This 16" full tang stainless steel blade is not for the faint of heart

In the blockbuster film, when a strapping Australian crocodile hunter and a lovely American journalist were getting robbed at knife point by a couple of young thugs in New York, the tough Aussie pulls out his dagger and says “That’s not a knife, THIS is a knife!” Of course, the thugs scattered and he continued on to win the reporter’s heart.

Our Aussie friend would approve of our rendition of his “knife.” Forged of high grade 420 surgical stainless steel, this knife is an impressive 16" from pommel to point. And, the blade is full tang, meaning it runs the entirety of the knife, even though part of it is under wraps in the natural bone and wood handle.

Secured in a tooled leather sheath, this is one impressive knife, with an equally impressive price.

This fusion of substance and style can garner a high price tag out in the marketplace. In fact, we found full tang, stainless steel

blades with bone handles in excess of $2,000. Well, that won’t cut it around here. We have mastered the hunt for the best deal, and in turn pass the spoils on to our customers. But we don’t stop there. While supplies last, we’ll include a pair of $99, 8x21 power compact binoculars, and a genuine leather sheath FREE when you purchase the Down

Under Bowie Knife

Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Feel the knife in your hands, wear it on your hip, inspect the impeccable craftsmanship. If you don’t feel like we cut you a fair deal, send it back within 30 days for a complete refund of the item price.

Limited Reserves. A deal like this won’t last long. We have only 1120 Down Under Bowie Knives for this ad only. Don’t let this beauty slip through your fingers at a price that won’t drag you under. Call today!

Down Under Bowie Knife $249*

Stauer® 8x21 Compact Binoculars

-a $99 valuewith purchase of Down Under Knife

êêêêê

“This knife is beautiful!”

— J., La Crescent, MN

êêêêê

“The feel of this knife is unbelievable...this is an incredibly fine instrument.”

— H., Arvada, CO

BONUS! Call today and you’ll also receive this genuine leather sheath!

Offer Code Price Only $99 + S&P Save $150

1-800-333-2045

Your Insider Offer Code: DUK370-01

You must use the insider offer code to get our special price.

Stauer ®

Rating of A+

14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. DUK370-01

Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.com

*Discount is only for customers who use the offer code versus the listed original Stauer.com price.

California residents please call 1-800-333-2045 regarding Proposition 65 regulations before purchasing this product.

•Etched stainless steel full tang blade ; 16” overall • Painted natural bone and wood handle • Brass hand guards, spacers & end cap • Includes genuine tooled leather sheath

—now ONLY $99!

The world comes out west expecting to see cowboys driving horses through the streets of downtown; pronghorn butting heads on windswept bluffs; clouds encircling the towering pinnacles of the Cloud Peak Wilderness; and endless expanses of wild, open country. These are some of the fibers that have been stitched together over time to create the patchwork quilt of Sheridan County’s identity, each part and parcel to the Wyoming experience. Toss in a historic downtown district, with western allure, hospitality and good graces to spare; a vibrant art scene; bombastic craft culture; a robust festival and events calendar; small town charm from one historic outpost to the next; and living history on every corner, and you have a golden ticket to the adventure of a lifetime.

By Mike Coppock

By Mike Coppock

By Matthew Bernstein

By Matthew Bernstein

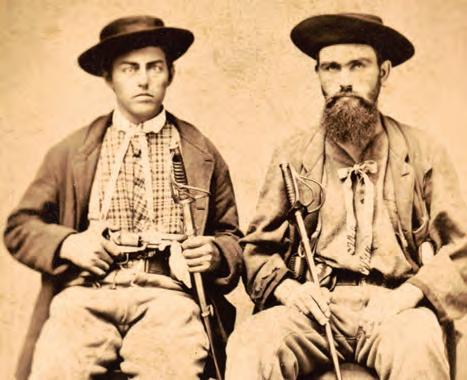

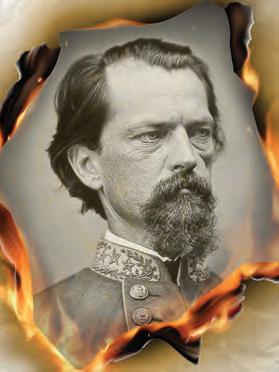

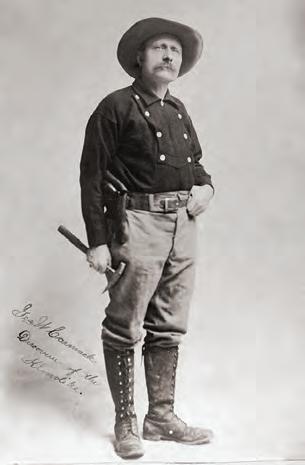

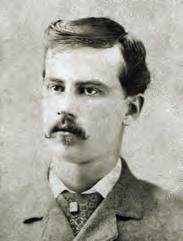

Kansan Patrick Cleary was as violent—and ill-fated—as ‘the Kid’ from New Mexico

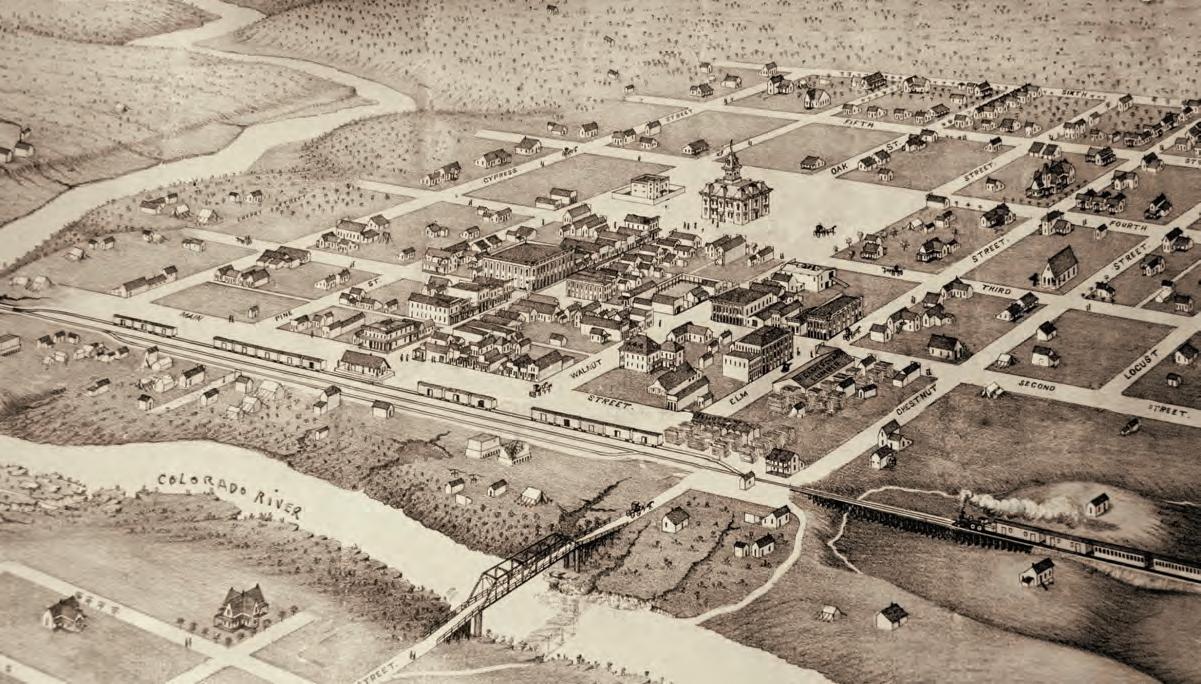

The west Texas boomtown of Colorado City was known for its wealth, vice and violence

By Candy Moulton

By Candy Moulton

SUMMER 2023

8 LETTERS

10 ROUNDUP

16 INTERVIEW

BY JOHNNY D. BOGGSActor Michael Dante writes about his Hollywood career, history and the West

18 WESTERNERS

Dancer ‘Klondike Kate’ Rockwell dazzled miners in Yukon Territory, Canada

20

‘Lion of Tombstone’ Wyatt Earp was something of a lamb in Wrangell, Alaska

Though happy in the kitchen, Alaskan Fannie Quigley took guff from no one

24 ART OF THE WEST

BY JOHNNY D. BOGGSRick Kennington loves the texture of paint nearly as much as the West he depicts

30 INDIAN LIFE

BY DENNIS GOODWINDid notable Lakota warrior White Bull kill George Custer at the Little Bighorn?

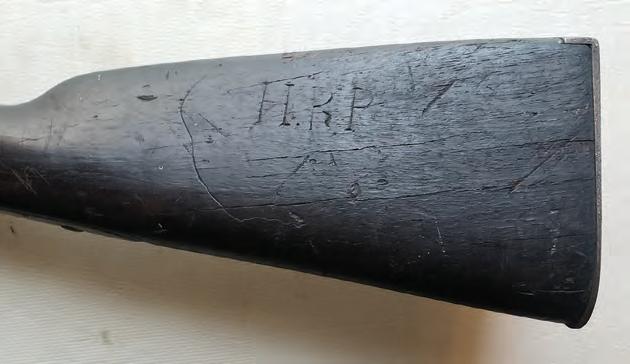

70 GUNS OF THE WEST

BY GEORGE LAYMANThe Springfield Model 1842 smoothbore musket had a storied career as surplus

