UNSOLVED MYSTERY: THE BOMBING OF UNITED AIR LINES FLIGHT 23

THE BRITISH B.E.2c REALLY

BAD? A 1908 DIRIGIBLE’S SPECTACULAR FAILURE PLUS CLASSIC ART FROM MODEL AIRPLANE KITS AUTUMN 2023 AVHP-231000-COVER-DIGITAL.indd 1 6/20/23 2:06 PM

ALASKA OR BUST! THE U.S. ARMY TAKES B-10 BOMBERS ON AN EPIC FLIGHT WAS

THAT

Beginning today, Nationwide Coin & Bullion Reserve will take orders on a first-come, first-served basis for these beautiful one ounce $50 Gold American Eagle coins. Gold Eagles are the perfect way for Americans to protect their wealth and hedge against inflation and financial uncertainty. This offer is for new customers only. There is a strict limit of one coin per household, per lifetime. Nationwide has set these one ounce $50 Gold Eagles at the incredible price of only $1,970.00 each. There are no mark ups, no premiums, and no dealer fees. This at-cost offer is meant to help ease the American public’s transition into the safety of gold. Call 1-800-211-9263 today and take advantage of this amazing offer!

FREE

their introductory offer. Had a very good experience. No issues whatsoever.

Richard

Richard

SILVER,

As a special thank you, for your order of one $50 Gold American Eagle, Nationwide will send you a brand new perfect MS70 condition Silver American Eagle, hand signed by legendary retired U.S. Mint Lead Sculptor Don Everhart, absolutely FRE E!

MENTION KEY CODE WHEN CALLING KEY CODE: AHM-230701 CHECK Ad creation date 5/24/2023. Actual

provide

CALL TODAY!

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT PACKAGES Now Available 1- 800 -211- 9263

Harris. The arbitration

advice or financial planning. Anyone considering purchasing metals or rare coins as

that may arise between customer and Nationwide Coin & Bullion Reserve, including its employees,

a confidential basis pursuant to the commercial arbitration rules of the

investment should consult

investment professional. Any

Coin dates may vary.

EXCLUSIVE AT-COST OFFER OFFER AT-COST EXCLUSIVE AT-COST AT-COST EXCLUSIVE EXCLUSIVE OFFER OFFER AT-COST EXCLUSIVE EXCLUSIVE OFFER OFFER U S ARMED FORCES HONORING ALL WHO SERVED PLUS FREE SILVER Call today to learn more about our special-arrangement packages that offer discounted premium-grade precious metals. FREE GOLD AND/OR SILVER COINS IN EACH PACKAGE. Rated “EXCELLENT” WHAT OUR CUSTOMERS ARE SAYING VERIFIED CUSTOMER REVIEWS I have made numerous purchases from… Nationwide Coin & Bullion and have always found the experience to be very easy and pleasurable. My representative has always been professional, knowledgeable and had my best interest at heart. Tom D. I received perfect coins... I couldn’t be happier with my purchase from Nationwide. Fast secure shipping, nicely packaged in excellent coin displays. Friendly salesman that are knowledgeable and make sure you have a great experience. David J. First time Buyer Made Easy... My rep called me and made it so easy to purchase gold for the first time. In fact I enjoyed it so much I bought gold a second time and will purchase gold every quarter. Received my coins today It was fast in shipping! The transaction was also smooth and the rep was knowledgeable. So great to know this company and its potential! Kalvin Laurence Purchased their introductory offer Purchased

M. FREE SILVER

price may be higher or lower due to fluctuations in the gold market. Call for the lowest current price. Nationwide Coin & Bullion Reserve is a retailer of precious

and rare

does not

an

and all

and disputes

to be settled by arbitration in the state of Texas, county of

shall be conducted on

American Arbitration Association. All transactions with

purchases

Coin & Bullion Reserve

to

Terms & Conditions

website

www.nationwidecoins.com/terms-conditions.

metals

coins and

investment

an

claims

are

and

from Nationwide

are subject

its

which are available for review on its

at

AT COST, ABSOLUTELY NO DEALER MARK UP! CALL NOW! $1,970 EACH Only Call Today! In God We Trust UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT ISSUED

EAGLES AVHP-230725-005 Nationwide Coin & Bullion Gold Eagles Coins.indd 1 6/2/2023 8:29:49 AM

GOLD AMERICAN

WELCOMEHOMEVETERANSCELEBRATION.COM 931.320.0869 | frances@visitclarksvilletn.com POW/MIA Remembrance Event Valor Luncheon Breakfast with a Hero Opening Night Dinner Featuring a Musical Patriotic Salute Legends and Legacies Concert Hank Williams, Sr. 100th Birthday Tribute Women Veterans Tea Veterans Picnic Welcome Home Parade AVHP-230725-003 Clarksville CVB.indd 1 6/13/2023 10:59:29 AM

AVIATION

AUTUMN 2023

26 NORTH TO ALASKA

When the U.S. Army Air Corps needed to rehab its image, it dispatched B-10 bombers on an epic mission.

BY DAVE KINDY

36 THE RAF’S LAST BIPLANE

The Gloster Gladiator looked outdated when World War II started. It was.

BY STEPHAN WILKINSON

BY STEPHAN WILKINSON

46 THE BOMBING OF UAL TRIP 23

A Boeing 247 was on its way to Chicago when it crashed, the beginning of a 90-year mystery.

BY STEVE WARTENBERG

BY STEVE WARTENBERG

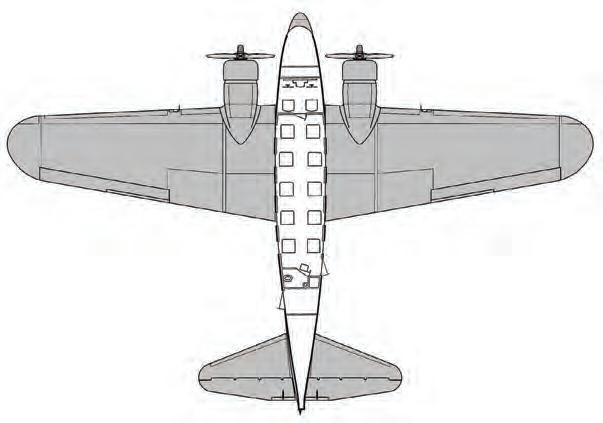

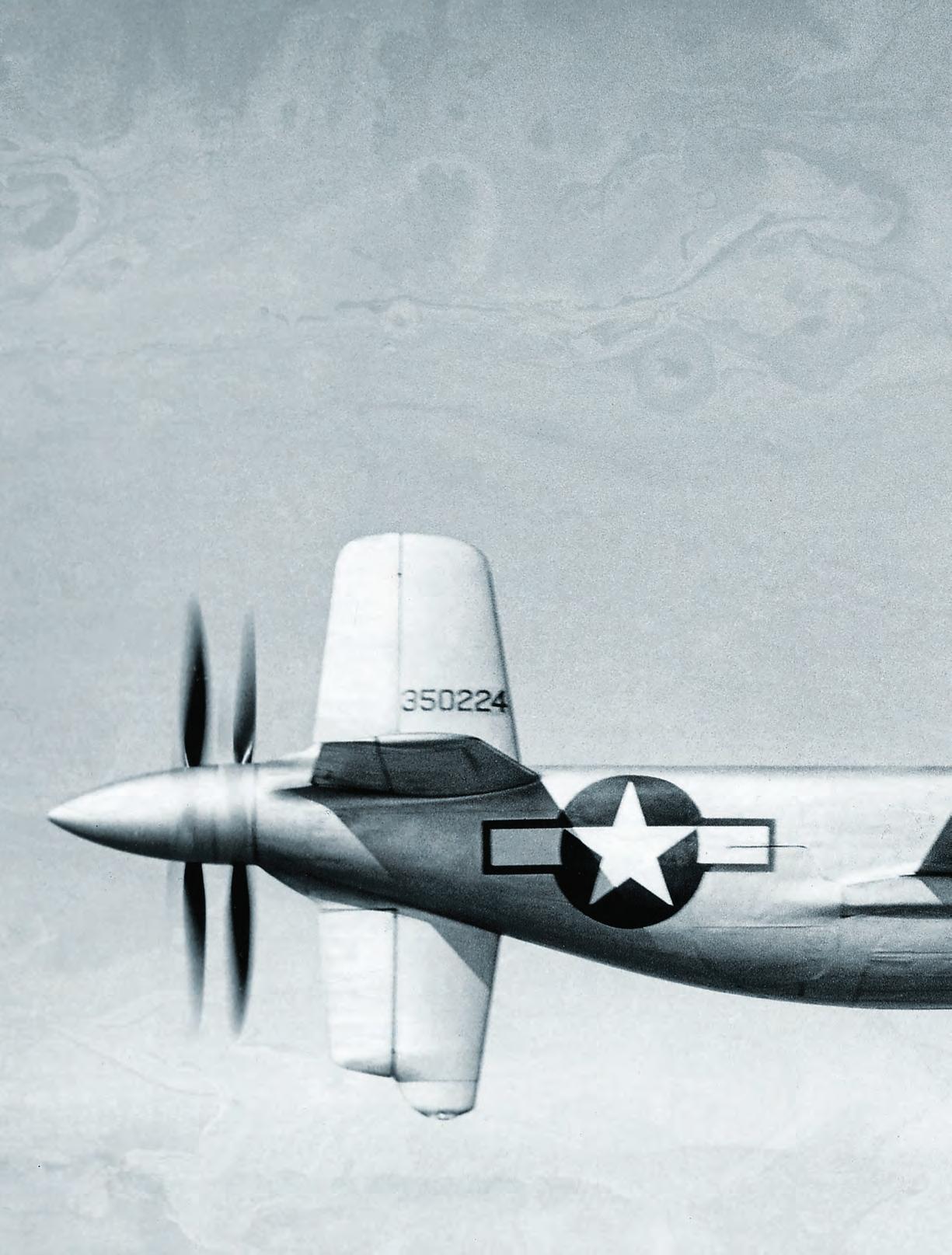

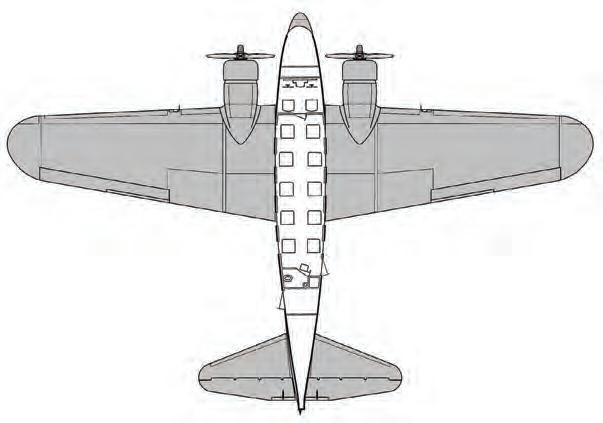

52 BETWEEN TWO WORLDS

Want propellers, jets or a mixture of both? These Douglas aircraft provided all three.

BY DAVID W. TEMPLE

BY DAVID W. TEMPLE

60 BAD REPUTATION

Why Britain’s B.E.2c doesn’t deserve all the brickbats tossed its way.

5 MAILBAG 6 BRIEFING 10 AVIATORS 14 FLIGHT LOG 16 EXTREMES 18 PORTFOLIO 24 FROM THE COCKPIT 66 REVIEWS 70 FLIGHT TEST 72 FINAL APPROACH DEPARTMENTS 46 60 52

ON THE COVER: A Ron Cole illustration depicts a Martin B-10 bomber of the 1934 Alaska flight as it overflies rugged northern territory.

BY ROBERT GUTTMAN 18

HISTORY TOP TO BOTTOM: THE GUY ACETO COLLECTION; MALCOLM HAINES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; U.S. AIR FORCE; SAN DIEGO AIR & SPACE MUSEUM/NEWSPAPERS.COM/PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY BRIAN WALKER AVHP-231000-CONTENTS.indd 2 6/20/23 7:16 PM

FEATURES

NORSE BY NORSEWEST?

Embrace your Scandinavian side with a 7" blade

If you looked out your window a thousand years ago and saw a fleet of Viking longships coming your way,you knew you were in trouble. For roughly two centuries, the Vikings voyaged, raided and pillaged wherever they pleased. As expert sailors and navigators, they reached as far from Scandinavia as Iran, Constantinople, North Africa and the New World in their quest to expand their kingdom.

A mini sword. Too organized and too aggressive, no one stood in a Viking’s way. That’s exactly the message that our Viking Blade sends. Crafted from Damascus steel with brass inlay, this 12" full-tang knife is essentially a mini sword. Paired with its hand-tooled leather sheath, this knife belongs in the collection of any avid aficionado.

Join more than 322,000 sharp people who collect stauer knives

The steel of legend. For centuries, a Damascus steel blade was instantly recognizable and commanded respect. Renowned for its sharp edge, beauty and resistance to shattering, Damascus steel was the stuff of legend. While the original process has been lost to the ages, modern bladesmiths have been able to re-create Damascus steel to create the best blades imaginable.

Sure to impress, naturally. Combining natural strength and natural wonder at a price that’s hard to beat, the Viking Blade is a study in Damascus steel that’s sure to impress. And should you ever find yourself facing a Viking horde, a flash of this knife will show that you’re not to be messed with.

Don’t delay: Order within the next week and we’ll offer this blade to you for just $99, a savings of $200! That’s the best bang for your buck we can possibly offer: our Stauer® Impossible Price. Get your hands on one of the fastest-selling knives in our company’s history today.

Knife Specifications:

• 12" overall length. 7" Damascus full-tang blade

• Includes genuine leather sheath

Viking Blade $299 $99* + S&P Save $200

California residents please call 1-800-333-2045 regarding Proposition 65 regulations before purchasing this product. *Special price only for customers using the offer code.

“This knife is everything promised. Beautiful beyond comparison. And completely functional. Love it.”

