Complete Houses, Designing NonFragmented Landscapes of Beds

“By dwelling we are also talking about shops, schools and public services”

- Lina Bo Bardi

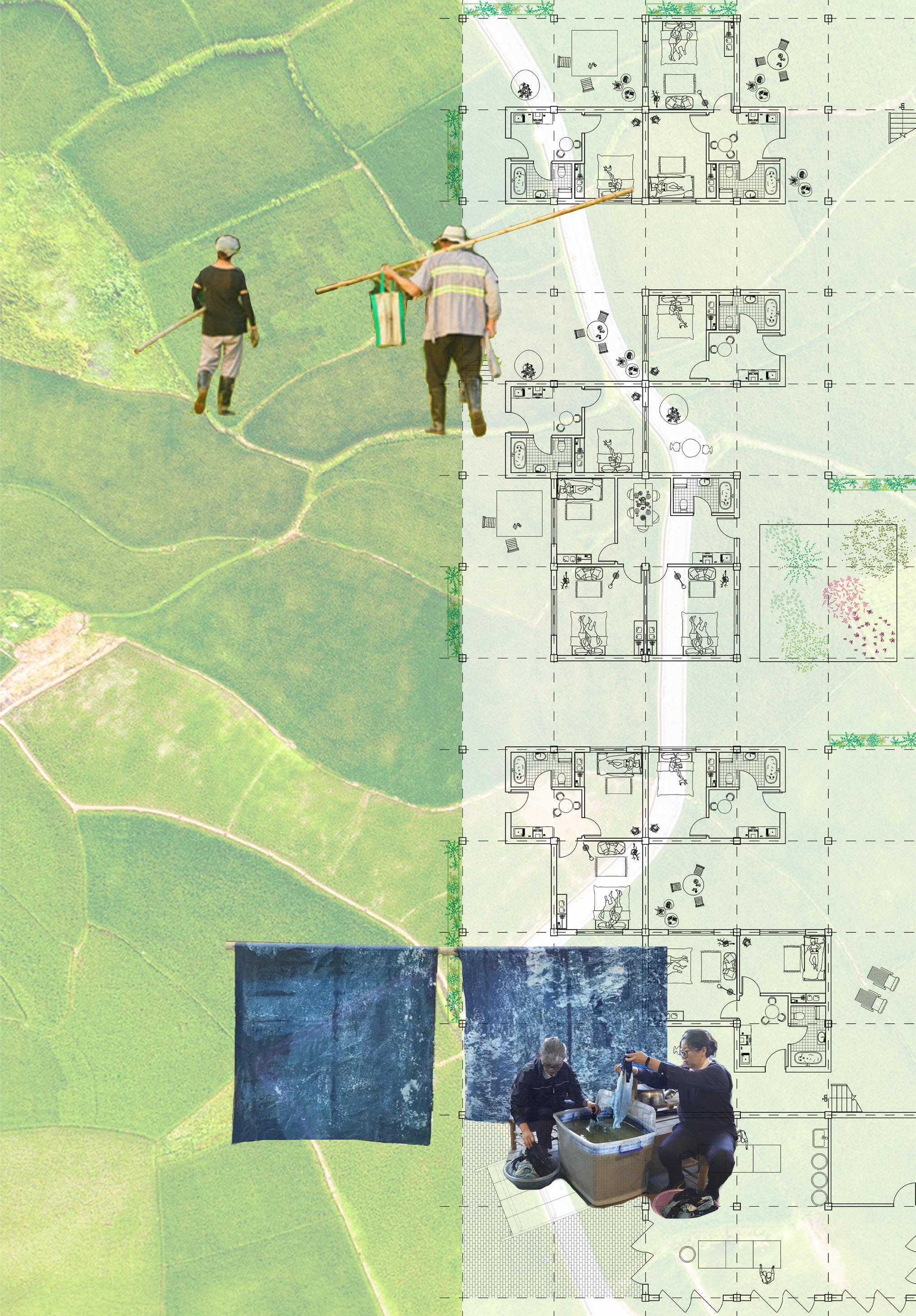

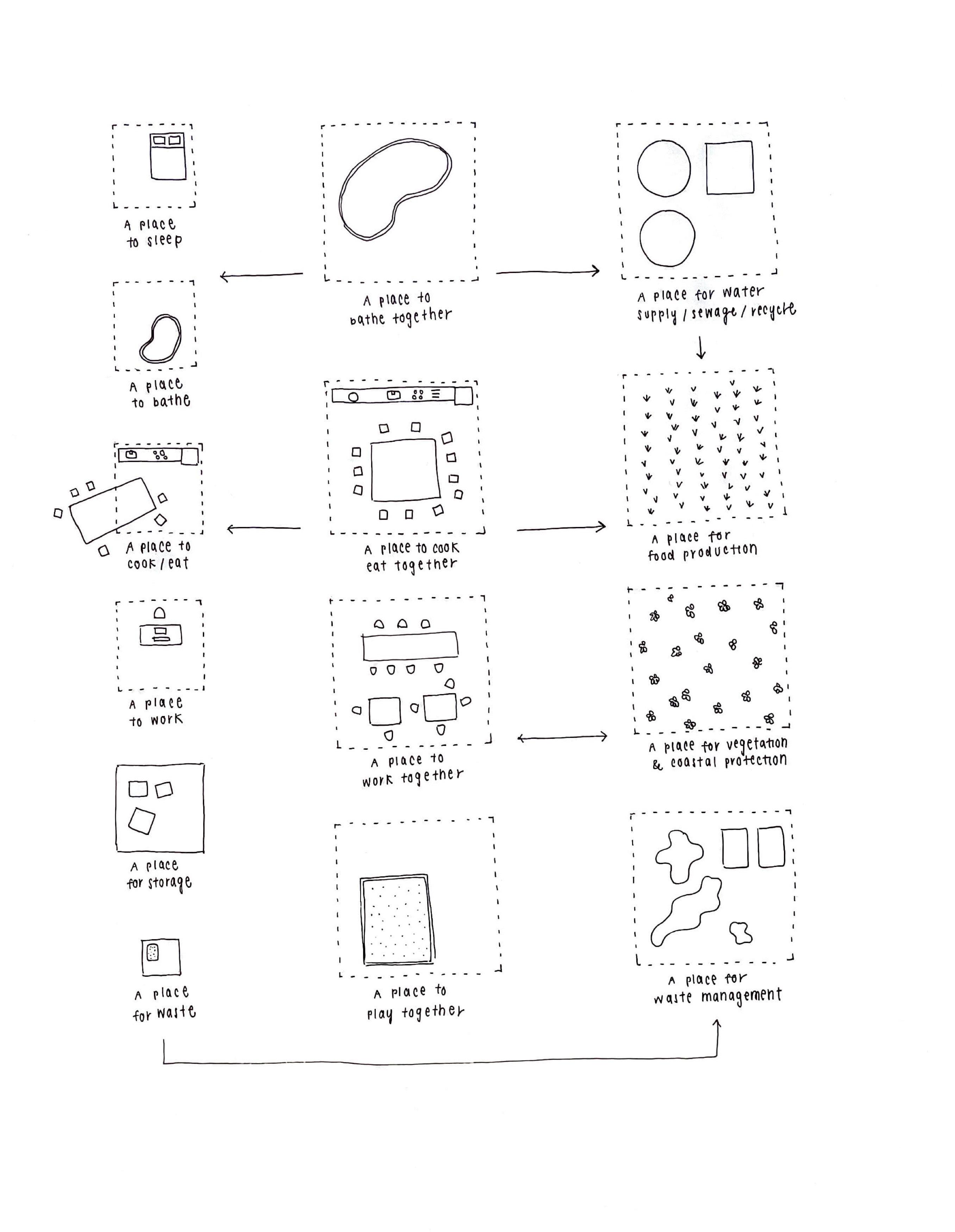

Taking further the concept of “Complete Streets” (safe, accessible to all, multiprogram, sustainable, and context conscious), we will re-imagine the relationship between buildings, bodies, and the environment through the design of “Complete Houses”. Considering housing not as the multiplication of private universes, but as centers of production, consumption, education, socialization, and health. Houses account for the largest major built space in the planet, but are still designed on the basis of individual desires that disregard collective implications. For that reason, we will work against the definition of the modern house as a sanctuary for rest, mainly designed for the nuclear family, inaccessible to a vast majority, and scarcely related to everything that comes in and out of it. In contrast, students will design landscapes with places to sleep, bathe, cook, eat, work, learn, exercise, play… Where people, materials, and food are part of the same network.

The aim of this Studio is to produce projects that eliminate the binary oppositions between “interior worlds” and “exterior worlds”. The intention is to reinsert in the house its productive logic and collective nature, and, invent less violent relations with its vital links to the exterior. Students will work against the fragmentation of life according to activities divided by age, gender, race, and class. We will work considering situations that force to place design where the urgencies are.

Studio Instructor Fernanda Canales

Teaching Associate Angel Escobar-Rodas

Studio Participants Tree Chen Xi Chen Angel Escobar-Rodas Emily Hsee Emily Hu Nana Komoriya Jennifer Li Sarahjane Mortimer Adrea Piazza Pa Ramyarupa Ali Sherif Cathy Wu

Midterm Critics

Anda French Natalia Garcia Dopazo Roi Salgueiro Michael Surry Slabs

Final Critics Dana Behrman Anda French Jennifer French Natalia Garcia Dopazo Kersten Geers Simon Hartmann Valeria Luiselli Clara Solà-Morales

10 What is a Complete House?

Defining the Complete House

36 Mapping the Ring of Fire Ring of Fire Project Regions

62 Studies Study: Global Study: Local Study: Landscapes Study: Utopia

136 Landscapes of 1,000 Beds

Matryoshka Tree House Tree Chen

Work and Food Xi Chen

Common Walls

Angel Escobar-Rodas

Fractured Memories, Fortified Places

Emily Hsee

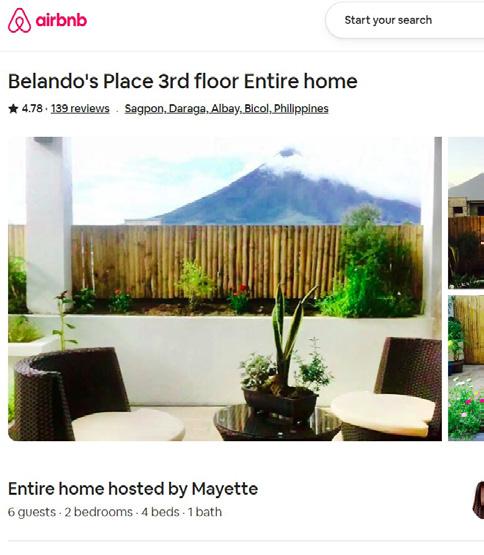

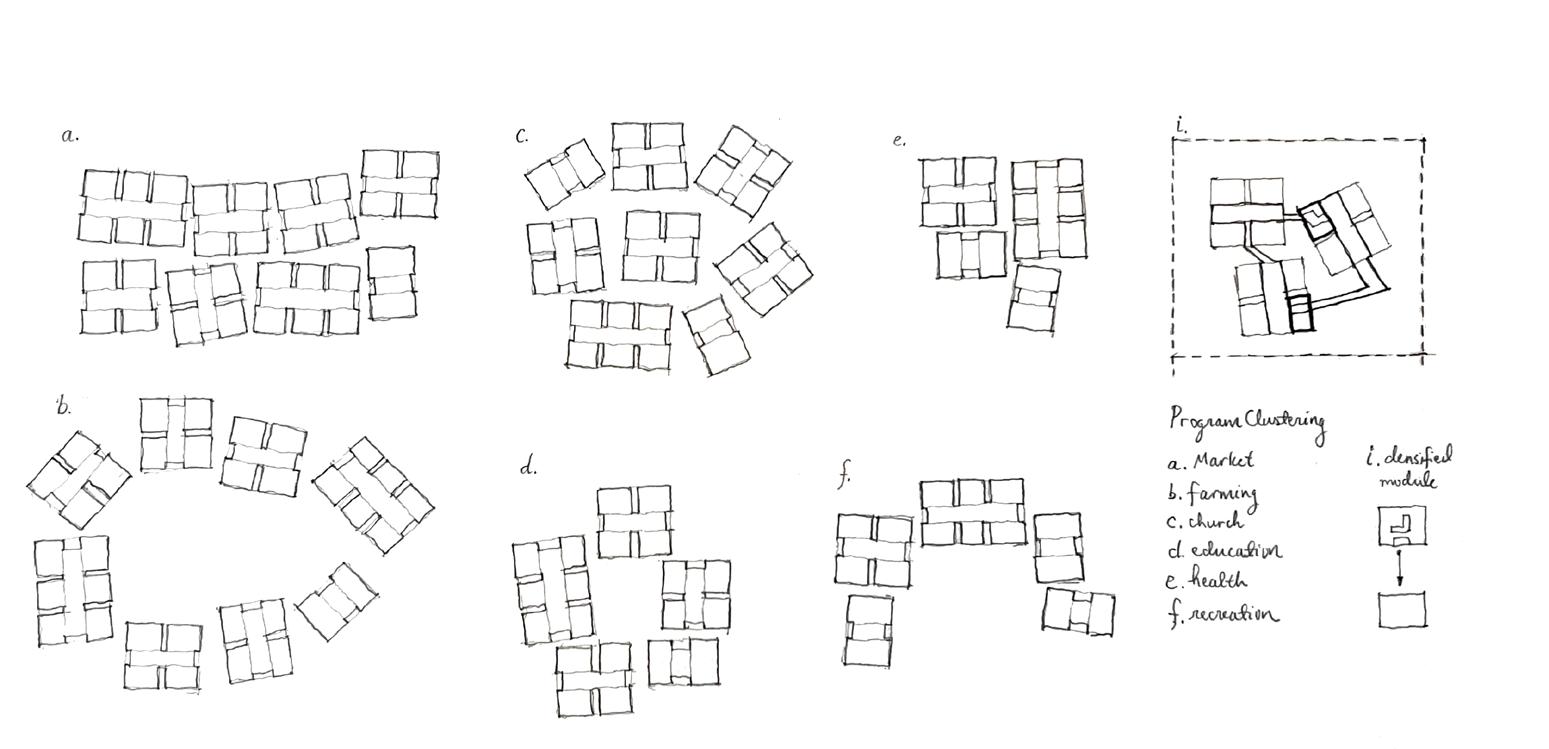

Hacking Homes for Volcano Guests

Emily Hu

Coastal Collective: Daily Rituals Nana Komoriya

Wet Collective Jennifer Li

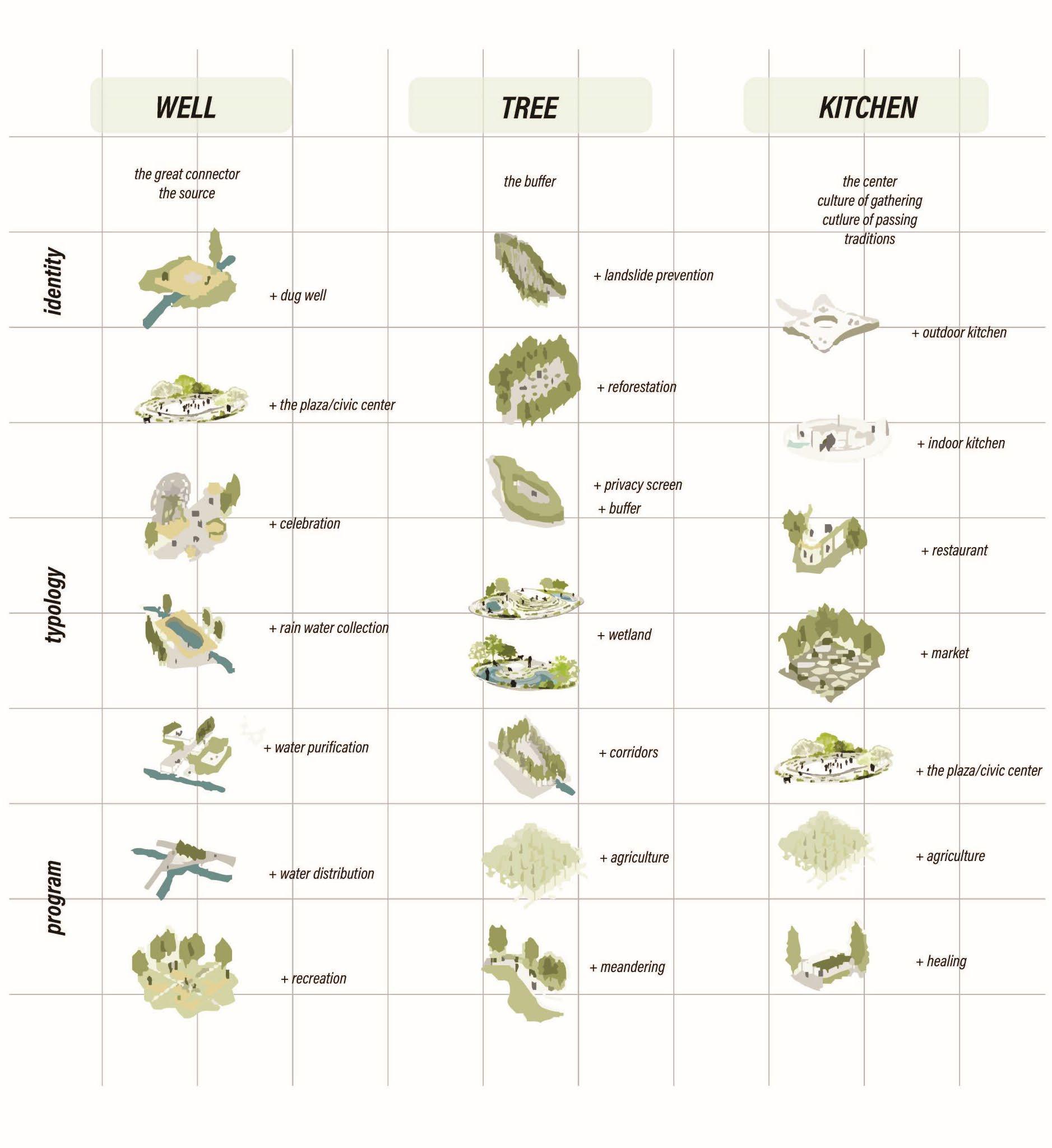

The Tree, The Kitchen, and The Well Sarahjane Mortimer

Rain Reservoir House Adrea Piazza

Inhabitable Embankment Pa Ramyarupa

Post-Industrial Refuge Ali Sherif

Quas Sunto Cuptat Ex Et Alicat Aut Et Faciendae Verum Quis Cathy Wu

270 Manifestos

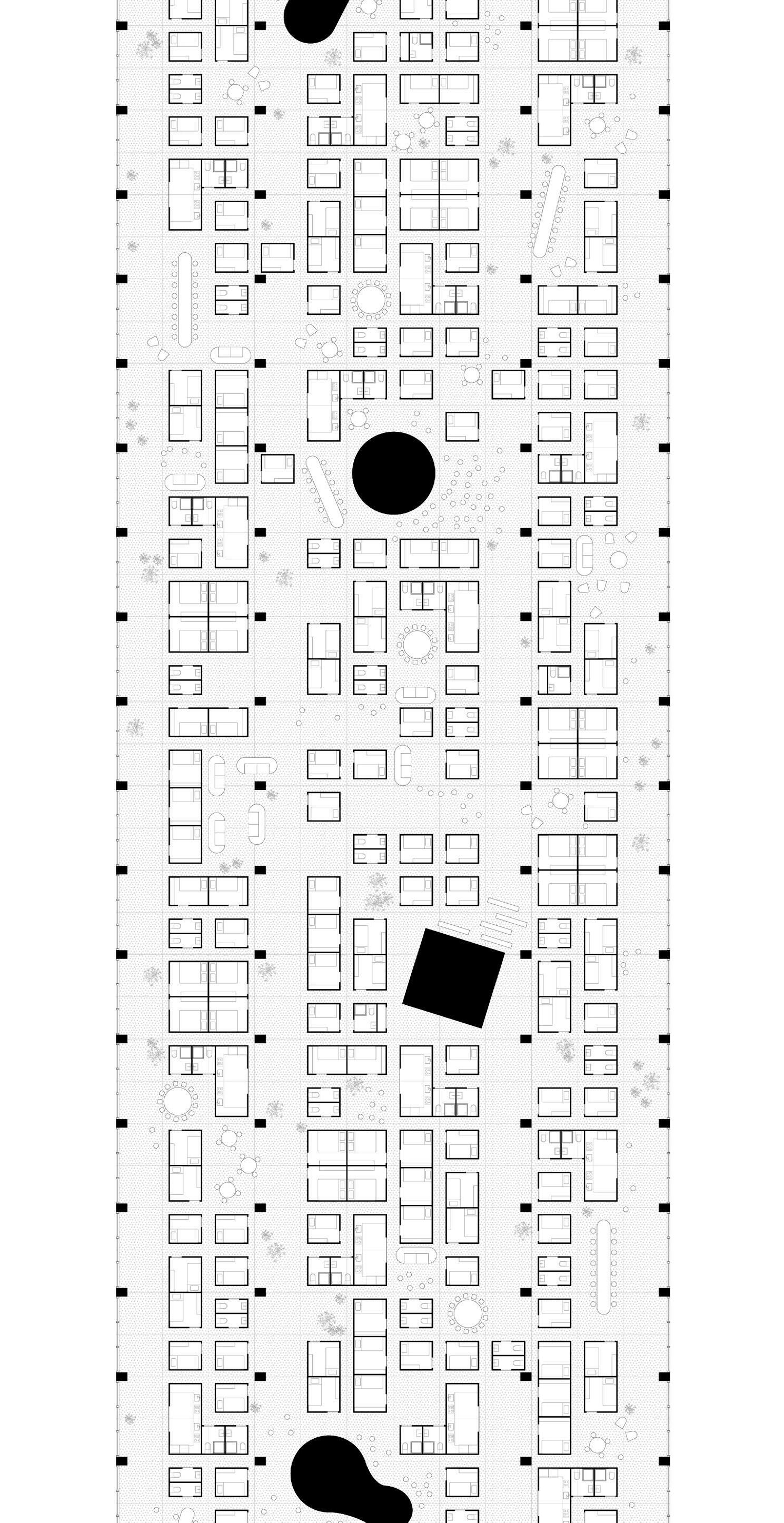

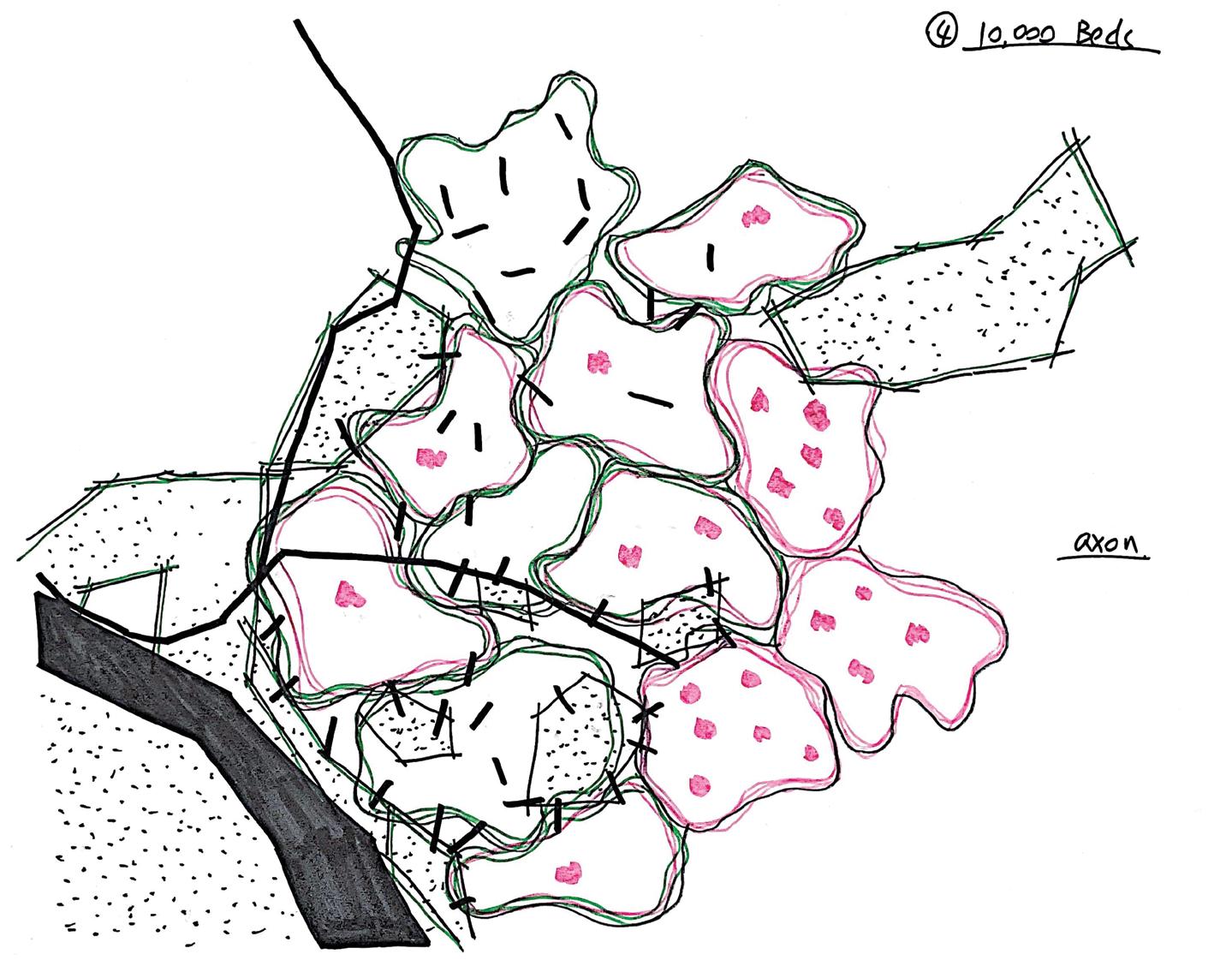

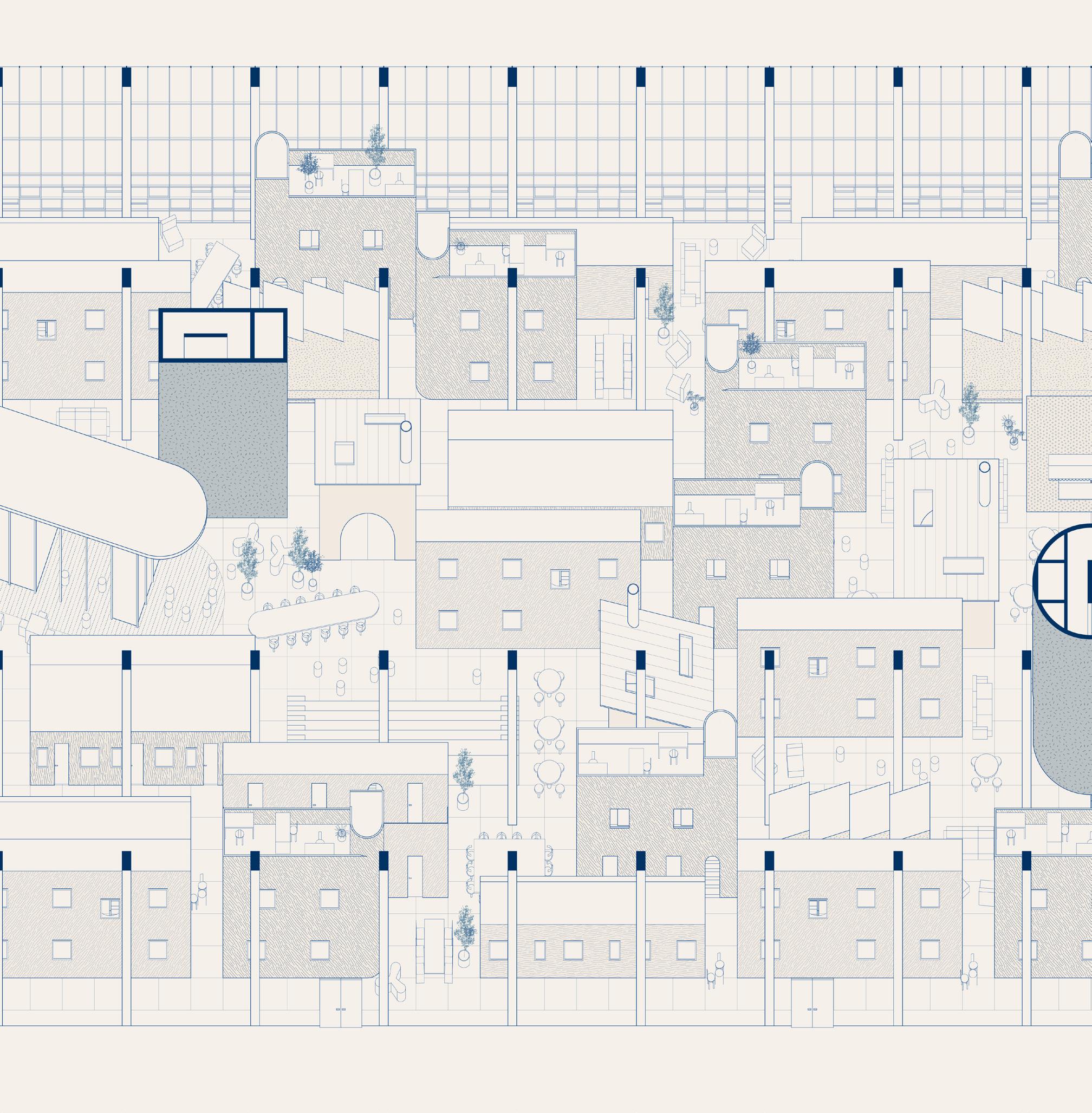

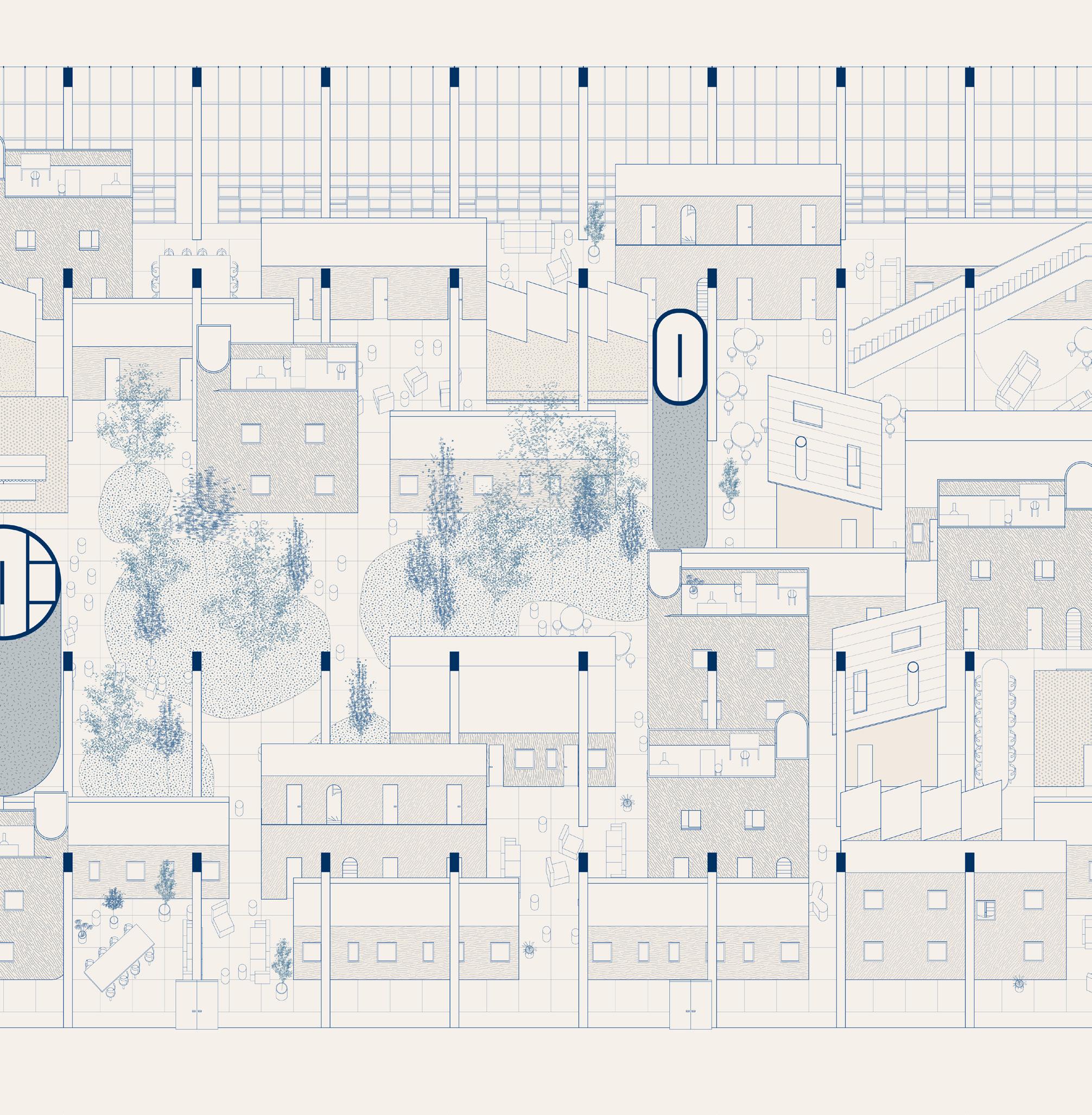

296 Landscapes of 10,000 Beds

Matryoshka Tree House Tree Chen

Work and Food Xi Chen La Via

Angel Escobar-Rodas

Fractured Memories, Fortified Places Emily Hsee

Hacking Homes for Volcano Guests Emily Hu

Coastal Collective: Daily Rituals Nana Komoriya

Wet Collective Jennifer Li

The Tree, The Kitchen, and The Well

Sarahjane Mortimer

Rain Reservoir House Adrea Piazza

Inhabitable Embankment Pa Ramyarupa

Post-Industrial Refuge Ali Sherif

Quas Sunto Cuptat Ex Et Alicat Aut Et Faciendae Verum Quis Cathy Wu

418 Contributors

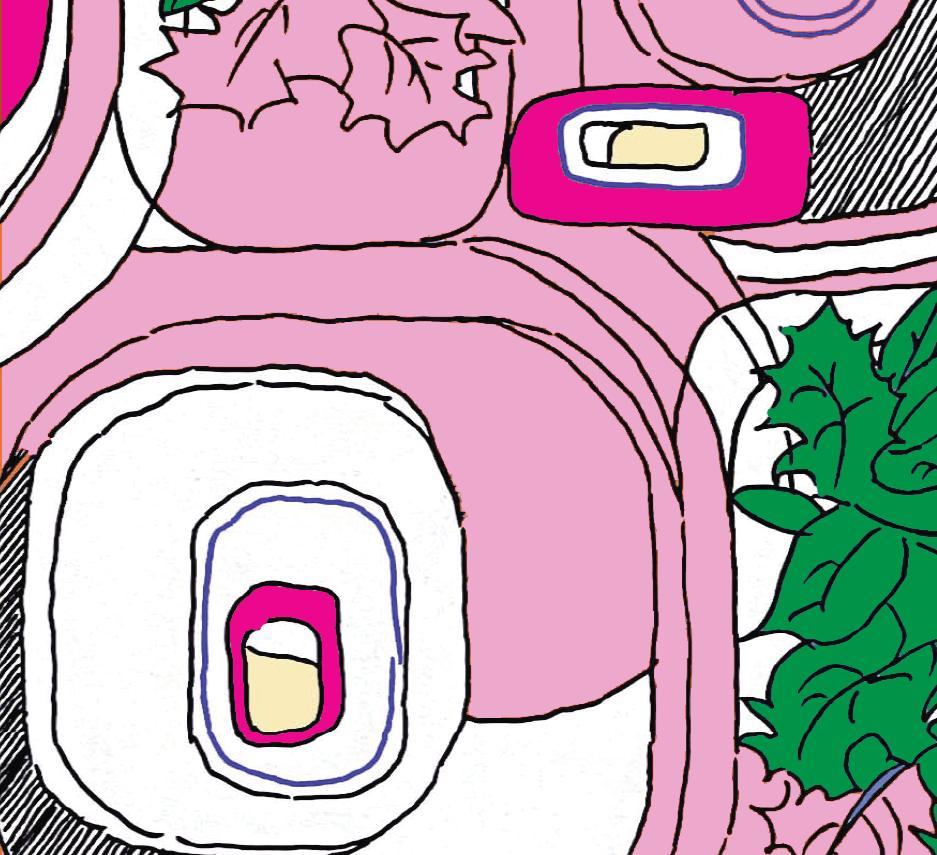

Marlon Riggs’ 1995 documentary, Black Is...Black Ain’t, explores the multiplicity of the Black experience in America through a variety of perspectives, media, and stories. Borrowing from this framework, students explored the myriad ways “House” can manifest. Together, we depart from the embedded perspectives that have driven housing crises around the world.

Our definitions of the Complete House, represented visually and in text, offer a dozen starting points for the collective project of imagining new ways to inhabit the world.

is an organic entity constituted of interdependent breathing cells and capillary layers.

Complete House :

1. Complementary distribution of layered indoor/outdoor public space.

2. Guaranteed intimate space.

3. Both vertical and horizontal access. 4. Flexible extension/subtraction of units. 5. Systematic efficiency. HOUSE IS INTERDEPENDENCE, HOUSE AIN’T INSTITUTION

Complete House :

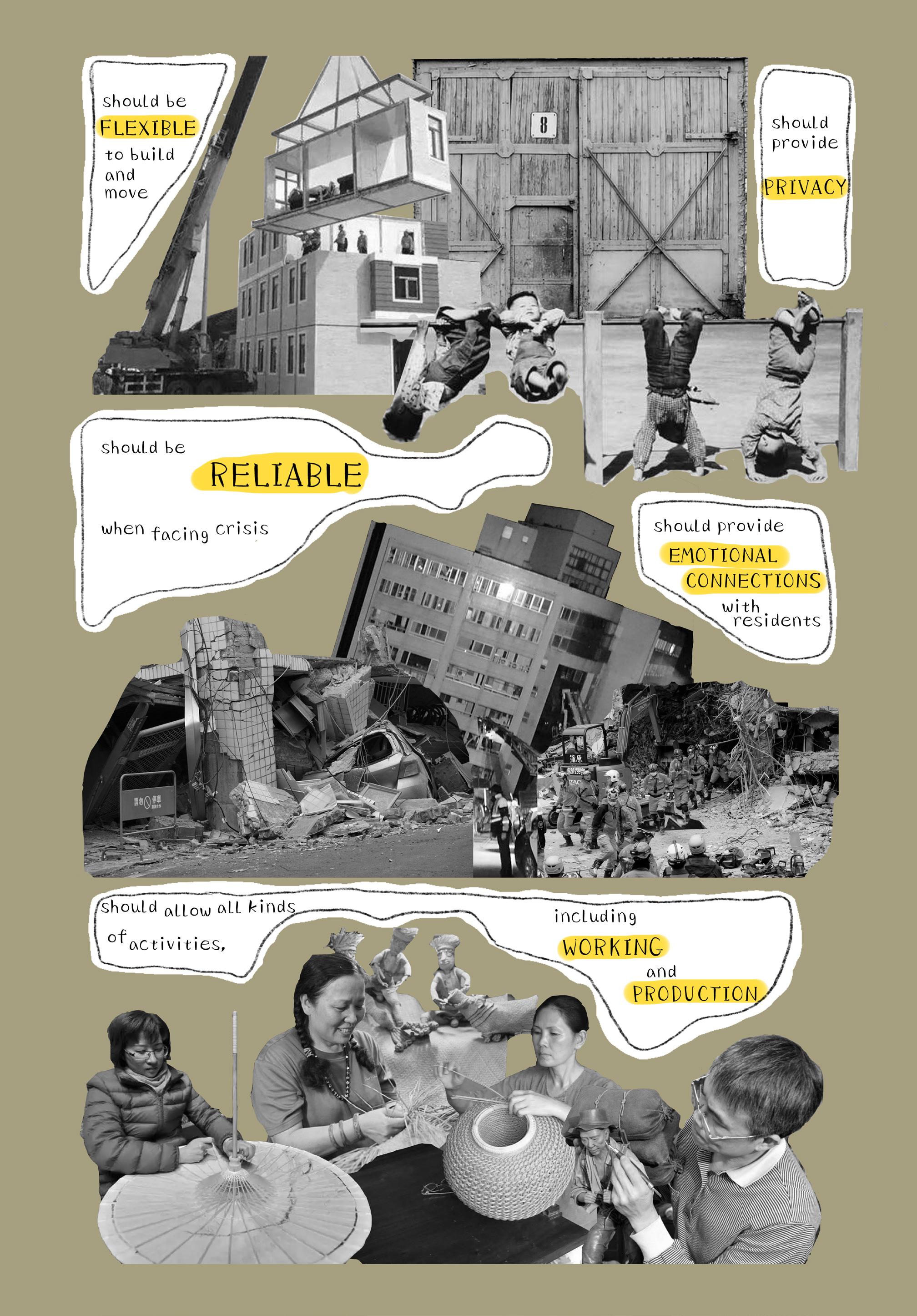

1. Complete house should allow all kinds of activities, including working and production.

2. Complete house should provide privacy.

3. Complete house should be reliable when facing crisis.

4. Complete house should provide emotional connections with residents.

5. Complete house should be flexible to build and move.

HOUSE IS RELIABLE, HOUSE AIN’T BURDEN

Complete house is a multifunction place that serves all people.

Complete House :

1. Allows for total privacy 2. Adapts to the ebb & flows of life 3. Is contiguous with nature 4. Is in symbiosis with community 5. Facilitates surrender (ultimate comfort & safety)

HOUSE IS PECULIAR, HOUSE AIN’T STANDARD

Complete House :

1. Offers solitude and proximity.

2. Feels protected and porous.

3. Feels anchored and moveable. 4. Offers stability and adaptability. 5. Demands cooperation and entanglement.

HOUSE IS COMPROMISE, HOUSE AIN’T IDLE

Emily

Complete House :

1. A house can be hacked to be shared with tourists and refugees.

2. A house can provide both income and aid.

3. Home-sharing encourages collective production and consumption

4. Home-sharing provides opportunities for care and education.

5. An open house bleeds into and mediates different programs.

HOUSE IS SHARED, HOUSE AIN’T UNWELCOMING

A

house normalizes sharing of underutilized assets and space between local hosts and their guests.Emily Hu

Complete House is:

1. a place of daily rituals

2. a sense of belonging

3. a celebration of culture and tradition

4. a collective togetherness

5. a extension of nature

HOUSE IS HOME, HOUSE AIN’T ALONE

Complete House pertains to the functions of living well and enjoyably: that includes with autonomy, communal belongings and services, and a comfortable space that everyone can call their own.

Complete House ensures : 1. flexibility 2. right to good air, water, sun 3. public amenities 4. neighborhood conviviality 5. ample space for self and things

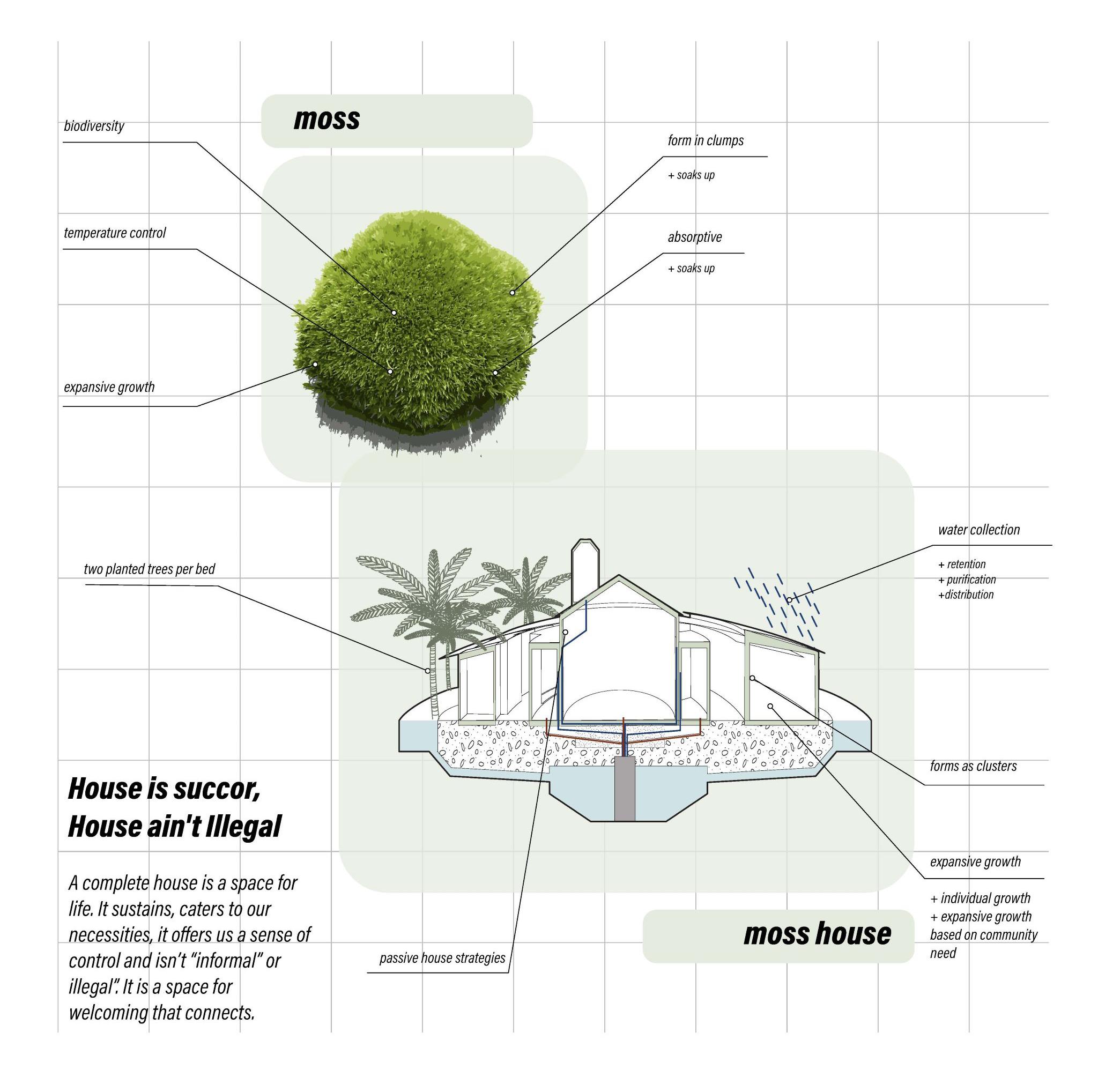

Complete House :

1. House is an organism, it breathes, grows and shrinks, is flexible, is not permanent

2. House connects to nature

3. House is space for rest, cleansing and nourishment

4. House welcomes outsiders and is open for gathering. House gives back (to community, to self )

5. House creates and stores memories

HOUSE IS SUCCOR, HOUSE AIN’T ILLEGAL

A complete house is a space for life. It sustains, caters to our necessities, it offers us a sense of control and isn’t “informal” or illegal”. It is a space for welcoming that connects.Sarahdjane Mortimer

Complete House :

1. unifies disparate parts

2. is a shared project

3. collectivizes resources and responsibility

4. is harmonious

5. is one’s own part of a whole

HOUSE IS MAKING IT YOUR OWN, HOUSE AIN’T YOURS ALONE.

Complete House :

1. celebrates neighbors and surrounding environments

2. is permeable

3. foregrounds community comfort and care

4. is interdependent on the ecology in which it is situated

5. is a sense of belonging

HOUSE IS IDEOLOGICAL, HOUSE AIN’T TYPOLOGICAL

Complete House :

1. is able to contain any and everything.

2. creates space for the quotidian and the ad-hoc.

3. provides the feeling of safety and of autonomy.

4. nulls the boundary between inside and outside.

5. is permanent, but flexible.

HOUSE IS A PLACE, HOUSE AIN’T A BUILDING.

Complete Houses are places that deconstruct the boundary between the individual and the collective to create healthier, more prosperous communities.

provides infrastructure and resources for expansion, division and modification.

It is complete while being incomplete.

Cathy WuComplete House :

1. part of a system while being autonomous

2.contributes to a community while being self-sufficient

3. built with accessible materials

4. both secure and social

5. shapes the residents as the residents shape the house.

HOUSE IS GROWING HOUSE AIN’T RIGID

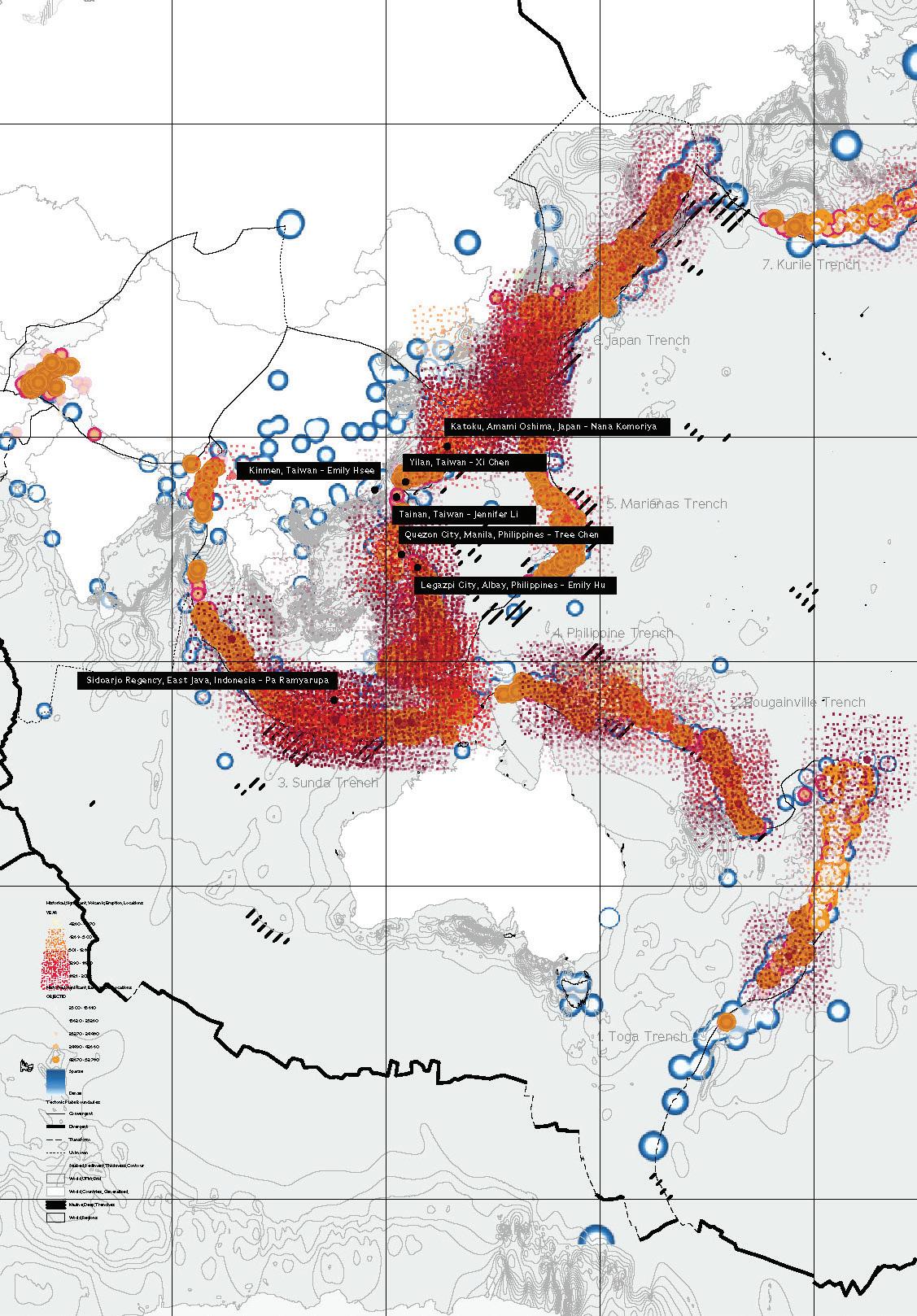

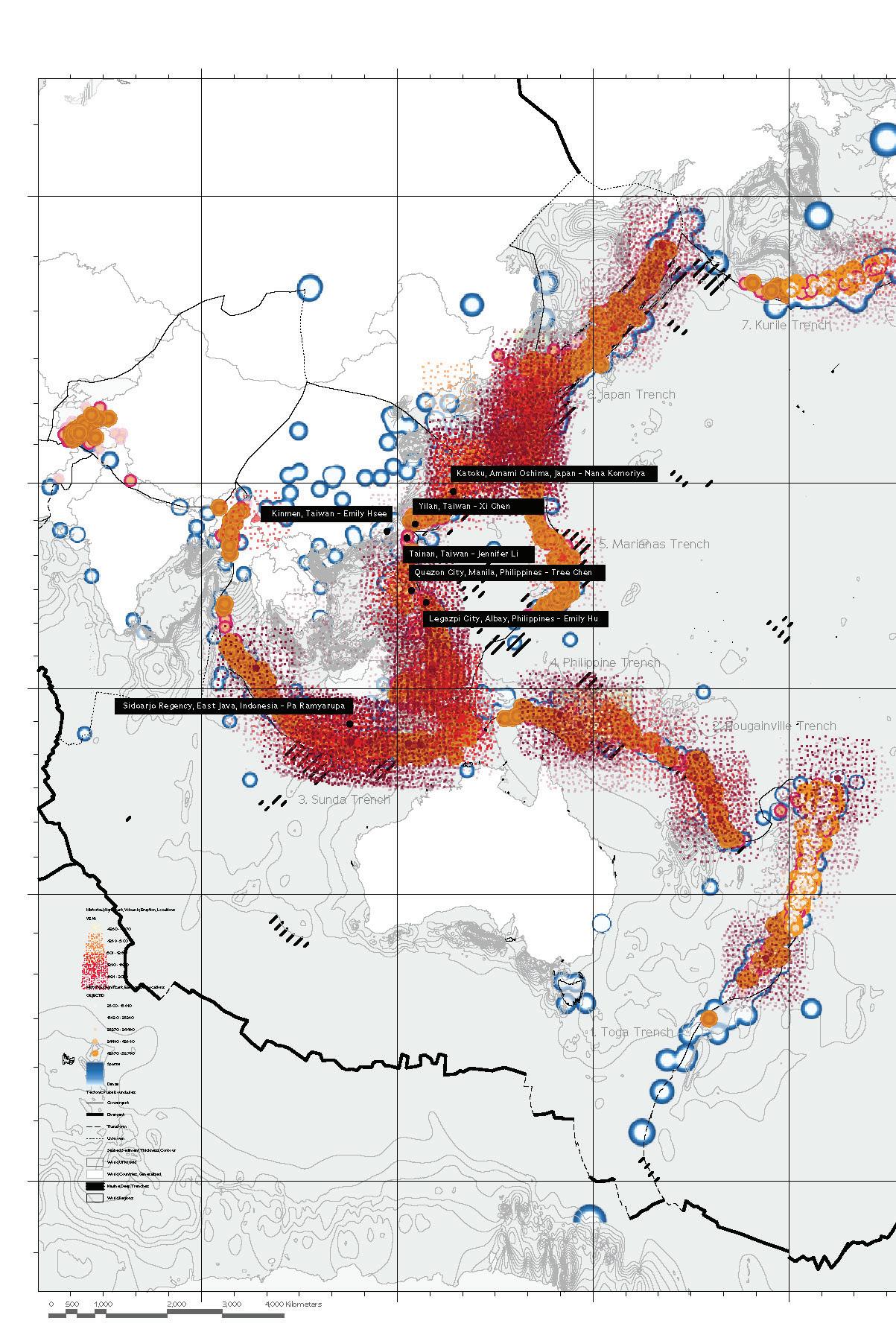

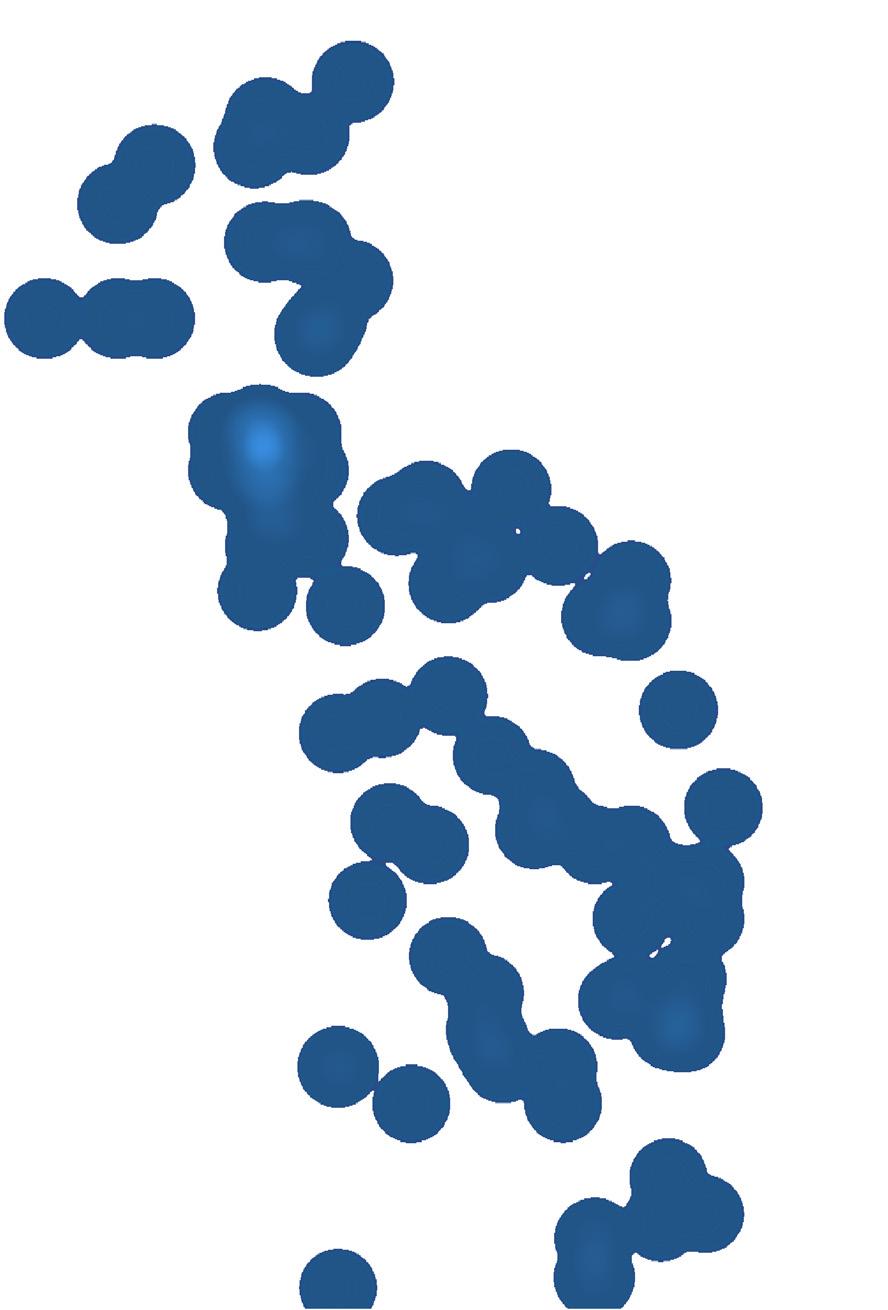

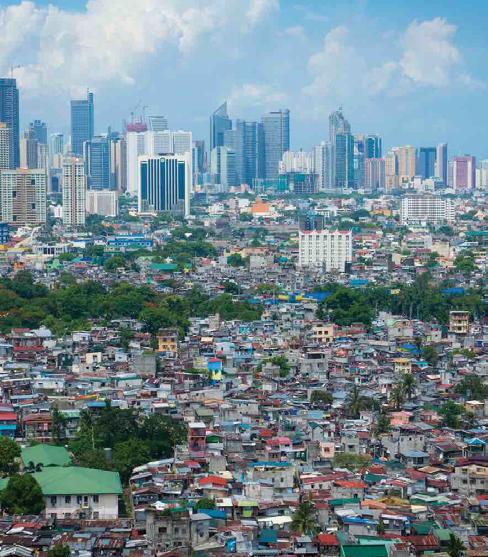

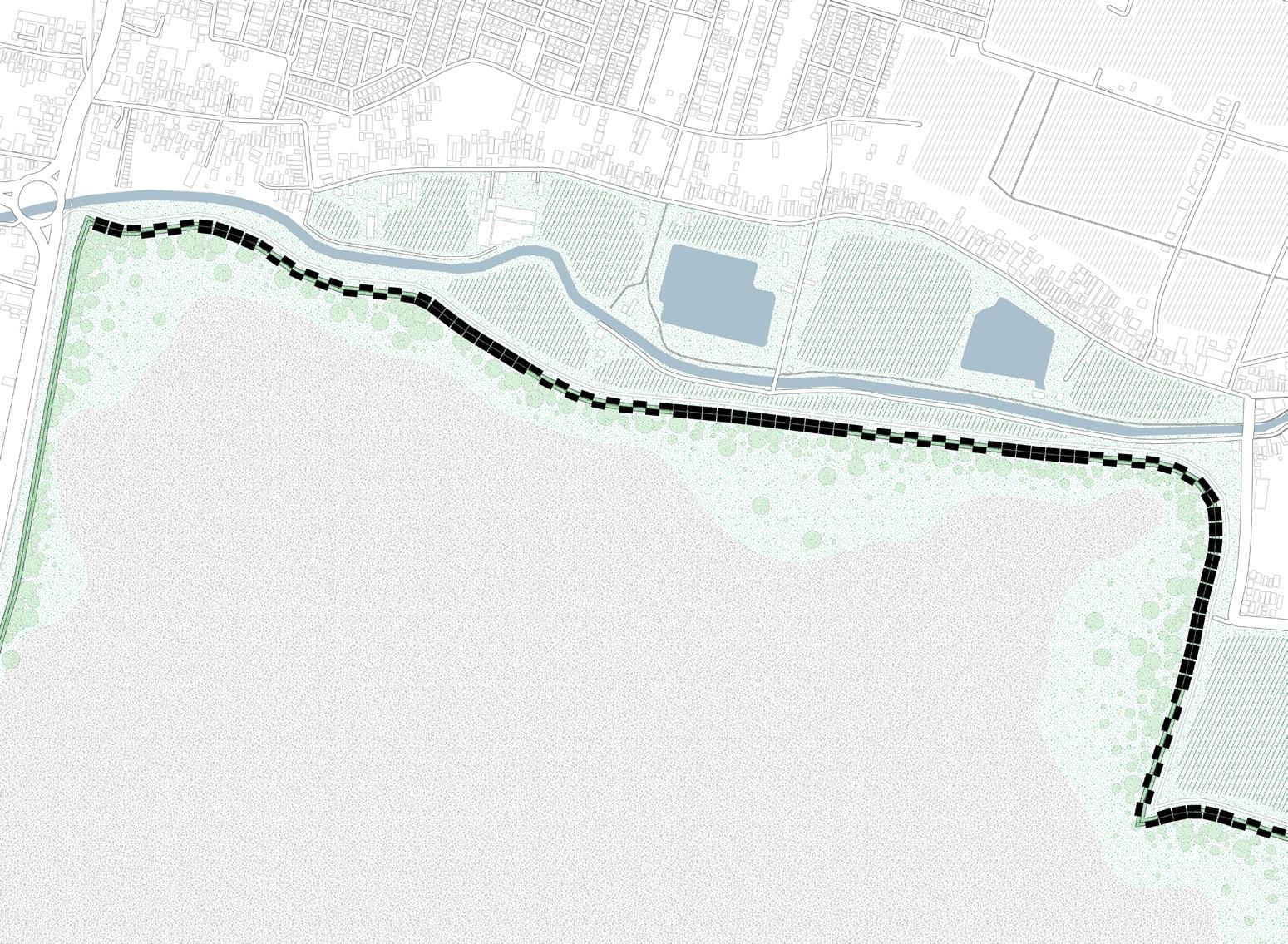

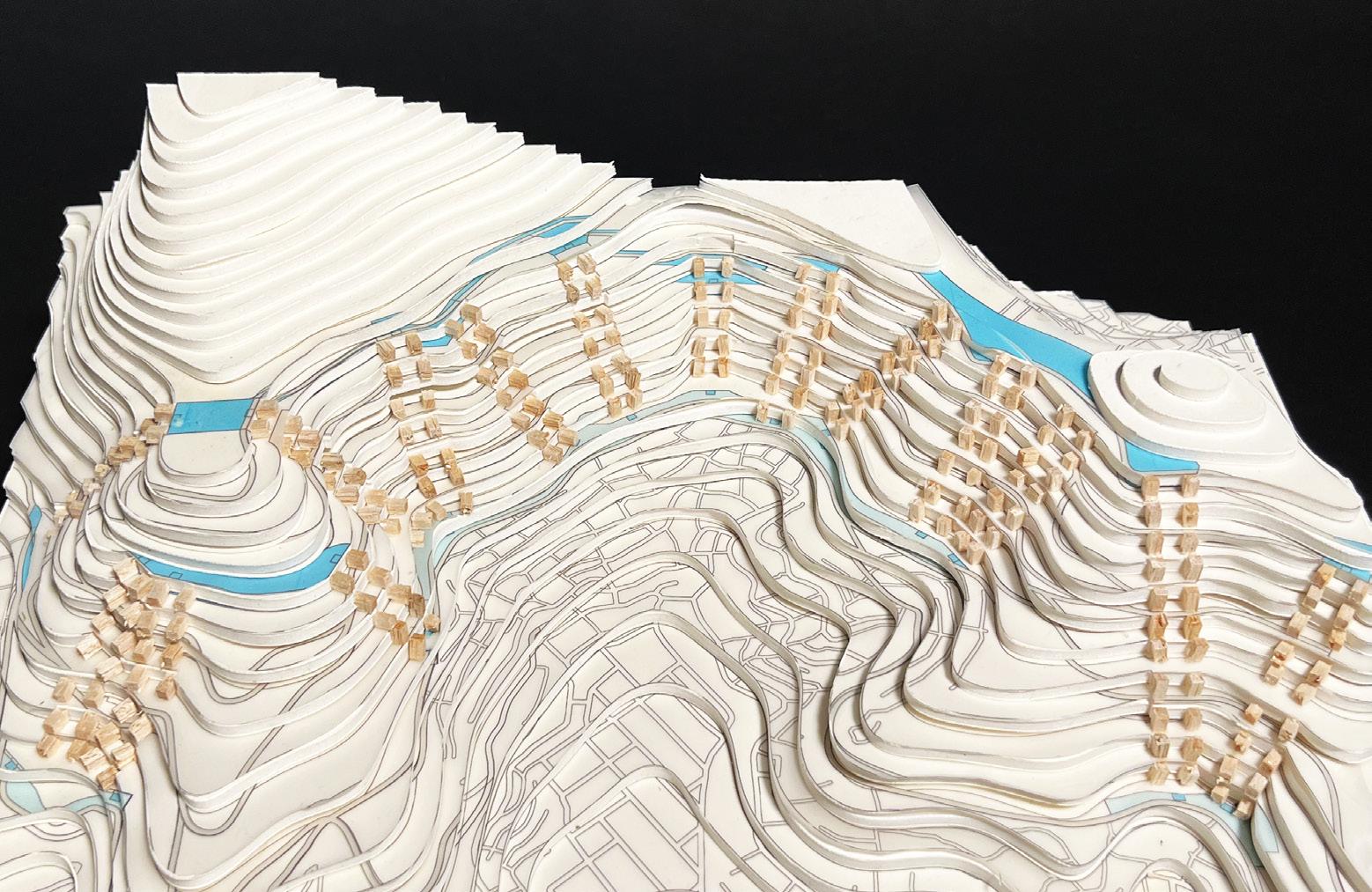

This region comprises a number of countries: the U.S., Mexico, Japan, Russia, Korea, China, Peru, Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, Sumatra, Alaska, Canada, Chile, Columbia, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, Honduras, Panama, Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia, the list continues. Home to natural landscapes and some of the most densely populated cities in the world from Los Angeles to Caracas, from Alaska to Singapore, the Pacific Ring of Fire provides a sample of the most crucial global matters concerning natural disaster, thus humanitarian affects. Students are invited to choose their specific setting in relation to crises. In studying geographies with radical conditions, the studio emphasizes that we can no longer avoid deep engagement in environmental and social urgencies.

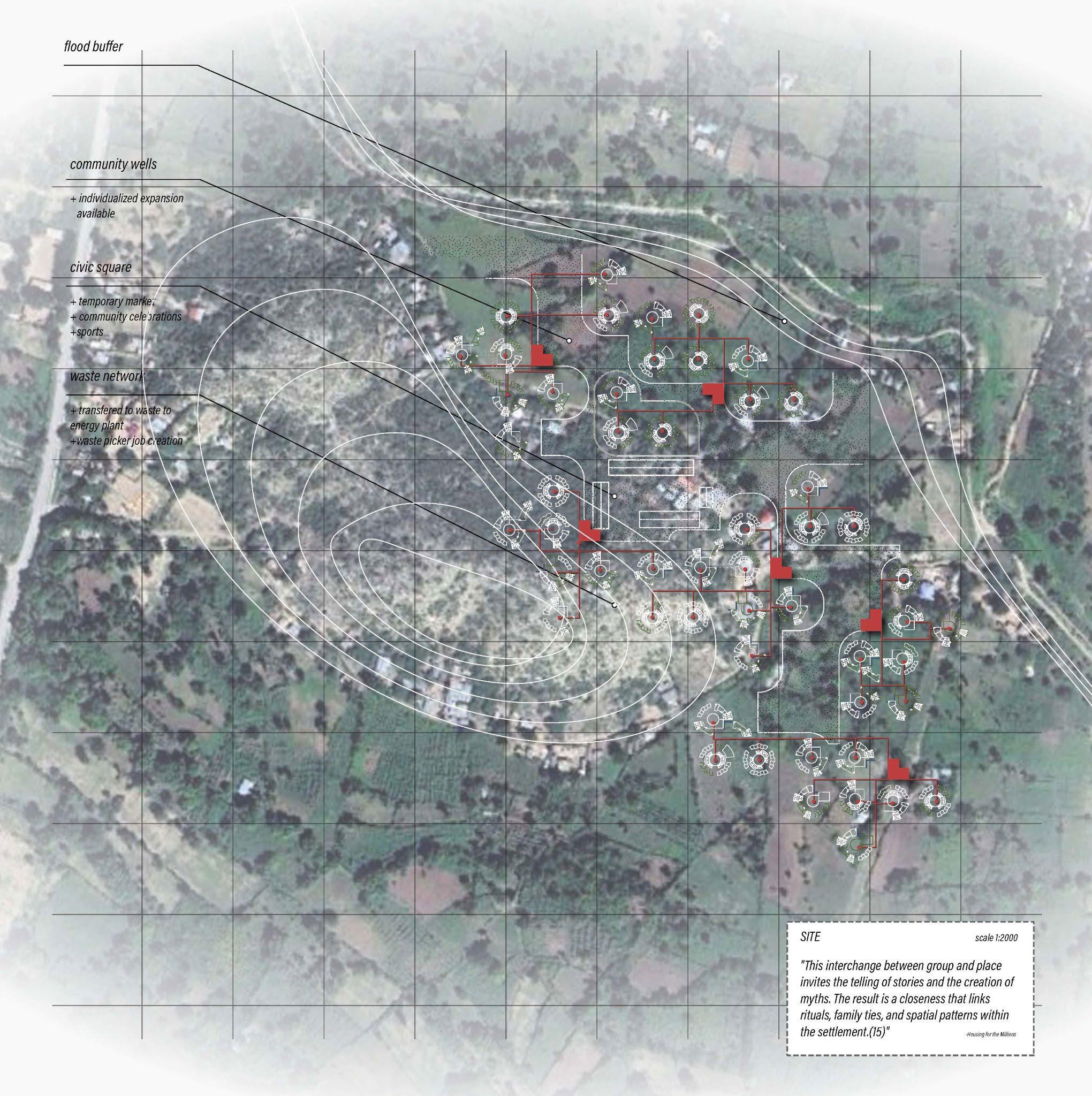

San Salvador, El Salvador - Angel Escobar-Rodas

Valle de Chalco - Adrea Piazza

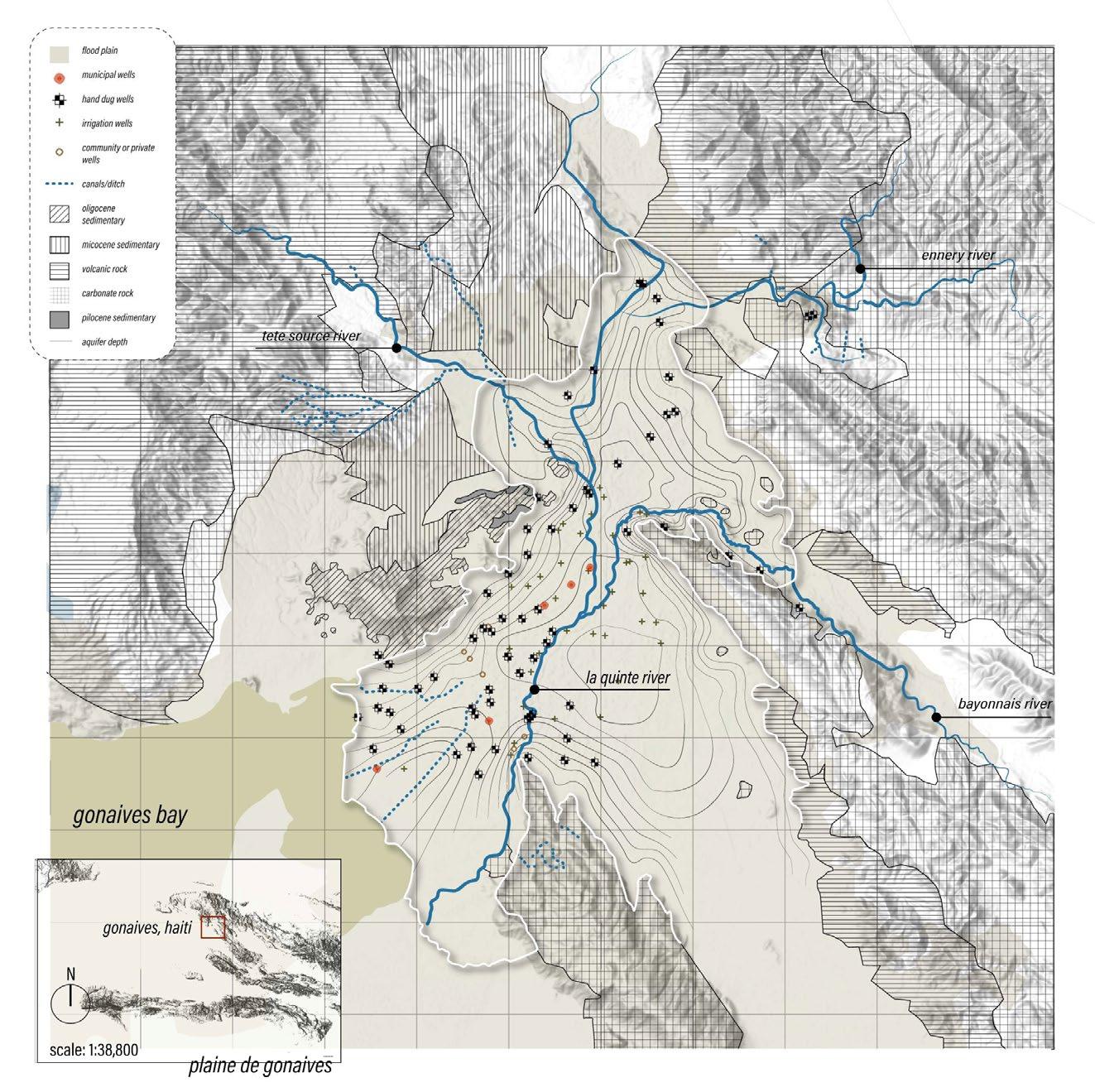

Gonaives, Haiti - Sarahdjane Mortimer

Valparaiso, Chile - Ali Sherif

Lima, Peru - Cathy Wu

San Salvador, El Salvador - Angel Escobar-Rodas

Valle de Chalco - Adrea Piazza

Gonaives, Haiti - Sarahdjane Mortimer

Valparaiso, Chile - Ali Sherif

Lima, Peru - Cathy Wu

Countries, Population Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster Major Historical Event

New Zealand, 5,000,000 Tauranga, New Zealand; Vanatu, Port Vila; Tonga, Nuku’alofa 2021 magnitude 8.1 Kermadec Island Earthquakes 1931 7.8 Hawke’s Bay earthquake New Zealand with 597 aftershocks

Countries, Population Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster Major Historical Event

Countries, Population Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster Major Historical Event

Countries, Population Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster Major Historical Event

Solomon Islands, 686,878; Papua New Guinea, 8,900,000 Port Mores by, PNG; Lae, PNG 2018 7.5 magnitude earthquake Papua New Guinea affecting 544,000 1998 7.0 magnitude earthquake, landslide and tsunami with 2,205 deaths

Countries, Population Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster Major Historical Event

Indonesia, 273,500,000 Jakarta, Surabaya 2019 6.9 Sunda Strait Earthquake Java 2009 7.9 Sumatra Earthquake Sumatra and tsunami with 1,115 dead and 2,180 injured

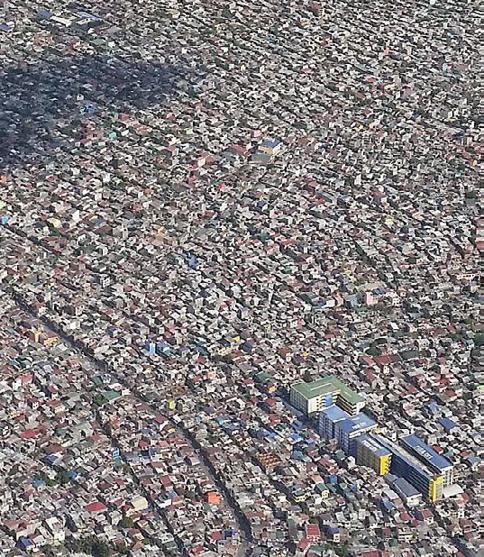

Philippines, Indonesia, totaling 115,637,249 Quezon City, Philippines; Manila, Philippines 2022 7.0 magnitude Luzon Earthquake and landslide 1976 8.0 magnitude Mindanao Earthquake Tsunami with up to 8,000 deaths

Guam (U.S. Territory), 170,180; Northern Mariana Islands, 58,310 Saipan, Saipan; San Jose, Tinian 2018 Super Typhoon Yutu affecting 135 1981 Mount Pagan Volcano Eruption

Countries, Population Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster Major Historical Event

Japan, 125,800,000 Sendai, Fukushima, Tokyo, Chiba 2021 7.1 Fukushima earthquake Tohoku, Japan 2011 9.1 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami with 15,899 deaths

Countries, Population Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster Major Historical Event

Countries, Population

Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster

Major Historical Event

Countries, Population Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster Major Historical Event

Kamchatka Peninsula, 322,079; Kuril Islands, 20,000

Sapporo, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky

2020 7.5 Earthquake in Kamchatka, Russia 1994 Shikotan Tsunami in South Kuril Islands/Northern Japan Hokkaido with 8 deaths

United States, Russia, totaling 8,162

Unalaska

2022 6.8 Earthquake Aleutian Islands

1946 8.1 underwater earthquakes and tsunami with 161 deaths

Micronesia, 115,021; Kiribati, 119,446; Samoa, 198,410 Port Vila, Vanuatu; Apia, Samoa

2018 Cyclone, flooding and landfall 2009 Tonga Eruption Tsunami with 189 deaths

Countries, Population Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster Major Historical Event

Cuba, 11,311,257; Hait,i 11,711,904; Dominican Republic, 10,694,700; Puerto Rico 3,252,407; Virgin Islands 106, 290 Havana, Cuba; Port-au-Prince, Haiti

2020 Puerto Rico Earthquake Sequence 2016 Hurricane Mathew in Haiti with 1,400,000 deaths

Countries, Population

Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster

Major Historical Event

Countries, Population

Major Cities

Recent Major Disaster Major Historical Event

Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica Mexico City, Mexico; Guadalajara, Mexico

2022 6.8 magnitude Earthquake in Mexico City 1985 8.0 magnitude Michoacán earthquake in Mexico City with 10,000 deaths and 250,000 without shelter

Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia Ecuador, Peru totaling 33,030,381 Santiago, Chile; Cali, Colombia; La Paz, Bolivia; Lima, Peru

2015 Illapel 8.4 magnitude Earthquake Caused Tsunamiaffecting Chile and Argentina 1960 Valdivia 9.5 magnitude Earthquake Tsunami with 1,600 deaths

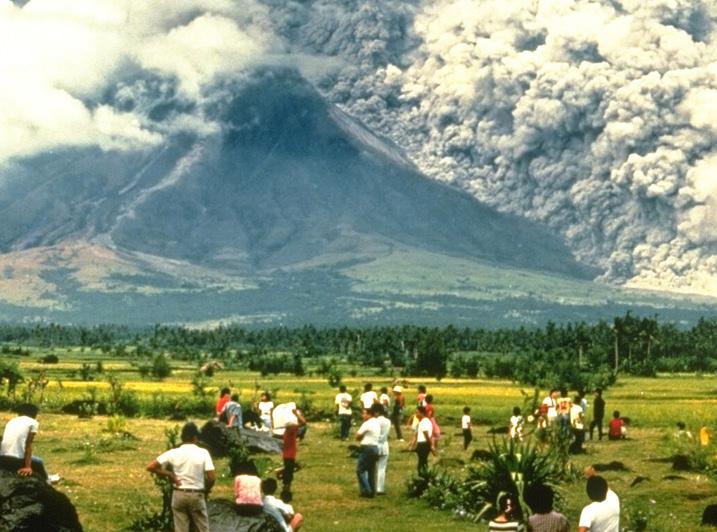

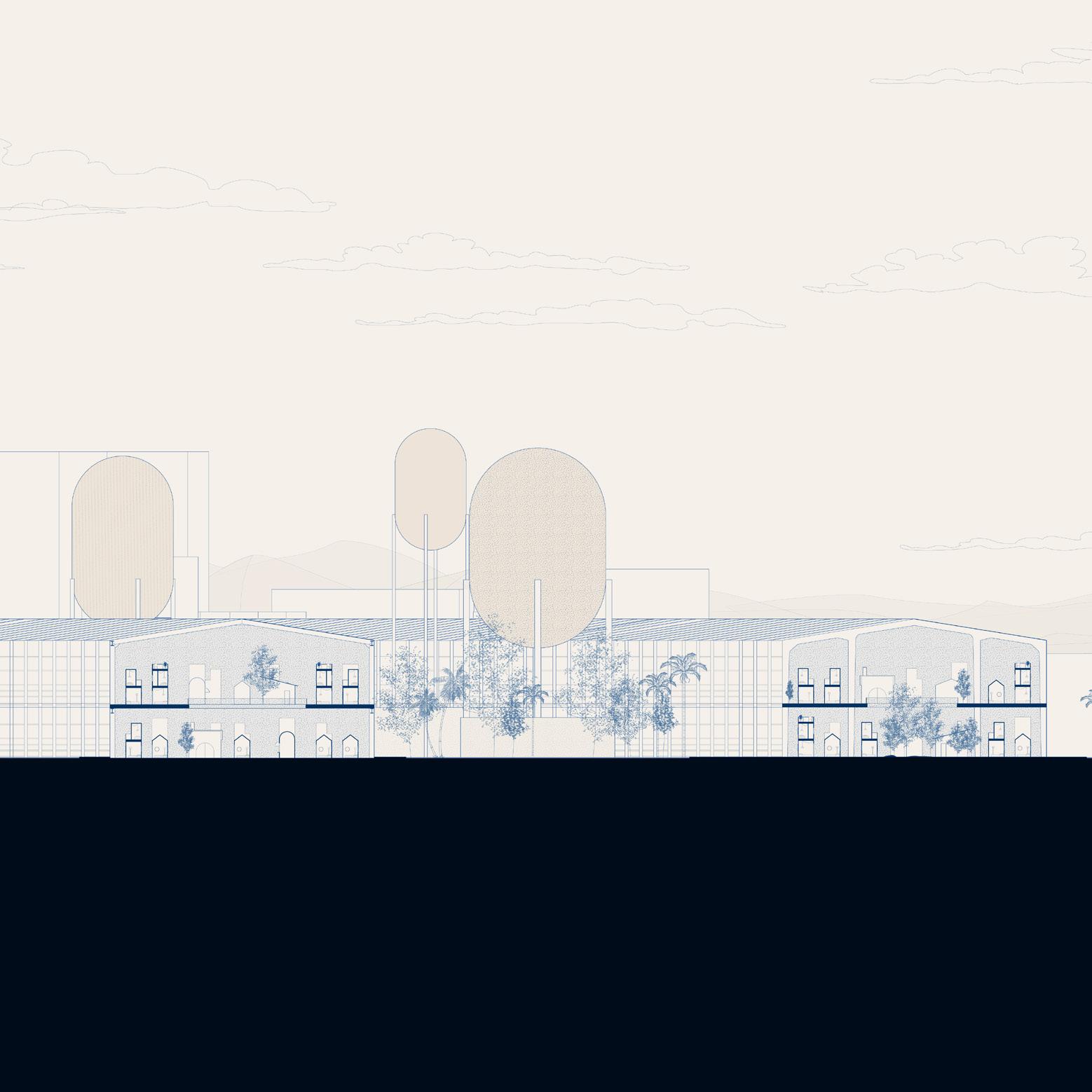

Each project settles in a specific Pacific Ring of Fire location, wherein concentrates 75% of the world´s volcanoes, 80% of the world’s tsunamis, and 90% of the world’s earthquakes: highlighting areas of inhabitation deemed most vulnerable to the extremities of disaster. Students study matters regarding locality, history, preservation, growth, and density to create proposals that respond in time to these critical contingencies.

