The Nordic island of Iceland is known for its dramatic landscapes with active and dormant volcanoes, high spewing geysers, hot springs, waterfalls, canyons, vast lava fields, and a lot more. Some of the planet’s largest glaciers cover parts of the island while imposing cliffs provide a home to thousands of seabirds. We head out from the capital, Reykjavík, in an anti-clockwise direction along the island’s circular route and are mesmerised by its beauty and diversity. Our deviations off the main road with a 4x4 vehicle lead to our best discoveries!

ailand’s “Nine Emperor Gods Festival” is a nine-day Taoist celebration also known as the “Vegetarian Festival”. Be warned that this colourful festival is intense with religious devotees performing ritualised mutilations on themselves while in a trance-like state!

Road-trip the remote outback and coastal landscapes of north-western Australia’s Kimberley region, one of the most sparsely populated places on earth. In this large area are beautiful land formations, waterfalls, crocodile-infested waterways, and long stretches of beach.

North Macedonia’s Lake Ohrid is a large lake shared by both Macedonia and Albania. e town of Ohrid has a lovely historic quarter and the towering ruins of a medieval castle. e shoreline is dotted with small villages and pristine natural attractions.

On our journey through Iran we pass through ve of its most unique villages: the troglodytic village of Kandovan; the stepped mountain village of Masouleh; Garmeh, a desert oasis; historic red pastel-coloured Abyaneh; and the mudbrick village of Kharanaq.

SHORT CONTRIBUTIONS

Meet the Photographer: Venezuela

Vilnius of Lithuania

“Counting Countries” Podcasts Sustainable

TOP LISTS

10 Great Reasons to Visit Iceland

9 Incredible Places to See Glaciers

10 Incredibly Remote Villages to Visit

Kyrgyzstan: Jailoos, Nomads and Yurts

Explore Kyrgyzstan, a travel destination with snow-capped mountains, raging rivers, glacial lakes, green jailoos with yurts and horses and, of course, small villages with cosy guesthouses and homestays serving tasty local cuisine.

THE FRONT COVER: Black Sand Beach, southern Iceland

Photographer: Peter Steyn

GlobeRovers Magazine

is currently a biannual magazine, available in digital and printed formats. We focus on bringing exciting destinations and inspiring photography from around the globe to the intrepid traveller.

Published in Hong Kong

Printed in U.S.A. and Europe

WHO WE ARE:

Editor-in-Chief - Peter Steyn

Editorial Director - Marion Halliday

Editorial Assistant - Tsui Chi Ho

Graphic Designer - Peter Steyn

Photographer & Writer - Peter Steyn

Advertising - Lizzy Chitlom

Social Media - Leon Ringwell

FOLLOW US: www.globerovers-magazine.com www.globerovers.com facebook.com/GloberoversMag pinterest.com/Globerovers twitter.com/Globerovers instagram.com/GloberoversMag

CONTACT US: editor@globerovers.com

“Not all those who wander are lost”. J.R.R. Tolkien John Tolkien (3 Jan 1892 — 2 Sep 1973) was an English writer, poet, philologist, university professor and author of The Hobbit, and Lord of the Rings trilogy.

Dear Readers,

In this 18th issue of GlobeRovers Magazine, we are pleased to present a variety of exciting destinations for your reading pleasure. Next year will be our 10th anniversary! e feature destination is the Nordic island of Iceland with its dramatic landscapes. Much of Iceland is a paradise for photographers, hikers, adventurers and anyone who appreciates the beauty and diversity of our living planet.

We also attend ailand’s “Nine Emperor Gods Festival” on Phuket Island and are amazed by the religious devotees who perform ritual mutilations on themselves while in a trance-like state!

In the Kimberley region of north-western Australia, we take a road trip through one of the most sparsely populated places on earth with its stunning landscapes and long stretches of beach.

We also travel to North Macedonia’s sublime Lake Ohrid to explore life on the shores of this large body of water, and then visit ve of Iran’s most unique and remote small villages, as well as Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. Also included is a photo exhibition about the Yanomami of the Venezuelan Amazon.

A special thank you to our sponsors and to our wonderful contributors who we feature on page 5.

Visit our website and social media. For easy access, scan the QR codes on page 7.

Feedback to editor@globerovers.com.

We travel so you can see the world!

Peter Steyn PhDEditor-in-Chief and Publisher

Travel Magazine

— for the intrepid traveller — Cominginthe

Subscribe NOW

GlobeRovers is published in July and December

Scan this code:

For iPhone: Download “ISSUU” App + search for “globerovers” For Android: Download the GlobeRovers App.

Apple Store Google Play

www.globerovers-magazine.com

pinterest.com/globerovers

facebook.com/GloberoversMag

twitter.com/globerovers

GlobeRovers, an independent travel magazine headquartered in Hong Kong, focuses on off-the-beaten-track destinations free of mass tourism.

A very special thank you to our awesome contributors in this issue. Without you, GlobeRovers Magazine just wouldn’t be the same!

Peter Steyn, Hong Kong (pages 10, 66, 132, and 148)

Peter is an avid explorer who always tries to travel off the map to unexplored destinations. He has photographed over 122 countries and is totally in love with Japan, Russia, Iceland, Central Asia, South Africa, and other exciting places. He is the Editor-in-Chief of GlobeRovers Magazine

Marion Halliday, Adelaide, South Australia (pages 92 and 166)

Marion is “Red Nomad OZ”, author, blogger and traveller who loves discovering and photographing nature-based attractions and activities all over Australia. Her travel blog and quirky travel guide Aussie Loos with Views provide Australian travel inspiration for other explorers.

Pongtharin Tanthasindhu, Bangkok, Thailand (page 110)

Pong was born in Thailand but grew up in India, Canada and Switzerland. In 2010, he decided to take a gap year from university to explore the world. Since then he has explored and photographed over 180 countries. He is a fearless intrepid traveller and passionate photographer.

Steven Kennedy, Kent, United Kingdom (page 122)

Steve is a PR professional and founder of the World Complete travel blog that documents his attempts to visit every corner of the globe... eventually. Through his accounts he hopes to pass on a few helpful hints and tips for other travellers along the way.

Ric Gazarian, Chicago, USA (page 144)

Ric is an avid traveller, travel blogger, professional photographer, drone pilot, author, podcaster, documentary producer and industry speaker. He is on a quest to visit every country in the world, has visited all seven continents and has travelled to over 140 countries.