EICHIN

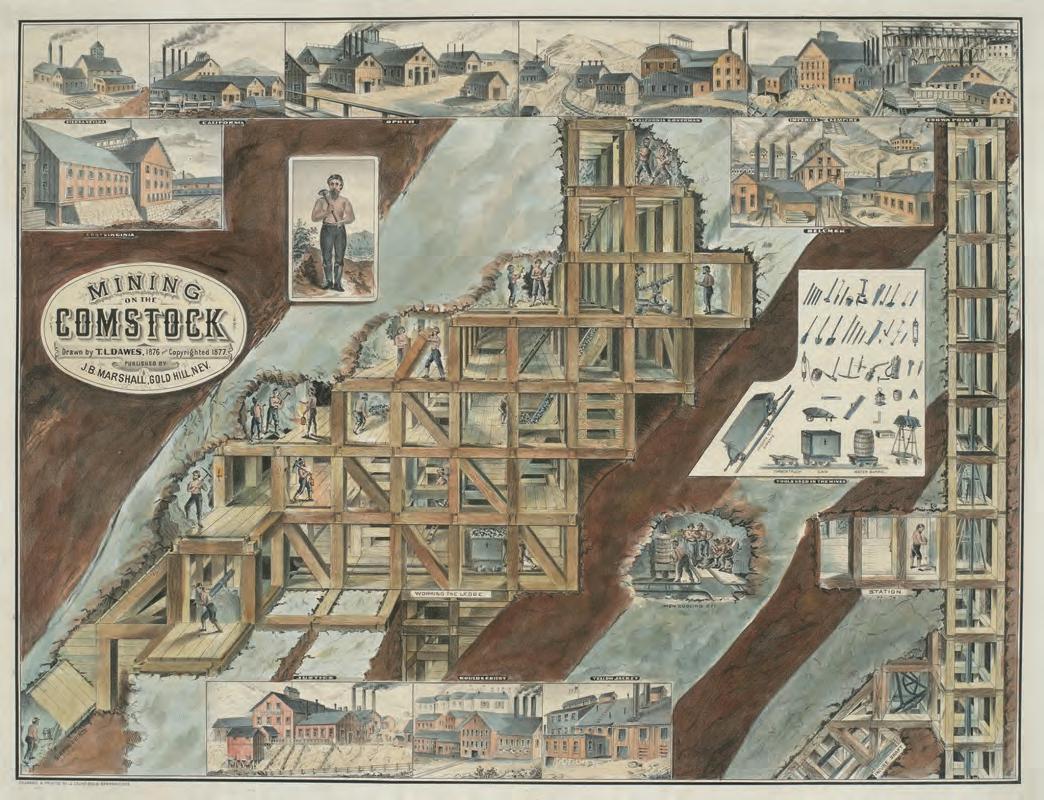

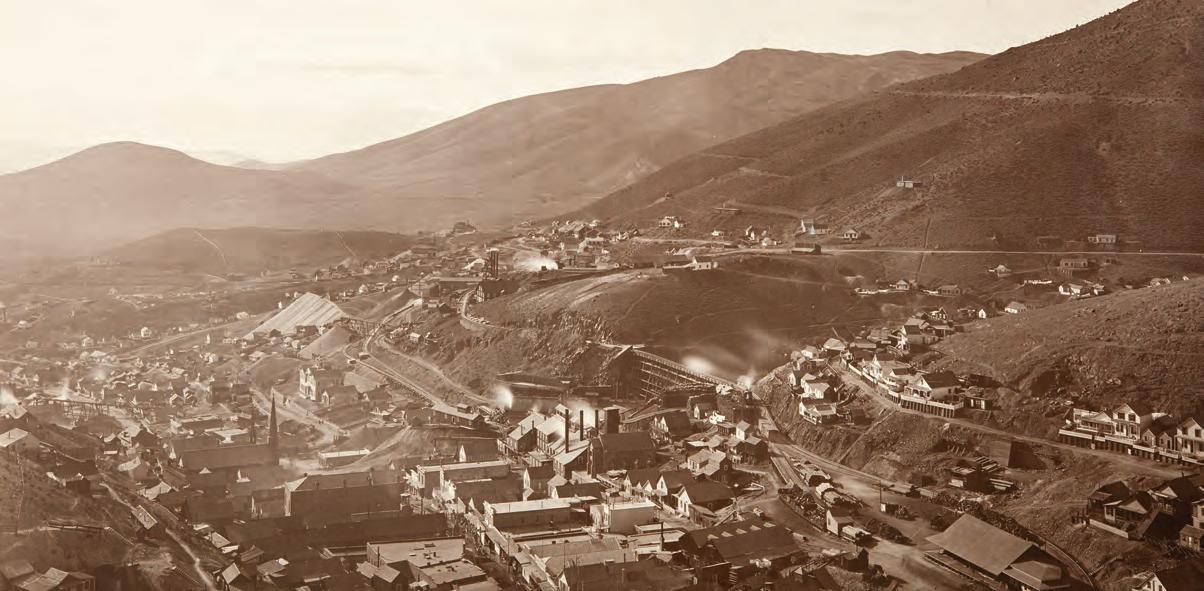

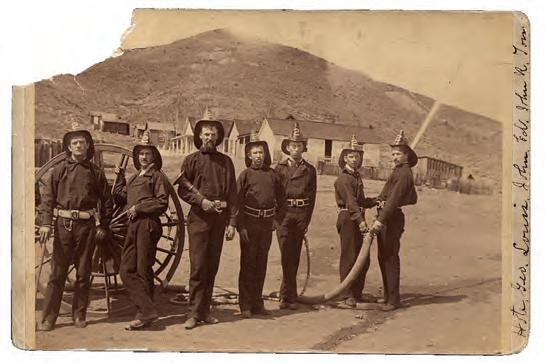

Gold Hill, Nevada, yielded plentiful gold and silver—and experienced tragedy

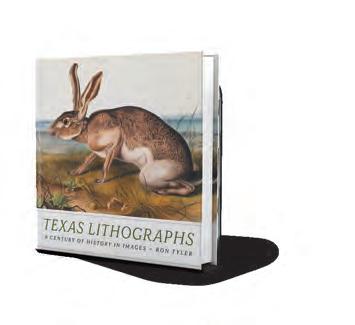

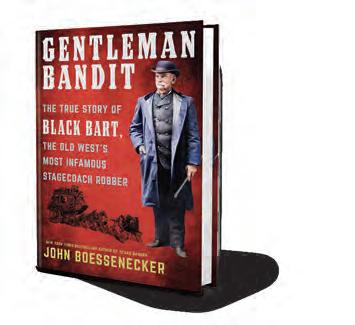

74 REVIEWS

Mike Coppock shares his favorite Klondike-related books and films. Plus reviews of books about ‘Dirty Dave’ Rudabaugh, Crow artist White Swan and others

80 GO WEST

Alaska’s Inside Passage is as stunning as ever, the accommodations far better

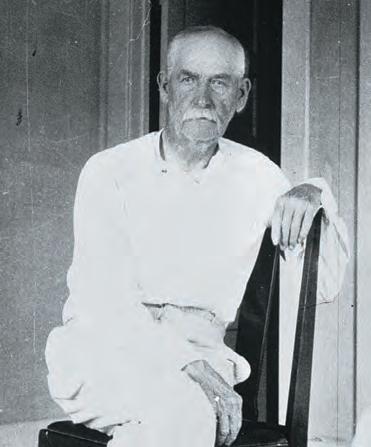

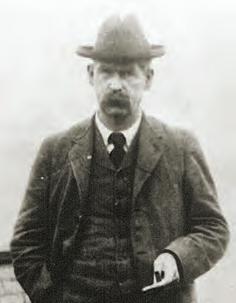

Spry 84-year-old John J. ‘Two-Step Jake’ Hirsch, of Tenakee Springs, Alaska, poses with a tool of his trade in 1936. Hirsch spent 57 years in the goldfields of Alaska and Canada’s Yukon Territory. At the time of this portrait he was mulling plans to start a fox and mink fur farm and boasting he’d soon appear on the big screen with Mae West. When a friend expressed concern Hirsch might overexert himself, Jake replied, “My father lived to 97, and he wouldn’t have died then if he had taken care of himself.” Hirsch himself died at the Alaska Pioneers’ Home in Juneau in 1944. He was 96. (Alaska State Archives, Skinner Foundation, ASL-PCA-44; colorization by Brian Walker)

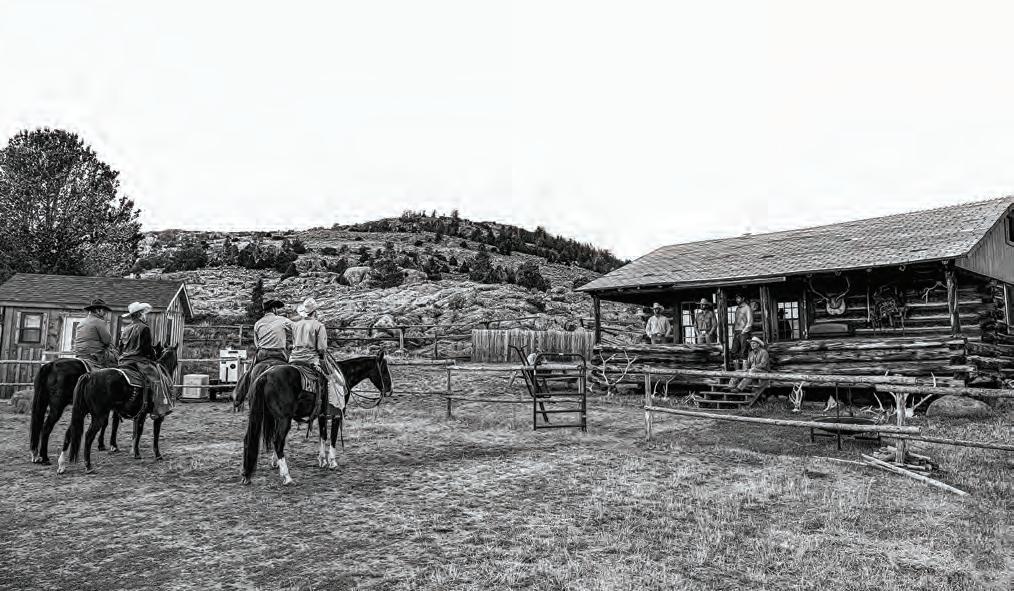

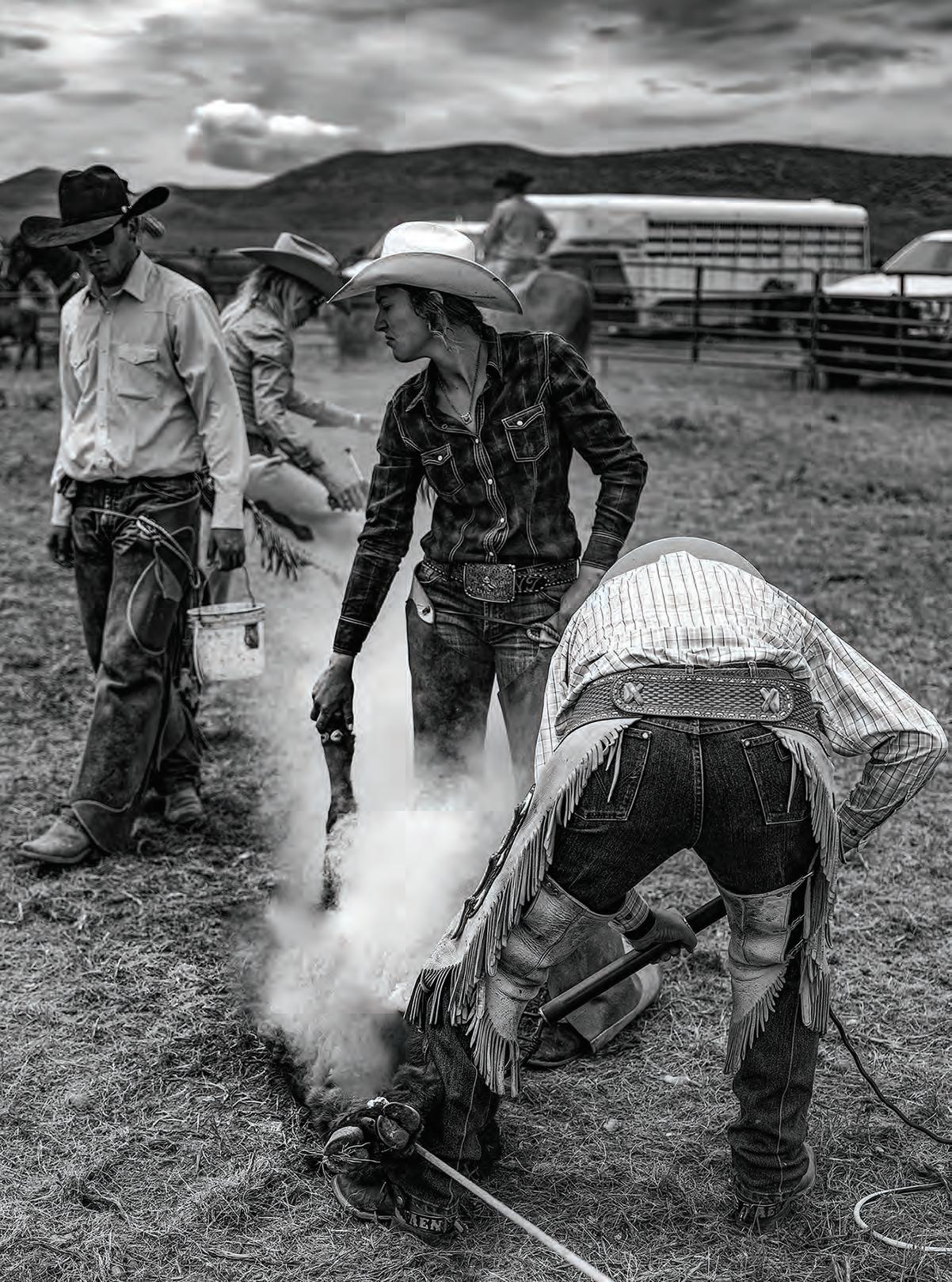

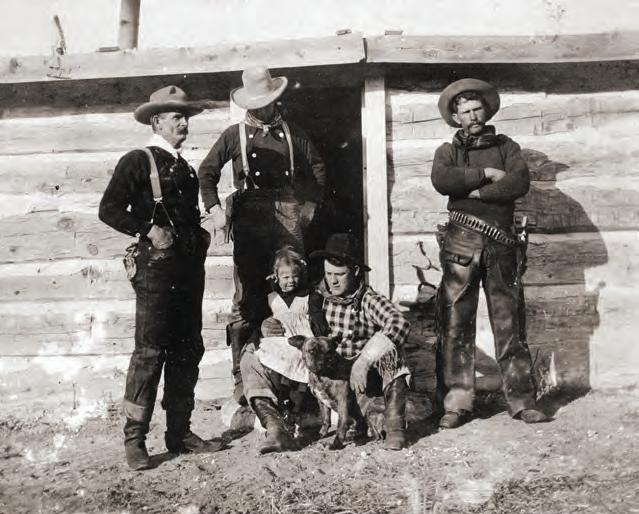

A photographer’s portrait of Wyoming’s Wagonhound proves little has changedWe share with you, our reader, a love of both history and the American West that makes our work a labor of love. Still, it is encouraging when peers recognize our efforts—and that brings me to our big news.

Wild West contributor Matthew Kerns has earned two of the top writing awards in the Western history niche for his April 2022 cover story “‘Texas Jack’ Takes an Encore,” which relates the life story of pioneering cowboy celebrity John Baker “Texas Jack” Omohundro (see P. 11 for details). Kerns won both the 2023 Western Heritage Award for best magazine article from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum and the 2023 Spur Award in the same category from Western Writers of America. The rare double win marks this magazine’s seventh lifetime Wrangler and sixth lifetime Spur.

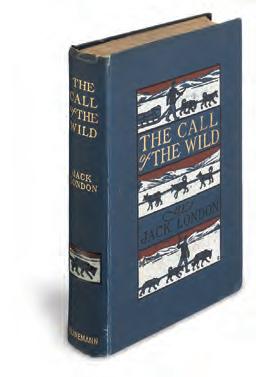

Wild West is honored by the awards and proud of our writers. Meanwhile, we’ve been hard at work. In this issue we range to the far north. In our cover story (see P. 30) Mike Coppock relates the colorful chronicles and characters of the 1896–99 Klondike Gold Rush from rough-hewn ports in southeast Alaska to northwestern Canada’s Yukon Territory. Among the betterknown figures who made their mark in the goldfields and boomtowns of the Klondike and southeast Alaska were Call of the Wild author Jack London and lawman Wyatt Earp of Tombstone, Arizona Territory, fame, whose time up north Coppock details in Gunfighters & Lawmen (see P. 20). Our Westerners profile (see P. 18) shines the spotlight on dancer and vaudeville performer “Klondike Kate” Rockwell, who whirled her way into prospectors’ hearts and beguiled them out of their gold dust. Finally, Go West (see P. 80), the destination page that closes each issue, features then-and-now maritime images of Alaska’s Inside Passage, the embarkation point for most Klondike prospectors.

Of the 100,000 hopefuls who set out from there for the goldfields, scarcely one-third completed the grueling trek up through dizzying mountain passes, across untamed wilderness and down lethal rapids on makeshift boats. Hundreds died due to accidents, exposure, starvation, illness, alcoholism, murder, suicide and other causes. It was—and in many areas still qualifies as—frontier.

