeuve préféré je choisirais la Loire. “

“C'est surtout des accès routiers qui longe la Loire.”

Legenda

Granite

Stones

Concrete

Mud

Dirt path

Meadows

Vegetation Mass

Trees

Fresh water

Brakish water

T0-Encounter

T2- Human-Manipulating

T4- Human&Quarry- Interact

T1-Human-Drawingintheconcrete

Dances of granites

Human&Quarry- Playing

T3-Plants-appear

T4- Human&Quarry-interact

Human&Quarry- Connecting

T4-

T5-

Garden of granites: A Journey Through Time and Elements

Welcome to the Garden of Granites, a unique sanctuary nestled within the ancient embrace of a granite quarry. This meticulously designed space, situated on the sturdy foundation of old industrial concrete floors, invites visitors on a dynamic exploration of geological wonders and natural beauty.

The garden’s pathways, intricately carved out of the rugged concrete, create a mesmerizing dance of length, width, and angles. Meandering through the space, visitors are encouraged to pause and absorb the sensory moments that unfold at every turn. The dripping granitic cliffs of the quarry, the untamed vegetation, and the colonised walls formed from leftover concrete slabs contribute to the multifaceted experience.

These vertical walls, adorned with spontaneous vegetation, seem to emerge organically from the ground, fostering a deep connection with the landscape’s geological history. As visitors engage in an embodied performance, navigating the dynamic circulations, they become part of a rhythmic dance with the elements— a dance with the granite walls and the flourishing vegetation.

In moments of quiet and intimacy, the garden offers a chance to reconnect with the granite’s grounding energy. Visitors can slow down, appreciating the protective aura of the granite formations. This sanctuary becomes a place where one can truly embody the energy, history, and stability that the granite symbolizes—a dance through time and elements that culminates in a profound connection with the geological essence of the site.

Prunus laurocerasus L. (Laurier-cerise)

Nasturtium officinale (Cresson d'eau)

Populus nigra (Peuplier noir)

Polypodium interjectum (Polypode intermediaire)

Alnus glutinosa (Aulne glutineux)

Parthenocissus tricuspidata (Vigne vierge à trois pointes)

Phyllostachys aurea (Bambou des rivières)

Ficus carica (Figuier)

Betula pendula (Boulot)

Senecio vulgaris (Séneçon commun)

centranthus ruber (Valeriane rouge)

Hedera helix (Lierre grimpant)

Polypodium vulgare (polypode commun)

Laurus nubilis (Laurier sauce)

Ilex aquifolium (Houx commun)

Silybum marianum (Chardon de marie)

Spartium junceum (Genet d'Espagne) maybe Cytisus scoparius

Clematis virginiana (Clématite de Virginie)

Pinus pinaster (Pin maritime)

Umbilicus horizontalis (Nombril-de-venus)

Cortaderia selloana (pampa grass)

Fraxinus excelsior (Frêne élevé)

