SPRING 2023 HISTORYNET.COM ACWP-230400-COVER-DIGITAL.indd 1 12/9/22 2:05 PM

OFFER

Super

Hammers have

. Here’s

they

$21.99 Personalized Garage Mats Grease Monkey or Toolman, your guy (or gal) will love this practical way to identify personal space. 23x57"W. Tools 808724 Tires 816756 $45.99 each Personalized Extendable Flashlight Tool Light tight dark spaces; pick up metal objects. Magnetic 6¾" LED flashlight extends to 22"L; bends to direct light. With 4 LR44 batteries. 817098 $31.99 Personalized 6-in-1 Pen Convenient “micro-mini toolbox” contains ruler, pen, level, stylus, plus flat and Phillips screwdrivers. Giftable box included. Aluminum; 6"L. 817970 $29.99 ACWP-230117-004 Lillian Vernon LHP.indd 1 11/23/22 12:55 PM

Personalized

Sturdy Hammer

a way of walking o

one

can call their own. Hickory-wood handle. 16 oz., 13"L. 816350

Personalized 13-in-1 Multi-Function Tool

Our durable

Vernon products are built

and manufacturing

or monogram. Ordering

free.*

*FREE SHIPPING ON ORDERS OVER $50. USE PROMO CODE: HISACW S3 LILLIANVERNON.COM/ACW The Personalization Experts Since 1951 OFFER EXPIRES 4/30/23. ONLY ONE PROMO CODE PER ORDER. OFFERS CANNOT BE COMBINED. OFFER APPLIES TO STANDARD SHIPPING ONLY. ALL ORDERS ARE ASSESSED A CARE & PACKAGING FEE. RUGGED ACCESSORIES FOR THE NEVER-ENOUGH-GADGETS GUY. JUST INITIAL HERE. Personalized Bottle Opener

tool

day with

cool brew.

$11.99 each

Personalized Grooming Kit Indispensable zippered manmade-leather case contains comb, nail tools, mirror, lint brush, shaver, toothbrush, bottle opener. Lined; 5½x7". 817548 $29.99

Lillian

to last. Each is crafted using the best materials

methods. Best of all, we’ll personalize them with your good name

is easy. Shipping is

Go to LillianVernon.com or call 1-800-545-5426.

Handsome

helps top o a long

a

1½x7"W. Brewery 817820 Initial Family Name 817822

Personalized Beer Caddy Cooler Tote Soft-sided, waxed-cotton canvas cooler tote with removable divider includes an integrated opener, adjustable shoulder strap, and secures 6 bottles. 9x5½x6¾". 817006 $64.99

ACWP-230117-004 Lillian Vernon RHP.indd 1 11/23/22 12:58 PM

All the essential tools he needs to tackle any job. Includes bottle opener, flathead screwdriver, Phillips screwdriver, key ring, scissors, LED light, corkscrew, saw, knife, can opener, nail file, nail cleaner and needle. Includes LR621 batteries. Stainless steel. 818456 $29.99

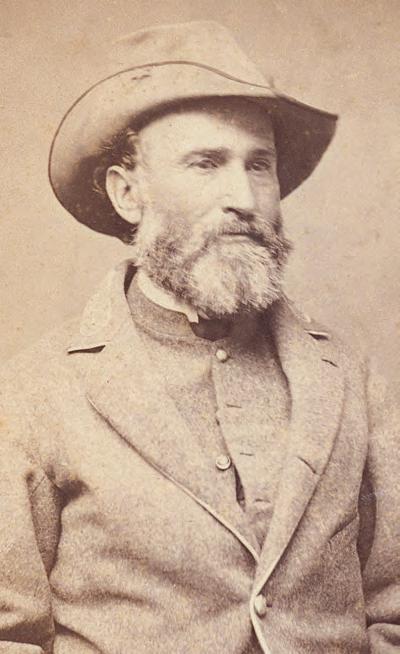

Spring 2023 2 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: HARPER’S WEEKLY; STATE LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES OF FLORIDA; BATTLES AND LEADERS OF THE CIVIL WAR; LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; COVER: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS/PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY BRIAN WALKER 22 Loose Lips Ambrose Burnside’s three-front war in North Carolina By Bruce Allardice ACWP-230400-CONTENTS.indd 2 12/13/22 8:44 AM

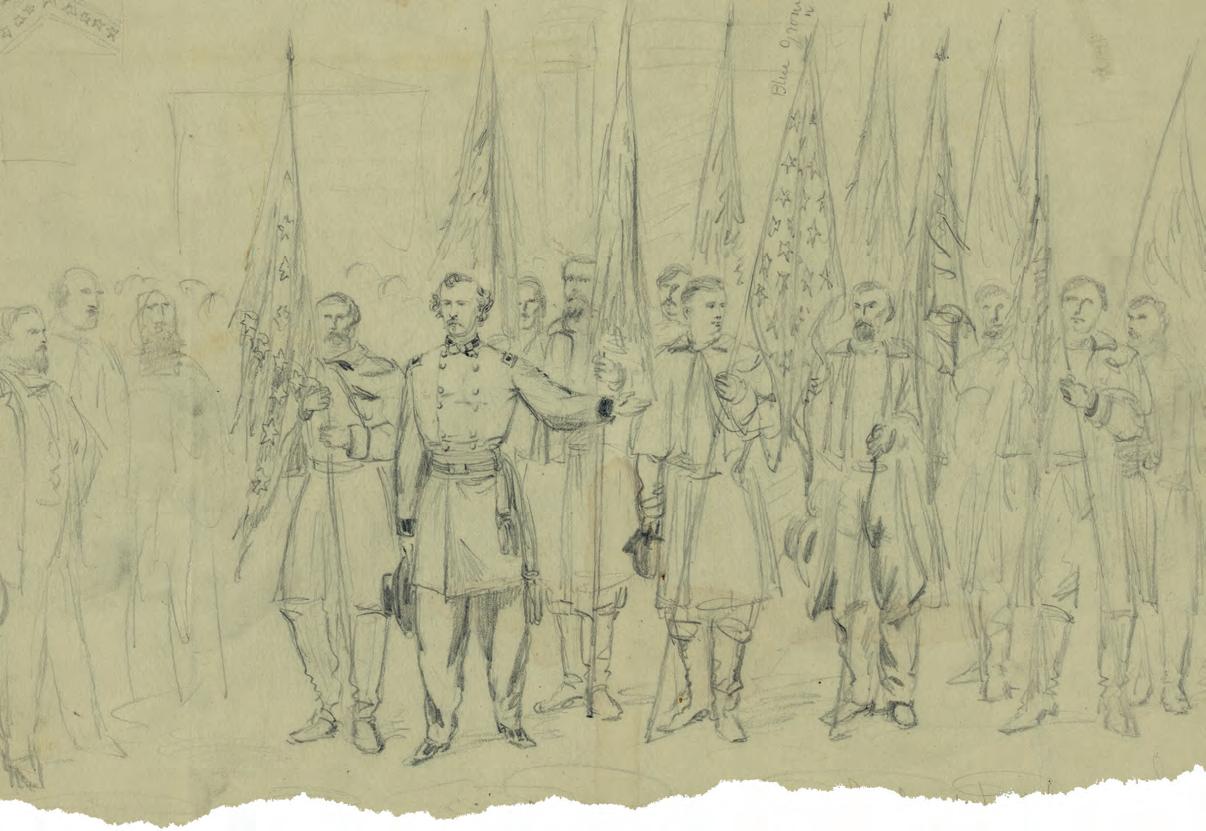

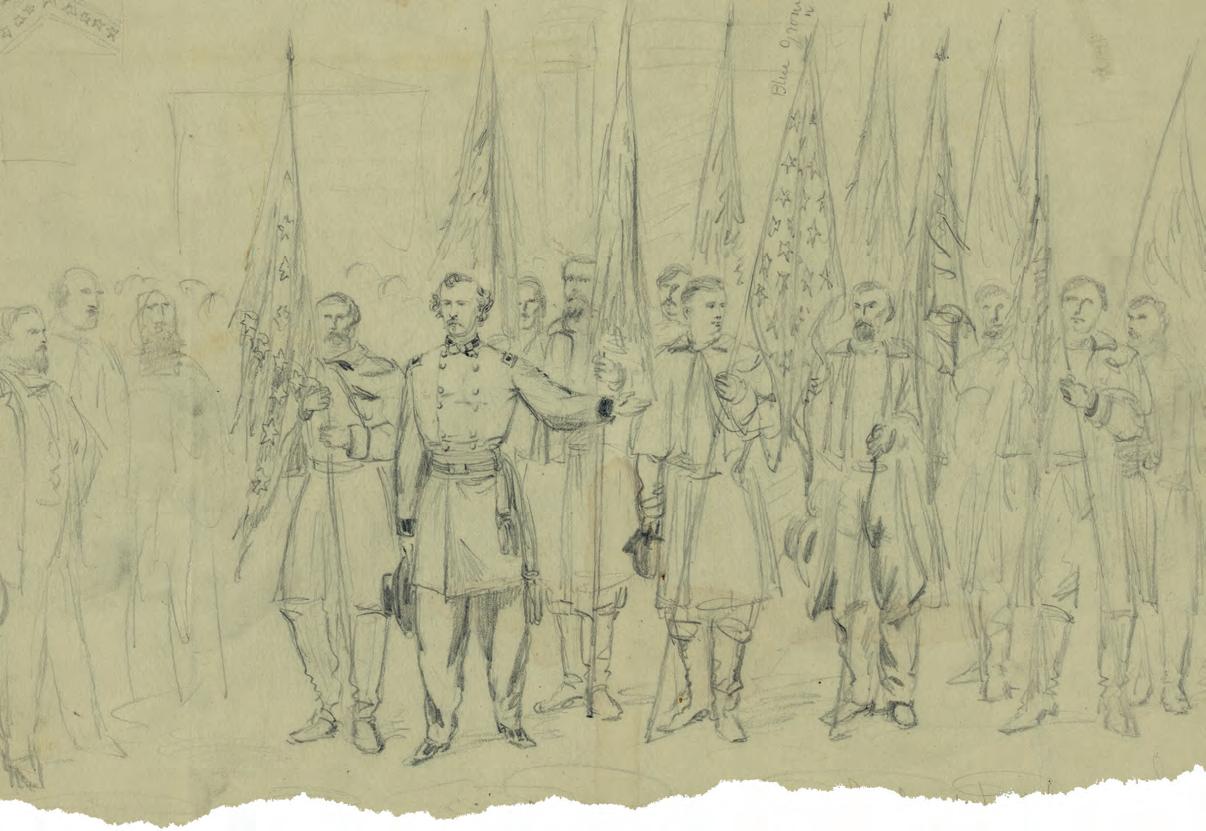

By Sheritta Bitikofer

SPRING 2023 3 Departments 6 L ETTERS An unresolved mystery; deserving credit for VMI’s other cadets 8 G RAPESHOT! Mapping faces of the war; Louisiana side hustle 12 REGIMENTAL PRIDE That time the 8th Vermont refused to back down 1 6 L IFE & LIMB State-of-the-art solution for wounded soldiers 18 FROM THE CROSSROADS Gettysburg memories yield a lesson in humility 20 SOUTHERN ACCENT The tables were turned three decades before the war 54 TRAI LSIDE Parker’s Crossroads, Tenn.: Forrest rides roughshod again 58 5 QUESTIONS Shining new light on a troubled Johnston–Davis alliance 60 R EVIEWS As the war wanes, Lincoln finds some divine guidance 64 FI NAL BIVOUAC Oh, the Humanity! ON THE COVER: MAJ. GEN. AMBROSE BURNSIDE, PHOTOGRAPHED BY MATHEW BRADY IN JUNE 1864. AS COMMANDER OF THE 9TH CORPS, BURNSIDE HAD RETURNED TO THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC AND THE FIGHTING IN VIRGINIA IN MAY 1864 DURING LT. GEN. ULYSSES S. GRANT’S ADVANCE ON RICHMOND. New! New! Illustrator of the Confederacy William Sheppard’s pad and pencil revealed an unexplored side of the war

30 46 Unfinished Business After Cedar Creek, Sheridan’s men were sure they hadn’t seen the last of Jubal Early’s battered army