In 1893 Frederick Jackson Turner delivered a speech entitled “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” to a gathering of the American Historical Association in Chicago. Turner famously quoted an 1890 Census Bureau bulletin

declaring the “closing of the frontier” in the Lower 48. “Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement,” the bulletin read, “but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line.”

Alaska is another matter altogether. To this day there are remote settlements accessible only to bush planes fitted with floats or skis, and the state nickname remains “The Last Frontier.” Just how much elbow room is there? At 570,951 square miles, it is by far the largest state—more than twice the size of Texas—and if all 736,081 of its residents were to stake his or her own claim, each would have the greater part of a square mile on which to prospect, fish, trap, hunt, raise a cabin, build an igloo or throw snowballs. Compare that to Washington, D.C., and its claustrophobic population density of 11,295 people per square mile. Granted, most Alaskans, like most Americans, live in cities and towns, but that only further frees up its wilderness.

Just ask such modern-day Alaskan frontiersmen as Heimo Korth. Subject of the 2004 biography The Final Frontiersman, by James Campbell, Heimo and wife Edna are among the few permanent residents of the 19-million-plus-acre Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Hacking out a subsistence living between seasonal cabins hundreds of miles from any town, the Korths eat mostly what they can hunt, fish and trap, and they haul in creek water daily just to survive. But they are free to live as they choose, and they wouldn’t have it any other way.

Have your own tales of the wild frontier? Drop us a line at WildWest@HistoryNet.com, and we’ll share your memories with fellow readers in the next Letters section. To keep up with our latest, sign up for our monthly email newsletter at HistoryNet.com/signmeup.

Now, “Mush!”

Wild West editor David Lauterborn is a published writer, author and photographer with two books and hundreds of magazine articles to his credit. A hopelessly addicted traveler to and onetime resident of the American West, he lives in historic Harpers Ferry, W.Va.

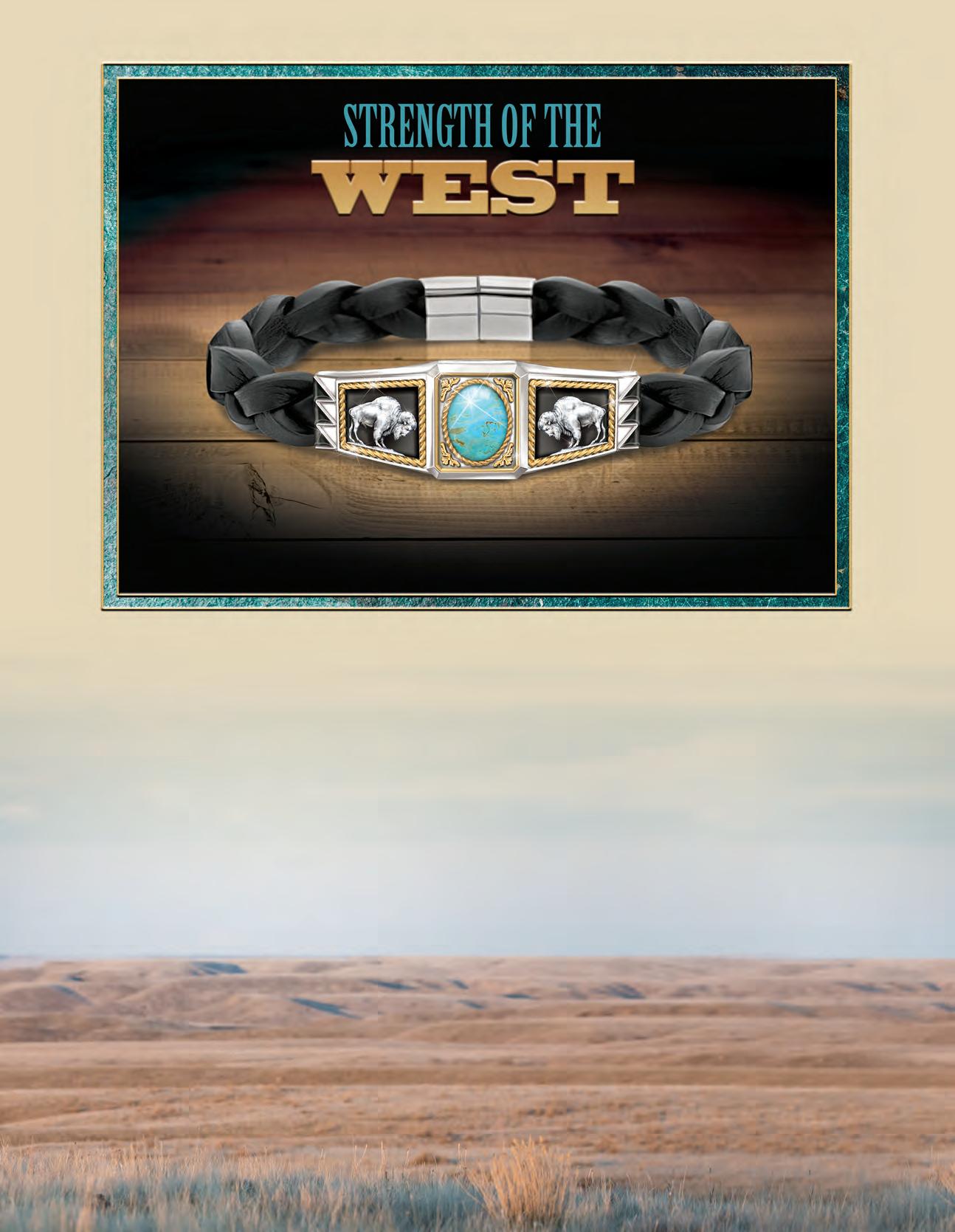

This black genuine leather bracelet is hand-crafted of solid stainless steel and ion-plated 24K-gold accents, and features an impressively sized genuine turquoise cabochon at the center. One of the oldest stones known to man, and used extensively in jewelry from America’s Southwest, it makes a strong statement along with the images of American bison.

The turquoise center stone is surrounded by a raised twisted rope design along with impressive scrollwork accents. On either side of the turquoise stone, you’ll nd masterfully sculpted images of the majestic bison on a black ion-plated background also framed by a raised twisted rope border. Decorative Western-style art motifs honoring the American

West complete the distinctive look. Adding to the meaning and value, the words “Strength of the West,” are boldly etched on the back. A magnetic clasp allows for easy wear and it’s designed to t most wrists.

This bracelet is an exceptional value at $119.99*, payable in 4 easy installments of just $30, and is backed by our unconditional 120-day full money-back guarantee. Each bracelet arrives in a velvet jewelry pouch along with a gift box and Certi cate of Authenticity. To reserve, send no money now; just mail the Priority Reservation. Don’t miss out—order yours today!

By Jerry D. Morelock historynet.com/bleeding-kansas-myth

By Jerry D. Morelock historynet.com/bleeding-kansas-myth

DAVID LAUTERBORN EDITOR

JON GUTTMAN SENIOR EDITOR

GREGORY J. LALIRE EDITOR EMERITUS

JOHNNY D. BOGGS SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

JOHN BOESSENECKER SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

JOHN KOSTER SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

BRIAN WALKER GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR

MELISSA A. WINN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

AUSTIN STAHL ASSOCIATE DESIGN DIRECTOR

ALEX GRIFFITH PHOTO EDITOR

DANA B. SHOAF EDITOR IN CHIEF CLAIRE BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

CORPORATE

KELLY FACER SVP REVENUE OPERATIONS

MATT GROSS VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES

ROB WILKINS DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING

JAMIE ELLIOTT SENIOR DIRECTOR, PRODUCTION

ADVERTISING

MORTON GREENBERG SVP ADVERTISING SALES mgreenberg@mco.com

TERRY JENKINS REGIONAL SALES MANAGER tjenkins@historynet.com

DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING NANCY FORMAN / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com

© 2023 HISTORYNET, LLC

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: 800-435-0715 OR SHOP.HISTORYNET.COM

WILD WEST (ISSN 1046-4638) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC, 901 North Glebe Road, 5th Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Tysons, Va., and additional mailing offices. postmaster, send address changes to WILD WEST, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900

List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc. 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com

Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519

Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001

The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet, LLC

PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

The enduring image of this notorious pre–Civil War struggle is that it was unusually bloody. But the casualty numbers suggest otherwise.

On the grounds of the Wyoming State Fair

The Wyoming Pioneer Museum is a must see for western history enthusiasts!

Among the collections you’ll find stories of area cowboy Wild Horse Robbins and his adventures gathering wild mustangs and an outstanding collection of American Indian artifacts. Rodeo contractor Charlie Irwin’s larger than life biboveralls are always a favorite among children visiting the museum, as is the tepee used in the film Dances With Wolves.

Important chapters in American history are told in Glenrock and across the surrounding countryside. It’s the early day tale of the West we know today.

From the emigrant trails to the Pony Express and the telegraph, Glenrock’s history is heavily intertwined with some of the most colorful chapters in American history. That story is told at the community’s Deer Creek Museum.

Venture north from Douglas, Wyo., on Highway 93 to Fort Fetterman to learn more about the pioneering days of the Bozeman Trail!

Visitors to Fort Fetterman — only 11 miles northwest of Douglas — are encouraged to walk the grounds where interpretive signs tell the story of the fort that was abandoned in 1882.

Visitors to the site will also find much more beyond the fort itself of interest. The area features many historic markers and beautiful vistas that add to the richness of the story of Fort Fetterman.

visit us online at

wyoparks.wyo.gov, or find our Facebook page for hours.

The Douglas Railroad Museum & Visitor Center is housed in the historic FE & MV Railroad Passenger Depot. The building is listed on the National Historic Register and is surrounded by seven historic railcars, including the Chicago Burlington and Quincy Railroad 4-8-4 Steam Locomotive #5633.

Discover how the West was truly won!

[Re. “The Trial of Billy the Kid, by David G. Thomas, Autumn 2022:] The image on P. 51 of the Billy the Kid Gift Shop [the former Doña Ana County Courthouse] in Mesilla, N.M., centers on the front entrance, featuring a painting of saloon doors with people looking out as you look in. I did that painting when I was 19 and living in Tucson with other artists at the time. The owner, whose name I can’t recall, bought the wood to my studio at Las Canastas, on Prince Street, and I painted it there. There were two wooden panels, and the batwing doors were overlaid after he purchased the panels and returned to Las Cruces. He was clear about wanting the people to be looking out, as though over a door.

So much fun to see it again! I am no w 79, and I’m sure the painting has been retouched many, many times since installation.

Rena Paradis Las Cruces, N.M.I was very pleased to see the informative article [“The Night the Ruggles Brothers Met ‘Judge Lynch,’” by Matthew Bernstein, Autumn 2022] on my notorious ancestors the Ruggles brothers, John and Charles. They were first cousins of my great-grandmother Augusta Florence Ruggles, who was born in Woodland, Calif., in 1860. She was the daughter of Fernando Cortez Ruggles, who came to Placerville looking for gold along with brother Lyman in 1850. Their brother Ely did not come with them from Pennsylvania, staying to care for the family’s farming interests, expecting to see his brothers if and when they returned.

Needless to say, by the time I came along in 1943, John and Charles were not mentioned much in the family. In fact, I had not heard of them until I saw your August 1995 article [“The Struggles of the Ruggles,” by Harold L. Edwards] and asked my grandmother about them. I had seen their names in our family’s genealogical records. She was 90 at the time and was still ashamed about this black spot on the family name. She had been born in 1904 in Esparto, Calif., and raised in Woodland. Undoubtedly she had known much about them but never mentioned it to me. There are still a number of Ruggles relatives in and around Woodland, though I am not in contact with them.

I am fortunate in that most of my close family lines are pioneers, some prominent, stretching back to [Massachusetts Bay Colony] Governor John Winthrop. I have read many of their accounts and still have Ely Ruggles’ book, Recollections of a Busy Life. I also have three journals my grandfather kept sporadically from 1919 until his death in 1967.

History was not of much interest to me while growing up, until I started looking into my family history and finding recognized historical figures from the [California] Gold Rush, Civil War, French and Indian War, and War of Independence. People I had read about in history books came alive to me. Thank you, Mr. Edwards and Mr. Bernstein for this enjoyable article.

Michael Lee San Carlos, Calif.Matt Bernstein responds: Thanks, Michael. After reading your letter, I dug up Recollections of a Busy Life . Fascinating stuff. I particularly enjoyed Ely Ruggles’ description of Pasadena, which he called “that paradise on earth.” Having lived in Pasadena, I couldn’t agree more.

I started out many years ago with the Louis L’Amour Western Magazine and was disappointed when that ceased printing, and I was turned over to Wild West. All these years later I am a big fan. I just want to say that if Wild West ever stops being printed, I will stop being a subscriber. I tried going electronic with a trade publication I subscribe to and never read it. I switched back to print. I spend way too much time on computers, so please keep the print edition coming. I love relaxing in a comfy chair and escaping to the ever compelling Wild West!

Larry Cagle Bandon, OregonEditor responds: We, too, spend way too much time on computers and are protective of the print edition of Wild West. Keystrokes just can’t beat the sound of rustling pages.

Send letters by email to wildwest@historynet.com

Many congratulations on a great Western magazine. I have been collecting Wild West since it first appeared in our local news agent back in December 1993. Each year since I have had the six bimonthly issues hardbound and have now quite an extensive Wild West library. As the magazine has recently gone quarterly, I’ll have eight issues (two years) bound into one volume—save a few dollars. I certainly look forward to receiving each issue and also your emailed newsletter.

