INTRODUCTION

ESALA LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE STAFF

MA (HONS) LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

MLA IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

EUROPEAN MASTERS IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

ESALA LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE STAFF

MA (HONS) LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

MLA IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

EUROPEAN MASTERS IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Welcome to the 2023-24 edition of the ESALA Landscape Architecture Programmes catalogue, which weaves together students’ work from across our three Landscape Institute accredited professional programmes:

MA in Landscape Architecture

MLA in Landscape Architecture

European Masters in Landscape Architecture

Landscapes are complex entities. They sustain us. They are powerful sensory spaces we dwell within or simply traverse. They are also the site of some of the most pressing challenges of our times. The question of how to design landscapes placefully, timefully and carefully in a climate and biodiversity crisis is central to our programmes. The work displayed in this catalogue reflects the students search for an answer to this question, each in their own unique and original way.

Their trajectory with us culminates in a research-led design course that seeds the opportunity for final year students to critically position themselves as soon-to-be Landscape Architects through a distinctive design proposal. The course is infused with a thinking-through-making ethos and landscape representation is used as an apparatus to delve deep into the geomorphological, ecological and cultural dimensions of unique places from which the projects grow:

The Critical Zone studio explores the geodiversity of the Highland Boundary Fault in Scotland. Interdimensional readings taking into account social and environmental fractures, points of tension and upheaval, have enabled students to define their own zones in need of critical attention, care and action.

The Quiet Places studio is a speculative research expedition into the Vatnajökull Glacier in Iceland – a complex landscape tied into multi-scalar earthly systems, and quickly disappearing due to Global Warming.

The work that surfaced from these studio units is distinctive, multi-layered and explorative. It offers exciting avenues for futures where a cohabitation between humans and other beings in rich living landscapes is still possible.

Many congratulations to all our graduates! The Landscape Architecture staff.

RUBY BANNING

XINYANG (EMILY) DU

ALICE FUTTER

CAMERON HARTLEY

ABIGAIL LANE

ELEANOR NIELSEN

ANJALI SAVANSUKHA

YUQING (JENNY) WANG

XINLING (AURORA) YU JUN

Designing along contentious boundaries, such as the dynamic cliff landscapes of Stonehaven’s coast, requires considerations beyond aesthetics to address the impacts on those who encounter the ever-changing and somewhat dangerous landscape. Inspired by the Isle of Arran Geopark on the westernmost point of the Highland Boundary Fault, this project responds to the criticism that Geoparks often exist in isolation by integrating with Scotland’s wider aims for economic growth in the coming decades.

The Geopark Pilot project transcends its role as a mere preservation and education tool; it endeavours to craft a new landscape that authentically reflects the unique context of its surroundings. This entails a blend of ecological diversification, sustainable tourism development, and community involvement. It takes viewers on a journey through deep time narratives and the awe-inspiring coastal sublime, intertwining ecological diversity with captivating human perspectives. Grounded in its context, the design aims to work directly with local residents to produce sculpture for recreation areas and incorporate new residents sustainably, forging meaningful connections with all who engage with it. Currently, the human-made elements of this landscape are succumbing to heavy weathering and erosion, which gives the impression that we are working against the natural processes and failing. By proposing a phased approach which has intended circumstances for rewilding, and by introducing different pathways which can withstand erosion or work alongside it, this design acts as an open-ended project which invites the landscape as being in a constant state of flux.

The graduating year has underscored the importance of directly responding to a place’s context, not only in the final output but also throughout the design process. Complex, dynamic sites demand a nuanced approach, necessitating detailed inventory and alternation through scales and perspectives to identify what truly matters and understand how it will evolve over time under the influence of dynamic systems.

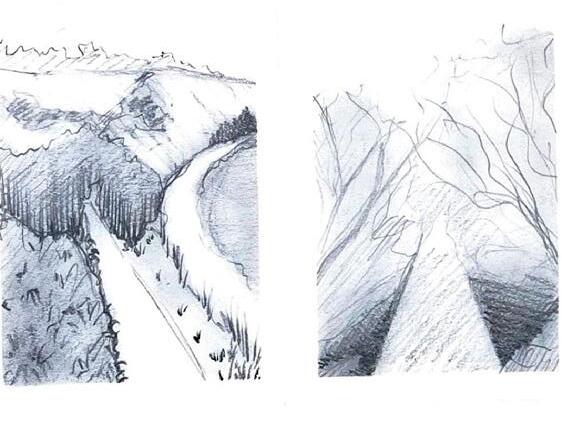

Opposite: Isle of Arran Coastal Zones Inventory (Ruby Banning), Course: Critical Zones 4A, 2023. Drawn from an image of my plaster model, this sketch collates intertidal elements, it’s terrestrial hinterland and the human inprint on the landscape to inform discourse about how to go around designing an area of complicated interfaces.

Below: Final visual sketch for Mineralwell Park (Ruby Banning), Course: Critical Zones 4A, 2023.

Above: Cliff-walk storyboard process drawing (Ruby

Course: Critical

2024. Proposals through the lens of the eye-level existing, aim to create a rhythm of design constants mixed with unique experiences evoke a feeling of moving through different portals, all of which reflect the underlying Geology of the Highland Boundary Fault Complex.

Below: Final visual (Ruby Banning), Course: Critical Zones 4B, 2024. Showing reflection pool with receding headlands and bays behind, coastal procsses and the colours reflective of the old red sandstone and igneous rocks of this specific site.

Middle:

At the point of installation, shallow water reflecting people, their surroundings, wind conditions and the tidal processes when it is fully in and the ocean spray can be seen efffecting it’s surface.

Bottom:

on (Ruby

4B, 2024. Now the empty ‘pool’ reflects the erosion which is constantly shaping the cliff landscape; jumping the main walkway back from the high tide mark ensures its accessibility for many more years, existing is rapidly being worn away.

XINYANG (EMILY) DU

Looking across deep timeframes and human culture, documents of human connection and landscapes have been created in a variety of formats. Landscape, as a direct device, captures glimpses of timeless history. This project investigates the Svinafellsjökull pro-glacial area and employs the unique glacial moraine topography to archive the process of geological change and provide a sheltering harbour for both local habitats with further ecological succession. Human gathering spaces facilitate the observation of landscape transformations and enable a physical integration into the history of Vatnajökull, contributing to the creation of new eco-cultural landscapes.

This project aims to record moments in the ever-changing landscape by focusing on regions affected by the Svínafellsjökull retreat, including the proglacial lake, glacial river Svínafellsá, and the moraine which formed an exclusive bowl-shaped edge. Working with the existing topographical features, three gathering points are selected within the design area, each with unique characteristics and opportunities to establish a distinctive mini-ecosystem in strategies for preserving a pro-glacial water system caused by evaporation and obstructed groundwater streams. The spherical form design of amphitheatres allows mosses, dwarf shrubs, and birch forests to flourish as lakes and rivers expand, providing human travel within the corridor of gathering places to contemplate and sense through the journey of lagoon transition, the journey of glacial history, the current condition in various time spots, and future interpretation of the post-glacial retreat while bringing the intention of non-human (vegetation and animal) activities alongside.

As the site ecology evolves and interventions are implemented, the local community will have the opportunity to document and observe the successes and challenges of the project. This interaction between visitors and locals will enhance a grounded understanding from both human and cultural perspectives, enriching the experience for all involved.

Below:

Our Future with Fungi is a project rooted in regenerative landscape practices centred around soil and fungi. The project consists of a large, expansive soil exploration testing site composed of six individual interventions of innovation and disruption: A staged Oil Spill, Biofuel Test Fields, Pesticide Test Fields, Community Mushroom Farm and a Coffee Ground Recycling Farm and a

These interventions are titled as such due to their radical and different approach to dealing with global issues such as pollution and intensive farming practices. They are situated within the Dumbrae Estate, Bridge of Allan, Stirling which is currently owned by the University of Edinburgh with existing re-forestation plans in progress.

This exploratory landscape is designed to educate and encourage generations of landscape professions to develop sustainable, less harmful practices to teach to others. Therefore, stewardship is key for this landscape to operate. An educational program has been designed to act as an outreach scheme to continually hire volunteers, ecologists, and mycologists and gain the attention of educational institutions within the local area and further a-field.

