SDG 16.2 end abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence and torture against children

SCHOOLS

EDUCATION

The FAWE Mirrored Approach to ending school related gender-based violence (SRGBV

A MANUAL FOR

AND

PRACTITIONERS

MANUAL FOR SCHOOLS AND EDUCATION PRACTITIONERS The FAWe Mirrored ApproAch To ending school relATed gender-bAsed violence (srgbv) sdg 16.2 end Abuse, exploiTATion, TrAFFicking And All ForMs oF violence And TorTure AgAinsT children

A

The FAWE Mirrored Approach to ending school-related gender based violence (SRGBV) Manual for schools and education practitioners

PUBLISHED BY

Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) FAWE House, Chania Avenue, off Wood Avenue, Kilimani P.O. Box 21394 - Ngong Road, Nairobi 00505, Kenya.

Tel: (254-020) 3873131/3873359 Fax: (254-020) 3874150 Email: fawe@fawe.org http://fawe.org/

AUTHORS & DESIGN

Community-based Leadership, Empowerment and Networking (CLEAN) UGANDA Team: Christine Semambo Sempebwa Julius Nkuraija Mary Kisakye Email: info@cleanuganda.ug http://cleanuganda.ug/

COPYRIGHT: All effort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this SRGBV Manual is accurate at the time of going to press; FAWE cannot be held responsible for any inaccuracies. Parts of this Manual may be copied for use in research, advocacy and education, provided that the source is acknowledged. This Manual may not be reproduced for any purposes without prior written permission from FAWE. ©FAWE

Cite: FAWE, (2021). The Mirrored approach to ending school-related gender based violence (SRGBV) Manual. Nairobi, Kenya. Forum for African Women Educationalists.

Acknowledgements

The development of The Mirrored Approach to ending school-related gender based violence (SRGBV) Manual was initiated and coordinated by the Forum for African Women Educationalist (FAWE) Regional Secretariat; led by the Executive Director, Mrs. Martha R.L Muhwezi and the Deputy Executive Director, Ms. Teresa Omondi-Adeitan. Special thanks to Julie Khamati, Programme Assistant; Juliet Kimotho, Advocacy Officer and Emily Buyaki, Communication Officer; for a for their technical input and guidance throughout the development process. Appreciation goes out to the entire FAWE team, the technical team from Community-based Leadership, Empowerment and Networking Uganda (CLEAN Uganda), and all the schools, institutions and individuals who made various contributions towards the successful development of this Manual.

| FAWE SRGBV Manual

ii

tAble of contents

FOREWORD i

Preface ii

Acknowledgements x

List of Tables vii

List of Figures vii

List of Acronyms & Abbreviations viii

Glossary ix

INTRODUCTION 1 11

1.1 Overview of the Manual 11

1.1.1 The Mirrored Approach 12

1.1.2 The target for the SRGBV Manual 12

1.1.3 Goal, Aims and Objectives 12

1.1.4 Outcomes 12

1.1.5 Materials needed to deliver the Manual 12

1.1.6 Time Needed 12

1.1.7 Participants 12

1.1.8 Facilitators 13

1.2 Structure of the SRGBV Manual 13

1.2.1 The 10 SRGBV Units and Appendices 13

1.2.2 Key tips for a facilitator 14

INTRODUCTORY UNIT: HOW TO USE MANUAL 15

Introduction 15

What is in this Unit? 15

Session 1: Climate setting 15 Session 2: Background to the Manual 15

Session 3: Practical techniques in using the SRGBV Manual 15

Session 4: Practical application of the facilitation methods used throughout the Manual 15

UNIT ONE: GENDER BASED VIOLENCE 22

Introduction 22

What is in Unit One? 22

Session 1: Introduction to Gender 22

Session 2: GBV causes, manifestation and perpetrators in the community 22

Session 3: GBV effects on developmental domains, learning, teaching and school environment 22

UNIT TWO: SCHOOL RELATED GENDER BASED VIOLENCE 32

Introduction 32 What is in Unit Two? 32

Session 1: SRGBV types, causes and contributing factors 32

Session 2: The consequences of SRGBV 32

Session 3: Identifying, preventing and responding to SRGBV 32

UNIT THREE: LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK AND COMMITMENTS 42

Introduction 42

What is in Unit Three? 42

Session 1: Global and regional frameworks that address SRGBV 42

Session 2: How to work within national frameworks to address SRGBV 42

Session 3: Mainstreaming SRGBV prevention into school systems and procedures 42

UNIT FOUR: A SAFE SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT 58

Introduction 58 What is in Unit Four? 58

Session 1: The importance of a teacher code of conduct and SRGBV policy 58

Session 2: Identifying areas that need addressing in and around the school 58

FAWE SRGBV Manual |

iii

UNIT

FIVE: IDENTIFYING SRGBV

68

Introduction 68

What is in Unit Five? 68

Session 1: Understanding changes during growing so as to address SRGBV 68

Session 2: Factors in and around school that contribute to SRGBV 68

Session 3: identifying an SRGBV survivor 68

UNIT

SIX: COMMUNICATION AND SUPPORT IN ADDRESSING SRGBV

87

Introduction: 87

What is in Unit Six? 87

Session 1: The importance of communication with children, adolescents and young people 87

Session 2: Involving parents and other adults during communication with learners 87

Session 3: Psycho social support 87

Session 4: Importance or counselling learners at risk or survivors of SRGBV 87

UNIT SEVEN: RESPONSE – SUPPORT, REFERRAL AND REPORTING

105

Introduction 105

What is in this Unit Seven? 105

Session 1: What is response? 105

Session 2: Direct support to learners 105

Session 3: Using the teachers’ Code of Conduct or SRGBV policy to address SRGBV 105 Session 4: Using the legal system to address SRGBV 105

UNIT

EIGHT: ACTION PLANNING AND PLEDGE

122

Introduction 122

What is in Unit Eight? 122

Session 1: Developing an action plan to prevent and respond to SRGBV 122

Session 2: Populating the plan 122

Session 3: The Pledge 122

TIME: 1 HOUR 30 MINUTES 122

UNIT NINE: MONITORING AND EVALUATION 132

Introduction 132

What is in Unit Nine? 132

Session 1: Monitoring and Evaluation 132

Session 2: Data collection 132

Session 3: Training Wrap-Up and Evaluation 132

APPENDIX I: Participants’ Registration Form 142

APPENDIX II: Pre Test Form 142

APPENDIX III: Training Programme Evaluation Form 143

APPENDIX IV: SRGBV Response Checklist 145

APPENDIX V Pledge Form 151

APPENDIX VI: List of Links 152

Bibliography 155

| FAWE SRGBV Manual

iv

list of tAbles

Table 1: Examples of GBV causes, manifestation and perpetrators 19

Table 2: Factors contributing to SRGBV 27

Table 3: Key principles for SRGBV planning to identify, prevent and respond to SRGBV 31

Table 4: Policy commitments and international agreements addressing SRGBV 34

Table 5: Regional Frameworks that address SRGBV specifically in Africa 36

Table 6: National policies as guides for SRGBV mainstreaming: Uganda 40

Table 7: National policies as guides for SRGBV mainstreaming: Nigeria 42

Table 8: Checklist for developing and implementing the school SRGBV policy 49

Table 9: Factors in and around the school that contribute to SRGBV 61

Table 10: Behavior Challenge Chart 65

Table 11: The difference between discipline and punishment 65

Table 12: Rights and responsibility 68

Table 13: Modes of communication by age group 80

Table 14: Reporting point analysis 112

Table 15: The DOs and DON’Ts of effective listening 107

Table 16: Example of sample form for documenting an incident of SRGBV 118

Table 17: Example of documenting an incident of SRGBV 113

Table 18: Example template for a school SRGBV prevention and response plan 122

Table 19: Examples of areas that one could consider under each outcome when developing Plan 123

