Ghost map of

Giacomo Gastaldi: the most cartographically accurate map of the world to date

GASTALDI, Giacomo

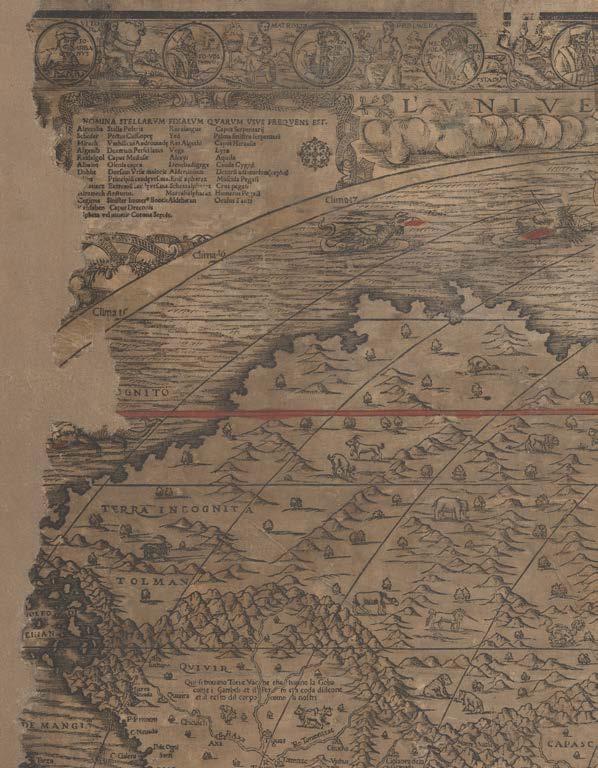

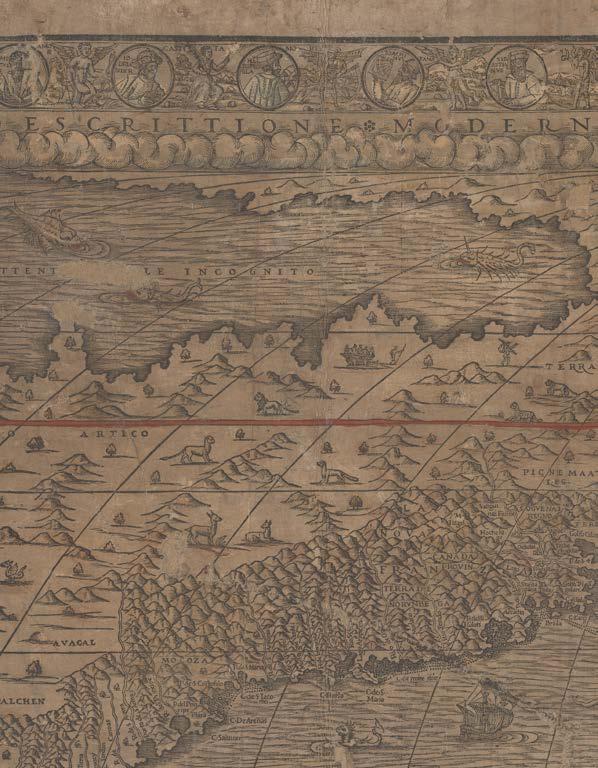

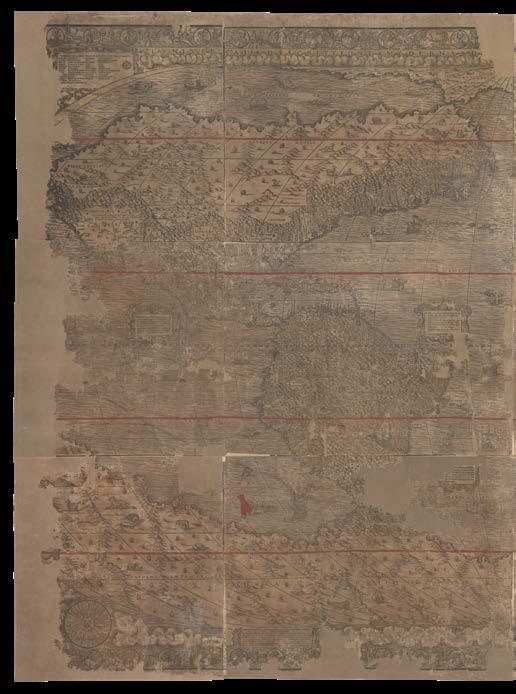

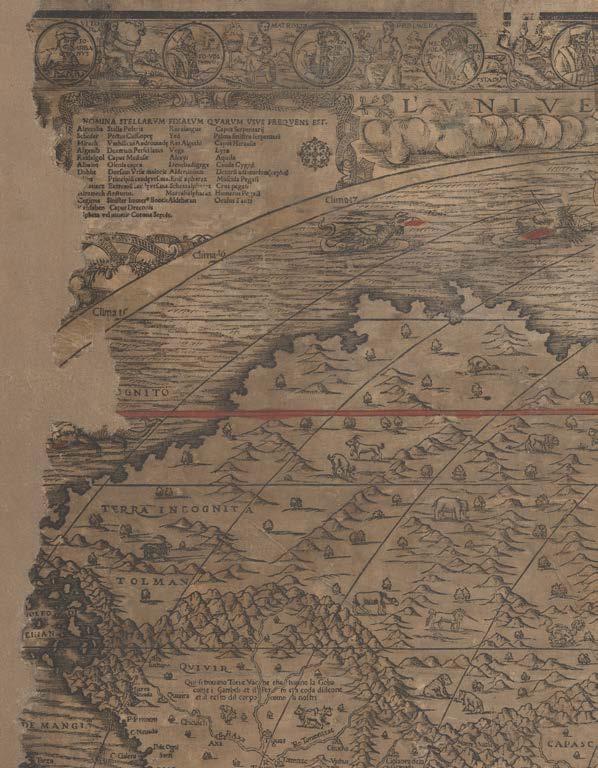

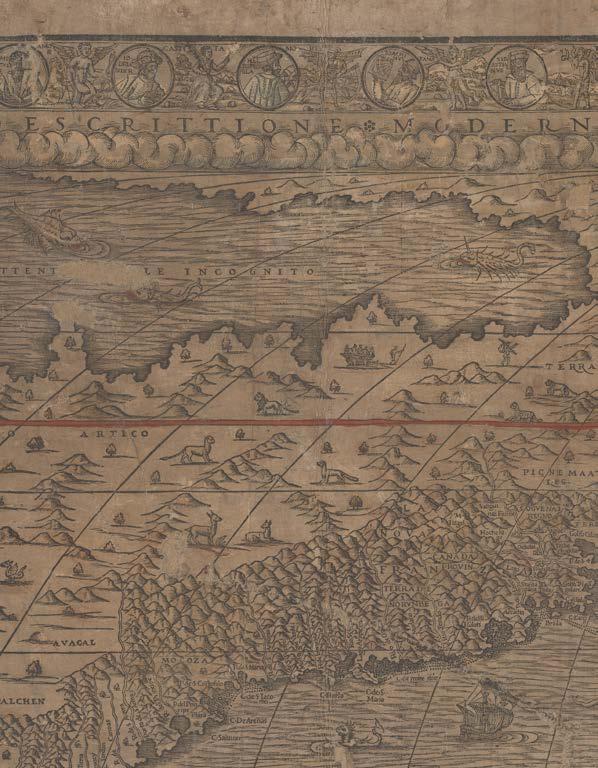

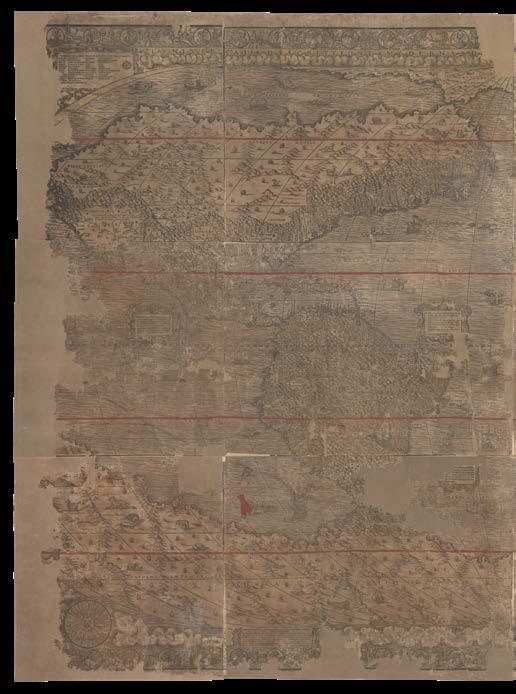

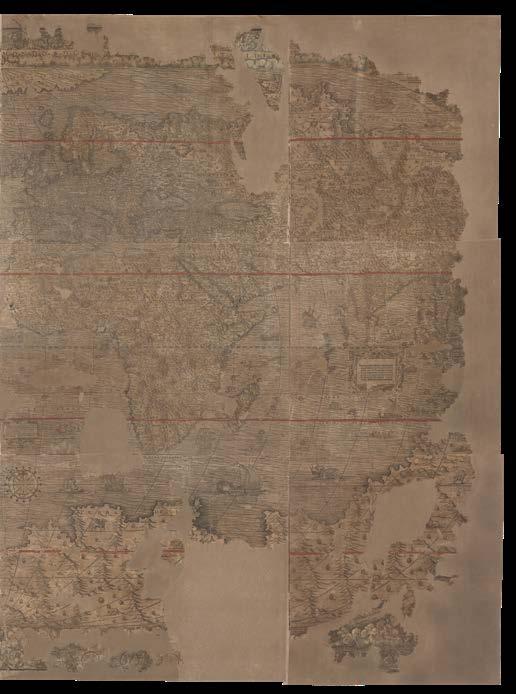

L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo di G[i]ac[omo] [Ga] staldi

Publication

[Venice], … Mathaei Pagani, [1561].

Description

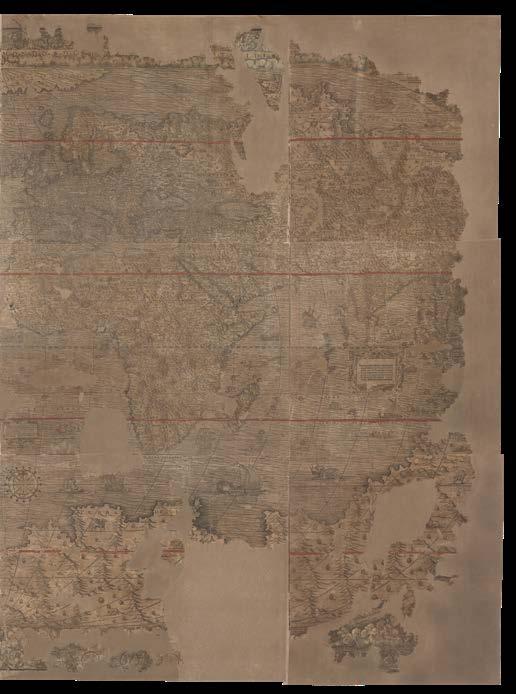

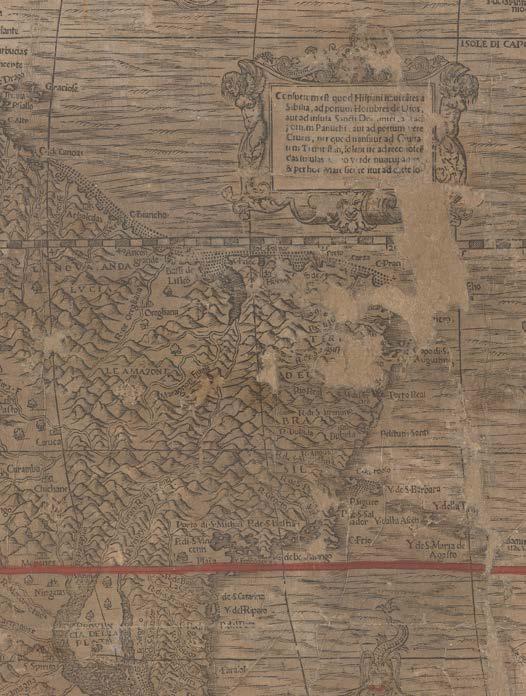

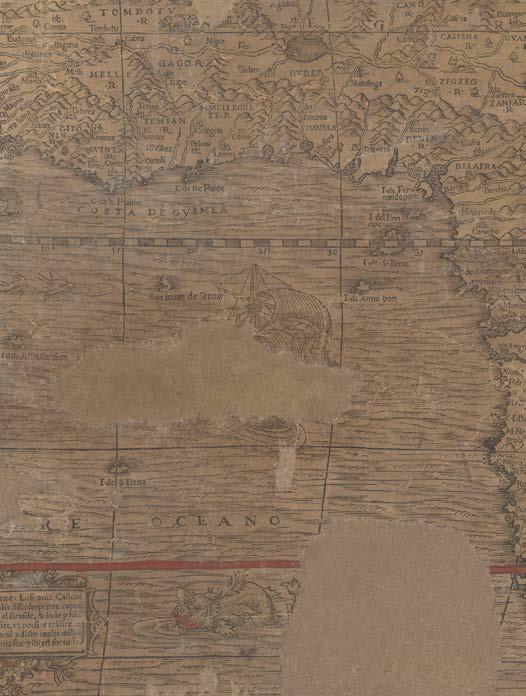

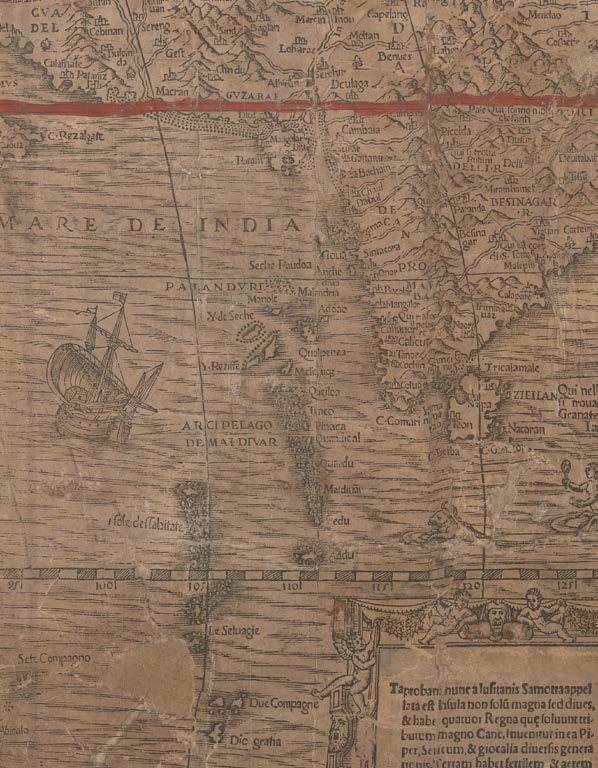

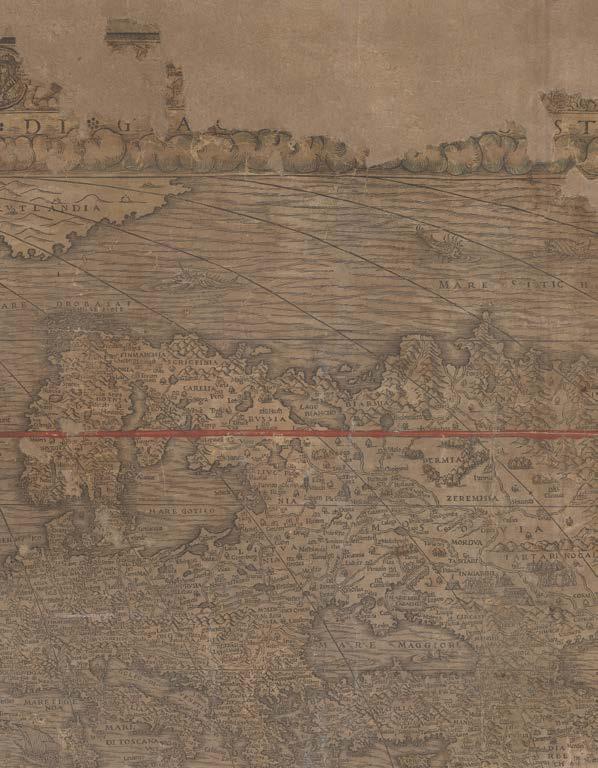

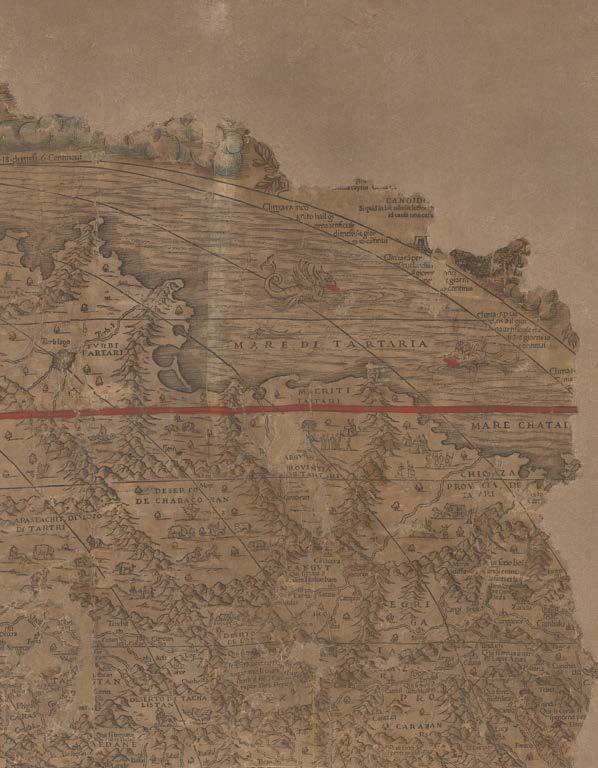

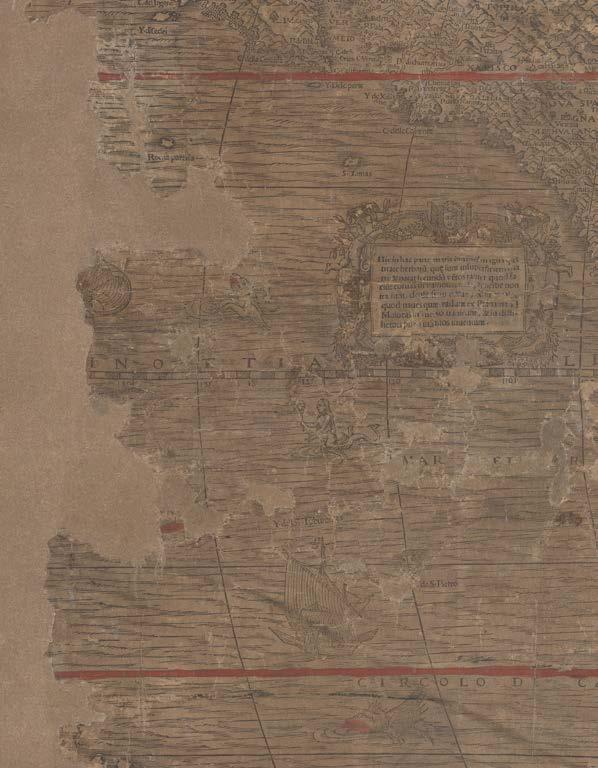

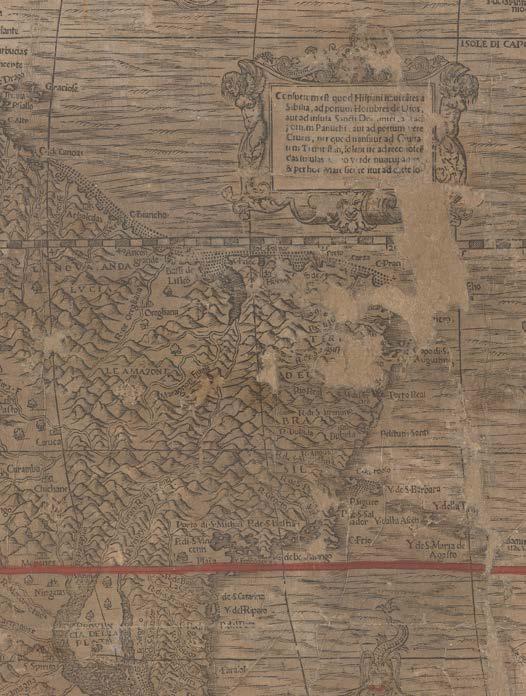

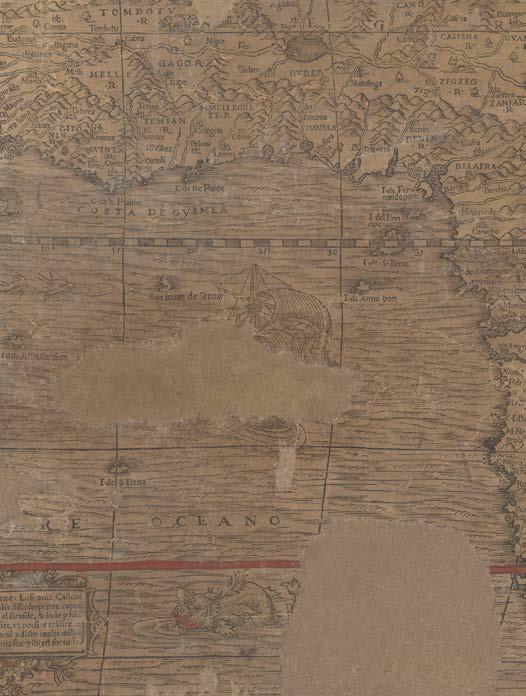

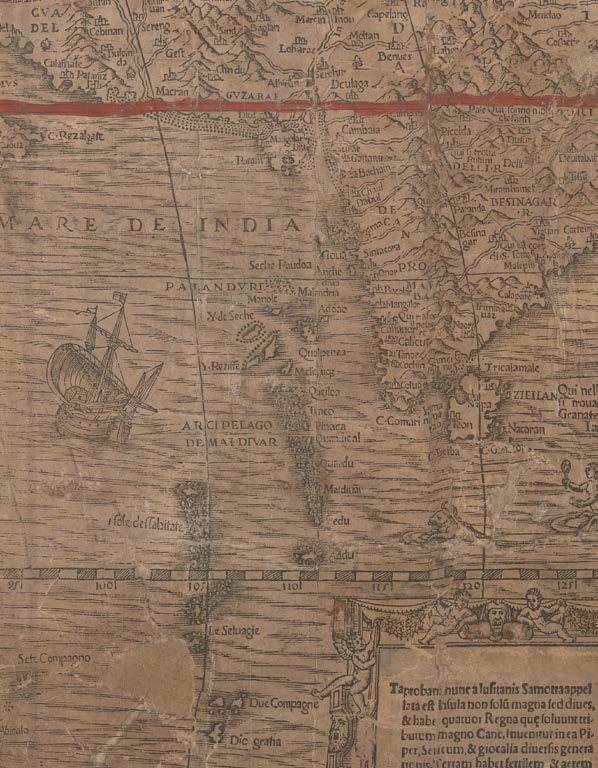

Xylographic map of the world, on 12 sheets, with contemporary hand-colour in part, substantial loss to several outer sheets, laid down on paper in the twentieth century.

