Chris Reed / Nina-Marie Lister

Chris Reed / Nina-Marie Lister

Chris Reed / Nina-Marie Lister

This studio explores themes of peri-urban, rural, regional, and continental connectivity and resilience through the lens of wildlife and landscape infrastructure projects throughout California. Our work is grounded in the intertwined challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss in the Anthropocene - now understood as a global polycrisis. We engage conversations, projects and precedents that address our relationships to other species and the environments we share and on which our futures depend. We consider new and reciprocal relationships with the creatures that co-exist with us. We explore the conceptualization and development of new hybrid assemblages, new infrastructural ecologies, new imaginaries that foster deeper relations, entanglements, and kinships between and among all of earth’s inhabitants.

Importantly, this is not an anti-human endeavor; rather, and perhaps most profoundly, it is an attempt to re-establish lost connections, re-affirm the culture of nature, re-embrace the living world, and re-engage us as social and ecological creatures through the multiple lenses of all who dwell among us – from surviving, to thriving and flourishing into an uncertain future.

Studio Instructors

Chris Reed, Nina-Marie Lister

Teaching Assistants

Jackie Chen, Tom Day

Students

Pawel Bejm, Pie Chueathue, Lucas Dobbin, Annabel Grunebaum, Sara Han, NaningLi, Emily Menard, Ashley Ng, Anne Tong, Senmiao Yang, Junia Yang, Zheming Zhang

Species Lens Review Critics

Jeremy Guth, Rosalea Monacella, Pablo Perez-Ramos, Beth Pratt, Amy Whitesides

(Network Ecologies) Review Critics

Craig Douglas, Rosalea Monacella

Site Visit Hosts

Tom Astle, Liam Connolly, Neal Darby, Tanya Diamond, Mari Galloway, Devlin Gandy, Joseph Harvey, Fran Pavley, Katie Rodriguez, Neal Sharma, Ahiga Snyder, Merav Vonshak, Damon Yeh

Mid-term Review Critics

Pablo Perez-Ramos, Rosalea Monacella, Amy Whitesides

Final Review Critics

Marta Brocki, Renee Callahan, Julia Czerniak, Jeremy Guth, Joyce Hwang, Mariana Ibanez, Fadi Masoud, Rosalea Monacella, Beth Pratt, with Sarah Whiting and Gary Hilderbrand

the Resort: Connectivity + Coexistence

Annabel Grunnebaum, Senmiao Yang

Tortoise and Tarantula: Tales from the Edge

Anne Tong, Junia Yang

Pawel Bejm

Peak to Valley: Movements, Migrations, Mobilities

Naning Li, Ashley

Chris Reed, Nina-Marie Lister

This studio explores themes of peri-urban, rural, regional, and continental connectivity and resilience through the lens of wildlife and landscape infrastructure projects throughout California. By examining the intersections of these diverse environments, the studio seeks to expand the scope of wildlife connectivity infrastructure, demonstrating how design thinking integrates with the work of wildlife biologists and advocates. This interdisciplinary approach aims to deepen our understanding of the threats faced by wildlife, while fostering the development of new and empathetic relationships across species.

Through a detailed investigation of various connectivity projects, this studio highlights the crucial role of landscape infrastructure in maintaining ecological balance and promoting biodiversity. The work delves into the complexities of creating infrastructure that not only supports human activity but also prioritizes the needs of wildlife, ensuring their habitats are protected and connected. By bridging the gap between urban development and natural ecosystems, the studio aims to showcase the potential for harmonious coexistence between human and non-human communities.

The studio’s efforts are made possible through the generous support of the Wildlife Crossing Fund and ARC Solutions.

The work is built on concepts of connectivity and mobility—of creatures, of seeds and roots, of habitats, of people.

“Nature doesn’t work without connection.”

Mary Ellen Hannibal, The Spine of the Continent

“…the language of design, architecture, and urbanism in… [Southern California] is the language of movement. Mobility outweighs monumentality…”

Reyner Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies

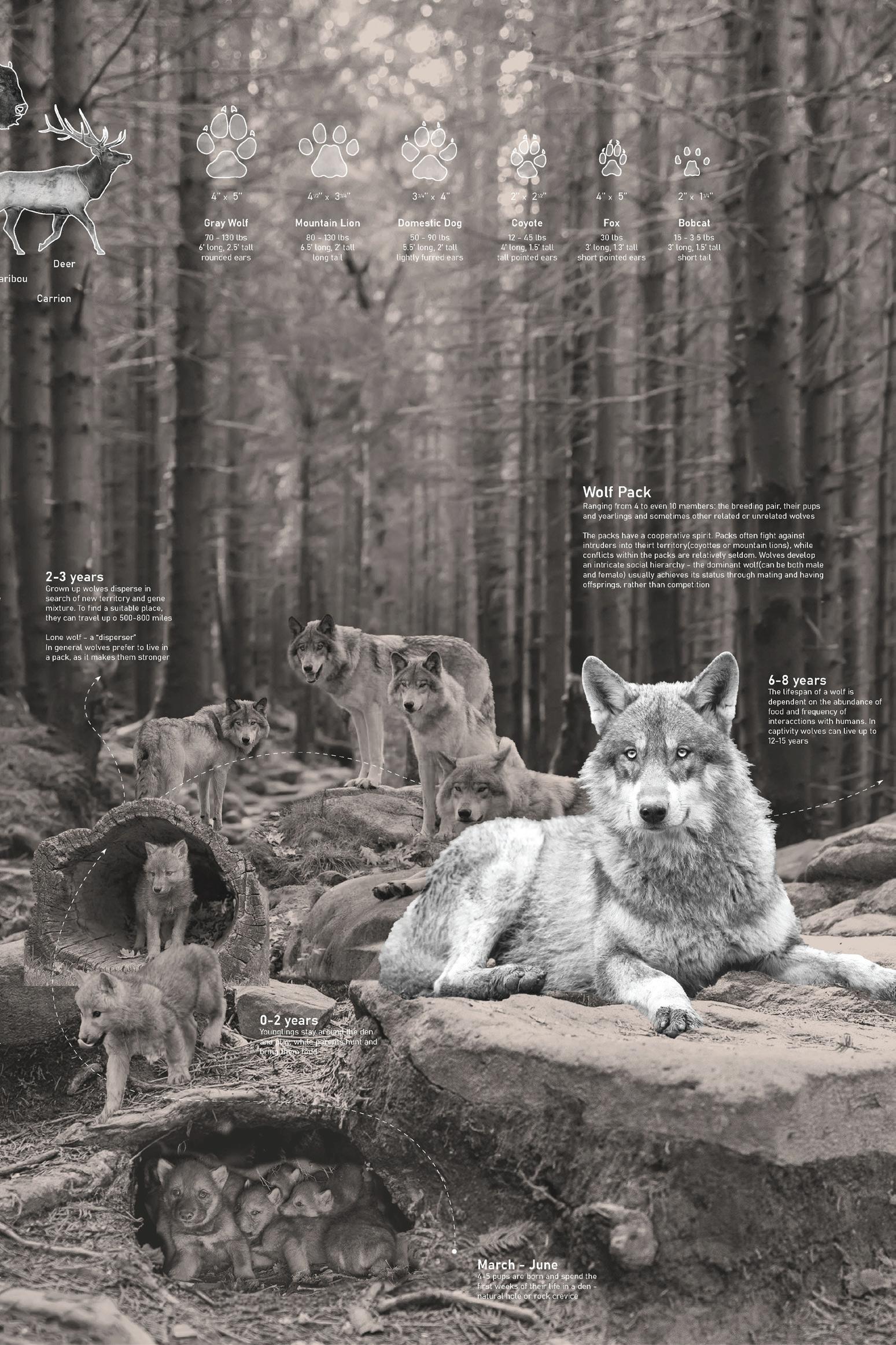

From a wildlife standpoint, a significant contributor to habitat destruction and biodiversity loss is human development through the process of urbanization, and the construction of infrastructure. Freeways, for instance, fragment habitats into smaller and small pieces, cutting off species from food, shelter and mates. They sever critical pathways for animals (and sometimes people, too) in their bigger ambition to connect places and people via high-speed vehicular roadways. Visible roadkill contributes to the death of millions of animals each year, not counting the myriad of invertebrates and insert swept away by vehicular drafts or smashed on windshields.

