The eyes are the window to the soul

Gavin Fraser

The eyes are the window to the soul

An architectural approach to helping the visually impaired in their mental, physical and social needs.

3

4

Colophon

University: Amsterdam University for the Arts - Academy of Architecture

Programme: MSc in Architecture

Project: Graduation project The eyes are the windows to the soul

Study year: 4th year

Date: 05.10.2022

Citation style: APA 7th edition

Student: Gavin McGee Fraser gavin.mgeefraser@outlook.com gavin.fraser@student.ahk.nl

Committee: Elsbeth Falk (mentor), Jo Barnett, Jeanne Tan.

5

Preface

Visual disabilities is a growing issue. As of 2022, approximately 253m people suffer globally from visual impairments. The unique set of characteristics surrounding visual impairment also raises several difficult but equally compelling opportunities within the field of architecture. The eyes are the window to the soul is a new architecturally centred approach to care for the visually impaired and blind.

Currently, care provisions for the visually impaired focus exclusively on the physical visual condition of the sufferer and how the mechanics of that issues can be resolved with traditional medicine. This is successful in treating the physical problem, but leaves much to e desired in relation to a person’s overall and mental wellbeing. In particular, the litany of mental health issues associated with visual impairment is rarely addressed. These issues fall into 2 primary categories. The first is as a direct consequence of diagnostics, testing, treatment, and oppressive clinical architecture. The second, relates to a far more expansive social sphere, wherein people with visual problems suffer from mental health issues relating to social isolation, loss of purpose, loss of income, the inability to carry out basic tasks, and a loss of self.

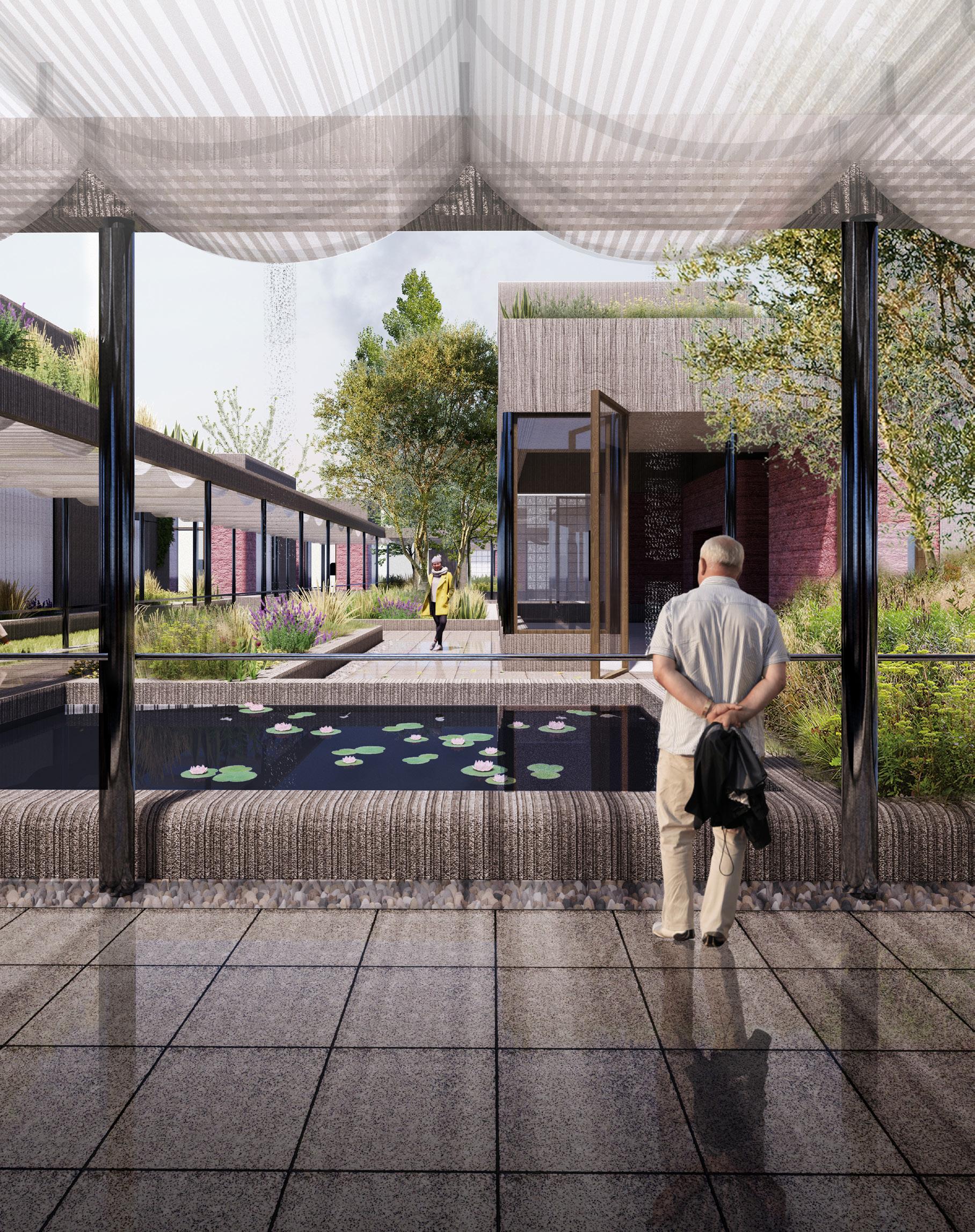

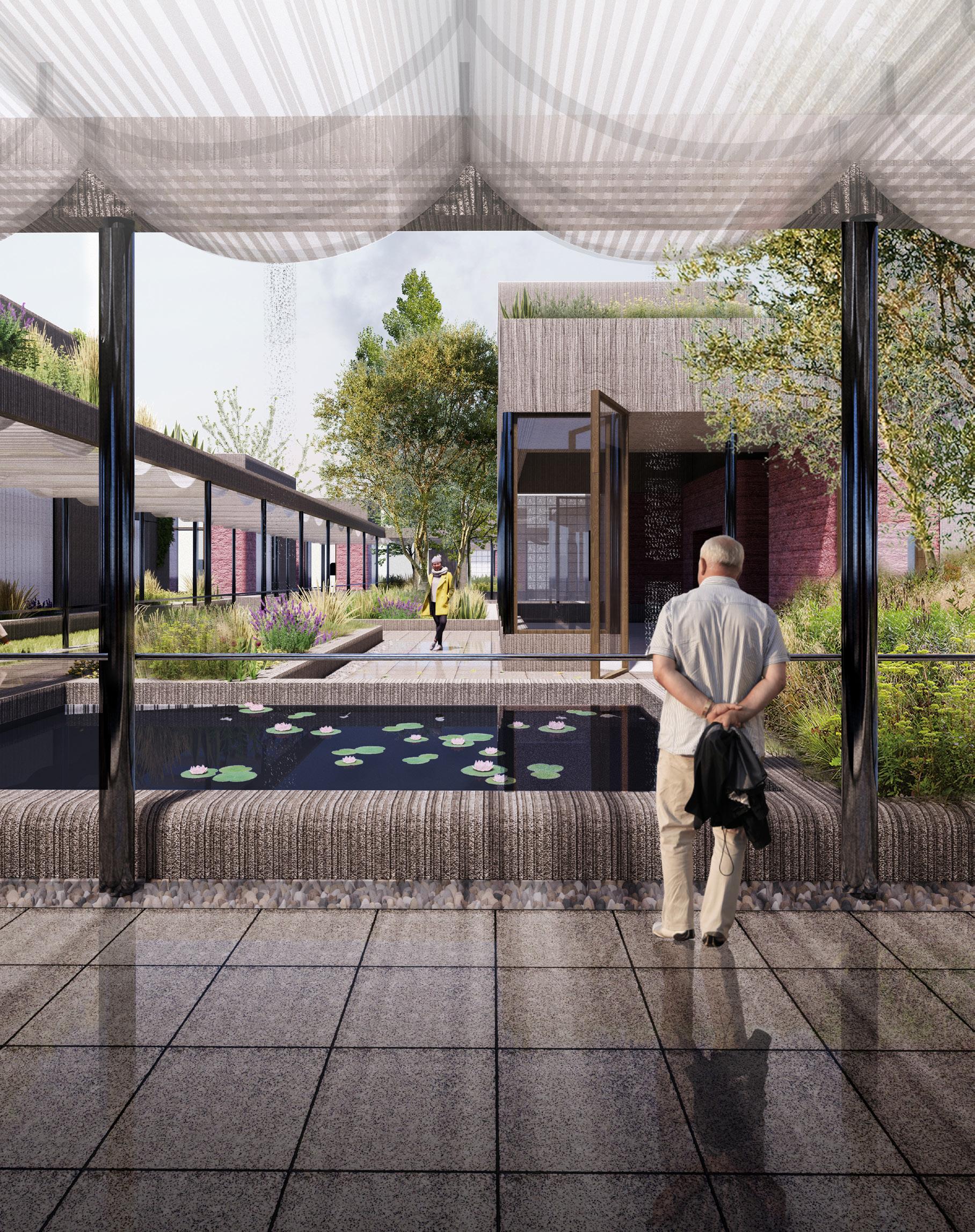

This project aims to address these current shortcomings in care for the visually impaired, by proposing a holistic combination of clinical and social programmes. Through a new smaller scale hospital architecture, the patient’s mental wellbeing is placed as an equal with the clinical aspects of care. This centre will redefine how we look at the traditional eye hospital architectural precedents through incorporating spaces to escape, reflect, socialize and grieve, all meanwhile in the backdrop of a communal atmosphere in a truly safe environment This new hospital will establish new approaches to managing the treatment, testing, diagnostic and clinical architecture challenges we face today.

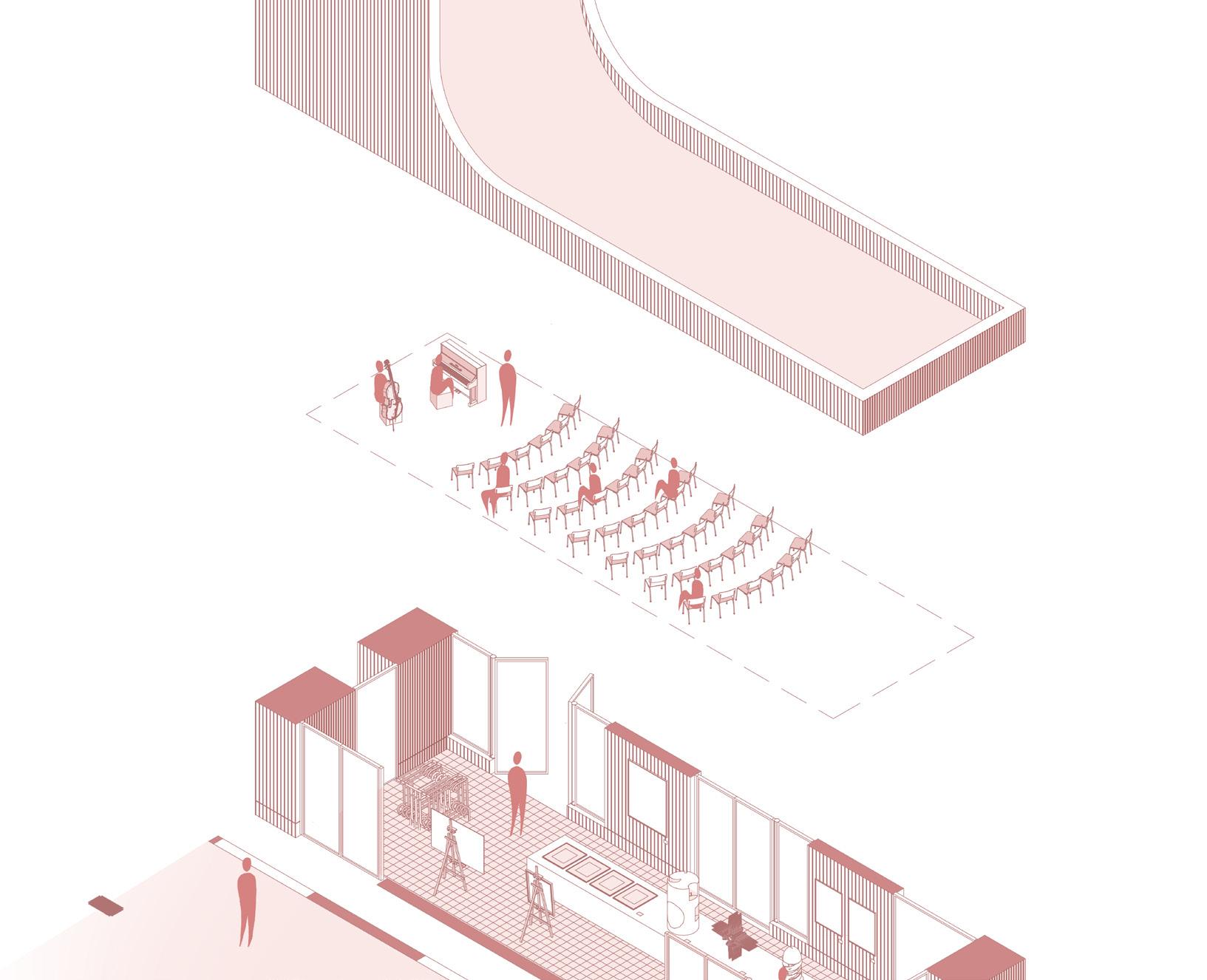

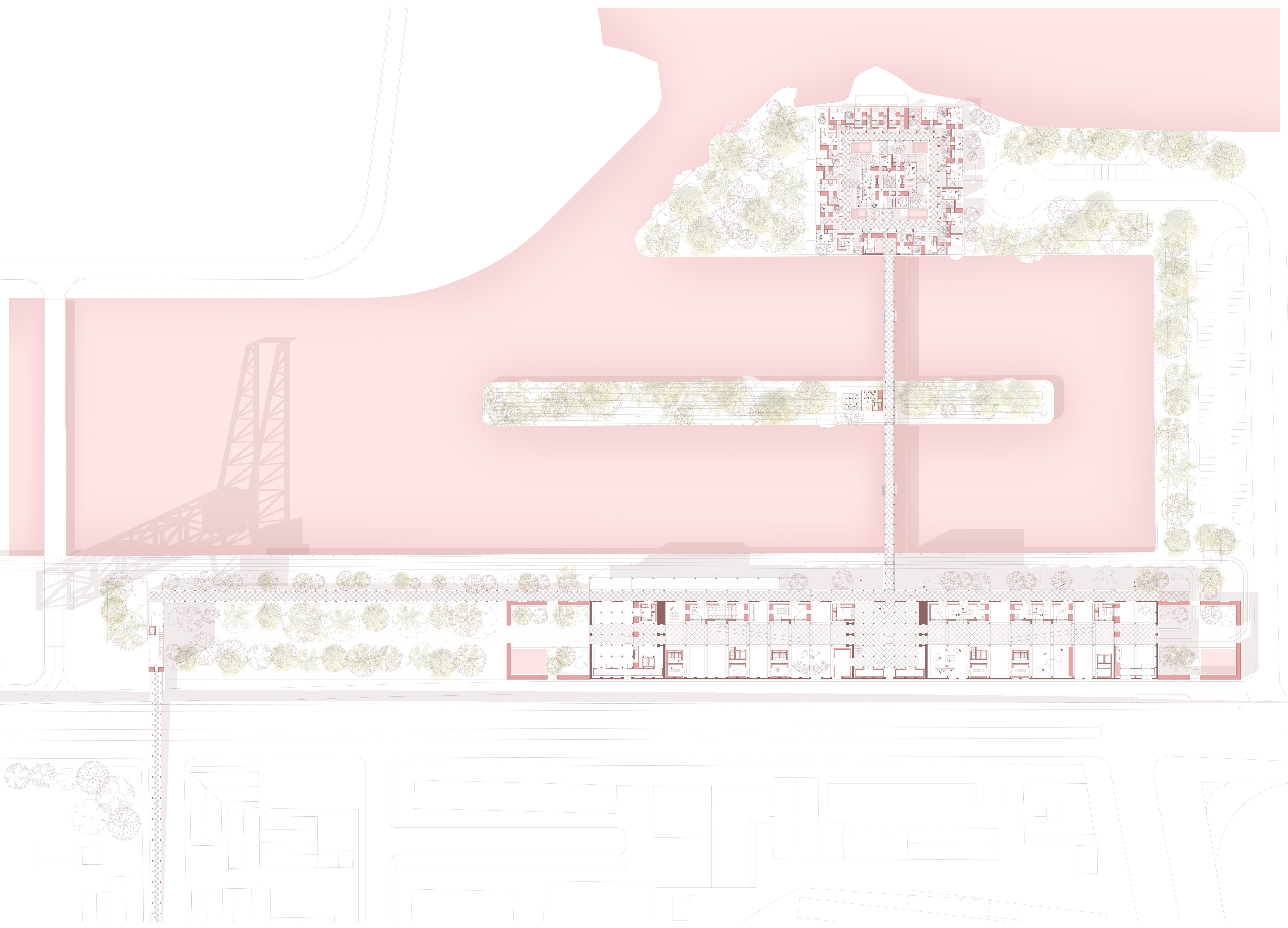

At the same time, a new social centre is created to supplement the new clinical approach. This new centre is an experimental ecosystem wherein traditional therapies are given a backseat to more alternative and physical forms of therapy. The core idea is that through providing therapies focusing on art, music, horticulture and movement, several social issues associated with visual impairments can be addressed. These therapies manifest themselves through several architectural interventions. Primarily, spaces are created for the therapy and tuition of these fields in a semi-private environment, coupled with highly public spaces for dialogue, exhibition, performance and social interaction with the wider community. Concurrent to the eye hospitals relative introversion, the social programme is the public face of the total plan. Through encouraging the visually impaired community to partake in these physical activities, we are encouraging a sense of self, a sense of accomplishment, and sense of purpose. A fortuitous byproduct of this is the exposure of the visually impaired community to the wider public, and creating valuable opportunities for education an financial independence.

