Edinburgh School of Architecture & Landscape Architecture

ma(hons)

2023 2022

ba

architecture *

–

ESALA Graduate Show 2023

Lauriston Campus, Edinburgh College of Art

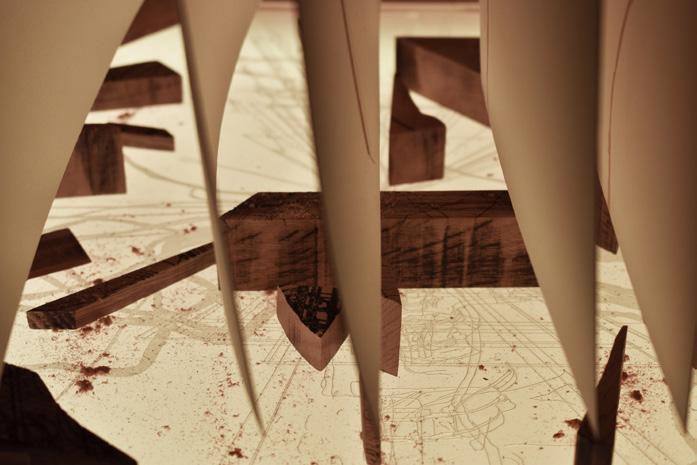

Photograph: Calum Rennie

ESALA Graduate Show 2023

Lauriston Campus, Edinburgh College of Art

Photograph: Calum Rennie

Lara Acikgoz • Tom Ai • Karen Akiki

Danah Aljamid • Ksenia Arkhipov

Cleo Averof • Matthew Baker • Daisy Bond

Molly Bonner • Ciara Briody • Ross Brown

Rhona Brown • Veronica Bucad

Rime Byfanzi • Eve Cameron

Caroline Chan • Wenzheng Chen

Eric Chen • Adam Chen • Candice Chen

Yihui Chen • Kathy Choi • Bruce Chu

Beth Clothier • Ella Dai • Guy Di Rollo

Sharon Ding • Zsofia Droppa • Deniz Oroglu

Joyce Fan • Emily Fang • Haoning Feng

Alice Feng • Laiba Feroz • Tom Ferris

Lauren Fraser • Xander Froggatt

Maddy Gale • Ruohan Geng

Anna Gillibrand • Alister Glen • Pippa Glynn

Kirsty Green • Ellie Greenwood

Millie Hambleton-White • Willa Hodson

Ellie Hong • Anita Huang • Whitney Huang

Eleanor Hung • Sasha Larmak

Seonaid Jervis • Beini Jiang • Megan Jones

Lauren Jordaan • Eugene Kam

Anfisa Karneeva • Brian Kim

Andrew Kowalski • Isabella Laird

Rosa Launder • Zhiyu Li • Rachel Li

Zifei Li • Moby Lo • Chang Lou

Cecily Lu • Sumaita Mahnur • Oliwia Mames

Kathleen Mcbride • Mira Mekki

Chiara Mesquita • Dylan Milne • Sofia Moggi

Soraya Mohammad Asri • Alicja Mrowicka

Hazel Neill • Kinza Nithianandan

Maja Nowaczyk • Rianna Onzivu

Elliot Osmond • Cameron Paul

Karolina Pavlikova • Drew Pimm

Joshua Powell • Emanuel Pruteanu

Jack Purves • Charlotte Rathbone

Estée Raus • Kevin Ren • Robert Robertson

Luna Rojas • Alicja Sadowska

Roshni Shah • Ananya Sharma • Amy Song

Airam Soriano • Milenka Soskin

Holly Spragg • Harris Stewart

Charlene Sun • Issa Tambourgi

Nathan Tollan • Elli Trimlett

Aysel Naz Tunay • Lola Turner

Marika Urbanska • Arian Vakili

Allen Walker • Safiyah-Vega Wilson

Felix Wong • Millie Wood • Ella Woods

Sasha Worth • Ji Wu • Yuhang Xue

Ella Aisher • Abdulrahman AlSuraya

Serena Arya • Harry Baldwin • Evie Barter

Hannah Bendon • Rona Bisset

Finn Brown • Alex Calder • Gordon Chen

Qiuyi Chen • Malanie Chen • Adela Chen

Una Chen • Ydian Chen • Eva Cheng

Gary Chen • Aspen Cheung • Paco Chow

Louis Clarkson • Andreea Colbeanu

Saoirse Cotter • Zara Coulter

Douglas Crammond • Tom Crenian

Alice Cross • Hannah Dlagleish

Chris Davies • Sally Dawson • Ziheng Ding

Max Edwards • Heba Elayouty

Shah Jehan Faheem • Bella Fane

Anna Floto • Ena Gavranovic • Emily Geens

Luca Gjessing • Marcus Hall • Harith Hashim

Belinda Haynes • Chentowe He • Jing Hei

Itske Hooftman • Bronwen Horler • Una Hu

Wenjing Huang • Megan Hunter

Montaha Idris • Lewis Jefferson

Yiyuan Jiao • Callum Johnson • Anna Kerr

Thames Klinchan • Shu Kok

Wiktor Krzystolik • Justin Lai

James Langham • Arya Li • Rose Li

Ritvik Loganathan • Yuanxin Lu • Serene Lu

Shuduo Lu • Lucy Lucas • Emma MacDonald

Hannah Maes • Rae Marino

Alissa Martnelli • Sam McKeown

Shay Miller • Danish Mohammad Razwi

Isla Murphy • Phoebe Murray

Campbell Murray • Simon Mydliar

Jeevan Nair • Natalie Ng • Harriet Nixon

Oscar Nolan • Quinthia Nsema Bayekelua

Peculiar Ogunbayo • Oreofe Ogunkoya

Louise Paterson • Luke Pearce

Jenna Penman • Anastasia Redmond

Freddie Reid • Xiaoye Ren • Lucia Riege

Diana Saab • Farah Saiful Bahrin

Joanna Saldonido • Rosie Shackell

Lara Sturgeon • Xindi Su • Kunyi Sun

Charlene Sun • Mengyang Tang • Holly Taylor

Joshua Teh • Julia Twardzisz • Fergus Tyler

Ed Varlow • Phoebe Vendil • Yuxuan Wang

Junyi Wang • Yusen Wang • Leia Wilson

Joohee Won • Lucy Wright • Fanxuan Wu

Alice Xia • Yuxiao Xue • Tianming Yin

Yoyo Yu • Jessica Zhan • Nandy Zhang

Xu Zhang • Tom Zheng

Zimo Yang • Elaine Yang • Shiying Ye

Aarusha Zahia • Amber Zhang

Cindy Zhang • Yile Zhang

Sophie Zhang • Qingyang Zhou

Mingyu Zhou • Yunlong Zhu year 1 year 2

Khaira Abimbola • Delan Aribigbola

James Armstrong • Emma Astely Birtwistle

Ksenia Bobyleva • Abigail Bowens

Stephen Brown • Vivian Chen

Kaiwen Chen • Charlotte Cole

Simona D'Sa • Laura Dew

Oghenetega Ejovwo-Digba

Thomas everett • Sabrina Findlay

Carl Flohr • Connor Fyffe

Alicia Gerhardstein • Amy Graham

Antonia Graham • Emily Grills

Morgan Hadeed • Jingzhi He

Beatriz Herrera • Isla Hibberd

Jessica Hindle • Lucy Hobman

Heorgina Inchbald • Harvey James-Bull

Allegra Keys • Alexandre Langlois

Tanya Lee • Siying Li • Vasilisa Litvinenko

Christian Liu Chang • Jiayu Lu

Sofie McClure • Ronana McCormick

Rajni Nessa • Ellie Nicholls • Tom Peng

Karina Rac • Isabella Rice

Natalia Rutkowska

Camila Sanchez Rodriguez • Ellis Shiels

Audrey So • Amily Sprackling

Devon Tabata • Ruoxin tan • Kelly tanim

Grace Thornham • Bartu Tort • Reece Tsa

Tessa Tsui • Xiaojun Wang • Xiaowen Wang

Charlotte Wayment • Cameron Whitelaw

Robert Witchell • Harry Wood

Amber Woodward • Jade Wu • Yichen Xia

Elizabeth Xu • Daniel Yanez-Cunningham

Cassandra Yang • Jasmine Yang

Yulin Yang • Shuyan Zhang

Jiahui Zhao • Songzhi Zou •

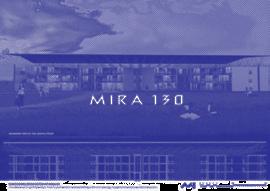

BA Final Year

Hagar Badawy • Kevin Chen • Eurus Feng

Max Fu • Jonathon Green • Jena Hwang

Mingrui Jian • Michael Kan • Ece Kantemir

Jiayi Liu • Meihan Liu • Esther Park

Daniel Pratt • Alon Shahar

Eloise Zha • Kaiyin Zhao

Folahan Adelakun • Aditya Aggarwal

Aisha Akinola • Caitlin Allison

Tallulah Bannerman • Michael Becker

Orla Bell • Lucy Boyd • Charlotte Brooks

Yuchen Cai • Gianluca Cau Tait

Freya Charlton • Arada Chitmeeslip

Leo Chiu • Sara Cinca • Alexander Dalton

Molly Deazley • Mhaira Dickie • Eilidh Duffy

Vicki Dunnet • Samantha Elliot

Coraline Fang • Olivia Fauel • Terry Feng

Yeldar Gul • Melisa Hamzaoglu

Jemima Harrison • James Haynes

Sophie Ho • Vivi Hsia • Niall Jacob

Tahlor Jarrett • Matthew Johnson

Jaaziel Kajoba • Riad Khawam

Geon Yeong Kim • Athina Kotrozuo

Hoi Ching Lee • Bingzhi Li • Lina Li

Shan Liang • Ching-En Lin • Chengke Liu

Ruoming Liu • Runqian Lu • Fly Luo

Hannah MacAulay • Yasmine MacCallum

Sebastian MacChio • Antonios Mavrotas

Astrid Jade McIntyre • Yufei Min

Regina Minnakhmetova • Hoi Yan Ng

Caoilin O'Meara • Hannah Ord

Mina Pabuccuoglu • Shuyue Pan

Xinyi Peng • Eve Pennington • Ionna Peponi

Mikele Perez-Jamieson • Christopher Pirrie

Peter Richardson • Sa-Ang-Ong Rodloytuk

Louis Ross • Divya Shah • Bruce Shen

Tanya Snell • Mei Hang Sou

Tereza Staskova • Samuel Symes

Adrian Tai • Eleanor Trew

Chloe Wendy Tunnell

Thomas Van Der Wielen • Valerie Wan

Yidi Wang • Yunan Wang • Zhe Wang

Lewis Watson • Zhenyu Wei • Mhairi Welsh

Cosmo Wezenbeek • Eleanor Alice Wilkes

Fraser Duncan Winfield • Ivy Yan

Tubohao Yang • Hechen Yuan

year 3 year 4

Editor

Laura Harty

Catalogue Design

Calum Rennie

June 2023

ISBN 978-1-912669-53-0

ba ma(hons) architecture 2023 2022 –*

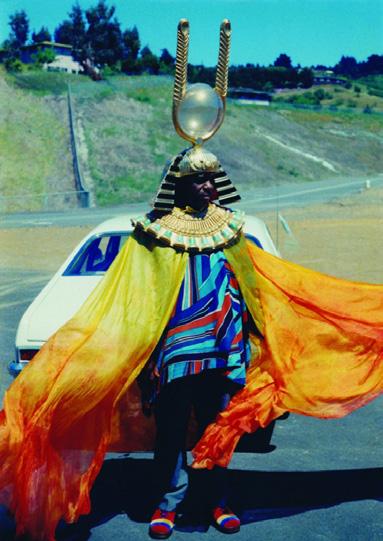

RIBA Accreditation Exhibition 2022

Matthew Gallery, Minto House ESALA

Edinburgh College of Art

Photograph: Rachael Hallett-Scott

Programme Director

Laura Harty

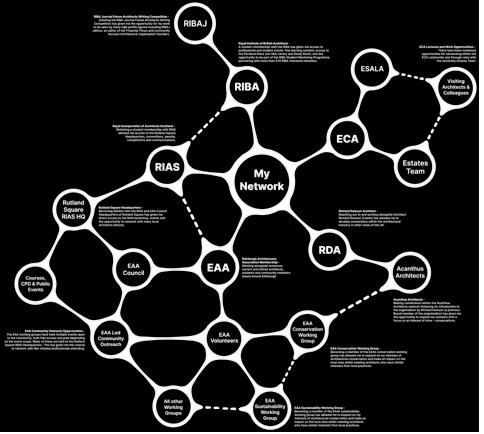

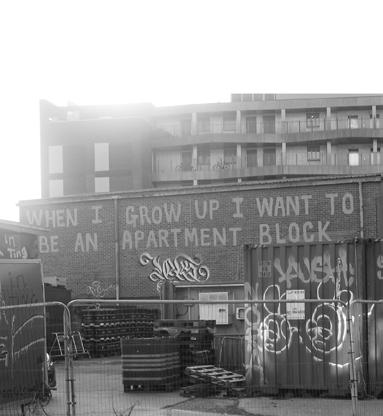

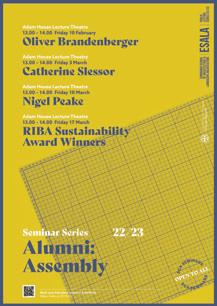

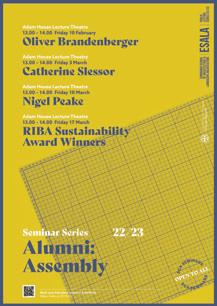

Welcome to the fourth edition of our annual BA | MA (Hons) Architecture catalogue. This publication collates and curates the wide range of courses which comprise our programme delivery across 2022 - 2023. You may notice that the design of this year’s edition marks a definitive shift from the initial three volumes. We have taken this active decision to register and consolidate significant curricula developments across carbon, resources and society, which have reverberated through the programme in the last academic year, and to commit to these changes through two further issues of this catalogue. A refreshed attention to the tangible, the collective and the shared experience of school life animates these pages. We have favoured images which showcase the potential and possibility of studying together, celebrating the collegiate and the participatory within our programme. This work illustrates agile, adept and collaborative architectural contributions across a range of scales, media and formats. These efforts have been recognised by RIBA, which this year awarded the BA| MA (Hons) a third successive Sustainability Award and by its visiting board, who commended our culture of making, our community engagement and the ‘clear researchled architectural agenda which engages with contemporary critical dialogues’. In taking stock to record and disseminate this work, we also recognise the associated spaces of thought provided by the libraries, galleries, parks, palaces and people of this rich and varied city. You may applaud the energy, commitment and drive of the our graduating cohort 22/23, and we certainly will, returning to these pages often to celebrate their magnificent efforts and a year well spent. Congratulations to all!

Editor Laura Harty

Catalogue

Design

Calum Rennie

June 2023

ISBN 978-1-912669-53-0

foreword

architectural design elements

environmental practices

architectural history intro. to world arch.

architectural design assembly technology & environment principles

architectural history revivalism to modernism

architectural design in place

technology & environment building environment

architectural history urbanism & the city

architectural design any place

technology & environment building fabric

design thinking & digital crafting year 2 electives

p.010 p.018 p.024 p.026 p.034 p.038 p.042 p.050 p.054 p.056 p.066 p.070 p.076 1*1 1*2 1*3 1*4 1*5 1*6 2*1 2*2 2*3 2*4 2*5 2*6 2*7

architectural design explorations architectural theory architectural placement working learning architectural placement reflection professional studies architecture dissertation year 4 electives architectural design tectonics architectural design logistics academic portolio part 1 student society arcsoc ecan! esala climate action now! public programme frictions / alumni geddes visiting fellow gloria cabral practice experience p.080 p.106 p.108 p.110 p.112 p.114 p.118 p.124 p.136 p.162 p.166 p.172 p.176 p.174 p.178 3*1 3*2 3*3 3*4 3*5 3*6 4*1 4*2 4*3 4*4 4*4 x*1 x*2 x*3 x*4

1*1 1*2 1*3 1*4 1*5

architectural design elements

1*6

environmental practices

architectural history intro. to world arch.

architectural design assembly technology & environment principles

architectural history revivalism to modernism

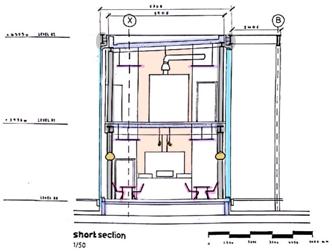

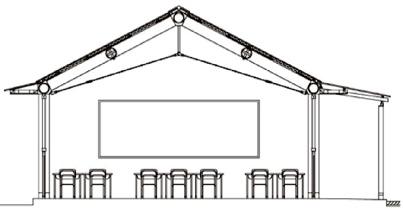

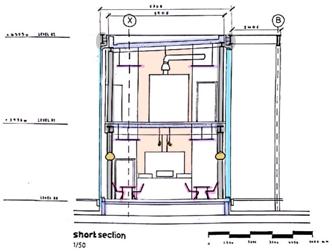

Architectural Design: Assembly

Final Reviews, Matthew Gallery

Photograph: Michael Lewis

architectural design elements

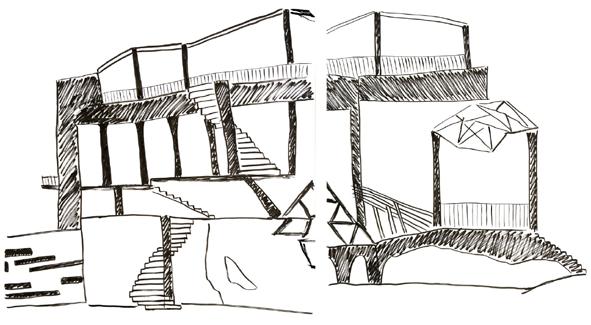

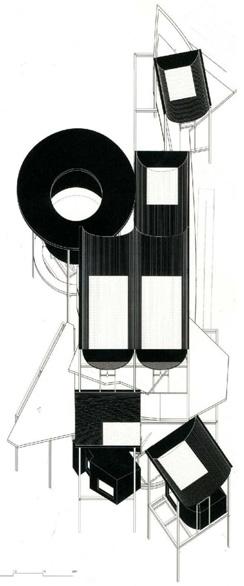

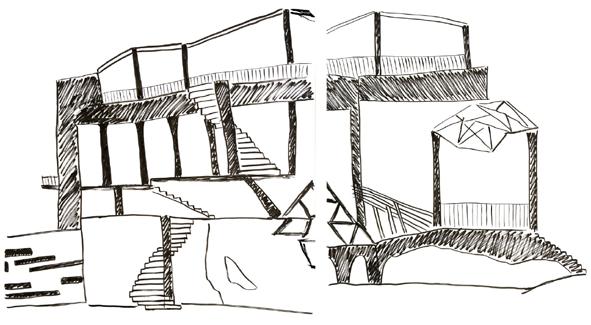

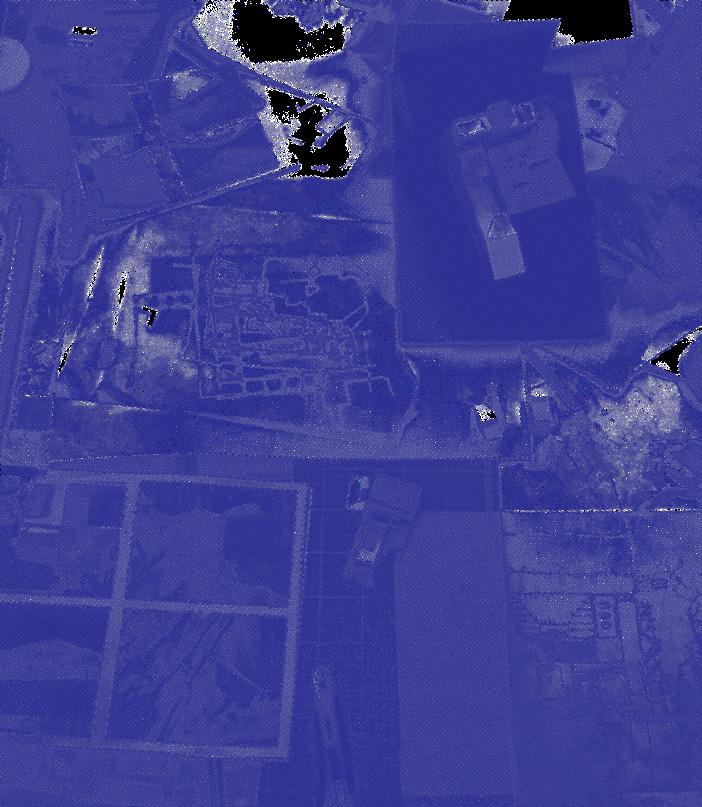

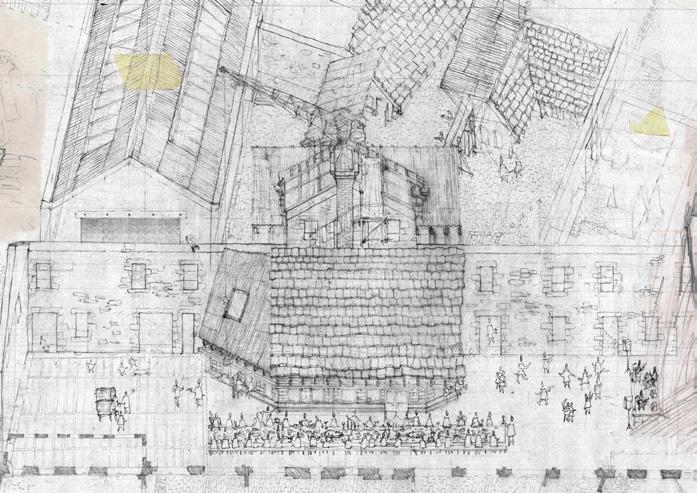

Group 3 (class)Room

Figure ground studies

Group 3 (class)Room

Figure ground studies

Course Organiser

Susana do Pombal Ferreira

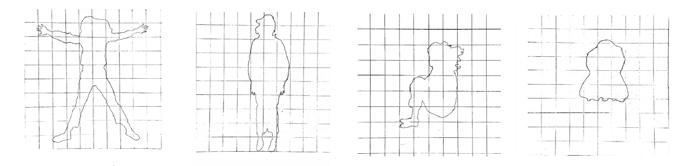

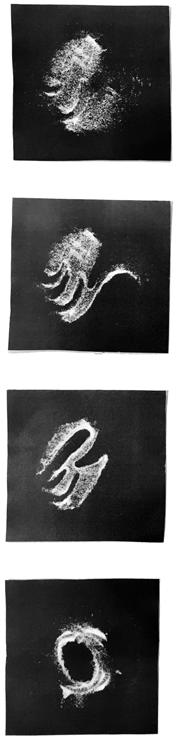

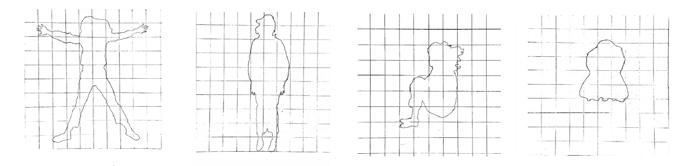

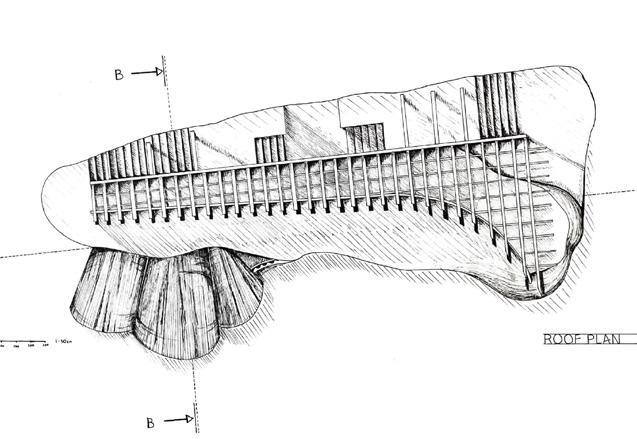

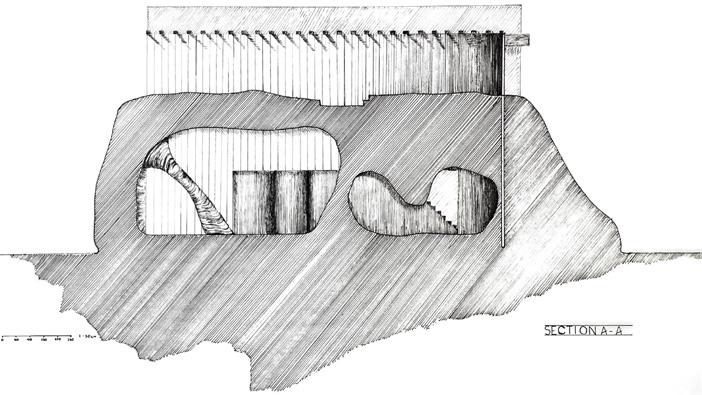

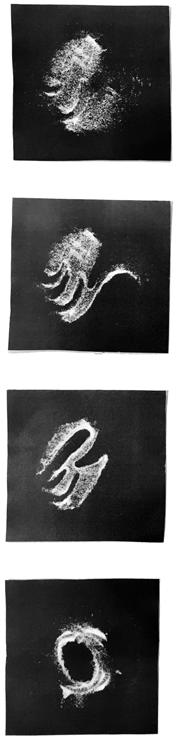

In Architectural Design: Elements students are introduced to the foundational knowledge and skills appropriate to the practice of architectural design. Students are encouraged to actively engage with hand-drawing and physical model-making, while learning a few basic digital methods and technologies for the manipulation, articulation, and dissemination of the work. Throughout the course, students work on various design projects, supported by weekly tutorials, and supplemented by lectures, city walks and workshops. The course emphasises the notion of practice, with tutorial days turned into true laboratories for exploration where students from BA/MA Architecture programme as well as from the BEng/Meng Structural Engineering with Architecture programme work, learn and make together. During the first few weeks of the course, students embark on a series of short exploratory tasks to learn about scale, the basic architectural elements, and the making of space. The course starts with playful mapping activities where students start learning about the relative size of things, using their bodies as reference. The next project invites students to study space through successive investigations of four basic architectural elements: Ground , Wall , Opening and Roof . The final project of the course builds upon the previous projects to challenge students to develop an architectural programme conceptualised for a location in Edinburgh’s Old Town. In particular, students are invited to draw from their own experience of the pandemic to design a (class) Room based on the principles of the open-air schools movement from the last century.

Studio Tutors

Clive Albert

Graham Currie

Michael Davidson

Naomi De Bar

Jack Green

Cath Keay

Shoko Kijima

Joanne McClelland

Derek McDonald

Darren Park

Irem Serefoglu

Julie Wilson

Teaching Contributors

Hazel Mei

Melisa Miranda Correa

Pilar Perez Del Real

Charlott Rodgers

Theodore Shack

Norman Villeroux

Review Critics

Gary Cunningham

Chris Dobson

Calum Duncan

Akiko Kobayashi

Michael Lewis

Fiona McLachlan

Charlott Rodgers

Tolulope Onabolu

Guest Lecturers

Clive Albert

Naomi De Bar

Calum Duncan

Laura Harty

Ivan J. Marquez Munoz

Joanne McClelland

Derek McDonald

1 * 1

014 grounding arch. design elements 1

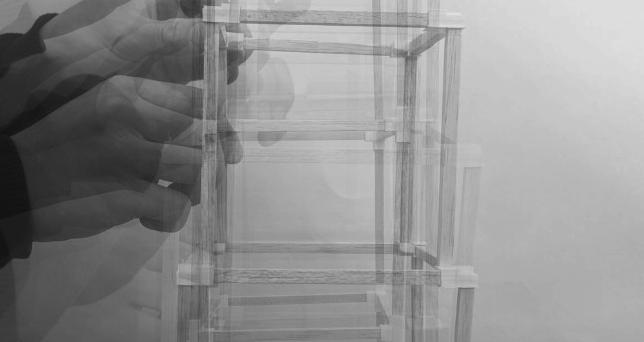

Grounding: body scale & body in space studies

Elements:

2

3

Elements: plan & section

015 ba/ma<hons> 1*1 1

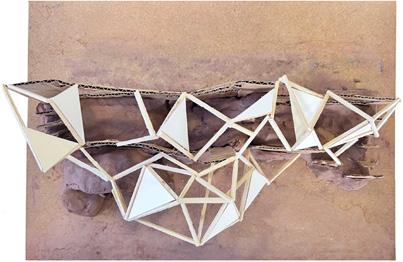

Chiara Mesquita

Amber Zhang

model

Adam Cheng

3 2

4

Caroline Chan Elements: light study 5

Ciara Briody (class)Room: conglomerate drawing

017 ba/ma<hons> 1*1 4

5

6 Brian Kim (class)Room: sketch model

7 Milenka Soskin (class)Room: inhabiting spaces perspective studies

8

Ksenia Arkhipov, Wenzheng Chen, Laura Dahlen, Fiona Eades (class)Room: group conglomerate drawings

9 Karen Akiki (class)Room: sectional perspectives

018 (class)room arch. design elements

6 7

019 ba/ma<hons> 1*1 8 9

environmental practices

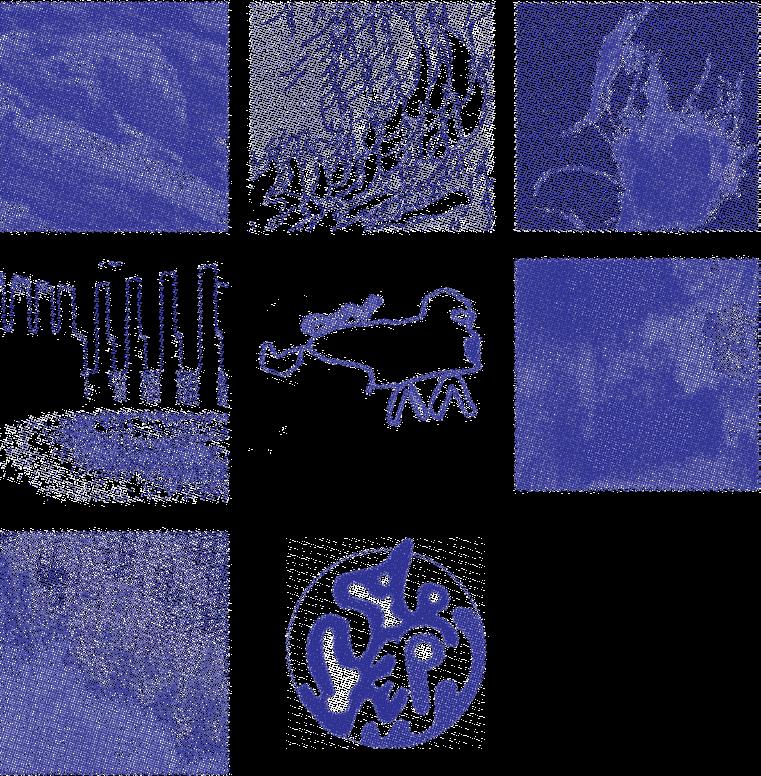

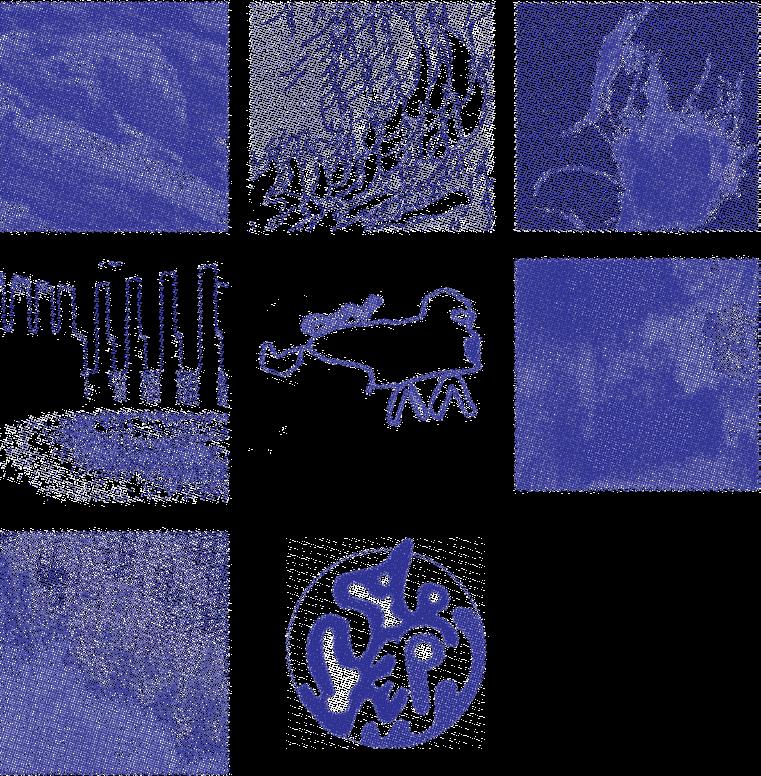

Lisa Mackenzie, Hector Thompson Environmental Practices themes

Lisa Mackenzie, Hector Thompson Environmental Practices themes

Course Organiser

Lisa Mackenzie

Environmental Practices takes first year students of architecture and landscape architecture on an open learning journey to better understand how to initiate design thinking through critical site related investigations. The course structure, teaching material and themes have been brought into alignment to support students as they develop an awareness of their own creative agency in the context of the climate and biodiversity crisis. During the semester students respond to weekly themes of rock, water, sunlight and shadow, field-soil-site, vibrant matter and atmosphere and time to contemplate the natural world as a living entity that exchanges with the world around it (and with the students themselves) in infinite and often apparently undetectable ways. Environmental practices introduces a range of theories and exercises concerned with interpreting the environment as a dynamic context where material and sensory knowledge are valued, discussed and brought into making practices. The staff team bring a range of disciplinary knowledge to support students as they develop a unique and personal ecological sensibility in their own design practice. It is our collective hope that we foster a culture of understanding architecture as a discipline of the socio-environmental world with the capacity to imagine future scenarios that are attentive, supportive and responsive to our shared planetary resources. The course culminates in the curation of a portfolio of work where we ask students to contemplate and document their approaches and reflect on the kind of designers that they would like to be in their own design futures. During the course we ask the students to take their time and think carefully about the thematic topics we have introduced to them appreciating that their work may not always reach conclusions but somehow prize open essential questions about their own agencies in addressing the environmental crisis that we face together.

