Housing the precariat

1/3 Why…

co-Housing for the precariat

An alternative model for housing development, and why we need it.

2/102 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 TE LAAT JE BENT CIJFERS: CBS/KADASTER — POSTER: YURI VEERMAN Gemiddelde huizenprijs in Amsterdam

227.000 277.000 292.000

95.000 210.000

518.000 547.000

Date · 6 May 2024

Version · B

Audience

Firstly architects that have to judge my graduation. Enthousiasmeren! (Voor de voorgestelde oplossing)

Secondly other people that are interested in putting housing first and profit second.

Outline

More and more people are becoming unhoused.

How on earth can we make housing affordable?

Housing coöperatives are part of the solution and the focus of this piece.

YOU ARE TOO LATE

Youri Veerman 2021

3/102

The working-class can no longer afford to live where they work.

How can we make housing affordable?

And how do we keep it affordable?

4/102

Introduction

History has shown us that, when a system or society becomes to unequal, revolutions happen and the system implodes. In this publication you’ll discover why housing, and the way we organize it, is the defining factor in how unequal society is (has become again). And who are most likely to start a revolution in response.

On the following pages you’ll find a short version of the journey that I made while researching my graduation project for the Amsterdam academy of architecture. We’ll start in the city where I study. A city that has a history of solving the problem of tremendous inequality (we’ll get to how). And, a city that is breaking down the mechanisms it created to solve it.

In the last decade the amount of registered homeless people in Amsterdam has doubled. These numbers don’t include those who are unhoused but manage because they find clandestine solutions through friends and family connections. They live in campers, on attics, in warehouses, and pay a premium for these places. No numbers exist on how many people are actually unable to afford a house. But there are numbers that might illustrate the gravity of the problem:

· Only an income in the top 1% of all people in The Netherlands will get you a mortgage on an average priced house.

· On a median income, only 3% of all houses in The Netherlands are for sale. These houses are obviously not situated anywhere near job opportunities.

5/102

In other words: If you have to work for money, and don’t own your house (a mortgage is not a house), you have a problem. This problem is not unique to The Netherlands. Many (post)colonial countries have similar problems. This study focusses on Amsterdam but the contents are of interest to anyone who cares about putting housing first and profit second.

The contents are organized in three sections and a conclusion to provide a starting point for the design (of my graduation project):

Section 1 · Why is housing unaffordable?

Section 2 · How can we make housing affordable?

Section 3 · Who should we build for?

Conclusion · Creating a model for co-Housing (what should we build)

6/102

7/102 Contents Part 1 · Why is housing unaffordable? Housing = Capital The original sin 14 Privatization of land Capital 16 noun Capital today 18 From land to real-estate Housing is capital 20 Globally around 40% of capital is housing (residential real estate). Housing is not a commodity 22 The supply of housing is finite Supply (of housing) is regulated by government 24 And bottlenecked by bureaucracy How money creation inflates housing prices 26 Money is debt (and private banks create most of it) The working class can no longer afford a house 28 Young people in Europe spend an increasingly disproportional amount of their income on mortgage or rent History repeats 30

8/102 A case study: How Amsterdam found solutions (and forgot what they solved). The solution is NOT more private enterprise 32 More privatization is often presented as a solution to the problems privatization is causing. What happens when solutions are privatized 34 Profit or surplus becomes the goal: Prices always go up! Property rights versus housing rights 38 Private property is sacrosanct. Housing rights are not. We need to talk about ownership 40 That means legal ownership. Not pseudo ownership, participation or community building. · Part 2 · How do we make housing affordable? Re-imagining ownership Ownership, a coin with two three sides 44 (Post) colonial societies have a very narrow, limited, and dogmatic understanding of how we can manage resources. Commons 46 Every ideology claims realism Socialism, liberalism, commonism 48 Balance (Housing) Cooperatives 50 Commons in housing On shared ownership and governance 52

Examples of countries and cities where cooperatives are institutionalized and have a long history are abundant in Europe.

to Amsterdam (The Netherlands).

Living is separated from working in our financial, institutional, legal, and popular frameworks and understanding. At the same, the number of people working from home has been increasing. This trend existed before, and exploded during covid.

The fundamental human need for a sense of community is well know to most marketeers. Housing developers are exceptionally well positioned to exploit this human trade, and cater to the happy few that can afford it.

9/102

principles

Existing structures in Europe 54

re-Using

56

Eight

for managing a commons.

historical structures

Back

Building for the precariat The contemporary working class 64 Society is changed. Our words and thus thinking has not. The precariat 66 Three

one problem Living & Working 68

Part 3 · Who should we build for?

groups,

One or two people 70 Family = 1 or 2 people Community as a service 72

Motivation 74

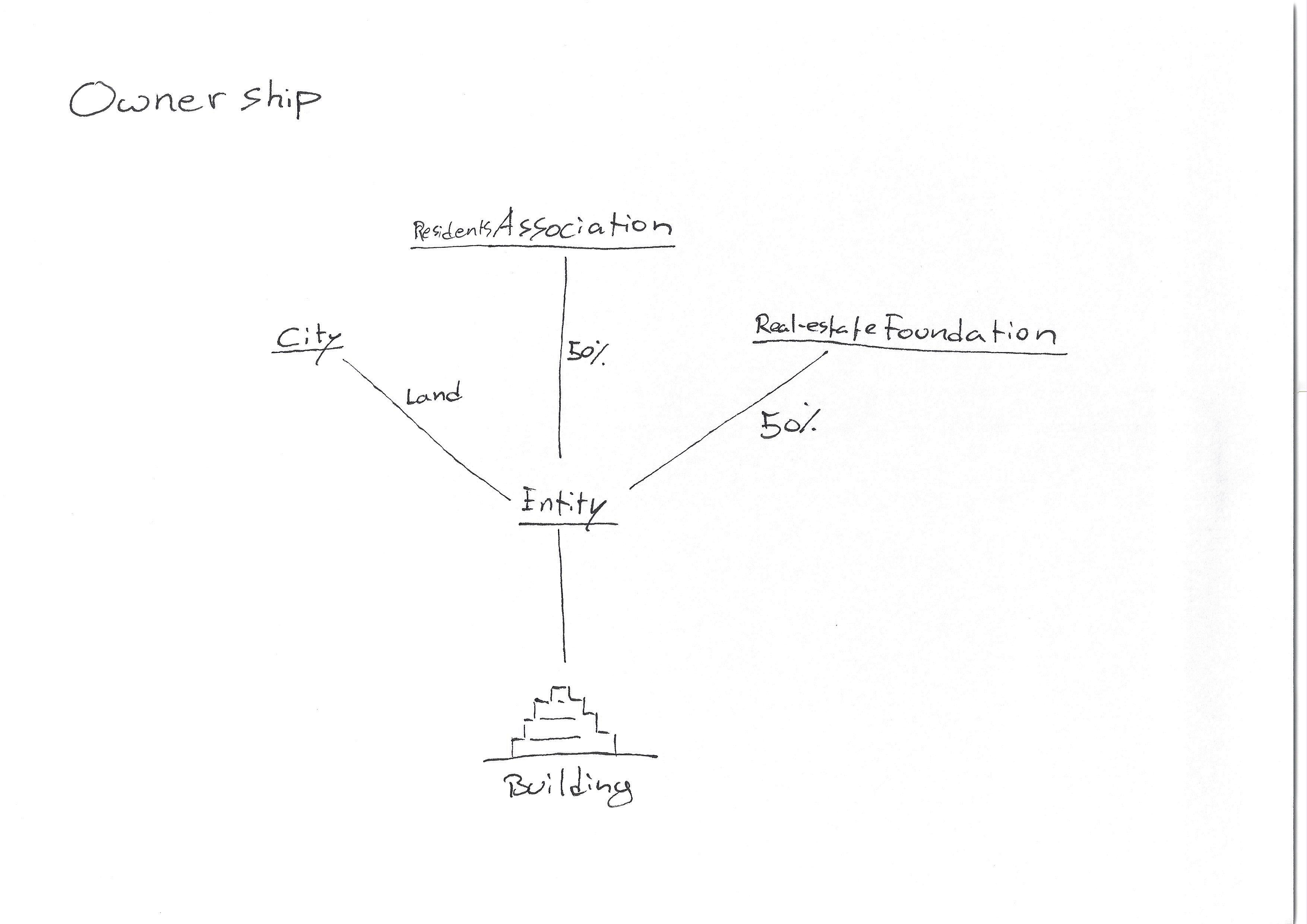

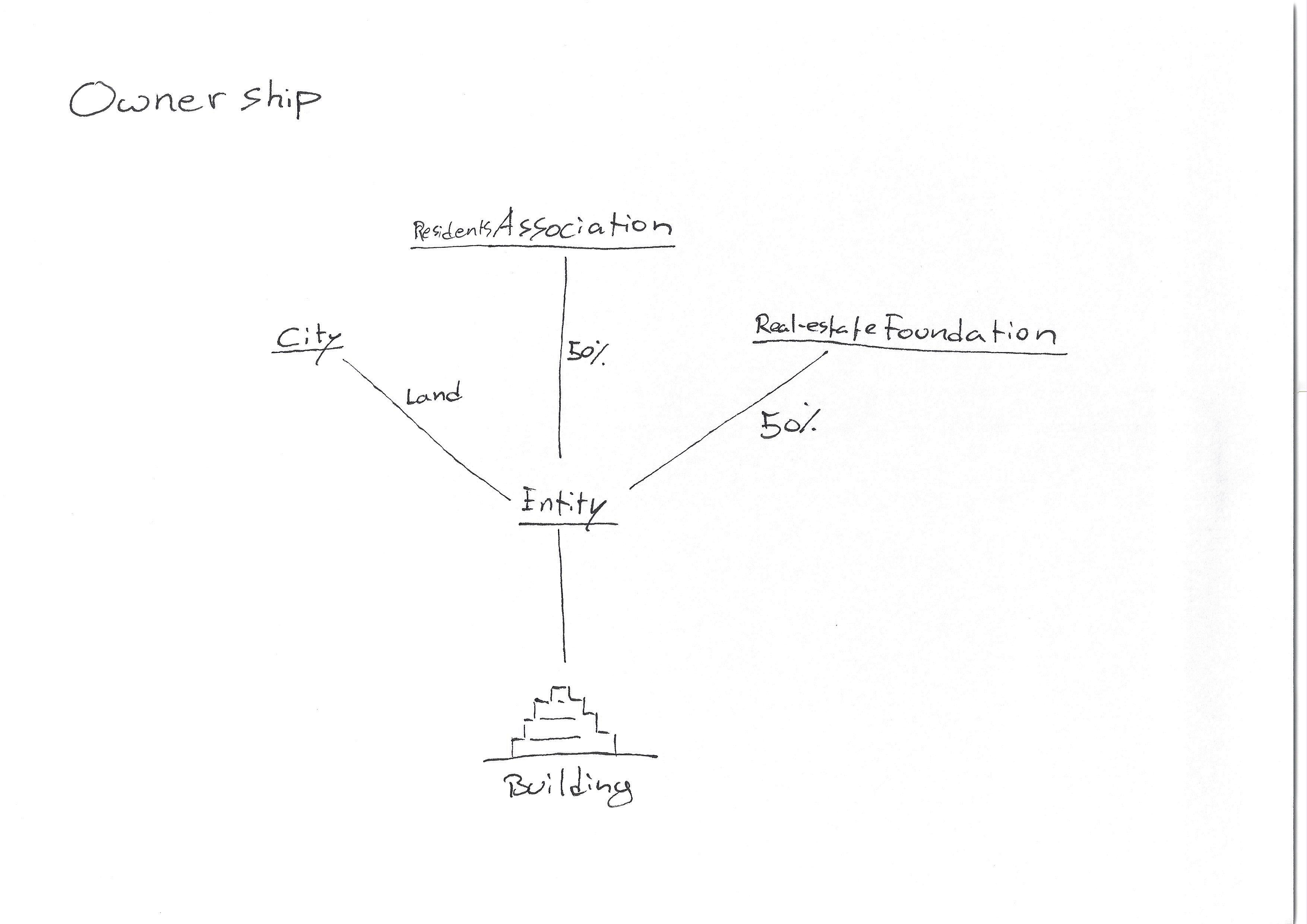

10/102 Autonomy, competence, and connection to others Community - building 76 What if we become co-owners, co-builders, and co-administrators Assemblage 78 Aesthetics of process Low-tech smart materials 80 How hi-tech materials only serve inflated profits for shareholders and what that means for our choice of materials. The yields of cooperation 82 Innovation instead of growth Conclusion An alternative model for housing development co-Housing 86 For the precariat co-Own 88 Residents own a share of the real-estate. Not the real-estate itself. co-Design 90 Clear choices to create connection and diversity co-Create 92 Connection to each-other and place co-Operate 94 Day to day operations co-Housing, a model for housing development 96

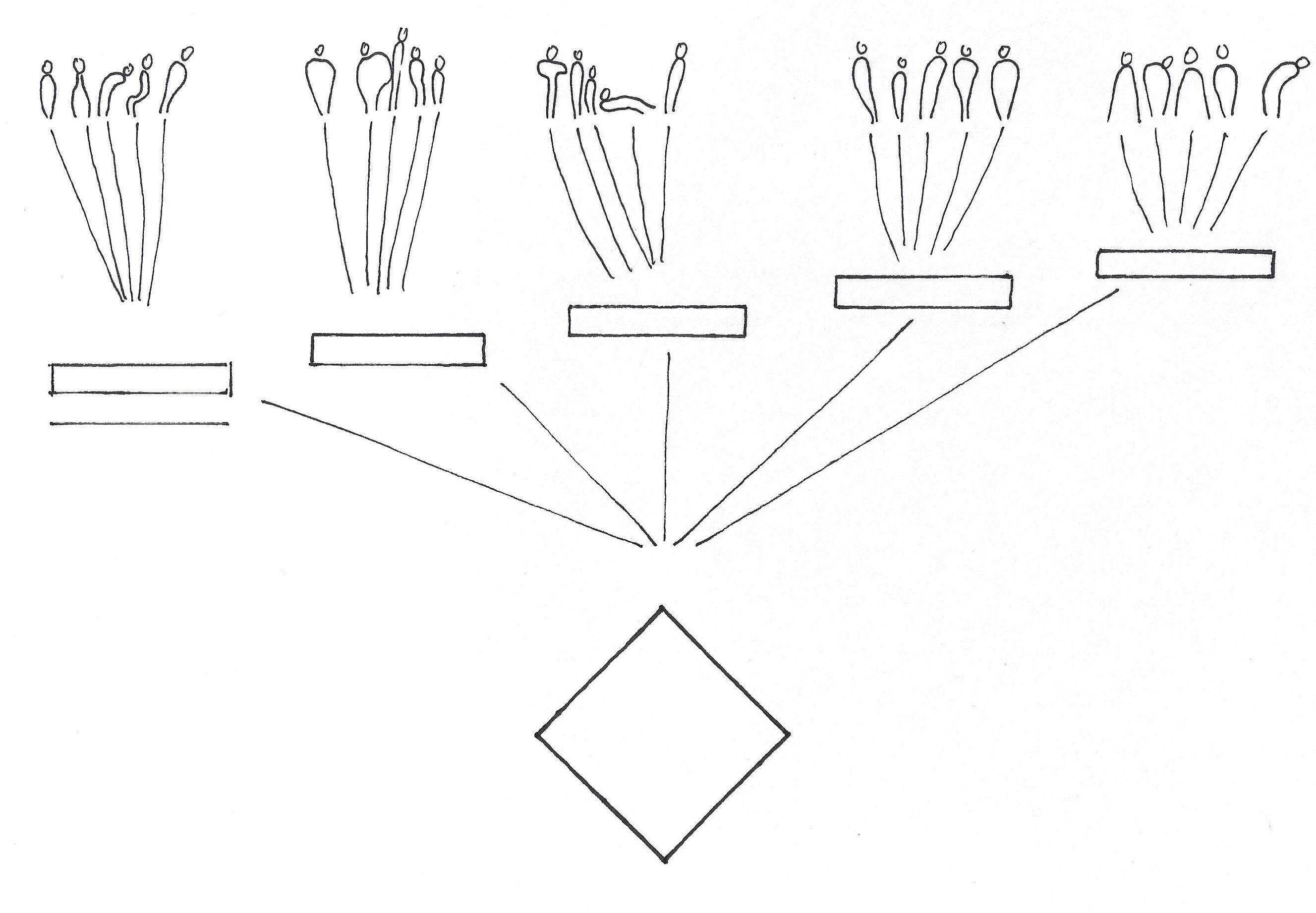

To scale the development of co-Housing in Amsterdam enough to reach the ambitions of the municipality, we need a new organization.

