The Time to Act Is NOW

Responding to disasters

Tackling health needs

Restoring identity after war

one God • World • Human Family • Church June 2023

6 30

FEATURES

On Shaky Ground

Multiple crises intensify aid efforts in Syria text by Arzé Khodr with photographs by Raghida Skaff

Unconditional Care

Church-run clinics tend to Egypt’s poor text by Magdy Samaan with photographs by Hanaa Habib

Erasing Identity

Destroying culture to destroy a people by Olivia Poust

A Letter From Georgia

by Luka Kimeridze

Living a Christian Life in the Land of Jesus text by Michele Chabin with photographs by Ilene Perlman

DEPARTMENTS

38 4

12 CNEWA.org CNEWA1926 CNEWA

Connections to CNEWA’s world

The Last Word: Perspectives From the President by Msgr. Peter I. Vaccari

t An icon decorates the nave of the Greek Orthodox church of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary in Kafr Yasif, Israel.

one CNEWA CNEWA1926

6

18 26

Back: A toppled dome lies amid the ruins of the Virgin Skete of Sviatohirsk Lavra in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine. The hermitage was destroyed by missile attacks in May 2022.

Photo Credits

Front cover, Tamara Abdul Hadi; pages 2, 30, 32-37, Ilene Perlman; pages 3 (lower left), 18-21, 24 (inset), back cover, Konstantin Chernichkin; page 3 (top), CNS photo/Paul Haring; pages 3 (upper left), 4, 6-11, Raghida Skaff; pages 3 (upper right), 29 (top), Molly Corso; pages 3 (lower right and far right), 12-17, Hanaa Habib; page 5 (left), courtesy Kolbe Hotel Rome; page 5 (right), Timothy McCarthy; page 22, Michael J.L. La Civita; page 23, Jesuit Refugee Service; page 24, Raed Rafei; pages 26-27, Zurab Tsertsvadze/ AFP via Getty Images; page 28 (upper left), Nino Gambashidze; pages 28 (upper right), 28-29, 29 (bottom), Antonio di Vico; page 38, CNS photo/Ali Hashisho, Reuters; page 39, the Rev. Ammar Yako.

ONE is published quarterly. ISSN: 1552-2016

CNEWA

Founded by the Holy Father, CNEWA shares the love of Christ with the churches and peoples of the East, working for, through and with the Eastern Catholic churches.

Give

The reach of

worldwide work of

Catholic Church is tremendous. When you remember CNEWA in your will, you contribute to the church’s constant efforts to answer the question put to Jesus: “And who is my neighbor?”

CNEWA connects you to your brothers and sisters in need. Together, we build up the church, affirm human dignity, alleviate poverty, encourage dialogue — and inspire hope.

Publisher

Msgr. Peter I. Vaccari

Editorial

Michael J.L. La Civita, Executive Editor

Laura Ieraci, Assistant Editor

Olivia Poust, Editorial Assistant

David Aquije, Contributing Editor

Elias D. Mallon, Contributing Editor

Creative

Timothy McCarthy, Digital Assets Manager

Paul Grillo, Graphic Designer

Samantha Staddon, Junior Graphic Designer

Elizabeth Belsky, Ad Copy Writer

Officers

Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan, Chair and Treasurer

Msgr. Peter I. Vaccari, Secretary

Editorial Office

1011 First Avenue, New York, NY 10022-4195

1-212-826-1480; www.cnewa.org

©2023 Catholic Near East Welfare Association.

All rights reserved. Member of the Catholic Media Association of the United States and Canada.

You can help lift up those caught in poverty by providing education, health care and job training. You can help shelter and reunite families in the aftermath of disasters. And your love and generosity multiply, your act of kindness is remembered in prayer. With

18 26 12 OFFICIAL PUBLICATION CATHOLIC NEAR EAST WELFARE ASSOCIATION Volume 49 NUMBER 2 6

Front: A Syrian refugee child plays by the edge of a garbage dump near their refuge in Bechouat, Lebanon, in 2012.

the gift that helps us deliver Christ’s light

the

the

your

to

you

Contact us today to learn more: 1-866-322-4441 (Canada) 1-800-442-6392 (United States) or visit cnewa.giftplans.org

bequest

CNEWA,

ensure your compassion, healing and hope live on.

Connections to CNEWA’s world

Earthquake Relief in Syria Continues

CNEWA’s humanitarian work in response to the 6 February earthquakes in Syria and Turkey continues.

CNEWA’s Beirut team is working with 10 local partners on the second phase of aid, following our immediate emergency response work, and is developing “sustainable help aiming at stabilizing families,” said Michel Constantin, CNEWA’s regional director for Lebanon, Egypt and Syria.

Churches in the Middle East

Msgr. Peter I. Vaccari, CNEWA president, attended the Symposium of Churches in the Middle East in Nicosia, Cyprus, organized by the Dicastery for Eastern Churches, from 20 to 23 April. The theme, “Rooted in Hope,” centered around “the state of the church in and throughout the Middle East” and welcomed some 250 Eastern church representatives and seven patriarchs, along with lay and religious men and women working with the church in the Middle East.

Archbishop Claudio Gugerotti, prefect of the dicastery, spoke during the first day of the event, emphasizing

In the first phase, CNEWA joined its partners on the ground in distributing emergency items. The second phase, which has already begun, includes home repairs, rental assistance for families whose homes became uninhabitable, basic furniture, psychosocial support programs, basic medication and long-term food packages.

To learn more, see Page 6. To support these relief efforts, go to: cnewa.org/work/emergency-syria.

the importance of “the presence, the heritage, the witness and above all the faith of the Christians of the Middle East” to the universal church, according to Vatican News.

While in Cyprus, Msgr. Vaccari visited St. Joseph School and a program for victims of human trafficking.

News From CNEWA in Canada

Adriana Bara, national director for CNEWA in Canada, participated at a meeting of the national French Christian-Jewish Dialogue in Canada, run by Temple Emanu-El-Beth Sholom in Westmount, Quebec, on 24 May. She gave the presentation

on “The Different Forms of Christianity” and spoke about the mission of CNEWA. Rabbi Lisa Grushcow presented on “The Different Forms of Judaism.”

The week prior, Dr. Bara participated in the meeting of Canadian Friends of Sabeel and Kairos Palestine in Toronto. Omar Haramy, the director of Friends of Sabeel and the main presenter, “emphasized the importance of the ‘meaningful pilgrimage’ to the Holy Land,” she said. “In his view, people should not only visit churches and buildings in the Holy land but also encounter people to understand their challenges and needs.”

4 CNEWA.ORG/MAGAZINE

Members of the Blue Marists prepare to distribute food packages to earthquake survivors in Aleppo in April.

Faith and Culture Award

CNEWA trustee Bishop William F. Murphy, bishop emeritus of Rockville Centre, received CNEWA’s Faith and Culture Award during a 19 April reception in Rome marking the reopening of the Rome office of CNEWA and its operating agency in the Middle East, Pontifical Mission.

“For his many years in service to the people of God as bishop, pastor, teacher and ambassador of peace in the Americas and throughout the world, CNEWA is privileged and honored to give its Faith and Culture Award to Bishop William F. Murphy,” said Msgr. Vaccari. “Always, as his episcopal motto, ‘No Other Name,’ declares, Bishop Murphy has placed Jesus in the center of his life, mission and work.”

CNEWA Out and About

CNEWA is taking its message to wider audiences across the country to promote its mission of supporting the pastoral and humanitarian work of the Eastern churches. Haimdat Sawh, development officer, represents CNEWA at these events, raising awareness and drawing more people into the mission of the agency.

In April, CNEWA was as an exhibitor at the annual convention of the National Catholic Educational Association in Irving, Texas, 11-13 April.

CNEWA was also an exhibitor at the Los Angeles Religious Education Congress, the world’s largest gathering of Catholic religious educators, 24-26 February, at the Anaheim Convention Center.

Golf Outing

CNEWA held its first golf outing at the Plandome Country Club in Plandome, New York, on 18 May. The event kicked off with breakfast at 10, followed by golf and tournaments in the afternoon. Twenty teams played the course, enjoying the bright and breezy day, which drew to a close with dinner, a presentation by Msgr. Vaccari, a live auction and a raffle.

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CNEWA 5

Msgr. Peter I. Vaccari, third from right, poses on the green with golfers at CNEWA’s inaugural golf classic at the Plandome Country Club, in Plandome, New York, on 18 May.

Save the Date: 5 December Second Annual Gala Dinner, New York City u There is even more on the web Visit cnewa.org for updates And find videos, stories from the field and breaking news at cnewa.org/blog

Bishop William F. Murphy, left, receives CNEWA’s Faith and Culture Award from Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan.

On Shaky Ground

Multiple crises intensify aid efforts in Syria

text by Arzé Khodr with photographs by Raghida Skaff

6 CNEWA.ORG/MAGAZINE

“Whatever words I may say would not be enough to describe that moment,” says Abir Ahmar Dakno about the 7.8-magnitude earthquake that hit southern Turkey and northern Syria in the early morning of 6 February.