Manila,

Volcano Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Volcano Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Volcano Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

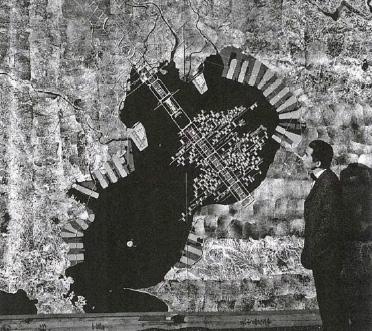

Quezon City, Manila, Philippines - Tree Chen

Legazpi City, Albay, Philippines - Emily Hu

Manila, Philippines - Tree Chen

Legazpi, Philippines - Emily Hu

Quezon City, Manila, Philippines - Tree Chen

Legazpi City, Albay, Philippines - Emily Hu

Manila, Philippines - Tree Chen

Legazpi, Philippines - Emily Hu

Volcano

Volcano

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Volcano Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Volcano Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Volcano Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Volcano Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

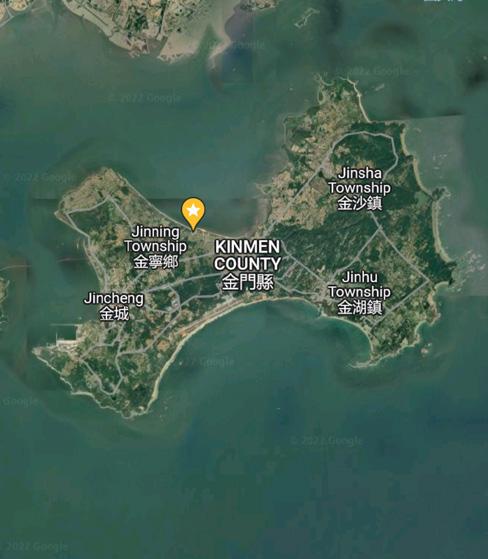

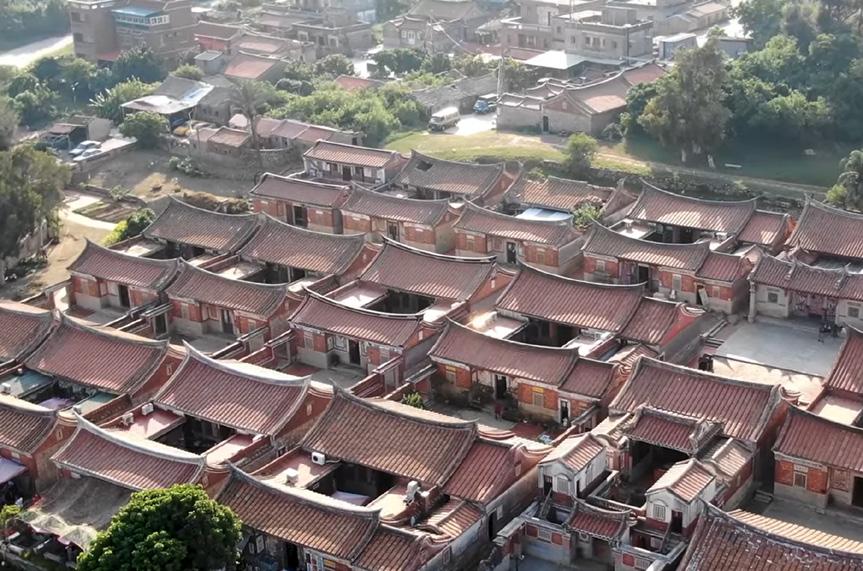

Kinmen, Taiwan - Emily Hsee

Tainan, Taiwan - Jennifer Li

Yilan, Taiwan - Xi Chen Yilan, Taiwan - Xi Chen Kinmen, Taiwan - Emily Hsee

Tainan, Taiwan - Jennifer Li

Kinmen, Taiwan - Emily Hsee

Tainan, Taiwan - Jennifer Li

Yilan, Taiwan - Xi Chen Yilan, Taiwan - Xi Chen Kinmen, Taiwan - Emily Hsee

Tainan, Taiwan - Jennifer Li

Volcano

Volcano

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Katoku, Amami Oshima, Japan - Nana Komoriya Kotaku, Japan - Nana Komoriya

Katoku, Amami Oshima, Japan - Nana Komoriya Kotaku, Japan - Nana Komoriya

Volcano

Volcano

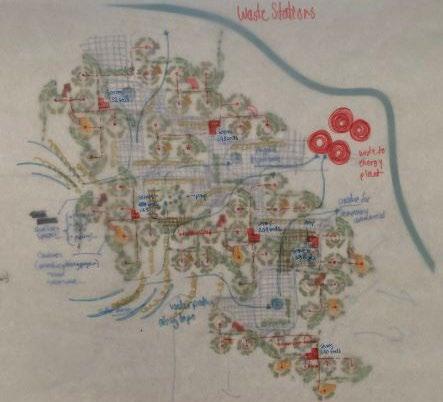

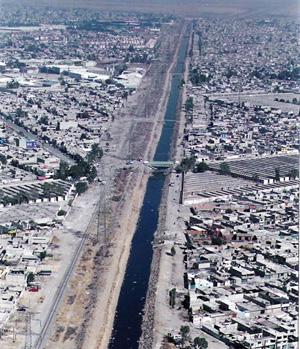

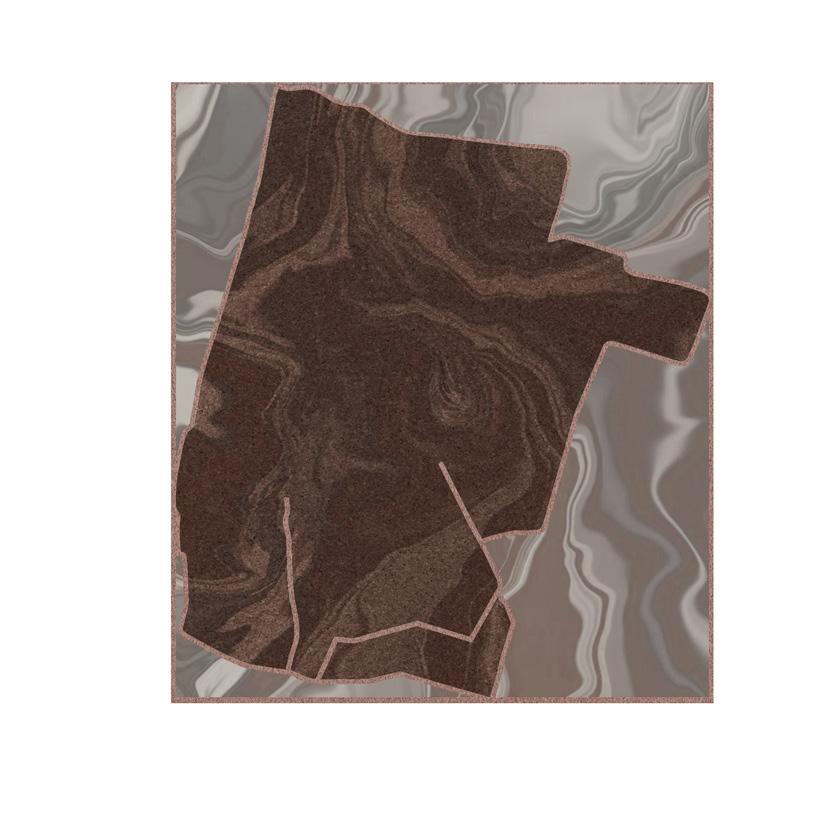

Valle de Chalco, Mexico - Adrea Piazza Valle de Chalco - Adrea Piazza

Valle de Chalco, Mexico - Adrea Piazza Valle de Chalco - Adrea Piazza

Volcano

Volcano

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

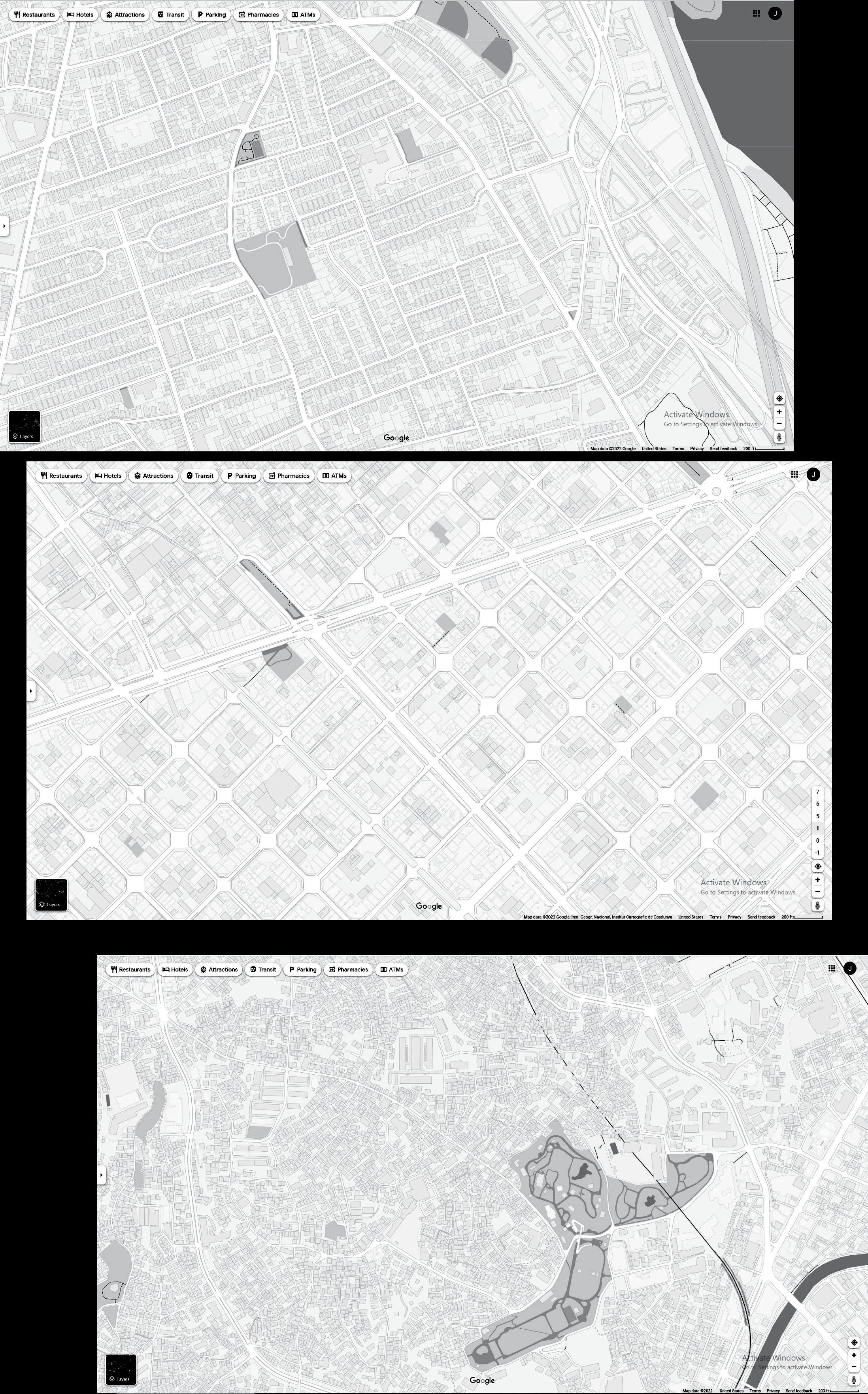

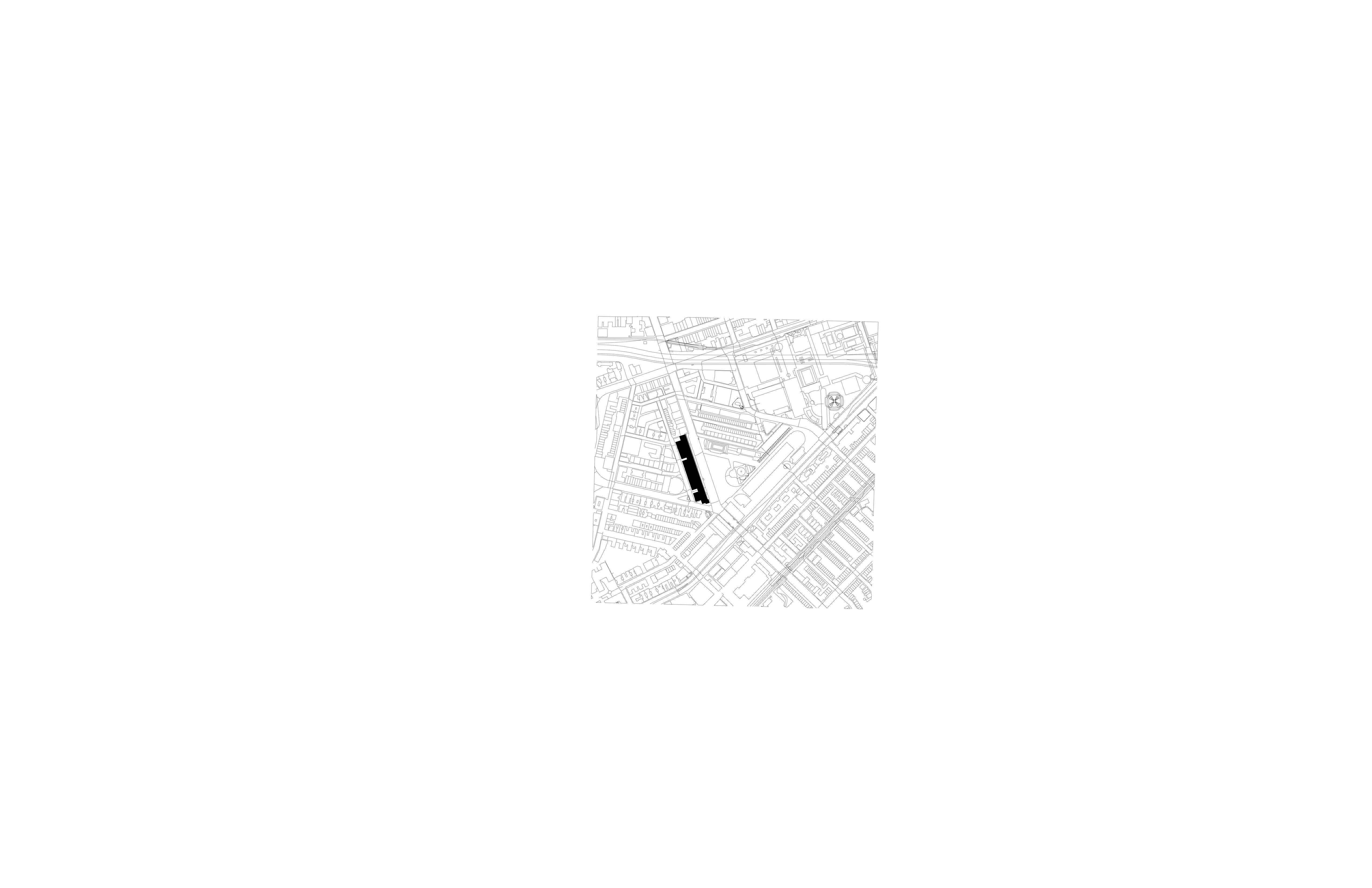

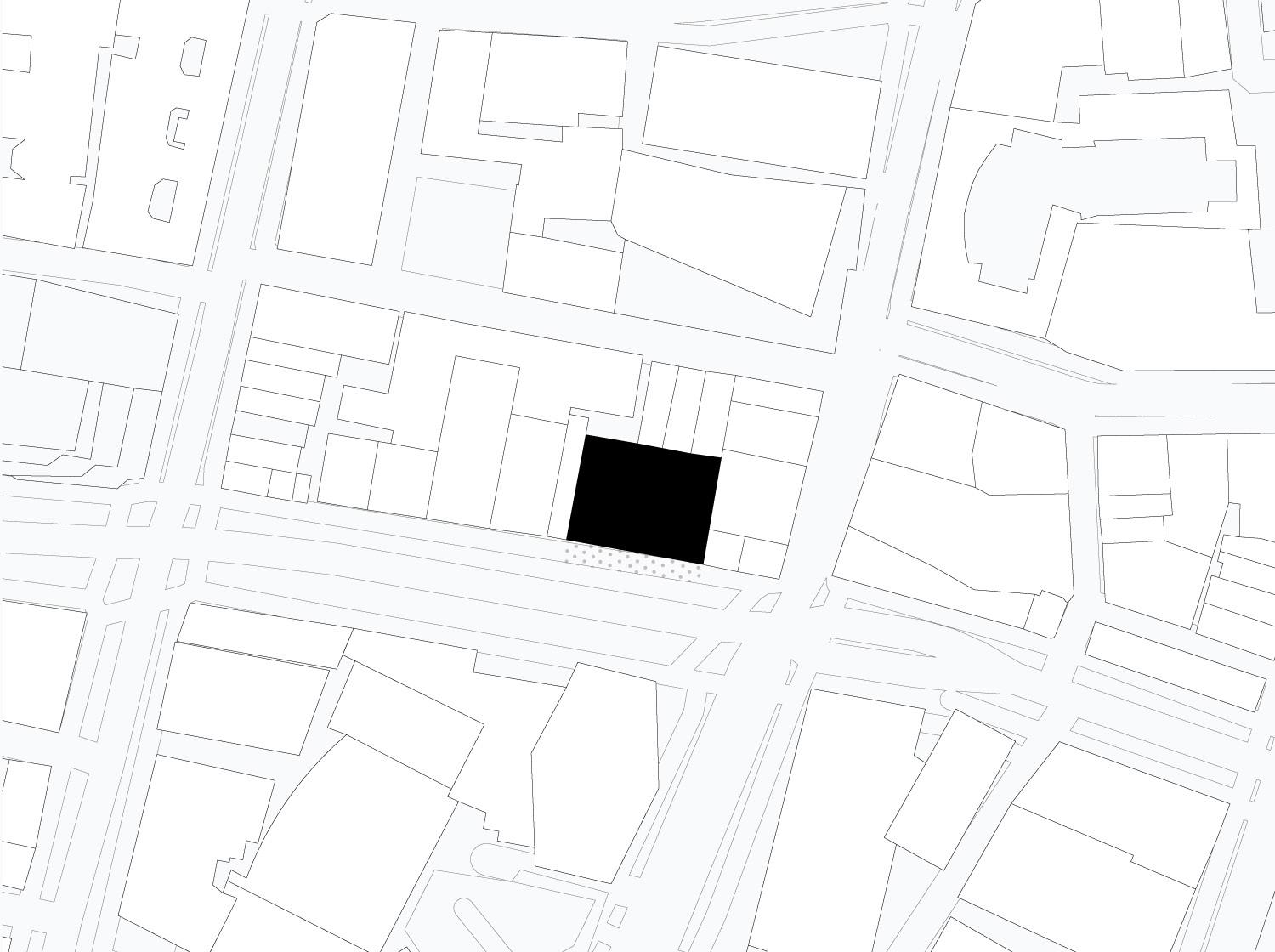

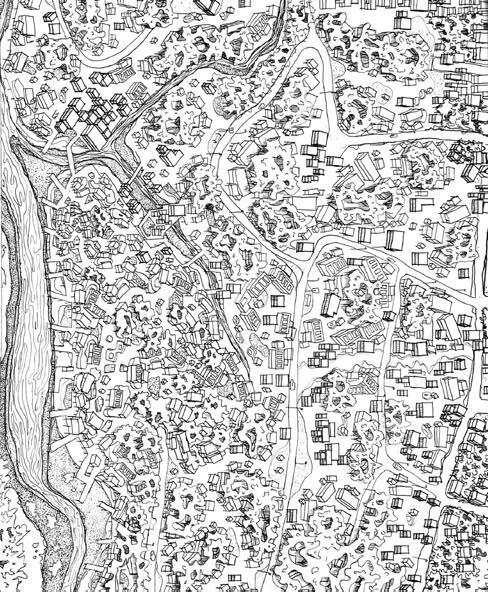

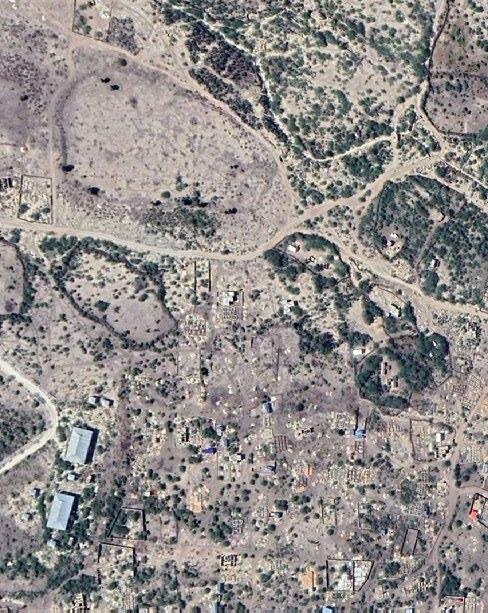

San, Salvador, El Salvador - Angel Escobar-Rodas San Salvador, El Salvador - Angel Escobar-Rodas

San, Salvador, El Salvador - Angel Escobar-Rodas San Salvador, El Salvador - Angel Escobar-Rodas

Volcano

Volcano

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Volcano

Volcano

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Lima, Peru - Cathy Wu Lima, Peru - Cathy Wu

Lima, Peru - Cathy Wu Lima, Peru - Cathy Wu

Volcano

Volcano

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

Fire Tsunami Sea Level Rise Flooding Typhoon Earthquake Landslide

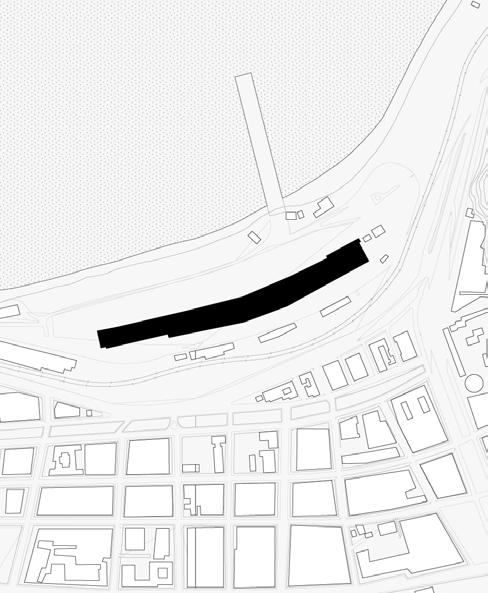

Valparaiso, Chile - Ali Sherif Valparaiso, Chile - Ali Sherif

Valparaiso, Chile - Ali Sherif Valparaiso, Chile - Ali Sherif

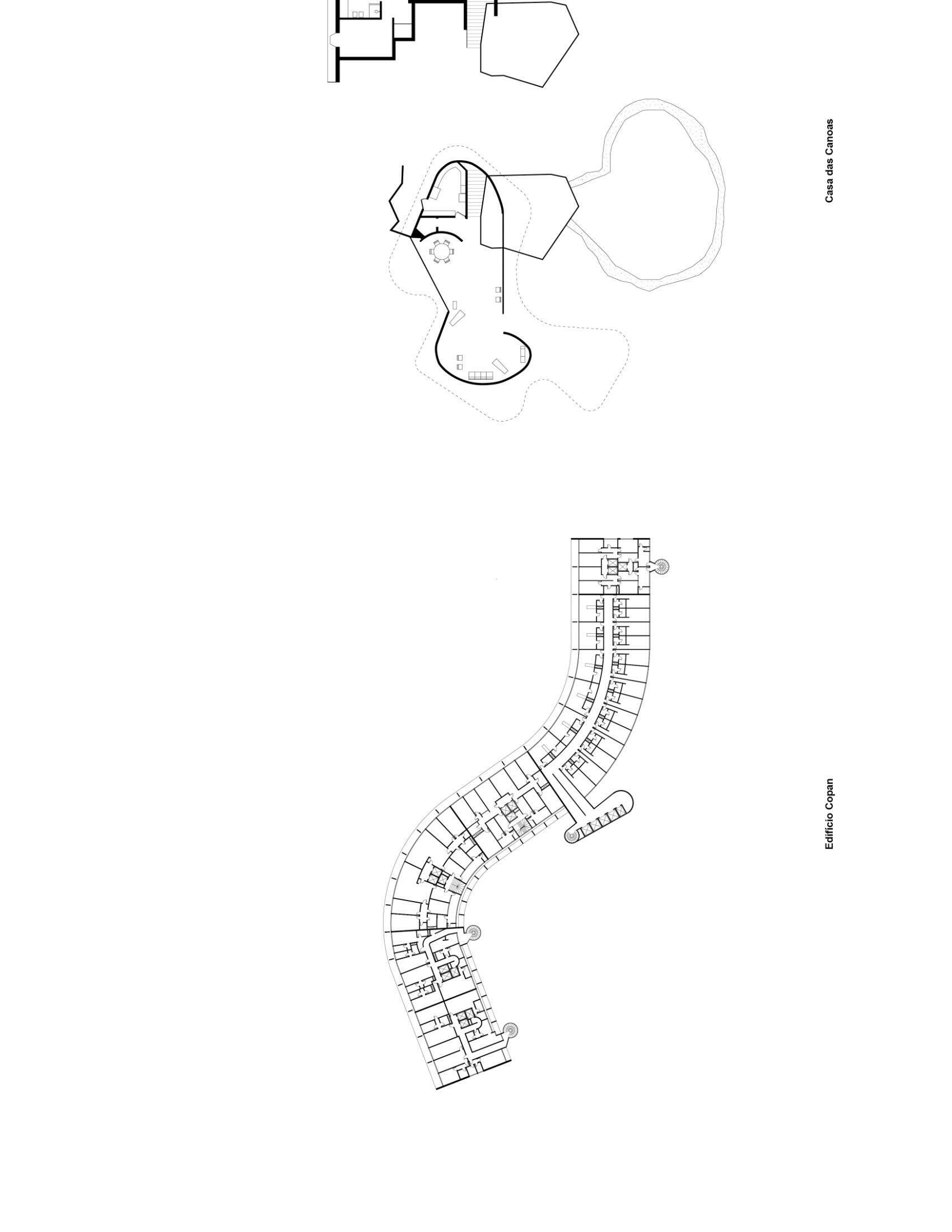

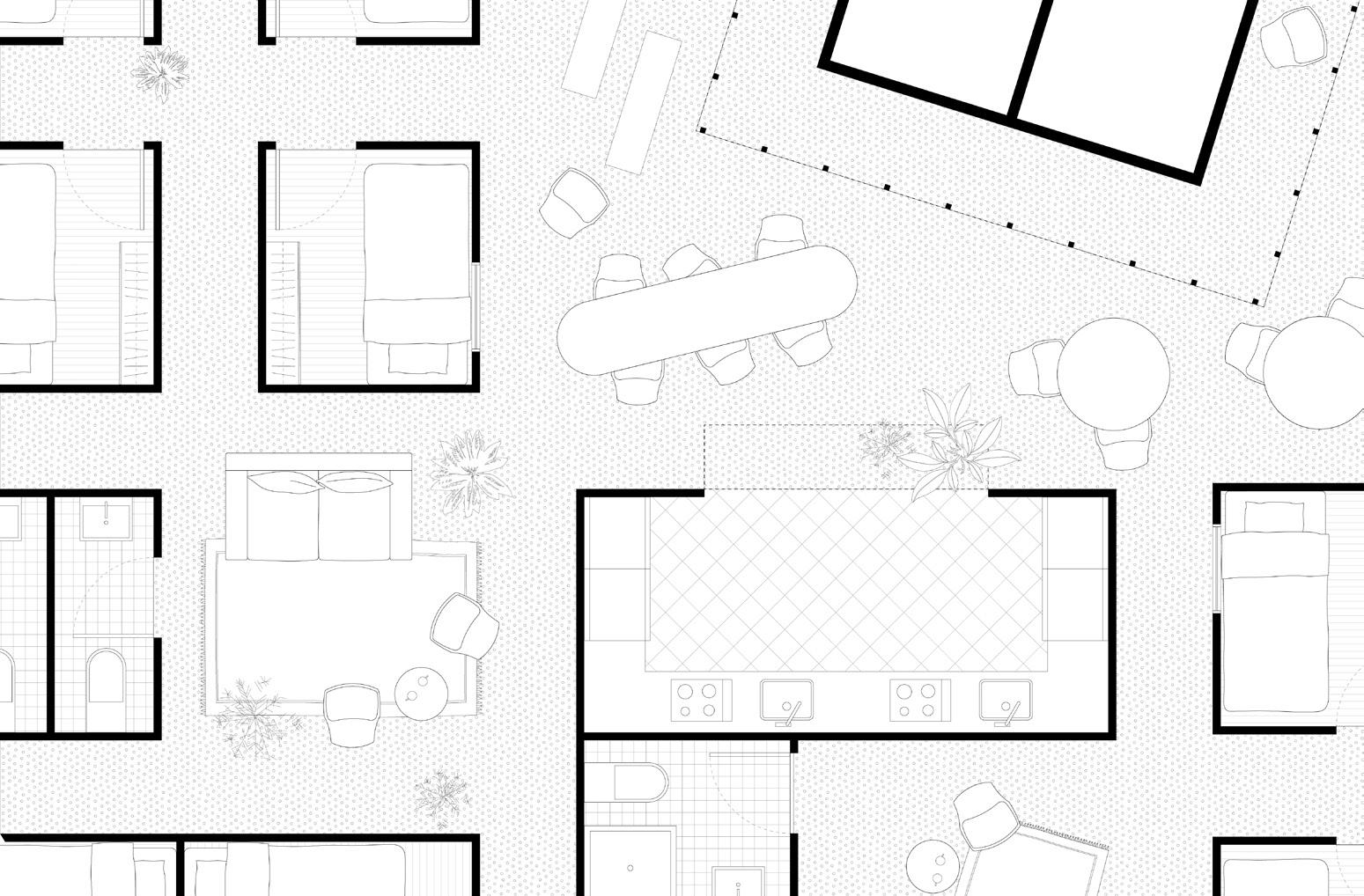

We investigated housing precedents around the world to piece together a shared under-standing of residential living. The following projects exist in different cities and contexts; they were built at different times and at different scales. Given their differences, they provide a wide array of identities, opportunities, and obstacles for us to learn from.

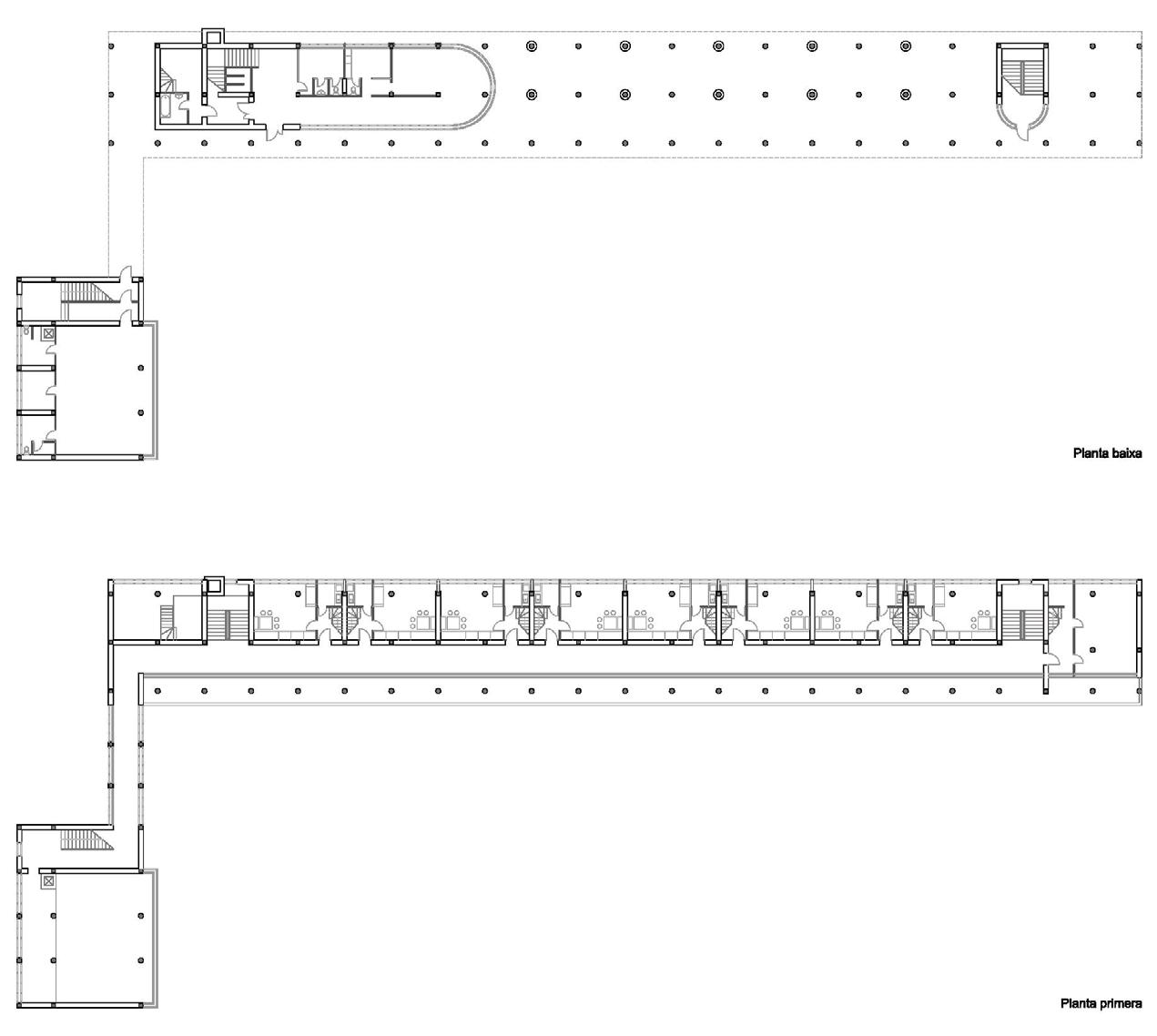

The Narkomfin Building serves as one of the first built precedents responding to the constructivist aim that embodied new socialist ideals. The main principal is the collectivization of all public areas corresponding to collective functions. The duplex flats are divided into two typologies, with first floor area to be open for all public access.

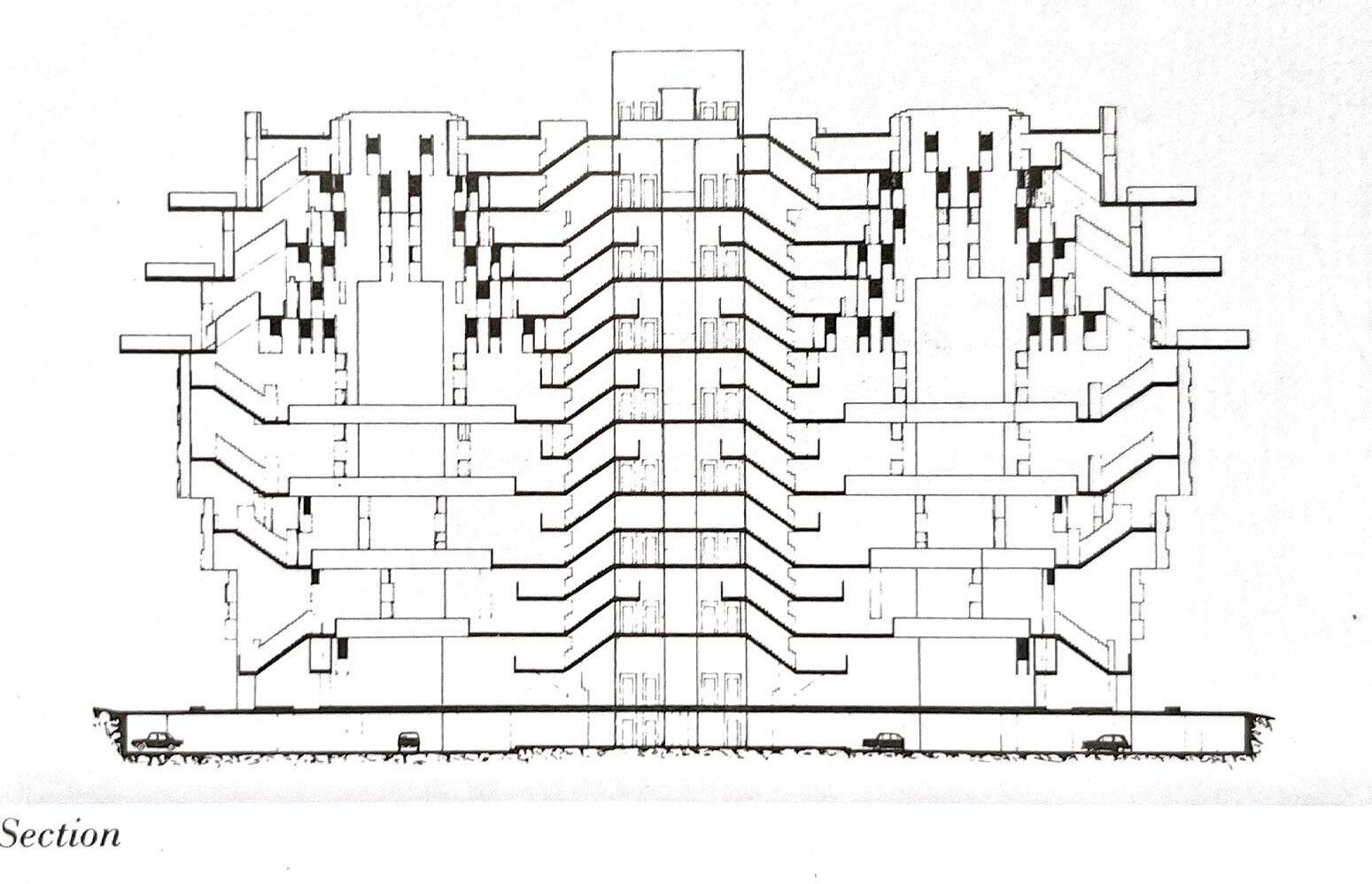

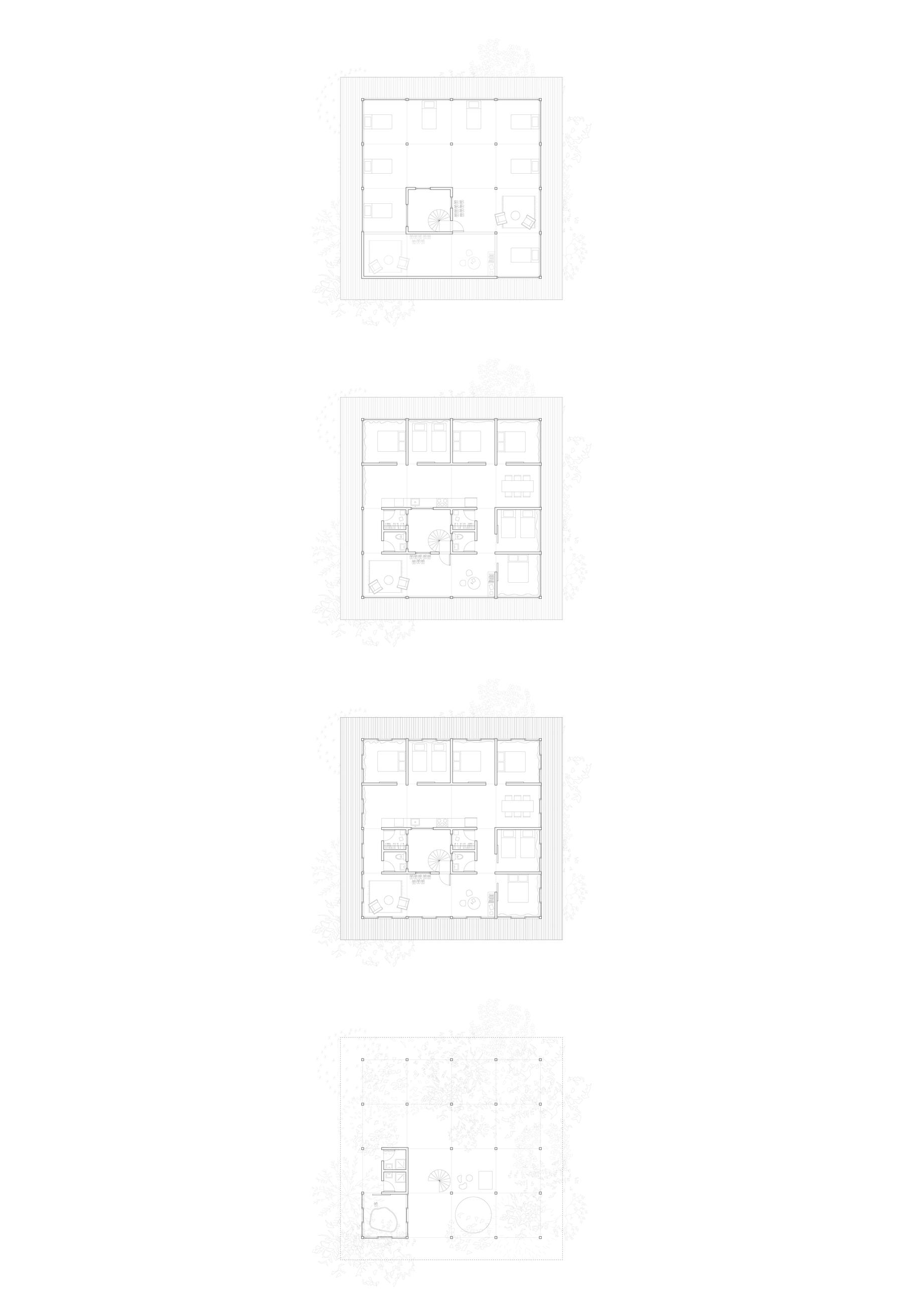

Top: Section 1:1250

Bottom: Plan 1:1000

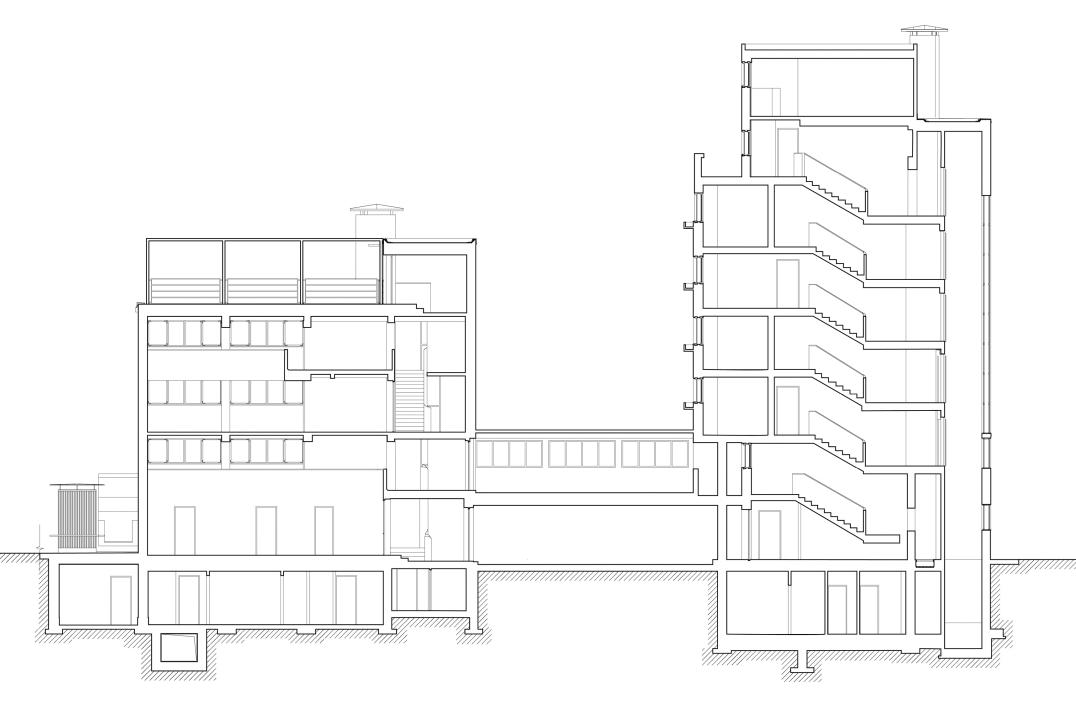

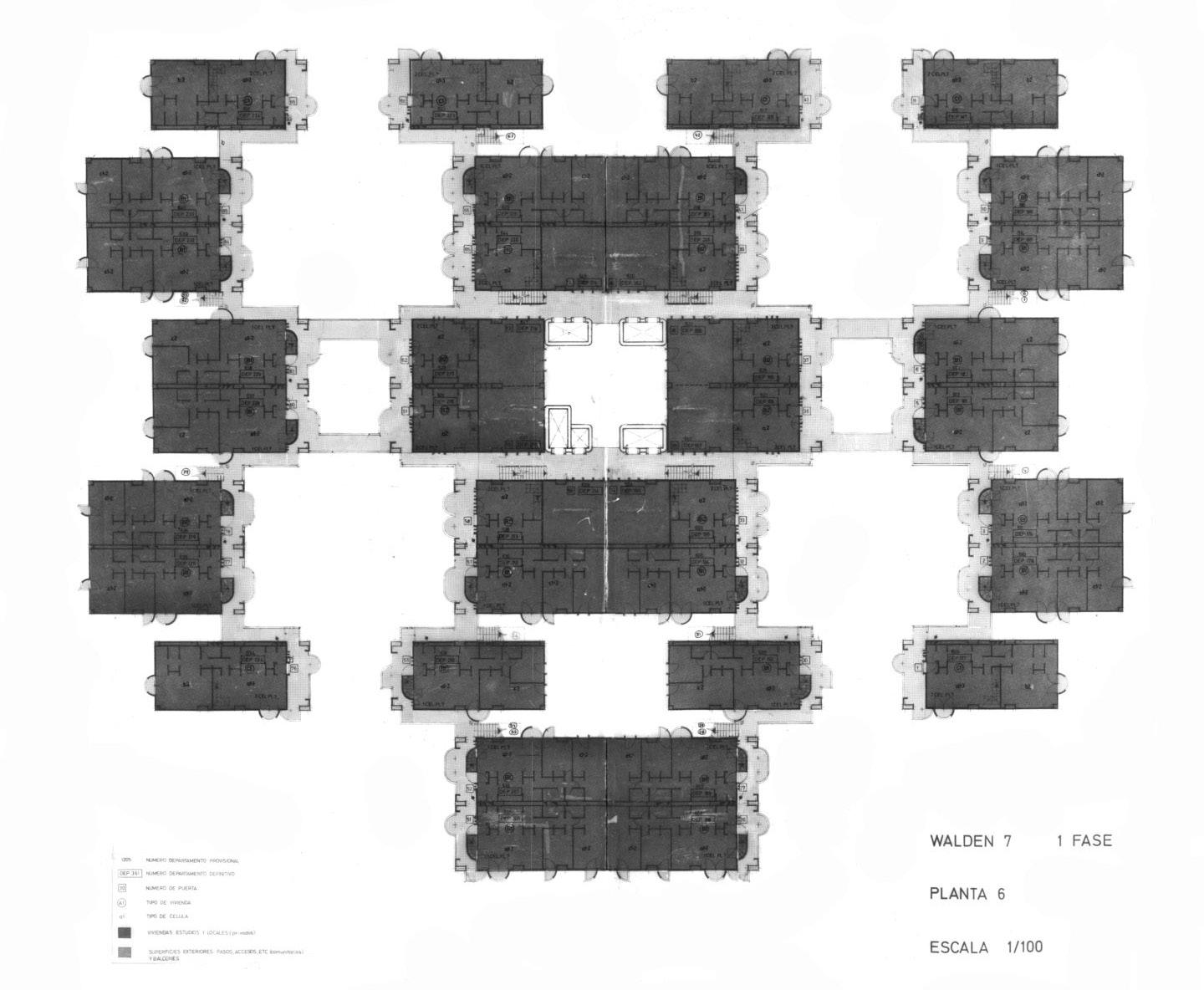

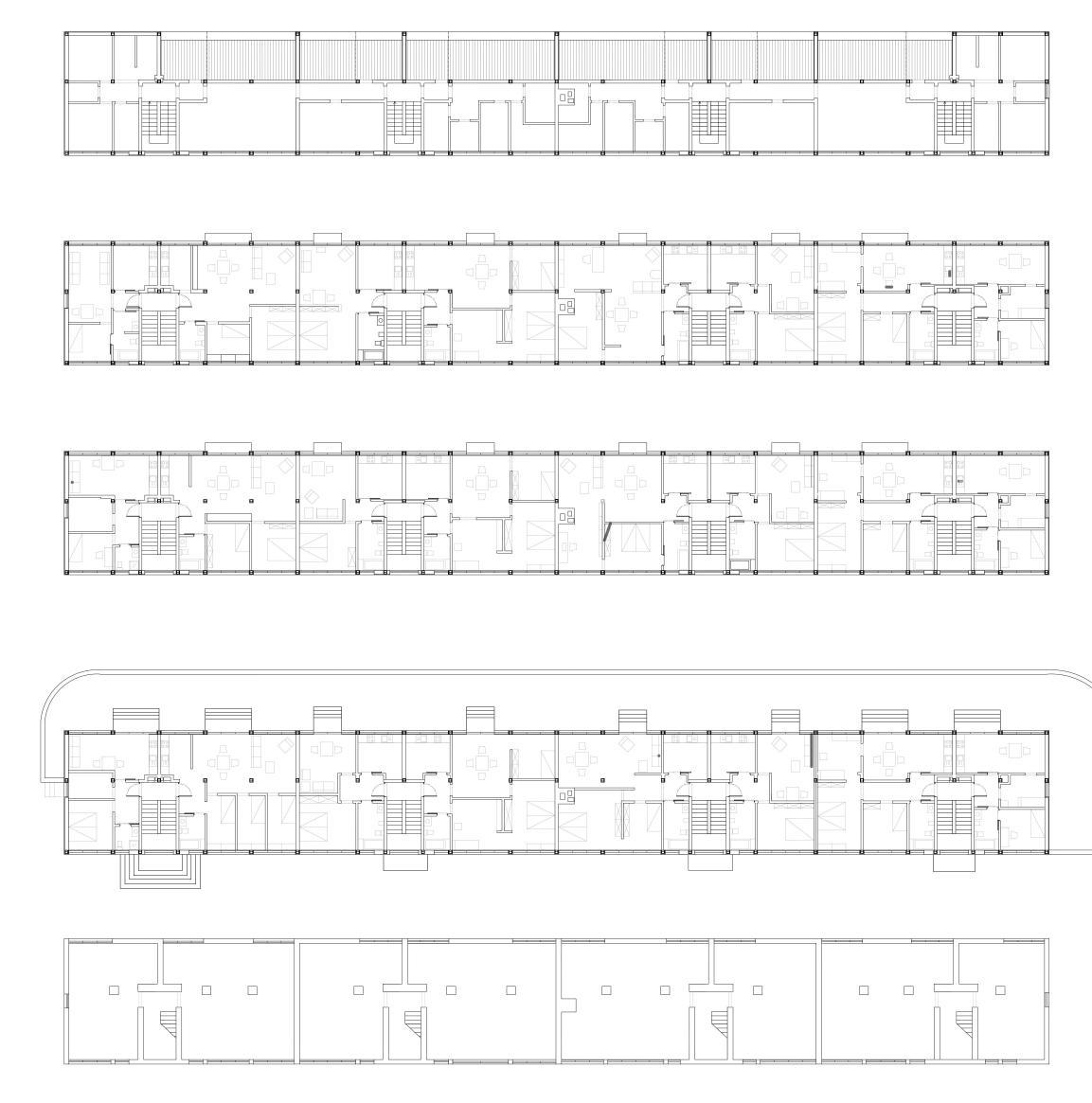

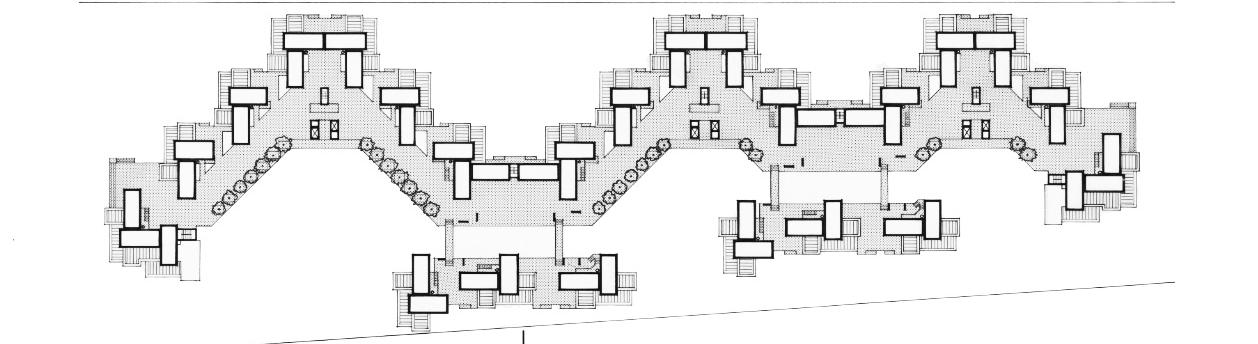

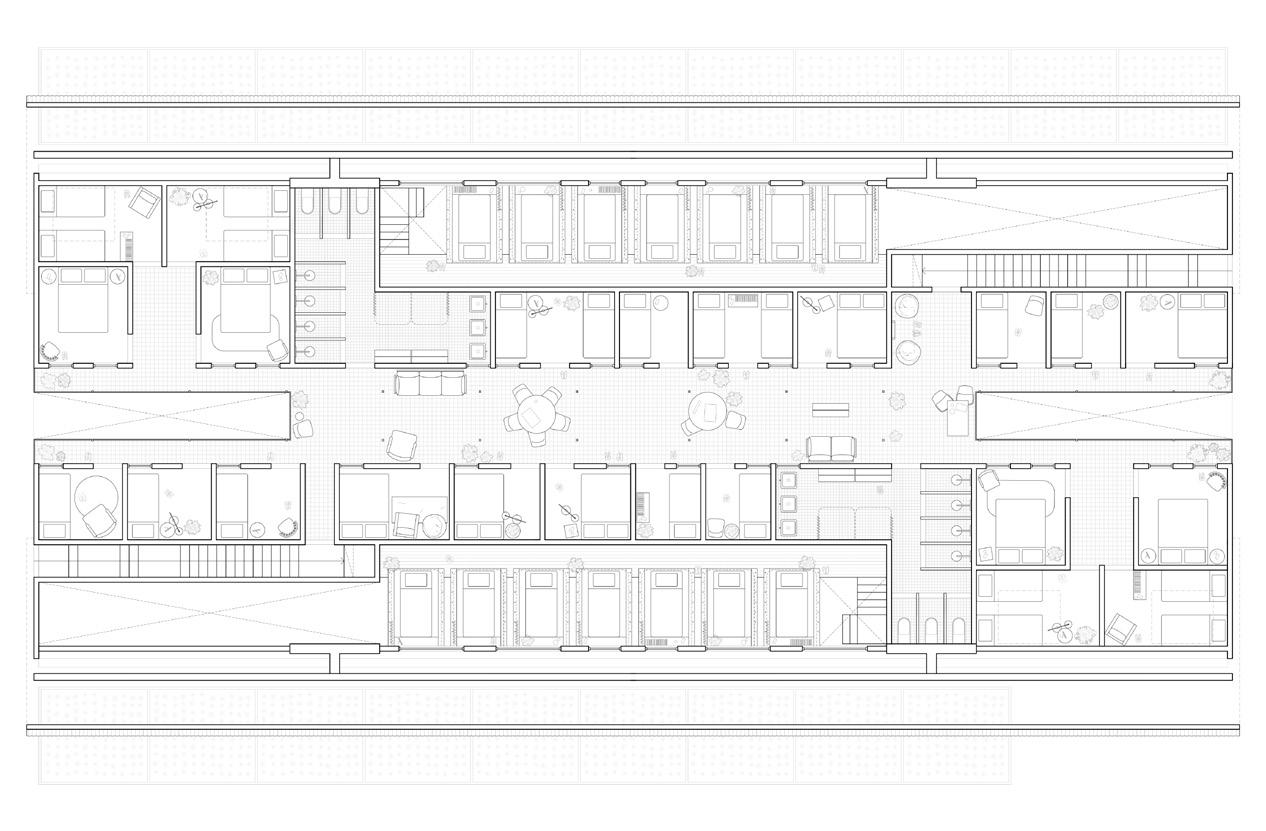

Walden 7 is a 14-story vertical labyrinth comprised of hundreds of 30 m2 square modules furnished to support an individual’s needs. Each apartment is made up of one or more modules, combined horizontally or vertically. Incremental shifts in the plan produce seven communal interior courtyards, connected by a system of bridges and walkways. This project challenges conventional notions of private life and standard apartment living.

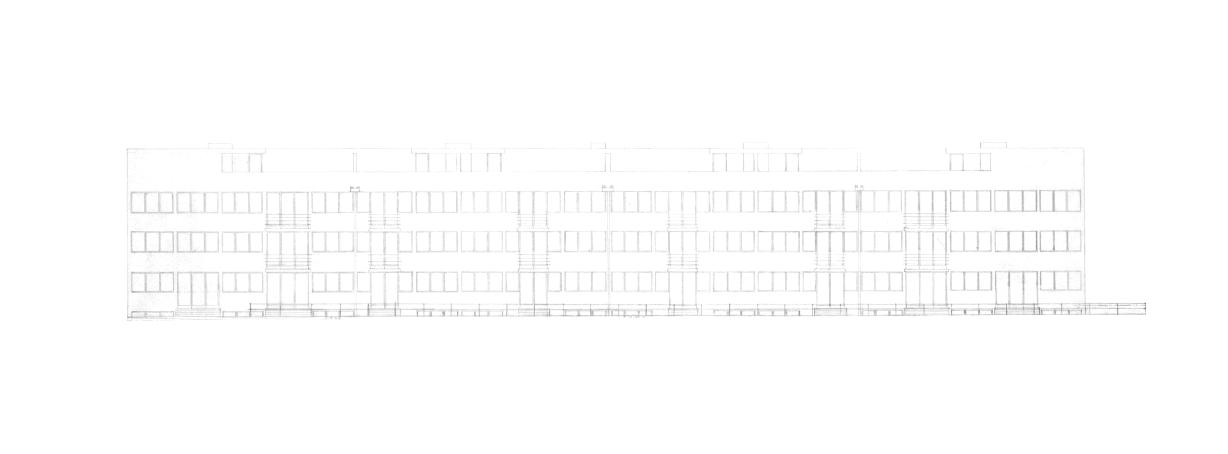

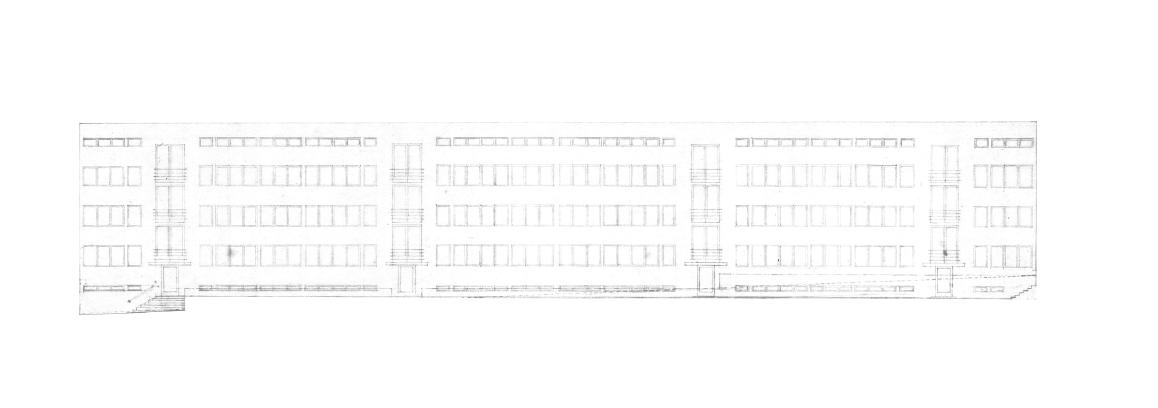

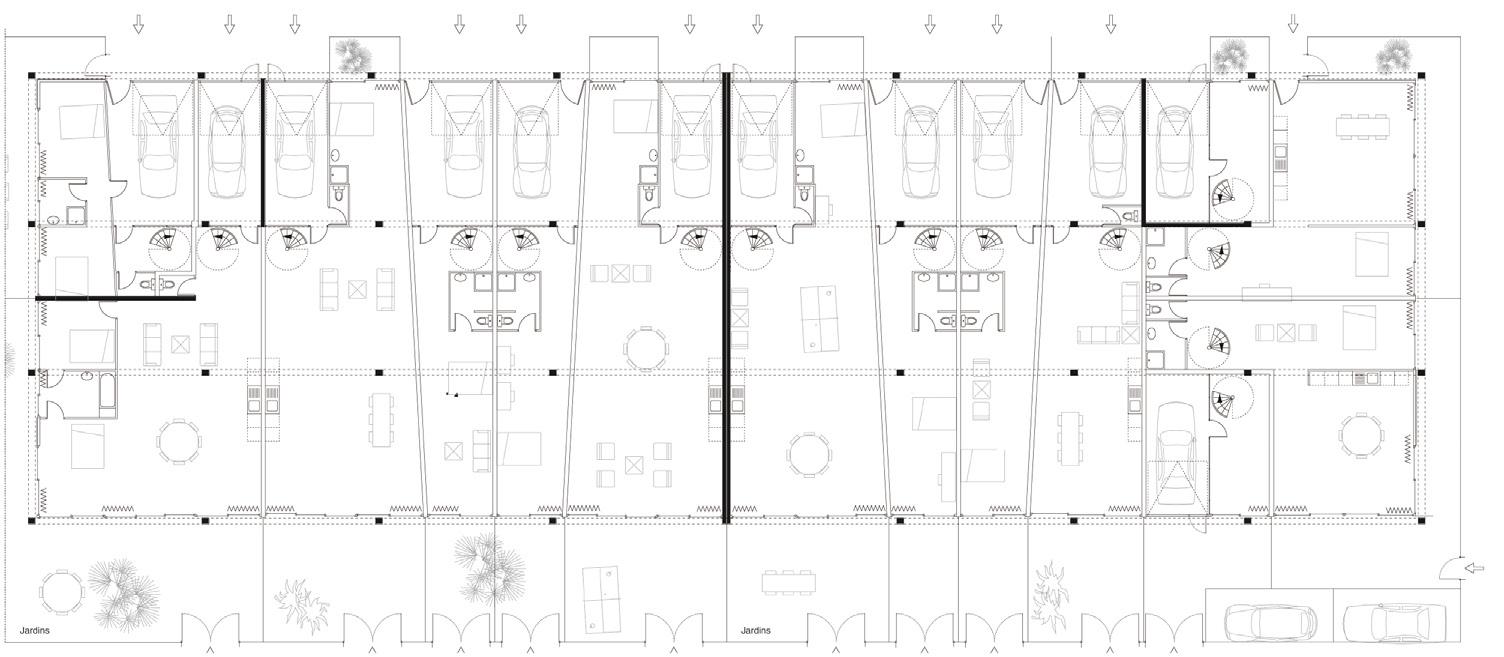

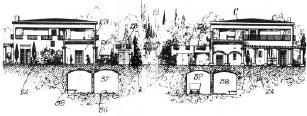

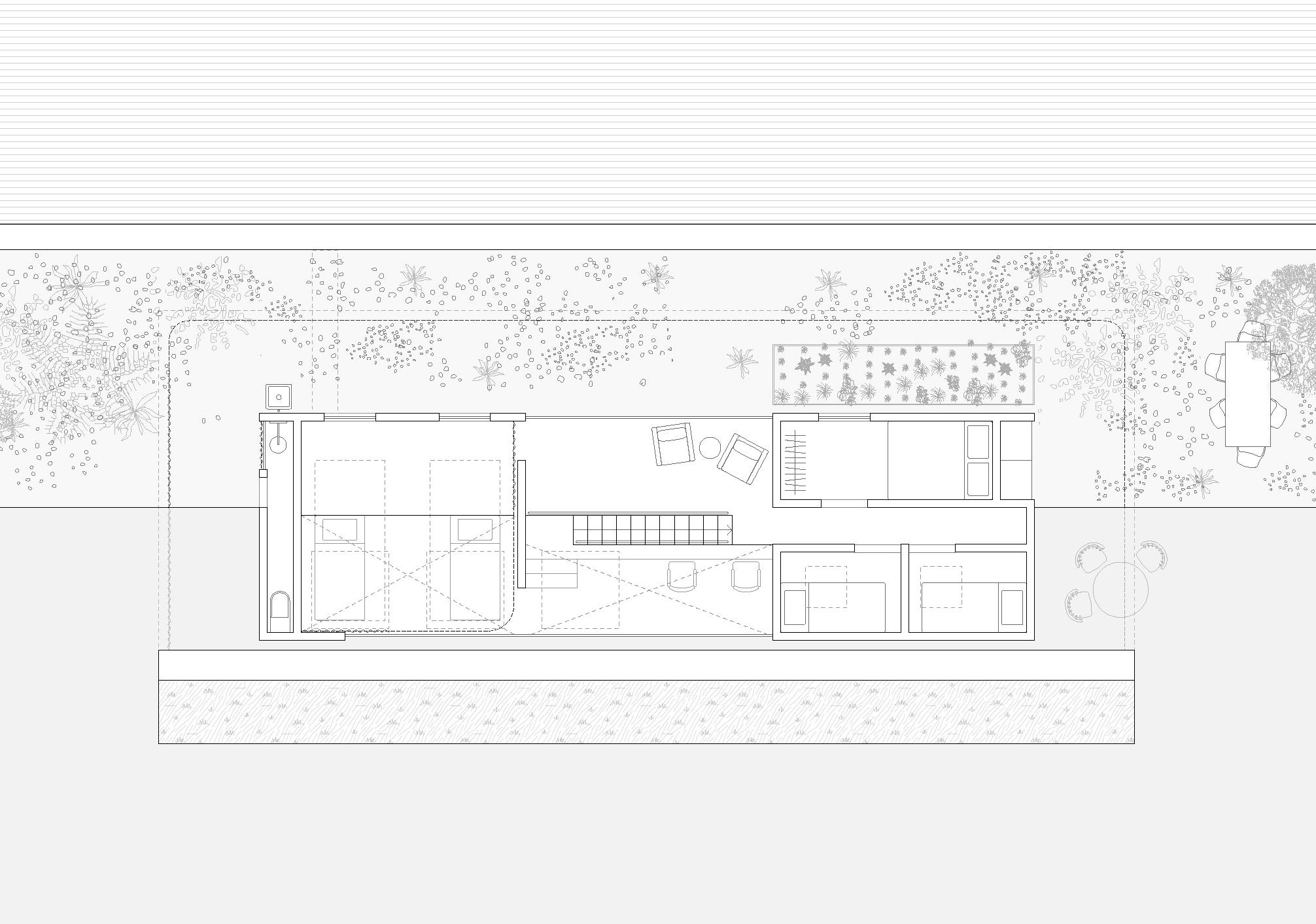

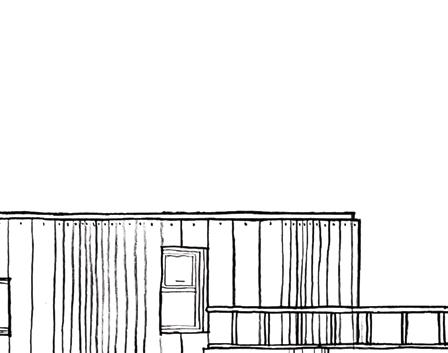

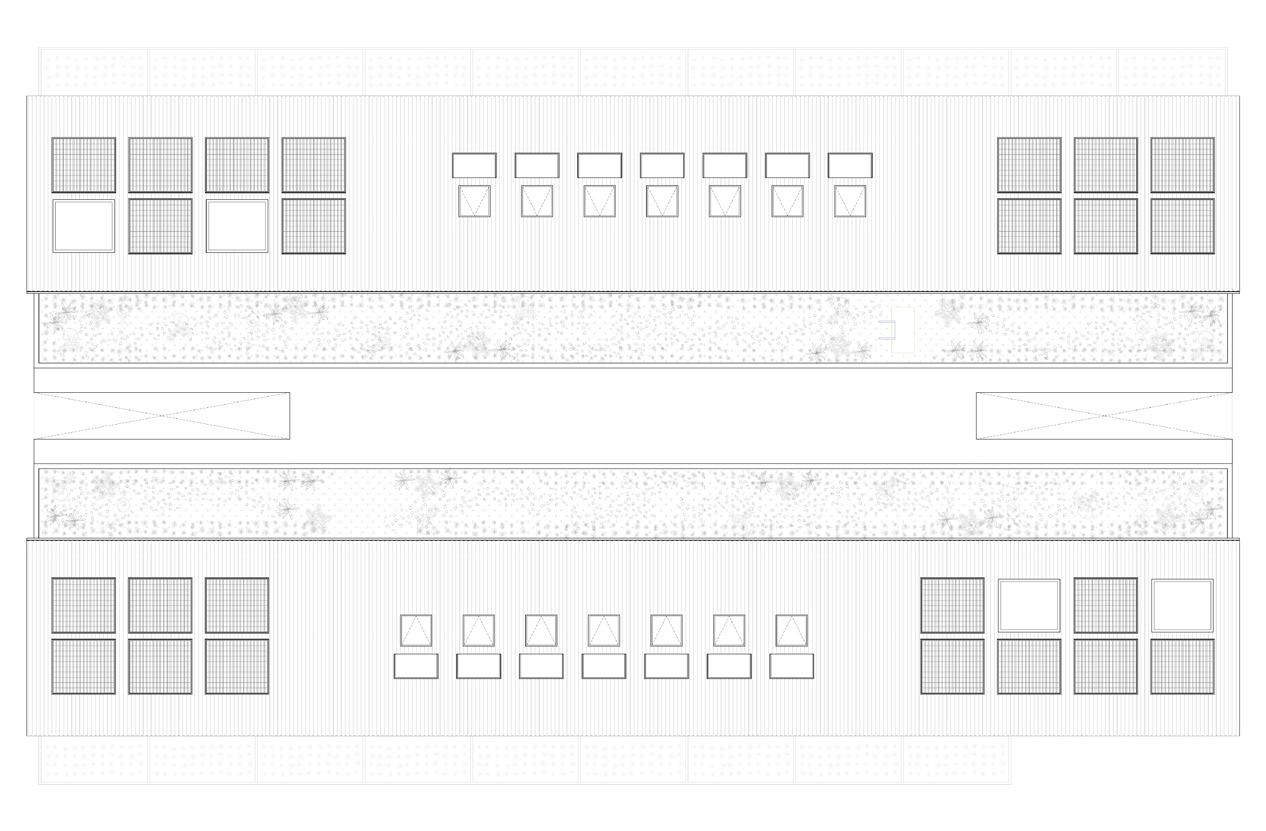

Mies designed houses 1-4 as a linear block of row houses on the Weissenhof Estate with rationalization, typification, and flexibility in mind. The exterior has a continuous and anonymous surface while the interior is designed with movable plywood partitions to allow for flexibility and customization. Mies references both the contemporary villa and early twentieth century mass housing in this project.