Please include your name and hometown @WildWestMagazine

Paul Raspin Riverside, Tasmania Australia

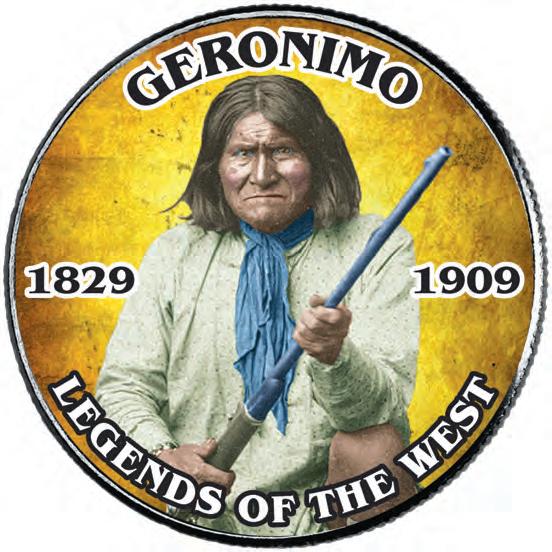

Nowown an exclusive US half dollar enhanced by Mystic to commemorate legendary Native American warrior Geronimo. Worth $9.99 – it’s yours FREE – send just $2.95 for shipping and guaranteed delivery.

A historic image of Geronimo has been bonded to a US half dollar. Taken in 1887, the portrait pictures the Apache leader during what was known as “Geronimo’s War.” This coin is available only from Mystic.

Send for your free Geronimo history coin today. You’ll also receive special collector’s information and other interesting coins on approval. Strict limit of one coin. Satisfaction guaranteed.

FREE Geronimo Coin

❏ Yes! Send me the Geronimo history coin. Enclosed is $2.95 for shipping and guaranteed delivery. Strict limit of one coin. Satisfaction guaranteed. Quick order at MysticAd.com/IU153

Name _______________________________________________________

Address _____________________________________________________

City/State/Zip ________________________________________________

❏ Check or money order

❏ Visa

Please send payment to: Mystic Dept. IU153, 9700 Mill St., Camden, NY 13316-9111

1 Wyatt Earp The “Lion of Tombstone” was over the hill, pudgy and graying when he headed for the Klondike in 1897, initially accepting a temporary stint as a lawman in Wrangell, Alaska (see related story, P. 20). He and a pregnant Sadie, his common-law wife, turned back at Juneau. A year later they again tried for the Klondike, setting out on the “rich man’s route” up the Yukon River from St. Michael, Alaska, before becoming iced in that winter with boxing promoter Tex Rickard and novelist Rex Beach. Finally giving up on the Klondike, the Earps joined the Nome Gold Rush, Wyatt and a partner opening the two-story Dexter Saloon.

3 Bill McPhee McPhee drifted into the Yukon in 1888 and later opened saloons in Forty Mile, Dawson City and Fairbanks. He grubstaked such successful prospectors as C.J. Berry and Frank Dinsmore, Berry later returning the favor by paying to rebuild McPhee’s fire-ravaged Fairbanks saloon. During the bitterly cold winter months McPhee transformed his Dawson saloon into housing for the poor, saving their lives. Not until 1921 did age and failing eyesight finally force the saloonman into retirement in San Francisco.

2

Jack London If London hadn’t ventured north, he would have been forever linked to maritime literature for his 1904 novel The Sea-Wolf. On arrival in the Klondike in 1897 he was no longer the young innocent. Among other escapades, he helped save a family from drowning on the Yukon River and spent weeks patronizing Klondike saloons. A year later, broke and battling scurvy, he continued downriver to the Bering Sea and worked his way home to California on a steamer. London was not only a great writer, but also the real deal.

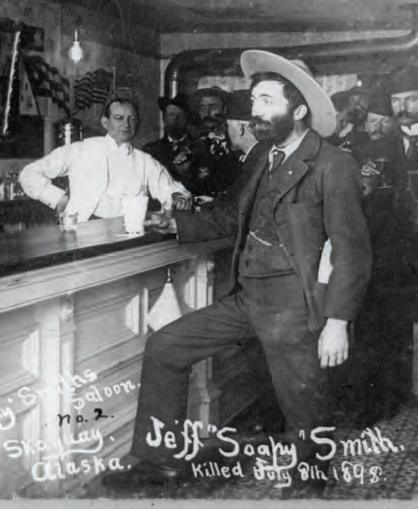

4 Jefferson “Soapy” Smith Elbowed out of Denver in 1897, Smith and gang headed north for the Klondike just as it boomed. Soon he controlled both Wrangell and Skagway through murder, intimidation and imaginative con jobs. It all proved bad for legitimate business, as homebound prospectors instead opted for the onward Yukon River route. Soapy met his end in a classic 1898 gunfight with vigilante Frank Reid on Skagway’s Juneau Wharf.

5 Clarence “C.J.” Berry Top dog of the “Klondike Kings,” Berry started out as one of McPhee’s bartenders before the saloonman grubstaked him. C.J. found so

much gold that he reportedly left a bucket of nuggets and a bottle of whiskey outside his cabin with a sign reading, Help Yourself. Unlike most riches-to-rags prospectors, however, he invested in oil-rich properties in California, exponentially increasing his fortune.

6

Harriet Pullen

The pioneering Pullen arrived in Skagway with only $7 and began making pies to sell to prospectors. With her profits she bought a cabin, sent for her husband and four kids and started a freighting business hauling goods over the White Pass Trail. When the rush subsided, she opened the Pullen House. Catering to high society, the hotel made Harriet and family a fortune. She died there in 1947.

day, and Texas Jack earned fame as the first entertainer to popularize the cowboy onstage. But his stardom was short-lived, as he was tragically stricken with pneumonia and died on June 28, 1880, a month shy of his 34th birthday. A heartbroken Morlacchi became a recluse and died six years later of cancer. Kerns is the author of the 2021 biography Texas Jack: America’s First Cowboy Star (read his award-winning article and a review of his book online at HistoryNet.com).

7

Sam Steele

The enduring image of the Mounties stems from the Klondike, and the superintendent of the North-West Mounted Police division in the Yukon was Steele. With relatively few men the no-nonsense Steele established customs posts atop passes into the Yukon, ensured prospectors brought enough goods to support themselves and tamped down on crime, bringing order out of disorder.

—Mike CoppockWild West contributor Matthew Kerns (below) has earned the 2023 Western Heritage Award for best magazine article from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. The award recognizes his April 2022 cover story

“‘Texas Jack’ Takes an Encore,” which relates the bittersweet story of iconic American cowboy John Baker “Texas Jack” Omohundro. A Virginian

This marks Wild West’s seventh lifetime Western Heritage Award. The award itself—a bronze by sculptor John Free of a cowboy on horseback known as the “Wrangler”—was first presented by the museum in 1961. Past recipients have included such Western legends as director John Ford, actors John Wayne and Kevin Costner, composers Dimitri Tiomkin and Elmer Bernstein, historians Robert Utley and Mari Sandoz, authors Elmer Kelton and Larry McMurtry and a host of other luminaries in Western music, film, television and literature.

Coincidentally, this year’s recipient of the Wrangler for best art/photography book—Ranchland: Wagonhound , by Anouk Krantz—is the subject of our feature portfolio (see P. 62). In it Wyoming native Candy Moulton examines the parallels between ranching in the Old West and life on Wyoming’s sprawling Wagonhound Ranch, the subject of Krantz’s spectacular images.

For a full list of recipients visit nationalcowboymuseum.org/collections/awards/wha.

You guessed it—in addition to his 2023 Wrangler, Matthew Kerns has also earned Western Writers of America’s 2023 Spur Award for best magazine article for his April 2022 cover story “‘Texas Jack’ Takes an Encore.” That’s a rare double win for Kerns and Wild West . It marks this magazine’s sixth lifetime Spur, an award WWA has bestowed on Western writers, poets, songwriters and screenwriters since 1953.

by birth, Omohundro fought for the gray in the Civil War and took up wrangling steers in postwar Texas. After working as an Army scout and trail guide alongside friend Will Cody during the Indian wars, Texas Jack toured with Buffalo Bill and Wild Bill Hickok in Western-themed stage productions. Omohundro later married co-star Giuseppina Morlacchi, a popular Italian prima ballerina. They were the celebrity couple of their

Among other Wild West contributors to receive 2023 Spurs are Melody Groves for best biography (Before Billy the Kid) and Candy Moulton for best documentary script (The Battle of Red Buttes, co-written with Bob Noll). Emmy-winning director Walter Hill won the spur for best screenplay (Dead for a Dollar). Best known for the films Broken Trail and Geronimo and an episode of the TV series Deadwood, Hill was recently interviewed by Wild West (read online at HistoryNet.com/ walter-hill-interview). Spurs will be presented at WWA’s annual convention, held this June in Rapid City, S.D. For a full list of recipients visit westernwriters.org/winners.

‘Since the days when the fleet of Columbus sailed into the waters of the New World, America has been another name for opportunity, and the people of the United States have taken their tone from the incessant expansion which has not only been open but has even been forced upon them.... The American energy will continually demand a wider field for its exercise. But never again will such gifts of free land offer themselves’

—So concluded historian Frederick Jackson Turner in his 1893 essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” in which he proclaimed the “closing” of the frontier to a gathering of the American Historical Association at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

On March 4 and 5, 2023, Holabird Western Americana Collections [holabirdamericana.com] of Reno, Nev., auctioned another 422 lots of artifacts recovered from the wreck of the steamship Central America , which sank in a storm off the Carolinas on Sept. 12, 1857. The ship went down with 425 of its 578 passengers and crew, among whom were men returning from the California Gold Rush. It carried a cargo of gold worth some $765 million. The top seller of the recent auction was a 2-pound gold ingot, which brought $138,000, far above its gold content value of $59,000. Another haunting relic, a daguerreotype of a young woman dubbed “Mona Lisa of the Deep” (above), fetched $73,200.

—Famed big-game hunter Ben Lilly (see “Lilly of the Field,” by Aaron Robert Woodard, Spring 2023 Wild West) whispered these words hours before his death near Silver City, N.M., on Dec. 17, 1936, just two weeks shy of his 80th birthday. The once vigorous outdoorsman, famed for his tireless, dayslong hunts after bears and mountain lions, had been in physical and mental decline for some time and confined to a bed in a county home for the indigent.

Wild West History Association members recently gathered at Oak Hill Cemetery in Lampasas, Texas, to unveil the repaired headstone of Albertus Sweet, who served two terms as sheriff (1873–78) of that town in the heart of the Lone Star State.

At a January event in Las Vegas, Nev., Lovig Auctions sold firearms and artifacts with reported ties to the June 25–26, 1876, Battle of the Little Bighorn. The items were from the collection of Wendell Grangaard, owner-operator of the since closed Guns of History museum in Mitchell, S.D. Among the 479 items were artifacts Grangaard reportedly tied to both 7th U.S. Cavalry and Lakota participants in the battle, including weapons alleged to have belonged to Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and Oglala war leader Crazy Horse. While some question the authenticity of Grangaard’s claims, Oglala Sioux Tribe President Frank Comes Out wrote Grangaard requesting the withdrawal of 111 items of “cultural significance to warrant protection under federal law.” Grangaard counters that he legally purchased all items over the past 60 years, thus federal repatriation laws don’t apply. “Wendell, in fact, did pay money for them,” said auctioneer Brian Lovig. “To me it’s the free market.”

On Dec. 9, 1880, the 38-yearold lawman was serving as a deputy city marshal in Belton, Texas, when killed in a gunfight while helping a fellow deputy make an arrest. Sweet’s remains were returned to Lampasas for burial, and in the intervening decades his headstone at Oak Hill Cemetery had suffered damage.

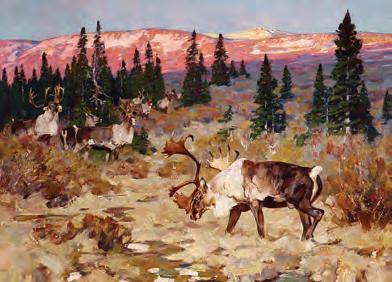

Ongoing economic woes haven’t hurt the art market much, judging by the results of recent backto-back Bonhams auctions. The Los Angeles division of the British auction house [bonhams.com] realized more than $5.4 million on the collection of the late financial analyst G. Andrew Bjurman, whose works spanned more than 150 years of Western art. A dozen lots fetched more than six figures, including Walter Ufer’s The Water Women ($567,375) and Oscar Edmund Berninghaus’ Ancient Forest ($542,175). Other top sellers included paintings by Frank Tenney Johnson, Maynard Dixon and Joseph Henry Sharp. That same day Bonhams realized nearly $2 million with a follow-up Western art auction. Highlights included wildlife artist Carl Rungius’ The Intruder (below, $529,575) and Charles Schreyvogel’s bronze The Last Drop ($353,175).

With his guns blazing and his reins in his teeth, Duke lit up the silver screen. Now that iconic scene comes galloping to life in a gleaming tribute to his Academy Award®-winning role.

The John Wayne: Heroic Charge Cold-Cast Bronze Masterpiece Sculpture is artisan hand-crafted in cold-cast bronze for a thrilling sense of motion. This fine collector’s edition stands tall in the saddle at 11 inches high and is available ONLY from The Bradford Exchange.