It was 4:17 a.m., three hours before sunrise, and the earth trembled for 45 seconds. Enveloped within the rumbling of shifting earth and crumbling concrete, children could be heard crying and families praying.

Minutes after the shaking stopped, throngs of residents of Aleppo, Syria’s largest city closest to the epicenter, were on the darkened streets in a state of sheer panic, despite the cold winter rain. Many survivors reported feeling terrified and thinking they were going to die.

According to a report released in mid-March by the Blue Marists of Aleppo, a local Catholic organization, some 458 people died and more than 1,000 people were injured in the ancient city. At least 60 buildings collapsed, and hundreds more were irreparably damaged. In less than a minute, hundreds of thousands of people were homeless.

Overall, the 7.8-magnitude earthquake — centered 98 miles north of Aleppo in Gaziantep, Turkey — stands as the deadliest natural disaster of modern times in present-day Turkey and the largest earthquake to impact Syria in two centuries, killing more than 53,000 people and internally displacing about 6 million in both countries combined. About 8,000 quakerelated deaths were reported in Syria alone.

Aleppo is no stranger to mass destruction. During Syria’s 12-year

civil war, the city was the site of intense fighting, from 2012 to 2016, which killed more than 31,000 people and destroyed 30 percent of the old city. Then, from one minute to the next on 6 February, life in Aleppo got exponentially worse. For the tens of thousands of survivors who lost family members, as well as their homes and businesses, their entire world collapsed that day.

Within hours of the quake, recovery efforts were underway as municipalities, aid organizations and community leaders organized emergency shelters in mosques, churches, schools, convents, parish halls and sports stadiums.

CNEWA-Pontifical Mission was among the church agencies to respond immediately, focusing relief efforts in Syria, providing shelter, food, medicine, blankets, clothing and other essentials for up to 3,000 people through its partners on the ground.

The situation remained tenuous for weeks, as hundreds of daily aftershocks — as well as larger quakes — kept locals on high alert. Nine hours after the initial earthquake, a second earthquake measuring 7.7 struck about 60 miles north of Gaziantep. Two weeks later, on 20 February, two more earthquakes shook the region — measuring magnitudes of 6.4 and 5.8 respectively.

At this point, the residents of Aleppo who had returned to their damaged homes thinking the situation had stabilized panicked and went back to the shelters, where some people stayed for almost 40 days.

Abir Ahmar Dakno heads the youth section of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul in Syria, which has been assisting Aleppines with their needs since the first quake hit.

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CNEWA 7

EMERGENCY RELIEF

Rawd Rafek stands in the middle of her burnt-out apartment in Aleppo. An electrical short circuit after the 6 February earthquake caused the fire.

“From Day 1, we realized the shelters were in need of everything,” she recalls. “Some were hosting 1,800 to 1,900 persons. Our work on the ground started immediately.

“Many women were in a state of shock and were not able to breastfeed anymore. We were in great need of baby formula or else we would face a disaster.”

Immediately, Mrs. Dakno and her colleagues contacted CNEWA’s Beirut office, whose “response was very prompt,” she says.

“They provided us with funds, and we were able to help many

shelters with food, blankets, baby formula, medication. We provided diapers for babies and for the elderly.”

The Society of St. Vincent de Paul created a crisis management cell of 40 volunteers — the youngest member was 19 — who distributed items in multiple shelters and entertained children who were, and still are, in great need of emotional support, says Mrs. Dakno.

Hikmat Sanjian started volunteering in spite of himself, after accompanying his friend Mrs. Dakno to a shelter. An engineer and

a professional dancer, Mr. Sanjian’s task was to distract the children while volunteers distributed food and supplies. He did so by inviting them to dance.

“Children don’t care about food,” he says. “Of course, all these items are important, but children want joy, they want to move, to laugh.”

He felt compelled to help, and his initial reluctance to volunteer gave way. In the days that followed, he visited the shelters daily, inviting the children to dance each time. He recalls a girl named Fatima, whose legs were amputated due to a war

“It’s true we are offering help, but we are finding great comfort. When we are asked to give two hours, we give four.”

The CNEWA Connection

Leyla Antaki, second from left, co-founder of the Blue Marists in Aleppo, and fellow volunteers prepare meals for earthquake survivors. Opposite, Michel Constantin, regional director for CNEWA’s Beirut office, distributes packages to school children at a center of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul in Aleppo.

injury. Fatima’s parents wanted to shield her from the dancing Mr. Sanjian was organizing. They feared she would be upset at being unable to participate. But he insisted that she join them, and she enjoyed herself fully, he says.

Laura Jenji, 24, her younger brother, Edward, 23, and their friend George Hamoui, 23, volunteer about 40 hours a week with the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. The three university students speak passionately about the work they do and the meaning it brings to their lives.

“It’s true we are offering help, but we are finding great comfort,” says Edward. “When we are asked to give two hours, we give four.”

“People really need us,” says George, who had started by helping in the shelters, but has since begun assisting with damage assessments of homes in the city. “It’s important to me that I keep on helping.”

On a field visit, Rawd Rafek, a young mother of twins, struggles to find the words to explain how an electrical short circuit after the earthquake sparked a fire that burned down her apartment. She is unable to finish a sentence without crying — a sign of the deep trauma she is suffering.

Mrs. Rafek had never wanted to leave Syria, even during the 12-year war, which forced her to flee her village and take refuge in Aleppo. However, the earthquake has left her with nothing and for the first time, she says, she is thinking about moving abroad.

CNEWA’s emergency response team, based in Beirut, moved quickly after a 6 February earthquake shook Syria and Turkey. The first stages of relief provided food, medicine, blankets, clothes and other essentials through the agency’s partners, such as the Blue Marists and the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. CNEWA has raised more than $1.5 million in emergency relief since the disaster first struck. In addition to the first wave of aid, the Beirut-based team has funded psychosocial programs, rental assistance and the relocation of families, minor repairs of homes and the supply of basic furniture.

To support this crucial work, call 1-800-442-6392 (United States) or 1-866-322-4441 (Canada) or visit cnewa.org/work/ emergency-syria

Dr. Nabil Antaki, 73, a gastroenterologist, and his wife, Leyla, are committed to staying in Syria and have made the promotion of solidarity in Syrian society their life’s mission.

“My wife and I took two major decisions in our lives,” he says. “The first one, in 1979, when we decided to come back to Syria from Canada; the second, in 2013, when we decided to stay in Aleppo despite the war because we saw there was work to be done here with our people.”

In 1986, Dr. Antaki, Leyla and Marist Brother George Sabe launched The Ear of God, a social solidarity project, which came to be known as the Blue Marists in 2012.

The Blue Marists have 155 team members, who support Aleppine families impacted by the war,

regardless of religious affiliation. They run 14 relief, educational and human development programs that serve the most vulnerable.

Jocelyne Orfali heads the Blue Marists’ Sharing Bread project, which provides a daily hot meal for 250 seniors who live alone in Aleppo. After accompanying her on a delivery one day, her 18-year-old son also decided to join the Blue Marists.

“People need us. That really makes you want to help,” says Mrs. Orfali.

Lexa Nuhad Luxa’s eyes light up every time he speaks about the Blue Marists. The 24-year-old national martial arts champion is trying to make ends meet as an aluminum technician and has found a sense of purpose working with the Blue Marists.

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CNEWA 9

“Believe me, when you see that despite all your difficulties and disappointments you can still help and give, you feel a great joy. You feel you can do something and you want to give more and more,” he says.

In the days after the earthquake, the Blue Marists were housing and feeding up to 1,000 families in Aleppo. Less than 30 minutes after the earthquake, they opened their center to hundreds of people for more than 20 days. They offered shelter, daily meals, medical care, medication and support. Since those who were sheltered returned to their homes, the Blue Marists

have been offering rent support and assistance for building repair. Brother George says he considers Syria’s economic crisis, including inflation and unemployment, to be the most significant challenge since the earthquake. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 90 percent of Syria’s population currently lives below the poverty line and basic food prices have soared 800 percent in the past two years. In addition to people losing their homes in the earthquake, many also lost their source of revenue: their shops and professional equipment.

The second challenge, he says, is “the ever-growing wish to leave the country.”

“People are worn out by 12 years of war, and then comes the earthquake,” he says. “The youth are very frustrated. There is a loss of meaning. ‘Why am I alive?’ they wonder.”

Syrians also felt abandoned by the international community immediately after the earthquake, he adds.

“We did not receive any international aid. We received

10 CNEWA.ORG/MAGAZINE

Blue Marists deliver a hot meal to a senior in Aleppo.

“There is a huge amount of work to be done for these people in order for them to be able to go back to their daily routine without the fear of losing each other.”

humanitarian aid from church organizations. The international organizations refuse to contribute to any rebuilding,” he says. “We are very grateful that Christian humanitarian institutions took the initiative to come to the aid of the Syrian Aleppine person.”

The openness of these church groups to help all Syrians, Christian and Muslim, “really shows how much our relationship with these institutions is based on deep human values,” says Brother George.

“We were overwhelmed by this solidarity shown to us by individuals and organizations. It is not only about the money. They are truly available and ready to help.”