Thor Pedersen, Copenhagen, Denmark (page 178)

Thor explores the world full time and has not been home to Denmark since 2013. With his Once Upon A Saga project he is aiming to become the frst person to visit 194 countries on an unbroken journey completely without fying. He is a goodwill ambassador for the Danish Red Cross.

Dave Seminara, St. Petersburg, Florida, USA (page 182)

Dave is a writer, former diplomat, and pathological traveller. He’s the author of four travel books, including Mad Travelers: A Tale of Wanderlust, Greed & the Quest to Reach the Ends of the Earth, and Footsteps of Federer: A Fan’s Pilgrimage Across 7 Swiss Cantons in 10 Acts.

GlobeRovers Magazine was created by Peter Steyn, an avid explorer who is constantly in search of the edge of the world. He will always hike the extra mile or ten to get as far off the beaten track as he can.

It is his mission to discover and present the most exciting destinations for intrepid travellers. He has visited over 122 countries and is poised to explore Turkmenistan and Mongolia in the near future. Peter’s home is wherever he lays down his cameras.

Afghanistan

Albania

Andorra

Argentina

Armenia

Australia

Austria

Azerbaijan

Bahrain

Bangladesh

Belarus

Belgium

Belize

Bolivia

Bosnia-Herzegovina

Brazil

Brunei

Bulgaria

Cambodia

Canada

Chile

China

Colombia

Costa Rica

Croatia

Cuba

Cyprus

Czech Rep.

Denmark

Ecuador

Egypt

El Salvador

Estonia

Finland

France

Georgia

Germany

Greece

Greenland

Guatemala

Honduras

Hong Kong

Hungary

Iceland

India

Indonesia

Iran

Ireland

Israel

Italy

Japan

Jordan

Kazakhstan

Kosovo

Kyrgyzstan

Laos

Latvia

Lebanon

Lesotho

Liechtenstein

Lithuania

Luxembourg

Macau

Macedonia

Malaysia

Maldives

Malta

Mauritius

Mexico

Moldova

Monaco

Montenegro

Morocco

Myanmar / Burma

Namibia

Nepal

Netherlands

New Zealand

Nicaragua

North Korea

Norway

Oman

Pakistan

Panama

Papua New Guinea

Paraguay

Peru

Philippines

Poland

Portugal

Romania

Russia

San Marino

Serbia

Singapore

Slovakia

Slovenia

South Africa

South Korea

Spain

Sri Lanka

Swaziland

Sweden

Switzerland

Syria

Taiwan

Tajikistan

Thailand

Timor Leste (East Timor)

Turkey

Ukraine

United Arab Emirates

United Kingdom

United States

Uruguay

Uzbekistan

Vanuatu

Vatican

Vietnam

Yemen

Zambia

Zimbabwe

122 and counting..

ICELAND Page 10

VENEZUELA Page 110

Use a QR Reader App on your phone (older models) or just your camera (newer models) to read these codes

NORTH MACEDONIA Page 132

From high above, the stark contrast between the azure waters of the North Atlantic Ocean and the volcanic black sand beaches is dramatic and eye-catching. Reynisfjara beach on the south coast of Iceland is the most famous, not only for its black sand, but also for the roaring Atlantic waves, majestic cliffs and imposing basalt rock stacks.

We travelled all around Iceland on the Ring Road with several detours, starting in Reykjavík, and then through the southern, eastern, northern, central, and south-western regions.

Words and Photography by Peter Steyn

Stephen Markley, American author of Tales of Iceland, summed up his experience of travelling through Iceland by writing: “ e problem with driving around Iceland is that you’re basically confronted by a new soulenriching, breath-taking, life-a rming natural sight every ve minutes. It’s totally exhausting.” I could not have said it any better!

Iceland is unique. Truly unique. A place that impresses every visitor beyond expectation. Even the most seasoned travellers promise themselves they’ll return and experience more of the magic that it has to o er. It would be impossible to enjoy all of Iceland in one lifetime!

If there is one place that all nature lovers and seekers of adventure must visit at least once, look no further than this small island nation, created and constantly reshaped by re and ice. No wonder it is referred to as “ e Land of Fire and Ice”!

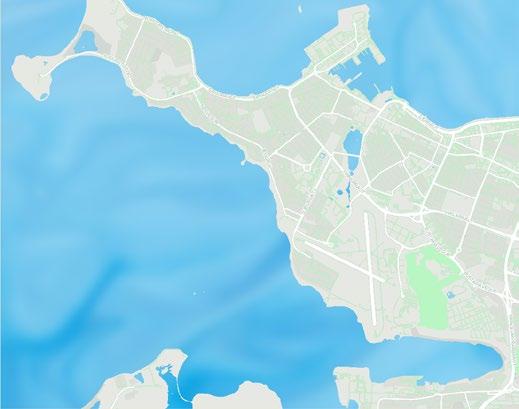

e Republic of Iceland, located in the North Atlantic Ocean, has a population of over 350,000 with Reykjavík as its largest metropolitan area where approximately two-thirds of the population live. Reykjavík is a modern city with advanced infrastructure, and when you’re here it sure doesn’t feel like you’re on a small, remote island best known for its violent volcanoes.

While Reykjavík is a lovely city in which to spend a few days, the landscapes and natural attractions that make up the “real” Iceland lie outside the city limits. As soon as you leave the sights and sounds of Reykjavík behind, you will quickly sink into the tranquillity of the countryside where the erce natural past and present of Iceland becomes evident.

Only 103,000 square kilometres (39,770 mi²) in size, the island is located on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

With its western part resting on the North American plate and the eastern part on the Eurasian plate, Iceland is volcanically and geologically active on a massive scale which has de ned its landscape over the past ve million years. Today the island is still at the mercy of volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and glacial movements that constantly reshape its topography.

In the Þingvellir National Park (anglicised as “ ingvellir”), the huge divide which continues to be created as the plates move apart is clearly visible.

Our journey around Iceland follows Route 1, popularly known as the Ring Road. From Reykjavík the road heads south-east to Vík, Iceland’s southernmost settlement. Known for its dramatic cli s and black sand beaches, the nearby Dyrhólaey Peninsula is a photographer’s delight.

From Vík, the road snakes to the north-east past numerous glaciers and lakes to the ord of Borgar örður eystri, and then turns northwest past incredible landscapes dotted with hot springs, waterfalls, lakes, and active volcanic areas.

West of the northern town of Akureyri the road splits, with one road heading south down the central plateau towards Reykjavík. e other heads further west to the West ords region, a large peninsula in northwestern Iceland known for its quaint villages, ords, cli s, breeding bird colonies, and mountainous coastline.

