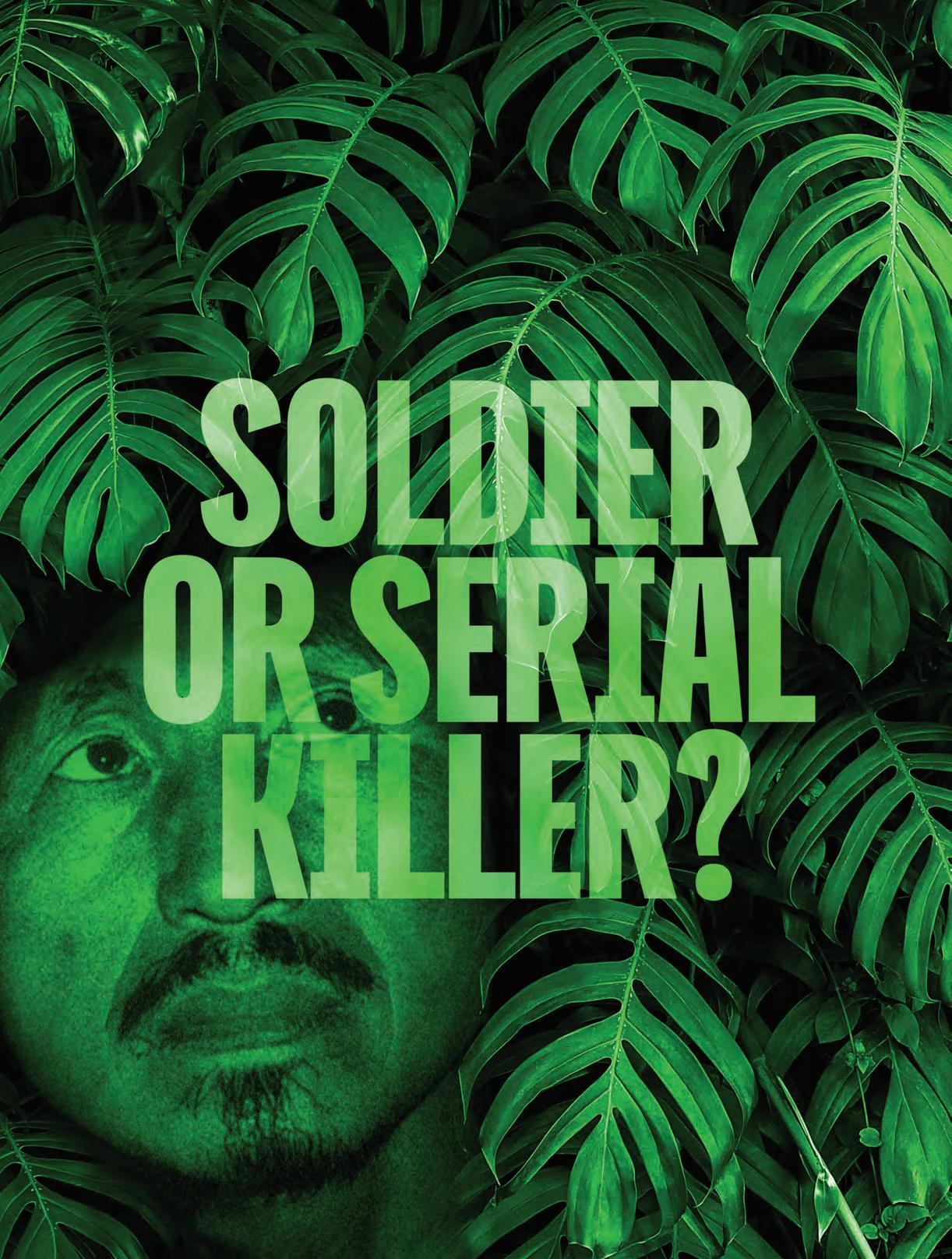

Rise of an Irish Special Forces Hero

Stonewall Jackson’s Dangerous Escape

Rise of an Irish Special Forces Hero

Stonewall Jackson’s Dangerous Escape

Hiding in the Philippines for 29 years, Japan’s famed WWII holdout left a trail of death

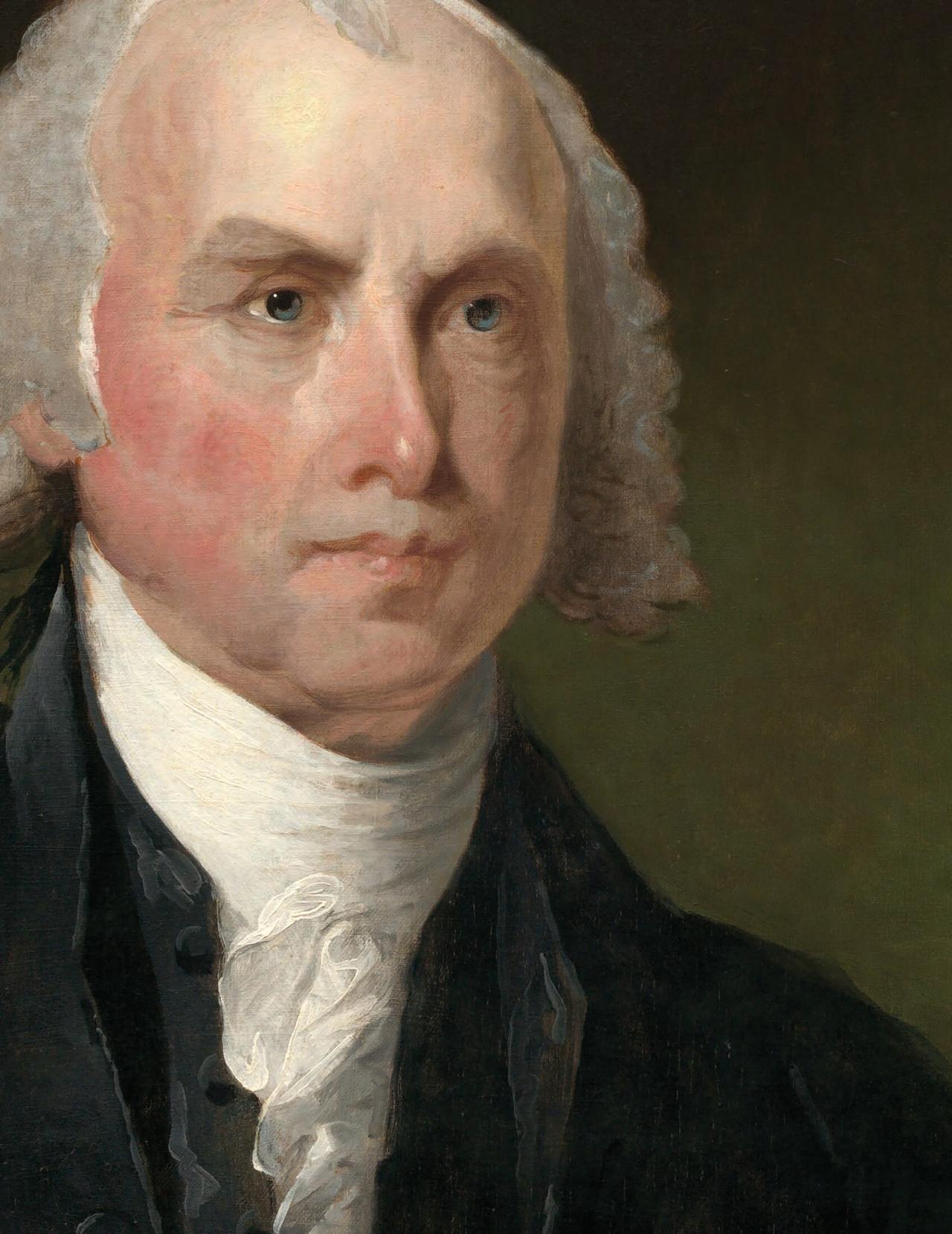

AUGUST 26, 1814

BROOKEVILLE, MARYLAND, BECOMES

“U.S. CAPITAL FOR A DAY” WHEN PRESIDENT JAMES MADISON TAKES REFUGE THERE.

EARLIER THAT WEEK, BRITISH TROOPS

HAD SET FIRE TO WASHINGTON, INCLUDING THE WHITE HOUSE AND CAPITOL BUILDING. MADISON FLED THE CITY, ALONG WITH MEMBERS OF HIS CABINET, AND SPENT THE NIGHT OF THE 26TH AT THE HOME OF BROOKEVILLE POSTMASTER CALEB BENTLEY. THE TOWN STILL CELEBRATES THE EVENT EACH YEAR.

For more, visit HISTORYNET.COM/TODAY-IN-HISTORY

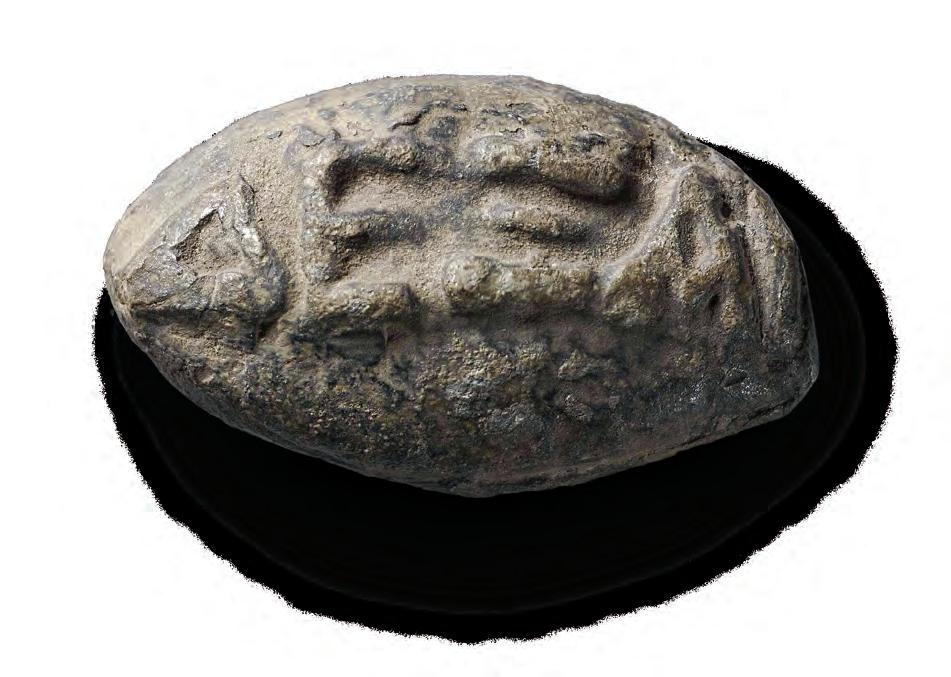

The history of bullets predates firearms by thousands of years. Bullets of many materials, even including lead, were used throughout the ancient and classical worlds by highly trained, deadly soldiers. Although the term conjures up images of suburban pranksters today, back then the “sling” was among the most feared weapons.

A sling would generally be as simple as two lengths of cord attached to a leather ammunition pouch. Slingers held both cords and spun the sling in a circle, generating centrifugal force, before letting one cord go with precise timing, sending the sling bullet flying. Different lengths of cord or release times could produce different speeds and ranges, and early slings are recorded as firing faster and farther than bows of the time. The current Guinness World Record for firing a sling bullet sits at 477 meters (about 1,565 feet), a distance reported as common by classical writers. The famed Welsh longbow, on the other hand, rarely exceeded 400 meters.