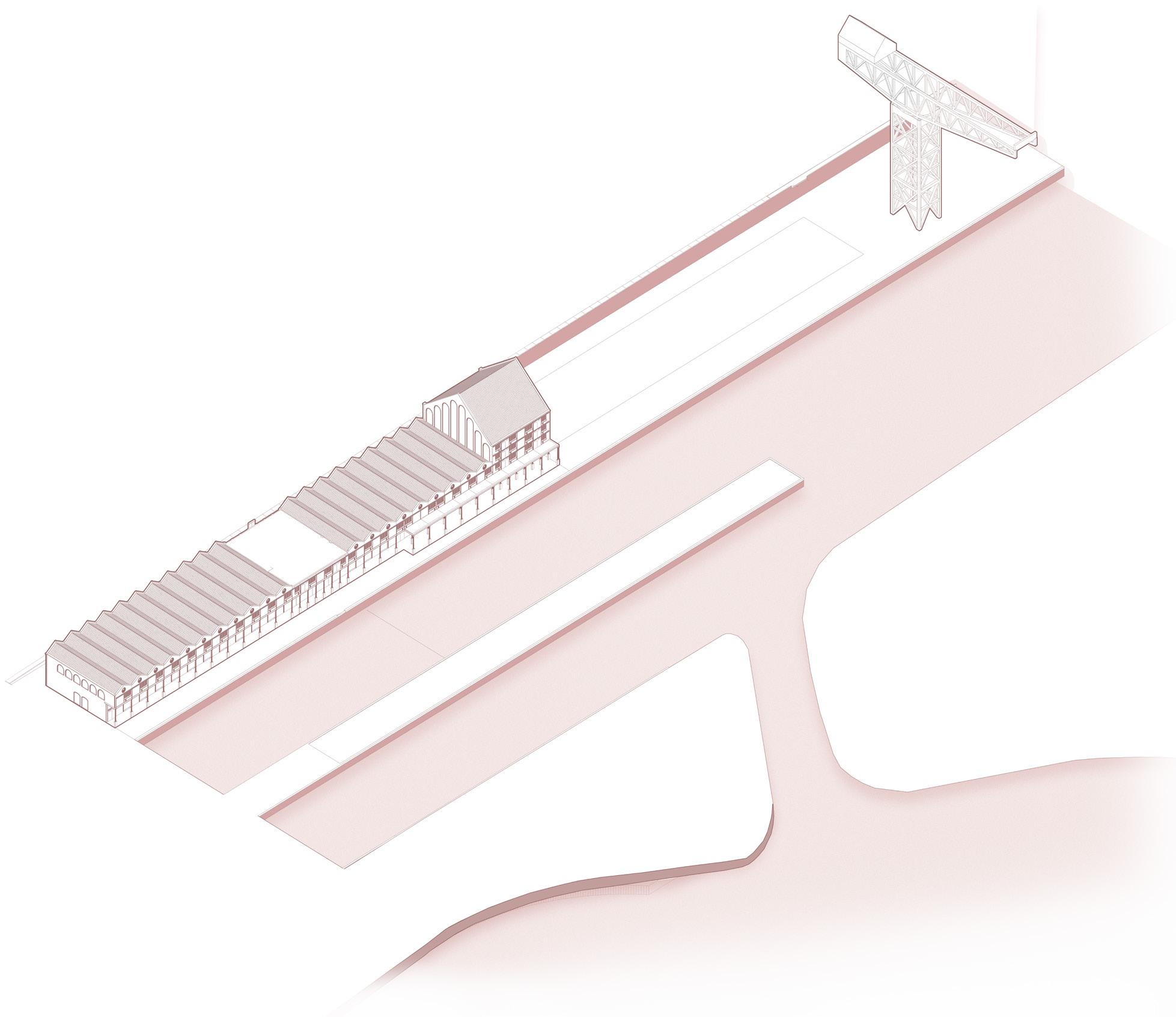

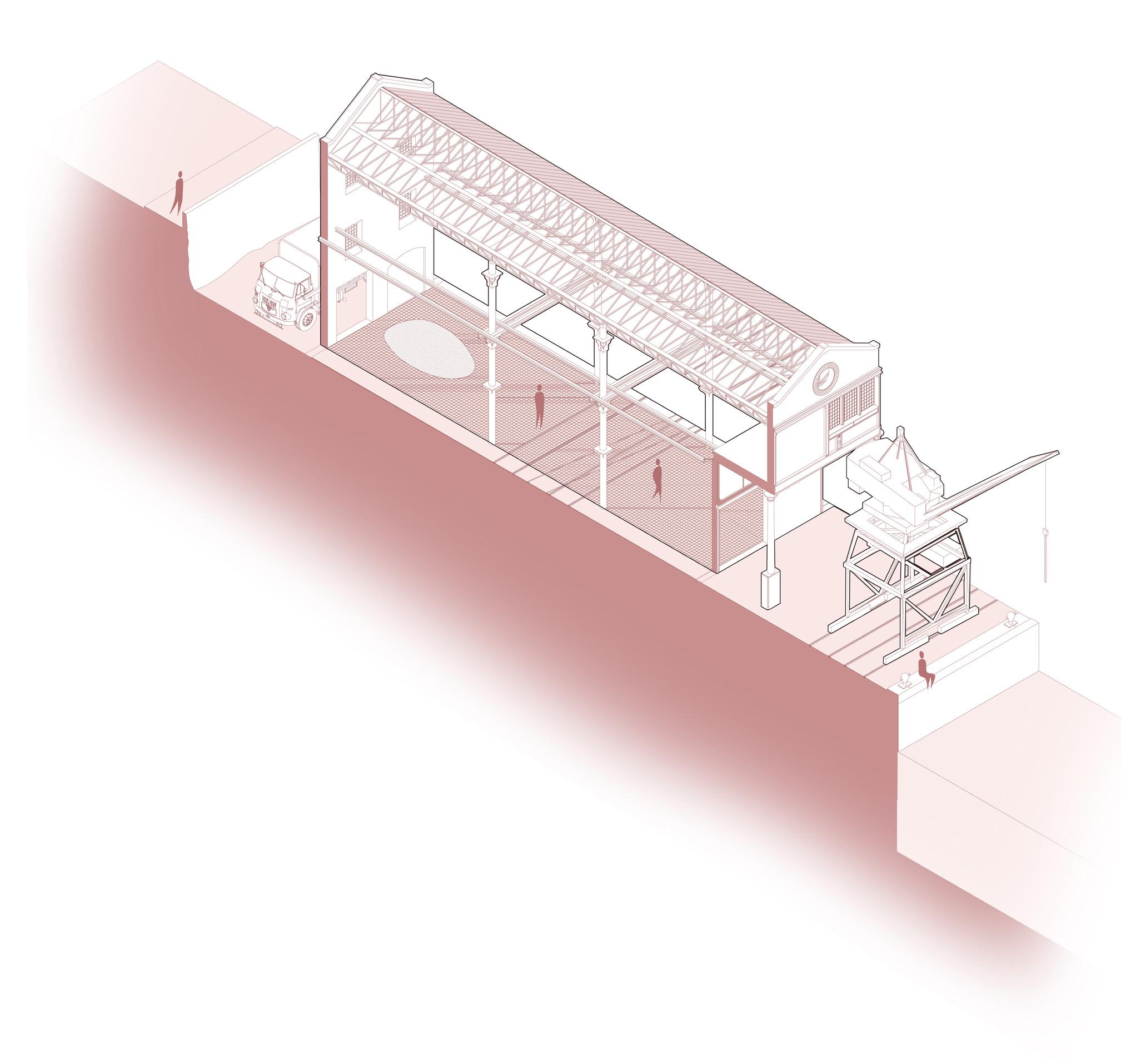

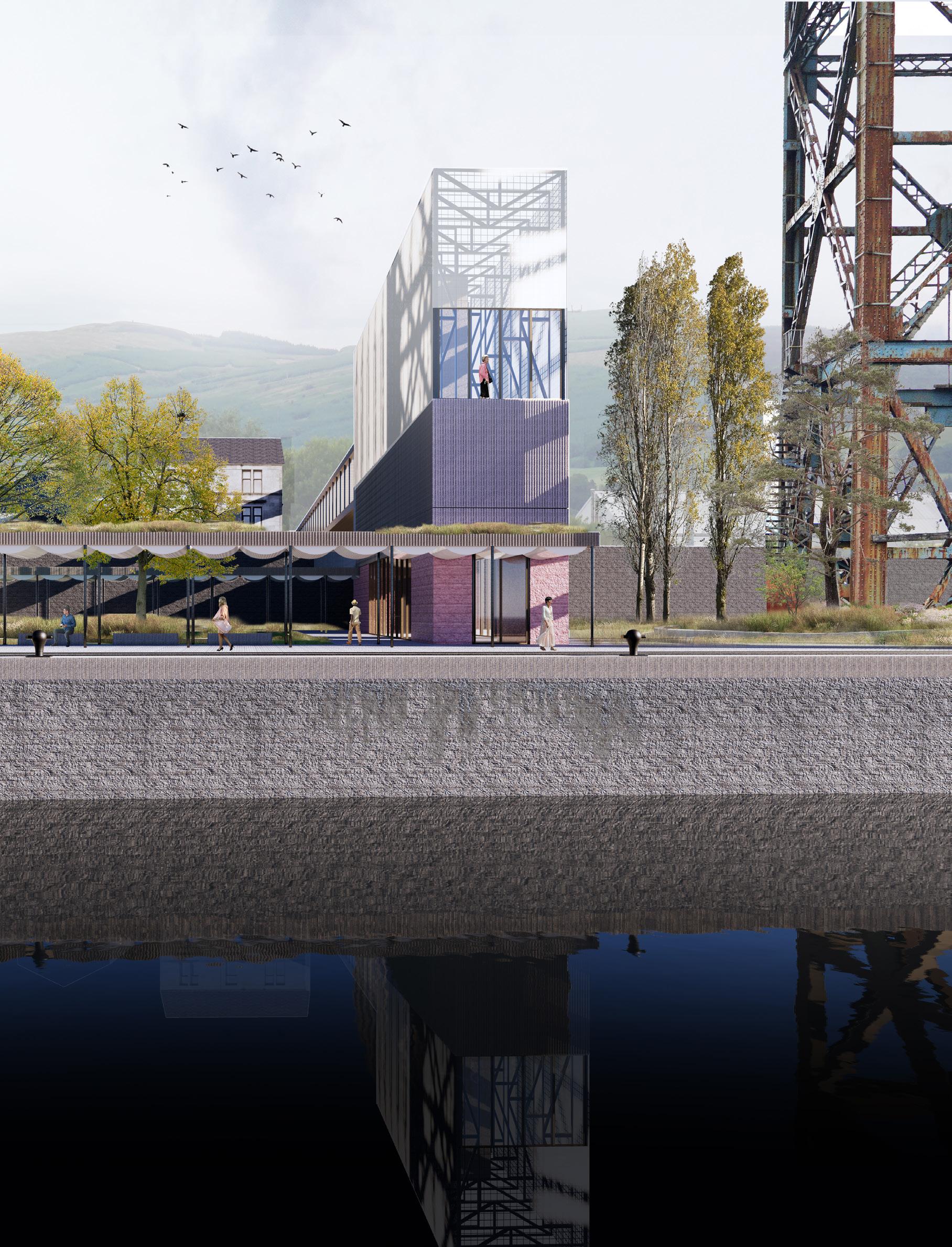

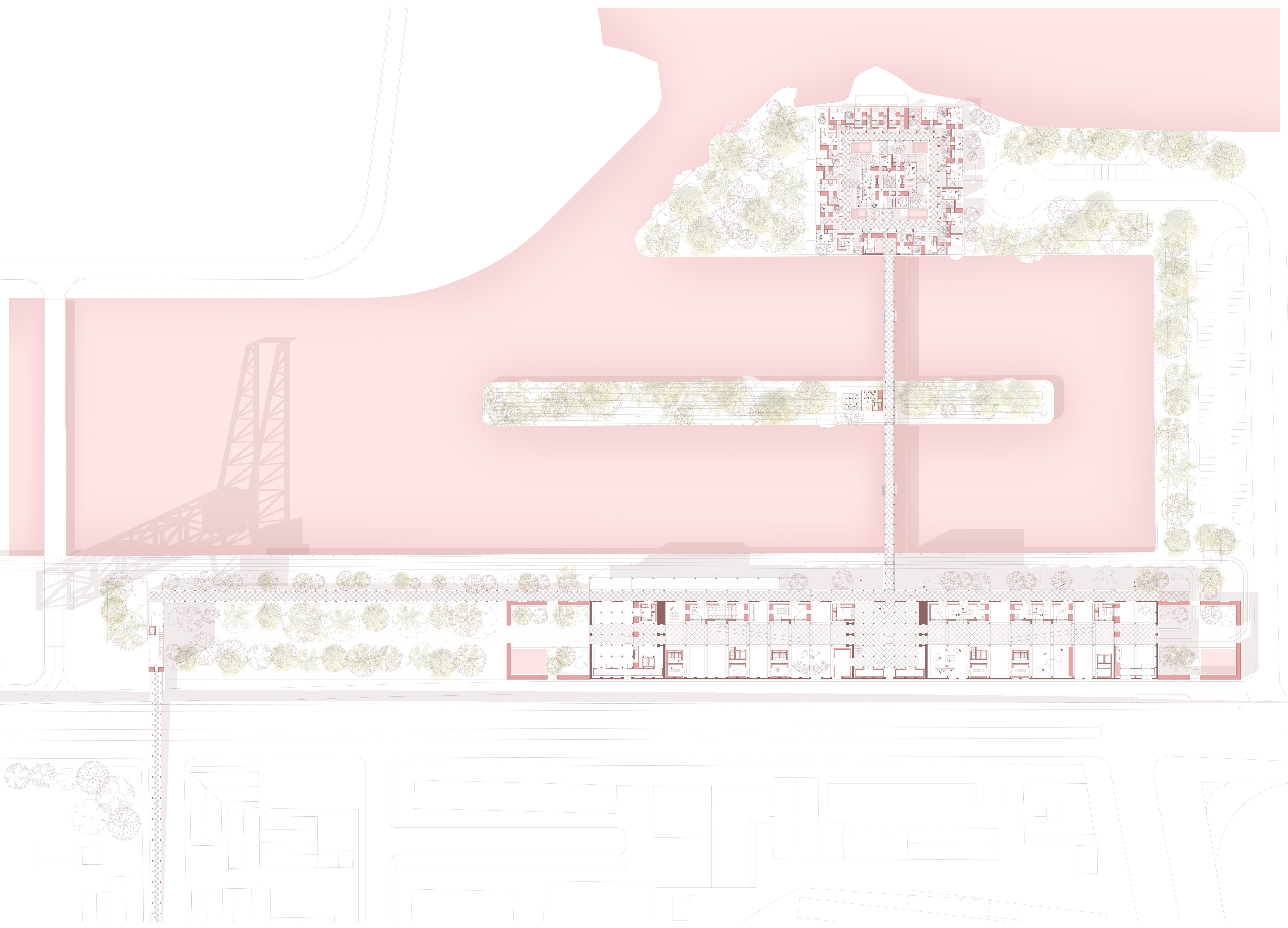

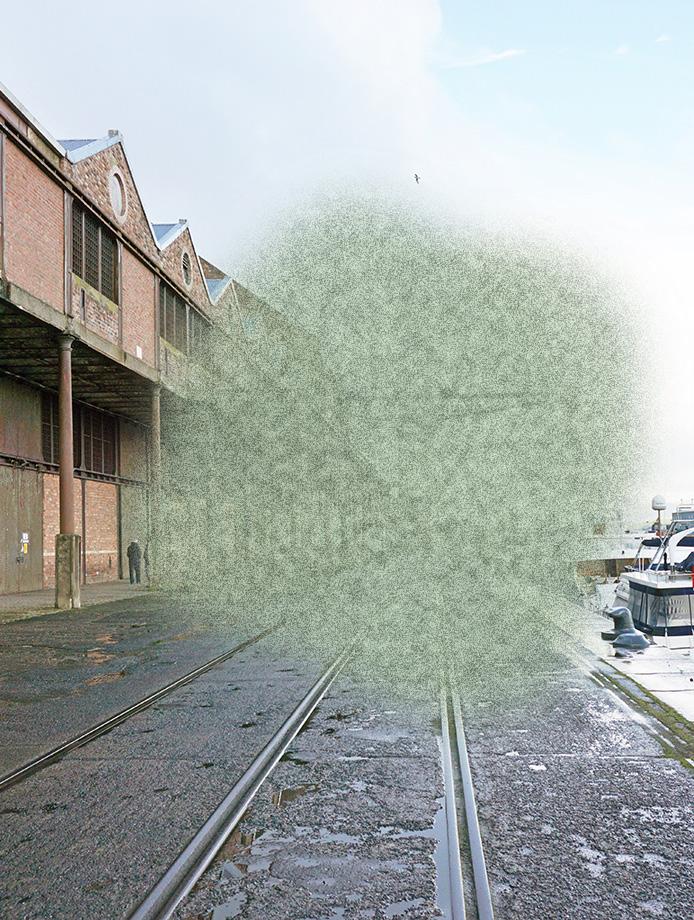

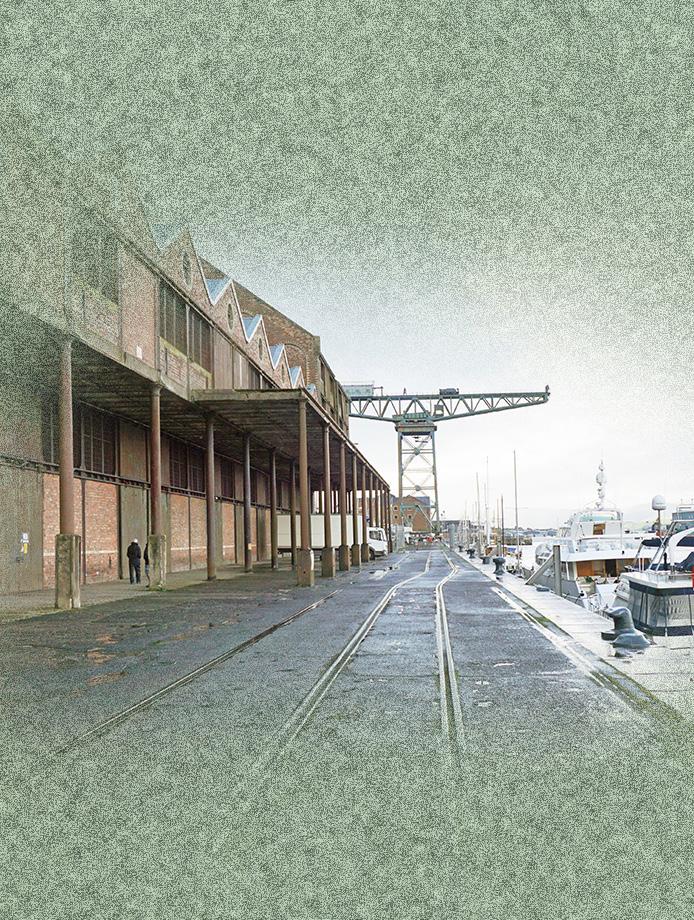

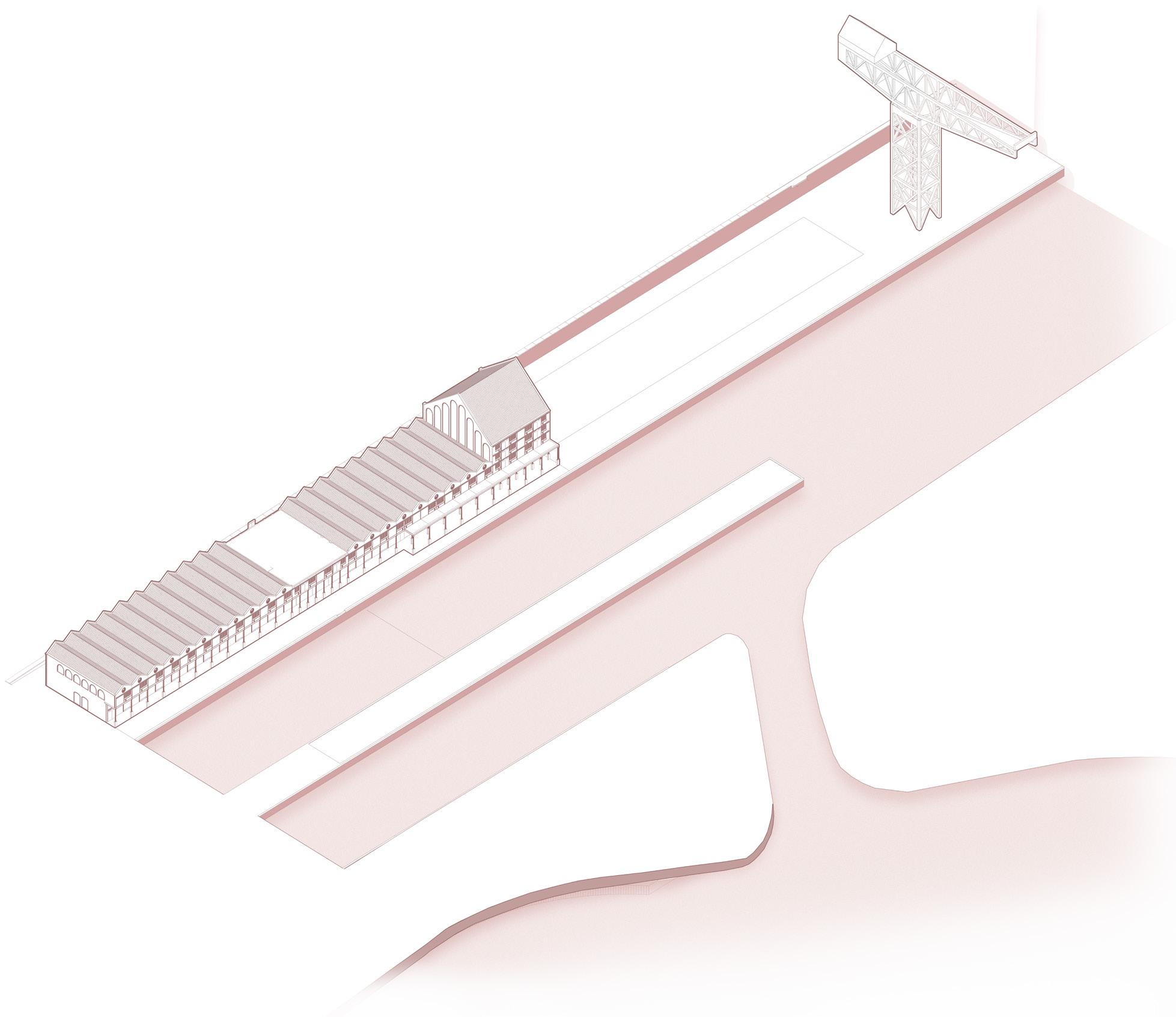

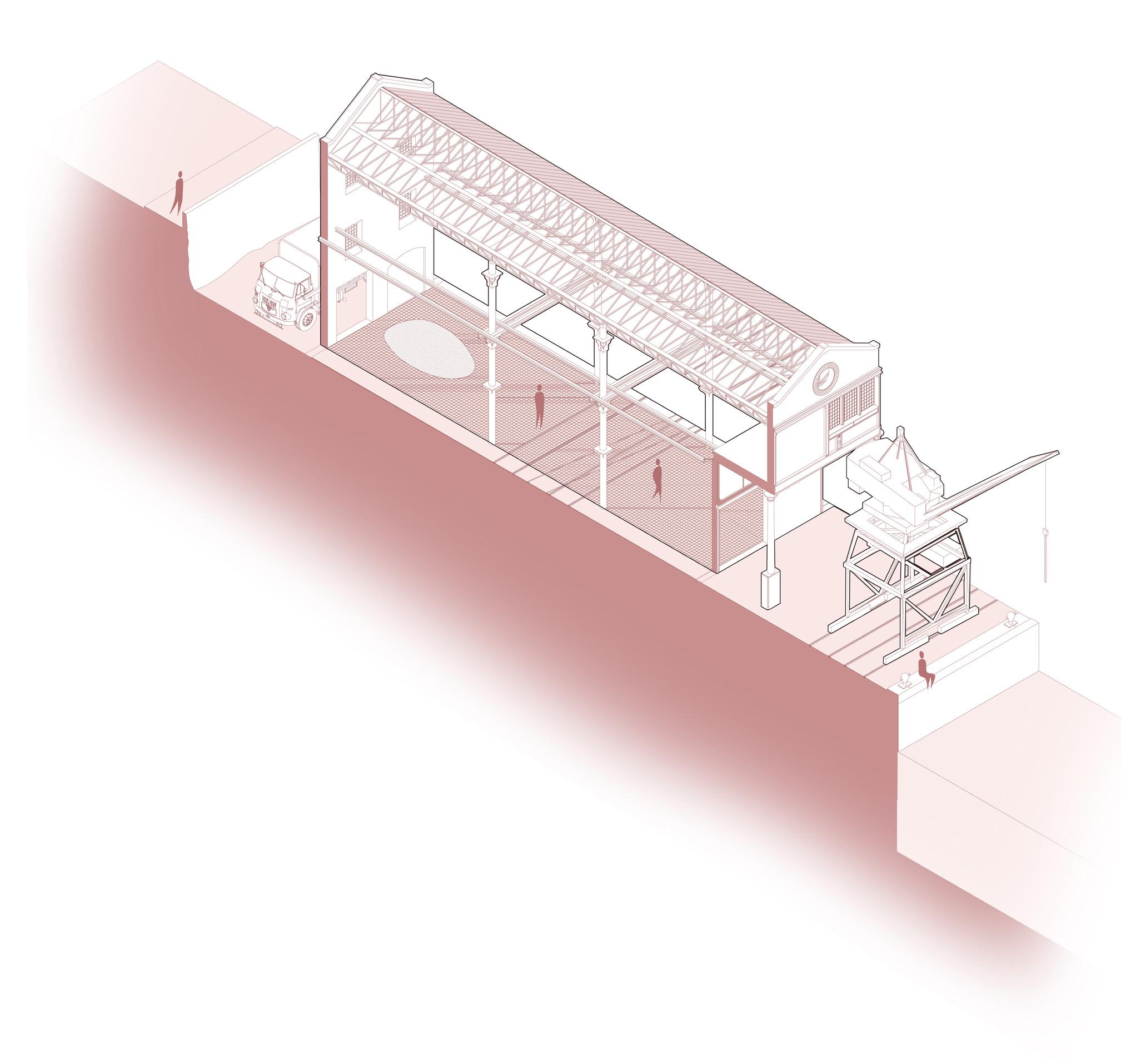

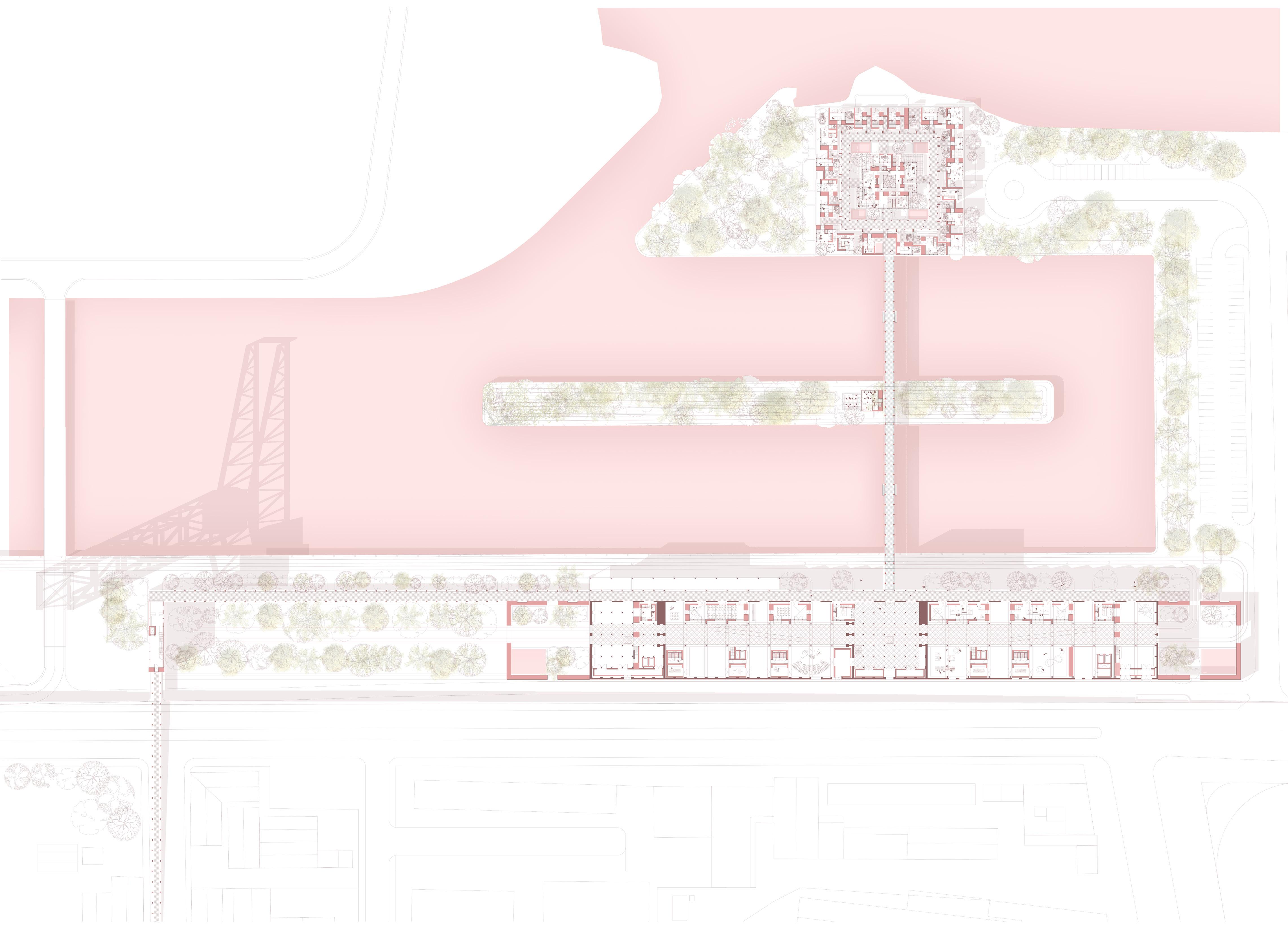

Both the social and clinical programme occupy a vast abandoned waterfront harbour complex in the city of Greenock. Not only is this project redefining care for the visually impaired, but it is also examining how we can reincorporate these industrial landscapes back into the community as a sensitive and meaningful addition to the social and architectural fabric of a place. The conclusion of this project is merely a start of a bigger conversation. A conversation about visual and mental health, and how architecture is currently responding, and how we as architects can do better.

7

8

Table of contents

Introduction

A personal view 10 - 13

Visual Impairment 14 - 17

Mental Health 18 - 35

The problem 36 - 41

The concept 42 - 59

The programme 60 - 71

The location 72 - 79

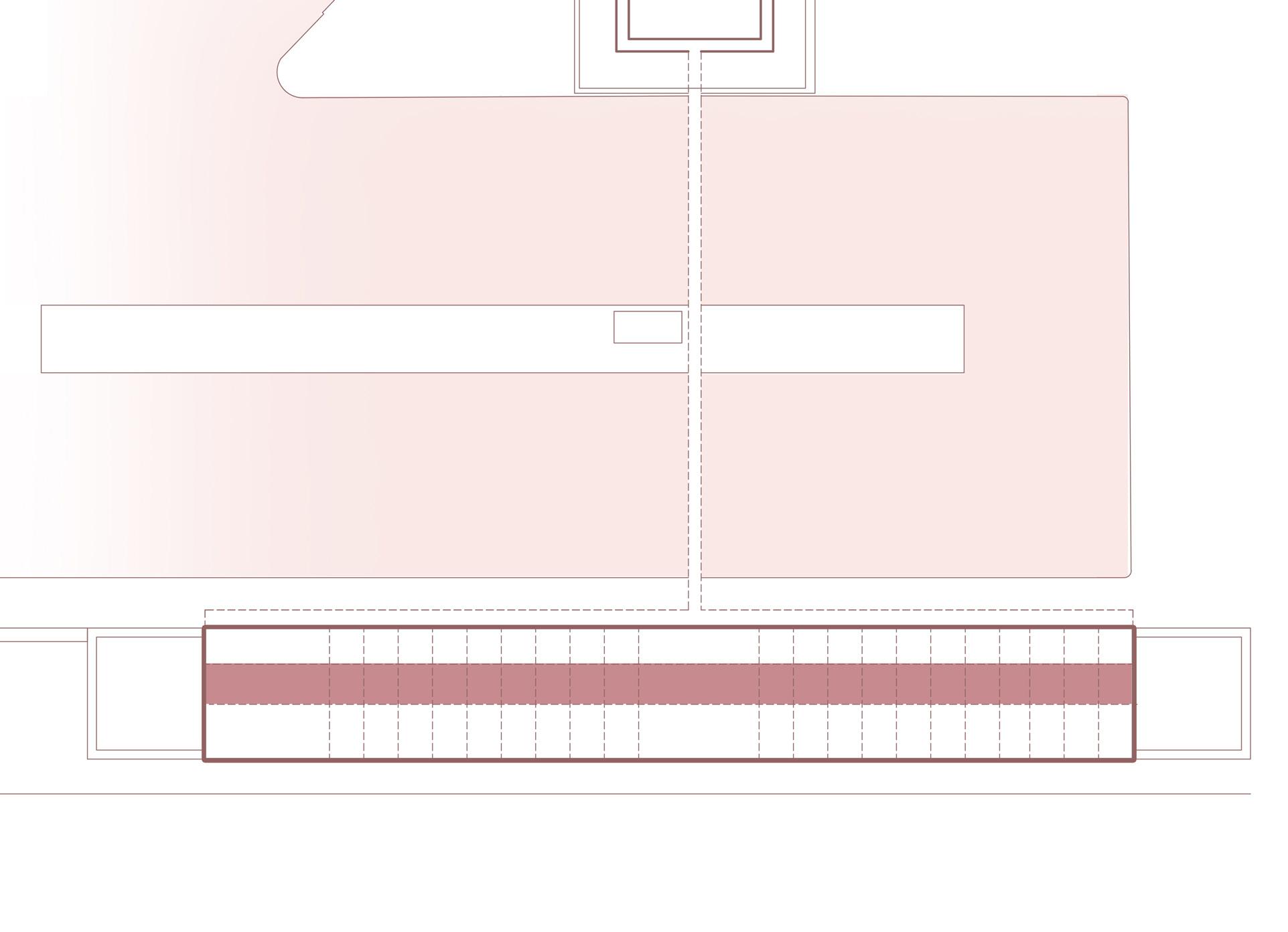

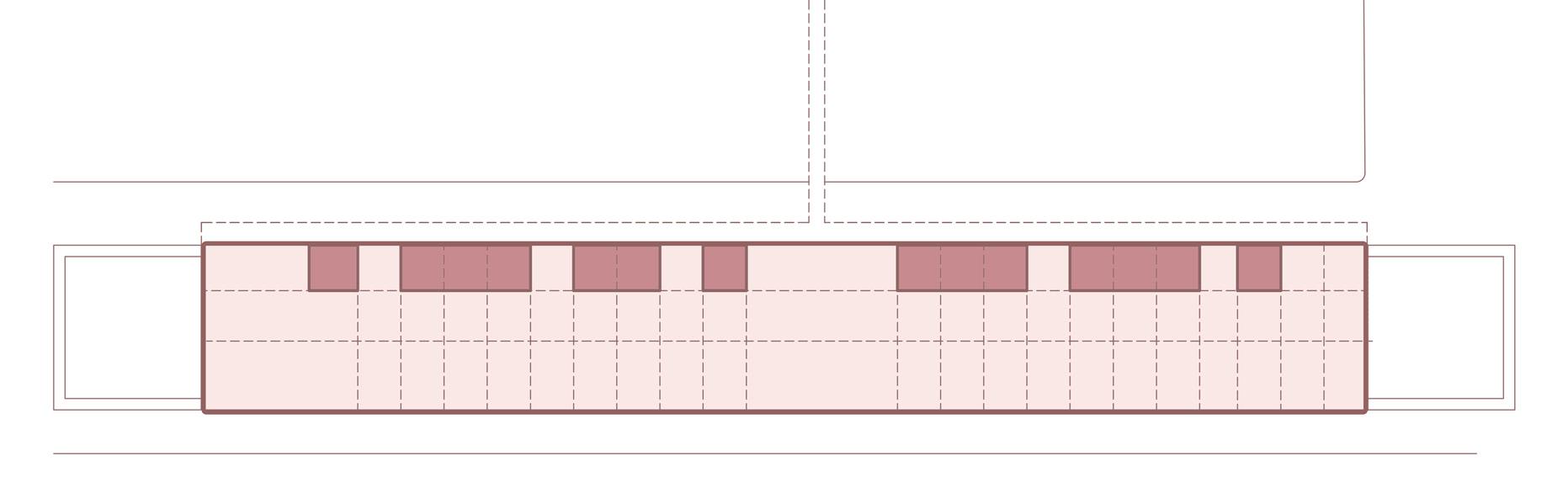

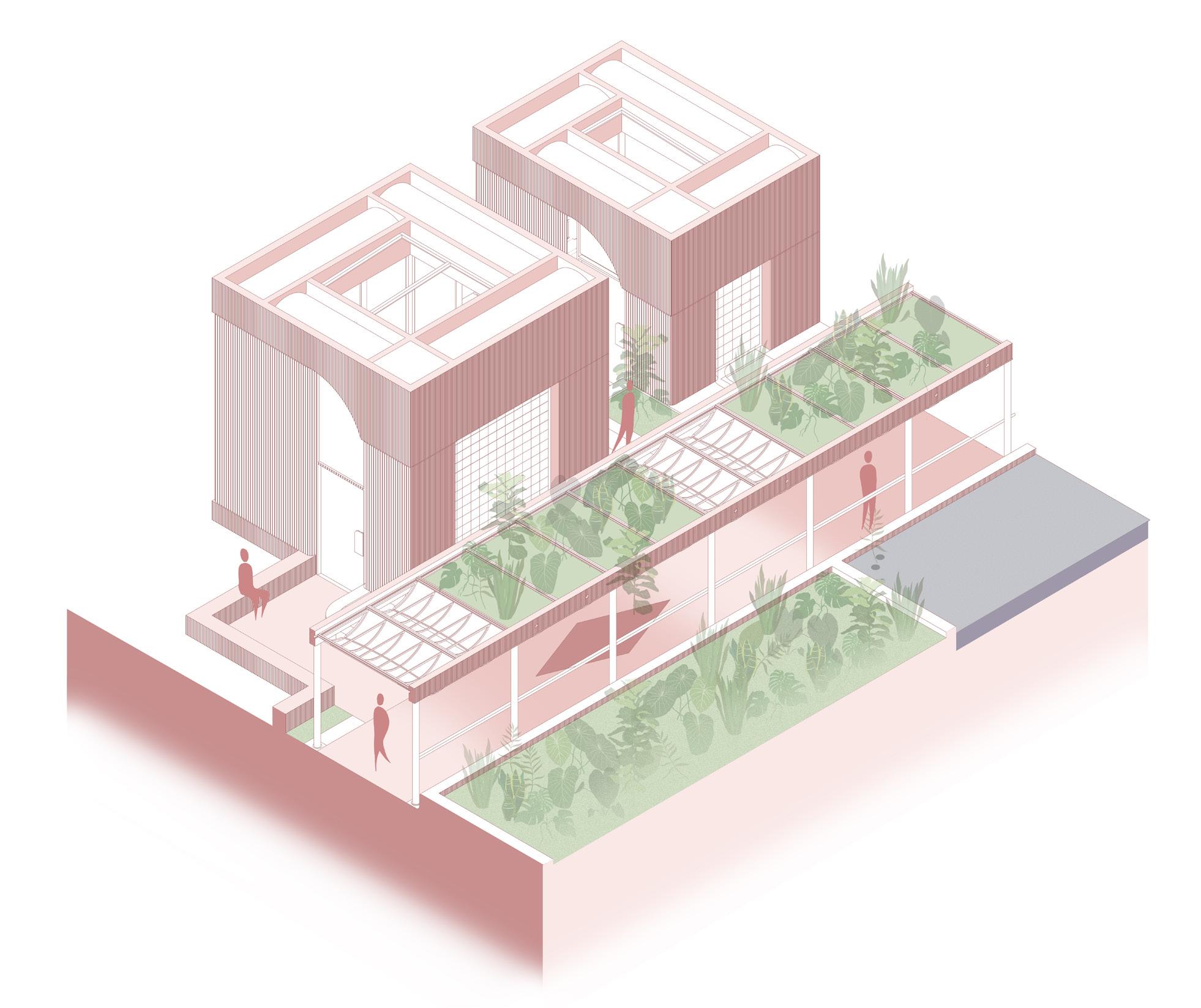

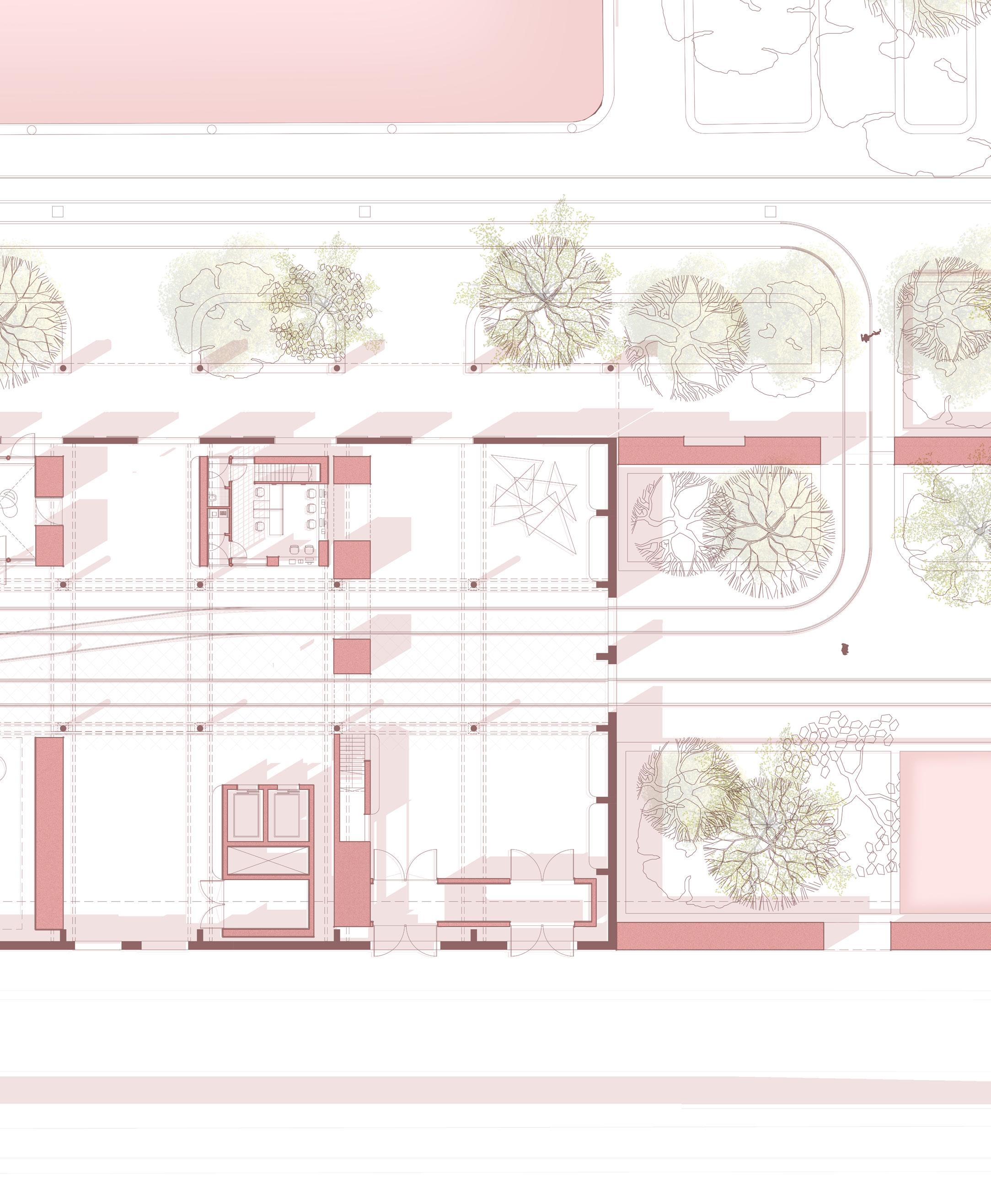

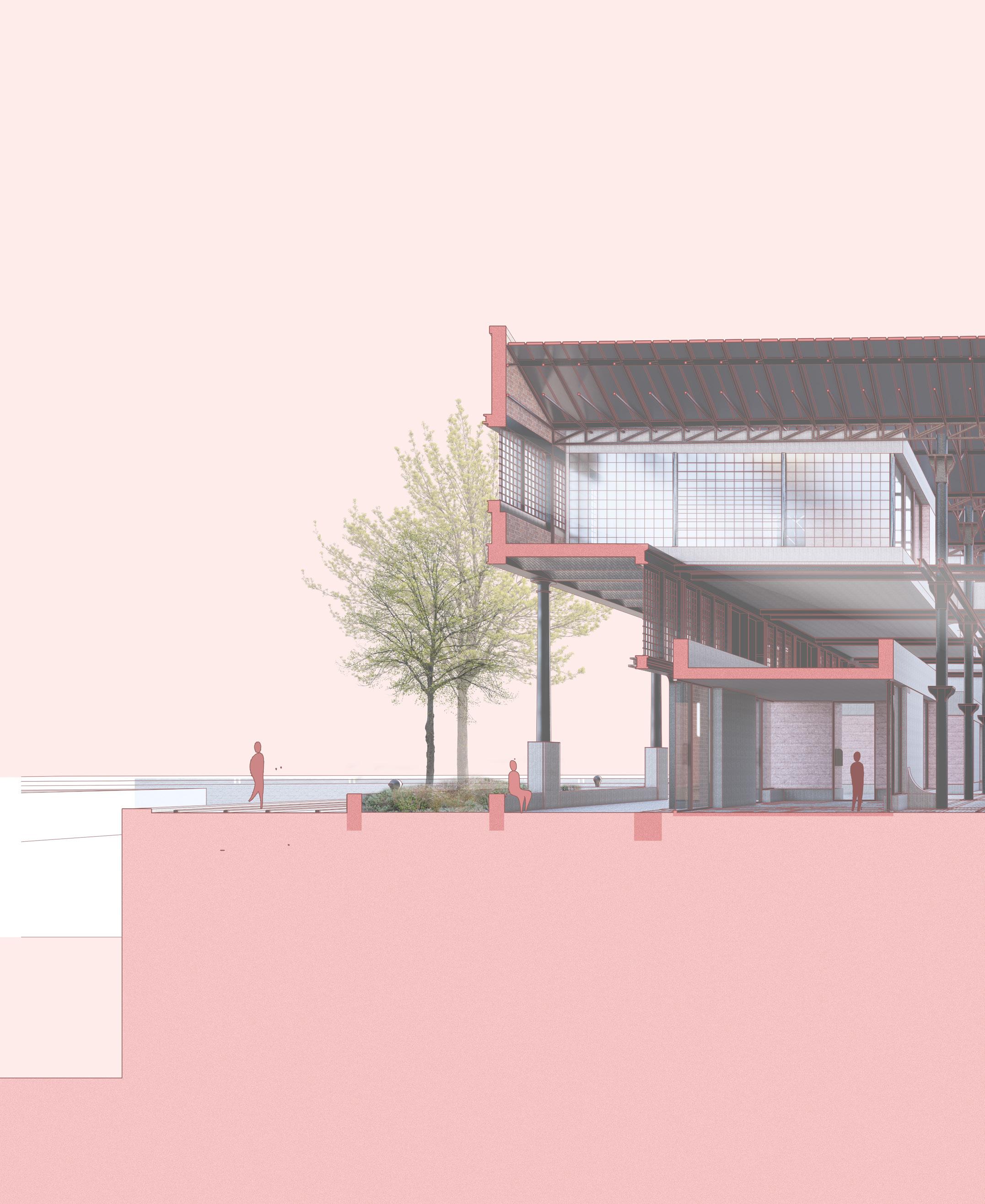

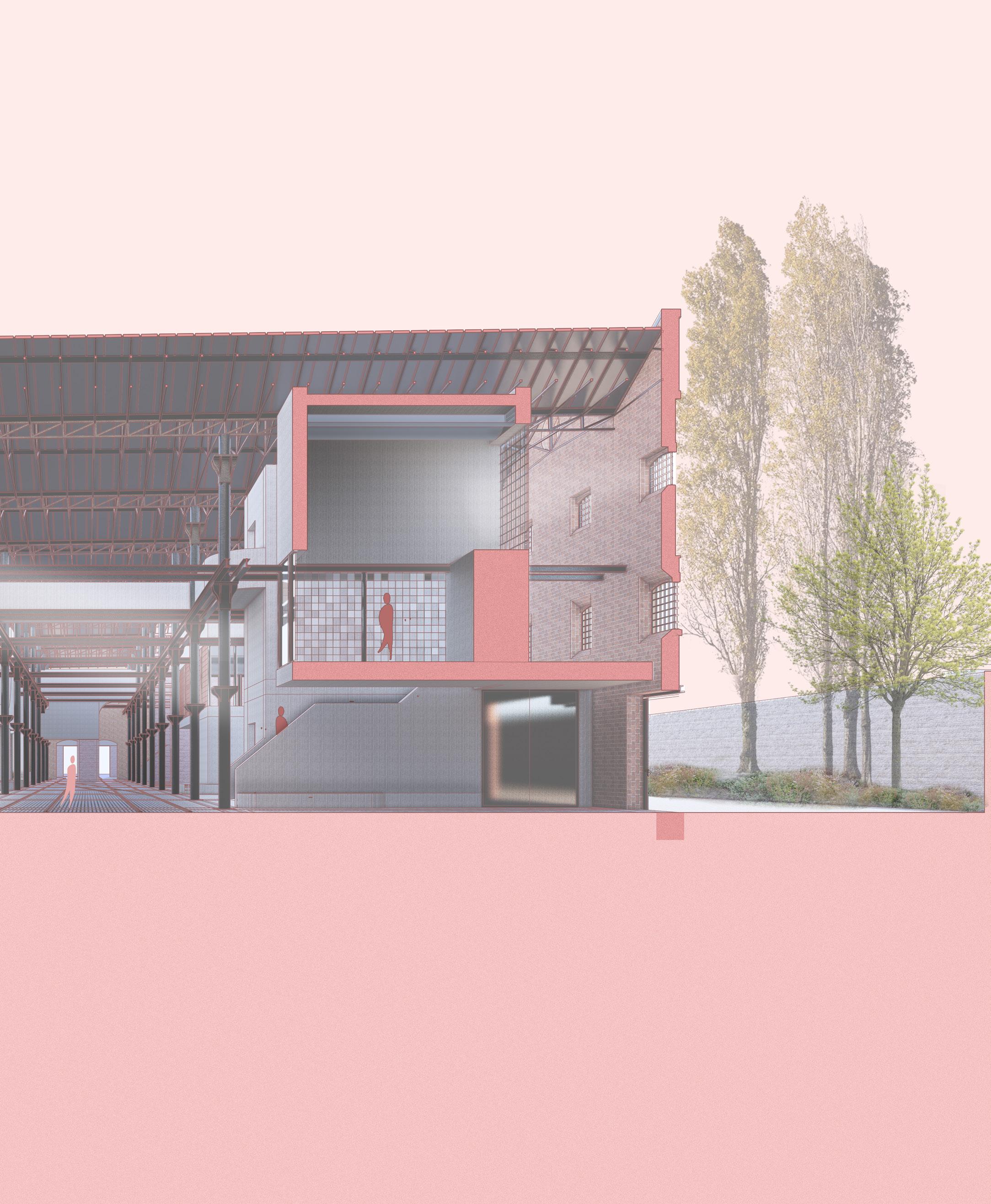

Sugar sheds 80 - 103

Design principles 104 - 111

Architectural characters 112 - 117

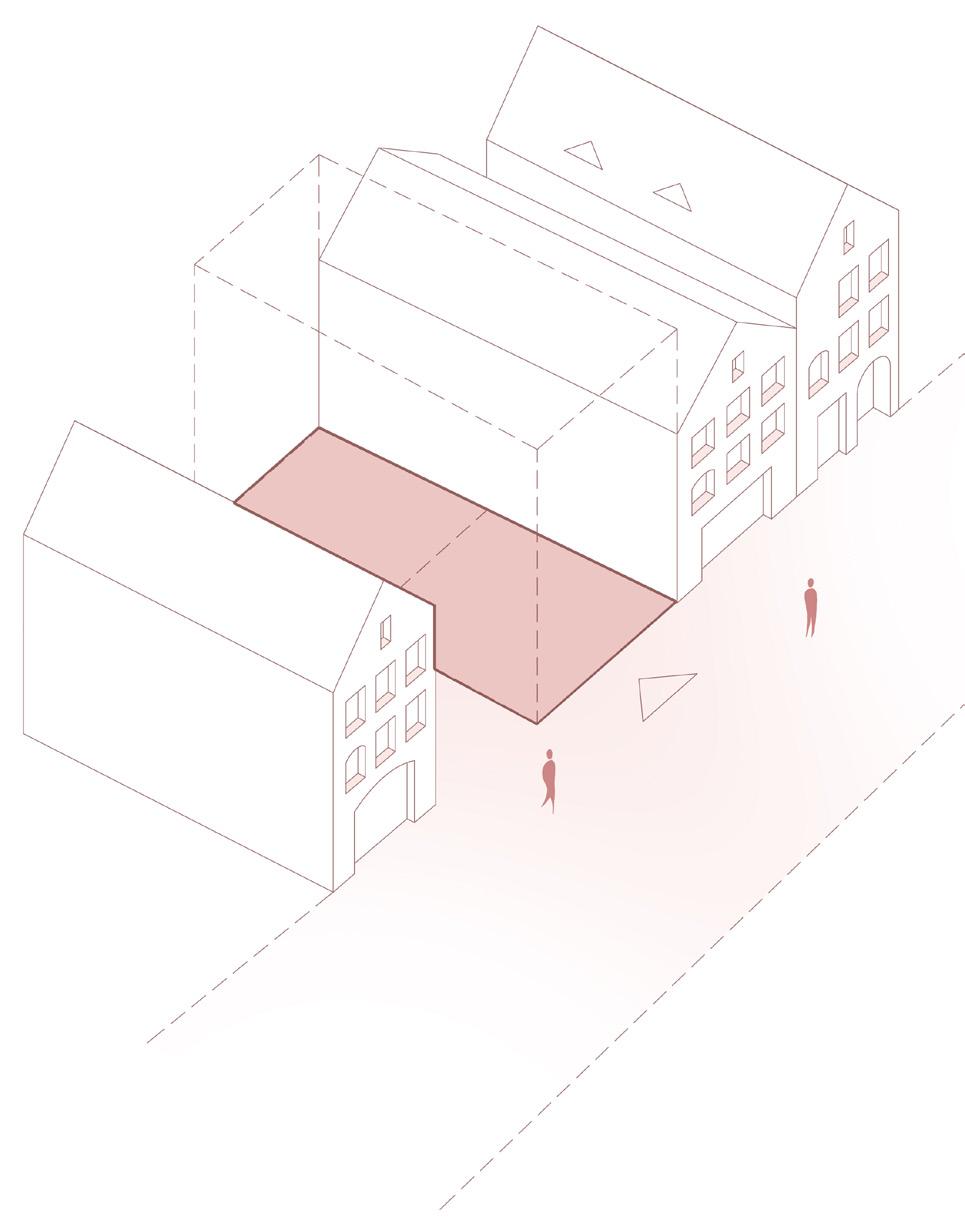

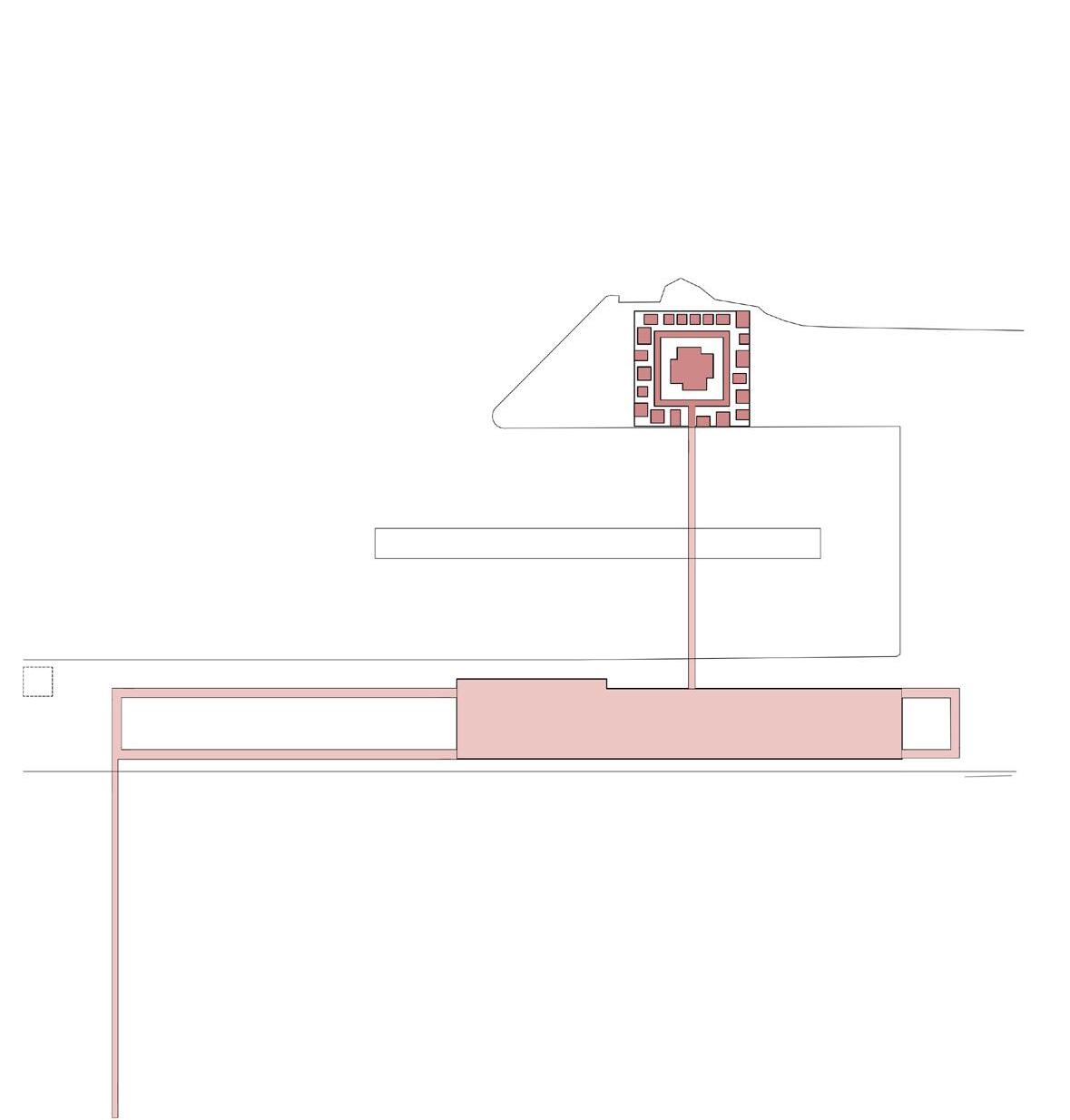

Design placement 118 - 145

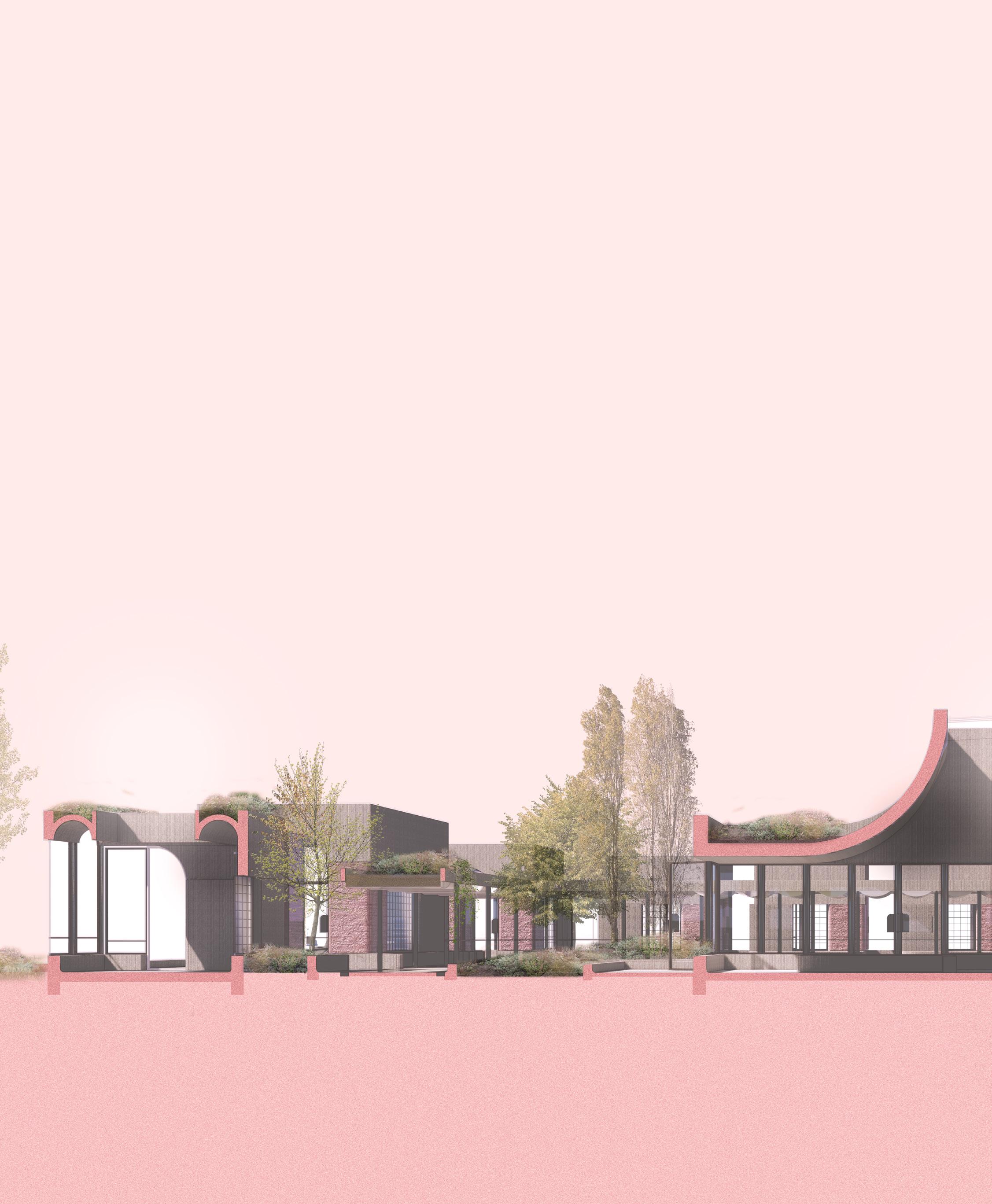

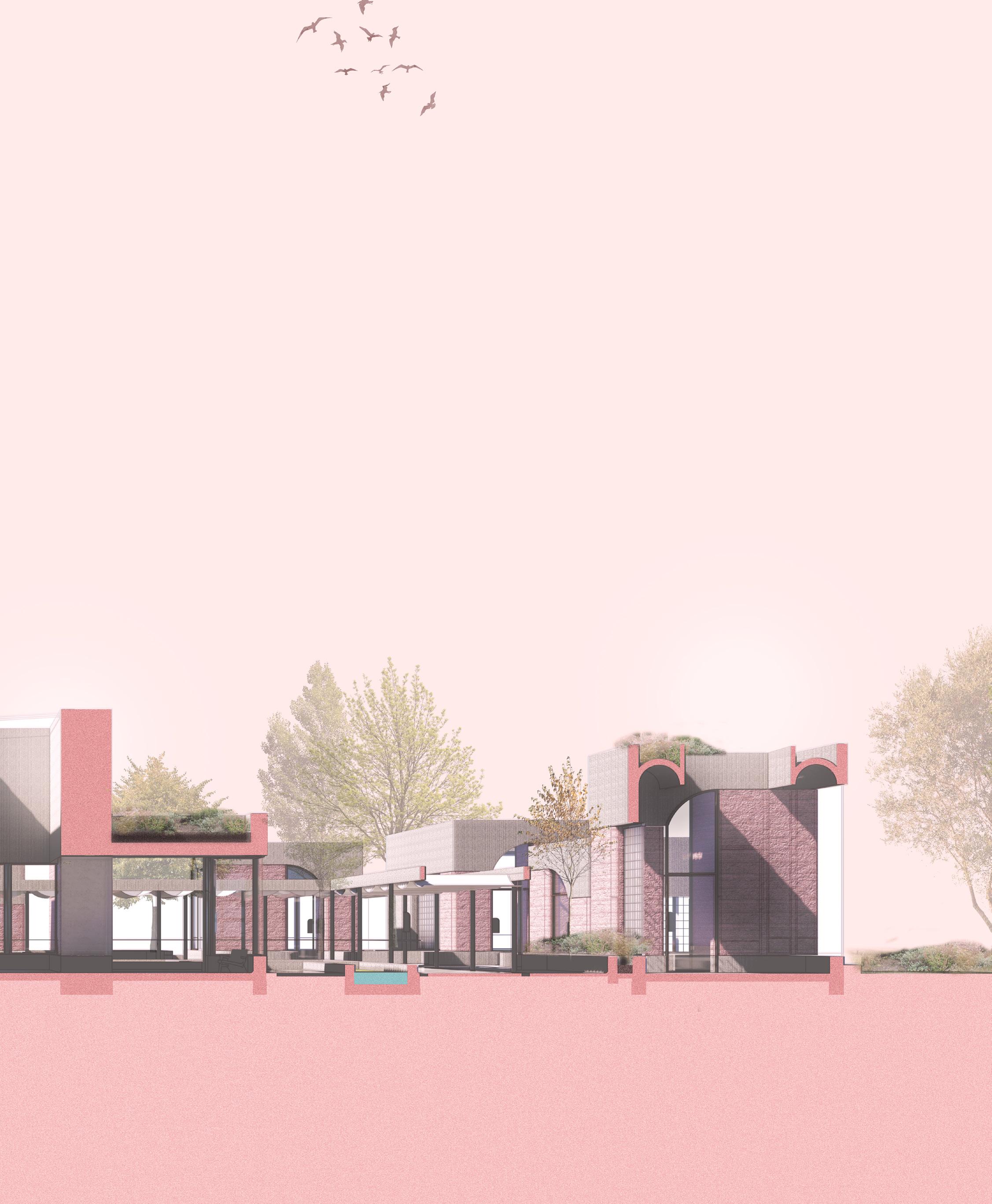

Architecture - a journey 146 - 215

Bibliography 216 - 221

Introduction Personal story

A personal view

If you were to wake up tomorrow without the vision in one eye, a desperation may fall upon you. If this were to happen, the next steps are obvious: check again, confide in someone you trust, and seek immediate medical attention. Many ophthalmology departments within hospitals all over the world consist of the same banal, even overbearing, un-inspired and closed labyrinthine architecture of endless complexity. These building are purely functional; they serve many specific purposes relating to the eye and visual health. Waiting within these spaces is not a moment of calm, it is a gut wrenching wait to find out what is going wrong with your vision, and more importantly, if it can be fixed. At the same time, you are surrounded by people of a similar disposition, some young, many old, and all moving around with a weight on their chests. Much like the ophthalmology buildings themselves, the eye as an object is extremely labyrinthine and endlessly complex. This complexity allows for there to be thousands of eye conditions, with some visual defects being physically understood from a physiological perspective, but not from an underlying cause perspective. A patient can, therefore, understand what is happening with their vision, the mechanics of vision loss, but remain with many unanswered questions.