Development at the fringes of cities continues to push into the remaining refugia or critical habitat, reducing or eliminating it altogether. Channelizing rivers, draining swamps, filling in wetlands, paving fields, cutting forests, removing soils, and other alteration of habitat continues at a rapid pace, even with various government-mandated mitigation measures in place.

Because of all of this, almost a million species are in decline, many are at the brink of extinction, others are threatened, others are simply struggling to survive and adapt at the pace of change brought on by urbanization and acceleration of climate change.

“To conserve nature in the Anthropocene, half Earth is not nearly enough. To conserve biodiversity over the long term across an increasingly human planet, conservation must become as integral to the human enterprise around the world as are social and economic development.”

Erle

Ellis, One Earth

In this complex set of contexts, then, we will ask: Can we imagine new civic landscapes and infrastructure that re-stitch California’s wildlands and re-connect humans and creatures in new, empathetic ways? The work interrogates and explores what large-scale urban habitat and civic infrastructure projects across California’s biodiversity hotspots might look like and how they might work—in the face of increasing urbanization and intensifying climate change. Proposals generated from the primary lenses of different endemic, endangered and introduced species; layer in humans as both users and audience (on/in the connectivity infrastructure versus driving, moving or inhabiting them); and account for intensifying threats of wildfire and biodiversity loss. The goal is to invent the basis for new infrastructural and creature-based ecologies—mixes of habitat, culture, geography, ecology, food webs, mobility networks, and lifestyles—adapted to a rapidly evolving and warming climate.

For us, though, we want to approach this through various non-human lenses first, excavating understandings of animal and plant worlds and the various interrelationships and evolutions that are at the basis of non-human sustenance in this arid environment. We want to see, hear, smell, feel and move through wildlife senses. We want to understand how the logics of animal movement, plant growth and habitat connectivity might shape a strategic re-tooling of territorial-scale infrastructure networks in order to allow creatures to better thrive, and for ecosystems to flourish, to become a positive contributor to climatic and urbanistic forces.

Importantly, we do so by creating a new civic imaginary (perhaps re-capturing a sense of civic pride and expression that accompanied early motorway infrastructure) that fully engages

humans within these environments and raises our collective consciousness—by integrating live-giving landscapes with human and wildlife use and bold civic expression, as appropriate to the contexts and environments in which the studio worked.

The resulting projects will be used in part to demonstrate to public agencies and both infrastructure and wildlife organizations across the North American continent the ways in which multifunctional landscape infrastructures can be imagined to re-knit ecosystems and communities in compelling ways

“…it is clear that for most of (pre)history, people ate wild animals, tamed them, and kept them captive, but also respected them as kin, friends, teachers, spirits, or gods. Their values lay both in their similarities with and differences from humans.”

Jennifer Wolch, “Zoöpolis,” Animal Geographies

As a starting point, we leaned into these complexities, and explore multifaceted entanglements between and with the creatures and worlds around us.

Jennifer Wolch’s contemporary writings are situated in a rapidly changing world profoundly affected by climate change, habitat destruction and biodiversity loss, and informed by feminist writings by Donna Haraway, Anna Tsing and others. Wolch argues convincingly that dualisms brought on by Western and modernist agendas (nature/culture, urban/wild, human/ non-human) have both contributed to, even exacerbated, the environmental crisis we all now face. Wolch posits that the divides that separate us as humans from the dynamic, living world and its profound diversity of creatures and species have caused us to lose connection to them, and thereby to lose our empathy with and for them (and with the environment as a whole). Importantly, though, hers is not an anti-people or reductionist, purist conservation stance: Wolch’s vision of a Zoöpolis, in which animals are invited back in, involves deeper, respectful, sometimes useful, sometimes spiritual relationships and understandings between animals and humans and that recognize commonalities and co-dependencies as much as differences.

On another front, Reyner Banham’s expansive conceptualization of four “ecologies” [1971] were a new way to frame the very non-European city he encountered in Los Angeles—and a new way to think about human-environment interrelationships. For Banham, ecologies were more about an intermixing of environment, culture, economics, geography, infrastructure, social demographics, and social life—rather than about a literal reading of scientific definitions of ecology as the study of the interrelationships

We can also extrapolate these ideas in framing new infrastructural projects throughout California that could lead to new intertwined relationships, kinships, of being with…

As we ponder such questions, we need to recognize the profound impact that urbanization has had on the varied environments and limited resources of significant parts of California. (We should also recognize our inherent bias in referring to landscape as a potentially

between organisms and their environment; or about a traditional understanding of architectural history and urban development in Western countries. The four ecologies he described—Surfurbia, the Foothills, the Plains of Id, and Autopia—were as much physical as they were imaginative constructs; but they importantly spoke to a set of entangled and complex conditions that gave rise to unique forms of urban life in this very American city. While his writings are now 50 years old, certain aspects of Banham’s framing persist and have caused many to consider additional ecologies that have developed since, or might develop as we move forward.

plunderable “resource.”). 20th-century approaches to infrastructure—single-minded, wasteful, polluting—have destroyed the diverse habitats and their environments that once existed, have squandered important resources by building over them or flushing them away. Wildfires, increasing heat, radical habitat and biodiversity loss, energy shortages, and strains on food and water supply are all indicators of this critical moment.

Following are the students’ hopeful responses to these multivariate challenges.