— Gene, Auburn, WA

1-800-333-2045

Your Insider Offer Code: VGK162-01

Stauer, 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. VGK162-01, Burnsville, MN 55337 www.stauer.com

AFFORD THE EXTRAORDINARY

AVHP-230725-007 Stauer Viking Blade.indd 1 6/5/2023 8:12:32 AM

99 Impossible Price

& PUBLISHER VISIT HISTORYNET.COM

Weapons

TOM HUNTINGTON EDITOR LARRY PORGES SENIOR EDITOR JON GUTTMAN RESEARCH DIRECTOR

STEPHAN WILKINSON CONTRIBUTING EDITOR

ARTHUR H. SANFELICI EDITOR EMERITUS

BRIAN WALKER GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR ALEX GRIFFITH DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY GUY ACETO PHOTO EDITOR

DANA B. SHOAF EDITOR IN CHIEF CLAIRE BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

CORPORATE

KELLY FACER SVP REVENUE OPERATIONS MATT GROSS VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES

ROB WILKINS DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING JAMIE ELLIOTT SENIOR DIRECTOR, PRODUCTION

ADVERTISING

MORTON GREENBERG SVP ADVERTISING SALES MGreenberg@mco.com

TERRY JENKINS REGIONAL SALES MANAGER TJenkins@historynet.com

DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING NANCY FORMAN / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com

© 2023 HISTORYNET, LLC

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: 800-435-0715 or shop.historynet.com

Aviation History (ISSN 1076-8858) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC 901 North Glebe Road, 5th Floor, Arlington, VA 22203

Periodicals postage paid at Arlington, Va., and additional mailing offices. Postmaster, send address changes to Aviation History, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900

List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc.; 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com

Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519, Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001

The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet, LLC

PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

Sign up for our FREE e-newsletter, delivered twice weekly, at historynet.com/newsletters HISTORYNET PLUS! Today in History What happened today, yesterday— or any day you care to search. Daily Quiz

your historical acumen—every day!

If?

the fallout of historical events had they gone the ‘other’ way.

MICHAEL A. REINSTEIN CHAIRMAN

Test

What

Consider

&

gadgetry of war—new and old— effective, and not-so effective. TRENDING NOW

The Vietnam War’s final bombing campaign hit the communists hard but resulted in unnecessary American losses. By Carl

Schuster historynet.com/linebacker-christmasbombing-vietnam

Came as a Surprise U.S. AIR FORCE AVHP-231000-MASTHEAD.indd 4 6/20/23 11:20 AM

Gear The

AUTUMN 2023 / VOL. 33, NO. 4

O.

Operation Linebacker II

LESSON NOT LEARNED?

NO HOT AIR

Regarding the article “A Sunday with Lilienthal” [Summer 2023], superb as it was, it was disappointing in that it stated, “By the 1890s, hot-air balloons were all the rage.” I feel oblig ed to remind you that hot-air balloons were not any kind of rage until the 1960s after the development, by Paul Yost, of the propane burner specifically designed for ballooning. Although the first balloon flight, originating in France in 1783 and conducted by the Montgolfier brothers, was raised by hot air produced by an internal blaze, on August 27 of that year the first hydrogen balloon went up, also in France. From that point on, hydrogen became the preferred method of lift for balloons until the 1960s.

Donald Gruber, Clinton, Illinois

A CAT’S LIFE

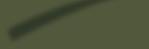

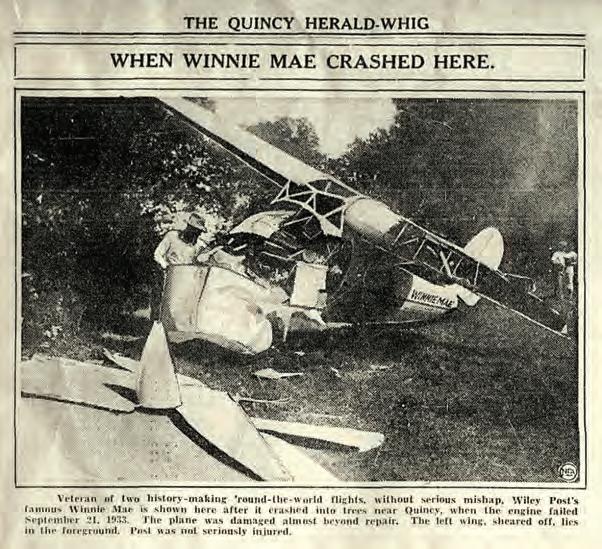

Your article on Wiley Post’s fatal crash in Alaska [Spring 2023] really resonated with me. I’ve been researching the history of Quincy, Illinois’ airports. Their most famous day at the now-closed Monroe Airport was September 21, 1933, the day Wiley Post nearly totaled his beloved Winnie Mae on takeoff. The scenario was eerily similar— loss of power shortly after takeoff with no chance to recover. This time he spent a few days in the hospital, but he doesn’t seem to have become any more cautious.

Mark Lueckenhoff, Ewing, Missouri

Mark Lueckenhoff, Ewing, Missouri

DON’T FORGET THE NAVY

MAILBAG

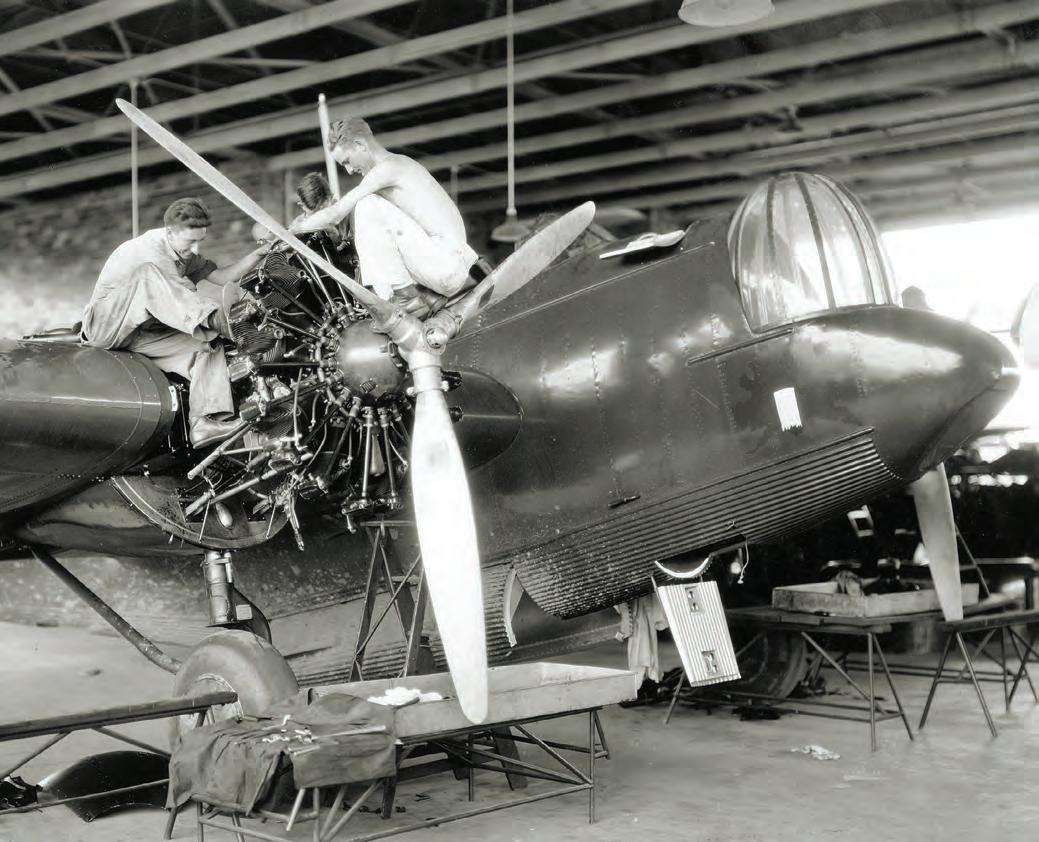

Regarding the Milestone about the Berlin Airlift [Summer 2023], my Mom and I spent the winter of 1948-49 at her family’s ranch north of Winnett, Montana, while Dad was on the Berlin Airlift. He was assigned to VR-8, a Navy transport squadron flying Douglas R5Ds (the Navy version of C-54s), redeployed to Rhein-Main near Frankfurt just after transferring to Hawaii. The commanding officer of VR-8 wrote a March 17, 1949, newsletter covering the first four months of the deployment and reported, “For the third consecutive month VR-8 has led all other squadrons engaged in the Airlift.” Surprisingly, I have never seen any media report of the Navy’s involvement in the Airlift, aside from a contemporary Winnett Times piece showing Aviation Machinist Mate First Class Paul B. Runsvold working on an aircraft engine. Dad said many of the R5Ds he overhauled later at NAS Corpus Christi still had coal dust in the bilges from transporting coal to Berlin.

James M. Runsvold, Caldwell, Idaho

I saw the “Briefing” item about the kittens that were born in the T-33 [“Career Change,” Spring 2023]. My wife and I were the first to adopt one of the “Cockpit Kittens” from the Hickory Aviation Museum/Humane Society of Catawba County last December. We drove to North Carolina and spent a little time in the shelter. The only one of the five (they were 12 weeks old at the time) that wanted anything to do with humans at that point was the kitten who popped his head up in the canopy in the photo and who is now a “Celebri-cat.” He was given the shelter name of Mohawk, but we changed it to a more appropriate name for a cat born in T-33 —T-Bird.

Jeff Rhodes, Hiram, Georgia

END OF THE ARROW

The excellent article on the demise of the Avro Arrow [Summer 2023] emphasized the thorough infiltration of the Arrow project by the Soviets. But I believe another facet of the story was at the heart of the project’s cancellation. From the time John Diefenbaker became prime minister of Canada in 1957, he embarked on a sweeping change in domestic agenda, particularly an aggressive agricultural policy, including a stabilized income for farmers, plus pension improvements. The money had to come from somewhere else in the budget. Two years later, the ax fell. The politics of that decision is, as mentioned in the article, a controversial subject to this day.

John A. Schrandt, Madison, Wisconsin

5 AUTUMN 2023

COURTESY MARK LUECKENHOFF

SEND LETTERS TO: aviationhistory@historynet.com (Letters may be edited for publication) @AVIATIONHISTMAG @AVIATIONHISTORY

AVHP-231000-MAILBAG.indd 5 6/20/23 11:21 AM

MIG KILLER REACHES USAF “HALL OF FAME”

AMcDonnell Douglas F-15C Eagle known as a “MiG Killer” was flown for the last time on a trip to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, on April 25. The only jet of its kind to destroy two enemy MiG29s, the airplane will go on permanent display after it is cleaned and restored to original condition.

BRIEFING

On March 26, 1999, Air Force pilot Colonel Jeff Hwang was flying the F-15 on patrol during the Kosovo War when he spotted a radar blip some 37 nautical miles away over the border in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Hwang, who went by the call sign “Claw,” alerted wingman Captain J. “Boomer” McMurray and both tracked the potential hostile aircraft as they flew along the border as part of Operation Allied Force. When they were within 30 nautical miles, the bogey split in two. It turned out to be a pair of Mikoyan MiG-29s, known to NATO as Fulcrums, flown by Yugoslav pilots.

As the enemy jets got closer, Hwang determined the threat was real and decided to engage. He fired two AIM-120 missiles at the targets while McMurray launched one. A few moments later, Hwang’s Fulcrums exploded. Hwang received credit for a double victory. It was later determined that one of his missiles took out both Fulcrums, earning fame for both the pilot and the jet, which had two green stars painted on it for the simultaneous shootdowns. (One of the MiG pilots ejected; the other was killed.)

Hwang retired in 2014, but his F-15C Eagle—tail number 86156—continued to soar on with the Massachusetts Air National Guard. Until this year, that is. Now this historic MiG killer has reached the “hall of fame.” —Dave Kindy

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE U.S. AIR FORCE (TOP AND BOTTOM); TSGT. JOHN HUGHEL, 142ND FIGHTER WING (CENTER) TOP: COURTESY AMELIA EARHART HANGAR MUSEUM (2); RIGHT: HISTORYNET ARCHIVES

The McDonnell Douglas F-15C Eagle makes its final approach to Dayton for delivery to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

6 AUTUMN 2023 AVHP-231000-BRIEFING.indd 6 6/21/23 11:34 AM

Colonel Jeff Hwang, photographed here in 2014 on the day he retired from the Air Force, shows off two stars symbolizing his MiG kills. Above: Lt. Col. Matthew “Beast” Tanis of the Massachusetts Air National Guard speaks to the press after delivering the aircraft to the Air Force museum.

NEW EARHART MUSEUM OPENS

On April 14, 2023, a new museum honoring Amelia Earhart opened in Atchison, Kansas, the city where the aviator was born in 1897.

The Amelia Earhart Hangar Museum features interactive exhibits that celebrate the legacy of the first woman to fly across the Atlantic (as a passenger in 1928 and solo in 1932) and inspire young people to follow in her footsteps. “We want people to take away the fact that she truly is relevant today,” says Karen Seaberg, the museum director and the founder and president of the Atchison Amelia Earhart Foundation.

The museum’s centerpiece is the last remaining Lockheed Electra 10-E, the same type of aircraft Earhart was flying on an attempted around-the-world flight when she disappeared over the Pacific in July 1937. In other exhibits, visitors can get a sense of what it was like to rivet an airplane, experience how aviators from Earhart’s time navigated by the stars and explore the Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines that powered the Electra. They can also hear recordings of Earhart’s voice and climb into a life-size reproduction of the Lockheed’s cockpit.

For aviation buffs, the big attraction is the Lockheed. The former owner, who had named the airplane Muriel, after Earhart’s sister, had hoped to

AIR QUOTE

restore the airplane and fly it around the world, but ill health intervened. “When we found out that she was going to sell the plane, we formed the foundation very quickly and raised the money to buy the airplane,” says Seaberg. “So that’s how it all started.” The foundation also spearheaded placement of an Earhart statue in the U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C. The statue was installed in July 2022 and a copy stands in front of the museum.