As you leave the ophthalmology department with a diagnosis and perhaps treatment – if there is one – a next step of vision loss begins. A brief consultation with an ophthalmologist covers the biological issues surrounding vision, but it leaves behind may facets of vision loss which lie without its remit. This is particularly the case with mental health. It is not the job of an ophthalmologist – the engineer of the eye – to delve into the mental implications of visual impairment, of which there are many: “shock, anger, sadness and frustration to depression and grief” are but a few detailed by Action for Blind people, a UK based charity.

12

The loss of vision is like many other chronic diseases, the physical ailment is rarely alone, and perhaps less damaging than its inherent mental complications. However, unlike many other chronic illnesses, the loss of vision is arguably the most feared. In the USA, a study found that blindness was the chronic illness Americans feared most, even more so than Cancer or paralysis (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020). Clearly, if a person becomes visually impaired, this fear can manifest itself through a variety of mental health and wellbeing challenges.

This topic has a significant level of personal importance to me. Although visual impairment and blindness affects predominantly the elderly, it can also affect young people. I have early onset macular neo-vascularisation. It started in September 2019 as a small blind spot in the central vision of my left eye, which every day for the following 3 months would increase in size. I became scared to open my eyes in the morning because of the fear I had lost more vision.

Two years later, and I am still suffering from the mental and physical effects of my new visual impairment. From small things, such as my inability to catch objects when thrown, to greater fears, progressive vision loss is damaging in numerous aspects of daily life. Regardless, the traumatic process of losing my vision and having to adapt mentally and physically to a deteriorating vision was challenging, exhausting, and unsupported. I received a flyer with some light advice about life as a visually impaired person. It is not enough.

I feel that not enough is being done to help people suffering from vision loss. It is a topic that I have experienced first hand, an experience that has left me coping with the damaging effects of visual impairment.

On the other hand, however, I am pursuing this topic as it is a reflection of who I am as a designer and future architect. I believe that architecture can be a tool to help people suffering with visual impairment, and this is the reason I am translating this challenging personal and societal affliction into an architectural response.

Visual Impairment

Visual Impairment

An unseen problem

Visual impairment is a very broad term varying in definition. A typical definition can include many common visual issues, such as near and far sightedness – myopia and hyperopia. Indeed, with these parameters, the total number of visually impaired around the world is approximately 2,2 billion, with 1 billion of these cases resulting from preventable, or untreated visual problems (World Health Organization, 2021).

However, in the context of this project, visual impairment has a more limited application, defined in line with the University of Pittburghs department of ophthalmology definition, simply being: “vision impairment means that a person’s eyesight cannot be corrected to a “normal”level” (University of Pittsburgh, n.d.)

Indeed, this definition would exclude near and far sightedness, as these can – typically – be corrected with glasses, lenses or surgery. The International center for eye health utilizes the World Health Organization’s standard definition of visual impairment, which is a visual acuity reading of 3/60. This means that a person is visually impaired if they see in 3 feet what a person with healthy vision can see in 60 feet. With this stricter definition in mind, it is estimated that there are 253 million people globally with visual impairment, of which 36 million are officially blind, meaning they have almost no vision at all. (Vaishali & Vijayalakshmi, 2019)

16

These more severe forms of visual impairment can be caused by a multitude of preventable and non-preventable visual conditions and diseases. However, the leading global causes of visual impairment and blindness are: cataracts, Age related macular degeneration, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, corneal opacity, and trachoma. (World Health Organization, 2021)

Regardless of the cause, visual impairment is a more common issue than many would believe. The United Nations Population Fund currently tracks the global population at approximately 7,875 billion. This means that approximately 3,2% of the world population are visually impaired with this stricter definition.

(World Population Dashboard, n.d.).

The proportion of visually impaired individuals to the rest of the population has, for many years, been decreasing. However, by 2050, it is expected that there will be approximately 703 million people suffering from visual impairments. This is a 277% increase on current figures. This is out of proportion with the expected population growth of 123% from 7,875 billion to 9,7 billion by the same time. This increase will largely be attributed to an aging population. Indeed, although the average visual impairment rate is 3,2%, or 1 in 30, currently 1 in 9 people over the age of 60 are visually impaired or blind, and 1 in 3 people over the age of 80 are visually impaired or blind. (Ackland et al., 2018)

Visual impairment, besides personally damaging, is extremely burdensome on society as a whole, and is estimated to cost up to $244 billion dollars annually in lost productivity. This problem is only set to grow into the near future with the expected rise in the global visually impaired and blind populations. (World Health Organization, 2021)

17

Mental Health

Mental health

A crisis clear to see

Growing rates of visual impairment, blindness, and lost productivity, while concerning, do not present a complete picture. Fundamentally, people with visual impairments are statistically more likely to suffer from mental health conditions, such as anxiety or depression (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020).

In the UK, a study found that within the average population where healthy vision was observed. 4,6% of respondents had depressive symptoms. However, in a sample of visually impaired respondents, they found this number to by higher, at 13,5%. (Nollett et al., 2019). This indicates that, in the UK, the visually impaired population experience depression at 3 times the average rate.

Another study in the Netherlands found that, although the overall prevalence of clinical depression was 5% for the visually impaired, they acknowledged that a third of visually impaired people studied had ‘subthreshold depression’, which is characterized by depressive symptoms not necessarily attributed to a mental condition. Within the same report, it was also highlighted that 7% of visually impaired respondents had an anxiety condition. (van Munster et al., 2021) Indeed, when considering “depressive symptoms” as a measure of mental health rather than clinically diagnosed conditions, a study in Australia found that 37% of visually impaired adults had depressive symptoms, and a study in the UK found this number to be higher at 43%. (Nollett et al., 2019 page 2)

20

Consequently, it has been proven that adults with visual impairments are at a higher risk of suicidal ideations. This risk increases as the severity of visual impairment increases. (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020) This is specifically true for the elderly visually impaired population, who are 3 times more likely to commit suicide than the general population.

(Nollett et al., 2019)

It is clear that members of the visually impaired community suffer from mental health issues at a higher incidence than the general population. However, these statistics represent numerous cumulative factors, specifically the severity of the visual impairment, the form in which the impairment manifests, and social factors.

Studies have shown that more severe visual impairment results in a higher incidence of depressive symptoms compared to more mild cases of visual impairment. Therefore, in principle, the less a person can see, the more depressive symptoms they exhibit. (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020). Interestingly, although depressive symptoms seem to increase proportionally with the severity of visual impairment, this relationship is not shared with anxiety and nervousness. Indeed, in a study of newly diagnosed glaucoma patients, it was found that 35% suffered from severe anxiety, this was even though they retained relatively unimpaired vision at the time of the study. (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020, page 3) This conclusion establishes that even

when visual impairment is not debilitating, mental health implications can arise even from a simple diagnosis.

The form and disease in which visual impairment manifests can also have an impact on a patient’s mental health. It has been established that different forms of visual impairment influence mental health and depressive symptoms in varying ways, although the extent to which this is the case is lacking definitive conclusions. For example, it has been established that sufferers of Pseudoexfoliative glaucoma were more likely to suffer from depressive symptoms than sufferers of open angle glaucoma. The key difference between the two forms of glaucoma Is that the Pseudoexfoliative is considerably faster acting and has less treatment option, although the resulting visual impairment has a similar appearance. Pseudoexfoliative glaucoma is rapid and traumatic, explaining the elevated presence of depressive symptoms (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020).

21

The speed in which vision loss occurs is an important factor in explaining depressive symptoms within the visually impaired. The rapid loss of vision can upheave a person’s way of life overnight. This may also explain why people with congenital visual impairment - visual impairment from birth - are at a lower risk of mental health issues than people developing visual impairments in later life. It is theorized that people that lose vision in later life, rapidly or otherwise, must readapt and relearn skills, contributing to depressive symptoms. (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020)

It is estimated that only 10% of the visually impaired have no light perception, meaning that they see nothing. (Ruthstein, 2016) Indeed, an area which has not been widely explored is how the appearance of visual impairment, which varies disease to disease, impacts a visually impaired persons mental health. However, if we take into consideration the previous findings of the severity in visual impairment against several common eye conditions, we can begin to draw some conclusions on the visual form of visual impairment that could be more damaging.

The leading causes of visual impairment in the UK are, in decreasing prevalence, Age related macular degeneration ARMD, Glaucoma, Diabetic retinopathy, Myopic degeneration, and optic atrophy. In all of these diseases, it is not common for an individual to be completely blind, and it is likely they will retain some form of vision.

However, the form in which that takes varies, and the inflience this may have on mental health is also highly specific.

Social factors also play a significant role in visual impairment and its associated mental health challenges. A study of visually impaired outpatients found that there could be a higher risk of depressive mental health issues in individuals living alone, and that have little social support networks. This is further compounded by age. The same study pointed to an elevated risk of mental health issues if the visually impaired person is younger in age.

(Nollett et al., 2019)

Indeed, according to the The Royal National Institute of Blind People Scotland, 2015 report by the Royal national institute for the blind UK, visually impaired younger people are at a higher risk of mental health issues. Furthermore, a comprehensive report into the experiences and opinions of the blind and visually impaired in the UK found that optimism and hope feature heavily in the conscious of the average visually impaired person. 31% of respondents said that they were “rarely or never optimistic about the future”. They found this to be the case specifically in the older visually impaired population. Furthermore, 26% of respondents stated that they “rarely or never felt useful”, and a further 19% stated that they “never felt relaxed”. (The Royal National Institute of Blind People Scotland, 2015)

22

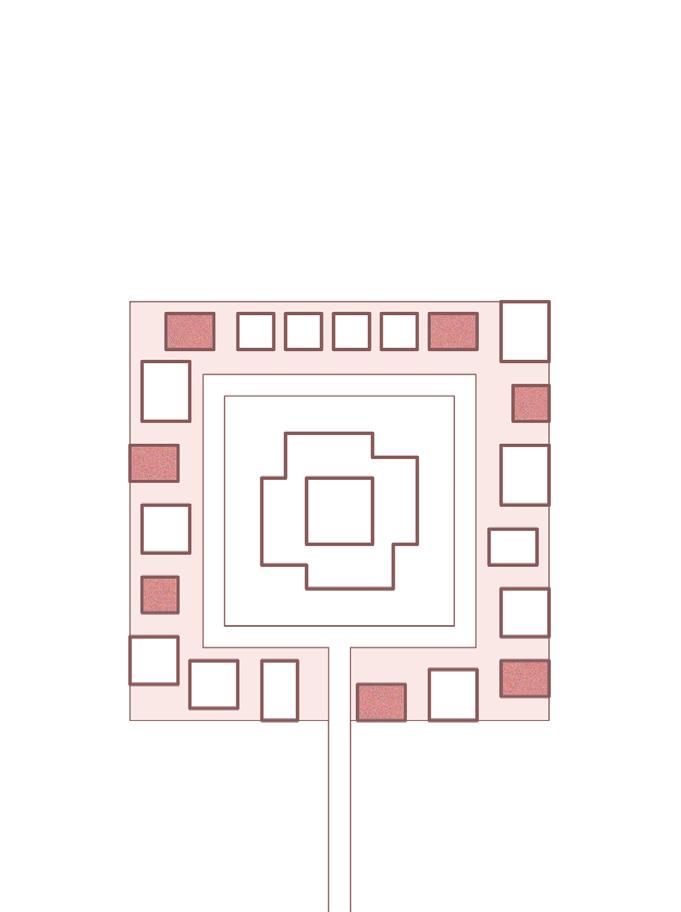

Macular Degeneration (ARMD), Myopic degeneration, and optic atrophy

This is a representation of a visual impairment caused by Age related Macular Degeneration (ARMD), Myopic degeneration, and optic atrophy. These diseases are characterized by their attack on the macular in both eyes, albeit sometimes at different times. This is a very small part of the Retina which is used to see fine detail. We use this part of our eye to read, write, recognize faces and draw. These conditions effect the macular in different ways, but the result usually is a central blind spot called a scotoma. This blind spot can vary in size, color, and density, but remains as a fixed and incurable scar in the central vision. In most cases, the peripheral, or side, vision is unharmed by these conditions, meaning that people can rely on this vision to navigate. This form of visual impairment is likely highly damaging and severe for mental health as it is a dramatic and fast acting vision loss that drastically limits the capabilities and independence of an individual to carry out standard daily activities and can limit their opportunities to work and study. Indeed, a study found up to 44% of Age-related Macular Degeneration (ARMD) patients displayed medium to severe depressive symptoms. Although this condition is bilateral, meaning it effects both eyes, it may not affect each eye symmetrically. Indeed, in such a case, 30% of ARMD patient exhibit severe depressive symptoms with the development of the disease in their other (healthy) eye. (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020)

25

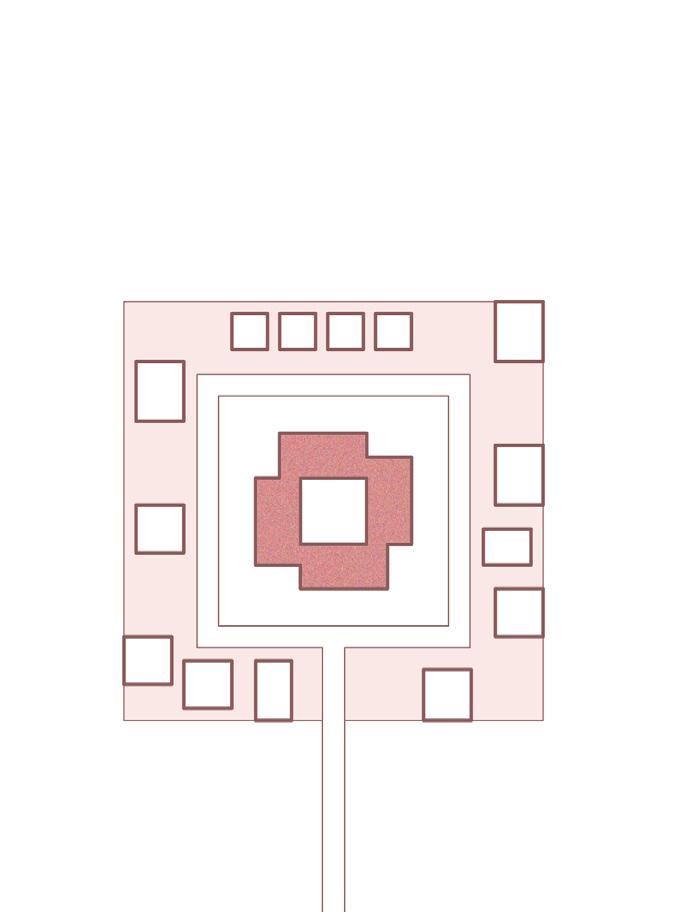

Retinitis Pigmentosa

Retinitis Pigmentosa

Here we are seeing the visual impairment caused by Glaucoma and another disease called Retinitis Pigmentosa. Here, the opposite is the case from the previous examples. Here the central, or macular, vision is untouched, and it is the rod and cone cells of the outer peripheral vision that deteriorate, causing blindness to the sides of your central vision. These conditions are characterized by their progressive nature. This is specifically the case of Retinitis pigmentosa, which often results in severe tunnel vision. However, unlike the rapid acting disease of the previous image, these are generally slower acting diseases presenting themselves over decades. In most cases, visually impaired people with these conditions retain some form of central vision late into life. This slow progression and retention of central vision may decrease the severity of mental health issues present.

27

Diabetic retinopathy

This image depicts the potential visual impairment of someone with Diabetic retinopathy. In this case, visual impairment is characterized by many smaller blind spots caused by damaged blood vessels in the eye. These blood vessels are damaged as a result of untreated, or poorly managed, Diabetes. This condition takes many years to develop, but the damage is irreversible. Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness in the working age population of the UK and is preventable through diet and proper diabetes management (The Royal National Institute of Blind People & NHS Glasgow and Clyde, 2010). The nature of this disease can change from person to person, and therefore, the severity and location of the visual impairment can vary. Therefore, the mental health consequences of this form of visual impairment are hard to define, however we can assume that there could be severe anxiety responses to this form of visual impairment due to its unpredictability.

29

Mental health

Why is this happening?

It is clear that visual impairment has significant impacts on mental health within the visually impaired community. Therefore, it is valuable to understand the underlying causes of these mental health issues. Although mental health problems relating to vision loss are experienced by many and through different means, it has often been compared, in the academic community, as a similar sense of loss as to that of a bereavement. In a report by Demmin and Silverstein, Vision loss related mental health problems were succinctly categorized into 3 themes: vision loss related distress, a reaction to the inability or complication of completing everyday tasks, and mental health reactions to visual treatments.

(Demmin & Silverstein, 2020)

As previously established, one of the largest mental health issues afflicting the visually impaired is Depression and depressions related symptoms. Through several studies, it has been established that the initial mental trauma of vision loss, and how it physically manifests itself in what a patient sees, can often be considered a precursor to depressive symptoms. It has been reported by visually impaired individuals that feelings of embarrassment, shame, frustration, anger, and social withdrawal, often accompany distress following visual deterioration.

These reactions to vision loss are often seen in visually impaired patients with depressive symptoms. Anxiety is another common issue faced by the visually impaired. For people with chronic visual illnesses, such as Retinitis Pigmentosa, the perceived pace of

30

visual deterioration is a leading cause of worry and anxiety. Indeed, the fear of further future vision loss is a leading cause of mental distress. (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020 page 5)

Furthermore, mental health issues in the visually impaired community are somewhat unique in their long term impacts. It has been noted that mental health issues, within the visually impaired populations, can cause something of a ‘snowball’ effect, in that visually impaired individuals often react to their depressive and anxiety related symptoms in a myriad of destructive ways. Indeed, patients suffering from depressive symptoms often self-reported their vision to be worse than actuality, when compared to ophthalmological examinations. This more severe outlook on personal health, in turn, causes more mental health distress. This depressive cause – effect relationship not only effects the mental health of the visually impaired negatively but may also harm their visual health through instigating negative health practices, such as poor diet and non-compliance with medical treatments ((Demmin & Silverstein, 2020)page 5).

Concurrent with the mental health distress caused by the physical presentation of visual impairment, the challenges these impairments impart on the daily life activities of the visually impaired also negatively impacts their mental health. So called ‘ADL’s’, or ‘activities of daily life’ are what most people would consider mundane tasks that are rarely given a second thought (Edemekong et al.,

2022). Specialty, this term was devised by Sidney Katz in the 1950s, to describe 12 components of every day living that provide a framework to describe an individual’s ability to function without assistance. These components cover many aspects, but fundamental activites are moving freely, feeding, clothing, and washing oneself appropriately and in correspondence with one’s context. In addition, Katz defined further considerations as ‘instrumental activities of daily life’. These are described as more complex, and requiring further consideration. These include, for example, transportation, driving, managing finances, managing communications, housecleaning and meal preparation. (Edemekong et al., 2022).

In general, and not specifically to the visually impaired, it has been established that the Inability, or a restriction, in the fulfilling of these ADL’s can lead to mental health issues and depressive symptoms. However, visual impairment diverges from other disabilities due to its impact on all of the considered ADLs (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020 page 5).

Although it has been noted that a person’s mental reaction to the physical condition of visual decline can create a ‘snowball effect’ with depression, so too is the case for mental health problems relating to the incapability of undertaking ADLs. Indeed, both depression and Visual impairment individually can lead to a decrease in our ability to perform ADL’S, however combined they can become more severe.

31

Another important consideration is that with a reduced ability to function independently, it can become more challenging to remain socially and communally active, which has been shown to put people at a higher risk of mental health issues. Perhaps most challenging, is the impact visual impairment can have on employment and study opportunities.

It has been established that the loss of access and contact to professions and activities core to a person’s identity can have severe mental health implications. Indeed, the inability to work is a risk factor in developing depression and anxiety as a visually impaired individual. These circumstances are especially problematic in the visually impaired population of working age, where the risk of depressive symptoms is higher due to a perceived lack of optimism for their futures (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020 page 5). Furthermore, the inability to work causes other concerns. For example, in the UK where only 22% of the visually impaired are in employment, 39% of the blind and partially sighted population say they struggle to meet ends meet financially. Of course, this limitation and financial stress can also impact an individual’s mental health. (The Royal National Institute of Blind People Scotland, 2015)

Lastly, in combination with the reaction to visual impairment and the impacts visual impairment may have on our daily lives, certain treatments for visual conditions may also induce mental health

problems. Indeed, for some conditions, such as Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD), the treatment of interocular injections – injections straight into the eye – can cause severe anxiety related reactions, due to the perceived pain and discomfort caused by these injections. In the case of AMRD, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors (anti-VEGF) injections, are used as a last resort to stop the growth of abnormal blood vessels in the eye, a leading cause of visual impairment in the elderly.

Indeed, 56% of AMRD patients say they have anxiety over this form of treatment. Furthermore, patients with AMRD showed further anxiety of the treatment’s efficacy and safety, due to its nature as the only treatment for AMRD, and the fact that the drugs used were not originally intended for this purpose, but rather as a form of Chemotherapy for some cancers. (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020 page 5).

Furthermore, treatments for the mental health side effects of visual impairment can also be damaging for a person’s mental state. Indeed, studies have shown that traditional forms of anti-depressant medication, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants, may in fact elevate a patient’s risk of some forms of visual conditions, specifically angle-closure glaucoma (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020 page 5).

32

Mental health

How are we treating mental health?

Notwithstanding the fact that visual impairment causes mental health issues, the treatments for said issues fall out with the remit of the traditional treatment path available for the visually impaired. Often, mental health treatments are specifically tailored to mental health issues as a singular condition, not as a consequence of another health issue, such as visual impairment. That being said, there are currently many treatment options utalised for general mental health issues. Primarily, these treatments fall into two categories, but can be implemented in tandem: talking therapies, and medications.

In the UK, many people rely on the National Health Service (NHS) for mental health support. Currently, many forms of talking therapy form the backbone of this service, through which services such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), Guided selfhelp and counselling cover many different mental health conditions. Specifically, Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the most practiced mental health treatments in the UK, where the focus is to actively engage patients to recognize negative patterns in their behavior in order to address them. This form of therapy is usually practiced by patients suffering from anxiety and depression, but it also has other uses. Many of the talking therapy forms practiced by the NHS, and beyond, revolve on a 1 to 1 model, but some are also offered in group settings, depending on the support being provided. (Mind, 2017) (NHS website, 2021)

34

Alternatively, medications can offer some support to people with mental health conditions. They are, however, not a cure or treatment, rather a symptomatic suppression medication. For depression and Anxiety, it is common for patients using the NHS to be prescribed anti-depressants. These are used to allow people to continue to function in their professions and personal lives meanwhile controlling symptoms of their mental health issues. (Mind, 2017) (Mental Health America, n.d.)

Both talking therapies and medications have been shown to aid people suffering from general mental health issues as a primary issue, which – in theory – can help members of the visually impaired community. Although there are no dedicated visual impairment mental health treatments perse, there are other strategies in place tailored for the visually impaired and other sufferers of chronic illness. where mental health issues may be of concern.

Self-management interventions (STI) are one such form. SPI relies of patients of a condition, such as visual impairment to take ownership over their condition and its progress. Specifically, SPI encourages chronic illness sufferers to closely watch the progession of their condition, and react to changes to both physical and mental issues. A criticism of this form is that it potentially places too much of a burden on the individual, especially at moments which are challenging. (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020) Similarly, Problem solving

intervention (PST) relies on personal agency on behalf of the patient, to identify problems they are having, define ambitions and potential solutions, and reflect on their progress. (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020)

Although potentially helping patient deal with emotionally or mentally distressing situations, their effectiveness on helping patients cope with mental health challenges is questionable. Furthermore, these options do little to address the key social mechanisms causing mental health issues in the first place. To that end, Visual rehabilitation is a form of practical intervention utalised to help people, specifically sufferers of visual impairment, to relearn how to do activities of daily life (ADL) with their new impediments. This revolves around teaching patients how to use assistance devices, travel safely, and move independently. This method may not directly respond to the mental health needs of the visual impaired, however, it focuses on a key component of why the visually impaired suffer from mentla health issues; being the ability to complete activities of daily life (ADL). (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020)

35

Innaccessible care

The problem

The Problem

Inaccessible care for the visually impaired

The current mental health treatments and strategies available would appear to be a positive option for members of the visually impaired community, if only they were actually accessible. The harsh reality of mental health support for the visually impaired is that, at best, it is deficient, and at worst, nonexistent. For people suffering from a mental illness as a primary health issue, their treatment is direct. For people with visual impairment, their visual health condition comes first, and their mental health complications second, if at all.

A study from the Netherlands found that more than half of people suffering from general visual impairment do not receive any form of mental health treatment for depression or anxiety, even with these treatments being available to them. (van Munster et al., 2021) A more detailed study of patients with Age-related Macular degeneration found that 91% had not received any form if mental health treatment or support. This is even though AMRD is well documented to cause mental health issues, not only relating to vision loss, but also to its treatments with interocular injections (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020). In another study of 143 visually impaired patients, it was found that although 12% had received antidepression medication, not one person received any form of talking therapy to help manage their visual impairment induced mental health issues (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020 page 8).

38

In the UK, It was found that, in general, only 17% of visually impaired and blind people received any form of mental health support during, or shortly after, their visual condition diagnosis. This is even though 2/3 of working aged people with visual impairment said that they would use this service if available to them (The Royal National Institute of Blind People Scotland, 2015). In Scotland specifically, of 400 blind and visually impaired people surveyed as part of a study, 63% were not offered mental health support, even though 83% suffered from mental health issues (TFN, 2019).

This disturbing reality about the unmet needs of mental health support for the visually impaired is a global and far-reaching problem. The core reasons for the lack of mental health support have been widely hypothesized, but several key themes repeat themselves: a lack of focus upon mental health needs within ophthalmology departments; a general lack of resources for mental healthcare, and a lack of pursuit for mental health treatment by the visually impaired.

In The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s report, ‘Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem’, it was concluded that health care providers should be actively monitoring patients for mental health issues, specifically because patients with chronic illnesses (not only visual impairment) which inhibit their physical functioning are at an elevated risk of mental health issues (Nollett et al., 2019). This

rarely appears to be the case in practice. It is clear, that in many parts of the world, primary health care providers – eye hospitals and ophthalmologists – do not have mechanisms in place to either identify, and therefore refer or treat patients for mental health issues. Furthermore, in previous studies, it has been found that eye care professionals do not have the relevant training, and therefore confidence, in treating people with mental health issues resulting from visual impairment, let alone identifying issues in the first place. This has widely been hypothesized as being a result of eye healthcare professionals focusing on the physical visual problem, not the adverse mental health side effects. (van Munster et al., 2021) Otherwise, it has been proposed that it is simply unfeasible for ophthalmologists to monitor or offer mental health support to patients as a result of their workload and limited time with patients (van Munster et al., 2021).

This speaks to a broader resources problem within general healthcare. It is estimated that 4% of the population of EU member states suffer from depression, and 5% with anxiety. Regardless, most counties in the EU struggle to provide appropriate and timely mental health care to people in need. In combination with existing societal stigmas relating to mental health, it is also clear that for many it is the cost of mental health treatment that creates insurmountable boundaries. For example, in Austria an average therapy session offered through the public healthcare provider costs €50, or approximately 4 hours’ worth of minimum

39

wage. In Italy, the average public therapy session is €19, or 3 times the minimum hourly wage, and in Denmark, the average therapy session costs €51, or again 3x the minimum hourly wage. In France, phycologists are not provided through the public health care system at all, forcing people in need to seek private health care options at their own expense. (DW, n.d.)

The issues facing mental health care accessibility goes further. There is currently an issue throughout Europe with extended waiting times for mental health treatmednt. Indeed, in many EU countries, a wait time of at least 1 month from first contact to appointment is common. In Germany, the average wait time is on average between 4 and 5 months, with some people waiting for more that half a year.

In the UK, for young people seeking mental health treatment the maximum waiting time from consultation to referral and treatment is 26 weeks, or almost 6 months. (Mental Health Foundation & The Scottish Government, 2016) In actuality, at least 1 in 4 people in the UK wait more that 3 months for mental health treatment (Campbell, 2020). Furthermore, according to the UK Royal College of Psychiatrists, up to 11% of people seeking mental health support had to wait more that 6 months for treatment. (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020) Significant wait time puts people’s mental health and lives in danger, as mental health problems are often time sensitive and can deteriorate quickly. Indeed, in the UK, extensive

waiting times have been attributed to 40% of people waiting for mental health treatment to resort to ‘emergency or crisis’ mental health services. (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020) . Significant waiting times for mental health treatment pose a problem throughout Europe, even in higher-income countries where resources for healthcare are more plentiful. However, one report in the UK found that medical practitioners indeed blame a lack of resources for ineffective mental health treatment (DW, n.d.):

‘Everything is cut to the bone; everyone does everything….being forced into greater efficiencies over the years is starting to tell; increased waiting time, increased triage and increase in crisis.’

(Mental Health Foundation & The Scottish Government, 2016)

It is not only an issue of health care providers and resources. It is also evident that the visually impaired themselves have difficulties in asking, or receiving, the mental health care they require. During consultations with eye care professionals, it is often the visual problem that forms the focus of discussion, and therefore the emotional and mental health needs of a patient are not discussed. Rather, there may be a focus on helping a patient with practical readjustment lessons to help relearn basic daily life skills. This may also be seen as in a roundabout means to helping a persons mental state, which may or may not be true. Indeed, at the time of diagnosis, the priority for most patients

40

is to address the visual problem at hand, through diagnosis and treatments (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020).

Consequently, it is also clear that patients may not even be directly aware of their mental health symptoms, or potential treatment options available to them. This usually guarantees that mental health concerns are not addressed at the time of diagnosis, arguably a time where mental health intervention is most necessary. It is also the case that many visually impaired and blind people simply ignore their mental health issues, and that there is a tendency to not ask for help because of an unwillingness to ask for mental health support, or to rely on support from others in general (van Munster et al., 2021).

Crucially, although a small majority of visually impaired and blind people receive mental health treatment and support, the form of mental health treatment also impacts whether it will be fully endorsed by the patient. For example, it is well documented that within the visually impaired community, anti-depressant medications, besides their potentially damaging visual side effects, are not a favored or necessarily effective method of mental health treatment. Indeed, although not widely available, many visually impaired patients prefer other psychological treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapy. (Demmin & Silverstein, 2020 (8-9

41

The concept Clinical + Social

A new approach

Clinical + Social

Visual impairment presents many clinical, personal, mental, and social challenges; many of which are currently being unaddressed. It has been proven that mental health within the visually impaired community is widespread and very damaging. The distress caused by vision loss itself, social isolation, anxiety over the future and personal finances, loss of purpose, and concerns about treatments, all compound each other into a complicated tapestry of mental health issues, which are not being addressed by conventional healthcare systems around the world.

Although a small share do received mental health support, it rarely addresses this ‘tapestry’ of issues that not only determine a person’s mental status, but also their general wellbeing – both inextricably connected. This blind spot in the care of the visually impaired community’s mental health and wellbeing is deeply concerning, but also presents several opportunities to change the way we look at care for the Visually impaired, their overall wellbeing, and their place in society.

The answer is to treat both the clinical aspects of visual impairments and the social aspects on an equal footing. By addressing both fafests of this layered problem in a single location, we can redefine how we look at care for the visually impaired, and therefore, care archtiecture for the visually impaired.

