shelter

an architectural typology to host women victim of domestic violence

Alice Dicker Quintino dos Santos

Alice Dicker Quintino dos Santos

Alice Dicker Quintino dos Santos dickeralice@gmail.com

Master of Architecture

Academie van Bouwkunst Amsterdam

June 2023

Comittee

Marcel Lok (mentor)

Hannah Schubert

Pnina Avidar

Examination comittee

Paul Kuipers

Susana Constantino

01. Introduction to topic: Violence against women and domestic violence 07 02. Fifty years of sheltering women within the Dutch context 09 03. Women’s refuge and spatial design: elaboration of project’s guidelines 27 04. The location: relations between the program and the cit y 69 05. The design 79 06. From arrival to departure: a journey through one's stay in the shelter 117 07. Bibliography 144

TABLE OF CONTENT

6 Percentage of women to experience violence throughout their life time around the globe (WHO report, 2018) Latin American and the Caribbean 25 25 Northern America 21 Western Europe 23 Northern Europe 30 Northern Africa 16 Southern Europe 20 Eastern Europe 18 Central Asia 29 Western Asia 35 Southern Asia 21 South-Eastern Asia 33 Sub-Saharan Africa 23 Australia and New Zealand 51 Melanesia 41 Micronesia 39 Polynesia 20 Eastern Asia

01. Introduction to topic: Violence against women and domestic violence

According to the World Health Organization “violence against women is a major human rights violation and a global public health concern of pandemic proportions”. The statistics show that one third of all women worldwide experience physical or sexual violence at least once in their lives. The high majority of the cases relate to former or current intimate partners, which is classified as domestic violence. Victims represented by these numbers can go through short and long term devastating physical, sexual and mental consequences, which affects their well-being and prevents them from fully participating in society.

In the past two decades, there has been much progress around the world in recognizing and bringing attention to violence against women. This recognition though hasn’t generated representative changes in the statistics that remain high. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has increased domestic violence risks with the lockdown measures, which have been reported to helplines and generate much concern.

When experiencing domestic violence many women are in need of support, often of a place to stay, to feel sheltered and to heal, where legal and psychological support is available. These facilities are already present in many countries around the world but not necessarily in enough amount and of adequate quality. This graduation project consists of designing such a place. Being a feminist woman, I am triggered by the social relevance of the topic and by the question of the role architecture can play around the theme.

7

Worldwide one every three women is subject to violence throughout their life (WHO report, 2018)

In the Netherlands one every five women is subject to violence (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights report, 2014)

8

02. Fifty years of sheltering women within the Dutch context

As illustrated previously violence against women is spread all over the globe in rather similar averages, with partner and ex-partner violence as the most representative cases. When zooming in The Netherlands the situation is not different, the issue is definitely present in Dutch society.

According to the latest FRA (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights) report 9% from the Dutch women experience physical or sexual violence from a current partner and 25% from an ex-partner since age of 15 years old. Around 60% of domestic violence cases, also consisting of other forms, relate to partner or ex-partner violence with more often women as victims.

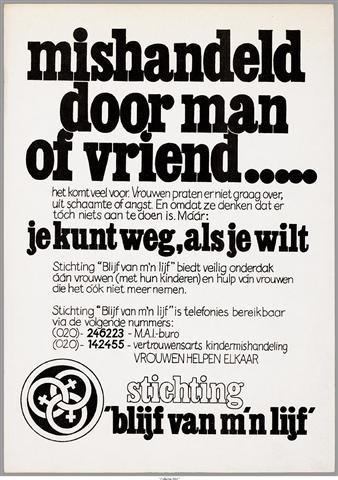

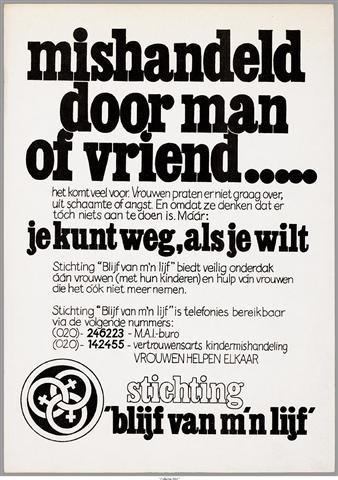

In the 70’s the Blijf van m’n Lijf movement has founded the first shelters in The Netherlands. Before the start of the movement domestic violence was considered a private issue in the country. From then to now much has changed and big steps have been made in treating partner and ex-partner violence as a urgent societal issue. Currently, the helpline Veiligthuis can be reached for advice, support and referencing to shelters while the Blijf van m’n Lijf movement has grown to solid organizations throughout the country.

9

10

The first years of shelter facilities

In 1974 the first Blijf van m’n Lijf house was founded in The Netherlands, a secretly located house where women could gather and escape domestic violence. In first years, these houses were often overcrowded, characterized by facilities with one shared living room and kitchen with a few bedrooms where up to 35 women and 50 children would stay.

Although in rather precarious facilities at first, women could find shelter, feel free and be safe. The unknown character of the locations presented many challenges, obliging the inhabitants to take actions such as quitting their jobs. In these shelters, the women would be themselves in charge and have much responsibility, finding solutions independently.

The following pictures by Bertien van Manen, made in the 70’s and 80’s in a anonymously located shelter illustrates the improvised character of the facilities. The images reveal though an inspiring atmosphere of mutual support, solidarity between women and sense of community.

11

12

Poster from a Blijf van m’n lijf huis, 1978

13

14

15

Pictures by Bertien van Manen, 1980, unknown location.

16

Current facilities:

The Blijf Groep and the Oranje Huis approach

With its roots in the 70’s Blijf van m’n Lijf movement, the Blijf Groep is an organization that currently offers support and shelter to women victim with domestic violence in Noord-Holland, which includes the city of Amsterdam. The institution has as its mission to help ending domestic violence, by providing support to all the involved parties: victim, perpetrator and children.

The Blijf Groep counts with three Oranje Huizen in Alkmaar, Almere in Amsterdam, buildings where all forms of help are offered. Housing units, contact with social workers and the Blijf Groep offices share the same location, positioned within the urban context in a known address. Women’s refuges have been hidden in the past, but the institution believes in an open approach in which the Oranje Huizen could be seen as a statement to society.

The newly built shelters offer steady support and infrastructure. Almost every resident gets its own private apartment in the complexes. In those buildings, that resemble any standard new built housing development in the Netherlands, there has been more attention to the individual than to the collective.

17

News item announcing the creation of a second Oranje Huis in Amsterdam, since the existing facilities are constantly overfull.

18

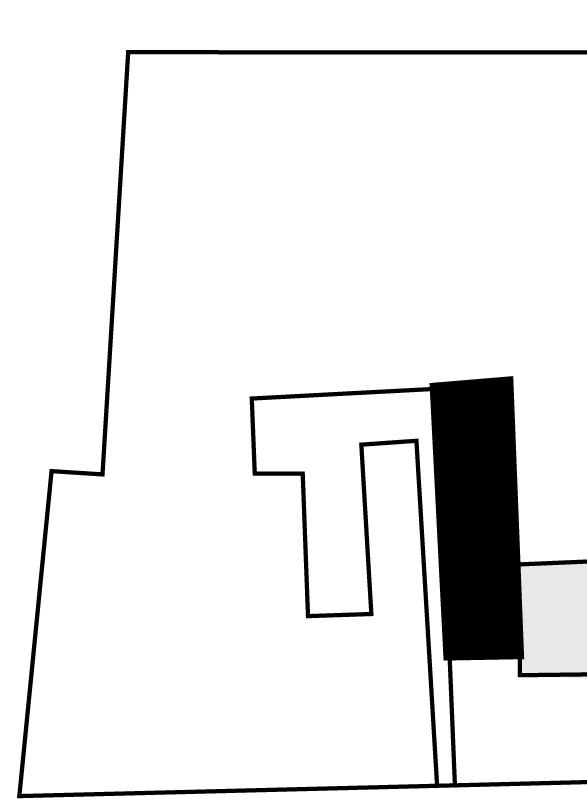

Oranje Huis Amsterdam

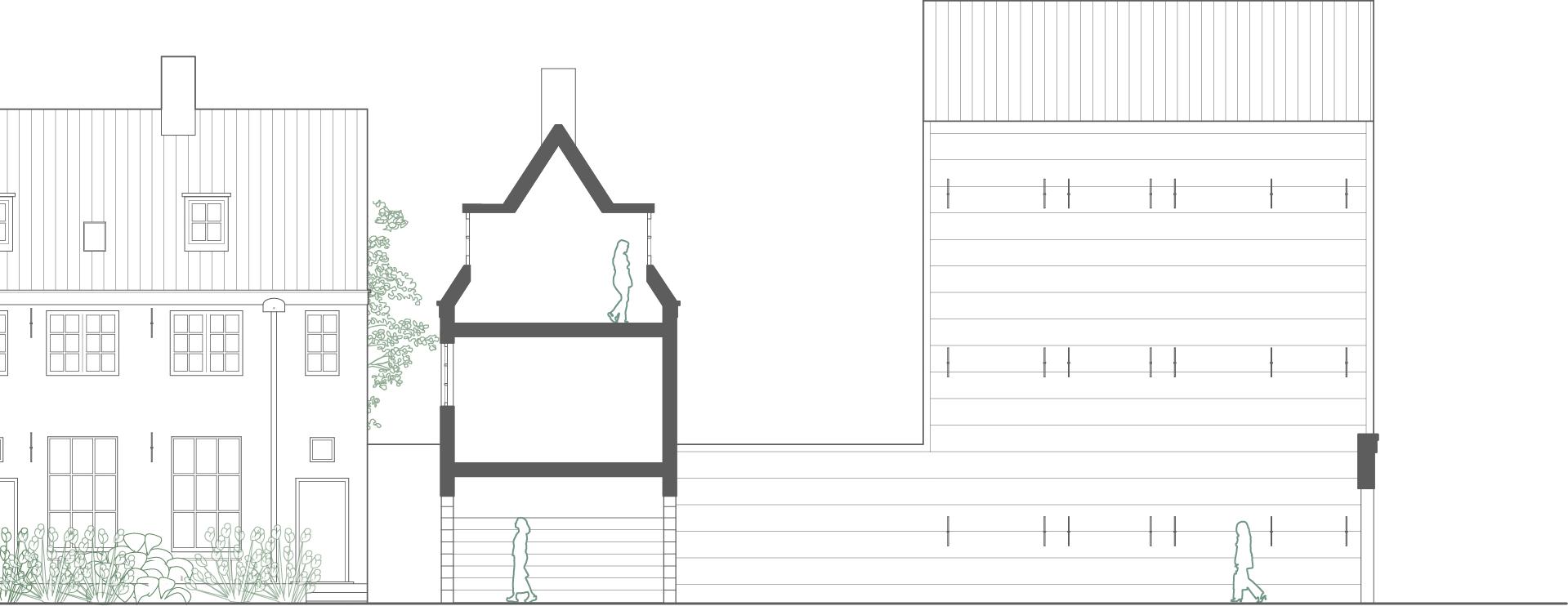

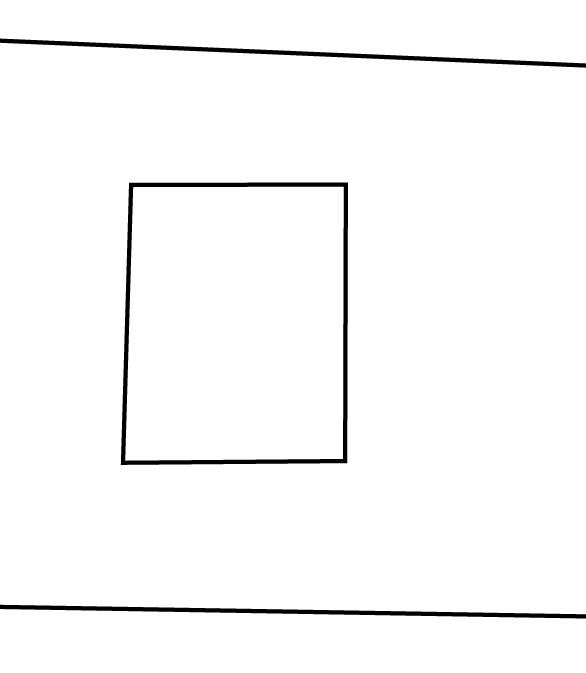

Located across De Hallen in Amsterdam West, the Oranje Huis in Amsterdam could go unnoticed. The main building’s characteristics such as typology, scale, facades and relation to context, could be compared to any standard housing block.

This Oranje Huis counts with 55 apartments and a few emergency beds. The program also includes a collective living room, a shared roof terrace, spaces dedicated to children and teenagers, the Blijf Groep offices and consultation spaces.

Women are placed in one, two or three-room apartments depending on availability and their needs. The apartments are both classified as crisis shelter and guided living, with time of stay varying from six weeks to around one and a half year.

Besides the described facilities in the Oranje Huis in Amsterdam, the Blijf Groep counts with other 35 satellite housing units spread through the city with addresses that remain unknown. In December 2021, the organization has received governmental approval for the development of a new women’s refuge in the city’s context due to a too high demand.

19

20

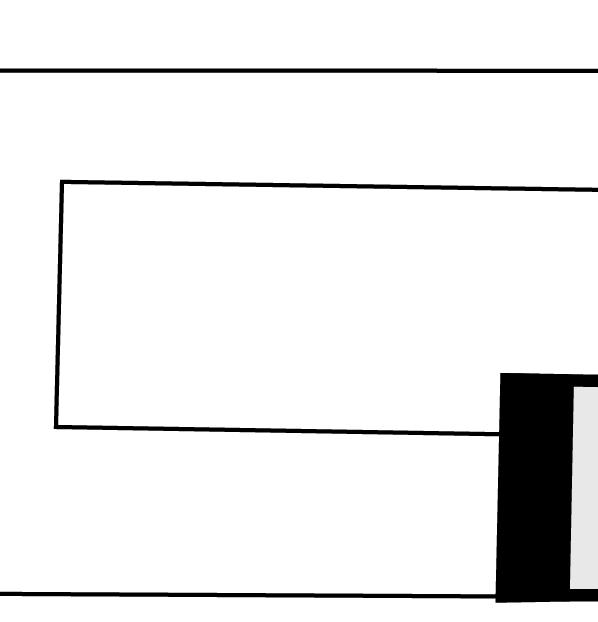

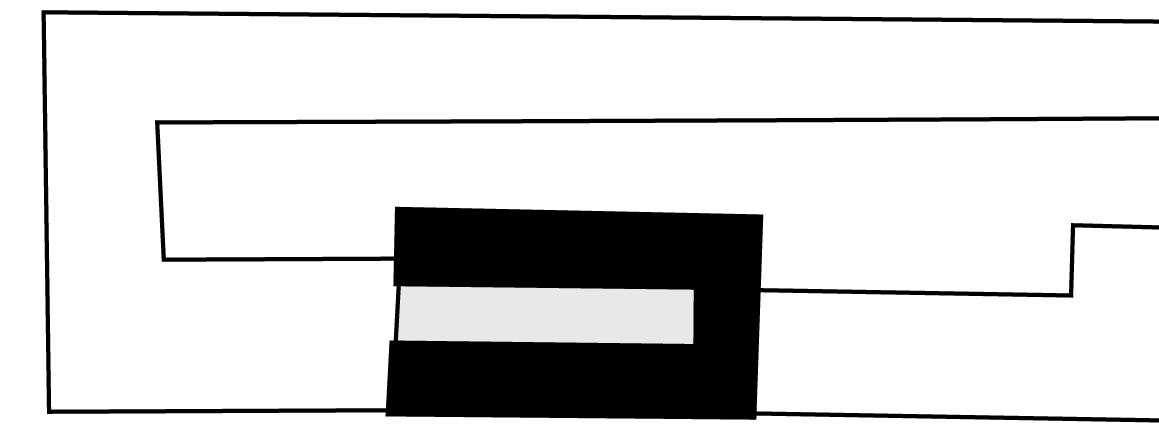

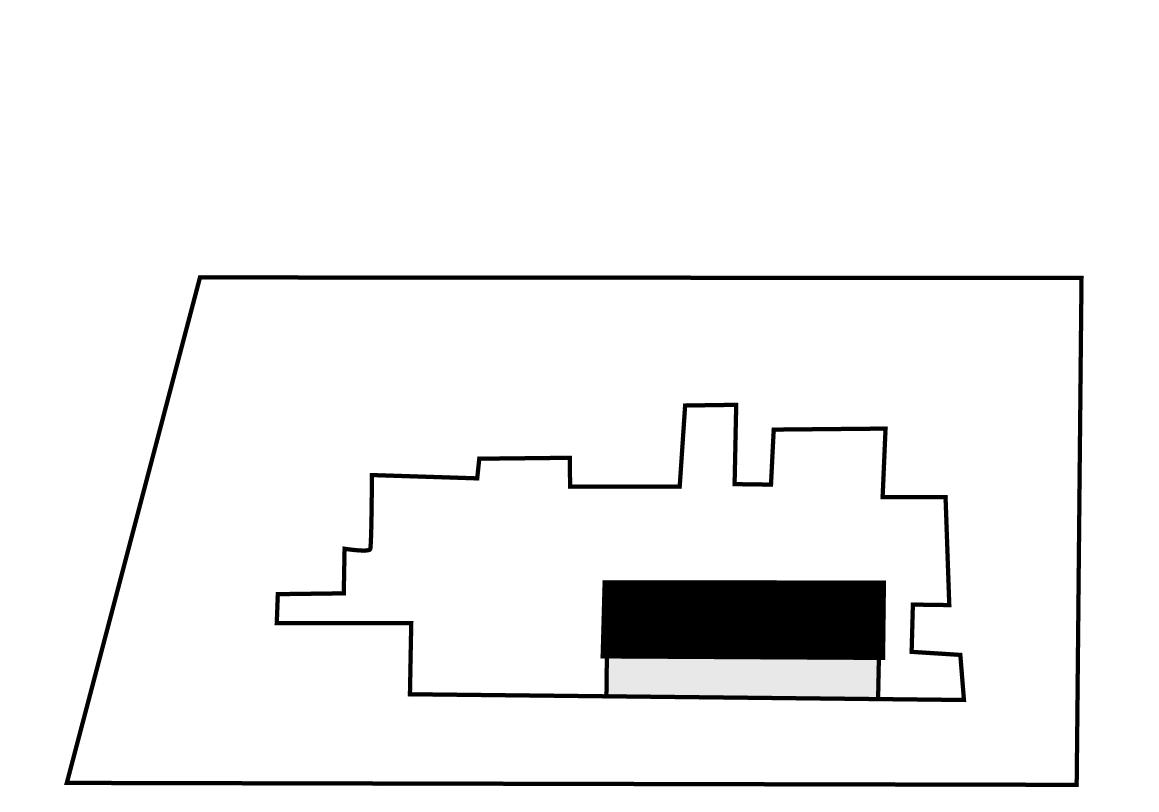

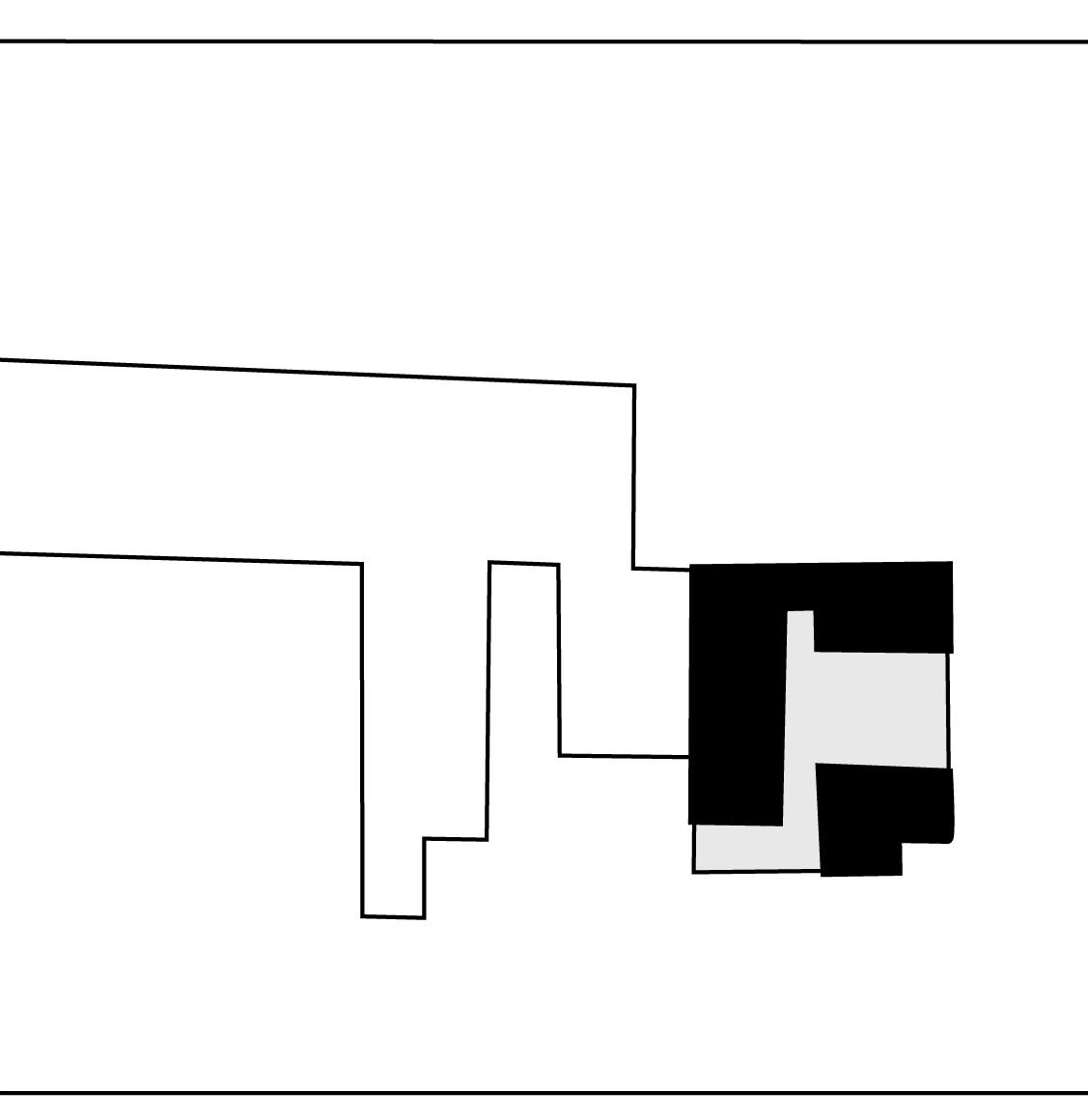

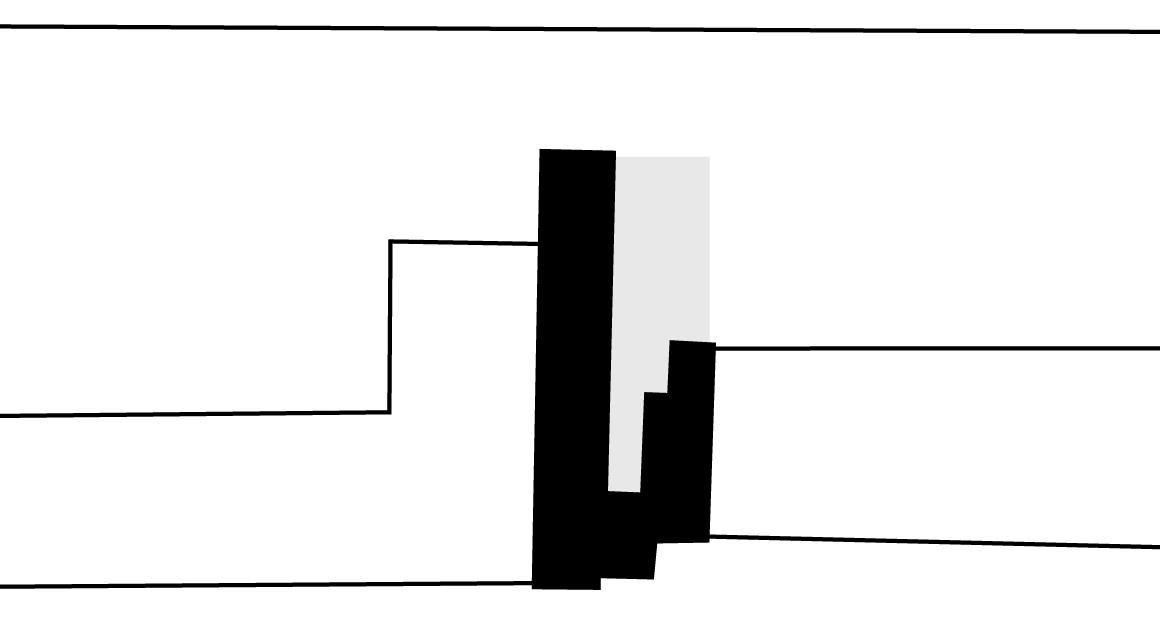

Location and surroundings of the Oranje Huis in Amsterdam

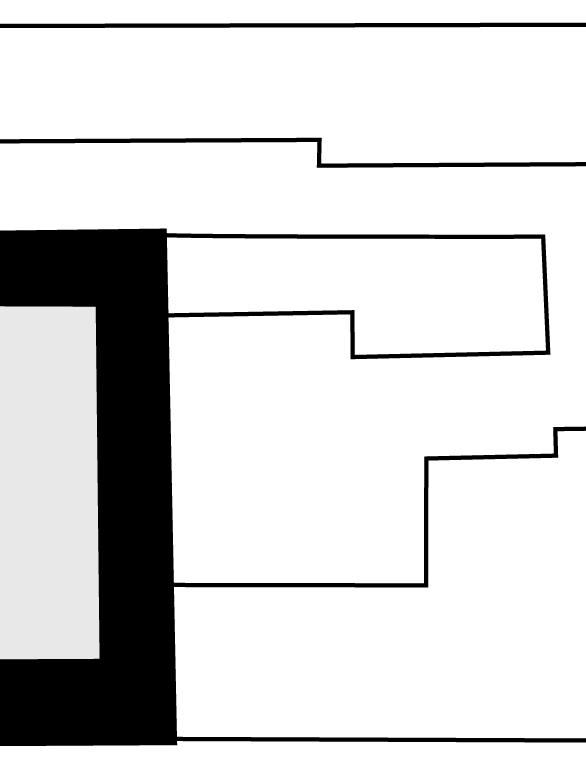

21 Standard floorplan | Oranje Huis Amsterdam

22

Oranje Huis main entrance, collective living room on right corner and glazed balconies that face the streets.

Collective living room located on ground floor with floor to ceiling openings towards the street.

23

Meeting rooms for appointments with social workers located on ground floor with privacy screens added to the windows.

Reception desk located by front door of the Oranje Huis.

24

Interior of a studio

Collective living room positioned on corridor's edge of standard floor.

25

Corridor that gives access to the housing units on the standard floors

Private living room in one of the housing units.

seclusion

inclusion

safety

collectivity

privacy

domesticity

scale

flexibility

connection with nature

temporality

appropriation

26

03. Women’s refuge and spatial design: elaboration of project’s guidelines

From visits to some of their facilities and interviews with people with a different relationship to the Blijf Groep a set of notions with strong spatial consequences were collected to be explored as guidelines for the design.

From this collection two pairs of ideas stand out containing contradictory concepts that are equally important to the configuration of a shelter. Firstly, being at the same time included to and secluded from city life. Secondly, living in a shared communal setting meanwhile privately as an individual. In the research and design process the Dutch hofjes and the urban structure of Amsterdam offered valuable inspiration in the definition of the project’s approach and insights on how to tackle spatially the mentioned notions.

The Maggie’s centers have also contributed to the formation of the guidelines to the design. These small scale healthcare support centers for cancer patients deal with very comparable spatial notions to the ones relevant to the design of a shelter for women. In their architectural brief the belief in the influence of spatial design in the well-being and recovery of their target group is clearly stated.

27

28

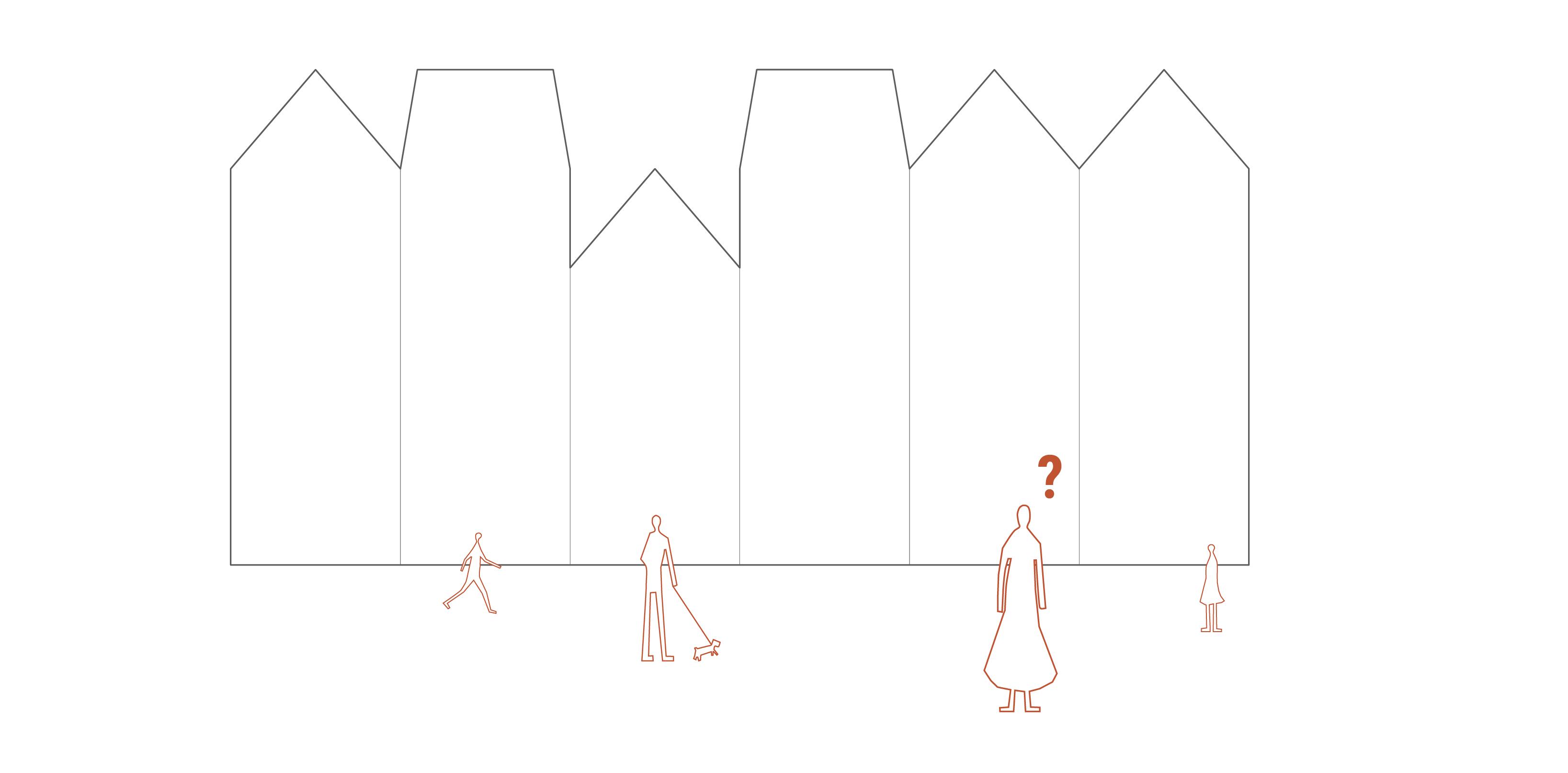

Seclusion | Inclusion

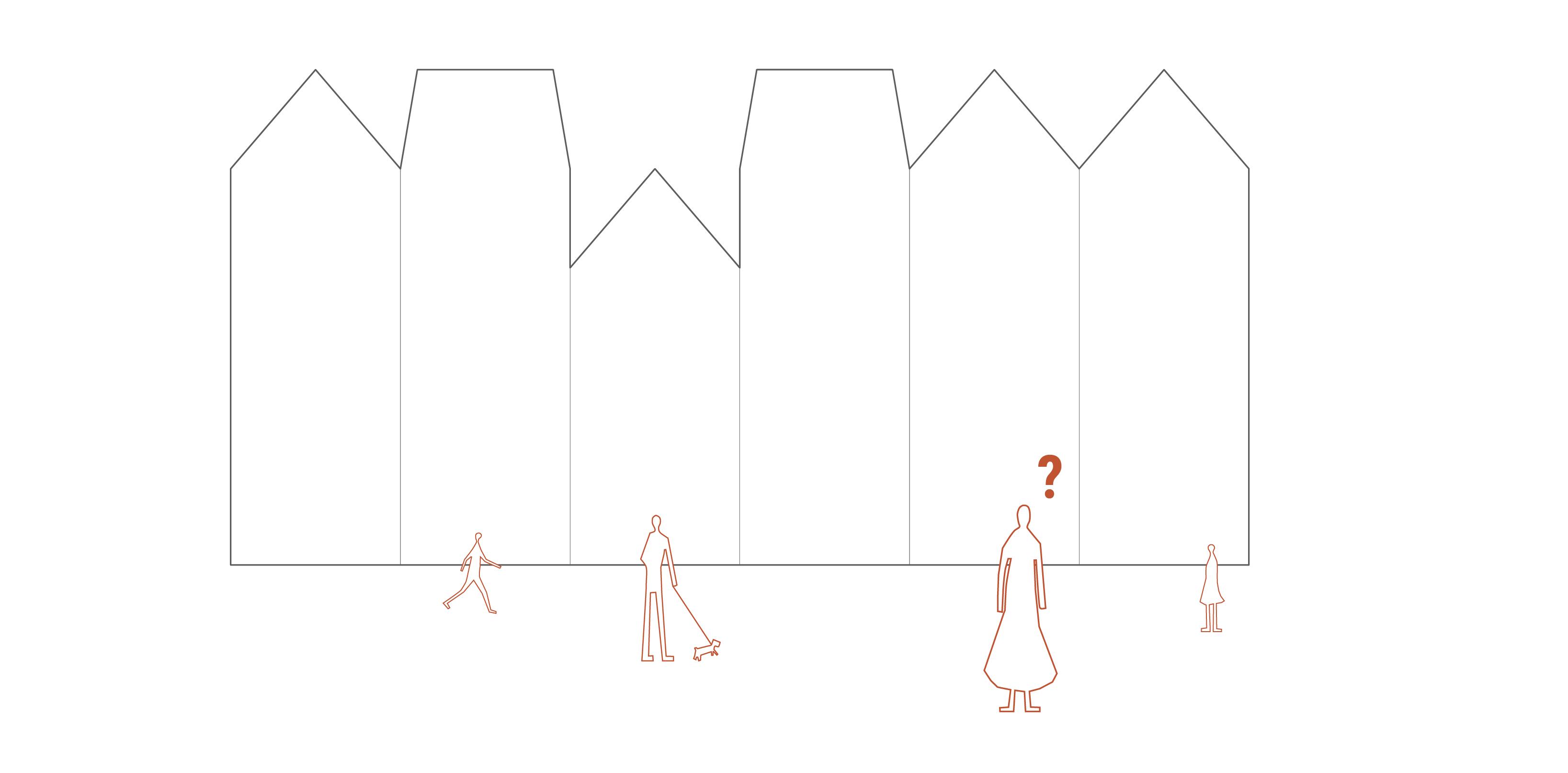

The ideal location for a women’s shelter would be within central areas of the city, areas where all services and facilities are easily accessible. While in recovery in a shelter, it is important that the inhabitants still feel part of society and city life.

Although ideally central keeping the inhabitants integrated to society, the building’s destined to women’s refuge should offer a somewhat secluded living environment. It is extremely important that the shelter’s inhabitants have a protective, safe space to reorganize their lives and recover. The contrast between finding inclusion and seclusion must be addressed by the building’s typology and design.

Within the urban structure of Amsterdam’s city center interesting hints and possibilities can be identified on how to deal with these demands. The city’s block structure with stone like facades towards the streets encloses a second hidden world of the protected inner blocks. The exuberant gardens of the canal district or the multiple hofjes and schools hidden in the inner blocks of Amsterdam are inspiring examples of protected spaces within the city structure that contain fascinating own atmosphere. The manner of approaching the inner block is an essential part of experiencing it and of enabling their semi-public protective character. An intriguing sequence of spaces separate physically and psycologically city and inner block.

29

30

The Suykerhofje

The Eerste Openluchtschool

The secret world of the inner blocks of central Amsterdam

31

The monumental gardens of the canal district

The Suykerhofje | access and spatial sequence between city and hofje

32

33

34

The canal district | access and sequence between city and gardens

35

36

37

The monumental gardens of the canal district

The

38

Hofjes of Amsterdam and their connection to the city context

A - behind a wall B - hidden in block C - facing street

39

Location of remaining hofjes in Amsterdam's city center.

The Hofjes of Amsterdam and their connection to the city context

40

A1. Zeven Keurvorstenhofje (1650) A2. Hofje van Brienen (1806) A3. Hodson-Dedelhof

41

Hodson-Dedelhof (1842) A4. Hodson-Dedelhof (1842) B1. Claes Cleszhofje (1626)

The Hofjes of Amsterdam and their connection to the city context

42

B2. Suykerhoffhofje (1667) B3. Grill’s hofje (1727) B4. Swigtershofje

43

(1744) B5. Nieuwe Suykerhofje (1755) B6. Zon’s Hofje (1755)

The Hofjes of Amsterdam and their connection to the city context

44

C1. Sint Andrieshofje (1617)

C2. Bosschehofje (1648) C3. Rijpenhofje (1737)

45

(1737)

C4. Looiershofje (1828)

C5. Catharina Hofje (1887)

The Hofjes of Amsterdam and their connection to the city context

46

D1. Venetiahofje (1650) D2. Karthuizerhof (1650) D3. Deutzenhofje (1694)

47

(1694)

D4. Covershof (1723)

D5. Van Brants Rushofje (1734)

The Hofjes of Amsterdam and their connection to the city context

48

D5. Rozenhofje (1744)

D6. Occo Hofje (1774)

D7. Hilmanhofje (1875)

49

(1875)

D8. Lindenhofje (1614)

D9. Constantiahofje (1863)

collective courtyard, circulation and sightlines towards private spaces | venetiea hofje

50

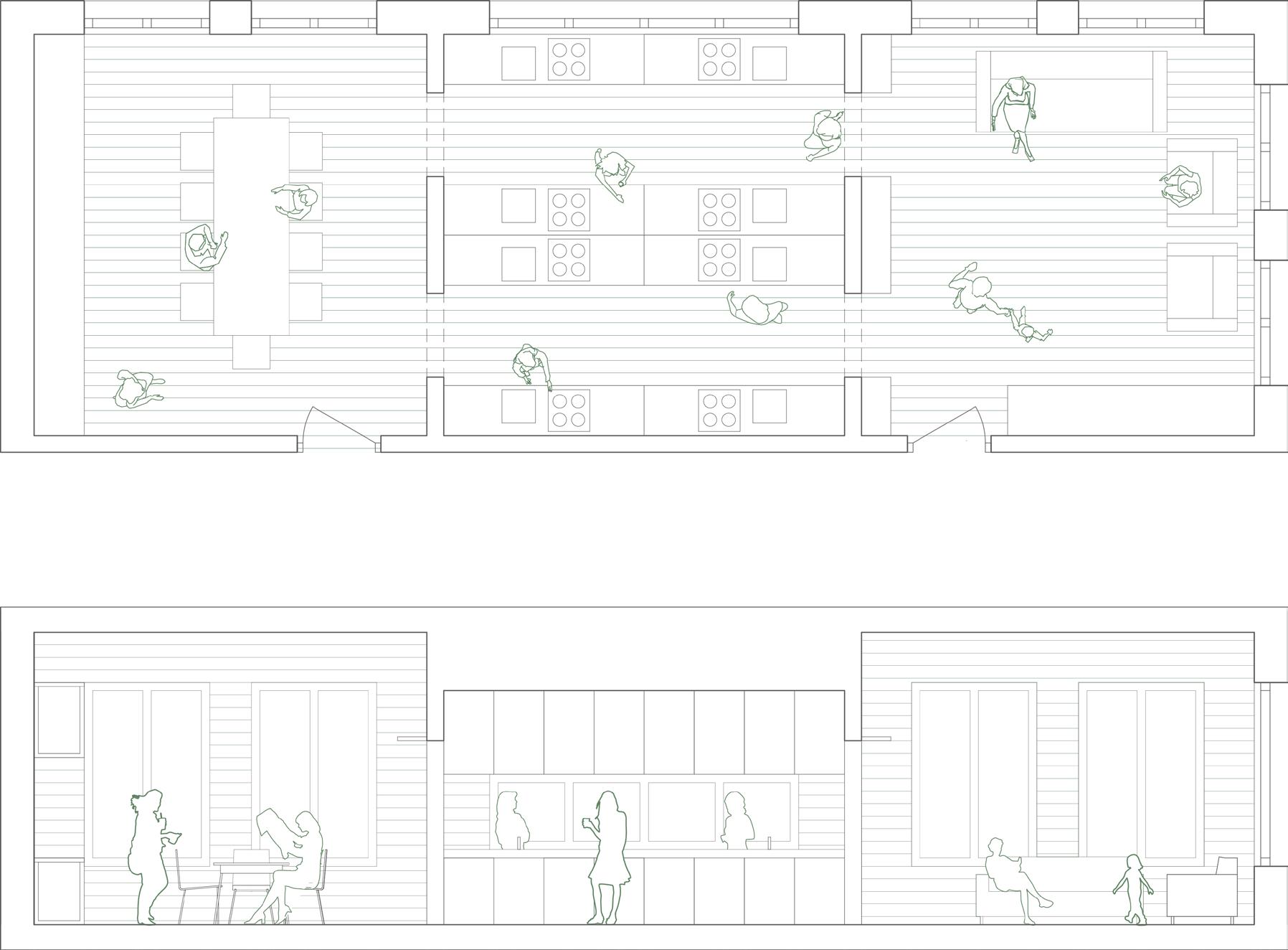

Collectivity

Within shelters a diverse group of women that face a similar trauma are gathered. The opportunity of sharing experiences and of supporting each other is an essential factor in their recovery process. It is important that the infrastructure of these buildings offers spaces that encourage collectivity and strengthen a sense of community.

In all successful studied references – the Maggie’s center Southampton, the hofjes and the shelters for women – the lively collective spaces are either linked to circulation or to daily life activities. The routine or main routes present in a building informally activates these shared spaces creating spontaneous encounters and encouraging communal life. Regular circulation spaces, if given generous proportions, natural light and linked to a simple function can be also transformed into a lively collective space.

51

52 hallways | blijfgroep haarlem collective spaces and circulation | maggie’s southampton

53

collective kitchen | blijfgroep haarlem

eye height

private space

eye height

collective space

housing units

collective garden

The Suykerhofje | level differences and sightlines between collective and private spaces

54

Privacy

In women’s refuge, just as important as the spaces that encourage collectivity are the private spaces that provide the chance to retreat. Throughout their stay, the shelter’s inhabitants are in need of space to restructure their private own and often family life.

Spatially the feeling of privacy relates mainly to seeing others and being seen. In the spatial design of shelters it is relevant to pay close attention to the transition between collective and private space, offering within a context of collective life enough corners for inhabitants to be on their own individual environment.

In the hofjes the gradations between collective and private space are often created by for instance subtle level differences between a lower collective garden and higher housing units. The height and density of vegetation in the communal gardens also play an important role in blocking or allowing certain sightlines. In Maggie’s center Southampton spaces with different degree of privacy were achieved by simply creating corners with more or less visual connection to the main shared space.

55

Venetiaehofje | sightlines blocked or allowed by the density and height of greenery.

56

57

Hofje van Brienen | height difference between collective and private areas.

Maggie's Southampton | gradation between collective and private areas - smaller corners created by the extension of the outer walls.

58

59

Safety

Safety is a key notion to this project, since the shelters are no longer positioned in a secret location other mechanisms should in an urban level guarantee the feeling of safety around it. Following the ideas developed by Jane Jacobs diversity of use in the city stimulates social control on the streets and safety on a urban level.

60

Flexibility

Domestic violence affects a diverse group of women, it has no limitation regarding age or family configurations. In the shelter organization it is important to take the varying profile of women in need of help in consideration, in order to adequately accommodate them and their families.

61

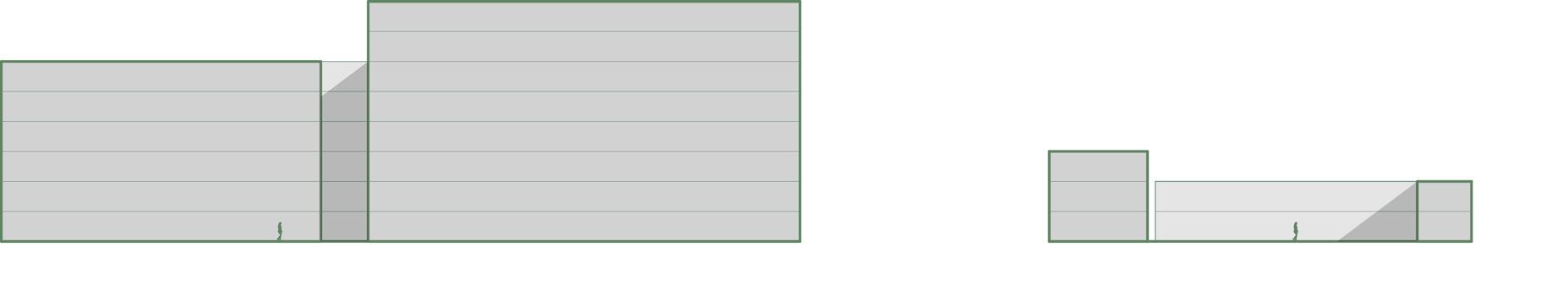

blijfgroep oranjehuis amsterdam

55 housing units

9000 m 2

venetiea hofje

17 housing units

1300 m 2 inside

700 m 2 outside

62

Domesticity, community and scale

A shelter for women is a temporary home. Although the stay is limited, varying from a couple of weeks to about a year, it is essential that the inhabitants are able to feel at home. The scale of such a place should therefore ideally remain small and domestic. The opportunity to engage with others can also contribute to the feeling of belonging to a place, to possibly create a functional community there sould be attention to the size and amount of inhabitants in the shelter.

maggie’s southampton

500 m 2 inside

1300 m 2 outside

12 housing units

1000 m 2 inside

200 m 2 outside

63

blijfgroep haarlem

64

Maggie's centers: Leeds designed by Heatherwick studio, Southampton designed by Studio AL_A, Manchester designed by Foster + Partners and Lanarkshire designed by Reiach and Hall Architects.

Domesticity and program

Just as the Maggie’s centers a shelter for women is also part of an institution. To achieve a domestic atmosphere the users of the building should not experience entering or staying on institutionalized ground. At maggie’s centers the careful positioning of offices and the absence of a formal reception or signage are helpful to create the wished domestic atmosphere.

65

Maggie's Southampton | careful positioning of institutional office space in relantionship to entrances and collective area.

Maggie's Southampton | the building is surrounded and enclosed by a dense garden. The openings are maximized and transitions between inside and outside are as fluid as possible.

66

Connection with nature

In an enclosed protective environment the contact with the outer world could become limited. While staying in the secluded spaces of the shelter the contact with the landscape through gardens or a natural environment may remind the residents of the context, the passage of time in a day or in a year, connecting them to the living world. In the Maggie’s centers for instance, every space is required to have at least one direct sightline towards an outer garden. “Sometimes, all that a person can bear, if they are in acute distress, is to look out of the window from a sheltered place, at the branch of a tree moving in the wind” (Maggie’s Architectural and Landscape Brief, 2015).

67

68

Project's location within the city center of Amsterdam.

04. The location: Relations between the program and the city

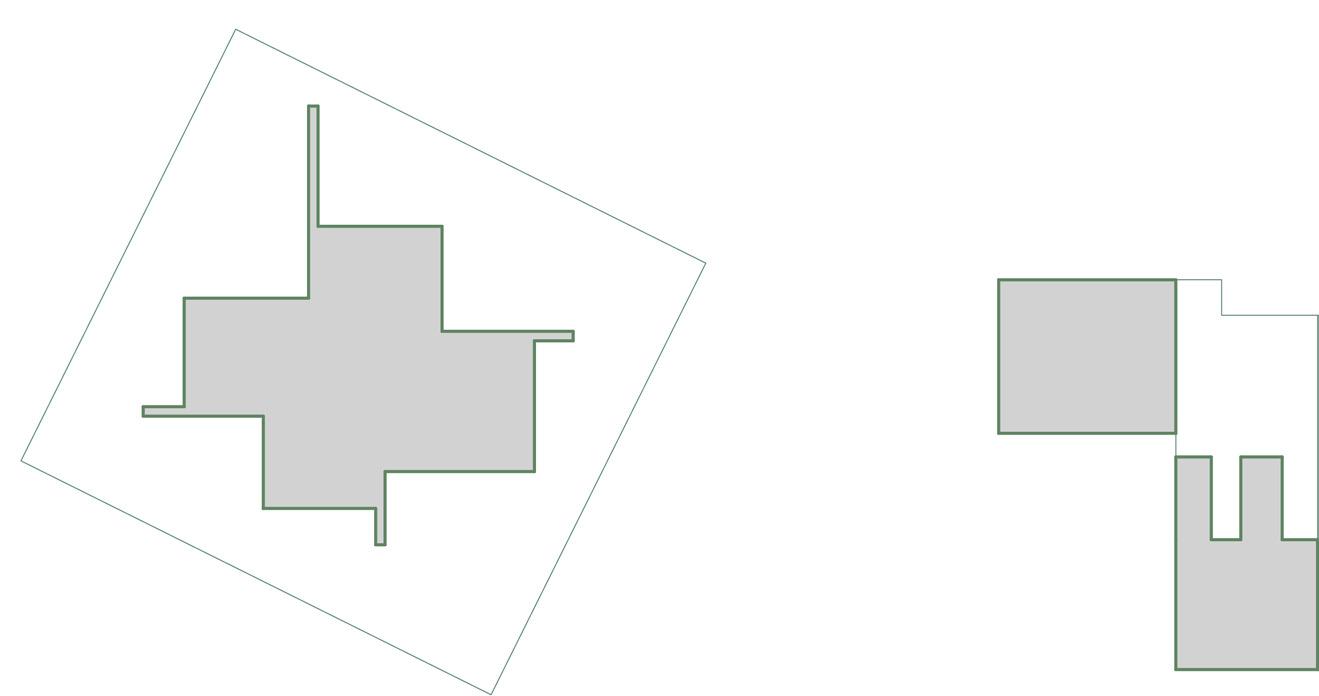

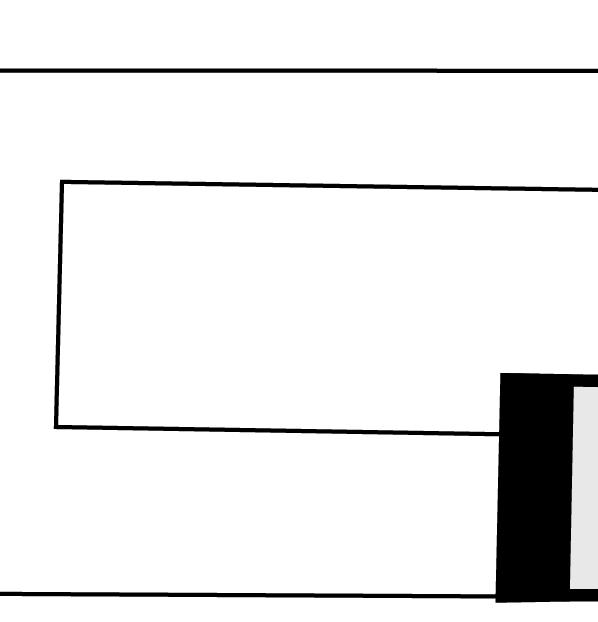

From the interviews realized during the research phase of the project, it became clear that the current shelters are composed of three different programmatic sections: the institution, the living and the healthcare facilities.

Each one of this programmatic sections relate to a different part of the recovery process women go through and would ideally be surrounded by diverse urban atmospheres with an own relationship to the city.

The institution relates to the moment of arrival and should be positioned with visibility in the urban context. Open 24/7 the building is a known address where people can find help and information. The living represents the path to go through, in this process the ideal scenario should provide a highly protective environment, secluded from busy city life. As last, the healthcare facilities relate to the departure or the preparation to pick up normal life. Surrounded by a small scale urban context, with little exposure, offering a glimpse towards the surrounding city.