list of figures

Figure 1: Transect diagram focused on SRGBV on way to and from school 53

Figure 2: Participatory map with “black spots” 53

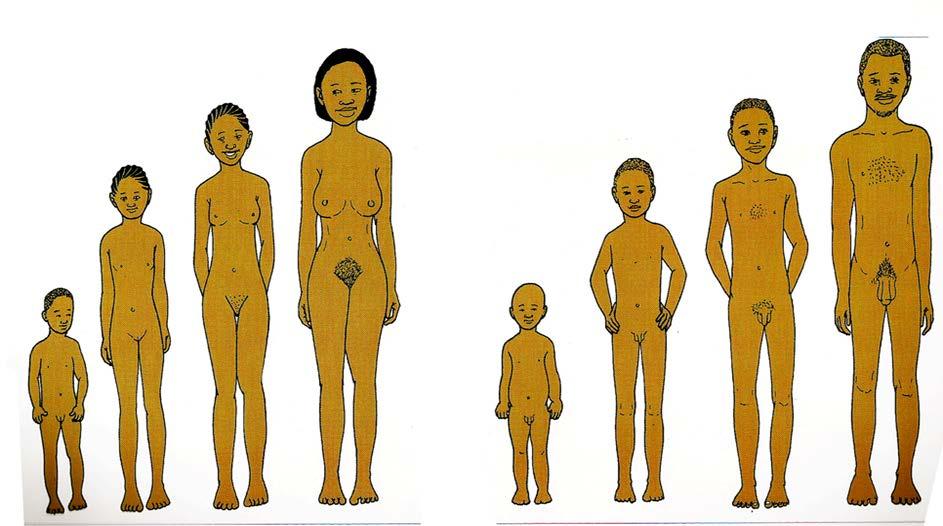

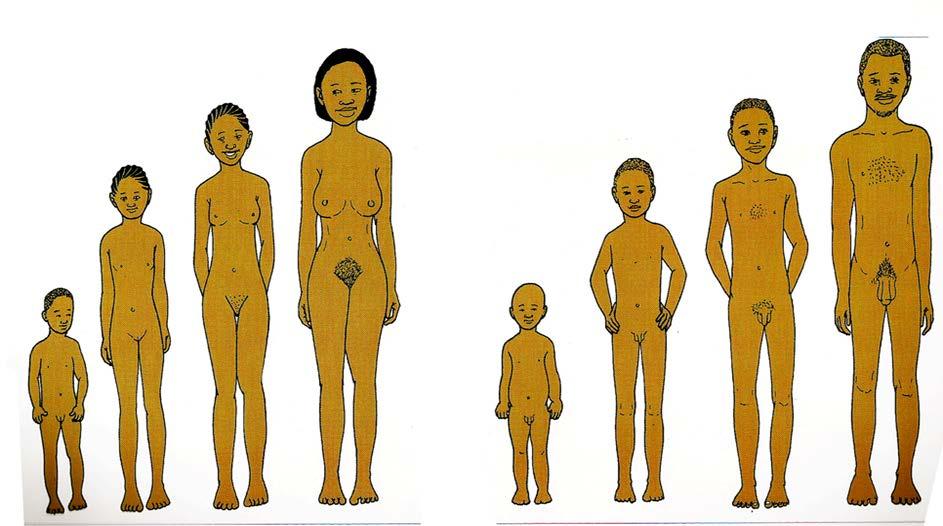

Figure 3: Growing up involves physical and emotional changes 58

Figure 4: Illustration for the Three Types of Response 98

Figure 5: Illustration for Reporting and Referral 100

Figure 6:The Problem tree

FAWE SRGBV Manual |

v

list of Acronyms & AbbreviAtions

ACPF African Child Policy Forum

AU African Union

CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women

CESA Continental Strategy for Education in Africa 2016-2025

CLEAN Community-based Leadership, Empowerment and Networking

CoC Code of Conduct

EAC East African Community

ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States

ESSP Education Sector Strategic Plans

FAWE Forum for African Women Educationalists

GBV Gender Based Violence

GPE Global Partnership for Education

GRP Gender Responsive Pedagogy

HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus

HIV/AIDS Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome

NGO Non-Governmental Organisation

OVC Orphans and Vulnerable Children

PSS Psychosocial Support

PTA Parent Teacher Association

PWDs Person with Disabilities

SADC South African Development Cooperation

SDGs Sustainable Development Goals

SRGBV School Related Gender Based Violence

SSA Sub Saharan Africa

STEM Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics

STIs Sexually Transmitted Infection

SVAC Sexual Violence Against Children

UN United Nations

UNCRC United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNGEI United Nations Girls Education Initiative

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

VAC Violence against Children

VACS Violence against Children Survey

WEF World Education Forum

| FAWE SRGBV Manual

vi

glossAry

Anxiety

Adolescent

Attitudes

Bullying

Child

Child abuse

Child sexual abuse

Coercion

Corporal punishment

Cruel and Degrading Punishment

Curriculum

Cyber-bullying

Defilement

Discrimination

Feeling of worry, nervousness, or unease about something with an uncertain outcome.

The United Nations defines a young person as age 10 to 19 years.

Individual views, opinions or feelings about something.

Behaviour intentioned to inflict injury and discomfort through physical contact, verbal attacks, or psychological manipulation, often repeated over time and involves an imbalance of power.

The UNCRC defines a child as person below 18 years of age.

Includes the physical, emotional, or sexual mistreatment of a child, or the neglect of a child, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child’s physical and emotional health, survival and development.

All sexual activity with a child is considered as child sexual abuse.

The action or practice of persuading someone to do something by using force or threats and intimidation.

Any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light.

Any punishment that humiliates, denigrates, scapegoats, threatens, embarrasses, mocks or frightens learners.

It includes: age-appropriate knowledge and skills students are expected to learn; learning objectives they are expected to meet; the units and lessons that teachers prepare and teach; the teaching and learning materials; the tests, examinations and other methods used to evaluate student learning.

The use of electronic communication to bully a person, typically by sending messages of an intimidating or threatening nature.

A sexual crime in with a person under 18 years.

Any unfair treatment or arbitrary distinction based on a person’s race, sex, religion, nationality, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, disability, age, language, social origin or other status.

Educational Institutions

Emotional health

Fear

Equity

Gender

Public and private institutions that admit learners for purposes of imparting knowledge and skills in a formal or non-formal manner from pre-school to higher education level.

Refers to the ability to appropriately manage and control one’s emotions.

Refers to the emotional response to real or perceived imminent threat.

Fair and impartial treatment, including equal treatment or differential treatment to redress imbalances in rights, benefits obligations and opportunities.

Refers to the social attributes and opportunities associated with being male and female and the relationships between women and men and girls and boys, as well as the relations between women and those between men. These attributes, opportunities and relationships are socially constructed and are learned through socialization processes.

FAWE SRGBV Manual |

vii

Gender-based violence

Grooming

Harassment

Human Rights

Inclusive education

Intimate partner violence

Learners

Violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering, against someone based on gender discrimination, gender role expectations and/or gender stereotypes, or based on the differential power status linked to gender.

Behaviour used to target and prepare children and young people for sexual abuse and sexual exploitation – often subtle and difficult to recognize.

Any improper and unwelcome conduct that might reasonably be expected or be perceived to cause offence or humiliation to another person; it could be words, gestures or actions that tend to annoy, alarm, abuse, demean, intimidate, belittle, humiliate or embarrass another or that create an intimidating, hostile or offensive environment.

Universal guarantees protecting individuals and groups against actions that interfere with fundamental freedoms and human dignity.

Education system and environment that reaches out to all learners including the most vulnerable, marginalized and hard to reach.

Behavior by a current or previous husband, boyfriend, or other partner that causes physical, sexual, or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviors.

Pupils, students, trainees and any person under 18 and less than 25 years of age, enrolled in a public or private educational institution.

Rape Forced sexual penetration vaginally, anally or orally, against a person’s will.

School

An educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students or pupils under the direction of teachers.

Sex Biological difference between men and women.

Sexual Violence Against Children (SVAC)

Survivor

According to UNICEF; this is sexual exploitation or abuse of a child, committed in person or remotely through the internet.

The preferred term for a person who has lived through an incident of violence (SRGBV and SVAC).

Victim A person who has suffered an incident of violence (SGBV and SVAC).