Let’s choose the rst option and head down the central plateau to the south past the massive Langjökull glacier and Þingvellir National Park, leaving the West ords region for another visit.

ere is no better way to conclude our visit to Iceland than to spend a full day at the Blue Lagoon— Iceland’s premier geothermal outdoor natural spa.

“I have fantasies of going to Iceland, never to return”

Edward St. John Gorey, American writer and artist

Most of Iceland’s interior is an uninhabitable wilderness, so the only way to get around on wheels is to take Route 1, also known as the “Ring Road”, a circuit of the coastal areas which provides relatively easy access to the many sights and attractions. In this article, we introduce you to Reykjavík and fi ve routes covering most of the island. We leave the Westfjords route for our next visit.

Reykjavík

Capital of Iceland with many attractions.

Southern Route Reykjavík to Vík along the North Atlantic.

Eastern Route Vík to Borgarfjörður eystri fjord.

Northern Route

Borgarfjörður eystri fjord to Akureyri.

Central Route

Akureyri to Þingvellir National Park.

South Western Route and the Blue Lagoon

Þingvellir National Park to the Snæfellsnes Peninsula and then south-west to the Blue Lagoon hot springs.

Reykjavík is one of the greenest cities in the world and is also rich in wildlife.

“Smoky Bay”, Reykjavík is the northernmost national capital in the world, and also Europe’s most westerly capital. e city harmoniously combines colourful buildings, eye-popping architecture, a vibrant nightlife, free-spirited residents, and is surrounded by a variety of wildlife and stunning landscapes, all of which combine to create its unique and capricious soul.

While Reykjavík has a population so minute that it hardly quali es as a city, it o ers a wealth of sights and activities that will appeal to culture, nature, and nightlife enthusiasts alike.

As the city is quite compact, a good way for new arrivals to explore the downtown area is to walk around, or rent a bicycle outside of winter. Start with the main shopping streets such as Laugavegur, Bankastræti, Austurstræti, Lækjargata, and Skólavörðustígur.

Along the way you will nd many colourful houses, lush gardens, plenty of street art, hot dog stands, and several resident cats—a much-beloved animal in Iceland.

While exploring downtown, look out for some of the most famous sights, including Sólfar, Höfði House, Hallgrímskirkja, Tjörnin Pool, Harpa Concert Hall, the Old Harbour, and many others.

A large abstract stainless steel sculpture of a Viking Ship is located near the Old Harbour, and is a short walk east of the

“In Reykjavík, where I was born, you are in the middle of nature surrounded by mountains and ocean. But you are still in a capital in Europe. So I have never understood why I have to choose between nature or urban”.

Harpa Concert Hall. Since being erected in 1990 to commemorate the city’s 200th anniversary, it has been a popular spot for photographers. e sculpture symbolises the country’s past and serves as a reminder of its history and heritage from the time when the rst Viking settlers came sailing to Iceland. Be here at sunset to admire the sun re ected in the stainless steel of this remarkable monument.

From Sólfar, there are clear views of Mount Esjan located about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) to the north-east of the city. e mountain is a popular recreation area for hikers and climbers.

Built in 1909 to house the French embassy, Höfði House is one of the most historically signi cant buildings in the Reykjavík area.

It is best known as the location of the 1986 Reykjavík Summit between President Ronald Reagan of the United States and General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev of the Soviet Union.

is historic event e ectively marked the end of the Cold War, and during the summit, images of the house were broadcast around the world.

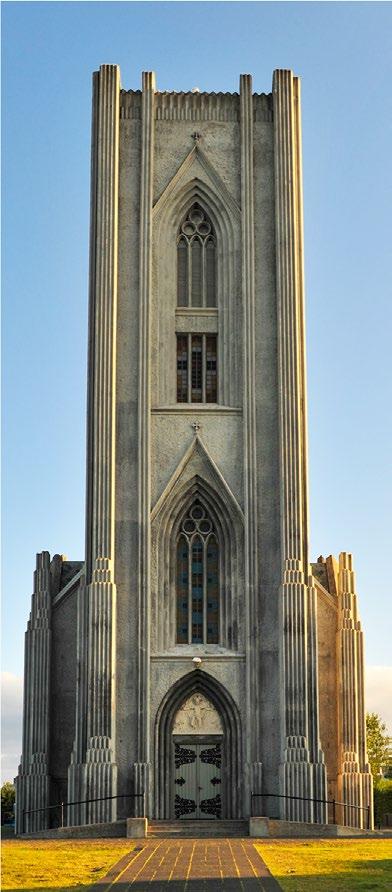

Opened in 1986, the towering Hallgrímskirkja (kirkja means “church’’ in Icelandic) is visible from almost any location around Reykjavík. At the top of this 74.5-metre-high (244 ) expressioniststyle church is a viewing platform boasting 360° views. Its concert organ, the largest of its kind in the country, is 15 metres (49 ) tall, has 5,275 pipes, and weighs 25 tonnes (27 US tons).

Its architecture was inspired by the beautiful basalt columns at Svartifoss (foss means “waterfall’’ in Icelandic) on the south-east coast. In front of the church, look out for the Statue of Leif Eiriksson (also spelled Erikson or Ericson), the Norse explorer from Iceland, thought to be the rst European to set foot on continental North America about 500 years before Christopher Columbus.

Tjörnin (meaning “pond’’ in Icelandic) lies at the heart of Reykjavík. is is a tranquil place, perfect for sitting and reminiscing; or feeding the birds. While the lake freezes over in winter, hot geothermal water is pumped in to keep a small area clear of ice for the waterbirds. Skating on Tjörnin is a popular pastime, especially when the city is adorned with Christmas lights.

A stroll in the adjoining Hljómskálagarðurinn park is delightful on a warm summer’s day. On the banks of the lake is the green-roofed Fríkirkjan í Reykjavík, or the Free Lutheran Church, consecrated on 22 February 1903

Also of interest is the Roman Catholic Cathedral of Christ the King, also known as Landakotskirkja (Landakot’s Church). Formally named Basilika Krists Konungs (Basilica of Christ the King) it is o en referred to as Kristskirkja (Christ’s Church). e church was completed and consecrated in 1929, and its architecture is said to have been inspired by the natural geology of the island.

e interior is traditionally Gothic, with a patterned tile oor, only one aisle, and no transepts (the two sections forming the arms of the cross shape). e Landakotsskóli, located on the church grounds, is Iceland’s oldest and longest-running private education institution for students from kindergarten to 10th grade.