Literature

Almagià, ‘Intorno ad un grande mappamondo perduto di Giacomo Gastaldi (1561)’, 1939

Burden, ‘The Mapping of North America’, 2007, page xxviii, 33, 37 and 38

Horodowich, ‘The Venetian Discovery of America: Geographic Imagination and Print Culture in the Age of Encounters’, 2018

Karrow, ‘Mapmakers of the Sixteenth Century and Their Maps’, 1993

Shirley, ‘The Mapping of the World’, 107 Sykes, ‘The Mythical Straits of Anian Author(s)’, in ‘Bulletin of the American Geographical Society’, 1915, Vol. 47, No. 3, pages 161-172

Tooley, ‘Maps in Italian Atlases of the Sixteenth Century, Being a Comparative List of the Italian Maps Issued by Lafreri, Forlani, Duchetti, Bertelli and Others, Found in Atlases’, in ‘Imago Mundi’, 1939, Vol. 3, pages 12-47

Woodward, ‘The Italian Map Trade, 1480 –1650’, in ‘History of Cartography’, Vol. 3, part I, 2020.

$378,700

Giacomo Gastaldi’s monumental and, until now, ghost map of the world, the discovery of which addresses generations of carto-bibliographic speculation, and justifiable confusion, about whether Gastaldi was responsible for two large wall maps of the world, or just one.

Gastaldi’s ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’ is, without doubt, the new map that Gastaldi described in some detail in his libretto (i.e. little book, or pamphlet), ‘La Universale descrittione del Mondo, descritta da Giacomo de’ Castaldi Piamontese’ (1561), and not, as was previously thought, the ‘Cosmographia Universalis et Exactissima iuxta postremam neotericorum traditio[n]em’, “A Jacopo a Castaldio” (c1561) (Shirley 107), known in one complete example, British Library (C18.n.1), and one lacking three sheets, at the BnF.

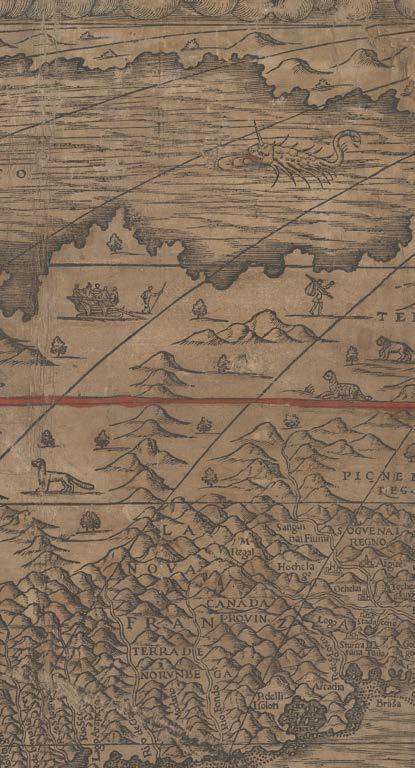

‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’ is now, by far, the most detailed map of the world to date, one of the first printed maps to name Canada, and to show it and North America in any detail, even more than that included in Paulo Forlani’s ‘Il Disegno del discoperto della nova Franza, il quale s’e havuto Ultimamente dalla Novissima Navigatione de’ Franzesi in quel Luogo: nel quale si Vedono Tutti l’Isole, Porti, Capi et Luoghi fra Terra che in quella sono...’ (1565/6) (Burden 33), the first separately-printed map of North America.

Were it unscathed, ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’ would also be the first map to show and to name Gastaldi’s most enduring cartographic invention, the Strait of Anian.

Gastaldi’s previous maps of the world

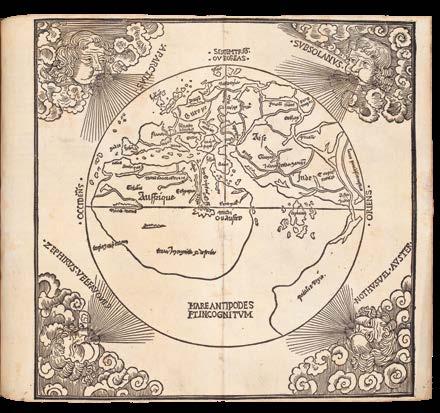

Gastaldi’s first map of the world, ‘Universale, Giacomo Cosmographo In Venetia MDXXXXVI’ (1546), was engraved in copper, on an oval projection, and became one of the most important and influential maps of the sixteenth century. Like the current map, Gastaldi borrowed its shape from Francesco Rosselli’s (1445–1513) 1508 map of the world, the first to display the whole surface of the globe within an oval projection encompassing all 360 degrees of longitude, and 180 of latitude.

Gastaldi’s smaller map was re-issued, with slight variations, at different dates up to the end of the century: “an influential prototype, it was reduced and redrawn for the Ptolemy-Gastaldi atlas of 1548 [‘Universale novo’], adapted in woodcut form by Pagano in 1550 [‘Dell Universale’], was the source for De Jode’s first world map of 1555 [‘Universalis Exactissima atquenon recens modo, verum et recentioribus nominibus totius Orbis insignita descriptio: quo nomine studiosis omnibus non tam utilis quàm maximè necessaria per Iacobum Castaldum Pedemont. Cosmogr. apud Venetos’]. Throughout the 1560s a later generation of Italian engravers and publishers - Forlani, Camocio and Bertelli - produced a number of confusingly similar derivatives” (Shirley). And “its adoption by Ortelius as a basis for his world map,

2

in the ‘Theatrum Orbis Terrarum’ (1570) gave the widest possible circulation to this presentation of the earth’s surface” (Tooley).

The sources of the geographical information in the ‘Universale’ (1546) “were various. For South Asia and Africa, the resemblance to Sebastian Cabot’s oval world map of 1544 is quite remarkable. In North America we can detect similarities with the manuscript world maps in atlases of Battista Agnese, especially for the overall shape of the continent and the northwest coast of America; the evidence of their similar projection and central meridian confirms this view. Gastaldi created at least three similar maps from the ‘Universale’: the ‘Universale Novo’ that formed part of the 1548 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography; the ‘Dell’universale’, a two-sheet woodcut published by Matteo Pagano about 1550; and the multisheet ‘Cosmo- graphia universalis’ (c1561)” (Woodward).

To this canon has previously been added a magnificent wall map, ‘Cosmographia Universalis et Exactissima iuxta postremam neotericorum traditio[n]em’, “A Jacopo a Castaldio” (previously c1561, now after 1571) (Shirley 107) (910 by 1810mm), in ten sheets on nine, held at the British Library, and long presumed to be the new map of the world described by Gastaldi in his ‘La Universale descrittione del Mondo’ (1561). However, the discovery of ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’, proves this not to be the case.

“… the mapamondo of Jaco piamontese di Gastaldi”

On the 30th of July 1561, the Council of Ten, the ruling body of the Venetian Republic, for which Giovanni Battista Ramusio was secretary, approved the publication in Venice of Gastaldi’s libretto, “the one which accompanies the mapamondo of Jaco piamontese di Gastaldi”. Subsequently, on the 18th of August 1561, Gastaldi’s associate of many years, as printer and engraver, Matteo Pagano, applied for a privilege for a map, presumably the one intended to accompany Gastaldi’s libretto “claiming that he had, with much effort, time, and expense, drawn and engraved a “mapamondo” in twelve sheets and was asking the senate to grant a privilege for fifteen years to prevent copying in wood or in copper” (Woodward).

The libretto was subsequently published as ‘La Universale descrittione del Mondo, descritta da Giacomo de’ Castaldi Piamontese’ (1561), and in it Gastaldi describes his new wall map of the world in some, very telling, detail. This includes that it will be distinguished by having 24 meridians and 24 parallels (12 in the northern hemisphere and 12 in the southern), but in the most significant departure from his own previous maps of the world, the boundaries between the continents will be clearly marked, including an emphatic assertion that “La terza parte nominata Asia, hai suoi costni verso Levante, benche nel detto Mapamondo pare che sia verso Ponente; il stretto detto Anian, & si distende con una line a per il golfo Cheinan, e passa nel mare Oceano de Mangi sino al Meridiano

che e al fin dell’isola di Giapam verso Levante, & seguit ando il detto Meridiano verso Austro,.... Questo fera il confin dell’Asia verso Levante dal Mondo nuovo” – “Asia terminates in the East, although on this world map, it appears in the West; the Strait of Anian extends with a line through the Gulf of Cheinan, and passes into the Sea of Mangi,… This is the border in the East between Asia and the New World”.

For many, it has been assumed that the map referred to, in Pagano’s petition, and in Gastaldi’s libretto, was ‘Cosmographia Universalis et Exactissima iuxta postremam neotericorum traditio[n]em’, by “Jacopo a Castaldio” (British Library C.18.n.1, and BnF ark:/12148/cb443700000, lacking 3 sheets). However, this map does not match Gastaldi’s description nearly so well as the current one.

For a start, one clue is surely in their titles: ‘Cosmographia Universalis…’ does not match that of the libretto, ‘La Universale descrittione del Mondo’; whereas the current map’s title, ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo di Giacomo Gastaldi’, has a very clear and close association.

More conclusively, there are some clear doubts as to the extent of Gastaldi’s authorship of ‘Cosmographia Universalis…’, which in style is much more like that of Giovanni Andrea Vavassore (fl.1530-1573), particularly as displayed in his magnificent ‘Procession of the Doge to the Bucintoro on Ascension Day’ (1565). As Woodward reports: the “undated ten-sheet woodcut map of the world with the title ‘Cosmographia universalis’ bears the unusual form of Gastaldi’s name “Jacopo a Castaldio”, and indicates that the map was “Revised by Giacomo Gastaldi, and by several other highly skilled scholars of the discipline, and corrected and enriched in almost infinite places”. The cartography is indeed similar to that expressed in ‘La Universale descrittione Moderno d[el] Mondo’, and includes information first submitted by Gastaldi in his libretto, and the discoveries of Jacques Cartier in the northeast of North America. However, ‘Cosmographia Universalis…’, would appear to be at least ten years later than ‘La Universale descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’, since it in all likelihood post-dates the Spanish victory at the battle of Lepanto in 1571. A dramatic vignette at the very centre of the map depicts a gentleman in Ottoman attire offering King Philip of Spain, “P.F.P” (i.e. Philippo fidei Promotor), the whole earth with one hand, while pointing in the direction of the “New World” with the other, implying that his work as defender and promoter of the true Christian faith worldwide has only just begun.

After examining the British Library example of ‘Cosmographia Universalis’, in 1939, Almagià was the first to point out several features that suggest it was not the map referred to in Gastaldi’s libretto, or Pagano’s petition, but a close copy.

Pagano’s petition was for a map of 12 sheets, while ‘Cosmographia Universalis…’ has ten (actually nine, but one was clearly intended to be divided into two).

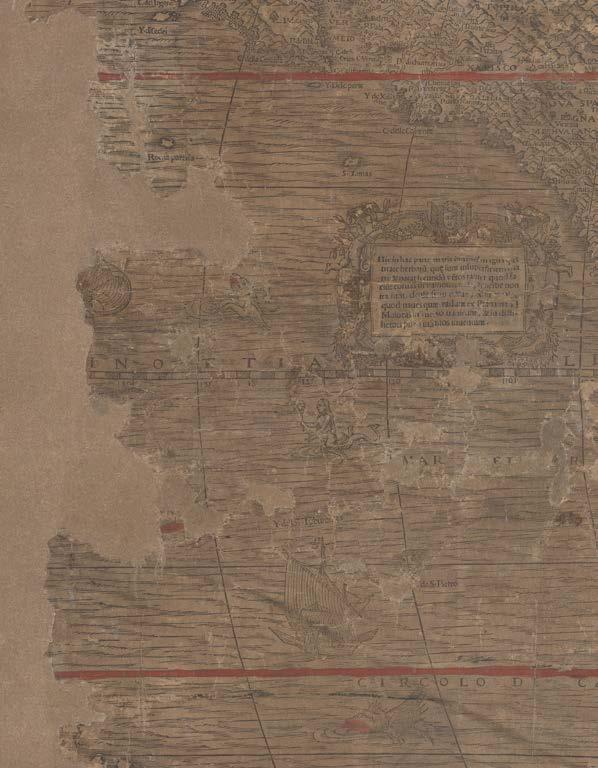

Pagano’s printer’s mark (clasped hands) is not on ‘Cosmographia Universalis…’, whereas it is on ‘La Universale descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’, lower left, at the very heart and centre of the compass rose. It was very unusual for Pagano not to sign his work.

Gastaldi did not normally collaborate with other cartographers, yet the full title of ‘Cosmographia Universalis… A Jacobo castaldio, nonnvllisque aliis hvivs disciplinae peritissimis nuncimum revisa, ac infinitis fere in locis correcta et locupletata’, clearly states that it was a collaboration: “revised by Giacomo Castaldio, and by several other highly skilled scholars of the discipline, and corrected and enriched in almost infinite places”. In and of itself, the form of his name, “Jacopo a Castaldio”, is unusual.

As Woodward reports, no text type is found in the white spaces clearly intended for it on ‘Cosmographia Universalis…’, suggesting that this was either a proof before letters or a very late pull of the blocks after the type had dropped out. The latter scenario is favored, “because the paper does not bear the watermark commonly used in Venice in the 1560s” [please noteno further information on the actual watermark is currently available]. The example of the ‘Cosmographia Universalis…’ in the BnF would seem to support the latter theory, as one cartouche with text survives on it.

Gastaldi’s libretto indicated that the boundaries between the continents would be clearly marked on his map, but they are not on ‘Cosmographia Universalis…’. Whereas ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’ is drawn with great pains to separate the continents, particularly Asia and America.

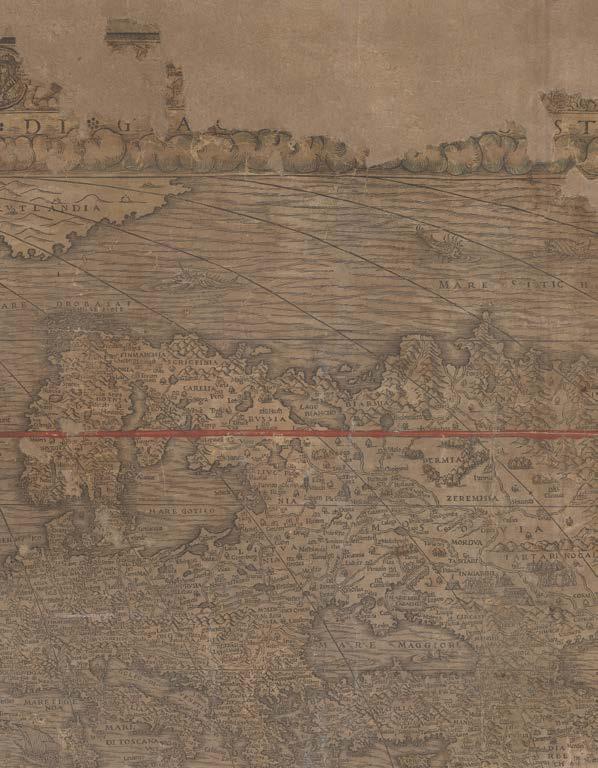

The libretto distinguishes 24 meridians and 24 parallels (12 in the northern hemisphere and 12 in the southern), but ‘Cosmographia Universalis…’ has only twelve parallels, whereas ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’, has all called for in the libretto.

All these points have continued to raise the possibility that there was a very similar, and earlier, 12-sheet map, made in 1561 with Gastaldi’s name on it, “that would repay a search” (Woodward).

‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’, the current map, is the result of that search, and fulfills all the criteria set out in Gastaldi’s libretto: including the correct number of meridians and parallels, and the crucial distinction of clarifying the borders between the continents, particularly, that between Asia and America: the Strait of Anian.

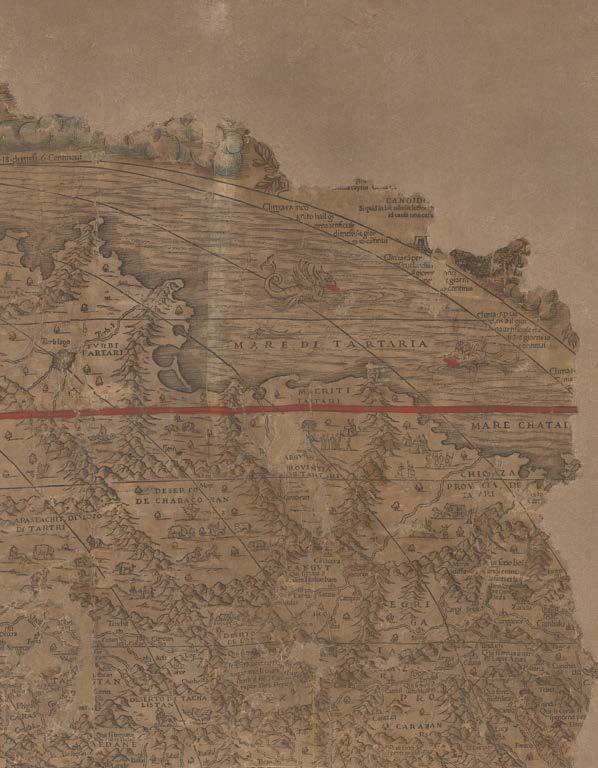

The myth of the Strait of Anian

While Gastaldi had previously maintained the long tradition of connecting the Asian and American continents in his maps before 1556, even though many of his contemporaries had already adopted the notion, his ‘Universale della parte del mondo nuovamente ritrovata’ (1556), printed in the third volume of Ramusio’s ‘Navigazioni e viaggi’, “shows him starting to hesitate, with this part of the world left blank and unfinished and the link between Asia and North America unclear. Five years later, he described his conception of the Strait of Anian as well as its placement on his 1561 wall map in a contemporaneous pamphlet, ‘La universale descrittione del mondo’ (1561), where he states that Asia “terminates in the East, although on this world map, it appears in the West; the Strait of Anian extends with a line through the Gulf of Cheinan, and passes into the Sea of Mangi... This is the border in the East between Asia and the New World”.