The process of mycoremediation

1 A mass of polluted soil is moved into testing fields

2 The polluted soil is inoculated with Pleurotus Ostreatus (Oyster Mushroom)

3 The mycelium network of the Oyster Mushroom settles and begins to fruit, starting the process of mycoremediation

4 After approximately 16 weeks pollutants are reduced to less than -200 ppm

5 After approximately 1 year, the soil is restored and ecosystems start to regenerate.

Above: Axonometric Soil Visualisation (Alice Futter), Course: MA4 Critical Zones, 2024.

Below: Community Mushroom Hub (Alice Futter), Course: MA4 Critical Zones, 2024.

Below:

The ever-increasing threat of climate change requires landscape professions to act fast in producing sustainable techniques to aid the caring for our dying planet. Entangled Landscape: Our future with fungi acts as a radical design president to demonstrate methods in which landscape professions from around the world can learn and then educate future generations on methods in which fungi and soil can work together to help save our planet.

Opposite: 1:1 Soil and Mushroom Interpretive Model (Alice Futter), Course: MA4 Critical Zones, 2024. Below: 1:1 Soil and Mushroom Interpretive Model (Alice Futter), Course: MA4 Critical Zones, 2024.

Reforming Rural Margins centres around the specific landscape typology that exists in much of the UK at the boundary between upland hills and lowland arable agriculture. Here, the reliance on subsidies and the struggle that upland farmers face in the current economy have culminated in a growing myriad of concerns for the future of this landscape and the deeply rooted traditional aspects of the unique and multi-generational culture.

The focus, in terms of landscape interventions, critically examines field, ownership and habitat margins whilst specifically taking note of the rigid, straight-line boundaries that have been in place on the site since maps were first drawn here. Further driven by the recent devastating floods in Angus in September, reforming these margins primarily considered management surrounding the burns, the almost tree-barren landscape, and how surface run-off might be slowed to increase infiltration and reduce the flood risk further downstream in larger settlements. Conjointly, the spatial configuration of these margins was considered through the eyes of more than humans with both the UK biodiversity crisis and the potential that hedgerows hold in supporting a manifold of species. Moreover, these planted margins hold numerous benefits for not just the farmer but generations of farmers to come through consideration of a changing climate and preparation for predicted effects.

At the farm scale, these two drivers were considered alongside the social dynamics of how farmers would collaborate across private land boundaries to implement any territorial-scale interventions through a new subsidy scheme. Ultimately, with the main goal of forming the foundations to galvanize rural communities to aid in a future with less globally imported food, sustainable changing farming patterns and a reliance on soil vitality.

The Highland Border Complex, where the Highlands meet the Lowlands, is a major geological boundary marked by vast topography extrusions within the Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park. From Conic Hill to Menteith Hills, the site is defined by this fault line. Between these two high points, the land is dominated by a large conifer plantation. These planted forests are mono-species with restrictive planting systems and have harsh management practices designed to increase the yield of timber production solely. Sadly, this anthropogenic exploitation results in the continued loss and extinction of wildlife and biodiversity.

The priority of the project is to transform the once-barren conifer plantation into a haven for wildlife and plant communities through assisted natural regeneration. Therefore the main design intervention consists of thinning and clearing the plantation which manipulates light and shade as well as protecting the vegetation and wildlife. Ultimately, this is breaking down the structure of conifer plantations.

A bold proposal which would inevitably be reversed if everyday people were not involved. Humans have significant control over nature’s survival and this project depends on the decided protection of humans. Enjoyment, approval and human gain ensure this protection. In which case, a long-distance walking route was designed to invite people to experience the changing nature and learn about the past and future of the site as they walk along the Highland Boundary Fault Line.

This walk takes you from exposed vantage points on Conic Hill and Menteith Hills into the transformed conifer plantation. Careful consideration was given to reducing the impact of introducing people potentially disturbing the evolving vegetation and thriving wildlife to protect the natural regeneration process.

This project spans a timescale of 150 years into the future, where a conifer plantation has been completely changed from the current exploitative situation to one where we celebrate and preserve the astonishing ability of nature.

Opposite: Proposal Viewpoint from Menteith Hills, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park (Abigail Lane), Course: MA Landscape Architecture, 2024.

Below: Underneath the Tree Canopy (Abigail Lane), Course: MA Landscape Architecture, 2024. Detailed Design plan of path system within evolving conifer plantation.

Above: Quarry Proposal Layered Drawing (Abigail Lane), Course: MA Landscape Architecture, 2024.

Below: Transition into the Forest Layered Drawing (Abigail Lane ), Course: MA Landscape Architecture, 2024.

Opposite: Forest Interior Layered Drawing (Abigail Lane), Course: MA Landscape Architecture, 2024.

ELEANOR NIELSEN

Land ownership in Scotland is the most unequal in the western world. With only 432 landowners, owning half of all Scotland’s rural land. This is mainly due to wealthy businesses buying land to plant trees on to help with their carbon offsetting, in the hope to reach the target of becoming carbon net zero. This creates problems for the local communities and tenant farmers working the land, as they lose their sense of place and livelihoods.

This project is centered around the Drumbrae estate. Land that has recently been bought by the University of Edinburgh with the aim to improve their carbon footprint, but and how right is it that land from Stirling is being used to carbon offset the University of Edinburgh. Planting this landscape with trees has its obvious benefits but what if there was a more productive use for the landscape. Throughout the project ways to create a more productive landscape, while still creating benefits for carbon offsetting the local area are explored.

This design proposes a rotational landscape that looks to create a system whereby agriculture, the environment, and people can work together with the aim of improving biodiversity of the site, as well as creating an education experience for people to learn about farming and the food production processes around them.

Years

16. 20 Years 17. 30 Years 18. 40 Years

Above: Landscape Visualisation in 0 years (Eleanor Nielsen), Course: Critical Zones – The Highland Boundary Fault, 2024.

Below: Landscape Visualisation in 10 years (Eleanor Nielsen), Course: Critical Zones – The Highland Boundary Fault, 2024.

Above: Landscape Visualisation in 5 years (Eleanor Nielsen), Course: Critical Zones – The Highland Boundary Fault, 2024.

Below: Landscape Visualisation in 25 years (Eleanor Nielsen), Course: Critical Zones – The Highland Boundary Fault, 2024.

As we find ourselves at this critical juncture in the ecological crisis, we are forced to watch as the effects of capitalogenic climate change unravel before our eyes. Watching calved icebergs melting at Hoffellsjökull was a really strange experience, convincing me of Timothy Morton’s (2016) Möbius strip analogy- We are hyper-aware that we ourselves are the monsters we must face. I wonder if world-building and myth-making practices can offer ways forward, and help us as a collective to chart uncertainty.

In her book “Staying with the trouble,” (2016) Post-modern guru Donna Haraway expresses the value of what she calls ‘Speculative Fabulation.’ She frames storytelling as an invaluable tool for rethinking ecological crises, and our place in the world.

Taking inspiraton from Haraway, in my final year project I experiment with the idea of stories as seeds that could germinate into pragmatic design solutions.

My ‘landscape laboratory’ at Hoffellsjökull takes the shape of a stage for performances to unfold over time. On this stage, human actors are able to realise a deeper ecological awareness, which, as physicist Fritjof Capra proposes, is intrinsically tied to greater spiritual awareness. Humans and more than human communities test out ideas related to microclimate and ecological succession, and protest climate injustice through activist design interventions against the powerful backdrop of a melting landscape.

This project aims to reestablish the connectivity between local residents and the soil that was brutally exploited by traditional productive activities along the Highland Boundary Fault. By converting the former Airlie Estate into a Land Exhibition Center, it presents farmers and land owners locally and around the world who are struggling to find a use of their land under the stress of climate change and extreme weather events, such as drought, intensive flooding and temperature rising, a new opportunity for their land to carry out sustainable economic activities.

The site is established under the influence of design interventions, existing natural dynamic systems, and potentially intensifying climate threats. The leading concept is to design and plan a starting point to allow local farmers to experiment with ways to celebrate, adapt to, and work with existing natural systems and rapidly changing climatic situations. It encourages solutions through natural water management, soil solutions and natural regeneration. While the experiment runs, opening up the place to the public as an exhibition and educational site will allow us to present and share knowledge with the world.

The exhibition center provides visitors the opportunity to experience a variety of land systems, including: the Rewetted floodplain, the Hybrid Forest, the Flooded home farm, and the Future farmland. Each area represents and showcases experimental sustainable land use activities that maximize economic productivity and biodiversity, aiming to explore our position as humans under current stress.