In April, two months after the first earthquake, humanitarian aid workers shifted from emergency response to the second stage of disaster relief, which includes relocating families to stable housing, carrying out minor home repairs, and replacing furniture and household items.

Mrs. Dakno says the survivors fall into one of three categories: those who lost their homes, those whose homes were damaged and need repair or new furnishings, and those who suffered severe trauma and are “terrified to go back home.”

The relief team of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul has been conducting field visits to identify the particular needs of families, which were already significant as a result of the 12-year civil war. While those whose homes were found unsafe and uninhabitable after the earthquake are receiving housing and rent subsidies, the vast majority of residents lost furniture and equipment, which they are incapable of replacing.

“Everybody’s plates and glasses were shattered. Just to replace these would cost people a little fortune,” says Mrs. Dakno.

Of great concern as well are the people’s psychological needs. “We have seen some very severe cases of trauma,” she says. “We are in tremendous need of psychological support.”

Due to the lack of professional therapists in Aleppo, the Society of St. Vincent de Paul is preparing online training sessions with counseling professionals in Beirut to help accompany earthquake survivors.

“We need professionals who would offer some of their time, to be constantly in contact with us,” she says. “Just as there are cracks in the buildings, there are cracks inside each one of us, and I’m afraid they are much more difficult to fix.”

Brother George observes the acute need for psychological support in the wake of the earthquake as well.

“When the earth was trembling, families got together and started praying,” he explains. “It was a moment of great fear. Now parents are afraid to let go of their children and children don’t want to leave their parents. There is a huge amount of work to be done for these people in order for them to be able to go back to their daily routine without the fear of losing each other.”

However, amid the destruction, the natural disaster has brought with it an opportunity for “new experiences, people’s love, solidarity, openness to the other, not only on an international level but also on a local one,” says Brother George. Despite the collective trauma, Aleppines seem to find solace in being there for each other.

“We were very open to each other. It was a beautiful ‘social earthquake,’ and we should learn from this experience to build the future that we want for ourselves.”

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CNEWA 11

Hear from earthquake survivors and relief workers in an exclusive video at cnewa.org/one Bring hope in Syria amid destruction cnewa.org I cnewa.ca u

Arzé Khodr is a freelance writer and playwright, based in Beirut.

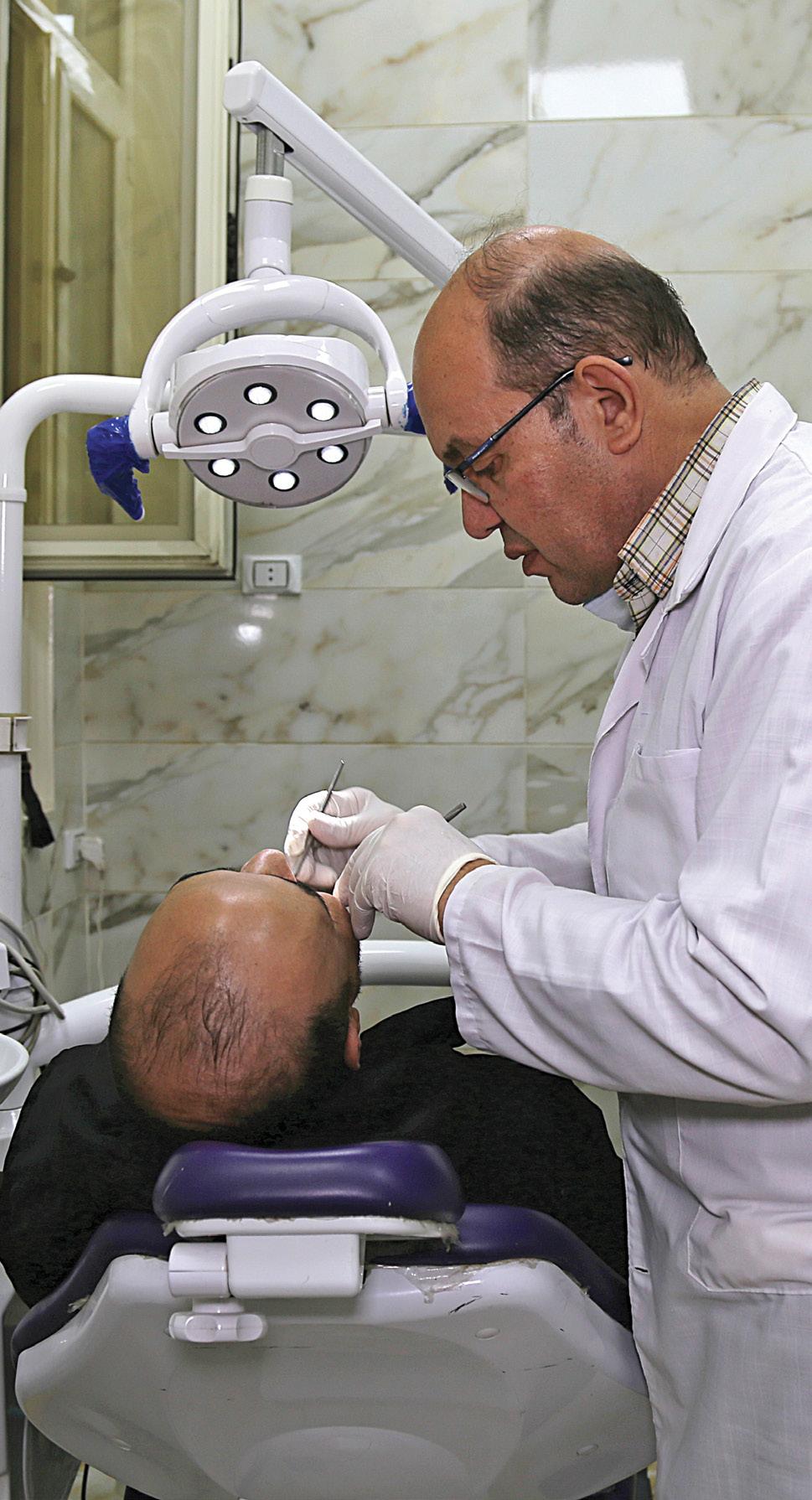

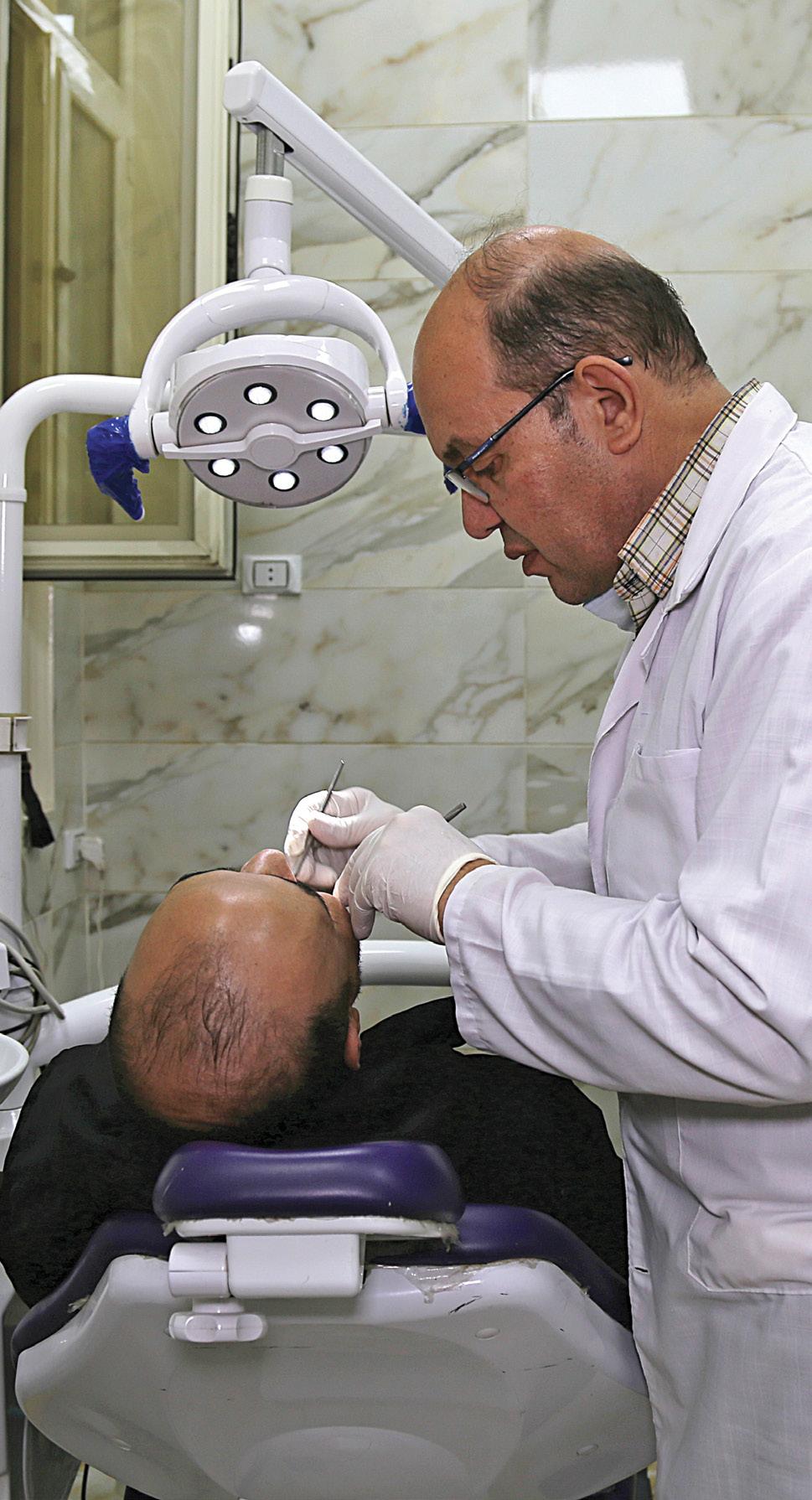

CareUnconditional

Church run clinics tend to Egypt’s poor

text by Magdy Samaan

On a chilly morning in March, patients began gathering within the thick stone walls of the old Franciscan dispensary in Cairo’s Klot Beik neighborhood, a bustling commercial district on the outskirts of the Egyptian capital.

