Tapachula Lives in Limbo

A student project of the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University

Supported by the Howard G. Buffett Foundation

How thousands of migrants became trapped in Mexico’s ‘open-air prison’

Tapachula

From March 3 to 12, 2022, 18 Cronkite students and three faculty advisers traveled to Tapachula, Mexico’s southernmost city, to report from what has become the frontline in the battle to stop northward migration to the U.S. Students found migrants from all over the globe blocked by Mexico authorities from continuing their journeys, swelling the city by thousands. These are their stories.

The team: Athena Ankrah; Laura Bargfeld; Taylor Bayly; Tirzah Christopher; Nathan Collins; Katelynn Donnelly; Mikenzie Hammel; Alyssa Marksz; Shahid Meighan; Emilee Miranda; Daisy Gonzalez-Perez; Drake Presto; Salma Reyes; Juliette Rihl; Jennifer Sawhney; Natalie Skowlund; Taylor Stevens; Geraldine Torrellas.

Faculty advisers: Rick Rodriguez; Jason Manning; Adriana Zehbrauskas. The trip and this book were generously funded by the Howard G. Buffett Foundation.

Photo by Tirzah Christopher/Cronkite Borderlands Project

Photo by Tirzah Christopher/Cronkite Borderlands Project

Full project online

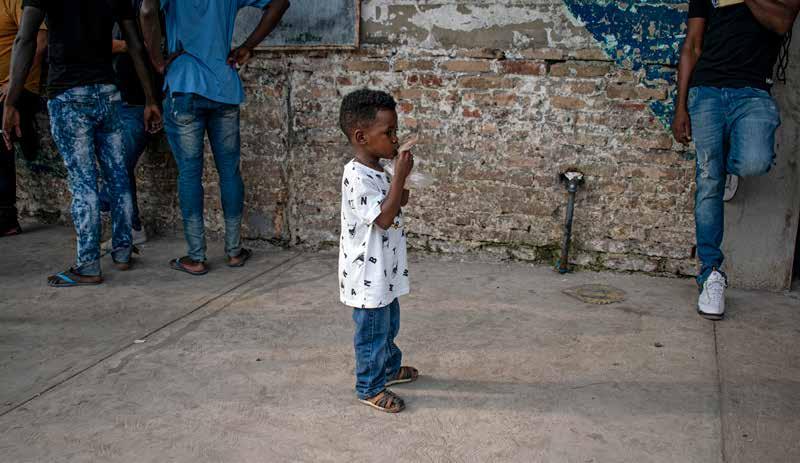

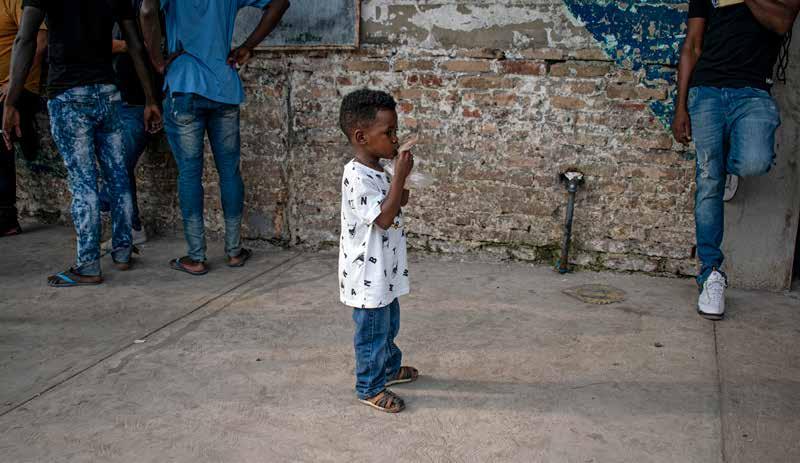

Naomi, 4, sits in Parque Bicentenario in Tapachula, Mexico, where her family has slept on sheets of cardboard for several nights waiting for their immigration applications to be processed. One in three of the migrants who travel to Mexico from South and Central America is a child, according to a report from UNICEF. (Photo by Taylor Bayly/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Naomi, 4, sits in Parque Bicentenario in Tapachula, Mexico, where her family has slept on sheets of cardboard for several nights waiting for their immigration applications to be processed. One in three of the migrants who travel to Mexico from South and Central America is a child, according to a report from UNICEF. (Photo by Taylor Bayly/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

PROJECT: TAPACHULA, MEXICO Table of Contents ‘Open-air prison’ in southern Mexico traps thousands of migrants ................ 1 Migrants’ mental health mostly ignored by Mexican government ................ 13 Migrants trapped in Tapachula wait for documents ............................. 19 Migrants still rely on money from family to live ................................ 21 Some migrant women turn to sex work for survival ............................. 26 Systemic gaps in health care affect migrants .................................... 29 The migrant journey to Tapachula is perilous ................................... 37 Black migrants see racism and dead end ........................................ 43 Children migrants wait for immigration documents and aid ..................... 52 Housing options limited for migrants in southern Mexico ...................... 59 Young migrants in Tapachula face fragmented childhoods ...................... 69 Tapachula residents react to migrant crisis ...................................... 78 Migrants endure wretched living conditions .................................... 85 M igrants die alone, unidentified ............................................... 86 Mexicans and Guatemalans work together along border ........................ 90 O rganizations work to educate migrant children ............................... 91 M igrants languish in Mexico immigration system .............................. 96

CRONKITE BORDERLANDS

Cover photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project

‘Open- air prison’ in southern Mexico traps thousands of migrants

By Taylor Stevens

TAPACHULA, MEXICO – The desperation here is palpable.

I t fills the stifling air as migrants line up in the hot sun outside the National Migration Institute in hopes of receiving an interview, their children close at hand and their visa applications tucked under their arms in colorful protected sleeves so the papers won’t get ruined on the nights their families sleep outside in the rain.

I t strains the voices of the asylum seekers protesting outside a news conference by Mexico’s president, as they chant demands for action

before some sew their mouths shut in defiant, gruesome silence.

A nd it wells in the eyes of displaced Haitians – struggling to deal with a system entrenched in anti-Black racism – when they throw rocks and set fires on the streets to bring attention to their plight.

T hese moments unfold day after day in Tapachula, a city of about 350,000 near the border of Guatemala that has long served as a waystation for migrants spurred north by political turmoil, gang violence, discrimination and

poor economic prospects in their countries of origin.

B ut as the United States has pressed Mexico to stem the flow of people heading to the U.S. in recent years, tens of thousands of migrants have become trapped here in Chiapas, Mexico’s poorest state.

T hey now face extreme limitations on their movements, few job prospects, poor living conditions and long waits for immigration hearings in an environment some have labeled an “open-air prison” and others have described as a southern

1

Yobel Ruiz and his daughter, Milaidy, 5, wait outside one of the immigration offices in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 8, 2022. The pair fled their home in Panama’s Darién Province the month before, after guerrillas kidnapped Ruiz’s wife. Ruiz hopes to be granted asylum and move to Florida, where a cousin lives. He still doesn’t know the fate of his wife.

(Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

extension of the U.S.-Mexico border.

“You see misery. You see anger. You see desperation,” said Freddy Castillo, a Haitian migrant who arrived in Tapachula last August. “People say, ‘Well, what did I come here for?’ You know, the situation is bad in my country. But that’s supposed to stay there, because I (want to) have maybe a better life someday.”

A s frustrations have reached a boiling point in the city, thousands of migrants set off in the rain Monday for the United States. The group intends to walk the length of Mexico and could grow to as many as 15,000 people, by some estimates – a number that would make this caravan the largest ever recorded in the country, according to The Guardian.

M any of the migrants who end up in Tapachula are from Honduras, El Salvador and other Central American countries, but others started their journeys from such far-flung places as Palestine, Cuba, Nigeria, Brazil and, recently, Ukraine.

A fter escaping the sometimes brutal conditions in their home countries, migrants moving up through South America must pass through the treacherous Darién Gap, a more than 60-mile stretch of jungle that connects Colombia to Panama, where robberies, rapes and encounters with animals are frequent.

T he journey takes multiple days for most migrants. And those who make it out alive sometimes view Mexico as a reprieve, said Yamel Athie, a Tapachula resident and community organizer who has been facilitating dialogue between migrants and locals. I nstead, they face only more challenges.

“I magine if you are from Africa or the Middle East or Haiti and you have spent months fighting to survive, to live, to eat, to pay for your trip,” Athie said. “And when you arrive here, with all of your emotions at the surface because you are reaching your goal, you smash into a wall. And it is a wall that will break your soul.”

The new caravan is yet another sign that although Mexico has stemmed the flow of migrants on their way to the United States, it hasn’t shut it off completely. In April, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported that U.S. officials encountered about 230,000 people attempting to cross the southern border – the highest monthly total in at least the past four years. An encounter is defined as either the apprehension or expulsion of a migrant.

And some analysts predict even more will come because of President Joe Biden’s stated intention to end Title 42 – a policy the federal government used during the pandemic to expel thousands of migrants under the guise of public health protections. Shortly after Biden’s April 1 announcement, groups of migrants took off from Tapachula for the United States, defying local restrictions on their movements. Some fought with police and Mexican immigration officials.