Top: Floor Plans (1:1000)

Bottom: East & West Elevation (1:1000)

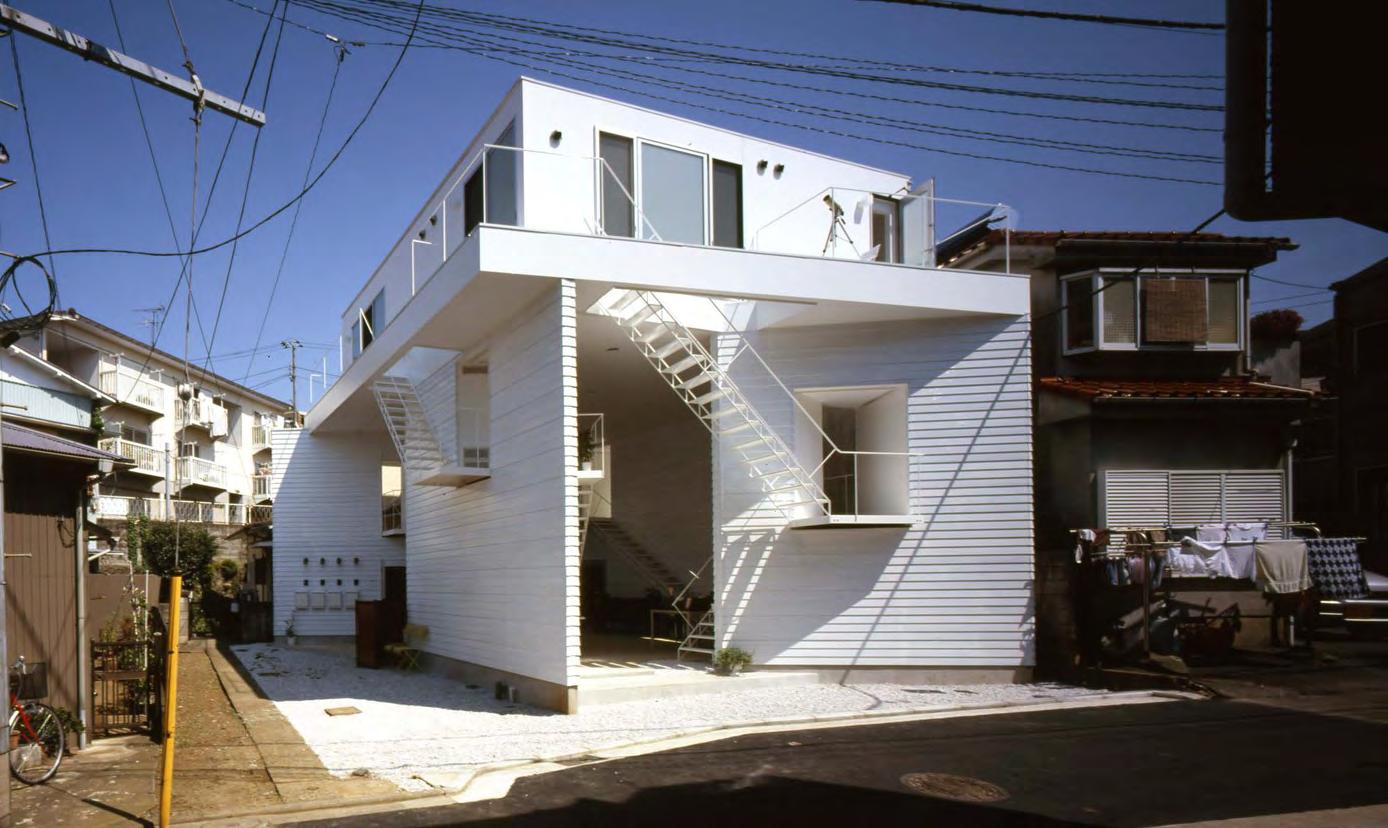

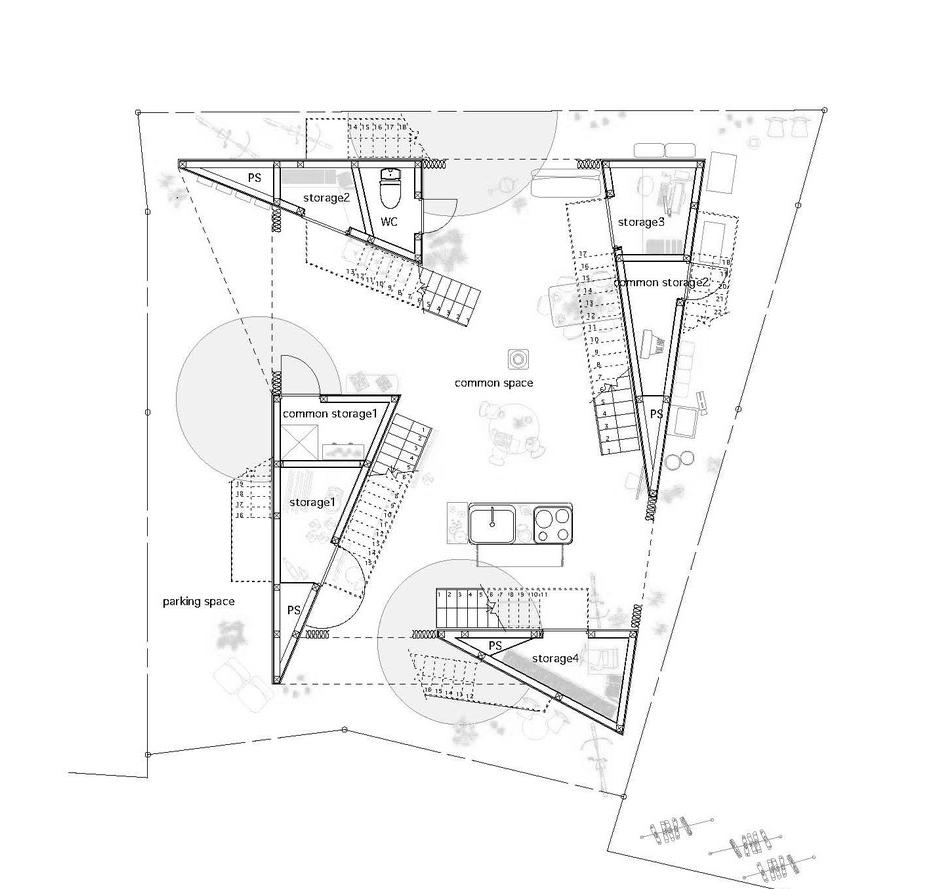

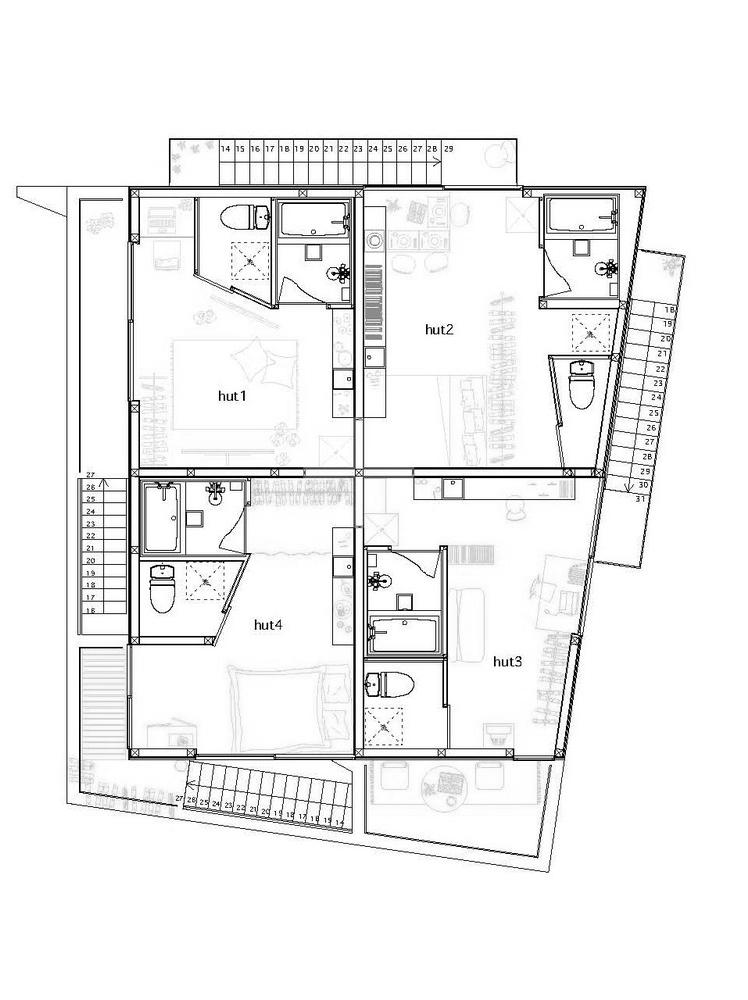

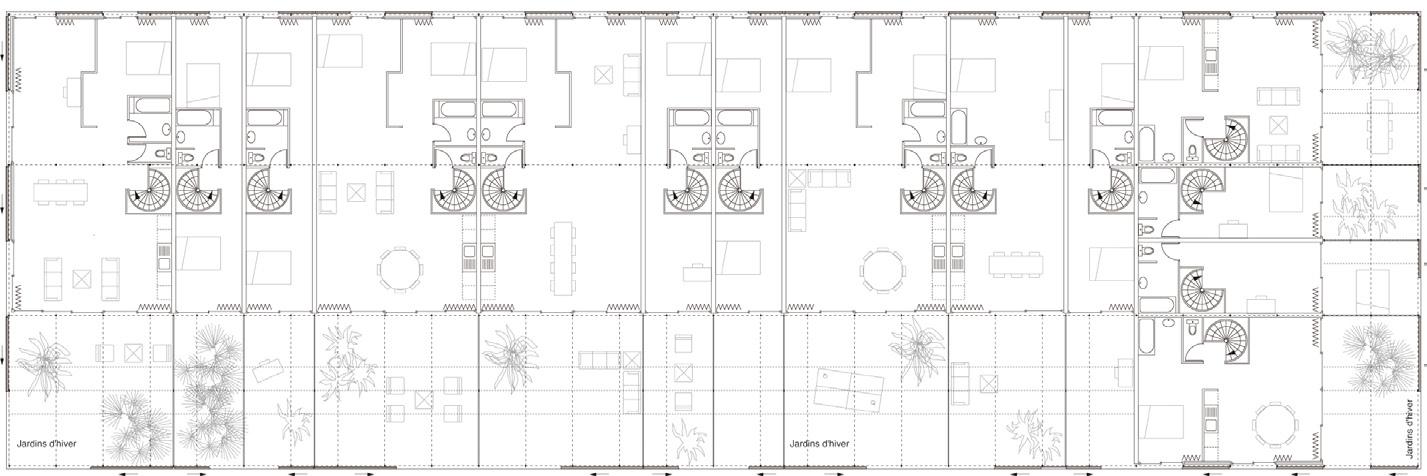

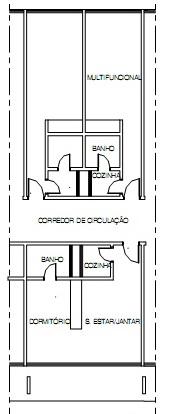

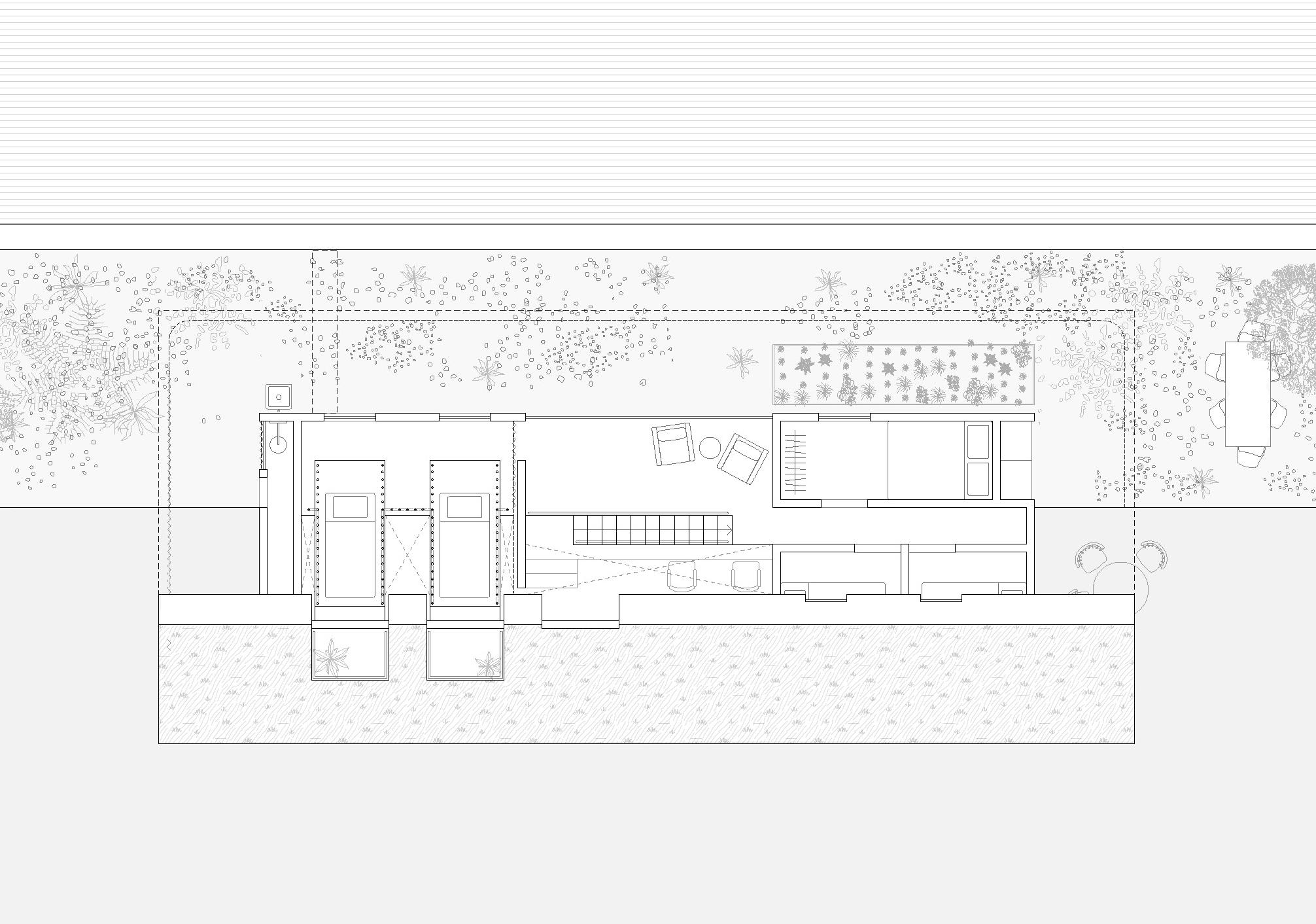

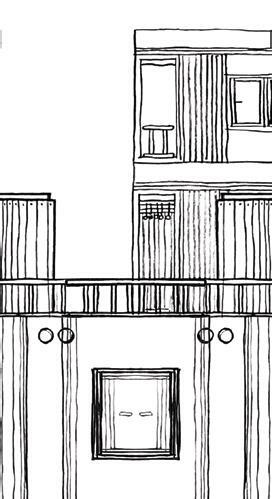

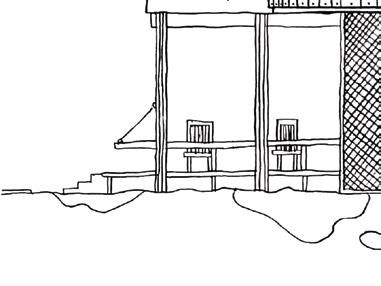

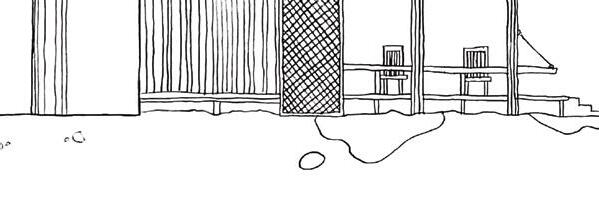

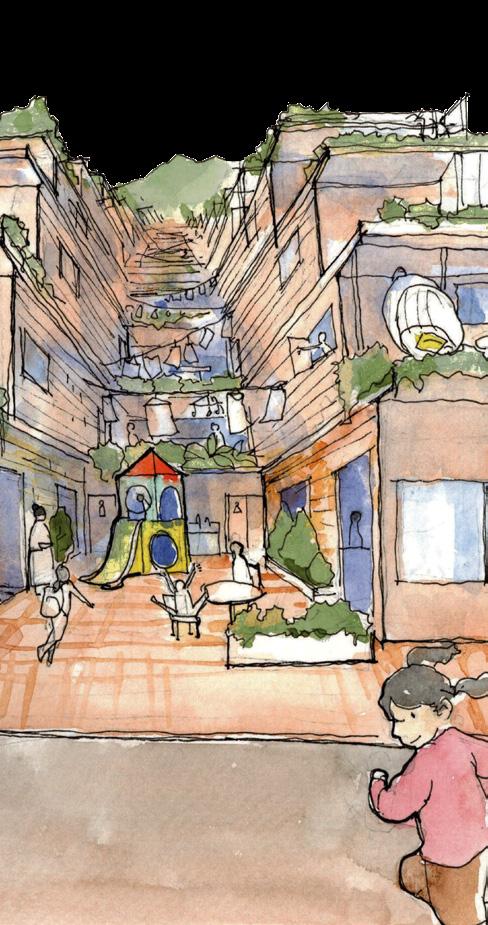

Four living units canopy a semi-public courtyard including kitchen, workspace, and access to storage areas - this space acts as multifunctional area for socializing, working, and viewing work by its artists and neighborhood. Stair landings serve as points of interaction with the interior while unit balconies face outward in a more private manner. Underfloor heating on the ground floor and large curtains grant continued use and comfort throughout the colder months.

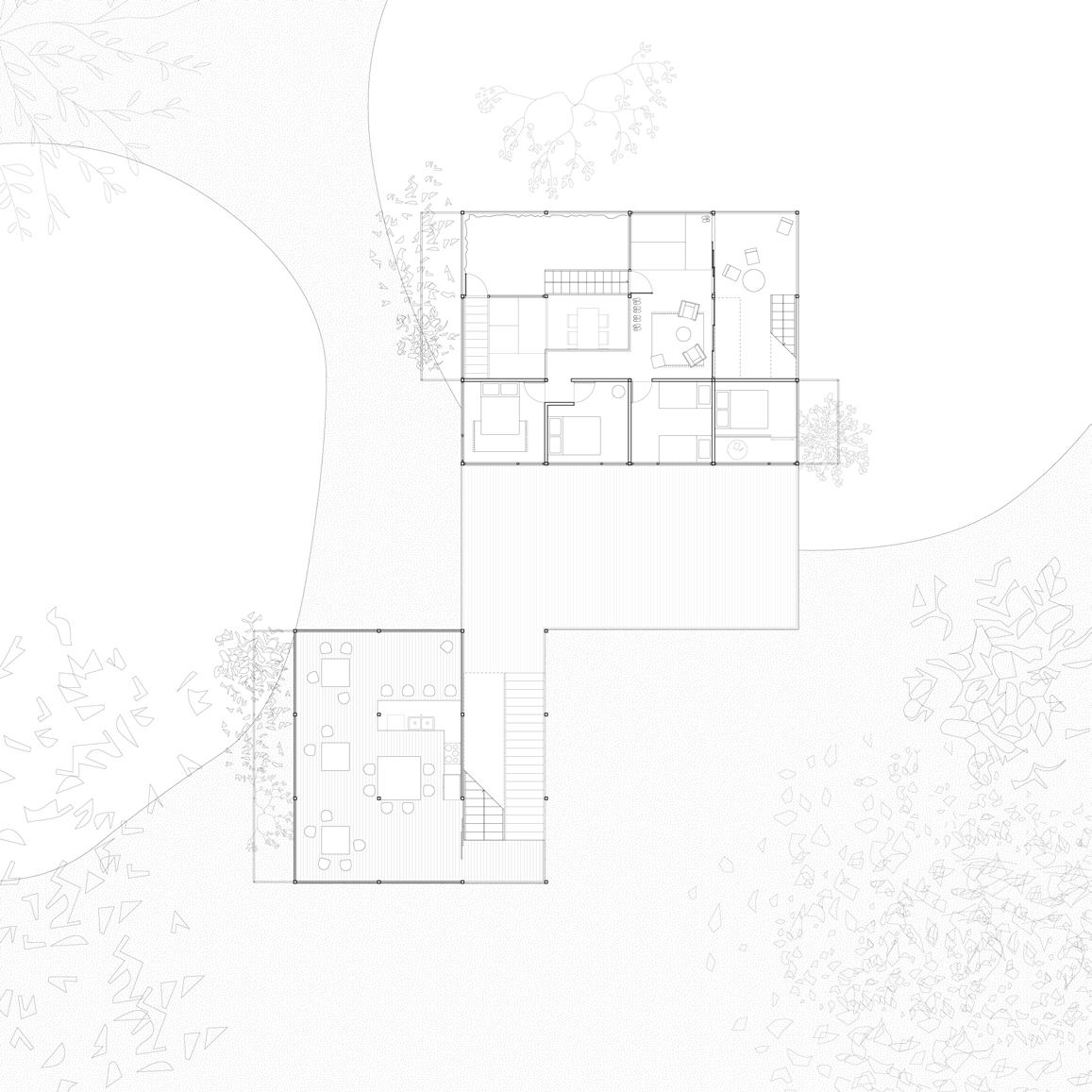

Top: 1:250 Plan 2F

Bottom: 1:250 Plan 1F

The layout of the development is defined by two parallel pedestrian streets and a linear park. The northernmost terraces block the noise of the railway underneath. The terraced form also allows every unit to have their own outdoor spaces. Brown insisted that every dwelling should have direct connection with the urban network.

Top:Site Plan

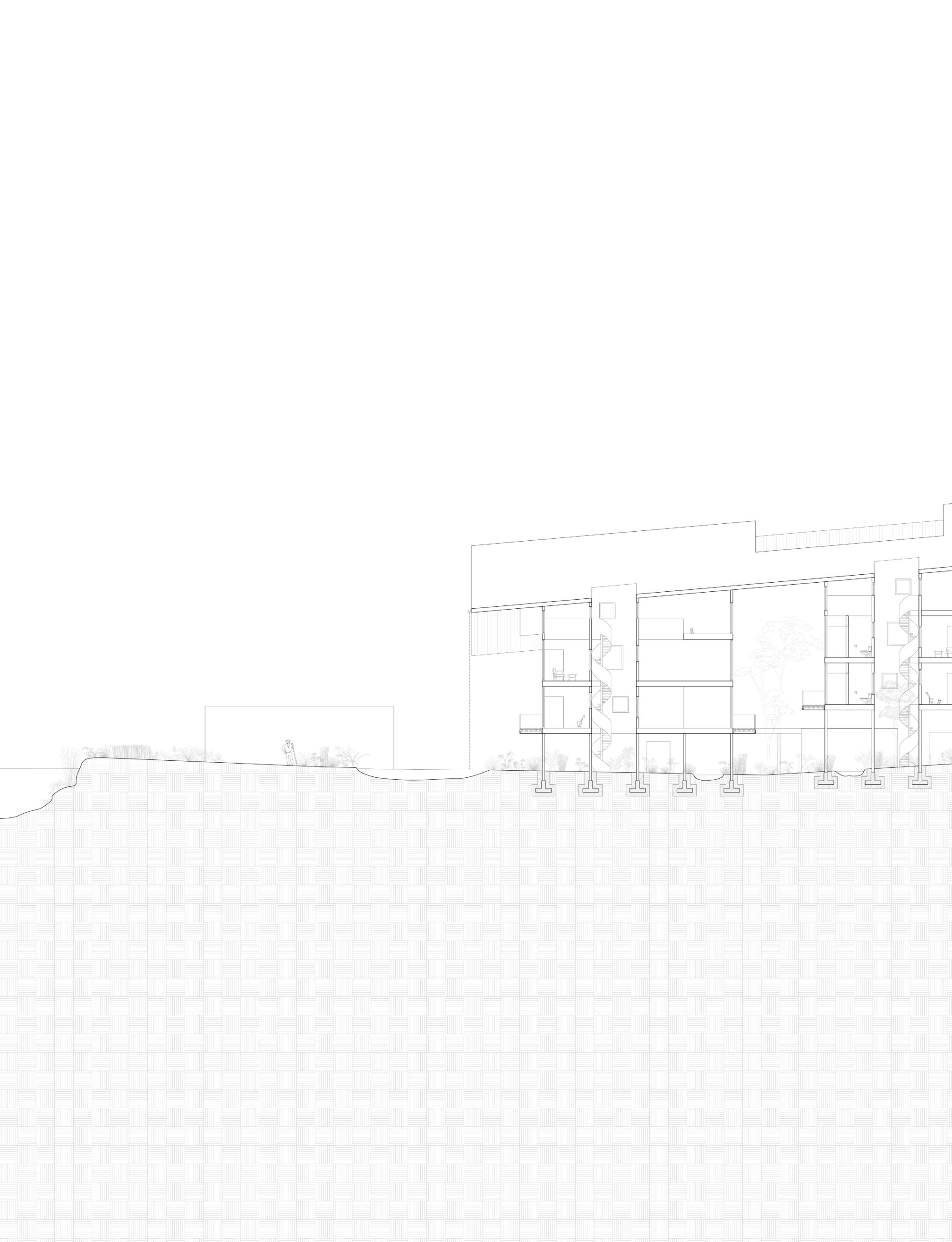

Bottom: 1:1000 site section

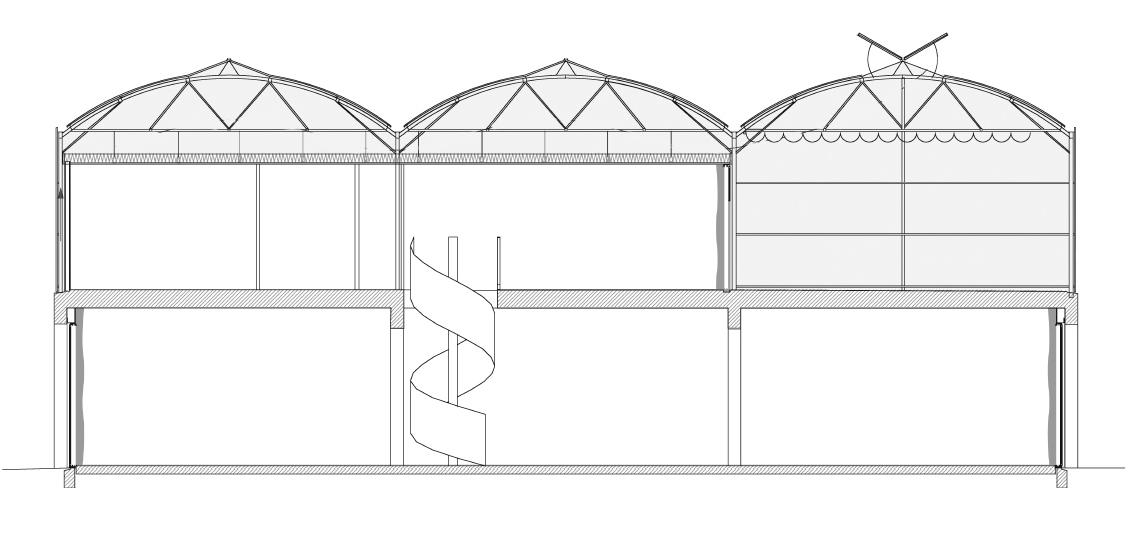

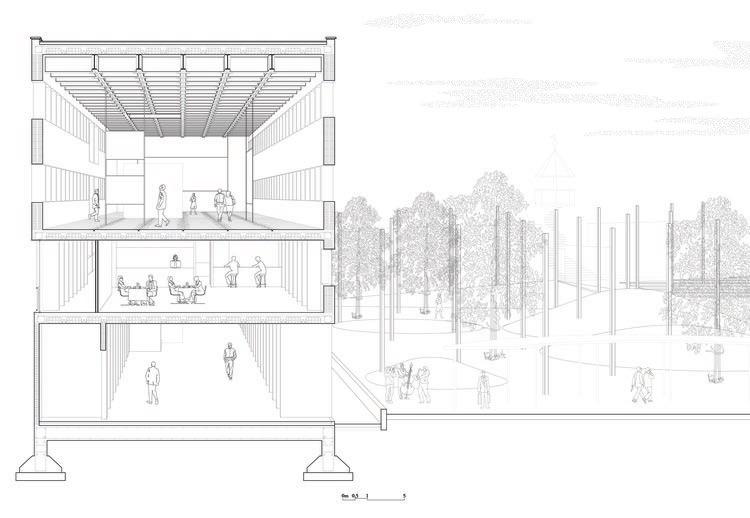

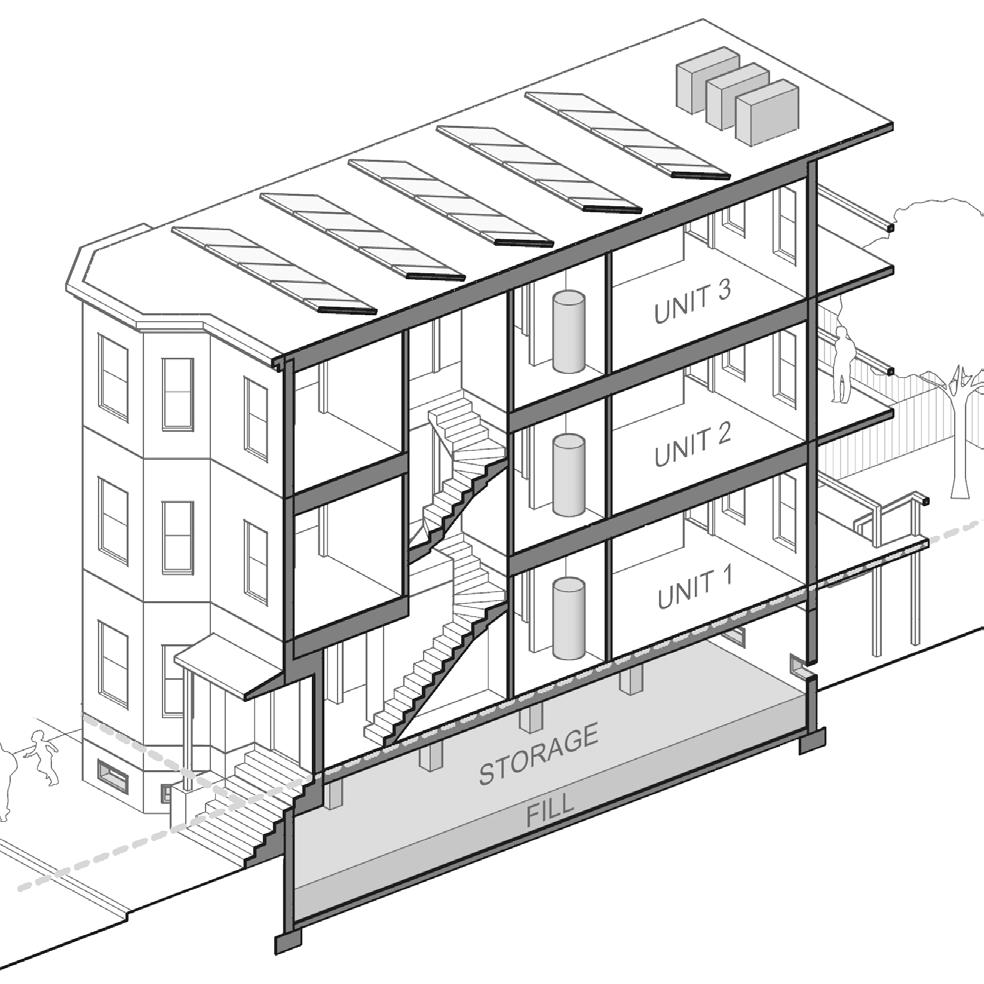

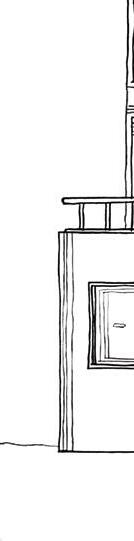

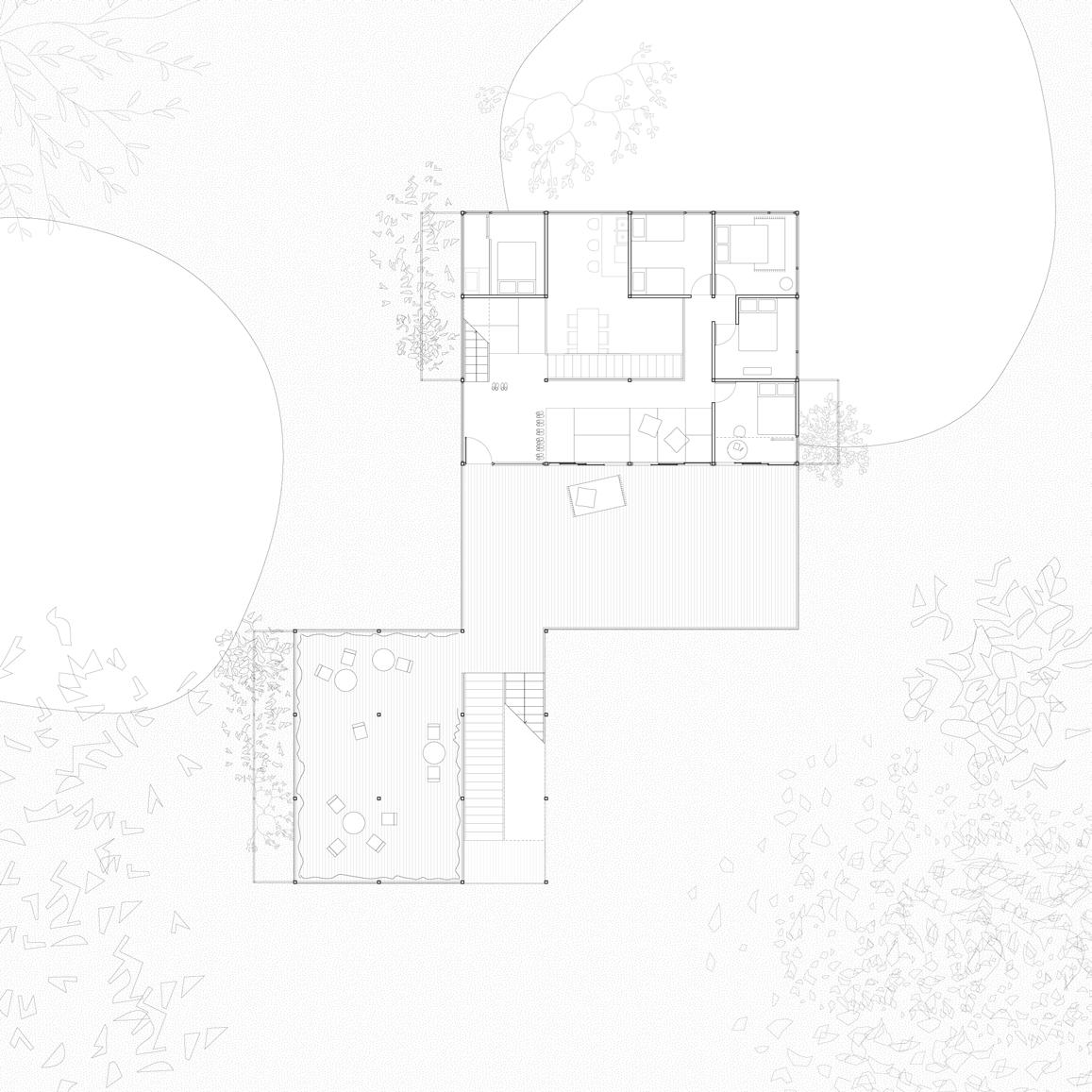

The project is built as simply and efficiently as possible, with a concrete base and a steel frame on top. The three-bay structure houses 14 duplex loft units. Each of the units is split on both levels with an entrance on the ground floor. The southernmost bay is designed as a greenhouse enclosure, with movable polycarbonate panels that allow for cross-ventilation and ample light.

Top: Section

Bottom: First and second floor plans

Milan, Italy, 1976

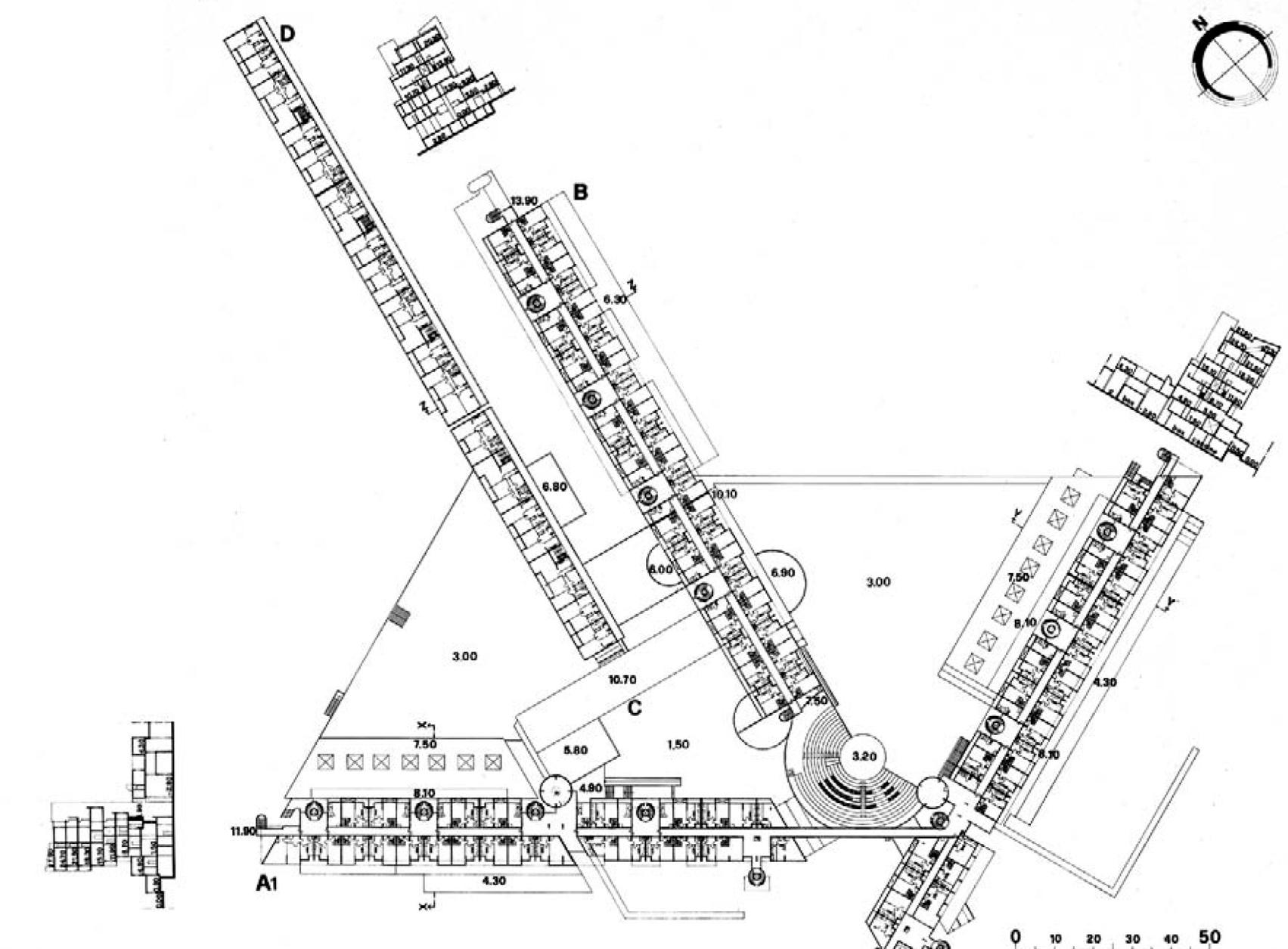

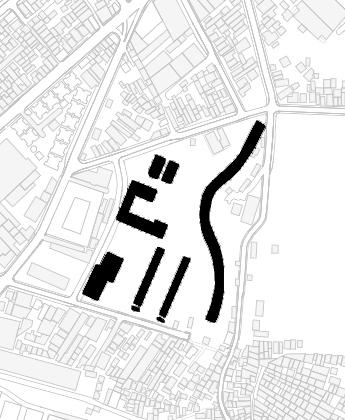

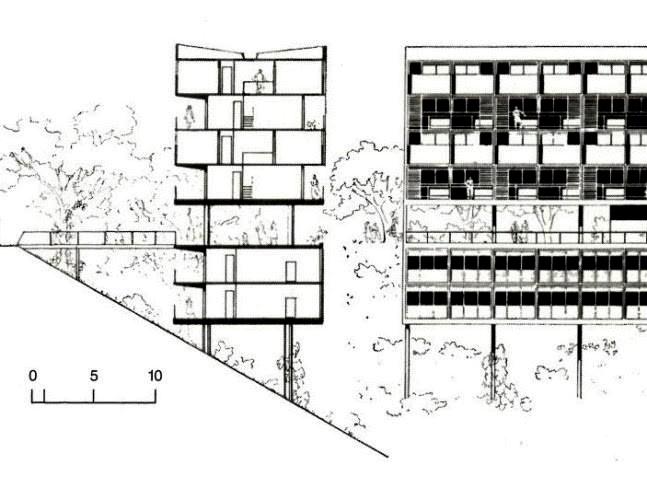

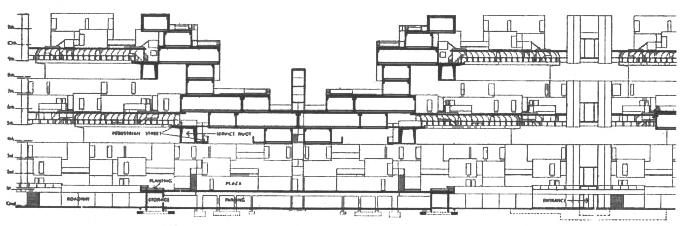

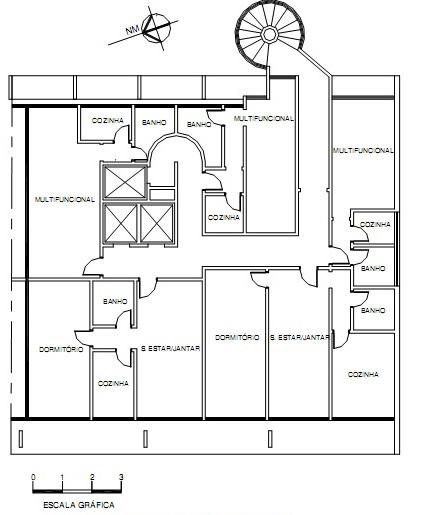

Inspired by the stepping forms, interior and exterior circulatory paths, and cellular spatial organization of Roman examples like Trajan’s Market, Aymonino incorporated the same features into A1 and A2, the 8-story blocks which form the southern boundary of the site.

This point of intersection is also home to an outdoor amphitheater; to either side, sheltered by the three apartment blocks, are two triangular piazze for communal use.

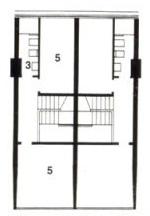

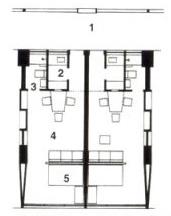

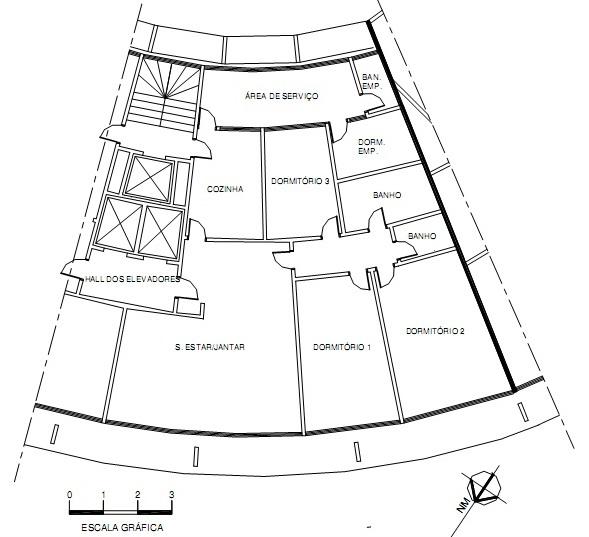

The first and second floor consist of single-level studio apartments. The third floor contains administrative offices, a children’s theater, nursery, and kindergarten. The fourth to sixed levels contain two-story family units.

Top: 1:2500 Plan

Bottom: 1:500 Section 1:500 Detailed Plan

Apartments 1st and 2nd floors

1 Corridor 2 Kitchen 3 Bathroom 4 Living-room 5 Bedroom

Apartments 4th and 6th floors Apartments 5th and 7th floors

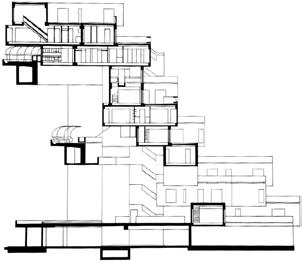

Consisting of 354 pre-fabricated modules arranged in 1-5 cube units, Habitat 67 reimagines the luxuries of single-family home living into an apartment complex. Each unit has a garden terrace and is accessed via a pedestrian street bridge. There are three elvator cores that stop every fourth floor at the bridges. Located on a peninsula, Habitat 67 was originally intended to be temporary for the 1967 World Expo.

Top: Floor Plans, 1:2500

Bottom: Sections, 1:2500

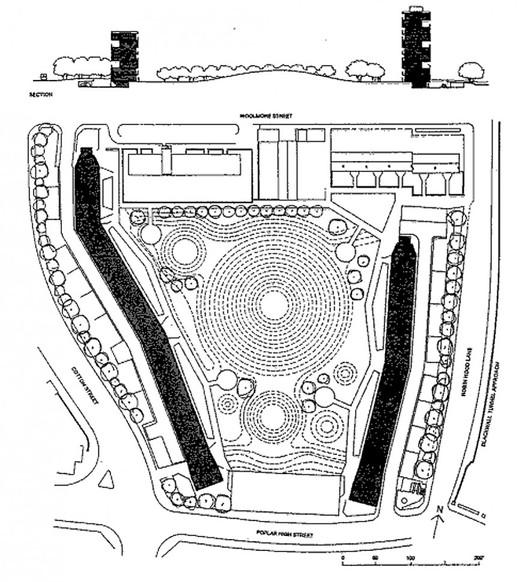

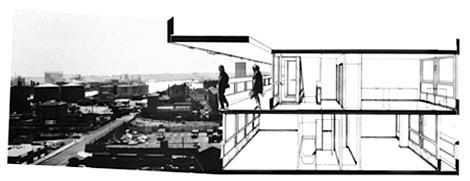

Robin Hood Gardens is a social housing project designed by Alison and Peter Smithson. Originally the project was compromised of two perimeter blocks with streets in the sky’s corridors. The housing was comprised of inward facing single story apartments and two-story maisonettes of two to six bedrooms. Ultimately the streets in the sky’s concept did not work because of the dead ends and lack of people walking by, which made the corridors dangerous for the users.

Top: Site Plan of Robin Hood Gardens by Alison and Peter Smithson

Bottom: Section Perspective by Alison and Peter Smithson

Top: Site Plan of Robin Hood Gardens by Alison and Peter Smithson

Bottom: Section Perspective by Alison and Peter Smithson

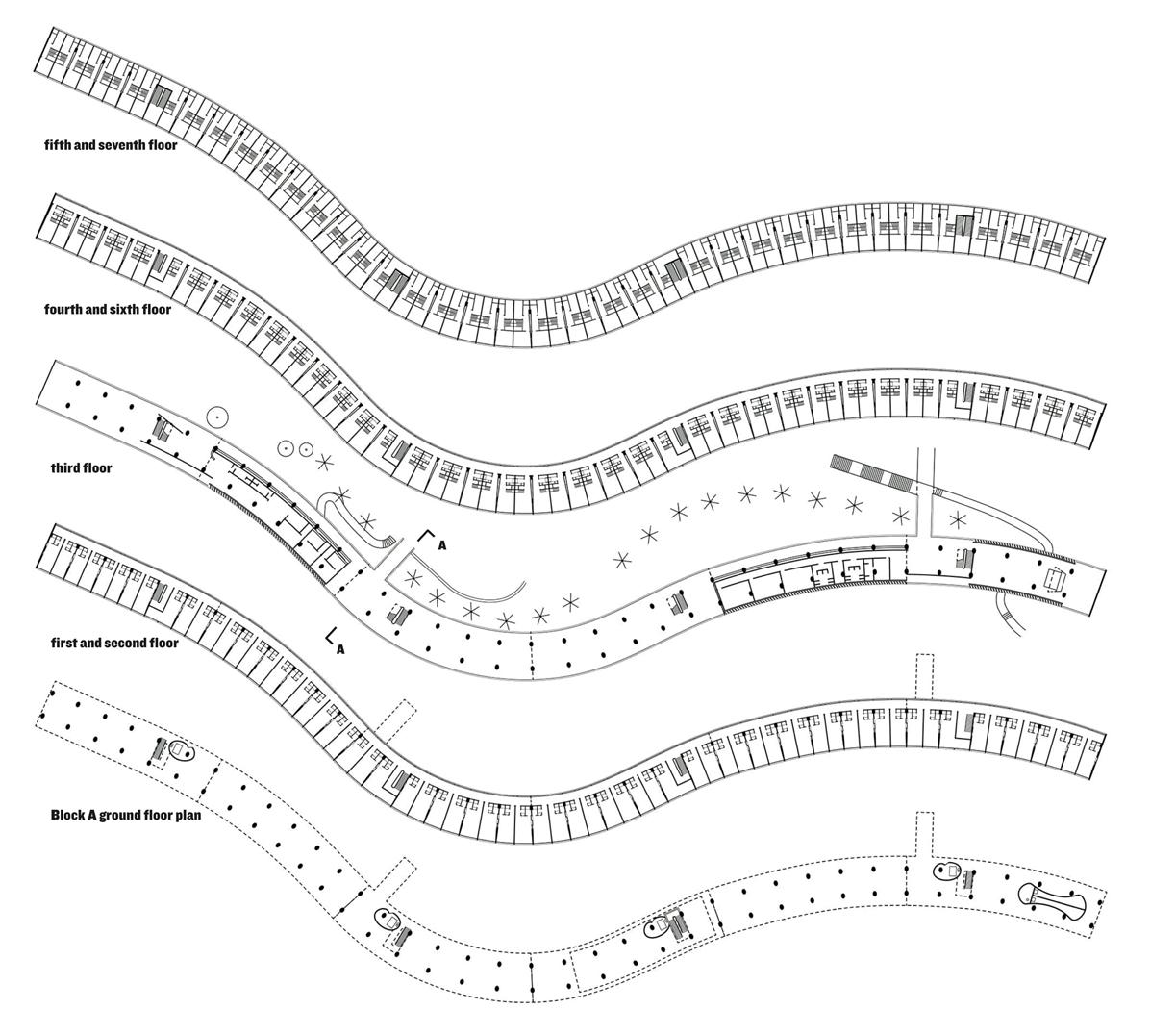

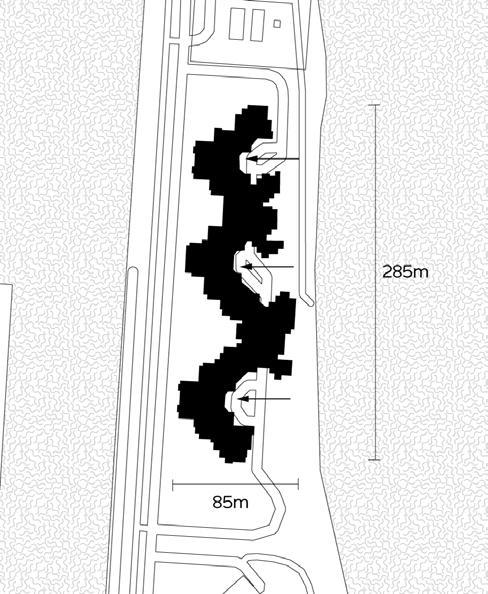

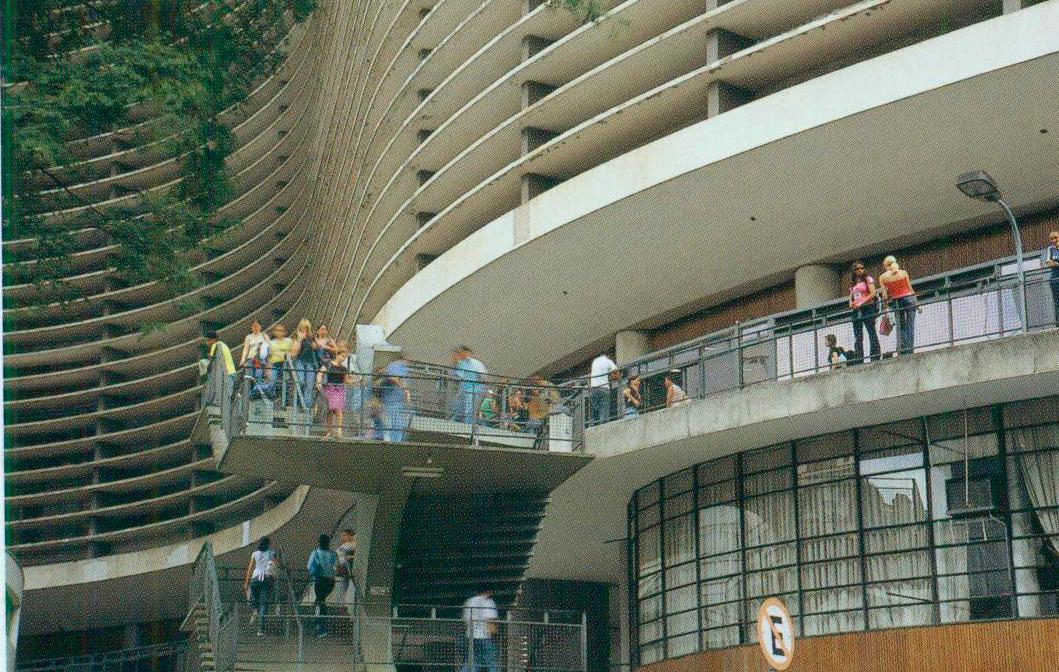

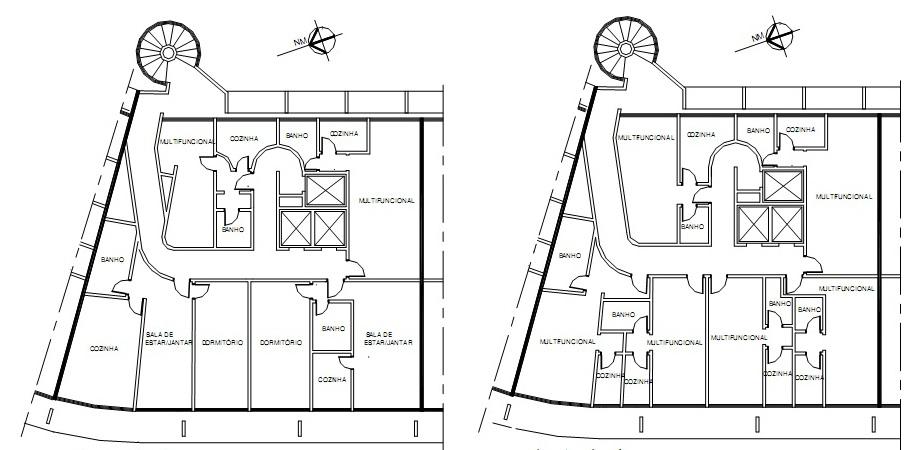

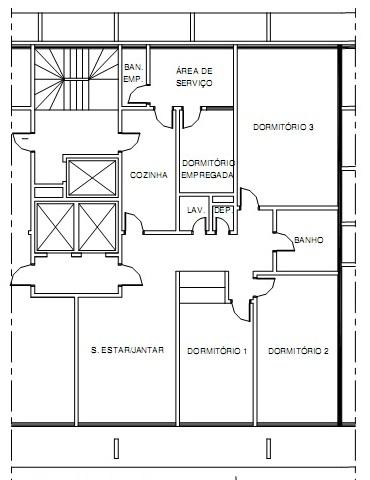

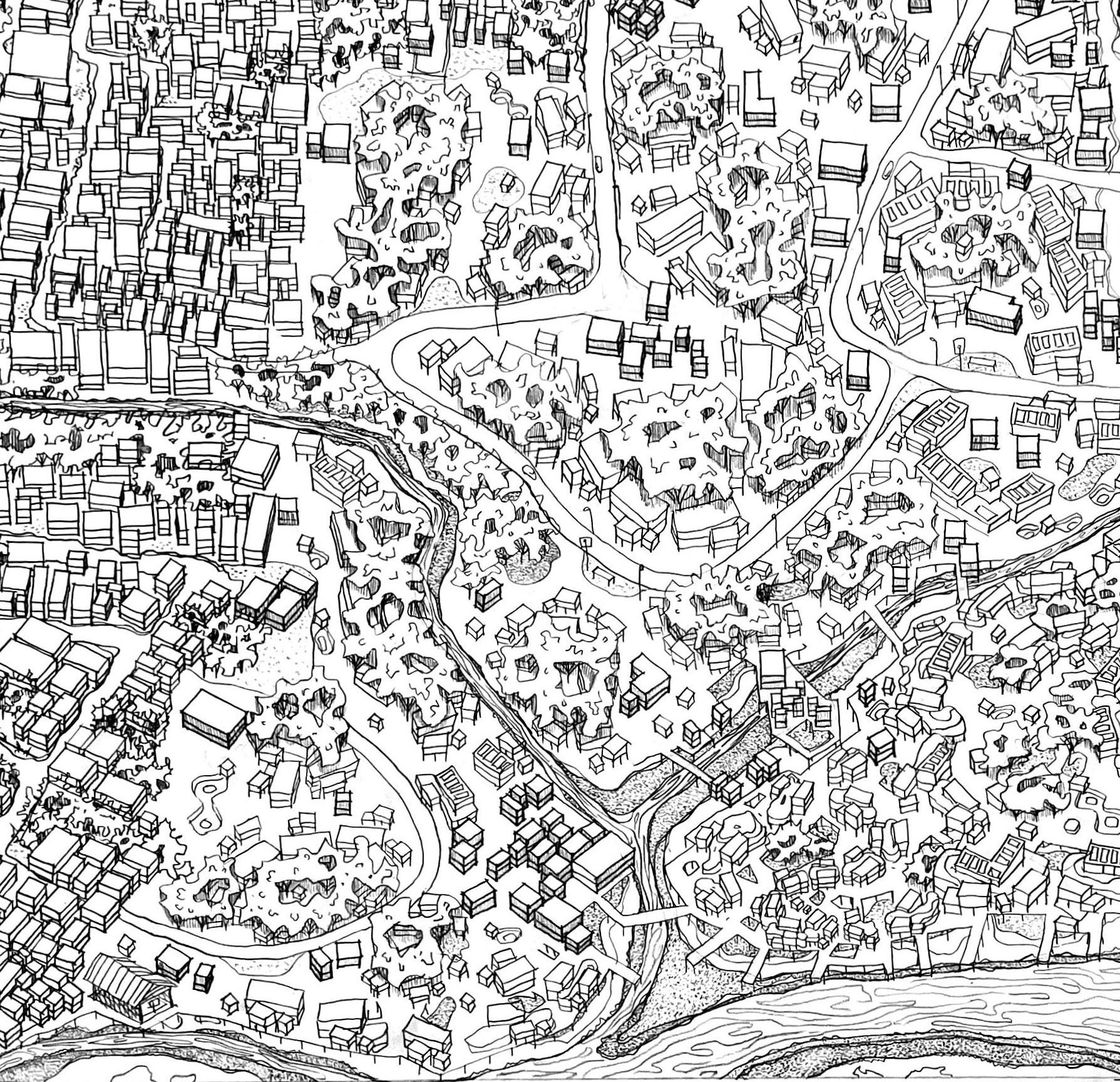

Architect: Oscar Niemeyer Program: Residential Area: 10,572.80 m2 Site Plan 1:10,000

1,494 2,038 1,160

Beds Inhabitants Units

Edifício Copan by Oscar Niemeyer is one of the largest buildings in Brazil. The 38-story building has its own postal code and is home to 70 businesses, including a church, a travel agency, a bookstore, and 4 restaurants. Niemeyer envisioned the sprawling tower to house a mixed cross-section of Brazilian society. Designed to accomodate a diverse group of clientele, the building’ss units ranges from tiny studio apartments for the working class to spacious, family-sized ones for well to do populations. The current 1,160-unit condominium has over 100 employees to conduct maintenance and to serve its 2,038 residents.

Block A Block B Block C Block D

Top: Edifício Copan has 1,160 units distributed in 6 blocks with 2,038 residents

Bottom: Block A has 64 apartments with 2 bedrooms, Blocks C and D have 128 apartments with 3 bedroomss, and Blocks B, E, and F have 968 aparments with kitchenettes and 1 bedroom

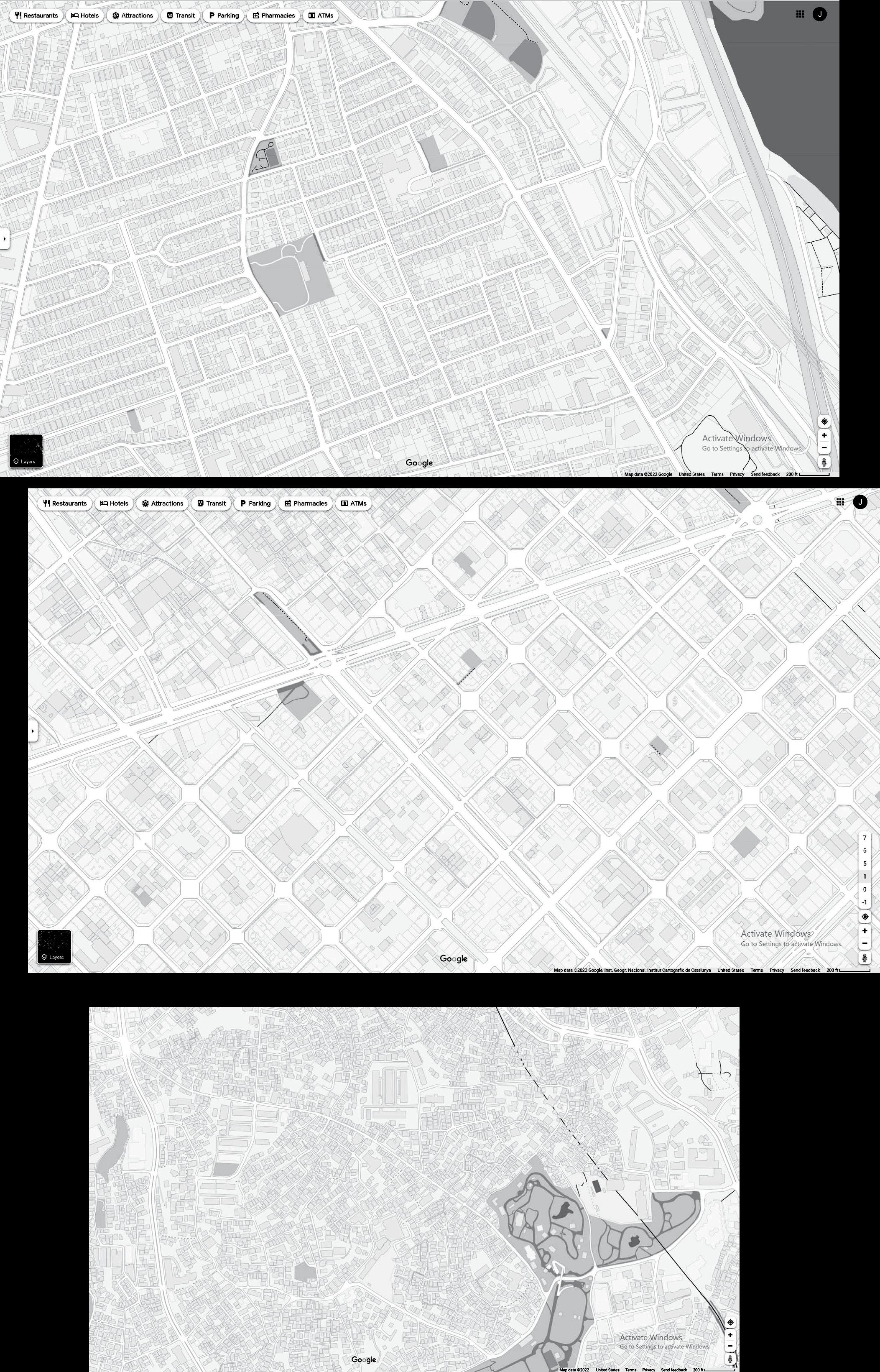

After looking around the world, we set our sights on Boston. We explored how people live at every scale, from the small triple-decker to a high-rise casino and hotel.

Certain questions remained important to us:

How much are we willing to share?

How can we redefine the concept of ownership?

How do people live together?

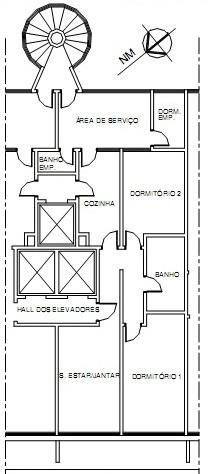

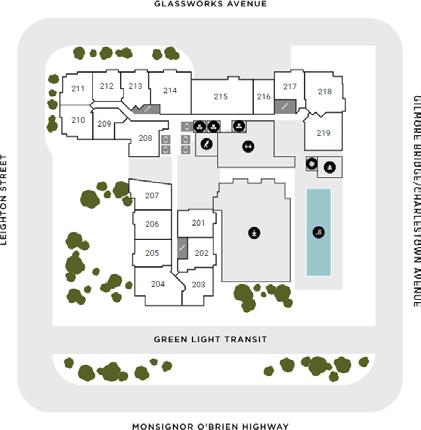

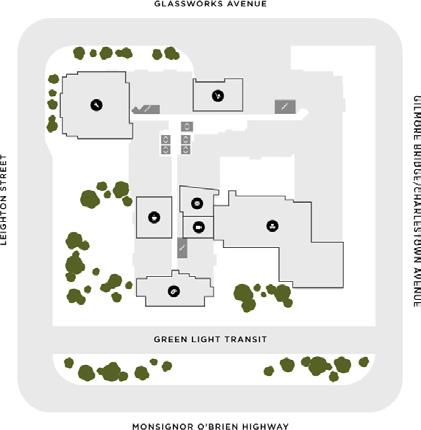

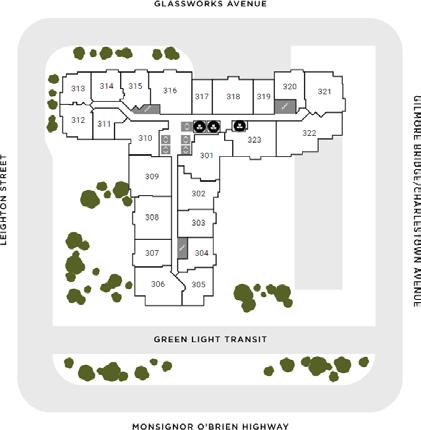

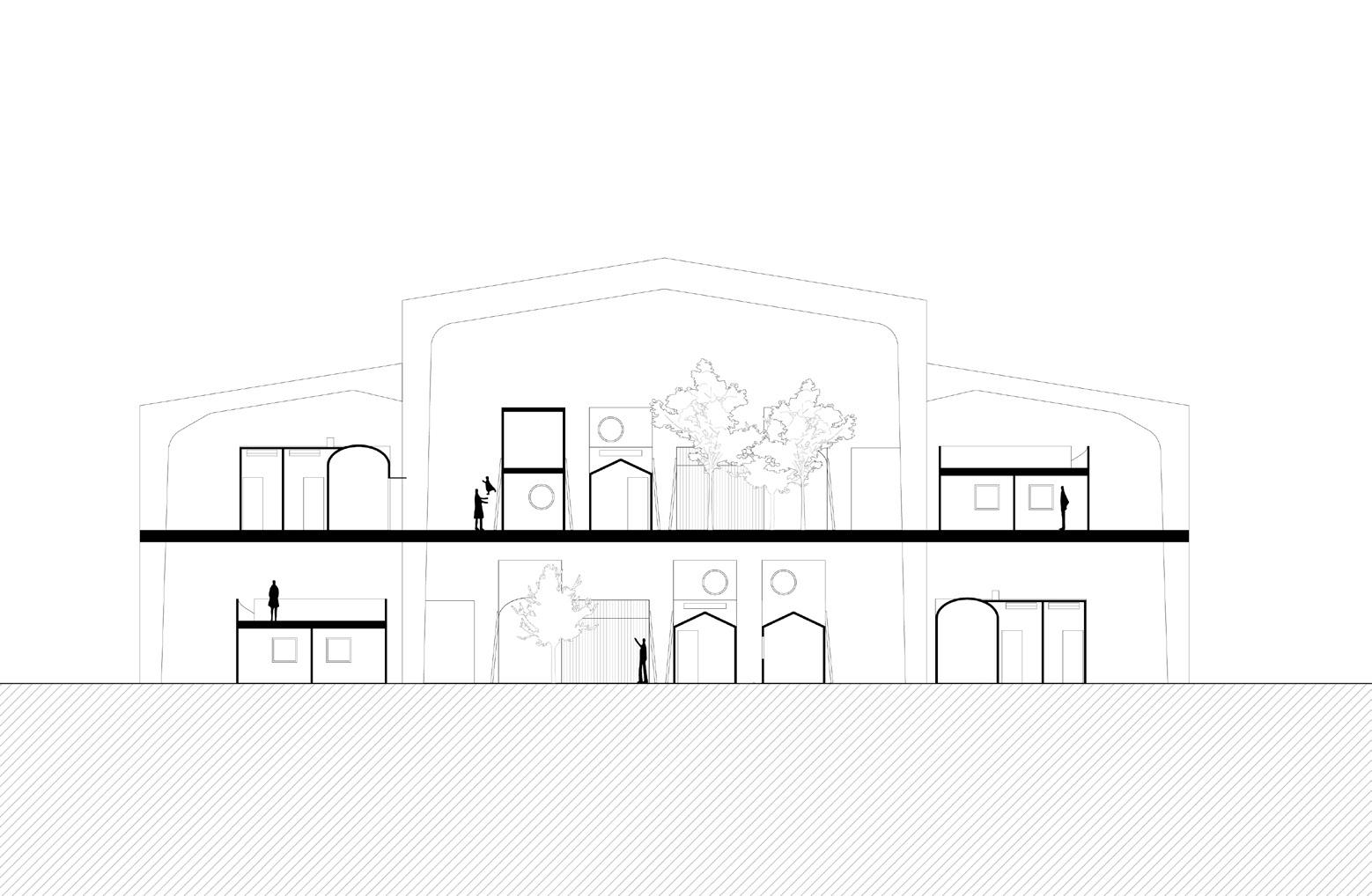

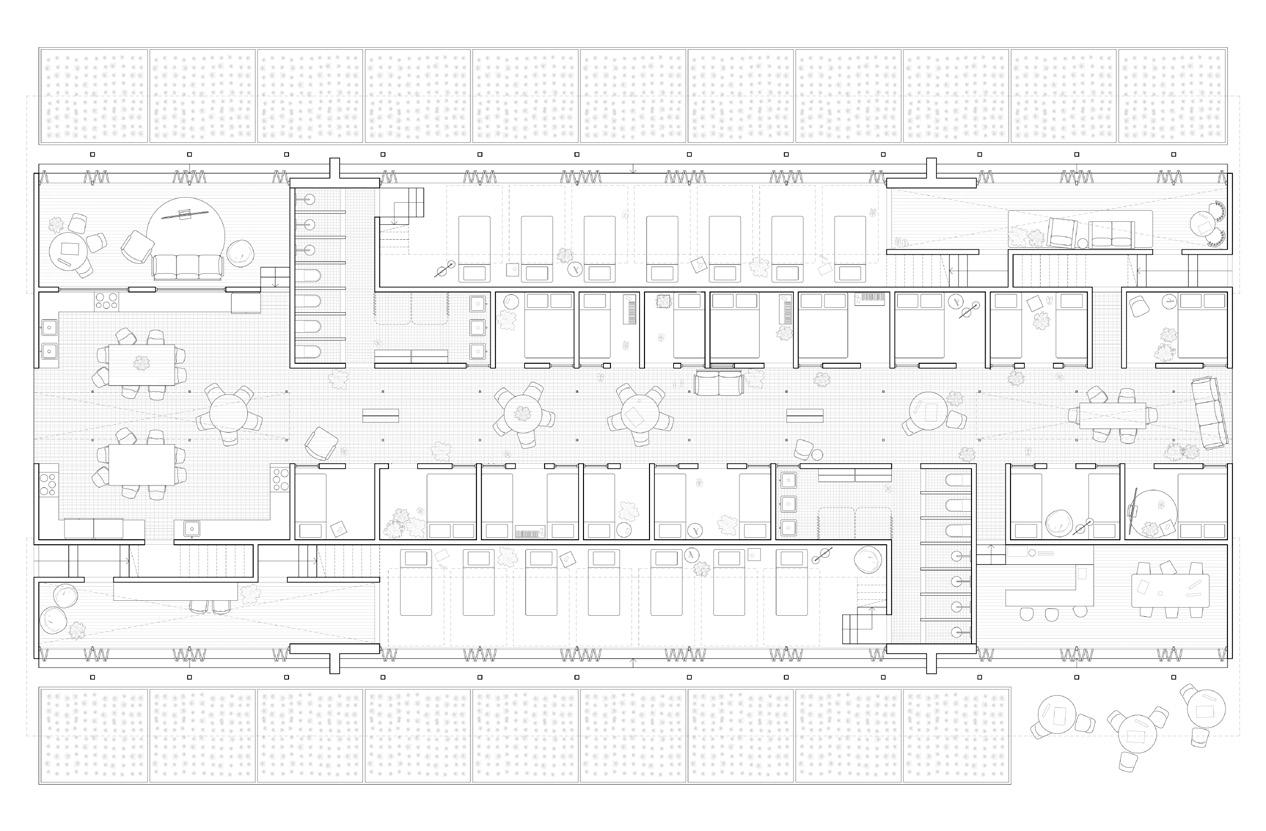

Soldiers Field Park is a dormitory that is a part of the Harvard University campus. It consists of four long buildings that bend and nestle around one another to produce spaces of collectivity inbetween. On the ground floor, there are enfilades cut through the buildings for circulation and access. There are many entry points with adjacent services including the mailroom, trash, recycling, maintenance. There are also many shared amenities such as lounges, playrooms, gym, and laundry woven throughout. This aggregation of living and community spaces create what feels like a village.

Top: First Floor Plan (1:1000)

Bottom: Public and Private Plan Diagram (1:1000)

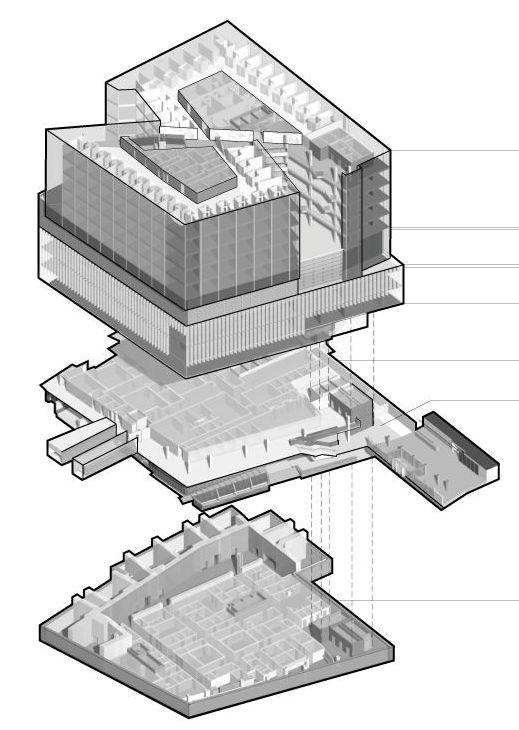

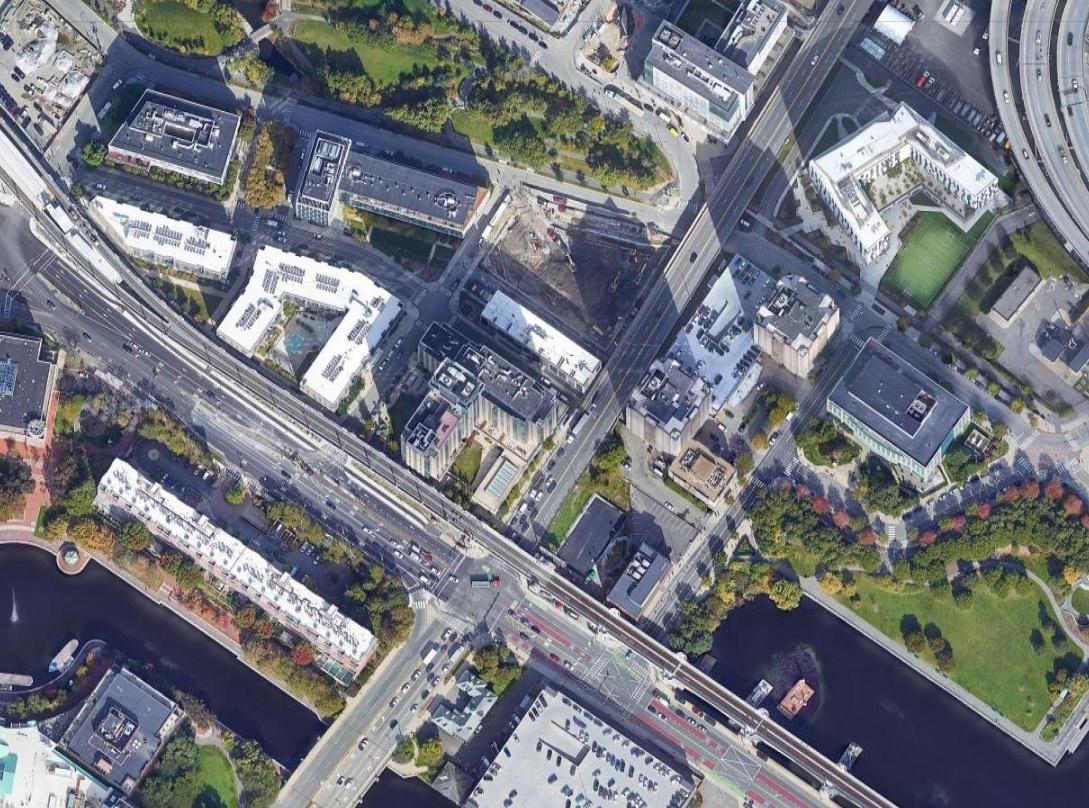

Patient rooms in Lunder Building of MGH are shifted from double to single rooms for infection prevention, privacy and greater patient/ family-centered care. The floor plate has a diagonal circulation spine to increase clinical connection and to minimize staff travel times.

Top: Section diagram, Plan 1:1000 Bottom: Satellite photo

Top: Section diagram, Plan 1:1000 Bottom: Satellite photo

Built in 1832 as a warehouse for commercial goods, Commercial Wharf was converted to condominiums in 1978. Many of the 94 residential units run the entire width of the building. As a result, apartments have both northern and southern exposure, with views over the harbor and Christopher Columbus Park. Units come with rights to parking and easy access to the Marina.

Top: View of Commercial Wharf from above.

Bottom: Site plan

150 m 25 m

Church Park Apartments is a horizontal skyscraper designed to emphasize the monumentality of Christian Science Center. The building is divided into three blocks with three separate cores, entrances and walkways connecting two parallel streets. The first floor is set back on the facades for a covered shopping street. The retail structure on the west side also provides outdoor terraces for the residents.

Top: Sample Units.

Bottom: Site plan.

Boston, United States, 1880-1930s

9 m 20 m

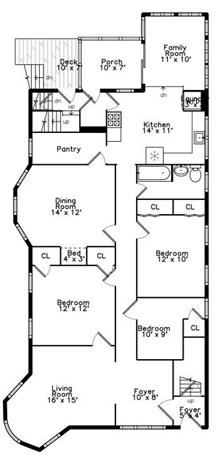

A unique symbol of Boston, the triple decker disguised three-family housing in homes that looked to be single-family, mimicking the early housing built by English colonists. Boston in the late 1800’s experiences industrialization, urbanization, and a population boom of immigrant communities - the triple decker was built to procide housing for this diverse demographic. Historically known for its ability to house multigenerational families and presently known for housing students, 84 (12 beds/decker) - 112 (9 beds/decker) triple deckers, or 4-5 neighborhood blocks, accumulate to house 1000 beds.

Top: Left: Typical Section

Right: Typical Plan

330m 207m

Bottom: 1:450 Site Plan of 1000 beds

The site marks arrival to Harvard’s campus from downtown Boston and areas south. The building’s configuration and image are based on interpretations of its physical context—the early-twentieth-century, five-story, brick-clad, U-shaped neo-Georgian courtyard houses and the mid-twentieth-century, twenty-story, concrete paneled modern towers.

Provide the gyms, resident entertainment lounge, and private covered parking garage. A courtyard opened to the residents. Located next to the new MBTA Lechmere station.

One of Boston’s first social housing projects, Cathedral Housing stands out in the city’s South End. The plan is designed as a series of towers, with a central cruciform tower of thirteen stories. The towers step down as they approach the edge of the site. The plan is designed to create open spaces and courtyards, meant for social use, between the building blocks. The housing complex contains a community building, with a basketball court attached to it.

HI Boston Hostel provides accommodation for travellers looking for cheaper, shared stays, as well as several other shared amenities including laundry, a kitchen, and bike share. It is located in Boston’s downtown near numerous tourist attractions and near access to various transportation options. The hostel brings many tourists into the area, and offers several room types, including a private room, 4-person room, and 8-person room.

Top: Fifth Floor Plan, 1:500

II.