11/102

12/102

Part 1 · Why is housing unaffordable?

Housing = Capital Housing = Capital

Part 1 · Why is housing unaffordable?

13/102

The original sin

Privatization of land

Privatization of land began with the rise of the nation state. In England for example it happened between the 15th and 18th century. Peasants in rural areas cultivated pieces of arable land individually and cooperatively. These selions where privatized by landlords with support of the state. In a gradual process the state created a legal framework that revoked the peasants traditional rights. This model was to be the basis for a pattern of thought, and a pattern of violence that was forced upon much of the world through colonialism.

The bases for collective systems existed in much of the world, but were replaced by western legal frameworks.These collective systems have largely been forgotten, and the collections of informal rights and customs that supported them are no longer viewed as relevant in the popular imagination. This process of nationalization was accompanied by privatization and justified by a discourse on increased productivity. This efficiency, as we now know, has a massive downturn. The system that was created is inhumane to most of its workers, it creates pandemics, and the exploitation of resources is pushing the natural systems - on which we all depend - beyond many planetary boundaries. Much of this transformation is enabled and sped up by financialization:

14/102

“A crucial consequence of the transformation of land into private property was the possibility for the landowner not only to sell land as any other commodity, but also to use it as collateral for financial loans. Still today, lending money against landed property is the largest source of credit and money creation. For landlords, owning land through property titles was not just a way to extract more surplus from agricultural production, but also a way to raise capital through the use of land as a financial asset.”1

15/102

Capital

[City] The city where the central government of a country or state operates from

[Money] Wealth or property that is owned by a business or a person and can be invested or used to start a business.

[Resources] A valuable resource of a particular kind. Wealth, property and power are implied when we discuss capital today but the third definition points to a deeper, older meaning. A meaning that existed before the term was coined. Capital existed before we - homo sapiens - gave it this name and we relied on its existence before we ever had the idea to say that we own capital. We did not own the water, did not own the air, did not own the land, and did not own the other creatures that inhabited these spaces. We used them and depended on them to live. I won’t argue against ownership here. What is important is that ownership - like every other intersubjective reality - is merely an idea, a construct, and not a law of nature or a divine fact of life.

The term capital first made an appearance in medieval Latin as capitalis. It had become common by the thirteenth century and use of the word probably begun in the first chartered towns of Europe. Here it was used to signify the principal part of a loan. The second part of a loan, the “usury”, is what we now call interest. It was a payment made to the lender in return for the sum lent. The sum lent is usually expressed in an amount of money. In other words: The

16/102

noun

2

money is merely the representation of a promise. In most cases the promise to allow someone to use a certain resource. Until the industrial revolution land was the resource that was usually lent and the interest on this loan is still known as lease or leasehold today. In summary: Lease, rent, and interest are the same thing.

The interest that was paid represented the surplus that needed to be produced and it resulted in the more or less stable existence of a rentier-class. In many places this was the nobility and clergy. With the industrial revolution came another kind of rentier-class. Capitalists would buy assets and have a more financialized mindset on what these assets where. They would, as a rule of thumb, expect a return of about 5% annually. This figure was so normalized that novelists of this era would write about it as if it where a rule.

Until the industrial revolution land was the resource that was usually lent and the interest on these loans is still known as lease or leasehold today. Towards the end of the industrial revolution - with shattering empires, wars, famines, and market collapses that ensued - everything changed.

17/102

Capital today

From land to real-estate

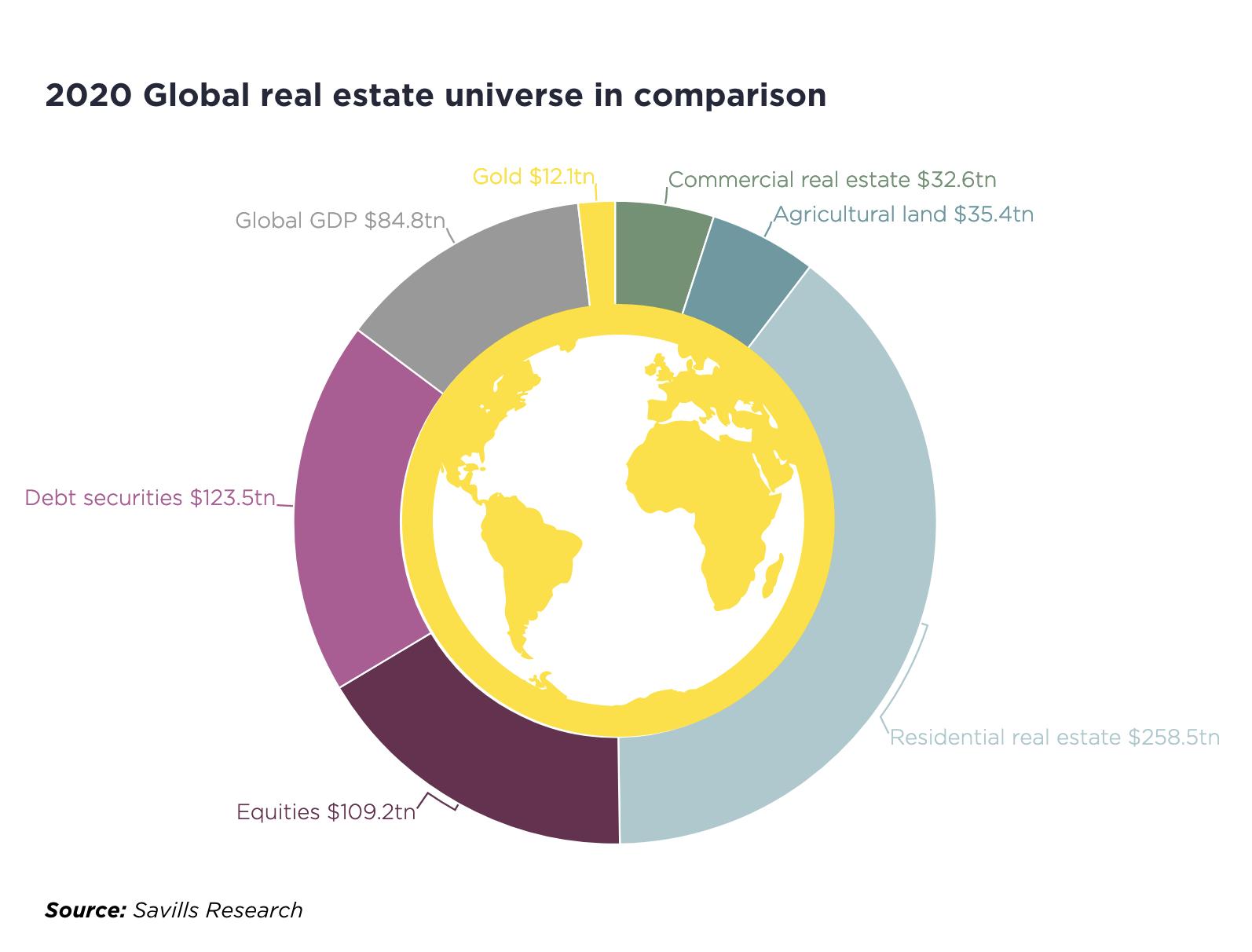

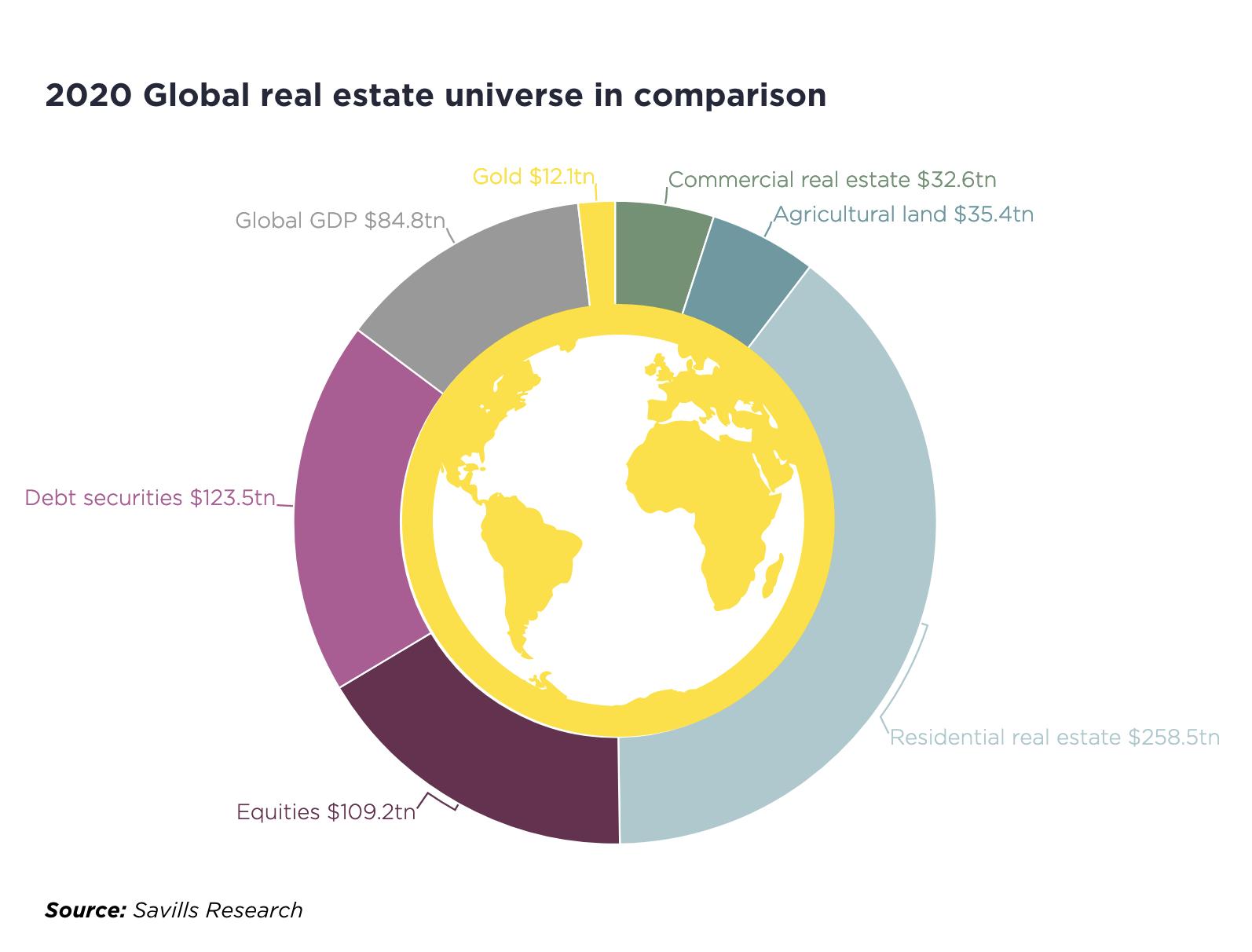

French economist Thomas Piketty has published extensively on capital, economy, and economic inequality. There is a lot that we can learn from these graphs but the key takeaway for us is what capital today actually means. Since 3 the industrial revolution there has been a complete transformation. Capital used to be almost synonymous to land but now it’s mostly housing. When we say capital today, we might as well say housing.

This is especially true for the global north and in Europe. The Netherlands has the dubious honor of having the most wealth stored in housing. In fact 60% of all capital is the primary residence of individual households. This does not even account for individuals or companies that own homes in The Netherlands solely as an investment. It is very difficult to make a comprehensive analyses of how much is owned by domestic and foreign investors and how much capital this represents.

