17 minute read

LuCAs & GALiAno In dialogue

from Cosentino C 20 21

by Cosentino

6

Interview Conversation

Lucas & Galiano in dialogue

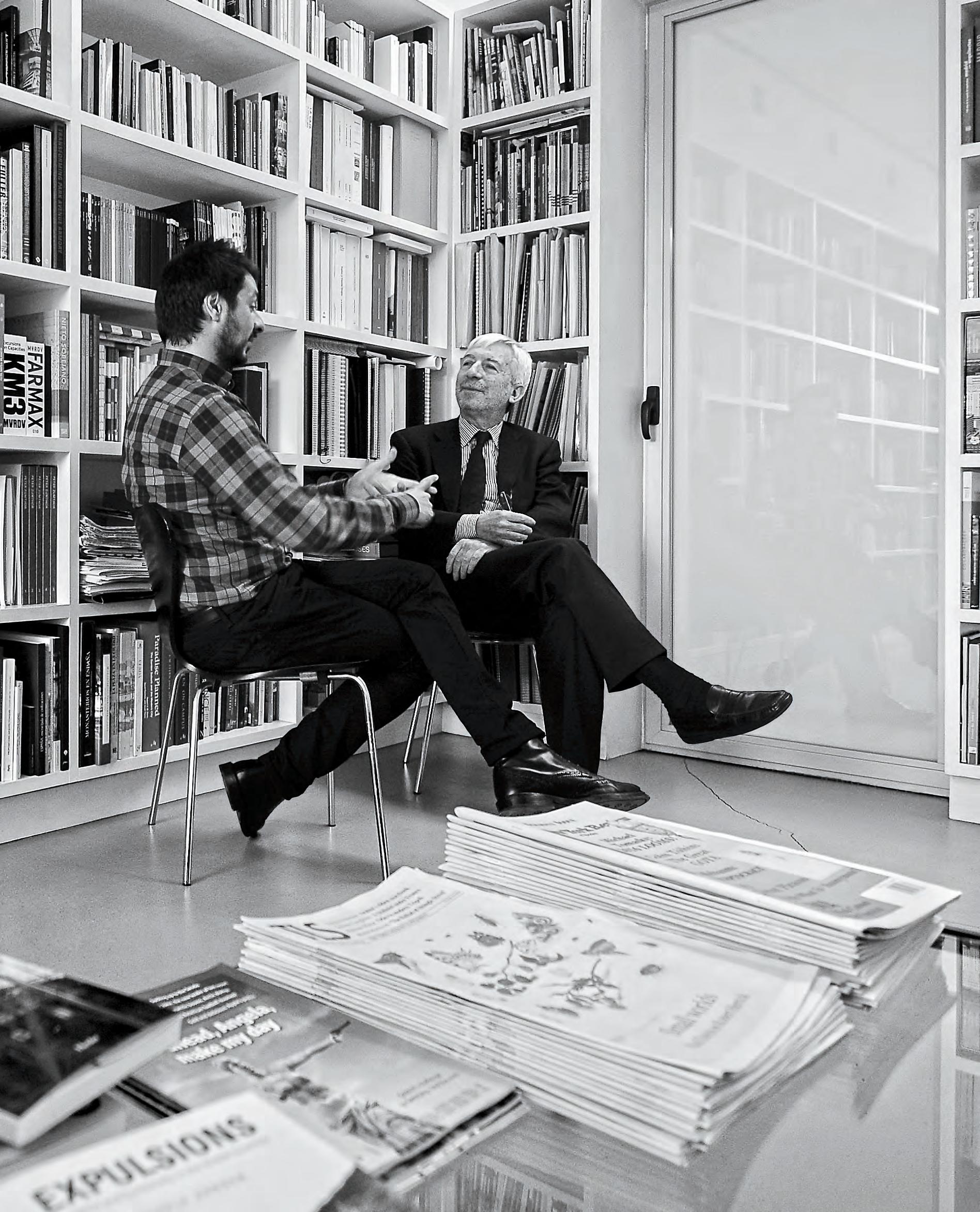

Photos: Miguel Galiano

La redacción de la revista Arquitectura Viva, en Madrid, acoge la conversación entre Luis Fernández-Galiano y Antonio Lucas, en la que repasan sus intereses literarios y la importancia de la poesía en su trayectoria y sus textos.

Luis Fernández-Galiano: No sé si sabes que hay muchos arquitectos que citan a poetas y los usan como una herramienta de inspiración.