I. II. I.

Bottom: Site Plan, 1:2500

Fresh Pond Apartments is a social housing complex developed in the early 1970’s. The project is made up of two 20 story towers with apartments ranging from one to three bedrooms. Each tower comes with laundry, a recreational space, a multi-use room, a conference room, and plenty of parking. Each space in the tower complex has been optimized but they lack spaces that build community.

no. 1 Bedroom 10’-4” x 15’-7”

no. 2 Bedroom 9’-0” x 15’-7”

Livingroom 13’-0” x 17’-6”

Closet Bath

Closet

Kitchen 8’-8” x 7’-5”

Top: Typical two bedroom layout

Bottom: Public v Private Diagram

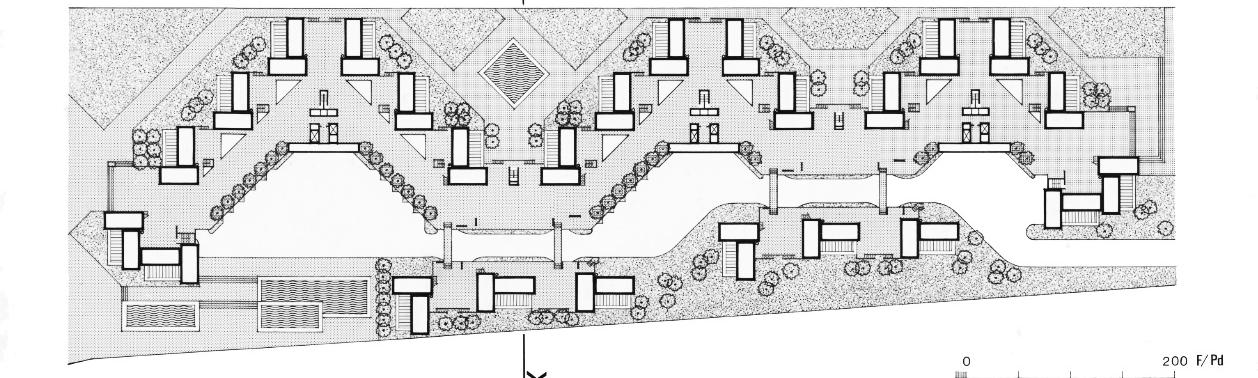

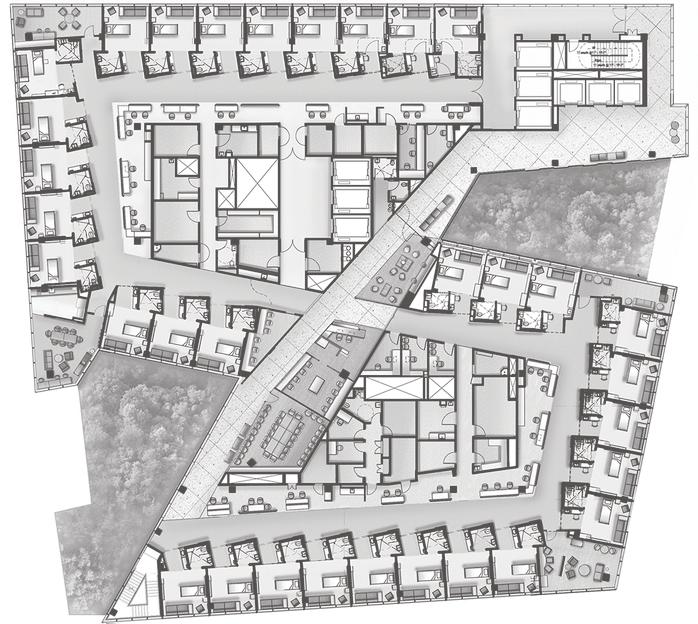

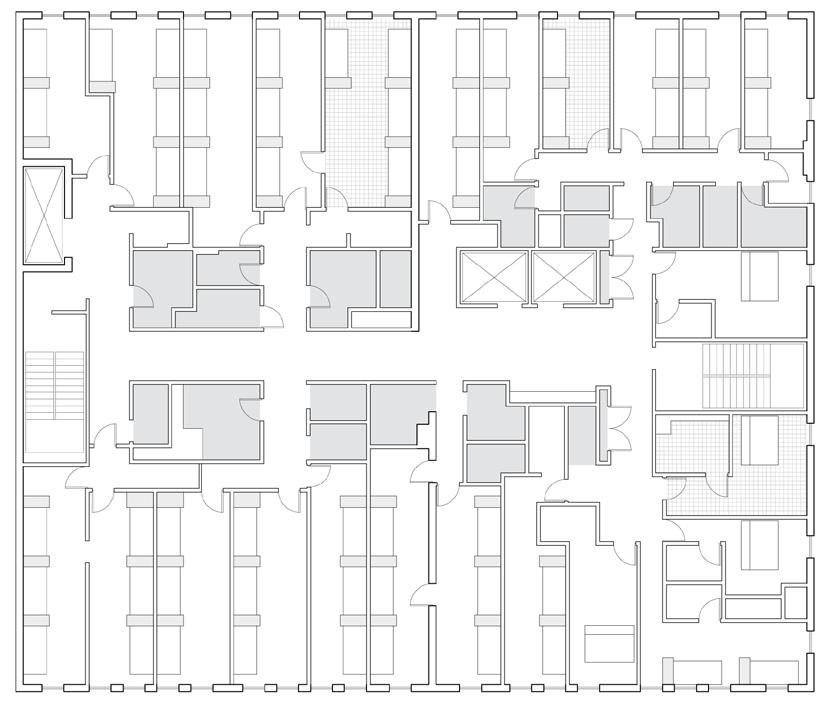

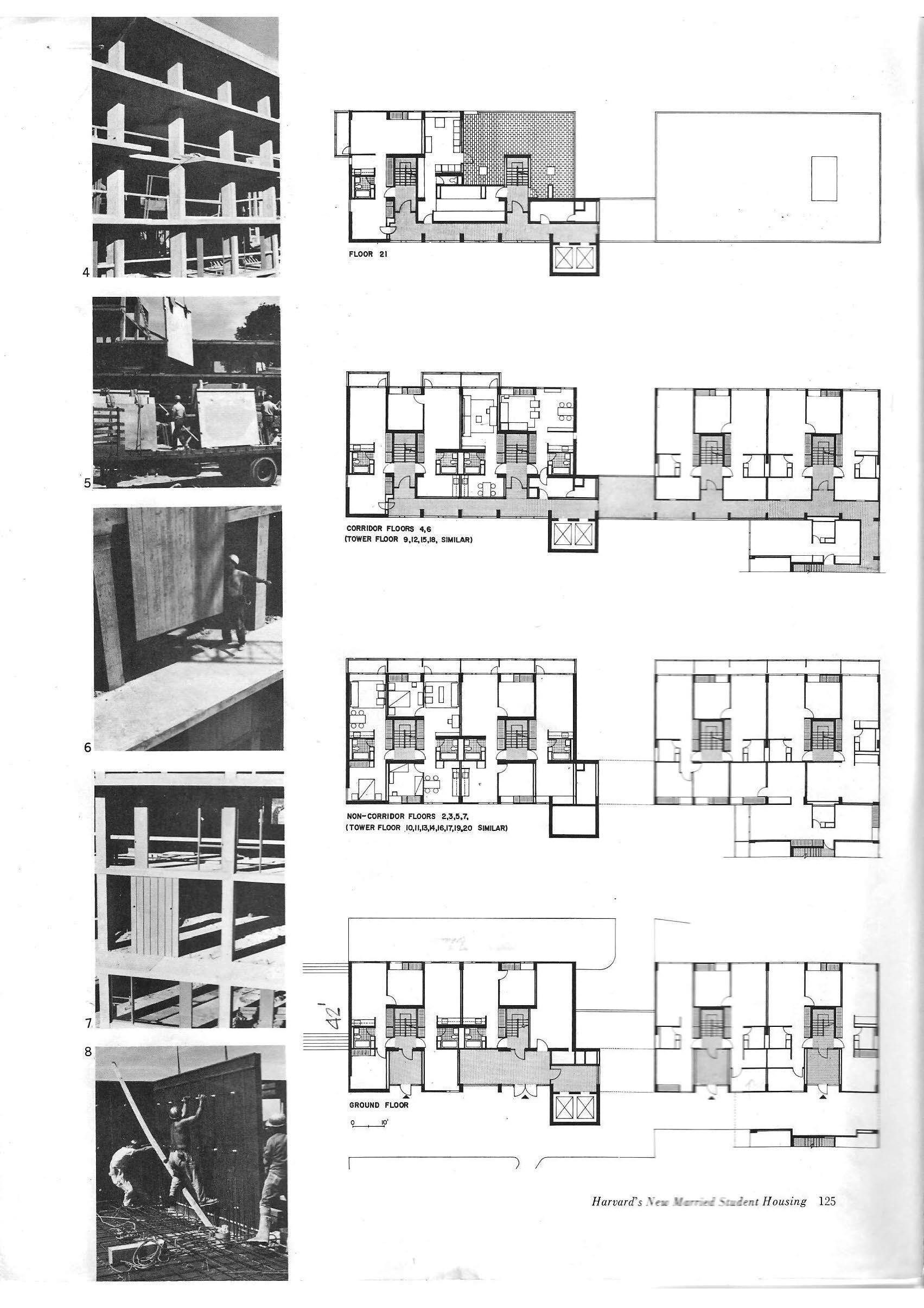

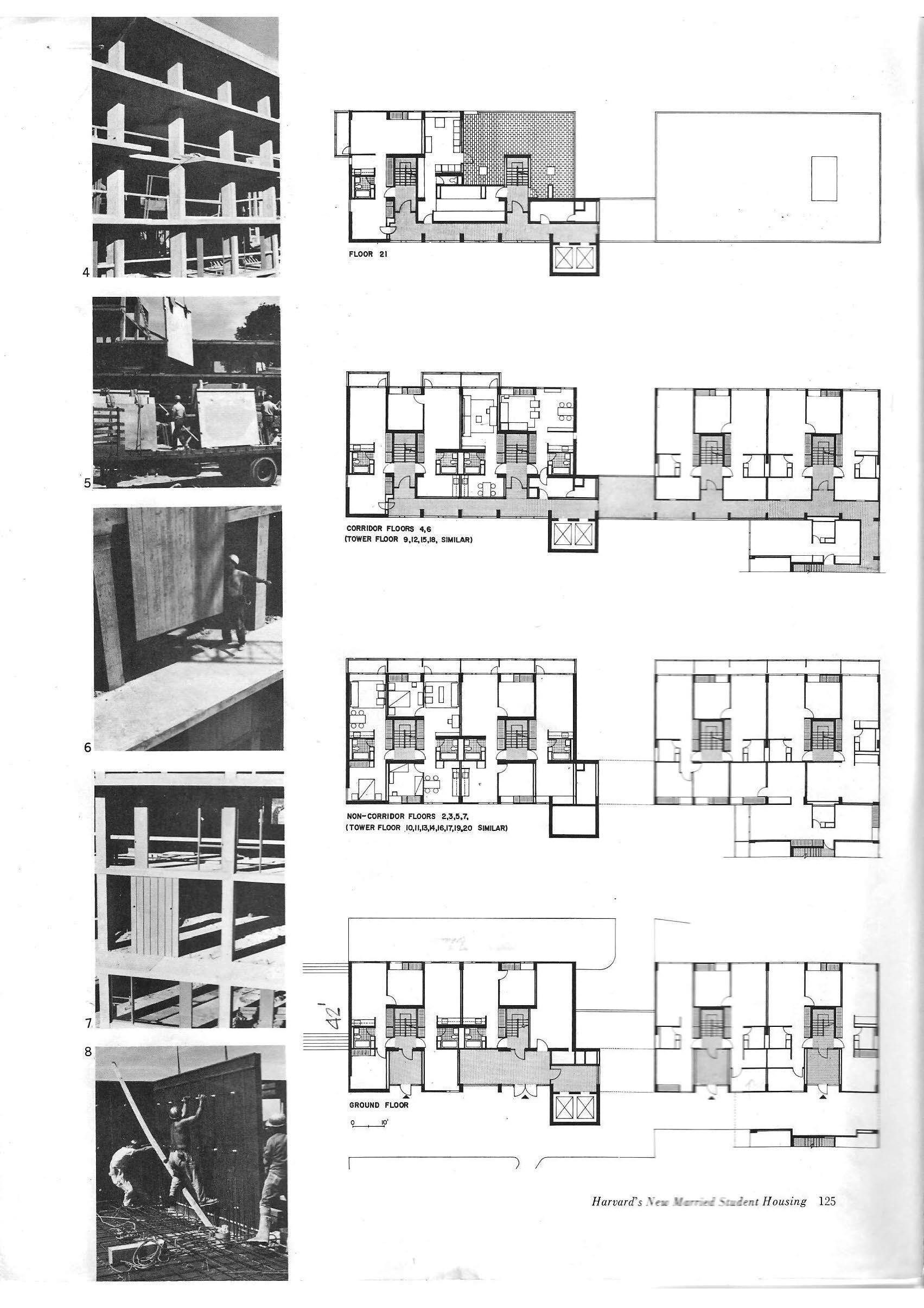

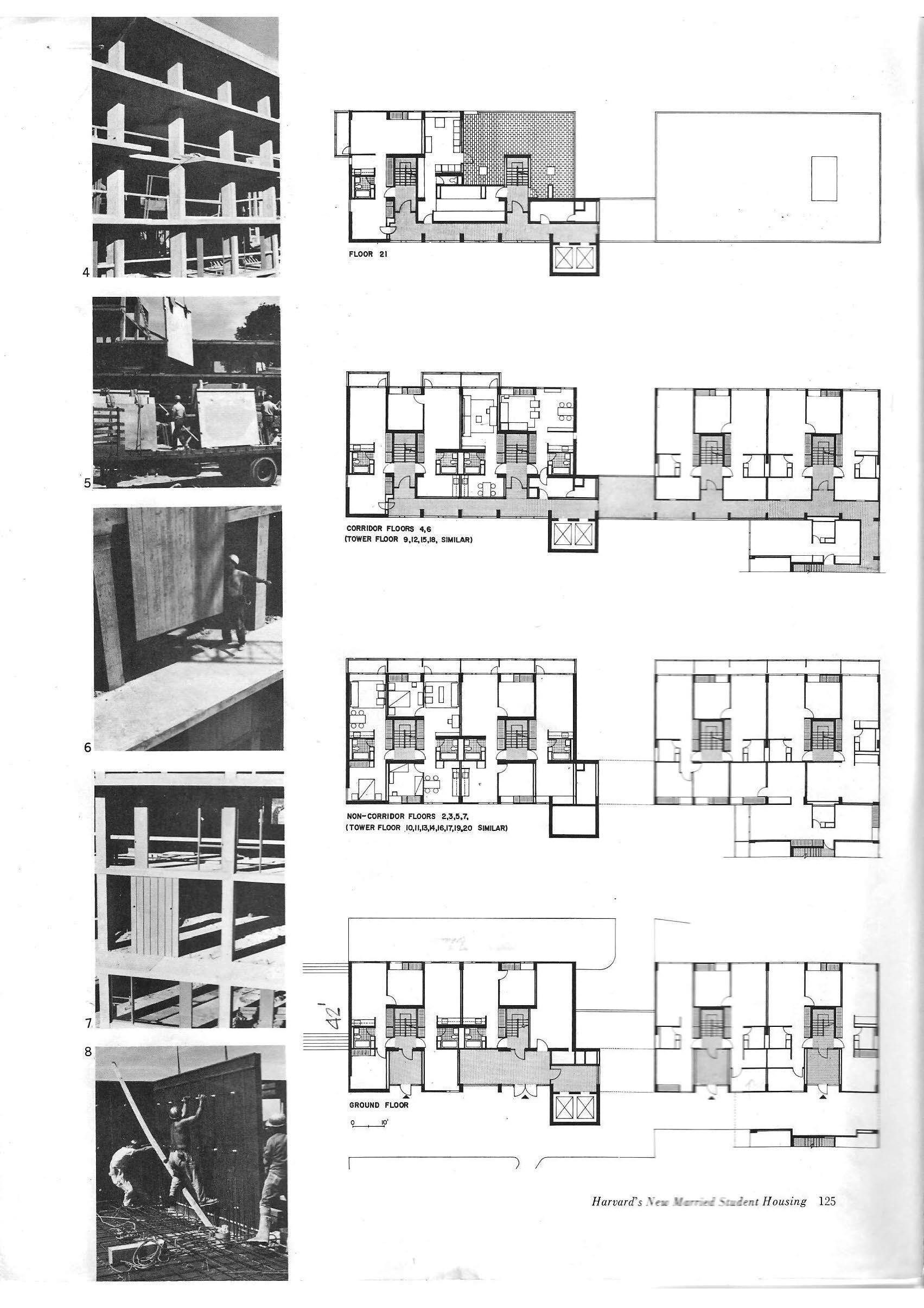

Peabody Terrace is Josep Lluís Sert’s vision of an ideal neighborhood. In addition to the 497 housing units, the 5.9-acre complex contains a playground, paved roof terraces, three nurseries, a drugstore, two laundromats with sitting rooms, coin operated laundry rooms, a large meeting room with a kitchen, two seminar rooms, basement and ground floor storage facilities, and a garage for 352 cars.

Floor 21

Corridor Floors 4, 6 (Tower Floors 9, 12, 15, 18 similar)

Non-Corridor Floors 2, 3, 5, 7

(Tower Floors 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 19, 20)

Ground Floor

tenants and those living on 5- and 7-story buildings

The following precedents offer insights into distinctive living. not deemed ‘architecture’ in the typical sense, thus, a ‘landscape’ of living.

These examples are rich with creative and hyper-local solutions to dwelling and begs the questions:

What does dwelling look like without an architect’s input? How does a home or community expand over time?

How do people choose to live without the oversight of a planning body?

110

Walmart parking lots have become a haven for campers, travelers, and unhoused individuals across the United States. While it is an informal system, users have developed a number of apps and websites to identify which stores—about half in total—allow overnight parking. While parking is free, it is widely accepted that you should buy something at the store before leaving in the morning.

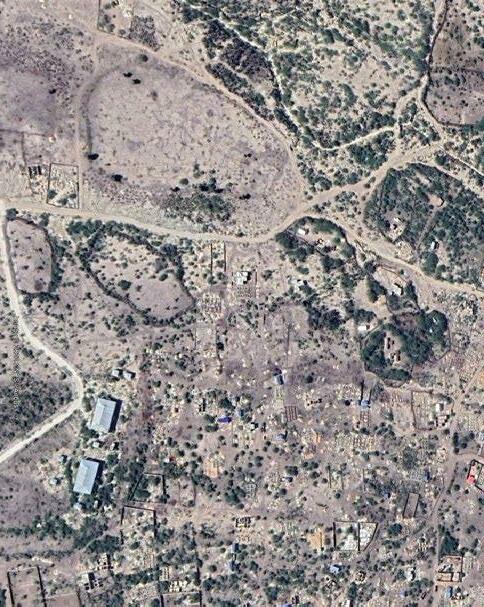

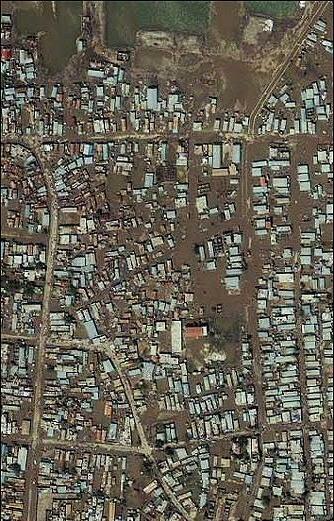

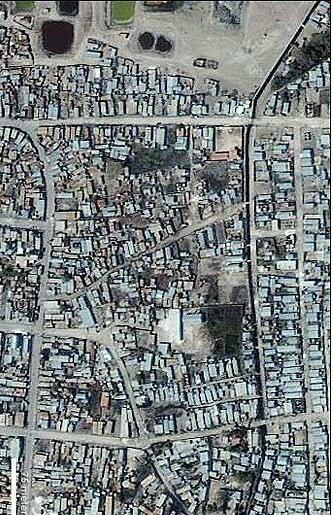

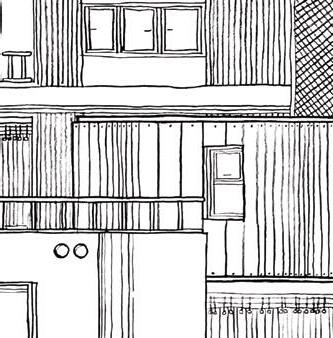

Over sixty percent of the city’s population live in “in”formal settlements. Informality here refers to the fact that these settlements were built without a permit. These settlements, however, have evolved over time to become extremely efficient in building method, speed, and area. A few building types have been standardized and replicated to create these settlements. At first glance, these neighborhood might seem bleak. To the contrary, these tight-knit communities have a bustling public sphere. Daily markets, soccer games, and hookah lounges are just some of the daily happenings within these narrow streets.

Shanty Megastructures is a dystopian vision created by artist Olalekan Jeyifous to bring awareness to the marginalized shanty communities of Lagos, Nigeria. Jeyifous envisions the shanty communities developing into mega structures that dominate the city landscape.

The urban village is a naturally formed community. It is surrounded by high-rise buildings. Residents here built up their own houses with all locally accessible materials. It’s a spontaneously formed community but has all the functions for life. They share the communal lavatory. A kindergarten, a market, two small local temples, and several spaces for public activities are in this urban village.

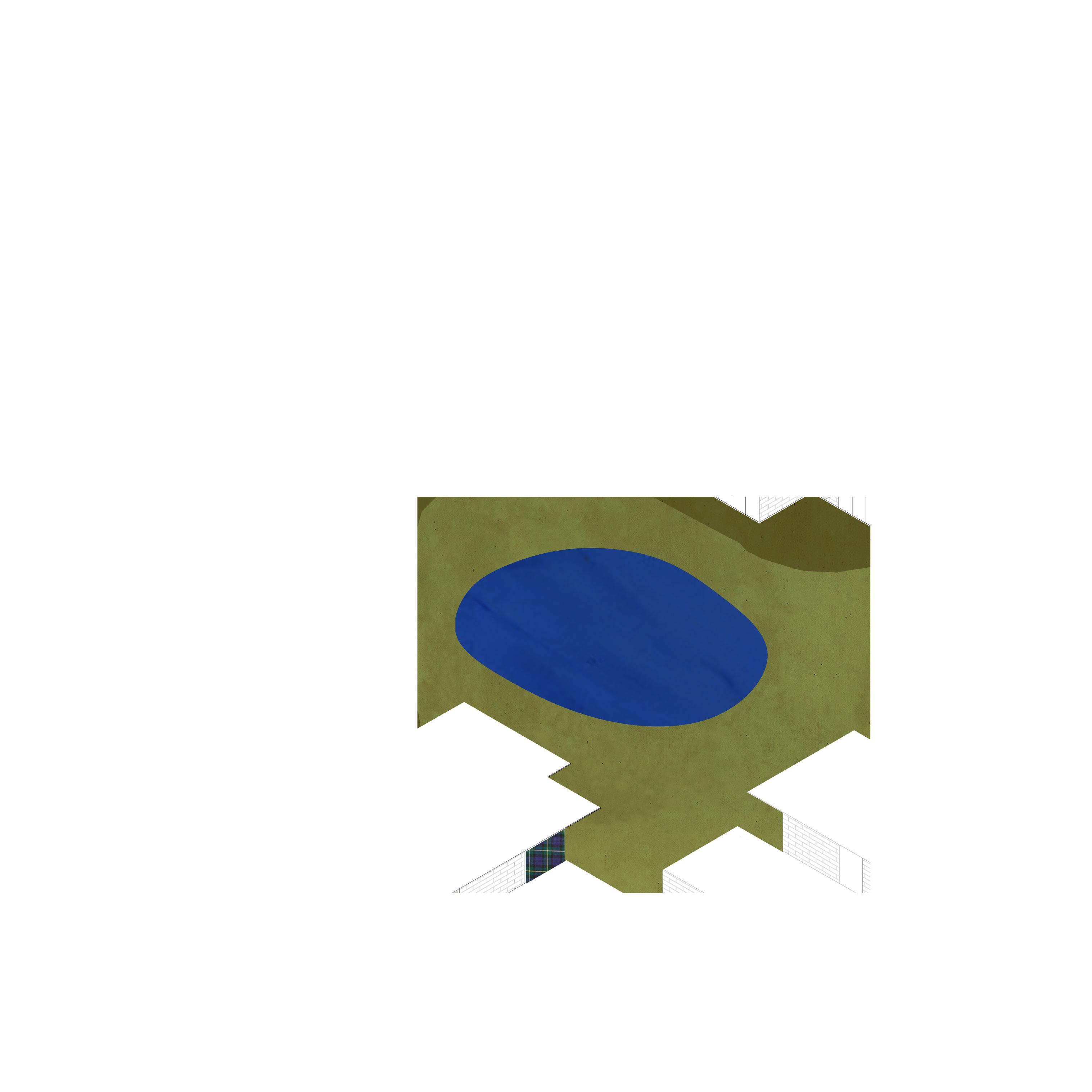

In reference to Tainan’s harbor history, MVRDV’s Tainan Spring (an adaptive reuse project of 54,600 sqm commissioned by the Urban Development Bureau of Tainan City Government) brings greenery to the city as an urban lagoon. Utilizing the previous China Town Mall basement structure, a sunken public plaza houses its main pool feature with structural follies meant for future shopes and kiosks. Planned for all seasons: water levels rise and fall in response to rainy and dry seasons, in hot weather mist sprayers reduce temperatures to welcome relief to visitors.

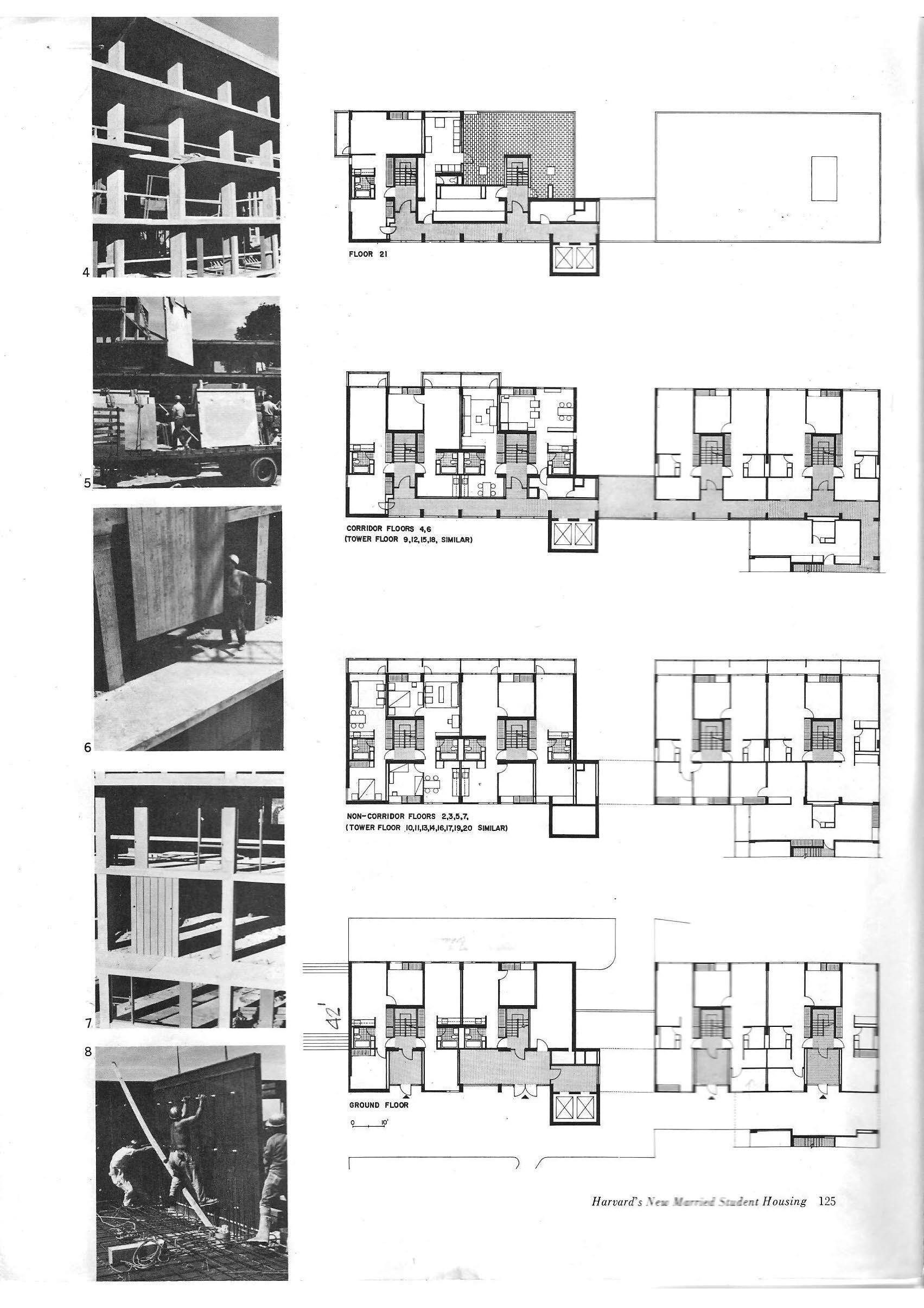

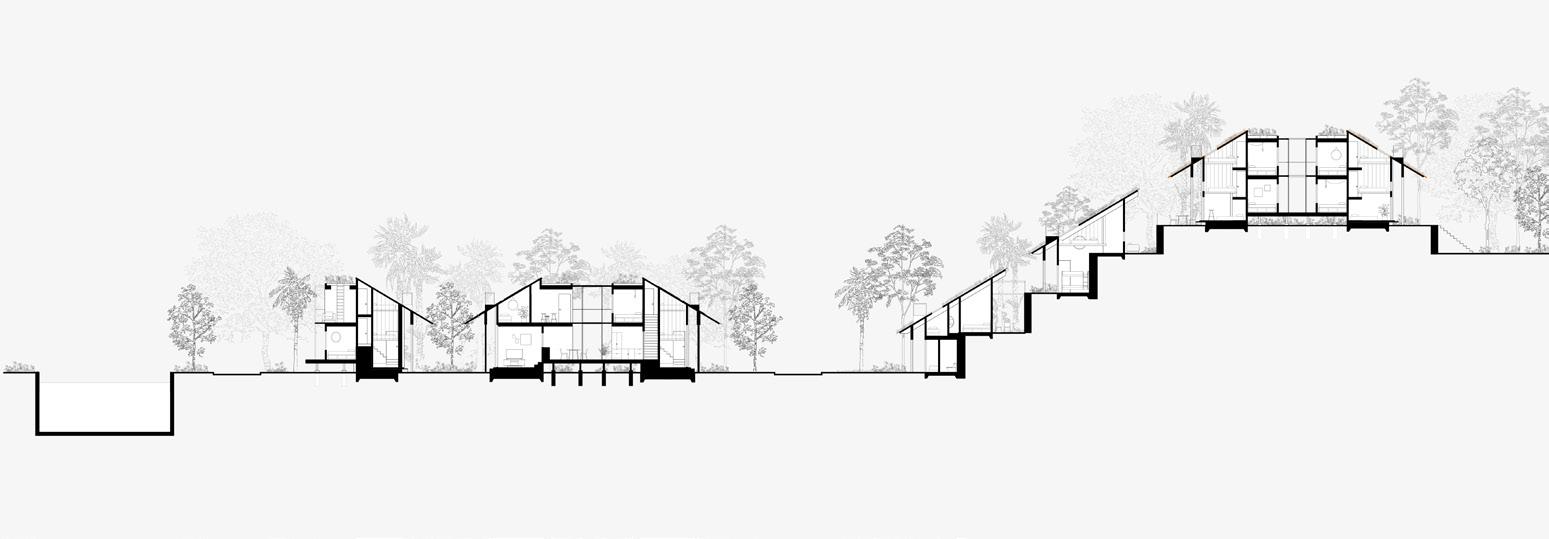

Home to some of the most stunning landscapes in the country, Masouleh is one of the many stepped villages that are quite common to find around the country, especially in Iranian Kurdistan and around Mashhad. They have been built on a hill so steep that the roof of one house is the pathway for the next. Surrounded by green valleys, misty forests, and 3,000m peaks, Masouleh is the ultimate trekking destination in Iran, offering several trails that include both day treks and multi-day treks.

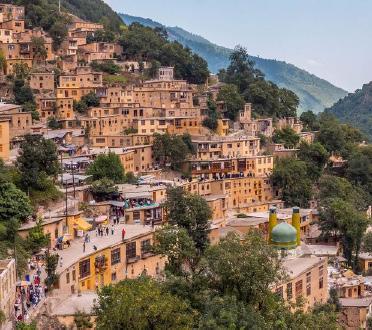

Simonopetra Monastery is an Eastern Orthodox monastery in the monastic state of Mount Athos in Greece. Simonopetra ranks 13th in the hierarchy of the Athonite monasteries. The monastery is built on top of a single rock, overlooking the sea 330m above. Currently, it houses 54 monks. Its hegumen is Archimandrite Eliseus.

Mounth Athos, Greece, 13th Century

Mounth Athos, Greece, 13th Century

Emperor Muhammad Shah rekindled an imperial interest in Hinduism that had not been so strong since the time of Akbar, 150 years before. He commissioned this painting that shows the acts of Rama, hero of a Hindu epic, who slays the demon of the golden city of Lanka at the top of the page. In the middle sections, various Hindu deities enjoy music, kite flying, and boating, while at the bottom the Krishna plays Holi with his lover Radha and other palace women. They shoot red-colored water at one another with plunger guns in celebration of the coming of spring.

Delhi, India, Mughal, 18th Century

Delhi, India, Mughal, 18th Century

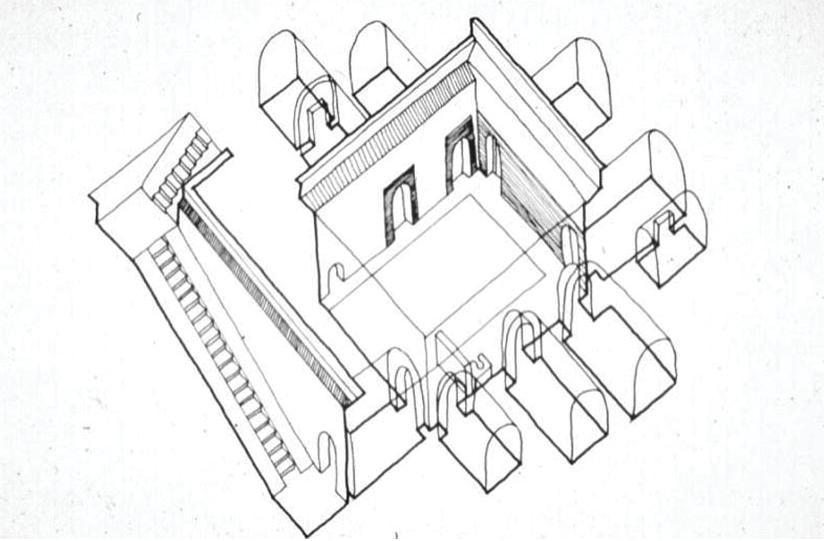

Yaodong dwellings carved in the ground each has a central courtyard surrounded by vaulted rooms constructed by clay walls. The courtyard, sunk in the ground up to 10 meters, serves as the primary source of natural light as well as the main distribution units. Mostly the guest rooms face the south, the kitchen and family room located on the east side. Each cave is covered with at least 2 meters of each. An interior corridor connects the sunken slope with a stair to provide access to the courtyard.

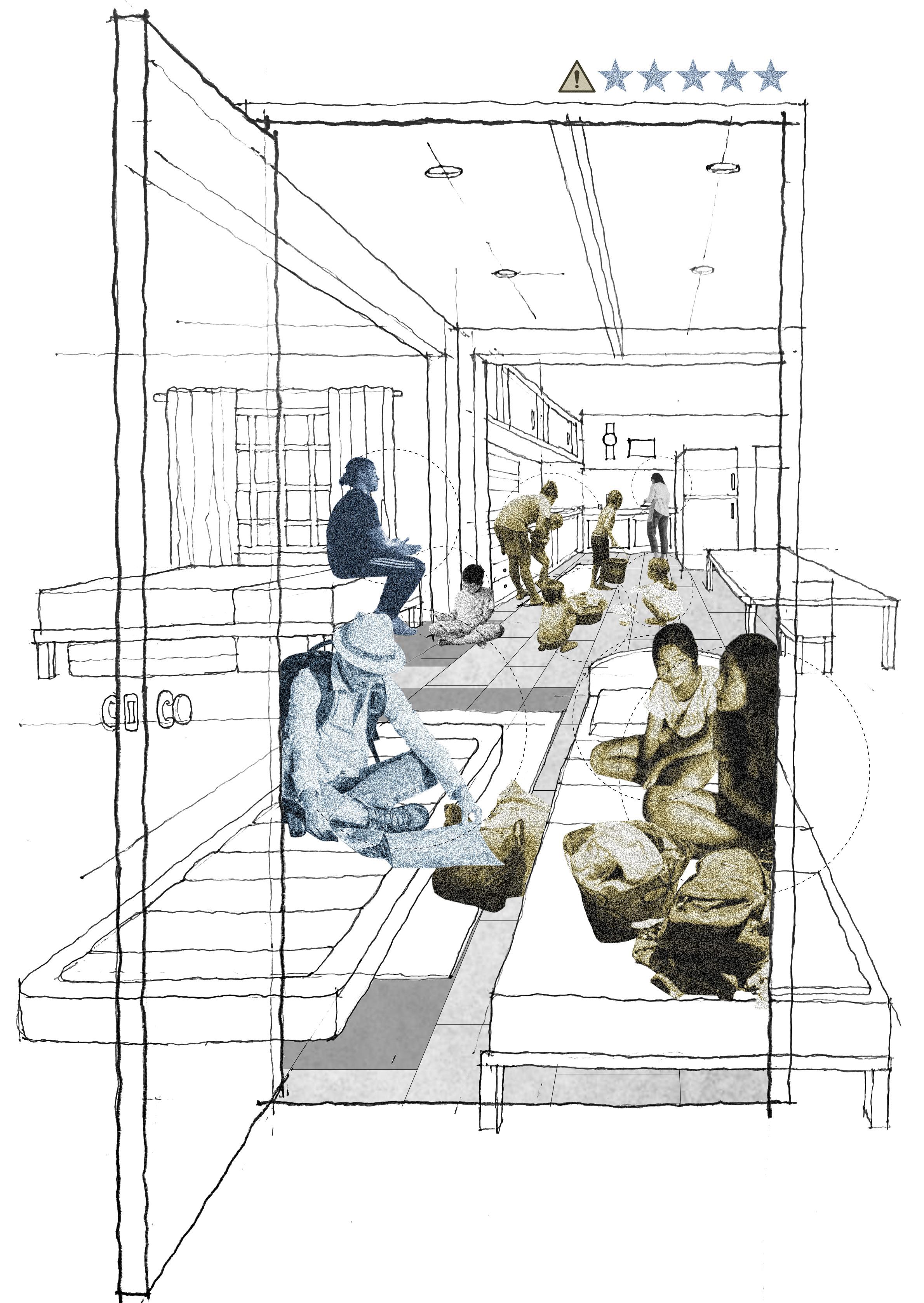

Upper Image: Market in Manila, Philippines

Numerous market stalls are densely packed in a large, open structure.

Lower Image: Shigeru Ban’s evacuee shelter intervention in Japan

Simple boxes and curtains are used to divide a gym into rooms to accommodate evacuees.

Kyoto, Japan, 1510

This illustration is one of the fifty-four paintings from the Tale of Genji by Tosa Mistunobu from 1510. The scenes depict the architecture and life in the captial city of Kyoto during the Muromachi Period. This representation style of blown off roofs (fukinuki yatai) reveals the interior and its relationship to the surrounding natural environment.

The Andes are some of the tallest, starkest mountains in the world. Yet the Incas, and the civilizations before them, coaxed harvests from the Andes’ sharp slopes and intermittent waterways. They developed resilient breeds of crops such as potatoes, quinoa and corn. They built cisterns and irrigation canals that snaked and angled down and around the mountains. And they cut terraces into the hillsides, progressively steeper, from the valleys up the slopes. At the Incan civilization’s height in the 1400s, the system of terraces covered about a million hectares throughout Peru and fed the vast empire.

The following precedents look at utopia projects.

The purpose of utopia thinking is to imagine a different reality in which we can ignore the multiple factors that influence lives. It allows for radical creative thinking.

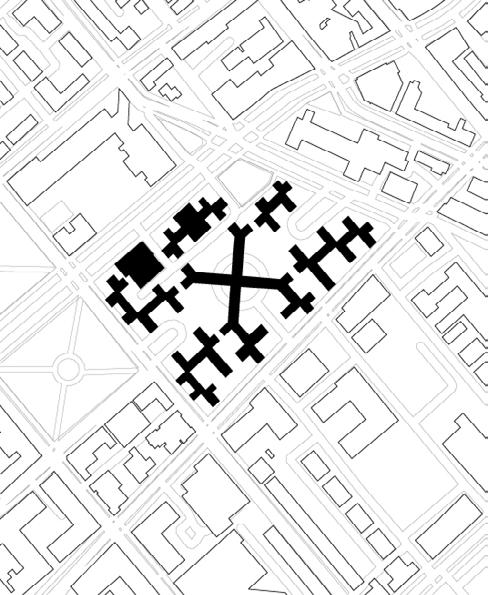

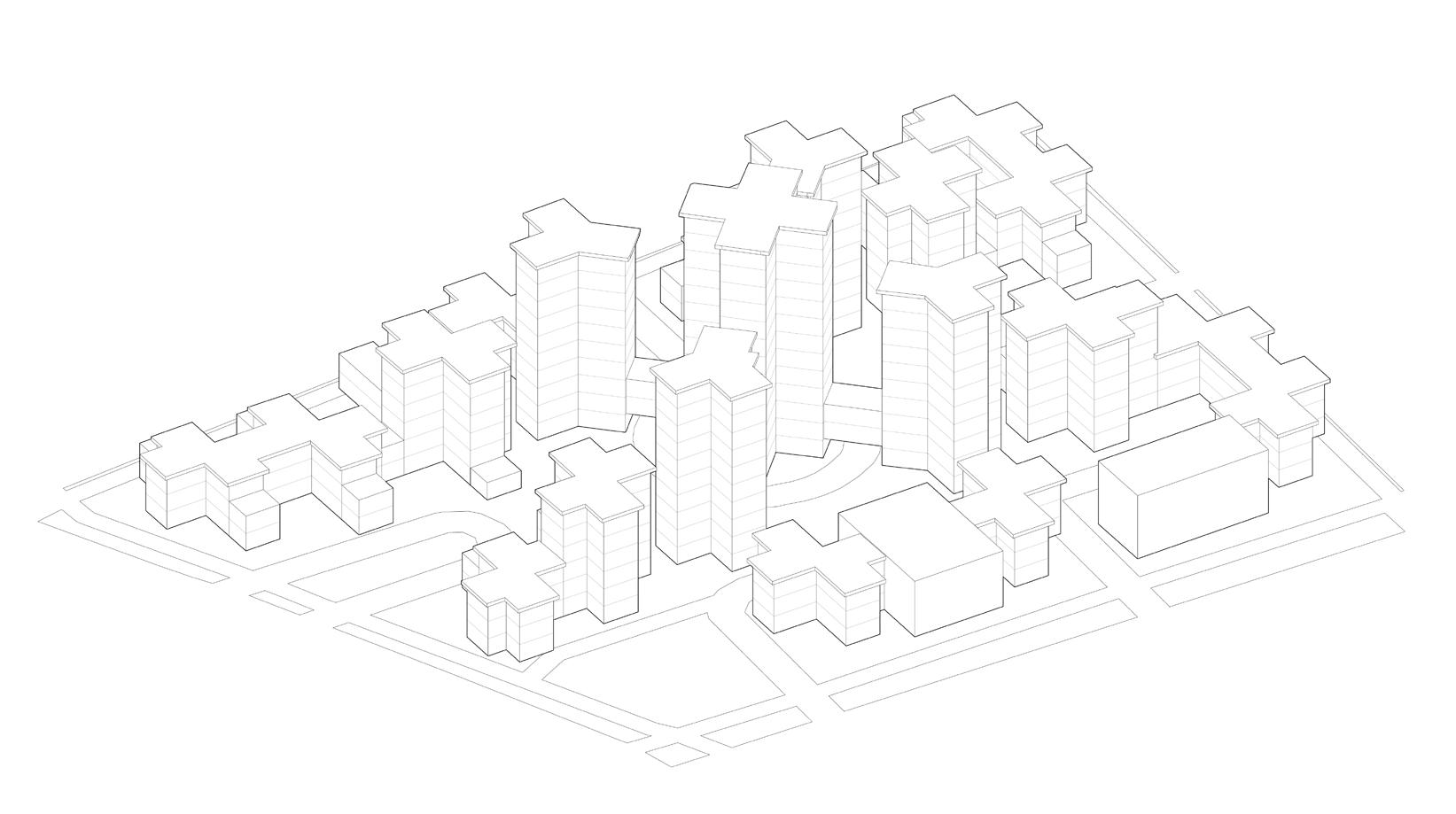

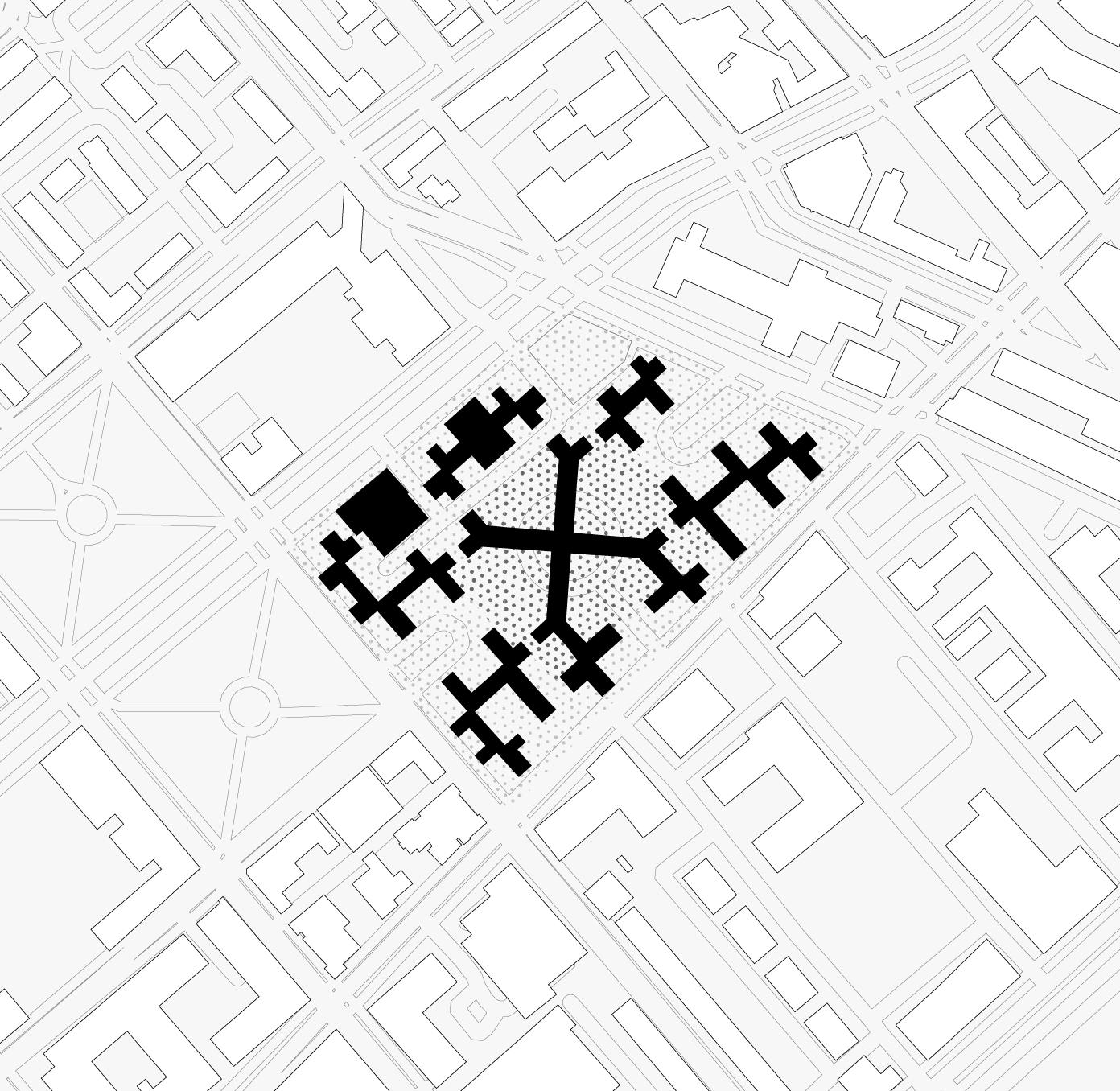

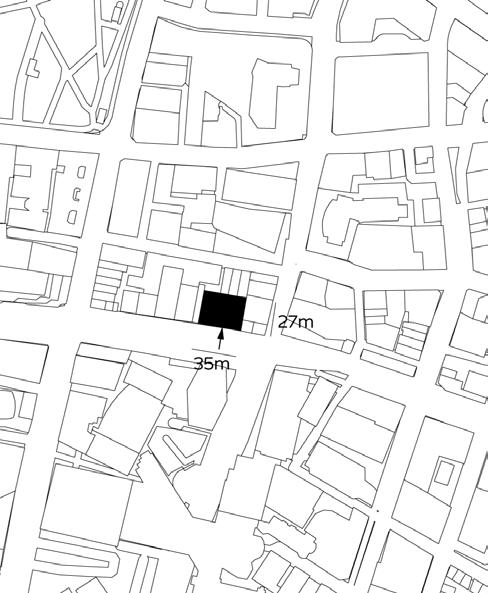

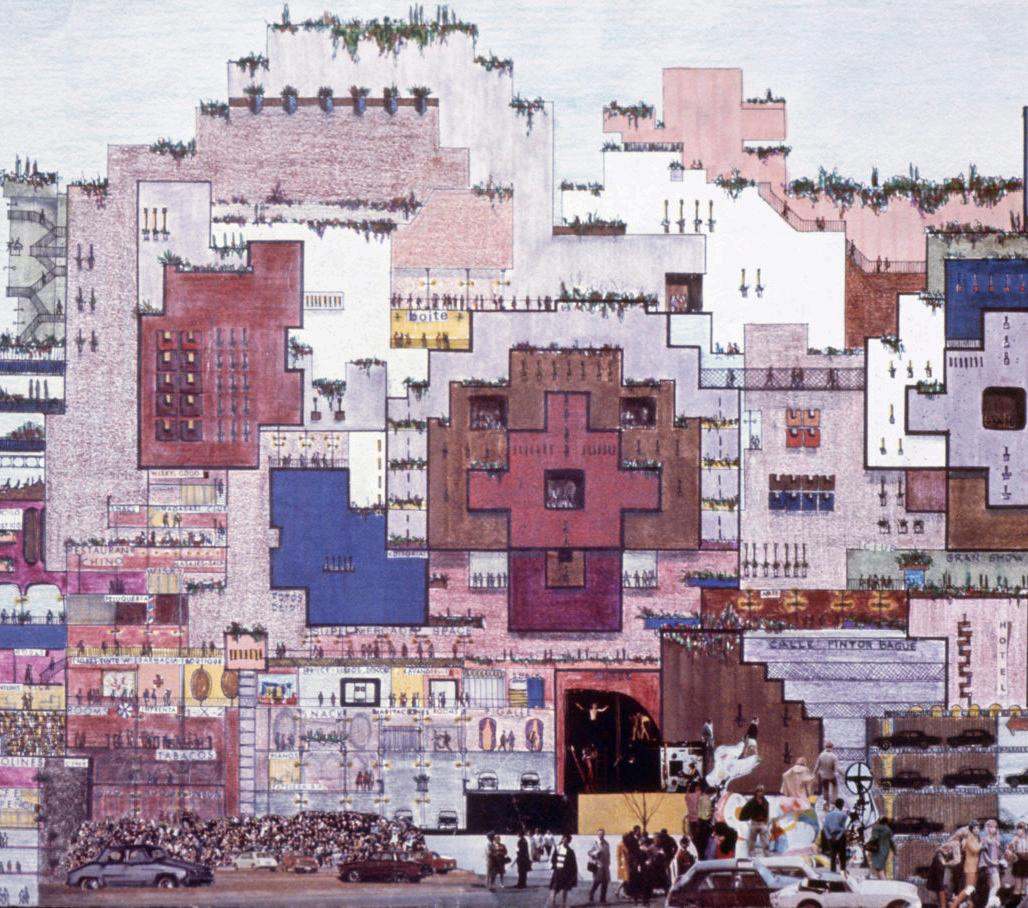

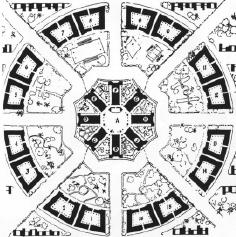

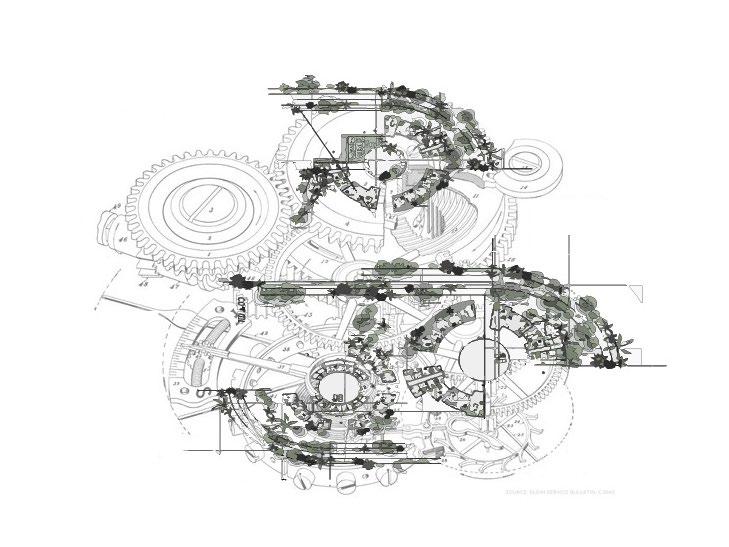

City in the Space by Ricardo Bofill is a housing project proposed for development in Madrid, Spain. The project intended to provide highdensity housing coupled with a system for growth. The design was viewed as a vision for future living, where geometric modular forms could be combined to create shared spaces as well as housing. The key to this plan was to be as flexible as possible in the construction method to take advantage of the norms at the time. A cluster of cubic modules would form true streets, gardens, squares, and arcades without increasing construction costs.

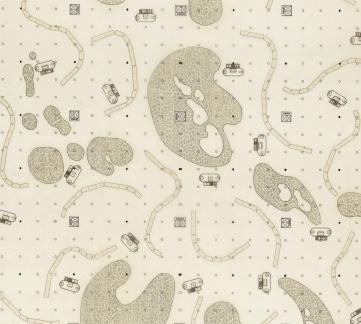

No Stop City was a reaction to modernist architecture. The city is an infinite, featureless grid structure that can be built anywhere, only interrupted by natural elements. The regular grid creates a generic framework, symbolizing walls, that allows for people to build their houses, tents, or campers anywhere they wished. The interconnectedness produced by the uninterrupted nature of the city would restore a human connection that was being lost due to industrialization. Andrea Branzi, one of Archizoom’s founders, explains, “The idea of an inexpressive, catatonic architecture, outcome of the expansive forms of logic of the system and its class antagonists, was the only form of modern architecture of interest to us. A society freed from its own alienation, emancipated from the rhetorical forms of humanitarian socialism and rhetorical progressivism.”

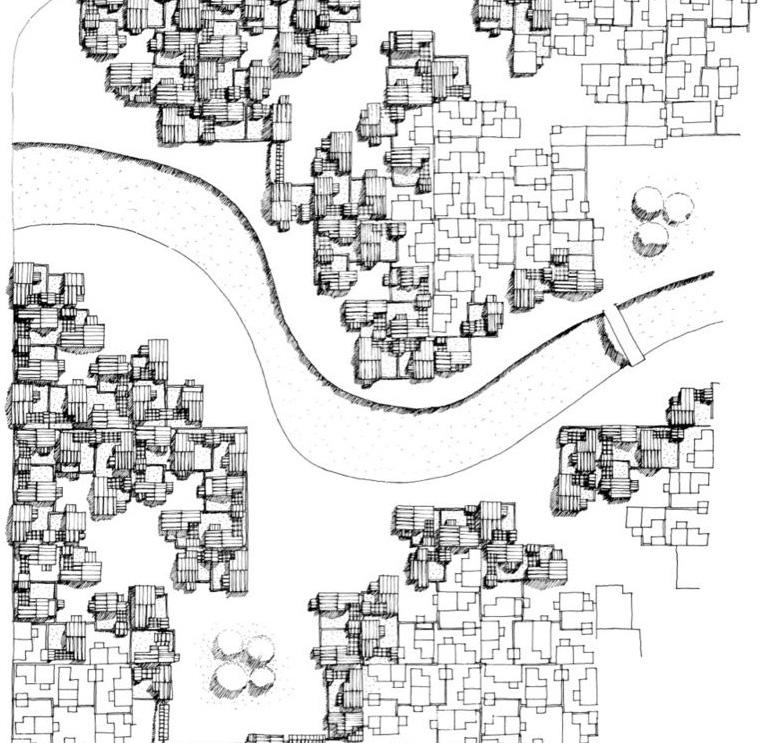

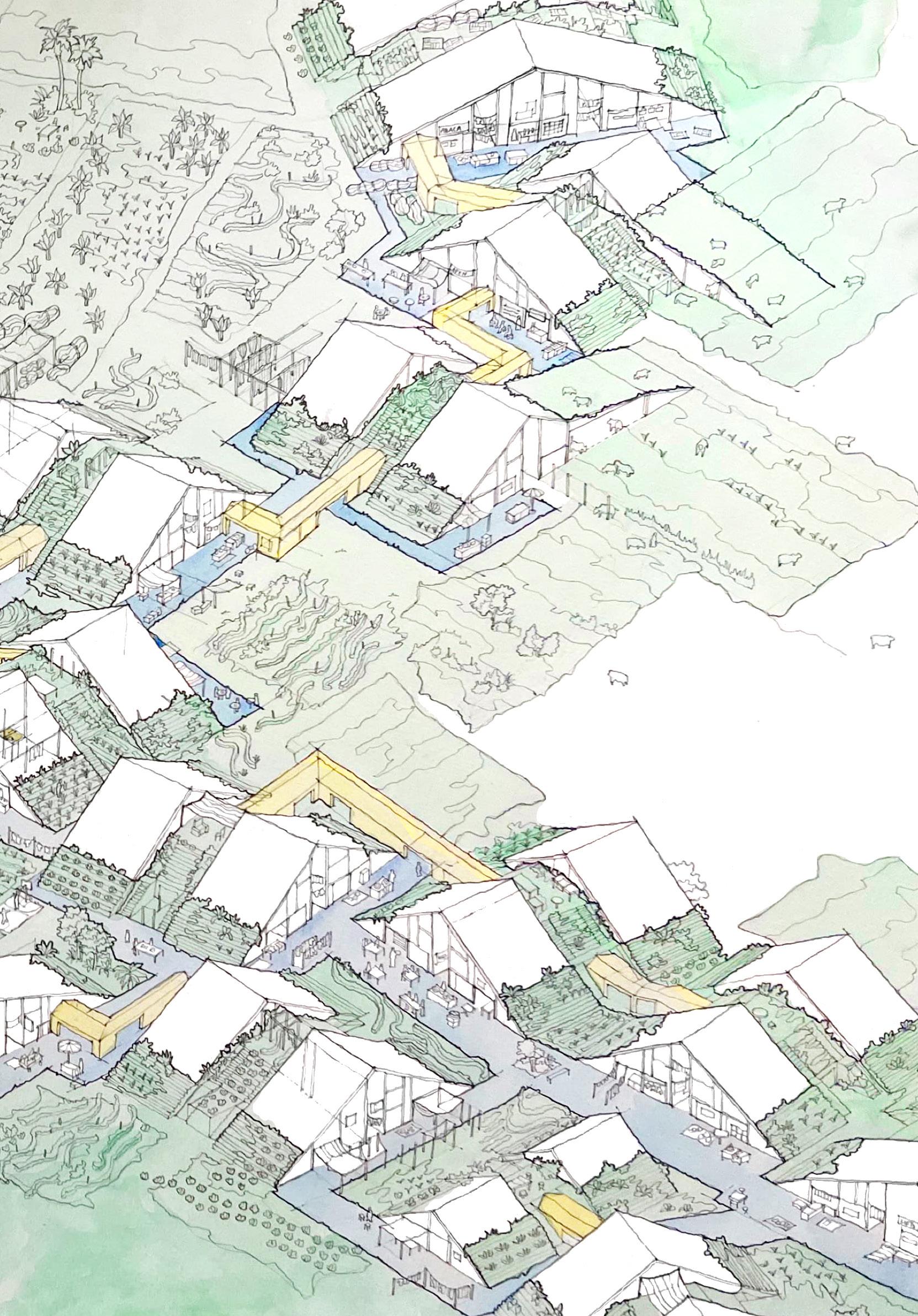

Located in Belapur, India, Charles Correa’s housing project is based around incremental growth of densely situated individual family houses. Each unit, which has its own plot and outdoor space, is allowed to grow to accommodate different needs of different residents. This low-rise and low-cost utopia containts numerous types of dwellings which cluster to form various hierachies and courtyards. The open spaces created by clustering intend to foster community, but they also carry stormwater flows during rain seasons.

Frank Lloyd Wright disliked dense, industrial cities, and wanted to create low-density neighborhoods that consisted of generous plots of land. He wrote an article that explained that the motorcar, telephone, and standardized machine-shop production would allow Americans the freedom to work easily outside of an urban center. He believed that houses should all come with their own plots of land, and that this would help families to grow and eat their own food. Wright developed this idea with his idea of spreading houses throughout the landscape.

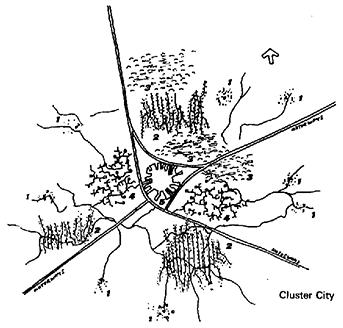

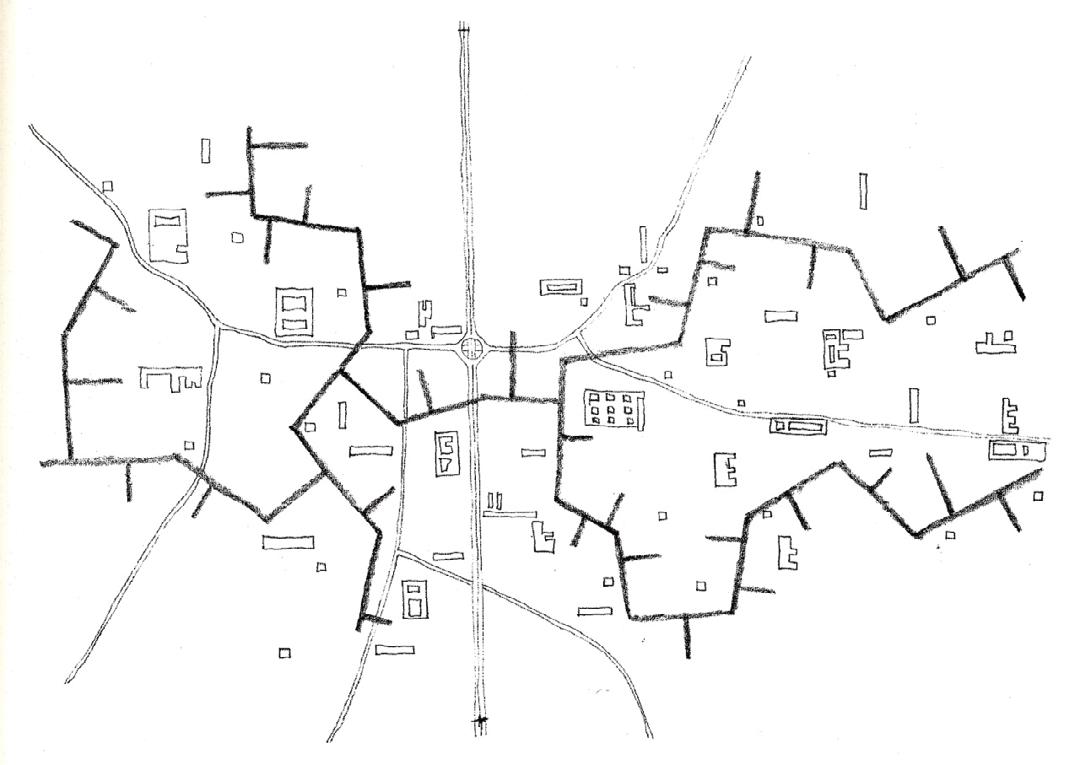

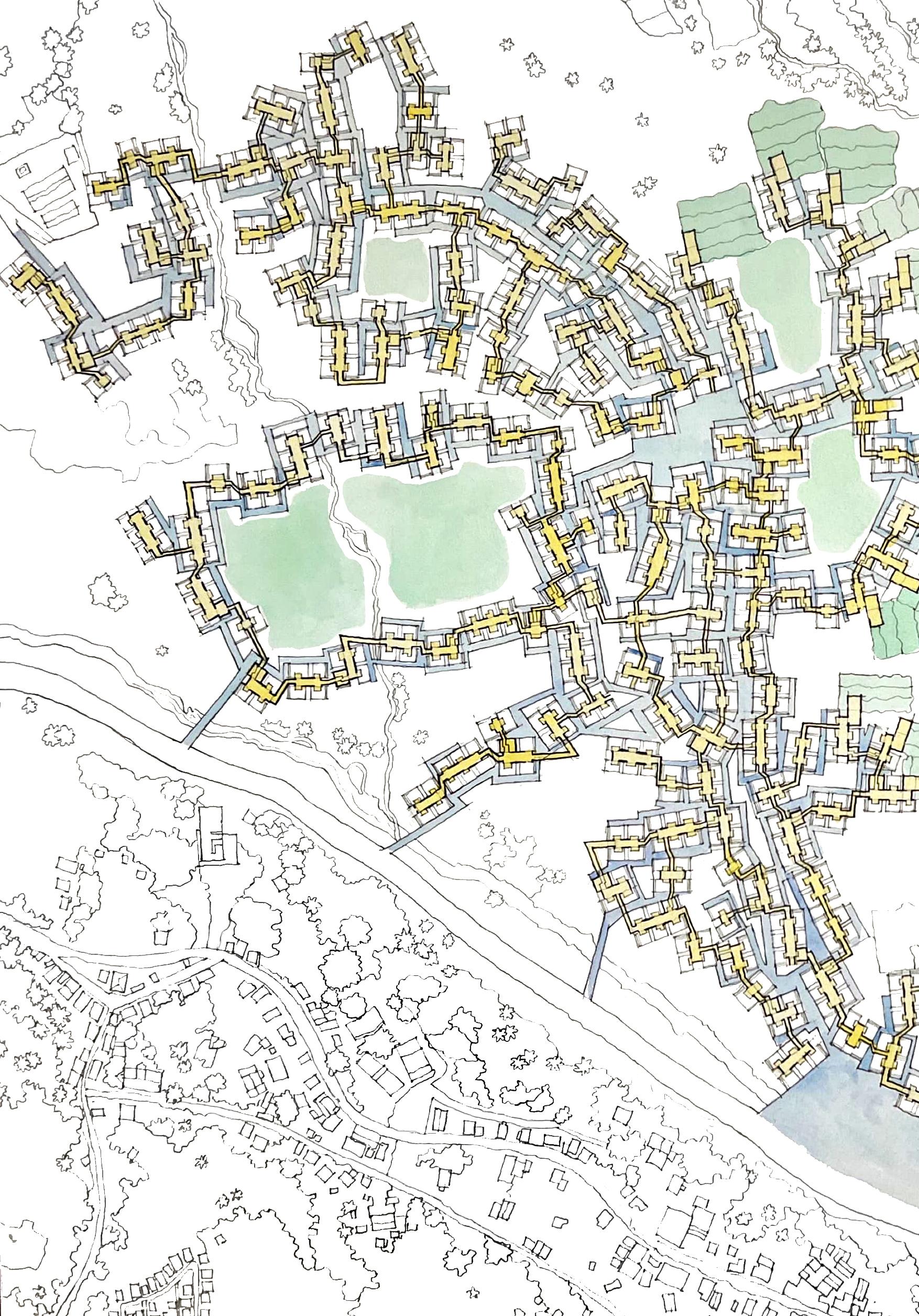

Cluster City is a utopian urban prototype elaborating clusters of street-twigs that programmatically overlaps house, street, district and the city. It represents an effort in establishing connections and spatial engagement through the introduction of a new programme; an architectural archive. A mix of activity is therefore developed between the public and private realm of the residential and the institutional, framing a socially-engaging urban network. This theory later influenced an American speculative fiction author, Ursula K. Le Guin. In her discription of city less as a machine, but rather as a network or an organism, she said the city testifies to values such as rationality, efficiency, proximity, interrelations, walkability, and organicity.

Alison and Peter Smithson, 1952

Alison and Peter Smithson, 1952

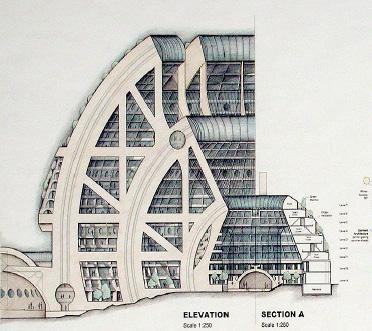

An ambitious project envisioned as an experiment in living frugally and with a limited environmental footprint, Arcosanti is an attempt at a prototype arcology, integrating the design of architecture with respect to ecology. Based on a set of four core values that include Frugality and Resourcefulness, Ecological Accountability, Experiential Learning, and Leaving a Limited Footprint. The Cosanti Foundation operates Arcosanti as a counterpoint to mass consumerism, urban sprawl, unchecked consumption of natural resources, and social isolation.

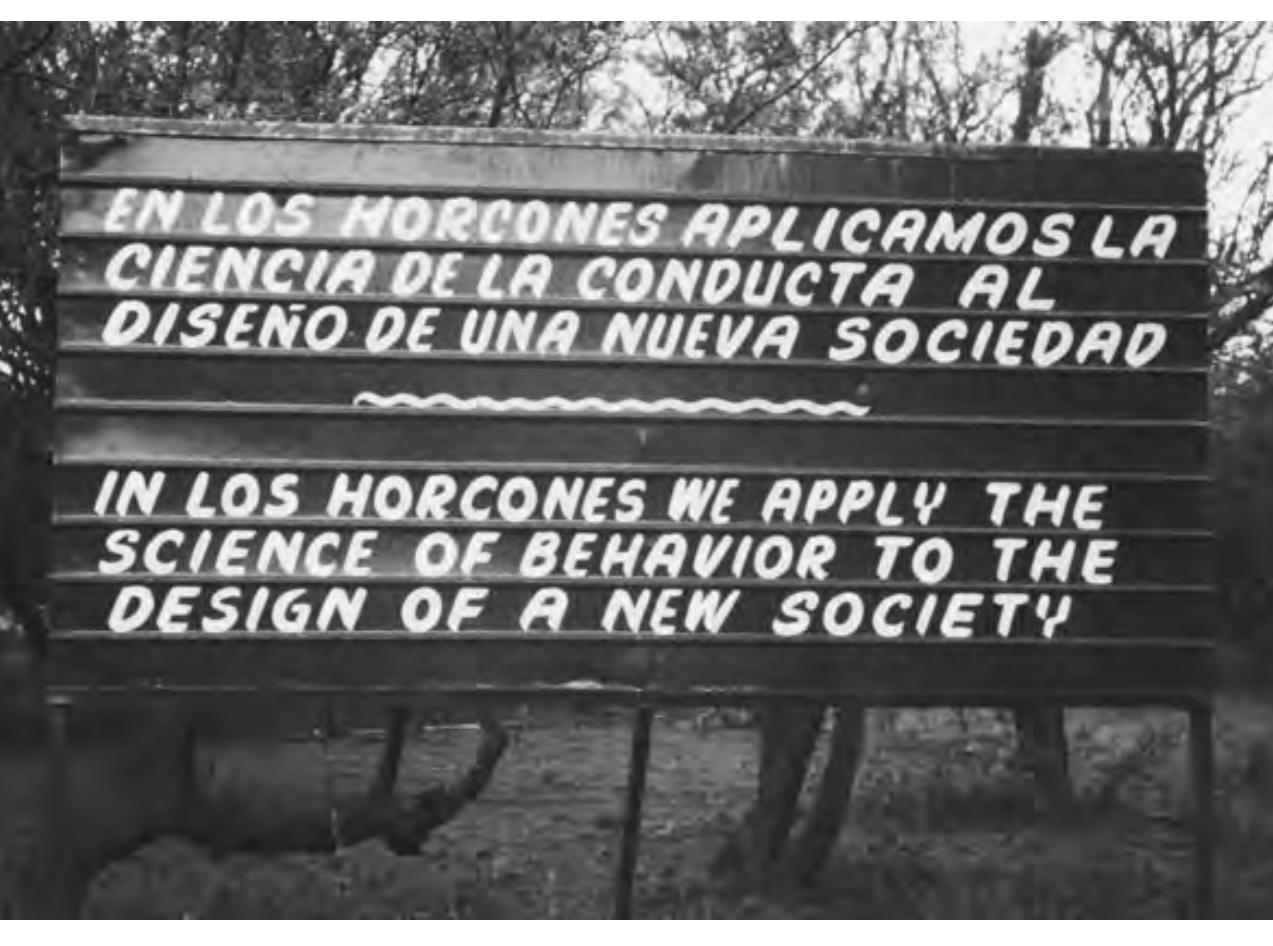

Los Horcones was a utopian behavioral community based on B. F. Skinner’s Walden Two. Members of the community shared all of their services and belongings; instead of referring to something as “my x,” they grew accustomed to saying “the x that I’m using.” Community members also shared parenting duties, and anyone besides the biological parents who became influential in one’s upbringing was known as a “behavioral parent.” Meals were shared in the communal dining room. There was no formal schooling; rather, all experiences throughout the day were considered educational.

During a time when industrializing Tokyo began experiencing urban sprawl, the emerging Metabolist movement advocated for a contemporary city symbolic of growth and regeneration. Kenzo Tange rejects the concept of a metropolitan city center in favor of a linearity referred to as a “civic axis.” This civic axis enacted in Tokyo Bay proposed that at each stage of development of a larger system, units are added continuously: the future axis of Tokyo would gradually extend over its bay. This planning of the city fixes a minimal infrastructure where development can take place, wherein transience is not simply allowed but encouraged to occur.

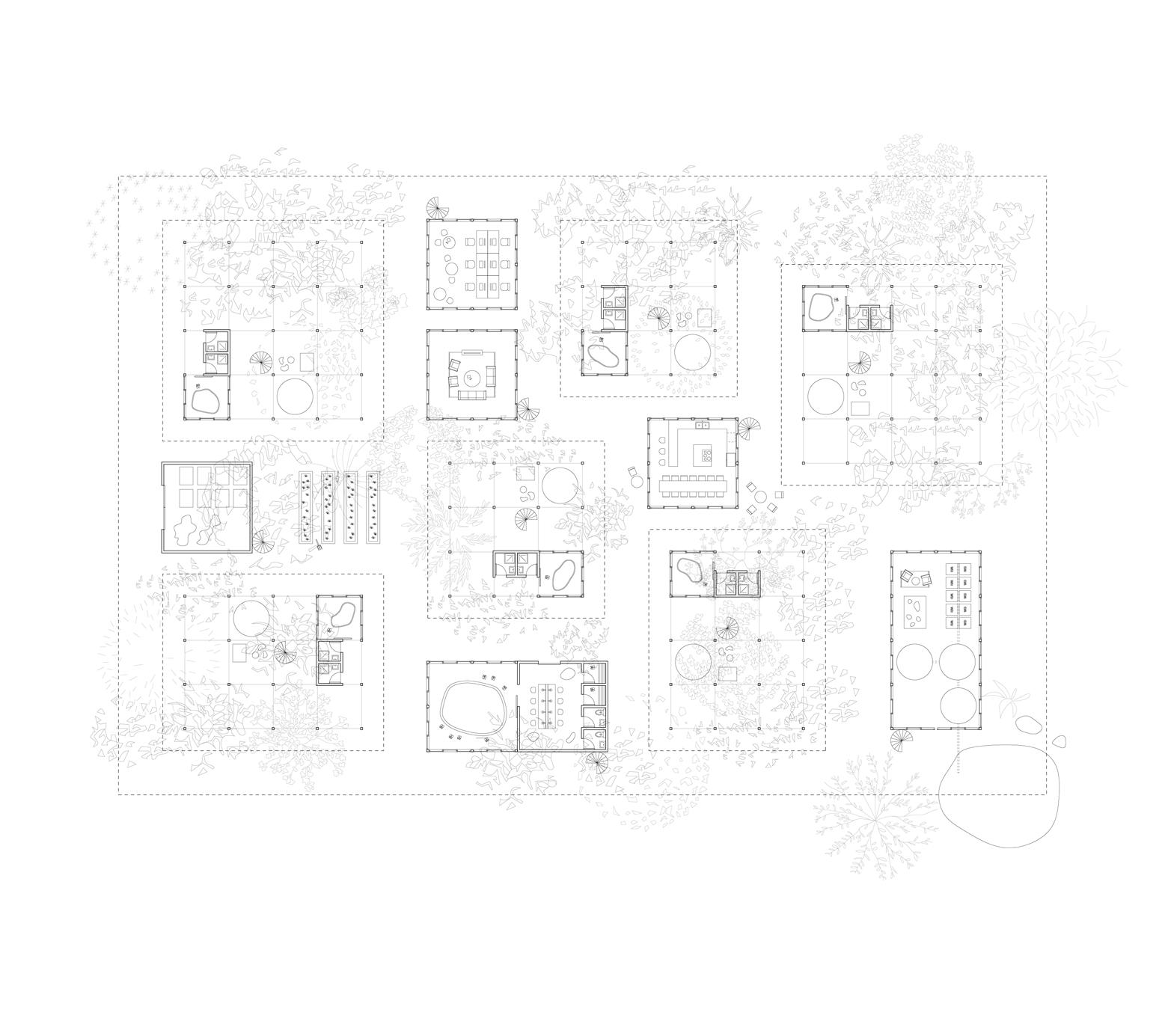

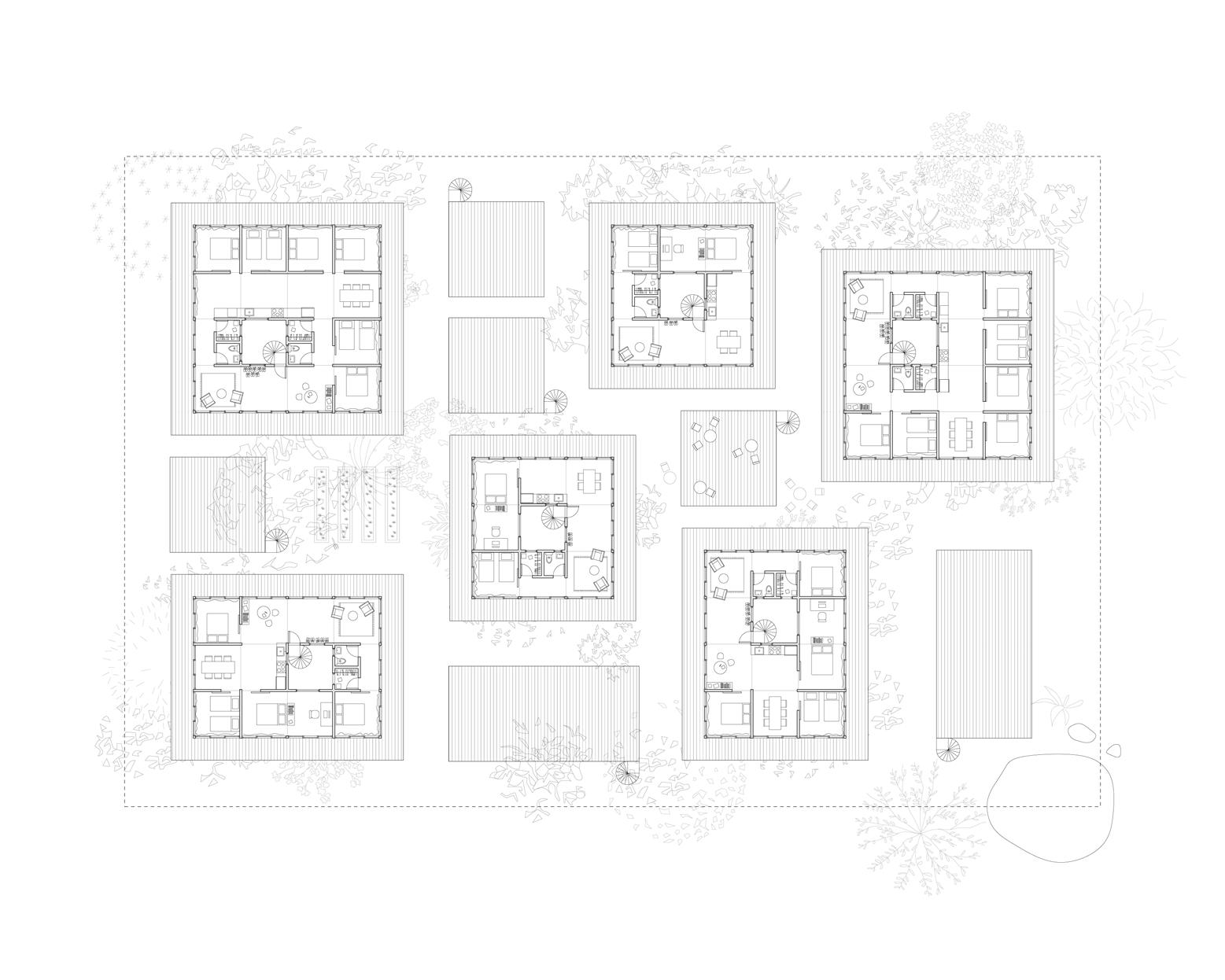

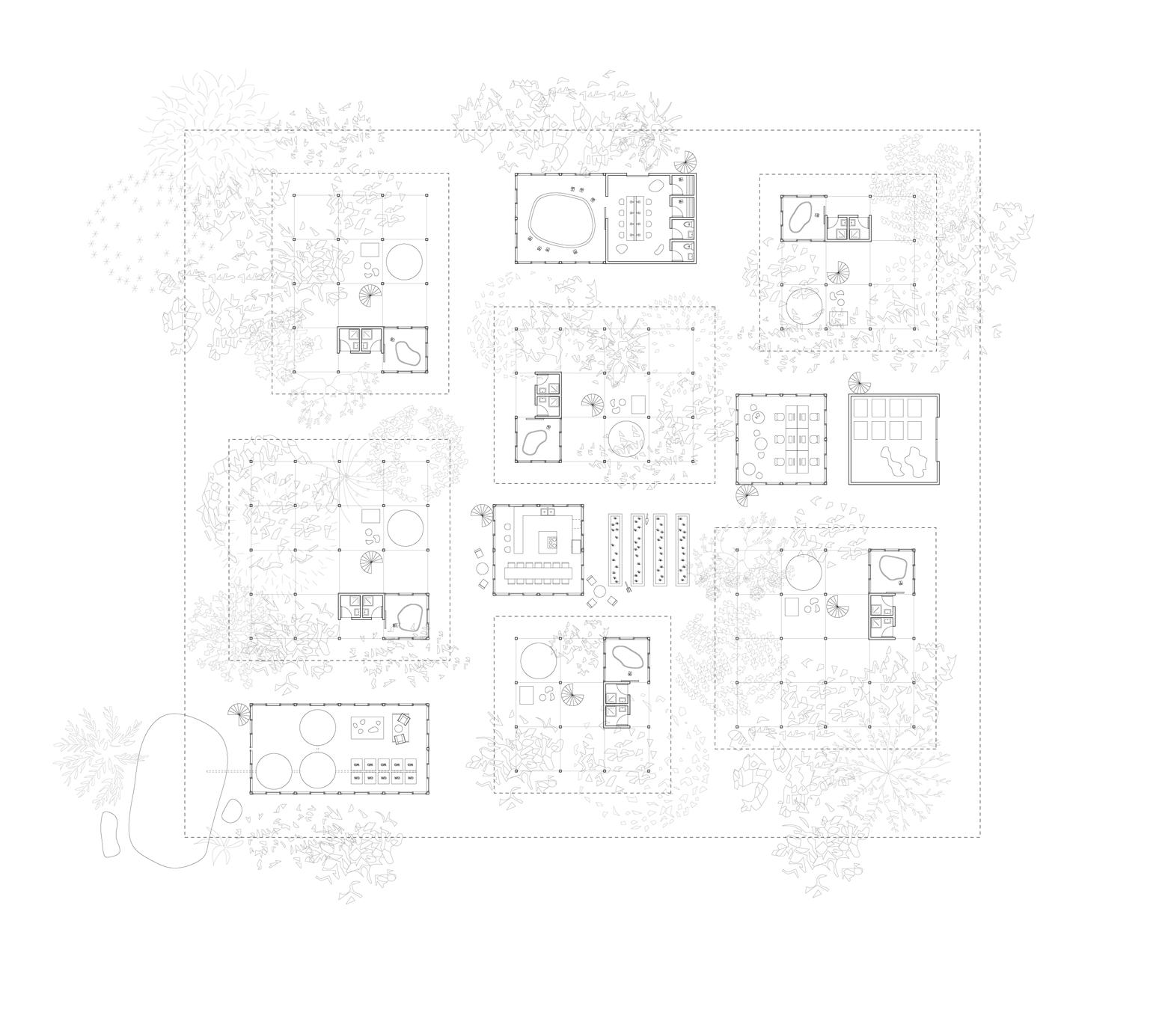

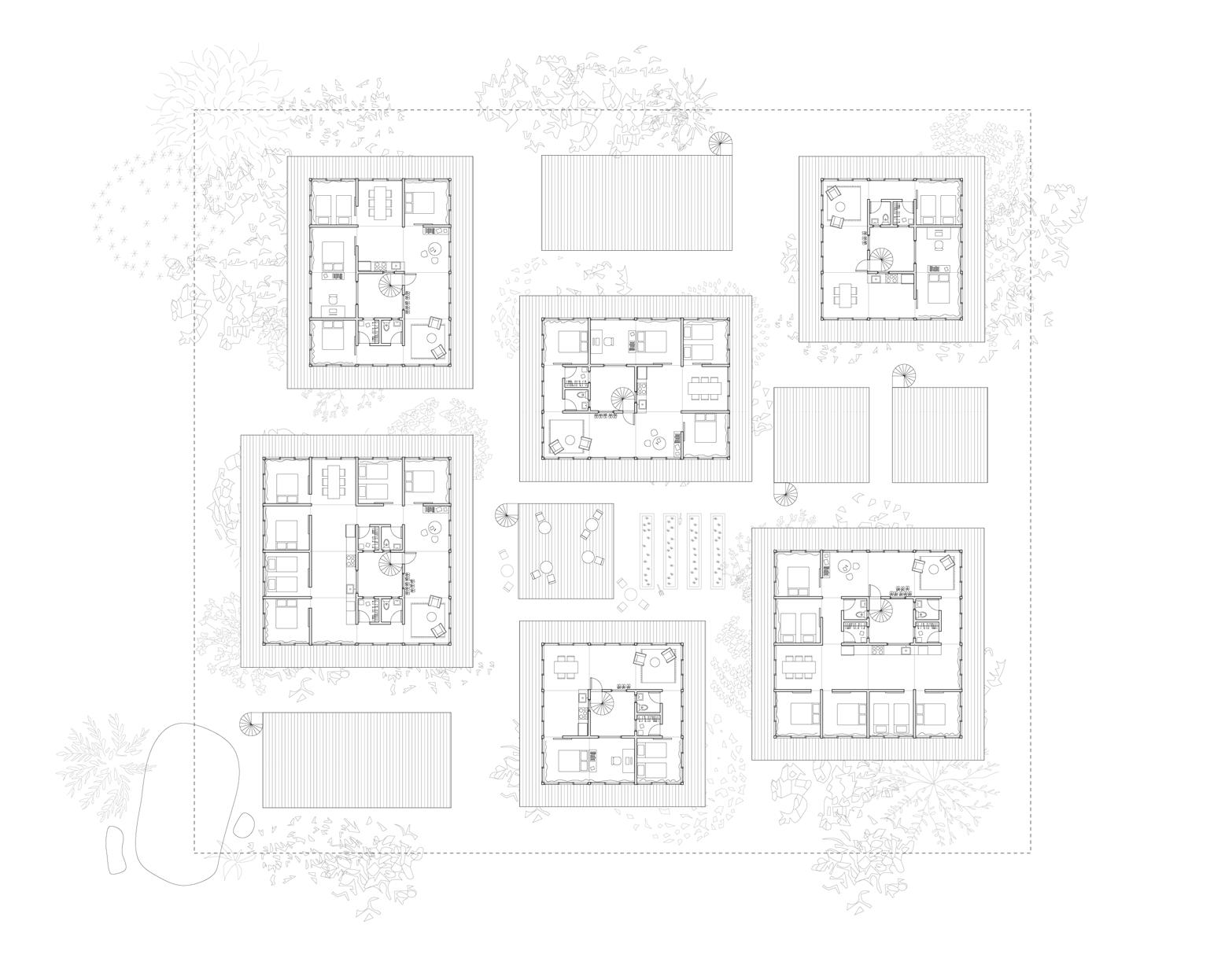

Kisho Kurokawa envisioned “Agricultural City” in 1960 as a proposal to replace the agricultural towns in Aichi, Japan that were destroyed by the Ise Bay Typhoon in 1959. The 500 meters by 500 meters structure is raised above the ground for flooding and agriculture and is designed to support a rural community with a shrine, school, and urban systems.

