Nutrition Unpacked

White Paper / 2021

White Paper / 2021

White Paper / 2021

White Paper / 2021

The purpose of this co-branded research initiative was to unveil unique local insights and knowledge gaps about nutrition through a combined academic and practical approach, able to go beyond overgeneralizations and biased interpretations. The research question addressed in this paper is the following: How might we ensure access to (quality) nutrition for all people regardless of their gender, race, or socioeconomic status, without compromising the livelihoods of (small) farmers and the boundaries of our planet?

Methodology

Phase 1 of the study relied on previous literature review, and quantitative analysis of data banks from public research institutions.

Phase 2 implemented the preliminary findings during six dinner events organized in Brazil, India, Zimbabwe, United States, Poland, and Japan, where local communities of stakeholders shared a meal and their thoughts about nutrition inequality.

Findings

Considering that access to nutrition is an equation of acceptability (knowing about nutritious foods and finding them acceptable), affordability, and availability, four directions were explored:

(i) social nutrition (food availability and consumption based on social factors as gender, culture, religion, economics, and politics)

(ii) food generation gap (nutritional status and mindset of different age groups)

(iii) hidden hunger (the mismatch between quality of food ingested and nutrient requirements)

(iv) ecosystem (the holistic view of a multi sector made of multi stakeholders, crucial to ensure Nutrition for All).

Exploring these directions helped establish a framework to better understand the perspectives and narratives around nutrition inequalities, which were later validated with stakeholders at the dinner events.

Improving (good) food communication, next to food education, is crucial to stem heavy marketing strategies spreading a surreal image of instagrammable food and to avoid dangerous misconceptions about body and health.

According to the UN SDGs, gender equality and female empowerment are pivotal to achieving food security for all, improving agricultural productivity, and ensuring the full participation of rural people in decision-making processes.

Today, poor-quality diets are the primary cause of morbidity and mortality in the world, due to both inadequate consumption of nutritious foods and excess consumption of harmful ones (Hirvonen, K. et al., 2020). Realigning food systems to deliver better health and environmental outcomes is therefore among the most important global challenges of the 21st century.

The conventional agricultural system shifted towards quantity over quality, and maximizing profits at the cost of nutritional value for the consumer. Due to the rise of big supermarkets and urbanization, small and medium grocery stores have disappeared from the street corners. Simultaneously, busy lives and hectic working rhythms encouraged the consumption of processed ready-to-eat and convenience foods.

Achieving universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water is one of the major targets for 2030 and implementing nutrition-sensitive agricultural water management means producing food in adequate quantity and quality while also safeguarding water and other natural resources (Bryan, E. et al., 2019; FAO, 2017; UNSCN, 2020). Biodiversity provides us with food and wellbeing. It filters our air and water, helps keep the climate in balance, converts waste back into resources, pollinates and fertilizes crops and much more (EC, 2020). People are largely unaware of the biodiversity crisis and of their role played through food choices. Genetic biodiversity is looked after by the wise hands and extensive knowledge of smallholder farmers who have the power to potentially reverse and restore the drawbacks of biodiversity. Hence, feeding the link between urban populations and indigenous farmers might enable an exchange of know-how in addition to new employment opportunities in food value chains (IFAD, 2016).

This research aims to be the first step towards the creation of an open source platform where data and real life experiences worldwide are mapped out. Moreover, the Nutrition for All approach could be employed for further research where we include even more stakeholders at the table and enable cross-cultural experience sharing.

One in three people worldwide is affected by malnutrition, making it the largest contributor to disease in the world.

Deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients.

Directly and indirectly, hinders child development, impacts education, and increases the likelihood of poverty in adulthood.

Every country in the world, both developed and de veloping, is affected by one or more forms of mal nutrition, making the fight against it, in all its forms, one of the most significant global health challenges, regardless of generational causes.

Urbanization and hectic working rhythms accelerate the speed of nutrition transition towards unhealthy foods, influencing both consumption practices and the livelihood of smallholder producers, just as poverty and social marginalization are underly ing causes of food insecurity and malnutrition.

Despite perceptions to the contrary, food-insecure and malnourished people are not always members of the poorest households. A large part of undernourished populations today live in middle-income countries. Many low and middle-income countries face undernourishment, obesity, and micronutrient deficiencies, implying a “triple burden” of malnutrition.

The mismatch between the nutrients we need for a healthy diet and the nutrients we consume.

This gap can be the result of availability, affordability, access, and/or food choices. The nutrition gap is a public health concern because it occurs across all age groups, and can negatively affect myriad aspects of health (FAO, 2013).

The doctor of the future will no longer treat the human frame with drugs, but rather will cure and prevent disease with nutrition.”

— Thomas A. Edison

Differences, variations, and disparities in health and living conditions among people, both individuals and population groups, which generates disparities in terms of economic income, access to social and health infrastructure, and asset distribution (Global Nutrition Report, 2020).

The forms of exclusion generated by inequality are among the main drivers of poverty, which in turn affect food security and nutrition. More than 820 million people don’t have enough to eat, yet, at the same time, no region is exempted from obesity (FAO, 2020).

Nutrition inequalities crosscut and include eating be havior and practices, food environment, living envi ronment, education and employment opportunities, cultural, and political context (WHO, 2008; UNICEF, 2019a). Dietary intake, nutritional status, and related conditions/diseases are influenced by location, age, ethnicity, wealth, and gender. The latter aspects spe cifically stress the connection between nutrition and the role that women have within the family system, by considering both intra- (biological or psychological), and extra-individual aspects.

Inequity affects people in multiple forms that in tersect with one another. Tackling inequalities in food and nutrition is a tremendous chal lenge worldwide.

In 2018, the United Nations published a report showing how complex ine quality can be (Goalkeepers report, 2019). This research project started by analyzing four types of inequal ity that are affecting access to nu trition worldwide.

Where someone is born has a significant impact on future potential. Lack of education and poverty are often structur al barriers to accessing healthy and nutritious diets in develop ing countries, yet behaviors and generational gaps in nutrition are overwhelmingly researched in de veloped countries.

Gender inequality is even more prevalent in underdeveloped countries. As they reach their teenage years, a boy’s world expands while a girl’s world contracts. This inevitably also affects nutrition. Several studies have already focused on the relationship between mother-children, while other aspects such as age, religion, and the position within the family are still key determiners for females to reach better nutrition.

If circumstances remain the same by the year 2030, two-thirds of students will not attain basic education. Studies are aligned on the direct connection between education and nutrition, just as they are with other socio-economic factors such as income and access to services.

Uncover valuable (local) insights and knowledge gaps about nutrition (equality) by bringing all stakeholders to the literal table.

Closing the nutritional inequality gaps is not just about understanding the differences in nutrition outcomes among different population groups. It also puts attention on the food ecosystems and processes that generate unequal distributions of these outcomes. Achieving nutrition for all, across all these dimensions, requires our food ecosystem to be completely reshaped.

In addressing the above problem statement, this research projects aims to explore the following question:

How might we ensure access to (quality) nutrition for all people, regardless of their gender, race, or socioeconomic status, without compromising the livelihoods of (small) farmers and the

Nutrition for All is a co-branded research initiative highlighting nutritional inequalities and gaps around the world. This white paper combines academic and practitioner views, to lend credibility while also giving a voice to grass-root communities, advocating for better solutions for underprivileged groups, and providing actionable outcomes.

This document is just one aspect of a broader intention to contribute and improve the agri-food system through concrete and actionable steps to align Prosperity with the social and environmental dimension,

The initial phase of the research provides not only a better understanding of the dominant behavior that determines the effectiveness of actionable recommendations, it also ensures that the report takes all stakeholders carefully into account.

Through the preliminary literary review, four initial directions were identified, serving as starting points to formulate the research problem and knowledge gaps.

Tradition and innovation covers all aspects related to food identity, cultural values and norms, consumer behavior, and food choices.

Globalization and nutrition transition focuses on the implications of the global food system, business consolidation, and implications for physical access to healthy nutrients.

