Francesca Benedetto / Gareth Doherty

Francesca Benedetto / Gareth Doherty

The studio reimagined five public spaces in the Medina of Tunis, Tunisia. Taking a long-term view over a 5 to 50-year timespan, the studio asked how three interrelated areas of focus— housing, health, and changing climates—intersect with the urban landscape. The project especially considered the design of nocturnal landscapes as one response to the rising temperatures associated with climate change. The five sites are centered on Dar Enaifer, Dar Fatma, Madrassa Chammaia, Fondouk El Henna, and Rue des Juges. We asked how these sites can be reimagined in ways that can act as catalysts for the reshaping of the entire Medina. Affiliated with the Critical Landscapes Design Lab, the studio took an approach to the design of urban spaces deeply grounded in the environmental, economic, human, and political ecologies of Tunis.

Through a grounded research method called “landscape fieldwork,” students engaged with the Medina and its residents to gain a deep understanding of everyday life and spatial patterns that do not show up in official statistics, documents, or records. The landscape fieldwork approach combines landscape architects’ projective skills and tools for site analysis (drawing, measuring, photographing, remote sensing) with the ethnographic methods of anthropologists (participant observation, unstructured interviews, and writing reflexive field notes) all as an integral part of the design process.

Students worked in groups of two or three on one of the given sites. Proposals ranged in scale from the renovation and reuse of existing public spaces and the structures that frame them, to urban design guidelines, as a prelude to reimagining the Medina itself.

The feasibility of projects has been tested in workshops with residents, property owners, and students. A reimagined Medina needs common design guidelines and policies that, through an aggregation of smaller, catalytic developments, will provide a coherent spatial approach that respects and works with the Medina’s UNESCO World Heritage status.

Studio Instructor Francesca Benedetto

Principal Investigator

Gareth Doherty - Critical Landscapes Design Lab, Atlas for the Medina of Tunis

Sponsor MATERIA Inc.

Teaching Associate Forrest Rosenblum

Students

Jiin Choi, Yingzhi He, Daye Kim, Jiazheng Li, Leah Li, Shuyue Liu, Yazmine Mihojevich, Courtney Sohn, Kun Wei, Jiaheng Xie, Ruijen Yang, Siqi Zhu.

Final Review Critics

Alistair McIntosh, Danielle Choi, Karen Janosky, John Peterson, Derwin Sisnett, Rebecca McMakin, Alberto Kritzler, Lucio Frigo, Areti Kotsoni, Sihem Lamine, Iheb Guermazi, Kate Bauer, William Granarola, Lauren Montague, Dean Sarah Whiting, and the Landscape Architecture Chair Gary Hilderbrand.

Report Design & Editors

Elizabeth Van Dyke, Zak Jacobi, Markel Uriu

Preface

20 Tunis Medina Database

46 Dictionary of Islamic Architecture

48 The Urbanized Night

50 Islamic Architecture Dictionary

56 Nocturnal Dictionary

60 Islamic Dictionary Research Map & Dictionary Database Collection

84 Nocturnal Dictionary Research Map & Dictionary Database Collection Fieldwork

96 Studio Trip Landscape Fieldwork

108 Nocturnal Artists

Atlas of Proposals

130 Nocturnal Panorama: Opening the Dar to the Public, the Garden, and the Night Jiin Choi, Yingzhi He, Daye Kim

152 Effusive Courtyards: Outside In, Inside Out Courtney Sohn, Siqi Zhu, Jiaheng Xie

176 Story of Water: Reactivating the Medina Through Water Xiaofan Ye, Shuyue, Liu

206 Porous Perimeters: Designing for Temporality in the Medina Yazmine Mihojevich, Ruijen Yang

244 Portal to the Sky: A Vertical Pathway to Medina’s Roofscape Leah Li, Kun Wei

272 Luminous Paper Peepshow

Backmatter

280 Acknowledgements

The studio has four overlapping phases:

1. Database (January 2023–February 2023):

A focused spatial and social study of the Medina conducted remotely and in-person.

2. Design (February–March 2023):

Designing alternative forms of public spaces and examining their implications for civic life and governance.

3. Scenario Development (March–April 2023):

Assessing the feasibility of projects and preparing a plan for implementing recommendations.

4. Implementation plan (April–May 2023):

An atlas of proposals for the Medina. The atlas will be in the format of a studio report and aimed at dissemination among a general audience throughout Tunis and beyond.

1. Dar Enaifer

Typology: House

Proposed Program: Working space

Students: Jiin Ahn Choi, Daye Kim, Yingzhi He

2. Dar Fatma

Typology: House

Proposed Program: New communal living typology for youth and couples

Students: Courtney Paige Sohn, Jiaheng Xie, Siqi Zhu

3. Madrassa Chammaia

Typology: School

Proposed Program: Independent design/ Heritage School

Students: Shuyue Liu, Xiaofan Ye

4. Fondouk El Henna

Typology: Foundouk

Proposed Program: Lab for artisan to work and exhibit their products

Students: Yazmine Mihojevich, Ruijen Yang

5. Rue des Juges

Typology: Ruin and impasse

Proposed Program: Neighborhood garden, public area

Students: Leah Li, Kun Wei

Jiaheng Xie

Siqi Zhu

Ruijen Yang

After a first extempore assignment where the students were asked to work on a double image collection on topics related to Islamic architecture and nightscapes, they worked on the creation of a database, a focused spatial and social study related to Tunis Medina. Their exploration considered Medina’s physical, social, and cultural landscapes.

To build the database collection, the students focused on the following questions:

- Where could your investigation be applied in the Tunis Medina area and the proposed five sites?

- How could your research be interrelated with the three areas of focus—housing, health, and changing climates?

- And how can it contribute to unveiling the site conditions that represent a value for the Medina’s identity, memory, and the life of its inhabitants and ecosystems?

- How could your research inspire the design of nocturnal landscapes as one response to the rising temperatures associated with climate change?

Arch Bab

Badgir

Bayt

Bazar

Brickwork

Burj

Caravanserai

DomeDomical Vault

Hassan Fathy

Fundok

Gardens

Hammam

Haram

Haud or Hauz

Hypostyle

Joggled Voussoir

Ka’ba

Kiosk

Madafa

Madrassa

Mashrabiyya

Masjid

Medina

Mihrab

Mimar

MinaretMosaics

Mosque

Mud Brick

Muqarnas

Pisé

Qanat

Qibla

Riad

Saqaqa

Squinch

Stucco

Susa

Tilework

Zilij

Alter-visuality

Absence of Daytime

Atmospherics of Darkness

Big Night

Black

Calculated Invisibility

Capital’s Night

City of Night

Cultural Infrastructure

Dark/Light Dialectic

Day/Night Binary

Dark Factories

Dark Landscape

Dark Market

Dark Windows

Darkness

[Refreshing] Darkness!

Electrical Grid

Energetics of the urban night

Gendered Night

Gloomy City

Heterotopian Night

Lights

Mainstream/Alternative

Nightlife

Night

Night’s Affective Atmosphere

Night Frontier

Night Governmentality

Night Territorialization

/ Deterritorialization

“Night Shift”

Night Space

Night-Sky

NTE

Nocturnal City

Nocturnalization

Nocturnal Sublime

Obscurity

Overillumination

Permanent Illumination

Residual/Alternative Nightlife

Second City

Sky Glow

Somnambulant

Soundscape

Unearthly

Urban Playscapes

Working Night

Walking

Zones of Darkness

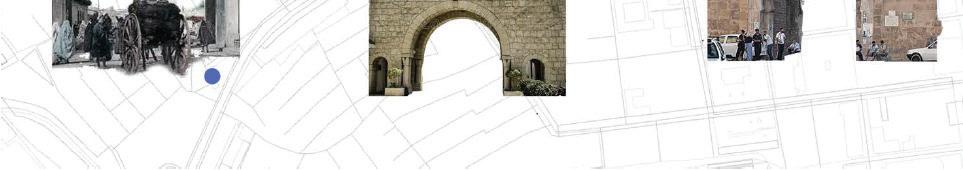

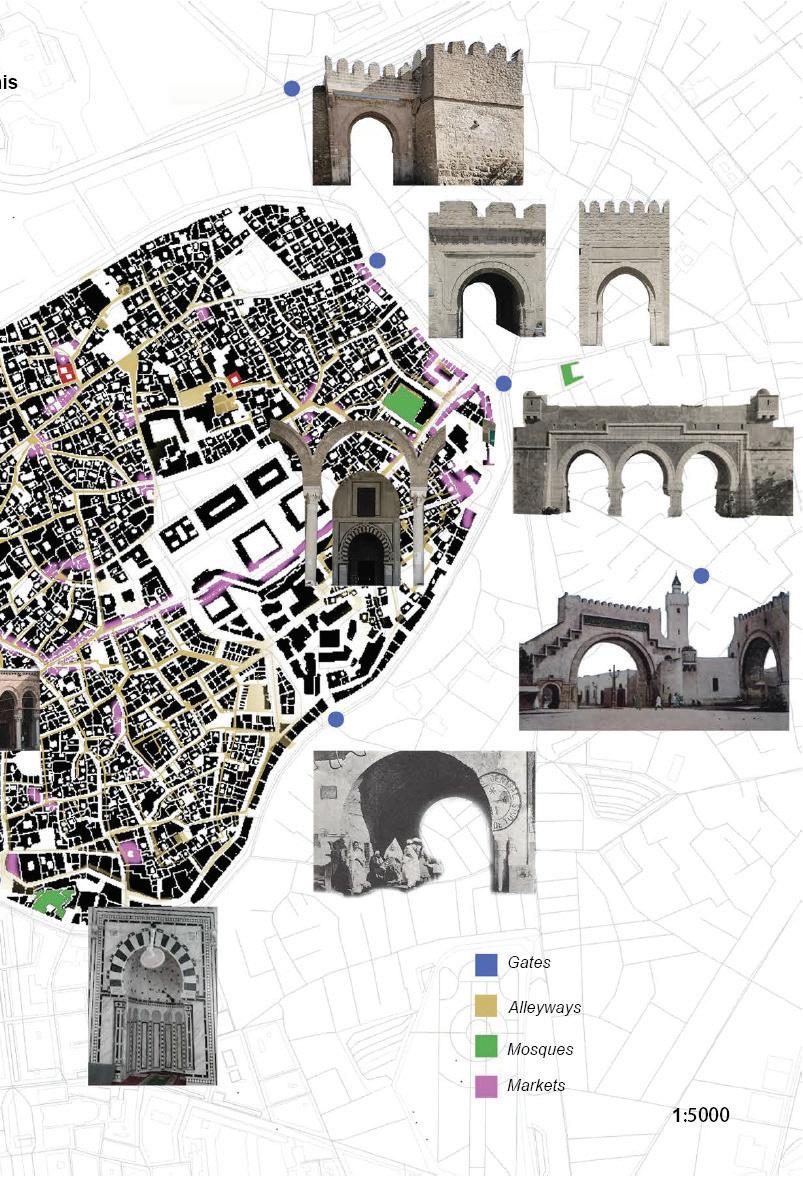

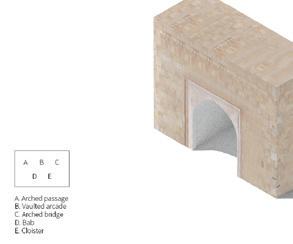

Arches–have been present in many of Tunisia’s architectures. Arches in various contexts manifest in different shapes, sizes, and forms, adapting diverse social activities. They also contribute to the vibrant urban life in Medina, Tunisia.

Gateway – The first type of arch can be seen in the gates in Tunis. The arches were integrated parts of the wall, which was built to protect the city from attacks in the past. In the past, these arches were the access points for merchants overseas to access the city, which also symbolizes the entrance to a new world and new life.

Alleyway – Another situation in the arches can be seen in the alleyways, where arches are placed layer by layer, generating corridors and sheltered streets between neighborhoods. These informal spaces generate different social activities depending on their widths. They are sometimes narrow, designed for private pass-throughs and sometimes wider, welcoming people to take a chair, sit outside, and enjoy the afternoon. Mosque – Arches could also be seen in mosques, where they lay in rows to form a web of space supported by columns. There are, in total, 160 columns in the al-Zaytuna Mosque, divided into 15 aisles to form the prayer hall. The height and details of the arches here differ from previous cases creating a more ceremonial and solemn feeling in the space.

Market – Arches are placed in multiple directions to form domes and covered tunnels, which become the market space in Tunisia. The souks of Tunis are a set of shops and boutiques that sell a variety of products, from fresh produce to local crafts. It is the social and cultural hub of Tunis. Door – Furthermore, the arch is a decorative element and style that appears in the doors of the domestic homes in Medina. Through the doors, people inside could have a glimpse of the street life outside; it is the frame of urban life in Medina and manifests in different colors, patterns, and forms to give character to individual homes.