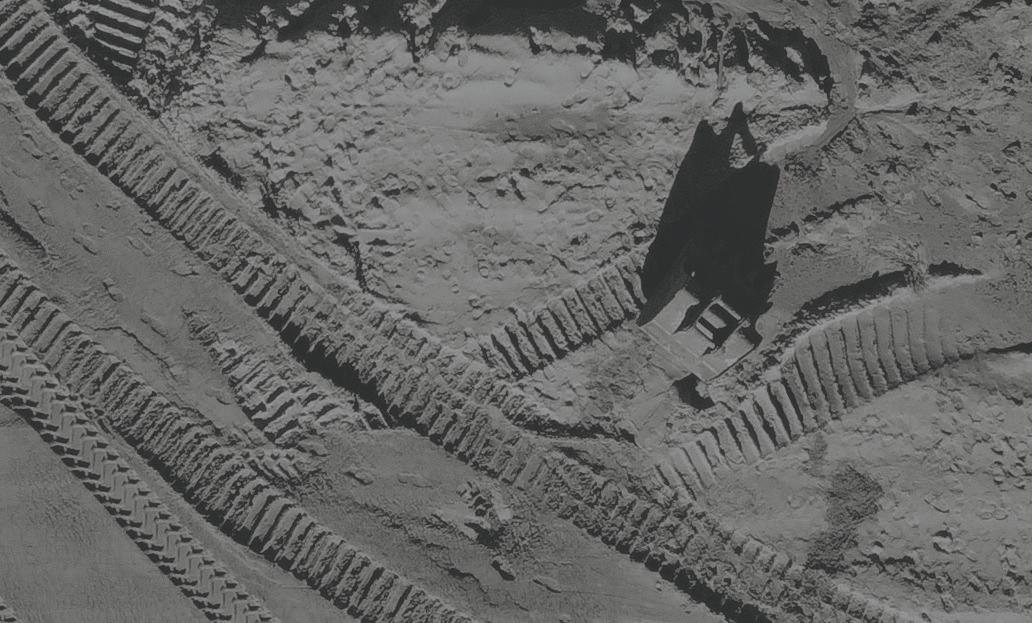

For 7 days in February 2024, students traveled with faculty, wildlife experts and studio sponsors across the Californian landscape. We visited critical biodiversity hotspots, cultural sites, and places where infrastructure and urbanization continue to have the greatest impact on wildlife habitat and connectivity. Students also visited potential sites for their project proposals, recording observations and conditions as a baseline for situating their work. Excerpts from the trip follow.

Peaks to Valley: Movements, Migration, Mobilities

Naning Li, Ashley Ng

Castaic Hoverpass

Zheming Zhang

HABITATS

The Right to Roam

Pie Chueathue

The Newt Normal

Lucas Dobbins

Re-thinking the Resort: Connectivity + Coexistence Strategies

Annabel Grunnebaum, Senmiao Yang

TACTICS

Tortoise and Tarantula: Tales from the Edge

Anne Tong, Junia Yang

Undercover Connectivity

Pawel Bejm

STRATEGY

Wings to Wilderness: Flights and Flows

Sara Han, Emily Menard

Naning Li Ashley Ng

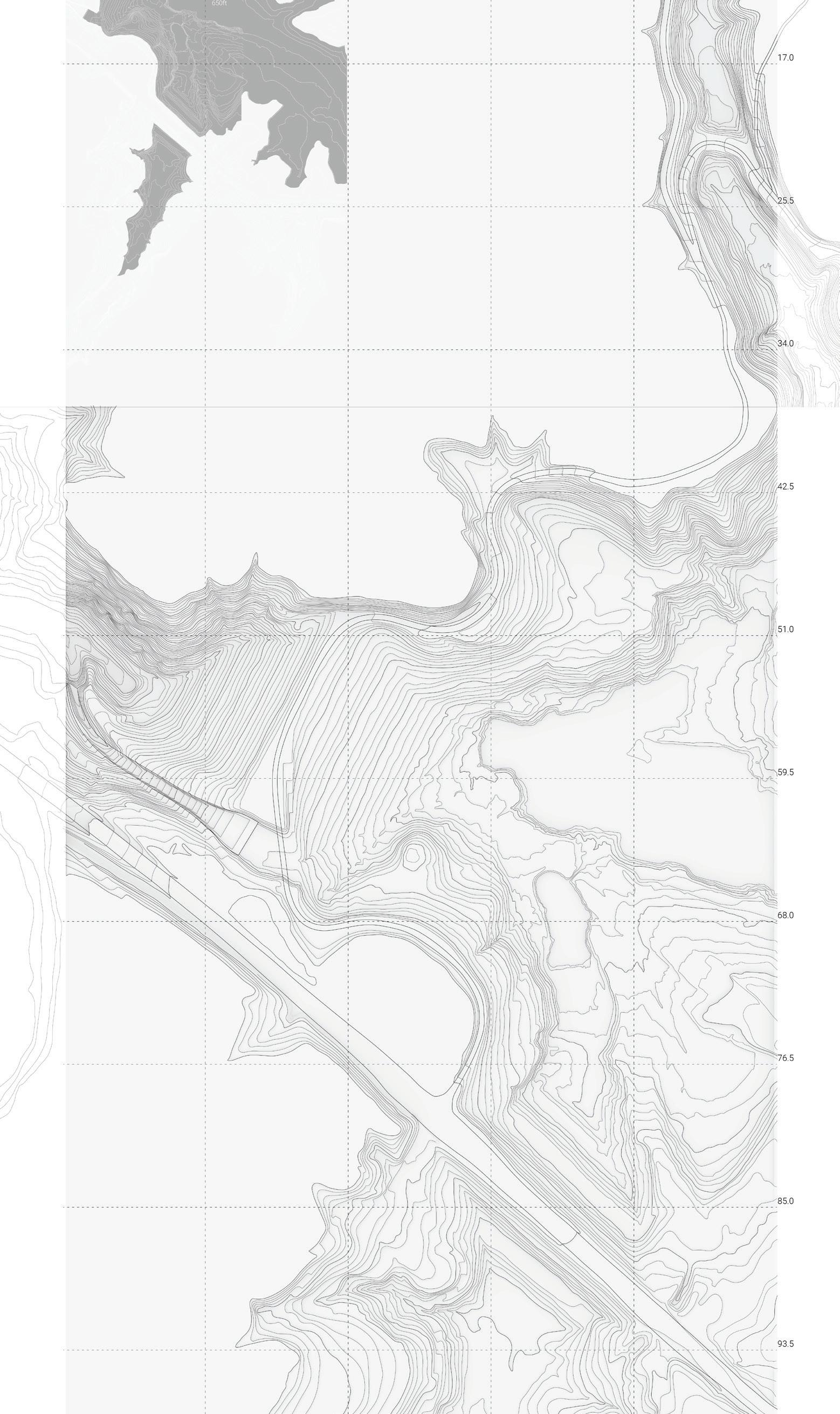

Our project explores the co-existing relationship between humans and wildlife in Mammoth Lakes, to design innovative crossings for the Mule Deer and to provide conditions for the future habitat expansion of the endangered species, the Sierra Nevada Bighorn. Mammoth Lakes is a year-round recreational area that is faced with issues of road-kill and deep-snow pack due to climate change. Due to their differences in visibility and habitat, the two species of Mule Deer and Sierra Nevada Bighorn, inspired a series of strategies ranging in scale from peak to valley.

The Mule Deer is facing road kills, habitat loss, climate change and diseases. The most severe problem is the road kills on I395, where mule deers cross twice a year during migration seasons. Traditional crossing projects face the problem of lack of funds and support, because of high costs and blocking of views. The interventions include two wildlife crossings, taking traffic, tourism, migration, seasonal user and visual effect into consideration. The Sierra Nevada Bighorn sheep is facing habitat loss, deep snow pack and increased predation, all worsened by climate change. In contrast to the Mule Deer, the Bighorn project is a more adaptable, “kit-of-parts” solution. The interventions focus on creating new habitat and providing snow protection through two key tools: gabions and fencing. Both of these can be used in various configurations to address habitat needs seasonally and scaled up for larger landscape interventions.

Through the lenses of both human and wildlife, the project promotes a coexistence among mule deer, bighorn, and human culture in a recreational context.

Zheming Zhang

Highways are an integral part of California life, and the varied and beautiful roadside sceneries make for an attractive driving experience. People enjoy driving. However, the backside of this road trip culture is isolated wildlife habitats in California. Mountain lions and many other wildlife face roads and vehicles as a major threat.