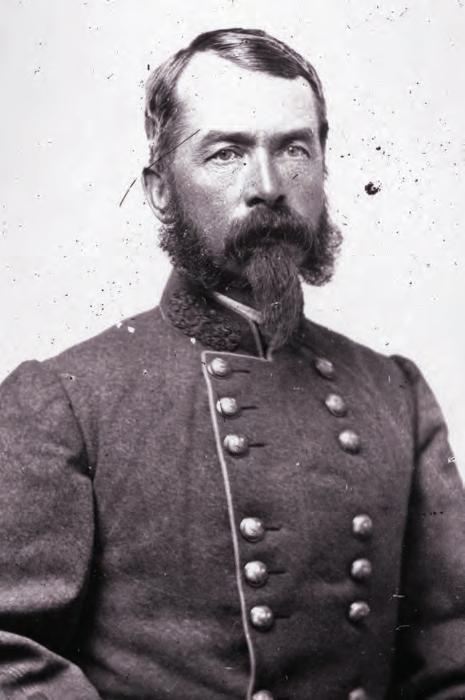

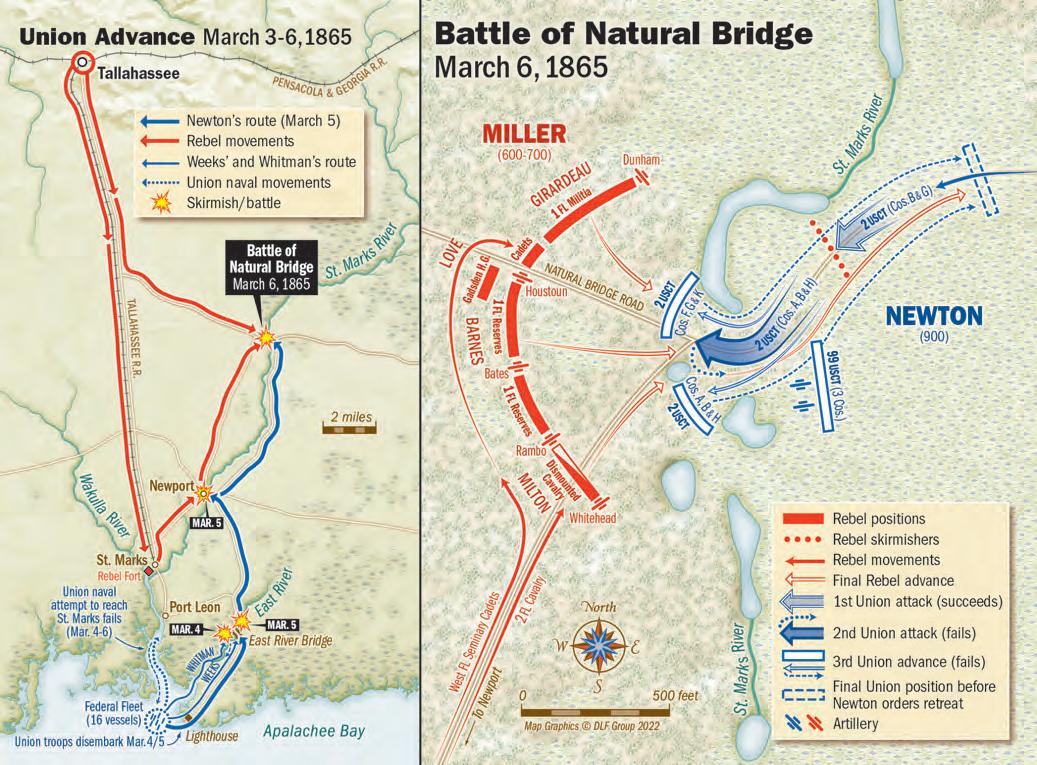

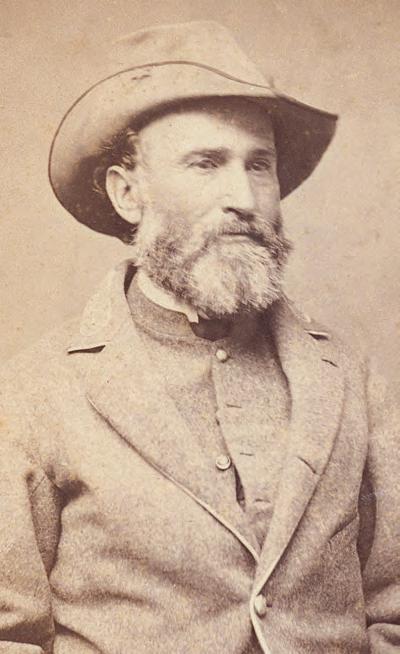

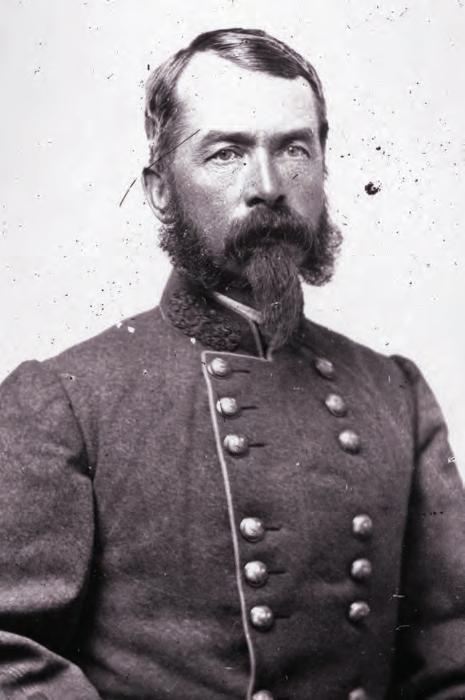

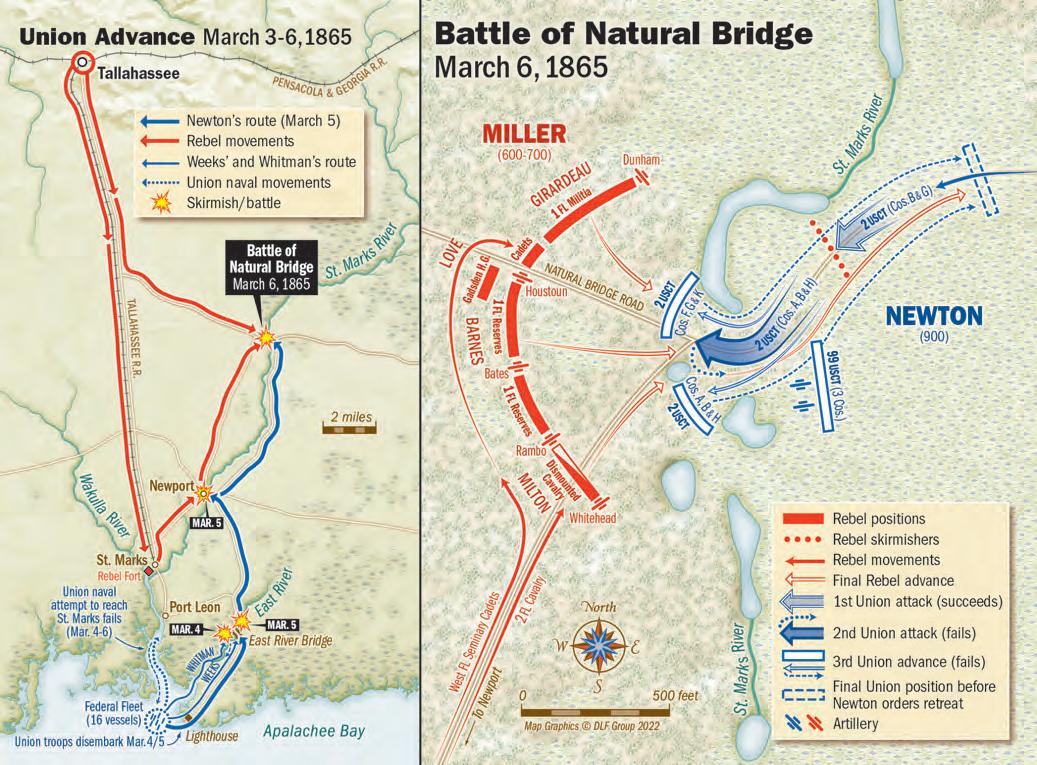

A. Noyalas Sunshine State Showdown An unexpected Confederate victory at Natural Bridge offered a little of everything

By Stephen Davis

By Jonathan

38 ACWP-230400-CONTENTS.indd 3 12/13/22 8:44 AM

Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001 The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HISTORYNET, LLC. PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

Publisher

BOARD Gordon Berg, Jim Burgess, Steve Davis, Richard H. Holloway, D. Scott Hartwig, Larry Hewitt, John Hoptak, Robert K. Krick, Ethan S. Rafuse, Ron Soodalter, Tim Rowland C ORPORATE Kelly Facer SVP Revenue Operations Matt Gross VP Digital Initiatives Rob Wilkins Director of Partnership Marketing Jamie Elliott Senior Director, Production Mel Gray Print Production Coordinator ADVERTISING Morton Greenberg SVP Advertising Sales mgreenberg@mco.com Terry Jenkins Regional Sales Manager tjenkins@historynet.com DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING MEDIA PEOPLE Nancy Forman nforman@mediapeople.com ©2023 HISTORYNET, LLC Subscription Information: 800-435-0715 or shop.historynet.com List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc., 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com America’s Civil War (ISSN 1046-2899) is published quarterly by HISTORYNET, LLC, 901 North Glebe Road, Fifth Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Vienna, VA, and additional mailing offices. Postmaster, send address changes to America’s Civil War, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900 Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519

Michael A. Reinstein Chairman &

Vol. 36, No. 1 Spring 2023 ADVISORY

Chris K. Howland Editor Jerry Morelock Senior Editor

Brian Walker Group Design Director Melissa A. Winn Director of Photography Austin Stahl Associate Design Director

4 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR LIBRARY OF CONGRESS/PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY

Sign up for our FREE weekly e-newsletter at:

HISTORYNET VISIT HISTORYNET.COM PLUS! Today in History What happened today, yesterday— or any day you care to search. Daily Quiz Test your historical acumen—every day! What If? Consider the fallout of historical events had they gone the ‘other’ way. Weapons & Gear The gadgetry of war—new and old— effective, and not-so effective. Confederate

was a rip-roaring, knock-kneed

his fondness for alcohol made him his own

Whiskey-Fueled Warrior TRENDING NOW ACWP-230400-MASTHEAD.indd 4 12/12/22 9:22 AM

Dana B. Shoaf Editor in Chief Claire Barrett News and Social Editor

BRIAN WALKER

historynet.com/newsletters

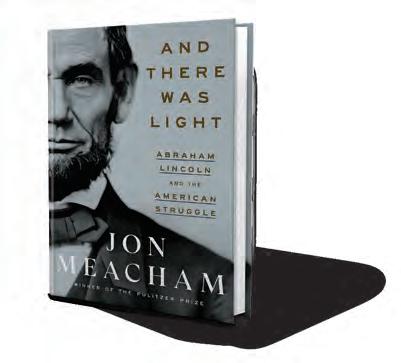

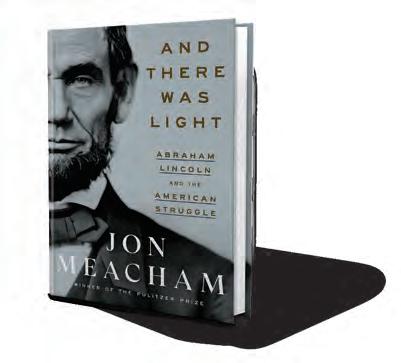

officer Nathan “Shanks” Evans

fighter—and

worst enemy. By Rick Britton historynet.com/shanks-evans-civil-war

When 1982 rolled around, the U.S. Mint hadn’t produced a commemorative half dollar for nearly three decades. So, to celebrate George Washington’s 250th birthday, the tradition was revived. The Mint struck 90% silver half dollars in both Brilliant Uncirculated (BU) and Proof condition. These milestone Washington coins represented the first-ever modern U.S. commemoratives, and today are still the only modern commemorative half dollars struck in 90% silver!

Iconic Designs of the Father of Our Country

These spectacular coins feature our first President and the Father of Our Country regally astride a horse on the front, while the back design shows Washington’s home at Mount Vernon. Here’s your chance to get both versions of the coin in one remarkable, 40-year-old, 2-Pc. Set—a gleaming Proof version with frosted details rising over mirrored fields struck at the San Francisco Mint, and a dazzling Brilliant Uncirculated coin with crisp details struck at the Denver Mint. Or you can get either coin individually.

Very Limited. Sold Out at the Mint!

No collection of modern U.S. coins is complete without these first-ever, one-year-only Silver Half Dollars—which effectively sold out at the mint since all unsold coins were

melted down. Don’t miss out on adding this pair of coveted firsts, each struck in 90% fine silver, to your collection! Call to secure yours now. Don’t miss out. Call right now!

1982 George Washington Silver Half Dollars GOOD — Uncirculated Minted in Denver 2,210,458 struck Just $29.95 ea. +s/h Sold Elsewhere for $43—SAVE $13.05

BETTER — Proof Minted in San Francisco 4,894,044 struck Just $29.95 ea. +s/h Sold Elsewhere for $44.50—SAVE $14.55

BEST — Buy Both and Save! 2-Pc. Set (Proof and BU) Just $49.95/set SAVE $9.95 off the individual prices Set sold elsewhere for $87.50—SAVE $37.55

FREE SHIPPING on $49 or More! Limited time only. Product total over $49 before taxes (if any). Standard domestic shipping only. Not valid on previous purchases.

1-800-517-6468 Offer

GWH132-01 Please mention this code when

Code

you call.

coin and currency issues

government. The collectible coin market is unregulated, highly speculative and involves risk. GovMint.com reserves the right to decline to consummate any sale, within its discretion, including due to pricing errors. Prices, facts, figures and populations deemed accurate as of the date of publication but may change significantly over time. All purchases are expressly conditioned upon your acceptance of GovMint.com’s Terms and Conditions (www.govmint.com/terms-conditions or call 1-800-721-0320); to decline, return your purchase pursuant to GovMint.com’s Return Policy. © 2022 GovMint.com. All rights reserved. GovMint.com • 1300 Corporate Center Curve, Dept. GWH132-01, Eagan, MN 55121 A+ To learn more, call now. First call, first served! FIRST and ONLY Modern Commemorative Struck in 90% Silver! BRILLIANT UNCIRCULATED -Crisp, Uncirculated Finish -Struck at the Denver Mint -Sold Out Limited Edition PROOF -Exquisite Proof Finish -Struck at the San Francisco Mint -Sold Out Limited Edition George Washington Reverse: Mount Vernon & Heraldic Eagle First in War, First in Peace, First on a Modern Commemorative Coin! SPECIAL CALL-IN ONLY OFFER Actual size is 30.6 mm ACWP-230117-003 GovMint 1982 George Washington Half Dollar.indd 1 11/23/22 12:48 PM

GovMint.com® is a retail distributor of

and is not affiliated with the U.S.

Shared quest

I enjoyed John Banks’ “Who Are They?” article in the Autumn issue [P.30], especially the mention of two photographs in the collection of the former Museum of the Confederacy. I was president of the MOC from 2004 until its combination with another museum to become the American Civil War Museum, where I was co-CEO until my retirement at the end of 2019.

We did indeed have fun with “Whose Little Girl Is This?” in 2012. That Associated Press article appeared in more than 500 newspapers around the world, and we got some “interesting” inquiries.

A woman from California claimed that she could speak with the dead. If we would only fly her to Richmond, she would have a séance and ask the little girl to identify herself.

Another man, also from California (aka the land of fruits and nuts), called to say that he knew the little girl because she was the ghost who haunted his house.

We got a great lead from another woman who contacted us. She was a retired photograph curator at the Smithsonian. While she had no idea about the little girl, she actually recognized the furniture and setting as from a studio in Vermont. We saw other images from that studio and believe she was correct. But, dang, there were no Vermont regiments involved at Port Republic (or nearby Cross Keys), so the mystery was not solved.

S.

Waite Rawls III Richmond, Va.