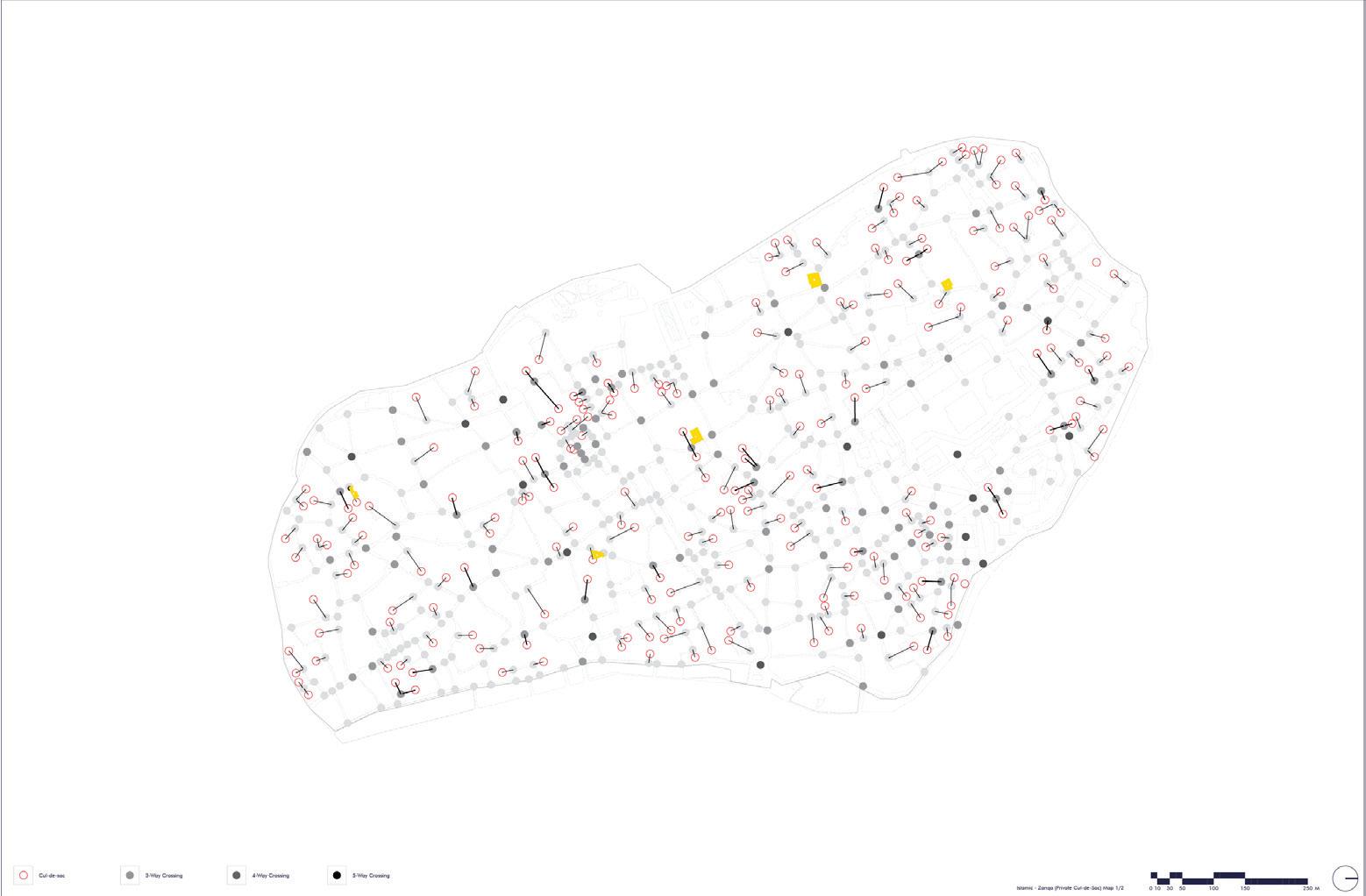

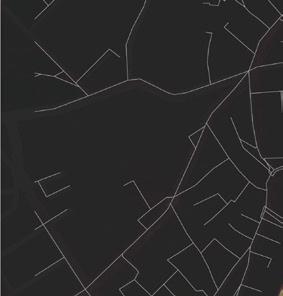

BAT’HA – Jiaheng Xie Bat’ha, Saha, and Rahba mean a public square or a place usually formed at the junction of three streets, in Tunis it is called M’qas or English crossing. As one of the most primitive public spaces, a crossing allows one to bump into familiar faces and generates unexpected conversations, suggesting that the more roads towards the same spot, the more public the crossing would be. Even plazas could be understood as the expansion and evolution of the most popular crossing. However, the shorter the distance between crossings and the more directions that a crossing has, increases the difficulty for people to navigate themselves, which has to be one of the most pronounced issues according to Medina’s residents. Besides, the cul-de-sac, a road or street that goes towards nowhere and does not meet the others as an atypical “one-way crossing,” contributes to the navigation problem. More commonly, the cul-de-sac condition is isolated, not part of the crossing system. Instead of simply repeating typical research pointing out all cul-de-sacs, this study combines the most public, a Bat’ha, and the most petite public, a cul-de-sac, to reveal how this compound network portrays Medina as a maze. In Medina, the walking experience could drastically shift because when a cul-de-sac crashes into a multi-way crossing, one will be immersed in a quiet environment. The lack of sound is the only signal to indicate the transition. Therefore, a continuous street system also implies a continuous soundscape with louder surroundings at the entrance of a cul-desac and almost no sound at the other end. Also, Medina is bound by heavy traffic and persistent noise. As to the richness of the soundscape, the varying loudness embraces the potential to navigate Medina residents’ personal and public lives.