A Visitor’s Experimenting Center, located in the middle of the Exhibition Center, breathes new life into the existing historical landscape and bridges history with the future; facilitating a place for visitors to observe and experience the experimental activities closely.

Opposite: The Land Exhibition centre masterplan (Yuqing Wang), Course: Landscape Architecture MA, Year 4. 1:5000 Masterplan of the proposed Exhibition Centre.

Below: Visitors’ Experiment Centre (Yuqing Wang), Course: Landscape Architecture MA, Year 4. Repurposed Historical garden as a proposed visitors’ centre showcasing key land experiments happening in the exhibition centre.

the extent of pollution in the existing Cortachy home farm.

experimental land, allowing flood to take control of the previous home farm along

minimal remediation intervention.

Bottom: Bioremediation study structure

4. An educational structure in the Vistors’ Experiment centre, allowing people to observe and engage with the experiment closely.

Höfn is a fishing town located in the southeast fjord of Iceland with just over 2000 people. The place has captured my interest due to its unique climate challenges. The melting glaciers in the region are leading to an unusual phenomenon – the rising of the land at a rate of 1.7 cm per year. This is affecting the most important industry in Höfn, which is the fishery, as the shipping channel is becoming shallower. The situation is worsening due to glacier deposit transportation and tidal sedimentation. Höfn experienced significant development since 2010, largely benefiting from the popularity of glacier tourism in Iceland. However, due to the accelerated melting of glaciers, the glacier is now moving backward and Höfn can no longer depend on glacier tourism as it has been. Therefore, it is crucial for Höfn to develop new strategies for future development, as the town’s progress is closely intertwined with climate change.

M. Jackson, a glaciologist, spent several years in Höfn studying the community living with glaciers. She pointed out the gap between glacier scientific research and the cultural identity of glacier residents. While scientific research is critical, the ice also deeply impacts social, political, and cultural processes. She also criticized the mono-storyline narratives towards glacier-related communities and asserted that the glacier is not the only story. Based on her argument, I believe that the story should be more complex, giving Icelandic people enough space to telling own stories about the changing environment, as Jackson encouraged Icelanders to see the glacier landscape change as their “changing backyards”.

JUN ZENG

This landscape project in Hofn, Iceland, is designed to address various soil issues in the area, particularly the degradation of farmland soil due to overgrazing and the deterioration of surrounding wetlands. Considering the scarcity and fragility of Icelandic soil, project decides to create a soil lab to help with soil problems.

The initiative aims to restore degraded lands by establishing a soil laboratory next to the airport in an area dense with agricultural activities. The laboratory conducts soil research and protection measures. Landscape designers have utilized rammed earth technology to design the walls of the laboratory, integrating the building’s appearance with the soil environment and creating an interactive landscape that fosters engagement between people and the lab, as well as the surrounding environment. This site serves both as a workspace for staff and a learning venue for visitors. There are places and activities in the lab for community to use, learn and share knowledges/outcomes they gain from the soil lab. It will serve as place for daily outdoor activities as well.

The appearance, layout, and functional choices of the laboratory all consider the natural climatic conditions of Hofn. Wind is a significant factor in the design: outdoor activity spaces are surrounded by buildings to reduce wind impact.

Above: Soil Lab Detailed Plan 1:500(Jun Zeng), Course: Design 4B, 2024. A3, Pen. Opposite: Soil Lab Outside Area Isometric 1:200 (Jun Zeng), Course: Design 4B, 2024. The drawing shows how people use the outdoor area during ‘Soil Festival’. There are two areas, left outside area is place for activities and festival use, right area is a place to feel the wind. A4, pen.

Local soil materials, mixed with clay and sand, are used to create rammed earth. This design is not only environmentally friendly but also reflects the local characteristics. The laboratory has two floors and features an interactive corridor that allows people to engage with both the interior and exterior of the building.

Opposite: Rammed Earth Wall 1: 20- Soil Lab (Jun Zeng), Course: Design 4B, 2024. The Drawing shows the design idea of the Soil Lab’ Building Material, I was inspired by the windy climate in Hofn, to create ‘windy’ walls use Rammed Earth techneque to the appearence of the soil lab, collecting soils from Hofn, to make a waving wall. A4, pen, acrylic, charcoal. 195cm*250cm, pen, acrylic.

Below: West-Facing Wall-A corridor from the Soil Lab (Jun Zeng), Course: Design 4B, 2024. The drawing reveals different experience created by different user groups, people interract with the wall, there is also an area for children. When designing the corridor, I draw the section of it to scale, work between plan and section, this way make me think about the whole space carefully. 1m*0.25m, pen, acrylic.

The design also includes an outdoor “Windy Feeling” area, equipped with platforms for sitting, standing, and lying down, facing a Wind Garden. Observating nature led me to plan a garden that incorporates elements resembling a river, areas of sparse grass for walking, with cotton plants at the visual heart of the garden. I also included windbreak plants to aid in the survival of other vegetation and added flowers and blueberries near the pathways. In designing this garden, I aimed to mimic nature, providing visual appeal while creating a beneficial microclimate.

TSZ KWOK (GORDON) CHENG

TINGTING DONG

LUISA GRASSI

YUXIN HAN

ALICE GARRETT HINDMARSH

JIONGRAN HUO

QIXIANG LAI

LINGE LI

TIANWEI LIAO

BINKUN LIU

SHARON (SHAOHUA) LIU

YIZHUO LIU

MENGFEI LUO

TIANZE LUO

HARUYUKI MIYATA

HO KWAN (LAYLA) NG

PENGJUI SHI

YI (ECHO) TANG

XINYUAN WANG

YIFAN WANG

WANQING YANG

YAWEN YANG

YIZHI ZHANG

ZHAOYUAN ZHANG

JIAJUN (KENNYS) ZOU

Under our insatiable pursuit of materialism amidst the global capitalism, our design imaginaries towards the proliferating Fourth Natures demand a critical reassessment. Abandoned to their own fate, and left to their own devices - these orphaned territories are at the precipice of a renewed biological paradigm, spearheaded from generations of extractivist industrial activities. Yet, they are often sheltered from a broader scientific understanding under terms of “derelictness”, the bountiful natural capital in place as mere shells to be eventually discarded, thought as defiled and banal to one’s experiential sensibilities. Therefore I propose an intervention in the form of a socioecological laboratory, taking place on the Wallace Craigie Mill of Dundee, a former jute preparing and spinning factory. I aim to interrogate contemporary discourses on brownfields centered around its ruinous motif as decor for a gentrifying future, instead to stage a process-oriented intervention that speculates on furtive and spontaneous inhabitations, existing in unpredictable and potentially fleeting timeframes. Participatory strategies guide the development and accessibility of these “meanwhile” sites through minimal, bodily engagements with the anthropogenic soil that allow room for a broader, unplanned series of successional ecologies, while cultivating care, ownership, or even a sense of guerilla-ship against a future, speculative series of contestations towards the industrial heritage.

Above: Choreographing dynamic system changes through “placemaking”, Course: Landscape Architecture

Design Exploration: Part 2, Critical Zones, 2023-2024.

Opposite: Multidimensional, socioecological trajectories of Fourth Nature, Course: Landscape Architecture

Design Exploration: Part 2, Critical Zones, 2023-2024.

Soils may not be as terrestrially comprehensible as the beings inhabiting it, or that tending to soil is mostly a means of producing consumerism. However they are extremely diverse, alive and nuanced matters - acting as a palimpsest of happenings above ground whose traces find its way into the matter. The evolutionary trajectory of the environment is inextricably tied to our aesthetic, moral and material priorities towards nature. Amidst the global capitalism embodied by extractivist views towards natural resources, thinking in attunement to soil can open up a design worldview that embraces the unresolved but pioneering ecologies of our future.

Opposite: Pedological diversities in forms of soil chromatographies and microscopic images, Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 1 & 2, Critical Zones, 2023-2024.

Below: Palimpsests of pedological histories unveiled through the bodily experience of pigment making, Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 1, Critical Zones, 2023.

Key:

Derelict (55.5404900, -5.3155193)

Mixed Woodland (56.1568733, -3.9164966)

Coniferous Woodland (56.0881446, -4.5352275)

Heathergrass (56.1590121, -3.9101961)

Coastal (56.984214, -2.181590)

Above: Planting Speculations, Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, Critical Zones, 2024. The ecological speculation becomes the design, or the lesson under the socioecological laboratory.