New Market Fan

I still remember my first trip to New Market about 25 years ago. I stopped there without any real expectations on my way home to Hagerstown from Roanoke. Never really thought of

Somebody’s Girl

The identity of the little girl pictured in this ornate case found on a Civil War battlefield remains a mystery some 160 years later.

myself as a Civil War person at the time, but I was curious as I drove by.

I had never heard before about the VMI Cadets who fought there, but after walking the battlefield and visiting the museum, I definitely wanted to learn more about them. I kept trying to wrap my head around what they must have been thinking and the bravery they showed in making that charge across that muddy field against those Union guns. It also made me want to learn more about the war in general.

Unfortunately, I’ve only been able to get back to New Market a few times since, so I was happy to see the article you had about the battle in the Autumn

issue (“Mowed Down Like Grass,” P.38). I never realized what the other VMI boys did on the other side of the battlefield. So it’s nice to see them finally get some credit.

I also love the painting by Keith Rocco shown in the article. We’re lucky the Civil War world has a lot of great artists like him out there.

Pete Falcone

Wilmington, Del.

Last Resort (cont’d)

I wanted to respectfully write in response to Tom Desjardin’s article about the 20th Maine at Gettysburg (“The Last Resort?”–Autumn 2022). Dr. Desjardin writes: “Apart from several dozen transfers from the disbanded 2nd Maine Infantry, Gettysburg was what one veteran called the 20th’s “first real, standup fight,” and later notes that Chamberlain’s “lack of combat leadership experience” surely would have

6 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR

COURTESY OF THE MAINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF HISTORY AND CULTURE

LETTERS

ACWP-230400-LETTERS.indd 6 12/12/22 9:23 AM

granted him “a misstep or two.”

It’s important to note that the 20th Maine had been in combat prior to Gettysburg. They fought at Shepherdstown Ford on September 19, 1862, firing at Confederate positions on the other side of the river, and taking three casualties. Most notably, they fought at Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg, with four men killed in action and 32 wounded, after which they were held in place for nearly two days. Their men had to hunker down behind dead bodies to find cover, and temperatures at night were below freezing. This was not as involved an action as other regiments; a frontal attack was aborted, and the regiment engaged the enemy from long range.

The months and weeks before and after that battle, however, involved actions to guard telegraph lines, fords, and also being held in reserve during major actions like Antietam.

It would be inaccurate to portray the 20th Maine as inexperienced troops. They had suffered many losses due to illness (more than 300), had fought in combat before, and had been serving together in different capacities for nearly a year.

I can see Dr. Desjardin’s point that they were not “experienced” or “crack troops.” But he clearly states that aside from the 2nd Maine transfers, they hadn’t seen action. There is no mention of the 20th Maine’s participation in two other major campaigns that included combat.

This all being said, I believe that Mr. Desjardin wrote an excellent and true article, highlighting the fact that the Confederate forces lacked the manpower to threaten the Union left flank at Gettysburg. It was illuminating, to say the least, and is a great analysis of what happened.

Justin Tkachuk Via E-mail

Tom Desjardin responds: While the 20th Maine experienced brief moments of combat and one prolonged engagement in the midst of a major battle,

History Made Here

Chamberlain and 20th Maine veterans, accompanied by various family members, pose by their Little Round Top monument in 1888.

Gettysburg was different in many ways—especially in the style of fighting, which those men had yet to see for any sustained period. Standing, loading, and firing while bullets whizzed by and comrades around them fell was the true test of unit effectiveness. The 20th Maine had not been thus tested before July 2, 1863.

Captain Lyman Prince read the regimental history at the dedication of its three monuments at Gettysburg. It is reprinted in full in the 20th’s section of the book Maine at Gettysburg. In it, he said: “But for the men of the 20th this was the first real stand up fight. They were under fire to be sure at Shepherdstown; they made a gallant advance at Fredericksburg, showing the stuff that was in them, but their losses were light in spite of their hazardous position; and the running fight at Aldie [Va.] was more trying to the legs and wind than the courage.”

At Shepherdstown, the unit marched up the steep bank on the enemy side and fired only briefly before being driven back down the bank, across the river, and into the safety of an empty canal on the Union side. At Fredericksburg, they had but one real maneuver

to perform just as they left the city and started up the long slope that led to Marye’s Heights. Here, part of the regiment encountered a rail fence lying straight across their path.

The soldier’s descriptions of the confusion and misdirection caused by this obstacle demonstrated their still underdeveloped skills at maneuvering under fire. Near the top of the heights, they moved in good order to replace another unit, then marched down the next night, then repeated the whole exercise the following day, but they never stood in line and traded bullets with the enemy.

Of the 41 casualties, four were killed outright and two mortally wounded, although one of those died of tetanus and not the wound itself. The casualty lists include an unusually high number of wounds by shell fragments, indicating they were hit from a distance, rather than by the enemy “standing up” in front of them.

What Captain Lyman seems to have meant is that, before Gettysburg, the unit had never stood in line of battle and exchanged fire with an enemy unit doing the same directly opposite them. This is a test of nerve and courage and often used as the best measure of a unit in years afterward.

WRITE TO US

E-mail: acwletters@historynet.com Letters may be edited.

@AmericasCivilWar @ACWmag

SPRING 2023 7

LETTERS

COURTESY OF THE MAINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF HISTORY AND CULTURE

ACWP-230400-LETTERS.indd 7 12/12/22 9:23 AM

A Blast of Civil War Stories

Faces of the Civil War

DIGITAL MAP SHARES POPULAR PHOTOS IN THEIR CONTEXT

The Library of Congress in November debuted an online exhibit mapping hundreds of portrait photographs from the Liljenquist Collection to events of the Civil War, including images of soldiers linked to the battles where they fought and died. The interactive map encompasses more than 100 battles, from Gettysburg and Antietam to lesser-known skirmishes. The faces of nurses are connected to the sites where they cared for the wounded. Prisoners of war are associated with the camps that confined them.

Some of the portraits are mapped to more than one location, if, for example, the person was present at more than one battle. Likewise, there might be more than one portrait of the same person mapped at a location if multiple photographs of them exist in the collection.

The Liljenquist Collection at the Library of Congress features more than 3,000 portrait photographs, including ambrotypes and tintypes, and small card photos known as cartes-de-visite of the men and women who served during the war for both the Union and

Confederacy. Among those represented are African Americans, sailors, nurses, veterans, and soldiers posed with family members.

The Liljenquist family began donating its collection to the Library of Congress’ Prints & Photographs Division in 2010 with an initial gift of more than 700 ambrotypes and tintypes. Since then, Liljenquist and his three sons—Jason, Brandon, and Christian—have continued to build the collection to include albumen photographs and cartesde-visite, manuscripts, patriotic envelopes, letters, and artifacts related to the Civil War.

Photo Collage

The Liljenquist Collection includes more than 3,000 portrait photographs, a mix of soldiers and civilians who served during the Civil War.

The interactive map allows users to zoom in to view locations in more detail and click to see associated portraits. Locations on the map show places where people in the images were and not where the photographs were taken, in most instances. For more information about each photograph, users can click on the thumbnail image to view details about the item. To view the map, visit: bit.ly/ LiljenquistMap —Melissa A. Winn

COURTESY OF ALBERT R. LABURE; LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 8 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR LIBRARY OF CONGRESS (5)

GRAPESHOT! ACWP-230400-GRAPESHOT.indd 8 12/13/22 8:46 AM

Luck of the Draw

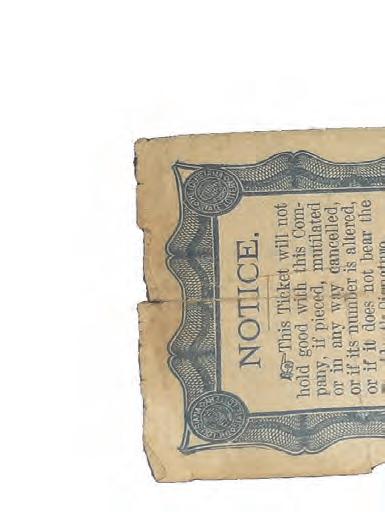

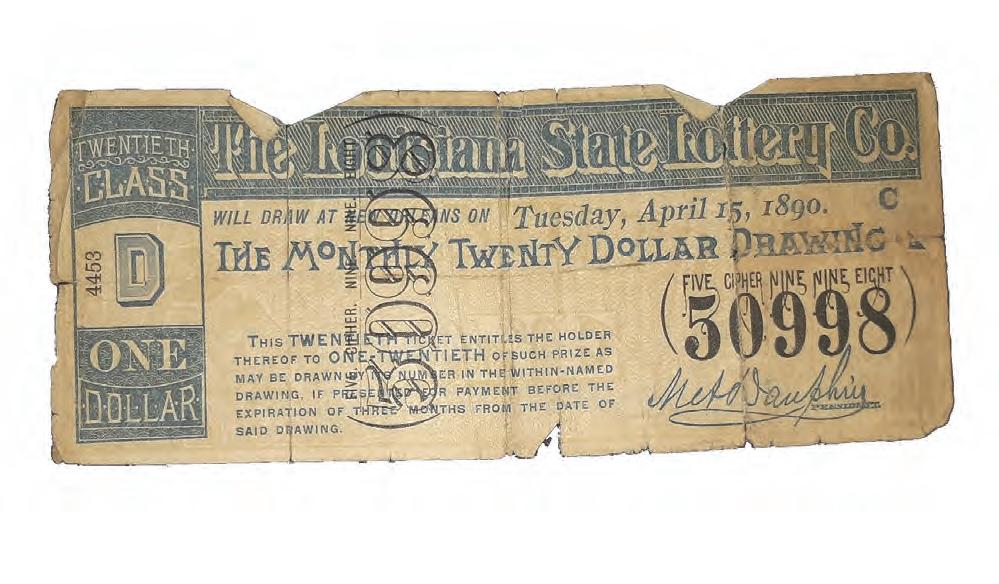

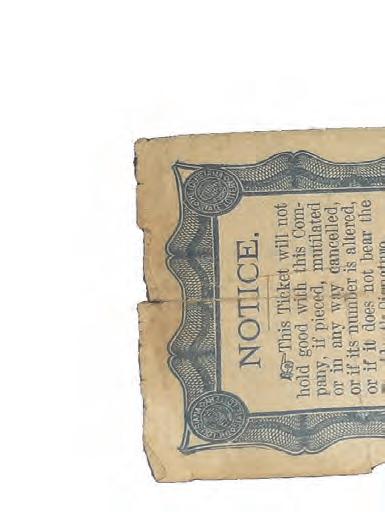

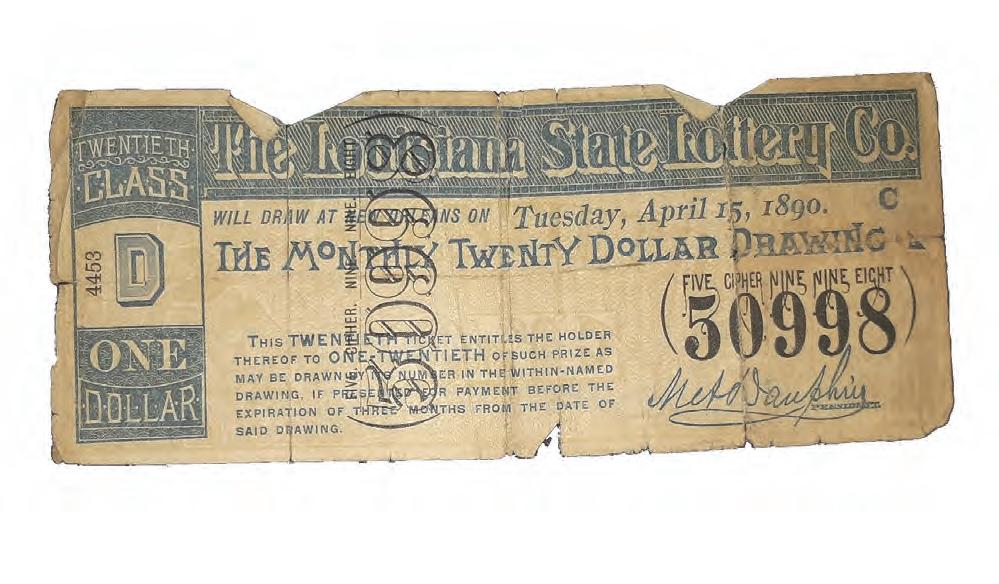

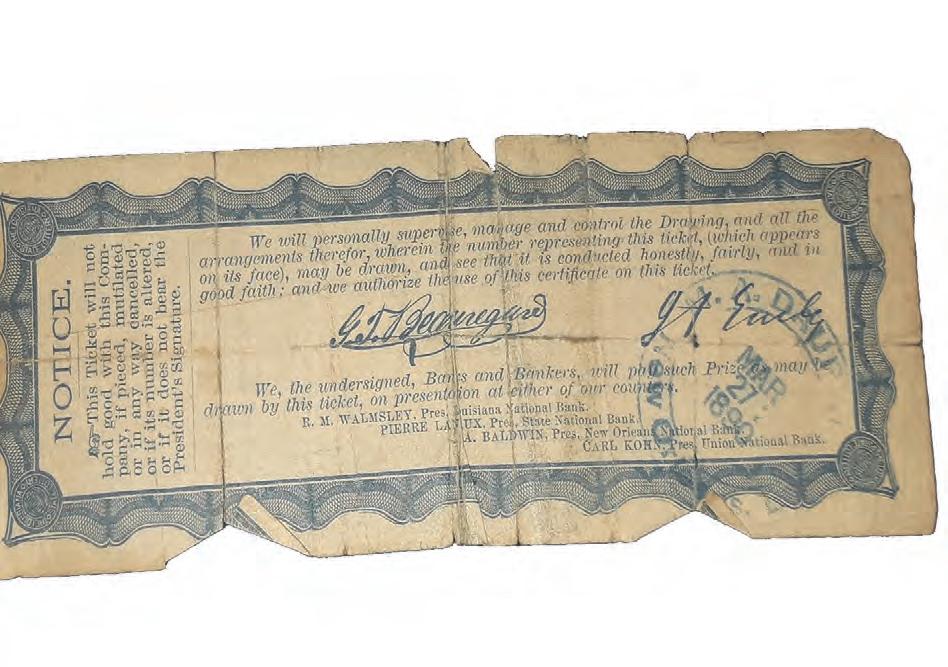

Former Confederate Brig. Gen. Francis R.T. Nicholls’ ascension to governor of Louisiana in 1888—his second, non-consecutive term in Baton Rouge—spelled the eventual death knell of the corrupt Louisiana Lottery Company. The end of that enterprise, however, also cut short an extremely lucrative deal for two other former notable generals in gray: P.G.T. Beauregard and Jubal Early.