Youth and education is related to (out of home) consumption practices of teenagers and the correlation between consumption practices and education.

The Ecosystem centers on human capital & potential, social position, affordability of healthy ingredients, and community building.

Exploring these directions establishes a framework to better understand the perspectives and narratives around nutrition inequalities that have already been extensively researched. More importantly, it serves to both unearth topics that are ‘under-investigated’ in the academic field, as well as identify a unique narrative for this research paper, in order to maximize the added value of the report to a broad spectrum of the food system.

Food as medicine

Community nutrition environment (Community kitchens)

Tourism

Racial discrimination

Female autonomy

Intrahousehold food allocation

Individualization + medicalization + technologization + de-politization

Food identity

Eating behaviour

Collective responsibility

ECOSYSTEM

Food generation gap

Minorities

Nutrition Access = Availability + Affordability + Acceptability

Gender + nutrition inequality

Food sharing

NUTRITION FOR ALL Implies a shared responsibility to find adequate measures that benefit all stakeholders across the complex food system.

A thorough analysis is performed to identify the perspectives of all stakeholders involved. The goals and core desires per stakeholder (consumers, producers, public controlled facilities, food processing companies, and governmental parties) are gathered in goal trees.

This technique offers insights into desires that stakeholders have in common, exposes conflicting interests, and enables operationalizing abstract goals into concrete, measurable criteria. The process results in a set of criteria (from all stakeholders combined) that form the basis for the research approach and the direction for data collection. This set of criteria is mapped out to visualize the interrelationships, and potential feedback loops are explored to determine the food systems’ behavior through balancing or reinforcing effects.

Food + feelings

Physical activity engagement (CSR)

Cognitive foods

GLOBALIZATION & NUTRITION TRANSITION

Hidden hunger

Indigenous: Fruit trees (Africa)

Food sovereignty

Biodiversity

Agroecology

Climate change

TRADITIONS & INNOVATION

Social nutrition

Lifestyle Value chains

Resilience

The subsequent phase of the study builds on the preliminary findings and aims to validate the insights by organizing Nutrition for All dinner events locally.

Based on the preliminary data, stakeholder analysis, systemic perspectives, and local challenges regarding nutrition, six dinner locations were selected for this validation process: Brazil, India, Zimbabwe, United States, Poland, and Japan. At these dinners, different stakeholders gathered around the table, shared a meal, and discussed their thoughts and perceptions about ‘Nutrition for All,’ from their own experience and environment.

Due to the current Pandemic and varying local regulations, dinners were organized in-person, hybrid, or via fully digital events.

6

12

Communitystewarts, food scientists, visual artists, rangers ,philantropists , healthcare prof essi onal s , n u t r i t i o n i s ,st cosoigol,stsi fml ,srekam …sremusnoc

Educators,farmers, scientists, climate activists, chefs, foodtechconsultants , entre peneurs , f o o d j o u r n a l,stsi p o ,srekamycil ,stsimehcladoof

110

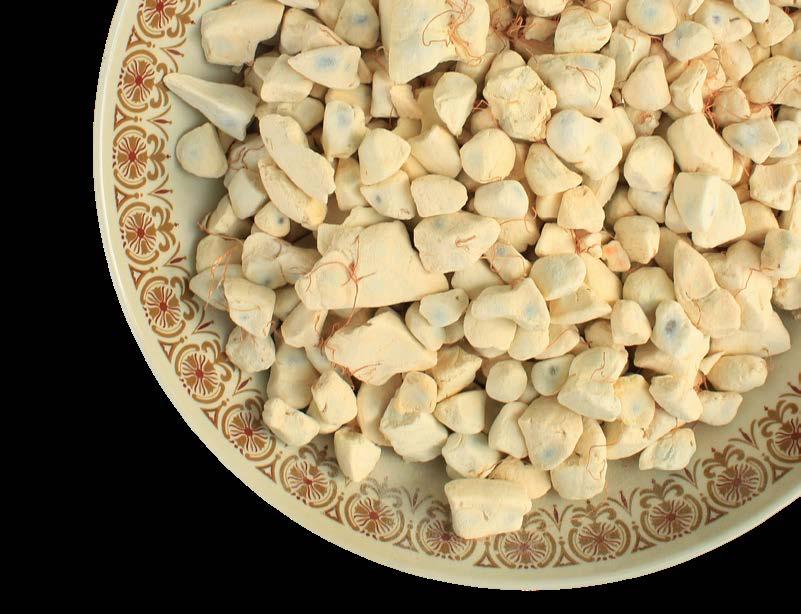

27 INDIGENOUS FRUITSFEATU R E D

In the research, a wide diversity of sources were consulted to maximize the value of the outcomes.

The preliminary research was performed based on academic literature related to nutrition inequality and the food system. This literature review formed the basis for identifying the interrelationships, correlations, and undesirable behavior of the food system. Relevant criteria were quantified based on data banks from public research institutions such as FAO, OWID, WDA, WFP, WHO and UNICEF. Qualitative analysis of these datasets formed decision support for the selection of dinner locations for the PHASE 2 validation.

Qualitative data from Nutrition for All Dinners at six locations across the world was collected by involving all stakeholders directly. All dinners were organized in collaboration with a member of the local eco system, enabling the inclusion of the community and relevant stakeholders. These local hosts were pivotal in inviting a delegation of all stakeholders (from consumer to policymaker), event communi cation, and language translation. The events were accompanied by a menu (served in person or deliv ered to their home) that featured one or more uncon ventional items, forgotten dishes, or indigenous fruits or vegetables.

To validate the preliminary findings, ten specific questions were care fully established for each loca tion to guide the conversation. The questions were phrased using inclusive language to create a safe environment for knowledge sharing across all disciplines/ backgrounds, as well as to avoid framing issues. The local hosts facilitated the conversation, while the research team passively took notes. Additionally, three non-location specific questions were presented at every dinner using the interactive sur-

vey tool, Mentimeter. These general questions aimed to apply to all stakeholders and to give a comparable overview of perceptions around nutrition throughout the six locations.

This unique approach enabled the discovery of new insights regarding local problem perceptions of future challenges, opportunities, and grassroots movements. In some cases, additional interviews were conducted with participants involved in promising initiatives. The insights gathered through the dinner events offer fundamental (local) nuances to preliminary findings that are crucial for finding adequate measures and actionable recommendations. This approach reduced opportunities for incorrect interpretation and overgeneralization of statistics and removed the authors’ bias. The combination of data research and grassroots practical validation by directly involving stakeholders increases opportunities for efficient policymaking.

Social nutrition analyzes food availability and consumption through the lens of social drivers such as gender, culture, religion, economics, and politics. Social Nutrition explains the connection between individual food habits and broader social patterns to explore why we eat the way we do.

Hidden hunger occurs when the quality of food does not satisfy nutrient requirements. This issue can be evaluated through different lenses: scarcity and contamination of natural resources, access to nutritious food, mass-scale production of monoculture, nutritional quality, food loss,and lifestyle changes.

Values, preferences, beliefs, practices, and desires shape consumer behavior and generational differences providing useful insights on food choices and the nutritional status of different age groups. Closing the food generation gap implies bringing people closer to each other and creating a deeper understanding and connection among different food perspectives such as sustainability, taste, waste production, traditions, and eating behavior.

To assure nutrition for all, it is essential to go beyond a focus on undernutrition, focusing instead on redefining the food ecosystem. Several recent reports link nutrition targets with environmental sustainability, food value chains, communities, and infrastructures, and highlight the fundamental transition towards a holistic multisector, multi-stakeholder approach.

