Understanding the collective behaviour of guineafowl

Vulturine guineafowl live together in large groups, and these groups form part of a large and complex society. Researchers in the ECOLBEH project are looking at how these animals deal with the challenges of living in such a society, and how doing so can help them survive the harsh Kenyan climate, as Prof Dr Damien Farine explains.

The vulturine guineafowl is a highly social species of largely land-based bird endemic to East Africa, where they live together in groups of between 15-60 individuals. While the main advantage of this behaviour is that it provides a degree of protection from predators, there are also other benefits. “The birds are likely to benefit in terms of finding food and water, navigating the landscape, and so on,” explains Prof Dr Damien Farine, Scientist at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behaviour, Eccellenza Professor at the University of Zurich, and Associate Professor at the Australian National University.

Making decisions as a group

As the Principal Investigator of the ECOLBEH project, Prof Dr Farine is studying the ecology of the collective behaviour of vulturine guineafowl. This involves looking at how these animals function as a group, for example how they decide where to go when group members have

different preferences. These birds live together in very stable groups, so they somehow must reconcile their differences and come to an agreement about what to do next. “What we found is that they use very simple rules, akin to voting: any group member can initiate movement, and the group follows the direction of the majority,” says Prof Dr Farine.

His study, based at the Mpala Research Centre in Kenya, relies primarily on using GPS tags to collect precise information on where each group – or in some cases each member of a group – has travelled over time. By putting GPS tags on all individuals from the same group, the research team can collect a wealth of information on where each group member is, as well as how they move relative to each other. “From this information, we could see that the group make democratic decisions –they essentially vote on where to go next,” says Prof Dr Farine. “However, not all individuals have equal influence – most of the time (but not always!) it is the males that decide.”