Below: Organic palimpsests framed as a series of jute manufacturing stages, Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, Critical Zones, 2024. Charting the material odyssey of the plant in ways it may be manipulated but also the wastes & byproducts that came out of it.

Key: Perforated surface drain to “reveal” the historic burn and to mimick the channeling of water

Jute and rubble soil making and mound making in the periodically accessible laboratory

Fragments of nature, edge effects and circulations

Mounted crushed rubbles as means of microclimate control, materiality leaving as is

Enhanced compost adopting jute fibres and carbonized organic materials, fabricating soils under Fourth Nature

Top: Visualizations on intersections between emergent ecologies and facilitative interventions, Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, Critical Zones, 2024.

Bottom: Organic palimpsests of cultural histories through soil making utilizing rubbles and jute textiles, Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 1, Critical Zones, 2023.

TINGTING DONG

I think my role as a landscape architect as identifying the contradictions that exist in the landscape and resolving them to maintain a sustainable ecological space that coexists between the landscape and human society. I am committed to creating better landscapes for cities and nature to co-exist in harmony. My design philosophy and practice is deeply rooted in my personal love of nature and my desire for coexisting landscapes. For me, landscape design is not only an aesthetic medium, but also a responsibility to address ecological and climatic issues and to develop sustainable ecological landscapes and biodiversity. I am committed to shaping landscape spaces with unique stories and coexistence by combining diversity, innovation and ecological sustainability.

In my project, I found through my research that the tensions in the landscape of the site are caused by a confrontational and friction-filled relationship between the existing elements (humans, wildlife and water), which I hope to transform into a better relationship - coexistence. Coexistence implies the possibility of a new model of sustainable urban development and a dynamic balance between the intertwining of human communities and nature.

Tensions stem from post-industrial pollution that affects soil and vegetation; expanding cities and active human activities that are forcing wildlife away from their former habitats; rising sea levels that are putting coastal habitats and city at risk; and flooding problems that are getting worse every year, especially endangering the historical buildings...

Above:Coexisting——Focus on the Tension (Tingting Dong), Course: Landscape Architecture Design: Terrain & Ecologies-SEM2, 2022

The urban public green space system emphasises both ecological and public benefits. Firstly, areas of existing green space with high ecological diversity are designated as reserves, where the emphasis is on building low disturbance facilities for human activities and prohibiting pet entry; and increasing green corridors in the city, i.e. optimising greenery along streets and pocket parks to improve the urban landscape while providing paths for wildlife movement in the city and between habitats;improving parks and public green spaces, and gradually transforming green spaces with low public and ecological benefits, such as golf courses, into urban green spaces that better reflect the idea of co-existing in the future.

LUISA GRASSI

75% of Iceland’s energy derives from hydropower. Whilst energy can serve many purposes, 80% of the energy produced in Iceland is used to power energy-intensive heavy industries (such as aluminium smelting).

The environmental implications of such projects are in stark contrast with Iceland’s reputation as a country that values nature and sustainability.

Reflecting on modes of energy production, the birth and death of systems, and infrastructural legacies, the aim is to explore and expose territorial transformations. By observing infrastructural and natural residues and speculating modes of deconstruction, the project wants to move away from the misguided longing for a return to nature in favor of a critical awareness.

Designing by removal, the proposal is an engineered disintegration of the Kárahnjúkar dam, perceived as the central node of the parasitic Kárahnjúkar Hydropower energy system. The action of deconstruction does not carry the arrogance of assuming a return to a ‘pre-dam state’, rather it allows the creation of a ‘laboratory of observation’ aimed at studying post-disaster ecological emergence.

Implicit within this work are questions of what qualifies as a design tool and how legislative planning can be used as an operational tool, spurring reflection on modes of production, legislation and multispecies survival within the Anthropocene.

1. Observing material interactions

2. Observing material interactions

3. Fictioning points of view

4. Fictioning points of view

5. Fictioning points of view

6. Interruption of flows: current conditions

7. Taking action: climbing the Kárahnjúkar dam

8. Detonation 9. Notches

10. New material interactions: erosion 11. Residues and reuse: sediment trap conglomerates

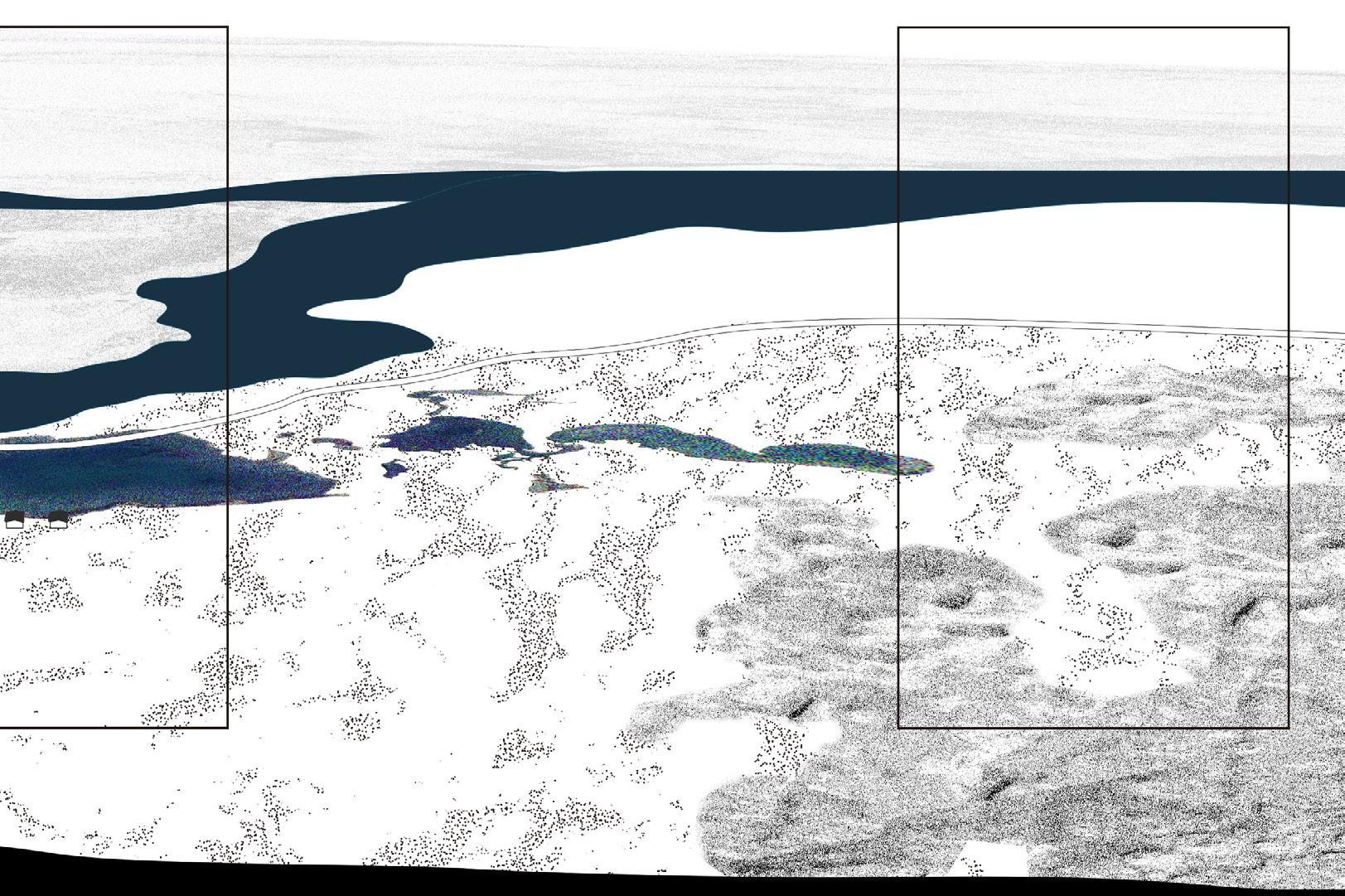

Above: Current conditions of the Jökulsá á Dal valley (Luisa Grassi), Course: MLAII Quiet Places, 2024.

Below: Laboratory of observation: speculating on species of emergence in a 50 yr timeframe (Luisa Grassi), Course: MLAII Quiet Places, 2024.

Above: Assemblages of emergence (Luisa Grassi), Course: MLAII Quiet Places, 2024.

Below: Birch forest emergence (Luisa Grassi), Course: MLAII Quiet Places, 2024.

