Menno Ninja Academ Kiwa

Floor

Dennis Jacoba Thais 2024 Rachel StijnShadyAcademy of Jana Wout

Floor Bas

C

Co

ve

Graduation Projects

Projects 2023-2024

Anna Bern

Suzanne Brugmans

Stijn Dries

Daniël van Eck

Bob Hartman

Dennis Koek

Roosje Rodenburg

Ellis Soepenberg

Merle Soeters

Ianthe Tang

Menno Ubink

Miks Berzins

Jelle Engelchor

Saskia Kleij

Nathalie Koren

Roelof Koudenburg

Daiki Mabuchi

Marija Satibaldijeva

Bas Tiben

Rachel Borovska

Max Daalhuizen

Marleen van Egmond

Sofie Ghys

Sander Gijsen

Floor Hendrickx

Jacoba Instel-Slooten

Jana van Hummel

Krijn Nutger

Wouter Sibum

Renan Dijkinga

Maro Lange

Vincent Lulzac

Dovilė Šeduikytė

Loretta So-Johnson

Martijn van Wijk

Shady Zenaldin

Arthur van Der Laaken

Minnari Lee

Iaroslava Nesterenko

Kiwa van Riel

Wout Velthof

Thais Gazzillo Zuchetti

Ninja Zurheide

Just societies

Just societies

Just societies

Just societies

Just societies

Just societies

Just societies

Just societies

Just societies

Just societies

Just societies

Liveable cities

Liveable cities

Liveable cities

Liveable cities

Liveable cities

Liveable cities

Liveable cities

Liveable cities

Synchronising with nature

Synchronising with nature

Synchronising with nature

Synchronising with nature

Synchronising with nature

Synchronising with nature

Synchronising with nature

Synchronising with nature

Synchronising with nature

Synchronising with nature

Memory of a place

Memory of a place

Memory of a place

Memory of a place

Memory of a place

Memory of a place

Memory of a place

Changing habits

Changing habits

Changing habits

Changing habits

Changing habits

Changing habits

Changing habits

Collective

This year, we’re celebrating the collective. As you have already experienced, neither studying nor working is something that you do alone. Every project requires collaboration between diverse specialists and a collective effort. We need each other, we learn from each other and only together can we create a bigger impact in our design professions. During the graduation weekend of 2024, we’re giving an equal platform to all 42 graduates. This exhibition showcases a group of designers with unique voices who are shaping a better future together. It is important to celebrate the autonomy of each project and at the same time to look for common ground. We aim to uncover shared values that unite this generation.

There is a sensitivity to the way in which this year’s graduates question how to act in a world full of fragmented collectives, where the needs of humans, animals and plants are often dismissed. They seek to establish a dialogue and common ground between animals and people, forgotten crafts and students, colonial past and river. Instead of fighting against diverse actors of collectives, they align with them, demonstrating empathy with the varied needs of both human and non-human communities. The graduation exhibition provides a moment to connect with the broader collective. This year’s graduates follow in the footsteps of previous generations and build on their legacy. This exhibition places a special focus on this rich, intergenerational community and examines how the discourse of our profession has changed over time. Where are we heading to in the future? We invite the graduates to enter a dialogue with the past generations and reflect together on our collective future.

Justyna Chmielewska, Curator

Anna Zań, Curator

Madeleine Maaskant, Director

Janna Bystrykh,

Head of Architecture

Anna Gasco,

Head of Urbanism

Joost Emmerik,

Head of Landscape Architecture

Just Societies

These graduates focus on social equality, societal awareness and justice in society. They tackle societal justice by spotlighting vulnerable groups of people in need of support and acknowledgement, not only by the society, but also by designers. They explore the role that they can play through placing focus on these vulnerable groups of people. These graduation projects strive for social justice and equality. They are sensitive to human needs. Through methods such as participation, they engage with communities, invite them to the table, start a dialogue and relegate themselves to the background, empowering people who are often unseen or unheard. These are socially engaged designers. They tackle the current social issues and give a voice to marginalised communities.

28

Discipline Architecture

Date exam

10.10.2023

Committee

Alexey Boev (mentor)

Daira Naugolnova

Peer Glandorff

Additional members

Micha de Haas

Ana Rocha

Anna Bern

Life in the children’s hospice

Introduction: I cared for my relative Anastasia, who passed away from cancer when she was eight years old. Afterwards, I volunteered at the ‘Lighthouse’ children’s hospice, where she spent her final month. Observation (problem): While volunteering, I found out that, according to the statistics, only 1 in 9 children are dying in a children’s hopsice and the rest are living in remission. So, a hospice is about life, not death. Every single hospice worker suffers burnout, on average within three years of working there. Almost every parent is prescribed antidepressants.

Solution: Provide a space that makes all inhabitants of the hospice feel mentally and physically healthier. The target groups are children, parents and all hospice workers.

Research in brief: Children in hospices face physical limitations, resulting in low-quality lives with limited socialising, experiences and intellectual growth. Adults suffer health impacts from the demanding physical and emotional workload. Parents, spending up to 90% of their time with their children, often quit their jobs. This, combined with negative prognoses and lack of emotional support, leaves nearly 95% of parents on antidepressants. Hospice workers suffer burnout from constant exposure to death, staff shortages and outdated facilities. While architecture can’t solve these deep-rooted issues, it can help individual doctors with their mental state to prevent burnout.

Concept in brief: Build a programme for each target group to give them a choice of space according to their mental state. Design a circular ‘space in a space’-shaped building to provide an endless loop for higher mobility in wheelchairs, freedom and new daily experiences. Having an explicit floor division: -1 floor is technical spaces, morgue + parking, 0 floor is public for daily visitors with maximum transparency, 1 floor is private for families living there permanently, with a garden. Place all spaces and rooms according to daily routing, but with the opportunity to discover new alternatives. Sustainability as a core task for design. Analysing life-cycle assessment phases and using CLT as main construction.

Life in the

the children’s the children’s hospice

Suzanne Brugmans 32

Discipline

Landscape Architecture

Date exam

27.08.2024

Committee

Maike van Stiphout (mentor)

Remco Rolvink

Jandirk Hoekstra † Additional members

Kim Kool

Roel Wolters

The route to Umu

Working together towards Kawongo’s resilient future

Throughout history, many people have settled near the rivers of Kenya because the fertile soils offered great opportunities for agriculture. However, this opportunity is now turning into adversity due to climate change and growing populations. Climate change is affecting different areas of the world disproportionately, with developing countries already feeling the extreme effects and having no means to counter them.

As a landscape architect, I want to contribute to finding ways to create more climate resilience in affected areas. With this project, I hope to inspire and empower the community of Kawongo, Kenya, to create a sustainable and resilient future for generations to come. This involves tackling the main environmental challenges they face and changing the way they work with the landscape through a step-by-step approach that still allows people to sustain their livelihoods.

The project focuses on creating a resilient landscape system centred around the local landmark of Umu Hill. In the plan, Umu Hill symbolises the historic roots of the community and the area of Kawongo. But Umu Hill also represents the way forward, showing that with a change in land use, the rest of the area can work towards becoming like the green, biodiverse hotspot Umu Hill is now. The problems identified during interviews and site analysis are addressed in a community-driven landscape strategy consisting of large and small-scale interventions, their optimal locations and contributors.

Seeing the community’s eagerness to think about climate change and their future has been truly inspiring. I have learned a lot from these people in the short time I’ve known them. Even with limited resources, their determination to tackle climate issues is clear.

This project highlights how important it is for us to work together and prioritise sustainable practices, both locally and globally. If we don’t act now, the future for these areas could be devastating.

I hope this project can serve as a wake-up call for people here and be an inspiration for other areas that are affected by climate change in the same way as Kawongo. Let’s make a positive impact on the world together!