Owing to Iceland’s renewable energy policies and its abundance of water and geothermal energy, bathing in steaming hot water is a favourite pastime amongst Icelanders. e greater Reykjavík area has no less than 18 heated swimming pools.

Icelandic swimming pools are closer to a luxury spa than the average communal pool. Some locations have both indoor and outdoor pools, a sauna, and even hot tubs.

e geothermal pools at Nauthhólsvík beach (3.4 km / 2 mi south of the downtown area) or Laugardalslaug (3.5 km / 2 mi east) are not to be missed.

Just 68 kilometres (42 mi) south-west of Reykjavík in a lava eld in front of Þorbjörn, a mountain on the Reykjanes Peninsula, is the famous Blue Lagoon geothermal spa. e milky blue water with white silica mud at the bottom of the pool is a sight to behold!

At the end of our journey through Iceland, we will return to cover our faces with this “white wonder” so silica mud, and relax in the hot water while reminiscing about our adventures in this amazing country.

e Old Harbour is located close to downtown Reykjavík and is the main port of departure for whale and pu n viewing tours as well as Northern Lights cruises.

Since the shipping industry moved to the new port, the original harbour has been tted with restaurants, cafés, museums, galleries and many shops. Most of the shops are located on the Eastern Pier, the most interesting part of the harbour.

At the Old Harbour is one of Reykjavík’s most iconic buildings, Harpa Concert Hall, with a unique artistic glass dome that echoes the shapes and forms of Icelandic natural wonders. e honeycomb exterior is mesmerising at night when the glass re ects a rainbow of colours.

Since opening in 2011, it has hosted numerous music festivals, world-famous bands, soloists and dance groups. Many theatre groups from around the world have also performed at Harpa.

Try to catch a live performance, as Harpa is home to the Iceland Symphony Orchestra, the Icelandic Opera and the

Reykjavík Big Band, all of which o er regular concerts throughout the year.

Since much of Reykjavík’s history is based on its seafaring past, the Reykjavík Maritime Museum is a must-see.

Located in a one-time sh freezing plant at the Old Harbour, it showcases how shing shaped the lives of the early Icelandic settlers and also became their main economic base.

On display are stories and artefacts from the past 150 years relating to the lives of the Icelandic shermen and women who nurtured this important industry.

In the old sh processing hall is an excellent exhibition outlining the history of Icelandic shipping.

A new underwater archaeology display is the latest exhibit to open at the museum.

Located on top of Öskjuhlíð, a hill south-east of downtown, is a cluster of hot water tanks that were converted to a public building in 1991. Resting on these tanks at a height of 25 metres (82 ) is Perlan, one of Reykjavík’s most striking buildings. Inside Perlan is the “Wonders of Iceland” exhibition showcasing Iceland’s history, glaciers and volcanoes.

Here you can also visit a real ice cave, watch planetarium shows, and stand on a 360° viewing platform high above the city and its surroundings. Öskjuhlíð is a perfect place to hike on a warm day.

Iceland is an ideal place for viewing the Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights), although they are usually not clearly visible in the city due to light pollution. On very cold nights, head out of town to places such as the nearby Seltjarnarnes peninsula for the best views.

Other attractions in and around the city include the National Museum of Iceland, Saga Waxwork Museum, Hafnarhús Art Exhibit, Volcano House, Einar Jónsson Museum, and the Kjarvalsstaðir Art Exhibit.

Strolling through the streets of Reykjavík is exciting, especially if you are interested in street art, as there has been a vibrant street art scene in the city centre since the 1990s. Sensational murals, created as part of the recent “Wall Poetry” project, adorn the facades of several buildings.

As you wander the streets, be sure to stop by one or more of the many restaurants serving local Icelandic seafood delicacies such as cod’s head cooked in chicken broth.

Don’t hesitate to sample the pungent fermented shark with a shot of Brennivín, Iceland’s trademark “Black Death” akvavit (also called aquavit or ákavíti in Icelandic), a spirit distilled from fermented potatoes and caraway seeds that has been produced in Scandinavia since the 15th century.

Also try whale meat which is available in some restaurants and supermarkets. For more picky eaters, Iceland is also famous for its mutton and lamb dishes.

A short distance from the city centre are many attractions not to be missed.

ese include:

e small Grotta Lighthouse, built in 1897 on the Seltjarnarnes Peninsula

to the north-west of Reykjavík, is a great place to view a sunset, take a morning walk and go bird watching.

Viðey Island is a short boat ride north-east of the Old Harbour and o ers spectacular views of the Snæfellsnes Peninsula and the mainland.

ere are several hiking and cycling trails, and the island is rich in wildlife and vegetation, making it a popular destination for photographers and those looking for a quiet place close to town.

Arbaer Open Air Museum, also known as Árbæjarsafn, is a small Skansenstyle village with more than 20 historic Icelandic houses. It was founded in 1957 on an abandoned farm to preserve a piece of old Reykjavík and Icelandic life amidst the rapid development of the city. e majority of the buildings here are authentic, and date mostly from the 19th century.

A er exploring the working and private lives of previous generations of Icelanders, we head south-east to explore the beauty and ruggedness of rural Iceland along the famous Ring Road!

Iceland is known for its delicious traditional Icelandic seafood delicacies and various meat dishes such as smoked lamb and lamb soup. However, some people claim that a few of the Icelandic dishes are among the most unpalatable and controversial in the world. Here are some of the most challenging dishes that you may–or may not–wish to try during your visit.

Gellur (cod tongues): Despite the English name, it’s not actually the tongue of the fsh that’s eaten, but the feshy, white, slimy, triangular muscle behind and below the tongue.

Hákarl (fermented shark): The traditional method for making hákarl is to bury the dead shark, usually a Greenland shark, in the ground and then urinate on it before letting it rot–or rather ferment–for 6 to 12 weeks. It is then hung up to dry for four to fve months to allow the ammonia to escape. Nowadays, the process is more hygienic, but the end result is still fermented shark with a strong, distinctive tangy taste and a lingering aroma of ammonia. It is normally served in small cubes as an appetiser, often followed by shots of Brennivín, an aquavit made from fermented potatoes and caraway seeds, marketed as “Black Death”. This is Iceland’s signature alcoholic drink and is the traditional beverage during Þorrablót, the mid-winter festival.