Even though the current, and only known, example, of ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’, is severely damaged, particularly at the outer edges, it is possible just to see that there is a continuous, definitive, and distinctive western coastline to the northern region of North America. The ‘Golfo di [C]hienan’ is clearly visible, as is ‘[Mare] di Mangi’, and it is this cataloguer’s certain belief that the “Streito di Anian” would have appeared immediately above: making ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’ the first map to show and name the Strait of Anian.

Gastaldi, like his predecessors and contemporaries, was very aware of “Ania”, a Chinese province mentioned in accounts of Marco Polo’s travels; quite possibly as a result of his collaboration with Giovanni Battista Ramusio, for whose ‘Viaggi’ he had provided maps, and who published a new account of Polo’s adventures in 1559. Gastaldi included this province on his large three-sheet map of Asia, ‘Il disegno della terza parte dell’Asia’ (1562); and for his influential map of North America, ‘Il Disegno del discoperto della nova Franza’ (1565/6) (Burden 33), Paulo Forlani adopts Gastaldi’s model for the “Streto de Anian”, dividing the Asian and American continents, and much else from Gastaldi’s cartography. Interestingly, Forlani would not include the Strait of Anian on one of his world maps during his lifetime, but it does appear in the 1651 re-issue.

Cartography

‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’ (1561) now usurps

‘Cosmographia Universalis…’ (after 1571) (see Burden page xxviii) as the most detailed map, by far, of the world, to date. It is one of the earliest printed maps to incorporate the discoveries of the three voyages of French explorer, Jacques Cartier, preceded only by Paulo Forlani’s first map of the world, ‘Paulus de Furlanis Veronensis Opus hoc ex.mi Cosmographi Dni. Jacobi Gastaldi Pedemontani instauravit’ (1560). However, Gastaldi’s map depicts all of the Americas, and particularly North America, in

much greater detail than Forlani does here, and on his separate map of North America, ‘Il Disegno del discoperto della nova Franza, il quale s’e havuto Ultimamente dalla Novissima Navigatione de’ Franzesi in quel Luogo: nel quale si Vedono Tutti l’Isole, Porti, Capi et Luoghi fra Terra che in quella sono...’ (1565/6) (Burden 33). In this last, Forlani does, however, incorporate Gastaldi’s ‘Streto di Anian’, in what has previously been considered its first appearance on a map.

None of this should come as a surprise, as Gastaldi had long been interested in the cartography of North America, having included the first regional maps of the area in his pocket Ptolemy of 1547-1548; and larger ones to Ramusio’s ‘Viaggi’ (from 1556).

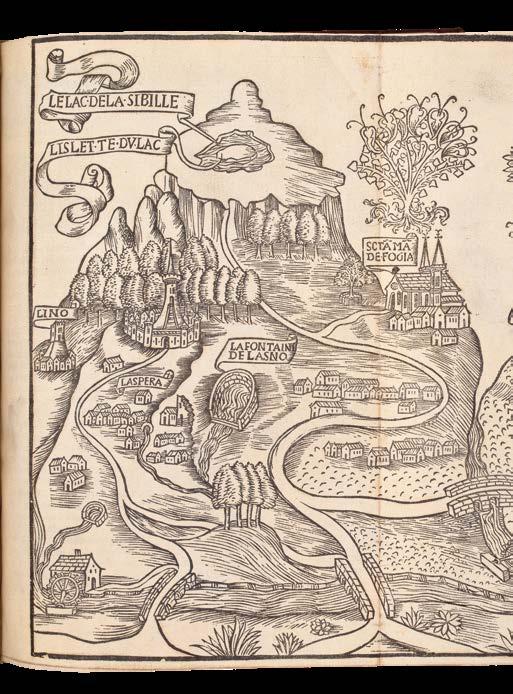

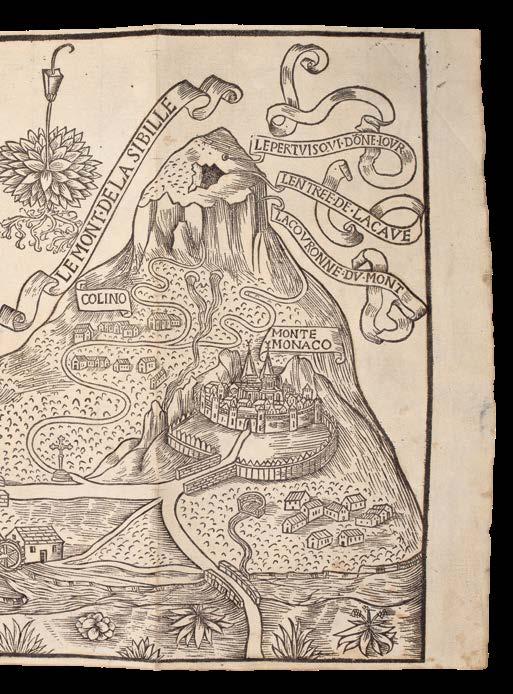

In the northeast of ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’ (1561), Canada is named, in which it is only preceded by Paolo Forlani’s world map, ‘Paulus de Furlanis Veronensis Opus hoc ex.mi Cosmographi Dni. Jacobi Gastaldi Pedemontani instauravit’ (1560) (Shirley 106); “M.Regal”, and “Hochelago” as the site of Montreal appear; “Stadacone”, the future site of Quebec City; and “Saguenai Regno”, now Saguenay, appear.

While the western portion of North America is still largely empty of topographic detail, it is full of large trees, mythical beasts, and mountain chains. California appears as an island.

In the southwest, Mexico and New Spain are filled with topographical detail and many toponyms, indicating a Spanish source for much of the information.

Chile bulges into the Pacific Ocean.

The “Streto di Magalenes” separates South America from “Terra del Fvego”, which remains attached to a very large southern landmass: “Terra Incognita”. Although much of the far western portion of that is now missing, it does look as if New Guinea was represented as a peninsula.

A ghostly spectre

The cartography expressed in Gastaldi’s ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’ (1561), was reiterated in many of the maps that followed it, casting a long and recognizable shadow, long before we now believe the ‘Cosmographia Universalis…’ (after 1571) appeared.

As previously discussed, Paolo Forlani’s ‘Il Disegno del discoperto della nova Franza, il quale s’e havuto Ultimamente dalla Novissima Navigatione de’ Franzesi in quel Luogo: nel quale si Vedono Tutti l’Isole, Porti, Capi et Luoghi fra Terra che in quella sono...’ (1565/6), incorporates Gastaldi’s model for North America, crucially including the Strait of Anian. So too does Giovanni Francesco Camocio’s world map in four sheets (1567) follow Gastaldi’s 1561 model, in most aspects; as does an untitled map of North America (c1569) (attributed to him by Burden 37), incorporate cartography as close in content to ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’ (1561), as to ‘Cosmographia Universalis…’ (after 1571), previously considered its forebear.

In 1569, Gerard Mercator adopted Gastaldi’s model for the Strait of Anian in his great 21-sheet map of the world. And in 1570, Paolo Forlani’s exceptionally rare map, ‘Al Mag.co Sig.nor Antonio Tognale Sig. nor Mio Osser.mo … tutte le navagationi del Mondo nuovo’ (Burden 38), relied heavily on Gastaldi’s ‘L’Universal Descrittione Moderna d[el] Mondo’ (1561), for the depiction of North America and the Strait of Anian.

A Renaissance map of the world

For his maps of the world from 1546 onwards, Gastaldi adopted the 1508 oval projection of Rosselli. Also, in common with Rosselli’s beautiful map, Gastaldi has, here, in his new map of 1561, incorporated a comprehensive, all inclusive, grid of lines of latitude and longitude, classical windheads, and clouds to represent the firmament. As is fitting for a world map of the Renaissance period, Gastaldi has embellished his map further with, at least to the surviving top and bottom borders, medallion vignette portraits of philosophers and astronomers, personifications of the seasons, and Pope Gregory’s capital virtues and sins.

Throughout the map is a series of legends that refer to the distant lands of southeast Asia, the Moluccas, Tabrobana, the Philippines, and the riches to be found there; as well as the Americas and South Africa.

At the bottom of the map, Gastaldi’s longtime collaborator, printer and engraver, Mattheo Pagano, has dedicated the map to Gastaldi himself, accompanied by a long poem, literally singing [“carmina”] Gastaldi’s praises.

In the top left is a list of constellations, bottom left, a compass rose, with Pagano’s signature interlocked hands at the centre, bottom right are the scant remains of another dial, top right, a long legend directed at the map’s audience.

The map is highly decorative: the land and sea are full of mythical animals, including the winged lion of St. Mark, the symbol of Venice; magnificent sea monsters, mermaids, and galleons; and compass roses.

The mapmakers

Matteo Pagano (1515-1588) engraved Gastaldi’s map of the Piedmont (1555), which now exists in only one impression; cut the small woodcut maps, composed by Gastaldi, that illustrate Giovanni Battista Ramusio’s ‘Navigazioni et viaggi’ (1550-1556); and published the libretto that accompanied Gastaldi’s 1561 map of the world [as here], as well as supplying the verse dedication to the map. The 1565 edition of the libretto was published by Francesco de Tomaso di Salò, who took over Pagano’s establishment after his death and over whose imprint Pagano’s fine reduction of de’ Barbari’s view of Venice was published. Pagano is also responsible for a number of works on the subject of lace-making.

Pagano, who also collaborated closely with Venetian mapmaker Giovanni Andrea Vavassore, “was active as a wood-engraver and publisher

from 1538 to 1562 in the Frezzaria, one of two parallel streets (the other was the Merzaria) that became the printmakers’ quarter between the Piazza San Marco and the Rialto. These streets became a cultural rendezvous for booksellers and their clients. As with Vavassore’s maps, Pagano’s are now extremely rare; none survives in more than three impressions. Although the style and content of maps by the two engravers were similar, Pagano seems to have been less of a copyist than Vavassore. His association with the leading sixteenth-century Italian cosmographer Giacomo Gastaldi was also much stronger” (Woodward).

A self-avowed “Piemontese”, Giacomo Gastaldi (c1500-1566) was born at the end of the fifteenth or the beginning of the sixteenth century. He does not appear in any records until 1539, when the Venetian Senate granted him a privilege for the printing of a perpetual calendar. By the time his first dated map, ‘Las Spana’, appears in 1544, he had become an accomplished engineer and cartographer: the ‘Germania’ that appears in the ‘Geographia’ of 1547/8 is dated 1542. Karrow has argued that Gastaldi’s early contact with the celebrated geographical editor, Giovanni Battista Ramusio, and his involvement with the latter’s work, ‘Navigationi et Viaggi’, prompted him to take to cartography as a full-time occupation. In any case Gastaldi was helped by Ramusio’s connections with the Senate, to which he was secretary, and the favourable attitude towards geography and geographers in Venice at the time: the senate gave him the notable title of “Cosmographer to the Republic of Venice”.

Woodward proposes that Gastaldi was from “one of the two towns named Villafranca in Piemonte, probably the larger one near Saluzzo, but no documents relating to his birth date and early life have surfaced…

From 1551 until his death, Gastaldi was commissioned many times by the Savi sopra la Laguna to draw maps related to problems regarding regulation of the fresh and salt waters of the Venetian lagoon, sometimes as assistant to Cristoforo Sabbadino, proto or director of the Magistratura alle Acque. Upon Sabbadino’s death, Gastaldi was proposed as his successor, but did not obtain a sufficient number of votes, probably because he was not a native Venetian…The first map he signed was the remarkably mature ‘La Spaña’ (1544), but he had obviously already been working hard on geographical matters, because he produced a large map of Sicily in 1545; his influential world map on an oval projection, the ‘Universale’, appeared only two years later; and the first compact edition of Ptolemy’s Geography appeared two years after that, but he had worked on it at least as early as 1542 (the date on the map of Germany)… Gastaldi’s 1548 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography was the first to appear in the vernacular, but it was clearly inspired by Sebastian Münster’s 1540 and 1545 Latin editions…

In the 1550s, in addition to a number of small regional maps, Gastaldi produced the maps for the three volumes of the ‘Navigationi et viaggi’ of Giovanni Battista Ramusio. Ramusio was the major link between

the information provided by the explorers and the Italian academic publishing scene. A diplomat in the Venetian service, he was also secretary of the Council of Ten, the ruling body of the Venetian Republic…

In the late 1550s and early 1560s, Gastaldi compiled several influential maps. The map of Italy was already finished on 29 July 1559, when Gastaldi received a privilege for it from the Venetian senate, along with other maps by him, including maps of the three parts of Asia and of Greece and Lombardy. We do not know why Gastaldi waited two years to print the map after receiving the privilege, particularly because the representation of Italy on his map of Europe (1560) is essentially the same. His ‘Italia’ (1561) is an excellent example of the judicious merging of information from portolan charts with regional maps, more successful in the Po Valley than in the central states or the south…

Gastaldi died in October 1566 after providing a wealth of geographical source material for a critical mass of engravers and publishers who had shops on the Merzaria or neighboring streets in the late 1550s and 1560s. These included first Fabio Licinio, then Giovanni Francesco Camocio, Paolo Forlani, Niccolò Nelli, Domenico Zenoi, Michele Tramezzino, Ferdinando (or Ferando) Bertelli, and Bolognino Zaltieri” (Woodward).

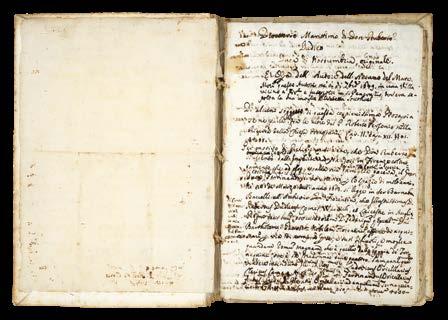

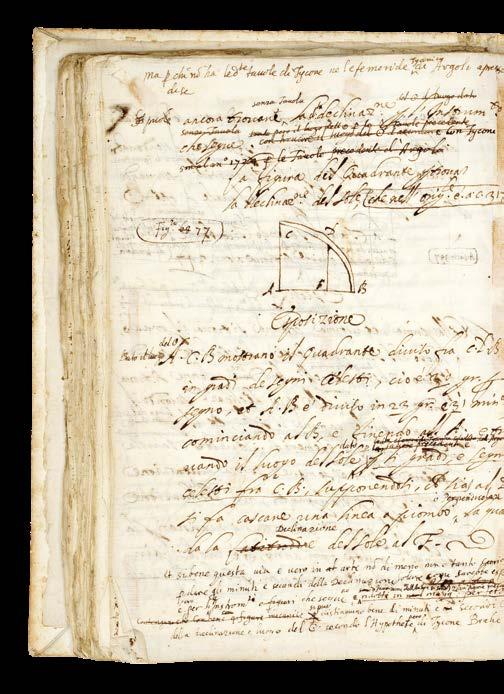

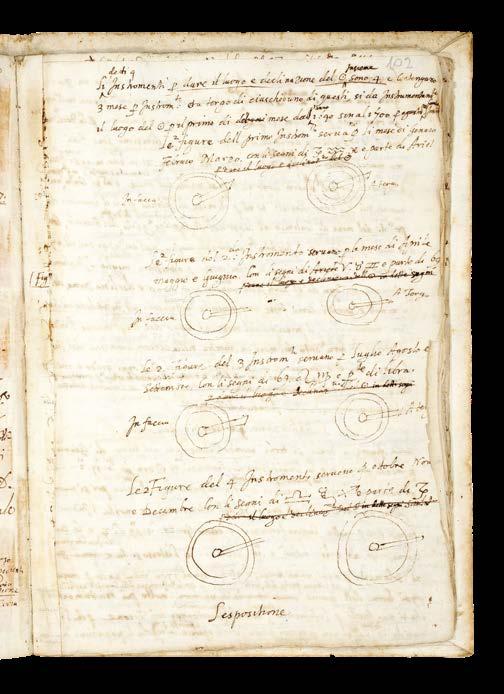

“It is called the ‘Direttorio Marittimo’, and was written in very faulty Italian for the use and instruction of the officers of the Tuscan fleet. In it most of the subjects enlarged upon in the Arcano, are treated concisely, including great circle sailing and all kinds of navigation ; the administrative management of a fleet, and its manoeuvres in a naval battle, etc.” (Leader)

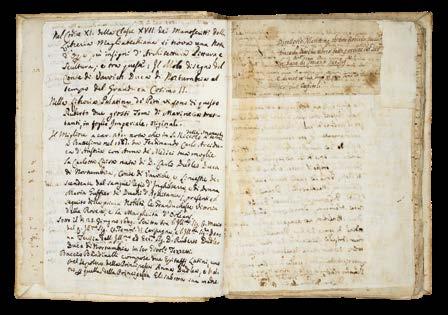

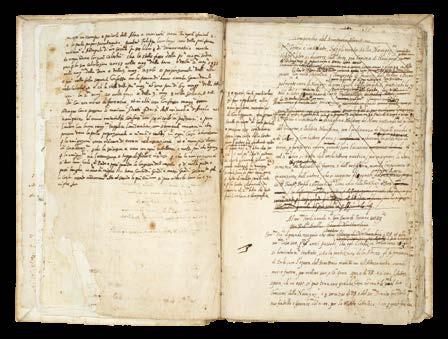

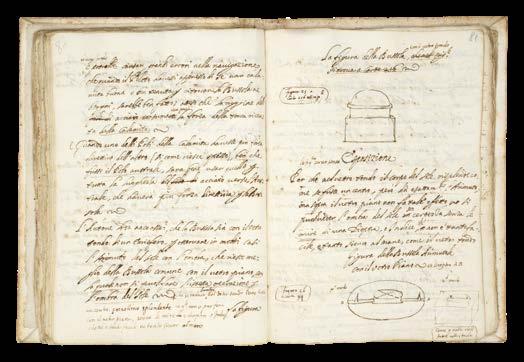

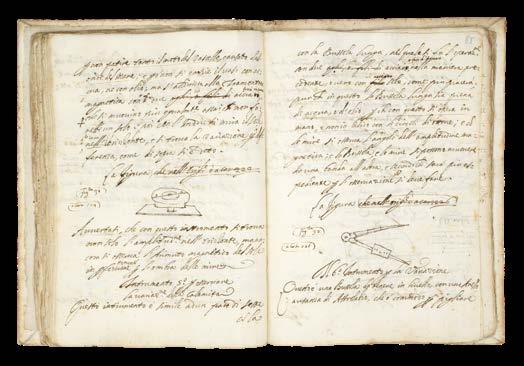

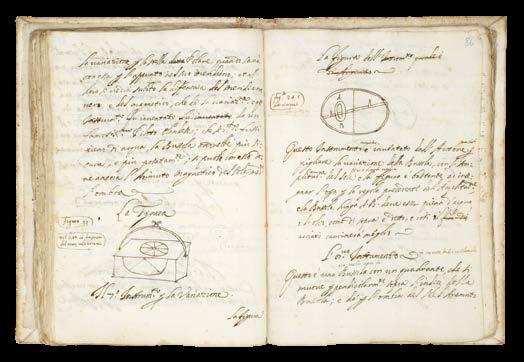

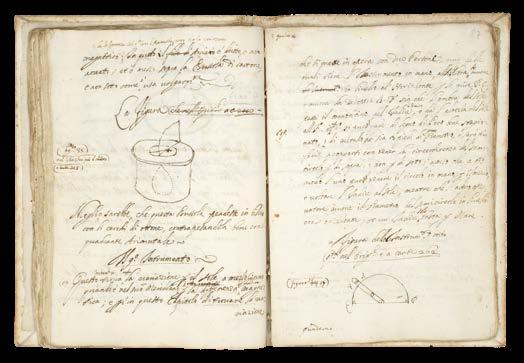

DUDLEY, Robert; and others

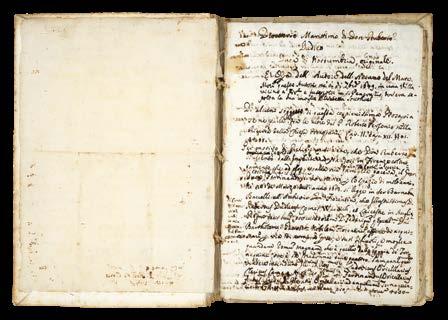

Direttorio Marittimo di Don Roberto Dudleo Duca di Northumbria fatto p[er] ordine del Ser[issimo]Gr: Duca di Toscana suo Sig[no]re e diviso in due Tomi et ogni Tomo in due libri co[n] suoi Capitoli

Publication [Firenze, c1637-1647].