18/102

19/102 300% 400% 500% 600% 700% 800% Figure 3.2. Capital in France, 1700-2010 Net foreign capital Other domestic capital Housing Agricultural land 0% 100% 200% 1700175017801810185018801910192019501970199020002010 National capital is worth almost 7 years of national income in France in 1910 (including 1 invested abroad). Sources and series: see piketty.pse.ens.fr/capital21c. 300% 400% 500% 600% 700% 800% Graphique 3.1. Le capital au Royaume-Uni, 1700-2010 Capital étranger net Autre capital intérieur Logements Terres agricoles 0% 100% 200% Lecture: capital national vaut environ 7 années de revenu national au Royaume-Uni en 1700 (dont 4 en Graphique 4.1. Le capital en Allemagne, 1870-2010 0% 100% 300% 400% 500% 600% 700% 800% Lecture: le capital national vaut 6,5 années de revenu national en Allemagne en 1910 (dont environ 0,5 année placée à l'étranger). Sources et séries: voir piketty.pse.ens.fr/capital21c. Valeur du capital national, en % du revenu national Capital étranger net Autre capital intérieur Logements Terres agricoles Graphique 4.9. Le capital au Canada, 1860-2010 0% 100% 200% 300% 400% 500% 600% 700% 800% 18601880190019201940196019802000 Lecture: au Canada, une partie substantielle du capital intérieur a toujours été possédé par l'étranger, et le capital national toujours été inférieur au capital intérieur. Sources et séries: voir piketty.pse.ens.fr/capital21c Valeur du capital national, en % du revenu national Dette étrangère nette Autre capital intérieur Logements Terres agricoles Graphique 4.10. Capital et esclavage aux Etats-Unis 0% 100% 200% 300% 500% 600% 700% 800% (autant que les terres) Sources et séries: voir piketty.pse.ens.fr/capital21c. Valeur du capital, en % du revenu national Capital étranger net Autre capital intérieur Logements Esclaves Terres agricoles

Housing is capital

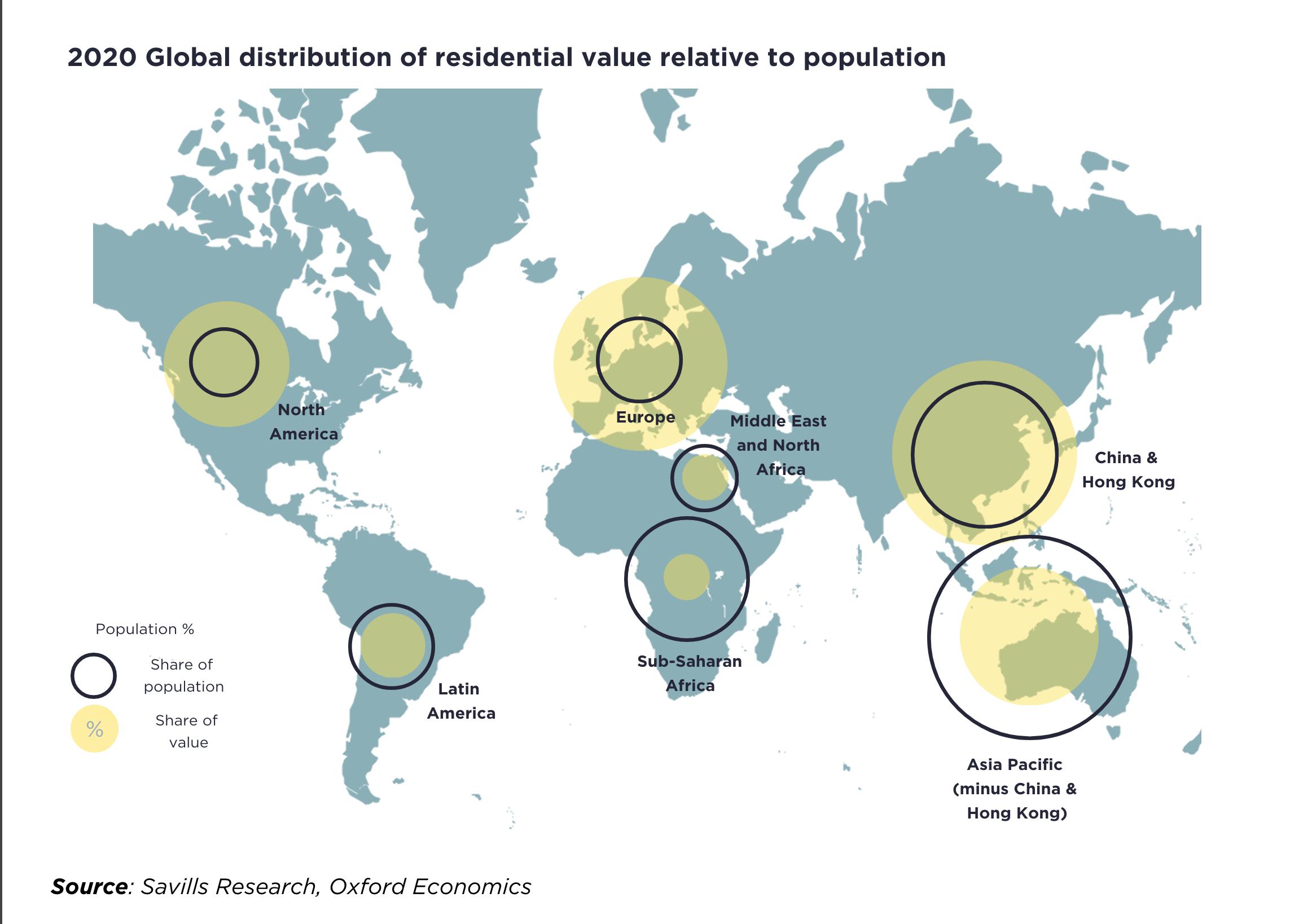

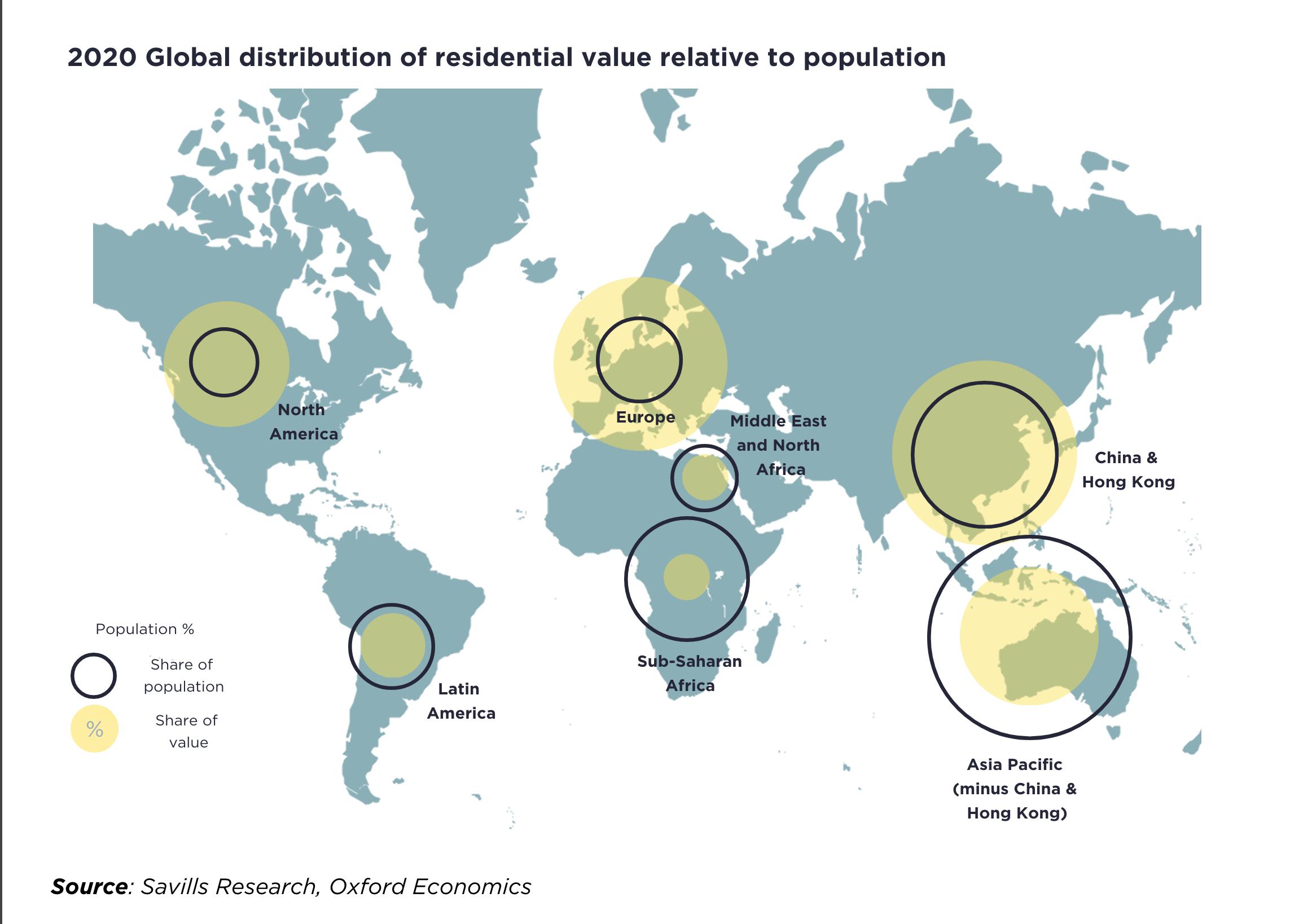

Globally around 40% of capital is housing (residential real estate). 4

A disproportional amount of residential wealth is concentrated in Europe, along with North America. Accounting for 43% of value despite being home to just 17% of the world population. In the wake of a low interest rate environment a lot of capital is looking for a both appreciation and income.

Europe has become a victim of it’s own succes and real-estate (in Europe) is viewed as a safe storage for global capital. As an asset class in western countries it accounts for as much as 70 or 80% of total capital.

For (global) investors in local housing markets the 5% rule for expected return on capital is more or less as it used to be in the belle epoque and just before. It was around this time - a little over a century ago - that people started to realize that this situation was detrimental to the stability of society and that land (housing today) was not a normal commodity.

20/102

21/102

Housing is not a commodity

The supply of housing is finite

What influences the price of housing? (if not ‘real’ supply and demand)

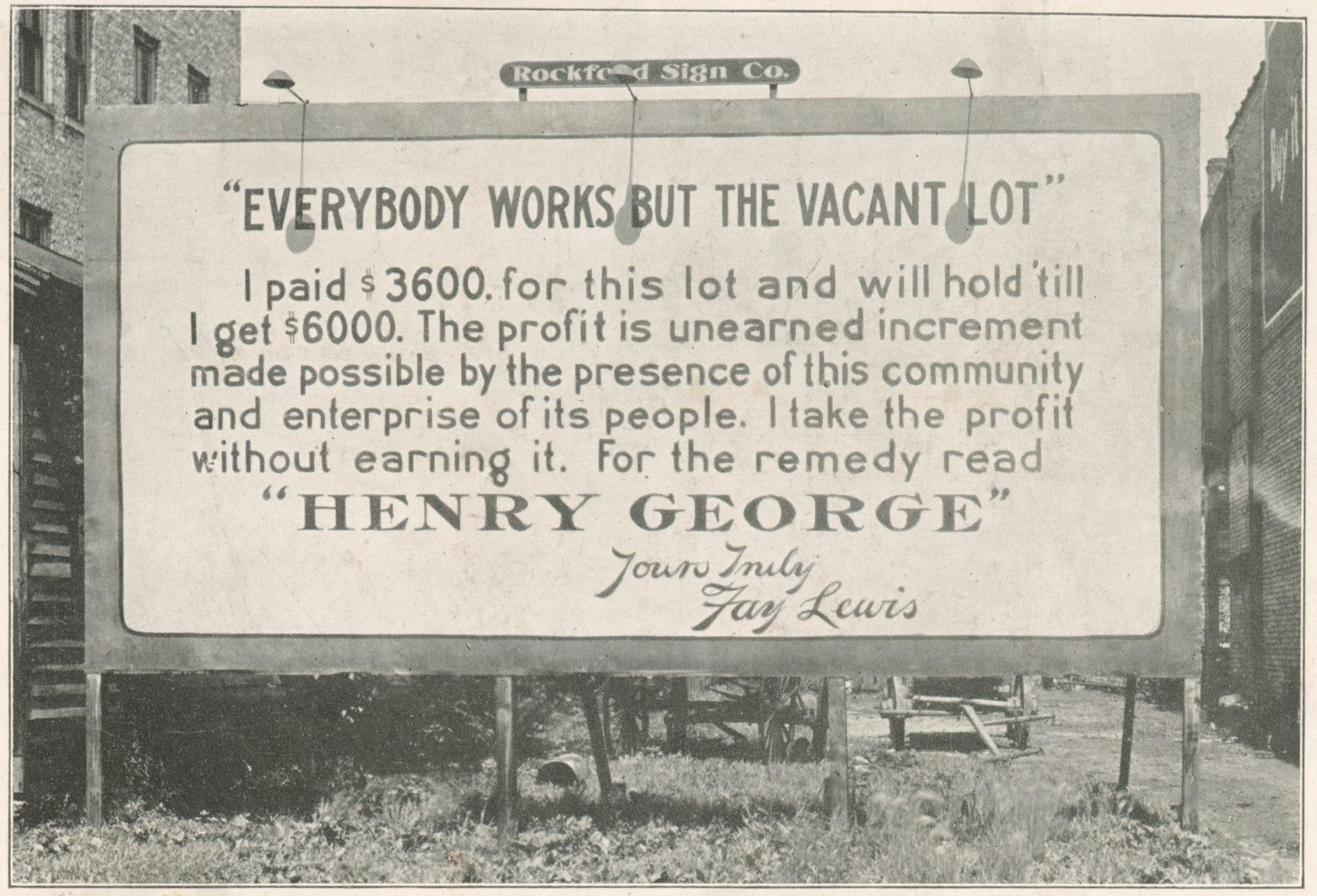

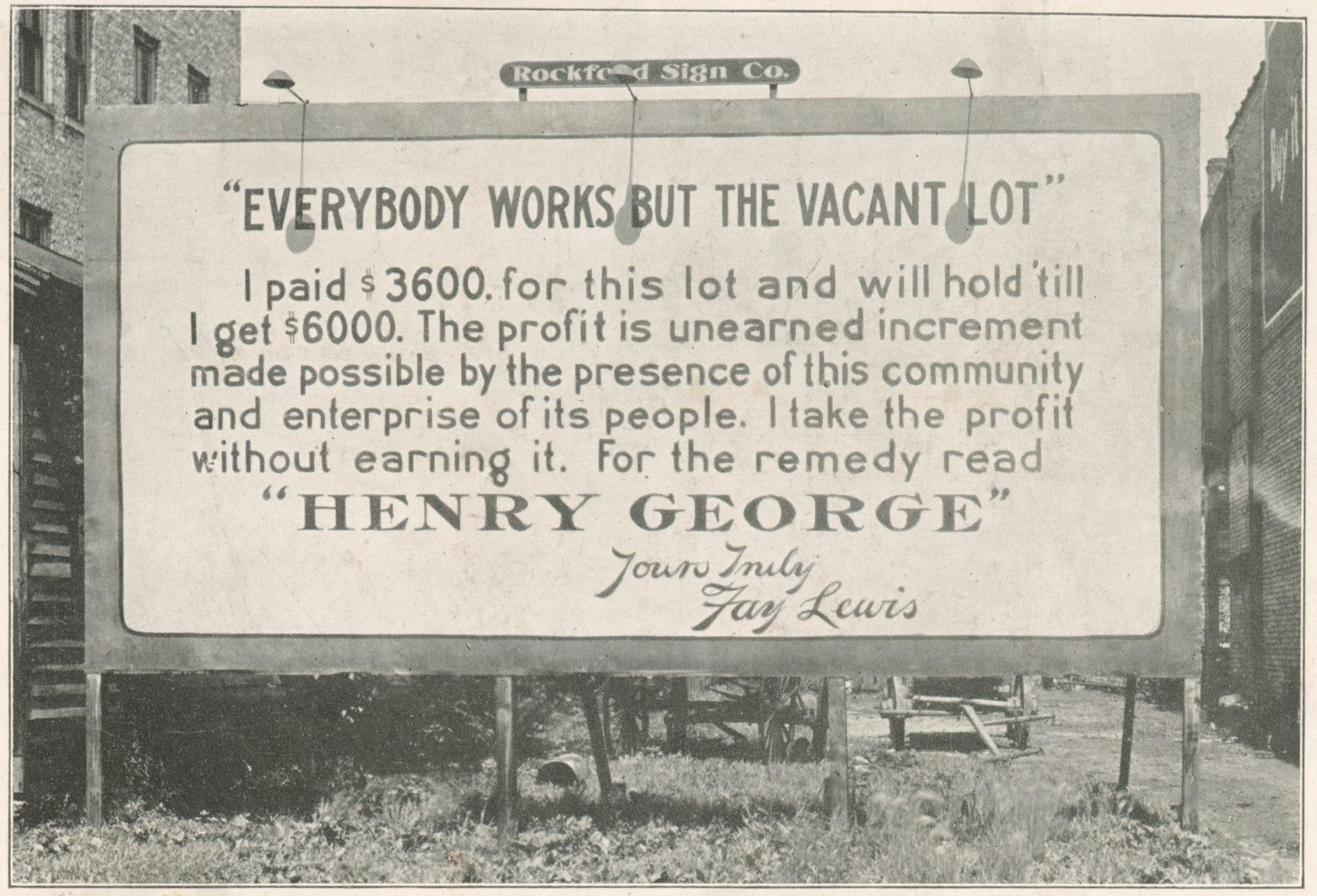

In 1914 Fay Lewis took notice of the rising financial inequality in society and came to the conclusion that there was only one culprit: Land, private ownership of land to be specific. He proposed a simple solution, taxing land. By taxing the value of land minus the investments made to improve it’s value, he pleaded for taxing the revenues on land. An idea that is proposed repeatedly by unknown and famous thinkers alike. Adam Smith was one of those proponents of taxing land and viewed it as the most efficient form of taxation. All of these thinkers knew that land was not just any commodity. In contrast to a commodity every piece of land is unique. More importantly, the supply is finite.