Lundi (puffn): The dark, almost purple meat of the puffn is normally smoked and served as tapas, broiled, or boiled in a milk sauce and can be found in restaurants across the country. Raw puffn heart is considered a delicacy and is said by connoisseurs to be the best part of the bird. Iceland is the summer home to tens of thousands of puffns, especially in Vestmannaeyjar (Westman Islands) where the largest Atlantic puffn colony in the world comes to nest.

Slátur (blood and intestines): Slátur (literally meaning “slaughter”) can be blóðmör which is a dish made of sheep intestines, blood and fat

and is often served with the sheep’s head (see below). Slátur can also be lifrarpylsa, a kind of liver sausage, which is more popular–and slightly less weird–to eat.

Súrir Hrútspungar (sour ram’s testicles): This dish is not as common as it used to be, but it has become a delicacy, mainly served at Þorrablót, the mid-winter festival. Cooks frst remove the outer membranes, boil them thoroughly and then pickle them in whey for several months. Once the testicles have reached the right level of acidity, they are pressed into a rectangular block, then sliced up as a pâté or appetiser and served along with other traditional Icelandic foods.

Svið (sheep’s head): Most Icelanders eat everything but the bones and brains. There’s an ongoing debate about which part tastes best: some say it’s the meaty cheek and tongue, while others claim the eyes, which are said to deliver a succulent pop when bitten. I personally think the soft cooked brain is the very best part!

Whale meat: Although whale meat–which can be eaten either raw or cooked–is tasty, you may not agree with the killing of these fascinating mammals. The meat generally comes from the Minke whale, and is mostly served to foreign tourists, as whale meat is not a traditional dish that is widely eaten in Iceland. Frozen whale meat is sold by some supermarkets and fshmongers. Hvalspik, meaning ‘whale fat’, is blubber and used to be one of Iceland’s main delicacies, although it is hard to fnd anyone who eats it today. The blubber is normally boiled and cured in lactic acid before consumption.

The Dyrhólaey promontory close to Iceland’s southernmost town of Vík offers stunning views over the pitch-black sand beach and the lighthouse. During the breeding season, puffns fnd nesting spots in the cliffs. In the opposite direction are the Reynisdrangar sea stacks and Dyrhólaey rock arch.

The Ring Road starts in Reykjavík and goes south-east to the town of Vík.

A er exploring Reykjavík, let’s follow the signboards to Route 1, better known as the “Ring Road”, leading out of the city in a south-easterly direction.

Outside the city limits, you will feel a sudden inner-awakening, and realise that you are in a very di erent place. e rst reminders that you are in Iceland are the many steam vents just outside the city.

A few hundred metres from the road, they appear to emerge naturally from the ground, though are more likely emitted from pressure valves in pipes which feed the steam into the city for heating.

Geothermal energy is used both for generating electricity and for heating, and Iceland has ve geothermal plants, each consisting of multiple wells.

Another frequent reminder that you are in Iceland are the pony-sized Icelandic horses, a breed developed in Iceland.

Don’t hesitate to stop and take a closer look at the horses but watch out for the wire fences that are sometimes electri ed to keep the horses in–or perhaps to keep tourists out!

Just 130 kilometres (81 mi) outside of Reykjavík is the rst waterfall (foss in Icelandic) of many along the Ring Road. Seljalandsfoss is located close to the main road and is one of the most impres-

sive waterfalls in the entire country. It drops 60 metres (197 ) and is part of the Seljalands river that has its origins in Eyja allajökull, a relatively small glacier (or jökull in Icelandic) to the north-east of the waterfall.

If you are brave enough, walk to the small cave behind the thundering falling waters.

e Ring Road continues in a southeasterly direction passing the Holtsós tidal lagoon, separated from the Atlantic Ocean by a narrow strip of sand.

Vestmannaeyjar (Westman Islands)

Before the next waterfall, Skógafoss, is a region with beautiful mountains, grasslands, and small farming communities.

Scattered across the area are several old abandoned farm buildings, painted bright red and covered with years of rust and brilliant green moss which make great photo opportunities.

Skógafoss, some 30 kilometres (19 mi) from Seljalandsfoss, is even more impressive. It is one of the biggest waterfalls in Iceland with a drop of 60 metres (197 ), and is 25 metres (82 ) wide.

For an exhilarating experience, walk right up to the thunderous water–but be prepared to be drenched. On sunny days the drizzle creates beautiful rainbows.

Climb the eastern side of the falls to the top where you can see the Skógá river a few metres before it tumbles over the cli s.

A good hiking trail starts here and climbs further up to the Fimmvörðuháls pass between Eyja allajökull and Mýrdalsjökull glaciers, both of which have active

volcanoes below their ice-caps. e hiking path continues all the way to Landmannalaugar in the Highlands of Iceland—a distance of 54 kilometres (34 mi) as the crow ies.

Just 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) south-east of Skógafoss past a lagoon, a small road turns le and comes to an end a er ve kilometres (3 mi).

From here you will get your rst view of an Icelandic glacier, Sólheimajökull It is possible to get reasonably close to the glacier, but its ice is quite black from the ash of historic eruptions.

Sólheimajökull is a glacial tongue of the massive Mýrdalsjökull glacier, which has a surface area of 600 square kilometres (232 mi²) and is the 4th-biggest glacier in Iceland.

Its massive ice cap hides the Katla caldera, where the mighty Katla volcano lives. Katla woke up on October 12th, 1918 and for the next 24 days caused havoc around the region.

Its next door neighbour, Eyja allajökull, is home to a volcano with a summit elevation of 1,651 metres (5,417 ) that erupted in 2010 and caused airspace closures across much of Europe.

Volcanologists are expecting the volcanoes under Mýrdalsjökull and Eyja allajökull to wake up again in the next few years, so hike cat-foot and don’t rouse the sleeping giants. If they do wake up while you are there, you’d better run, real fast and in the right direction!

If you are into plane wrecks, then hike directly south of Sólheimajökull to the nearby lagoon by the beach to see the

The small village of Skógar lies within view of Skogáfoss waterfall and two towering glaciers.Icelandic horse. Icelandic horse. Skógafoss.

“Sólheimajökull Plane Wreck”. In 1973, a United States Navy aircra (Douglas C-117D) encountered severe icing and the crew were forced to crash-land on the lake by the beach. All seven crew members survived, but the aircra was unable to be salvaged so was le at the crash site. e wreck has remained relatively intact over the years and makes a great photo opportunity.