To be clear, Beauregard and Early were not part of the company’s notorious criminal endeavors. Their role was simply to be present when the lottery tickets were drawn, with both paid a princely sum of $20,000 per year (equivalent to $200,000 today) for the task.

When founded in 1868, the company was given free rein by state legislators to conduct monthly lotteries for the next 25 years. It was at the time the nation’s only legal lottery system, guaranteeing a hefty profit for company officials.

Nicholls suffered three catastrophic combat wounds during the Civil War, losing an eye, a leg, and his left arm. His innovative campaign slogan while running for governor was: “All that is left of him is right.” Once elected, he quickly strove to rid Louisiana of the fraudulent venture, although that ultimately occurred during the term of his successor, Murphy J. Foster.

Shown above are the front and back sides of an LLC lottery ticket, signed by both Beauregard and Early. Albert R. LaBure

SPRING 2023 9 COURTESY OF ALBERT R. LABURE; LIBRARY OF CONGRESS LIBRARY OF CONGRESS (5)

QUIZ

Answers: A.7, B.9, C.5, D.1, E.10, F.6, G.4, H.8, I.3, J.2

Factor Match the officer with the battle (example: Phil Sheridan and Cedar Creek) to whose outcome he extensively contributed— positively or negatively. A. Ambrose Powell Hill (+) B. George H. Thomas (+) C. Manuel Chaves (+) D. Don Carlos Buell (–) E. Franz Sigel (–) F. John Bell Hood (–) G. Charles Zagonyi (+) H. John B. Magruder (+) I. Lew Wallace (+) J. David G. Farragut (+) 1. Perryville, 1862 2. New Orleans, 1862 3. Monocacy, 1864 4. Springfield, 1861 5. Glorieta Pass, 1862 6. Franklin, 1864 7. Antietam, 1862 8. Galveston, 1863 9. Chickamauga, 1863 10. New Market, 1864

George H. Thomas

The Human

CONVERSATION

ACWP-230400-GRAPESHOT.indd 9 12/13/22 8:46 AM

PIECE

Never Forget

Standing for Now

The NAACP reportedly has threatened to sue should there be a transfer of the property and its memorial, which was erected in 1912.

Officials in Virginia’s Mathews County have come up with a novel approach to keep one of its Confederate monuments standing for the foreseeable future. According to the Gloucester-Mathews Gazette-Journal, the county’s board of supervisors had prepared a quitclaim deed that, if approved, will hand possession of the monument and the plot of land upon which it stands to the Mathews War Memorial Preservation Inc., created by David M. “Sonny” Fauver, a member of the Lane Armistead Camp of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. The plot, adjoining the county courthouse, measures 80.97 square feet.

The Gazette-Journal reported that the deed stipulates the corporation is responsible at all times for maintaining the property and monument in an “appropriate” manner, and does not allow the placement of any flag or banner on the ground there other than the U.S. flag or those of the Commonwealth of Virginia or Mathews County.

CIVIL WAR ILLUSTRATED

At the onset of the Civil War, newspapers North and South alike often used humorous illustrations to lighten the collective mood of their readers. This cartoon was created before the war’s first major battle at Manassas, Va. It shrewdly portrays what veteran officers usually encountered when commanding volunteer soldiers with previous experience holding weapons only for hunting wild game.

BATTLE RATTLE

10 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR GRAPESHOT!

“Sunk by a torpedo! Assassination in its worst form!”

in

James Alden, captain, USS Brooklyn,

reference to USS Tecumseh’s fate at Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864

COURTESY OF JAY WERTZ; COURTESY OF THE HARRIET BEECHER STOWE CENTER, HARTFORD, CT CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: MARK SUMMERFIELD/ALAMY STOCK

PHOTO; NAVAL HISTORY AND HERITAGE COMMAND; COURTESY OF RICHARD H. HOLLOWAY

ACWP-230400-GRAPESHOT.indd 10 12/14/22 9:02 AM

Texas Born and Bred

After spending time in North Carolina and Alabama, the Dance family of Virginia finally settled in Texas, in the small community of Columbia, on the Brazos River south of Houston. Shortly after their arrival in 1853, James Henry Dance and his three brothers—Perry, David, and Isaac—set up their own machine shop. During the Civil War, the principal products they produced were revolvers.

All four Dance brothers enlisted in the 35th Texas Cavalry, but eventually only 1st Lt. James Henry Dance remained to fight. The other brothers returned to Columbia to manufacture pistols, which they would do for the remainder of the war. Had the Federals’ Brazos River Expedition in November 1862, under Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ command, managed any reasonable success, the Dance Brothers’ operation might have been affected. That was not to be.

Shown above is one of their more popular firearms, known as the Dance Dragoon Revolver. This .44-caliber, six-shot model was extremely well-

EXTRA ROUND

Orange Crush

crafted and featured an octagonal barrel that distinguished it from the Colt sixshooter. The one here was carried by Corporal John Howard Hargrave, who enlisted in Whitfield’s Texas Cavalry in 1862. Hargrave was from a colonial family, his father having fought under George Washington in the Revolutionary War.

Whitfield’s Texas Cavalry saw action in more than 80 engagements, fighting under Sterling Price, Earl Van Dorn, and Nathan Bedford Forrest from Arkansas to Georgia. Hargrave was with the unit until the war’s end and lived until 1920. His pistol remained in his family until only recently.

Of the five Dance Dragoon Revolvers known to exist, only Hargrave’s has a cryptic serial number made using chevrons that appears in several places on the revolver. Hundreds of these revolvers were carried during the war. The Texas cavalrymen in that lot were particularly proud and trusting of this home-grown firearm. Jay Wertz

The introduction of oranges in North America is credited to early Spanish explorers. While frigid conditions in the northern part of the continent were not conducive to growing the delicious fruit, states flanking the Gulf of Mexico offered the perfect climate for their cultivation. In 1835, extremely frigid conditions ruined crops in Georgia and the Carolinas, but Florida’s orange groves survived. From that point forward, sweet oranges flourished throughout the Sunshine State.

The hotter weather and availability to oranges caused an exodus to Florida by many Northerners after the Civil War. The Southern Homestead Act of 1866 also played a part in this mass migration, as it was meant to distribute land to freedmen and pro-Union Southern Whites. The vocations of Florida’s new influx of citizens varied and included butchers, wheelwrights, lawyers, and fishermen.

A smattering of artistic people made their way south, too, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose famed novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was credited by many—Abraham Lincoln, among them—as the Civil War’s impetus. In Florida, Stowe embarked on a career as a painter. She found the orange alluring, and believed the fruit (and its use as a cure for scurvy) would also contribute to a cultural awakening in the former slave state.

Implored Stowe to her friends in the North: “To all who want warmth, repose, ease, freedom from care…come! Come! Come sit in our veranda! This fine land is now in the market so cheap that the opportunity for investment should not be neglected.”

Stowe grew her own grove of orange trees and also spent her waning years committing them to canvas. One of those is shown at right. —Edward Windsor

SPRING 2023 11 GRAPESHOT!

COURTESY OF JAY WERTZ; COURTESY OF THE HARRIET BEECHER STOWE CENTER, HARTFORD, CT CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: MARK SUMMERFIELD/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; THE CITADEL; COURTESY OF RICHARD H. HOLLOWAY ACWP-230400-GRAPESHOT.indd 11 12/13/22 8:47 AM

REGIMENTAL PRIDE

Shining Moment

One ‘Boiling Caldron’

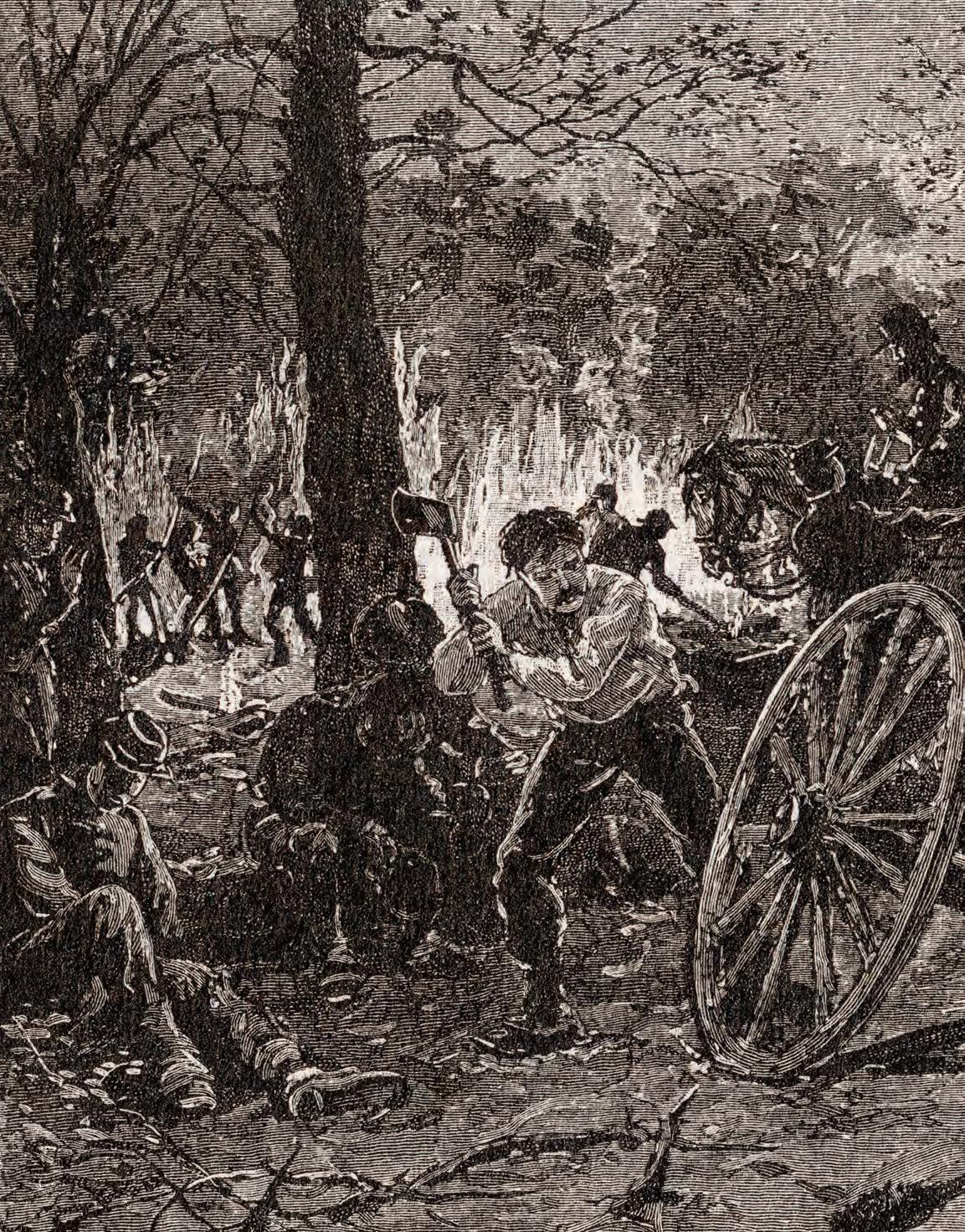

FIERCE CLASH AT CEDAR CREEK PROVED TO BE A FITTING CODA FOR THE RESOLUTE 8TH VERMONT

By Alex McCarthy

SQUIRE E. HOWARD AWOKE before dawn on October 19, 1864, to what he thought was thunder. The clamor, though, wasn’t coming from the clouds but from the fog enveloping the left flank of the Union Army of the Shenandoah at Cedar Creek—and the sounds accompanied a raging band of Confederate soldiers. “It was like the howls of the wolves around the wagon train in the early days of the great prairies,” he would write.

Captain Howard and his comrades in the 8th Vermont Infantry had anticipated another fight at some point, just not in the dead of night. Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early, however, wasn’t known to readily accommodate his opponents.

The Rebels’ initial fog-shrouded thrust that morning was chaotic, as the sleeping Union troops were quickly overwhelmed, many choosing to flee half-clothed rather than put up a fight. The retreat, recalled Captain D. Augustus Dickert of the 3rd South Carolina, was “a living sea of men and horses.”

When the attack began, the Union army’s colorful commander, Phil Sheridan, was resting 12 miles away in

E. Howard

Winchester. His subordinates on site scrambled to respond, fortunate to receive additional time when famished Confederates stopped mid-attack to pilfer food and supplies from Union camps.

Among those trying to make sense of the situation was Brig. Gen. William H. Emory, the 19th Corps’ commander. Knowing he was ordering a likely suicide mission, Emory directed 8th Vermont commander Colonel Stephen Thomas to engage Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon’s attacking Confederates head-on. Gordon’s Division totaled roughly 2,000 troops. Thomas, in command of the 2nd Brigade that day, had about 800 men from four regiments, including the 8th Vermont.

Meeting again on the Cedar Creek battlefield 19 years later, Emory grasped Thomas’ hand and reflected: “I never gave an order in my life that cost me so much pain as it did to order you across the pike that morning. I never expected to see you again.”

Formed in 1862, the 8th Vermont quickly developed a sterling reputation for bravery. Thomas, Howard, and

12 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR

PICTURES NOW/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; HISTORY OF THE EIGHTH REGIMENT VERMONT VOLUNTEERS 1861-1865

This counterattack by Vermont troops, including the 8th Vermont (shown at rear), spurred Union victory at Cedar Creek, as shown in a painting adorning a wall at the Vermont State House.

ACWP-230400-REGIMENTAL.indd 12 12/12/22 3:34 PM

Squire

Captain Moses McFarland were but a few of the regiment’s eventual list of standouts.