Nutrients are like a community, they need to work together to work well.” — Nutrition for All dinner participant, Zimbabwe

Sovereignty

EatingDiverseFunction

MealOneSocialConditions

Measure

Body KnowledgeNatura astyChoi

Economy

ColorfulCompassion

Health En ifeHeal t h y

F a m i ly

ulCarb

GroundMedicineAffectionGreen

G o od Balance

sKeepHyperColor

Densi t yInterestingVeganTricky

Sources

Necessity

Sciencebased

FoodPleasureSustainable Nourishm e tn

GenerationalGastronomyReal

sure Meal

cs

ce s

Happy Loca l

l Forward Sel f V e g e t a b el

Imp ortant

Ecology

MindEnhancementBiochemistry

Need ConnectionSeasonalOrg

Fields

Source Fruits

Acceptable Processes

CommonWealth

Plant Event Auxillary Taking

12

NUTRITIONAL VALUE OF FOOD CONSIDERED DURING SHOPPING

MOST CRITICAL FACTORS TO ENSURE NUTRITION FOR ALL

The level of food education has been widely discussed as one of the dominating determinants of nutritional intake (Bann, D. et al. 2018; Costarelli, V. et. al., 2019; Hamersma, S. & Matthew, K., 2019; Mujica-Coopman, M. et al., 2020; Tach, L. et. al., 2020; Tullis, R. & Ryalls, E. D., 2019; Xu, Y. et al., 2020).

Around the world, people appear to share the same difficulty in understanding what food is healthy. Generally, knowledge about food - also known as food literacy - is shaped at home, school, the workplace, or in the community.

Improving food communication, as opposed to relying solely on food education, addresses a wider scope of where consumers can gather information about their foods.

During the dinners in all locations, participants confirmed their perception that food literacy has decreased significantly. Food literacy can be divided into two different dimensions: declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge.

The widespread loss of declarative knowledge became apparent when indigenous fruits, served to open the dinner conversations, were rarely all identified.

This aspect is further confirmed by the language used to refer to these fruits: in India, the term “ancient foods” is predominantly used by young generations, but not by adults or elderly people. The younger generation in India is more disconnected from nature and local food traditions.

Next to the diminished declarative knowledge, people lack hands-on experience. This procedural knowledge is required to make proper and nourishing food decisions. Promoting intuitive eating and showing consumers how to shop for and prepare ingredients may be as important as improving the declarative knowledge about food.

One of the drivers behind the lack of awareness about health and nutrition.

The ecosystem and its interactions play a crucial role in shaping our food preferences. (Social) media, advertising, and global markets greatly influence consumers’ choices. Consumers have grown accustomed to a surreal image of perfect foods: shape, color, and no ‘brown spots’. However, such uniformity is rarely seen in nature.

Better food communication is needed to shift the public perception towards eating “ugly” foods because these fruits and vegetables contain valuable nutrients that otherwise go to waste.

Participants of the dinner in Japan highlighted that they think that the remarkably high (visual) quality standards cause a lot of food waste in the value chain, which in the end also negatively affects the affordability.

There are a lot of advertisements for products such as chewing gum and processed foods but not for carrots.”

— Polish consumer

It is generally consumers with low food literacy who are more susceptible to misleading marketing practices, as emerged in the dinners involving South America and India.

Packaged, often highly processed, foods attract consumers for their nutritional information (such as “high in vitamins,” “low in sugar”) while fresh and more nutritious foods do not provide any of this information.

This aspect is exacerbated by an altered perception of quality, as a consequence of heavy marketing strategies.

Fruit and indigenous food are delicious but not always attractive. When it’s not bright, it’s hard to sell. A lot of perception of food is linked to marketing.”

— Indian consumer

On the other hand, these misleading marketing practices drive consumers in the US to opt for organic food products because they perceive them as safer, rather than more nutritious.

The opposite extreme can also generate detrimental effects in nutritional intake. The high consumer trust in processed foods due to food safety guarantees creates susceptibility to nutritional claims on food packaging. Conversely, healthy eating policies have adopted a rhetoric of empowerment, which puts a lot of emphasis on individual responsibility for health (Bergman, K. et al., 2019; Haman, L. et al., 2015).

This individual responsibility is often interpreted as a moral duty. (Madden, H. & Chamberlain, K., 2010). This may lead to obsessive healthy eating that, in actuality, turns out to be unhealthy. Misconceptions about body positivity and healthy self-acceptance may drive people from obesity to obsession.

Eating disorders appear to be especially challenging for people in countries where mental illnesses and support are perceived with feelings of shame. The lack of proper food communication makes it difficult for them to receive necessary support and guidance.

Another enabler for proper nutrition that is presented in literature is conviviality - the pleasure of eating together, or commensality- the act of eating together. Participants from the dinner in Japan proudly recommended their national tradition of school meals (kyushoku) and food education for children, where children prepare, share, and clean-up lunch together.

When a child has a problem with appetite, they put the child with other children to eat from one plate, and the child tends to eat better.” — Zimbabwean consumer

Workplace canteens, as well as University restaurants, are more than just places where you can eat. Research

a positive influence on fruit and vegetable intake (Hartmann,Y. et al., 2018). In Poland, children from kindergarten are involved in food activities through gardening.

Creating a garden together, selecting the seeds, watering them, taking care of them, and eventually picking the food from the garden and eating together has demonstrated beneficial effects both on children’s wellbeing and nutrition.

The Szkoła Na Widelcu Foundation (Poland) teaches adults and children how to prepare healthy food. It organizes cooking workshops and classes for children and parents as well as for school canteen employees. They also run cooking programs, TV shows, awareness campaigns, as well as publish recipes. https://www.szkolanawidelcu.pl

Fruta Feia (Portugal) distributes fruits and vegetables that do not satisfy market standards with the campaign “BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE EAT UGLY FRUIT.” https://frutafeia.pt/en

Veg Power (United Kingdom) is an awareness advertising campaign addressing kids to inspire them into veggie living habits. The campaign includes humorous video stories, posters, and activities for schools. https://vegpower.org.uk

Digital Green is a global development organization that empowers smallholder farmers to lift themselves out of poverty by harnessing the collective power of technology and grassroots-level partnerships. It uses youtube and asks people who grow food biodiversity to film themselves https://www.digitalgreen.org

Community kitchens, even in multi-family housing structures (e.g., apartment buildings), may be an effective strategy to improve cooking skills, social interactions, and nutritional intake. They have the potential in rural environments to have a significant impact on consumption behavior due to the lack of competing social activities.

Introduce local Food Icons (like pan Ziółko = Mr. Herb in Warsaw) to make nutritious food popular, increase consumer curiosity, and create a sense of connection. People are looking for information about healthy eating in their communities, yet, getting professional support is often out of financial reach. These efforts can stress the connection between being healthy and food procurement. It’s important that these partnerships between institutions and influencers are shared on social media to spread awareness.

Edutainment - People feel too busy to acquire new knowledge. Food awareness can be conveyed through stress relieving, creative activities to help people unwind from their busy life and gain competences on nutrition. Organizing edutainment programs in collaboration with the workplace can have a great impact on increasing awareness about proper food choices. Potentially, Manga could be used to spread positive messaging around nutrition. It’s a visual narrative art form which has become universal. Manga has proven that the combination of both visuals and words allows the brain to understand and retain more information in a shorter period of time (Murakami, S. & Bryce, M., 2009); Smeaton, K. et al, 2016).

Nurturing the next generation Women shape our food identity, as powerful decision-makers yet often lack solid nutrition knowledge

Women have enormous influence on future consumption practices through their transfer of knowledge onto future generations. They are also typically the ones that make food decisions for others. For this reason, it is most important that women improve their knowledge about food and nutrition.

Gender inequality and reduced educational access for women often inhibit their personal development, and eventually that of the next generation.

Women empowerment has been widely reviewed as an effective strategy to improve the prosperity and livelihoods in developing countries.

According to the UN’s SDG’s, gender equality and women’s empowerment are pivotal to achieving food security for all, improving agricultural productivity, and ensuring the full participation of rural people in decision-making processes.

Maternity is one of the most important drivers for the nutritional intake of children. And, the influence that parents have on the nutritional intake of their children appears to be effective life-long. During the Nutrition for All dinners, a majority of the participants stressed that they derived their knowledge about food from their mothers. This does not mean, however, that this knowledge is necessarily correct.