From Sólheimajökull it is almost 30 kilometres (19 mi) to Iceland’s southernmost settlement, the town of Vík.

Vík, o cially known as “Vík í Mýrdal”, is a seaside village located 187 kilometres

(116 mi) by road south-east of Reykjavík. With only about 750 inhabitants, the village is the largest settlement in the entire southern region.

Vík lies directly south of Mýrdalsjökull, home to the Katla volcano. An eruption of the volcano is long overdue and could melt enough glacial ice to trigger a massive ash ood, possibly large enough to obliterate Vík.

Scientists predict that the only building that would survive such a ood would be Vík’s church, located on the nearby hillside above the town. Vík residents regularly practise an evacuation drill which includes

rushing up to the church at the rst sign of an eruption.

Recently, high levels of dangerous gases were emitted from the volcano in an area where glacial water ows into a nearby river. e level of the glacial river on the north side of Katla has also been unusually high. It is therefore widely believed that an eruption will occur soon; the only question is exactly when.

e beaches around Vík with their long stretches of black sand are among Iceland’s most beautiful and unique. Don’t expect to get a suntan here though, as this is one of the wettest areas in Iceland.

Black Beach Suites is an ideal retreat for short trips from Reykjavík to explore some of Icelandʼs most spectacular sites, such as Seljalandsfoss, Skógafoss, Dyrhólaey, Westman Islands, Jökulsárlón Glacial Lagoon, Skaftafell National Park and of course the famous black sand beach itself. From the suites, you can sometimes see the amazing Northern Lights.

The elegant suites are in a class of their own, offering all the amenities, stunning views and great service in an area known for its exquisite landscapes. Spacious and suitable for individuals, couples and smaller families, they can accommodate up to four people. Each has a kitchenette and bathroom, and is equipped with underfloor heating.

Contact: +354 779 1166 blackbeachsuites.is

In summer, between May and August, many visitors are drawn to the Dyrhólaey cli s west of Vík to watch the many seabirds, especially the pu ns (lundi in Icelandic) that burrow into the shallow soil of the cli s during nesting season.

Iceland is home to between eight and 10 million pu ns, more than 60% of the world’s entire Atlantic pu n population.

Dyrhólaey is quite famous for the

Reynisdrangar, a cluster of three basalt sea stacks rising 66 metres (217 ) up from the ocean, and situated under Reynis all mountain near Reynis ara beach.

According to legend, the rocks are three trolls who stayed out too late and were caught in the sunlight, then immediately turned into stone (see page 28).

e views from the 120-metre-high (390 ) cli s near the Dyrhólaey Light-

house are magni cent over the long black sand beaches and basalt sea stacks.

e lighthouse is located at the southernmost point of Iceland’s mainland, and the turn-o from the Ring Road is about 13 kilometres (8 mi) before reaching Vík.

Sólheimajökull, Iceland’s southernmost glacier, is an outfow of the mighty Mýrdalsjökull glacier, which sits atop Katla, Iceland’s third most active volcano. Should Katla erupt, scientists expect a massive food, or jökulhlaup, to gush down from underneath Sólheimajökull and wash over the Ring Road into the Atlantic Ocean.

The east coast offers mountains, several glacial tongues, lakes, and villages.

FromVík, the Ring Road heads north-east up along the coast. e rst 70 kilometres (43 mi) passes through some beautiful landscapes with mountains, rivers, waterfalls, rolling farmlands and quaint homesteads.

At the 71 kilometre (44 mi) mark is Fjaðrárglúfur canyon, one of the most stunning landscapes on this route. e canyon is up to 100 metres (328 ) deep and about two kilometres (1.25 mi) long, and has steep walls sprinkled with several small waterfalls.

Scientists believe that the valley was formed at the end of the last ice age about

10,000 years ago, although the bedrock of the canyon is about two million years old.

e beautiful river Fjaðrá which ows through the canyon and later joins the larger Ska á river, was formed by the outow of a glacial lake which wore away the so rock, leaving behind the more resistant rock formations. e contrasting colours of the dark rocks, foaming white water and verdant moss of the canyon make it

an ideal place for nature photographers, especially at the time of the midnight sun and the Northern Lights. Hike along the ridges above the canyon and descend carefully to swim in the crystal clear turquoise water, but breathe deeply as the water is freezing cold.

Ten kilometres (6 mi) north-east of the canyon are some oddly shaped rock formations known as Kirkjugólfð

(meaning “ e Church Floor”). ey are almost hidden in a eld just northeast of Kirkjubæjarklaustur village—nicknamed “Klaustur” by locals. While there never has been a church on this site, the rocky area resembles a man-made church oor.

e area is an 80 square metre (861 ²) expanse of columnar basalt, eroded and shaped by glaciers and wind over centuries.

Columnar basalt is formed when a lava ow cools suddenly and contracts, the cracks forming short hexagonal prismaticshaped columns which look similar to a honeycomb built by honey bees. Formations like this are not uncommon in Iceland.

e Hljóðaklettar cli s in the Jökulsárgljúfur National Park in the far north also have large formations composed of columnar basalt.

A few hundred metres north-west of Kirkjugól ð is Stjórnarfoss in the Stjórn

river that originates in Geirlandshraun mountain. is waterfall is quite hidden and while seldom visited by travellers, is well worth a visit.

A more impressive waterfall which can be seen a short distance east of Stjórnarfoss, is the intriguing Fjólafoss, about 20 metres (66 ) high against the cli s. When a strong wind blows right towards it, the falling stream is literally pushed into the air and back over the cli s. It appears as if the water only falls one-third of the way down the cli and then disappears!

Another work of art by nature’s hand is located 14 kilometres (9 mi) north-east of Kirkjubæjarklaustur village. At Foss á Síðu the river Fossá drops down 30 metres (98 ) over a basalt cli before it continues to the Atlantic ocean.

Foss á Síðu is fed by a small lake called Þórutjörn. When the ow in the river is light, strong winds coming from the sea

cause the water to ow uphill. What makes this waterfall so spectacular is its surroundings that are lightly covered with bright green moss and other lush vegetation.

According to an old story, a ghost roams Foss á Síðu. e ghost is a dog named Móri, who carries a nine-generation curse on the family of a man who led an evil way of life. Some say Móri has disappeared, but there are also people who believe that he still roams around the farm and the waterfall.