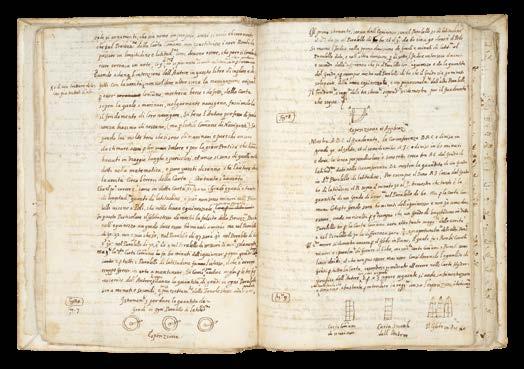

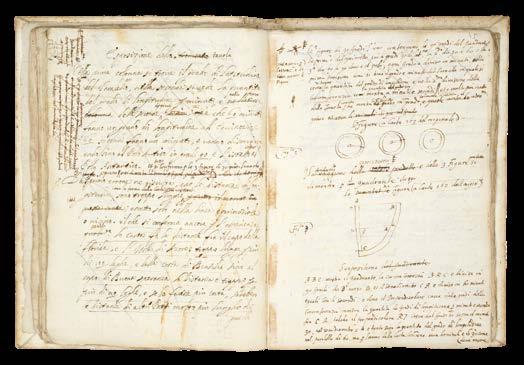

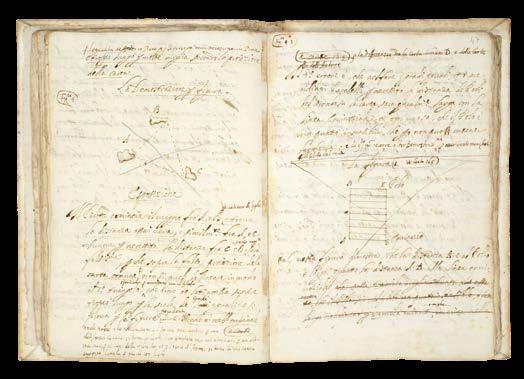

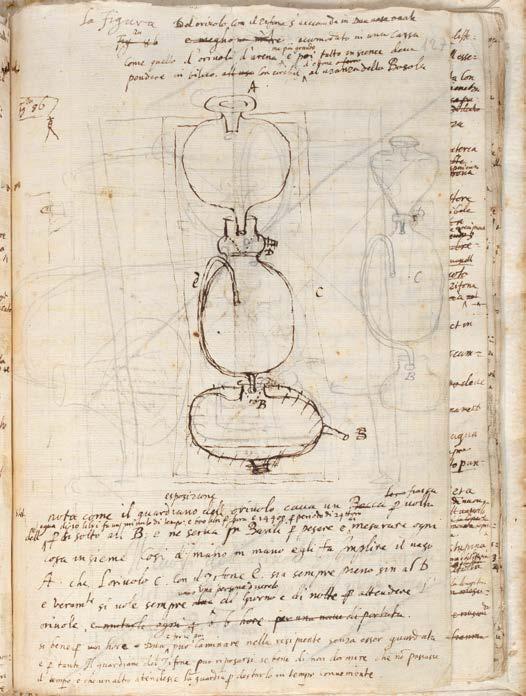

Description

Folio (290 by 196mm).

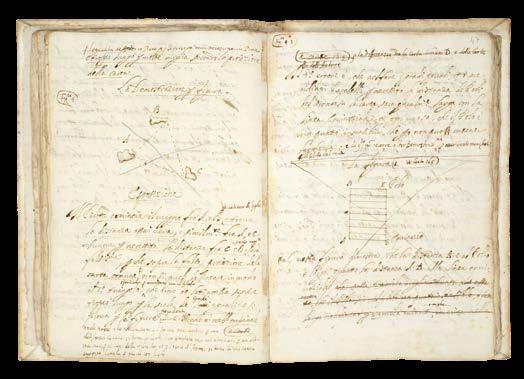

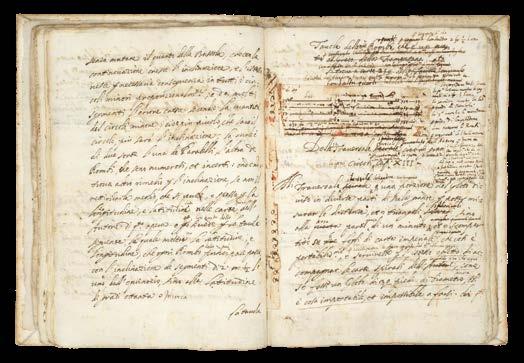

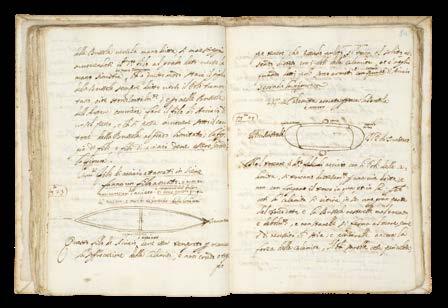

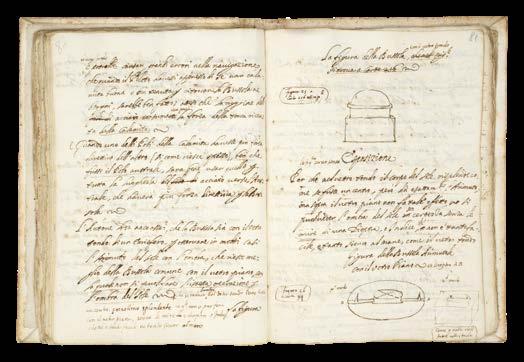

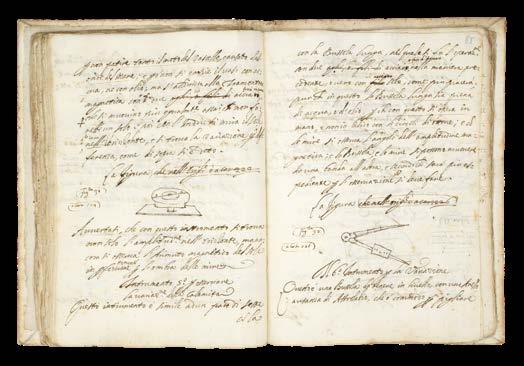

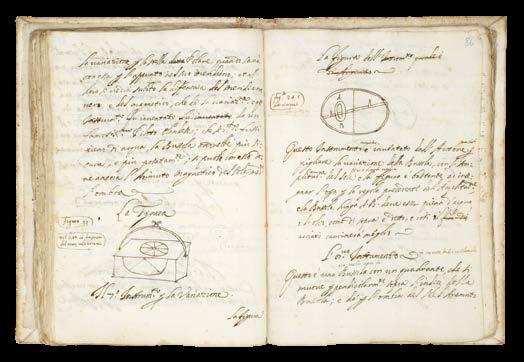

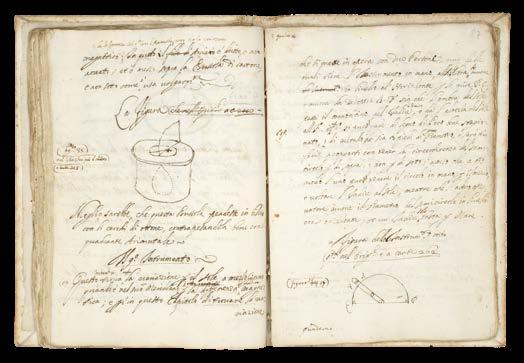

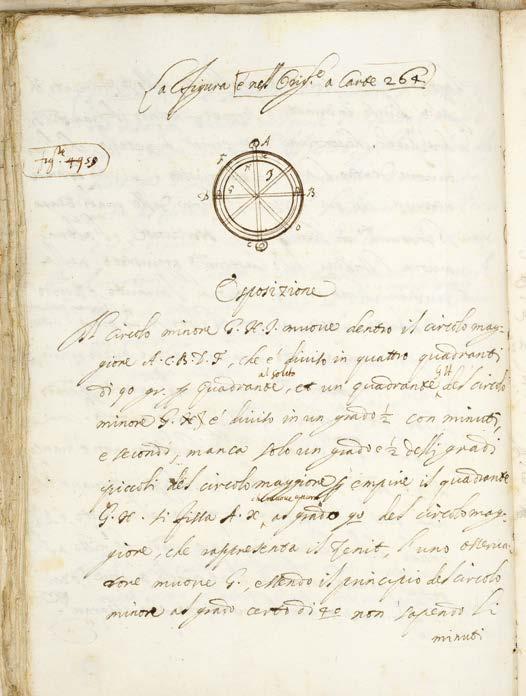

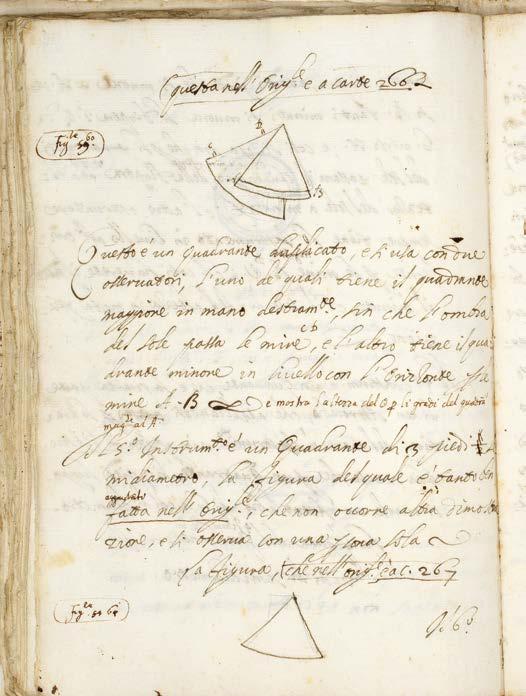

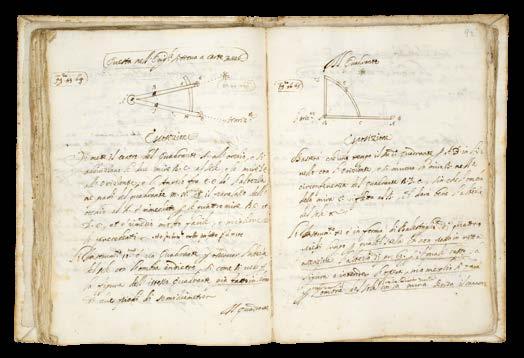

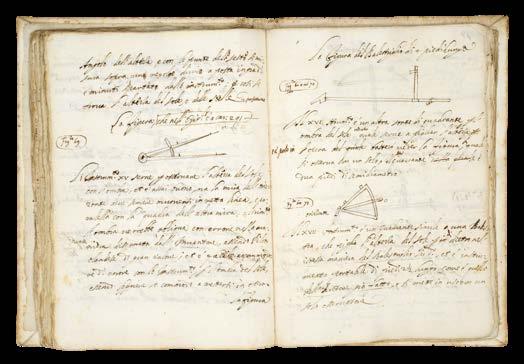

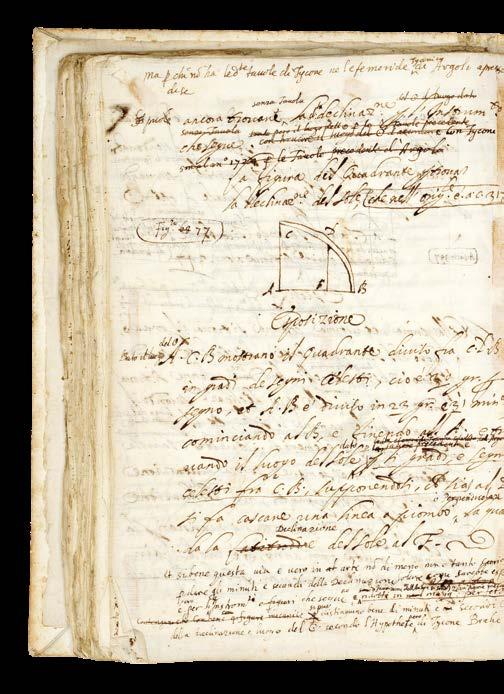

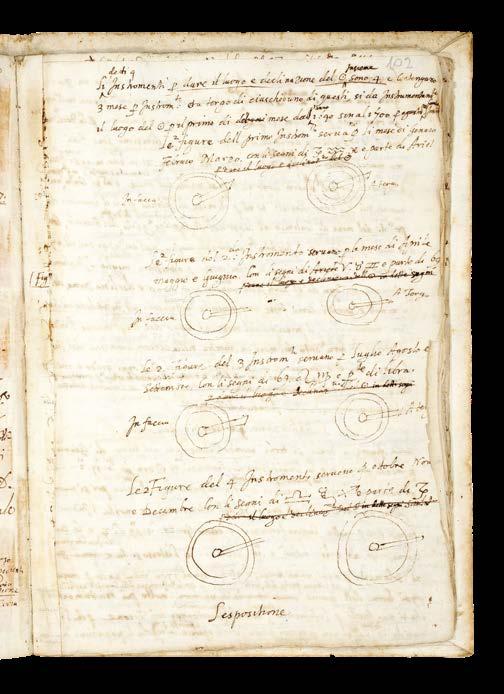

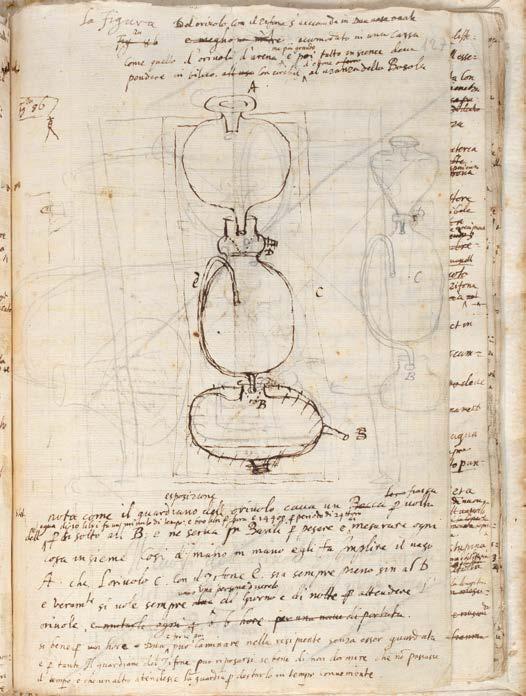

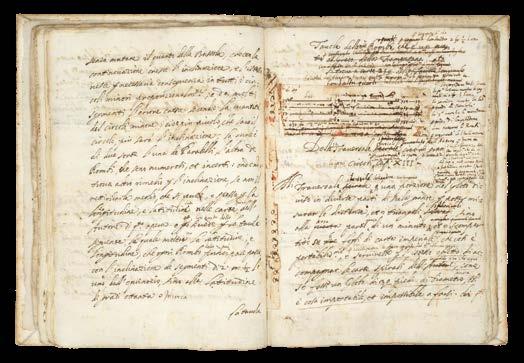

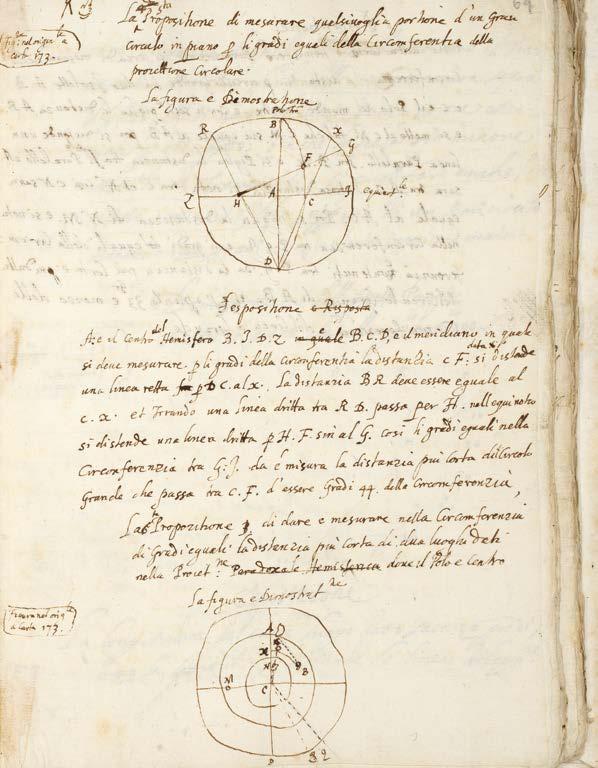

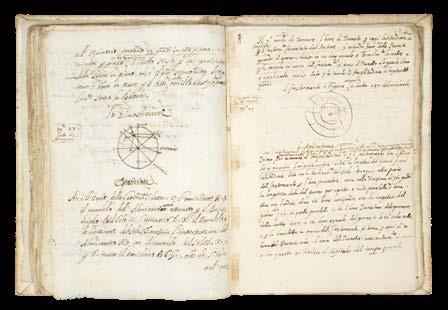

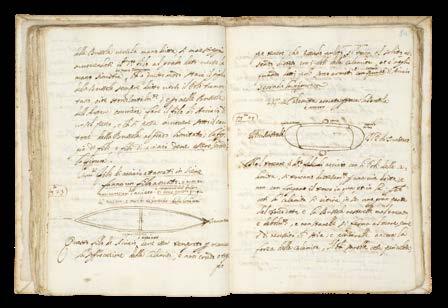

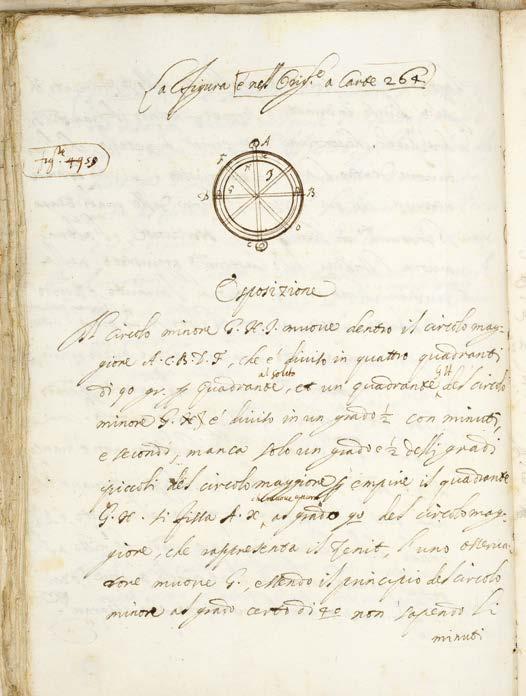

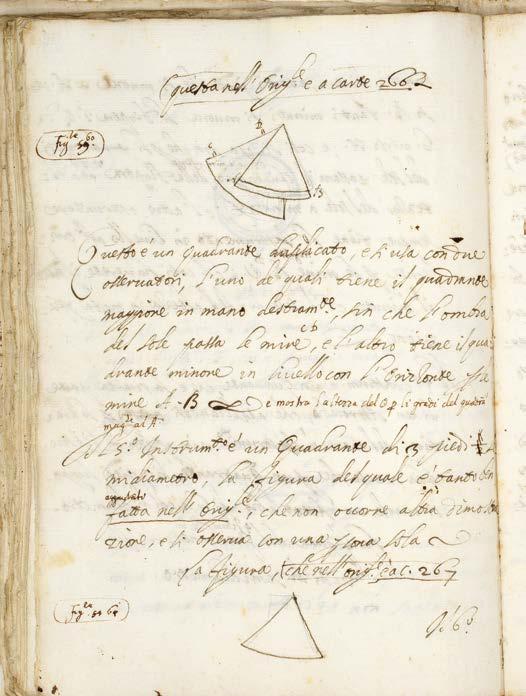

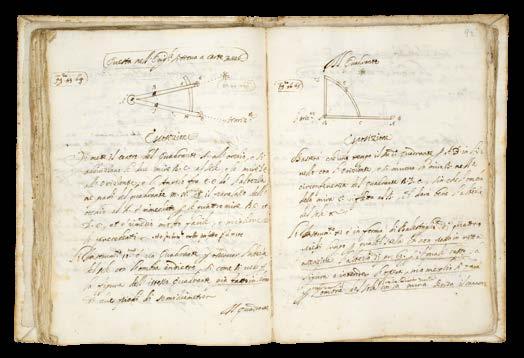

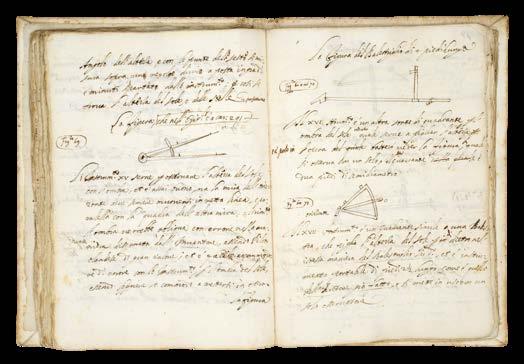

Original working autograph and holograph manuscript, in Italian, illustrated throughout with diagrams, and drawings of instruments, on seventeenth-century Italian paper, with various watermarks including a Sun (similar to Heawood 3893) and a Medici Coat-of-Arms (similar to Heawood 786), extensively revised at the time, some pages edited with pasteovers, others excised; early drab Italian stiff paper wrappers, stabbed and sewn as issued.