When we realize that housing is not a commodity it also becomes clear that the price of it should not be governed by a logic that is successfully applied to potatoes of lollipops. With this in mind, the solution to inequality seems obvious. Tax housing and the land it’s build upon. This is the easiest and most efficient tax a government can impose. After all, contrary to other forms of capital and labour, it’s not easy to move a plot or building. This may leave you wondering; Why hasn’t it been done? And: Why don’t we just do it?

22/102

This is exactly what’s happening in cities all over the world today. Today it’s not about land. Its about

where building houses is allowed.

23/102

5

Supply (of housing) is regulated by government

And bottlenecked by bureaucracy

To make things worse most western countries have a very elaborate and vast set of regulations, laws, and institutions to govern; What is build, where it is build, and how it’s build. This web is difficult to navigate even for professionals and the time of the procedures associated with each step to creating a new building is too lengthy for most people to even consider it.

Historically of course these legal frameworks make sense. The squalor and unsanitary conditions of booming industrial cities full of uneducated laborers required a set of rules to improve living conditions in te the city. These rules where meant in particular to prevent inhumane living conditions that where created in self built slums and small developments of appalling quality built by slumlords.

These laws are still in place but by now the effect they’re having is very different from what it was meant to be. The complexity of it all is causing, in effect, a monopoly for wealthy individuals that have the money and time to acquire a plot, and sit on it for years or decades. The result is arrested development and housing shortages.

24/102

While getting something build got increasingly difficult, the contrary happened on the other end. Selling or renting housing has become a matter for the market. Government has created increasingly liberal regulations and stimulated the ‘free’ market (‘free’ in brackets because a free market doesn’t stifle supply). In effect our government is bottlenecking how much is build and making building feasible only for the rich and owning class while at the same time allowing them to ask whatever price they want. It is logical that housing has become unaffordable!

The way in which housing is created has resulted in an actual shortage of housing but that by itself is not enough to drive the prices up in the way we have witnessed. What money is (or isn’t) is at least as important.

25/102

How money creation inflates housing prices

Money is debt (and private banks create most of it)

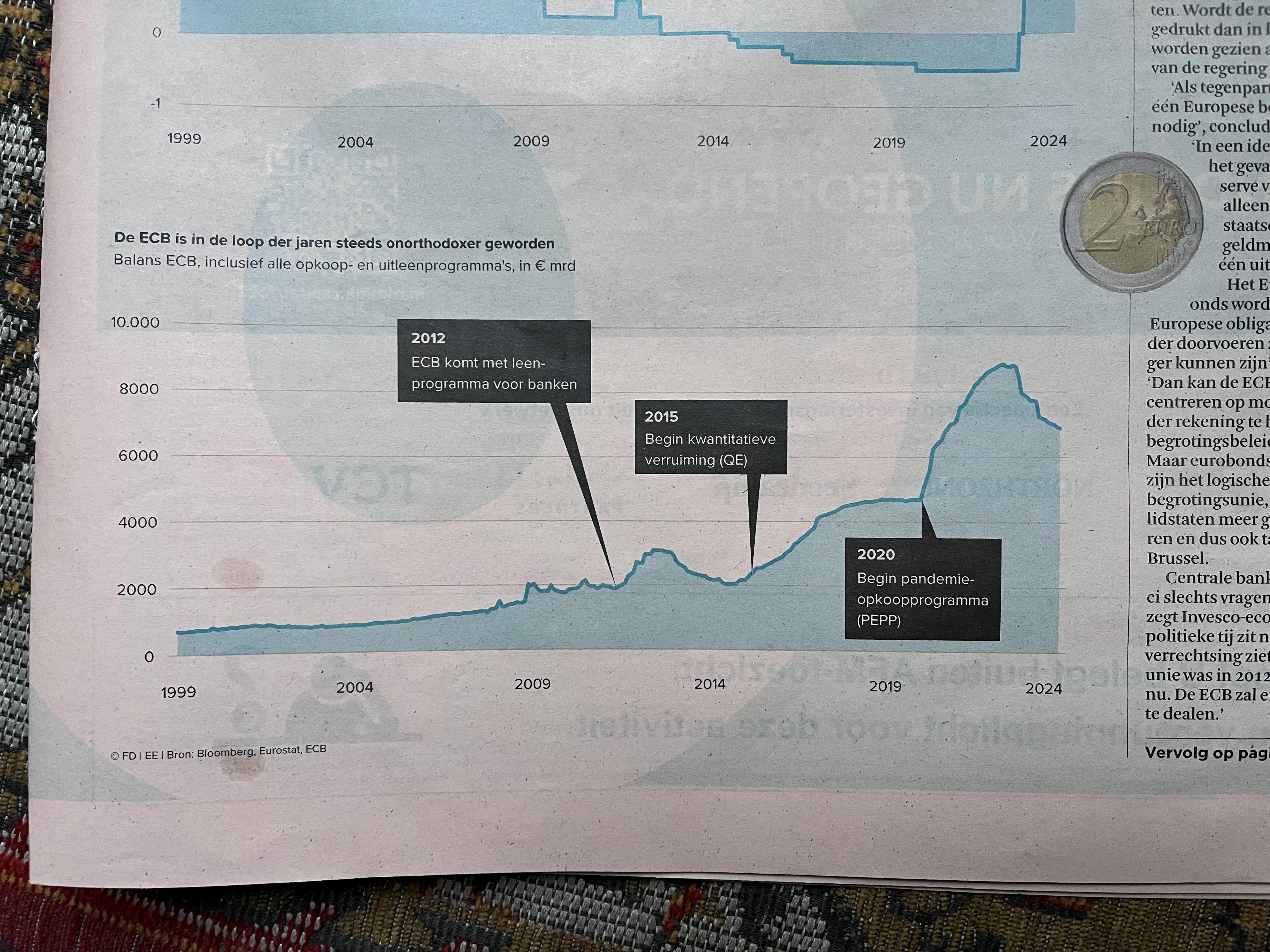

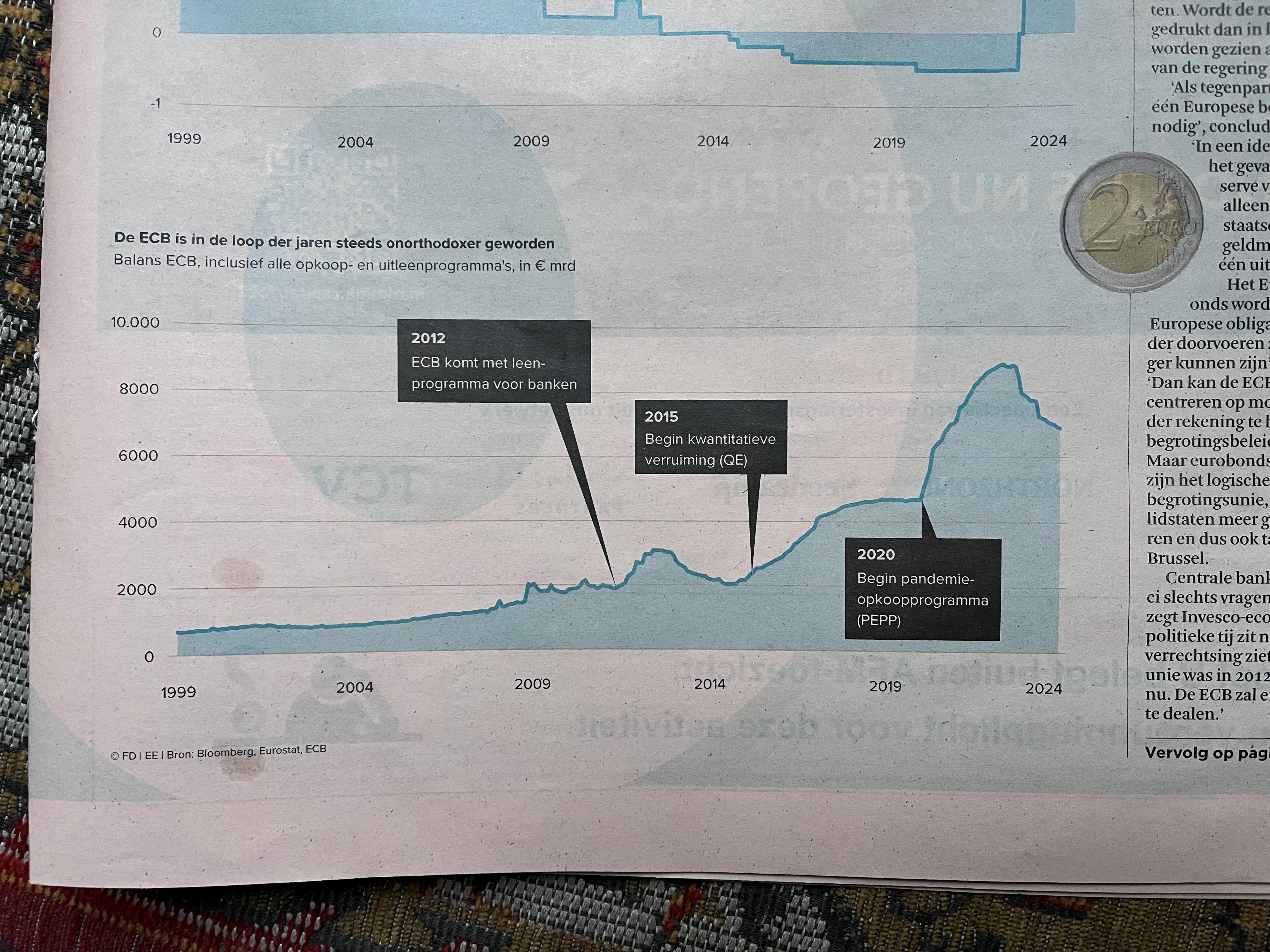

Each crises, in todays system, leads to central banks printing a lot of money. We have a crises about every 7 to 10 years but normally there is at least one mechanism that limits how much money is created: High interest rates.

Covid caused central banks all over the world to keep interest rates at around 0% for a prolonged period of time. This resulted in massive investments in housing; Money was gratis, particularly for the owning class who already had collateral. For the people with access to this newly created money, housing (in Europe) was a safe and attractive investment.

In this low to no interest environment banks started printing money like crazy. To get an idea of the magnitude if what is happening we need to look at the worlds reserve currency, the dollar: Our latest crises is the corona pandemic and Russian invasion of Ukraine. Between 2020 and 2023 the federal reserve bank printed 80% of all $ in existence. The European central bank had a similar 6 policy (quantitative easing) and printed an equally insane amount of Euro’s (graph on right).

All of this money has no place in the real economy. It is impossible to spend on actual services or products. This money goes directly into financial assets and inflates their value. Because real-estate is perceived as safe, and because it’s

26/102

not going anywhere, a lot of this newly created money goes directly into 7 housing. It is, for practical and legal reasons, impossible to create that many houses in such a short period. So this influx of money just inflates prices (a lot).

27/102

The working class can no longer afford a house

Young people in Europe spend an increasingly disproportional amount of their income on mortgage or rent

In the Netherlands for instance the median net income is €2500 monthly while 8 the government considers €1150 monthly to be middle rent and allows companies to advertise it as such while providing subsidies and immaterial support to the creation of this category of rental apartments. This is obviously insane and disproportionate. If spending half your income on housing is a step in the good direction just imagine what many are spending now.

Capital and the growth of capital necessitates returns on investment. As is clear by now, that means financial returns on investments in housing. The returns on these investments must be produced, they are the surplus produced by a working-class.

This surplus is transferred through mortgage or rent. Many people view these transactions as a force of nature. But they are only possible when the state, with its monopoly on violence, enforces ownership. In effect rent and the interest paid on mortgages are the means by which wealth created by the working class is transferred to the rentier class.

28/102

We see this excess mostly in cities with plenty of opportunity for expats and young professionals but the prices tend to spill over to the surrounding areas and well connected urban centers further away.