Opposite Foss á Síðu is Dverghamrar (Dwarf Rocks) with hexagonal basalt columns topped by cube-jointed basalt stones

Over the centuries, Icelandic folklore has drawn inspiration from a fusion of Christianity, polytheism, paganism, and even Irish mythology. Add this brew to an insanely bizarre volcanic landscape of mystical caves, honeycombed rocks, moss-covered lava felds, boiling geysers, and rocks in twisted shapes, and it’s not hard to see why Icelandic folktales are bursting with mysticism and supernatural beings.

Supernatural and mythological beings played an important role in the beliefs of ancient Icelanders, and Icelandic folklore is rich with tales about them that have been passed down from one generation to the next over the centuries.

There are four types of Icelandic mythical beings: trolls; “hidden people”; elves; and other creatures of lesser signifcance such as the nykur (a sinister grey “water-horse” with backward-facing hooves, usually found in lakes and rivers), the Lagarfjót worm (a serpentine-like creature that lives in glacial-fed Lake Lagarfjót), as well as sea monsters, ghosts and more.

As you travel through Iceland, you will most likely come across many stories about trolls, “hidden people” and elves. There is no clear difference between “hidden people” and elves, so they are often grouped together. However, trolls are very different creatures.

Trolls are the only beings who exist in the fesh as opposed to the spirit, so while trolls are visible, the others are invisible. They are much larger than humans, being able to grow up to several hundred feet tall. Trolls live in the mountains and only come down to villages at night to forage for food. They can only survive in the darkness of night, and if they are caught in the sunlight, they immediately turn to stone. These unfortunate stone trolls can be seen all

over the country, the most famous being the Reynisdrangar basalt sea stacks situated under Reynisfjall mountain near Dyrhólaey and Reynisfjara beach.

Elves are human-sized or smaller creatures that resemble humans with pointed ears. The “hidden people” or “hidden folk”, referred to as huldufólk, are inter dimensional human-like creatures. These “fairies” are believed to be peaceful beings who coexist alongside humans, unless they are angered by them! They go about their daily activities, such as fshing, farming, and raising their families, and according to legend, they sometimes even lend a helping hand to good humans who need to be rescued.

A 2007 survey by the University of Iceland found that 62% of Icelanders have some level of belief in the existence of “hidden people”. Many Icelanders claim to have seen and even communicated with the elves despite their invisibility. Such people are jokingly referred to as “Elf Whisperers”.

Do young people still believe these fairy tales? Apparently many do to some degree, and it has been stated: “These creatures do not literally exist, nor are they a complete fabrication. They can best be described as personifcations of the forces of living nature, so they really do exist. In any case, they are alive and kicking all over Iceland.”

For Icelanders, the moral of these stories is that people need to be constantly reminded to respect and protect nature. If you respect and honour Mother Earth, she will be on your side, live peacefully alongside you, and even come to your aid when needed. However, if you do not respect nature and defy its elements, it will rise up against you and may even obliterate you.

shaped like horseshoes. Dverghamrar is believed to be a dwelling place of some of Iceland’s elusive “hidden people” so is treated with great respect by the locals.

A high proportion of Icelanders still believe that elves, “hidden people” and even trolls live with their peaceful families at several locations in Iceland.

e road north of Foss á Síðu gets more impressive the closer it gets to the massive Vatnajökull glacier (translated as “Glacier of Lakes”). Vatnajökull is the largest and most voluminous ice cap in Iceland covering about 8,000 square kilometres (3,089 mi²), approximately 8% of the surface of Iceland. It is the second largest in surface area in all of Europe a er the Severny Island ice cap of Arctic Russia.

Along the Eastern Route, the rst glacier clearly visible from the Ring Road is Skeiðarárjökull, about 43 kilometres (27 mi) north-east of Foss á Síðu. Skeiðarárjökull is a large outlet glacier that ows down from the south-western region of the Vatnajökull ice cap. e glacier is enormous, but like other glaciers in Iceland, it has been retreating rapidly over the past few decades, and a lagoon has now formed at its terminus. It is known for its glacial “outburst oods” or jökulhlaups, which are caused by Grímsvötn, Iceland’s most frequently active volcano near the summit of Vatnajökull. Grímsvötn lies about 50 kilometres (31 mi) from the terminus of the glacier where the meltwater emerges.

Before we get to see three more of Vatnajökull’s glacier tongues, let’s rst make a stop at another impressive waterfall.

Located 58 kilometres (36 mi) northeast of Foss á Síðu, and a short distance from one of Vatnajökull’s tongues, is Svartifoss, one of Iceland’s most photographed waterfalls. It is unique in that the falling water is surrounded by dark lava columns, and the base of the waterfall is covered in sharp rocks, so when standing close to the falls you are surrounded by an arena of basalt columns. ese columns have inspired many Icelandic architects, most visibly in Reykjavík’s Hallgrímskirkja.

A few hundred metres from Svartifoss is Skaftafellsjökull, the largest of Vatnajökull’s south-western glacier tongues. Ska afellsjökull is another perfect example of how climate change is steadily a ecting the glaciers of Iceland. Over the last decade, this glacier has been receding dramatically, and the signs are quite remarkable.

Enthusiastic hikers should check in with the Ska afell Visitors Centre and then hike the two kilometres with an elevation of 390 metres (1,280 ) to Svartifoss. Along the route are great views over the glacier.

A short drive south along the main road is Svínafellsjökull. is glacier has deep blue ice, gleaming white snow, and veins of black ash, reminders of eruptions

from the past. In summer the colouring is less vivid, while in winter the intensity of the blue ice is captivating.

It is quite easy to get very close to Svínafellsjökull. However, a glacier is no place to wander around without a qualied guide and the necessary equipment. Close to the glacier ice is a metal plaque attached to a rock that commemorates the disappearance of German hikers Matthias Hinz and omas Grundt. ese guys went missing on August 17, 2007, and multiple search teams were unable to nd their bodies. A few clues le behind by the hikers suggest that they slipped and fell into a crevasse and most likely slid deep down into the frozen belly of the glacier. Never to be seen again, until maybe one day when the glacier melts down.

This massive ice cap is up to 1,000 metres (3,280 ft) deep and conceals at least three active volcanoes–Grímsvötn, Öræfajökull and Bárðarbunga. Vatnajökull is also the mother of about 30 outlet glaciers (glacial tongues), of which the most signifcant and accessible are Breiðamerkurjökull, Skeiðarárjökull, Skaftárjökull and Svínafellsjökull. Vatnajökull is also the source of numerous glacial rivers, and glacial lakes such as the impressive Jökulsárlón lagoon at the foot of Breiðamerkurjökull. Here, large icebergs drift across the lake into the Atlantic, where many wash up on nearby Diamond Beach.

