Li Hu / Huang Wenjing

Li Hu / Huang Wenjing

Li Hu / Huang Wenjing

Nexus of Ecology, Education, and Design

- A New School of Design on an Island at Yangtze Estuary

This studio project touches upon two important areas relevant to our collective future—ecology and education. This is a future in which we must change the way we live, as the threshold for climate change is about to be crossed and this future lies in the hands of our young people. The task at hand is the design of an architectural design school within a new college at Yangtze Estuary on Chongming Island, China. The studio explores new modes of operation needed to face the complex and difficult, yet still hopeful, realities. Each student transforms seminal ideas into spatial ideals as they imagine their own design school.

Studio Instructors

Li Hu (LH) and Huang Wenjing

Teaching Assistant Zihao Wei

Students

John Adrian, Olivia Champ Tremml, Maddie Farrer, Sophie Gföhler, Connor Gravelle, Ryan Han, Connor Kramer, Vinzenz Leuppi, Tanil Raif, Gustavo Ramirez, Lilly SanielBanrey, Yihan Yang

Midterm Review Critics

Scott Cohen, Chris McVoy, Mohsen Mostafavi, Angela Pang, Jia Ruo, Ron Witte

Final Review Critics

Eric Bunge, Elizabeth Christoforetti, Scott Cohen, Michael K. Hays, Andrew Holder, Grace La, Jing Liu, Angela Pang, Albert Pope, Frano Violich

Studio Manifesto

8 Li Hu and Huang Wenjing Research

14 Students and Studio Instructors Experiments

74 Students and Studio Instructors Design

Olivia Champ Tremml and Lilly SanielBanrey

Sophie Gföhler and Vinzenz Leuppi

Connor Gravelle and Ryan Han

Maddie Farrer and Tanil Raif

Yihan Yang

Education as Spatial and Cultural

Architecture as Means to Gather and Connect

Human beings are a part of, not separate from, nature. Ecological issues are also social issues. The ground we call Earth is slipping away under our feet. The climate code red, the tipping points, the future of no future—we need to act today.

It is within this bigger picture that our site of intervention, a plot on Chongming Island at the Yangtze River Estuary, looks ever more precious and vulnerable. We hope to explore how we can ground ourselves together with other species on this carefully reserved small piece of land surrounded by a charming yet danger-ridden ecological system. We need to change our mode of operation as architects— from drawing up master plans in bird’s-eye view (yet without any concern for birds), to being genuinely grounded and concerned about the social-ecological systems of which humans are merely a part.

We need to reexamine the obvious, such as the air, to understand the delicate interdependency between us as human beings and other living beings. We will study the water-soil-plant conditions under which insects, amphibians, birds, and people can thrive happily together. More importantly, we will explore how design can encourage healthy lifestyles and new communal relationships with nature.

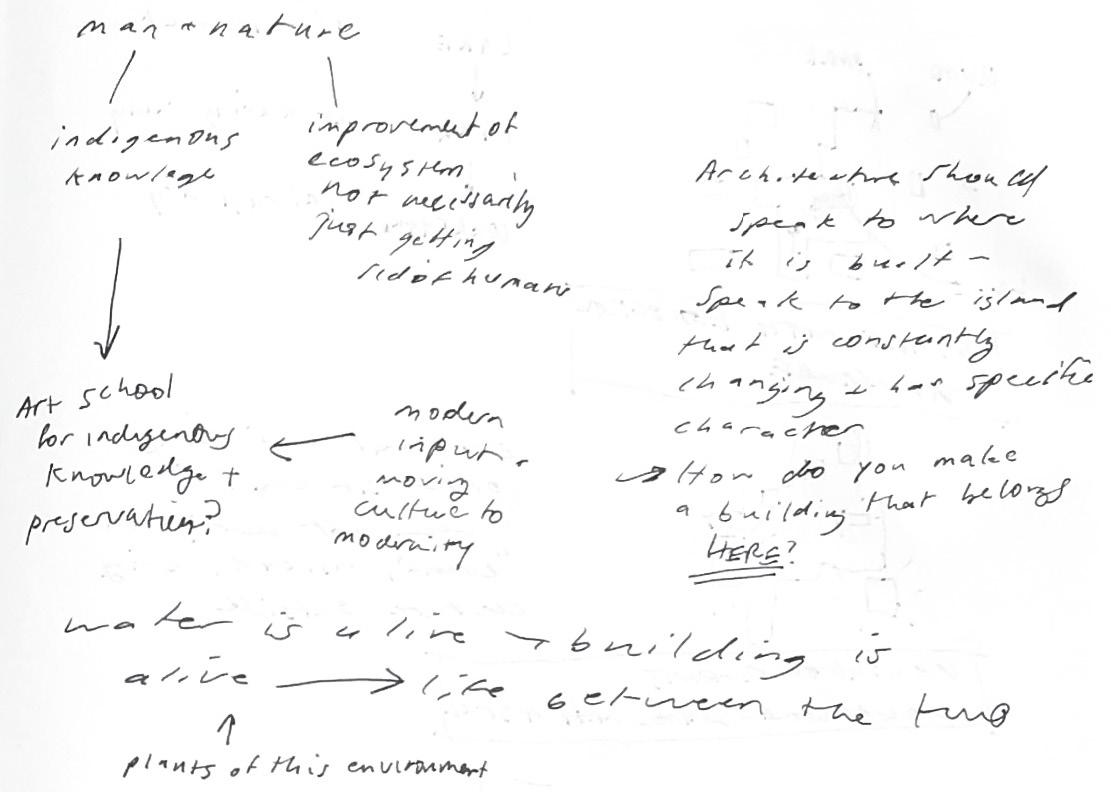

What is the essence of teaching and learning today? More specifically, how do we make a new design school, from seminal ideas to spatial ideals? We ask each student to imagine their own.

We believe in the immense impact of a constructive community on learning. Imagine a community of designers. We are interested in discovering new spatial relationships among

different components of teaching, learning, and campus living. We want to investigate ways of injecting life/livelihood into a design school with the goal of nurturing interesting souls. Education should be imbued with cultural activities. Can we bring culture out of cultural buildings? Can teaching happen outside classrooms?

As uncertainty is the only certain thing in a complex system such as the education of multidisciplinary designers, we need physical and mental spaces that are flexible and adapt to change. We need to build resilience into the core of future designers.

Architecture as Means to Gather and Connect

The world is a complex system of elements, constantly interacting and in flux. Architecture is a vessel, a medium through which we interpret increasingly complex issues at work. It is a means to gather and connect in tangible ways. Take each project as a new beginning. We hope to cultivate a genuine interest in broader issues and curiosity for new things, along with sensitivity to matters and materials, in our students. And we want them to discover for themselves what is really needed, what is called for, and what must become.

We will be searching for architecture that connects us with people, to meet, exchange, and share; architecture that connects us with nature—trees and birds, sea and land, air and light; and architecture that connects us with our inner selves.

Instead of didactic teacher-pupil relationships, we see the design studio as a constant dialogue, in which new knowledge and understanding form and new ideas and reflections emerge. We encourage our students to ask questions and seek solutions, to heighten their awareness and enact changes. We learn from each other; we learn from the world.

Research

Programming

Storyline

Hybridization and Reinvention Focuses

Radical

Presentation

We begin with research. Research into the history and current conditions of design schools; research into the site and the broader context; research into the social ecosystem, wetlands, and the various challenges. However, the purpose of research for designers is to be informed and inspired so that we can design. There’s no need to get buried under tons of information.

Programming

As Louis Kahn believed, an architect’s first job is to “rewrite the program.” We encourage students to analyze the given programmatic components and the very purpose of design schools, reexamining the past and developing their own vision for the future.

Design a storyline and work out the architecture from the inside out; architecture fabricates an intricate network of relationships between things.

Strategies: Hybridization and Reinvention

Hybridization and reinvention will be two design strategies that we encourage this studio to explore. As always, students will also be encouraged to experiment and develop their own design strategies.

Focuses

A social-ecological approach; the future learning environment; and the integration of design and engineering

Radical and Poetic

Each student is expected to develop a piece of architecture in depth. We look for radical yet poetic designs that are born authentically out of each student’s own interests.

Presentation

We ask each student to explore suitable and unique methods of presentation that can best convey to others the power and impact of their respective designs.

As designers, we constantly learn from people and our environment, from nature and human connections. To make architecture which is unexpected and imaginative, we must unlearn existing formulas and languages, listen and sense hidden meanings—discovering what is essential within each project.

This starts with research. A loose and open approach to research makes room for chance and unpredictability, for delight and surprise. As architects, we have a complex project with many ingredients. Chopping them up and mixing them together leads to unexpected combinations and new hybrids. The best buildings have tension between forces, creating a feeling of drama and emotion. Those seeds are planted from the start. – LH and Wenjing

Chongming is an island where the Yangtze River meets the sea, formed over millions of years. It is now an ecologically sensitive and preserved island. Most of its land areas are used for agriculture, a few villages, and wetland natural reserves. For the Shanghainese, it is a popular destination for weekend excursions as well as a site for many seasonal migrating birds. New construction is only allowed on a small area of the island, regulated for specific uses. – LH and Wenjing

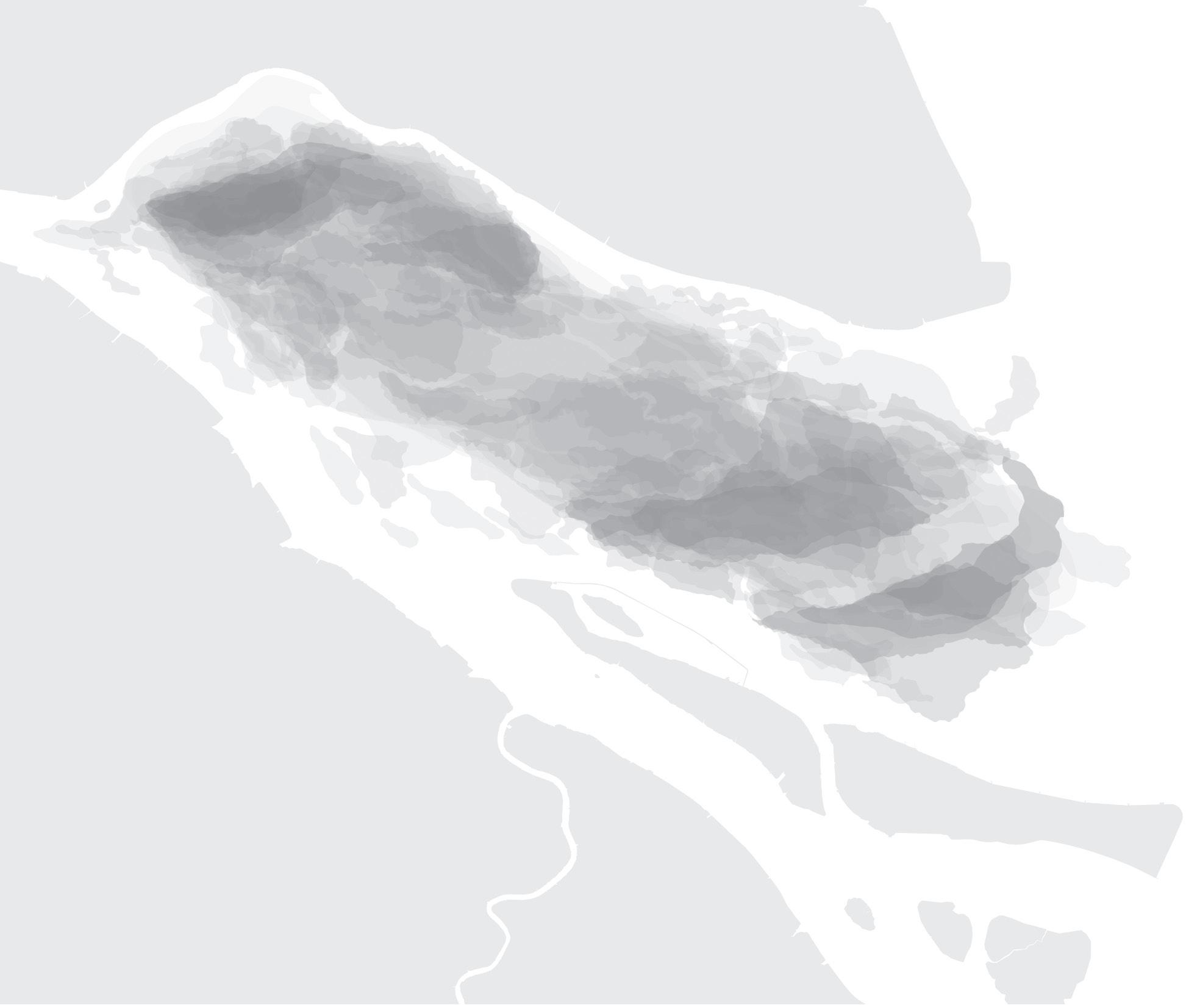

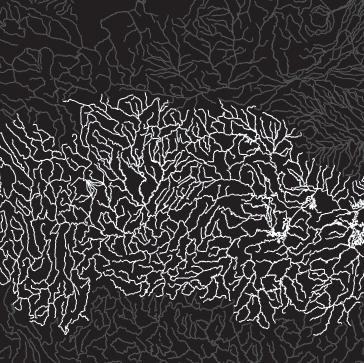

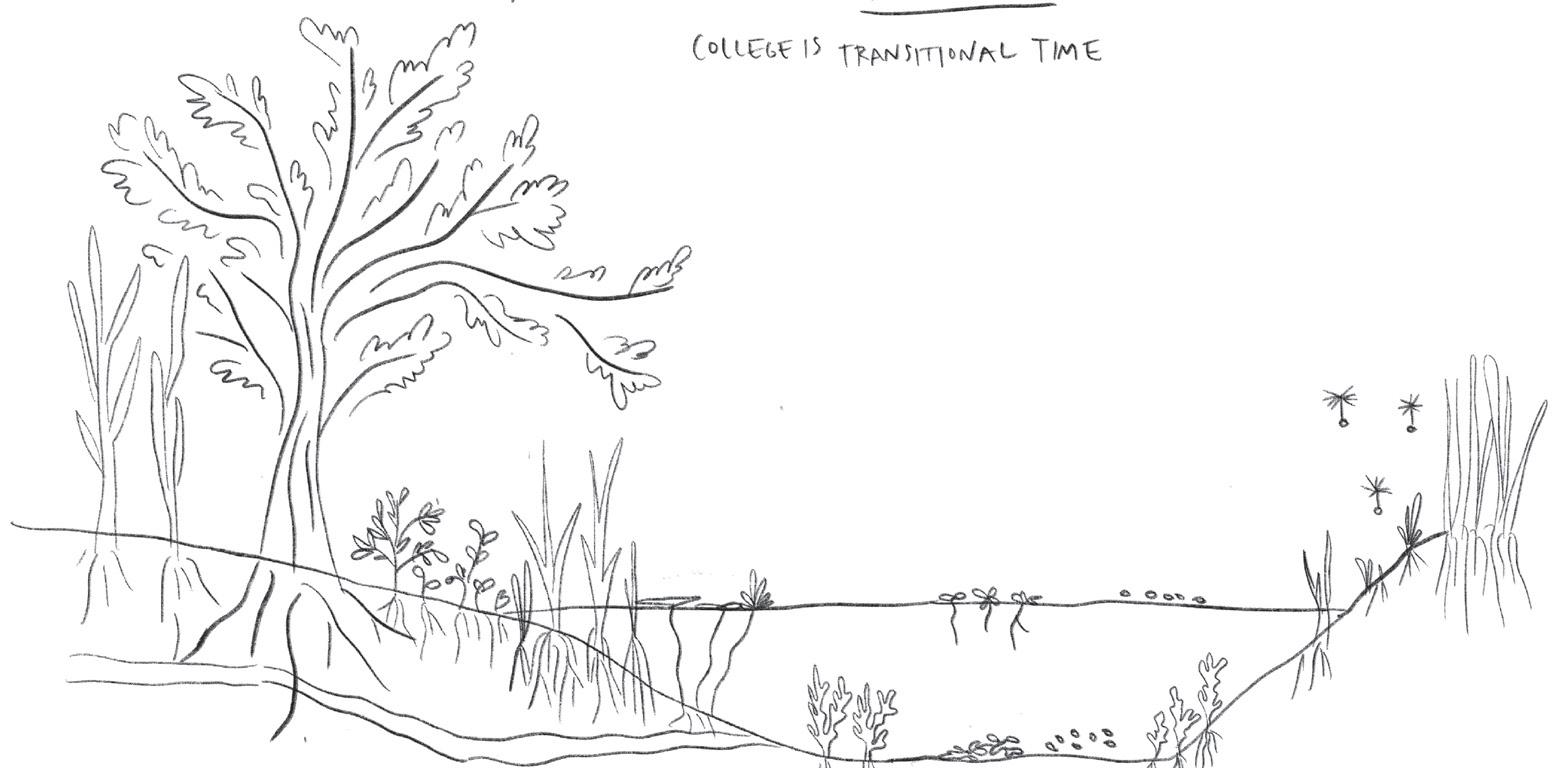

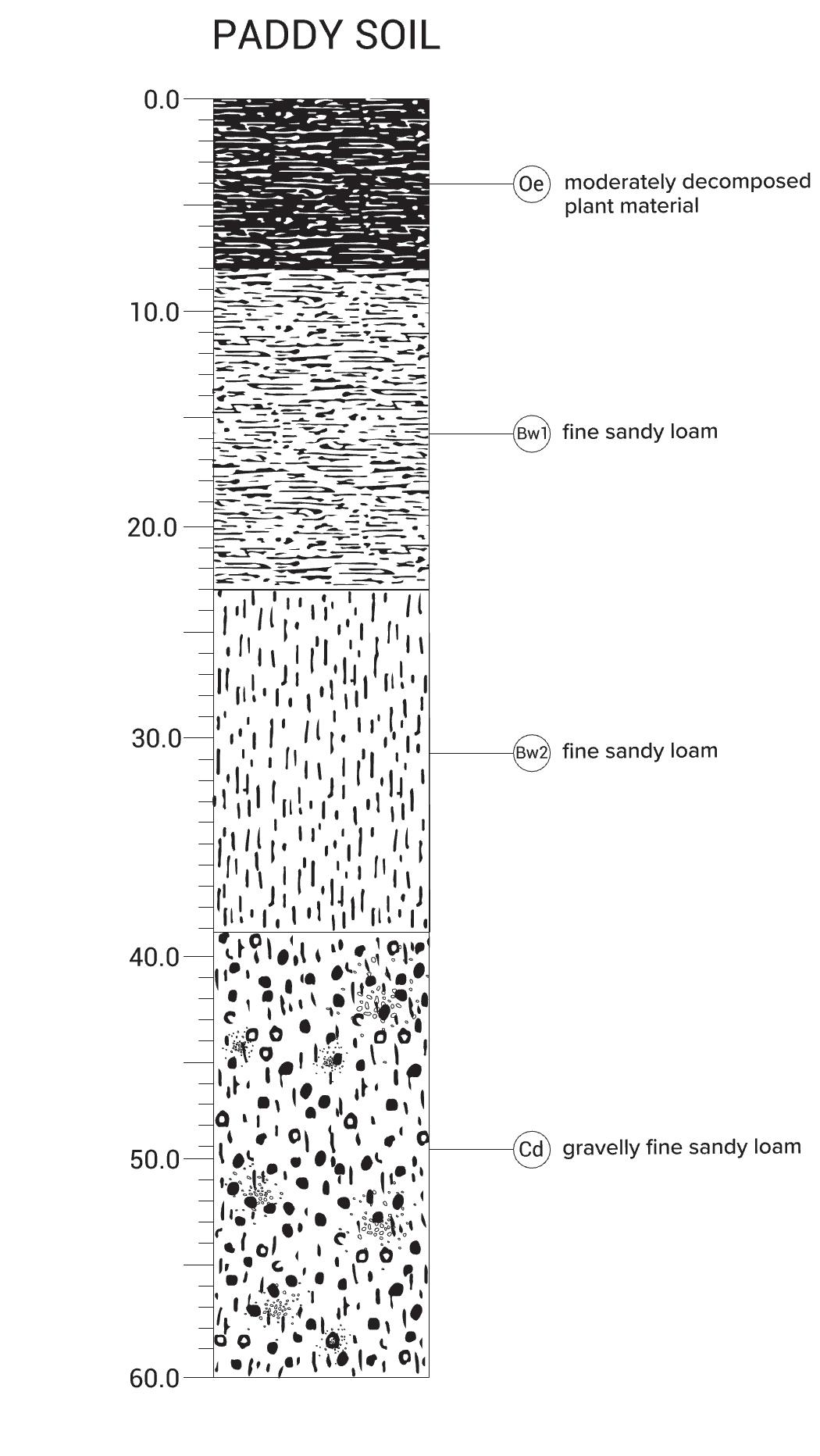

Chongming Island is an alluvial plain, which means it is subject to constant change and fluctuation. It is known for agricultural usage, but over the last few decades, it has become colonized. Visualizing these fluctuations led to a variety of realizations. Urban and sealed surfaces are rapidly increasing in Shanghai, and these are carrying over to Chongming Island. Even though the island is still naturally growing, the wetland surface—that acts as a natural habitat for many species—is decaying and shrinking.

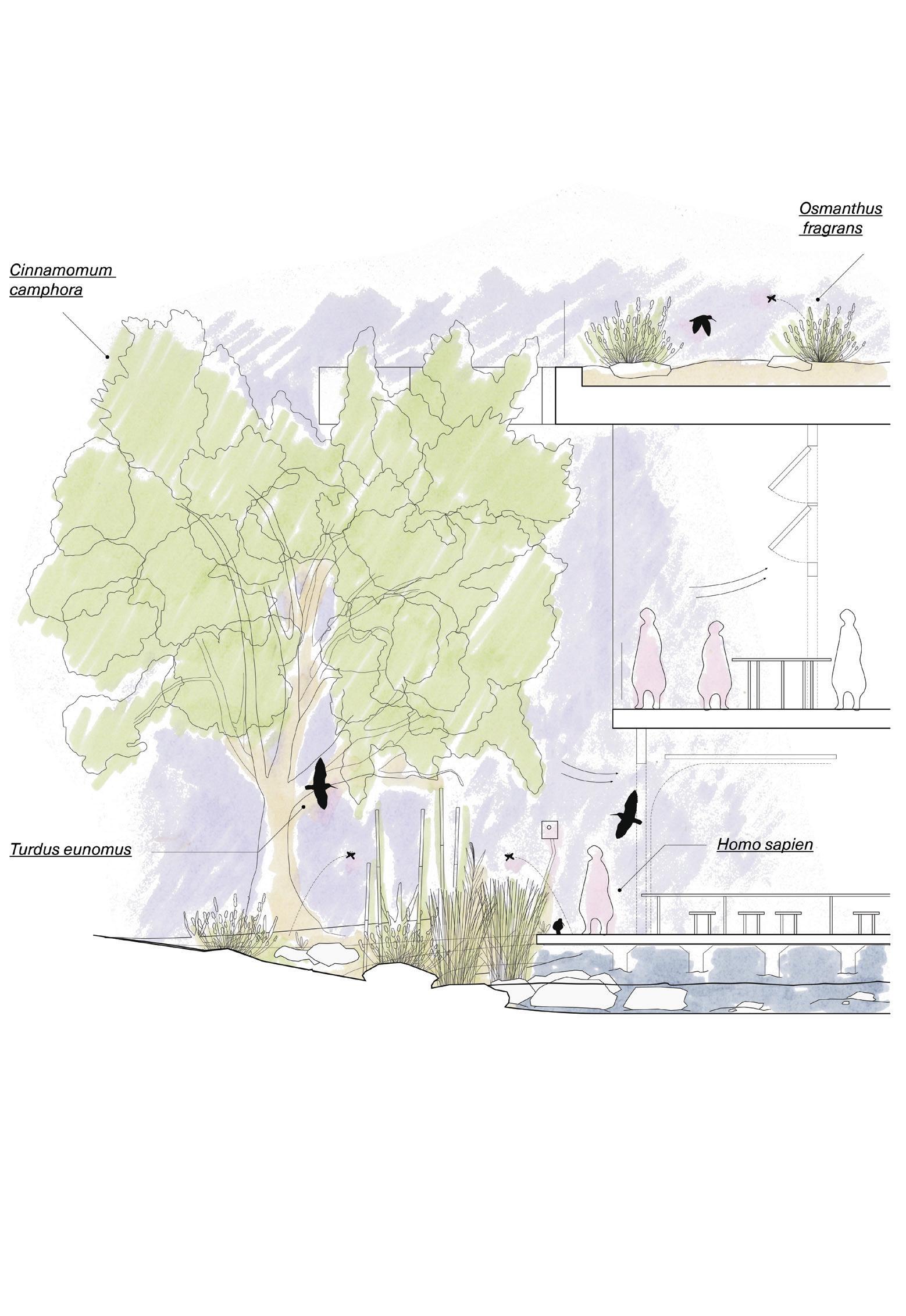

One world effect is that the local loss of natural habitats impacts the bird population and biodiversity. As Chongming is one stop on the East Asia Bird Migration corridor, this means a local loss of biodiversity has a global effect. Local situations and knowledge matter on a global scale, and we can no longer operate in a humancentric system.

The modern project has been in flight, unconcerned with planetary limits. Suddenly, there is a general movement toward the soil and new ways that people might inhabit it.

From a post-human perspective, politics should stretch beyond only human actors. This rethinking is an immensely more complex undertaking. New forms of citizenship and new types of attention and care must shift toward a biocentric perspective. – Vinz and Sophie

The island has never been just one thing. Its shores, estuaries, and composition have always been in flux. Chongming’s identity constantly changes because of the displacement of material upstream from the Yangtze, China’s longest river. The river is 23,000,000 years old, 6,300 km long, has 30,165 m3/s of water discharge, and 5,170 m of grade change. Chongming Island sits at the mouth where the river empties into the ocean.

What is most shocking is realizing that the island is coming and going. Its ground is an accumulation of sediment that was once suspended in the Yangtze River. Questioning our relationship to the ground is a provocative place to start this project. – Connor G.