The earliest written description of the use of a sling as a weapon is the famous fight between David and Goliath in the Book of Judges. Goliath, described as a giant armored warrior, was challenged by David, a young Israelite shepherd. The sling was a common weapon used by shepherds to scare off predators, owing to its simple construction. The young David fired a single stone that struck Goliath’s forehead, killing him instantly.

Though David’s underdog victory is treated as unlikely by modern audiences, maybe we give the slinger too little credit. According to the fourth century bce Roman writer Vegetius, “Soldiers, despite their defensive armor, are often more aggravated by the round stones from the sling than by all the arrows of the enemy. Stones kill without mangling the body, and the contusion is mortal without loss of blood.”

The value of slingers is evident in the craftsmanship of lead bullets like this one, produced in Athens some time after 400 bce. One side bears the image of a winged thunderbolt, while the other features the Greek word “Dexai,” or “Catch!” Taunting messages like this were not uncommon on ammunition—a tradition soldiers across the world have kept alive ever since.

A bronze copy of the ancient Roman sculpture known as the Winged Victory of Brescia stands atop a World War I ossuary in the Passo del Tonale of Italy’s Rhaetian Alps. This is one of many remarkable scenes captured by photographer Attila SzalayBerzeviczy for his two-volume book series, “In The Centennial Footsteps of the Great War,” showcased by MHQ

A documentary filmmaker on the trail of Japan’s most famous World War II holdout details his killing of civilians.

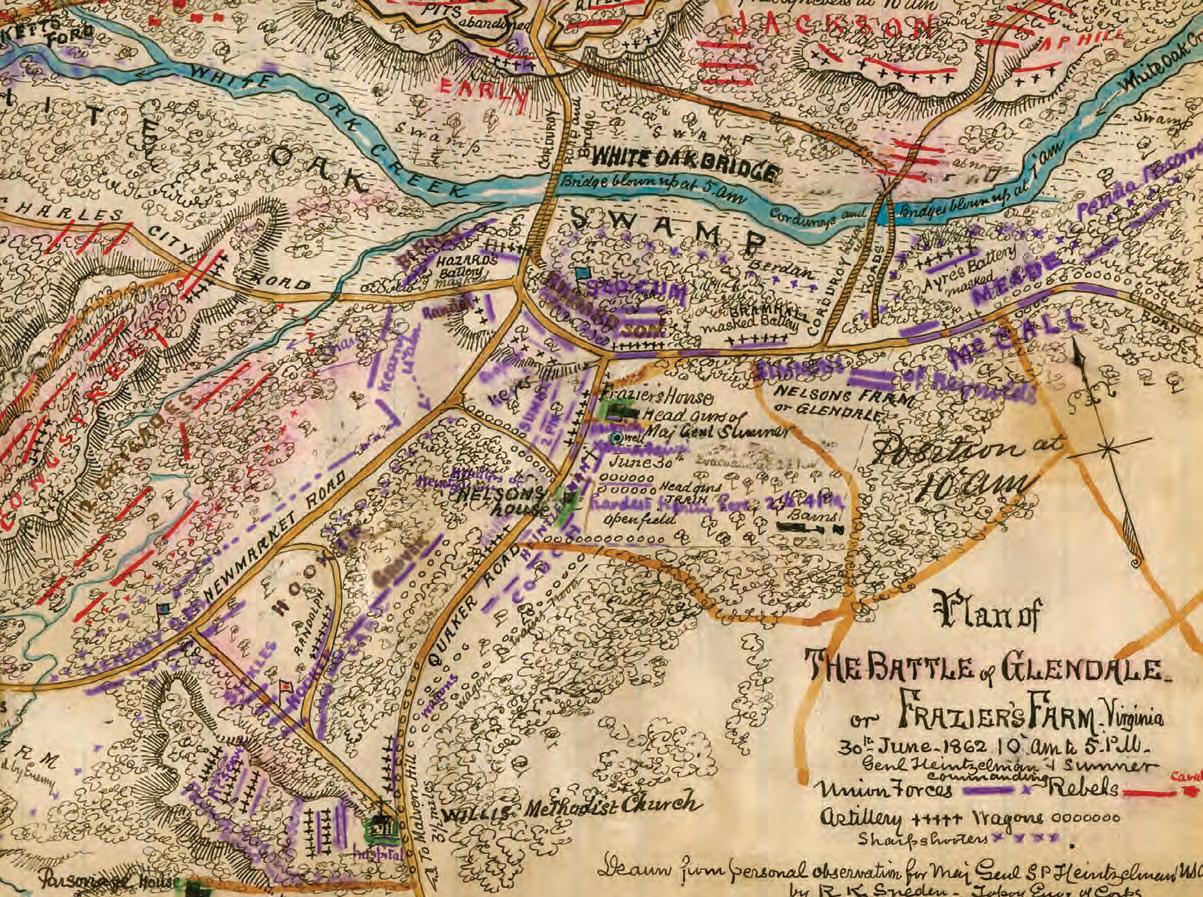

How a Union cavalry force separated Stonewall Jackson from his staff and gave him quite the run for his money.

He was a middle-class Irishman. His commander was an aristocrat. Only one of them would rise to greatness as a leader of World War II Special Forces in combat.

PORTFOLIO Photographer and adventurer Attila Szalay-Berzeviczy takes readers on a haunting visual world tour of World War I.

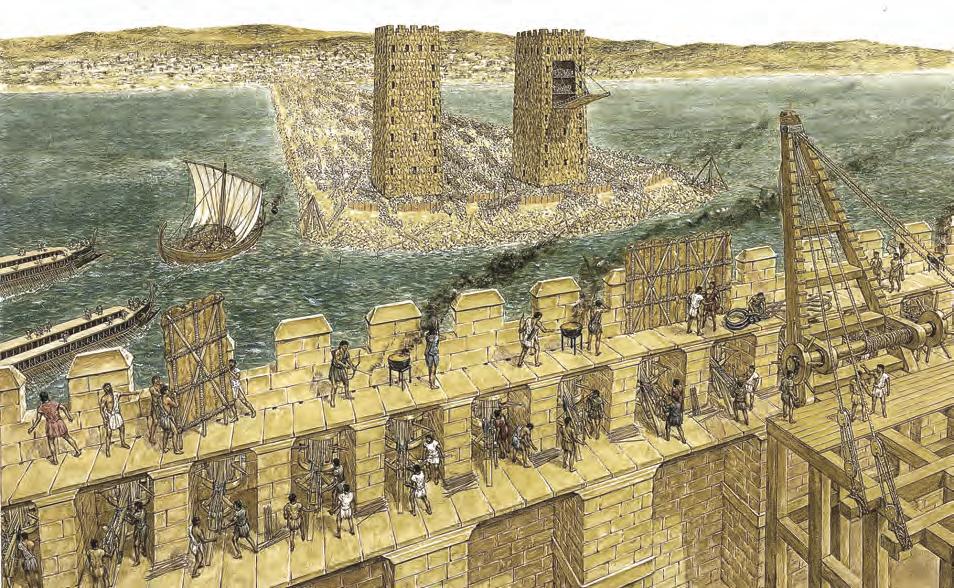

The sea had long protected the city of Tyre from invading forces. But Alexander the Great had other plans.

Three rival kingdoms on the Korean peninsula struggled for power in a high-stakes chess game of battle and wars.