A little further south is one of the smallest glacial tongues in the area. e southernmost glacier tongue, known as Falljökull, looks quite dramatic as it “ ows” down the hills, though the receding of this glacier is clearly visible.

One can only imagine how much more impressive these glaciers would have been just a few decades ago. Falljökull, a popular destination for hiking and climbing, is very close to Storalekjargljufur and Graena allsgljufur, two canyons that are well worth a hike. Climbing the glacier’s natural ice sculptures and exploring the tunnels, glacial mills (moulins) and cold

water beneath its ice layers is an unforgettable experience.

From Falljökull the main road rst heads south, then snakes to the north-east between the ocean and more of Vatnajökull’s tongues. e 48 kilometre (30 mi) scenic drive from Falljökull leads to one of Iceland’s most spectacular scenic spots, Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon. It lies at the head of the Breiðamerkurjökull glacier in the south-eastern section of the Vatnajökull ice cap.

Large blocks of ice are constantly breaking o from Breiðamerkurjökull to form icebergs. As they travel through the lagoon, they o en become resting spots for the many resident seals.

While it is not very wide, Jökulsárlón is up to 250 meters (820 ) deep, making it the deepest lake in Iceland. Formed when the glacier began to retreat from the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, it continues to grow.

While the ice around it is dark in places due to the black ash from previous volcanic eruptions, the view over the glacier and the lagoon lled with dri ing icebergs is a scenic landscape never to forget.

e surface of Jökulsárlón is at sea level, so salt water ows into the lagoon at high tide and back out into the sea during low tide, taking chunks of dri ing ice from the lake into the sea, then washing the ice onto the nearby beach.

Right across the road from Jökulsárlón is Diamond Beach (Breiðamerkursandur), very aptly named a er the large, glittering pieces of glacier ice against its black sands. e chunks of ice are brought by the tides from the lake and dropped onto the beach by the rugged waves.

e winding road continues along the coast in a north-eastern direction, passing several small scenic coastal villages including Höfn, Breiðdalsvík and Seyðis örður, then a er 330 kilometres (205 mi) reaches Borgarfjörður eystri.

Iceland is a nature lover’s paradise with a vast uncharted wilderness of caves, lava fields, glaciers, lagoons, rivers, mountains, volcanoes, and more.

Jökulsárlón Glacier and Glacial Lake

Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon and nearby black-sand Diamond Beach, littered with chunks of broken icebergs, are among Iceland’s natural crown jewels. Jökulsárlón, which roughly translates from Icelandic as “Glacier River-Lagoon”, is Iceland’s deepest lake and is flled with runoff water from Breiðamerkurjökull, one of the many glacial tongues of Vatnajökull ice cap.

Along this lengthy road, which at times clings to a narrow strip between the volcanic sandhills and the rough waves of the Atlantic, are many more waterfalls, Icelandic horses, and quaint coves by the sea. Very spectacular and dramatic landscapes!

Höfn (meaning “harbour”), is the largest settlement on this stretch of coast, with a population of a little over two thousand, and a good place to spend a day or two. e town, with its natural harbour, sits at the tip of its own peninsula and is surrounded on three sides by the Atlantic Ocean, which can freeze over during extreme periods. Be here in July when the town celebrates its annual Lobster Festival.

Whooper swans can o en be seen in summer on the beaches along the road north of Höfn around Þorgeirsstaðir While many of them migrate in winter to the more temperate climate of the British Isles and western lowlands of Europe, some can be seen year-round in the southern regions of Lake Mývatn, which does not freeze due to its thermally heated water source.

Whooper swans undertake what is probably the longest sea-crossing of any swan species, migrating about 1,400 km (900 mi) between Iceland and the British Isles.

Just over 100 kilometres (62 mi) north of Höfn lies the small town of Djúpivogur in the Beru örður ord. e main road in this area hugs the edge of the volcanic hills high above a steep gravel slope down to the rough waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. Djúpivogur is home to Langabúð, a compact red building that is one of the oldest commercial buildings in Iceland, dating back to 1790. From here it is only 440 kilometres (273 mi) south-west to the Faroe Islands.

Along the north-western part of Beru örður ord is the beautiful Fossárdalur waterfall in the Fossá river. e 15-metre-high (49 ) waterfall is located only a few hundred metres from the Ring Road. Further along this road, just before Streitishvarf lighthouse, is a high waterfall dropping from Smátinda all mountain.

e scenic road continues north from here to the settlement of Breiðdalsvík, then around the Fáskrúðs örður ord and up to Seyðis örður.

e town of Seyðisfjörður, 212 kilometres (132 mi) north of Höfn and at the end of a 27-kilometre-long (17 mi) scenic pass branching o from Egilsstaðir on the Ring Road, is one of the most scenic towns in eastern Iceland. Located at the entrance to the Seyðis örður ord, the town has less than 700 inhabitants and feels very remote from the rest of Iceland.

e town is best known for its muchphotographed little blue Lutheran church (Seyðisfjarðarkirkja), colourful wooden buildings, cosy cafés, cra shops and the surrounding mountains—the most prominent being Mt. Bjólfur to the west and Mt. Strandartindur to the east.

e next major settlement to the north, Bakkagerði, is 95 kilometres (59 mi) from Seyðis örður in a pleasant bay on the Borgar örður eystri ord. Bakkagerði has about 130 inhabitants and is an ideal starting point for hikes to Stórurð (“ e Giant

Boulders”) and Álfaborg (“Elf Rock” which some locals believe is the home of the queen of the elves), as well as for visiting a pu n colony.

e famous church in Bakkagerði dates back to 1901. Don’t miss Lindarbakki, a renovated turf house built in 1899. You will be convinced that Mickey Mouse and the elves live in this cosy little red house. e house is typically Icelandic and has a traditional Scandinavian green roof, covered with turf on several layers of birch bark on gently sloping wooden roof boards.

Bakkagerði’s harbour is home to thousands of pu ns nesting around a small rock called Hafnarhólmi. Here you will also see many fulmars, common eider, gulls and kittiwakes.

e 72 kilometre (45 mi) drive from Borgar örður eystri to Héraðssandur, in the far north-eastern part of Iceland, passes very dramatic landscapes including more columnar basalt rock formations.

e panoramic views over the ocean from the hills near Héraðssandur are truly magni cent.

Just south of Héraðssandur we leave the east coast and drive north-west to explore the northern part of Iceland.