The dispensary is situated within an Italianate complex of buildings, constructed in 1859 to house the convent and various apostolates of the Franciscan Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, the first order of Catholic women religious in the city. Today the sisters run 15 schools and five dispensaries throughout Egypt.

The dispensary in Klot Beik sees about 150-200 patients daily and has been serving the area’s most vulnerable residents since its founding. It offers several specialties, including dentistry, gastroenterology, otolaryngology, ophthalmology and dermatology. However, it is best known for its otolaryngology clinic.

Sister Suhair Mamdouh, the dispensary manager, is trained to conduct a few minor procedures, such as ear irrigations. Procedures

carried out by the sisters are usually offered without charge. Fees are applied for a visit with a doctor, but even these fees are waived if a patient does not have the means to pay.

Sister Suhair conducts an initial exam of Hassan Suleiman’s ear. The 70-year-old, who is dependent on the government pensions distributed to Egypt’s poor, has come to have his ear irrigated.

“They are good people,” he says of the dispensary staff. “When my four children and I need treatment, we come here. They help us a lot.”

Sister Suhair underlines how the dispensary continues to live up to the spirit of the congregation’s Italian founder, Blessed Maria Caterina Troiani, in its care for all people, regardless of race, class or religion.

“We accept the patient on the grounds that this person has value and is beloved and appreciated by God,” she says.

Starting in the 19th century, several Catholic orders of religious men and women came to Egypt and built schools, dispensaries and

orphanages to serve the poor. Health care has been an integral part of their mission.

The Klot Beik Dispensary — known locally as the Saba Banat (Seven Daughters) Dispensary, referring to the seven sisters who established the service in Egypt — is one of about 30 dispensaries operated by Catholic religious

12 CNEWA.ORG/MAGAZINE

with photographs by Hanaa Habib

congregations and providing lowcost or free health care to Egypt’s poorest residents.

With the current economic crisis in Egypt, these services have become even more important for vulnerable populations. The rising cost of living has put medical care out of reach for millions of Egyptians struggling to make ends meet.

RESPONDING TO HUMAN NEEDS

Sanaa Hosni, 52, traveled to the dispensary from Al Hassanin, a village in Giza, south of Cairo, with her 12-year-old son to have an abscess in his ear removed. Her local outpatient clinic would have cost her many times more, she says.

“There are other places that ask the same price I pay here, but there is no attention, cleanliness or order,”

she adds, “and the doctor there conducts the checkup quickly and does not answer my questions.”

Mrs. Hosni says she struggles to make a living selling detergent to

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CNEWA 13

Sister Suhair Mamdouh examines a patient’s ear at a dispensary founded by her order in Klot Beik, a Cairo neighborhood.

The CNEWA Connection

Parents are given a prescription for their child after receiving medical care at the Klot Beik Dispensary. Opposite, a church-run dispensary in Kafr el Dawar, south of Alexandria, provides eye care among its many services.

government took office in 2014. The most prominent project is a new administrative capital in the desert east of Cairo, costing $58 billion. Egypt is currently struggling to repay the loans that funded most of these projects.

Egypt’s population has exploded in size in the past few decades, placing a heavy burden on its already inadequate infrastructure, from child services to the care for the aged, including educational and health care facilities and responsible agricultural and commercial development programs. About a tenth of Egypt’s 105 million people are Christian, most belonging to the Coptic Orthodox Church, and many are engaged in social service programs that benefit all Egyptians, Christian and Muslim. CNEWA supports many of these activities, including health care. Easing these burdens allows these initiatives to better support patients by lowering, and in some cases covering, their medical expenses.

To support this crucial work, call 1-800-442-6392 (United States) or 1-866-322-4441 (Canada) or visit cnewa.org/work/ egypt.

provide for her two children. Still, her family is faring better than others.

“Some families have five or seven children,” she says. “These families are suffering greatly. They can’t afford meat. I know many people who go to the butcher to buy only a bone to make soup.”

In 2022, since the start of the war on Ukraine, the Egyptian government devalued the Egyptian pound three times, stripping the currency of more than half of its value, while commodity prices doubled. A fourth devaluation was anticipated in spring 2023, but the government was reluctant to take that step, as inflation had

reached the limit of what most Egyptians could afford: In February, Egypt’s annual core inflation rate reached 40.26 percent, the highest level in the country’s history.

The government blames the economic crisis on the coronavirus pandemic and the war in Ukraine. However, after granting Egypt a $3-billion bailout last December, the International Monetary Fund stated in its January report that those world events accelerated but did not cause the crisis in the country.

Egypt has spent heavily on nonrevenue-generating luxury megaprojects, such as expressways, monorails and new city infrastructure, since the current

In the backdrop, 29.7 percent of the Egyptian population is living in poverty, according to 2019-2020 statistics. This segment of the population is expected to rise significantly, as millions of people, currently considered lower-middle class, continue to lose their financial footing under the economic strain.

Father Kirollos Nazim heads the development office of the Coptic Catholic Patriarchate of Alexandria. He says the number of people seeking medical assistance from church-run clinics has swelled in recent months and increasingly for stress-related conditions, such as diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease.

“As basic needs become more expensive, people are no longer able to cover the cost of treatment,” says Father Nazim, adding that Egypt’s poor population keeps growing, despite efforts on the part of the state to help.

“We find more and more people asking for our help, and this makes us feel responsible to continue and improve the quality of our service.”

Sister Mariam Faragalla, superior of the Franciscan Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, says the dispensary has not raised its fees despite inflation.

“That would increase the burden for poor families, and we cannot put more pressure on them,” she says.

14 CNEWA.ORG/MAGAZINE

A medical checkup at the Klot Beik Dispensary costs 50 Egyptian pounds ($1.62). The Egyptian government had been providing similarly low-cost or free health care services for the poor, but these services have deteriorated over recent decades. Care is possible in a private clinic or hospital, but the cost is more than four or five times the dispensary fee.

Over the past three decades, Egypt’s population has almost doubled to 105 million people — becoming the most populous country in the Arab world — and

with it the proportion of the country’s poor. This growth has outpaced the government’s ability to invest in health care, education and infrastructure, making these state services insufficient, crowded and obsolete, and resulting in a decline in the country’s human development indicators.

Samira Muhammad waits outside the dispensary to have a tooth extracted. The 68-year-old widowed homemaker lives in Al Haram, west of Cairo, with her eldest son, a house painter, who struggles to support his wife and three children

due to irregular work and rising costs.

Without a pension or a regular income, Mrs. Muhammad says she cannot afford to pay for her health care needs.

“Who can afford 300 or 400 pounds for a doctor at a private clinic? I needed an X-ray, which cost me 500 pounds, and God sent people to help me,” she says referring to a providential experience in her life.

“How much does a chicken cost? How much does a kilo of rice cost?” she continues. “The need increases

“

The poor know that they will not be exploited or disregarded here. ”

every day, and we don’t know how to catch up.”

Sister Clara Caramagno, provincial of the Franciscan Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, describes the dispensary as “a shelter for the poor.”

“When we closed during COVID-19, people would knock on the door asking where they could go,” she adds.

The sisters are currently having a new dispensary built on the second floor of their convent in El Berba, a poor village in Abu Qirqas, Minya, about 180 miles south of Cairo.

Sister Clara says El Berba lacks health care services and a new dispensary would be a great help for the people. While the congregation covered the finishing

costs, the price of medical equipment has exceeded their budget. Sister Clara is praying for a solution.

“I am sure that when I work for the poor, God himself comes and intervenes,” she says. “I have great faith in God; I have seen miracles in the past in this house.

“I think of the poor; God thinks of the sisters. There is a contract between us,” she adds smiling.

The Franciscan Minim Sisters of the Sacred Heart, founded in Italy by Blessed Maria Margherita Caiani in 1902, operate a dispensary in Kafr el Dawar, an industrial city almost 20 miles southeast of Alexandria, as well as an orphanage for girls. Four

Sister Mariam Faragalla, superior of the Franciscan Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, speaks with locals outside the Klot Beik Dispensary, which her order founded and operates.

sisters run the dispensary, which serves about 150 patients. Most patients come from the countryside nearby, where the poverty rate is higher and health services are poorer.