Youth

The United Nations for statistical purposes defines youth as persons between the age of 15 and 24 years

Note: Where United Nations definitions are used, they are without prejudice to other country specific definitions. The Mirrored Approach to ending school-related gender based violence (SRGBV) Manual is designed by the Forum for African Women Educationalist (FAWE), a key education actor in Africa, based on her experiences, related literature and stakeholder views. It is a guide to primarily enable: school administrators, teachers, learners, community members and other duty-bearers to identify, prevent and address SRGBV in and around schools. This is within the wider context where SRGBV is seen as a global concern that is detrimental to educational attainment, health and well-being of all learners, especially the most marginalized. Additionally, SRGBV has serious implications for the achievement of SDGs 5.2 , 5.3 , 8.7 and 16.2 .

| FAWE SRGBV Manual

viii

The United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’, sets out to attain a fairer and more sustainable world for all and carries the strap-line, ‘Ensuring that no-one is left behind. Despite this, there is global consensus and evidence that school-related gender-based violence (SRGBV) devastates the lives of millions of learners and is likely to affect the SDG targets for education, gender equality and elimination of all forms of violence, if left unaddressed. In 2016, UN Women noted that 246 million children are subject to some form of gender-based violence (GBV) in and around school every year. SRGBV affects all learners across all levels and spans geographical, cultural, social, economic, or ethnic boundaries. It is worse in conflict situations and affects girls, young women, children with disabilities and other vulnerable minorities more disproportionately. SRGBV has far reaching and adverse consequences leading to anxiety, low self-esteem as well as depression. It negatively impacts school performance and educational outcomes, at times with life-long impact. In sub-Saharan Africa, early school drop-out is linked to higher incidence of teen pregnancy, early marriage, and HIV infection (Jukes et al., 2008), and other STIs (Baird et al., 2012).

Globally, efforts are underway to address SRGBV and schools have been identified as one important setting for conducting violence prevention efforts (UN Women, 2016). The African Union (AU) through its Continental Strategy for Education in Africa 2016-2025 (CESA 16-25), under Pillar 3 and strategic objectives 2 and 10 avers with the call to address SRGBV throughout the education and training systems. Commitment is further exemplified through the Gender Equality Strategy for the Continental Education Strategy for Africa (GES4CESA 16-25) that FAWE developed on behalf of the AU.

The Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) agrees with the global community and the AU that until SRGBV is eliminated in and around schools across the world and in Africa, many of the life changing targets of the 2030 Agenda and Africa’s Agenda 2063; specifically, SDG4, SDG 5, SDG 16:2 and CESA 16-25 will not be achieved. In an effort to address SRGBV in Africa and joining efforts by others like: United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative (UNGEI), UN Women, Global Partnership for Education (GPE), and building on her previous efforts, including her Tuseme Manual and Gender Responsive Pedagogy: A Toolkit for Teachers and Schools, FAWE has developed The Mirrored Approach to ending school-related gender based violence (SRGBV) Manual.

It is hoped therefore that this resource which gives insight into SRGBV will help strengthen the capacity of schools and other education institutions, practitioners and school communities to identify, prevent and address SRGBV.

FAWE SRGBV Manual |

foreword

ix

Hon. Simone De Comarmond, Chairperson, FAWE Africa Board

PrefAce

Martha Rose Lunyolo Muhwezi Executive Director, FAWE Africa

Since the 2000 World Education Forum (WEF) in Dakar, Senegal, Africa through its regional and national frameworks have devised strategies and invested resources to expand access to education and improve institutional environments; to support and meet the learning needs of all children, youths and adults. As a result, Education in Africa has expanded drastically in recent years and the median proportion of children completing primary school across countries has risen from 27% to 67% between 1971 and 2015 (World Bank, 2020).There has also been significant achievements in closing the gender gap in low income countries (UNESCO, 2016). Additionally, it was noted that, when enrolled, girls stand an equal or better chance than boys of continuing to the upper grades of primary school (UNESC0, 2016). The median proportion of children completing lower secondary school across countries has also risen drastically, from a mere 5% in 1971 to 40% in 2015 (World Bank, 2020). Even gender gaps in secondary school enrolment have been narrowing down. According to UNICEF, 2020; globally, in 2000, there were more out-of-school girls of lower secondary school age than boys, the opposite is true today. Moreover, in contrast to primary education, the gender disparity disadvantages boys at the secondary level in many countries; although the disadvantage is typically less extreme than it is for girls. The largest gender gaps at the expense of girls are observed in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), (UNICEF, 2020).

While SSA governments are aware of the value of educational attainment for all as an essential strategy for national development and economic growth (MasterCard Foundation, 2019); under CESA 16-25, SRGBV remains a continental concern across all regions (ACPF, 2014; African Union, 2020). Although educational establishments are recognized as places of learning, personal development and empowerment schools are too often places of discrimination and violence, particularly against girls. Consequently, there is need to understand specific contexts and practically streamline SRGBV prevention into the systems of schools and educational institutions in Africa.

FAWE has therefore developed this Manual, based on a Mirrored Approach which lays emphasis on institutional-wide reform that is centrally concerned with SRGBV prevention and response, in an inclusive, learnercentered and gender responsive manner. Within this approach, the Manual provides practical guidelines on how to identify, prevent, respond to, report, refer and track progress made on efforts to address SRGBV in a planned, monitored and sustainable manner. FAWE hopes that the SRGBV Manual will be a reference material for not just in-service and out-service teachers but will be utilized by other stakeholders who look to address SRGBV in schools, institutions and at operational and policy level.

| FAWE SRGBV Manual

x

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Overview of the Manual

This manual is designed to equip users with knowledge and skills in a participatory and gender sensitive manner. The knowledge and skills will facilitate change in: attitudes, relationships, practices, systems and structures enabling response to SRGBV in and around schools. The manual uses a variety of training techniques and diverse content including school, individual and wider contexts and experiences. Bringing it down to school and individual level makes it easier to cascade the training to: other members of the school, parents and members of the community. At every stage of the training, gender balance and sensitivity should be observed. However discretion can be used to have separate groups for males and females, especially when it comes to cascading the training down to the parents and community. This broad and inclusive design will ultimately contribute to influencing change systems, structures, laws and norms in a sustainable manner.

1.1.1 The Mirrored Approach

The Mirrored Approach, was conceived by FAWE in response to the global call to address SRGBV. The approach draws strongly from FAWE’s GRP and Tuseme models and other good practices in Africa. It seeks to address SRGBV specifically in the African context, in a holistic and integrated manner. The Approach is a twin track that aims to strengthen: duty bearers; school administrators, teachers; parents and community, as well as the rights-holders, the learners. The approach gets the whole school community to work together to identify SRGBV and design tailored strategies to prevent and respond to SRGBV. Monitoring, evaluation and measuring effectiveness of the approach are key components outlined in the manual. An SRGBV checklist that can be used before the training and at regular intervals, in order to assess progress, is included as Appendix IV.

FAWE SRGBV Manual | 11

1.1.2 The target for the SRGBV Manual

The primary target is school administrators and teachers, who will be equipped with the training and delivery skills required to address SRGBV. They in turn will involve learners, parents and the wider community in addressing SRGBV, in and around schools. This target was arrived at building on FAWE’s extensive experience using her GRP training in-service and pre-service teachers in Burkina Faso, Chad, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. Results returned over the years show that school administrators and teachers are important cogs in the wheel of change and can lead to significant involvement of parents and the wider school community, in education interventions. This notion is supported by other key development players, with successful cases from across the world (UNICEF, 2019; UN Women, 2016; USAID, 2009).

1.1.3 Goal, Aims and Objectives

The Goal of the training is to contribute to improved practices to identify, prevent and address SRGBV in and around schools and other education institutions; for a safer SRGBV free environment. The aim and objectives and the envisaged outcomes that contribute to the goal are given below.

AIM: To create better school systems and structures that will lead to elimination of SRGBV in and around schools and other educational institutions.

Objectives are to:

1) Identify prevailing forms and drivers of SRGBV.

2) Develop interventions within the school systems and structures that address the drivers of SRGBV.

3) Monitor progress and measure effectiveness of the interventions and review and improve interventions.

1.1.4 Outcomes

The expected outcomes include:

1) Enhanced school leadership and community capacity and engagement to identify, prevent and address SRGBV.

2) Established and operational code of conduct (CoC)/ SRGBV policy that addresses SRGBV in and around the school.

3) Improved capacity of teachers and other school duty-bearers to identify and address SRGBV in an inclusive, child-friendly and gender-responsive manner.

4) Strengthened gender sensitive, child-centred, age-appropriate, participatory approaches, that address SRGBV, incorporated in school systems and structures.

5) Established and operational child-friendly, inclusive and gender-responsive response (reporting and referral) system.

6) Improved parental awareness and capacity to identify and address incidents of SRGBV in a timely and child-friendly manner.

7) Improved safe and secure (physical) environments in and around schools.

8) Established, operational and effective system to report, monitor, evaluate and create accountability on how SRGBV is addressed in and around schools.