Antonio Lucas: Tú mismo, por ejemplo. Acabo de leer un texto tuyo en el que hablabas de Aleixandre, de Machado…

LFG: Sí, tienes razón, aunque en este caso yo me considero más un escritor usando a otros escritores, tiene menos mérito. Me refería a arquitectos que construyen.

AL: Hay una complicidad, principalmente de lenguaje, entre la arquitectura y la poesía. Ambas disciplinas comparten conceptos abstractos, voluminosos, como vacío, espacio, luz, forma… Son parte de la práctica arquitectónica y, naturalmente, también de la poesía. A la hora de dar cuerpo a una serie de emociones o perspectivas del mundo, construir el lugar es el primer indicio de lo arquitectónico y lo poético. La emoción que puede sentir un poeta ante una construcción física, ante una forma concebida con intención puramente utilitaria, puede ser, más allá de lo icónico, el principio de una emoción, de un sombro, de una duda. Y lo mismo sucede con el arquitecto ante el poema: está viendo levantar un idioma que puede ser paisaje, refugio, alero desde el que arrojarse. Forma parte de nuestra emoción el mirar, y sentir, y descubrir cómo algo se construye desde la nada y adquiere entidad. Un poema también es un ejercicio de arquitectura.

LFG: Ha habido algún arquitecto poeta, pero no muchos. Miguel Ángel era uno, con sus extraordinarios sonetos. Aunque es verdad que los hombres del Renacimiento eran arquitectos, pero también artistas, literatos…

AL: Miguel Ángel tenía unos excelentes epitafios en cuartetos de enorme calidad. Son un buen ejemplo de poesía del Renacimiento. Ahí está la voz de un poeta.

LFG: Es, sin embargo, algo que no encontramos tan habitualmente en el siglo xx, donde se da una cesura mayor. Aunque hay un poeta arquitecto que es catedrático de estructuras en Barcelona, Joan Margarit.

AL: Así es. Un poeta de línea clara, de lenguaje directo, muy cercano y limpio, aunque también hábil en el juego de luces y sombras. Pienso ahora en otro artista realmente intenso, el escultor Eduardo Chillida, también con formación de arquitecto, que escogió como lema de su obra un verso de Jorge Guillén: «Lo profundo es el aire». Rafael Moneo también es un buen lector de poesía y en algunos de sus conceptos teóricos asoma esa predilección suya por algunos poetas. Es decir, si bien no hay tantos arquitectos poetas, sí existen vasos comunicantes entre unos y otros.

LFG: En Los desengaños mencionas a una serie de poetas que imaginas que están presentes en tu escritura de forma capilar, entre ellos a T.S.Eliot o Ezra Pound. ¿Los lees en inglés o en castellano?

AL: Los leo en español. Soy torpe con los idiomas y lo lamento. Leo buenas traducciones, pero me pierdo mucha intensidad y calambre en el trasvase. Pound y Eliot son dos poetas incalculables. Me interesa más Eliot que Pound. Me seduce el proyecto casi

El arquitecto y director de Arquitectura Viva, Luis Fernández-Galiano (Calatayud, 1950) y Antonio Lucas (Madrid, 1975), poeta y periodista de El Mundo, se reúnen en Madrid para hablar de poesía y arquitectura.

The architect and director of Arquitectura Viva, Luis Fernández-Galiano (Calatayud, 1950) and Antonio Lucas (Madrid, 1975), poet and journalist of El Mundo, meet in Madrid to talk about poetry and architecture.

In the offices of the magazine Arquitectura Viva, Luis Fernández-Galiano and Antonio Lucas discussed their literary interests and the importance of poetry in their texts.

Luis Fernández-Galiano: Do you know that many architects quote poets and use them as tools for inspiration?

Antonio Lucas: You yourself, for a start. I’ve just read a text of yours in which you spoke of Aleixandre, Machado…

LFG: Yes, that is right, although I think I am more of a writer using other writers, which has less merit. I was referring to architects who actually build.

AL: There’s a complicity, mainly of a linguistic nature, between architecture and poetry. Both disciplines use loaded, abstract concepts, such as void, space, light, form... It’s part of the architectural practice, and naturally also of poetry. When giving shape to a series of emotions and world outlooks, building the place is the first sign of the architectural and the poetic. Beyond the iconic, a poet’s rush of emotion at the sight of a physical construction, before a form conceived with purely utilitarian intentions, can be the beginning of an emotion, a shadow, a doubt. And it’s the same for an architect confronted with a poem, witnessing the rise of language that can be a landscape, a refuge, an eave to jump off from. Our emotions include looking, seeing, and feeling, and discovering how something is built from nothing and becomes an entity in its own right. A poem is also an exercise in architecture.