“Each of the square units composed of several households is autonomous, linking these units together creates a village. The living units multiply spontaneously without any hierarchy, gradually bringing the village into being as the traditional rural settlement has developed throughout Japanese history.” – Kisho Kurokawa

Kisho Kurokawa, Japan, 1960

Kisho Kurokawa, Japan, 1960

Alice Constance Austin designed a city plan with a kitchen-less house moving the domestic labor of women to the shared, common space. Separating the service and served, this ideal city promoted innovations in food preparation and transportation between civic and private spaces. Austin’s plan for utilized design strategies that propose the architect’s introduction to precedents such as Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City in the United Kingdom. The location of all major civic buildings: from education to assembly allows for citizens to congregate at the center of the city plan, with residences appearing in the outer rings.

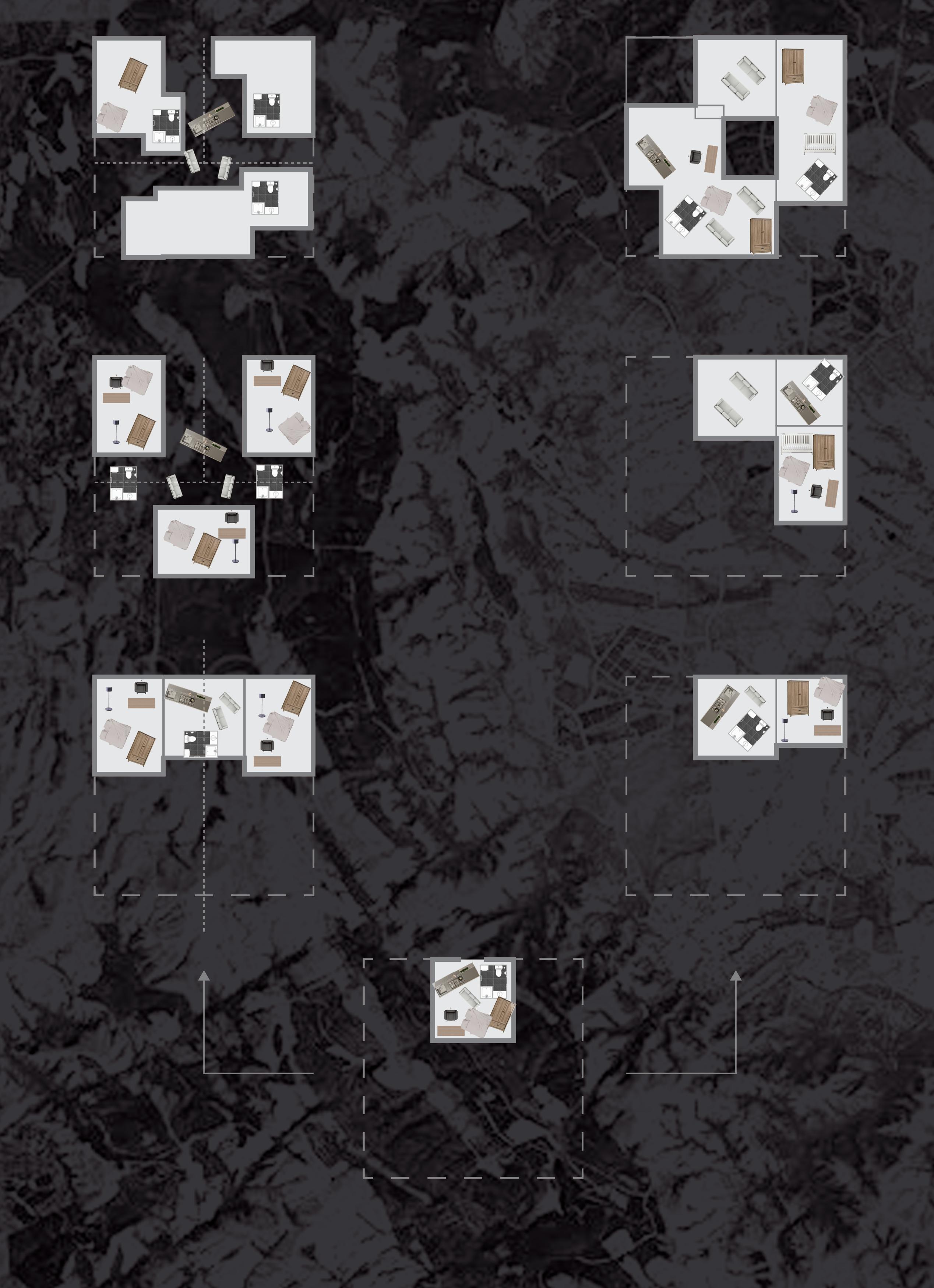

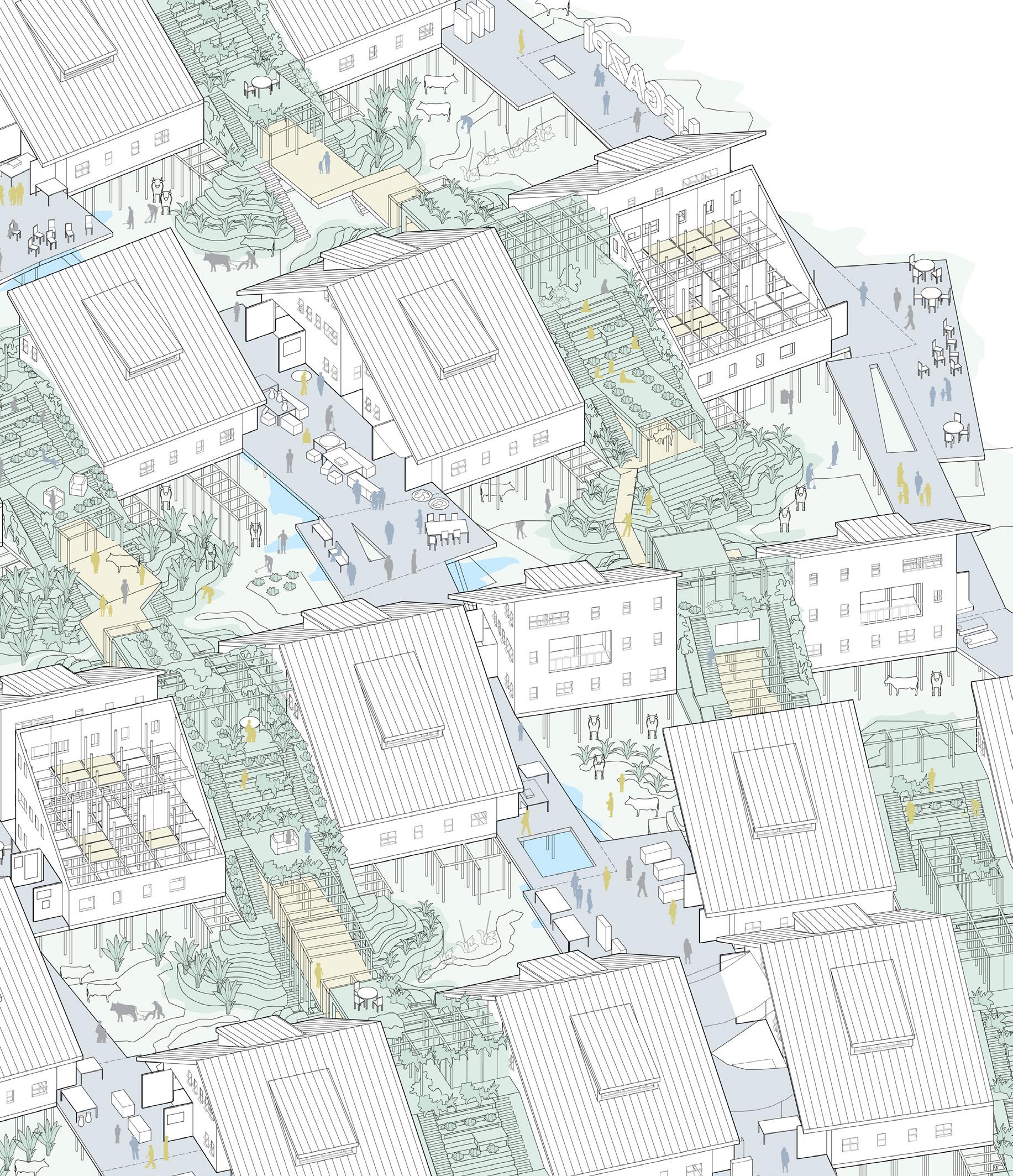

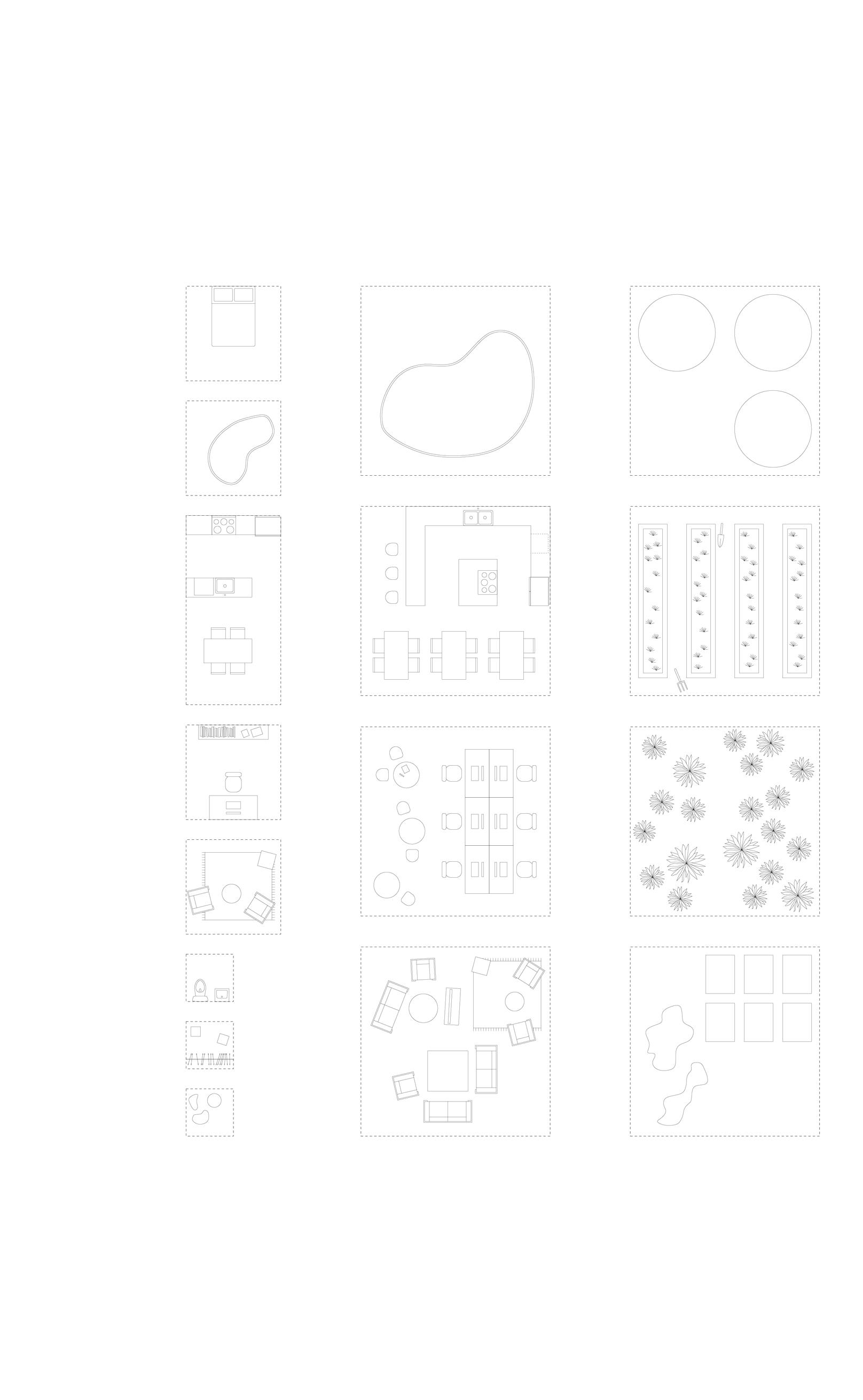

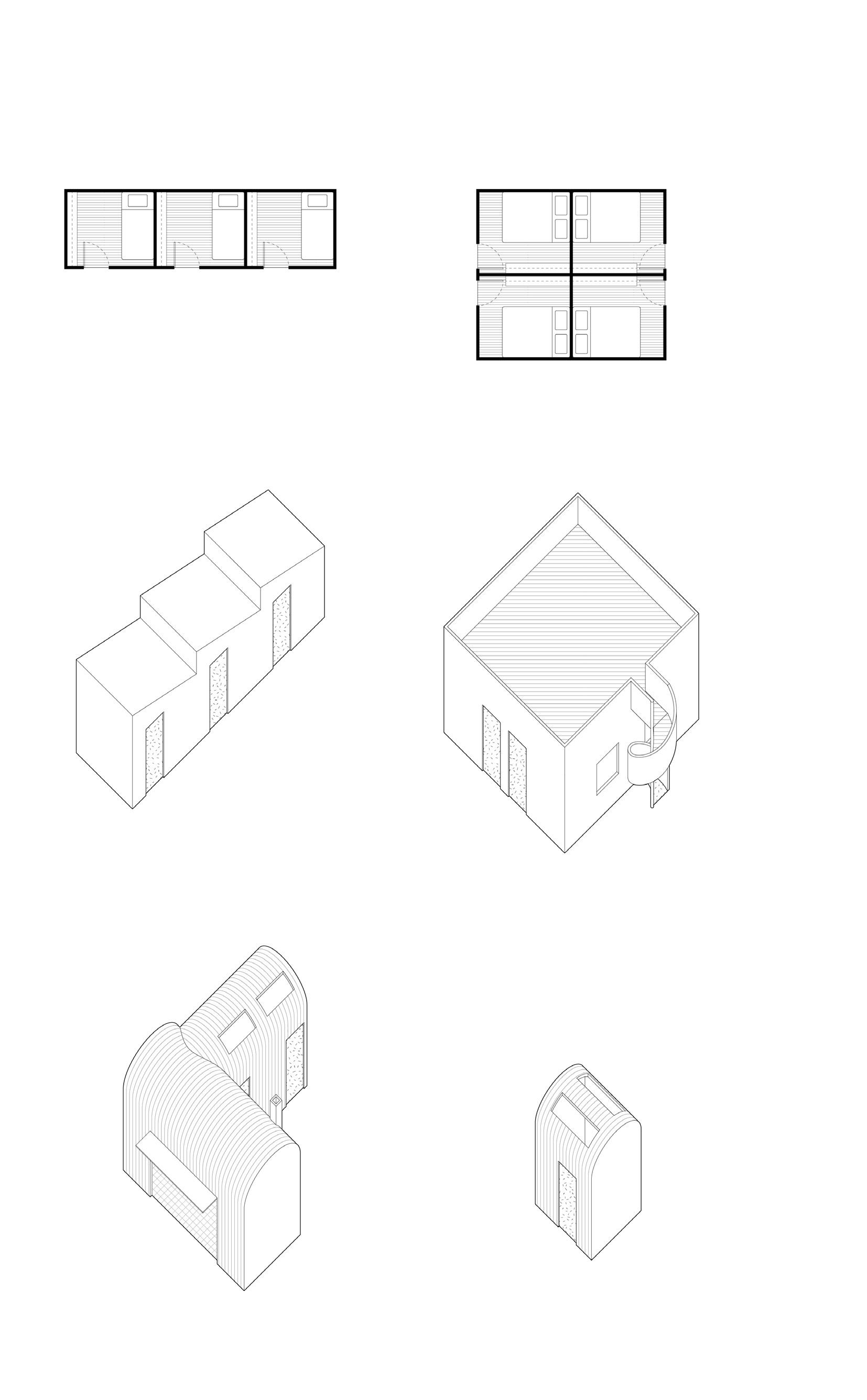

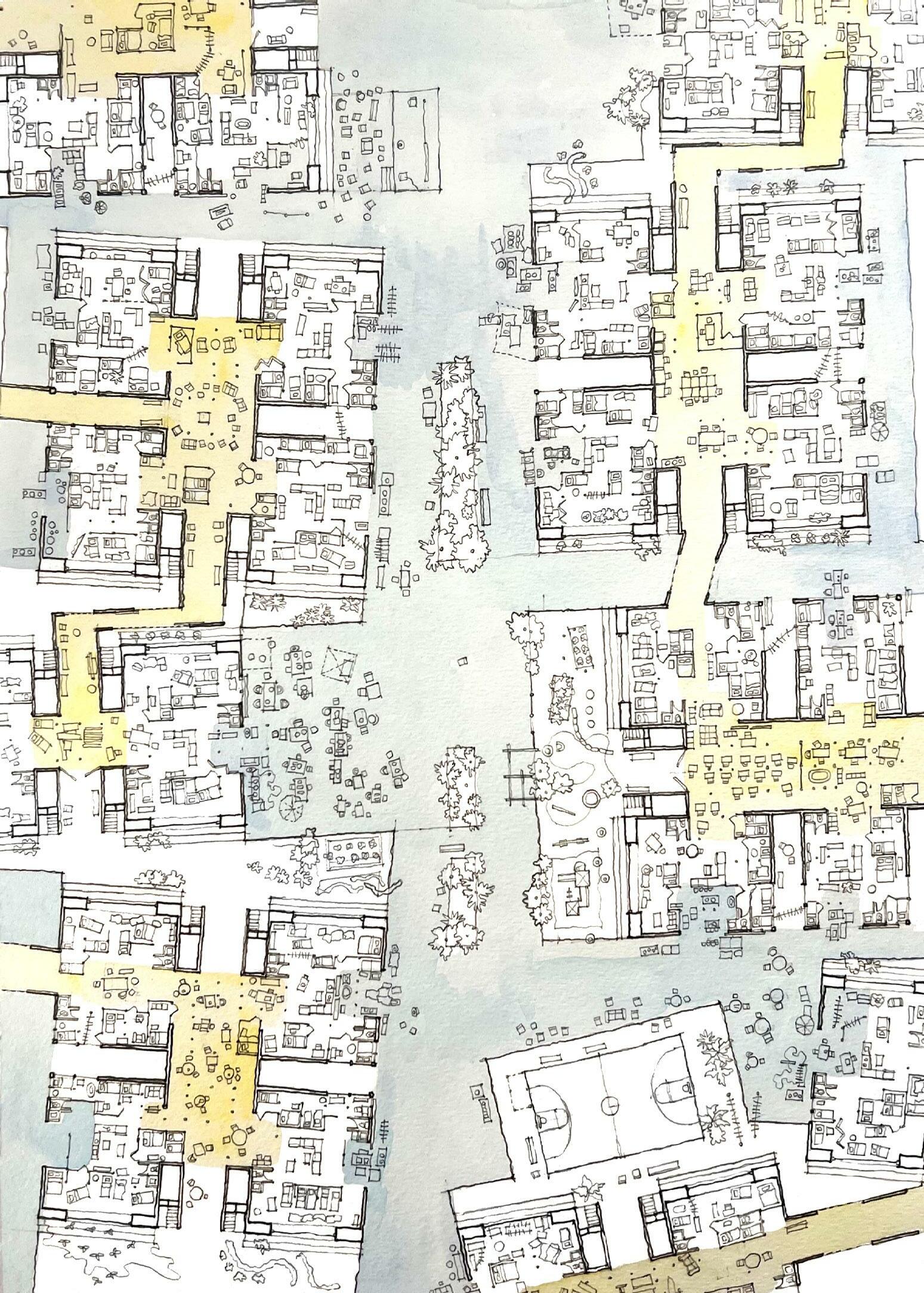

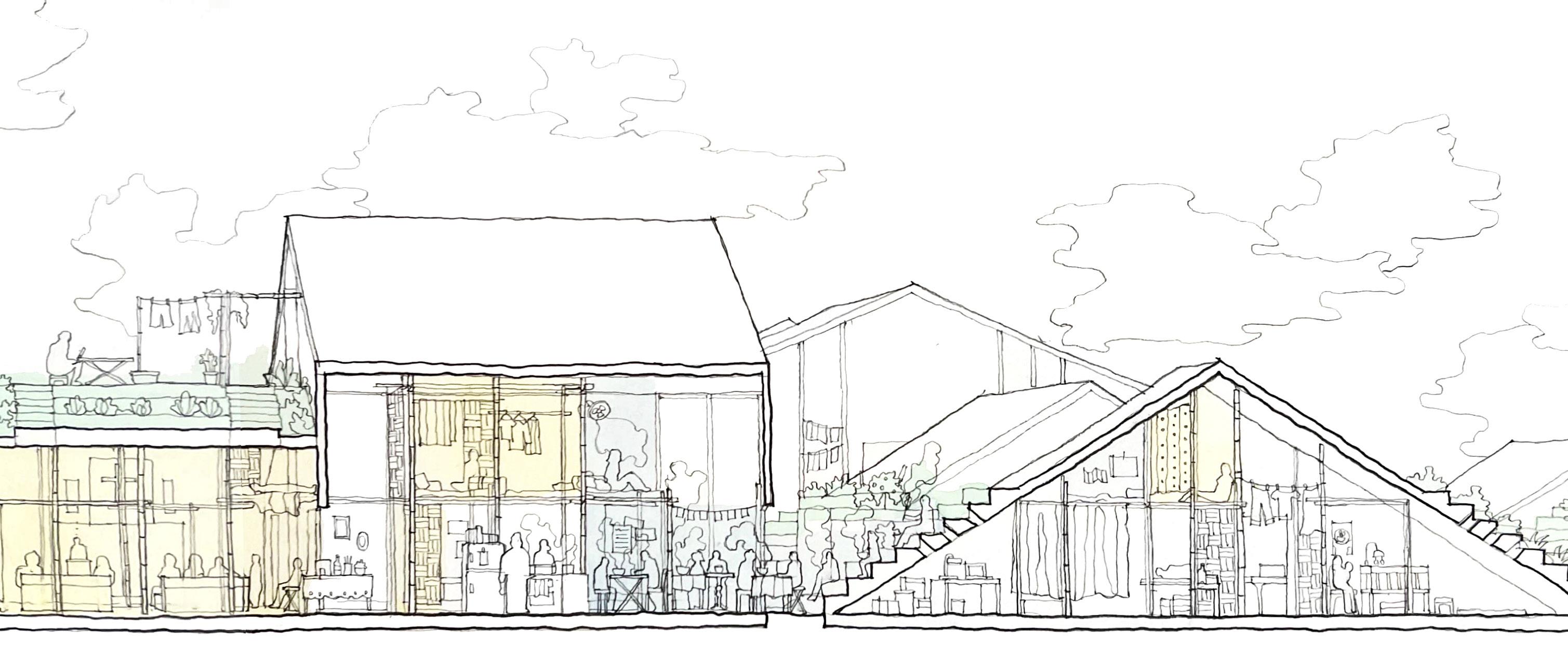

Students are tasked to view architecture not only as an individual buildings, but also as its housed elements and collective infrastructure redefining notions of habitation as well as challenging the typical definitions of seclusion and enclosure, public and private.

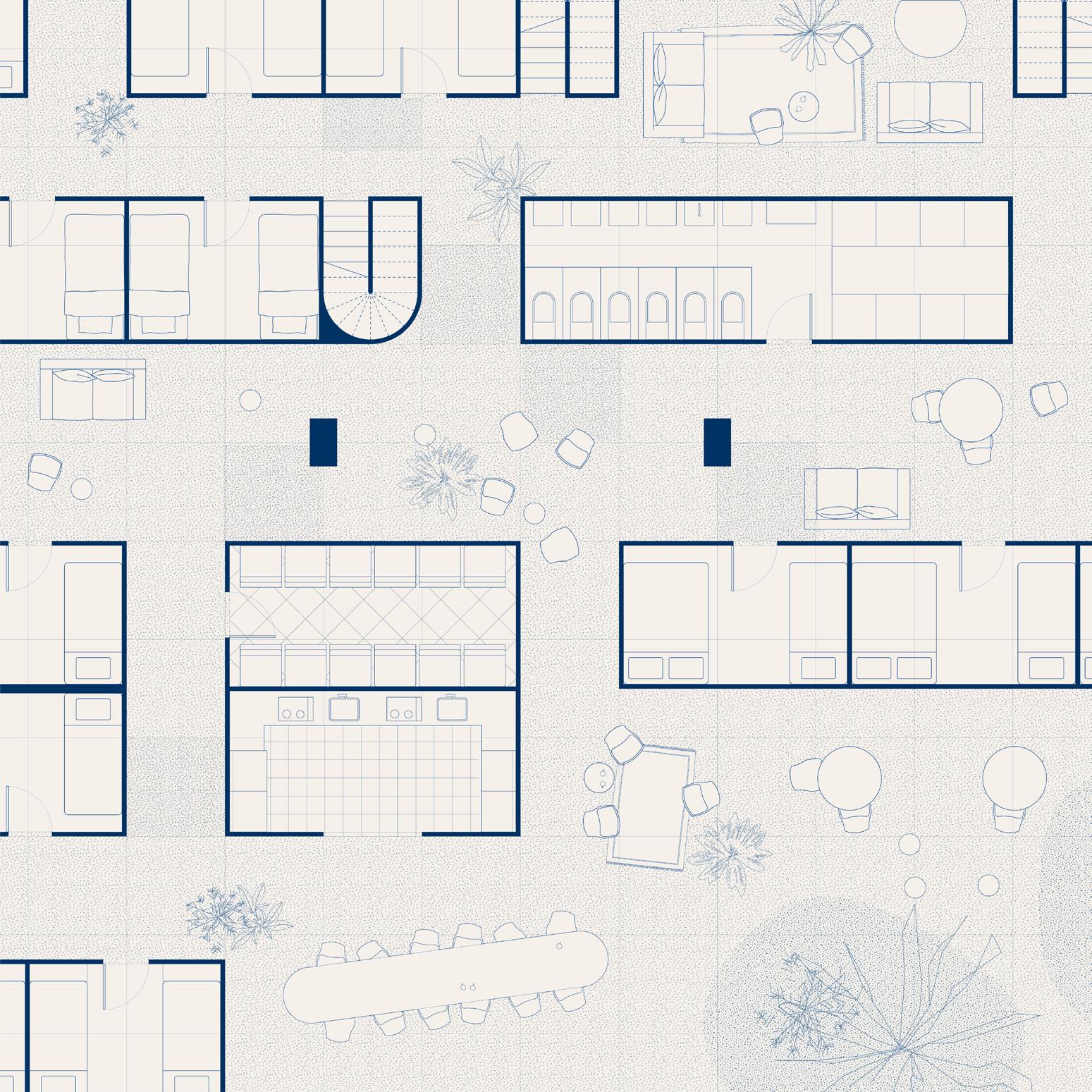

Asked to define elements of a shelter - a bed, a piece of furniture, basic components that provide safety and privacy - students critically rethink forms of subtraction, addition, and re-use. With 1,000 beds the studio means to redefine livelihoods through combining services and densifying housing spaces.

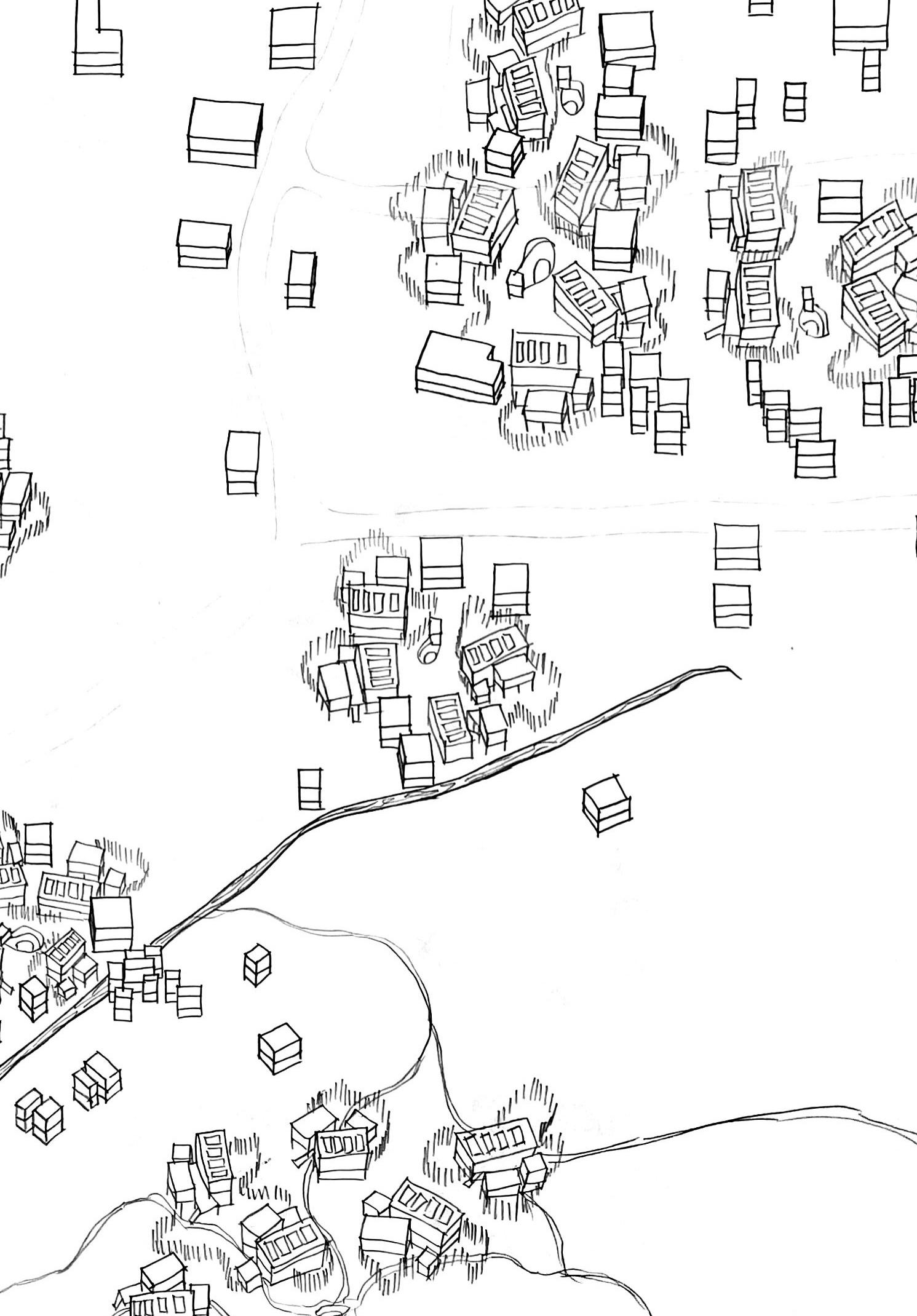

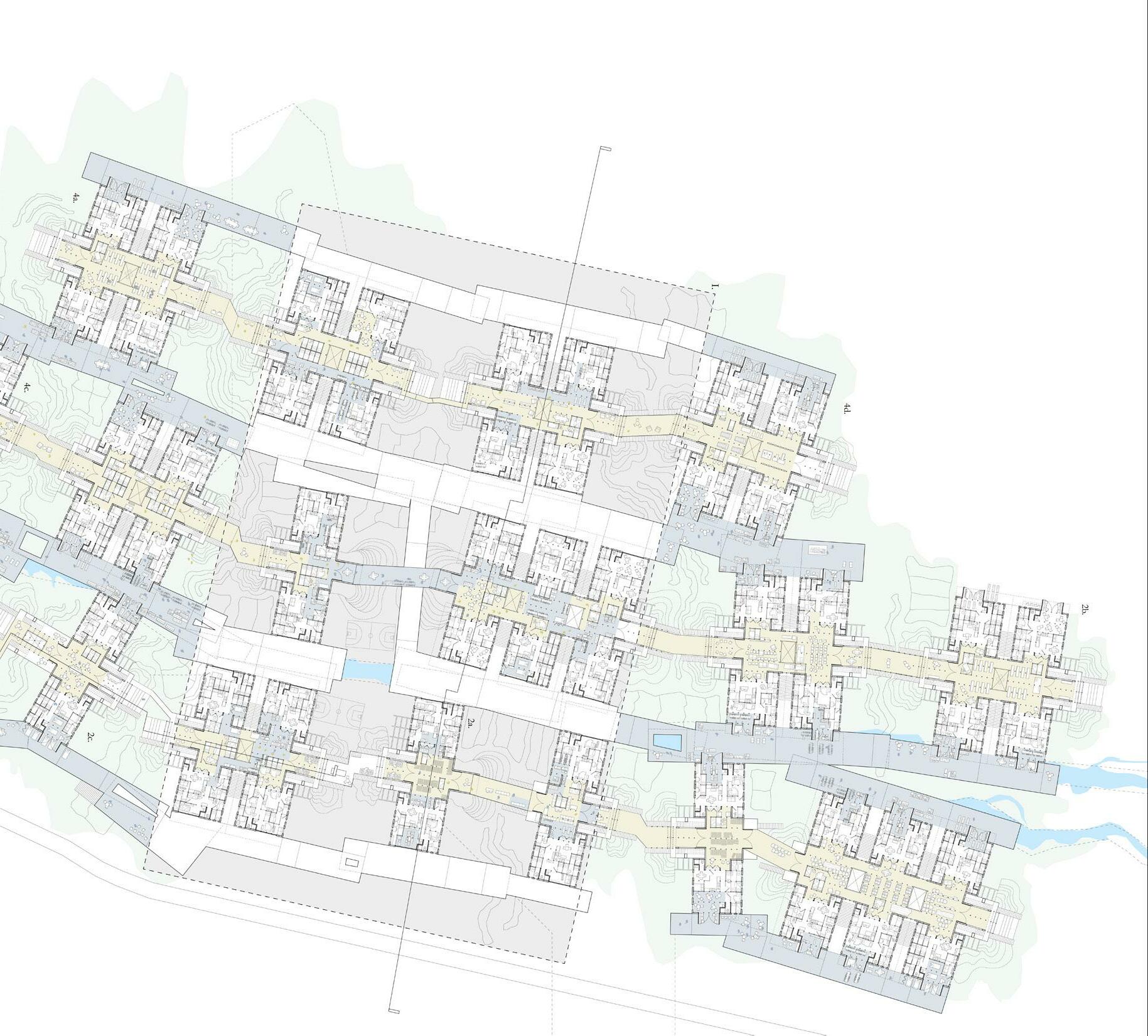

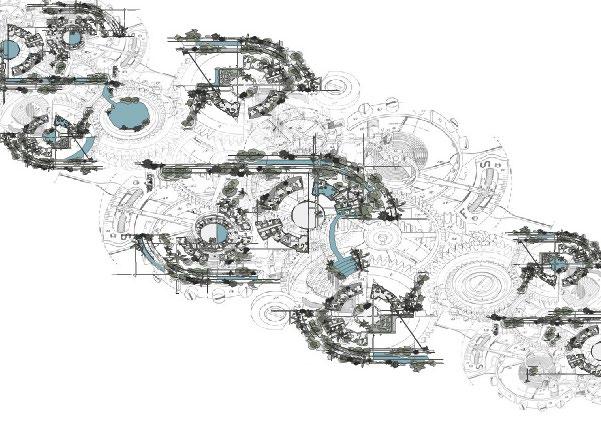

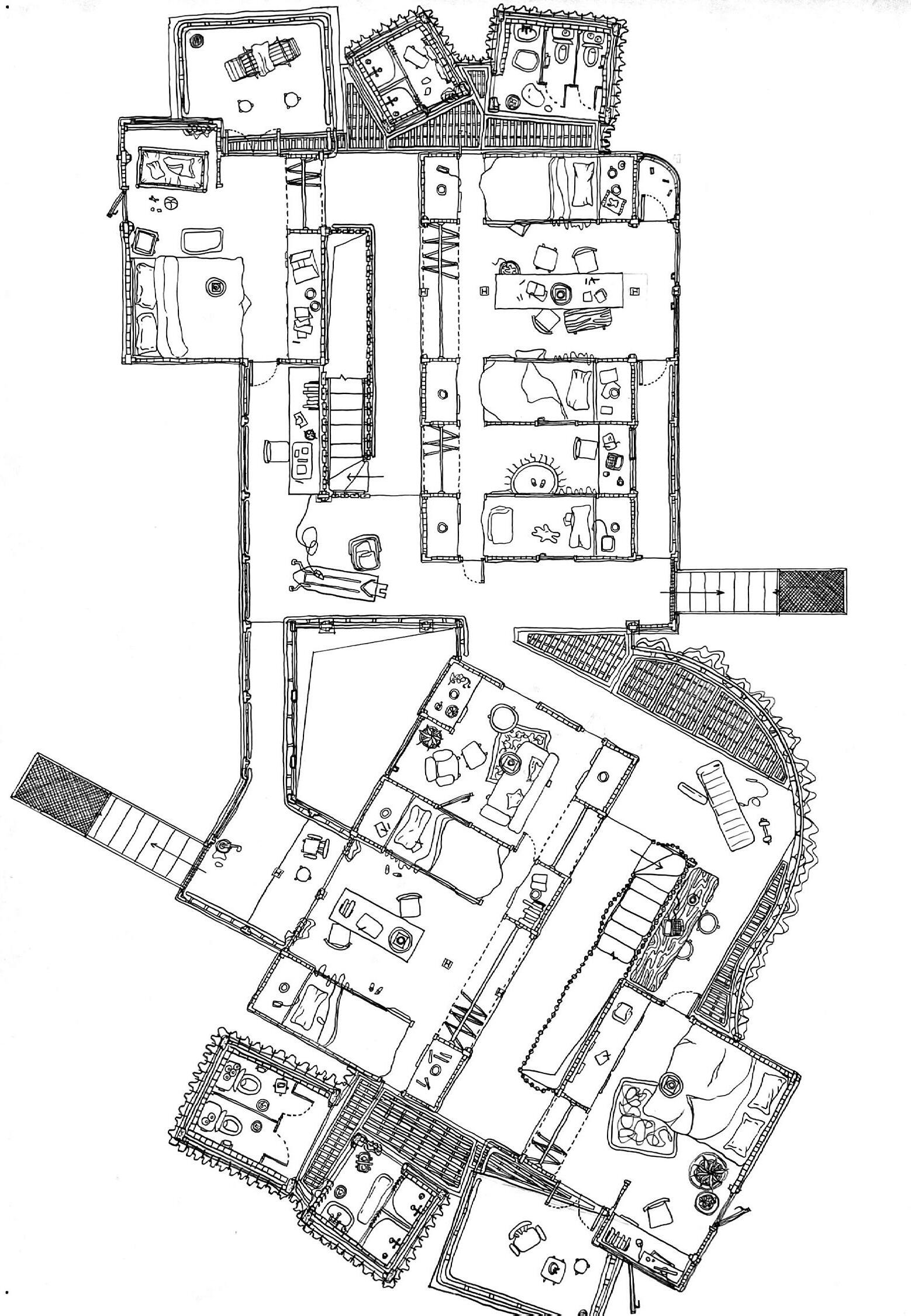

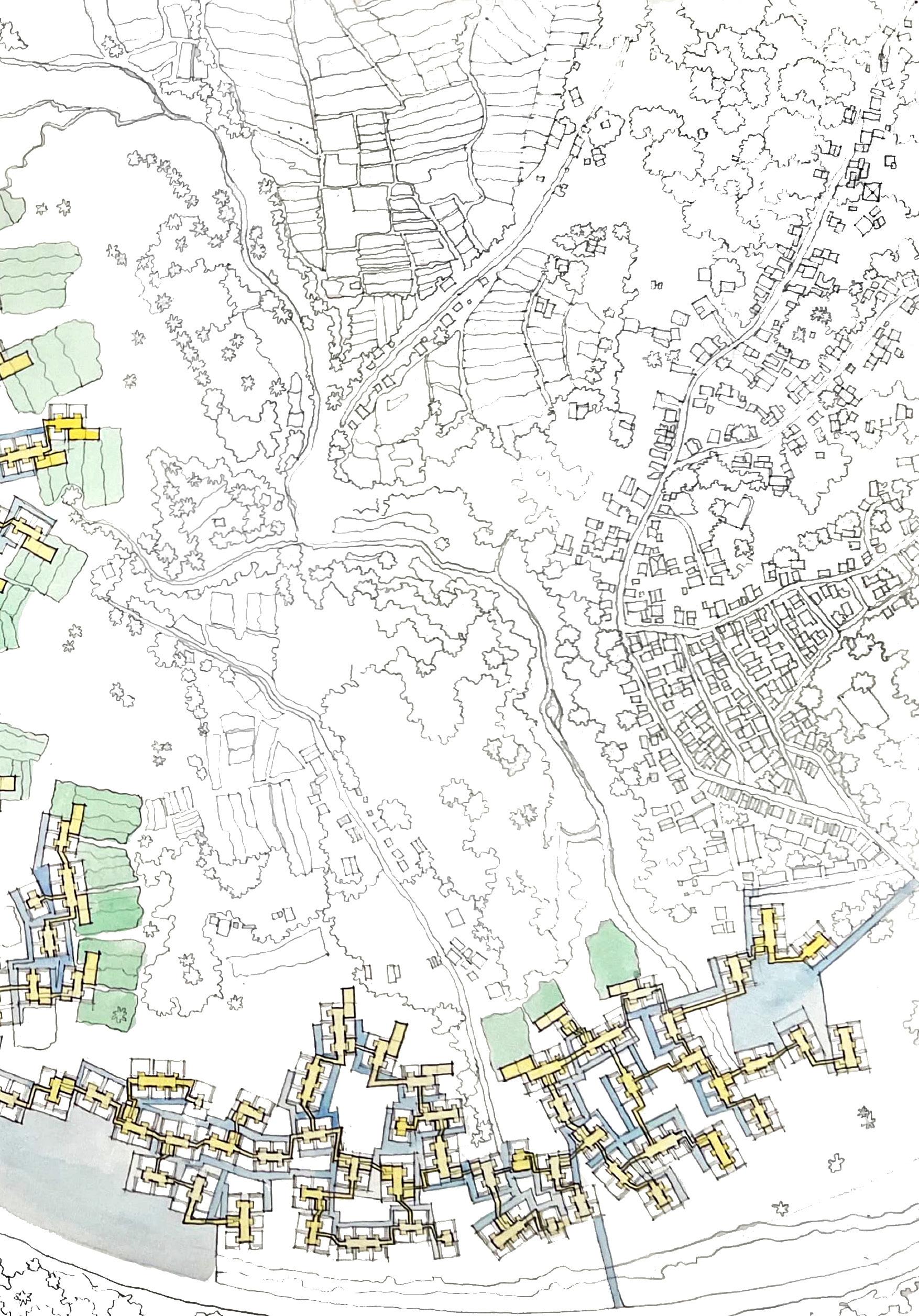

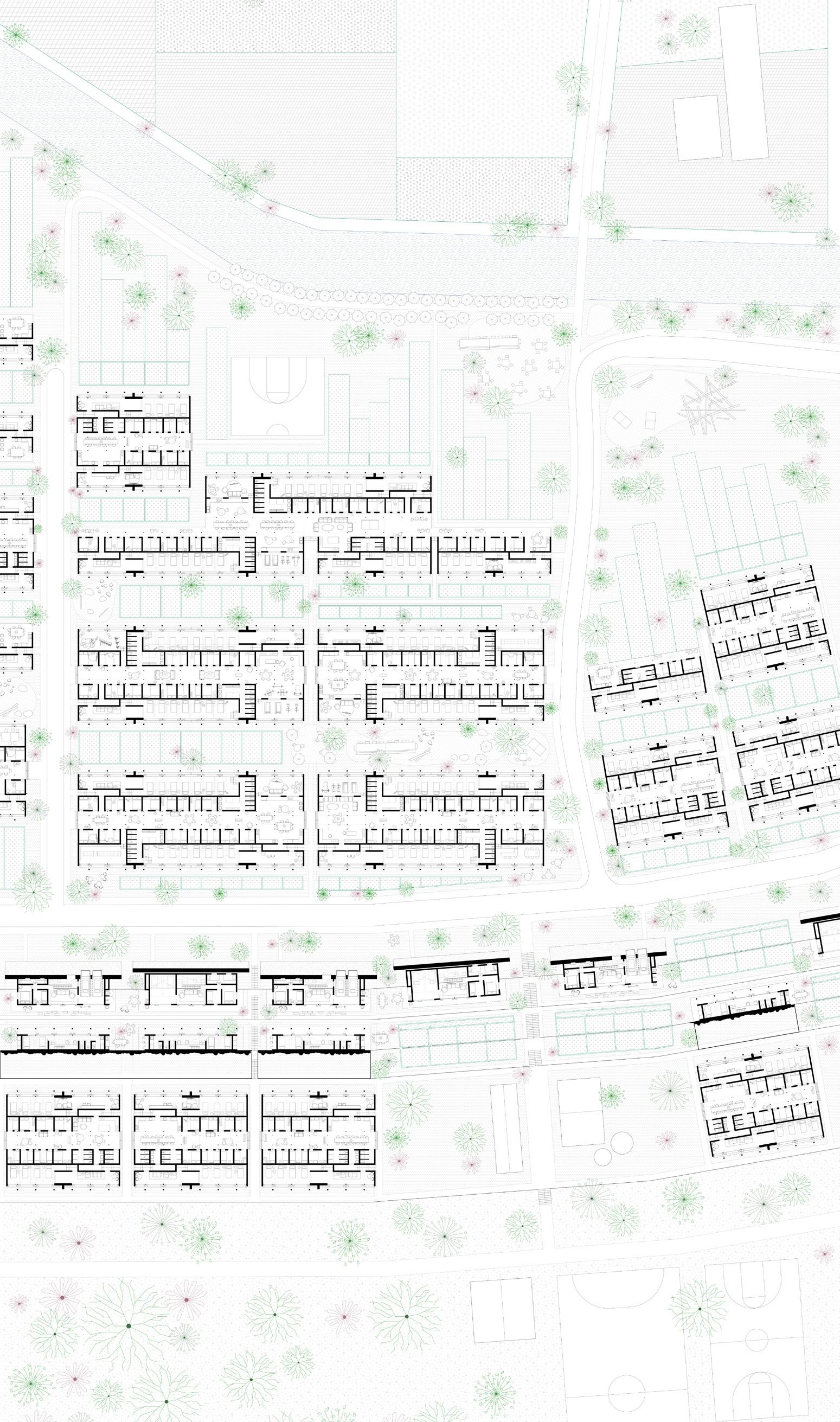

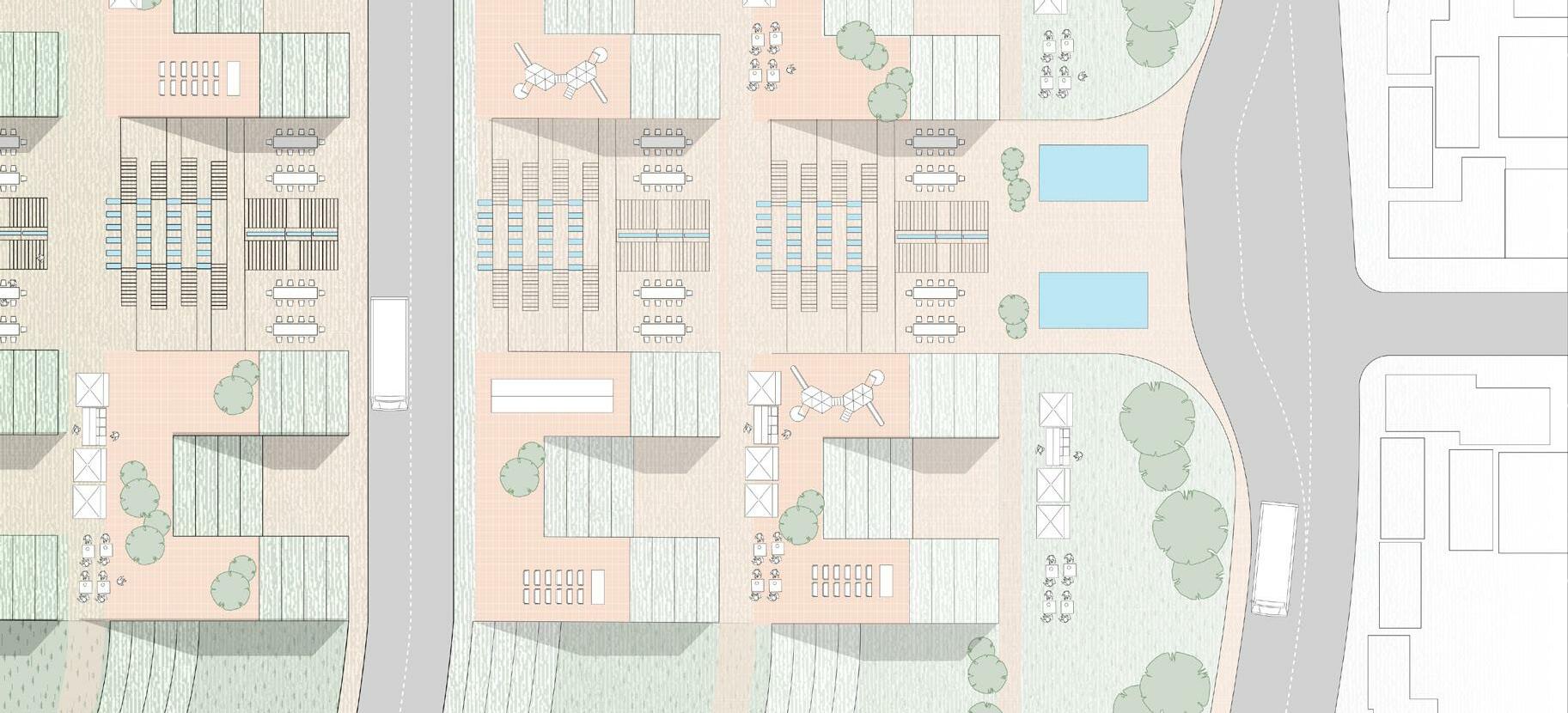

Full life circle community

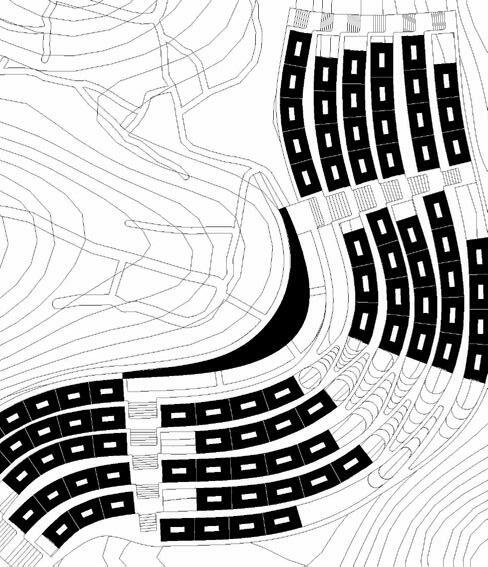

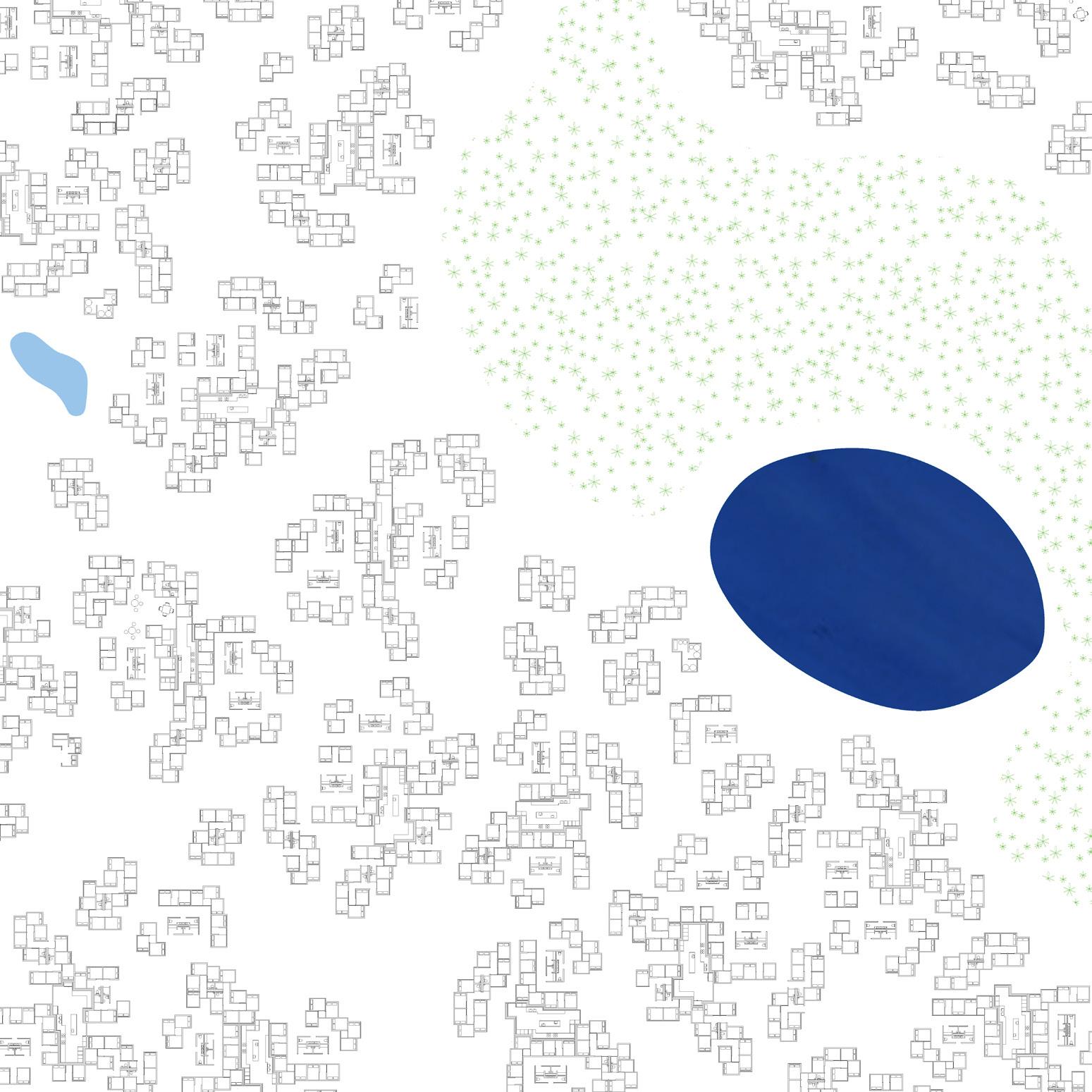

Site Plan 1:20,000

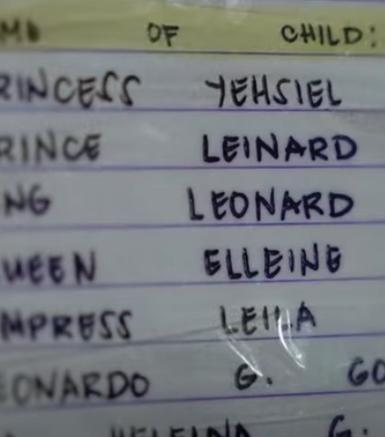

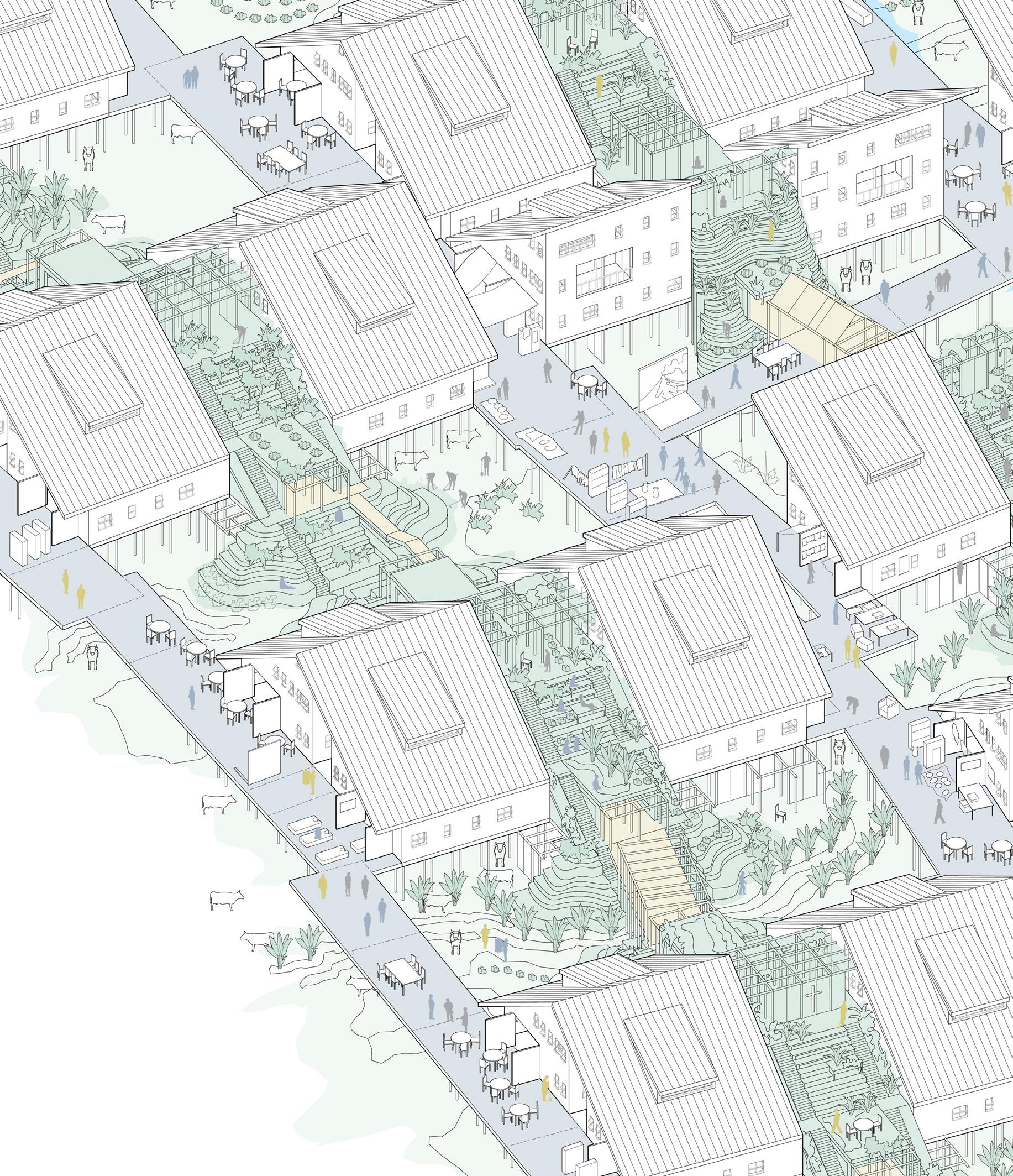

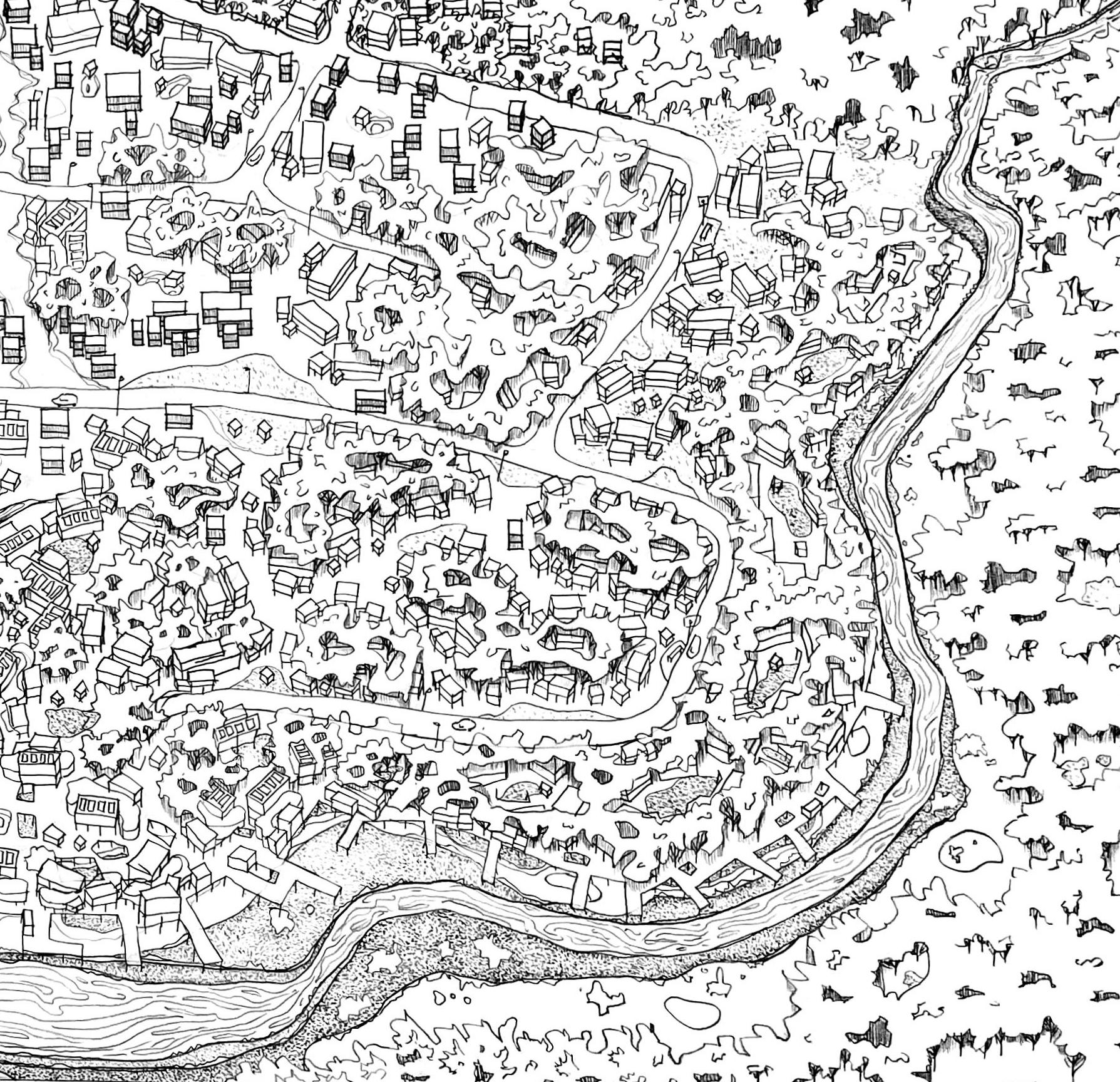

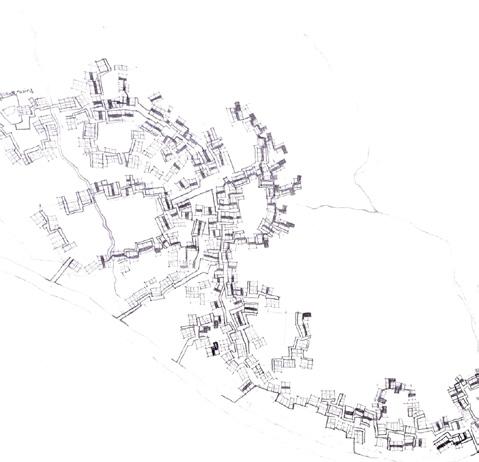

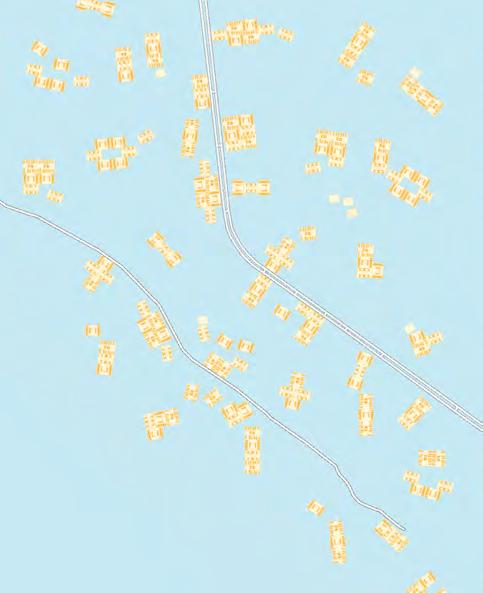

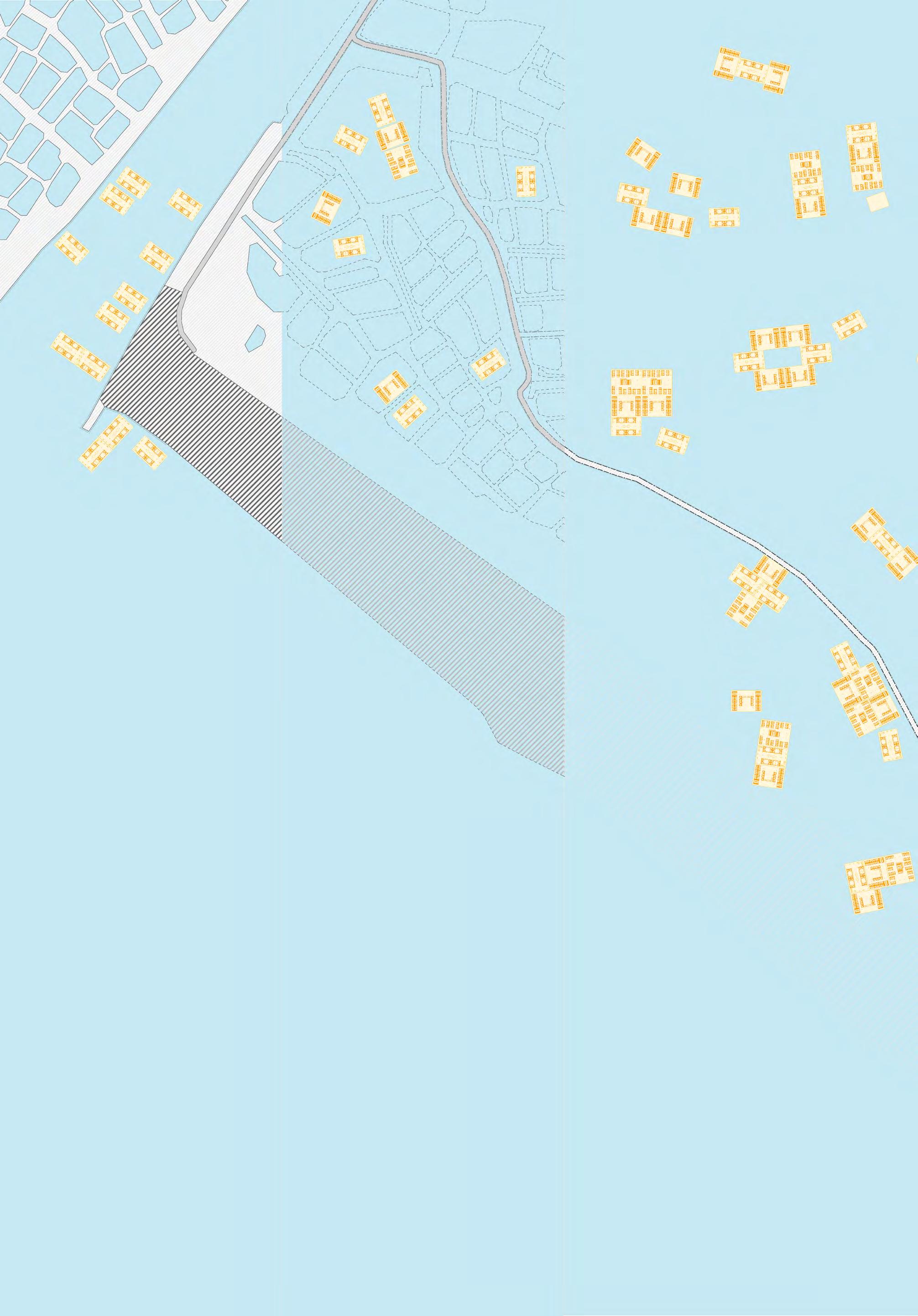

Site: Bagong Silangan, Quezon City, Manila, Philippines Crisis: Pandemic Baby Booms/Wetness Area: 106,163 m2

1,000 1,075 71

Beds Inhabitants Units

Pandemic Baby Booms: In the Philippines, the pandemic has resulted in an explosion of unwanted pregnancies, because access to birth control was curtailed. Many of these unwilling mothers are teenagers, some just 15. Most women who are too poor to raise another child, unwed, or too young to bear any children seek the help of backstreet abortionists and abortion pill traders. Others turn to peddling their unwanted child. Full-life cycle should be considered in this area with the system of public education and medical facilities.

Wetness: Houses in the foreground were immediately destroyed upon vacation to stop other people moving onto the site. Many people live in appalling conditions on platforms just feet above Manila water courses. Human waste is going straight into the rivers, causing high levels of water pollution and loss of ecological diversity.

Orchid is my eighth child in this family. His constant snoring kept me awake for the whole night. Three of my children slept on the mezzanine while the other five are squeezed by each other in the hammock.

Early morning in Bagong Silangan is chilled. It smells wet from the nearby creek. Marjorie’s husband used to walk along this creek to his place of work, a primitive port hut close to the river. He has been doing the job of fish hauler since 15 years old. After two years of being quarantined from the pandemic, Marjorie got pregnant twice. Through the open door, I can hear the radio is on. Sweet lullaby is flowing in the air. The baby is sleeping tight. I can see her still doing her school work, mumbling some English terms. I know how hard it is to get Cytotec, a type of aborting drug costing 350 pesos, in such a young age. No pharmacy stores or convenience stands are offering it to teenage girls.

With a few more steps I will be at the biggest morning market nearby. It is the place where I will be at when the housework is overwhelmed. All kinds of deals happen here. I remember witnessing some of my neighbors selling their fresh-born baby with the price of 196 dollars. I do not have the ability to read but Naoui, my oldest son, told me once that there are posters on the street saying 60 to 70 percent of women are facing the major problem of getting pregnant unexpectedly in this country. It is not surprising to me since that the pills tend to run out sooner and sooner.

An ambulance is stopping in front of Narie’s hut. It is very rare since that clinics are running short of vehicles for quite a long time. The electricity boxes are covered by tons of posters again. Sky is the only place where I can stare at and dream about settled life for one second.

It is hard to identify this place through smells.

I smell fish. I smell soil. I smell streams. I smell polluted trash bags. I smell rotten veggies. I smell overnight labors. I smell unclean hair. I smell playful vibes of children. I smell pills and pills bags.

I smell hecticness.

It is hard to identify this place through sounds.

I hear winds. I hear leaves. I hear cables and wires. I hear deals. I hear smiles. I hear cries. I hear screams. I hear sighs. I hear ambulance. I hear didactic conversations. I hear rules. I hear ignorance. I hear uneducation. I hear fun.

I hear hope.

It is hard to identify this place through touch.

I feel wet dirts. I feel concrete. I feel trees. I feel fabric. I feel metal sheets. I feel wooden plates. I feel plastic bags. I feel ruins. i feel curtains. I feel human’s sweat. I feel warmness from a hug. I feel sports. I feel unity.

I feel life.