Significant demand is expected for this exclusive presentation, limited to 295 casting days. Make it yours in four installments of $42.50 for a total of $169.99*, backed by our unconditional, 365-day money-back guarantee. Send no money now. Return the order coupon today!

Actress Raquel Welch, 82, died in Los Angeles on Feb. 15, 2023. Ranked among the sexiest stars of the 20th century, she debuted in Westerns on the small-screen series The Virginian (1962–71) before co-starring in Bandolero! (1968) with James Stewart, who said of her performance, “I think she’s going to stack up all right.” As rebel leader in 100 Rifles (1969) she stopped a Mexican troop train, and the show, with a shower beneath a water tower.

Academy

Award–winning producer Walter Mirisch, 101, died in Los Angeles on Feb. 24, 2023. Founder of the independent Mirisch Corp., he produced 68 films for United Artists, including Man of the West (1958, starring Gary Cooper) and The Magnificent Seven (1960, starring Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen and those other five gunmen). The first Western Mirisch produced was Wichita (1955), starring Joel McCrea as a pre-Tombstone Wyatt Earp.

On Feb. 4, 2023, historian Bob Ernst, 80, died in Perkins, Okla. For the past three decades Ernst dedicated himself to researching the stories of lawmen who died in the line of duty for the U.S. Marshals Service. He and co-author George Stumpf compiled their accounts in the 2006 book Deadly Affrays: The Violent Deaths of U.S. Marshals. Ernst also wrote the 2009 book Robbin’ Banks and Killin’ Cops, about Depression-era Oklahoma outlaw Lawrence DeVol, as well as articles about lawmen for various Western association journals.

Author Gerald (“Jerry”) Kean Keenan, 90, died in Longmont, Colo., on Nov. 19, 2022. Among the four feature articles in the June 1988 premier issue of Wild West was Keenan’s “Cheyenne Island Saga,” about the dramatic September 1868 Battle of Beecher Island. In the 1996 compilation book Best of the Wild West that article was the first included. Over the decades Keenan wrote seven more Wild West features. His last, “Fury on the Spokane Plains” (August 2018), told of the little remembered Yakima War in what is now the state of Washington. Keenan, who was born in Waukon, Iowa, and grew up in Milwaukee, also wrote books, including Encyclopedia of American Indian Wars, 1492–1890 (1997), The Wagon Box Fight: An Episode of Red Cloud’s War (2000), The Life of Yellowstone Kelly (2006), The Terrible Indian Wars of the West: From the Whitman Massacre to Wounded Knee, 1846–1890 (2016) and West of Green River: A Novel of the Bonneville Expedition, 1832–1835 (2011). He edited Western Writers of America’s Roundup magazine from 1978 to ’80 and later wrote articles and book reviews for that publication.

A 26-mile stretch of Highway 9 in Claiborne Parish, La., has been dedicated as the “Sheriff Pat Garrett Memorial Highway.” Garrett, the slayer of Billy the Kid in New Mexico Territory in July 1881, was born on June 5, 1850, in Alabama’s Chambers County, but at age 3 he moved with his parents, John and Elizabeth Garrett, to Claiborne Parish. The Garretts established a farm 6 miles northeast of Homer, La., and also kept a second home in town. John and Elizabeth both died in the late 1860s, and all the property was auctioned off to satisfy debts. In January 1869 Garrett saddled his horse and rode west in search of a new life in Texas and, later, New Mexico Territory. The memorial highway runs between Homer and Junction City, appropriately passing the site of the Garrett family farm (a historical marker was erected at the location three years ago). Both the historical marker and memorial highway were projects originated by the Claiborne Parish Public Library.

Through April 7, 2024, Santa Fe’s Museum of International Folk Art [internationalfolkart.org] presents “Ghhúunayúkata/ To Keep Them Warm,” an exhibit of 20 parkas representing six Alaska Native communities: Yupik, Iñupiaq, Unangan (Aleut), Dena’ina, St. Lawrence Island Yupik and Koyukon.

Crafted out of a selection of furs, skins and intestines, the items range from historic mid-19th century parkas to contemporary garments. Illustrations, photographs and traditional dolls provide context for how parkas are used in both ceremonial and everyday life.

North Dakota’s legendary people, like Lewis and Clark, Sakakawea, Sitting Bull, Custer and places like Theodore Roosevelt National Park have a story as fascinating today as it was 200 years ago. Visit the Northern Plains with its frontier army forts and Indian villages standing ready to greet you.

Come, explore today!

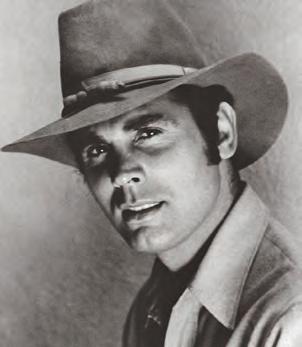

Michael Dante, 91, appeared in nearly 200 big- and smallscreen productions. Western film buffs would recall him best from such movies as Westbound (1959), with Randolph Scott; Apache Rifles (1964) and Arizona Raiders (1965), both with Audie Murphy; and as the title Blackfoot chief in Winterhawk (1975). Born Ralph Vitti (Dante picked his professional name after signing with Warner Bros.) in Stamford, Conn., in 1931, he started acting in the fourth grade and majored in drama at the University of Miami. Before moving to Hollywood, he played professional baseball in the Boston Braves and Washington Senators organizations. Nursing a shoulder injury, he took a screen test arranged by big band legend Tommy Dorsey and left pro ball. From 1994–2008 he hosted the radio series The Michael Dante Classic Celebrity Talk Show , out of Palm Springs, Calif. Dante has since turned to writing both nonfiction and fiction, including the autobiography Michael Dante: From Hollywood to Michael Dante Way (2013); My Classic Radio Interviews With the Stars: Vol. 1 (2021), co-authored by wife Mary Jane Dante; and such novels and novellas as the post–Civil War Six Rode Home (2018), the Western sequel Winterhawk’s Land (2017) and the redemption tale Macabe’s Journey (2022), all from BearManor Media. Dante [michaeldanteway.com] recently took time to speak with Wild West about his various careers.

Jesse James. He was a colorful character, very deceptive and knew the territory and despised the railroad. I wanted to make him a colorful character. He was a great horseman, and he and his brother were a team, and his gang was a family. He began to get a little too aggressive, which led to his demise. I made notes about his character, but I never got a chance to play him.

I had read a great deal about him and had tremendous respect and love for native Americans. He was my favorite because he was a visionary and a militarist, a deep thinker, had a high element of a spiritual side. That is the kind of man I am. I could make a wonderful marriage to this character and do something exciting and interesting and show to the American audience what kind of man and leader he was.

But [producer David Weisbart] passed away after the seventh show—died of a heart attack on the golf course—and we were knocked off the air because of political correctness. Custer became a very bad name, unfortunately, so we were off after 17 shows. So I never really got a chance to share with the audience what I eventually was going to contribute to the character and the story.

What are some favorite memories from your days playing pro baseball?

I was underage but signed to a pro contract with a $6,000 bonus. When I received that bonus, the first thing I did was buy our family a brand-new four-door Buick—whitewall tires, radio and heater. It was a beautiful sedan.

Number two was putting on the major league uniform. The Washington Senators invited me to spring training in 1955 in Orlando, Fla., and the first moment I put on the uniform, I sat by my locker, turned my back on everyone and just shed tears.

Who was your favorite ballplayer and what movies did you like as a boy?

Joe DiMaggio. The Westerns.

We loved Westerns and the Dead End Kids. We didn’t have any money, but theaters had exit doors. After the first running of the movie and the serials, they would open the side doors. Everybody would exit out of the side instead of going out the front. We used to sneak in!

What made you turn to writing?

It evolved. I didn’t realize I was pursuing the career of my life by treating it as an art form. It gave me encouragement from my acting experience, what I was reading, and I took notes. So I put these thoughts down on paper and thought maybe someday I’d be fortunate to write these stories, or a book or novella or screenplay, or a combination of all these things.

During my radio show and then COVID I had an ample amount of time to put these words and thoughts together.

If you were interviewing Michael Dante, what would you ask?

I would ask, “Why did you refuse a number of film and TV series?”

I did what I wanted to do, and I did it well.

Visit historynet.com/michael-dante-interview to read more.

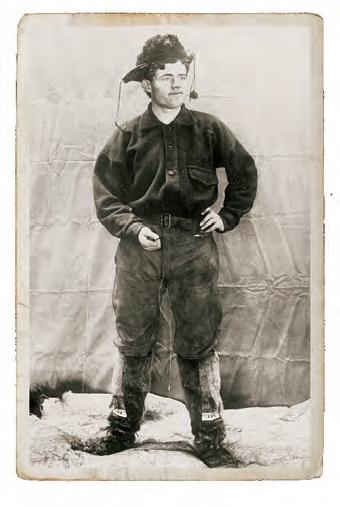

That was among several monikers attributed to dancer and vaudeville star Kathleen Eloise Rockwell (1880–1957), who, headlining as “Klondike Kate,” trod the rough boards of theater stages in post–gold rush Yukon Territory, Canada. Taken during her 1899–1902 heyday, this portrait of innocence proves only that appearances can be deceiving. Born in Kansas and raised in Washington, Kate was a flirt from an early age, enjoyed singing and dancing for older men, and was eventually expelled from boarding school. After failing to break into show business in New York City, she returned to Washington before venturing north in 1899. Kate reportedly sneaked into the Yukon, so the story goes, dressed like a boy. But it wasn’t boyish looks that got her notice as a member of the Savoy Theatrical Company in Dawson City. It was there in 1900 she met

Greek-born Alexander Pantages, owner of the Orpheum Theater and future movie theater mogul. Their stormy affair waxed and waned through 1914, when Pantages married a musician and settled a breach-of-promise-to-marry suit with Rockwell out of court. In the meantime, Kate dazzled miners with her numbers, including one called the Flame Dance, in which she emerged onstage wrapped in a continuous length of red chiffon and then spun before the footlights till fully revealed in skin-colored tights. She made a fortune in tips before the spotlight dimmed. In 1954 Kate appeared as a guest on the Groucho Marx game show You Bet Your Life alongside Walter Knott of Knott’s Berry Farm fame. The pair split winnings of $57.50—a far cry from Kate’s nightly take in the Yukon. A recluse in her dotage, she died in obscurity three years later in Sweet Home, Ore., at age 76.

At least a half dozen times in his life Wyatt Earp placed himself in harm’s way by pinning a tin star to his lapel. He policed two Kansas cow towns—Wichita and Dodge City—before making headlines in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. Chroniclers also record later stints as a deputy in Kootenai County, Idaho, and Cibola, Ariz. But few recall the time Earp served as a lawman in frontier Alaska amid the Klondike Gold Rush.

By year’s end 1896 Earp had hit a low point. Financial woes had forced him and common-law wife Josephine Sarah Marcus (“Sadie” to Wyatt) to change addresses often in San Francisco, for a time even living with her parents. Then came a break, as he agreed to referee a high-prof ile heavyweight boxing match between up-and-coming Cornishman Bob Fitzsimmons and brawler Tom Sharkey that December 2. Things went bad from the start. As Earp climbed through the ropes into the ring, he revealed a concealed .45-caliber Colt revolver, which he

had to surrender on the spot to a police captain before the crowd of 15,000.

In the eighth round Fitzsimmons landed a devastating uppercut, and Sharkey fell forward rather than backward, receiving what may have been an unintentional blow to the groin from Fitzsimmons. After ordering the fighters to their corners, Earp declared Sharkey the winner, citing Fitzsimmons’ foul. The crowd exploded with anger.

Fitzsimmons’ promoters took the decision to court, the boxer’s attorney claiming Earp had telegraphed friends to bet on Sharkey. Though the judge dismissed the baseless allegation as hearsay, the damage was done. Adding insult to injury, Earp was fined $50 for having carried the concealed pistol into the ring.

His reputation sullied and pockets empty, Earp was desperate for an income. In stepped fate.

On July 14, 1897, the steamship Excelsior docked in San Francisco, disembarking gold-bearing prospectors rife with rumors

of a major strike in Canada’s Yukon Territory. Two days later the steamer Portland unloaded “a ton of gold” in Seattle, confirming the rumors. At the time Wyatt and Sadie were in Yuma seeking funds for a mining venture. They sold everything they had for the passage to Alaska.

Within months more than 40 ships sailed for Alaska from San Francisco alone. Many were derelicts scheduled to be broken up in shipyards.

By then Earp himself had become something of a derelict. Pushing 50, he had grown a belly and jowls, and his trademark handlebar mustache had begun to turn gray.

Other Old West derelicts would make their way to the Klondike. Denver con man Jefferson “Soapy” Smith told his cousin, “Alaska is the last West,” before heading north to terrorize Wrangell and Skagway. Serial adventurer Luther “Yellowstone” Kelly ventured to Alaska to map the interior. Lawman Frank Canton, John Clum of Tombstone and Geronimo fame, showman “Arizona Charlie” Meadows, Denver madam Mattie Silks and “Captain Jack” Crawford, the “Poet Scout” of the West, all went north.

Wyatt and Sadie had underestimated their travel costs, given gold rush prices, and were close to going broke as their ship approached Wrangell, Alaska.