44

A new approach

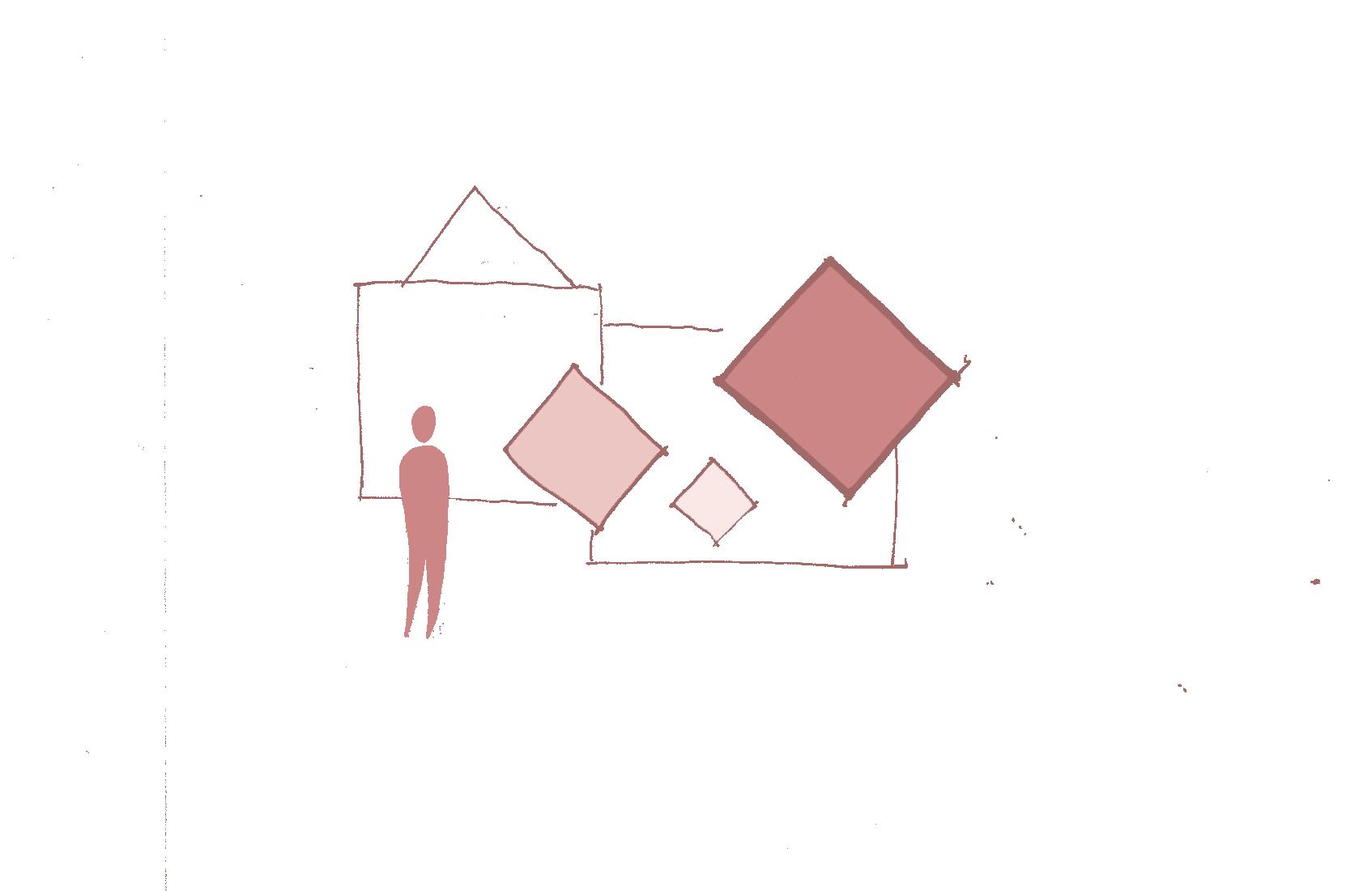

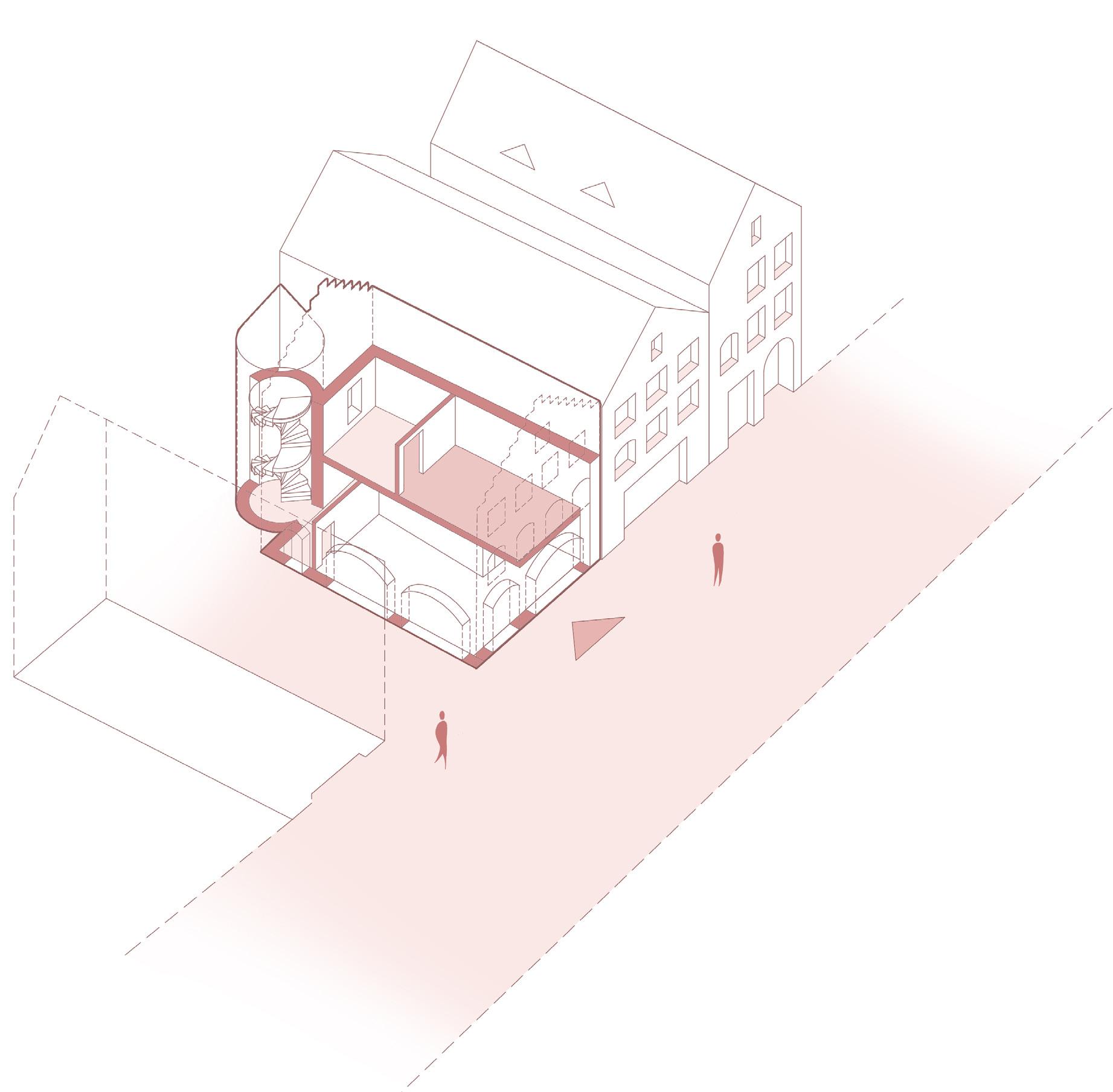

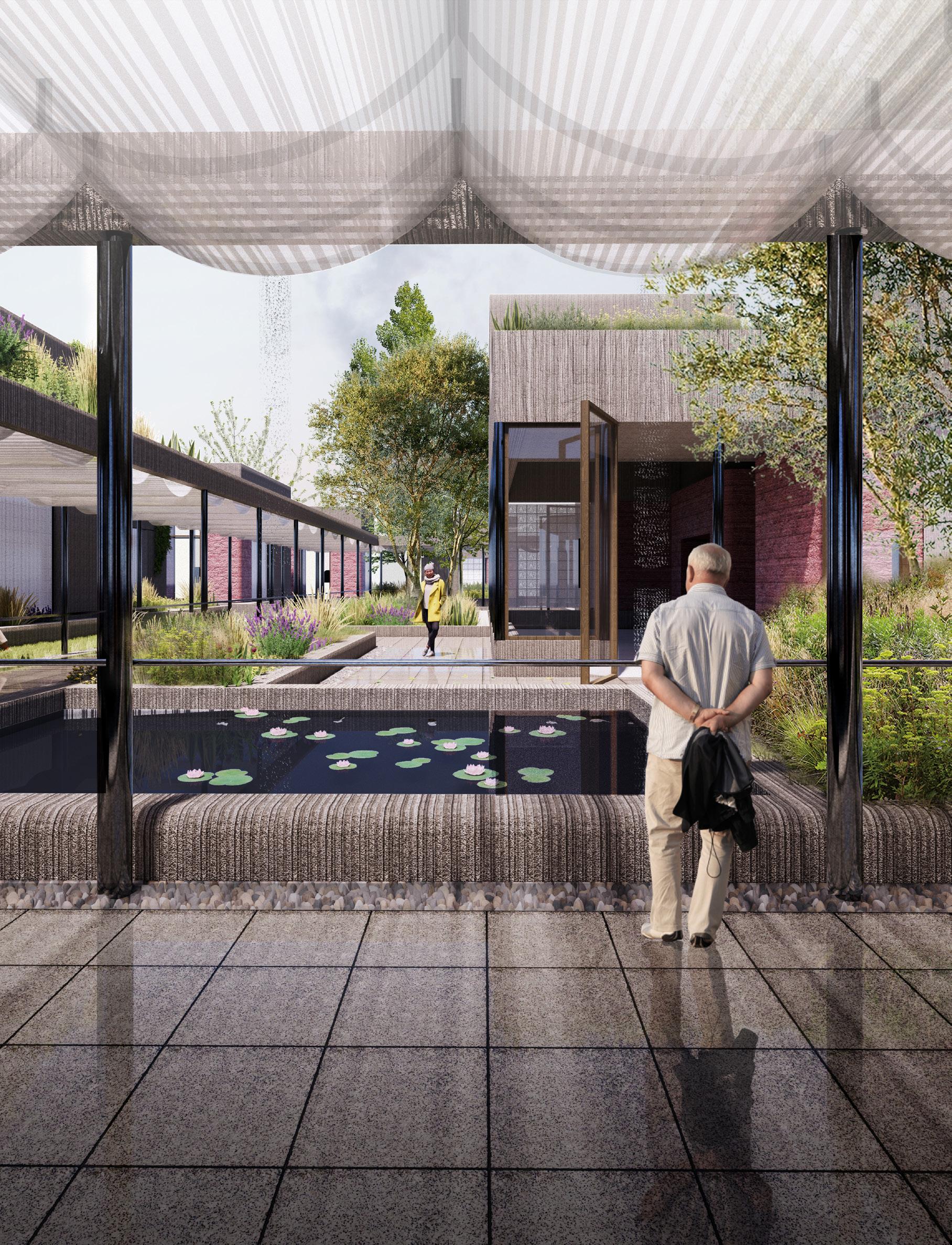

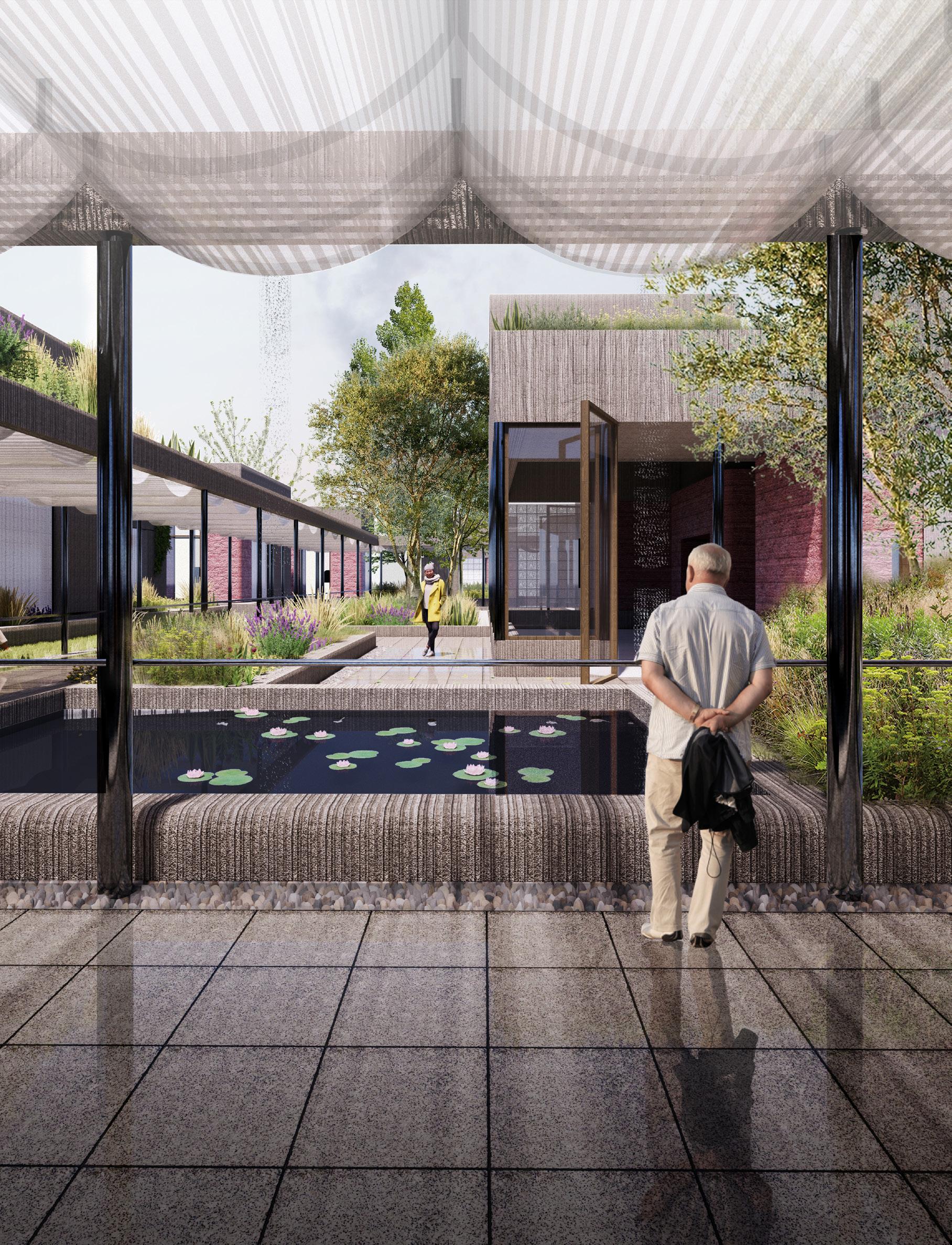

A new kind of eye hospital

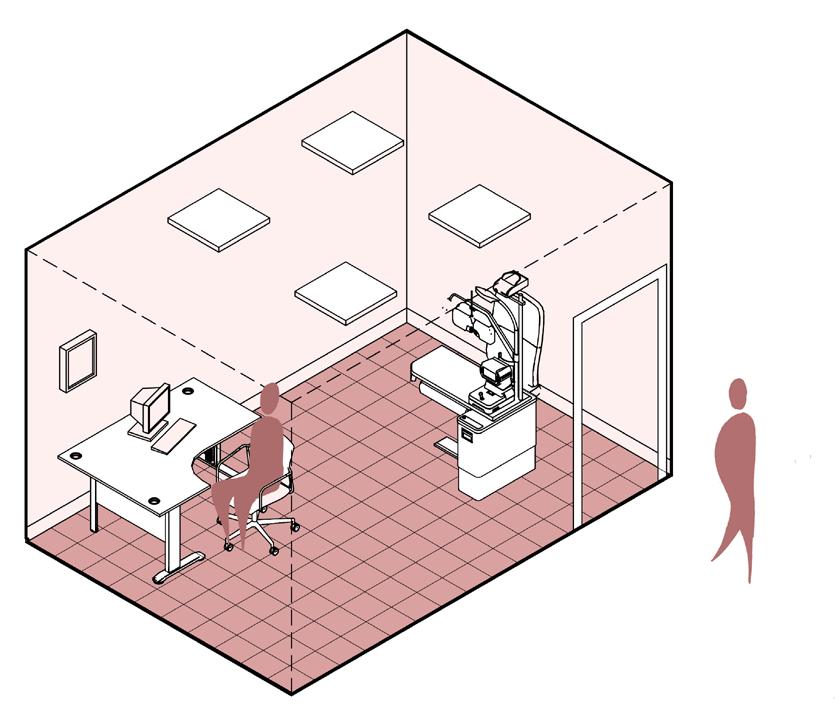

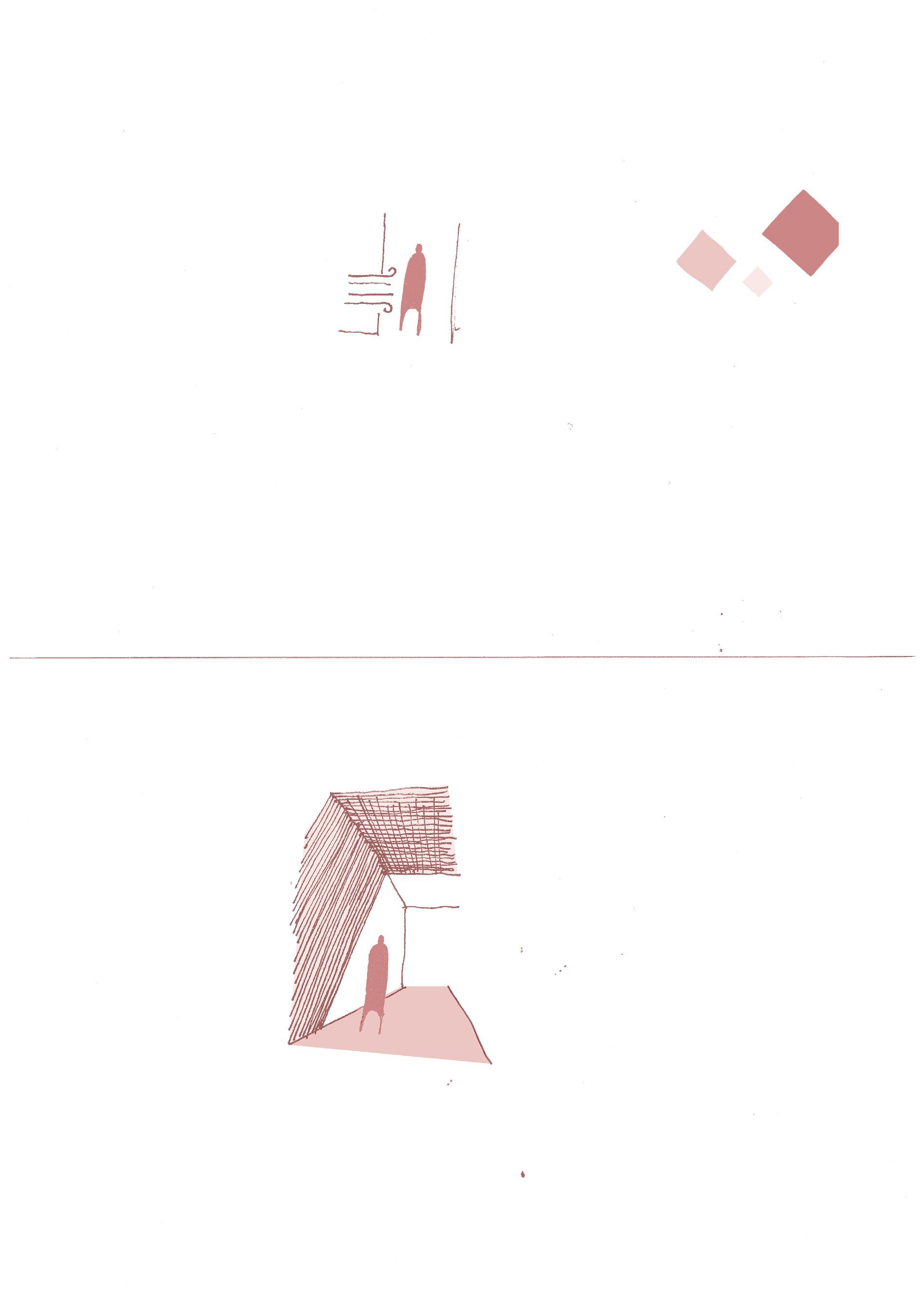

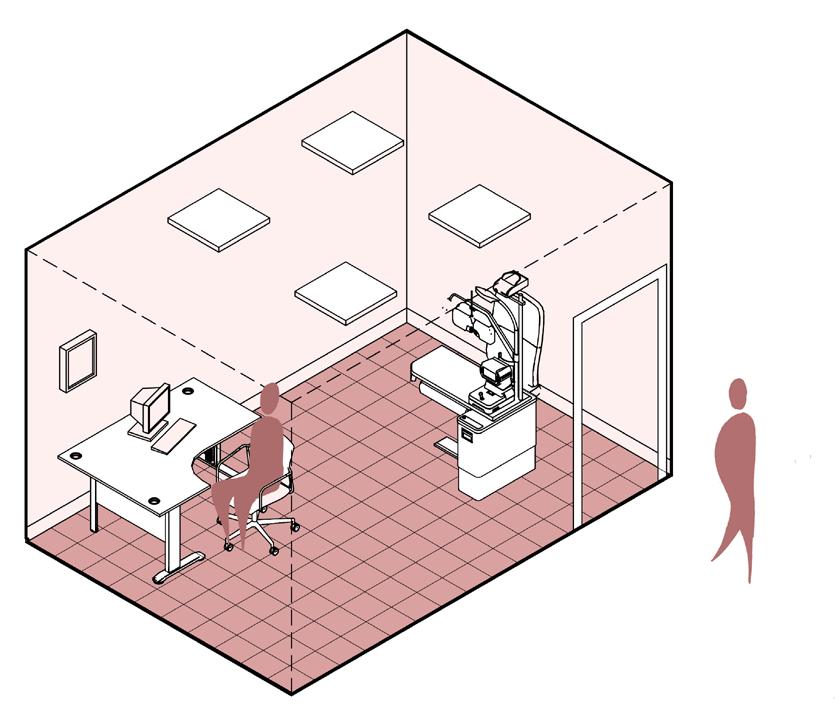

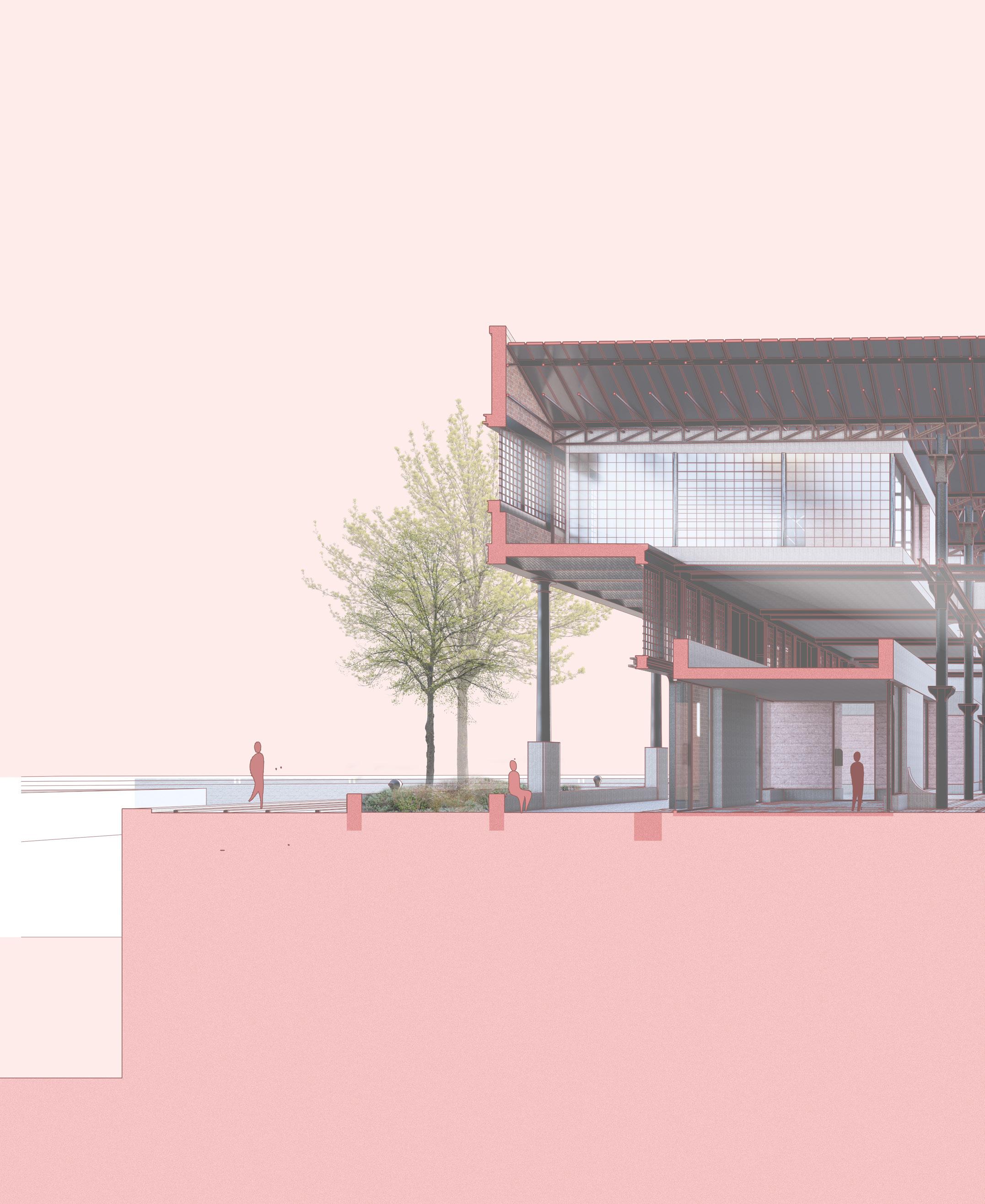

The current architectural norm for eye hospitals and eye departments within hospitals leaves much to be desired. Considering that mental health and wellbeing challenges start in these buildings, we should approach how they are designed in a different way. These spaces are crucial in changing how we define care for the visually impaired. A patient will arrive at an eye hospital already in a state of emotional stress. This stress is associated with the loss of vision, or stress for others, such as our child or loved one. These spaces are where patients go through the motions of testing, waiting, consultation and potential treatment. Each step of this process brings with it unique challenges, which can cause varying reactions.

Indeed, various forms of testing can be intrusive and mentlaly taxing, without giving direct answers. An an angiography fluorescein exam, for example, is the injection of a detectable dye into the bloodstream, which can be detected using certain devices. This is used to better understand the vascular structure of the eye and quickly identify issues. It can cause significant discomfort and stress, as the the dye is very cold, which you feel running through your body. Another test is an OCT and fieling test, which involves a patient sitting for an extended period of time without blinking. This can be very fatiguing. After these tests, there are usually extended periods of time where a patient has to wait for the results. This wait is also extremely anxious. The results from these tests are usually examined by a consultant opthalmologist (an eye doctor). From this review, patients will potentially be diagnosed. This diagnosis can further present

46

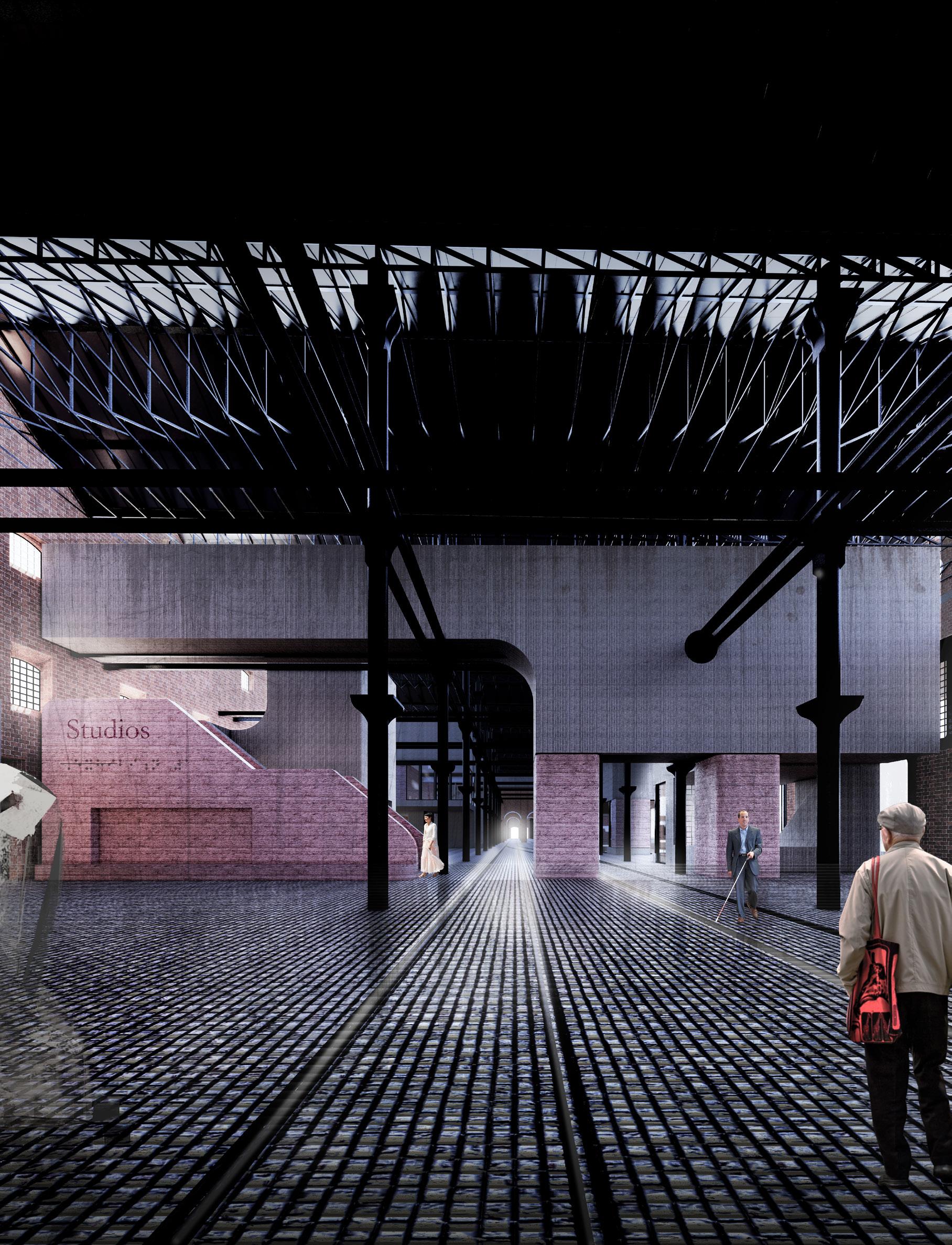

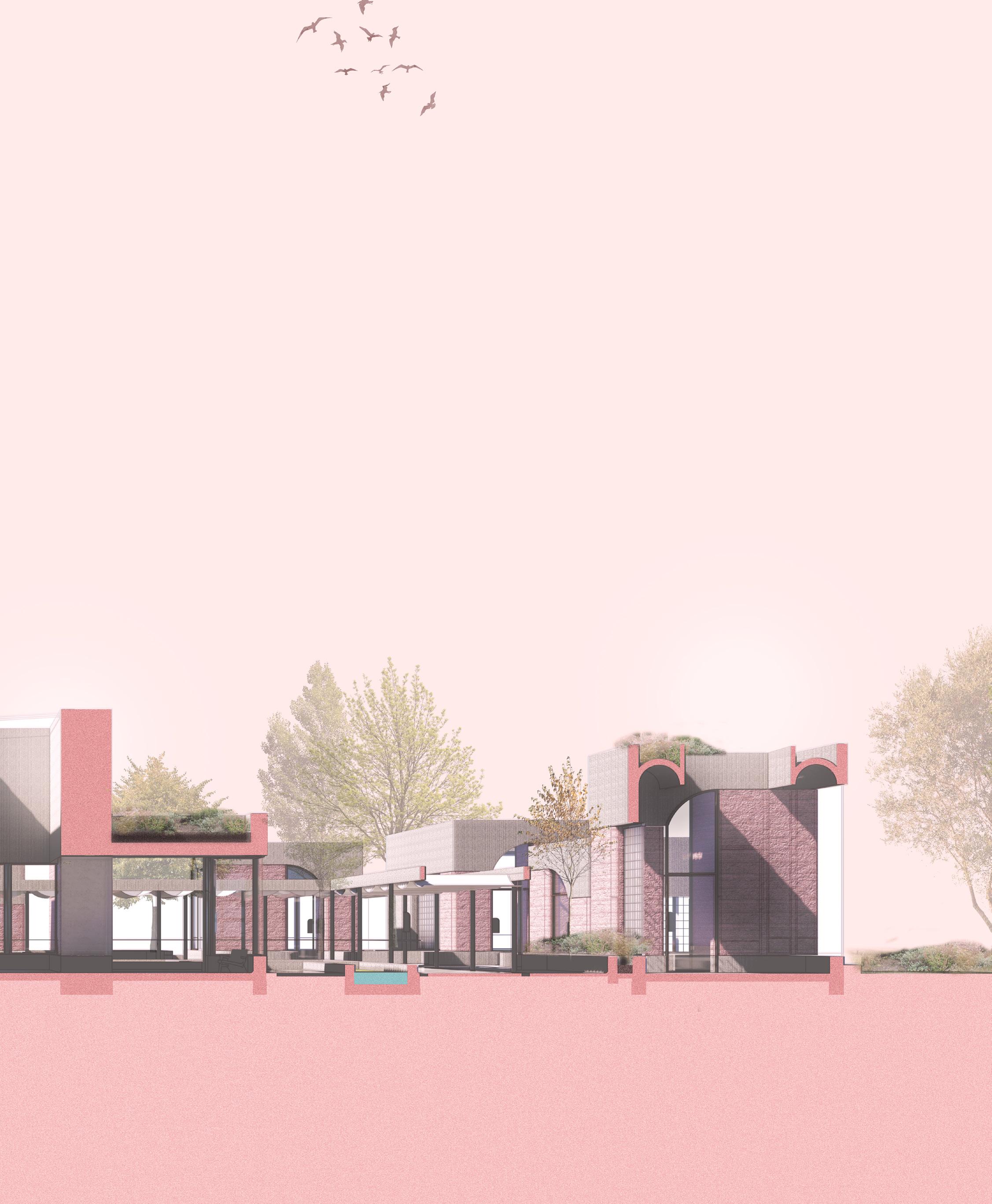

eye hospital architecture leaves much to be desired

Current

significant challenges for the wellbeing of a patient, as usually there is no time or space to process challenging information in safe and pressure free environment. This same conclusion also applies to treatments.

These challenging processes of visiting an eye hospital are compounded by tbe often hostile architecture in which they are housed. It is common to find that all of these processes are contained in a windowless complex of labaryinthine corridors, changes in level and interconnected spaces. As part of a survey, and from personal experience, it is well known that changes in level and unclear routing through a space pose some of the greatest challenges to the visually impaired. As these departments are the representaton of eye health, why are they not the representation of inclusive architecture for the visually impaired? Why are they not setting an example. These spaces shoudl be the embodiment of inclusive design for the visually impaired as to make the entire process as pain free as possible. A consequnce of these spaces is that they are claustrophobic and offer little opportunities to escape either visually (with a window), or physically outside. The feelings of being trapped is common. The spaces are not designed to spend time. When a person received devestating news, it is important that there is space to grieve in ones own time, meanwhile remaining in a safe environment. The eye hospital of today is a machine of efficiency. There is no space or time to allow a person to process their emotions, as there are too many other patients to manage, and there are no intermediate

spaces provided apart from the collective waiting areas. These waiting areas are a hostile space, too. The waiting areas should provide an opportunity to balance the introversion of grief with the collective support of a community. There is often, however, no community spirit in the common waiting room, only some chairs, magazines and a coffee machine.