Studio Tutors

Susie Wilson

Book Artist, Printmaker

Neil Bancroft

Landscape Architect

Theo Shack Architect

Mike O’Dell Architect

Emma Henderson Architect

Yulia Kovonova

Visual Artist

Michael Davidson

Architect, Designer

Joanna Doherty Architect

David Lemm Designer

Cath Keay Artist

Rebecca Wober Architect

Miriam Hancill Artist Contributors

Charlott Rodgers

Camassia Bruce

Landscape Architect

Felicity Barlow Artist

1 * 2

022 – environmental practices 1

023 ba/ma<hons>

4

1

Anna Gillibrand

Sun and shadow

2

Ellie Trimlett Water

3

Adam Chen Vibrant Matter

4

Anita Huang

1*2 2 3

Vibrant Matter

024 5

Students running water experiments with artist Felicity Bristow

6 Joyce Fan Field-soil-site

7 Zifei Li Water

– environmental practices 7 5 6

8 Karen Akiki Sunlight and shadow

8

architectural history introduction to world architecture

Fountains Abbey, Yorkshire

Photograph: Alistair Fair

Photograph: Alistair Fair

Course Organiser

Peter Clericuzio

Architectural History 1A introduces students to the study of the history of the built environment in a range of global contexts from ancient Mesopotamia to Europe in the 1750s. The course is deliberately broad in its chronological and geographical focus, and the range of building types considered. It aims to foster not only a core knowledge of, for example, ancient classicism, medieval Gothic, and the Renaissance, but also to introduce key themes in architectural history, such as the roles of designer and patron, questions of gender and colonialism, and the role of energy in shaping the built environment. The coursework and assessment introduce skills necessary for success at university level, encouraging an independent, reflective and analytical approach. The course is followed by Architectural History 1B: Revivalism to Modernism.