6 Flashback

12 Comments

15 At the Front

16 Laws of War

Japan’s Enemy Airmen’s Act

19 Battle Schemes

World War I in the Alps

20 Experience

Between suicide and capture

24 Behind the Lines

Ancient Persia’s roads of war

26 War List

History’s least violent conflicts

31 Weapons Check

The Uzi submachine gun

32 Letter From MHQ

85 Culture of War

86 Classic Dispatches

Rome’s revenge on the Rhine

90 War Stories

First Jewish American MOH

94 Reviews

Caesar’s civil war

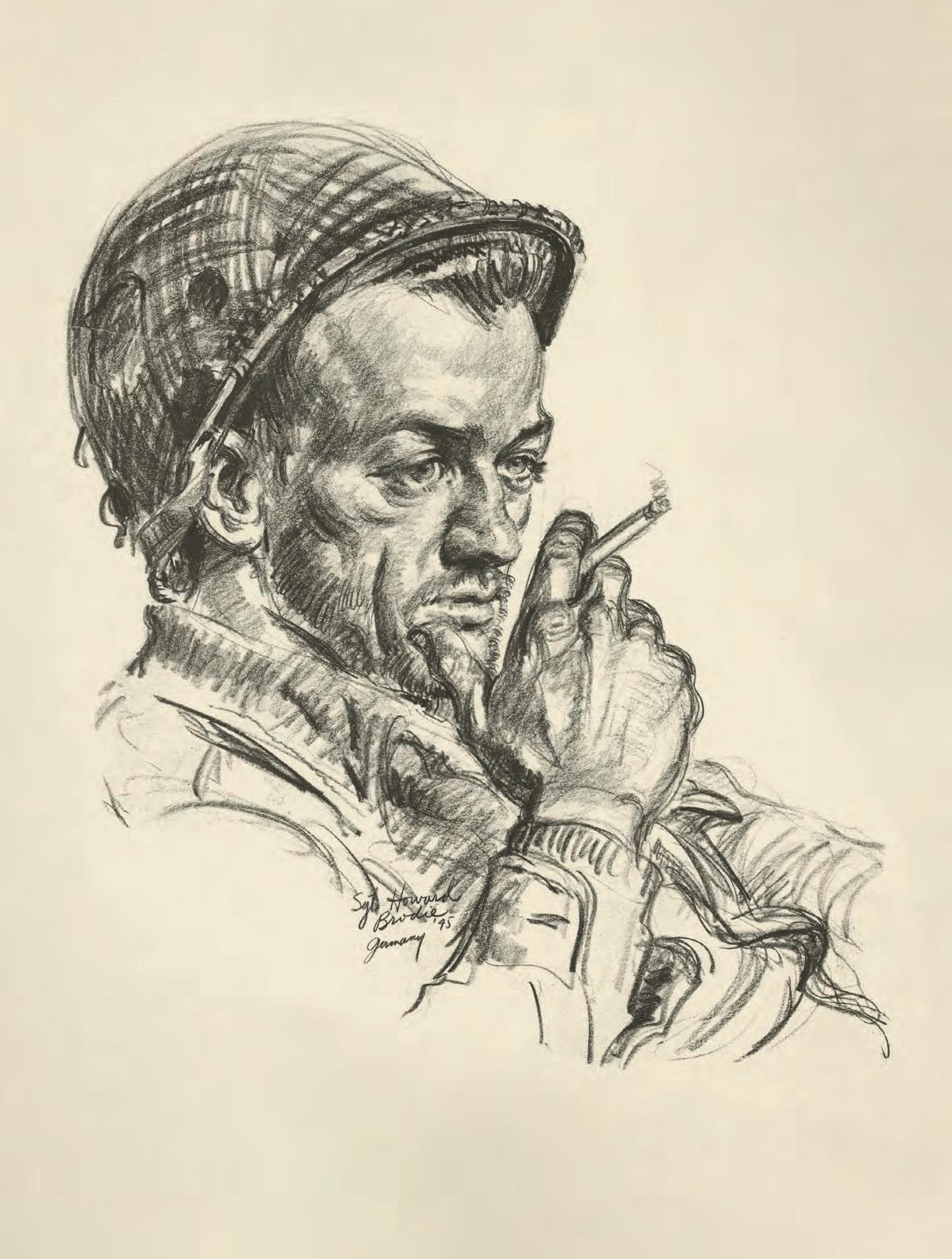

96 Faces of War

U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Elwin Miller

On the Cover

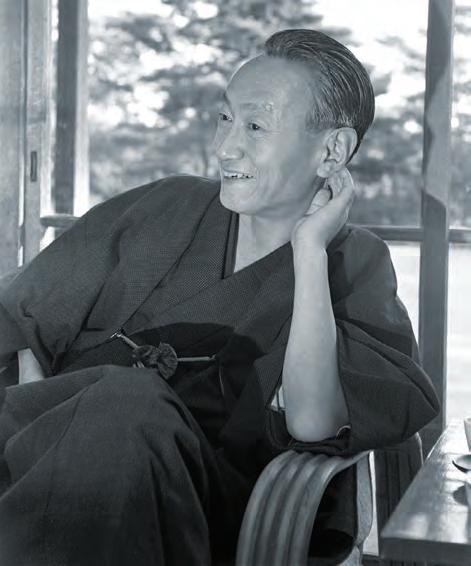

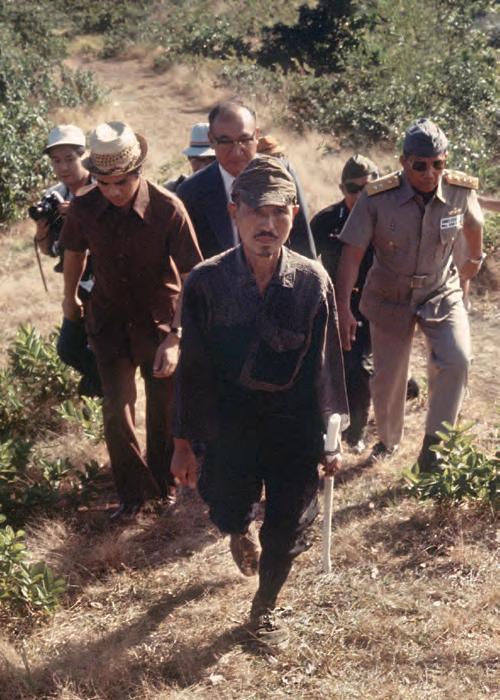

Hiroo Onoda, deployed to the Philippines as a soldier in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II, hid in the jungles of Lubang Island from 1945 until 1974. His story of “no surrender” made him a hero in Japan and something of a pop culture icon. But many Filipino civilians lost their lives at Onoda’s hands.

a light on these brutal killings.

Parliamentarians and Royalists clash in England’s bloody Civil War which would see the rise to power of Oliver Cromwell and the infamous beheading of King Charles I. TODAY: Archaeologists excavating a site in Warwickshire, England in 2023 near the Civil War’s first battle site discover a bullet-riddled gatehouse and evidence suggesting a previously unknown Civil War skirmish.

British forces are soundly defeated by a force of about 20,000 Zulu warriors led by King Cetshwayo at Isandlwana during the first battle of the Anglo-Zulu War. TODAY: Thousands of members of the Zulu nation recreate the events of the battle in South Africa alongside British reenactors in a commemoration of the historic victory anniversary, with the current Zulu king among guests.

Benjamin Ferencz, left, Chief Prosecutor for the United States, presents evidence against Nazi war criminals of the SS Einsatzgruppen mobile death squads during their war crimes trial in Nuremberg’s Palace of Justice. TODAY: After a long career pursuing human rights and criminal justice, Ferencz, the last surviving Nuremberg Trials prosecutor, is awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in January 2023 at age 102.

Grant, so I was inspired to read more about him. Mosby seems politically complicated. He claims to have hated slavery, but owned a slave? He felt it was his duty to fight for the south, but he always believed the war was about slavery? His men executed captured Union soldiers, but only in retaliation? I wonder if Mosby was truly so principled during his guerrilla operations, or if former Confederates only grew a conscience after the war ended.

Lars Ostbrook, Bethesda, Md.

I loved learning about animals in war (“Animal Healers,” Winter 2023 issue) and seeing their pictures. They are heroes too. I also liked reading the Letter from MHQ about war’s effect on nature. War is so destructive and can make people, plants and animals suffer for generations. The stories are very dynamic and bring up so many different facets of war. Kudos to the new editor!

B.J. Collins, Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

I lived in Northern Virginia for a good while, where a lot is named after Colonel John Mosby, but I thought of him as purely a southern bandit. In “To Catch the Gray Ghost” in the Winter 2023 issue, I was surprised to learn that after the war, Mosby became a Republican, and campaign manager for General

Have thoughts about a story in MHQ?

Something about military history you’ve always wanted to know?

Send your comments and questions to

mhq@historynet.com

I enjoyed the crazy gadgets in the Winter 2023 article “Devices of Deception.” It reminded me of the 1960s TV show Get Smart. I feel like TV and movies make us nostalgic for the low point of spying—Cold War espionage sure was secret, but it was just as often clumsy, ineffective, or wrong-headed on both sides. For real behind-the-lines heroes, with useful gadgets and techniques, look no further than the OSS or SOE of WWII. Then again, it’s not like clumsy Cold War spy work ever stopped. Just look at Russia’s bold-faced assassinations, or China’s weirdo balloon. Who knows what kind of hare-brained spy work is going on right now that we don’t know about?

Garth Morley, Chattanooga, Tenn.

What actually started the Spanish-American War? What were the reasoning and objectives behind it?

Geoffrey A. Walker, Worcester, Mass.

By 1825 the once-intercontinental empire of Spain had declined to the point that its mainland colonies had achieved independence, leaving it only strategic island possessions, including the Philippine, Mariana, Caroline and Marshall islands, Puerto Rico and Cuba. By the 1890s independence movements were challenging Spanish rule in the Philippines and Cuba. Concurrently, the United States had

achieved its self-proclaimed “Manifest Destiny” by expanding its borders from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean—and faced the question of whether or not it should extend its sphere of influence beyond the Western Hemisphere. As the country’s trade expanded, the perceived threat from growing rival powers such as Germany or Japan made control of naval coaling stations increasingly desirable.

In February 1895 a guerrilla war for independence broke out in Cuba, to which the Spanish commander, Gen. Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, responded with a mass population “reconcentration” and other draconian measures that raised worldwide revulsion (although the British would soon be using

concentration camps of their own on the South African Boers). Widespread American sympathy for the Cuban cause was intensified by the media—essentially Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst trying to outsell each other—although the presidency of William McKinley represented a widespread sentiment toward avoiding war with Spain. More on the material side was the 50 million dollar investment that American companies had in Cuba’s sugar crop.

This political standoff was dealt a decisive blow when the U.S. Navy battleship Maine visited Havana Harbor and blew up on the night of Feb. 15, 1898. The cause remains in dispute, but on March 28 a U.S. Navy court of inquiry declared it the result of an underwater mine exploding from outside and setting off Maine’s magazine. Over the following weeks, “Remember the Maine, to hell with Spain,” typified the popular mantra. On April 21 McKinley ordered a naval blockade around Cuba and on the 25th Congress declared war on Spain. Its ultimate outcome would be a coup de grâce to Spain as a global power and a turning point in the United States’ evolution into one, as it came away with control over Cuba and possession of Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam. To that would be added Hawaii, which the United States annexed on July 7 of that same year.

How often have there been conflicts like Vietnam and Afghanistan, in which one side won virtually all the battles, but ended up losing the war?

James Conway, Bedford, Pa.More often than you may realize. As long as there have been armies there has been a difference between a tactical victory, taking an immediate objective, and a strategic victory, which involves achieving the war’s ultimate goal.

An ancient classic is Cannae, Hannibal Barca’s tactical masterpiece, on Aug. 2, 216 bce. His double envelopment and annihilation of 48,500 Romans, as well as 19,300 captured, against 5,700 Carthaginians killed, is still studied today. Yet it failed in its most important strategic mission. Although shaken, Rome refused to discuss peace and simply scraped together another army—making it clear to other kingdoms on the Italian peninsula that allying with Carthage would still be a bad

idea. Eventually the Romans found a general capable of matching Hannibal. Publius Cornelius Scipio brought them victory at Zama on Oct. 19, 202 bce

A more recent and bizarre example would be the invasion of British North America by the Irish Brotherhood, or Fenians, with the objective of seizing the Niagara Peninsula to be ransomed back for an independent Irish republic. The only real battle, at Ridgeway in 1866, was handily won by the invaders, most of whom were seasoned Civil War veterans facing inadequately trained Canadian militia. They still ended up having to withdraw from their untenable position—to be arrested by U.S. authorities for violating the Neutrality Laws.

Arguably the most forgotten comparison of strategy and tactics hides amid the American War for Independence. Gen. George Washington and his Continental Army lost most of their battles and only won four outright (Boston, Trenton, Princeton and Yorktown), but they were the right ones at the right time. The ultimate outcome showed that Washington, learning from experience as he went, had evolved into a superb grand strategist. The same could be said of the disciple he detached to retake control of the south, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, who also lost most of his battles but who, like Washington, did not defeat his enemy so much as wear him down. Or as Greene himself said in an analysis that the North Vietnamese Army or the Taliban might have recognized: “We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again.”

Jon Guttman is MHQ’s Senior Editor.

Jon Guttman is MHQ’s Senior Editor.

ZITA BALLINGER FLETCHER EDITOR

JON GUTTMAN SENIOR EDITOR

JERRY MORELOCK SENIOR EDITOR

BRIAN WALKER GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR

MELISSA A. WINN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

ALEX GRIFFITH PHOTO EDITOR

DANA B. SHOAF EDITOR IN CHIEF

CLAIRE BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

CONTRIBUTORS

JOHN A. HAYMOND, M.G. HAYNES, JUSTIN D. LYONS, CHRIS MCNAB, GAVIN MORTIMER CORPORATE

KELLY FACER SVP Revenue Operations

MATT GROSS VP Digital Initiatives

ROB WILKINS Director of Partnership Marketing

JAMIE ELLIOTT Senior Director, Production ADVERTISING

MORTON GREENBERG SVP Advertising Sales mgreenberg@mco.com

TERRY JENKINS Regional Sales Manager tjenkins@historynet.com

DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING

NANCY FORMAN / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: SHOP.HISTORYNET.com

United States/Canada: 800.435.0715; foreign subscribers: 386.447.6318

Subscription inquiries: MHQ@omeda.com

MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History (ISSN 1040-5992) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC, 901 North Glebe Road, Fifth Floor, Arlington, VA 22203. Periodical postage paid at Vienna, VA, and additional mailing offices.

Postmaster: S end subscription information and address changes to: MHQ, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900. List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc. 914.925.2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com

Canadian Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519, Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001

© 2023 HistoryNet, LLC. All rights reserved. The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet, LLC.

PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

American soldiers look at the looming wreck of a Messerschmitt 323 at Tunisia’s El Aouina airport circa June 1943. The Germans hoped the six-engine transport plane, designed to carry 140 troops, could help reinforce their strength in North Africa, but Allied troops crushed the remnants of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s once-proud army. The year 2023 marks the 80th anniversary of key final battles in World War II North Africa.