Brugmans The route

route to Umu

Stijn Dries 36

Discipline Architecture

Date exam

06.05.2024

Committee

Laura Álvarez (mentor)

Peter Kuenzli

Niels Groeneveld

Additional members

Bastiaan Jongerius

Machiel Spaan

Housing the precariat

Two thirds of the houses in The Netherlands are built for what a household is in the popular imagination: two parents and two point four children. In fact, two thirds of households in the Netherlands are comprised of one or two people. There is a massive mismatch between supply and demand. Neither the market, nor the government, is creating what people need: affordable and suitable housing for one of two inhabitants.

Resident-owned co-housing is emerging as part of the solution to the unfolding housing crisis. As with any emerging concept, the word ‘co-housing’ carries an aura of vagueness and ambiguity. Co-housing is a typology to create affordable, and suitable, housing for the contemporary working class (precariat). It can play a pivotal part in guiding us to a system where co-ownership is a viable and desirable option in the popular imagination.

This thesis offers a concept for co-housing and positions it as a typology that can help us to create affordable, and suitable, housing for the contemporary working-class: the precariat.

Housing

Housing the precariat

Daniel van Eck 40

Discipline

Urbanism

Date exam

23.05.2024

Committee Tess Broekmans (mentor)

Marie-Laure

Hoedemakers

Martin Aarts

Additional members

Hein Coumou

Sander Maurits

Zaanse Wind

A strategy for the housing shortage

Zaanstad borders Amsterdam, the largest city in the Netherlands. It is a municipality with a fascinating history and lots of opportunities for urban renewal. In addition, it is part of the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area (Metropool Regio Amsterdam, MRA), a region facing the major challenge of rectifying the overheated housing market. The national government is trying to regain control over the situation, while the market is demanding to be left alone. As a result, the process of area development is stalling and the building target of 900,000 homes by 2030 is slipping further and further away. This design proposal highlights the opportunities that exist for the densification of Zaanstad.

The municipalities are the parties that are responsible for the implementation of the housing goals that have been set. This is therefore where the key to finding the solution lies. Zaanstad is a municipality with abundant spatial opportunities. By linking these to the urban challenges, such as creating a future-proof peat landscape, an economically robust city and a socially strong city, the housing challenge can be leveraged.

For this reason, I advocate a proactive stance from municipalities in my design. By taking control themselves, they can maintain a grip on the housing challenge, thus turning it into an opportunity for the city, rather than a threat.

In my design, I demonstrate the opportunities presented by the housing challenge. Around the train station, I transform a decaying industrial area into a compact urban district with a Zaanse mix of functions. Connected to the site’s history, with attention paid to the existing landscape, the goal is to create a neighbourhood where both current Zaanstad residents and new city inhabitants feel at home. Part of the design is the developed Zaanse building block. This is a concrete translation of the urban challenges combined with the site’s opportunities, shaped into an attractive and flexible urban building block.

The design is a response to a threat that I see Dutch cities are facing. Under the immense pressure of the housing challenge, many plans have been realised with a single goal: building as many homes as possible. My design shows that building lots of homes does not necessarily mean that there is no room for broader urban challenges. The Zaanse Wind of the housing challenge offers the city these opportunities.

Discipline Urbanism

Date exam

14.11.2023

Committee Martin Aarts (mentor)

Bram Jansen

Hans van der Made

Additional members

Hein Coumou

Ania Sosin

Bob Hartman

A city with status

How the housing of status holders in the existing urban structure can contribute to their integration and acceptance.

Last year, the asylum crisis dominated the news, with around 400 people sleeping outside at its worst. This crisis is caused partly by the fact that some 15,000 residence permit holders (‘statushouders’, or status holders) are still living in asylum seeker centres (AZCs) due to the lack of available (social) housing. These status holders need to be accommodated elsewhere in the country. Countless examples, like the asylum hotel in Albergen and elsewhere in the country, demonstrate that the current method of ‘spreading’ does not offer a solution. For this reason, I have designated regions that are promising for the reception of status holders, using several criteria. Accommodating them within cities is an absolute must.

With my graduation project, I want to demonstrate that accommodating status holders in cities contributes to better integration and acceptance. For this purpose, it is crucial to unmix status holders on the basis of age, family composition or sexual orientation. These different groups are then excellent to mix with local residents. For instance, single young persons mix well with students, single-person households, first-time buyers and families. As a result, besides housing for status holders, I also add housing and facilities for the locals of Eindhoven. This makes the alternative accommodation location of added value not only for the status holders, but also for Eindhoven.

I then designed an urban plan for a site in Eindhoven, showing how the various residential areas fully match the needs of the relevant target groups, providing every opportunity for optimal integration and acceptance. With my graduation project, I want to show that the asylum crisis in the Netherlands is a spatial challenge and that, as an urbanist, I can contribute to the discussion on alternative ways of accommodating people.

A city with

with status

Discipline Architecture

Date exam

22.01.2024

Committee Jarrik Ouburg (mentor)

Wouter Kroeze

Krijn de Koning

Additional members

Paul Kuipers

Txell Blanco Diaz

Dennis Koek

Modus Vivendi Monument of social integration

Modus Vivendi stands as the monument of social integration, serving as an ode to the social encounter and flexibility that we have lost in our polarised, intercultural society, yet so desperately need. The monument is a socio-architectural sculpture that honours, facilitates, and stimulates social exploration, discovery, and interaction in our intercultural co-existence.

Contemporary society is diverse and multifaceted. However, we primarily coexist passively alongside one another, seldom actively engaging with each other. Biased perceptions and assumptions stemming from the in-group / out-group theory, often in a mostly imaginary, intangible space, lead to segregation and polarisation among various societal groups.

The research question in this project revolves around the role architecture should play in the social integration of intercultural society. Public architecture assumes a crucial role in physically bringing together these diverse groups and subgroups. Architecture with a public function should thus be designed less from conventional guidelines such as pragmatic, economic, historical, or habitual perspectives, but predominantly from a social standpoint, where the social usage of space and spatial social awareness of oneself and others always remain central.

The meaning of ‘Modus Vivendi’ is a way of living or a way of dealing with differences, of continuing what binds us together, even if we do not share the same values and norms: a co-existence. Philosopher Eberhard Scheiffele’s quote, “making the familiar strange by studying the unknown”, thus serves as the guiding principle in the research, development, and realisation of the socio-architectural project Modus Vivendi.

The social monument Modus Vivendi stands as the public, physical space to honour, facilitate, and stimulate this social exploration, discovery, and interaction. True to its nature as a monument, this architectural sculpture of mass and counter-mass serves as both a homage to and a catalyst for our social flexibility.

The research, the developed theories, and the realisation of the socio-architectural project Modus Vivendi are based on scientific theoretical studies from sociology and environmental psychology. This has resulted in an architectural design of the social monument, which also serves as a manifesto for a shift in mentality regarding the social aspect of design in public architecture.

Vivendi Vivendi

1 Axonometry Monument of Social Integration

2 Situation

3 Sociospaces

4 Visualisations

5 Sections 6 Pouring layers of concrete

7 Visualisations

8 Sections Building Physics 9 Visualisations

Discipline Architecture

Date exam

09.07.2024

Committee

Ira Koers (mentor)

Arjen Oosterman

Peter Defesche

Additional members

Bart Bulter

Arna Mačkić

Roosje Rodenburg

For GERRiT

Beyond ‘building is business’, repurposing the Bowling – Amsterdam-Noord

When Gerrit unsuspectingly gets up one May morning in 2015 to start his day at the Bowling on the Buikslotermeerplein in Amsterdam-Noord, he finds an unpleasant surprise on the doormat: he must vacate the Bowling within 24 hours, as the building is to be demolished immediately. Just a month before this sudden decision, Gerrit had conversations with the municipality indicating that he could use the Bowling for another five years to bowl with mentally disabled people and host bingo nights with the neighbourhood. It is a painful and distressing decision, affecting not only his heart, but also his wallet. Gerrit and his wife had just taken out a loan of 160,000 euros for renovations to the Bowling, but without the Bowling, there is no business model to recoup the investment and they end up in debt relief.