This project aims to bridge wildlife habitats over the highway through the form of a rest stop. Taking advantage of people’s gathering at a rest stop, Castaic Hoverpass turns it into an education base where travelers will come to observe and record both the wildlife crossing and wildlife sightings. The large plate-like building floating above the highway transforms the once ordinary rest stop into a regional destination and center of attention. Human activities are restricted within the building, leaving enough space and a sense of security for wildlife. The crossing has an ecological environment similar to the surrounding area, which includes chaparral and other shrubdominated ecosystems. Combining a wildlife crossing and a rest stop into one building emphasizes the human structure’s potential to support wildlife welfare. Its compact footprint atop the highway also gives back the current sprawled rest stop to habitat restoration.

“The Right to Roam” reimagines the purpose of infrastructure at the Lexington Reservoir in San Jose, California, to enhance wildlife connectivity. This project aims to establish a foundation for new infrastructural and organism-based ecologies—a blend of habitat, culture, geography, ecology, food webs, mobility networks, and lifestyles—adapted to a rapidly evolving and warming climate. The design initiative shifts the focus from human-centric to species-centric perspectives.

The proposal includes a redesigned fish ladder to replace the existing rigid concrete channel at the reservoir. By dechannelizing this concrete waterway, the new landscape will attract steelhead trout, facilitating their migration from downstream to upstream for breeding and reproduction. Additionally, the redesigned landscape will foster the emergence of microhabitats, supporting a diverse array of species and enhancing overall ecological resilience. This innovative approach aims to harmonize human infrastructure with natural processes, promoting a sustainable and interconnected ecosystem.

Newt populations are in decline across California combating implications of urban development, roadways, mountain bike trails, pesticide use, poor water quality, and long periods of drought. The California Newt has limited range, with remnant pockets of populations threatened today by habitat fragmentation. With their bright red color used to signal toxicity, the Newt faces few predators aside from the garter snake, with which it is engaged in an evolutionary toxic arms race. Newts must migrate seasonally between dry upland habitat and water bodies where they breed. Often, these habitat patches are separated by roads, resulting in a high degree of road mortality as Newts migrate en masse. In a recent survey by community scientists known as ‘The Newt Patrol’, it was found that 39.2% of adult Newts at the Lexington Reservoir do not complete the round trip to and from the reservoir. Without intervention, the local Newt population is predicted to rapidly decline to under 1000 adults in 15 years and may face extirpation in 57 years. However, reducing the road-based mortality rate to 20% would allow the population to reach over 4700 individuals in 100 years, and a further reduction to 17.667% would sustain the Newt population at its current size.

This design proposal addresses road mortality by prioritizing the creation of new breeding habitat in upstream areas such as Limekiln and Trout Creeks. The strategy involves lowering the water levels in the reservoir seasonally to increase the littoral edge, encouraging a more productive and natural reservoir environment. Additionally, floating treatment wetlands are implemented to cleanse the water and create a more diverse, safe, shared, and protected habitat where humans and nonhuman species may coexist.

Annabel Grunnebaum Senmiao Yang

Our project aims to design an innovative wildlife crossing in South Lake Tahoe, focusing on connecting fragmented habitats and enhancing ecosystem health. The crossing addresses the critical pressure point between the state park and the California Tahoe Conservancy, disrupted by a busy highway and a bridge, which currently results in frequent roadkill incidents.

The project site is located beside the Upper Truckee River, which is part of a diverse watershed comprising marshes, residential areas, an airport, a golf course, and rocky hills. The region is home to various species, including bobcats and black bears. Bobcats, known for their adaptability, often avoid water and prefer dry crossings, while black bears, despite their size, are similarly affected by habitat fragmentation.

This wildlife crossing design in South Lake Tahoe represents a holistic approach to habitat connectivity, balancing ecological restoration with community engagement and recreational needs. By addressing key pressure points and enhancing habitat continuity, we aim to create a sustainable and thriving environment for both wildlife and humans.