The dispensary was founded in 1972 in response to the increasing number of people who would come to the convent to see Sister Efisia Motci, who had developed an effective ointment to treat burns.

“Because of the efficacy of the ointment, the place was reputed to

16 CNEWA.ORG/MAGAZINE

“Some families have five or seven children. These families are suffering greatly. They can’t afford meat. I know many people who go to the butcher to buy only a bone to make soup. ”

have a holy lady,” says Sister Afaf Nassih, superior of the community. “She was not just a nurse to them; she was a saint who performed miracles.”

The dispensary today addresses several health needs. On this day, an elderly woman in typical rural attire sits in front of Dr. Ismail Arafa, the otolaryngologist at the dispensary, who raises his voice to address her. “You need a hearing aid,” he says several times until she hears him.

She responds, her hands raised: “I don’t have money to buy it.”

Dr. Arafa tells his assistant not to take the examination fee from her, but neither he nor the sisters can offer more care because the cost of such devices exceeds the dispensary’s budget. Dr. Arafa advises the woman to go to the government hospital and apply for a state-funded hearing aid, which may take months to process.

Issam Abu al Yazid, 52, suffers from a subconjunctival hemorrhage, or eye bleeding. Despite working as a health insurance employee at the state-run El Miri Hospital, where he is entitled to free treatment, he chooses to come to the dispensary.

“In other dispensaries, doctors don’t talk to patients. Instead, they are told, ‘You need to come to my private clinic,’ which costs four or five times what they pay here,” explains Mr. Al Yazid. “Here, it is like an examination in a private clinic, but at a lower price.”

The depreciation of the Egyptian pound and inflation have increased the cost and scarcity of medicine, surgery and treatment for chronic diseases, despite the government’s attempts to provide hard currency to import these goods.

“The cost for medical services has become astronomical for most Egyptians,” says Dr. Reneh William Naoom, a dermatologist at the dispensary. “As soon as I grab the pen to write a prescription, it is

common to hear the patient say: ‘Be careful, doctor, don’t write anything expensive.’ Here, they only pay 50 pounds, while they would pay at least about 300 pounds for the same service in outpatient clinics.”

Dr. Ashraf Boulos, an orthopedist, has been working at the clinic since 1990. He is usually very busy, as he is well known in town.

“The compensation I get at other clinics for the same time is three or four times as much,” he says. “But I feel the time I spend here is a blessing for me.”

The church’s mission to establish new health care services in Egypt collides with a lack of vocations to religious life, says Father Nazim. To overcome this problem, an increasing number of lay people are being trained in the mission, he says.

Dr. Nader Michel, S.J., a cardiologist and a Jesuit priest, works at another church-run clinic in Cairo. To promote ongoing excellent care in church-run clinics, he has been organizing regular professional training and development seminars since 1993. About 45 nurses — 15 lay people and 30 women religious from several congregations in Cairo and Alexandria — participate in these sessions.

He says church-run health care facilities treat many patients because they “have a history” of having qualified nurses and doctors who provide good care with “respect and appreciation for the human being.”

“The poor know that they will not be exploited or disregarded here,” he says.

Based in Cairo, Magdy Samaan is the Egypt correspondent for The Times of London. His work also has been published by CNN, the Daily Telegraph and Foreign Policy.

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CNEWA 17

Witness the care provided by church-run dispensaries in Egypt in an exclusive video at cnewa.org/one Help provide health care to the poorest cnewa.org I cnewa.ca u

Only the battered and charred walls of the Hryhoriy Skovoroda National Literary and Memorial Museum remain standing, like ribs surrounding a chest cavity, void of the heart and lungs that once beat and breathed life.

“Hryhoriy Skovoroda forged the spirit of the Ukrainian nation,” says Hanna Yarmish, who heads the educational department of the museum in Kharkiv.

“The enemy destroyed everything to destroy the identity of our people,” she says, referring to Russia and its attack on the museum in its full-scale war launched against Ukraine on 24 February 2022. “It was a direct hit. Damage was huge.”

The museum dedicated to the 18th-century Ukrainian poet and philosopher was obliterated in a Russian missile strike last year on 6 May, which Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy identified as a targeted attack.

Monuments, art works, churches, museums and libraries are not always unintended casualties of war. Often, attacks on heritage sites and objects are tactical measures used by perpetrators of violence to erase a culture, history and tradition — and with them, a people.

As of 17 May, UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, had documented 256 cultural sites in Ukraine damaged since the war began. These included 110 religious sites and 22 museums, with the greatest number in the Kharkiv, Donetsk, Luhansk and Kyiv regions.

Three months earlier, the U.N. Human Rights Office expressed

Hanna Yarmish stands by the ruined Hryhoriy Skovoroda National Literary and Memorial Museum in Kharkiv, Ukraine. The plaque reads, “Famous Ukrainian enlightener, philosopher and poet H.S. Skovoroda spent the last years of his life and died in this building.”

SEEKING JUSTICE AND PEACE

19

concern about the “severe targeting of Ukrainian cultural symbols,” including “Ukrainian literature, museums and historical archives,” and that “cultural and educational institutions” in occupied regions were seeing Ukrainian “culture, history and language” replaced by the “Russian language and with Russian and Soviet history and culture.”

The destruction of cultural artifacts is a fact of conquest throughout human history: the sacking of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade; the iconoclastic dynamiting of the Buddhas of Bamiyan by the Taliban; book burning in China’s Qin dynasty and in Nazi Germany; forced assimilation

of Indigenous children by the United States and Canada; the looting of African nations by colonial powers; and the destruction of cultural sites in Ukraine.

In 1933, motivated by ideological and sociopolitical developments, including in Nazi Germany, Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin defined two terms to describe these crimes of destruction. The first, “acts of barbarism,” referred to the premeditated extermination of a people; the second, “acts of vandalism,” referred to the premeditated destruction of cultural heritage.

He later coined the term “genocide” in his book “Axis Rule

in Occupied Europe,” published in 1944. Two years later, the United Nations incorporated Mr. Lemkin’s “acts of barbarism” into the official definition of genocide when declaring it a crime and codifying it at the 1948 Genocide Convention. Yet, “acts of vandalism” were not incorporated. While the current definition of genocide does not include cultural heritage crimes, this form of violence is still considered a war crime.

The International Criminal Court held its first trial pertaining to cultural heritage crimes in 2016 for attacks on mausoleums and a mosque in Timbuktu, Mali, about which Fatou Bensouda, then the

“It’s inevitable that cultural heritage sites ... are going to become casualties of this war.”

The CNEWA Connection

A monument at Sviatohirsk Monastery in Donetsk Oblast is covered in sandbags to protect it from destruction. Opposite, Russian soldiers emptied the Kherson Art Museum of 10,000 artworks in November. Ihor Rusol, a museum employee, stands amid the emptied storage racks.

court’s chief prosecutor, said: “Let us be clear: What is at stake here is not just walls and stones. The destroyed mausoleums were important, from a religious point of view, from a historical point of view, and from an identity point of view.”

“Walls and stones” often belong to a much bigger story, and are not simply structures or raw materials, but memory preserved.

Conflict in the Caucasus, first in the waning years of the Soviet Union (1988-94), and most recently in 2020, pitted Azerbaijan against its neighbor Armenia over disputed territory with shared histories, resulting in the destruction of Armenian monuments, mainly Christian, in the Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhichevan regions.

Armenia is an ancient Christian nation with deep roots in these historically diverse regions, and Christian sites and symbols were quick targets easily identifiable as “Armenian.” In this conflict, Azerbaijani military systematically demolished churches, cemeteries and “khachkars,” uniquely carved Armenian cross stones.

Azerbaijan has gone one step further and denies these sites ever existed, says Armenian-born Simon Maghakyan, a researcher and doctoral candidate in heritage crime at Cranfield University in Bedford, England.

According to Mr. Maghakyan, the goal of Azerbaijan’s denial is to erase Armenia’s history in NagornoKarabakh and Nakhichevan and to destroy any evidence that could

As a global agency, CNEWA frequently engages with cultures that are at risk of disappearing — a phenomenon that is prevalent in persecuted minority communities — either due to war or other tragic social, political or environmental circumstances. Through its programming, CNEWA offers support to communities at their most vulnerable, including in Ukraine, Armenia, Syria, Iraq, Ethiopia, India, Israel and beyond. While many cultural heritage sites and objects are irreplaceable, the preservation of a community’s cultural identity by way of its people is essential. CNEWA is committed to being present to persecuted and suffering peoples, to help rebuild and to share their community’s culture and history.

To support CNEWA’s work, call 1-800-442-6392 (United States) or 1-866-322-4441 (Canada) or visit cnewa.org/donate.

identify these regions as having been Armenian. He attributes this tactic to “political elite and authoritarian thinking” that claims its legitimacy by punishing and oppressing “an enemy … until their last gravestone becomes dust.”

In 2019, he and historian Sarah Pickman prepared a report that compares data on Armenian sites in

Nakhichevan from 1964 to 1987 with data from 2005 to 2008. Earlier records identify close to 28,000 Armenian khachkars, other headstones, flat tombstones and churches. The later data indicates none.