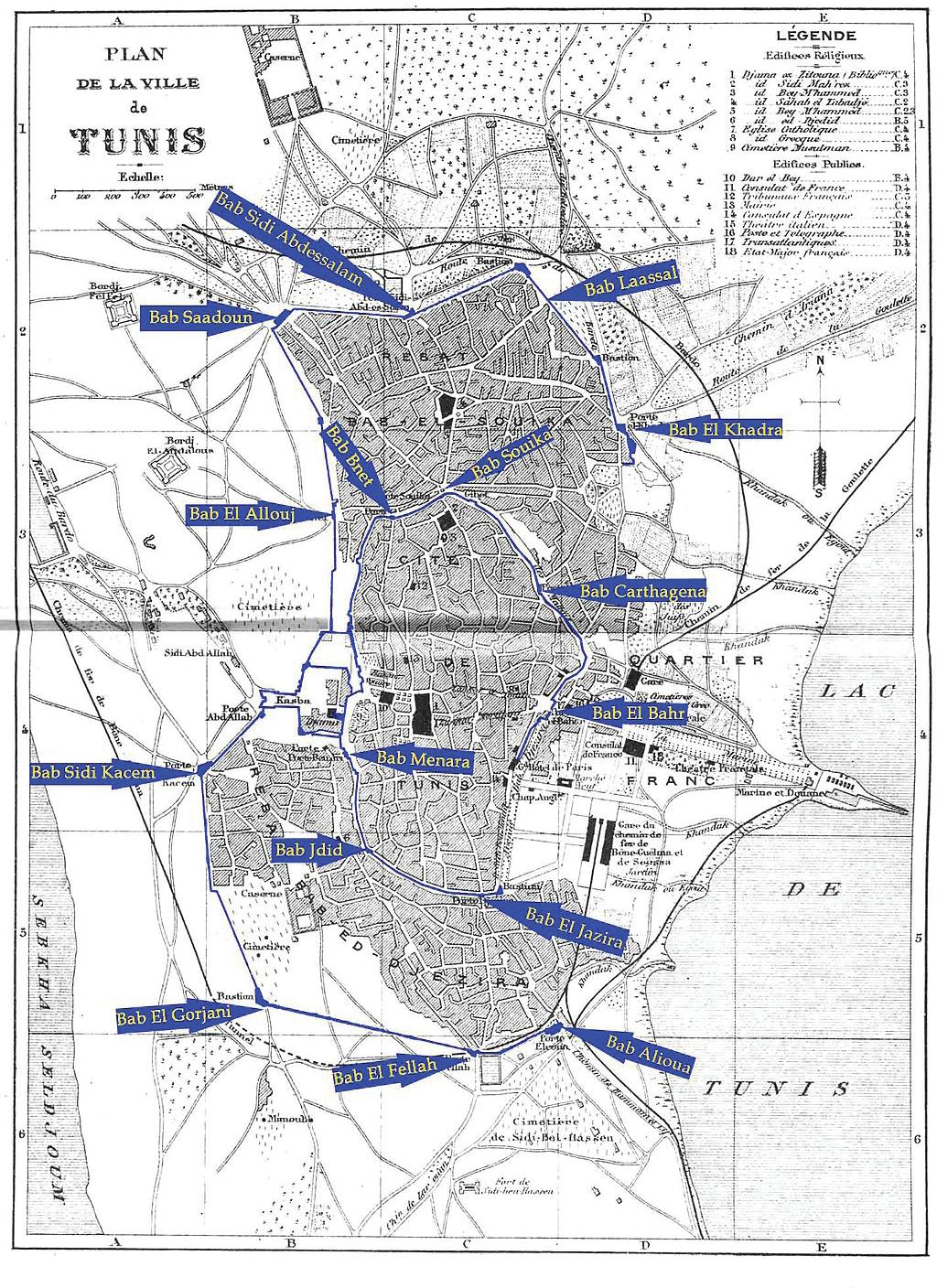

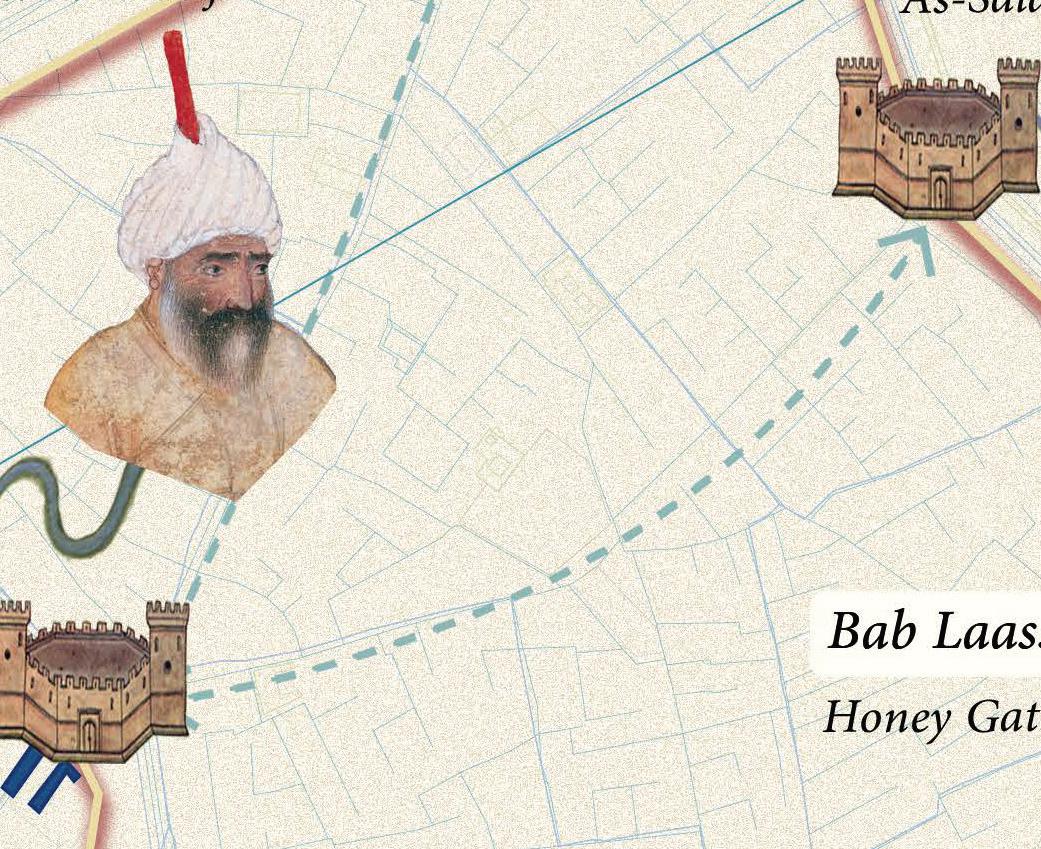

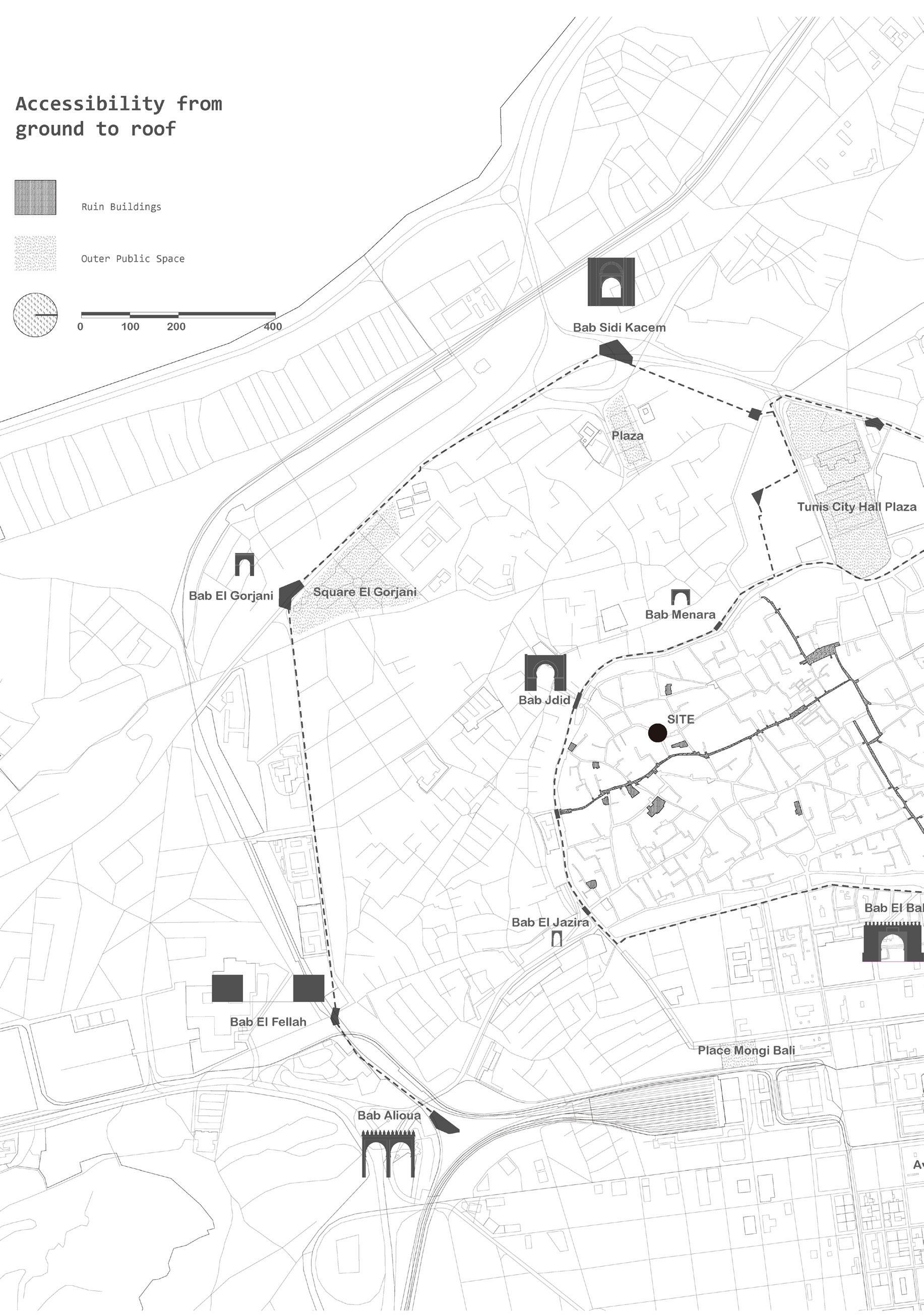

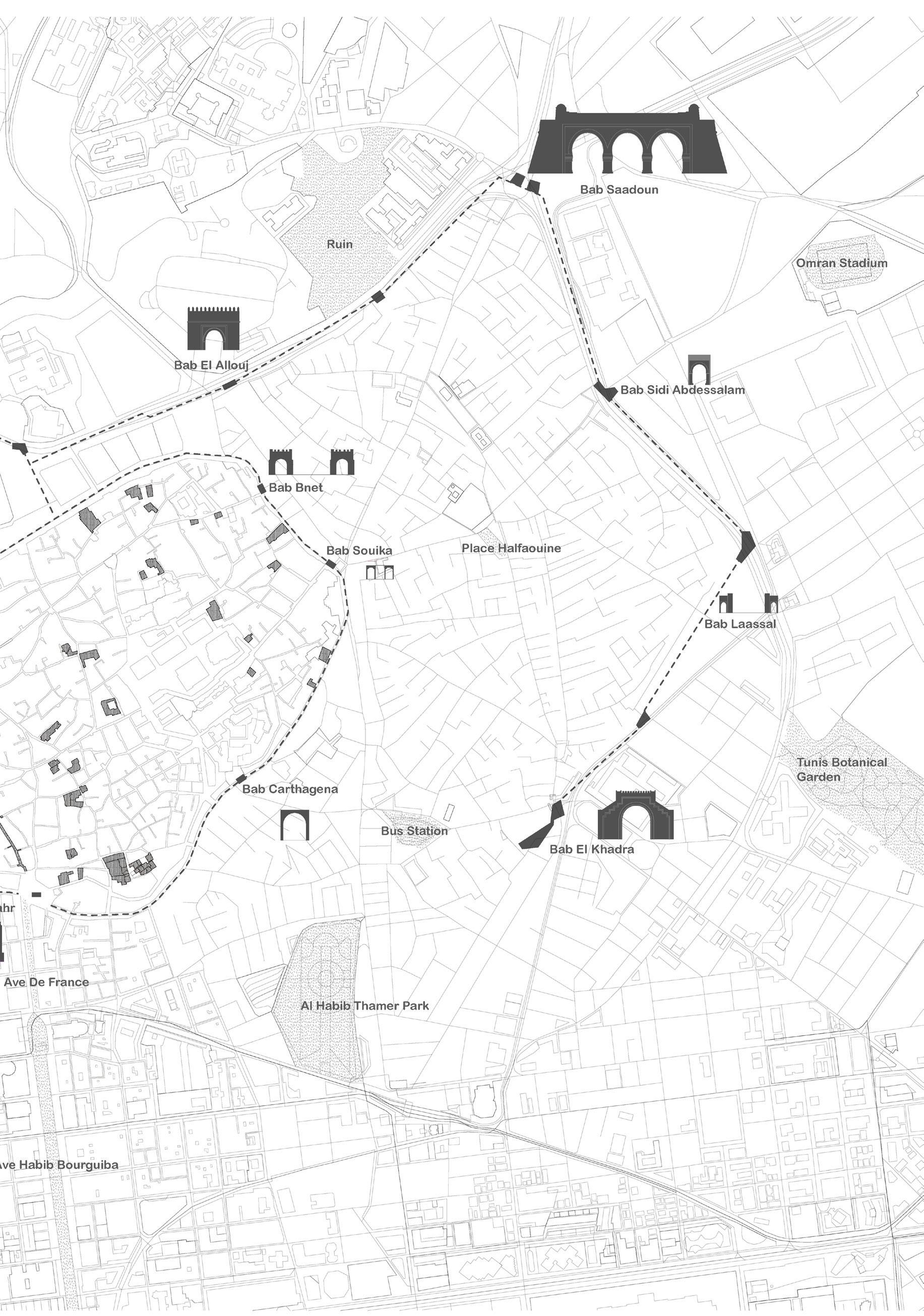

BAB – Shuyue Liu

History: At the time of the establishment of the Arab conquerors, the Medina was a post-military front and a fortified city surrounded by ramparts. After settling down,

it was transformed to accommodate the town’s commercial, political, economic, and cultural growth.

Economic activities: The gates played an essential role in the economic activities of the Medina. They allowed the circulation of goods and people and were closed at night to ensure security. It is thus quite natural that the Medina of Tunis sheltered several new ones each time the economic or political situation required it. Not only were doors opened, but ramparts were built, too.

Two enclosures: With the development of Tunis, two suburbs were built and expanded outside the first ramparts towards Bab El Jazira (to the south) and Bab Souika (to the north). The construction of a second enclosure encompassing the Medina and its two new districts was ordered.

Stories behind the names: Names were taken from prominent holy men and spatially connected to a religious space, or named after an outside landscape or landmark.

Goods categories: These categories are related to religious purposes: caps, women’s veils, etc. Others were used daily: containers, leather slippers, medical plants, silk or garments, things imported from outside, wool products, and fragrances.

Hammams, traditionally known as Turkish baths, embody a significant cultural element within Islamic traditions and are celebrated for their stunning architectural designs and historical importance. These baths, evolving from the Roman thermae, were embraced by the Islamic communities and transformed into both a place for bathing and a central social hub, marked by its architectural grandeur.

The entrance of the hammam is typically a spectacle of Islamic art–replete with geometric patterns, elegant calligraphy, and often, a mesmerizing display of tile work. This gateway leads to the Camekan–a transitional space where visitors shed their daily attire and prepare to immerse themselves in a timeless ritual. Three interlinked chambers are central to the hammam's design, with each defined by its own temperature. The ‘sogukluk’ or cold room, dressed in mosaics and marble, serves as an area for relaxation and mental preparation for the warmth ahead. The ‘ılıklık’ or warm room is a space of gentle transition under a dome that filters light through small

glass openings, creating an ambiance of peace and soft illumination. It’s a prelude to the ultimate hammam experience. The sıcaklık or hot room lies the grand marble stone, göbektası, set under an impressive dome, often with starry glass windows that cast a celestial light. This room, with its steam and ethereal light, coupled with the soft sound of water, transports one to a realm of serene bliss. Marble envelops the room, and small basins and fountains are scattered for bathing purposes.

Beyond its visual and sensual appeal, the hammam’s architecture is a testament to intelligent design, optimizing space and heat distribution. The domes and arches, staples of Islamic architecture, are not just aesthetically pleasing but also functional in maintaining the environment within. The heating systems, ingeniously placed, ensure a consistent and comfortable warmth, especially around the central marble that bathers often lounge upon.

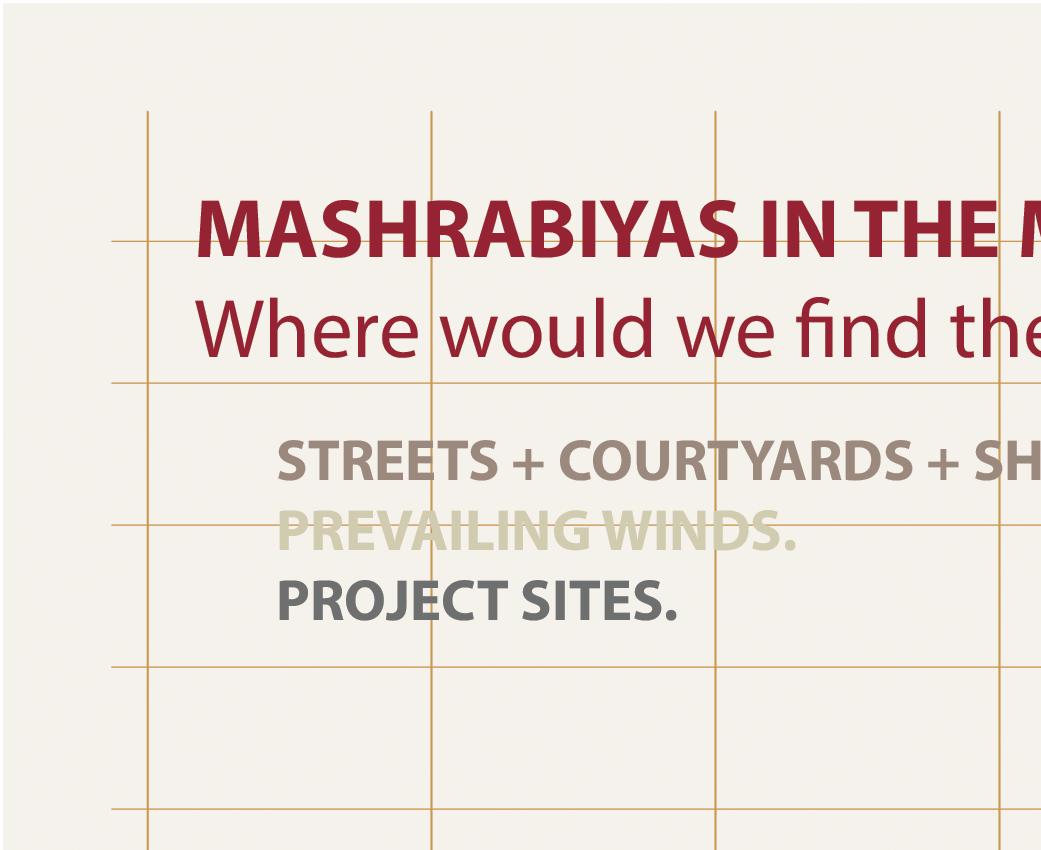

MASHRABIYA – Jiin Choi

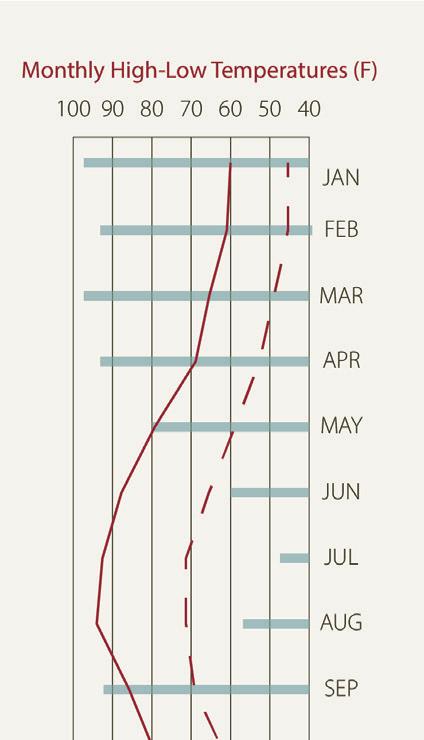

Mashrabiya is an Islamic architectural feature that extends the function of a window. Protruding from the façade of a building, the ornate wood lattice of mashrabiya filters the harsh sunlight while allowing interior occupants to look outside. The combined structure of awnings and vents creates a passive cooling system that is much needed in the desert climate of Tunisia, where summer highs exceed 90°F and daily temperatures can change by 15°F. Mashrabiya thus creates pockets of shelter that connect interior spaces with the exterior while shaping the exterior experience of the streetscape. A mapping study of the Medina of Tunis focusing on the prevailing winds, streets, and the shadows cast on those streets considers mashrabiyas as a design feature mediating private spaces with the public streetscape in an area with few outdoor gathering spaces.

The Medina has always continued to grow throughout its history, attracting, at the same time, the required crafts and knowledge for its expansion. Soon, the artisans’ workshops and the merchants’ stalls grew, expanded, and regrouped into small markets dedicated to their respective trades. These souks share the streets of the Medina and draw its borders.

Souk El Attarine, built in 1240.

The Souk El Attarine, or 'Souk of Perfumers', is the oldest in Tunis. When this souk was built, nobles and business owners were the only ones with the right to do this job. Therefore, it was considered one of the finest. Fragrance compounds of rare and valuable scents were sold; there was also incense from India and Yemen and some cosmetics.

Souk El Berka, built in 1612.

The Souk El Berka is the old souk of enslaved Black people in Tunis. This souk later became the souk of jewelers. This souk has a square form, with a wooden platform in the middle, which was the place where enslaved people were presented and waited for the outcome of their sale. Potential buyers sat on benches around the souk and participated in the auction. The abolition of slavery in Tunisia was declared in 1846 and caused the transformation of the Souk El Berka into a souk for jewelers specializing in silverware. When I compare this historical souk with the current one, it is clear that the current souk of Medina maintains a historical footprint that defines its scope. The drawing shows the route people take in the different markets. They buy, store, and trade.

MOSAIC – Ruijen Yang

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass, or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decorations and were particularly popular in the ancient Roman world. Mosaics today include murals and pavements as well as artwork, hobby crafts, and forms of industrial construction.

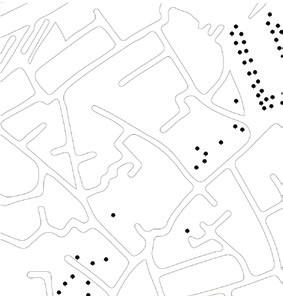

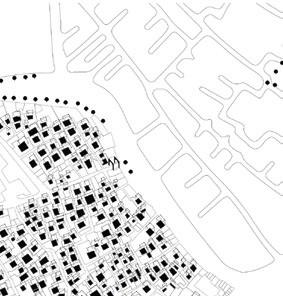

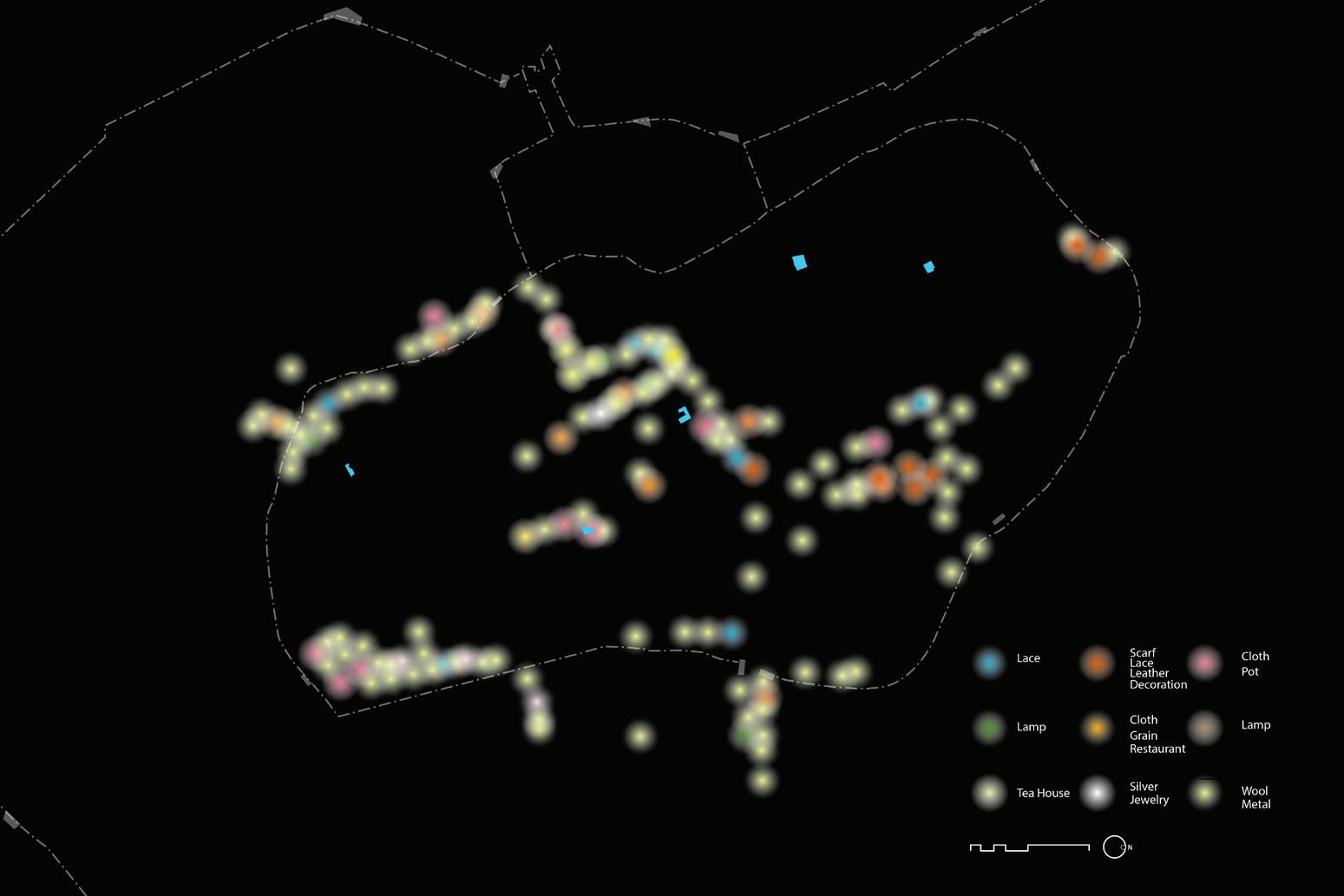

The map of Medina is designed in a mosaic style, utilizing a satellite image to showcase the locations of various handicraft shops in the area. The map highlights the close relationship between the density of handicraft shops and the main commercial street, with most of the shops situated within the strict system.