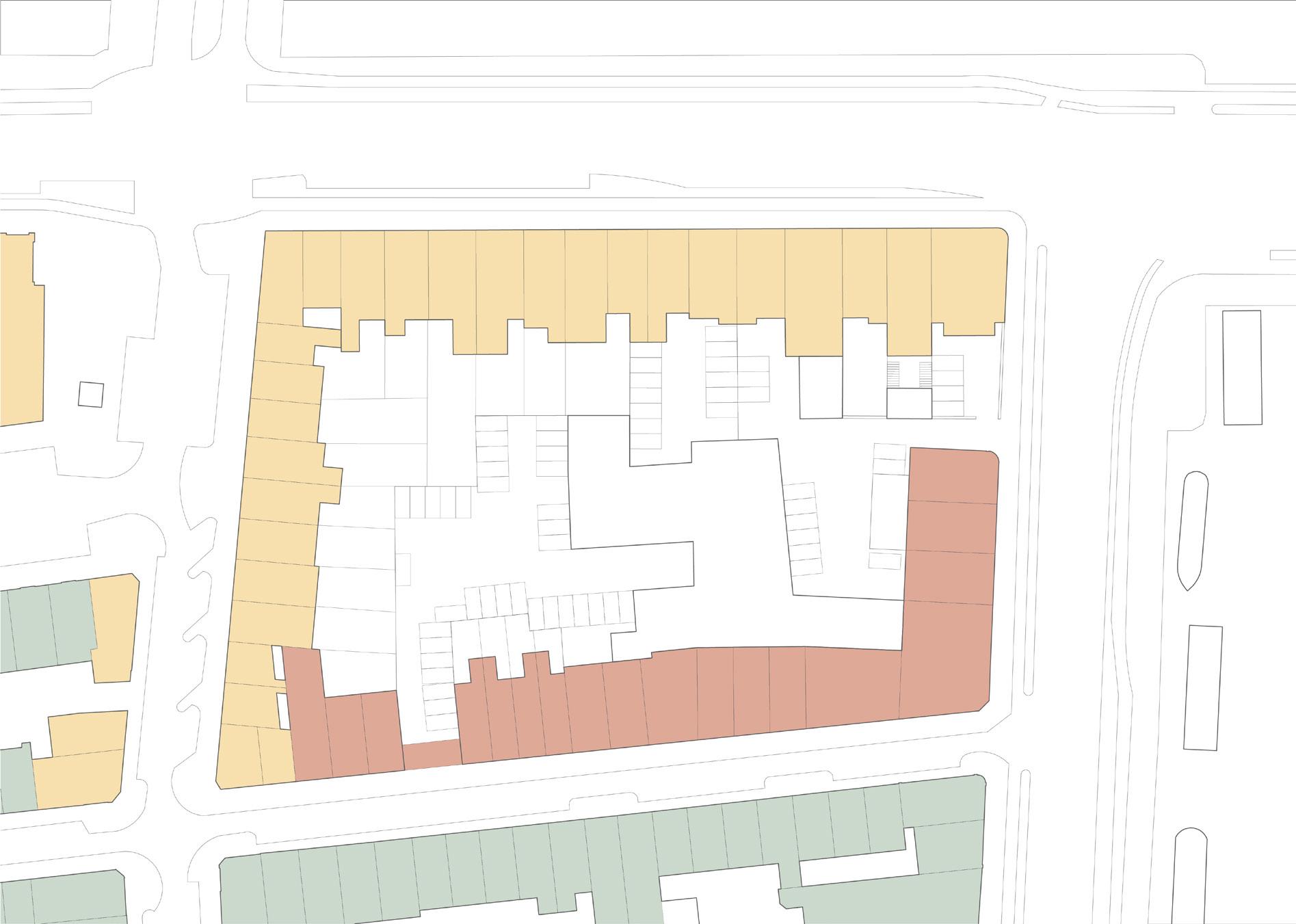

The chosen project site consists of an existing block in the city center of Amsterdam. Positioning the shelter on this location integrates it to urban life. The area of easy access places the inhabitants close to all infrastructure and every facility they may need during their stay.

Currently, the interior of the chosen block is almost entirely occupied by parking facilities with two entrances that face different urban atmospheres – a busy larger scale axis and a calm small scale street. The site offers the perfect setting to host the three programmatic sections of a women’s shelter each with its own relationship with the city context.

69

70

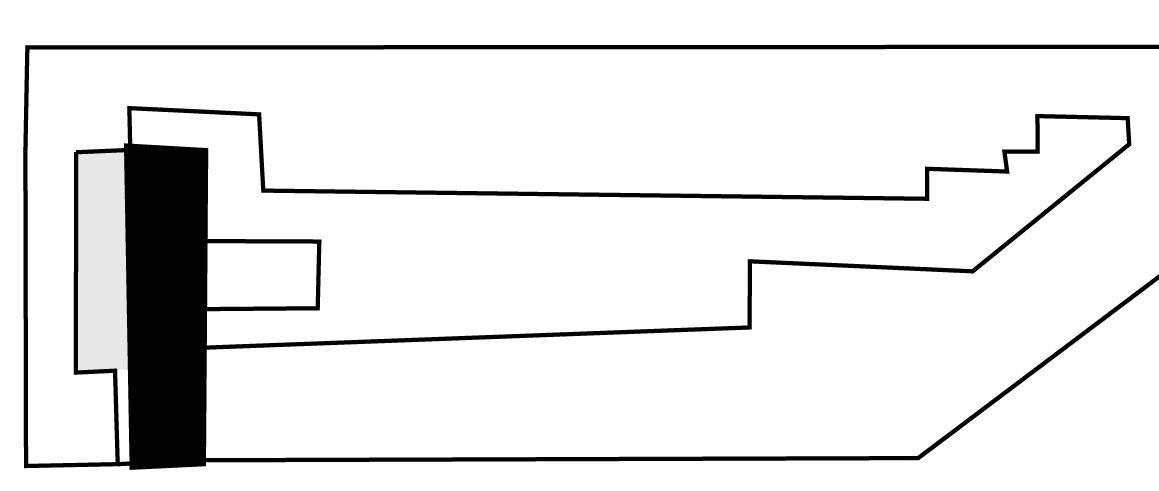

Amsteldijk street profile | the interrupted built structure gives access to parking facilties.

Stadhouderskade street profile | large scale urban axis

71

Govert Flinckstraat street profile | the interrupted built structure gives access to parking facilties.

Hemonystraat street profile | small scale street

As previously mentioned in its current situation the inner block is almost entirely occupied by indoor and outdoor parking facilities. Another context is also present though, on the west side of the block a collection of private gardens with impressive full grown trees creates a beautiful privacy buffer between private life and parking facilities.

72

HEMONYSTRAAT

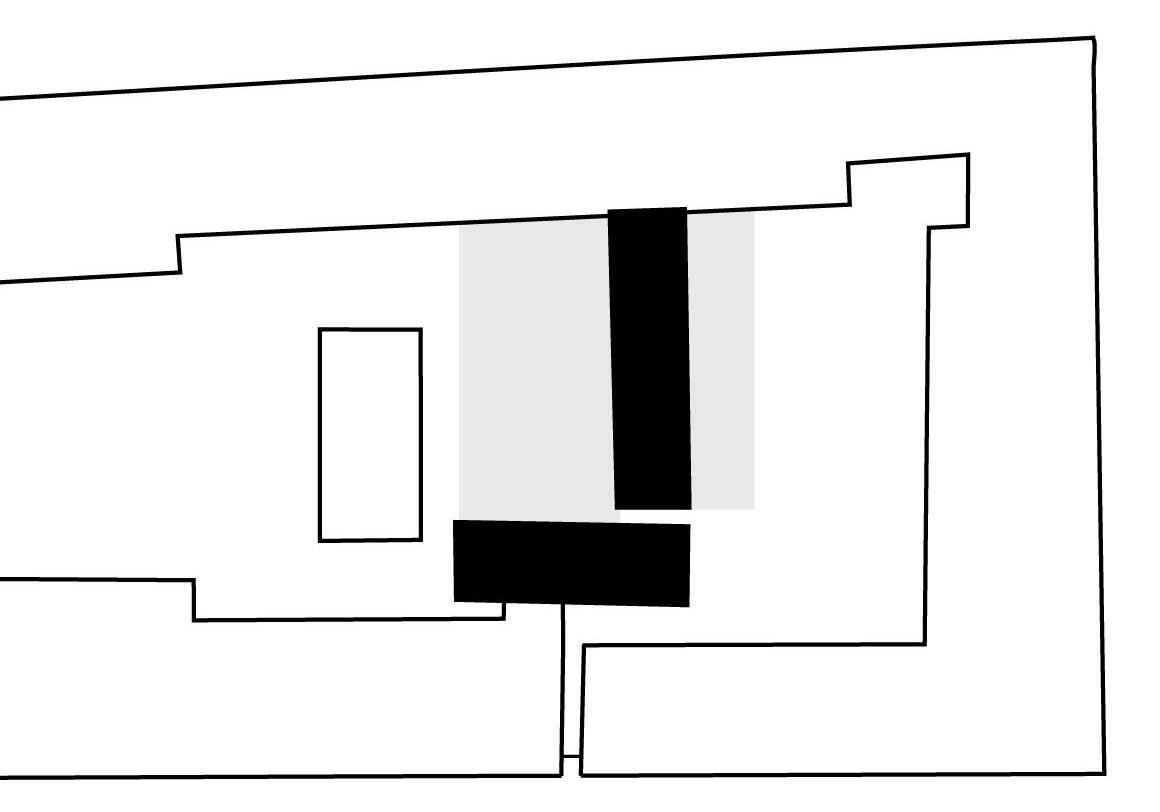

Location's current situation

GOVERT FLINCKSTRAAT

Elements to be demolished

73

STADHOUDERSKADE

AMSTELDIJK

N

74

The parking facilities and a parking entrance to be transformed as a new access.

75

The existing garden and the beautiful privacy buffer created by the greenery.

Functions within the project's site

The project’s city block and its immediate surroundings host a wide variety of functions which stimulates social control on the streets, people coming and going all day long, providing safety on a urban level.

sports facilities

horeca offices

retail

76

77 working + living living working + living + services 01 02 03 04 05 06 01 02 03 04 05 06 56% living + 29% services + 15% working 58% living + 42% working 48% living + 18% services + 36% working 88% living + 4% services + 8% working 60% living + 20% services + 21% working 45% living + 22% services + 33% working