Mostly, I rely on what I remember from what my mom told me. She told me to eat a lot of proteins, but now I think maybe I eat too much protein. But there is no way to know.”

Apart from the fact that parents form the primary source of food knowledge among children, they also shape the acceptability of certain foods by exposing their children to different tastes and allergens at a young age. In Poland, mothers seem to play an especially crucial role in the food literacy of their children.

She gave me proper nutrition and now chocolate bars are not tasteful for me. I prefer dried mangos.” — Polish consumer

Involving children in the preparation and experimentation of foods has been shown to improve acceptability.

Following the notion of an acquired taste, children adjust their preferences based on their food intake. Feeding them with sugar dominated diets will decrease their acceptability to fresh vegetables and bitter fruits.

In India, women play a central role in households concerning food choices. They are generally responsible for buying food, employing the food literacy they inherited from the previous generations. However, this passed-down knowledge is not supported by an in-depth understanding of the foods, generating a harmful loop that can enable malnutrition and susceptibility to nutritional diseases.

We’re told to eat this and that but we’re never told why.”

— Indian consumer

Misperceptions, combined with limited access to education, make consumers potentially vulnerable to misleading commercial practices about nutrition, and can affect eating behavior.

Despite being the second largest (82.631 MT) producer of fruits worldwide, India’s average intake of fruits is very low (1.5 servings), and is even lower among the younger generation. Low awareness about the benefits of fruits and vegetables plays a crucial role in this statistic.

Meanwhile, women still struggle with gender balance. In Zimbabwe, for instance, it is perceived as a waste of time and money, as in the end, women will just get married. 32% of girls in Zimbabwe are married before the age of 18. Across the country, girls drop out of school due to pregnancy or marriage reasons.

Society doesn’t care for girls to go to school.“ — Zimbabwean consumer

Women and girls are disproportionately affected by the limits on their access to education and employment opportunities, which weakens their bargaining position within the family.

Women are additionally disadvantaged when it comes to access to nutrition. Women decide carefully what is best for the family because they are perceived to possess the know-how about food.

They cook the food but when they come into their eating they receive the leftovers”

Women also have a higher probability of suffering hidden hunger and reduced consumption of foods with minerals, proteins, or iron, compared to men. This also occurs in India. Females are breastfed for shorter durations, and when growing up, they often eat last and the least, waiting until after the breadwin ner and children receive sufficient food.

Undernourished girls become undernourished mothers who give birth to the next generation of undernourished children.” — Former

UN Population Fund’s country representative for India

FEMALE EMPOWERMENT

A key component in the fight against nutrition inequality.

Platos Sin Fronteras (Colombia) develops nutrition education programs for both restaurants and women to prepare more nutrient-dense fruit and veggie-based meals. Through workshops and cooking practices, women are empowered and act as mentors for social change. www.platossinfronteras.cow

The Millet Sisters is a network celebrating women that still possess the knowledge about biodiversity and sustainable and crafts: The Millet Sisters, UNDP in India, Mobile biodiversity festival. www.foodforward.in/videos/millet-sisters

Women in agriculture: cooking their way to empowerment and visibility (Lebanon) is training women on food preparation and marketing, realised by the International Labor Organization (ILO), to create their own cooking and catering lines, generate income, and increase their visibility in the agricultural sector. www.ilo.org/beirut/ media-centre/multimedia/WCMS_534498/lang-en/index.htm

The Reggio Emilia Approach is an educational philosophy based on the belief that all children possess endless potential for development and learning in relationships with others. The philosophy includes a number of distinct characteristics such as the participation of families and the community. www.reggiochildren.it/en/reggio-emilia-approach

Strengthen parent-children relationships through in-school nutrition classes, involving educational institutions as a trusted place of growth and knowledge in order to build a supportive environment and provide opportunities to eat better. Even if women are usually the primary decision-makers for household nutritional intake, encouraging the whole family in training about gardening, cooking, and nutritious values of food could be an effective strategy to improve the dietary intake of the entire family.

UTANGI is a pilot project born during the Food and Climate Shapers boot camp organized by the FFI and FAO. The project recognizes a business opportunity for female farm workers in learning how to repurpose food waste into nutritious products. This is made possible through the establishment of community kitchens in peri-urban farming areas that serve as educational and production centers. In addition to being a safe space for women, the Community Kitchen acts as a platform to upscale female farmworkers through better farming nutrition, entrepreneurial, and life skills, by providing training, workshops, and both personal and professional support

Today, poor-quality diets are the primary cause of morbidity and mortality in the world, due to both inadequate consumption of nutritious foods and excess consumption of harmful ones (Hirvonen, K. et al., 2020).

Worldwide food production exceeds 2,750 kcal per person per day (Bahadur KC, K. et al., 2018), surpassing the amount required to feed the global population, yet hunger is on the rise in some parts of the world, with around 821 million people considered to be “chronically undernourished.”

Realigning food systems to deliver better health and environmental outcomes is therefore among the most important global challenges of the 21st century.

In Zimbabwe, participants stressed that food choices are predominantly based on price, without taking the nutritional value into account. Similar challenges on nutritional variety appear in India as emerged from the Nutrition for All dinner.

Even if they have more to spend, they will likely not make proper choices, because they don’t know what constitutes good nutrition.

The only context in which people look at varieties is in the restaurants, otherwise every single day people eat the same foods.” — Indian consumer

A closer look at urbanized environments and western countries highlights other notable aspects.

Represents a key obstacle for nutrition security in lower-economic urban areas.

This phenomenon, prevalent in areas such as the Bronx in New York, was also brought up by dinner participants in Brazil. Due to the rise of big supermarkets, urbanization, and consolidation, small and medium grocery stores have disappeared from the street corners.

These megastores are often located in areas that can only be accessed by car or public transportation and in which households have larger budgets.

However, all consumers, including well-educated and wealthier people, face this difficulty of distance. It decreases people’s ability to change habits and improve diets. Distance and effort appear to be valued higher than nutritious quality. People seem less willing to go to supermarkets that offer nutritious quality over other shops that are closer.

Simultaneously, limited time availability, busy lives, and hectic working rhythms stimulate the shift to wards more processed and convenience foods, caus ing nutrient deficiencies to increase despite exces sive calorie consumption. Drivers for this behavior are unbalanced tradeoffs between convenience vs. quality and price.

People are too busy to pack their lunch so they have to buy their food on the go, but they don’t want to spend too much money either.“

— Urban consumer in the US

The demand for time efficiency has been implicated by changes in food consumption patterns such as a decrease in food preparation at home and an increase in the consumption of ready-prepared foods. Convenience food is required because people have too many problems scheduling everyday life (Jabs, J. & Devine, C. M., 2006). The average American thinks “How can I have my hunger satisfied as quickly as possible and for the least amount of money? What products do I know and where can I find those?”

I don’t believe in persuading people. I am more interested in understanding how to push the government to stop sustaining those who produce food that makes us sick and then using our taxes to keep hospitals because of that.” —

Polish plantbased activist

Improving affordability and availability of nutritious foods is only one side of the coin in ensuring quality nutrition. Food choices are influenced by peers, media, and social status.

Social media and TV are becoming a sort of Neocolonialism (hamburgers, Mcdonalds, pizza), especially for the new generations.”

In more areas of the world, people derive socioeconomic status from eating western foods. It is a way to express what you can afford.

Many distance themselves from cheap “indigenous” local foods because they are connected to less developed, lower economic classes.

Some dinner participants in Zimbabwe even highlighted feelings of shame around eating indigenous fruits and vegetables.

According to our participants in Brazil, the price of healthy fresh produce is low and therefore associated with a low economic social status. In other words, by consuming western foods that are often highly processed, consumers in Brazil gain social status. As stated by a Brazilian policymaker, rural producers are increasingly selling their organic crops to afford western “ultra-processed” foods.

People need to overcome physical and psychological barriers to shift towards healthier diets. Food preferences have been influenced and shaped by industrial foods that are high in sugar, salt, and fat.