1 * 3

Lecturers

Alex Bremner

Kirsten Carter McKee

John Lowrey

Margaret Stewart

Senior Tutor

Anne Galastro

Tutors

Alastair Disley

Rory Lamb

Mohona Reza

Natcha Ruamsanitwong

Mahnaz Shah

Dimitrij Zadorin

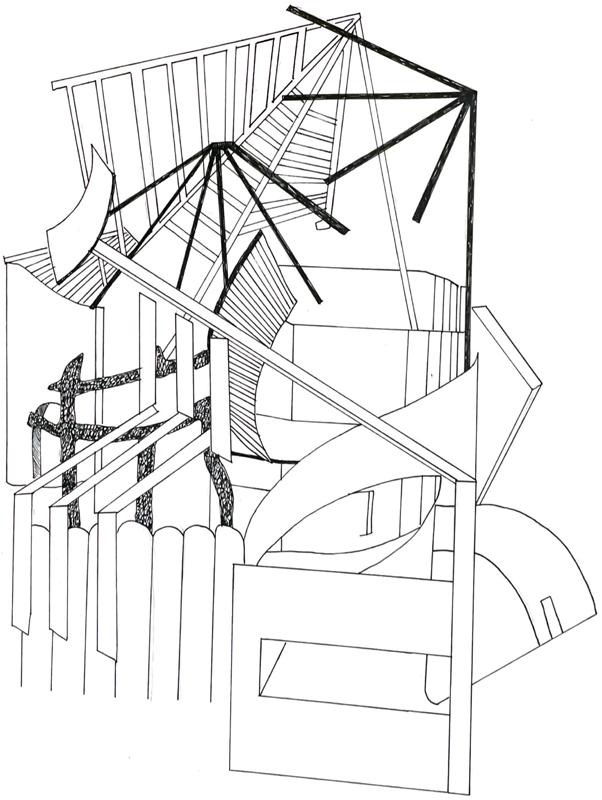

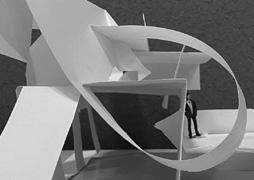

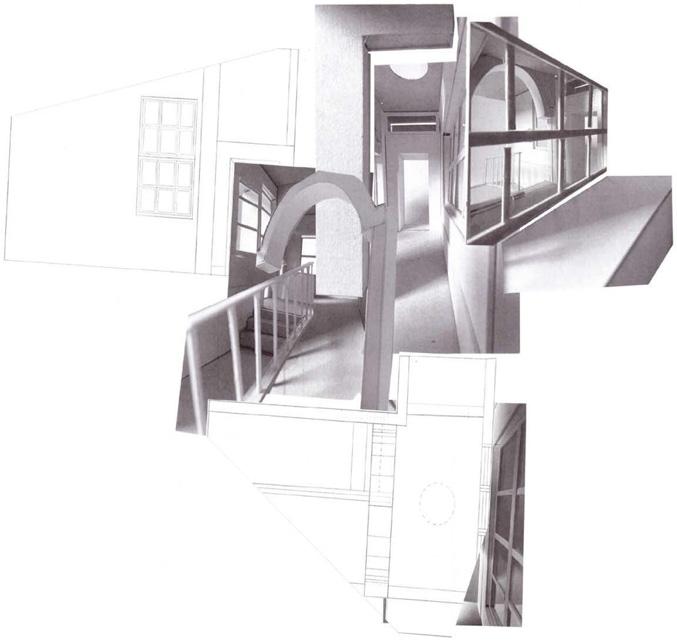

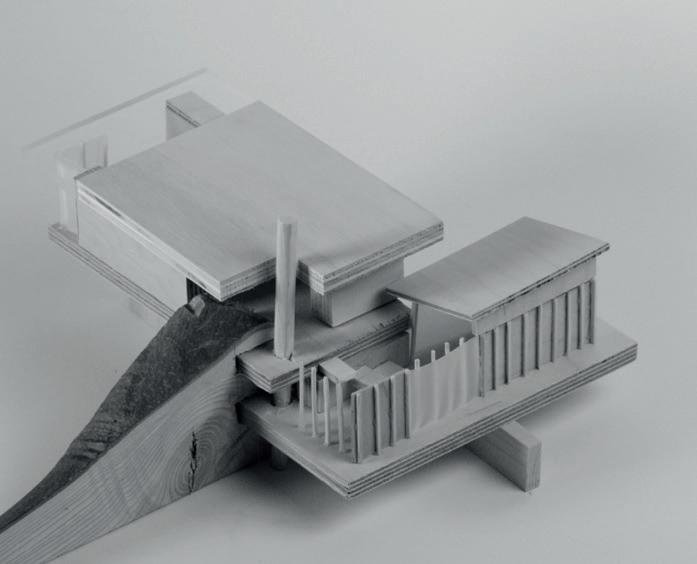

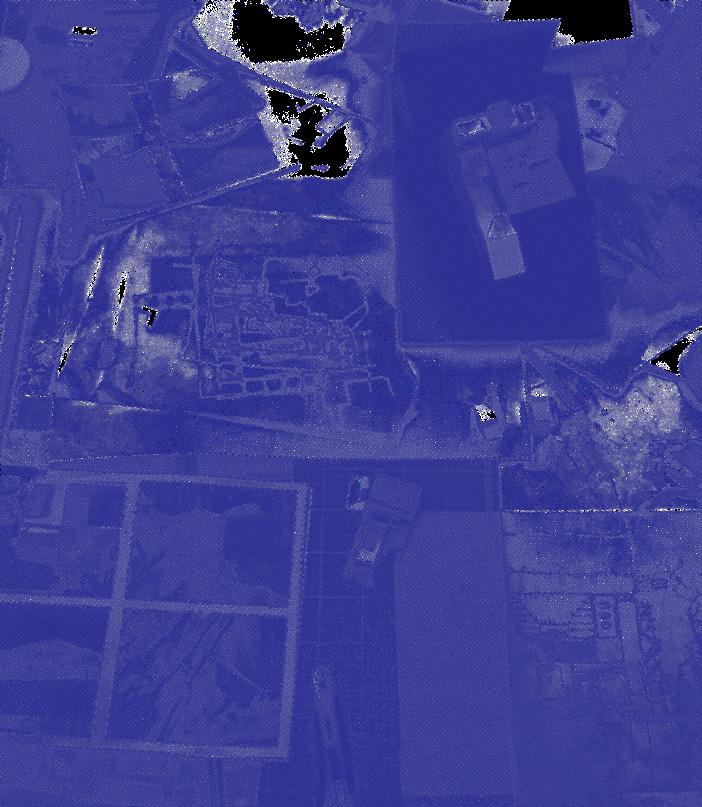

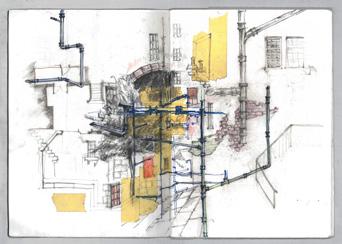

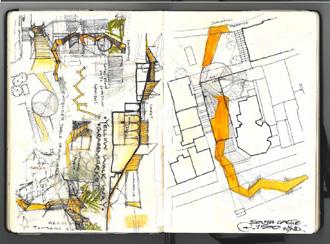

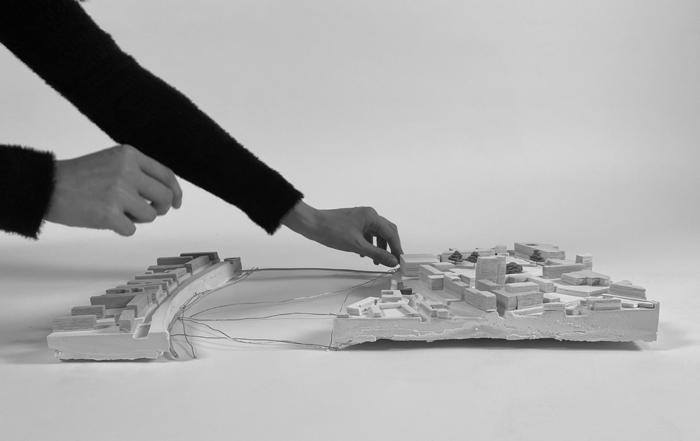

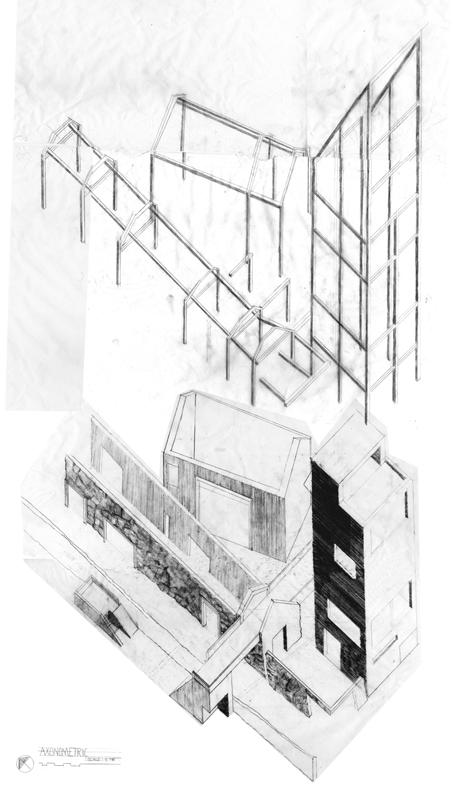

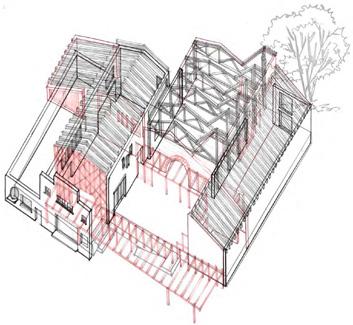

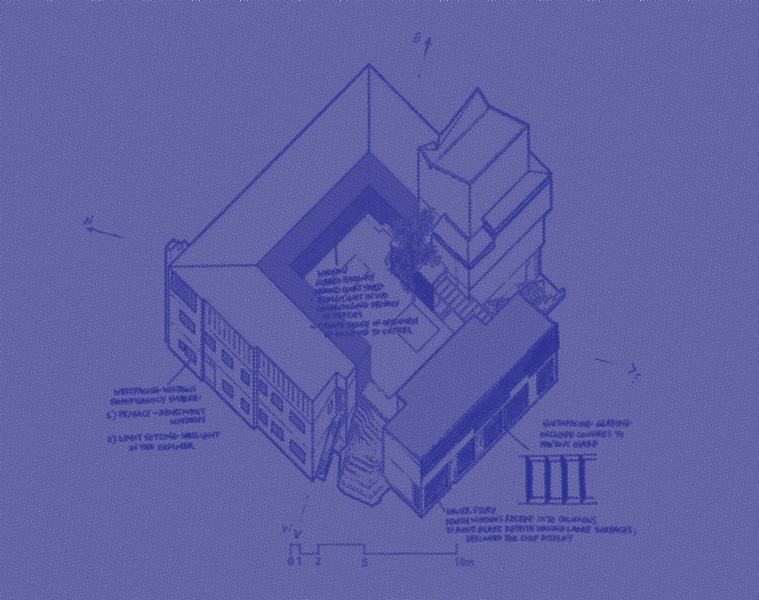

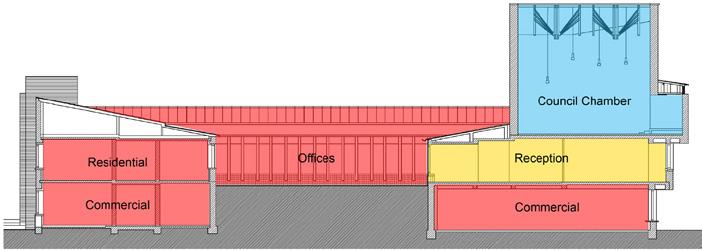

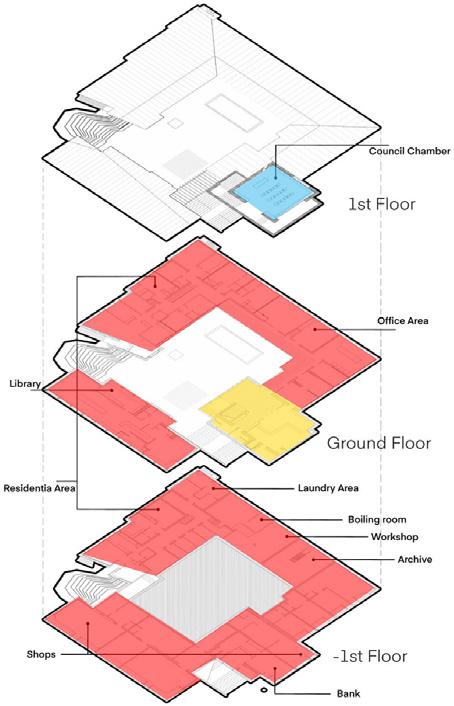

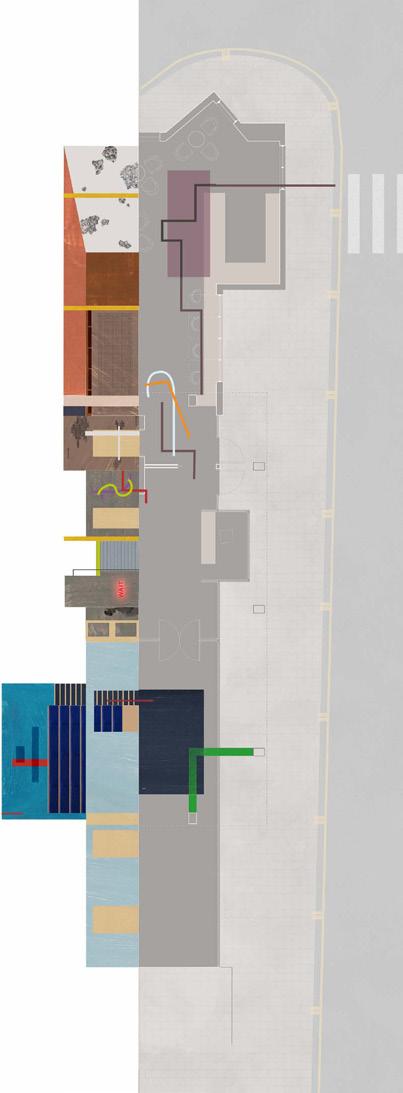

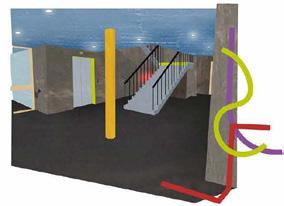

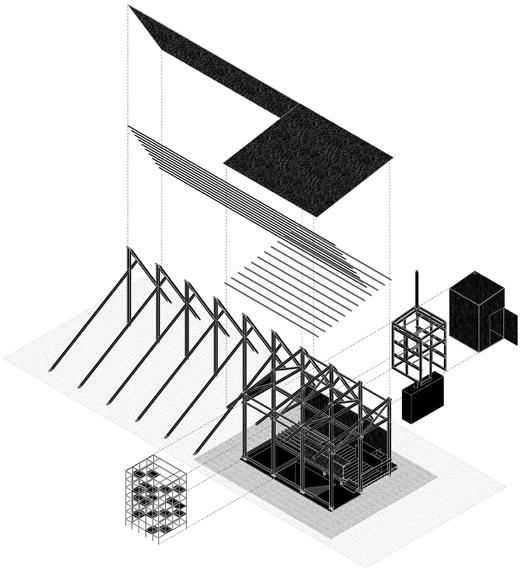

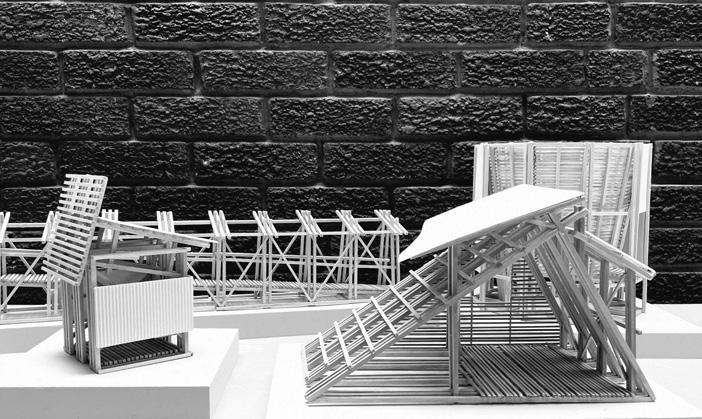

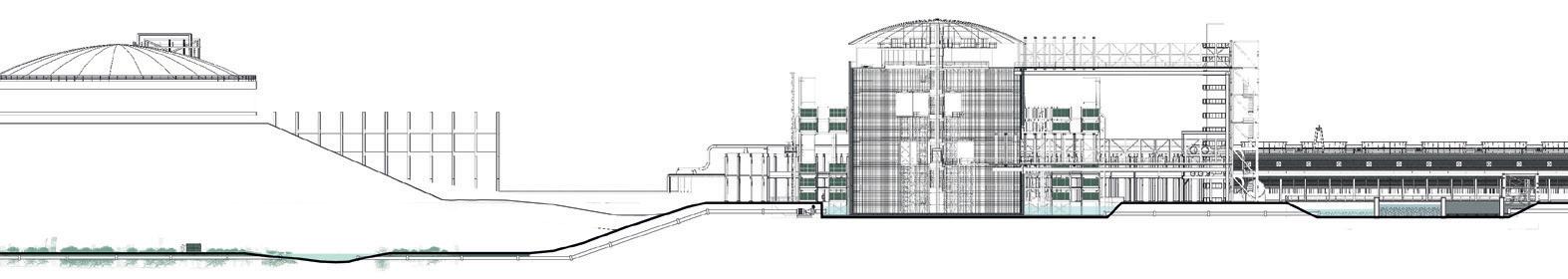

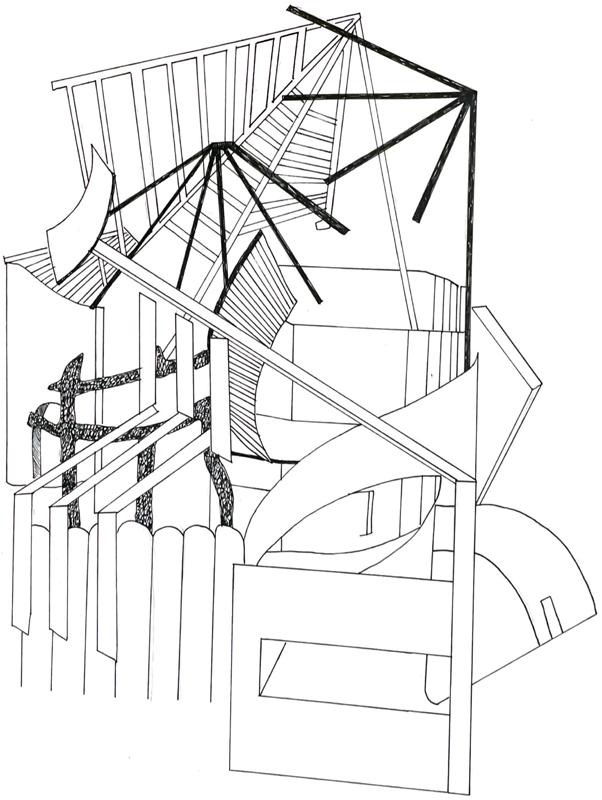

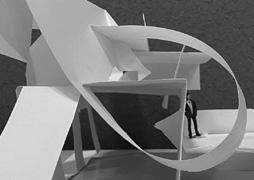

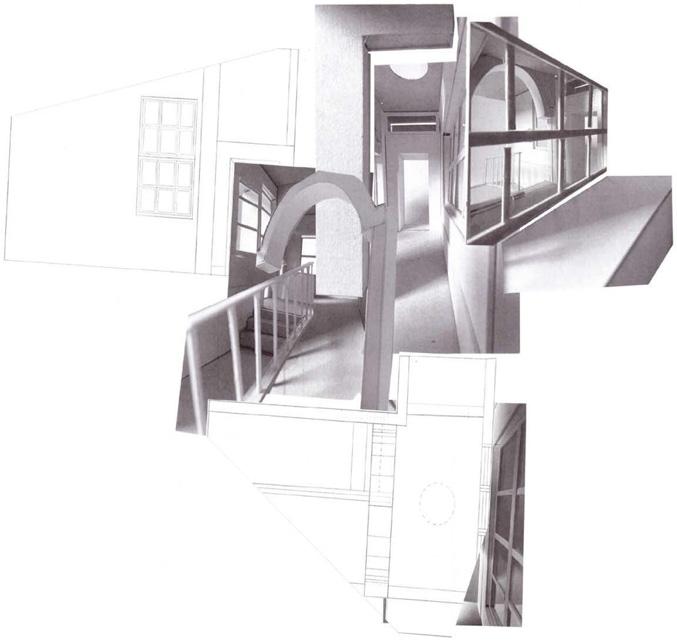

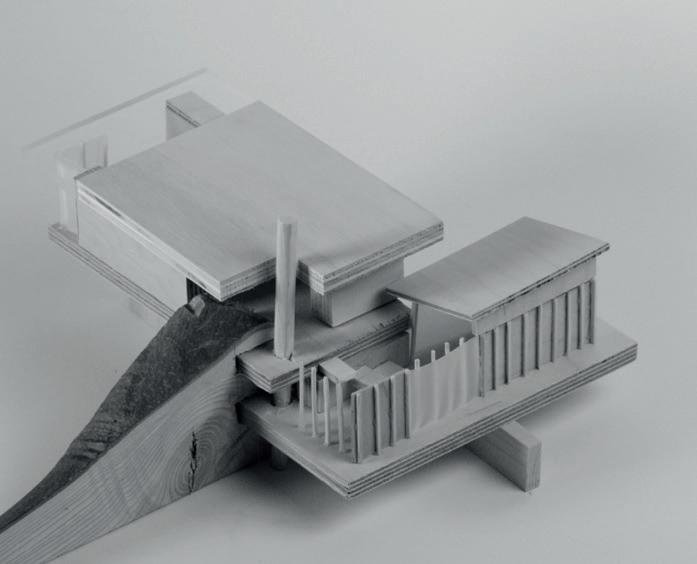

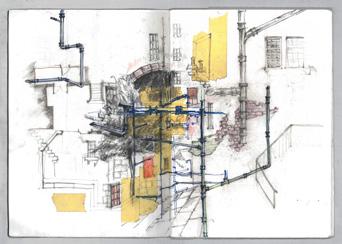

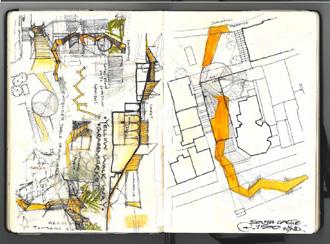

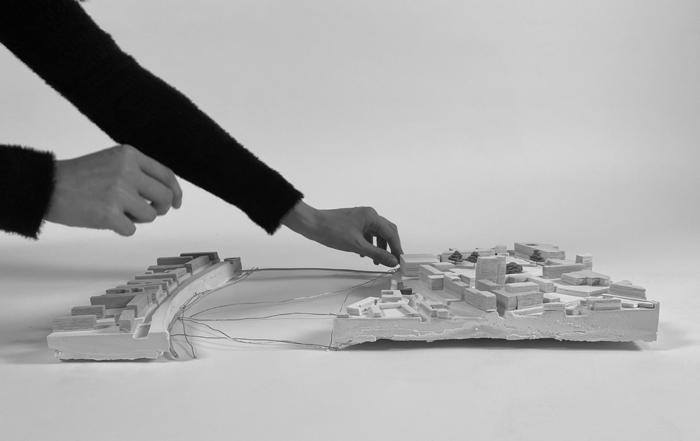

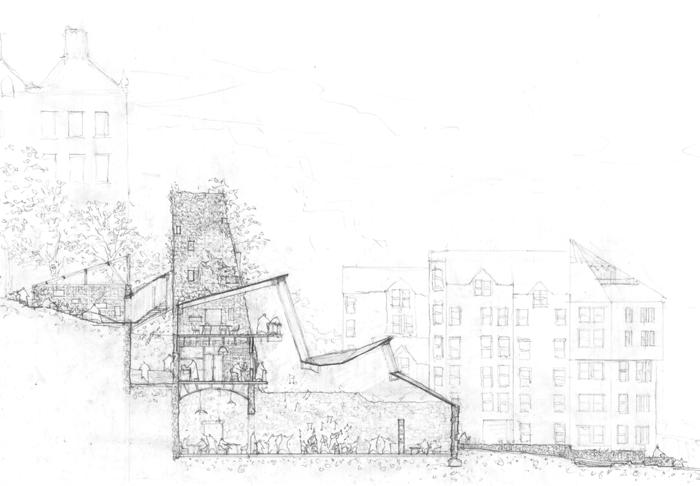

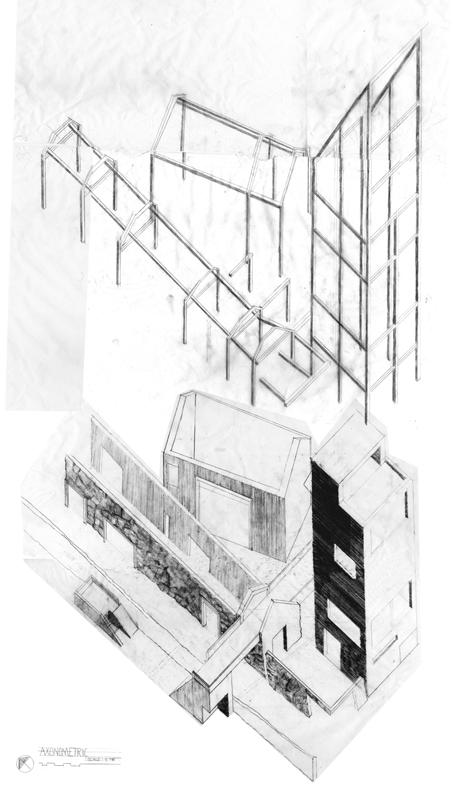

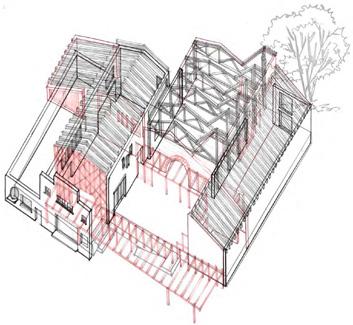

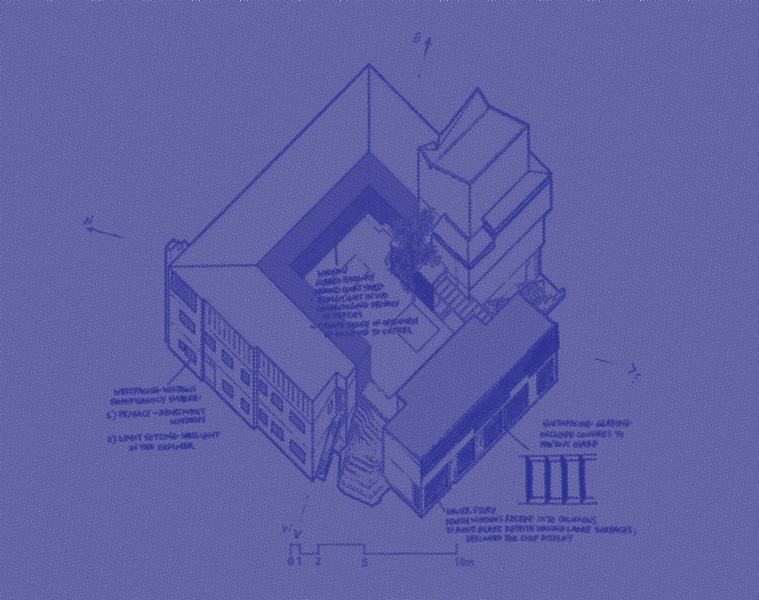

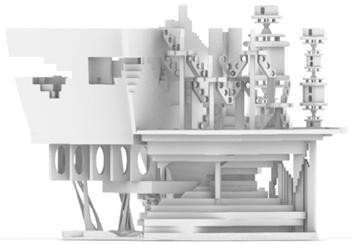

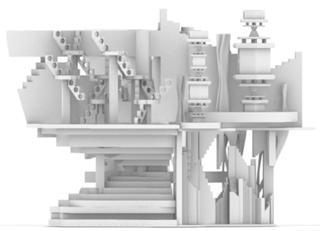

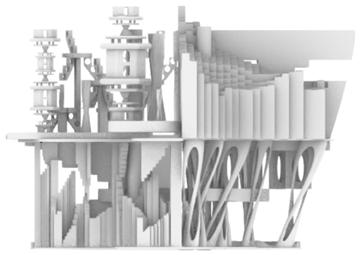

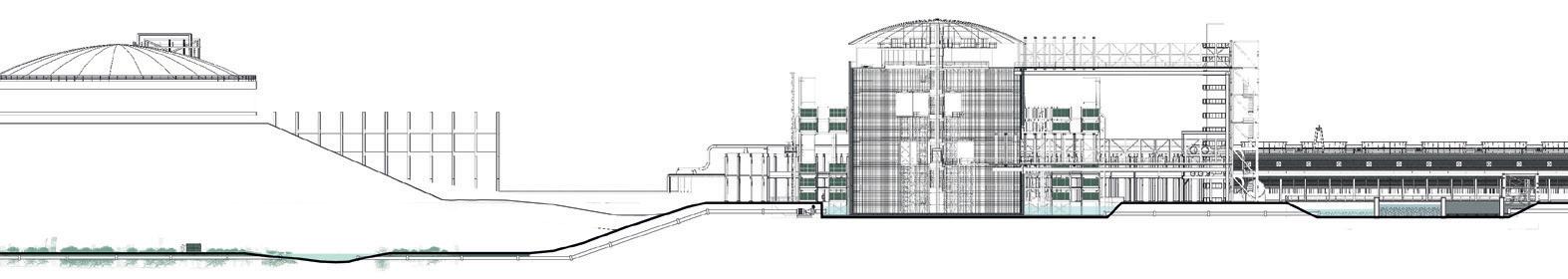

architectural design assembly

Assembly Studio reviews

Assembly Studio reviews

Course Organiser

Michael

Lewis

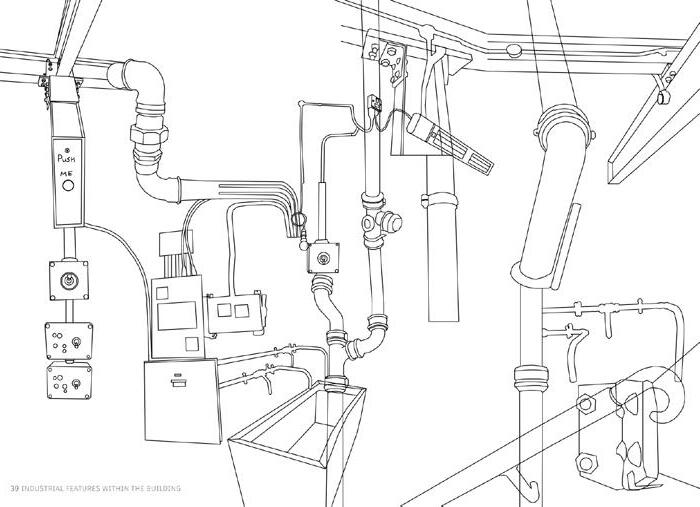

At a fundamental level, architecture is an assemblage – as a construction sequence of various complementary materials, as a negotiation of new and old, as a cultural product enmeshed with all the myriad dynamics of politics, gender, race, economics, and ecology, as a representational language that incorporates all forms of visual media, and as a pluralistic methodology that has continued to morph over centuries of practice. In Assembly, we have begun to unpack these questions through close observation, mapping, drawing, physical modelling and the development of deliberate architectural interventions. The course begins with an understanding that the world is a dynamic system whose health is dependent on reciprocity and sensitive calibration. This reality is echoed in how we thus think about architectural assemblage - that as critical designers, it is incumbent upon us to assemble strategies that respond with care to their social and political context, as well as the considered use of materials to create spaces that situate in their built and environmental context with intent and responsibility. In order to develop meaningful architecture, we must first understand the context it situates within, the criteria against which it will be judged, and calibrate the negotiation of intervention to existing condition. We have approached architectural assembly through an ecological lens in which students have been mapping and exploring ESALA’s campus on Chambers Street to understand how our existing buildings operate as a network of interconnected material components and symbiotic programmes. We have used this understanding to develop material and programmatic responses that enmesh themselves with the community and city that surround them, focusing on questions of adaptive reuse and the future of architectural education.

* 4

Studio Tutors

Clive Albert

Graham Currie

Michael Davidson

Naomi De Barr

Joanna Doherty

Angus Henderson

Emma Henderson

Shoko Kijima

David Lemm

Joanne McClelland

Derek McDonald

Darren Park

Julie Wilson

Review Critics

Jeanita Gambier

Tahlor Jarrett

Akiko Kobayashi

Estefanía Macchi

Kanto Maeda

Katie May Munro

Aythan Lewes

Caryl Steven

Felix Wilson

Sigi Wittle

Andrew Wyness

Guest Lecturers

Chalk Plaster

O’Donnell Brown

Archetype Method

GRAS

Kanto Maeda

1

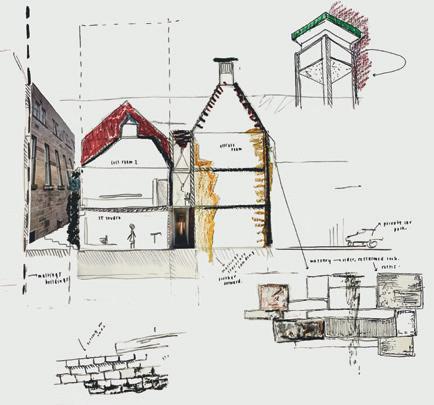

030 1 2 adapting chambers street arch. design assembly 3

031 ba/ma<hons> 1

4 1*4

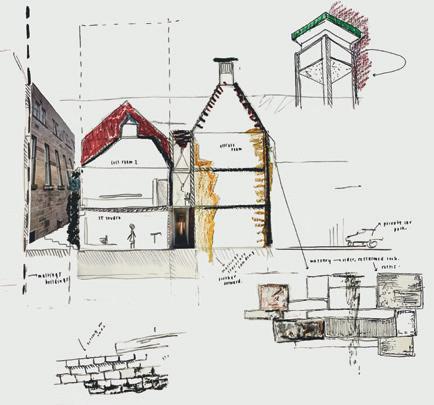

Caroline Chan Hybrid Landscape 2 Brian Kim Sketchbook development 3 Anna Gillibrand Maltings materiality study 4 Joyce Fan Ecologies of Reciprocity

032 adapting chambers street arch. design assembly 5 Cleo Averof Proposal perspective 6

Sasha Worth Proposal axonometric 7, 8

7 5 6

Stewart Harris Parti model Proposal collage

8

034 adapting chambers street arch. design assembly 8 Megan Jones Proposed section 9 Chiara Mesquita Material & light sectional study 10 Alicja Mrowicka Development models 11 Brian Kim Proposal axonometric 12 Adam Chen Following light plan study 13 Ella Dai Proposal perspective 8 10 9

035 ba/ma<hons> 1*4 11 12 13

technology & environment principles

Structures Workshop

Structures Workshop

Course Organiser

Pilar Perez Del Real

This course introduces students to critical structural, technological and environmental principles than underpin architectural design. It seeks to shape an understanding of how buildings need to work functionally to keep their occupants safe, sheltered and comfortable and how such considerations can produce deeper, more meaningful architecture. The course is constructed around three themes: Structures, Materials and Environment. The principles of sustainability is a key topic that runs through all three subjects areas. Participants learn how buildings can be interacting systems and that structural, material and environmental strategies are interlinked. The Structures theme explores how architectural structure not only provides stable and safe enclosures for us, but also how an understanding of structure is vital in the generation of architectural form. Students explore how architectural shape and form are achievable with different materials. They are then able to understand and predict the behaviours of key structural configurations. The Materials theme examines the materials used in architecture. Starting from what we can mine and harvest. Then the creation of buildings components is explored and how these can be assembled to make parts of buildings. The key principles and techniques in connecting and ordering parts of a building to make good architecture are considered in detail, with hands on tutorials involving real construction material samples. The Environment theme investigates the fundamentals of sustainable development and its relationship to architecture. It examines how, at a strategic level, architecture can respond proactively to sustainable agendas. Students learn about the principles of passive solar designs and applying a fabric first approach in order to make buildings comfortable whilst working with the external environment. The topic engages with energy conservation issues and carbon reduction strategies.

Tutors

Georgina Allison

Derek McDonald

Elaine Pieczonka

Jane Robertson

David Seel

Rebecca Wober

1 * 5

038 structures, materials & env. t&e principles 1

Sasha Worth Building envelope study

2 Anna Gillibrand, Sasha Worth Precedent structural analysis: Quartermile, Edinburgh

2 1

3 Adam Chen Live/Work Studio design

039 ba/ma<hons> 3 1*5

architectural history revivalism to modernism

Mortonhall Crematorium, Edinburgh Spence Glover Ferguson, 1967

Photograph: Alistair Fair

Mortonhall Crematorium, Edinburgh Spence Glover Ferguson, 1967

Photograph: Alistair Fair

Course Organiser

Alistair Fair

This course is a compulsory part of the MA (Hons) Architecture programme, but also serves other degrees, including the MA (Hons) Architectural History and Heritage. In addition, it is a popular elective course taken by students from across ECA and the wider University.

Architectural History 1B explores how designers and patrons responded to the idea of modernity in a series of global contexts between c. 1750 and 2000. It begins with the stylistic revivals of the nineteenth century before turning to the advent of new materials and structural techniques. As the course moves into the twentieth century, the development of new architectural forms and approaches to space are discussed. The course includes focused discussion of the work of key designers such as Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto but also stresses the contribution of others to the built environment – from the first qualified women architects of the early twentieth century to the commercial house-builders who constructed suburbia. The course concludes with an investigation of the globalisation of modernist practice, and the reactions against Modernism of the late twentieth century. The coursework engages with the city of Edinburgh, which provides a rich series of examples for study.

As with Architectural History

1A, the course aims not only to provide a foundational knowledge of recent architectural history but also to encourage an independent, reflective approach which sets architecture in wider contexts. The course is followed in second year by Urbanism and the City: Past to Present.

Lecturers

Richard Anderson

Alex Bremner

Kirsten Carter McKee

Peter Clericuzio

Alistair Fair

John Lowrey

Angus Macdonald

Senior Tutor

Anne Galastro

Tutors

Alastair Disley

Rory Lamb

Scarlett Lee

Mohona Reza

Natcha Ruamsanitwong

Mahnaz Shah

Dimitrij Zadorin

1 * 6

2*1 2*2 2*3 2*4 2*5

architectural design in place technology & environment building environment

2*6

architectural history urbanism & the city

2*7

architectural design any place technology & environment building fabric design thinking & digital crafting year 2 electives

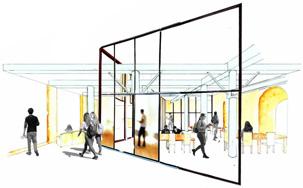

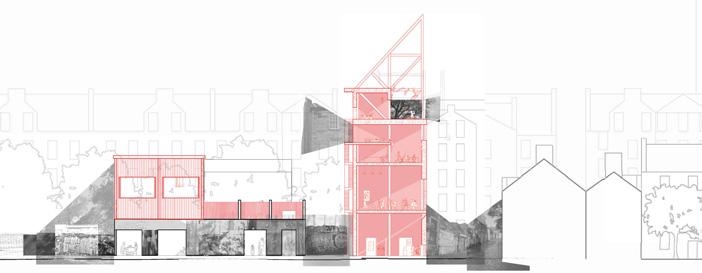

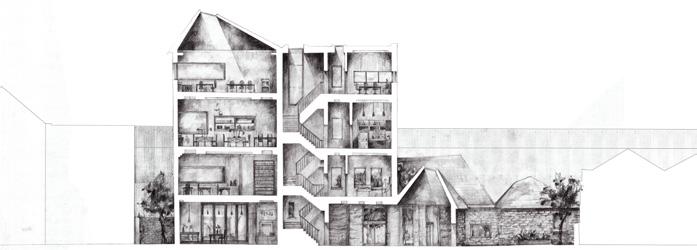

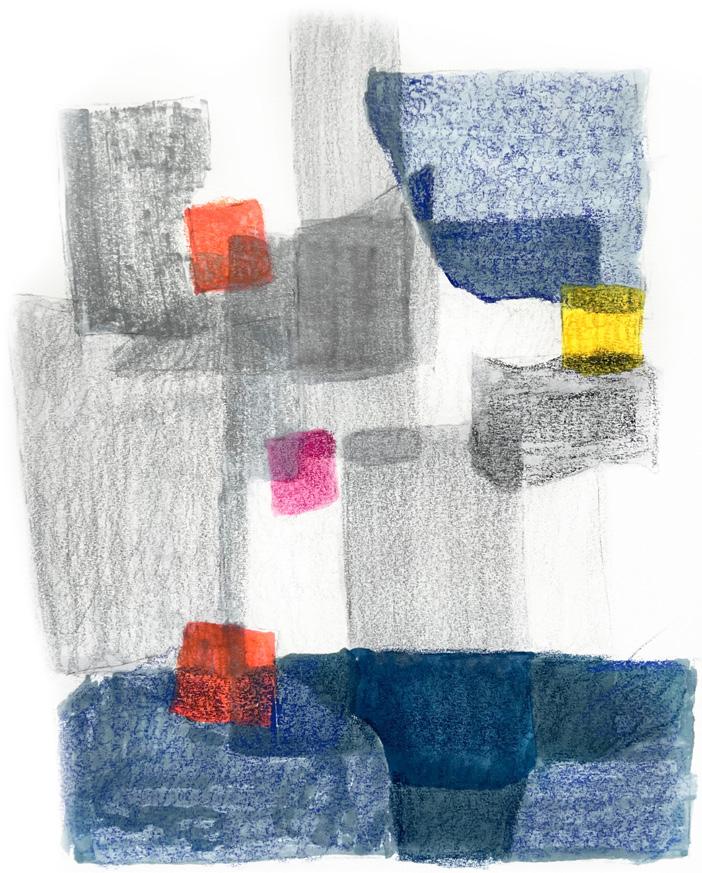

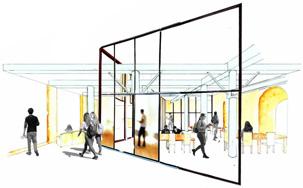

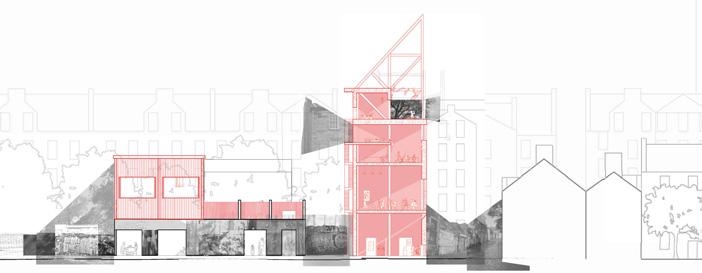

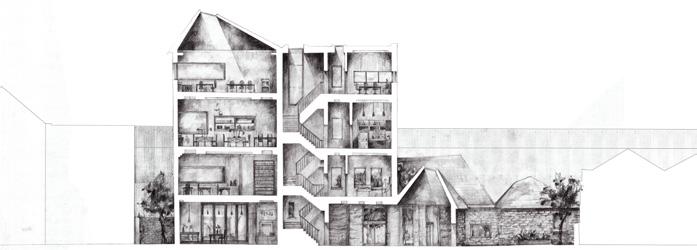

Architectural Design: Any Place

Open Studios, Minto House

Photograph: Calum Rennie

architectural design in place

Ed Varlow Studio work desk

Ed Varlow Studio work desk

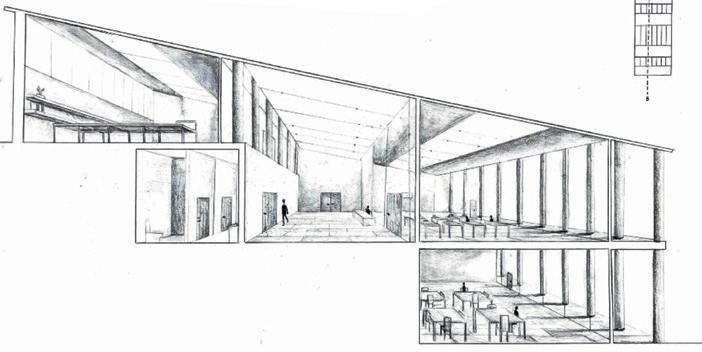

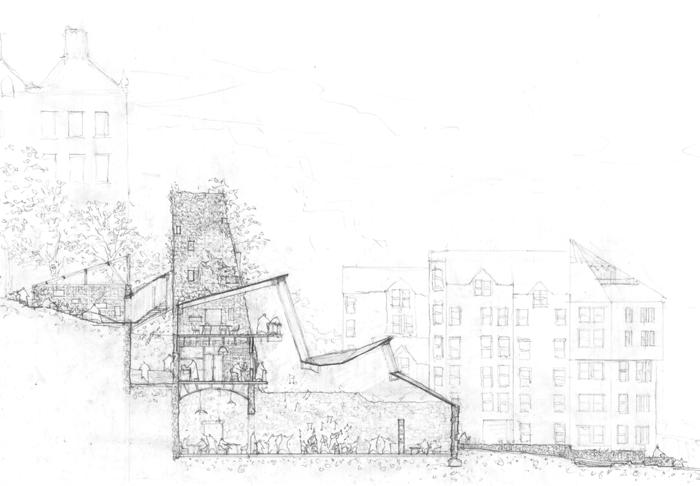

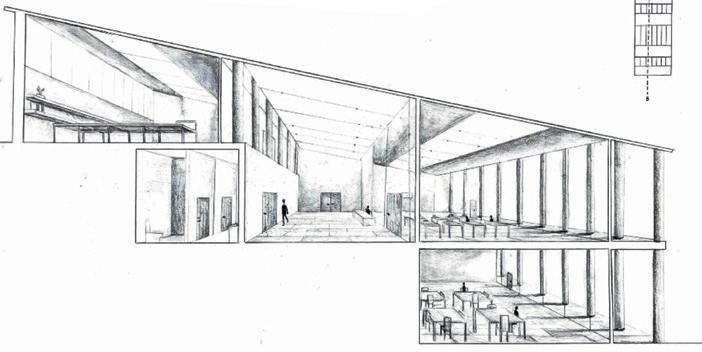

Course Organiser

Rachael Hallett Scott

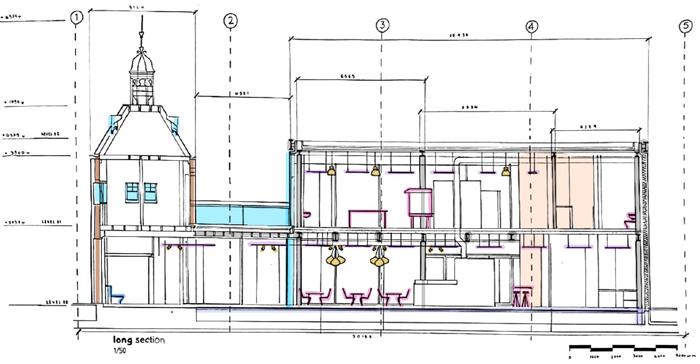

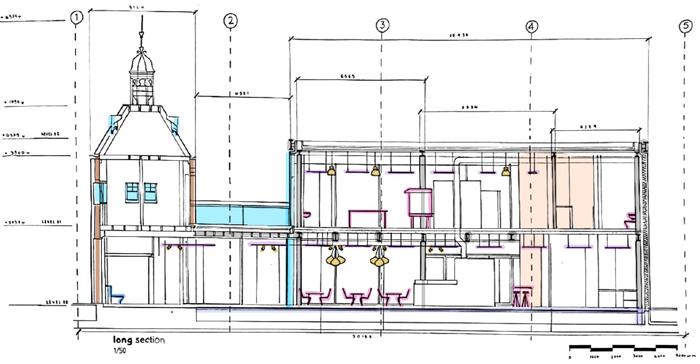

Architectural Design: In Place takes the concepts of site and situation as its focus. These core themes are supplemented by those of, public and private, place and identity. Woven through the semester there is also a keen interest in how we build in this time of Climate Emergency. The course aims to explore the interconnection of social, sustainable and spatial principles that underpin and inform the design of inclusive buildings and places. Collectively these threads of investigation inform a set of design exercises that expand on critical and self-reflexive dimensions of architectural design that were introduced in Architectural Design: Elements and Assembly. The course begins with research and analysis of precedent buildings at city, building and human scales. This is followed by a close examination of 3 local sites and their physical, social and environmental contexts. The findings from these pair and group exercises inform student’s individual designs for a hybrid work and community building. Each site includes elements of existing buildings and students are encouraged to critically reflect on how they work with this fabric and their choices of materials in light of the Climate Emergency. Each week learning is supported through a series of thematic lectures, briefings and studio teaching. In Place also addresses the use of digital media through ‘Recipes for Representation’ a series of lectures and workshops that investigate the use of digital drawing tools, alongside analogue skills, to explore the representation of architecture.

Studio Tutors

Georgina Allison

Mark Bingham

David Byrne

Mark Cousins

Paul East

Kieran Hawkins

Jamie Henry

Nikolia Kartalou

Fiona Lumsden

Andy Summers

Nicky Thomson

Rebecca Wober

Recipes for Representation Tutors

Angus Henderson

Theo Shack

Review Critics

Adam Burgess

Gary Cunningham

Laura Harty

Shirley Hottier

Akiko Kobayashi

Robin Livingstone

Kanto Maeda

Ana Miret Garcia

Fiona McLachlan

David Seel

Guest Lecturers

Thomas Bryans

Gunnar Groves Raines

Jamie Henry

Kanto Maeda

Sayan Skandarajah

Felix Wilson

2 * 1

046 1 context study arch. design in place

047 ba/ma<hons> 1

Lucas Gjessing Site investigation 2 Student visit to Talbot Rice Gallery & In Place studio review 3 Harriet Nixon Site analysis 4 Joanna Saldonido Site analysis

2*1 3 2 4 5

5 Joohee Won, Bella Haynes Site model

048 arch. design in place work+community building 6

049 ba/ma<hons> 6

9 In

2*1 9 7 8

Ed Varlow Work + Community Building: section & model 7, 8 Phoebe Vendil Work + Community Building: axonometric & section

Place studio model installation

050 9

Work

axonometric 10

Work

section 11 Natalie

Work

model

12

Work

precedent

work+community building arch. design in place 11 10 9

Wenjing Huang

+ Community Building:

Joanna Saldonido

+ Community Building:

Ng

+ Community Building:

study

Wenjing Huang, Jessica Zhan

+ Community Building:

study

12

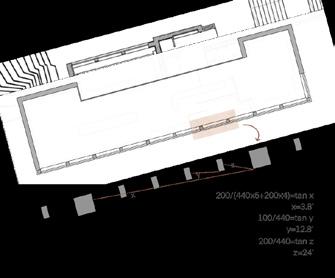

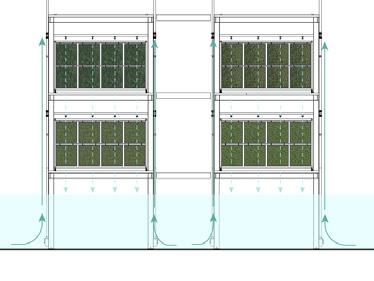

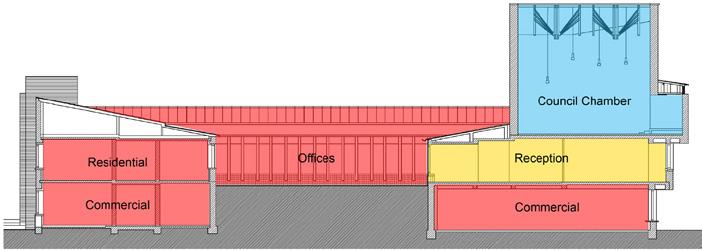

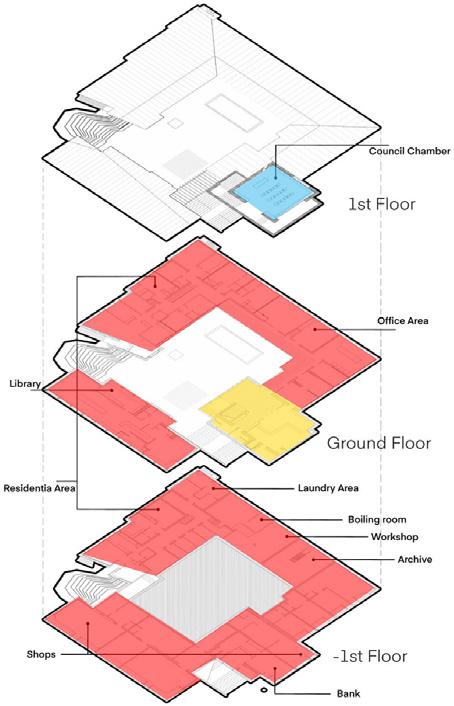

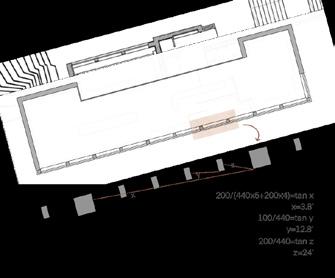

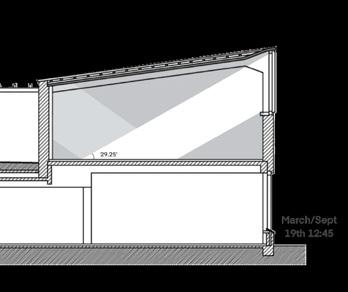

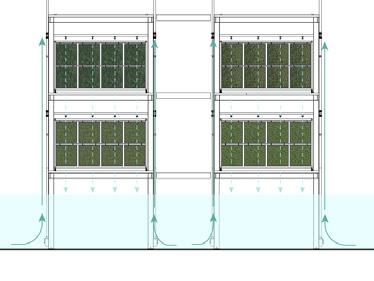

technology & environment building environment

Merl Sun, Jessica Zhan

Säynätsalo Town Hall

Alvar Aalto, Finland

Passive heat gain designs in the Town Hall

*

Course Organiser

W. Victoria Lee

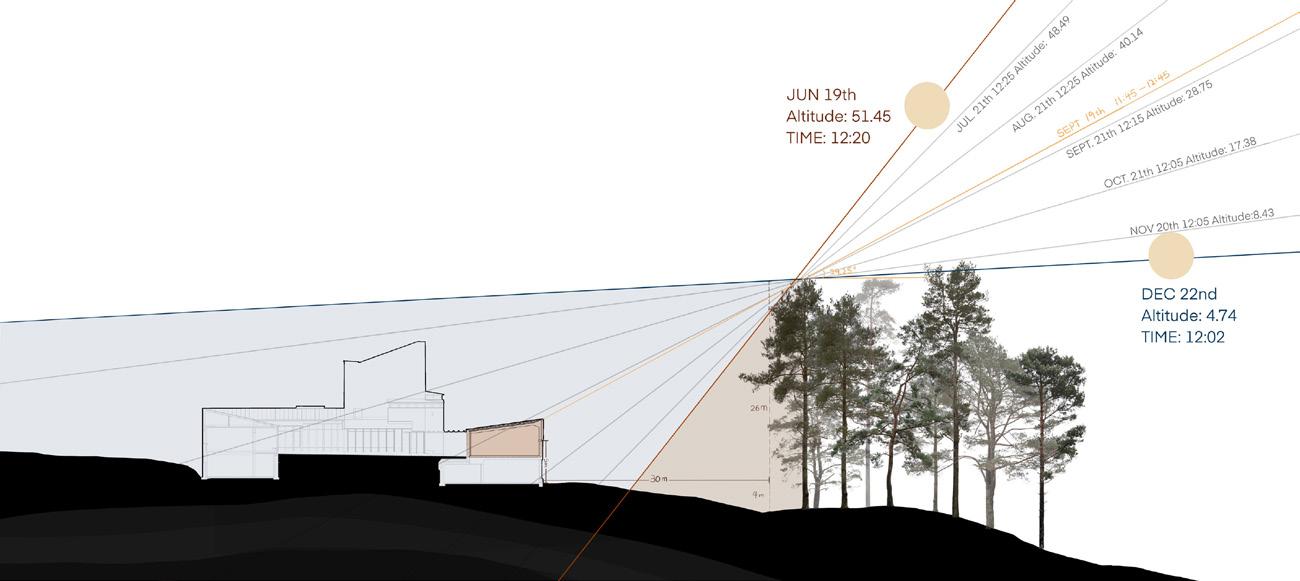

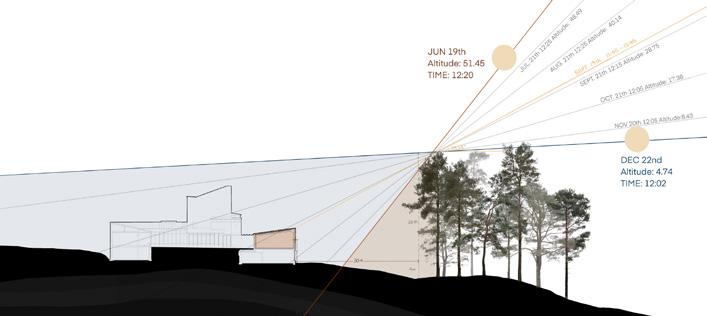

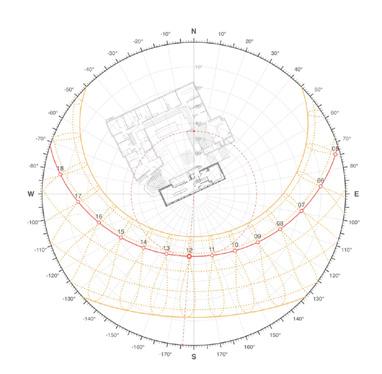

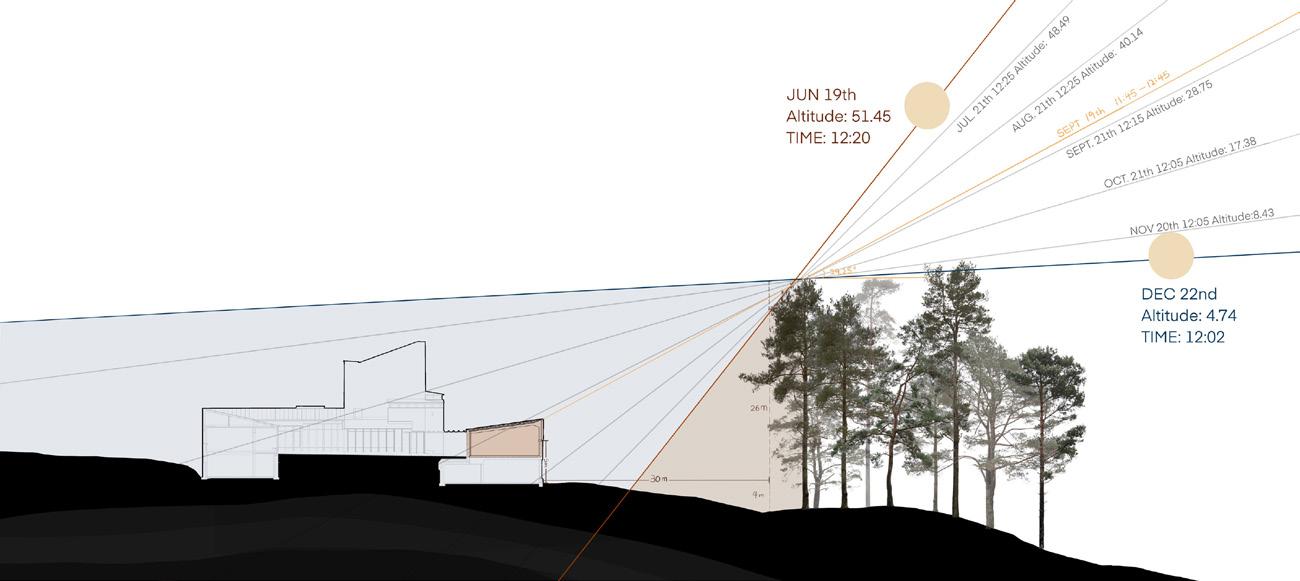

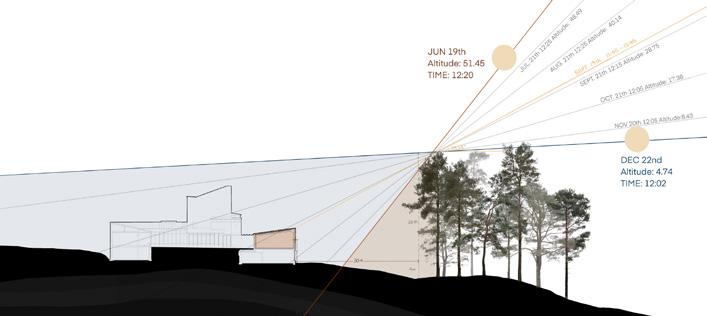

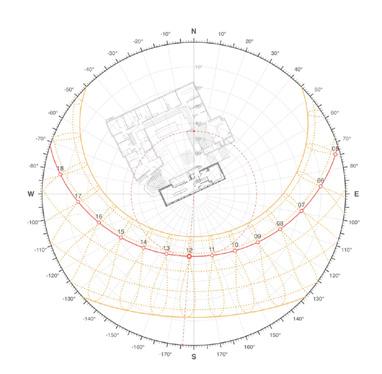

Building on first year courses Technology and Environment: Principles and Architectural Design: Assembly , TE2A: Building Environment further develops students’ understanding, analysis, and integration of environmental design in architecture. The course examines the roles of energy, light, heat, ventilation, and sound in building design. The course also introduces sustainable technologies, buildings performance assessments, building services and their implications for design. This course focuses on passive design strategies, but introduces mechanical (active) systems as a supplement. An emphasis is placed on the bioclimatic approach to architectural design, which advocates for designs that cater to the biology and psychology of humans whilst being responsive to the natural environment; with appropriate and thoughtful use of technology. The course covers a wide range of environmental design topics, including the following:

◊ Macro- and micro-climates

◊ Solar geometry, daylighting, and artificial lighting

◊ Passive heating and cooling strategies

◊ Wellbeing, comfort, and other occupant needs

◊ Building heat and energy balances

◊ Natural and mechanical ventilation systems

◊ Building services and water conservation

◊ Acoustic fundamentals

Victor Olgay

The four interlocking and interacting components of bioclimatic design from Design with Climate: bioclimatic approach to architectural regionalism

Tutors

Pilar Perez del Real

Elaine Pieczonka

Tutors

Pilar Perez del Real

Elaine Pieczonka

2 * 2

David Seel

Environmental analysis and climate change adaptations of a design precedent

Säynätsalo Town Hall, Finland

Alvar Aalto

1

Merl Sun, Jessica Zhan

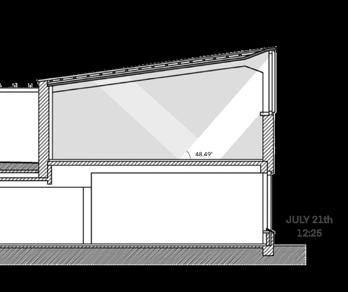

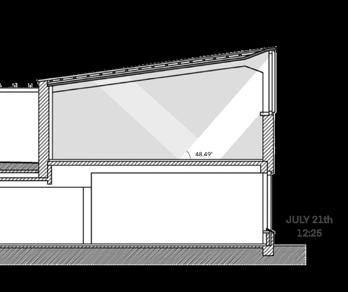

Passive heat gain designs in the Town Hall: thermal zoing in plan and section

2

Solar analysis of the Town Hall

054 1

analysis & adaption t&e building environment

comfort

Solar Analysis (cont.)

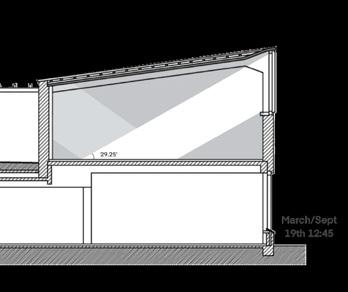

f.g.31 Library's orientation to the sunpath

f.g.32 Shadow mask of shading from pine

There is no available drawings for the wall and roof assembly of materials. For the walls, the library clearly uses a brick cladding, a secondary the interior. The bricks are recycled old bricks that Aalto repurposed. creates a special, rippling effect as light shines on the walls, and matches a big part of the town's identity. The timbers used in Aalto's design comes the carbon footprint of transporting materials to site and further emphasises Aalto uses a metal exterior cladding with timber structure and plaster roof design.

Left - f.g.37: Sun puddles in section from the southeast September 19th

21st

To fill in the gap for wall and roof makeup, two modern buildings referenced to find the most likely assembly. Gallery Building in London comparable assembly for the walls,18 and Community Centre in Reinossa Inferences are also made based on our existing knowledge about material roof based on drawings.

f.g.31 Library's orientation to the sunpath f.g.32 Shadow mask

- f.g.37: Sun puddles in section from the southeast facade on July 21st and March/

f.g.33 Section view of pine trees' relationship to the library and shadow obstruction

shadow mask overlay of f.g.40: SE glazing shadow mask overlay of underheated period

diagrams are made for each window on July 21st and March/September 19th (f.g.37 & 38). Based on average is the only month with potential overheating problems, but luckily the sun puddle on the 21st is only from the northeast, and is small around solar noon from the southeast. Aalto's elevated windowsill direct gain into the room. The rest of the year suffer from potential underheating, but from September to negative on top of the cold temperature (will be elaborated in Heat Balance). The sun-puddle on March/ solar noon is much larger compared to July, almost reaching the back of the room, but there will be no the northeast because solar azimuth decreases rapidly between summer and winter solstice. Figures 39, complete shadow mask overlayed with overheated and underheated periods of the library. Looking at there is only a shading from 5-7am and 2:30-4pm from the vertical frames for the overheated month shading from the pine forest at all. However, there is a lot of shading in the underheated periods, specifically

outdoor

Left September Top September

f.g.43 Wall assembly

f.g.39: SE glazing shadow mask overlay of overheated period f.g.40: SE glazing shadow mask overlay of underheated period f.g.41: underheated

f.g.32 Shadow mask of shading from pine tree

f.g.39: SE glazing shadow mask overlay of overheated period f.g.40: SE glazing shadow mask overlay of underheated period

f.g.33 Section view of pine trees' relationship to the library and shadow obstruction

f.g.39: SE glazing shadow mask overlay of overheated period

in the coldest months of October to February from the pine forest. This means that the current shadings (though the forest isn't intentionally designed) does the opposite of what is good for passive solar gain - little shading in overheated periods and much shading in underheated periods. It can be expected that mechanical heating and cooling load will be huge for the library.

Sun puddle diagrams are made for each window on July 21st and March/September daily temperature, July is the only month with potential overheating problems, but luckily large in the morning from the northeast, and is small around solar noon from the southeast. controls much of the direct gain into the room. The rest of the year suffer from potential March is when ∆S is negative on top of the cold temperature (will be elaborated in Heat September 19th at solar noon is much larger compared to July, almost reaching the back direct sunlight from the northeast because solar azimuth decreases rapidly between summer 40, and 41 shows the complete shadow mask overlayed with overheated and underheated the southeast glazing, there is only a shading from 5-7am and 2:30-4pm from the vertical of July, with no shading from the pine forest at all. However, there is a lot of shading in

18. Caruso St John Architects. (2017). Gallery Building in London. Detail, 2017(1/2), 19. RAW. (2018). Community Centre in Reinosa. Detail, 2018(7/8), 66-71.

f.g.33 Section view of pine trees' relationship to the library and shadow obstruction

f.g.33 Section view of pine trees' relationship to the library and shadow obstruction

Even though brick is used to clad the entire building, its does not in fact act as a thermal mass for the library. As shown in Figure 42, the floor is lined with wooden panels, and the wall and ceiling are lined with plaster. Bricks are outside the thermal envelope of the building, thus does not help store heat for the room. There are no other thermal masses in the library.

Even though brick is used to clad the entire building, its does not in fact act as a thermal mass for the library. As shown in Figure 42, the floor is lined with wooden panels, and the wall and ceiling are lined with plaster. Bricks are outside the thermal envelope of the building, thus does not help

of vertical

forest 21st Left

f.g.42 Interior of the library (img.com)

055 ba/ma<hons>

plan edges library plan Calculations of clothing for metabolic rate velocity outdoors, comfort at 19 ˚C in f.g.33 Section view of pine trees' relationship to the library and shadow obstruction 2 2*2 clothing rate comfort

Part A: Environmental Analysis in Current Climate - Room Analysis

rate comfort

metabolicclothingrate comfort in

f.g.34 Dimensions

library for SE

facade

https://www. reduces https://doi. clothing rate

f.g.35 Shadow mask of wooden on the library (SE facade)

f.g.34 Dimensions of vertical wooden frames in the library for SE facade (top) and NE facade (bottom)

Sun puddle diagrams are made for each daily temperature, July is the only month with large in the morning from the northeast, and is controls much of the direct gain into the room. March is when ∆S is negative on top of the cold September 19th at solar noon is much larger compared direct sunlight from the northeast because solar 40, and 41 shows the complete shadow mask the southeast glazing, there is only a shading from of July, with no shading from the pine forest at

f.g.40: underheated in the coldest months of October to February means that the current shadings (though the

September 19th

Top - f.g.38: Sun puddles in section from the northeast facade on July 21st and March/ September 19th

Sun puddle diagrams are made for each window on July 21st and March/September 19th (f.g.37 & 38). Based on average daily temperature, July is the only month with potential overheating problems, but luckily the sun puddle on the 21st is only large in the morning from the northeast, and is small around solar noon from the southeast. Aalto's elevated windowsill controls much of the direct gain into the room. The rest of the year suffer from potential underheating, but from September to March is when ∆S is negative on top of the cold temperature (will be elaborated in Heat Balance). The sun-puddle on March/ September 19th at solar noon is much larger compared to July, almost reaching the back of the room, but there will be no direct sunlight from the northeast because solar azimuth decreases rapidly between summer and winter solstice. Figures 39, 40, and 41 shows the complete shadow mask overlayed with overheated and underheated periods of the library. Looking at the southeast glazing, there is only a shading from 5-7am and 2:30-4pm from the vertical frames for the overheated month of July, with no shading from the pine forest at all. However, there is a lot of shading in the underheated periods, specifically

f.g.41: NE glazing shadow mask overlay underheated period

Thermal Mass

21st Part A: Environmental

in the coldest months of October to February from the pine forest. This means that the current shadings (though the forest isn't intentionally designed) does the opposite of what is good for passive solar gain - little shading in overheated periods and much shading in underheated periods. It can be expected that mechanical heating and cooling load will be huge for the library.

Left - f.g.37: Sun puddles in section from the southeast facade on July 21st and March/ September 19th

Top - f.g.38: Sun puddles in section from the northeast facade on July 21st and March/ September 19th

(cont.)

Material & Assembly - U-value Calculations

In In Out Out

f.g.41: NE glazing shadow mask overlay of underheated period

is used to clad the entire building, its does not in fact for the library. As shown in Figure 42, the floor is panels, and the wall and ceiling are lined with plaster. thermal envelope of the building, thus does not help room. There are no other thermal masses in the library. f.g.42 Interior of the library (img.com)

Wall

f.g.44 Roof assembly

Roof

The U-Value of windows are obtained from CIBSE's given value for double-glazed windows with 30% area of wooden frame. This is an estimation based on drawings and calculations, given in figure 45.

f.g.45 (Right) Dimensions for estimating percwntage of wooden frame in glazing

21st

of October to February from the pine forest. This current shadings (though the forest isn't intentionally opposite of what is good for passive solar gain - little periods and much shading in underheated periods. that mechanical heating and cooling load will be huge

Top - f.g.38: Sun puddles in section from the northeast September 19th

Thermal Mass

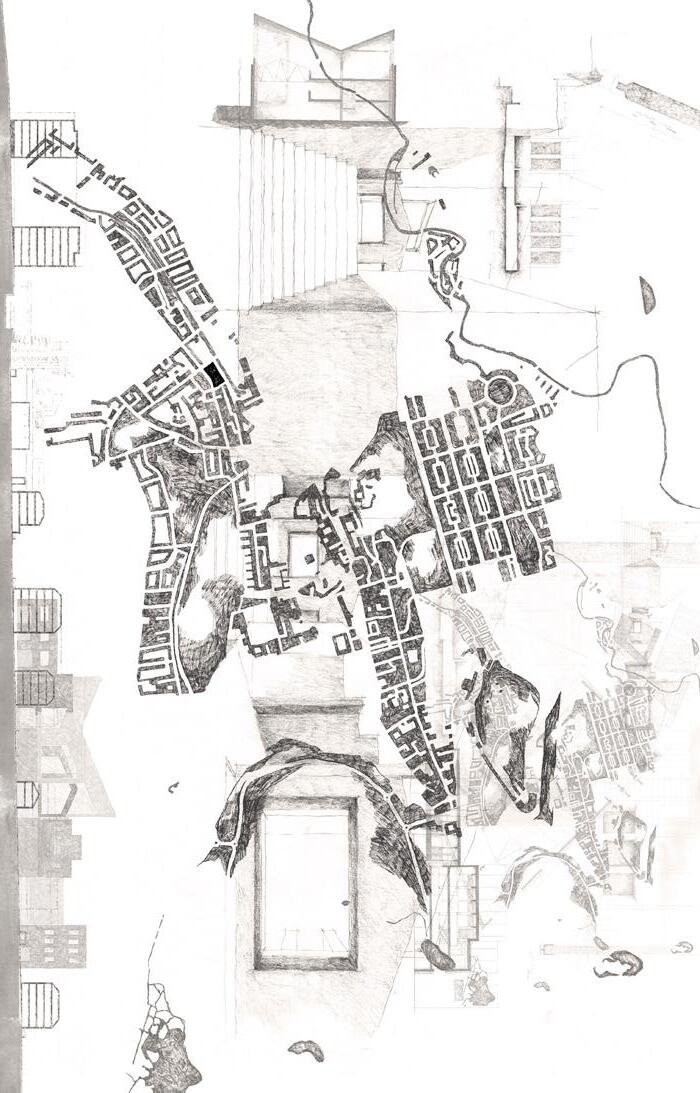

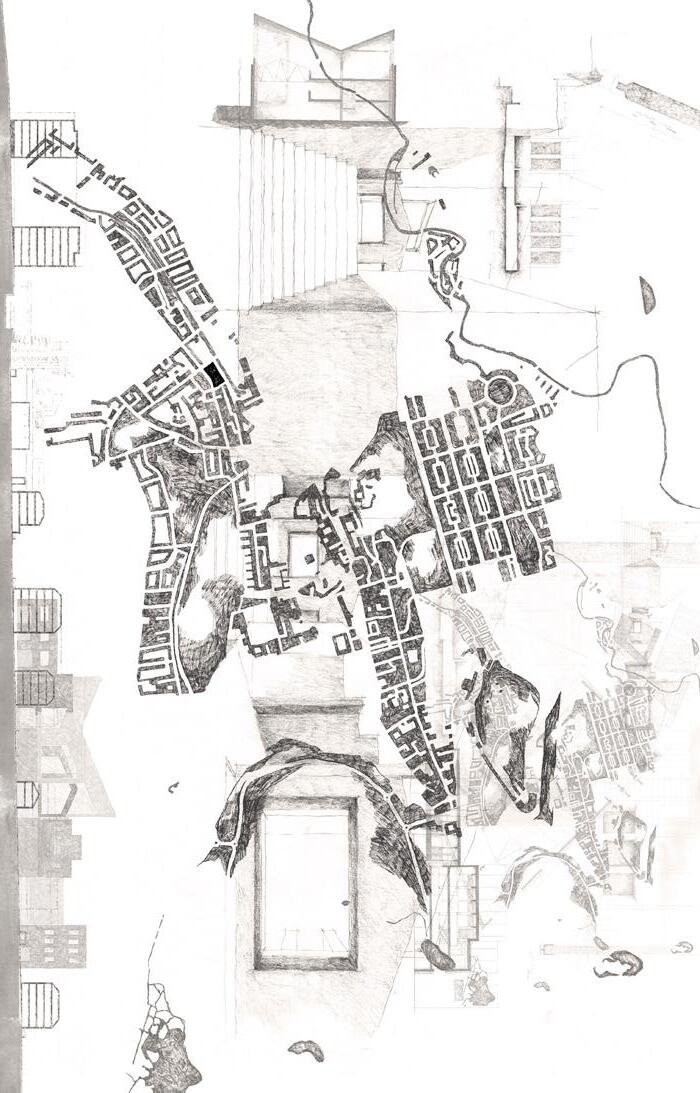

architectural history urbanism & the city

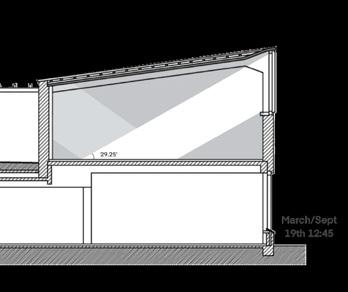

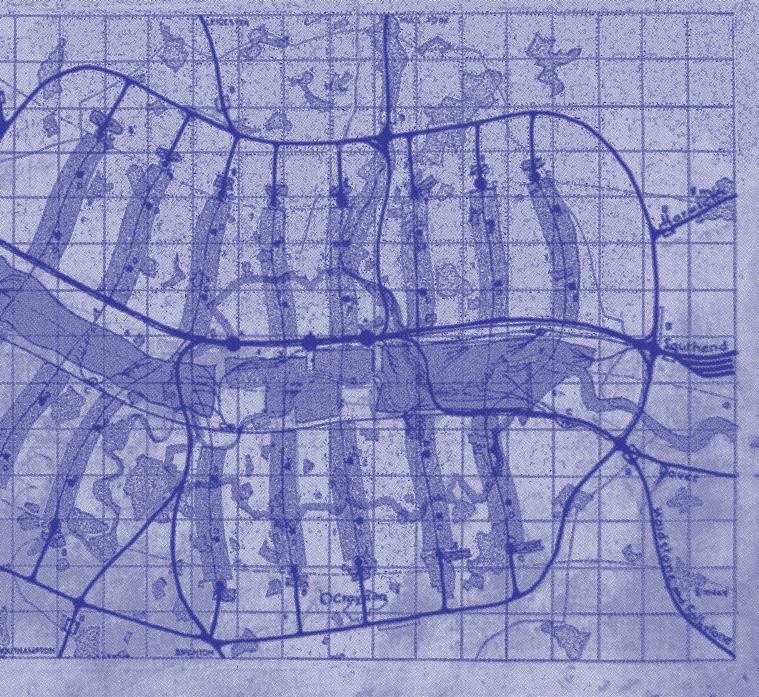

A Master Plan for London

Arthur Korn and Felix Samuely in The Architectural Review 91, 1942

Discussed by Christabel Walker

Course Organiser

John Lowrey

This undergraduate course investigates the global history of city design and urbanism from ancient times to the contemporary period. Through an interdisciplinary course bibliography and readings in key historical texts on urbanism, students will grasp the major historical trends and philosophies of urban emergence and development. Tutorials centred on Edinburgh site visits and training in research and writing will prepare students to perform first-hand research and compose original scholarship on the built environment.

The goal of this course is to give students a critical acumen for evaluating the architectural transformation of the urban realm across disparate cultures and far-flung geographies over time, from Antiquity to the present day.