In spring 1942, Japan’s military was the virtual master of its area of operations. It had overrun most of Southeast Asia and a huge swathe of the western Pacific with startling speed after Dec. 7, 1941, and the campaigns in mainland China seemed well in hand. The Dutch and French colonial territories had fallen to the Japanese, as had the British territories of Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong, and besieged United States forces in the Philippines were on the verge of defeat. The Empire of Japan was ascendant. The imperial government assured its people that Japan’s Home Islands were safe from retaliatory attacks by any of the Allied powers.

That assurance was shattered at noon on April 18, 1942 when 16 B-25B Mitchell bombers, launched from the US Navy aircraft carrier Hornet, roared in over the island of Honshu, vectoring in from different points of the compass. It was a hit-and-run attack. After dropping their bomb loads on Tokyo and five other cities, the American aircraft made for the Chinese mainland, where all but one ditched or crash-landed.

In terms of battle damage assessment, the Doolittle Raid did not accomplish much physical damage to high-value military targets, but the psychological effects of the mission were tremendous. It provided a major boost to American morale, both in the military and on the home front, and it shocked the Japanese out of their illusions of invulnerability. The attack also provoked two Japanese reactions of far-reaching consequences that resulted in the deaths of thousands of people, most of whom had nothing to do with the raid.

A month after Doolittle’s strike, the Japanese army launched the Zhejiang–Jiangxi Campaign, a reprisal operation against Chinese who had assisted Doolittle’s aircrews. The campaign also sought to deny Allied access to China’s eastern provinces, either as a launching point or escape route. Japanese forces killed more than 10,000 Chinese civilians in direct retaliation for the air raid on the home island. In the four months of the punitive operation (May–September 1942) as many as 250,000 civilians were slaughtered.

While that death toll mounted, the Japanese government drafted official policies specifically aimed at Allied aircrews who carried out aerial attacks against Japanese targets—past, present, or future. In July 1942, the War Ministry issued Military Secret Order 2190, which stated: “An enemy warplane crew who did not violate wartime international law, shall be treated as prisoners of war, and one who acted against the said law shall be punished as a wartime capital crime.” The wording of that directive seemed straightforward enough, citing international laws of war as the determiner of what was lawful conduct and what was criminal. However, it quickly became clear that the Japanese applied a questionable interpretation on what constituted “criminal” conduct by enemy aviators.

On Aug. 13, 1942, Gen. Shunroku Hata, the Supreme Commander of the Japanese Forces in China, issued Military Order No. 4, an edict that later became infamous as the Enemy Airmen’s Act. The four sections of the order specified that “bombing, strafing, and otherwise attacking” civilians, private properties, or non-military targets was a crime punishable by death. While the language of the order seemingly allowed for contingencies, allowing for cases where “such an act is unavoidable” (as extant international laws of war had already determined), the Japanese chose to interpret every attack against targets in their sphere as criminal instead of as acts of legitimate warfare. The Enemy Airmen’s Act was also an ex post facto order since it stated, “This military law shall be applicable to all acts committed prior to the date of its approval.” That provision was specifically aimed at the American airmen who had flown in the Doolittle Raid.

Eight of Doolittle’s aviators fell into Japanese hands in China. They were tried by a Japanese military tribunal in a cursory trial where they were all sentenced to death, even before Military Secret Order 2190 was issued. When the Assistant Chief of Staff of Imperial Army Headquarters sent Order 2190 to Japanese forces in China, he amended a memorandum which stated, “concerning the disposition of the captured enemy airmen, request that action be deferred… pending proclamation of the military law and its official announcement, and the scheduling of the date of execution of the American airmen.” The condemned aviators were moved to Tokyo. The sentences of five were commuted to life imprisonment. The other three men—1st Lt. Dean Hallmark, 1st Lt. William Farrow, and Sgt. Harold

The law would be applied “to all acts committed prior” to its approval date.

Spatz—were executed on Oct. 15, 1942. The U.S. government knew about the executions during the war, but U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt suppressed the information. The Allies initiated a postwar investigation for a war crimes prosecution against the Japanese officers who conducted the trial of the Doolittle aviators.

The Enemy Airmen’s Act was the template for subsequent edicts that the Japanese enacted against captured Allied aircrews, especially as American air raids against the Home Islands escalated in intensity and destructiveness. Between 1944 and the signing of Japan’s surrender on Sept. 2, 1945, as many as 132 Allied airmen were convicted by the Japanese in summary courts-martial, condemned to death as criminals and executed. At Fukuoka, 15 captured airmen were executed after Emperor Hirohito’s announcement of impending surrender. This was the culmination of a practice repeated throughout the war, as the Japanese subjected captured Allied airmen to interrogations that used torture to extract confessions (usually written in Japanese without

English translation), summary trials, and execution by firing squad or beheading. Yet even that perfunctory process was not enough for some senior Japanese officials. Near the end of the war, the Commandant of the Military Police in Japan wrote an official memorandum to his subordinate commanders complaining that those field expedient trials, hasty as they were, unnecessarily delayed the executions of enemy airmen prisoners. As a direct result of that complaint, at least 90 American aviators were executed in the last weeks of the war.

After the war, Allied war crimes tribunals targeted Japanese personnel involved in the deaths of captured aviators. Senior military officers under whose authority the trials and executions of airmen were conducted were obvious targets for prosecution, but so too were rank-and-file Japanese soldiers personally implicated in the abuse and murder of prisoners of war. Tsuchiya Tatsuo, a prison camp guard, was tried as a Class A war criminal and charged with eight specifications of torture and cruelty to prisoners. In particular Tsuchiya was accused of the prolonged tor-

airmen captured within the jurisdiction of the Japanese 10th Area Army. The Formosa Military Law declared that “the severest punishment” would be applied to enemy airmen who bombed or strafed objectives of a non-military nature, who “disregarded human rights and carried out inhuman acts,” or who entered 10th Area Army’s jurisdiction with any intent of committing such acts. All 14 trials were completed in a single day. No defense was allowed. The defendants were not permitted to speak on their own behalf. Afterwards the 14 airmen were shot and buried in a ditch on the morning of June 19, 1945.

Isayama’s defense counsel (an American jurist) argued that because senior officials in Tokyo had approved the use of death penalty in the summary trials of the 14 American POWs, Isayama’s tribunal had no choice but to sentence the airmen to death. Isayama himself, his attorney insisted, was required to order capital sentences to be carried out. The American Military Commission found the argument unconvincing. Isayama and his co-defendants were all found guilty. The Chief of the Japanese Judicial Division and the military intelligence officer who oversaw the interrogations and torture of the POWs were both sentenced to death. Both sentences were later commuted to life imprisonment. Isayama and the others received prison sentences ranging from 20 years to life.

Mitsubishi G3M2s of the Imperial Japanese Navy fly over Chongqing, China in early 1940. Over 10,000 Chinese civilians there were killed amid 268 Japanese air raids.

ture of a prisoner named Robert Gorden Teas. Eight witnesses swore out affidavits detailing how Tsuchiya beat Teas to death over a period of five days. In December 1945, Tsuchiya was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labor.

In July 1946 a US Military Commission tried Lt. Gen. Harukei Isayama, former commander of the Japanese Formosan Army, along with seven of his subordinates. The charge against Isayama was that he “did permit, authorize and direct an illegal, unfair, unwarranted and false trial” of American prisoners of war, and that he then ordered a Japanese Military Tribunal to sentence those prisoners to death and ordered the carrying out of the executions. The American court charged Isayama for war crimes involving 14 American aviators shot down and captured between Oct. 12, 1944, and Feb. 27, 1945. The earlier date was critical, because that was when the Japanese had implemented the Formosa Military Law—an edict repeating the dictates of the Enemy Airmen’s Act but applying specifically to all

Aside from the fact that the Japanese treatment of enemy airmen was a clear violation of extant international military law, it was also a colossal hypocrisy. Beginning in 1937 with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War, the Japanese military had repeatedly targeted Chinese cities with the deliberate intent of terrorizing and murdering the Chinese population. From August to December 1937, Japanese bombing raids hammered Nanjing, targeting power plants, water works, and even the city’s Central Hospital. Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Chongqing were bombed numerous times. In Chongqing alone, more than 10,000 Chinese civilians were killed in at least 268 separate Japanese air raids. In a direct connection to the Doolittle Raid, the Japanese flew 1,131 bombing attacks against Chuchow— Doolittle’s intended destination—killing 10,246 people in that city alone.

In the Second World War, every major power conducted aerial attacks on its enemy’s civilian population. No nation could claim complete innocence of that. However, the Japanese implementation of the Enemy Airmen’s Act was war crime compounded upon war crime. MHQ

John A. Haymond is the author of Soldiers: A Global History of the Fighting Man, 1800-1945 (Stackpole Books, 2018) and The Infamous Dakota War Trials of 1862: Revenge, Military Law, and the Judgment of History (McFarland, 2016).

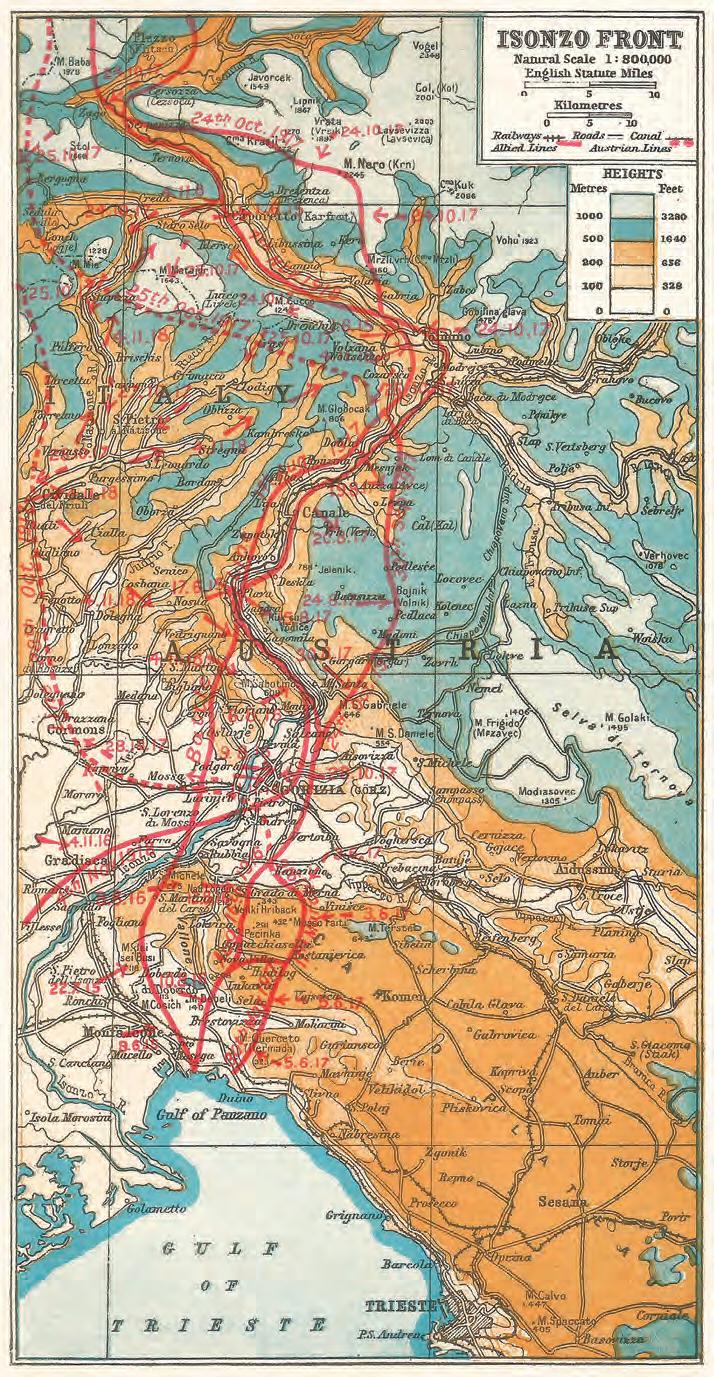

When Italy entered World War I in 1915, Italian Army Chief of Staff Luigi Cadorna set his sights on a 400-mile line down the Isonzo River from northeastern Italy to present-day Slovenia, offering options of either seizing the port of Trieste or threatening Vienna. Mountains, ridges and rivers favored the defense. The first offensive proved only one of 12 battles of the Isonzo, which added up to a bloodbath on a par with Verdun and the Somme. Although the Italians slowly gained ground over the next two years (with 950,180 Italian and 520,532 Austro-Hungarian casualties) it was all swept away when the AustroHungarians, with a contingent of Germans, counterattacked in the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo (Oct. 24 to Nov. 19, 1917), also known to posterity as the Battle of Caporetto. MHQ