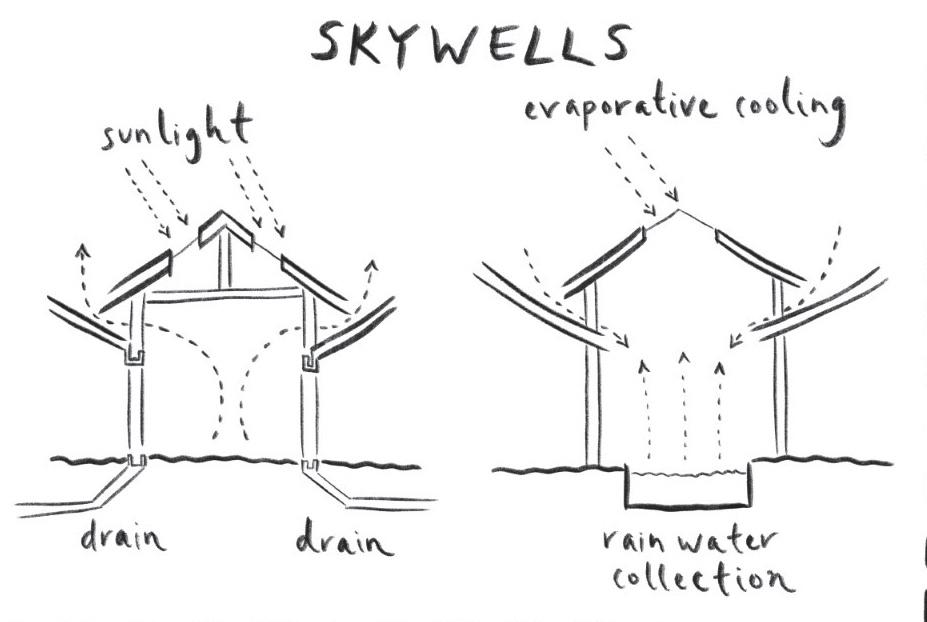

Ecology is not purely a science. A sociological perspective helps us understand the many players in the environment, visible and invisible. We need to train our eyes to see what’s invisible. The air, insects, birds, and trees are all actors mixed together in the system. Designing with the sun and the wind goes beyond studying thermodynamics; it requires common sense and deep feeling toward the earth and climate. – LH and Wenjing

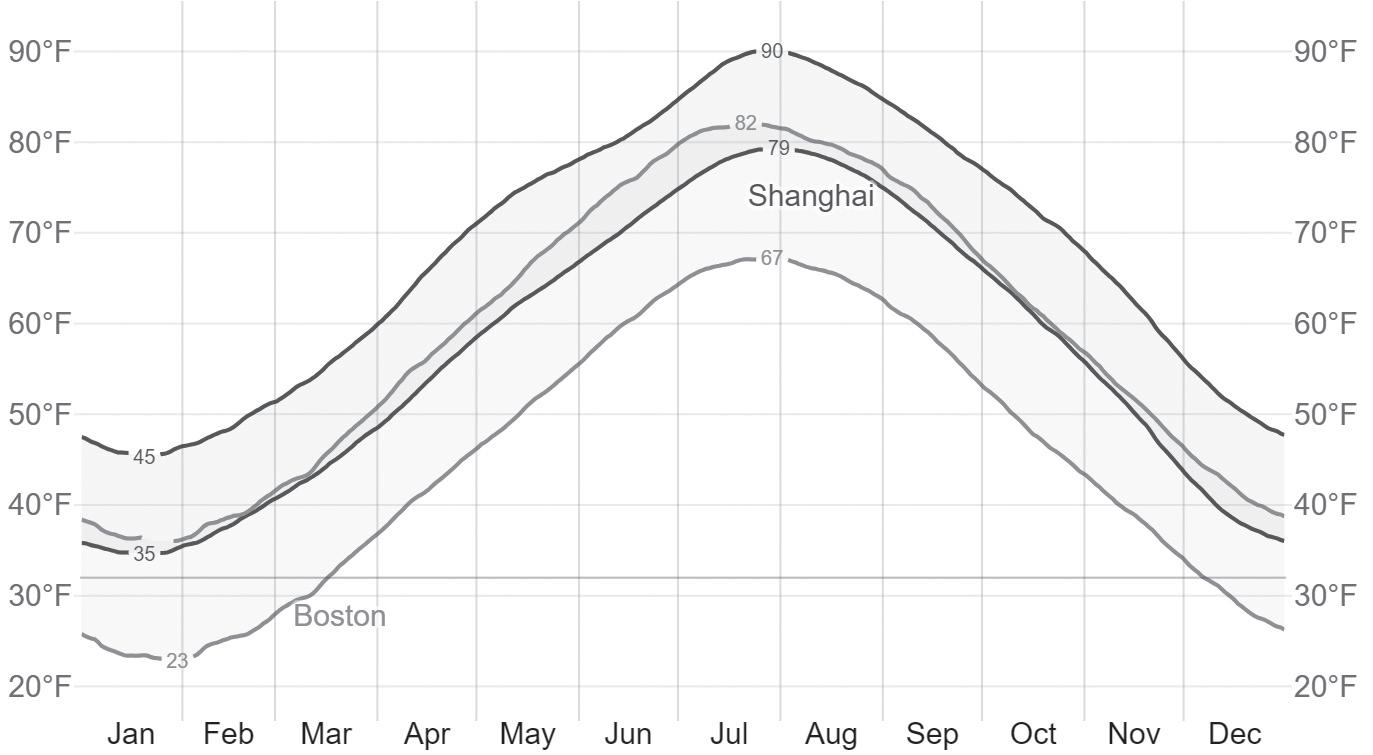

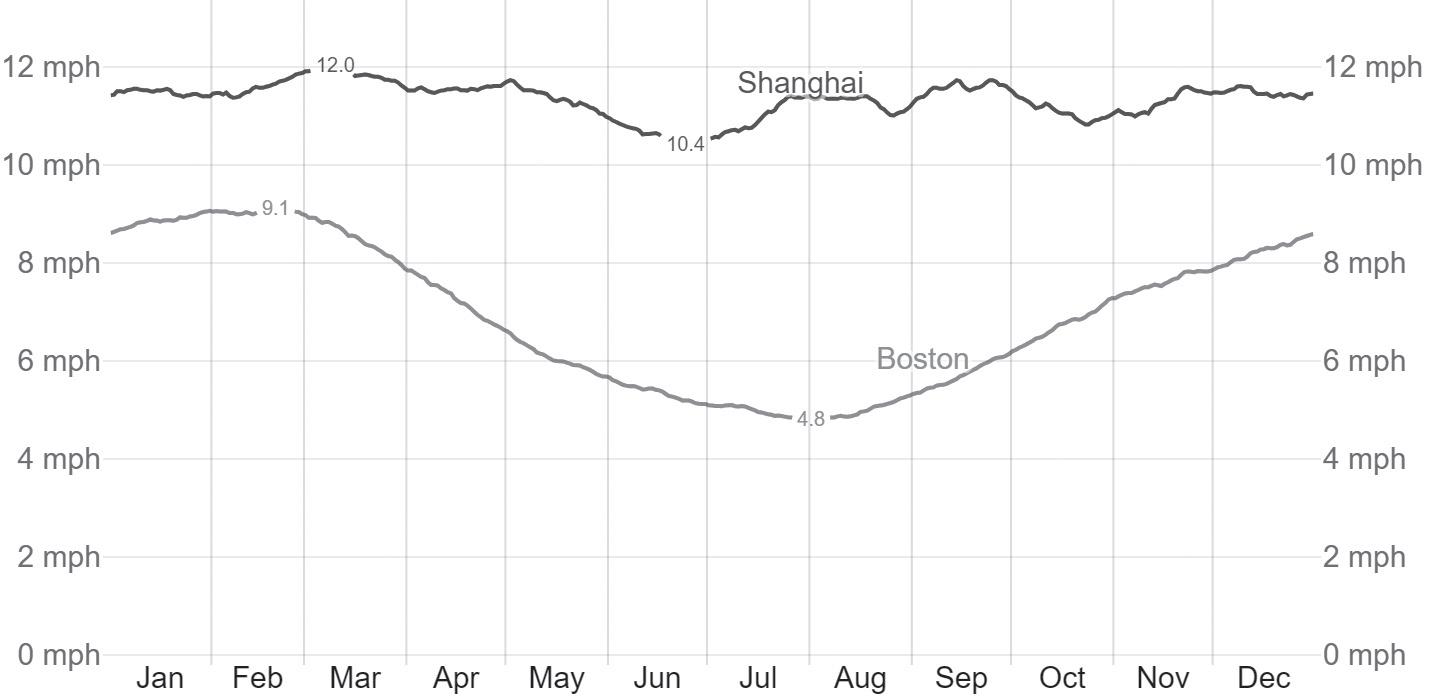

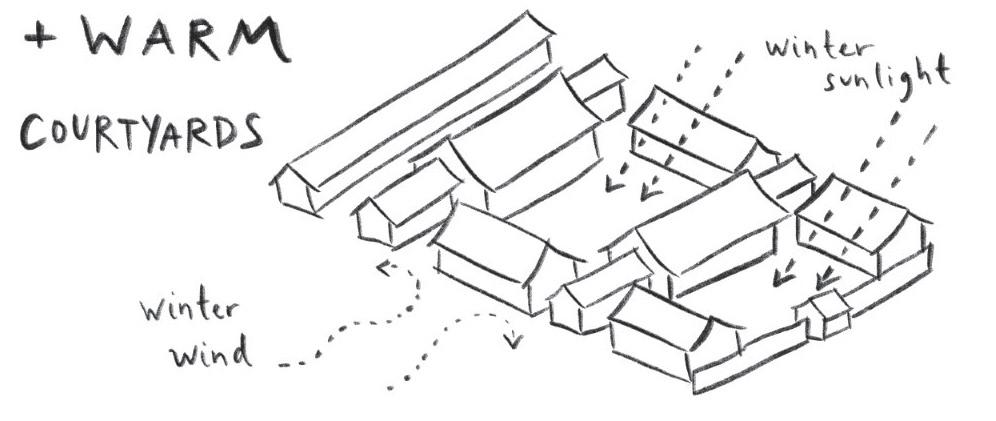

The climate of Chongming Island encourages a building that adapts to the changing conditions of the seasons and breathes with the island’s ecology. Seasonal variation churns through cycles of wet and dry, as the island’s coast and wetlands constantly negotiate dramatic changes in water levels. Monsoon season brings extreme precipitation, cloud cover, and humidity in the summer. Winters are relatively mild and dry.

The wind responds to the unique overarching geologic features of the area, changing direction from the north over the land in the winter to the south over the ocean in the summer. In the mild transitional seasons, the key months for our design school’s residency, passive strategies such as natural ventilation, evaporation cooling, and humidification work together to produce comfort conditions. – Vinz and Sophie

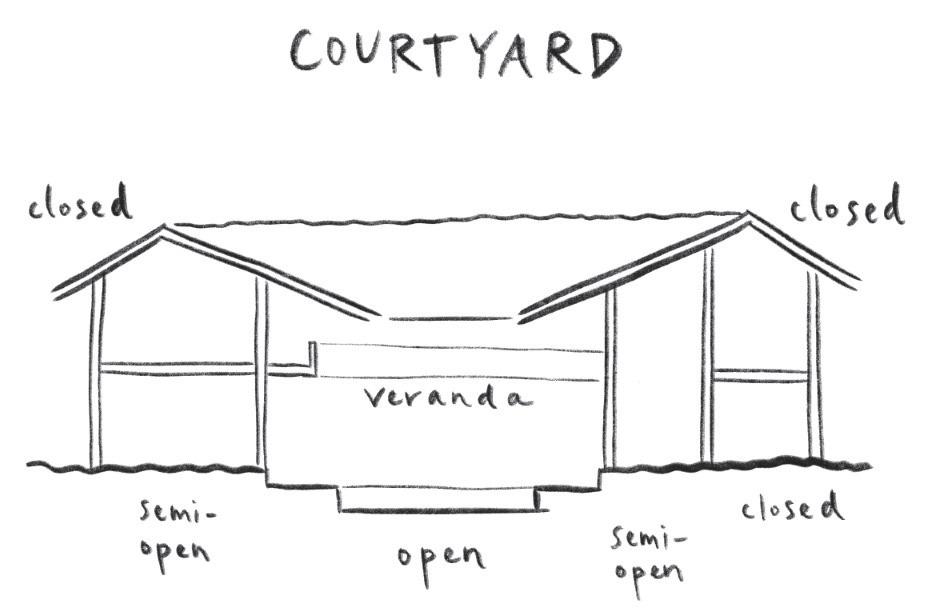

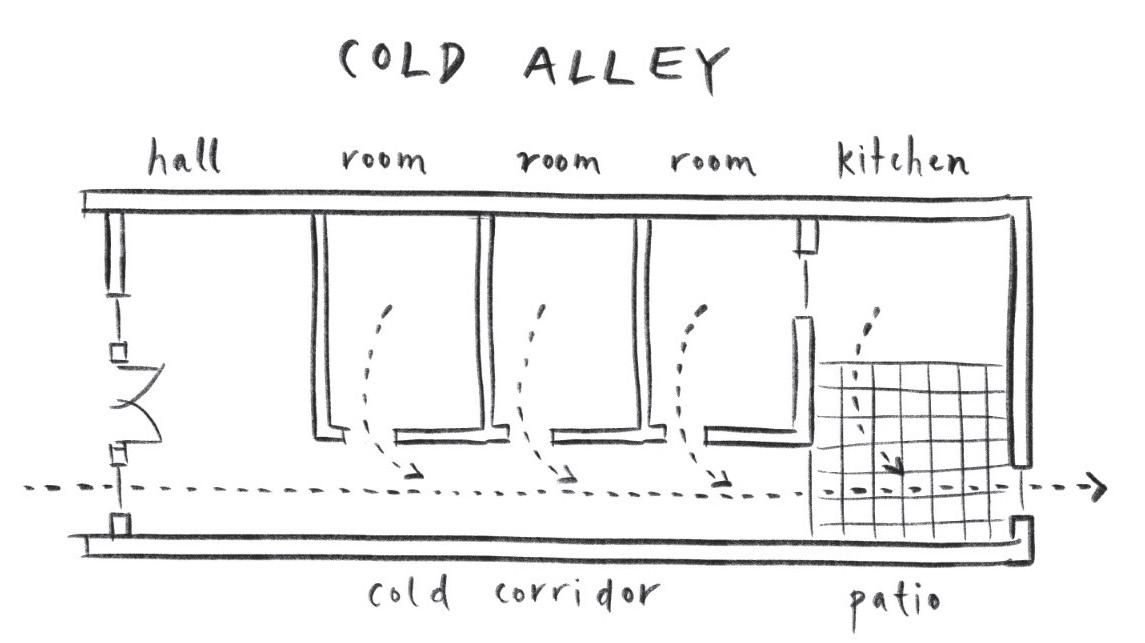

Shanghai and the greater region of the island have four distinct seasons, so our architecture has to uniquely balance opening itself to the outside and weathering more extreme climate events. Southeast China has centuries-old sensibilities regarding human relationships with the sun, wind, and water. For this region, comfort is best resolved through natural ventilation and orientation in relation to the natural elements.

Our designs should build on the wisdom of lived experiences finessed throughout history, folding in a renewed sense of urgency to design with nature. – Olivia

Our site is peculiar: open and simple. The land is relatively flat and currently undeveloped. The “local” inhabitants are plants and animals; people are relatively recent additions. Digging one meter down, you hit groundwater. The conditions present an opportunity to make a special place on the island, learning from the nearby Yangtze River Estuary wetlands. Our goal is to create an environment within the campus for future designers to grow. – LH and Wenjing

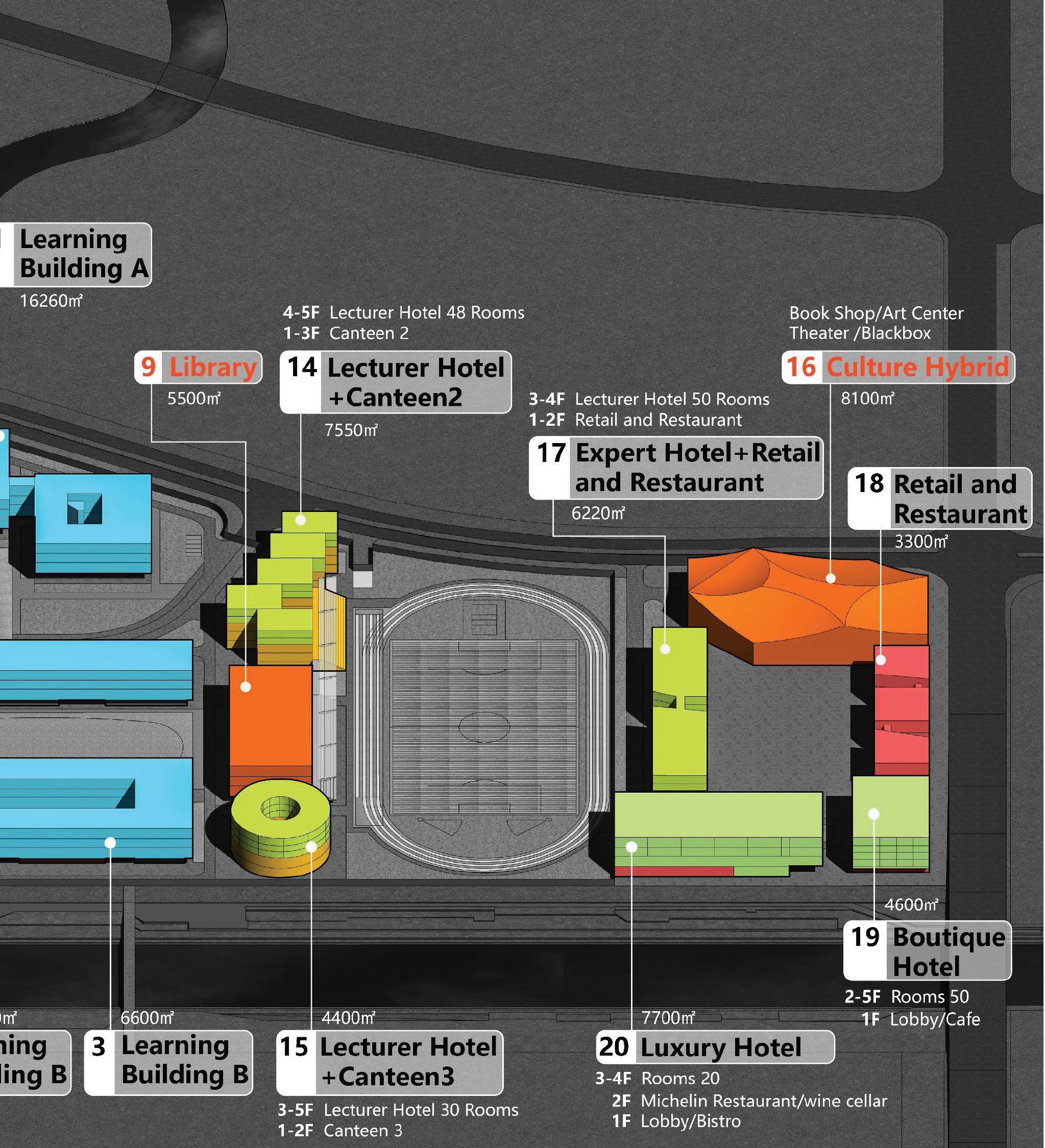

The plot is within the campus of a new college on Chongming Island, 80 m x 80 m in plan, with a height limit of 24 m, and a maximum building area of 13,500 m2. The college campus is within a development area zoned for education and research. It is adjacent to two other college campuses. Two subway stops provide convenient access from the center of Shanghai to this island.

A river walkway and bridge bring the public and local community past the new site for the design school. Adjacent to a new entrance for the campus, the design school is a gateway between the college and the island. – LH and Wenjing

The meta task of designing a design school while in design school gives us an opportunity to think in both practical and idealistic ways. How do you craft a school for ambitious yet grounded designers on an island?

This studio gives us a chance to reflect on our personal education experiences thus far and imagine how to improve upon them. Placing a design school on Chongming Island demands a global view and the ability to dream larger than life. It is a destination for people to migrate to from all over the world, like the birds that flock to the island. It is an interesting challenge to critique design education from within it; it feels like our responsibility to give some insights back to our school as we near the end of our individual design education journeys. – Olivia

Chongming Island is a historically and ecologically rich land, but it is continuously evolving in both form and function as evidenced by the project site itself: a flat, square tabula rasa plot within a superimposed master plan.

Since few defining conditions currently exist, the new design institute should interact with and respond to local ecologies while manufacturing its own extroverted context within the university campus.

– Connor K.

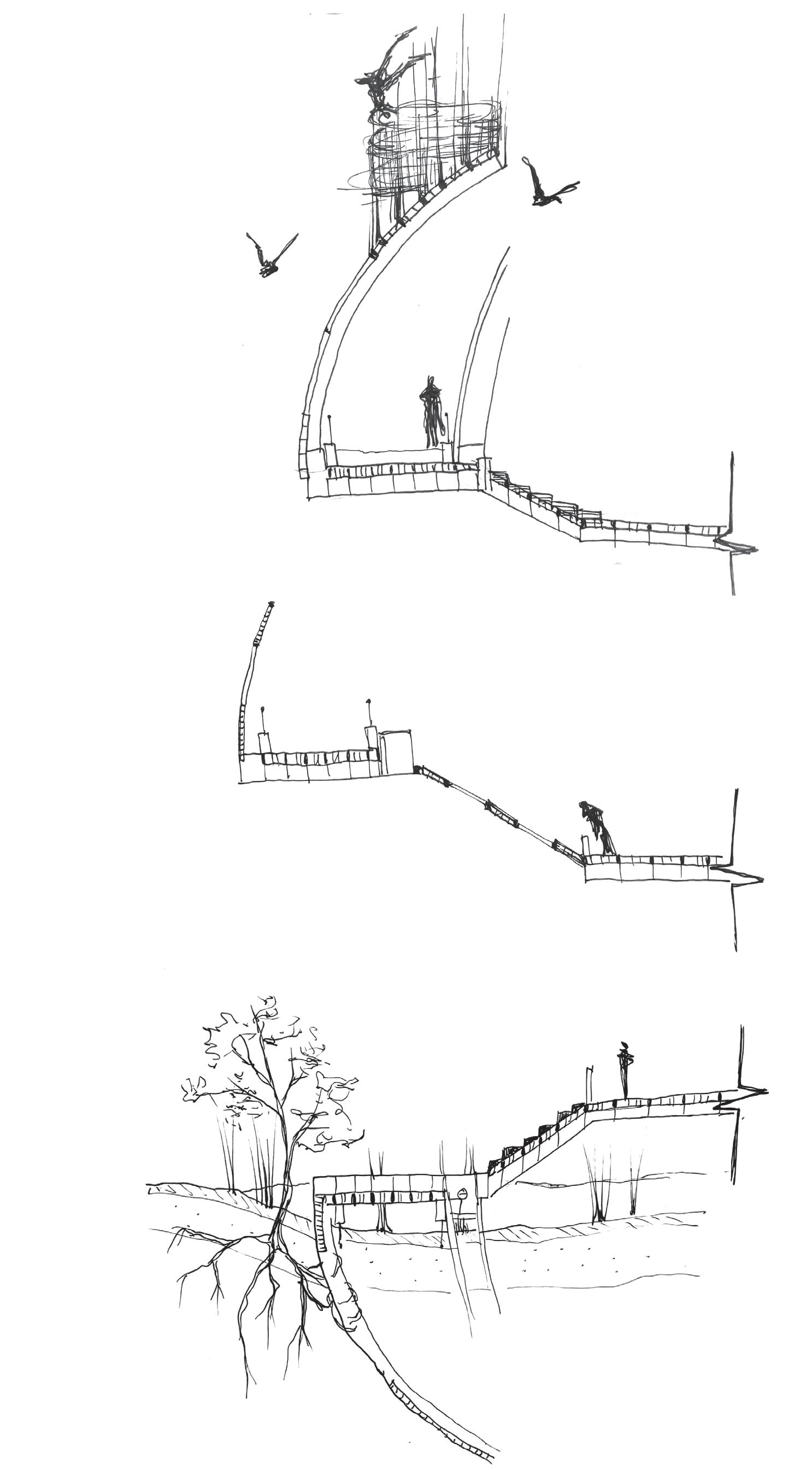

Our goal across the site is to create axes of circulation and connection between the campus and the public. This means crossing over a river and expanding the wetlands toward the public.

The new vision for a design school is the building as a bridge and an extended wetlands park, which breathe together the functions of the school with the life of the ecosystem. – Vinz and Sophie

The site is located at the south center of the campus, bridging residential and cultural programming from east to west and extending a constructed wetlands park across the master plan toward the river. As a microcosm of the whole, the school of design can join many forces across the site lines, allowing for loose indoorto-outdoor connections, ebbing and flowing according to the school’s needs, or gathering people and ideas from the rest of campus. – Lilly

How do we understand the natural history of the site? How do we manifest the natural environment within the school? Water is all around you on the island; you should feel its presence even inside the building. The wetlands filter and clean the water of the world. How can the wetlands help design students find a healthier balance in life? – LH and Wenjing

Wetlands provide a habitat for thousands of species, promote biodiversity, and serve as the stage for a natural equilibrium. They function as a CO2 sink, clean the air and water, and act as a sponge regulating flooding all over the world: they are a perfect machine. The recent dramatic reduction of wetland surface in favor of frontier expansion with sealed grounds and economic outlooks can be situated in the current tragedy of climate change. As a consequence, flooding becomes more frequent, a loss of biodiversity is evident, and a chain reaction of events ensures the worsening of human living conditions.

How do we expand knowledge from the local to the global? How do we deal with the critical situation of the Earth? What are the various ways to explore new modes of coexistence between all forms of life? How to we develop a biocentric rather than a human-centric perspective?

– Vinz and Sophie

Chongming Island has a history of traditional land use and industrialization of reclaimed land along with a recent shift toward ecosystem tourism. Our site consists of reclaimed land with a high water table. In the future, rising sea levels will increase soil erosion.

There are three strategies for this: absorption, storage, and contouring. Building campuses on either side of the local tributary will increase the impermeable surface area. With climate change, the land will require more retention basin area. Therefore, we will convert the site back into natural wetlands to allow for increased groundwater storage through the underground connections between adjacent bodies of water.

Humans can inhabit the zone above the wetlands, while the equally important life of the land flourishes in its rightful place.

Coastal engineers fighting soil erosion due to rising sea levels advise against human retreat, emphasizing the need for a symbiotic relationship between people and the coast for the entire ecosystem to survive. – Maddie and Tanil

Wetlands are a transitional zone, soaking and drying at their interwoven edges. Species migrate, collect, and nestle into this extended edge. In this school, it’s the fuzzy fertile edges, the third spaces of overlap, the ecological transition zones, where a vibrant life unfolds. In Ways of Being, James Bridle describes the more-than-human relationships we inhabit as nourishment coming from within the messy entanglements of life. – Olivia and Lilly

“Life is soupy, mixed up, and tumultuous. Muddying the waters is precisely the point because it is from such nutritious strains that life grows.” – James Bridle

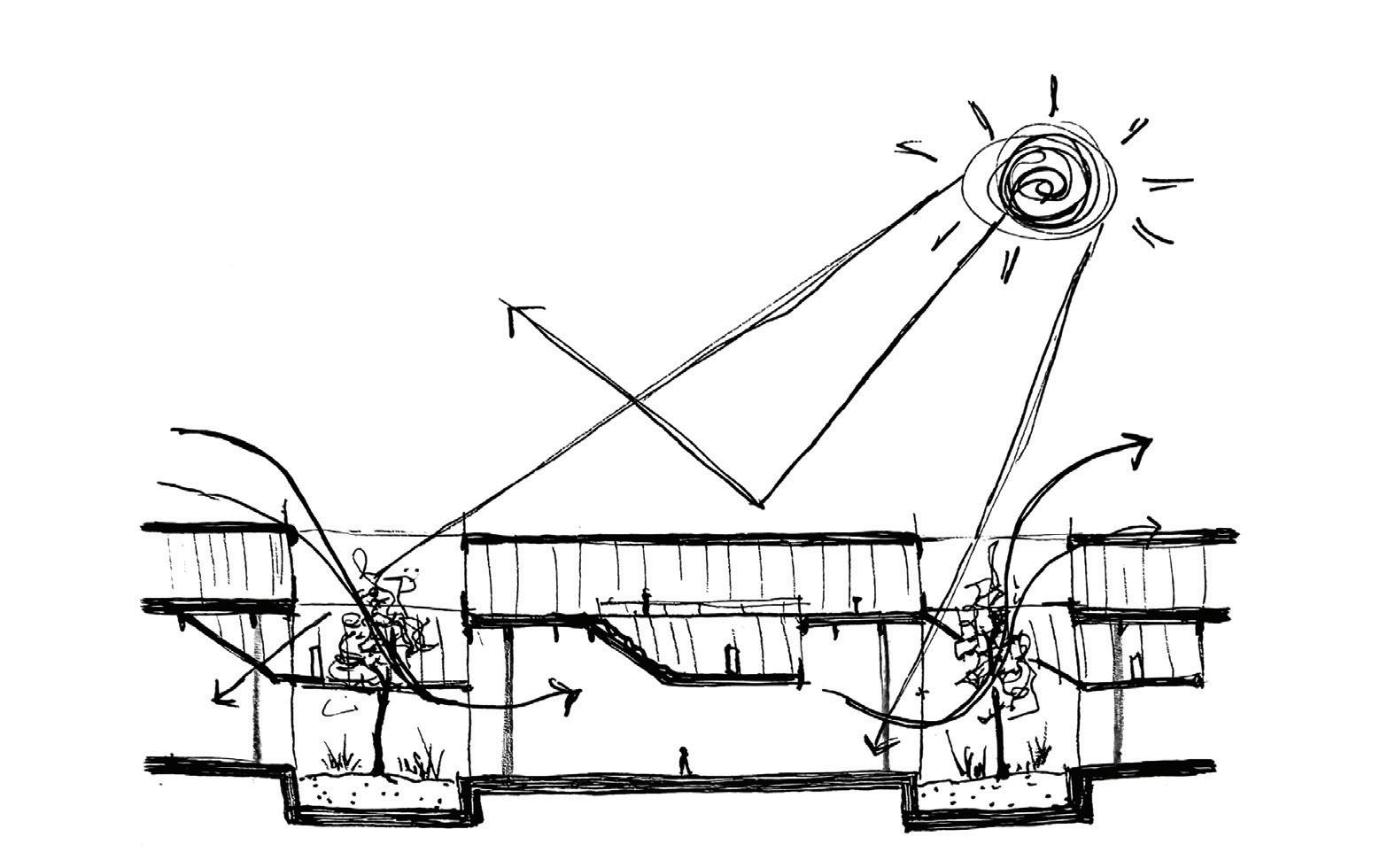

From the hermetically sealed to the adaptive and integrative, the creation of a building in tandem with nature pulls back the line of enclosure from the edge of slabs. Eating away at floors and roofs when appropriate allows for the pulling of a dominant north-south wind and various sun angles through the building.

The open architecture lets life spill in or out, tying the rhythms of work more closely to the cycles of the surroundings. – Olivia and Lilly

The environment, which is too often imagined as inert empty space or as a resource for human use, is, in fact, a world of fleshy beings with their own needs, claims, and actions.

– Maddie and Tanil

Every day is different in the life of a designer. A complex and rich experience comes from meaningful interactions with nature—the different species by day and by season—like a narrative unfolding. – LH and Wenjing

A “holobiont” is a holistic biological entity composed of a host organism and an intricate consortium of microorganisms encompassing bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

This collective assemblage forms a dynamic and interdependent ecosystem that is existentially intertwined with the host’s physiological and ecological interactions. This symbiotic relationship is an obligatory one.

The highlighting of the term should bring us to the understanding that we live under the myth that there can be individuality in a biological sense. Symbiosis is the strategy that supports life on Earth. We are all holobionts by birth. – Vinz and Sophie

I cross the same intersection at the northeast end of Gund Hall’s entrance every day. There is a low point in the intersection of the brick sidewalks where water pools when it rains.

I think about how the simplest act of noticing and paying attention is a form of reciprocity with our world, and it creates a sense of presence and awe in the everyday.