T0-Encounter

T2- Human-Manipulating

T1-Human-Digging-Givingbacktotheriver

T3-Plants-Collecting

T4- Human- Modeling

T4- River-sharing

T4- Vegetation- Appearing

T5- Human& River- Connecting

A River Encount

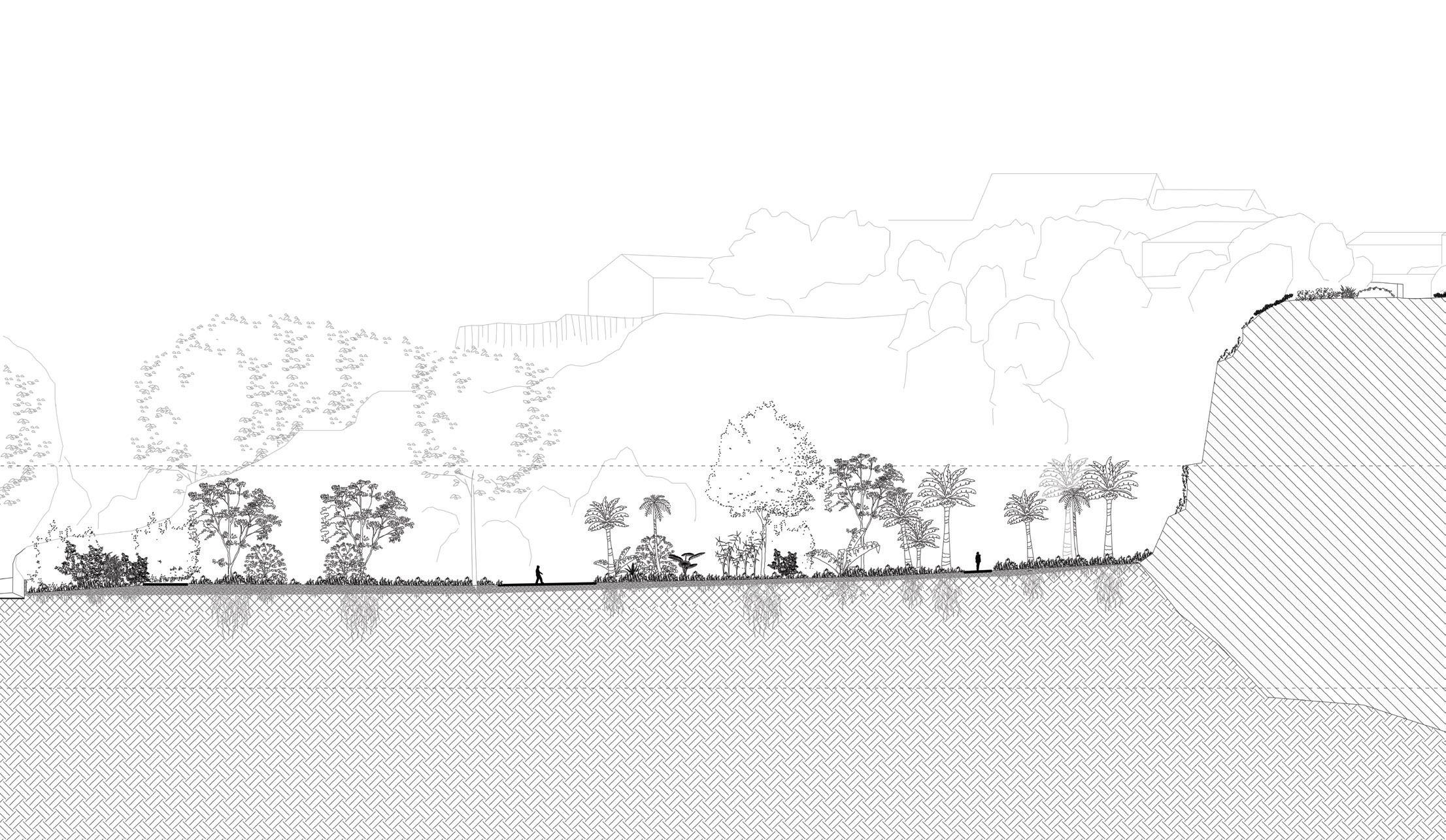

This section of the garden spans from the foot of the quarries to the river’s quays, where stone mounts and concrete quays suffocate the water. By creating a breach in this wall, we are letting it breathe and move beyond the confines we imposed. The tides and currents spread freely, both vertically and horizontally, revitalising the land. The river is a living chronicle of history and wisdom, it has witnessed every epoch of the city.

Water, ever fluid and dynamic, rushes forth, carving landscapes with each ripple and wave. This river, the lifeblood that drew settlers here, connects us to the source in the distant mountains thousand kilometres upstream and to the sea eighty kilometres downstreams, carrying whispers of salty spray with the tide. The river, rich with knowledge, carries stories from upstream, wisdom from the sea, and secrets from lands overseas. It is a reservoir of ancient truths and future promises. The energies of the river—motherly, protective, and inspiring—remind us of its enduring presence. It flows consistently, whether calm or agitated, teaching us to keep moving forward. The river, a symbol of constancy, shows that time is fluid, urging us to reflect on the past and learn from it.