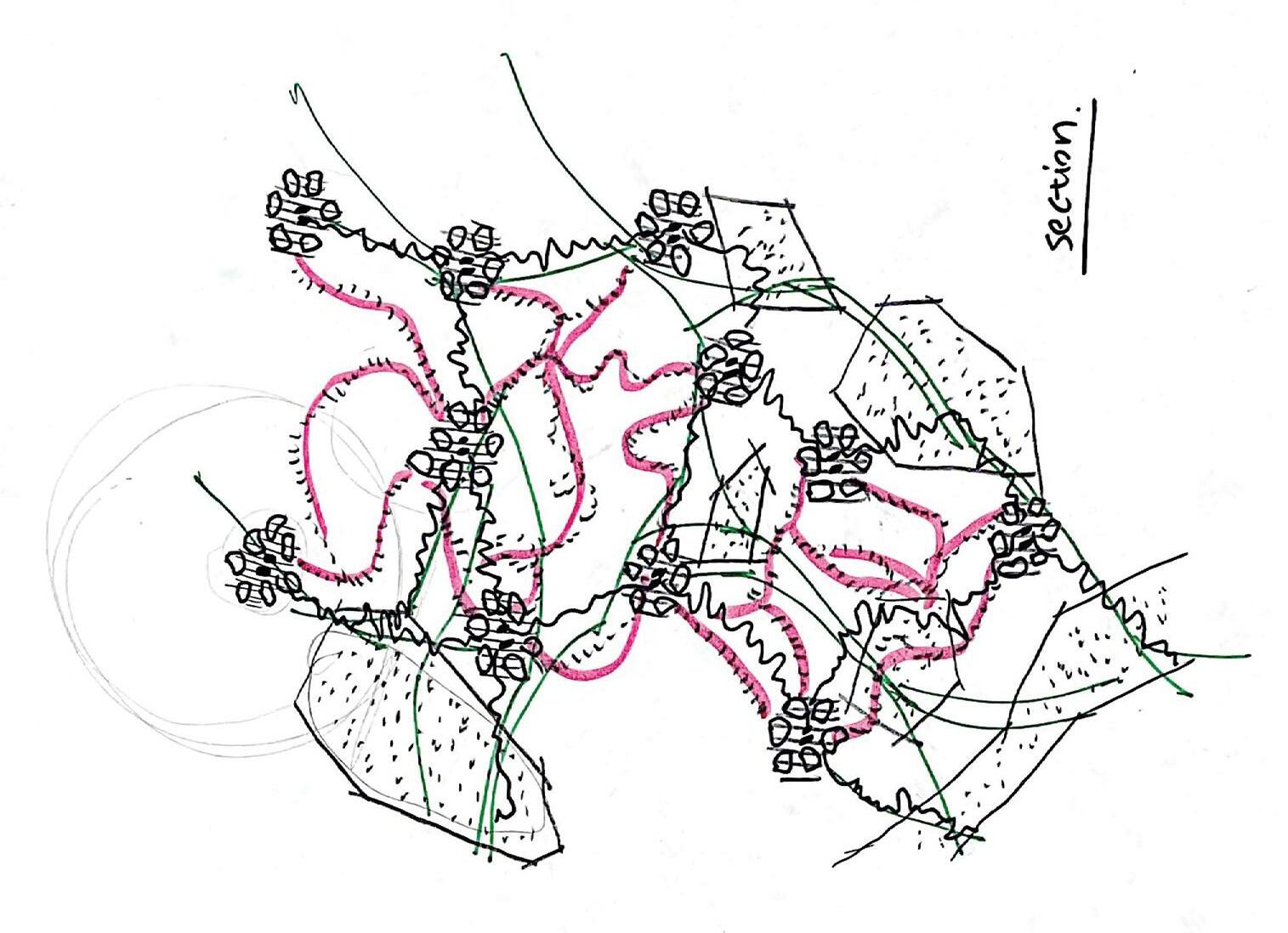

Top: Cluster Plan 1:300

Bottom: Cluster Terrace Diagram 1:300

Top: connection of clusters (pink: walking paths; green: underground sewage system)

Bottom: distribution of clusters within existing neighborhood

Tree Qi Chen

Tree Qi Chen

First phase: introducing, collaborating & merging new clusters to existing neighborhoods

Tree Qi Chen

Tree Qi Chen

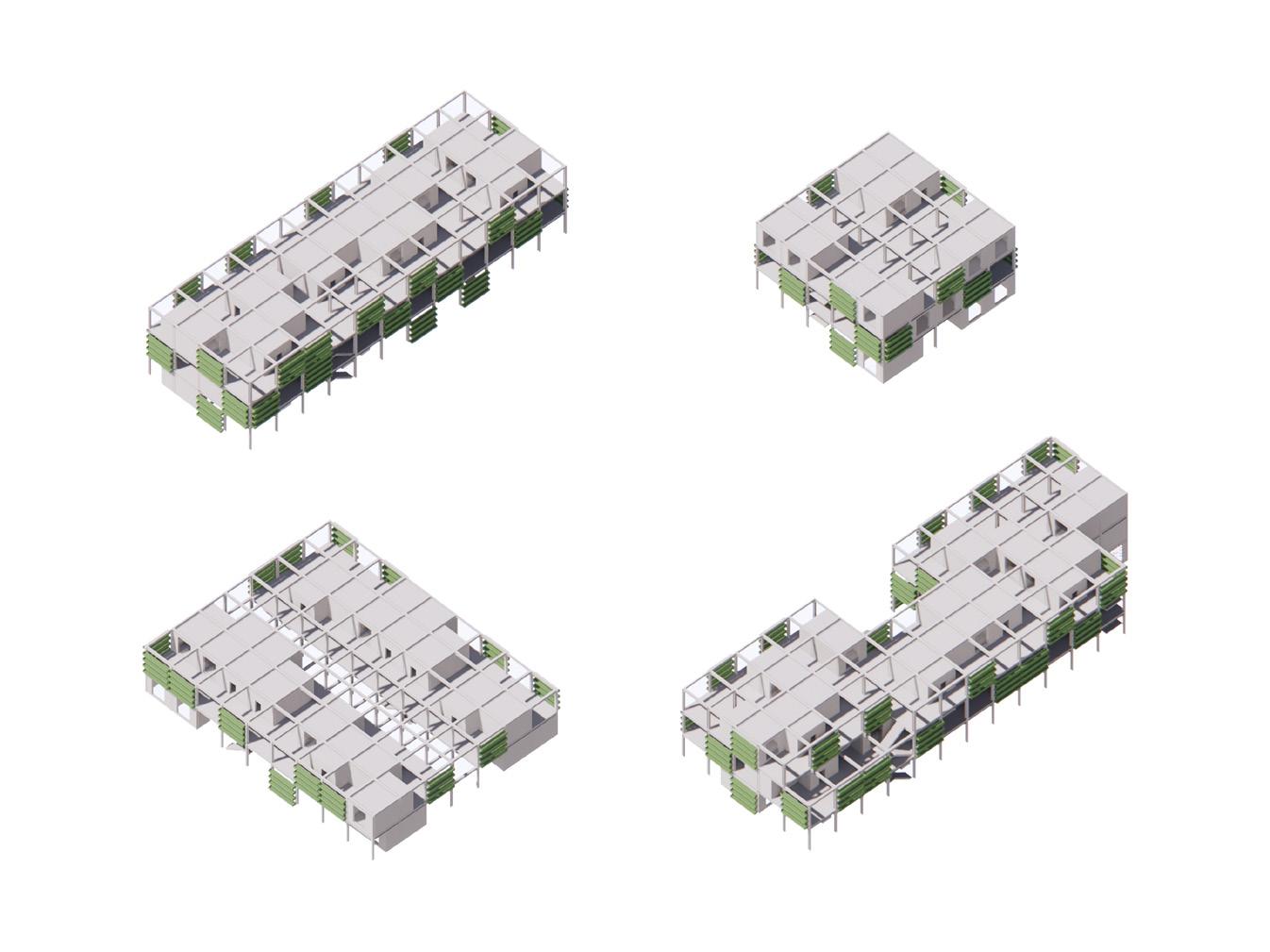

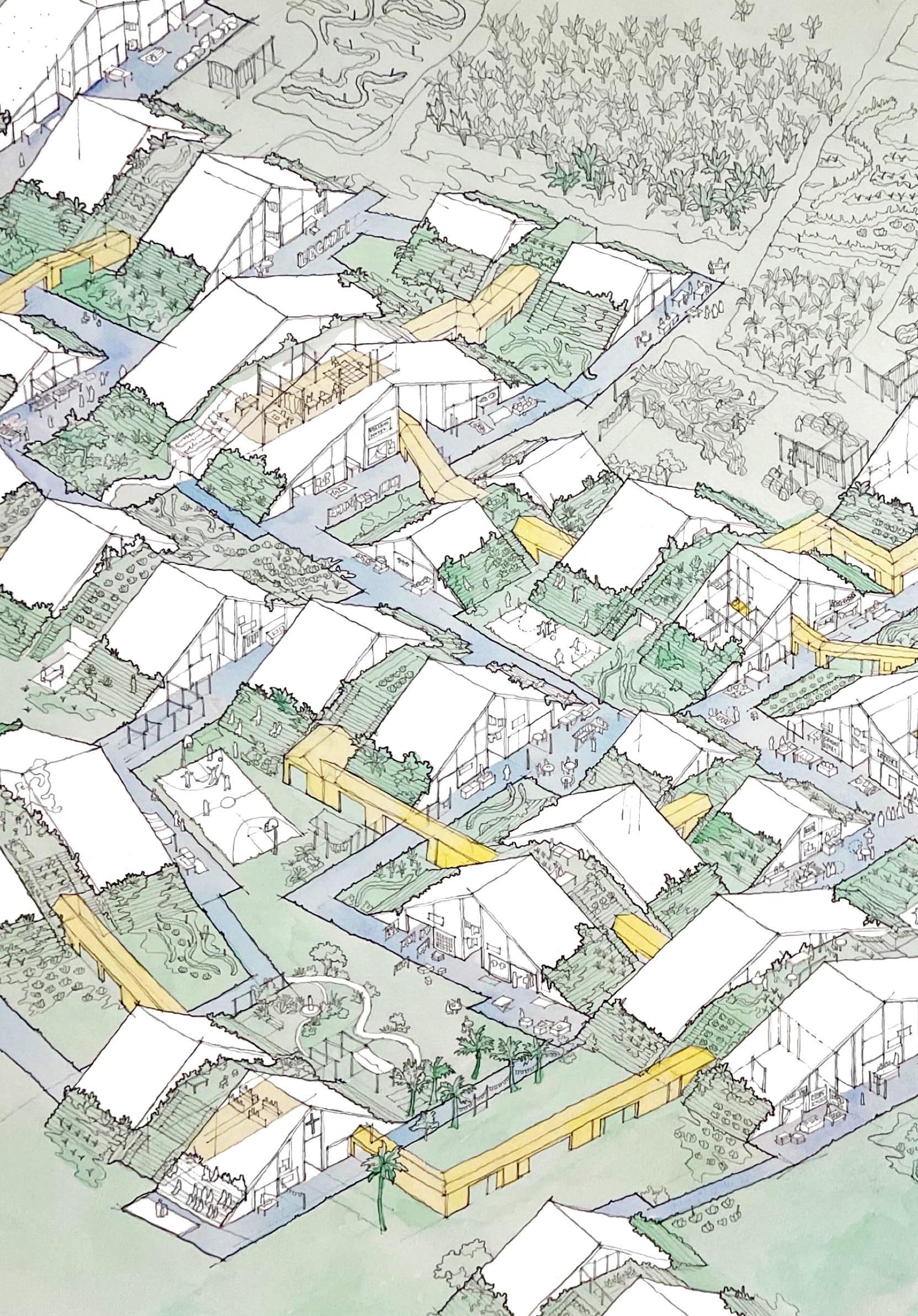

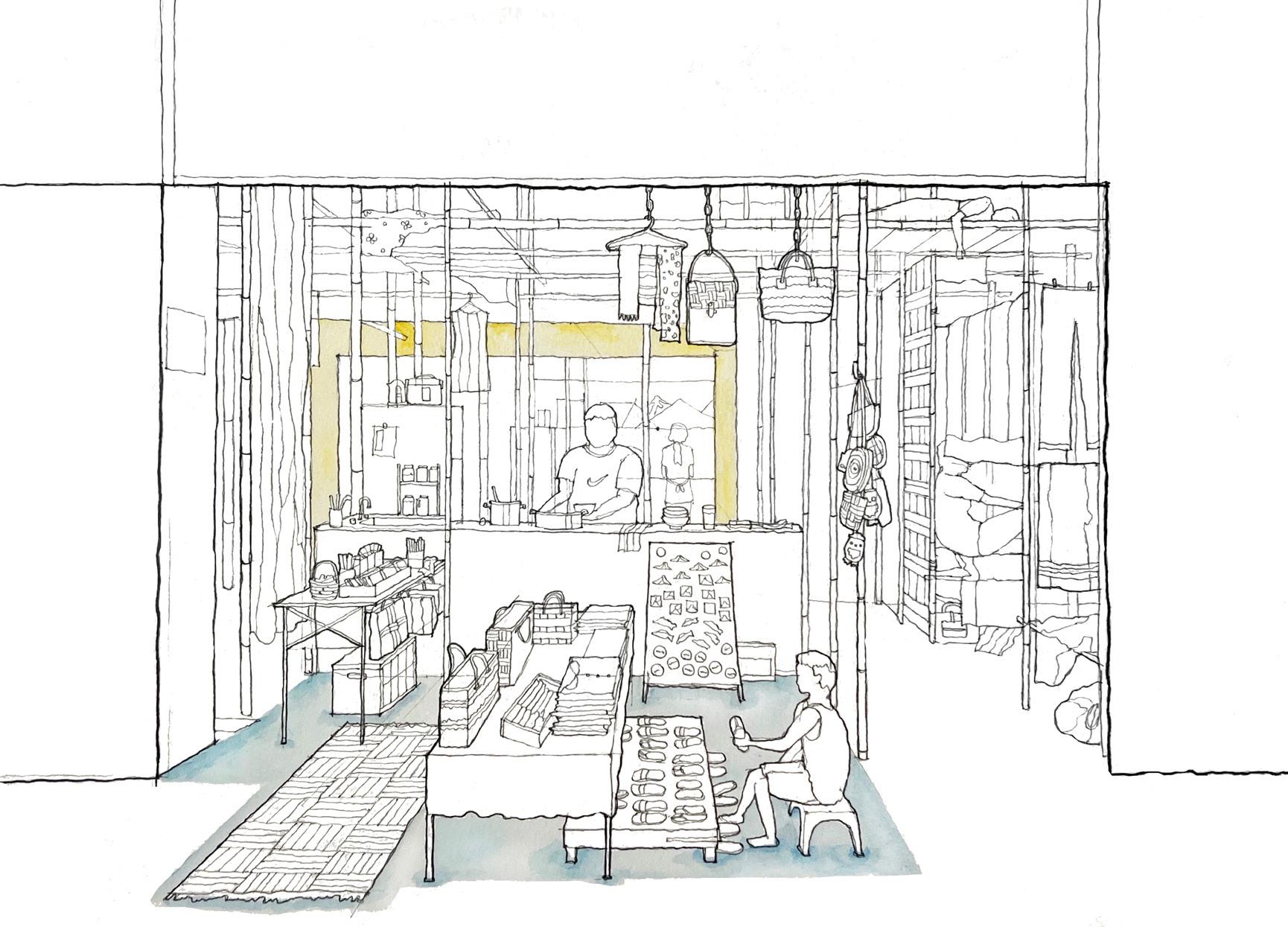

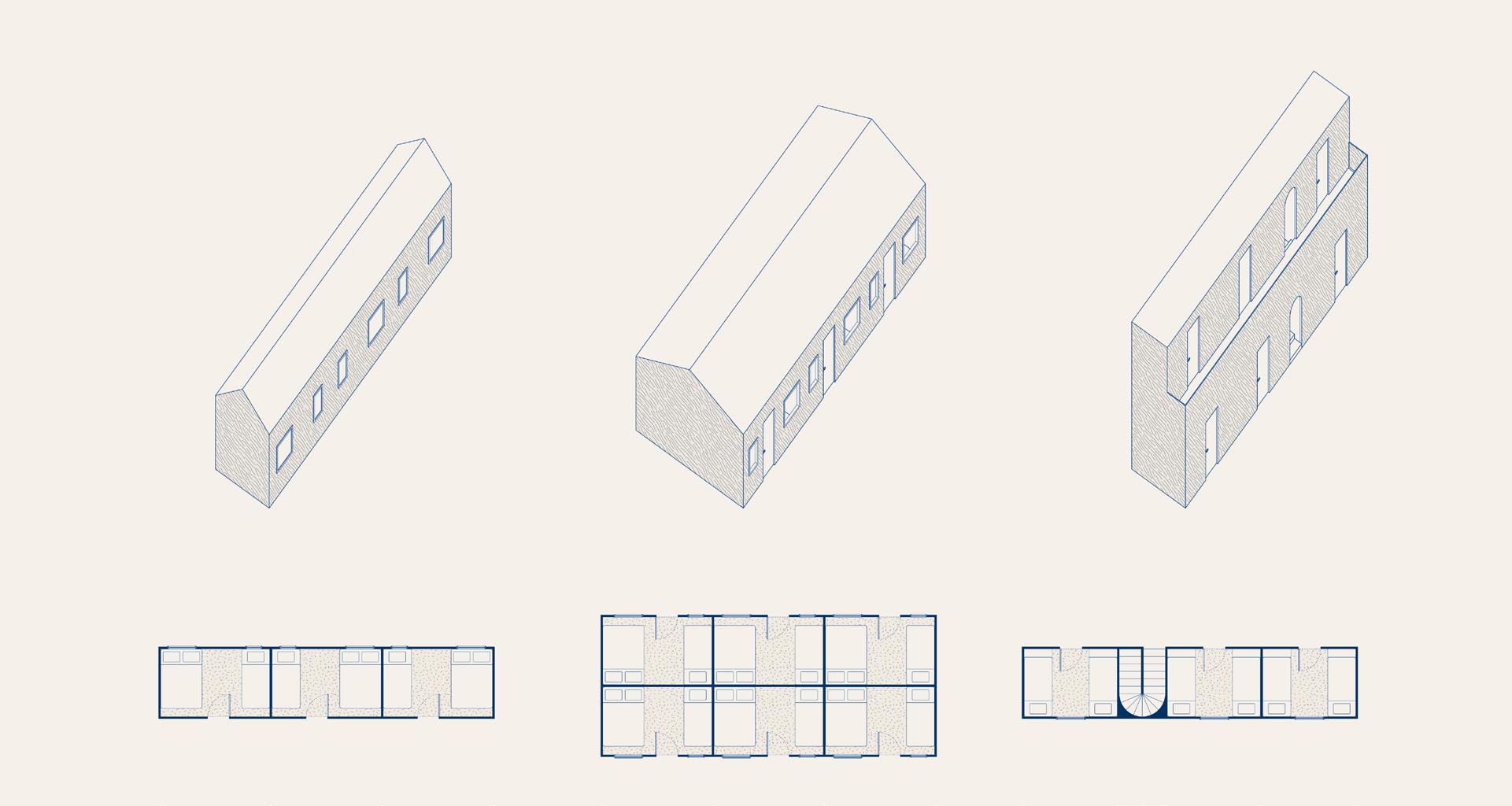

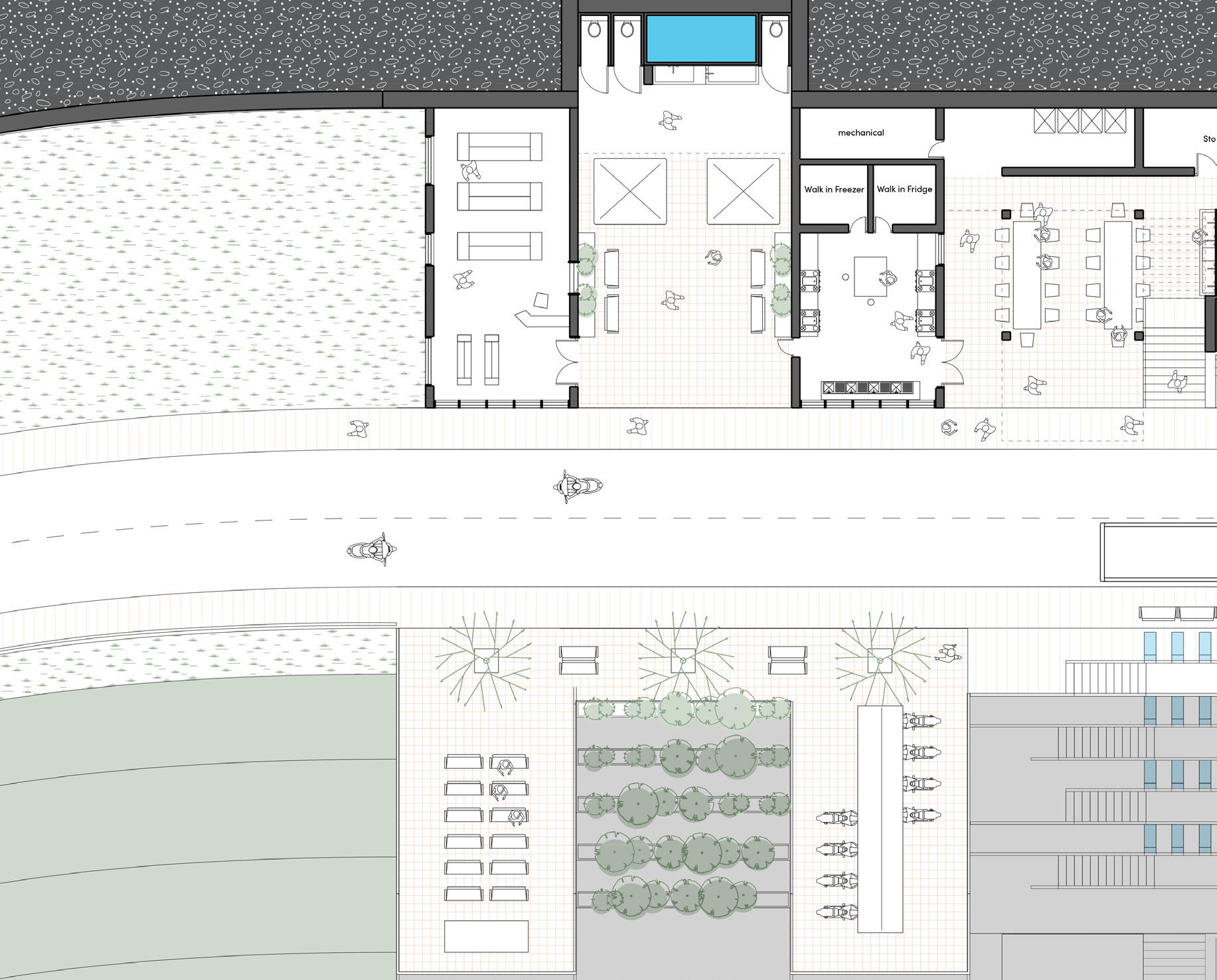

A community contains workshop and food production.

Site Plan 1:20,000

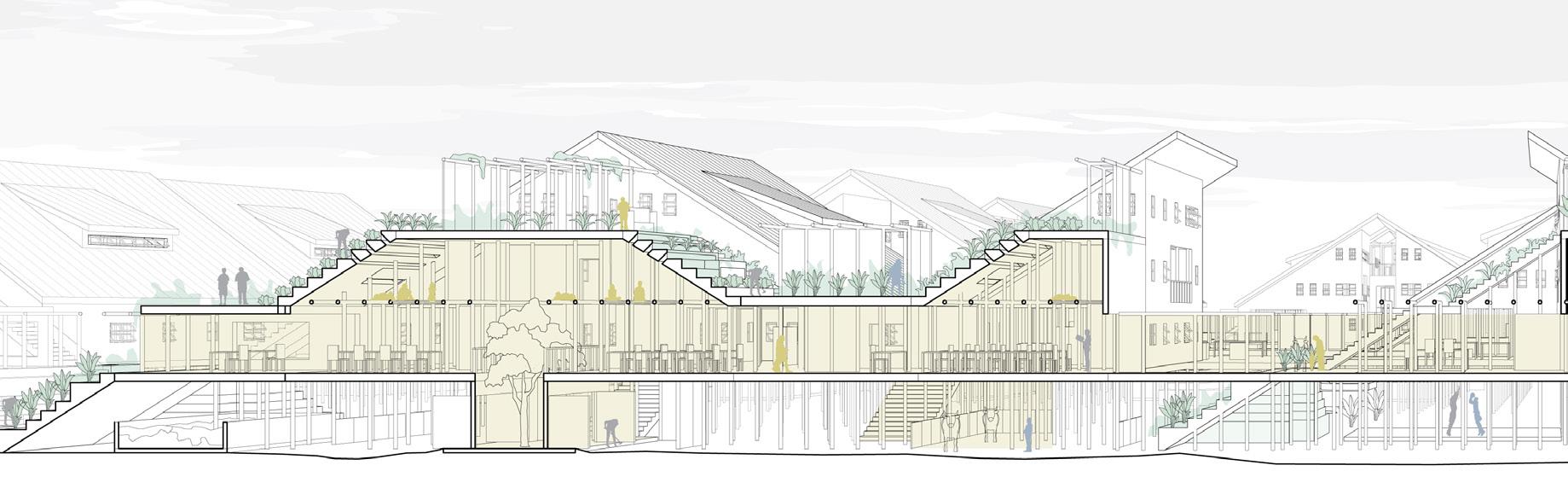

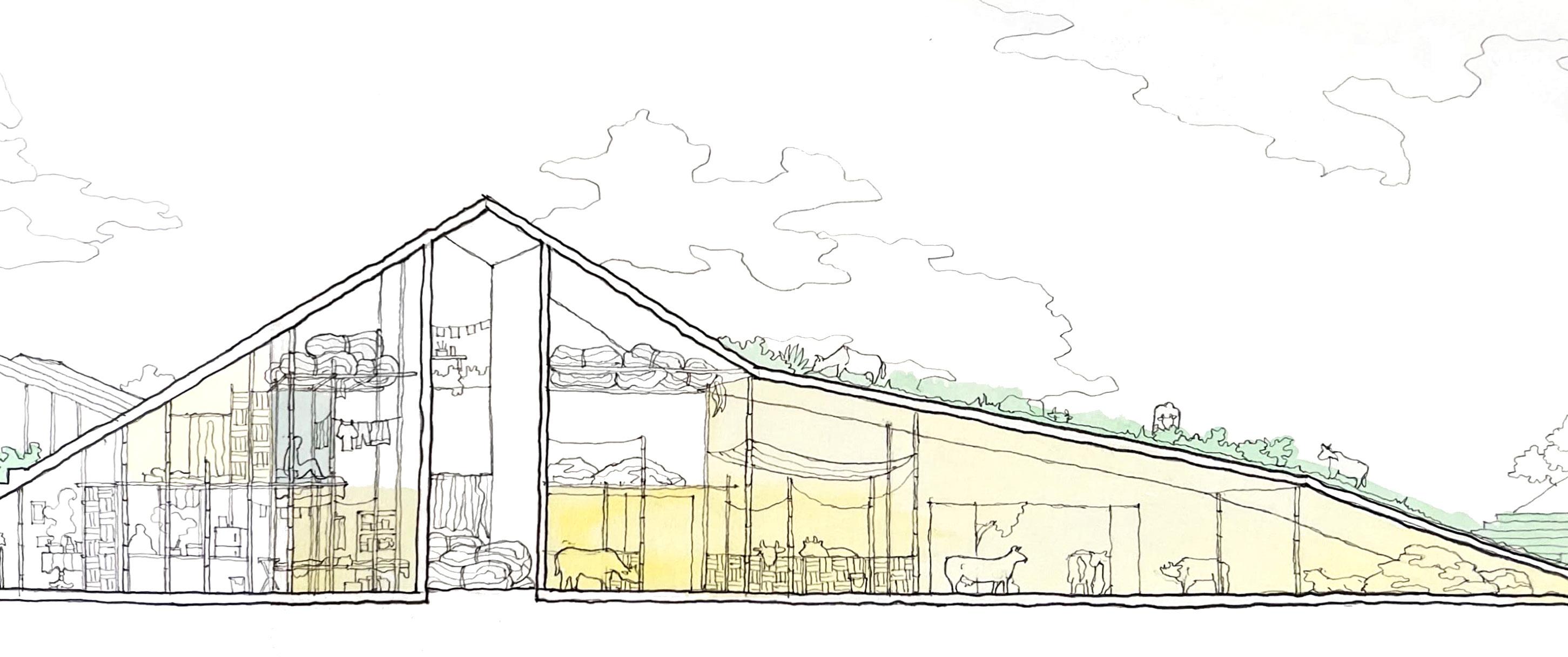

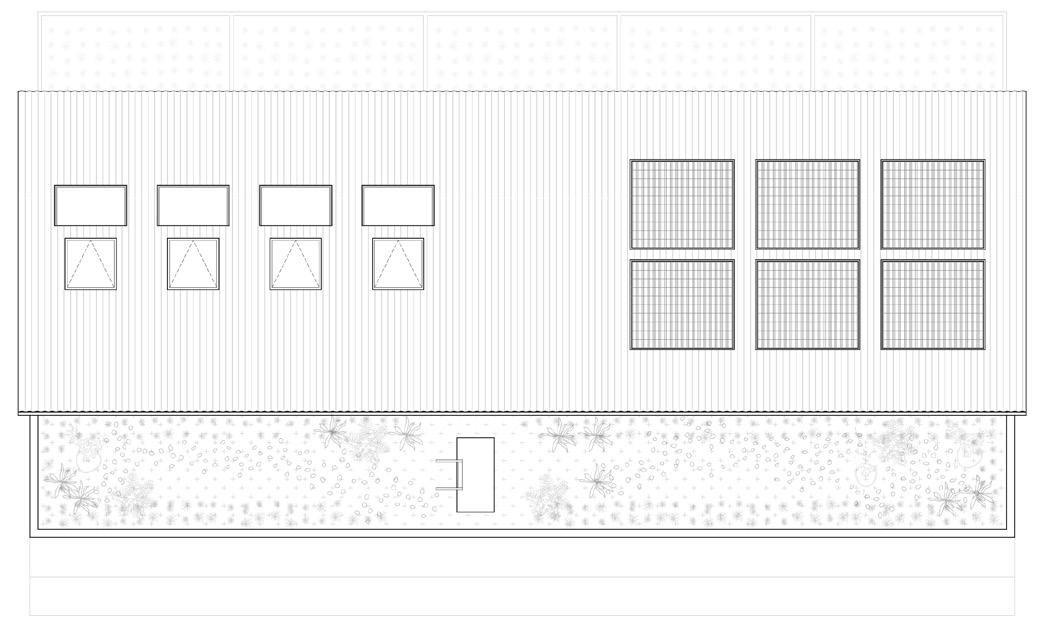

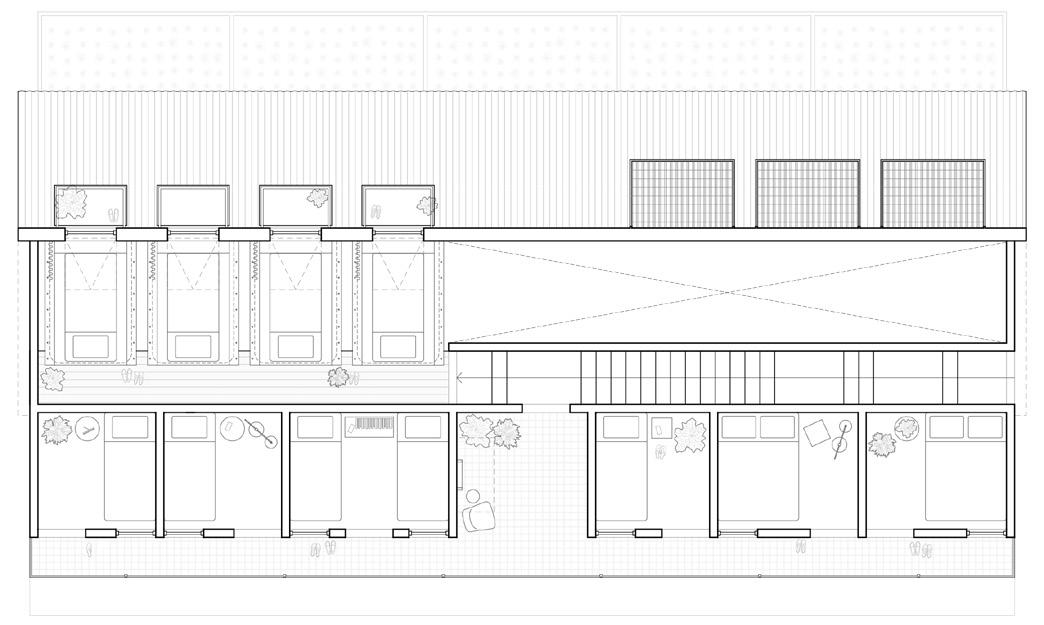

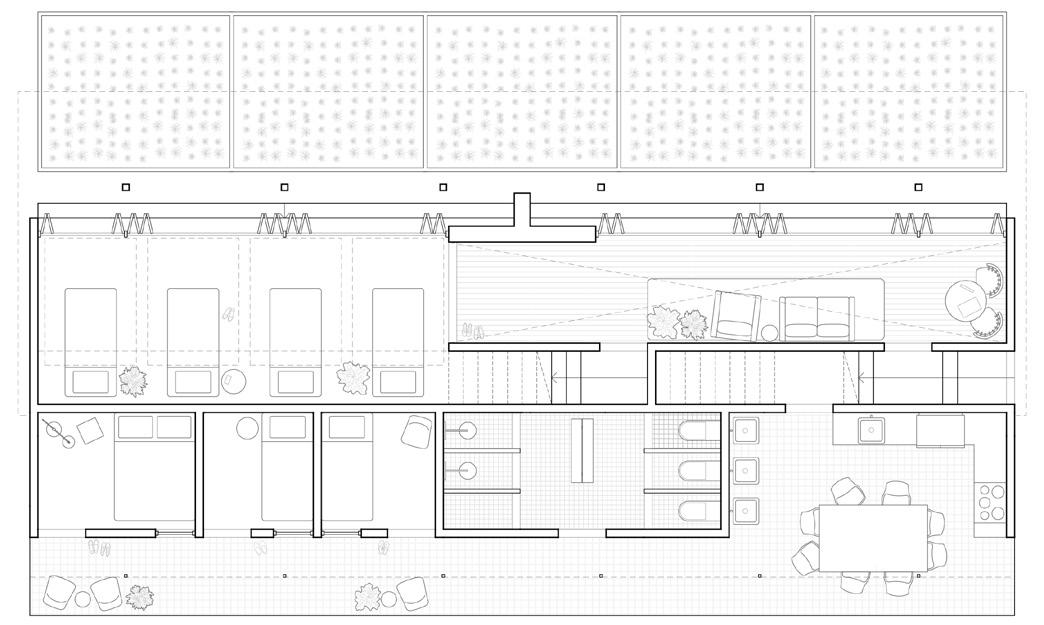

Site: Yilan, Taiwan Crisis: Earthquake, disappearing of traditional handcraft Area: 81,000 m2

1000 1800 29

Beds Inhabitants Units

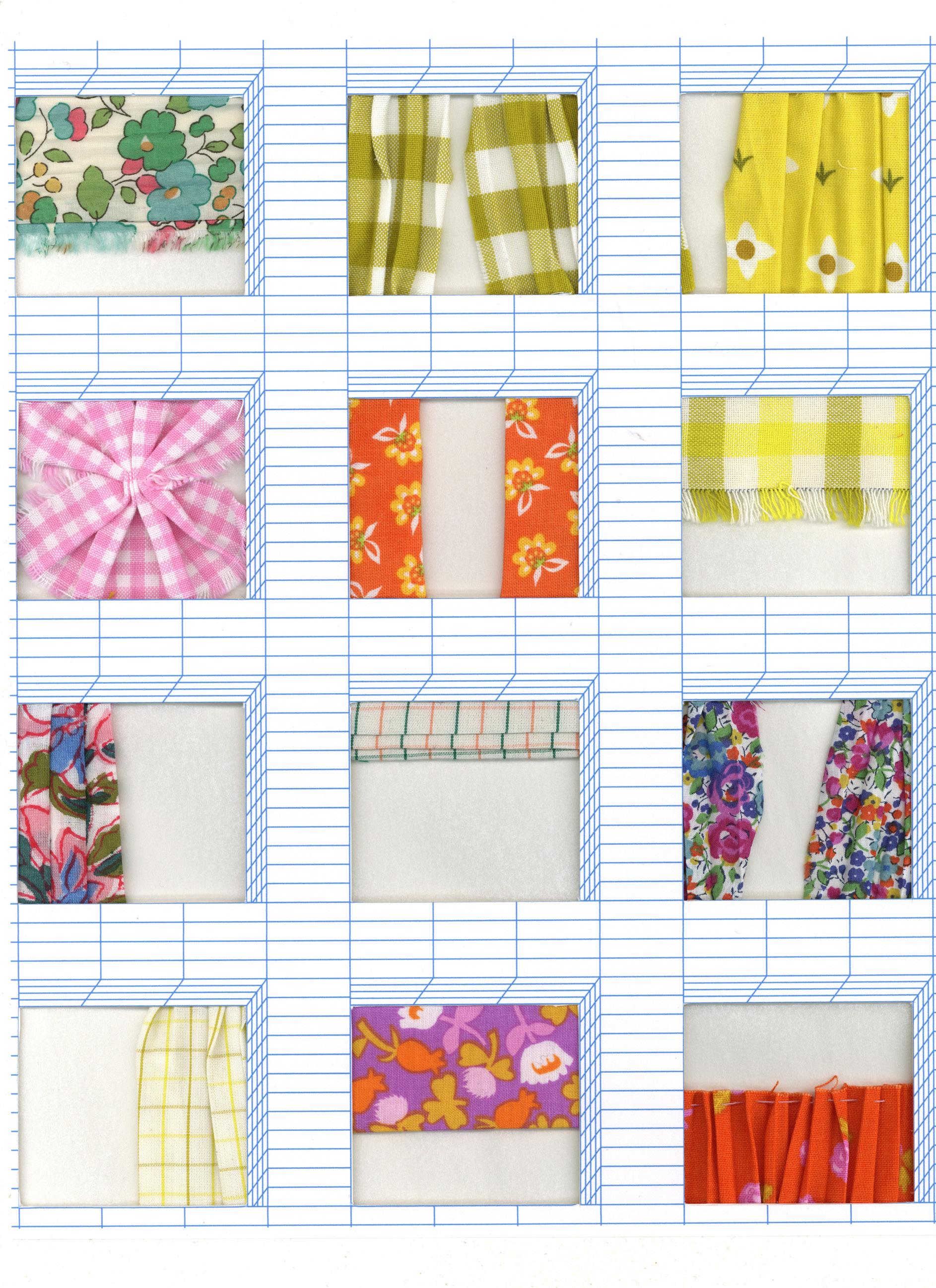

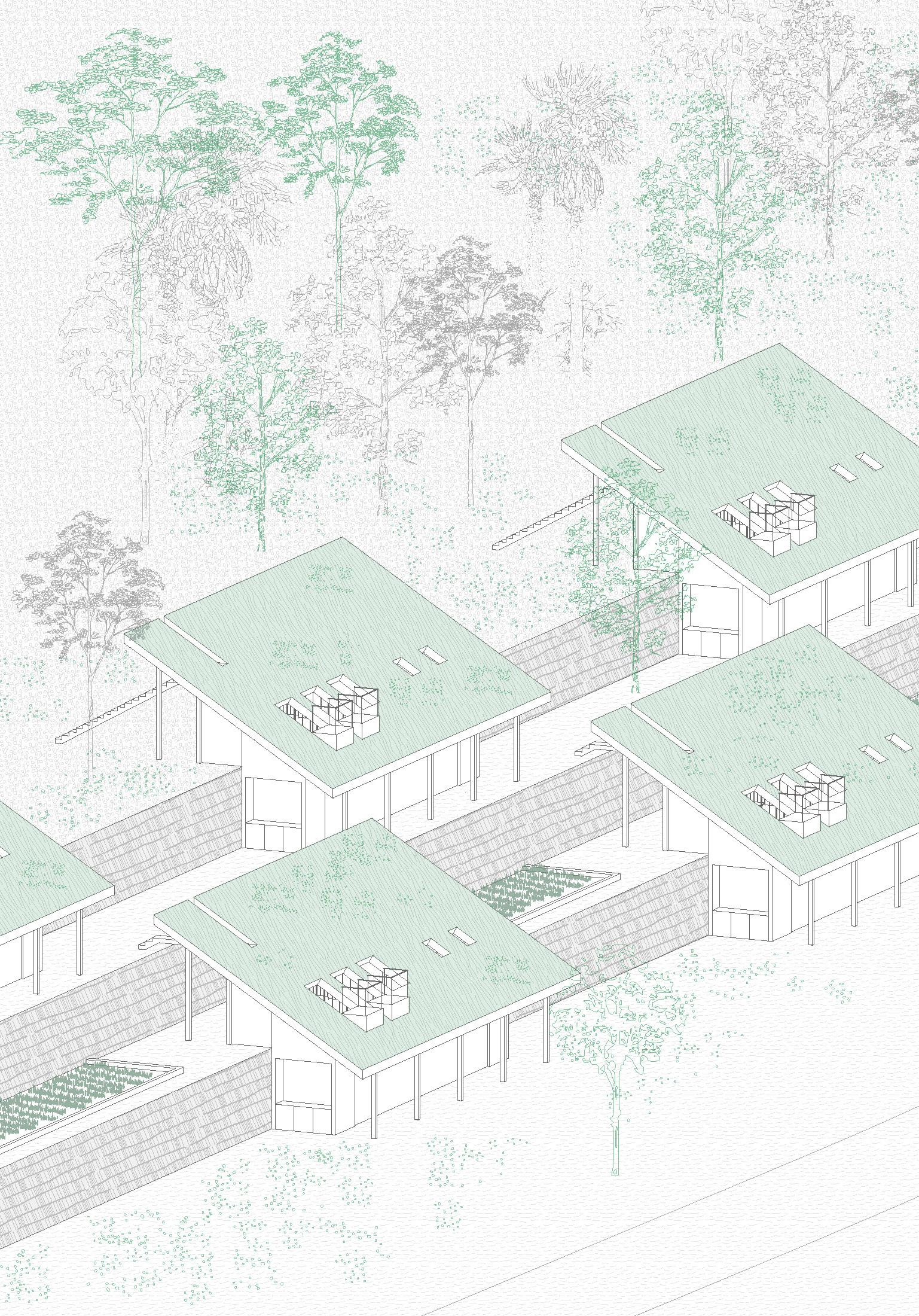

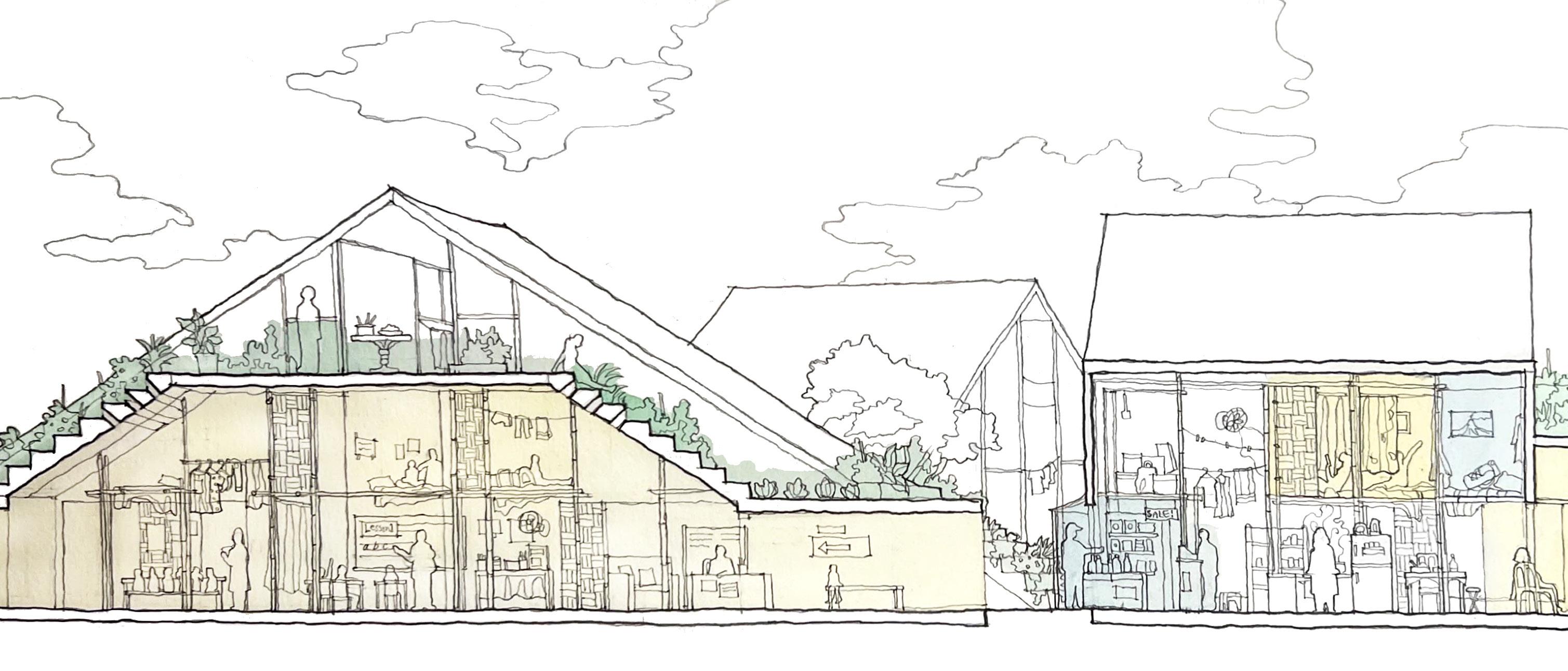

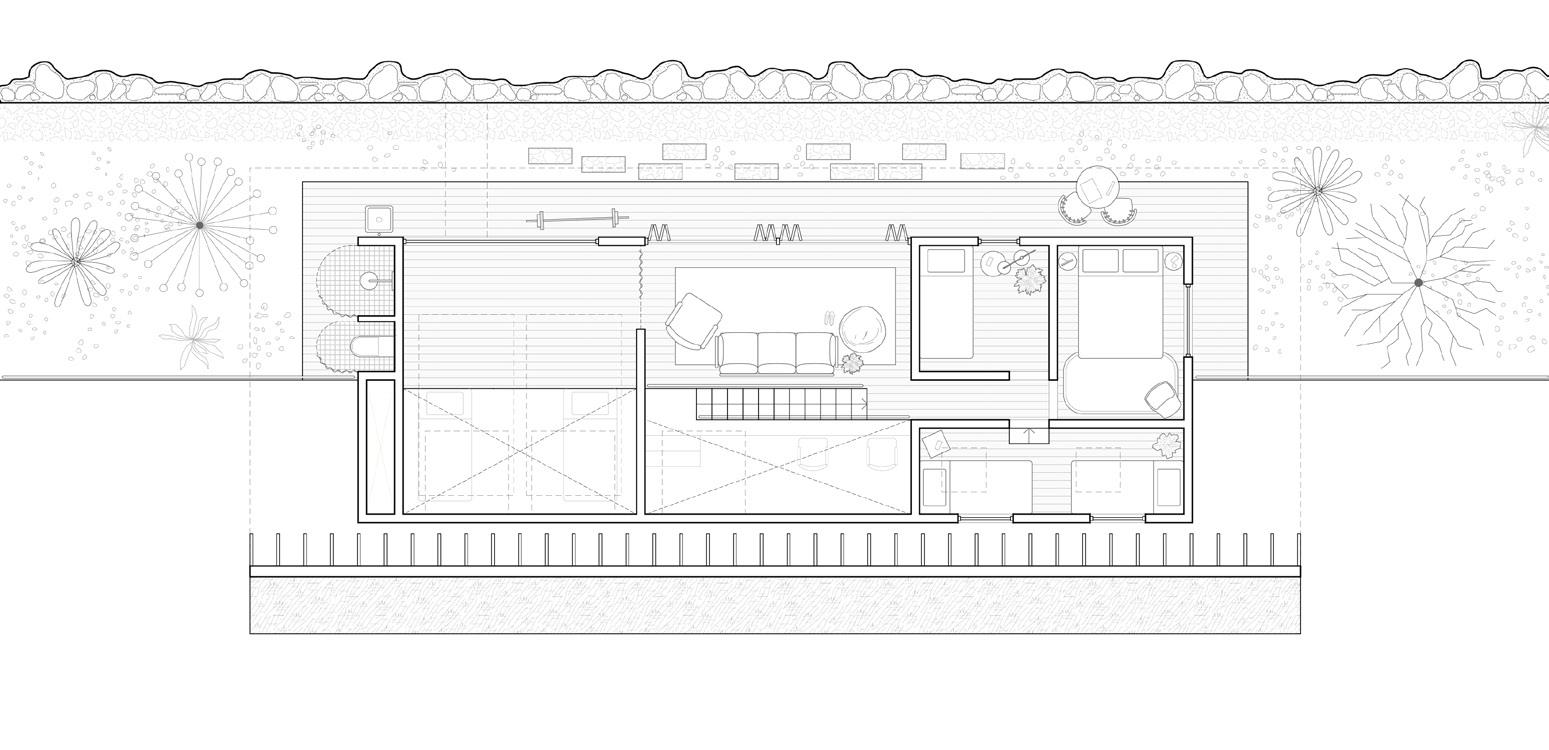

The earthquakes happen continually in Yilan, Taiwan. This project copes with the earthquake with the specific structure, multiple stairs for escaping, and lower height. The steel structure used in this project has good earthquake-resistant capability.

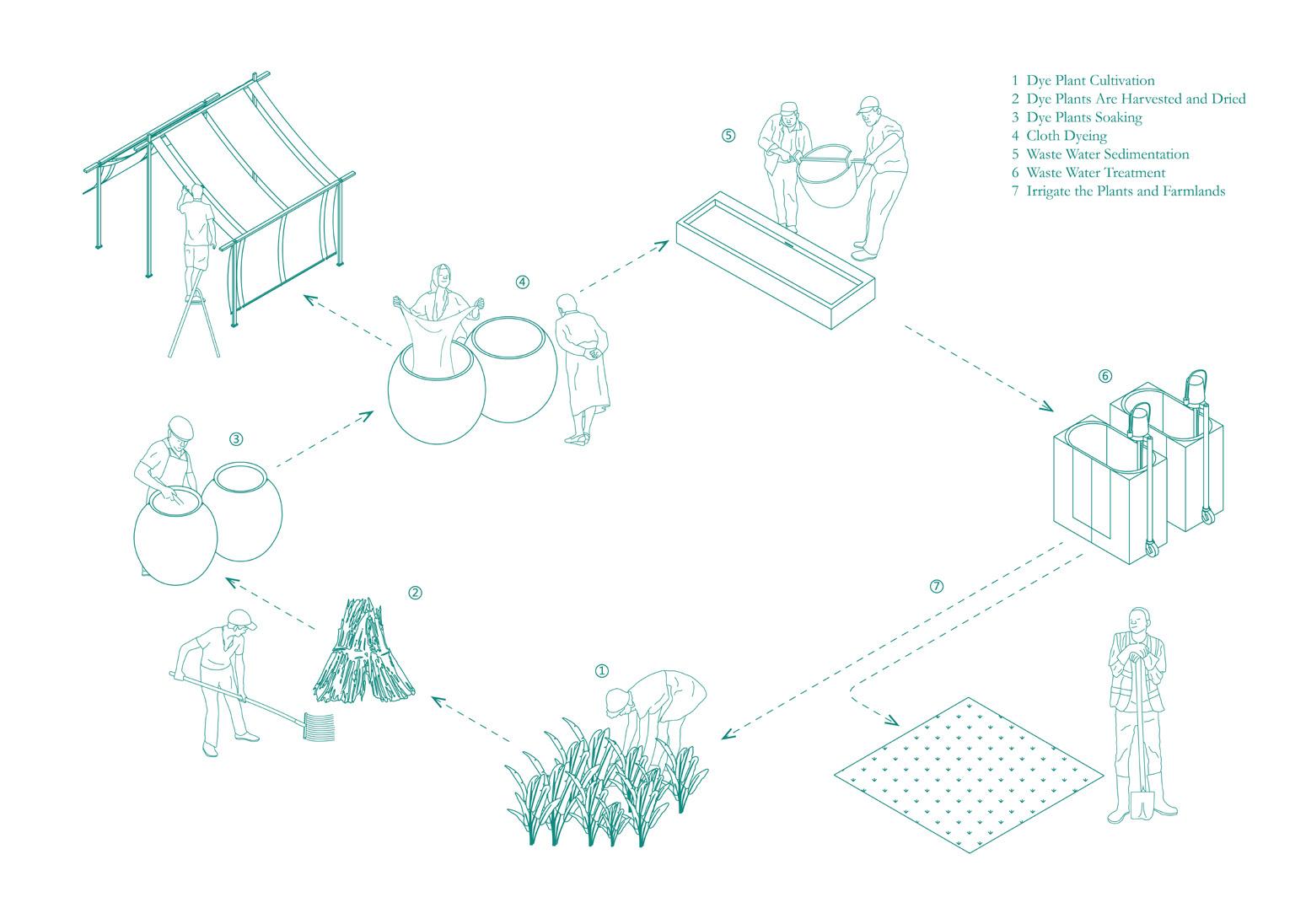

Another crisis is the disappearance of traditional handcraft. In Yilan there are many kinds of traditional handcraft techniques are gradually lost because of modern technology. However, the techniques are significant parts of the local culture. This project chooses to have workshops in the community for traditional dyeing techniques.

1. Yilan Cuo, house in Yilan.

Yilan, an agricultural county.

Birdview of Yilan.

Earthquake in Yilan.

Earthquake in Yilan.

Earthquake in Yilan.

Traditional dyeing techniques in Yilan.

Traditional dyeing techniques in Yilan.

Traditional dyeing techniques in Yilan.

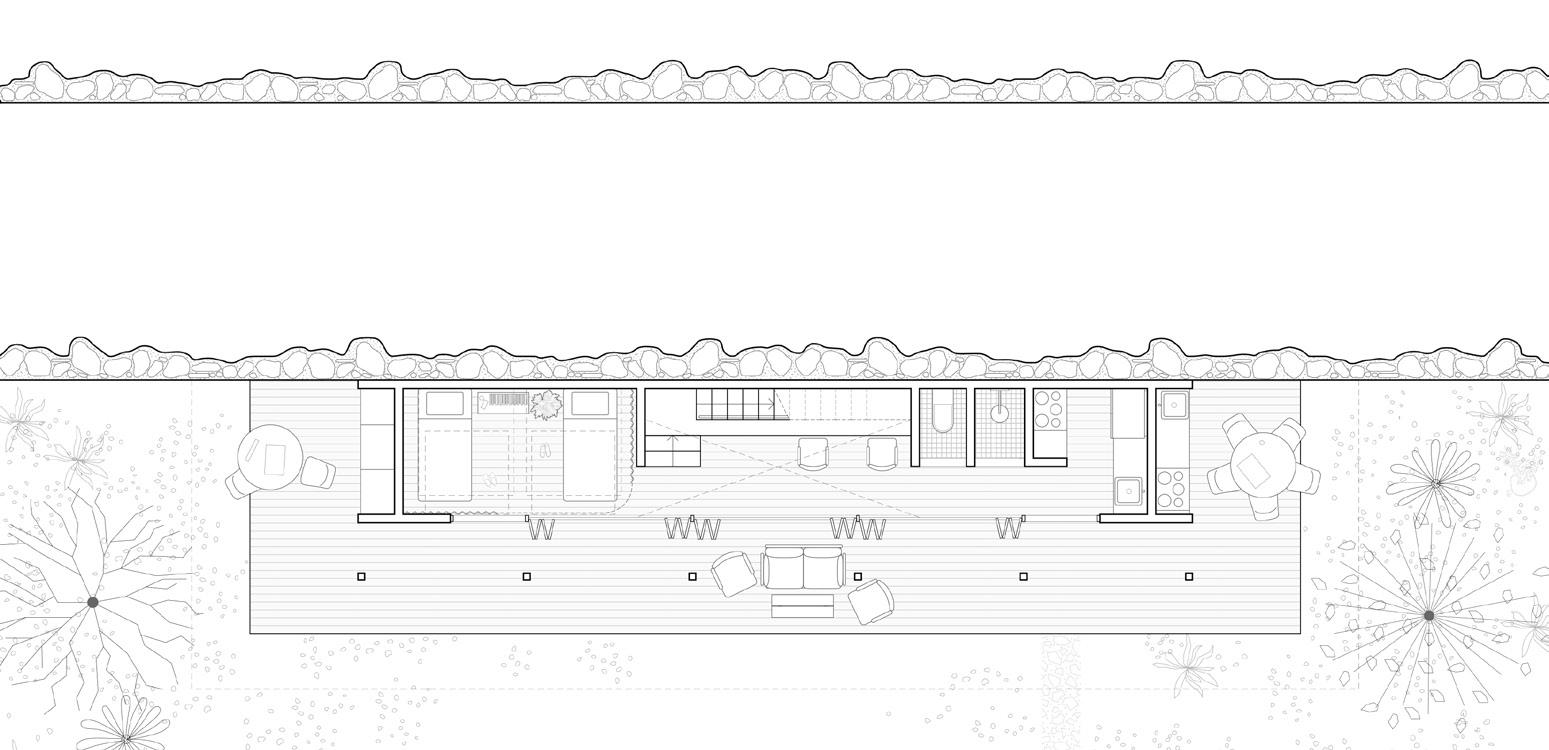

On the edge of the city Yilan, swathes of farmland showed up. The new community is surrounded by large farms and green fields. The farms are also extending into the community. Wake up in the morning, and the aroma of breakfast permeates around. When you open the door, you can smell that. It is all from the communal kitchen and dining hall. The aroma wafts through the open corridor and fills the whole building. The communal kitchen and dining hall are the most active area in the community. Residents cook their meals together here and chat with each other. These are the important social spaces in the community, and the social activities happened naturally.

The buildings standing between the fields and farms, are the vertical farms themselves. The façades of the buildings are filled with green plants. The plants block the heat of the sun and make people feel cool when walking in the building. The farm produce will be used in the communal kitchen.

The corridors are all open, gentle wind will blow throw them. People hang their laundry in the corridors. Children play together and run through the corridors. Some people will pull up a chair and sit in the corridor, to enjoy their leisure time. If to a rainy day, they will sit together, have a cup of tea, watch the rain, and feel the cool weather. The corridors are like open living rooms for the residents, they will have a close relationship with their neighbors.

Residents and visitors shared the community. Some of the units are the b&b for travelers. It is a good chance for the visitors to feel local people’s life. Visitors from out of town can also bring something new to the community. For example, they also cook their meals in the communal kitchen, which is different from the local people’s way. The workshops it is always busy. People move around and put the dyed cloth on the shelf. These workshops are also open to visitors, they can learn how to dye and create their own works. The traditional techniques can be reserved and inherited positively and efficiently.

The building is open to all directions, without a complete and closed wall. It can have a view of the fields and city environments all around when standing in the building. Three kinds of units are provided for different components families. The farmland is between two buildings, providing food for the residents. Communal workshops, kitchens, and dining rooms are for all the residents and visitors.

up d o wn up

d o wn Xi Chen 1:300 F2 Module Plan

up

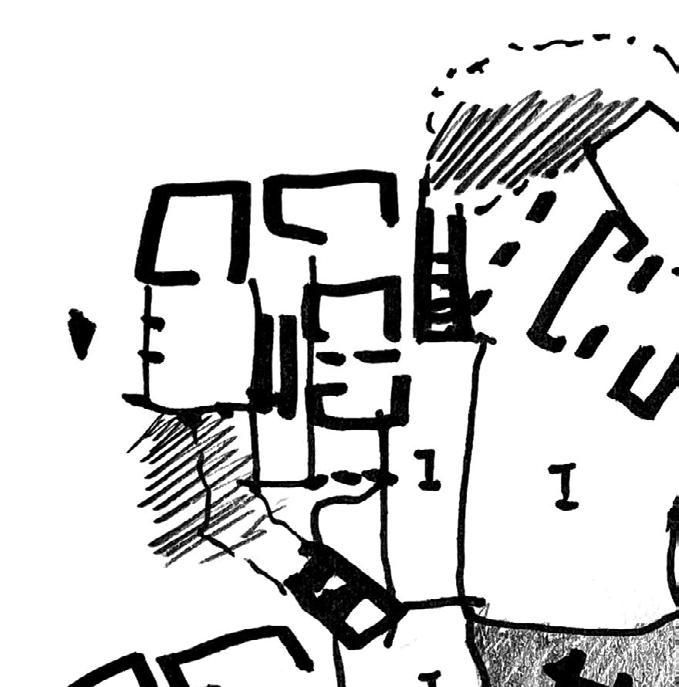

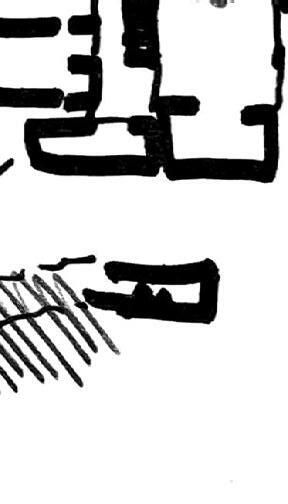

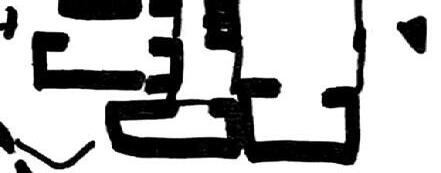

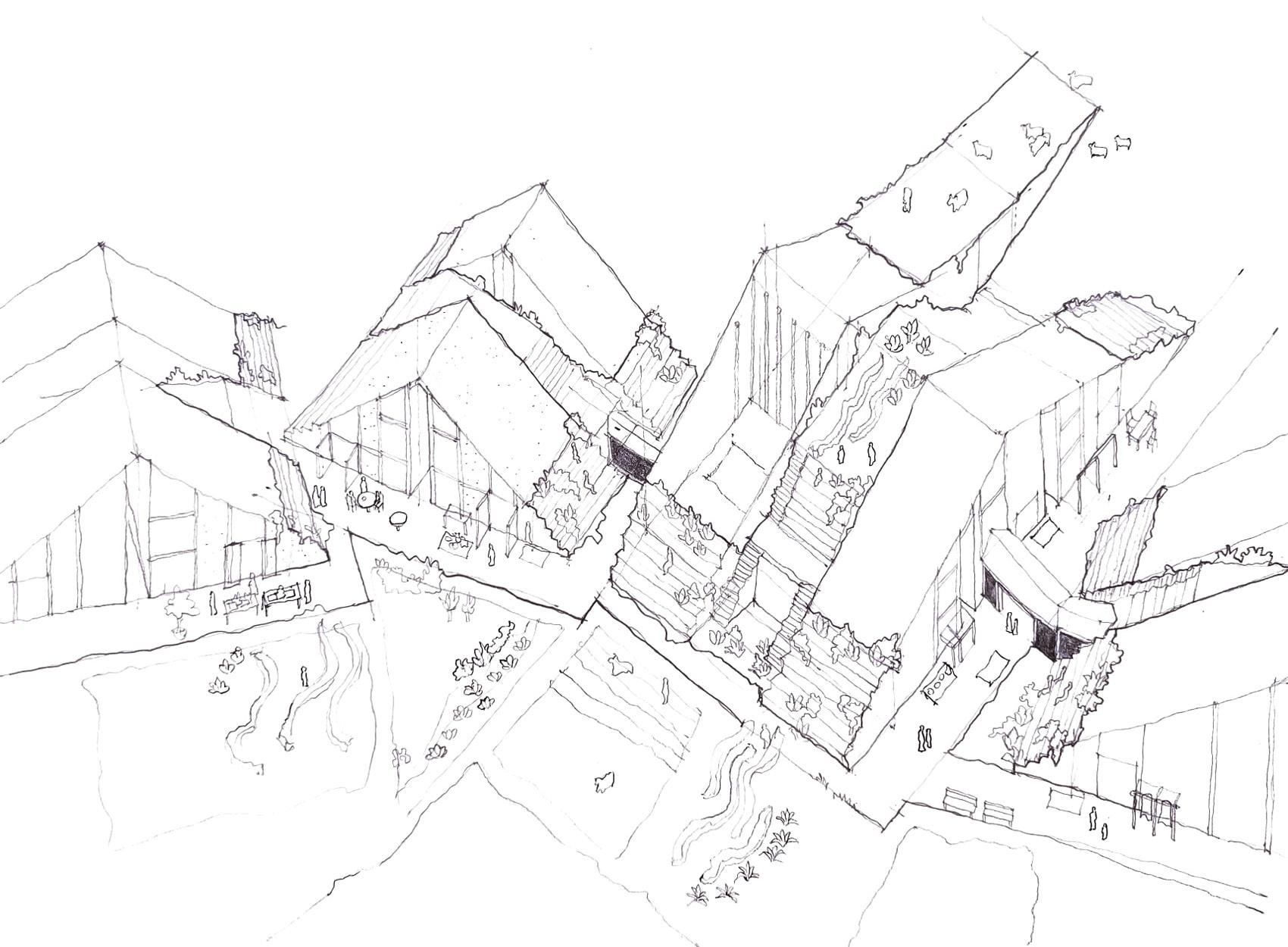

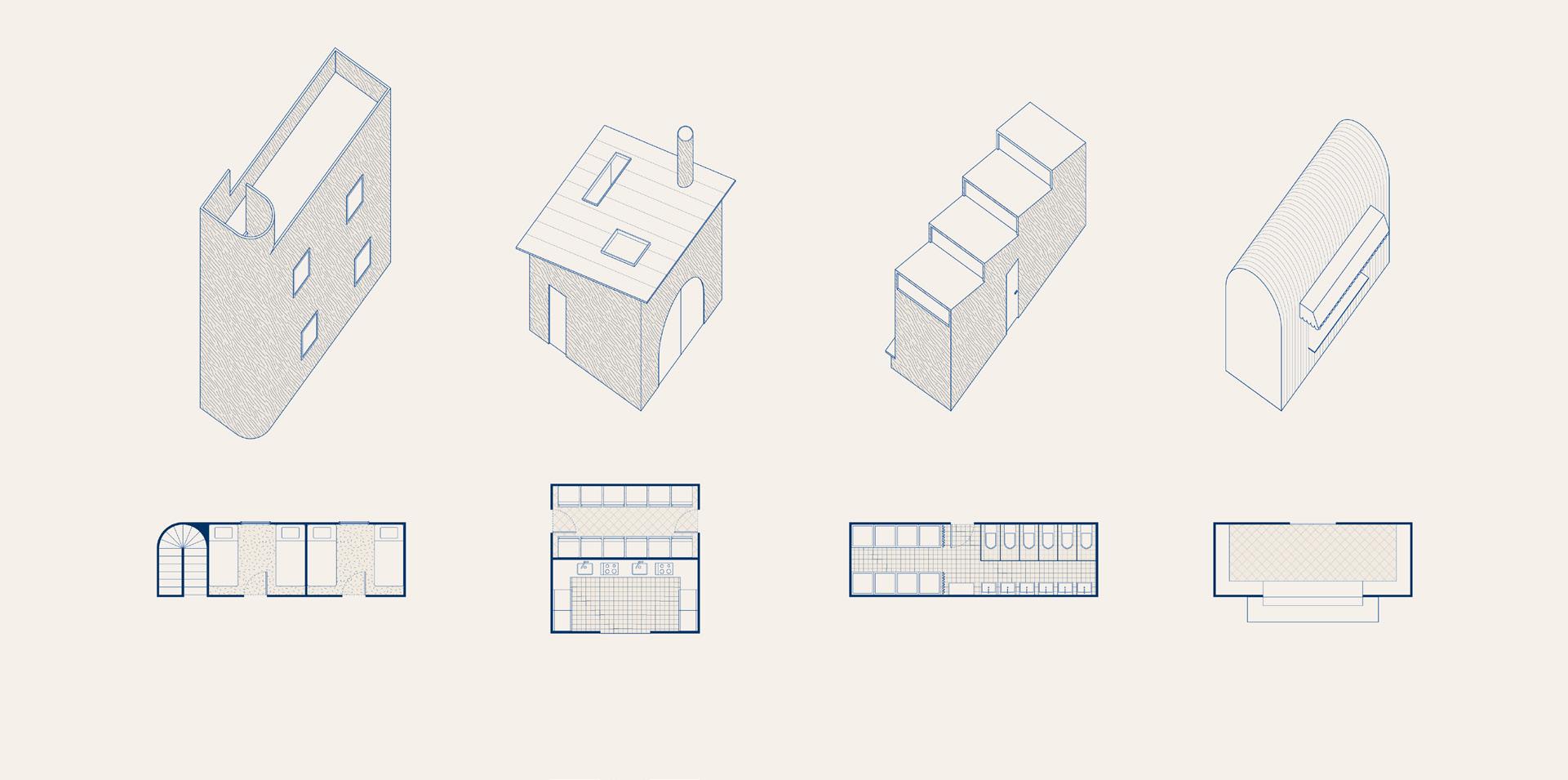

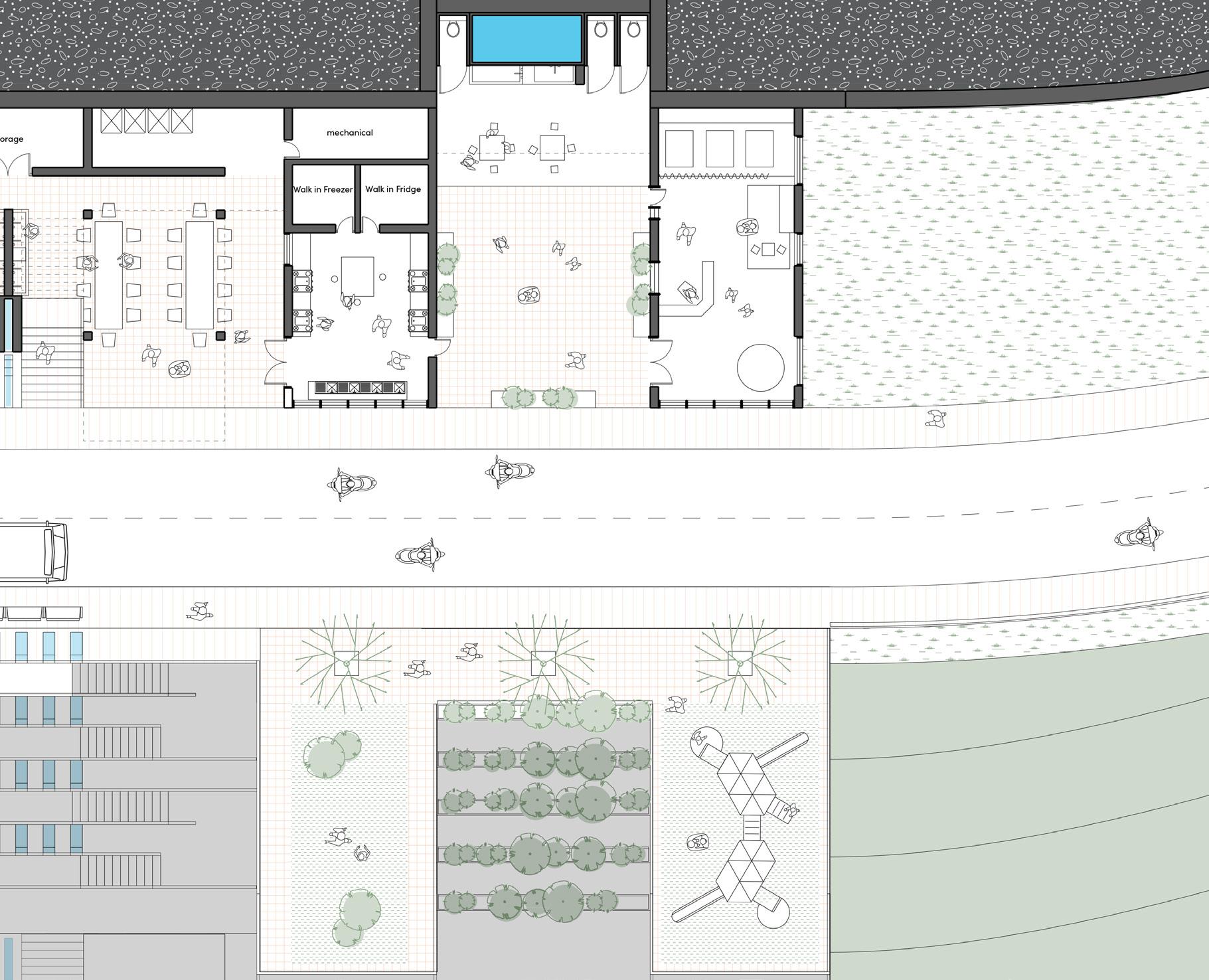

Augmenting existing pockets of space

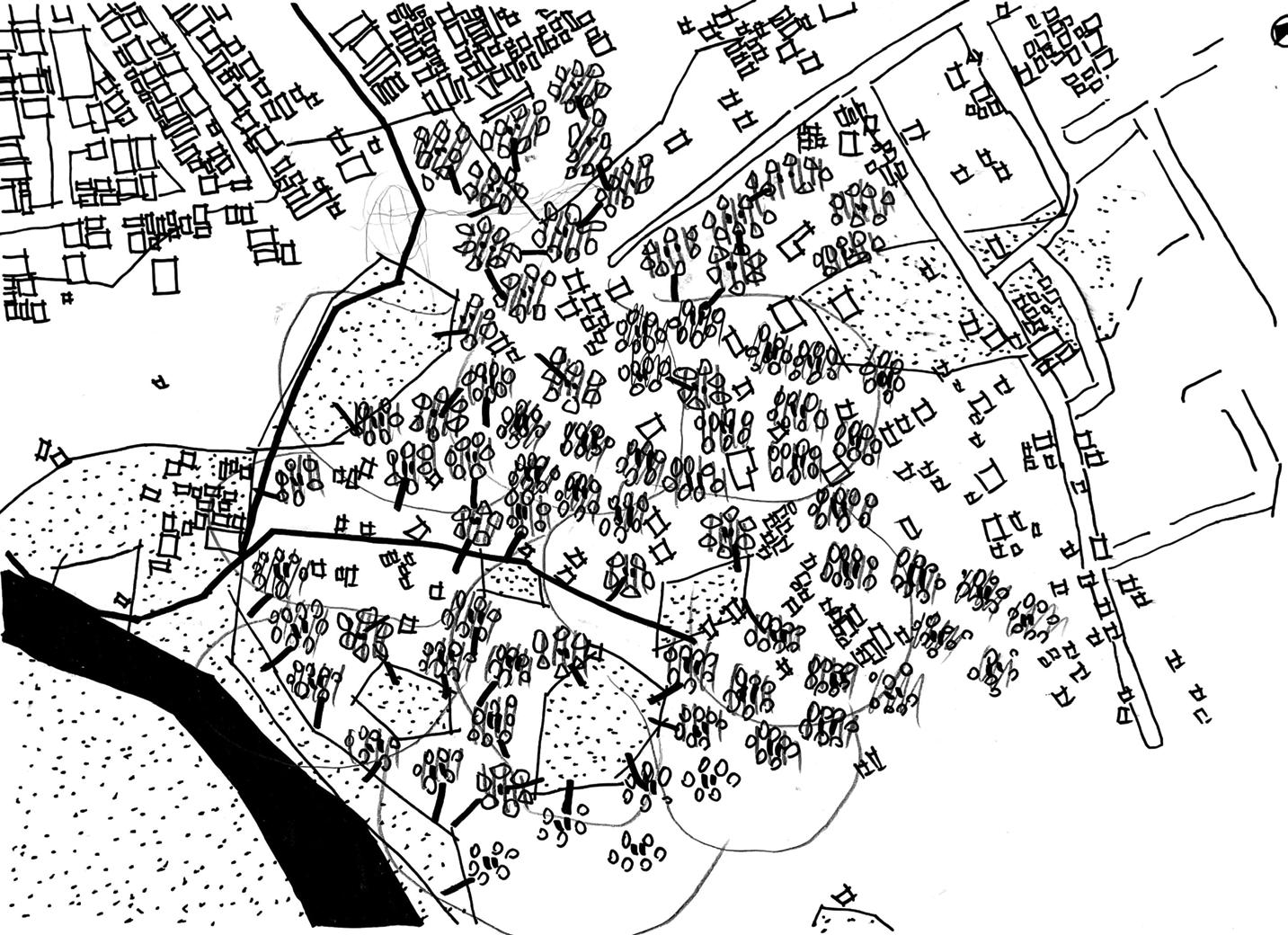

Site Plan 1:20,000

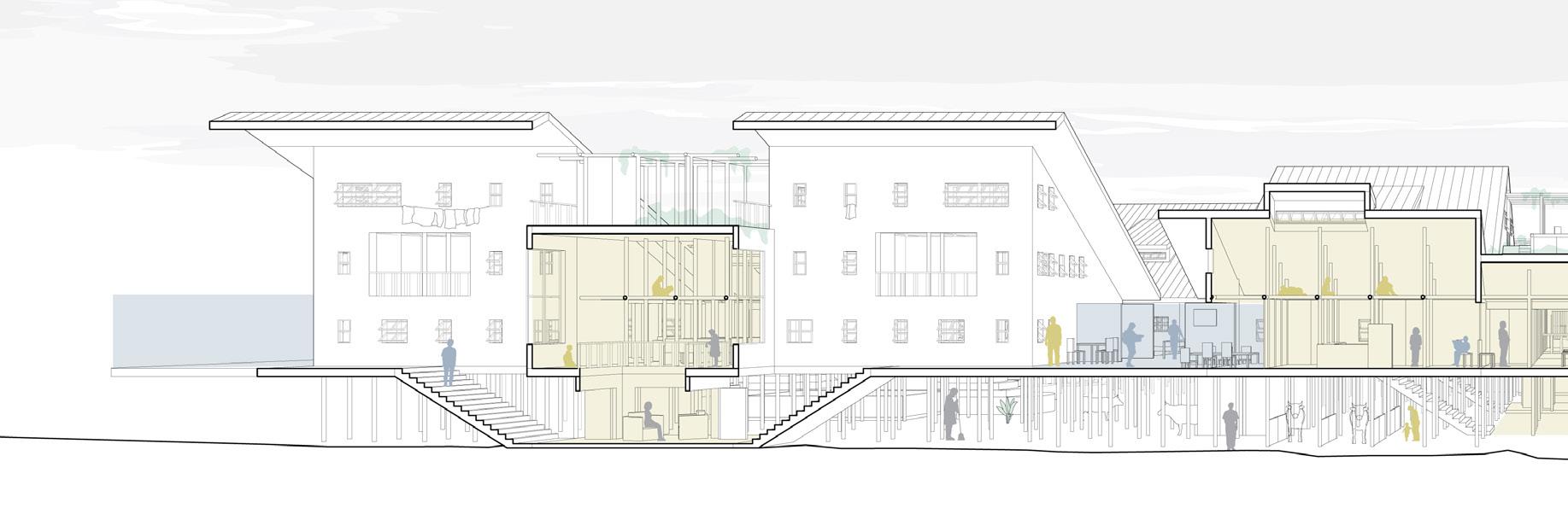

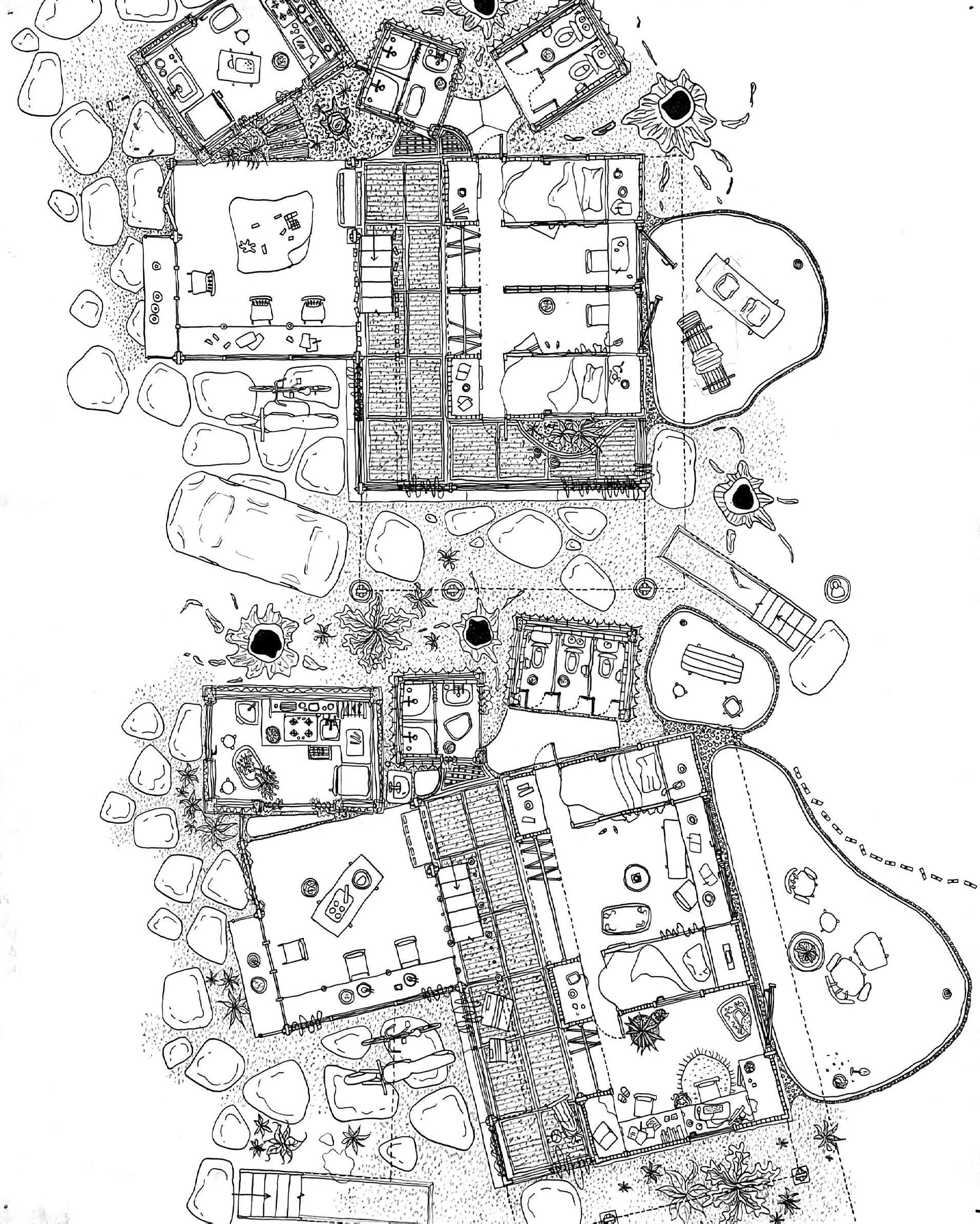

Site: San Salvador, El Salvador Crisis: Earthquakes Area: 19,848 m2

1,008+ 2,000+ 216

Beds Inhabitants Units

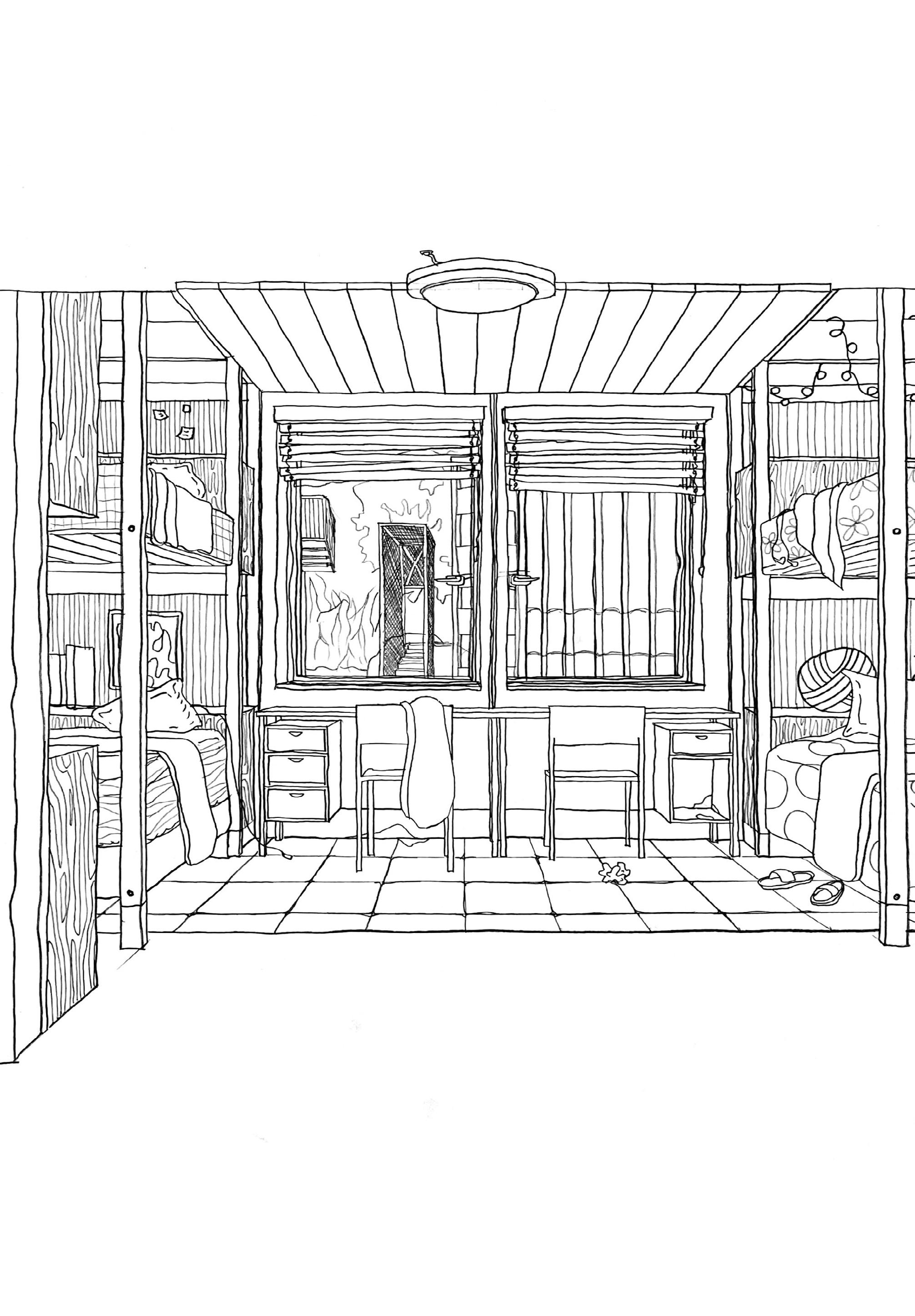

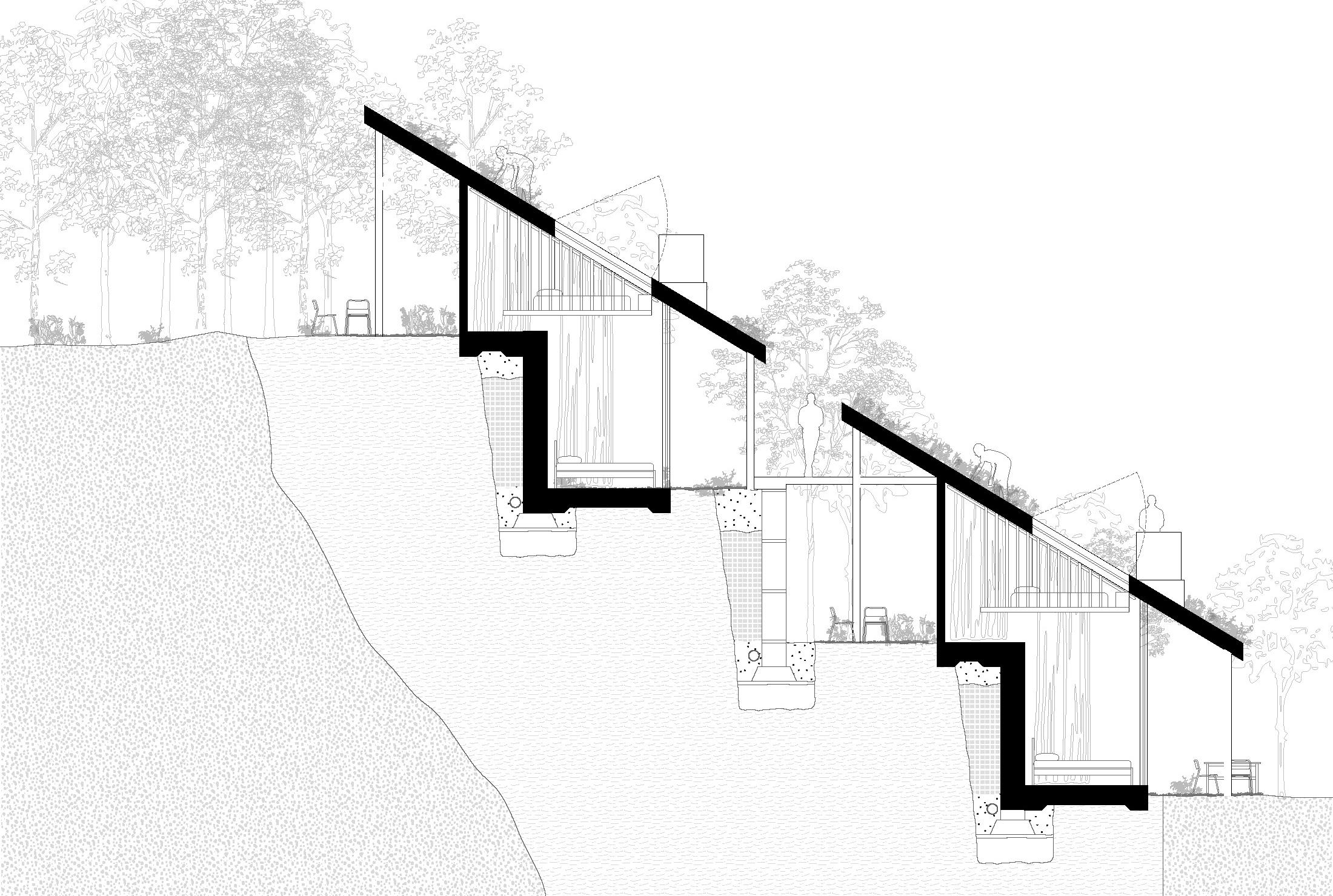

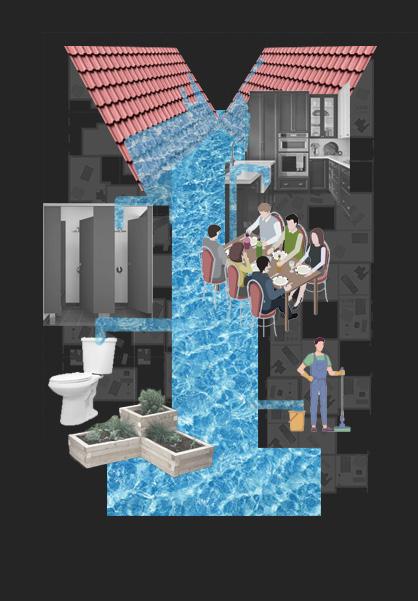

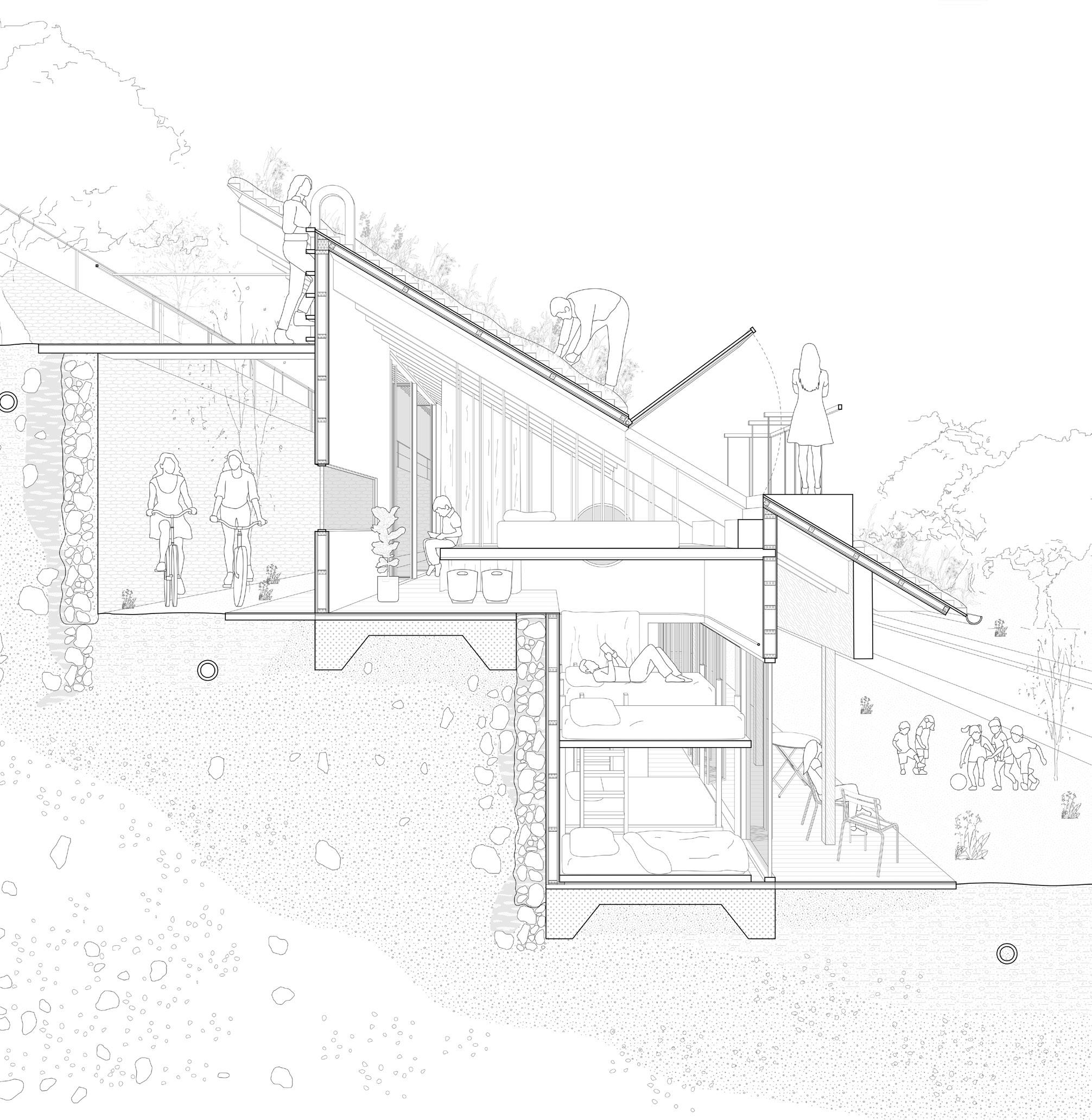

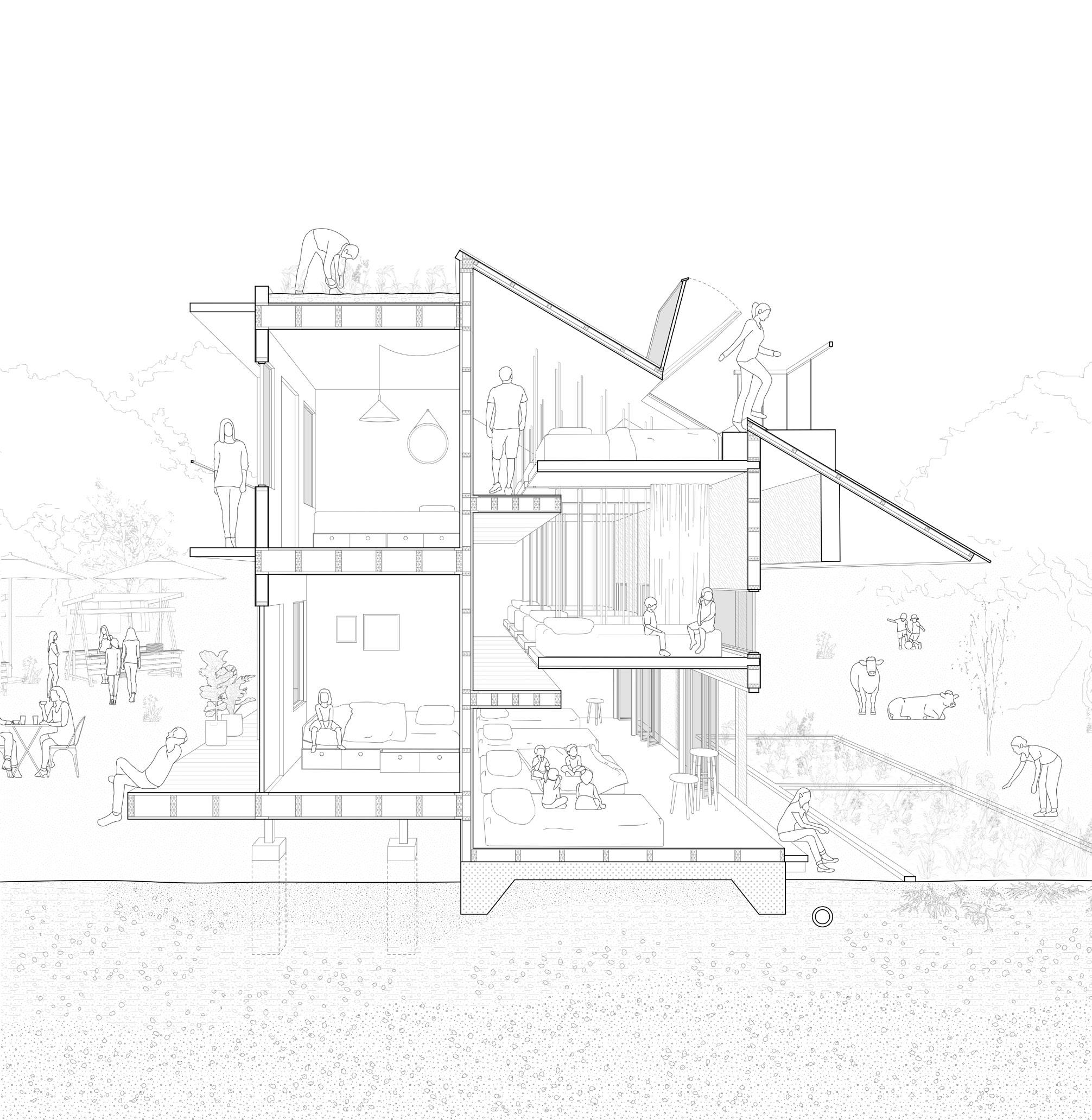

Earthquakes are a sudden and violent shaking of the ground, sometimes causing great destruction, and a prolonged period of low rainfall coupled with wasteful management of water. The architecture of this project responds with thick anchoring walls and a series of amenities that become safe havens during emergencies. To address drought this project collects rain and recycles grey water throughout.