This resonates with Chongming Island’s changing conditions, from monsoon rain to the dry season, a condition that the school’s residents should notice and feel: the weight of changing days as inspiring moments through the monotony of human schedules. – Maddie

Through dialogue and reflection, we find ourselves. Design with a sense of humor. To create is to connect with yourself, to nature, and to others. Encourage generosity. Unlearning is a journey of discovery and freedom. – LH and Wenjing

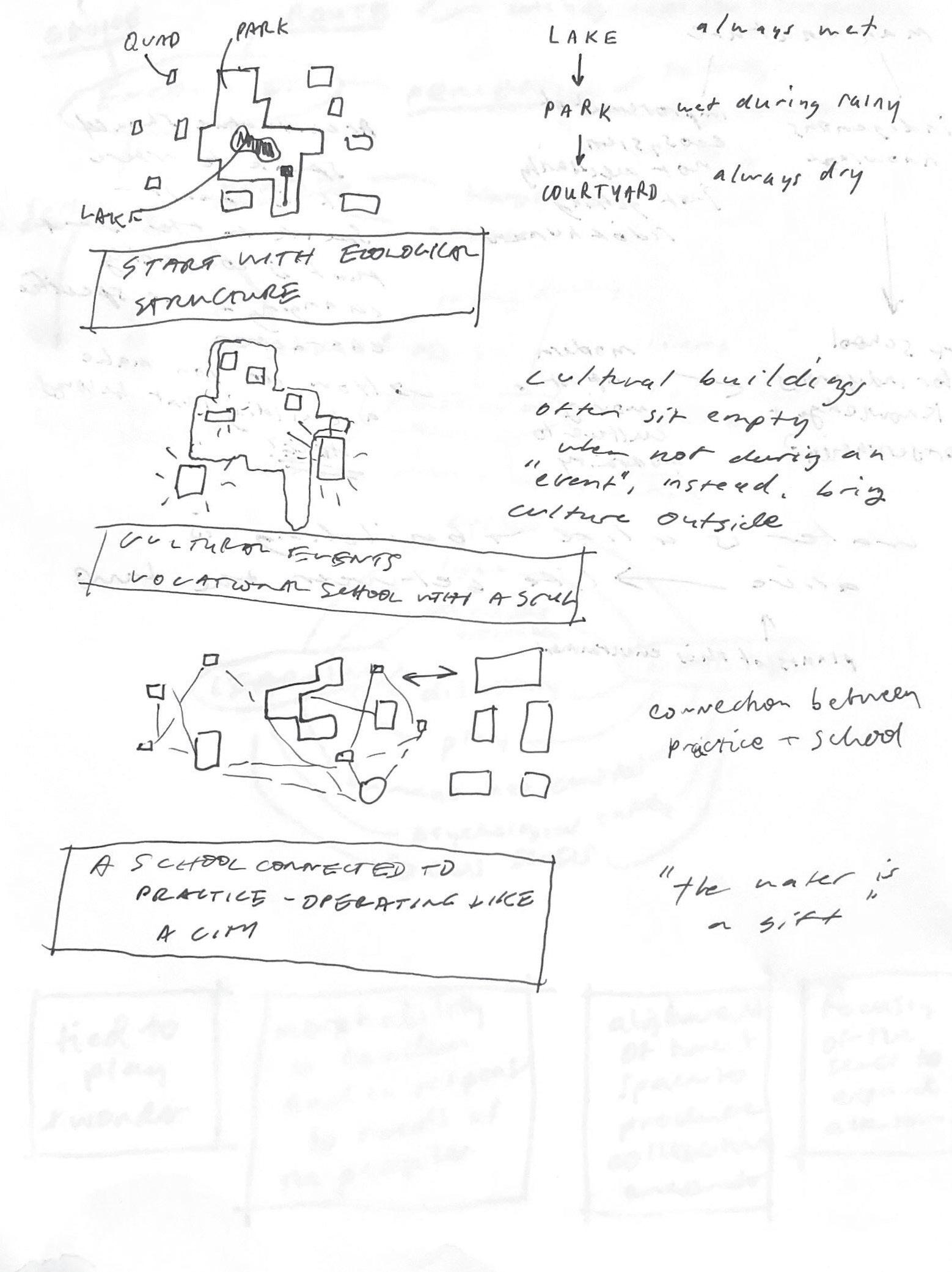

What is the structure of a design education? How do we design for different kinds of learning? How does the shape of a curriculum influence the form of the school?

What are the current trends in design education, and do different locations adhere to similar curriculum structures?

How do you design a design school? When and where do students between majors interact? When does the outside world engage with the curriculum? – Connor G.

In Gund Hall, we lack cross-disciplinary connection and feedback from public visitors. We hold reviews behind intimidating closed doors and invite only those within our discipline to critique work that affects a broader population. – Maddie

Connections across disciplines are tenuous, as most curriculums do not actively build interdisciplinary opportunities into requirements. Responsibility to venture out and explore other disciplines falls on the students. Most stay within their departments. – Connor G.

What are the social dynamics inherent to design schools, and how can they be a catalyst for the shape of pedagogy and architecture? Chongming has a rich tradition of craftspeople within the community; the design school could benefit from local engagement with craftspeople who bring pride to their making.

The island’s unique ecology and natural materials create a strong identity, which informs both the sensibility of the local craftspeople and the design school’s pedagogy of learning from nature.

By connecting these interlocking actors—the design school, the community of craftspeople, and the island’s species—the school of design may find rooted innovation, reinforcing a profound sense of community and place.

– John and Gustavo

We take inspiration from the museum experience to redesign the school experience as a living museum. Museums concern the past, present, and future, inviting visitors to choose their own adventure through a narrative of time across space. Museums are cultural sites that empower communities to make as a collective. Schools are often siloed by discipline, focusing on didactic teaching methods rather than learning through playful imagination. School is a personal pursuit, centered around the individual.

The living museum as a design school model encourages contact and collaboration with local ecologies, community, and industry. – Maddie and Tanil

Learning takes shape across a fluid continuum between interactions and encounters with others. Open spaces that allow people to congregate, share knowledge, and transform ideas into form are third spaces of learning. The informal nooks, hallways, and gathering places between traditional classrooms—the in-between spaces to venture and linger—are key architectural opportunities to design for knowledge sharing.

Design education should allow for both breadth and depth of experience. Departments thrive by cultivating their unique identities when given the breathing room, but they should also share knowledge, resources, and spaces. Sharing encourages disciplines to intermingle, to learn from each other, and to hybridize approaches. Guarding allows disciplines to sink into their specialized practices.

It is a beautiful phenomenon in the crowded forest that trees entangle their roots to share resources and communicate, but each species’ unique canopy above grows apart to allow room for light and air to seep in and nourish symbiotic relationships for the whole forest. We use the analogy of “crown shyness” for the design school’s interdepartmental relationships.

Every department needs breathing room to cultivate its unique identity, but they share the same nutrient ground and flourish from intertwining their roots. – Olivia and Lilly

Many design educations today do not provide practical training or outside engagement with industry. Design schools need an incubator: a physical space for students to explore ideas between academia and practice, inside and outside of the school.

Design education should build reciprocal relationships between the institution, industry, and the community. A new pedagogy introduces interprofessional studies and professional work experience into the school curriculum, its physical spaces, and its programming. These collaborative classes and events bring together students, professionals, faculty, and the surrounding campus in a new architectural typology: the incubator. – Connor K.

Like the spongy wetlands, design schools fall in between different conditions: thinking and making, learning and unlearning, theory and practice, ideal and grounded.

At the core, designers are makers. Workshops and studios are the center of their experience. But each discipline places a different value on informal learning, which is perhaps the most important kind of learning. Fluctuating between thinking and making encourages informal learning. The school of design should give students a chance to pause and reflect individually or communicate and collaborate collectively. The students may learn informally from each other, as peers are the greatest teachers. – Yihan

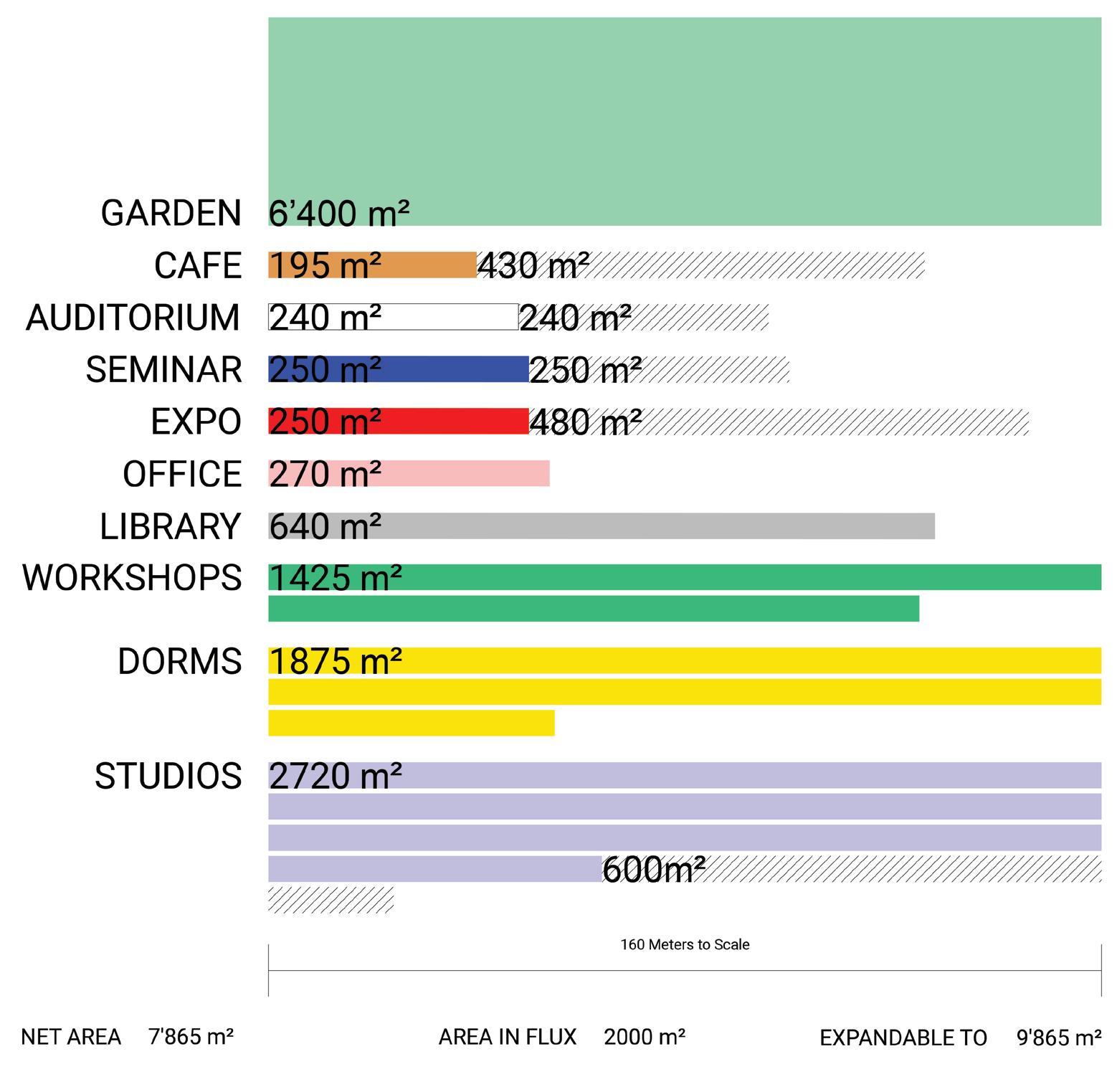

The program for this project is large and sophisticated. The design school functions like a small city, so we encourage students to think big.

The final outcome is the design of a school of design for 300 students in a new college with three-year programs. The studio aims to collectively develop a vision that fits the college, the site, and the time that we are situated in.

A functional program serves as the basis, but it can also be regarded as merely a point of departure—any desire to tweak or rewrite the program according to one’s own take on how to educate and nurture designers today will not only be tolerated but also encouraged. – LH and Wenjing

Labs and Workshops

(7: Textile, Metal, Ceramic, Glass, Wood and Organic, Synthetic and Composite, Media Lab)

Design Studios

(15 studios for 5 majors: Industrial Design, Furniture Design, Communication Design, Textile Design, Fashion Design)

Design Library

Total Building Area: 13,500 m2

with a Botanical Garden

Rooms

Lecture Hall (330 seats)

Exhibition Space

Dormitory (for 100 students)

Café

Programs should breathe, expanding and contracting to be used in different ways or to be tucked away if unnecessary. The school’s functions bleed into one another and fluctuate in an interdependent relationship with each other and with the surroundings.

We think it is important to reduce the overall area of the building on the ground so that the wetlands park is proportionally the greatest programmatic entity, both functionally and symbolically. – Vinz and Sophie

The environment at the school represents an ecology of creative making; the architecture should reflect the diversity of disciplines and their overlapping practices.

Designers of all backgrounds should share workspaces, as workshops are the essential “bridge” spaces for a design school’s social life.

Bridge spaces are the connective tissue between departments; exchange is inevitable when you share tools and tables while making ideas tangible. How and when departments come together should be more intentional in the architectural planning. – Connor G. and Ryan

A design school balances chaos with quiet. Part of the education is learning how to quiet and how to spark the mind.

College life teaches students to think and make, think and rest. The school offers places to get lost in the stories of other people and species, other times, and other places. It should be a place where designers can make a creative mess and get comfortable in their own skin. Students should ferment in the library, in the museum, in the knowledge and memory of nature.

Architecture should allow us to nestle into ourselves and our good nature. Classrooms are havens for listening without judgement, taking risks together, and believing the best in people.

–Olivia and Lilly

What is a workshop? It is a collection of tools, which extend the hand and start with a distinct function that can adapt and change for unexpected uses. What is a studio? A house for creative processes that can unfold sequentially or fluidly in surprising combinations.

Shared studios and workshops are theaters of “How did you make that?”

What is a library? A collection of knowledge, memory, and history in many forms that encourages reading between the lines. What is an exhibition? A gathering of materialized ideas. Both are places to steep, like tea, in inspiration. – Olivia and Lilly

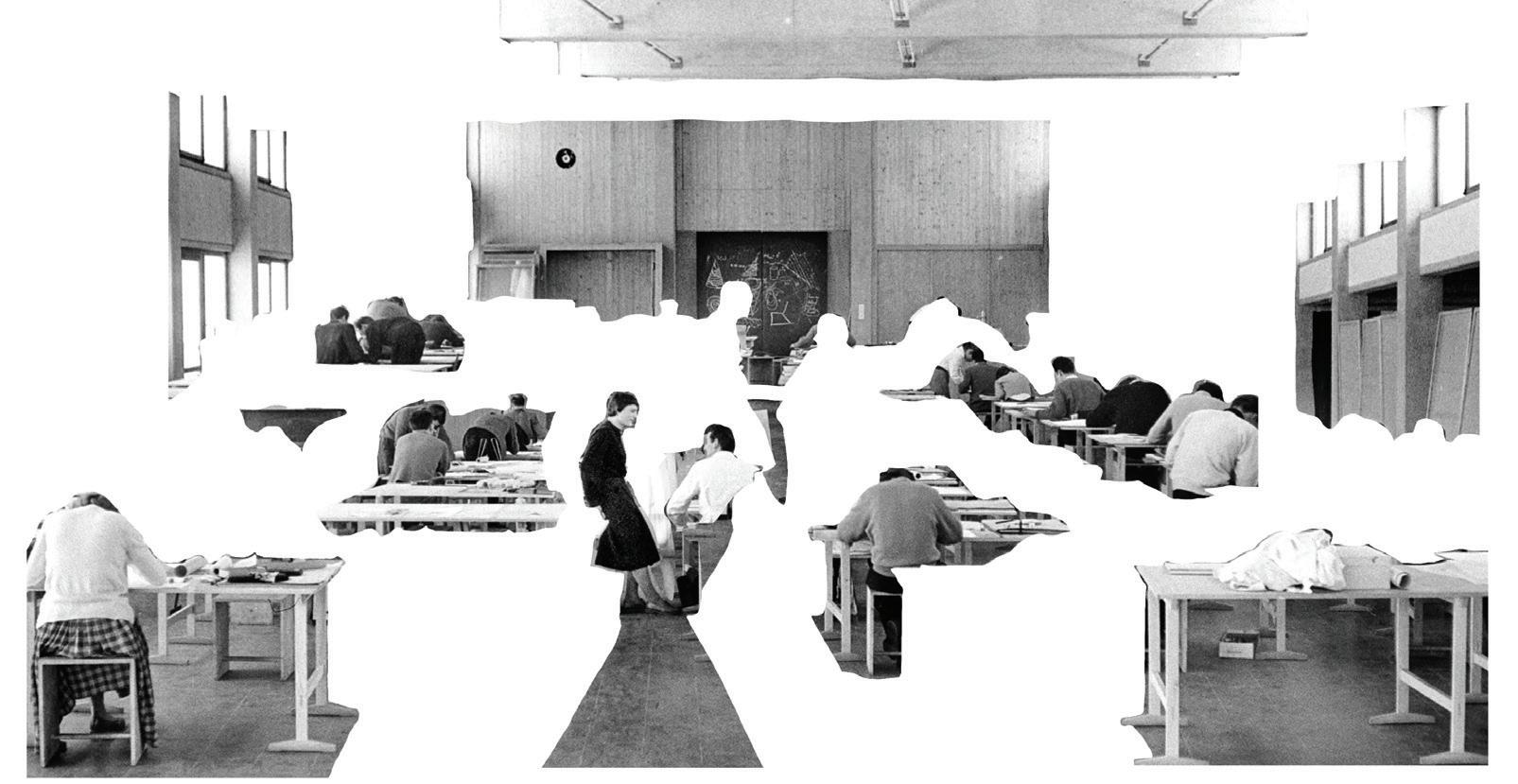

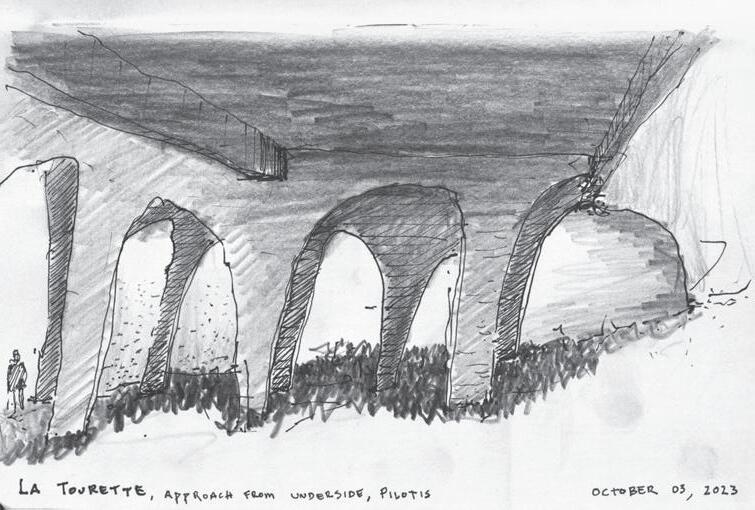

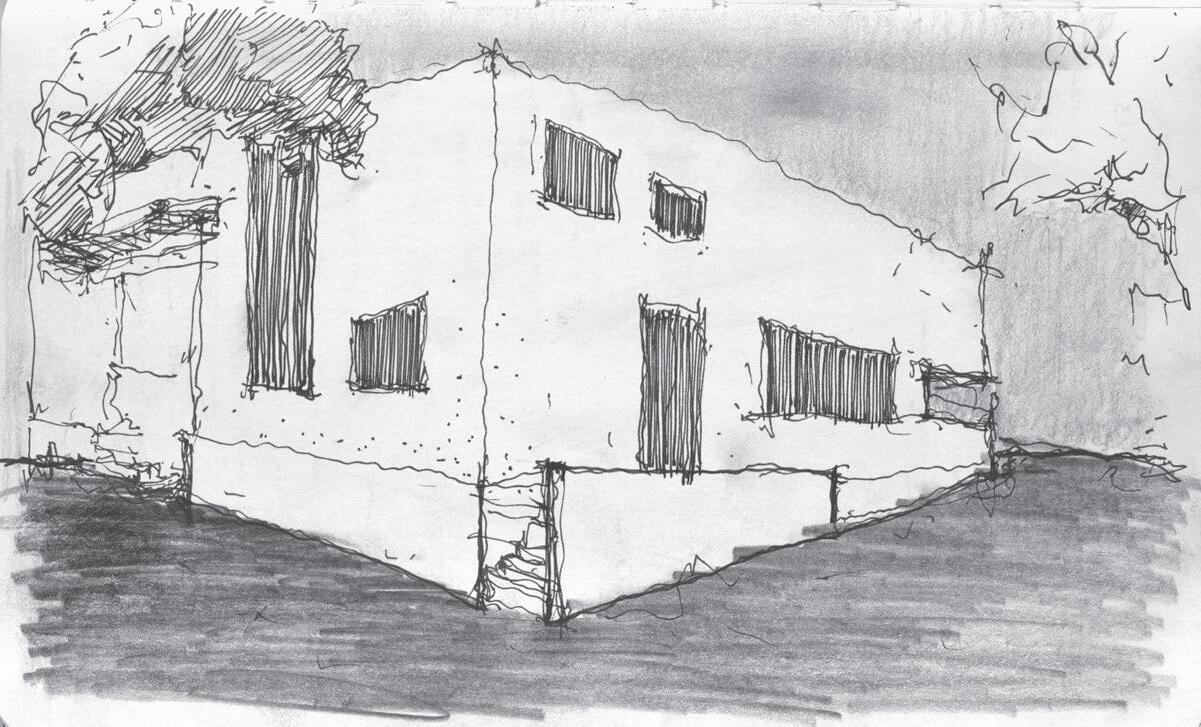

Instead of a site visit to Shanghai, the studio took a trip to see the two most important sources of inspiration for this project: the Convent of La Tourette and the Bauhaus. We also visited some offices of architects and consultants who we believe are radical in their design innovations and creative collaborations that align with the studio’s goals. – LH and Wenjing

It is impossible to overstate the influence of the Convent of La Tourette on generations of architects and designers, but for this studio in particular, it is an inspiration for the integration of communal learning, meditation, and living in a modest yet deeply influential way.

The impact the Bauhaus had on design education, thinking, and practice has reached far beyond its relatively short existence. A hundred years later, the idealism and experimentation of the Bauhaus still speaks.

We approached each architectural and consultant office with questions and curiosity.

The sharing of ideas and conversations between students and practitioners is a humbling experience that encourages generosity in mind and in action.

We looked to the Bauhaus for its new teaching methods and pedagogy. To forget the rules and reinvent them in a constant process of learning and unlearning is the way of the Bauhaus and the spirit of our studio. – LH and Wenjing

The Bauhaus philosophy stretched deeper than education to propose a new unity between architecture and the arts, bringing technical proficiency together with imaginative design; through this individual and collective education, one could grasp one’s life as a whole. It was a total design of the arts and of life, combining working and living.

The layout is simple: a pinwheel of two schools, a dorm, and a shared living space, all connected by a bridge over a public street. One wing is the technical school, the other is the workshop, and they share common eating, gathering, and performances in a living-festive hall.

These hybrid spaces explore relationships between humans, space, and nature, proposing that the activities of life could transfer between rooms and from inside to outside. Consequently, all spaces and their functions flowed into one another, sharing energy between working and living. People danced like machines across the stage and into the canteen. Art and technology intertwined in the design process, transforming workshops so that “the factory becomes the living room.” Work and life are one at the Bauhaus.

On our tour across the campus, our guide posed questions that the Bauhaus students asked themselves a hundred years ago and that still ring true today: Can we survive this world? How much machine can we find in humans? How much human can we find in machines?

Collective learning means trial and error, experiments and play, full-body exercises to synchronize the mind, heart, and hand. When seeking inspiration from peers, masters are students and students learn from masters.

This place, the people, and the materials themselves had spirit vibrating with inner life. The Bauhaus brought energy and character to space and to the creative processes that unfolded within it.

The (in)famous “form follows function” Bauhaus design manifesto derives from nature rather than machines, teaching students to fearlessly discover the natural world. While design could never reach a synthesis as perfect as nature’s, this utopian mindset encouraged ambition and optimism, both to which our studio manifestos aspire.

Building like a crystal to dematerialize architecture and produce what is light and transparent yet also mirrored and introspective, Walter Gropius deployed new technologies to make new spatial conditions and a new architectural language possible. Glass walls wrapping the workshops symbolize both an openness to the outside world and self-reflection in making.

Following Gropius’s legacy at the GSD, in our studio we hoped to produce our own deeply meaningful architectural language tied to pedagogy.

Le Corbusier sought the ineffable intuitive feeling that drives design: a sense of tension and poetry. When you can’t speak of the most amazing things, you make them. – LH and Wenjing

Visiting La Tourette at the start of the project allowed us to begin with that inspired feeling and work from there. Our goal is to achieve the radical and poetic.

Imagination needs diversity and the space for cognitive freedom; to daydream. A monastery, a school, or other places of study should allow opportunities for the mind to wonder and wander, stringing together random associations that lead to new ideas and realizations.

We design from the inside out; how one moves through space drives the form of the building. There are many ways to move through the Convent of La Tourette, a choreography from slow and meditative to brisk and efficient. Le Corbusier reimagines the historical cloister layout with a crisscrossing of paths that all connect to gathering places, intricately weaving paths for collective encounters.

La Tourette unifies spiritual life, common life, intellectual life, and individual life into a new collective typology. To eat and pray together, study and sing together, monks gather under a common roof but float above the earth shared by more-than-humans.

The small details everywhere mark the presence of Le Corbusier’s thoughts. The Convent of La Tourette is endearing, full of care. This architecture has a soul. It speaks beyond its time and to many people, generating a life of its own. The visit spurred questions that carried through to the design task at hand. What is the necessary building character of our time? What is the norm today, and why do we break it?

The pilgrimage up the hill is of intentional effort toward a building above the horizon line. The architecture’s subtle touchpoints hover above the sloping earth.

From the inside, the architecture frames views of the valley: a building in communion with place reminds us that we are more than ourselves. How do we make the building become the topography, a meditation

on the land? – Maddie

Gaps between architectural components breathe room to let nature into the monastery. The connective tissue pulls apart to allow light and air through the building, producing surfaces that invite nature to inhabit them equally. The convent floats above the ground, allowing every room to grow and shrink and shapeshift for its unique purpose, without disrupting nature. Canons of light and walls of glass modulate light and views for contemplation.

Why is modesty important today? Design should strive to use the minimum resource to achieve the maximum effect. We have more tools today to help us use less. The Bauhaus and the Convent of La Tourette both successfully achieved a modest and rich life.

– LH and Wenjing

At the Bauhaus, a vibrant social ecology aspired to democracy between students, masters, faculty, and workers. Collective living struck a balance between sharing experiences in the curriculum and daily life, while allowing for individual contemplation to find one’s role and niche.

Living together in modest quarters encouraged a colorful cast of characters to adapt to each other. Masters lived in houses clustered together like an artist residency in the woods. Every home was a stage for the individual master to live and think, think and make; a tranquil village immersed in nature.

Living at La Tourette is modest, modular. A simple bookshelf, bed, desk, sink, balcony, and candle holder are necessary objects of daily ritual. The Modulor creates a unity between the architecture and the human scale.

Modest architecture brings you to a place of focus, to think

and rest, study and dream.

Humans accelerate the climate crisis by consuming, polluting, and wasting too much. With simplicity and reduction, people have more appreciation and feeling for the changing and special moments of the everyday.

Simplicity and bareness in architecture awaken our innate senses toward textures, temperatures, and acoustics; deeper fuller experiences ground us as humans and register our existence in a moment of time.

Walking, singing, and talking produce long and powerful sounds, echoes of collective life throughout the Convent of La Tourette along the musical rhythm of windows.

The team members of dUCKS scéno wear many hats—they are engineers, stage technicians, and architects—constantly collaborating outside their group to design hybrid cultural spaces. They take the culture out of cultural buildings and embed it into unexpected places, everywhere, and for everyone.

The dUCKS are constantly reinventing themselves and are nimble in their design approach every time, as social and cultural environments are alive and constantly changing. They step into the shoes of many users, balancing the practical with the theatrical. Their job is to prepare architecture for the cultural world and its energy.

The conversation revolved around the questions of what culture is and how we design for it. Culture is a collective art composed of people, space, artifacts, and ideas—not a performance. It takes time to cultivate by pushing the boundary and uncovering cultural material at the local scale.

Culture is the nature of humanity—we make it together. Culture is political, not dreamy, and as designers we should encourage it to be political, not always beautiful.

What kinds of spaces encourage cultural production? Urban spaces the most, as everything is cultural when many forces collide in the city. The building is a small city, and we should try to create an urban culture in our buildings.

Culture is a way to doubt—to ask, maybe we can do better?

Educational buildings are oriented to learning and practicing culture. Designers get used to creativity and doubt together, so the philosophy of a design school should encourage a healthy amount of doubt, or critique. In our studio, we should continuously ask ourselves: “When do you let culture into education? Why? For what purpose?”

Transsolar KlimaEngineering designs sitespecific and dynamic building environments in collaboration with other architects around the world. Temperature and humidity, light and shadow, air and water are some of their key materials in building simpler and more robust architectural systems.

Designing comfortable spaces comes from tuning in to the body’s feelings, not measuring absolute temperature, humidity, or airspeed. Transsolar excels at combining intuitive design methods with advanced measurements to prove the balance of forces affecting comfort conditions.