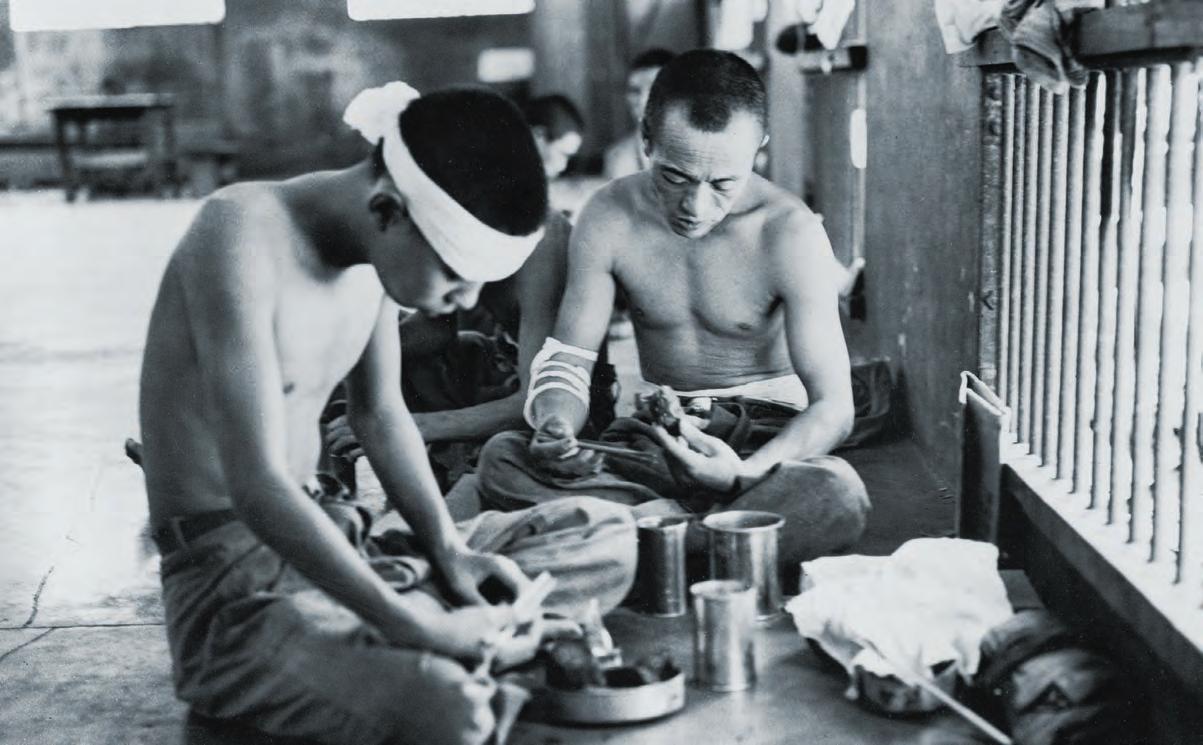

Shohei Ooka was drafted into the Imperial Japanese army shortly after New Year’s Day in 1944. The 35-year-old Ooka was an unlikely soldier. A professional literary critic fluent in French and English, he loved European culture and considered himself a disciple of French philosopher Stendhal, famed for his romanticism and liberal principles. A husband and father of two young children, Ooka resented being drafted to fight in the war. Scribbling a caption on a February 1944 photo of himself in uniform, Ooka wrote: “Second Class Private—and not very happy about it. I must try to keep my hatred for the military from turning into a hatred for humankind.”

After reporting to a depot in Tokyo and receiving several weeks of poor training, he was packed off with a newly formed infantry battalion to the Philippines to help stave off the impending American landing on Mindoro. Two U.S. regimental combat teams landed there on Dec. 15, 1944 to pave the way for an assault on Luzon, facing less than 1,000 Japanese troops effectively abandoned by Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita. Wandering in the jungle, the Japanese prowled for food and succumbed to malaria as they sought to hide from American forces. Ooka and his comrades camped in the mountains for 40 days “until an attack by American forces on January 24 sent us scattering in every direction,” he wrote.

Driven to the edge of his sanity, Ooka attempted to hide in the jungles but was captured on Jan. 25, 1945. He spent the duration of the war in an American POW camp on Leyte. Repatriated to Japan at the end of 1945, Ooka became a writer and worked as a lecturer on French literature at Tokyo’s Meiji University. Ooka was haunted for the rest of his life by the war, which he documented in his autobiographical 1948 book Taken Captive. His 1951 war novel Fires on the Plain, based on his and other POWs’ gruesome experiences, was later adapted into an award-winning 1959 film.

The following excerpt is Ooka’s account of his failed suicide attempts and capture by American forces from an

English edition of Taken Captive, translated and edited by Wayne P. Lammers. Recurring themes in the book are Ooka’s feelings of guilt about comrades who died, his failure to understand his own behavior in brutal circumstances and his decision to stop fighting. The book opens with a quote from Tannisho, a 13th century Japanese Buddhist treatise, which reads: “It is not from goodness of heart that you do not kill.”

My life today owes itself to the accident that the hand grenade I carried was a dud. Of course, since they say that 60 percent of the hand grenades issued to Japanese troops in the Pacific were duds, my good fortune cannot be considered an especially rare stroke of luck.

The relative ease with which I was able to cross over the line that should have marked the end of my life probably owed to my physical infirmity at the time.

In my mind I tried to picture the faces of all those I had loved, but I could not bring any of their images into focus with the clarity of a picture. Feeling a little sorry for them as they milled vaguely about in the depths of my consciousness, I smiled, said, “So long,” and struck the head of the fuze against a nearby rock. The fuze assembly flew off, but the grenade failed to explode.

I examined the grenade minus its fuze. A hole ran down from the middle of the grenade from its now exposed top, and at the bottom of this hole was a small round protuberance—obviously the detonator. I looked at it and shuddered. This was the only time during my day and night alone in the woods that I consciously experienced genuine terror.

I gathered up the pieces of the fuze assembly and put them back together. The slender rod that fit down into the hole appeared too short to reach the detonator inside. I struck the assembly against the rock again, but the grenade remained intact.

I had to smile. The irony of fate that refused to grant me even a quick and easy death seemed funny to me somehow. Everything that had befallen me in the last twenty-four hours had been altogether one great irony. I clicked my tongue in irritation and hurled the grenade deep in the forest…

I next attempted to kill myself with my rifle. Sitting up, I removed my right boot and then held the barrel to my

Driven to the edge of his sanity, Ooka tried to hide in the jungles but was captured.

forehead with both hands as I tried to push the trigger with my big toe. (I had learned this arrangement from the veterans during basic training in Japan.) To my chagrin, I immediately lost my balance and rolled over onto my side. I’m sure to botch it up this way, I thought. Recalling a story I had read about a man who shot himself twice in the mouth but succeeded only in blowing away his cheek, I decided it would be wiser to wait until my fever subsided at least a little.

In this case, too, if I had been more determined, I would surely have thought to push the trigger with a stick…Instead, I behaved like a man who only halfheartedly wished to kill himself. At the same time, I must ultimately consider myself fortunate that the rifle barrel in my hands moved away from my forehead when I lost my balance and fell over, thus preventing me from realizing that I could in fact shoot myself in that position.

I laid the rifle down beside me. Instead of putting my right boot back on, I took off my left boot as well and lay down again. I seem to remember the sun having climbed quite high into the sky by this time. I had apparently been contemplating and going through the motions of my suicide in an extremely dilatory fashion. My thirst must have remained, but I have no recollection of it.

I do not know whether I dozed off or passed out, but the next thing I remember is gradually becoming aware

of a blunt object striking my body over and over. Just as I realized it was a boot kicking me in the side, I felt my arm being grabbed roughly, and I returned to full consciousness.

One GI had hold of my right arm, and another had his rifle pointed at me, nearly touching me. “Don’t move. We’re taking you prisoner,” the one with the rifle said.

I stared at him and he stared at me. A moment passed. I saw that he understood I had no intention of resisting.

Later, at the POW camps, the Americans often asked me: “Did you give yourself up, or were you taken prisoner?” No doubt they wanted to see if it was true that we Japanese would kill ourselves rather than give ourselves up.

I made a point of answering proudly, “I was taken prisoner.”

“Do you think we killed our prisoners?” they asked next.

“I’m not fool enough to believe that kind of propaganda,” I answered.

“Then why didn’t you give yourself up?”

“It’s a question of honor. I have nothing against surrendering as such, but my own sense of pride would not let me submit voluntarily to the enemy.”

Now that I am no longer a prisoner trying desperately to hold onto my self-respect, I can take a different view of the event. Since I gave up all resistance quite willingly

when faced with that rifle, I can admit that I did, after all, give myself up. The difference between surrendering to the enemy with a white flag raised and casting down one’s arms when surrounded is merely a matter of degree.

The first GI gathered up my rifle and sword while the second kept his weapon trained on me. “Get up and start walking,” he said.

“I can’t walk.”

“Walk, walk,” they both repeated.

We went down the path I had come up the day before. I stumbled from one tree to the next as far as the dry streambed and then sank to my knees with nothing to hold onto. One of the GIs put his arm through mine to help me along.

Noticing the canteen at his waist, I said, “Water?”

He shook his canteen to show me it was empty and said, “No.” He turned to look at his companion.

“No,” he said.

We reached the clearing of the day before, where I had first descended into this canyon. Helmets, a mess kit, a pot of half-cooked rice, a crushed gas mask and sundry other items lay strewn about. I saw no blood, but I did not doubt that many men from my unit had died there. One of the sergeants had been carefully ripening some bananas. Seeing them scattered on the ground made my heart weep.

The climb to our former command post was arduous. As we neared the hut, the GI who was helping me walk shouted continually, “Don’t shoot. Don’t shoot.”

At the hut, they turned me over to four or five other GIs, who checked me carefully for hidden weapons. I was then escorted along the ridgeline to a plateau cultivated by the Mangyans [indigenous people of Mindoro island, Philip-

pines]. A force of some five hundred Americans had set up camp there…

The interrogation must have taken at least an hour. The commander repeated certain important questions several times. Trying to be sure I gave the same answer every time made me tense. The effort exhausted me.