I know you are coming back from your trip to Los Angeles. I hope it went well. I know it is hard to visit a city that has gone through so much in recent days with all the death and displacement that has come due to the aftershocks of the big earthquake. I hope you were able to pitch in some help and I am glad you are back for a little bit; it makes me so happy. After a long trip away from home, I wanted to welcome you back with some of my famous pupusas. I am going to the Thursday market that sets up by your Tio Majano’s place. Hopefully, Doña Carmen has good maiz this time. I remember walking around the different stands with you when you were younger. Your favorite stand to stop at was the empanadas that Aurelio used to sell on the steps up to your friend Marta’s family place. You liked playing at the laundromat that was close by too. I am glad we have been reusing the grey water from the laundromat to grow vegetables in the pocket gardens since In-Between was started because we are not suffering as much as we would have during these last drought seasons. I hear that the droughts in Los Angeles have made the earthquake aftermath much worse. You can tell me about that when I see you later.

When you read this, you will probably have noticed that your Abuela and I have made some changes to the place. We decided to replace the hammocks in the courtyard; that is an adventure we can tell you about later! Your private space was not touched; we know it’s important to you. We considered converting your space into another garden, JK! Have some of your Abuela’s horchata—it is in the fridge next to the tamales.

Love, Abuelo

I make my way through the hustle and bustle of San Salvador to my cousin’s home. When I arrive, I feel the temperature drop, I feel shade from the sun. I feel stones beneath my feet and plants graze my arms. As I follow the steps to her home, I smell the foods being sold at the stands, I hear children laughing, and hear water running. As I arrive, I feel the coldness and texture of the walls at her entrance. She brings me to an opening where I feel the sun touch my face, I hear birds chirping, I hear kids playing in the distance, I hear music playing, I smell the moisture in the air, and I hear water dropping onto something that sounds like stone or clay.

I walk to my room for the night, I feel the fabric of a hammock graze my arm and the coolness of the walls on my hand. When I reach my room, I hear muffled sounds outside, I feel the smoothness of the walls around me, and I fall asleep to a sense of enclosure around me. I wake up to the aroma of coffee and the sound of roosters outside. I feel as if I am in the countryside, not in the middle of the city for a second.

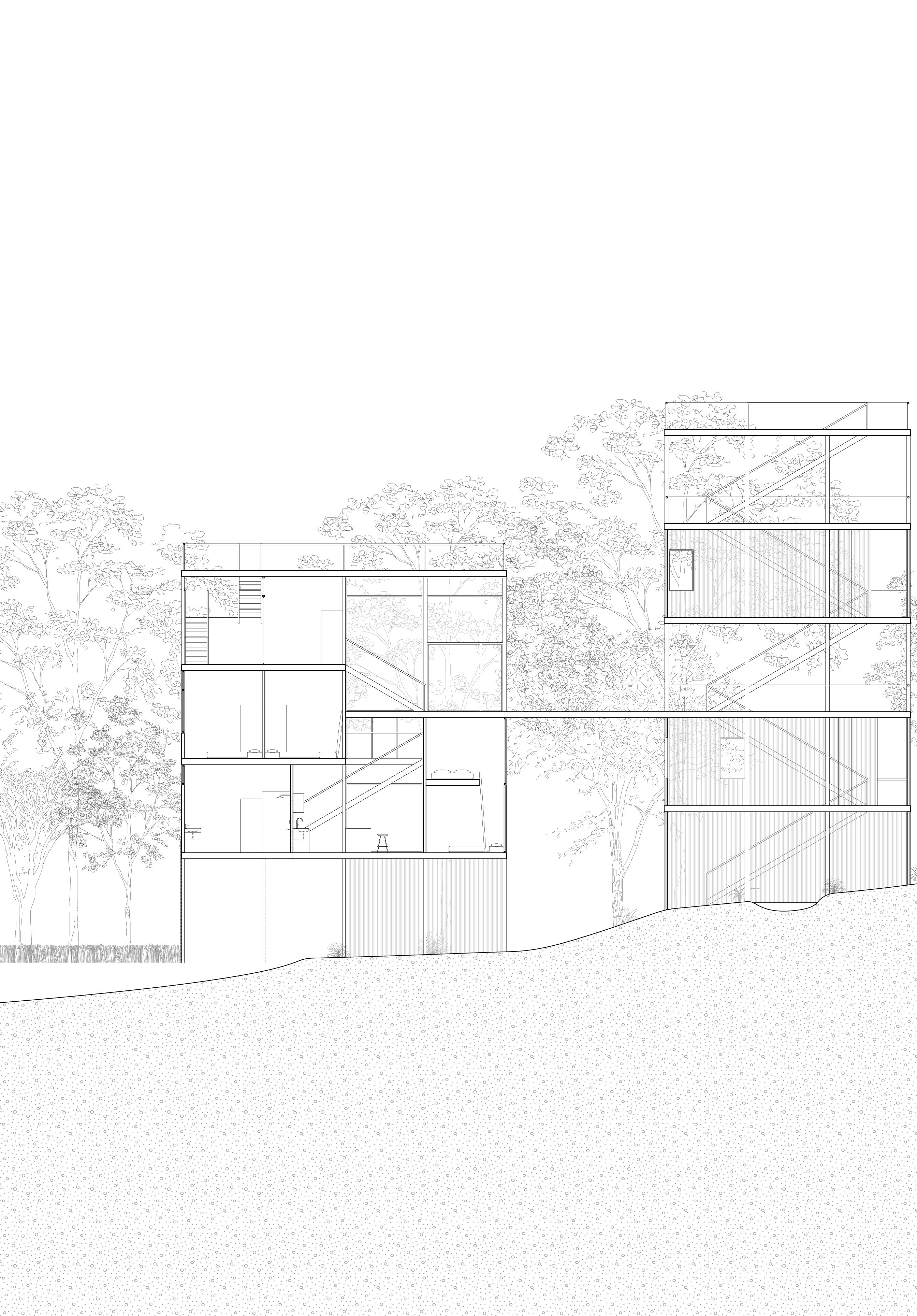

60’ 0” (18.29m)

Angel Escobar-Rodas25’ 0” (7.62m)

55’ 0” (16.76m)

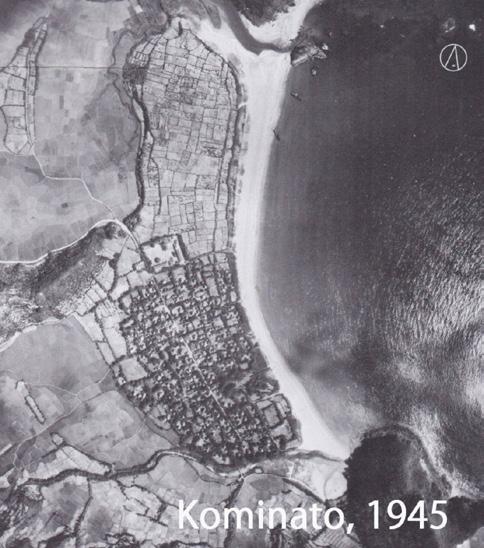

What happens between the remnants of war and the threat of typhoons?

Site: Kinmen, Taiwan Crisis: Typhoons Area: 150.5 km2

1000 1500 500

Beds Inhabitants Units

In the summer of 1958, a shower of artillery shells scattered over the beaches of Kinmen Island in Taiwan. Overnight, the island became a symbol of conflict. Kinmen was a military stronghold for half a century and while it finally lowered its guards, the memory of war lingers. Former military infrastructures have become entertainment venues, damaged buildings have been repaired by new materials. These interventions reflect hope after conflict, but also the piecemeal nature of Kinmen’s collective memory and identity.

Today, Kinmen is threatened by a different kind of destructive force: typhoons frequent the island and destroy existing (traditional) housing. But Kinmen’s practice of mending and rewriting its violent history offers a way to re-imagine housing in this time of crisis. I’m interested in co-opting the bunker, the existing protective shelter for a different kind of destruction, alongside coastal structures, the protective infrastructure from water and wind, and the courtyard home, the site of Kinmen’s social culture.

Emily

There is chatter in the courtyard. The voices float into my room and under my covers, dispersing the sound of the heavy muted ocean waves. The water had sounded more threatening than usual.

I think about the old myth my friends told me as we were walking up the mountain to school. Thousands of people once battled right where our homes are. We always argue about whether the story is true and we never agree. I stand on my tiptoes and look through the aperture. The warm sand is too bright…but wait, if I squint the wave breakers almost look like barricades.

I ponder this as I follow the voices out of my resting place. My eyes adjust to the sunlight that streams into the courtyard from above. The whole block is here and someone brought sorghum beer. Soon, the laughter swells and rises out of the earth, and I forget, once again, about the stories of war.

We’re washing the last of the dishes outside when the clouds begin to darken. We know this routine well. We retreat into the terrain just as the familiar pitter patter begins. The wind picks up, the trees sway far above us. My belly is full, and I know I am in the safest place I can be. The rocky interior, rooted in the stable ground, feels smooth and worn from touch. I decide the stories aren’t true.

The aftermath is everywhere and nowhere. Lodged between the memory of war and the threat of natural disaster, the island exists in a blurry present. Barricades line a coast that has already been eroded, bulleted walls crack and crumble after the typhoon. Two forces meet in the middle. The destructed is destroyed again. In Its wake, rebuilding begins.

You won’t remember entering inside, but you will know when you’re home. The smell of salt from the ocean will mingle with the smell of steaming fish from the next room over. The whistling of the wind will join the gentle tapping of the branch against the roof. The rocky terrain will become smooth under your hands. When the warm sun fades, the familiar pitter patter begins. As we begin our retreat, the sound quiets, the carpet is soft under our feet, the stories begin. The bombs… the bloodshed… the storms… but the home is a different ending to the cyclical story of destruction. In the dizzying process of repair, the gap left behind is a door you can slip into, the thickening a shelter where you can put your head down to rest.

Fractured Memories, FortifiedHomesharing with Mayon’s Tourists and Evacuees

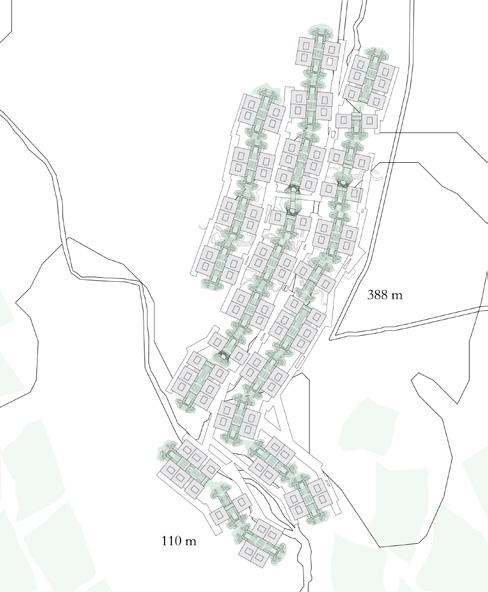

Site Plan 1:10,000

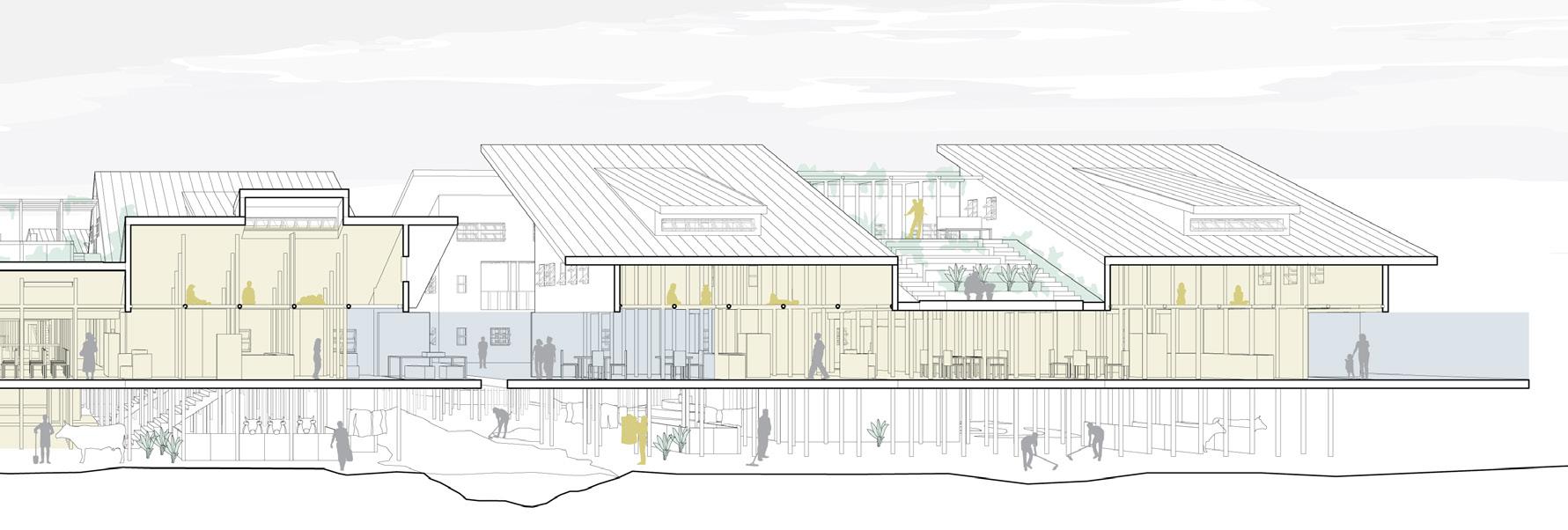

Site: Legazpi City, Philippines Crisis: Volcano Area: 40,000 m2

~1,000 ~1,000 100

Beds

Inhabitants Units

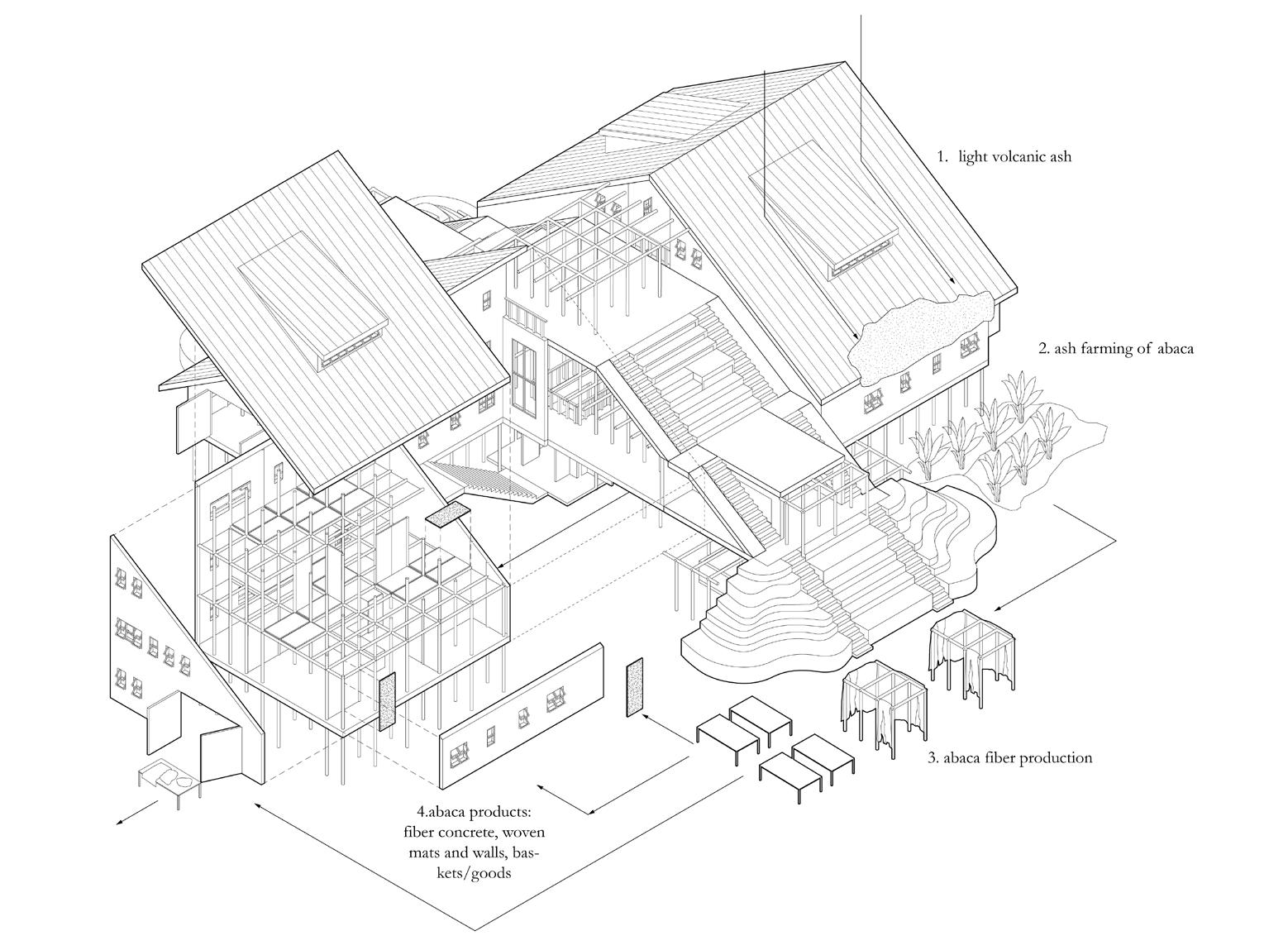

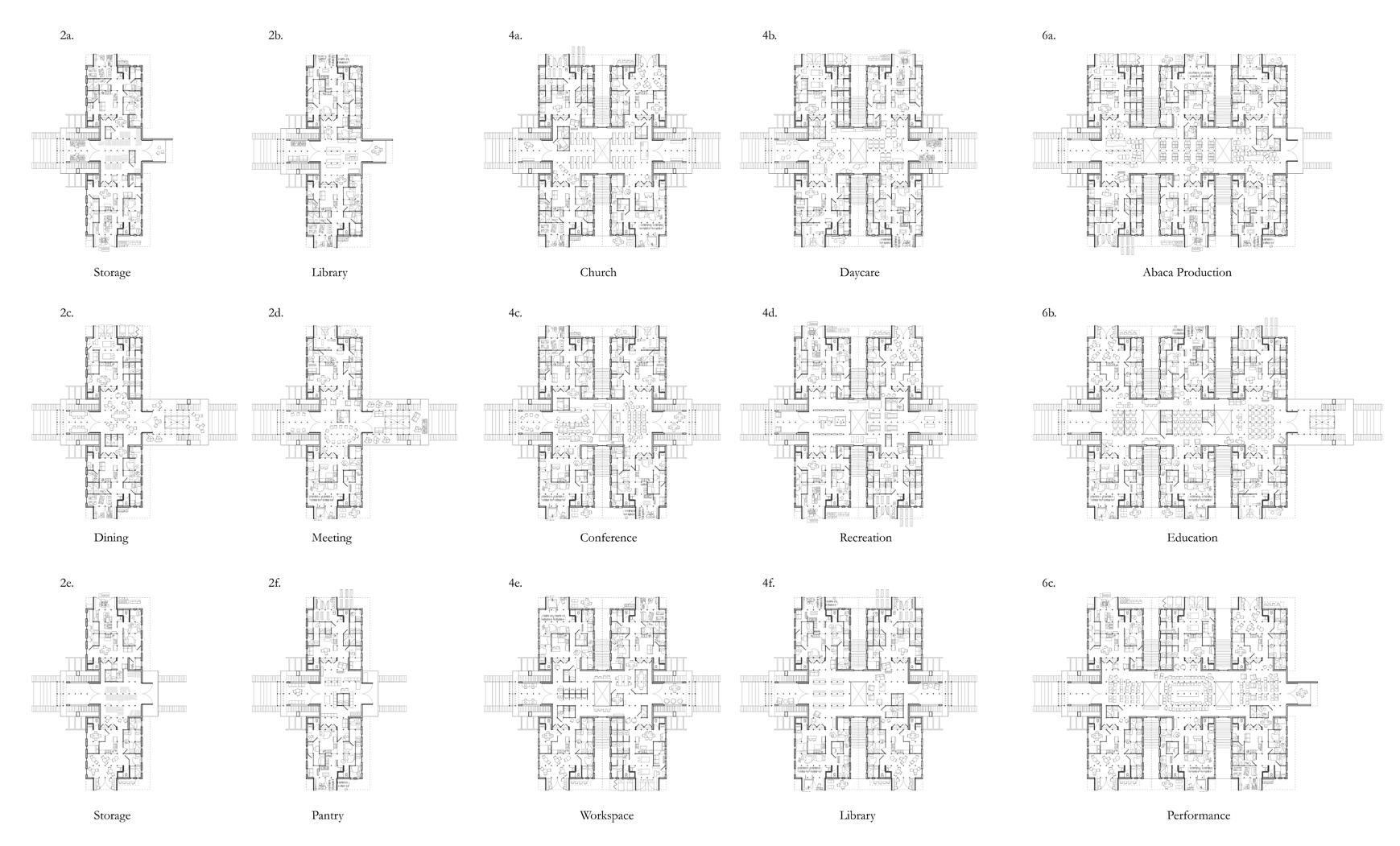

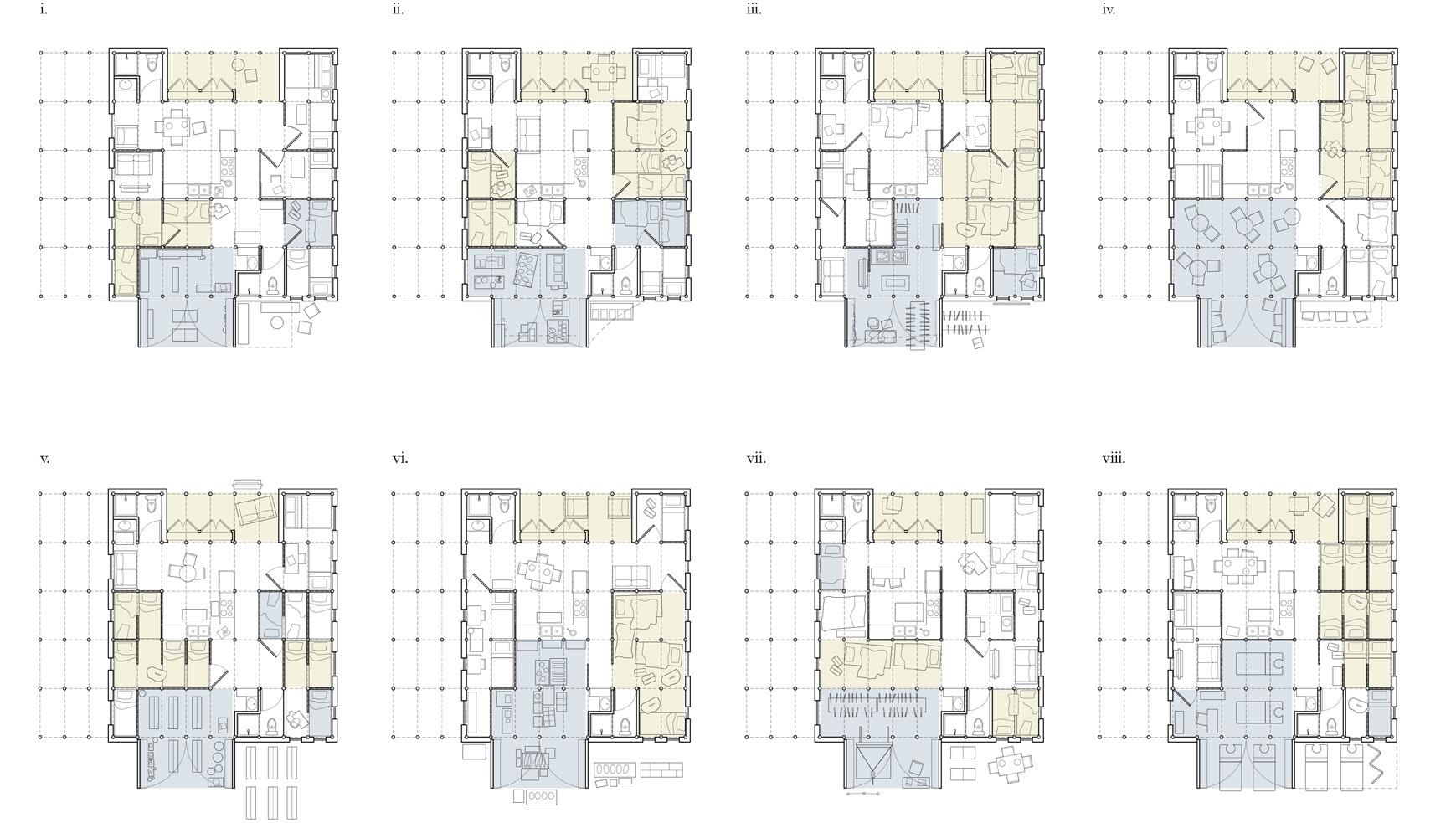

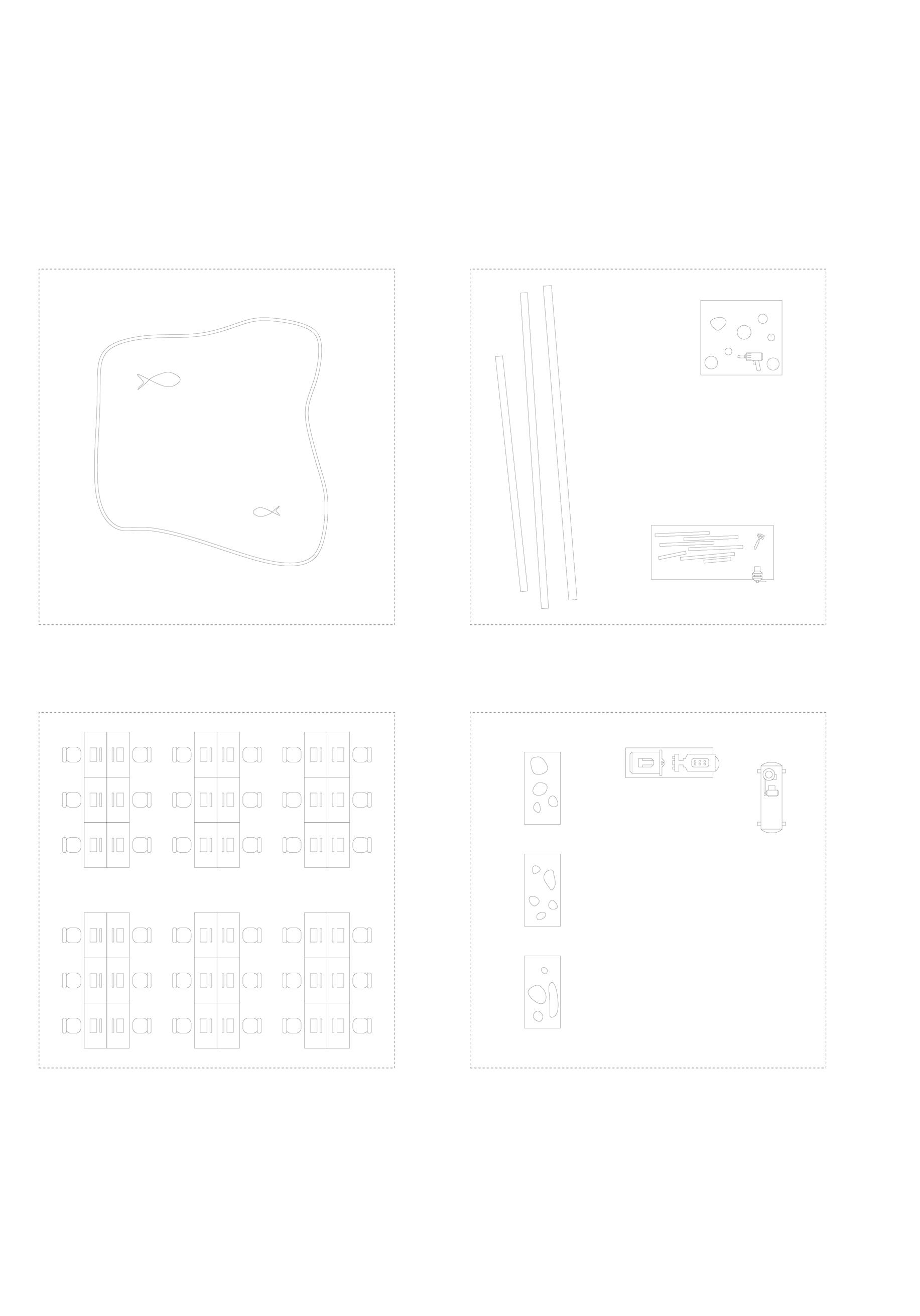

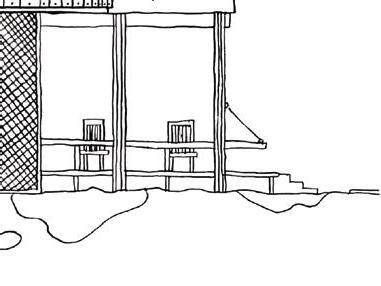

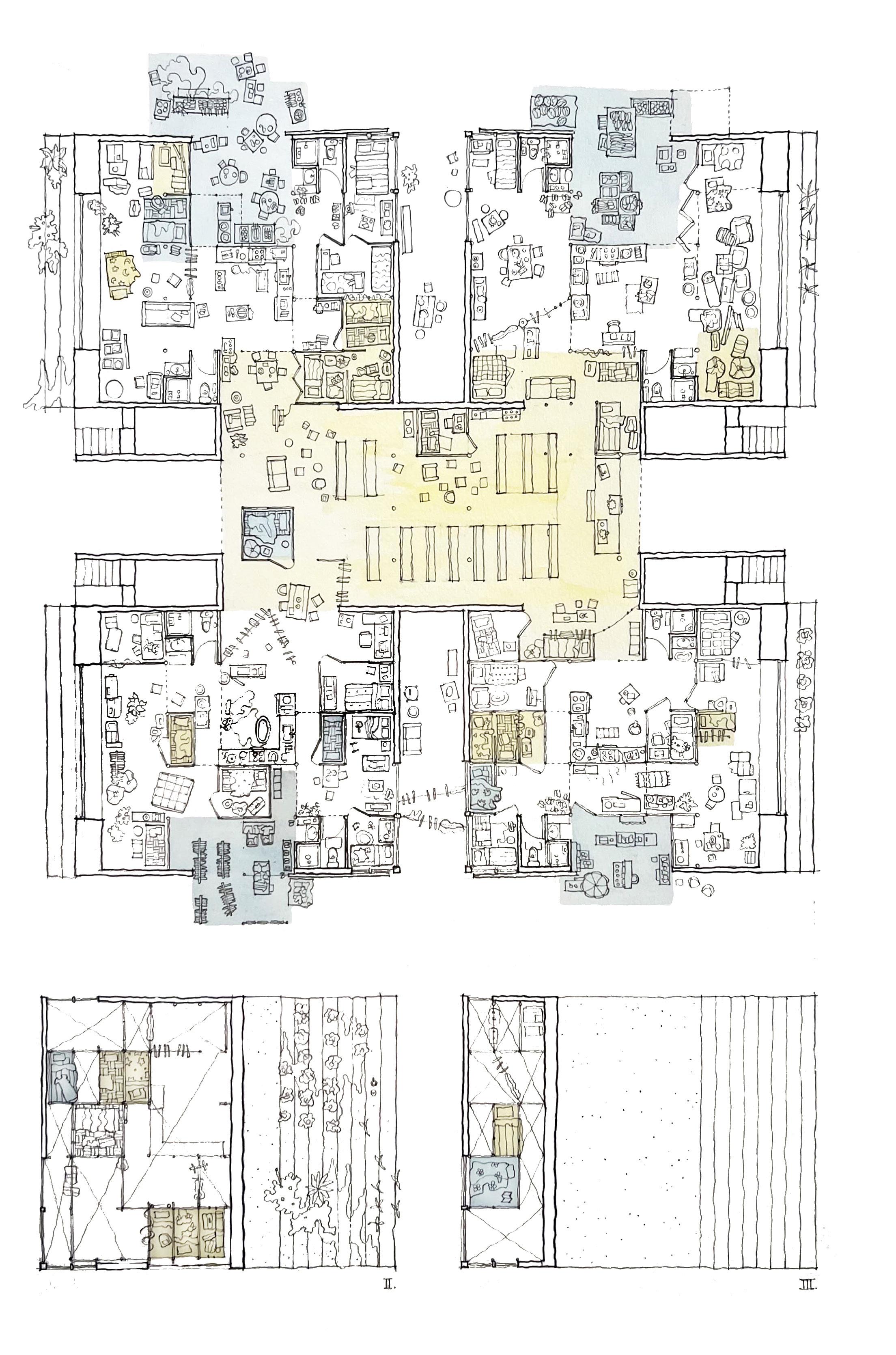

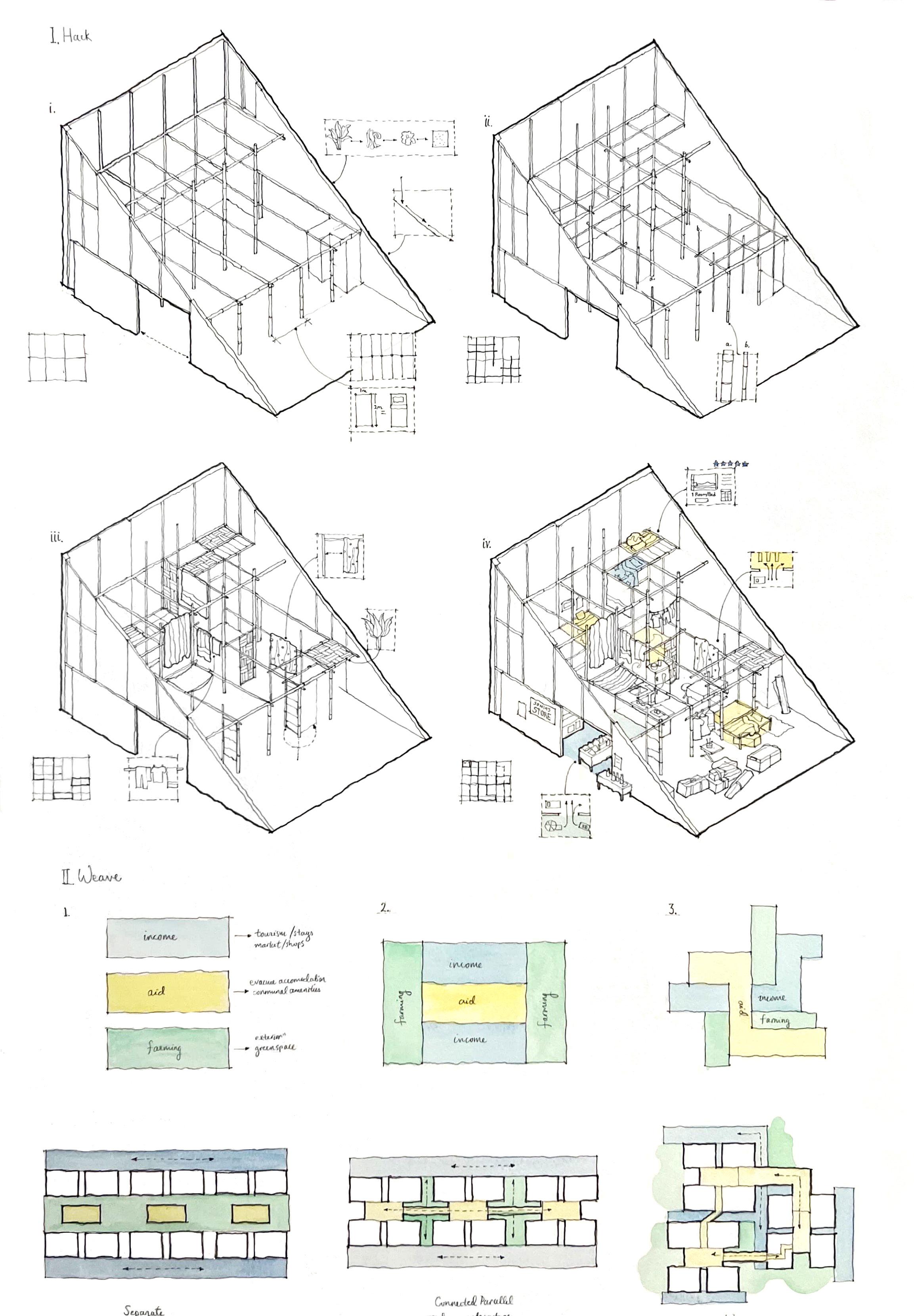

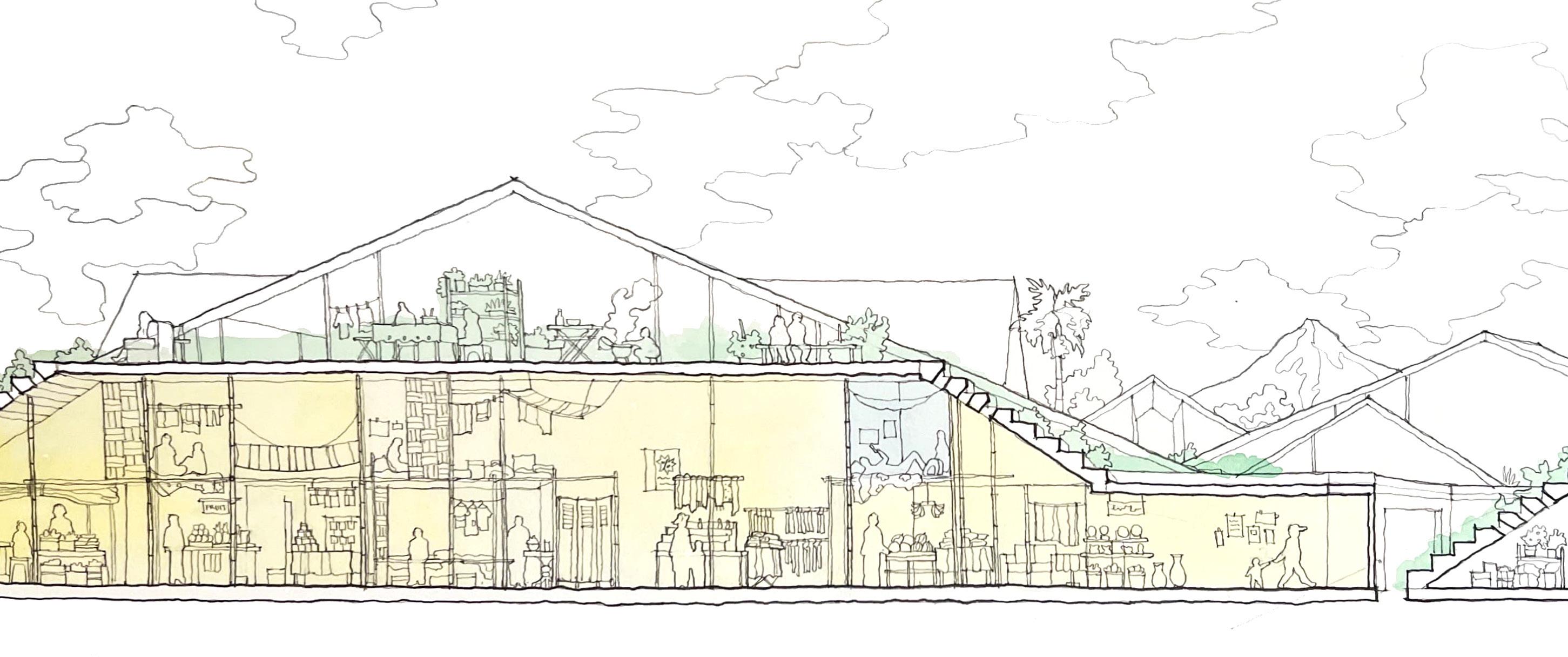

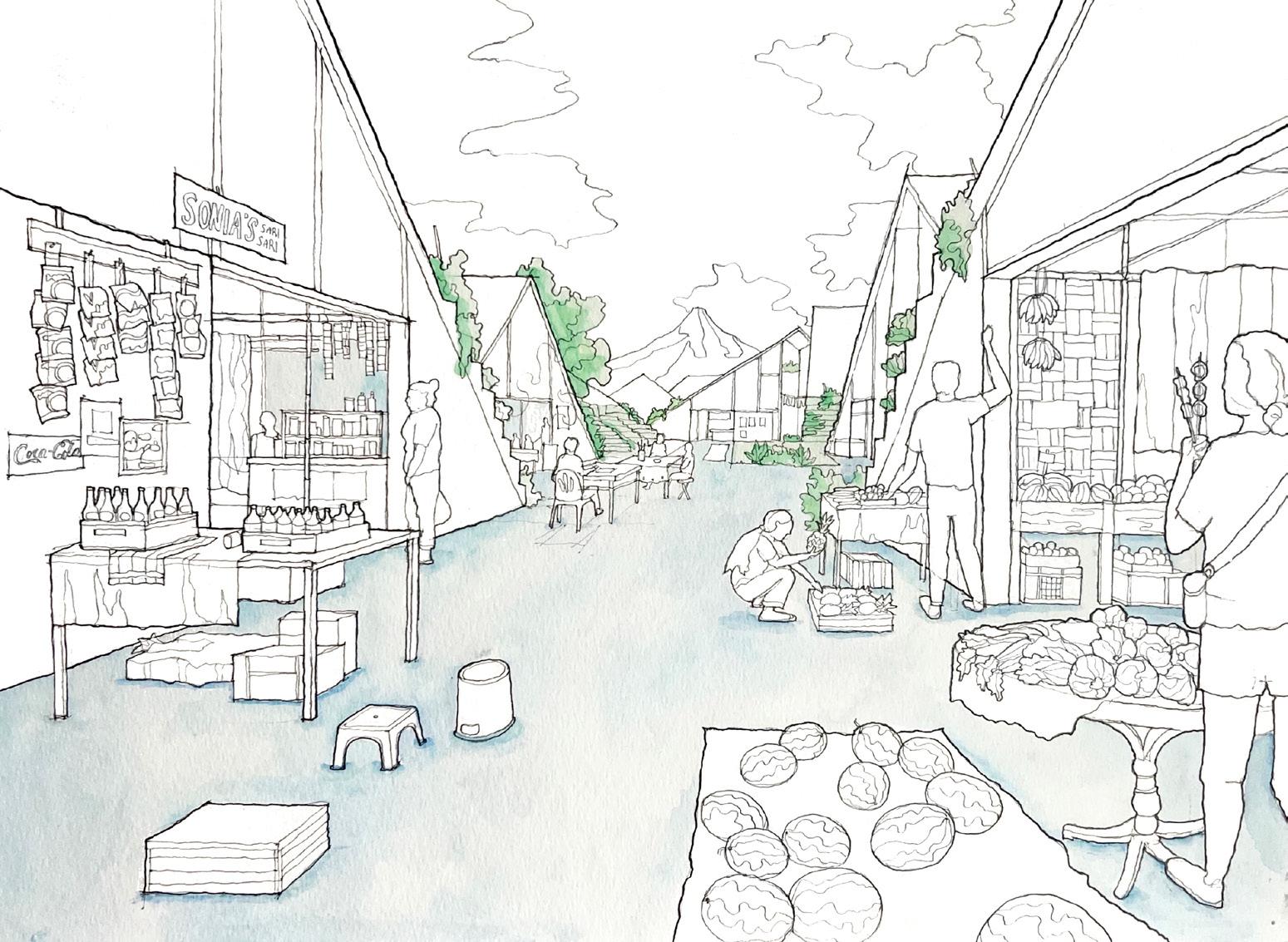

Hacking Homes for Volcano Guests responds to the nearby active volcano Mayon. The site is outside the immediate danger zone and at the very periphery of possible ashfall. The project responds to this climatic condition, as well as the social crises associated with eruptions: sheltering volcano evacuees and hosting volcano tourists.

Residents are provided the opportunity to generate income from volcano tourists and, simultaneously, encouraged to offer shelter to farming families fleeing from the volcano’s danger zone.

The roofs are prominent and pitched so that ash will slide off them and into the farm lands. The interior hacking infrastructure is made of bamboo, and the infill is woven abaca because these grow in the province near Mayon. The exterior envelope is concrete with abaca fiber waste because it is a sturdy and safer material to protect from air and ash. The buildings are elevated to accommodate the terrain and protect from flooding and runoff as a result of distant eruptions. The modules are oriented along the streams for wind and to allow for views towards the volcano.

Emily Hu

From this distance, the volcano is a beautiful and terrible sight.

Business is good. Tourists fill the market streets, disappearing in and out of our front door stalls with new dresses, souvenir bags, and, of course, volcano ice cream. The air is warm and the streets full of lively chatter. The outsiders bring with them an atmosphere of excitement, reflected in their eyes so eager to witness Mayon’s show. This morning, I sold three baskets woven with abaca, which grows abundant in the fertile soils of Mayon. “I’ve always wanted to see a volcano eruption”, a tourist remarks, browsing through my merchandise, “It’s just not the same on TV”. A tourist couple is staying in my sister’s old room. Yesterday, after a day out on Lignon hill, they came home and cooked dinner for us. I showed them my abaca weaving and they helped close shop at night. My family is thankful Mayon brings the visitors to us. We are lucky for good business, but tourists are not the only guests staying with us. Running the opposite direction, two farming families from near Mayon’s base have recently been welcomed to our home. One stays near the kitchen and the other above my room. Three more families are homed in spaces between the church pews out back; the neighbors have brought out blankets and food for them. We all take care of each other. Their stories are much different. They bring with them tense anticipation. The women help Grandmother prepare food and I watch the children as they play. Our home is crowded and busy, but it is a good busy, full life and community.

At the end of the day, I close the front doors and head inside. Walking through the warm kitchen, I enter the chapel. The neighbor, sitting on his couch, greets me as I sit and join the service with countless neighbors and guests. “Can I go play with the other kids?” an evacuee child asks his mother. “Just be careful near the kitchens and come back soon; you still have school tomorrow.”

Whether with excitement or fear, we are all watching Mount Mayon.

Emily Hu

Top: People onlook Mayon’s eruption

Emily Hu

Top: People onlook Mayon’s eruption

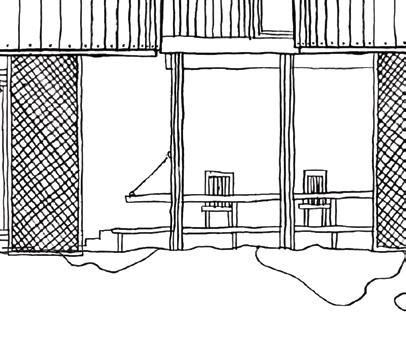

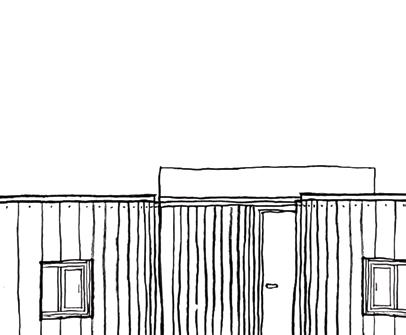

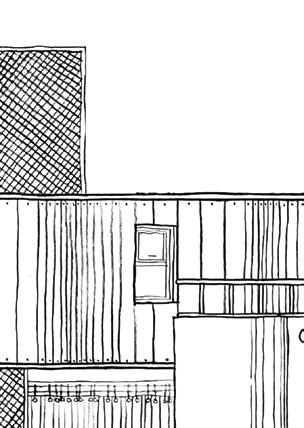

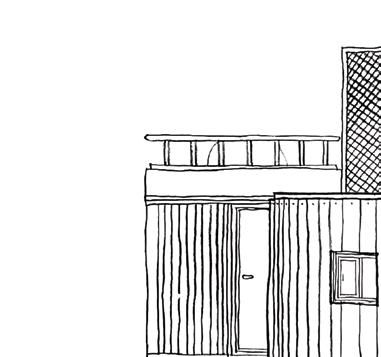

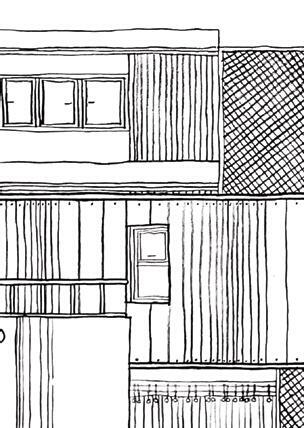

The market street is lively and full of activity; open doors host restaurants, convenience stores, clothing shops, and a host of other businesses. Tourists with their cameras and bags come in and out, strolling through the wide street while people peek out of their windows above. The air is warm and the homes, welcoming. Houses with their steep roofs line the street

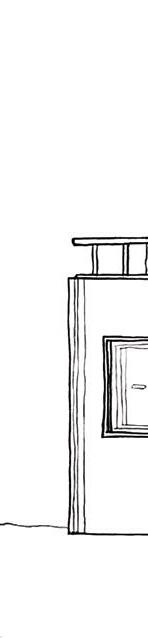

Entering through the large open doors of the home, there is a forest of bamboo poles extending up a couple floors. Mats, woven from abaca, are walls and floors which infill the tan bamboo grid; the abaca pieces are tied in a makeshift way, yet the home appears orderly like a well-packed suitcase. In the center straight ahead, there is a kitchen where several people cook together. Some children, sleeping in the lofted abaca mats above, peek out from their compartments and watch the scene. From the kitchen, the space is open to the back; the church pews are visible from the living space.

The home’s backyard veranda turns into a chapel, and a sofa and small table sit between the kitchen and pews. The church is also a forest of bamboo, and several families sleep in the gridded extra spaces above. Four homes lead to the chapel, and two large doors at the sides open up to the outside.

Farming and agriculture cover the exterior; crops grow on the fields and onto the roof of the chapel and other “back-buildings”.

Abaca production cycle

Abaca production cycle

Top: Site Plan

Bottom: Plan cluster possibilities, module possiblities

Emily Hu

Emily Hu

Site sections with income, aid, and farming

Emily Hu

Emily Hu

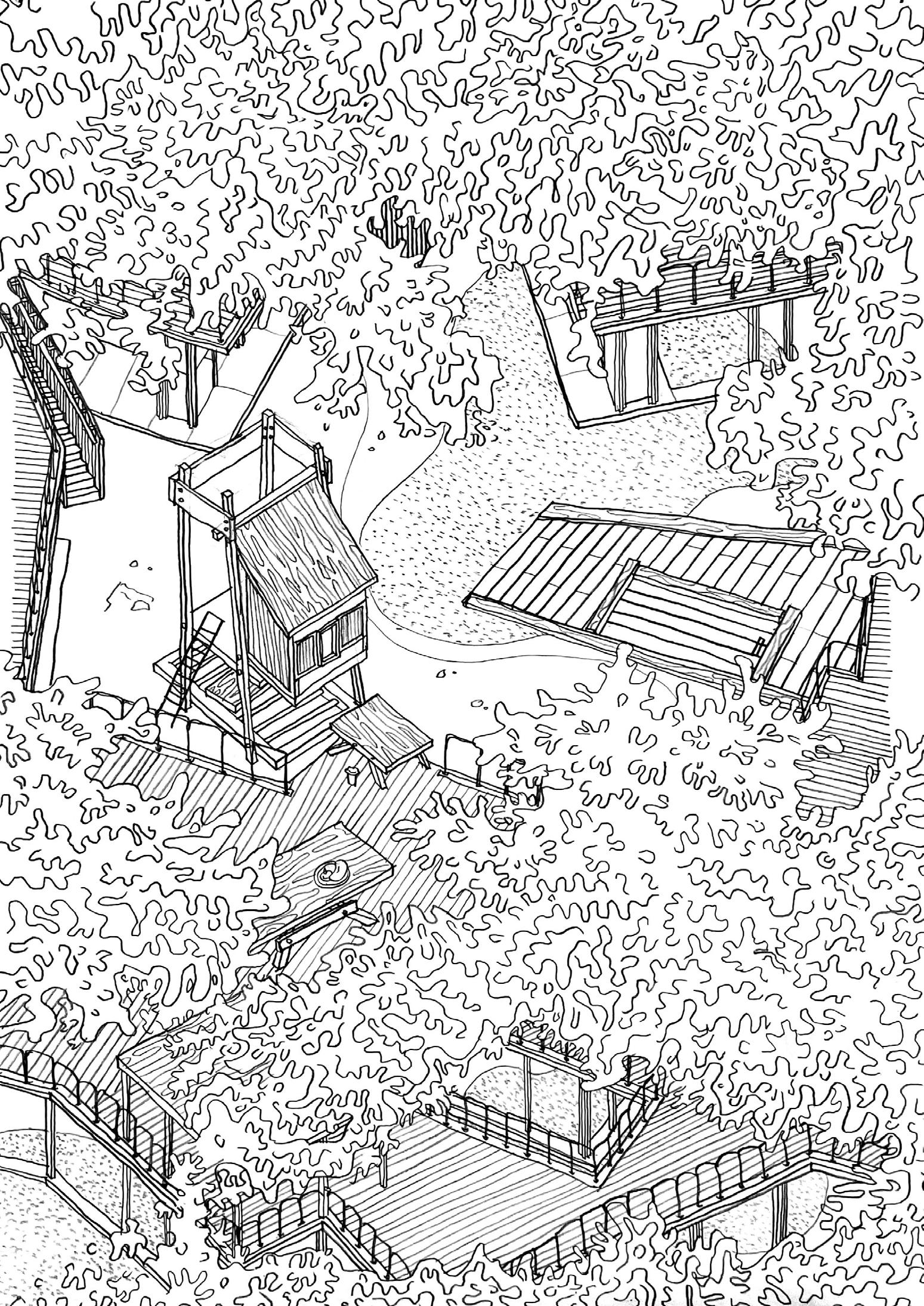

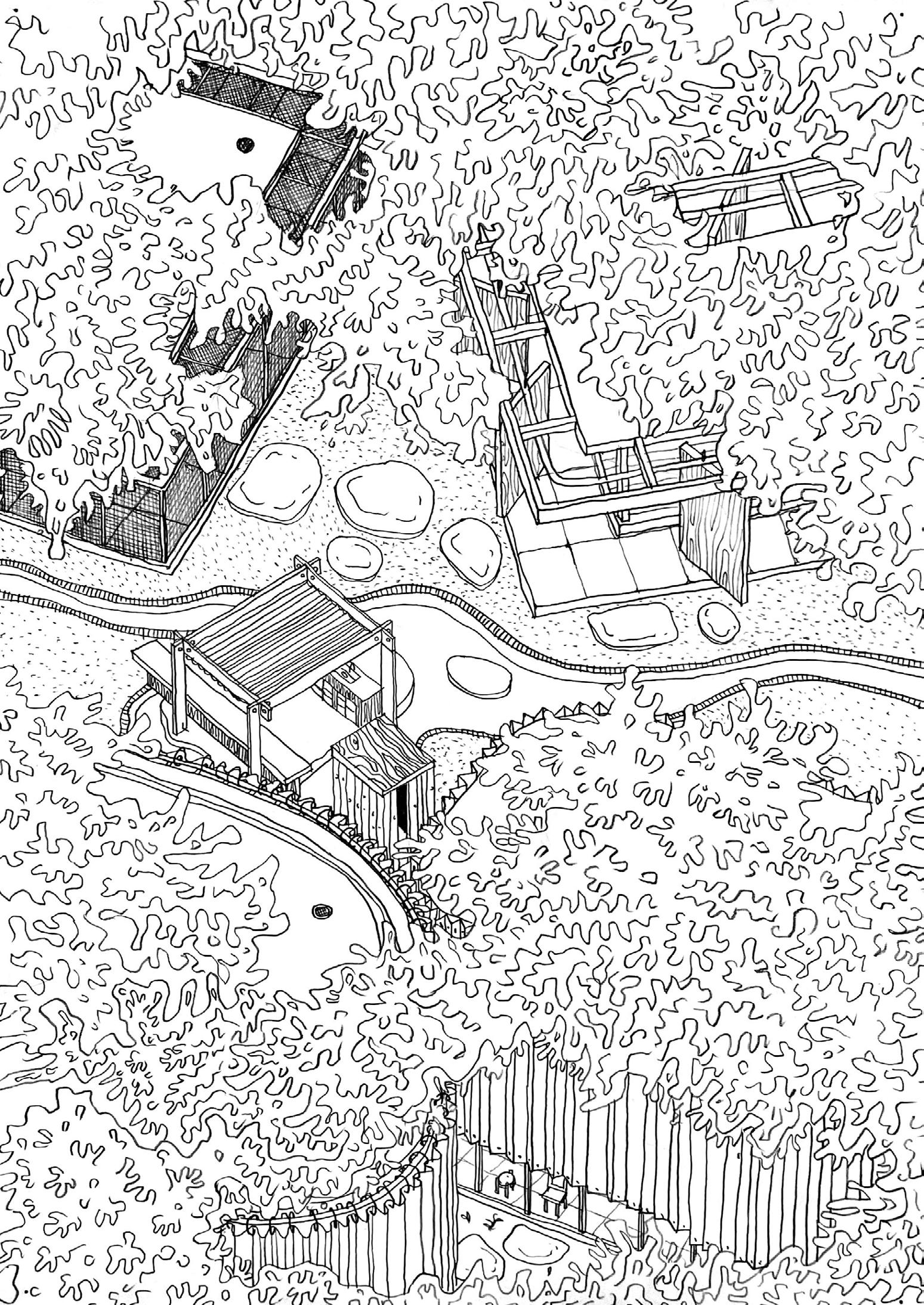

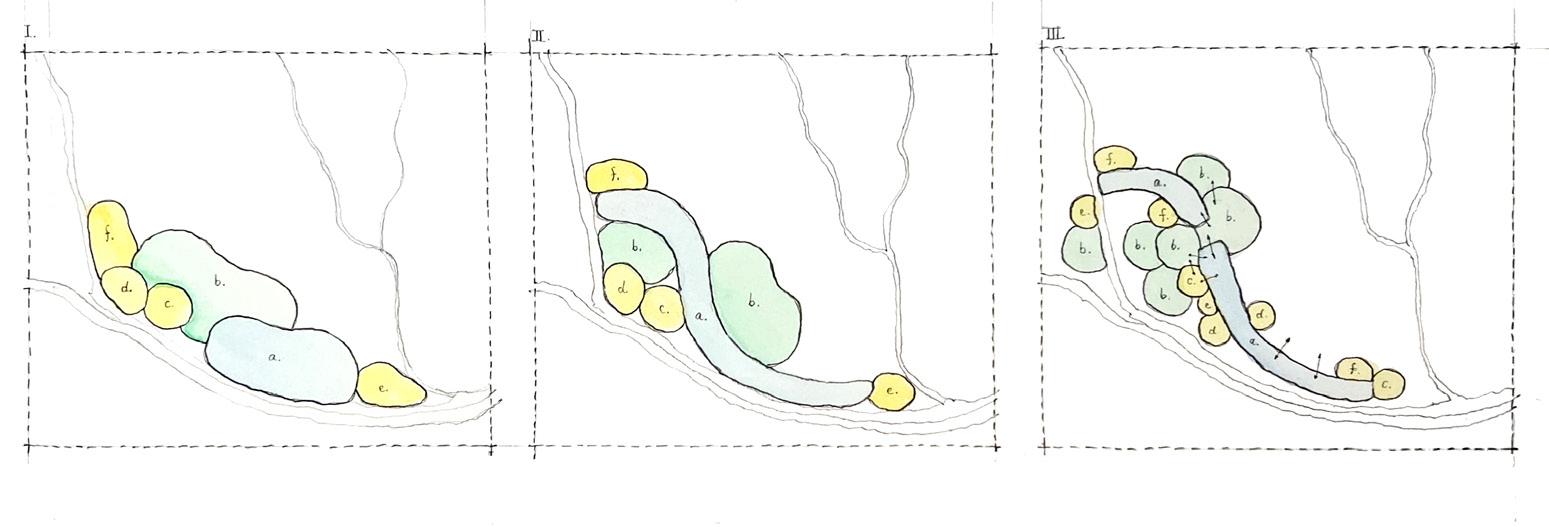

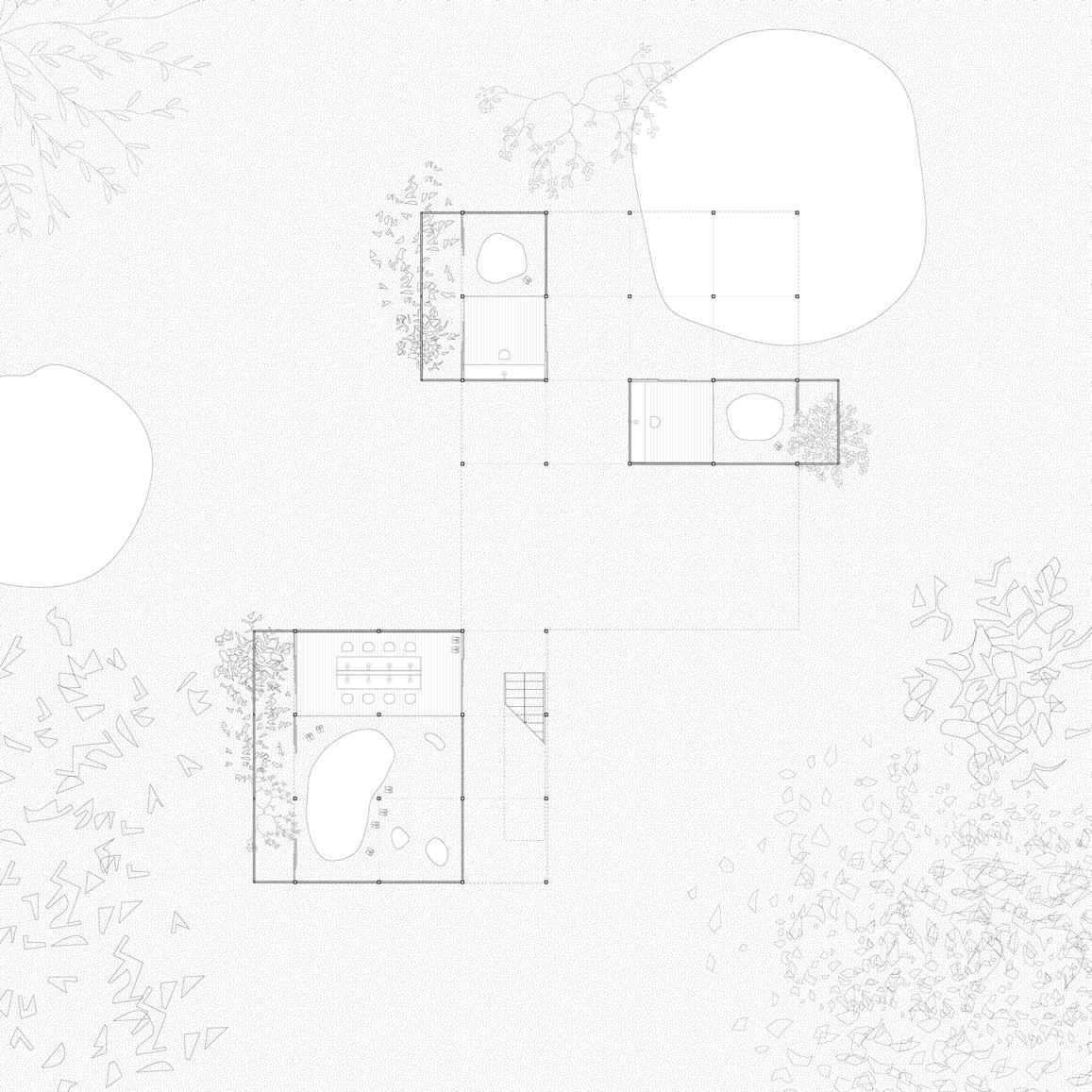

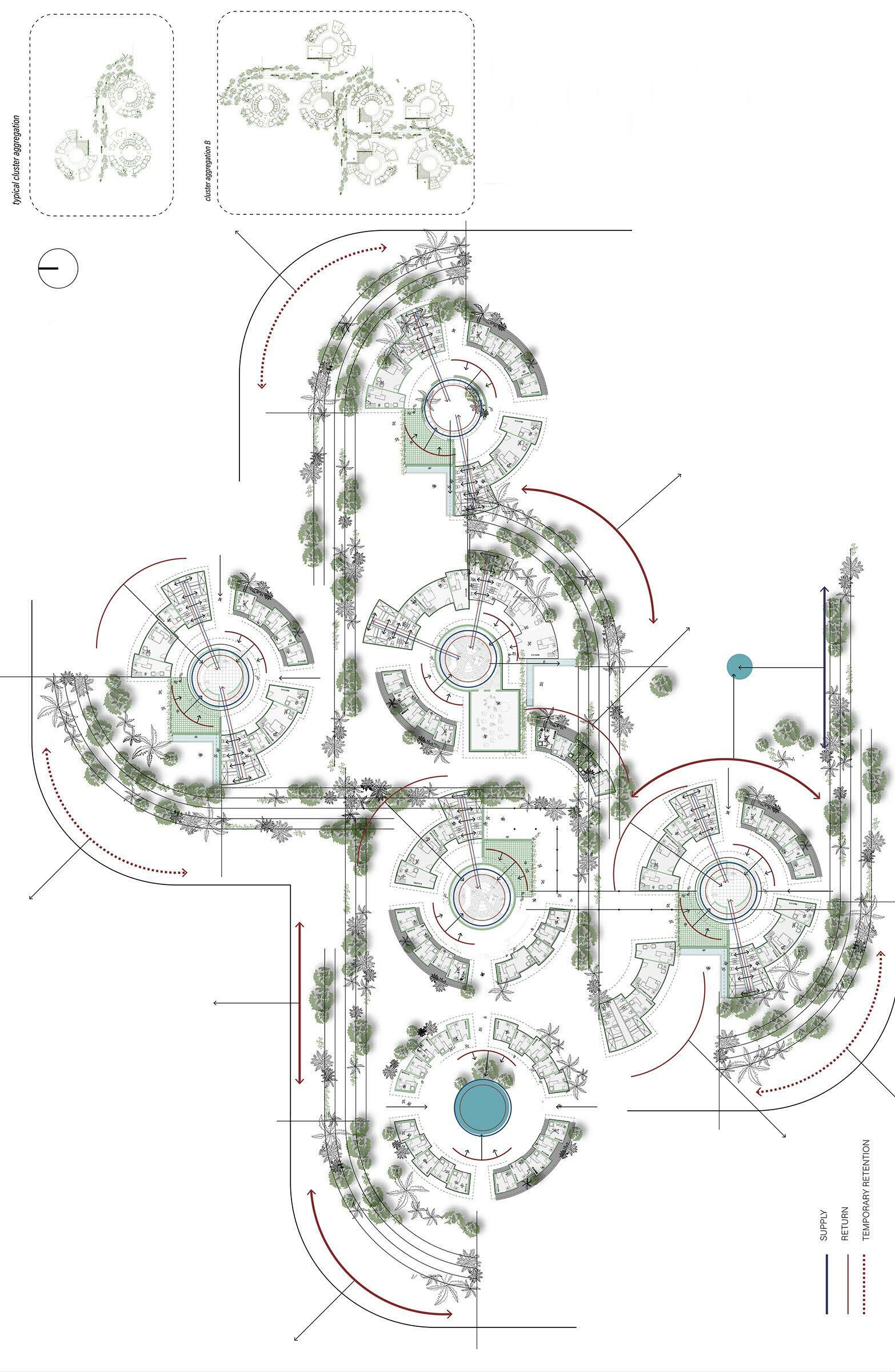

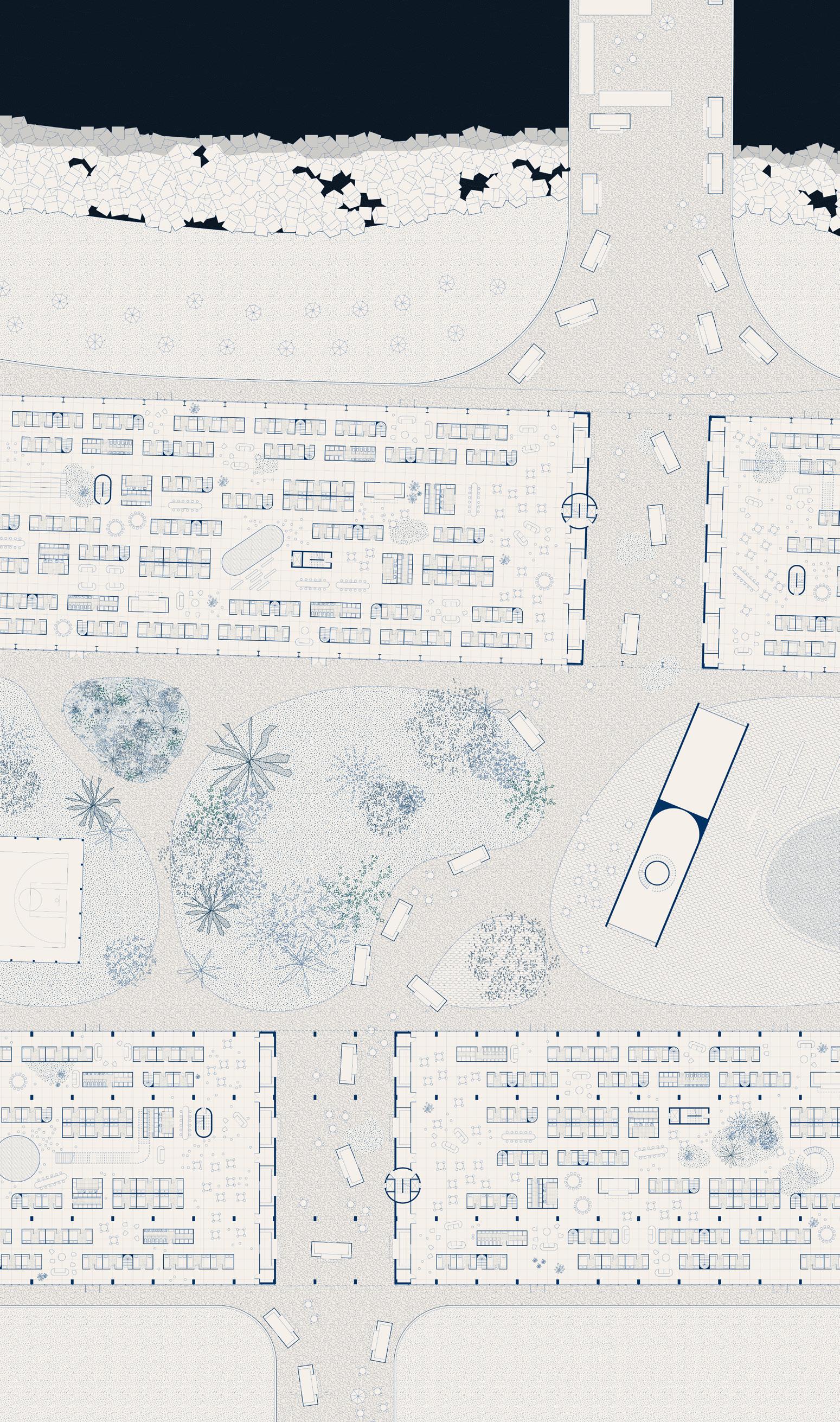

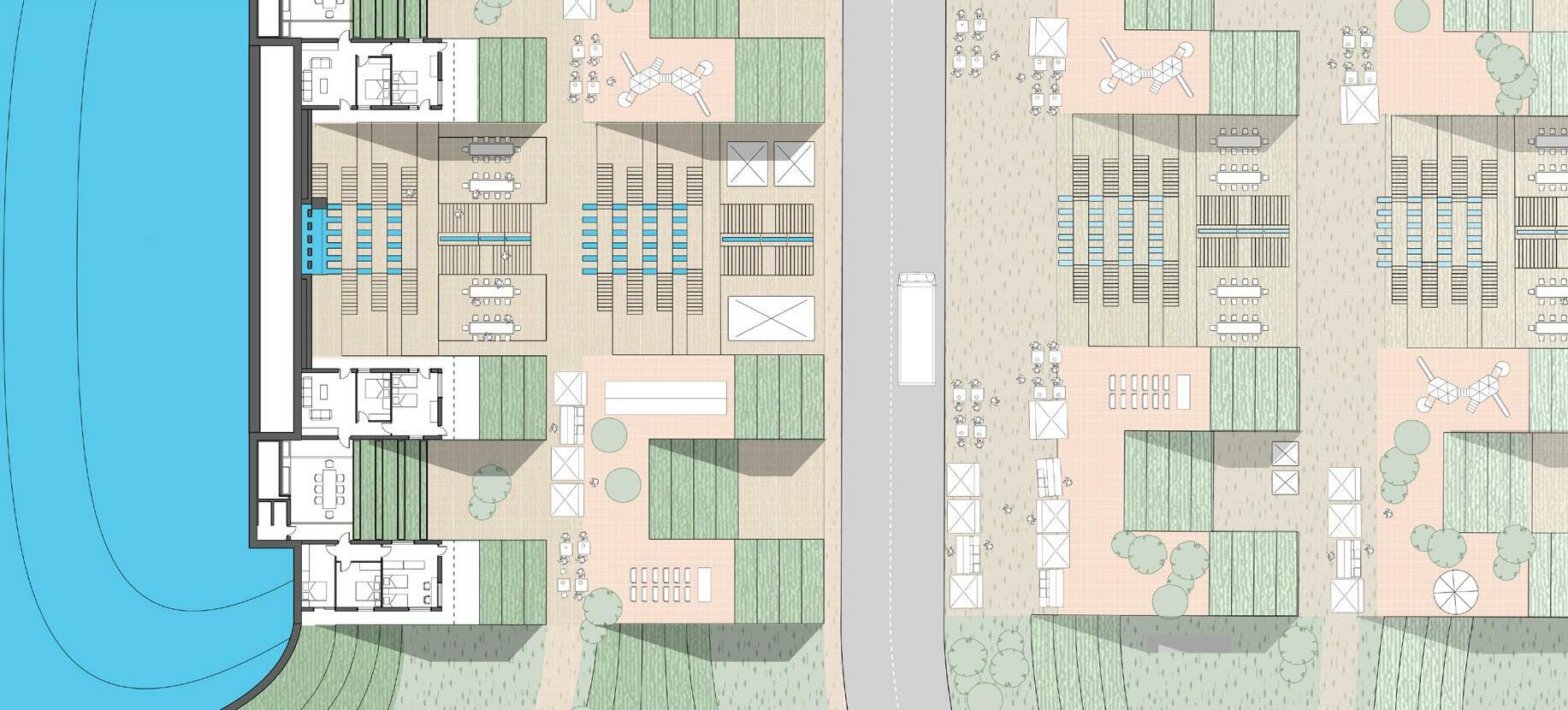

Protecting the shoreline through daily rituals and collectivity

Nana Komoriya

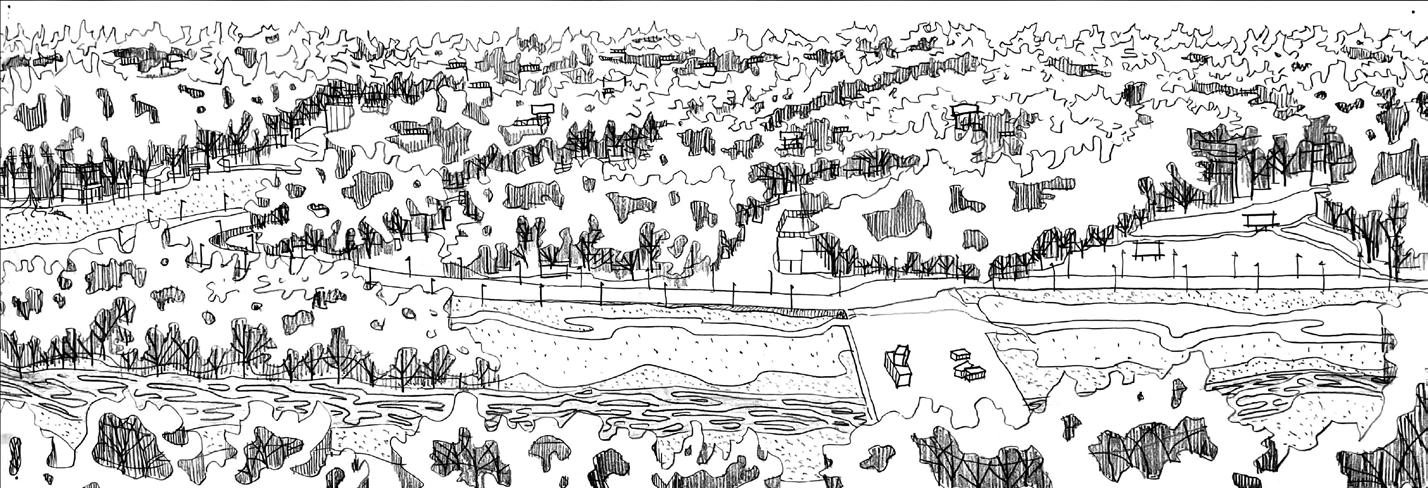

Site: Katoku, Amami Oshima, Japan Crisis: Coastal Erosion, tsunami Area: 45,000 m2

Site Plan 1:20,000

1000 1000 60

Beds Inhabitants Units

Katoku Beach is one of the last untouched beaches in Japan. Located on Amami Oshima, an island in the Ryukyu trench in the south of Japan, Katoku Beach is sometimes referred to as “Jurassic beach” as it is one of the last remaining beaches in Japan that has not been subject to concrete intervention. Japan is prone to coastal erosion and its related disasters including typhoons and tsunamis to which the immediate defensive response is to build a protective concrete seawall. In 2013, the local government of Amami Oshima executed public works that disrupted the natural course of the Katoku River that merges with the ocean. This interference led to the disappearance of the naturally occurring sandbars in the ocean that helped protect the shoreline from breaking waves and erosion. The following year, two typhoons hit the coast of Katoku. Without the sandbars, the tsunamis caused severe erosion to the shoreline and damage to the native Pandanus Forest that lines the beach and protects the village. As a response, there is a proposal to construct a 6-meter concrete seawall along the beach and river bend to protect the coastline from further erosion and future tsunamis. Rather than an intervention that protects by creating a physical barrier against the sea, this project intends to design an architecture that rests gently on the land and provides a framework to support daily rituals in which the protection of the shoreline is integrated as part of everyday living.