78

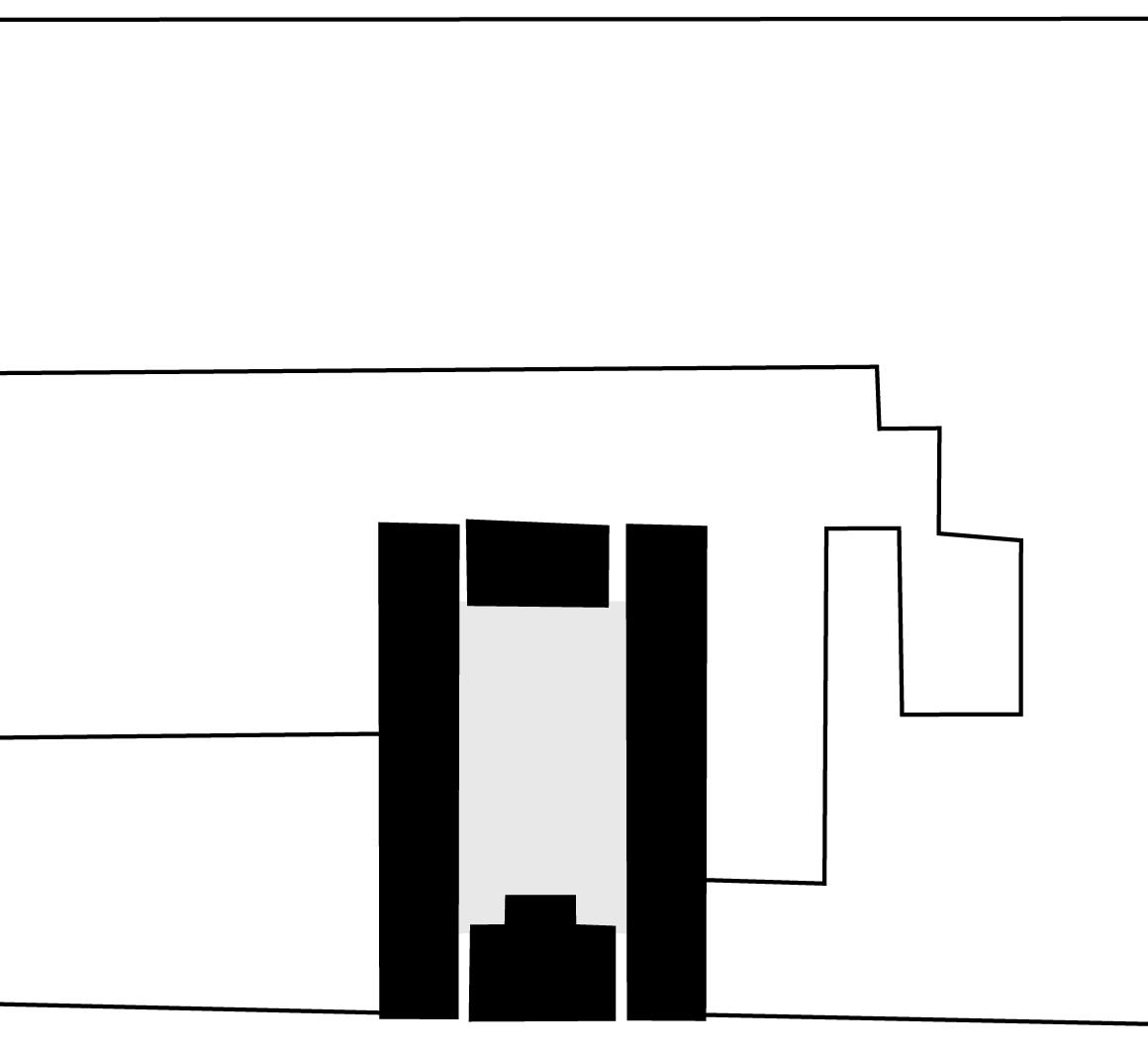

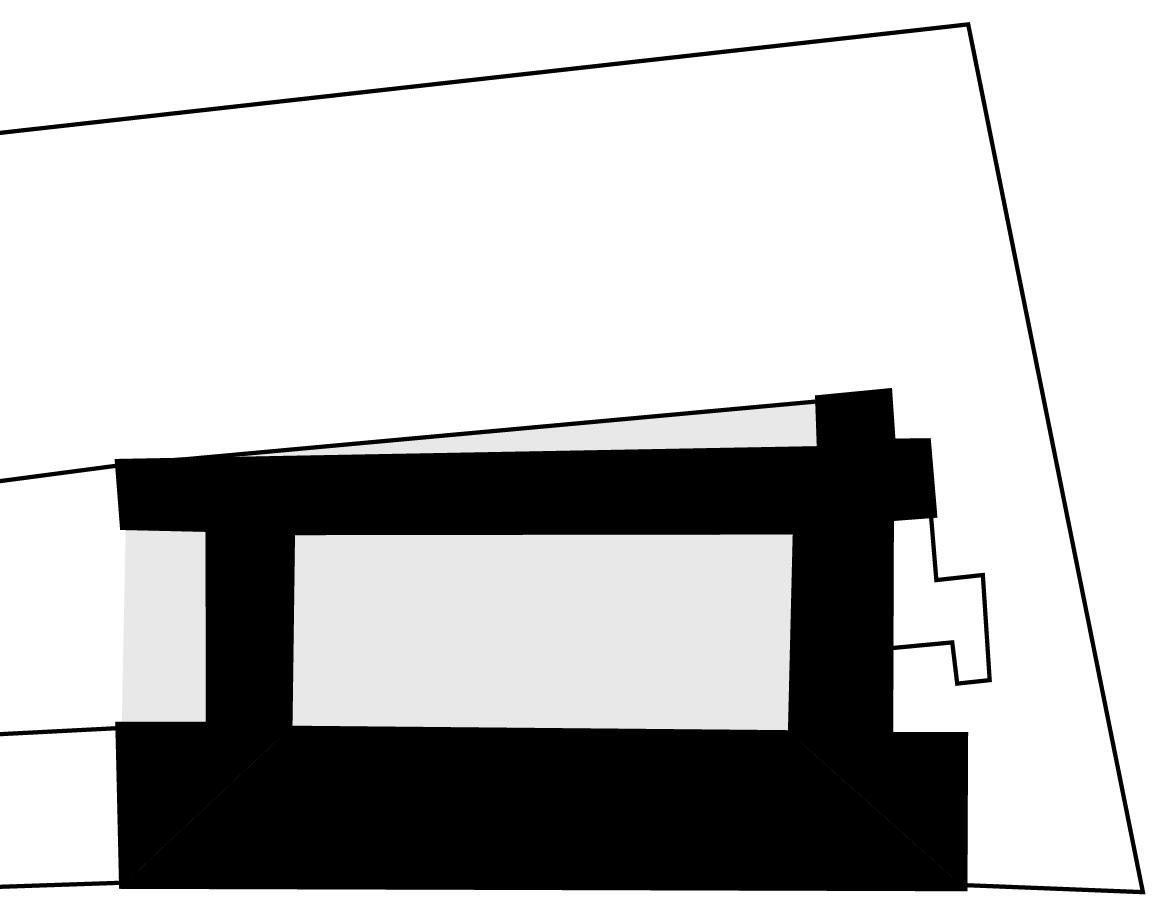

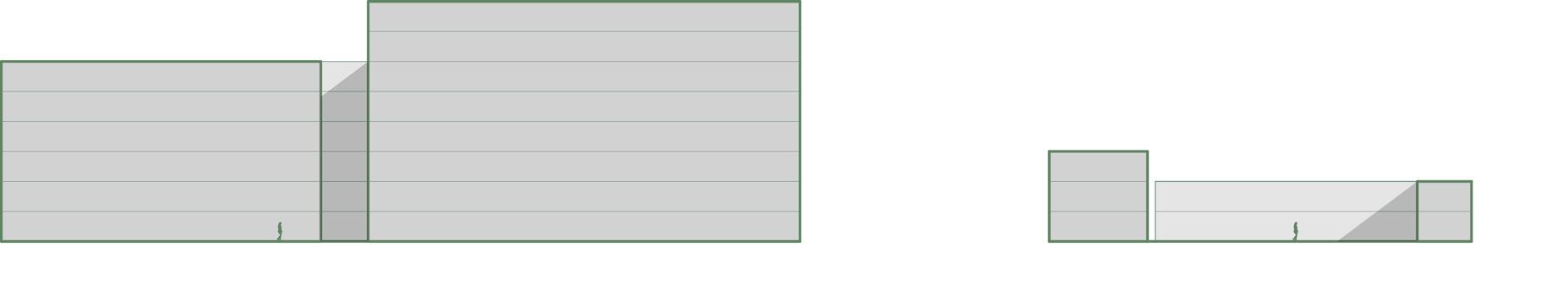

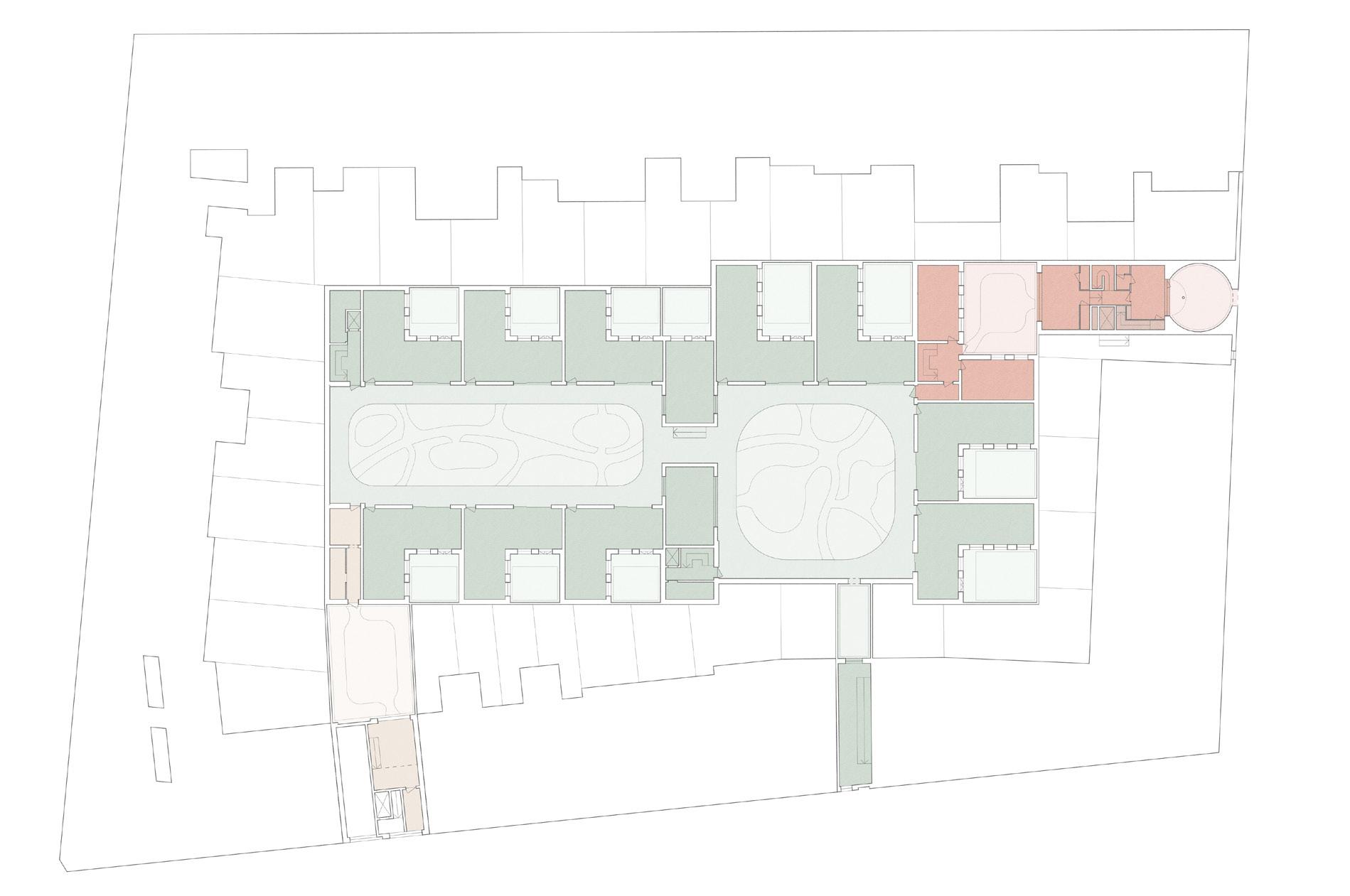

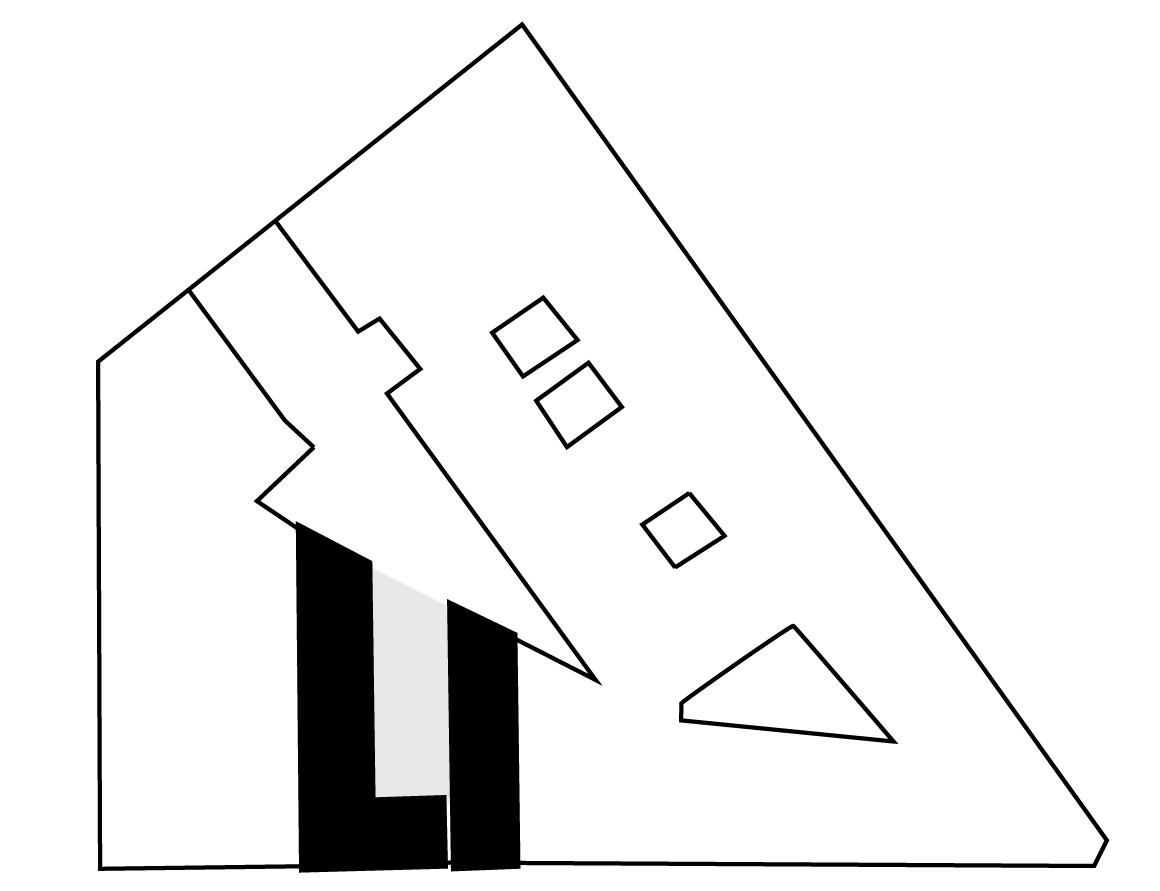

05. The design

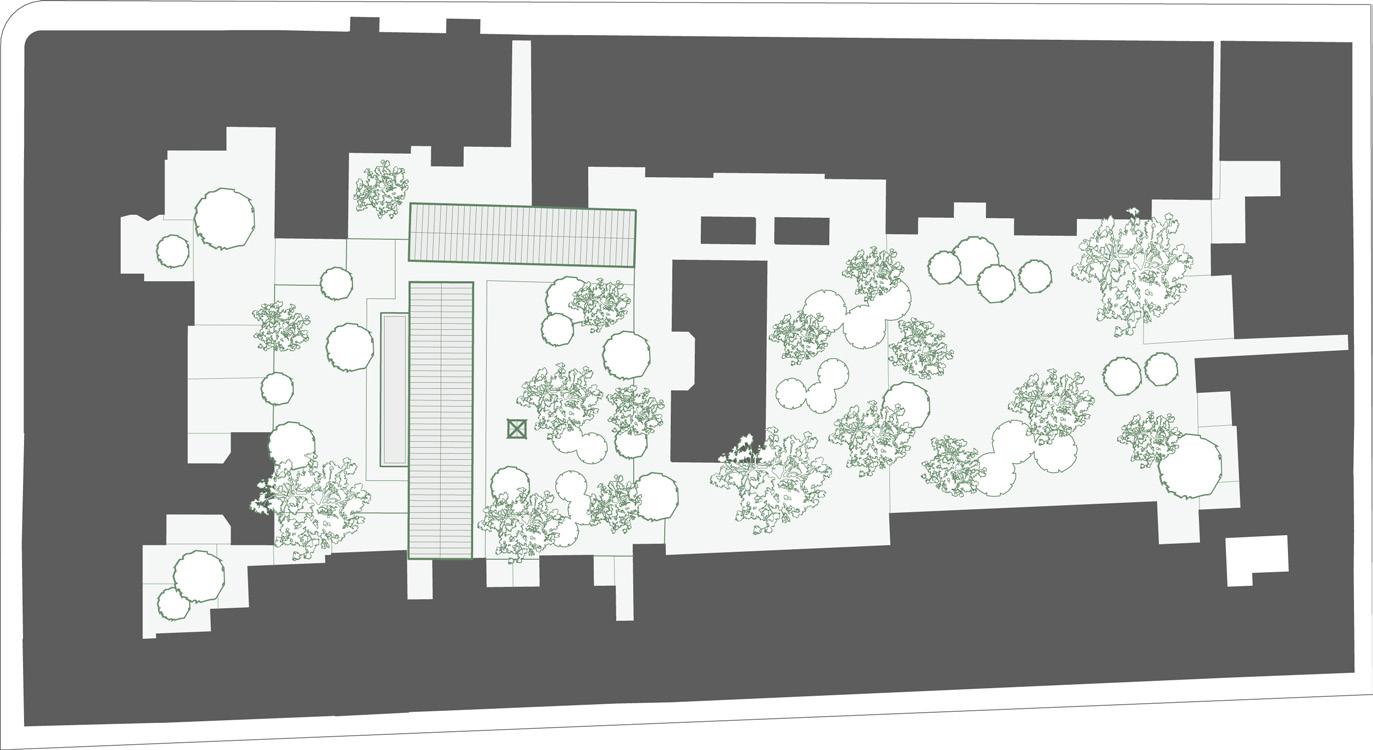

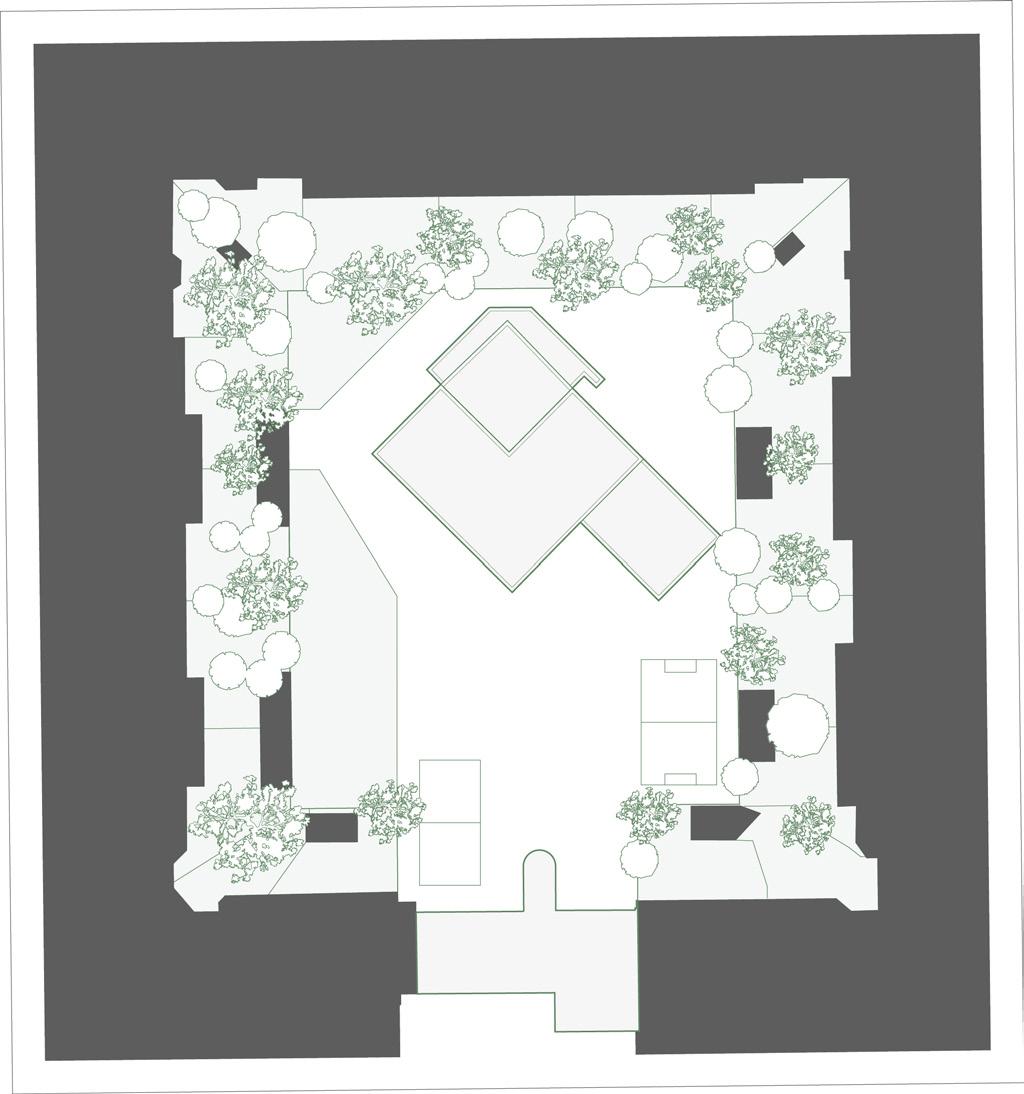

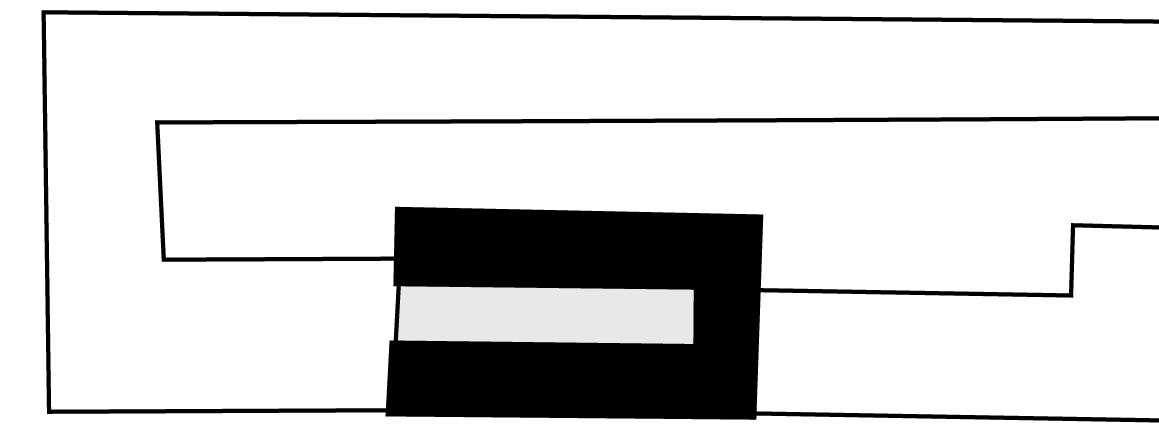

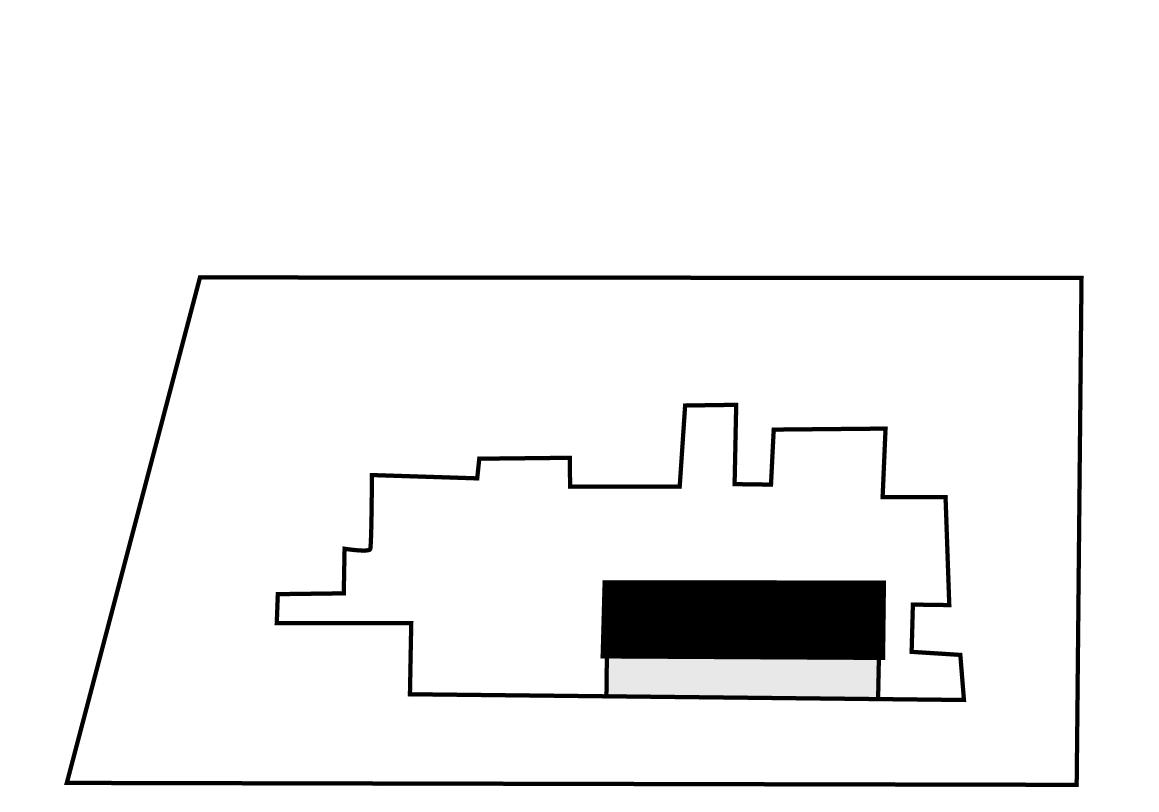

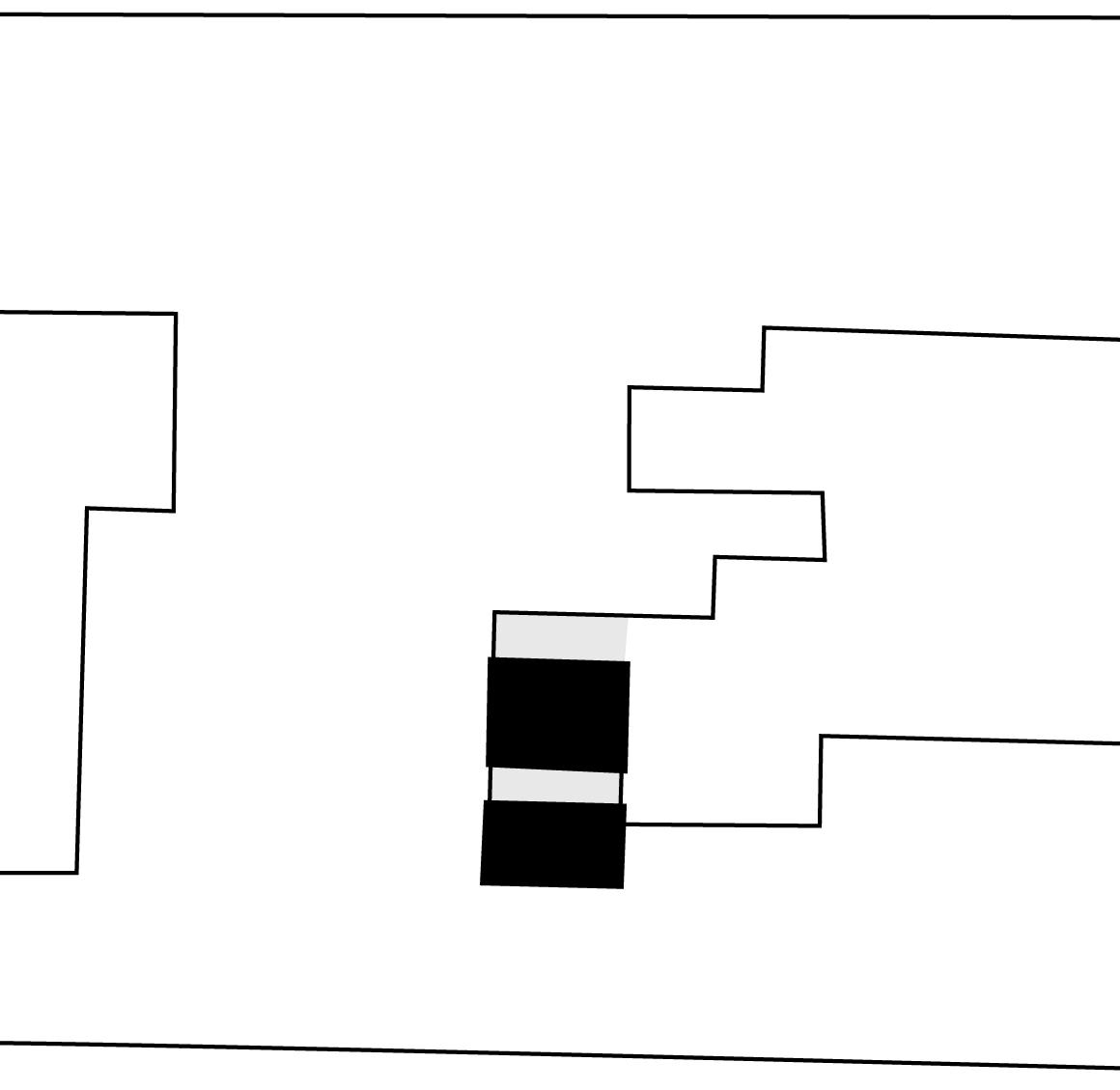

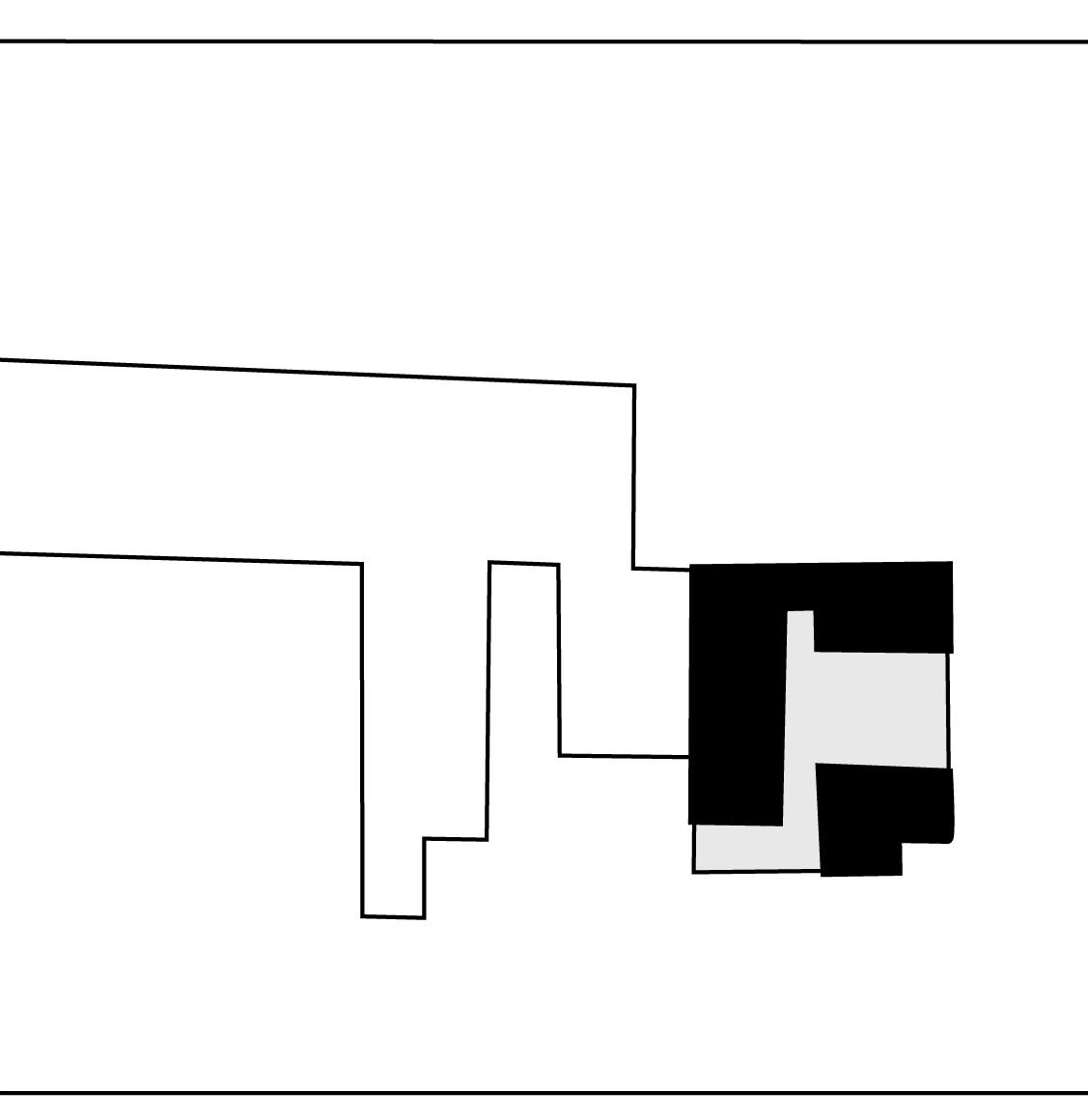

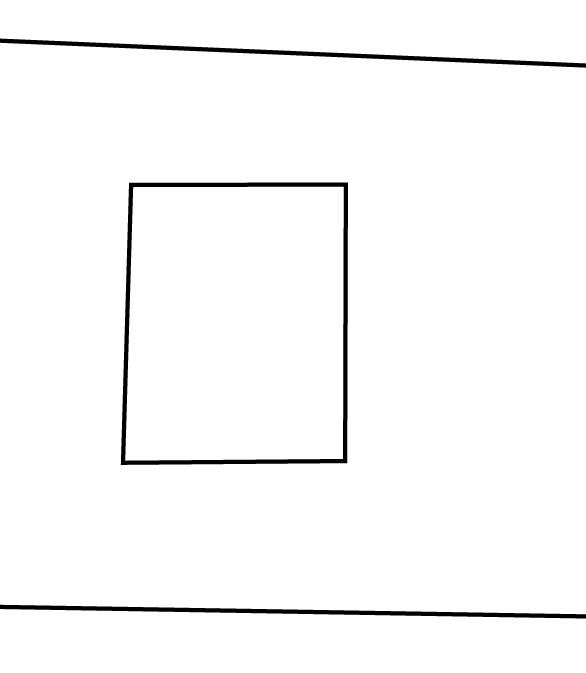

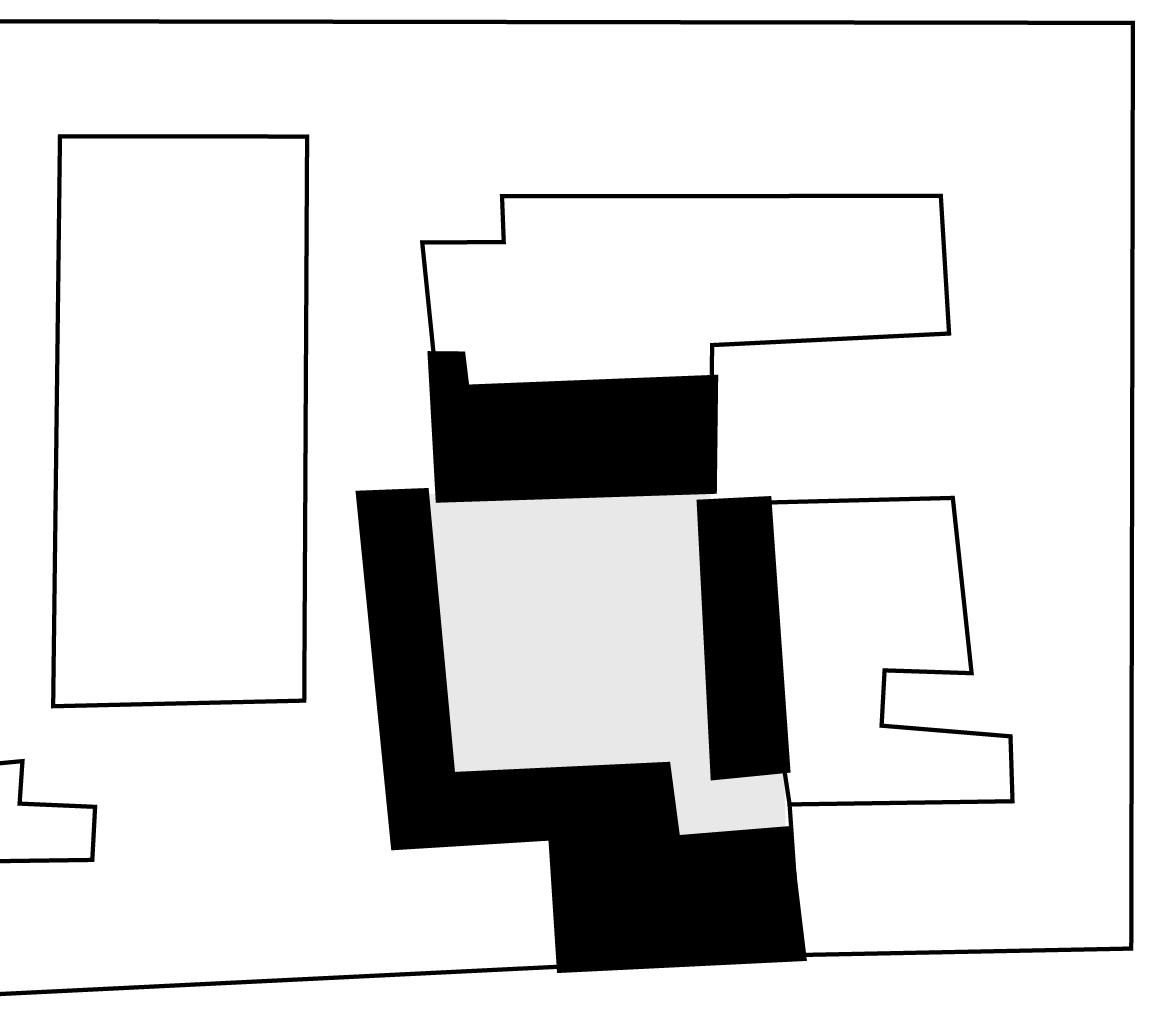

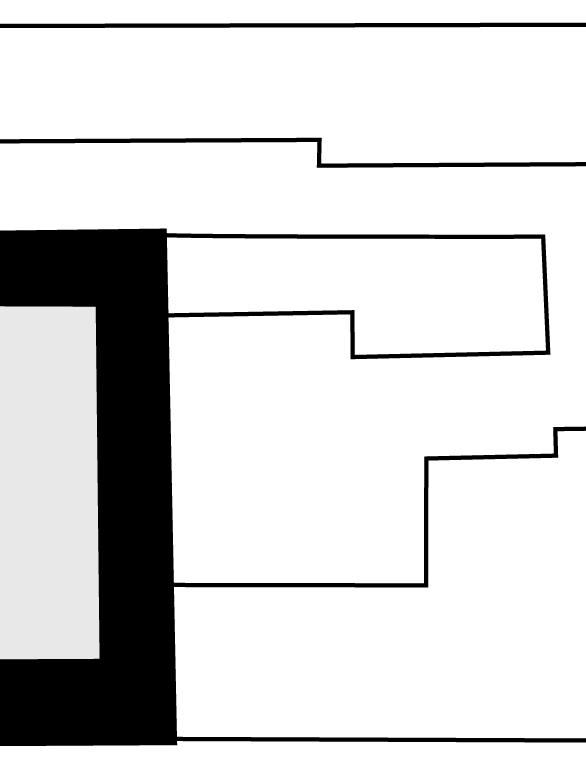

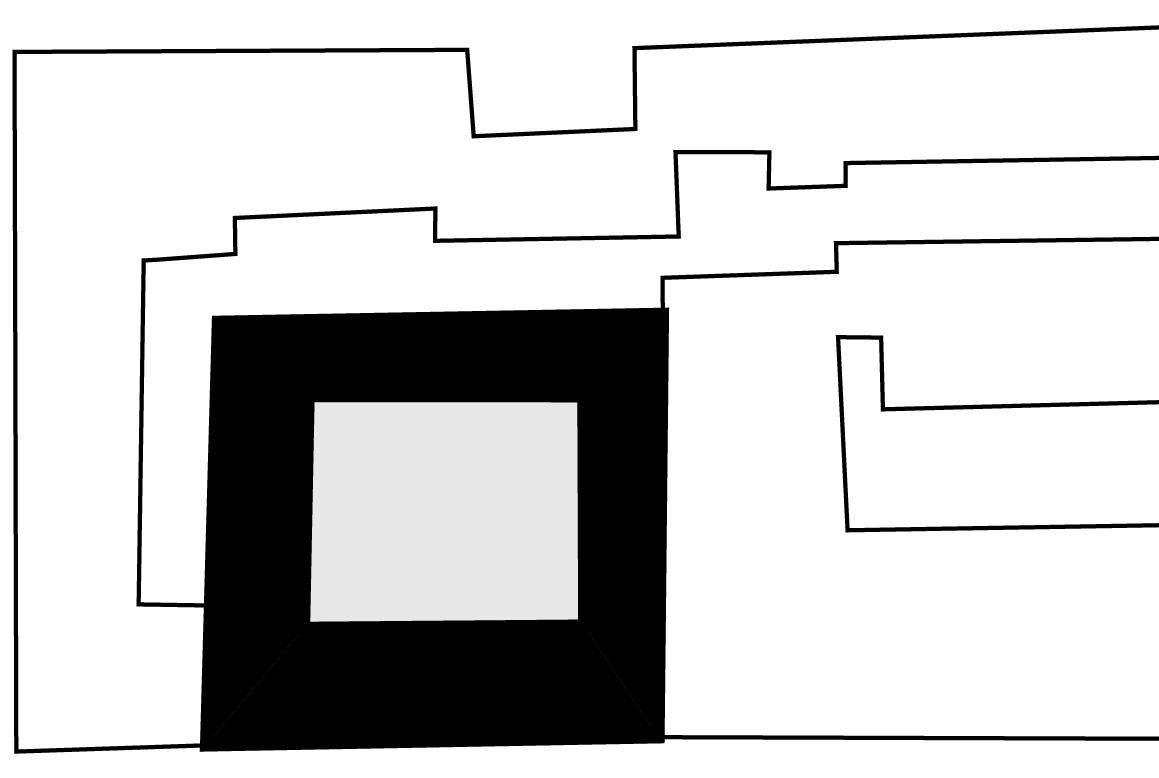

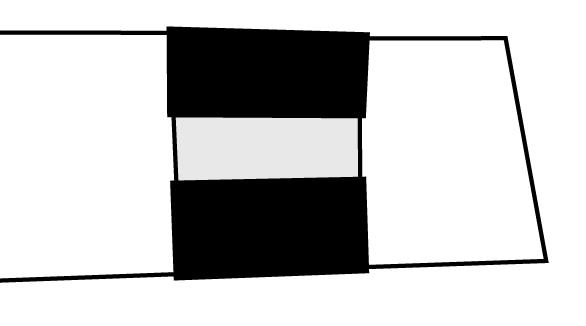

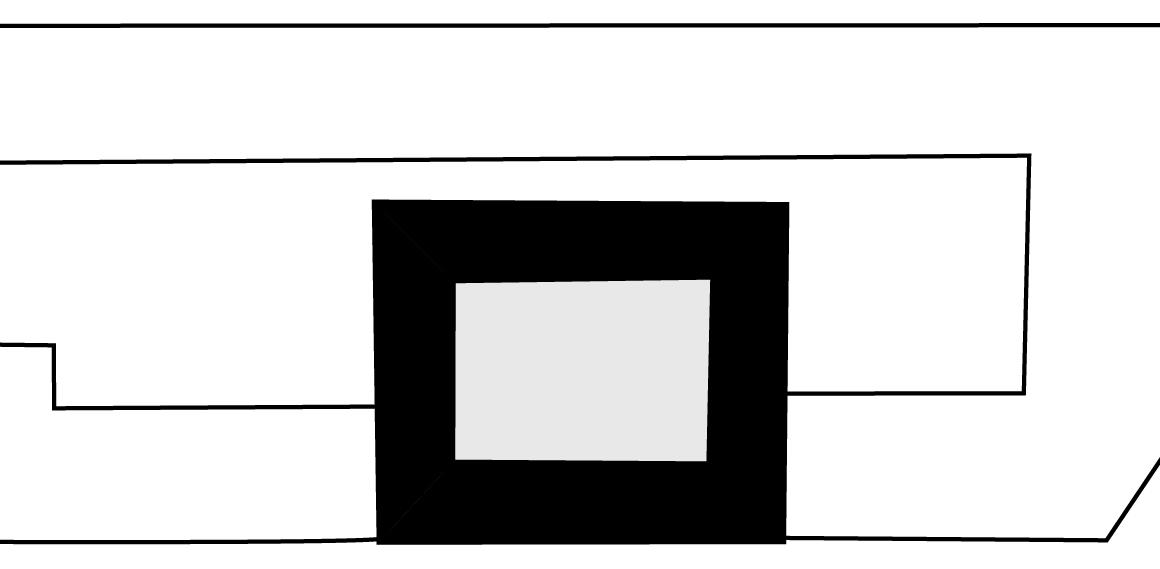

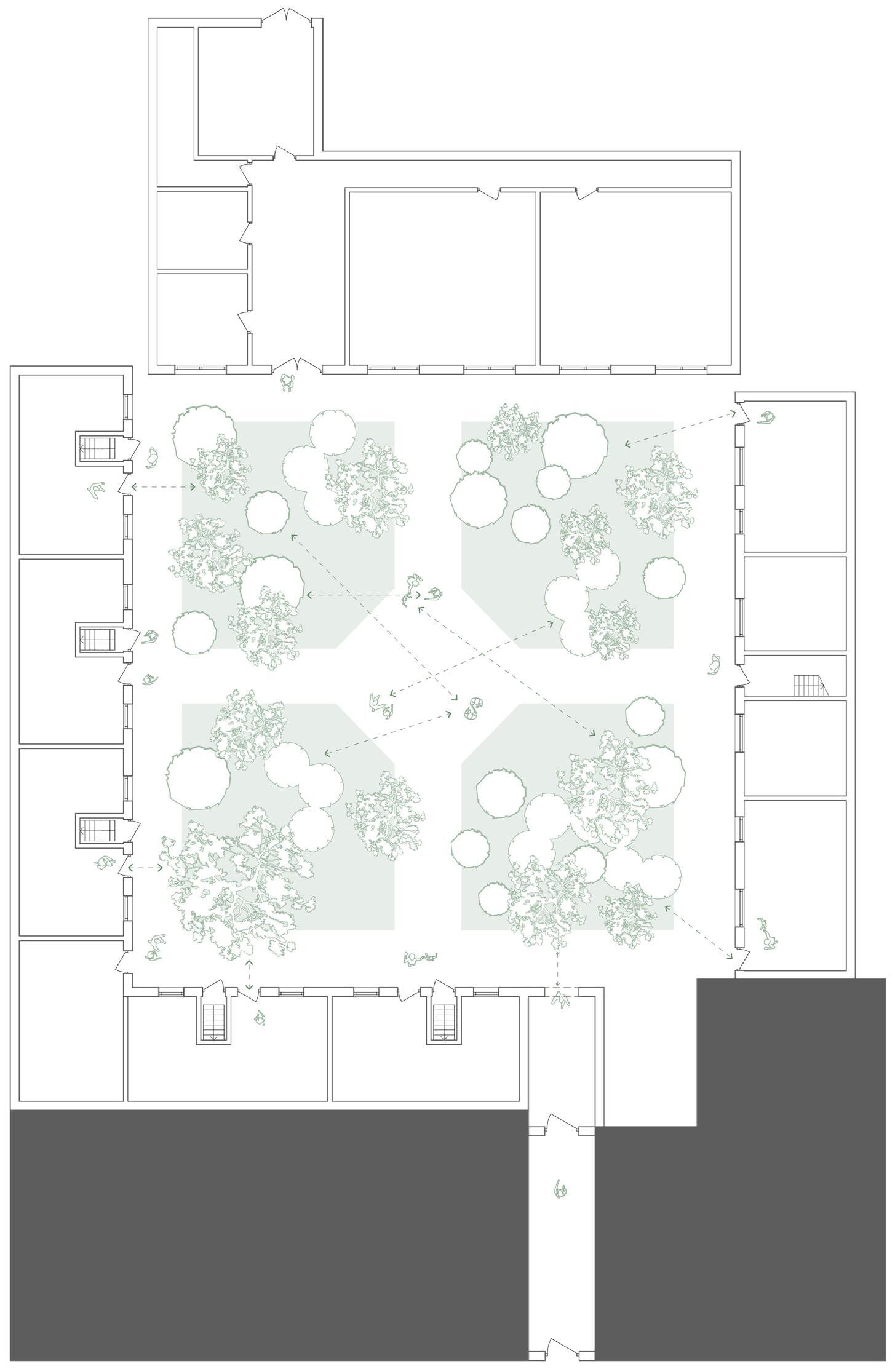

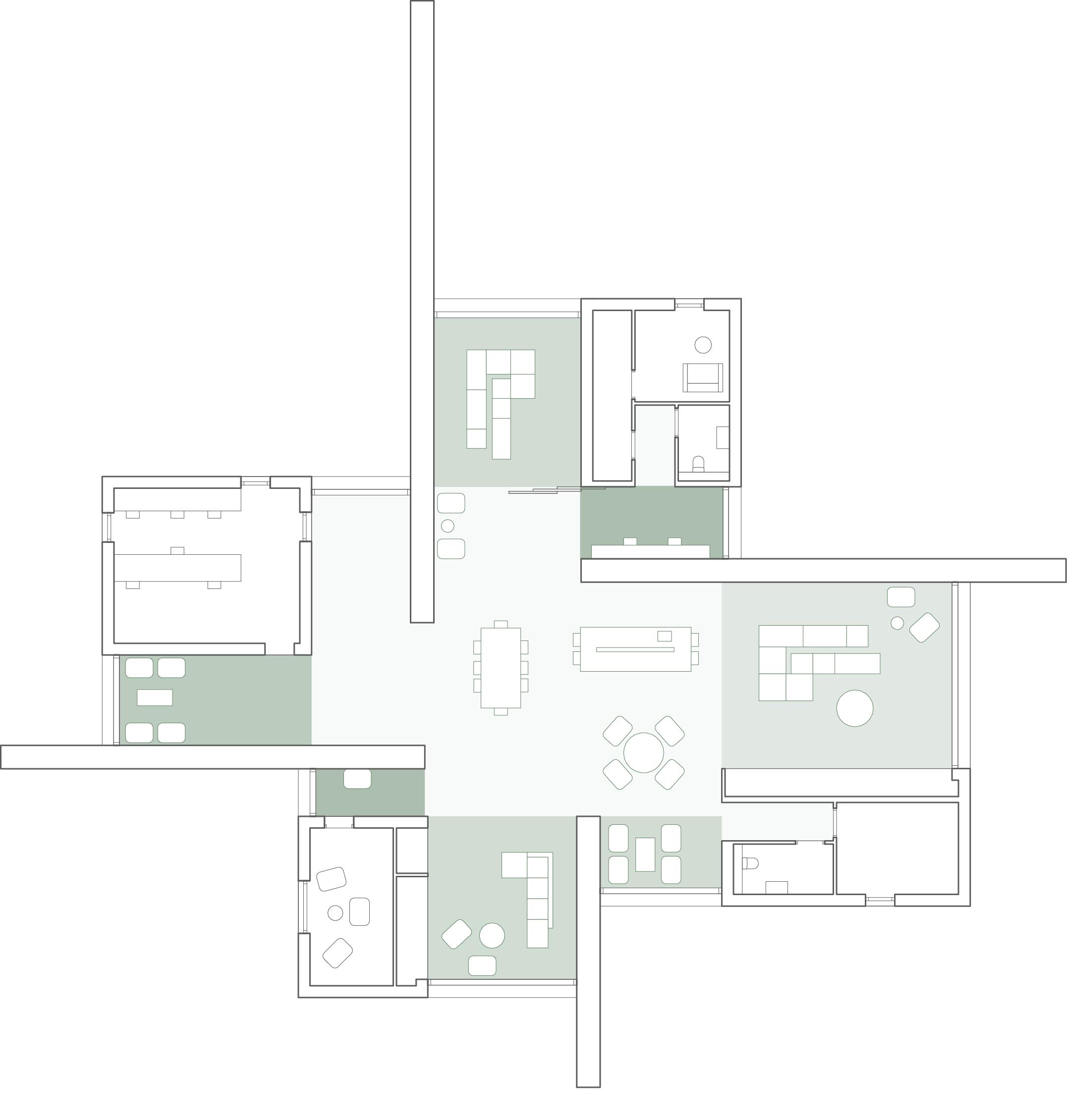

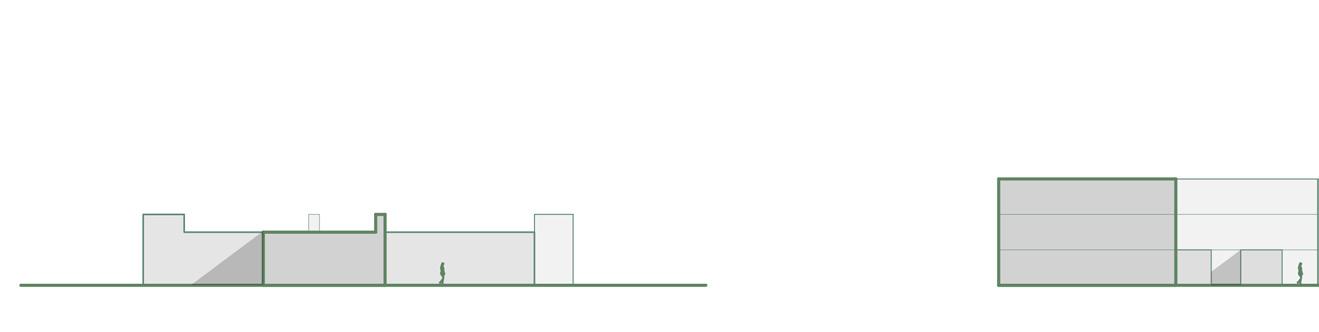

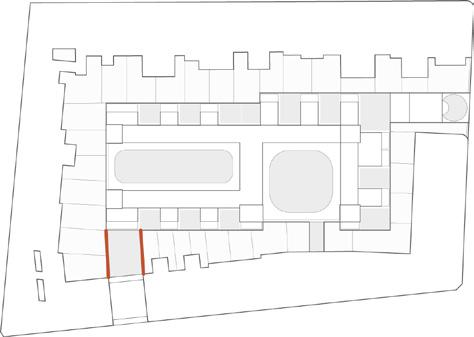

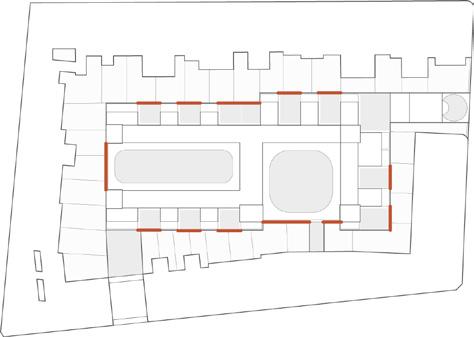

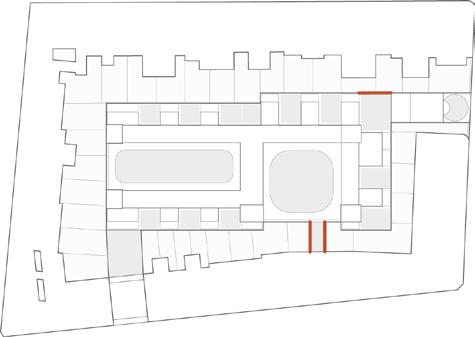

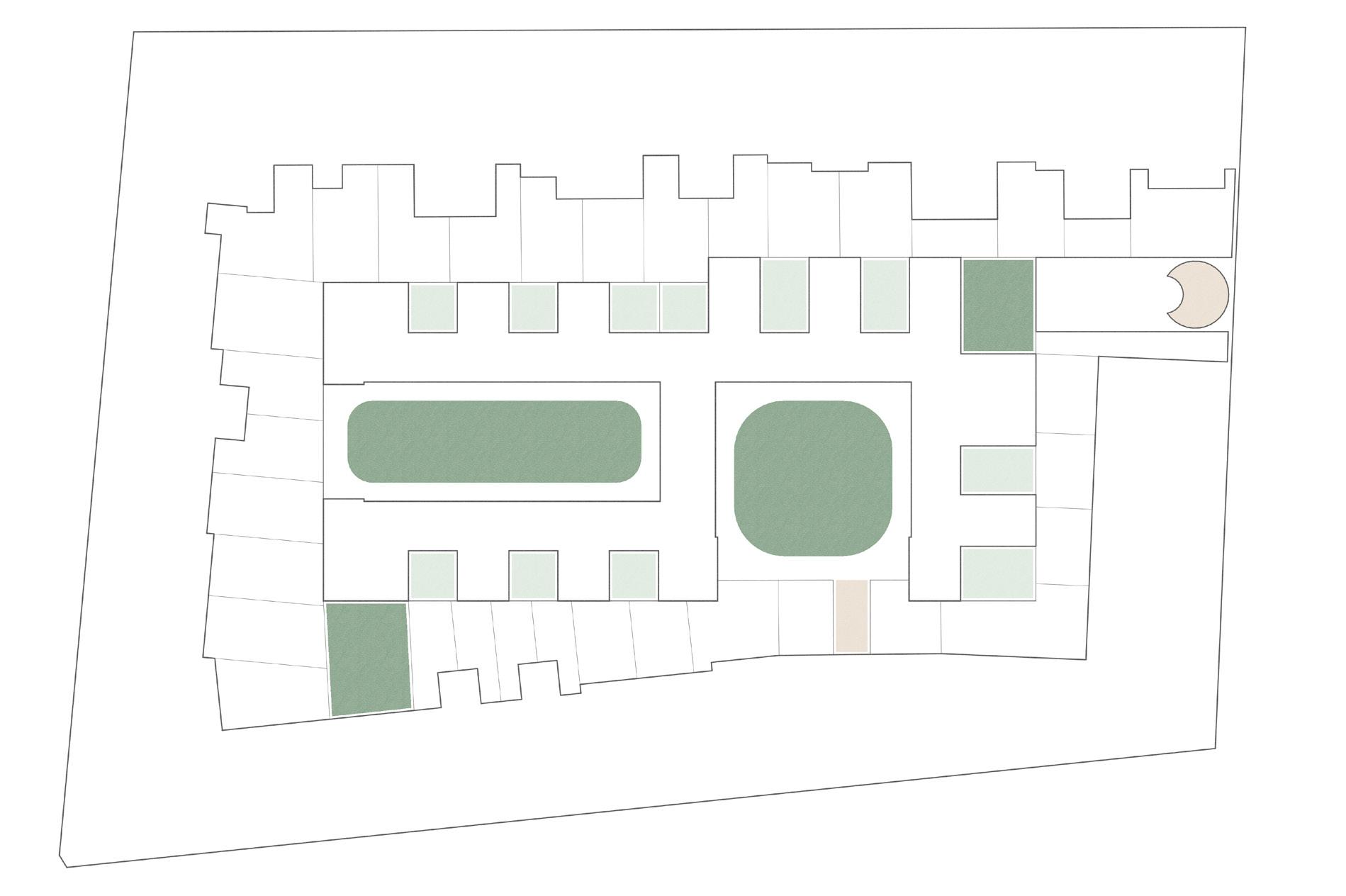

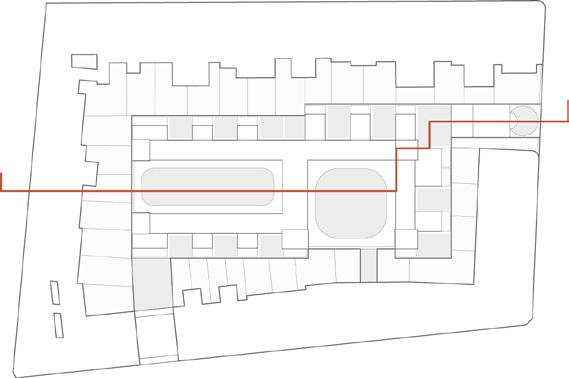

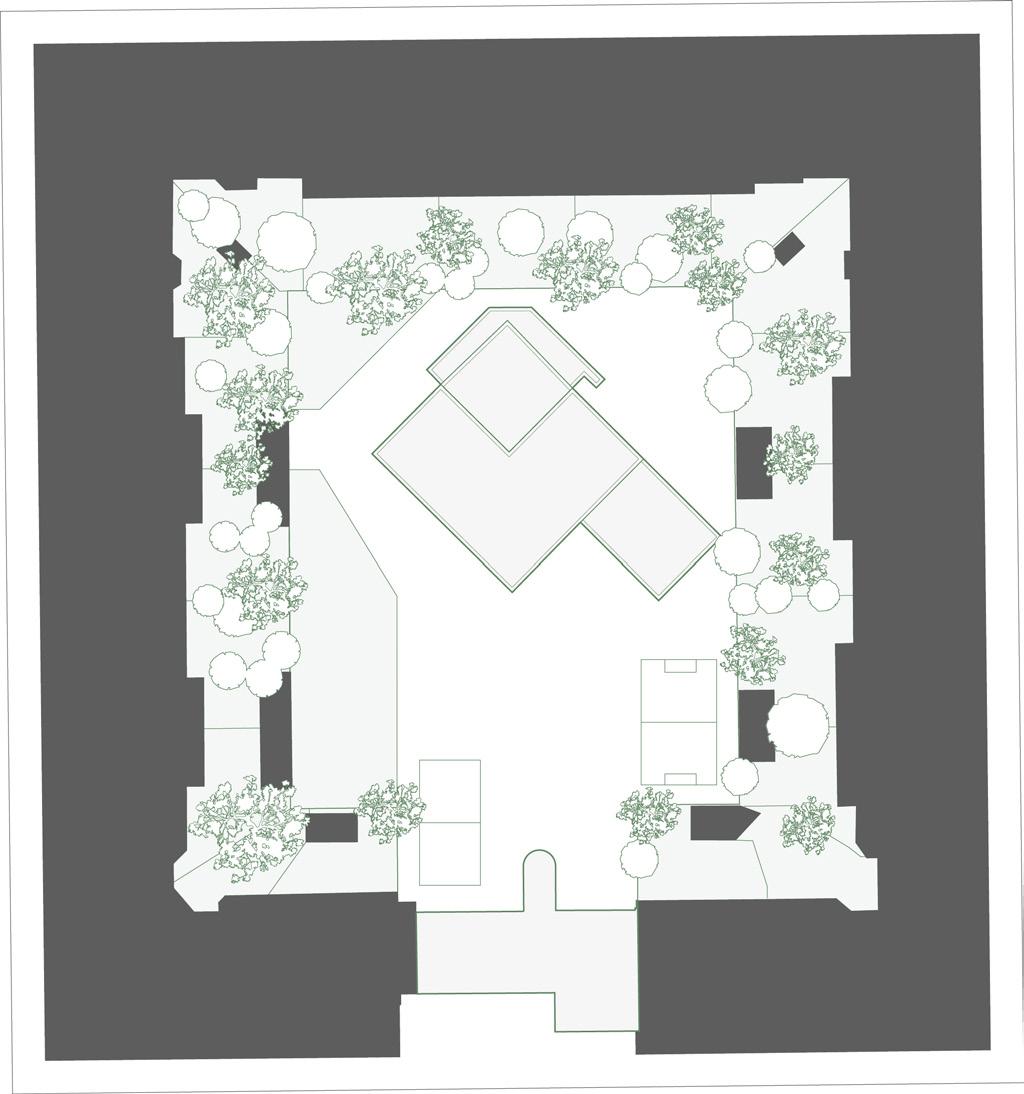

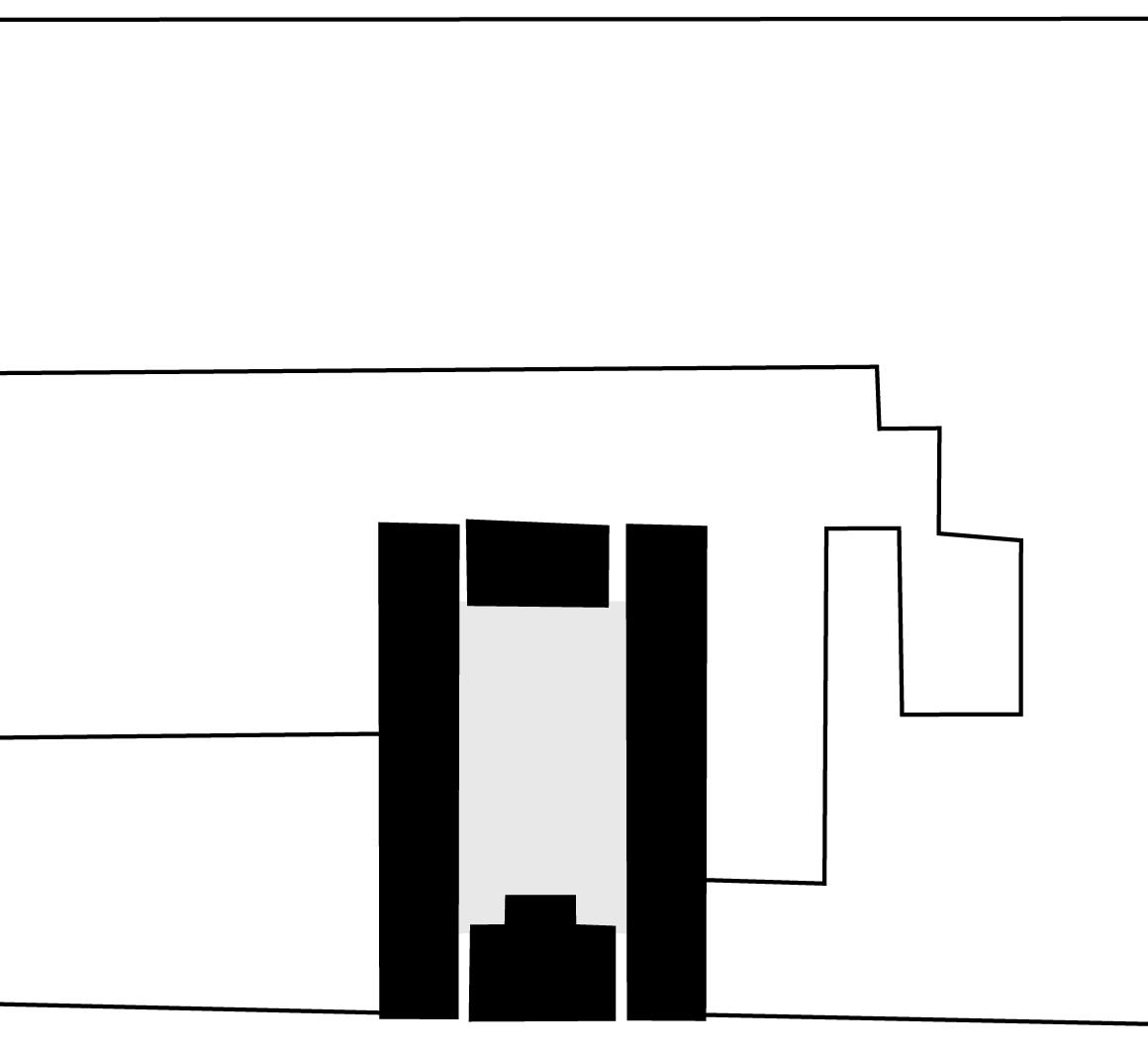

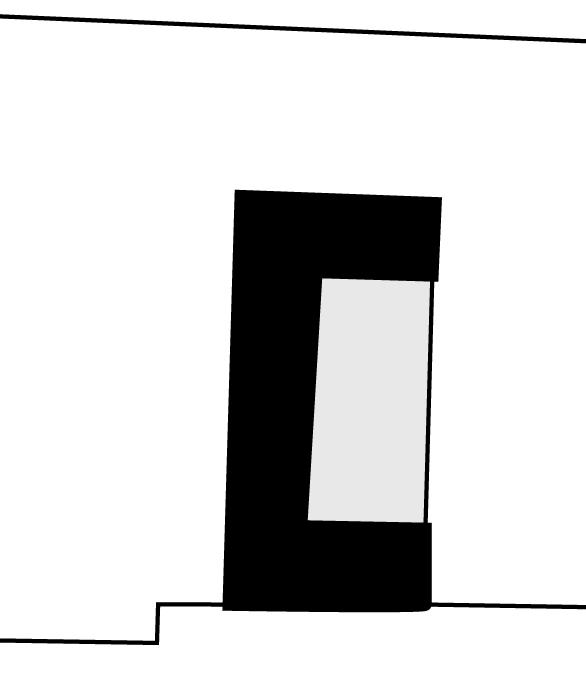

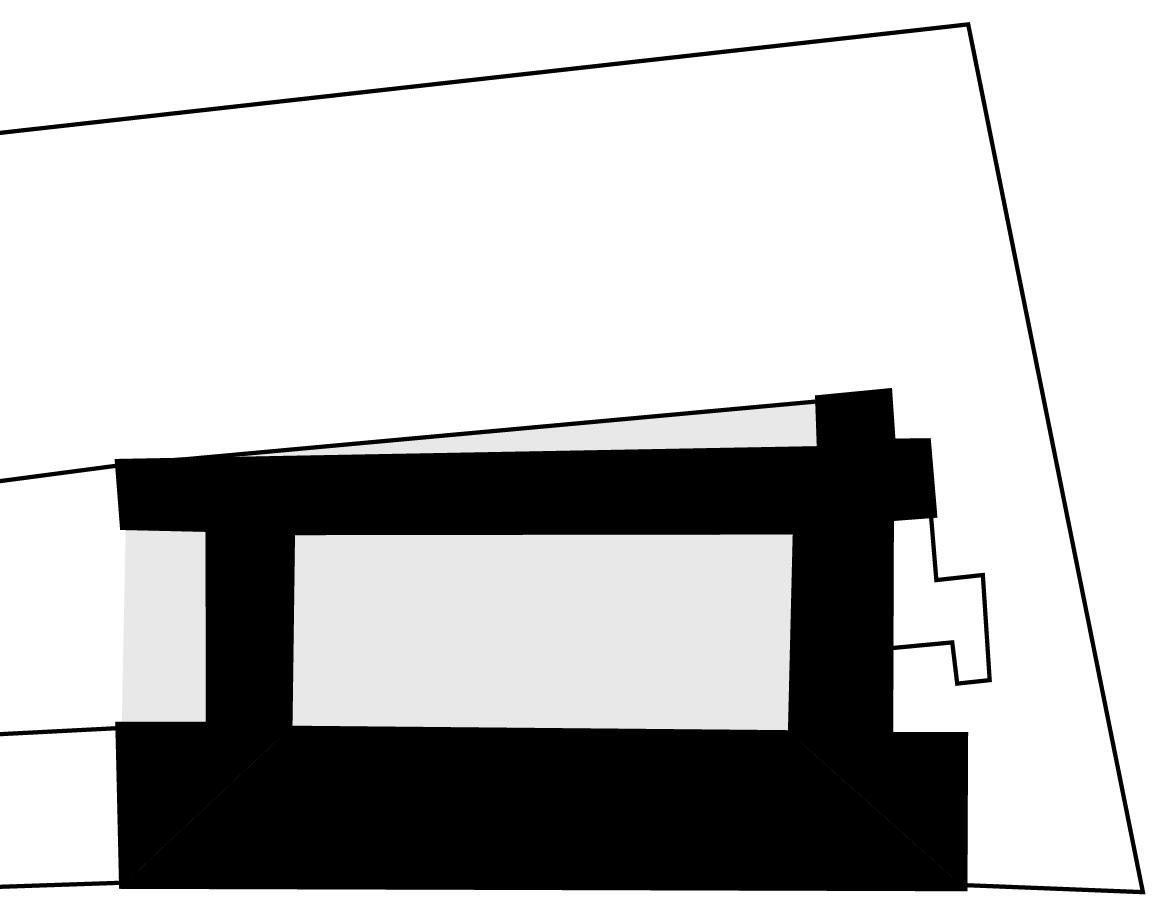

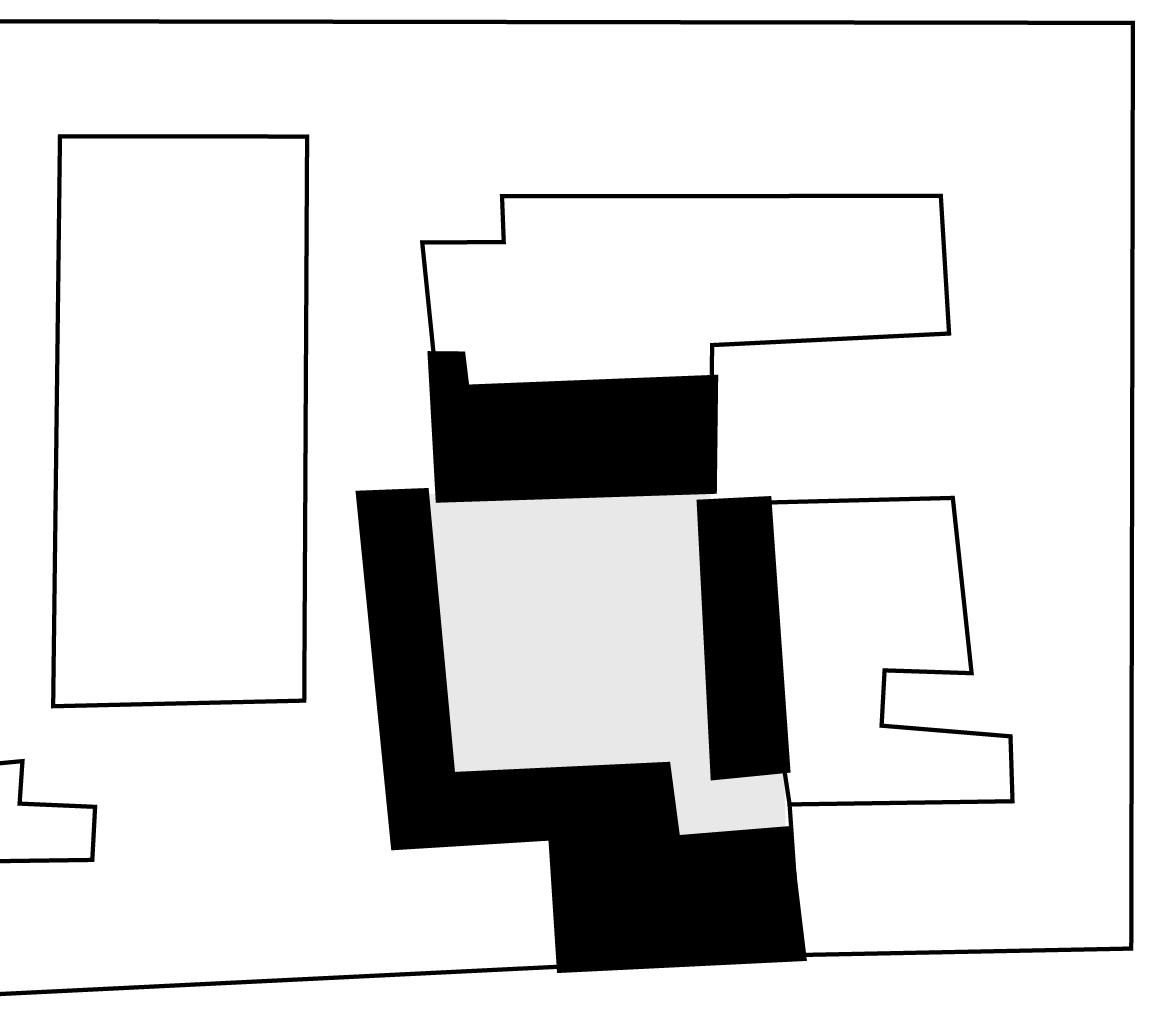

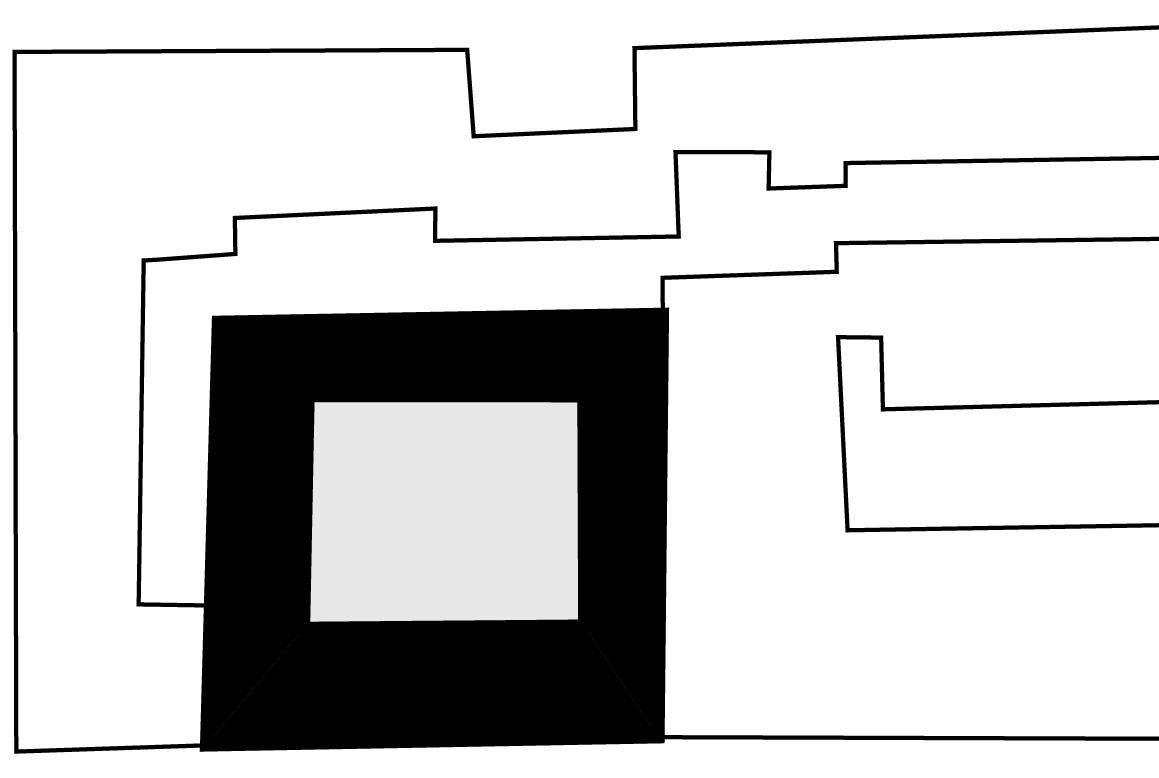

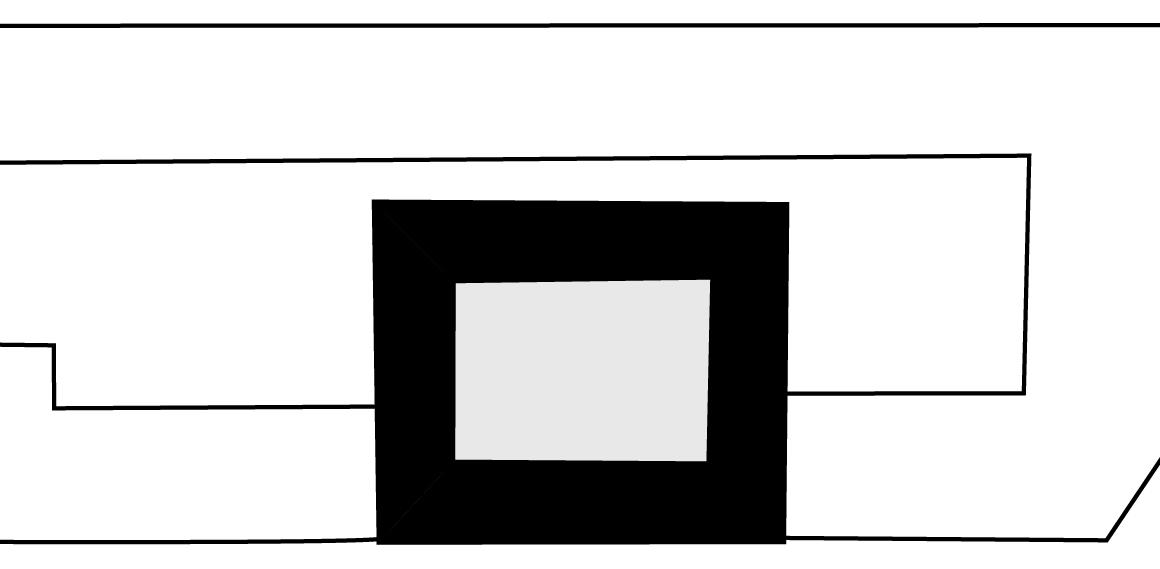

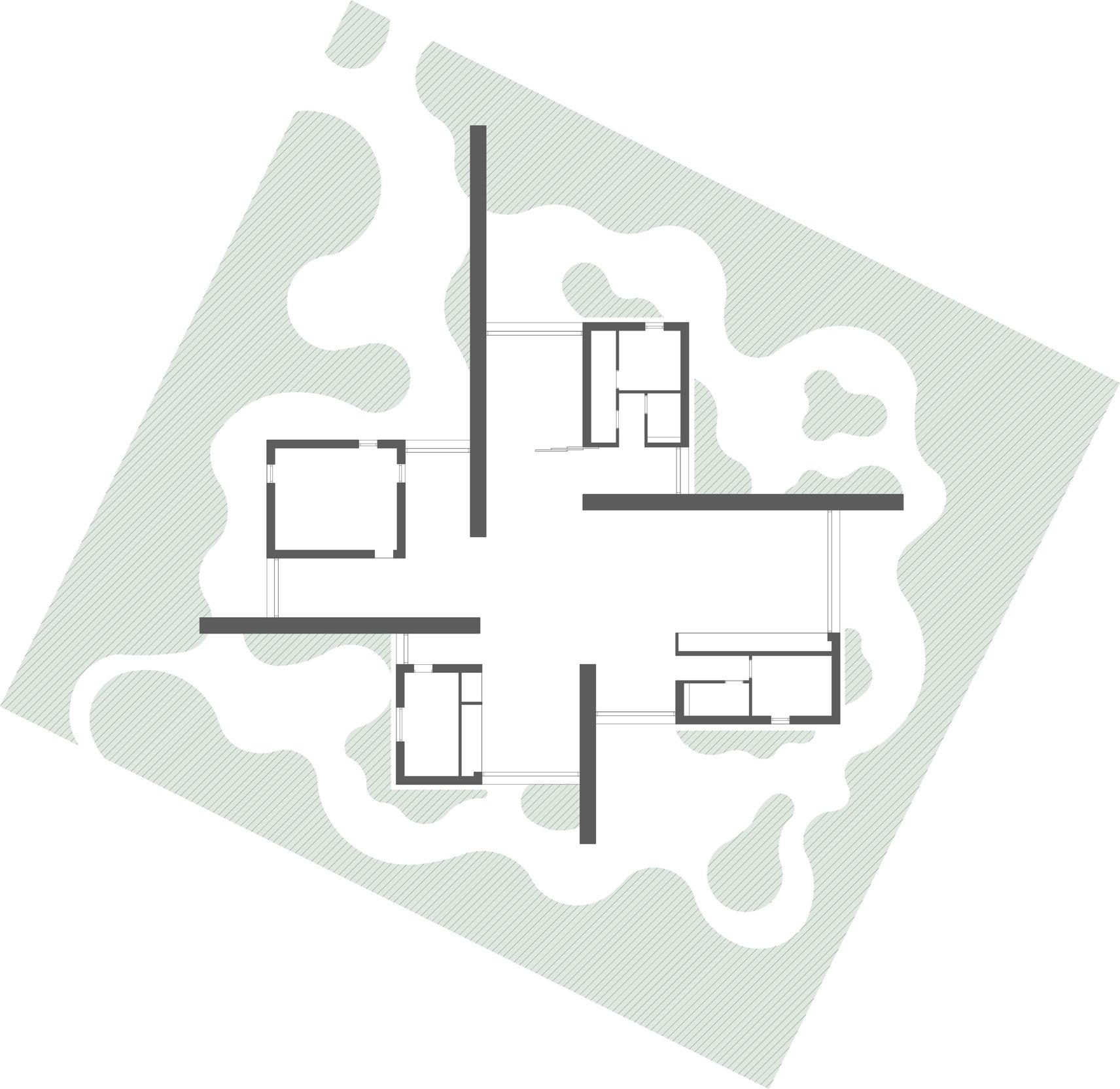

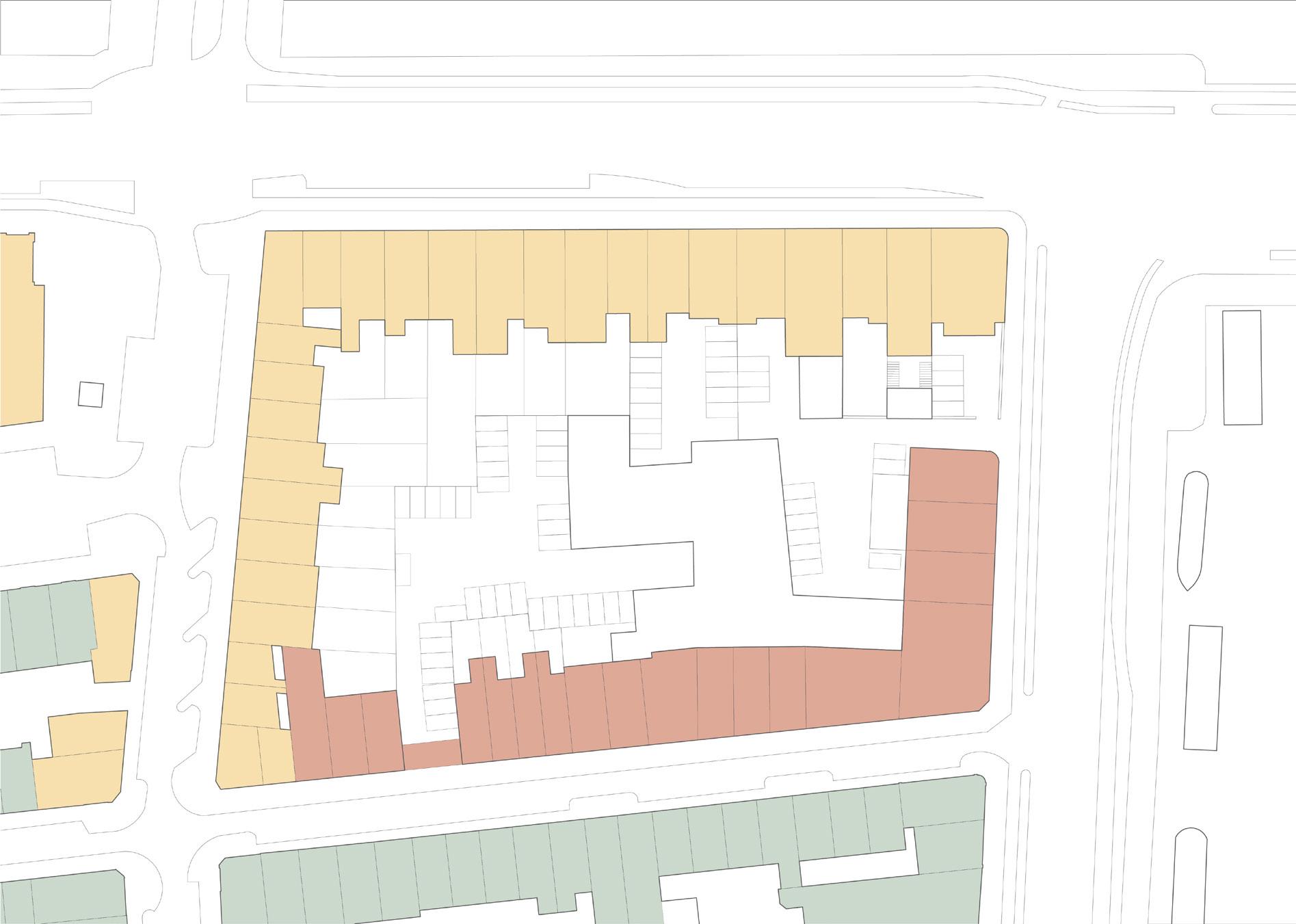

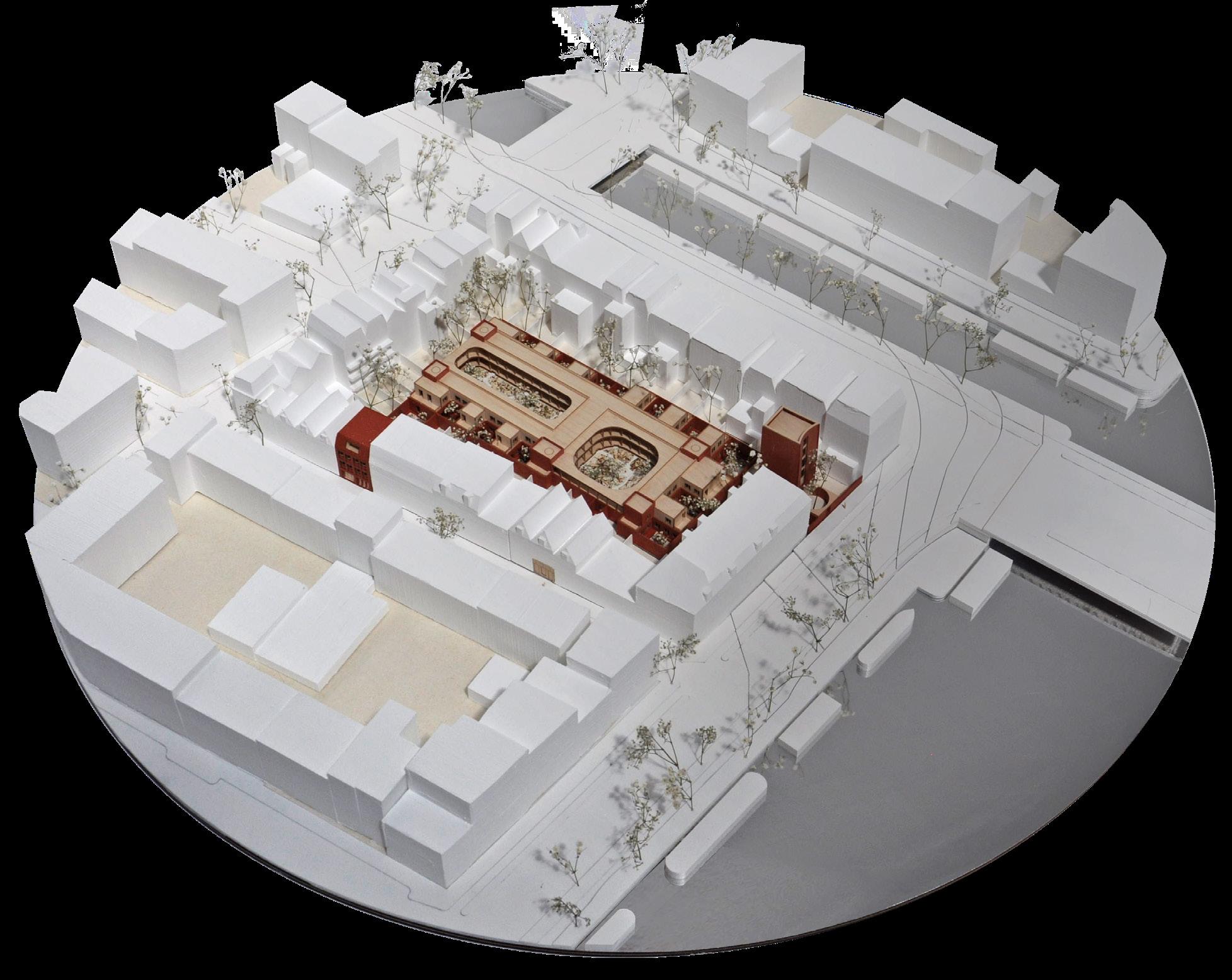

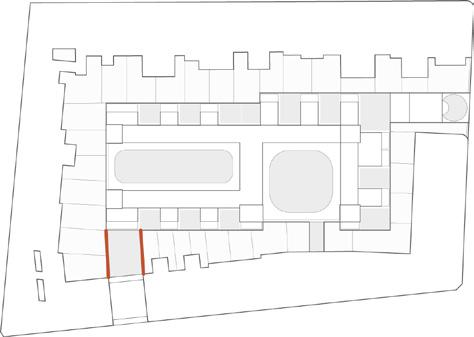

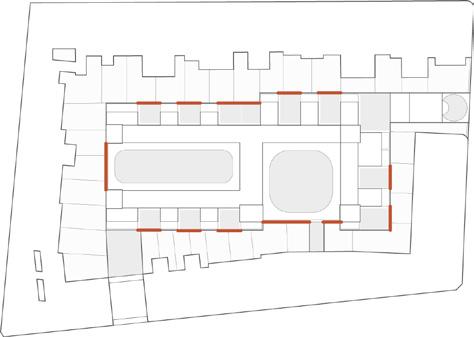

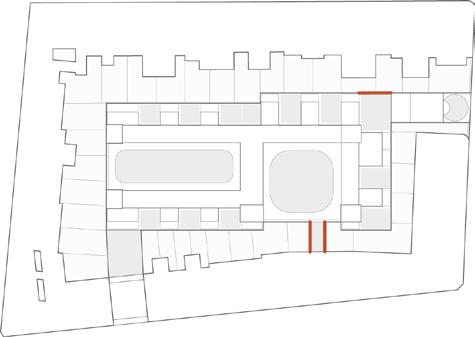

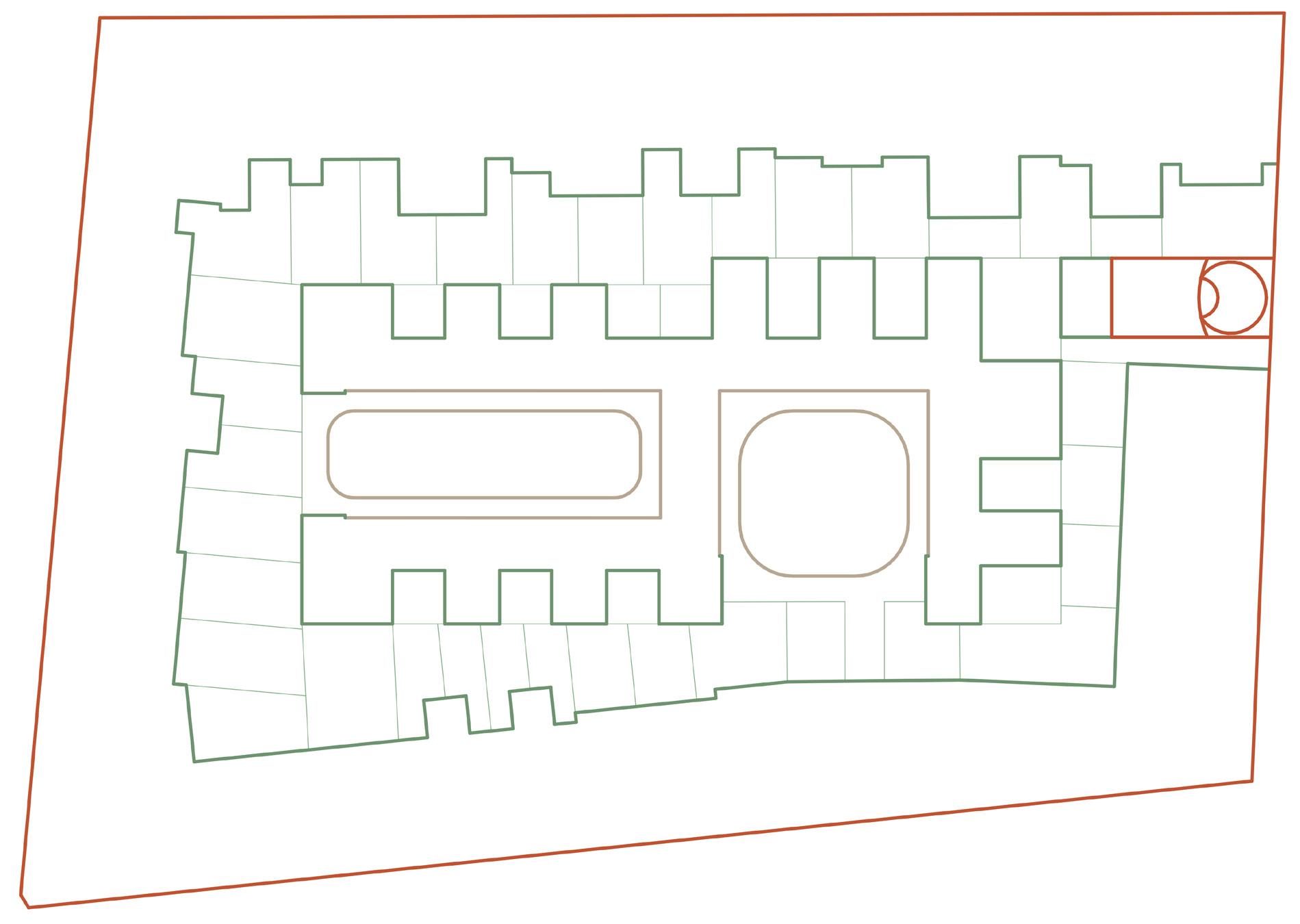

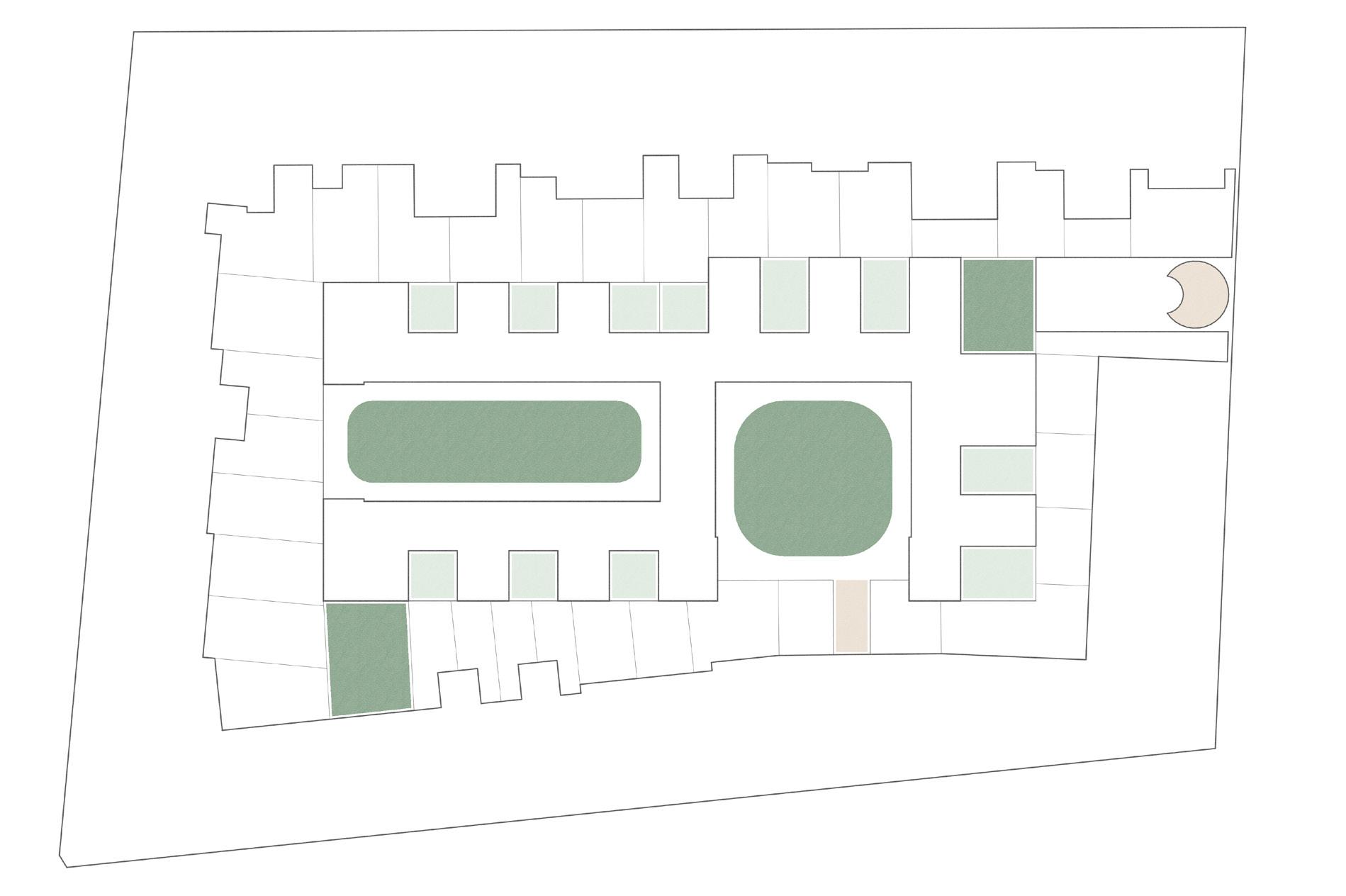

The project’s proposal is to complete the interrupted built structure of the block and occupy its interior following the inspiring tradition of the Dutch hofjes: to make use of the urban structure to host vulnerable groups around a communal garden. The block encloses the shelter offering a centrally located, but highly protective living environment where women and their children can find space to feel safe and recover.