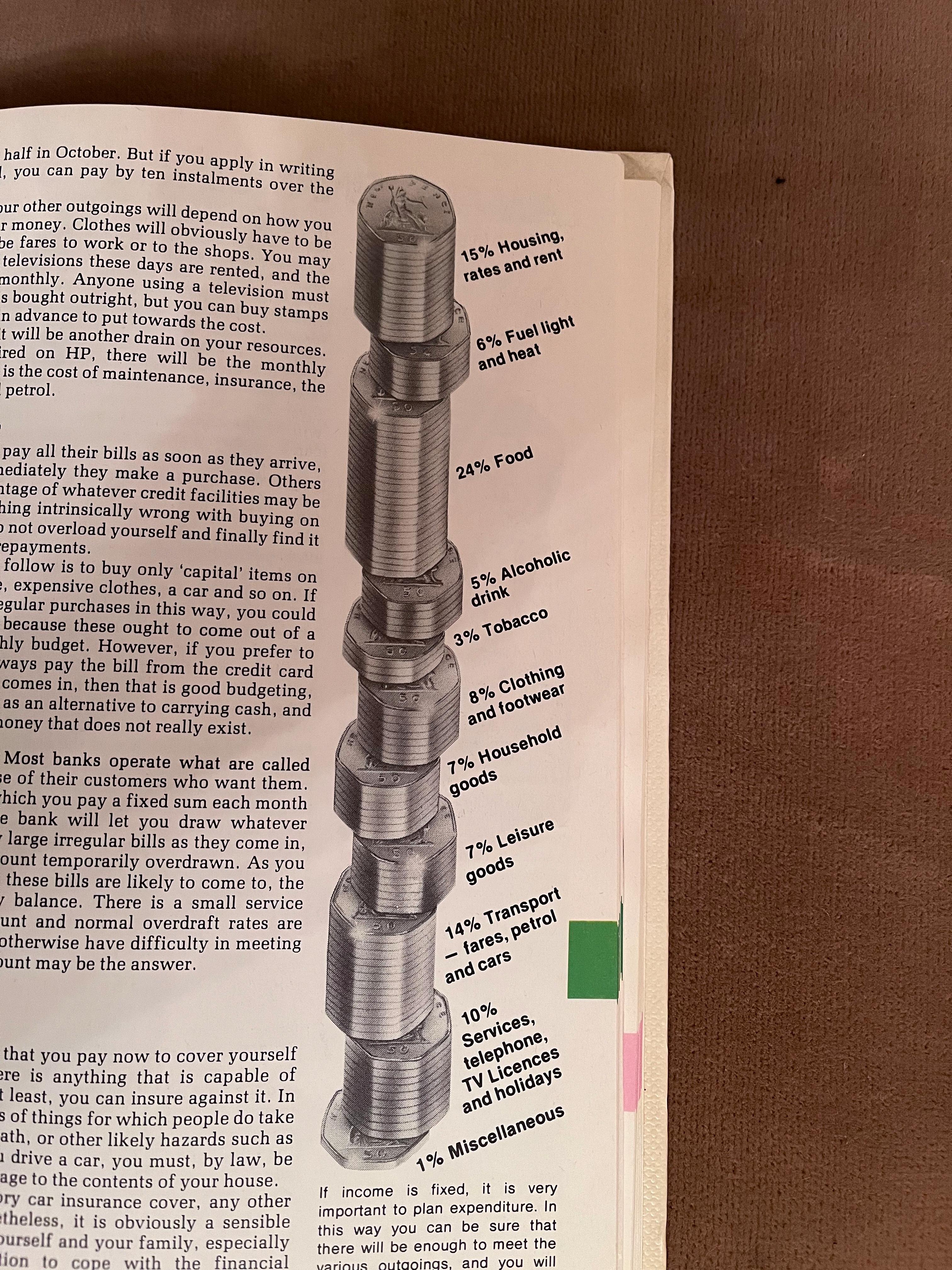

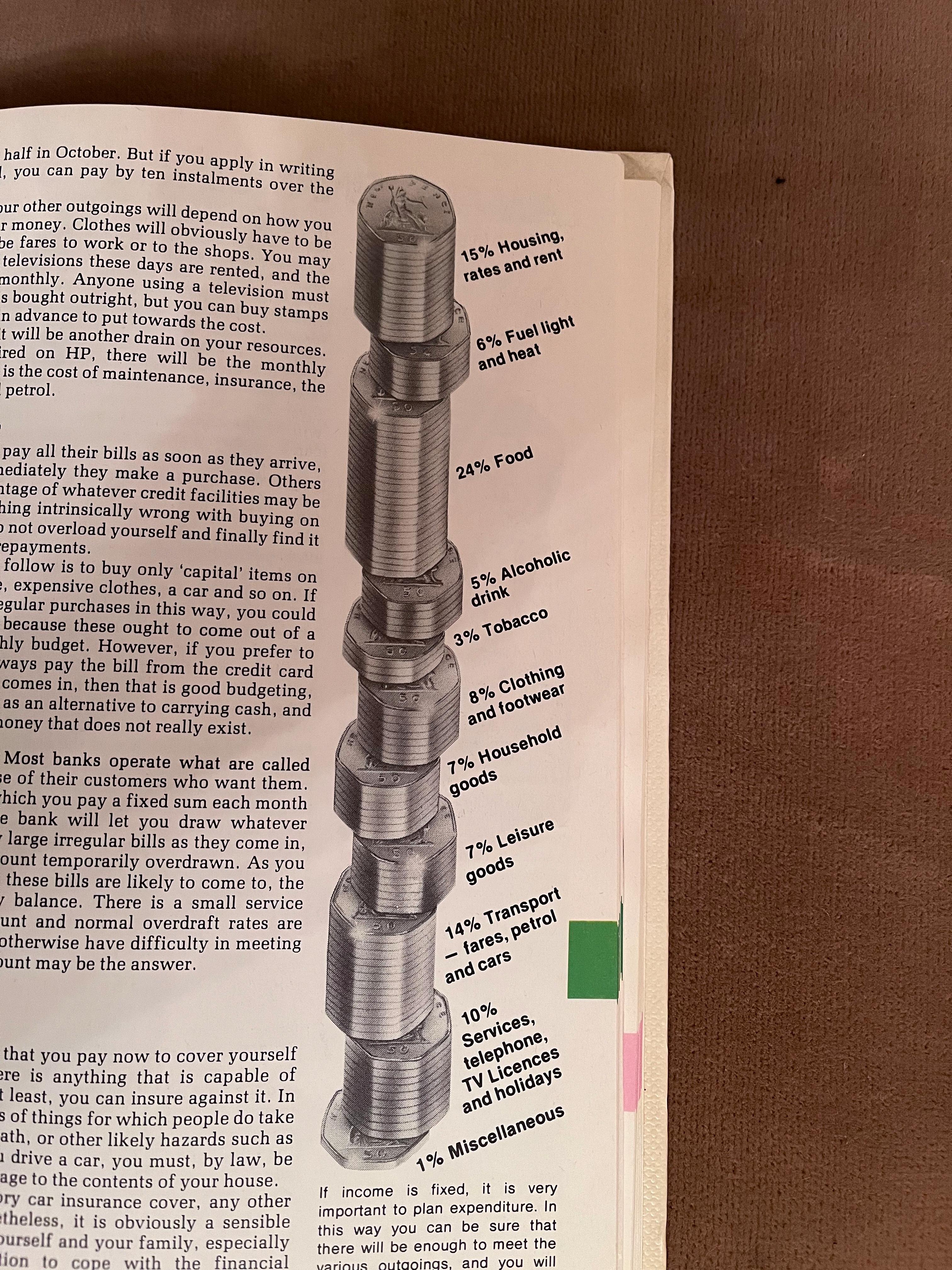

In the 1980s it was considered normal to 9 spend about 15% of income on housing rates and rent. Now it is not unusual to spend over 50% on the same.

The working class can no longer afford a house in the city. This is very problematic because a city depends on the people that keep it going.

What would a city be without the working class?

29/102

History repeats

A case study: How Amsterdam found solutions (and forgot what they solved).

The appreciation of land in a city is largely caused by the community that lives and works in that city, agglomeration effects, and municipal investments in the construction and maintenance of infrastructure and public space.

In 1896 the municipality of Amsterdam introduced a leasehold system10 (erfpachtstelsel) on ground that was ready for construction. Land was no longer sold but rented out with long term contracts and the rent due was given a word: canon. The main reasons for switching to leasehold were 3 fold:

· Preventing speculation with buildable land.

· Increasing the municipal influence on the use of the land.

· The increase in value of the land benefits the community.

A benefit to people who initiated projects was that they didn’t have to finance an initial investment of buying the ground. The creation of this form of leasehold was accompanied by tax-laws that allowed payments on this specific form of rent, the canon, to go untaxed. The system allowed the community to benefit on the long-term and encouraged development on the short-term.

In 2007 the city of Amsterdam owned about 80% of its land and a large portion of that land was leased under a contract that gives users and investors security about their future rights while periodically adjusting the amount that is paid to

30/102

the municipality for inflation. In 2017 the city of Amsterdam changed tack. It listened to entrepreneurs and homeowners who did not like the bill they received when their new canon was calculated.

Under the new system people can simply pay for their leasehold upfront and forever. This step undoes 1/3 of over a century of proven policy and is undoubtedly the first step in undoing this wisdom entirely. After all why would we need an extra spatial planning instrument on top of zoning plans? This merely complicates things and hampers development (by private enterprise).

31/102

The solution is NOT more private enterprise

More privatization is often presented as a solution to the problems privatization is causing.

While the city of Amsterdam is breaking down it’s policies that help ensuring the cities succes on the long-term, smart business owners are proposing this very model. Invest in the future and capitalize on that future when it is there. They do however propose one vital difference: The proceeds of the appreciation of land don’t flow back to benefit the community through government. They flow into the pocket of a shareholder, who then decides what is best for the community. This is already happening in many places. These tests with privatizing public space are dwarfed by the ambitions of some entrepreneurs.

Marc Lore for example, a former ceo of Walmart, is working on an idea called Telosa. This future city aims to be ‘the most sustainable city in the world’ and is rendered as a green oasis full of water in the middle of a generic desert. After reading Progress and Poverty, the 1879 manifesto by Henry George, Marc became a proponent for the idea of creating a land trust. He proposes that this private foundation mimics the way startups pay their employees and he says ‘he’s planning the city much in the way he’d launch a business’ Marc makes 11 no secret of the fact that he thinks government would more or less squander any income and value created by this city. Alongside this privately run

32/102

endowment, the city of Telosa is supposed to have some sort of participatory governance. What that means is unclear. Marc must have merely scanned Progress and Poverty and conveniently missed the essence. As Henry George put it: We must make land common property.12

Fortunately there are those who did catch the essence and we are witness to the creation of community land trusts. Instances where the land is owned by those that depend upon it and who give it economical value.

33/102

What happens when solutions are privatized

Profit or surplus becomes the goal: Prices always go up!

Prices always go up and what is worse: Any cost is externalized at the first opportunity that arises. From a business perspective focussing on short and medium term revenue makes sense. For humanity not so much. Allowing housing to become a business and the main component of accumulating surplus value has a few horrific consequences on the long term.

The social consequences of the way we organise housing are multiple and complex. Affordability, or rather, the lack of affordable housing is pervasive throughout the world and history. It might be surprising that the author of this publication doesn’t live in Lagos or India but in The Netherlands. Even in countries that have tackled this very problem before it is (again) at the top of peoples minds. We will often refer to Amsterdam because it is familiar territory for me. And in Amsterdam there is a legacy of dealing with this issue, a fabric of laws and institutions that solved this very issue about a century ago. But, people forget….. Today, The Netherlands is a country, and Amsterdam is a city, where a large number of people have no-where to live. That doesn’t always mean you’ll find them under a bridge. Some of them are 25 or 30 and still live with their parents, move from sofa to sofa, or live in a place where they don’t want to live, like a shortstay hotel. These are shitty circumstances where the

34/102

basic needs (not to mention human rights) of people aren’t met. The size of this group is unclear because they’re not registered as being homeless . 13 Imagine being in this situation and noticing that refugees are getting a house while you’re not. There is no place for you but there is for them, in your own country….. It’s easy to end up with nationalism, and there starts the slippery slope to fascist ideology. Superficial reasoning can easily lead us to finding an ‘other’ and blaming them for what we don’t understand. Add to this the emptiness that many people feel in an individualistic, secular society where consuming is the common way of expressing identity, and it becomes clear that something needs to change.

The economical consequences of the way we organise housing are as difficult to quantify as the social and ecological consequences. Within Europe, The Netherlands is referred to as the champion of part-timing. Viewed through a feminist lens it’s old fashioned and bad for women because they’re usually the ones part-timing when they have children. I would argue the reason for working less in The Netherlands is simple: Working more means getting punished! On one or two median salaries it’s impossible to buy a house. It’s often even impossible to rent on the ‘market’ because the earnings requirements are too high (3 or 4 times the rent). The only solution for many people is social housing. And to get into that…. You can’t make much money. The result being, people simply work less. I haven’t found any up to date numbers on what this effect costs the economy, but my thesis is that it’s huge.

35/102

The ecological consequences of the way we organise housing can be seen in this picture of Max van Noorden surfing on the highway in 1995. It can tell us a lot about what’s wrong with the way we organise housing. Especially in relation to work.

39% of global CO2 emissions is the result of the building industry and building operations . Another 23% is caused by transportation and while this picture is 14 iconic precisely because there are no cars, most people have no other way to get to work.

What we build and where we build is responsible for almost 2/3 of our CO2 emissions and the vast majority of our buildings are houses. We have to 15 reconsider how we organise housing, who we are building for, where we build, what we build, and the materials we use.

36/102

37/102

Property rights versus housing rights

Private property is sacrosanct. Housing rights are not.

All institutions in (post) colonial societies are geared towards one goal: The protection of private property. In the Netherlands for instance this translates into fines for picking mushrooms on publicly owned land. In many states in USA you’re allowed to shoot people trespassing on your property. Even if they’re just there for mushrooms.

Often a violation of private property is punished more readily than killing a fellow human. This order of things makes sense for societies that thrived on disowning other peoples and declaring ownership over their sources of sustenance and welfare. Those sources include their bodies, their labor, andeven until today - their lands.

The ferocity of the systems in place persists. States enforce this property rights with violence. While many (post) colonial societies have written down other basic rights among which is the right to housing, the right to housing is not treated as sacrosanct. Especially when opposed by the right of private property. What we need is a complete paradigm shift. A change of the structures of ownership and the financial models that underpin how we develop cities.

38/102

If our laws and institutions begin to see housing and where it’s build as a common resource we’ll see a paradigm shift towards a more just, inclusive, and equitable society.

If everyone that doesn’t have a house would have one, the financial pressure on society would decrease substantially. Not just because of the cost of collecting debt (in The Netherlands it costs 17bjn to solve 3,5bjn in uncollectible debt16). But all the other costs that are incurred to society when we fail to assist the homeless and the hopeless (people that struggle to pay for housing). This includes medical support, child support, mental support, and policing.

39/102

We need to talk about ownership

That means legal ownership. Not pseudo ownership, participation or community building.

When it comes to housing, addressing ownership is crucial for creating longterm stability and security. While participation and community building are important, they are not enough on their own to address the underlying issues of housing insecurity and inequality.

Pseudo-ownership, such as renting, leasing, or mortgaging may provide some short-term benefits, but it does not provide the same level of security and control as true ownership. Without ownership, residents have little control over the long-term maintenance and management of their homes, and they are vulnerable to rising cost and gentrification.

Community building and participation are important for creating a sense of belonging and connection, but they cannot solve the structural issues of housing inequality on their own. Only by addressing ownership can we ensure that residents have the power and control to shape their own communities and protect their homes from the whims of the market.

In short, ownership is essential for creating stable and secure housing, and should be the primary focus of efforts to address the housing crisis.