On May 20, a U.S. federal judge blocked the Biden administration from ending Title 42, agreeing with a complaint from 24 states that the move would increase illegal

2

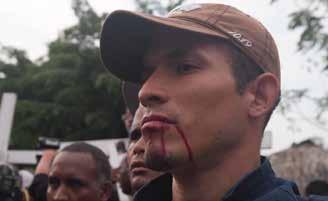

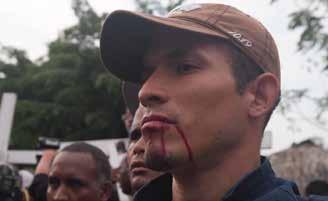

Haitian migrants clash with the Mexican National Guard in front of the National Institute for Migration in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 4, 2022. During the protest, migrants threw rocks and set street fires in frustration with their conditions in the city of 350,000 people. (Photo by Drake Presto/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

immigration. He also ruled that the administration must provide public notice and a comment period before ending the policy. The administration has announced it intends to appeal the ruling.

Despite migrants’ frequent complaints of poor conditions in Tapachula, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico offered little recognition of and few solutions during his remarks at a news conference in the city March 11.

The best way to help migrants, he said during a brief discussion of the issue, was not to improve conditions in Mexico but to create work programs for them in Central America.

“People don’t hit the road because they enjoy it but because of necessity,” he said. “The majority of the migrants are young people

who want to move forward and progress in life – so we have been proposing that there be investment in Guatemala, in Honduras, in El Salvador.”

That approach mirrors the United States’ “root causes” strategy, which seeks to address the forces that push people to leave their home countries as part of an effort to stem migration before it begins. But the strategy would do nothing to help improve conditions for the migrants who protested beyond the white tent set up for López Obrador’s visit.

Wairiuko Samuel Kimani, an asylum seeker who said he fled his home country of Kenya after his family learned he was gay, survived 10 days in the rainforest in Panama. He said being in Tapachula has been worse even than that. At least in the jungle, he saw a way out.

“These people you see here,” he said, motioning around to the mass of migrants nearby, “they are very frustrated because we thought getting out of the Darién Gap was all. We thought that was our living nightmare. But actually Mexico is.”

‘The job of President Donald Trump’

D uring a religious festival in early March, three national flags were posted in the middle of the Suchiate River, which separates Chiapas state and Guatemala –the Mexican flag, the Guatemalan flag and the stars and stripes – a symbol of U.S. influence here, although its border is more than a thousand miles to the north.

U nless they pay a coyote who takes a different route or they have the means to fly over Tapachula, many of the

3

Katerine Martinez, 28, has her mouth sewn shut during Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s visit to Tapachula on March 11, 2022. López Obrador told local officials the best way to help migrants was not to improve conditions in Mexico but to create work programs for them in Central America. Not all the migrants in Tapachula are from Central America. (Photo by Drake Presto/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

thousands of migrants who make the journey north through Central America each year will cross the Suchiate here.

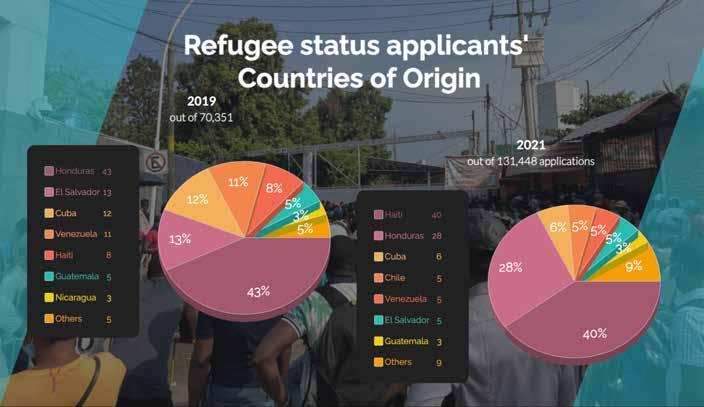

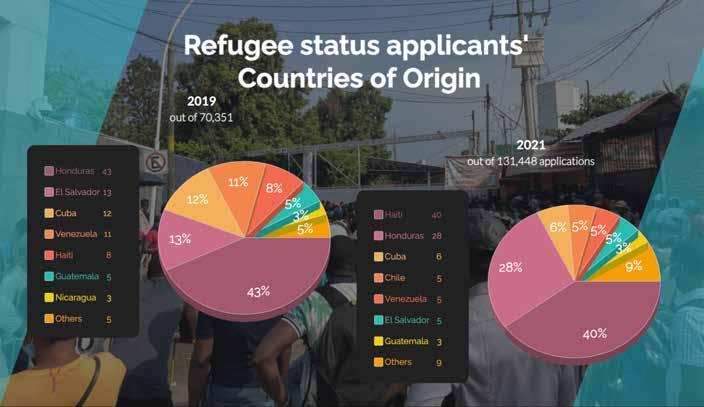

A bout 70% to 80% of all asylum applications in Mexico are filed in Tapachula, according to the local refugee office. In 2021, that number was 89,000 applicants. And because the city is so close to a main route into the country from Guatemala, Tapachula is “always going to be a place of pressure and then relieving that

took root in 2019, after thenPresident Donald Trump threatened to impose tariffs starting at 5% on Mexican imports if the country didn’t increase efforts to “reduce or eliminate the number of illegal aliens” coming to the United States.

F earing the potential impact to its economy, Mexico – whose biggest trading partner is the U.S., and vice versa – struck a deal promising to deploy members of

“I absolutely believe that U.S. pressure on Mexico has a lot to do with why Mexico has militarized its southern border and is trying to keep migrants out of the country – to stop flows of people coming to the U.S.-Mexico border,” she added.

L ópez Obrador, for his part, has said the shifts in Mexican policy are not a result of his bowing to U.S. pressure. Instead, migrants are being kept in the south to protect them from the powerful gangs that operate near Mexico’s northern border, he said.

“We don’t want them to come to the north where they might become drug addicts or victims of crime,” he said in a press conference in January 2020.

W hatever the motivations, experts say the policy shifts that resulted from the 2019 deal have significantly restricted the movement of migrants.

B efore the agreement, “people were for the most part getting through Mexico,” said Arturo Viscarra, a staff attorney with the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, a nonprofit migrant advocacy and civil rights group that is working in Tapachula.

pressure and then pressure again” when it comes to migration, said Rachel Schmidtke, an advocate for Latin America with the global nonprofit Refugees International. B ut the pressures here have felt higher than ever in recent years, thanks to a complicated cocktail of government bureaucracy, politics and pandemic-related challenges that have further exacerbated the difficult conditions for migrants. The same cocktail has strained Tapachula residents, who face great competition for jobs and housing.

M ost experts agree that the current situation in Tapachula

the National Guard to its border with Guatemala. The deal also expanded the Migrant Protection Protocols, also known as the “Remain in Mexico” program, which requires grants to stay in that country while awaiting immigration processing in the United States. Most applications for asylum or other forms of entry are denied.

S chmidtke said Mexico’s harder line toward immigration has in part reflected its own values, noting that the country doesn’t want “a lot of refugees or migrants.” But the U.S. also plays a “pretty significant role in Mexico’s immigration policies,” she said.

B ut the National Guard’s increased militarization of the southern border has since made it “more difficult” for people to get through the country, he said.

J ust one month after the countries signed their deal, the Mexican National Institute for Migration held more than 30,000 migrants in detention – “the highest number of detentions made in a month in the last 13 years,” according to Refugees International.

I n Tapachula, Kimani, the Kenyan migrant, described the city as a prison, noting that many migrants struggle to leave without proper paperwork.

“I think this, all this you see here, is the job of President Donald Trump,” he said, gesturing to the masses of people gathered

4

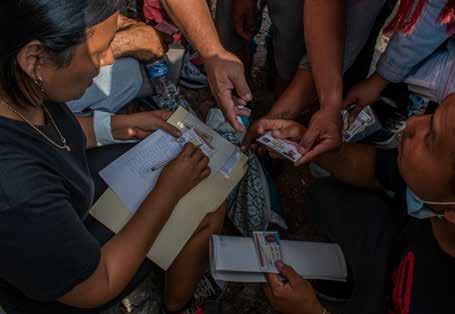

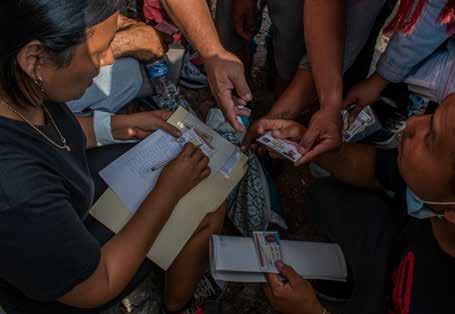

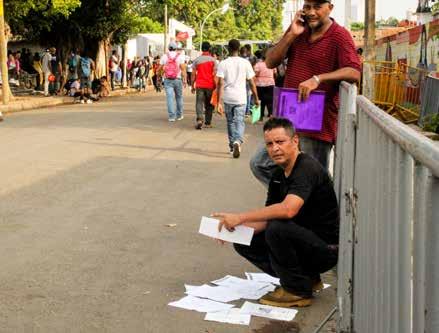

Venezuelan migrants compile a list of their names and immigration numbers at a protest outside the COMAR office in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 9, 2022. The group planned to give the list to COMAR and ask that their immigration paperwork be expedited. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

outside the National Migration Institute office.