As a young designer, I walk around the Buikslotermeerplein, which will be the starting point for an attempt to work differently than ‘building is business’. It is not for nothing that I choose this location, where the pressure of construction takes its toll, and the identity of the area and its current users are slowly being pushed out by a new generation of ‘Noorderlingen’ (residents of Amsterdam-Noord). Demolition and new construction take precedence over reuse. A certain level of care is missing that ensures the preservation of irreplaceable values – both the physical and social values. Why are so many buildings being thoughtlessly demolished and why does the construction of new neighbourhoods come at the expense of the current inhabitants? Is there a way for the old and new to coexist or will there always be friction? And where is that friction actually desirable?

It quickly becomes clear to me: the Bowling needs to be stripped down, so that the monumental values of the building become visible and should be repurposed as a clubhouse for the neighbourhood and a place for Gerrit where he can organise activities for disabled people and the neighbourhood.

Rodenburg For GERRiT

GERRiT

Discipline Urbanism

Date exam

25.06.2024

Committee Martin Probst (mentor)

Ania Sosin

Arjen Oosterman

Additional members

Martin Aarts

Andrew Kitching

Ellis Soepenberg

Groeten Uit

Do It Together Urbanism

What if a marginalized neighbourhood could invite designers to strengthen their community through design?

In the past year, I have researched how I could put people centre stage in the redevelopment of post-war neighbourhoods in the Netherlands. Post-war neighbourhoods are the textbook example of a ‘problem neighbourhood’ in the Netherlands. There are countless different challenges that are being tackled by all different types of professionals. Big data has resulted in these communities becoming branded as ‘a problem’.

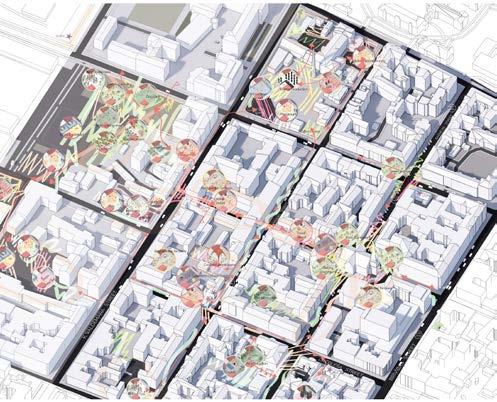

I have developed a method through working with the community of Poelenburg in Zaandam, known as the first Dutch problem neighbourhood. ‘Do It Together Urbanism’ (D.I.T. Urbanism) could be a method with which designers could help empower people, so they can become a client in the redevelopment of their neighbourhood. With this method, I am trying to bridge the gap between the social and spatial realms within these neighbourhoods. There is a lot of effort and time being put into participating with people. Through my research, I have found that how we participate needs to match the capacity of the community. I wanted to be invited into the community, to learn what the community sees as an opportunity that we could work on in the design I am inviting you to join the journey of being invited into neighbourhoods.

1 Story design of Poelenburg, Zaandam. Conclusive drawing of 100 stories collected during my time in Poelenburg.

2 You can’t do urbanism alone, even though there are many personal lessons that I’ve learned, doing it together is what creates an empowered community.

3 Poelenburg is isolated in Zaandam.

4 Timeline of the neighbourhood Poelenburg

5 Personal journey with ups and downs in Poelenburg

6 Do It Together Urbanism. Outlining the three steps of Do It Together Urbanism.

7 Example of one Story Design and how to create a Bridge of Empowerment.

8 Sections of Poelenburg, during the day and at night, showcasing the difference of perception lighting makes.

9 Organogram of all the parties working in Poelenburg. Showcasing that people in the neighbourhood are not the client of the forces in these big area developments

10 Working together and creating a way of personalising the process of urbanism can create an empowered community.

11 In order for people to participate in their neighbourhood, they will have to have their basic needs met. If this is not the case, we should help empower people to get to this level.

12 Spatial analysis of Poelenburg

SPATIAL ANALYSIS

Discipline Architecture

Date exam

11.07.2024

Committee

Pnina Avidar (mentor)

Bart van der Salm

Peter Dautzenberg

Additional members

Jo Barnett

Jochem Heijmans

Merle Soeters

Designing a Future for the Past Architectural exploration on how to reduce inequality for children

The goal of my graduation project was to explore how architecture could contribute to reducing the inequality of opportunities for children. Based on my own experience as a tutor teaching in an underprivileged neighbourhood, the Bijlmer in Amsterdam, I decided to do so by designing a school.

However, not just a straightforward school. The building had to become a place that inspires, stimulates learning and interaction, feels safe and offers privacy, and plays a central multifunctional role in its neighbourhood and community.

It will not surprise you that the neighbourhood I chose was indeed the Bijlmer in Amsterdam. The exact location is the empty space that was left after the plane crash in 1992. The memory of this disaster has been represented in the facade and the building fills the gap of the initial urban plan.

The school itself is intended to facilitate movement, connection and interactive learning opportunities. This is achieved, in part, through the interaction of children with people in the community using the building and its public functions as well. Thus, the building is intended to facilitate blending and connection through its multifunctional spaces. The aim is to create a vibrant place within the neighbourhood, which is in line with the functions outlined for this area by the municipality.

Designing a Future for Designing a Future for the Past

Past

Discipline

Architecture

Date exam

13.05.2024

Committee

Jan Peter Wingender (mentor)

Gus Tielens

Ira Koers

Additional members

Jolijn Valk

Geurt Holdijk

Ianthe Tang

From vulnerable to resilient

An innovative type of housing for closed youth care

“Locking up vulnerable people under the pretext of care has been one of the biggest mistakes that has been made.”

Nando, experiential expert secure youth care February 2022 and over 134,000 signatures later. After years, the many abuses have received the necessary and, above all, proper attention within politics and media, thus setting in motion the end of secure youth care. This is urgently needed, because the problems come at the expense of the care and development of hundreds of vulnerable, innocent young people; a process that still carries great social relevance today. This calls for the introduction of an alternative type of housing. That is why a city-centre, innovative type of housing was introduced for vulnerable young people who cannot grow up at home, where they can grow up and develop in connection with society in the most everyday way possible. From protected assisted living for young people between 12 and 18 to independent living in group form for young adults up to 27 years old as part of the follow-up care. Moving on within the same building in an environment and network that is already familiar to them offers them longer-term housing prospects and enables the transition into society to be more gradual; a place that was designed, in essence, on the basis of the interests and needs of the young people. They step, with their vulnerable past, into a space where they are guided towards a resilient, independent future. The mega-residential palazzo functions as the supporting building typology in this regard. It is a modern version of a classical palazzo; a highly suitable form language due to the protected character without losing the connection with its environment. This is created through an integrated public-social care programme that borders the public neighbourhood street that runs straight through the building. The large scale at building level is a response to the robust character of the surrounding building blocks in the Kadijken neighbourhood, the location of the assignment. Within this palazzo there are also reduced palazzos at housing level to align with the desire for small-scale housing. In this way, the palazzo as a whole forms a village in itself. Based on the central orientation of the building typology, the shared space lies at its core, which gradually transitions to a smaller unit before finally reaching the individual private domain of the young person in the outer ring of the building; The place where the young person begins and closes their day with a view over the city.

Their future.

vulnerable to resilient

Discipline Architecture

Date exam

22.04.2024

Committee

Elsbeth Falk (mentor)

Ard Hoksbergen

Lorien Beijaert

Additional members

Jo Barnett

Patrick Roegiers

Menno Ubink

Leerhuis Banne Buiksloot

Appreciating the existing by building on the existing

The topic of choice for my graduation project is a revitalisation design of a secondary school in Amsterdam Banne Buiksloot. When I started this graduation project, I noted that in our current educational system, we allow school institutions to innovate their curriculum. The idea is to provide different types of education suitable for various individuals instead of one flavour for everyone sounds as a good thing. However, the so called ‘conceptscholen’ also stimulate separation and segregation in the physical domain.