The commander took out a Japanese soldier’s diary and told me to translate what it said. I welcomed this respite from the barrage of questions and set about translating the diary line by line. It was written in a childish hand, and the opening entry was from when our company had been stationed in San Jose [city in eastern Mindoro]. The author declared he had stopped keeping a diary after joining the army, but since he could not find anything else to do for diversion, he had decided that setting things down in a diary when off duty would in no way compromise the discharge of his responsibilities…The entry went on and on in this jejune vein—words placed there in case the diary fell into the hands of his superior officer, no doubt. That was all, however. There were no further entries.

The author had not inscribed his name, and I did not recognize the hand, but I knew it had to have belonged to one of our young reservists from the class of 1943. Though these greenhorns had proved themselves to be utterly ignorant of anything, they were also kind and generous and worked hard to cover for the cunning and indolence of us older men. They knew nothing about pacing themselves to conserve their strength, so when they fell ill they were quick to die.

I looked up from the diary. The commander was looking at me with eyes that seemed to hold both sympathy and familiarity. We spoke at the same moment.

“That’s all.”

“That’s enough.”

This brought my interrogation to an end.

The commander turned sideways and said in a low murmur, “We’ll get you something to eat, now. Someday

I saw no blood, but I did not doubt that many men from my unit had died there.

you’ll be able to go home.” I lay there vacantly, my spirit too tired to respond.

One of the soldiers returned the papers to the haversack. The owner’s name stitched on the flap flashed before my eyes. It had belonged to “K,” the son of the rakugo [a type of Japanese solo stage performance] critic, the fellow who had protested “Aren’t we going together?” when we were preparing to evacuate the squad hut and I decided I would get a head start. My shock was immense. I turned my face away and screamed, “Kill me! Shoot me now! How can I alone go on living when all my buddies have died?”

“Be glad to,” I heard someone say. I turned toward the voice to find a man leveling his automatic rifle at me. “Go ahead,” I said, spreading my chest, but my face twisted into a frown when I saw the playful gleam in his eye. The commander walked away as though he had never even heard my cries.

A package of cookies fell on my chest. I looked up to see a ruddy young soldier with a dark stubble of a beard standing over me. His face was blank. When I thanked him, he silently shifted the rifle on his shoulder and walked away.

I resumed my observation of the American troops around me. Never before had I seen men of such varied skin tones and hair color gathered together in a single place. Most of them seemed to be off duty—though a few had work to do. A man with a mobile radio unit on his back stopped near me with the entire sky spread out behind him. He adjusted something and then moved on. One group of men was taking turns peering through what looked like a surveyor’s telescope on a tripod. Far away in the direction of the telescope pointed rose a range of green mountains. Somewhere among those mountains was the ridge over San Jose where our detached platoon was camped. I gazed off at the distant range, caressing each beautiful peak, each gentle mountain fold with my eyes. The platoon could be under attack even now, I thought. I mentally reviewed everything I had said during my interrogation, trying to reassure myself I had said nothing that could be harmful to them.

A burly, middle-aged soldier approached and took my pictures. Coming closer he said, “What’re you sick with?”

“Malaria,” I answered.

He felt my forehead with his hand. “Open your mouth,” he commanded. When I obeyed, he tossed in five or six yellow pills and said, “Now take a drink.” After watching me wash the pills down he explained, “I’m the doctor,” then walked off.

Flames rose from the hut that had housed our command post, as well as from the squad hut with the sick soldiers where I had first rested the day before. I had never seen columns of flame rise so high. Perhaps the huts had been doused with gasoline to help burn the corpses of the dead.

Evening approached. The American troops built fires in the holes I had thought looked like graves and started preparing dinner. An amiable-looking youth brought me some food. I had no appetite. I merely nibbled at a cookie… Except for being awakened several times during the night to take more pills, I slept soundly.

The next morning the commander said, “Today we return to San Jose. The troops will board ship directly south of here, but you will go from Bulalacao [a city on the southeast coast of Mindoro, opposite San Jose on Mindoro’s southwestern coast]. Can you walk?”

“I’ll do my best.”

With GIs supporting me on either side, I managed to stay on my feet all the way down the mountain. Several Filipinos carried me by stretcher from there to Bulalacao, ten kilometers away. Once they had hoisted the stretcher onto their shoulders, all I could see from where I lay was the bright sky and the leafy treetops lining both sides of the road. Watching the beautiful green foliage flow by me on and on as the stretcher moved forward, it finally began to sink in that I had been saved—that the duration of my life now extended indefinitely into the future. It struck me, too, just how bizarre an existence I had been leading, facing death at every turn. MHQ

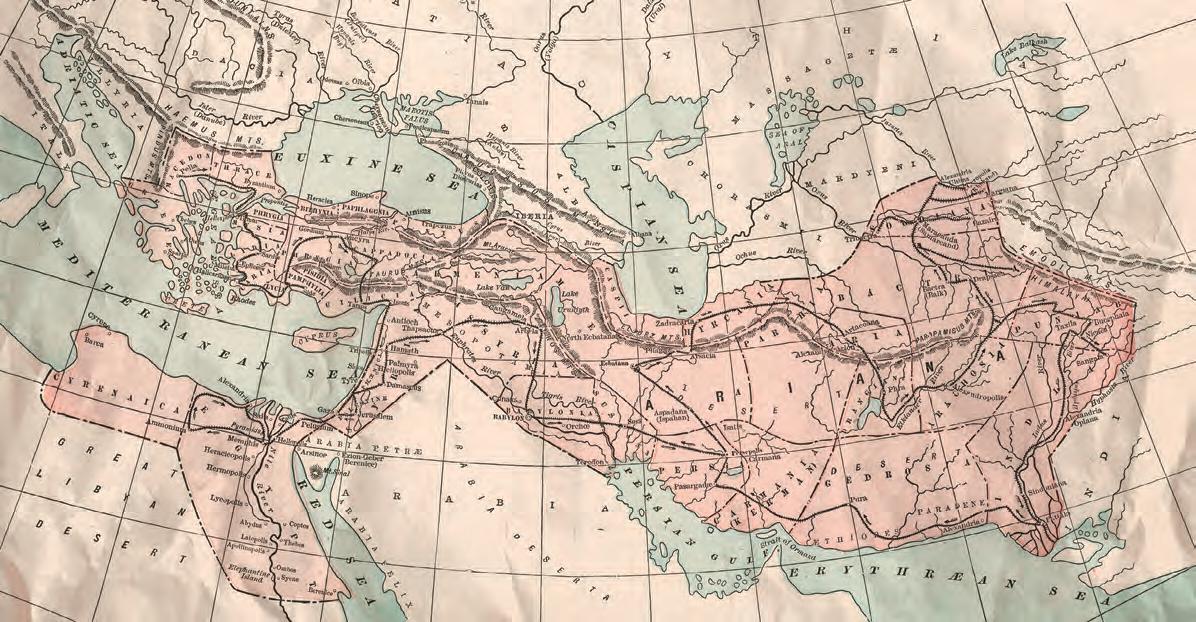

Everyone, it seems, is familiar with highways constructed by the ancient Romans. Those elegant, stone-paved roads pop up as supporting actors in every novel, film, or television show set in Roman times. Yet few people seem aware that this vast Roman transportation network was preceded by another system of imperial highways that was much older yet just as incredible—the Royal Road of Achaemenid Persia (ancient Iran).

It is no exaggeration to call the Achaemenid Empire (550 bce–330 bce) the world’s first superpower. Persia conquered lands and conducted military operations on three continents: Asia, Africa, and Europe. Not even the mighty Assyrian Empire in Mesopotamia which preceded it could make such a claim. The Persians were at first considered minor players in the region. Nobody suspected that Persia would rise to greatness as it accompanied Median allies to bring down the Assyrian Empire. Yet in 550 bce, Persian king Cyrus II—later dubbed “Cyrus the Great”—overturned his Median masters and established the first Persian Empire. The Persians became rulers of the civilized and densely populated Mesopotamian core. Over the next 64 years, Achaemenid Persia would push the boundaries of its expanding empire west into the Balkans, as far as modern Bulgaria, south as far as Libya in North Africa, and east into the jungles of the Indian subcontinent.

Persia inherited the problems of ruling a vast empire. Difficulties resulted from the vast distances between the Persian capitals and outlying satrapies. This problem proved a tough nut for the Persians to crack. Ironically, the Persians’ rapid rate of expansion throughout its early years would only exacerbate the issue. Persia’s third ruler, Darius I (522–486 bce) realized the potential benefit to be gained by connecting the empire’s various and distant parts. Along the way to earning the moniker “Darius the Great,” he initiated a program of road construction, maintenance, and administration that would last well beyond not only his lifespan, but that of his empire’s as well.

The terrain encompassed by the Persian Empire varied widely from the foothills of the Zagros Mountains in Iran to the plains, deserts, and even swampy marshes of Central Mesopotamia. It included the lofty peaks of the Hindu Kush and the vast deserts of Egypt. Innumerable rivers required bridging or permanent ferries to cross. Much physical labor was required to make steep slopes and soggy marshes traversable. Under Darius I, engineers connected the principal cities at the heart of his empire, including the royal palaces at Susa, Babylon, Ecbatana, Pasargadae, and Persepolis. The Persian court rotated annually between these locations, which also led to an interconnected network of garrisons and storehouses required to facilitate the security and transport of the mobile royal court. The intricate highway-based infrastructure expanded. Ancient Greek historian Herodotus described rest stations and inns located every 30 kilometers, essentially a day’s travel. These facilities provided fresh horses for royal messengers, food for travelling officials and merchants, and secure resting places for sanctioned trade caravans. The Persians regulated access to and use of the Royal Road through a system of licensing and taxation with the issuance of viyataka, a type of official pass.

Many royal posting stations were adapted to pass simple messages through the use of signal beacons, relaying from one station to the next and covering vast distances in an incredibly short period of time. These simple messages provided warning to the Great King of an impending situation or developing problem, to be followed up by a more detailed message carried by swift horse and imperial rider.

The Persian road system allowed news to be delivered from anywhere in the empire to the royal court within a day or two of its occurrence—a remarkable achievement in ancient times. This provided the Persians a significant military advantage in terms of being able to speedily react to intelligence. Imperial stations along the Royal Road ensured the king’s commands were delivered in the shortest possible time.

Today, the total length of the Royal Road network is estimated at 8,000 miles. This includes the identification of Persian highways stretching from Kyrgyzstan and India in the east, to Türkiye and Egypt in the west. The network crisscrossed the vital Mesopotamian heartland, connecting cities, regions, and cultures.

The Persians were at first considered minor players in the region.

Very few Persian highways were paved. Yet even Persia’s unpaved highways, with a standard width of roughly six meters, were considered flat and durable enough for traffic by wheeled vehicles that otherwise struggled to cross predominantly sandy or rocky terrain. These highways were more than sufficient to handle chariot, wagon, cavalry, and foot traffic.

Persian roads greatly facilitated the movement of large armies. Alexander the Great made extensive use of the Persian road network even while he was tearing that ancient empire to shreds. A failed 330 bce attempt by a Persian general to stop Alexander’s army from proceeding down the Royal Road through a natural chokepoint became known as the Battle of the Persian Gates. The value of the Persian highways appears to have been abundantly clear to Alexander. He took advantage of the interior lines they provided him throughout his eastern campaigns.