YUXIN HAN

The Clyde River is an important economic corridor for Glasgow and used to be known for its timber industry, one of the pillars of the city’s development. Experiencing a transition from timber to services, problems have arisen along the shoreline, such as fragmentation and vacancy. Part of the area has been transformed into cultural and educational land, but the lack of masterplanning has led to a lack of connectivity.

The government proposed the ‘2050 Clyde River Development Corridor Strategy’, which aims to revitalise both sides of the river, improve connectivity and the urban fabric, and adapt to future needs. While this has been successful, insufficient consideration has been given to established functional sites such as commercial sites and car parks.

Dead wood has become a barrier to sustainable urban functioning, affecting roads and ecological zones and causing drainage difficulties. However, dead wood is a valuable ecological resource during decomposition and provides important living space for plants, animals and microorganisms. Therefore, it becomes an important design priority to reuse dead wood to maintain site functions and to ensure urban structural coherence and sustainability while tracing the city’s timber culture. The story of the timber trade is told through the reuse of dead wood and the creation of different spatial environments to create different experiences.

Opposite: Different Forms of Wood (Yuxin Han), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 1 Critical Zones, 2023.

Mall Mire Community Woodland has transitioned from a coppiced forest to a community education forest, boasting a diverse vegetation that provides a pristine environment for dead wood decomposition.

Visitors can walk among the trails and immerse themselves in the huge trunks of the trees, as if they were at the site of the felling. The entertainment facilities stacked with timbers have become a space for children to experience the dead wood. Over time, these withered trees will grow new plants.

Below:

ALICE GARRETT HINDMARSH

Anthropogenically-induced climate change shows few signs of reversing before the point of no return. The resulting environmental change generates points of tension between an established populace and the landscape, calling for an adaptive approach to design and management strategy.

For the Icelandic population, the experience of environmental impact is especially visceral due to a shared cultural identity rooted in the Icelandic landscape, hence, my project philosophies pursue concepts of Indigenous animism by flattening ontological hierarchies of human exceptionalism and disputing the subject-object binary. This resulted in a proposed series of interconnected interventions that bridge the widening gap between the landscape processes and human inhabitants present between the Hoffelsjökull outlet glacier and the town of Höfn in southeast Iceland.

Manipulated by glacial meltwater, Site 1 records climate warming through the erosion of man-made structures. Eroded pieces are intercepted downstream at Site 2, the location of a decadal community excavation exercise. Excavated pieces are transported to Site 3 -- their installation and subsequent disintegration providing substrate and shelter for developing post-glacial ecologies. A full breakdown of this process-driven intervention series can be found on the following pages.

Ultimately, environmental changes resulting from a warming climate will likely never cease. However, this project explores how they can be understood in new ways whereby proximal human communities of glacial landscapes can actively participate in the process of ushering in a healthy post-glacial future.

Above: Collaged exploration excerpt of Intervention Site 1 (Alice Garrett Hindmarsh), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, Quiet Places, MLA2. Opposite: Assemble, Disassemble, Reassemble: Integrating process-driven interventions into an existing dynamic system (Alice Garrett Hindmarsh), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, Quiet Places, MLA2.

1. Sediment is sheared under the Hoffelsjökull outlet glacier.

2. Sheared sediment is transported with meltwater downstream.

3. Sheared sediment is deposited at the coastline of Höfn.

4. The coastline is routinely dredged for ships to access the harbour.

5. Dredged sediment is transported to a new location for processing.

6. Dredged sediment is compressed into reproducible blocks.

7. The two forms of the interlocking and reproducible blocks.

8. When stacked, the blocks resemble the columnar jointing of Iceland.

9. An example of how the two block forms stack together.

10. The stacked forms also resemble floating ice bergs of outlet glaciers.

11. Blocks are installed in the Hoffelsjökull glaciofluvial channel (Site 1).

12. Four examples of erosion that break down the block structures.

13. The Höfn community measures and reports on block breakdown.

14. Broken and eroded block pieces are transported downstream.

15. Transportation changes the texture and shape of eroded material.

16. Broken pieces are captured by a series of large groynes (Site 2).

17. Accumulated pieces are excavated from the groynes during a decadal communiy event .

18. Pieces are transported and installed in a site of post-glacial ecological succession using community vehicles (Site 3).

19. Different plant species establish in and around the broken pieces.

20. Biological erosion causes the pieces to break down further, forming a substrate that can host more ecological succession.

21. Site 3 becomes a rich area of pioneer species in a post-glacial future.

JIONGRAN HUO

Icelandic sheep farming, once one of the mainstays of the country’s economy, has been in decline due to import trade and environmental issues. This project aims to revitalize sheep farming by designing a journey for tourists to experience the Icelandic sheep landscape, which overlaps with the farmers’ sheep herding routes, so that the tourists can learn to know and love the Icelandic sheep landscape, and become supporters of the farmers’ cause. Sheep farming in Iceland is distinctly different from other countries in that it allows farmers to be self-sufficient, and this cyclical process allows visitors to realize why the tradition of sheep farming should not be abandoned. The journey to the highlands takes us through meadows, gorges, waterfalls, mosslands, wetlands and rivers, always at a distance from the sheep, where the changing environment makes for a dynamic and interesting sheep landscape. And deep in the highlands is the most pristine.

Iceland, the completely free sheep landscape represents the unique charm of Iceland. The journey ends back at the sheep pen in the Kirkjubæjarklaustur to celebrate the return of the sheep with the local farmers.

The experiential journey maintains Iceland’s own primitiveness, allowing visitors to spend a short time getting the most authentic experience of life in Iceland, and to join the once disillusioned farmers in their renewed love of their land.

The terrain of the pasture is flat and surrounded mainly by fragile mossland, wetlands and rivers. The secondary road next to the pasture is the town’s access road from the Ring Road into the highlands to Laki (Lakagígar), which has a great advantage of accessibility, so as a starting point for the journey, the visitor is able to get in touch with the local farmers and the sheep at this pasture to get acquainted with the Icelandic sheep farming culture, and to experience close moments with the Icelandic sheep.

Above: Proposal sheep shelter analysis (Jiongran Huo), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2. Quiet Places Studio, 2024.

Below: Proposal farmer’s shelter analysis (Jiongran Huo), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2. Quiet Places Studio, 2024.

Exploration:

Peatlands are of great ecological value and play an important role in carbon storage and water management. And now Flanders Moss, the oldest and largest surviving marshland in the UK, is facing a range of problems including ring breaks and flooding. The aim of my plan is to blur the boundaries, the first part of which is to create a complete network of wetlands, connecting drains, including individual patches, and creating a buffer zone of wetland corridors along the river, which will help the surrounding land to store more floodwater, filtering effluent flowing from agricultural and grazing land to the river, and relieving downstream flooding pressures. The second part of the project is to create an ecosystem where plants and animals can fully communicate. Re-wetting the land at the edge of the peatland and adding wetland farmland in the middle of the peatland and the agro-pastoral land will effectively link the whole ecology, increase the communication between plants and animals, and break down the otherwise rigid boundaries.

The journey of peat moss, from bud to end, is strewn with twists and turns. Flanders Moss, the UK’s most extensive remaining bogland, has also experienced a complex journey from birth, to prosperity, to decline over the past 10,000 years. However, just as the moss withers and then lays the foundation stone for new life, so the Flanders Moss of the 21st century, and indeed the future, is on the verge of rebirth, pregnant with infinite new possibilities.

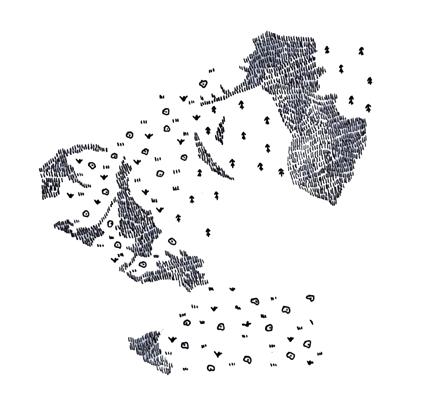

Opposite: The beginning of the story: moss (Qixiang Lai), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, 2024.

Below: Measure (Qixiang Lai), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, 2024.

In many years, the land adjacent to the peatland will come together as a complete and active ecosystem. Wildlife is active in the peatland and crosses through ecological corridors. Flooding is mitigated and controlled and becomes part of the wetland network system. The land also receives more attention for peatland tourism and local land users receive more economic income from the wetland farmland.