The only known manuscript example of any part of Robert Dudley’s magnum opus, ‘Dell’arcano del mare’ held in private hands.

An astonishing survival: a working manuscript, seemingly specifically assembled for the eyes and instruction of the officers of the Tuscan Navy, the Knights of St. Stefano, rather than for a public audience. This suggestion is borne out by the wording of the first title for the work that Dudley has crossed out (page 2): ‘Compendio del Direttorio Marittimo: Il pr[im]o Tomo e intilato, Supplemento della Navigare. Nel pr[im]o libro si discorre dell ‘arte, piu Curiosa di Navigare...’.

This was also the theory of Sir John Temple Leader, previous owner, and Dudley scholar: “It seems probable that the Arcano del Mare was only a resume of several previous works by Dudley. One of them is the MS. volume, quarto size, of which I possess the original, mostly in Dudley's own hand. It is called the ‘Direttorio Marittimo’, and was written in very faulty Italian for the use and instruction of the officers of the Tuscan fleet. In it most of the subjects enlarged upon in the Arcano, are treated concisely, including great circle sailing and all kinds of navigation ; the administrative management of a fleet, and its manoeuvres in a naval battle, etc. The book is in ancient covers of thick paper, and preceded by a dedication to the Grand-Duke, and by a sketch of Dudley's own naval life, written in his own hand with all his corrections and underlinings” (Leader, page 19).

Leader acquired the ‘Direttorio’ from Florentine librarian, collector, and bookseller, Pietro Bigazzi, from who he also acquired Gian Carlo de’ Medici’s (1611-1663), first edition of ‘Dell’Arcano del mare’, and a second edition, too. Leader writes about all three works, and the story of their acquisition, in his ‘Life of Sir Robert Dudley’ (1895).

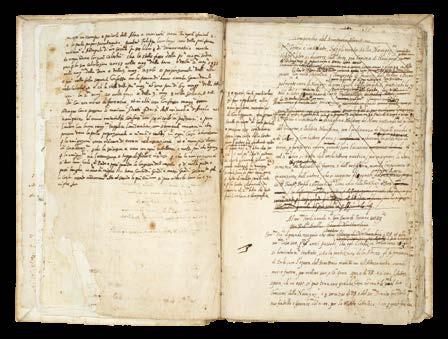

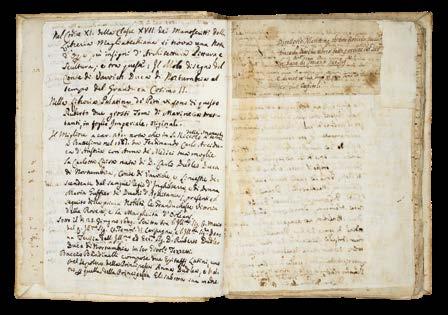

The texts of the ‘Direttorio’ have clearly been written by Dudley, over time, but from at least as early as 1643-1644, and are further annotated by him up until 1647 (he died in 1649), and then further annotated by others, up until the publication of the second edition of 1661. They include: Dudley’s autobiography, in which he sets out his credentials as an expert in all things maritime - exploration, navigation, naval warfare, and architecture; several drafts and a completed version of a theological preface, or ‘Proemio’, which was eventually published in the second edition of the ‘Dell’arcarno del mar’ (1661); 28 chapters of material related to the text of the first edition of the ‘Dell’arcano del mare’ (1646-1647); theoretical navigational material not published in either edition of the ‘Dell’arcano del mare’.

3

Collation

282 pages, foliated in pencil; pages [i-iv] biobibliography by Domenico Maria Manni; 1: title-page; 2: additional draft title-page, and dedication; p3-14: prospectus of contents (cancelled), followed by autobiographical ‘Proemio’; p15-139: ‘Direttorio Marittimo’, revised texts of 28 chapters of ‘Dell’arcano del mare’, incorporating theological ‘Proemio’, pp39-40; p140-146 addenda.

Condition

A few leaves missing between folios 86 and 87 (chapter xix and the beginning of xx), some lower margins trimmed, occasionally crossing the text.

Literature

R. Dudley, Dell’Arcano del mare, 6 books in 3 volumes, Florence, 1646-1647; Dell’arcano del mare, second edition, Florence, 1661; Arthur Gould Lee, The Son of Leicester, the Story of Sir Robert Dudley, London, 1964; J. T. Leader, Life of Sir Robert Dudley, Florence, Barbera, 1895; J. F. Schutte, S. J., ‘Japanese Cartography at the court of Florence; Robert Dudley’s maps of Japan, 1606-1636’, in Imago Mundi (23), 1969, pages 29-58; Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti, Notizie degli aggrandimenti delle scienze fisiche accaduti in Toscana nel corso di anni LX. del secolo XVII, 3 volumes. Florence, 1780; Manoscritti e alcuni libri a stampa singolari esposti e annotati da Pietro Bigazzi. Firenze, Tipografia Barbera, 1869.

$631,200.00

Contents

Pages [i-iv]: later bio-bibliography

Written by Domenico Maria Manni (1690-1788) director of the Bibilioteca Strozzi, polymath, editor and publisher, also a member of Academia dell Crusca. He owned the ‘Direttorio’, according to Giovanni Targioni -Tozzetti (1712-1783), see ‘Notizie degli aggrandimenti delle scienze fisciche: accaduti in Toscana nel corso dianni LX del scolo XVII Florence’, 1780, volume I., page 80. These notes include mention of the manuscript design by Dudley of the Mole at Livorno in the time of Cosimo II (1590-1620) which was then in the Magliabechiana library. Manni also notes two imperial folio volumes, in the Palatina di Pitti library, of “Marine Treatises”, i.e. Dudley’s manuscript Treatise on marine architecture, began before 1610, in English and continued in Italian, by Dudley, until about 1635 (see Maria Enrica Vadala, ‘Il Trattato dell’architettura maritima di Roberto Dudley, storia e dispersione di un manoscritto’, Studi secenteschi, vol. 61 (2020), pages 193-237).

Manni writes: “Leaving aside many superfine circumstances which have given the Author the opportunity of attending to the theory and practice of the art of navigation, it will suffice to say that as a young man he had a natural sympathy for the sea, so that although he had a very pleasant charge on land in 1588 under his father, then Generalissimo, he nevertheless wanted to exercise the maritime militia, on which the greatness and reputation of the Kingdom of England then depended. Desirous still of discovering new countries (which pert made to manufacture and arm vessels of war), Author confided much in the great knowledge and experience of the famous seafarer and learned mathematician Abram Kendal of England, his master. Hence it followed that in 1594 he began his voyage to West India to discover and open the passage of the Guyana or Walliana Empire in America, and at that time he was much nominated as a great and rich nation; as he did with good success being General by sea and land with his vessels and people etc.”

Pages 1-2: Title-pages and Dedication

Dudley opens his ‘Dorettorio’ with a heart-felt dedication, officially to Grand Duke Ferdinand II, as was proper, and as he did ‘Dell’arcano del mare’. However, in this instance, he goes to great pains to go above and beyond that dedication to extend his tribute to the “Generalissimo del Mare”, i.e. Gian Carlo de’ Medici (1611-1663), Cardinal from 1644, “High Admiral of the Tuscan Navy”, “General of the Mediterranean Sea”, and “General of the Spanish Seas”. Gian Carlo was the second son of Cosimo II de’Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Maria Maddelena of Austria, and the recipient of a superb example of ‘Dell’arcano del mare’, with which the current manuscript was previously housed.

Humbly, Dudley hopes that “in [the ‘Direttorio] one can find something not useless for the common good of Navigation for your Highness and for Prince Giovanni Carlo Medici”. And thanks the Medici family for their support during the “past 37 years that he has been in voluntary exile … and under their protection”, dating the dedication to 1643-44.

Dudley then notes that he took the trouble to finish the ‘Direttorio’ in the best way that his experience in 50 years of maritime affairs (i.e. since 1594) has been able to produce and plan, but if he has erred in anything he hopes he will be excused.

Pages 3-14: ‘Supplem[en]to della Navigaz[io]ne perfetta Tomo primo libro I :proemio’.

Dudley writes of his many maritime achievements in exploration, warfare, and naval architecture, clearly intending to give authority to the following texts: " Setting aside many superfluous circumstances which have occasioned the author to turn his attention to the theory and practice of the art of navigation, suffice it to say that he is Nephew of three Grand Admirals of England (or Generalissimi of the Sea, which is one of the highest offices held under that of the Crown) and that he had from his youth a natural sympathy for the sea, and this in spite of his having in 1588 held the very honorable post of Colonel in the land forces, which he exercised under the command of his father, the General in Chief and Grand Master of England…" As Tyacke reports: this ‘proemio’ or autobiographical preface is not printed in the first edition of the ‘Dell’Arcano del mare’; nor is it the “theological proemio” which is printed in the second edition of 1661; but rather an account of Dudley’s career before he arrived in Florence. It is clearly designed to establish his credentials and to add great authority to the ‘Direttorio’. The text describes how Dudley had learnt the art of navigation and maritime discipline at about the age of 17, had experience of battle under his father the Earl of Leicester, and of navigation, and of designing warships and of participating in sea battles. There is a version of the text he wrote for Richard Hakluyt’s ‘Voyages…’ (1600) (volume III page 574) about his voyage to Trinidad and to the Orinoco, and Guiana in 1594 (see George F. Warner, ‘The voyage of Sir Robert Dudley …to the West Indies’, (15941595), Hakluyt Society, 1899).

In this autobiographical preface Dudley writes: “Si contento, non di meno, che consumasse il capricio e la spesa dall India Occidentale, p[er] scoprire et aprire il passo dell Imperio di Guiana o Walliana in America molto nominato in quel tempo pazione grande e vicca si come fece essendo Generale per mare... si fece padrone dell Isola della Trinita scopri la Guiana” – “He was happy, nevertheless… to discover the West Indies and open the way to the Empire of Guiana or Walliana in America, much known at that time as a great and wealthy country, and to be the General for the sea voyage … he made himself master of Trinita Island [Trinidad]; He discovered Guiana”. Dudley always claimed

that he got to the river Orinoco in Guiana, in 1594 before Sir Walter Ralegh.

Dudley then writes about the famous learned mariner and mathematician Abraham Kendal who was his ship’s master on his voyage to Trinidad, and then records how he had sent Captain Wood on a voyage to China (which in the event was unsuccessful). He records his own participation in the raid on Cadiz to destroy the Spanish fleet being assembled in 1596; he says in this and other voyages he practised navigation and the maritime and military disciplines, using great circle sailing and longitude: ‘di gra circoli e della longitude’, adding the words “come Arcano” – “as in the Arcano”, presumably a bit later.

He says that mariners have not well understood, nor practiced, navigation, according to great circles, and the other “spiral and horizontal methods”, with practical longitude.

It is his intention to explain how to do this, and a later insertion, by Dudley, in the margin, says that the first book teaches the method of using the hydrographical and general charts of the Author.

Page 14 ‘Proemio’

This is a theological preface to the ‘Direttorio’, and Dudley assures the censors that these potentially troublesome mathematical matters were in fact created by God himself along with natural and supernatural elements. Dudley formulates his argument for scientific knowledge, of which there are three types: the natural, supernatural, and the efficacy of the scientific (i.e. geometry and mathematics, see page 39) “le cose mathematiche sono certe, sicure et infallibili p[er] dimonstrazione e pero sono pui excellenti delle cose naturali...ma sono inferiori, delle cose supernaturali et immutabili”. An earlier version, on page 15, has crossed out “intelletto humana non arriua” – “Mathematical things are as certain and infallible by demonstration and therefore they are superior to the natural senses …but they are inferior to the supernatural things to which the human intellect cannot reach”.

There are no fewer than four early versions of the theological ‘Proemo’ in the ‘Direttorio’, two of which are incomplete revisions of difficult passages. However, the “theological proemio” which appears on pages 39-40 of the ‘Direttorio’ is published in the second edition of the ‘Dell’arcano del mare’ (1661), but not, apparently, in the first edition. Either it, or something similar must have been available to Lucini or Bagononi, the publishers of the second edition of 1661.

; p3-14: prospectus of contents (cancelled), followed by autobiographical ‘Proemio’; p15-139: ‘Direttorio Marittimo’, revised texts of 28 chapters of ‘Dell’arcano del mare’, incorporating theological ‘Proemio’, pp39-40; p140146 addenda.

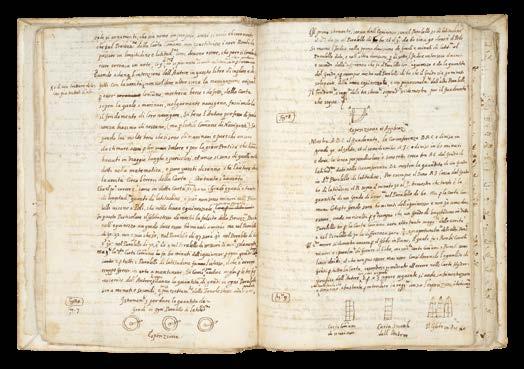

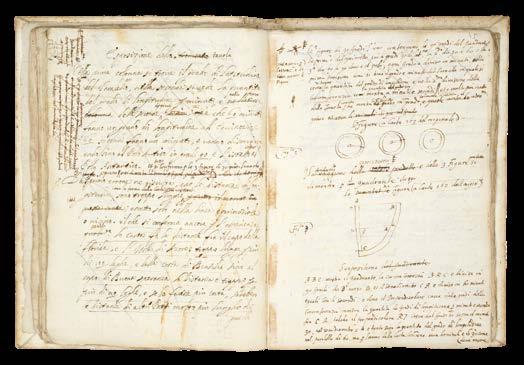

Pages 14-139 text from ‘Dell’Arcano del mare’ (1646-1647) This section of the ‘Direttorio’ is composed of early versions of important passages in Books One, Two and Five of ‘Dell’Arcano del mare’: a compendious study of naval

theory and practice, treating of longitude and latitude and Great Circle sailing. They appear as drafts and revisions of twenty-eight chapters (lacking part of Chapters 19 and 20); but the order and headings of the chapters does not correspond with that of the ‘Dell’arcano del mare’.

The subjects in this part of the ‘Direttorio’ cover many of those in the ‘Dell’arcano del mare’: how to navigate along known and unknown coasts; knowing which winds prevail; currents and the times of tides of places; how to use ‘Tables of Ephemerides’ for celestial observation; how to ascertain magnetic declination values with a meridian compass across the globe. In the field of cartography, Dudley considers how to determine latitudes and longitudes across the oceans, and explains the errors of “horizontal” or common charts in navigation. He proposes the use of mathematical instruments, as well as celestial observation, to accomplish correct navigation.

Interestingly, he also proposes to establish longitude by the use of a clock “oriuolo mecuriale”. As in the ‘Dell’arcano del mare’, Dudley focusses on his preferred method of navigating by Longitude and Great Circle sailing - using his own invention of tables of “traversali sfericali”, and his charts based on what we now call “Mercator’s projection”, giving his latitudinal values.

Here the ‘Direttorio’ is heavily re-worked with some passages entirely re-written by the author in the margins, and in places makes direct reference to the text of the ‘Dell’arcano del mare’. This suggests that some parts of the ‘Direttorio’ may well have been written during, or after, the text for the ‘Dell’arcano del mare’, was being printed. On page 3 of Dudley’s autobiographical ‘proemio’, Dudley adds “come Arcano” –“like the Arcano”; on page 122, a reference to the “master of the Arcana, who holds the secret of longitude” is mentioned; further on pages 21- 22 when in discussing the method of using the “spiral” charts (Cap 8 and 9), Dudley refers to the “carte hydrografice del 2[do] libro” – “hydrographic charts in Book 2”, which is exactly where they appear in the published ‘Dell’arcano del mare”.

These chapters of the ‘Direttorio’ are illustrated with numerous small drawings, and a number of larger diagrams, but the numbering of the figures, while referencing specific charts, do not correspond to the engraved figures in the published ‘Dell’arcano del mare’. It is possible that the references may correspond to the set of 268 manuscript charts now preserved in the BSB, in three volumes (Cod icon 138-140). Similarly, these chapters also contain text not found in the published ‘Dell’arcano del mare’. Dudley describes the likely effects of bad weather in high latitudes above 66°N, and the usual weather in temperate and tropical latitudes (pages 133-134); and ‘Cap XXIV’ contains Dudley’s explanation of how to find the North Star with a diagram (page115).

Pages p140-146 addenda

Apparently new text, in which Dudley formulates his ideas on the application of science to navigation on the high seas: “la 2 da parte di q[ues] to libro tratta de naviagare con scienza in alto mare Cap 6”; incomplete sections on astronomical and military subjects; and a few additional notes in other hands.

Dudley and the Medicis

Robert Dudley (1573-1649) first published his ‘Secrets of the Sea’ in 1646 when he was 73. It was the culmination of his life’s work, and a testament to his close bond with one of the greatest ruling families of Italy, it is dedicated to Ferdinand II de’Medici. For his services to three Medici Grand Dukes of Tuscany (Ferdinand I, Cosimo II, and Ferdinand II), as philosopher, statesman, civil and military engineer, naval architect, hydrographer and geographer, mathematician and physician, Dudley was rewarded with status during his lifetime, a public funeral and a memorial monument upon his death.

Dudley was the son of the Earl of Leicester (the one time favourite of Elizabeth I) and Lady Douglas Sheffield, the widow of Lord Sheffield. Although born out of wedlock, Robert received the education and privileges of a Tudor nobleman. He seems to have been interested in naval matters from an early age, and in 1594, at the age of 21, he led an expedition to the Orinoco River and Guiana. He would later, like all good Tudor seamen, sack Cadiz, an achievement for which he was knighted.

His success upon the high-seas was not matched, unfortunately, by his luck at court, and at the beginning of the seventeenth century he was forced to flee, along with his cousin Elizabeth Southwell, to Europe. Eventually, in 1606, he ended up in Leghorn, Italy, which he set about turning into a great international naval and commercial seaport, in the service of Ferdinand I.

Dudley, successful at last, married his cousin, converted to Catholicism, helped Ferdinand wage war against the Mediterranean pirates, by designing and building a new fleet of fighting ships for the Italian navy, served as Grand Chamberlain to three Grand-Duchesses of Tuscany in succession: Maria Maddelena, widow of Cosimo II; then Christina of Lorraine, widow of Ferdinand I; then to Vittoria della Rovere, Princess of Urbino, and wife of Ferdinand II, who created Dudley Duke of Northumberland.

Gian Carlo de’ Medici (1611-1663).

It is not surprising that Dudley should dedicate his ‘Direttorio’ to his greatest patrons, Grand Duke Ferdinand II, and Gian Carlo de’ Medici. Nor that they should have owned examples of his greatest work, ‘Dell’arcano del mare’. What is very pleasing is that this working manuscript for the ‘Direttorio’, should also once have been in the possession of at least two other previous owners of both Gian Carlo’s first edition ‘Dell’arcano del mare’: Pietro Bigazzi, Florentine bookseller; and Sir John Temple Leader.