Most importantly, engineering for comfort is about not wasting and valuing modesty. Designers should aim to conserve heat and energy, material volume, and surface area.

Transsolar presented unique examples of how to teach clients to engage with with buildings. For dynamic and naturally ventilated buildings to properly function, people need to learn how to interact with the building, how to open and close it to the outside and how to develop a new active relation to architecture. In addition to training people to use buildings more actively, the spaces themselves should be more flexible in function, able to be used in many ways. This way, buildings have renewed energy, life, and dynamism, inspiring connections with people.

Simple is key: essence above complexity.

Marcus Lager is a carpenter first. His philosophy is one of simple construction with a carpenter’s sensibility. After starting small and scaling up to build the first timber multistory building in Germany, LAGERSCHWERTFERGER now combines experimentation in timber and hybrid timber buildings ranging from small details and joinery to larger assemblies of structures.

Responsible material choice is the answer to a sustainable future. Building with wood should be second nature.

Design to use wood’s organic grain direction for new structural capacities. Account for flexibility in its expansion and contraction with humidity. Bring warmth to atmospheres. Building with timber speaks to the environment—its climate, vegetation, and place. Timber construction is absolutely usual. We need to continue using it in new ways with the same sensibilities.

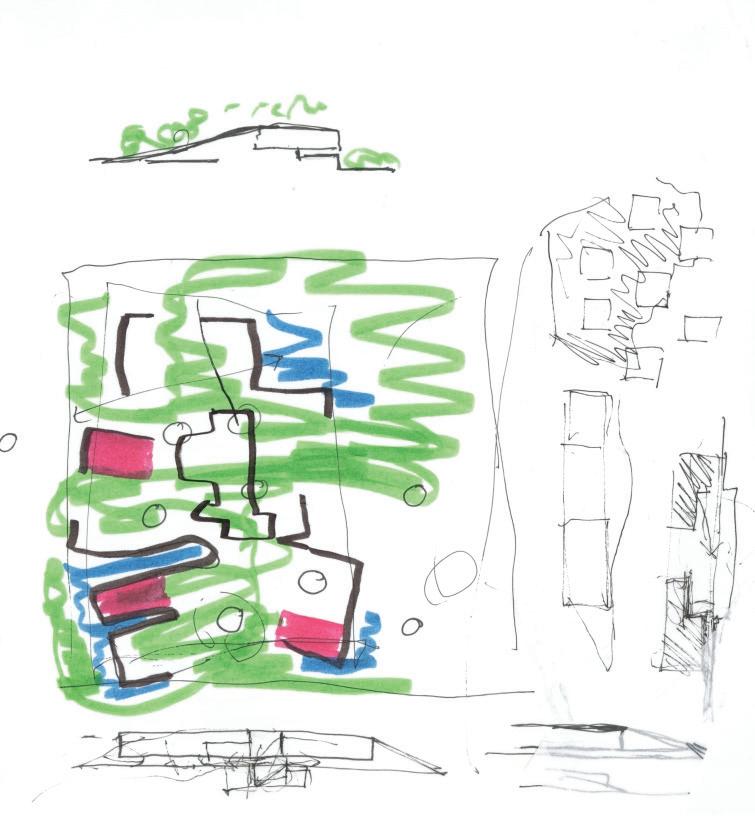

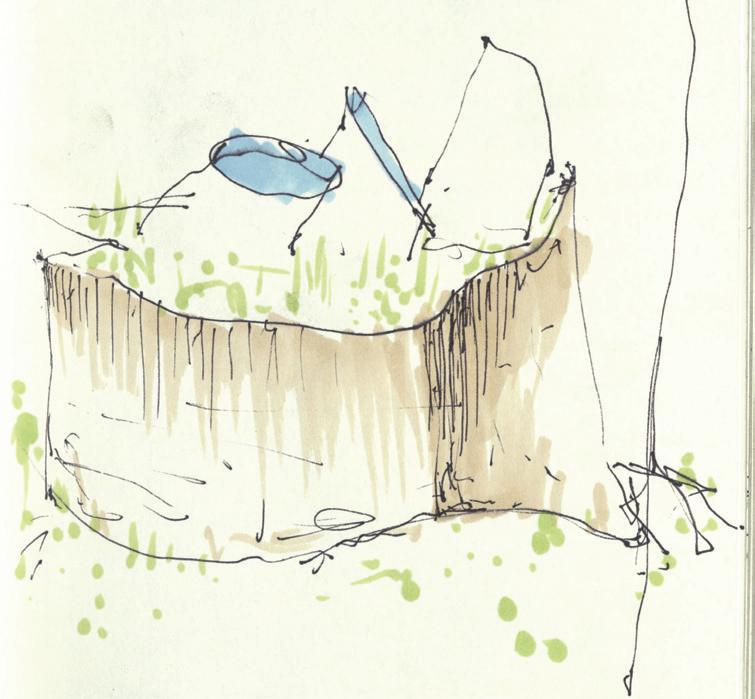

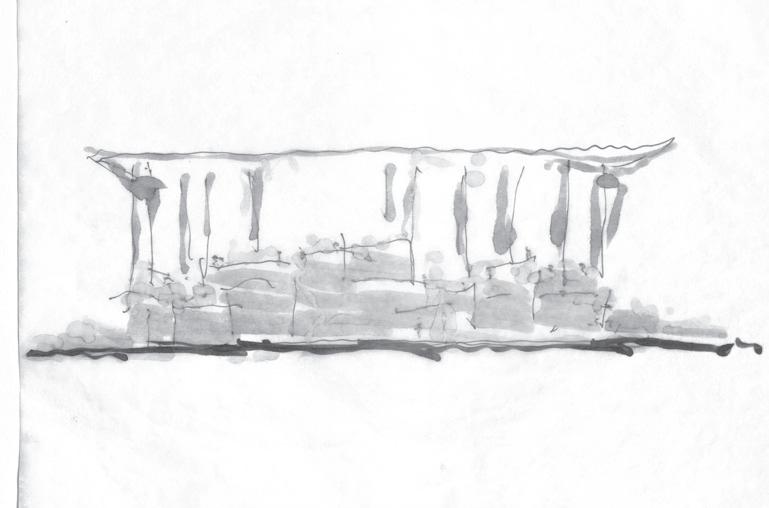

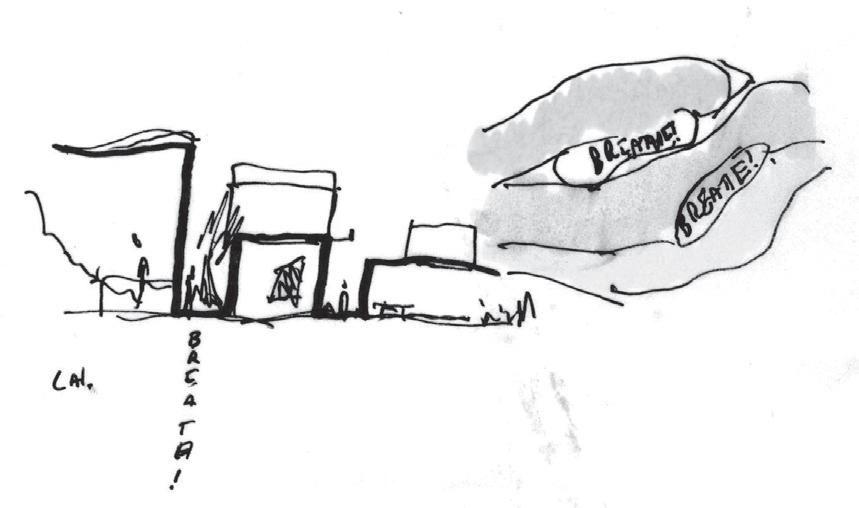

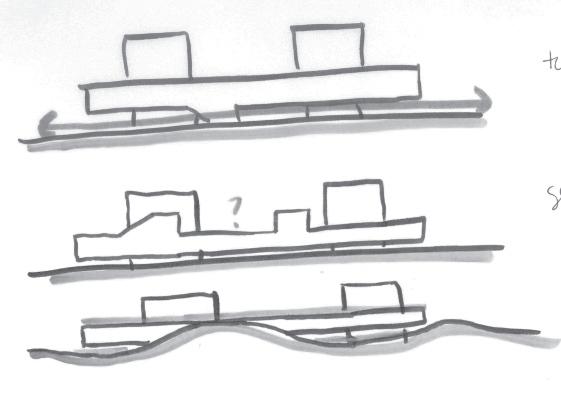

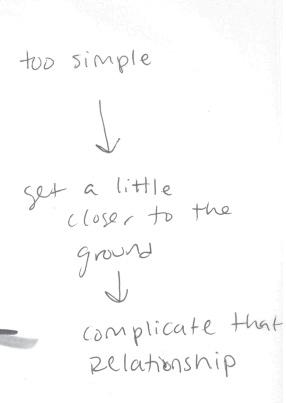

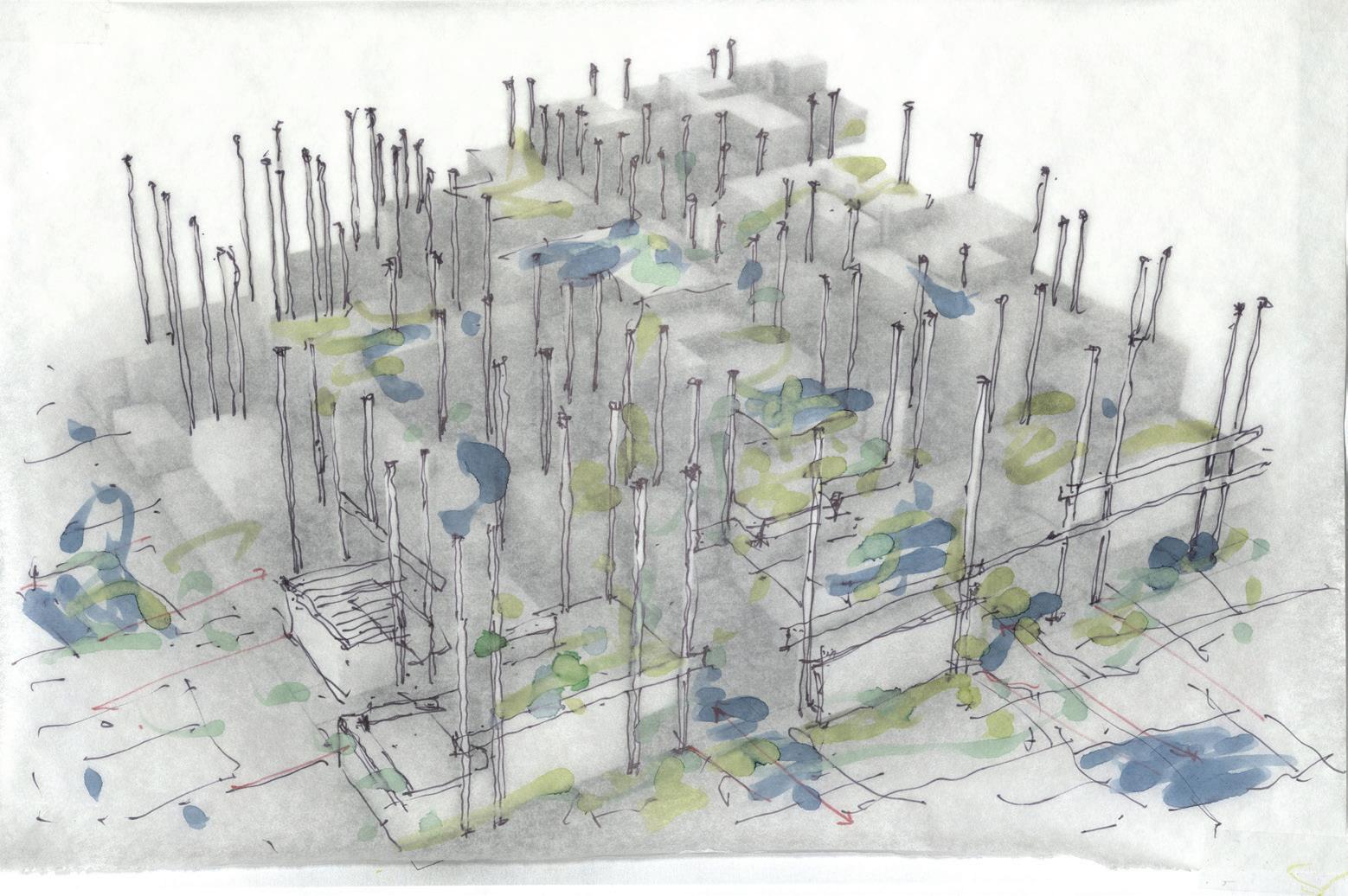

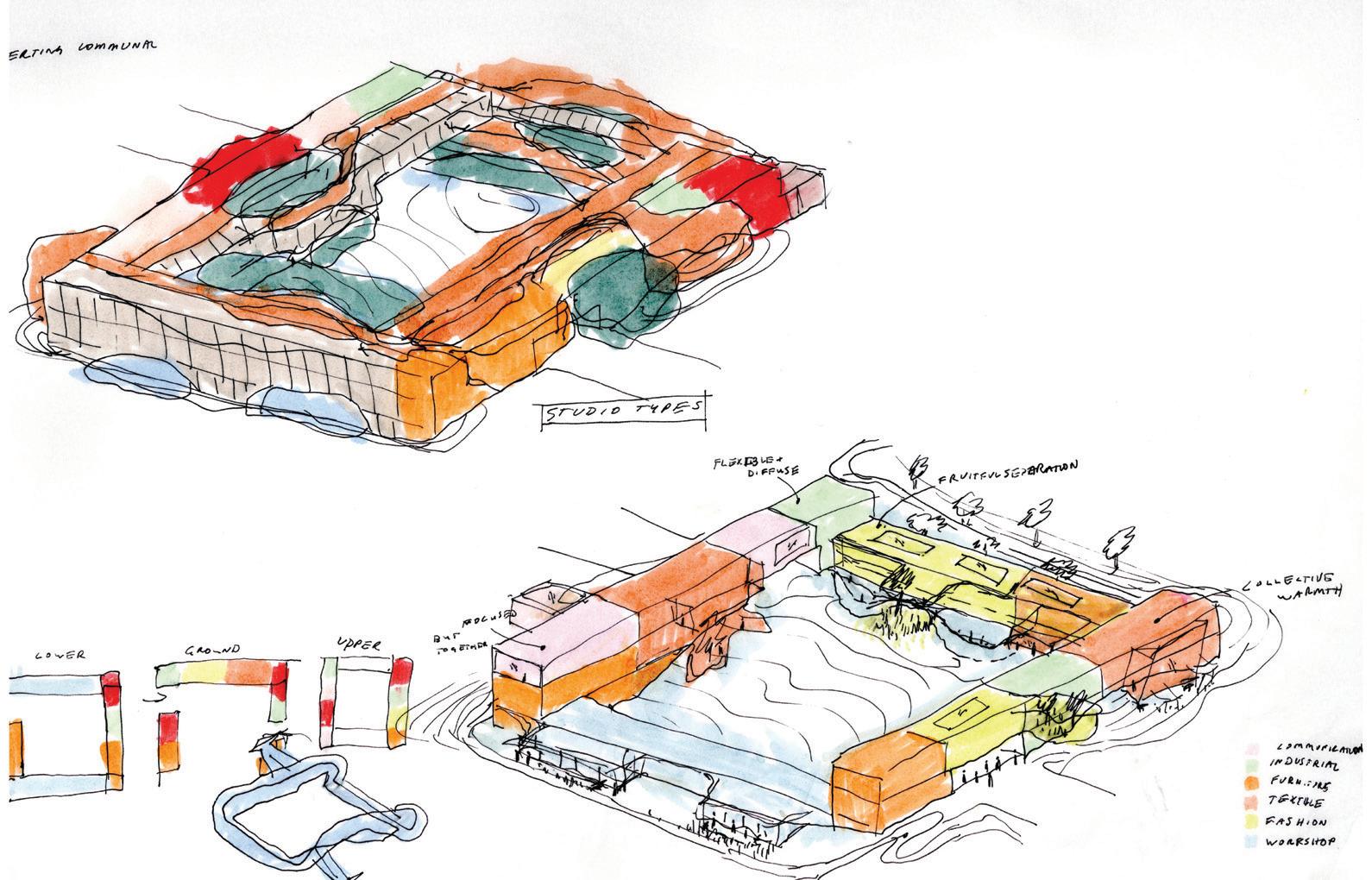

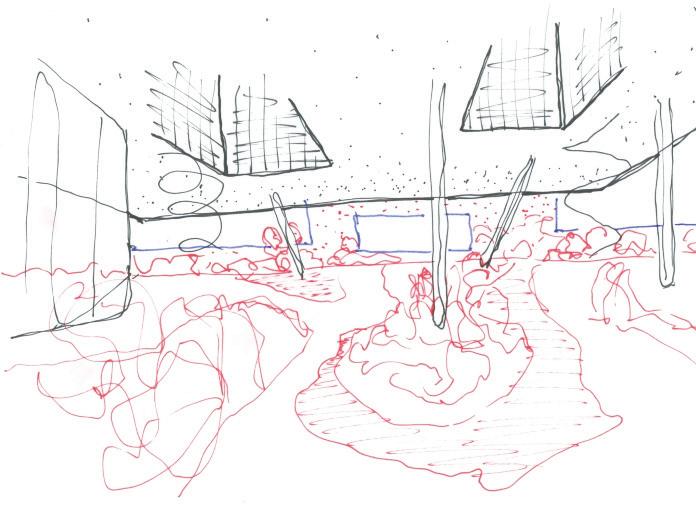

Early designs might be naive, but they should be passionate and sincere. What should the future design school look like? How do we design our life? Can we place ourselves in wetland ecology? Initial design experiments are a fuzzy landscape of concepts and ideas which are murky, messy, and unburdened as students start to unpack the problems while dreaming up possibilities. Designs gradually gain clarity and precision as they move along. We encourage students to think with their minds and hands together. Fly high and land somewhere grounded. Every student is unique. We focus on what is most special in each of their approaches to a collective set of questions.

– LH and Wenjing

Pieces of wetland and sky

Assisting flood water retention

Dialogue across an open valley

Present and aware of passing time and specialness of site

Breathe!

Inner routes

Spaces of care, storage, venture, lingering

Formless, a delicate weave of members

Exaggerated overhangs, shade is everything

Breaking up volumes allows for ventilation

Resist a monolithic horizon with sectional break up

Connect ecology above and below for more porous movement between grounds

Nature is the mediator between work and life, a buffer space

Restorative nature of outdoors helps quiet the stress and chaos of a creative life

Bring the garden inside Chinese scholar’s gardens place small natural environments into urban settings

The careful curation of plants, trees, rocks, light, shadow, and white walls creates depth and experience.

A commune of designers in residence

A village

Living and working is one thing

Leave some gaps

Human cohabitation with natural environments

Above: Section sketches by

Inner life spilling outside

Proximate zones collide and recombine Fluid movement between mixed uses

What character does the architecture want to be?

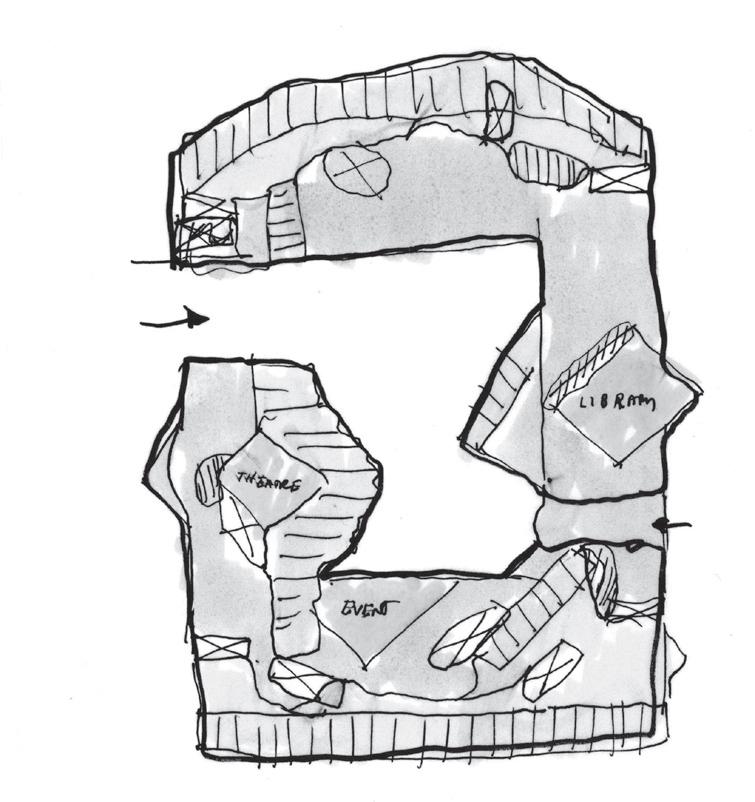

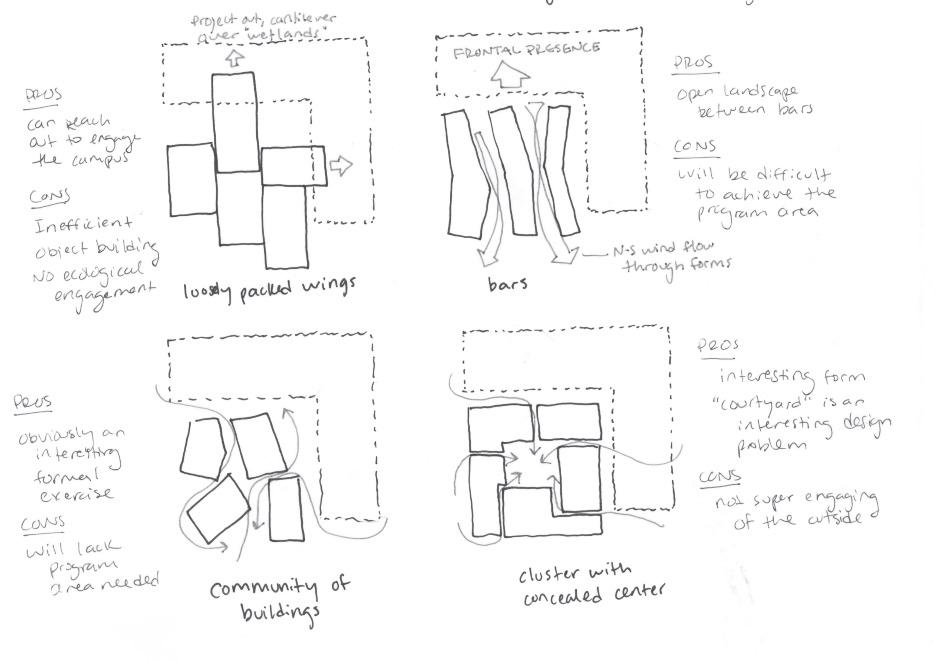

Loosely packed wings, community of buildings, cluster with concealed center, bars, or mat?

One home for 300 designers or 300 homes for each designer?

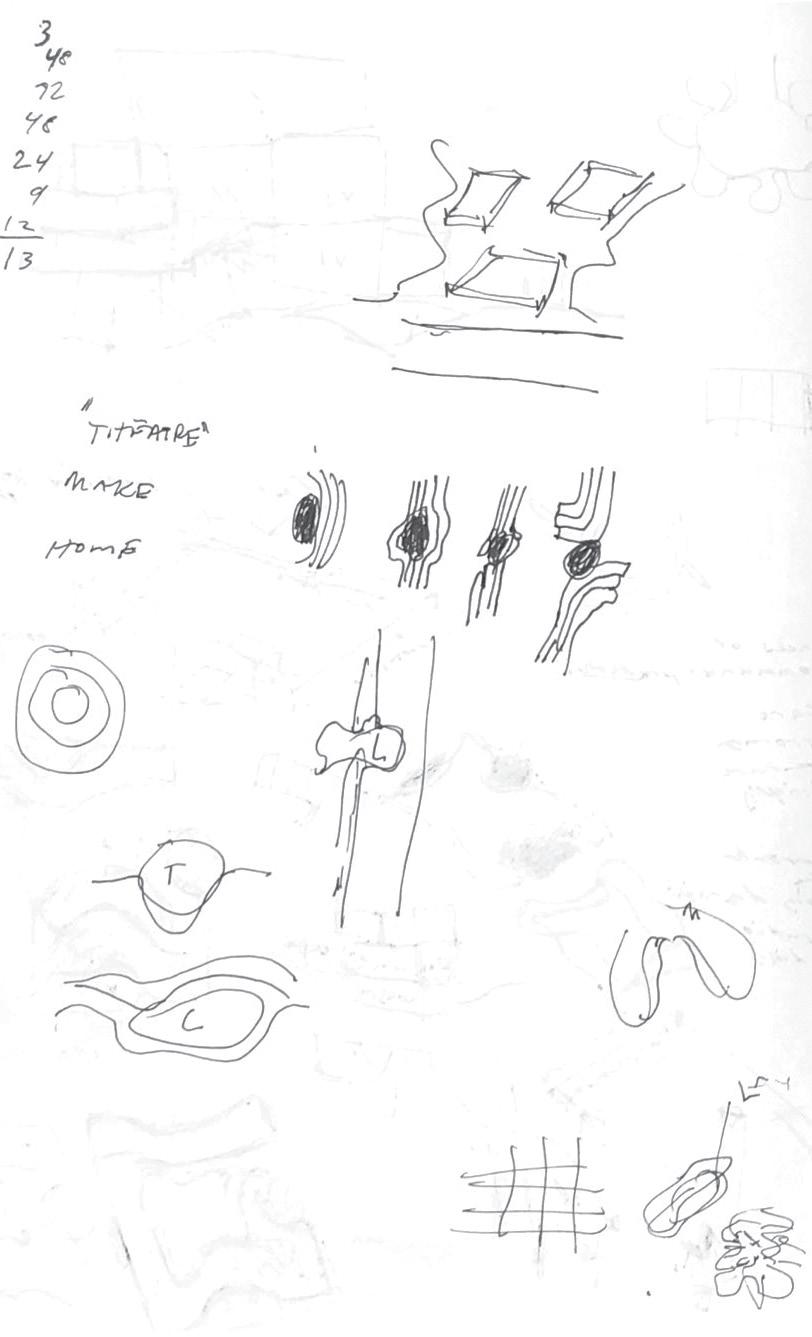

“Theater”—Make—Home

Lungs—physiological / ecological Layers—inner relationship between work/live Gates—cultural

A new hybrid species of architecture between realms of public/private

Protection—Experimentation Space to go outside of ourselves—fully within oneself

Breathing building

Nature invited to patios, mutual spaces for visitors and students

When do work and life conflict?

In a healthier environment, you can have it all

Strategize locations for rest and leisure along an efficient path to work

Open structure

A gradient building as bridge

What is the new figure of civilization that you see here?

Every member overlaps each other: plaid, network, connections, stepping

This system produces differentiation and suggests a collective

A new theory of architectural components, an aesthetic of systems and assembly

Timber lends itself to expression of joints, forests rely on interconnection between species

Material is a holistic organism

This produces a civilization, a relationship among parts

A formless language and disappearance of architecture functions smoothly with this mild climate

Porous space

Elevated garden

Draw people in from across campus

Pool and flood the center

Gathering, a pilgrimage to the school of design

Pockets and pinch points

Mobilize stagnant programs to mold, shift, and displace each other in productive tension

Linger on the stoop, breathe in the courtyard

Wandering and finding oneself in a community

Cul-du-sac

Student ramp flows between studios

Relationship ramp combines exibition and views

Visitor ramp merges library, cafe, and performance

Threads Scheme

Public and private loops

Cyclical nature

Individual volumes linked by continuous, collective space

A composition across the site

Smooth and unified from outside, jagged center for inner life

School towards interior, public protrudes out for curiosity and wonder Ground water seeps in and out around the crater

Dynamic form shaped by the breeze and movement of people

Crowning the structure with shade

Intricate weaving and tapestry terracing

How can the ground liberate from the building?

Despite our best efforts, architecture damages the earth

Soil excavation, ecosystem displacement, hydrology diversion

Lighten human footprint wherever possible

Courtyards formed by a corridor platform

Start with a mass and carve space out

Sponge/school has holes for breathing air and absorbing water

“What,” “How,” and “Why” are essential questions. “What” is the clear and firm thing you want to achieve. “How” is strategies, languages, and approaches to accomplish your aim. Even in a clear direction there can be various approaches and operations. “Why” is the reasoning, incentives, and drives behind the creation of ideas being presented. – LH and Wenjing

The midterm review is a critical moment to make a big push and reconnect with the initial questions posed by the studio. It is a large collective effort and a time for decisions. Come to the conversation with questions and openness, the flexibility to adapt. We pause and reflect on where we came from and where we are going. Moving forward we focus, detail, and refine.

To arrive at this point is a journey of discovery. Together with the students, we nurture their unique interests and tailor conversations to their organic method of working.

The final projects balance boldness and subtlety, complexity and simplicity, meaning and emotion. The students’ passion and poetry are reflected in their design school manifestos.

Each design considers what is really needed and yet is not entirely complete, leaving space for improvisation and the inevitability of future change. – LH and Wenjing

The design school is an alive and nutrient puddle of people, ideas, and nature.