An unusual multi-level social structure

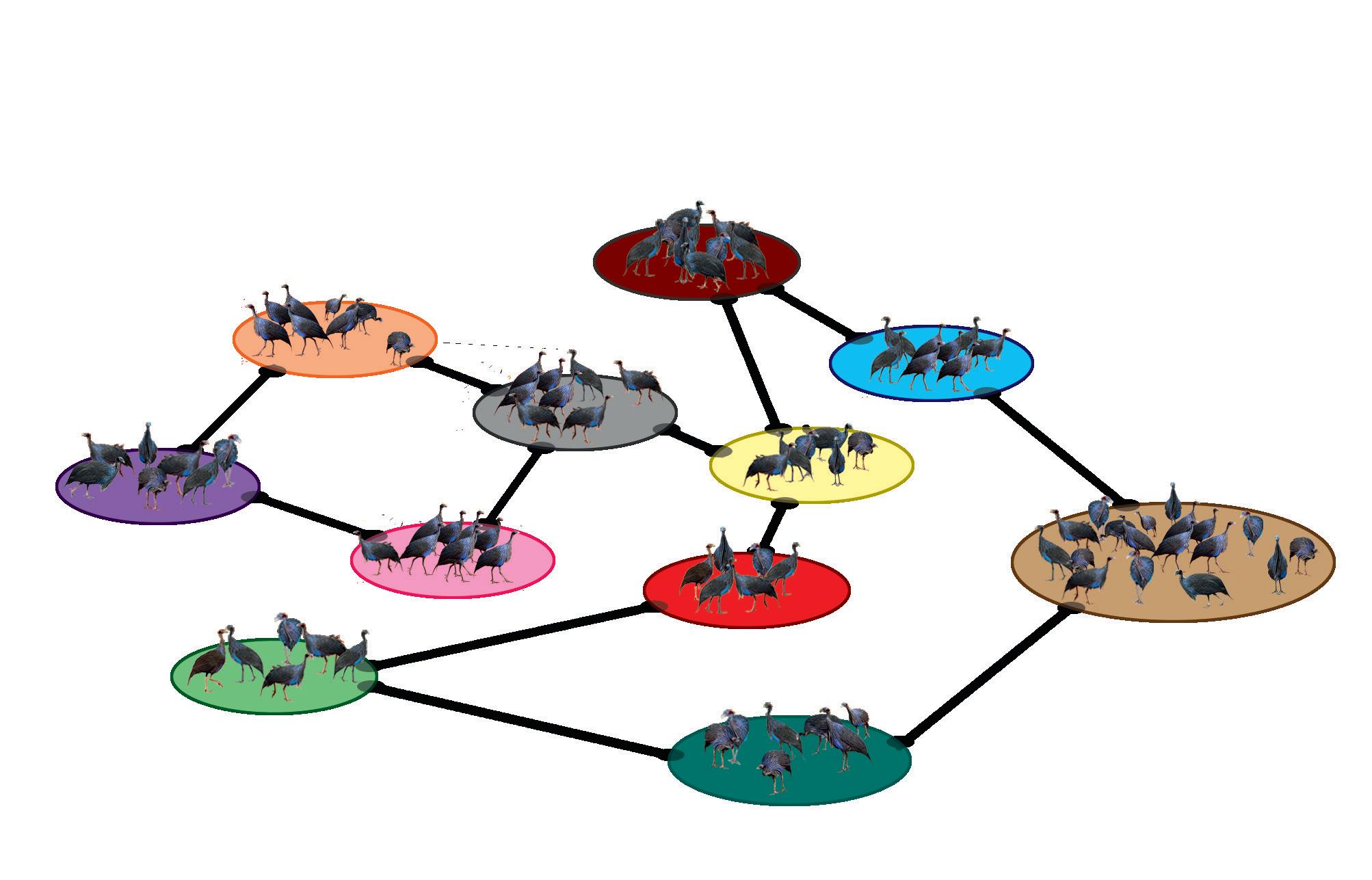

As the first project ever conducted on this striking species, and one of the very few behavioural studies ever conducted on any guineafowl, Prof Dr Farine was also excited to gain some new insights into their social systems. Almost immediately, the team made a startling discovery. “We found that groups sometimes come together with other groups to form super groups. This is quite unusual among birds and it has some similarities to primates and other large mammals that live in so-called multi-level societies,” outlines Prof Dr Farine.

This unexpected social structure for birds has been uncovered thanks to Prof Dr Farine’s work in tracking the movement of several groups of guineafowl. “Every group in the population we’re looking at has between 2-6 GPS-tagged birds, and every member is marked with a unique combination of colours on its legs. This allows us to identify all the

members, and we can say where that group has been from the GPS tags,” he outlines. By combining the large-scale deployment of GPS tags across all of the groups in the population with repeated observations of individually-marked birds within each of the groups, Prof Dr Farine and his colleagues have been able to gain fresh insights into the behaviour of vulturine guineafowl. “We’ve been able to show how each group moved and interacted with other groups, and how the membership of each group has been very stable over several years,” he says. “Groups also contain multiple males and multiple females, all of which can breed if the conditions are right, which again is unusual among birds.”

The project’s research has also yielded new information about other aspects of these birds’ behaviour. Researchers have found that young males in a group will help their mothers with raising the next generation of offspring, and that there are strict dominance hierarchies. “The males in particular have a clear alpha, beta, and so on. When interacting with each other, individuals are very strategic, investing only in fighting with their closest competitors for rank,” says Prof Dr Farine. These patterns in social structure within groups and across the population raise

evolved in the same environment. “It also gives us an opportunity to gain insights into how such animal groups – which includes many primates – solve some of the challenges associated with living in large, stable groups,” continues Prof Dr Farine.

away from Mpala together to go in search of resources,” continues Dr Farine. “An exciting question we’re trying to answer next is to determine how groups know where to go.”

We’ve been able to show how each group of vulturine guineafowl moved and interacted with other groups, and how the membership of each has been very stable over several years. Groups also contain multiple males and multiple females, all of which can breed if the conditions are right

Dealing with drought

Recently, Prof Dr Farine’s study area has experienced one the most severe drought in half a century. This dramatic change in conditions has allowed researchers to understand how living in a group and forming a multi-level society helps these birds deal with the environmental challenges of living in a semi-arid landscape. The droughts have forced groups to leave their regular home ranges at Mpala in search of food, yet Prof Dr Farine says it can be difficult for the birds to know where to look. “Because group members stay together all of the time, the information that they have about their landscape is limited,” he explains.

One hypothesis is that the females know where to go, as when they come into a group they also bring their prior knowledge, which may include an awareness of food sources. However, Dr Farine says that testing this hypothesis is quite challenging. “We don’t know where the females have come from before they enter our population,” he explains. “In future we hope to increase the scale of our tracking to multiple populations to also capture the movement of female guineafowl as they move from group to group.”

Female dispersal

Another topic of interest is looking at how females decide on where to go when they leave their groups in search of new ones, and how they

new landscapes. “One female recently completed a 48 km round trip, to the northern border of Laikipia County, in search of a group to join. These movements, which are typically done alone, have revealed some interesting insights on dispersal ecology,” outlines Prof Dr Farine.

“First, we’ve found that the females change HOW they move, allowing them to move very large distances with almost no increase in the energetic cost of displacement. They achieve this by a combination of moving straighter and faster, which is more energy-efficient.”

The team found that changes in how the birds move mean that they can travel up to 33.8% further in a day of dispersal with only an approximately 4.1% in the total daily cost of movement. It can however be very challenging for these females to find new groups to enter. “It seems that they are not always welcome,” says Prof Dr Farine. “As a result, we often see females who have made long journeys away from Mpala turning around and heading straight back to their natal group. They often end up staying there for six months until the next window of opportunity to disperse –typically a rainy season – presents itself. As a result, we’ve observed some females only successfully dispersing at more than two years old, which is very late for any bird species.”