Tutors

Nikolia Kartalou

George Jepson

Robbie MacFarlane

Mahnaz Shah

2 *

3

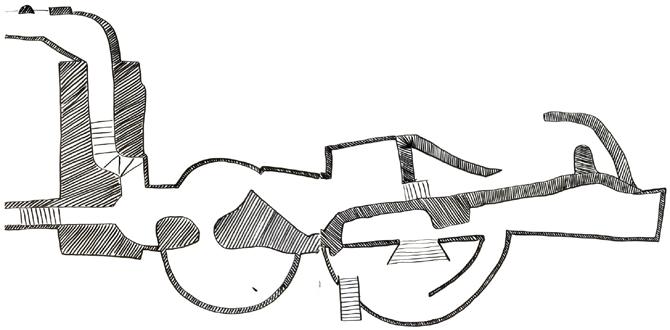

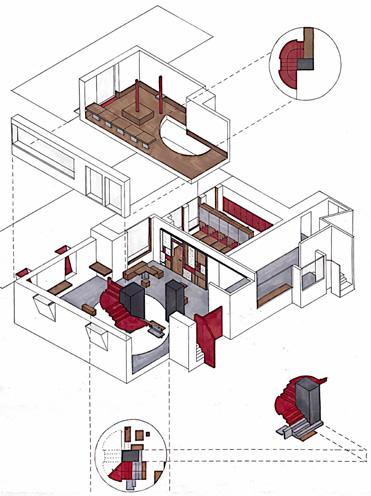

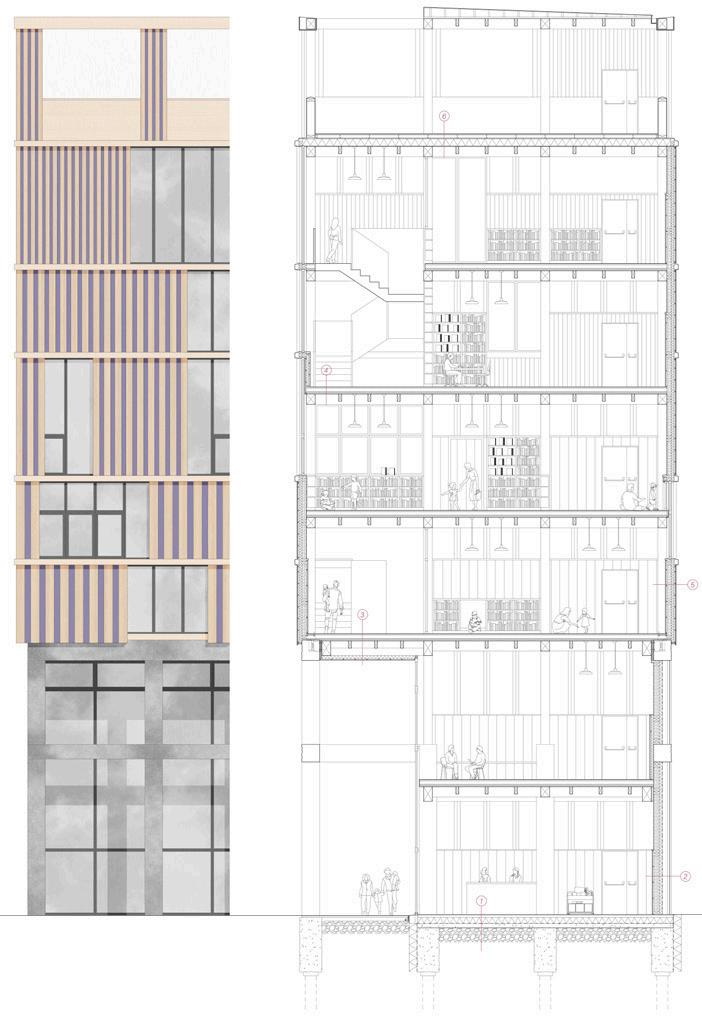

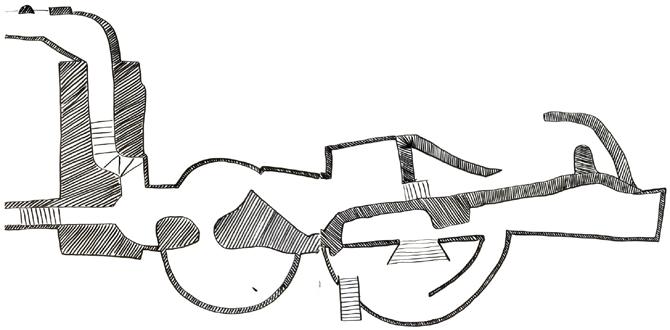

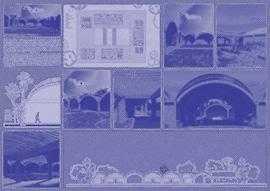

architectural design any place

Phoebe Vendil Studio work in progress

Course Organiser

Ana Miret García

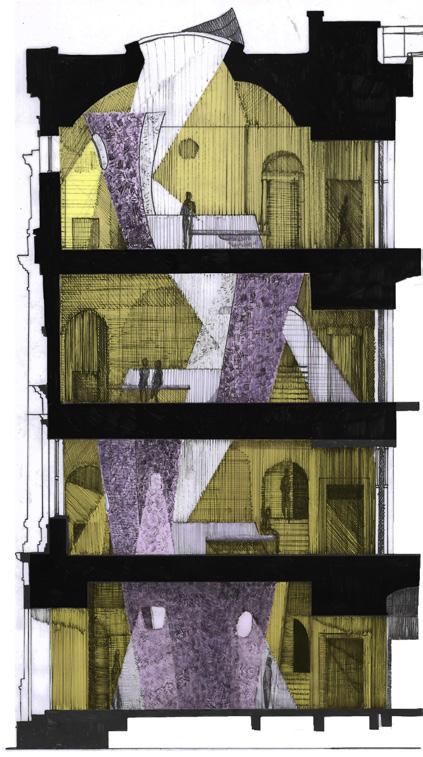

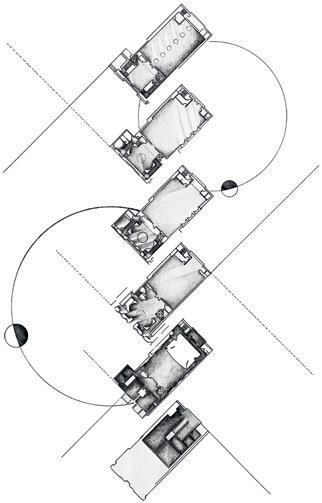

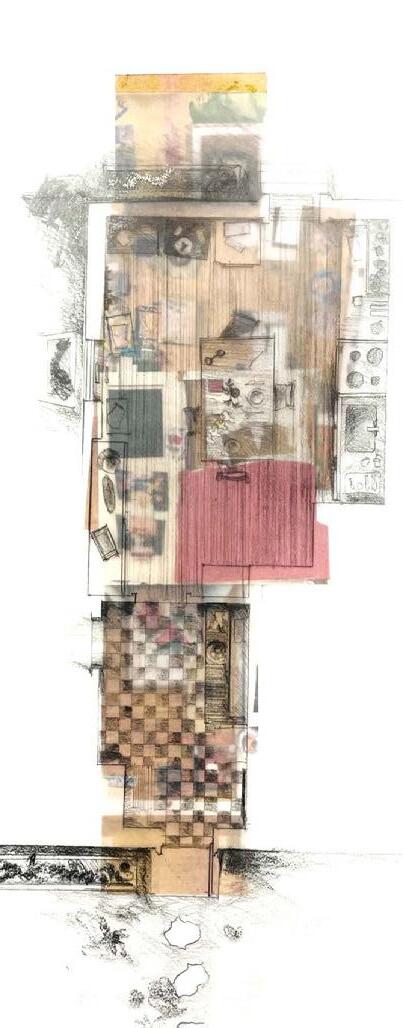

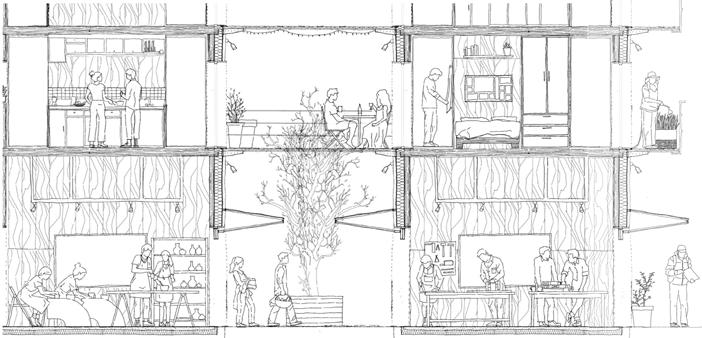

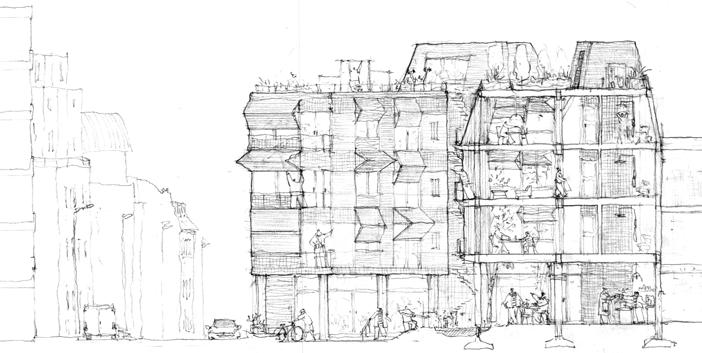

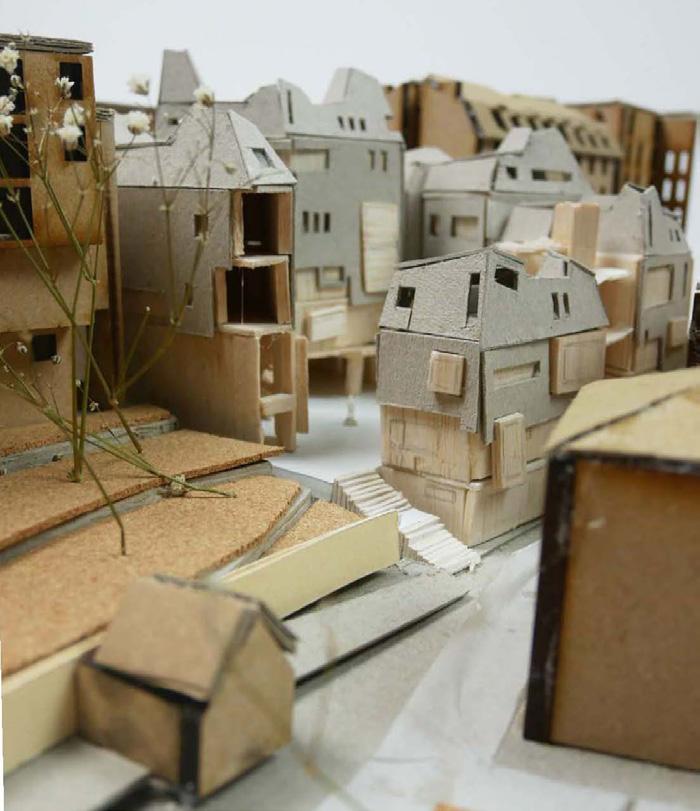

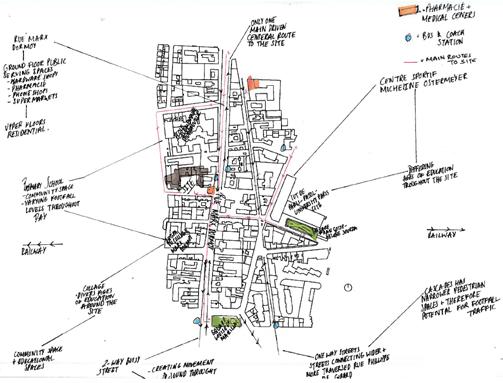

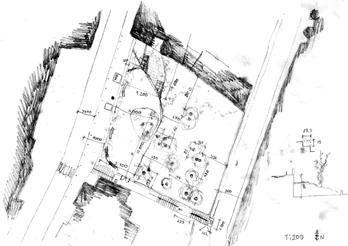

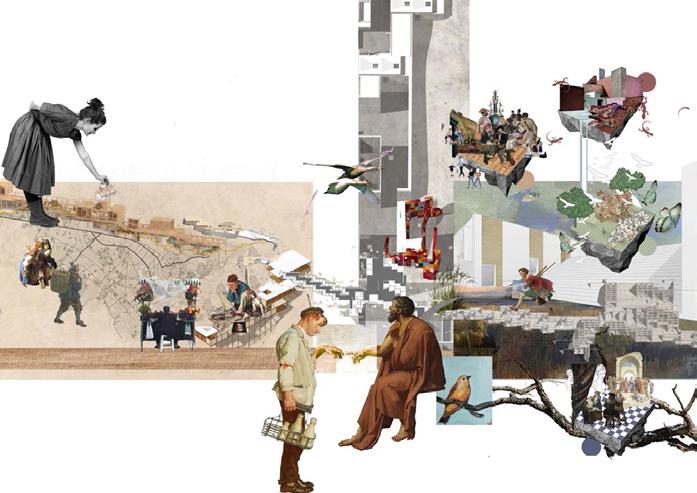

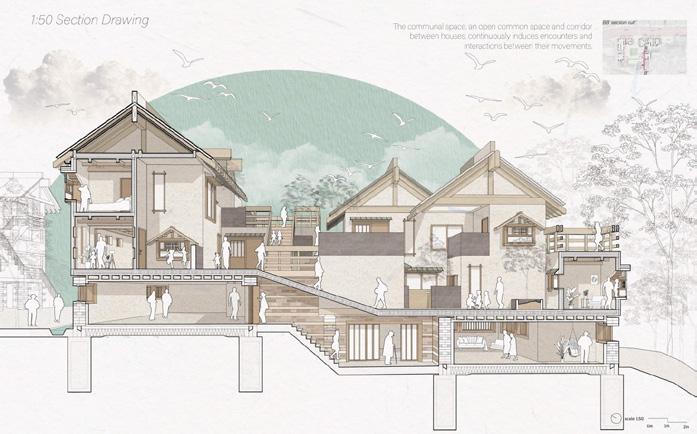

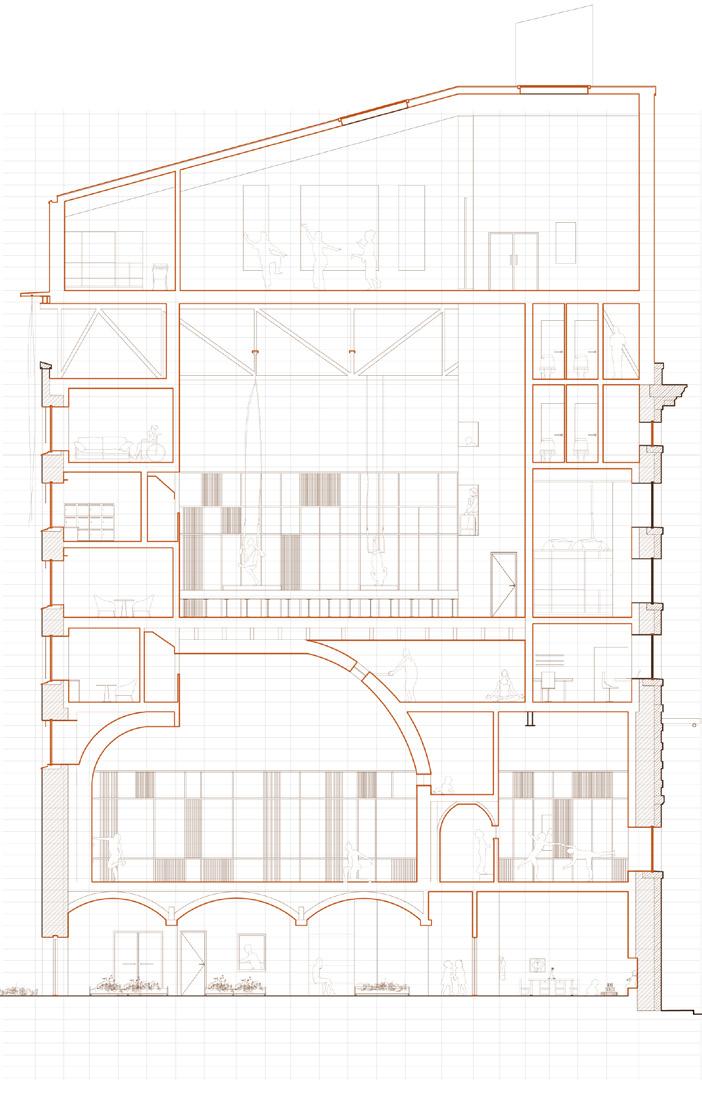

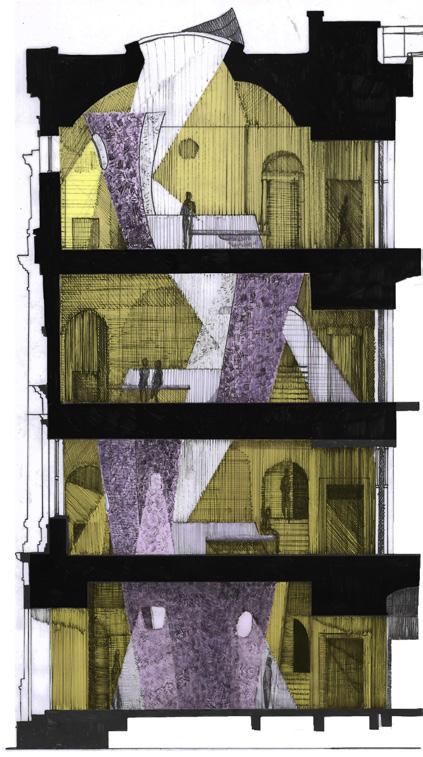

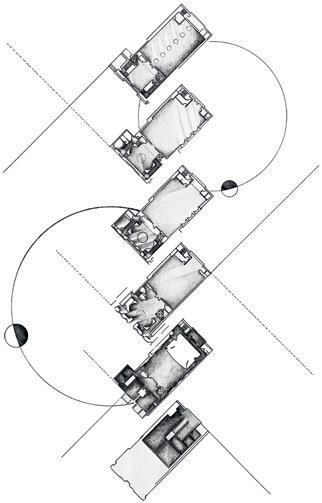

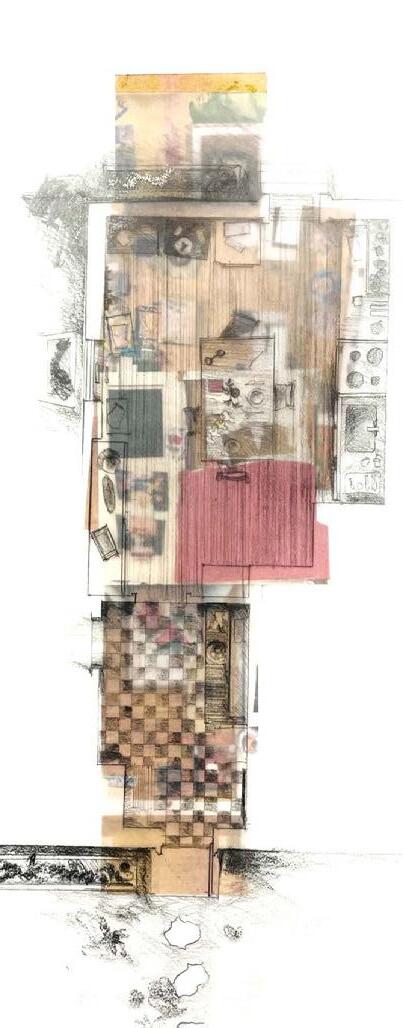

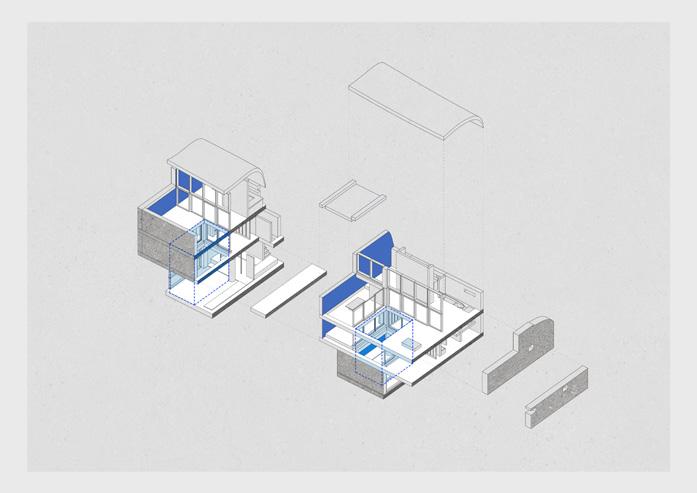

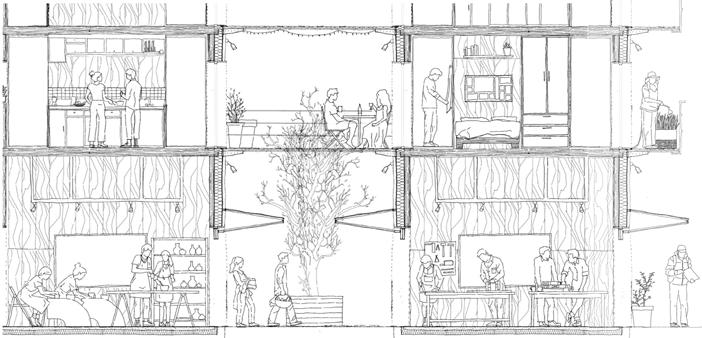

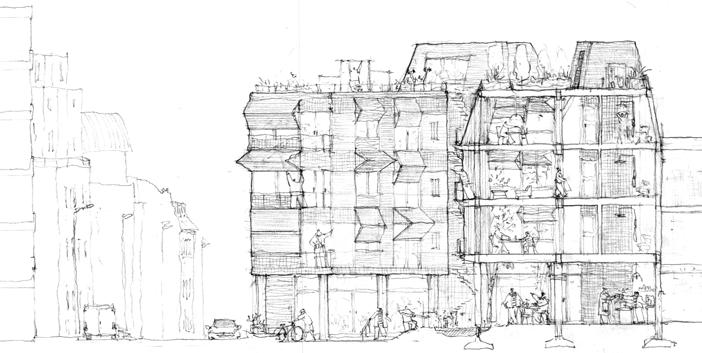

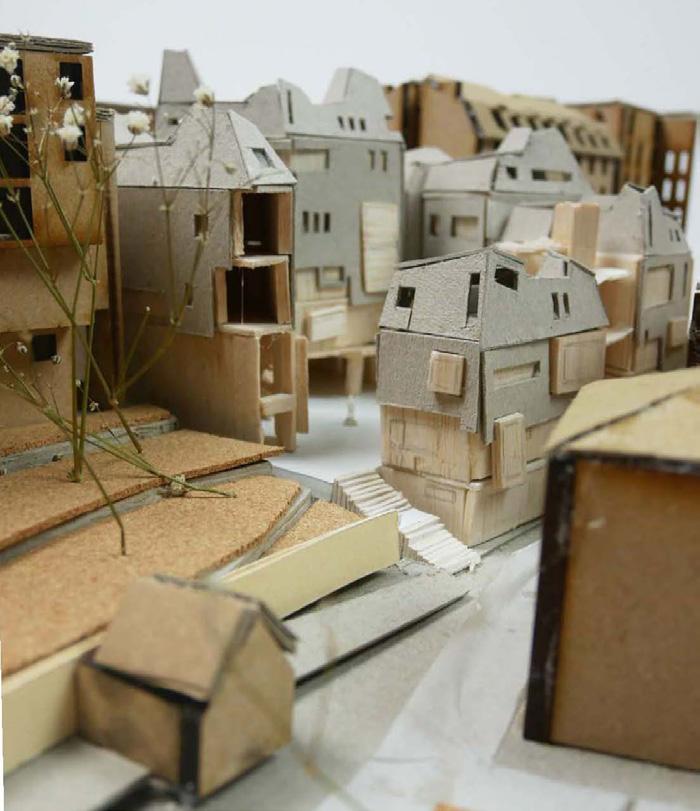

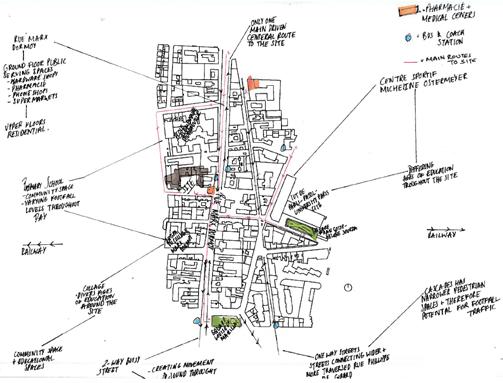

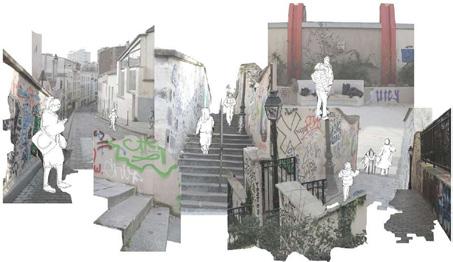

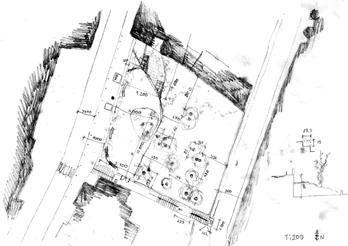

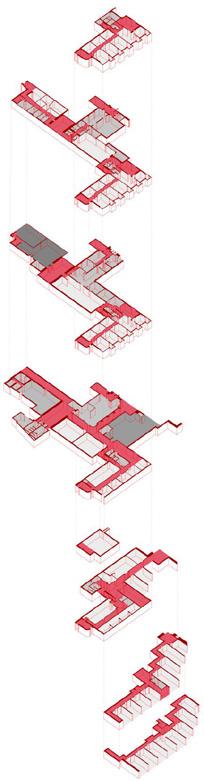

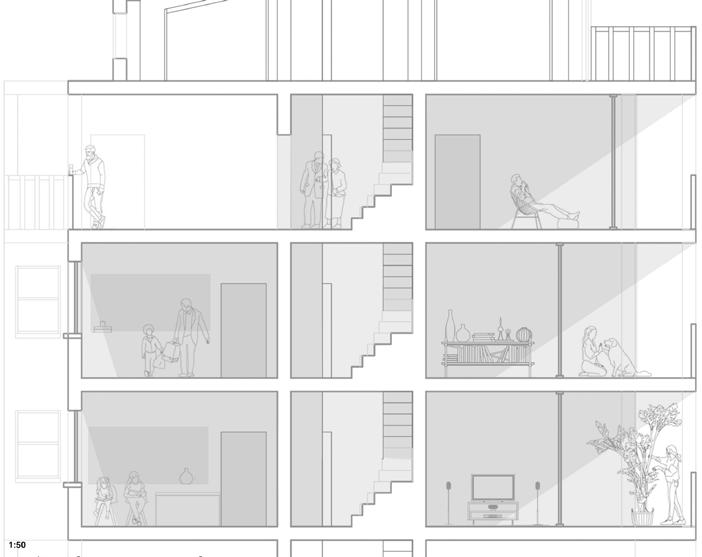

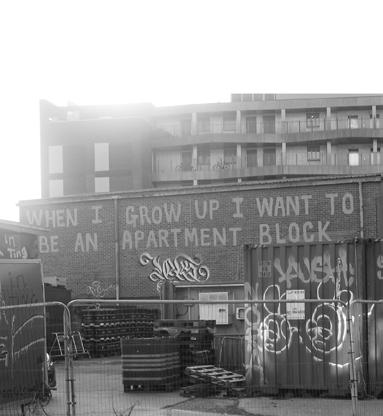

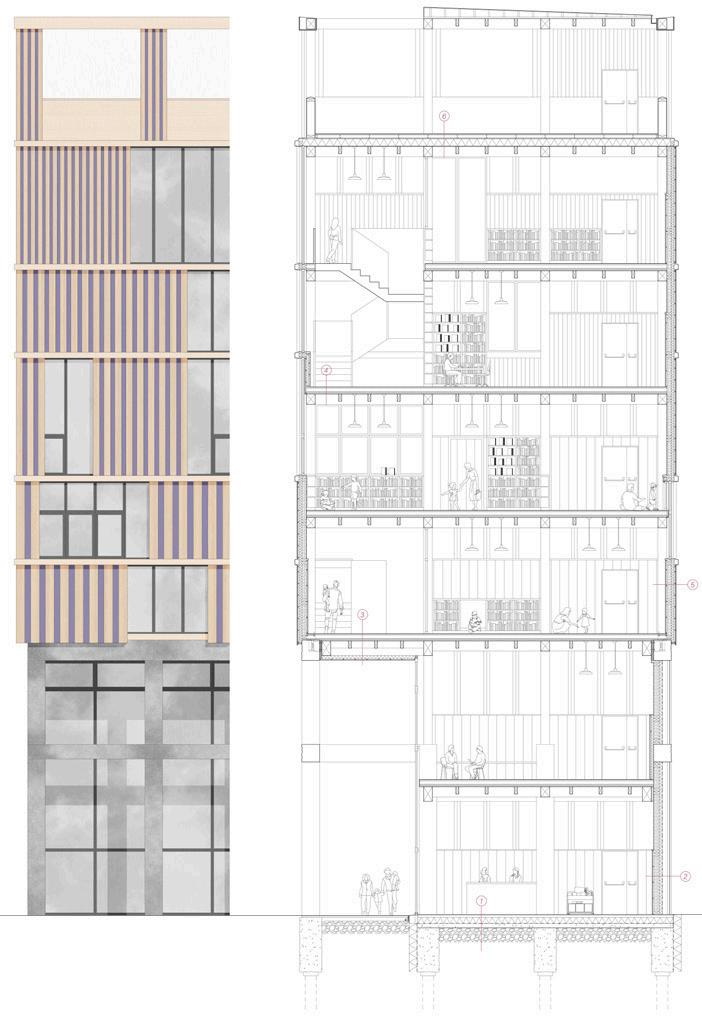

Any Place is thematically focused on circumstances and conditions beyond the local. It moves away from preconceived local knowledge to consider issues of unfamiliarity within a foreign context. This thematic focus is supplemented by a broader interest in the city as a condition for architecture. Students investigate a range of everyday practices that constitute the experience of the contemporary city. This year Any Place deals with the topic of dwelling in the context of the city of Paris, France. Working through five studio exercises and complemented with weekly seminars and representation workshops, students explore programmatic, spatial and tectonic aspects of architecture, including their integration within broader socio-cultural contexts and environmental dynamics. During the first part of the semester, students explore -through film- specific ways of living in the city of Paris. Then, they develop a structured analysis of selected precedents of residential buildings. The combination of the previous material provides the basis for initial spatial strategies around the design of an apartment for a specific lifestyle.

After a site visit to Paris, the process converged in the design of a residential building for multiple occupants located on a selected site in the areas of Belleville and La Chapelle. The process is informed by a critical design methodology based on iteration, aimed to both identify and implement architectural strategies by working through a wide range of media including physical and digital architectural drawings, models and video making.

Studio Tutors

Georgina Allison

Mark Bingham

David Byrne

Mark Cousins

Nikolia Kartalou

Michael Lewis

Fiona Lumsden

Andy Summers

Rebecca Wober

Thomas Woodcock

Support Tutor

Jack Green

Sustainability Tutor

David Seel

Representation Tutors

Rosie Black

Angus Henderson

Theo Shack

Review Critics

Sam Boyle

Shirley Hottier

Alex Liddell

Thomas Longley

Charlie Porter

Nicky Thomson

Student Critics

James Armstrong

Kaiwen Chen

Alicia Gerhardstein

Ralf Merten

Camila Sanchez R.

Alon Shahar

Guest Lecturers

Peter Clericuzio

John Lowrey

Shirley Hottier

2 * 4

Harriet Nixon

Weissenhof Building, Mies Van Der Rohe: precedent study diagrams

2

James Langham

Collage plan of Paris

3

Joanna Saldonido

Amelie’s family home: floor plan

4

Natalie Ng

Nexus World Housing, OMA: precedent study axonometric

5

Lucas Gjessing

Small apartment inhabitation: 1:2 model

060 1

apartment dwelling arch. design any place 2 3 1

061 ba/ma<hons> 2*4 4 5

6

063 ba/ma<hons> 2*4 6

Natalie Ng Customised Housing in Belleville, Paris: axonometric

7 Oscar Nolan The Playground Apartments: axonometric

7 8

8 Harriet Nixon Room Categories: 1:200 model Artists Workshops & Housing in Belleville, Paris: detailed section

064 apartment dwelling arch. design any place 9 10

065 ba/ma<hons> 9

Ed Varlow Residential Building in Belleville, Paris: section 10

Rona Bisset Collective 24 Ateliers d’Artistes de Belleville, Paris: section 11, 12

2*4 12 11

Douglas Crammond Unité housing in Belleville, Paris: 1:200 & 1:50 models

field trip paris

17–19.02.2023

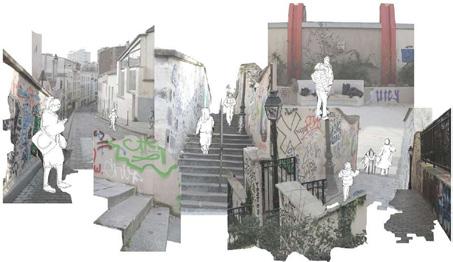

During the trip to Paris, we visited the three sites preselected for residential design in the areas of Belleville and La Chapelle, guided by Luis Burriel Bielza, associate professor at ENSA Paris- Belleville. Each student chose their preferred site and, in groups, produced a complete site survey. Students also visited some of the most relevant Le Corbusier buildings of Maison La Roche, Studio Molitor, Suisse Pavillon, and Maison du Bresil. The visits to Pavillon de l’Arsenal and the Cité de l’Architecture & du Patrimoine provided a general overview of the context of housing in Paris.

11 Bella Fane 12 Isla Murphy 13 Lucas Gjessing 14 Phoebe Vendil 15 Douglas Crammond 066

field trip arch. design any place 11 12 13

“Wandering through the streets of Paris a beige landscape with pops of colourful doors, bins, graffiti and people appear. The streetscape is rather chaotic, no one style carried on from one building to its neighbour, but every building appears to be carefully created and true to itself.”

“This is my first time visiting Paris and my first time studying facade design. The richness of materials and geometric beauty is completely different from Edinburgh, and it is something I have never experienced before in China.”

“During the site visit, particular focus was given to the surrounding urban grain in an attempt to better understand the materiality and characteristics of the local area. Predominantly, buildings were coated in smooth white plaster, though older examples additionally expressed the natural finish of stone. More modern examples began to use timber cladding and window frames, introducing a new, more contemporary materiality. Whilst the majority of new constructions used flat or walkable roofs, the angled attic storeys used a combination of zinc cladding and slate tiles, though both express a similar colour.”

“We flew out to Paris for the weekend and visited multiple museums and key architectural buildings. This trip was really valuable for my learning and widened my knowledge of architecture.”

ba/ma<hons> 067 2*4

Wenjing Huang

Rona Bisset

Lucas Gjessing

Douglas Crammond

13 14 15

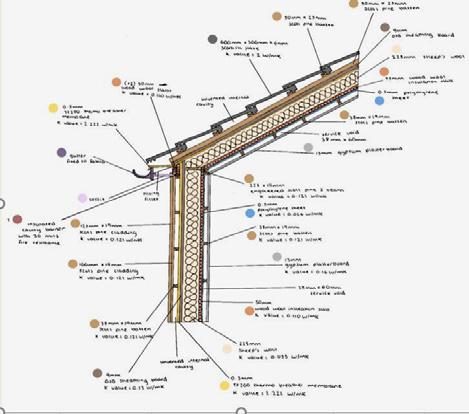

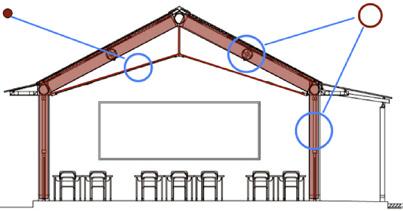

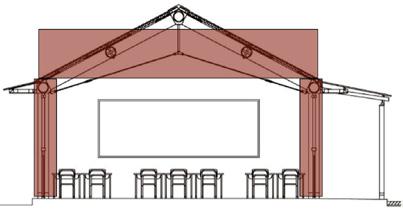

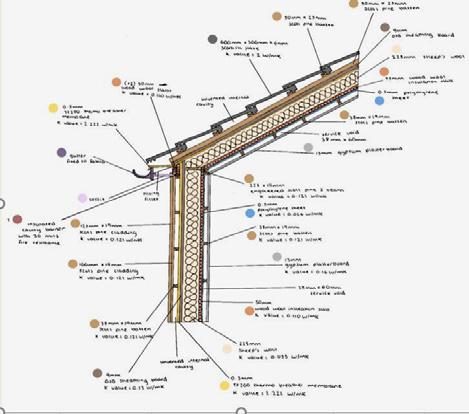

technology & environment building fabric

Site visit to the Potterrow Project March 2023

Photograph: Dimitris Theodossopoulos

2 * 5

Course Organiser

Dimitris Theodossopoulos

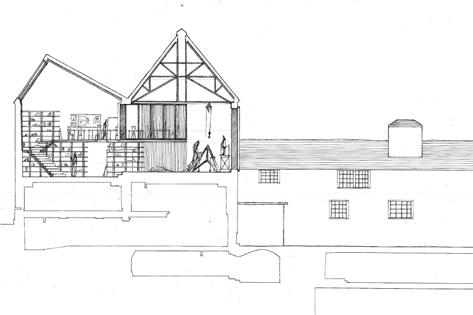

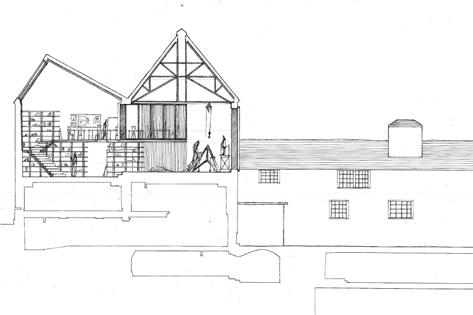

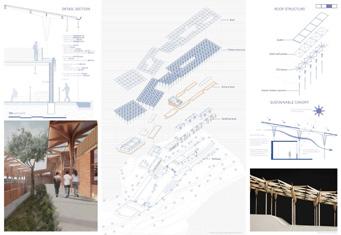

The course explores how building structures (timber, steel, concrete, masonry) are shaped around their response to loads and the need for environmental comfort and protection. The learning experience is formed by observation of good practice and assessment of performance through numerical study of a small structure, and the design of a building envelope and roof informed by their assembly strategy and tectonic expression. The course constantly aims to empower student participation and inverting the classroom - pre-recorded lectures inform the work of the class into smaller discussion groups. This learning environment moves around key concepts, good practice or case studies, allowing the students to explore aspects like structural loads; manufacturing and properties of materials; shaping frames around load-paths, bending moments and stiffness; assembly and performance of building envelopes etc. The students respond regularly to the taught material through illustrated essays that nourished observation and reflection skills, empowered by site visits (Potterrow, the Mont at the old Sick Children Hospital, Norton Living) or records from earlier ones (Haymarket, St James, CALA homes).