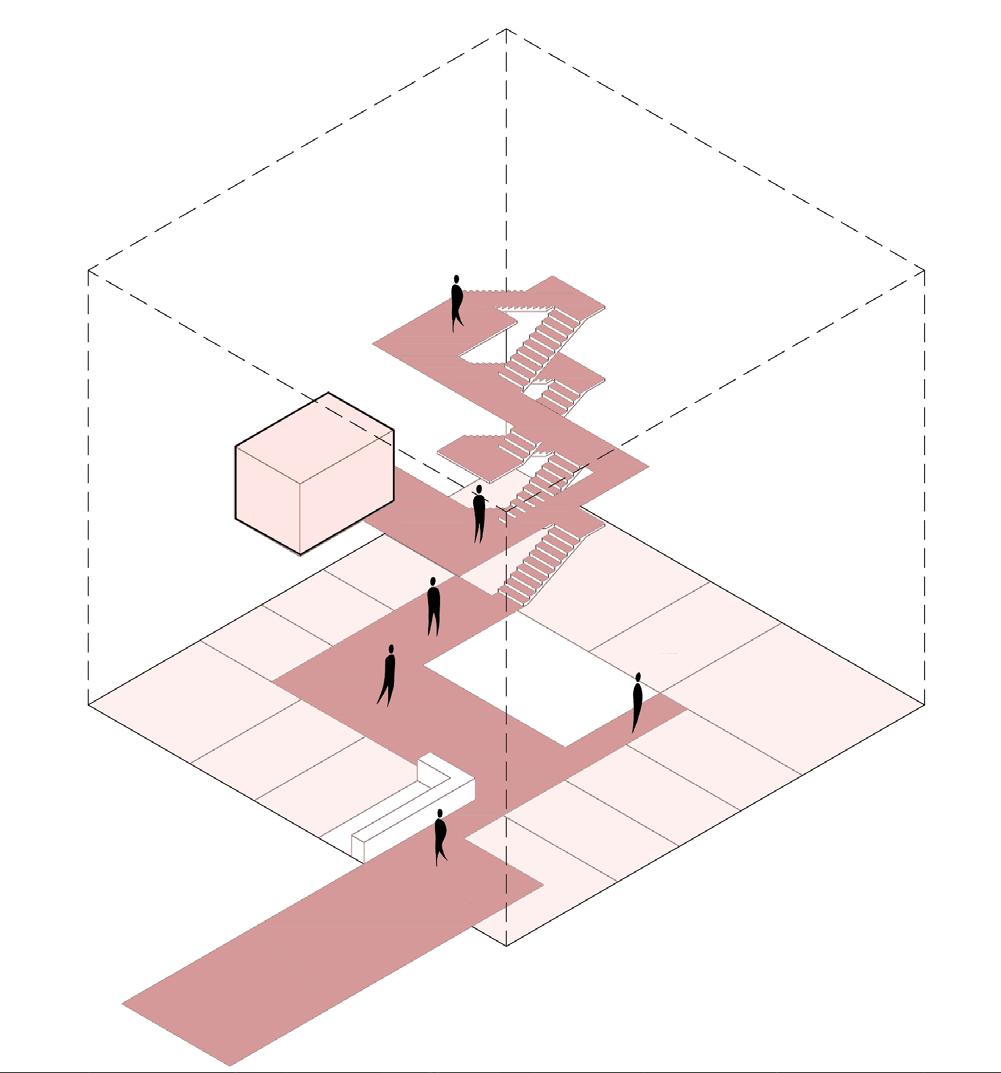

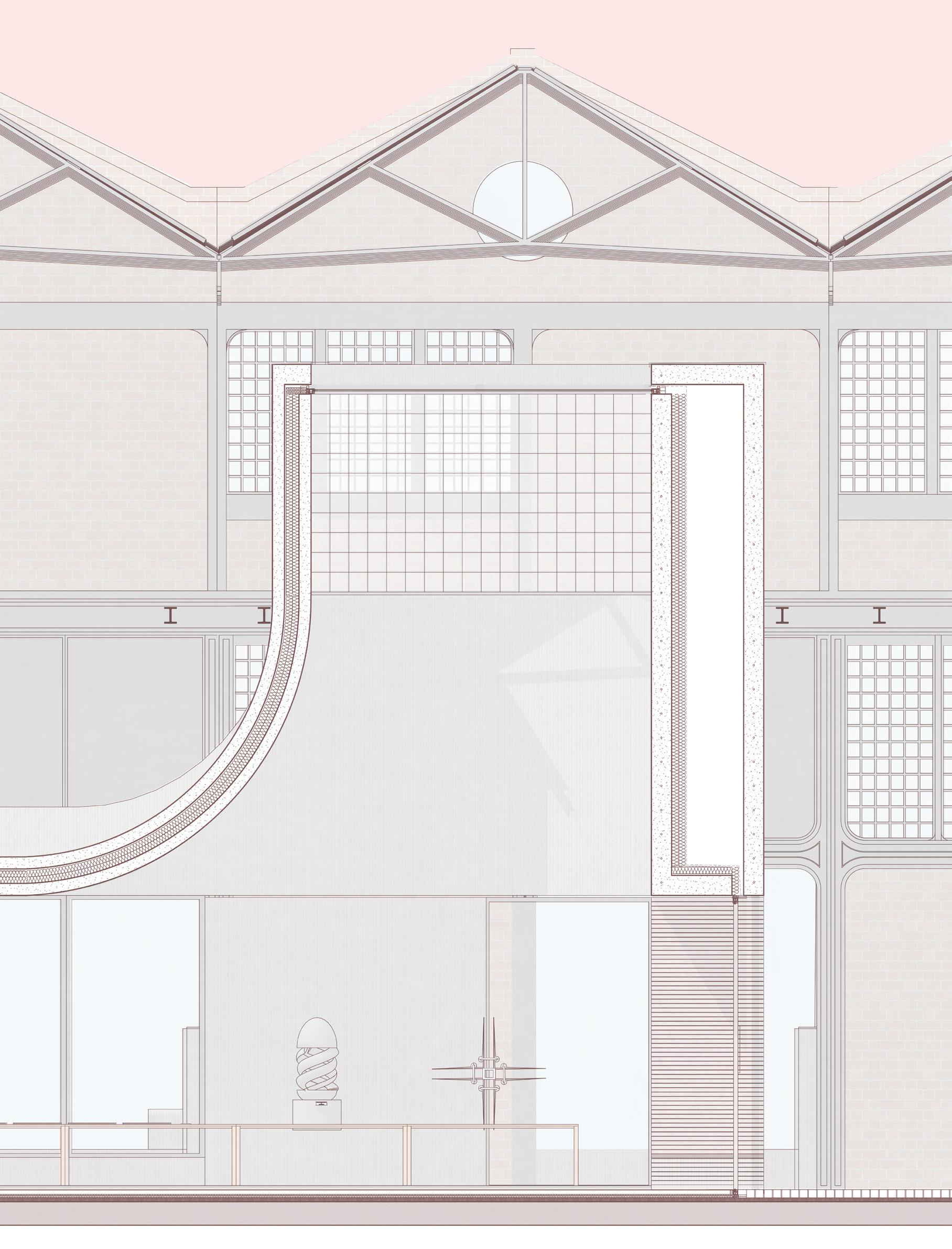

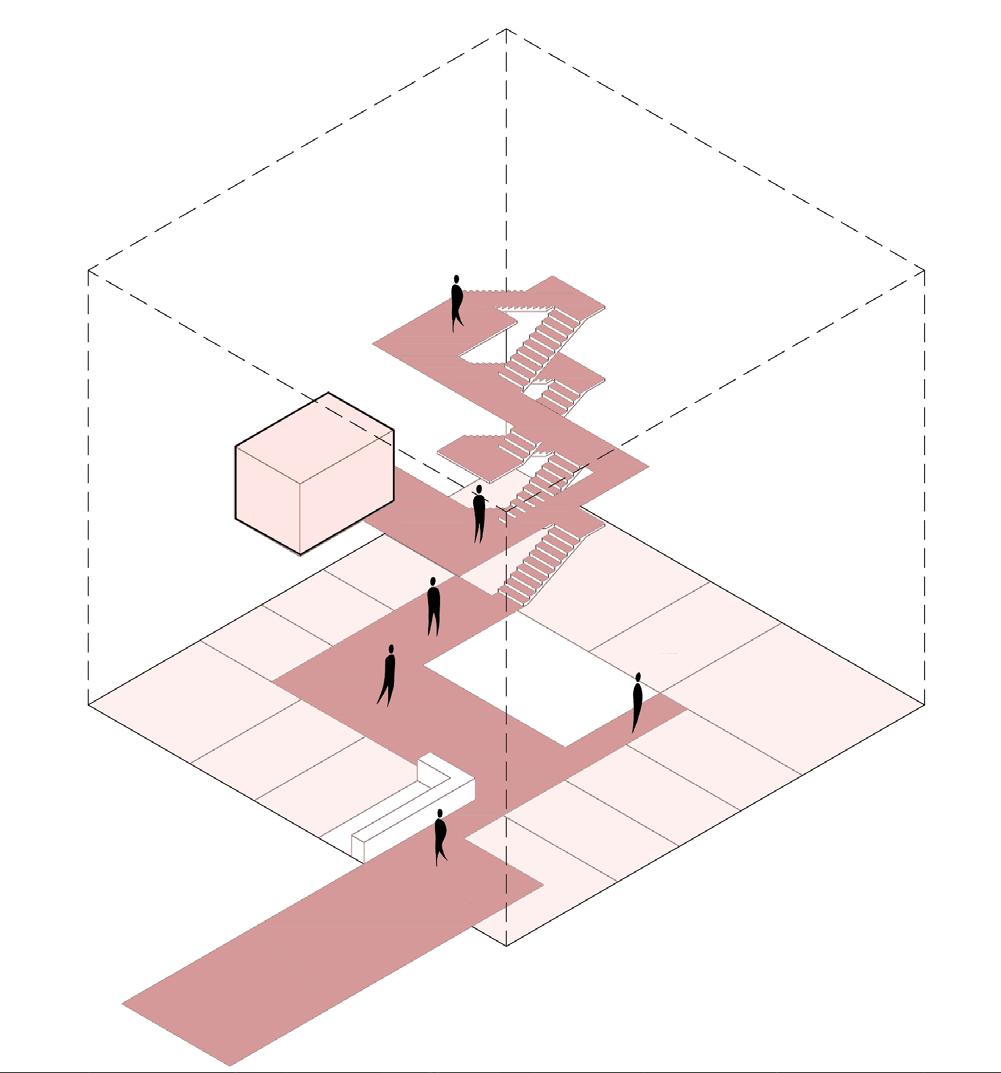

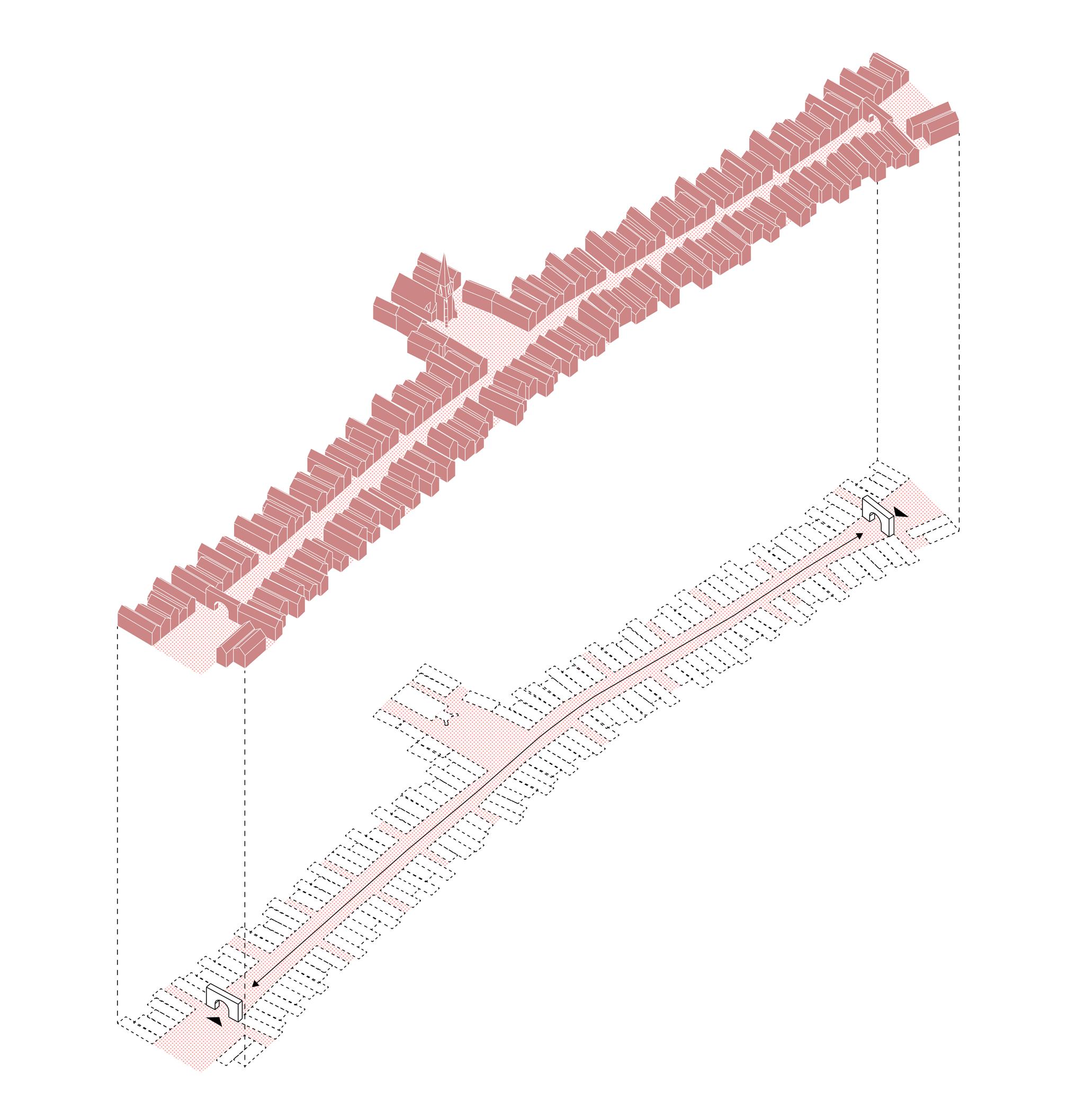

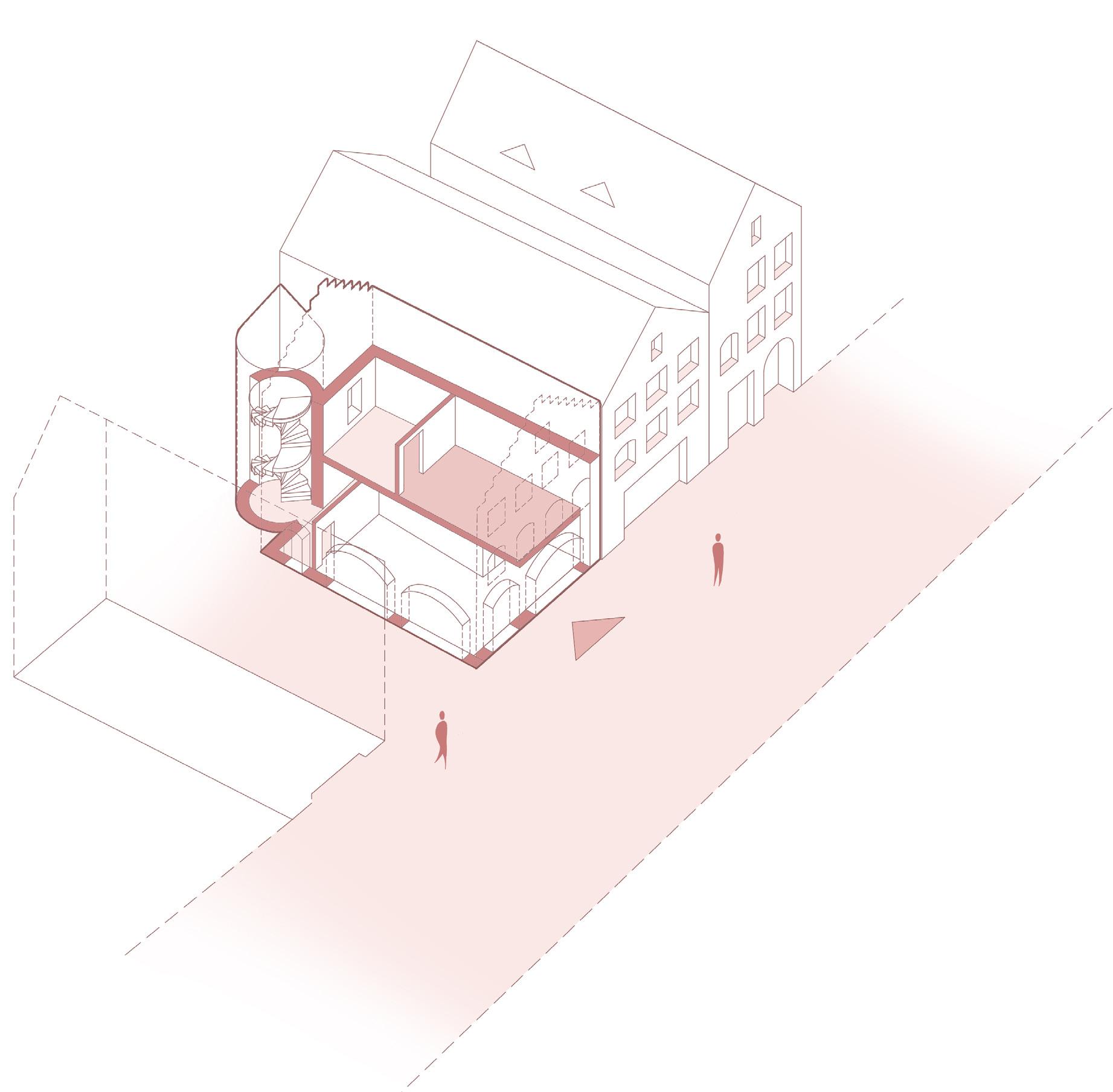

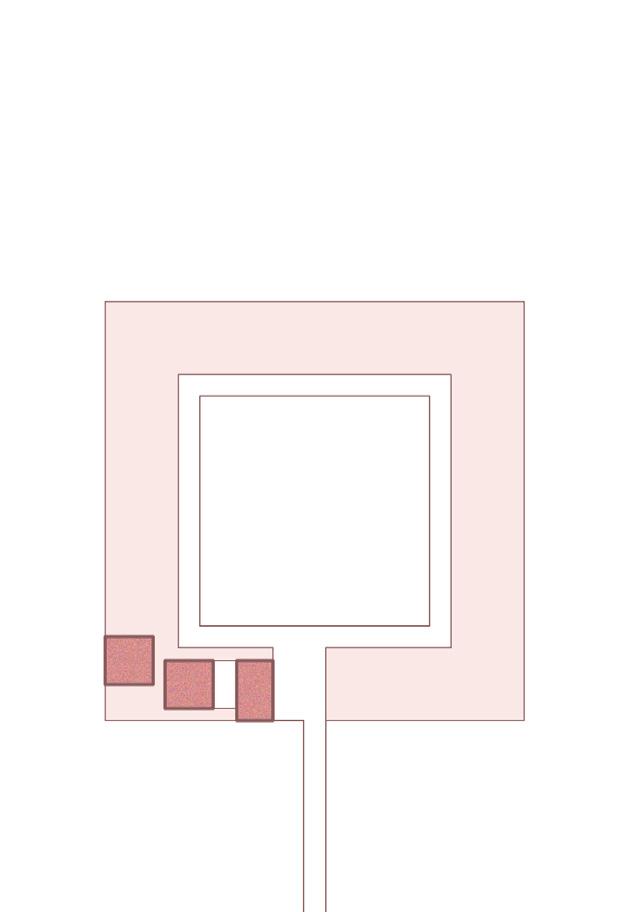

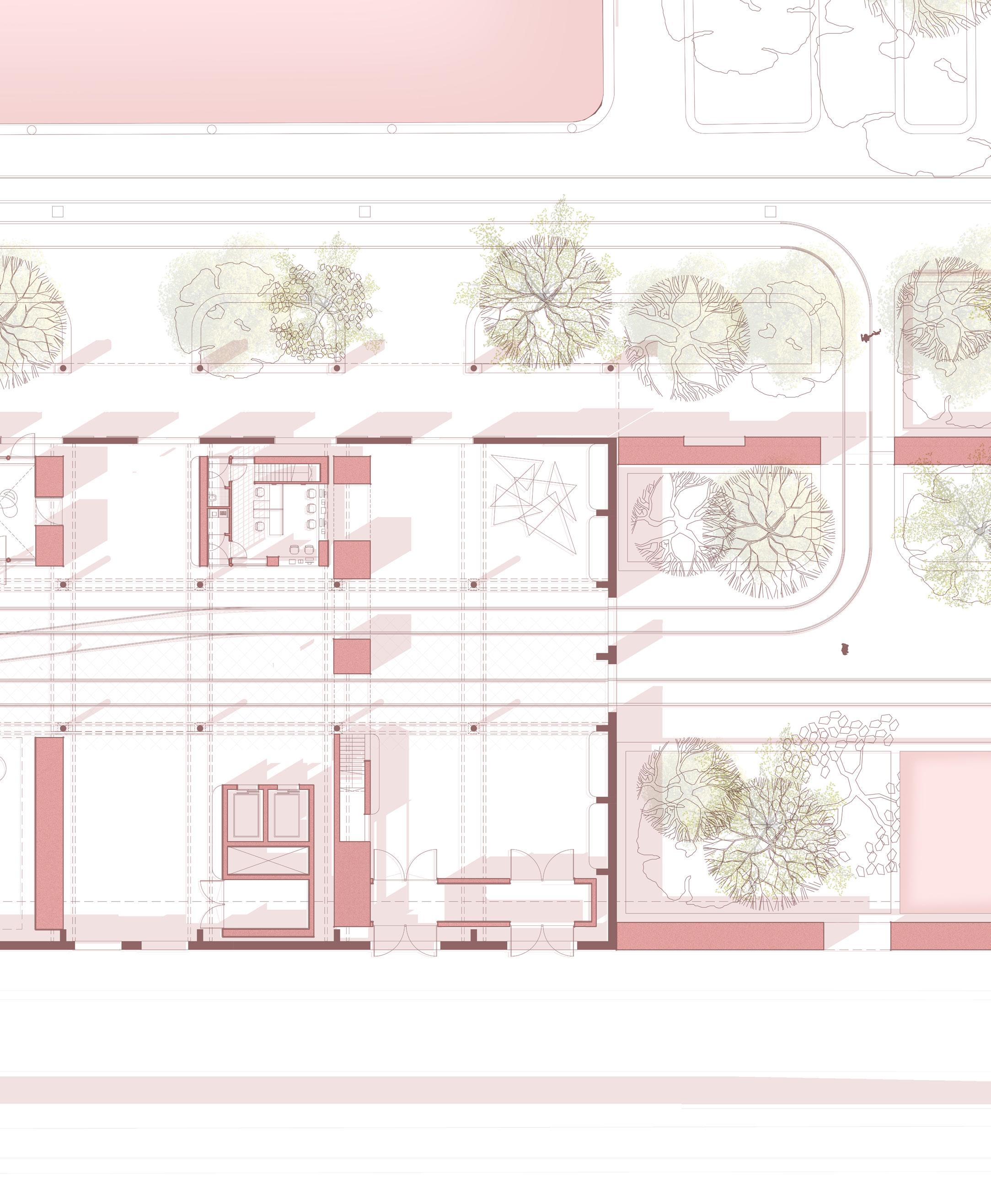

To create a new approach to this architecture is to not forget about the structural nesseccities of the eye hospital. The programme that is required is universal; reception, testing, waiting, consultation, surgery and so on. The question is how can we position these example of fixed programme in a way that fosters a better wellbeing for the patients. The idea for a new clinical approach is simple: create a new eye hospital typology with the spaces and freedoms required to escape, rest, and assemble as a communuty. A new clinical approach will follow several starting points. First, the new hospital must be an independent entity, not bound or inside of another institution. In doing so, it is possible to locate the eye hospital directly without getting lost. Secondly, once inside the hospital, it should have a clear and level route which is navigable and simple. This guarantees that patients with visual defects are able to find themselelves back where they started, in case they get lost. From this route, the key programmatic spaces should be easily accessible and directly entered. Third, once inside the reception, testing, consultation, and surgical spaces, there should always be views out and away from the hospital, providing visual escape. Fourth, there should be intermediate spaces to espace from the

48

Community - supporting each other

Views out - visual escape

Clear routing + physical escape

eye hospital, as a safe and comforting environment to grieve, reflect and process challenging treatments and diagnoses. These spaces must be secluded and private, and have a safe outside space. These spaces will provide opportunities to escape both visually and physically, meanwhile in a controlled environment. Lastly, these secluded spaces should be complimented and contraasted with a more communal area. This communal heart should function as a space for social interaction and support, in a non clinical architecture. That is to say, it should funciton more like a living room than a waiting area. This space should be the primary place for waiting, and offers multiple opportunities to meet, cook and socialise with other poeple in a similar situation. This communal heart idea is not new, and have been applied to other chronic illnesses, such as cancer.

Maggies centres are communal based buildings with a focus on helping cancer sufferers process challenging emotions and news. Each centre follows a key philosophy, where in each design should create a:

“welcoming and positive space in which people with cancer, and their family and friends, could meet other people in similar circumstances and receive support including advice on their treatment, how to manage stress and get psychological support.”

(Maggie’s Centres, n.d.)

These centres been proven to improve the mental outlook of cancer patients, reduce negativity, and

help cancer survivors focus on the future meanwhile moving away from concerns over their future health.

(University of Aberdeen & Maggie’s Centres, 2018)

Maggies centres provide a relevant reference for a “communal heart” to support the visually impaired community and their families. Fundamentally, the concerns that cancer sufferers face, can often be seen in the visually impaired. For example, in Maggies centres specific support is provided to help cancer sufferers and their families manage financial concerns, depression, anxiety, and fears over medical treatments and side effects (Maggie’s Centres, n.d.). Evidently, there are many parallels.The Communal heart in this plan will be positioned in the centre of the hospital as to allow for the best access to the clinical programme.

These new approaches and components should redefine the 21st century eye hospital by placing the patients mental and social wellbeing as an equal to their visual and physical health.

50

Maggies centre, Lanarkshire, Scotland

Maggies centre, Lanarkshire, Scotland

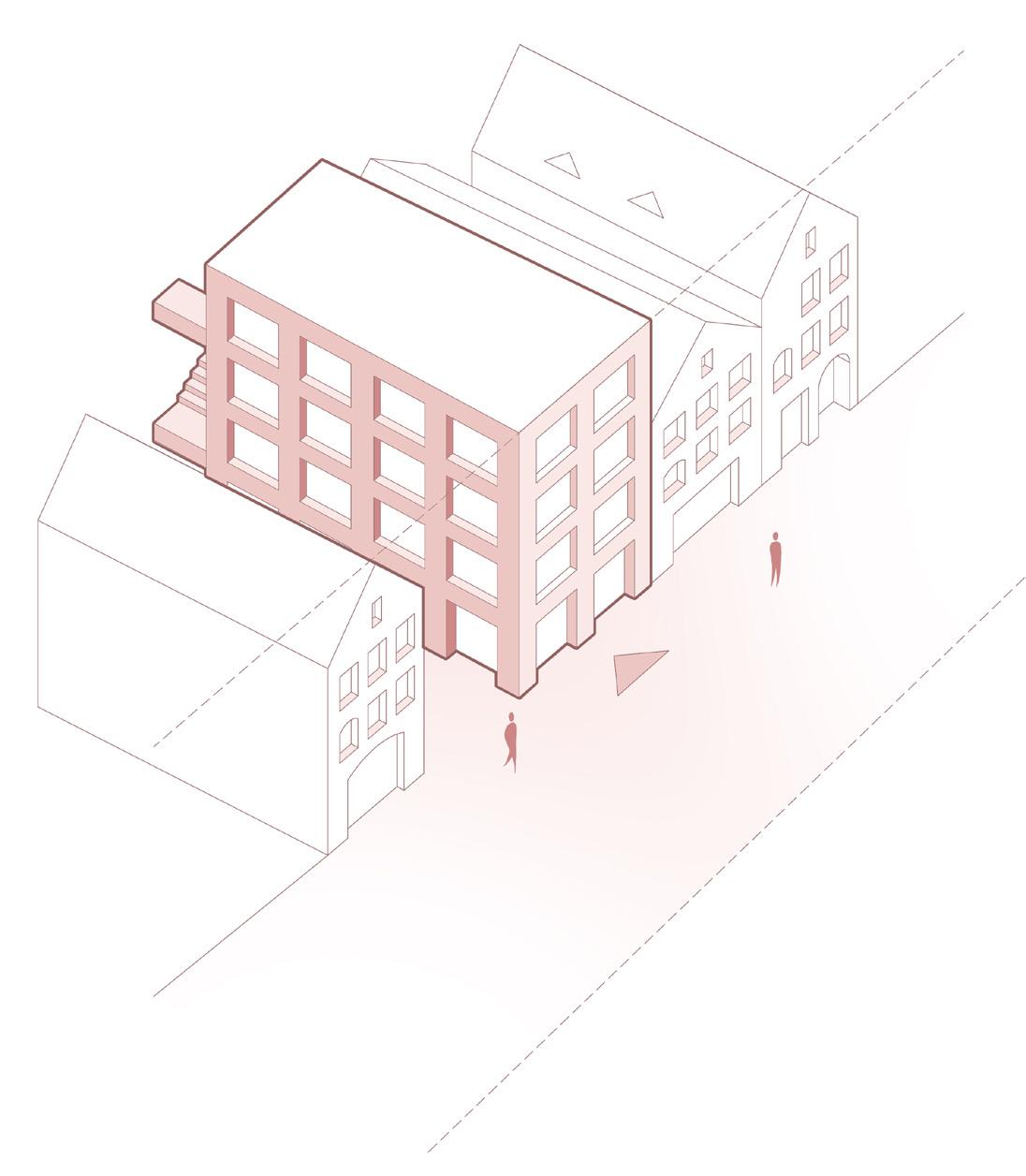

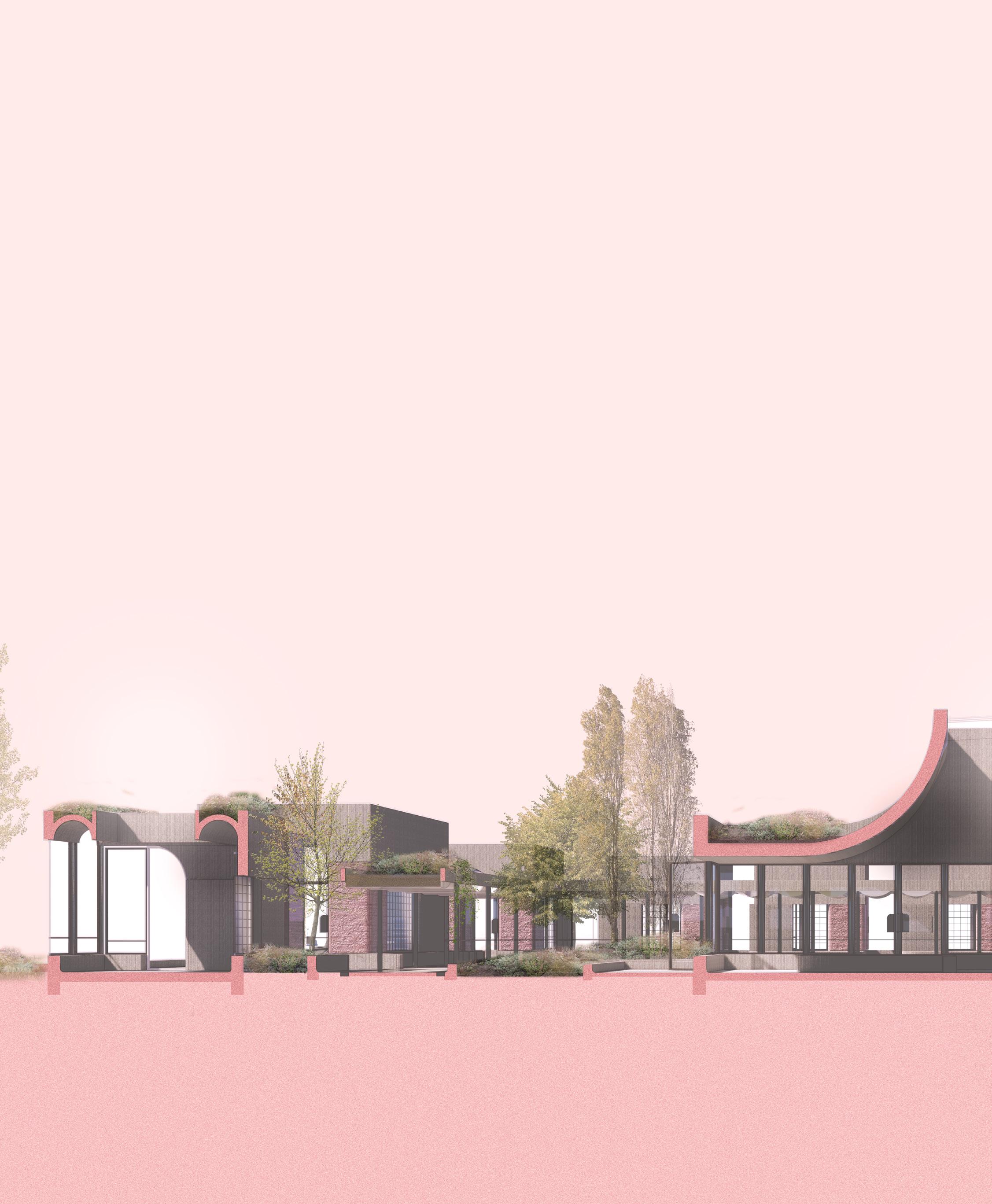

A new approach Social programme

In combination with new clinical approach, a social approach is also required to help the visually impaired community with the non medical and social challenges that they face. In particular, the loss of social interaction, disconnection between the visually impaired community and the wider public, loss of sense of purpose, loss of work and study, loss of income and financial uncertainty. It is neccessary that new social programmes are put in place to aid with these challenges.

Alternative therapies, such as art, music and horticultrual therapies, offer many opportunities to aid people with chronic illnesses cope with mental health and wellbeing challenges. 5 members of the visually impaired community were asked to consider various alternative therapies and indicate if they qualified as something in which they would partake. The majority of the findings indicate that more physical therapies, involving direct movement and intervention in the arts, music, dance, water, and horticulture, yield a more positive response from respondents, with horticultural therapy being the most practiced by respondents, with 40% saying that they practice some form of gardening or horticultural activity. At the same time, music therapy had not been practiced by any of respondent, however was the most desired form of alternative therapy as listed in the survey.

These opinions form an interesting foundation for potential physical therapies within a community support space for the visually impaired. Furthermore, these opinions of physical alternative therapies are

52

substantiated through academic research, and are proven to help other chronic illnesses, mental health, and wellbeing issues. Taking the findings of this survey as a base, 4 forms of physical alternative therapies were explored in more detail: art therapy, music therapy, and horticultural therapy.

(Fraser, 2022)

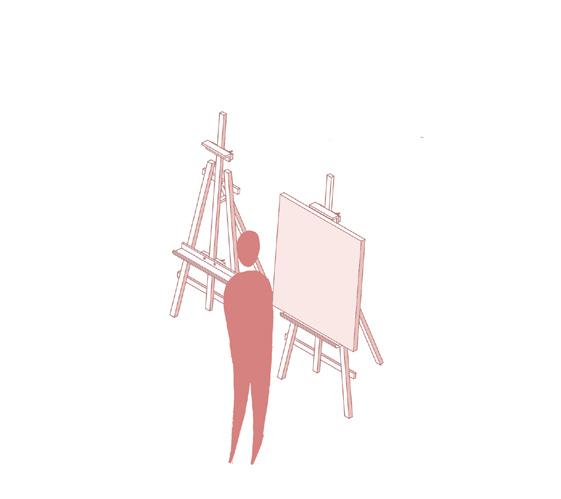

Art therapy is a well-established field of alternative therapy that, according to the American Art therapy association, is:

“an integrative mental health and human services profession that enriches the lives of individuals, families, and communities through active artmaking, creative process, applied psychological theory, and human experience within a psychotherapeutic relationship”

(DiGiulio, n.d.)

Many would assume that art therapy is a field in which would be difficult to apply to the visually impaired community. However, there have been numerous case studies and examples that demonstrate otherwise. Scott Nelson is an artist that lost his vision later in life. He is well documented for his explorations regarding his visual disability, and how it has positively impacted his work. Furthermore, his belief that art is not limited to the visual domain initiated several exhibitions for blind and visually impaired artists, In a hope to raise awareness over this hidden fold of the visual arts. Indeed, Nelson is a great proponent of art therapies, and how they can positively impact a visually impaired persons self-esteem and mental health:

“Mental visual activity persists even after loss of

sight; and that self-esteem is attainable through engagement in the visual arts regardless of the degree of visual activity”

(DiGiulio, n.d.)

Nelson, and many other visually impaired artists, believe that the art is an effective form of therapy, and that it can be used to help understand, process and even document vision loss in a healthy and productive way. Indeed, it is often not the product that is relevant or important with art and art therapy, but rather the process and the investment of time that is more enriching, both of which are deeply fulfilling. In that vein, they form in which the art takes is rarely important, however more tactile forms of art and physical creations appear to be more stimulating due to the fact that many visually impaired people use touch as a means of navigating space and physicality. In the process of making art, an individual can rely on many sources of inspiration. In art therapy, this can often be a form of catharsis, a release and documentation of an emotional state towards visual impairment, in which can help a visually impaired person process challenging emotions and work towards improving their mental health. In that sense, art therapy is well known to allow people to be self-expressive, potentially in a manner more effective than speech. The act of personal reflection and the process of making art can support a persons feeling of selfaccomplishment with a completed piece, allowing them to feel more independent and capable, improving the mental health and overall wellbeing of a visually impaired person. This is supported

53

by the average art therapy workshop, where in there may be a set of loose goals established at the beginning, but it is up to the individual to fill in the blanks, requiring participants to show personal agency and intervention. Indeed, one participant in an art therapy study for the visually impaired stated that during the process:

“I’m more free, like I feel more like myself when I draw something indirect…. I feel good, you know”

(DiGiulio,

n.d.)

Consequently, Art therapy has been proven to improve the mental health and physical wellbeing of visually impaired participants. Specifically, art therapy has shown to be effective in its addressment of several instigators of mental health issues in the visually impaired. In participating in art therapy, the visually impaired are able to express feelings, emotions and frustrations through an original creative work, This cathartic outlet has bene shown to be beneficial for the mental health of the visually impaired. Furthermore, the process of making an artistic output is relaxing, and shown to be intellectually and creatively stimulating. This process, as well as a final outcome, has been shown to give people with visual impairment a greater feeling of accomplishment and self-esteem. This boost to a person’s self-image is also conducive to giving a person more purpose, and a feeling of usefulness. This is especially important with visually impaired participants that struggle to complete activities of daily life, and the associated mental health issues that brings. Lastly, the benefits of participating in

art therapy as a collective experience for the visually impaired allows for greater social interaction within the visually impaired population, aiding in the common visually impaired induced loneliness and isolation. (DiGiulio, n.d.) Notwithstanding the mental health and wellbeing benefits of art therapy for the visually impaired, other benefits can also be implemented. As part of a new community support architecture, art therapy can play an important role in expanding the visibility of the visually impaired. In using art therapy, it is also possible to expose the capabilities of the visually impaired to the wider public and community, demonstrating the abilities of the blind and visually impaired community.

54

Art therapy being used with visually impaired children

Music therapy can play an equally important role in the mental health and wellbeing support for the visually impaired. Markus Dauber, a prolific musical therapist based in Greece, conducted a study over a 2-year period with a client – or patient – called Maria. At the start of their interactions, Maria was 26 with severe visual impairments. It was noted that at the time of first contact, Maria exhibited many extremely negative emotions, and a fragile mental health situation. Indeed, Maria demonstrated many classical signs of visual impairment related mental health issues – as previously discussed in this paper – specifically: lack of purpose, loneliness and social isolation, lack of hope for the future, and extreme anxiety over her visual condition and its limitations on her daily life. As with many in the visually impaired community, Maria showed a dissatisfaction with the support and educational resources for the visually impaired in her area.

(Dauber, 2011)

At a local community centre for the disabled, Maria began to participate in musical therapy. In his study, Dauber elucidates upon 3 core components of musical therapy, and how they can be applied to the visually impaired: listening, singing (or musical practice), and performance. Listening forms a core foundation of this form of alternative physical therapy, wherein it is important to understand the needs of the visually impaired person, and assess how they can best express themselves through music. This initial phase extends to the fomat through which a person wants to interact with

music, and in the case of Maria, she chose singing as her expressive tool. This personal freedom and autonomy provides a contract to that of the average daily lifes of a visually impaired individual. Indeed, Maria often struggled to function independently, and required assistance to move from place to place and participate in every day tasks. The freedom to choose independently as part of a music therapy session immediately provides the visually impaired an opportunity to take person ownership and agency, fostering positive emotions.

In this study, the form of musical therapy focused on the therapist playing an instrument to the direction of the patients wishes, with the patient accompanying – in this case by singing. It was identified that, although very beneficial, the reflection of personal expression and the playing of instruments or singing did not provide the wider recognition of ability that was necessary to provide Maria with greater self-esteem and a greater satisfaction with her work. Therefore, Dauber initiated a performance for Marian towards the local community, The appreciation of her work by the wider community helped Maria connect with other people, meanwhile establishing a greater satisfaction with her musical abilities:

“Maria was animated with energy and enthusiasm during her performance and received feedback from audience members that they were moved by what she shared. She had felt isolated and unable to convey to others what she was going through.

56

Music therapy

Now she felt she had a way to communicate and emotionally connect to others about her experience”

(Dauber, 2011)

Music therapy can take many forms. Another study conducted into musical therapy focused on visually impaired children in the playground. Unlike the previously explored study, this investigation looked into musical therapy within a group setting, rather than a singular one-to-one format. Furthermore, the study began to explore the role of the physical environment through which the therapy could be administered; through creating a route for the children to navigate, 6 musical interventions with simple instruments were installed, in order to study how visually impaired children would navigate the musical environment. The initial idea of the study focused on preliminary conclusions that:

“For blind children, the auditory system is a primary source through which they connect with and understand the social and physical world. Sound can be used to provide feedback on children’s location, and can be used to promote independent movement from one place to another”

(Kern, 2002)

From this format, several interesting observations were made. First, the children overwhelmingly gravitated to the musical stations along the path, rather than spend time in between spaces. The musical spaces seemed to be very attractive and engaging elements within the test environment. At the same time, because the musical installations were attractive to the visually impaired children,

a community began to form around them. It was found that it was not just the musical elements of the stations that attracted participation, but also the social relationship and interactions being formed as a consequence. These interactions were observed to decrease social isolation and loneliness in the children. Furthermore, these musical interventions also provided unique opportunities for the children to express themselves creatively, regarding their emotions but also artistically. In one particular example, a group of children worked collectively to imagine that they were on a boat at sea, using the instruments available to them to create such an illusion. This teamwork further demonstrated the unique social and personally expressive properties musical therapy can bring to visually impaired children, and perhaps also visually impaired adults. Therefore, similar to art therapy, the process and social properties of these physical activites fostered mental health and wellbeing benefits.

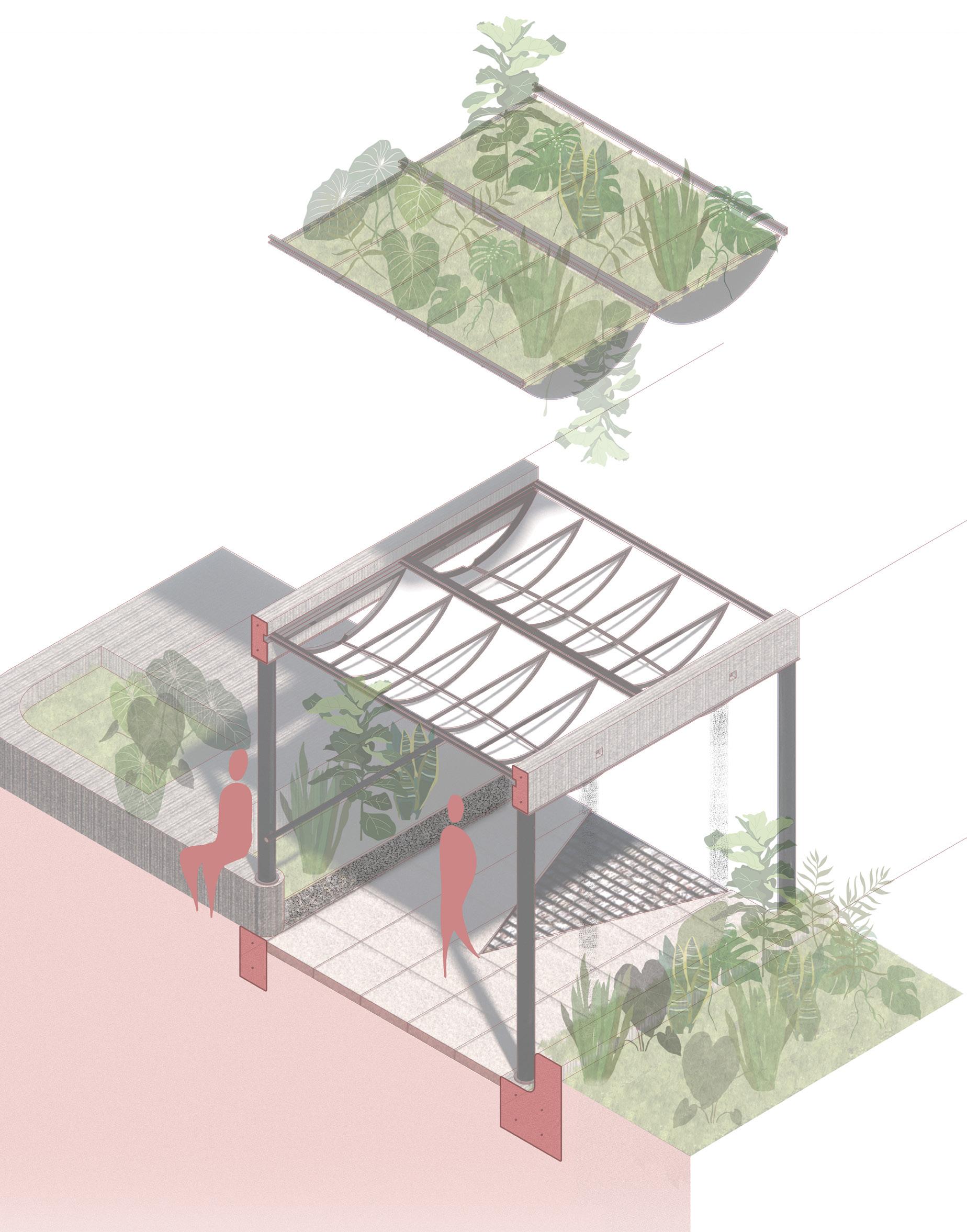

Horticultural therapy has been used as a form of alternative treatment for thousands of years and has been adopted to treat a myriad of health conditions, specifically chronic illness and mental health issues. It has been proven that participation in horticultural therapy instills in participants a sense of responsibility over their work and involvement in gardening, through providing opportunities to become a caretaker of something living and in our environment. For this reason, Horticultural therapy has been shown to be very beneficial for people with low self-esteem, social isolation, and depression, all

58

horticultural therapy

of which negatively impact the visually impaired population. (George, 2021) Indeed, according to the Lewis Ginter botanical gardens, horticultural therapy provides a sensory rich experience for the visually impaired, with Dr Jean Larson going further to say:

“In the garden, the brain looks at nature with a non-directed focus,” Larson explained. “As someone watches a butterfly, hears a bird or hears the trickling of a water fountain, the body has the ability to shut down, reboot and refresh.”

(Kirk, 2019)

A study looking into the specific effects of horticultural therapy on mental illness, found that, overall, it resulted in a general improvement of mental illness symptoms. (Siu et al., 2020) In particular, it was established that horticultural therapy reduces stress and anxiety, meanwhile promoting greater tranquility and improving cognitive functioning. At the same time, it was also discovered that this form of therapy also induces greater self-efficacy, self-esteem, quality of life and social cohesion within the participant group. Furthermore, and potentially most importantly, it was found that Horticultural therapy helped people with mental illness to find a purpose and find satisfaction in tasks they perceived to be personally meaningful. This also suggested that people with disabilities, such as visual impairments, may benefit from horticultural therapy as a vocational practice.

Although these findings were specifically tailored to people with mental illness, many of these findings could specifically benefit the visually impaired and their mental health and wellbeing needs. Indeed, not only is this form of activity preferable from a visual disability perspective due to its rich inclusion of many senses – taste, smell, touch, and sound, but it has been proven to improve self-worth and instill a greater sense of purpose and work ethic in participants – key areas of mental health issues in the visually impaired. Furthermore, when applied to the chosen location for this project, horticultural therapy could foster a greater appreciation for fresh food and produce, meanwhile educating the visually impaired and local populations on local, sustainable and healthy eating practices.