Gian Carlo de’Medici shared Dudley’s passion for all things maritime. The second son of Cosimo II de’Medici, Gian Carlo was made “High Admiral of the Tuscan Navy” in 1638, held the title of “General of the Mediterranean Sea”, and appointed “General of the Spanish Seas” by Philip IV of Spain during the 40 years war. In 1644, he reluctantly resigned his naval appointments when Pope Innocent X appointed him Cardinal. As a young and attractive man, he found the religious life a trial, and in 1655, the Pope returned him to Florence, after he became a bit too friendly with Queen Christina of Sweden. There he remained until his death, working in close collaboration with his brothers, in the government and cultural enrichment of the grand duchy. Gian Carlo was “passionate about science, letters and above all music.

Founded the Accademia degli Immobili and contributed to the construction of the Teatro della Pergola, inaugurated in 1658.... and enrichment of the Galleria Palatina di Palazzo Pitti” (Cardella, Lorenzo. ‘Memorie storiche de' cardinali della Santa Romana Chiesa’. Rome, Stamperia Pagliarini, 1793, VII, 51).

The close bond between Dudley and Gian Carlo is attested to by a letter written in September of 1638 from Dudley to Gian Carlo, who had just been appointed High Admiral of the Tuscan Navy, offering his homage and swearing his fealty, saying, that “if his nautical experience of many years merited employment in the service of his Highness, he, though old, would be always ready to obey the Admiral’s commands” (John Temple Leader in his ‘Life of Sir Robert Dudley,...’ 1895, pages 115-116).

Domenico Maria Manni, Pietro Bigazzi, and the Biblioteca Moreniana (Moreniana Library).

A Florentine bookdealer and collector, Pietro Bigazzi was also a librarian, and clerk of the Academia della Crusca, from 1854. His large library had come from a number of sources, including that of Domenico Maria Manni (1690-1788) director of the Bibilioteca Strozzi, who has supplied the four pages of bio-bibliography at the beginning of the ‘Direttorio’. See ‘Manoscritti e alcuni libri a stampa singolari esposti e annotati da Pietro Bigazzi’, Firenze, Tipografia Barbera, 1869, in which it is noted: “manuscript ceded, many years ago, to Mr. Temple Leader, a distinguished English gentleman, domiciled among us; solicitous repairer of the Tuscan Memoirs”.

The Biblioteca Moreniana “was created when the Provincial Deputation of Florence acquired the bibliographic collection that had belonged to Pietro Bigazzi.

The collection of literary writings, the majority of which were part of the library owned by Domenico Maria Manni and Domenico Moreni, consists mostly of records on Tuscan history and culture. Later, several other literary collections from well-known scholars and collectors of Tuscan antiquities were added. In 1942, the library was housed in Palazzo Medici Riccardi and opened to the public. Other historically significant collections of manuscripts were added later. Today the library is managed by the Metropolitan City of Florence” (Biblioteca Moreniana, online).

John Temple Leader (1879-1903)

Possessed both the first and second editions of Dudley’s ‘Dell’Arcano dell mare’, and this manuscript, the ‘Direttorio Marittimo’. He describes his relationship with Pietro Bigazzi, the Florentine bookdealer from whom he purchased all three items, in his biography of Dudley: “Long ago I bought from Signor Pietro Bigazzi, together with many other books which had belonged to Dudley, the first two volumes and the fourth of the ‘Arcano del Mare’, the first edition of his great work which was published at Florence in 1646-47. The third volume was wanting, perhaps lent to some friend who had forgotten to return it. Two or more years after this, Signor Bigazzi brought me, as a New Year’s gift, the missing volume of this very same incomplete set. He had discovered it on the low wall or ledge of the Palazzo Riccardi, and bought it from the salesman who had permission to sell his books there. My joy on thus unexpectedly receiving the missing part may be easily imagined by collectors and lovers of old books. The four volumes thus happily reunited after a long separation were in the old binding with the arms of a Cardinal of the Medici family” (pages 18-19).

Other Dudley manuscripts related to ‘Dell’arcano del mare’ Manni noted that the Palatina di Pitti library held two imperial folio volumes, in manuscript, of “Marine Treatises” by Dudley. They were on marine architecture, begun before 1610 in English, and continued by Dudley in Italian until about1635 (see Maria Enrica Vadala: ‘Il Trattato dell’architettura maritima di Roberto Dudley, storia e dispersione di un manoscritto’, Studi secenteschi, vol. 61 (2020), pp. 193-237) The Bayerische Staatsbibliothek holds several manuscripts by Dudley related to the ‘Dell’arcano del mare’, including: a of 268 manuscript charts, in three volumes, (Cod icon 138-140); and another relating to naval architecture and the conduct of naval warfare (Cod.icon 221) British Library (Add MS 22811)

Provenance

1. Domenico Maria Manni (1690-1788), polymath, editor and publisher, also a member of Academia dell Crusca, and Director of the Biblioteca Strozzi, who has supplied 4 pages of bio-bibliography at the front of the manuscript;

2. Pietro Bigazzi, Florentine collector, librarian, and bookseller, a number of annotations in pencil, including on the flyleaf (“Ms citato del Targioni negli aggrandimenti Vole 10 pag.80”), sold to:

3. Sir John Temple Leader (1879-1903), who also bought Gian Carlo de’ Medici’s (1611-1663), first edition of ‘Dell’Arcano del mare’, and a second edition, from Bigazzi;

4. By descent to Richard Luttrell Pilkington Bethell, 3rd Baron Westbury (1903-1917), who sold Leader’s collections “piecemeal”

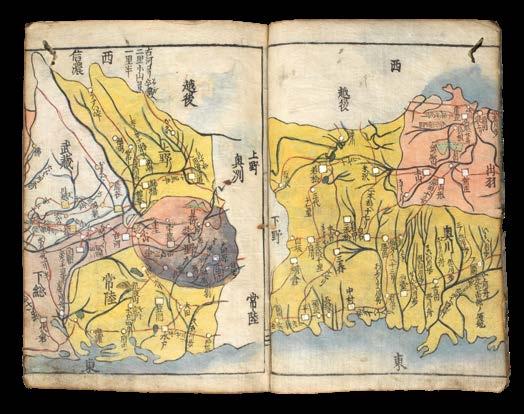

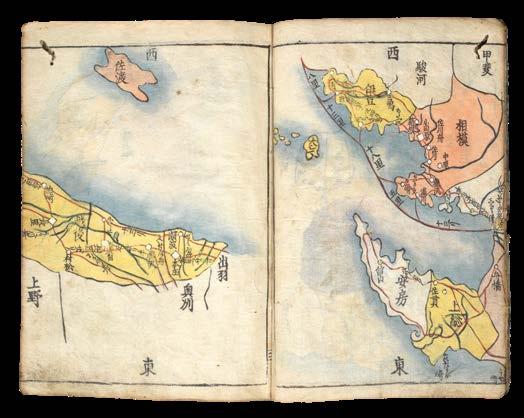

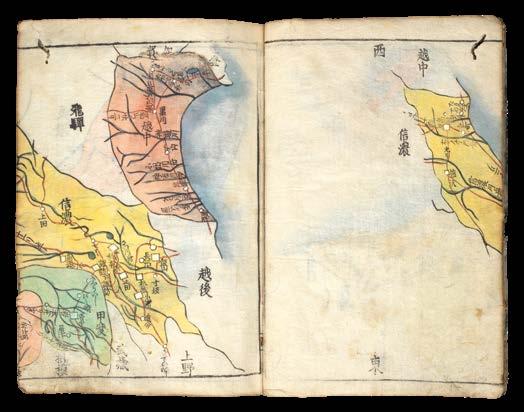

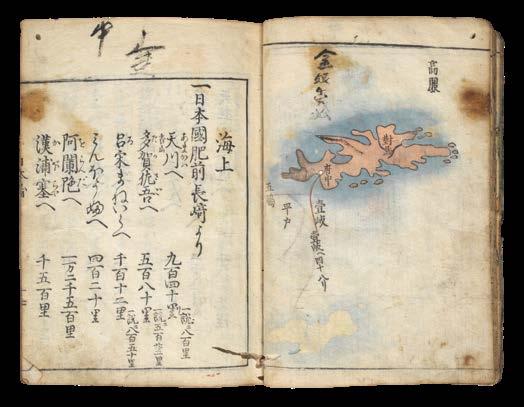

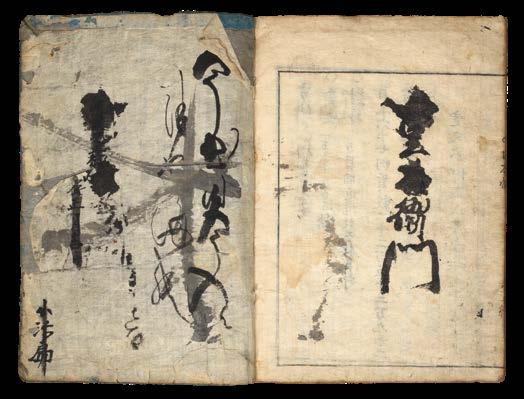

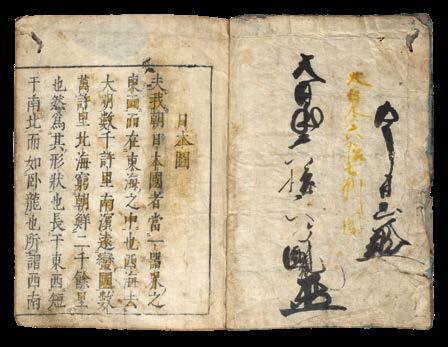

NAKANO, Kozaemon.

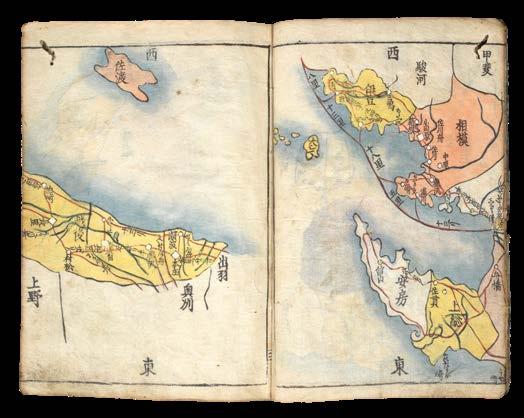

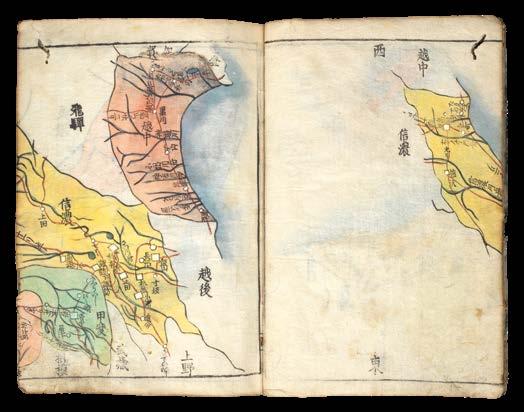

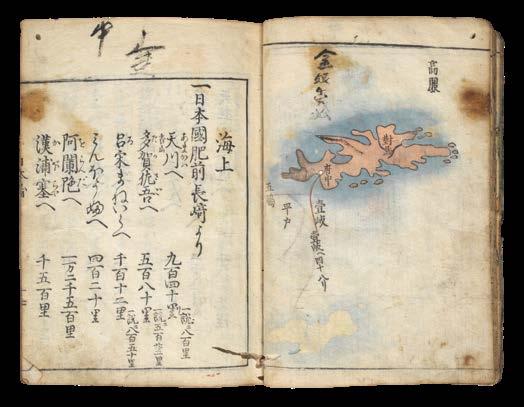

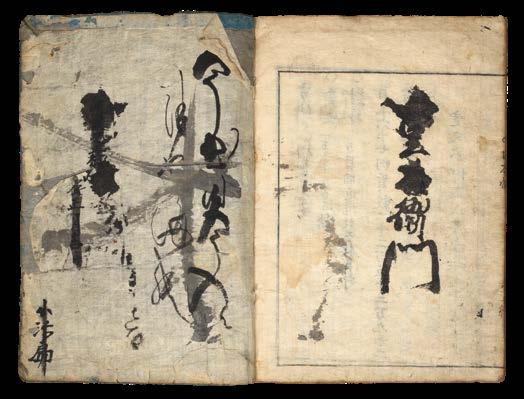

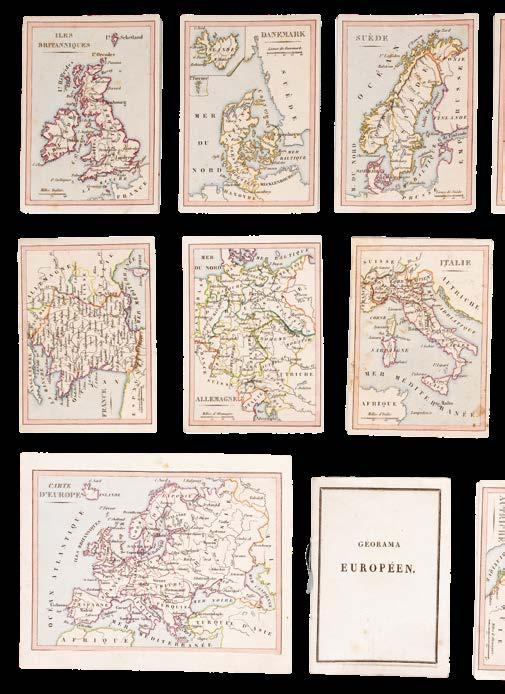

Atlas of Japan 日本分形圖, or Nihon zu 日本図 [Map of Japan]

Publication

[Kyoto], Yoshida Tarobē, 1666.

Description

Octavo (195 by 140mm). 67 woodblock leaves bound in fukurotoji style, including 16 maps with contemporary hand-colour in full, some separations at folds, minor worming and staining; original blue paper wrappers, worn and lacking original label, stitching renewed; housed in a modern, lavenderblue cloth chitsu box, silver-flecked paper, manuscript paper label, bone clasps.

References

Harley & Woodward, The History of Cartography, 2.2, pp.413 and ill. 11.44.

$47,700

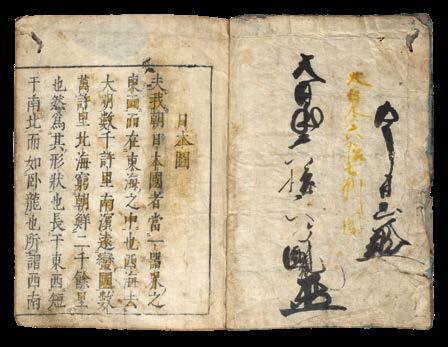

The first atlas of Japan printed in Japan

First edition of the first atlas of Japan to be printed in Japan.

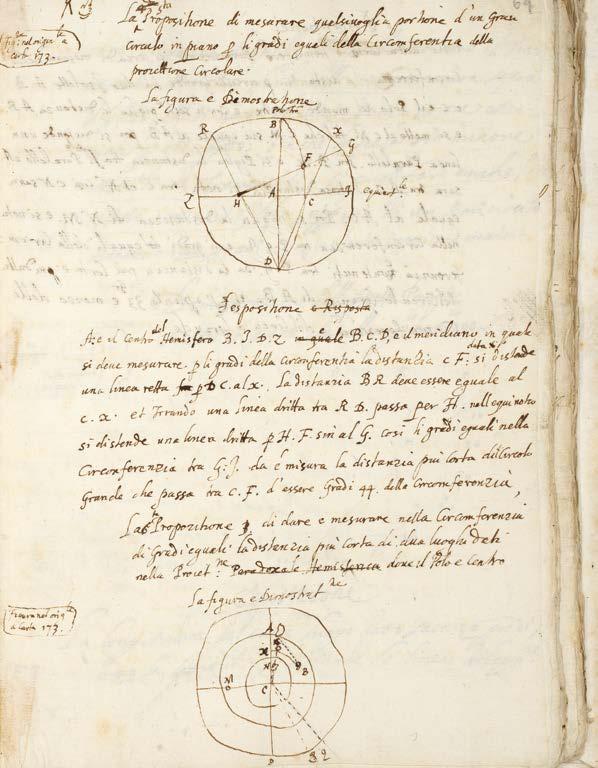

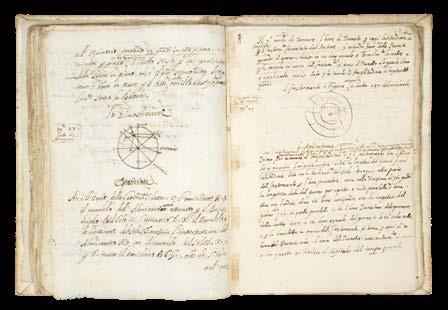

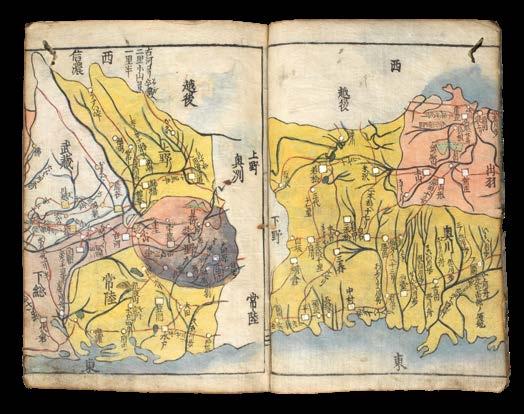

In an increasingly literate society, there was a growing demand for maps among the wider Japanese public of the seventeenth century, not solely for tax collection purposes or measurements of rice production. Although efforts to map Japanese provinces had begun as early as 735, it was not until the Keichō period (1596-1615) that the government commissioned the first official map of Japan, commencing in 1605 and reaching completion in 1639.

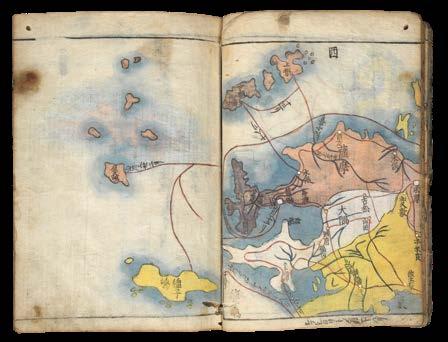

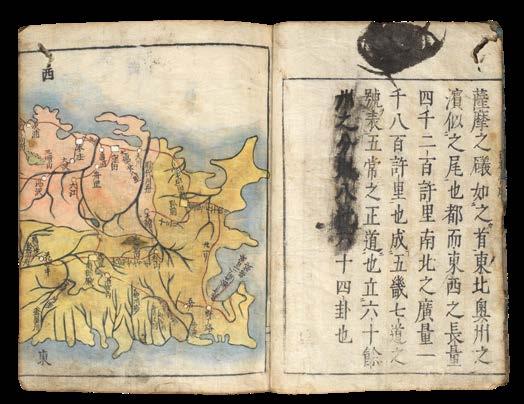

This present album-style atlas was produced by dividing this 1639 ‘Keichō map’ of Japan into 16 parts. Although this was the first time a full atlas of Japan has been printed in Japan, the reprinting of more decorative single maps - such as the 1662 map Shinkai Nihon Oezu (‘Newly Revised Map of Japan’) - proved to be more popular with the general public. The entire atlas was neither reprinted nor reproduced until the Shinkan jonkoku ki (‘Newly Published Notes on the Provinces and their Inhabitants’) in 1701.

Despite its focus on recording accurate distances and landmarks, the atlas reads like a journal. It is written in the first person, with the author recounting their impressions of the food, music, and people encountered along the journey. There are references to festivals, vacancy rates, ‘delicious’ restaurants, and ‘one of a kind’ places to visit. The author draws upon metaphors, comparing the south sea to a ‘crouching dragon’, and speaks of the fatigue and weariness of the journey across Japan.

The striking part of this example is not only in the anecdotal details nestled between the dry recording of distances, but in the personal interaction with the physical atlas itself. The title page has been heightened in yellow ink, and some doodling on the inside covers betrays the hand of a previous owner. The wrinkled wrappers and later re-stitching reveal that the atlas is worn from loving use rather than neglect.