A lthough experts and migrants blame Trump for some of the on-the-ground realities migrants face in Mexico, Kimani said U.S. politics continue to drive changes here even under a new administration.

H e said he’s heard from several migrants who began their journeys after Biden was elected in 2020, in hopes that they might benefit from the Democrats’ softer approach to immigration.

B ut while the rhetoric has changed significantly under the new president, many U.S. immigration policies have remained much the same – and they continue to send ripple effects from the southern border of one country to the other.

“M ost people came because they thought Biden would have a new effort or a better effort toward migration,” Kimani said. “According to what I have read, he hasn’t done much.”

Below: The U.S flag is set up in the Suchiate River, which separates Mexico and Guatemala, during a 10-day religious festival on March 4, 2022. Some observers have called the nearby city of Tapachula, Mexico, the “new U.S. border,” and the flag served as a physical representation of that idea. (Photo by Drake Presto/ Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Rosbalis Parez and her son, Daniel Alejandro, 2, wait in the crowd outside the COMAR office in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 9, 2022. The Venezuelan migrants have been living in a tent close to the office while waiting for their immigration paperwork. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Above: National Guard officers stand between an immigration office in Tapachula, Mexico, and the dozens of migrants awaiting entry on March 8, 2022. In recent months, there have been multiple clashes between migrants and law enforcement in the city of 350,000. Below: A young girl waits with her family outside an immigration office in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 8, 2022. Obtaining the necessary paperwork to move freely throughout Mexico can take months.

(Photos by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Above: National Guard officers stand between an immigration office in Tapachula, Mexico, and the dozens of migrants awaiting entry on March 8, 2022. In recent months, there have been multiple clashes between migrants and law enforcement in the city of 350,000. Below: A young girl waits with her family outside an immigration office in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 8, 2022. Obtaining the necessary paperwork to move freely throughout Mexico can take months.

(Photos by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

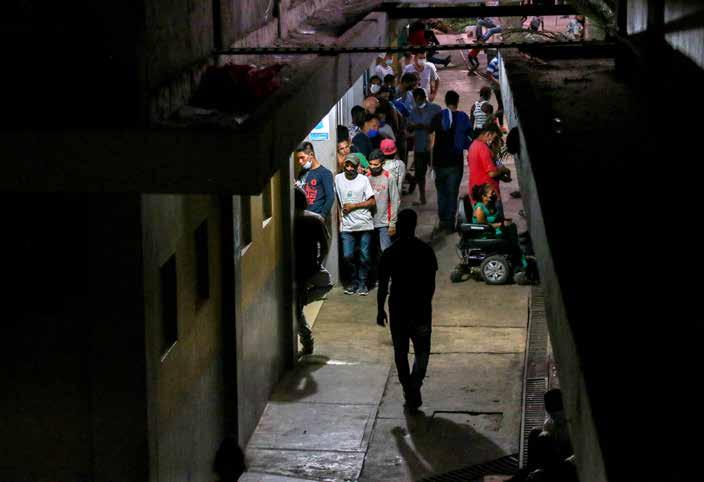

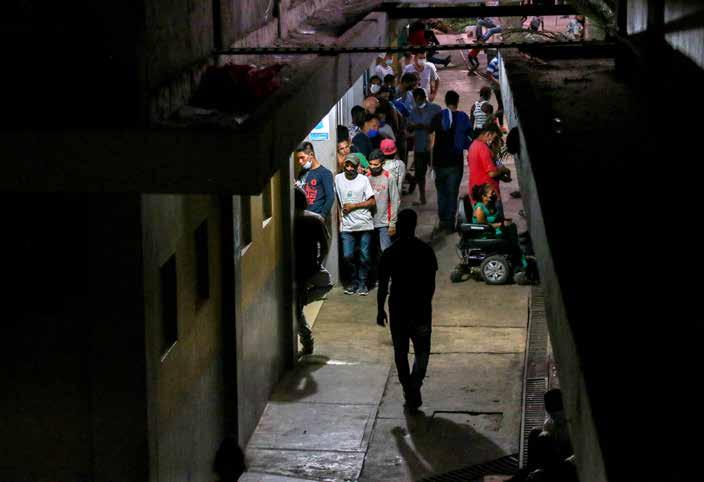

‘I need free movement’

On a muggy day in March, migrants line the wall up and down a colorful mural outside the National Migration Institute office, desperate to obtain an audience with officials who could grant them an earlier immigration appointment. The energy in the air is at once frenetic – as if a protest could erupt at any moment – and listless, as the day gets hotter and they go longer without food and water.

“E very day people are here,” Kimani said, “because they’re trying to reduce their dates. There are people whose dates have been reduced, but I don’t know how they choose who they reduce their dates for.”

N ear the office, National Guard members with shields keep the crowd at bay, avoiding eye contact with the migrants huddled before them.

Am ong the group are Maria Linares and Yandry Mijares of Venezuela, who said they fled the government corruption and violence of their home country in hopes of securing a better life for their son and daughter.

Bu t after they arrived in Tapachula in January, the family found that their struggles were only compounding. Unable to find work, they struggled to pay rent and instead had to sleep on the streets each night. Unable to buy food, their children were facing malnutrition. And without proper immigration documents, they said, their asthmatic son

can’t get a prescription for an inhaler.

Li nares spread paperwork out across her hands showing that each family member had a different immigration appointment date – all of which were weeks into the future.

Ev en under normalcircumstances, the process to apply for asylum or a humanitarian visa in Mexico can be long and complex, requiring multiple appointments, interviews and documents. And the stakes are high for people like Linares and Mijares, who are sometimes stuck in limbo for

weeks or even months without proper immigration papers.

A s they wait for their applications to be processed, migrants are required to stay in the state where they submitted their claim. In the meantime, they become effectively stuck in Tapachula, with limited housing and job opportunities.

Th ose who try to leave the city without authorization risk detainment in the governmentrun immigration center known as Siglo XXI, and they could be deported to their home countries. Me xico’s already challenging immigration process was further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which prompted the United States to effectively close its borders to migrants under Title 42. Since Title 42 was enacted, Schmidtke said, many migrants became “basically incentivized to stay longer in Mexico.”

Th e number of asylum applications had already been rising in Mexico, doubling “each year from 2015 to 2019,” according to the U.S.

7

Tapachula Chiapas, Mexico

Daniela Cisneros and her son, Mesias, 5, rest outside an immigration office in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 8, 2022. The family arrived at 4 a.m. to wait for her husband’s immigration appointment. Cisneros and her son weren’t able to get an appointment until 10 days later.

(Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Congressional Research Service. But by 2020, the Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid, known by its Spanish acronym of COMAR, faced steep backlogs, which it was able to work through only with help from the U.N. High Commissioner. The agency in 2021 again struggled “to meet record demand” for asylum claims.

Al though the number of applications has spiked, not all these migrants want to achieve refugee status in Mexico –particularly because doing so could complicate their efforts to ultimately get legal protection in the United States. And not all the applicants are necessarily eligible for asylum, an international protection available only to people who can prove a “wellfounded fear of persecution” based on their race, religion, political opinion, nationality or membership in a particular social group.

M exico does offer asylum to a broader subset of people than the United States. People whose home countries face “generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive human rights violations, and other

circumstances that have seriously disturbed public order” are also eligible for asylum under the Cartagena Declaration, a nonbinding agreement reached in 1984.

I n some cases, migrants apply for asylum in Tapachula as a protection against deportation because they can’t be booted out

of the country until their claim has been processed. Others apply so they can obtain a humanitarian visa free of cost, according to Alma Cruz, who is in charge of COMAR’s Tapachula office.

Th e visas, which are issued by the National Institute for Migration and are valid for six months to a year, facilitate access to important government services, including education, health care and permission to work, according to Refugees International.

T hat’s why long waits for humanitarian visas pose such a problem for migrants stuck in Tapachula.

“T he people are coming to us, and if you ask them, they don’t want to be here,” Cruz said.

“They don’t want to be refugees here. The complaint of the people is, ‘I need free movement in Mexico. … I need a humanitarian visa. I need to go out from here as soon as possible.’ And COMAR is not the source of the problem.”

W hile they wait for documentation, masses of migrants in Tapachula spend

8

‘It’s better not to come right now’

Two people hug as they wait to enter the COMAR office in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 9, 2022. Mexico’s complicated process of applying for asylum typically takes months, and many applicants are unsuccessful. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Migrants help unload produce at Mercado San Juan in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 5, 2022. They work at the market from 2 a.m. to 2 p.m. daily, earning the equivalent of $10 a day. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

long days in parks or in the city square, where the men often bide their time playing chess and the women braiding each other’s hair.

So me resell goods on the streets, keeping a watchful eye out for city employees who could shut them down for operating without work permits. Others beg passerbys for money for food or other necessities.