Thomas, gray hairs sprinkled throughout his dark beard, was a 51-year-old state representative with no military experience when the war broke out. A Democrat, he was hand-selected to lead the regiment. Though at first hesitant, “his patriotism overbore all his doubts,” wrote George Benedict in Vermont in the Civil War

Howard had enlisted as a sergeant in Townshend, Vt., and received a Medal of Honor for heroism during the 1863 Bayou Teche Campaign. McFarland would be one of the 8th’s heroes at Cedar Creek. A 43-year-old father with piercing eyes, he was regarded for his stamina and drive. He also was no stranger to death, as only two of his five children survived past the age of 4.

In the summer of 1864, the regiment was called east from Louisiana to help repulse Early’s near-successful raid on the U.S. capital. It was then assigned to the 19th Corps’ 1st Division when Sheridan took control of the Army of the Shenandoah in August 1864.

At the Federals’ September 19 victory at Third Winchester (Opequon), the Green Mountain boys clashed with a soon-to-be familiar foe, Gordon’s Division—holding their line for two hours amid a relentless firefight.

Thomas then led a valiant bayonet charge, telling his men “we’ll drive them to hell.” Implemented without orders from above, the charge was another block in Thomas’ budding reputation as an inspirational leader.

“What Sheridan was to the army under him, Colonel Thomas was to his regiment,” Howard wrote. “Many had been the critical moments in our history when his level head and iron nerve had been our salvation.”

They were shocked, however, to see men in blue uniforms charging at them, whooping and hollering. Some of the Vermonters responded by opening fire.

“Captain, we are firing on our own men,” insisted Lieutenant Aaron K. Cooper, hunkered down next to McFarland. As McFarland replied, “I think not,” Cooper—his guard down—was riddled with bullets.

The men in blue coats were indeed Confederates, benefactors of the raids on Union tents earlier in the attack. “As the great drops of rain and hail precede the hurricane, so now the leaden hail filled the air, seemingly from all directions,” recalled Private Herbert E. Hill.

8th Vermont Infantry [3-Year]

Assigned

19th Corps/Army of the Gulf/ Army of the Shenandoah

Mustered In Brattleboro, Vt.

Active February 1862–June 1865

Total Served 1,772

Total Casualties 345

Notable Engagements

Occupation of New Orleans; Port Hudson; Third Winchester (Opequon); Fisher’s Hill; Cedar Creek

Notable Figures

Sgt. Henry W. Downs; Capt. Squire E. Howard; Col. Stephen Thomas; John L. Barstow; William H. Gilmore

Steadily pushed back, the 8th managed to re-form in a ravine. McFarland, though, received news that Mead had been wounded, and Captain Edward Hall, his second-in-command, mortally wounded. The regiment was now in McFarland’s hands.

Hand-to-hand combat broke out. “Men seemed more like demons than human beings,” recalled Private Hill, “as they struck fiercely at each other with clubbed muskets and bayonets.”

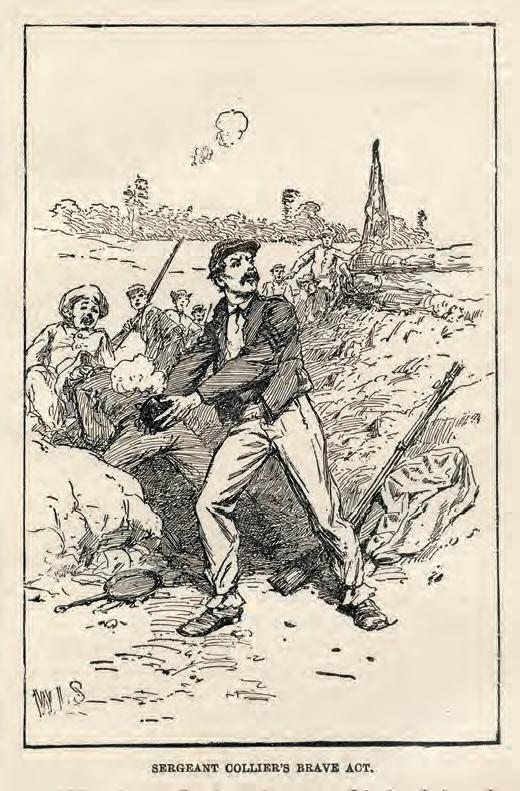

The fiercest struggle was for the 8th’s colors. Corporal Alfred S. Worden had to fight off a bayonet attack by a stocky Confederate, who was shot dead by a fellow Vermonter. Corporal John Petrie, holding the colors, would be mortally wounded, crying out as he fell to the ground: “Boys, leave me…take care of yourselves and the flag!” But when fellow color guard Corporal Lyman F. Perham scooped up the colors, he was shot and killed almost instantly.

At Cedar Creek, with Thomas now in charge of the 2nd Brigade, command of the 8th Vermont was handed to Major John Boardman Mead, a 33-year-old father of two. The undersized regiment did not hesitate in accepting the challenge of a showdown with Gordon, but as McFarland later wrote: “It was a sacrifice to the God of war of the few that the many might be spared, a propitiation offered against hope that out of defeat might come victory.”

The engagement with Gordon would last less than half an hour, many comparing the fighting to hell itself and the combatants to demons. After clawing their way uphill in the fog, the Vermonters entrenched in a wooded area.

Engaged in what he called “the boiling caldron [sic] where the fight for the colors was seething,” Howard would be wounded twice, and later wrote that bayonets were “literally” dripping with blood amid the chaos, and that only one member of the color guard avoided being killed or wounded.

“It seemed as though we were passing into the very jaws of death and that the gates of hell were open to receive us,” McFarland wrote.

Overrun and taking heavy losses, the Federals eventually had no choice but to fall back. Howard, one of his shoes filling with blood from a wound, heaped praise on those who continued to engage in brutal bayonet clashes.

Although the regiment briefly re-formed to try to halt the Confederate surge, it was fruitless. “Longer resistance would have resulted in [the regiment’s] entire death and

SPRING 2023 13 REGIMENTAL PRIDE PICTURES NOW/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; HISTORY OF THE EIGHTH REGIMENT VERMONT VOLUNTEERS 1861-1865

ACWP-230400-REGIMENTAL.indd 13 12/12/22 11:16 AM

capture,” Mead wrote. It was indeed a horrific scene across the battlefield. Captain John W. DeForest of the 12th Connecticut recalled seeing pools of blood everywhere. “The firm limestone soil would not receive it,” he wrote, “and there was no pitying summer grass to hide it.”

As noted on the 8th’s memorial at the Cedar Creek and Belle Haven National Historical Park, the regiment had 110 killed or wounded out of 164 engaged, including 13 of 16 commissioned officers. But was the horrible sacrifice worth it? Those who survived said yes, having bought critical time for their army to re-form their ranks and launch its decisive counterattack.

Recounted Hill: “Bleeding, stunned, and being literally cut to pieces, but refusing to surrender colors or men, falling back only to prevent being completely encircled, the noble regiment had accomplished its mission.”

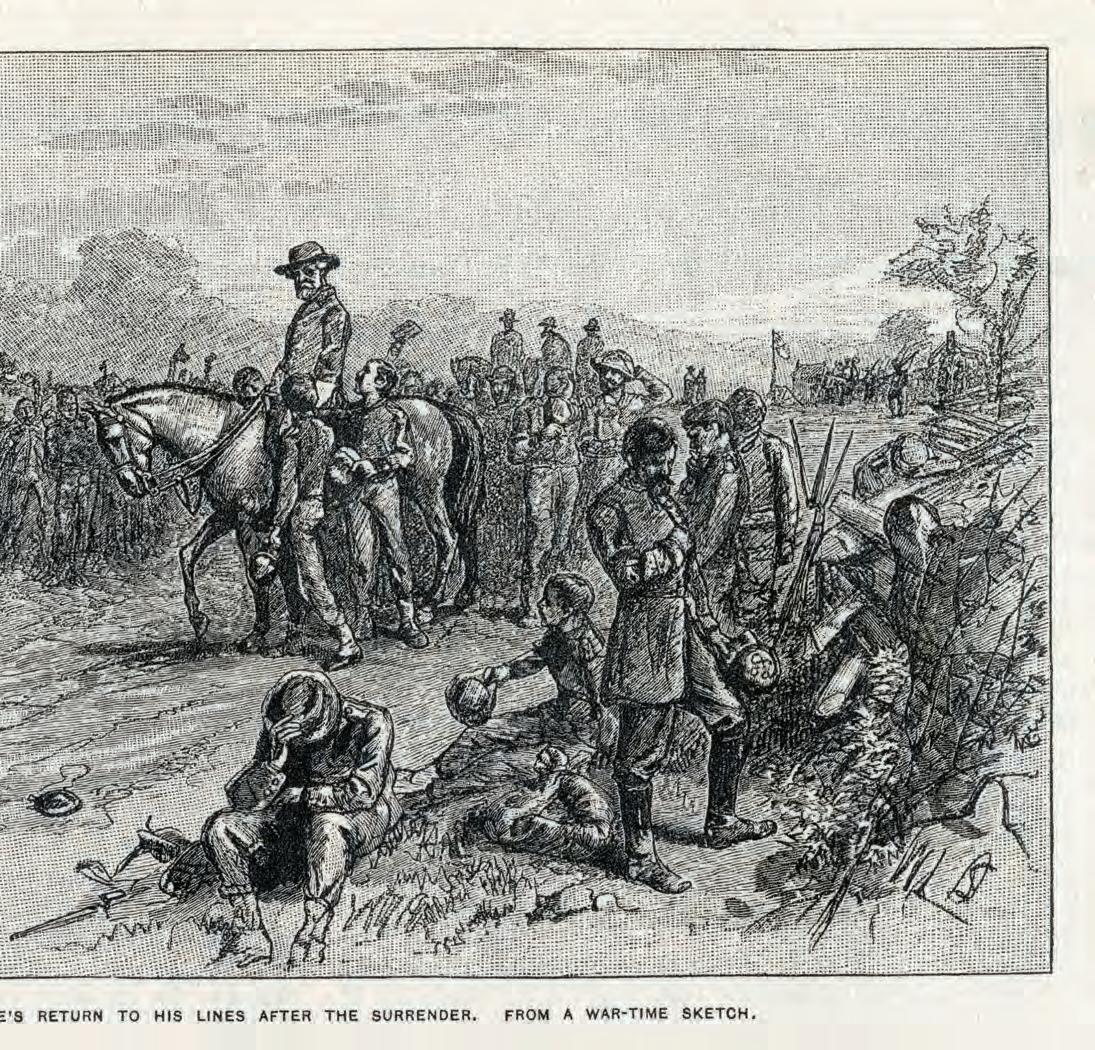

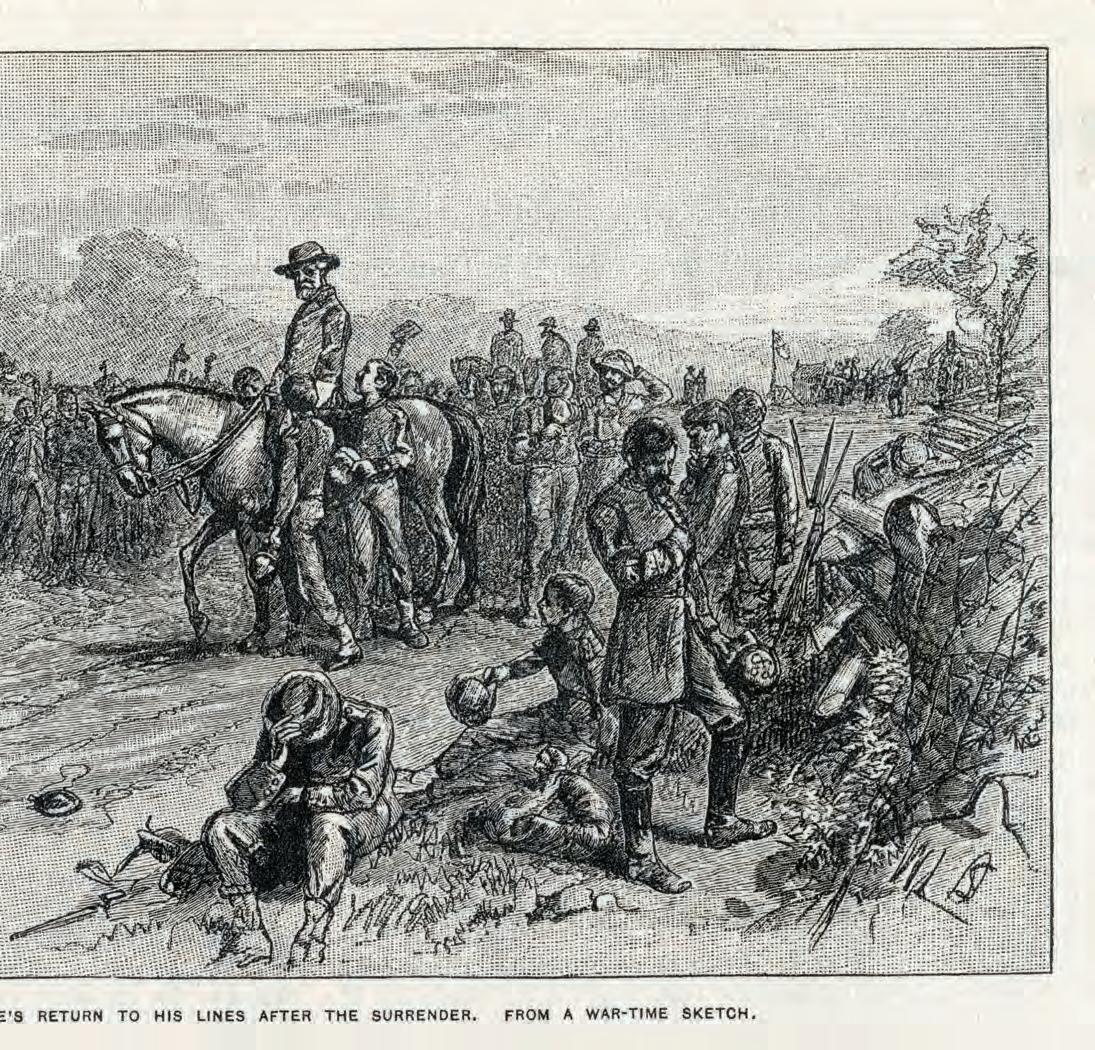

Incredibly, the 8th Vermont was not done fighting for the day. Howard was among those taken to a nearby field hospital, but Thomas took the lead in rallying the men. And, in what would long remain a contentious issue, the Confederate army decided to halt its attack. According to Gordon, that was Early’s call. The commander, he claimed, was satisfied enough with the morning’s progress: “Well, Gordon, this is glory enough for one day. This is the 19th. Precisely one month ago today [at Third Winchester] we were going in the opposite direction.”