The school purposefully slows down and intertwines making and reflecting. Designers deliberately travel between the theater of “How did you make that?” and productive contemplation.

Everything is in progress, nothing is precious.

Designers learn by looking, mingling, and exchanging with each other. Muddying up the disciplinary edges provides mutual benefit. Puddles are shared creative spaces that seep outside and pool with people, ideas, and nourishing inspiration.

The design school needs to breathe fresh air and ideas from its surroundings. It gives back an endless garden for the entire campus.

A rich education balances deep and broad experiences. Departments need autonomy and expertise, while the garden interconnects through shared roots. In the design school, every day is different across a rainforest-level of diverse spaces.

Olivia Champ Tremml, Lilly Saniel-Banrey

Design schools need to take a deep breath. Breathe in fresh air and ideas—inhale the surroundings and people from many places—to release something beautiful and vibrant back to the world. Designers in community learn how to synchronize their rhythms of making and living for themselves and with others. Our aspiration is to cultivate an environment for designers of all species to thrive: a new kind of symbiotic design school, akin to an artist residency village.

As a break from our current linear and parallel pedagogy, we invite the puddled pedagogy. Designers thrive in shared spaces that collect people and their ideas and creations in nature— puddles—acknowledging that designers learn by looking, mingling, and exchanging with each other, driven by the curiosity of “How did you make that?” The school is a place to stir up inspiration and unsettle nutrient grounds for designers’ imagination.

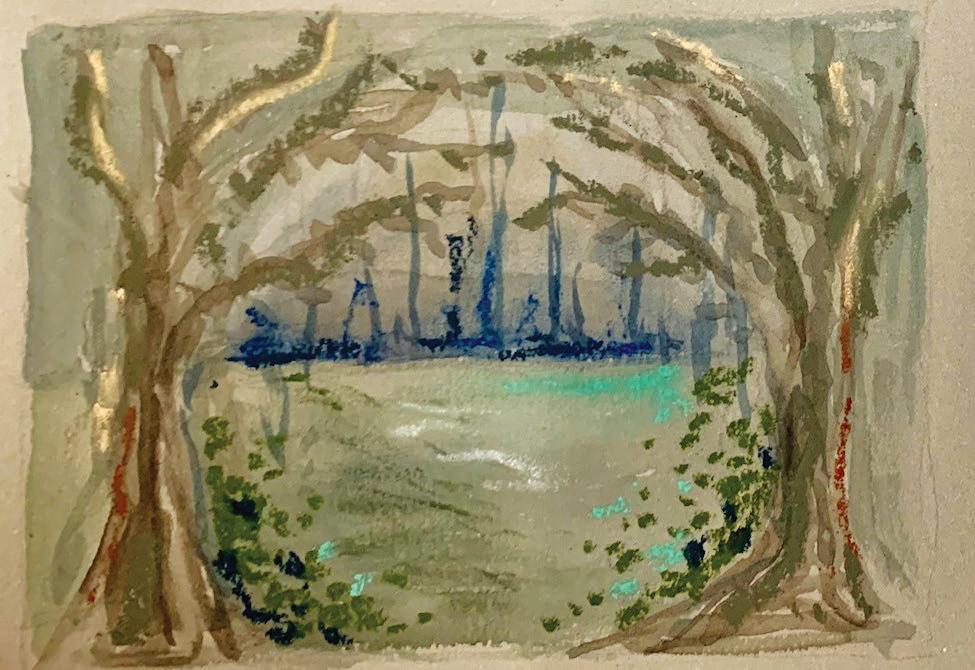

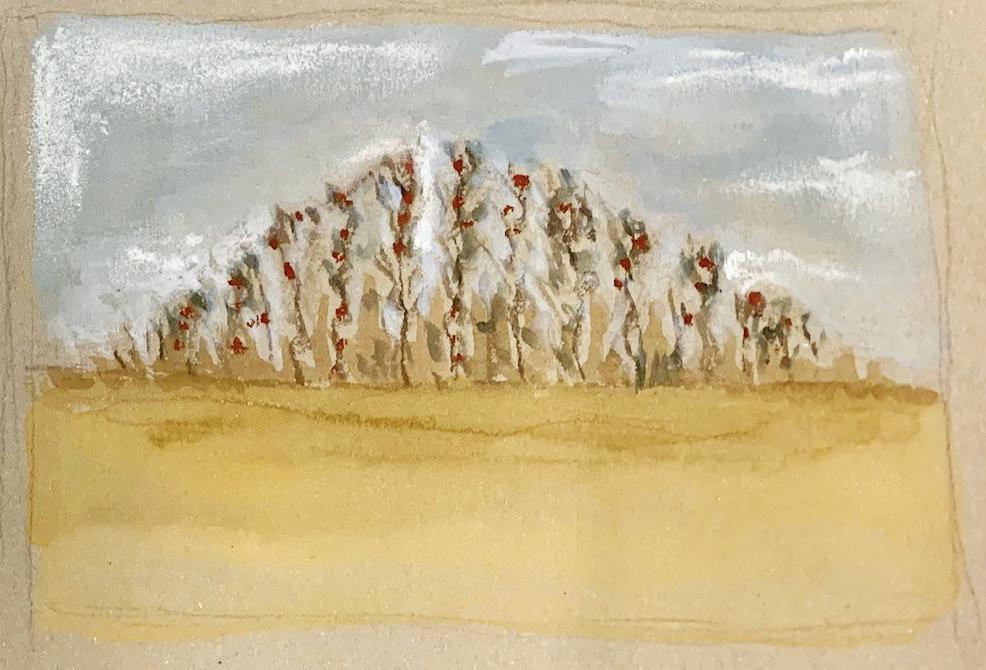

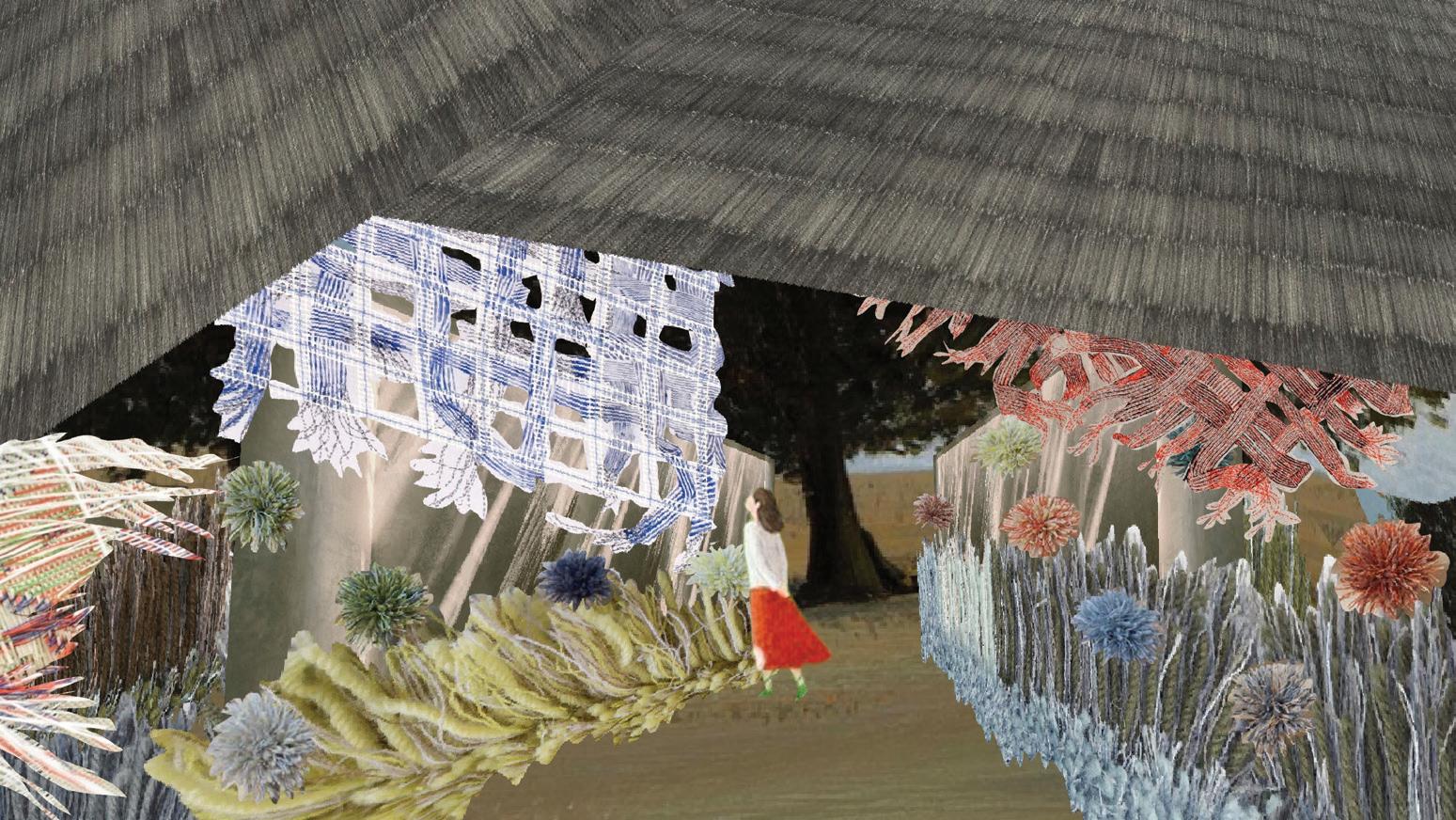

We invite a cycle of individual reflection and communal making into the design school’s daily and spatial journey, unfolding as a series of realms between theater and home. Workshops and public spaces pool with people and intertwine with an endless garden, producing the school’s social fabric. This allows for a rainforest-level diversity of spaces, including more-than-human species and designer species alike. Students travel between work and home through restorative landscapes. The school acts as a garden for the campus, an ever-evolving experience for both student and visitor. We borrow from the continuous experiential environment of the Chinese garden as a layering of spaces to unfold a story through chapters. By hybridizing school with garden, the designer is constantly tied to place. In being tied to place, the school embodies an empathy for the many ways of being.

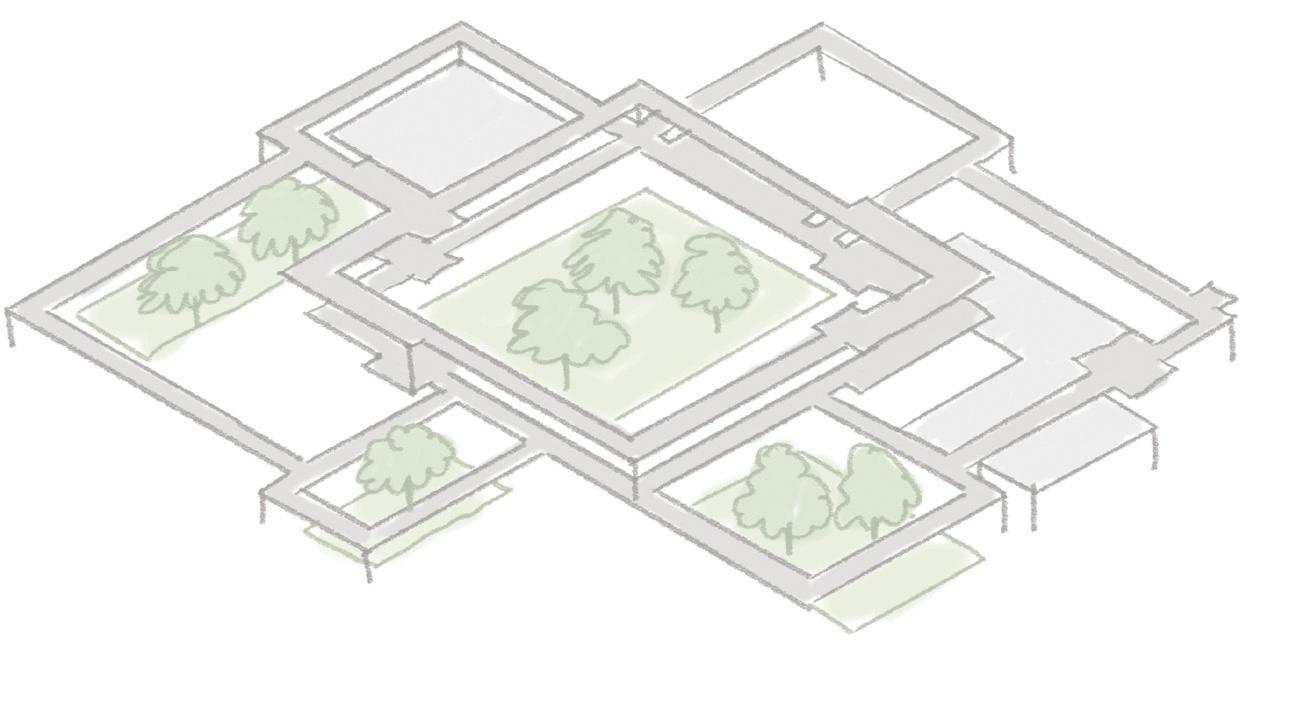

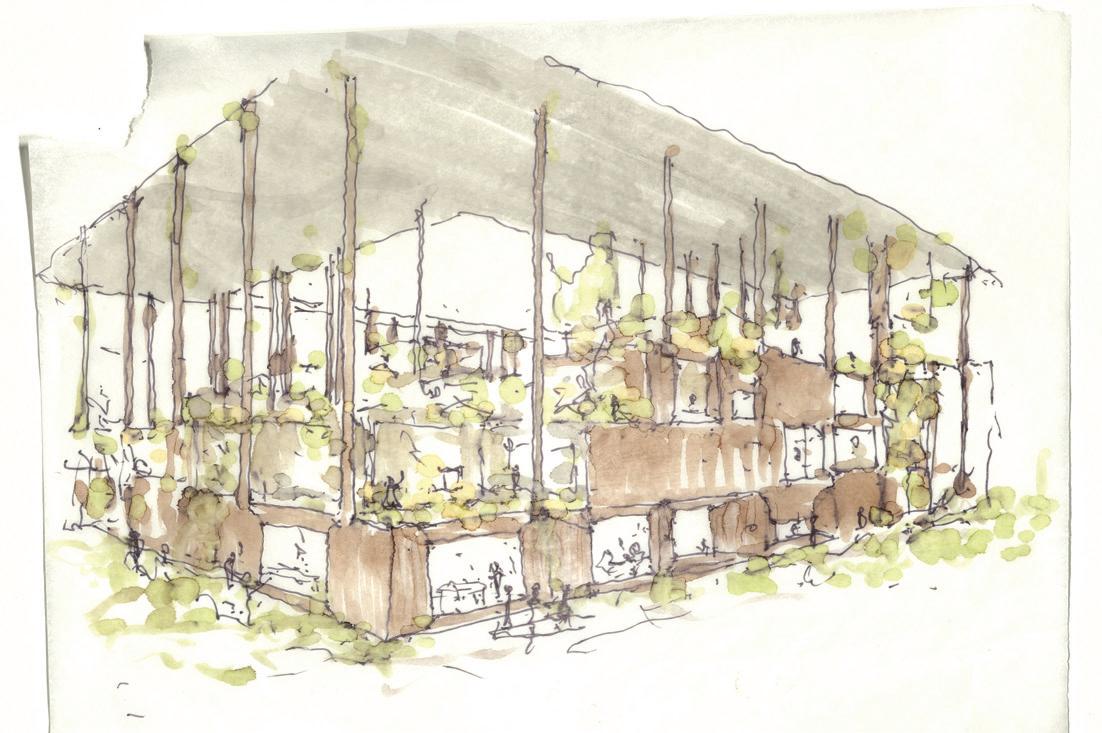

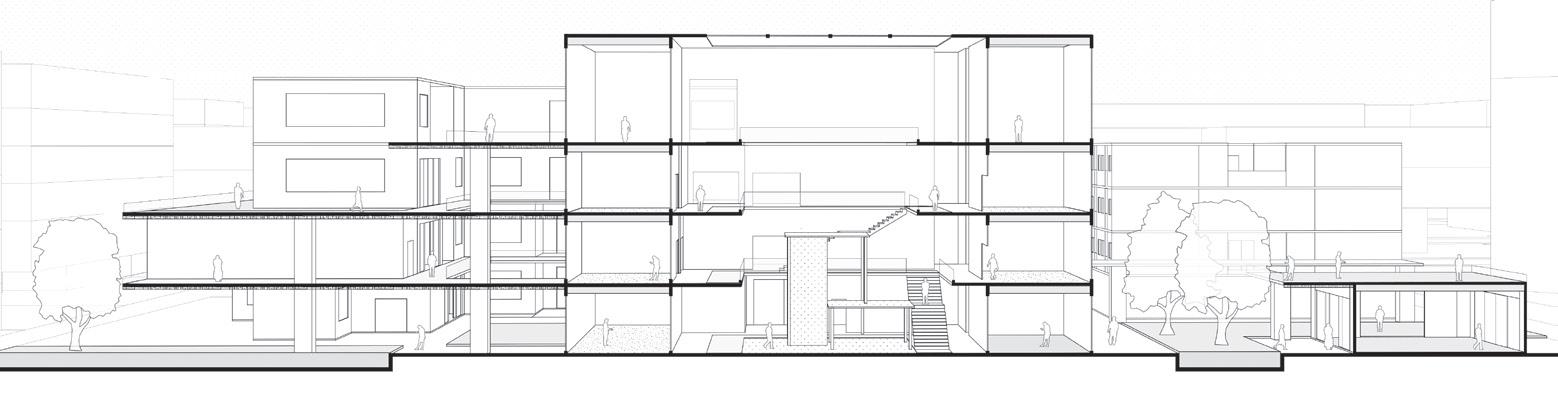

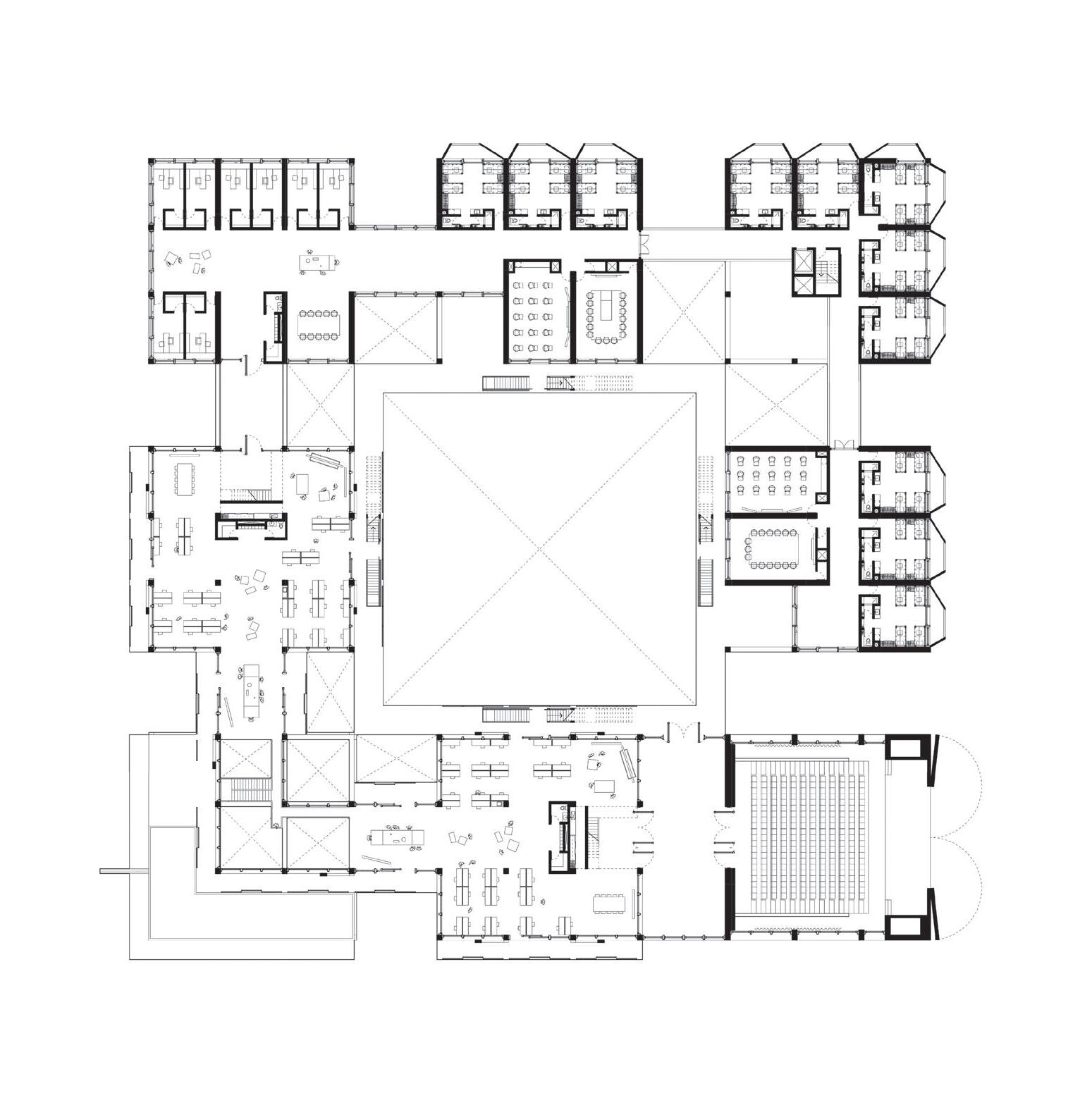

Above: Ground floor plan. Departments cluster across the landscape like bacteria cultures. Gardens create breathing room and areas to expand outside. Common courtyards and elevated walkways stitch departments together.

Above: Second floor plan. Gardens rise into the sky and students inhabit lush canopies. Dwelling and individual contemplation on the second floor respects the inner life of and community among designers while providing

and

Above: Fragment models in paper mâché and foraged plants. Architecture is a measuring device for the fluid landscape, lifting above and rooting down into the ground where necessary. The building registers water levels and experiences seasonal shifts. It gestures for species to land, explore, nest, or visit.

Right: Rendering (collage and hand drawing). Spaces to allow curiosity to wander. Making is an expression of care: for the land, for materials, for people. Deep thought and sensitive touch infuse design objects with profound care.

Above: Section drawings and sketch. The section rises and falls as an extension of the landscape and a series of rooms. Roof planes negotiate scales and provide extended canopies. The planes react to nature by lifting to let light through, tilting to drain water, and flattening for organisms to inhabit them.

Left: Winter and summer renderings of dorm showing the seasons passing. While the school offers many narratives, it also reflects a consistent story through the year: the student taking everything in over time, slowly and deliberately, both humbled and elevated by making and living in communion with others.

Massing model (watercolor and foraged plants). The design school gives a garden back to the campus as an unfolding experience through a diversity of spaces. A forest in spirit, nutrient grounds and spacious canopies bring breadth and depth to the students’ and visitors’ experiences.

School for Chongming Island

The design school is the bridge to ecological being.

Acknoweldgement of the interdependence of human and non-human actors.

To learn from nature, we surround and place ourselves within it by extending the artificial garden wetland to the fullest. The site itself becomes the most valuable object, physically and intellectually.

1. It must be able to breathe and act adaptively to an ever-changing condition.

2. It must teach awareness by confronting the human with different scales and promote symbiosis.

3. It must act as an entry for the public to the site as well as to the mindset conveyed by the school (of ecology) and as an exit for this mindset to spread.

Sophie Gföhler, Vinzenz Leuppi

A holobiont is a holistic biological entity composed of a host organism and an intricate consortium of microorganisms encompassing bacteria, viruses, and fungi. This collective assemblage forms a dynamic and interdependent ecosystem that is existentially intertwined with the host’s physiological and ecological interactions. This symbiotic relationship is an obligatory one. We propose symbiosis as a key strategy for design, confronting the complex relationships between the earth and its more-than-human actors. In order to learn from nature, we place ourselves within it by extending the wetlands to the fullest. The site becomes the most valuable object, physically and intellectually.

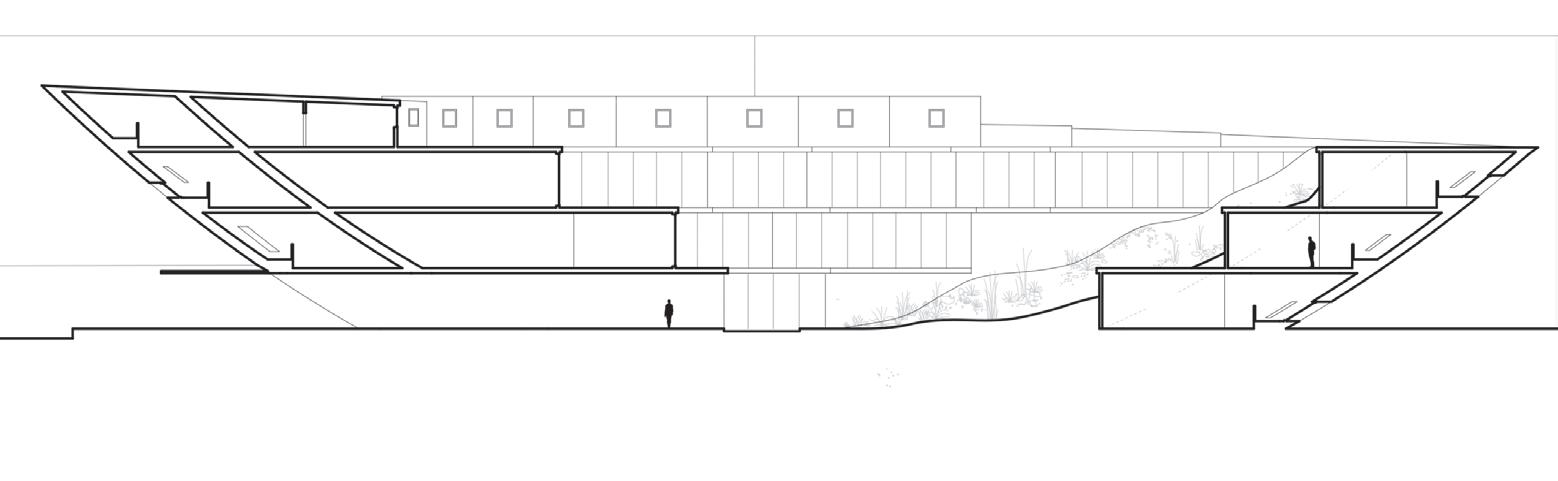

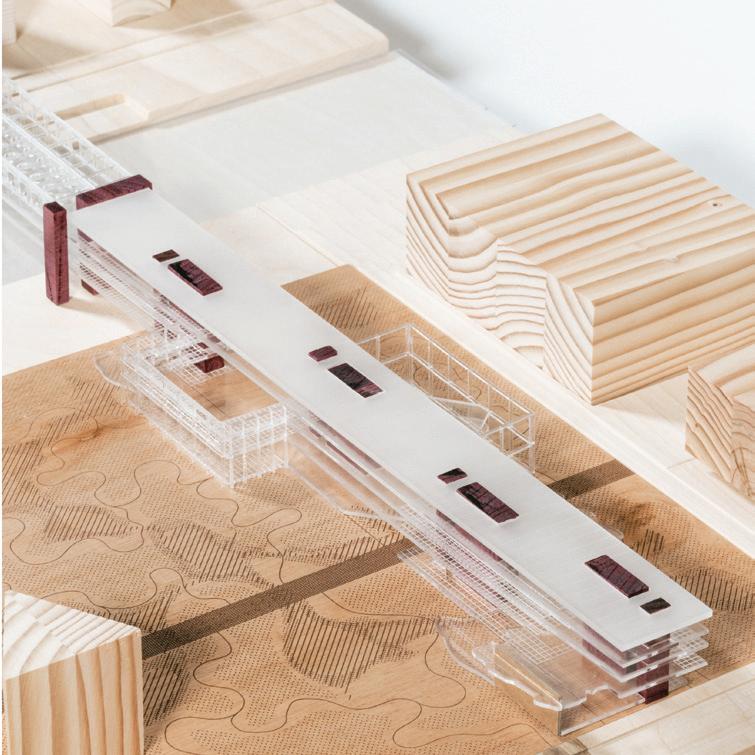

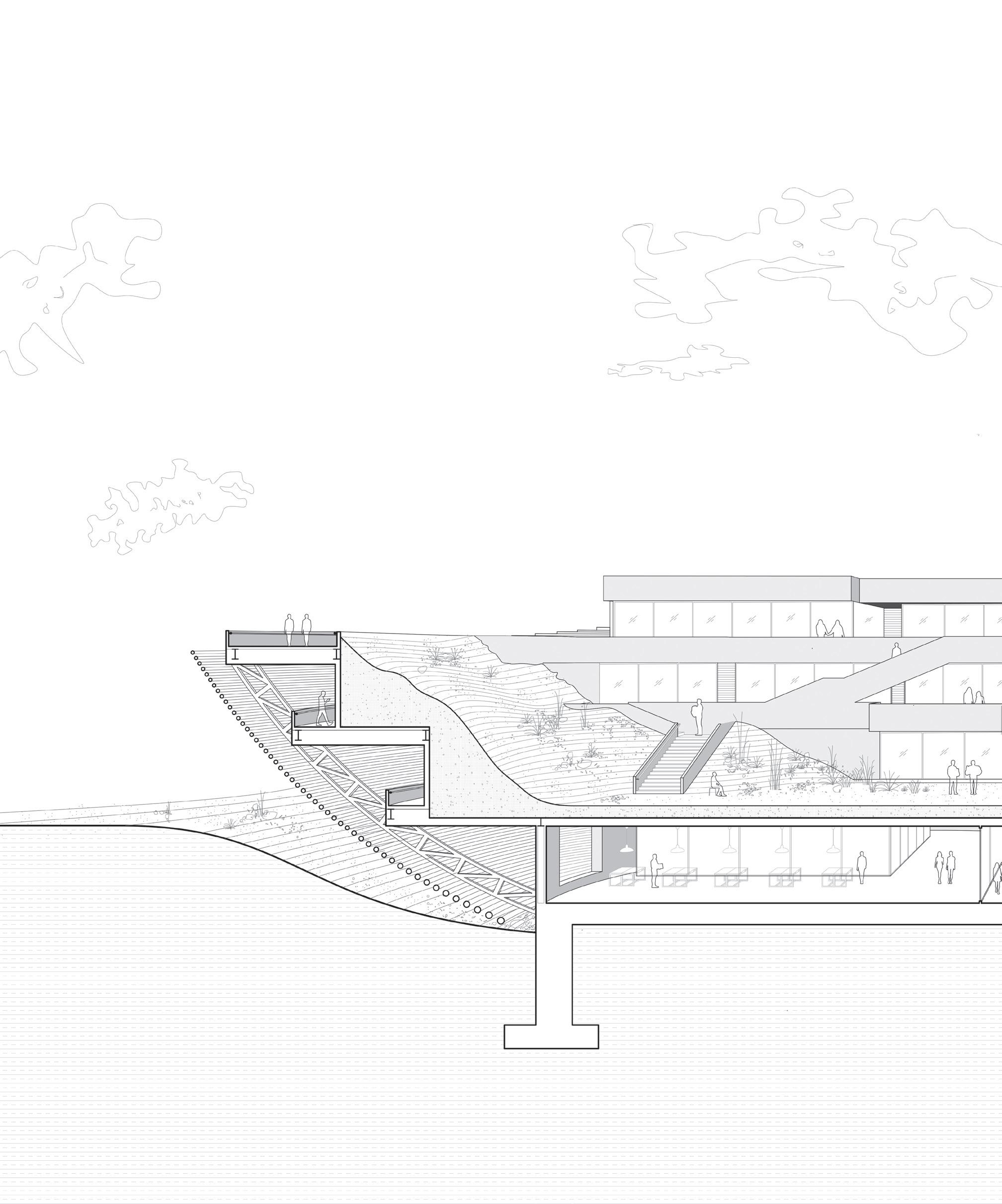

The School of Ecology is a long linear structure, which crosses the river and connects the northern and southern university campuses, acting as a physical and metaphorical bridge and entry to the mindset of the school and its large public wetlands garden. The garden passes through and under the slightly elevated building, symbolically giving nature a right of way. By encouraging the public to enter the wetlands park, the school creates public engagement to spark environmental activism.