Tucked away at the foot of the mountains by the ocean is the small village of Katoku that I call home. Any direction that I look to, my eyes are flooded with vibrant colors of green and blue.

From the mountains behind my home, I hear the trees rustling in the breeze. From the ocean, I hear the calming cadence of the waves breaking on the shoreline. On days when the ocean and air are still, I can hear the water running through the river. The air is always clean and smells slightly salty and faintly of trees.

A bed of pandanus trees lies between the beach and the village with gaps between the thick bushes revealing glimpses of the deep blue color of the Pacific Ocean. I have spent countless hours wading in these waters, watching, and feeling the movement of the tides, waiting for the perfect wave to catch.

I have fond memories of long summer days, playing in the ocean, in the river, and in the sand. I would build sandcastles and forts at the mouth of the river where it meets the ocean. I would catch fish in the river with my homemade net, which I would bring home to cook for dinner. When my neighbors smell the fish grilling, they’d pop in and we’d share a meal. We’d talk stories and laugh into the night — with the cadence of the ocean, with the river, and with the mountains. This is the place that I call home.

Nana Komoriya

Katoku

Nana Komoriya

Katoku

Between the mountains and the ocean is the small village of Katoku that I call home. From the mountains, I hear the rustling of trees in the breeze. From the ocean, I hear the calming cadence of the waves breaking on the shore. From next door, I hear the joyful laughing and chattering of my neighbors. On days when the ocean and air are still, I can hear the water running through the river. The air is always clean and smells slightly salty and faintly of trees.

I know exactly how the water in the river and the water from the ocean feel like – shifting in temperature with the four seasons. In the summer, I like to sit in the sand where the shoreline breaks, feeling the sun beat down on me as the cold-water washes over my skin and the tide tugs at my body calling me to sea.

At the end of each day, I like to sit in a hot bath letting the worries of the day slowly seep out of my body. I sit quietly in the bath listening to the trickling of the bath water, to the night birds calling goodnight, to the running water of the river, to the cadence of the ocean.

Nana Komoriya

Top: Katoku Beach

Bottom: Katoku River merging with the ocean

Nana Komoriya

Top: Katoku Beach

Bottom: Katoku River merging with the ocean

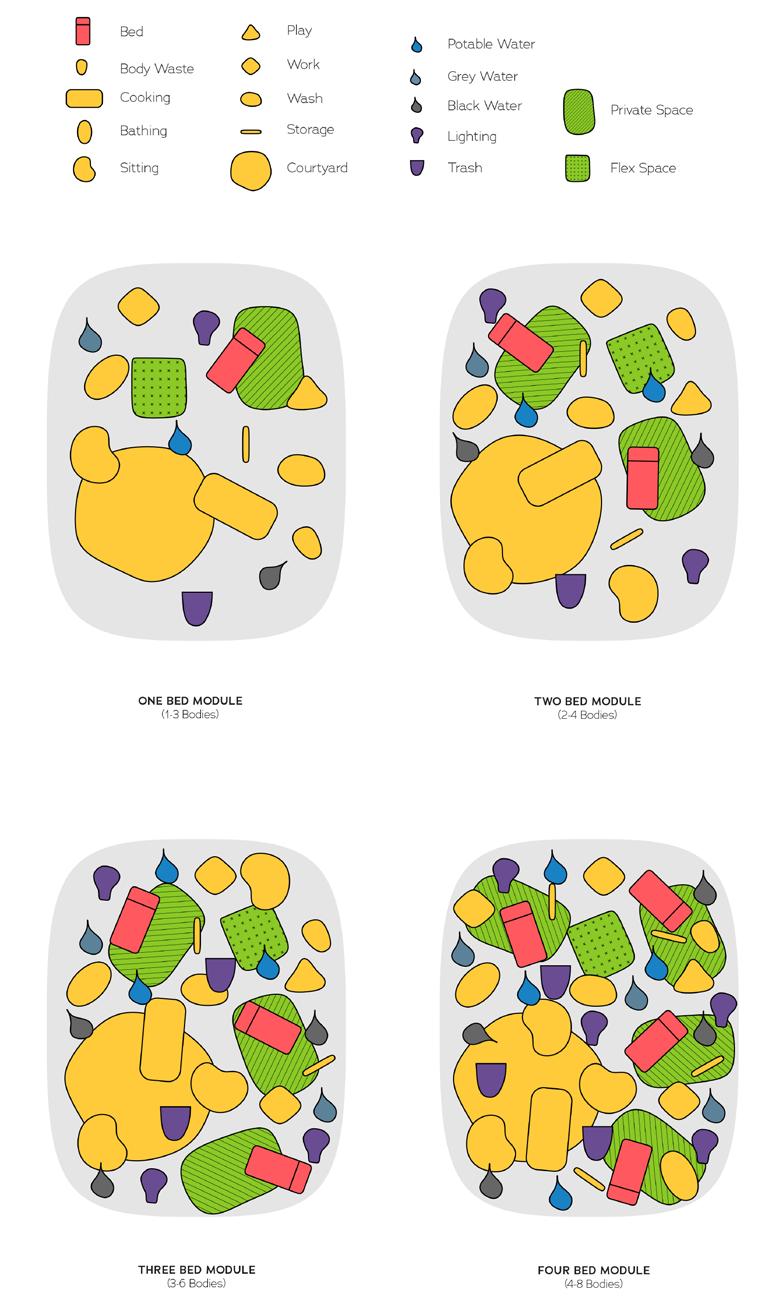

The Minimum Dwelling Plan Diagram (1:200)

1. 9. 13. 2. 10. 14. 3. 11. 15.

4. 12. 16.

5. 6. 7. 8.

1. A place to sleep 2. A place to bathe 3. A place to cook & eat 4. A place to work 5. A place to enjoy 6. A place to excrete 7. A place for storage 8. A place for waste

17. 19. 18. 20. 9. A place to bathe together 10. A place to cook & eat together 11. A place to work together 12. A place to enjoy together 13. A place to supply water 14. A place for food production 15. A place for coastal vegetation 16. A place to manage waste

17. A place for fish farms 18. A place for research 19. A place for timber construction 20. A place for weaving

01 A Village of 100 Beds (1:400)

2 x Unit 01 (10 Beds)

2 x Unit 02 (16 Beds)

2 x Unit 03 (24 Beds)

02 A Village of 100 Beds (1:400)

2 x Unit 01 (10 Beds)

2 x Unit 02 (16 Beds)

2 x Unit 03 (24 Beds)

Site Plan of 1,000 Beds (1:3000)

Site Plan 1:20,000

Site: Tainan, Taiwan Crisis: Flooding + Sea Level Rise Area: 9,650 m2

1024 1536 512

Beds Inhabitants Units

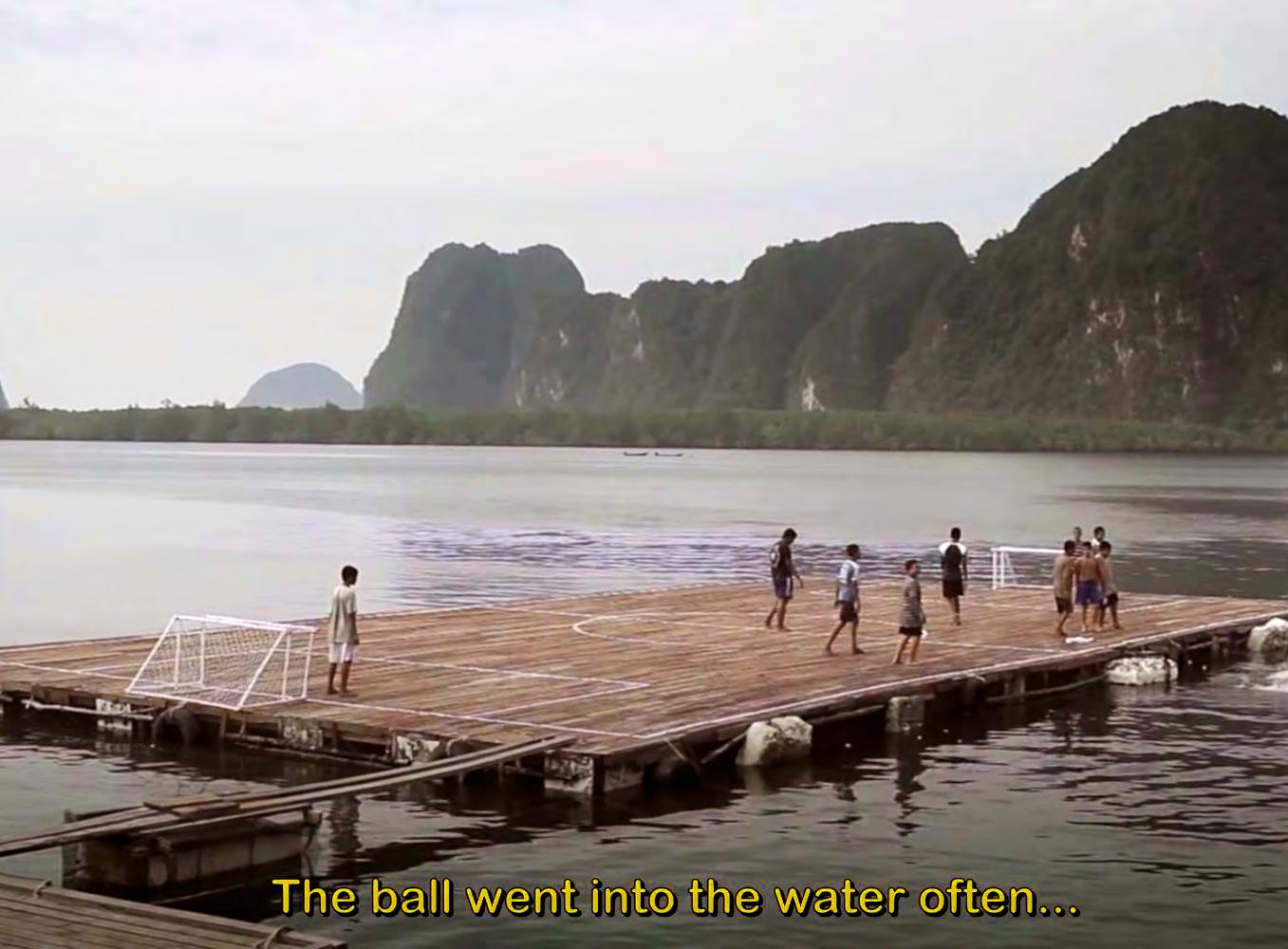

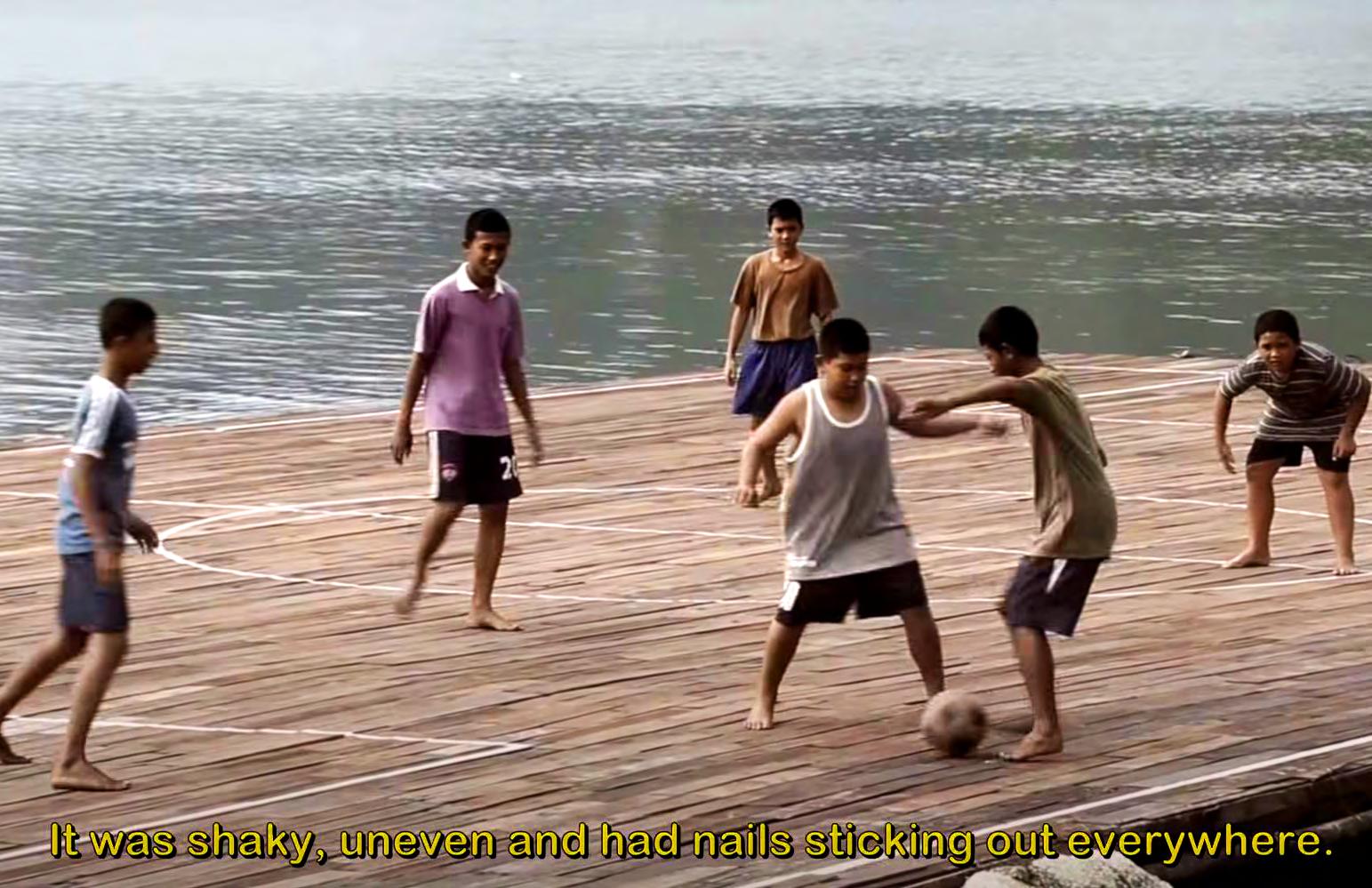

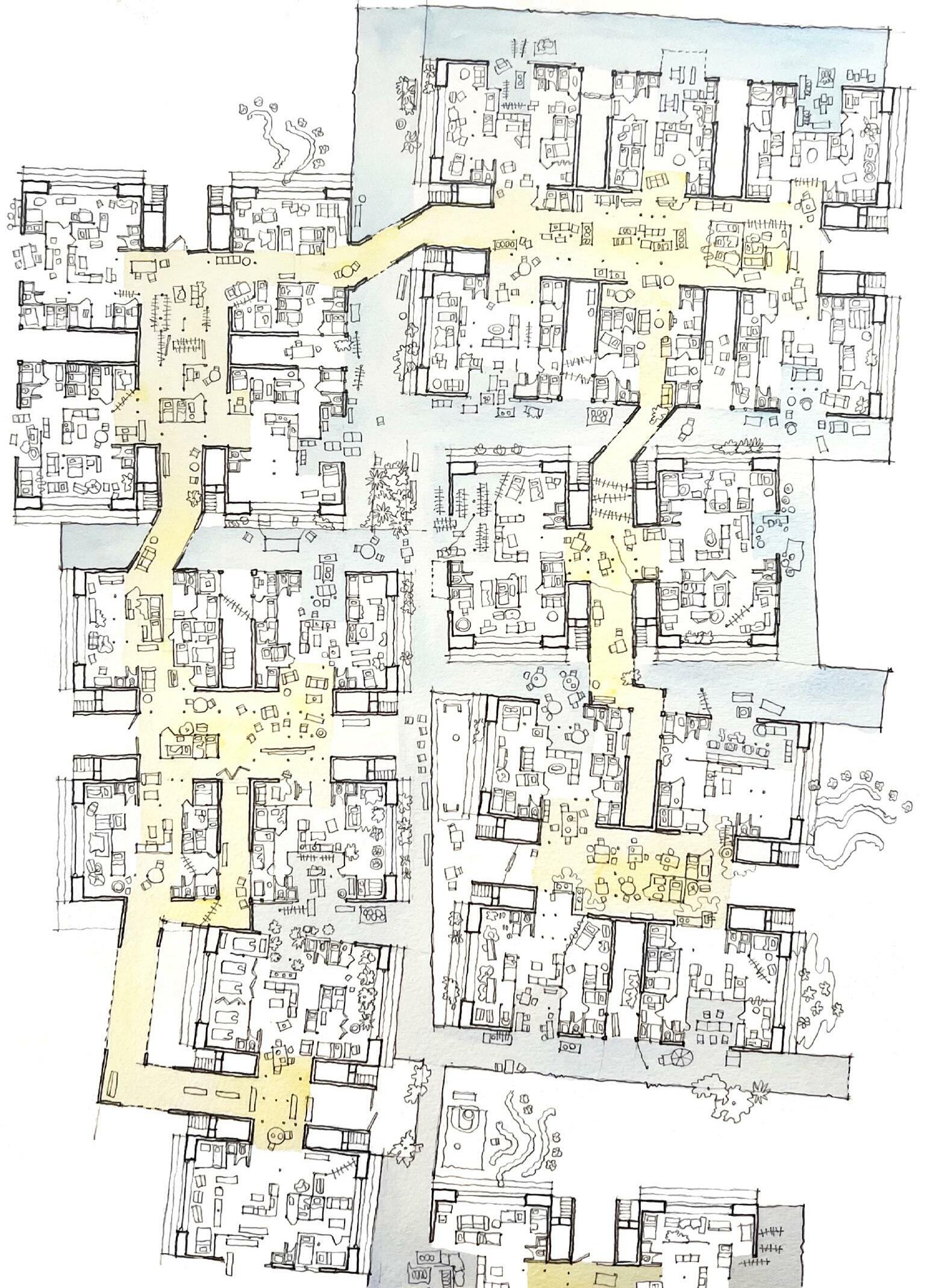

The sea around Taiwan rises at twice the rate of global sea level rise (up to 2 feet or 0.6 meters by 2050). Including the impact of increasingly severe flooding in southern Taiwan, the city of Tainan will be immersed due to its low-lying coastal terrain within decades. This imminence propels the question of how housing can radically adjust to its surrounding conditions with revived directives of how to share daily life. Wet Collective characterizes a way of life contingent with and on water: a self-organizing community that promotes openness and flexibility through conjoining shared amenity spaces, extending in-betweens, and employing moving infrastructures while centering the space of home.

Elder: First, the floating restaurants appeared - tourists and young folk lined up for days at a time; I hadn’t seen the farms like this in my lifetime. Was it because they could choose the specific milkfish in the water to eat? Was it the live prawn catching that kept bringing them back? Nonetheless, some must have enjoyed it enough that they stayed even with the recent flooding. It’s been happening so often the farms are becoming too full too quickly, and now I have to submerge half my body to step on the old grass trails.

The visitors though, they witnessed the flooding and built up the floating restaurants - little rooms to call their own - and made the restaurant their kitchen. I visit every now and then to see how they’re getting along; it feels like their kitchen is the living room and the water is their kitchen.

More have been popping up recently, and I think I will join them soon. I passed another floating house, a small school, and strangest and most impressive of all, they are starting to make gardens in the water.

Youth: I wake up to the constant tide, I’ve never known land like 媽媽 speaks about it. My land is always rocking, moving, calm, angry, but never still. Today though is still-er than last night’s gusts. It blew us closer to the gardens, which I’m sure 媽媽 will make me bring some sweet potato home after school.

The aunties have caught a good 25 pounds (10kg) of prawn and are already tending to the washing. Soon they will call me down to help with distributing into different storages, and probably be sent to bring some to Teacher.

I’m out of bed and packing my things - pen, notebook, lunch, my new green goggles, extra snorkel. Wait - I hear the school bell coming! Is school early? Is it because our house is in a new position in the school route? They’re

Jennifer L i

Top and Bottom: Screencaps from Ko Panyee short film, © TMB Panyee FC

Jennifer Li

Jennifer L i

Top and Bottom: Screencaps from Ko Panyee short film, © TMB Panyee FC

Jennifer Li

Welcome to our collective on the water, first I’ll take you through our workshop area here at the edge, careful, if you trip you’ll go overboard!

Stepping through, hear the chatter? They’re going over alphabets in Chinese, Taiwanese, Cantonese, Spanish, and English today. Let me get the sliding door for you, maybe we should keep it open for better air flow right now.

Ahead is the courtyard, the children play with removable squares in the floor to see fish and stick their hands in the saltwater, some like to wade and - ! - sorry if you got wet, they also like to kick the water around. We’ll have to maneuver around the drying laundry, most of us fold our clothing here and discuss the day’s events, and of course gossip. One of the neighbors are waving - to your left! Oh, now to your right!

I’ll get the sliding doors for you again, this is our lively kitchen; the smell really just wafts through, huh! They’ve been preparing gua bao 割 包 at least twice a week now because everyone can’t get enough of them! The older generation is used to them with pork but we’re much more used to 割包 with prawn, milkfish, and shrimp honestly.

Oh, we’ve got more friends on the stairs, maybe we should go up there too - you’ll be able to hear the waves a little better over the sizzling and clatter. The stairs are rather shallow and lengthy compared to what land-folk are used to; you can sit here if you’d like with your feet over the edge. Let’s take a break here perhaps, let me get you something to eat.

Ready? Let me help you up. If we go along, we can set up the platform that connects our house to another’s - let’s go figure out what they’re doing over there, shall we -

Jennifer L i

Top and Bottom: Screencaps from Ko Panyee short film, © TMB Panyee FC

Jennifer Li

Jennifer L i

Top and Bottom: Screencaps from Ko Panyee short film, © TMB Panyee FC

Jennifer Li

A

Amenity Court 64 32 16 16

Inhabitants Beds Bathrooms Showers

16 1.5 1 1

Units Floors Kitchen Vehicle

1 1 2 1

Courtyard Workshop Workspaces Mini-Library

This series of dwelling sets showcase different proportions of enclosure to collective space. Amenity Court does this through two gradients: first through the ability to enlarge and share a living room, then to a centered courtyard.

B

Boarding Bathhouse 111 74 2 17

Inhabitants Beds Bathrooms Showers

74 2 1 1

Units Floors Kitchen Vehicle

1 17 Water Park Pocket Publics

This sharing method occurs through individual bedroom units attaching to open hallways that act as living rooms. Bedrooms are added and removed to give and take between pockets of collective space or “living room.”

C

Long Hall 96 64 10 26

Inhabitants Beds Bathrooms Showers

64 2 1 1

Units Floors Kitchen Vehicle

1 1 4

Playground Workshop Workspaces

An inverse of Amenity Court’s units, individuals in this scheme take ownership of their frontal space in long hallways and decks that allow a more private experience from its collective center.

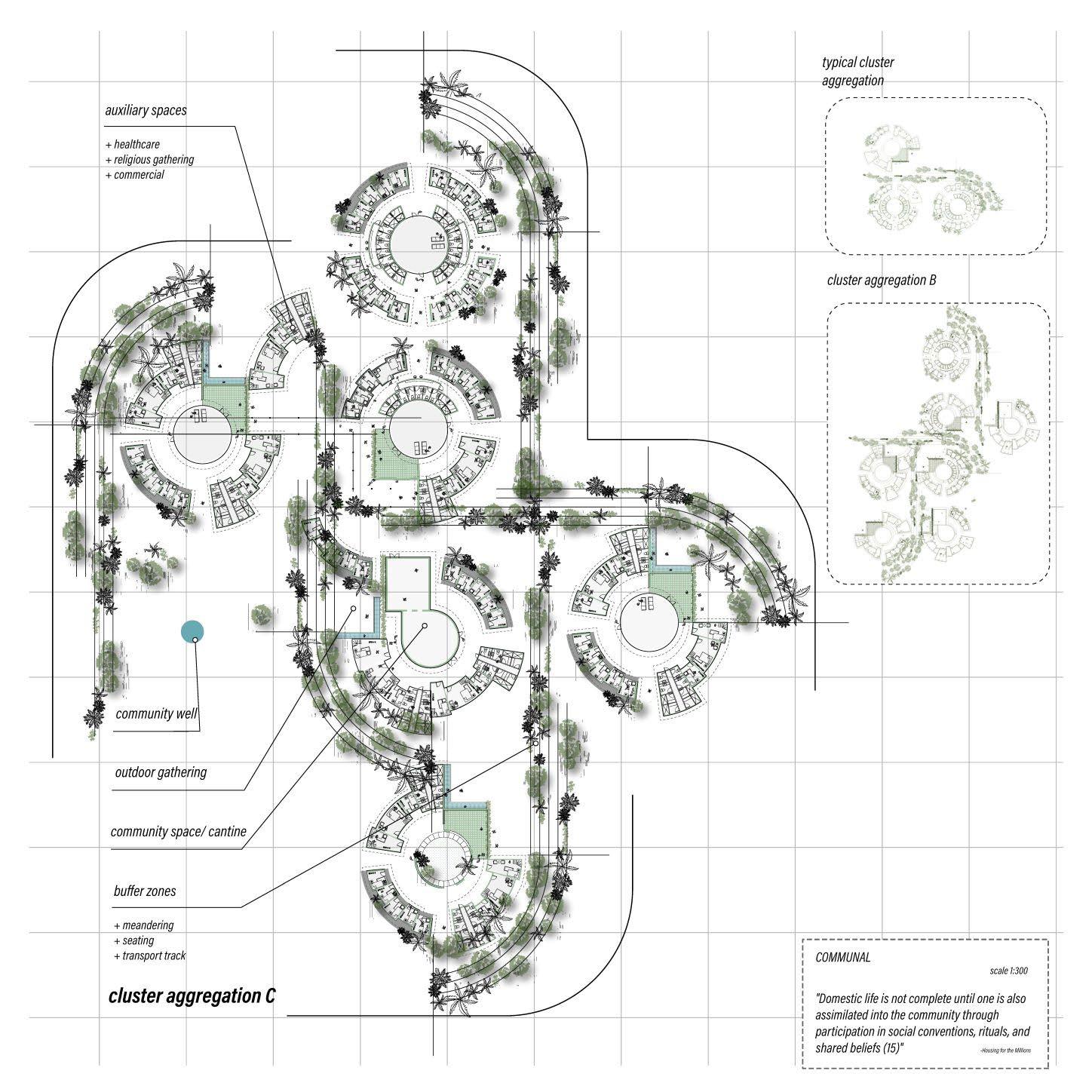

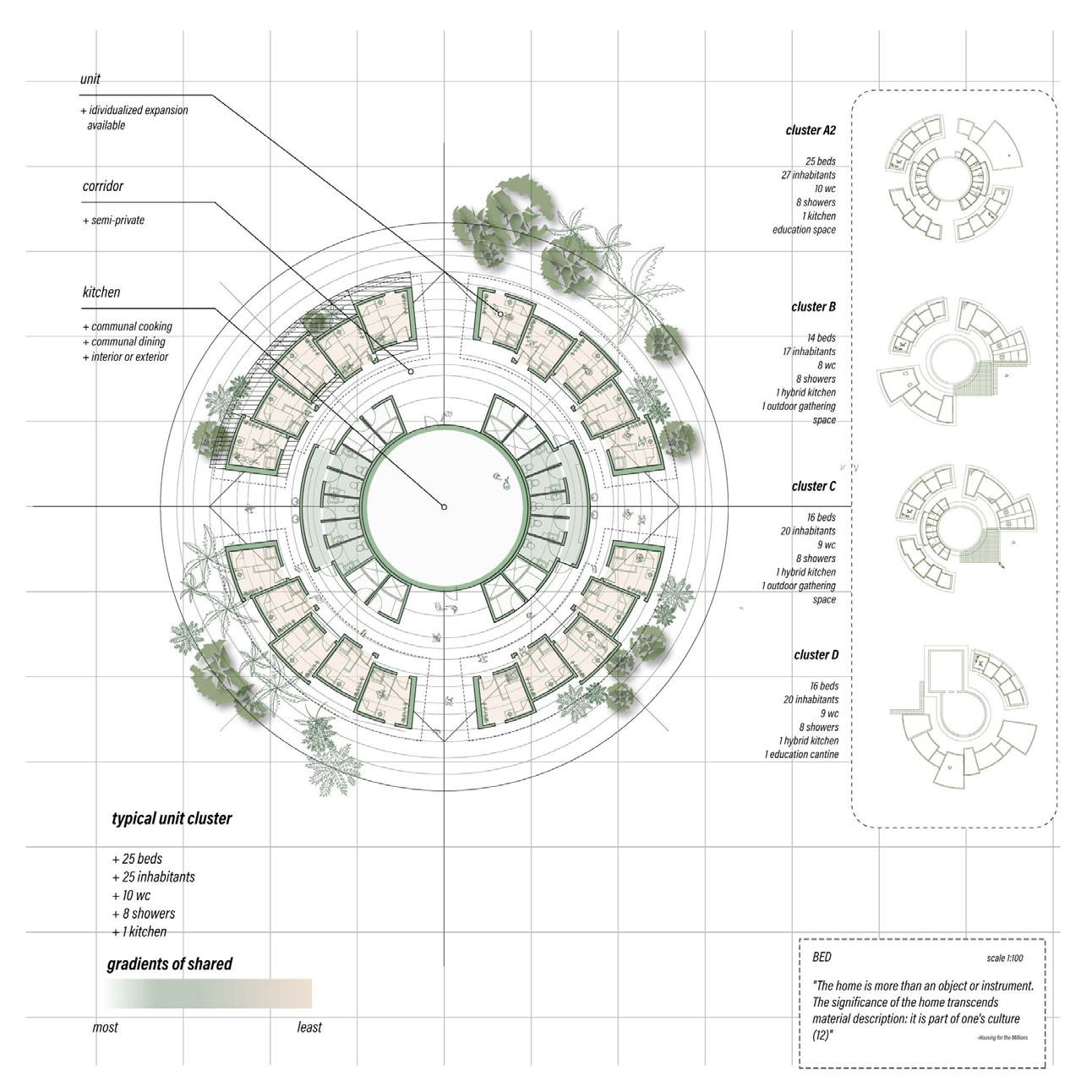

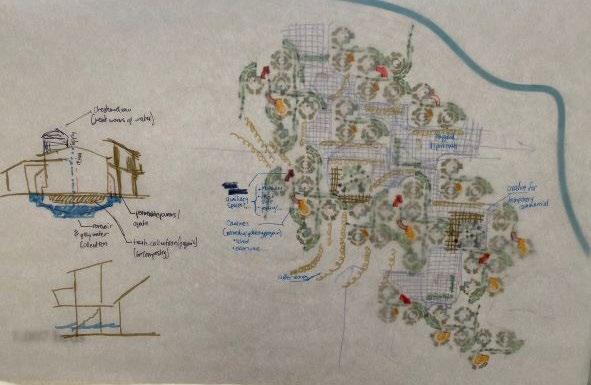

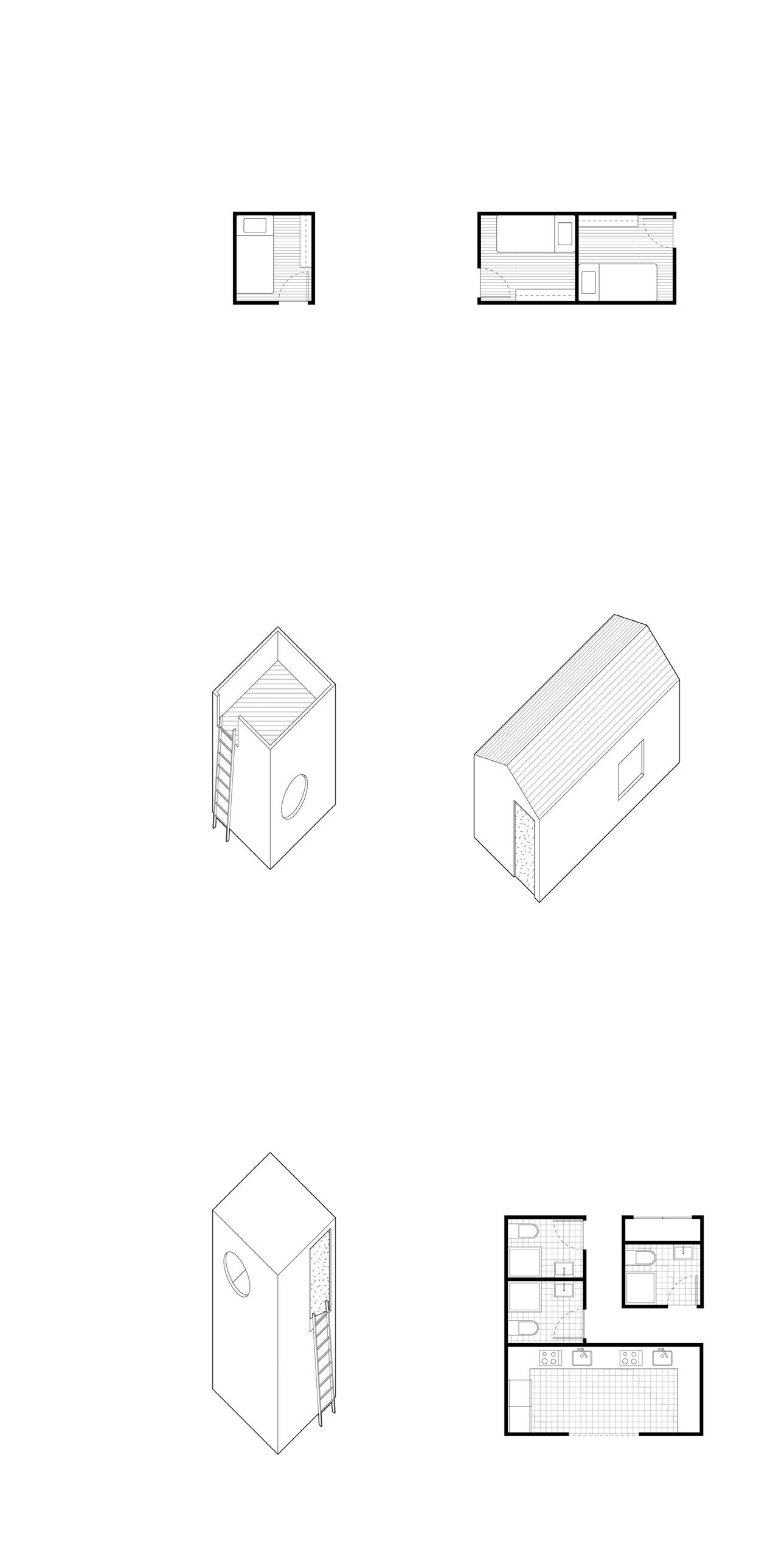

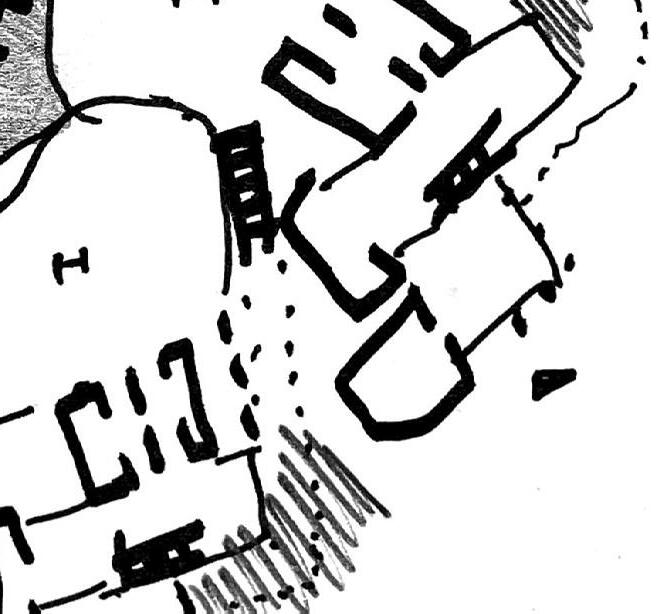

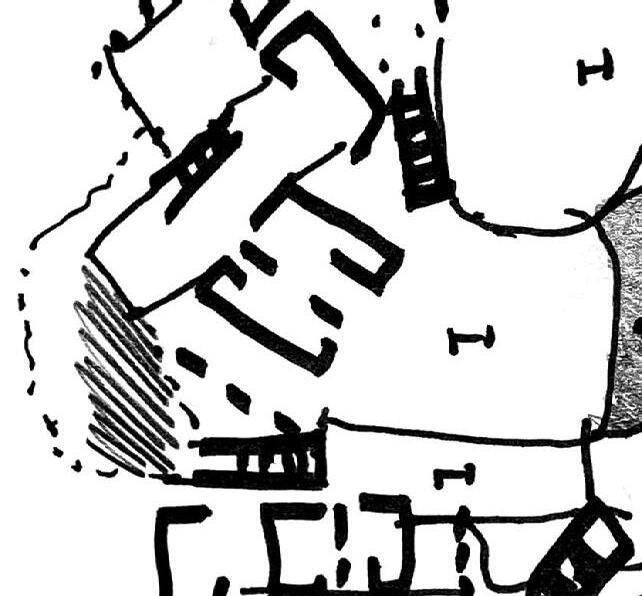

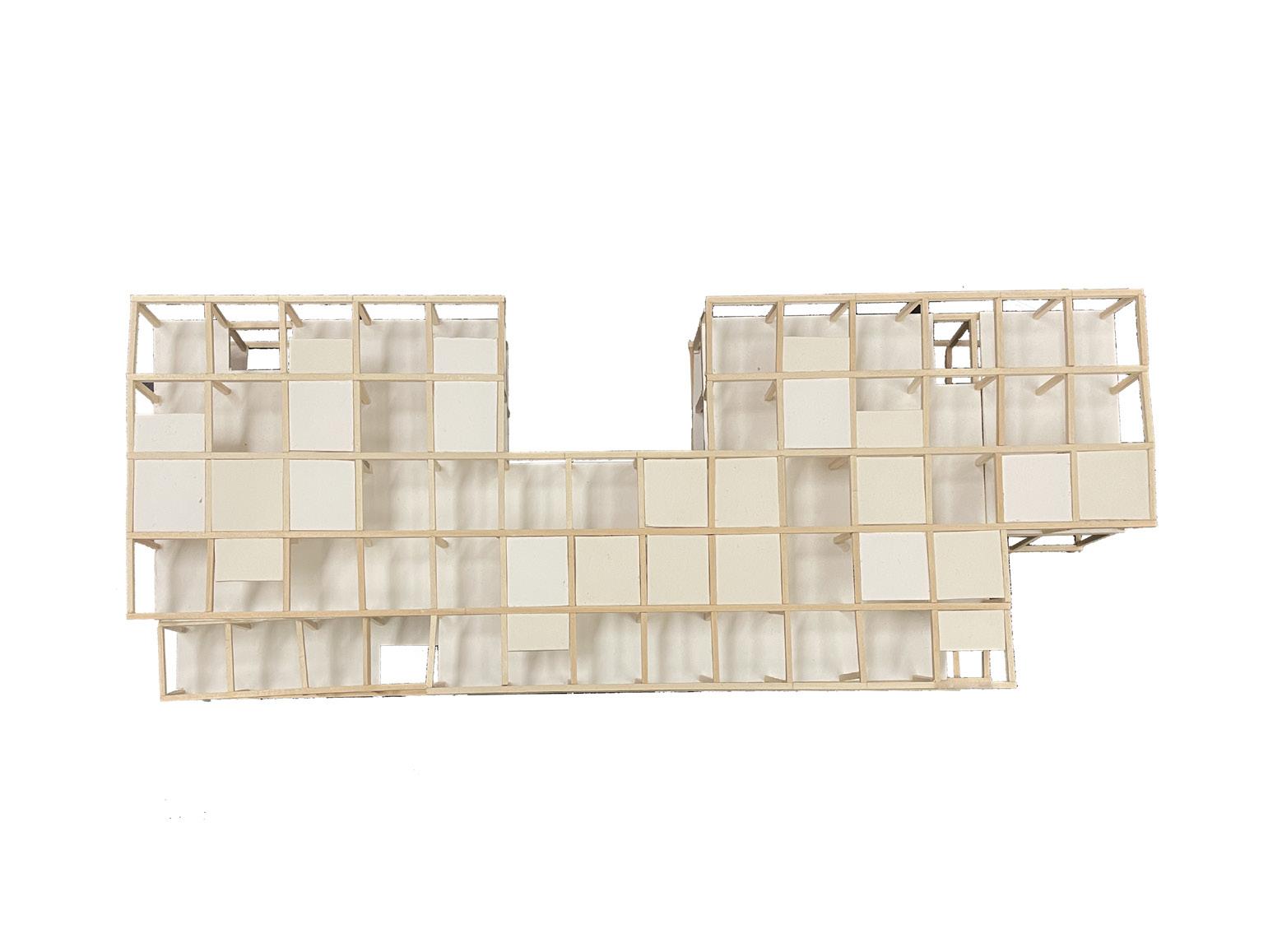

Site: Gonaives, Haiti Crisis: Hurricanes, Flooding, Landslides Area: 2,400 m2

1100 1200 1000

Beds Inhabitants

Units

The north of Haiti, where Gonaives is located, lies in the path of hurricanes. It is thus prone to flooding and landslides due to deforestation and inproper construction. paradoxically, this area is also prone to droughts and lacks the sufficient infrastructure for clean water.This proposal focuses on mitigating the risk of flooding wit three strategies, 1) planting two trees for every bed on the site, 2) elevated communal spaces as safe havens, 3) focusing on drainage, water collection, and water rederection.

In the case of emergency, water flow is rederected into canals that lead to communal wells, and crows gather in the elevated kitchens and educational spaces. Canals and drainage systems in the housing clusters collect water to be treated for everyday use, and untreated water used for laundry and agricultural purposes.

Sarahdjane, Mortimer

The Tree, the Kitchen, and the Well

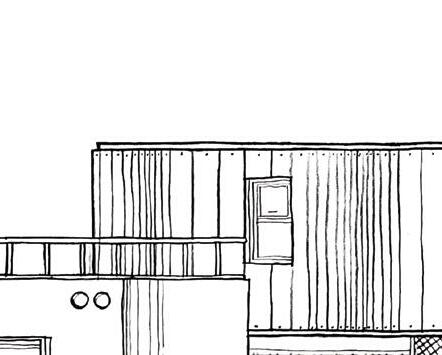

It was nothing like the existing broken fabric leading up to the cascading mountains. Was it a village? The grid was askew but it was almost more organized than what we had passed by. I pressed my face to the glass as though it offered me a closer look.

The tree lined enclosures seemed to lead to concentric rows of small apartments, some double storied, and others single. There was a place to wash your hands before you entered the corridor, and what seemed to be small terraces or personal gardens lining the outside of the curved wall. We came across a few of these curved wall moments before a moment of open. The curved walls seemed to be hiding something, but the lead up was amongst the trees, more open and much more welcoming.

Kids playing around this elevated water source, almost like a well but unrecognizable from the others. It was almost like a connector of sorts, the place of gathering where everyone was free to roam, sit, catch up with their neighbors all while providing key nourishment for their homes.

On one end children threw water at each other, cooling themselves from the noon sun that beat on their tiny little head and arms; on the other end, women and adolescent children washed clothes and separately young men pumped water from the source, loading it onto their wheelbarrows.

“what’s that dad? 15 years driving to grandma’s, and I don’t remember this part?”

“Good eye” he replied. “it’s a growing development of neighborhoods derived from the communal act of cooking. If you see those elevated mounds surrounded by the low curved walls, with the smoke expelling from the top, those are the kitchens, raised to avoid the floods, and central to each cluster.”

As we took a few more turns toward our destination, I could see that within the interior corridor, were all the doors I expected to see on the outside. The classroom spaces seemed more open, and the rest seemed to take you to a maze of sorts, hidden to the outside viewer. Small windows never facing each other was the only indication of what the inhabitant cherished… their personal items, their memories…

As it faded from view, my father looked to me through the rear-view mirror

“we could stop and take a closer look on our way back if you’d like”

I smiled, tuned back to recapture the view in my head….“I would love that!”

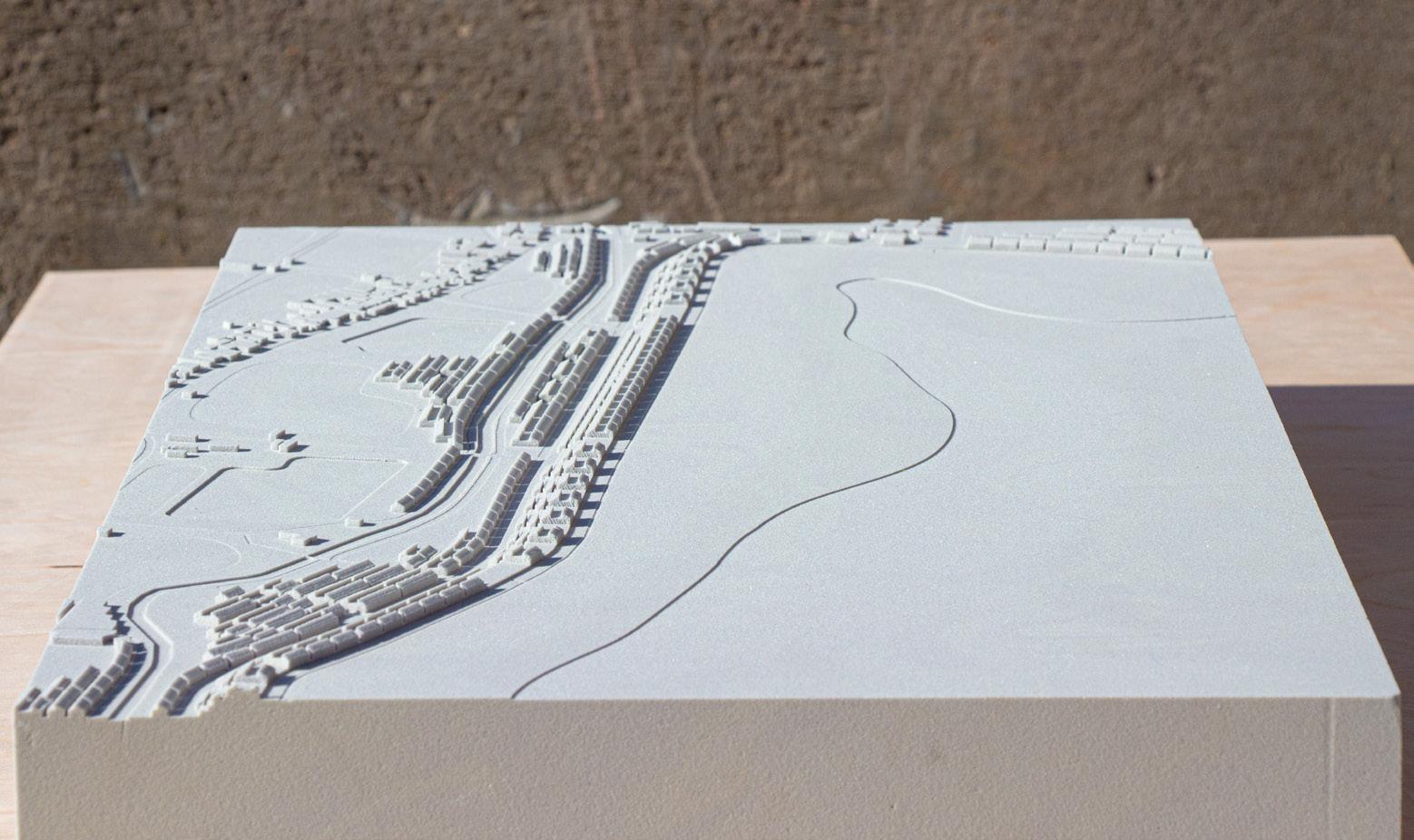

The Tree, the Kitchen, and the WellBottom:

Sarahdjane Mortimer

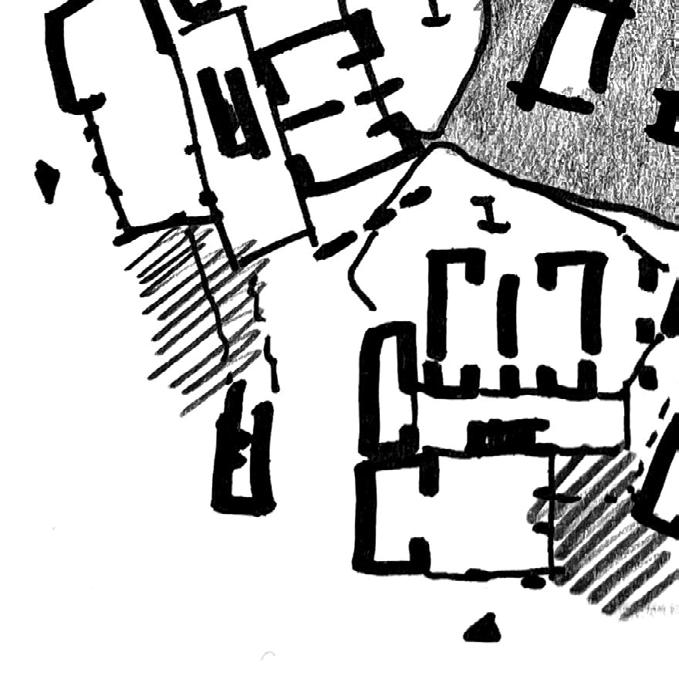

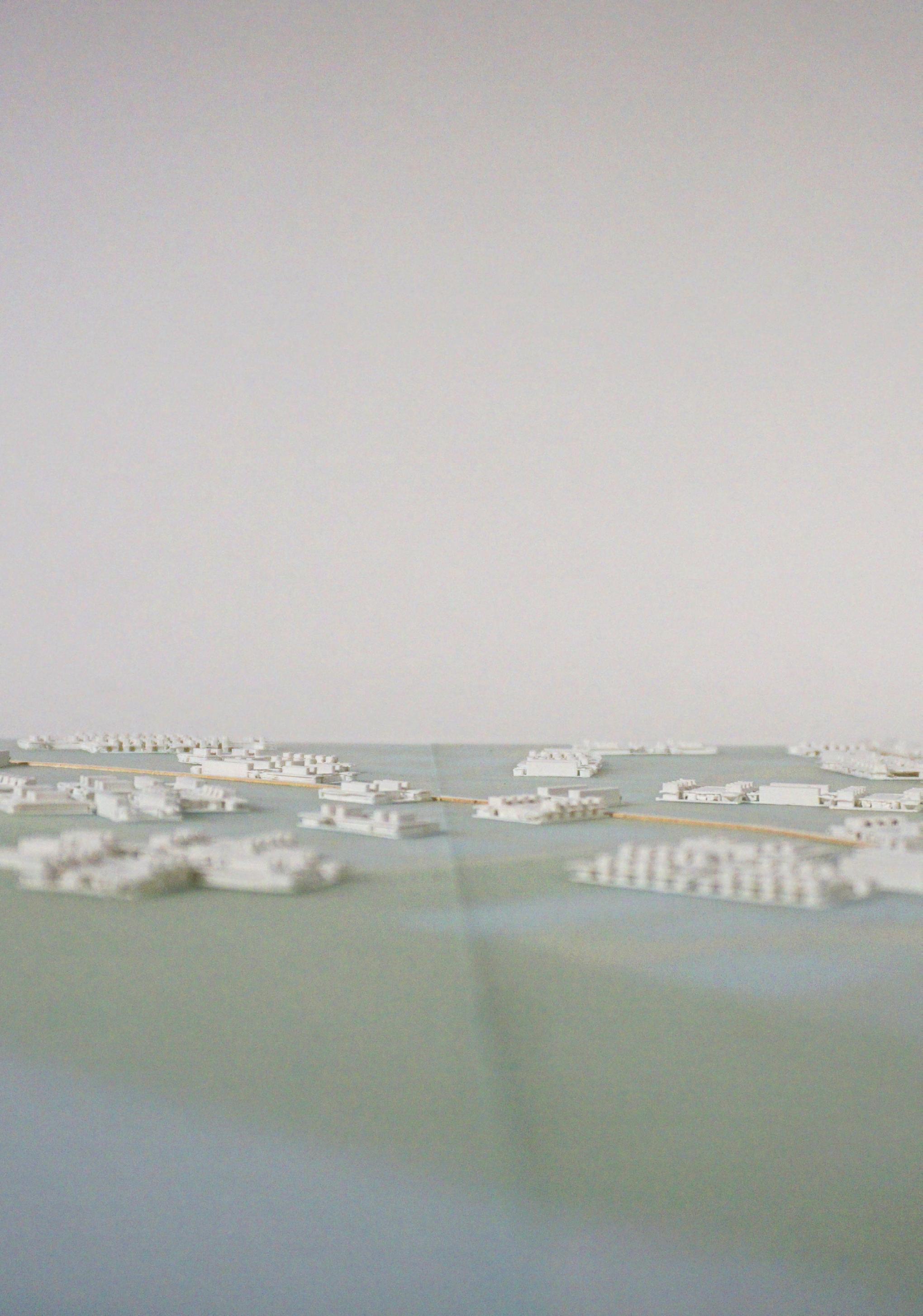

Top:matrix of program

Units on ladscape, Physical model

Sarahdjane Mortimer

Top:matrix of program

Units on ladscape, Physical model

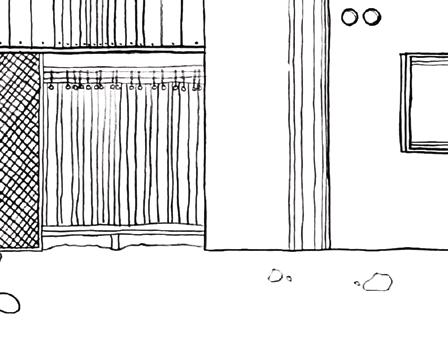

When you follow the curve of the clusters you stumble upon a few moments. From open air, to covered canopy, youre guided to moments of buffer zones leading you to communal wells that serve up to six clusters. here, children play and community gathers.

You slip into the opening of private shared space. The outer wall is most private with entrances to some double heighted and some double storied places of rest. The core fo each cluster is a kitchen, a new layer of public.

Left: cluster aggregation

Top: Site analysis

Bottom: Unit cluster

Sarahdjane Mortimer

Sarahdjane Mortimer

Sarahdjane Mortimer

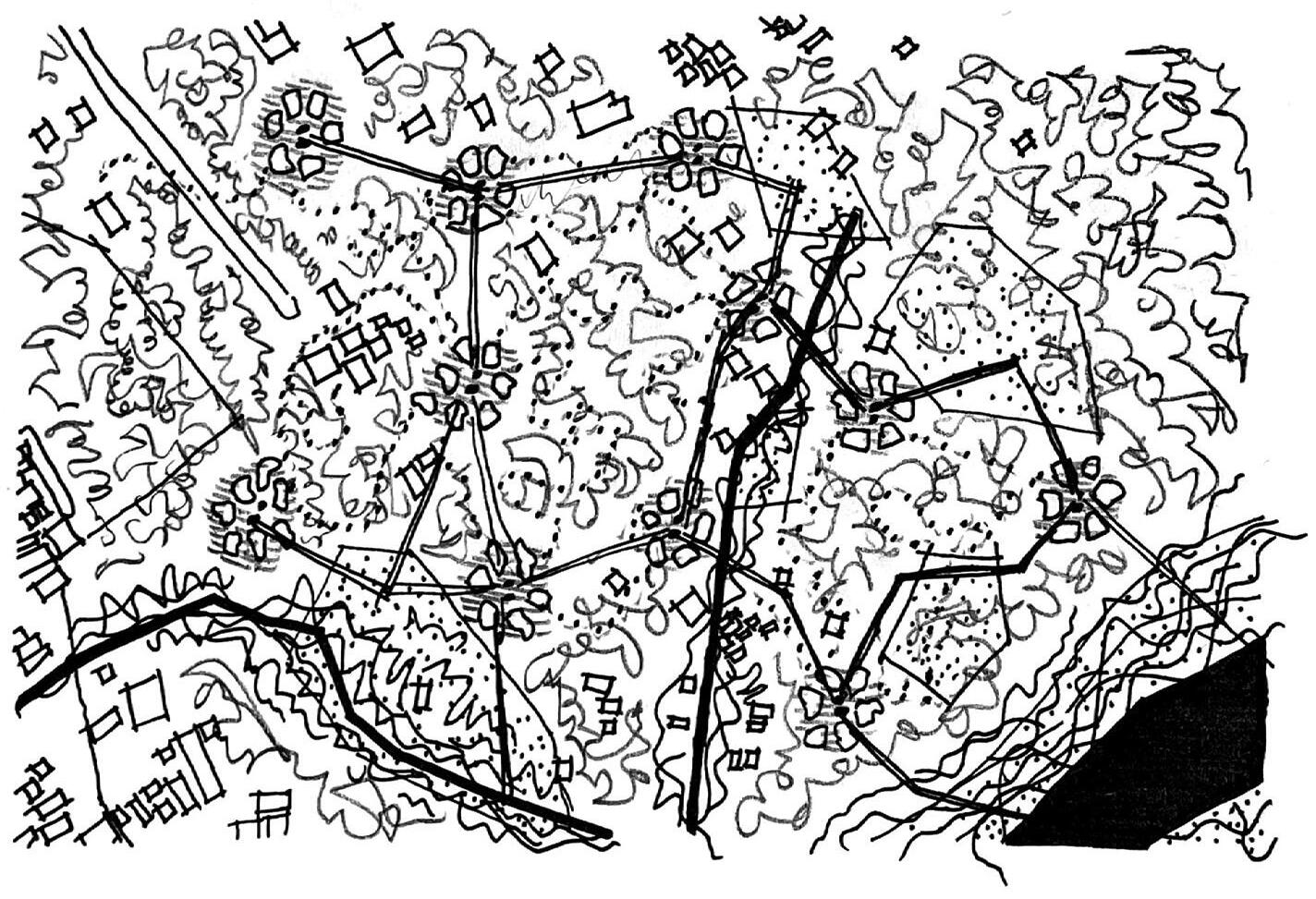

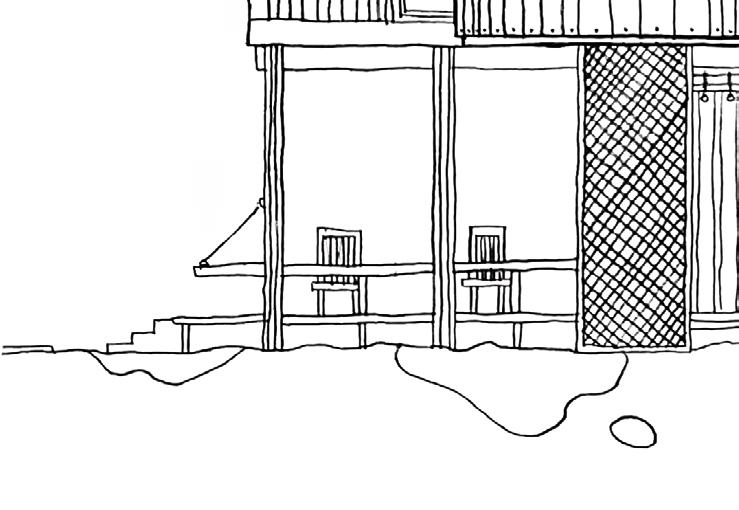

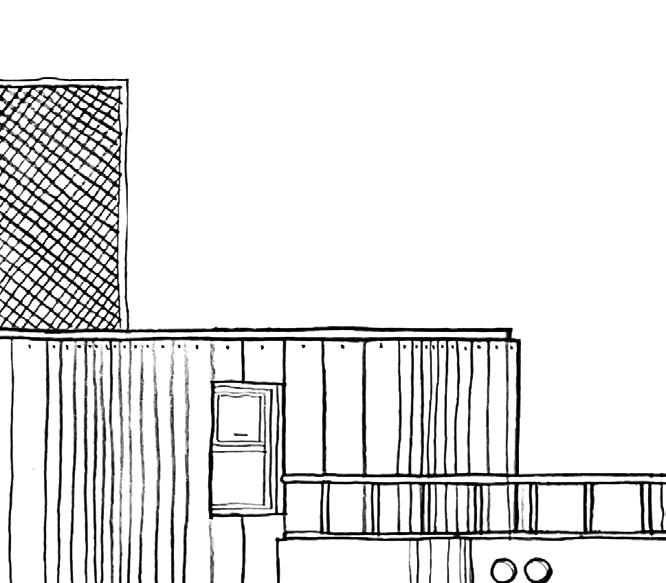

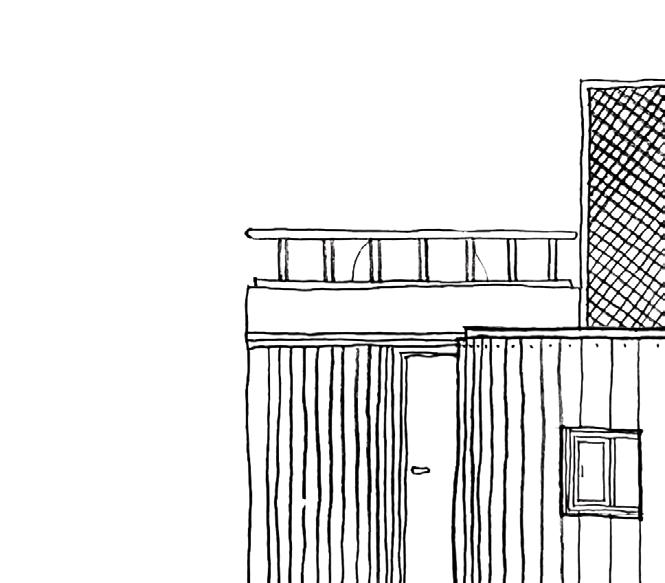

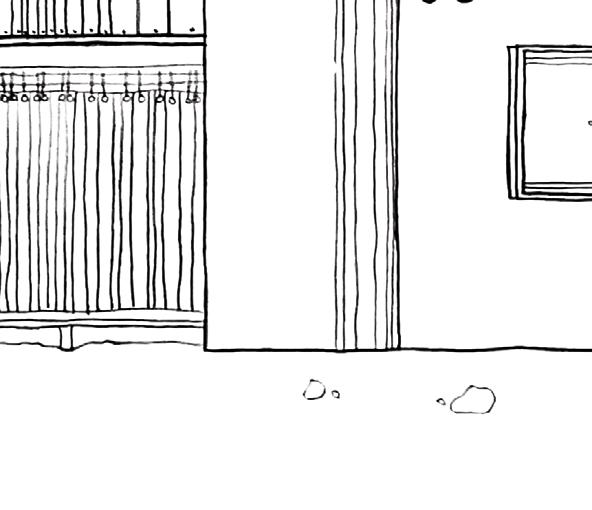

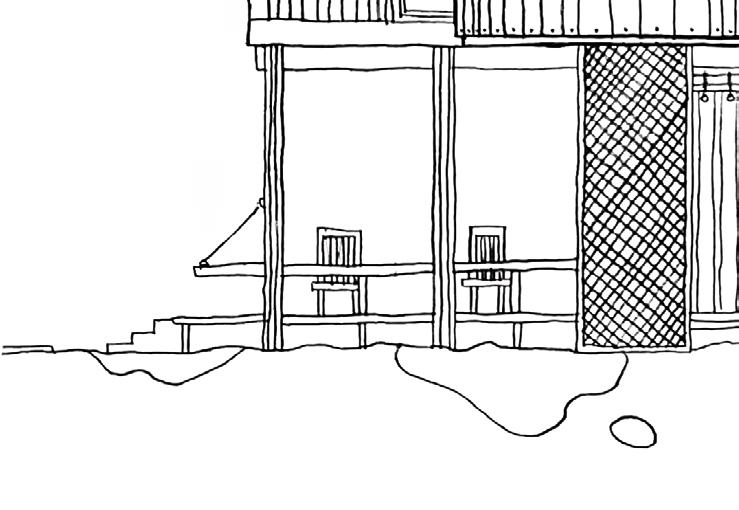

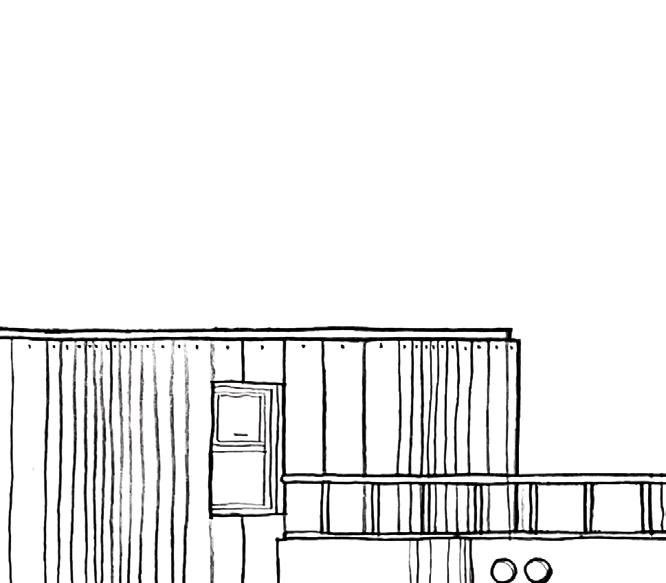

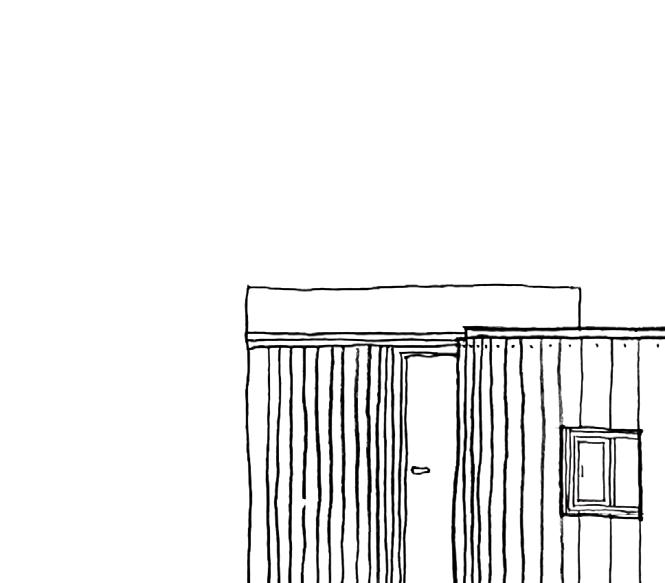

Top: Common space sketches

Bottom: hydrology and waste section sketched

Following page: Unit and waste sketches

Sarahdjane Mortimer

Sarahdjane Mortimer

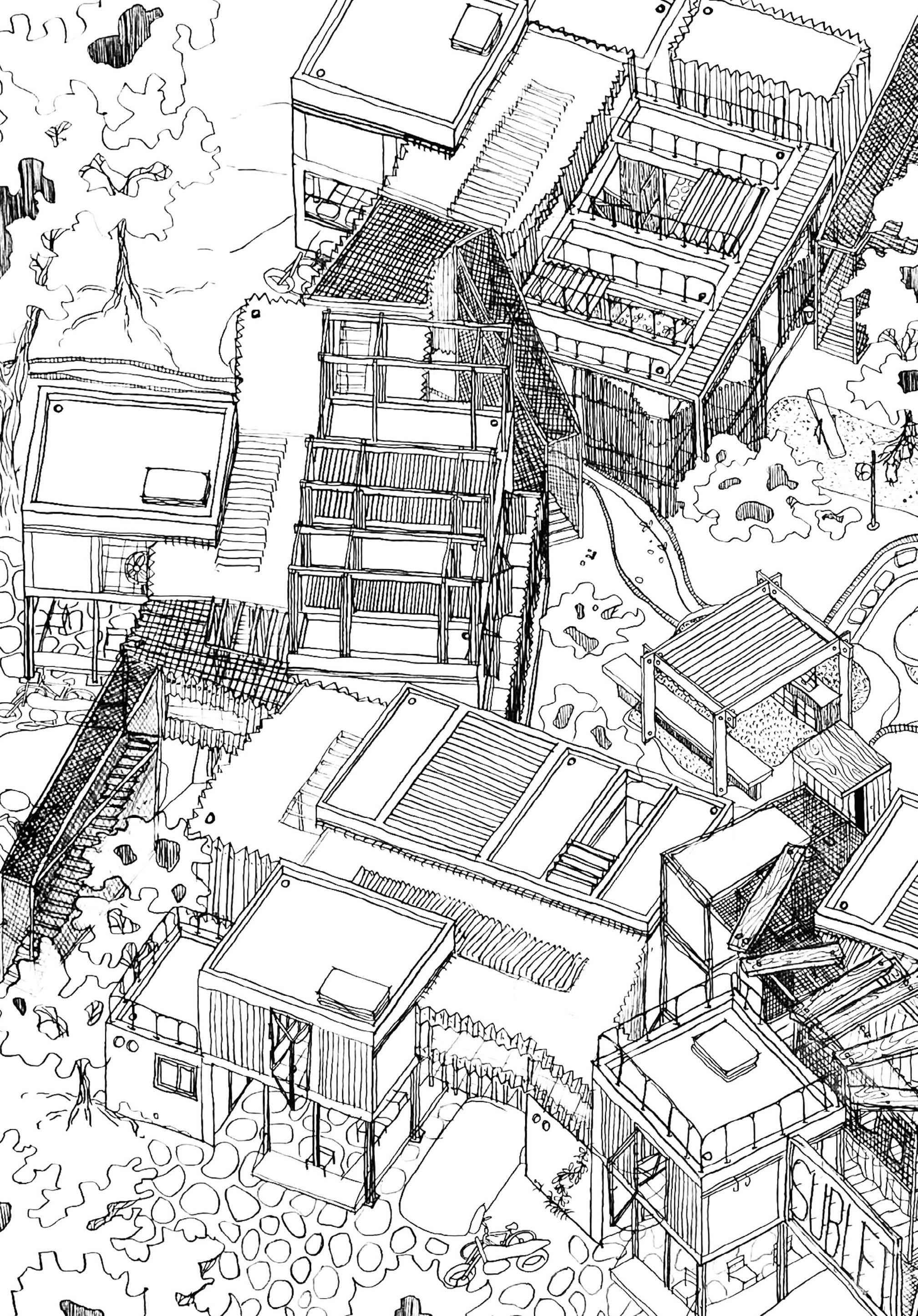

Managing water and mitigating flood risk with a rainwater reservoir

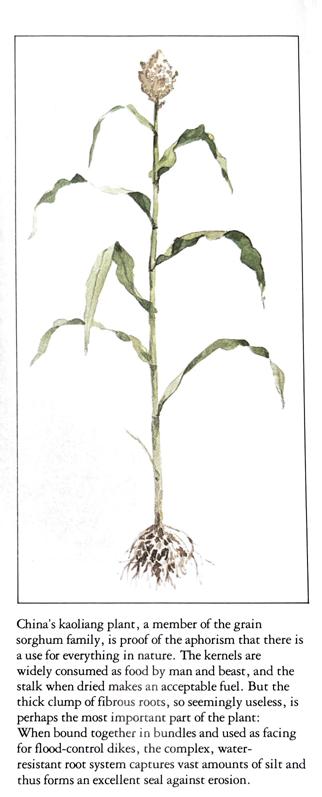

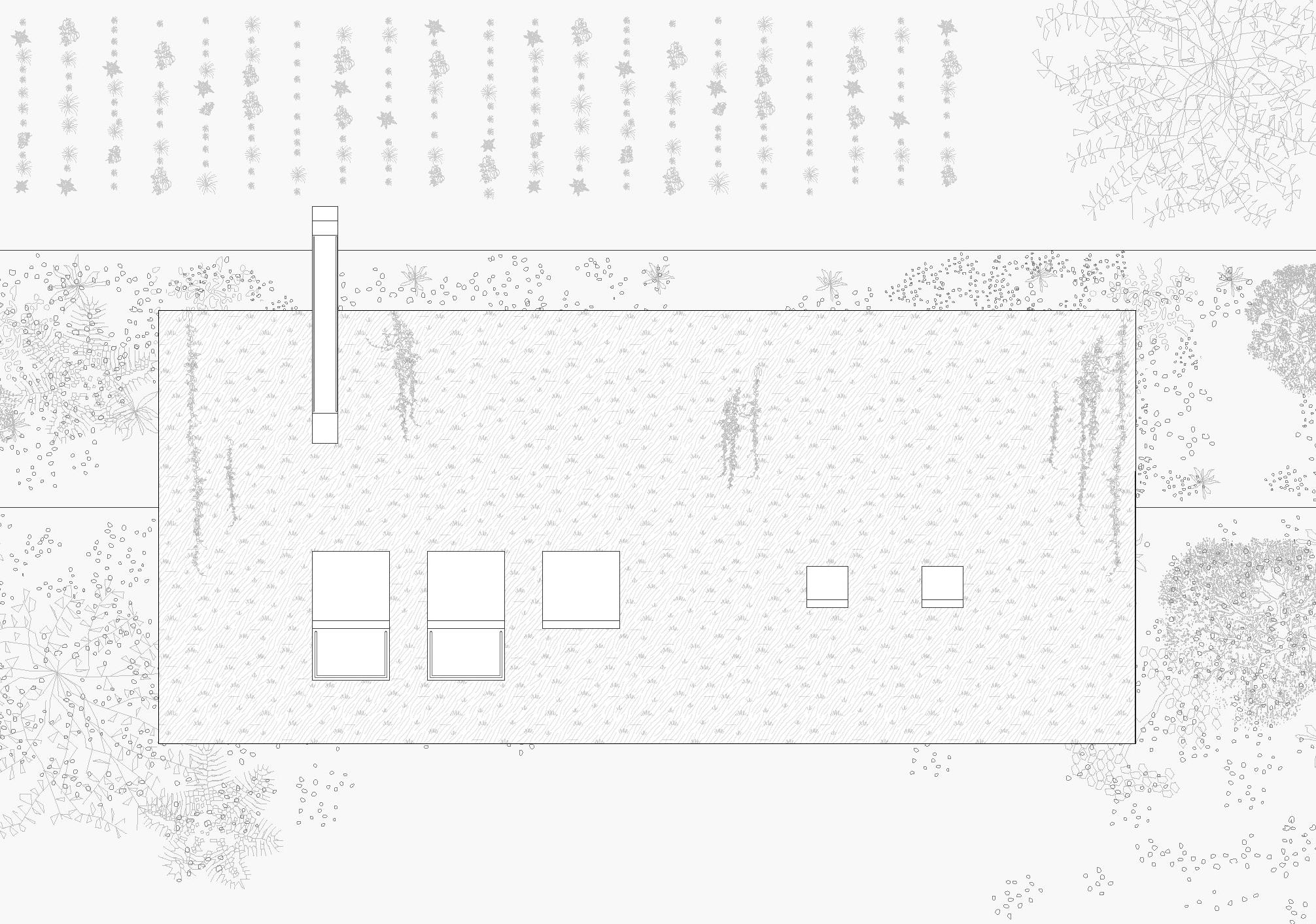

Site Plan 1:10,000

Site: Valle de Chalco, Mexico Crisis: Flooding and water management Area: 15,000 m2