By the end of the day, however, Confederate troops were again in retreat. Upon learning of Early’s surprise attack, Sheridan had mounted his charger, Rienzi, and ridden furiously to the battlefield from Winchester. Sheridan’s presence helped produce an inspired Federal counterattack that broke the Confederate line and reestablished Union control of the battlefield.

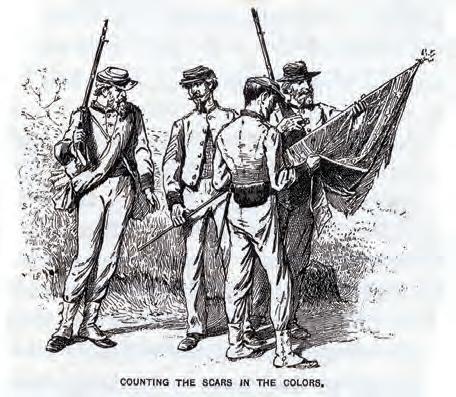

Green Mountain Esteem

Prominent clashes for the 8th Vermont in both Louisiana and the Shenandoah Valley are cited on the obverse of its regimental flag. “Cotton” refers to the clash Union gunboats and troops had with CSS J.A. Cotton at Bayou Teche.

The 8th Vermont, freshly removed from the “gates of hell,” had a big hand in the counterattack, flipping the script against a familiar foe: Gordon’s Division. Thomas led the way, and even when his horse was killed under him, he remained galvanized. Now under a bright sun, Early’s army was driven from the battlefield. The Vermonters followed the Confederates as far as Strasburg, about four miles. Most, unfortunately, would spend a difficult night without blankets, tents, or fires.

Cedar Creek marked the regiment’s last major action of the war. From that point on, it served mainly in a defensive role in the Valley.

Thomas received a Medal of Honor for his efforts in the battle, formally recognized for “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked.” (Three members of the 1st Vermont Cavalry also received Medals of Honor, as did Lt. Col. Amasa Tracy of the 2nd Vermont.)

Thomas became a Republican and reentered politics after the war, serving as Vermont’s lieutenant governor and in various other political and business positions before his death in 1903 at the age of 94. McFarland dedicated himself to repairing buildings and locations that had been damaged during the war before he died at 89 in 1911. Howard died in 1912 at the age of 72.

Cedar Creek was essentially the final major blow for the Confederacy in the Valley, but in reality Jubal Early wasn’t quite finished just yet, as you’ll read in Jonathan A. Noyalas’ article, “Unfinished Business,” on P. 38.

For the Vermont soldiers, the battle was probably their most celebrated day. A large painting by Civil War veteran Julian Scott, hanging prominently in the state house in Montpelier, depicts the 1st Vermont Brigade’s counterattack. It features members of the 8th Vermont, including Thomas—visible in the background.

Mead recovered from his Cedar Creek wound, and in his official report to the adjutant general in September 1865 he acknowledged the regiment’s record of bravery and fearlessness: “I hope I may not be charged with egotism when I say, the 8th regiment was not excelled by any other in service in devotion to the cause for which it was raised, in its readiness and willingness to meet all necessary exposure and danger incident to a soldier’s life.”

Alex McCarthy writes from St. Louis, Mo.

14 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR

VERMONT STATE CURATOR’S OFFICE

REGIMENTAL PRIDE

ACWP-230400-REGIMENTAL.indd 14 12/12/22 11:16 AM

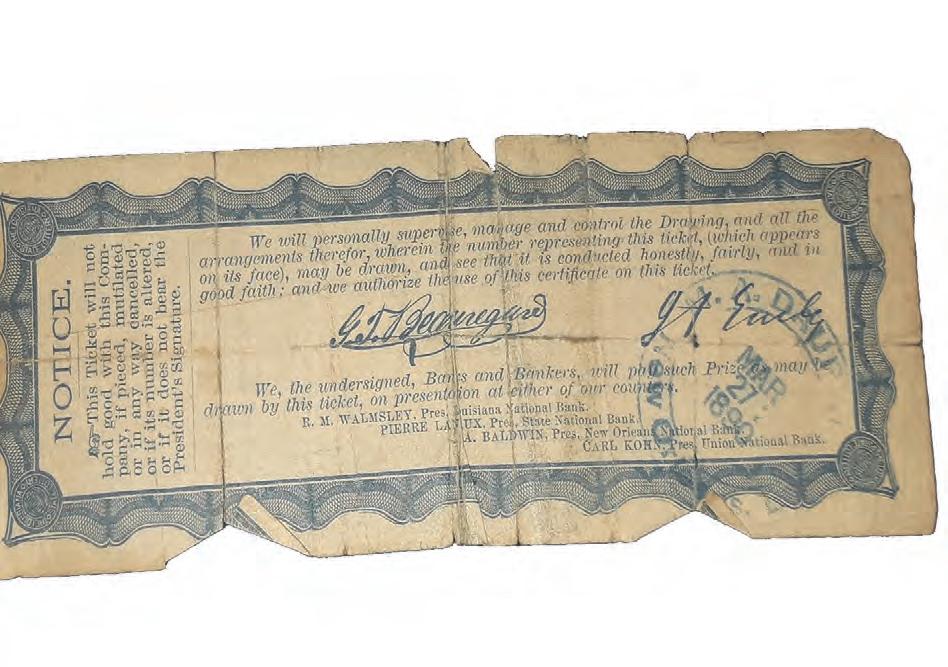

TODAY IN HISTORY

AUGUST 26, 1814

BROOKEVILLE, MARYLAND, BECOMES “U.S. CAPITAL FOR A DAY” WHEN PRESIDENT JAMES MADISON TAKES REFUGE THERE. EARLIER THAT WEEK, BRITISH TROOPS HAD SET FIRE TO WASHINGTON, INCLUDING THE WHITE HOUSE AND CAPITOL BUILDING. MADISON FLED THE CITY, ALONG WITH MEMBERS OF HIS CABINET, AND SPENT THE NIGHT OF THE 26TH AT THE HOME OF BROOKEVILLE POSTMASTER CALEB BENTLEY. THE TOWN STILL CELEBRATES THE EVENT EACH YEAR.

For more, visit HISTORYNET.COM/TODAY-IN-HISTORY TODAY-MADISON.indd 22 9/28/22 2:51 PM

16 LIFE & LIMB Arms Race A PROSTHETIC LIMB GAVE CIVIL WAR AMPUTEES A CHANCE TO AGAIN HOLD THEIR LOVED ONES IN A TIGHT EMBRACE ACWP-230400-LIFEANDLIMB.indd 16 12/12/22 9:24 AM

The Day the War Was Lost It might not be the one you think Security Breach Intercepts of U.S. radio chatter threatened lives 50 th ANNIVERSARY LINEBACKER II AMERICA’S LAST SHOT AT THE ENEMY First Woman to Die Tragic Death of CIA’s Barbara Robbins HOMEFRONT the Super Bowl era WINTER 2023 WINTER 2023 Vicksburg Chaos Former teacher tastes combat for the first time Elmer Ellsworth A fresh look at his shocking death Plus! Stalled at the Susquehanna Prelude to Gettysburg Gen. John Brown Gordon’s grand plans go up in flames MAY 2022 In 1775 the Continental Army needed weapons— and fast World War II’s Can-Do City Witness to the White War ARMS RACE THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MILITARY HISTORY WINTER 2022 H H STOR .COM JUDGMENT COMES FOR THE BUTCHER OF BATAAN THE STAR BOXERS WHO FOUGHT A PROXY WAR BETWEEN AMERICA AND GERMANY PATTON’S EDGE THE MEN OF HIS 1ST RANGER BATTALION ENRAGED HIM UNTIL THEY SAVED THE DAY JUNE 2022 JULY 3, 1863: FIRSTHAND ACCOUNT OF CONFEDERATE ASSAULT ON CULP’S HILL H In one week, Robert E. Lee, with James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson, drove the Army of the Potomac away from Richmond. H THE WAR’S LAST WIDOW TELLS HER STORY H LEE TAKES COMMAND CRUCIAL DECISIONS OF THE 1862 SEVEN DAYS CAMPAIGN 16 April 2021 Ending Slavery for Seafarers Pauli Murray’s Remarkable Life Final Photos of William McKinley An Artist’s Take on Jim Crow “He was more unfortunate than criminal,” George Washington wrote of Benedict Arnold’s co-conspirator. No MercyWashington’s tough call on convicted spy John André HISTORYNET.com February 2022 CHOOSE FROM NINE AWARD WINNING TITLES Your print subscription includes access to 25,000+ stories on historynet.com—and more! Subscribe Now! HOUSE-9-SUBS AD-11.22.indd 1 12/1/22 5:22 PM

Eye of the Beholder

Though often mocked today as Gettysburg’s “ugliest” monument, the 20th Massachusetts’ “Puddingstone” boulder memorial held special significance to the unit’s veterans.

Point of Order

MANY UNION VETERANS HAD TO SWALLOW SOME PRIDE WHEN PLACING THEIR GETTYSBURG MONUMENTS

By D. Scott Hartwig

WHEN I WORKED at Gettysburg National Military Park, I regularly encountered visitors who imagined that some type of grand government master plan had created the park and accounted for the order and symmetry of its hundreds of monuments. Yet there is no master plan. The battlefield we see today with its orderly placement of monuments evolved over many years. The park was officially created by congressional legislation in 1895, but most of the regimental monuments were erected in the 1880s, before the U.S. government assumed responsibility for managing the battlefield.

At the time, the field was managed by the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, an organization created in 1864, which initially viewed the battlefield as a monument to the Union victory of July 1863. It sought to acquire land where evidence of the conflict still existed, such as Culp’s Hill, East Cemetery Hill, and parts of Little Round Top—with their bullet-riddled trees, artillery lunettes, breastworks, and entrenchments.

In its early years, the GBMA was largely a local organization with a modest budget. Although it supported the idea of marking positions of Union Army units “by tablets, obelisks and other monumental structures,” its efforts centered on lobbying Northern states to pass laws and appropriate funds to make this a reality.

In 1880, the GBMA underwent a transformation, electing a new slate of officers and directors who had a larger vision than the original board. One of their decisions that would have far-reaching consequences for how regimental monuments would be located and what their inscriptions could say was to invite the amateur historian John B. Bachelder to join the board. Although he had not served in the Army during the war, Gettysburg had become Bachelder’s life work, and he was considered the expert on the battle. Former Union Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum wrote that Bachelder “can tell more of what I did there [at Gettysburg] than I can myself.”

In July 1883, the board elected Bachelder as Superin-

18 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR

COURTESY OF THE ADAMS COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY MAURICE SAVAGE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; COURTESY OF THE ADAMS COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY

FROM THE CROSSROADS

ACWP-230400-CROSSROADS.indd 18 12/12/22 12:26 PM

tendent of Tablets and Legends. In this role he approved the proposed location, design, and inscription for regimental monuments.

When monuments went up had much to do with when state legislatures appropriated funding for them. Massachusetts, for example, appropriated $500 in March 1884 for each regiment and battery of the state that had fought at Gettysburg. It would be up to the veterans of each unit to raise any additional funding necessary beyond this total. The result was almost all Massachusetts’ regimental and battery monuments went up in 1885 and 1886.

In October 1885, the 15th, 19th, and 20th Massachusetts placed their monuments—with Bachelder’s and the GBMA’s approval—on the southern edge of the famous Copse of Trees, to which they had advanced during the repulse of Pickett’s Charge on July 3. Bachelder, however, had second thoughts on allowing units to erect their principal monument at the point of their farthest advance. Ten other regiments had crowded into the same space the three Massachusetts regiments had in the counterattack to drive back the Confederate breakthrough near the Copse. If he allowed all these regiments to follow the Massachusetts example, the result would be a jumble of monuments near the trees. This, he believed, would “mislead the public in the future rather than illustrate the battle.”

While it was understandable that veterans wished to place their monument where they had lost the most men or achieved their greatest success, this could lead to clumps of monuments that would baffle future generations not steeped in Gettysburg’s history, not to mention foment interminable arguments between veterans over who was where and when.

of the 15th, 19th, and 20th Massachusetts to move their monuments from their advance positions at the Copse to their July 2-3 lines of battle. The veterans agreed, though for the 19th Massachusetts that meant moving its monument to the second line of battle, where it had served in support. To soften the blow, each regiment was allowed to place an iron tablet at its advance position, where their monuments had originally been placed.

The new policy was generally a success, bringing a sense of order to how the field would be marked. Through the 1880s, the GBMA opened avenues that followed the Army of the Potomac’s general lines while creating access to the monuments being erected. But determining “line of battle” proved to be a gray area. For example, all the monuments to Caldwell’s 1st Division, 2nd Corps, are in the Wheatfield area to which the division advanced on July 2, rather than where the division was in line on the southern end of Cemetery Ridge most of the day. Artillery batteries were tricky because many of them moved numerous times throughout the battle. In these cases, Bachelder and the GBMA compromised and worked with veterans to meet the spirit of the policy but still honor the service of the unit.

Wish We Were Here

Later moved, the 19th Massachusetts’ memorial was first placed at the regiment’s July 3 advance position near the Copse of Trees.

To resolve the issue, Bachelder met with Secretary of War William C. Endicott and Regular Army officers who had been in the volunteer service during the war. They reached a decision “that the desire of the memorial association would be better carried out if the lines of battle were marked, rather than the lines of contact when any regiment left their position to go into action.”