40/102

41/102

Promised Land: Housing from Commodification to Cooperation (accessed November 29th 2022) 1

Pier Vittorio Aureli, Leonard Ma, Mariapaola Michelotto, Martino Tattara, and Tuomas Toivonen

3

2 http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/capital21c/pdf/

Oxford Advanced American Dictionary (accessed July 29th 2022)

4

Savills & oxford economics (accessed November 29th 2022)

Fay Lewis, 1914, Rockford, Illinois

5 https://techstartups.com/2021/12/18/80-us-dollars-existence-printed-january-2020-october-2021/ 6

7 CBS (accessed 30 November 2022)

statista.com - Oswald M. 97% Owned: How is money created, 2012, Queuepolitely

8 Neil Tennant, The dairy book of home management 1980, Milk marketing board, UK 9

Ontwikkelbedrijf Gemeente Amsterdam, 111 jaar erfpacht Amsterdam, 2007

The Diapers.com Guy Wants to Build a Utopian Megalopolis. 01-09-2022. https://cityoftelosa.com/

2021/09/01/the-diapers-com-guy-wants-to-build-a-utopian-megalopolis/ (Accessed 2022-30-12)

Henry George, 1879, San Fransisco, Progress and Poverty, Book VI The Remedy, Sixth Printing, p328

Bergsma, R. Reedijk, N. Craats, J. 10 spoedzoekers aan het woord. 19-06-2018. platform 31

Global alliance for building and construction, 2019 global status report for buildings and 14 construction, 2019, UN environment programme

15

Schlanger, Z. Construction Causes Major Pollution. 20-08-2020. huffpost.com

jaarlijks ongeveer 17 miljard euro uitgegeven aan het oplossen van schulden. Dat is veel méér dan

de daadwerkelijke waarde van alle schulden bij elkaar namelijk zo'n 3,5 Miljard

42/102

10

11

12

13

16

43/102

housing

Re-imagining ownership Reimagining ownership

· Part 2 · How do we make

affordable?

Part 2 · How do we make housing affordable?

Ownership, a coin with two three sides

(Post) colonial societies have a very narrow, limited, and dogmatic understanding of how we can manage resources.

The coin is the perfect representation for this narrow view of what capital means. It’s perceived to have only two sides, socialism and liberalism.

Socialism and liberalism are political and economic ideologies that have different perspectives on how to organize and manage resources and power in society. However, both of these ideologies can be understood as based on the centralization of surplus value and power in certain groups or institutions.

In a socialist system, the goal is typically to eliminate or drastically reduce the role of private ownership of the means of production, such as factories and land, and to replace it with collective ownership by workers or the state. This is based on the belief that capitalist systems result in the exploitation of workers and that the value created by labor should be distributed more fairly.

However, in practice, socialist systems have often centralized economic and political power in the state or ruling party, which can lead to the concentration of surplus value and power in a small group of individuals or institutions. This can lead to the same kinds of exploitation and inequality that socialist systems are meant to prevent.

44/102

Similarly, liberalism is based on the idea that individuals should have the freedom to pursue their own interests and accumulate wealth through private enterprise. This can result in the centralization of economic and political power in wealthy individuals or corporations (owned by wealthy individuals) who control a disproportionate share of resources and influence in society.

In both cases, the concentration of surplus value and power can lead to the marginalization of certain groups in society and limit their ability to participate in political and economic decision-making. There are also ‘groups’ that are not even considered to be a part of society. Animals, plants and other species are entirely outside the scope of liberal and socialist idealisms but fundamental to the existence of our species.

Therefore, it is important to consider alternative political and economic systems, that prioritize the distribution of ownership, and management of resources and decision-making power, in order to promote a more equitable, just, and sustainable (in the sense of surviving on the long term) society.

45/102

Capital Liberal

Most Dutch citizens have only this dichotomy as perspective on the ownership of capital But, market/state or liberal/socialist are two sides of the same coin: Concentration of capital and power

Socialist

Commons

Every ideology claims realism

“Just as communism, fascism, or neoliberalism, commonism is an aesthetic of the real. It is a belief, a make-believe that claims realism. At least it claims to stand closer to our contemporary ecological and social reality than capitalism. But is is also closer to how social relationships really function, and much closer to what humanity in general is about.”17

Commonism is a political and economic ideology that emphasizes the collective ownership and management of resources, particularly those that are considered part of the "commons" such as air, water, land, and natural resources. In a commonist system, these resources are viewed as belonging to all members of society and are managed collectively for the benefit of all, rather than being controlled and exploited by centralized interests.

One of the key principles of commonism is that the management of the commons should be guided by a decision-making processes that ensures the participation and input of all members of society. This includes developing and implementing policies and regulations that protect the commons and promote sustainable use of resources.

In terms of managing capital, commonism aims to promote economic activity that is sustainable, equitable, and benefits all members of society. This can be

46/102

Commons

Burgerij, gemeengoed, of het volk.

Het idee van de commons wordt in veel sectoren hervonden als alternatief organisatie model. Tegelijk is het nog vrij onbekend en heeft het geen herkenbaar gezicht.

Dat is niet gek als je bedenkt dat het juist om het spreiden van macht gaat. Paradoxaal genoeg is het ontbreken van een symbool misschien ook wel waarom het zich moeilijk verspreid.

achieved by encouraging the use of cooperatives, mutual aid networks, and other forms of collective ownership and management that prioritize the needs of the community over individual profit.

In contrast to liberalism and capitalism, which often prioritize private property rights and individual profit over the needs of society as a whole, commonism emphasizes the importance of shared ownership and collective decision-making in the management of resources and the promotion of social and economic well-being. In contrast to both socialism and liberalism it is a system that decentralizes power and property.

Wikipedia comes close to what what commonism is and digital technologies seem to hold a significant promise for processes of collective decision making. Unfortunately this potential Is often hijacked by government (in some countries) or private interests (in other countries).

47/102

B O u W en & e IG en DOM B O u W en & e IG en DOM 18

Socialism, liberalism, commonism

Balance

The course of the past century has largely been defined by liberalism The most elaborate (and diverse) counter-narrative is socialism. These dominant isms have always coexisted with other isms. One such is commonism.

Each of these ideologies has different strengths and weaknesses and can contribute to a more just and equitable society in different ways. Socialism, liberalism, and commonism are all political and economic ideologies that can play a role in shaping and organizing society in different ways. In fact it would be erroneous to assume that there is only one system in place. While liberalists would like to believe that only activities that are reimbursed with money have value, this is far from how society works. Reproductive labor is just one clear example of this fallacy.

Socialism, for example, can play an important role in promoting economic and social equality. By eliminating private ownership of the means of production and prioritizing collective ownership and decision-making, socialist systems aim to create a more egalitarian society in which resources are distributed more fairly. However, as I mentioned earlier, socialist systems can also be prone to

48/102

centralizing power and resources in the state, which can lead to its own set of problems.

Liberalism, on the other hand, can play a role in promoting individual freedoms and autonomy. By prioritizing private property rights and individual freedom, liberal systems can allow individuals to pursue their own interests and accumulate wealth through entrepreneurship and innovation. However, liberalism can also result in the concentration of economic and political power in a small group of individuals or institutions, leading to inequality and marginalization.

Commonism, is an ideology that emphasizes collective ownership and decision-making. It can play a role in promoting sustainable and equitable use of resources. By prioritizing the commons and promoting democratic decisionmaking in the management of resources, commonist systems can help ensure that resources are used in the best interest of society as a whole, rather than being concentrated in the hands of a few.

Overall, each of these ideologies has something to offer in terms of promoting a more just and equitable society. By drawing on the strengths of each and addressing their weaknesses, we can work towards creating a more sustainable and equitable society.

49/102

Selection and scope

Doing justice to the range of cooperative developments around the world and throughout history is a nigh impossible project. This selection is meant tot be both small enough to encourage discovering them in depth and broad enough to showcase a large range of possibilities. At the same time it is meant to give some insight into the history and possible futures for cooperative development.

Sources

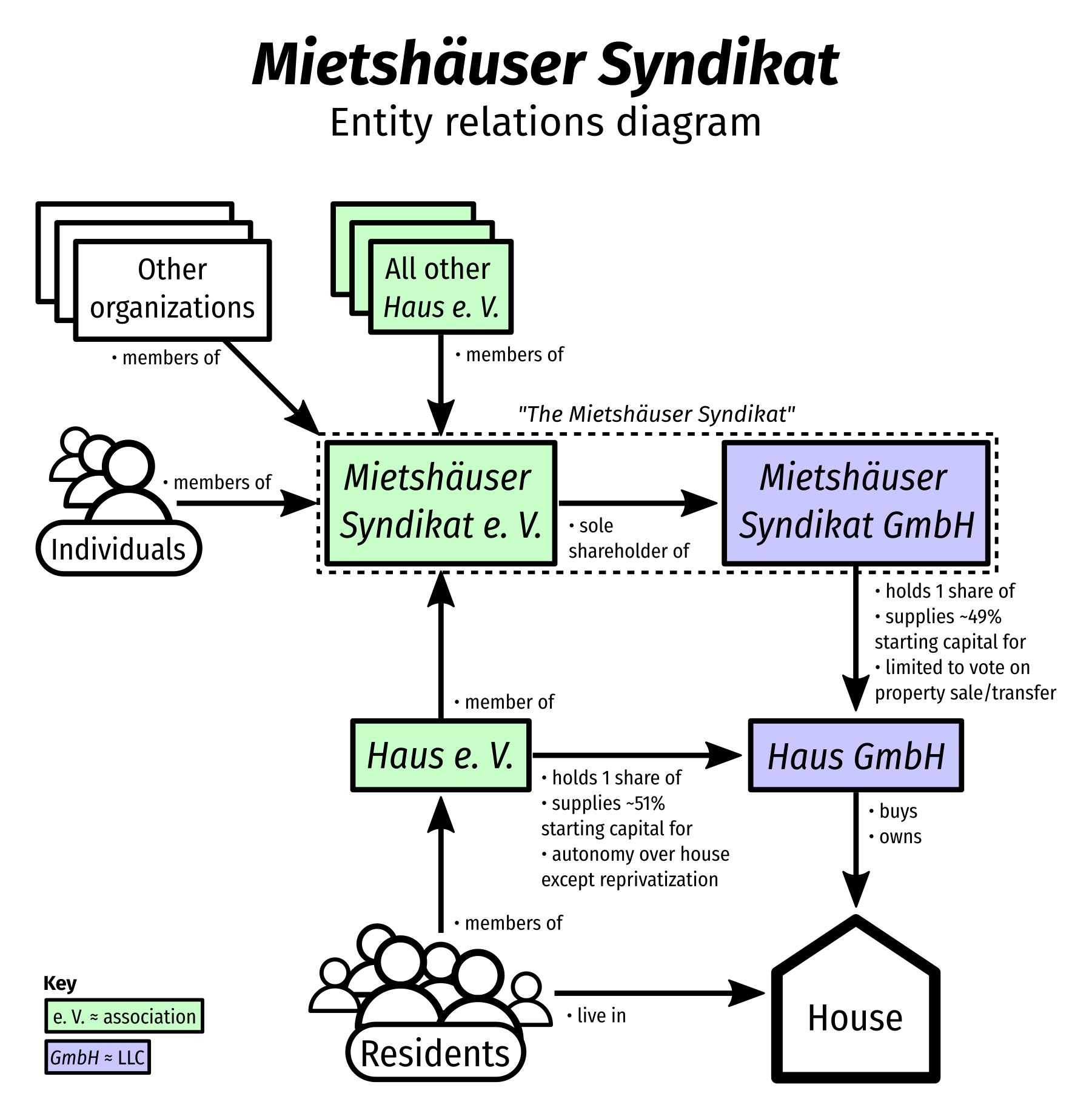

(Housing) Cooperatives

Commons in housing

Some texts are written to illustrate the development of cooperative dwelling. Others are translations of publications by and about the organizations. These texts have been curated and put together to give a broad view of the ideals, complexities, realities and stages in the development of cooperative dwellings.

When it comes to housing, the commons is not a new form of economic and social organization. Cooperatives have been an established type of organization throughout history and in many countries. Well known as a contemporary example is Zurich.

Bouwmaatschappij tot verkrijgen van eigen woningen (de Key)

National capital in relation to national income

Historic development for western countries

· Other domestic capital

· Housing Agricultural land

Bouwmaatschappij tot verkrijgen van eigen woning. Now known as Lieven de Key

Hundreds of similar initiatives in the Netherlands and many more abroad

50/102

1780 1810 1850 1880 1910 1920 1950 Source: Capital in France · Piketty · Piketty.pse.ens.fr/capital21c

18 Reference projects

700% 600% 500% 400% 300% 200% 100% 0% Value of national capital (% natinal income)

Sargfabrik

Sargfabrik

Sargfabrik

Cooperations In

Cooperations the and abroad

Cooperations In the Netherlands and abroad

The Swiss housing sector offers market-rental and private-ownership. But, in addition to these forms of ownership, housing cooperatives play an important role and are so well established that they display a broad variety in typology, size, and ideology.

La Borda

La

La Borda

Kalkbreite

Housing cooperatives emerged around the 1850s and resurfaced whenever and wherever both government and market failed to deliver suitable and affordable housing.