Tutors

Jane Robertson

Georgina Allison

Glo Lo

Guest Lecturers

Allan Haines

EDICCT

Ana Bonet-Miro ESALA

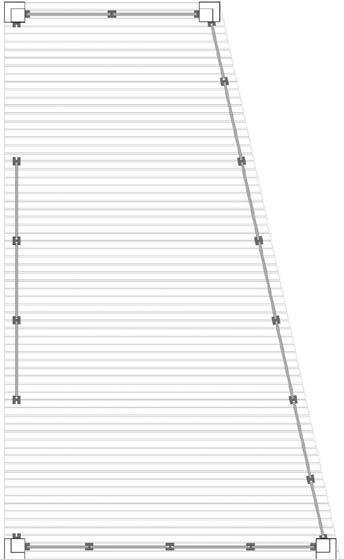

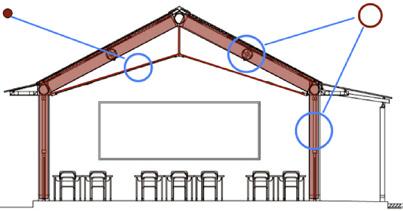

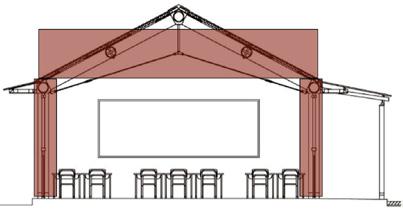

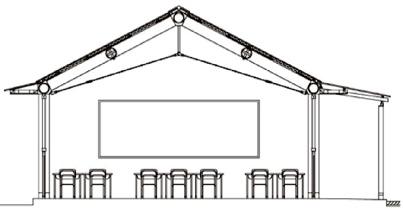

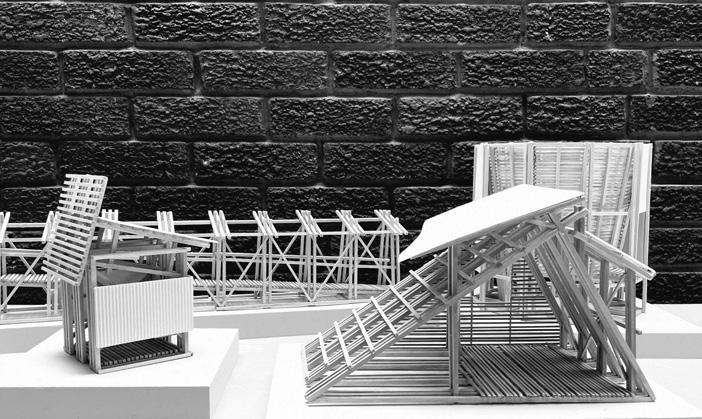

Joanna Saldonido, Douglas Crammond, Ed Varlow, Harriet Nixon

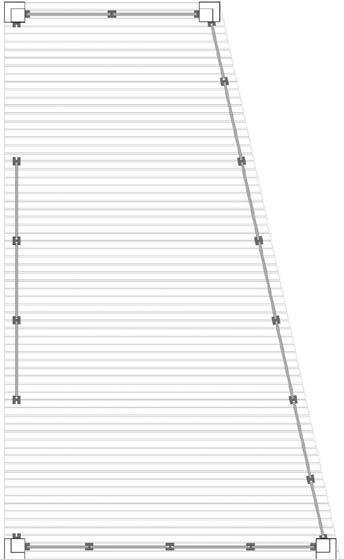

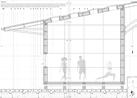

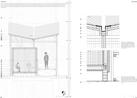

Project 1: Design around Structural Perfromance

Precise sizing and detailing of light timber shelters in St Marks Park, Edinburgh to protect users from weather but also enhance their appreciation of the park by giving a structure and framing routes and visuals. A lean, closely spaced frame was for example a design that enabled a flexible, multipurpose structure that was easy to reconfigure by the users by sliding standardised light timber panels. The solution was developed by analysing and assimilating similar pavilions of varying transparency and prominence of timber as structure. The resulting flexible structure was then detailed with robust and durable connections. Together with extensive calculations for the sizing of the timber beams and columns, the Embodied Carbon Content was evaluated alongside a steel frame alternative, making us realise the professional targets and the surprising incidence of steel connections.

070 sample projects t&e building fabric

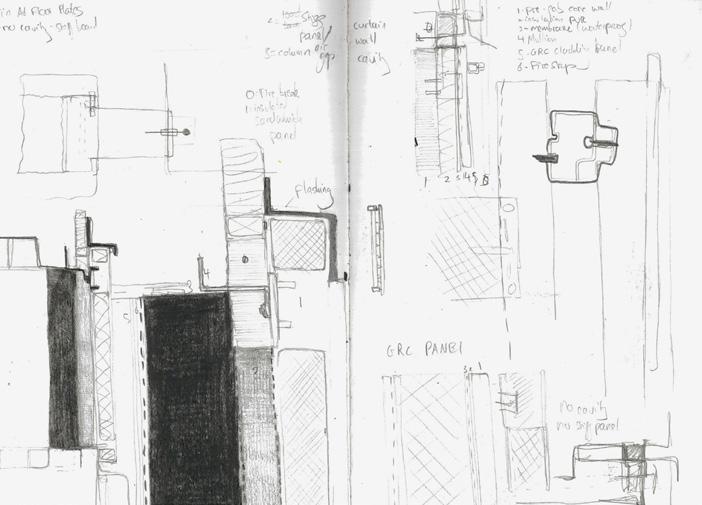

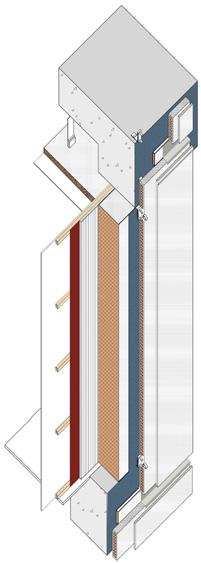

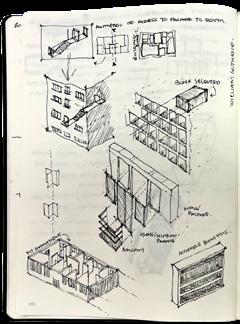

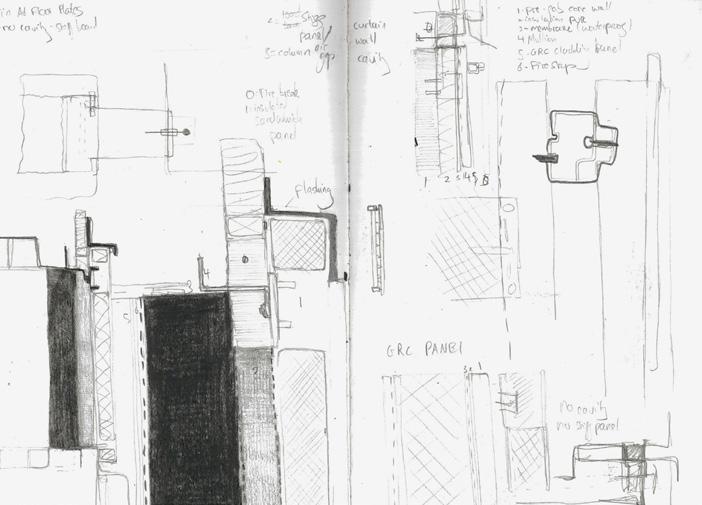

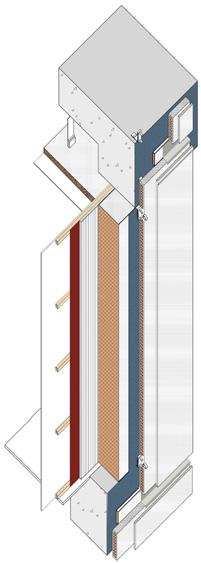

Project 2: Design around Building Envelope

Explorartion of a building’s envelope as a means to support the choice of material systems required in design projects, by structuring the way precedents are studied and developing strategies around a specific aspect of performance or communication. This happened by exploring a detailed strategy of a material system to inform the design resolution and materiality in the Design: Any Place project, using any of their 3 sites in urban Paris. A 1/100 scale was recommended for a design inquiry that can be effectively informed by technical resolution. Tectonic and communication themes explored were solid/ light; permanent/ temporary; sustainability; process and hierarchy; permeability of the natural environment, global vs local. Often this distilled to particular material systems like CLT or the grading of concrete’s durability using GFRC (glass-fibre RC).

071 ba/ma<hons> 2*5

James Langham, Sam Mckeown, Jenna Penman, Isla Murphy

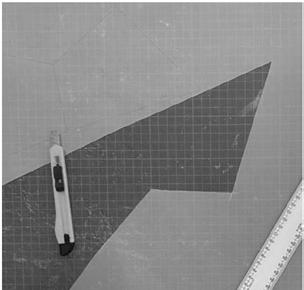

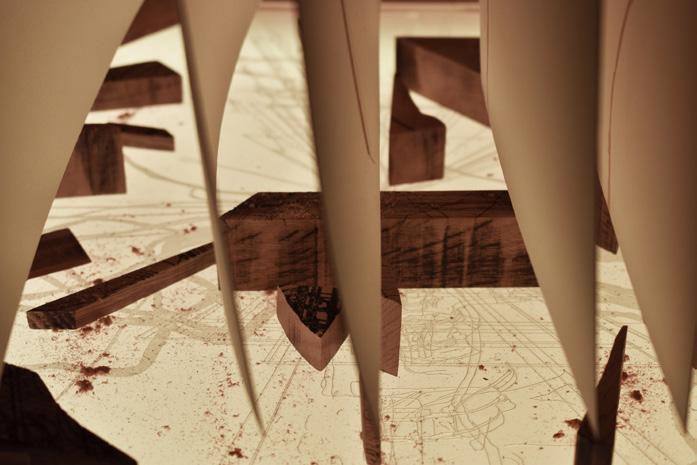

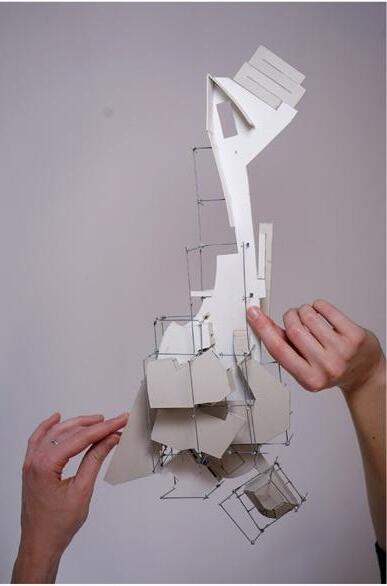

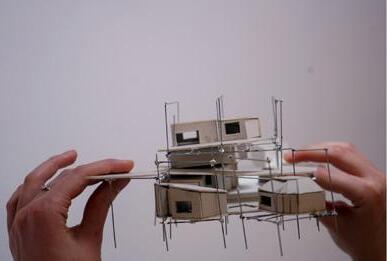

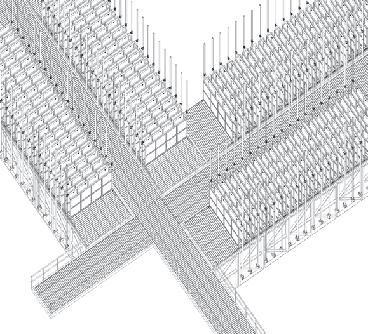

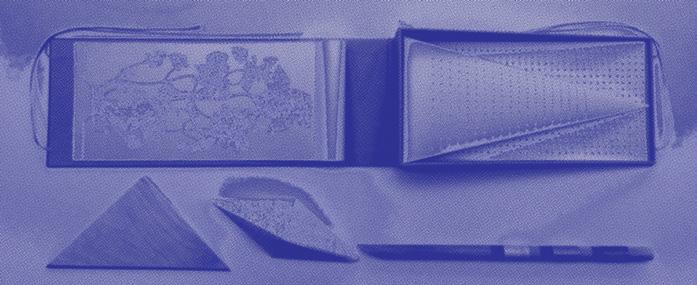

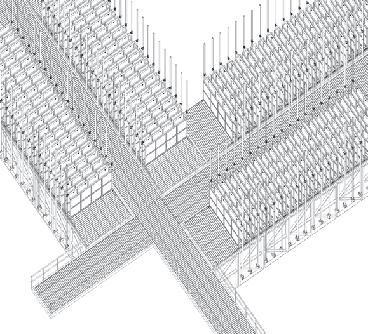

design thinking & digital crafting

Whole Student Group

Protostructure Installation

Minto House

Course Organiser

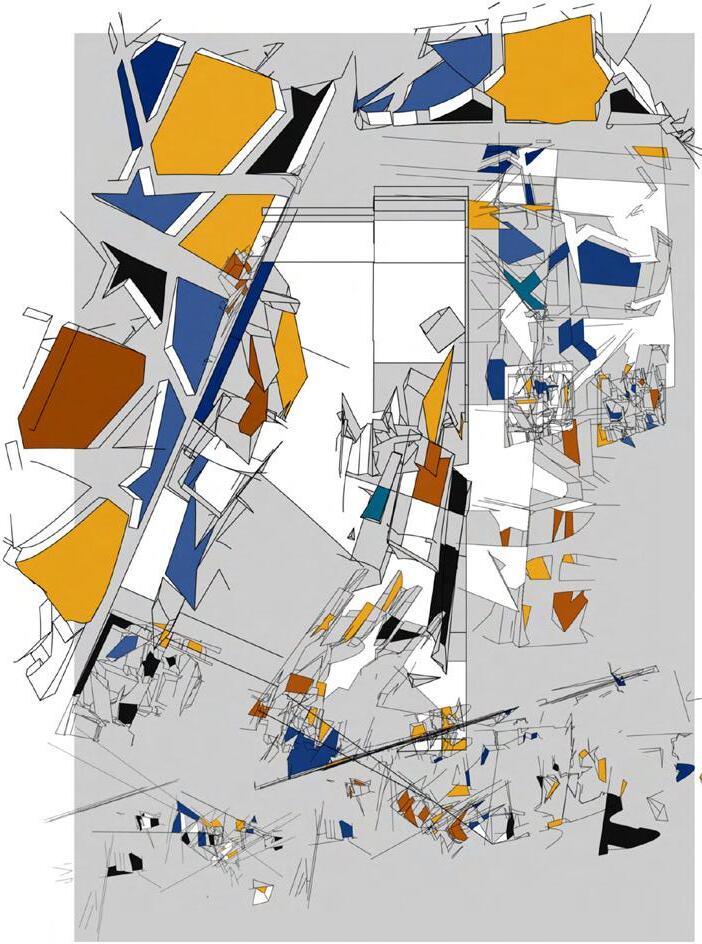

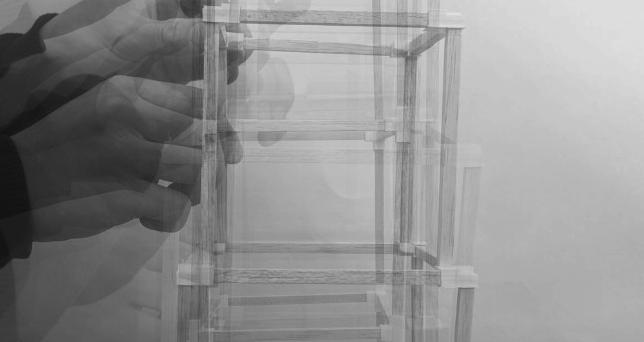

Yorgos Berdos

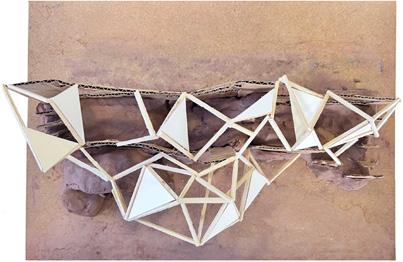

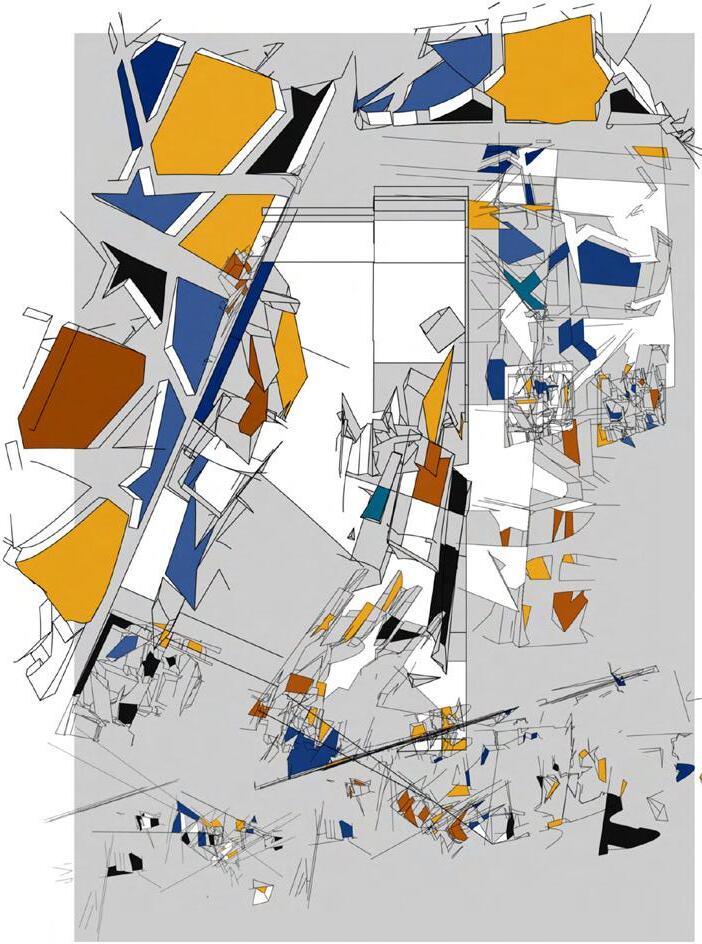

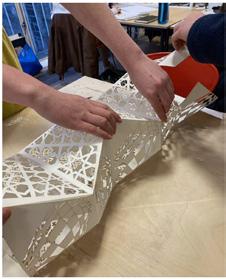

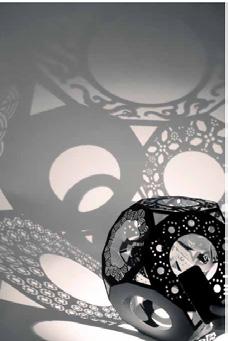

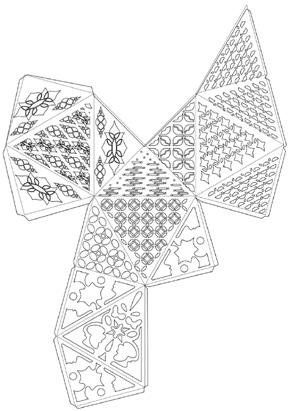

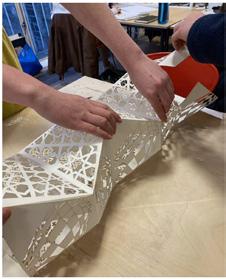

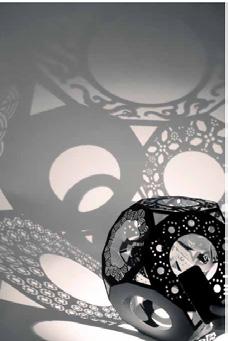

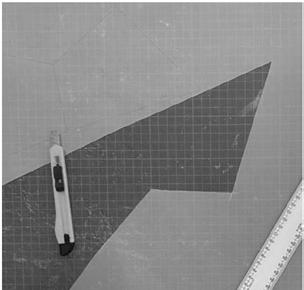

This course represents an introduction to computational design, with a focus on generative design tools and digital fabrication across scales. The students explore how these fields interact and complement each other. The technological possibilities to transform the digital into the physical by a variety of means is also explored. The focus is set on parametric and algorithmic design approaches and the related digital crafting techniques. The participants get introduced to the digital work flow, managing data sets related to design and fabrication. The course engages with digital computation and digital fabrication techniques and strategies on two levels of discourse: a theoretical and an applied one. The methodology of the digital work flow is introduced. Furthermore, the participants are educated in developing a critical and analytical approach to computational design and digital fabrication by getting introduced to basic strategies in terms of digital computation and fabrication and offering an insight to the current theoretical debate regarding the ‘Digital Turn’ in architecture. The first four weeks comprise an introduction to the theoretical approaches behind the Digital Turn. The participants complete individual analysis of a given case studies, critically reflecting on particular design and compositional aspects and present the reached conclusions. In parallel to this stage the students are offered a set of tutorial hours for the dedicated software packages, and an introduction to a diverse range of digital fabrication techniques. The participants are required to apply the newly gained knowledge in terms of form generation and to make extensive use of the designated online and offline learning recourses throughout the semester. They are also expected to read key literature and to maintain their reading throughout the study period.

During the final weeks of the semester, the students work collaboratively to conceptualise, design, produce detailed drawings, fabricate, and install a protostructure within a given budget, real life constraints and minimizing its material footprint. The protostructure is then installed prominently within the school of architecture, celebrating all the learning and exploration achieved during the semester.

Teaching Assistants

Yeldar Gül

Athina Kotrozou

Antonis Mavrotas

Contributors

Cesar Cheng

Digital Bluefoam

Giovanni Panico

Ice Chitmeesilp

ESALA Y4 student

Fab Pub, Mamou Mani

2 * 6

074 - design thinking & digital crafting 1

075 ba/ma<hons> 2 2*5 1

James Langham Exquisite Tower: concept sketches

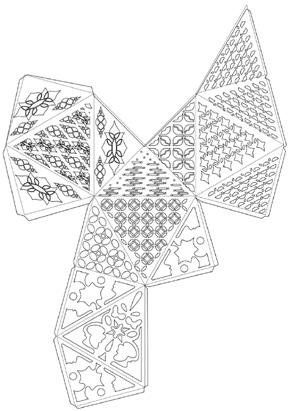

2 Hannah Bendon, Shu Kok, Diana Saab, Joshua Teh Abstracting the patterns

3

Adela Chen, Quiyi Chen, Tom Zheng, Mingyu Zhou Abstracting the patterns

3 4

4 Lucas Gjessing Abstracting the patterns

Whole Student Group

Protostructure: fabrication & installation

6 Adela Chen, Quiyi Chen, Tom Zheng, Mingyu Zhou

Exquisite Tower: digital renderings

7

Whole Student Group

Exquisite Tower

076 - design thinking & digital crafting 5

5 6

077 ba/ma<hons> 2*5 7

year 2 electives

Jane Hyslop Selected Works, 2014

Sample images from across elective courses

Jane Hyslop Selected Works, 2014

Sample images from across elective courses

Spanning sites across the city, and populating some of the best loved quarters and buildings of the capital, the University of Edinburgh hosts a wide range of departments, specialisms and specialists. Within the BA | MA Architecture Programme, we invite students to explore the possibilities hidden behind the doors and minds of this rich learning environment, exploring beyond the discipline into diverse fields of enquiry. All students progressing to Year 2 require to take an elective course in Semester 2. This can be any level 8 elective from any Course or College across the university which is open to incoming students. The breath and scope of this selection may seem overwhelming, and as such we provide a useful handout well in advance of the selection period to assist with narrowing the extent of the search. We ask that students take seriously this moment to expand and tune their learning experience, reflecting on evidence from previous academic cycles to consider how and why they have chosen this degree pathway, and what, where and how they may wish to deploy these skills in future. A careful choice of elective might steer, supplement or challenge existing learning, so thinking carefully about how such a choice might consolidate foundations for future learning is vital, considering what it mean and how one might use it in the future.

www.drps.ed.ac.uk/23-24/dpt/drpsindex.htm

Sample Electives

Africa in the Contemporary World Architectural Acoustics

& Spatial Sound

Architectural History

& Heritage in Practice

Body As Artistic Material

Calculus and its Applications

Composing for Voices & Instruments

Contemporary Cinema

Creative Musicianship

Creative Social Work & the Arts

Design and Society

Engineering Design

Fashion Design

Introduction to Queer Studies

Jewellery and Silversmithing

Landscape Architecture Theory

French, German, Italian, Spanish Korean, Japanese, Arabic, Gaelic Medical Biology 1