In effect, regiments and batteries would mark the principal position they occupied in the general line of battle rather than to where they eventually advanced. Inscriptions on each monument could explain the regiment’s actions and movements. Once a regiment had erected its principal monument, it could place an advance position marker/monument/tablet if desired. In December 1887, the GBMA formally adopted this “line of battle” policy.

One of Bachelder’s first tasks was convincing veterans

The War Department continued this policy after the creation of Gettysburg National Military Park in 1895, when it assumed responsibility for all the lands of the GBMA. It generally worked well for the Army of the Potomac, but when the Confederate side of the field began to be acquired, Army of Northern Virginia veterans had little interest in erecting monuments on their “line of battle” positions, which were where their attacks originated from, not where they suffered their principal loss. But they also had less incentive than Union veterans to erect monuments, for starting in the 1890s the War Department marked the position of every brigade, battery, division, and corps of both armies with iron tablets. These tablets adhered to the same line of battle policy and typically marked where units were in position immediately before the fighting began.

Monuments are about memory, and numerous battles were fought over the years between veterans, and with the GBMA, over where a particular monument would be placed and what constituted the unit’s position in the line of battle on a particular day of the battle. But overall, the association’s policy was a success and reflected Bachelder’s vision in making the Gettysburg battlefield comprehensive for generations to come.

SPRING 2023 19

THE CROSSROADS COURTESY OF THE ADAMS COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY MAURICE SAVAGE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; COURTESY OF THE ADAMS COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY

FROM

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.

ACWP-230400-CROSSROADS.indd 19 12/12/22 12:26 PM

Separation Clause

South Carolina’s 1832 threat to secede was later realized in 1860, an impetus to the Civil War, as ridiculed by this political cartoon.

‘Have we come to this?’

WITH SECESSION AT STAKE IN 1830, S.C. LEGISLATOR PLEDGES UNION

By Brian C. Neumann

THE UNITED STATES came perilously close to civil war during the 1832 Nullification Crisis. After Congress passed a high protective tariff in May 1828, dramatically increasing taxes on many imported goods, protests erupted across the South—growing particularly violent in South Carolina. Hurt by a decade of economic decline and a series of slave panics, many South Carolinians considered the tariff a plot to impoverish the South and undermine slavery. Many championed nullification, insisting that states had the power to declare federal laws null and void. The most radical Nullifiers went even further, calling for outright disunion and armed resistance.

Nullifiers won control of the General Assembly in 1830, and just two years later held a commanding three-fourths majority. The state’s governor, senators, and most congressmen were also Nullifiers. In November 1832, a state convention issued the Ordinance of Nullification, declaring the tariff unconstitutional and threatening to secede if the fed-

eral government moved to enforce it. Nullifiers mobilized for war, with 25,000 men volunteered to defend their state against federal “tyranny.” As one volunteer proclaimed, “the fact is now probably obvious that we must fight.”

Yet South Carolina was starkly divided, with 40 percent of voters—generally older men, those owning fewer slaves—fiercely opposed to nullification. In their view, the Union was a bold but fragile democratic experiment, the “last hope of liberty” in a world ruled by kings and emperors—that nullification would prove humanity was incapable of self-government.

Southern Accent is produced in partnership with the Nau Civil War Center at the University of Virginia, which promotes scholarship, teaching, and public outreach regarding the United States in the Civil War era. It draws upon UVA’s rich resources, faculty, and students.

Among these “Union” men was William McWillie, a state legislator from Camden. Born in 1795, he had served in the War of 1812 and was admitted to the bar in 1818. A planter who owned nearly 200 enslaved laborers, he reportedly considered “the law more a pastime than a profession.” Elected to the General Assembly in 1829, he would spend several years, however, arguing against nullification. His oratory skills particularly shone

20 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR SOUTHERN ACCENT

GRANGER, NYC 914 COLLECTION/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO ACWP-230400-SOUTHERN.indd 20 12/12/22 9:25 AM

during a December 1830 debate on whether a state convention should be called to nullify the tariff. The “hopes of mankind,” he argued, rested on survival of the Union.

Mr. Chairman—I agree to the fullest extent...as to the importance of the resolutions now submitted to the consideration of the committee; not only to this state, but to the United States; and perhaps to the world. The subject overwhelms me….

When we nullify, I am persuaded, it will be the beginning of violence, and this republic will be no more. Have we come to this? Are we prepared to say we will no longer be called the countrymen of Washington; and that the history of the revolution and [the War of 1812] shall no longer be our history? Are we prepared to say, that the eagle, the emblem of our national glory, shall no longer be our eagle? That our beautiful standard, the standard of stars and stripes, emblematical of the union of these states, shall no longer be our standard? Are we prepared to discard this standard, with which is associated all that we have of national character, and around which our fathers rallied when they drove the proud oppressors from our shores: that standard which has floated broad and high, triumphant and glorious in the rush of many a fight, where the strongest of our countrymen have striven, and the bravest have bled? Can we deface its honors? Will we trample it in the dust? Shall all that has been said of it in rhetoric, in poetry and in song, be heard no more? No. I at least for one, must answer no—of this my conscience will be clear….

bow at the feet of despotic power? Was I a slave? No! I was then as I now am, a freeman; a citizen of this happy, vast and powerful republic; an American citizen….

I would ask this committee, if...our beautiful and happy institutions, on which rest not only our own national character and glory but the hopes of mankind, are to be permitted now to perish? Is man destined ever to be the slave of legal forms? Is liberty but an ignis fatuous gleam...ever to be pursued, but never to be grasped? I trust not—I believe that man is capable of self government—it is for us...to prove the fact—it is for us to assert the dignity of his nature, and shew his capacity for self control. God grant that the predictions of our enemies may not be fulfilled—but that our government, the world’s last hope, may continue forever in her onward course; and that her example may be to the enslaved nations of the earth, like the pillar of cloud by day, and of fire by night; conducting them to happiness and freedom....

If the American people are true to themselves, this will be. Our fields shall ever brighten under their golden harvests; our commerce shall press the bosom of every sea; our armies shall hurl back the invaders strength; and our fleets, whitening the heavens with their canvass, shall sweep the ocean with the thunder of their cannon….

About Face

Unionist William McWillie later pledged to secede as governor of Mississippi over the issue of slavery.

We have been told [by Nullifiers] that the object of the north and west is to emancipate our slaves, to destroy our property. This is an argument I did not expect to hear in this house. It is a subject, although a slaveowner, on which I have no apprehensions…I have no fears in this matter from the general government; but I have sometimes feared the effect of our own madness and temerity. If any thing would be likely to destroy the value of this property, it would be disunion and civil war. We might then hear the shout of liberty, from quarters which would appal [sic] the stoutest hearts. We might realize the horrors of St. Domingo; where the labours of man, the monuments of art, where infancy and age; woman’s feebleness and man’s strength, were swept away in one vast, overwhelming tide of blood…

We have been told that our government is the most positive despotism on earth—and that our people are the most oppressed. Can this be true? Has my life been all one delusion? When in the midst of revelry and of songs, the joyous acclamations of freemen, and the thunder of artillery, I have celebrated her triumphs and her glory—was I deluded? Were manacles then upon my hands, and did I

Oh God! Let my country live to see this... consummation, in which all the fond hopes of the patriot’s heart shall be lost in the fulness of fruition; and that we, as one people, may go forward, gloriously and forever with freedom’s soil beneath our feet, and...the broad and glorious banner of stars and of stripes, the banner of the union, proudly streaming o’er us.

Nevertheless, in 1832, state officials passed an Ordinance of Nullification to bring the nation closer to civil war. In reply, about 9,000 South Carolinians joined paramilitary Union Societies, vowing to fight even their own friends and neighbors. Congress defused the crisis in March 1833, agreeing to lower tariff rates over the next nine years. But even when the ordinance was voided, tensions remained high. “[T]he tariff was only their pretext,” Jackson wrote, “and disunion and a Southern confederacy the real object. The next pretext will be the negro, or slavery, question.”

Having moved to Mississippi, McWillie was elected to Congress in 1849. Amid another sectional crisis in 1850, he pledged enduring devotion to the Union, although he was quick to blame Northern abolitionists rather than Southern radicals for endangering the country. As governor of Mississippi in 1857-59, however, he pledged to dissolve the Union rather than surrender slavery.

Brian Neumann is the author of Bloody Flag of Anarchy

SPRING 2023 21

ACCENT

SOUTHERN

GRANGER, NYC 914 COLLECTION/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO ACWP-230400-SOUTHERN.indd 21 12/12/22 9:25 AM

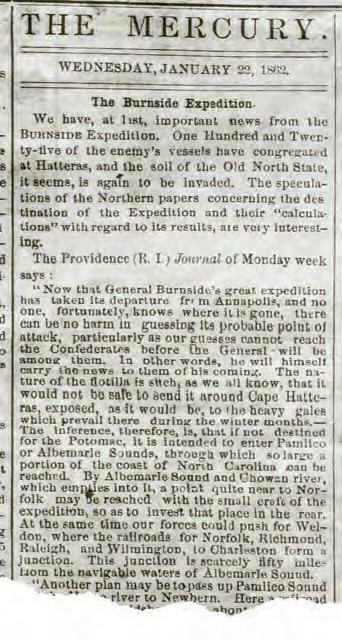

LoOse lips

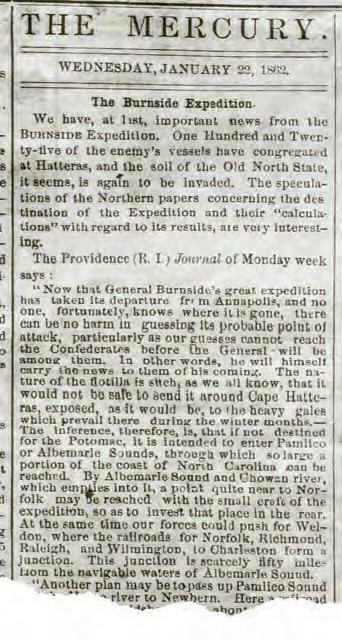

Northern newspapers were culpable in aiding Confederate intelligence during Burnside’s North Carolina Expedition of 1862

By Bruce Allardice

By Bruce Allardice

22 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR

ACWP-230400-BURNSIDE.indd 22 12/13/22 8:50 AM

In January 1918, as U.S. participation in World War I neared its first anniversary, historian James G. Randall of the University of Illinois wrote perhaps the definitive article on Northern newspapers and military secrecy during the Civil War. Randall’s magisterial account, appearing in The American Historical Review, served a dual purpose. He intended it both as an overview of a dilemma Union armies faced during the Civil War and as a gentle reminder to U.S. newspapers that might feel emboldened to follow suit in similar scenarios in World War I. “The Ameri-

can Civil War presents a significant field for study in this connection,” Randall wrote, “for the double reason that a period of remarkably keen journalistic enterprise coincided with a time of laxity in the matter of press control. Acting under no effective government restraint, the newspapers of the North, though in many ways deserving of admiration, undoubtedly did the national cause serious injury by continually revealing military information.”

As Randall showed, occasions when Northern newspapers were all too ready to publish sensitive military information to an eager public—

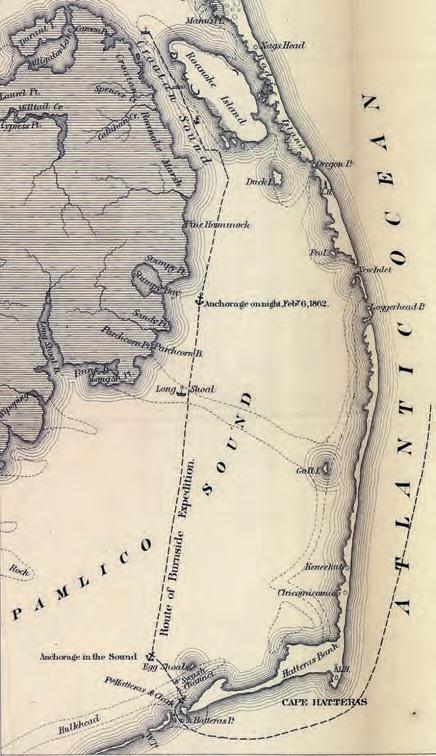

Firm Base

Union troops land on Roanoke Island early in Ambrose Burnside’s 1862 North Carolina Expedition. Control of the island, defended by 3,000 Rebel troops, was essential to any hope of the expedition’s success.

SPRING 2023 23

ACWP-230400-BURNSIDE.indd 23 12/13/22 8:50 AM

and to ever-vigilant enemy spies and commanders—were plentiful.

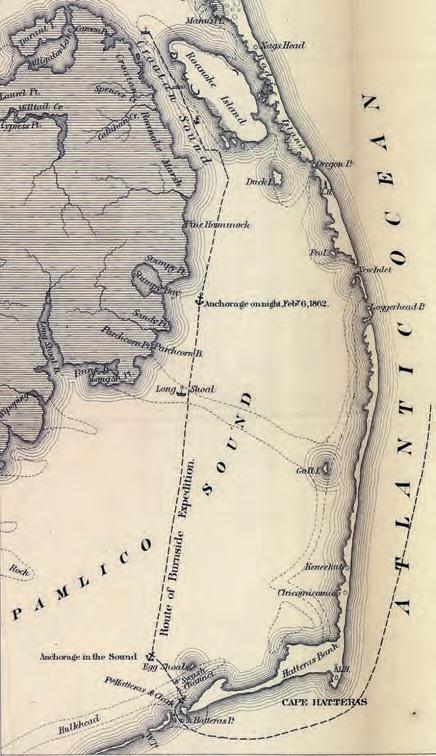

The process of how military intelligence has been gathered and implemented has evolved gradually since the Civil War, and continues to evolve today. Modern U.S. Army doctrine breaks the process down into four general categories: Role; Target; Intent; and Functions. Below, by examining Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s 1862 North Carolina Expedition, we expand on Randall’s 1918 thesis through the lens of this modern Army doctrine.