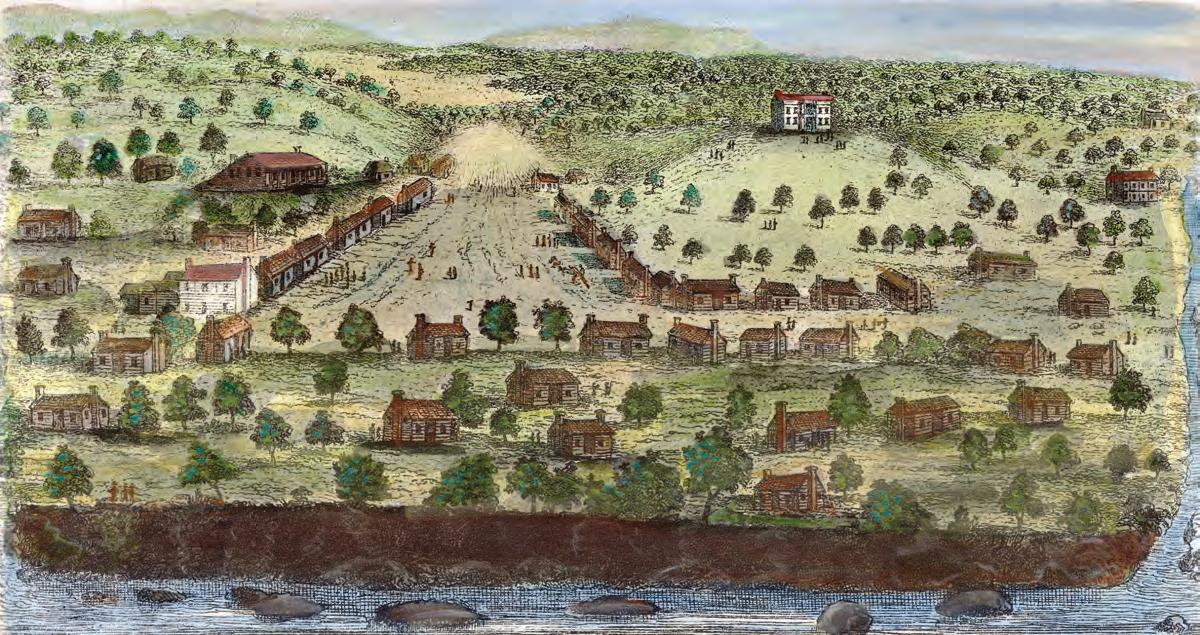

Wrangell had always been a wild place. During the gold rush a flotilla of riverboats hauled prospectors and cargo from its port up the Stikine River into the Canadian interior. Town itself comprised a motley collection of 139 cedar plank and log structures. It also held a courthouse, a jail, a customhouse, a sawmill, a brewery, a boardinghouse, a restaurant, a handful of saloons, three stores and a shoemaker’s shop. Rough plank boardwalks kept locals out of the mud under what seemed a constant rain.

Though Soapy Smith made his headquarters up the coast in Skagway, his gang initially held Wrangell in the same grip of terror, demanding a percentage of each saloon’s take and openly robbing and even murdering prospectors along the trails leading to the interior. That Wrangell was the only place in Alaska where dance hall girls performed in the nude spoke volumes about the port.

The U.S. marshal for the District of Alaska was desperately seeking a deputy to temporarily police Wrangell, as the man he’d hired wouldn’t arrive for weeks. The marshal had been keeping law and order as best he could, but eventually he’d have to return to the district capital at Sitka. It must have seemed a godsend, then, when out of the blue none other than Wyatt Earp approached him about the position. Earp considered Wrangell a “hell on wheels” town, worse than Tombstone had been.

Still, he needed the money, so he accepted the temporary duty.

Realizing he represented the hated law to a sordid collection of gunmen, prostitutes, pimps, gamblers and thugs, Earp planned to sit things out as quietly as possible until his replacement arrived. That the Smith gang controlled vice in town was to his advantage. He and Bat Masterson had had dealings with Soapy when the three of them were mining the miners in Creede, Colo. How much Earp was counting on that acquaintance in order to survive in Wrangell is unclear. But he knew that as long as he kept his nose out of Soapy’s business, he’d be safe. Then it happened. One evening a burly town tough got drunk and began shooting up a saloon. Bystanders sent for the pudgy marshal. When Earp arrived and demanded the man surrender his gun, the intoxicated shooter broke into a smile. “I know you!” he exclaimed. “You’re Wyatt Earp!” Twenty years earlier Earp had thrown the man and his drunken cowboy cohorts out of a Dodge City saloon. For the rest of that evening in Wrangell the antagonists stood at the bar reminiscing about the “good old days.”

Though amused by the incident, Earp also recognized it as a close call and a reminder to lay low for the duration of his time in town. Thankfully, within 10 days of Wyatt and Sadie’s arrival his replacement arrived. As soon as the new deputy marshal stepped from the gangplank, the couple caught the first northbound steamer to Juneau. Local wags joked that Wrangell had proved “too wild for Wyatt.”

In Juneau the couple learned Sadie was pregnant, and they decided to return to San Francisco. Better to deliver their child in her parents’ home than on the Alaskan frontier. No sooner had they arrived Stateside, however, than Sadie suffered a miscarriage.

The lure of riches soon drew the couple north to Alaska again. This time they took the “rich man’s route,” sailing up the Yukon River bound for Dawson. But they were iced in for the winter. Come spring, they drifted back downriver and soon headed to the new strike in Nome, where Earp opened the Dexter, the only two-story saloon in the district. So, it was back to mining miners.

When the Earps finally left Alaska, in 1900, they carried $85,000 on them.

BY DENNIS GOODWIN

BY DENNIS GOODWIN

She was tough as grizzly bear claws,” one observer wrote about Fannie Quigley, who forged her own path from a dugout on the Great Plains to the Pacific Coast and then north to Alaska.

Born in Wahoo, Neb., on March 18, 1870, little Frances Sedlacek was known as “Fannie” from childhood. It was a childhood tempered with hard times. Wahoo was a village of largely Czech-speaking Bohemian immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian empire who in 1870 were being assaulted by the triple hardships of a locust plague, record-breaking blizzards and a seven-year drought. As if fate hadn’t stacked the deck against Fannie sufficiently, illness took her mother when the girl was only 5. Within a year her father remarried, and Fannie soon had three more siblings for whom to care, adding to her already

heavy workload. Like many such children of hardship, she surely longed to escape the drudgery of life on her family’s windswept homestead.

So, at age 16 she left home to follow the westward-leading Burlington and Union Pacific railroads. As she cooked for the work crews, Fannie soaked up the spirit of the frontier. Though she spoke only her parents’ native Czech at home and had scarcely any schooling, she soon learned English from the roughneck workers. As might be expected, in and among the more traditional English words and phrases she picked up some pretty colorful exclamations. Those expressions only enhanced her rough-edged persona.

Fannie followed the tracks for more than a decade. When she finally ran out of west, she turned her gaze north, having heard

the rumors of a gold strike in the Klondike region of Yukon Territory in northwestern Canada. It was a cinch most of the miners rushing toward potential riches hadn’t bothered to pack cooking supplies among their picks, shovels and pans. Hot meals, she reasoned, might be as precious to them as gold. By 1898 she’d scraped together the money for passage to Alaska.

Some accounts suggest Fannie worked for a couple of years as a dance hall girl in a Dawson saloon. Whether true or not, she soon reverted to her skills as a cook. Packing a sled with a sheet-metal Yukon stove, a tent, cooking supplies and a shingle advertising Meals for Sale, she set out for the remote gold camps. As she didn’t have money to spare for dogs, little Fannie lugged the sled herself. Despite the intense physical effort, she found her hunch was right. Miners were drawn to her mobile diner like bears to a honey tree. Not content with merely cooking for a living, Fannie jumped into the prospecting game herself and started acquiring mining claims. She also staked her claim to a ruggedly handsome miner named Angus McKenzie, whom she married on Oct. 1, 1900. The couple soon opened a roadhouse near the settlement of Gold Bottom, southeast of Dawson.

According to reports in Dawson’s Daily Klondike Nugget, the McKenzies’ marriage fell somewhat outside the bounds of wedded bliss. They were said to mix it up regularly with fights resulting in mutual black eyes. Three years after they’d tied the knot, it unraveled, and Fannie stomped out the front door. That stomping extended into a 500-plus-mile hike down the banks of the Yukon River to Rampart, Alaska.

After prospecting around Rampart, Fannie pursued rumored gold in several neighboring camps. None filled her pockets, so in 1906 she followed another lead south to Kantishna, a camp in the shadow of towering Mount McKinley. Originally called Denali, a Native Alaskan word meaning “High One,” the mountain had been renamed by a prospector in 1896 in support of then presidential candidate William McKinley, despite the fact the politician had never, and would never, set foot in Alaska. (The Interior Department restored the name Denali in 2015.)

Between 1907 and ’19 Fannie staked some 26 claims. While most didn’t pan out, one thing did gleam for her in Kantishna—another good-looking fellow. Long-legged Joe Quigley was a locally known frontier jack-of-all-trades who combined the skills of hunting, carpentry, mining and blacksmithing. Fortunately, their pairing proved far less explosive than that of Fannie and her ex. On Feb. 2, 1918, the couple married and for the next

two decades worked their Red Top Mine, leased other claims, and fed and boarded guests at their Kantishna residence.

The Quigleys made quite an interesting visual impression, with Joe topping 6 feet and Fannie not quite reaching 5. She more than compensated for her diminutive stature with her feisty personality. One day she and Joe ventured out separately to hunt. Joe returned to the cabin emptyhanded, his shame only escalating at the sight of Fannie proudly dressing out the carcasses of two caribou, a bear and a moose. Never one to mince words, she tossed him her skirt. “Here,” she blurted, “you do the housework today. Gimme your pants.”

By necessity Fannie learned a wide range of wilderness skills. Another day Joe showed up with his nose split open in the wake of a bush plane accident. Without hesitation Fannie cleansed the wound and stitched it with catgut. “I sewed him the way I do my moccasins,” she later related, “with a baseball stitch.”

During her years as a Kantishna homesteader Fannie also became known as one of the best cooks in Alaska. Despite the brief 10-week frost-free growing season, her prolific garden provided a steady supply of vegetables, even in winter. She utilized the mine shafts and tunnels of the Red Top to keep her produce frozen year-round. Her recipes for blueberry or rhubarb pie included a step city slickers’ recipes didn’t list—mushing one’s dogs 125 miles to the nearest town (Nenana) for flour and sugar. The secret ingredient in those pies also took a little doing—shooting a nice fat bear and dragging it back to the cabin to be rendered into lard for her flaky crusts.

By the mid-1930s, whether due to environment or temperament, the Quigleys’ marriage was showing signs of wear and tear. In 1937 they leased their mining claims to the Red Top Mining Co. and split the income as part of a divorce settlement. Joe then headed to Seattle. Fannie kept the Kantishna cabin, where she died at age 74 on Aug. 22, 1944. Her legacy lives on. In 2000 Fannie was inducted into the Alaska Mining Hall of Fame, while the Quigleys’ old cabin remains standing and open to visitors within Denali National Park and Preserve.

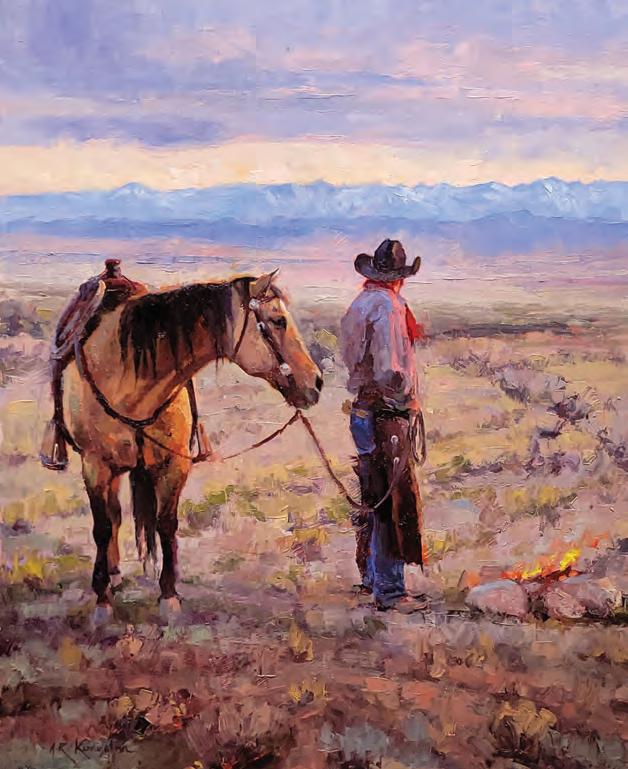

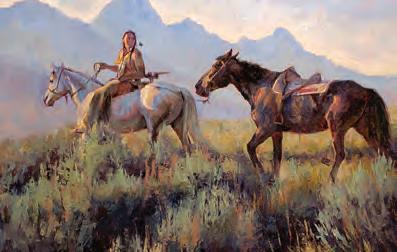

Whatever subject or scene Rick Kennington paints—American Indians in the saddle or in camp, contemporary or Old West cowboys at work—his blend of techniques lends his works a life of their own. But that wasn’t always the case.

“I used to paint thin with many layers,” recalls the artist [rickkennington.com] from his home studio in North Salt Lake, Utah.

Rick KenningtonHis mentors told him to use more paint—and when one’s mentors include such masters in their own right as Grant Redden, Jason Rich, Chad Poppleton and Charles Dayton, one listens.

“I was instructed to purchase the larger tubes of paint to encourage me to have heavier loads of paint on my pallet and to have the stiffer bristle brushes to help gather heavy loads,” Kennington explains. “Over time I became fascinated with paintings that have a high paint quality—meaning, the paint and texture have aesthetic appeal.