Meanwhile, the catalog section of the website features two distinct types of mosaics. The first type combines graphics using mosaic tiles of similar shapes and sizes, while the second type employs tiles of different shapes and sizes to generate images.

The riad is the heart of the home of Tunis, meaning a high-walled garden. The riad is the interior courtyard present in almost every home in the Medina. The courtyard is regionally and culturally specific. Due to the hot, arid climate, the courtyard typology provides shade and shelter from winds while offering ventilation and cooling to the home’s interior. Culturally, the courtyard serves as a hybridized private outdoor area. This is important in Islamic tradition for allowing families to have a private space where women are not required to have full modest attire as they might need in public. Additionally, the courtyard allows the family to gather together and host visitors, as hospitality is fundamental to Tunisian culture.

The riad offers respite from the exterior conditions and symbolizes an oasis of the home within the desert. Found within the walls of the garden are shade, confinement, plants, and water, all elements that are scarce in the desert environment of Tunisia. The riad further symbolizes luxury and contains special elements that denote its significance as one of the primary spaces of the home.

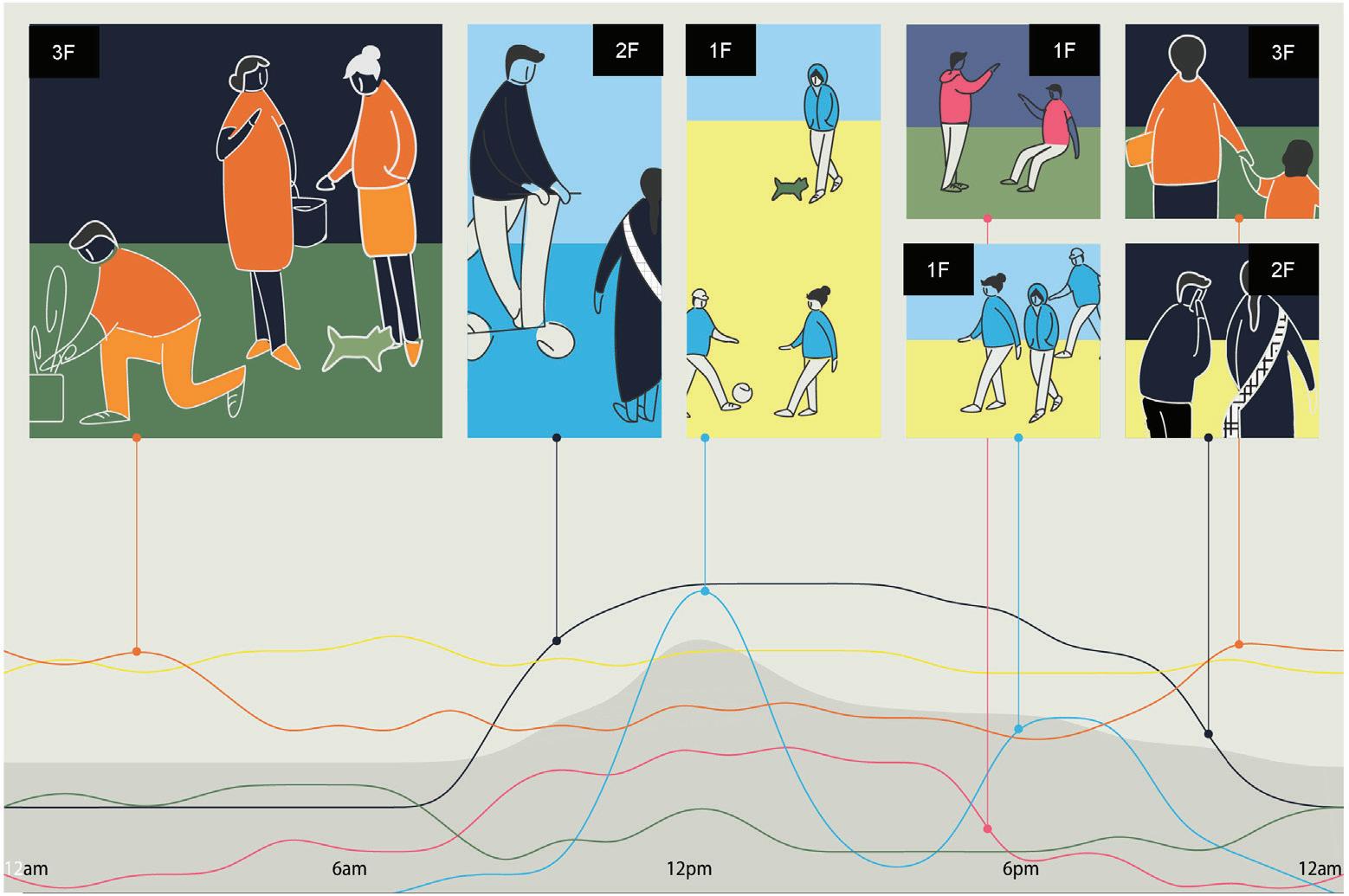

Throughout a typical day, the usage of the riad will vary. In the morning, a family will typically rise and eat breakfast in the early hours, using the cool temperatures for productive activity and chores. As the temperatures rise, activities will become more sedentary. Tunisians enjoy a large midday meal, but afterward, they rest in the hottest part of the afternoon. As the sun sets, the riad becomes busier as everyone returns home and prepares supper. In the later evening, as temperatures cool, the riad may become the most comfortable region in the house, and this nascent nocturnal occupation can serve as a driver for interventions in the Medina.

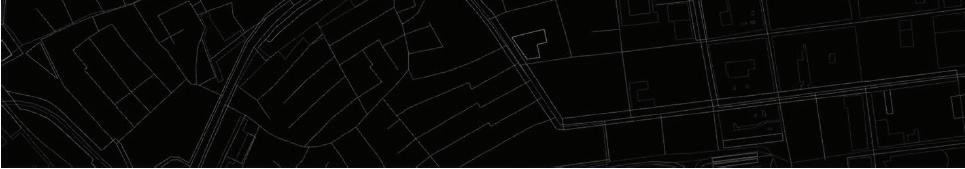

Within the urban ring, the 270-acre Tunisian Medina is made up of winding streets, arched passages, and alleys. The harmony and unity of its urban structure are striking. White houses form the urban landscape of Tunisia. Important buildings built in different styles (such as the Great Mosque built in 732) and single-style buildings (such as the Turkish-style mosque built in 1675) harmoniously form a whole.

Tunisia had a major influence on the architecture and decorative arts of the East Maghreb region. With its palaces, houses, madrasahs, and souks, Tunisia differs from typical Islamic cities in terms of spatial organization and daily life. The Medina is an outstanding example of how traditional human settlements have evolved with socioeconomic and sociocultural changes. The old city of Medina still retains the style of hundreds of years ago, showing a lively Arabian market scene. Walking in here is like walking through a museum of Arab culture. The buildings on both sides of the road are not high; most of them only have two or three floors. Most of the buildings have arched roofs. The winding and narrow roads between the buildings are paved with stones. Only two people can pass face to face. Most of the merchants in the shops are residents who have lived there for a long time, and are leisurely selling various commodities. Locals enjoy the leisurely way of life that the ancient city brings. In this closed Arab world, there are 2,800 handicraft workshops and more than 3,000 shops. There are a variety of small workshops and small shops that perform their duties, such as blankets, spices, headscarves, handicrafts, and snacks. In a limited space, people’s activities are limited, but the roofs are an untouched place. The roof is rich in layers, and with a bit of vertical treatment, the range of people’s activities can be expanded. Here, we study the height difference between the five sites and their connections to the surrounding areas.

Souk refers to a marketplace consisting of multiple small stalls or shops. The origins of souks can be traced back to ancient caravan trade routes, Souks located along these routes connected major cities with each other, forming networks in which goods, culture, and information were exchanged. In this case, through the lens of the souk, we can not only capture the economic activity itself but also understand the street system in Medina and the types of spaces that attract citizens to stay and gather. The database collections study two characteristics of souks in Tunisia. First is the variety and distribution of commodities in Medina. Second is the typology of commodity display space. Typically, in

the Medina, similar goods are sold in a certain area for consumers to pick and compare. After studying several souk streets, I found the division of goods could also be considered instead of for specific categories by broad groups. In this case, I analyze these 15 categories and divide them into three groups, where the types of commodities are mixed.

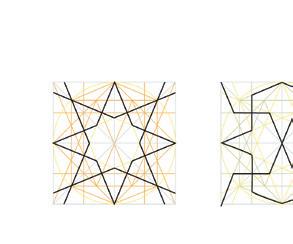

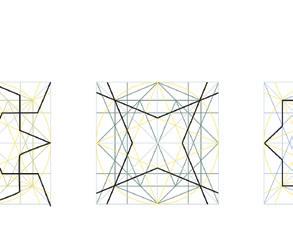

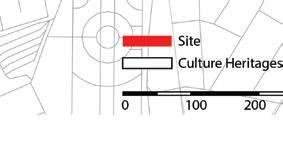

Tilework is an outstanding decoration element in Islamic architecture, thus, it is not uncommon to see traditional Tunisian architecture decorated with tilework. The map overlays a typical tilework pattern with cultural heritages and monuments, indicating where various tileworks could be found.

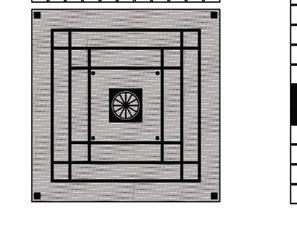

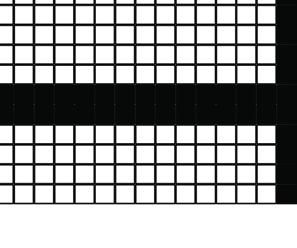

A big portion of the tilework patterns is generated from geometric patterns. The patterns of tilework seem to repeat infinitely, inspiring wonder and contemplation of eternal order. Those Islamic geometric patterns draw heavily from mathematics and emphasize the importance of unity and order. The secret of the sophisticated patterns is the underlying grid. Those invisible reference lines are essential to every pattern. The grid helps determine the scale of the composition, keeps the pattern accurate, and facilitates the invention of incredible new patterns.

The illustrated database shows some of the most common-to-see tilework patterns on cultural heritage buildings with extracted color palettes from those patterns. A wide range of blues, greens, reds, and yellows are wildly used to create visual harmony. The bright colors, intricate geometric patterns, and glazed ceramic characterize the tilework an important part of the cultural heritage of Islamic architecture, celebrating its beauty, craftsmanship, and artistic significance.

The study of goods focuses on two aspects: the relationship between merchants and customers and the position of goods on display. There are two ways a souk opens. When semi-open, consumers cannot enter the shop but can look and pick from the city streets. When it is fully open, the consumer can walk in and pick it up. How the door is opened greatly affects how the product is displayed. For example, flat doors provide additional places to hang and display goods. Other events above the souk can use the upper floor to display goods.

Yazmine Mihojevich

A qanat is a water transportation system that directs the flow of water from a well or aquifer through an underground aqueduct to the surface. It originated in 3000 BC in present-day Iran. The qanat is made up of a “mother well” that is its main source of water for the qanat, vertical access shafts or karez that provide access to the aqueduct for maintenance, a qanat channel, and an outlet. A network of dams, gates, and channels is then used to distribute water. A qanat typically begins below the foothill of a mountain and gently slopes downward so that water flows through gravity alone. At times, qanats are divided into smaller canals called kariz. While still in use in some areas, qanats are abandoned for environmental and cultural reasons. The introduction and expansion of irrigation systems impacted qanats by reducing the water table. As newer technologies arose and urban migration took place, maintenance labor and practices were lost. Yet, as a technology designed to manage water in arid and semi-arid environments in North Africa and the Middle East, the repair, maintenance, and use of qanat may provide a sustainable method of water transportation in increasingly water-scarce regions.

'Dark Windows' refers to the idea that windows during the night can showcase the liveliness and validity of a city. This concept derives from the phenomenon that during the night, people leave their working space, such as the office building, and crowd into other parts of the city, such as shopping malls, restaurants, and homes. Hence, we can tell where the busiest place is by the light transmitted from the window. Nightscape mapping is the visualization of the opening hours from different programs. The database collection studies how the covering materials and interior programs influence the light transmission of an elevation.

Tunisia mainly relies on natural gas for its electricity, but also invests in renewable energy sources such as wind and solar. The government has implemented policies to promote energy conservation and reduce consumption. Still, the country’s population and economy have put pressure on the grid, leading to occasional power outages and shortages. In the 1980s, off-grid solar photovoltaic systems were installed in rural areas not connected to the national electricity grid to meet the needs of local residents. These systems, which are aimed at low-income populations, have reduced energy expenditure and have been mostly subsidized by the state budget. However, the expansion of the national electricity grid has limited the potential for solarpowered decentralized electrification. In the meantime, a new effort has been made to build a giant solar plant in Tunisia’s deserts to generate energy for Tunisia, Italy, and Western Europe.

The space of “nighttime” originally could have been valuable to any gender. Still, women are always told that it is unsafe to go out at night, and it has become only accessible and beneficial to men. What happens if a woman dares to go

out at night? She becomes victimized or criminalized.

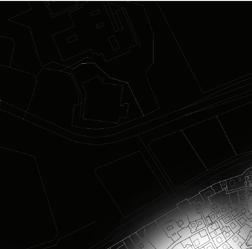

Though women’s rights in Tunisia have made significant progress in recent decades, women still struggle for their rights in many areas of life. The law on violence against women was not approved until 2017. Before that, the Tunisian criminal code allowed rapists to escape punishment if they married victims. Without any extra protection from legislation or public awareness, light fixtures become the only element that gives women a sense of security. This map indicates where potential luminosity comes from, including commercial activities, lighted monuments, and other illuminated cultural facilities.

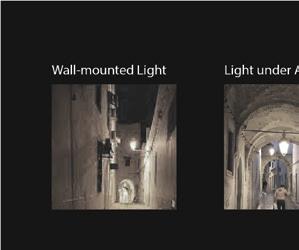

The database shows various illuminated settings in Medina: wall-mounted lights, lights under arches, courtyard lights, lights from suqs, lights from heritages, streetlight poles, light projection, and signage lighting. Various types of light fixtures with different projections are also used to satisfy different needs.