Proposal

This program is aiming to take the National Festival in iceland as an opprotunity to achieve the idea called Bio-community. The defination of biocommunity is a community that has a very close relationship between Human & Non-human. "The birds are standing on the windowsill, singing. You cycling on the street, and a puffin is coming back from far away sea, carrying three sand eels. And the puffling is waiting, calling for food. The island is covered by white and blue flowers, and they are breathing, witnessing the life force flowing." Such dynamic scenes always show the strong connection of all things in the world. At the same time, the utopian vision also calls on us, as humans, to consider beyond human thinking and the idea of coexisting with nature. This project connects everything through landscape creation. On Heimaey Island, which gathers all the life and elements of Iceland, the program use the role of the island as a microcosm to experimentally reconstruct the natural relationship of this land. Through landscape design, this program integrates time, space, and life to achieve the ultimate goal: Bio-community.

As a landscape architect, I see my role as both safeguarding and advancing cultural heritage. I’m dedicated to preserving the essence of our landscapes while also introducing innovative approaches to enrich and evolve our cultural experiences. My design practice is deeply influenced by my love for nature and respect for cultural traditions. For me, landscape architecture is a medium for the pursuit of aesthetics while carrying the responsibility of protecting the all environment. In my design projects, I integrate past and present, visible and invisible elements through creative design to create landscape spaces with unique stories and harmonious diversity.

Touching traces:in the vast world, traces and symbols are ubiquitous. Exploring how landscape traces embody memories, viewing them as bridges between spaces.

Exploring narratives:I delve into how my design practice allows me to uncover hidden narratives within the landscape, including subterranean spaces and microbiomes.

Engraving time: time poses both challenges and opportunities in design, allowing for the creation of enduring landscapes that offer rich experiences.

In the complexity of the site space, I found certain rules, which are mainly divided into lane space, indoor space, natural space and Flanker space. These traces in spaces of different scales bring unique emotional experiences to people, thus forming deep memory points. Through the combination of these special traces, Flanker space, as the end of the route, forms the most complete spatial emotional experience in the entire site, forming a new Flanker trace space, which finally converges at one point from line to surface, reaching the emotional climax of the entire site.

I prioritize strengthening neglected ecosystems, such as intertidal zones, to create sustainable landscapes rich in cultural and ecological elements. By delving deeper into hidden stories and microecologies, I enrich my understanding of a place, recognizing the transformative power of time in shaping ever-evolving and enduring landscapes. These landscapes offer immersive and ever-changing experiences, reflecting the intricate interplay between history, culture, and the environment.

Historically, the ancient pine forests in Glenmore have shown tenacious natural regeneration capabilities after large-scale logging. After the First World War, artificial pinewoods were planted on a large scale in pursuit of higher yields, resulting in dense understory vegetation. The degree of closure is extremely high. Since very little sunlight can penetrate the dense pine needles and branches, the species richness is greatly reduced compared with the natural ancient pinewoods.

At the same time, the natural regeneration of pine trees cannot proceed smoothly, resulting in a single age of the forest. In order to better respond to the vision of a more sustainable future forestry in Scotland’s Forestry Strategy 20192029, building forests with richer species and more tree age stages is obviously a more conducive choice to face various challenges in the future.

In order to better promote natural regeneration, enrich pine forest species, and bring more economic benefits to the local area, a planting nursery want to design in Glenmore to cultivate Scots pine and forest wildflowers to accelerate the natural regeneration of pine forests in the surrounding areas. Form a regional gardening center integrating seedling cultivation, wildlife observation and rescue, home gardening product provider, nature education, and leisure and entertainment.

The production cycle of scots pine seeds is closely related to the production landscape of the site - the nursery. The seeds of Scots pine need to mature after a two-year growth cycle. If artificial cultivation is required, the seeds need to be harvested and stored before they are fully mature.

While breeding scots pine seedlings, the site also breeds understory plants, providing sources of germplasm for regions and individuals who need to promote understory biodiversity.

Opposite: The relationship between lake and around path (Bingkun Liu), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, 2024.

Below: Aerial view of nursery (Bingkun Liu), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, 2024.

1. View of greenhouse , where you can see the seeds from germination to seedling stage.

2. In the windbreak zone, you can see the saplings growing in their natural state.

3. The understory planting bed near the lake shore provides shelter for the understory plants after the upper pine trees grow up. Different native understory plants of the pine forest are used to create the planting bed.

4. The viewing platform on the lake can provide people with a good view of the seven granny pine trees growing on the small island

5. Remaining dead wood in the site was placed near the end point to form a complete display of the Scots pine life cycle.

6. The view at the end is the best. You can see entire nursery production process and the mountains in the distance.

Following the trail around the lake, one can clearly see the entire life course of the Scots pine from its infancy to its death. (Bingkun Liu), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, 2024.

The problem background is based on the real-world challenges encountered in my past projects: due to a lack of owner or societal support and insufficient project maintenance funding, landscape projects deteriorated and disintegrated earlier than expected. Some phased development large-scale projects could only complete the construction of the first two site areas, and the park, after completion, gradually became dilapidated and deserted due to a lack of funding and the level of attention from owners and society.

I am more inclined to interpret “outreach” as “going out and establishing new connections” and “communicating with these connections”. I attempt to create this strategy within the framework of climbing plants to strengthen their connection with surrounding surfaces.

Exploring: mycelial network

Establishing: vine branches

Developing: vine tendrils

These three stages correspond to the following three chapters. In the first chapter, I will introduce the origin of this strategy and expand the spatial and temporal dimensions of connections in course practice. In the second chapter, I elaborate on the importance of social connections to the project and why social connections need to be built on the foundation of frameworks and course practices. The third chapter will describe the thought process and course practice that further strengthens connections by combining “perception theory” and spatial transformation methods.

Above: Exploring: Mycelial Network, Establishing: vine branches, and Developing: vine tendrils (Sharon Liu), Course: Academic portfolio, 2024.

Opposite: Project with “Out And Reach” strategy (Sharon Liu), Course: Context & Grounding - Within the Folds, 2024. In these two projects, the scope of connectivity extends from spatial to temporal dimensions. This not only reinforces the significance and rationality of the projects themselves but also plays a crucial role in broader social relationships.

Addressing this project’s connectivity objectives, I particularly focused on the scales of farmers’ livelihoods, agricultural production, sales, and transportation; the scales of residents’ and campus activities in daily life; and the sales scales of restaurant businesses, thus forming a framework targeting routes covering farmers’ and urbanites’ activities.

Opposite + Below: Strategy framework (Sharon Liu), Course: Terrain & Ecologies-Design (with) Climates, 2023. Near the school, these elements are combined to form a closed-loop route of growing, picking, cooking, and selling agricultural products with the school and the community.

My intention was to invite viewers through explicit landscapes, allowing hidden spaces to become thematic expressions, stimulating exploration. While this intent was present in previous design concepts, it lacked stronger representation. Hence, I devised an exploratory journey: 1. A clearly defined starting point with a journey objective.2. As the target islet falls under UNESCO protection, alternative islets were explored. 3. Selecting a nearby exhibition islet as the journey’s end, recreating unique landforms and small-scale art structures along the way.

The site initiates with a clearly defined entry point marked by artificial traces, gradually transitioning to intermittent pathways, granting visitors freedom to explore natural areas and guiding them to other landforms. Observations along the way allow viewers to form their own interpretations.

Below:

YIZHUO LIU

Landscape architects in my opinion are intermediaries between nature and human beings, playing the role of a bridge between nature and human beings. In my final semester design, I focused on the heritage of the landscape, its current condition and the possibility of redevelopment. I focused on Perth Lade, an old canal built in the 18th century. Since its construction in the Middle Ages, many mills, factories and private businesses have used the Perth Lade to supply water and electricity. Through a search of historical maps and documents, I found as many as 19 sites of mill industries along the Perth Lade. Linen, leather, bleaching products and whisky were important export commodities to many places and Perth thrived on the trade of these mills, known by residents as ‘the heart of Perth’

With the advent of the industrial revolution in the 19th century, these mills slowly failed to keep up with the demands of the transition and despite such a rich history, my walkabout survey found that only a small number of these industrial sites have survived along the Perth Lade, many of which are fairly small in scale

With the decline of the mills, the Perth Canal has gradually become unloved, and this once busy man-made canal is now in a state of disrepair. The lack of maintenance and regeneration has led to an increase in anti-social activity in the vicinity of the Perth Canal, with up to 11 anti-social gatherings reported in 2021 alone, and a public reluctance to travel through the area.