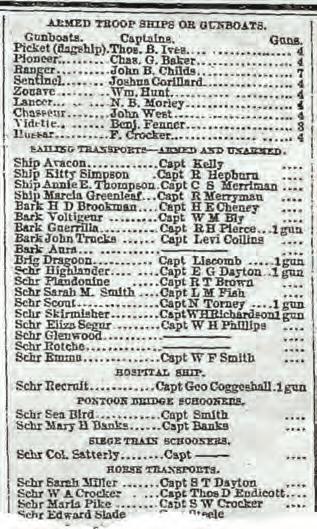

In the fall of 1861, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, the Union Army’s general in chief, endorsed creating a “coastal division” for operations against Confederate coastline targets. “Little Mac” tapped Burnside, an old friend, to organize and lead the expedition.

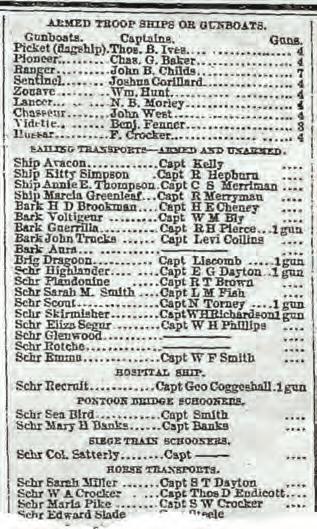

Burnside formed mostly newly raised regiments, many specially recruited in New England coastal communities where most would have some experience with boats. He organized his force into a three-brigade division of about 15,000 men, concentrated at Annapolis, Md. In early January 1862, this force, transported by a large armada, left Annapolis and attacked the North Carolina sounds. It achieved some success, against badly outnumbered and ill-equipped Southern opposition.

Confederate military leaders were known to regularly scan Northern newspapers for information. In late 1861, the lines along the Potomac River were ill-guarded, and Confederate pickets could be found within 20 miles of Washington, D.C. That, along with an abundant number of Confederate sympathizers in the capital and Maryland, usually allowed nextday access to these newspapers.

General Robert E. Lee, Randall noted, “constantly perused the columns of these journals with the eye of a military expert on the lookout for information.” Lee would then pass the newspapers on to President Jefferson Davis, with comments on items he believed were of special interest.

Randall cited four specific instances when Lee had made moves in response to what he had discovered in these papers.

After the First Battle of Bull Run, acerbic Union Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman, complained that “the press…gave notice of [our] movement on Manassas, and enabled [Joseph] Johnston’s army so to reinforce [P.G.T.] Beauregard that our army was defeated.”

The Official Records of the War provide evidence that Confederate intelligence operatives regularly received information on Burnside from Northern newspapers. For example, on January 4, 1862, Confederate Colonel Thomas Jordan forwarded the following extract from the December 28, 1861, National Intelligencer to the War Department in Richmond.

“General Burnside is awaiting the arrival of gunboats and transports at Annapolis. Sixteen transports, four schooners, and five floating batteries are already there. The naval rendezvous will be at Old Point Comfort [Fort Monroe], and it is said that Captain Goldsborough is assigned to the command.”

From an intelligence standpoint, it is in the categories of capabilities and order of battle that Northern newspapers did the most damage. On September 28, 1861, with the expedition still in the planning stages, the national magazine Harper’s Weekly proclaimed that Burnside would lead “at least 10,000 men” in a move to flank the rebel armies in northern Virginia, and “to take Norfolk in the rear.” That was a remarkably accurate estimate of the force eventually used, that it would be commanded by Burnside, and that Norfolk was the likely target, as the Confederate port stronghold could be taken only from North Carolina’s Pamlico and Albemarle sounds, via canals connecting those sounds to Norfolk.

Such disclosure of Burnside’s numbers was critical. As has been well-documented, McClellan tended to let his operational choices in 1862 be influenced by a gross overestimate of Confederate army numbers. The flip side is that an accurate knowledge of Burnside’s numbers and capabilities better enabled the Confederates to conjecture on Burnside’s destination.

Boatloads of Expertise

L.-R.: Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough and Ambrose Burnside. Goldsborough led the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, providing the mission’s naval thrust. Made a midshipman when he was only 7, he spent an incredible 61 years in the U.S. Navy.

Worse would come soon. On October 7, The Providence Evening Press reported that Burnside “expects to have ten regiments [about 10,000 men] under his command,” and named several of the regiments. This information made

24 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR

HARPER’S WEEKLY PREVIOUS PAGE: CLASSIC IMAGE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; THIS PAGE: HARPER’S WEEKLY (2) ACWP-230400-BURNSIDE.indd 24 12/14/22 10:28 AM

For Your Information

In late 1861, his expedition still in the planning stages, Burnside held a grand review in Annapolis. For eager readers on either side, Harper’s Weekly left no secret that the army pictured here was indeed “Burnside’s Expiditionary [sic] Force.”

it south, as The Savannah Morning News soon echoed that report of Burnside’s numbers and projected he was aiming for the Chesapeake Bay. (That isn’t to say the information provided in those early days couldn’t be sketchy. There were inaccurate newspaper reports that Brig. Gens. Isaac Stevens and Thomas W. Sherman would have commands in the expedition.)

On October 23, Burnside was ordered to concentrate his division at Annapolis. It took less than a week for this rendezvous location to leak out, with The New York Herald of October 30 conveniently informing the world that the 51st New York Infantry was not only part of the expedition but also had been ordered to Annapolis. Newspapers kept up a steady stream of reports detailing the exact regiments, and their commanders, ordered to join Burnside.

The actual destination of the expedition, however, had not been settled yet. Newspaper accounts speculated on three likely targets, the same three targets that any competent Confederate officer would have assumed: the Chesapeake Bay area, in conjunction with a move by McClellan’s main army; the North Carolina sounds; or the Charleston–Savannah region, reinforcing Union troops already at Port Royal, S.C. Here Burnside committed an error. On November 7, while in New York City securing vessels, he addressed a gathering of exiled North Carolina Unionists. It was unnecessary for a

serving general to address a civilian gathering, and Burnside’s interest in North Carolina was widely reported. Fortunately perhaps, other early November newspapers speculated his target would be Port Royal.

Early Confederate intelligence was divided on the potential point of attack. As early as October 1861, spies connected to Rose Greenhow’s Washington-based ring reported the target to be North Carolina, but as late as January 4, 1862, Jefferson Davis had received information that the Potomac River was Burnside’s target, in connection with an advance by McClellan’s army.

In a true gift to the Confederacy, The New York Herald (which seems to have been the worst of the Northern newspapers when it came to leaking secrets) ran a lengthy article in early November giving the names of all the regiments and their commanders then at Annapolis, plus their strengths, their armament (mostly Enfield rifles), and even details of the baggage train that had been gathered. From this information on numbers and capabilities, the Confederates could easily discern that the expedition was not equipped for large-scale operations outside coastal areas.

On November 19, one Washington newspaper listed the 15 regiments and their commanders that made up Burnside’s division. On the 28th, the Herald printed a complete breakdown of Burnside’s troops, with biographies of the officers, the names of the transport vessels, even details of their pontoon train. The next day The Philadelphia Press also listed the regiments, the names of the generals and colonels, and the names of the staff officers and vessels. We know from The Official Records that these lists of units and vessels were remarkably precise. Every newspaper report of the expedition gave fairly accurate information about its strength and

SPRING 2023 25

HARPER’S WEEKLY PREVIOUS PAGE: CLASSIC IMAGE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; HARPER’S WEEKLY (2) ACWP-230400-BURNSIDE.indd 25 12/13/22 8:52 AM

Burnside was ordered to concentrate his Division at Annapolis. It took less than a week for that to leak out.

order of battle, although at this time reports varied on the destination and timing of the expedition. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper admitted the expedition’s destination to be unknown, but “it may be Mobile, New Orleans or Galveston”—all in the Gulf of Mexico. Both The New York Tribune and The Chicago Tribune considered the York River (Chesapeake Bay) the likely target, working in conjunction with McClellan’s main army.

Perhaps the worst leak—certainly the most visual—came from Harper’s Weekly. Its January 4, 1862, issue featured a full page of illustrations of “Genl. Burnside’s Expedition,” depicting the fleet, with the names of the vessels given.

Harper’s admitted that the destination “is, of course, secret” but surmised that it would operate from a base not far from Fort Monroe (i.e., either the Chesapeake Bay or North Carolina).

Just from the list of vessels, and their known

The Usual Suspect

Harper’s Weekly was a leading source of the critical information typically shared by many Northern publications. The size of Burnside’s force is evident in this Harper’s illustration from its January 4, 1862, edition. It was quite clear this wouldn’t be a minor operation.

tonnage, the Confederates could estimate both the numbers of troops the ships could transport and the amount of supplies carried, which would serve to narrow the list of possible targets.

In case the Confederates did not have Harper’s handy, on the same day The Washington Evening Star provided similar information, adding that the vessels were almost fully loaded and ready to depart. This newspaper identified the caliber of the cannon on each ship, the ship’s draught and size, and told the world that the Annapolis boats would meet up with other naval warships already at Fort Monroe. Confirming the Fort Monroe speculation, The Lowell (Mass.) Daily Citizen of January 9 printed a letter from a captain of the 25th Massachusetts Infantry saying he had been ordered to prepare only three days’ rations, indicating a long cruise (i.e., to Port Royal or the Gulf) was not contemplated.

In fact, on January 2, 1862, Burnside had met with McClellan and final orders were issued for the expedition to depart as soon as possible, for the North Carolina sounds. The transports left Annapolis on January 9-10, rendezvoused with other vessels at Fort Monroe on the night of the 10th, and finally departed for Hatteras Inlet (the entrance to the North Carolina sounds) on January 11. Northern newspapers promptly reported all these moves. The Port Tobacco (Md.) Times of January 9, followed by The Philadelphia Press and The Baltimore American, announced Burnside’s departure. On January 11, The Washington Evening Star noted that while the troop vessels had sailed by the 10th, vessels loaded with “stores, etc.” would not depart for two or three more days.

The fleet’s arrival at Fort Monroe could be seen from nearby Confederate-held Norfolk. As early as January 9, newspaper reports circulated that Burnside’s advance vessels had reached that bastion. The Newark (N.J.) Journal reported on January 13 that Burnside and his staff arrived at the

26 AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR WETDRYVAC/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; HARPER’S WEEKLY HARPER’S WEEKLY

ACWP-230400-BURNSIDE.indd 26 12/13/22 8:52 AM

The route that Goldsborough’s naval vessels followed to reach Roanoke Island had them proceed down the Atlantic Coast from Fort Monroe, Va., and cross into Pamlico Sound just past Cape Hatteras. Considering the time of year, those vessels inevitably battled dire weather and rough seas throughout. The hazardous nature of the voyage appeared in this illustration published in The London Illustrated News on February 22, 1862.

fort on the 11th, while The Providence Journal and Washington Evening Star assured readers that Burnside was heading toward Pamlico Sound.

Burnside seems to have been aware of these newspaper leaks, although (as can be seen) his efforts to stop them failed. On January 10, The New York Tribune blandly and incorrectly asserted that “the secret of [Burnside’s] destination and field of operation has been well kept.” The Boston Morning Journal of the 13th even claimed that “General Burnside is determined that no indiscreet correspondent shall make public any details concerning his expedition, or its destination, until it is safe to do so” and claimed that Burnside had quarantined reporters on one of his ships to prevent word leaking out. Given the tsunami of leaks to the press, one wonders if these newspapers took what they wrote seriously, or whether they were trying to “butter up” the general in order to get more “scoops.”

Burnside himself became a chief offender. On January 14, The Cincinnati Daily Commercial gave out all the details of the expedition. The report was datelined the 5th, but not released until nine days later, as Burnside had asked the reporters not to release it until he deemed it “safe” to do so. This report (accurately) named the North Carolina coast, and Roanoke Island, as the first targets. It cited a force of 16,000 men and 53 cannons, astonishing (and accurate) detail that a Mata Hari would have been proud to have discovered.

The vessels were said to contain only eight days’ worth of coal and 10 days of food, confirming a short voyage (i.e., North Carolina). And with the troop-laden vessels still at sea, several Northern newspapers (from The Washington Evening Star to The Cleveland Daily Dispatch) printed these facts, and specified the Tar Heel State as the target. As the voyage

to North Carolina, which normally was a matter of a few days, could take—and, in fact, did take—weeks to complete due to gale-force winds, Burnside’s notion of when it was “safe” to unleash the newspapers seems wildly optimistic, almost criminal—certainly a violation of any notion of secrecy.

The Philadelphia Inquirer of January 18 published a report in such detail that it could have come only from a member of Burnside’s staff. After listing the brigades and regiments in each brigade, with their commanders (accurately in each case), it furnished a list of all the company officers of every regiment, down to the 2nd lieutenants, and on which vessels each regiment had embarked. Details of the pontoon train, the cost and composition of the artillery ammunition, names of even the junior signal officers, and more, were disclosed. The article claimed that “Gen. Burnside has afforded the press every facility for obtaining” these priceless details, which casts serious doubts on Burnside’s later claims that he clamped down on security.

Lest anyone on either side was still in doubt as to Burnside’s target, The New York Sun of January 24 printed a long article on the expedi-

SPRING 2023 27 WETDRYVAC/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; HARPER’S WEEKLY HARPER’S WEEKLY

That’s One Treacherous U-Turn

ACWP-230400-BURNSIDE.indd 27 12/13/22 8:52 AM

Making Themselves at Home

Federal troops disembark at Roanoke Island on February 7, 1862. The island soon became the site of a prosperous, though shortlived, Freedman’s Colony.

Left:

tion complete with a map of the North Carolina sounds. The New York Herald on the 28th printed another map of the region and filed a long report on ships that Burnside had lost in the storms, together with the names of the units on board the lost ships. The names of the five ships lost, with their cargoes, match up with the actual losses. In addition, the reports on the storm and the difficulties the ships had in getting over the shallow inlet waters, explained to the world the reasons for the delay in the attack. This almost-real-time update would be the last actionable newspaper leak prior to the attack.

It took until February 5 for the entire fleet, buffeted by gales that almost sank Burnside’s headquarters vessel, to anchor off Roanoke Island and transfer to shallower draft vessels that could enter the sounds. The troops commenced their attack two days later. The newspaper reports thus gave the Confederate authorities nearly three full weeks’ notice of the intended site of attack. Southern newspapers even reported the impending attack, and urged the government to react, though there was still some doubt as to where in the sounds the first attack would be made.