With the rise of many innovative concept schools, such as Agora, Steve Jobs, and Kunskapsskolan schools, the landscape of our secondary school education system is undergoing significant changes. The emergence of these school concepts brings forth not only new challenges for policymakers, but also for neighbourhoods. These school concepts, born out of certain ideologies, will regularly inhabit existing school buildings in an existing context. Attracting a niche group, students may come from different parts of the metropolis rather than residing nearby. As a result, there is often a lack of connection between the school users and the local residents.

It is precisely here that I want to focus on during this thesis project. In addition to the challenges new school concepts present for the quality and unity of an educational system, I had a hunch that if we want to make a concept school succeed, it requires a functional building that suits the concept of the school, but more importantly will complement the existing community.

My role as an architect is to design and to convince with ideas as answers to questions that haven’t been asked yet. The complex segregation phenomenon is constantly changing in terms of its form. Therefore, it’s possible that multiple answers from different fields can be given to this question. However, the power of design, in my case interdisciplinary design, can only give so many answers and interpretations that it will trigger the start of a debate and make the impossible possible. With this graduation project, I dare to dream and will give an insight into how to apply my manifesto on school buildings.

Banne Buiksloot

Liveable Cities

Cities are where the human and the non-human needs collide. These are places that call for a redefinition of the ways of living together. How can we, as designers, create liveable, healthy and safe cities for all beings?

These graduate projects tackle the question of how we can live better, healthier and safer lives, with respect for the needs of both nature and people. These projects examine this complex duality. They are about how to live in a new and improved way within our vulnerable and constantly changing urban environments. The question is: how can we live together in the future with enhanced quality of life, while in harmony with our environment?

Discipline Urbanism

Date exam

12.10.2023

Committee Herman Zonderland (mentor)

Toms Kokins

Viesturs Celmiņš

Additional members

Iruma Rodriguez

Martin Probst

Miks Bērziņš

Riga,

liveable city

A snapshot of a dream

Analysis/Problem statement: Riga's city centre faces multiple challenges: it resembles a ‘doughnut city’, a drive-through city, and a parking city, with limited pedestrian areas, and struggling businesses, leading to a perception of it as undesirable for living. So, what’s missing? How can the city centre become desirable again?

Statement: A liveable Riga must use its spaces, rather than leaving them inaccessible in anticipation of a perfect plan. It should prioritise walkability, reduce car dependency and have ample room for communal activities. Permanent and temporary interventions, co-created by all stakeholders, are vital. The municipality's framework should empower both private owners and communities to participate in shaping the city.

Tools: Effective urban planning combines top-down strategies with bottom-up initiatives. Local traffic reorganisation and green space additions are feasible actions. Encouraging rules for landowners and activists can expedite the process of enhancing the urban fabric. Ģertrūdes superblock: The Void Function toolbox jumpstarts the design process by exploring varied scenarios for empty plots ranging from parks to cultural venues. Ģertrūdes Superblock exemplifies this approach – aiming to leave a big impact by focusing on many smaller interventions around the central Ģertrūdes old church, without disrupting major streets. The size of the project area allows for sensitive implementation of functions, leveraging existing neighbourhood energy.

Conclusion: The city needs to live for it to be lived in. This project aims to build enthusiasm and explore the possible outcomes of acting now. Instead of waiting for monumental changes, let’s try making it more liveable today. Collaboration between the city and landowners is essential in fostering a liveable and diverse city centre.

Moreover, not all plots need development; spaces for ‘permanent temporarity’ – open spaces in the urban fabric – offer a welcome break from the busy city life. Riga's transformation hinges on collective efforts to create a vibrant, inclusive city centre.

Riga, live

liveable city

1 Riga, liveable city – a snapshot of a dream.

2 Urban sprawl/Central voids in the urban fabric.

3 Void Function toolbox.

4 Placing functions in a sensitive way.

5 Ģertrūdes superblock.

6 Ģertūdes old church – the green heart of the neighbourhood.

7 Market, playgrounds, community gardens and cafés.

8 Cultural centre of the neighbourhood.

Discipline

Landscape Architecture

Date exam

21.05.2024

Committee

Thijs de Zeeuw (mentor)

Fiona de Bell

Remco van der Togt

Additional members

Marieke Timmermans

Charlotte van der Woude

Jelle Engelchor

All Philippine

Searching for a new role for landscape architects

*and myself

At the beginning of my graduation route, I asked myself which type of landscape architect I wanted to be. My social way of working in previous projects provided an opportunity for participation that could be utilised in the long graduation period. This was something that rarely arose at the Academy, but which I believed that a landscape architect should be familiar with. That is why I decided not to take the traditional approach of imposing a master plan, but opted for an approach aimed at the needs and wishes of ‘ordinary people’. I chose to focus on the village of Philippine in the Zeeuws-Vlaanderen region, a small place without clear spatial challenges. What caught my attention were the silence, and the unique scenes and challenges of rural border regions.

With participation as the guiding principle, I tried to understand the crucial needs of the village inhabitants. During a seven-day visit, I observed the local community, listened to their perspectives and I drew initial conclusions about what was on people’s minds in Philippine. Conversations with the inhabitants revealed various themes, such as the needs of farmers, senior citizens and young people, and the impact of policy that had transformed the village into a commuter community. A second visit, including a brainstorming session with several inhabitants, led to a story that focused on the role of water in the community in light of the historical connection between the village and the Westerschelde estuary, and the current problems with water management.

The result of the participation is a water system that connects Philippine with the Flemish hinterland and the Westerschelde. This system makes forgotten qualities visible and adds new functions. The design not only made water palpable and sustainably available for agriculture, but also initiated other developments in the village. The most important intervention in the plan is the diversion of a watercourse, in which water from Flanders is directed via a canal to a storage reservoir. A new canal directs water to a natural depression where it can be sustainable stored and managed. This canal is flexible in use, with opportunities for the local population to let in or close off water. The canal also has a recreational function and helps the historical fortifications surrounding the village visible. The bastions are used for developments aimed at senior citizens and young people, while the canal contributes to the redevelopment of the city centre around the old harbour.

Discipline Urbanism

Date exam

20.11.2023

Committee Hans van der Made (mentor)

Ruwan Aluvihare

Marco Roos

Additional members

Léa Soret

Huub Juurlink

Saskia Kleij

The Living City

Over the past few thousand years, humans have used nature for their own needs, causing enormous environmental damage. Human actions have led to climate change and the extinction of many plant and animal species. This is not only harmful to nature, it is also self-destructive. The effects of climate change make areas uninhabitable and lead to increasing shortages of food and drinking water. If we continue on this path, the outlook for humanity is bleak.

To survive, we must adapt our way of life. We need to critically examine how we relate to nature. Instead of just taking, we must give something back, also in cities. With the construction of cities, we have created stone landscapes focused on human convenience and efficiency. However, these cities simultaneously disrupt natural processes and landscapes. The effects of climate change emphasise that this urban design is ultimately unsustainable. We need to find a balance between humans and nature.

In this graduation project, I explore how cities can be transformed into resilient cities where the needs of plants, animals, and humans are seen as equal. Using a new design methodology, I transform the neighbourhood of Overvecht in Utrecht into a nature-inclusive and resilient part of the city. Humans are no longer at the centre; instead, an integral approach to urban design is the base of the project. This way, we live more harmoniously with nature, give space to nature, and ensure a

Living City

1

2

Nathalie Koren 96

Discipline Urbanism

Date exam

10.07.2024

Committee Jaap Brouwer (mentor)

Rob van Dijk

Frank Suurenbroek

Additional members

Sebastian van Berkel

Marijke Bruinsma

A Sensitive City

A new layer in the design of the city

During the design of the city, there is a strong emphasis, on the one hand, on spaces, routes, movement and activity. On the other hand, the design is very much focused on what we see, because this is our most developed sense. Apart from what we see, sensory stimuli that we receive from hearing, smelling, feeling and tasting are the effect of what we are designing, rather than something we actually take into account in the design.