LFG: There have been poet-architects, but not many. One was Michelangelo, with his

extraordinary sonnets. Of course the masters of the Renaissance were architects, but also artists, men of letters…

AL: Michelangelo wrote some excellent epitaphs in quartets of great quality. They are a good example of Renaissance poetry. In them rings the voice of a poet.

LFG: Yet this is something we do not commonly find in the 20th century, where there is a wider gap between architecture and poetry. One architect-poet is a professor of Structures in Barcelona, Joan Margarit.

AL: Indeed. He was a poet of clear lines, who wrote in a straightforward language, very accessible and clean, though also skillful in interplays of lights and shadows. I am now thinking of another, truly intense artist, the sculptor Eduardo Chillida, who also had architectural training. He used a verse of Jorge Guillén as motto for his work: “Deep is the air.” Rafael Moneo is also an avid reader of poetry, and his predilection for certain poets shines through in some of his theoretical concepts. So, there may not be that many poetarchitects, but there definitely are connections between poets and architects.

LFG: In your book Los desengaños you mention a number of poets you imagine having a capillary presence in your writings, among them T.S.Eliot and Ezra Pound. Do you read them in English or in Spanish?

AL: I read them in Spanish. I’m rather limited when it comes to languages, and I regret it. I read good translations, but a large share of the intensity is lost on me. Pound and Eliot are two incalculable poets. I’m more keen on Eliot than on Pound. I am drawn to

Pound’s almost ‘infinite’ approach, but find Eliot’s more firmly materialized. Pound is a babel of culture, with an overwhelming tableau of layers, textures, and backlights, but Eliot has a freer hand. Pound’s ambition is all very well, but as far as I’m concerned, the true poet is Eliot. His world view, his capacity to concretize a perspective of humanity in a poem, as he does in The Waste Land or Four Quartets, is of a magnitude beyond the reach of all the rest.

LFG: For us, too, he was a legend, in part because he was a great literary critic, a bit like our own Juan Ramón Jiménez, who was not only a great poet but also a great erudite of poetry. I remember being young and learning the first stanzas of The Waste Land by heart. But I was partly schooled in Great Britain, so inevitably read in English. In any case, when I read poets whose languages I do not speak, I like to read them in bilingual editions. Even without understanding the original language, there is something in the sound that you suddenly pick up. For example, I did not previously have much of an opinion of Pessoa as a poet. I considered him a prose writer, a master of thought. I never thought of him as a great poet until I read him in a bilingual edition.

AL: I agree, and do the same: contrast, study, compare. It happened with Adam Zagajewski, the Polish poet, one time we had a reading together. His poems took on a fullness and flight that I only grasped when he read them aloud, even though I didn’t really get the message. On the other hand, Pessoa was a chest full of people, an extraordinary neurotic, a figure endowed with a rare psychopathy for words. And a poet shared by so many as to give rise to statements as dumb and gimmicky as: “There’s a Pessoa for every occasion.” More seriously, how extraordinary and passionate his poetry is! One can’t have enough of Pessoa.

LFG: I will admit that for me, too, there were two mythical figures, the Pessoa of The Book of Disquiet and the Borges of short stories, and that only as an adult did I begin to appreciate them as poets. I find Borges the poet absolutely dazzling, though not many feel the same way.

AL:Borges is a poet of tremendous depth. It probably has to do with what you state so well: that reading the poet Borges requires more time and more knowledge, more experience, more sediments of life. You need to have all the tempos well in place. Your view of the world has to have already often touched upon him. I have the same experience with artists like Morandi; the more time passes, the more entity he acquires. Something light which may even seem monotonous later takes on very delicate nuances, to the point that the brushstroke and repetition become a categorical thought. It’s after much exposure to Pollock that one gets to Morandi better.

LFG: With what editions was your generation educated? Mine first had the brown books of Austral, and later the gray ones of Losada.

AL: We mainly had Visor, Hiperión, and Pre-Textos. These three publishers have been part of the sentimental education of several generations. In my case there was a special relationship with Visor, so much that I have been going there every fortnight since I started at the university at 17, to this day. We have gotten a lot of nourishment from that bookstore and publishing house.

LFG: There’s another thing I’ve realized has changed over time, and it’s that our generation hated Lorca. Lorca was picturesque, or, in Borges’s words, an Andalusian professional. And Poet in New York was for us like a surrealist delirium. For our generation, the great poet was Machado. Juan Ramón was too complicated. He was a figure we yearned to love, but did not manage to connect with.