Above: Samples of water collected under the microscope on 10.16 and 10.20 (Yizhuo Liu), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 1, 2023. Opposite: Site 2 section (Yizhuo Liu), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, 2024.

The plan aims to explore the public green space along the Perth Lade and integrate it with Perth’s historic mill site, using a landscape approach to recreate the site along the Perth Lade to evoke a sense of identity for the city’s residents and to make the site economically viable to help maintain the Perth Lade sustainably in the future.

Opposite: Perth Lade and the main canal in the Scottish Highlands (Yizhuo Liu), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, 2024. Below: Perth Lade Archaeological History (Yizhuo Liu), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2. 2024 .

Using the historic use of the mill’s current site as a cue, the plan will create a historic community landscaped green space on two open spaces along the Perth Lade, integrating the landscape with the historic site so that residents can enjoy the open and unused spaces along the Perth Lade while generating some economic benefit and maintaining the ecology of the Perth Lade in a more sustainable way.

Opposite: Site 1 Pre-analysis sketch (Yizhuo Liu), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, 2024.

Below: Site 1 Dyeing Plants Garden in four seasons (Yizhuo Liu), Course: Landscape Architecture Design

MENGFEI LUO

Iceland is often regarded as a treeless land, but this is not because the climate is unsuitable for trees, but rather because Iceland’s trees were once heavily logged. My research focuses on the mutual remodelling of natural and social landscapes, from an empty, uninhabited island to a degraded, owned landscape, which seems to create a timeless social order. The transformation of the Icelandic environment from woodland to grassland is not just a shift from a pristine natural landscape to a degraded landscape. The changes in Iceland are the result of intentional human alteration of the land. This is closely related to the changes in the landscape caused by the monastic system in medieval Iceland, where church-owned woodlands were over-exploited. It was not until the transformation of Icelandic industry that the Icelandic government realised the crisis of the birch tree and began to advocate its planting. Birch, as an old native tree species in Iceland, seems to be closely related to the changing social patterns in Iceland. A century ago, Icelanders had hardly seen a tree and had a very vague concept of “tree”. This project aims to enhance Icelanders’ understanding of ‘trees’ while demonstrating how tree planting can help restore the environment and combat future climate crises.

For the project in Iceland, I sorted out the timeline of Iceland’s trees. Under the influence of the Little Ice Age and the Anthropocene, the main groups of trees in Iceland can be divided into three periods, the Sequoia at the very beginning, the pines in the middle period, and the birch in the later period. I extracted the trunk textures of these three trees and made the pavement of the road along their timeline. When people walk on the road, they can observe the changes in the texture of the pavement and feel the process of changes of typical Icelandic trees, and it also helps Icelanders to build up their knowledge of trees from the perspective of light, shadow, colour, texture and life. The planting of birch trees in the project also responds to the history of social transformation in this space.

Opposite: Interpretation of tree (Mengfei Luo), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2. Quiet Places Studio, 2024. Below: View of Kirkjubæjarklaustur (Mengfei Luo), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2. Quiet Places Studio, 2024.

Above: Timeline of iconic tree species (Mengfei Luo), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2. Quiet Places Studio, 2024. Below: Trace the tree(Mengfei Luo), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2. Quiet Places Studio, 2024.

As Christophe Girot eloquently articulates, there exists a fundamental dichotomy for every designer: the scientific understanding of landscapes stands in stark contrast to the more subjective, poetic, and emotionally charged perceptions of these spaces (Girot, 2013). This juxtaposition has captivated my intellectual pursuits over the last two years, driving me to explore a new paradigm through which to comprehend landscapes. The prevalent methodologies in landscape design are heavily laden with formalistic science, prescriptive positivism, and even echoes of mechanical materialism. There is a pressing need for a novel paradigm that not only acknowledges the rich tapestry of the past but also seamlessly incorporates the possibilities of the present and the future, thereby crafting a cohesive and meaningful narrative that expands the operational field of landscape on a broader scale.

In pursuit of this, I have dedicated two years to an immersive practice in grounding, modeling, geography, among other dimensions, aiming to foster a deeper connection with the land, space, and nature itself. This inquiry assumes even greater significance in the context of a climate crisis, prompting us to ponder—how can we proactively respond to the myriad changes we face? Is the answer rooted in design, science, or perhaps a rekindling of the human spirit? While immediate or definitive responses may elude us, it is my hope that the ensuing exploration of design practices offers some illumination and inspiration to readers.

Delving into the intricacies of grounding details not only fortifies the research but also provides it with a solid foundation. Thus, when we direct our focus towards examining water, grounding emerges as a formidable tool to scrutinize the scientific paradigm and the very essence of positivism. Armed with this methodological approach, our comprehension of the intricate subject matter of water deepens significantly. By anchoring our investigations in a thorough understanding of grounding principles, we not only enhance the rigor of our research but also unlock new dimensions of insight into the nature of water and its myriad complexities.

Employing diverse methods to comprehend space and the natural world, the fusion of these elements is exemplified in the uniquely characteristic and delicate terrain of Iceland, facilitating a profound observation of land transformation. By engaging various perceptual lenses, the human observer attains a fresh perspective on the world, ultimately leading back to a contemplative examination of the local landscape. This intricate interplay between perception, environment, and reflection not only enriches our understanding of the dynamic relationship between humanity and nature but also encourages a deeper appreciation for the intricate beauty and fragility inherent in the landscapes we inhabit.

Opposite: PLA model: topology, river, sediment, Iceland (Tianze Luo), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploratiion: Part 2 - Iceland Group, 2024.

Below: Landscape approach to understanding the site (Tianze Luo), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 1 - Iceland Group, 2023.

Our ancestors tried to understand nature through their imagination. It was a time when people did not have a scientific view. They connected the sky and the underworld with strong parallel lines of standing stones. You can hear narratives in the relations between the Sun and Moon, light and shadow, and water flow and sun and moon movement from this place. These works explore a way of appreciating nature that humans have lost without realizing it. Machrie Moor preserves many artifacts and is full of memories of past human relationships with nature. People started to live and cultivate this area 5000 years ago, but they abandoned the site in 800 BC because the cold climate changed it into barren land and formed peat. A peatland has huge benefits for the climate crisis, but it is a very sensitive environment. It needs a vast of time to form peat, and degraded peat will release the carbon stored. The preservation of the peatland is a critical issue for climate change, and important not to lose our precious historic archives stored in the peat.

The project will try to preserve this archive and recall a way of seeing nature our ancestors used via remains. A light corridor is designed to be filled with light at sunrise on the summer solstice. A moon-shaped pool captures the movement of the sky like a mirror. Water ripples on the pool make circles similar to prehistoric art on stones. I believe that we can know where we are only after we know ways of appreciating nature in this vast world.

Above: Peatland Vegetation Assemblage (Haruyuki Miyata), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2 + Critical Zones Studio, 2024. Opposite: Interaction in a peat bog (Haruyuki Miyata), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2 + Critical Zones Studio, 2024. An artist performance with butterflies and further excavation for artifacts. 1:10.

Opposite: Interaction in a fen (Haruyuki Miyata), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2 + Critical Zones Studio, 2024. An artist performance under the moonlight in a moon-shaped pool. 1:10.

Below: Peat Bog System (Haruyuki Miyata), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2 + Critical Zones Studio, 2024. 1:10.

Above: A fen zone (Haruyuki Miyata), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2 + Critical Zones Studio, 2024. 1:200.

Below: A fen zone 2 (Haruyuki Miyata), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2 + Critical Zones Studio, 2024. 1:200.

Above: A peat bog zone (Haruyuki Miyata), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2 + Critical Zones Studio, 2024. 1:200.

Below: A peat bog zone 2 (Haruyuki Miyata), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2 + Critical Zones Studio, 2024. 1:200.

‘Whisper of Time’ is dedicated to revitalising Tay Forest Park by re-imagining its forestry practices and amplifying its inherent natural charms. The project draws inspiration from “In Phrase of Shadows,” which perceives beauty as a natural quality shaped by the interplay of light, shadow, and natural environment. Rooted in a philosophy of simplicity, I appreciate the transient and imperfect nature of existence and aspire to create a harmonious balance between the elements of nature.