This research shows that the city has a lot more to offer than that which we can perceive with our eyes; something we are still insufficiently aware of as designers and for which we barely have any design tools. By making sound, smell, touch and other sensory experiences fully-fledged components of the whole design process, we can design cities that are not only functional, but also feel pleasant, smell good and have pleasing acoustics, all of which have a major impact on our behaviour and well-being.

The results of the research into sensitive design were tested at a location that could do with some sensitivity: the Alexanderknoop area in Rotterdam. This is a dynamic spot at a strategic hub that plays an important role in the structure of the city. In spite of its prime location, it is not pleasant to live and stay in and around the Alexanderknoop. The heavy infrastructures produce a lot of negative noises, smells and vibrations, and the human dimension is sorely lacking.

The results of the research consist of interesting findings and guidelines for sensitive design. It highlights design based on a sensitive and social profile, interventions at district level that have a sensitive effect on a smaller scale and the need for ‘luwteplekken’: quiet places offering refuge from the hustle and bustle of the city. The smallest possible scale is sought in this research and in that way, we become more aware of the importance of sensitive design.

Sensitive design is not an end in itself, but should be an obvious topic in relation to all other spatial aspects involved in urban design. It is only this way that we can rid ourselves of the idea that a good city is only visually stimulating. It is ultimately about human well-being in a sensitive, attractive urban environment.

A Sensitive

Sensitive Citystream City

1 Overstimulation in the urban environment.

2 The sensitive profile.

3 Perception of the Alexanderplein.

4 ‘Luwte’.

5 A tranquil basis.

6 Experience route from the Rotte river to the Hollandse IJssel river.

7 A sensitive Alexanderknoop.

8 The ‘luwteplek’.

9 The Alexanderpark.

10 Profile of the city centre.

Roelof Koudenburg 100

Discipline

Urbanism

Date exam

27.05.2024

Committee Martin Aarts (mentor)

Henk van Blerck

Marieke van der Heide

Additional members

Koen Hezemans

Huub Juurlink

Where city, loam and stream merge

An alternative for Assen

In recent decades, insufficient attention has been devoted to the opportunities, threats and support of soil, water and nature (structures) when planning cities. This has often resulted in developments that have a parasitic or suboptimal relationship with the landscape, pay scant regard to soil, and exacerbate drought or flooding In addition, the urban expansion lobby remains undiminished. That often leads to the loss of scenic beauty and ecosystem services. At odds with this is the knowledge that investing in the existing city provides a qualitative boost to urban facilities, increases support for public transport and improves the quality of life.

Assen is continuing to develop towards 100,000 inhabitants and is therefore faced with a fundamental choice: will it opt for the familiar practice of expansion under increasingly intense (political) pressure or will it choose the radical option of infill development and transformation? This research demonstrates the advantages of such a radical shift in thinking about the future of the city. The starting points are the preservation of the green character around and in the city, as well as investing in the existing city through densification and transformation. However, the soil-water system play a decisive role in this urbanisation strategy. As a result of this, the urban area will become better able to withstand climate change and increased pressure on biodiversity.

The graduation project begins by defining the identity of Assen. This research develops a development strategy for this that is both rooted in the historical landscape while also taking the new reality into account, namely the formulated challenges and opportunities heading towards 2070. When considering the future prospects, it is crucial to base this on water, soil and nature in order to subsequently show the spatial consequences for the economy, society and energy.

The future prospects provide the starting points for a development strategy at the urban level in which it is specified which type of infill development and transformation is possible and where. Moreover, an adaptive trajectory of densification and transformation in Assen is drawn up that offers a sustainable alternative to the current policy.

The aim of this graduation project is to demonstrate the need for a radical shift in the way cities, in this case Assen, can and must be developed. But above all it shows how the city can make better use of its growth by developing a symbiotic relationship with soil and water, thus making the city more liveable and future-proof. A city where stream, loam and city merge!

Koudenburg

Where

city, loam and stream

1 Poem dedicated to the Drentsche Aa.

2 Analysing the local water system in the Stadsbedrijvenpark Assen.

3 The current practice demands an alternative.

4 Not a tabula rasa, but layers of potency.

5 Thinking in terms of stream and loam actually enhances the existing city!

6 View – inviting prospect.

7 Core concept.

8 The stream valley in the Stadsbedrijvenpark

9 View of the heathland in the Stadsbedrijvenpark.

10 Stream and loam have an impact down to the smallest scale.

11 Bird's eye view of current situation.

12 Inviting prospect 2070.

Daiki Mabuchi 104

Discipline Landscape Architecture

Date exam

16.11.2023

Committee

Marieke Timmermans (mentor)

Yttje Feddes

Hiroki Matsuura

Yuka Yoshida (expert)

Additional members

Jana Crepon

Philippe Allignet

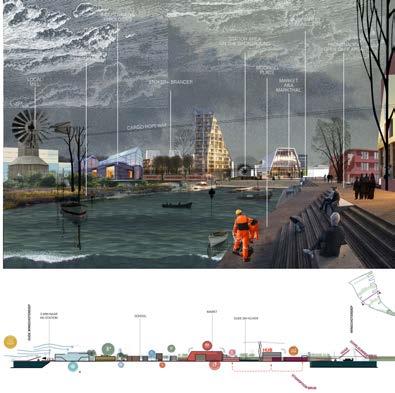

Reverse Transformation of Urban River Public Space in Tokyo

While the Tokyo metropolitan government has made efforts to improve the river space environment since 1980, such as creating a river terrace or transforming the flood wall into dike-type protection, these measures have limitations regarding the construction conditions. Even now, many river spaces remain underutilised due to the flood wall. In the near future, I think Tokyo’s high-density urban environment will require a new method of flood protection that offers the quality of public spaces.

The main goal of this project is to reconnect people to the river by enhancing the accessibility and quality of the river space. The project consists of three different approaches. The first approach is connecting the city fabric to the river through walkable streets, allowing people to reach the river space from the inner city more smoothly. The second approach is integrating important public spaces into the river space, such as parks or major spots around the river. The third approach is creating new river spaces as continuous public spaces along the river with identities considering the surrounding urban context and the river landscape.

Based on the Sumida River, these designs seamlessly connect and form a new urban public spaces network that makes the river a focal point of the city again. Those new river spaces contribute to enhancing the quality of life in Tokyo by providing essential elements such as fresh air, panoramic views, greenery, and relief from urban heat. Eventually, they serve as a refuge from the hectic urban lifestyle in Tokyo.

1 Three design methods.

2 Impression: Residential Pedestrian Street.

3 Plan drawing: Flood protection Sumida Park.

4 Impression: Flood protection Sumida Park.

5 Plan drawing: Ryogoku square.

6 Section drawing: Sedimentation Wetland.

7 Impression: Sedimentation Wetland.

8 Plan drawing: Sedimentation Wetland, River Forest.

9 Model (scale 1:100).

Discipline Urbanism

Date exam

11.07.2024

Committee Martin Probst (mentor)

Johan De Wachter

Māra Liepa-Zemeša

Additional members

Markus Appenzeller

Hiroki Matsuura

Marija Satibaldijeva

The Future of Riga’s Microrayons

Growing up in Latvia, like many, I lived in a Soviet-era apartment building in a neighbourhood called a ‘microrayon’. These areas remain a significant part of life in Latvia today, but many are stuck in the past, losing touch with their original principles and ideologies.

Now, the challenge is clear: these microrayons need a reboot. They need to adapt to today’s issues and fit in with how people live now.

In Latvia’s capital, Riga, the condition of apartments and microrayons has been shaped by events following the Soviet Union’s collapse. These neighbourhoods often have a negative reputation. With my graduation project, I aimed to shift that perspective by emphasising their potential and figuring out how to prepare them for the future.

Why microrayons of Riga? The city faces more significant challenges with microrayons. Ownership changes and the larger size of these areas make it more challenging to get everyone on the same page compared to smaller places in Latvia. In those areas, it’s easier to renovate, because they’re smaller and there are fewer people to agree on things.