“It’s amazing at times to remember how different my mindset was 20 years ago,” he says.

“I thought I had a good handle on painting. However, the more I learn and study, the more I realize I have much further to go. I enjoy seeing how my work has evolved and progressed over the years.”

That progression began in boyhood when he watched his older sister draw and sketch and tried to match her skills. His parents fostered their son’s budding interest with gifts of drawing pads, pencils and instructional art books. Family trips to Jackson, Wyo., stirred Kennington’s love of Western subjects.

“I remember walking into the Legacy Gallery, which is no longer there, and being blown away by all the paintings from the best contemporary artists…artists such as Bill Anton, Clyde Aspevig, Tom Browning and Jason Rich,” he recalls. “I wondered how amazing it would be to have my artwork hanging on the walls in a gallery like that.”

Thus inspired, Kennington worked hard and earned an art scholarship to Salt Lake Community College. He later transferred to the University of Utah, where he attended workshops, learned from established artists and gradually shed bad habits.

“I remember asking one of my mentors, ‘How do I get my work in a gallery?’” he recalls. “After a thoughtful pause came the sincere reply, ‘Become

so good at painting that they can’t ignore you.’ I took that to heart and continued to improve my skills.”

His focus on the West came naturally.

“I come from deep-rooted Western pioneer stock,” he says. “In the late 1800s my great-greatgrandfather William Henry Kennington settled Star Valley, Wyo., where he raised his family.”

The artist spends most of his time in the studio, though he paints plein air a few times a year. “Painting outdoors is more of a break for me,” he says.

“I enjoy paintings that look like paintings,” Kennington says of his more recent work. “I aim for accuracy in drawing, value and color. But I enjoy using thick paint and challenging myself with a looser, or Impressionist, approach.”

The artist’s commitment to the West remains as firm as his commitment to his craft. “Growing up in the West and being outdoors is a major part of my life,” Kennington says. “I’ve enjoyed growing up around horses, ranches and the Western landscape. Much of the Western ranches and landscapes have been lost with new development, especially in Utah. I feel art is a way to help preserve and maintain the history and culture of the West.”

Kennington has family roots in Wyoming’s Star Valley and grew up around horses and wide-open landscapes, influences that shine through in such works as (clockwise from top left) Finders Keepers (a 24-by-36-inch oil) A Light on the Horizon (a 24by-20-inch oil) and Hauling Ass (a 30-by-18-inch oil).

THE LAKOTA WARRIOR MARKED A DECADE-PLUS STRING OF VICTORIES, BUT HIS CLAIM TO HAVE KILLED GEORGE CUSTER IS SUBJECT TO DEBATE

BY DENNIS GOODWINAfter solemnly surveying the mingled corpses of fellow warriors and 7th U.S. Cavalry troopers on the hillside above Montana Territory’s Little Bighorn River (the Greasy Grass to Indians), the pair of Lakota warriors focused on the lifeless body of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer at their feet. “Long Hair thought he was the greatest man in the world,” one said. “Now he lies there.” White Bull, the warrior he was addressing, had killed two men in battle that morning, June 25, 1876. “Well,” White Bull replied, “If that is Long Hair, I am the man who killed him.”

Historian Stanley Vestal recounted this alleged conversation in the February 1957 issue of American Heritage, published a decade after White Bull’s death. Vestal had interviewed the warrior chief and said White Bull had asked not to be revealed as Custer’s killer during his lifetime, to avoid retaliation.

“A tall, well-built soldier with yellow hair and a mustache saw me coming and tried to bluff me,” White Bull had told Vestal. The soldier drew a bead on the warrior with a rifle. Before he could fire, White Bull rushed in, and the soldier threw the rifle at him, missing. According to White Bull, the two then locked in hand-to-hand combat. Amid the dust and smoke, he noted, “It was like fighting in a fog.” Grabbing White Bull’s braids, the soldier pulled the warrior close and tried to bite off his nose. White Bull called for help from a pair of fellow Lakotas, but their blows mostly landed on their friend as the combatants whirled around. Finally, the soldier drew his pistol. Wresting it away, White Bull repeatedly struck the soldier over the head with it and then delivered two shots—one to the soldier’s head, another to his chest. Though he didn’t recognize the man he’d killed, White Bull knew he’d slain a worthy opponent.

With the publication of Vestal’s article Minneconjou Chief White Bull joined the short list of

5 Countries, 5 Pure Silver Coins!

Travel the globe, without leaving home—with this set of the world’s ve most popular pure silver coins. Newly struck for 2023 in one ounce of ne silver, each coin will arrive in Brilliant Uncirculated (BU) condition. Your excursion includes stops in the United States, Canada, South Africa, China and Great Britain.

Each of these coins is recognized for its breathtaking beauty, and for its stability even in unstable times, since each coin is backed by its government for weight, purity and legal-tender value.

2023 American Silver Eagle: The Silver Eagle is the most popular coin in the world, with its iconic Adolph Weinman Walking Liberty obverse backed by Emily Damstra's Eagle Landing reverse. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the U.S. Mint.

2023 Canada Maple Leaf: A highly sought-after bullion coin since 1988, this 2023 issue includes the FIRST and likely only use of a transitional portrait, of the late Queen Elizabeth II. These are also expected to be the LAST Maple Leafs to bear Her Majesty's effigy. Struck in high-purity

99.99% fine silver at the Royal Canadian Mint.

2023 South African Krugerrand: The Krugerrand continues to be the best-known, most respected numismatic coin brand in the world. 2023 is the Silver Krugerrand's 6th year of issue. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the South African Mint.

2023 China Silver Panda: 2023 is the 40th anniversary of the first silver Panda coin, issued in 1983. China Pandas are noted for their heart-warming one-year-only designs. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the China Mint.

2023 British Silver Britannia: One of the Royal Mint's flagship coins, this 2023 issue is the FIRST in the Silver Britannia series to carry the portrait of King Charles III, following the passing of Queen Elizabeth II. Struck in 99.9% fine silver.

These coins, with stunningly gorgeous finishes and detailed designs that speak to their country of origin, are sure to hold a treasured place in your collection. Plus, they provide you with a unique way to stock up on precious silver. Here’s a legacy you and your family will cherish. Act now!

You’ll save both time and money on this world coin set with FREE shipping and a BONUS presentation case, plus a new and informative Silver Passport!

BONUS Case!

2023 World Silver 5-Coin Set Regular Price $229 – $199 SAVE $30.00 (over 13%) + FREE SHIPPING

FREE SHIPPING: Standard domestic shipping. Not valid on previous purchases. For fastest service call today toll-free

1-888-201-7070

Offer Code WRD287-05

Please mention this code when you call.

SPECIAL CALL-IN ONLY OFFER

Not sold yet? To learn more, place your phone camera here >>> or visit govmint.com/WRD

GovMint.com® is a retail distributor of coin and currency issues and is not a liated with the U.S. government. e collectible coin market is unregulated, highly speculative and involves risk. GovMint.com reserves the right to decline to consummate any sale, within its discretion, including due to pricing errors. Prices, facts, gures and populations deemed accurate as of the date of publication but may change signi cantly over time. All purchases are expressly conditioned upon your acceptance of GovMint.com’s Terms and Conditions (www.govmint.com/terms-conditions or call 1-800-721-0320); to decline, return your purchase pursuant to GovMint.com’s Return Policy. © 2023 GovMint.com. All rights reserved.

possible candidates for the man who killed Custer. While the lens of time will forever blur the specifics of Custer’s death, two facts remain clear— White Bull was a dynamic participant in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, and his demonstrated courage over 11 years on the warpath is well documented.

In 1932 Vestal visited the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation, in northcentral South Dakota, to interview 83-year-old White Bull, who poured out his life story to the prolific journalist and biographer. According to his own account, the future warrior chief entered the world in April 1849 in the Black Hills of what a dozen years later would be designated Dakota Territory. Known as Bull-Standing-With-Cow until the summer of his 16th year, he was born into a lineage of strong Sioux warriors. His father, Makes Room—like his father before him—was a chief of the Minneconjou, and his mother, Good Feather Woman of the Hunkpapa, the favorite sister of the legendary Sitting Bull.

The games of Bull-Standing-With-Cow’s youth often centered on simulated combat. He and his friends formed their own warrior societies and learned the intricacies of warfare by play fighting. To count coup on one’s enemy by striking him with a hand or a stick was considered especially courageous.

Up to four warriors were permitted to count coup on a single foe in the same fight—the most honored being the one who counted first coup. Such feats were recorded in the language of feathers. The man striking first coup could wear a single eagle feather lodged upright in his hair at the back of his head. A second coup was identified by a feather angling upward, a third by a horizontal feather and a fourth by one sloping downward. In their war games Bull-Standing-With-Cow and friends would count coup on each other and keep score by sticking small feathers in their hair.

As childhood gave way to adolescence, Bull-Standing-With-Cow grew determined to make his reputation as a warrior. In July 1865 noted Minneconjou warrior High Hump recruited volunteers for a war party. White soldiers had violated a recent treaty, and High Hump resolved to seek enemy scalps and horses.

Sixteen year old Bull-Standing-With-Cow didn’t need to be asked twice, and Makes Room saw there was no stopping him. After presenting his son with a fast dapple-gray pony, the chief had half brother Horse Tail, a medicine man, create protective “medicine” for the boy and his horse. Horse Tail hung a leather pouch painted with a war eagle around the gray’s neck, then painted its legs and jawline with wavy red lines. After fastening a soft eagle plume

in Bull-Standing-With-Cow’s hair, he finally draped a leather thong suspending an eagle-bone whistle around the boy’s neck.

“Nephew,” he declared, “this medicine will make your horse strong and long-winded.”

Following an evening of singing and dancing, the warriors left camp early the next morning. One evening several days later a scout pinpointed an enemy camp. Anxious to be the first to the fight, Bull-Standing-With-Cow slipped away from camp early. When the sun broke over the horizon, he made a solo charge into the soldiers’ remuda. Cutting out eight horses, he blew his eagle-bone whistle to scare them into a run.

Unfortunately for him, the whistle also roused the enemy. Moments later the neophyte warrior found himself the target of a running pursuit by 10 mounted bluecoats. Lashing his pony’s flanks while bullets whizzed past, he likely prayed his uncle’s medicine would indeed make his horse “strong and long-winded.” Just when his pony began to tire and the soldiers were about to catch up with him, he encountered his own war party. His pursuers abruptly retreated.

Bull-Standing-With-Cow’s daredevil spirit and eight captured horses made quite an impression on his friends. Meanwhile, the dissatisfied High Hump organized another raid. Near the headwaters of the Powder River the party encountered seven bluecoat scouts driving horses. Bull-StandingWith-Cow was riding down on one of the scouts with his lance when the soldier whirled in his saddle and fired a revolver at nearly point-black range. Miraculously, the bullet missed. Moments later Bull-Standing-With-Cow stabbed the bluecoat in the shoulder, counting first coup. By the time the party turned for home he’d counted three coups and stolen 10 horses.

When Bull-Standing-With-Cow returned to camp, his father arranged a victory dance for his son. Astride his horse, resplendent in warpaint, the boy warrior rode toward a black pole in the center of the ceremony grounds. “From this day,” proclaimed his Uncle Black Moon, “Bull-StandingWith-Cow will lay down his boy name. From this time, he shall be called by the name of his grandfather, White Bull.”

In the coming years White Bull racked up an impressive string of coups, finally realizing the future he’d envisioned when he and young friends ran about play fighting and sticking small feathers in their hair. As a member of both the Minneconjou and Hunkpapa bands of the Lakota Nation, he fought in nearly every battle waged by either band—and who knows, he just may have counted coup on Custer.

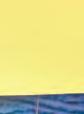

ago, Persians, Tibetans and Mayans considered turquoise a gemstone of the heavens, believing the striking blue stones were sacred pieces of sky. Today, the rarest and most valuable turquoise is found in the American Southwest–– but the future of the blue beauty is unclear.

On a recent trip to Tucson, we spoke with fourth generation turquoise traders who explained that less than five percent of turquoise mined worldwide can be set into jewelry and only about twenty mines in the Southwest supply gem-quality turquoise. Once a thriving industry, many Southwest mines have run dry and are now closed.

We found a limited supply of turquoise from Arizona and purchased it for our Sedona Turquoise Collection . Inspired by the work of those ancient craftsmen and designed to showcase the exceptional blue stone, each stabilized vibrant cabochon features a unique, one-of-a-kind matrix surrounded in Bali metalwork. You could drop over $1,200 on a turquoise pendant, or you could secure 26 carats of genuine Arizona turquoise for just $99

Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. If you aren’t completely happy with your purchase, send it back within 30 days for a complete refund of the item price.

The supply of Arizona turquoise is limited, don’t miss your chance to own the Southwest’s brilliant blue treasure. Call today!

Jewelry Specifications:

•Arizona turquoise • Silver-finished settings

Sedona Turquoise Collection

A. Pendant (26 cts) $299 * $99 +s&p Save $200

B. 18" Bali Naga woven sterling silver chain $149 +s&p

C. 1 1/2" Earrings (10 ctw) $299 * $99 +s&p Save $200

Complete Set** $747 * $249 +s&p Save $498

**Complete set includes pendant, chain and earrings.

Call now and mention the offer code to receive your collection.

1-800-333-2045

Offer Code STC789-09

You must use the offer code to get our special price.

*Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without your offer code.