Once constrained and neglected, the breaking of dikes lets us hear her voice again. We invite visitors to wander through broken asphalt, past the delicate bushes of “Angélique des estuaires”, and crowl under the graceful branches of “saule cendré”. Fragments of pavement allow us to sit by the river, no longer five metres above but with our feet in its waters or mud, depending on the tide. Here, we reconnect with the river, humbled by its power and beauty. This river, once feared, now offers a newfound sense of peace and reassurance. In this garden, the tide dictates our entrance, sharing its rhythms with us and inviting us to embrace our shared responsibility with this majestic, living force.

Polypodium interjectum (polypode intermediaire)

Angelica heterocarpa (Angélique des estuaires)

Alnus glutinosa (Aulne glutineux)

Schoenoplectus triqueter (Scirpe triquètre)

Salix cinerea (Saule cendré)

Pyracantha coccinea (Le Buisson ardent)

Betula pendula (Boulot)

Centranthus ruber (Valériane rouge)

Hedera helix (Lierre grimpant)

Polypodium vulgare (polypode commun)

Fraxinus angustifolia (Frêne à feuilles étroites)

Ilex aquifolium (Houx commun)

Umbilicus horizontalis (Nombril-de-Vénus)

Symphyotrichum lanceolatum (Aster à feuilles lancéolées)

Buddleja davidii (Arbre à papillon)

Decolonizing landscape architecture requires prioritizing the preservation and restoration of local ecosystems, recognizing their intrinsic value, often degraded by colonial practices. This approach emphasizes the interconnectedness of all living beings, focusing not only on aesthetics but also on ecological integrity and resilience.

At our study site along the river Loire, it is essential to protect both the original landscape of the riverbank and the new ecosystems that have emerged from the ruins of industrial exploitation. One significant aspect that needs attention is the tidal landscape that was removed with the construction of the quay walls. These walls, built during the colonial era to facilitate shipping, replaced natural tidal zones that once supported diverse ecosystems. Restoring elements of the tidal landscape is crucial to reestablish ecological balance, allowing for the return of habitats that thrive on the dynamic interaction between land and water.

In addition to the restoration of the tidal areas, the new ecosystems that have taken root on the post-industrial ruins, including plant and animal life reclaiming the quarry, must also be preserved. These emergent ecosystems represent the resilience of nature and offer a unique opportunity to integrate them into future site development.

By adopting sustainable land management practices—such as native plant restoration, habitat creation, and the renewal of tidal zones—landscape architects can ensure that both the original riverbank landscape and newly formed ecosystems are protected. This helps preserve the ecological heritage of the site while fostering its natural regeneration.

Ultimately, decolonizing landscape architecture centers on ecological stewardship, fostering healthier, more sustainable environments for both human and non-human communities.

Terra Nullius

“Terra Nullius,” is a concept rooted in the erasure of shared spaces. Historically, Terra Nullius, meaning “nobody’s land,” signified the belief that lands unclaimed by Europeans were void of ownership and ripe for taking. This mindset led to the death of the commons during Europe’s enclosure period, where shared lands were fenced off, privatized, and restricted from public use.

Here, we endeavor to recreate a common space, a cultural and agricultural landscape shared harmoniously with the river. Influenced by the tide, this area transforms as different parts of the fields flood and drain, creating diverse vegetation zones. The tidal rhythms dictate the landscape, fostering various ecosystems that thrive in the estuary environment.

In this section, you’ll find sheep grazing peacefully, their presence maintaining the grasslands. Pollard willows stand ready for cutting, their branches woven into the water ditches and retention walls. This traditional practice not only preserves the landscape but also enhances its resilience against flooding. This part of the garden offers abundant opportunities for participatory projects, inviting visitors to engage in the work and maintenance of the land. Through these activities, we challenge the notion of ownership. The tidal area becomes a shared space, a common ground where humans and the river entity coexist and collaborate.