The museum addresses the fact of Earhart’s disappearance and lets visitors vote on their solution to the mystery. But Seaberg stresses that Earhart’s final flight is not the museum’s focus. “Our mission is really to get people interested in her story,” she says. —Tom Huntington

Hear more from Karen Seaberg and take a look at the museum by going to historynet.com/ earhart-museum

7 AUTUMN 2023 NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE U.S. AIR FORCE (TOP AND BOTTOM); TSGT. JOHN HUGHEL, 142ND FIGHTER WING (CENTER) TOP: COURTESY AMELIA EARHART HANGAR MUSEUM (2); RIGHT: HISTORYNET ARCHIVES

Left: The Earhart statue that stands outside the museum is a copy of one recently placed in the U.S. Capitol. Right: Visitors admire Muriel, a Lockheed 10-E like the one Earhart was flying when she disappeared in 1937.

“This business of looking is the most important part of a fighter-pilot’s job. You’ve got to have a rubber neck and you’ve got to keep it moving the whole time from the moment you get into the air to the moment you arrive back at your base.”

—ROALD DAHL,

FROM THE STORY “SHOT DOWN OVER LIBYA” (1942)

AVHP-231000-BRIEFING.indd 7 6/21/23 11:34 AM

RESTORED WELLINGTON HIGHLIGHTS RAF EXHIBIT

Good things come to those who wait. That’s the case with the Vickers Wellington bomber that serves as the centerpiece of a new exhibit at the Royal Air Force Museum Midlands in Cosford, England. Opened in May, the exhibit returned the venerable Wellington— one of only two remaining—to the public eye after a restoration that took more than a decade. (The other surviving Wellington is at the Brooklands Museum in Weybridge, Surrey.)

The twin-engine Wellington, with its unique “basket weave” or geodetic internal structure, was the RAF’s most advanced bomber at the start of World War II. The prototype first flew in June 1936; after that airplane crashed in 1937, the Wellington received an extensive redesign and emerged as the Mk.I. By the time production ceased in October 1945, the British had built more than 11,400 Wellingtons, making it the most-produced British bomber, although by war’s end it had been relegated to transport and naval roles. The museum’s Wellington was built in 1944 and served for navigation training during the war. It remained with the RAF until 1953 and then went on

AERO ARTIFACT

display at the RAF Museum in London. In 2010 it was shipped to the Midlands location for the start of restoration work, which included replacing all its Irish linen covering.

The bomber now provides the focus for the museum’s new permanent exhibit, “Strike Hard, Strike Sure: Bomber Command 1939–1945,” which opened on the 80th anniversary of the famous Dambusters expedition. Flown on May 16, 1943, by 19 Avro Lancaster bombers led by Wing Commander Guy Gibson, the mission targeted German dams in the Ruhr Valley with specially designed “bouncing bombs.” Besides the Wellington, the Bomber Command exhibit includes a Bristol Blenheim bomber and the Victoria Cross that was awarded to Gibson.

You can find the museum’s website at rafmuseum.org.uk/midlands

MALTA HAS FAITH

The story of the Sea Gladiators that defended the Mediterranean island of Malta during the early days of World War II has become a legendary tale of courage against overwhelming odds (see the story about the Gladiator that begins on page 36). Three of the airplanes became known, retroactively, as Faith, Hope and Charity. Outnumbered Sea Gladiators did duel against Italian aircraft over Malta, but there were more than three of them and they were later reinforced by British Spitfires. Nonetheless, the airplanes became Maltese heroes at a time when the beleaguered island needed them most. Today only one—or part of one—remains. The airplane later christened Faith now resides, wingless, in Valletta’s National War Museum.

8 AUTUMN 2023 TOP: RAF MUSEUMS (BOTH); LEFT: IWM GM 3776 TOP: DAKOTA TERRITORY AIR MUSEUM/WARREN PIETSCH AND BEN REDMAN; RIGHT: U.S. NAVY

AVHP-231000-BRIEFING.indd 8 6/20/23 11:23 AM

Left: The restored Wellington is a focus for a new Bomber Command exhibit at the RAF Museum Midlands. Right: A view of the interior highlights the bomber’s “basket weave” construction.

RAZORBACK RETURNS TO THE AIR

The P-47D-23 Thunderbolt from the Dakota Territory Air Museum in Minot, North Dakota, which was featured in last issue’s “Briefing,” has returned to the sky. On May 13, 2023, the Razorback version of the World War II fighter lifted off a runway in Bemidji, Minnesota, at the end of an eight-year restoration by AirCorps Aviation. Test pilot Bernie Vasquez flew the 35-minute flight. Eventually the airplane will receive the paint scheme of Bonnie, a P-47 flown in the Pacific Theater by Bill Dunham of the 342nd Fighter Squadron of the Fifth Air Force’s 348th Fighter Group. Dunham, who retired from the Air Force in 1970 as a brigadier general, scored 15 of his 16 victories with the P-47.

MILESTONES

PACKING HEAT

On September 11, 1953, a U.S. Navy F3D Skyknight fighter took off from Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS) at China Lake, California. The Skyknight, armed with an experimental heat-seeking AIM-9A Sidewinder missile, homed in on an unmanned F6F-5K Hellcat drone. The Skyknight released the prototype missile and the F6F erupted in flames. It was the first successful test of the air-to-air Sidewinder and the culmination of years of research at China Lake.

The Sidewinder was the brainchild of Navy physicist William B. McLean, head of the NOTS Aviation Ordnance Division. McLean theorized that a heat-seeking missile would be more effective than the radarguided missiles being developed concurrently. While the first-generation Sidewinders had limitations—they were useful only at short ranges, for example—they were still more effective than anything else in the Navy’s arsenal. The Navy adopted the Sidewinder in 1956, while the Air Force didn’t accept it until 1964.

The Sidewinder’s first use in battle came in 1958, when U.S.-backed Republic of China pilots downed four Red Chinese MiG-15s and -17s with AIM-9Bs during the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis. The weapon proved only partially successful in Vietnam, but later variants increased its success rate. The Sidewinder is still in the U.S. arsenal and those of 31 other nations, with the more than 110,000 missiles produced accounting for approximately 270 aircraft kills. The AIM-9X Block II, built by Raytheon, is the latest variant. It can hit targets in a 360-degree radius from the launch point, including targets on the ground. —Larry Porges

9 AUTUMN 2023

TOP: RAF MUSEUMS (BOTH); LEFT: IWM GM 3776 TOP: DAKOTA TERRITORY AIR MUSEUM/WARREN PIETSCH AND BEN REDMAN; RIGHT: U.S. NAVY

Images taken on September 11, 1953, capture the first successful test of a Sidewinder, which took out a F6F-5K Hellcat drone.

AVHP-231000-BRIEFING.indd 9 6/20/23 11:24 AM

Learn more about the Sidewinder at historynet.com/fox-two

A PISTOL

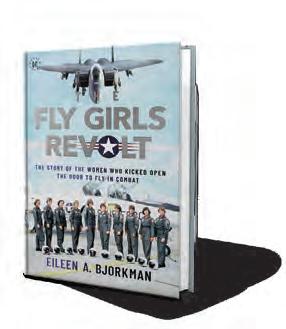

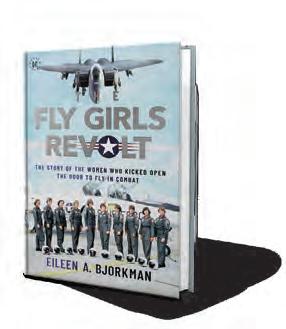

BY EILEEN A. BJORKMAN

AVIATORS

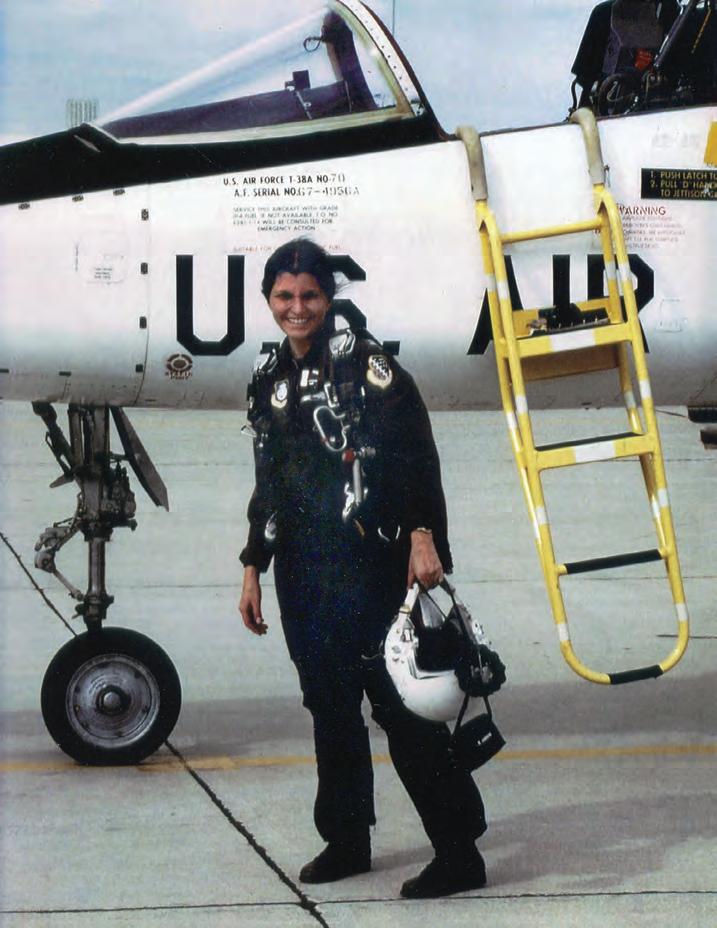

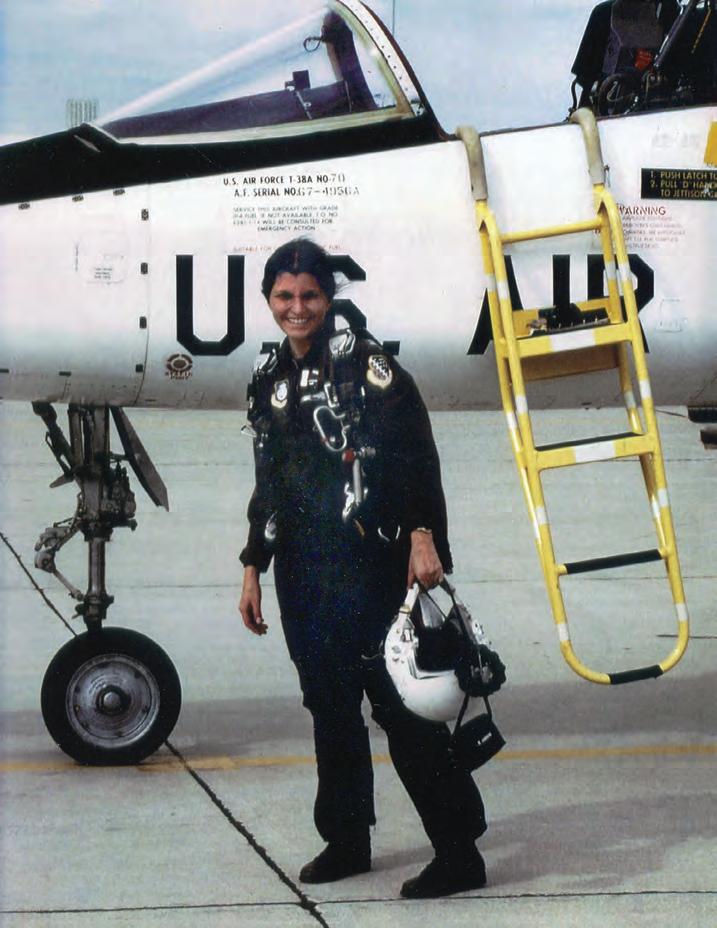

In 1981, Captain Carmen Lucci appeared to have an unlimited future in the U.S. Air Force. The Ohio native had earned a full scholarship as Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s first female AFROTC cadet, and in 1975 she had received her Air Force commission as a distinguished graduate. Her next stop was the University of Tennessee Space Institute, where she earned a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering. In 1977, she entered Air Force active duty.

Lucci had her sights set on being an astronaut, so during her first assignment at Los Angeles Air Force Station, she applied to attend pilot training and the flight test engineering course at the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School (TPS). Accepted to both, she turned down pilot training to attend TPS and arrived at Edwards Air Force Base in June 1980. She

was the fourth woman to attend Air Force TPS; all the others had also been engineers, since the Air Force had just recently begun to train women pilots.

One of Lucci’s TPS classmates, fighter pilot Carl Meade, arrived at Edwards a few days before the class started and checked into the visiting officers’ quarters. The clerk on duty commented, “One of your classmates is already here. And she’s quite a pistol.”

Meade thought, “She? A pistol?”

About 30 minutes later, he received a message from the pistol: “I’m Carmen. Let’s go to dinner.”

The two became fast friends, occupying quarters near each other and studying frequently together with two other classmates. They had hectic schedules, with student flights during the mornings and academics in the afternoons. Evenings and weekends were for analyzing data, writing reports and endless reading and homework to learn the theoretical underpinnings of everything from aircraft climb performance to out-of-control spins.

Lucci loved to fly. During test missions with her in the backseat of a McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom, classmate Ted Wierzbanowski remembered that they often had a little free time after collecting the test points they needed for the day. As they flew back to Edwards, Lucci often prodded him for a little extra excitement by saying, “Teddy, do me another Immelmann!” Bob Hood recalled how much fun he and Lucci had on their last flight together as they flew a low-level route in a Northrop T-38 Talon over the desert terrain north of Edwards. However, when Lucci wasn’t zipping through maneuvers in a jet, her lifestyle was more low-key. She cooked, played backgammon and regularly stole cookies from the lunch that Meade packed for himself every day. In 1979 she had married Air Force Captain Thomas Humes.