Instead of tearing everything down, let’s work with what we have. Improve the buildings and neighbourhoods – it’s like giving them a makeover. This isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s a crucial aspect of ensuring our city grows in a thoughtful and sustainable way.

So, how can these microrayons contribute to a climate-friendly future for Riga?

In my project, I discovered qualities of microrayons, and I developed strategies that are about accepting the situation – embracing qualities of Riga and it’s microrayons; strategies that can be applied in all Riga’s microrayons and together can contribute to a climate-positive Riga.

With my project, I wanted to inspire the people of Riga and all over Latvia. Living in these neighbourhoods can be part of making our future more sustainable.

Satibaldijeva

The Future

Future of Riga’s Microrayons

1 Timeline of Latvia.

2 Summary of microrayons.

3 Lungs of Riga – vision.

4 Strategy of micrroayons.

5 Strategy of Purvciems.

6 Land ownership situation in Purvciems.

7 Master plan.

8 Principle of ‘creating mobility hubs in microrayons’ in Purvciems.

9 New Swamp park in Purvciems to strengthen identity.

10 Improved main street of Purvciems.

11 A view towards improved courtyard in Purvciems.

12 Maquette.

Microrayons

Bas Tiben 112

Discipline Urbanism

Date exam

28.08.2024

Committee Eric Frijters (mentor)

Wouter Pocornie

Maike van Stiphout

Additional members

Ad de Bont

Liza van Alphen

The ring of connection

Ring canal as natural heritage in the Bijlmermeer polder

The Bijlmer was originally designed as a futuristic neighbourhood intended for families, but it is now primarily known as the first deprived area in the Netherlands. This reputation arose due to various factors, leading to Amsterdam families opting not to live there.

The Bijlmermeer polder already had problems before the residential district was built. As a result of repeated flooding and rising saline groundwater, the polder was unsuitable for agriculture. To make housing construction possible, the polder was therefore raised with sand, which destroyed its original quality. Even after the neighbourhood was built, social problems led to repeated interventions that eroded the original design concept. Today, while the Bijlmer no longer looks like a disadvantaged area, it lacks a clear identity, and urban green spaces seem to be disappearing due to spatial developments.

My fascination with combining nature and urban development inspired my graduation project. The central question of the project is: “How can sustainable densification in Amsterdam Zuidoost (Amsterdam Southeast) be effectively achieved, with specific attention to strengthening the local character and ecosystem, where urban and nature development coexist to create a place-specific biotope where humans and animals live together in a reciprocal relationship?”

The project’s main intervention is the creation of an ecological canal around the current Bijlmermeer polder, which now includes a larger polder system than the original one. This canal forms an ecological and recreational network through Amsterdam Zuidoost and acts as a spatial framework for various developments. The elevated location of the canal enables a freshwater connection between the Holendrecht and the Gein rivers, thus establishing a green-blue corridor between the Diemerscheg and the Amstelscheg.

Through specific developments in Brassapark and the D-neighbourhood, this project demonstrates how the Bijlmer can be densified in a site-specific way, respecting its history while integrating contemporary urban ideas. Additionally, the project shows that nature and urban development can reinforce each other, thereby enhancing the original concept of living within a landscape.

The ring

ring of connection

1 Intervention: Ecological ring canal from Amstelscheg to Diemerscheg.

2 Masterplan Greater Bijlmermeerpolder.

3 Landscape modifications for the realisation of the ring canal.

4 Standard dike profile: 58m wide park as a continuous ribbon through Southeast.

5 Urban planning scheme for D-Neighbourhood.

6 Axonometry D-Neighbourhood: Dike and pumping station as landscape elements.

7 Axonometry D-Neighbourhood: Varied building heights create an urban biotope.

8 Section D-Neighbourhood.

9 Visualization Bijlmer Ring Dike in D-Neighbourhood.

10 Visualization inner courtyard in D-Neighbourhood. 11 Visualization central square in D-Neighbourhood.

Synchronising with Nature

This category focuses on finding ways to live in better alignment with nature. It is about adapting to it and becoming resilient. Instead of fighting it, we should adapt to our environments by gaining a better understanding of landscape dynamics: natural rhythms, wind flows, vegetational succession, river flows, etc. These projects focus on coexistence with other-than-human life, radically changing our human-centred perspective. We are all one with the planet. These projects understand the natural systems and work with their forces. Just like in Judo, you don’t fight, you utilise the strength from surrounding forces to your advantage.

Nature

Rachel Borovská 130

Discipline

Landscape

Architecture

Date exam

28.02.2024

Committee

Gert-Jan Wisse (mentor)

Nikol Dietz

René van der Velde

Additional members

Marit Janse

Ziega van den Berk

Wind Woven

Ecological restoration of Breda’s urban fabric through wind

Urban heat islands pose a significant challenge in today’s cities, and the need for cooling and preserving biodiversity are pressing issues. While efforts to combat urban heat islands often revolve around interventions like depaving, greenifying and reclaiming space for green-blue networks, the impact of ventilation on cooling is frequently overlooked in design. Stemming from a deep fascination with the thermodynamic performance of wind, this project aims to rectify this oversight by focusing on understanding wind behaviour and patterns in our everyday environment, using weather, climate and atmosphere as design mediums.

Through delving into multiple scales, this research-by-design project is dedicated to uncovering the conditions necessary to enhance the cooling capacity of wind, starting from two primary wind directions. In the Netherlands, the southwesterly winds typically bring strong cold winds, peaking from autumn to spring. Conversely, during summer, warm air from the east can exacerbate the urban heat effect if it’s unable to surpass urban obstacles, such as closed streets, or densely built or planted areas, which has a negative impact on human comfort and contributes to the loss of ecological habitats.

Wind patterns are explored as a design tool along the eight-kilometre-long railway corridor site of Breda, stretching from east to west. Railway corridors play a crucial role in ventilating urban environments due to their expansive linear profiles and open surfaces, making them essential in shaping the local climate. They also serve as crucial ecological corridors providing extensive linear migration routes for various wildlife and generate airborne trails for seeds. Paired with the ventilating capacity of the railway, the areas surrounding this eight kilometre stretch transform into an ideal testing ground for landscape architecture and urbanism to investigate and implement various landscape interventions and cooling compositions.

Rather than treating these design areas as blank slates, they are seen as integral elements contributing to ventilation, (airborne) ecology and cooling principles. They are infused with wind as a medium, composing a green wedge that weaves through the existing context and structures, connecting neighbourhoods through a biodiverse, ecological network. A park-like necklace woven by wind alongside the railway strip of Breda.

1 A park-like necklace woven by wind alongside the railway strip of Breda.

2 Wind rose. In the Netherlands, southwesterly winds typically bring strong cold winds peaking from autumn to spring. Conversely, during summer, warm air comes from the east.

3 Exploded axo. Wind patterns are explored as a design tool along the eight-kilometre-long railway corridor site of Breda, stretching from east to west. This railway corridor cuts through the most vulnerable climatopes which pose the biggest risk in the accumulation of heat during warm periods and contribute to the worsening of the heat island effect. Railway corridors are crucial in ventilating urban environments due to their expansive linear profiles and open surfaces, making them essential in shaping the local climate.

4 Matrix.

5 Matrix 2. Wind patterns in various street orientations, configurations and typologies are collected in a matrix.

6 Plan West A0. The west area of Breda’s wind stream is the most exposed to prevailing southwestern winds. Building upon the existing tree framework, houtwallen originally established as protective lines for the protection of fields and filtering wind streams, the plan further elaborates on the composition of outdoor rooms, carefully shaped by the placement of new trees and enhancing the existing tree structure.

7 West blue grasslands. Impressions of a “wind room” in summer. Topography is raised along the edges of the new tree structure. Slight variation in topography creates sheltered areas for informal paths and ensuring that the main recreational areas are shielded from strong gusts. At the planted edges they create shelter for smaller insects and pollinators.