The vegetation here is tailored to the estuary’s unique conditions, respecting the ebb and flow of tides. We honor and share the knowledge of how humans have historically adapted to living with the tides, fostering a deep respect for the natural cycles.

In Terra Nullius, we invite you to immerse yourself in a landscape where the concept of ownership fades, replaced by a shared stewardship with the river. This area stands as a testament to the power of communal effort and the wisdom of living in harmony with nature’s rhythms.

Alnus glutinosa (Aulne glutineux)

Pyracantha Koidzumii (Pyracantha de l'europe)

Juncus spp. (Jonc)

Phragmites australis (Roseau à balais)

Typha latifolia (Massette à larges feuilles)

Angelica heterocarpa (Angélique des estuaires)

Iris pseudacorus (Iris des marais)

Fraxinus excelsior (Frêne élevé)

Salix viminalis (Saule des vanniers)

Salix alba (Saule blanc)

Salix caprea (Saule marsault)

Alnus incana (Aulne blanc)

Rosa canina. (Églantier)

Ligustrum vulgare. (Troène)

Crataegus monogyna (Aubépine)

The concept of terra nullius—the belief that land uninhabited by “civilized” people could be claimed—has its origins in Western philosophy and played a pivotal role in global colonization. This notion dismissed Indigenous relationships with the land and justified its seizure for European expansion. On a local level, similar processes occurred in the United Kingdom with the enclosure movement, where common lands were privatized, displacing rural communities and severing their access to shared resources. Both terra nullius and enclosure reflected a Western mindset that treated land as property, available for ownership and exploitation.

Land ownership in the Western context is closely linked to profit and extraction. When individuals or entities own land, they often manage it for a singular purpose—typically the activity that yields the most financial gain. This approach, focused on maximizing profit, can lead to the exploitation of natural resources and limits the land’s potential for diverse uses, reducing its ecological and social value.

In contrast, the commons represent a system of shared land or resources, collectively managed by a community. The commons encourage multi-use practices, where different users engage with the land for various purposes, promoting a more sustainable and balanced relationship with the environment. This approach allows for multiple interests—such as different types of agriculture, nature conservation, and recreation—to coexist, fostering a healthier ecosystem.

To sustain the commons, a form of governance is necessary, ensuring the fair and sustainable use of shared resources. This governance structure, which can be seen as a foundational political entity, enables collective decision-making and accountability, supporting a resilient system that balances diverse community needs and preserves the environment.

The old granite quarry along the Loire in Nantes vividly illustrates the impact of ownership and mono-use at the expense of diverse ecosystems. Many elements within the site reflect how single-use development has shaped the landscape. The quays, which border the embankment of the river, were built during the colonial era for the shipping industry, leaving no room for natural, ecological embankments. The old mill factory, along with its surrounding area, is almost entirely covered with asphalt and concrete, suffocating any existing ecosystems. The quarry itself, with its long history of stone extraction, left the land barren and scarred, fully exploited for human purposes.

This is a landscape that has been systematically deprived of life through mono-use and exploitation. However, as soon as these singular activities ceased, life began to return—plants, animals, and new human communities started to reestablish themselves. This process mirrors the dynamics described by Anna Tsing in The Mushroom at the End of the World, where she beautifully explains how new forms of life and community can emerge in the ruins of capitalist exploitation. Once the resources are extracted and ownership-driven activities leave, nature and human connections reclaim the land, illustrating the potential of the commons where multiple uses and ecosystems can thrive together.

Yet, as the site is transformed into a new “city park,” it risks repeating the same cycle of mono-use, this time under the guise of urban development. The new-born community, which has organically formed after the site was abandoned, is given no space in the park’s planning, and the land is being sealed again into a singular, controlled purpose. This highlights the ongoing challenge of moving away from ownership-driven, singular approaches toward a more inclusive, multi-use model that aligns with the principles of the commons.

Lesglanneuses

Musee des imaginaires

Musee des imaginaires

The “Musée des Imaginaires,” housed in a former industrial mill, is at the heart of our garden. This iconic building is being transformed to host both the Musee Jules Verne and the Musée des Imaginaires, offering a unique opportunity to reshape Nantes’ imaginary, rooted in its landscape.