(Siu et al., 2020)

60

The Programme

Clinical + Social

63

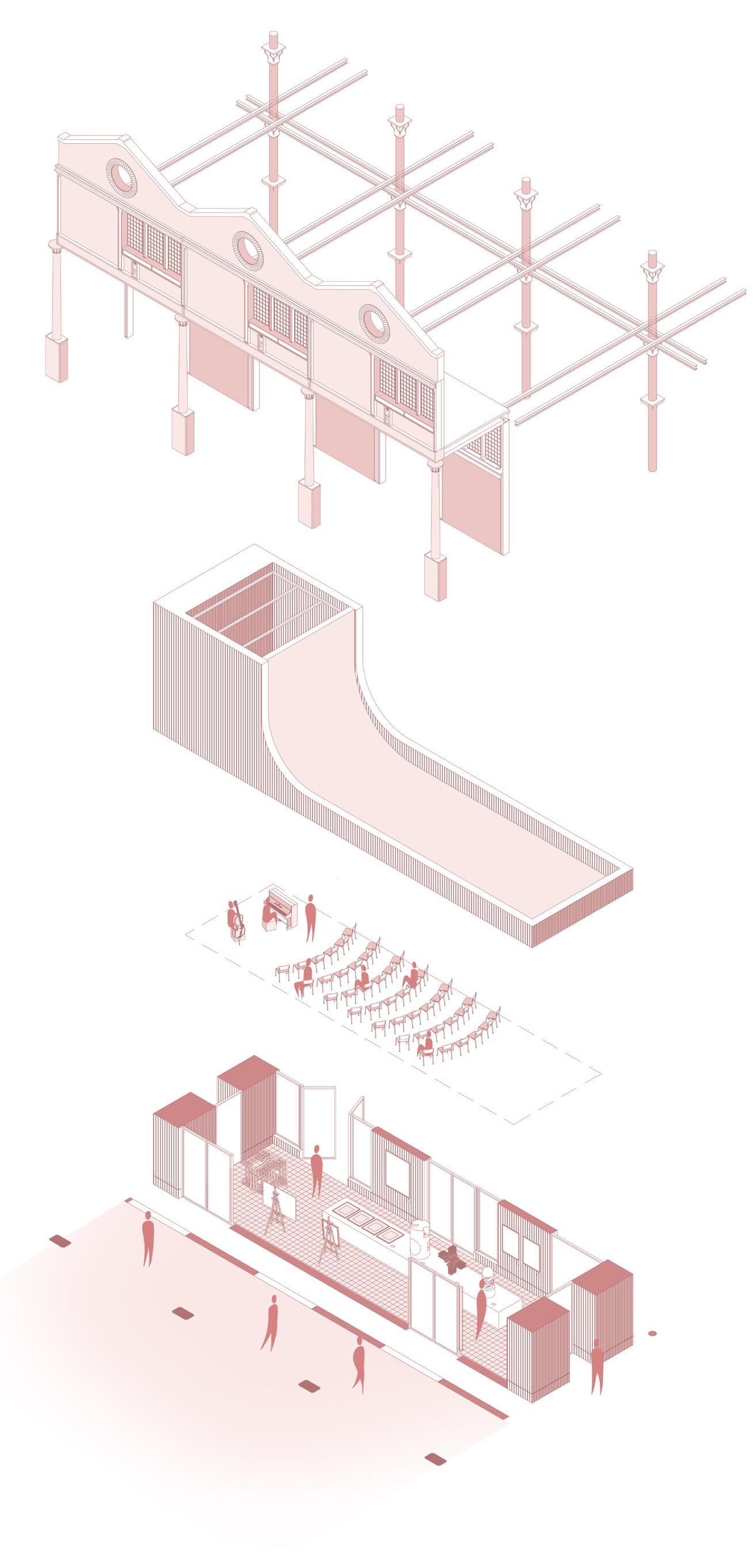

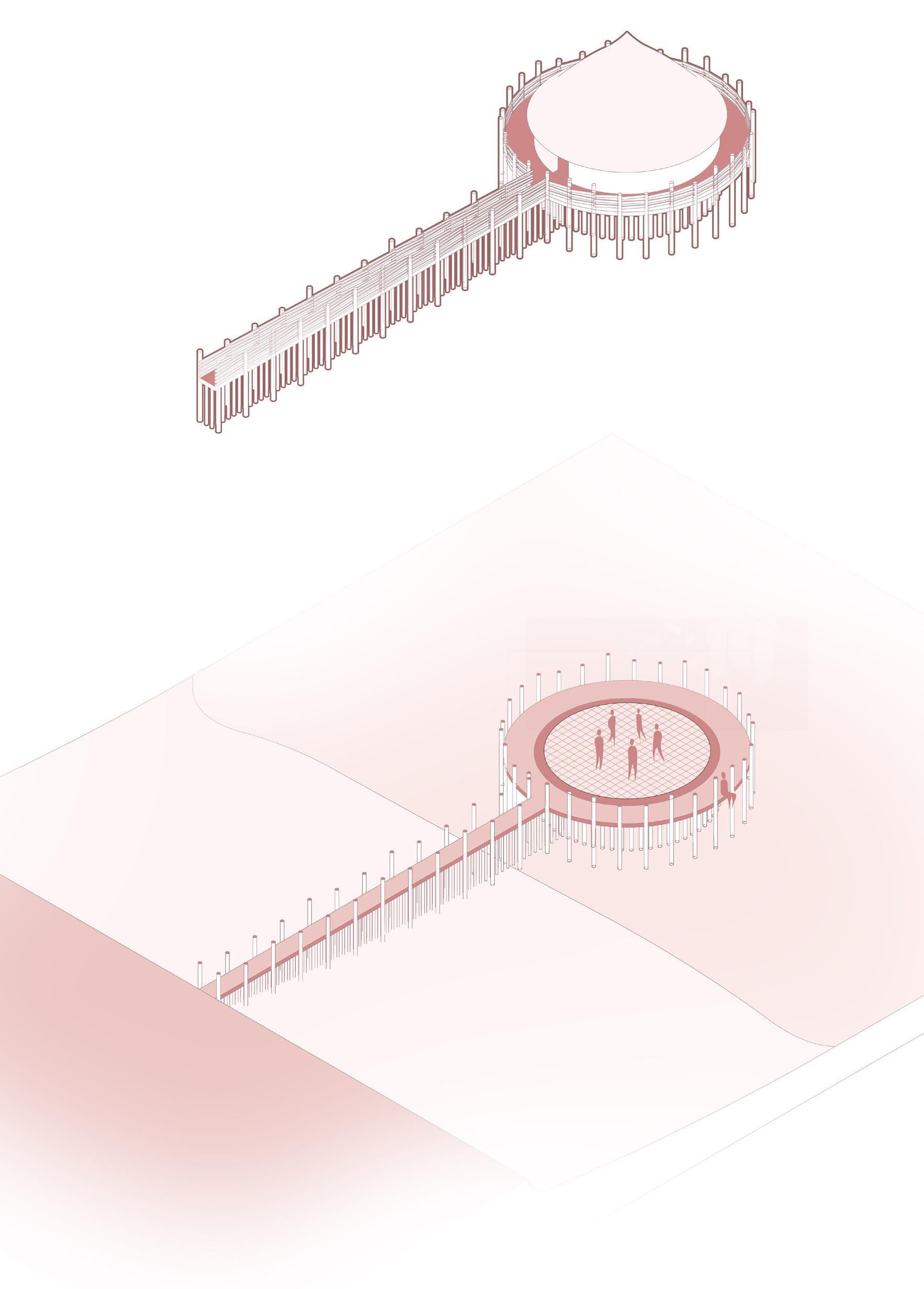

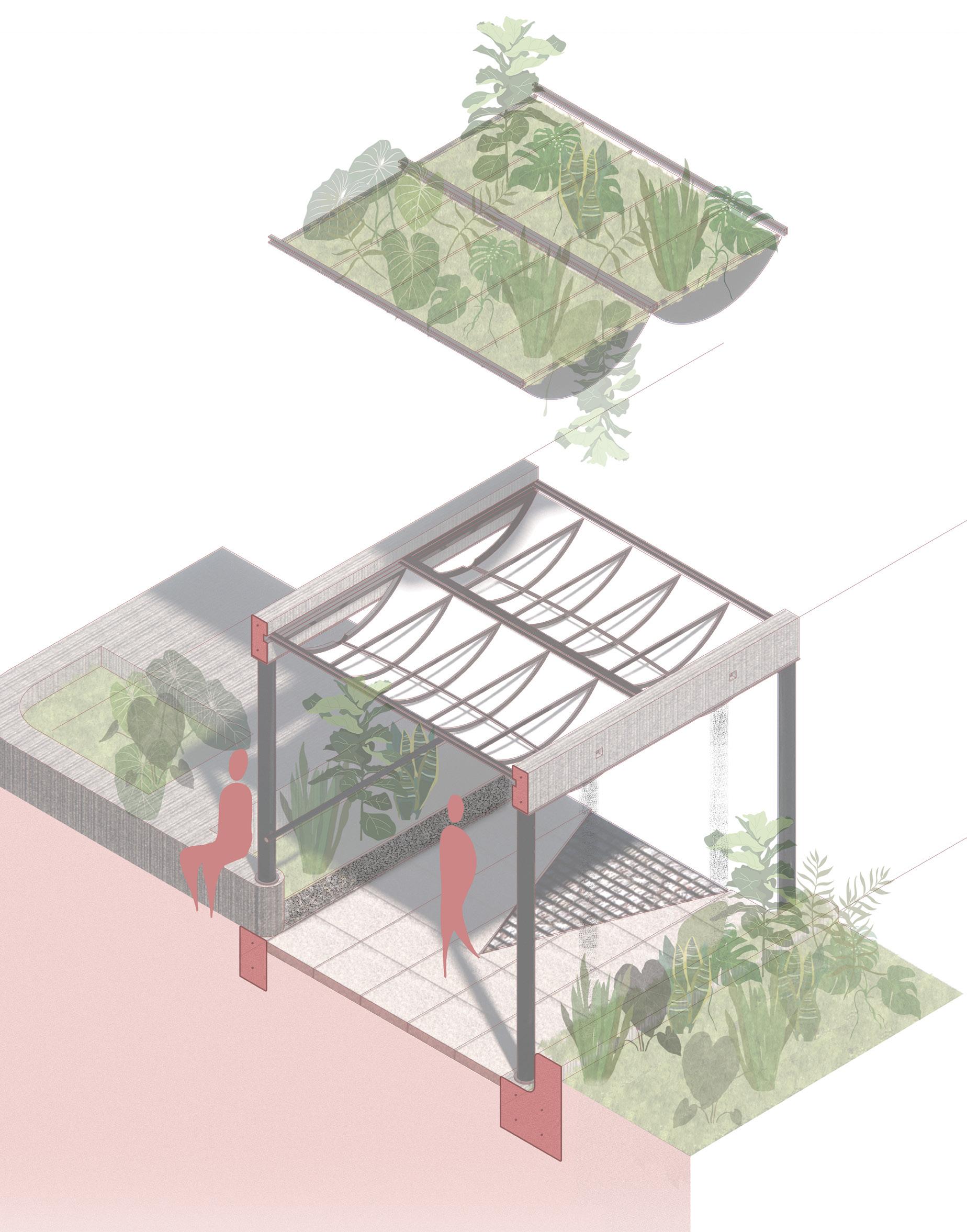

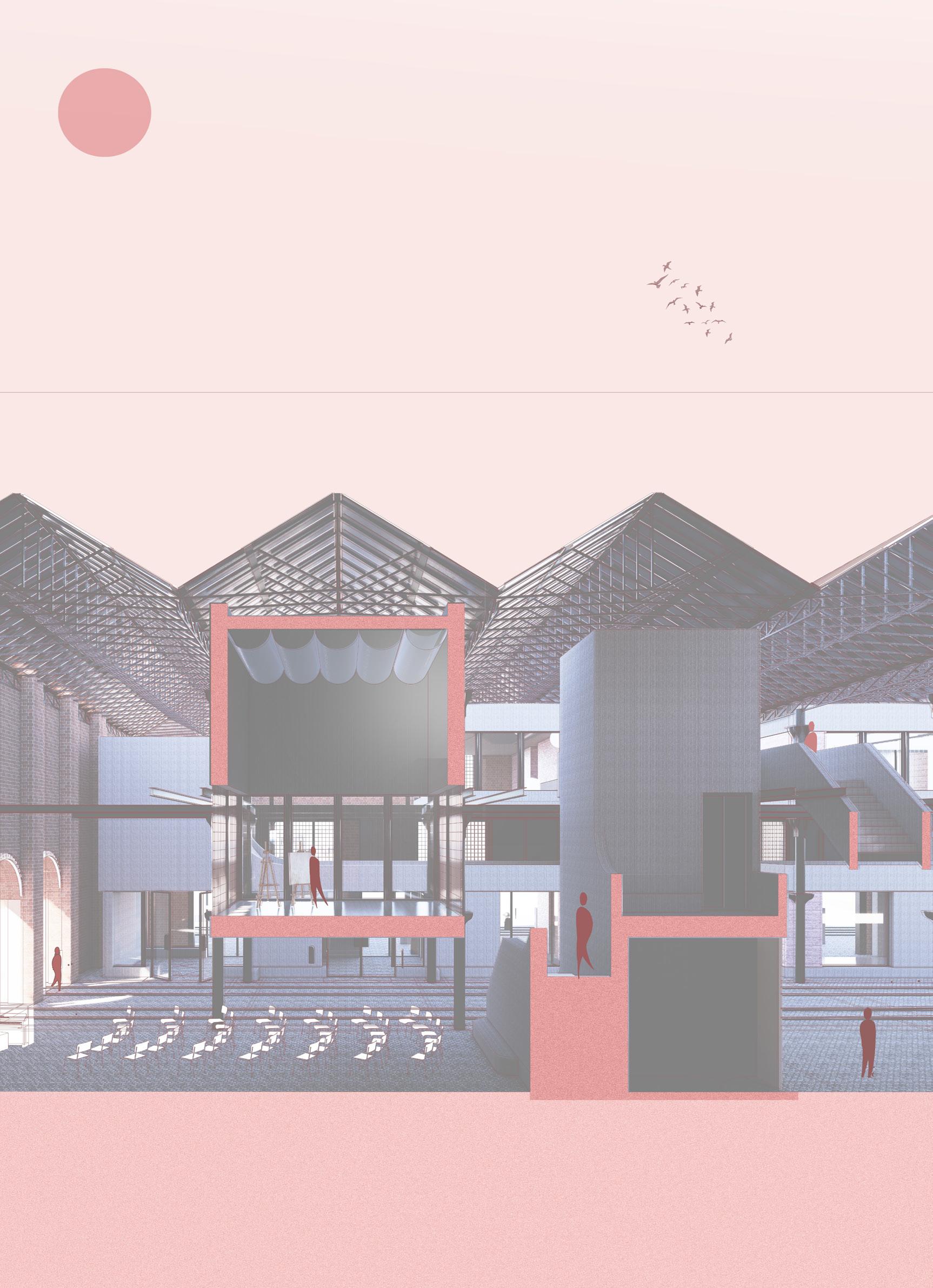

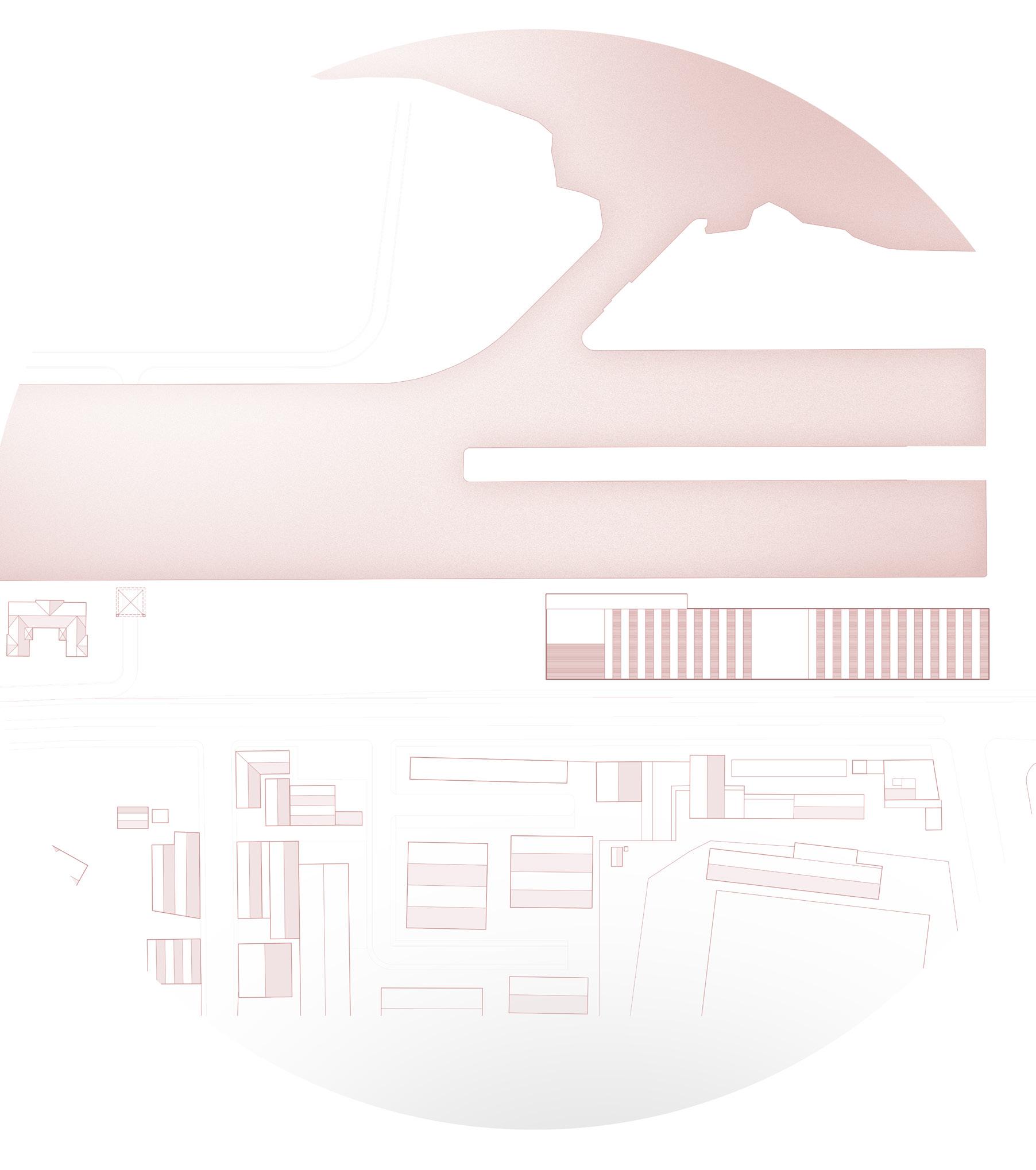

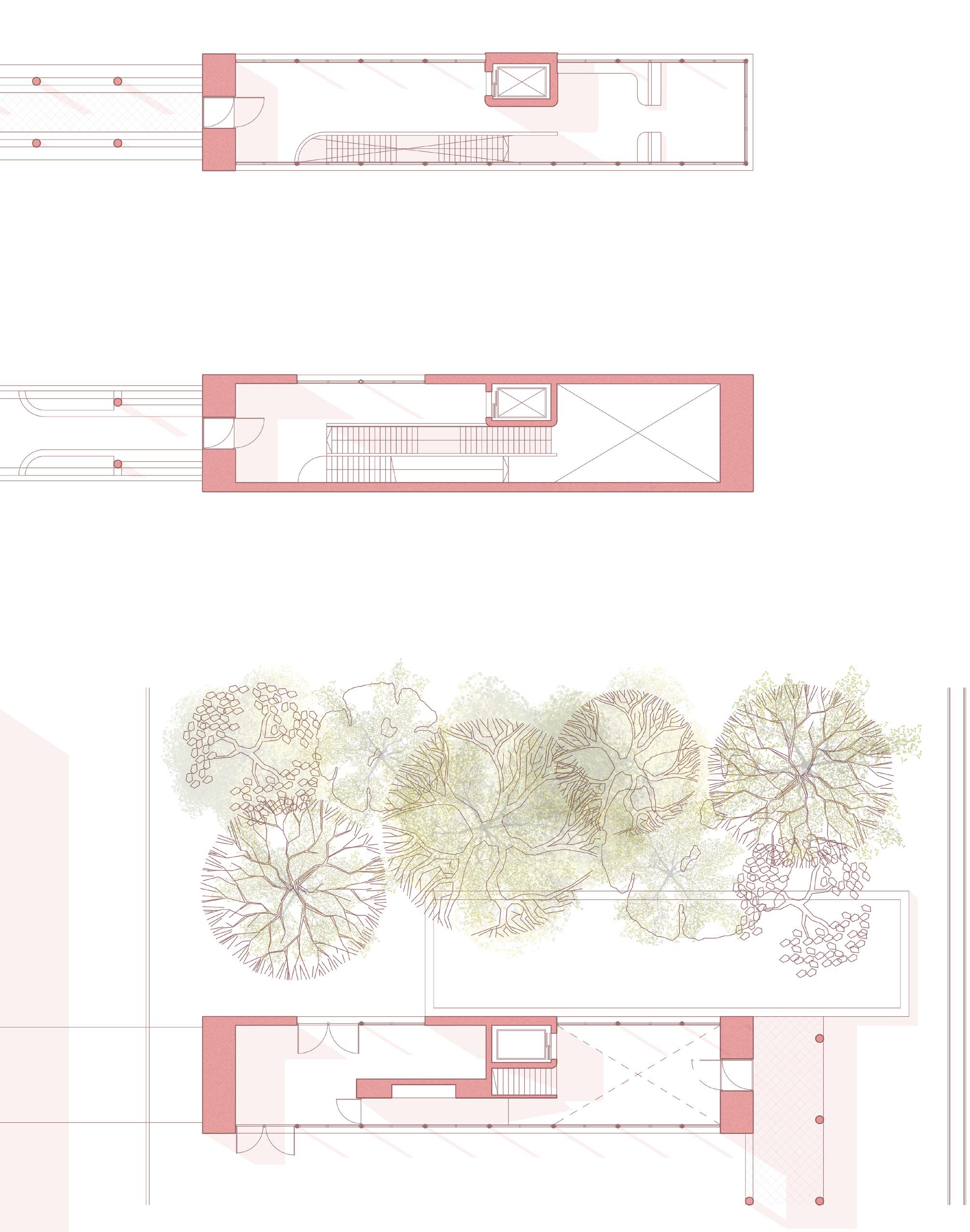

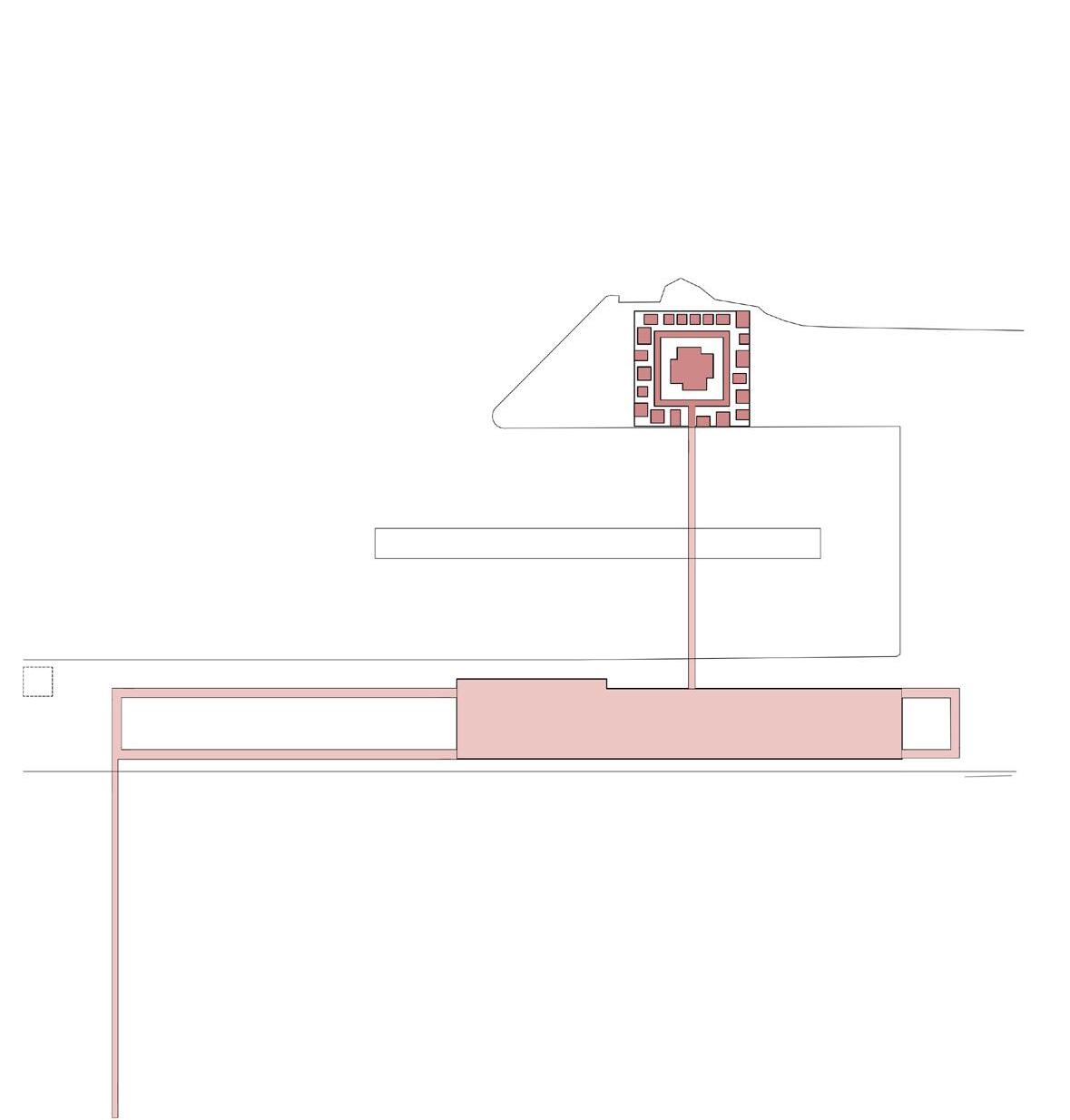

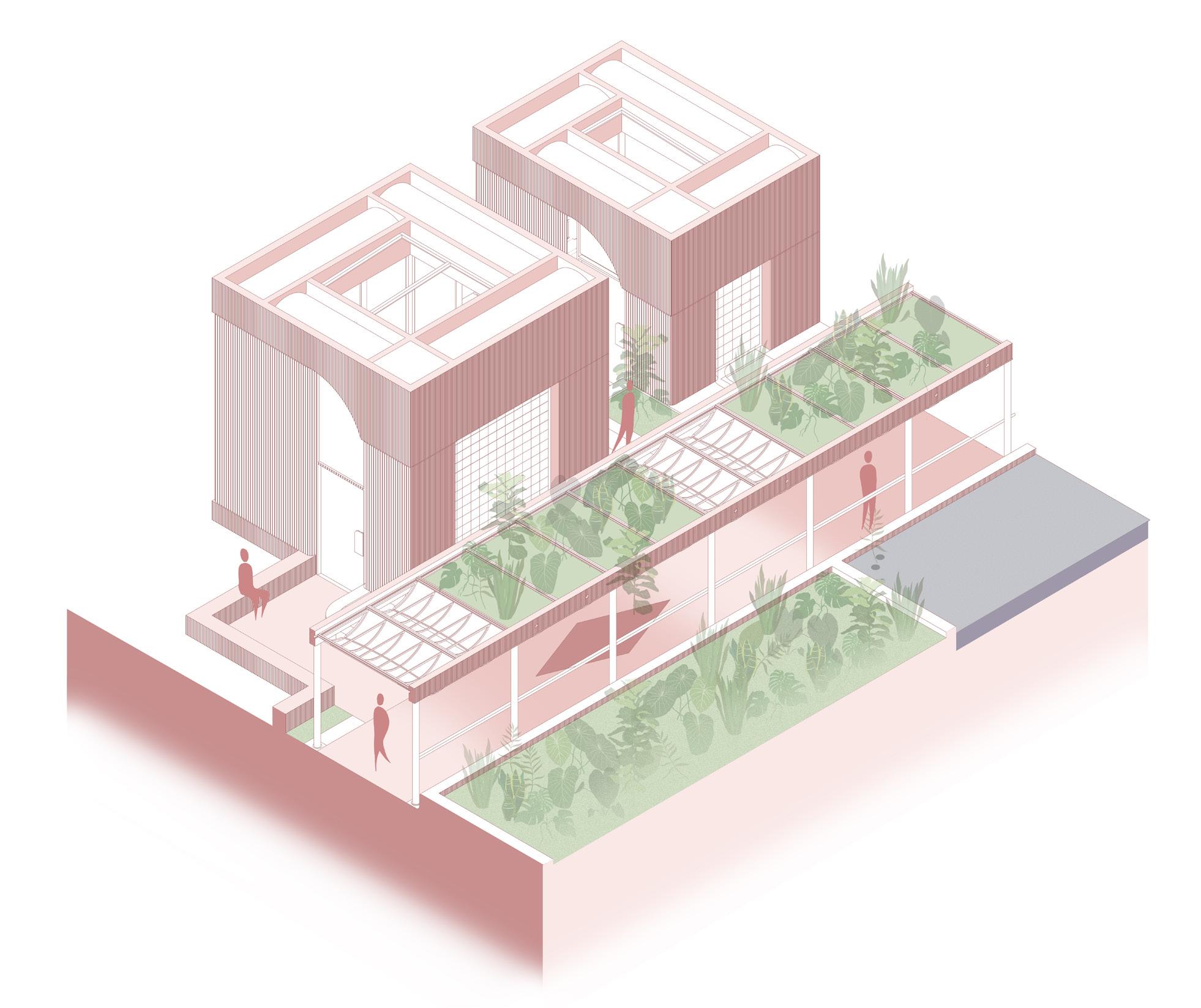

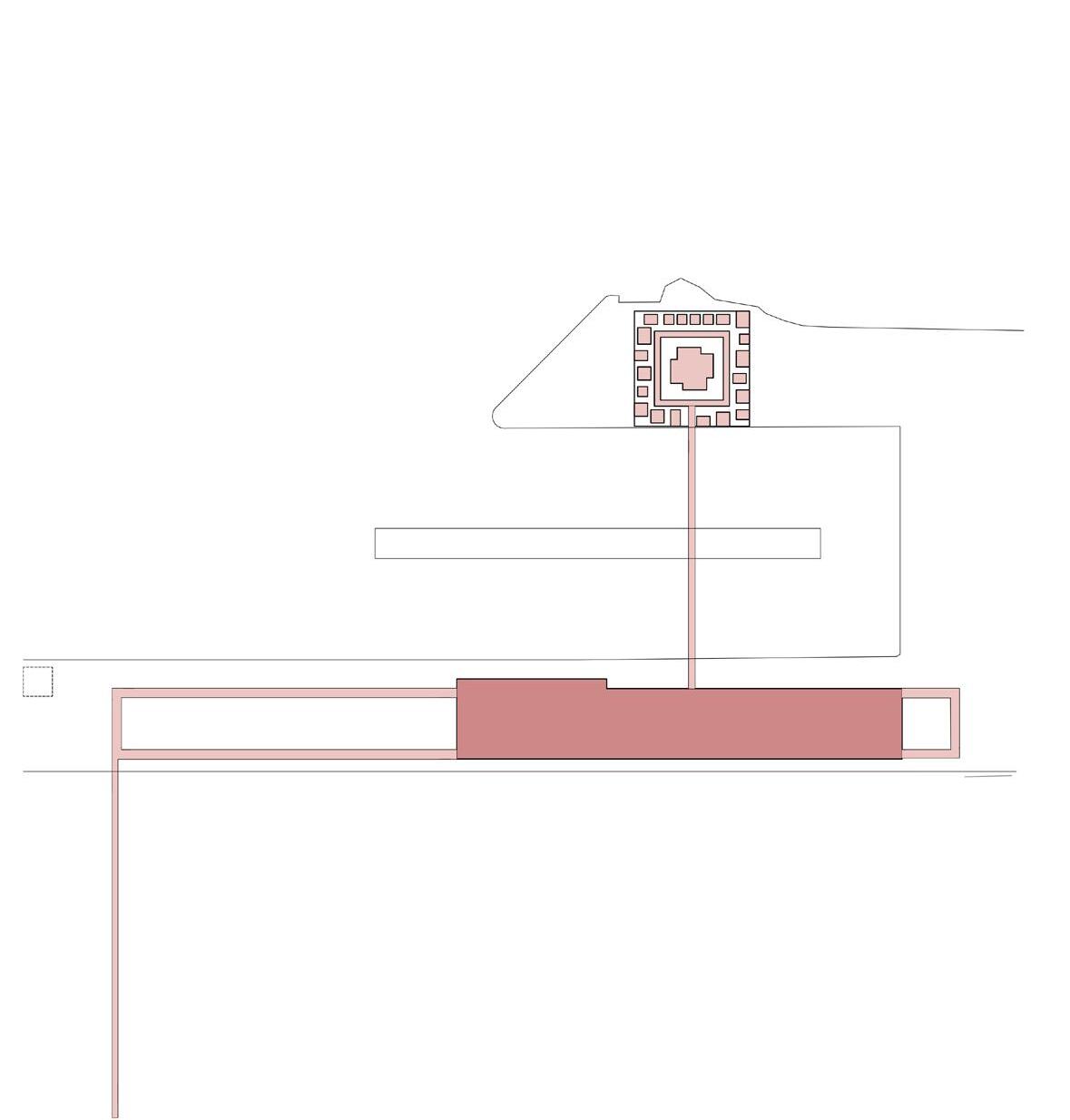

Architectural concept Clinical + Social programme

‘The eyes are the window to the soul’ is a new approach to care architecture for the visually impaired and blind (VIB), that aims to challenge current architectural standards. To do so, the project is composed of 1 core idea, improving the poor state of mental health and wellbeing in the visually impaired and blind community.

As previously established, visually impaired and blind communities suffer mental health and wellbeing challenges. These challenges are broad, but are generally caused by the following 6 factors:

1. Diagnosis and physical visual health issues

2. Potential treatment strategies

3. Inability to live independently and undertake daily activities

4. Inability to work and study, leading to a loss of purpose

5. Loss of social connectivity causing social isolation

6. Financial concerns

From this list, it is possible to divide these factors into 2 categories. The first is mental health and wellbeing challenges presented by healthcare environments, for example, diagnosis, physical visual health, and treatment strategies. The second is mental health and wellbeing challenges caused by personal and societal difficulties, such as an inability to live independently, work, study, social isolation, and financial difficulties.

64

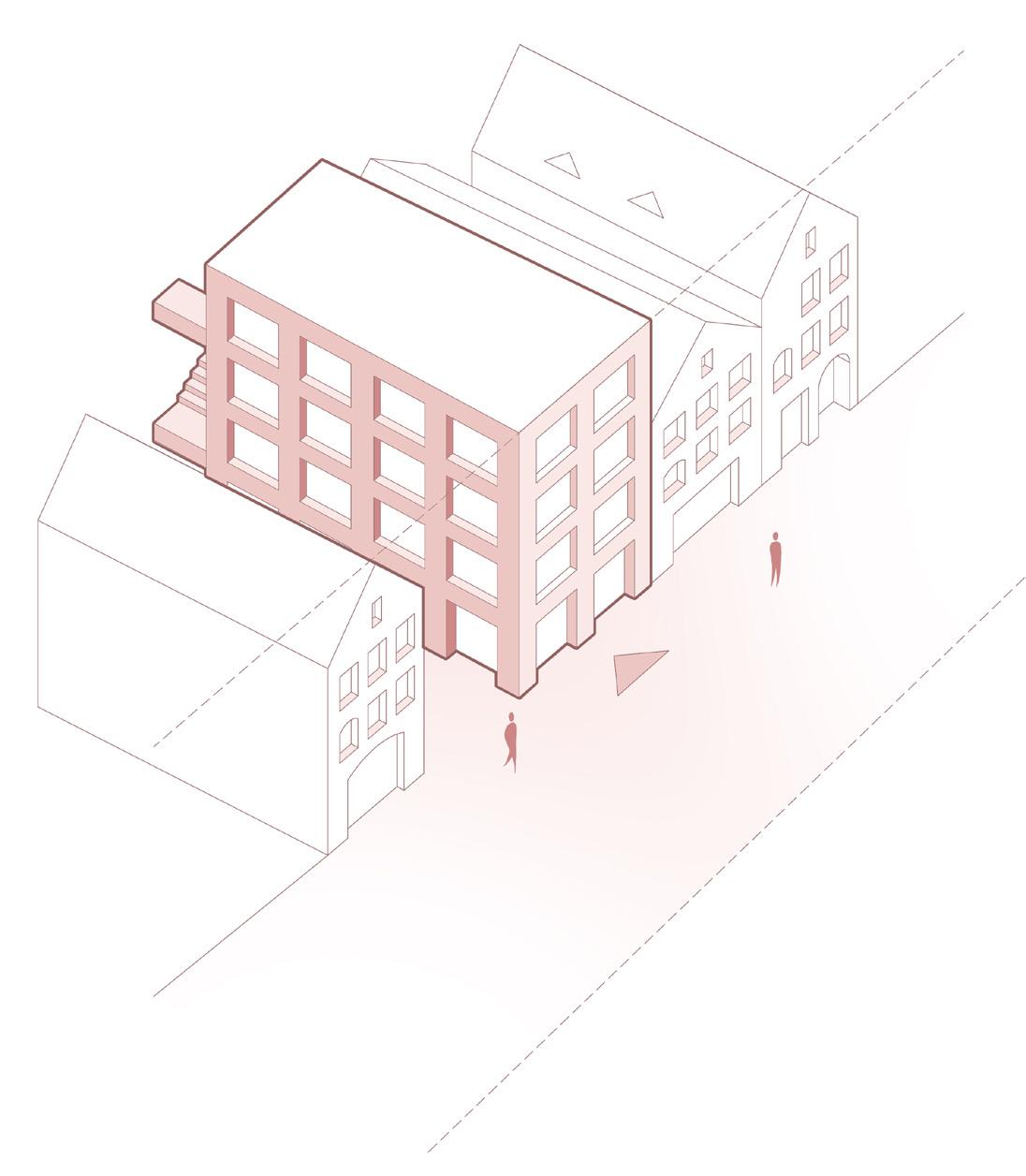

Through addressing both elements, it is possible to not only treat the physical issues of visual impairment, but also the mental health and wellbeing challenges of the visually impaired communities, greatly improving quality of life. In combining these 2 components, a new way of approaching the treatment and integration of the VIB community into wider society can be achieved, redefining visual care through architecture.