O scar Sierra, who fled Honduras with his wife and three children in early January, looked for formal work when he arrived in Tapachula but found his options limited. He considered a particular job only to learn that it required grueling hours from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m., with a daily wage of 150 pesos (about $7.50).

“I t is heavy,” he said, standing with his wife and three children in front of the city steps where

they slept their first night in Tapachula. “The people are taken advantage of.”

Si erra said his family had a good life in Honduras and never imagined they would have to leave everything. But as their piñata business became more successful, gangs took notice and began extorting them for money. They were quickly in over their heads, estimating that they owed thousands in protection money. And they feared that they would be killed when the payday came.

Th at’s when they left everything they owned and got on a bus to Tapachula.

Th e family ultimately hopes to make it to the United States to restart their business. In the meantime, they’re trying to pay the bills by churning out piñatas in their small apartment at a rate of four or five per day.

But at 2,000 pesos a month, the apartment isn’t cheap, and they’ve had trouble making rent.

“T he economic situation is complicated,” said Lizeth, Oscar’s wife.

Go vernment jobs programs can help some migrants, but not everyone can take advantage of them.

Af ter finding ways to make money, obtaining shelter is among the biggest challenges migrants face in Tapachula.

La ndlords often charge them exorbitant rents, which some migrants counter by sharing a unit with others to split the cost. Athie, the community organizer, said space was so limited in December that some homeowners began charging people to sleep on their roofs.

9

Migrants sign up for a day’s work at Mercado Laureles in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 8, 2022. They can earn a modest income by helping maintain public spaces, such as parks and markets, through a government work program. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

10

Haitian women braid hair in Parque Benito Juárez in central Tapachula, Mexico, on March 8, 2022. With few work opportunities, many migrants have come up with creative ways to earn a living. (Photos by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

“They put up plastic tarps, and people charged them for this,” she said. “It is very sad.”

So me migrants end up in shelters, but space is limited and they often are over capacity, according to a March report from the humanitarian aid organization UNICEF. So those who can’t find work often end up sleeping on the streets; the lucky ones finding an out-of-the-way corner or a thick piece of cardboard to provide some support from the hard ground.

De spite their limited resources and different backgrounds, some migrants do their best to help others.

On one occasion, a group pooled their money together so they could prepare a community meal near the town square – a small act of solidarity within a population that so often ends up fighting for scraps.

“M any of the children were very hungry –not just the Haitian children, but Venezuelan children, all of us,” said Wilnot Devalsaint, a Haitian migrant who has been in Tapachula since late last year. “So what do we do among all of us? We asked, ‘Do you have 10 pesos, 5 pesos, 4 pesos, 20 pesos?’ And so we put it all together to make food. To help each other.”

Fo r all the challenges migrants have faced here, Athie said, their influx also has strained longtime residents of Chiapas state, leaving them with fewer jobs and housing options. Some even see the presence of so many outsiders in the small, poor city of Tapachula as something of an invasion, she said.

“T he local people feel really harmed by the presence of migrants here,” Athie said.

Os car Ulises Sol Diva, a lifelong Tapachula resident, said he has stopped walking his dog at night over fears of violence. He said he understands the obstacles migrants face but noted that many permanent residents in the community don’t have much to give – they’re struggling themselves to find work and to feed their families.

“I don’t know,” he said, “it makes us mad sometimes, with the migrants. They want everything. They say, ‘Give me, give me!’”

A thie, whose family migrated to Mexico from Lebanon, said she has tried to help both sides better understand one another through a community Facebook group she started. On it, she advocates for “a dialogue and a language where we are able to share the co-humanity of everyone and the necessities that we all have.”

Be cause in an area that’s long been shaped by migration, for better and for worse, experts say it’s unlikely that the flow of people through Tapachula will end anytime soon.

Ki mani and other migrants, however, said that if they’d known

11

Eduin and his son, Samid, 4, pick up trash on the grounds of Mercado Laureles in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 8, 2022. The family, who provided only their first names and are seeking asylum, left Venezuela two months earlier and are living in a shelter while they apply for refugee status. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/ Cronkite Borderlands Project)

what awaited them in Tapachula and on their journey here, they would have never left home.

“If you are not in immediate danger, if it’s something you can control, it’s better not to come right now,” Kimani said he would advise other migrants. “Here, people are sleeping out. They don’t have food. They don’t have somewhere to sleep. People are desperate.”

Don’t come, he added, unless “you are willing to be that kind of desperate.”

12

Darwin Chevez and his girlfriend, Anna, relax on their “bed” in Parque Bicentenario in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 8, 2022. While living in the park for three months, the pair slept on a piece of cardboard and walked 4 kilometers to a river to bathe. They have since arrived in California and are looking for work. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Oscar and Lizeth Sierra and their three children pose on the steps where they slept after arriving in Tapachula, Mexico, two months earlier. They left their home and thriving piñata business in Honduras after falling $180,000 behind on extortion payments to local gang s. The family eventually hopes to go to the United States. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

‘An abandoned issue’: Migrants’ mental health mostly ignored by Mexican government

By Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project June 16, 2022

By Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project June 16, 2022

TAPACHULA, Mexico – The migrant crisis is evident everywhere in this city of 350,000 near Mexico’s southern border.

Migrants queue up at dawn to apply for immigration documents. Sidewalks overflow with migrants peddling fried rice and flat bill hats. A park, once a popular tourist attraction, is a makeshift campground. The sounds of Spanish, Hatiatian Creole and other languages rise above the teeming streets.

But one facet of the crisis simmers, invisible and largely ignored: The devastated mental health of migrants passing through Mexico on their way to the U.S.

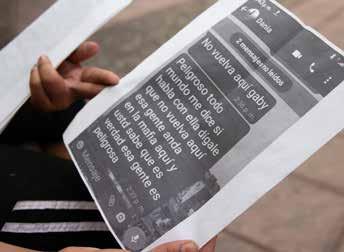

For most migrants in Mexico, trauma is inescapable. It’s in the gang violence, domestic abuse and lack of basic necessities that prompt them to leave home, and it’s on the journey through Panama’s Darién Gap – a perilous route where rape, assault and death are common. And trauma waits for them in Mexico, where any hope of respite vanishes as they spend months sleeping in the streets, struggling to find work or sewing their mouths shut to protest the torpid immigration system.

Experts say it’s even in the migration and asylum process, which requires migrants to recount over and over again the violence they’ve endured.

The migration system “seeks to destroy the souls and minds of the people,” said Yamel Athie, a Tapachula psychologist and migrants’ rights activist.

13

SYH, 42, from El Salvador, sits at Hospitalidad y Solidaridad shelter in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 5. Her full name is being withheld for her protection. Shelters have been at the forefront of providing much-needed mental health services for migrants. (Photo by Laura Bargfeld/ Cronkite Borderlands Project)

The Mexican government does little to prioritize mental health for its own people, let alone people from other countries. Mexico trails its peers in both mental health spending and number of mental health professionals, making services hard to access all around.

And even where services are available, providers face numerous obstacles. Many migrants avoid seeking help because of the stigma attached to mental health issues, or because they come from cultures where trauma is so commonplace it goes unrecognized. Some don’t see the point in starting therapy or medication in a place they view as temporary. Others are simply too busy trying to survive.

Nongovernmental organizations are working tirelessly to fill the gap in need, creating innovative, culturallycompetent services to meet migrants where they are.

Still, providers and experts agree that the problem eclipses all existing resources. As the migration crisis in Tapachula continues to worsen, they said, so, too, will migrants’ mental health.

“This is not just a crisis,” said Nadia Santillanes, a social anthropologist at University of California, San Diego’s Center for Global Mental Health. “This is going to be permanent.”

Cycle of trauma

After walking for eight days, her feet blistered and cracked, SYH finally arrived in Tapachula from El Salvador.

The mother of three, who asked to be referred to by her initials to protect her identity, was anguished over leaving her home and family behind. But she felt she had no choice: After she and her partner refused to continue paying extortion money to a local gang, the gang kidnapped her and attacked her with an aluminum bat, she said. Fearing for her life, she fled.

Within her first few days in Tapachula, a sympathetic stranger helped connect SYH with Hospitalidad y Solidaridad, a shelter for refugees and asylum seekers. There, she was given a medical examination and two sessions with a psychologist. Just being able to vent about what she’d been through, she said, was cathartic.

“That helped me a lot, to get it off my chest,” she said.

SYH’s circumstances are common. The majority of migrants passing through Tapachula are from El Salvador, Honduras, Venezuela, Cuba, Chile and Haiti, where poverty, government corruption and gang violence are everyday occurrences.

In many migrants’ cultures, violence and trauma are so common they are normalized, experts said. And around the world, mental health treatment often still is thought of as only for people with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia or severe bipolar disorder, and require institutionalization. More common symptoms, like depression and anxiety, are overlooked.

Pair those factors with most migrants’ realities as they struggle in Mexico to find work, shelter and feed their families, and it’s not surprising that relatively few seek mental health support.

“They are busy with other things. They are concerned with other things,” said Dr. Ietza Bojorquez, a researcher in the Department of Population Studies at El Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Tijuana, Mexico. “They are not going to seek a psychologist because they are blue.”