All identifiable Armenian monuments in Nakhichevan were destroyed by 2006. But Nagorno-

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CNEWA 21

Karabakh, where several Armenian cultural and religious sites remain, is an area of continued concern for Armenian cultural heritage as conflict continues in the disputed region.

Despite provisional orders from the International Court of Justice in 2021 to “punish acts of vandalism and desecration affecting Armenian cultural heritage,” Azerbaijan announced in February 2022 its establishment of a working group to identify “falsified” Armenian monuments in Azerbaijani-occupied territories of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Mr. Maghakyan explains Azerbaijan’s announcement really means “Armenian churches would have their Armenian inscriptions polished out,” which is “a very direct violation” of the court order.

Amr al Azm is an archeologist and co-founder of The Day After, a nonprofit organization

working to support a “democratic transition in Syria” after 12 years of civil war. He coordinates The Heritage Protection Initiative, an affiliated nonprofit focused on the protection of Syrian cultural heritage.

He says in conflicts that involve sectarian, nationalist or extremist ideological aspects, one side or both sides in the conflict “will want to incorporate the ‘purity’ or the ‘exclusivity’ of their identity at the expense of others.”

“That often will translate into the extermination, not just of the physical other, but also of the historical existence of the other.”

From 1999 to 2004, Mr. Al Azm worked at the Scientific and Conservation Laboratories, which he founded within the Syrian government’s General Department of Antiquities and Museums. He left Syria in 2006 to accept a university position in the United States. He

Khachkars are distinct Armenian cultural symbols systematically destroyed in the conflict over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhichevan regions. Opposite, an icon of Mary in a Melkite Greek Catholic church in Yabroud, Syria, was defaced by extremist rebels.

recalls how five years later, after the Arab Spring, conflict spread rapidly across Syria, and “every village, every hamlet, every city became a battlefield.”

“And because Syria is so rich in cultural heritage, you could almost say that every Syrian lives either on top of an archeological site, right next door to an archeological site, or within a stone’s throw of an archeological site,” says Mr. Al Azm. “It’s inevitable that cultural heritage sites … are going to become casualties of this war as well.”

Unauthorized excavations, looting and bombings plunged

22 CNEWA.ORG/MAGAZINE

Syria into a cultural preservation crisis. All six Syrian UNESCO World Heritage Sites are on the agency’s endangered list including: the old cities of Aleppo, Bosra and Damascus; the site of Palmyra; Krak des Chevaliers and Qal’at Salah ElDin; and the Byzantine-era villages of northern Syria.

Looting is the greatest threat to Syrian heritage, more than bombings or the smashing of icons, says Mr. Al Azm. After the Arab Spring and the start of ISIS occupation, ancient cities with great cultural and archeological significance became prime sites for antiquities trafficking.

When ISIS arrived in Iraq in 2014, heritage sites were targeted and destroyed. The tomb of the prophet Jonah in Mosul, a significant site for the three Abrahamic religions, was blown up, bulldozed and had salt sown into the soil to “extirpate heresy,” explains Mr. Al Azm, and

ancient statues in the Mosul Museum were smashed.

“It is an obliteration of our past and an effacement of our identity,” said Omar al Taweel, the site coordinator for UNESCO’s “Revive the Spirit of Mosul” initiative, who spoke of the archeological destruction in Mosul at a U.N. Arriaformula meeting on 2 May.

Other religious sites in the ancient city, like Al Aghwat Mosque and Al Tahira Church, are still undergoing restoration and reconstruction for damages that occurred during the ISIS occupation.

Sviatohirsk Monastery of the Caves in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine, was shelled within weeks of Russia’s invasion and then again in May and June 2022. Shelling in the first five days of June 2022 destroyed churches and buildings, killing five monastics and three lay monastery employees, according to

the monastery website. At the time, the monastery was functioning as a shelter for some 450-500 refugees.

“One got the impression that the fire on the territory of the Lavra, starting from 1 June, was carried out purposefully and accurately from various types of artillery weapons,” the website reads, also referencing “shelling from both sides.”

Church structures in the complex — including Dormition Cathedral and its dependency, All Saints Skete — faced serious damage or complete destruction from the heavy shelling. The wooden skete of All Saints, which dates to 1912 and included two churches, burned to the ground on 4 June. Ukrainian officials place responsibility for the destruction of the buildings squarely on the Russians as a targeted attack. However, damage to some Ukrainian cultural institutions has also come from their proximity to targeted areas.

Unauthorized excavations, looting and bombings plunged Syria into a cultural preservation crisis.

“Walls and stones” often belong to a much bigger story, and are not simply structures or raw materials, but memory preserved.

The convent of the Dominican Sisters of St. Catherine of Siena in Qaraqosh, Iraq, was reduced to rubble during the city’s occupation by Islamic State. Inset, Hanna Yarmish, left, and a fellow museum worker tend to a statue of Ukrainian philosopher Hryhoriy Skovoroda, which was saved from destruction.

Valentyna Myzgina says the windows of the Kharkiv Art Museum, where she is director, were broken when a nearby building was heavily bombed in March 2022.

“A half-century of history of the museum passed before my eyes,” says Ms. Myzgina, who has worked at the 103-year-old museum for 53 years. “This is when I cried for the first time [since the war began].”

This museum’s 75,000-piece collection prior to World War II dropped to 5,000 pieces by the war’s end and was rebuilt to 25,000 pieces by February 2022. Ms. Myzgina describes it as “one of the best, richest museums in Ukraine.”

The current collection made it out of the bombing relatively unscathed. Only two paintings were damaged. The museum’s library, however, suffered water damage, resulting in the partial damage or complete loss of the books and manuscripts.

The preservation of the collection became top priority after the shelling. The director worked with a team of women to evacuate the exhibits and the building was repaired, including the roof and windows, and a heating system was installed.

“A painting is like a small child,” says Ms. Myzgina. “It doesn’t like drafts.”

“Everyone [in this war] has their own front,” she continues. “We had a front here, and I think the women who did all this are heroines.”

Looting and the trafficking of Ukrainian cultural artifacts started as early as 2014, primarily by “paramilitary non-state

actors,” says Mr. Al Azm, who tracks antiquities trafficking through the Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research Project, which he also cofounded.

This changed, however, when Russian President Vladimir Putin declared martial law last October in four then-occupied regions of Ukraine — Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk and Luhansk — giving Russian forces official clearance to loot Ukrainian art and artifacts.

By early November, members of the Russian Federal Security Service, who had been occupying Kherson Regional Art Museum since July, began emptying it of its collections, says Alina Dotsenko, the museum director. They had obtained the museum’s digital database from a former employee. Of the museum’s 14,000 items, 10,000 were transported to Crimea, she says.

“Ukraine’s losses are unimaginable. It is impossible to compare with [World War II]. Now the losses are worse,” says Ms. Dotsenko. “Who was stealing then? Simple soldiers. Maybe officers.

“Now it was well organized. … It was done at the level of their country, their state.”

Khrystyana Hayovyshyn, deputy permanent representative of Ukraine at the U.N., addressed the crime of state-sponsored looting at a U.N. Arria-formula meeting on 2 May, saying more attention should be paid to cultural heritage crimes committed by states. She described Russia’s “looting of cultural property” as a means of “negative cultural appropriation” and “neocolonialism” intended to erase the distinct nationhood of Ukraine.

“Cultural looting is supposed to underpin the Russian narrative about Russians and Ukrainians as ‘the same people,’ ” she said, referencing a claim made by President Putin that is rejected by Ukraine.

Hanna Skrypka says she witnessed this Russian narrative in action when

she was forcibly held by Russian military at the Kherson Regional Art Museum on 1-2 November and was made to type lists of the items the Russians were removing.

“I have the impression that they need to take all the tangible evidence, that is, material heritage, documents and works of art that identify [Ukraine] as a separate nation,” says Ms. Skrypka, a museum employee. “They want to create such a general notion that everything is theirs.”

Once freed from the museum, she contacted Ms. Dotsenko, and they succeeded in tracing the art to the Central Museum of Tavrida in Crimea.

The storage rooms at the museum in Kherson are now full of frames, emptied of the works of renowned Ukrainian artists, including Shovkunenko, Pymonenko, Skadovsky and Aivazovsky.

“In artistic works, there is an imprint that Ukraine has its own history — our Scythian roots, the strengthening of the Cossacks. This is something of our own … and it could be shown as proof of our uniqueness, of our Ukrainian identity. They are taking all of this away little by little,” says Ms. Skrypka.

“They need to take every last thing. Even the memory, the one that we could pass on to our children and grandchildren, in the form of works of art.”

Olivia Poust is communications assistant for CNEWA and editorial assistant of ONE. Konstantin Chernichkin, a video journalist in Ukraine, and Mariana Karapinka in Philadelphia contributed to this report.