They are craving chips, fried food, and pizza because that is what their body and mind are used to. Healthy food products will not taste alike. So the first few times, the vegetables will not taste amazing to them which is often why they do not continue eating this way. Have you ever stopped eating sugar? The first few days are hard, your body goes through cravings but then it’s much better and everything tastes so much sweeter.” — Urban consumer in the US

The food environment affects diets by influencing how revenue is spent on food based on affordability, convenience, and desirability of various foods and what kind of food is available (Herforth, A. & Ahmed, S., 2015). Many agricultural initiatives, as part of our food environment, aim to improve incomes, increase food availability, and reduce food prices.

In some developing regions, such as Zimbabwe, small farmers produce a lot of fruit and vegetables for the market, but the inadequate diet intake and malnutrition remain high. Whenever it has been produced, it has been sold.

What farmers eat themselves are typically the items that they cannot sell, often far from a balanced diet.

Why does this happen? The right question could be “What are their priorities? Buying some fruit and vegetables or sending kids to school, treatments in hos-

The Farm to Table movement fulfills the purpose of increasing awareness by connecting consumers and producers. Who the farmer is and where the food is grown are at the very center of the movement, just as the promotion of local foods and a community-supported agriculture arrangement.

Healthy Buddha (India) – home-delivers fresh organic products, directly to customers, in Bangalore for a healthy lifestyle. https://healthybuddha. in

Community fridge initiatives (UK) – provide nutritional access for everybody in low economic urban areas and are an effective strategy to reduce food waste. https://www.hubbub.org.uk/ the-community-fridge

HealthyRetailSF (USA) – is a project that transforms corner stores into spaces, especially in the food desert areas, where fruit and vegetables are accessible and visible to consumers. http://www. healthyretailsf.org

Nature & More by Eosta (Netherlands) – is a “trace & tell” consumer trademark and online transparency system of Eosta - where ecology meets economy. It offers fresh organic fruits & vegetables from all over the world, GMO-free, pesticide-free and free from artificial fertilizers, but with the grower’s story and full transparency about its impacts on the planet and people. https://www.eosta.com/en/nature-more

“Children’s cafeterias” (JAPAN) – are places for children in difficult family or financial circumstances to receive free or low-cost meals, support, and care. These cafeterias are referred to as a ‘third space’, because they are outside the two usual social environments home (first space) and the workplace (second space). https://www.nippon. com/en/currents/d00244

”Fruit is the new Fast”. Peeling a banana is like opening a snack, eating an apple is even faster than opening a snack. Make fresh fruit a popular snack through promotional campaigns and stressing the idea that fresh fruit is actually faster than the processed and ultra-processed food.

Fruit byproducts such as peels, stems, shells, and seeds have high nutritional and functional values. Utilising those byproducts is an opportunity to produce new nutritious food while reducing food waste. The new products should be prepared within existing production lines and efforts.

The food certification marks are symbols which convey assurance to the quality, standard, and accuracy of the goods. Implementing food certifications (such PDO and PGI) to officiate the value of indigenous fruits and vegetables can reshape the perception that people have about them from one of low acceptance to one of pride in consuming their indigenous foods.

Achieving universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all is one of the major targets for 2030 under SDG 6. Extensive data shows that access to safe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services has an important and positive impact on nutrition (WHO,2015).

Ecosystem

Climate vulnerability and inadequate knowledge and practices around water have detrimental effects on access to nutritious food and water.

Poor water management and insufficient water treatment may cause overexploitation, pollution, and eutrophication, ultimately bringing water availability into jeopardy.

Hidden Hunger

Water contamination and poor sanitation facilitate the transmission of several infectious diseases, many of which can cause loss of body fluids, and subsequently the micronutrients within, leading to severe undernourishment, dehydration, and eventually death.

Reduced availability of water drives water competition among different users (energy, cooking, farming) and different areas (urban and rural), fueling the rise in the price of water. There is a need for increased awareness of domestic water-use such as the treatment of wastewater and its relationship to soil fertility.

Having clean water and avoiding contamination is all about proper water management and training people, especially women. For the vast majority of households, women are the primary providers, managers, and us-

ers of water. Women are responsible for finding and collecting water for drinking, cooking, sanitation, and hygiene. Today, women around the world spend a collective 200 million hours collecting water (UNICEF, 2017).

In their efforts to get water for their families, women are often forced to choose between dirty water, or no water at all.

It is crucial that they understand the importance of having clean water and how to cope with it so they can differentiate between water suitable for cooking, and that which should only be used for toilets.

Water scarcity can have an impact on the food chain in both production and nutrition. “It is not possible to have water stress (through competition) without some degree of nutrient stress,” reports a scientific paper focusing on the strict correlation between water and nutrients in plants (Nambiar, S. & Sands, R., 2011).

Many areas have poor irrigation because they are not able to store water properly and yet don’t have any reserves. Poor water management causes people in urban areas to buy water for household activities (filling a 5000 L water tank in Zimbabwe costs $80).

Ecosystem

Implementing nutrition-sensitive agricultural water management means producing food in adequate quantity and quality while also safeguarding water and other natural resources.(Bryan, E. et al., 2019; FAO, 2017; UNSCN, 2020).

Water is also negatively impacted by deforestation.

Prior research (D’Almeida et. al, 2006) shows that deforestation affects water dynamics, leading to irregular rainfall patterns including drought and flooding (D’Almeida, C. et al., 2006). However, recent research indicates that deforestation may influence not only the “water yield” but also the “water access to people.”

Hidden Hunger

A 1.0-percentage-point increase in deforestation decreases access to clean drinking water by 0.93 percentage points, suggesting that deforestation may have the same extent of effect on access to clean drinking water as that of the decrease in rainfall (Mapulanga,A.M. & Naito,H., 2019).

The LANN+ Project (Germany) – seeks to empower rural households to plan for and sustainably practice nutrition-sensitive strategies with regard to accessing adequate and healthy food, diet diversity, and a sanitary environment with a specific focus on vulnerable family members. The project takes into consideration the link between WASH and nutrition through the implementation of WASH activities, especially for toddlers. It addresses caregiver hygiene behaviors and the safe treatment and storage of drinking water, and promotes correct hand washing as well as the use of hygienic latrines. The project has been implemented in various countries in Africa and Asia. https://www.welthungerhilfe.org/our-work/focus-areas/agriculture-and-environment/lann

JERRY (Netherlands) – is a jerrycan water filter that self-rinses the filter during its use - enabling approximately 10,000 liters of water to be filtered of 99.99% of its bacteria without having to replace or clean the filter cartridges. https://jerrycanfilter.com

Design tailored, water management activities based on nutrition-sensitive agricultural approaches, selecting strategies that are appropriate to the local agricultural market systems (eg. supplement irrigation in rainfed production systems, actions to increase infiltration of rainwater into the soil, improve soil water storage) for producing more nutritious foods and achieving good nutritional outcomes, especially in vulnerable communities.

Organizing water training programs, addressed to children, to introduce the basic concepts of water; where it comes from, why it is crucial in their lives, and how to manage this magical natural element everybody expects to be available without limitation. Water education impacts children’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors towards water usage and lays the foundation to empower children to become better custodians of water.

Promote maintenance training of boreholes for the whole community to ensure the ongoing maintenance of these water sources. This would help to prevent communities from using unsafe sources that can expose people to high levels of infection, further compromising their nutritional status.

Bringing nature back into our lives is one of the main messages within the EU Green deal. Half of global GDP, €40 trillion, depends on nature. Biodiversity provides us with food and wellbeing, filters our air and water, helps keep the climate in balance, converts waste back into resources, pollinates and fertilises crops and much more (EC, 2020).

Over the past few decades, monocultures have exhausted our soils consequently affecting all ecosystems.

Nine crops account for a staggering 66% of all crop production by weight, and only 30 crops supply 95% of the calories that people obtain from food, reducing the benefits from diets and nutrient diversification.

Various species, such as birds and insects, are disappearing from our ecosystems. In Poland, green shoots or leaves of at least 58 species of wild plants have gradually decreased to near zero, mainly due to replacement by a few cultivated vegetables (Łuczaj,

L., 2010).