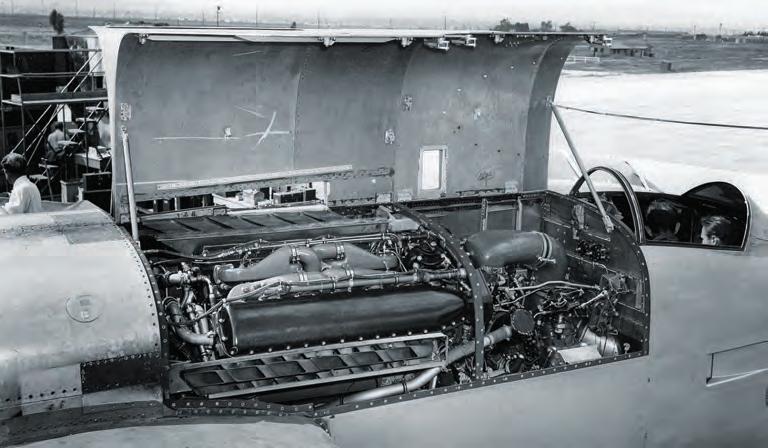

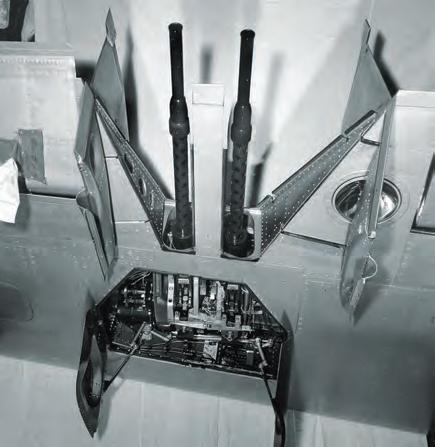

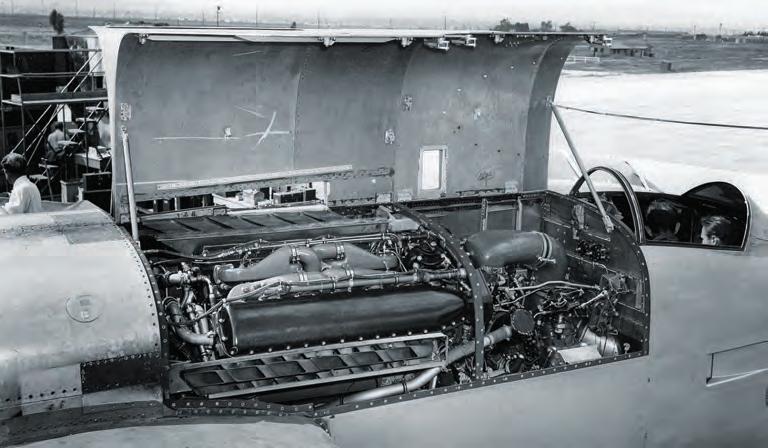

On March 3, 1981, Lucci was scheduled to fly an early mission with classmate D.J. Halladay, a Canadian Armed Forces captain, in the school’s variable-stability Douglas B-26 Invader. The B-26 had been extensively modified so the flight control system could be altered to make it seem as though it was a different type of aircraft. By repositioning a few dials, the civilian test pilot instructor, Stephen Monagan, could make the B-26 behave like a lumbering B-52, a nimbler C-130, or even an aircraft that didn’t exist, giv-

10 AUTUMN 2023 COURTESY THE AIR FORCE TEST CENTER HISTORY OFFICE

Carmen Lucci was one of the first women to attend the U.S. Air Force’s Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Lucci never had the chance to reach her full potential.

CAPTAIN CARMEN LUCCI AIMED TO BE AN ASTRONAUT, BUT FATE INTERVENED

AVHP-231000-AVIATORS.indd 10 6/20/23 11:49 AM

5 Countries, 5 Pure Silver Coins!

Your Silver Passport to Travel the World

The 5 Most Popular Pure Silver Coins on Earth in One Set

Travel the globe, without leaving home—with this set of the world’s ve most popular pure silver coins. Newly struck for 2023 in one ounce of ne silver, each coin will arrive in Brilliant Uncirculated (BU) condition. Your excursion includes stops in the United States, Canada, South Africa, China and Great Britain.

We’ve Done the Work for You with this Extraordinary 5-Pc. World Silver Coin Set

Each of these coins is recognized for its breathtaking beauty, and for its stability even in unstable times, since each coin is backed by its government for weight, purity and legal-tender value.

2023 American Silver Eagle: The Silver Eagle is the most popular coin in the world, with its iconic Adolph Weinman Walking Liberty obverse backed by Emily Damstra's Eagle Landing reverse. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the U.S. Mint.

2023 Canada Maple Leaf: A highly sought-after bullion coin since 1988, this 2023 issue includes the FIRST and likely only use of a transitional portrait, of the late Queen Elizabeth II. These are also expected to be the LAST Maple Leafs to bear Her Majesty's effigy. Struck in high-purity

99.99% fine silver at the Royal Canadian Mint.

2023 South African Krugerrand: The Krugerrand continues to be the best-known, most respected numismatic coin brand in the world. 2023 is the Silver Krugerrand's 6th year of issue. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the South African Mint.

2023 China Silver Panda: 2023 is the 40th anniversary of the first silver Panda coin, issued in 1983. China Pandas are noted for their heart-warming one-year-only designs. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the China Mint.

2023 British Silver Britannia: One of the Royal Mint's flagship coins, this 2023 issue is the FIRST in the Silver Britannia series to carry the portrait of King Charles III, following the passing of Queen Elizabeth II. Struck in 99.9% fine silver.

Exquisite Designs Struck in Precious Silver

These coins, with stunningly gorgeous finishes and detailed designs that speak to their country of origin, are sure to hold a treasured place in your collection. Plus, they provide you with a unique way to stock up on precious silver. Here’s a legacy you and your family will cherish. Act now!

SAVE with this World Coin Set

You’ll save both time and money on this world coin set with FREE shipping and a BONUS presentation case, plus a new and informative Silver Passport!

BONUS Case!

2023 World Silver 5-Coin Set Regular Price $229 – $199 SAVE $30.00 (over 13%) + FREE SHIPPING

FREE SHIPPING: Standard domestic shipping. Not valid on previous purchases. For fastest service call today toll-free

1-888-201-7070

Offer Code WRD314-05

Please mention this code when you call.

SPECIAL CALL-IN ONLY OFFER

Not sold yet? To learn more, place your phone camera here >>> or visit govmint.com/WRD

GovMint.com® is a retail distributor of coin and currency issues and is not a liated with the U.S. government. e collectible coin market is unregulated, highly speculative and involves risk. GovMint.com reserves the right to decline to consummate any sale, within its discretion, including due to pricing errors. Prices, facts, gures and populations deemed accurate as of the date of publication but may change signi cantly over time. All purchases are expressly conditioned upon your acceptance of GovMint.com’s Terms and Conditions (www.govmint.com/terms-conditions or call 1-800-721-0320); to decline, return your purchase pursuant to GovMint.com’s Return Policy. © 2023 GovMint.com. All rights reserved.

GovMint.com • 1300 Corporate Center Curve, Dept. WRD314-05, Eagan, MN 55121

AVHP-230725-004 GovMint 2023 World Silver Coin Set.indd 1 6/5/2023 11:50:28 AM

ing students the opportunity to see how different flight control system designs made it easier or harder to fly an airplane. The B-26 was nearing retirement; it was only going to be used for a few more flights and would be replaced by a more modern Learjet.

The three aircrew took off from Edwards about 7:30 a.m. for a local flight of about an hour. After the B-26 failed to return on schedule, Meade—who was supposed to fly the aircraft next—and other TPS personnel called nearby military bases, thinking the crew might have diverted for an emergency. No one had seen the aircraft. Airborne pilots searched near Edwards, thinking the Invader might have landed on a lakebed. Nothing. A formal search party was launched. The students went to their afternoon classes.

About 3:00 p.m., someone entered the classroom with grim news: wreckage from the B-26 had been located. There were no survivors.

The class sat in stunned silence until the instructor dismissed them for the day.

Investigators determined that the left wing had separated from the B-26 during maneuvers at about 8,000 feet.

Meade delivered a eulogy for Lucci at a memorial service a few days later. After the service, a flight of F-4s thundered over the chapel at low altitude to honor the fallen aviators. Inside the chapel, their names were later engraved on a plaque dedicated to test personnel lost in accidents at Edwards.

Three decades later, on March 16, 2012, many of Lucci’s classmates attended a dedication ceremony to name a control room at the test pilot school in honor of her supreme sacrifice. Colonel Noel Zamot, TPS Commandant at the time, said in an Air Force news release: “Tenacity, character, discipline, integrity, confidence, and intellectual curiosity are timeless values and they are what make you successful at the United States Air Force Test Pilot School and in life. Captain Lucci exemplified those values.”

About the same time in 2012, one of aircraft wreck-finder Pat Macha’s teams visited the B-26 crash site. Macha and his teams made several visits to the site over the next few years. During the final visit, a team member noticed a chain in the dirt. When she picked it up, it still held Lucci’s dogtags, badly bent from the severe impact, but otherwise in perfect condition. Macha’s “Project Remembrance,” which returns personal items located in aircraft wreckage to families, kicked into gear. The Lucci family passed the tags along to her classmates, who mounted them in a shadow box to accompany the small display already outside the control room named for her. On September 20, 2019, Lucci’s classmates assembled once again to dedicate the shadow box and remember a pilot whose promising life had been cut short. “The dedication shows how the flight test community never forgets and also reminds folks that what this community does is risky, but also that those risks are worth the capability we bring to the warfighter,” said Wierzbanowski. “The dedication brought back a lot of good memories and a lot of sadness. It should remind us all that every day is a blessing.”

Carmen Lucci is still the only female flight test engineer to lose her life as a student or graduate of any test pilot school in the world.

12 AUTUMN 2023 TOP: HISTORYNET ARCHIVES; BOTTOM: U.S. AIR FORCE/JET

FABARA

Above: The B-26 in which Lucci died had been modified so it could mimic the handling characteristics of different aircraft. Left: Classmate Ted Wierzbanowski unveils a shadow box outside the Carmen Lucci Control Room at the Test Pilot School during the dedication ceremony in 2019.

AVHP-231000-AVIATORS.indd 12 6/20/23 11:49 AM

TODAY IN HISTORY

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT VISITED BEAR RUN IN SOUTHWESTERN PENNSYLVANIA AND REQUESTED A SURVEY OF THE AREA AROUND A PARTICULAR WATERFALL. PITTSBURGH BUSINESSMAN EDGAR J. KAUFMANN HAD COMMISSIONED WRIGHT TO BUILD A COUNTRY HOME WITH A VIEW OF THE WATERFALL. THE FAMOUS ARCHITECT SURPRISED HIS CLIENT BY INSTEAD DESIGNING THE HOME OVER THE WATERFALL. FALLINGWATER COST $155,000 TO COMPLETE IN 1941. THE HOME WAS MADE AVAILABLE TO VISITORS IN 1964.

For more, visit HISTORYNET.COM/ TODAY-IN-HISTORY

DECEMBER 18, 1934 TODAY-FALLINGWATER.indd 22 3/31/23 4:38 PM

MORRELL’S FOLLY

THE RISE AND FALL OF A CALIFORNIA DREAM

BY RICHARD J. GOODRICH

Was San Francisco’s John Morrell a stockswindling grifter or a deluded visionary? In 1906, Morrell, president of a business venture he called the National Airship Company, announced plans to build a fleet of airships to link America’s cities. It was an enticing dream: dirigibles, nearly a quarter of a mile long, that could cross the country in a day or reach London in 24 hours. A San Francisco businessman could fly to New York for lunch and be back home in time for bed. The railroads were dead, Morrell promised. Air travel was the future.

Although Morrell’s vision outpaced early 20th-century technology, he attracted numerous investors in San Francisco. After all, this was the hometown of August Greth and Thomas Baldwin, the innovators behind America’s first dirigibles. Greth had taken his California Eagle aloft in October 1903; Baldwin had flown his California Arrow the following August. Perhaps Morrell could build on their success.

In August 1907, Morrell unveiled his first airship. Named Ariel, it was 600 feet long and driven by five automobile engines. Before the maiden flight, an October gale snapped the balloon’s tether lines and drove it across San

Francisco Bay. The trees of Fair Oaks, California, shredded the fragile fabric and destroyed the airship.

Dismayed but undefeated, Morrell started work on a replacement. At the same time, the National Airship Company opened a sales office in Portland, Oregon. Advertisements in the Oregon Daily Journal announced that the company planned to have its new dirigible in service by April 1, 1908. The airship would fly the San Francisco to Portland route, carrying 100 passengers and 30 tons of mail. Investors purchasing stock at the bargain rate of ten cents a share could expect exponential returns.

The company’s ambitious claims attracted the interest of the federal government, and the U.S. Post Office opened an investigation into

14 AUTUMN 2023 HISTORYNET ARCHIVES TOP: HISTORYNET ARCHIVES; BOTTOM: AVIATION HISTORY COLLECTION/ALAMY

FLIGHT LOG

Above: John Morrell’s 450-foot-long dirigible gets inflated in Berkeley, California, prior to its one and only flight. Top: On May 23, 1908, Morrell took the airship aloft. The sag visible in the middle of the envelope is a sign of impending trouble. The craft managed to reach a height of about 150 feet before failing completely and crashing to the ground.

AVHP-231000-FLIGHTLOG.indd 14 6/20/23 11:26 AM

whether Morrell’s activities constituted mail fraud. Meanwhile, a disgruntled investor named S.L. Jacobs filed a complaint against Morrell in San Francisco Police Court, claiming that he had violated section 564 of the California Penal Code—making false statements about his company to investors. Morrell was arrested and released on bail while awaiting a trial.

Morrell realized that he required a working dirigible to establish his legitimacy. Hoping for a quick result, he scaled back his ambitious plans. The new airship would be smaller, only 450 feet long and 60 feet in diameter. It would serve as a proof of concept and a training vessel, a preparatory step toward a 1,250-foot behemoth that Morrell envisioned.

As the airship neared completion, Colonel Fedor Postnikov, a former Russian army balloonist, expressed concerns about the quality of Morrell’s materials. The envelope, made of light canvas coated with varnish, might have been sufficient for a small balloon, Postnikov informed reporters, but the fabric was unlikely to resist the pressures found in a larger airship. Morrell dismissed Postnikov’s qualms: he said his envelope employed a secret varnish that made it stronger than it appeared. The airship would be fine.

