EXIT

Georges Georges Rousse Rousse James James Casebere Casebere Giacomo Giacomo Costa Costa Roland Roland Fischer Fischer Igor Igor Mischiyev Mischiyev Aitor Aitor Ortiz Ortiz Gordon Gordon Matta-Clark Matta-Clark Aziz+Cucher Aziz+Cucher AES AES Group Group

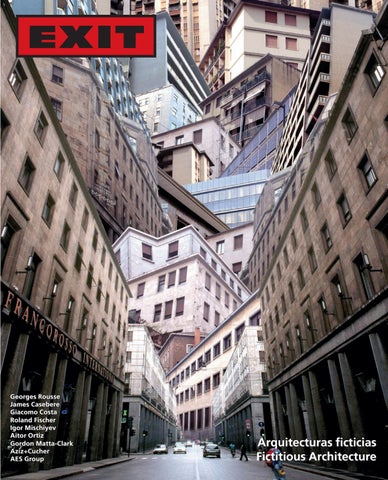

Arquitecturas ficticias Fictitious FictitiousArchitecture architecture