AL: You hated Lorca? That’s new to me, and quite snobbish. The early Juan Ramón, the modernist one, is definitely cloying. Even he disowned it in his later years. I think Juan Ramón was rediscovered with the publication of his American work in full, in that excellent volume titled Lyric of the Atlantis, published by Galaxia Gutenberg/Círculo de Lectores. There we have a Juan Ramón in exile and often in agony. Essential. A Juan Ramón who doubts, is hurt, estranged from enjoyment and verbiage. A poet full of conflict. Every good poem has conflict within. Poetry is not an

‘infinito’ de Pound, pero está mejor concretada la propuesta de Eliot. Pound es una babel de la cultura, con un juego de láminas, texturas y contraluces sobrecogedor, pero suelta mucho más la mano Eliot. Está muy bien la ambición de Pound pero, para mí, el poeta-poeta es Eliot. La cosmovisión, la capacidad de concretar en el poema una perspectiva de la humanidad —como en La tierra baldía o Cuatro cuartetos— es de una totalidad inalcanzable para el resto. LFG: Para nosotros también era un mito, en parte porque era un gran crítico literario, un poco como nuestro Juan Ramón que no solo era un gran poeta sino un gran erudito de la poesía. Yo recuerdo que, cuando era joven, me aprendí de memoria las primeras estrofas de La tierra baldía. Pero yo me eduqué en parte en Gran Bretaña, e inevitablemente leía en inglés. Sin embargo, cuando leo a poetas cuyo idioma no conozco, me gusta hacerlo en ediciones bilingües aunque no entienda el idioma, porque hay algo de la sonoridad que de repente recuperas. Por ejemplo, nunca había tenido una gran opinión de Pessoa como poeta. Lo juzgaba un gran prosista, un maestro de pensamiento, pero no pensaba que fuera un gran poeta hasta que leí una edición bilingüe.

AL: Estoy de acuerdo, y hago como tú: contrasto, estudio y comparo. Me pasó con Adam Zagajewski, el poeta polaco, con quien compartí un recital. Sus poemas adquirían una rotundidad y vuelo que solo sentí cuando los leyó él en voz alta, aunque no entendiese realmente su mensaje. Por otra parte, Pessoa es un baúl lleno de gente, un neurótico extraordinario, un tipo de una psicopatía rarísima con las palabras. Y un poeta repartido entre tantos que se puede decir eso tan bobo y ‘marketinero’ de que hay un Pessoa para cada ocasión… Fuera de broma: qué propuesta tan insólita y apasionante la suya. Pessoa no se acaba nunca.

LFG: Confieso que para mí había dos personajes míticos, el Pessoa del Libro del desasosiego y el Borges de los cuentos. Y que solo

escape from the world, but a way to pin yourself to the present. Even the most hermetic of poets anchors you to your time more strongly. A great poem is like a washing machine, with a lot of ground wire.

LFG: The one I was most dazzled by was the early Miguel Hernández, who wrote like Góngora without realizing it. With a plasticity and rhythmic harmony, archaic, yes, but beautiful.

AL:He was extraordinary, with that sparkle of the greatest Baroque poets. An intuitive type. Poetry was his original substance and his temperament. The most popular Miguel Hernández is the one of the battlefield, because he lived as he did and the details of his biography make him more emotive, perhaps more commercial. But there’s also a Miguel Hernández who was powerfully lyrical, inspired, even abstract, which is another form of poetry in action, coming from pure intuition.

LFG: On the other hand, when you are very young, you like love poems, naturally. Many verses by Salinas or Aleixandre that I can no longer bring myself to re-read revolve around the theme of love.

AL:This is where architecture and poetry part ways: the former is a craft that develops over a long time, the latter is a mark of youth. What’s rare is a 70-year-old poet writing with the intensity that some have shown in old age: the Aleixandre of Poems of Consummation, the Caballero Bonald of Manual de infractores, the mature Gamoneda... If poetry has its spark plug in a young ‘metabolism,’ old poets happily run contrary to nature. It’s fabulous.

LFG: Well, José Hierro’s last book has some very gripping verses that you do not expect from a person of his age and circumstances.

AL:For sure. There’s a sonnet in that book, titled New York Notebook, which goes:

“After all, all has been nothing, even though one day it was all.