The heterotopia is a concept developed by Michel Foucault in “In Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias” (1967). Heterotopias are “other spaces” or counter-sites that represent contests and invert the sites they speak about. While it is possible to locate a heterotopia, they remain outside of all places. Foucault outlines five principles of hetero-topology. Foucault describes the first principle as two types of heterotopias – crisis utopias and utopias of deviation. A crisis utopia is a place where individuals are placed in a state of crisis – most often in relation to gender and sexuality in what Foucault called “primitive societies.” The location of a honeymoon hotel or train is an example of a crisis heterotopia – nowhere places. Heterotopias of deviation include prisons, psychiatric hospitals, or rest homes. The second principle concerns a heterotopia whose connotation, from sacred to contagion, changes over time – like a

cemetery. The third principle concerns heterotopias that contain multiples in a single space, such as a theater, the cinema, or – the oldest heterotopia, according to Foucault – the garden. The fourth principle states that heterotopias occur from a break in traditional time. Examples include museums and libraries- that accumulate time and festivals and fairgrounds that enact a transient form of time. Lastly, the fifth principle indicates that heterotopias contain openings and closings to enter and exit either on compulsory measures or through permission or gestures such as rites or purifications. Hammams, Scandinavian saunas, and American motels are examples.

A mirage is a naturally occurring optical phenomenon in which light rays bend via refraction to produce a displaced image of distant objects or the sky. The word comes to English via the French (se) mirer, and from the Latin mirari, meaning "to look at, to wonder at." A mirror combines a realistic view with an illusory one at a distance, creating a hybrid scene. Maps can identify locations where this effect is possible, such as open spaces on streets or courtyards in the Medina. The mirage connects these spaces to the sky, altering the perceived scale and imbuing the nightscape with a sense of mystery.

The Medina of Tunis exudes a unique charm at night, and countless commodity shops form on commercial streets for people to visit. The research focuses on Tunisian festivals and analyzes Medina’s public and private activity spaces and walking paths. These activities are often related to historic buildings. They are like elders in the old city, carrying people’s memories and stories of the Medina.

Nyctinasty refers to the movement plants exhibit in response to the onset of darkness and the associated changes in sunlight and temperature. Some plants may fold their leaves to “go to sleep,” while others have flowers that bloom at night. The nightblooming nature of the Tunisian national flower, jasmine, displays a poetic parallel to the cycle of daily Muslim prayers that occur according to the position of the sun. Such

circadian rhythms invite a closer look at the various gradients of darkness and nighttime. Twilight is categorized differently according to specific functions, and the lengths of day and night vary across the seasons. Identifying the open spaces and mosques that might be open and active at nighttime suggests that nodes in the Medina might be considered in relationship to our project sites.

The literal translation of dark factories is an industrial site that is fully automated so that production takes place without direct human intervention. With the abundant solar and wind resources in Tunisia, the renewable energies obtained during the day could support lots of energy production in otherwise dark factories at night.

This concept of "dark factories" extends to the production of agriculture at night. In order to adapt to climate change, many farmers in the West have moved agriculture activities to the nighttime. Some benefits include the prevention of heat illness and avoidance of pests.

Production of culture

The Tunisian movie The Last Nomads depicts daily life, especially the nightlife of an Algerian tribe that lived deep in the desert of Tunisia. Most cultural activities happen at night, when people sing songs, play music, and dance their tribal traditions. As the nomads have an ancient and productive way of living in their environment and still maintain their old living habits, a lot of traditional cultures are preserved and reproduced in new conditions.

Production of knowledge

The fourth image depicts the Dobson Factory telescope traveling in Tunisia. As the telescope scrolls in the desert at night, it will observe celestial information and data, then send back the signals to the other end, where researchers can understand and learn more about astronomy.

This image depicts Tunisian families relaxing at the beach in Sousse, Tunisia, on July 26, 2015. As people are not allowed to wander around in the city after sunset, the beach becomes a space of freedom and grounds for producing social life in Tunisia.

The term somnambulant encompasses the characteristics of sleepwalking. The act of walking while asleep implies a disorientation and disconnection between what is “seen” and what is physically experienced. A sleepwalker who awakens amidst an episode will suddenly find themselves in a foreign landscape with no notion of how they arrived there, experiencing a sharp schism between the world they dreamt of and the one they physically occupied. While sleepwalking, any world can be experienced in complete independence from the one actually traversed, but there may be echoes of reality that pervade the dream. In exploring the Medina, I wanted to focus on this disorientation and sudden jarring experience of finding oneself lost or rediscovering where one is with a familiar landmark.

Sleepwalking usually occurs in the deepest phase of sleep and is more frequent earlier after falling asleep. Sleep is cyclic, so deep sleep cycles occur approximately three to four times per night with the REM cycle. This cyclical nature of the circadian rhythm is just one of many cyclic ways in which humans experience the world. This is why I consider the design of the night with the sleep cycle and thus the world of dreaming in mind. The map illustrates Medina through the lens of disorientation. White lights surround major landmarks, where one would have a clear point of visual reference for orientation within the Medina. Darker areas are further from known landmarks and represent an area where disorientation could be more likely. The streets of the Medina are nonorthogonal and augment this disorientation. Nevertheless, they are paved in various materials such as cobblestone, brick, or asphalt. These differing materials serve as a clue for navigation in the Medina at night.

"Unearthly," an adjective, strange in a mysterious and sometimes frightening way. Seeming not to belong to this Earth or world; supernatural; ghostly; unnaturally strange; out of the ordinary; unreasonable or absurd. On the contrary, "earthly" is an adjective that happens in or relates to this world and this physical life, not in heaven or relating to a spiritual existence.

Matthew Beaumont explains, “As for our ancestors, the night itself remains in some

innate sense ominous, threatening.” Mark Fisher reminds us that the fear of night is a category that has “fundamentally to do with the outside” and is more readily to be found “in landscapes partially empty of humans.”

A prehistoric landscape, then, comes to seem palpable beneath the pavements of the city at night. In this half-familiar environment, it is difficult to entirely eliminate archaic convictions.

At night, with the absence of humans, the urban environment becomes somehow unfamiliar, as if nocturnal birds were occupying the empty streets and homeless cats were singing and hunting at night. Earthly: Moon in the Islamic Civilization. For desert tribes and caravan travelers, who kept their activity to a minimum in the pitiless heat of the day and preferred to travel by night, it was natural that the moon take precedence over the sun in timekeeping. The lunar calendar used by pre-Islamic Arabian tribes continued to be used, with modifications, to regulate social and religious life following the advent of Islam

A soundscape, a sound or combination of sounds that forms or arises from an immersive surrounding, is the acoustic environment humans perceive in context. It commonly regenerates a wildlife environment by recording in the forest or underwater. A soundscape, therefore, could be artificial and be manipulated and designed. Cinematic sound is one of the best examples of bringing an audience to an imaginative world. It does not rely on visual perception. Minds and ears are enough to picture sublime surroundings. When darkness surrounds one, one’s visibility is minimized; meanwhile, the ability to perceive and reimagine the same place as a completely different world is maximized by its soundscape.

The research aims to evoke the audience’s acoustic imagination through a visual approach. This map interpretively captures the sound of the breeze traveling through the badgir, people talking in Arabic, praying and reading Quran paragraphs, and noise from the kitchen. All sounds could enormously increase a sense of belonging in Medina. Just imagine, after dinner, families step out of their homes for a walk around the neighborhood. The louder they hear conversations, the closer

they are to public spaces and social lives. Therefore, soundscape design would also be a substitute way-finding system that helps people navigate after sunset. Possibilities for a dynamic soundscape to be applied in Medina are diverse and not confined by static locations. For instance, bird sounds won’t stick to the same place. It’s moving around or between greenery, meaning that a trace of sound could be designed to encourage an acoustic parallax effect. A well-imagined soundscape can enhance human perceptions of the authentic Medina and help navigate around in a dim environment.

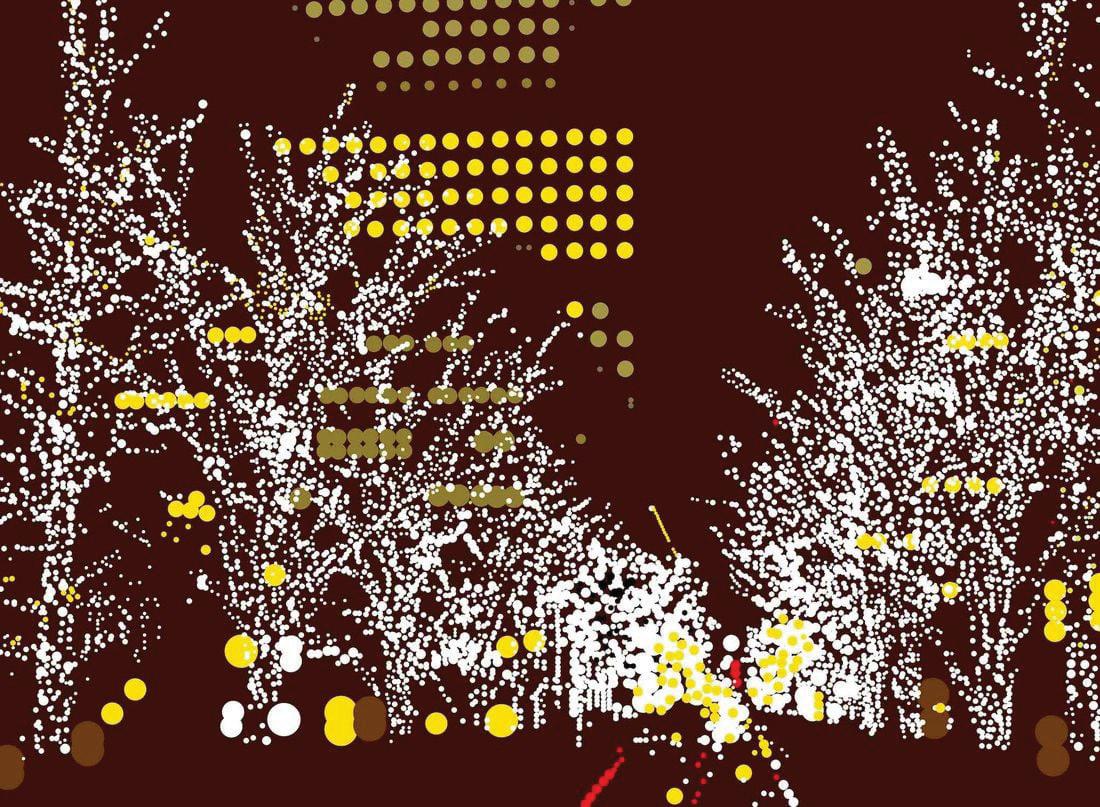

Medina’s suq is lit at night with different lights that reflect and penetrate the surrounding environment to create a night scene of different colors. The various objects sold in the suq, the eaves used for shade during the day, and the different colors of the walls all make the medina show different colors at night. I have tried to examine how lights are illuminated in the medina and how they interact with the environment to form the nightscape. I found that lights can shape the space at night, so I illustrate the difference between different street lights and local decorative lights in the medina. My research focuses on exploring the different atmospheres created by the night environment.

Cycles, Nocturnal Database Collection - Jiin Choi.

Research Map & Dictionary Database Collection - Ruijien Yang.

Siqi Zhu

Jiaheng Xie

Courtney Sohn

Siqi Zhu

Yazmin Mihojevich

During the studio fieldwork, the students explored and observed the Medina’s landscape in different moments of day and night. They developed their research on-site with the support of a group of students from L’École Nationale d’Architecture et d’Urbanisme de Tunis (Fatma Habel, Amal Ben Ammar, Noura Tounekti, Aymen Baroudi, Amine Maatouk, Abir Chhibi, Wafa Ben Salem, Fares Rtibi, Soumayya Larbi, Nawres Chihi, Salma Guenounou, Sana Haddaji, and Nour Messaoudi) to better engage with the Medina and its residents.

Events, conferences, and site visits punctuated our time in the Medina of Tunis and the surrounding territory. The group of Loeb fellows 2023 (Mariana Alegre, Dario Calmese, Pamela Conrad, Claudia Dobles Camargo, Natalia Dopazo, Badruun Gardi, Shamichael Hallman, Rebecca McMackin, Derwin Sisnett, Alberto Krizler) were led by John Peterson and Anna Lyman. They took part in this fieldwork and, more broadly, the studio research and all the activities organized during our time in Tunis.

Besides their specific research in the field, the students were exposed to a series of activities and talks to better understand the Medina, its history, and the way it’s inhabited and perceived.

Among these were walking explorations across the Medina and the City of Tunis guided by Moncef Guellaty, editor and founding member of the Tunisian section of Amnesty International, and Ahmed Abdelkafi, a Tunisian economist and businessman who is very active in imagining the future of the Medina. This experience led us to be immersed into a journey where different timelines overlapped; from one side, we could hear the echos of our guides’ memories of the city when they were adolescents, moving around the streets and the roof of the Medina as the characters of the movie Halfaouine: Child of the Terraces (Férid Boughedir, 1990). On the other side, Moncef and Ahmed shared the same projective sight of the future of the Medina, showing care and profound attachment to the city and its identity. Another immersive Medina walk was with Iheb Guermazi, a journey across ‘the medinas’ of Tunis to understand the historical evolution of the Medina and its relation with the ville nouvelle and the larger

environment of Tunis territories, as well as the different communities that inhabit and inhabited the city.

Thanks to the generosity of Amel Meddeb Ben Ghorbel, we were given the great opportunity to have workshops and lectures at Dar Lasram, an extraordinary example of the residential palace in the Medina, now the headquarters of the ASM, the Association for the Protection of the Medina of Tunis. Here, we had the chance to learn about the history of the Medina thanks to a series of panels and presentations by Amel Meddeb Ben Ghorbel (ASM), Lucio Frigo (Materia Inc.), Gareth Doherty (Harvard GSD), Leila Ben Gacem (Blue Fish), Dhafer Ben Khalifa (Collective Creatif), Sihem Lamine (Harvard CMES), Iheb Guermazi (Ph.D. MIT), Sadika Ghouma (ASM), Zoubeir Mouhli (formerly, ASM), Faïka Béjaoui (formerly, ASM), Montassar Jmour (Institut National du Patrimoine, INP), Sofia Guellaty (MILLE World), Nadia Siméon (Deputy Director, Aga Khan Award for Architecture).