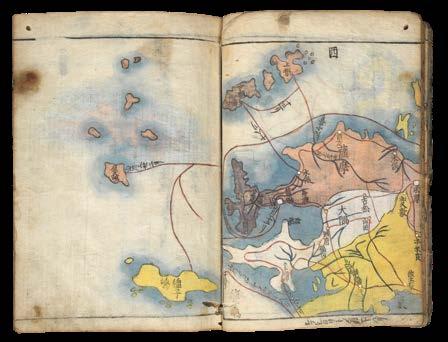

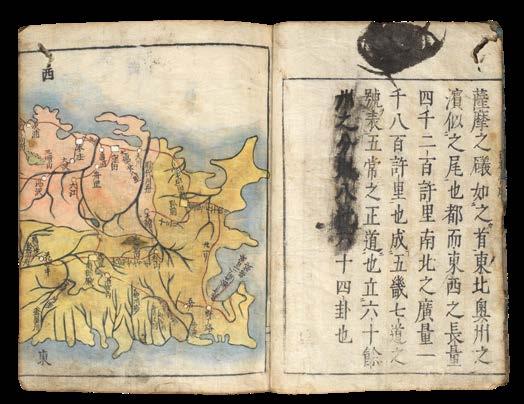

This atlas was most likely designed as a travel guide, with handcoloured maps of 16 provinces and textual details on the distances between various landmarks, towns, castles, and countries across the sea. Roads and sea routes are outlined in red, with blue to indicate bodies of water. Different regions on the maps are hand-coloured in pink, yellow, and green, and circles and squares are coloured with white to indicate towns and districts. The atlas covers Aomori in the north to Tsushima in the south.

Background

The conventional cartography of Japan before the Europeans, and indeed continuing into the nineteenth century, is known as Gyoki. Gyoki maps were characterised by an artistic championing of their home country, balancing wayfinding information with decorative depictions not bound by scientific precision. Deriving from an eight century Buddhist monk credited with this style, Gyoki maps portrayed provinces as coloured globules drawn with curved lines, with red outlining major routes between cities.

4

Despite being aware of more accurate map-making techniques after the Europeans had arrived in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, the Gyoki map had become a conventional method of depicting Japan. With its decorative flair and lack of measurement scale, this stereotypical style of cartography was particularly noticeable during the Edo period (16031867), when Japan was in isolation and more concerned with charting its own coastlines than it was distant shores.

The rice paper used to produce Gyoki maps had two major limitations. The first is that it was strong and inconvenient to fold. This incentivised publishers to produce maps on screens or scrolls, rather than in atlas form. Secondly, the roughness of the woven paper made it difficult to woodblock print small details. Instead, the Gyoki style involved stating the orientation and distances literally in the text itself, rather than drawing maps to scale.

One advantage over contemporary European techniques, however, was that several colours could be stencilled or brushed on top of the woodblock printed ink. This allowed for easier polychromatic printing than intaglio copperplate engraving. With its vibrant colour, lack of scale, red outlined routes, and literal recording of distances between destinations, this present atlas is fully steeped in the Gyoki tradition.

Rare. We are only able to trace five examples: University of British Columbia, the Library of Congress, the American University, UC Berkeley Libraries, and Kyoto University. The hand colouring of the maps differs to the example held at the University of British Columbia, and the example in Kyoto University is without colour.

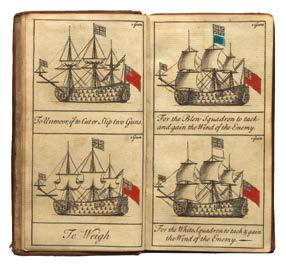

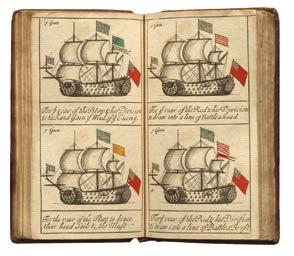

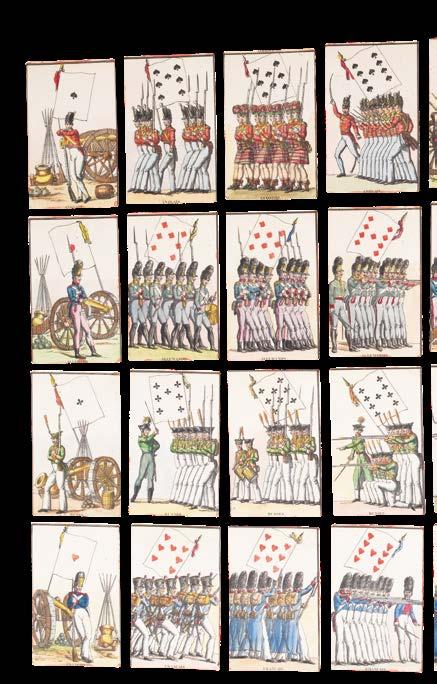

GREENWOOD, Jonathan

GREENWOOD, Jonathan

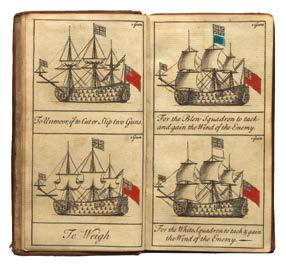

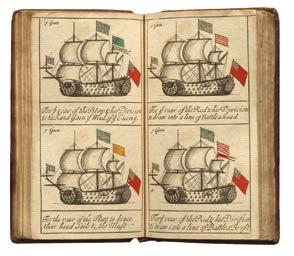

The Sailing and Fighting Instructions or Signals as they are Observed in the Royal Navy of Great Britain

Publication [?London, 1714-1715].

GREENWOOD, Jonathan

Description

The Sailing and Fighting Instructions or Signals as they are Observed in the Royal Navy of Great Britain.

Publication [?London, 1714-1715].

Description

Duodecimo (149 by 77 mm), unpaginated, engraved title, 2pp. dedication, 70 engraved plates, 65 with original hand colour, manuscript calculation in ink to front free endpaper, dated in a contemporary hand March 4 to title page, contemporary sheep, blind stamped and tooled, spine in six compartments separated by raised bands, title piece to spine, title in ink.

References

Duodecimo (149 by 77 mm), unpaginated, engraved title, 2pp. dedication, 70 engraved plates, 65 with original hand colour, manuscript calculation in ink to front free endpaper, dated in a contemporary hand March 4 to title page, contemporary sheep, blind stamped and tooled, spine in six compartments separated by raised bands, title piece to spine, title in ink.

References

Commader Hilary P. Mead, ‘The Earliest English Signal Book’, Proceedings of the US Naval Institute 61 (1935); William Gordon Perrin, British Flags, Their Early History, and Their Development at Sea: With an Account of the Origin of the Flag as a National Device, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922); James Tritten, Doctrine and Fleet Tactics in the Royal Navy, (PP Publishing, 2015).

$10,000

Commader Hilary P. Mead, ‘The Earliest English Signal Book’, Proceedings of the US Naval Institute 61 (1935); William Gordon Perrin, British Flags, Their Early History, and Their Development at Sea: With an Account of the Origin of the Flag as a National Device, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922); James Tritten, Doctrine and Fleet Tactics in the Royal Navy, (PP Publishing, 2015).

The first printed English signals book

A scarce naval signals book, the first to be printed in the English language.

The first printed English signals book

The book was the enterprising production of Jonathan Greenwood. Greenwood was born about 1656 and apprenticed in June 1670 in the Stationers’ Company, where he was made free in 1679. He presumably had naval connections, but no other works of his are known and no other record of him as a publisher survives (Mead).

A scarce naval signals book, the first to be printed in the English language.

The book was the enterprising production of Jonathan Greenwood. Greenwood was born about 1656 and apprenticed in June 1670 in the Stationers’ Company, where he was made free in 1679. He presumably had naval connections, but no other works of his are known and no other record of him as a publisher survives (Mead).

The growth of the British navy led to a demand for a record of the signals used at sea. Commanders might have to manage “as many as a hundred ships in battle, many of which were still privateers”: the vessels might not be trained in Navy discipline (Tritten).James II was the first to co-ordinate British flag signals while still Duke of York, and various manuscript works followed, in an inconvenient folio size.

The growth of the British navy led to a demand for a record of the signals used at sea. Commanders might have to manage “as many as a hundred ships in battle, many of which were still privateers”: the vessels might not be trained in Navy discipline (Tritten). James II was the first to co-ordinate British flag signals while still Duke of York, and various manuscript works followed, in an inconvenient folio size.

Greenwood saw the opportunity for a small, cheaper book aimed at “Inferior Officers who cannot have recourse to the Printed Instructions”; although the instructions to the fleet were confidential, the signals were not (Perrin). Each signal is shown by an engraving of a ship displaying the flags of the appropriate signal, coloured where necessary, with an explanation underneath. In the dedication, he explains that he has “disposed matters in such a manner that any instruction may be found out in half a minute”.

Greenwood saw the opportunity for a small, cheaper book aimed at “Inferior Officers who cannot have recourse to the Printed Instructions”; although the instructions to the fleet were confidential, the signals were not (Perrin). Each signal is shown by an engraving of a ship displaying the flags of the appropriate signal, coloured where necessary, with an explanation underneath. In the dedication, he explains that he has “disposed matters in such a manner that any instruction may be found out in half a minute”.

Although Greenwood’s work was not an official publication, it was used by at least one Mediterranean fleet commander (Tritten).

Although Greenwood’s work was not an official publication, it was used by at least one Mediterranean fleet commander (Tritten).

The book is dedicated to the six Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, including Sir George Byng, whose son John, also an Admiral, was famously executed in 1757 “pour encourager les autres”, according to Voltaire, after failing to relieve the British garrison during the Battle of Minorca.

The book is dedicated to the six Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, including Sir George Byng, whose son John, also an Admiral, was famously executed in 1757 “pour encourager les autres”, according to Voltaire, after failing to relieve the British garrison during the Battle of Minorca.

96 DANIEL CROUCH RARE BOOKS X MARKS THE SPOT

20 5

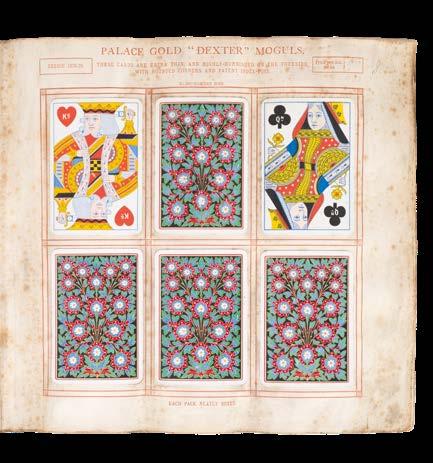

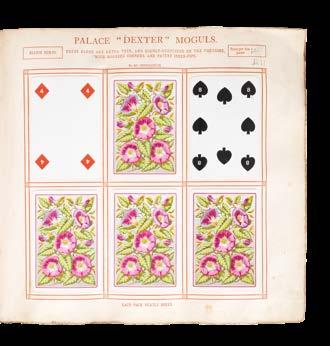

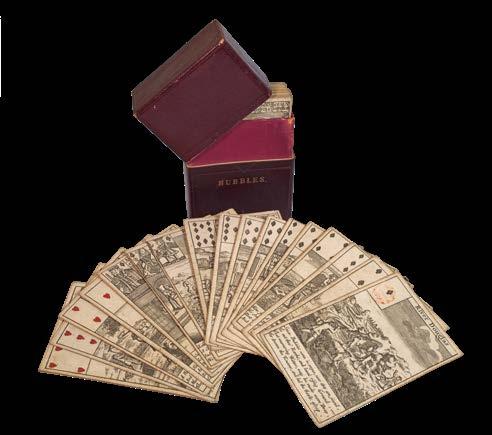

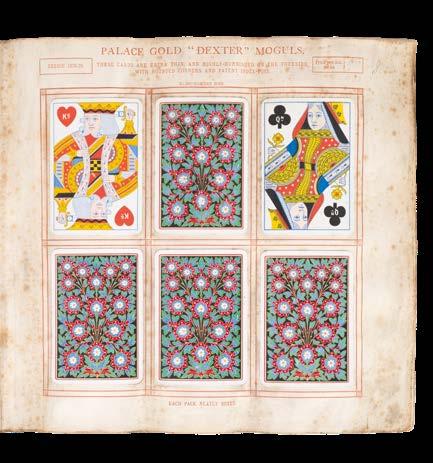

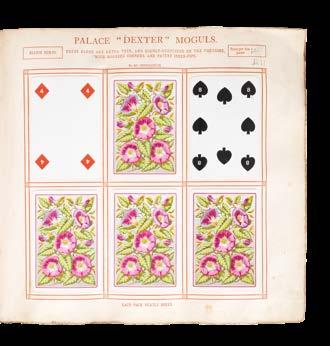

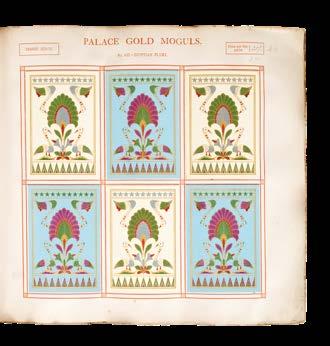

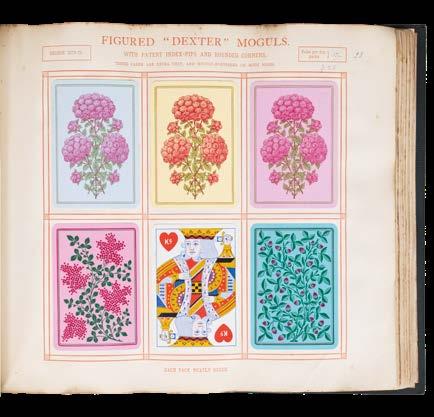

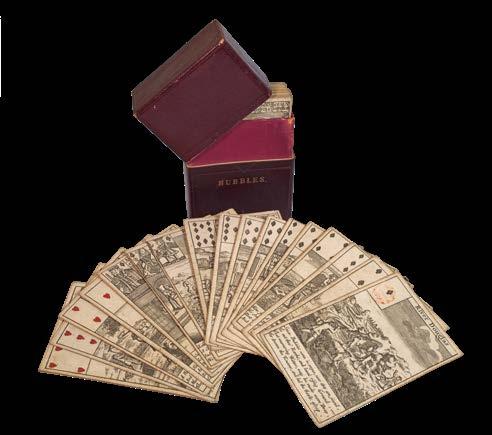

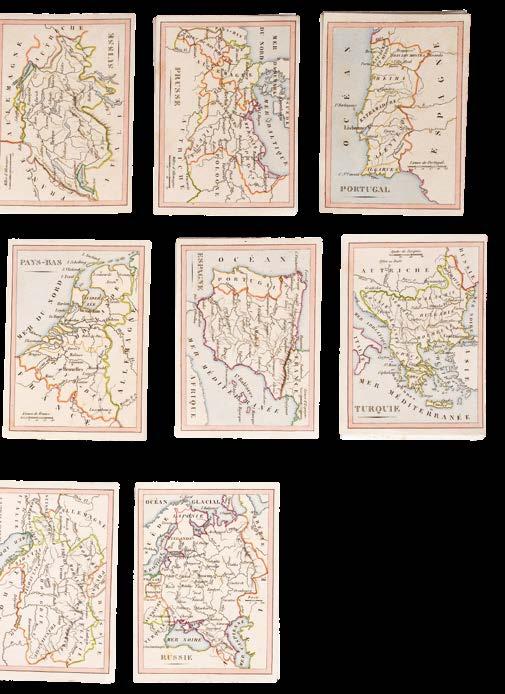

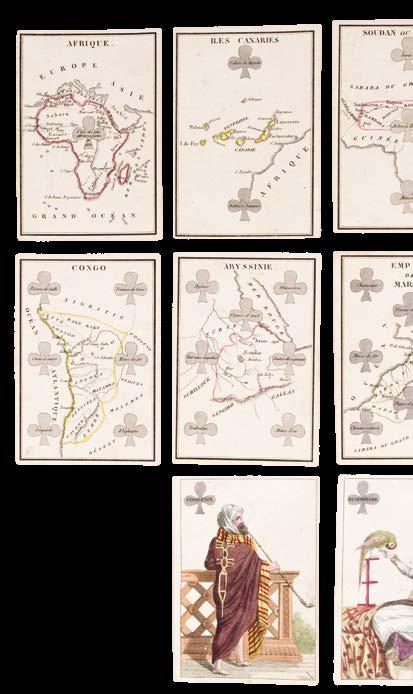

BOWLES, Thomas

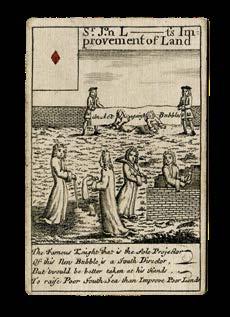

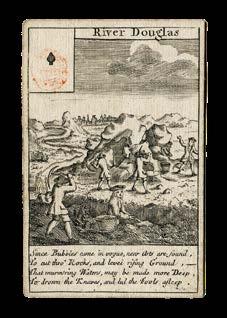

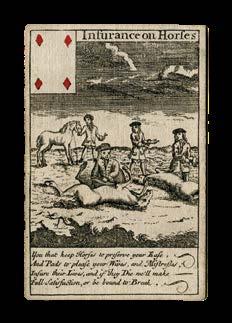

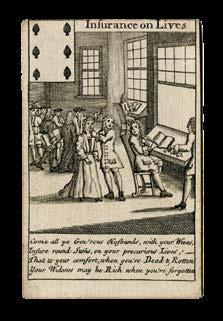

[South Sea Bubble playing cards]

Publication

[London, Thomas Bowles, 1720].

Description

52 engraved playing cards with text, suits coloured by hand, stamp to one, versos blank.

Dimensions

95 by 63mm (3.75 by 2.5 inches).

References

Baynton-Williams pp.103-104; Hargrave pp.197-199; van den Bergh pp.20-21.

Bubble or nothing

The Maker

Thomas Bowles (II) (1688-1767), followed his father into business in 1714. He went on to become a leading, and highly successful, London print seller and publisher. As a retailer, he also catered to map buyers; he published what might be termed “good shop stock”: separately published plans of London and environs, including an early pocket plan of the city, maps of England and Wales, Scotland, the British Isles, the world and so on. He was also a partner in a number of atlas projects, notably Owen and Bowen’s road-book, the ‘Britannia Depicta’ (1720), Moll’s ‘New Description of England and Wales’ (1724), ‘The World Described’ (1726 onward) and the ‘Large English Atlas’ in the 1750s.

Then, often working in conjunction with his brother John, he published numbers of interesting broadsheet maps depicting important events of the period, such as theatre of war maps, siege-plans and battle-plans that would interest and inform his customers, in order to supplement the brief accounts in the news-sheets of the day, which were mostly unillustrated.

A newspaper advertisement from 12 March 1720 states that the Bowles firm was shortly to publish a deck of playing cards, depicting the effects of the ‘South Sea Bubble’.

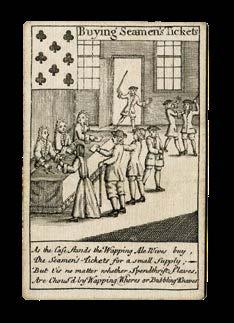

The Cards

The South Sea Bubble is the most notorious episode in the history of eighteenth-century financial speculation. It was a fevered attack of mass madness, which affected all levels of society, as a significant proportion of the British population became convinced that their fortunes would be transformed by investing in the South Sea Company. The Company was formed as early as 1711, and was promised a monopoly on all trade to the Spanish colonies in South America, in return for taking on and consolidating the national debt. Unfortunately, the Treaty of Utrecht, which ended the War of Spanish Succession, severely restricted the trading rights of the Company, since it confirmed Spain’s sovereignty of its colonies in the New World. However, that did not stop the Company from attempting to convert their ‘assets’ (i.e. the National Debt) into shares, which they mis-sold on the basis of wildly exaggerated profits from their South Sea trading. Between January and May of 1720, shares in the South Sea Company soared from £128 to £550 each.