This history of untreated trauma, combined with the dangers migrants face on their journeys, the hardships they endure once in Mexico and the sense of loss they feel from leaving their homes, snowball into what some experts call “migratory grief.”

“They’re making the decision to move away from their countries. They’re experiencing mental health issues before even starting the process of migration,”

14

SYH, whose full name is being withheld for her protection, believes this necklace kept her safe when she fled El Salvador. As of March, she is recovering from her journey at a shelter for refugees and asylum seekers in Tapachula, Mexico. (Photo by Laura Bargfeld/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

said César Infante, a researcher at Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health.

Many migrants expect their situations to improve once they arrive in Mexico, he said, only to be immersed yet again in violence, deprivation and scarcity of food, water and shelter.

“So at the end, people end in crisis, no?”

The sluggish migration process, which often keeps migrants trapped in Tapachula for months, can cause these crises to spiral. Multiple migrants have died by suicide in Tapachula in recent years, according to local news media reports.

The problem is widespread: According to data and testimony recorded by the global NGO Doctors Without Borders, of the thousands of migrants in Mexico it interviewed during mental health consultations in 2018 and 2019, the majority appeared to have anxiety, depression and PTSD. More than half said they had been exposed to violence on their migration route. Of the women surveyed, a third said they had suicidal thoughts.

And that was before the pandemic. In March 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump implemented Title 42, a controversial public health order that drastically restricted migration from Mexico and Canada in an attempt to stop the spread of COVID-19. This left many migrants stuck in limbo, unable to move forward in the U.S. asylum process. (The Biden administration has attempted to end Title 42 but has been blocked in federal court.)

In the pandemic’s early days, Bojorquez said, some migrant shelters implemented lockdowns that prevented people from coming and going freely, which made many feel even more trapped.

“The feeling of autonomy is very important for mental health,” she said. “That was lost during that time.”

Even the migration system itself is traumatic, doctors and aid workers said, as people must recount what they’ve been through in great detail at multiple steps in the process.

Although some of the government employees who conduct immigration interviews now receive

sensitivity training, retraumatization is still “inherent” in the asylum process, said Blaine Bookey, the legal director for the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies at the University of California, Hastings College. The legal requirements for establishing eligibility and credibility require applicants to provide a granular level of detail, she said.

“To some extent, even utilizing the best practices, it just is a traumatizing process,” Bookey said, adding that she believes every client she’s ever had has needed mental health support.

At Hospitalidad y Solidaridad in Tapachula, as SYH prepares to apply for asylum, shelter staff have

warned her how emotionally demanding the process can be. She’ll likely have to tell her story many times over, they told her. Still, she’s determined to move forward.

15

A closet holds donated items at Jesuit Refugee Services, an international organization that supports migrants in Tapachula, Mexico. Psychologists at the organization host support groups for men, women and adolescents. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

“I think mental health is an abandoned issue in Mexico,” Infante said. “Not only for migrants but for everybody.”

– César Infante, researcher at Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health

“What happened to me, I will never forget,” she said. “But I have to be strong and get on.”

‘We have zero pesos’

Mexico’s refugee agency, the Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados, known by its Spanish acronym COMAR, recognizes the dire need for more mental health services for migrants, said Alma Cruz, who heads COMAR’s Tapachula office.

But her agency receives no money from the federal government to address it.

“We have zero pesos” for mental health services, she said. “It’s a big, very big problem.”

In Mexico, it’s not only migrants’ mental health that goes overlooked. Doctors, researchers and NGO workers agreed that the country barely addresses the mental health needs of its own citizens: In 2017, only 2% of Mexico’s overall health budget – just more than $1 per person – was allocated to mental health. In a 2011 report, the World Health Organization described Mexico’s mental health workforce as “insufficient” and “poorly distributed.” And for people in Tapachula,

the nearest psychiatric hospital is in Tuxtla, five hours away by car.

“I think mental health is an abandoned issue in Mexico,” Infante said. “Not only for migrants but for everybody.”

In 2019, a group of experts began working with the Mexican Secretaría de Salud’s mental health council to draft a plan to address migrants’ mental health. But the COVID-19 pandemic and staff turnover at the ministry interrupted the effort, said Bojorquez, who was part of the group. There has been no follow-up since.

“I think mental health is an abandoned issue in Mexico. Not only for migrants but for everybody.”

– César Infante, researcher at Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health

Cruz, the COMAR worker in Tapachula, said federal agencies recently sent migrants to Tuxtla for psychiatric care in a few severe cases. But for the majority of migrants, their mental health goes unattended.

16

A photograph of the women’s group is displayed at Jesuit Refugee Services in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 10. The group, which began in 2019, helps migrant women process the trauma they’ve endured through such activities as art projects and creative writing exercises. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Darwin Chevez, 30, left home in Nicaragua because of the tumultuous political situation and failing economy. But living in Tapachula was even worse, he said in March. He and his girlfriend spent their nights on a piece of cardboard under a tree in the park, trying to sleep while constantly worrying about being robbed, kidnapped or deported.

At one point, he became depressed when he thought about returning home and realized he couldn’t. He had only 200 pesos left, the equivalent of $10.

Mental health services would have been helpful, Chevez said, but he didn’t hear of any.

“For all the immigrants who arrive in Mexico, it’s hard because they don’t receive any medical care from any institution,” said Chevez, who has since left Tapachula and arrived in California.

Where government response lags, migrant shelters and NGOs long have acted as a safety net. Now, many in Tapachula are adding mental health to their already long list of services.

Fray Matías Human Rights Center, a local nonprofit, has teams of social workers, lawyers and psychologists that work to comprehensively meet each migrant’s needs. At the international organization Jesuit Refugee Services, psychologists run support groups for migrant men, women and adolescents. And at Global Response Management, an international medical NGO, intake workers screen patients and refer them to appropriate mental health services.

Above all, organizations on the ground have adopted a “psychosocial” approach that addresses migrants’ mental health in a culturally competent way, such as through group activities centered on family, community and self-expression.

“How they speak about mental health is revolutionary,” said Santillanes of UC, San Diego, who has studied mental health protocols in shelters in Mexico.

When Mirta arrived in Tapachula three years ago, she had just escaped domestic violence, had left her three

17

Laura Benitez, coordinator for Global Response Management, prepares to see patients at the organization’s pop-up medical clinic in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 9. Working regularly with migrants, she often hears stories of the difficulties they’ve been through, and she recently restarted therapy to protect her own mental health. “I think a lot of people in activist or humanitarian groups, they are so busy helping people, they don’t put their mental health as a priority,” she says. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

children behind in Guatemala and was sleeping in the street, her mental health in ruins.

She soon joined a support group at Jesuit Refugee Services, where twice a week she bonded over food, conversation and such activities as painting and jewelry making with other women who had survived similar experiences.

She could breathe again, said Mirta, whose last name is being withheld for her protection.

“I’m always, always going to be grateful for this service,” she said. “Why? Because it’s changed my life.”

Although such services are essential, they are scarce. Marilú Cárcamo Menéndez, the psychologist who runs the women’s group at Jesuit Refugee Services, said the group has helped about 100 women since its inception in 2019 but hasn’t been able to accommodate everyone who wants to be involved.

For the migrants who can access mental health services, caring for them isn’t always easy, doctors and health care workers said.

Dr. Jorge Eduardo Montesinos Balboa, one of only a handful of psychiatrists in Tapachula, said giving medications can be particularly challenging. For example, antidepressants are supposed to be managed over the course of a year – but with patients who are migrating, there’s often little or no opportunity for follow-up.

“One just barely begins to offer medicine and you put them on a plan for a year, but who knows if they will be able to do that? Who knows what is going to happen?” he said.

It can also be hard on the health care workers themselves who, by working closely with migrants, are susceptible to vicarious trauma.

Laura Benitez, a project manager at Global Response Management, often spends her days taking migrants to the hospital and connecting them with other services. Listening to their stories weighs heavily on her, she said. She recently restarted therapy as a way to protect her well-being.

“I think a lot of people in activist or humanitarian groups, they are so busy helping people, they don’t put their mental health as a priority,” she said.

Despite the challenges in providing care, medical and NGO workers agreed that more resources need to be put toward making sure migrants’ comprehensive needs are met. On top of general mental health services, specialized services are also lacking, Benitez said, such as grief counseling and services for people with intellectual disabilities.

But shelters and NGOs are already stretching their resources thin. In the end, they often are the only line of defense for migrants’ mental health.

“In general, without NGOs here, people would be suffering way more,” Benitez said. “Because government doesn’t do enough.”

18

How the Mexican government has failed to solve the migrant crisis in Tapachula, Mexico

By Drake Presto/Cronkite Borderlands Project

By Drake Presto/Cronkite Borderlands Project

In Tapachula, migrants sew their mouths, start fires and blockade roads, in protest against the Mexican government’s slow process for those seeking asylum and work visas. In some cases, migrants have been trapped in the city for years.