These outcomes depend on the sum of knowledge and skills that is acquired through the units. It is therefore very important to cover all the units carefully and exhaustively.

4. Markers, chalk, sticky notes, manila masking tape, to aid in writing and putting up information.

Where the training is to be delivered virtually, short videos and attendant support slides can be prepared. Support short videos and slides on units and sessions that are going to be delivered can be uploaded on to a digital platform where participants can easily access them. Group work during virtual sessions can be done in breakout rooms, these are available on Zoom and other online platforms.

1.1.6

Time Needed

The manual has approximately 5 days of training content. Based on lessons learned from tested approaches; it is suggested that the training is spread out and conducted at different intervals in the school calendar. This could mean covering a section each week, fortnight or month, without disrupting the school activities. Each school should work out the most convenient way of covering the training content. Pre-service teachers, may have more time to handle more hours of training and may wish to handle the training in a shorter period of time.

1.1.7 Participants

1.1.5

Materials needed to deliver the Training

Essential materials you should have for delivering a training based on the manual include:

1. A copy of the Manual (one per person).

2. Notebook for each participant to use during training.

3. Large pieces of flipchart paper or chalkboard for facilitators to record information for the group to see.

In order to allow full participation and ensure that the school programme is not disrupted, work with 20 to 25 participants during physical meetings and 10 to 12 participants during virtual meetings. All provisions should be made for inclusion and gender responsiveness. For example, ensure that: physical venues and online facilities are accessible and special needs compliant; assistive devices and personnel for the blind and sign language interpreters for the deaf are available; lactating mothers can breast feed and have provision for their babies and caregivers etc. Address religious, ethnic and cultural diversity e.g. do not hold trainings on days or at times when participants are engaging in religious, cultural or ethnic activities, unless you have cordially agreed. For virtual training, ensure

all participants can use the technology and no one will be excluded. This may necessitate a pre-training familiarization session/ dry run.

1.1.8

Facilitators

Ideally, the training should be conducted by two facilitators, preferably a male and female. If working with educationists that handle special groups with unique characteristics, e.g. PWDs, children in conflict, child mothers, ensure that you are conversant with inclusiveness and know the SRGBV challenges of such groups. Otherwise, enlist support from technical persons who are aware of the characteristics and SRGBV needs of these groups. In some cases, you may need support of sign language interpreters, people who speak and are fluent in the language and culture of the school community, counsellors, and mentors during the training.

1.2

Structure of the SRGBV Manual

The Manual has ten units with explicit instructions on preparation and facilitation of sessions. Each unit begins with an introduction that briefly outlines the key content it covers. Units have a brief description of the 2-4 sessions therein; the estimated time required to cover each session; the learning objectives; a list of materials and resources to use for facilitation; preparation guidelines and facilitator support notes; guidelines for wrap up and reflection. The general glossary of terms too can be used to support delivery of the unit content, while the footnotes, Appendix IV and bibliography collectively have information, extensive links and references for additional reading.

1.2.1 The 10 SRGBV Units and Appendices

Introductory Unit: Outlines how to use the manual, both as a training and reference resource. It highlights: The goal, aims, objectives and outcomes of the training. It gives details of preparing and conducting a training and how to use the knowledge and skills acquired to address SRGBV.

Unit 1

Gender based violence (GBV): Defines the broad concept of gender and gender based violence. This enables participants realize that gender is socially constructed right from birth. The unit explores the causes, manifestation and perpetrators of GBV in the community and shows that SRGBV is not disconnected from GBV in the community.

Unit 2

SRGBV: Describes SRGBV giving insight into: types of SRGBV; causes, contributing factors and consequences. It further outlines the guiding principles and roles of teachers and education practitioners in preventing and addressing SRGBV.

Unit 3

Legal and Policy framework and commitments: Introduces the importance of legal and policy frameworks and commitments in addressing SRGBV. This ensures that participants understand that school level commitment is rooted in global, regional and national commitments. School management therefore must ensure there are school level policies to address SRGBV.

Unit 4

Safe school environment: Examines the basic standards a safe school should have. It emphasizes the important role of the governance and management bodies in preventing and addressing SRGBV. Key among their roles is establishing and enforcing a teachers’ code of conduct and school SRGBV policy, with adequate awareness and support across the school community.

Unit 5

Recognizing SRGBV in and around the school: Identifies physical and emotional changes and other factors in and around the school that can contribute to SRGBV. Within this context, the unit explains how to identify and support victims and survivors of SRGBV.

Unit 6

Preventing and responding to SRGBV: Describes the importance of communication and psycho-social support and counselling as key elements in engaging with children, adolescents and young people while preventing and addressing SRGBV.

Unit 7

Reporting, referral and follow up: Describes response to SRGBV in and around schools and other educational institutions. It explores reporting and referring cases of SRGBV, looking at the means and tools that can aid response in and around schools.

Unit 8

Action Planning: Explains how to develop an institutional SRGBV action plan for the school/ institution in line with the national education system. The plan components include: specific targets; a specified execution time frame; resources to use and people who will be responsible.

Unit 9

Monitoring and Evaluation: Defines monitoring and evaluation and explains the purpose of monitoring and evaluation of SRGBV prevention and response in and around schools. The unit looks at the hierarchy of monitoring and evaluation aims and indicators as well as data collection, management and utilization.

Appendices

Appendix I- Participants’ registration template.

Appendix II- SRGBV pre-test form.

Appendix III- Training programme evaluation form.

Appendix IV- SRGBV response checklist

Appendix V- Pledge Form

Appendix VI- List of links for further reading

1.2.2 Key tips for a facilitator

• Be an open-minded learner: Pay attention, guide and suggest rather than direct. Try to understand different points of view and divergent ideas; note and learn from any new ideas and knowledge generated.

• Place emphasis on preparation: Prepare at least a day in advance. Be clear about the learning objectives of each session and confident in using the appropriate processes/ tools to reach these objectives. In case of virtual training, be conversant with the package and attendant tools and ensure participants have the relevant package and are conversant with using it.

• Promote sharing: Encourages participation. Be very observant and note whether gender affects equal opportunity to participate in activities and answer questions. This could be carefully discussed during reflection, without finger pointing or blaming any individual.

• Control expectations: Participatory processes can encourage participants’ unrealistic expectations of “something good about to come”. Control such expectations, notably emphasizing the purpose of the training and what can be expected or not.

• Employ adult learning principles: Remember that you are working with adults, with their own personal experiences, ideas and even biases. Employ adult learning principles: Additional tips in Appendix VI.

introductory unit: How to use tHe mAnuAl

INTRODUCTION

This unit introduces facilitators and participants to the goal, aims, objectives outcomes and the practical application of the manual. The sessions herein will enable facilitators and participants to develop group dynamics and work well together, an important first step in addressing SRGBV. The unit provides foundational tips and techniques on content delivery and how to apply the knowledge and skills to identifying and addressing real life SRGBV situations.

What is in this Unit?

Session 1: Climate setting

The session looks at aspects of climate setting including getting participants to feel welcome and work as a group. It further looks at the overall aim and objectives of the training and participants’ expectations.

Session 2: Background to the Manual

1 hour 05 minutes

Session two introduces the manual and gives the participants’ foundational knowledge on SRGBV. 30 minutes

Session 3: Practical tips and techniques on how to use the Manual

This session gives a brief description of the facilitation methods primarily used throughout the manual. 30 minutes

Session 4: The session gives participants the opportunity for practical application of the facilitation methods primarily used throughout the manual. 40 minutes

Total 2 hours 45 minutes

Session 1: Climate setting

TIME: 40 MINUTES

FAWE SRGBV Manual | 15

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

By the end of this session, participants should be able to define the aim and objectives and outcomes of the training and feel comfortable working as a group.

METHODS USED:

1) Working pairs.

2) The “talking circle.”

3) Brainstorming.

4) Small group discussions.

MATERIALS NEEDED:

• Flipcharts or chalkboard.

• Masking tape.

• Markers or chalk.

• Sticky notes or

• Manila pieces (15 by 10 centimetres).

• Slides and/ or short videos.

• Applications e.g. Zoom (virtual training)

PREPARATION NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR:

1) Write on two separate flipcharts or project the aim and objectives and the outcomes of the training (See section 1.1.3).

SUPPORT NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR:

Begin with an activity that sets the group dynamics in motion and make everyone feel involved right from the start. Once you have got the attention of all participants and they have started warming up to each other, get into the session. You can use a song or a game, as an ice-breaker to get everyone involved. For ideas of ice breakers, refer to Appendix VI.