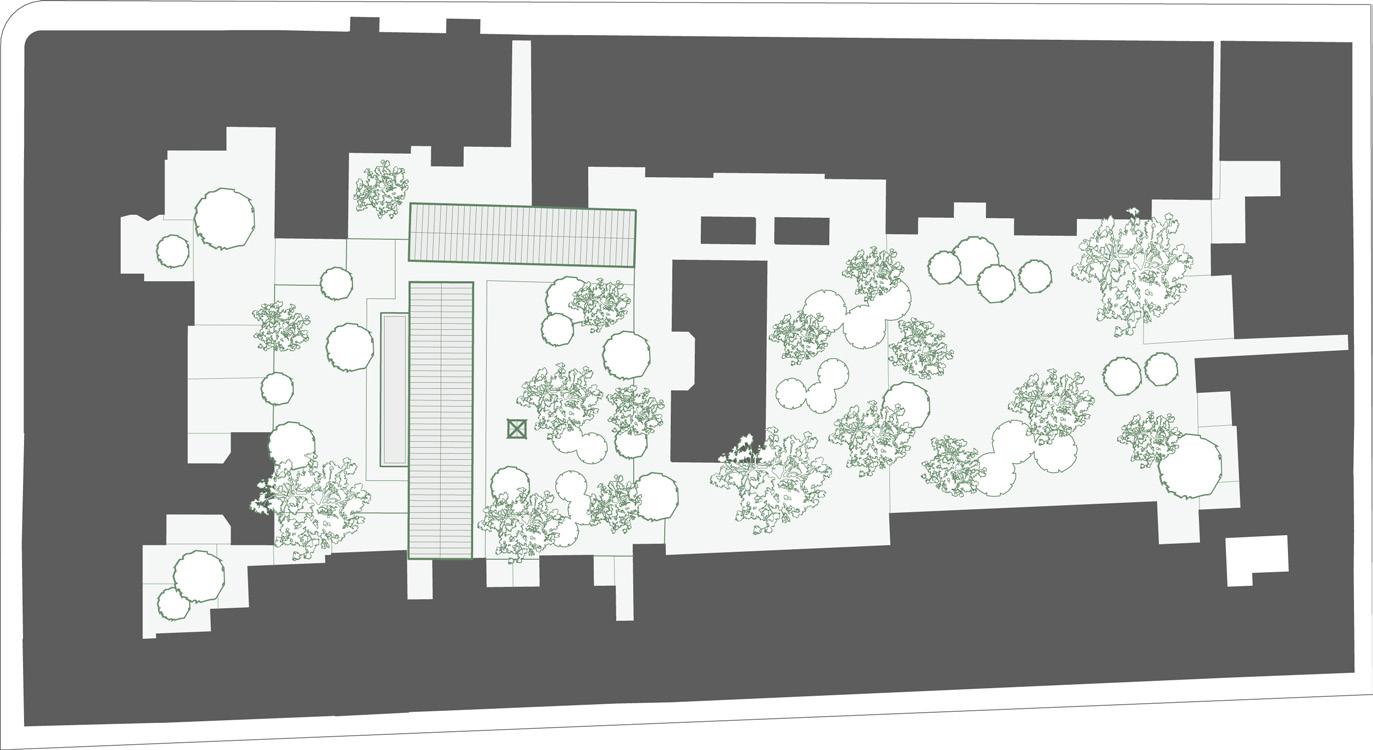

Along the Amsteldijk the block is completed by the institutional building, while the existing entrance to the parking at the Govert Flinckstraat gives places to the healthcare facilities. The parking spaces are removed from the inner block’s ground, being placed in a new underground parking garage. The existing edge formed by the private gardens is extended, completing the beautiful green privacy buffer between the shelter housing units and building block.

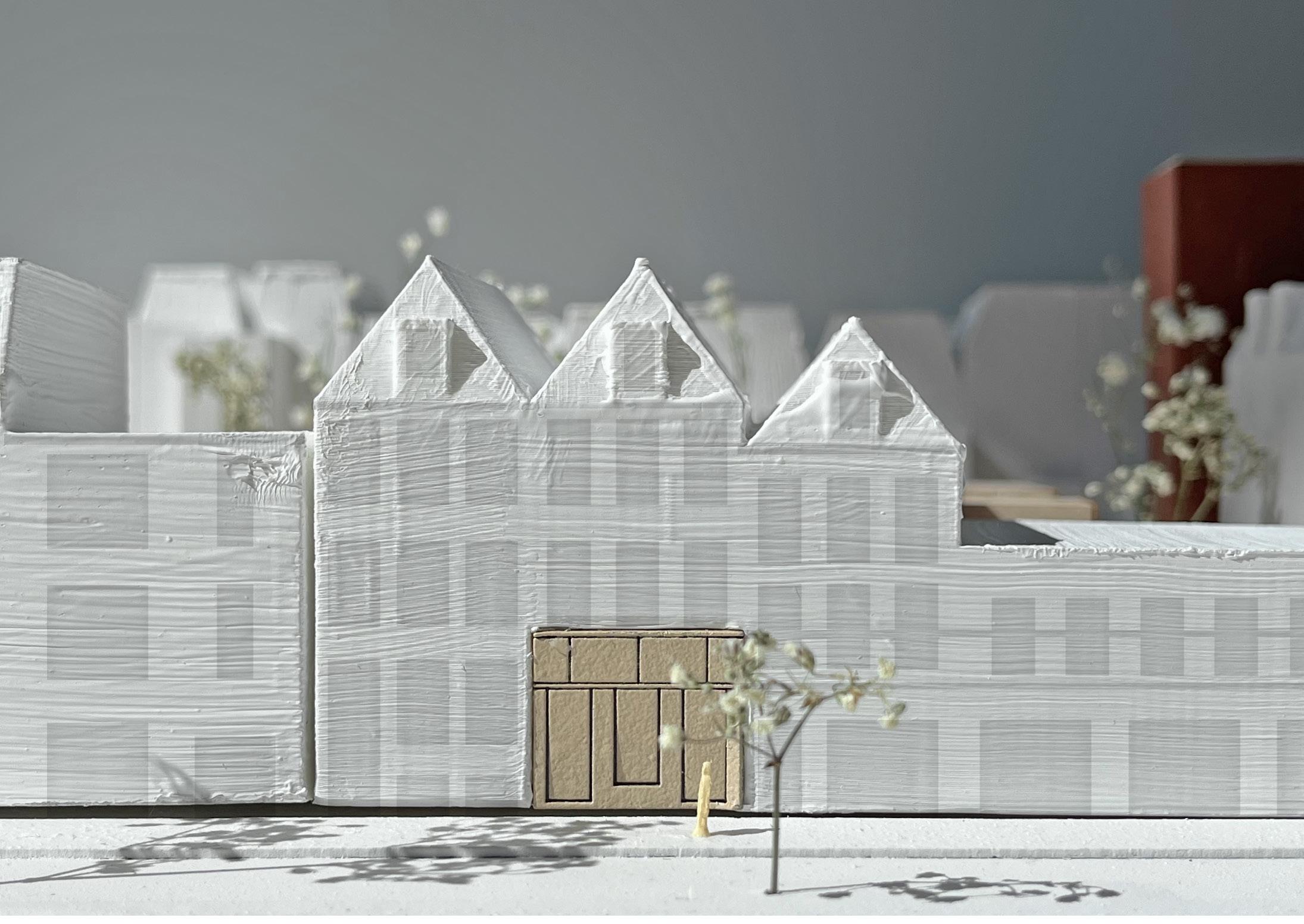

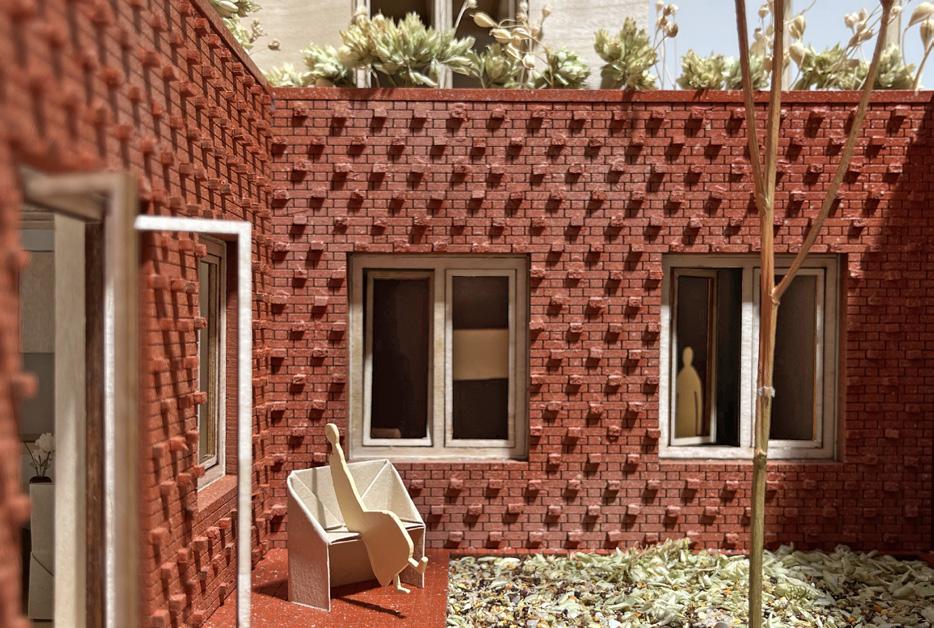

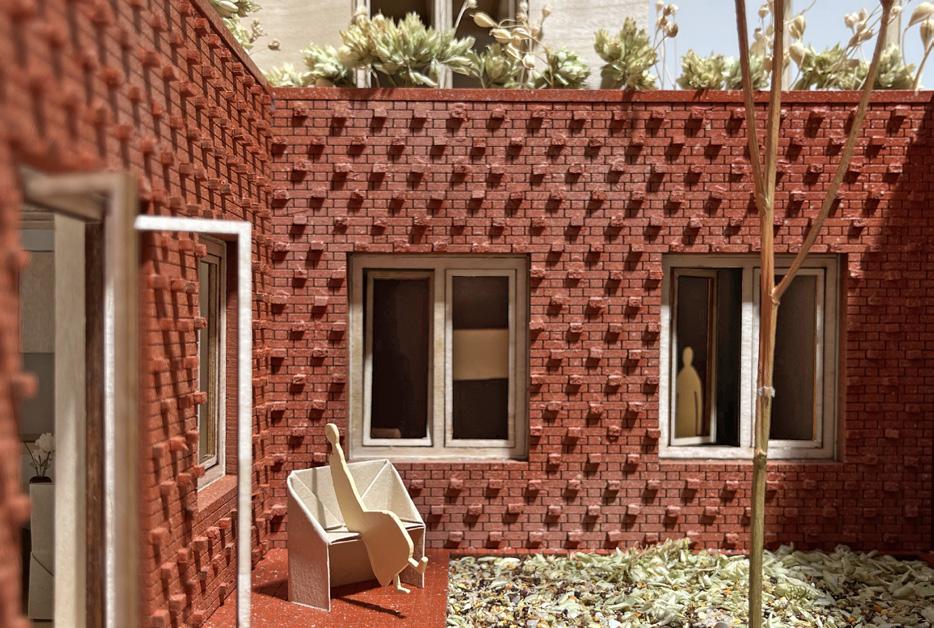

Conceptually approached as a fortress within the city, the volumetric expression and materiality of the design relate strongly to the logic already present in block. The building is designed around a sequence of enclosed gardens that create the scenery for the daily life of the shelter, offering connection with time and place in this protective living environment.

79

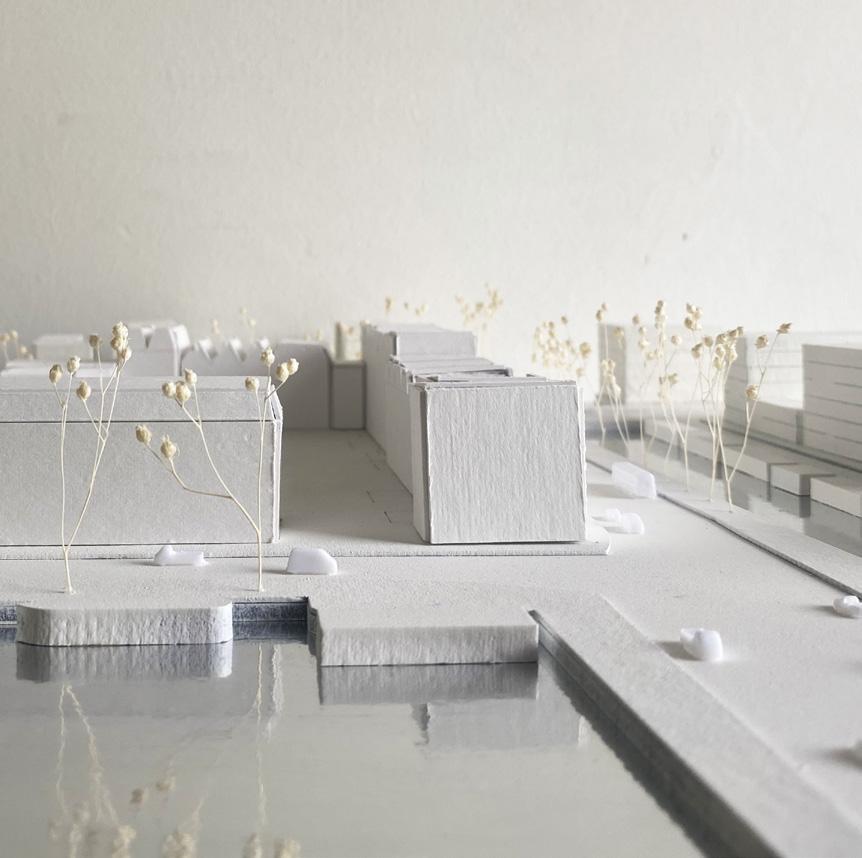

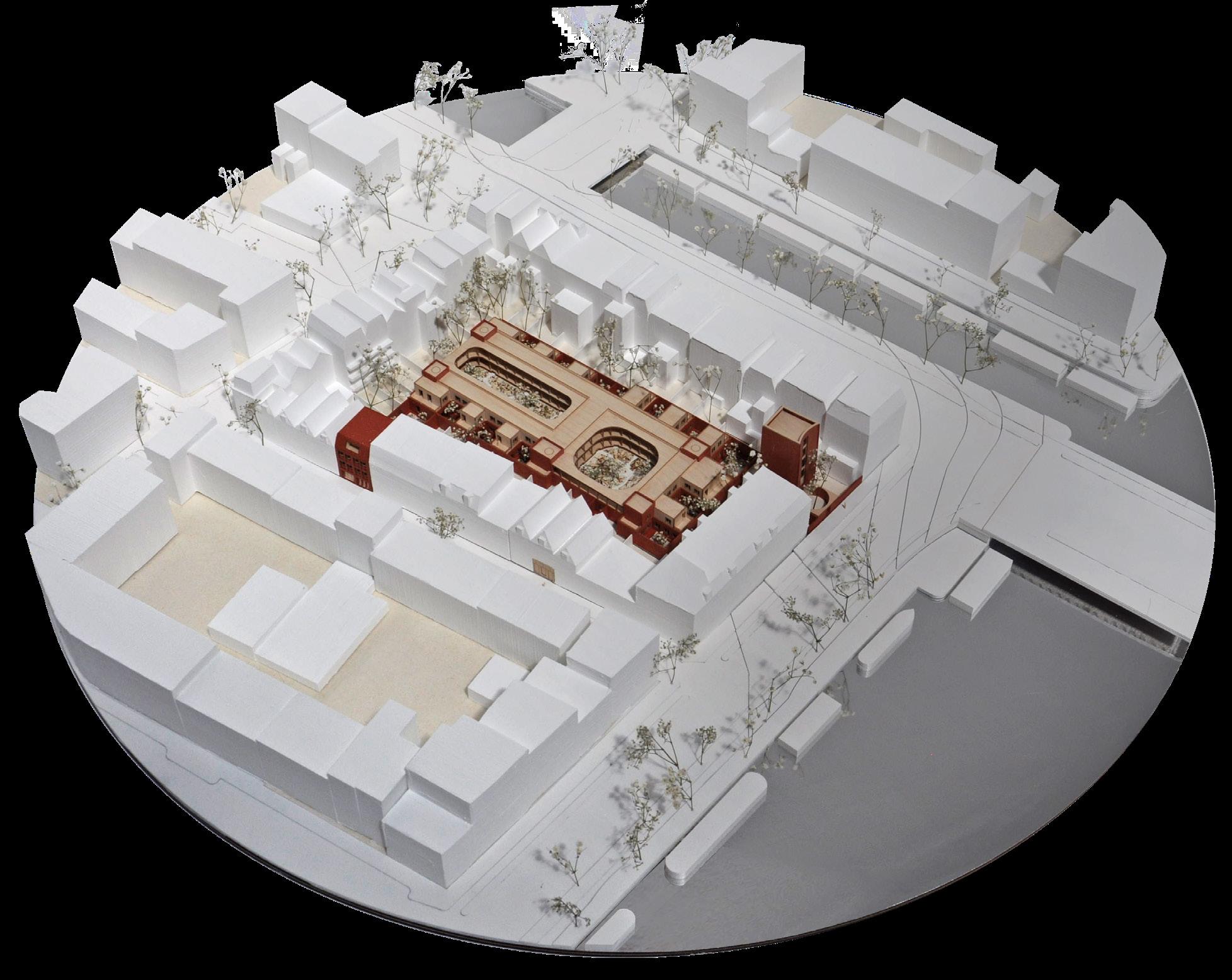

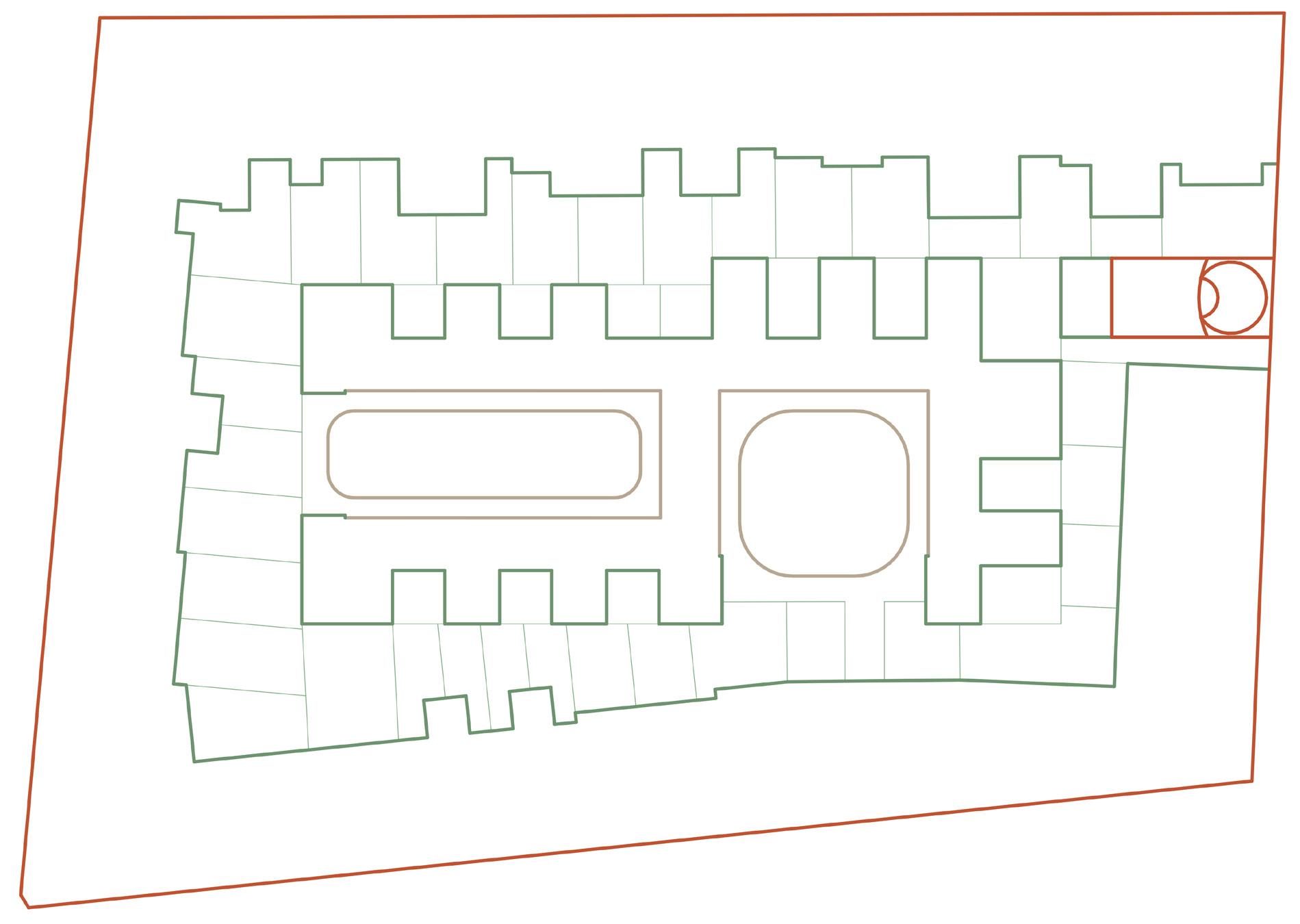

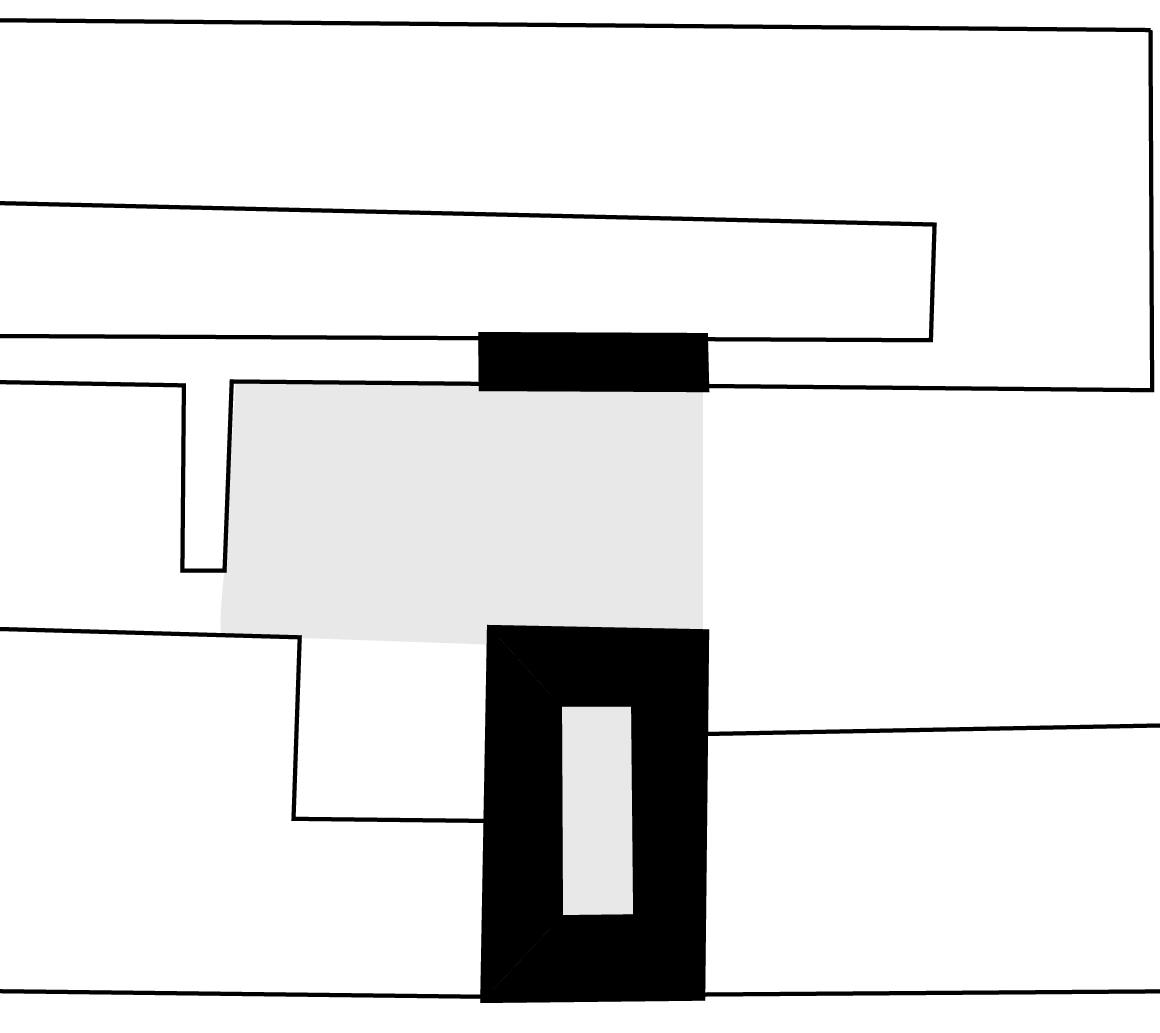

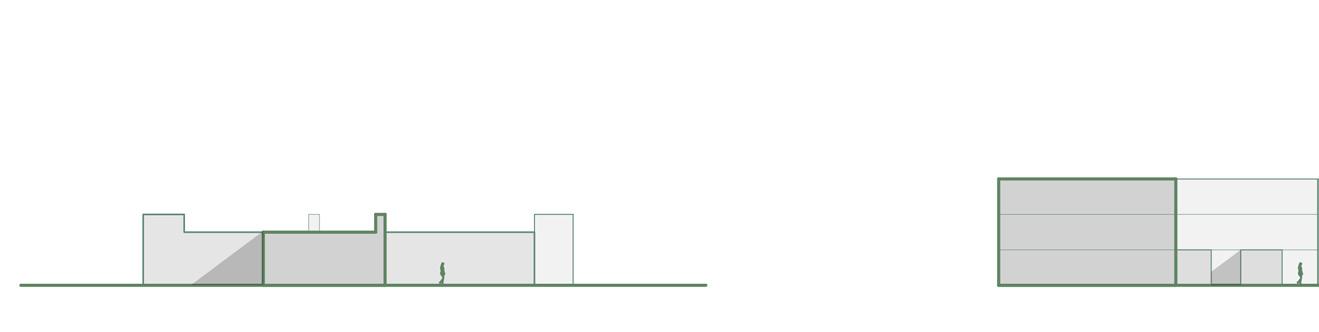

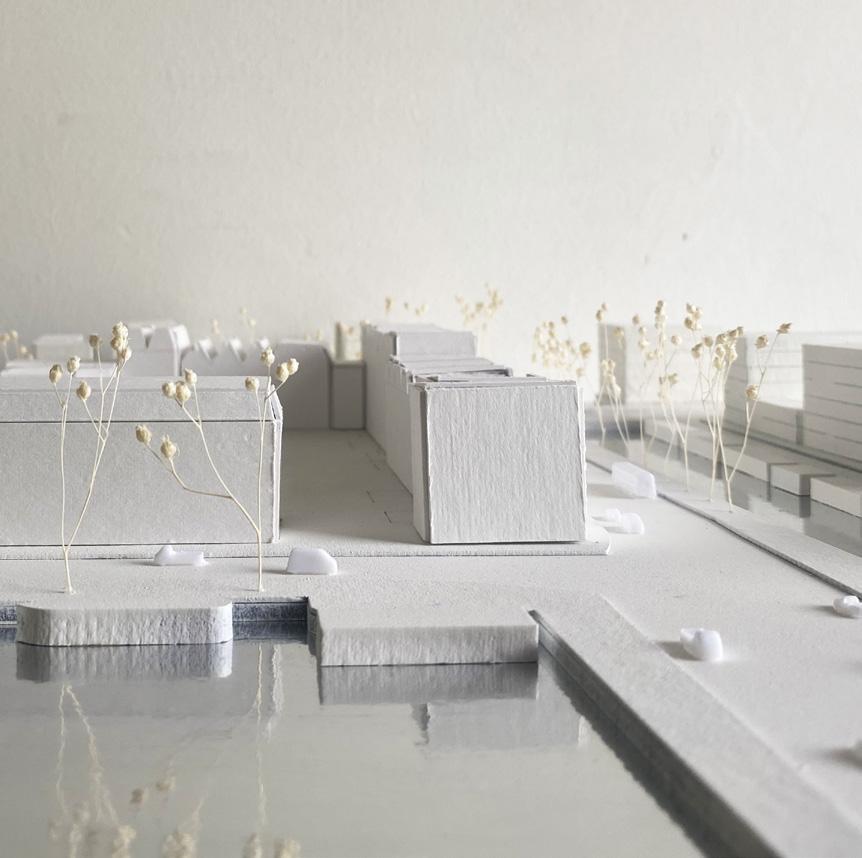

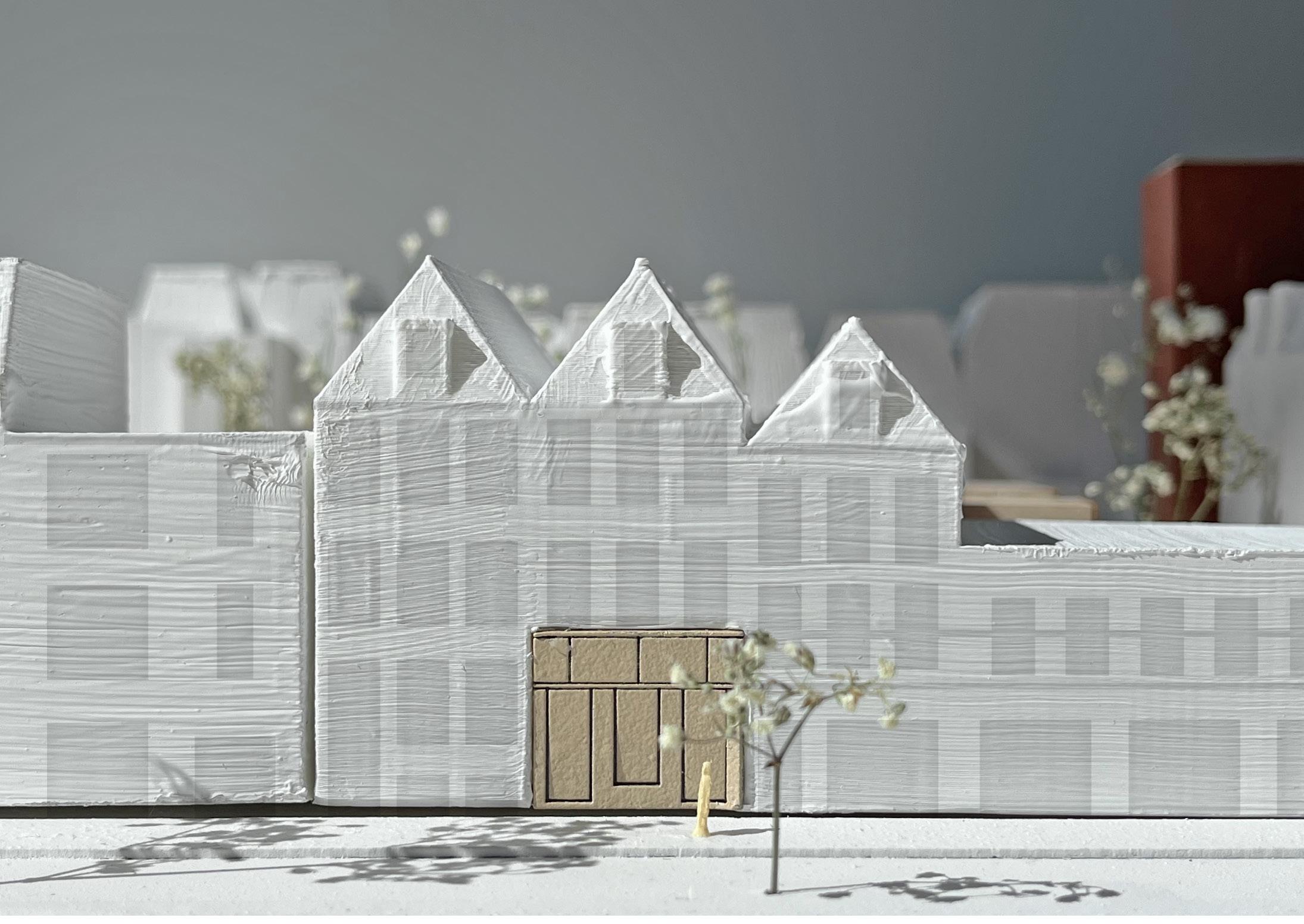

Overview proposed interventions | model scale 1:250

80

81

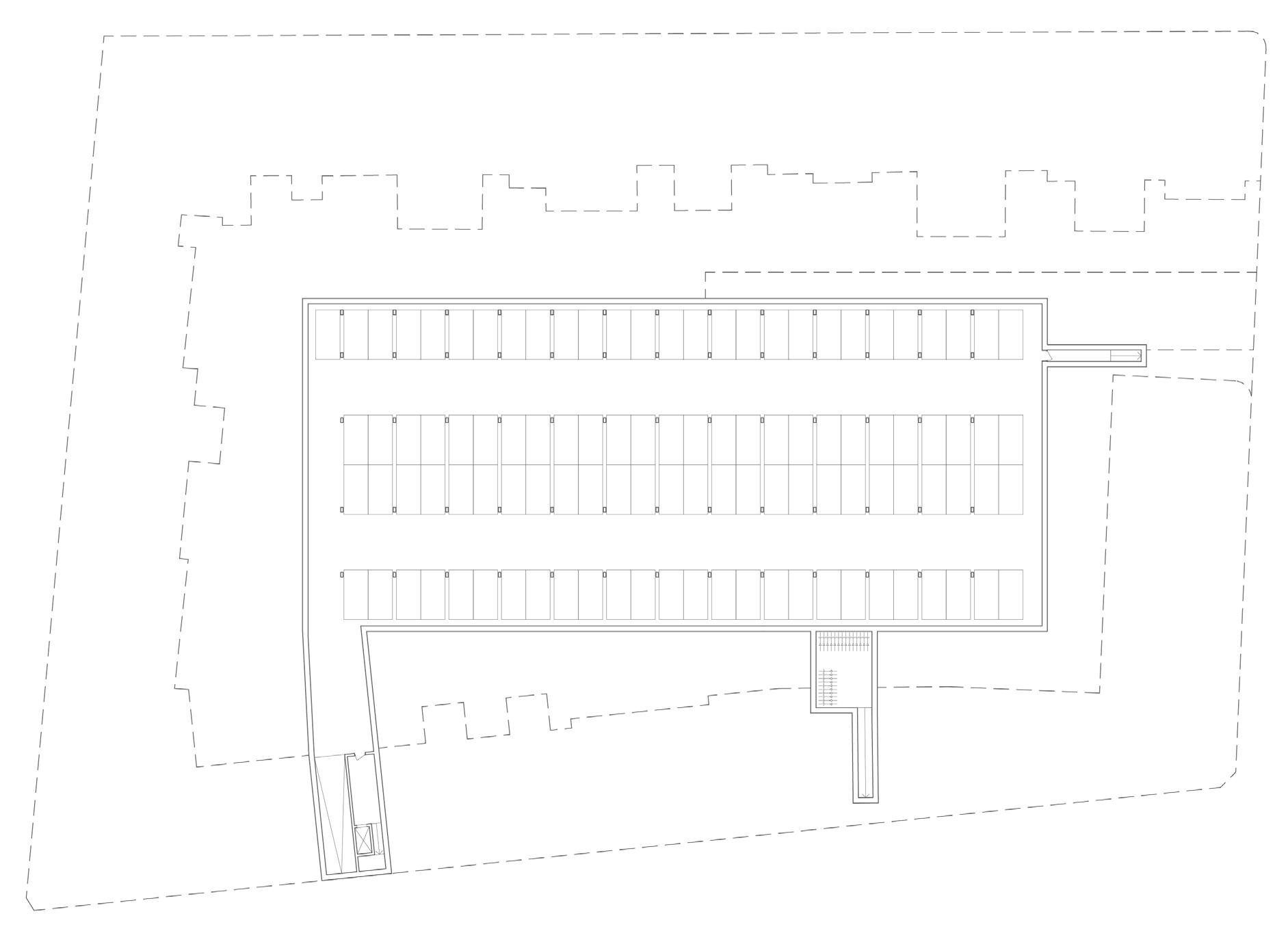

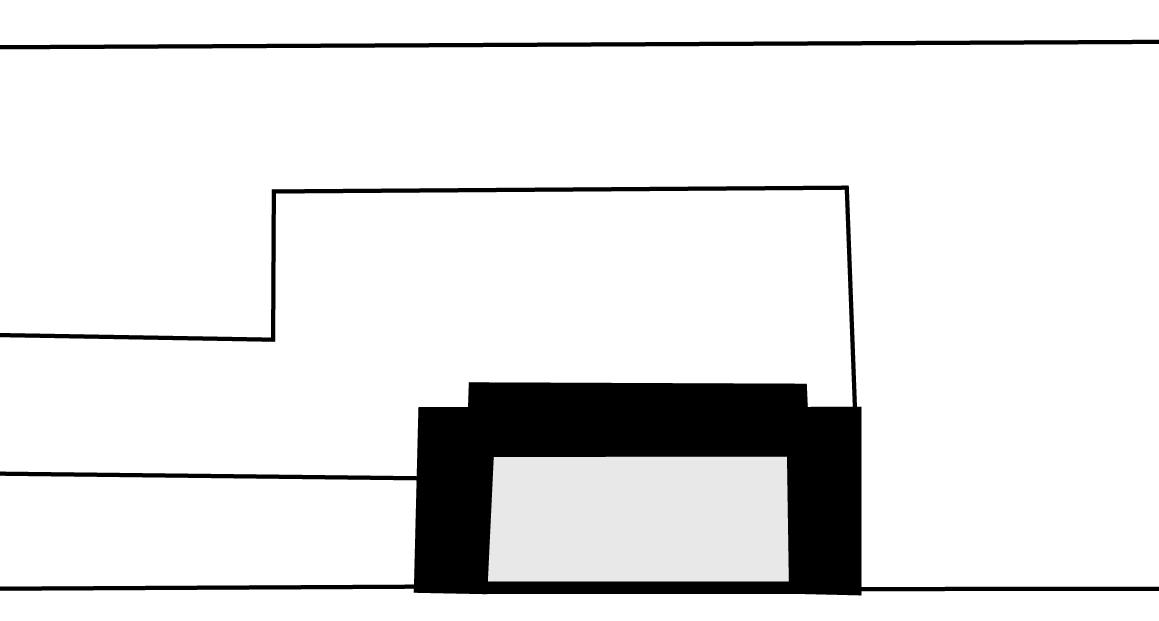

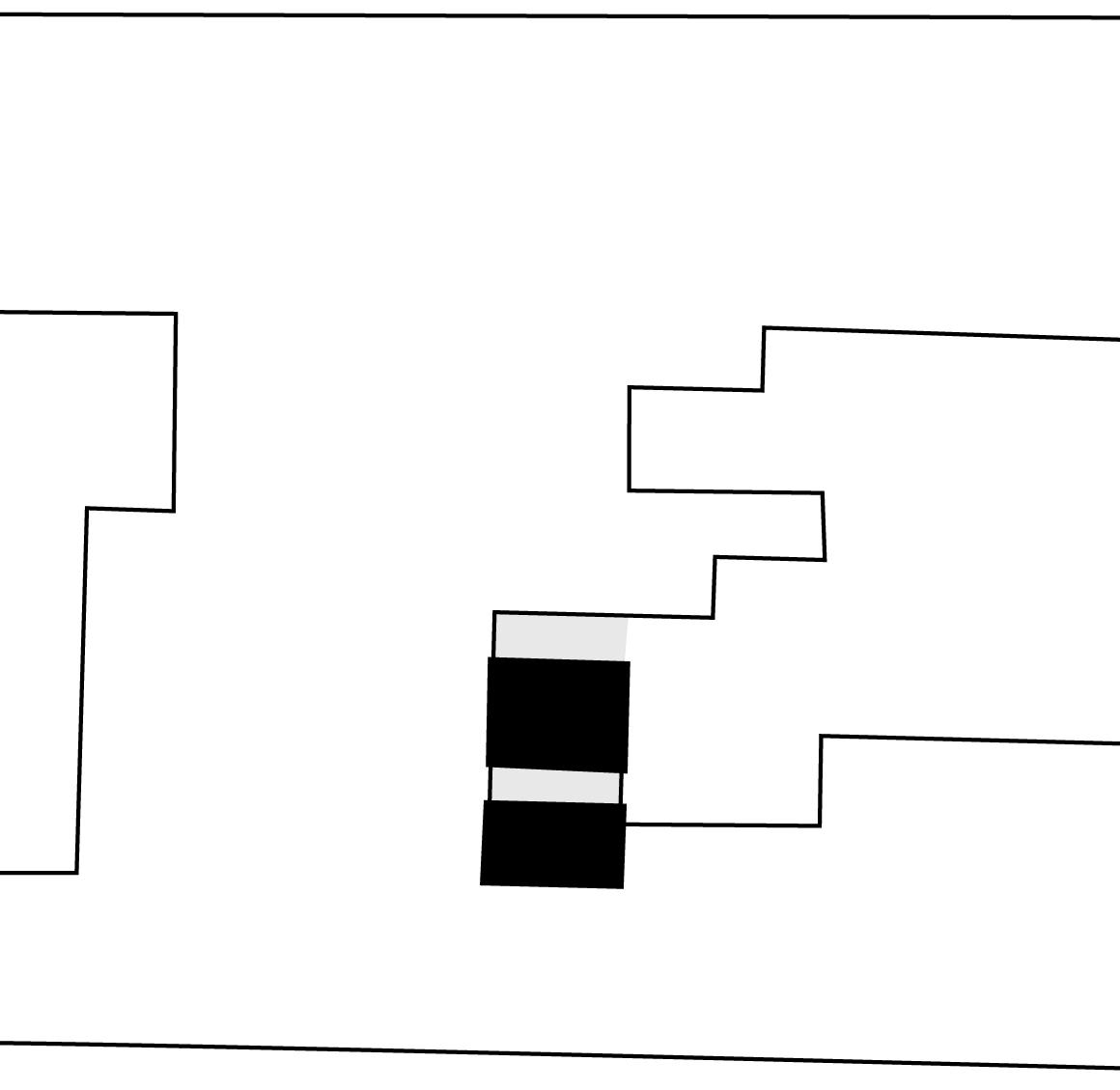

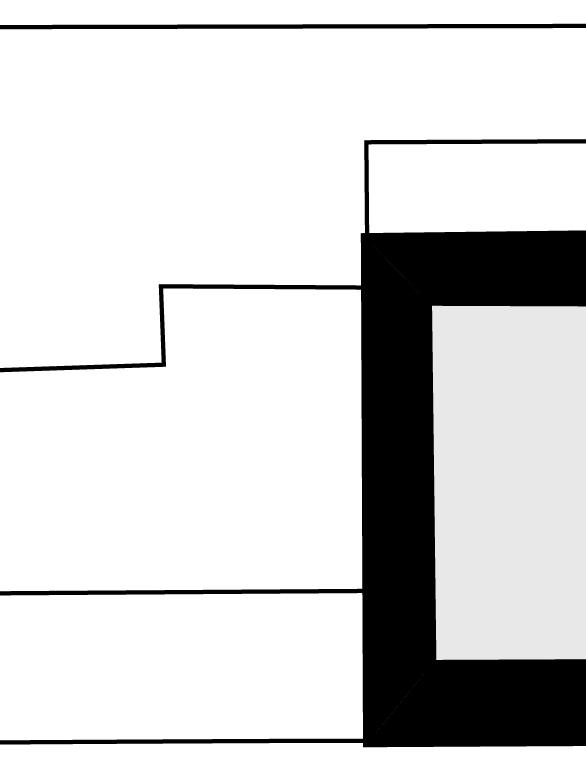

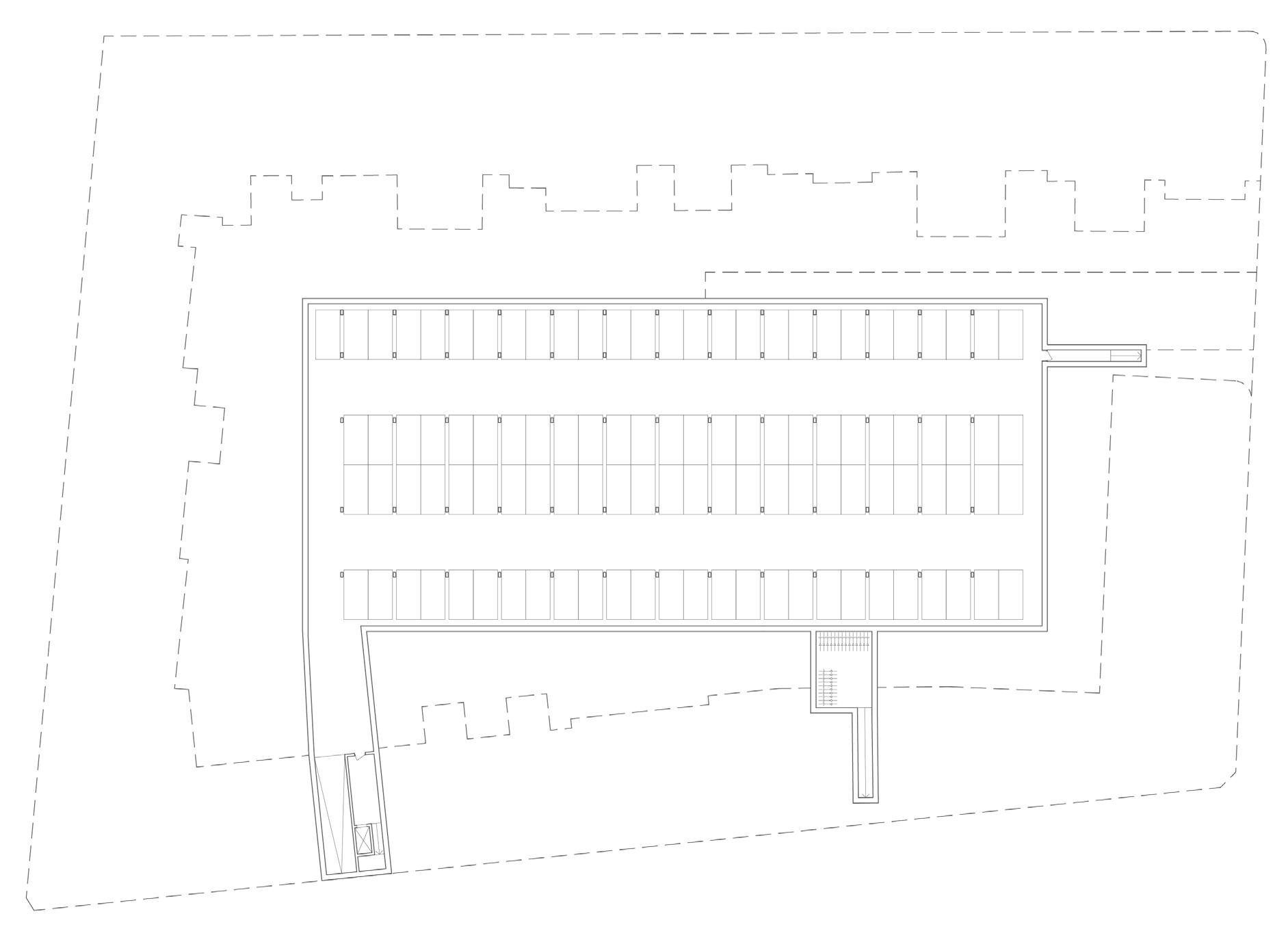

Floorplan souterrain | underground parking garage hosts the cars currently parked on the inner block, creating space for the project's intervention.