Architecture as a vessel of communication and education takes the sustainable principles identified and applies these ideas to our architecture. Mimicking the wetlands, our building programmatically breathes and adapts to an ever-changing condition. Programs bleed into one another and breathe to the outside. The building curates framings of the surroundings at varying scales to create an active confrontation with the environment. In the spirit of interconnectedness between people and nature, the wetlands park drives the architecture informing the school of design with environmental approaches.

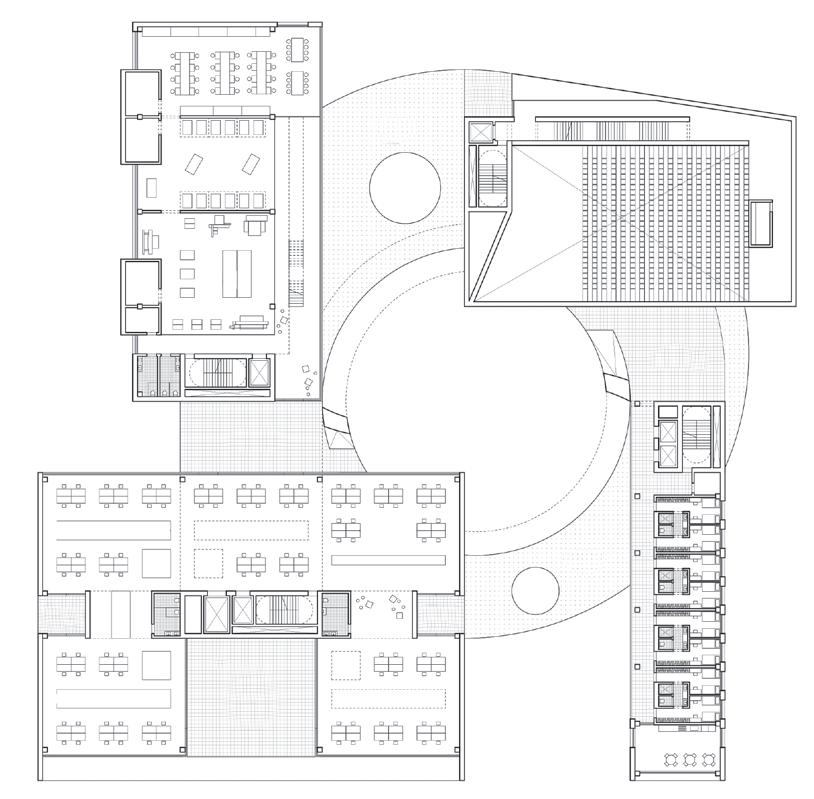

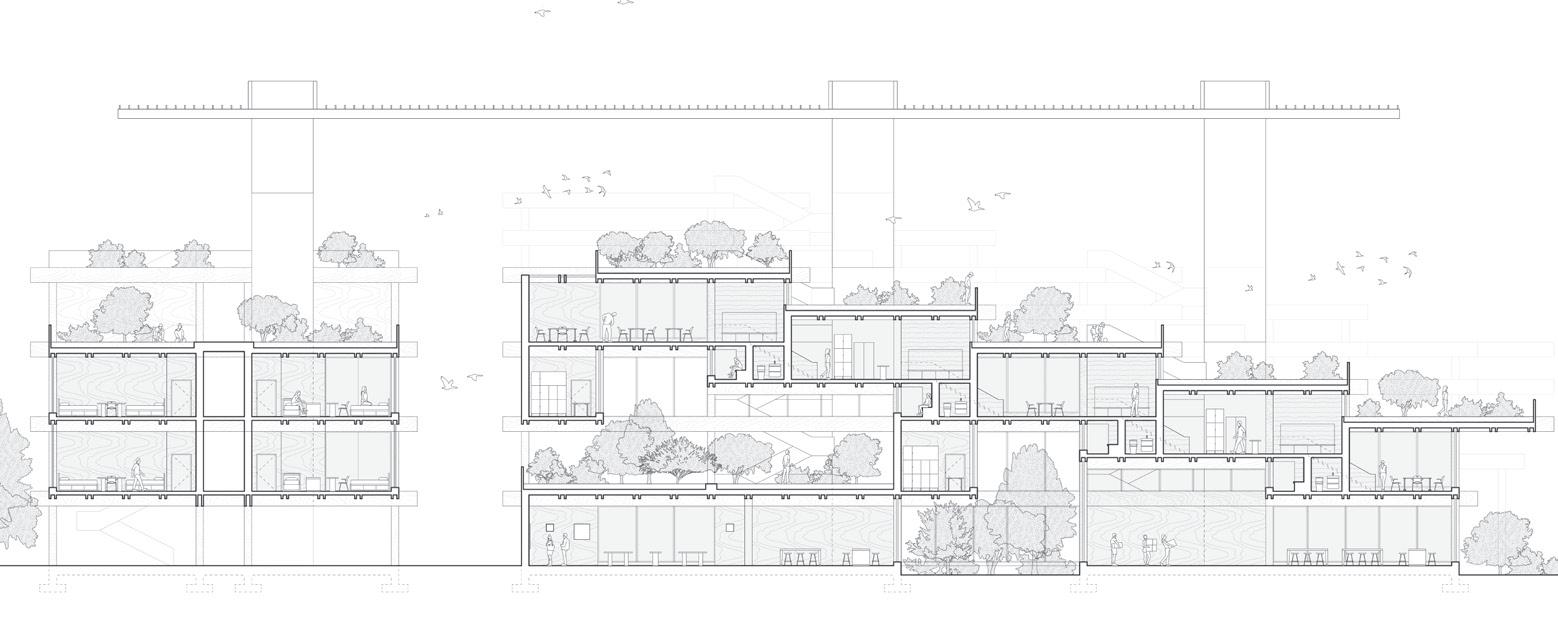

Top: Ground floor plan. The ground floor is completely open and slightly elevated to allow the garden to continue underneath and through it. Through the precise placement of predominantly public functions, programmatic spaces can expand, contract, or transform in order to be used in different ways.

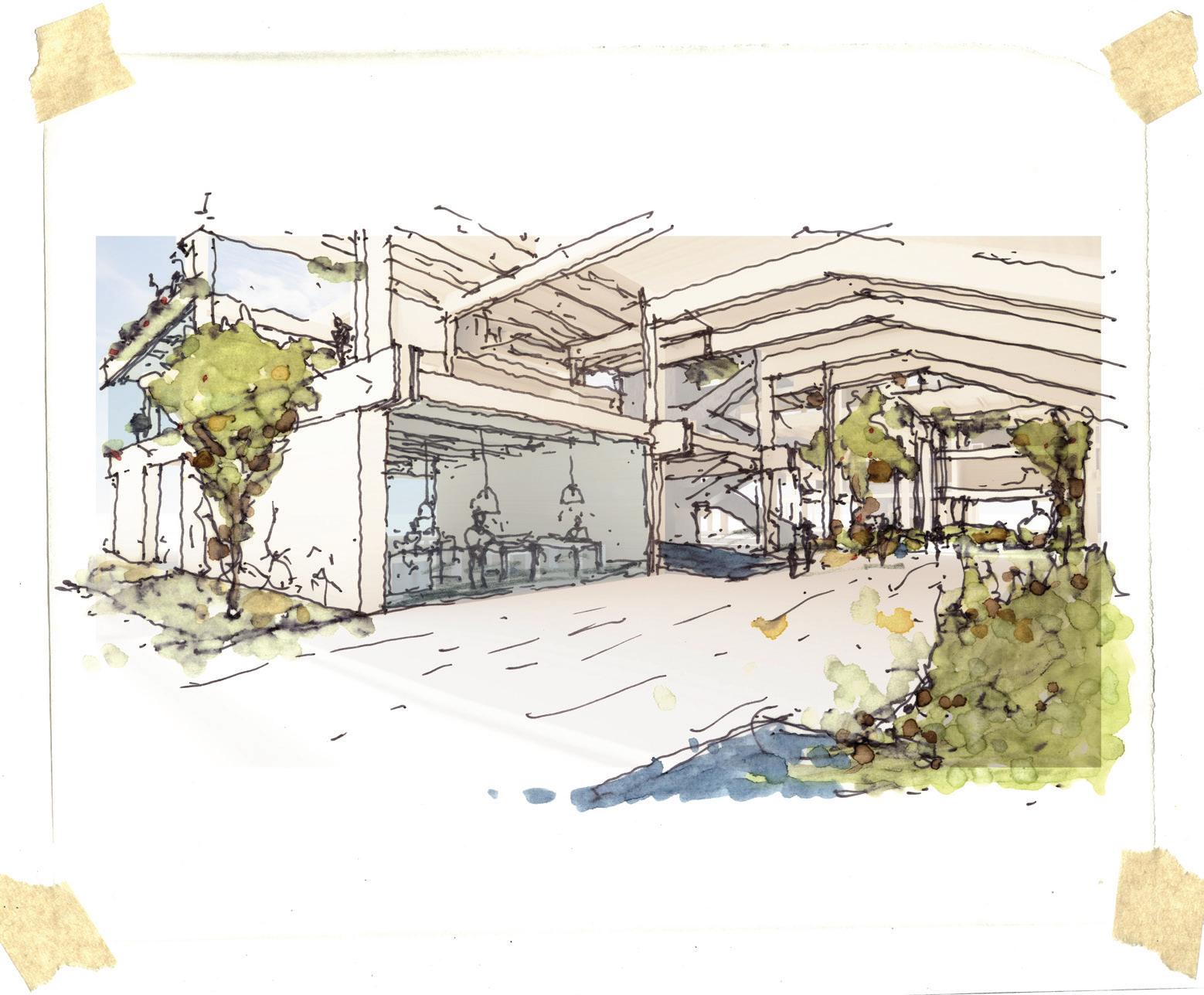

Top: Rendering of interior. The principles of porousness, interconnectivity, and transparency are demonstrated in the interior multistory spaces that connect the workshops and studios, the theory and practice.

Bottom: Section drawing. The section illustrates our building’s function as a bridge that only occasionally touches the ground. Like the displaced facade, subtle floor height changes signify the building’s fragmentation as a reaction to the park’s wildness.

Above: Program diagrams. Programs bleed into each other and into the outside. Breathing programmatic functions adapt to environmental and pedagogical fluctuations. Additional unfolding elements allow for the expansion, contraction, or transformation of public outdoor space to programmatic rooms and vice versa, reducing the built floor area by 2,000 m2. Nature is not a passive entity, but rather an active component of the school.

Right: Rendering of facade. Shading elements are hung at different distances from the facade, exemplifying fragmentation. They create subspaces where light falls differently and changes the viewer’s perceptions.

Final Review _ Sophie Gföhler / Vinzenz Leuppi

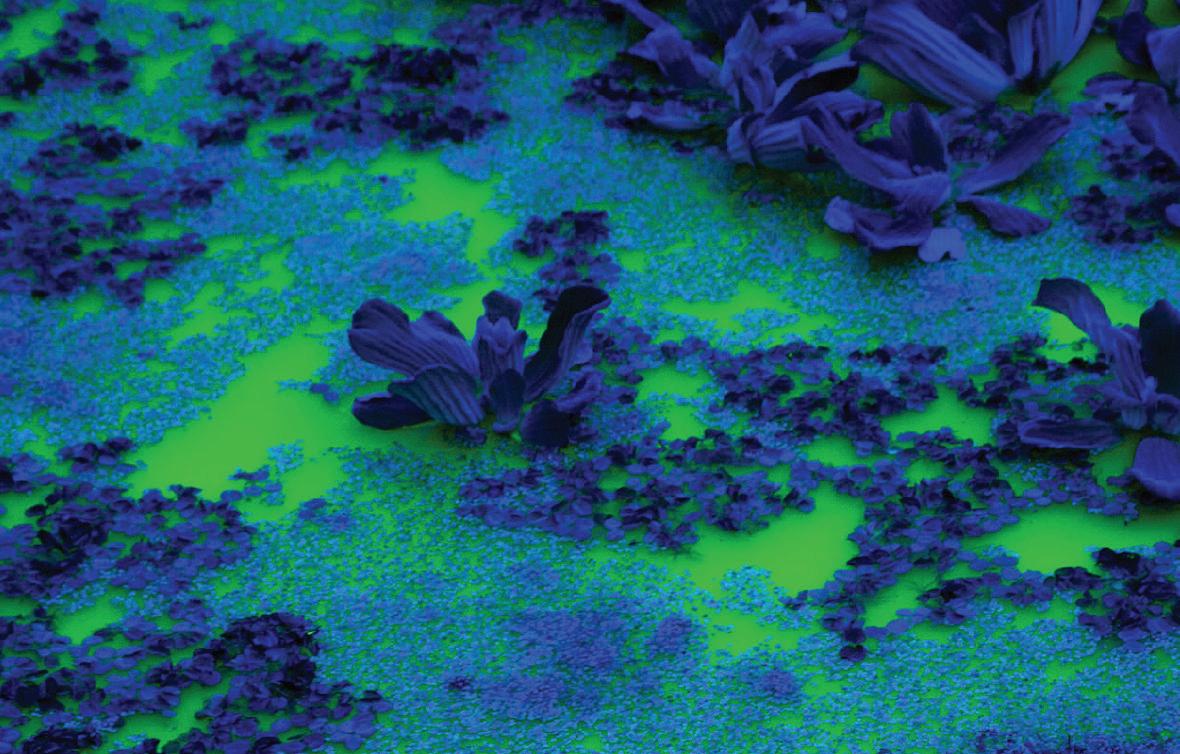

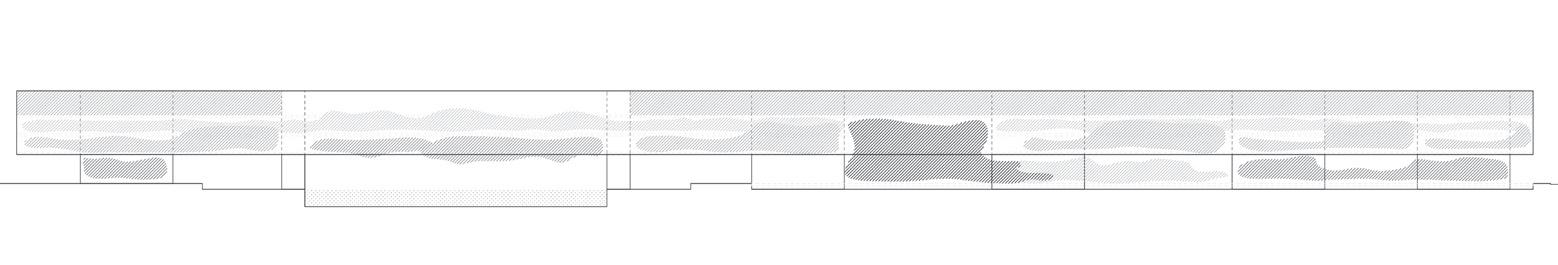

Next page: Site plan drawing. The wetlands garden acts as a sponge with the changing water levels. From the tectonic shifts of our building, a grid is devised and extended onto the entire site, in which a collage of aerial shots of Chongming is composed. The garden reflects various habitats on the island and alienates them by changing their scale. The garden implies the relationship and symbiosis between different scales of life.

of model. The proximity between humans and non-humans and their interdependence and design principles adopted from nature lead to a radical school, whose pedagogy will perpetuate and spread these principles.

The design school is an open, collaborative, and connective professional incubator.

The Incubator

... is a physical space designed to bridge academia and practice, inside and outside. It encourages a reciprocal relationship between the institution, industry, and the community by providing collaborative studios for interprofessional studies as well as professional work; exhibition and innovation galleries for showcasing products and technologies; and public gathering and workshop programs—each shared by students, professionals, and the surrounding campus.