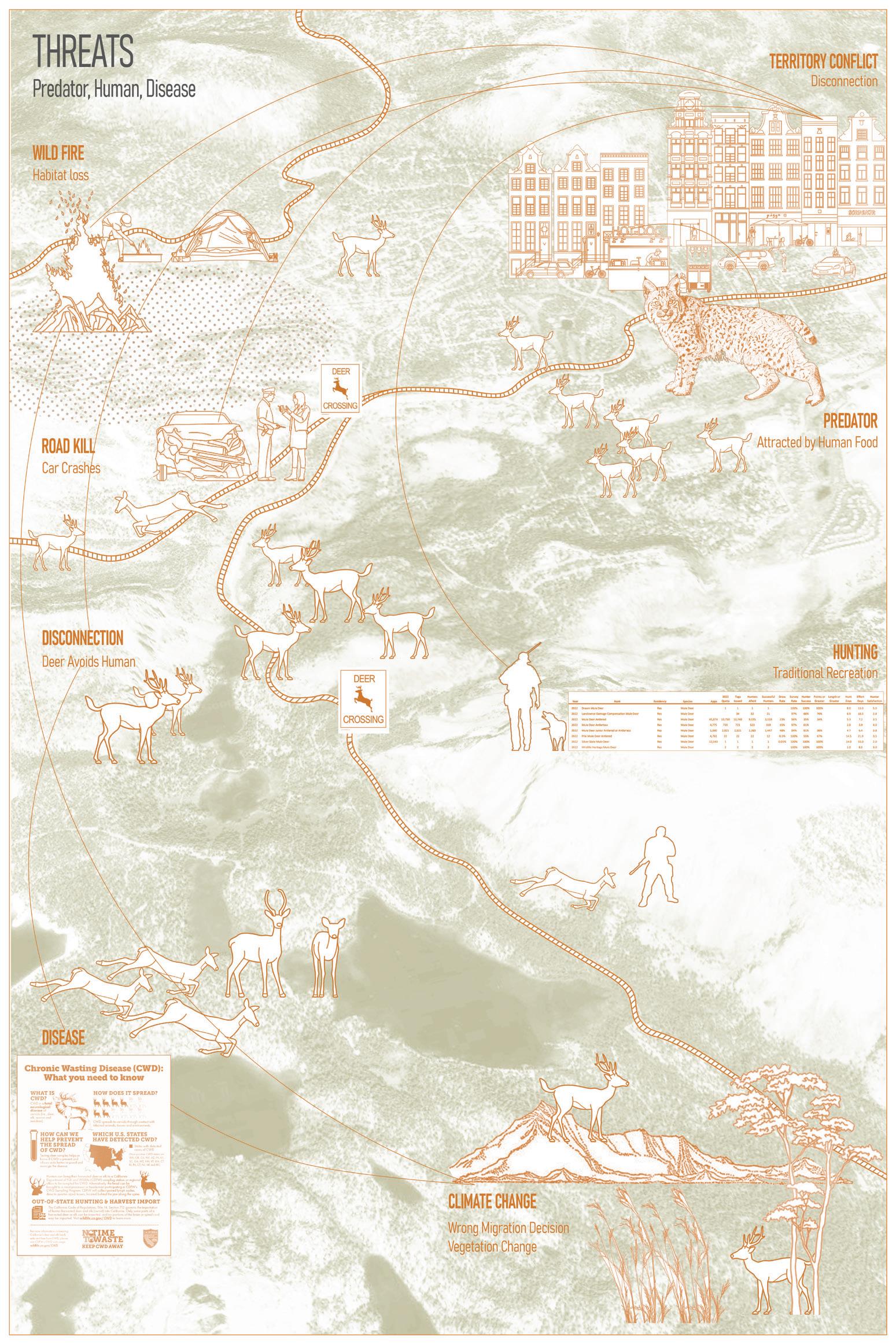

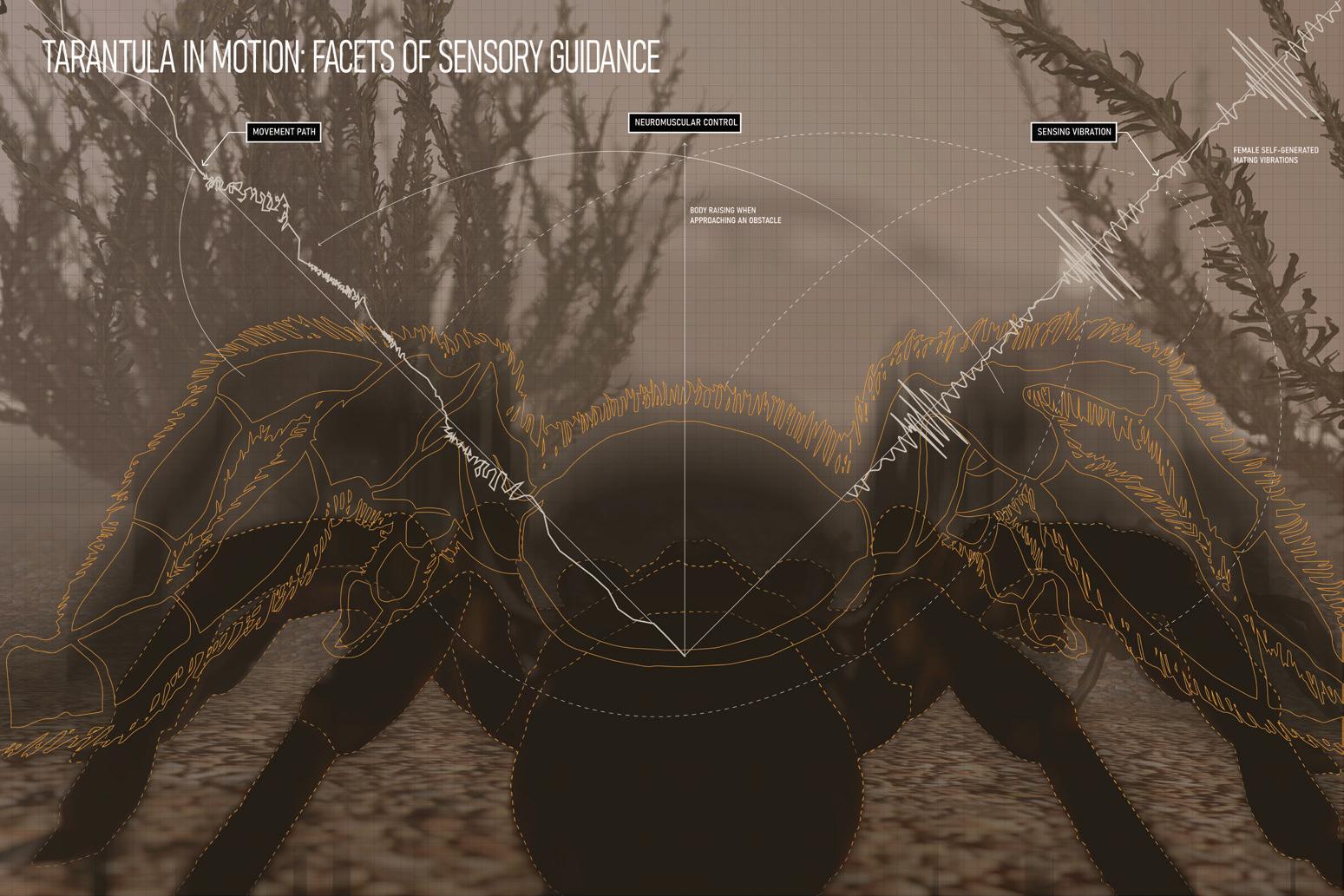

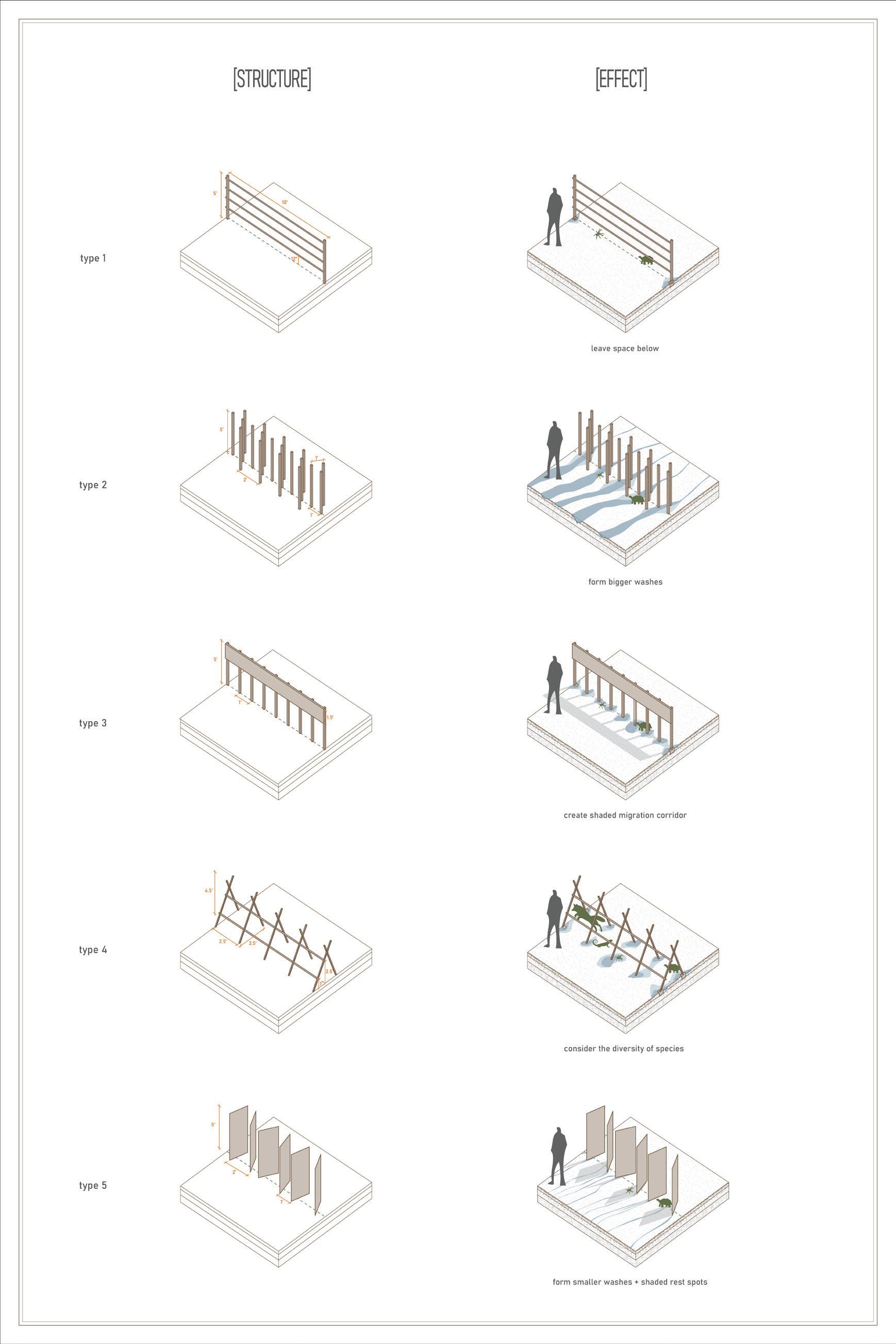

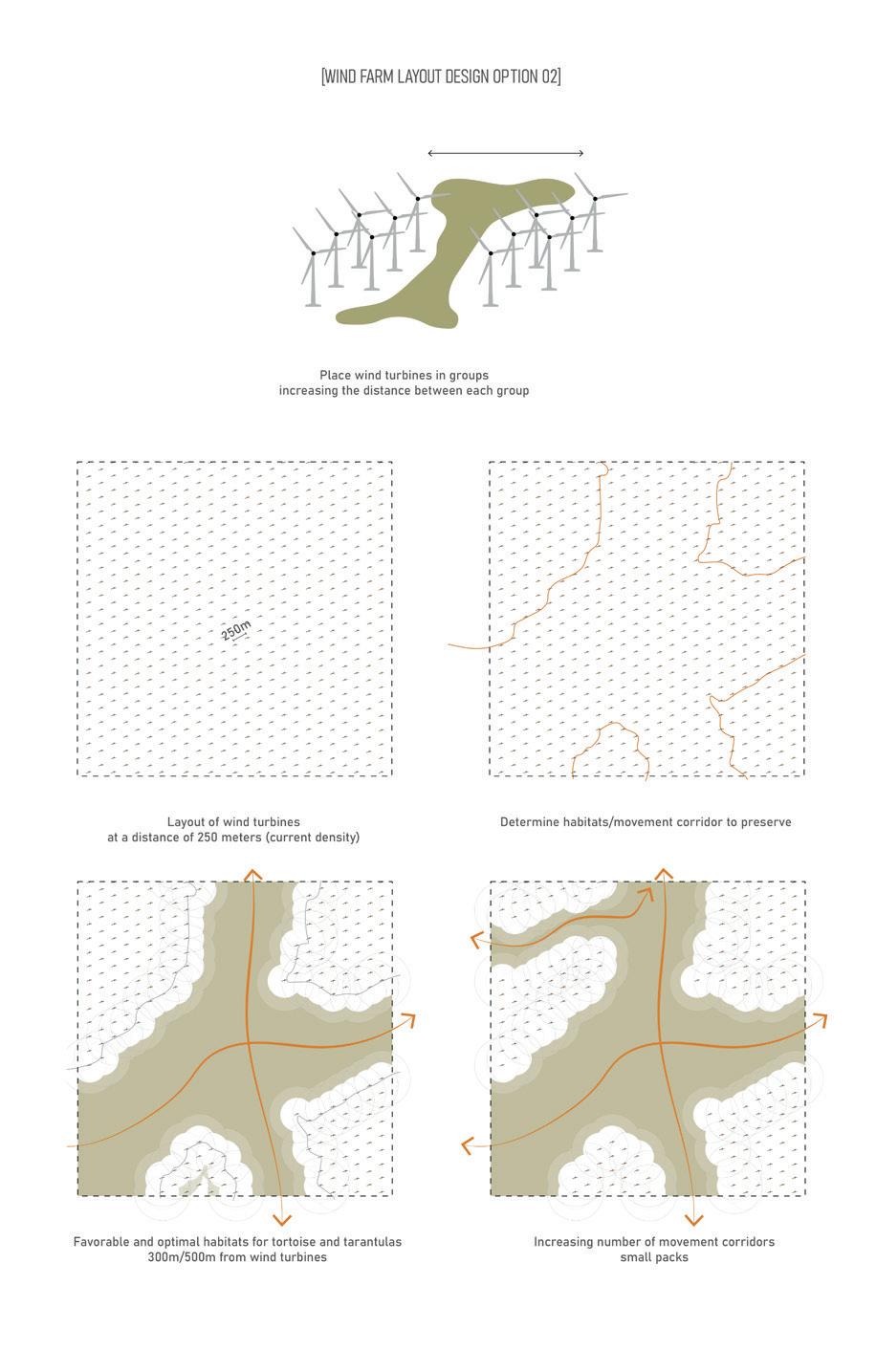

Anne Tong Junia Yang

The project focuses on the “edges” where life thrives and human development encroaches in Mojave Desert. It brings animal agency to the forefront, particularly focusing on the desert tortoise and Mojave tarantula.

Rethinking anthropogenic infrastructure systems by optimizing the “edges” created by solar and wind farms and their ancillary infrastructure addresses the cutting-edge issue of renewable energy developments potentially turning an oasis into a dead zone. The project imagines the possibilities for human and non-human coexistence. Through design and policy recommendations, it promotes wildlife connectivity and envisions a paradigm where coexistence thrives amidst progress.