Persian roadways evinced mythological origin stories from Greeks who encountered them. One attributed the construction of the Royal Road to the Syrian warrior goddess Smiramis, who the Greeks believed to have founded ancient Babylon. Another Greek legend gave the credit to Memnon, a mythical king of Ethiopia and conqueror of all the territory between Susa and Troy.

When the Romans arrived on scene in the 2nd century bce, the decaying Persian road network no doubt contributed to the speed with which Pompey the Great subdued the entire Eastern Mediterranean. Many, if not most, of the Roman roads eventually constructed across Asia Minor, Judah, and Mesopotamia were laid atop the old

Persian thoroughfares. A portion of one such stretch has been positively identified near Gordium in modern Türkiye, displaying multiple strata of road construction stacked atop one another.

Considering the massive scope of the Achaemenid Persian road system, one might be surprised to find so little evidence of it today. In 2019, archaeologists discovered the long-buried ruins of a Persian postal station in the village of Toklucak, Türkiye. Ongoing excavations along the Syr Darya River in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan offer enticing insights into the Royal Road that once connected Mesopotamia with the ancient lands of Bactria and Ferghana. Bridge footings, deliberate cuts into steep slopes, and foundations of once bustling inns and postal stations are slowly emerging.

The principal reason why so few remnants of Persia’s road system have been found is the fact that people still essentially use it—the modern road system to a large degree still utilizes the routes first surveyed and graded by Achaemenid Persians some 2,500 years ago. Royal Roads passing through historically restrictive terrain as the Cilician Gates are now asphalted motorways through which thousands of vehicles and even more people traverse each day. Those commuters remain blissfully unaware that the foundation for their comfortable journey was first laid down in the 6th century bce.

M.G. Haynes is a 28-year U.S. Army veteran and a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He holds degrees in History and Asian Studies and is an award-winning author of military and historical fiction.

The Mongol Subjugation of Novgorod (1238)

In 1238, a 40,000-man Mongol horde led by Genghiz Khan’s grandson, Batu Khan, embarked on a campaign of conquest against the Rus. By the end of 1238 they had taken 14 major cities and razed them for failing to heed Batu’s ultimatums. Only two major cities in the northern Rus territories were spared: Pskov and Novgorod, which pledged fealty to the Great Khan and agreed to annually pay a tax based on 10 percent of their produce. Novgorod, a vital fur-trading center, was surrounded by potential enemies, including not only the Mongols, but the Swedes and an order of German warrior-monks known as the Teutonic Knights. Both western powers coveted the lands to the east, declaring their purpose to spread Catholicism while destroying the Eastern Orthodox Church. Appointed kniaz (prince) of Novgorod in 1236 at age 15, Alexsandr Yaroslavich was compelled to choose his friends and enemies carefully. He knew resisting the Mongols was suicide, but they tended to spare those who surrendered and left them to their own domestic affairs...whereas the Swedes would seize land and the Germans would kill nearly everybody. As the Mongols marched on Novgorod in 1238, the spring thaws hampered their horses, halting the campaign 120 kilometers short of its objective. Seizing his opportunity, Alexsandr met the Mongols and accepted their terms. Pskov did the same. The Mongols moved on, establishing their western headquarters at Sarai under a yellow banner for which their force became known as the Golden Horde. Alexsandr made the right choice. He would later have to battle both his western enemies, defeating the Swedes on the Neva River on July 15, 1240 (for which he acquired the moniker Alexsandr Nevsky) and the Livonian Knights at Lake Peipus on April 5, 1242. Credited with preserving Russian civilization at a time of terrible duress, Alexsandr did so by knowing both when to fight and when not to.

What if they gave a war and nobody came? Better still, what if they gave a war and nobody noticed? During the English Civil War, the United Provinces of the Netherlands sided with the English Parliament. As one consequence many Dutch ships were seized or sunk by the Royalist navy, which by 1651 was based in the Isles of Scilly, supporting the last diehards in Cornwall. On March 30 Lt.

Adm. Maarten Harpertsoon Tromp arrived at Scilly, demanding reparation for damages to Dutch ships. Receiving no satisfactory answer, Tromp declared war but then sailed away—and never returned. Critics of that so-called “war” have since noted that as an admiral, not a sovereign, Tromp was really in no position to formally declare war. The issue seemed moot in June 1651 when a Parliamentarian fleet under General at Sea Robert Blake arrived at Scilly to compel the last Royalists to surrender.

So things stood until 1986, when historian Roy Duncan chanced upon Tromp’s idle threat and in the course of investigation concluded that, the utter lack of hostilities notwithstanding, the Netherlands and Isles of Scilly had spent the past 335 years at war but had never gotten around to declaring peace. That oversight was finally remedied on April 17, 1986, when Dutch ambassador to Britain Jonkheer Rein Huydecoper formally declared one of history’s longest conflicts at an end—adding that it must have horrified the islands’ inhabitants “to know we could have attacked at any moment.”

Along with winning independence, in 1585 the Republic of the Netherlands closed off the Scheldt River to trade from the Spanish Netherlands to the south, adversely affecting Antwerp’s and Ghent’s access to the North Sea while serving to Amsterdam’s advantage. Spain accepted that arrangement again in the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia, but in 1714 Spain ceded the southern Netherlands to Habsburg Austria. Between 1780 and 1784 the Netherlands allied with the fledgling United States of America in hopes of gaining an advantage over Britain but was defeated. Seeking to take advantage of that situation, on Oct. 9, 1784, Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II sent three ships, headed by the large merchantman Le Louis, into the Scheldt. Calling his bluff, the Dutch sent the warship Dolfijn to intercept the Austrians, firing a shot through a soup kettle aboard Le Louis. At this point the Austrian flagship surrendered. On Oct. 30 Emperor Joseph declared war and the Netherlands began mobilizing its forces. Austrian troops invaded the Netherlands, razing a custom house and occupying Fort Lillo, whose withdrawing garrison broke the dikes and inundated the region, drowning many locals but halting the Austrian advance. France mediated a settlement signed on

From top: Prince Alexsandr Nevsky negotiated with Batu Khan rather than risk open war with the Mongols; Adm. Tromp of the Dutch navy declared war against the Isles of Scilly but sailed off without starting any fighting, creating a 335-year bloodless conflict; Great Britain and the United States of America nearly fought a war which began with the shooting of a pig, while France and Brazil in 1963 nearly waged a war over lobsters.

Feb. 8, 1785, as the Treaty of Fontainebleau, upholding the Netherlands’ control over the Scheldt but recompensing the Austrian Netherlands with 10 million florins.

With the signing of the Treaty of Paris on Jan. 6, 1810, Emperor Napoleon imposed his Continental System throughout Europe and placing a trade embargo on one of his remaining enemies, Great Britain. That included Sweden, Britain’s longtime trading partner. A booming smuggling trade led Napoleon to issue an ultimatum on Nov.13, 1810, giving his reluctant ally five days to declare war and confiscate all British shipping and goods found on Swedish soil, or itself face war from France and all its allies. Sweden duly declared war on Nov. 17, but there were no direct hostilities over the next year and a half—in fact, Sweden looked the other way while the Royal Navy occupied and used its isle of Hanö as a base. Ironically, this delicate standoff was upset by a Frenchman, Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, who with the death of Sweden’s Crown Prince Charles August on May 28, 1810, was elected crown prince on Aug. 21. Although King Charles XIII was Sweden’s official ruler, his illness and disinterest in national affairs caused him to leave Crown Prince Bernadotte as the de facto ruler—who put Swedish interests above France’s. Relations with Napoleon deteriorated until France occupied Swedish Pomerania and the isle of Rügen in 1812. Bernadotte’s response included the Treaty of Örebro on July 18, 1812, formally ending the bloodless war against Britain and thus declaring a soon-to-be bloodier war against Napoleon’s France.

Both the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 ended with unfinished business regarding the boundaries between the United States and British North America. On several occasions both countries came to the brink of further conflicts. One such was the “Aroostook War” regarding unresolved land claims between Lower Canada and Massachusetts, exacerbated in 1820 when a new state, Maine, broke away from Massachusetts. By 1839 the U.S. had raised 6,000 militia and local posses to patrol the disputed territory while British troop strength rose to as high as 15,000. There were no direct confrontations. Two British militiamen were injured by bears. The decisive action came in 1842 in the form of negotiations between British Master of the Mint Alexander Baring, 1st Baron Ashburton and U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster. As was often the case, the resultant Webster-Ashburton Treaty was a com-

promise. Most land went to Maine, leaving a vital area northeast for the Halifax Road to connect Lower Canada with the Maritime provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. In 1840 Maine created Aroostook County to administer civil authority in its expected territory, from which the incident got its name in the history books.

Since at least the 1844 American presidential election that got James K. Polk elected on a slogan of “Fifty-four-Forty or Fight,” the United States set its sights on raising the northern border of the “Oregon Territory” (including what is now Oregon, Washington, Idaho and British Columbia) to 54 degrees 40 minutes north latitude, rather than 49 degrees north as it had been in 1846. That border bisected San Juan Island, in the Straits of Juan de Fuca between Seattle and Vancouver, where on June 15, 1859, American resident Lyman Cutlar caught Charlie Griffin’s pig rooting in his garden and shot it dead. Cutlar subsequently offered to compensate his British neighbor $10 for his loss. Griffin angrily demanded that local authorities arrest Cutlar. The U.S. authorities would not countenance Britain arresting an American citizen. Soon both sides were reinforcing the island with troops and offshore warships. Things came to a head when the governor of British Columbia ordered the commander of the British Pacific Fleet, Adm. Robert Baynes, to invade the island. At that critical hour Baynes became the voice of reason when he disobeyed the order, declaring that he would “not involve two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig!” News of the standoff spurred Washington and London to negotiate while reducing troop strength on San Juan to 100 each. Finally in 1872, an international commission headed by Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany settled the matter by ceding the entire island to the United States. Total casualties: one British pig.

Following the American Civil War a committee of radical nationalists called the Irish Brotherhood, or Fenians, embarked on three attempts to capture large areas of British North America to ransom for an independent Irish republic. Although the participants were mostly hardened Civil War veterans—from both sides—their first attempt to seize the Niagara Falls peninsula in 1866 failed. A second attempt launched from New York and Vermont in 1870 was a greater failure—largely because the Fenians were facing better-prepared militiamen now defending their own sovereign state, the Dominion of Canada. Although the Irish Brotherhood itself had given up on the idea, Col. John O’Neill set out west for one more try, planning to invade Manitoba and form an alliance with the half-blood Métis, then rebelling against the Canadian authorities for land,

ethnic and religious rights. By late 1871, however, Ottawa was acquiescing to Métis demands. Consequently the Métis had no intention of allying with the Fenians.

Undeterred, at 7:30 a.m. on the morning of Oct. 5, 1871, O’Neill led 37 followers to seize the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post and the nearby East Lynne Customs House in Pembina. Of 20 people taken prisoner, a young boy escaped and ran to the U.S. Army base at Fort Pembina. While about a thousand Canadian militia marched south to deal with the threat, Capt. Loyd Wheaton led 30 soldiers of Company I, 20th U.S. Infantry Regiment to the settlement. O’Neill later said he was loath to fight bluecoats alongside whom he had served during the Civil War. The Fenians fled north, but O’Neill and 10 others were quickly captured. By 3 p.m. the crisis was over. Canada had seen off its last invasion threat without firing a shot. Taken to St. Paul, Minnesota, O’Neill was tried twice for violating the Neutrality Acts and twice acquitted on the grounds that he had not really done so. Unknown to O’Neill, in May 1870 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had straightened out the disputed Canadian border, resulting in Pembina no longer being a quarter mile north of the border, but three-quarters of a mile south in Dakota Territory. O’Neill gave up his invasion ambitions under an avalanche of public ridicule over not only failing to conquer Canada but failing to even find Canada!