San Francisco refused permission for a second launch, so Morrell relocated to nearby Berkeley. He tried to keep his official launch date a secret, but the news leaked. On May 23, 1908, thousands of people arrived to watch the first flight. The balloon, a bulging, misshapen sack filled with 500,000 cubic feet of hydrogen-based illuminating gas, strained against its tether lines. The official crew consisted of fourteen men and two photographers. Morrell spent the final minutes before launch evicting adventurers who had stowed away in the netting beneath the airship.

Shortly before noon Morrell ordered the tether lines slackened. His crew started the ship’s five engines. As the dirigible rose, the envelope appeared to be unevenly inflated. The rear end of the envelope was fine, a taut, smoothly stretched surface. The bow, however, seemed underinflated, a section of limp, wrinkled fabric. Morrell was unconcerned, believing the pressure would equalize along the length of the airship. He ordered the flight to proceed.

The balloon climbed to 150 feet. As it ascended, its longitudinal disparity worsened. The weight of the forward engine, which was inadequately supported by the underinflated section of the balloon, dragged the nose down.

With the nose deflated and a gigantic tear visible in the rear section, Morrell’s dirigible begins its final descent. This marked the end of Morrell’s attempts at building airships.

As the tilt increased, the trapped gas rushed aft, exacerbating the problem. Morrell shouted orders to his crew in a vain attempt to level the unbalanced airship, but it was too late. The ship pitched forward and entered a shallow dive.

The stressed fabric burst with a loud crack. Stitches unraveled along a weak seam and pressurized gas poured through the tear. The dirigible accelerated toward the ground. The crowd screamed; panicked onlookers fled the impact zone. “Down plunged the airship,” wrote the San Francisco Call . “It heaved from side to side, like some wild monster, attempting to shake off the desperate, clinging forms, hanging like spiders from its sides.”

Some of the crew jumped clear as the dirigible’s nose plowed into the ground. Others were buried beneath torn canvas, sundered nets and snapped steel tubing. Rescuers emerged from the frightened crowd and tore the balloon with knives to free the trapped men. Injuries ranged from broken bones to internal injuries and concussions. A propeller struck Morrell, cutting him and breaking both of his legs.

The dirigible was destroyed, but, miraculously, no one died in the crash even though most of the crew ended up in the hospital. In the days that followed the accident, souvenir hunters looted the wreckage. By the time Morrell left the hospital, little remained of his dream.

Morrell blamed the accident on his investors—their lawsuits had forced the accelerated pace of development, he said, leading to a flawed product. Nevertheless, he had produced a dirigible, delivering a version of what his stock prospectus had promised.

He vowed to try again, promising to build a bigger and better airship, but legal difficulties occupied his attention for the next year. The Berkeley police department forbade further flights in the city, and, although he managed to convince the courts of his legitimacy, he never built another airship. The age of the airplane had arrived in California, but it would still be decades before transcontinental jets—not leviathan dirigibles— whisked San Francisco businessmen to New York for lunch.

15 AUTUMN 2023 HISTORYNET ARCHIVES TOP: HISTORYNET ARCHIVES; BOTTOM: AVIATION HISTORY COLLECTION/ALAMY

AVHP-231000-FLIGHTLOG.indd 15 6/20/23 11:26 AM

THE THICK AND THIN OF PROPER SPIN

IT WASN’T THE ENGINES THAT DID IN THE WESTLAND WHIRLWIND

BY MATT BEARMAN

EXTREMES

It could have been a game-changer. The twin-engine, single-seat Westland Whirlwind, produced by a small company in southwest England, looked like a formidably potent weapon. The four 20mm cannon packed close together in the nose could take out a tank when nothing else flying could. It was also innovative. It had a bubble canopy, intakes in the wing’s leading edges, slats and Fowler flaps. It had a slab-sided fuselage over the wing, which was the ultimate solution to high-speed interference drag. When it first flew on October 11, 1938, the Whirlwind was arguably the fastest, most heavily armed fighter in the world.

Today, very few have heard of it. Westland built only 114 and the Royal Air Force sent the Whirlwind to Scotland to keep it out of the fighting during the Battle of Britain. It has often been labeled a failure. The reason given has always been the inability of its two 885-hp Rolls-Royce Peregrine engines to deliver speed at altitude.

The RAF’s testing program had given the aircraft a clean bill of health and a ceiling of 31,000 feet. However, as the first trickle of aircraft began to arrive with No. 25 and 263 Squadrons in 1940, service pilots began to question why the altitude performance wasn’t what it was

during test flights. “It must be emphasised…that the performance of the Whirlwind above 20,000 feet falls off rapidly, and it is considered that above 25,000 feet its fighting qualities are very poor,” read one report. “The maximum height so far attained is 27,000 feet but on every occasion that a height test has been carried out there has been a minor defect, either in airscrew revolutions or in lack of boost pressure.”

The reply from the technical director of the test facility was straightforward—the aircraft in service were identical in all respects to the one tested, so the difference couldn’t be explained. The Whirlwind’s own designer, the eccentric W.E.W. “Teddy” Petter, blamed a fall-off in boost pressures delivered by the superchargers with height at “twice the rate anticipated.” By doing so, he placed the blame with the RollsRoyce engines division.

The key difference between the tested prototype and the Whirlwinds in service was considered too minor to be worth commenting on officially at the time. It was the propeller. The prototype sent by Westland to the RAF had a oneoff Rotol propeller design, not the de Havilland/ Hamilton propellers that the production Whirlwinds

The metal blades of the de Havilland props were very thick for a high-performance fighter— they had a 9.6% thickness-to-chord ratio (at the standard measuring point 70% of the way out

16 AUTUMN 2023 CHARLES BROWN/RAF MUSEUM, HENDON LEFT: RAE, FARNBOROUGH; RIGHT: RAF MUSEUM, HENDON

received.

A Westland Whirlwind shows what it can do on April 20, 1944. By then the airplane had been classified as a failure. At low altitudes the Whirlwind was formidable, but its performance declined as it climbed.

AVHP-231000-EXTREMES.indd 16 6/21/23 11:35 AM

along the blade). For comparison, the Spitfire’s blades were similar, but at 7.6% the ratio was smaller. This wouldn’t matter at low speed, but in a climb at 15,000 feet the tip of the Whirlwind’s propeller moved at Mach 0.72. Here, the difference between the 6% ratio at the tip of the Spitfire’s prop and the 8% of the Whirlwind’s was literally critical, meaning the tips approached the speed of sound. But an even bigger problem came with the combination of a thick profile blade with a constant speed mechanism.

That mechanism was—and remains—a widely used solution for keeping an engine turning at the optimum speed to produce maximum horsepower, whether the aircraft is moving slowly or at its maximum speed. This is done by changing the “bite”—the angle of attack of the propeller blades. Increasing the blades’ angle of attack increases the drag and thus the braking effect on the engine. To maintain a constant RPM at varying speeds, the pilot controls the propeller’s pitch. A constant speed unit automates the process, with the pilot setting the desired RPM. The unit senses if shaft speed drops, and “fines” the blades appropriately by changing pitch. The Whirlwind had two de Havilland constant speed units under its sleek cowls.

Dynamic tests in 1938 showed that the massive onset of drag above critical Mach would cause the blades to pivot—reduce pitch—as the constant speed mechanism hunted for a lower-drag condition to maintain RPM. Mach number lowers with altitude, so as the Whirlwind climbed at a constant RPM, relative Mach over the blades increased. Moving steadily inwards, more of the blade “went critical” as the phenomenon of compressibility created shock waves, drag rose exponentially and the blade turned farther to compensate.

This could reduce the blade angle of attack beyond zero. Add in any amount of aircraft pitch (and in a climb at altitude the aircraft would be pitched several degrees higher than line-of-flight) and shock waves would run up and down the blades as they spun. Wildly varying dynamic pressures would pass into the ram-air intakes, which sit immediately behind the blades. The intermittently windmilling prop would produce fluctuating boost pressures on top of reduced RPM.

It was very shortly after receiving the report about “very poor” fighting qualities above 25,000 feet that Sir Hugh Dowding, the head of Fighter Command, made his decision to keep the Whirlwind away from any fighting in the south, sealing its reputation as the fighter that missed the Battle of Britain. “The limiting factor in the present fighting against ME 109s in the South of England is the performance, manoeuvrability and climb at

high altitudes, and a difference in service ceiling of 2,000 feet is a very important advantage,” Dowding said. “It therefore seems to me quite wrong to introduce at the present time a fighter whose effective ceiling is 25,000 feet.”

Ultimately the cancellation of the Whirlwind in November 1940 was an economic decision. Rolls needed to concentrate on developing and producing Merlin and Griffon engines, and it was never too sensible (“extravagant,” as Dowding called it) to produce a fighter that required two engines to do what another might with one.

Contrary to popular belief, the Whirlwind went on to serve successfully for another three years, unaltered, in the role of a low-level strike aircraft over the English Channel and occupied France. More than one veteran has commented that they felt comfortable taking on Fw-190s in 1943 in the unmodified, undeveloped 1938 Whirlwind. Down low nothing could catch a Whirlwind. It was maneuverable, practically viceless and its pilots learned to love it.

There is little doubt that the thick blades with the wrong airfoil section held the Whirlwind back. By the time fighters were doing 420 mph and higher at altitude with two-stage superchargers and blade tip speeds of over Mach 1, the blades were very thin and had profiles that had been developed to negate compressibility completely. But by then the time had passed for the Whirlwind and the much-maligned Peregrines that powered it.

17 AUTUMN 2023 CHARLES BROWN/RAF MUSEUM, HENDON LEFT: RAE,

RIGHT:

FARNBOROUGH;

RAF MUSEUM, HENDON

AVHP-231000-EXTREMES.indd 17 6/20/23 11:28 AM

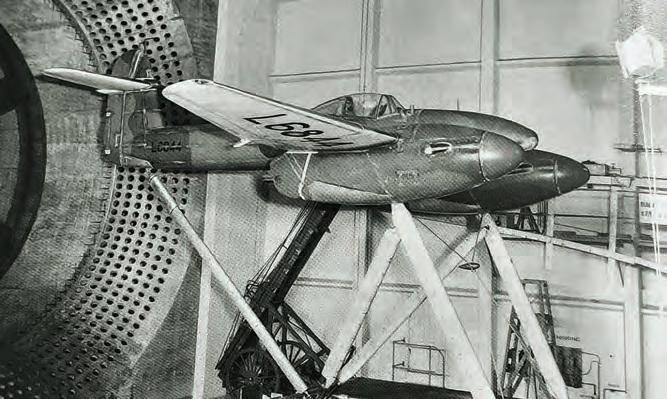

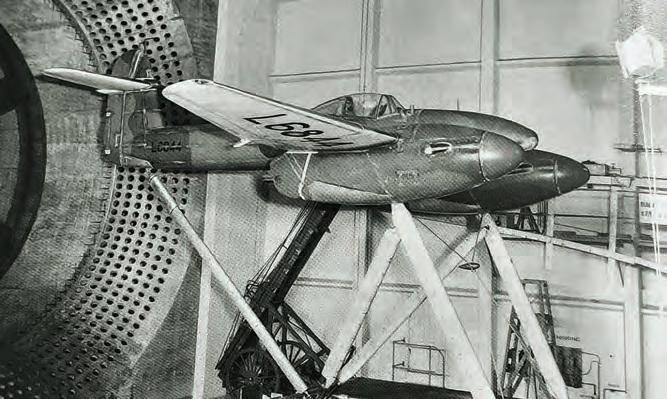

Left: The Whirlwind prototype undergoes testing in 1938 at the Royal Aircraft Establishment’s giant wind tunnel at Farnborough. Right: The prototype had different propellers from those used in the production airplanes, the reason for the drastic difference in performance at altitude.

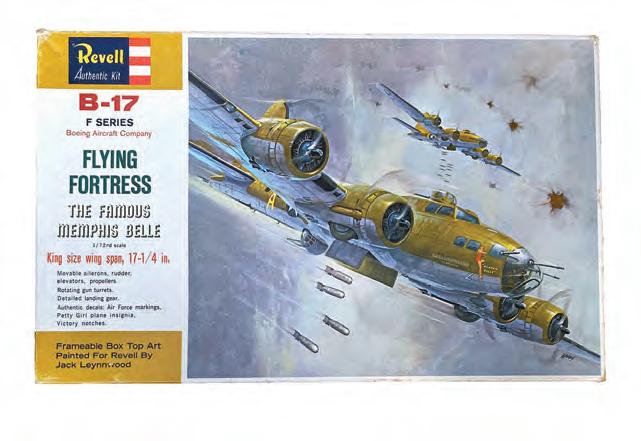

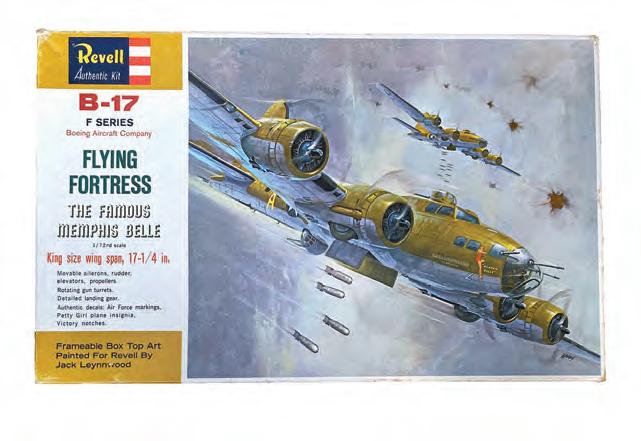

Jack Leynnwood was one of the most prolific model box artists, producing more than 600 pieces for the Revell company. One of his best-known illustrations is the artwork for Revell’s Boeing B-17F, the famous Memphis Belle. While Leynnwood was true to the detail of the bomber itself, his painting almost makes the four-engine beast look like a dive bomber delivering its payload on target. Since that target was a workbench, the art did its job very well.

