HISTORY |

By Albert ‘Skip’ Theberge and James Delgado

Understanding the Unthinkable

The Titanic Disaster and Its Aftermath In the night of 14 April 1912, the unthinkable happened. The mightiest ship afloat, the brand-new White Star Line ship Titanic, was on its maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York. The ship was advertised as unsinkable. And, if unsinkable, why should there be adequate lifeboats for all of the passengers and crew? The ship departed from Southampton on 10 April. Less than five days later, it was at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. More than 1,500 people perished within three hours of striking an iceberg, which ripped the bottom out of the ship. How this happened is a story told many times. Human hubris, unswerving trust in the infallibility of technology, and the commercial impetus of fast Atlantic passages all contributed to the loss of the ship and the accompanying loss of life. Even as the ship was settling in the waters of an icy North Atlantic, some survivors reported that there was a belief among many passengers that the ship was the safer place to be; accordingly, not all the lifeboats were filled to capacity. This accident shocked the international community. The British and American

governments investigated the accident – the British determined: “That the loss of said ship was due to collision with an iceberg, brought about by the excessive speed at which the ship was being navigated.” Certainly, that was the major factor. However, like many accidents, there were a number of contributing causes. These included: watertight bulkheads that were improperly designed; an insufficient number of lifeboats and life rafts; apparent lack of concern by the captain about reports of ice prior to collision with the iceberg; little training of crew in emergency procedures including lowering of lifeboats; no radio watches on nearby ships

which could have assisted in lifesaving efforts; and, remarkably, not even binoculars for the ship’s lookouts. Both the British and American governments arrived at similar conclusions and recommendations following the loss of the Titanic. The chief recommendation was that all ships be equipped with sufficient lifeboats for passengers and crew, that all ocean-going ships maintain 24-hour radio-telegraph watches, and that bulkheads be designed such that flooding of any two adjacent compartments would not result in sinking of a vessel. These recommendations and others were adopted by the first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) at a conference held in London in 1914.

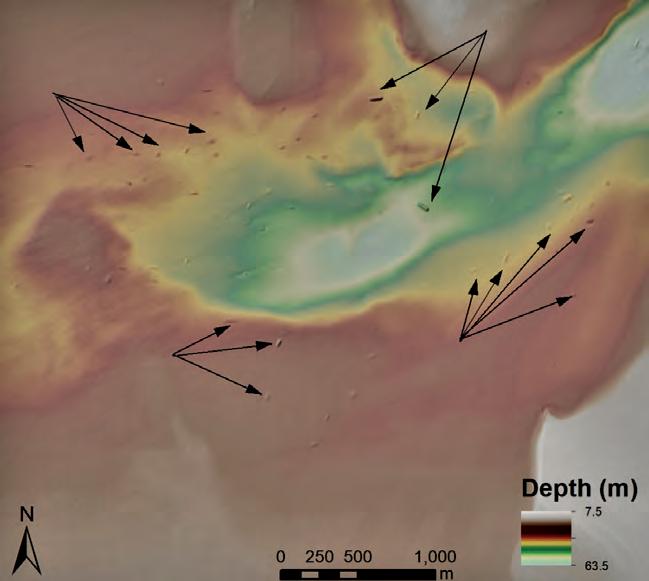

Development of Seafloor Mapping Technologies

Length of steamship Titanic compared with highest buildings.

Commercial concerns saw an opportunity in the Titanic disaster and began searching for a means to determine the presence of icebergs and other unseen or submerged obstructions forward of moving vessels. European and North American inventors joined the race. In 1912, Reginald Fessenden, a Canadian inventor and radio pioneer, joined Submarine Signal Company, a forerunner of today’s Raytheon, and began work on an electro-acoustic oscillator similar to a modern transducer. This oscillator was originally designed for both ship-to-ship communication and to receive reflected sound from an underwater object. In late April 1914,

24 | Is s u e 1 2021 | Hydro i nt e r nat i o na l

24-25-26-27_history.indd 24

18-03-21 14:39