Connor Kramer

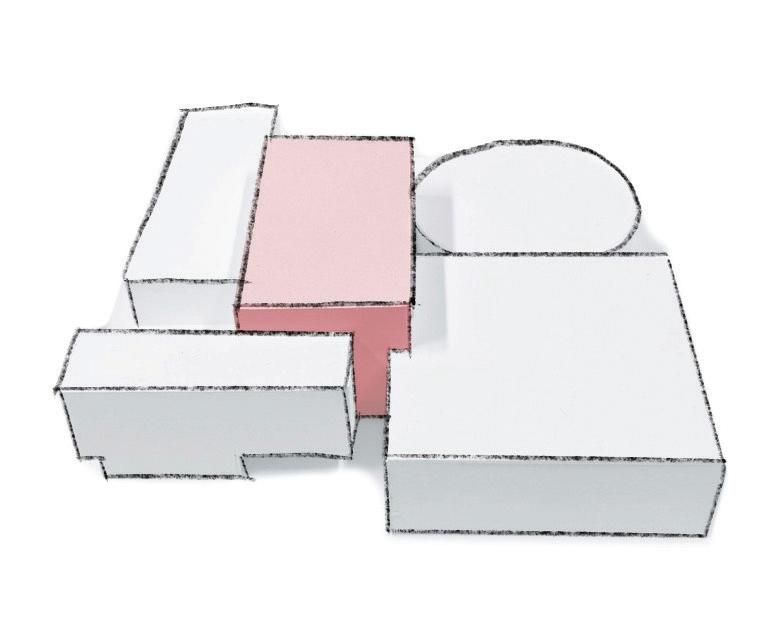

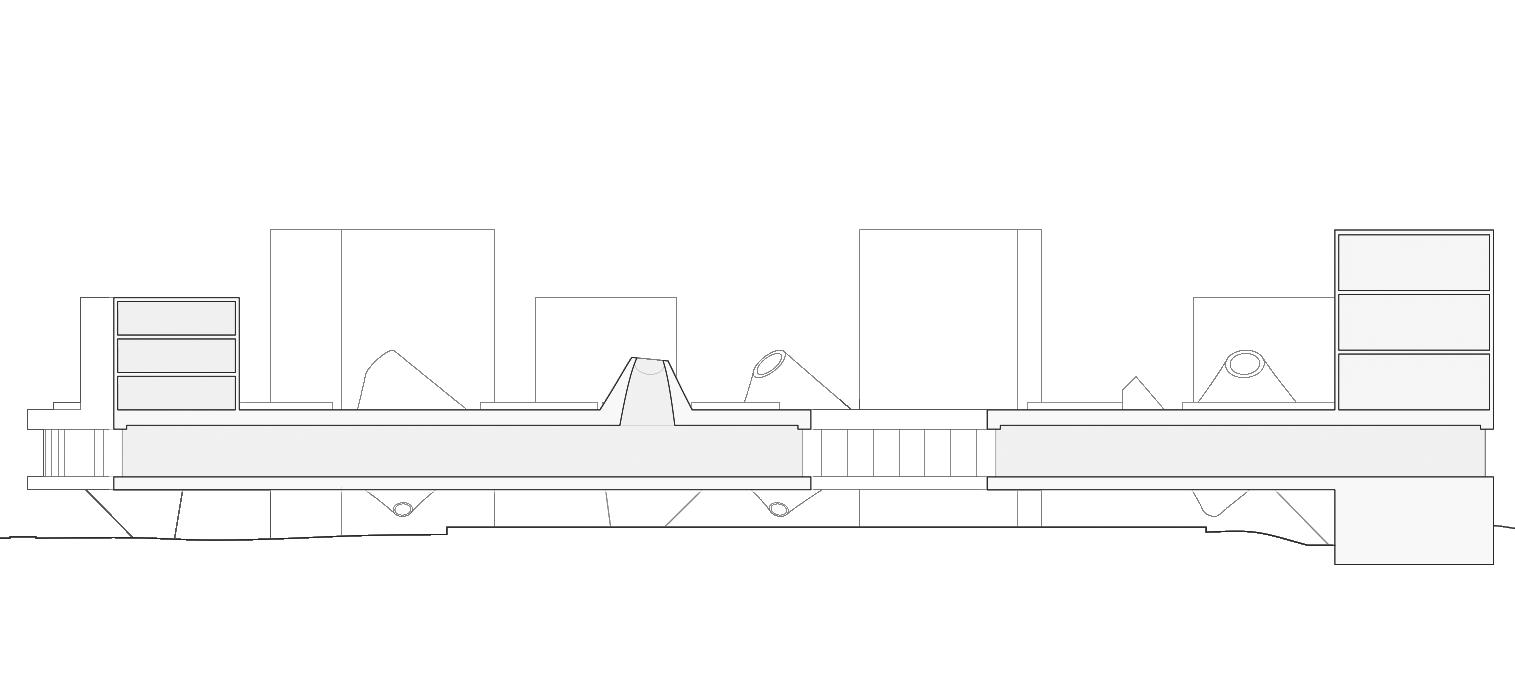

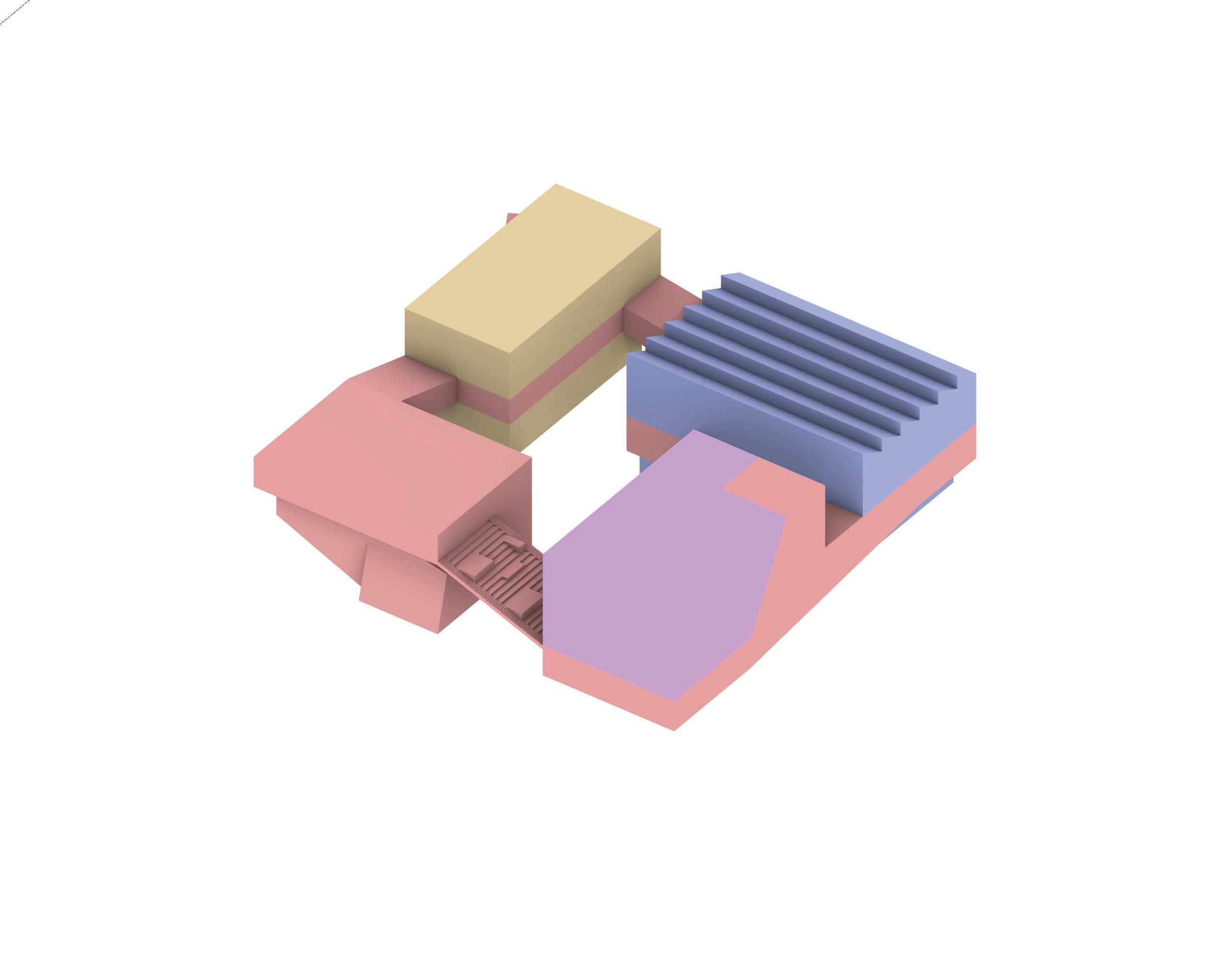

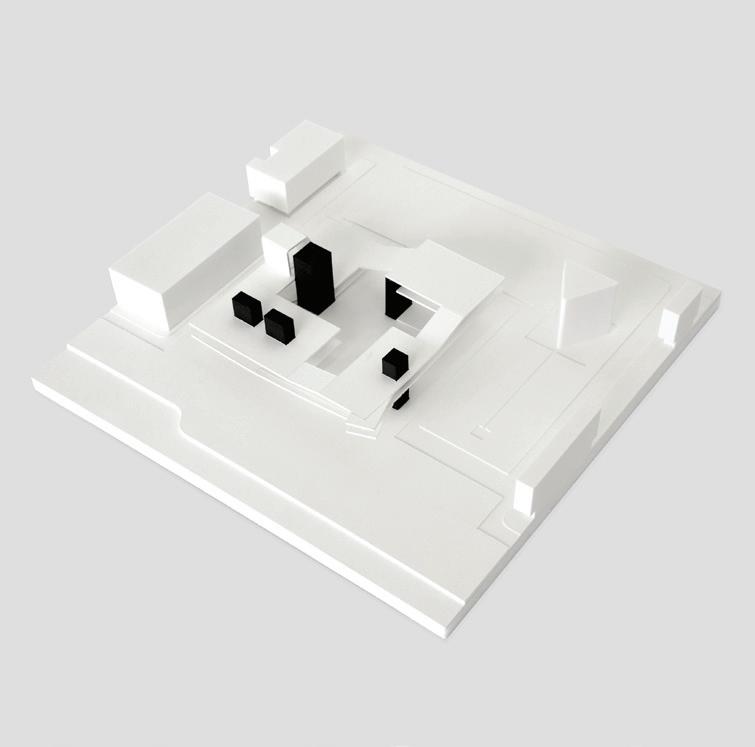

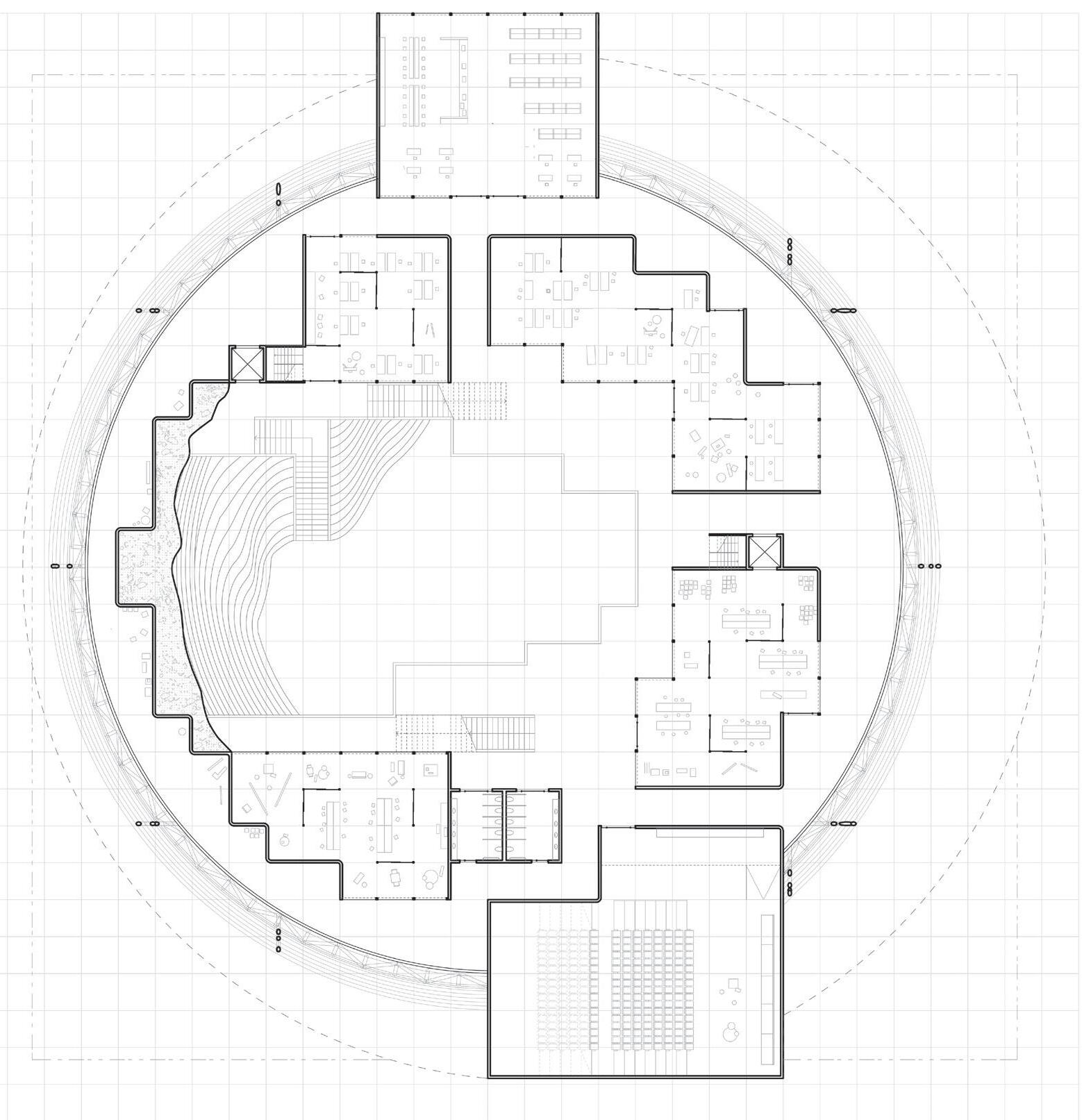

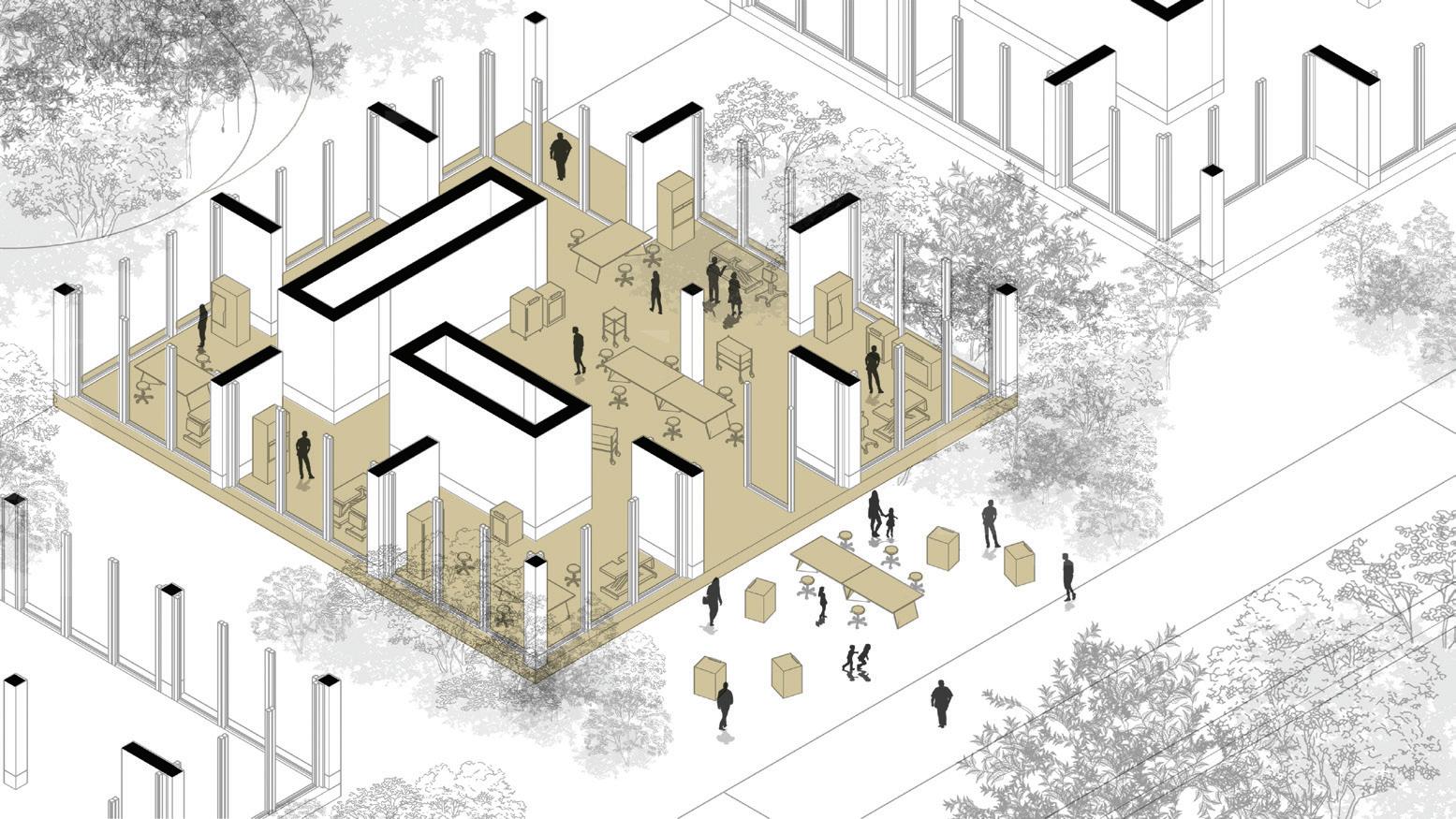

This design school’s defining pedagogical position is to connect academia and practice by providing students and professionals a dedicated architecture in which research, collaboration, and engagement can continuously occur: a professional incubator. The spatial model of this new kind of design education deliberately toggles a part-to-whole reading and defines a connected, creative micro-campus encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration, practical experience, and public interaction. Chongming Island Design Institute (CIDI) is a design school conceived as a set of typologically specific volumes linked by a continuous formal element, the professional incubator. The project seeks to create its own context by responding to broader ecological conditions and defining a condensed microcampus of design school disciplines and functions. Individual volumes emerge, each containing a primary academic function— studios, workshops, dormitories, and auditorium—linked by the professional incubator. The school’s unique pedagogy combines education and research with synchronous professional practice and innovation, which is embedded in this compositional model of adjoining blocks interlinked with a continuous shared space.

To further interdisciplinary interaction, adjacent blocks both support each other along a common threshold and contain moveable partitions to encourage collaboration between design studios. The blocks are deliberately generic, awaiting a proliferation of student work to bring them to life. The structure rises above a constructed wetland park and encircles a central courtyard, enlivened both by the surrounding ecology and by the human activities spilling outside. This natural forum space seeks to redefine the connection between architecture and ecology, academia and practice, campus and community.

Previous: Rendering of school entrance. The design school is a condensed, creative micro-campus that creates its own immediate wetlands context. The louvered workshop space and public auditorium act as a front door toward the rest of the university campus.

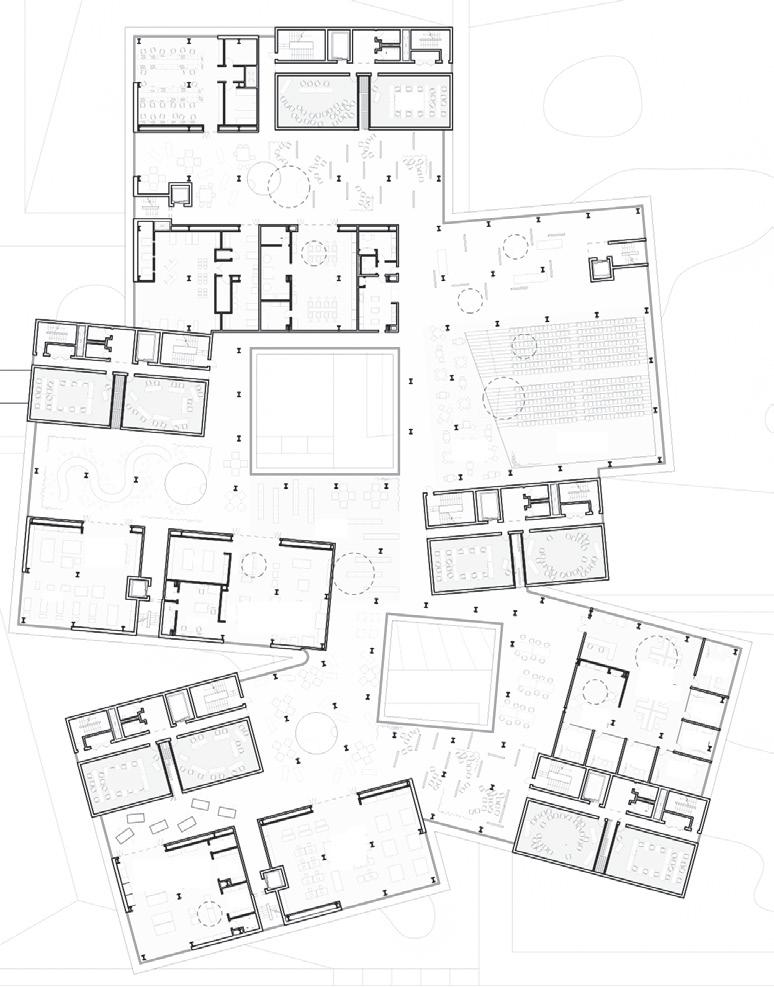

Above: Ground floor plan. The ground floor plan reveals the main building blocks: workshops, public gathering, dorms, and studios. Each block leaves space to maintain corridors across the site and a mix of green and blue natural spaces.

Above: Upper floor plan. The professional incubator rises and falls between levels, connecting the adjacent blocks in a continuous dedicated space for designers to engage in professional practice.

Above: Diagrams of micro-campus and incubator. Snaking and shapeshifting between blocks, expanding into multilevel spaces, or condensing into circulation zones, the incubator absorbs sectional shifts to stitch the school’s spaces and functions together.

Top: Unrolled section diagram. The semi-public incubator contains hybrid spaces for new pedagogical opportunities between practice and academia, inside the school and in the outside world. This includes combining a community workshop with a design library, a collaborative studio with a connective stair, a café with an overlook study lounge, and an innovation gallery with an auditorium.

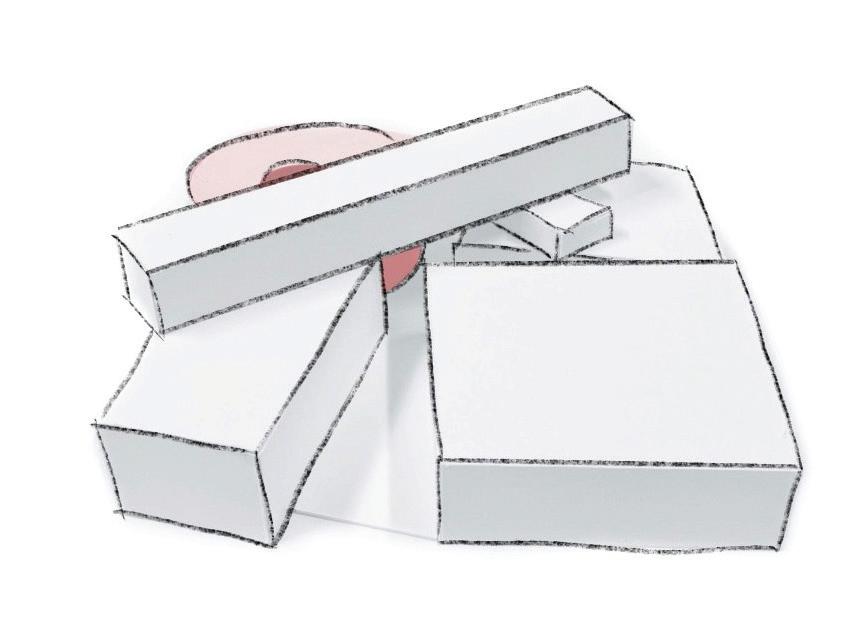

Bottom: Massing models. Typologically specific volumes linked by the professional incubator fluctuate between a part-to-whole reading.

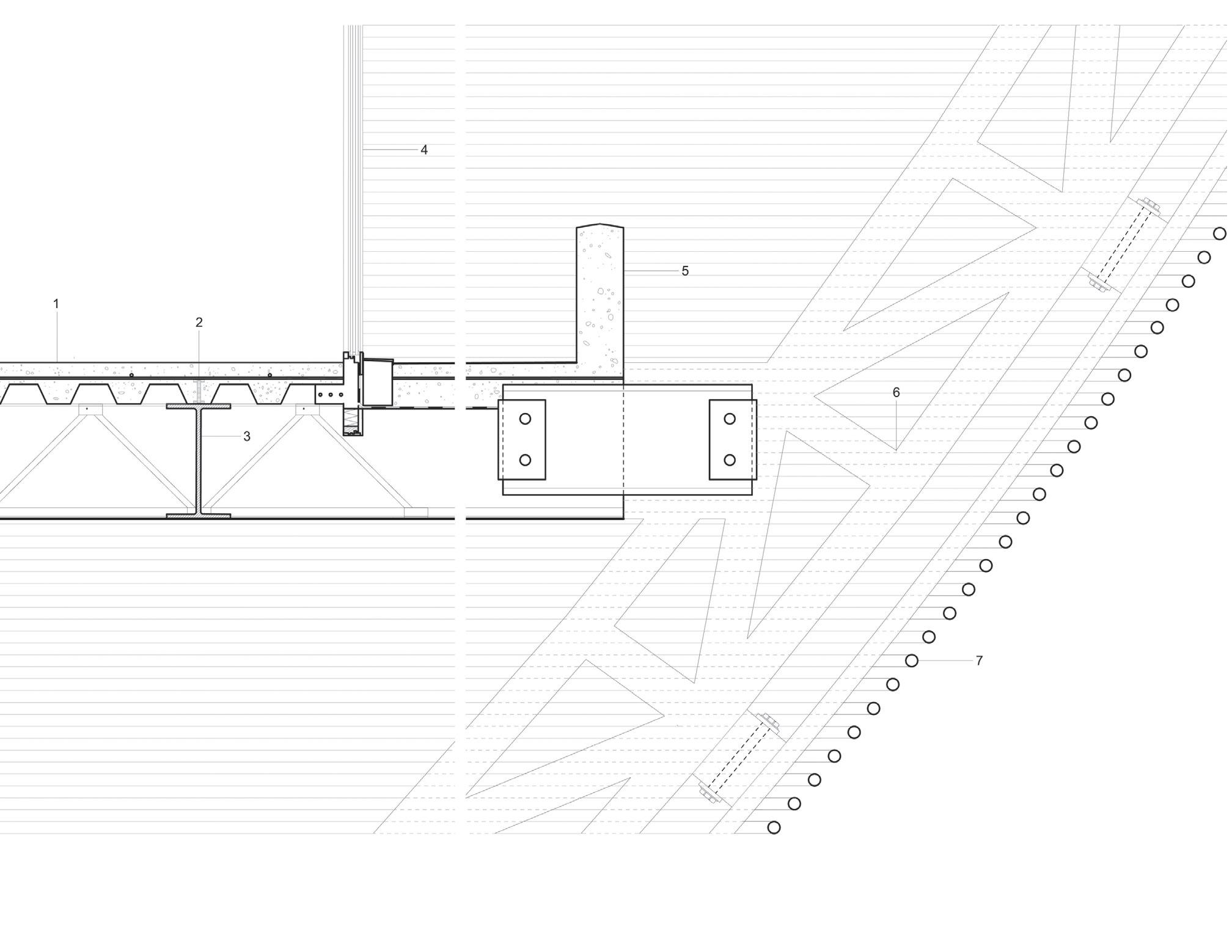

FIXED BAMBOO LOUVER

ALUMINUM FRAME

SLIDING DOUBLE-GLAZED GLASS WINDOW WALL

ALUMINUM MULLION

CAST-IN-PLACE CONCRETE FLOOR SLAB

CAST-IN-PLACE CONCRETE EDGE BEAM

ALUMINUM WINDOW TRACK EMBEDDED IN FLOOR SLAB

CAST-IN-PLACE CONCRETE SLAB EXTENSION

ALUMINUM AND GLASS GUARDRAIL

FIXED DOUBLE-GLAZED GLASS PANEL TERRACE PAVERS

Top: Rendering of studio interior. Operable louvers that block harsh rays but allow views to the building’s surroundings and clerestory windows within a sawtooth roof regulate precious light in studios and animate workspaces with atmospheres that connect to nature.

Left: Detail drawing of facade.

Bottom: Section drawing. Environmental strategies work in tandem to heat, cool, and ventilate the building in response to Chongming Island’s unique climate. The spatial arrangement around a central courtyard maximizes natural ventilation. Natural and overhead lighting illuminate workspaces to accommodate student schedules. Combining rainwater filtration and collection with wetlands absorption and irrigation mitigates water levels across mild and monsoon seasons.

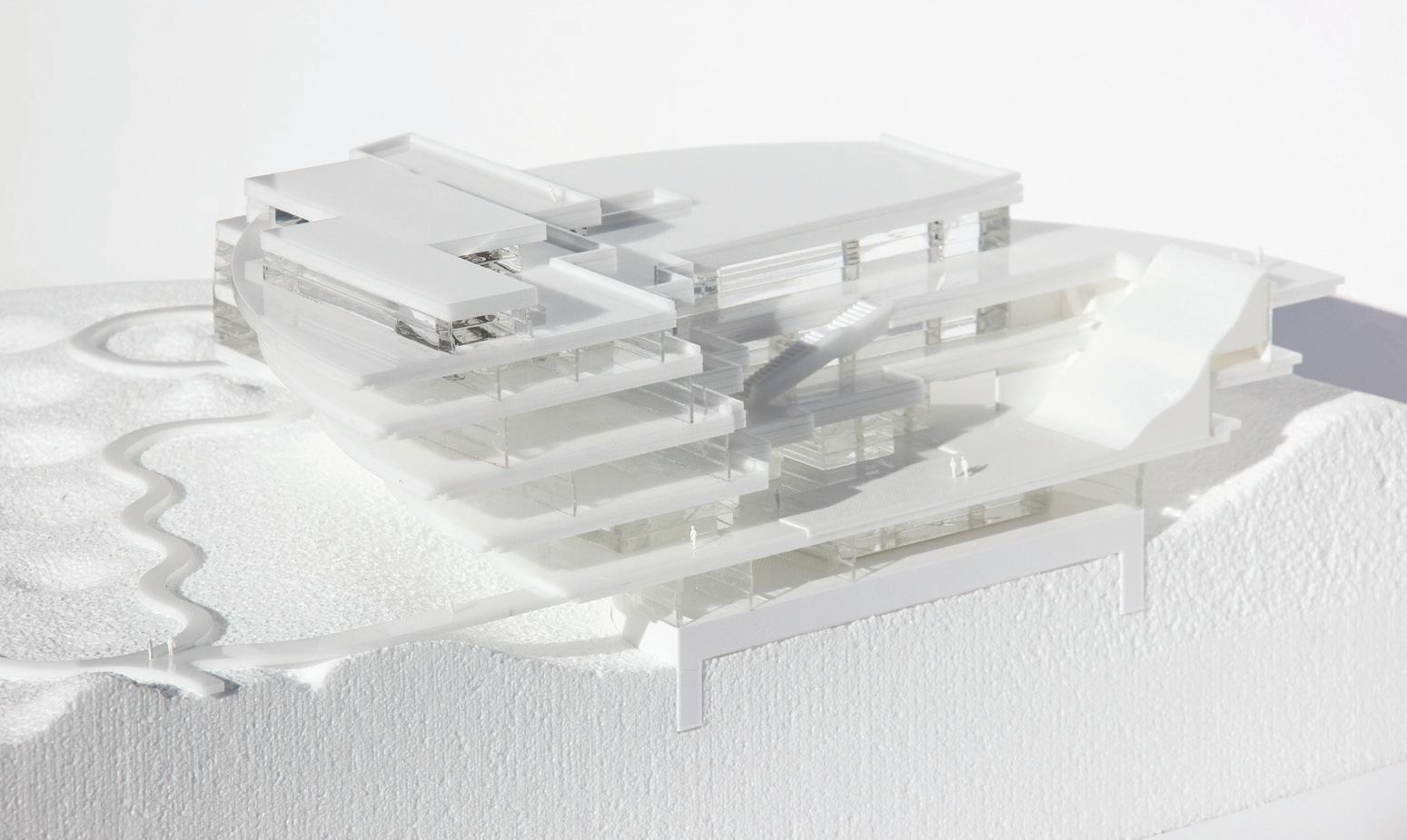

Photograph of sectional model. The architectural language brings together consistency and subtle variation, specifically tuned to programmatic functions and oriented to natural elements. Through a collection of discrete volumes and a connective professional incubator, the project becomes a physical manifestation of its pedagogy: bridging education and practice, campus and community, architecture and ecology.

The design school is an ecology of students together in moments of serendipitous exchange for dialogue and debate.

Identify what is fundamental, let complexity emerge in its realization.

Every aspect of a building has the potential to be meaningful, from the sound of rain on the roof to the spaces swelling in the heat.

Even the simplest buildings embody a wide history of materials and ideas across the globe.

. . . even if you don’t mean it. Know what your architecture is saying, for whom, and why.

Concrete, glass, and steel are materials. So are air, water, and sound. History is a material, too.

Recognize who came before and who will arrive after.

Architecture bears witness . . . to everyday life, but by itself it cannot speak.

. . . and ideas organize form.