Visitors are invited to engage with the Nantes landscape in the park surrounding the building. The park’s paving cracks to allow vegetation to flourish, creating a seamless transition from outside to inside, blending nature with architecture.

A key feature is the quay overlooking the Loire. We plan to dismantle it and repurpose its concrete structure into a wide staircase, allowing visitors to sit close to the water, fostering a deeper connection with the river.

This adaptive reuse highlights our commitment to sustainability, using recycled materials found on-site, in line with our decolonization and non-extraction approach. Between the building and the water, affordable, comfortable spaces will host a bar, creating a communal gathering spot.

The Musée des Imaginaires will be a place for the people of Nantes to reinvent their identity, moving away from colonial narratives to one deeply rooted in the landscape and pre-colonial culture. This space will celebrate a culture intertwined with the natural world, offering a place for collective imagination and environmental reconnection. Here, the community can explore and create a new imaginary Nantais, inspired by the beauty and wisdom of the natural landscape.

The circle

The Circle

At the heart of our garden lies “The Circle,” a central space where the river, the quarry, the city, and their histories converge. Crafted from recycled granite cobblestones once extracted from the quarry, The Circle embodies the meeting of sky and earth. Its slight inward curve allows rainwater to form a thin, reflective layer, creating a mirror effect that invites contemplation.

Visitors are drawn to the center of The Circle, a destination inviting them to pause, look around, and listen. Here, the voices of nature—the river, the quarry, and the vegetation—speak to those who have learned to listen again. The imposing quarry walls surround us, confronting us with the consequences of our behavior towards the landscape and ourselves, inspiring a moment of humility.

But The Circle is more than a place for listening; it is an invitation to respond, to transform listening into movement. The smoothened cobblestones form a flat surface, perfect for dance and performance. The Circle, situated at the center of the quarry, is encircled by small tribunes made of stacked concrete slabs, providing a place for people and nature to observe the performers together.

Jardin Extraordinaire:

Salvia leucantha cav. (Sauge du Mexique)

Phlomis fruticosa L. (sauge de Jerusalem)

Musa basjoo (Bananier du Japon)

Dicksonia antartica (Fougere arborescence)

Acalypha wilkesiana (Foulard)

Prunus laurocerasus L. (laurier-cerise)

Opuntia robusta (figuier de barbarie)

Agave americana L. (agave)

Viburnum rugosum (Laurier-tin)

Gunnera tinctoria (Gunnera du chili)

Salvia guaranitica (sauge guarani)

Manihot grahamii (Manioc)

Hibiscus moscheutos (ketmie des marais)

Senna didymobotrya (bois d'epingle)

Ensete ventricosum (Bananier d'Abyssinie)

Paulownia tomentosa (Paulownia)

Phyllostachys aurea (Bambou des rivières)

Ficus carica (figuier)

Hedera helix (Lierre grimpant)

Buddleja davidii (Arbre a papillon)

Yucca filamentosa (yucca filamenteux)

Colocasia esculenta (Taro)

Farfugium japonicum (Cellier)

Fatsia Japonica (Fatsia)

Catalpa ovata (Catalpa jaune)

Amicia zygomeris (Amice a fleurs jaunes)

Cortaderia selloana (pampa grass)

This project has been a long journey, beginning with critical questions about the profession of landscape architecture, my role within it, and how it couldbecome more ethical and sustainable. The decolonial movement offered me a new perspective, reshaping how I view the field. Through this approach, I identified key themes that could guide landscape architecture toward more ethical and sustainable practices. These themes did not emerge all at once; they grew and evolved throughout my research and work. The site, located between the old granite quarry in Nantes and the Loire River, helped contextualize my findings and refine my ideas. It also provided an opportunity to explore my own path within the profession.