Top view of proposed interventions | block's new situation | model 1:250

82

83

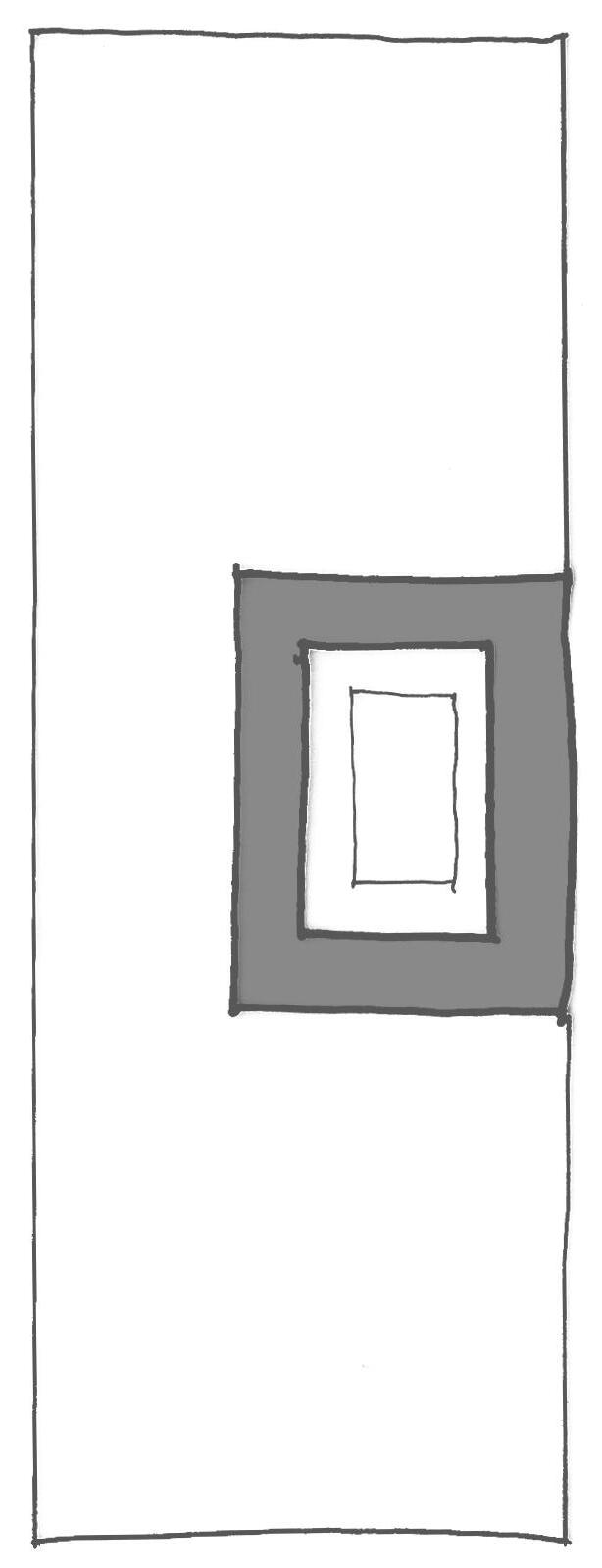

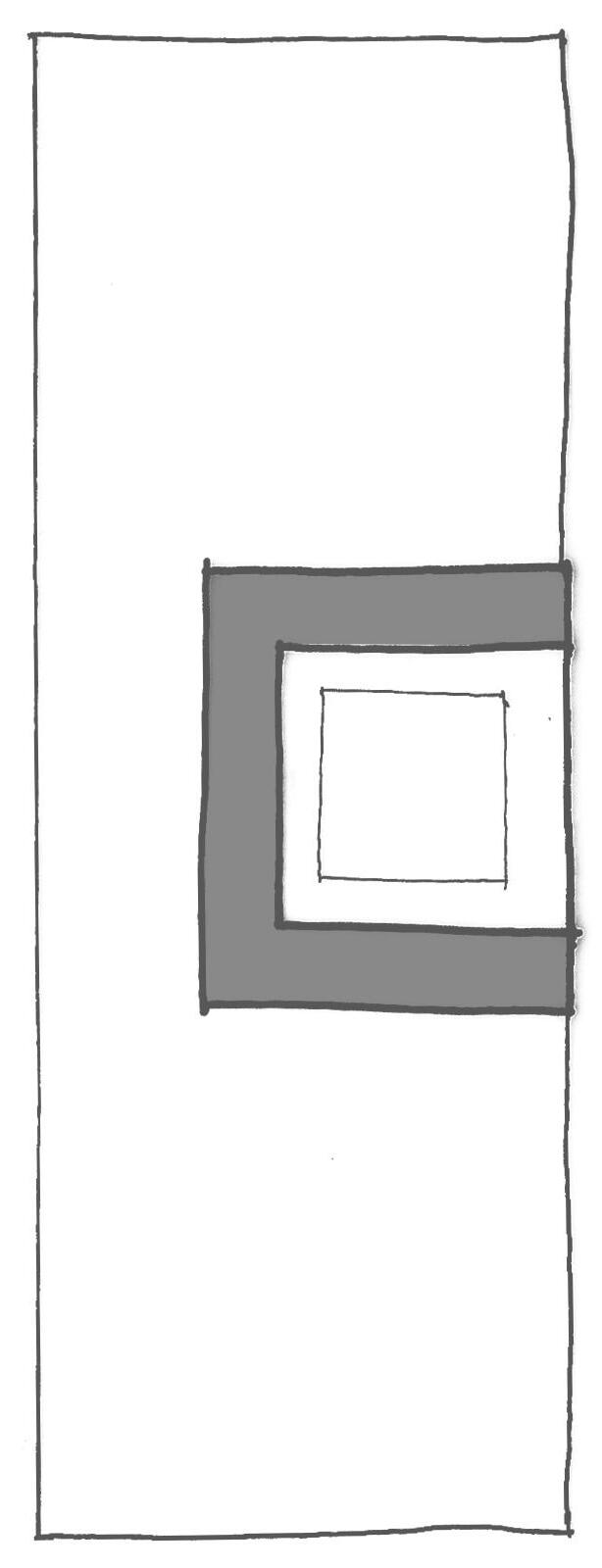

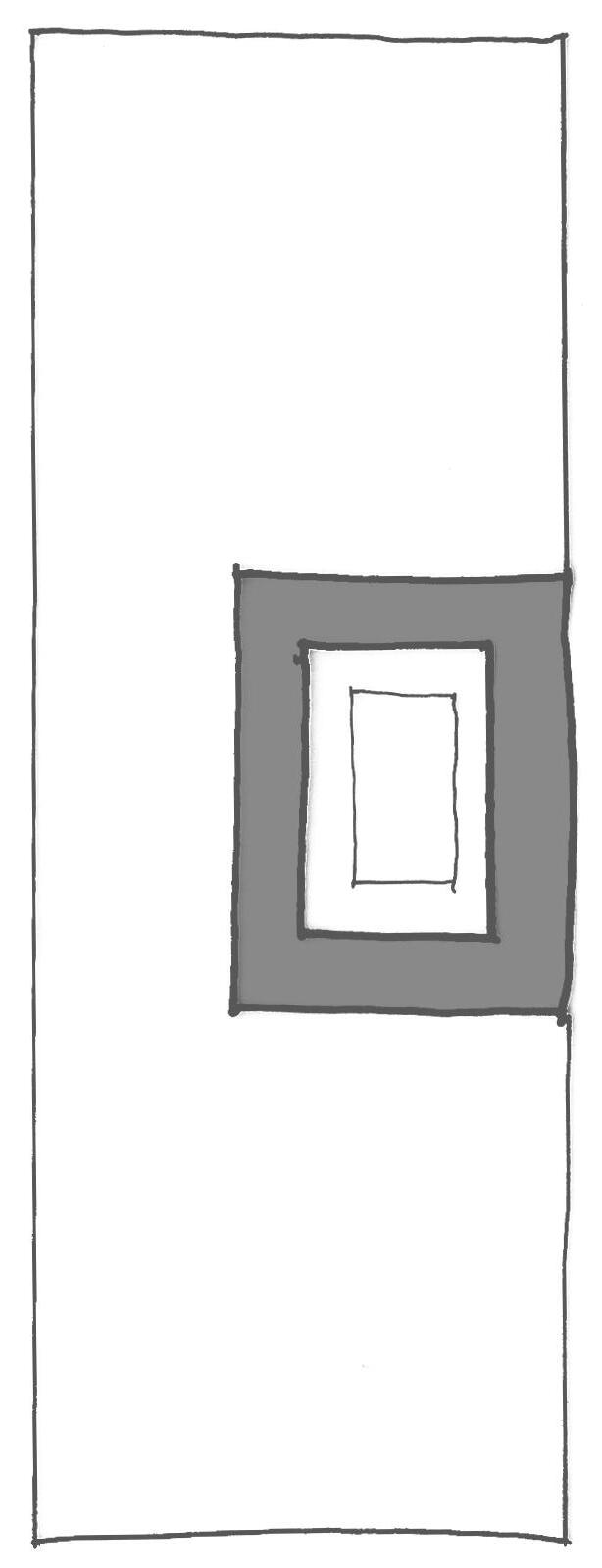

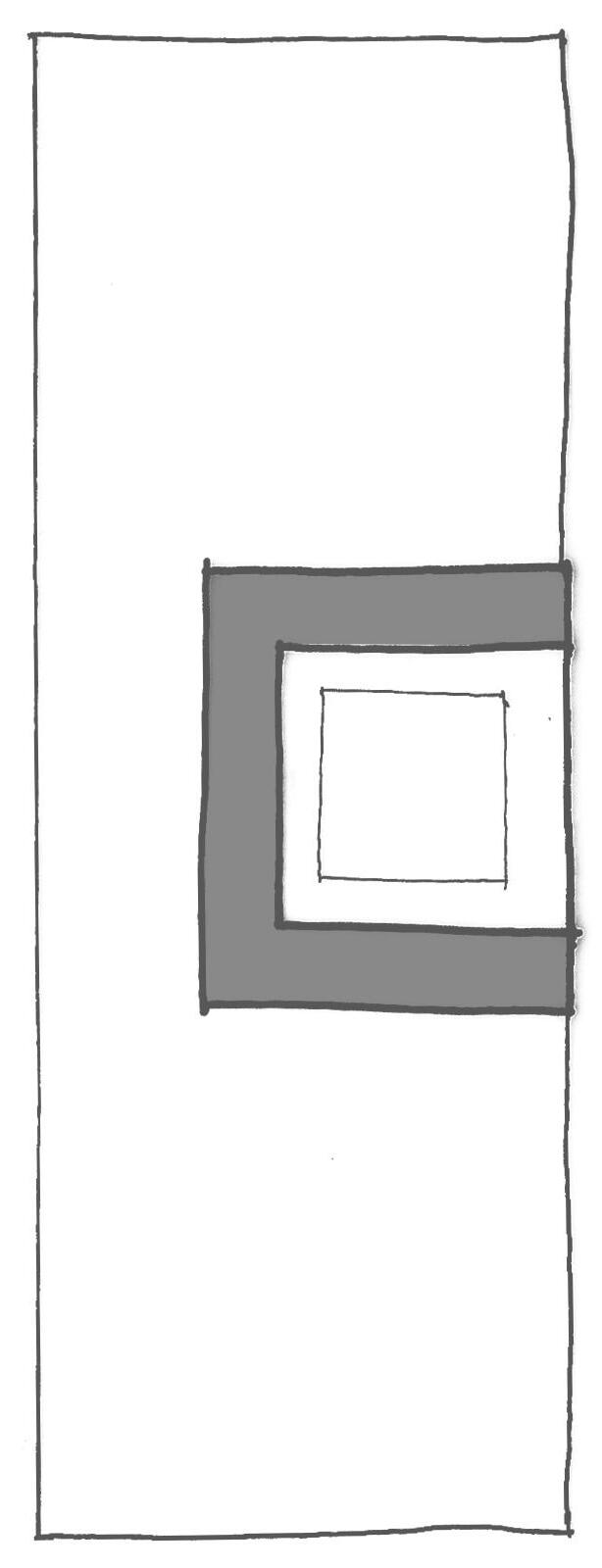

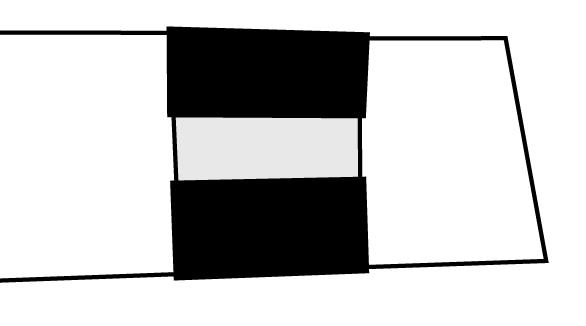

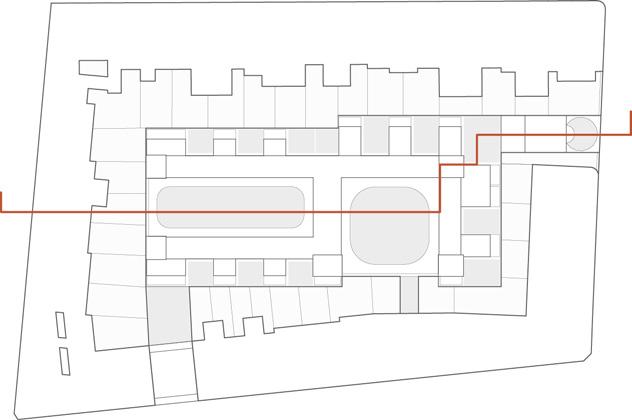

Fortress within the city | scheme mass and void

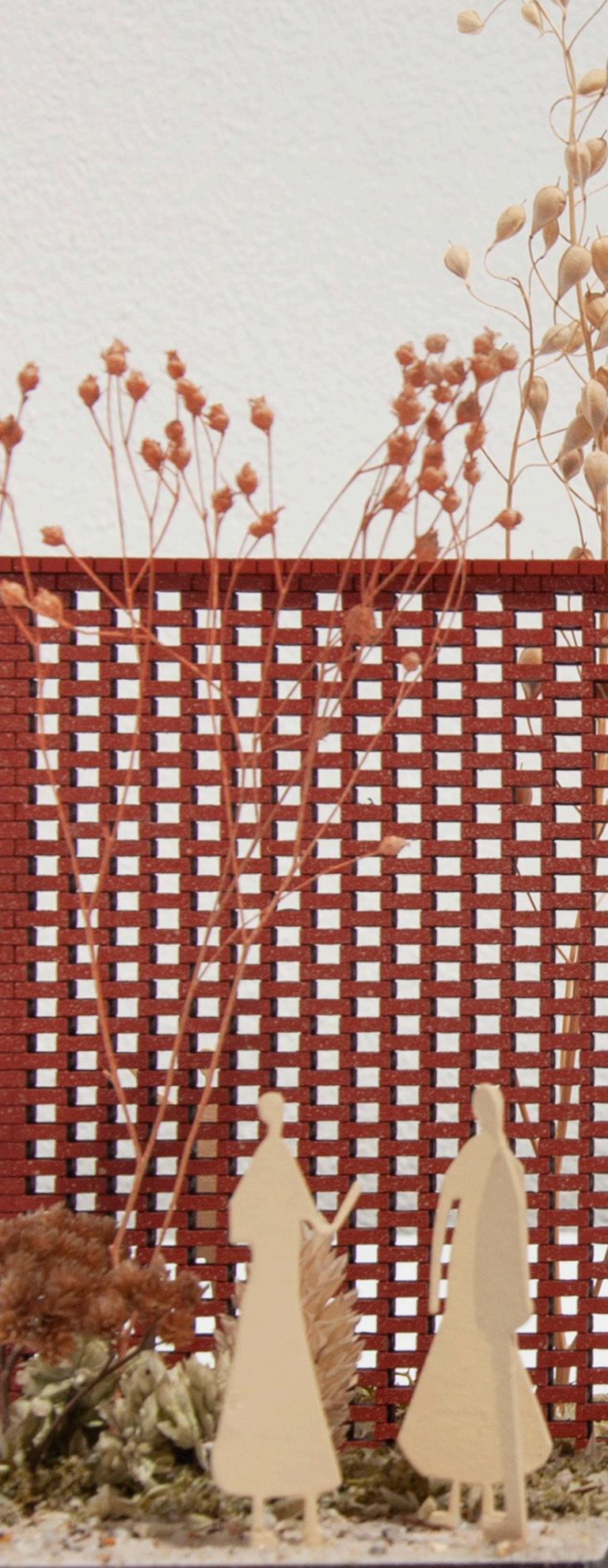

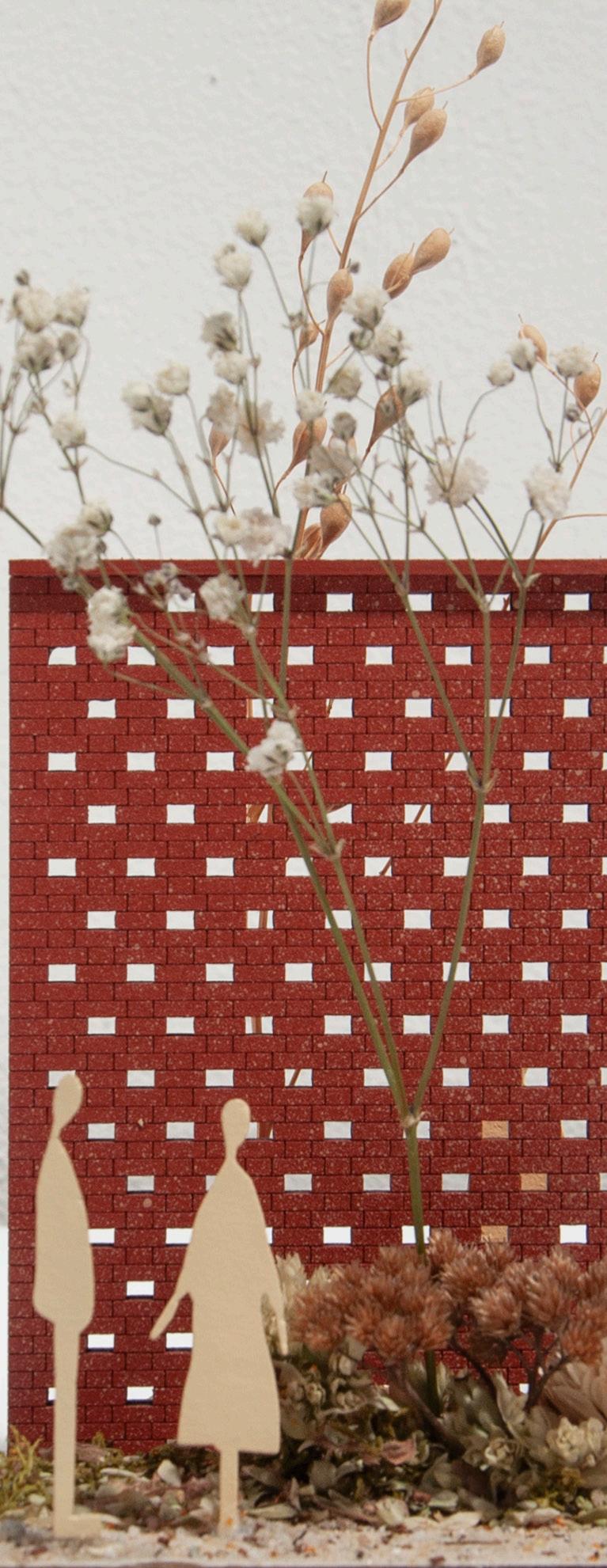

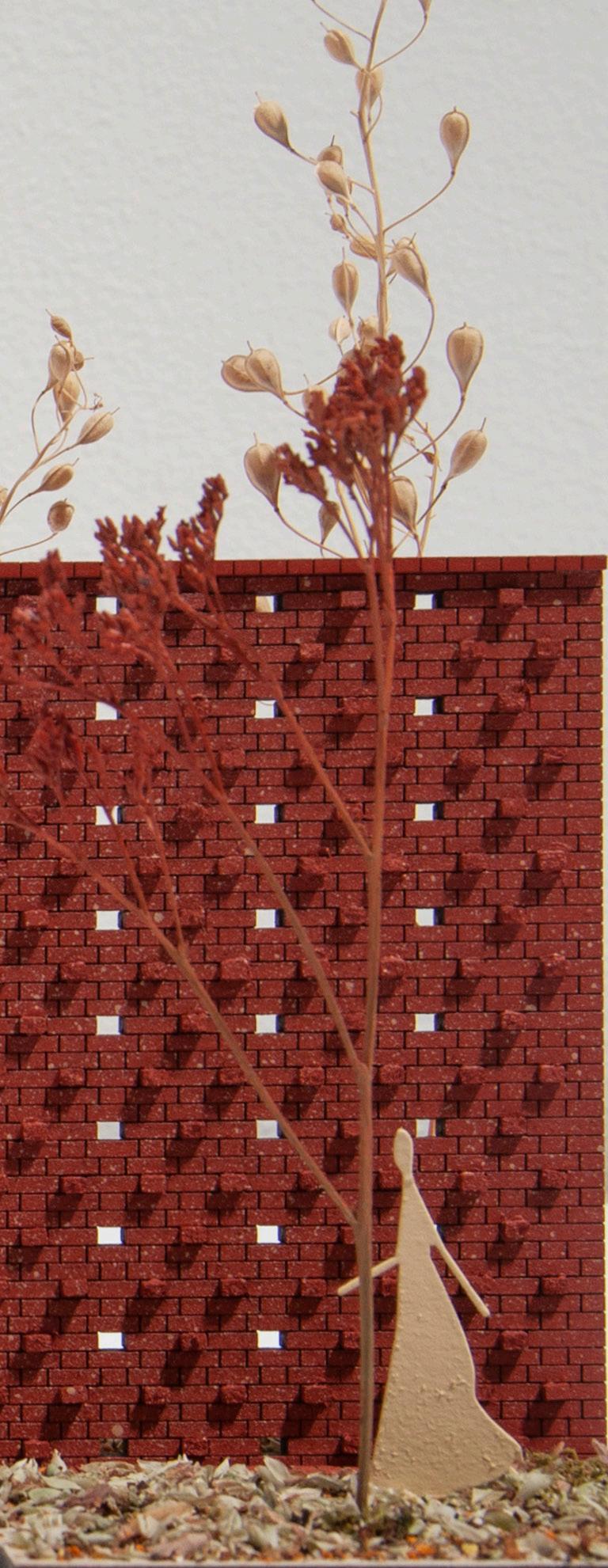

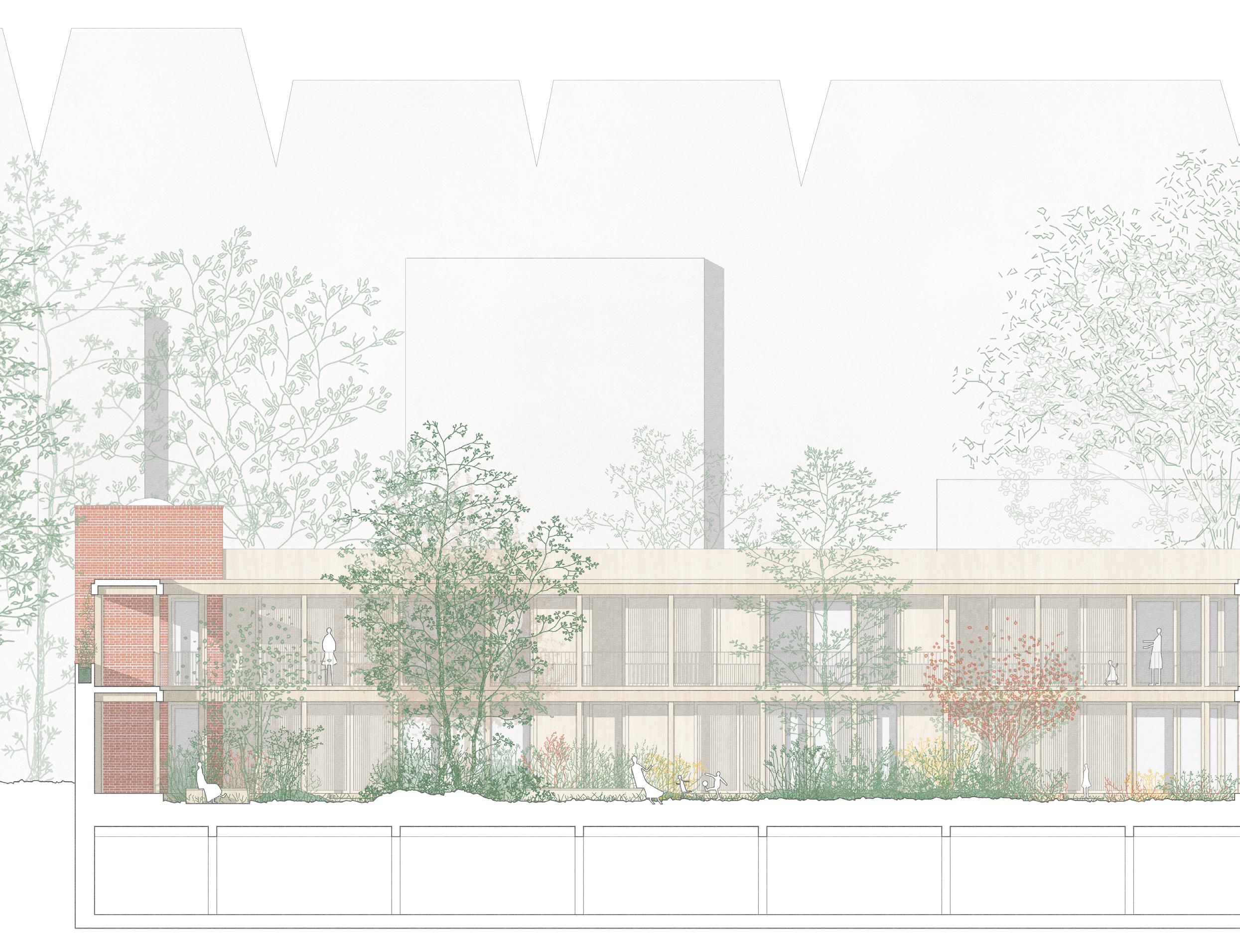

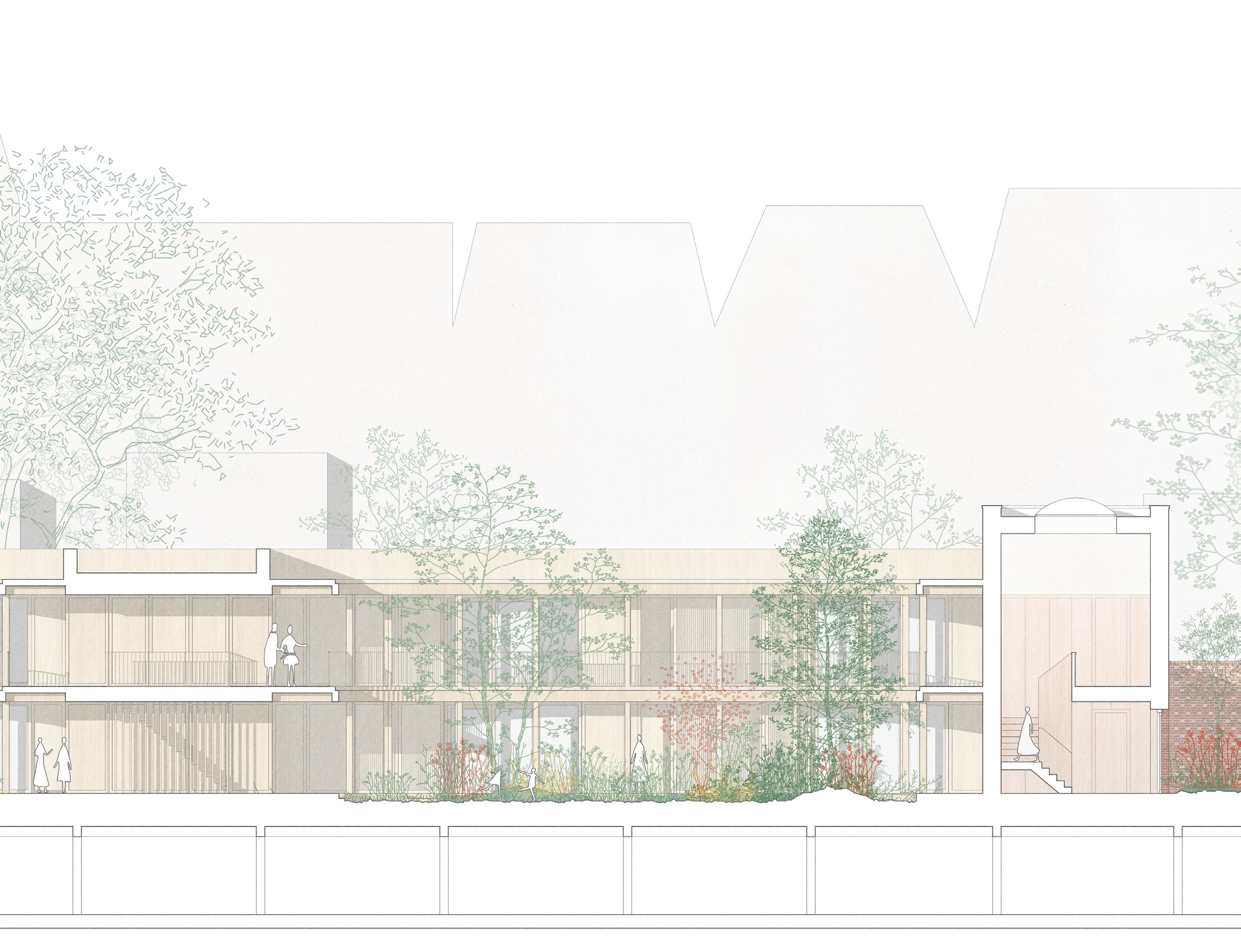

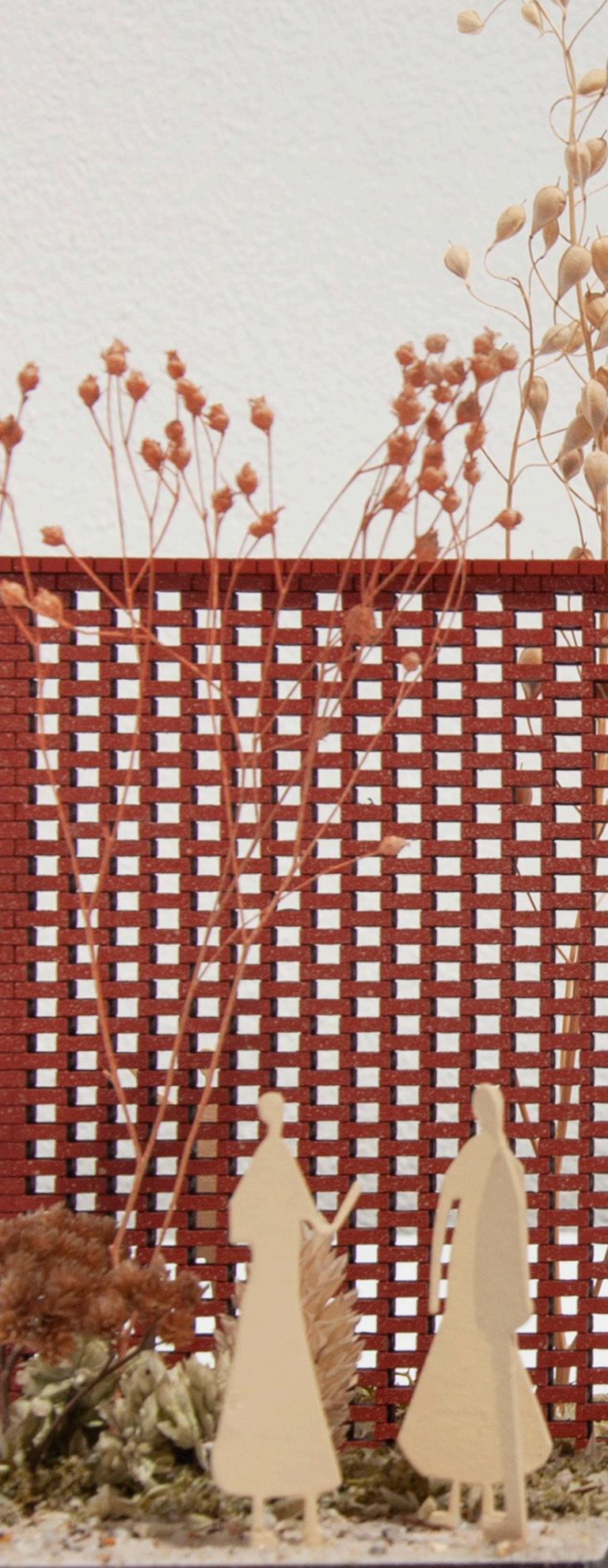

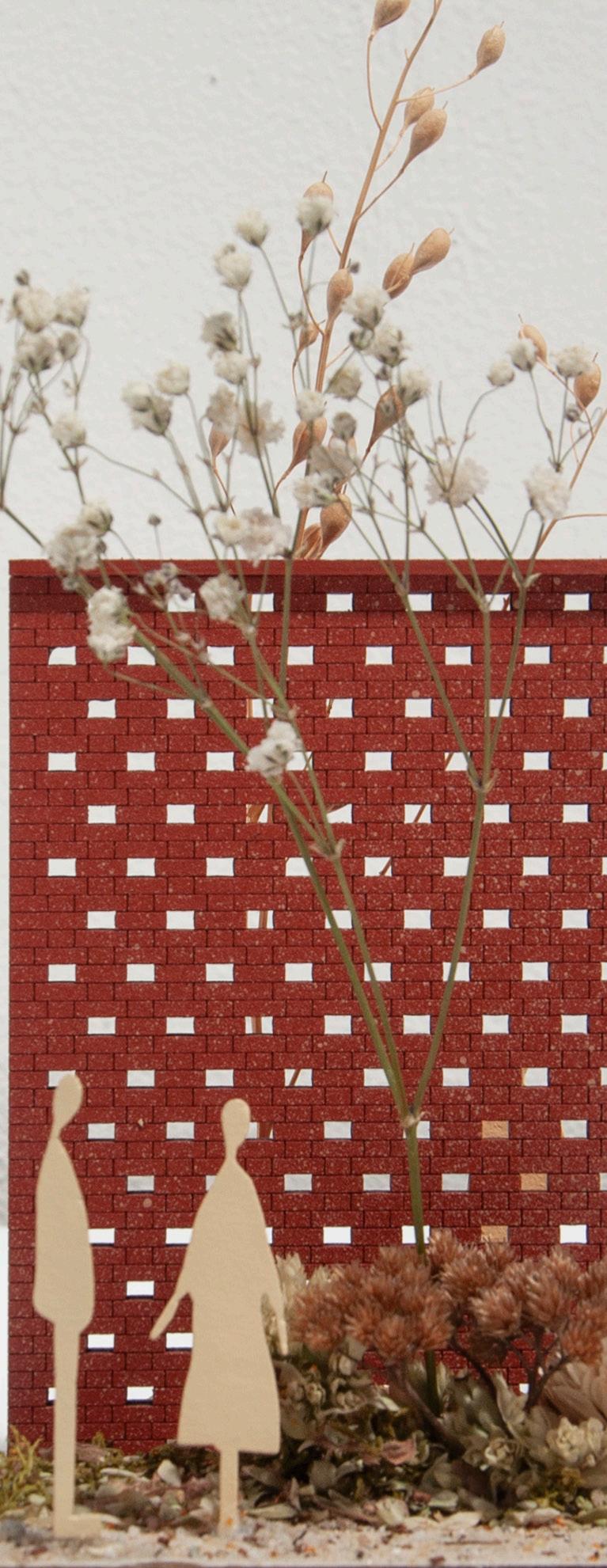

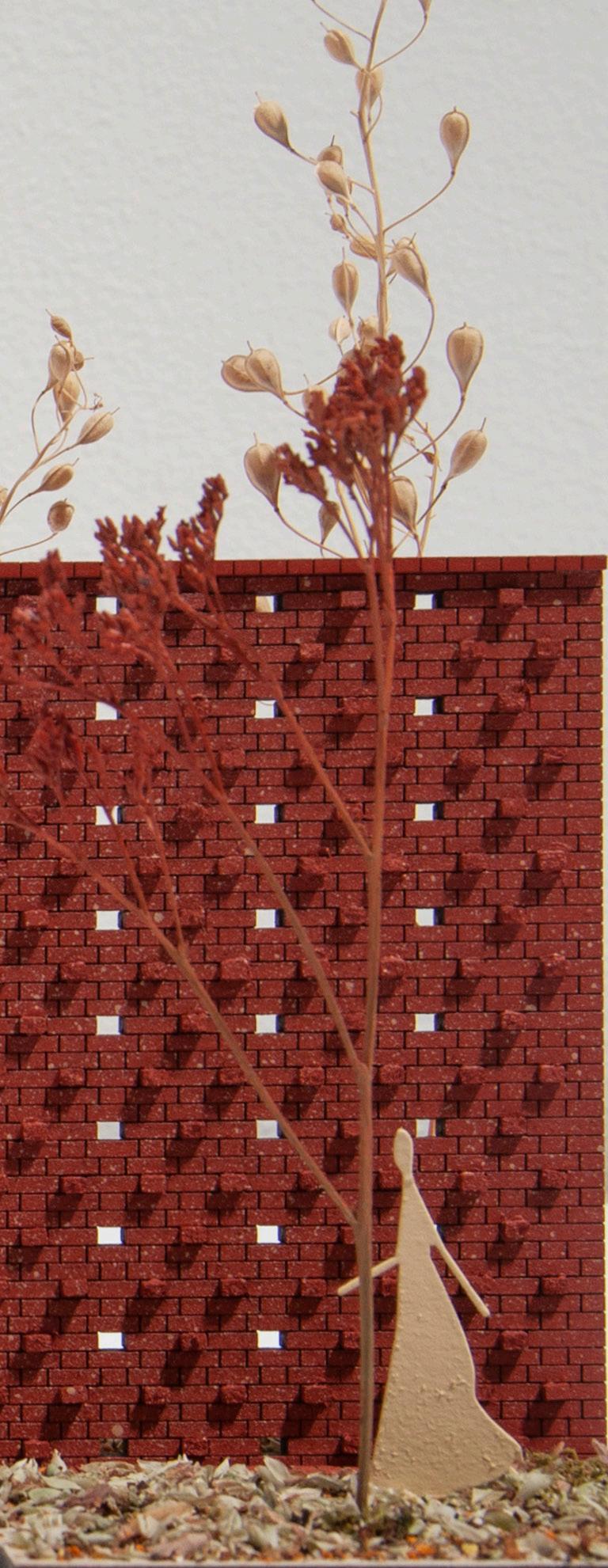

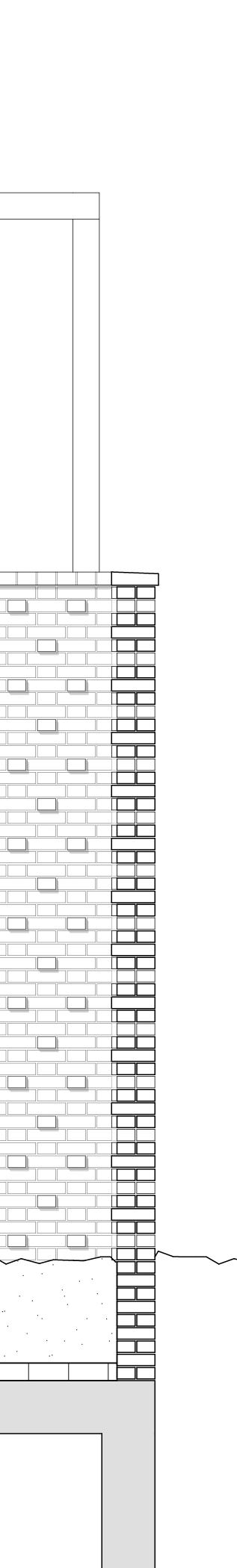

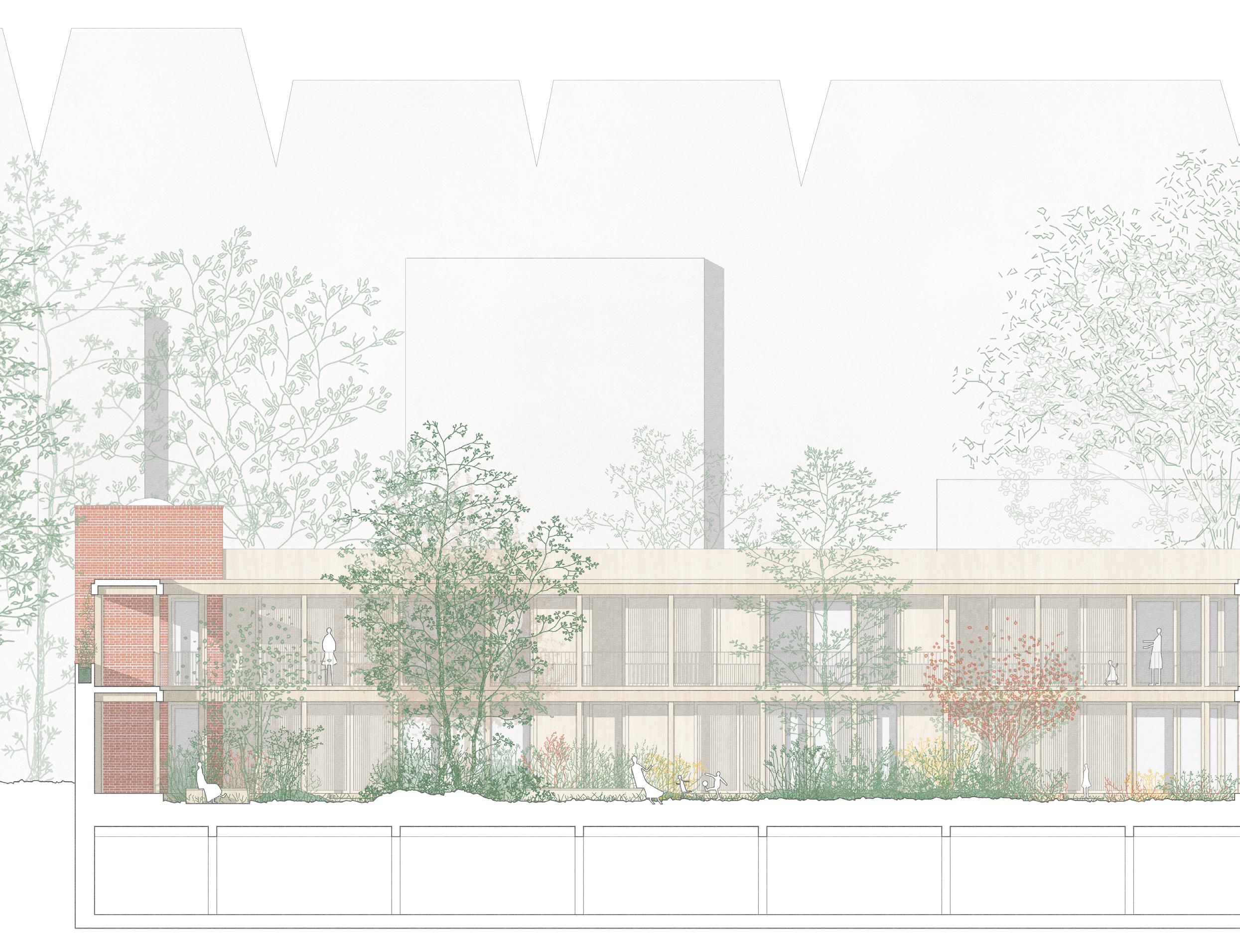

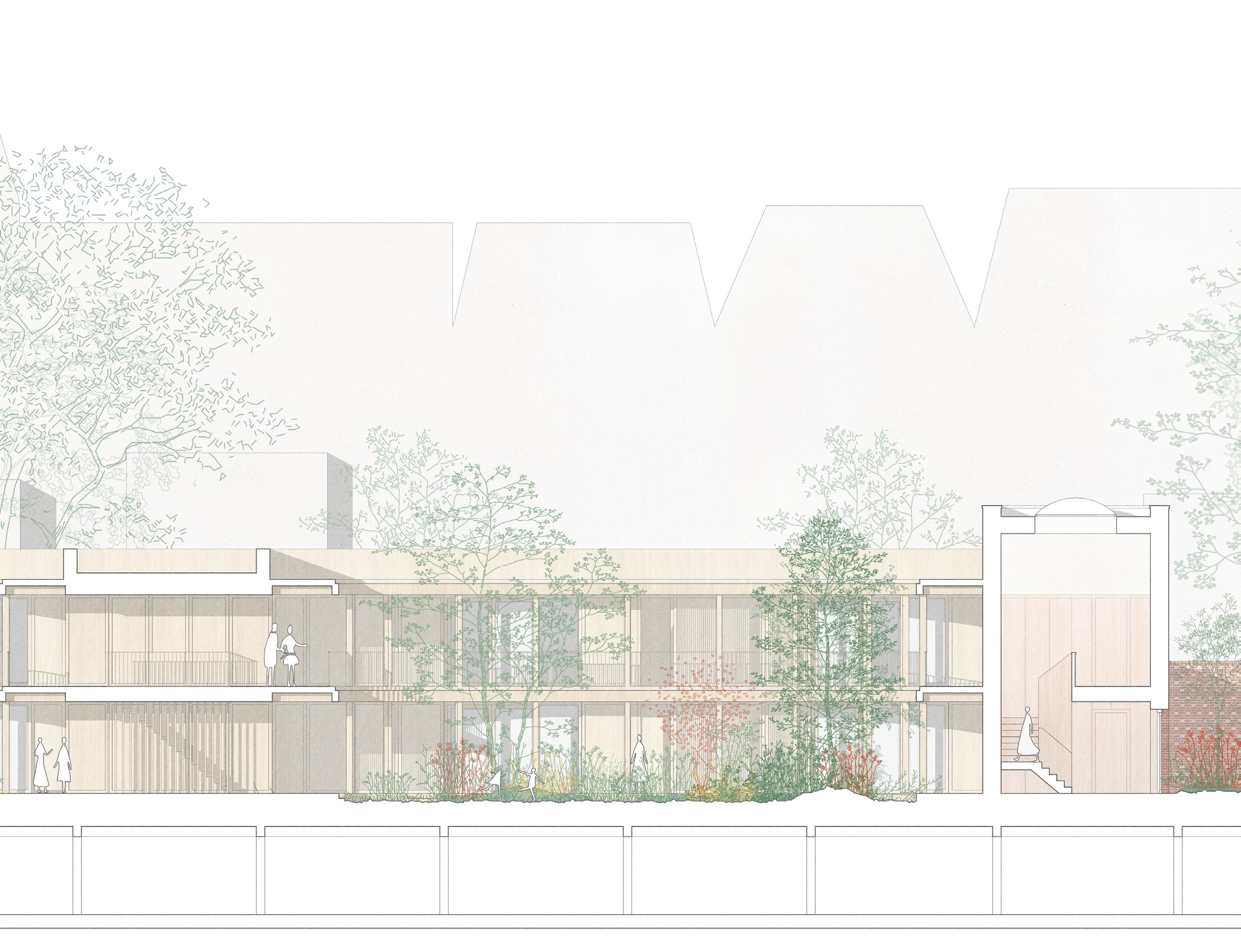

The project's interventions and the city block are together conceptually approached as a fortress within the city, that takes advantage of the existing buildings to create an enclosed protective living environment. The limits of the shelter are clearly defined by a continuous steady terra cotta color brick wall. Facing many gardens of different character, this continuous wall presents varying levels of permeability - beneficial for biodiversity - depending on the private or collective character of the gardens enclosed by it.