Ideas for introductions: In pairs, participants tell each their preferred name with an accompanying adjective, e.g. Jolly Jane, Talkative Tony, Serious Sarah etc. In addition to this, ask each person to tell the other something they like and something they dislike. For virtual training, using a conferencing programme e.g. Zoom you can break the participants in pairs using timed breakout rooms. After participants have got to know each other in pairs, ask them to get into a circle. In the circle, give a ball to one participant who introduces their neighbour, saying their preferred name and adjective and what they like and dislike and the neighbour does the same in return. The ball should then be thrown around the circle randomly, until everyone has had a chance to introduce their neighbour. For the virtual training, get the participants out of the breakout rooms. Apply the talking circle concept, ask the person introduce the person they were paired with, randomly select people until everyone has been introduced. This exercise is fun and gets everyone, even the shy members of the group involved.

16 | FAWE SRGBV Manual

ACTIVITY 1: INTRODUCTIONS (30 MINUTES)

1. Welcome participants and introduce yourself.

2. Facilitate warm up ice-breaker.

3. Ask the participants to introduce themselves in pairs or in a wider group or combine both.

4. Distribute folded pieces of manila to create name tags which participants can put in front of them, where they are sitting, for quick identification. For online training, the names will be visible for everyone. However, ensure the people are referred to by their preferred names, in case these are not the ones on the conferencing platform.

ACTIVITY 2: GROUND RULES (5 MINUTES)

1. Explain that, as adults, the participants should develop ground rules to guide and harmonize the group during their time together.

2. Ask two participants to take lead and ask their colleagues to formulate ground rules, with one asking while someone writes them on a physical flipchart, slide or online whiteboard and sticks them on the wall or shares them for everyone to see. Based on the ground rules, they could also elect among themselves people to take on roles like: time keeper, in charge welfare and in charge entertainment.

ACTIVITY 4: EXPECTATIONS (15 MINUTES)

1. On pre-cut pieces of manila or sticky notes, ask participants to write their workshop expectations. For virtual training, participants can use the chat option and the facilitators can transfer them onto a slide or stickies on your online white board.

2. Stick them on the wall or share your screen, so that everyone can see them and see how they match with the training objectives. Also note any expectations which are not directly aligned to the training aim and objectives and make sure you address them. For example, sometimes participants ask for certificates, or tee-shirts. (Remember tip on controlling expectations, under section 1.2.2).

3. Tell the participants that there are certain outcomes they will realize in the mid and long term because of going through this training. Take the participants through the outcomes and allow some questions. Put up the flipchart or share screen on outcomes for everyone to see.

WRAP UP:

ACTIVITY 3: AIM, OBJECTIVES AND OUTCOMES (15 MINUTES)

1. Ask participants for the aim and objective the training, without reading them up.

2. Allow for two or three responses. (Your co-trainer should note them down- using a flipchart, chalkboard, slide or online whiteboard).

3. Ask two volunteers to read the aim and objectives in the manual.

4. Ask a volunteer to stick the flipchart you prepared with the aim and objectives on the wall where everyone can see it or have it available for sharing as a shared screen.

1) Congratulate participants on being part of a training that will be Interesting and participatory.

2) Remind them that they bring knowledge to the training and that you look forward to hearing more from each individual.

3) Remind everyone to call other participants by their preferred name.

4) Explain that some of their expectations cannot be met (e.g., giving them tee shirts), but you will work together to meet the workshop’s aim and objectives. Tell them that at the end of the training there will be an evaluation to see whether or not the aim and objectives of the training were met.

5) Remind them that the ground rules should be followed throughout the training.

6) Revisit any issues in the “Parking Lot” before you move on to the next session.

Session 2: Background to the Manual TIME: 30 MINUTES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

By the end of this session, participants should have foundational knowledge on the manual.

METHODS USED:

1) Pre-test.

2) Brainstorming.

3) Discussions.

MATERIALS NEEDED:

• Flipcharts or chalkboard.

• Masking tape.

• Markers or chalk.

• Sticky notes or

• Manila pieces (15 by 10 centimetres).

• Slides and/ or short videos

• Printed or online Google Forms pre-test forms.

• Application e.g. Zoom (virtual training)

PREPARATION NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR: Have the pre-test form prepared and printed out or shared online beforehand. Prepare any support notes on flipcharts, slides or online white board before the session. Clearly mark sections of the manual you will be referring to avoid delays and fumbling.

SUPPORT NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR: A pre-test enables you to see whether participants have had any knowledge on SRGBV, and if so, what do they know? How, when and where did they acquire the knowledge? A simple pre-test form is attached as Appendix II. The pre-test form enables you to see gaps and determine which areas to concentrate on. The online pre-test form can be created in Google Forms. The responses will all automatically be collected in one spreadsheet.

ACTIVITY 1: SRGBV PRE TEST (10 MINUTES)

1) Ask participants to fill in the pre-test form.

2) In case of the virtual training, share the Google Forms link.

3) They can ask you or the co-facilitator for guidance where they are not clear.

ACTIVITY 2: BACKGROUND TO THE SRGBV MANUAL (20 MUNITES)

1) Using flipcharts, slides or online whiteboard, introduce participants to the 10 units and their key objectives.

2) After introducing each unit, allow time for some questions as this session sets the foundation for the following training/ content sessions. Questions raised should be noted down or recorded as they help in preparing for the detailed sessions.

WRAP UP:

1) Tell participants that as teachers and those working with children, adolescents, young people; they have a very important role to play in identifying, preventing and responding to SRGBV. This manual will therefore help them to increase their knowledge and skills towards working with children, adolescents, and young people and other duty bearers while addressing SRGBV.

Session 3: Practical techniques in using the SRGBV Manual TIME: 20 MINUTES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

By the end of the session, the participants should have foundational knowledge of delivery skills that are participatory and fun but also respect diversity among the participants.

METHODS USED:

1) Brainstorming.

2) Discussions.

MATERIALS NEEDED:

• Flipcharts or chalkboard.

• Masking tape.

• Markers or chalk.

• Sticky notes or

• Manila pieces (15 by 10 centimetres).

• Slides and/ or short videos.

• Applications e.g. Zoom (virtual training)

PREPARATION NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR:

Make sure all participants have a copy of the SRGBV Manual

SUPPORT NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR:

From the Manual, on flipchart, slides or online whiteboard, create a list of facilitation tips and any other reference materials for using during the session. Otherwise, refer to the tips under section 1.2.2.

ACTIVITY 1: FACILITATION TIPS (10 MINUTES)

1) Take participants through the tips for a facilitator.

2) Begin with one or two and ask participants for some tips.

WRAP UP:

1) Wrap up the session by discussing the rest of the tips and share your screen or put them on the wall where everyone can see them.

ACTIVITY 2: METHODS/ TECHNIQUES: (20 MINUTES)

1) Tell participants that there are several facilitation methods and techniques that one can use for different sessions.

2) Explain that using different methods helps to among other things break monotony and keeps participants both active and involved.

3) Ask volunteers about facilitation techniques they know of have used in the past. Write them down and your co-facilitator can guide a discussion on how these methods help the facilitator to get others involved.

4) Ask which technique they like most and why.

5) Introduce participants to the techniques in notes to the facilitator below.

Session 4: Practical application of the facilitation methods used throughout the Manual

TIME: 40 MINUTES

FAWE SRGBV Manual | 19

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

By the end of the session, the participants’ should have foundational practical delivery skills that are participatory, fun and respect diversity among the participants.

METHODS USED:

1) Brainstorming. 2) Discussions.

3) Small group discussions. 4) Role play.

MATERIALS NEEDED:

• Flipcharts or chalkboard.

• Masking tape.

• Markers or chalk.

• Sticky notes or

• Manila pieces (15 by 10 centimetres).

• Slides and/ or short videos.

• Applications e.g. Zoom (virtual training)

PREPARATION NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR:

Make sure all participants have a copy of the manual.

SUPPORT NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR: Have any reference materials for using during the session e.g. ice breakers.

For facilitation methods, refer to the section below.

Participatory Facilitation Methods Below are brief descriptions of the facilitation methods primarily used throughout the manual.

Brainstorming: The method is used as a first step to generate initial interest and essential involvement of the participants in a training activity. The facilitator asks the participants to think of ideas and all views are accepted and respected. This activity encourages participants to expand their thinking about an idea and look at a topic from different angles and perspectives.