19

Video by Drake Presto/ Cronkite Borderlands Project

20

Video by Drake Presto/Cronkite Borderlands Project

Migrants far from home still rely on money from family to live

By Nathan Collins June 28, 2022

TAPACHULA, Mexico – Martin Nore sells odds and ends –baseball hats, a stock pot, a blender – in front of a memorial dedicated to Benito Juarez, Mexico’s first Indigenous president, while he waits for documents that would allow him to continue his migration north.

The Haitian’s journey to the United States has been stalled in southern Mexico for nine months. To survive while waiting for his Mexican papers, Nore is selling what he can without a permit, which draws the scrutiny of government inspectors and the ire of local vendors, who must pay for business permits.

But Nore, 40, says he has little choice. No one will hire him.

“When I walk into a store here and ask about work, they say, ‘No, no, no, I don’t work with Haitians!’” Nore said, standing near his makeshift storefront in Parque Central Miguel Hidalgo, in downtown Tapachula.

In addition to his sales, Nore depends on money sent to him by family members in Haiti. Their ultimate goal is to fund his migration to the United States

21

Haitian migrant Martin Nore, 40, relies on money from family to survive in Tapachula, Mexico, where this photo was taken March 4. He says the local economy clearly benefits from migrants. “We come here, we spend money. If someone’s relative or friend sends us money, we spend it here.” (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

so that once there, Nore can find work to in return support them through remittances – money sent across national borders, usually by wire transfer.

Nore saves what he makes from his business, and when he doesn’t have enough to pay for more merchandise, his father in Haiti sends him money. A transfer during a weekend in March allowed Nore to nearly triple his inventory.

45% of financial flows entering those countries globally, according to a 2020 article in Southern Economics Journal from researchers at Texas A&M.

As in Nore’s case, money from remittances flows in both directions – from home to help the migrants on their way, then from the migrant back to home once they’re established in their new country. These money transfers are big business for the

“Basically, decisions on how to migrate, when to migrate and where to migrate are (decided) by … economic differentiation … and the incentive to improve your life by leaving,” said Raul Hinojosa-Ojenda, a professor of economy and Latin American migration at UCLA.

“Projections show that not only are we going to need a lot of more immigrants in the next 10 years, there’s also going to be a lot more remittances,” HinojosaOjeda said. “We anticipate a trillion dollars in remittances in the next 10 years to Mexico and Central America.”

But sending and receiving money on the individual level isn’t cheap or easy. In Tapachula, migrants wait hours in lines to get money from home, only to be turned away for lack of verification, bureaucratic delays or simply because the offices ran out of money.

For migrants like Nore, remittances are measured in small increments – enough to get a business going or save up to bring their families to join them.

Even with this help, Nore struggles financially, although he noted the local economy clearly benefits from the migrants who have flooded into Tapachula over the past few years.

“We (migrants) come here, we spend money. If someone’s relative or friend sends us money, we spend it here,” he said.

For the estimated 30,000 migrants scattered around Tapachula who are waiting to continue their migration journeys, there are the limited avenues for survival –selling goods without a permit, joining the long lines of people seeking government assistance or collecting remittances from home.

Remittances have long been crucial to the foreign direct investment of developing countries – representing about

places where they are received, a boon to local and national economies alike.

Remittances are increasingly vital to economies throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. The World Bank reported that remittances to countries in those regions increased by 25.3%, to $131 billion, from 2020 to 2021.

In Tapachula, the effects on the local economy have been explosive.

From 2020 to 2021, remittances sent into Tapachula doubled from $20 million to just more than $41 million, according to DataMexico, which is a joint project between Mexico’s Secretary of Economics, Banco de Mexico and Datawheel. Additionally, remittances make up nearly 4% of Mexico’s overall GDP, according to the Wilson Center, a research institute.

And while Tapachula’s economy grows from remittances, municipal inspectors force Nore and other migrant vendors off the street for selling goods without a permit multiple times a day.

Near Nore’s space, five or six vendors are peddling their wares on the same streets around the park. On a narrow road behind them are dozens more merchants selling produce out of wheelbarrows, trying to operate in less visible areas of the park.

Nore’s merchandise is neatly lined up on a black tarp, ready to be scooped up at a moment’s notice if municipal workers try to shut him down.

A vendor nearby barters in Spanish; the seller next to Nore speaks Creole. Elsewhere in the city, the diversity among

(Video by Emilee Miranda/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

migrants is seen in the parks, heard on booming speakers in passing cars and in smells wafting from different foods prepared and sold in the many markets intertwined among Tapachula’s aged architecture.

On a humid March afternoon, Nore is approached by a halfdozen municipal workers, wearing tan vests with black patches on their breast pockets reading “Inspector.” They speak to one another and to Nore, and their tone switches from serious to jovial when they notice journalists’ cameras and microphones. They soon leave.

Nore said local officials should let migrants earn a living while

23

Martin Nore of Haiti sells goods on the street in downtown Tapachula, Mexico, on March 6. Because he lacks a vendor permit, Nore must keep a close eye out for city officials. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

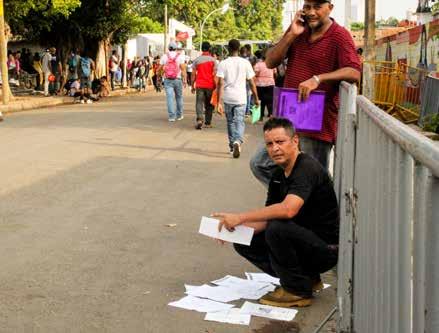

People line up outside Coppel, a money transfer business on March 8 to receive money transfers. Not everyone leaves happy: Such businesses often run out cash. (Photo by Drake Presto/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

waiting for documents that will permit them to continue north.

“We immigrants do good here,” he said. “Spending money in this economy. It works. But we have passed through a lot of misery. And they don’t help us.”

About 90% of remittances are sent in the form of cash, but high transfer fees – an international transfer through Western Union costs $45 or about 940 pesos –diminish the amount that can be sent.

More problematic is what Hinojosa-Ojeda at UCLA calls a lack of local investment opportunities, so the remittances are used to launch more migrant journeys.

“When you send a lot of cash back to villages, where there are no banks, no mechanism

for saving the money – most remittances are used to finance more people leaving because that’s the best return on your money,” Hinojosa-Ojeda said.

Businesses that process wire remittances frequently have limited amounts of cash on hand, so customers who line up early usually are in a better position to receive their money. But there’s no guarantee, and more time waiting in line means less time looking for work, securing documentation or tending to a business.

Claudia Matute, a legal resident of Mexico who’s originally from Honduras, is living solely on remittances while she waits for her daughter to be released from Siglo XXI in Tapachula – Mexico’s largest immigration detention facility. She said her daughter, Genesis Graciela, who’s also from

Honduras, has been detained for 15 days for illegally crossing into Mexico in order to join her mother.

To get her money, she joins migrants in similar straits lining up, at least one day a week, outside Coppell – which processes money transfers – in Parque Central Miguel Hidalgo. Coppell employees step out onto a cobblestone walkway, moving down the snaking line of 20 to 30 men and women, handing out vouchers to those who will get their money. The last one goes to the man directly in front of Matute.

Through tears, she starts sending texts and voice messages on her phone.

“They should have a special bank for (migrants) so that they are not struggling,” Matute said.

24

Claudia Matute, originally from Honduras and now a legal resident of Mexico, shows a photo of her daughter, Genesis Graciela, 28 – who was being held in Siglo XXI detention center in Tapachula, Mexico. (Photo by Drake Presto/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

“They can’t keep up because the demand from foreigners is too high.”

Elektra, another money transfer business, also was low on cash that morning, she said, adding that it’s wrong to be denied cash that’s sent legitimately.

Sadio Ansou, a Senagalese migrant also waiting at Coppell to pick up a large wire transfer from his brother, said he wants to establish roots in Tapachula, but money transfer businesses either don’t have enough money on hand or won’t accept his transfer documents.

“I want to buy a house,” Ansou said, pulling a tattered handwritten document displaying his money order information from a plastic multicolored folder.

He won’t get his wire transfer on this day, and he isn’t sure he ever will.

Like many migrants awaiting documents, Ansou can’t find work or provide for himself. Wire transfer difficulties compound his desperation.

“What do I do now?” he asked. “I have no family here.”

For Nore, Ansou and Matute, economic stability is day-to-day or week-to-week. Nore hopes to make it farther north to secure a more viable way to make a living, with long term goals of bringing his family to the United States from Haiti.

He says that he and two other people pay 4,000 pesos a month for a small apartment near the center of Tapachula. That’s nearly $200, in a country where the average minimum wage for legal workers is $7.50 a day.

Despite his struggles, Nore said he doesn’t consider Tapachula an “open-air prison,” as some migrants and officials call it. But he blames U.S. politicians for

turning a blind eye to the issues in Tapachula and in Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.

Until the international focus changes, Nore and other migrants

will continue to peddle their goods on the street, queue up at daybreak to receive remittances or government assistance, and continue to wait for the Mexican government to issue travel documents.

25

Senagalese migrant Sadio Ansou says he wants to buy a house in Tapachula, Mexico, but difficulties claiming cash transfers from Senegal prevent that. (Photo by Drake Presto/ Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Sex work equals survival for some migrant women in Tapachula, Mexico

By Emilee Miranda July 4, 2022

TAPACHULA, Mexico – For migrants in this overwhelmed city, many women from very different parts of the globe turn to sex work for the same reason: survival.