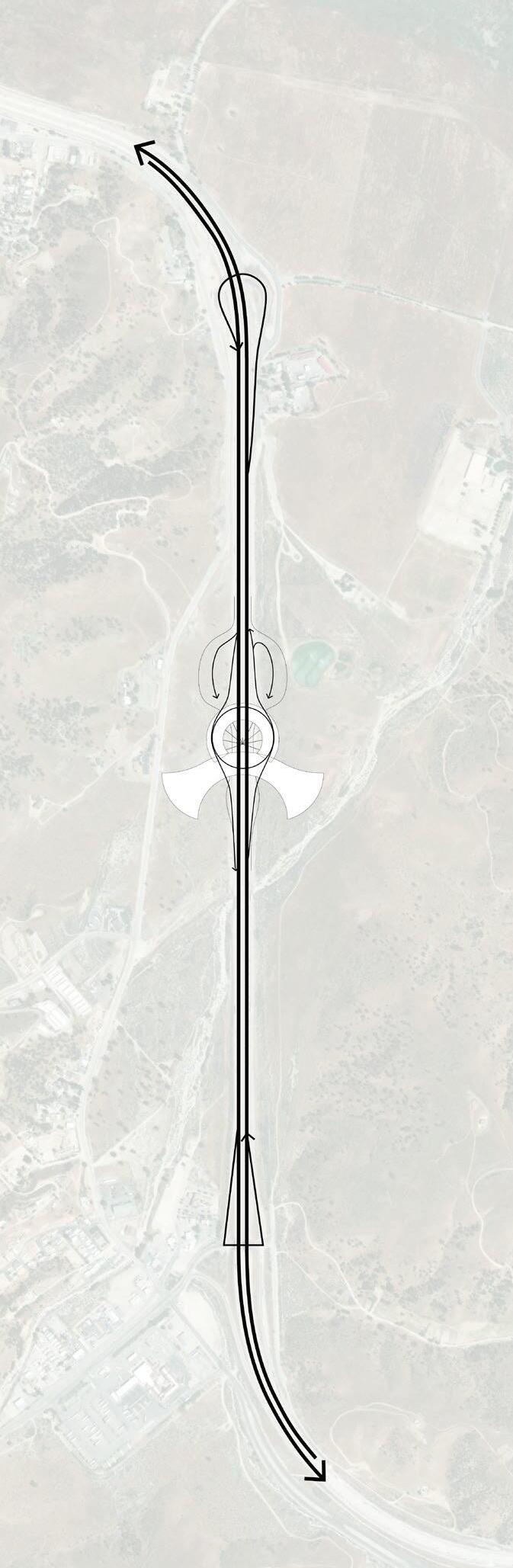

Pawel Bejm

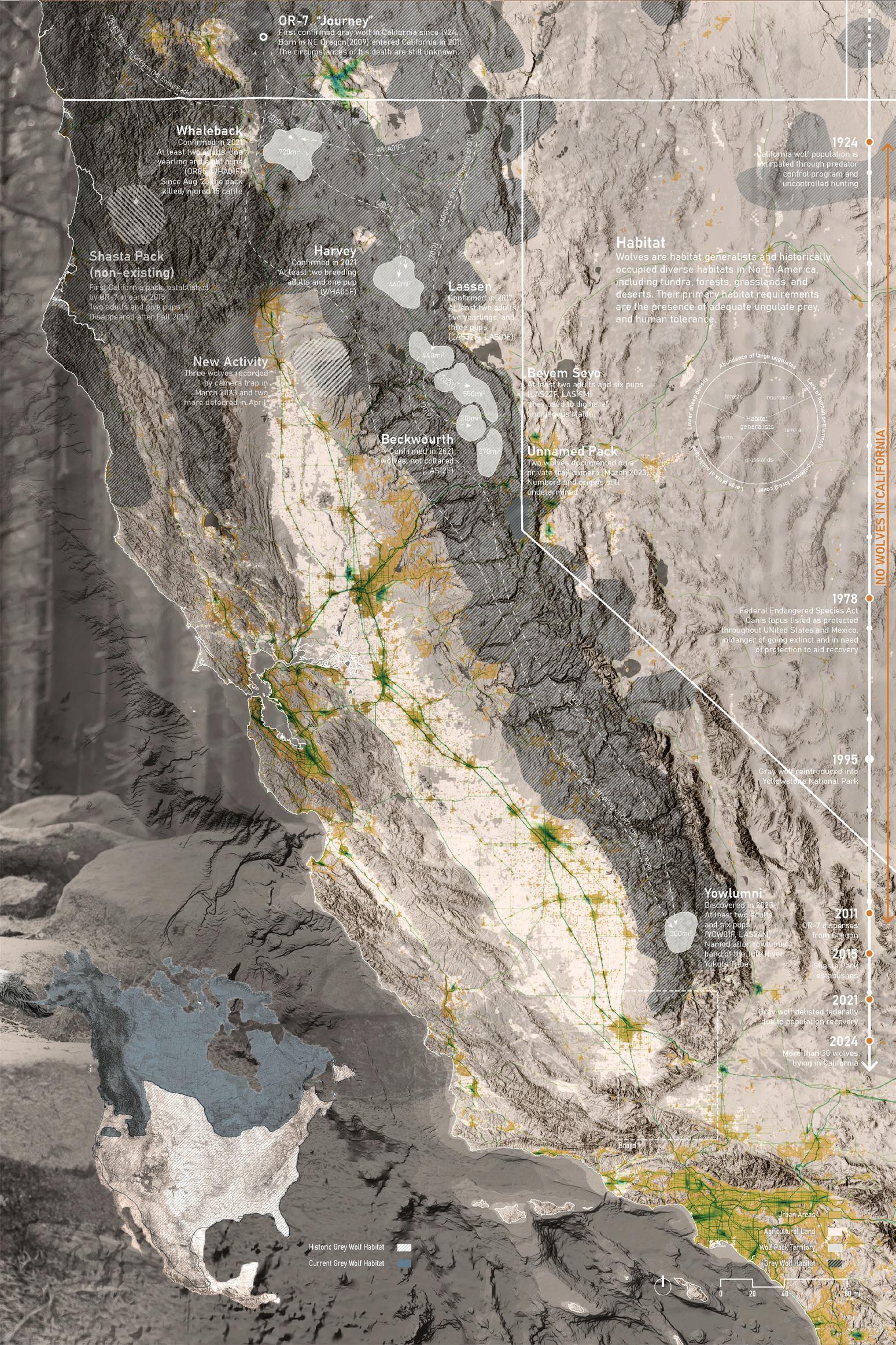

It is easy to protect animals that are likeable. But how to protect big predators which are essential for the health of our ecosystems, like the grey wolf? It is not possible to change the general negative perception of the “bad wolf” and gain wider support for their protection. Instead, a different strategy is necessary. The wolves will follow their wild prey wherever it goes. By connecting deer, elk, and other ungulate territories, wolf connectivity can be “secretly” expanded without rising too much attention. At the same time, the biggest obstacle in realizing most wildlife crossings is their high cost.

Therefore, instead of focusing on a single megastructure, the project aims to identify connectivity potentials of the existing “holes” in the otherwise impermeable barrier of the highway. It seeks to adaptively reuse elements currently designed with traffic efficiency in mind, like culverts, underpasses, and turnaround bridges. However, instead of optimizing them for cars, the project puts animals in the center of attention.

In the form of the 2024 Wildlife Revision of the highway design standards, a new set of adapted designs can be applied across California to form a decentralized network of wildlife crossings. Instead of focusing on a one-off, expensive project, this “undercover wildlife infrastructure” can thereby be integrated into the road construction budgets, resulting in the expansion of a much more permeable and wildlife-friendly highway network.