Energizers/Icebreakers: Energizers, icebreakers or warm-ups, are games that lighten the mood and help participants relax, have fun and re/connect with each other. They can be used at the beginning and end of each sessions and between session and activities.

Group Discussion: This method is based on the principle of the trainer taking on the role of a group facilitator or guide. It enables participants to discuss issues in a participatory manner. The facilitator can guide the discussion using guiding questions and can encourage discussion through positive gestures like nodding, eye contact, moving around the room, etc.

Role-Play: Performing role-plays is an effective method for participants to put into action the skills learnt through the training. Role plays can be used for continuous practice and help participants remember and keep knowledge and skills alive. Role-plays can however be emotional; it is therefore very important to emphasize that participants are acting as characters and not themselves.

“Talking Circle “symbolizes completeness and creates a safe environment where everyone is equal and all views are respected. An everyday object such as a ball or pencil can be used as a talking object. When the talking object is placed in someone’s hands; it is that person’s turn to share his or her thoughts, without interruption. The object is then passed to the next person for example in a clockwise direction. Whoever is holding the object has the right to speak and others have the responsibility to listen. Silence is an acceptable response. There must be no negative reactions to the phrase, “I pass.” For virtual training, the same principle can be adopted, with the participants mentioning the agreed upon object and who they are passing it on to. E.g. “I am passing the ball to Donald”.

Observation: Working with a co-facilitator, take turns observing how the group is working together and responding to the activities and discussions. If you are facilitating the sessions alone, you can still observe how the group is reacting and working together. This will enable you create a balance between active and quiet or non-responsive participants. You can use this by engaging one or more of the facilitation techniques.

Feedback from participants: Whatever method you use, feedback from participants is very important. Invite participants to share their views on the sessions. You can get feedback on content delivery areas that were not adequately covered and areas for improvement

Self-assessment: As you train, you are also learning new things and getting feedback from participants. Always assess yourself at the end of each unit and each day looking at whether you achieved the objectives of the unit/s and sessions; what you could have done differently and how to handle upcoming sessions.

ACTIVITY 1: (40 MINUTES)

1) In groups or virtual breakout rooms of 5 to 7 people, ask participants to prepare a 5 minutes presentation on introducing the manual. They should use at least three techniques and involving the whole group; with two people acting as facilitator and co-facilitator. Discuss what worked well and what could have been done better in each session.

WRAP UP: Thank participants and formally close the introductory unit by asking a few participants for any key lessons learned. Ask them to note them down in their note books as KEY LESSONS- INTRODUCTORY UNIT. Ask the group to note down three ways they can use or apply what they have just learned and circle the one thing they plan to do first.

PERSONAL REFLECTION: Remember, these tips can help you work with learners and other adults including; coworkers, parents and members of the community. In your free time, work in pairs or small groups to try out different facilitation skills and help each other to identify strengths and weaknesses.

unit one: gender bAsed violence

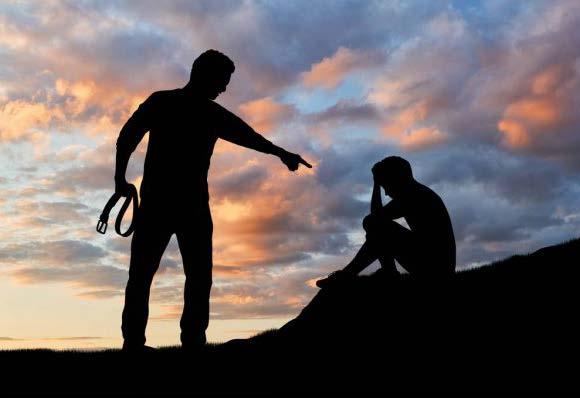

Unit One introduces the broad concept of gender and gender based violence (GBV). The sessions provide information on how gender is socially constructed and begins at birth. Sessions further show that the way girls and boys and women and men are socially seen and treated in society may have a bearing on GBV. Sessions also look at, what causes GBV and how it manifests in communities. The unit shows that SRGBV is not disconnected from violence in the lives of learners, teachers and the school communities.

UNIT

OUTCOMES:

By the end of Unit One you should be able to: 1. Understand that gender is socially constructed and begins at birth. 2. Define GBV and its causes and manifestation in the community. 3. Understand how GBV affects education. 4. Reflect on what you can do as an individual to address SRGBV. What is in Unit One? Session

22 | FAWE SRGBV Manual

manifestations and perpetrators

manifestations

Session 1: Introduction to Gender TIME:

STOP!

1: Introduction to Gender The session introduces the gender concepts and brings out the difference between sex and gender. 30 minutes Session 2: GBV and its causes,

Session 2 looks at forms of GBV and gives examples of cause,

and perpetrators in the community. 30 minutes Session 3: The effects of GBV on individuals and development This session explains how GBV affects learning and the developmental domains (physical, mental, social, emotional and linguistic). 01 hour Total 2 hours

30 MINUTES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

By the end of this session, participants should be able to:

1) Define gender and sex and the related gender concepts.

METHODS USED:

1) Brainstorming.

2) Small group discussions.

3) Discussion.

MATERIALS NEEDED:

• Flipcharts or chalkboard.

• Masking tape.

• Markers or chalk.

• Sticky notes or

• Manila pieces (15 by 10 centimetres).

• Slides

• Applications e.g. Zoom (virtual training)

PREPARATION NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR:

1) Put the definitions of gender and sex on flipcharts, slides or online white board.

2) Label two flipcharts or slides WOW and HOW ABOUT.

3) Prepare flipcharts, slides or online white board with examples of statements about sex and gender.

4) Write two big signs, SEX and GENDER on separate flipcharts.

SUPPORT NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR:

Below are notes to support facilitators understand key gender concepts that are important in preventing and responding to SR/GBV.

Definitions of Sex and Gender

Sex:

• Biological (male or female).

• Universal (factors are the same around the world).

• Born that way.

• Generally unchanging (with the exception of surgery).

• Does not vary between or within cultures.

Gender:

• Socially constructed roles, responsibilities and behaviours (masculine or feminine).

• Cultural.

• Learned.

• Can change over time.

• Varies within and between cultures.

Gender norms:

Are ideas about how men and women should be and act. We internalize and learn these “rules” early in life. This sets up a life-cycle of gender socialization and stereotyping.

FAWE SRGBV Manual | 23

Gender awareness:

Awareness of the socially determined differences between men and women, boys and girls, and how these differences affect their opportunities. This is important if we are to observe gender equality and address SR/GBV.

Gender stereotypes:

Structured sets of beliefs about the personal attributes, behaviours and roles of a specific social group, based on their sex. These beliefs are often biased and lead to exaggerated images of women and men that are used repeatedly in everyday life; for example, a belief that early years and Home Economics teachers should always be female and Science teachers should always be male. Girls should be nurses, while boys should study to be doctors. As we see below, gender stereo types can lead to gender bias and can result in and encourage SR/GBV.

Gender bias: An unfair difference in the way women or men, girls or boys are treated. Lack of gender awareness is likely to lead to gender bias. Where there is gender bias, some form of SRGBV is likely to happen, because female and male learners will be treated differently. For example, if there is a bias that boys are strong and girls are weak, boys may be “disciplined” through corporal punishment and manual labor, while girls may be asked to write an apology letter.

Gender barriers: Obstacles that prevent access to relationships, respect, authority, education and other rights, on account of being female or male. Lack of awareness of the socially constructed and determined differences between females and males, can lead to a pre-determined way of thinking. This is likely to lead to gender biases and barriers. For example, if society believes girls cannot perform well in Science subjects, it may create biases when selecting girls to answer questions during science lessons. This may ultimately create barriers in their science Technology, Engineering Mathematics (STEM) education trajectory.

Gender roles: Are social and behavioral norms that, within a specific culture, are widely considered to be socially appropriate for individuals of a specific sex. These are formed right from birth and often determine the traditional responsibilities and tasks assigned to girls and boys, women and men. Like gender, while they are conceived from birth, gender roles can evolve over time, in particular through the empowerment of women/ females and transformation of masculinities.

Gender relations: Constitute how men, women, boys and girls interact with one another. This arises from the roles men and women are expected to play in society. Sometimes SR/GBV arises out of gender relations and the unequal power relations that are created. For example if boys are brought up to believe they are “men” and are more important than girls, then they can abuse girls, believing it is the right thing to do. Sexual violence is sometimes based on society looking at women and girl’s roles as cooking, getting married and having babies.