Hear from museum workers on location in Ukraine on the impact of the war on cultural sites at

cnewa.org/one

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CNEWA 25

u

A Letter From Georgia

by Luka Kimeridze

by Luka Kimeridze

26 CNEWA.ORG/MAGAZINE

On 7 March, lawmakers in Georgia cast a majority vote to pass the Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence. While advocates argued its purpose was to meet the need for enhanced national security against foreign actors, those who opposed it — including a strong proportion of young adults — argued the law aimed to cripple, marginalize and eventually eliminate two essential actors in the democratic process — independent media and civil society — both viewed as threats by the political elite.

Collective outrage grew across the capital, Tbilisi, after the law was passed. People rushed from their homes and workplaces to the Parliament building and held a public protest. The demonstrators were effective, and the law was repealed on 10 March.

In the former Soviet country, many civil society groups — armed with social activism and shadow reports — play the crucial role of government watchdog. The media in turn reports on the activities of these groups, as well as on the government.

The law, which according to protestors would have aligned Georgia with Russian NeoImperialism, was intended to monitor media and civil society groups that receive funding for philanthropic and advocacy work from foreign grant-making organizations, private foundations and international development agencies — mostly based in Europe and the United States. The underlying assumption, according to this interpretation, is that these groups promote foreign interests that favor the West and a future that includes Georgia as a member of the European Union.

The parliamentary vote on 7 March was met by the unprecedented unity of Georgian civil society. In addition to citizen protests, more than 436 civil society organizations, among them Caritas Georgia, signed a petition opposing the law and staunchly supporting a vision for Georgia’s future within the E.U.

Situated in South Caucasus, Georgia has been exposed to the influences of both Western and Eastern civilizations, which have played a significant role in shaping Georgia’s history and have led to a rich tapestry of traditions, beliefs and customs over the centuries.

Among the oldest nations in the world, Georgia derives its heritage and identity from the Colchis, among the ancient indigenous Kartvelian tribes, who lived in present-day western Georgia from the Middle Bronze Age and formed part of the first European civilization. In the early fourth century, Georgia adopted Christianity through the evangelization of St. Nino. Over the centuries, as the Christian faith developed in Georgia, it became an important outpost of Christianity, together with Armenia, even as Islam enveloped parts of the region after the middle of the seventh century. Georgian monastics were agents of cultural encounters and contributed to the spread of Byzantine ideas to the Georgianspeaking lands.

Georgia’s proximity to the Persian and Ottoman Empires, as well as its historical interactions with the Silk Road, also infused it with elements of Eastern culture. Even today, Georgia continues to navigate the complexities of its dual cultural heritage.

Still, many Georgians aspire to align the country with the Western values of democracy, human rights and economic development by

SEEKING JUSTICE AND PEACE

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CNEWA 27

Demonstrators gather outside Georgia's Parliament building in Tblisi, Georgia, on 9 March to protest the so-called “foreign agents” law.

Caritas Georgia operates numerous institutions and programs that support human and social development. Clockwise from bottom left, children attend class at the Harmony Center in Tblisi, Georgia; Fatima and her three children are assisted by the St. Barbare Mother and Child Care Center in Tbilisi; a man enjoys a warm meal at a food program; young adults learn woodworking; young mothers attend a culinary arts program; a woman plays piano at a day center with programming for seniors.

seeking closer ties with the E.U. and NATO. In its first decades of post-Soviet independence, Georgian society was trending toward a greater realignment with Europe represented, as well, in government policy. These aspirations led to various reforms aimed at modernizing institutions, improving governance and promoting European integration. The younger generation, in particular, is keen on embracing Western ideals and lifestyles.

However, this government has faced criticism on the path to European integration, including of the proposed Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence. The E.U. has underlined that creating

and maintaining a supportive environment for civil society organizations and ensuring media freedom are at the core of democracy; the law’s adoption was inconsistent with these aspirations and with E.U. norms and values.

Last year, at a crucial summit of the E.U. in Brussels, Ukraine and Moldova were granted the status of “candidate countries” to join the E.U., while Georgia received only the prospect of candidacy. The European Commission set out compulsory requirements for Georgia to receive candidate status, clearly outlining the flaws of the current government: political polarization, lack of independence and effective accountability of state

institutions, shortcomings in the electoral framework, lack of a fully independent, accountable and impartial judiciary, threats to free and independent media, and lack of protection for the human rights of vulnerable groups. The European Parliament also required Georgia to follow through on “de-oligarchizing” its government by eliminating the excessive influence of vested interests in economic, political and public life.

Georgia’s integration into the E.U. is crucial for a myriad of reasons, including to eradicate poverty — currently, 17.5 percent of the population lives below the national poverty line — to improve

28 CNEWA.ORG/MAGAZINE

education and quality of life, reduce income inequality, offer stronger social welfare services to the underserved and decrease political polarization.

Although the law was targeted at nonprofit organizations practicing advocacy, social activism, the promotion of the democratization of government institutions and the eradication of corruption, it would have had a damaging effect on charitable nonprofits as well, that is, those offering social welfare services, such as Caritas Georgia, as 20 percent of their total budget often comprises foreign donations.

International and local social welfare organizations work in close partnership and cooperation with the government, significantly extending the limited capacity and resources of the latter to fill in the gaps of social welfare programs offered country-wide. Social service organizations, such as Caritas Georgia, funded mostly by foreign

donors, give opportunities to vulnerable children, shelter victims of violence, secure lonely seniors a dignified life, promote the integration of persons with disabilities in the labor market, nourish hundreds of underserved people daily in a soup kitchen, provide emergency relief and promote economic and social development.

Had lawmakers not revoked the law on 10 March, social welfare organizations would have been hindered from developing relationships with foreign donors, and donor acquisition would have worsened substantially due to the hostile climate. In sum, impeding the work of social welfare organizations would have left thousands of beneficiaries without assistance in the alleviation of their suffering and without access to lifegiving opportunities.

In addition to extending the capacity and resources of various social welfare programs country-

wide, nonprofit organizations sometimes will have greater knowledge and expertise in a particular area of need, which should be harnessed for the benefit of underserved populations.

Nonprofit organizations in Georgia are essential and diverse in their roles. They make significant contributions to meet societal needs, promote citizen engagement, establish accountability and advocate for positive change. These organizations play a crucial part in constructing a society that is inclusive, resilient and equitable. Marginalizing their contribution by labeling them as “agents of foreign influence” significantly deteriorates the health of the nonprofit sector in Georgia at the expense of tens of thousands of beneficiaries.

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CNEWA 29

Luka Kimeridze, based in Tblisi, is the communications and development director for Caritas Georgia.

Living a Christian Life in the Land of Jesus

text

by Michele Chabin

with photographs by Ilene Perlman

text

by Michele Chabin

with photographs by Ilene Perlman

Stefan Amseis, a resident of Ramle, a religiously diverse city in central Israel, always wears a cross around his neck.

These days, however, the 30-yearold, who identifies as an Arab Christian citizen of Israel, is being extra careful due to the deteriorating security situation following reports of a recent uptick in Jewish extremists spitting at Christians and vandalizing Christian property.

“When I’m in Jerusalem I’m concerned that nationalistic or ultra-Orthodox Jews will spit at me if they know I’m Christian,” says Mr. Amseis, an editor of the Arabic edition of The Holy Land Review (As-Salam Wal-Kheir), the magazine of the Franciscans of the Holy Land.

Small groups of fanatical Jews have been harassing Christians for years, but the number of incidents shot up this winter, soon after Israel’s new government took office on 29 December.

“We have seen bolder attacks in broad daylight on some church properties,” says Joseph Hazboun, CNEWA-Pontifical Mission’s regional director for Palestine and Israel. Mr. Hazboun has a front-row view of the situation from his office in the Christian Quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City.

He enumerates some of the incidents, including the vandalism of the cemetery of the Anglican church on the Mount of Olives and the February attack on the Church of the Flagellation on the Via Dolorosa, where an Orthodox Jewish American tourist destroyed a towering statue of Jesus. The attacker screamed, “No idols in the holy city of Jerusalem!” as he hit the statue’s face with a hammer.

Nuns and priests are spat upon and cursed out frequently as they

walk through the narrow, winding streets of the Old City, which is also home to a group of young Jewish extremists.

Bishop Rafic Nahra in Nazareth, patriarchal vicar for Israel and auxiliary bishop of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem, says the police are not taking the actions of extremists seriously. There have been almost no arrests.

“We know that the government doesn’t support the attacks, but its response has been weak. If synagogues were being attacked, the response would be stronger,” he asserts.

Rabbi David Rosen, the Jerusalembased director of international interreligious affairs at the American Jewish Committee, says the government is making some efforts, but not enough.

“More security is being provided and more cameras have been installed in vulnerable areas, but the real problem is that the police don’t have legal grounds to act against some of the instigators,” he says. “Spitting isn’t a hate crime under Israeli law. What’s needed is legislation to show these actions aren’t being taken lightly.”

Bishop Nahra attributes at least some of the government’s inaction to Israel’s inner turmoil.

“There are deep divisions within Jewish society, and our ‘small’ problems seem like nothing to them,” the bishop says. “But this feels like discrimination.”

Since March, hundreds of thousands of Israelis have taken to the streets to protest the new government’s plans to alter the country’s court system and expand Orthodox Jewish authority in the public sphere.