Behind Benito Juarez Park, in Tapachula’s center, women sit in pairs or stand by themselves outside the bars and restaurants. Their heavy eyeshadow and bright lips are juxtaposed with their casual blouses and sandals. They blend in among the chaos of the square but stand out to the men looking for their services.

Nearly half the migrants who crossed Mexico’s southern border in 2021 were women, according to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. When women, especially single mothers, arrive in Tapachula, they lack job opportunities and proper work permits, according to Cristian Gomez Fuentes, coordinator for Brigada Callejera de Apoyo a la Mujer Elisa Martinez center in Tapachula.

The organization, which provides medical care, counseling and many other services to sex workers, in February reported a 70% increase in prostitution in Tapachula over the previous several months. The group, founded 35 years ago in Mexico City, has worked in Tapachula since 2017.

26

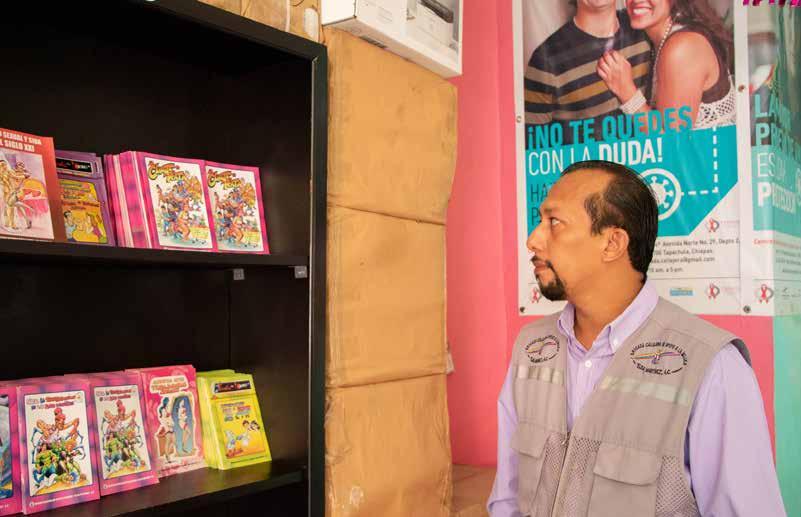

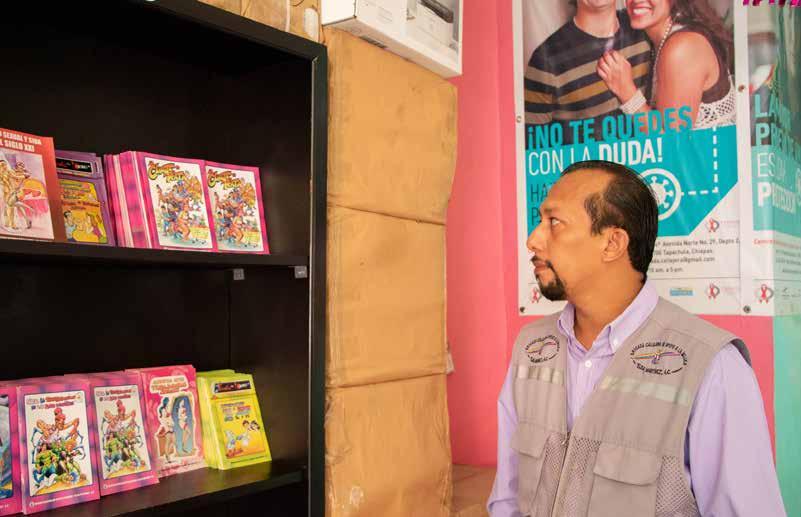

Cristian Gomez Fuentes is the coordinator for Brigada Callejera de Apoyo a la Mujer Elisa Martinez in Tapachula, Mexico, which provides medical services, contraceptives and educational material to sex workers. These comic books, which feature Brigada Callejera’s founder and her late husband, are given to sex workers as a fun, educational tool related to their work. Topics covered include HIV/AIDS, human rights and human trafficking. (Photo by Jennifer Sawhney/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Some migrant women become sex workers – defined as adults who receive money or goods in exchange for consensual sexual services or erotic performances – because they consider it the only way to provide for themselves and their families during the weeks or months they’re stalled in Tapachula, waiting for documentation that will allow them to continue north toward the United States.

“What you have is all these women who come, and they are taken into this sector, which is not what they expected,” said Itzel Vizcarra, head of the International Office for Migration, an United Nations agency that aids migrants in Tapachula.

Because of the stigma of sex work – the women often try to hide their activities from their families –accurate statistics on how many migrants turn to sex work in Tapachula aren’t available, according to a 2020 research study in the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved.

“The vast majority, the only place where you can work without documents to start with is in a botanical center [park] or in a bar or directly in the street,”

Gomez Fuentes said. “In sex work, they can subsist day-by-day and be able to send a little resource to their families who are left behind in their country.”

Migrant women often are subject to abuse and harassment while working, depending on whether they work indoors or out, according to the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. Women working in more formal settings, such as bars, are more likely to receive some protection from managers, staff and other co-workers. Abuse from clients and immigration officials is more common for migrant women working in informal outdoor settings, the study said.

According to a research article published in PLOS ONE in 2018, sexual and psychological abuse by clients often occurs during condom negotiation, or as the result of intoxication. When women are arrested by immigration officials, Gomez Fuentes said, they’re often assaulted and robbed to pay a fee, and most will not report abuse out of fear of deportation.

“They were really afraid of all kinds of violence with authorities, especially international migrants, fear

27

Brigada Callejera de Apoyo a la Mujer Elisa Martinez provides free medical services to sex workers in Tapachula, Mexico. Complaints of mistreatment, expensive STD testing and incorrect test results at government-run medical centers and private pharmacies have been a central concern for many who seek treatment there. (Photo by Jennifer Sawhney/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

of being deported because the deportation process is horrible,” said Belen Febres-Cordero, a former research assistant at the Center for Gender and Sexual Health Equity, a research center affiliated with the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University.

In addition to abuse, migrant sex workers are underpaid, said Elvira Madrid Romero, founder of Brigada Callejera. Workers make 200 to 300 pesos a day (up to $15), she said, which was a slight increase in recent months but still not nearly enough, especially when local business owners and landlords routinely overcharge migrants.

Sex workers in Tapachula often turn to Brigada Callejera for medical assistance and other help without judgment.

“We work defending the rights of sex workers. … It’s not black and white,” Madrid Romero said.

Brigada Callejera offers general medical care and HIV and syphilis testing at its center in north-central Tapachula. It also distributes comic books that provide educational material related to the center’s work, including AIDS and condom use. Team members also go directly to places where migrants work, providing testing for HIV and discussing sexual and reproductive health, as well as human and labor rights.

For sex workers who become pregnant, Gomez Fuentes said, workers from the center ensure they get proper treatment, which many clinics and hospitals will not provide because of the women’s status. They help track the pregnancy, provide vitamins and perform prenatal check-ups. When women go into labor, the team will direct them to health centers so they can get proper treatment at no cost.

In addition to basic medical services, access to medicine and STD and HIV/AIDS testing, Brigada Callejera de Apoyo a la Mujer Elisa Martinez provides condoms to sex workers. Brigada Callejera workers distribute them to sex workers at parks, bars and nightclubs in Tapachula, Mexico. (Photo by Jennifer Sawhney/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

“For moms,” Gomez Fuentes said, “it is true that they have the pressure to be the provider of the family’s home and are mainly the head of the family because they have to take care of everyone, paying rent, water, electricity and food.”

Lack of access to and knowledge of sexual and reproductive health also is a problem among sex workers, according to the study in the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. Distance, time and cost play a large role in women not seeking out resources, such as HIV/STI testing, condoms and contraceptives. Others forgo help for fear of disclosing their status as a sex worker to local health clinics. Febres-Cordero said some women don’t know how HIV spreads or pregnancies occur.

“Simply because they are migrants, they do not receive the proper attention they should give them,” Gomez Fuentes said.

As jobs for migrants remain scarce in Tapachula, women will continue to work the bars and streets. For most, keeping their families alive in hopes of someday continuing their journey north outweighs the risks of sex work.

“Sex work is survival,” Madrid Romero said.

Cronkite reporter Jennifer Sawhney contributed to this story.

28

‘Nothing here is enough’: Systemic gaps in health care system affect migrants in Tapachula

By Laura Bargfeld July 19, 2022

TAPACHULA, Mexico – On a cool Monday morning in early March, dozens of people – migrants and citizens alike – line up outside a public health clinic as rush hour traffic hums by.

One man’s knee is wrapped. Another has a large growth on his face. A teenager is pregnant. Mothers and fathers hold

coughing babies, some parents cough themselves. A child vomits onto a pink cloth on a woman’s shoulder.

As she waits, Karla Matute, 35, holds the right hand of her son, Joryí, 7, whose left hand is wrapped in thin gauze at the wrist. They are migrants from Honduras.