No doubt Leynnwood’s painting of Jimmy Doolittle’s North American B-25 Mitchell over Tokyo (opposite) prompted many young modelers to take that kit home, too. The box promoted an “exclusive record offer” for a 7-inch vinyl record that told the story of the Doolittle raid, but Leynnwood’s painting provided the real incentive to buy.

XXXXXXXXXX

AVHP-231000-PORT-MODELS.indd 18 6/20/23 11:30 AM

ARTISTS AND MODELS

AIRPLANE KITS WERE GREAT—BUT SOMETIMES THE ART ON THE BOX WAS EVEN BETTER

BY GUY ACETO

BY GUY ACETO

PORTFOLIO

Some of us literally built our passion for aviation at kitchen tables and basement workbenches as we carefully followed directions to create airplane replicas we could hang in aerial battle from the bedroom ceiling.

For me, it was the artwork on the model box—that painting of a favorite airplane— that could make an eight-year-old give up lawn-mowing money faster than you could ask, “Do you need glue with that?”

For the most part, the artists who created that compelling art went unsung. Commercial art is an immediate business

19 AUTUMN 2023 AVHP-231000-PORT-MODELS.indd 19 6/20/23 11:30 AM

ARTISTS AND MODELS

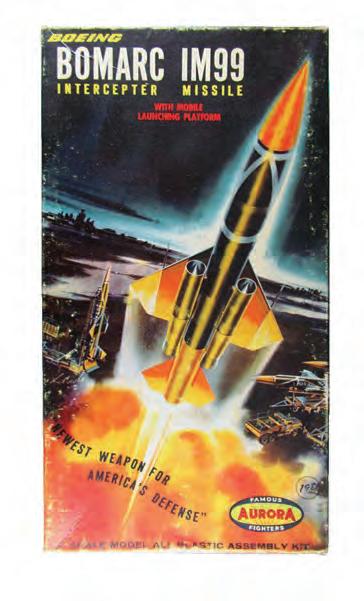

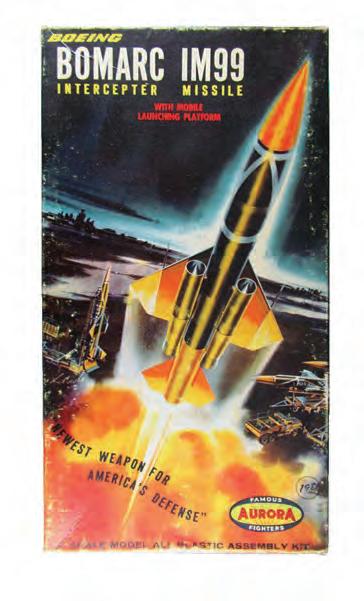

Jo Kotula’s painting of a nighttime launch of a Boeing BOMARC IM-99 guided missile uses bold colors to blast off the hobby shop shelf. The original art, painted on relatively thin illustration board, measures about 26 by 30 inches. Kotula was born in Poland and came to the United States with his parents as a child. Self-taught, he found a job illustrating U.S. Air Force training manuals before creating art for the Aurora and Revell companies.

ALL IMAGES FROM THE GUY ACETO COLLECTION EXCEPT LEFT: HERITAGE AUCTIONS AVHP-231000-PORT-MODELS.indd 20 6/20/23 11:30 AM

where the all-important deadline rules, and the names of many of the artists who produced captivating box art in the 1950s and ’60s have been lost. But just because commercial artists rarely see their work on gallery walls, that doesn’t mean they are any less talented than an artist being lauded at an opening in Soho. The illustrators of those model boxes did their job by captivating modelmakers with their art. Lured by the box illustrations, kids like me bought and built the kits, read the books about the airplanes we had constructed and, in some cases, found aviation turning into a lifelong obsession.

Artists like Jack Leynnwood, Jo Kotula, Roy Grinnell, John Steel and Roy Cross were only a few of the talented illustrators who produced the paintings on the outside of cardboard boxes full of plastic possibility. Collectors today seek out their original art, which can command prices well beyond what the original artist received for the work.

In these pages we offer an all-too-brief collection of some art from these overlooked masters.

John Steel served in the Marines during World War II before going to the Art Center School in Los Angeles on the G.I. Bill. He produced art for Revell, Monogram, Lindberg and Aurora. He’s better known for his dramatic paintings of destroyers and aircraft carriers, but the Nieuport 11 and Albatros D3 are just two of several World War I fighters he produced. (Notice how Aurora misspelled Albatros on the box!)

21 AUTUMN 2023

ALL IMAGES FROM THE GUY ACETO COLLECTION EXCEPT LEFT: HERITAGE AUCTIONS AVHP-231000-PORT-MODELS.indd 21 6/20/23 11:31 AM

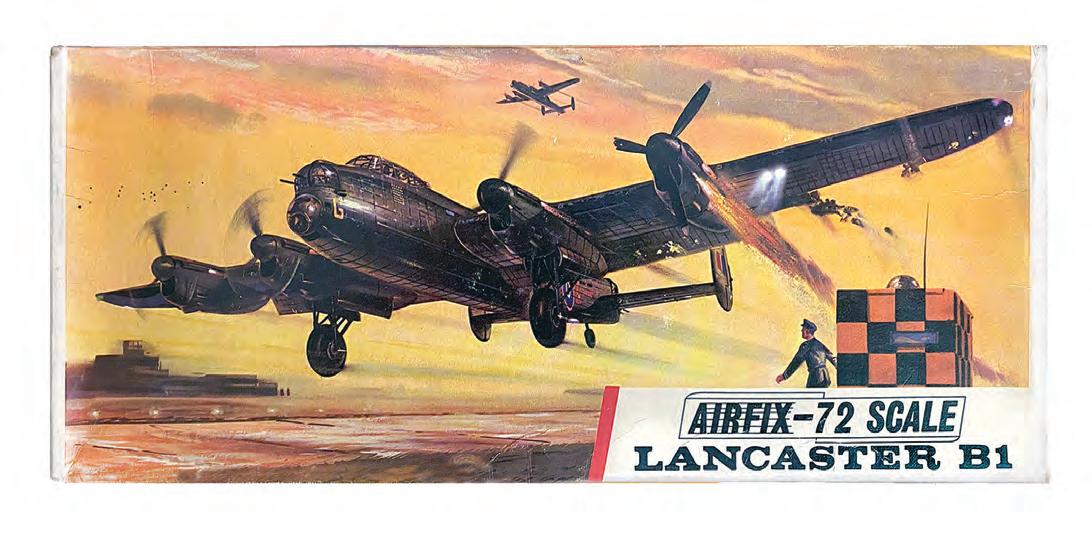

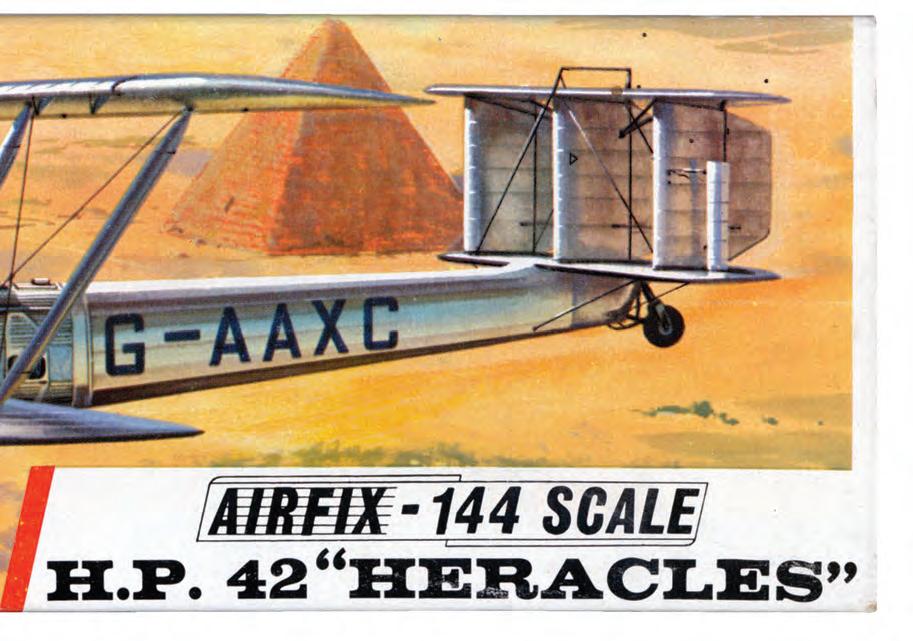

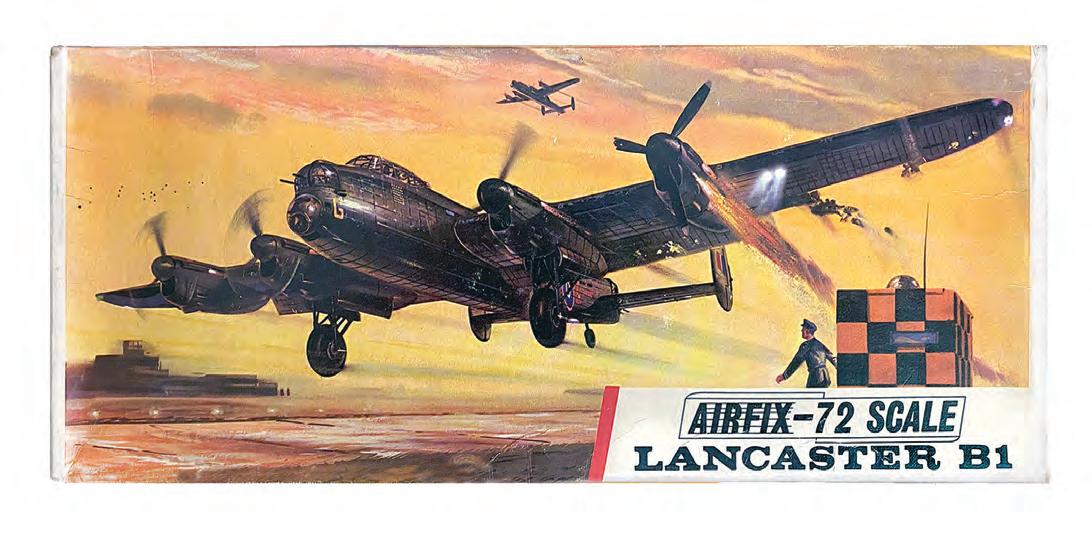

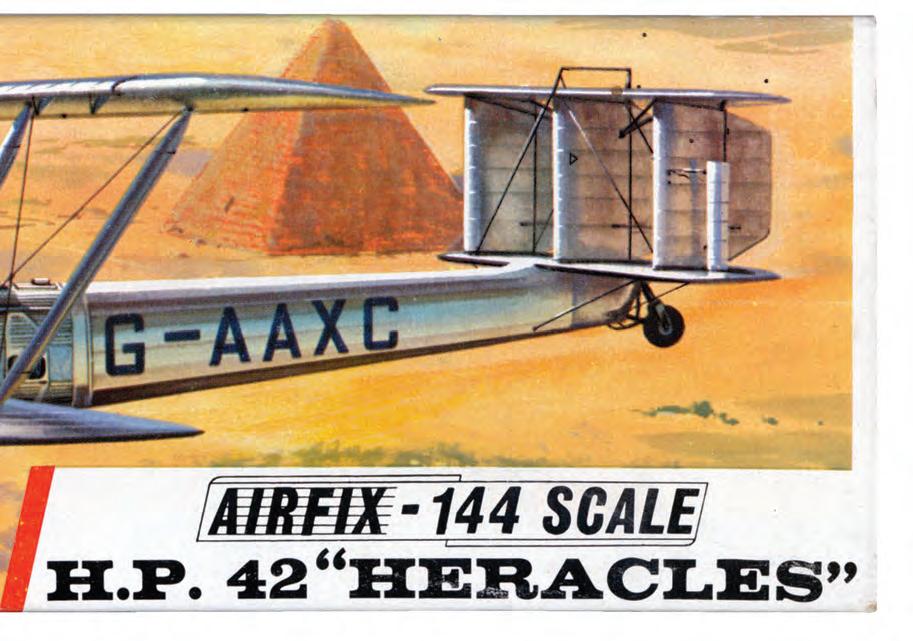

Cross had done aircraft drawings for the British Air Training Corps Gazette before doing illustrations for Fairey Aviation. He started contributing paintings for Airfix in 1964 after writing the company and saying he could improve on the art they were using. His illustration of the colossal Handley Page H.P.42 Heracles (top) shows it wasn’t an idle boast. Cross’ art for an Avro Lancaster B1 (above) depicts a typically compelling image of a battle-damaged bomber barely making it back to base—but surely it made its way up to many a cash register.