Modernism and After

Oceanography

Physical Geography

Planning for a start-up

Psychology of Music

Science, Nature & Environment

Scottish Studies: Creating Scotland

Sound Recording

South Asia in the World Sustainability, Society & Environment

The Business of Edinburgh

Visual Narratives in Design & Screen Cultures

2

* 7

3*1 3*2

architectural design explorations

3*3 3*4 3*5

architectural theory

3*6

architectural practice working learning

architectural practice reflection

practice experience

professional studies

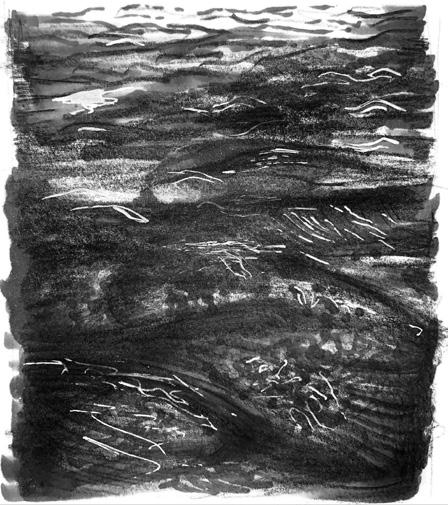

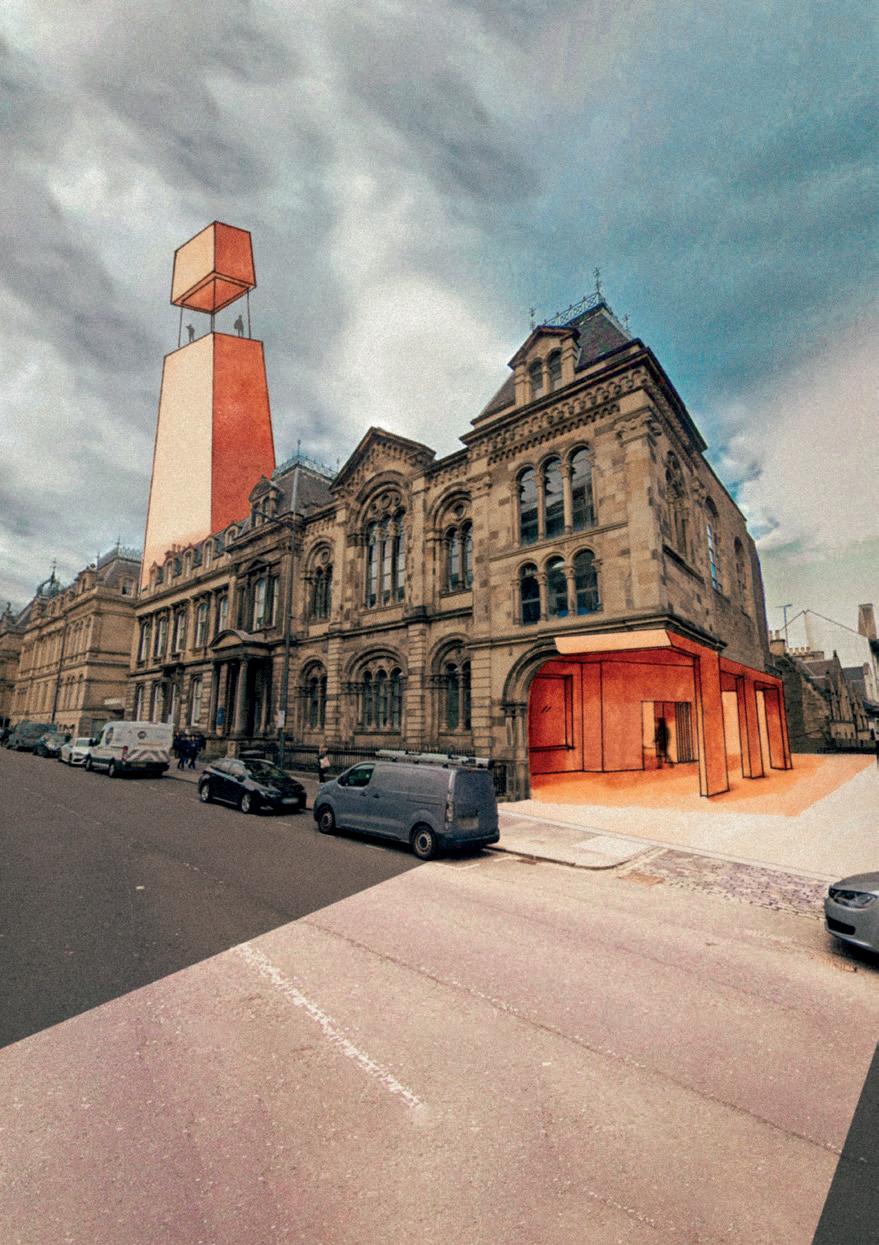

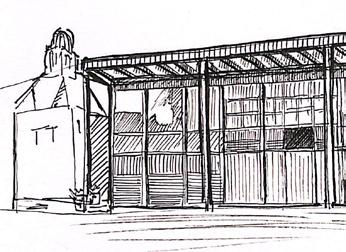

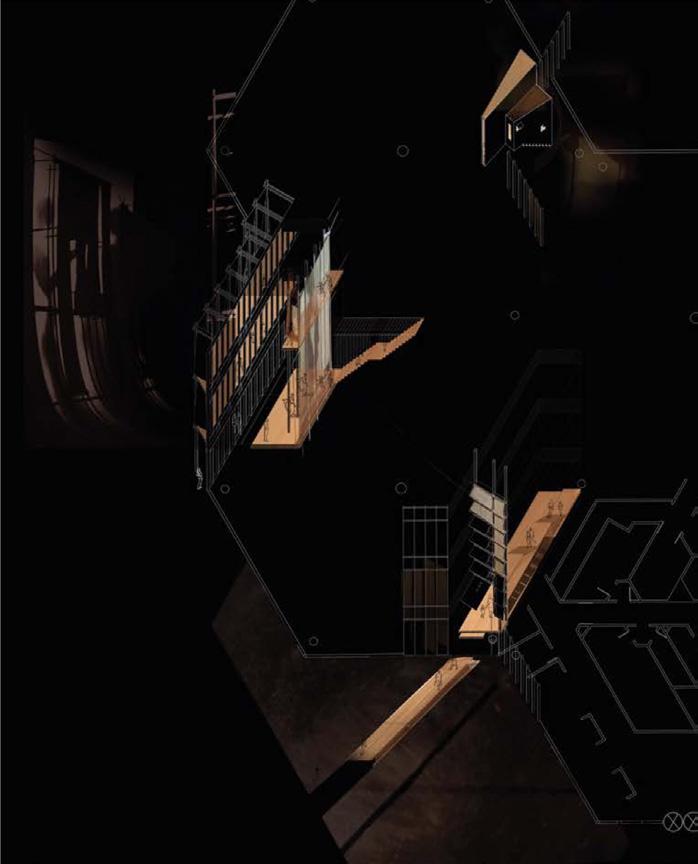

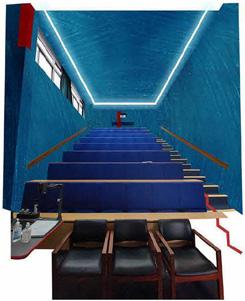

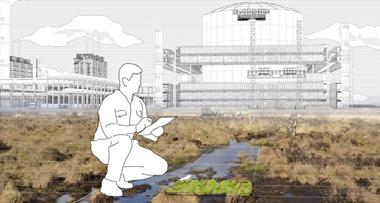

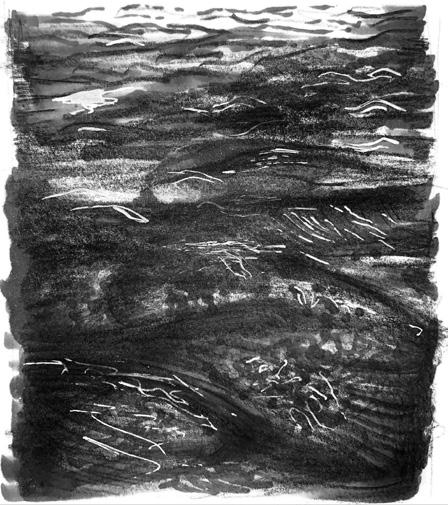

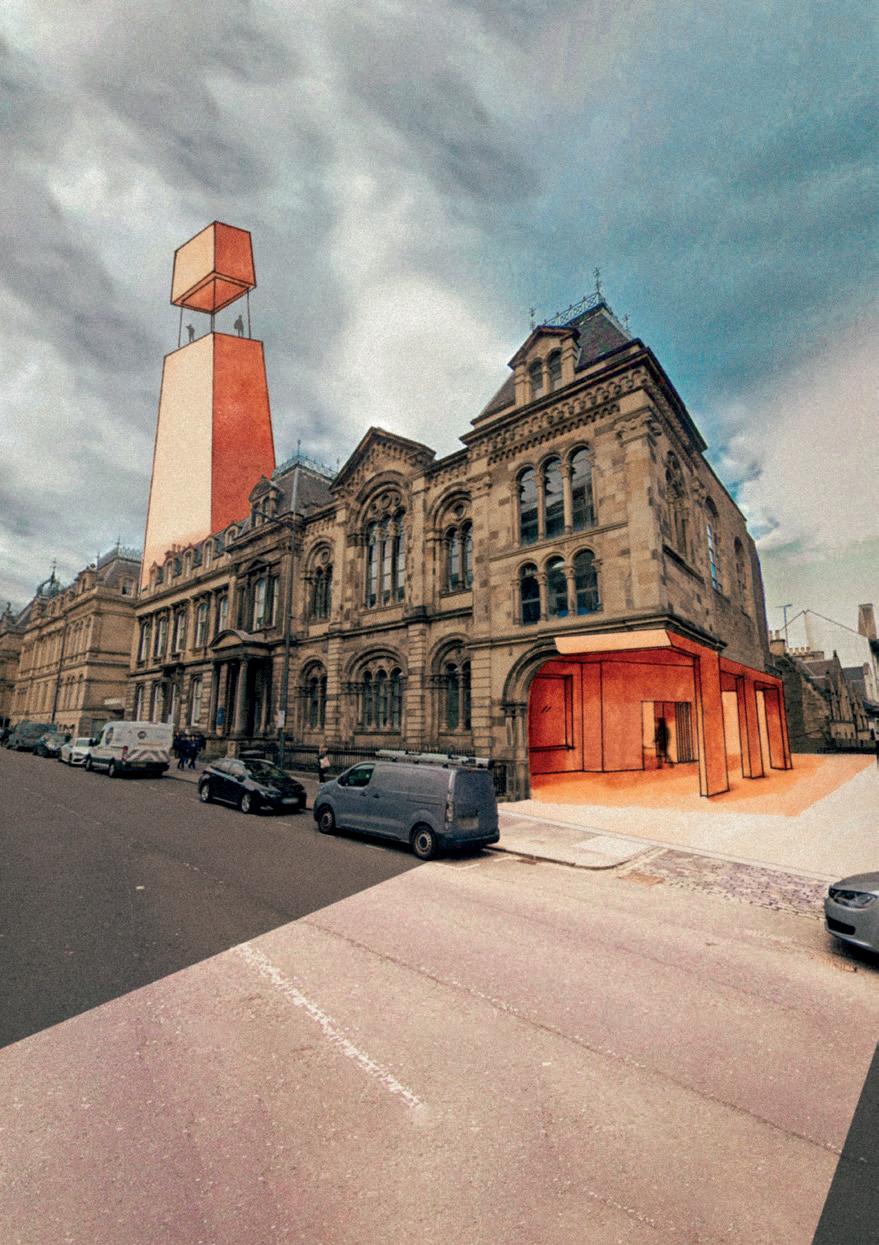

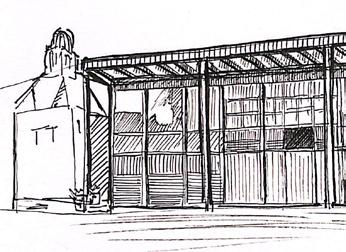

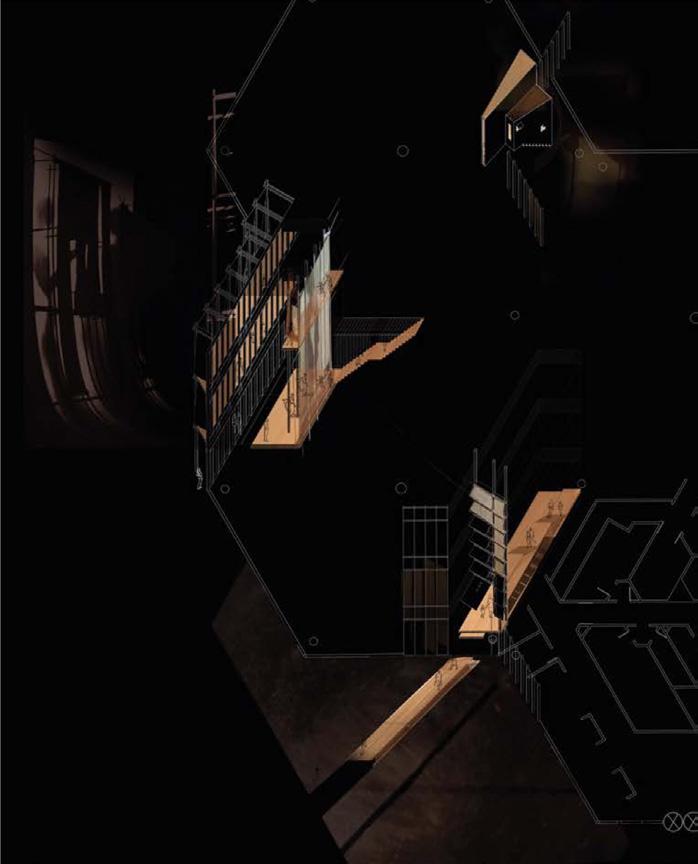

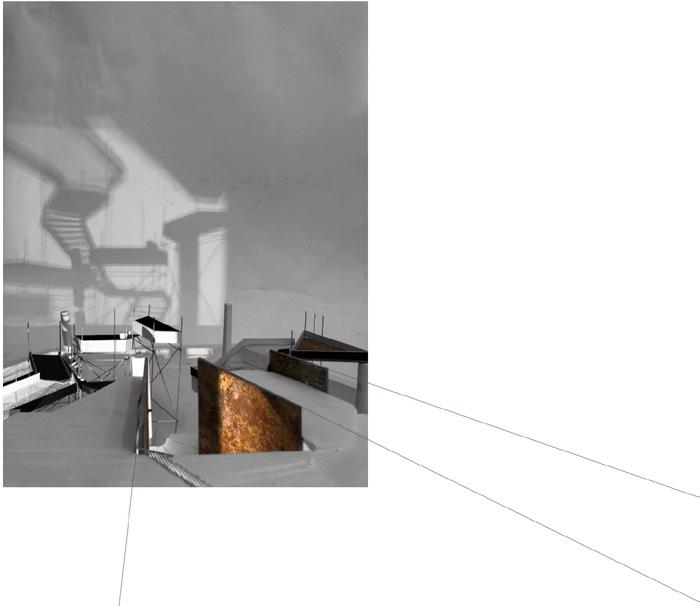

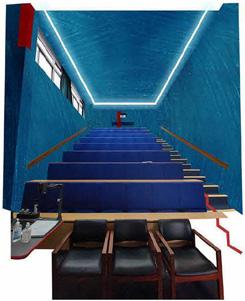

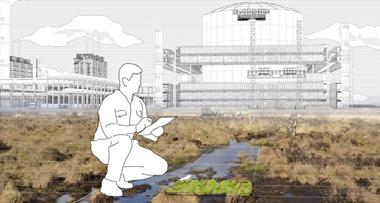

Architectural Design: Explorations

The Empty Space

Exhibition for Hidden Door 2023

Photograph: Iain Robinson

architectural design explorations

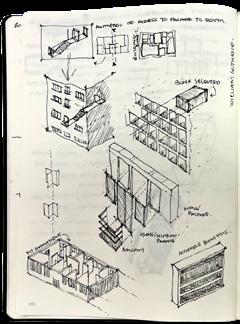

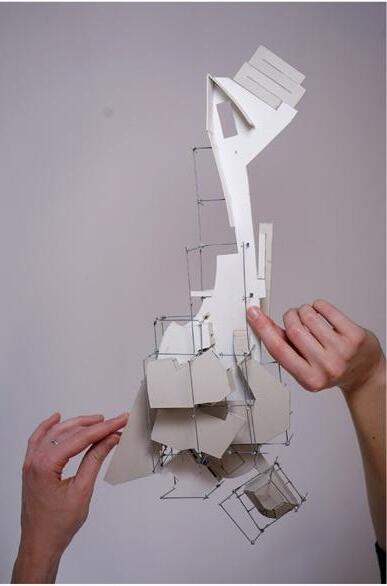

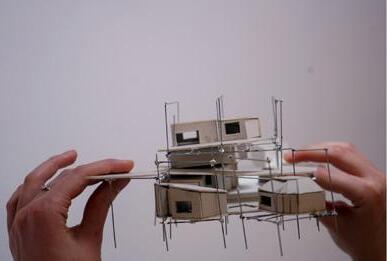

Audrey So, Shuyan Zhang, Xiaowen Wang Folded Tectonics

Audrey So, Shuyan Zhang, Xiaowen Wang Folded Tectonics

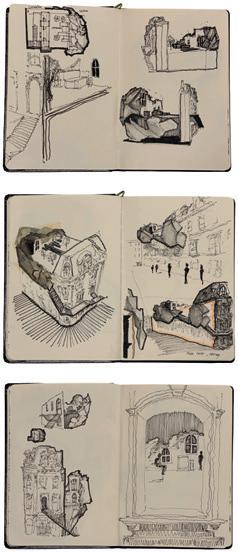

Course Organiser

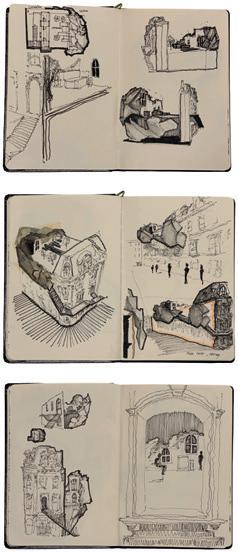

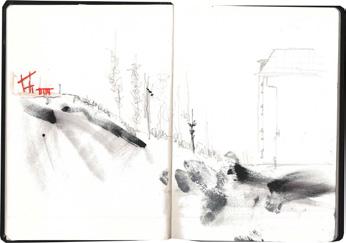

Simone Ferracina

Explorations extends Stage 2 level architectural design and communication skills by foregrounding experimentation. The course focuses on developing familiarity with a range of approaches to architectural design research, and with the relevant protocols and techniques. Students are asked to undertake a rigorous and creative exploration that investigates specific design themes based on the identification of key problems, opportunities, sources, methodologies and strategies. Seeking a more nuanced understanding of the design process, the course turns the studio into a laboratory for creative exploration, and a site for experimentation and discovery—not only for finding answers and solutions, but for designing and pursuing questions. The course is offered in a number of parallel design studios that sustain the overarching pedagogical aims while investigating a broad spectrum of distinctive subthemes, preoccupations and methods. During the 2022-2023 academic year, units explored a range of different topics: Unit 1 investigated emptiness and sound in relation to the vacant Scottish Widows HQ building in Edinburgh; Unit 2 interrogated the reactivation and reuse of discarded and de-valued objects, prototyping new materials and assemblies and developing 1:1 interventions for social enterprises in Granton; Unit 3 developed competition proposals as a way to reclaim architectural practice as a fundamental mode of operation for architects; Unit 4 explored the notion of trust in the context of blockchain and distributed ledger technologies; Unit 5 considered existing buildings and how to retrofit them to increase their performance today and in the future; Unit 6 investigated the hedgerow as a lens through which to develop architectural projects that are sensitive to questions about climate change and the loss of biodiversity.

Technique

Dan

Joseph

Sue

Giles

Ryan

Hamish

Sophie

Kanto

Tobi

Georgia

Unit 1 The Empty

Unit 2 Radical

3 The Competition Studio Unit 4 Cryptoarchitecture Unit 5 Metamorphosis Unit 6 Lines in the Landscape 3 * 1

Tutors

Anderson

Barnes

Yen Chong

Davis

Hillier

Jackson

Lewis-Ward

Maeda

Phillimore

Whitehead

Space

Harvest Unit

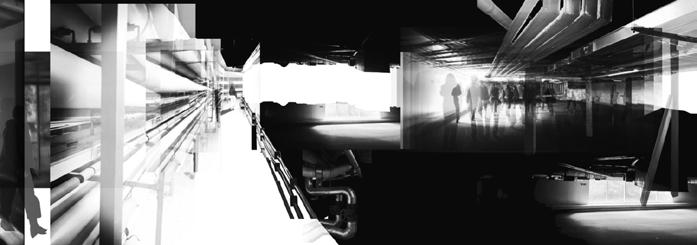

unit 1 the empty space

1 Emily Grills, Isla Hibberd, Alon Shahar A Theatre of Human Movement

2 Charlotte Cole, Georgie Inchbald, Devon Tabata An Exercise in Gloam: new rhythms of refuge

Studio Leaders

Suzanne Ewing, Andrew Brooks

When confronted with an empty building, architects are often tasked with filling it, usually driven by a programme for designated use. The unit asked: what if we explored emptiness, unused or neglected parts of the city’s built fabric, as bare stages, already latent with crossings of light, sound, particulate matter, temperature, ecologies, traces of past events and occupation, clues as to forms or manners of how life is lived? This unit’s focus was on site-specific techniques and time-based media that, through attentive collection, re-siting and translation, bore witness to rhythms, conditions or events that became the composite armature for further design direction.

Concerned with architecture and experience, temporal aspects of architectural design, sound and space, and architectural field/work techniques, the unit is particularly interested in exploring sound and the sonic imagination in relation to architecture. We draw from sound artists who explore the inherent spatiality of sound, which emphasises a bearing witness within an event rather than reading from a distance visually.

A further iteration of work from the unit is installed in the Scottish Widows building in June 2023 as part of the 2023 Hidden Door Festival.

hiddendoorarts.org/event/ the-empty-space-esala-exhibition

3

Georgie Thornham, Amber Woodward Is a Space defined by a line?

Contributors

William Mann

Witherford Watson Mann

Kanto Maeda

Guy Morgan

Review Critics

Nikolia Kartalou

Eirini Makarouni

Maria Mitsoula

084 the empty space arch. design explorations

085 ba/ma<hons> 3*1 1

086 the empty space 2 arch. design explorations

087 3*1 ba/ma<hons> 3

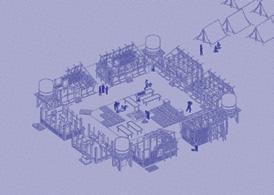

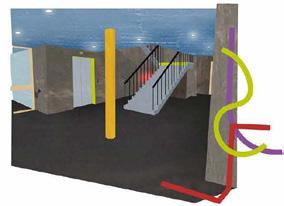

unit 2 radical harvest

1 Laura Dew, Thomas Everett, Issy Rice

Stereotomic: Constructing with History

2

Tega Digba, Rajni Nessa, Tessa Tsui Reclaimed Tyre-Forms

3

Audrey So, Shuyan Zhang, Xiaowen Wang

Folded Tectonics

4 Abi Bowens, Stephen Brown, Songzhi Zou

Urban Playscape

Studio Leaders

Simone Ferracina, Asad Khan

Unit 2 proposed a model of architectural education that both foregrounded the climate emergency—and the urgent need to develop low-carbon protocols for design—and actively engaged with local communities and stakeholders, understanding the two—carbon and society—as facets of the same problem.

On one side, students harvested and diverted low-value, discarded, second-hand, or deconstructed materials and building components, prototyping workflows and tectonic assemblies for reusing and repurposing them, and returning them to ecologies of use and value. On the other, they worked with stakeholders and social enterprises in Granton (Edinburgh Palette, Plan A, JK Consulting, the Granton Garden Bakery, Soul Water Sauna) to deliver live-build projects that are thoughtful, collaborative, and guided by the community’s needs and aspirations.

The focus of the unit was therefore not on the conception of a project alone, but on the different phases of its construction: from the harvesting of materials to the invention of building recipes; from site preparation, and the coordination with local enterprises, to its actual construction along the Granton waterfront.