84 Conceptual principles

85

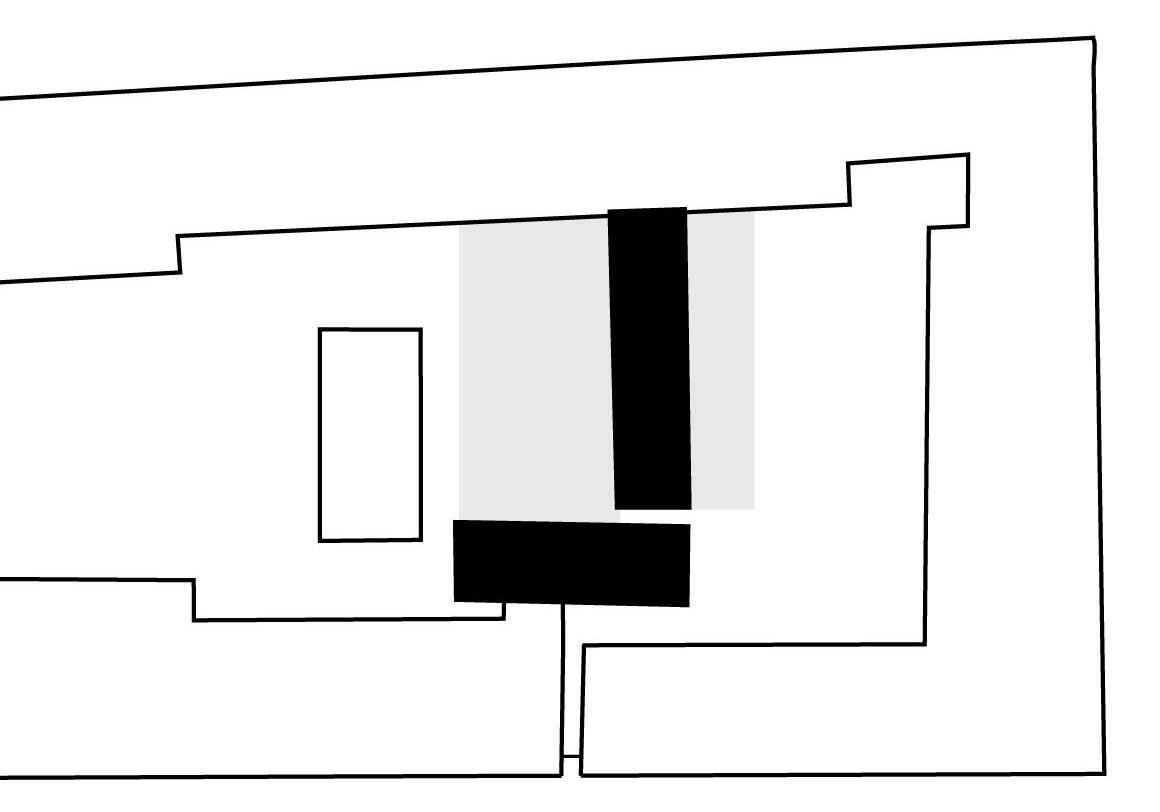

Front | public city life

Back | the world of the inner block and private life

Core | the spaces for communal life

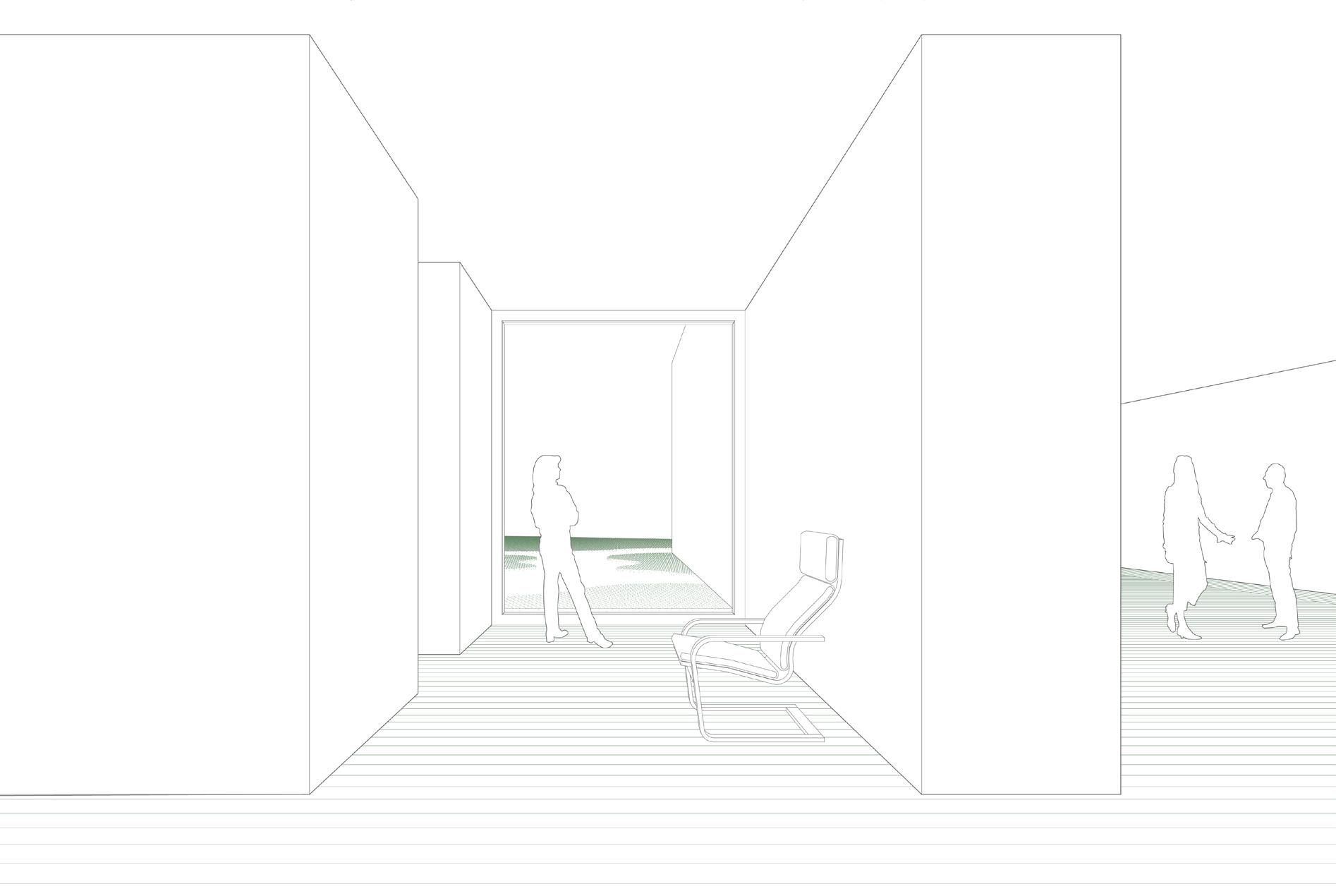

Architectural atmospheres

86

87

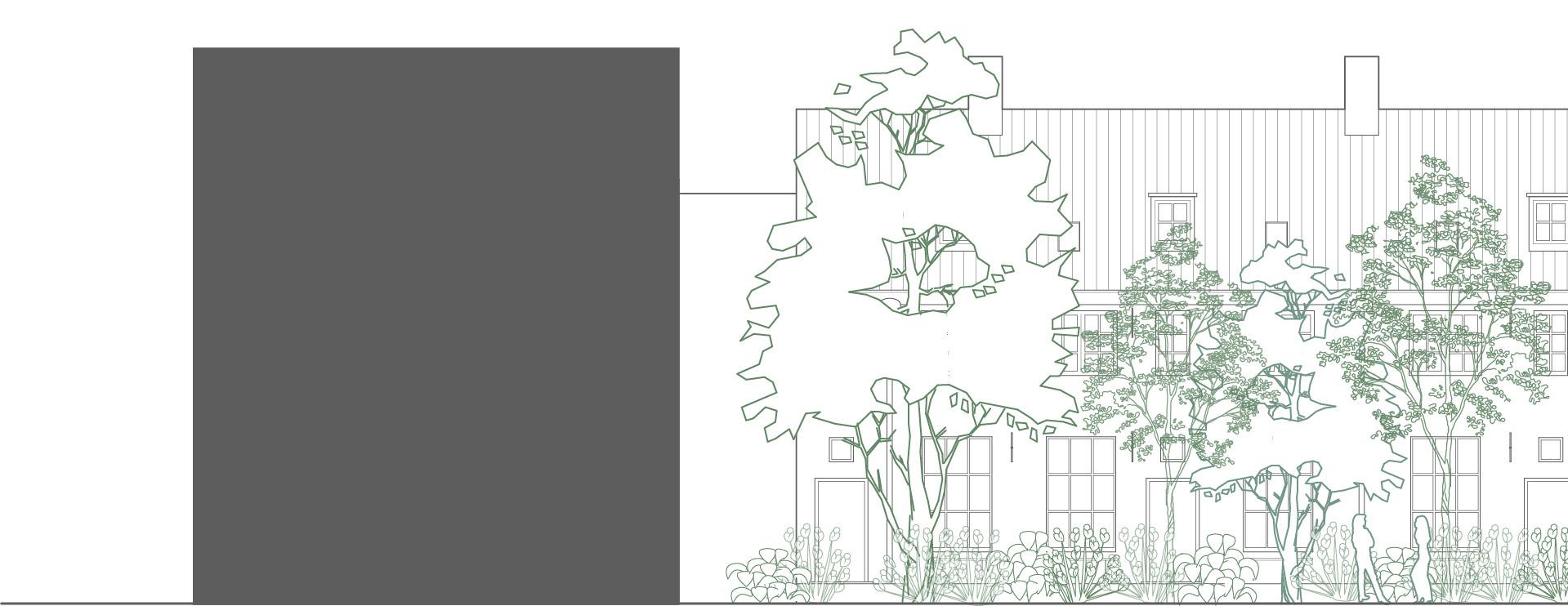

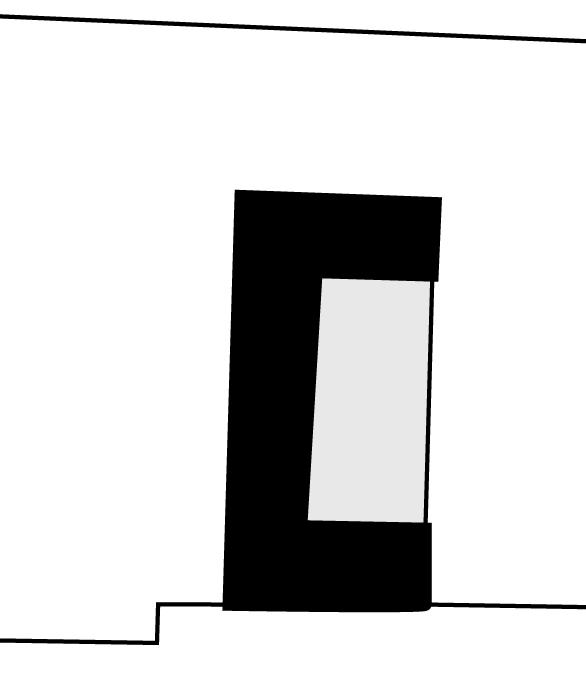

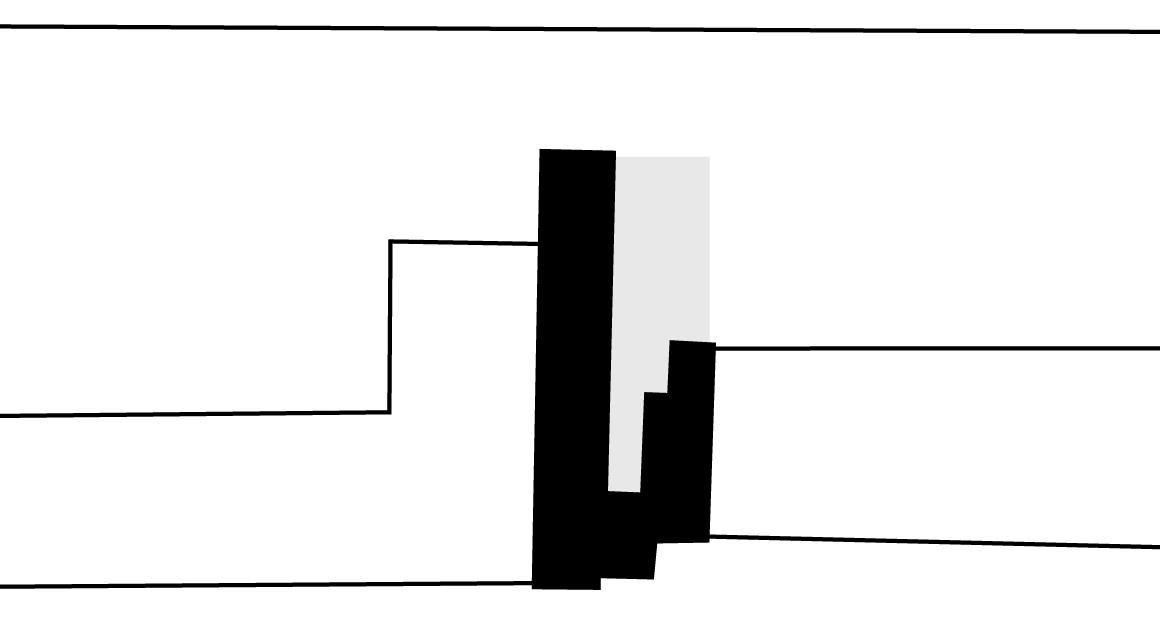

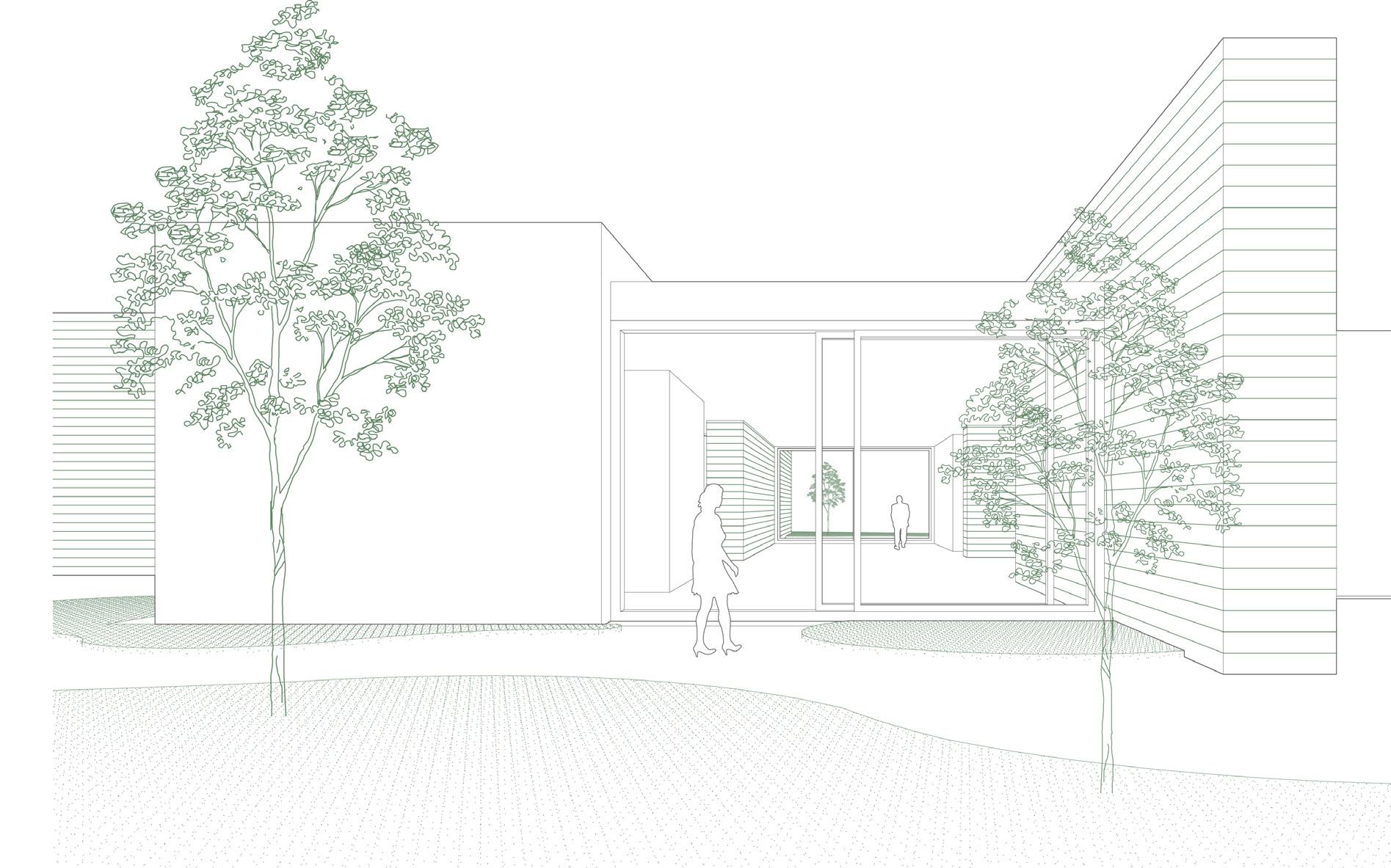

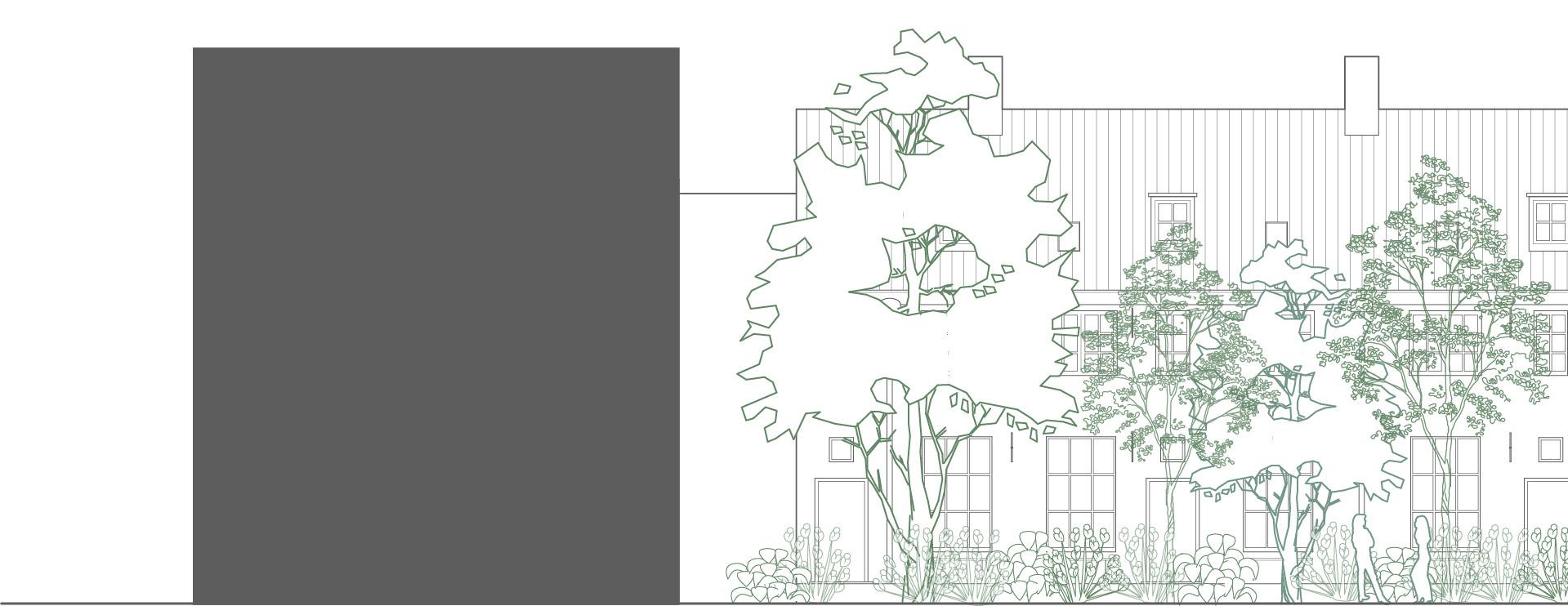

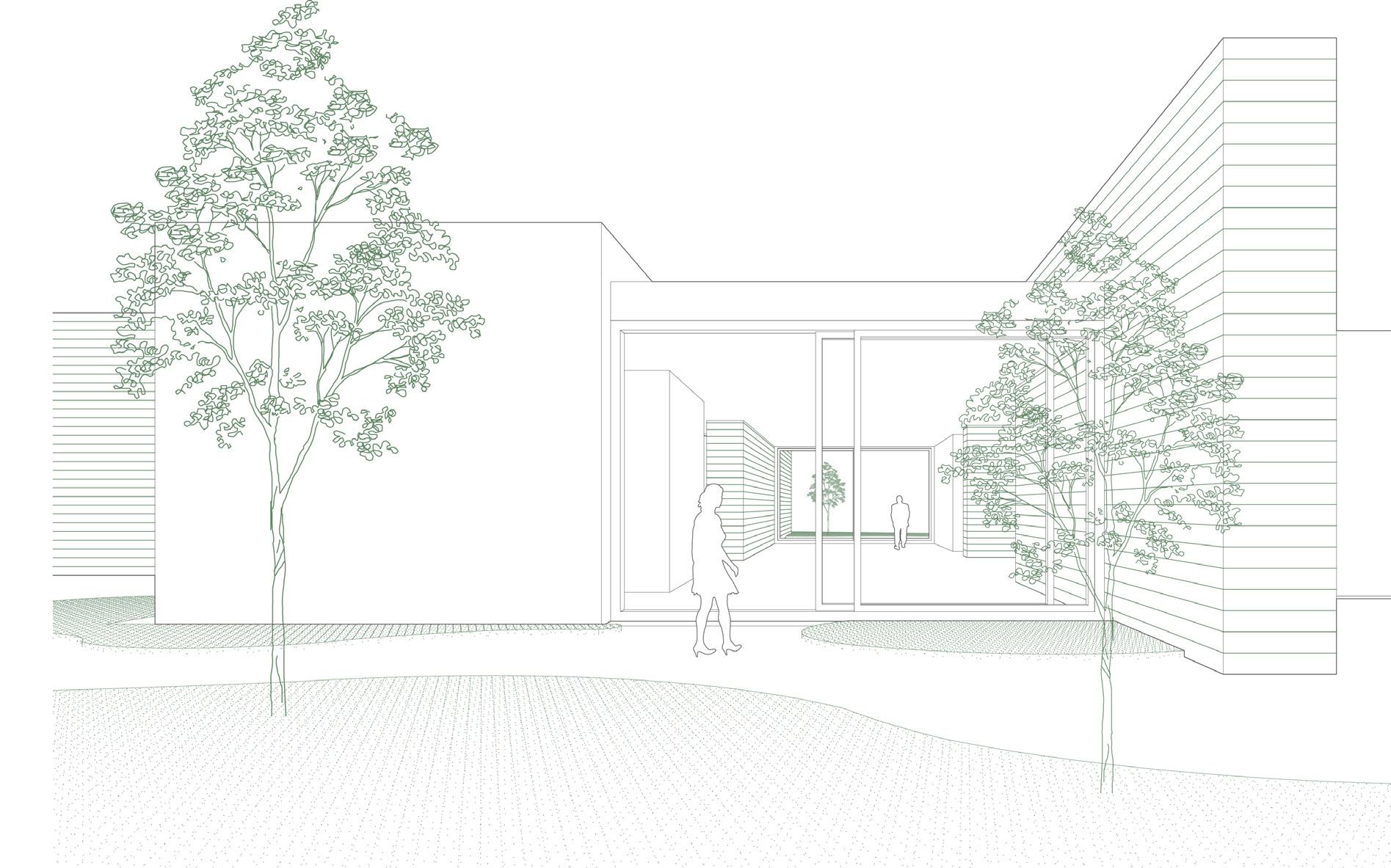

Front | the institutional tower relates to the context by contrast, the detached volume slightly higher than its sorroundings gives a clear address to the institution behind the shelter.

88

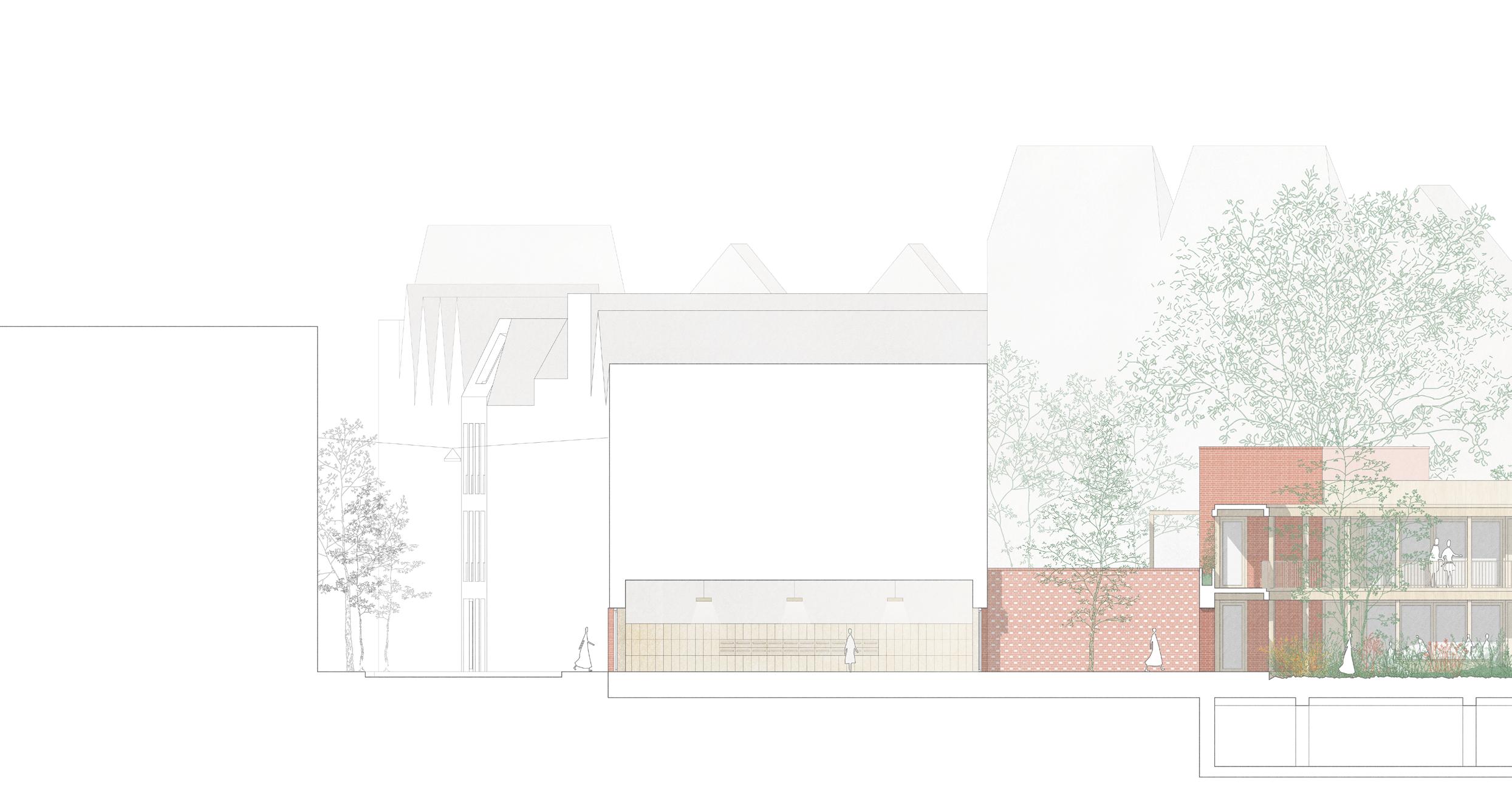

Front | the healthcare facilities relate to the city by blending in to the surroundings, the choice of material, volumetry and facade design camouflages the building in the block's context.

89

Front | transformation of existing plint, previously entrance to the parking facilities to give access to the shelter in a domestic normalized manner.

Back | the volume of the housing units is broken down into smaller elements, the multiple setbacks on first floor reduce the impact to the neighboring gardens while creating a link with the small scale of the informal extensions against the back facades of the existing building block.

90

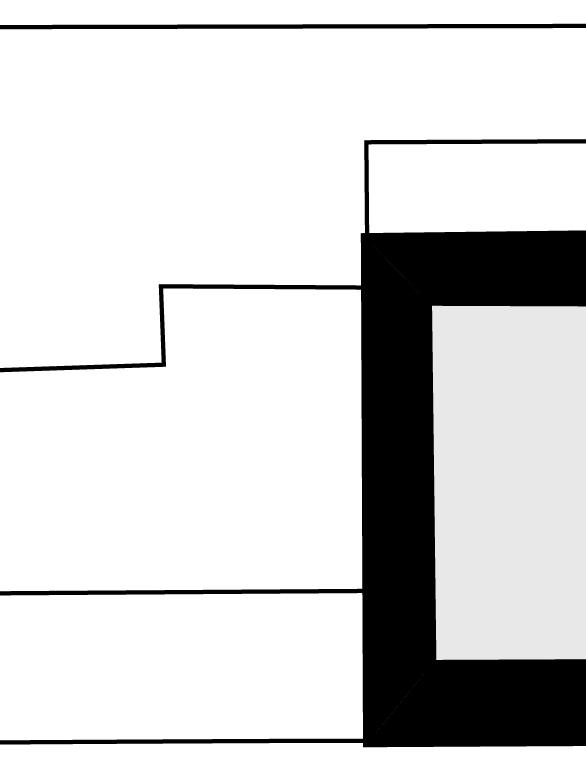

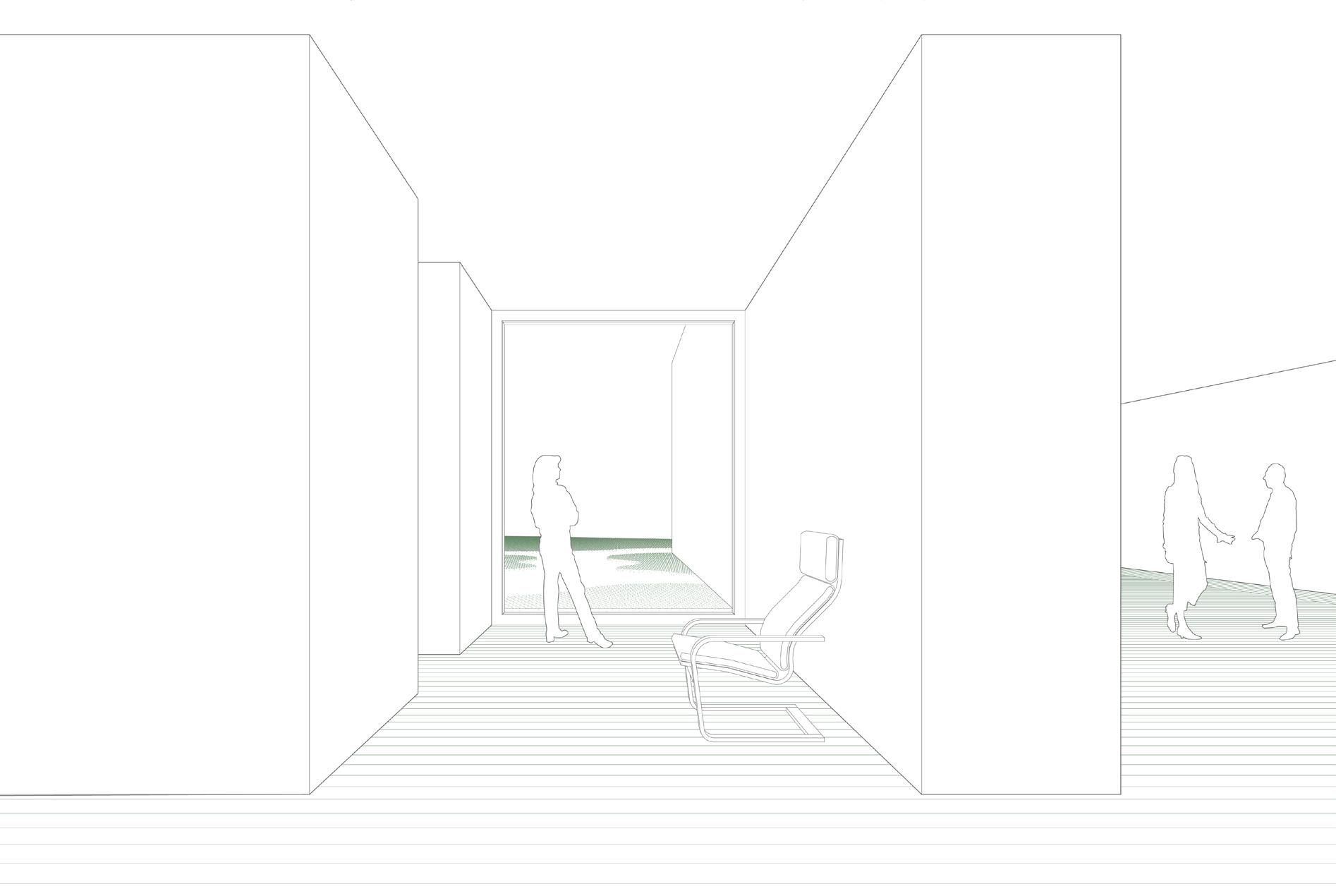

Core | the collective courtyards are designed with a refined light wood expression with round edges, creating the setting for communal life to take place.

91

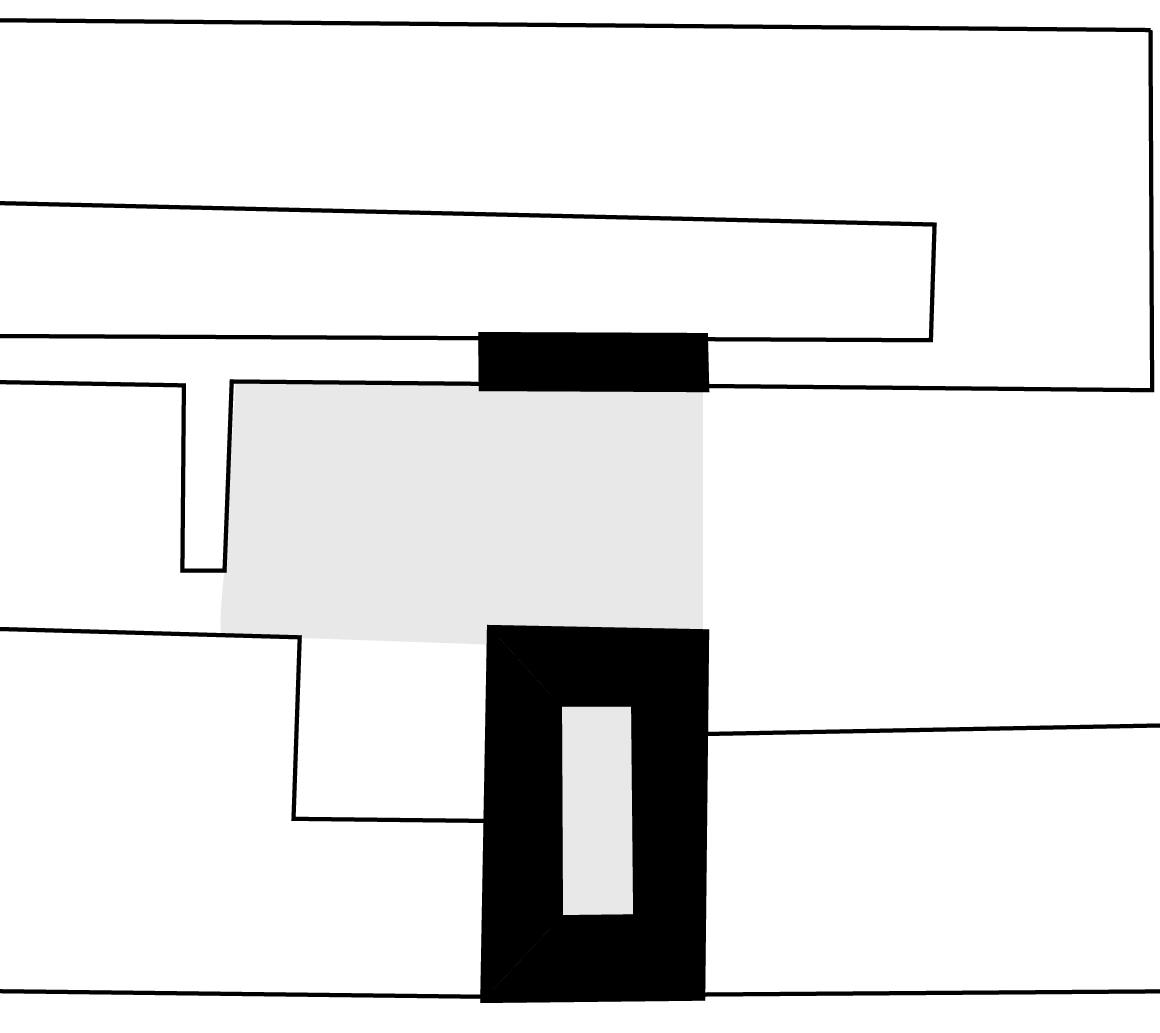

Hortus ludi | the garden of paradise

Hortus contemplationis | the garden of contemplation

Transitioning gardens | the link with the city

The hortus conclusus | the enclosed garden

The project is organized around a sequence of enclosed gardens. While living within the designed secluded setting these gardens create the scenery around which the daily life of the shelter will take place. The gardens give orientation and connection to the sense of place and time while shaping the transitional sequences between city and shelter, essential to enabling the unique atmosphere of the block’s inner world.

92

Introduction to the link transitional gardens, the lush gardens of paradise - scenery for communal life in the shelter - and the contemplation gardens dedicated to introspective moments of privacy.

93

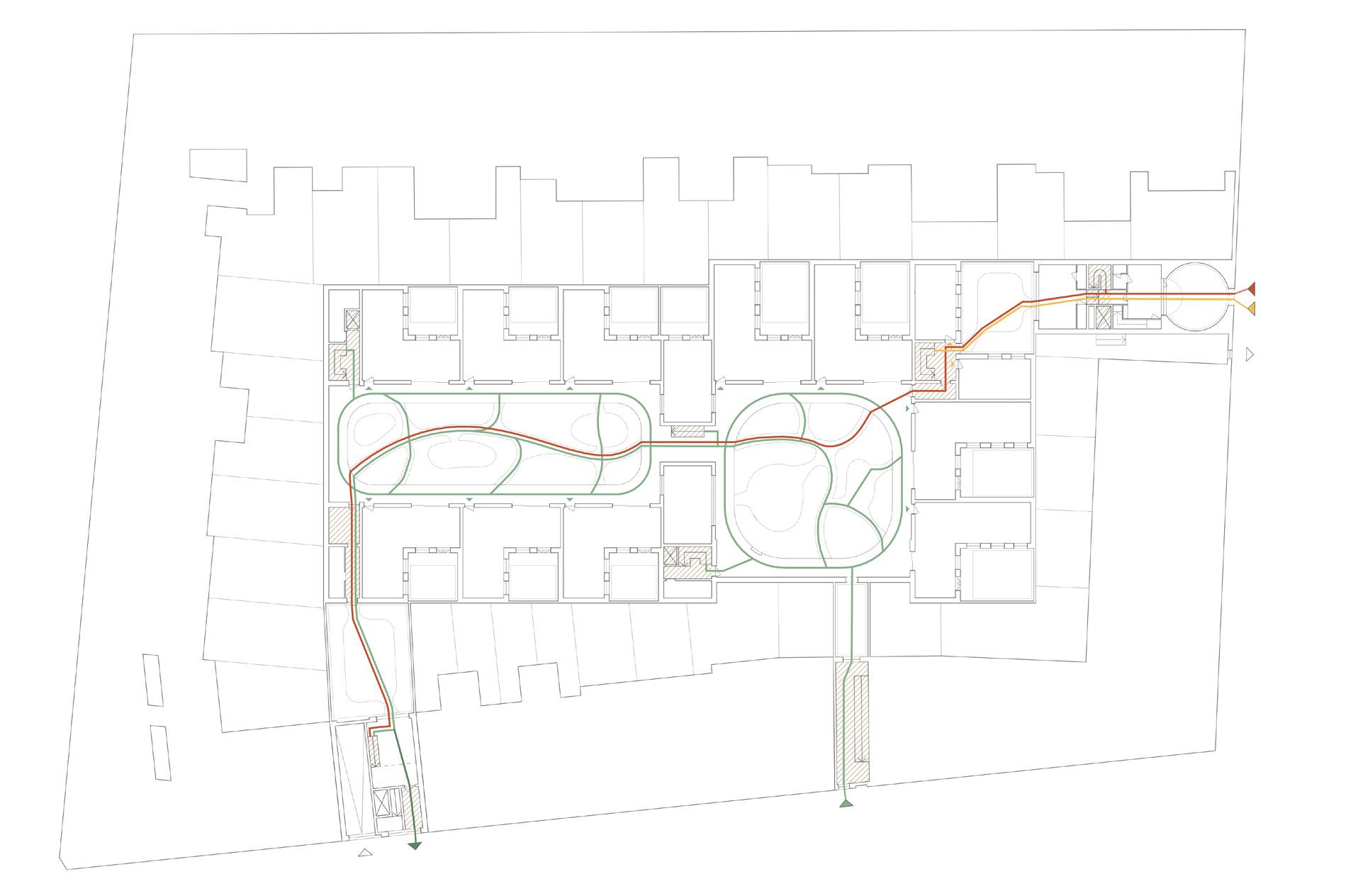

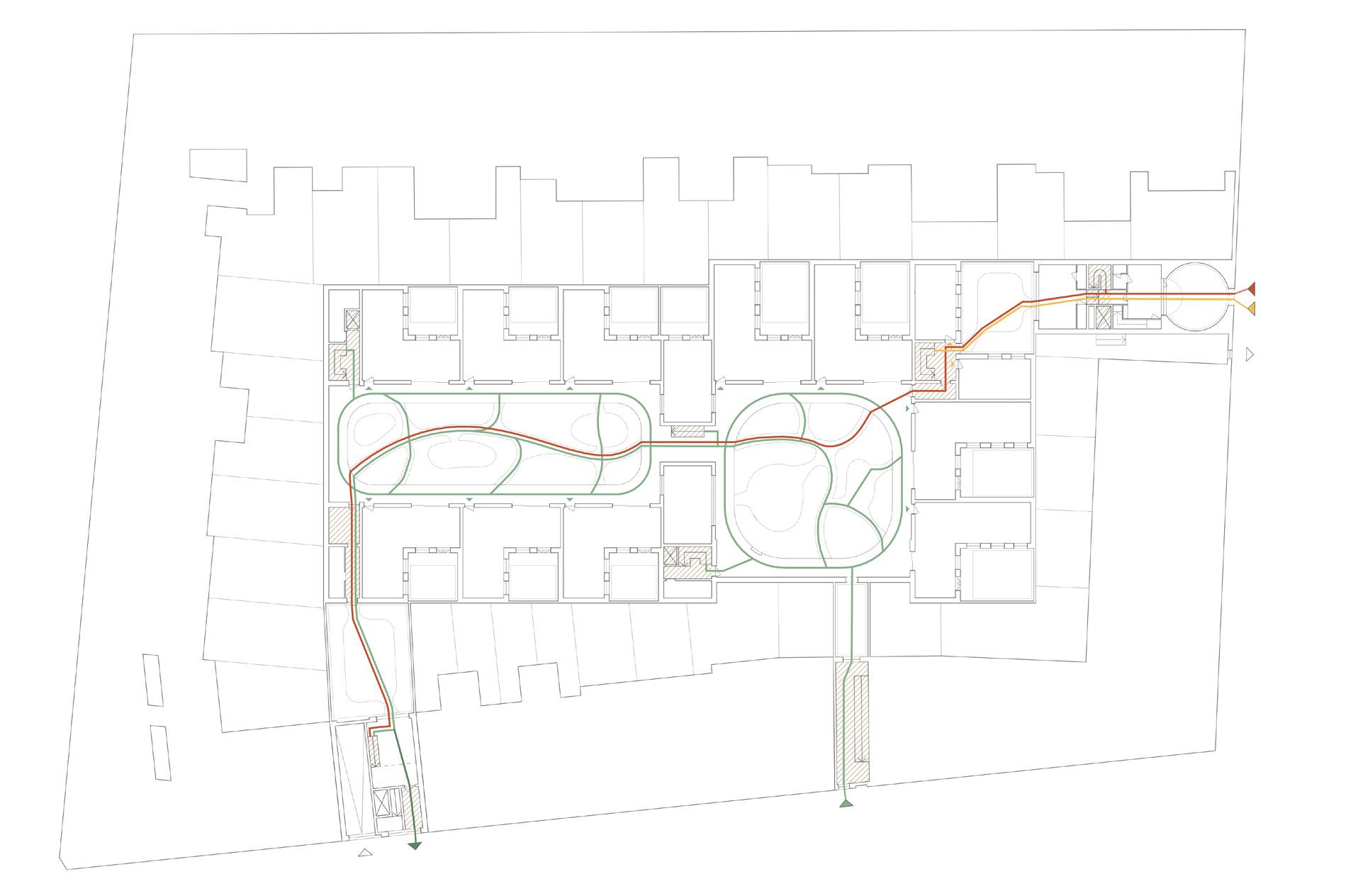

Circulation

Staff

Residents

Emergency beds

Departure

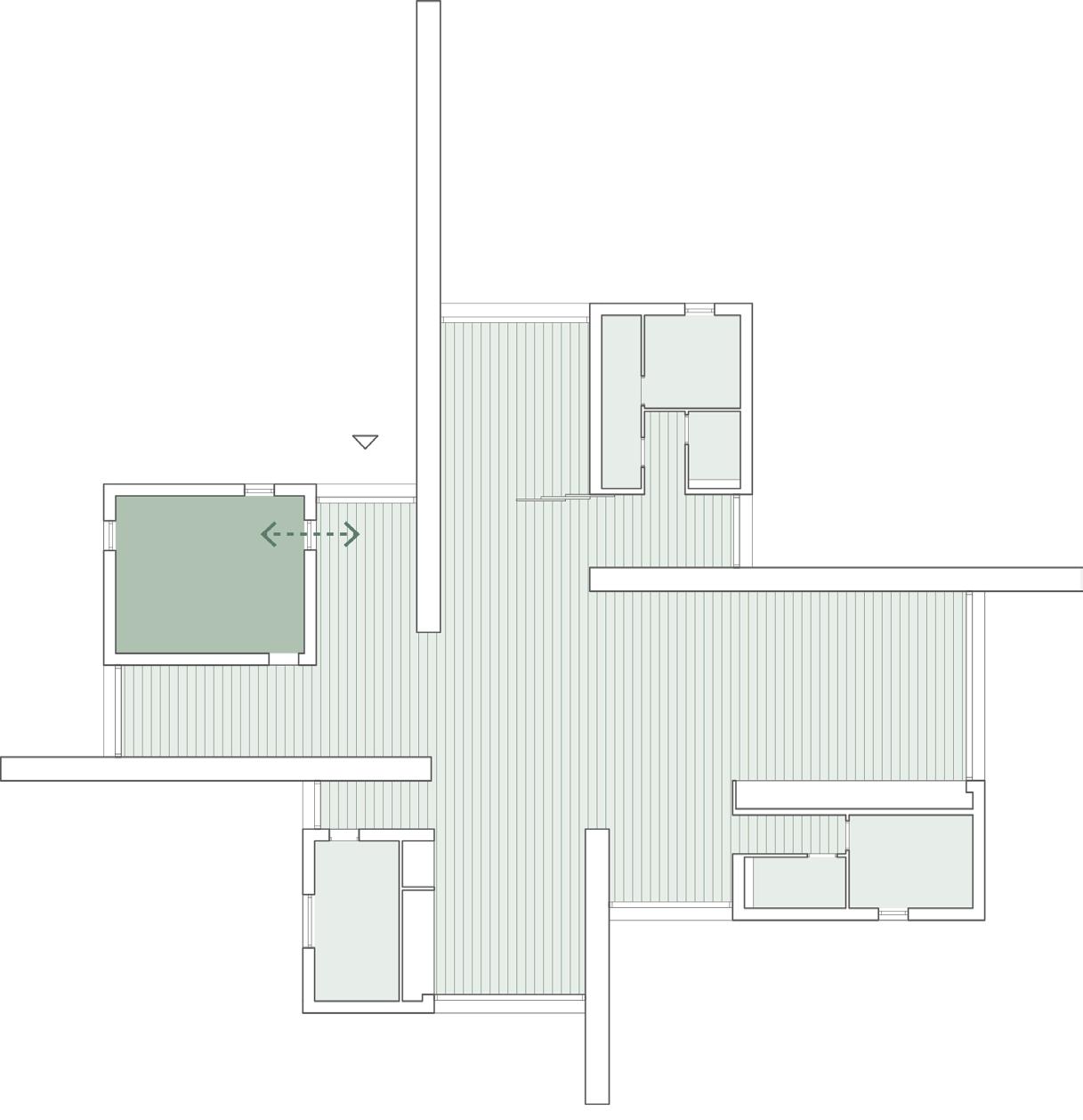

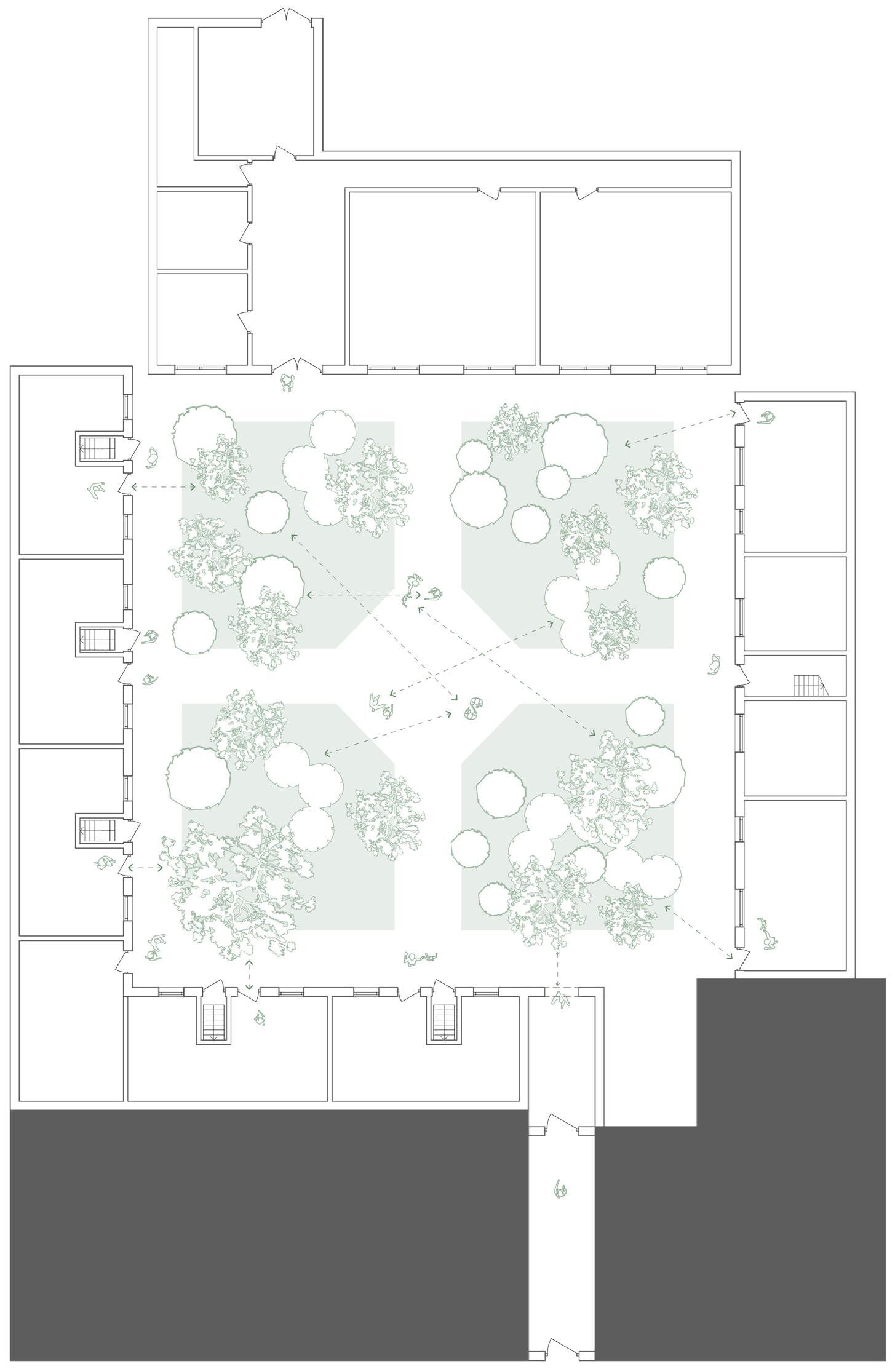

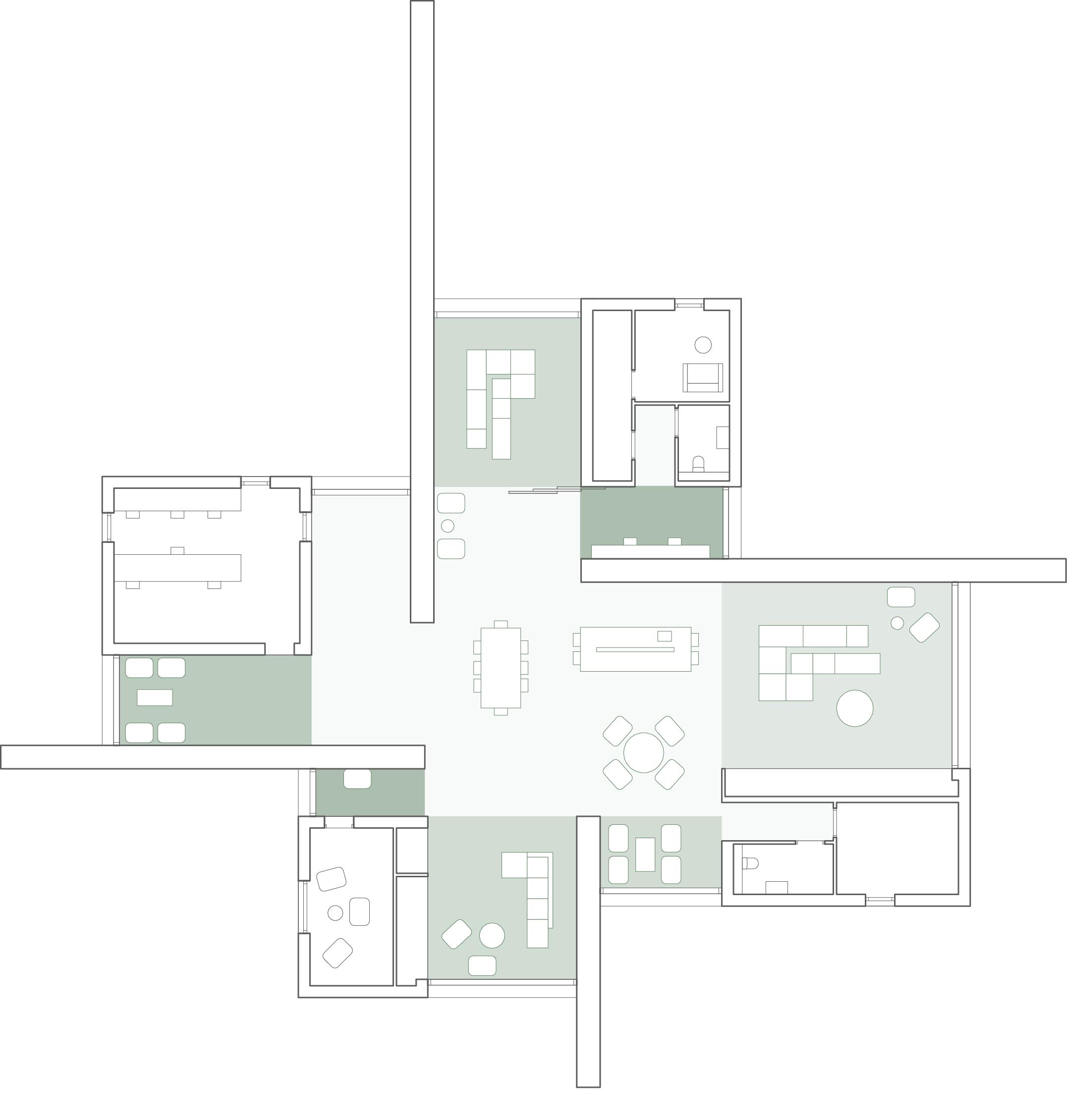

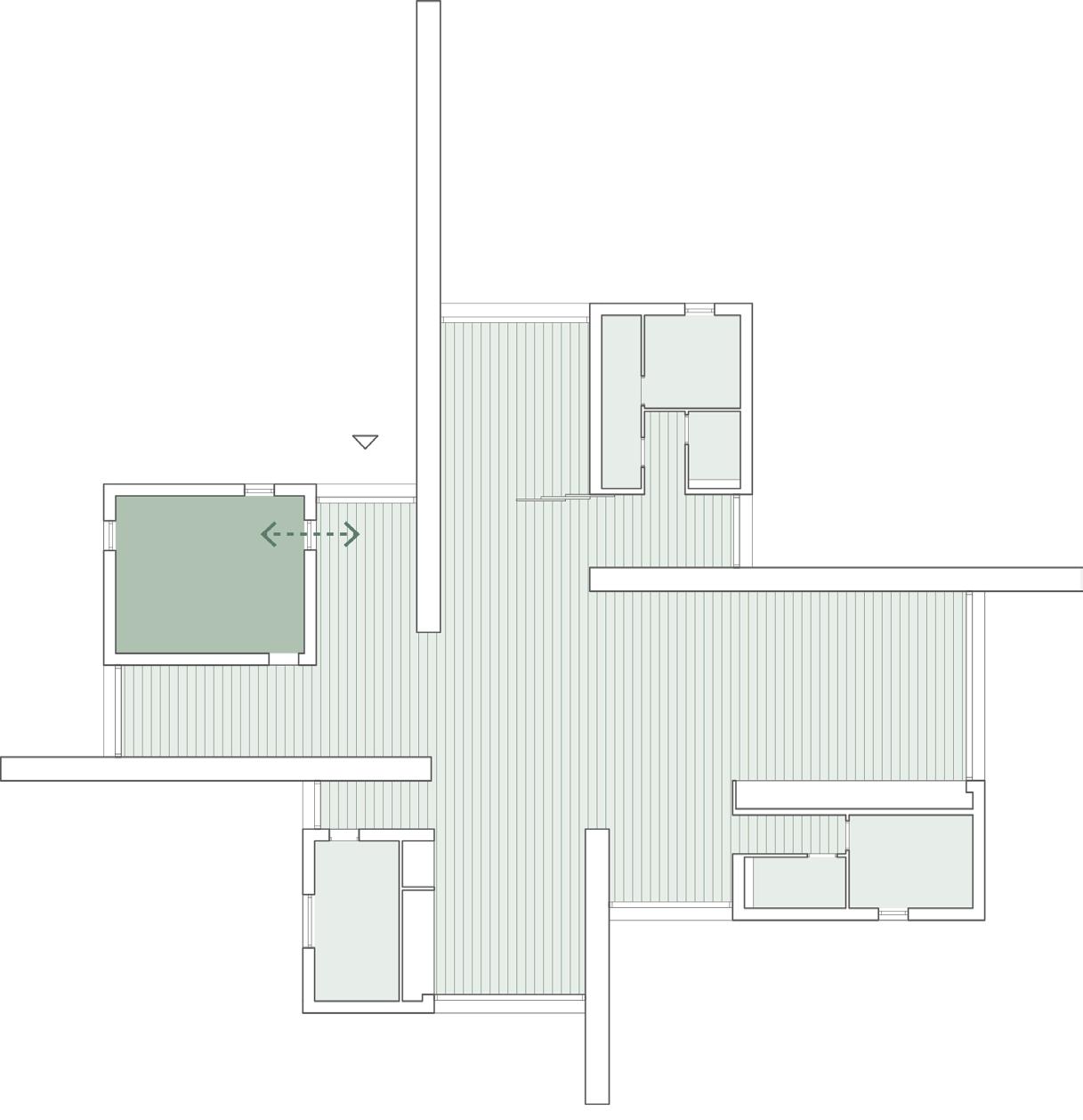

In order to allow inhabitants to feel at home, the domestic and institutionalized program components of the project were dealt with as independent parts of the design. The circulation routes between them allow spontaneous interactions between institution and inhabitants without intrusion in one’s domestic private life. The various paths to access the housing units offer more exposed on private routes towards one’s home.

94

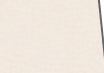

Program

The three programmatic components of the shelter relate to different moments of one’s stay. The institution plays an important role in the narrative of arriving, the living on the path to go through in daily life and as last the healthcare facilities, related to the conscious preparation for departure.