Some of the key themes I explored included: reassessing design approaches, iterative design processes, and reconsidering land use and ownership, among others. I addressed these themes throughout the project, with varying degrees of success. For instance, reassessing the design process led me to create an entirely new approach, one that was deeply personal, relying on emotions and artistic practices. This closely aligned with the ideas I uncovered in my research. However, the iterative design process proved more challenging. Genuine participatory design is complex and requires a deep, ongoing commitment from the outset. Given the scope of this project and the limited time and resources, the participation element was modest. I engaged with friends and families familiar with the site to exchange ideas, but this cannot be considered a full participatory process, nor would it be honest to claim so. Yet, it was present in some small way.

This project also opened new doors, particularly through the integration of dance, which became an important aspect of my research and something I continue to pursue outside the project. The connections between different disciplines have provided me with great energy and inspiration for my future career and studies.

In the end, the design itself is simple, grounded in the idea of creating a park where visitors can reconnect with the natural forces of the site. The approach was to work with the existing landscape, making space for natural elements to be felt and experienced. This included inviting the river back in, respecting the ecosystem of the quarry by supporting the rewilding processes already underway, and creating pathways for visitors that encourage a sense of humility toward nature. Once all the elements were in place—river, rock, mud, concrete, vegetation, and animals—it was a matter of choreographing the movement of these forces alongside the visitors. The result is a choreography of time, space, and interactions, where all elements move together in harmony.

The intervention is simple, using minimal materials and reusing what is already present on the site. While straightforward in execution, it carries with it many ideas, some academic, that may or may not resonate with others. Ultimately, the garden should speak for itself.

As Anna Halprin, the American dancer and choreographer, and wife of landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, once said: "Just as the ancients danced to call upon the spirits in nature, we too can dance to find the spirits within ourselves that have been long buried and forgotten."

Through this project, I discovered the power of dance—a gateway to feeling connected to the land and to reconnecting with myself. Like Halprin, I believe there is hope for a more sustainable and ethical future. This hope is not based solely on technical achievements but also lies within each of us. Art and dance are ways to tap into and share this inner light because beauty unites, and optimism is contagious.

Let’s cultivate and share our love for the land. That is the mission of a landscape architect, and that is what I aspire to become.

Thank you.

Decolonizing landscape architecture is not a one-time achievement but an ongoing process of inquiry and reflection. Every outcome from this journey is a product of critical thinking, and rather than being an endpoint, it represents a step in a continual effort to challenge and dismantle the power structures and colonial legacies present in the field. Landscape architects must remain dedicated to evaluating their work, questioning assumptions, and adapting to new knowledge and perspectives as they arise.

This commitment to ongoing deconstruction requires openness to learning and change. Decolonizing practices must evolve alongside shifting cultural, social, and environmental contexts. Practitioners should embrace the fluidity of the process, knowing that designs and methods are never static or final, but subject to constant improvement and re-evaluation.

A key aspect of this evolution is reforming landscape architecture education. By integrating diverse perspectives, Indigenous knowledge, and non-Western histories, the profession becomes more inclusive and better equipped to address complex, global challenges. Engagement in advocacy is also crucial, as landscape architects can play a role in promoting policies that protect Indigenous rights, encourage sustainable land use, and support cultural preservation. Through this ongoing commitment to critical reflection, adaptation, and advocacy, the decolonization of landscape architecture becomes a continuous and essential pursuit.

Clément, Gilles. "The Garden in Movement." In Planetary Gardens: The Landscape Architecture, edited by Alessandro Rocca, 2007. Basel: Birkhauser.

Watson, Julia. Lo-TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism. Tashchen, 2019.

Bird Rose, Deborah, and Libby Robin. "The Ecological Humanities in Action: An Invitation." Australian Humanities Review, 2004.

Mignolo, Walter D. "Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto." TransModernity 2, no. 1 (2011): 44–66.

Antrop, Marc. "A Brief History of Landscape Research." In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies, edited by Peter Howard, Ian Thompson, and Emma Waterton, 2013.

Mignolo, Walter D. "Interview - Walter Mignolo/Part 2: Key Concepts." E-International Relations, 2017.

Naji, Said. Architectures du Bien Commun: Pour une Éthique de la Préservation. Métis Presses, 2019.