When Matute gets to the front of the line, she shows the nurse a letter from the Mexican

government’s refugee agency, known as COMAR, giving her permission to seek free treatment for her son. She says someone from the Red Cross told her that he may have a fractured arm.

They came to the clinic, Matute said, after a public Tapachula hospital told her they could not treat Joryí for free because she hadn’t started the asylum application process and they aren’t Mexican citizens.

29

Karla Matute, 35, holds her son Joryí, 7, in a crowd outside El Parque Bicentenario in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 5. Joryí’s arm was injured in a clash outside an immigration office, and Matute has struggled to get him medical care. (Photo by Taylor Bayly/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Public directories list more than a dozen hospitals in Tapachula –but depending on interpretation of law and policy by hospital staff – some turn migrants away if they can’t pay, others only treat them after a referral from a primary care clinic, and others only after they have paperwork proving they are in the asylum system. The situation is confusing for migrants seeking care.

The nurse asks, “Where do you live? I need your proof of address so that you can pass through to consultation.”

“Parque Bicentenario,” Matute replies, referring to a park in the city center where she and her son sleep in a tent.

The nurse looks up, confused.

“In the park?”

After further discussion, Matute and Joryí are allowed inside.

Health care in Tapachula was not built for this moment. It is a city of 350,000 in one of Mexico’s poorest, most under-resourced states. Tens of thousands of migrants heading north are stuck here as they await asylum meetings, humanitarian visas and other documents that will allow them to gain residency or legally continue their journeys to Mexico’s border with the United States.

And as policies enacted by Mexico and the U.S. have trapped migrants in Tapachula for months at a time, the city’s health care system has been entirely overwhelmed. The crush comes in addition to the ongoing effects of the pandemic, limited amounts of medication, the high costs of medical testing, paperwork

inefficiencies and reports of discrimination based on race and nationality.

But experts say the situation in Tapachula would be far more dire without the involvement and dedication of nonprofits, nongovernmental organizations, and local health officials.

Under Mexico’s complex health care system, the law guarantees that all people, citizens or not, have access to basic care. That care is provided by a complex web of coverage that includes private insurers (for those who can afford it), employeeprovided coverage, and various public coverage programs. But migrants can’t always access care, say experts and advocates. Communication between policymakers and providers on how to cover migrants and under which programs has been slow and unclear.

30

Haitian migrants – from left, Christela Saint-Louis, 30, Dorvensky Junior Dorme Saint-Louis, 1, Erliwe Germain, 29, Blandina Docile Germain, 5 months, and Dieulifoute Dorme, 33 – sit on the floor of the home they share in Tapachula, Mexico. After migrating from Haiti to Chile to Mexico, they’ve faced numerous challenges in receiving consistent and effective medical care. (Photo by Laura Bargfeld/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Underlying these challenges is the inability of Tapachula’s health care system to meet the needs of its own citizens. Medical providers face resource shortages and structural challenges brought on by limited government funding. Chiapas state has a poverty rate that far exceeds that of other Mexican states; almost 70% of the state’s population qualified for free public health care in 2020, according to Mexico’s Government Institute of Statistics and Geography.

Migrants, particularly women, children and those with chronic conditions, are among the most vulnerable to these gaps and disparities.

‘They threw them in the trash’

When Erliwe Germain went into labor in September, she had been sleeping in Tapachula’s Central Park for five days. Hungry, tired and unable to find housing, she made her way to the public hospital, an experience she described as difficult and scary.

Germain gave birth in a room with seven other mothers. They didn’t even clean the baby, she said, only giving one unidentified injection and no followup care.

Germain had arrived in Tapachula with her husband, Dimitry Docile, just a few weeks before that. The couple, who are from Haiti, had been living in Chile, but she said they were subjected to racism there and wanted better for their unborn daughter. They migrated north and eventually made their way to Tapachula.

Having a baby in Tapachula has allowed Germain to get permanent residency status in Mexico, which affords her access to more services. Germain’s cousin, Christela Saint-Louis, and her cousin’s husband, Dieulifoute Dorme, are not so lucky.

Saint-Louis said her year-old son was born in Chile before the family started the journey to Tapachula with Germain. She suffers from ongoing medical issues that have gotten worse on the trek north.

Although UNHCR, the U.N. agency for refugees, claims they should be able to seek care and

31

Christela Saint-Louis, 30, has been taking medications she received at a local clinic for lung problems, but she says they haven’t helped and her symptoms are worsening. (Photo by Laura Bargfeld/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Leila Castro’s 7-month-old daughter developed diarrhea while the family stayed in the Albergue Jesus El Buen Pastor shelter in Tapachula. The child also has a lung condition.

(Photo by Laura Bargfeld/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

gave them the paperwork to do so, Saint-Louis said, they haven’t gotten the help they need.

In Haiti, Saint-Louis said, doctors operated to remove fluid in her lungs, and she had ongoing medical care after migrating to Chile. However, after walking through the Darién jungle from Colombia to Panama for five days, her breathing problems started again. She said she has lost weight and the pills she was given at a clinic in Tapachula, an antibiotic and antiinflammatories, don’t work for her.

Dorme, who developed a rash on the journey, said the antifungal ointment he was given didn’t work either. Their children are well-prioritized by local organizations, he and Saint-Louis

said, but in their experience, care for the adults is minimal.

Leila Castro came to Tapachula in March with her 7-month-old baby girl and 4-year-old son. They were dropped off at the shelter Jesús El Buen Pastor by immigration officials. Castro left behind two more children in Honduras.

One recent night, Castro’s daughter developed diarrhea, and then a rash on one shoulder. Castro said the doctor and nurse on staff at the shelter gave her electrolytes for the diarrhea but had no medication to treat the rash.

As the baby coughed, Castro held her tightly. The girl has a lung condition, and her health already

is complicated, Castro said, but she intends to keep trying to find treatment for her daughter.

Roberto Báez Castillo was detained by immigration authorities just a day after arriving in Tapachula in late February. He was taken to Siglo XXI, the city’s immigration detention center, where he remained for 11 days.

When he got there, he said, he showed officials the prescriptions for his three-month supply of antiretroviral medication, which he’d received for free in Panama to treat HIV. But the paperwork didn’t matter, said Báez, who has been living with HIV for 12 years.

“These are all the documents I gave them so they would know I have my condition. And yet my

32

Roberto Báez Castillo, a Cuban migrant who traveled to southern Mexico from Panama, says his three month supply of HIV medication was thrown away when he was held 11 days at Siglo XXI, a detention center in Tapachula. (Photo by Juliette Rihl/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

medications were thrown away at Siglo XXI,” he said. “They threw them in the trash.”

As he waited outside the COMAR office, he recalled his long struggle with getting the medication he needs to manage his condition.

Báez, who is gay, said he fled Cuba to escape ongoing, violent discrimination from authorities. He spent a year in Peru without medication. Eventually, he made his way north to Panama City, where he finally started getting medical care in mid-2019.

On this day, he spoke with someone at the UNHCR office in Tapachula who told Báez the agency would connect him with a local nonprofit that serves HIV patients. It’s progress, but he remained distressed that it could be another week before he would get antiretrovirals, putting him at further risk for complications from the virus.

‘Not as bad as it was’

To understand how so many gaps in access exist for Tapachula’s

migrant population, it’s necessary to look at the complex network of available care.

The vast majority of primary health care for migrants is provided by NGOs – nonprofit, nongovernmental organizations –including shelters, many of which are still reeling from the huge increase in migration over the past few years and the effects of the pandemic.

“Nothing here is enough,” said Laura Benitez, the project manager for Global Response Management’s site in Tapachula. Among other things, the international NGO provides free medical services in Tapachula on a walk-up basis. No paperwork is necessary.

Benitez, who also has experience working with migrants in Tijuana, said things have been especially difficult in Tapachula since 2019, when U.S. demands that Mexico slow northward migration led Mexico City to institute a containment policy for migrants who entered the country from Guatemala. The previously transient population became a

static one, overwhelming health and aid workers.

“The health system collapsed, basically,” Benitez said, “and there’s not many NGOs. If we compare this with Tijuana, it’s like, we don’t have enough.”

Global Response Management addresses a need among migrants for good primary care they can easily access. The agency recently moved its office from a public clinic to a park complex called Tapachula Station, where other services, including dentistry, are available. Workers treat such issues as dehydration, foot injuries, fevers and skin conditions.

The team of fewer than 10 serves 20 to 50 people a day, and Benitez predicts those numbers will increase as word of their new location spreads.

“I’m sure in a few weeks, we’ll have more patients,” she said.

Paperwork has been a major barrier for migrants seeking medical care, Benitez said. When migrants apply for asylum in Tapachula, their first point of contact is with the COMAR office to get an appointment date and time. At that appointment, they receive official documents that allow them to more easily access services, including health care at public clinics and hospitals.

However, Benitez said, at the end of 2021, asylum seekers were receiving appointments as far as six months out, causing delays for those with urgent health needs.

“In six months, they cannot work, they cannot leave, they don’t have money, they don’t have food to eat, and they don’t have access to medical health services because they don’t have the document,” she said. “So it was desperate times. It was chaos.”

Although wait times have improved, COMAR staff members

33