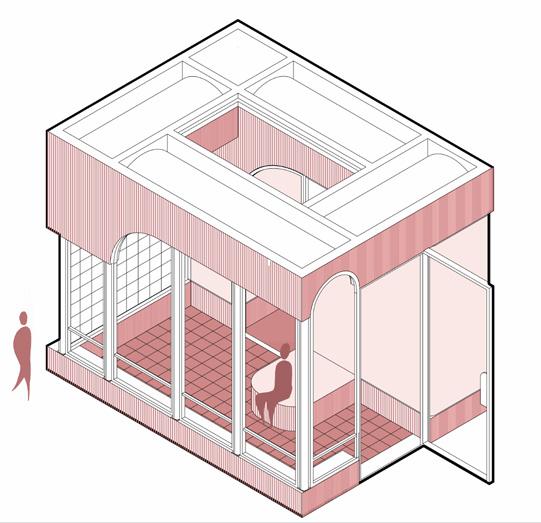

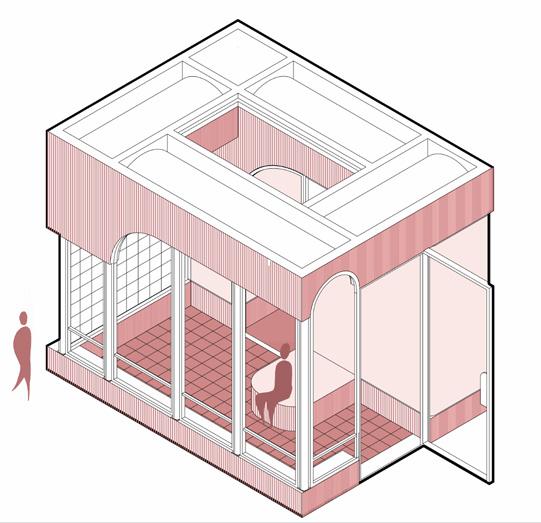

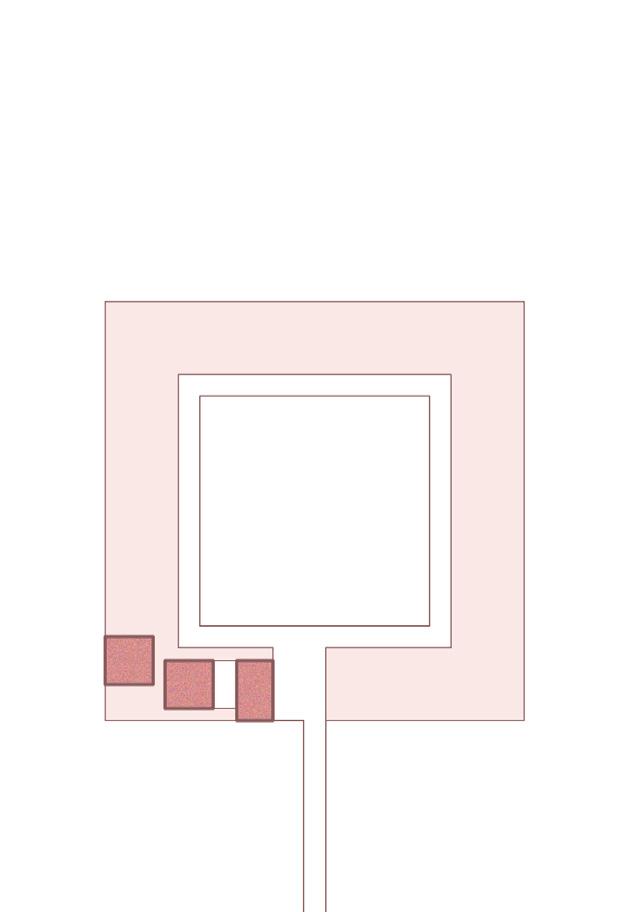

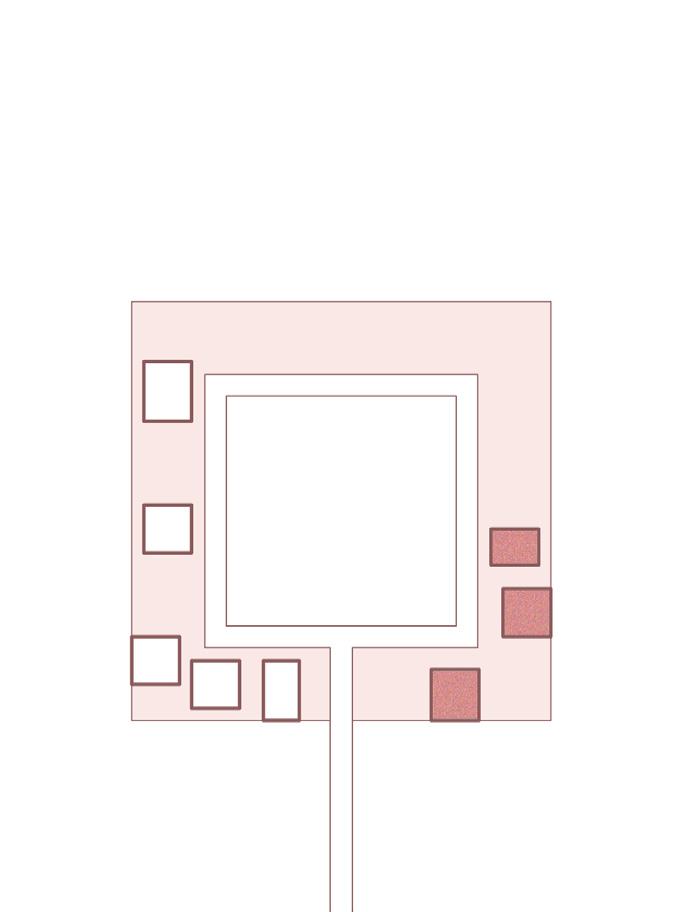

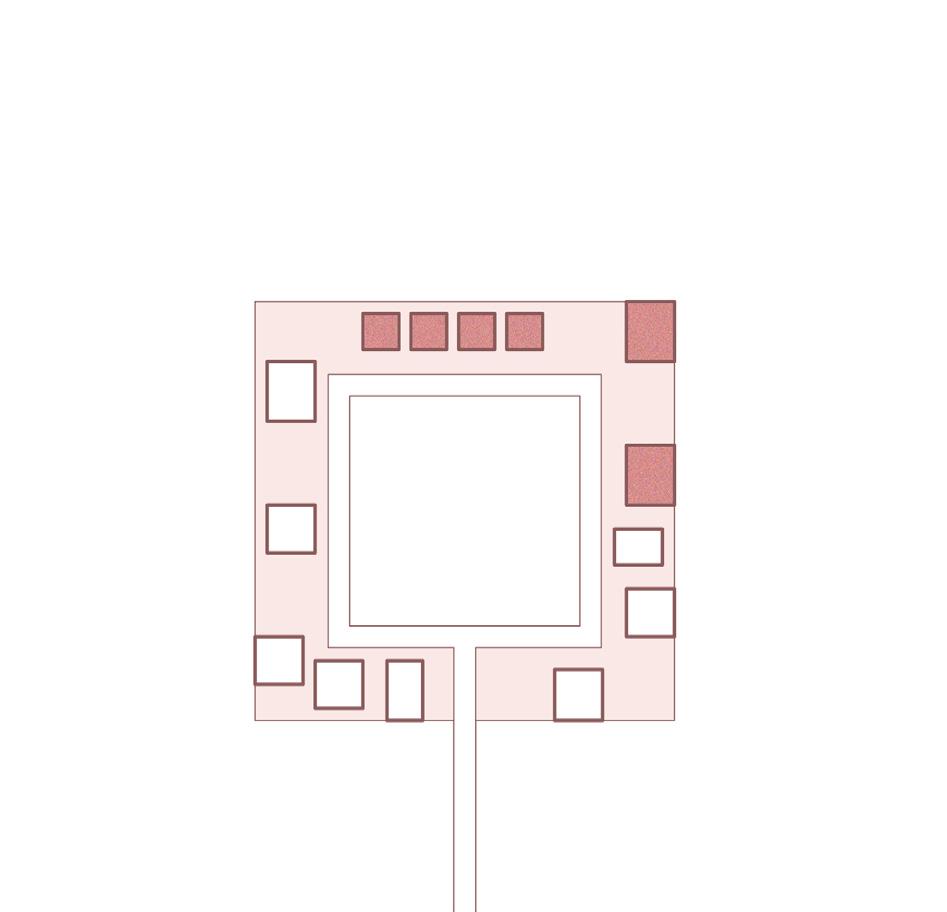

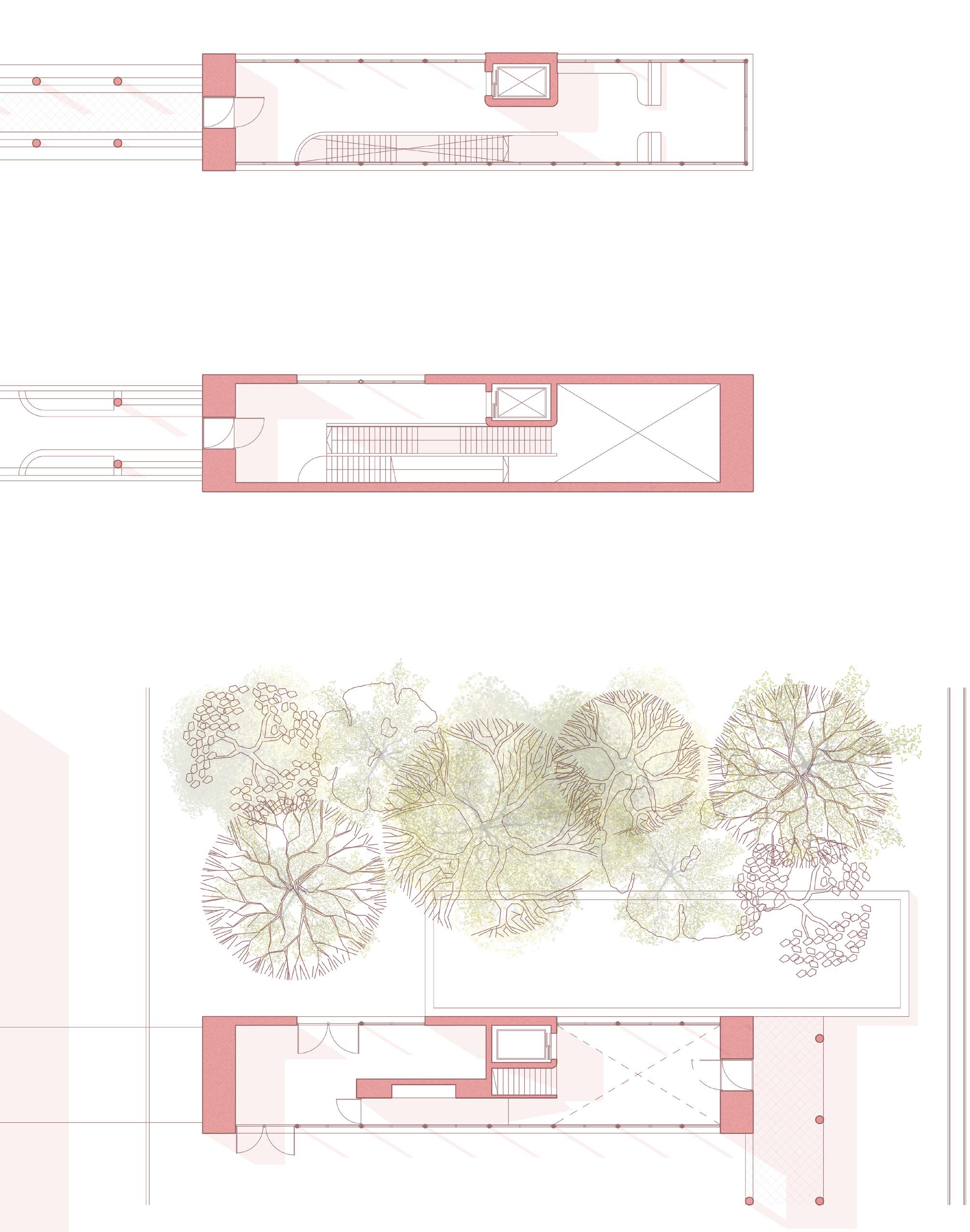

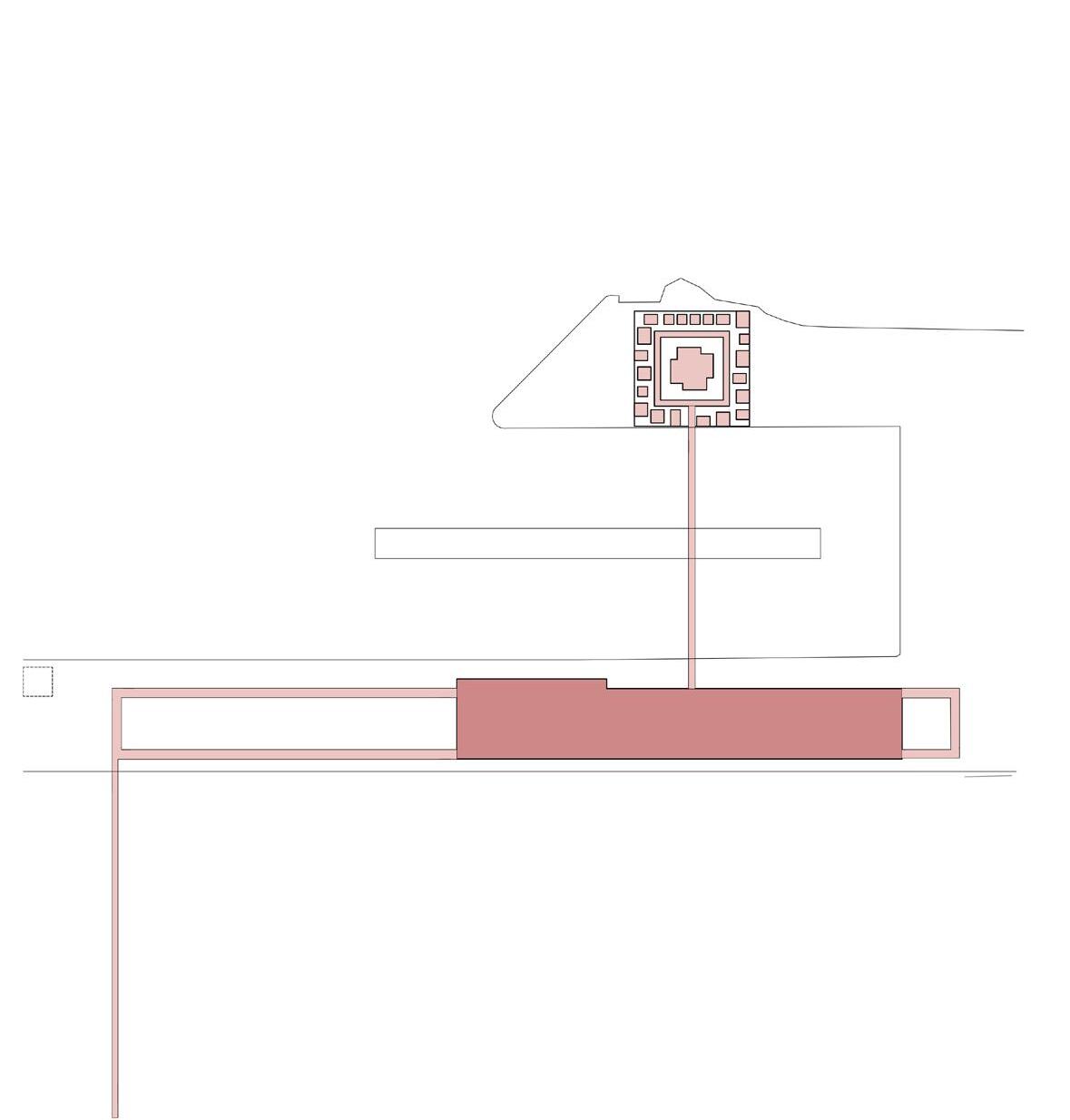

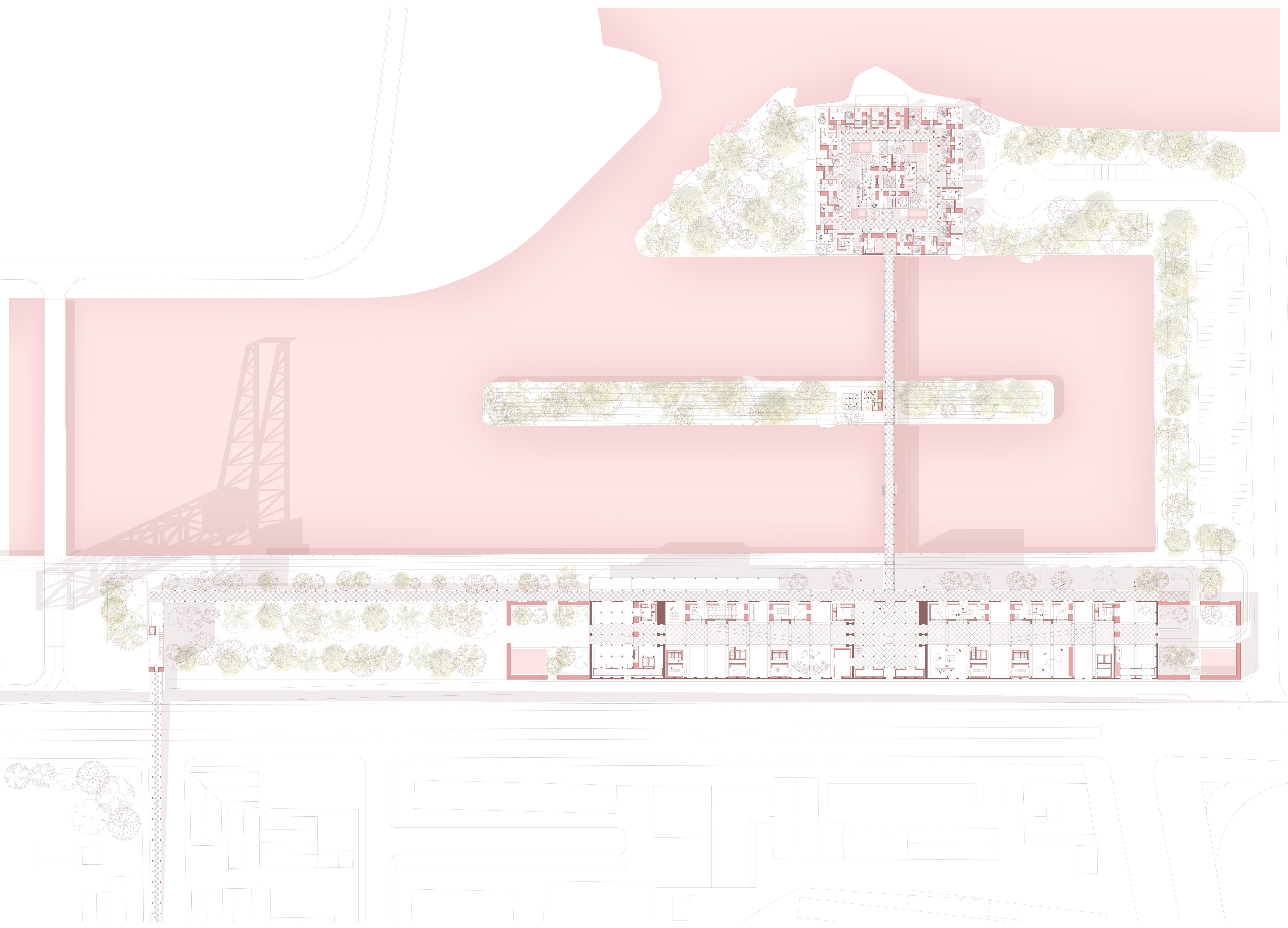

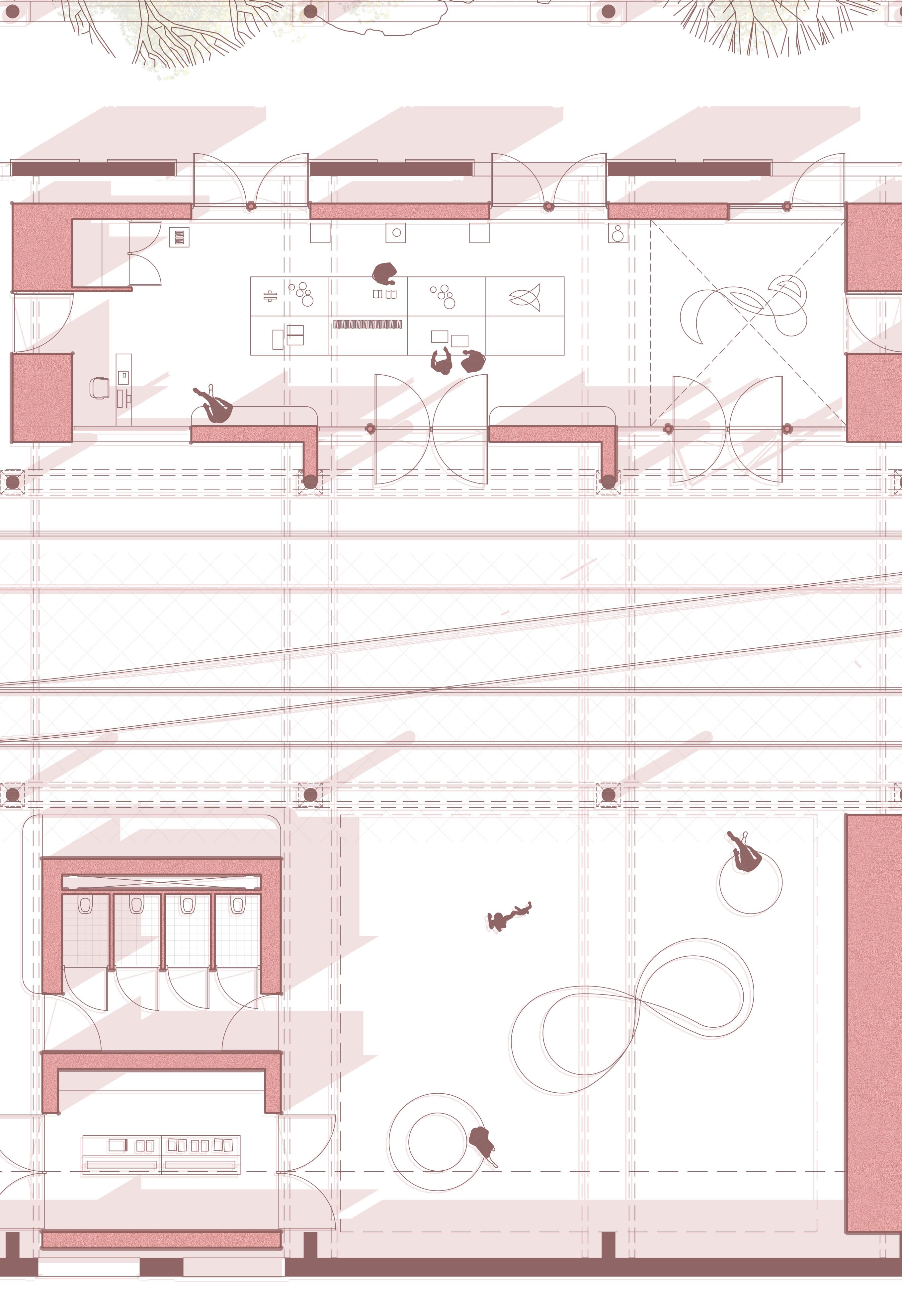

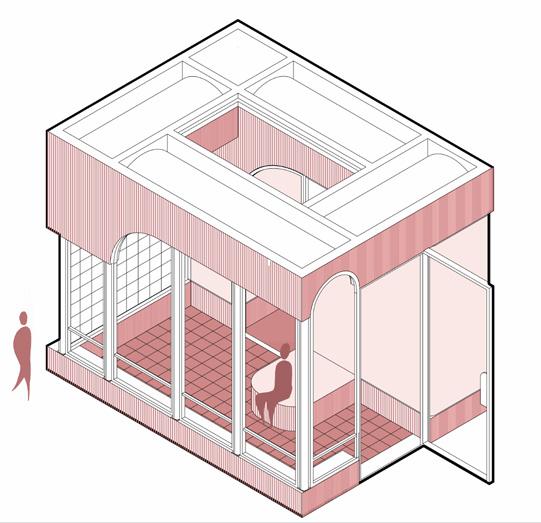

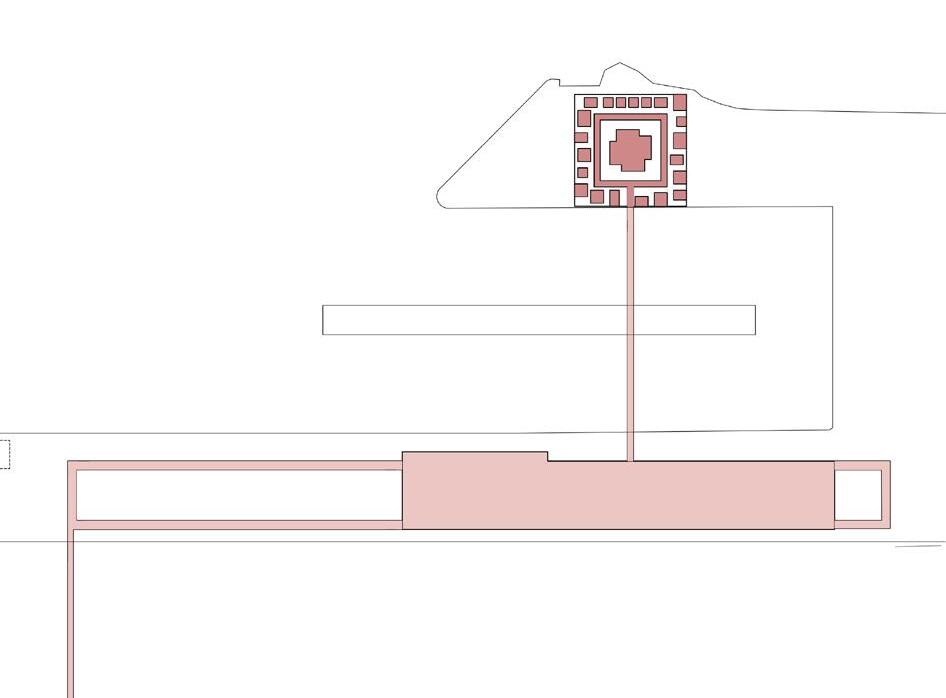

The first challenge of improving the mental health and wellbeing of the VIB starts at the beginning: diagnoses and treatment. Specifically, how can we provide an architectural environment that supports spatially the acceptance of bad news and the mental health concerns of treatments? The answer should be to address the currently hostile hospital and clinical environments through which many VIB people are diagnosed, treated, and processed. As part of the new new centre, a new dedicated regional eye hospital will be created to serve the population of the West of Scotland. This new building will be composed of traditional healthcare programme, as for example:

1. Reception and administrative space - 150m2

2. Testing and consultation rooms - 100m2

3. Waiting areas - 150m2

4. Operating theatres and surgical suites - 100m2

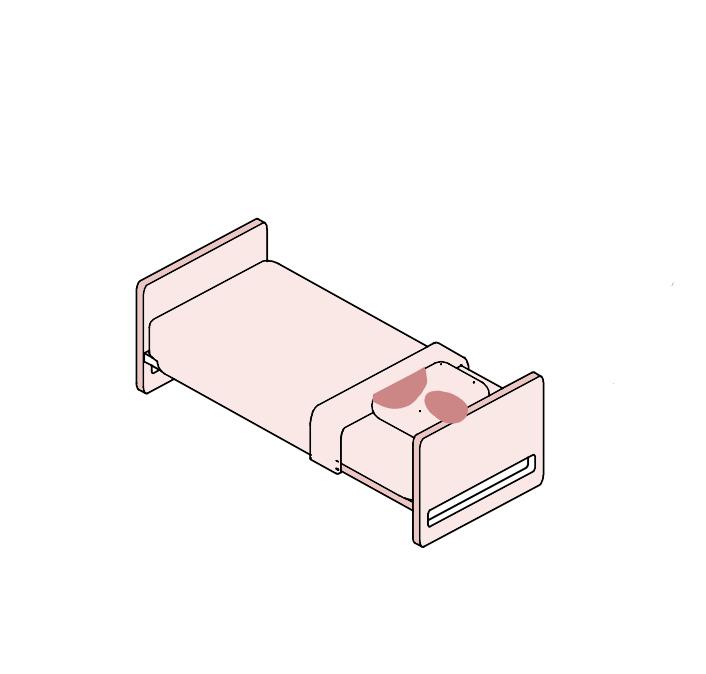

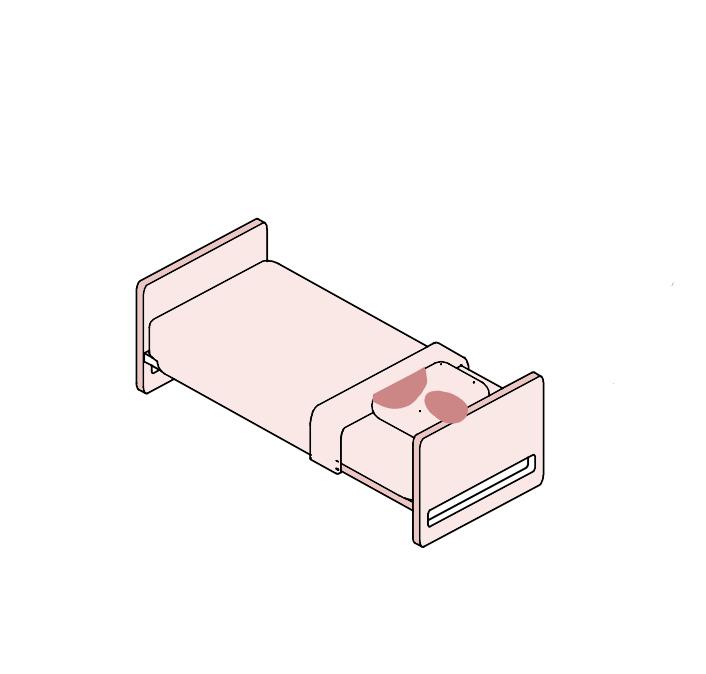

5. Accommodation - 50m2

Suplementing this will be more progressive programme such as spaces to escape, reflect and come together as a community. The goal of creating a new eye hospital is to change the dynamic set by many (most) current eye hospitals. It is a widely recognized problem that architecture has a great responsibility and power in the emotional states of patients being treated or receiving negative news. This new architectural intervention seeks to develop a radical new approach to this problem.

66

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Views out - visual escape

Clear routing + physical escape

Community - supporting each other

A new approach

A new approach is to apply the current programme but in a new way. A way which is navigable, on one level, with views out, and possibilities to escape and be alone, as well as possibilities to be social and have company.

69

The role of an eye hospital is to focus on the physical issue with the patient. The second component addresses the next step, where after a VIB person has received physical treatments or diagnoses for their visual condition, new challenges such as work, adapting to reduced independence and mobility, social isolation, and financial problems, significantly impact on the mental health and wellbeing of the VIB community.

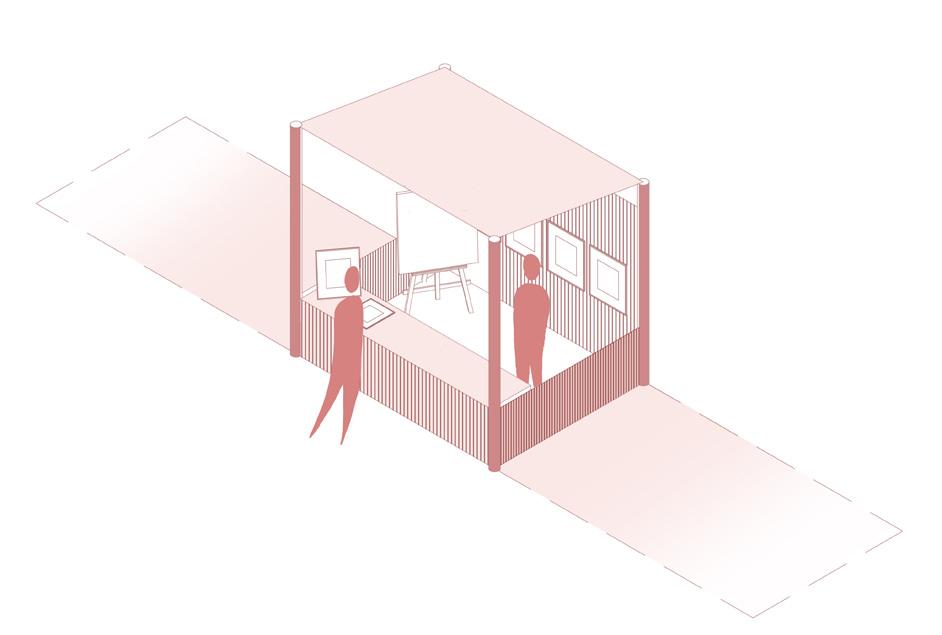

Alternative therapies offer a unique opportunity to help the visually impaired process challenging emotions in a productive manner. The process of making, performing and exhibiting can give a sense of purpose, potential financial return, and reconnect the visually impaired with the wider community, by directly exposing the abilities and virtues of the new programmatic approach to care.

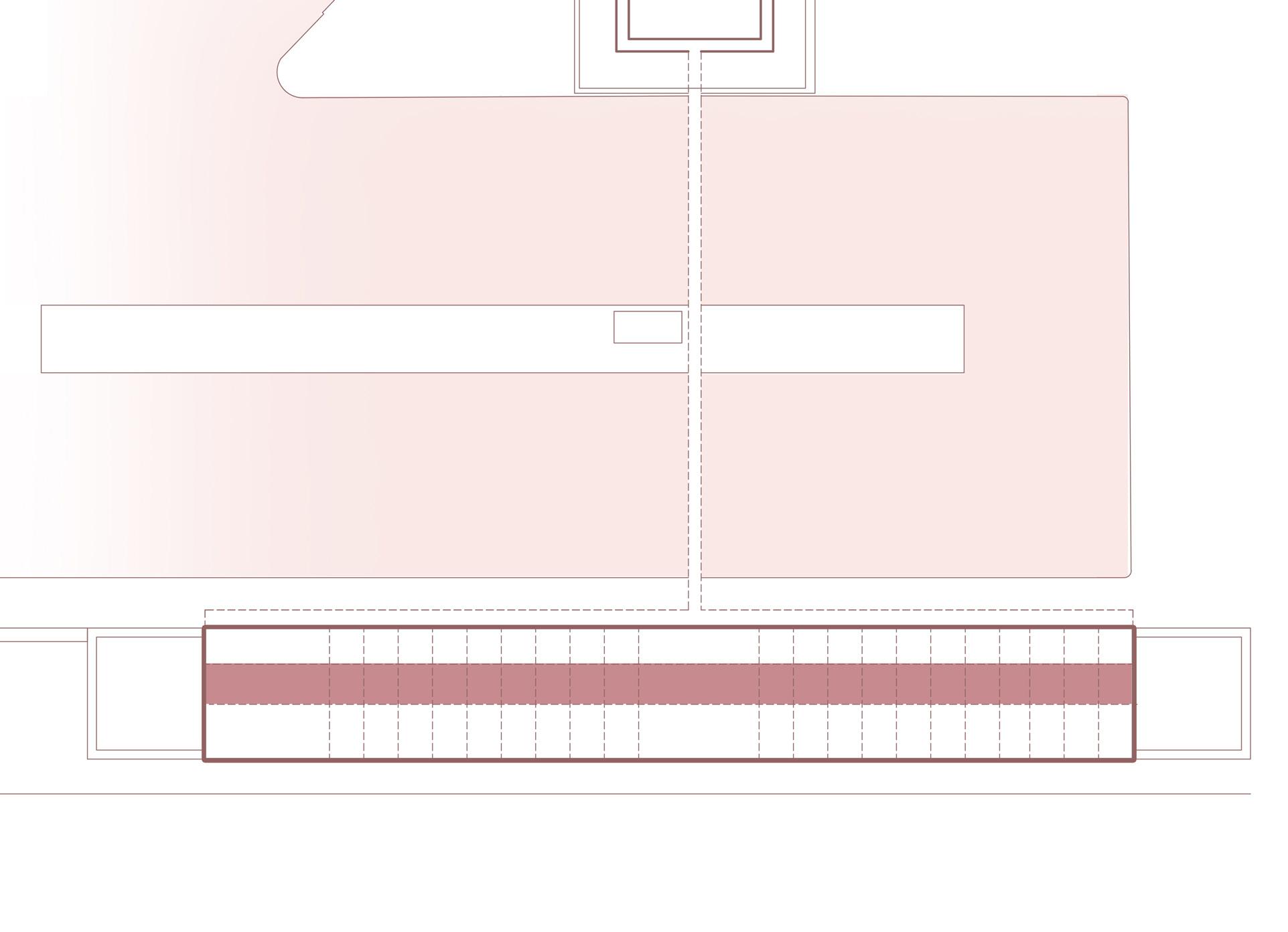

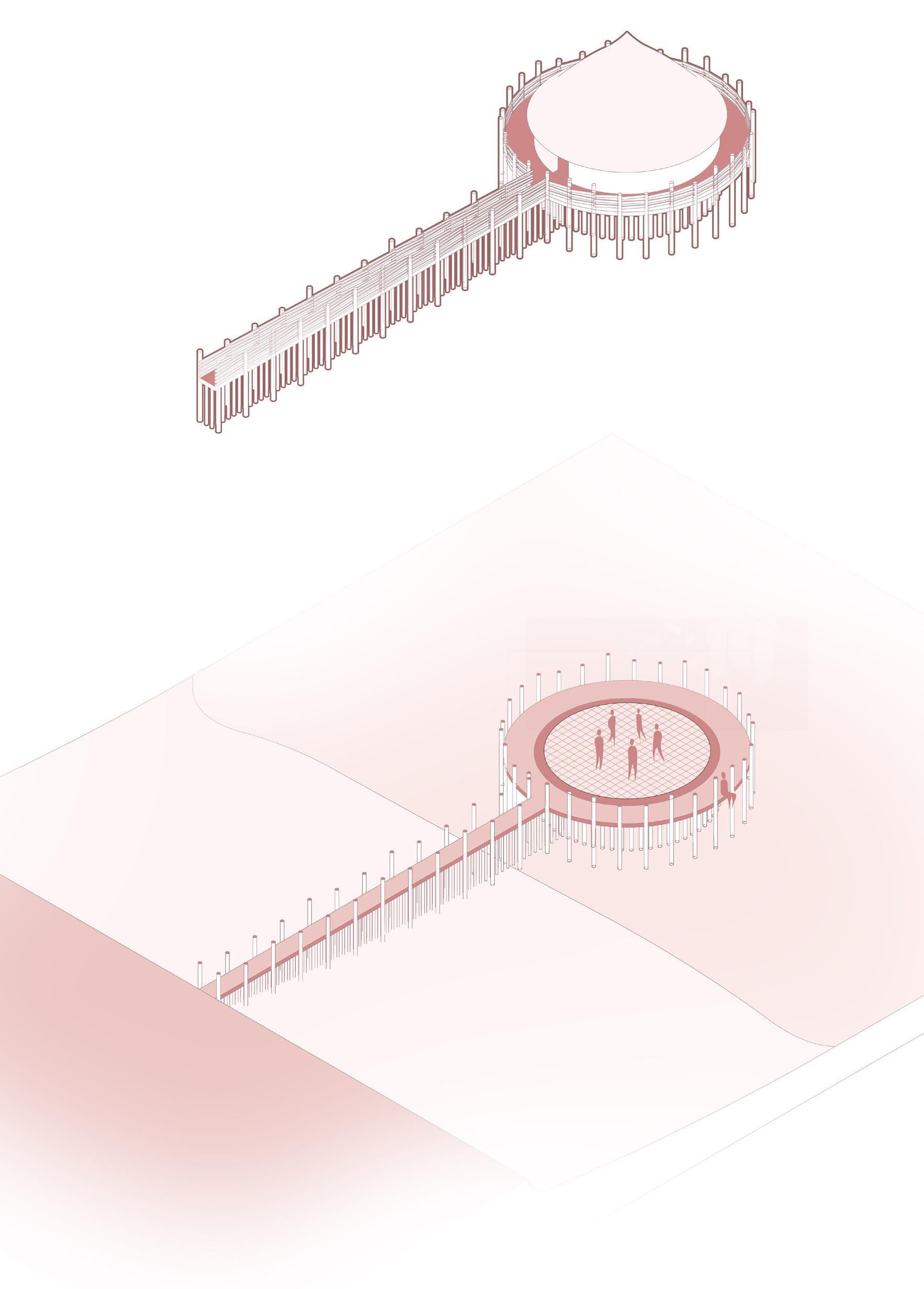

The question is how can alternative therapies, which support mentally, financially, and socially the VIB population, be supported and implemented spatially though architecture? The answer is to create a new social centre, where several forms of alternative therapies address key mental health and wellbeing challenges by creating:

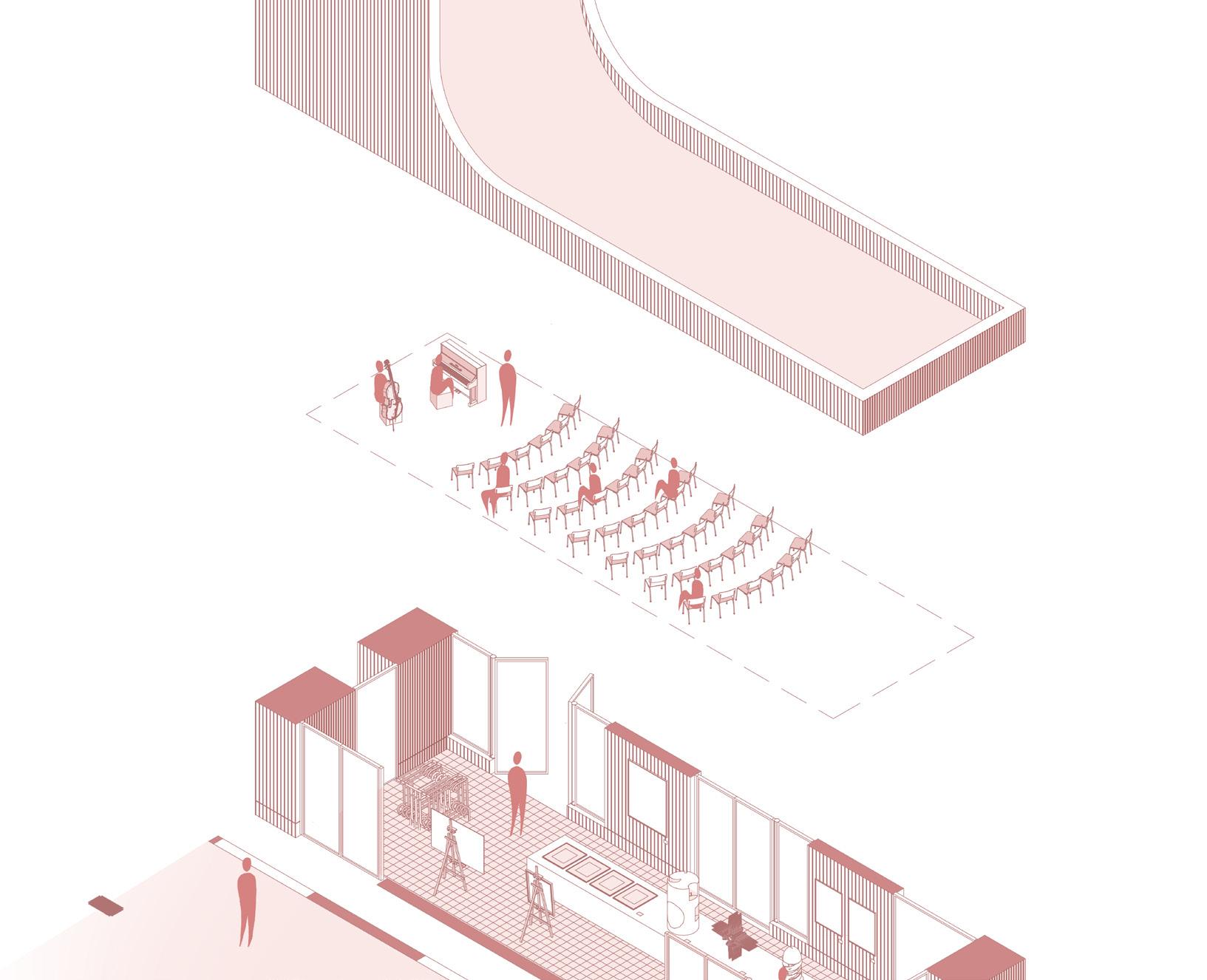

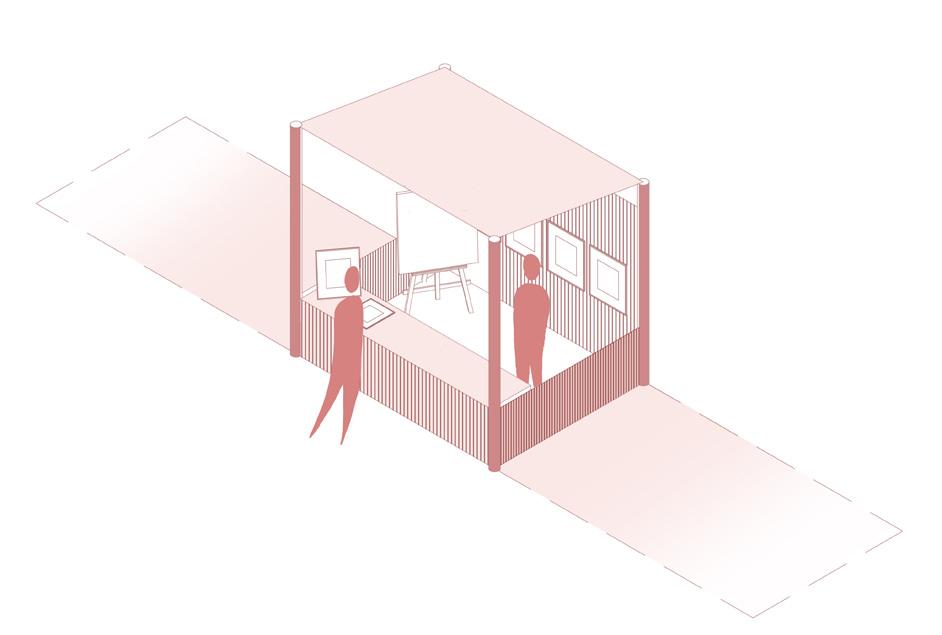

1 A series of studios/ practice spaces for Art, 200m2

2. A series of studios/ practice spaces for Music therapy - 200m2

3. Gardens for horticultural therapy

This programme will be supplemented by a series of highly public and visible performance/ exhibition spaces - connecting the centre to the wider public.

Furthermore, there will ebe spaces for greater entrepreneurship (4) , which will encourage the visually impaired, as well as the wider communities, to develop their own interpretation of the values emboddied by the new social centre. In essence, there will be spaces for greater personal expression, where there will be safety to try and fail. This sense of personal ownership is designed to give back a greater sense of purpose, and compliment the more structured and rigid programme of alternative therapies.

70

1.

4.

3.

2.

1.

4.

3.

2.