Voskoboynik, Daniel M. "To Fix the Climate Crisis, We Must Face Up to Our Imperial Past." 2018.

Voskoboynik, Daniel M. The Memory We Could Be. 2018.

Waldheim, Charles. "Introduction: Landscape as Architecture." Harvard Design Magazine 36 (2013).

Rabie, Kareem. "Reviewed Work: The Conflict Shoreline: Colonization as Climate Change in the Negev Desert by Eyal Weizman and Fazal Sheikh." The Arab Studies Journal 24, no. 2 (Fall 2016): 195–199.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, translated by Alan Sheridan. London: Penguin Books, 1977.

Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Duke University Press, 2018.

Murphy, Keith M. "Arturo Escobar, Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds." Anthropological Quarterly 92, no. 3 (2019): 949+.

Raxworthy, Julian. "Decolonizing Landscape Architecture." In The Routledge Companion to Criticality in Art, Architecture, and Design, edited by Chris Brisbin and Myra Thiessen, 2018.

Neumeier, Beate, and Kay Schaffer, eds. Decolonizing the Landscape: Indigenous Cultures in Australia. Cross/ Cultures 173, 2014.

Ansari, A. "What a Decolonisation of Design Involves: Two Programmes for Emancipation." Journal of Futures Studies 23, no. 3 (March 2019): 129–132.

Hilal, S., and Alessandro Petti. Permanent Temporariness. Art and Theory, 2019.

Ferdinand, Malcom. Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World. Translated by Anthony Paul Smith. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2021.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Shin, Sarah, and Ben Vickers, eds. Altered States: The Library of Esoterica. London: Strange Attractor Press, 2019.

Bird Rose, Deborah. Vers des Humanités Écologiques. Paris: Wildproject, 2020.

Césard, Nicolas, Catherine Larrère, and Baptiste Morizot, eds. Politiques du Flamant Rose: Suivre et Habiter avec les Êtres Vivants. Paris: Éditions Wildproject, 2021.

Fanon, Frantz. Les Damnés de la Terre. Paris: François Maspero, 1961.

Clément, Gilles. Éloge des Vagabondes: Herbes, Arbres et Fleurs à la Conquête du Monde. Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, 2012.

Ghosh, Amitav. Le Grand Déménagement: Raison et Culture dans un Monde Bouleversé. Paris: Wildproject, 2021.

A la criee, Guide Indigene de detourisme, de Nantes a Saint Nazaire. Edition A la criee, 2016

European association of social anthropologists, Understanding Rituals. Daniel de Coppet 1992

Nulle terre sans guerre, A la lisere du bocage, histoires de luttes territoriales pour la defences des communaux. Printemps, 2015

Les carnets du paysage, Cheminements. Actes Sud, Ecole nationale supérieure du paysage, 2004

Catherine Vadon, Aventures Botaniques, d’Outre-mer aux terres atlantiques. Jean-Pierre G.

Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture. Routledge, London and New York. 1994

Claire Ratinon & Sam Ayre, Horticultural Appropriation. Rough Trade Books x Garden Museum, 2021

Catherine Benoît, JARDINS D’ESCLAVES/JARDINS BOURGEOIS DANS LES ZONES SACRIFIÉES DES AMÉRIQUES. Éditions de l’Association Paroles | « Sens-Dessous », 2020

Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place, The perspective of Experience. Regents of the University of Minnesota, 1977.

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Thijs de Zeeuw, Lada Hršak, Erik A. de Jong, Hannah Vollam, Anna Torres, Philippe Allignet, Fay Aldhukair, my parent and all who have supported me throughout this journey of writing and completing this project. Your encouragement, guidance, and unwavering belief in me have been invaluable. I am truly grateful for your contributions, whether they were big or small, and I couldn’t have completed this project without you. Thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Graduation Project

Vincent Lulzac | 2024

Master in Landscape Architecture

2024 Academy of Architecture | Amsterdam University of the Arts

Commission members

Thijs de Zeeuw | Lada Hršak | Erik A. de Jong