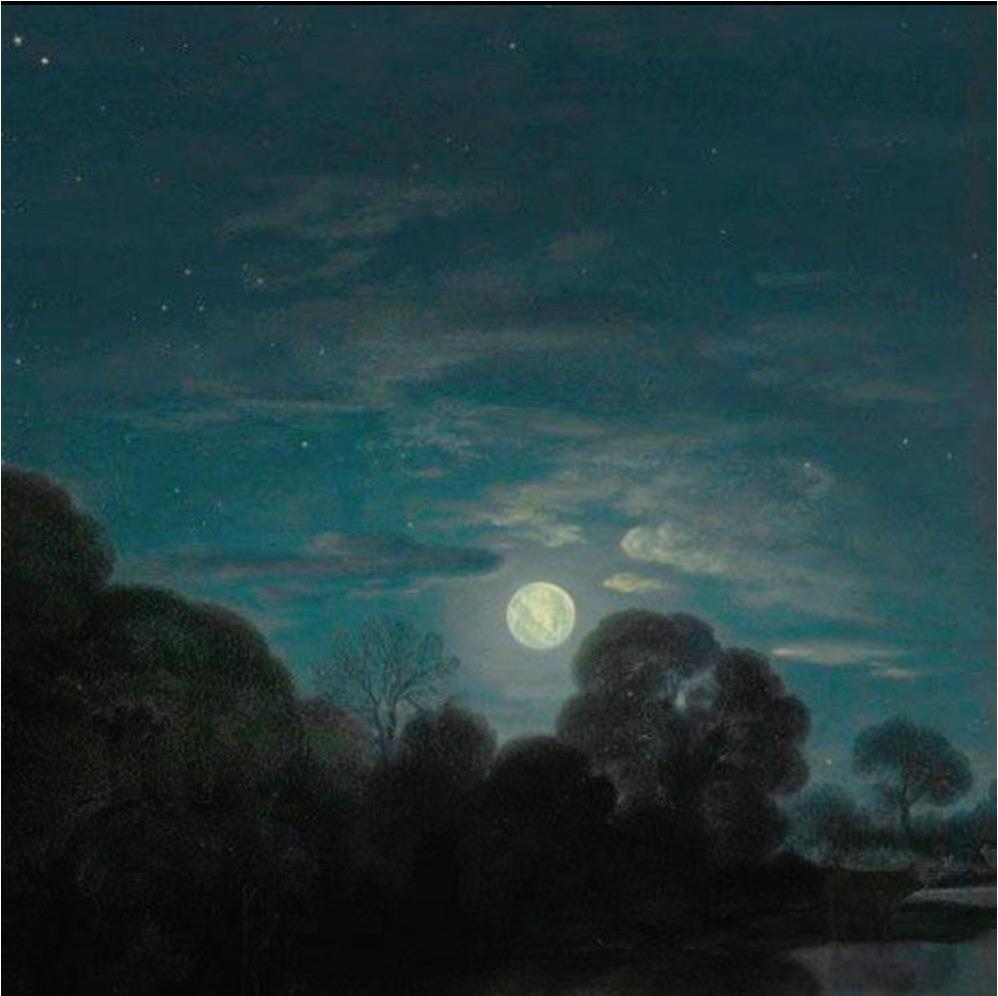

The Tunisian social entrepreneur Leila Ben Gacem (Blue Fish) hosted many memorable events at her Dar Ben Gacem, an exquisite boutique hotel in the Medina, from dreamy food experiences to night concerts on the roof, to the screenings under the starry sky of documentaries like The Medina Of Tunis: A Multi Heritage City by Nourchen Ben Fatma.

The students were asked to explore the research topics of their database collection, considering their specific site of urban investigation and thinking about the following questions: what are the possible open spaces you can work on? What are they connecting? What elements of your research can you bring to observe these specific sites? What program can you envision in those areas, specifically in your investigation site?

A required outcome of their work was to create a programmatic manifesto to envision nocturnal and daytime activities for the considered areas and their surroundings.

The students were requested to adopt a "nocturnal" artist so that every drawing could have a nightscape correspondence. The goal was to represent the project at night.

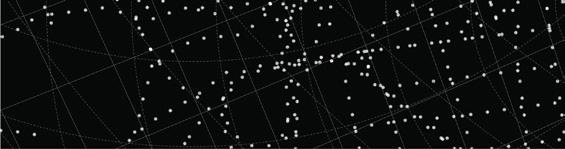

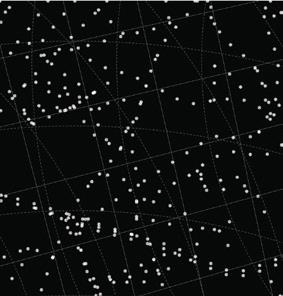

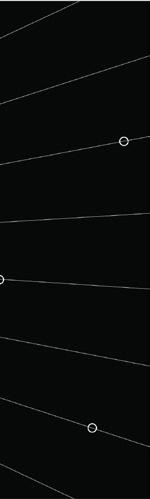

This meant to represent different light conditions related to the specific nocturnal time and the moon calendar to make the presence of the sky a strong character in the design itself. Representation had a crucial role in the investigation of the atmosphere, which was essential to narrate the students’ proposals. They were asked to select one of the proposed nocturnal artists and to reinterpret their own drawings according to that artist’s approach. The artwork presented was very different. Collectively, they ranged from the baroque landscapes and light effects of Adam Elsheimer in his Details from the Flight into Egypt (1609) to the clouds and lightning of Madelon Vriesendorp's illustration in her Postcards Collection (1972); from the oversized celestial body in Donato Creti's Astronomical Observations (1711) to the photographic fireflies captured by Tsuneaki Hiramatsu in his Creatures of Light – Nature’s Bioluminescence or the luminescent marine fauna in Wes Anderson's The Life Aquatic of Steve Zissou (2004); from the dotted Nighttime Cityscapes (2014) by Yukino Ohmura to the colorful glimpses of the universe by Kazumasa Nagai; from the scientific approach of Edmund Weiss in his Astronomische Nachrichten (1859-1909) to the playful Astronomia Playing Cards (1829) at the Beinecke Library at Yale; from the surrealist nocturnal landscapes of Abdul Mati Klarwein to Agnes Pelton visionary symbolism of her Orbitis (1934) the starry sky of Ed Ruscha in his Any Town in the U.S.A. (1981); from the star atlas for the Ottoman navigators in the Celestial Chart (1919) by Güverte Yüzbasisi to the Escher illusions of the video game Monument Valley designed by Ken Wong and developed by Ustwo Games.

Details from the Flight into Egypt - Adam Elsheimer, 1609.

Observations - Donato Creti, 1711.

Nachrichten - Edmund Weiss, 1859-1909.

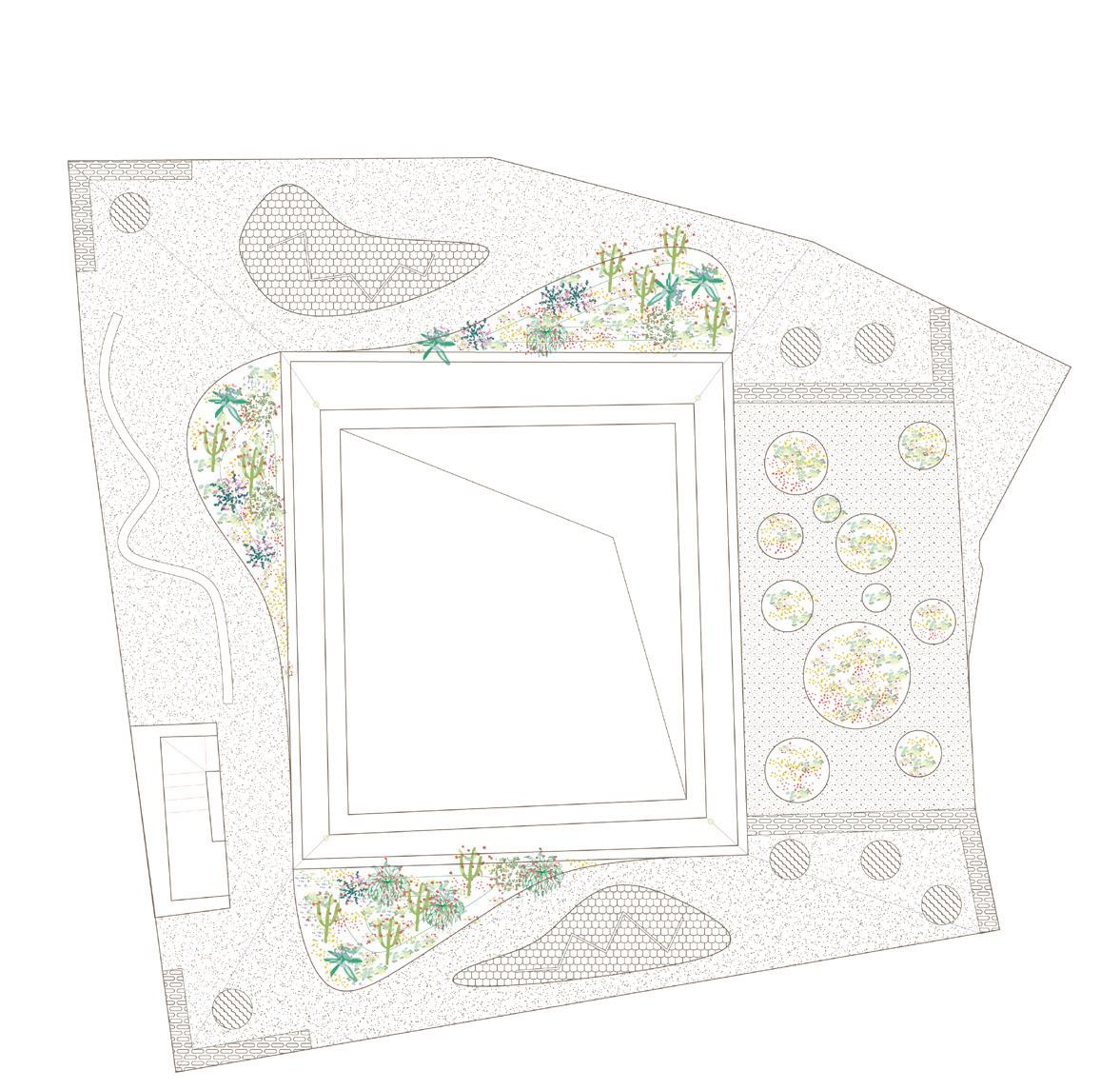

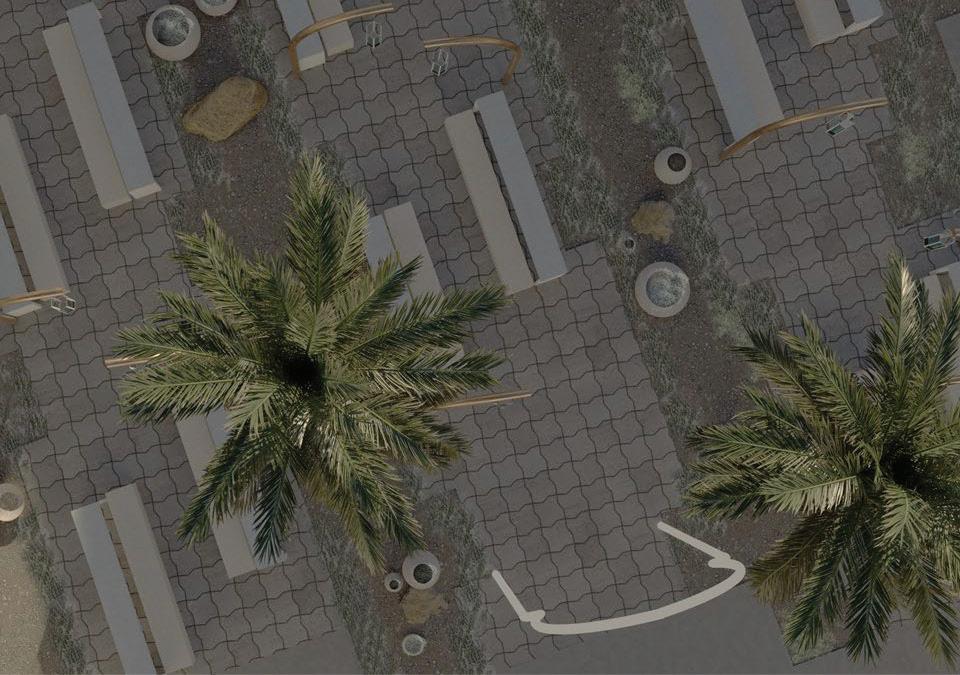

Located adjacent to multiple cultural institutions and a public plaza, Dar Enaifer has the potential to connect and expand on these resources to honor Tunisian heritage by demonstrating a way to adapt the private home typology to a use that can be shared with the larger public. This project considers three elements as a cluster to realize this potential: the plaza (Place du Tribunal), the Dar (Enaifer), and the rooftop.

In the plaza (where the Museum of the City of Tunis is located), tweaks in the paving define it as a public space that welcomes gatherings, with flexible furniture that adapts to daily uses and festive gatherings. Accessibility to the drainage system is improved so that irrigation is available for existing and additional trees.

Steps from the plaza are the cultural center (Tahar Haddad) and Dar Enaifer, where a cafe and coworking space can serve locals and attract visitors. A new spiral staircase forms the public entrance to a roof garden that spans and joins the spaces above Dar Enaifer with that of the cultural center and the headquarters of the Association for Safeguarding the Medina (Dar Lasram). With an integrated plant trellis, rainwater collection system, and mashrabiya-inspired cupola, the staircase forms an iconic space within the courtyard and glows as a landmark at night - a structure we hope serves as a prototype that can be more broadly implemented to create additional landmarks and connections throughout the city. Up on the rooftop, the garden is planted with nightblooming plants to provide a public space that is especially vibrant after dark, an important time of relief as daytime temperatures become more extreme.

By connecting and expanding on adjacent resources, we hope this opening of the Dar allows locals and visitors to access nocturnal panoramas and optimistic visions of the future of the Medina.

The Medina of Tunis is characterized by an urban fabric of residential density and privacy. Streets are narrow, and homes are inward facing, with much of the city’s activity happening within the courtyards and on the rooftops. Public spaces take on the characteristics of the streets, with archways defining seating areas, plants providing daytime shade, and lit street crossings providing opportunities for gatherings amongst neighbors at night.

Many residents of the Medina are artisans, and the traditional crafts have been economic staples for generations. Artisans currently struggle to find apprentices to pass on their trades or places to display their work and share their knowledge with the public. Through the reuse and renovation of two adjacent Dar homes, Dar Fatma, we aim to redefine the public space of the Medina through a hybrid public-private program emphasizing the gathering space of the courtyards and rooftops and revitalizing the artisan tradition.

The outfacing public characteristics of the Medina are internalized into the courtyards by transforming the interior façades, physically expanding the public realm, and increasing the courtyard's adaptability to its adjacent programs. This expanded flexibility allows for the integration of a private live-work artisan studio with galleries and cafes for public access to the artisan crafts.

At the center of the Dar, a new archway merges the two courtyards into one, creating an internal “crossing.” A continuous circulation

path of roof terraces winds around the courtyards, with fragrant shrubs and fruit trees providing shade for leisure and gathering. At night, sound and smell become the primary senses that allow one to experience the variety of the plants and programs of Dar Fatma. The arch framed by climbing plants is a characteristic of the Medina, which greatly influences the public usage of the street below. On an urban scale, the project aims to reintroduce this typology throughout the Medina, specifically on streets leading to Dar Fatma, to transform and revitalize the public spaces of the Medina.