Waving Israeli flags and calling for democracy, the protesters have organized general strikes and weekly demonstrations that have blocked major highways. They say

the proposed laws are both undemocratic and theocratic, claiming Israel was founded as a secular country and as a homeland for Jews of all stripes.

What is described as far-rightwing and ultra-Orthodox Jewish parties within the prime minister’s coalition support the expansion of Jewish settlements in Palestinian territories, higher budgets for ultraOrthodox institutions, and the exemption of ultra-Orthodox men from mandatory military service.

Just before the start of Passover, the ultra-Orthodox parties, whose members comprise nearly half of the 64-seat governing coalition, pushed through a law that allows hospitals to ban non-Passover foods, such as bread, during the holiday.

The law impacts not only secular Jews, but the country’s religious minorities.

“The law shows a lack of consideration for non-Jewish citizens of Israel, and goes against the democratic values of the state,” says Mr. Hazboun. “It’s no different than a Muslim faction that would want to impose the wearing of the hijab or to prohibit alcohol.”

Of greater concern is the coalition’s efforts to weaken the authority of the Supreme Court, whose rulings over the past two decades have tended to be moderate, especially regarding the rights of women, non-Orthodox Jews and minorities.

If the so-called “judicial overhaul” bill passes without significant modifications, it would take only 61 lawmakers in the 120-seat Parliament to overturn many Supreme Court rulings. Another bill would give parliamentarians a much larger say in who can serve as a judge.

Neri Zilber, an Israel-based policy adviser at the Israel Policy Forum, describes the situation as “the most severe constitutional crisis” in Israel’s 75-year history.

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF CNEWA 31 ACCOMPANYING

THE CHURCH

Parishioners attend a Holy Thursday liturgy at the Greek Orthodox Nativity of the Virgin Mary Church in Kafr Yasif, Israel, on 13 April.

“The bills would usher in majoritarian rule: The majority in Parliament and the government would be able to decide to pass any law or make any decision they so choose.”

A sweeping judicial overhaul could result in no real protections for things like minority rights, Mr. Zilber warns. In theory, it could effectively ban all Arab parties running in elections on the grounds that these parties do not recognize Israel as a Jewish and democratic state.

“We could have a situation where Arab citizens, who are 21 percent of the population, have no political representation,” he adds.

Of the 182,000 Christian citizens of Israel, about 138,000 are Arab,

according to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Many but not all identify as Palestinian. Christians comprise roughly 2 percent of Israel’s population of 9.7 million, while Muslims make up 18 percent. Arab parties typically run in national elections and sit in the opposition in the Knesset. However, Ra’am, an Islamic party, made history in 2021, when it joined the then-moderate governing coalition. Despite the deepening rifts in Israeli society, Mr. Zilber sees one silver lining: All aspects of Israeli society, including its moderates and leftists, have become much more proactive in setting a course for the country’s future. According to opinion polls conducted this spring,

if elections were held soon, the current prime minister and his party would be unable to form a government.

“This could be a stepping stone to vote in a more reasonable government,” says Mr. Zilber.

Arab citizens, including Christians, worry that the priorities of the present government will result in even less support for the already underserved Arab and non-Jewish sectors.

“We fear that the unprecedented budget allocation ($9.7 billion) passed by the previous government to bridge the gap between Arabs and Jews will be frozen and used to fund settlements and the National Guard,”

32 CNEWA.ORG/MAGAZINE

“Spitting isn’t a hate crime under Israeli law. What’s needed is legislation to show these actions aren’t being taken lightly.”

– Rabbi David Rosen

“When I’m in Jerusalem I’m concerned that nationalistic or ultra-Orthodox Jews will spit at me if they know I’m Christian.”

– Stefan Amseis

said Thabet Abu Rass, co-executive director of the Abraham Initiatives, a nonprofit organization that advocates for Arab equality in Israel.

While the Arab sector has many concerns, government funding and initiatives to fight organized crime and violence within Arab towns and cities is at the top of the list, says Mr. Abu Rass.

In 2022, 112 Arab citizens and four non-citizens died due to criminal activity within the Arab community perpetrated by its own members. Of these, 87 percent were killed by gunfire. Five victims lost their lives in circumstances related to policing, according to the Abraham Initiatives.

“The security minister should be ensuring public safety for all Israeli citizens, but he is doing nothing to bring safety to the Arab community,” says Mr. Abu Rass.

Other major concerns are aging infrastructure and not enough land to accommodate natural growth within Arab municipalities.

The village of Kafr Yasif in Galilee is a case in point. The scenic, hilly village, dotted with lovely stone houses and beautiful churches, is home to Christians, Muslims and Druze. The Christian community, which comprises almost 60 percent of the population, has award-winning

schools and thriving youth groups, but there is not enough housing to accommodate the residents’ grown children who want to reside there.

This housing shortage — which affects all Israelis but is especially acute in Arab municipalities — has motivated many young people to move to the nearby cities of Akko and Haifa, and even abroad after graduating from university.

In the quiet moments before leading a Holy Thursday liturgy in the recently built church of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary, the Greek Orthodox pastor, the Reverend Atallah Makhouli, strikes a serious note.

“We Christians have been here for generations upon generations.

Looking in on the activities,

Sister Maha Sansour, the head nurse, warmly greets every patient and staffer. But her smile turns wistful when she steps back into the corridor.

“There are deep divisions within Jewish society, and our ‘small’ problems seem like nothing to them. But this feels like discrimination.”

– Bishop Rafic Nahra

The CNEWA Connection

While Christians are a minority within a minority in Israel, the church’s social service programs are numerous. And they care for Christians, Jews and Muslims — all segments of society. One such initiative, the St. Vincent de Paul French Hospital in Nazareth, provides health care to patients regardless of their faith. CNEWAPontifical Mission funds have gone toward rehabilitation projects, operational expenses, play areas for children with special needs and upgraded services.

To support this crucial work, call 1-800-442-6392 (United States) or 1-866-322-4441 (Canada) or visit cnewa.org/work/israel.

We hope to be here for many, many more. But the future of our children depends on peace,” says Father Makhouli.

He notes that Palestinian militants had fired more than 30 rockets into Galilee on 6 April, and violence in the West Bank and Jerusalem had soared in recent weeks. Yet even peace will not prevent young people from leaving if they cannot maintain a good quality of life and do not have the ability to build homes, he adds.

“The government doesn’t give us the land to expand the village. It’s an old problem.”

Due to their small numbers, Christians in Israel also face the threat of assimilation, says Josef Shahada, a leader in the Greek

Orthodox community and an educator in Kafr Yasif.

“We live between Jews and Arabs, a minority in Israel, but also within Arab society,” which can make it difficult to maintain a unique identity, he adds. This is especially true when Christian students attend Israeli universities and find jobs that further mainstream them into Jewish or Muslim Israeli society.

Back in Nazareth, Bishop Nahra says the fact that Christians in Israel are highly educated, westernized and for the most part financially secure is both a blessing and a challenge.

To help children and their families feel more connected to Jesus and the church, the Latin Patriarchate of

Jerusalem has identified several areas in need of improvement.

One priority is to enhance the faith formation of the schools’ catechism teachers, so they can teach the Christian faith with enthusiasm and joy. A second priority is to encourage more family participation in church services and activities.

“Israel is a very secular and very expensive society, so people have to work very hard,” he says. “There’s little time to build family life. Parents often don’t go to Mass, so the children don’t have a liturgical life.”

The Catholic churches are also collaborating to provide opportunities for the country’s Catholic young adults — whether they be Roman Catholic or Eastern Catholic — to meet, socialize and hopefully marry.

As frustrated as he is by the Israeli government’s longstanding funding roadblocks to Christian institutions, Father Abdel Masih Fahim, a Franciscan and the coordinator of Christian schools in Israel, is gratified that Christian schools will soon have their very first history of Christianity textbook.

In terms of curriculum, Israel has never distinguished between Christian and Muslim Arabs. For decades, the education ministry has required all schools in the Arab sector to teach history and other subjects from an Islamic perspective, including in Christian schools.

Until now, Father Fahim points out, Christian schools “have been required to teach from Islamic history books that ignore 600 years of Christian history, from the birth

34 CNEWA.ORG/MAGAZINE

Mira Laham and her son, Taim, in the maternity ward of St. Vincent de Paul French Hospital in Nazareth. Opposite, Father Atallah Makhouli serves the Greek Orthodox faithful in Kafr Yasif.

of Jesus until the advent of Islam in the seventh century. We have courses in the Arabic language that take texts from the Quran. So, we asked [the education ministry], why not draw from texts from Christianity, the Gospel or the Bible?”

This long-yearned-for textbook is in its final stages, he says.

For 125 years, the St. Vincent de Paul French Hospital in Nazareth has cared for patients of all faiths, just as its

founder, Mother Leonie Sion of the Daughters of Charity, had envisioned.

Today, the 140-bed hospital operates as a general public health facility under the regulations of the ministry of health. Yet, much like the country’s Christian schools, it receives only a fraction of the funding state hospitals receive. The National Insurance Institute pays for the care of individual patients, but not for hospital renovations or new medical equipment.