People are largely unaware of the biodiversity crisis and even fewer of the mutual correlation between biodiversity and our food choices. Rapid urbanization (87%) (UN, 2018), low food literacy, and a gradual transition towards westernized diets reveal a progressive loss of traditional food cultures and crop diversity. Processed foods are relatively inexpensive, available, and easier to store than higher quality food like fruits and vegetables. However, these industrial products rely on low-price, standardized inputs facilitated by monocultures.

The conventional agricultural system shifted towards prioritizing quantity over quality, and maximizing profits at the cost of nutritional value for the consumer. Biodiversity will only be preserved if it generates revenue.

Genetic biodiversity is in the hands of smallholder farmers. They are the people constantly developing new varieties. But, legislation demands standardized crop production, which makes the small farmers lose their autonomy. And, most of these smallholders are located far away from the market.

The local seeds that these farmers work with are appreciated, but they are being forgotten.

The biggest issue is related to farmers and their capability to produce different varieties because they are only able to grow differently if there is education and designed policies.” — Polish ornithologist.

Traditional farming principles that have been used around the world for centuries carry the potential to reverse the negative effects on biodiversity and restore life beneath the soil. Local communities can act as the guardians of our ecosystems and restore the lost knowledge of indigenous communities. They live in respect of food and nature and treasure all resources they provide to us. Nothing is wasted. Only what is going to be consumed is harvested. If an animal is hunted, every part of it is going to be used to treasure and respect that life that was taken. In some indigenous cultures, it is forbidden to sell the products they grow or find because they are sacred.

Ecosystem

There is a contradiction in national policies regarding land development. While the policies aim to make indigeneous communities food producers, the local culture does not allow them to sell what they grow.

The preservation of a nutritious variety of food is a fundamental determinant of health. As long as we keep considering food a commodity, hidden hunger, malnutrition, and famines will increase.

Contribute to fighting hidden hunger both via direct consumption and by being sold to provide income to small farmers.

Many wild foods are rich in micronutrients and can alleviate deficiencies making diets more nutritious and balanced (FAO, 2019a).

The diverse range of indigenous fruit trees is a source of untapped potential for food and nutrition security. We need to reintroduce these forgotten fruits and vegetables into our local kitchens and diets. Diversity should be valued and celebrated.

Increased mobility and globalization has made more people consider themselves ‘world citizens’ which creates opportunities for indigenous foods to be accepted through trending traditional cuisines. In this way diversity creates added value for farmers, as opposed to cultivating nondifferential crops.

Participants of the dinner in Japan expressed high appreciation for the fruit and vegetable surprise box that they received and some are now applying to similar subscription models. The health aspect, combined with the fact that these foods, that cannot be found in the supermarkets, are in season and relatively cheap, were valued. Also, both the surprise in what you will receive, as well as the time saved, were appreciated.

Sociobiodiversity (Brazil) – is a public policy concept that studies native peoples and cultures from an ecological, sustainability, and food point of view, to conserve ecosystems. The appreciation and conservation of traditional ways of life. http://planetaorganico.com.br/site/index.php/ green-rio-2019-english/

The International Anti-Poaching Foundation (Zimbabwe) – promotes plant-based diets in order to protect the environment and the animals. Through educational activities, they try to influence people to eat healthily and consume less meat. https://www.iapf.org/

Terrius (Portugal) – is a group of “young people” with the desire to build a distinctive and innovative project in the agri-food sector, based on the establishment of local partnerships of trust and fair trade with small producers. Terrius adds value to local products, including by recovering PDO and PGI certifications, which promote the preservation of the natural heritage and the recognition of the region. https://terrius.pt/en/home-en/

Frutos de Goiás (Brazil) – offers ice cream, made with traditional fruits from the central western part of Brazil. https://www.frutosdegoias.com.br/ nossos-sabores/picole/linha-tradicional

Improving the financial literacy of farmers at the grassroots level is needed to stimulate sustainable agriculture. Farmers currently focus on yield rather than the profitability per land. If farmers start considering all profits and losses, then their operations potentially become more economically viable and environmentally friendly.

Pre-curated subscription boxes of healthy seasonal food that are rarely available in supermarkets. Consumers hardly ever opt for unfamiliar products when doing their regular groceries. On the other hand, they appreciate surprise ingredients when sourcing through subscription models. The delivery service makes locally-grown fresh food affordable and accessible, and also safeguards the small producers and farmers of the territory. Also, the surprise effect can satisfy the consumers’ curiosity through unknown products in the box.

Teaching an appreciation of indigenous food and its benefits, while also sharing the techniques for how to use fresh products to extend their consumption window, such as by making smoothies, sorbets, and chips. Also providing tips on how to process these indiginous ingredients at home can increase curiosity and the acceptability of lesser-known fruits and vegetables as they are introduced to people’s diet.

As more and more people move to urbanized environments, rural communities are depopulating. Today, 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, a proportion that is expected to increase to 68% by 2050 (UN,2019). As younger generations leave their homes, critical functions in the ecosystem, such as jobs and craftsmanship, are lost, deteriorating the sovereignty of the rural community.

This depopulation also affects other businesses, due to a declining customer base and the rise of supermarkets, market consolidation has made it impossible to have a thriving small business model. These developments inhibit rural communities to sustain a local availability and variety of fresh foods.

The local food markets are very important for the families’ maintenance, and for the indigenous groups, but they are decreasing a lot.” — Policymaker in Brazil

Hidden Hunger

This market consolidation trend has facilitated the replacement of fresh, traditional diets in rural areas with processed foods due to their longer shelf lives and low pathogen risk.

The shift in diets from fresh to processed foods has exacerbated the disconnection to the local food system, which is getting lost, especially in urban areas.

Undernourishment continues to be concentrated among populations based in rural areas, although a growing number of poor people living in urban areas are also affected. Improving the link between the urban populations and smallholder farmers is crucial to enable rural people to take advantage of new market and employment opportunities in food value chains (IFAD, 2016).

My father was an organic farmer but wasn’t able to find the right way to sell his products. Rural areas need cities to be alive at the same time urban areas can be sustainable only if they are surrounded by prosperous and productive rural areas especially in the agriculture sector.”

— Indian consumer

It is essential to collaborate with smallholder farmers and the rural area to warrant sustainable urbanization and ensure healthy nutritious food in rural and urban contexts. Rural areas provide a wide variety of flora and fauna and natural resources that can contribute to employment, economic growth and prosperity, preserving the environment and cultural heritage.

Ecosystem

Natural resources are being depleted and vital ecosystems degraded to produce food that is ultimately never consumed, while there are people living in chronic hunger.

Wasted nutrition appears very differently in urban environments compared to rural areas. In rural areas, most food is wasted due to agricultural infrastructure,

refrigeration (cold-chain), poor (procedural) knowledge about storage, and insufficient skills to improve the palatability of produce. In urban areas, food is mostly wasted due to an abundance of availability and also lack of knowledge. They go to the supermarket where they find everything that they need.

We don’t eat the same as previous generations, because we source food differently. Our Grandparents gathered food from locals, now we have just to go to the supermarket. We are eating differently.” — Urban consumer in Poland

Food Generation Gap

Improving cooking skills can help to reduce food waste through a better understanding of how to repurpose leftovers.