After nothing, or after all

I knew that all was only nothing.”

como adulto he empezado a apreciarlos como poetas. El Borges poeta me parece deslumbrante, pese a que no muchos lo compartan.

AL: El poeta Borges es de un alcance profundísimo. Probablemente tiene que ver con eso que apuntas, y es que la secuencia del poeta Borges requiere más tiempo y más conocimiento, más experiencia y más poso de vida que el narrador. Te tiene que pillar con los tempos muy bien armados. Que tu mirada sobre el mundo se haya rozado ya muchas veces con él. Me pasa también con artistas como Morandi, cuanto más tiempo más entidad adquiere. Una pintura tan leve, que incluso puede parecer monótona, luego despliega unos matices muy delicados hasta convertir la pincelada y la repetición en un pensamiento rotundo. Después de ver mucho Pollock se llega mejor a Morandi.

LFG: ¿Con qué ediciones se educó tu generación? En la mía fueron primero los morados de Austral y luego los grises de Losada.

AL: La nuestra principalmente fue con los de Visor, Hiperión y Pre-Textos. Esas tres han formado parte de la educación sentimental de varias generaciones. En mi caso, con Visor tengo una relación especial, tanto es así que desde que empecé la facultad con 17 años, hasta hoy, suelo pasar una vez cada quince días por allí. En esa librería y editorial nos hemos nutrido muchos.

LFG: Otra de las cosas que me he dado cuenta de que con el tiempo ha cambiado es que nuestra generación odiaba a Lorca. Lorca era el pintoresquismo, o en palabras de Borges, era el andaluz oficial. Y Poeta en Nueva York nos parecía un delirio surrealista. En nuestra generación Machado era el gran poeta. Juan Ramón era muy complicado, era un personaje que queríamos amar, pero con el que no conseguíamos conectar.

AL: ¿Odiabais a Lorca? Primera noticia. Eso es muy esnob. Respecto a la primera parte de Juan Ramón, la modernista, es empalagosa. Él también renunció a ella en su madurez. Yo creo que a Juan Ramón se le descubrió de nuevo con la publicación de toda la obra americana en aquel excelente volumen titulado Lírica de una Atlántida, que publicó Galaxia Gutenberg/Círculo de Lectores. Ahí está un Juan Ramón exiliado, agónico en tantas ocasiones.

Esencial. Un Juan Ramón que duda, dañado, lejos ya del enjoyamiento y la palabrería. Un poeta de mucho conflicto. Todo buen poema tiene un conflicto dentro. La poesía no es una forma de huir del mundo, sino de enclavijarse al presente. Hasta el poeta más hermético te afianza mejor a tu tiempo. Un gran poema es como una lavadora, suele tener toma de tierra.

LFG: A mí el que me deslumbró fue el primer Miguel Hernández, que escribía como Góngora sin darse cuenta. De una plasticidad y de una armonía rítmica, arcaica sí, pero bellísima.

AL: Ese que tú dices es extraordinario, con esa ráfaga de los grandes poetas barrocos. Un tipo intuitivo. La poesía era su sustancia original y su temperamento. El Miguel Hernández más ‘paseado’ es el de batalla, porque vivió como lo hizo y las condiciones de su biografía lo hacen más emotivo, más comercial quizá. Pero hay un Miguel Hernández poderosamente lírico, inspirado, incluso abstracto, que es otra forma de poesía en acción, llevado por una intuición pura.

LFG: Por otro lado, cuando eres muy joven lo que te interesa es la poesía amorosa, claro. Muchas de las cosas que ya no puedo volver a leer de Salinas o de Aleixandre tenían que ver con ese único tema.

AL: Aquí la arquitectura y la poesía divergen: el primero es un oficio de largo desarrollo, la segunda es una constancia de juventud. Lo extraño, a veces, es ver a un poeta con setenta años escribiendo con esa potencia que demostraron algunos en la vejez: el Aleixandre de los Poemas de la consumación, el Caballero Bonald de Manual de infractores, el último Gamoneda… Si la poesía tiene su bujía en un ‘metabolismo’ joven, los poetas viejos van felizmente contra natura. Es fabuloso.

LFG: Bueno, el último libro de José Hierro tiene frases que te dejan conmovido y que no esperas de una persona de su edad y sus circunstancias.

AL: Sin duda. Hay un soneto en ese libro al que te refieres, Cuaderno de Nueva York, que bajo el título ‘Vida’ comienza así:

«Después de todo, todo ha sido nada, a pesar de que un día lo fue todo.

Después de nada, o después de todo supe que todo no era más que nada».