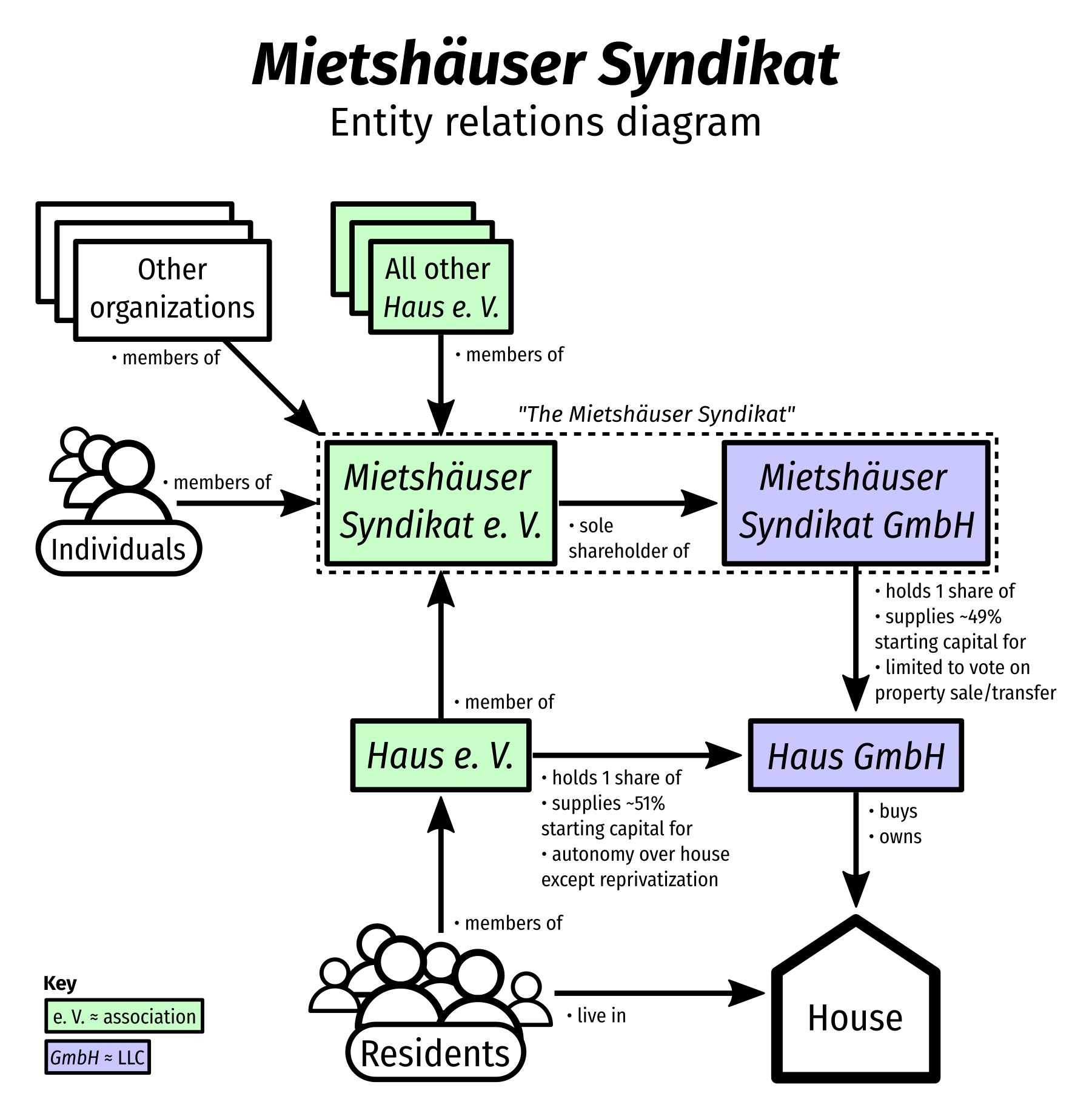

Mietshäuser Syndikat Paul

Mietshäuser Syndikat Paul

Mietshäuser Syndikat Paul

Kalkbreite De Warren

The Dagenham Breach Housing Co-Operative

The Dagenham Housing

The Dagenham Breach Housing Co-Operative

Kalkbreite, Zurich

De Warren

De Warren

Urban village project

Urban village project

Urban village

Following the 2008 recession the largest asset management corporation in the world (blackstone) entered the real estate market.

Following the 2008 recession the largest asset management corporation in the world (blackstone) entered the real estate market.

Others followed suit. The effect of this is not accounted for in the graph

2008 recession the largest management corporation the real estate market. Others followed of this is not accounted for graph

Others followed suit. The effect of this is not accounted for in the graph

51/102

1970 1990 2000 2010 19

Clairmont Strasse

2010

Clairmont Strasse

1970 1990 2000 2010 19

Clairmont

Strasse

On shared ownership and governance

Eight principles for managing a commons.

The commons have been managed successfully for a long time. That is before the age of modern empires. Their hegemony means that we have largely forgotten how to manage a commons.

Luckily some people have been studying this phenomenon and Elenor Ostrom is an eminent thinker in this field. One of her projects describes 8 Principles for Managing a Commons:18

1. Define clear group boundaries.

2. Match rules governing use of common goods to local needs and conditions.

3. Ensure that those affected by the rules can participate in modifying the rules.

4. Make sure the rule-making rights of community members are respected by outside authorities.

5. Develop a system, carried out by community members, for monitoring members’ behavior.

6. Use graduated sanctions for rule violators.

7. Provide accessible, low-cost means for dispute resolution.

8. Build responsibility for governing the common resource in nested tiers from the lowest level up to the entire interconnected system.

52/102

53/102

Existing structures in Europe

Examples of countries and cities where cooperatives are institutionalized and have a long history are abundant in Europe.

Housing cooperatives are relatively unknown in The Netherlands. This is surprising because on average, 10% of Europeans live in housing cooperatives. Overall, the key lessons from a study by CECONDHAS (their name alone 19 makes the topic unsexy) of countries with a lot of co-operative housing suggest that co-operative housing can provide an effective and sustainable housing solution at scale.

For the Netherlands the involvement of residents is something people are not used to. If co-housing ever becomes institutionalized in the Netherlands there are a lot of things to be learned from countries that haven’t lost this tradition and form of housing.

Key takeaways, and potential pitfalls, from the CECONDHAS study are:

Governance and management

Co-operative housing requires a high level of resident involvement in governance and management, which can be challenging to achieve in larger co-operatives. Co-operatives may struggle with decision-making, conflict resolution, and accountability.

54/102

Access to finance

Co-operative housing in The Netherlands faces difficulties in securing financing for new developments or renovations. This can make it difficult for cooperatives to be created and expanded to provide housing for more people.

Legal frameworks

Co-operative housing faces legal barriers, such as restrictive zoning regulations or a lack of legal recognition for co-operatives. This limits their ability to operate and grow.

Stigma and perception

Co-operative housing faces negative perceptions and stigma. It is not well understood in The Netherlands and there is a strong cultural preference for homeownership or traditional rental / social rental housing.

What countries like Poland, Switzerland, Austria, and Sweden show us on the other hand is that it can a be successful and coveted way of living. In Poland for instance, housing co-operatives manage over 2.5 million dwellings, which is approximately 20% of the total housing stock in the country. Co-operative housing has been an important source of affordable housing for many people in Poland and has helped to address the shortage of housing in urban areas.

In Sweden housing co-operatives manage approximately 17% of the total housing stock. Co-operative housing has been successful in providing affordable and high-quality housing for many people in Sweden, and cooperative buildings are often well-maintained and energy-efficient.

55/102

re-Using historical structures

Back to Amsterdam (The Netherlands).

Legal structures, social structures, informal power structures, and institutions are different everywhere. To become more concrete we need to get more specific.

During the 19th century, Amsterdam experienced rapid population growth due to industrialization and urbanization. This led to a housing shortage, as the existing housing stock was inadequate to meet the needs of the growing proletariat. The result was that cellars, attics and floors in the working-class neighborhoods were split up, and courtyards filled with shacks.

In these years of emerging liberalism, little was to be expected of the government in terms of improving housing conditions. At the time, government intervention in market forces was considered undesirable, and the freedom of property owners was considered untouchable. Real estate investors were also reluctant to increase the supply, as there was little profit to be made from decent workers' housing. (These circumstances sound very familiar to contemporary ears)

The first to react where private investors who build neighborhoods around what was then the centre of town. As can be expected from purely capitalist dynamics these neighborhoods had cramped streets and blocks, the houses where poorly build, and the apartments where cramped and unsanitary.

56/102

Property owners took advantage and charged excessively high rents for socalled 'weekly houses' which left little money for decent clothing and healthy food. Due to the poor condition of the working class families and the poor hygienic conditions, epidemics regularly broke out. Improving public health and housing became closely intertwined themes in big cities.

To address this problem, the government implemented the first housing act (woningwet 1901) and initiated a program of urban renewal and housing construction. One of the key figures, and well known, in this effort was the architect Hendrik Petrus Berlage. Berlage designed a number of new housing developments, including the Plan Zuid neighborhood in the early 20th century. This neighborhood featured a mix of housing types, as well as parks and green spaces.

This ‘socialist’ answer (Berlage buurt) to problems caused by capitalism is well known in the Netherlands and abroad. Less known are the Cooperative movements that spearheaded the changes in the political landscape of those days:

During a brawny meeting on the 2nd of November 1868 some five hundred laborers signed up to pay 10 cents (een dubbeltje) a week to the yet to be formally established Coöperative Bouwmaatschappij tot verkrijging van eigen Woningen (The Cooperative Construction Company for the Procurement of Private Homes in Amsterdam).

The idea was simple; Affiliated workers paid a dime every week, after a year they had a share of f 5, -. With 2,000 members, f 10,000 was thus

57/102

put in cash per year. Enough for the construction of fifteen to twenty plots with a ground floor and an upstairs apartment. These could then be raffled among the members. Each winner of a plot then paid off the construction costs with his rent and with the letting of a floor at f 1.- per week. In twenty years they would be the owner of the entire house. With the cash flow, the association would be able to build more and more homes.

Many members, paying a dime every week - while a considerable number of them were short on cash - turned out to be a lot of effort and required proper organization. Eight workers joined the board of the new organization. All craftsmen who served their bosses every day for about 12 hours. Trying to build and administer the association turned out to be to much. Within six months the first chairman was responsible for the disappearance of 100 guilders and the police had to prevent meetings from turning into a scuffle. The remaining board members were not discouraged. They believed in their cause and by 1875h De Bouwmaatschappij managed to build 26 ‘dubbeltjespanden' (dime houses), as they have come to be known in Amsterdam. This gave rise to new problems. There were dubious rental transactions, new homeowners asked the subtenants for (to much) money, others wanted to make quick repayments and it was unclear what to do with owners who did not pay their rent.

Eventually the organization nearly imploded and two board members from the cities elite turned out to be part of the solution to the housing cooperative’s difficult start. There was also a Supervisory Committee with five notables. These gentlemen were able to open doors previously closed to the organization. It worked. From 1878 housing production started to gain momentum. Solid homes with affordable rents were being build. The realization of 180

58/102

‘dubbeltjeshuizen’ in 1879 was a major victory and around 1900 the Bouwmaatschappij was the largest housing association in Amsterdam with just under a thousand homes.

The emerging labor movement and socialism left their mark on nineteenthcentury social housing. In fact, the cooperative Construction Company for the Procurement of Private Homes in Amsterdam, founded in 1868, has been called the first act of communism in the Netherlands. Workers wanted to build and manage homes themselves through cooperatives. These housing cooperatives sprang up like mushrooms, with a handful to several hundred houses owned by each of them.

The legal structures and institutions that where build on this legacy still exist. Yet, history did not turn out as these pioneers had hoped. The savings of the workers turned out to be inadequate everywhere and the urban elite were always needed to realize the building plans. In addition, the government distrusted the cooperative model aimed at profit-sharing and refused loans and subsidies.

Fast forward to today, and much of this legacy has been undone. Many social housing cooperations merged into a a few giant housing corporations who’s actions are controlled by the national government. A government that is currently taxing instead of subsidizing ‘affordable’ housing (verhuurdersheffing). This forces the corporations to sell a lot of their financial assets (houses) to private owners. Owners that proceed to charge the highest price they can.

59/102

In other words: Shared ownership of cooperatively owned houses were first put under central control of the government, and then sold to private investors. History show’s that it will be about half a century before the situation is sufficiently dire for the working-class to take action and demand their right to housing. Luckily the City of Amsterdam is already waking up to this fact and has expressed the ambition to start creating more housing cooperatives. 10% of the total housing stock by 2045 , about 40.000 dwellings. 20

Assuming that these ambitions are to be realized, an important question arises: For who should we build?

60/102

61/102

April

P.6 Gemeente Amsterdam Eindrapport actieplan aan de slag met wooncoöperaties, 2020, Amsterdam

62/102

17 Elinor

18 CECODHAS

19

20

Dockx, N. Gielen, P. Commonism, A new Aesthetics of the Real, Amsterdam: Valiz, 2018, P.55.

Ostrom

Housing Europe and ICA Housing, Profiles of a Movement: Co-perative Housing

around the World,

2012,

· Part 3 · Who should we build for?

Building for the precariat Building for the precariat

Part 3 · Who should we build for?

63/102

The contemporary working class

Society is changed. Our words and thus thinking has not.

We are stuck with a skewed definition of what the working class is today. Things used to be clear: More/higher education equals more prestige equals higher pay. Those at the bottom formed unions to protect themselves from those at the top and a dedicated company men was rewarded with stability and security.

In todays society this not how it works and things are evolving faster than our language is able to keep up. The working class still evokes images of blue overalls and Orwellian scenes with large production facilities as a backdrop. This still exists in some places but much of the working class has since been put into a cubicle and behind a screen.

Besides Blue collar workers and white collar workers there is now another type of worker. I’m not sure what name to give to that worker but I am sure that it is a worker without a clear status and without any acquired rights. I’m also sure that business favors this type of worker precisely because there are no (legal)frameworks for them. They can be used and let go whenever it suits the company.

On top of a lack of stability and security in their income this kind of worker is doing the job they are required to do for one main reason: To pay rent. As

64/102

we’ve learned this rent keeps increasing because there is a mismatch between supply and demand, a shortage of suitable housing.

“…. [the] shortage of houses is not something peculiar to the present; it is not even one of the sufferings peculiar to the modern proletariat in contradistinction to all earlier oppressed classes. On the contrary, all the oppressed classes in all periods suffered more or less uniformly of it…”21

This is what Engels wrote on housing shortage in 1872. The problem tends to contain the solution. If all oppressed classes sufferd from a shortage of houses, the availability of suitable housing is fundamental in combatting oppression.

The question that remains is: Who is the oppressed class today? And what kind of houses do they need?

65/102

The precariat

Three groups, one problem

The term "precariat" was popularized by Guy Standing, a British economist and professor at the University of London. He has written extensively on the topic of the precariat and the changing nature of work in the modern world. In his book "The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class," Standing describes the 22 precariat as a growing class of people who are living and working in precarious conditions. This includes people who are employed in temporary or part-time jobs, who work in the gig economy, who are self-employed, or who are unemployed and struggling to find work.

Standing argues that the rise of the precariat is a result of globalization, automation, and the weakening of labor protections and social safety nets. He warns that the precariat is a potentially dangerous class, as its members are often excluded from the benefits of the welfare state and may be more likely to engage in social and political unrest.

I would like to add to Guy Standings definition of the precariat that, in addition to precarious working conditions, housing is a key component in the precarity and insecurity experienced by a lot of people in contemporary capitalism. And, it is the combination of precarious work and precarious housing that makes people angry.