“Food is just like fashion, eventually it comes back.” — American consumer

Mobile Farmers Market via Fresh Approach (US) – is a mobile farmers’ market that serves communities, selling affordable, locally-grown fruits and vegetables with discounts for shoppers receiving federal assistance benefits. https:// www.freshapproach.org

Tagurpidi Lavka (Estonia) – buys food products, especially organic products, from small farmers in rural areas of Estonia and sells them in and around Tallinn. http://tagurpidilavka.ee

“Zimbabwe right now is a perfect incubator for veganism” (Zimbabwe) – This program intends to rebuild and revitalize the gardens in rural Zimbabwean schools and in so doing create the conditions needed to teach effective agricultural techniques and practices to the schools’ pupils. The food produced will be used to provide a meal a day for the pupils and any surplus food will be sold back into the local community. This is a grassroots empowerment program with the hope of spreading the community garden program across all schools in rural Zimbabwe. https://www. cuisinenoirmag.com/chef-nicola-kagora-zimbabwe

Spudnik Farms (India) – is an example of community-supported agriculture designed to not only to shorten the distance between farmers and consumers, but also to secure a livelihood for small and marginal farmers. https://www.spudnikfarms.com

I Am Grounded (Australia) – is a snack company that combines the benefits of upcycled coffee fruit, plant micronutrients, and natural energy to support a healthy sustainable lifestyle. https:// iamgrounded.co

Matriark foods (USA) – upcycles farm surplus and fresh-cut remnants into healthy, delicious, low-sodium vegetable products for schools, hospitals, food banks, and other food services. https://www.matriarkfoods.com

Open Food Network (Global) is an open-source platform enabling new, ethical food supply chains. Food producers can sell online and communities can bring together producers to create a virtual farmers’ market supporting the local food economy. https://www.openfoodnetwork.org

Dynamic pricing based on expiration dates, and personalization based on preferences would stimulate consumption of potentially wasted food, however, it is crucial to re-brand these products and educate people about ugly foods.

Providing a safe environment for farmers to talk about their surplus and learn about how to turn these ‘less desirable’ items into attractive products could help reduce food waste on the farms. It would also support continuous improvement practices to be more efficient and sustainable while increasing the reputation of the farms among their communities.

Exchange platforms to fill crucial positions in the rural ecosystem could benefit both urban and rural populations. For example, the Jap anese culture has a very strong sense of duty and expectation regarding their working lives. As such, there are a num ber of people who feel that they have not chosen their current life, and are interested in such an opportunity. This solution might be even more relevant post-COVID, given the resulting unemployment.

Supporting team

Sara Roversi Founder Future Food Institute

Chiara Cecchini Co-Founder Future Food Americas

Claudia Laricchia Head of Institutional Relations FFI

Chhavi Jatwani Design & Innovation Lead FFI

Francisco Álvarez

Gastronomic Scientist & Dietitian-Nutritionist FFI

Easter Weiss Press & Media Relations FFI

Júlia Dalmadi Project Manager Germany

Erika Solimeo Researcher Italy

Jan Kees Klosse Researcher Netherlands

Anastasia Constantini Researcher Belgium

Júlia Dalmadi Project Manager Germany

Erika Solimeo Researcher Italy

Jan Kees Klosse Researcher Netherlands

Anastasia Constantini Researcher Belgium

Climate Shaper, Bioscientist

Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

• Eco concept store to promote conscious consumption

• Edible garden projects for apartments

• ‘Root to leaf’ cooking initiative in vulnerable communities

Amanda Rodriguez

Strategic Operations Manager working towards a regenerative FOODture

New York, United States

• Microgrant Program Manager @ Startup CPG

• Host, Startup CPG Podcast

‘Edible Issues’ Co-Founders

Bangalore, Karnataka, India

• Who Feeds Bangaluru (WFB) exploratory research

• ‘Investigating the Case of Missing Vegetables’

• ‘Tracing Our Food’ with the Urban Design Collective

Nicola Kagoro

Climate Shaper, Founder at African Vegan on a Budget Harare, Zimbabwe

• Chef & Project Manager @ International Anti-Poaching Foundation, the World’s first and only female Plant Based + Armed Anti Poaching Unit

• Environmental, culinary health, and grassroots activism in South Africa & Zimbabwe

Co-Founder @ Polish Society of Lifestyle Medicine

Warsaw, Poland

• Research & Teaching Assistant @ Lifestyle Medicine Department of the School of Public Health

• Co-Founder & Author @ The Feedness

Chris Krause – Director Hazuki Yasunaga – Manager

Tokyo, Japan

• Kyobashi Living Lab

Agrawal, S. et al. (2019). Socio-economic patterning of food consumption and dietary diversity among Indian children: evidence from NFHS-4. Eur J Clin Nutr 73, 1361–1372). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-019-0406-0

Alesso-Bendisch, F. (2020). Prologue: Community Nutrition Resilience— What and Why. In: Community Nutrition Resilience in Greater Miami. Palgrave Studies in Climate Resilient Societies. Palgrave Pivot, Cham. https:// doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27451-1_1

Allcott, H. et al. (2018). Food deserts and the causes of nutritional inequality. W.P. 24094. http://www.nber.org/papers/w24094

Asakura, K. & Sasaki, S. (2017). School lunches in Japan: Their contribution to healthier nutrient intake among elementary-school and junior highschool children. Public Health Nutr. 2017 Jun;20(9):1523-1533. https://doi. org/10.1017/S1368980017000374

Bahadur KC, K. et al. (2018). When too much isn’t enough: Does current food production meet global nutritional needs?

PLoS ONE 13(10): e0205683. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0205683

Balz, A.G. et al. (2015). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: new term or new concept? Agric&Food Secur 4,6 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-015-00264

Bann, D. et al. (2018). Socioeconomic inequalities in childhood and adolescent body-mass index, weight, and height from 1953 to 2015: an analysis of four longitudinal, observational, British birth cohort studies. The Lancet. Public health, 3(4), e194–e203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S24682667(18)30045-8

Barragán, R. et al. (2018). Bitter, Sweet, Salty, Sour and Umami Taste Perception Decreases with Age: Sex-Specific Analysis, Modulation by Genetic Variants and Taste-Preference Associations in 18 to 80 Year-Old Subjects. Nutrients, 10(10), 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10101539

Bergman, K. et al. (2019). Public expressions of trust and distrust in governmental dietary advice in Sweden. Qualitative Health Research 29 (8):1161–73.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318825153

Bird, J. K. et al. (2017). Risk of Deficiency in Multiple Concurrent Micronutrients in Children and Adults in the United States. Nutrients, 9(7), 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070655

Borelli, T. et al. (2020). Local Solutions for Sustainable Food Systems: The Contribution of Orphan Crops and Wild Edible Species. Agronomy 2020, 10, 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10020231

Boyer, D. et al. (2019). Diets, Food Miles, and Environmental Sustainability of Urban Food Systems: Analysis of Nine Indian Cities. Earth’s Future, 7(8), 911-922. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EF001048

Bryan, E. et al. (2019). Nutrition-sensitive irrigation and water management. WBank, Washington, DC. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/103404

Carly, N. (2020). Nutrition sensitive agriculture: An equity-based analysis from India, World Development, Volume 133, 105004, ISSN 0305-750X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105004.

Chapoto, A. et al. (2018). Can smallholder farmers grow? Perspectives from the rise of indigenous small-scale farmers in Ghana. Conference, July 28-August 2, 2018, Vancouver, British Columbia 277225, International Association of Agricultural Economists. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.277225

Charity, M. et al. (2015). Determinants of Street Food Consumption in Low Income Residential Suburbs: The Perspectives of Patrons of KwaMereki in Harare, Zimbabwe.IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSRJHSS) Volume 20, Issue 4, Ver. III (Apr. 2015), http://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol20-issue4/Version-3/ M020437883.pdf

Chopera, P. (2018). Examining Fast Food Consumption Habits and Perceptions of University of Zimbabwe Students. International Journal of Science and Healthcare Research Vol.3; Issue: 1; Original Research Article ISSN: 2455-758 https://ijshr.com/IJSHR_Vol.3_Issue.1_Jan2018/IJSHR_Abstract.001.html

Christian, M.S. et al. (2014). Evaluation of the impact of a school gardening intervention on children’s fruit and vegetable intake: a randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11(1), 99. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12966-014-0099-7

Cohen, J. F. W. et al. (2016). Healthier standards for school meals and snacks: impact on school food revenues and lunch participation rates. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(4), 485-492. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.031

Conrad, Z. et al. (2018). Relationship between food waste, diet quality, and environmental sustainability. PLoS ONE 13(4): e0195405. https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195405

Costarelli, V. et. al. (2019). Socioeconomic inequalities in relation to health and nutrition literacy in Greece, International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, Vol. 70(8) https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2019.1593951

D’Almeida, C. et al. (2006). A water balance model to study the hydrological response to different scenarios of deforestation in Amazonia, Journal of Hydrology, Volume 331, Issues 1–2, Pages 125-136, ISSN 00221694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2006.05.027.