22

AUTUMN 2023

AVHP-231000-PORT-MODELS.indd 22 6/20/23 11:31 AM

ARTISTS AND MODELS

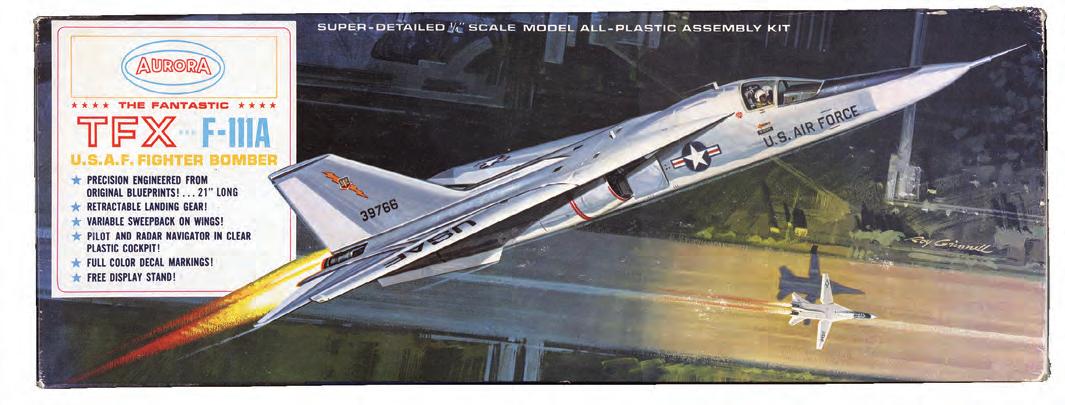

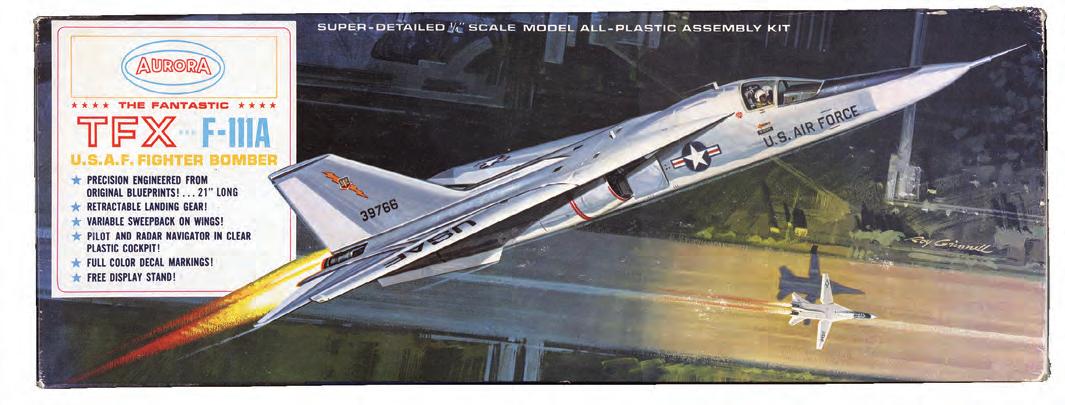

In 1966 Aurora released two versions of General Dynamics’ new swing-wing F-111 (although the U.S. Navy never bought the carrier version of the jet, the F-111B).

Aviation artist Roy Grinnell created a pair of paintings for the two kits, both full of vibrant colors and with the airplane in full afterburner. Grinnell’s aviation art has become widely sought by collectors and has appeared in issues of Aviation History.

AVHP-231000-PORT-MODELS.indd 23 6/20/23 11:31 AM

PROPER IDENTIFICATION

BY TOM HUNTINGTON

I love the Library of Congress. It’s a great place to do research in person, if you are lucky enough to be in Washington, D.C. There’s nothing like the experience of sitting in the Main Reading Room of the Thomas Jefferson Building and gazing up into the magnificent dome high above.

FROM THE COCKPIT

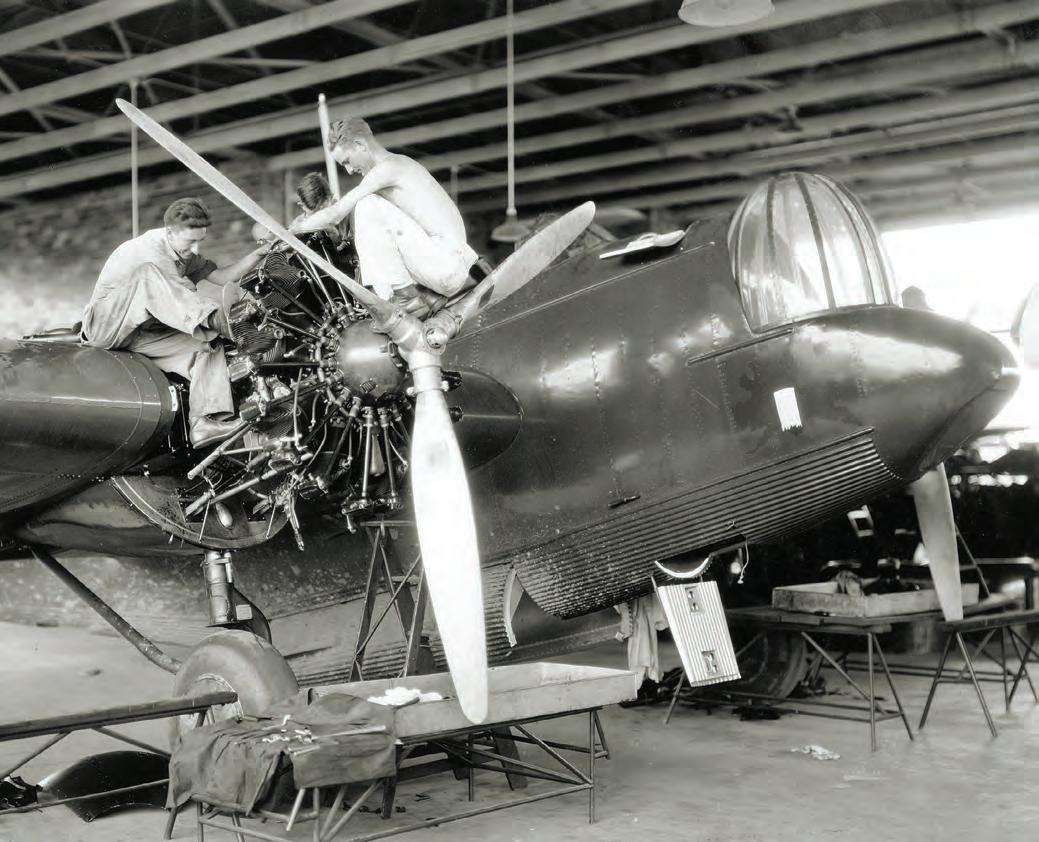

But I am usually gazing into my computer screen as I use the library’s online resources to help photo editor Guy Aceto get historic photographs for Aviation History. There must be hundreds of thousands of them online. Sometimes, though, you do have to visit the physical library to download high-resolution versions. And there is one other drawback: quite often the information about the photos is lacking. For example, we recently used an LOC image of the Curtiss NC-4 (above right), the first airplane to cross the Atlantic, in the magazine’s newsletter. (Do you subscribe to the newsletter? Why not? It’s free. Just go online to historynet.com and click on “Newsletters.”) The library’s identifier for the photo-

graph was simply “Amphibious Airplane.” I once came across an image that had a similarly generic identification, something like “Seaplane on the Anacostia River.” Closer inspection revealed it to be a photograph of Charles Lindbergh and his wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, sitting in the Lockheed Model B Sirius seaplane that they were using to make a flight to China in 1931. (The photo’s description was so obscure that I can no longer find the image, but trust me, it’s on the LOC website someplace.)

Just the other day I was looking through some photos I downloaded during a visit to the library last fall. One of them was identified by a single word—“Airplane”—and dated 1934. As I looked closer, I realized this photo (above left) showed Lt. Col. Henry “Hap” Arnold, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s son, James, and a woman I assume to be James’ wife, Betsey. They are standing in front of one of the Martin B-10 bombers that Arnold was preparing to lead on an epic flight to Alaska and back in 1934. (You can read all about the flight starting on page 26.)

The image is part of the Harris & Ewing Collection, from a Washington, D.C.-based photo agency founded by George W. Harris and Martha Ewing that began operations in 1905. After the agency closed shop in 1945, it donated its photos to the library, which has around 70,000 of them. Some 41,000 are from glass negatives, like this one. (You can see that a portion of this negative had broken off.)

The point of this story is that you never know what you might find when you search for Library of Congress images. In fact, if you have time on your hands, go to the library’s website (loc.gov) and do your own search. Use any keyword you like: aviation, airplane, pilot. And if you find something really interesting, tell us about it.

24 AUTUMN 2023 PHOTOS: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; PORTRAIT: PATRICK WELSH

Left: General Henry A. “Hap” Arnold shows off a Martin B-10 bomber to James and Betsey Roosevelt. The Library of Congress’ identification for this photo was simply “Airplane.” Above: The Curtiss NC-4 flying boat, a.k.a. “Amphibious Airplane.”

AVHP-231000-COCKPIT.indd 24 6/20/23 11:46 AM

Tom Huntington

The Day the War Was Lost It might not be the one you think Security Breach Intercepts of U.S. radio chatter threatened lives 50 th ANNIVERSARY LINEBACKER II AMERICA’S LAST SHOT AT THE ENEMY First Woman to Die Tragic Death of CIA’s Barbara Robbins HOMEFRONT the Super Bowl era WINTER 2023 WINTER 2023 Vicksburg Chaos Former teacher tastes combat for the first time Elmer Ellsworth A fresh look at his shocking death Plus! Stalled at the Susquehanna Prelude to Gettysburg Gen. John Brown Gordon’s grand plans go up in flames MAY 2022 In 1775 the Continental Army needed weapons— and fast World War II’s Can-Do City Witness to the White War ARMS RACE THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MILITARY HISTORY WINTER 2022 H H STOR .COM JUDGMENT COMES FOR THE BUTCHER OF BATAAN THE STAR BOXERS WHO FOUGHT A PROXY WAR BETWEEN AMERICA AND GERMANY PATTON’S EDGE THE MEN OF HIS 1ST RANGER BATTALION ENRAGED HIM UNTIL THEY SAVED THE DAY JUNE 2022 JULY 3, 1863: FIRSTHAND ACCOUNT OF CONFEDERATE ASSAULT ON CULP’S HILL H In one week, Robert E. Lee, with James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson, drove the Army of the Potomac away from Richmond. H THE WAR’S LAST WIDOW TELLS HER STORY H LEE TAKES COMMAND CRUCIAL DECISIONS OF THE 1862 SEVEN DAYS CAMPAIGN 16 April 2021 Ending Slavery for Seafarers Pauli Murray’s Remarkable Life Final Photos of William McKinley An Artist’s Take on Jim Crow “He was more unfortunate than criminal,” George Washington wrote of Benedict Arnold’s co-conspirator. No MercyWashington’s tough call on convicted spy John André HISTORYNET.com February 2022 CHOOSE FROM NINE AWARD - WINNING TITLES Your print subscription includes access to 25,000+ stories on historynet.com—and more! Subscribe Now! HOUSE-9-SUBS AD-11.22.indd 1 12/21/22 9:34 AM

NORTH TO

XXXXXXXXXX

26 AUTUMN 2023

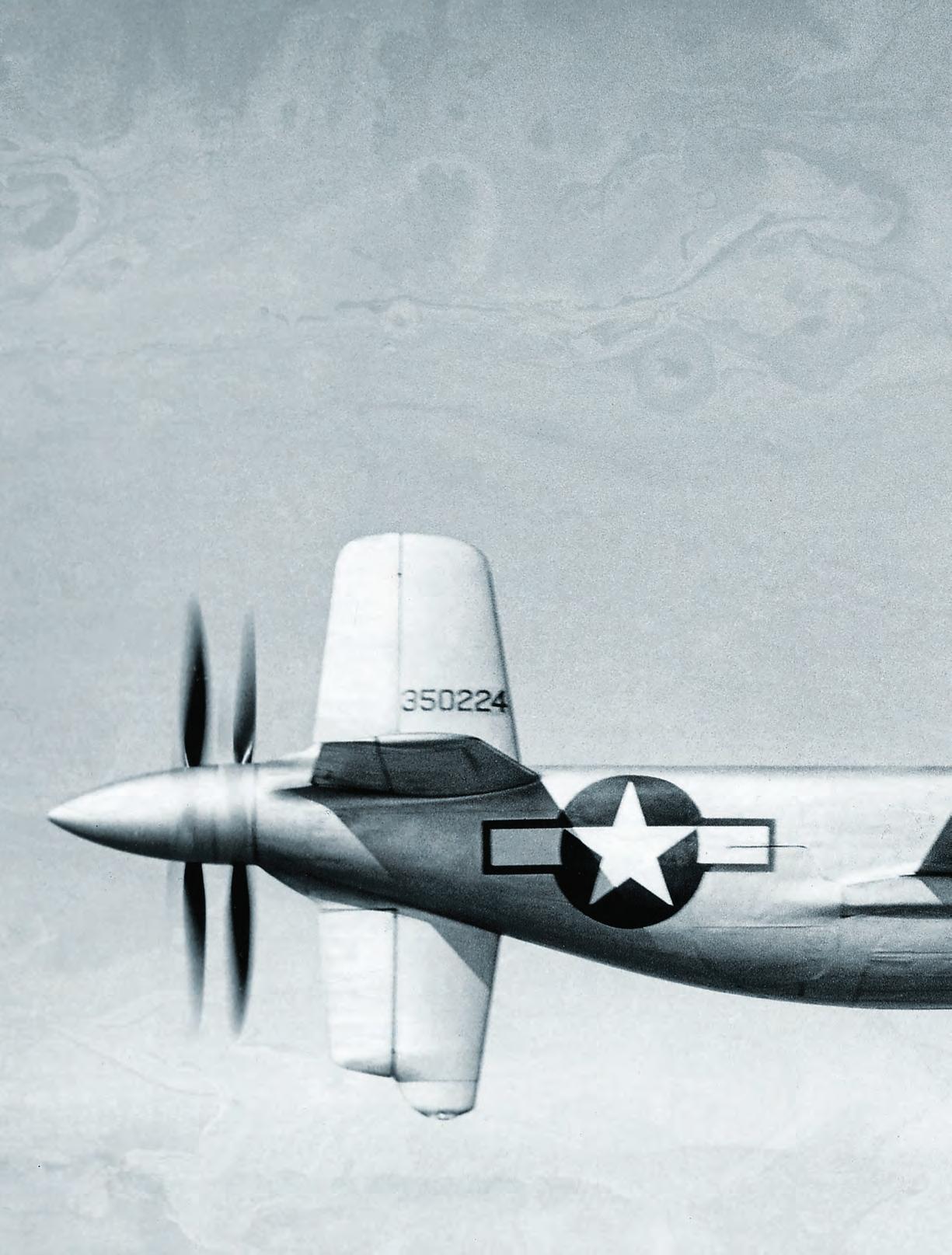

One of the ten B-10s from the 1934 Alaskan flight cruises above the northern territory in an illustration by Ron Cole. Commanded by Lt. Col. Henry “Hap” Arnold, the mission was intended to add some luster to the U.S. Army Air Corps’ tarnished reputation.