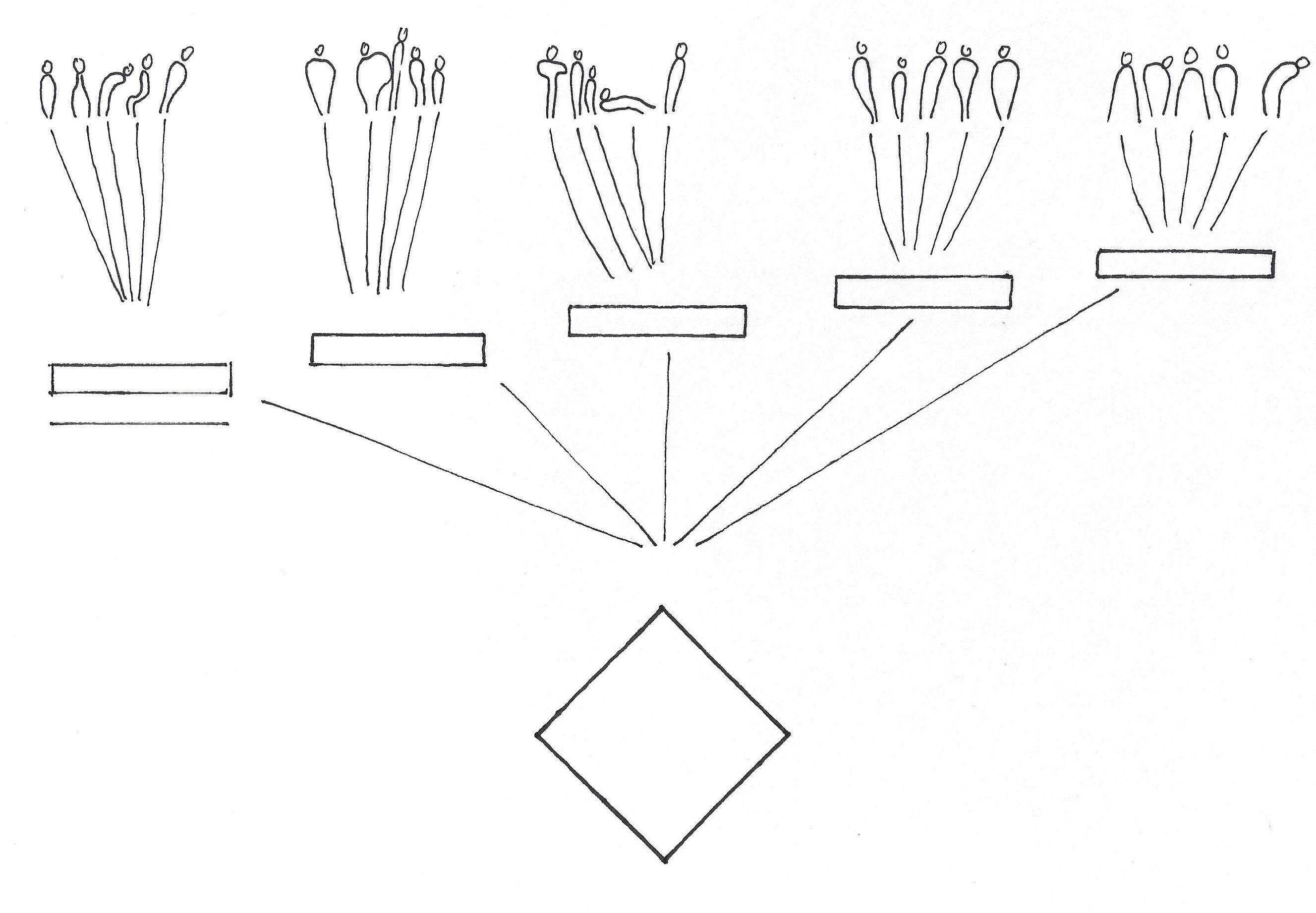

Standing identifies three main groups within the precariat:

66/102

1 · Atavists

This group consists of older workers who have fallen out of stable employment and find themselves in a precarious situation. They may have lost their jobs due to automation, globalization, or other factors, and struggle to find new work. Atavists may have experience and skills, but they are often seen as outdated and are left behind by the changing economy.

2 · Nostalgics

This group consists of younger people who are unable to find stable employment and have grown up in an era of economic instability. Nostalgics may have higher education degrees, but they are often overqualified for the jobs that are available to them. They are often burdened by student loan debt and may struggle to find affordable housing.

3 · Progressives

This group consists of those who are actively choosing to work in nontraditional, precarious jobs such as gig work, freelancing, or entrepreneurship. Progressives may value flexibility and autonomy over stability and security, but they often lack the benefits and protections of traditional employment, such as healthcare, retirement benefits, and legal protections.

These groups share a common experience of precarity, but they have different backgrounds, values, and outlooks on life. From the (news and social) media I get the impression that these groups point at each-other for the problems they experience. They don’t have a sense of what the real cause is. Furthermore, giving them a sense of security and agency is not only related to work. It’s related to housing, and the combination of these two.

67/102

Living & Working

Living is separated from working in our financial, institutional, legal, and popular frameworks and understanding. At the same, the number of people working from home has been increasing. This trend existed before, and exploded during covid.

The industrial revolution caused a lot of people to seek work outside of their home. Traditional modes of sustenance like farming and artisanal production that was usually done from home became a thing of the past. For most people working and living became separated in a practical sense. Not because they preferred it but because artisanal production (including small scale farming) became economically uncompetitive.

As a result many people moved to cities where industrial production and the necessary housing for the labourforce was mostly unregulated. The resulting squalor, filth, and disease in many cities caused a delayed but enduring division between living and working, both spatially and practically.

By now we have moved into an economy where most people are highly educated and work jobs that don’t put a heavy burden on their environment. There is a wide range of professionals that can easily work from home, and many technologies to reduce the burden of many productive activities on their environment.

68/102

Obviously typical desk work doesn’t cause any harm to your neighbor when done from home but it is also great to have a bakery, auto repair shop, or cabinet builder in your neighborhood. Most importantly, people like working close to home or even at home. It also takes a tremendous burden away if you don’t need to drive to work by car. In terms of time and money on a personal level and in terms of not harming the environment on a communal level. It is no surprise that more and more people are working from home.

The nature of people may not have changed as much as our financial, legal, and institutional frameworks around housing. They still enjoy working near home. What has changed dramatically is their relations, in particular in terms of family.

69/102

One or two people

Family = 1 or 2 people

Before the industrial revolution a typical household had many members of an extended family. Along with this technical (industrial) revolution came a revolution in the definition of what family means. Family conjures a nostalgic image of an extended family at a large dinner table. Those days are long gone for most people.

Family may also conjure another image, that of a (heterosexual) couple with two children. The so-called cornerstone of society or nuclear family. Most of us still have this image of what a family meant in the 1980’s. And we build as if it’s still 1980’s. But it’s not. A lot has changed I’m even talking about the great diversity of constellations in which people choose to live together. What I’m talking about is the plain fact that in The Netherlands 2/3 of households is one or two people. Families of 1 or 2 are the vast majority, the norm!

When we add to that the fact that 2/3 of housing the current housing stock is designed for people with (two) children there can be only be one simple conclusion. We need to build homes that cater to one or two people. No more.

I would add to this simple observation a thesis: If, from now on, every new house in The Netherlands is build specifically for (and really attractive to) one or

70/102

two people, all other problems related to housing will be solved. Sounds simple but the proof is in the pudding.

By catering to this group of citizens a lot of additional problems could be addressed. Loneliness, experienced by 40% of Dutch adults , could be 23 reduced. Pollution, from commuting to work, friends, and family might be greatly reduced. And the psychological need for people to be part of community can be met in the most logical location. Right at home.

This graphic novel by from the 80s is well known in The Netherlands and illustrates how we still perceive family.

Far less infamous is this successive work by the same author. “To continue without family”

71/102

Community as a service

The fundamental human need for a sense of community is well know to most marketeers. Housing developers are exceptionally well positioned to exploit this human trade, and cater to the happy few that can afford it.

72/102

sensible mode of living and takes into account space for social encounters and adaptation to the evolving lives and thus needs of people. The Urban Village Project, and other concepts like it have a lot of potential qualities but they are generally not owned by their residents. In their words the urban village project proposes: “a radical new financial model where users subscribe to their homes”

Calling the subscription model new is and factually wrong. Calling it radically new is great marketing if your customer base is a generation eager for change. Factually, this model offers those who can afford it a sense of safety and security in knowing that their neighbors have a similar economic background. It requires an investment of money.

It’s like a Mcdonalds hamburger. You buy it because is seems attractive but it’s not gratifying. There is some flavor but not the nutrition your body expects. It seems attractive but it can never give what you want; being part of a community. It requires an investment of time, attention, and social interaction to áctually become part of a community.

73/102

Motivation

Autonomy, competence, and connection to others

To build and maintain a community requires time and effort. The necessity is there and many people feel that necessity. What it also requires - besides time and effort - is motivation.

Motivation can be difficult to come by for the precariat. A large portion of the contemporary working class, the precariat, has little or no agency at their job. Their actions are at best directed by another human but often they are controlled by an algorithm. This destroys the fundamental quality that humans have to change the world for the better. It erodes their motivation.

According to neuropsychologist Johannes Visser what we consider worthwhile, what motivates us, has three components: Autonomy, competence and connection to others. These factors can be internal but they can also be external. People perform better if they are motivated but the systems that are designed to maximize the economical output of the precariat appear to be designed to destroy every last bit of motivation.

If we consider a day in the life of someone delivering packages in terms of autonomy, competence, and connection to others; How will their motivation be affected? An app. on their phone tells them where to go, how to get there, and how fast to get there. (They’re always to slow). So much for autonomy. So what

74/102

about competence? The tasks are repetitive, simple, and yes, they’re always to slow (incompetent). Now finally, connection to others: They’re in their vans, alone, all-day. I’ve seen some of them on video-calls with their families while driving, clearly the job is not giving them any connection to others. This is one obvious example but the same is true for many and an increasing amount of jobs around the globe. As we’ve seen another fundamental aspect of the jobs that define the precariat is the precarity associated with them. The money that they receive in return is not motivating. It is merely a necessity that they acquire it to pay for the fundamentals of staying alive. The primary expense being housing.

Their homes could be alternative - or hopefully additional - source of motivation. It is as important or even more important in terms of time spend. Autonomy, competence, and connection to others can be something that home offers. But in many cases it doesn’t.

There is vast amount of rules and institutions (in The Netherlands) that prevent home owners from changing their houses in size or appearance. Many of these rules are useful but the effect is stifling non the less. If we consider renters there is an even larger lack of autonomy. In most cases the only thing people are allowed to change is the finish of their floors.

Currently, for many of us that fall within the precariat, both labor and the house are a source of our precarious state of existence. What they can be and what they should be is quite the contrary, an arena for self determination and a source of motivation.

75/102

Community - building

What if we become co-owners, co-builders, and co-administrators

In a literal sense; The act of building can be the act of building a community and the act of maintaining can be the act of maintaining a community.

In part 2 we’ve looked at the the commons and housing cooperatives as a possible solution to the ever rising prices for housing. But the unavailability of affordable and suitable housing is not the only thing this would solve.

The physical and mental process that a group of inhabitants need to go though in order to successfully build or maintain their homes, will result in a sense of community.It is this fundamental need for a connection to others that many people simply can’t find on a regular basis, in our individualized society.

Privately owned and social housing doesn’t cater to the need for connection. co-Owned housing might, when the building and governance are designed well.

76/102

77/102

Assemblage

Aesthetics of process

The smooth and monochromatic aesthetics of (neo)liberalism are determined by a small elite of socially compatible people. Social fickleness is managed by appropriation or rejection. Appropriation happens in fast media. Social platforms, fashion, art, and advertising adapt quickly to reflect what engages people. The architecture of our buildings can also be understood as media. The story it conveys is one of the dominant few. The affluent, the powerful, and their architects.

At times this aesthetic conveys a sense of duty, diligence, care, and morality. (Plan zuid). At other times it conveys necessity, urgency, and a calvinist disposition (wederopbouw wijken). More recently this aesthetic conveys the simplistic economy of scale and repetition (woongebouwen). At all times and most noticeable in modernism it can only maintain its pure and clean form by rejecting polluting practices. By rejecting iterative processes, by rejecting time, by rejecting people.

This rejection of life is fixed in rental contracts, zoning plans, building codes, and an application process for buildings - that can only exist in one fixed formrather than building (as a process). Designing a new set of laws, institutions and processes will take some time but the buildings they produce would be markedly different from what we see today.

78/102

When we allow buildings to become learning and adapting entities rather than fixed images it will become possible to improve instead of replace, and to include instead of exclude. Over time buildings and cities will become places where colors, shapes, and people will frequently clash. These clashes will be precisely what enables us to negotiate our differences on an ongoing bases.

79/102

Low-tech smart materials

How hi-tech materials only serve inflated profits for shareholders and what that means for our choice of materials.

If technical innovation rarely benefits the people that operate the technologies, it makes sense to employ technologies that are easy, simple to understand, and simple to reproduce. Simple materials composed intelligently can have transformative power for how society functions. If we combine this with a direct approach to the relation between the laborer and his house the results for those who accumulate surplus will be severe. There will simply be far less overproduction, far less surplus to accumulate.

Seen in this light the role of the government should be to allow laborers to use simple materials to build their own house. The complexity of the rules and institutes that enforce them opposes this way of thinking. Now imagine a simple case study - four walls and a roof. Given a place to build, anyone can do that. And most people would do a great job of it when the resulting space would benefit their quality of life in a sustainable - that’s to say lasting - way.

I do realize that building with your own hands is not for everyone. The task of creating something entirely from scratch just seem to large. What people are very good at, to a man, is adapting what they find.

80/102

It is no surprise that most housing cooperatives spring from existing conditions. It should thus be the task of architects and developers to create frameworks, existing conditions made of low-tech smart materials. Conditions that are ready, and readily understandable, for people to adapt.

What is interests the human perception is not that which is still. It is that which moves, adapts, changes, surprises. And that is exactly what people will do….. when it is allowed.

81/102

The yields of cooperation

Innovation instead of growth

The idea of shared ownership and shared responsibility to ones direct environment makes sense instinctively. What that instinct doesn’t explain is how this change could influence society on a fundamental level.

Liberalism, neoliberalism, ánd socialism have attempted to banish love to the domain of the nuclear family. Social (re)production and care is classified as private and not acknowledged as being vital for economic production. Again, this us true for both socialist and liberal societies.

In any case, separating reproduction and economic production creates false dichotomy, the economic and private domain are interdependent and intertwined, as are market/state, work/family, and technology/people. The perceived dichotomy only makes sense from a perspective of those who benefit from this administrative separation.

Those who benefit from this administrative separation also accrue the benefits from technological innovation. A worker still works 8 hour days, no matter how fast his or her computer is….. This insight is by no means new. It was Panzieri who wrote:25

82/102

“Capitalism and technological innovation are one and the same”

What this means is that yes, there is more production. More production of surplus. And all of this surplus is accrued by a small, owning class.

Panzieri (1921-1964), an Italian translator and interpreter of Marx’s writings supported Marx’s insight that cooperation between workers was a fundamental condition for capitalist production. During the course of the industrial revolution, up to the creation of the welfare-state, the capitalist organization of production transformed from a system of coercion to a system of persuasion.

In other words: Capitalism adapted for a while. The state had to create better conditions for the working class to keep them productive. This led to a better balance between state ‘socialism’ and capitalist production when viewed through the eyes of a working class person.

Other theorist at the time of Panzieri mused on themes like the 4 hour workweek. Ideas that clearly never materialized and possibly never will. The only way to short circuit capitalism’s tendency to overproduce and accumulate is by short circuiting the elaborate schemes by which the proceeds of overproduction are transferred.

Financial wealth is transferred to the owning class in multiple ways. Housing is a cornerstone in this process. Rent and interest is why surplus is generated and how it changes hands. If we want to change this, we have to change how we organise housing for the precariat. If we do that well, technological innovation may lead to better lives instead of economic growth for the lucky few.

83/102

Engels, F. The housing question, 1872 , pt. 1, a. 2. available online

Standing, G. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class, 2014, Bloomsbury