Gender sensitivity: The ability to perceive existing gender differences, issues and inequalities. The good news is that as members of the community and people with a duty to look after those entrusted to our care, we can be supported to become gender sensitive. Once we become gender sensitive, we can start taking corrective action to address the negative social constructs that contribute to SR/GBV.

Gender responsiveness: Coming up with strategies, plans and actions that address the different needs and aspirations of women and men, girls and boys. It involves taking action to correct or prevent gender bias and discrimination so as to ensure gender equality and equity. This could include having gender responsive laws, policies, bye laws, pedagogy etc.

Gender equality: Means that women and men, girls and boys have equal conditions for enjoying their full human rights and for contributing to, and benefiting from, economic, social, cultural and political development. It involves valuing males and females and the roles they can play; giving them opportunities for equal participation in all opportunities and spheres of life.

Gender equity: The process of being fair to women, men, girls and boys. To ensure fairness, measures must often be used to compensate for historical and social disadvantages that prevent women and men, girls and boys from operating on a level playing field.

Examples of statements about sex and gender

1) Women are born to cook, clean the house and take care of the children. (Gender)

2) Girls menstruate when they reach puberty. (Sex)

3) Boys get deep voices at puberty. (Sex)

4) Men are born to work, buy school needs and pay school fees. (Gender)

5) Girls cry a lot and are very emotional. (Gender)

6) Boys are strong and do not cry easily. (Gender)

7) Women breast feed babies. (Sex)

8) Boys are better than girls at Mathematics. (Gender)

ACTIVITY 1: INTRODUCTION TO GENDER (30 MINUTES)

1) Pin up the flipcharts of sex and gender, and on definitions of sex and gender. For virtual training, share your slides or notes.

2) Refer participants to the flipcharts or screen with the definitions of sex and gender and explain the concepts to them.

3) Read a sample statement, and then ask participants to stand next to the sign “sex” or “gender,” depending on whether the statement reflects biological or socially constructed roles (or what is considered masculine or feminine). For virtual training, you can ask participants to have two manila cards, one with sex and one with gender on it. They should raise the card that they feel corresponds with the statement, near their face, where it is visible. This exercise is meant to get participants into the discussion about how gender is “socially made” not “born”.

4) After participants have had time to decide whether the statements relate to gender or sex, ask the questions below. Allow participants to express their opinions and justify why they related the statements to sex or gender.

• Why do you think this statement is related to sex?

• Why do you think this statement is related to gender?

5) End the session by asking participants in groups or online breakout rooms of 5 to 6 to quickly draw and label pictures of any 3 of: 1) nursery school teacher, 2) Mathematics teacher, 3) school driver, 4) school cook, 5) head teacher and 6) school nurse.

6) Discuss the pictures and find out why they drew a male or female for each role.

WRAP UP: Thank participants and formally wrap up the session by asking participants on a sticky note of one color to “write a “WOW”- something you learned that was important to you”. On another sticky note of a different color, “write a “HOW ABOUT”? A question or other idea you might have”. Post your notes on the two flip charts (labeled WOW and HOW ABOUT). For virtual training, they can write their “wow” and “how about” to the facilitator only in the in-meeting chat. Spend the next five minutes reading and reviewing the notes. Highlight the important points. Put any issues that are not addressed in the “Parking lot” and address them by or at the end of the unit.

Session 2: GBV causes, manifestations and perpetrators in the community

TIME: 30 MINUTES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

By the end of this session, participants should be able to define what causes GBV and how it manifests in the community and who some of the perpetrators are.

METHODS USED:

1) Brainstorming.

2) Small group discussions.

3) Discussion.

MATERIALS NEEDED:

• Flipcharts or chalkboard.

• Masking tape.

• Markers or chalk.

• Sticky notes or

• Manila pieces (15 by 10 centimetres).

• Slides.

• Applications e.g. Zoom (virtual training).

• 25 pieces of green manila and 25 of pink manila cards 10 by 15 centimetres (you can use any other two colours).

• Two containers e.g. box, bowl or basket marked GBV and PREVENTION.

PREPARATION NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR:

1) Be familiar with the four types of GBV (psychological/ emotional, physical, sexual and economic).

2) Prepare some examples of the definitions of the four types of GBV on flipcharts, slides or online white board.

3) Prepare causes, manifestations of GBV and the possible perpetrators on flipcharts, slides or online white board.

SUPPORT NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR: Gender Based Violence (GBV)

This is violence or abuse that is based on gender roles and relationships. It can be either psychological/emotional, physical, sexual and economic, or combinations of the four. In the following section are brief descriptions of the types of GBV with a few examples. The examples are by no means exhaustive and participants can add to them based on their communities and experiences.

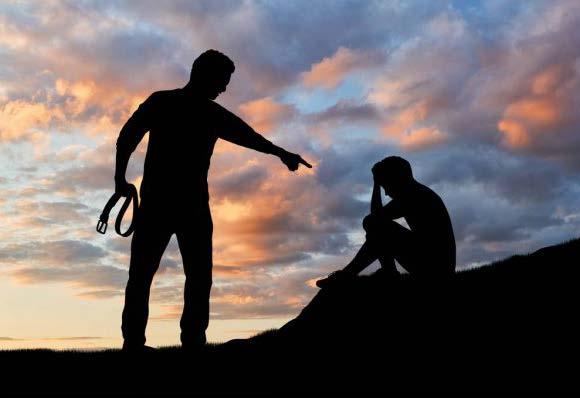

Psychological/emotional Violence: This is any act that causes psychological harm to an individual. Examples are: bullying, making threats, teasing; intimidation, lying about someone, insulting someone, humiliation and ignoring someone.

Physical violence: It is any act which causes physical harm as a result of unlawful physical force. It can take the form of: corporal punishment, holding/ restraining a person against their will, punching, kicking, hitting, shoving, wrestling, throwing something at someone,

pinching, scratching, biting, burning or scalding and forcing to swallow food or liquid.

Sexual violence: This constitutes any sexual behaviour or act performed on an individual without their consent. It can take the form of: rape, defilement, intimate partner violence, sexual harassment, indecent touching and exposure, sexually explicit language, sexually suggestive remarks or offers, sexual and inappropriate material (pictures, videos etc.).

Economic violence: This is any act or behaviour which causes economic harm to an individual. It could be in the form of: not providing adequate shelter, food, clothing and other basic necessities; exploiting others for economic gain; property damage; restricting access to financial resources, education, labor markets etc.

Causes, manifestations and perpetrators of GBV

There are several causes of GBV in the community. The causes are usually rooted in socio-cultural norms and beliefs. The abuse of power and exploitation of unequal power relationships also contribute to GBV. Note that whether the power is real or not; the victim always perceives the perpetrator as more powerful. GBV in the community has many causes, manifests in many forms and anyone can be a perpetuator as outlined in Table 1 below.

Table 1 Examples of GBV causes, manifestations and perpetrators

Causes Manifestation

Peer pressure.

Poverty and misuse of cultural norms, traditional family structures.

Poor legal systems and structures; corruption; pressure from cultural and religious institutions.

Poor enforcement of the law. Alcohol and substance abuse.

Bullying, intimate partner abuse, sexual harassment.

Control of access to goods, services, money, favour etc.

Implementation of discriminatory laws. Impunity or lack of legislation and sanctions against perpetrators.

Use of excessive force to maintain order and or security. Use of arms or force to inflict physical harm and access goods or services.

Perpetuator (more “powerful” person)

Peers, older children, both males and females.

Husband, father, head of household, clan heads.

Justice law and order duty bearers. Elected leaders, village elders, religious and cultural leaders.

Soldiers, police, robbers, gangs.

FAWE SRGBV Manual | 27

ACTIVITY 1: INTRODUCTION TO GENDER BASED VIOLENCE (GBV) (30 MINUTES).

1) Introduce the participants to GBV using the definition in the facilitator notes. Ask participants for some examples of violence suffered by women because they are women and by men because they are men. Note their answers and thank them.

2) Use the flipchart, slide/ notes on power and introduce how GBV is due to abuse of power and unequal power relations. Go through each type of power and ask participants if they know anyone who has experienced GBV because of the abuse of the power. Note the answers, as they may guide future sessions.

3) Introduce participants to the four types of GBV using examples in the notes.

4) Divide the participants into 3 groups or online breakout rooms and ask them to come up with 5 examples of GBV in the community and what causes them.