8 West beehive autumn. Impressions of a “wind room” in autumn. Strong autumn wind streams are filtered and slowed down through the branches of the trees and shrubbery. Spiders balloon their way through the air and travel long distances with the help of the wind breezes.

9 Plan East. The east stream is essential for welcoming summer’s warm winds. It plays a crucial role in funneling and continuously channeling the winds with as little interruptins as possible, while also cooling them down through the shadows catsed by the tree canopies and glide over water surfaces with no roughness.

10 Wind disperser. The center of the stream is an industrial climatope, an area undergoing transformation called ‘t Zoet. The potential of this area as a disperser was explored through its extended green-blue network to the west of the river Mark and built area composition. The composition and ratio of water, built and planted areas allows the “cooling”wind streams to disperse into (and cool) the surrounding climatopes.

11 Wind woven axonometries. The combination of topography, water surface, vegetation type and roughness have a significant impact on wind pattterns and create a wide range of microclimates in an area.

Discipline

Landscape Architecture

Date exam

18.03.2024

Committee

Hanneke Kijne (mentor)

Willemijn van Manen

Anna Maria Fink

Additional members

Ruwan Aluvihare

Jacques Abelman

Max Daalhuizen

Botanical Rebellion

The city is a beautiful exchange between humans and nature. Despite strict management rules and guidelines, flora and fauna thrive and survive in nooks and crannies, where ownership and responsibilities are unclear. These inspiring natural processes, which are in direct opposition to plans and policies, formed the main source of inspiration for my graduation project.

In this interaction, a new nature emerges in the urban environment, featuring plants and habitats for animals, made possible by the rich variety of conditions and soil types collected by the city’s residents. These are places such as vacant lots, guerrilla and rooftop gardens, flowerpots on sidewalks, and windowsills.

These unique places are at risk due to rigid and systematic planning that allows no room for natural processes, seeking to achieve a final image immediately. Plans that do not consider the specific context, resulting in the disappearance of the quality and beauty of natural processes in the city. It is about time that the unique quality and beauty of natural processes in the city receive more attention.

Botanical Rebellion is a call to create more space for natural processes in the city. In Botanical Rebellion, these natural and social values take centre stage. Sensitivity is developed to recognise such places, and conditions are created for the emergence of new nature and social initiatives in the city, where there is significant pressure on public spaces. The focus lies on an active exchange between humans and nature.

As a designer, I create space for humans and nature in this way, encouraging city dwellers to take care of their environment by recognising the value of every stage in natural processes.

Botanical Rebellion Botanical Rebellion

Discipline Landscape Architecture

Date exam

13.05.2024

Committee

Saline Verhoeven (mentor)

Marit Janse

Jandirk Hoekstra †

Hanneke Kijne

Additional members

Thijs de Zeeuw

Willemijn van Manen

Marleen van Egmond

Het deinen van de duinen

“Deinen” refers to a rhythmic, swaying, or gently rolling movement, often associated with the sea, wind, or other natural elements.

A poetic vision for a resilient and future-proof landscape system in and around the Schoorl Dunes.

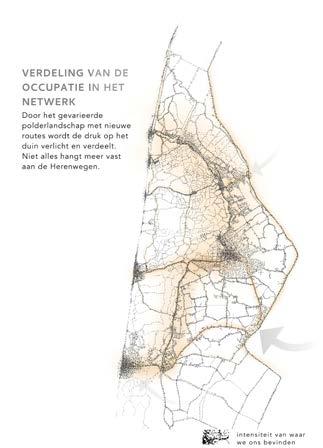

“Het deinen van de duinen” provides insight into the close relationship between dune and polder, and how they are inextricably linked through the water and soil systems. By activating the polder landscape with new landscape experiences, both ecological and recreational pressures on the dunes are relieved.

Over 150 years ago, this landscape in North Holland consisted only of shifting sand, where no plant dared to grow. The inhabitants of the villages pleaded for a solution to the drifting sand. Countless efforts to plant marram grass and pine trees eventually anchored the dunes. The landscape transformed from a harsh and wild area into a sanctuary for humans and animals. Landowners invited artists to the area, who admired and captured the striking contrasts between the high dunes and flat polders.

Today, this landscape has become a recreational hotspot, known for its campsites and holiday homes. However, pressure on the dunes continues to rise. It’s not just recreational activities that are stressing the landscape, but also climate threats such as the nitrogen crisis, which is causing grass encroachment in the dunes. Rising sea levels threaten the width of the dunes, and the pine forest contributes to soil acidification. Summer droughts cause groundwater levels to drop, drying out the dunes and leading to potential drinking water shortages. Monocultures in vegetation, agriculture, and bulb cultivation have led to a significant decline in biodiversity. While agriculture once coexisted with nature, it is now a separate system serving primarily functional purposes.

What was once a dynamic system is now set in stone. The landscape is unable to adapt and lacks future value. The natural logic of the landscape is lost, and a new, ecologically based vision is needed. This graduation project explores the ecological foundation and how the landscape can regain its natural dynamism. The goal is to make the landscape future-proof and resilient, capable of facing upcoming challenges. Like the artists of the past, this project offers a renewed landscape experience between dune and polder.

Egmond

Het deinen

dein deinen van de duinen

1 Poetic reimagination of the landscape.

2 Masterplan.

3 The eight systems of the landscape.

4 Habitat type cross-section of the landscape.

5 Design principles.

6 Problem analysis.

7 Close-up masterplan Philistine polder.

8 Habitat types water corridors.

9 Close-up masterplan dunes.

10 Visualisation of the drifting dunes.

11 Occupation of the network.

12 Visualisation of the network.

Discipline Architecture

Date exam

29.08.2024

Committee

Lisette Plouvier (mentor)

Jo Barnett

Yttje Feddes

Additional members

Susana Constantino

Marten Kuijpers

Sofie Ghys

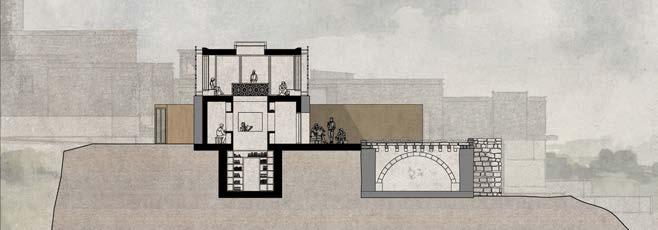

Rooms of water

A future drinking water treatment plant for Antwerp

Nestled along the right bank of the Scheldt River near the city of Antwerp in Belgium lies the former historic Sint-Filips Fortress. In a lush natural landscape in the middle of the Antwerp harbour, a harmonious interplay of water and land unfolds. The design of the building honours the dynamic tidal movement of the river’s fluctuating presence. The Scheldt River is not a static object but a living system that constantly changes. Almost twice a day, the site undergoes a transformation between ebb and flood, a rhythm that is mirrored in the architecture. Time become fourth dimension here, offering a different experience with each visit.

The building hosts a future drinking water treatment plant that taps into brackish river water. This place invites people to wander within its treatment halls, frames views along the river, and celebrates this unique place. Inside, the building consists of spaces filled with water and light, offering a glimpse into the treatment process. Here, water can be experienced in all its different forms, from its source to its transformation into drinkable water and even refreshing swimwater. A series of outdoor swimming pools fulfil the joy of living next to one of the busiest rivers in Europe, each embracing the lingering warmth born from the purification process. By integrating utility function with recreational functions, this project not only serves a functional purpose but also emphasises the critical role of freshwater as a precious resource for the future.

of water

1 FROM ESTUARY TO SITE

To understand the characteristics of the location, the conditions of the river were analysed from the macro scale of the estuary to the micro scale of the site.

2 THE OUTSKIRTS OF THE CITY OF ANTWERP

The project location is nestled between sea and city, industry and landscape, surrounded by industrial grandeur, bustling port activities, small remnants of polder villages and the ever-changing Scheldt River.

3 EMBRACING THE RIVER’S TOUCH

Through time and tide, the façade will reveal the dynamic character of the river. The brackish waters of the Scheldt will continuously deposit new layers on the surfaces, with green deposits gradually overtaking the horizontal lines of the formwork.