95

Institution Living Healthcare

96

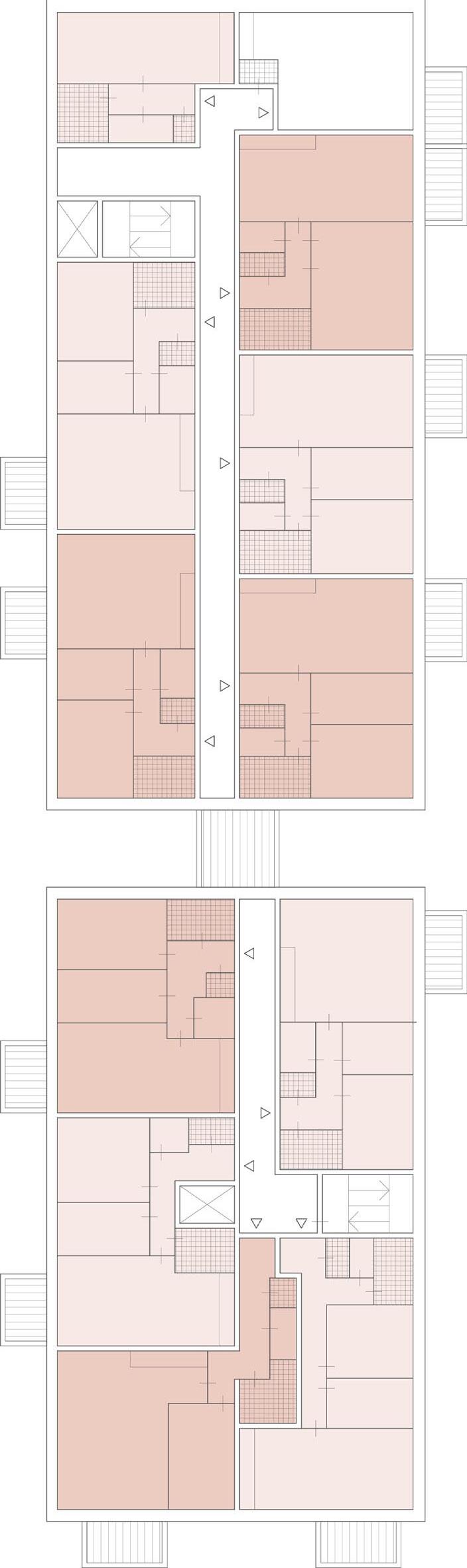

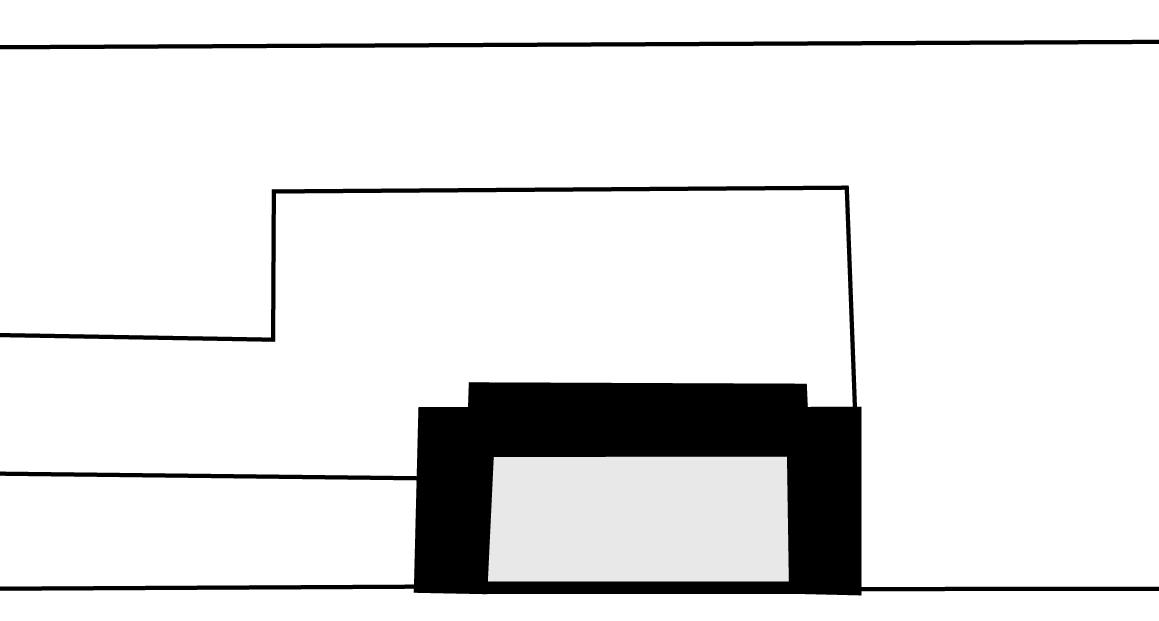

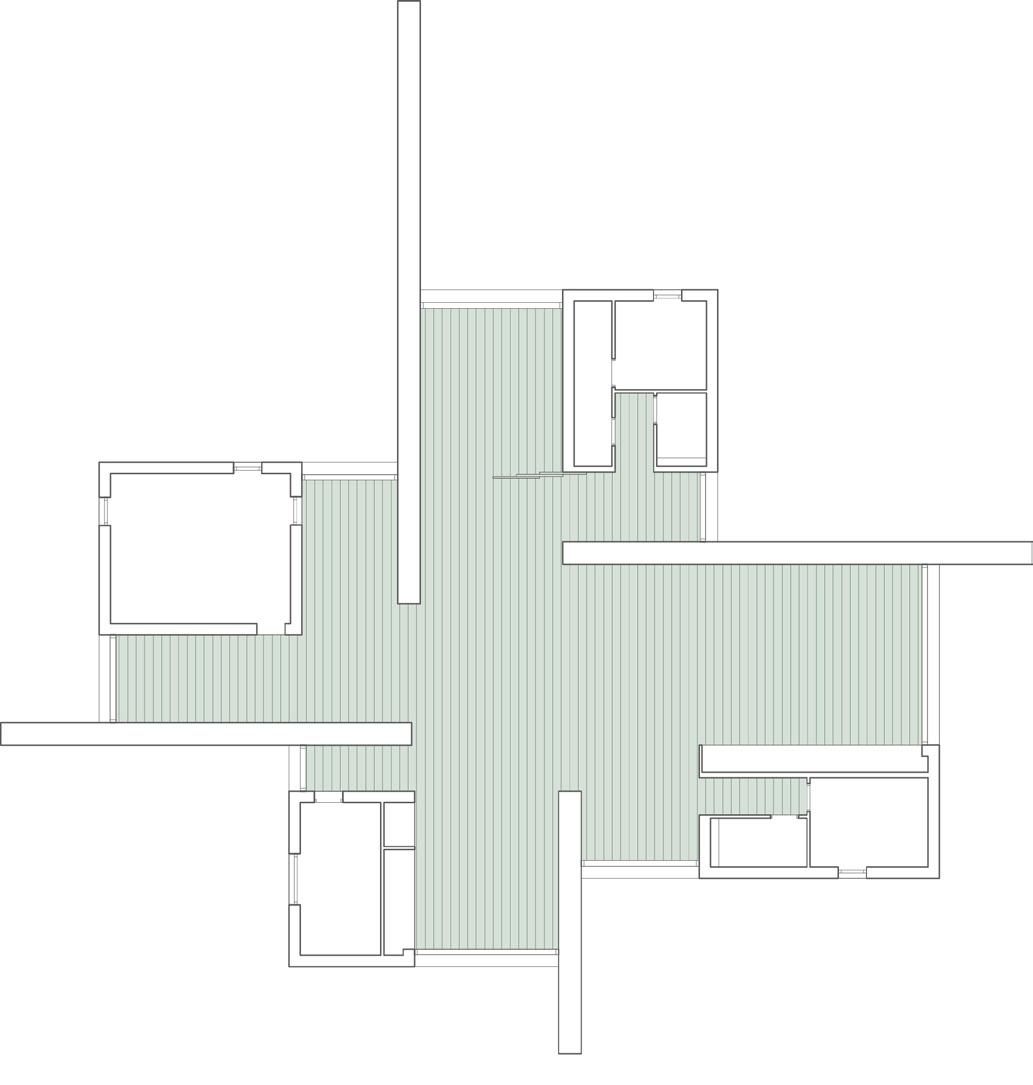

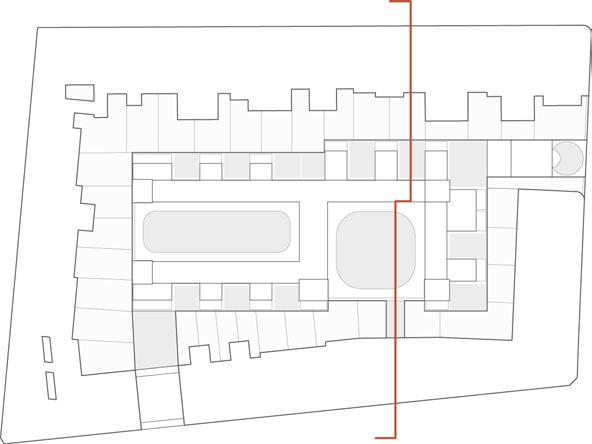

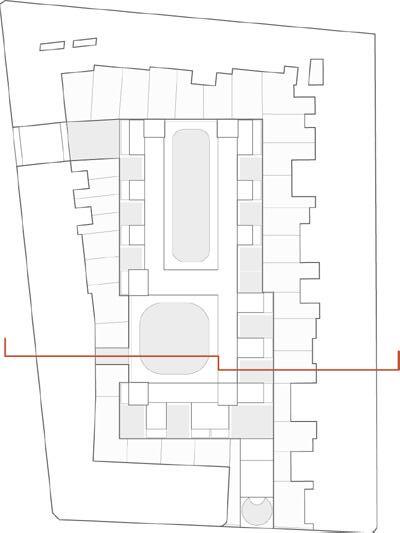

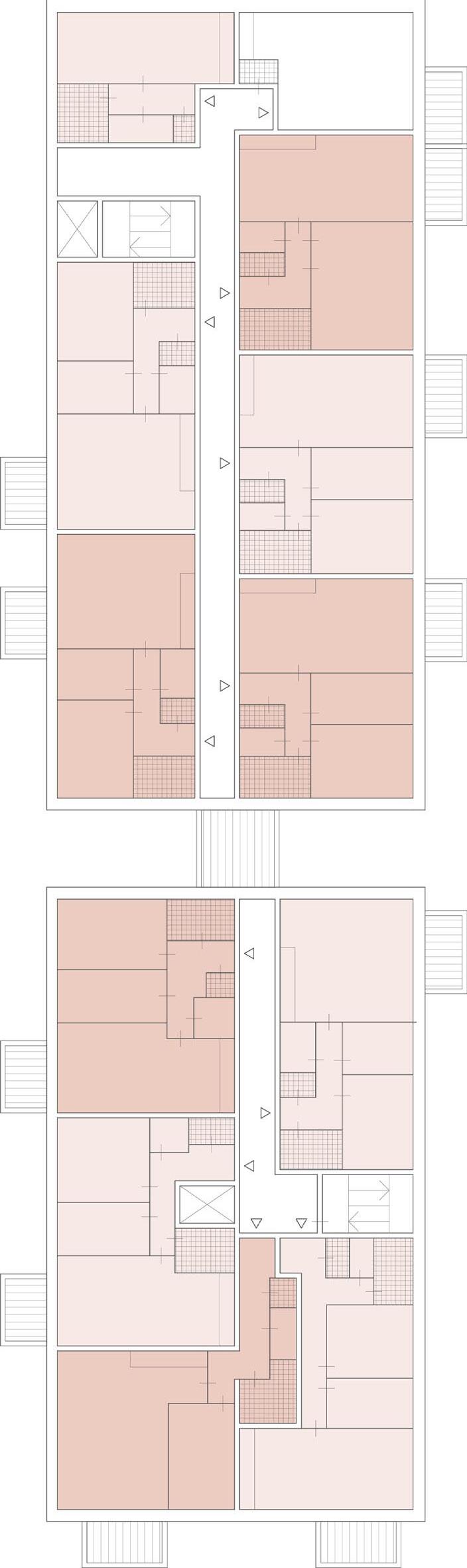

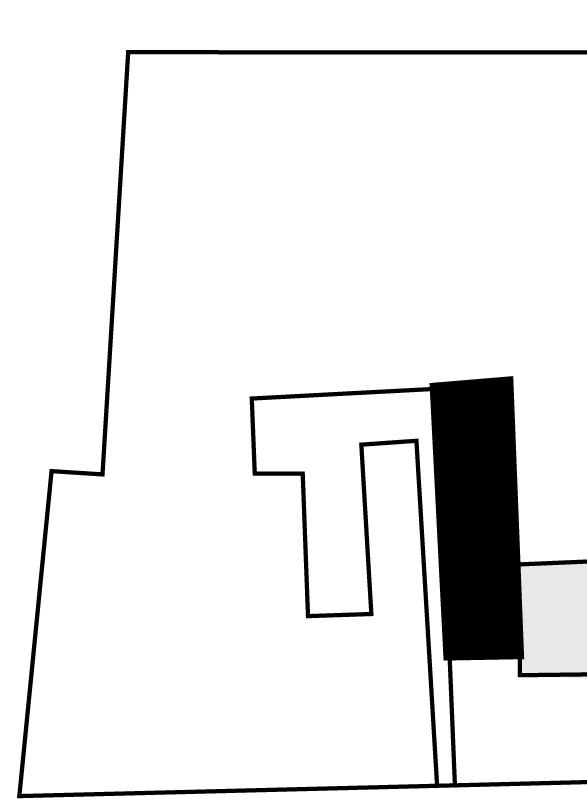

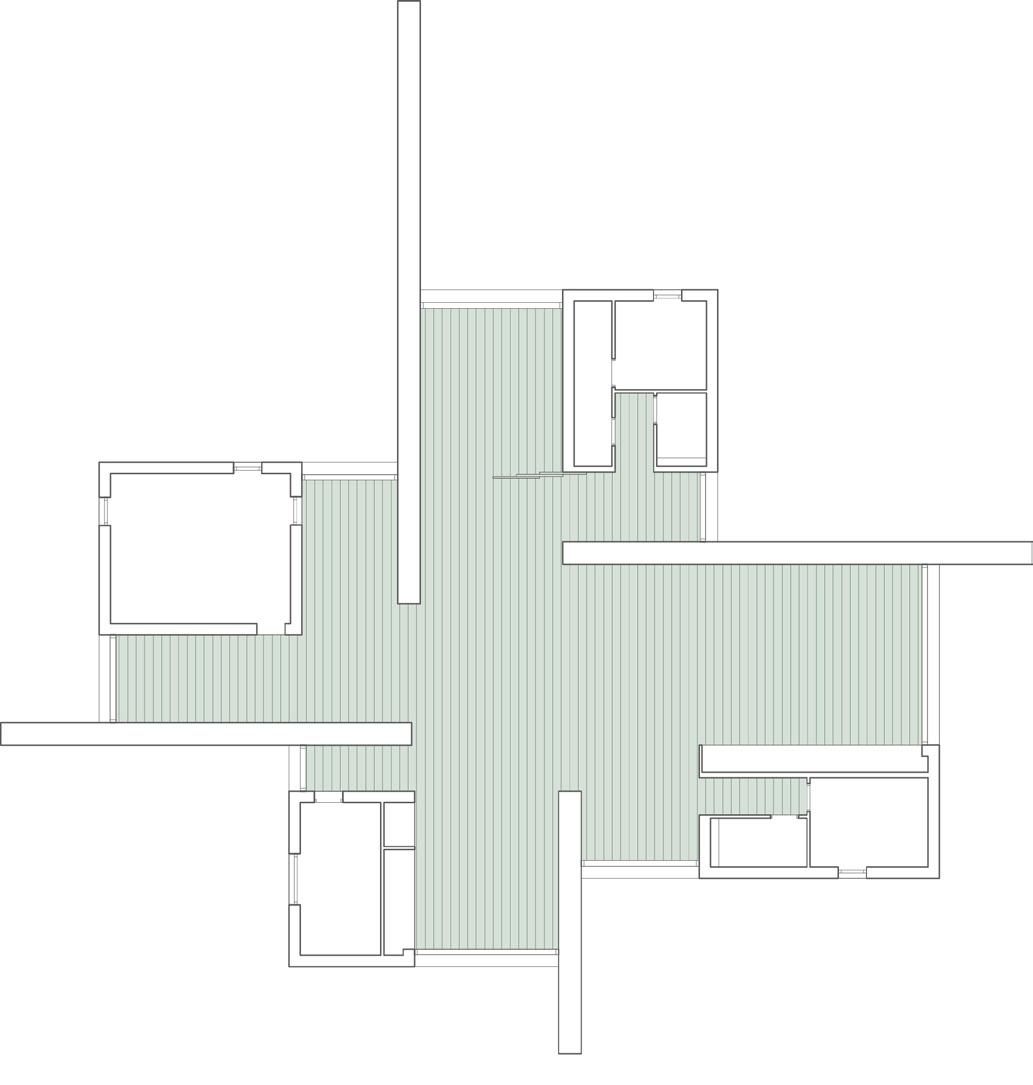

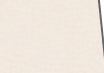

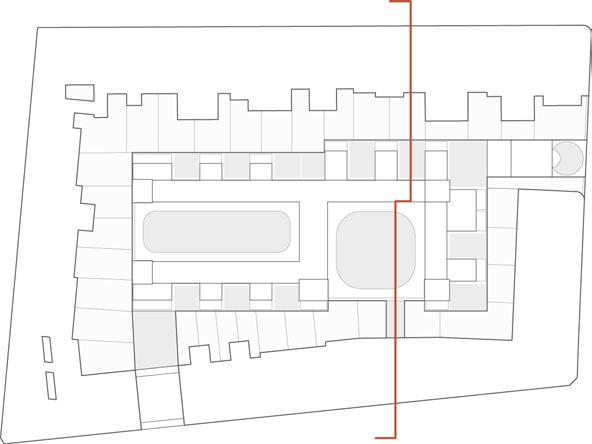

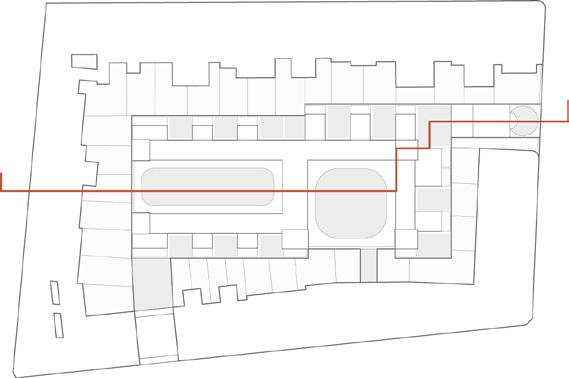

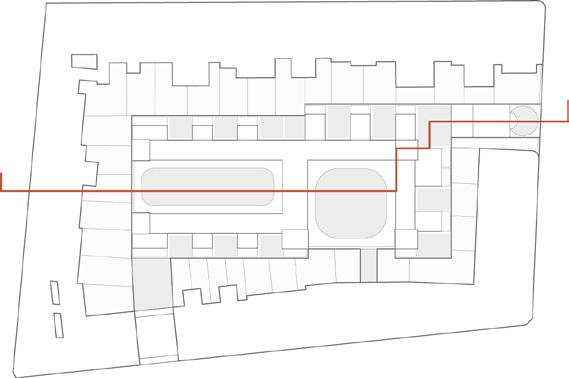

Ground floor plan

97 N

98

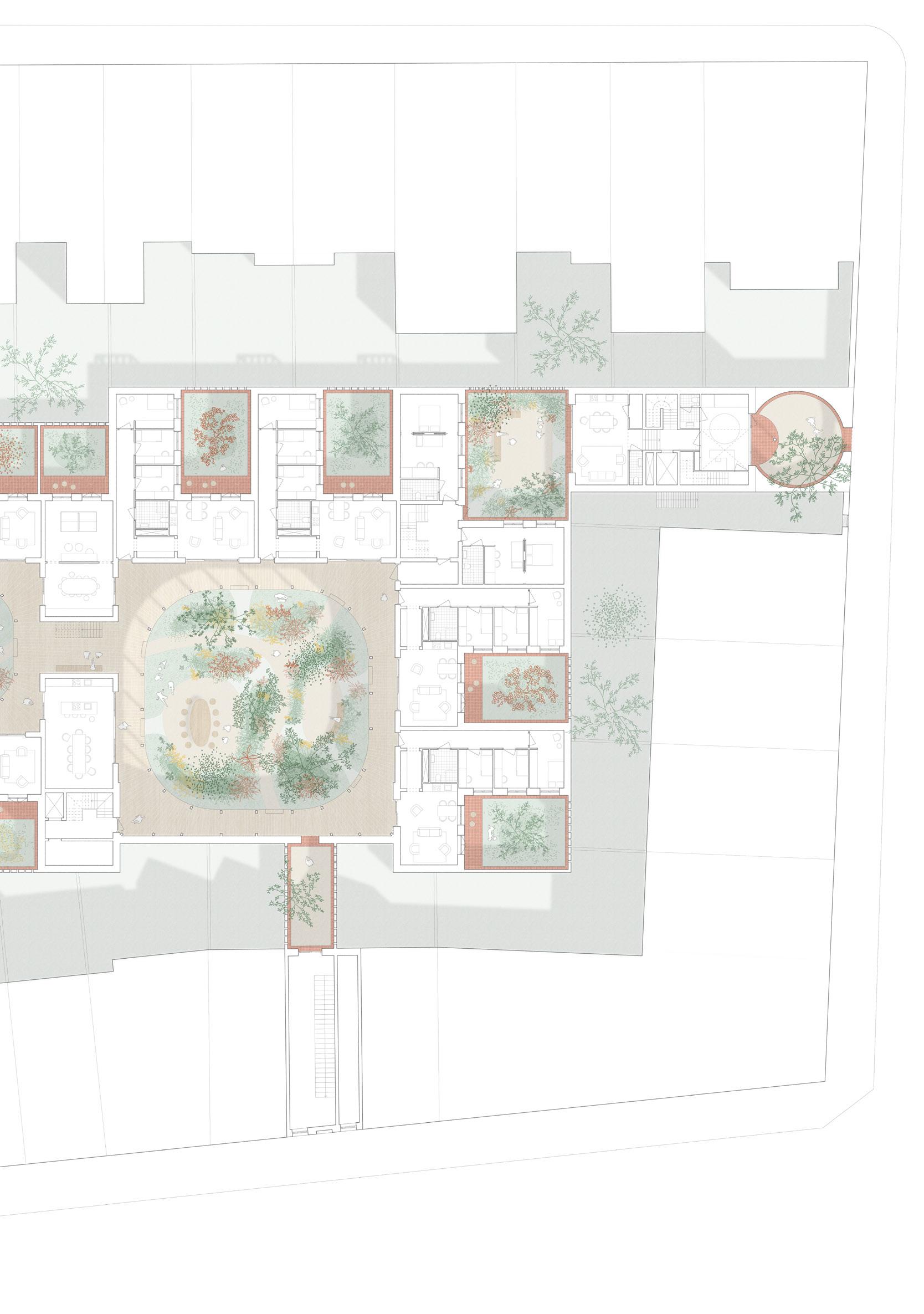

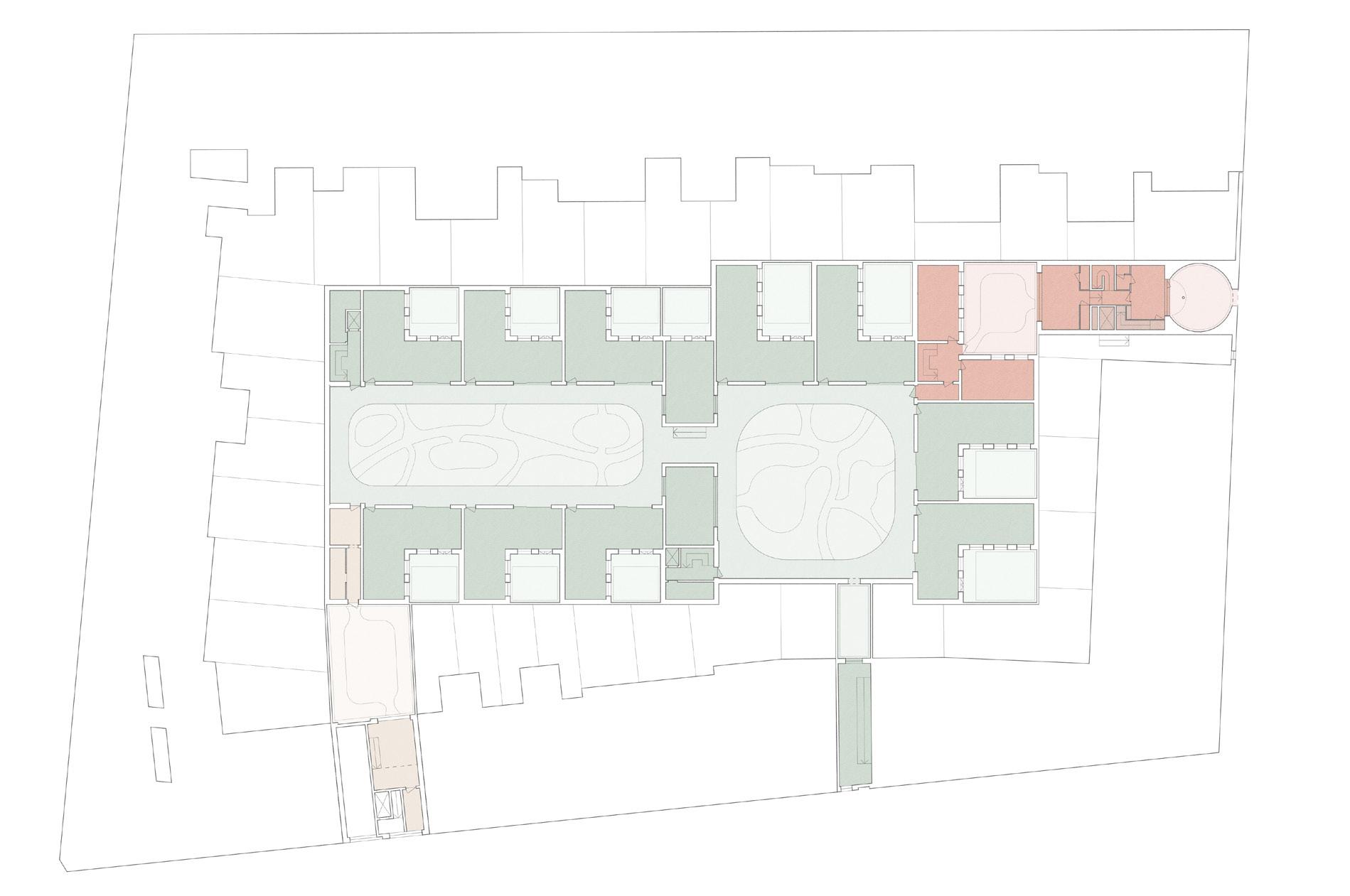

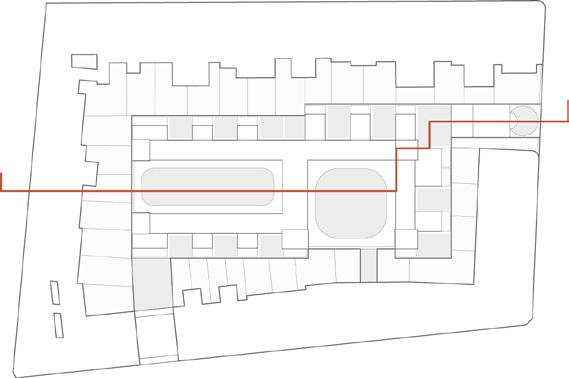

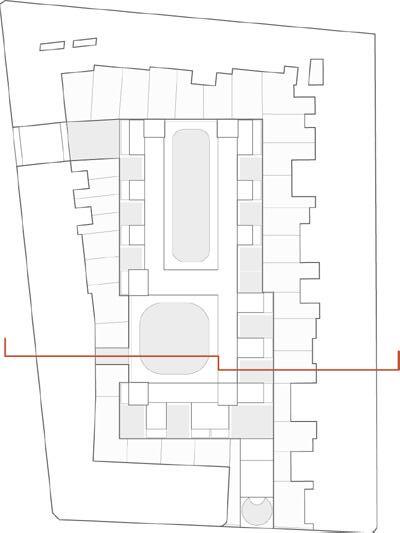

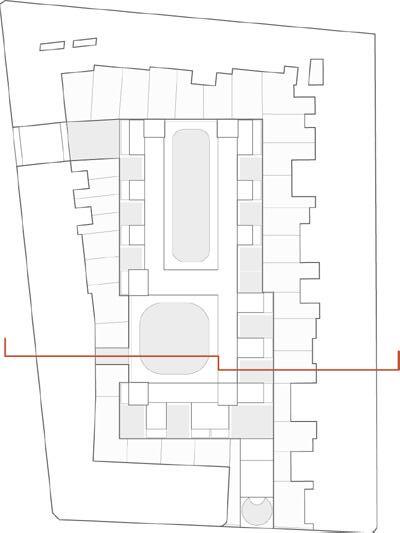

First and additional floors plan

99 N

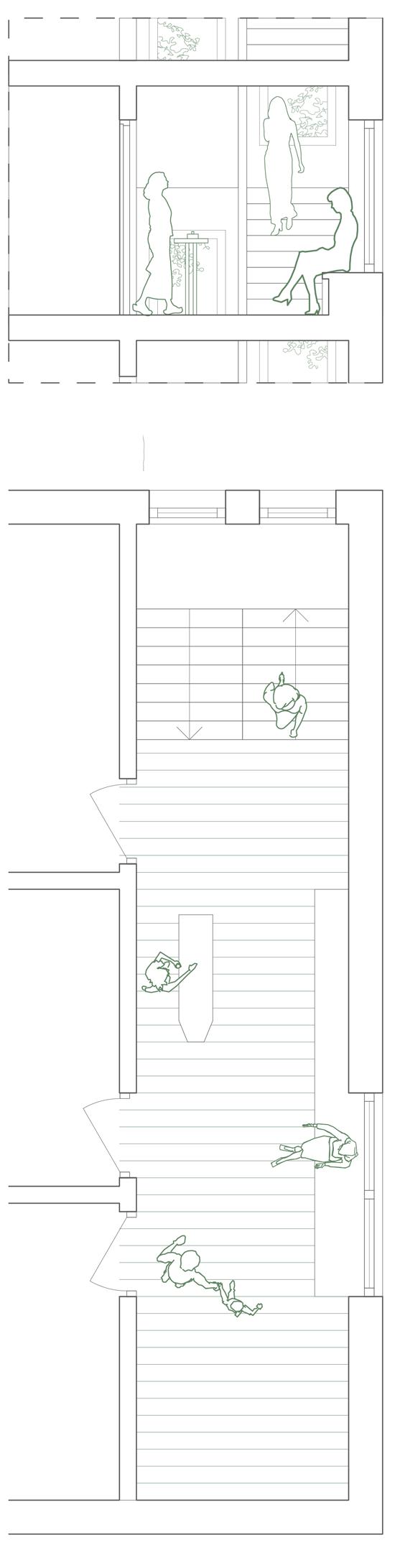

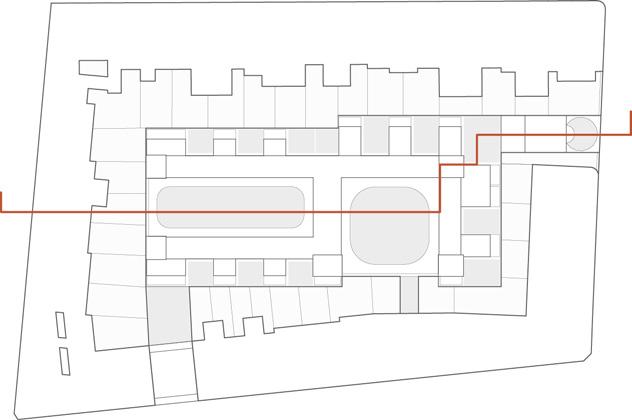

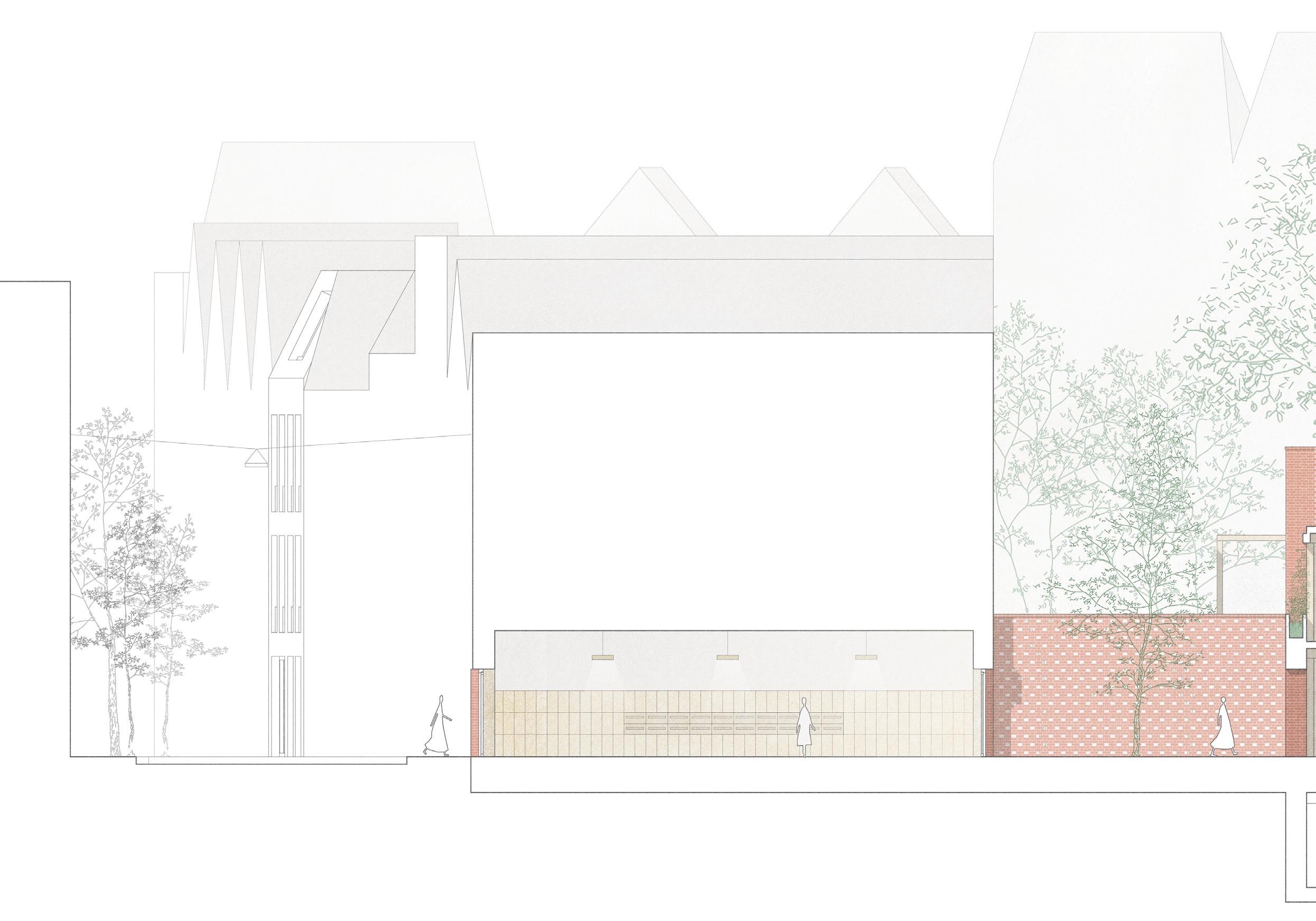

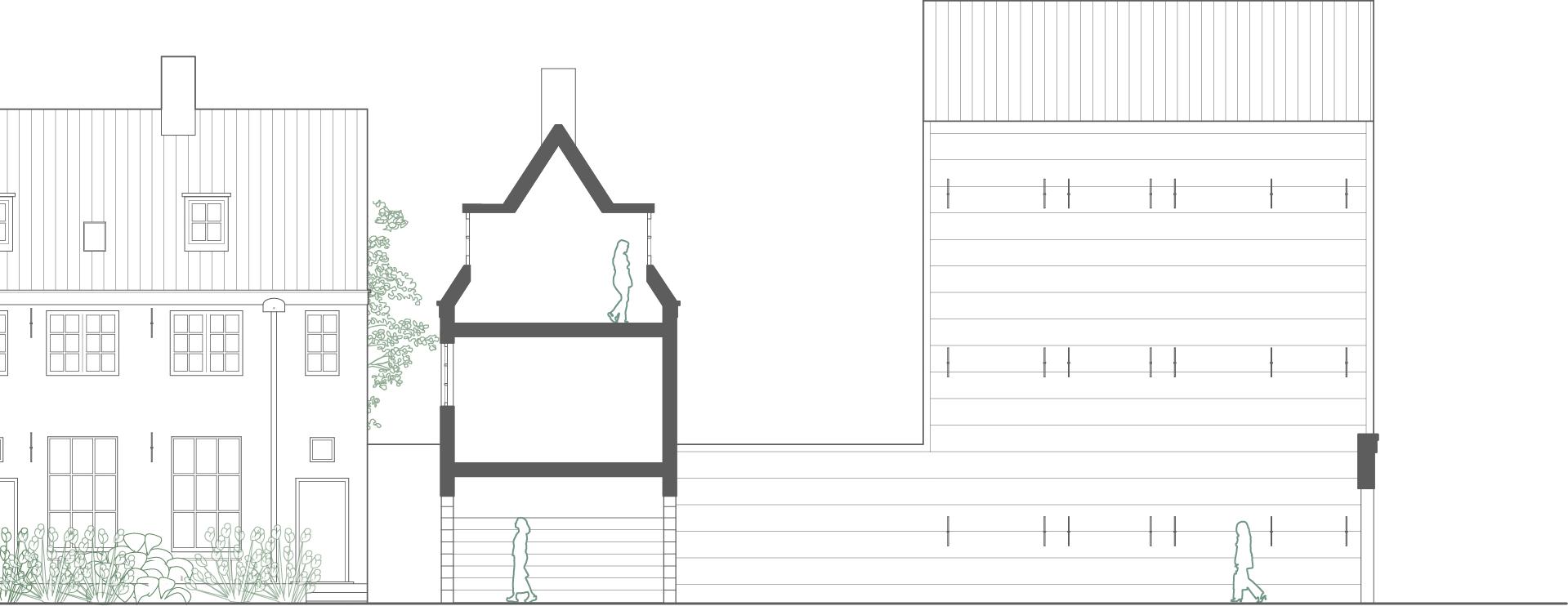

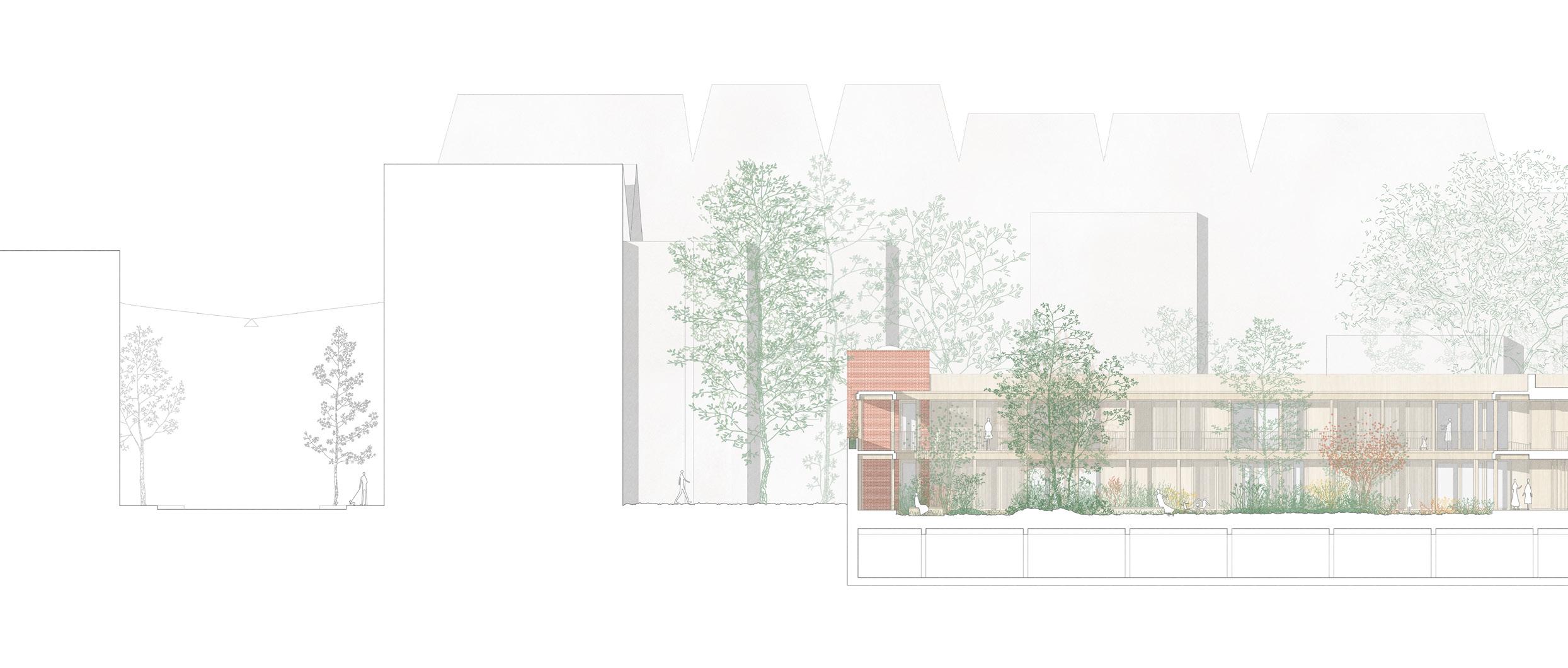

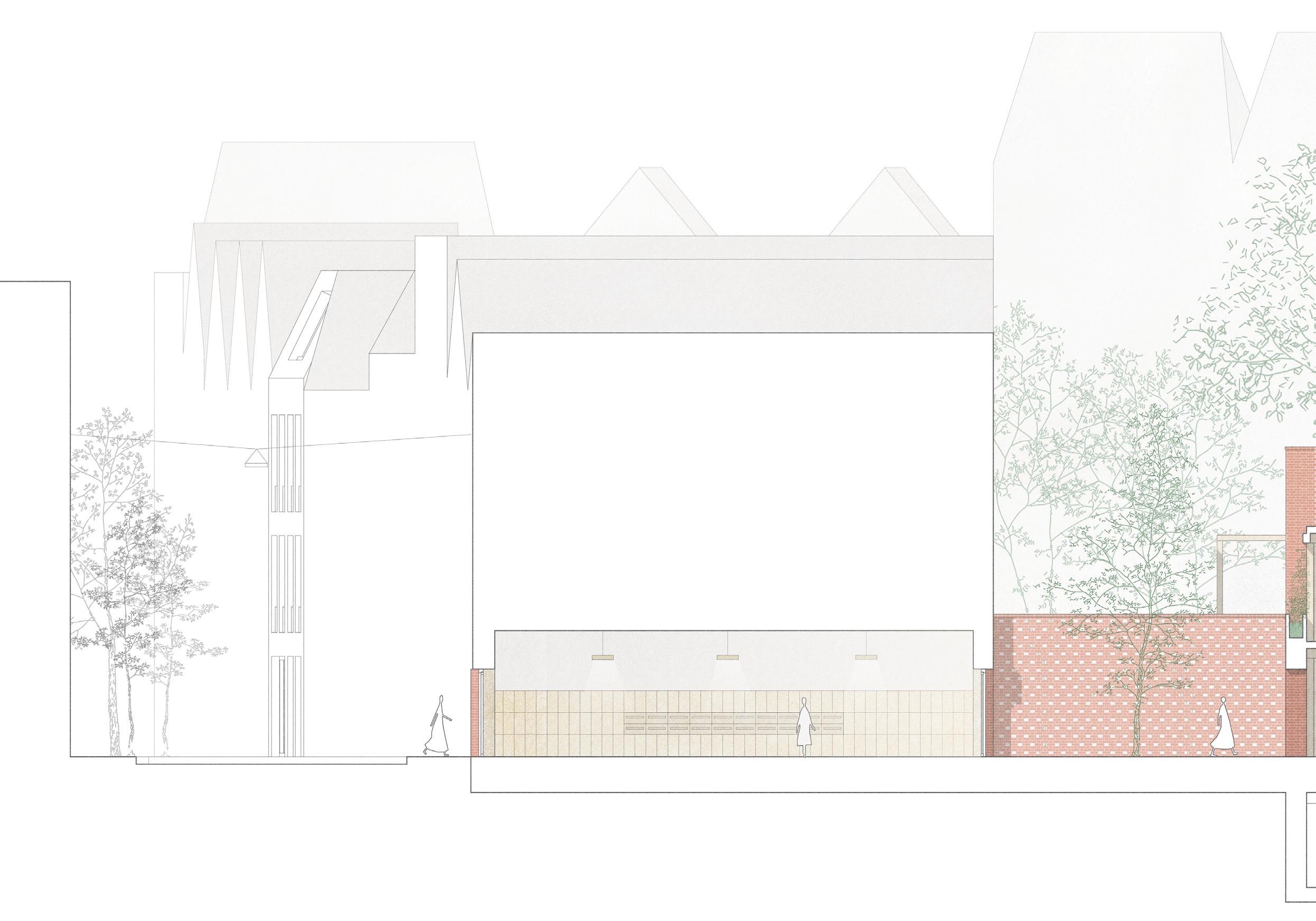

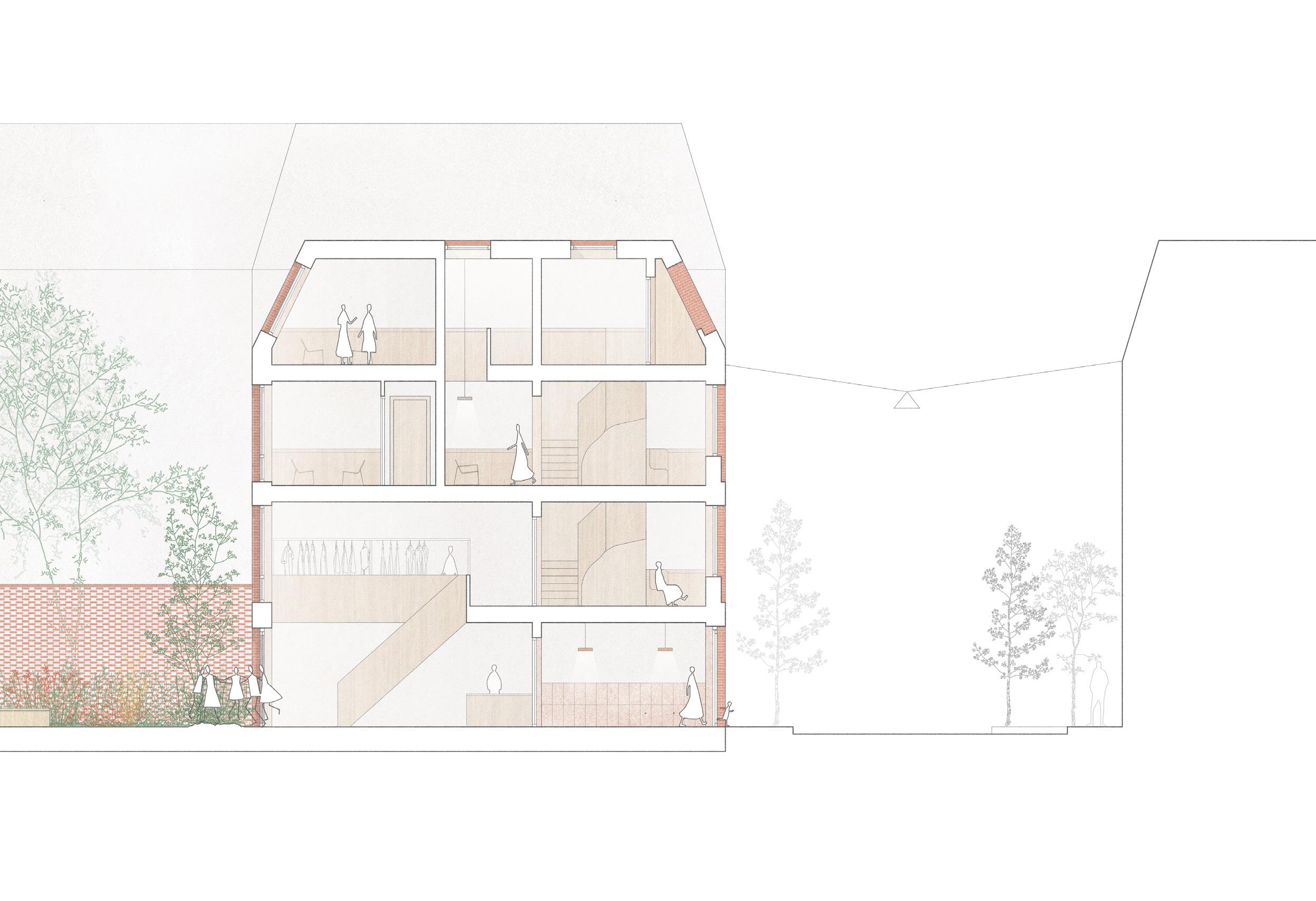

The arrival | longitudinal section

100

101

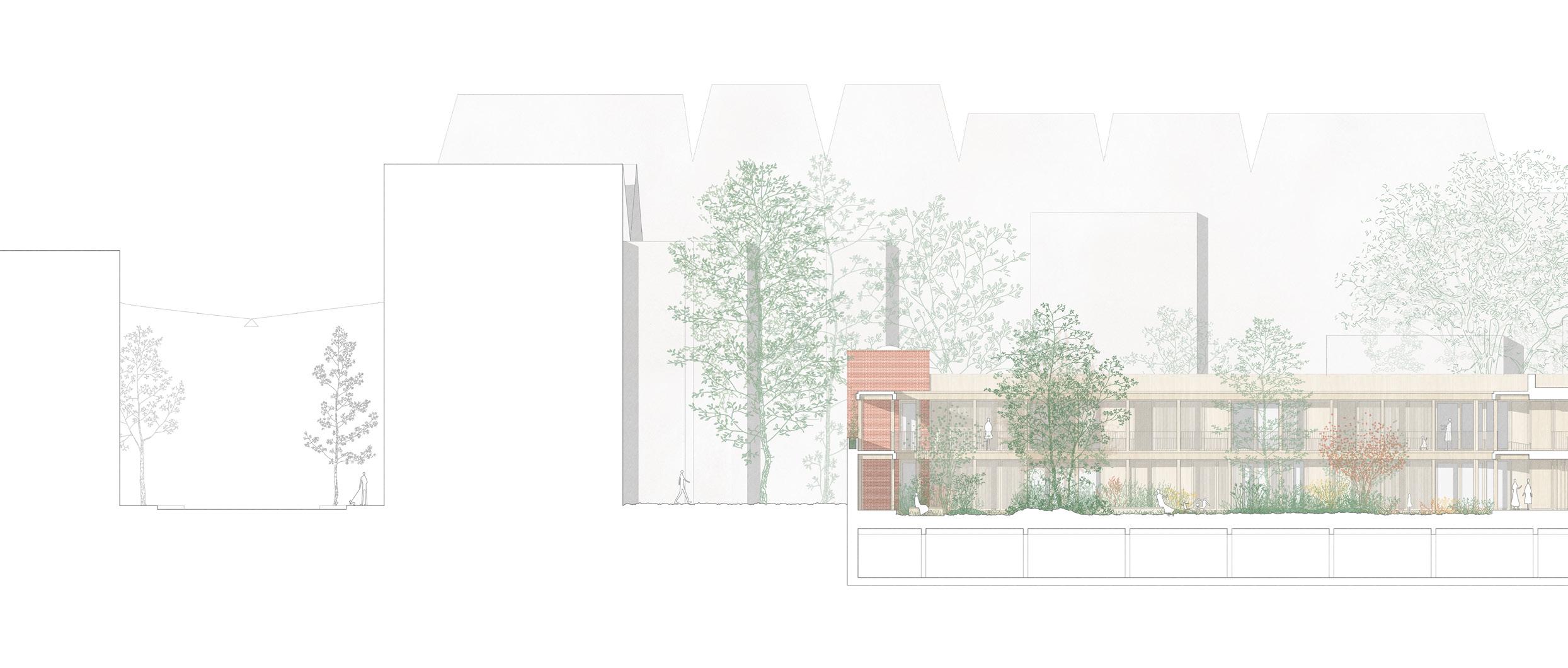

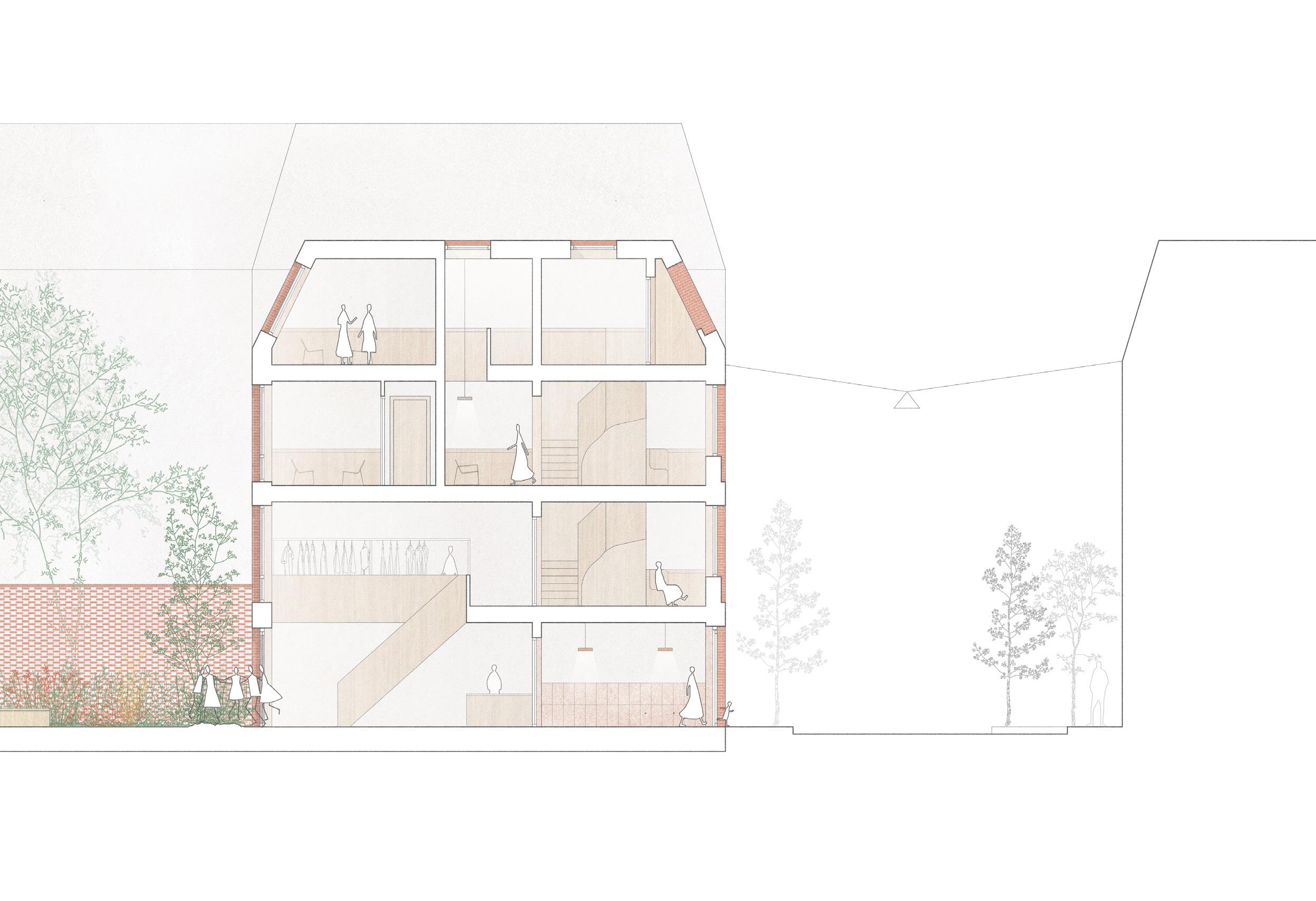

102 The path | transversal section

103

104

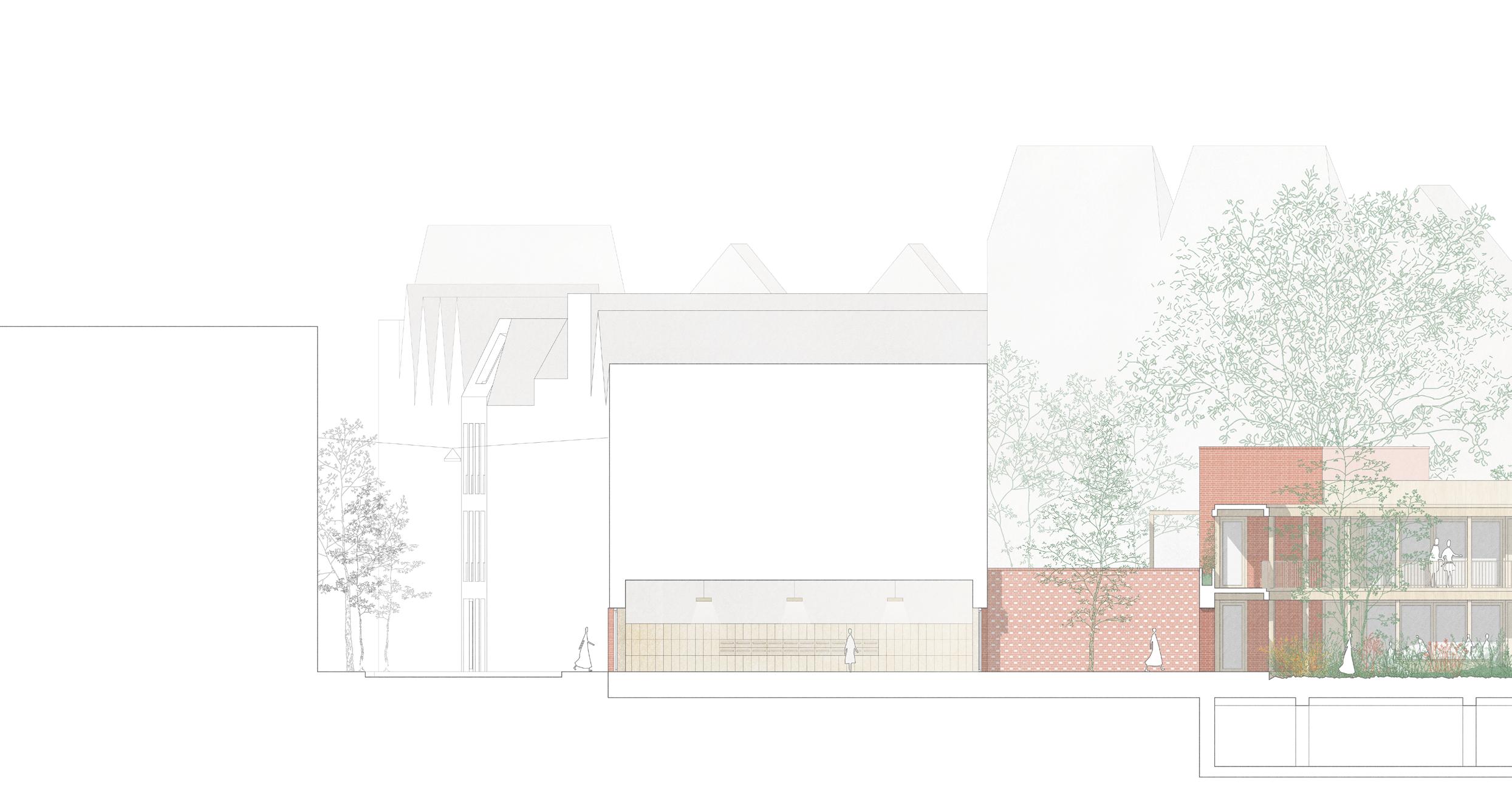

The departure | transversal section

105

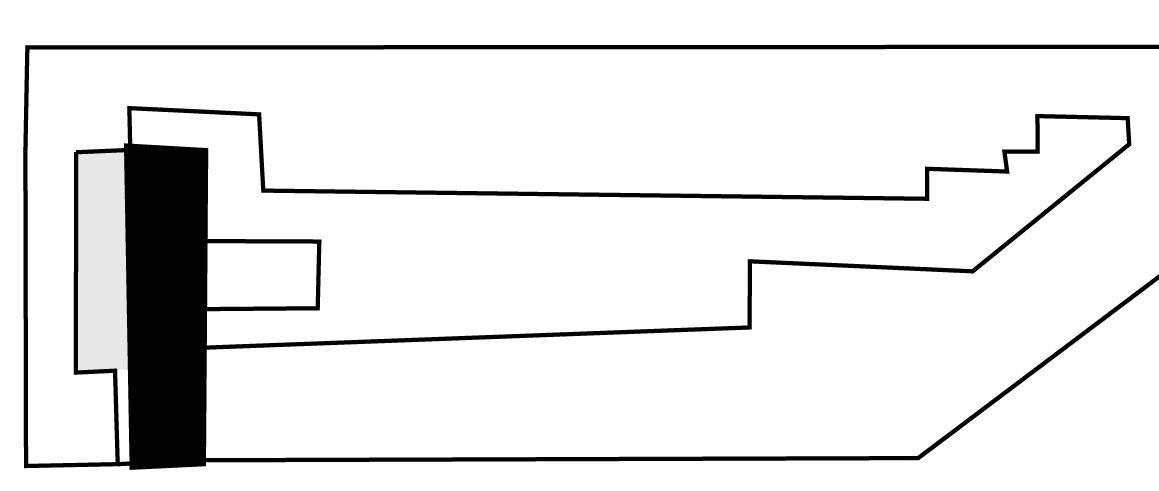

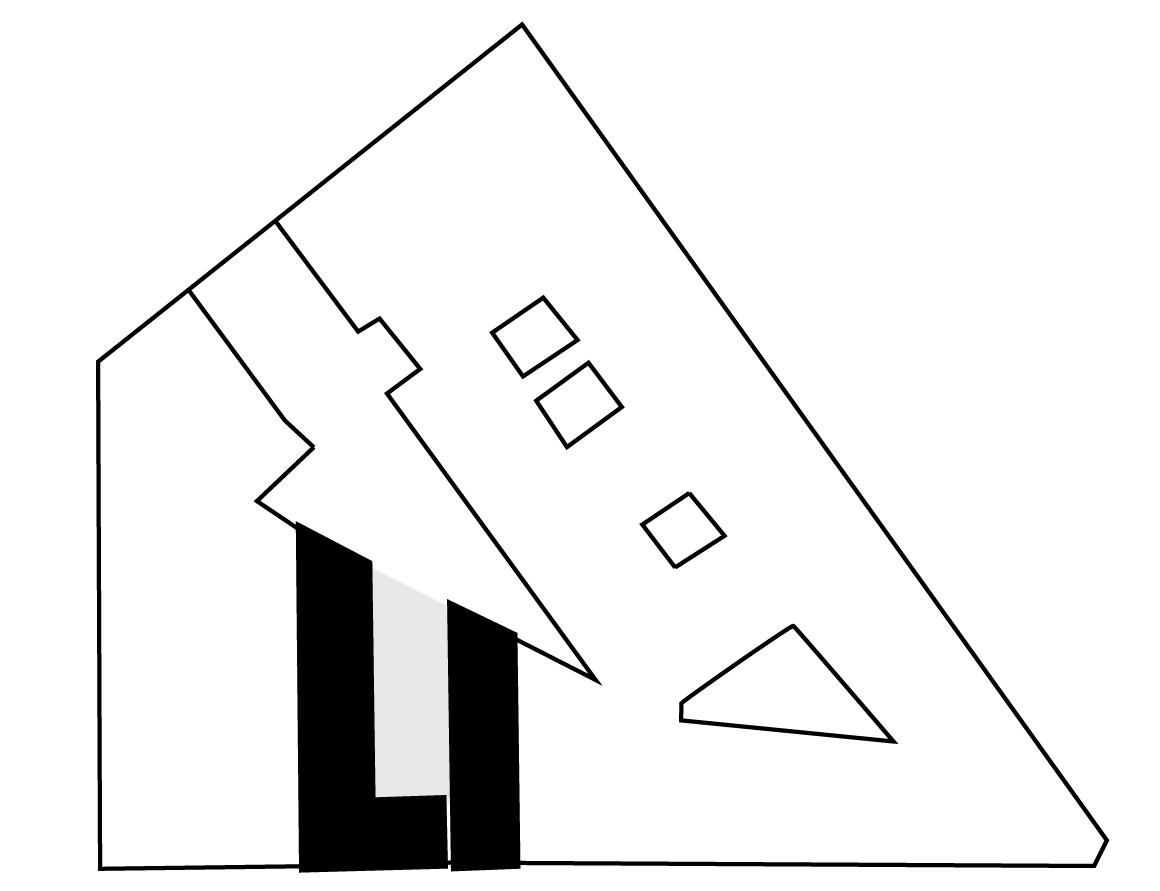

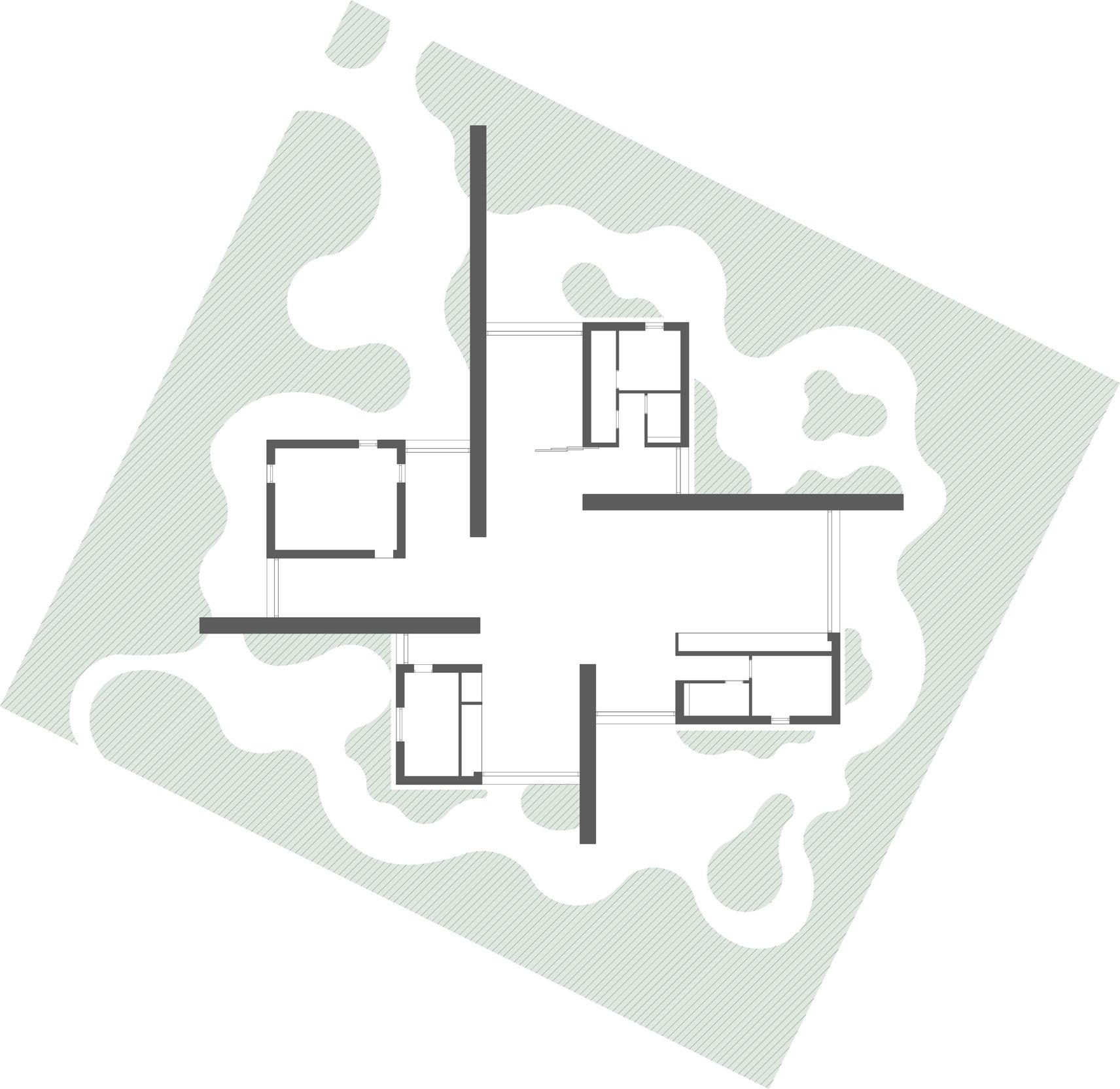

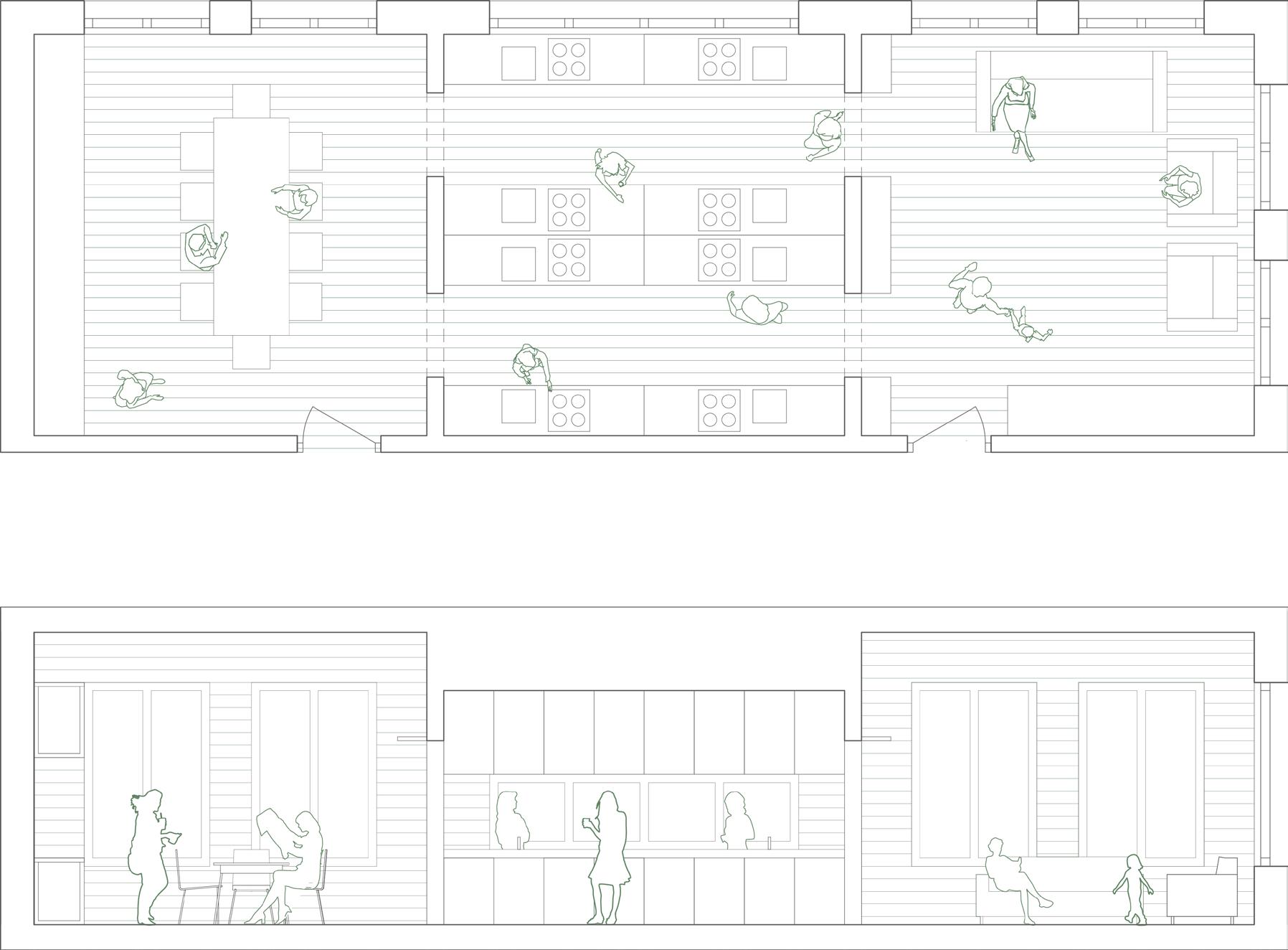

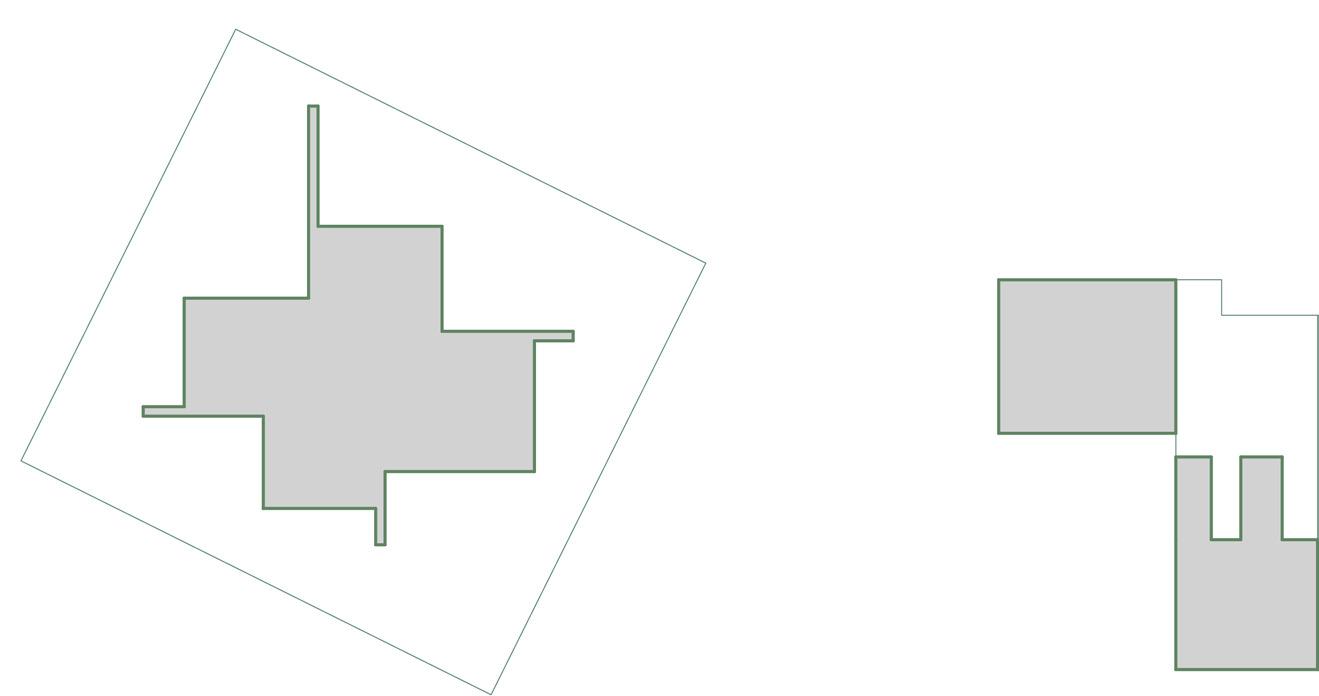

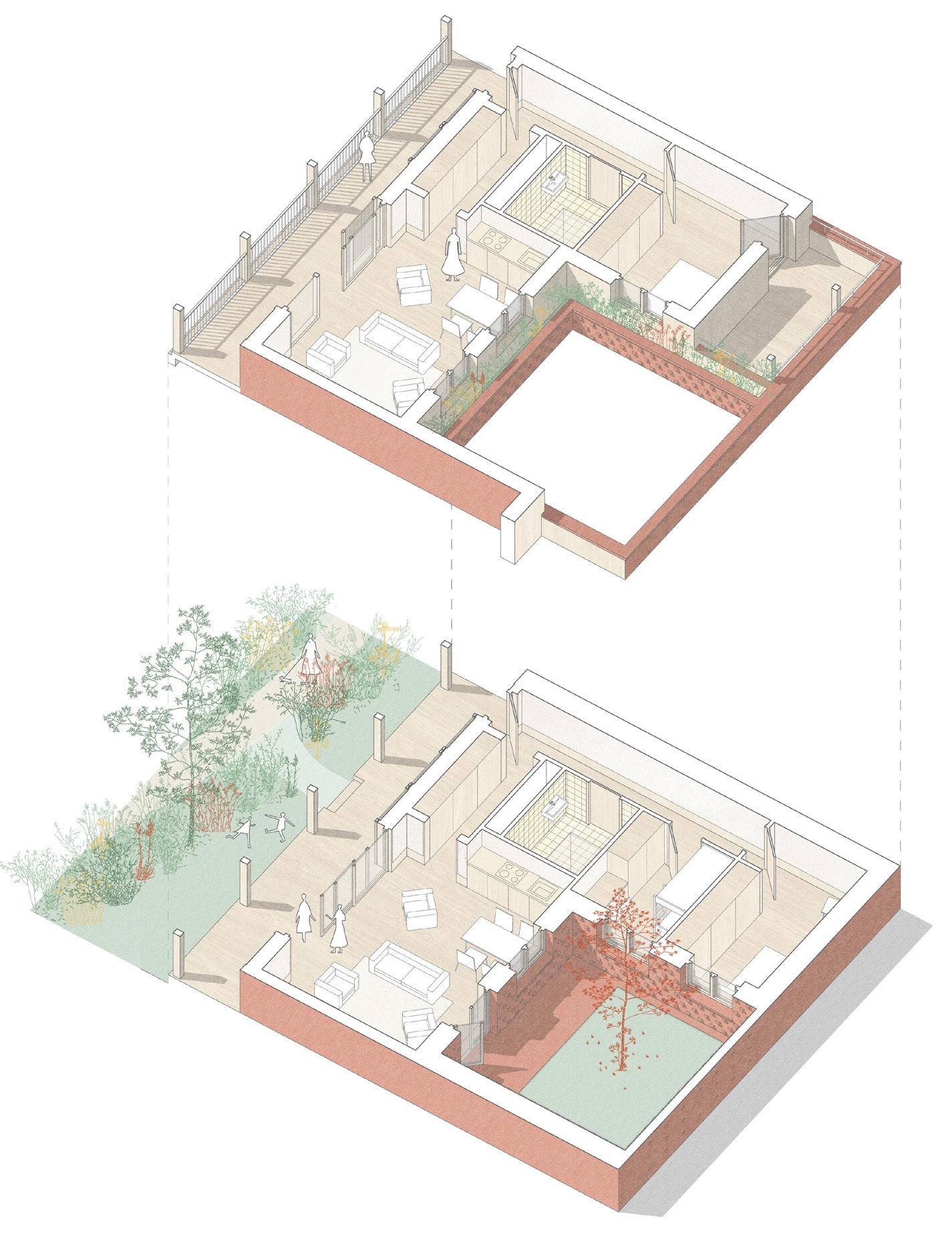

The housing types

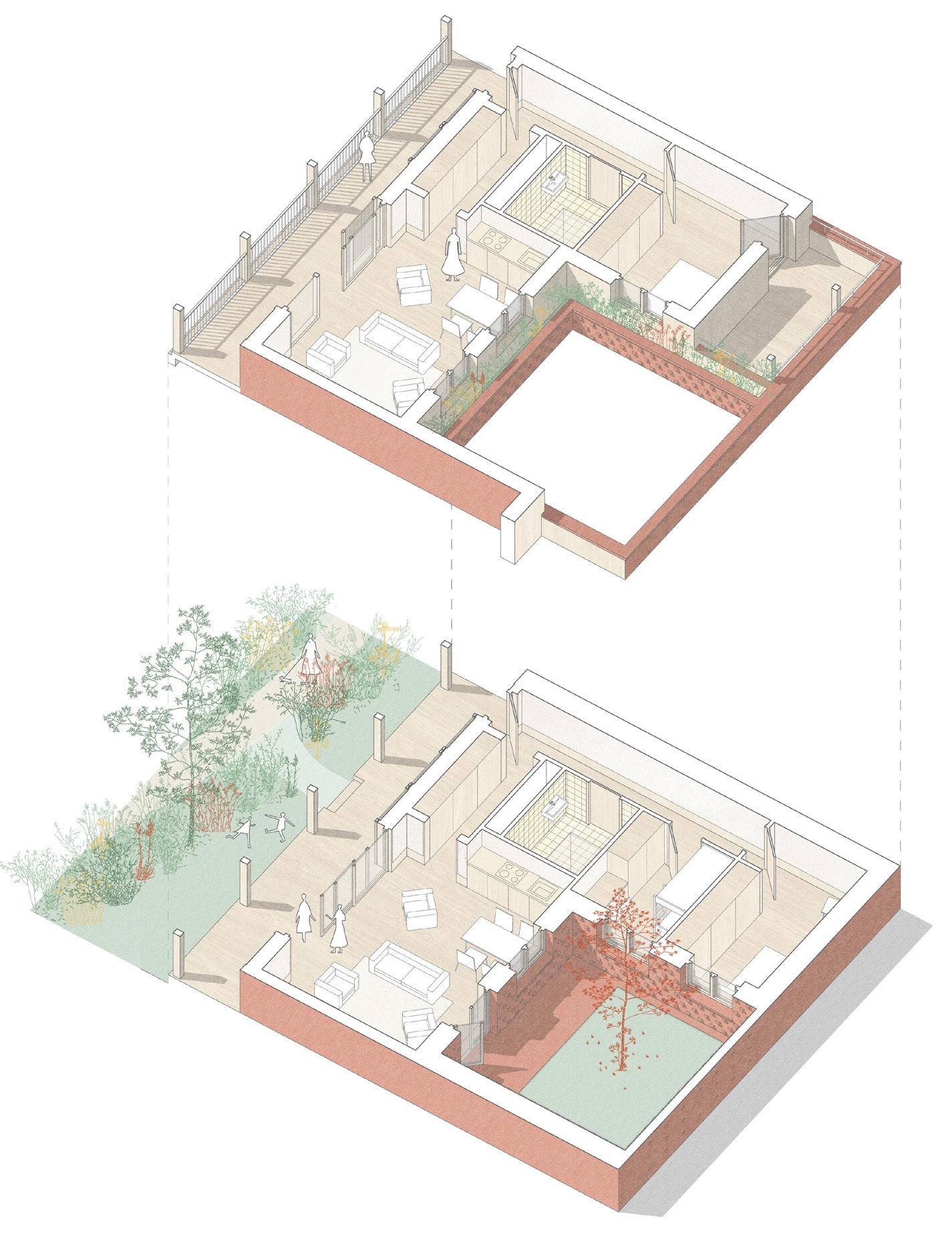

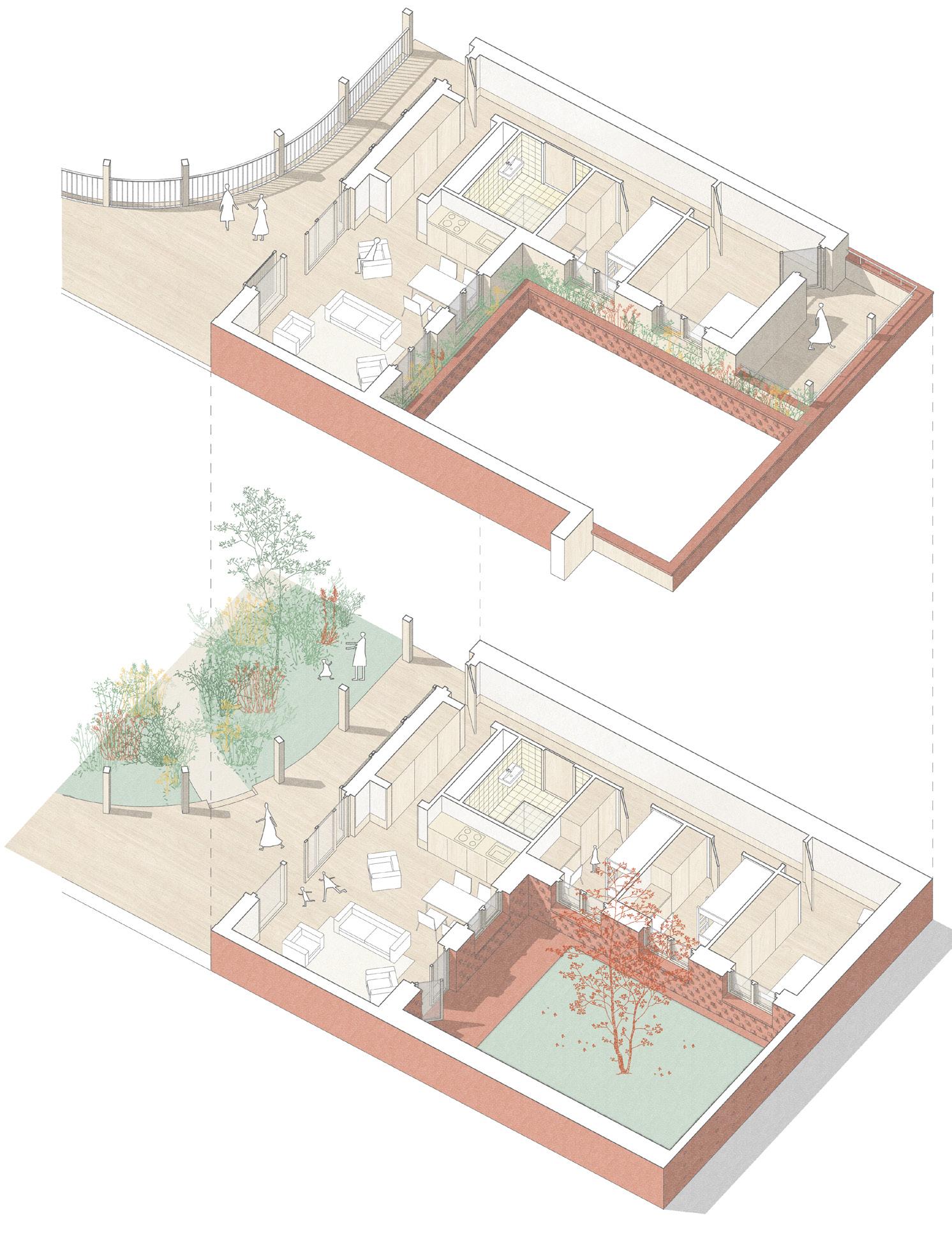

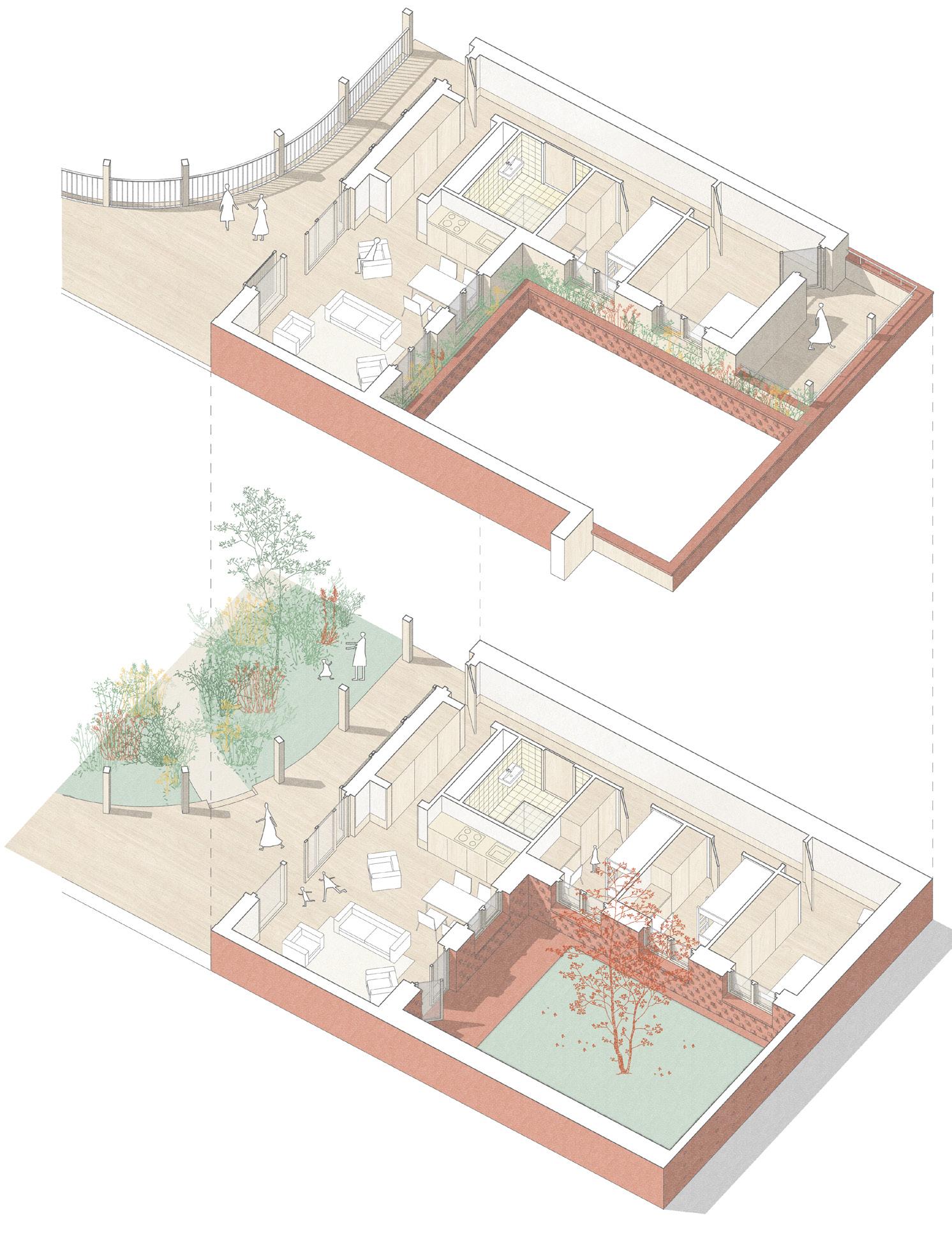

The diverse L-shaped housing types were designed to host varying family configurations of women in need of shelter. Large sliding doors allow the inhabitants to entirely open up and share experiences with a community around the collective courtyards. Wooden privacy screen allows them to also close off when introspective moments around the private garden of contemplation are needed.

106

107

108

109

Double oriented living rooms on ground floor and first floor, connected to both the collective gardens of paradise and the private gardens of contemplation.

110

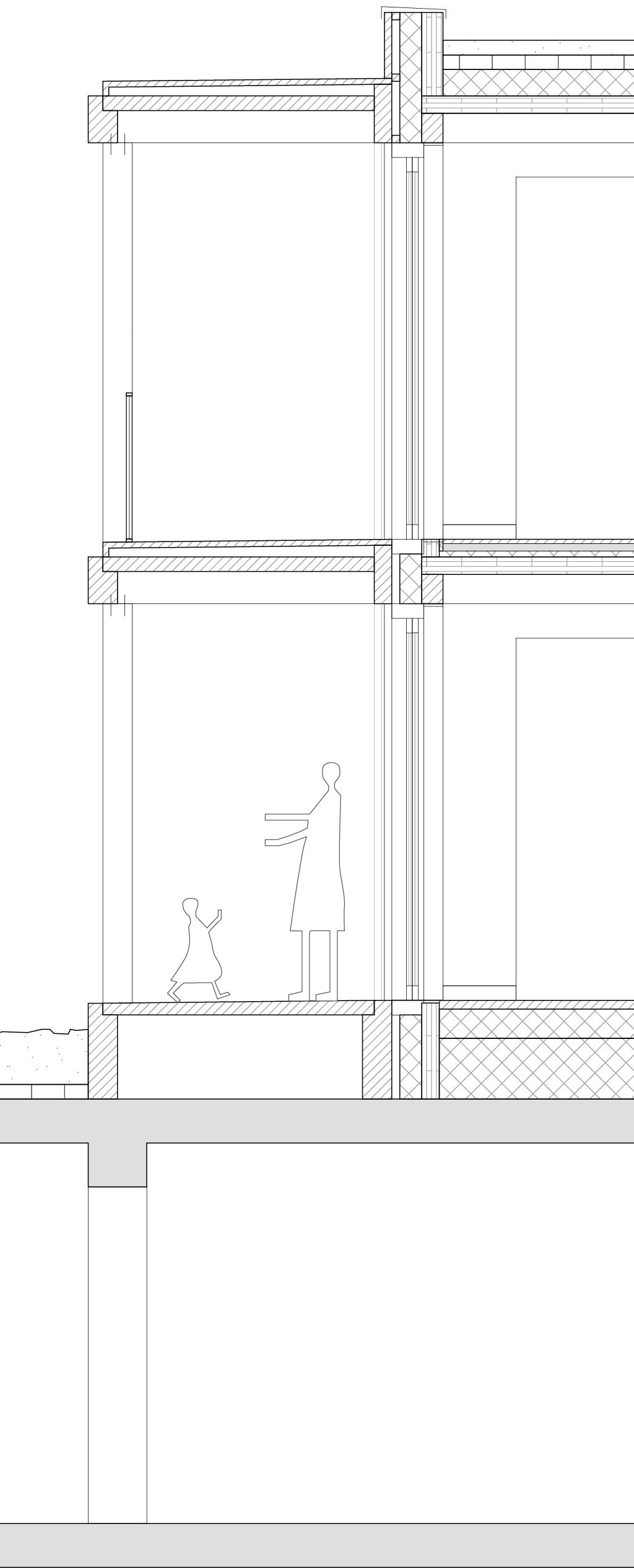

1 6 7 5 9 10 8 4 3 2

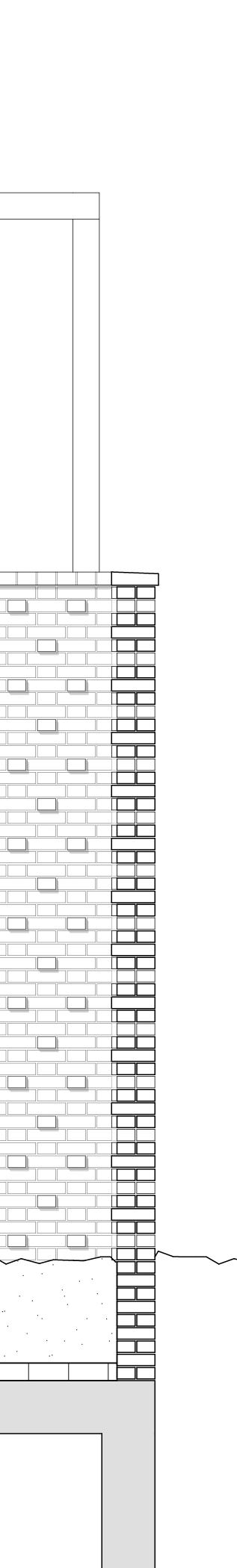

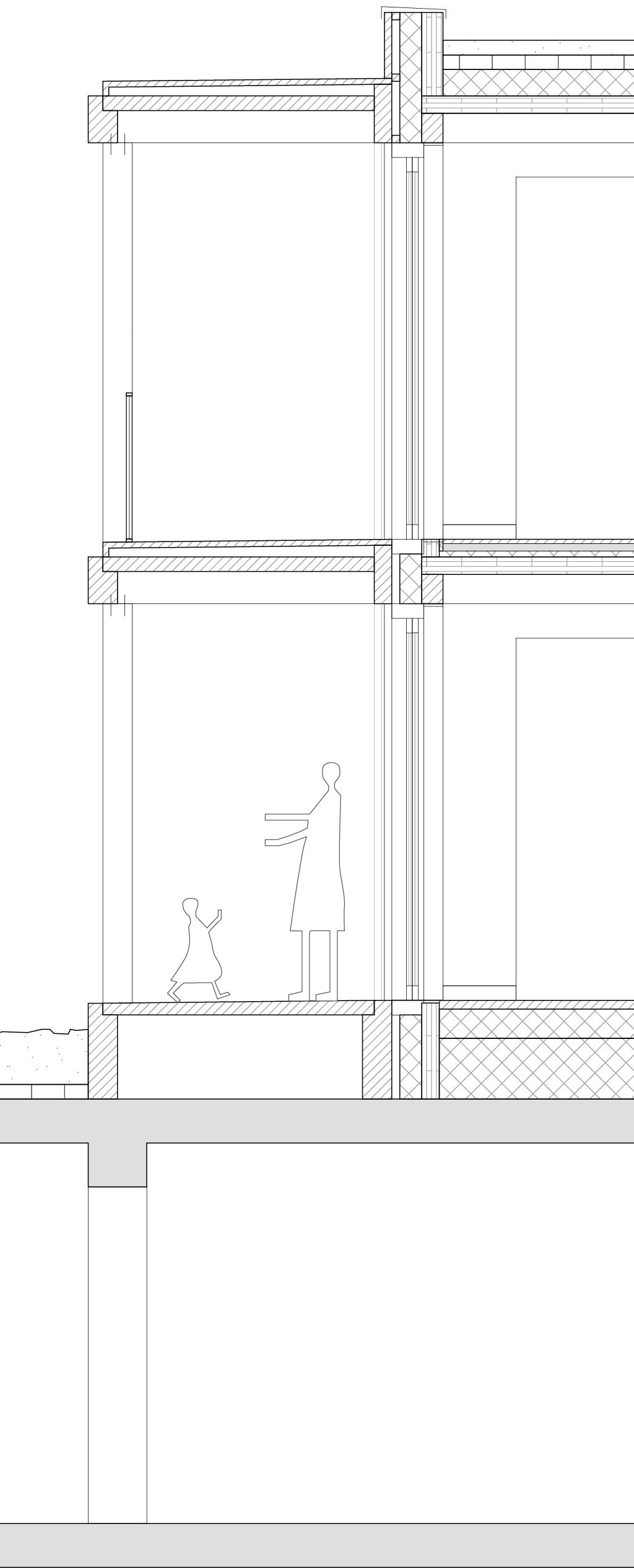

Facade fragment garden of paradise

1. CLT detention roof

2. Sliding Oak privacy screens

3. Oak sliding doors

4. CLT wall, insulation, oak panels

5. Aluminium balustrades

6. Oak deck system

7. Oak glulam collumns and beams

8. Wooden flooring, floating floor CLT slab, oak glulam beams

9. Detention garden

10. Concrete basement

111

112

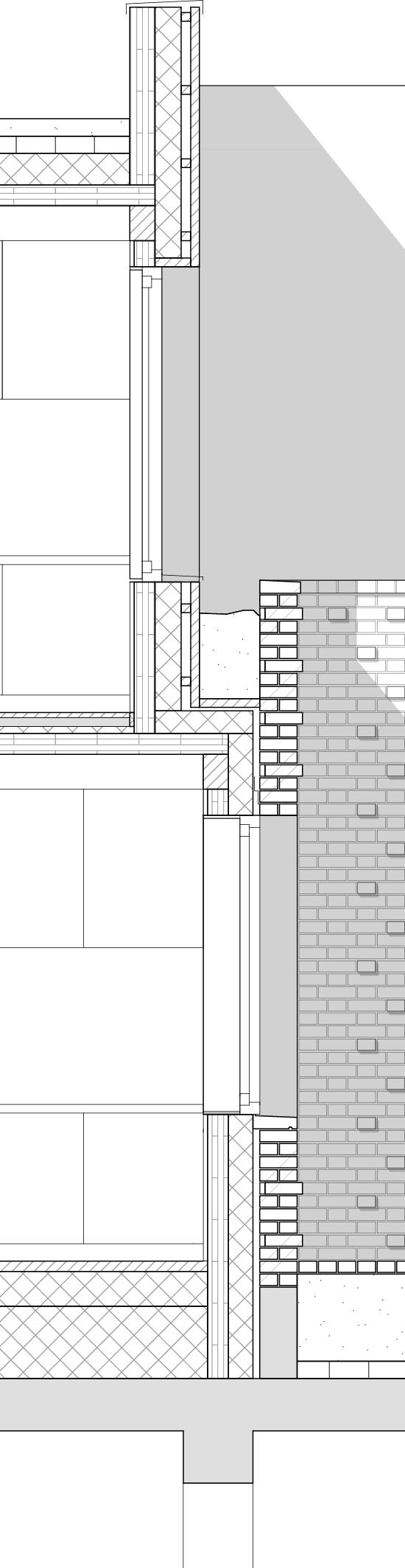

1 6 4 7 5 3 2

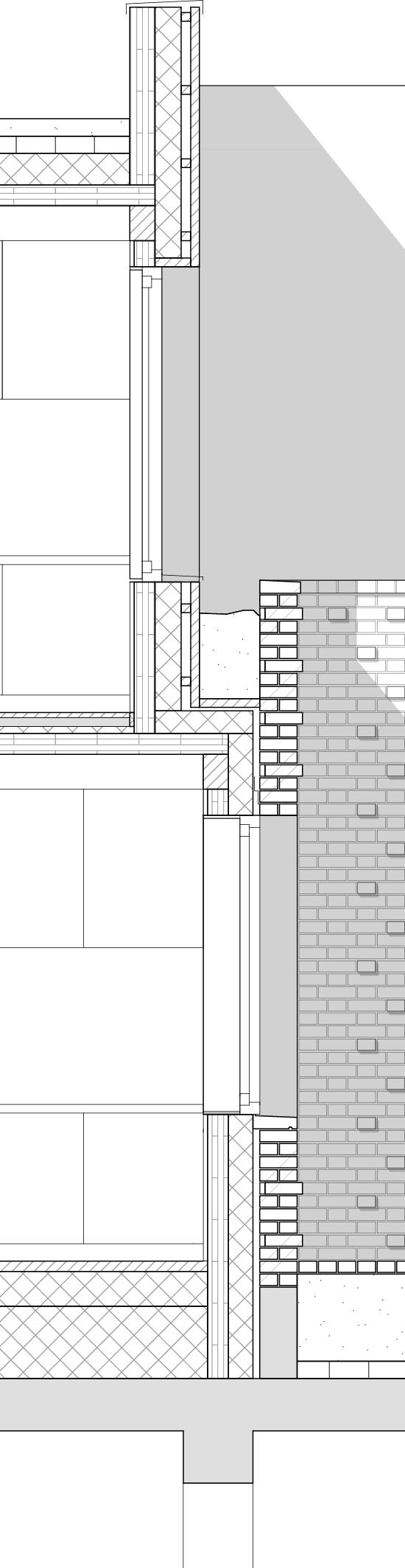

Facade fragment garden of contemplation

1. CLT detention roof

2. CLT wall, insulation, oak cladding

3. Oak window frames

4. Planter

5. Wooden flooring, floating floor CLT slab, oak glulam beams

6. CLT wall, insulations, terra cotta color brick, thick format, flamish bond with sticking out headers

7. Concrete basement

8. Open brickwork garden wall, terra cotta color, thick format, flamish bond with sticking out headers

9. Detention garden

113

8 9

114

115

116

06. From arrival to departure: A journey through one's stay in the shelter

A shelter is a temporary home. In the limited time women and their children stay, they go through a recovery process, experiencing different narratives within the building. While designing, the various moments of one’s stay and the daily life in the shelter were imagined as a sequence of spaces.

A journey from arrival to departure that could last from a couple of weeks to a year. Inspired by the understanding of the role transitions and gradations between spaces play in the Dutch hofjes in the definition of the atmosphere of those spaces, the designed narrative gives special attention to transitions. Between the diverse program components, the shelter and the city and the spaces dedicated to communal or individual experiences. The following chapter illustrates the most defining moments of this journey.

117

118

When arriving for the first time, the institutional tower makes the shelter recognizable and visible from a considerable distance (01). The almost monumental volume communicates the strength of this institution and the protective character of the spaces found behind the front door.

While approaching it, the first monumental impression gives place to a new experience. The circular arrival square welcomes new comers embracing them and a beautiful existing tree, while separating physically and psychologically the reality of the city and the new process about to start (02).

Under a double height space the reception desk can be found, while a lowered ceiling area offers a comfortable corner to sit on a designed piece of furniture. The mezzanine of this reception space creates a private setting where intake conversations can take place. If in need of help, the new inhabitants of the shelter cross a door followed by a long corridor getting gradually closer to a lush colorful garden, arriving in a domestic, recognizable living room.