Encouraged by this apparent success, hundreds of smaller “Bubbles”, or joint-stock ventures, were created, and gained similar momentum. In an attempt to ward off competition, the South Sea Company put its weight behind The Bubble Act, passed in June of 1720, which required all jointstock companies to have a Royal charter. Once the Company had received its own Royal seal of approval this way, its shares almost doubled in price to an astronomical and unsustainable £1050. Consumer confidence waned,

6

then collapsed, and by September the share price had returned to £175, and the bubble was well and truly burst. Fortunes won were now largely lost. By 1721, investigations revealed a tangled web of corruption and fraud, involving company and government officials.

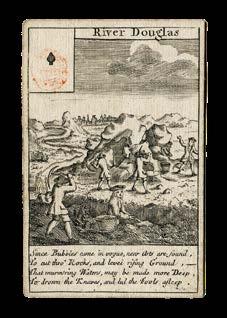

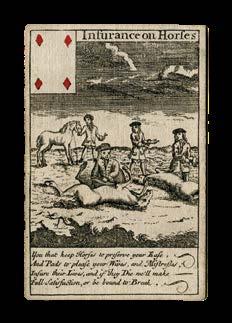

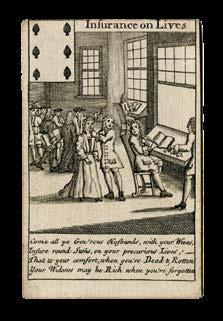

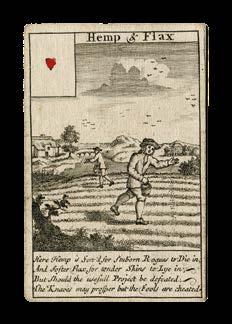

In this complete, and very rare as such, pack, each playing card is assiduously dedicated to satirizing actual companies, individual “Bubbles” associated with the larger fraud, and ridiculing those foolish enough to invest in them. Many famous, and some not so, seemingly madcap schemes are cruelly illustrated and then renamed in rhyme: beginning with the Ace of Spades, and the ‘River Douglas’, a canal scheme in Lancashire that foundered; and including the failed York Buildings insurance scheme, ‘Puckle’s Machine’ gun, ‘Raddish Oil’, Holy Island Salt,… Some schemes attempted to sanitize the mean streets of Britain, by employing the poor, looking after orphans, and clearing out brothels, and no opportunity to be bawdy has been missed. At an early date the most offensive rhymes have been expurgated, affecting the Queen of Spades ‘Bastard Children’, Six of hearts ‘Errecting Houses of Office in N. Britain for Strangers & Travellors’ [ie toilets], Three of Diamonds, ‘Office for cureing the Grand Pox or Clap’, and the Ten of Clubs which is about ‘Bleeching of Hair’.

As expected, many of the cards depict Bubbles associated with America: the ‘Pensilvania Company’ (with contemporary corrective pasteover), the Bahama Islands, and ‘Settling Collonies in Accadia North America’ (complete with cannibalism); numerous Fisheries: ‘Royal’, ‘Grand’, and ‘Whale’; and ‘Cureing Tobacco for Snuff’.

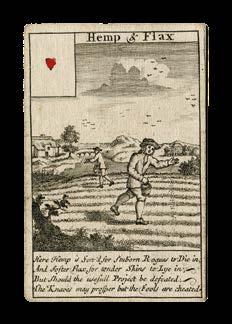

Scotland, having just about weathered the collapse of the Darien Scheme, and John Law’s Mississippi venture, was also greatly affected by the South Sea Bubble. Scottish money flooded into London, investing heavily in three of the companies depicted in Bowles’ cards: the York Buildings insurance scheme, and the Grand Fishery of Great Britain, as well as house fire insurance companies, like the ‘Rose Insurance from Fire’ company, on the 7 of clubs. Other Scottish industries that come under fire include: ‘Correcting Houses [ie outdoor loos] of Office in N. Britain for Strangers & Travellors’; ‘Hemp & Flax’; ‘Drying Malt by the Air’; and ‘Stockings’ manufactory.

The Ace of Spades, which shows the industry expanding around the River Douglas, bears the lines:

“Since bubbles came in vogue, new arts are found To cut thro’ rocks, and level rising ground; That murmuring waters may be made more deep, To drown the knaves and lull the fools asleep”.

The Six of Spades, which shows the newly established life insurance companies, reads:

“Come all ye gen’rous husbands with your wives Insure round sums on your precarious lives, That to your comfort, when you’re dead and rotten, Your widows may be rich when you’re forgotten”.

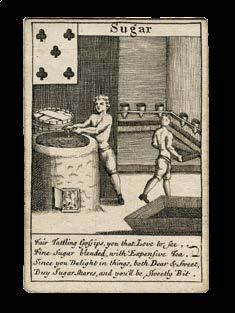

The Five of Clubs, entitled ‘Sugar’, is accompanied by the rhyme:

“Fair tattling gossips, you that love to see

Fine sugar blended with expensive tea,

Since you delight in things both dear and sweet, Buy sugar shares, and you’ll be sweetly bit.”

As is usual for the date, the Ace of Spades bears the red ink Tax Stamp, which was obligatory on packs of cards from 1711, and is why the Ace of Spades is traditionally the leading card in any pack. It is known that Bowles created two sets of playing cards to commemorate the South Sea Bubble disaster, and both are very rare, especially when complete. The companion set depicts domestic scenes of despair, and is more common.

As well as providing a scathing social commentary, these cards form fully functioning decks, with the suit mark and value of each card shown in miniature in the upper left corner.

This rare and entertaining deck of cards offers valuable contemporary insight into the feverish atmosphere, trades and fashions of the day.

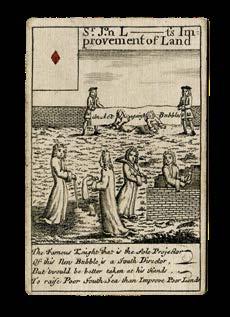

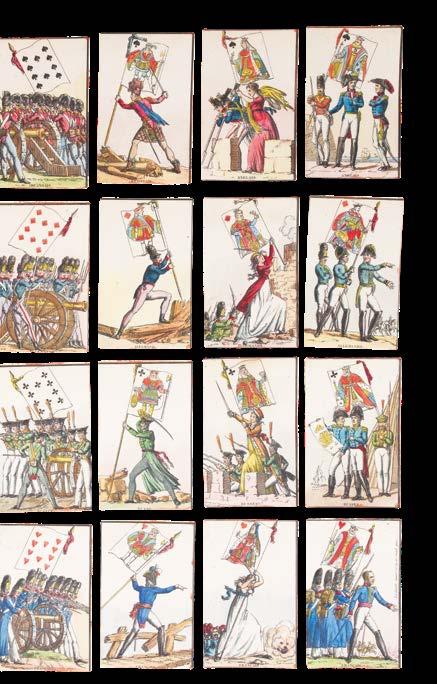

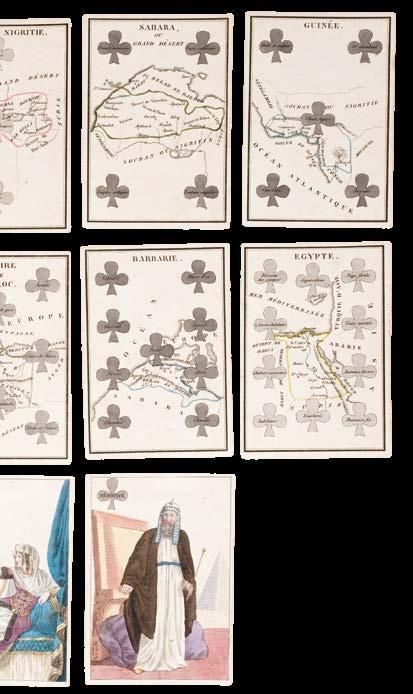

[ANONYMOUS]

A saintly deck

52 engraved playing cards with original hand-colour, with red tax stamp to Ace of Spades.

Dimensions

94.5 by 63.2mm. (3.75 by 2.5 inches).

$28,400

The Maker

Neither the artist nor the publisher of these cards is named on the deck.

The Cards

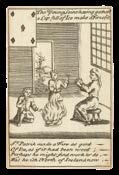

Themed around the lives of the saints, the cards are both informative and comic in nature. Above the detailed illustration on each card, there is a short description outlining the scene, while below four lines of verse give a more humorous interpretation. For example, the image on the Two of Spades, which shows a man kneeling in prayer before a stag in a field, is captioned, “St Eustachius is converted and admonished by a hart”. The verse below the illustration describes how:

“In days of old when beasts did preach A hart did St Eustachius teach; Sure Rome that time did now allow So many idle priests as now”.

The values of the cards are shown by a miniature representation given in the upper left-hand corner, the court cards shown as traditional English full-length Jacks, Queens and Kings.

[The Lives of the Saints] Publication [London, c1740]. Description

7

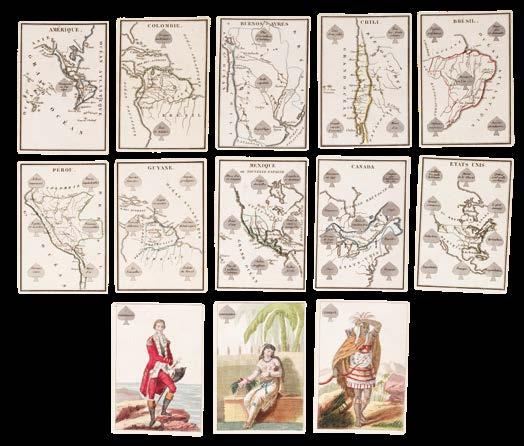

[after ROBERT DE VAUGONDY, Gilles and Didier]

Amerique partie Septrenionale [and] Amerique partie Meridionale

Publication

A Paris, chez Petit, rue du petit Pont a l’image Notre-Dame, [1767].

Description

A pair of handheld fire screens, engraved map with with original hand-colour, French text to verso, with wooden handle.

Dimensions

(greatest dimensions) 280 by 250mm (11 by 9.75 inches).

$7,500

“...n’a ete découverte que depuis 276 ans”

A pair of handheld fire screens of both North and South America.

Face screens were used to shield the face from heat from a fire or stove, this had a dual purpose to it, one being preventing a red flush to the skin which would be considered unbecoming, the second was to prevent the thick white makeup used by ladies in the eighteenth century, of melting.

The presents screen also doubles as an educational tool, with the verso depicting a map of North America, and the recto a brief history of the continent. Although the screen is not dated the text mentions America being discovered by Christopher Columbus in 1491, some 276 years ago, giving us a date of 1767.

The map is based on the work of Gilles and Didier Robert de Vaugondy (fl.1730-1780), one of the leading Parisian mapmakers of the eighteenth century, who published a very similar map of North America in their hand-held ‘Atlas Portatif’ of 1748.

Little is known about the publisher Petit (fl.1755-1784), whose premises was on the ‘rue petit Pont, although the holdings of several museums suggest that he specialised in the production of handheld fire screens; with screens displaying scenes from contemporary plays, as well as more educational fare.

Due to the screens ephemeral nature, eighteenth century examples in such fine condition are particularly rare.

8

[after ROBERT DE VAUGONDY, Gilles and Didier]

L’Afrique

Publication

A Paris, chez Petit, rue du petit Pont a l’image Notre-Dame, [1767].

Description

Handheld fire screen, engraved map with with original hand-colour, French text to verso, with wooden handle.

Dimensions (greatest dimensions) 280 by 250mm (11 by 9.75 inches).

$3,000

Africa on a fire screen

Rare handheld fire screen with a map of Africa.

Face screens were used to shield the face from heat from a fire or stove, this had a dual purpose to it, one being preventing a red flush to the skin which would be considered unbecoming, the second was to prevent the thick white makeup used by ladies in the eighteenth century, of melting.

The presents screen also doubles as an educational tool, with the verso depicting a map of Asia, and the recto a brief history of the continent. Although the screen is not dated, the text to a similar screen depicting North America mentions, America being discovered by Christopher Columbus in 1491, some 276 years ago, giving us a date of 1767.

The map is based on the work of Gilles and Didier Robert de Vaugondy (fl.1730-1780), one of the leading Parisian mapmakers of the eighteenth century, who published a very similar map of Africa in their hand-held ‘Atlas Portatif’ of 1748.

Little is known about the publisher Petit (fl.1755-1784), whose premises was on the ‘rue petit Pont, although the holdings of several museums suggest that he specialised in the production of handheld fire screens; with screens displaying scenes from contemporary plays, as well as more educational fare.

Due to the screens ephemeral nature, eighteenth century examples in such fine condition are particularly rare.

9

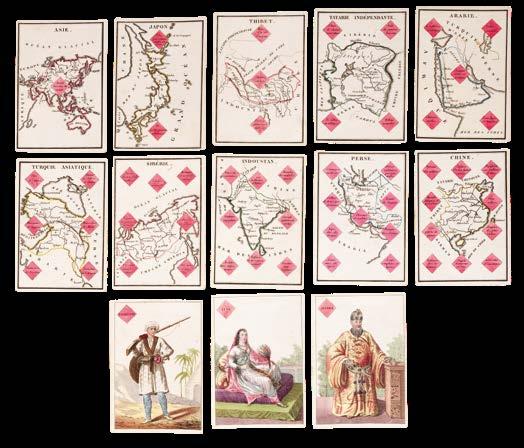

[after ROBERT DE VAUGONDY, Gilles and Didier]

L’Asie Publication

A Paris, chez Petit, rue du petit Pont a l’image Notre-Dame, [1767].

Description

Handheld fire screen, engraved map with with original hand-colour, French text to verso, with wooden handle.

Dimensions (greatest dimensions) 280 by 250mm (11 by 9.75 inches).

$3,000

Asia on a fire screen

Rare handheld fire screen with a map of Asia.

Face screens were used to shield the face from heat from a fire or stove, this had a dual purpose to it, one being preventing a red flush to the skin which would be considered unbecoming, the second was to prevent the thick white makeup used by ladies in the eighteenth century, of melting.

The presents screen also doubles as an educational tool, with the verso depicting a map of Asia, and the recto a brief history of the continent. Although the screen is not dated, the text to a similar screen depicting North America mentions, America being discovered by Christopher Columbus in 1491, some 276 years ago, giving us a date of 1767.

The map is based on the work of Gilles and Didier Robert de Vaugondy (fl.1730-1780), one of the leading Parisian mapmakers of the eighteenth century, who published a very similar map of Asia in their hand-held ‘Atlas Portatif’ of 1748.

Little is known about the publisher Petit (fl.1755-1784), whose premises was on the ‘rue petit Pont, although the holdings of several museums suggest that he specialised in the production of handheld fire screens; with screens displaying scenes from contemporary plays, as well as more educational fare.

Due to the screens ephemeral nature, eighteenth century examples in such fine condition are particularly rare.

10

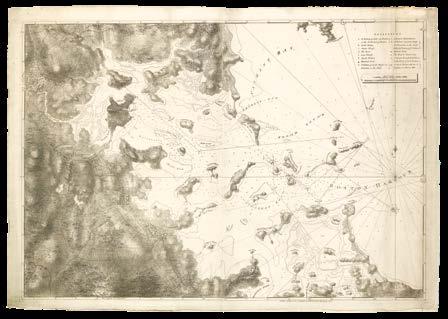

DES BARRES, Joseph Frederick Wallet

[Chart of the Harbour of Boston]/ Nautical Remarks and Observations for the Chart of the Harbour of Boston. Composed from different Surveys; but principally from that taken in 1769, by George Callendar, Late Master of His Majesty’s Ship the Romney

Publication

London, 5th August, 1775.

Description

Large aquatint and etched engraving, on two sheets joined, unfolded and uncut, with the LVG watermark, together with, pamphlet, quarto (280 by 230mm), original blue wrappers, typographic title, pp. 5-(12), there are no pages 3-4 which agrees with the John Carter Brown example.

Dimensions

705 by 1040mm (27.75 by 41 inches).

References

Boston Engineering Department, List of Maps of Boston, pp. 70-71; Cumming, British Maps of Colonial America, pp.51-56; ESTC N12343 (pamphlet); Guthorn, ‘British Maps of the American Revolution’ 59/3, Holland’s original manuscript; Krieger and Cobb, Mapping Boston, p. 106, plate 19; Nebenzahl, Bibliography of printed battle plans, 3; Sabin 10061 (pamphlet); Sellers and Van Ee, 945; Stevens, Bibliography of the Atlantic Neptune (unpublished) pp. 211-216; Streeter, II:706.

$23,300

“Et la Lumiere fut” (Genesis I:3)

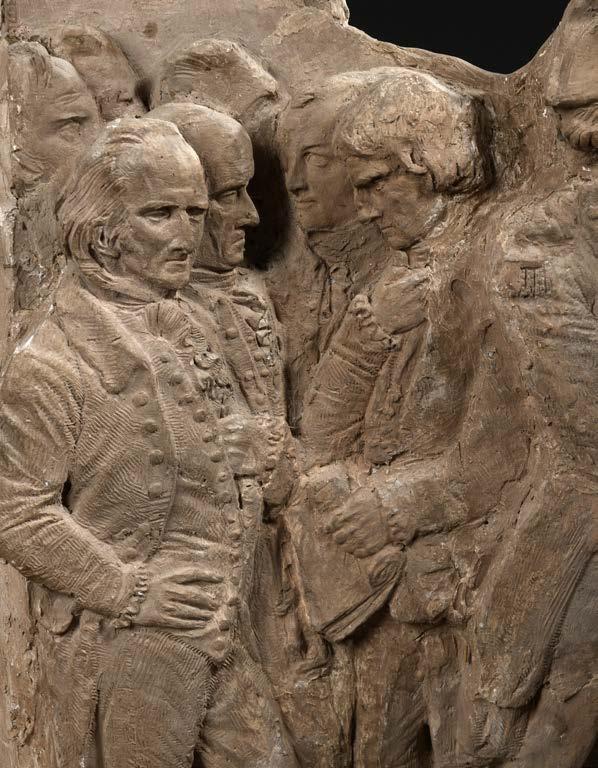

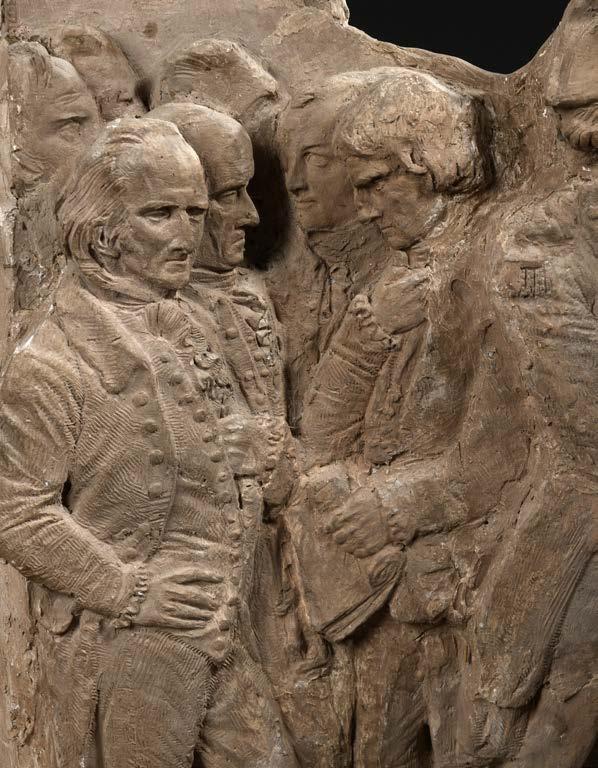

An allegory of the printing of the Declaration of Independence, depicting Benjamin Franklin proffering the newly-printed broadside, surrounded by all 56 Signers, Founding Fathers, and other important Enlightenment figures of the Americas.

This preliminary maquette is a new discovery, and is almost certainly the first state of this iconic bas-relief. Having been packed away in a longforgotten wooden crate by the family of Victor Pavie, lawyer, printer, publisher, and close friend of David d’Angers, it has not previously been exhibited.

David d’Angers’s finished frieze, ‘Les Bienfaits de l’imprimerie en Amerique’, was cast in bronze, and created to commemorate the 400-year anniversary of Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of moveable type. It was also a bald political statement, demanding freedom from the tyranny of Empire, which history has shown can be achieved by the enlightenment that printing brings. David d’Angers’s sculpture can be seen as a “quest to redefine the notion of a monument in a period marked by both intense historicism and the ever-accelerating rhythms of modernity… His theoretical and aesthetic innovations greatly contributed to our modern obsessions with memory and celebrity, and provide a timely reminder of the possibilities for politically-engaged artistic practice in the twenty-first century” (Bowyer).