26 carats of genuine Arizona turquoise ONLY $99

A.

B.

A.

B.

AN

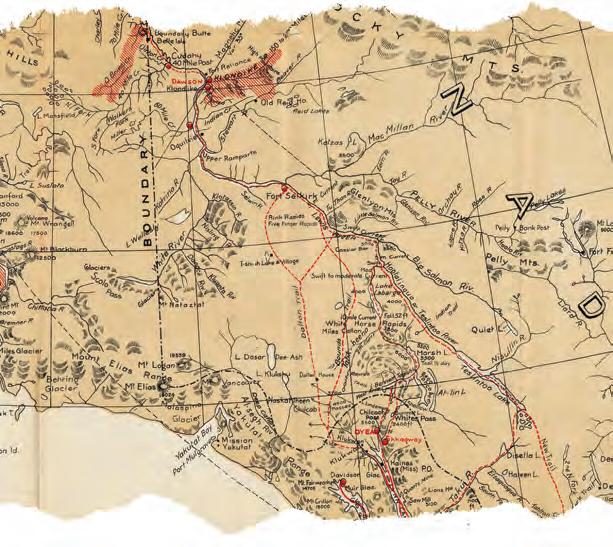

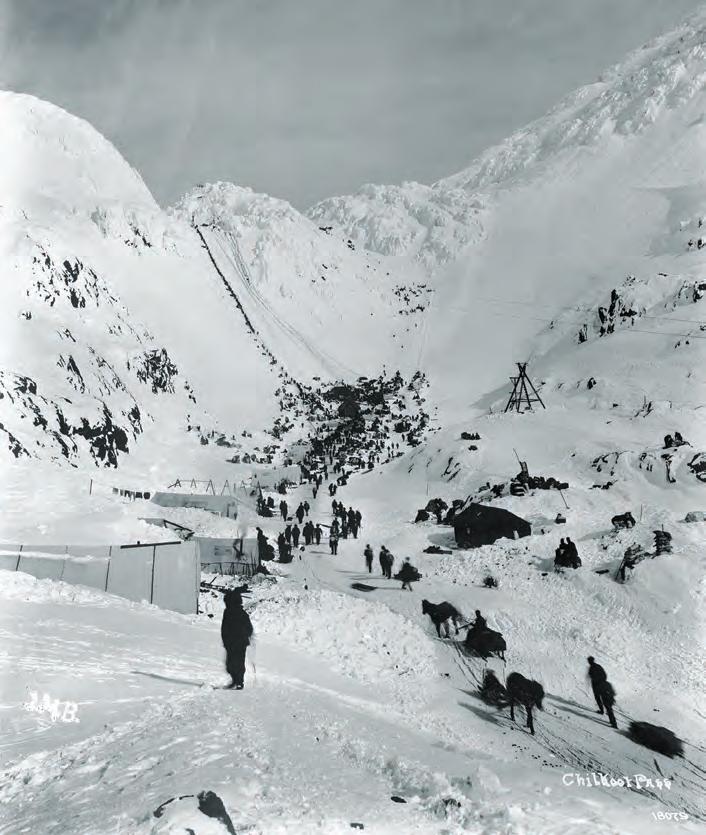

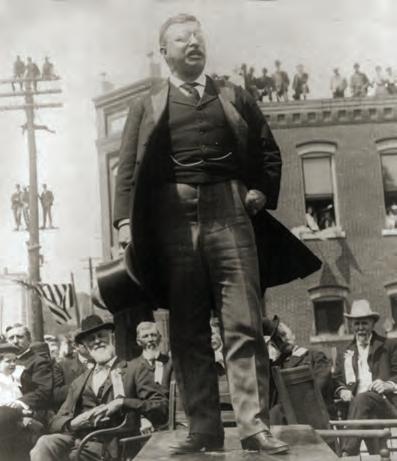

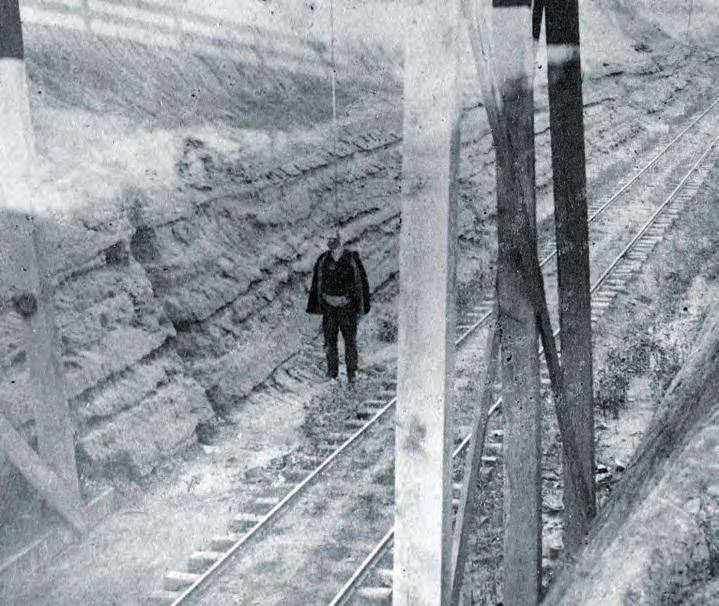

BY MIKE COPPOCKThe High Road to Riches...or Heartbreak Klondike hopefuls clog the route to 3,525-foot Chilkoot Pass in 1898, at the height of the gold rush. The average miner would make more than 30 round trips to ferry his supplies the 33 miles from Dyea, on the southeast Alaskan coast, up to Lake Bennett, in British Columbia, Canada. This was but the first step in the long, hazardous land-and-water route north to the goldfields.

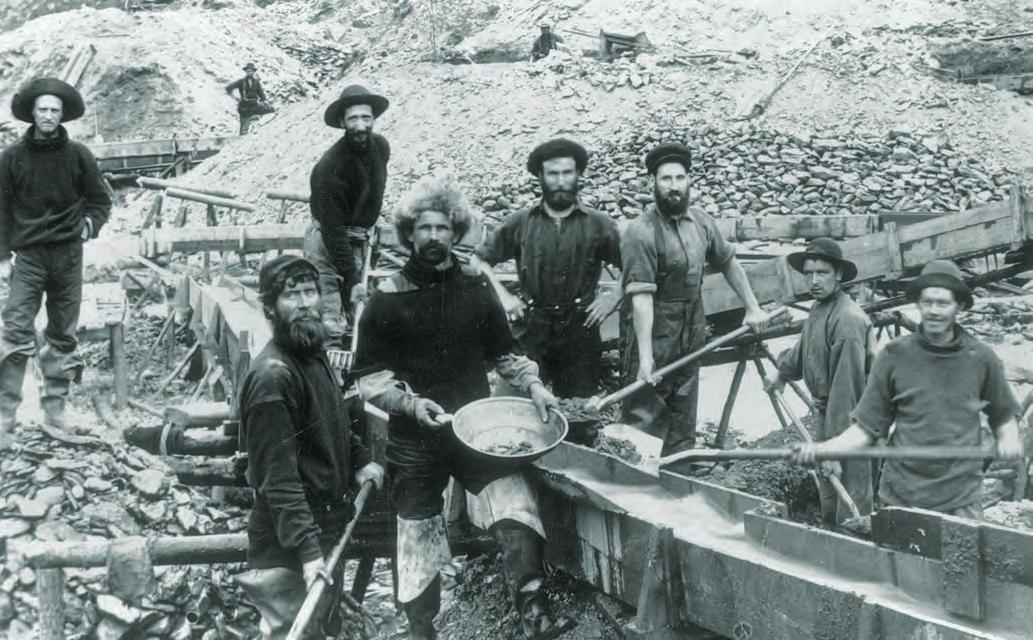

George Carmack strutted into Bill McPhee’s smoke-filled saloon in the settlement of Forty Mile, Canada, at the confluence of the Fortymile and Yukon rivers. Days earlier, on Aug. 16, 1896, Carmack and his Tagish brother-in-law, Keish (aka “Skookum Jim” Mason), and nephew Káa Goox (aka “Dawson Charlie”) had found gold far to the east on Rabbit Creek, a tributary of the Klondike River. Carmack ordered a round of drinks for the house, shouting, “There’s been a big strike upriver!” Few of the bar patrons paid much mind. After all, it was “Lying George” doing the talking. But the gold nuggets the excited prospector slapped down to pay for the drinks did catch their attention.

These “Sourdoughs,” so named for the fermented dough they used to make everything from bread to flapjacks, were a unique breed. They drifted north by ones and twos when most Americans were heading west to the Pacific. They liked to claim they were prospectors, but only a few actually found gold.

They were also extremely eccentric. Four partners kept a moose in their cabin as a pet. Others, like Frank Buteau, rigged up sails to propel their sleds —in Buteau’s case because he couldn’t afford dogs. Another hardy, albeit penniless, soul was rumored to have fashioned dental plates for his fronts from tin spoons and teeth pulled from the skulls of a mountain sheep, a wolf and a bear he’d shot. With typical Sourdough gusto he then stewed and ate the bear with its own teeth.

These adventurers barely peppered the vast region. The 1890 federal census recorded only 31,795 residents (including 4,303 whites and 23,274 Native Alaskans) in the adjacent 663,000-square-mile District of Alaska, whose governor was appointed by the president of the United States. Little more than 2,000 souls dwelled along the banks of the 1,980-mile-long Yukon River itself, which flows westward through Canada’s Yukon Territory and Alaska to the Bering Sea.

As soon as Carmack left the bar, or perhaps before, bystanders inquired at the recorder’s office about the location of Carmack’s claim. Time was ripe for a major strike; the value of gold shipments from the Yukon had increased from $30,000 in 1887 to $800,000 in 1896. Within days some 1,500 Sourdoughs descended on the Klondike River, just upstream from where it empties into the Yukon. Taking its name from the river, the gold-bearing region of central Yukon Territory became known as the Klondike. Through the bitter winter months of 1896–97 each prospector worked his solitary claim, having scant communication with the outside world.

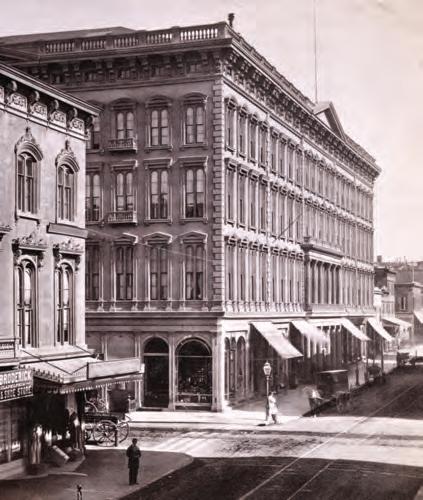

With the spring ice breakup hundreds of miners rafted down the Yukon to the sea. Many hadn’t emerged from the interior for decades. Nearly all had been destitute the previous spring. At the former Russian trading port of St. Michael, Alaska, they boarded the southbound coastal steamers Portland and Excelsior. On July 14, 1897, Excelsior docked in San Francisco, unloading more than a dozen free-spending Sourdoughs who ignited rumors of quick wealth. Two days later 5,000 people crowded Seattle’s waterfront to greet Portland The Seattle Post Intelligencer published an extra edition with reporter Beriah Brown’s news the ship had brought “more than a ton of gold” from the Klondike.

The Klondike Gold Rush was on.

Gold fever swept Seattle. Thousands of hopefuls jammed the streets to elbow and snarl their way to the docks. Store clerks quit by the hundreds. Streetcar service ground to a halt as operators resigned on the spot. Hotels booked up and restaurants were packed to bursting as people flooded to town. There was also an epidemic of stolen dogs, presumably smuggled north for use pulling sleds. Meanwhile, a ragtag fleet composed of anything that would float hastily assembled for a return voyage to the ports of entry in Alaska.

Seattle Mayor W.D. Wood was attending a conference in San Francisco when he read about Portland ’s cargo. He promptly telegraphed in his resignation as mayor, raised $150,000 and bought a steamer to take him and paying passengers to St. Michael. John McGraw, president of Seattle’s First National Bank and the state’s former governor, booked passage on Portland for its return voyage. One man dying of lung disease boarded Portland, insisting to distressed relatives he would rather die trying to get rich than rot on his deathbed in poverty.

Within months of the news more than 40 ships out of San Francisco alone were making regular passages to and from Alaska—no matter that many had been condemned and were waiting to be broken up in local shipyards. More than 100,000 people would ultimately set out for the Klondike.

The gold rush drew such Old West refugees as lawman Wyatt Earp (see Gunfighters & Lawmen, P. 20), Tex Rickard and Frank Canton; madam Mattie Silks; frontier scouts Jack Crawford (“Poet Scout” of the West) and Luther “Yellowstone” Kelly; and Indian fighter “Arizona Charlie” Meadows. They mingled with thousands of inexperienced men and women willing to stake everything on a shot

at striking it rich as the United States emerged from a horrific economic depression. People who had never lived off the land—schoolteachers, bank tellers, unemployed seamen, basketball coaches and single mothers with children to feed—all headed north. In 1887 steamship captain Billy Moore—who, guided by Skookum Jim, had pioneered the White Pass trail into the Canadian interior—claimed a 160-acre homestead at the mouth of the Skagway River. But the crush of follow-on prospectors ignored his claim. When surveyors of the city of Skagway later platted a street straight through the middle of Moore’s house, the grizzled old captain emerged swinging a crowbar only to be subdued by a mob.