Connor Gravelle, Ryan Han

Connor Gravelle, Ryan Han

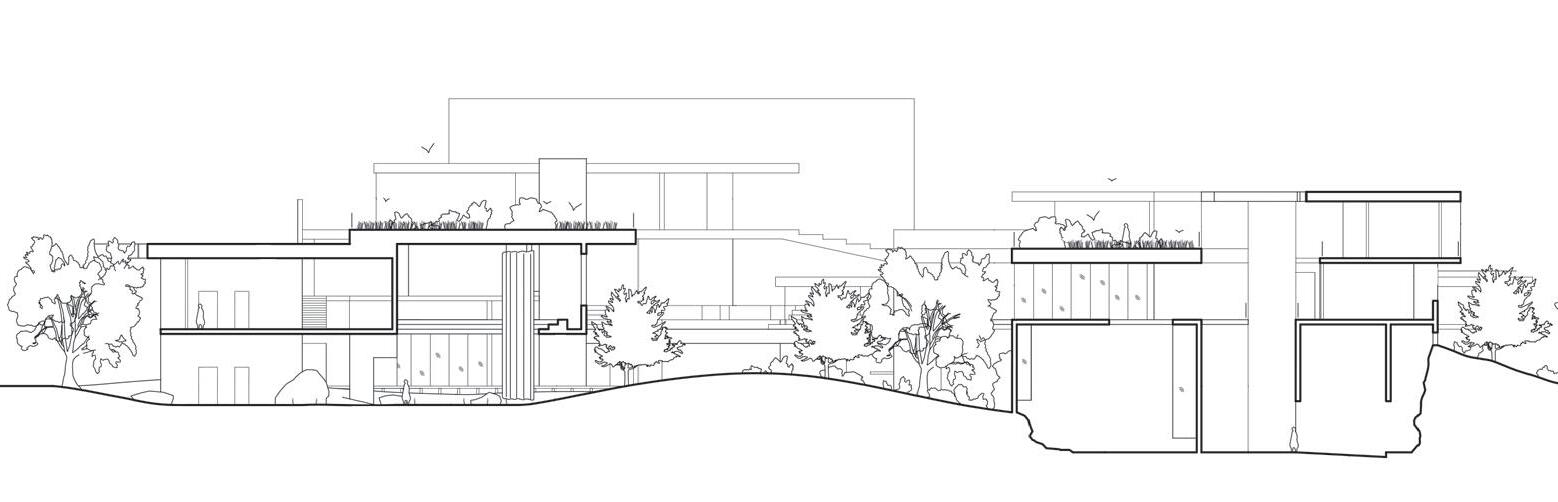

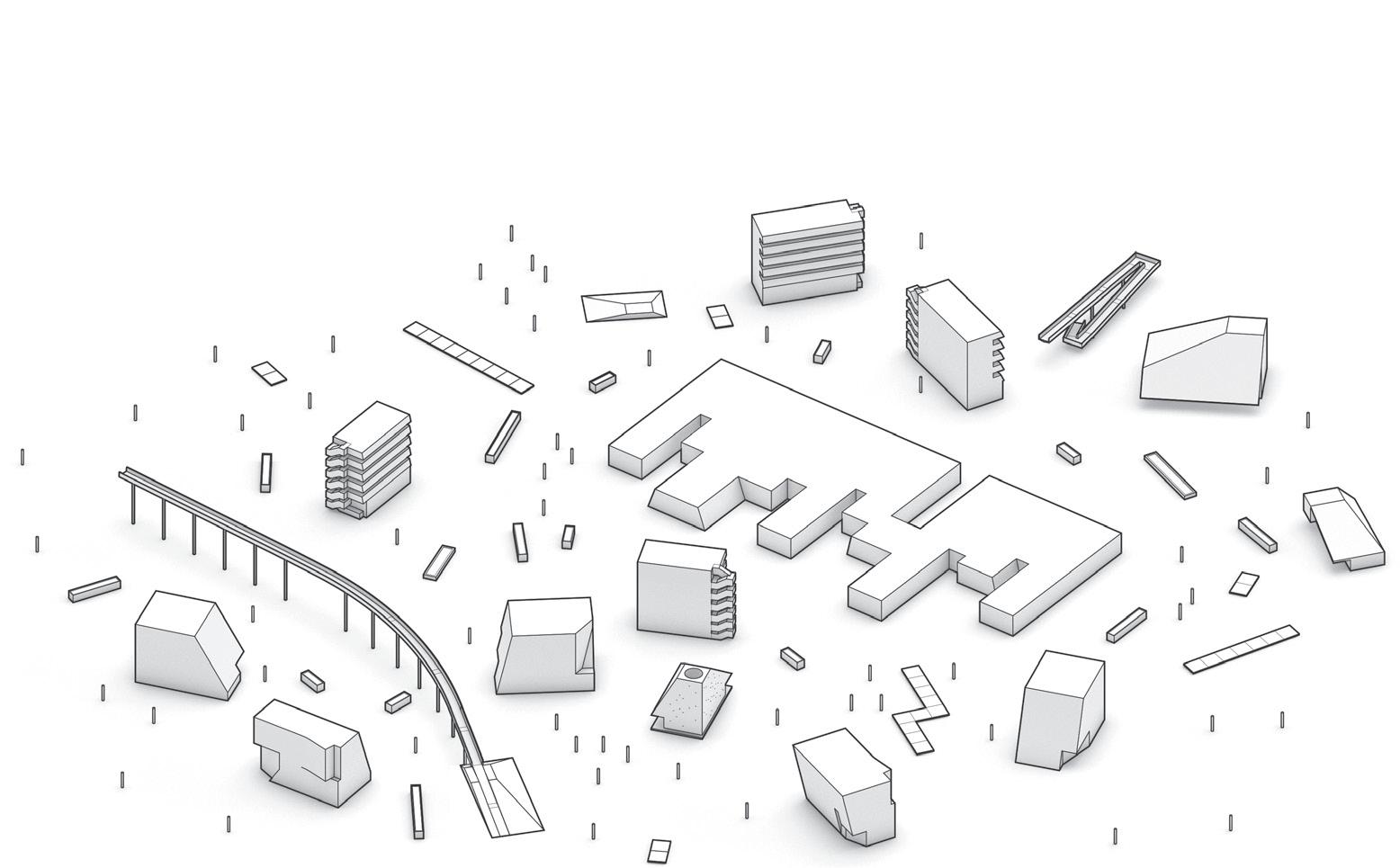

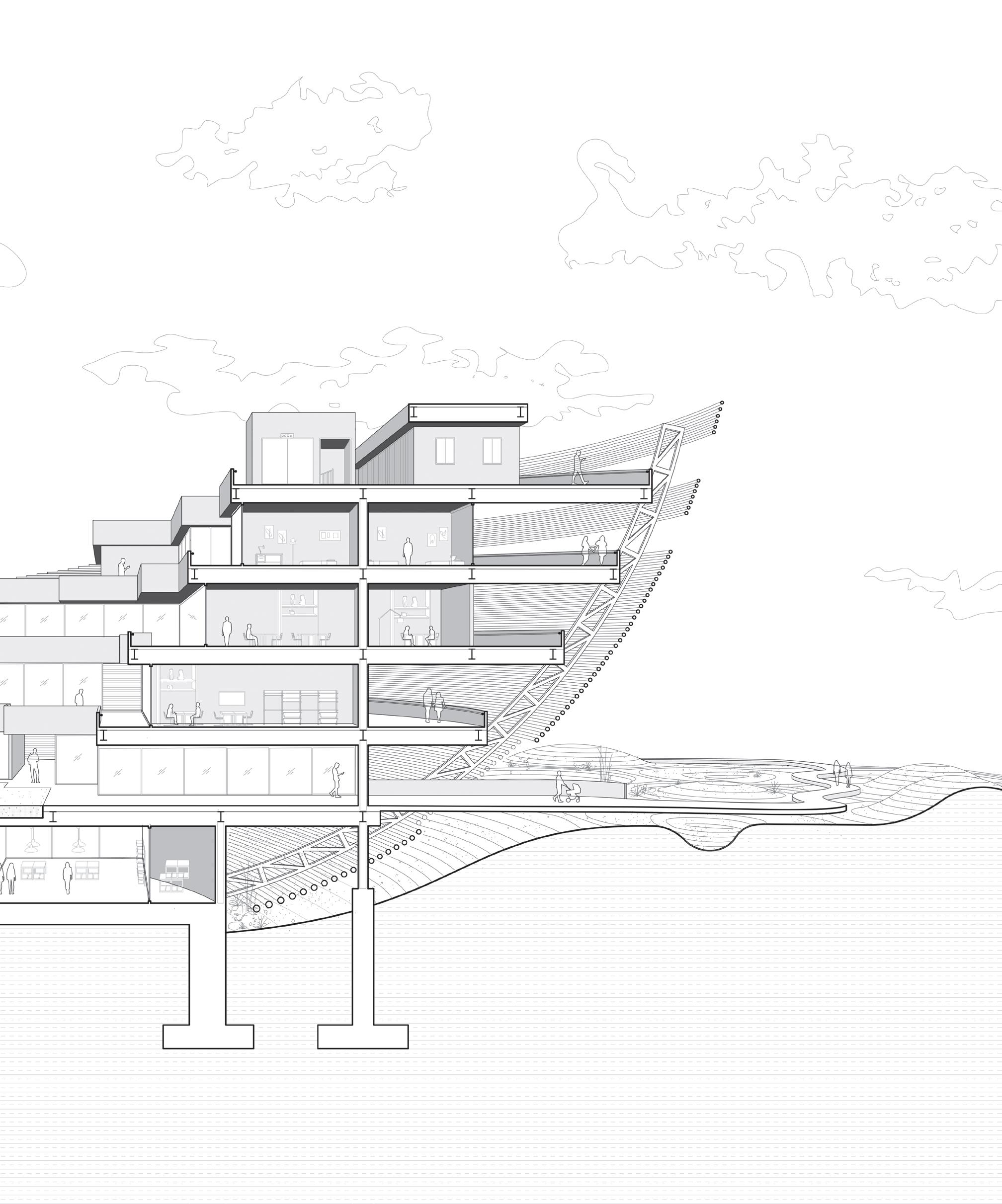

We started this project by radically questioning what ecology really means: how do different or unlike things come together? How do forces, materials, or bodies produce forms of cohabitation? Cohabitation means occupying the same space and existing side by side, creating an ecology of housemates, neighbors, and visitors. Our proposal recasts ecology as an interrelation between groups of people, more-than-human species, and climatic forces within a new school of design. This project envisions architecture as a facilitator of spatial ebbs and flows that define when and where these agents relate to each other within the system, whether by mere adjacency and intersection or by more intentional entanglement.

Building on an artificial wetland, an ecology rich with spatial and social diversity, this architectural proposal shifts the challenges of the building site conditions into exciting design opportunities. The unideal ground (too wet), hot (and wet) summers, and surprisingly cold winters fundamentally shape the building. Sunlight carves the massing to let light pass through, facade systems regulate temperature extremes, and pilotis carry the weight of the building above the porous earth. The permeable design of the school becomes a spatial filter between two distinct sides: a busy university campus and a public-facing canal.

This project considers the role of architecture as a mediator between increasingly complex natural and human systems as they enmesh with one another, producing a cultural moment on this specific site. Using the design school as an experiment, we speculate on how architecture can be a stage for the machinations of life to play out between various participants— humans, flora, fauna, wind, light, and heat.

workshops

Bottom: Diagram of characters. The cast of architectural characters includes five studio towers, four housing blocks, three pavilions, an interstitial level, a flowing landscape, a berm, a planter, a terrace, a pathway, and a ramp. Our project is both one building and a little city, as well as an ecology of parts and pieces.

Above: Ground floor plan. The new design school channels existing flows adjacent to the site, from the existing river walkway to the south and the campus masterplan to the north. The building’s jagged southern edge responds to climate forces by creating porosity toward the river, southern sunlight, and dominant south-north wind. The crenulation adds more surface area so that every dorm room can enjoy exposure to these natural forces and views. The straight northern edge facing the rest of the campus presents a unified front between the design departments.

Above: Upper floor plan. The towers become more pronounced as they pull apart on the upper levels, giving classrooms more focus and student housing more privacy. Studios and dormitories have generous windows and balconies to experience the island’s seasonal shifts.

Rendering depicting the passage from inside to outside. A daily journey through the school takes multiple speeds from the ramps, corridors, paths, and nooks collecting and allowing people to circulate through the building. These flows encourage chance encounters and reflection between spaces and landscapes.

Photograph of model. Designing from the inside out, we carved apertures to correspond with each space’s function and produce an intentional relationship between framed views of nature with the interior. People become more aware of and attuned to their surroundings through these visual relationships.

Photograph of model. A bridge across the river becomes a pathway for the dissemination of knowledge from the school and an invitation for the public and community to engage in design discourse. The school of design acts as a gateway to the larger campus plan and an invitation to the constructed wetlands park.

Above: Rendering of site. A shifting earth and porous wetland ground leads to the questions: How do humans move across a fragile wetland site? How can the ground be free from the weight or force of architecture? Our project explores the tension between common ground as territory—a contested space of ownership—and ecology, a relational space. From a bird’s-eye perspective, the new school of design floats above the artificial wetland and announces a new kind of cohabitation between the ground, the air, and the architecture.

The design school is a living museum: a structure of contact and collaboration with local ecologies, community, and industry.

The shift in the role of museums, from didactic educators to co-creators, is essential for fostering imagination and addressing social paralysis, emphasizing imagination as a civic infrastructure and empowering communities to tell their stories and envision change.

Connecting with nature instills slowness and gratitude while enhancing imagination. This urges a design approach that curates and cultivates imagination beyond human beings, emphasizing awe as an undervalued emotion that can be harnessed for positive change.

Promote interaction, education, and mutual benefit between human and nonhuman life, emphasizing the importance of ecological balance and sustainability. The nonhumans are equal residents in a place where architectural structure itself becomes a testament to the interdependence of life. The well-being of all entities is intertwined and mutually nurtured.

Building vibrant, diverse local economies with local ownership and investment fosters agency and control over communities’ futures. Use local materials for creative opportunities, giving back to the Earth what we take from it.

Maddie Farrer, Tanil Raif

In this project, we invite connection between human and nonhuman, academia and civility to shape radically optimistic realities. We confront the traditional didactic relationship between teachers and pupils to further extend learning towards the public, the land, and the location. Our proposal reimagines the design school as a living museum, providing an education that encourages collaboration and imagination between local ecologies, community, and industry.

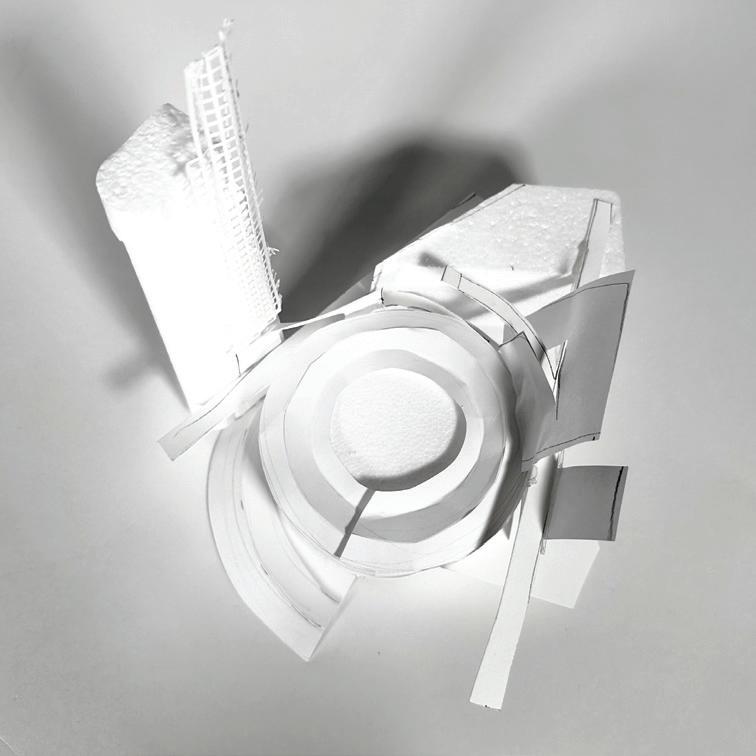

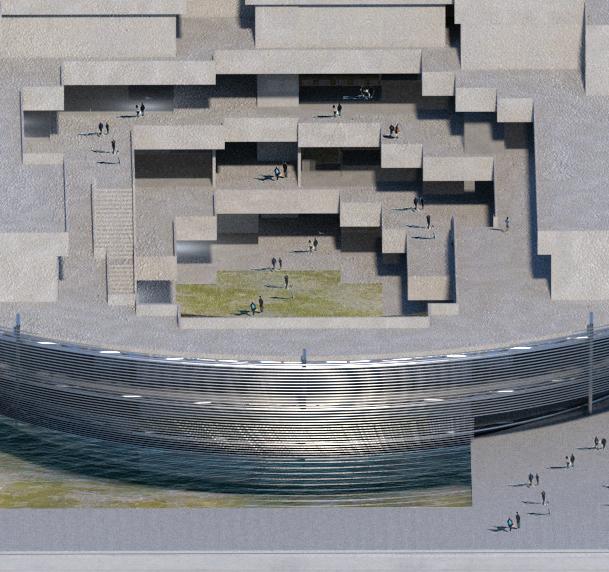

Architecture should create relationships by inviting ecosystems, people, and ideas together. The form of our building combines the uniqueness of the island—a protected, self-sustaining community— with a valley, a shape that naturally gathers, and a loop of exhibition space as connective tissue between the students and visitors. Together, the site, valley, and loop form the living museum, a place where designers look toward one another in addition to the land and to local industry. The design school invites the public to become part of the education by hybridizing learning with displaying and learning with living.

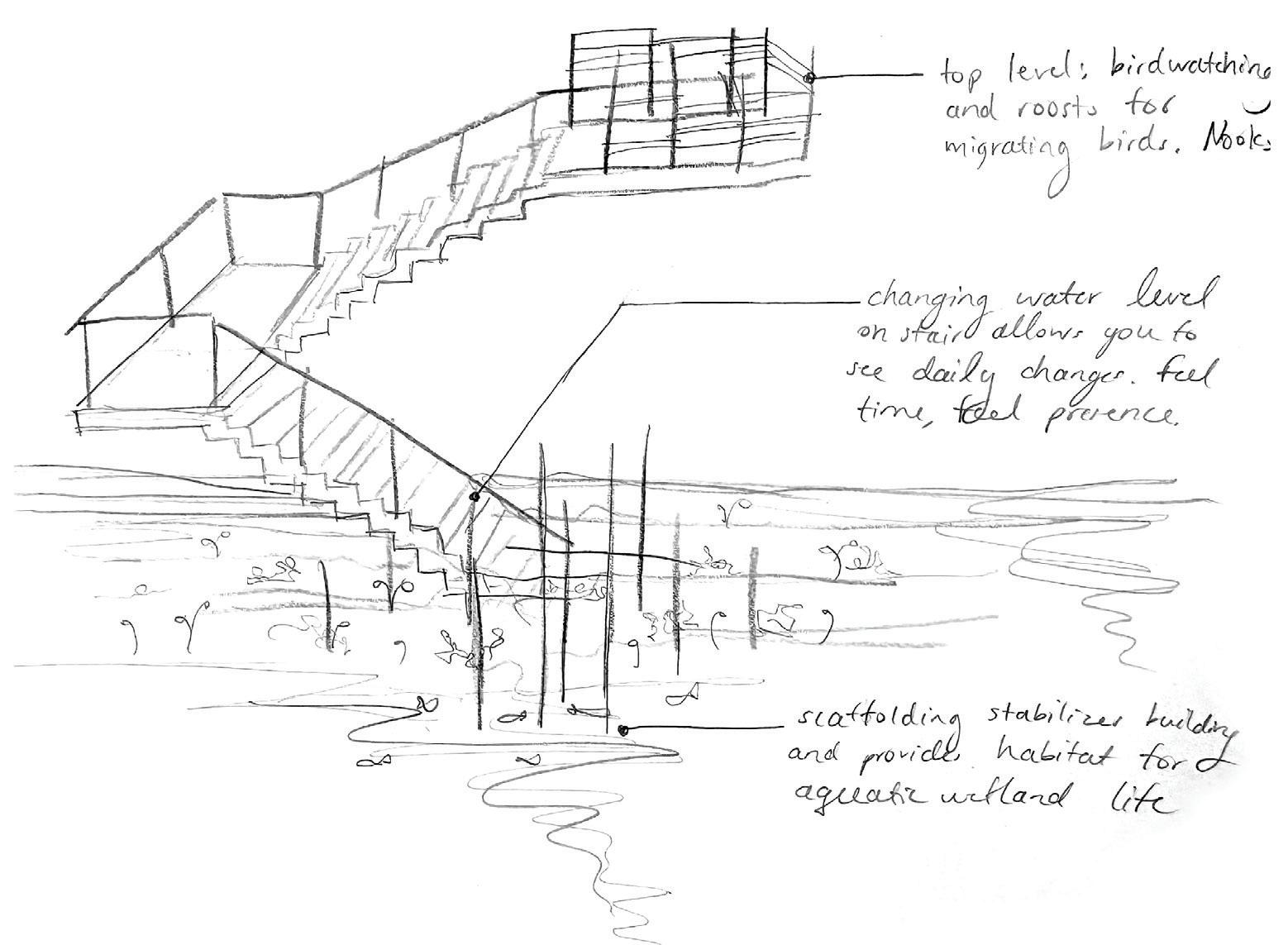

Viewing the land as an equal inhabitant, we lift human life above the ground plane to allow the wetlands to continue fulfilling their natural purpose of absorbing and storing water. The crater’s tapered form creates a smaller and less disruptive human footprint than a traditional structure on the wetland site. This design choice anticipates higher water levels in the future and recasts the school’s site as a water retention basin that works in tandem with other natural bodies of water. As the water levels rise and fall with the wet and dry seasons, the school’s residents feel the turning of time through their daily schedules and connect with cycles larger than those on the human scale.

Top: Rendering from within the crater. Our intent is not to control nature, but to create a scaffolding for nature to take over. Visting public and students inhabit the school just as migratory birds nest and indigenous grasses take root in the wetlands.

Bottom: Sketch diagram. Our formal language combines the island’s existing ecology with a valley that collects and a loop that connects. The valley has a minimal footprint on the site to maximize space and breathing room for the vital wetlands.

Exterior rendering. The Crater is a beacon for designers and the public alike. It reads both as an otherworldly mass and a beached object, recalling the hull of a ship docked in the wetlands. A complex and pixelated inner world peaks through the reflective screen. The juxtaposition between inside and outside, between grounded and hovering, provokes awe and inspiration, which are powerful emotions that drive radical thinking.

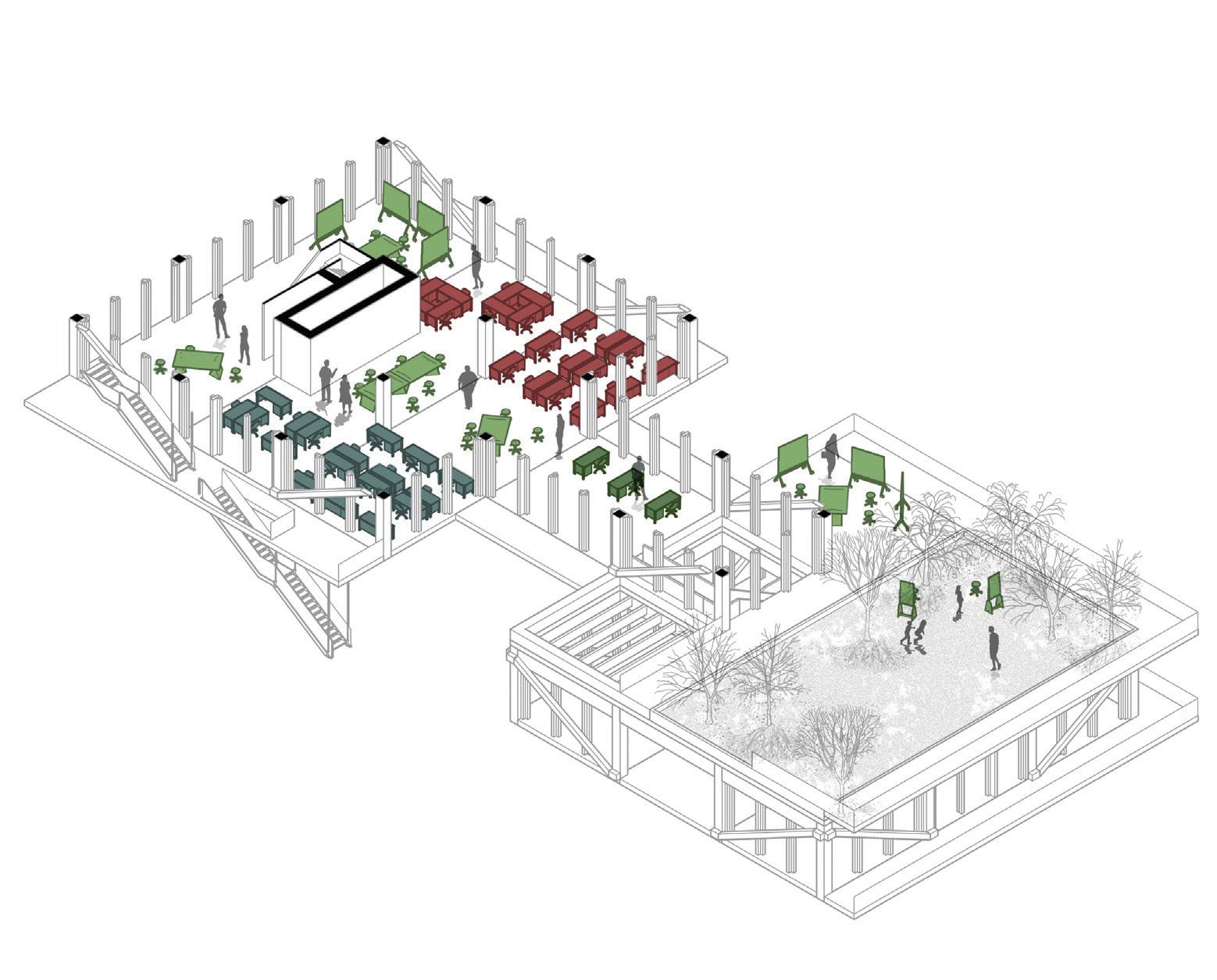

Above: Ground floor plan. The lowest level of the building sits within the basin, occupied by workshops with flexible partitions, offices, and classrooms for students and faculty. All spaces are enclosed by sliding glass doors to allow for natural ventilation and access to the shared courtyard. Due to a suitable climate, the hallways and terraces are mostly open to the air. Walking paths weave between the grided layout at the center and the edge of the encompassing circle. This interstitial zone invites the public to engage with students via exhibitions and pin-up walls of works in progress.

Above: Upper floor plan. On the upper levels, pin-up walls and display nooks continue to wrap the perimeter. These public passages connect the library, auditorium, and community room, which poke outside the main volume to communicate the public programs on the exterior. Turning inward, studios face toward each other across the valley so that social collaboration may spill out onto balconies and intersect with the exhibition tissue. The top two levels of the building host dormitories to maintain privacy and views of the campus and river.

of exhibition space. Exhibition walkways flow around the academic rooms closer to the center of the valley. The rhythm breaks when people gather around pin-up walls that punctuate the path. Pin-ups and studio displays become public events, inviting people from industry and the local community. The pedagogy engages the vital connection between academic work and practice outside the school.

Above: Section perspective drawing. The overarching strategy of making a valley turns the reclaimed land on the site back into wetlands. Nestling the bowl-shaped building in the ground at a few points reduces the large overall footprint of the school with its complex spatial requirements. The land still feels the weight of the building, but the reduced footprint gives something back to the wetland ecosystem. Entries to the building are generous extensions of open-air walkways, so visitors can wander into and through the building freely.

and

programs into cascading levels allows for views of the landscape and access to fresh air and sunlight on every floor.

Above: Rendering of facade. The aluminum tubing facade unifies the school from the outside and allows the mostly open-air campus to breathe with the changing seasons. The shiny material reflects its surroundings and attracts human and non-human visitors from far away. Once inside, people can look out at the landscape through the perforated wall while shaded from the elements by the rainscreen.

Photograph of model. The design school as a valley explores new spatial relationships between the island ecology and school’s social structure, between design practice outside the crater and the inner life of the designers’ village. Central educational spaces look onto each other and the land; disciplines connect with each other and the public. Hybridizing the school and the living museum encourages visitors to learn from each other and from the world around them.

The design school is an exhibition of spaces showing the fluctuation between thinking and making. The School of Design is a Sponge . . . that absorbs and integrates nature into the learning experience, allowing students to immerse themselves in a natural setting and design in nature.

+

as the Core Workshops should be exhibited to show how projects are created for the public and other students to learn from each other. The Thinking + Making Complex operates as sponge tissue linkage across the school.

This pedagogy offers the opportunity for all design majors to share a foundational year of learning and for students to take electives outside their discipline to encourage exchange between departments. The architectural organization strikes a balance between learning within studios, workshops, and informal spaces of exchange.

Yihan Yang

I approach reimagining the school of design as an urban designer from a bird’s-eye view, learning from the patterns across Chongming Island and zooming in on the school as a small city within the larger university campus. Borrowing from the concept of a “Sponge City,” this urban design strategy utilizes wetlands as both a key functioning landscape and a design analogy. Wetlands naturally act as sponges by filtering and absorbing water, maintaining the health of habitats by cleaning out toxic materials and making sites more resilient to flooding. They also create porous habitats for diverse creatures to move freely between wet and dry conditions. Using the wetlands as an analogy for the design of a school, this project proposes a porous design education where students immerse themselves in a natural setting and design within nature, absorbing and integrating lessons from nature into their learning experience.

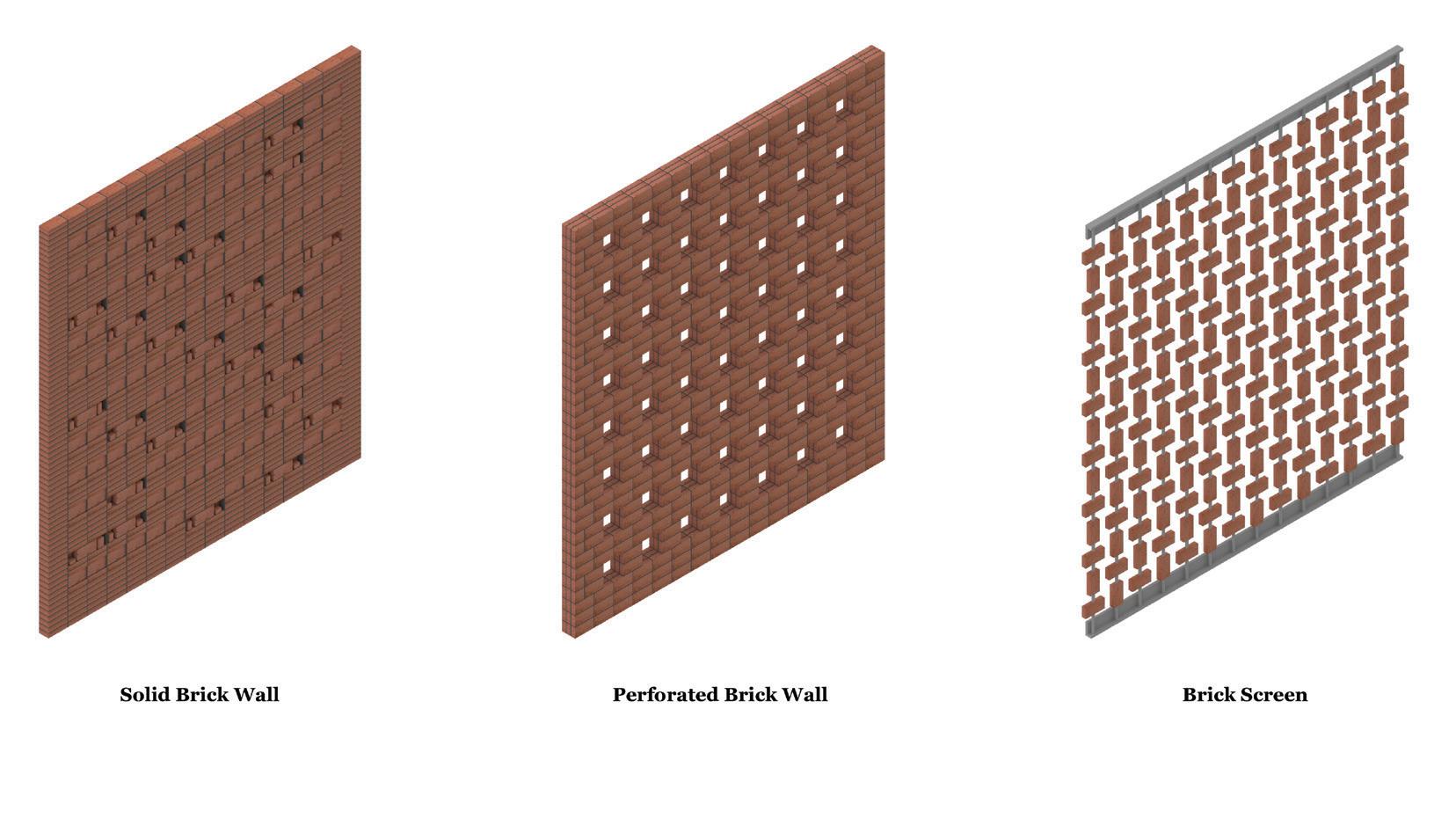

The design of the building acts like a sponge both in its internal arrangement and its materials. Natural spaces and terrace gardens are interwoven between classrooms to give students the experience of nature throughout the building. A perforated facade, made from the bricks of the island’s demolished buildings, lets natural light and fresh air into the building so that it breathes like a wetland. The patchwork of recycled bricks recall the local cultural heritage of Chongming.

The Thinking + Making Complex is an exceptional zone within the school that hybridizes workshops with exhibition space for the public to pass by and see designers in the process of making. This newly imagined space emphasizes combining the study of traditional craftsmanship on the island with experimentation in the classroom, rooting the design school’s connection to the island while inspiring contemporary makers.

Bottom: Diagram of brick details. The three typologies of brick construction are solid, perforated, and screen brick walls. Each allows a different amount of light in and views out according to the function of the

Above: Photograph of sectional model and section rendering. The Thinking + Making Complex at the center of the design school courtyard is mostly composed of glass. The shift in material from bricks allows people to see into the inner life of studios and exhibitions more easily.

The design school is a platform for the social dynamics between the island’s interlocking actors, linking students and faculty to Chongming Island’s culture and ecology by integrating local craftspeople and flora.

The school fosters engagement between students, staff, and faculty as well as the local community, ecology, and visitors. Learning and teaching relies on robust connections with the broader campus community, Chongming Island, and the public, paving the way for innovative thinking within and beyond the school.

Incorporating the community and its values into the design school encourages cross-collaboration and accentuates the distinct traditions of the region. Students learn to design with the common sense of local craftspeople attuned to their surroundings.

To imbue the school with a genuine sense of place, we integrate the island’s ecology into the pedagogy and materials. Designing with the island’s flora, fauna, climatic variations, and seasonal shifts forges a robust relationship between the natural and school environments.

John Adrian, Gustavo Ramirez