The existing forestry strategy employed in the Tay Forest Park follows a clearfelling method structured across seven stages spanning a 50-year timeline. While this approach proves efficient for forest regeneration, the extensive tree harvesting across various zones prompts concerns regarding its long-term visual and ecological impact. Considering the forest park’s designation as a public recreational space, optimising its aesthetic appeal becomes paramount.

I think of trees as sculptures. Their original planting determines their future shape. Similarly to sculpting, it is more feasible to carve the existing structures rather than completely rebuilding everything. This led me to re-imaging the forestry practice in Tay Forest Park. Recognising the imperfections of the existing situation, the method I propose for this project is more gradual. This project is using continuous cover forestry (CCF) to create small mosaic spaces and gradually transform the existing conifer plantation into a diverse and dynamic forest ecosystem.

Above: Model of coniferous plantation (Layla Ng), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, Critical Zones Studio, 2024 Opposite: The growing plants (Layla Ng), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, Critical Zones Studio, 2024.

At the same time, trails are designed showcasing ‘forest narratives’ for visitors and interlink with the Allean Forest, fostering deeper engagement with nature. Through this gradual metamorphosis of the landscape, visitors can fully immerse themselves in the tranquillity of the forest, forging a profound connection with its innate beauty and serenity. In future, the tree collection can be gradually extended to cover the entire Forest Park. Through an ongoing process of adaptation and refinement, the existing coniferous forests will form the basis for continuous evolution.

Opposite:

PENGJU SHI

Natural cemeteries and woodland cemeteries not only provide urban residents with more natural wild green spaces, but also provide a place for the deceased to return to and promote the development of the ecological environment. At the same time, natural cemeteries can be combined with local history and culture to form monumental cultural landscape spaces, enriching the functional and spatial attributes of green spaces. Most importantly, due to the special attributes of cemeteries and the influence of cultural beliefs, the cemetery space can often avoid the negative impacts of urban expansion and the negative impacts of some human activities, such as construction and development, arable land expansion, and other human activities will try to avoid occupying the cemetery space, so that the special characteristics of the cemetery space can better protect the ecology and provide shelter for some rare species, thus forming a healthier ecosystem. Such a green space not only avoids the impact of large-scale development on the ecosystem, but also integrates with the urban space, providing a space closer to nature for urban residents.

Natural cemetery spaces are integrated with cultural and natural spaces, not only promoting woodland and natural ecology, but also providing unique landscape spaces for people to enjoy

Opposite: Ritual spaces in natural cemeteries (Pengju Shi) Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2,Critical Zones, 2024. Below: Cemetery space 100 years later (Pengju Shi), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, Critical Zones, 2024.

Natural cemeteries primarily incorporate natural burials and promote nature’s nutrient cycles and microbiological diversity through the natural decomposition of corpses, thereby promoting plant diversity and natural regeneration of the natural environment.

Opposite: Decomposition and material recycling processes (Pengju Shi), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, Critical Zones, 2024.

Below: Dynamics of natural cemetery space (Pengju Shi), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 2, Critical Zones, 2024.

With the development of society, humans have a deeper understanding of the landscape. Olwig (1996) argued that the equivalence between landscape and nature nowadays damages the complications of the landscape. He emphasized the landscape¡¯s substantive, which means ¡° real rather than apparent¡±. It represents that society requires the landscape designee to have a thorough thought. in a deeper layer. Not only does society encourage the landscape to have deeper thinking, but also, I as a realist, consistently strive to deeper thinking toward landscape design. During my two years of studying in Edinburgh, I was impressed every day in these two years by the ¡°design makes life better¡± motto that I wrote when I applied to the University of Edinburgh. Kienast et.al (n.d.) claimed landscape research is a discipline that needs interdisciplinary collaboration and needs to consider different spatial and scales because of its complexity. The complexity of the landscape has always attracted me to deepen my thinking toward landscape.

After graduating from the University of Edinburgh, I will be working in the landscape field, where I aim to implement projects and continue exploring the ‘depth of the landscape’. That will benefit my understanding of landscape more practically. My goal is to make a real difference in people’s lives and the ecology, and I eagerly looking forward to a future that I am passionate about.

Above: The Ross Theatre Renovation (Echo Tang),Course: Material Knowledge and Detailed Design, 2022 Opposite: Ending is Begining (Echo Tang), Course: Context and Grounding Context-Concept-Content, 2022. Next: Moving in Glenrothes (Echo Tang) Course: Terrain and Ecologies-Design (With) Climates, 2023.

Olwig, K.R. (1996) ‘Recovering the Substantive Nature of Landscape’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 86(4), pp. 630-653.

Kienast, F. et al. (n.d.) ’Change and Transformation: A Synthesis’, in A Changing World. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 1–4.

XINYUAN WANG

I summarize my identity as a designer as a reconciler of contradictions. One of my guiding philosophies is a commitment to sustainable design, emphasizing efficiency, reconciling the tension between meeting the material and spiritual needs of the present generation and providing adequate resources for the next generation, and striving to strike a balance between functional requirements and environmental care. This definition of identity will influence my views on the responsible use of resources (Space), How to balance biodiversity and the economy, and how to incorporate renewable energy into landscape projects.

In my four projects, I will explore three interrelated themes that reflect my professional understanding and the current direction of sustainability in the field of landscape architecture: the rational use of sandstone in Scotland, the development of ecological corridors in Scottish woodlands (mechanisms for rotational production of trees), and the application of innovative hydroelectric technologies in the Morse River Hydroelectric Park project in Iceland (power production and environment). These themes are not only of personal importance to me (which was an important part of my understanding of the historical development and prospects of the profession), but are also increasingly relevant to today’s socio-ecological context, especially in terms of combating climate change.

Above: My plan for the woodlands and corridors of the leven catchment (XinYuan Wang), Course: Landscape Architecture Design: Terrain & Ecologies-Unit 1 Designing (with) Climates, 2023.

Below: Rotation strategies (XinYuan Wang), Course: Landscape Architecture Design: Terrain & Ecologies-Unit 1 Designing (with) Climates, 2023. This map shows the road-agricultural-pastoral analysis, in addition to the river-agricultural-pastoral rotation strategy.

Above: Plan (XinYuan Wang ), Course: Landscape architecture design: Context and Grounding-Unit 1 Within the folds , 2022. The stage and the auditorium were designed using the local Scottish sandstone.

Below: Sections (Top right, middle left), as well as a multi-purpose sandstone auditorium area (XinYuan Wang), Course: Landscape architecture design: Context and Grounding-Unit 1 Within the folds, 2022. Sandstone stage with large, medium, and small temporary facilities.

YIFAN WANG

In my eyes, the entire landscape of the Earth resembles a reclining giant, with the landscape itself being the body of this giant. The narratives about the origin of the world in various cultures are strikingly similar. In ancient Chinese mythology, the death of the giant Pangu gave birth to nature: his blood became winding rivers, his sweat transformed into lakes, his hair grew into grasslands and forests, his bones ascended into rugged mountains, his left eye became the sun, his right eye turned into the moon, the tears in his eyes scattered into the stars, his breath turned into wind and fog, and his voice became thunder. Similarly, in the distant Norse mythology, there is also a giant named Ymir, whose body transformed into the various layers of the world: his flesh turned into the earth, his blood into the seas, his hair into vegetation, his skull propped up the sky, and his brain turned into clouds.

These myths, spanning from the West to the East and from ancient times to the present, have inspired people living on Earth to imagine the creation of the world with

remarkable consistency. Viewing the landscape as a body is a profound act of imagination that transcends human senses. When we gaze at the mountains and rivers, it feels as if we are sharing the same view as our ancestors did millions of years ago, experiencing a connection that transcends time and space.

We should understand and perceive the landscape in the same way we read our own bodies, protecting the Earth as gently as we care for our skin and cherishing every bit of greenery as we would treasure our own hair. As a future landscape architect, I aspire to soothe the Earth’s wounds and sorrows gently, like a healer, using delicate methods to restore its health and vitality.

Above: The world and the five elements (Yifan Wang), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 1, 2023-2024.

Opposite: Dance on the lava field (Yifan Wang), Course: Landscape Architecture Design Exploration: Part 1, 2023-2024.

Nature is a vast living organism, encompassing countless systems. Every water body, woodland, and wilderness acts like organs and tissues within a body, each with its own distinct functions and characteristics. Under the governance of the entire natural system, these elements work together to maintain equilibrium.