Devideen, Y. et al. (2020). Enhancing nutrient translocation, yields and water productivity of wheat under rice–wheat cropping system through zinc nutrition and residual effect of green manuring, Journal of Plant Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2020.1798997

Dong, J. Y. et al. (2020). Soy consumption and incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus: the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Eur J Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02294-1

EC (2020). EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Bringing nature back into our lives. Communication From The Commission To The European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic And Social Committee And The Committee Of The Regions, Com(2020) 380 Final https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:a3c806a6-9ab3-11ea-9d2d-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

El Mujtar, V. et al. (2019). Role and management of soil biodiversity for food security and nutrition; where do we stand?, Global Food Security, Volume 20, Pages 132-144, ISSN 2211-9124, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2019.01.007

Evang, E.C. et al. (2020). The Nutritional and Micronutrient Status of Urban Schoolchildren with Moderate Anemia is Better than in a Rural Area in Kenya. Nutrients, 12(1), 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010207

Fagundes, A. A. et al. (2020). Food and nutritional security of semi-arid farm families benefiting from rainwater collection equipment in Brazil. PLoS ONE 15(7): e0234974. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234974

FAO (2013). NARROWING THE NUTRITION GAP:INVESTING IN AGRICULTURE TO IMPROVE DIETARY DIVERSITY

http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/agn/pdf/Narrowing_Nutrition_Gap_2013.pdf

FAO (2017). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture and food systems in practice. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7848e.pdf

FAO (2019a). The State Of The World’s Biodiversity For Food And Agriculture. http://www.fao.org/3/CA3129EN/CA3129EN.pdf

FAO (2019b). The State of the United States of America’s. Biodiversity for FAO. http://www.fao.org/3/CA3509EN/ca3509en.pdf

FAO and WHO (2019). Sustainable healthy diets – Guiding principles. Rome. http://www.fao.org/3/ca6640en/CA6640EN.pdf

FAO(2020). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) http://www.fao.org/publications/sofi/en/ FAOSTAT DATABASE - http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

Fisk, C. M. et al. (2011). Influences on the quality of young children’s diets: The importance of maternal food choices. British Journal of Nutrition, 105(2), 287-296. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510003302

Food Systems Dashboard- https://foodsystemsdashboard.org/

Fuller, D. et al. (2013). Does transportation mode modify associations between distance to food stores, fruit and vegetable consumption, and BMI in low-income neighborhoods?The American journal of clinical nutrition, 97(1), 167-172.https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.036392

Gabriel, A. S. et al (2018). The Role of the Japanese Traditional Diet in Healthy and Sustainable Dietary Patterns around the World. Nutrients, 10(2), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10020173

Galbete, C. et al (2017). Food consumption, nutrient intake, and dietary patterns in Ghanaian migrants in Europe and their compatriots in Ghana. Food Nutr Res.;61(1):1341809. https://doi.org/10.1080/16546628.2017.1 341809

Galiè,A. et al. (2019) Women’s empowerment, food security and nutrition of pastoral communities in Tanzania, Global Food Security, Volume 23, 2019, Pages 125-134, ISSN 2211-9124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2019.04.005.

Ghinea, C. & Ghiuta, O.-A. (2019). Household food waste generation: young consumers behaviour, habits and attitudes International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology volume 16, pages 2185–2200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-018-1853-1

Ghosh-Dastidar, B. et al. (2014). Distance to store, food prices, and obesity in urban food deserts. American journal of preventive medicine, 47(5), 587595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.005

Giovine, R. (2014). Big demand(s), small supply – Muslim children in Italian school canteens: a cultural perspective, Young Consumers, Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 37-46. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-03-2013-00359

GLOBAL NUTRITION REPORT (2020), https://globalnutritionreport.org/ reports/2020-global-nutrition-report/

Goalkeepers report (2019) https://www.gatesfoundation.org/goalkeepers/ report/2019-report/#ClimateAdaptation

Golden, C. D. et al. (2016). Ecosystem services and food security: assessing inequality at community, household and individual scales. Environmental Conservation -1(4):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892916000163

Govende, L. et al. (2016). Food and Nutrition Insecurity in Selected Rural Communities of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa-Linking Human Nutrition and Agriculture. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijerph14010017

Grzymisławska M. et al. (2020). Do nutritional behaviors depend on biological sex and cultural gender? Adv Clin Exp Med. 2020;29(1):165–172. https://doi.org/10.17219/acem/111817

Haman, L. et al. (2015). Orthorexia nervosa: An integrative literature review of a lifestyle syndrome. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 10 (1):26799. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw. v10.26799

Hamersma, S. & Matthew,K. (2019). Does Early Food Insecurity Impede the Educational Access Needed to Become Food Secure, University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research Discussion Paper Series. https://files. eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED602225.pdf

Hamrick, K. S. & Hopkins, D. (2012). The time cost of access to food–Distance to the grocery store as measured in minutes. International Journal of Time Use Research, 9(1), 28-58. https://.doi.org/10.13085/eIJTUR.9.1.28-58

Hartmann,Y. et al. (2018). Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables by Low-Income Brazilian Undergraduate Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 10(8), 1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10081121

Herforth,A. & Ahmed,S. (2015). The food environment, its effects on dietary consumption, and potential for measurement within agriculture-nutrition interventions. Food Sec. 7, 505–520 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-0150455-8

Hirvonen, K. et al. (2020). Affordability of the EAT–Lancet reference diet: A global analysis. Lancet Global Health https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214109X(19)30447-4

Hubley,T. A. (2011). Assessing the proximity of healthy food options and food deserts in a rural area in Maine. Applied Geography, 31(4), 12241231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.09.004

Iacovou,M. et al. (2013). Social health and nutrition impacts of community kitchens: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2013 Mar;16(3):535-43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980012002753

IFAD (2016). Sustainable urbanization and inclusive rural transformation

https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/40253256/urbanization_brief. pdf/566d380f-4eda-426d-9d1a-30faac61329b

IFAD (2018). Developing nutrition-sensitive value chains In Nigeria. https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/40271299/Nigeria+WEB.pdf/ fa132ac3-ca9a-4b04-83a6-d5f8c053be12

ILSI India (2019). Consumption levels of sugar among rural and urban populations in India: national nutrition monitoring bureau surveys.

https://www.nin.res.in/survey_reports/sugar_study_report_part-1.pdf

Jabs, J. & Devine, C. M.(2006). Time scarcity and food choices: an overview. Appetite. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2006.02.014

Jaguś, A. (2020). Monitoring of the ground environment in Poland. Inżynieria Ekologiczna, 21(3), 24-32. https://doi.org/10.12912/23920629/125378

Joassart-Marcelli, P. et al. (2017). Ethnic markets and community food security in an urban “food desert”. Environment and Planning a, 49(7), 1642-1663. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17700394

Just, D. R. et al. (2014). Chefs move to schools. A pilot examination of how chef-created dishes can increase school lunch participation and fruit and vegetable intake. Appetite, 83, 242-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. appet.2014.08.033

Kairiza, T. & Kembo, G. D. (2019). Coping with food and nutrition insecurity in Zimbabwe: does household head gender matter?. Agric Econ 7, 24 . https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-019-0144-6

Koiwai,K. et al. (2019). Consumption of ultra-processed foods decreases the quality of the overall diet of middle-aged Japanese adults. Public Health Nutr. 2019 Nov;22(16):2999-3008. Epub 2019 Jun 20. PMID: 31218993. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019001514

Liem, D.G. & Russell, C.G. (2019). The Influence of Taste Liking on the Consumption of Nutrient Rich and Nutrient Poor Foods. Frontiers in Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2019.00174