5

Emma Astley-Birtwistle, Emily Sprackling, Simona D’Sa Tectonic Recombinations

Contributors

Minto House Workshop

Akiko Kobayashi

Marcelo Dias

EALA Impacts

Edinburgh Palette

JK Consulting

Granton Community Gardeners

Soul Water Sauna

Move On Wood

Granton Castle Walled Garden

Edinburgh Science

Andrew Cardwell

Review Critics

Moa Carlsson

Akiko Kobayashi

Sonakshi Pandit

088 radical harvest

arch. design explorations

089 ba/ma<hons> 3*1 1

090 radical harvest 3 2 arch. design explorations

091 ba/ma<hons> 3*1 5 4

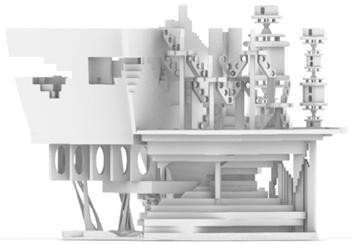

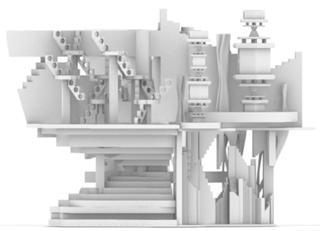

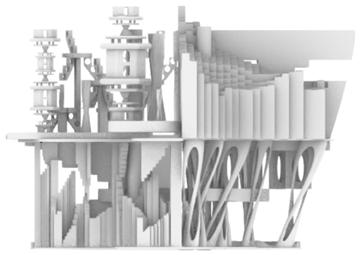

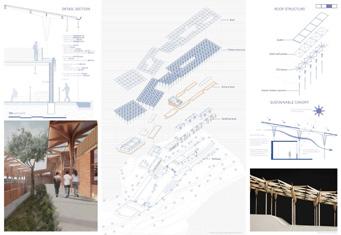

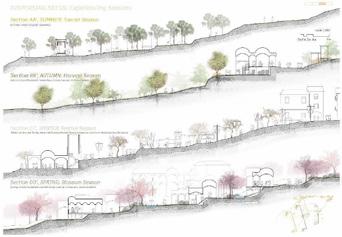

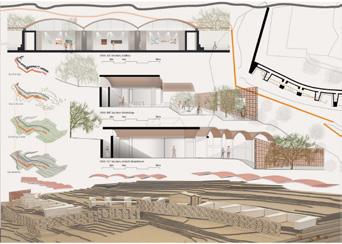

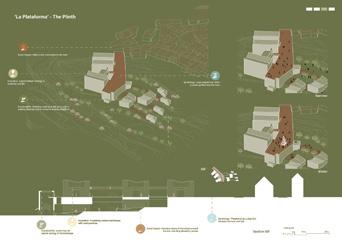

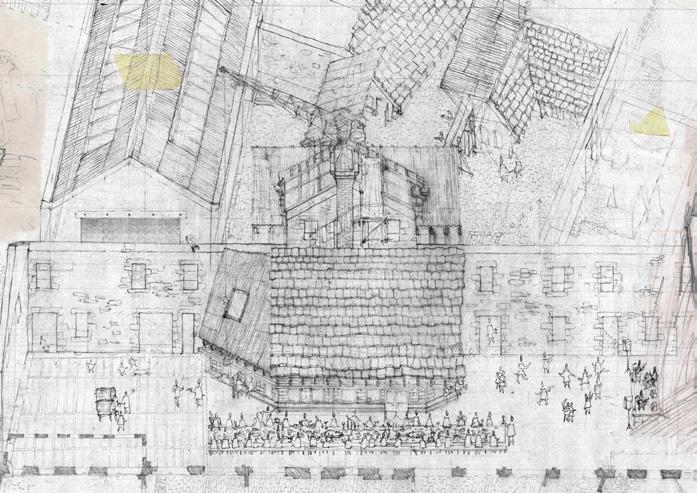

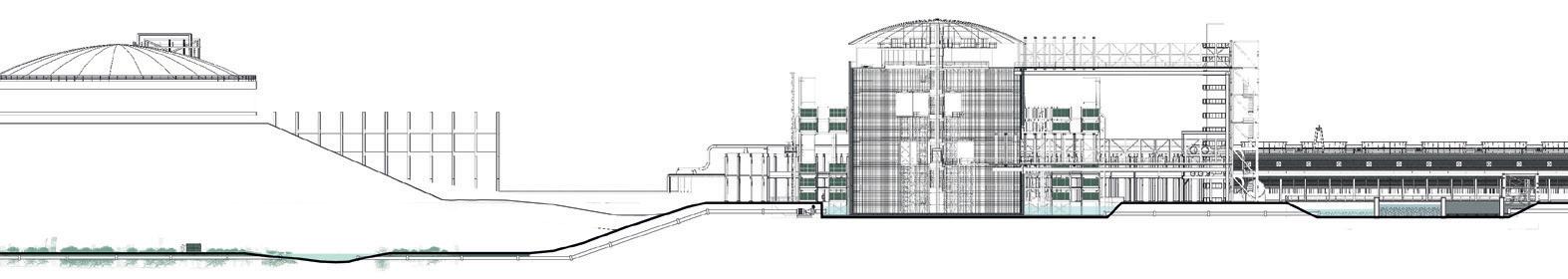

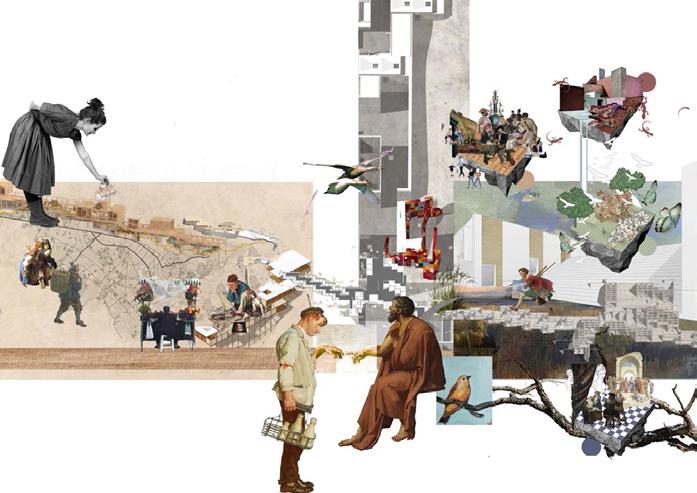

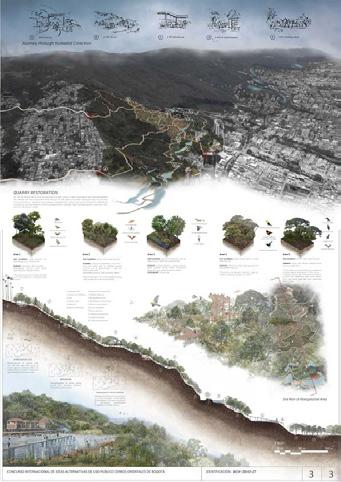

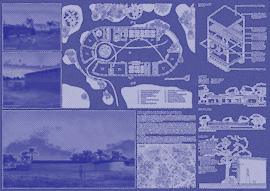

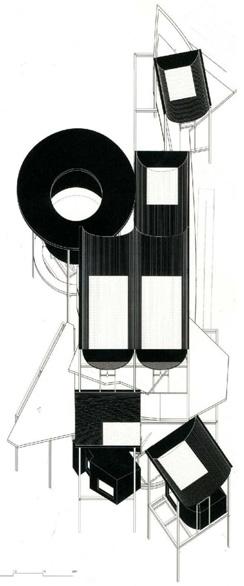

unit 3 the competition studio

Nominations & Awards

Gaudi La Coma Artists’ Residences Competition

Kevin Chen, Michael Kan, Kelly Tanim Buildner Sustainability Award

Leon Ding, Jiayu Lu, Cassandra Yang Shortlisted Project

Delan Aribigbola, Sabrina Findlay, Cristian Liu Chang Shortlisted Project

Allegra Keys, Ellis Shiels, Bartu Tort Shortlisted Project

Studio Leaders

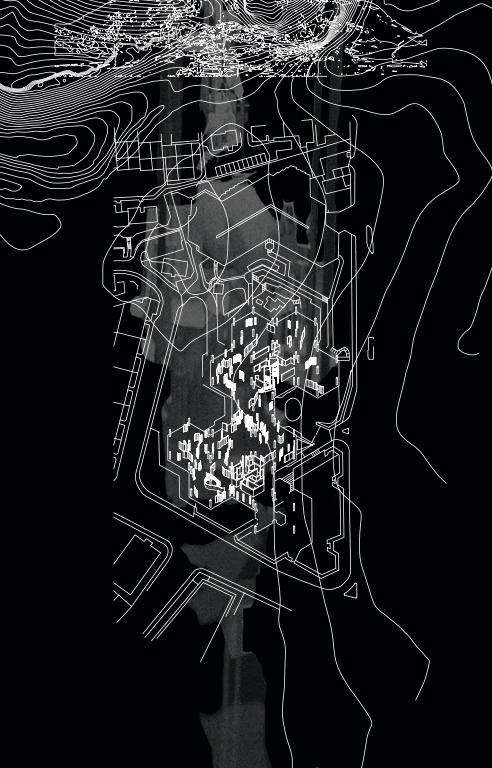

Ana Miret Garcia, Jack Green

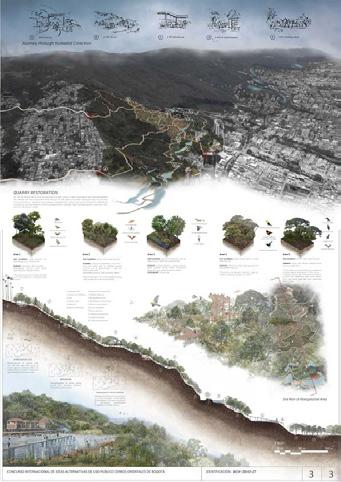

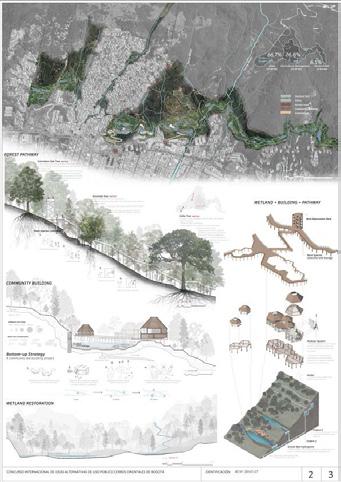

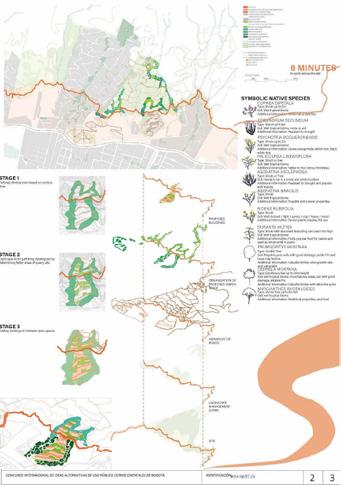

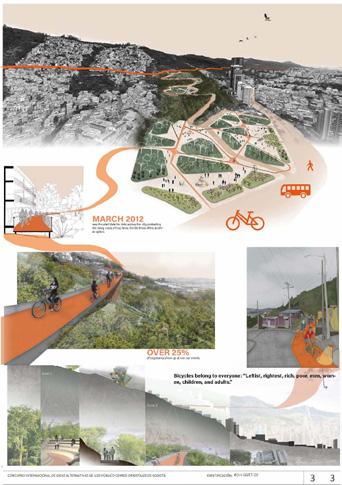

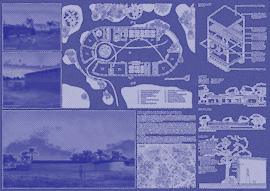

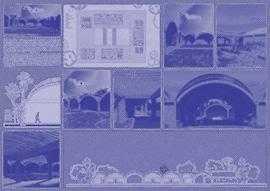

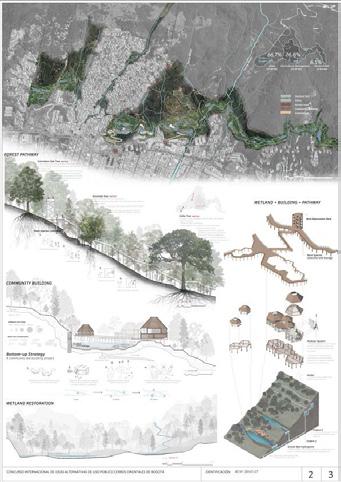

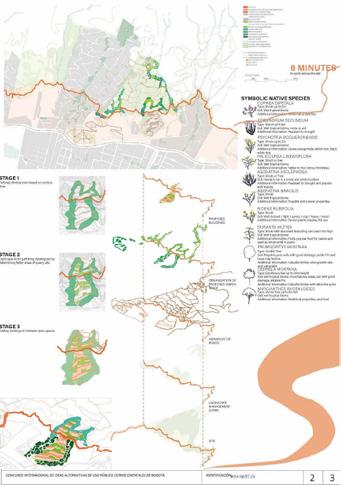

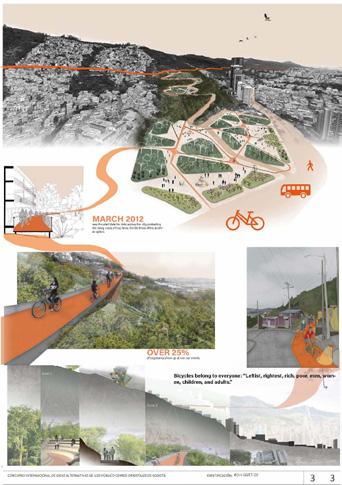

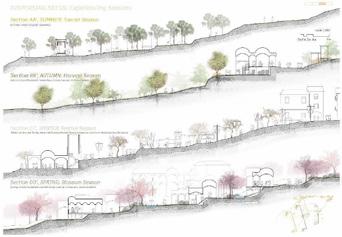

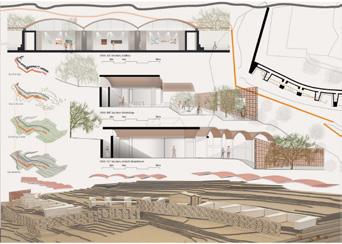

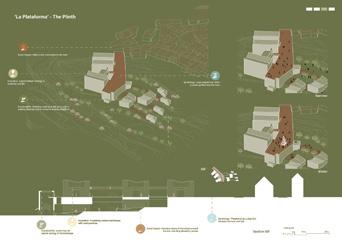

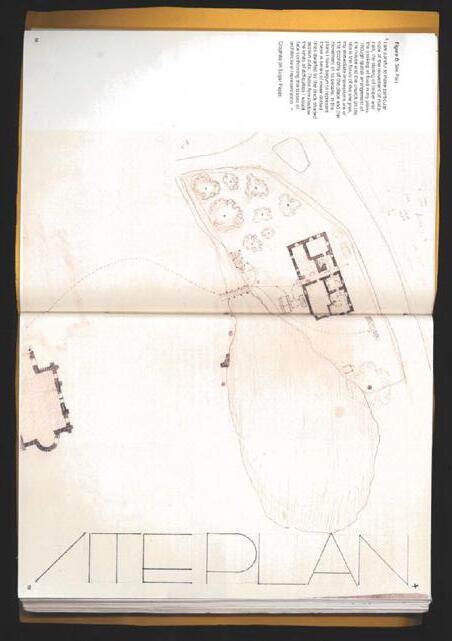

Within this unit, students take part in two International Architectural Ideas Competitions. This offers students a platform to immerse in pressing international debates beyond academia. We aim at developing shared strategies across two distinct foreign contexts. The first competition seeks to identify methods to redefine and environmentally protect the urbanrural diffuse border of the Eastern Mountains of Bogotá, Colombia, in a context of overpopulation and intense human activity. The second competition seeks to tackle the phenomenon of rural depopulation by developing a sustainable artists’ residence and educational complex that celebrates Gaudi’s intellectual heritage in a small village of Huesca, Spain. The ethos of the unit, ‘learning from the Global South’, demonstrates that the methods developed for the first competition in Colombia can be successfully redeployed to inform the second competition in Spain, ultimately giving rise to a “body of work” that integrates multiple design arguments and formats into an intellectually consistent whole.

Conversation across two projects

1

Leon Ding, Jiayu Lu, Cassandra Yang

Allegra Keys, Ellis Shiels, Bartu Tort

Public Use Alternatives in the Easter Mountains of Bogotá Competition

2

Kevin Chen, Michael Kan, Tanya Lee, Esther Park, Kelly Tanim, Jade Wu

Humedal colectivo

3

Delan Aribigbola, Sabrina Findlay, Allegra Keys, Cristian Liu Chang, Ellis Shiels, Bartu Tort Bicilínea

Gaudi La Coma Artists’ Residences Competition

4

Kevin Chen, Michael Kan, Kelly Tanim Canopy

5

T anya Lee, Esther Park, Jade Wu

Dispersing seeds

6

Allegra Keys, Ellis Shiels, Bartu Tort Lines in the Landscape

7

Delan Aribigbola, Sabrina Findlay, Cristian Liu Chang Plataforma

Contributors

Helena Rivera

Review Critics

Moa Carlsson

Iván Márquez Muñoz

Ralf Merten Modolell

Laura Miani

092 arch. design explorations competition studio

093 ba/ma<hons> 3*1 2 1

094 4 3 arch. design explorations competition studio

095 ba/ma<hons> 3*1 5 6 7 8

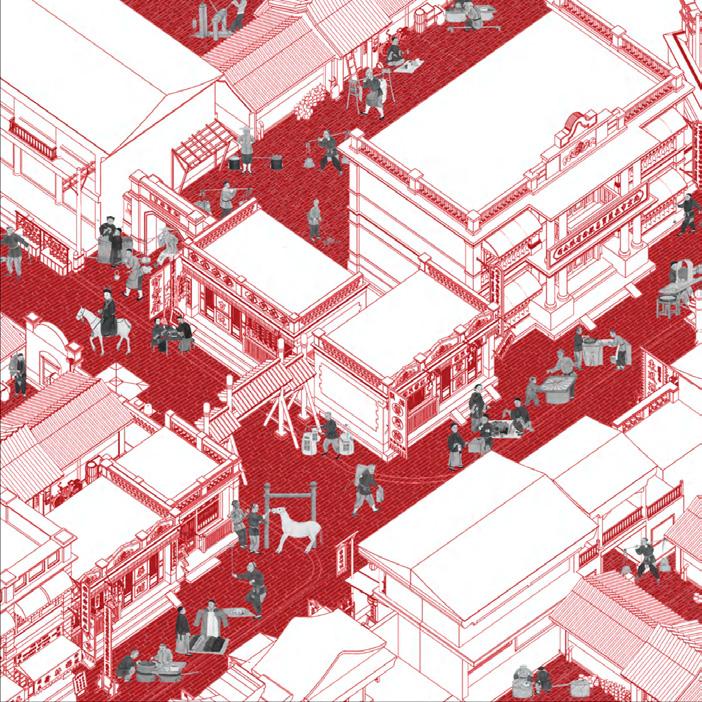

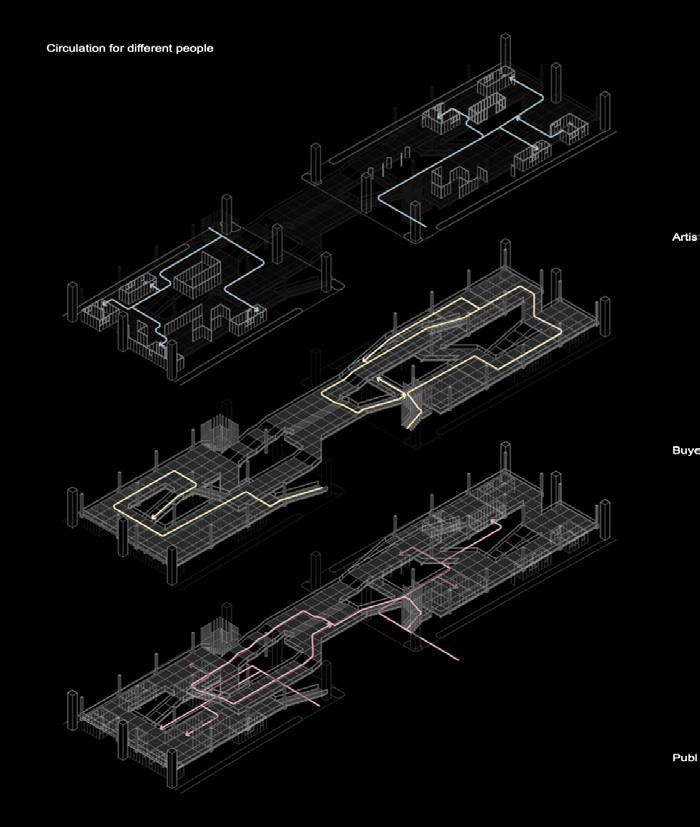

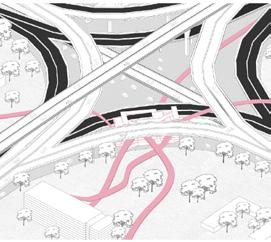

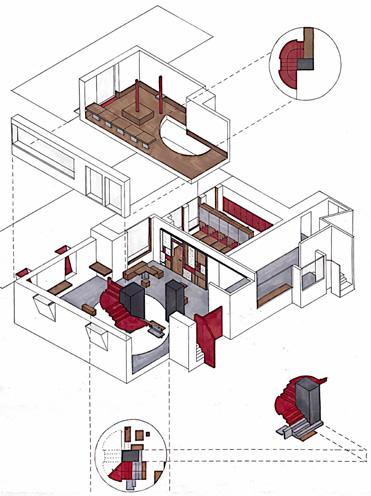

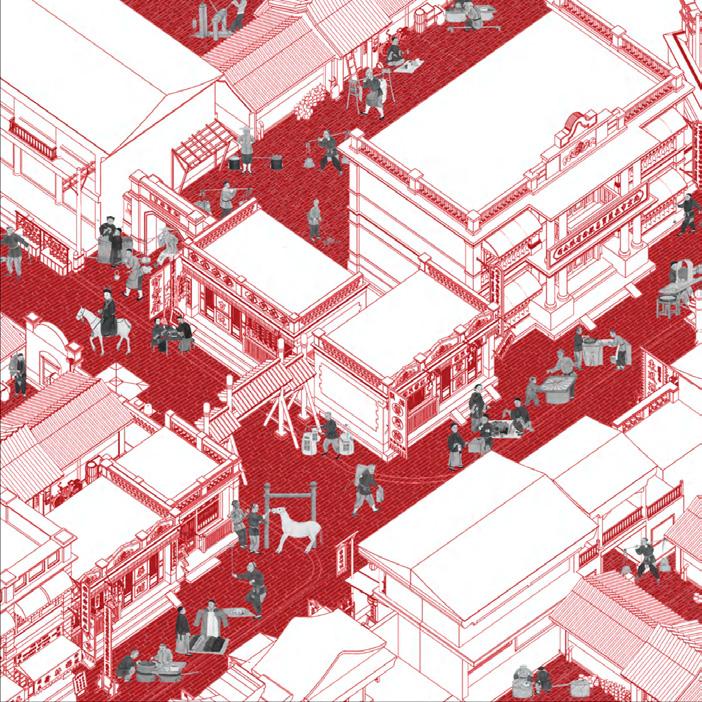

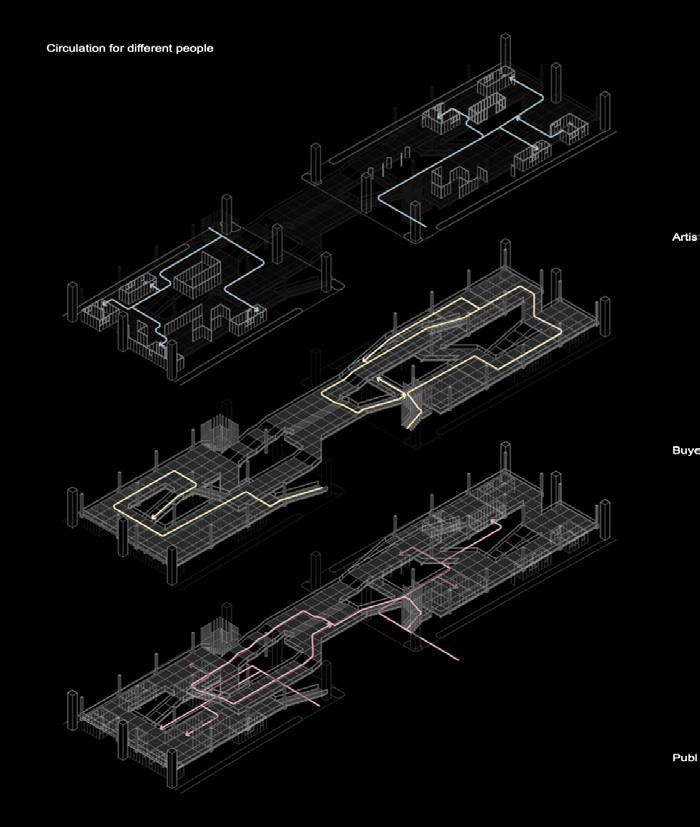

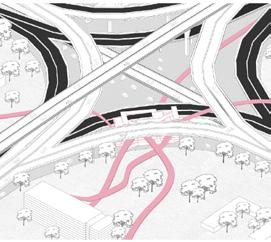

unit 4 cryptoarchitecture building on trust

1

Meihan Liu, Jiayi Liu,Eloise Zha

LWAL

2

Jingzhi He, Ruoxin Tan, Jiahui Zhao Ghost Market

3

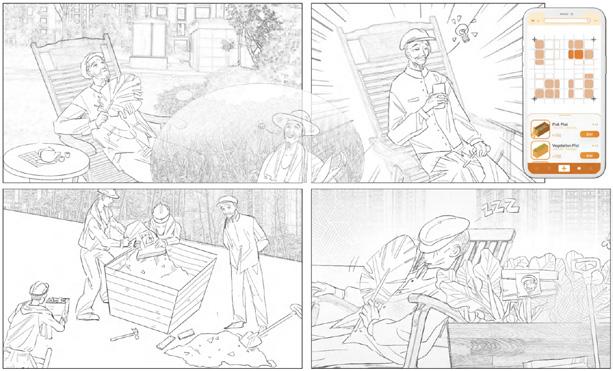

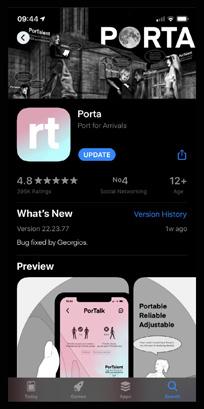

Ksenia Bobyleva, Kaiwen Chen, Ece Kantemir Porta

Studio Leaders

Yorgos Berdos, Andy Summers

Blockchain and smart contract applications are drawing a lot of attention, with an accelerating pace and promise to change the way we exchange, store information and trust each other. One of their main features is that they move the crowd from being the source of supply to being the intermediary who runs and owns the market itself. Despite their recent popularity, the possible spatial expressions of these relatively new technologies remains widely unexplored. But how can these technologies be viewed in an architectural or even spatial and physical context? Unit 4 explored ways in which blockchain and distributed ledger technologies in general may impact the ways we produce, reproduce, and think about architectural design across different scales.

Contributors

Julia Baeck

Sasha Belitskaja

Theo Dounas

Alexander Grasser

Wang Hongyang

096 cryptoarchitecture

arch. design explorations

097 ba/ma<hons> 3*1 1

098 cryptoarchitecture arch. design explorations 2

099 ba/ma<hons> 3 3*1

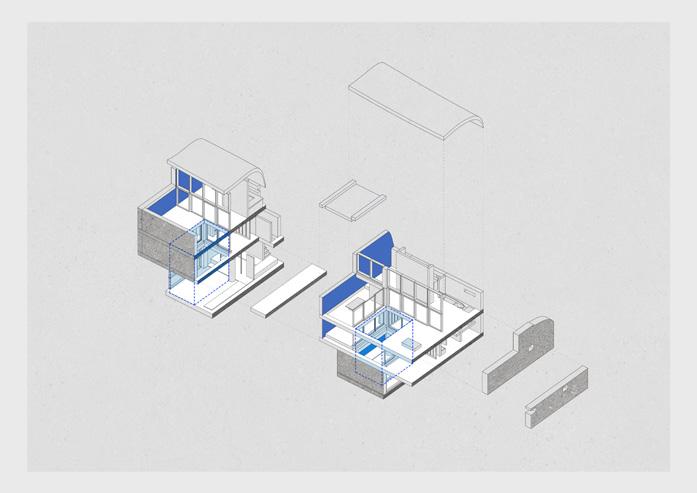

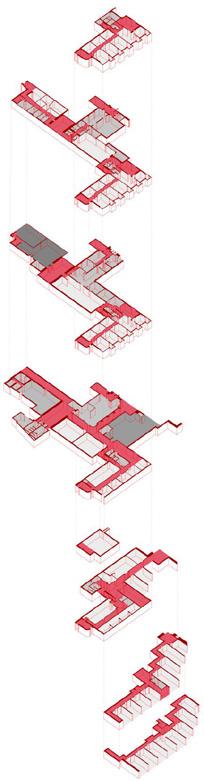

unit 5 metamorphosis

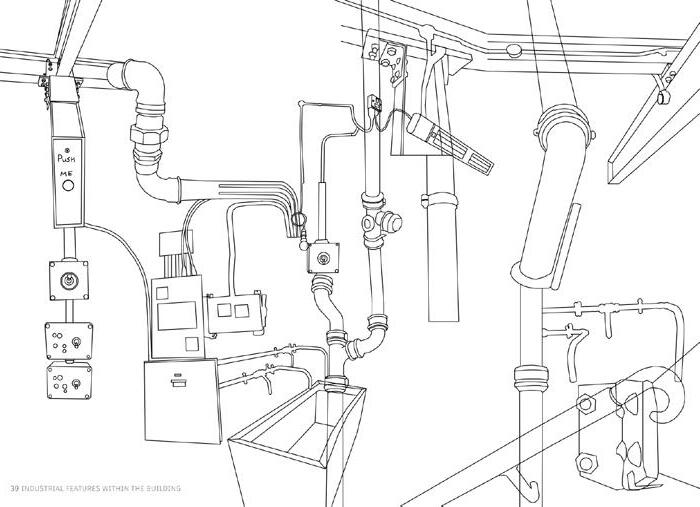

1

Jessica Hindle, Lucy Hobman, Sofie McClure

The Biscuit Factory

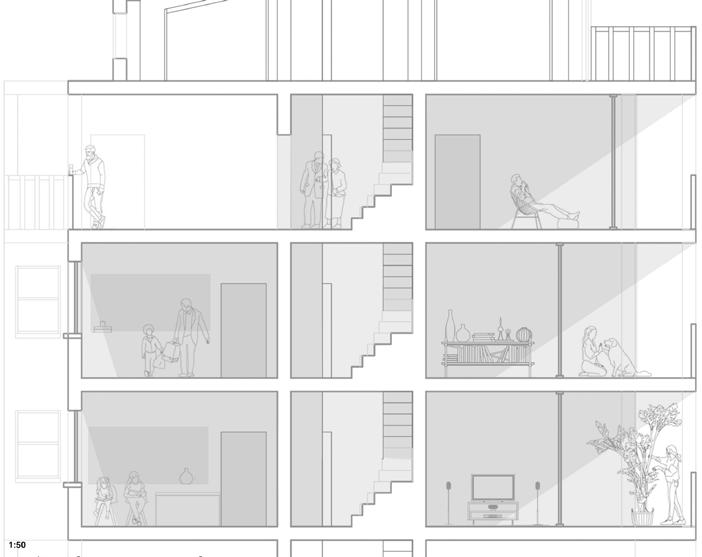

2

Beatriz Herrera, Natalia Rutkovska, Harry Wood Edinburgh College of Art Architecture Building

3

James Armstrong

33–49 Giles Street

4

James Armstrong, Daniel Pratt, Cameron Whitelaw 33–49 Giles Street

Studio Leaders

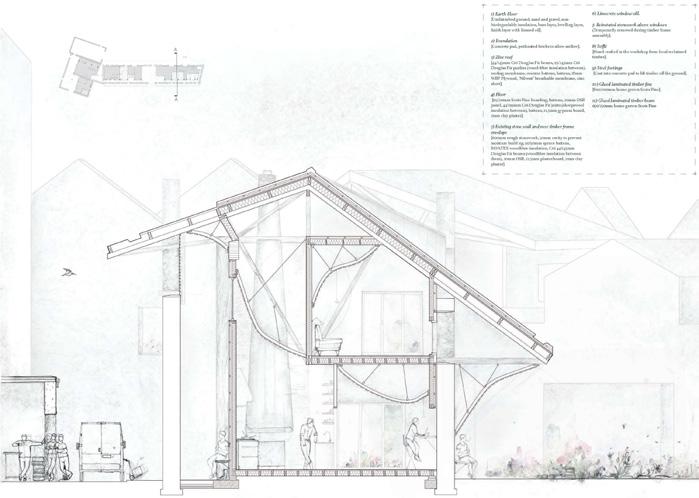

Pilar Perez del Real, Georgina Allison

Unit 5 aimed to help students understand the importance of transforming and reusing the existing built environment to adapt it to current standards and new functions while dramatically reducing the environmental footprint of older, energy-inefficient buildings. To support the path to meeting net-zero carbon targets, we imagined new possibilities and explored approaches for the reactivation of different buildings in order to extend their life and upgrade their performance. If we live in a world with finite resources, how can we create a future that is restorative and regenerative? In this unit, we explored three interlinked strategies: retrofit (to minimize the impact of the construction industry, and to promote the adaptive reuse of buildings); adaption (also considering climate change and the accompanying increase in frequency of so-called ‘exceptional climatic events’); and reuse (we adopted circular-economy principles to decouple construction activity from the consumption of resources).

Contributors

Calum Duncan

Review Critics

David Byrne

Alex Liddell

David Seel

100 metamorphosis

arch. design explorations

101 ba/ma<hons> 3*1 1

102 metamorphosis arch. design explorations 2

103 ba/ma<hons> 3*1 4 3

unit 6 lines in the landscape hedgerow

habitats

1 Freya Wang, Yulin Yang, Dorothy Zhao Foraging School

2

Reece Tsa, Alicia Gerhardstein, Tom Peng Mushroom Farm

3 Elizabeth Xu, Harvey James-Bull, Robbie Witchell Culross Community Preservation

4 Jasmine Yang, Eurus Feng, Jena Hwang Pickling Production

Studio Leaders

Andrea Faed, Thomas Woodcock

Through encouraging biodiversity – a variety of plant and animal life – Unit 6 explored, at the micro-scale, hedgerows, lines in the landscape, typically rich in biodiversity, and looked at what habitats were created from the spaces we leave behind.

Hedgerows accommodate shelter, perches, homes, and provide food sources. They provide a vantage point for birds, navigation beacons to bats, sunlight protection to plants, cover for mammals, footholds for introduced vegetation. They also act as habitat corridors, helping animals to travel through open farmland while staying under cover. They vary in structure and thickness, sometimes planted in two rows with a path in the centre. In Dorset they can be up to 4m thick and in Devon, hedgerows can include turf held up off the ground in hessian sacks. Hedgerows also create wind shadows - they slow the wind down for a distance five times the height of the hedge.

Variations in hedgerows’ physical make-up was researched and surveyed across territories and recorded in drawings and models. In the essence of the hedgerow, a Community Food Store was designed.

Contributors

Ted Swift

Maich Swift Architects

Margaret Stewart

Review Critics

Andrew Brooks

Kate Carter

Suzanne Ewing

Rachael Hallett Scott

104 lines in the l.scape

arch. design explorations

ba/ma<hons> 1

106 lines in the l.scape arch. design explorations 2

107 ba/ma<hons> 3*1 4 3

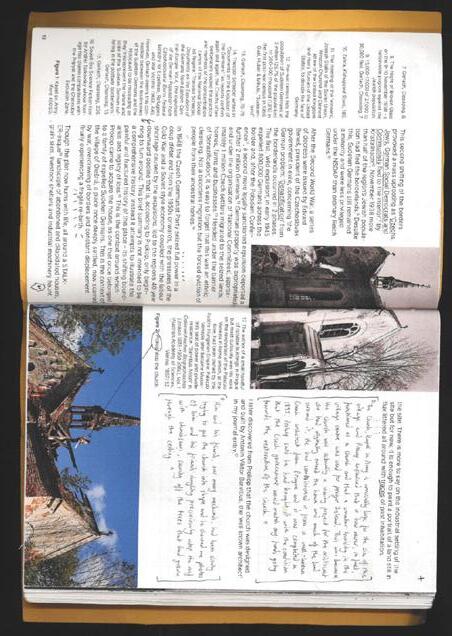

architectural theory

Disembodied Architecture

Emma Astley Birtwistle Week 4 Journal Entry

Over 15% of the world’s population live with various degrees of disabilities, struggling to live in the hostile and exclusive environment that our built fabric presents.1 This journal investigates the innate problem integrated in both our architectural past and present, presenting a new motive which challenges ‘ableism,’ and what theorist Sara Hendren terms ‘normalcy,’ calling for a new directive centred towards inclusive design. Throughout history, space has been characterised by dominant values of a standardised conventional body type. As explained by theorist Robert McAnulty, in both classical art and architectural aesthetics, the unified body of the Vitruvian man became an appropriated model, so buildings could replicate harmony and order. 2 However, this only extended an estrangement of disabled bodies to the built environment. First hand, I have witnessed the struggle exclusive design can cause. My grandfather was wheel bound for 15 years of his life, struggling to keep up with the standardised ergonomic living of his Edwardian house. Subsequent elements of the property were changed and retrofitted, from the installation of a lift to handrails and temporary ramps. Nevertheless, if the buildings design had simply addressed the potential needs of all occupants, his daily struggle would have been significantly reduced. Undoubtedly, the profession must clearly undergo a systematic critique of ideals held by architectural theories and practices, sensitising architects to reconnect with physical and social concerns.

Furthermore, this subjugating architectural style can further be traced to the theory supporting modernist architect Le Corbusier. His conception of space was built on a narrative of the ‘Modular man’ and principles which generalised bodily forms.3 Although, on analysis, despite marginalising minority groups within his standardisation, Corbusier does address the average capabilities of our population. After all, without set architectural guidance, do the possibilities of design not remain limitless? Nonetheless, architect Rem Koolhaas revolutionises Corbusier’s exclusive and oppressive architectural perspective in the construction of Maison de Bordeaux, France (1998). Designed for a client confined to a wheelchair, the houses’ innovative design creates a spatial structure allowing for a multiplicity of choices for pedestrian movement, with a central lift connecting three-floors.4 Thus, with Koolhaas establishing a greater programmatic dynamism, design becomes emancipating, as presented in Jos Boy’s ‘Disordinary Architecture Project,’ commencing a cultural shift.5

Architecture of Disabilities calls for radical reorientation. A demystification of inherent assumptions of ‘normalcy’ which underpin recent contemporary architectural thought, to situate experiences of impairment as a new foundation for the built environment. Fundamentally, with our countries ageing population of rapidly changing needs and desire, our future relies on inclusive design, embodying new theories and forms to incite a liberation from the societal marginalisation of the disabled.

Course Organiser

Moa Carlsson

This course explores the relationship between theory and architecture. Exploring various forms of architectural theory—such as essays, lectures, books, case studies, films and other media—students developed skills to read, reflect upon, critique and discuss architectural theory, and means to apply theoretical knowledge to real world situations. This involved close reading of texts from within and outside of the discipline of architecture. We also analysed a range of case studies to better understand how theory can challenge assumptions and offer new ways of thinking about key problems. Through reading, writing and group discussions, we explored different ways of thinking about architecture in a range of geographic, social, political, historical and material contexts.

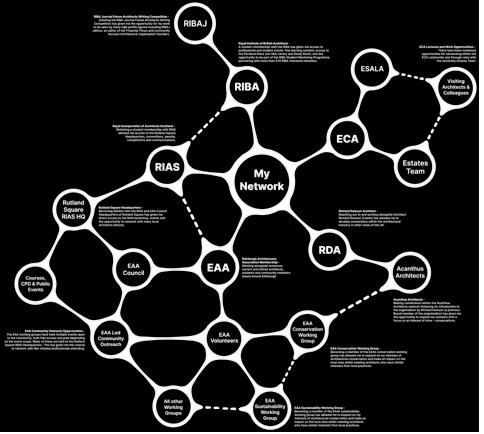

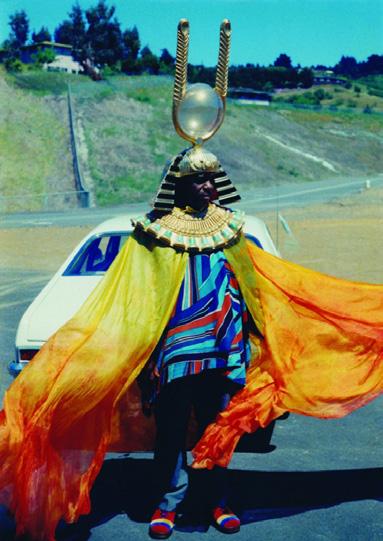

The eleven weekly modules involved thematic explorations of architectural discourse and practice, and sample different strands of architectural and critical theory, including theories of the environment, critical disability theory, modernism, postmodernism, new materialism, decoloniality, critical race theory, information theory and more. We made a class visit to the Pianodome in Leith, and had a private screening of the documentary ‘Scotland, Slavery & Statues’ (BBC/Urquhart Media 2020).

Journal Entry

References

1 Sara Hendren

What Can a Body Do?

How We Meet the Built World

2 Robert McAnulty

“Body troubles,” in Strategies in Architectural Thinking

3 Le Corbusier

Modular I and II

4 Kim Dovey, Scott Dickson

Architecture and Freedom?