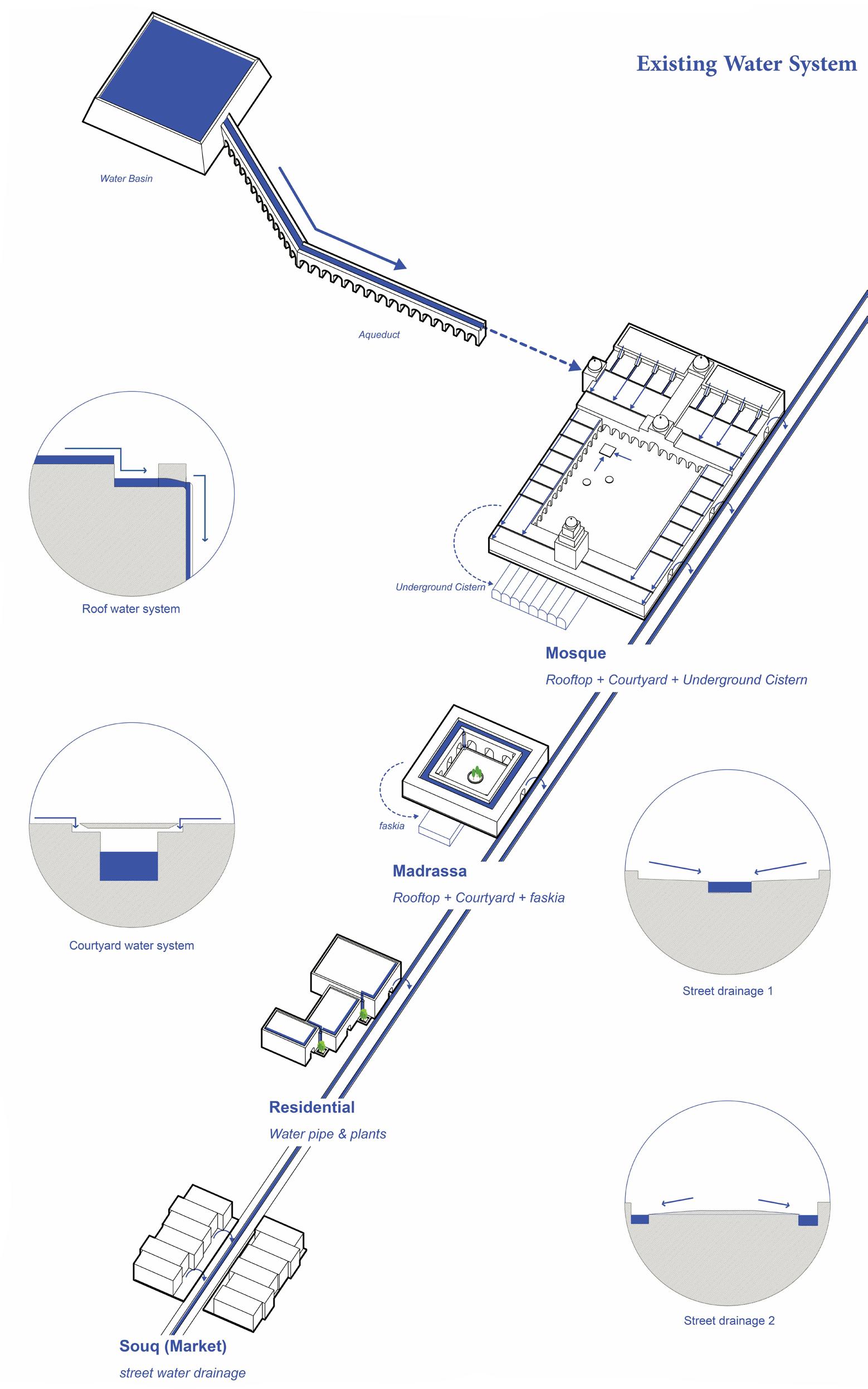

The vision is to bring new life to the urban landscape by reviving the traditional water path system and creating a dynamic, fluid garden. This garden system will serve as a multifunctional corridor, connecting the street, courtyard, and rooftop horizontally and vertically. Doing so will not only provide a home for birds but also serve as an indicator of the hidden greenery in the courtyard.

The fluid garden system will have many benefits for the community:

1. It will provide much-needed shade, creating a cooler microclimate and mitigating the effects of the urban heat island.

2. The lush vegetation will enhance the beauty of the area, providing a welcome respite from the concrete jungle.

3. The system will emit a refreshing scent, adding a new sensory dimension to the space.

In addition, the fluid garden system will have practical benefits. The plants can be used to extract essential oils, providing a material source for perfume-making. Furthermore, the system will provide food and shelter for nocturnal birds, increasing biodiversity in the area.

The existing storage and transportation system will be modified to create more vivid and poetic water features that further enhance the water landscape.. For example, mist, fog, and fountains will be incorporated into the design, adding to the beauty and tranquility of the space.

By reactivating the traditional waterpath system and creating a fluid garden, we can transform the urban landscape into a vibrant and dynamic space that benefits both people and wildlife.

Water System

Street Water Flow System Map

Clean Drinking Water Transportation Map in Ancient Time

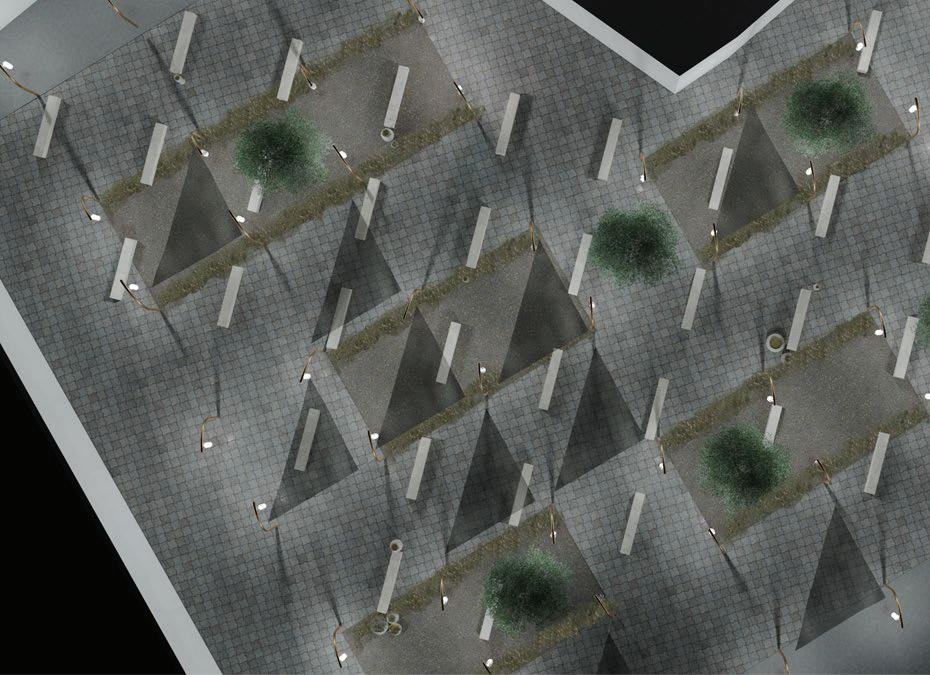

The Fondouk El Henna, a former caravan inn with no known owner, is deteriorating. Yet, artisans continue to work in its interiors despite the historical building’s poor conditions. Our project envisions the Fondouk El Henna as a flexible work, education, and exhibition space where the existing artisans may continue their operations alongside programming that exposes and elevates their crafts. A difficult building to find, the Fondouk El Henna will be made publicly accessible through a path that captures visitor flows and activates the public sphere. Flexibly designed for active vendor use during the day and public use at night, the path links a series of open spaces from the entrance of the Medina to the Fondouk El Henna. Through these building and path interventions, we hope to connect a restored Fondouk El Henna to the public sphere and, in doing so, support the Medina’s robust artisan and vendor economy.

Program Analysis - Porous Perimeters. Yazmine Mihojevich, Ruijen Yang.

Researching the

El

June 2022

October 2022

August 2022

Vendor Activity

Vendor Voids

Arch Typology - Porous Perimeters. Yazmine Mihojevich, Ruijen

Additional Light Structure

Remained Component

Remained Vault

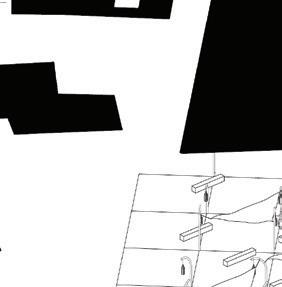

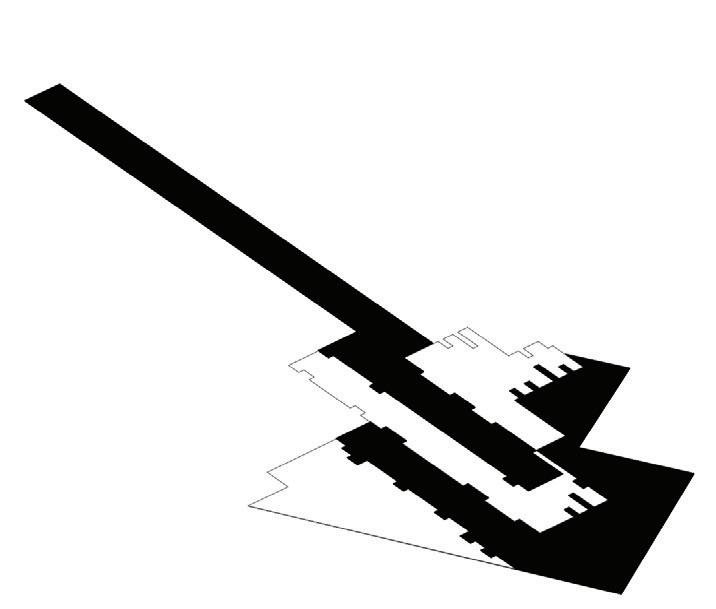

The Medina of Tunis has a rich history dating back centuries. After such a long time, many historical buildings have been preserved. The city’s texture and culture reflect everything that it has experienced. However, some buildings have decomposed, and some have collapsed completely. The old city has preserved some of the more ancient activities, such as commercial districts and handicrafts. In contrast, a large number of residents have also left.

Medina is not only the carrier of culture; it has become a World Cultural Heritage Site, but at the same time, it cannot meet the needs of modern people. The crowded streets and the lack of public space all require consideration for longer-term development, especially at night. We have thoroughly studied the links between the site and the external city, the internal function distribution, and internal advantages. If modern people’s activities are integrated into the ancient city, it will develop into a new Medina without losing its original spirit.

We consider extending the limited space vertically, from the ground to the open roofscape. We suggest using the ruined part to create a portal, release more room for the public, and allow a connection to rooftops. Furthermore, we integrate people’s activities, local plants, festivals, religious activities, commercial activities, architectural functions, and forms to create a new environment.

Therefore, we will consider the site and take light interventions to preserve its existing characteristics. We recommend introducing a program for art performances, cafes, and bars on different floors in our project area to attract people. Thus, the site will be safer, more open, and multifunctional. In the meantime, we can utilize the existing ruined space to make the staircases to connect each platform. The daytime sunlight and nighttime lighting will illuminate the portal in the continuous arches. With more buildings collapsing, there will be more chances to connect the roofscape from different districts, giving Medina a vibrant vibe day and night from different districts.

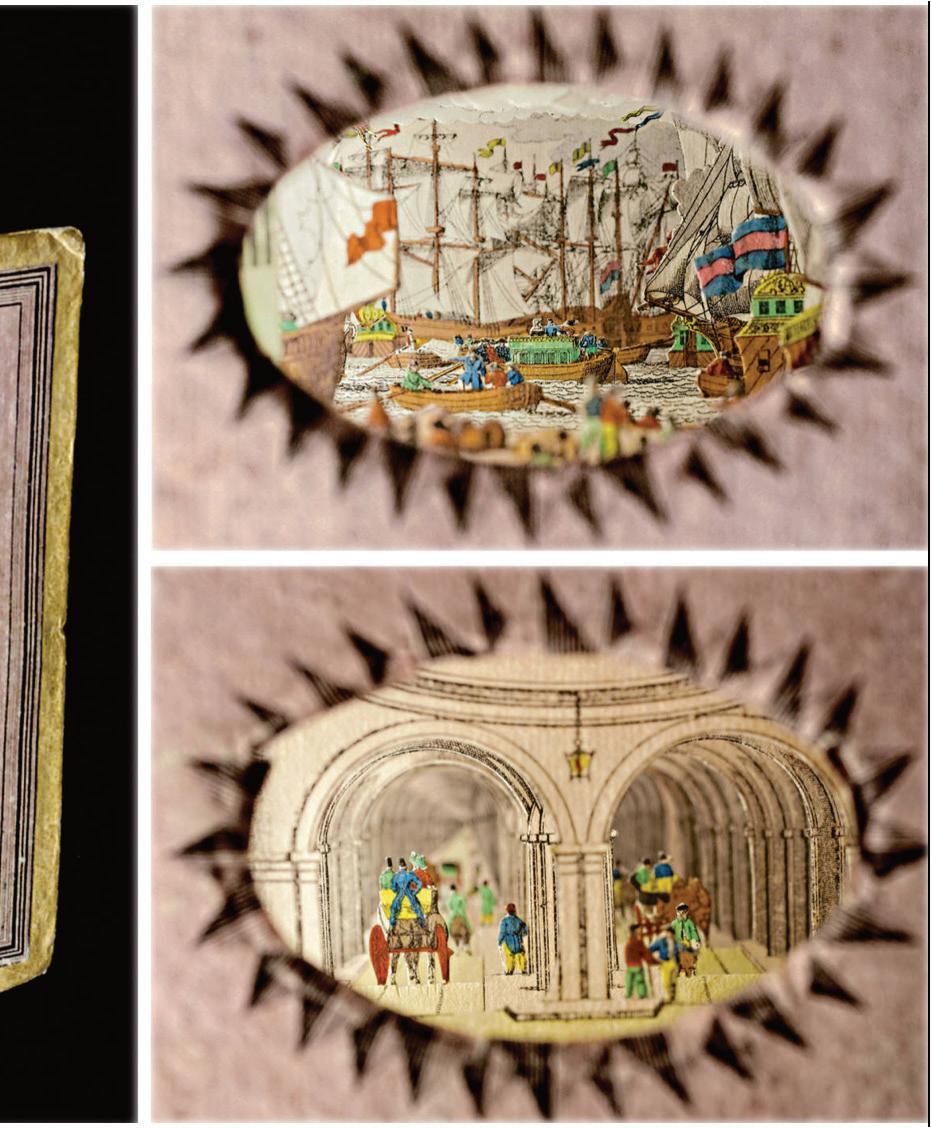

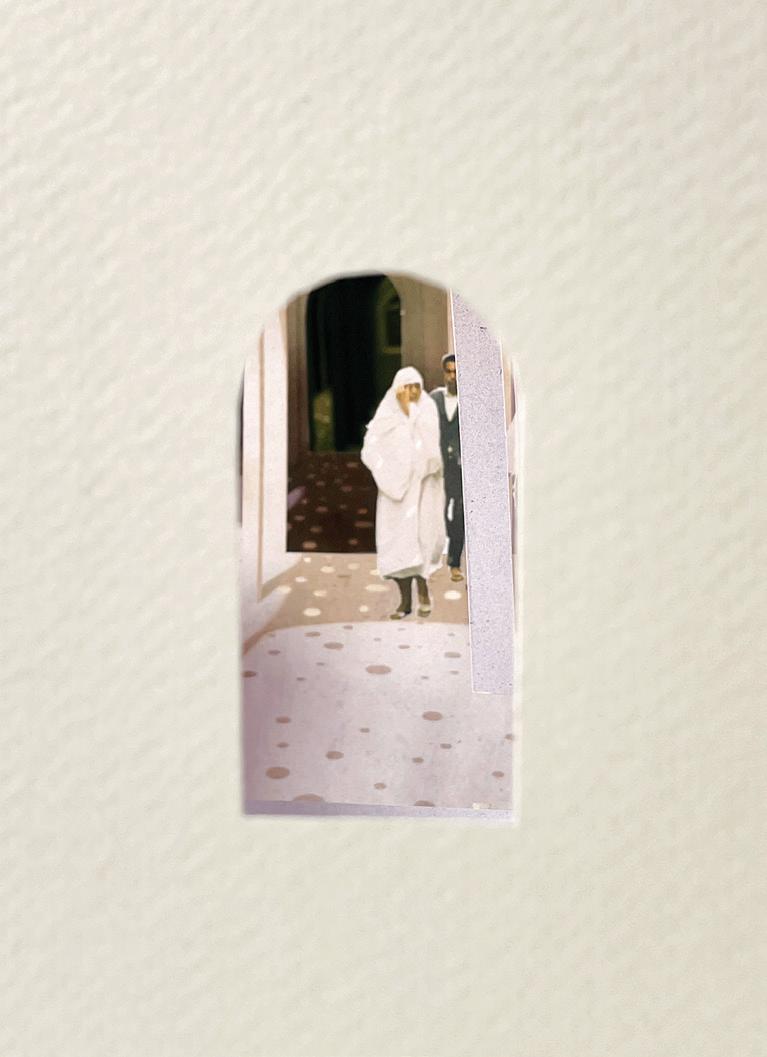

Every group built a maquette reinterpreting the idea of the paper peepshows' physical models.