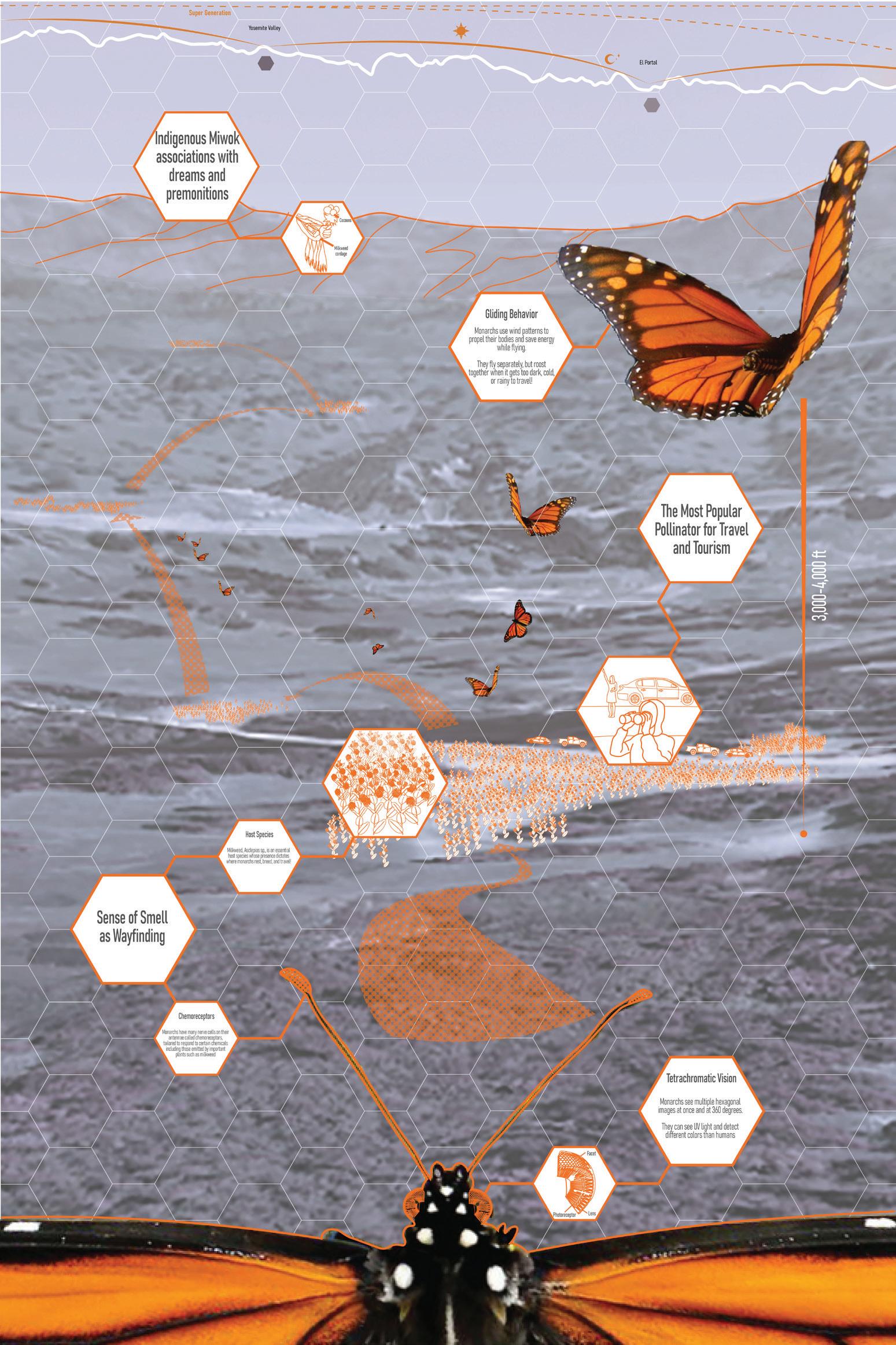

Sara Han Emily Menard

National parks are incredible sources of biodiversity and culture, but how we access them has become a quintessential problem that can and will dictate the future of these resources. In Yosemite, cars idling for hours along expansive road systems dominate the landscape. Once hailed as a pristine wilderness, the Valley has undergone a profound metamorphosis over the decades. What was once cherished for its natural beauty and untamed landscapes has gradually transformed into a bustling thoroughfare, teeming with vehicles and human activity. This evolution, spurred by modernization and the rise of mass tourism, has cast a shadow over the ecological integrity of Yosemite National Park, particularly within its iconic valley. The introduction of automobiles in 1913 rapidly resulted in significant traffic. Originally conceived as a scenic byway, Yosemite Valley has evolved into a congested thoroughfare, leading to habitat fragmentation and ecological degradation.

In response to these formidable challenges, a paradigm shift is necessary—a reevaluation of Yosemite Valley’s infrastructure and management practices through a wildlife-centric lens. Our project, Wings to Wilderness, endeavors to reimagine Yosemite Valley not as a conduit for human access, but as a sanctuary for biodiversity. We aim to create a revolutionary national park model centered upon coexistence and more-than-human landscapes.

Marta Brocki

Marta is Associate Director of ARC Solutions and a graduate from the Bachelor of Urban and Regional Planning program at Toronto Metropolitan University where she worked as a Research Assistant and Project Coordinator at the Ecological Design Lab from 2013-2020. Her interests, in research and practice, center on the implementation of green and adaptive infrastructure, specifically for enhanced landscape connectivity.

Renee Callahan

Renee Callahan has over 30 years of professional experience in federal, state, and administrative law, policy, and research. As Executive Director of ARC Solutions, Renee leads an interdisciplinary not-for-profit partnership working to ensure wildlife crossings are built whenever they are needed, with a focus on fostering design innovation in the next generation of wildlife infrastructure solutions.

Jeremy Guth

Jeremy Guth is a founding Partner of ARC Solutions and co-initiated the ARC International Wildlife Crossing Infrastructure Design Competition with Dr. Tony Clevenger in 2008. He has been a trustee of the Woodcock Foundation since 2003 and developed the foundation’s large landscape conservation program with a particular focus on the preservation of ecological connectivity between Canada and the United States.

Nina-Marie Lister

Nina-Marie is Professor and Graduate Director in the School of Urban & Regional Planning at Toronto Metropolitan University and Visiting Professor of Landscape Architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. A Registered Professional Planner (MCIP, RPP) trained in ecology, environmental science and landscape planning, Prof. Lister’s research, teaching and practice centre on the relationship between landscape infrastructure, biodiversity and ecological processes-specifically in the context of ecological design for resilience, health and well-being.

Beth Pratt

Beth is Regional Executive Director of the California Regional Center of the National Wildlife Federation. She has worked in environmental leadership roles for over twentyfive years, and in two of the country’s largest national parks: Yosemite and Yellowstone. Beth is the author of the book, When Mountain Lions are Neighbors: People and Wildlife Working It Out In California.

Chris Reed

Chris Reed is Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture and Co-Director of the Master of Landscape Architecture in Urban Design Program at the Harvard GSD. He is also Founding Director of Stoss Landscape Urbanism. He is recognized internationally as a leading voice in the transformation of landscapes and cities, and he works alternately as a researcher, strategist, teacher, designer, and advisor. Reed is particularly interested in the relationships between landscape and ecology, infrastructure, social spaces, and

Studio Report Title Instructors

Chris Reed, Nina-Marie Lister

Report Design

Sara Han

Report Editor

Sara Han

Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture

Sarah Whiting Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture and Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture

Gary Hilderbrand

Copyright © 2024 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Text and images © 2024 by their authors.

Enormous thanks to Beth Pratt and the Wildlife Crossing Fund, and to Jeremy Guth, Renee Callahan, Marta Brocki, and ARC Solutions for their generous financial support, and for the knowledge and resources they shared. The success of students’ experiences throughout the semester were due in no small part to these individuals and organizations.

We would also like to thank our teaching assistants, Tom Day and Jackie Chan, who helped to prep an enormously complicated studio and trip with calm and patience and a friendliness that exceeded all expectations. Thanks, too, to Landscape Chair Gary Hilderbrand and GSD Dean Sarah Whiting for their ongoing support of this three-year teaching collaboration.

Finally, heartfelt gratitude to Sara Han, who graciously and professionally took on the task of organizing the semester’s work and assembling this report. Sara’s high-quality work is self-evident; her deft and skills at beautifully and thoughtfully bringing it all together are, perhaps, less visible. We so very much appreciate Sara and this impressive effort!

Image Credits

Cover photograph by Tyler Schiffman Interior photographs from Unsplash

The editors have attempted to acknowledge all sources of images used and apologize for any errors or omissions.

Harvard University

Graduate School of Design 48 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138

gsd.harvard.edu

Studio Report

Spring 2024

Students

Harvard GSD

Department of Landscape Architecture

Pawel Bejm, Pie Chueathue, Lucas Dobbin, Annabel Grunebaum, Sara Han, Naning Li, Emily Menard, Ashley Ng, Anne Tong, Senmiao Yang, Junia Yang, Zheming Zhang