4 INVITING PUBLIC INTO THE PROCESS

This project redefines the traditional concept of a drinking water facility by making it accessible to the public. Like a museum, the building creates a space that educates and inspires, a space that blends architecture with infrastructure.

5 THE JOURNEY OF TREATING RIVER WATER INTO DRINKING WATER

6 WATER COURTYARD

A water courtyard symbolizes the water reservoir below, which remains the only part that will not be visible to the public.

7 ENTRANCE HALL

8 BETWEEN INFRASTRUCTURE AND ATMOSPHERE

The public spaces are positioned above the treatment areas, offering views into the halls below and allowing the technical spaces to function independently from the public areas.

9 NESTLED ALONG THE SCHELDT RIVER

The project is situated on the inner bend of the Scheldt River, in relation to the former location of the Fortress of Sint-Filips.

10 TIME AS A FOURTH DIMENSION

The interaction between water and land is ever-changing. Day and night, ebb and flow, continuously reshape the landscape, with each moment bringing subtle transformations.

11 A BUILDING THAT FLIRTS WITH THE WATERLINE

In the building, the rising water level flirts with the structure through windows that interact with the changing tides. Each visit, or even within a single visit, the shifting river conditions influence the experience of the architectural space.

12 LIGHT AS AN INTUITIVE GUIDE

The public circulation spaces meander between the treatment halls, illuminated with soft lighting, while the halls themselves feature industrial lighting. The contrast between dark and light areas guides visitors from hall to hall.

Discipline

Architecture

Date exam

28.08.2024

Committee Rob Hootsmans (mentor)

Kamiel Klaasse

Jana Crepon

Additional members

Machiel Spaan

Donna van Milligen Bielke

Sander Gijsen

Vernieuwd Bouwzicht

A farm with a future and a representation of a renewed relationship between humans and nature

Since the radical reclamation of ‘s-Graveland in the 17th century, when sand was extracted as building material for the expansion of Amsterdam, the reclaimed landscape has been shaped in various ways. The subsequent spatial development of the various country estates, with Gooilust as the ultimate example, indirectly reflects the constantly changing relationship between humans and nature. This dynamic relationship is expressed in both landscape architecture and architecture and fits within the broader development of Western culture. Think of the staging of 15th-century Italian villas in their landscapes, 16th-century French and English gardens, and modern parks such as Parc de la Villette in Paris.

Meanwhile, humans and technology have exhausted nature. Human influence is causing the climate to change rapidly, forcing us to rethink our relationship with nature and how we interact with it. As with any change, (political) tensions increase, and the contrasts between countryside and city are magnified. To address the current nature and climate crisis, the livestock population must be reduced. This will lead to the disappearance of farms unless new revenue models and a farming system are developed that are in balance with nature. This project envisions a renewed relationship between humans and nature by transforming a dairy farm into a place where building materials are grown and harvested. With the farmer as innovator, the aim is to contribute to improving nature and climate by cultivating natural and renewable resources. Through sustainable forest management and the cultivation of bio-based materials, the landscape of Gooilust can supply materials for sustainable housing, while offering farmers a new business model.

The core of this transformation lies in the redesign of the Bouwzicht farmstead and the surrounding landscape, adding a new layer of time to the Gooilust estate. Architecture and landscape come together here, symbolising the new relationship with nature. The transformation calls for a new interpretation of the farmstead and landscape, building on the tradition of self-sufficiency and circularity. Existing buildings are reused and transformed with the addition of harvested materials from the landscape. In this way, the Vernieuwd (Renewed) Bouwzicht farmstead is united with the landscape, becoming an exhibition of historical layers and a representation of a new relationship with nature.

Vernieuwd Bouwzicht

1 Analysis of the development of the Gooilust estate, which serves as a basis for continuing change and envisioning a new relationship between humans and nature within the framework of the estate as an experimental garden.

2 The cultivation, harvest, and application of natural building materials with the renewed (production) landscape in the foreground and the transformed farmhouse in the background.

3 Site plan and accompanying visualisations of a walkable route along the new crops from two different years.

4 Context model (1:200) and floor plan drawing of the transformed farmhouse.

5 Fragment of the home extension and patio between the house and the workshop.

6 View of the front facade of the renovated house. Interior image of the transition from inside to outside through the added dining room space.

7 Visualisation of the new dining table with a view over the landscape and the yard.

8 Image of the yard with the open barn on the left and the workshop on the right.

View of the workshop in the original stable.

9 Image of the storage warehouse where the harvest is stored and dried.

10 Calculation of the CO2 balance of the storage shed and visualisation of the structural construction in detail.

11 Foto fragment maquette nog aan te leveren / Photo of model fragment still to be provided.

Calculation of the CO2 balance of the home extension and fragment model of the extension.

12 Visualisation of the farm seen from the existing forest, symbolizing the union of nature and agriculture.

150

Discipline Landscape Architecture

Date exam

11.07.2024

Committee

Jorryt Braaksma (mentor)

Jean-Francois

Gauthier

Marlies Vermeulen

Additional members

Berdie Olthof

Kim Kool

Floor Hendrickx

The Future is FOREST

We are becoming increasingly aware of the size and impacts of climate change.

The construction industry still has a long way to go when it comes to reducing CO2 emissions. For example, 11% of global CO2 emissions are caused by the production of building materials, such as concrete, steel and glass. One of the serious alternatives in order to reduce CO2 emissions in this regard is to build with wood more often.

Using this as the starting point in my graduation project, I investigated what the Dutch landscape would look like if we were to produce our own wood in a sustainable way for timber construction. The graduation project examines what sustainable forestry is, which wood is needed for modern timber construction (e.g. CLT), and how and where we can best produce that in the Netherlands. In addition, forests can also offer us a lot more, such as biodiversity, cooling (climate mitigation), CO2 capture, regulation of a healthy water regime, valuable recreational areas, etc. These are all functions that are included in the plan.

Using the design, I subsequently researched what forestry might look like in a stream valley in the sandy soil of North Brabant, as this is one of the landscapes in the Netherlands that is potentially very suitable for forestry. In addition to working with the landscape system, I also researched which economic and social strategies could drive this change in the landscape, so that the plan can be supported by the local community. Finally, forests also have their own sociocultural significance. The shift towards a (production) forest landscape has a great impact and in spite of the sometimes industrial scale of this undertaking, this design seeks space for experience, education, recreation and adventure.

With this graduation project, I want to show the potential of this multifunctional landscape, both productively, socially and for the climate.

Future is Forest

1 Building with wood helps us to reduce the amount of CO₂.

2 Layered production with pioneer species for faster and more diverse forest development.

3 The basis of sustainable timber production is to ensure diversity and the correct scale.

4 The potential Dutch production forest based on water, soil and wind.

5 Setting up the entire production chain on a regional scale.

6 Three guiding principles as strategy for the transformation of the area.

7 Borders of the new sustainable production forest. 8 Recreation in the production forest.

9 Under the trees; making stratification in a production forest visible.

Jacoba Istel-Slooten 154

Discipline Architecture

Date exam

21.11.2023

Committee

Jolijn Valk (mentor)

Dingeman Deijs

Dirk Sijmons

Additional members

Jeroen van Mechelen

Rogier van den Brink

WilderNes

An ecocentric school

My graduation project, ‘WilderNes’, is a school designed based on the natural processes of its location, the Polder de Nes. Polder de Nes is an outer-dike polder located north of Amsterdam on the border of the Markermeer and the peat meadow landscape of Waterland. Here, children will learn directly and indirectly about the impact of human actions on our natural environment. Moreover, to make human influence visible and enhance the natural value of the place, the school is part of a landscape design that returns a portion of the cultural landscape of the polder to nature, allowing it to become wild again.

Through this symbiosis of landscape and architecture, children in WilderNes learn to view their natural environment from a new perspective— one in which they, too, are part of the ecosystem.