Model paper peepshows were introduced in the mid-eighteenth century in Ausburgto to allow people to experience specific vistas of the moments of life or events that were usually not visible. They provided an idea of tridimensionality and perspective capable of creating an illusion of three-dimensionality and visual depth using a sequence of two-dimensional representations placed on display vertically and at a certain distance, like in theater scenography. This typology of models became pretty diffuse because of the simplicity of the material (paper) and the techniques to realize it, and they are considered the predecessors of virtual reality. A vast collection of paper peepshow models is present at the Victoria and Albert Museum, with around 360 pieces.

The students could choose the scale of the model differently according to the aspect of the proposal that was more crucial to unveil.

This artifact showed the spatial characteristics of the students' interventions and the nocturnal atmospheres (sky, stars, moon, lights), together with plants, animals, and human beings. Particular attention was given to the activities and the program, and the gathering possibilities ranged from more intimate spaces to larger spaces for assembly. The students selected a specific hour, day, and month they wanted to represent in their peepshow. It has been suggested, when relevant, to illustrate both daytime and nighttime.

The models used abstract approaches to show different points of view on the five sites of investigation. Besides the experience of “peeping,” they offered the chance to take photographs through those holes, framing views as a special moment of discovery and wonder in the narrative of the projects.

Francesca Benedetto

Francesca Benedetto is a design critic in landscape architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and founder of YellowOffice, a firm based in Milan focused on landscape architecture and urbanism, combining research and design. The practice brings together several scales of design processes, from territorial strategies, urban planning, public spaces, parks, pavilions, and cemeteries to objects, videos, illustrations, maps, and exhibitions. The recurrent themes of this research revolve around the relationship between the city and nature, ideas of public spaces, and geographic disciplines, always observed through the lens of visual arts.

Gareth Doherty

Doherty is associate professor of landscape architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. Doherty explores and unravels narratives and practices of landscape architecture that have not yet been formally documented. This work is essential to establish the precedents required to diversify the design disciplines and expand upon the limited and limiting traditional design canons. Doherty works in Islamic and, for comparative purposes, postcolonial societies, valuing the everyday and experiential aspects of landscapes, be they professionally designed or not.

MATERIA, founded by Lucio Frigo, is a real estate development firm focused on regenerating urban neighborhoods and cultural landscapes. It excels in leveraging local materials, workforce, and culture in its projects, which include school campuses, cultural districts, and affordable housing. Emphasizing partnerships with leading architects and universities, MATERIA fosters a critical approach to the built environment. A key aspect of its strategy is a strong focus on stimulating both cultural and economic vitality, ensuring that communities can thrive within contemporary urban developments while preserving their heritage and identities.

Leila Ben Gacem

Founder of Dar Ben Gacem, Blue Fish

Sihem Lamine

Associate Director of the CMES Tunisia Office

John Peterson Curator of the Loeb Fellowship

Anna Lyman Program Director of the Loeb Fellowship

Mariana Alegre Loeb Fellow 2023

Founder Ocupa Tu Calle and Sistema Urbano

Dario Calmese Loeb Fellow 2023

Artist and Founder The Institute of Black Imagination

Pamela Conrad Loeb Fellow 2023 Founder Climate Positive Design

Claudia Dobles Camargo Loeb Fellow 2023

First Lady and Presidential Advisor Costa Rican National Decarbonization Plan

Natalia Dopazo Loeb Fellow 2023 Feminist Urban Planner

Badruun Gardi Loeb Fellow 2023 Founder New Nomad Institute

Shamichael Hallman Loeb Fellow 2023 Director of Civic Health and Economic Opportunity Urban Libraries Council

Rebecca McMackin Loeb Fellow 2023 Director of Horticulture, Brooklyn Bridge Park

Derwin Sisnett Loeb Fellow 2023 Founder and CEO Adaptive Commons

Alberto Krizler Loeb Fellow 2023 Co Founder Reurbano

Fatma Habel

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Amal Ben Ammar

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Noura Tounekti

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Aymen Baroudi

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Amine Maatouk

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Abir Chhibi

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Wafa Ben Salem

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Fares Rtibi

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Fakher Kharrat

Director of L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Soumaya Larbi

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Nawres Chihi

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Salma Guenounou

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Sana Haddaji

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Nour Messaoudi

L'Ecole Nationale d'Architecture et d'Urbanisme de Tunis

Moncef Guellaty

Editor and Founder of Tunisian Chapter of Amnesty International

Ahmed Abdelkafi Tunisian economist and businessman

Iheb Guermazi

Lecturer in Middle East, South Asian, and African Studies at Columbia University

Amel Meddeb Ben Ghorbel

Association de Sauvegarde de la Medina de Tunis

Dhafer Ben Khalifa

Cofounder and President Le Collectif Creatif Tunis

Sadika Ghouma Association de Sauvegarde de la Medina de Tunis

Zoubeir Mouhli

Formerly Association de Sauvegarde de la Medina de Tunis

Faïka Béjaoui Formerly Association de Sauvegarde de la Medina de Tunis

Montassar Jmour Institut National du Patrimoine

Sofia Guellaty Founder and Creative Director at MILLE World

Nadia Siméon

Deputy Director Aga Khan Award or Architecture

Khaled Azzam

Founder at Khaled Azzam Architecture

Mohammed Alzamanan Health and Safety Director at Diriyah Gate Development Authority

Barbara Anglisz

Heritage Field Researcher

Ghazi Gherairi

Representative of the UNESCO for Tunisia

Mehdi Sethom Cofounder Tunistoric

Paola Pietrantoni Cofounder Studio Atomic

Gabriele Negro Cofounder Studio Atomic

Ikram Saidane-Hamdi

ISA Chott Mariem

Alistair McIntosh

Lecturer in Landscape Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Danielle Choi

Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Karen Janosky

Lecturer in Landscape Architecture

Director of the Master in Landscape Architecture Program at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Alberto Kritzler

Lecturer in Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Areti Kotsoni

Research Associate at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Kate Bauer

Project Manager at the Bloomberg Center for Cities at Harvard University

William Granara

Research Professor of the Practice of Arabic at the Harvard University Center for Middle Eastern Studies

Lauren Montague

Executive Director at the Harvard University Center for Middle Eastern Studies

Yves Marbrier

Design Consultant

Moises Lino e Silva

Assistant Professor of Anthropological Theory at the Universidade Federal da Bahia

Sarah M. Whiting

Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Gary R. Hilderbrand

Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture

Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Forrest Rosenblum

Teaching Assistant at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Issam Azzam

Research Assistant at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Yasmine El Alaoui El Abdallaoui

Research Assistant at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Sofia Castell

Research Assistant at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Liz Van Dyke

Research Assistant at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Zak Jacobi

Research Assistant at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Markel Uriu

Research Assistant at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Barhoumi, Issam, Super moon over Medina of Tunis, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index. php?title=File:Super_moon_over_Medina_of_ Tunis.jpg&oldid=876179938.

Baynes, Thomas Mann, Peepshow showing Masquerade, Haymarket, published by S&J Fuller, London, c.1826 (c) Victoria and Albert Museum, London Photographer - Dennis Crompton.

Boughedir, Férid, director. Halfaouine: Boy of the Terraces. CinéTéLéFilms, 1990. 1 hr., 38 min.

Chambers, Jack S., Martyn, Keith. 1952. Swan Lake, A Werner Laurie Ballet Show Book. peepshow. Published by Werner Laurie. London. Museum no. Gestetner 296. Photography: Dennis Crompton. (c) Victoria and Albert Museum

Creti, Donato. 1711. Astronomical Observations, Oil on canvas. Viale Vaticano, 00165, Rome, Italy. Musei Vaticani. https:// www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/ en/collezioni/musei/la-pinacoteca/sala-xv--secolo-xviii/donato-creti--osservazioniastronomiche.html.

Elsheimer, Adam. 1609. Flight into Egypt, Oil on copper. Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

Faber, G. W. 1835. Perspectivische Ansicht des Tunnel unter der Themse. peepshow. Germany. Museum no. Gestetner 118. Photography: Dennis Crompton. (c) Victoria and Albert Museum.

Faber, G. W. 1851. The Thames Tunnel at London. peepshow. Germany. Museum no. Gestetner 176. Photography: Dennis Crompton

Hakim, Besim S. 1975. Tunis Husaynid (17051881): Urban Design and Planning Principles in Traditional Arabic-Islamic Cities: Building Heights. Besim Hakim Archive. https://www.archnet.org/publications/13198.

Hakim, Besim S. 1975. Tunis Husaynid (17051881): Urban Design and Planning Principles in Traditional Arabic-Islamic Cities: Open Spaces. Besim Hakim Archive. https://www.archnet.org/publications/13191.

Hakim, Besim S. 1975. Tunis Husaynid (17051881): Urban Design and Planning Principles in Traditional Arabic-Islamic Cities: Economic Activities. Besim Hakim Archive. https://www.archnet.org/publications/13186.

Hiramatsu, Tsuneaki. 2008-2011. Hotaria parvula (Japanese Firefly). Digital Image. www.500px.com/minoltan

Klarwein, Mati. 1977. Private Property. Oil on canvas. © Klarwein Family. http://www. matiklarweinart.com/en/gallery/privateproperty-1977.htm.

Moon, Francis Graham, Sir. 1796-1871. playing card maker. Astronomia. 1829. https:// collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/10995117.

Morrison, Lois. 1993. My Garden from Weeding Height. National Art Library. Gestetner Collection. Leonia, N.J: Lois Morrison. (c) Victoria and Albert Museum

Nagai, Kazumasa. 1983. Artists Paint Toyama, 100 Landscapes by 100 Artists. Offset Lithograph.

Nagai, Kazumasa. 1980. Japanese Design (Group of 4 Posters). Posters.

Nagai, Kazumasa. 1983. Kazumasa Nagai Quebec. Poster.

Nagai, Kazumasa. 1965. The Mind, Life Science Library. Silkscreen.

Nagai, Kazumasa. 1981. Poster for the Magazine TENRI. Screenprint. Kazumasa Nagai. Poster for the magazine TENRI. MoMA

Nagai, Kazumasa. 1982. Sakura. Woodblock Print.

Ohmura, Yukino. 2014. Tokyo Station. Mixed Media, Sticker on Panel. Mu Gallery. https:// yukino-art.tumblr.com/.

Ohmura, Yukino. 2014. Tokyo Illumination. Mixed Media, Sticker on Panel. Mu Gallery. https://yukino-art.tumblr.com/.

Ohmura, Yukino. 2014. Shunan 2. Mixed Media, Sticker on Panel. Mu Gallery. https:// yukino-art.tumblr.com/.

Pantaleon, Heinricus, Thomas Guarin, and Chambolle-Duru , binder. 1581. Militaris ordinis Iohannitarum, Rhodiorum, aut Melitensium equitum : rerum memorabilium terra marique, à sexcentis ferè annis pro republica Christiana, in Asia, Africa, & Europa contra Barbaros, Saracenos, Arabes & Turcas fortiter gestarum, ad praesentem vsq[ue] 1581 annum : historia noua libris duodecim comprehensa,omnibus Christianis lectu iucundissima. Basileae: [Thomas Guarin].

Pelton, Agnes. 1934, Orbits, Oil on Canvas.

Pheby, John. 1995. The Oxford-Duden Pictorial English Dictionary. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Pirî Reis. 1525. “Fol. 277b Coastline of Tunisia with the Ports of Bizerte and Tunis: Walters Ms. W.658, Book on Navigation, Kitb-i Bariye”. Manuscript.

Ruscha, Ed. 1981. Any Town in the U.S.A. Screenprint. Gagosian Gallery.

Ustwo Games, Monument Valley II+ (Apple Arcade), Ustwo Games, Android, iOS, Microsoft Windows, London, England. 2022

Vriesendorp, Madelon. 1973. New York Juicer, from New York Series. https://www.madelonvriesendorp.com/ newyorkseries?pgid=jwdjqmau-9201b6cf-62474782-b259-161af03b0c70

Weiss, Edmund. 1888. Bilderatlas der Sternenwelt : eine Astronomie für jedermann. Esslingen bei Stuttgart: J. F. Schreiber.

Wikimedia Commons contributors. Collection Personelle Bertrand Bouret. 1888. File:Tunis remparts portes.Jpg. In Wikipedia. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tunis_ remparts_portes.jpg

Yüzbasisi, Güverte. 1919. 1) [Celestial Chart]. (Composite: Seyr-i Sefâinde Müstamel Kevâkib Atlasi : Kevâkib Ne Sûretle Bulunur Ve Pusula Tashihi Ile Mevkii-Yi Sefine Tayininde Nasil Istimâl Olunur. The Printing House of the Naval Forces.

Yüzbasisi, Güverte. 1919. 6) [Celestial Chart]. (Composite: Seyr-i Sefâinde Müstamel Kevâkib Atlasi : Kevâkib Ne Sûretle Bulunur Ve Pusula Tashihi Ile Mevkii-Yi Sefine Tayininde Nasil Istimâl Olunur. The Printing House of the Naval Forces.

Tunisian Nightscapes: Nocturnal Landscapes in the Medina of Tunis

Instructor

Francesca Benedetto

Principal Investigator

Gareth Doherty - Critical Landscapes Design Lab, Atlas for the Medina of Tunis

Sponsor MATERIA Inc.

Report Design & Editors

Elizabeth Van Dyke

Zak Jacobi

Markel Uriu

Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture

Sarah M. Whiting

Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture

Gary R. Hilderbrand

Copyright © 2024 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Text and images © 2024 by their authors.

Harvard University Graduate School of Design 48 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138

gsd.harvard.edu