5) Ask each group to make a presentation after which the wider group responds and discusses the causes and types of gender in the community.

WRAP UP: Thank participants and summarize the causes and types of GBV in their community.

Give out the pink and green manila cards and ask participants to write down on the pink cards a form of GBV they have been knowingly or unknowingly encouraging and on the green cards one kind of GBV they have been knowingly preventing. Collect the cards in the containers marked, GBV and PREVENTION. With the co-facilitator, pass the containers round and ask each participant to read out one act of GBV and one act of PREVENTION. Tell them that we can all be perpetrators knowingly or unknowingly but we can also all prevent GBV. For virtual training, ask the participants to share with the facilitator only on in-meeting chat, one kind of GBV they have been knowingly preventing. After a few minutes, ask them to share a form of GBV they have been knowingly or unknowingly encouraging. Record the types of GBV and prevention raised by participants on flipcharts or slides marked WRAP UP SESSION 2 UNIT 1.

Session 3: GBV effects on developmental domains, learning, teaching and school environment

TIME: 60 MINUTES

28 | FAWE SRGBV Manual

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

By the end of this session, participants should be able to show how GBV affects developmental domains (physical, mental, social, emotional and linguistic), learning, teaching and school environment.

METHODS USED:

1) Brainstorming.

2) Small group discussions.

3) Role plays.

4) Discussion.

MATERIALS NEEDED:

• Flipcharts or chalkboard.

• Masking tape.

• Markers or chalk.

• Sticky notes or

• Manila pieces (15 by 10 centimetres).

• Slides

• Applications e.g. Zoom (virtual training)

PREPARATION NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR:

1) Ask participants to give an example of GBV and how it can affect learning, teaching and the school environment. Get about three examples and discuss them as a group.

2) Have 3 to 4 scenarios of how GBV affects learning, teaching and the school environment typed and printed out on a sheet of paper.

SUPPORT NOTES FOR THE FACILITATOR: While GBV happens in the community, it can affect the school environment. This is because the pupils, students and teachers and other duty bearers come from the community and move between school and home every day, or go home for holidays. Below are some scenarios that show GBV can affect developmental domains (physical, mental, social, emotional and linguistic), learning, teaching and the school environment.

FAWE SRGBV Manual | 29

Scenario 1:

Jane is 10 years old in primary four and is always late for class. Her mother is a single parent who has three other children to look after. Jane has to do house work and help her mother make pan cakes before she goes to school each day. This often makes her worry because no matter what she does to try to get there on time, her mother always has something for her to do before she leaves for school, and it makes her late. Sometimes she does not even want to go to school because of the punishment she receives from her teacher. She makes her stand at the front of the classroom, and the other children laugh at her. After sitting down, Jane finds it difficult to concentrate in class. She has not reported anything to her mother, who only gives her money for exercise books when they sell pancakes.

Scenario 2:

Tom is 12 years old and lives with his father and four sisters. His father lost his source of income when his hardware store closed down during the country wide lock down due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, he started drinking heavily. Due to the curfew and lockdown, he now drinks from home. He sends Tom to the shopping centre to buy him alcohol. Tom does not like buying alcohol for his father because when his father gets drank, he sometimes verbally abuses them and at times beats their mother. Tom has now become angry and he beat up a boy at school who said his father is a useless drunkard. He used to perform very well but his grades have steadily kept going down. He tried to raise the issue with his uncle, but the uncle rebuked him saying a son cannot report his father’s behaviour and that as a man, he should not whine but be strong.

Scenario 3:

Tony who is 15 years old has a disability and because of his disability, he finds it difficult to walk fast or ran. At home, when he was younger, his parents used to tell him to hide when visitors came over. He was also not allowed to go to church and to the shopping centre with his sisters. At school, he often sits alone while other children play during the school breaks and finds it very difficult to climb the stairs to his classroom. Some children tease him because of his disability. Tony dreads going to school because his legs hurt when he climbs the stairs to his classroom and the children laugh at him.

Scenario 4:

Dinah a refugee is 5 years old, she is in top class in the infant section of the community school which she attends with her older sister Mary. There is a child in Dinah’s class who pinches her when teacher Ida is not looking in their direction. This child who is much bigger than Dinah sometimes drinks her porridge and eats the snack that World Food Programme provides for her, saying refugees are bad people who eat their food. Dinah used to perform very well but because of the bullying, she has started forgetting the things she is taught in class. Dinah is afraid to report the child whose father is the village chief.

Scenario discussion questions:

1) Who is the powerful person in this scenario? (It could be more than one person)

2) What kind of power have they abused and how? (E.g. social through peer pressure and bullying).

3) Who is the victim?

4) How are they affected as a result of this abuse of power?

5) Where does this abuse happen? (It could be more than one answer e.g. at home and in the classroom etc.).

ACTIVITY 1: GBV AND POWER (20 MINUTES)

1) Tell the participants that since gender is socially constructed; GBV often has its source in the community; it involves the abuse of power and exploits unequal power relations. The power could be real or perceived. However, the victim of the abuse believes the power is real.

2) Share one scenario and ask a volunteer to read it.

3) Use the scenario discussion questions to guide a discussion on the scenario.

4) Note the answers on a flip chart, slide or online white board and share them with everyone. Note emerging patterns. The scenario may show that a victim can suffer abuse at home, on the way to and from the school, at school and in the community.

WRAP UP: Thank participants and ask them to start thinking about what they can do to address such a scenario. Ask them to write the summary in their note book, under the heading: UNIT TWO: WHAT I CAN DO TO ADDRESS GBV IN MY COMMUNITY.

ACTIVITY 2: GBV SCENARIOS GROUP DISCUSSION (40 MINUTES)

1) Divide the participants into 3 groups or online breakout rooms and give each group one fresh scenario (not the one discussed in activity 1).

2) Ask them to develop a 5 minute role play about the scenario. (While during the virtual training they may not be able to fully act, they can creatively use their voices, facial expression and improvised props to come up with interesting role plays).

3) Each group presents their scenario.

4) The others discuss the scenario based on the discussion questions.

5) Ask each group being critiqued to note the answers and based on them makes a summary of how GBV affects learning, teaching and the school environment. Each group will write out their summary on a flipchart or type it out.

WRAP UP: Thank participants and ask them

• What went well?

• What was difficult?

• What needs to be done differently next time?

WRAP UP: Thank participants and formally close training on Unit One by asking a few participants for any key lessons learned. Ask everyone to note them down in their note books under the heading; KEY LESSONS LEARNED UNDER UNIT ONE. Ask the group to write three ways they can use or apply what they have just learned and circle the one they plan to do first.

PERSONAL REFLECTION: Tell participants, “There are social norms that deem some forms of GBV as normal, acceptable, or even justified and therefore perpetuate GBV. GBV may go unnoticed because we have lived and accepted it for so long. We need to start critically looking at what happens around us and see whether there are forms of violence that have become acceptable over time. This is important since gender issues start from birth. Read more about gender in early years and in the school setting in the FAWE Gender-Responsive Pedagogy in Early Childhood Education A toolkit for teachers and school leaders, in Appendix IV”.

FAWE SRGBV Manual | 31

unit two: scHool relAted gender bAsed violence

Introduction

Unit Two is at the heart of the manual. It introduces the facilitators and participants to SRGBV. The sessions provide facilitators and participants with information on: types of SRGBV in and around their schools; and causes, contributing factors and the consequences of SRGBV. The unit outlines the guiding principles and roles of teachers and education practitioners in preventing and responding to SRGBV.

UNIT OUTCOMES:

By the end of Unit One you should be able to: 1. Understand the types of SRGBV and their causes and contributing factors. 2. Define the consequences of SRGBV.

3. Introduce ways of identifying, preventing and responding to SRGBV.

What is in Unit Two?

Session 1: SRGBV types, causes and contributing factors

This session:

• Introduces the types of SRGBV

• Defines some of their causes and contributing factors. 60 minutes

Session 2: The consequences of SRGBV

Session 2 defines the consequences of SRGBV. 30 minutes

Session 3: Identifying, preventing and responding to SRGBV

This session introduces ways of identifying, preventing and responding to SRGBV in and around schools. 60 minutes

Total 2 hours 30 minutes

Session 1: SRGBV types, causes and contributing factors

TIME: 90 MINUTES

32 | FAWE SRGBV Manual

LEARNING OBJECTIVES