For a couple of nights, women who have just arrived sleep in one of the emergency bedrooms, while their situation is analyzed. Not being allowed to leave the building on these first days, the first collective garden of paradise offers an opportunity to be outside while finding company and distraction with other children and women (03).

When having their situation fully analyzed, the new inhabitants are invited to cross a transitional space that marks the start of a new chapter in their stay: the moment in which they get their own home. This next step starts with the first impression of the lush and lively collective courtyard (04).

119

The arrival | zoom in floorplan

120

121

The arrival | zoom in section

122 01 The institutional tower | main access | arrival sequence

123 02 The arrival square | arrival sequence

124

03 The emergency beds collective garden of paradise | arrival sequence

125

04 The collective courtyard | garden of paradise | arrival sequence

126

127 The collective courtyards | zoom in section

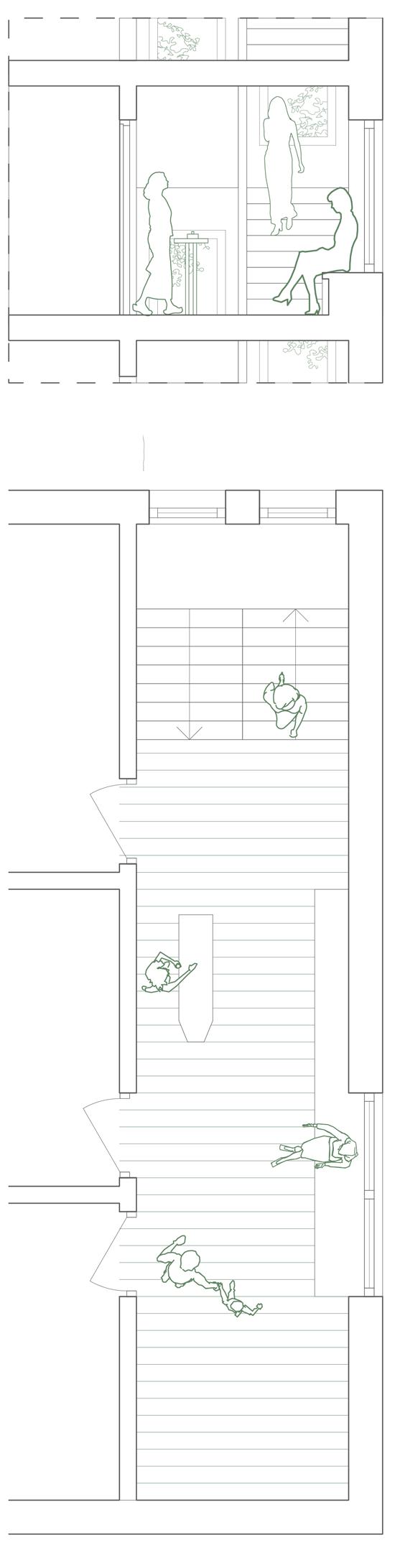

After getting their own home, women do not approach the building from its official institutional front door, but via the back small scale street, where a camouflaged door, part of the plinth of a historical building can be found (05). The access to the housing units is domestic and normalized. The entrance hall and a transitional garden gives access to the larger collective courtyard.

The collective courtyard offers various route options towards the dwellings. One can opt for a private walk through the garden in between dense vegetation or a walk through the gallery passing by the shelter’s collective kitchen and living room, where spontaneous encounters with others may take place (06).

While living in the shelter, women may experience days of sharing experiences and difficulties with others, opening their living rooms entirely to the collective courtyards while children could play outside (07). On days where privacy is needed, one can close off and live around their own garden of contemplation. Reflecting and observing the passage of time through the changing light and shadow on the brick façade or the seasonal transformations of a fruit tree in the center of the gardens (08).

128

129

The path | zoom in floorplan

130

131

|

in

The path

zoom

section

05 Daily entrance to shelter through Govert Flinckstraat | path sequence

132

133

05 Daily entrance to shelter through Govert Flinckstraat | path sequence

06 Access to housing units through collective couryards | path sequence

134

07 Living room open to the communal live of the collective couryards | path sequence

135

08 Living room open to introspective garden of contemplation | path sequence

136

137 08 The garden of contemplation | path sequence

138

At first daily, later weekly or whenever wished one walks through the long collective courtyard (09), crossing a transitional space and moving towards meetings scheduled with social workers or phycologists. On the way to and back from the appointments, one is invited to find a private seat behind the stairs with direct view to the outer world. A glimpse to regular city life while being alone and reimagining the future.

It is also from this building that in an official or unofficial event women may say goodbye to the many people who have supported them throughout their stay. Crossing an until now undiscovered door and hallway, one leaves the shelter for the last time looking towards the future, back to normal life (10).

139

|

The departure

zoom in floorplan

140

141

|

in section

The departure

zoom

09 The collective courtyard | garden of paradise | departure sequence

142

10 The departure through the Govert Flinckstraat | departure sequence

143

Violence against women report World Health Organization, 2018

Halfjaarrapportage Veilig Thuis Amsterdam Amstelland, 2021

Violence against women: an EU-survey 2014

De Oranje Huis aanpak Els Kok, 2016

Het Hofje: Bouwsteen van de Hollandse Stad 1400-2000 Willemijn Wilms Floet

Handboek voor Hedendaagse Hofjes Peter van Assche, Peter Zuiderwijk, Sander van der Ham, Kirsten Hannema, Marieke van Diepen, Dennis Lohuis, Sarah Carlier, Peik Suyling and Jeroen van Mechelen

The Enclosed Garden: History and development of the Hortus Conclusus and its reintroduction into the present-day urban landscape , Rob Aben, Saskia de Wit, 1999

Maggie's Architectural and Landscape Brief, 2014

CLT handleiding voor architecten en bouwkundigen, INBO

Blijf van m'n Lijf: 40 jaar vrouwenopvang (youtube)

Blijf groep: https://www.blijfgroep.nl

Maid: Hard work, low pay, and a mother's will to survive , Stephanie Land, 2019

144

07. Bibliography

Acknowledgments

For the support, inspiration and input many thanks to:

Marcel Lok

Hannah Schubert

Pnina Avidar

The Blijfgroep

My dear friends from the academy and D80 studio, where most of the development of this project took place.

Office Winhov

My Brazilian and Dutch families

Caro

Lizzy

Elena

Gwen

Niene

Roosje

Marcela

A very special thanks to my beloved partner Nout. My biggest supporter, who has been by my side during the whole intense academy experience. Without you I would never have come so far.

Alice Dicker Quintino dos Santos

Alice Dicker Quintino dos Santos