Performance and exhibition

An importany part of the social cenre to to expose the abilities and creativities of the visually impaired community, and in doing so, reconnect them with the wider public. At the same time, these spaces offer the opportunity to be rented for income

73

The Location Greenock, Scotland

75

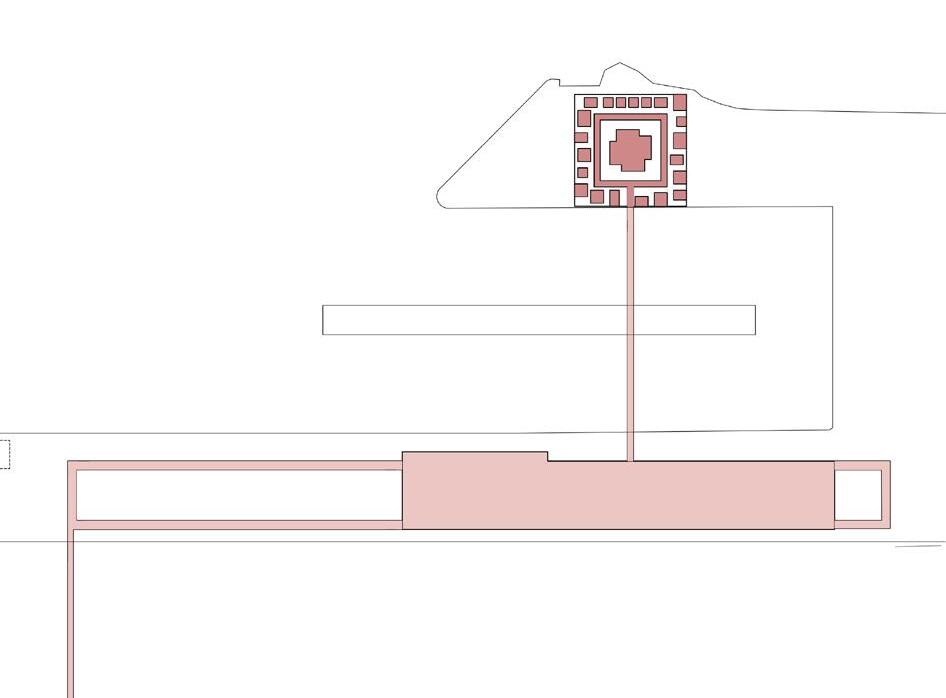

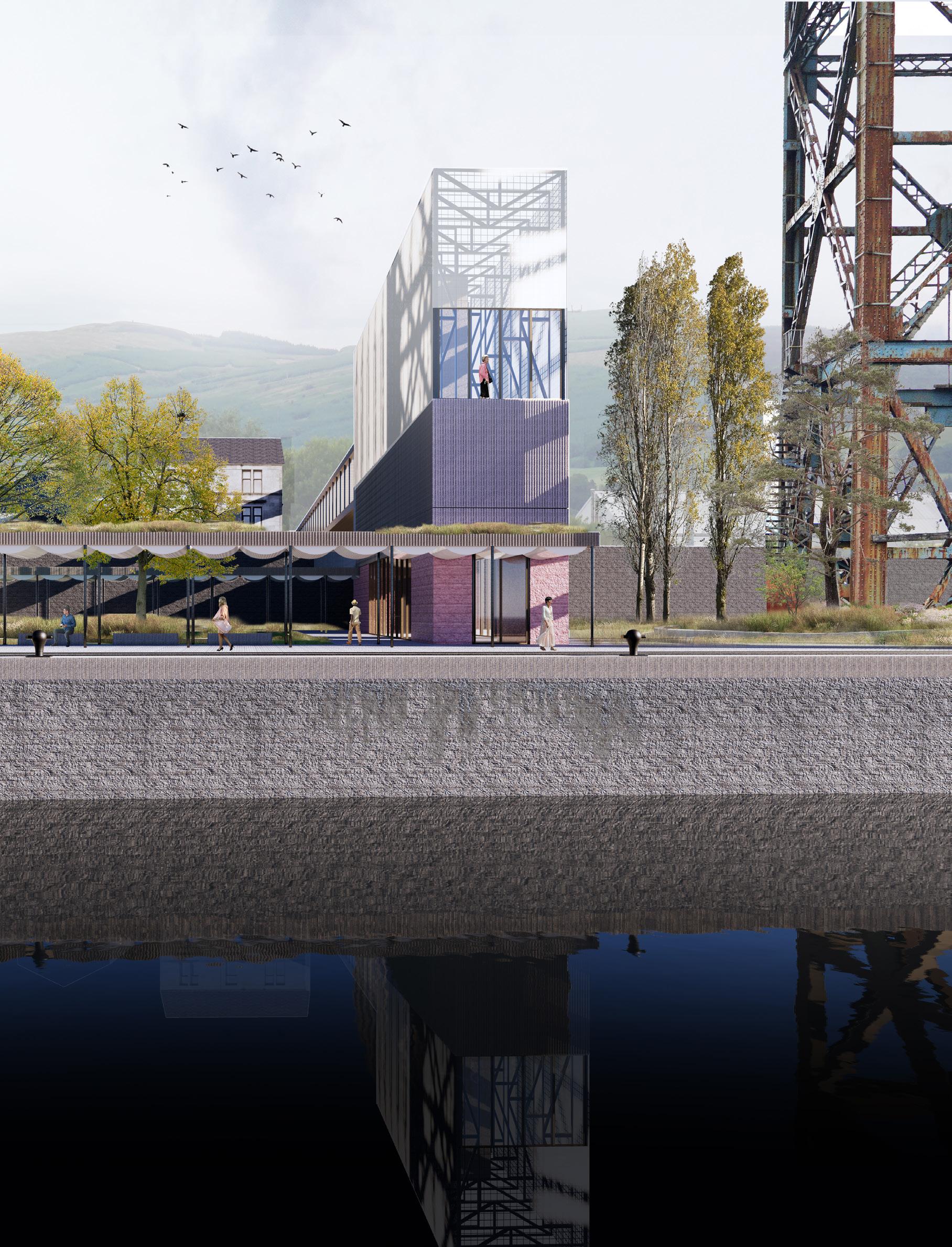

Greenock

A bitter sweet location

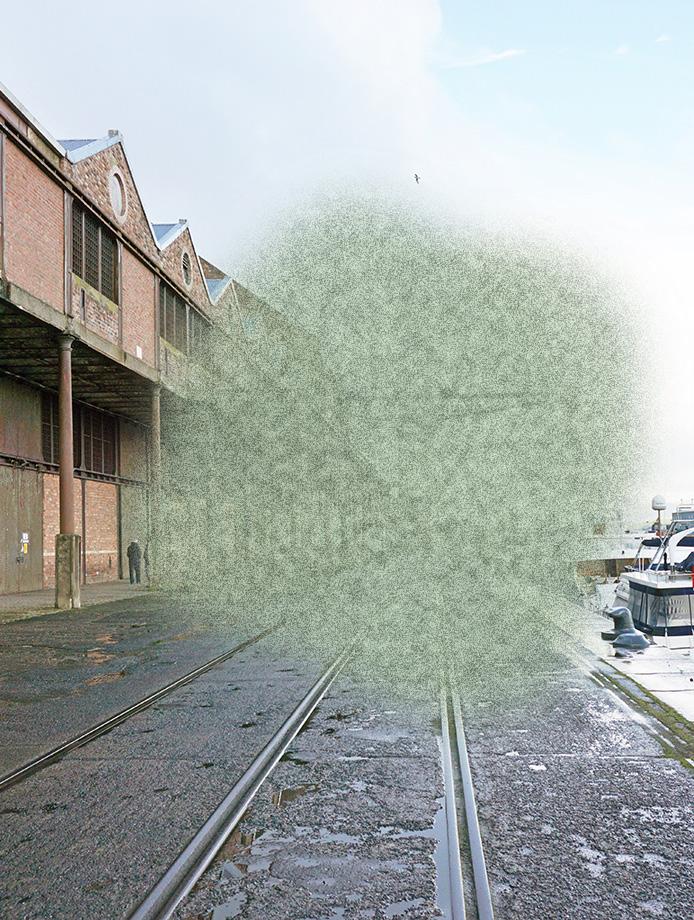

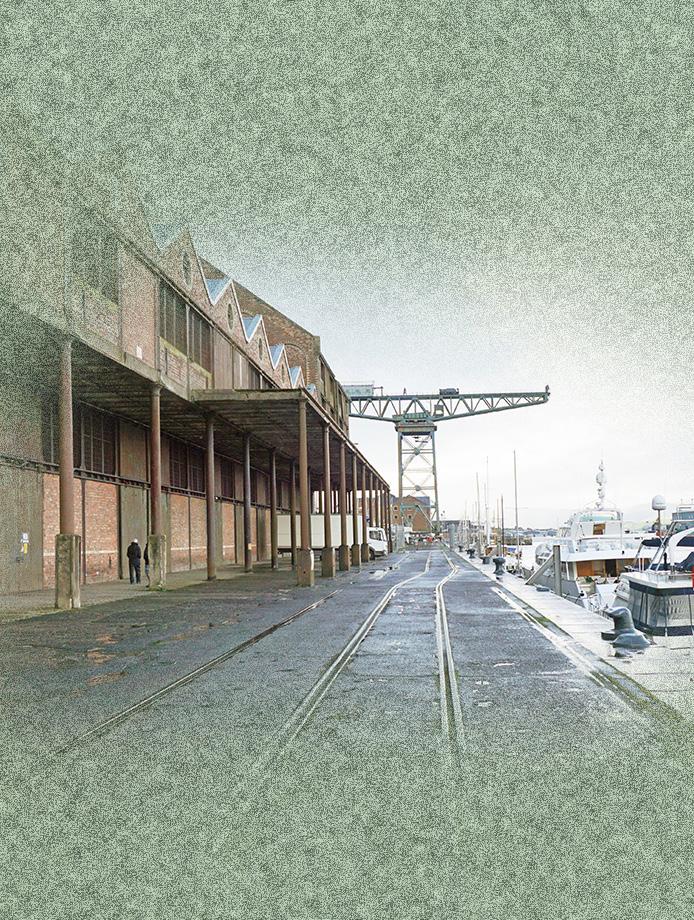

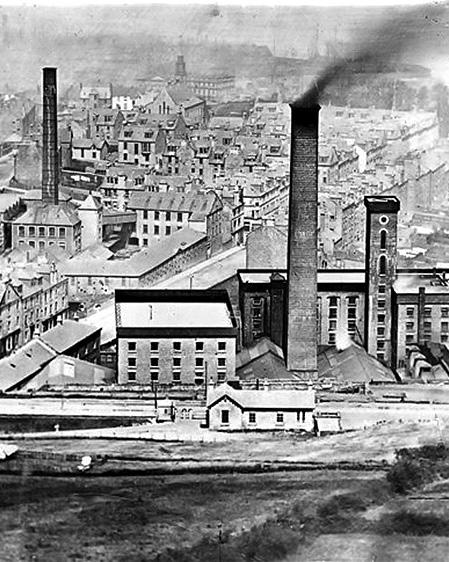

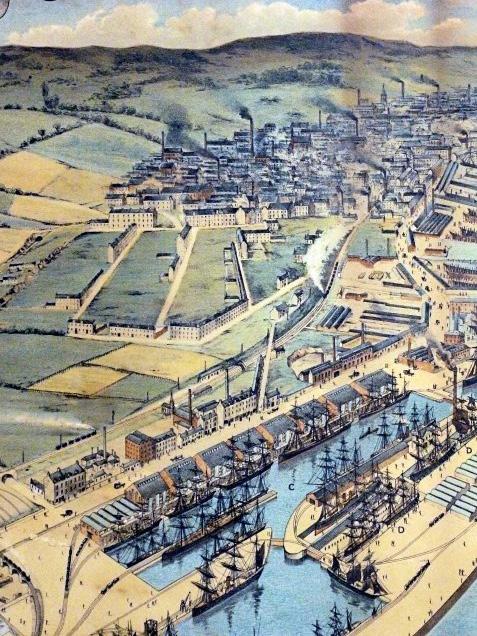

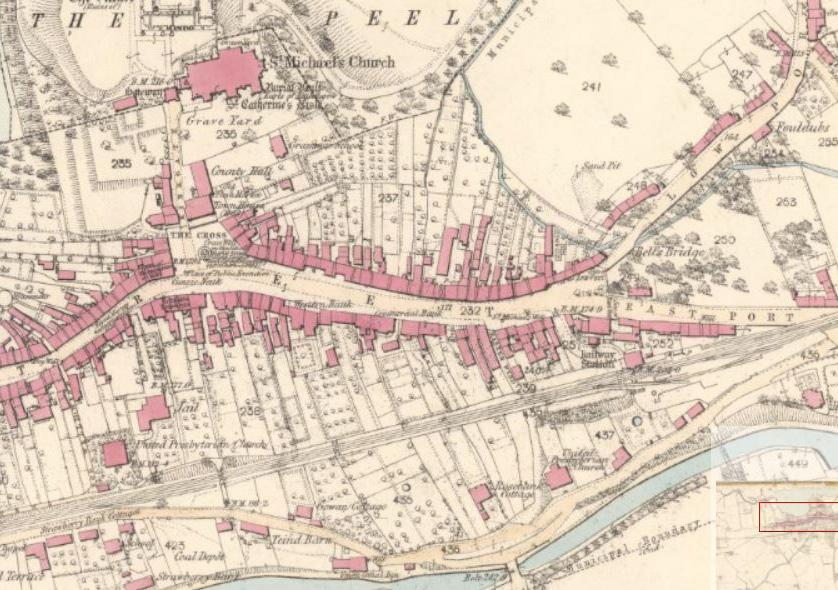

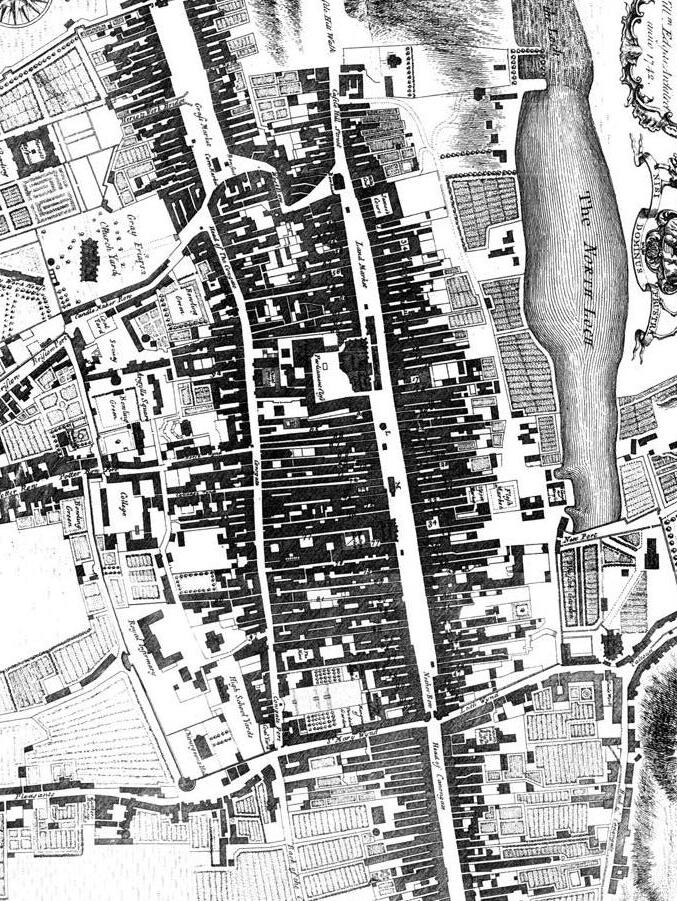

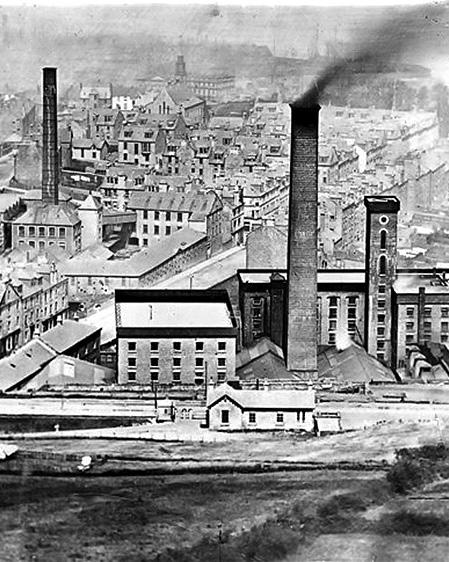

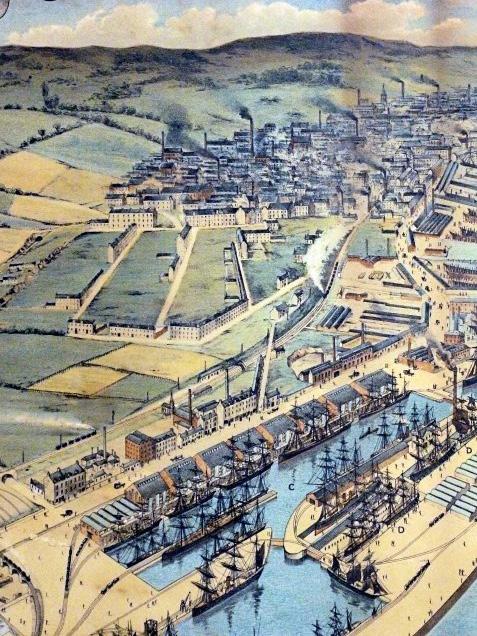

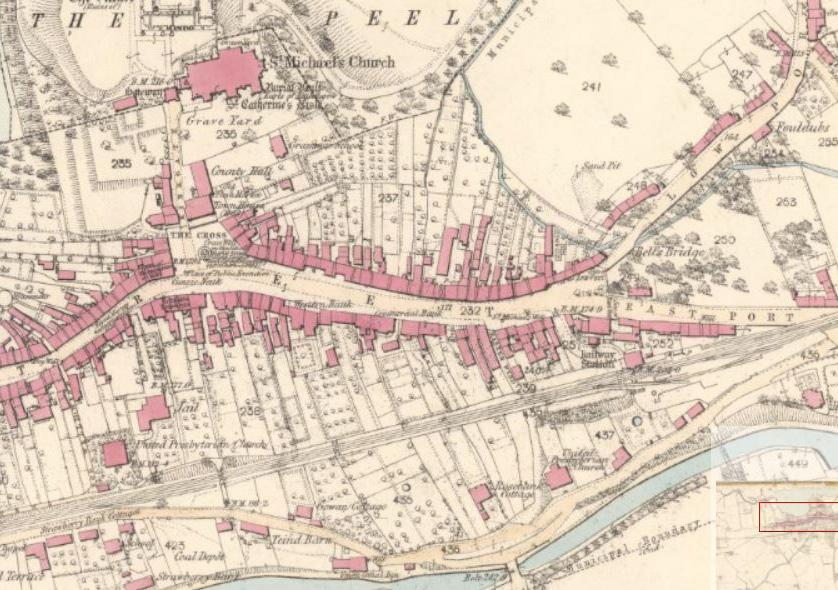

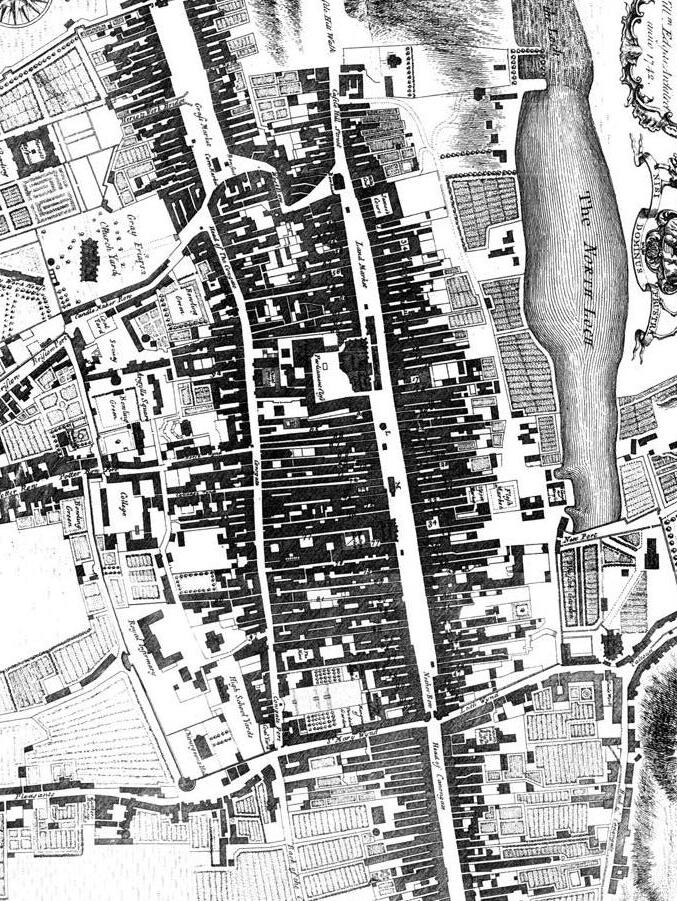

The next question is where such a project should be? The project location is Scotland, UK. Scotland is a small northern European country surounded by the Atlantic ocean on one side, and the North sea on the other. Nestled on the banks of the River Clyde, Greenock is a city of many contrasts. On the one hand, the city stands prominently at the estuary of the river, upon a intersection with the Atlantic ocean and many sealochs. Its prominent position on the rivers edge, as a welcome for ship visiting the inner Clyde and beyond to the city of Glasgow, tells something about its history.

Indeed, Greenock is a city steeped in a history of the seas and trade. From the 17th century Greenock began taking advantage of the larger city of Glasgow’s relatively inaccessible and shallow position on the River Clyde, Greenock and a neighbouring town, so called Port Glasgow, capitalised on an explosion of transatlantic trade from the UK colonies. (https:// www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk/portglasgow/ portglasgow/index.html) This trade, relying initially heavily on the slave trade, brought many new products to the shore of Scotland, namely Tobacco, cotton, and Sugar.

For Greenock, it would be sugar that would amass great fortunes for the town. Indeed, from the 1750s to the 1990s, the sugar industry provided much of the economic activity for the city. At its peak, there were at least 14 sugar refineries, or sugar houses, operating approximately 400 ships per year, equating to 25% of the UKs sugar trade. The industry declined

76

77

View overlooking Greenock Hardbour

View overlooking Greenock Hardbour

79

through the second half of the 20th century, leaving with it many unemployed, a town in a depressive decline, and a network of abandoned pieces of infrastructure and architecture, still held dear to the local communities.

Perhaps the most important remnant of the sugar industry in Greenock is the higher that average rates of visual impairment and blindness to that than the rest of the country. The rate of visual impairment and blindness within the total Scottish population is 6,5%. In the Greenock area – and surrounds – this figure stand at 10%. Greenock is being disproportionately affected by visual impairment and visual disabilities. Looking closer at Greenock in particular, we can see that it is Diabetic retinopathy that causes most of the visual impairment and blindness in people of working age (The Royal National Institute of Blind People & NHS Glasgow and Clyde, 2010a).

Diabetic retinopathy is not a stand alone condition but is a complication of poorly managed and treated Diabetes. In Greenock, an area of Scotland long associated with sugar importation and production, Diabetes is a damaging legacy and one of the leading health problems for the local population. Indeed, of the 44000 people living in Greenock, approximately 4400 have Diabetes, or 10%. Zooming out a little, the Scottish average is 5,2%. Clearly, there is Diabetic health crisis in the West of Scotland and Greenock in Particular. Diabetes, and therefore Diabetic retinopathy, is a result of

poor diet and nutrition. This area of Scotland is, in general, very unhealthy, with the West of Scotland being called the “sick man of Europe”, with some of the lowest life expectancies in Europe. (McCartney et al., 2011)

Furthermore, Diabetes is an issue of growing prevalence. Approximately 500000 people in Scotland are currently at high risk of developing the condition. More notably, in the Greenock area, there has been a 24% increase of diabetes diagnoses between 2011 and 2018. (Understanding Scottish Places, 2018)

(Diabetes Scotland, 2015)

(British Heart Foundation, 2021)

(Inverclyde Health and Social Care Partnership, 2019)

(The Royal National Institute of Blind People & NHS Glasgow and Clyde, 2010a)

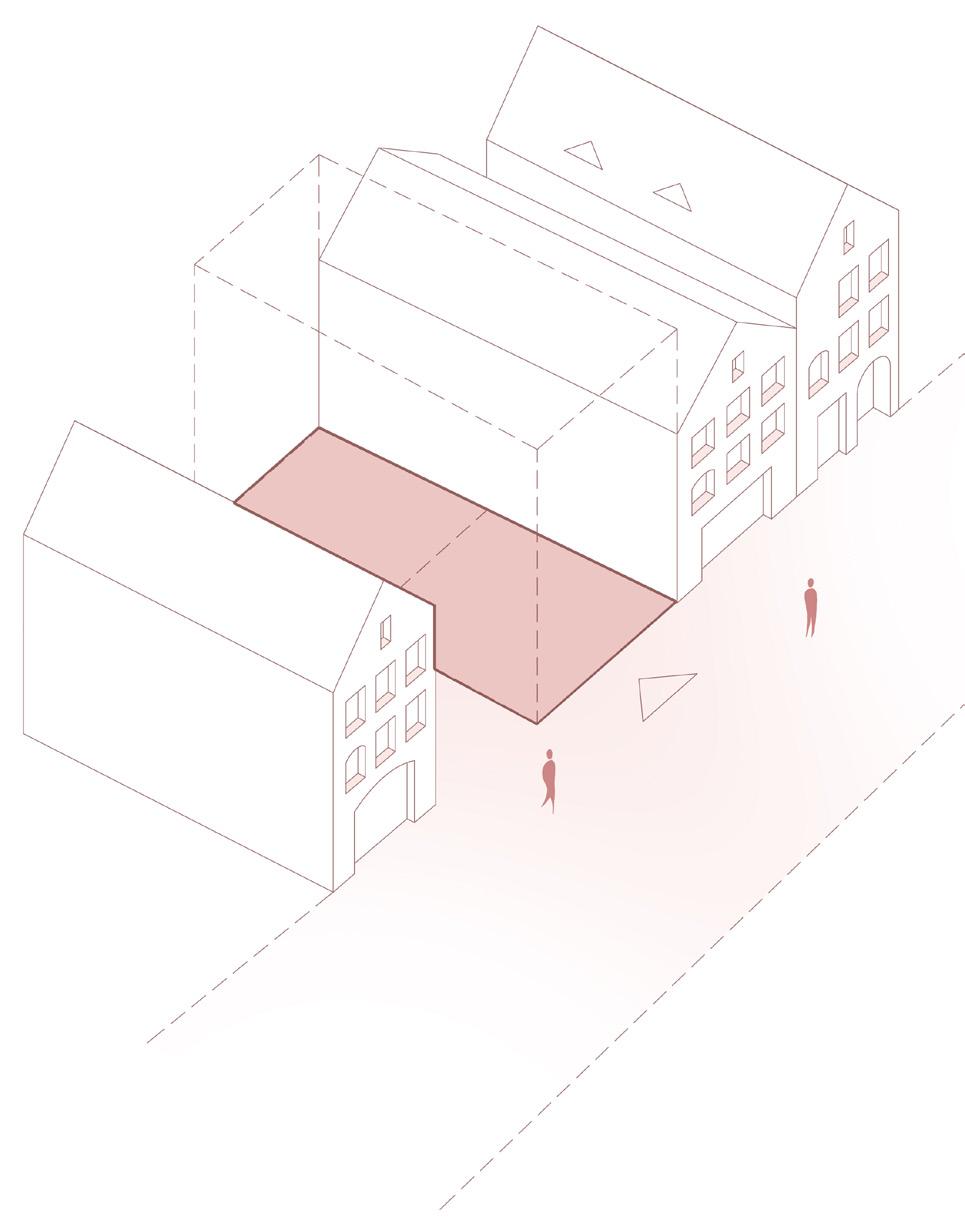

This city offers the perfect location for the intridcution of a new Visual care campus on the principles of a new eye hospital and social centre.

80

Sugar refineries dotted the urban landscape

Sugar refineries dotted the urban landscape

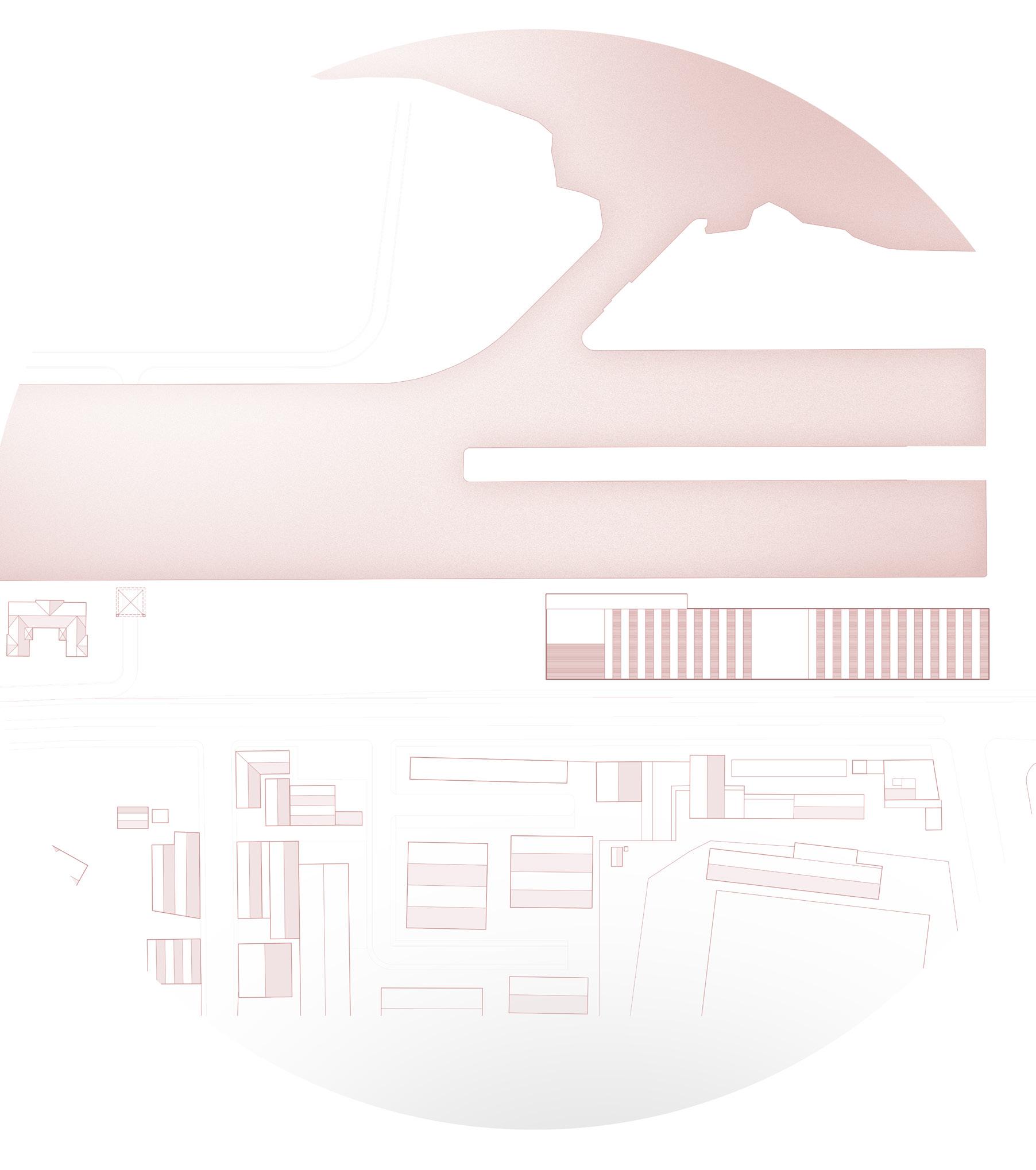

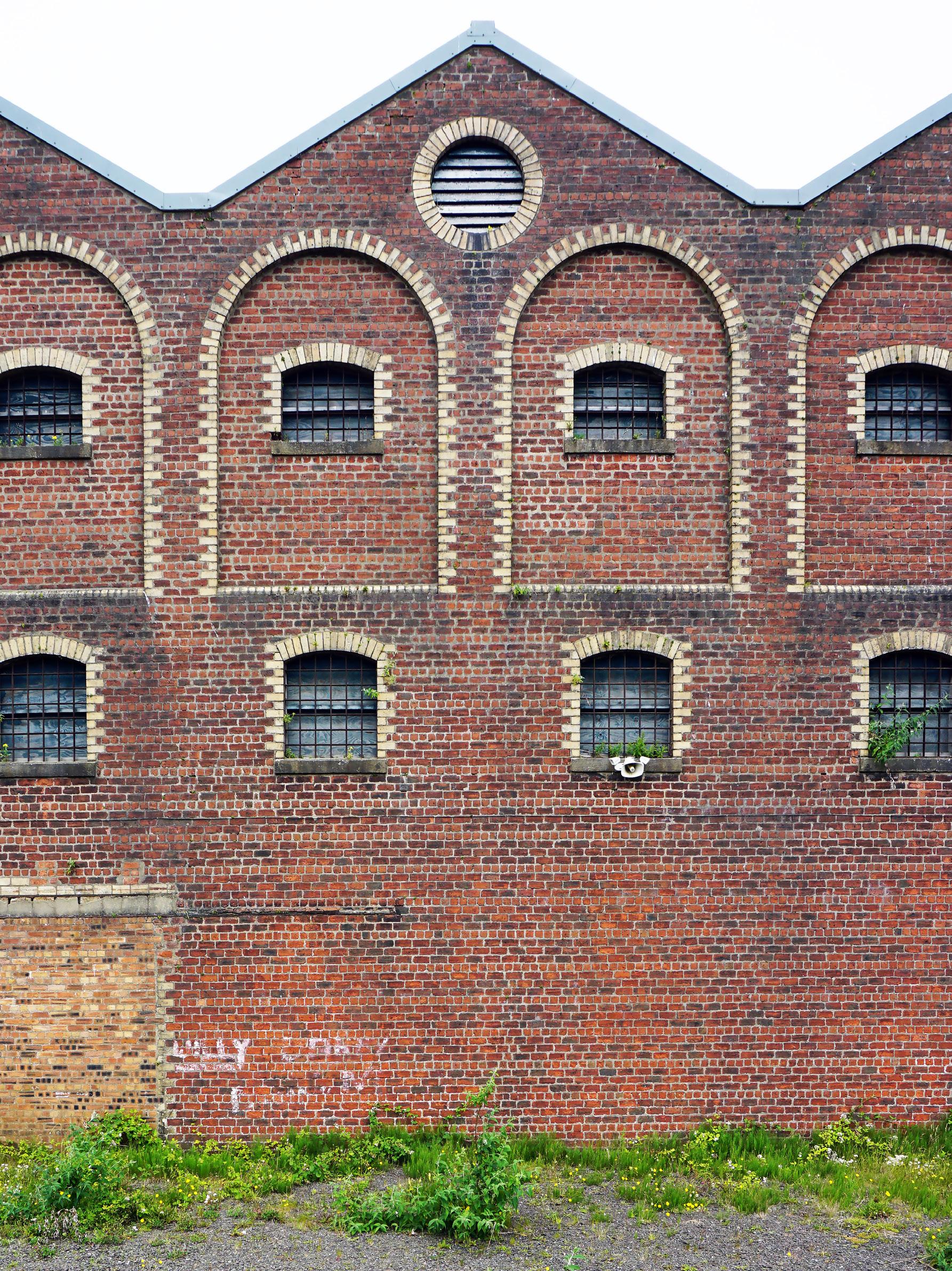

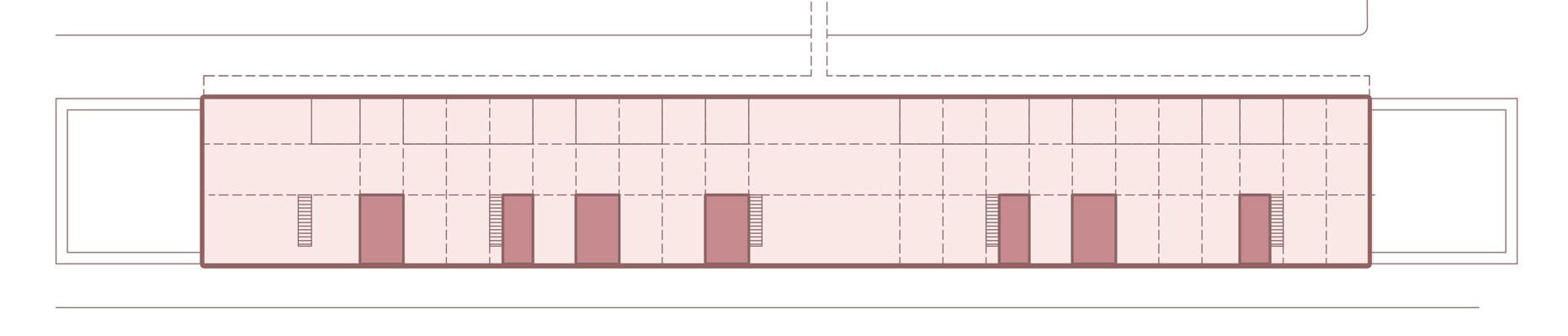

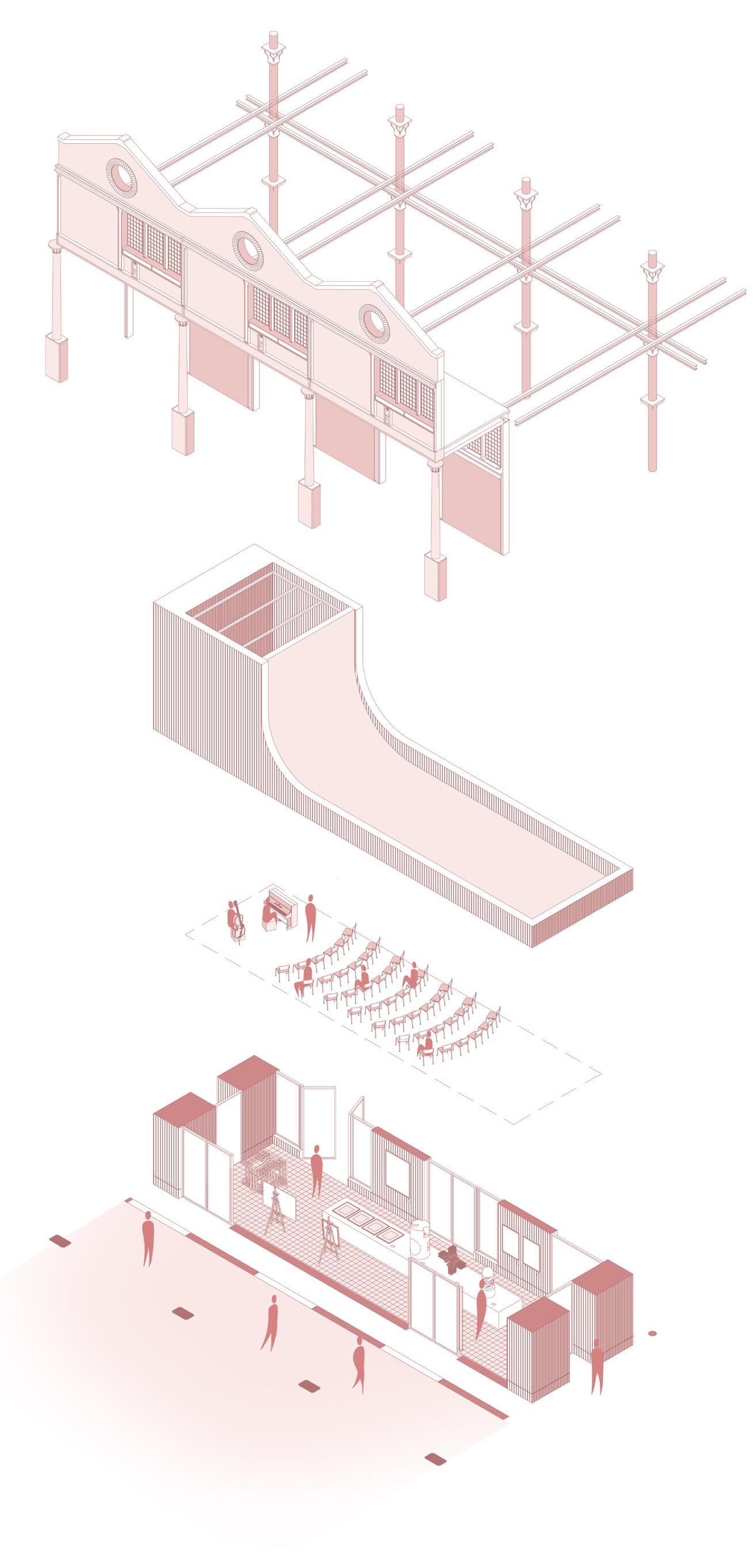

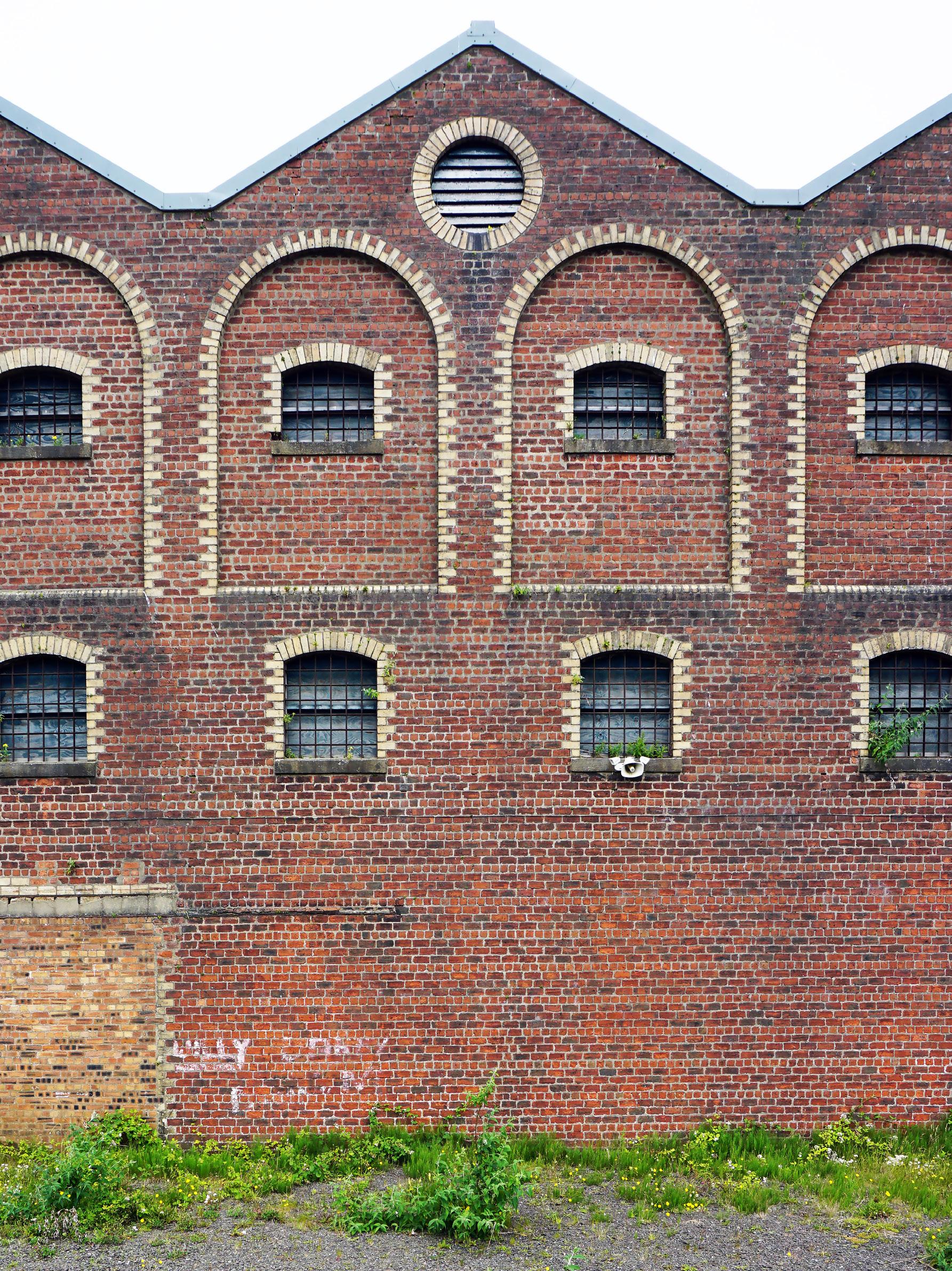

Sugar sheds Existing building

Existing site

James Watt Sugar Sheds