AVHP-231000-ALASKAB10S.indd 26 6/20/23 6:41 PM

TO ALASKA

IN 1934, AN OFFICER NAMED HAP ARNOLD ESTABLISHED HIMSELF AS A RISING STAR IN THE ARMY AIR CORPS BY LEADING A REMARKABLE 8,290-MILE ROUND TRIP

BY DAVE KINDY

XXXXXXXXXX

AVHP-231000-ALASKAB10S.indd 27 6/20/23 6:42 PM

The date was set and preparations were underway. It would be a challenging mission, especially for 1934—a roundtrip flight from Washington, D.C., to Alaska with 10 of the Army Air Corps’ newest bombers, the Martin B-10. If successful, it could provide the air service with some much-needed positive news following an airmail fiasco from the previous winter, while also providing photo-reconnaissance of what was becoming recognized as a strategically important territory.

Lt. Col. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold would lead the mission. He had been taught to fly by the Wright brothers and was one of the world’s first military pilots. Later Arnold would be remembered as “the father of the Air Force” and his leadership of this difficult assignment foretold his future as commanding general of the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II. “Arnold was a visionary,” says Dik A. Daso, author of Hap Arnold and the Evolution of American Airpower and Architects of American Air Supremacy. “He had a way of seeing the technology and recognizing what it was capable of, then compelling his people to do it. You see that time and time and time again.”

The operation also focused attention on junior officers who would also play important roles in the approaching global conflict. These men—Ralph Royce, Malcolm Grow, Harold McClelland and others—flew the airplanes, led photo-reconnaissance missions, coordinated logistics and handled other key assignments. Many were later promoted to crucial commands as

Hap Arnold (standing fifth from left) was a rising star in the Army Air Corps. Flight surgeon Major Malcolm Grow stands third from left with executive officer Hugh Knerr to his left. Major Ralph Royce stands to Arnold’s left. Communications officer Harold McClelland kneels second from left.

America fought the air war across Europe and the Pacific. According to a 2011 Air Power History article by Kenneth P. Worrell, the Alaskan flight “brought together a select group of airmen who in a few short years would rise to top air force leadership roles during World War II.”

By the summer of 1934, the Army Air Corps was desperate for positive publicity. Earlier that year, a scandal had erupted over airmail contracts awarded during President Herbert H. Hoover’s administration. The new president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, canceled those contracts and ordered the Air Corps to fly the mail until the government negotiated new agreements with the airlines. That effort was a disaster, serving only to

28 AUTUMN 2023 PREVIOUS SPREAD: RON COLE; ABOVE: NATIONAL ARCHIVES TOP: NATIONAL ARCHIVES; MAP BY BRIAN WALKER

AVHP-231000-ALASKAB10S.indd 28 6/20/23 6:42 PM

expose the Air Corps’ inadequacies. Most of the aircraft it flew were antiquated World War I bombers that lacked the rudimentary communication and navigation technology necessary to deliver the mail. Much of the flying happened after dark and during the extreme weather conditions of a harsh winter. Absent adequate avionics and pilots skilled in nighttime flying, the Air Corps suffered a series of tragic mishaps. In less than two months, Army aircraft had 66 major accidents—resulting in the deaths of 13 crewmembers. By the time private carriers resumed flying the routes that spring, the Air Corps’ reputation had suffered severe damage. Congress launched an investigation and called General Benjamin Foulois, chief of the Air Corps, and Lt. Col. Oscar Westover, the assistant chief of the air wing, to testify.

To recover from the debacle, the Air Corps brass decided to undertake a daring 8,290-mile roundtrip flight from Bolling Field in Washington, D.C., to Fairbanks, Alaska. In 1934, the American territory—not yet a state—seemed impossibly remote. Fairbanks was about 2,000 miles away from Seattle, Washington, and there were few transportation options to reach any point in Alaska. No highways connected this faraway land to the rest of the United States and just a few rail lines reached it via Canada. Of course, in 1934 nonstop air flights from the con tinental United States would have been difficult and dangerous.

At the time, many Americans viewed Alaska as a remote backwater with little strategic importance. One who did not was airpower advocate Billy Mitchell. In 1935, the former col onel would address Congress about the territo ry’s value. “I believe that in the future, whoever holds Alaska will hold the world,” he said. “I think it is the most important strategic place in the world.”

In addition to focusing America’s attention on Alaska, the mission would showcase the Air Corps’ newest bomber: the Martin B-10. Looking like something out of a “Flash Gordon” comic, the oddly shaped aircraft sported green house-like canopies and a bulbous nose jutting out beneath a glass-enclosed gun turret. It may have looked unusual, but the B-10 represented a revolution in aviation design. It was a huge leap forward from the Army’s existing biplane bomber, the lumbering Keystone LB series that had entered service after World War I. A mono plane with an all-metal airframe and a crew of three, the B-10 had an enclosed cockpit and rotating gun turret, and its twin 775-hp Wright

General Hap Arnold’s Journey Creating America’s Air Force , Robert Arnold, Hap Arnold’s grandson, notes the significance of the

29 AUTUMN 2023 PREVIOUS SPREAD: RON COLE; ABOVE: NATIONAL ARCHIVES TOP: NATIONAL ARCHIVES; MAP BY BRIAN

WALKER

WASHINGTON DAYTON MINNEAPOLIS WINNIPEG EDMONTON HAZELTON WHITEHORSE FAIRBANKS CANADA UNITED STATES PRINCE GEORGE REGINA AVHP-231000-ALASKAB10S.indd 29 6/20/23 6:42 PM

B-10’s advances. “At last, the Air Corps had a sleek, streamlined, 200-mile-per-hour, midwing monoplane that could really get up and move,” he recalls his father, the late Col. W. Bruce Arnold of the Air Force, as saying. “By God it was metal. It had retractable landing gear. Basically, it was a junior version of the B-17 yet to come. It was the whole future of Army Air Corps aviation right there in one airplane.”

The future did take some getting used to, though. Two of the Army airplanes that crashed delivering the mail were XB-10s, accidents that happened because the pilots forgot to lower the retractable landing gear.

The plans for the Alaska trip called for 10 B-10s to make the flight, with stops in Dayton, Ohio; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and the Canadian cities of Winnipeg, Manitoba; Regina, Saskatchewan; Edmonton, Alberta; Prince George and Hazelton, British Columbia; and Whitehorse, Yukon. Initially, Westover was sup-

posed to lead the mission, but he had to remain in Washington to deal with Congress in the wake of the airmail issues. So, in June 1934, Colonel Arnold was on his way to Wyoming for a fishing trip with his wife when he received orders to return to Washington and take charge of the Alaska flight. The last-minute notice, Arnold later commented, created “a great deal of unnecessary worry, labor and money. Months of warning should have been given to responsible authority instead of a few days.”

In some respects, Arnold was a surprising choice as commander. On one hand, he was a respected military pilot with a solid record of success as an administrator in various Air Corps departments, as well as a commander of March Field in California. Arnold had won the very first Mackay Trophy for “most outstanding military flight of the year” in 1912 for a successful air reconnaissance mission he flew despite turbulent conditions. However, he had also run afoul of military brass as an acolyte of Billy Mitchell, who had been court-martialed in 1925 after accusing his superiors of “treasonable negligence” in the management of their duties. Arnold had testified for Mitchell at the court-martial and the Army responded by angrily packing him off to a post in the backwater of Fort Riley, Kansas. In the years since, Arnold had managed to prove his worth to Foulois and Westover, who saw his value as a leader and planner.

Indeed, the new mission commander immediately found himself drawn into a maelstrom of preparation and planning. “Arnold had experience in logistics from World War I,” says Daso, who is also executive director of the Air Force Historical Foundation. “He understood that a lot of calculations needed to be made in advance. He was the intellectual power behind the logistical deployment of all the supplies they were going to need for the flight.” Those supplies included making sure there was plenty of fuel, oil, spare parts and other materiel necessities for the airplanes and crews.

Arnold soon realized the intended start date of July 10 did not leave him enough time to prepare. He postponed the takeoff date. Foulois, his boss, was not pleased. Arnold stuck to his decision, writing to his wife, Eleanor “Bee” Arnold, that “I was holding the sack with regards to safety, hazard, success and risk. I in turn told them I would not say when I would start on the flight until the planes were ready.”

The trip was complicated by a longshoremen’s strike on the West Coast, which would

30 AUTUMN 2023 BOTH: NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES

AVHP-231000-ALASKAB10S.indd 30 6/20/23 6:42 PM

Top: Arnold strikes a pose for photographers in the cockpit of the lead B-10. Above: One notice pilots saw on their instrument panels was a reminder to lower the gear before landing. Two B-10s flying the mail had come to grief because their pilots had forgotten this important step.

hinder the delivery of supplies to Alaska. Canadian rail services couldn’t handle it all, so Arnold had to arrange additional sea transport. The U.S. Navy wasn’t inclined to assist its rival branch, so the Army located an old barge that could carry half the fuel.

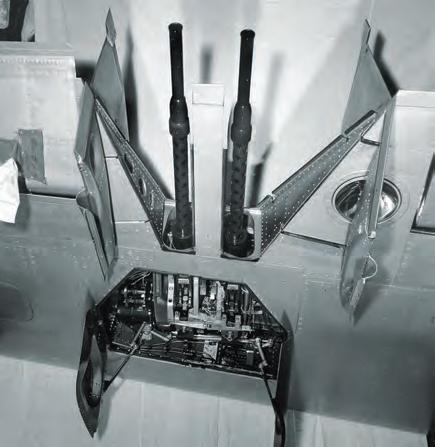

In the meantime, departure was delayed by the installation and testing of new radios for the B-10s. The delay was worth it because the new equipment demonstrated just how important technology was for the future of flight. “This is the first distance flight where radio contact is maintained with the ground for the entire time,” Daso says. “It’s a gamechanger in avionics.”

The original plan called for 20 officers and 10 enlisted men. Realizing the need for ongoing maintenance, Arnold changed the roster to 14 and 16, respectively. “I prefer mechanics to joy riders,” he told Westover. Also, four officers and four enlisted men would support the fliers from four Douglas O-38 observation airplanes while an advance team of four went ahead to Alaska. The B-10s received extra fuel tanks to extend their range from 1,240 miles to 1,370, and were

outfitted with cameras so they could conduct reconnaissance operations over Alaska.

The mission roster included a long list of future World War II aviation leaders. Operations officer Major Ralph Royce would go on to lead the very first bombing mission against the Japanese in the Philippines; communications and meteorological officer Captain Harold M. McClelland became known as the “father of Air Force communications”; and executive officer Major Hugh J. Knerr later ensured that U.S. forces had adequate supplies of bombs and bombers in Europe during the war. “A whole bunch of general officers pop out of this flight,” Robert Arnold says. “Typical of Hap, he begins accumulating them along the way so they can play major roles for him later.”

Arnold also added Major Malcolm Grow as flight surgeon. He wanted the experienced military doctor along to make sure the men were handling the stress of the arduous journey. In addition, Grow had served in Alaska as post surgeon at Chilkoot Barracks from 1925 to 1927. During World War II, Grow received credit for

31 AUTUMN 2023

BOTH: NATIONAL ARCHIVES NATIONAL ARCHIVES

THE MISSION ROSTER INCLUDED A LONG LIST OF FUTURE WORLD WAR II AVIATION LEADERS.

AVHP-231000-ALASKAB10S.indd 31 6/20/23 6:42 PM

The ten B-10s wait wingtip-to-wingtip before departing from Bolling Field. The Douglas O-38 observation aircraft that will accompany the bombers are at the end of the line.

developments that helped save the lives of bomber crews, including a new lightweight body armor. He later became the first surgeon general of the U.S. Air Force.

Arnold felt confident that he would be ready for a July 19 departure from Washington, D.C. That day, after ceremonies attended by Foulois and Elliott Roosevelt, one of the president’s sons, the B-10s left Bolling Field for Alaska. With Arnold at the controls of the lead bomber, the airplanes began roaring down the runway and taking to the air at 10:01 a.m. All 10 aircraft made a pass over Washington, D.C., then headed west for Dayton for refueling before traveling to Minneapolis for the first overnight stay.

The mission encountered problems almost immediately. Two of the Martins had mechanical difficulties and turned back for repairs. They caught up with the rest of the squadron in Minnesota later that same day. The rest of the flight went according to plan, except for an added day in Edmonton that Arnold ordered so maintenance crews had plenty of time to do necessary work. The only downside, at least according to the squadron commander, were the crowds gathered at each stop to see the unusual airplanes and the men flying them. “I’m getting goodwilled to death,” Arnold wrote in a letter to his wife.

On July 24, the squadron landed in Fairbanks, where the mayor declared a two-day holiday in honor of the mission and presented Arnold with the key to the city. After a series of celebrations, the aircrews got down to the business of

32 AUTUMN 2023 TOP: NATIONAL ARCHIVES; BOTTOM: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE U.S. AIR FORCE NATIONAL ARCHIVES

AVHP-231000-ALASKAB10S.indd 32 6/20/23 6:43 PM

The Alaskan flight flies in formation on the first day of the flight. Below: As one of Grow’s journal entries indicates, the mission ran into early difficulties when two of the airplanes experienced engine trouble. After repairs, they caught up with the rest of the flight at the first overnight in Minneapolis.

photographing Alaska from the sky. There was only one glitch during the threeweek stay in the northern territory. On August 2, two B-10s and two of the O-38 support aircraft were in Anchorage on a goodwill mission and to conduct photo reconnaissance. A pilot from one of the Douglas airplanes was at the controls of one of the bombers, which he had only flown a few times, and he turned a fuel valve in the wrong direction, causing the engines to quit on takeoff. (Arnold had committed the same error earlier in the journey, but at a higher altitude that allowed him to recover in time.) The B-10 made a forced landing about 100 feet from the shore in Cook Inlet. There was no major damage, except for immersion in the ocean. “We are salvaging the plane now,” the squadron commander wrote to Bee. “However, I doubt if the plane will ever be used again on account of the salt water bath.”

The extra mechanics Arnold brought with

him saved the day. They had the bomber back in service within a few days after salvaging it and rebuilding the engines. “They are a mighty fine bunch,” Arnold said proudly of his enlisted men.