Making large movements as a group

Despite having the ability to fly, vulturine guineafowl almost exclusively move by walking on the ground. “ They can travel for 50 kilometres or so without flying. the furthest they fly is the 10 to 20 m that is required to cross a river. Otherwise they walk the whole way,” continues Prof Dr Farine. As part of his

work in the ECOLBEH project, Prof Dr Farine has studied the energy efficiency of groups making these big movements, which has yielded some interesting findings. “When we compare the long-distance movements that groups make with those made by individuals during dispersal, we find that groups gain less efficiency benefits than dispersing individuals,” he outlines. Moving as a group is less efficient than moving alone. “This is likely because groups constantly face conflicting preferences about where to move, causing them to frequently slow down or even stop as they resolve these,” concludes Prof Dr Farine.

Moving forward with the project

The project’s primary focus is the vulturine guineafowl, yet this research also holds relevance to our understanding of social structures and collective behaviour in other species. These birds don’t conform to established ideas about how birds are thought to behave, one point which stimulated Prof Dr Farine’s interest. “These guineafowl have quite similar structures within their groups to those found in baboon societies living in arid environments,” he explains. Certain aspects of collective behaviour have long been thought of as being unique to primates, but now the

question arises of whether other organisms are capable of expressing similar types of behaviours, a topic Prof Dr Farine hopes to investigate further. “We’d love to continue working on this, subject to continued funding and the goodwill of our Kenyan hosts,” he says. “A lot of what we’ve learnt about social evolution, social biology and human evolution has been gained by studying species like baboons, and the vulturine guineafowl is a very interesting and complementary species in this respect.”

While the drought has made it difficult to tackle some of the questions that researchers had initially planned to look at around collective decision-making, cooperative breeding and changes to group structure, Prof Dr Farine says it has also opened up new avenues of investigation. One centres around the movement patterns of the guineafowl. “For example, we’ve found that vulturine guineafowls have started making nomadic movements, and these movements are likely to capture some really fine-scale information about the state of the environment.” he outlines. The guineafowl could effectively be used as environmental sensors, providing important information for land managers and conservationists. “The guineafowl can effectively tell us on a dayby-day basis what conditions are like on the ground,” continues Prof Dr Farine. “We are only studying them in a very small area, but if you could tag birds over a much larger area, you could potentially sense this information over thousands of square kilometres.”

Researchers in the project are helping build a deeper picture of conditions on the ground, which can then inform decision-making in areas like conservation, land management and planning. Alongside building a stronger evidence base, Prof Dr Farine also hopes to fill in some gaps in our understanding of social evolution, and the capacity of different species to evolve certain types of social behaviours.

Vulturine guineafowl are highly vocal, and their calls can be heard a long way. This could allow groups to communicate with— and track the location of—other groups in the landscape.

ECOLBEH

The Ecology of Collective Behaviour

Project Objectives

The project aims to understand the fundamental building blocks of animal societies. This includes

• how and why groups form

• how groups are maintained (e.g. how groups make consensus decisions to remain cohesive)

• how animals navigate their social landscape (e.g. how dispersing individuals integrate into a new group)

• how multilevel societies allow animals to overcome harsh conditions and adapt to novel climates.

Project Funding

“When we consider social behaviour in birds, we quickly find that researchers have almost exclusively studied birds only when they are breeding. This is distinct from primatologists, who follow primate groups all year round, and investigate other aspects of their social behaviour,” he says. The aim is to bridge these two disciplines and bodies of knowledge. “We’re taking more of a primatology-like approach to studying these groups of guineafowl, rather than focusing solely on their social behaviour during the breeding season,” explains Prof Dr Farine. “This is helping us uncover new insights – our research is also causing us to rethink many of the assumptions in our field.”

The project is now over halfway through its overall funding term, with Prof Dr Farine exploring different options to extend this research. One possibility is in collaborating with other research projects working in related areas. “We hope to work with other projects that work on plant communities and other species, like small mammals, to gain a more integrated insight into what happens when drought hits these types of eco-systems,” he says. “This is something that is very special about working at the Mpala Research Center, which is a gathering place for leading ecologists to do their research.”

This Project has received funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 850859.

Laboratory Members https://sites.google.com/site/ drfarine/lab-members

Contact Details

Project Coordinator, Prof. Dr. Damien Farine Eccellenza Professor

Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies

University of Zurich

Associate Professor

Division of Ecology and Evolution Research School of Biology

Australian National University

Affiliated Scientist, Department of Collective Behavior, Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior

E: damien.farine@ieu.uzh.ch

E: damien.farine@anu.edu.au

W: https://sites.google.com/site/drfarine/home

Prof. Dr. Damien Farine is currently an Eccellenza Professor at the University of Zurich, an Associate Professor at the Australian National University, and an Affiliated Scientist at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior. He was previously a Principal Investigator at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior, a Principal Investigator at the Centre for the Advanced Study of Collective Behaviour, and a Lecturer at the University of Konstanz. Prior to this, he was a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Oxford and a Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute fellow based at the University of California Davis. He studied his PhD at the Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology at the University of Oxford. In 2018, he was awarded the Christopher Barnhard award for Outstanding Contributions by a New Investigator by the Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour. In 2019, he was awarded an ERC Starting Grant on The Ecology of Collective Behaviour. He has also been included in the 2019, 2020, and 2021 ISI Highly Cited Researchers lists.

Prof. Dr. Damien Farine