There have been numerous conflicts over territory and others over the natural resources they produce. One example began in 1961 when French fishermen seeking spiny lobsters off Mauretania tried their luck on the other side of the Atlantic and discovered crustacean gold on underwater shelves 250 to 650 feet deep. Soon, however, the French vessels were intercepted and driven off by Brazilian corvettes upholding a government claim that that part of the Continental Shelf was their territory, as was any sea life that walked on it. On Jan. 1, 1962 Brazilian warships apprehended the French Cassiopée, but the next time two Brazilian corvettes went after French lobstermen they were in turn intercepted by the French destroyer Tartu. By April 1963 both sides were considering war. Fortunately, an international tribunal summarized the French claim as being that lobsters, like fish, were swimming in the sea, not walking on the shelf. This prompted Brazilian Admiral Paolo Moreira da Silva’s counterclaim that that argument was akin to saying that if a kangaroo hops through the air, that

A map of northern Maine shows the disposition of the Maine militia as well as troops of the U.S. and British armies during the so-called Aroostook War. The border conflict ended with the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty.

their military capabilities while still eying one another suspiciously. On Oct. 18-20, 1986, India staged Operation Falcon, an airlift that occupied Zemithang and several other high ground positions, including Hathung La ridge and Sumdorong Chu. The PLA responded by moving in reinforcements, calling on India for a flag meeting on Nov. 15. This was not forthcoming. In the spring of 1987 the Indians conducted Operation Chequerboard, an aerial redeployment of troops involving 10 divisions and several warplane squadrons along the North East India border. China declared these activities a provocation, but India showed no intention of withdrawing from its positions. By May 1997 soldiers of both powers were staring down each other’s gun barrels while Western diplomats, recognizing similar language to that preceding the 1962 clash, braced for a major war. Cooler heads seem to have prevailed, for on Aug. 5, 1987, Indian and Chinese officials held a flag meeting at Bum. Both sides agreed to discuss the situation and in 1988 Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi visited Beijing, reciprocating for the first time Zhou Enlai’s April 1960 visit to India. The talks were accompanied by mutual reductions in forces from a Line of Actual Control that was agreed upon in 1993. With the crisis defused, there would be no major Sino-Indian border incidents again until 2020.

made it a bird. The matter was finally settled by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on Dec. 10, 1964. By it, Brazilian coastal waters were extended to 200 nautical miles but permitted 26 French ships to catch lobsters for five years in “designated areas,” paying a small percentage of their catch to Brazil. Otherwise the two nations might have warred for a pretender to the throne of the true lobster—spiny lobsters, a.k.a. langustas, don’t have claws like their North Atlantic cousins and are thus not considered true lobsters. Although often used for “lobster tails,” some might not find them tasty enough “to die for.”

While the United States and the Soviet Union were having a nuclear Cold War faceoff, in October 1962 border tensions in the Himalayas between India and the People’s Republic of China flared when Indian troops seized Thag La Ridge. The People’s Liberation Army reacted in force, inflicting a stinging defeat on the Indians at Namka Chu. Over the next 24 years both sides reformed and improved

The disagreement over the exact national boundaries dividing little Hans Island involved two of the least likely adversaries, both members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization: Canada and Denmark. Lying in the Kennedy Channel between Ellesmere and the autonomous Danish territory of Greenland, Hans was divided in half by a line that left a gap in its exact border descriptions. That gap went ignored until 1980, when the Canadian firm Dome Petroleum began four years of research on and around the island. Matters took a more specific direction in 1984, however, when Canadian soldiers landed on Hans and left behind a Maple Leaf flag and a bottle of whisky. In that same year the Danish Minister for Greenland Affairs arrived to plant the Danish flag with a bottle of schnapps and a letter saying, “Welcome to the Danish Island.” These provocations heralded decades of escalating mutual visits and gestures that left all manner of souvenirs behind. Finally, on Aug. 8, 2005—following a particularly busy July—the Danish press announced that Canada wished to commence serious negotiations to settle the remaining boundary dispute once and for all. Even so, it took the Russian “special military operation” against Ukraine to remind the world how serious war could be, resulting in the rivals unveiling a plan on June 14 for satisfactorily dividing the unresolved remnants of Hans Island between the Canadian territory of Nunavut and Danish Greenland. MHQ

Pistol grip The combined pistol grip and magazine housing gives the weapon an excellent center of balance in the grip hand and fast reloading through an intuitive “hand-finds-hand” principle. As an additional safety feature, the button on the back of the grip had to be fully depressed by the grip hand before the weapon would fire.

Magazine The standard Uzi magazine holds 32 rounds, although shorter and extended magazines are available.

Telescoping bolt The front part of the bolt wrapped around and past the breech end of the barrel, to keep the bolt mass high but the weapon length short.

Receiver The main body of the Uzi was simple pressed steel with the cocking lever running along the top of the weapon.

The Uzi submachine gun (SMG)/machine pistol is an iconic firearms design, with a silhouette possibly as recognizable as that of the AK-47. It emerged in a unique time and space in post-World War II history. In 1948, the newborn State of Israel, surrounded on all borders by active enemies, recognized the need to rationalize and update its chaotic weapons inventory. Israel Military Industries (IMI), the official state arms manufacturer, commissioned two engineer officers to design a new SMG for the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). One of them, Capt. Uziel Gal, lent his name to the winning weapon, which went into service as the 9mm Uzi SMG in 1954 alongside the 7.62mm FN FAL as the standard infantry battle rifle. Gal’s overall design was inspired by the Czech CZ 25, but he perfected it in a weapon cheap to produce, easy to fire, simple to service, and ruggedly dependable. As with the CZ 25, the Uzi incorporated the magazine housing into the pistol grip and used a telescoping bolt with a blowback action. It could race through a magazine at a cyclical rate of 600rpm and was accurate up

to 200 yards (fired in the semi-automatic mode; automatic fire accuracy is much less, about 50 yards).

The Uzi cut its teeth in the IDF’s wars of the 1950s and 60s, where it proved ideal for urban and close-quarters combat. It also achieved major export success, particularly to foreign special forces. The Uzi evolved over time, replacing its original wooden stock with folding metal varieties, developing even smaller Mini and Micro variants, and adopting various rails and accessories. Yet in regular Israeli military service, the rise of the assault rifle in the 1970s led to the IDF’s replacement of both the FN FAL and the Uzi by the 5.56mm Galil assault rifle. Uzis continued in special forces, armored crews, and auxiliary service until the 2000s, and endures to this day on international markets. MHQ

Chris McNab is a military historian based in the United Kingdom. He is the author of The Uzi Submachine Gun (Osprey Publishing, 2011).

Chinese spy balloons. North Korean nuclear “saber-rattling.” Taiwan invasion threat. South China Sea land grab. U.S. ICBM test targets Pacific island. Russia challenges Japan over Kuril Islands. With today’s news headlines filled with such reports from the Asia-Pacific region of the globe, the roots, history and background of the political, military, economic and cultural conflict in that strategically important hemisphere is a major theme in several articles in this issue of MHQ. Today in 2023 the rising hegemonic Asian-Pacific power increasingly dominating the region is the People’s Republic of China (PRC, formerly known during the half-century-long Cold War as “Communist China” or “Red China” led by Mao Zedong). U.S. politicians and military leaders long assumed throughout the Korean War era that Mao’s Communist China was simply a subservient client-state of Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union. They assumed that the wily Stalin was Mao’s puppet-master and that all communist countries around the globe were centrally controlled from Moscow. It took the Korean War (1950–1953), the Sino-Soviet split and bloody border battles between the USSR and China (1961–1979), China’s “Cultural Revolution” purge of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) (1966–1976) and, importantly, U.S. President Richard M. Nixon’s reopening of U.S.-China relations in 1972 for U.S. policymakers to finally realize that China controlled its own destiny.

In 1941 the principal, rising hegemonic power in the Asia-Pacific region was Imperial Japan, against which the U.S. and its Allies fought a brutal, costly war until victory was won in 1945. In this issue, a trio of articles focuses on the U.S. war against Japan during World War II in the Asia-Pacific Theater (1941-1945), providing graphic insight into how brutal, unforgiving and costly any conflict waged against a tough and dedicated enemy can be—hardearned lessons that should be kept in mind as tensions rise around the world today.

The stories of two Japanese soldiers, Shohei Ooka and Hiroo Onoda, who fought in the Philippines, present the horrors of war at the tactical level. Both men had very different personalities. Both endured brutal combat under extreme conditions opposing U.S. forces liberating the Philippines. Their fates, however, were nearly the opposite. After failing in his attempts to commit suicide, the starving and injured Ooka, suffering from malaria, reluctantly al-

lowed himself to be captured. By contrast, Onoda hid in the mountains for 29 years, reemerging periodically to terrorize and murder Filipino farmers tending their fields. Both men approached the topic of their war experiences differently after repatriation to Japan. Ooka—a sensitive and well-respected poet and author—dealt with the trauma of wartime philosophically, examining the moral choices a person makes in war with a critical eye and also turning his attention to postwar social issues. By contrast, when Onoda finally surrendered in 1974, he was honored as a national hero in Japan and spoke often of his convictions as a soldier in the emperor’s army, boosting public pride and nostalgia in the country towards the World War II era. In her upcoming documentary, filmmaker Mia Stewart— great-niece of a farmer murdered by Onoda—raises troubling questions about Onoda’s true legacy. Was he a hero or simply a multiple murderer?

Maintaining this issue’s focus on World War II in the Pacific, Laws of War examines the Enemy Airmen’s Act enacted by Japan—an analysis stainding as a cautionary tale about how easy it is for dictatorships to drift into state-sanctioned murder. In August 1942, aghast at the sheer effrontery that the Allies would actually do to Japan what Japanese army and navy air forces had been doing to Nationalist China since 1937 and the Allies since 1941, Japan enacted the Enemy Airmen’s Act which essentially legalized war crimes against captured Allied airmen. This act eventually authorized the trial and execution of hundreds of Allied airmen POWs. Military “kangaroo courts” condemned hundreds of Allied aircrew members to death. Helpless POWs were then shot, beheaded, beaten to death or tortured through sadistic “medical experiments.” It was, in effect the “bureaucratization of brutality.” This prompted the Allies to try those officers and soldiers found responsible as war criminals. Importantly, the Enemy Airmen’s Act shows that hubris combined with unlimited political power is a truly deadly mix.

We hope that examining the history of the Pacific theater of World War II from these different perspectives will educate readers about how the war shaped the region and the different effects that the Pacific War had on human beings across many nations. History, of course, cannot actually be “repeated,” but it would be foolish and a folly of the highest order not to study it and learn from it.

—Jerry MorelockThis issue of MHQ highlights different aspects of World War II in the Pacific, during which Japanese officers carried swords such as this one. Although the bloody conflict in the Pacific ended in Allied victory in 1945, geopolitical struggles are still taking place in the region which shape global politics today.

Three decades after World War II ended, Japanese soldier Hiroo Onoda emerged as a valiant holdout. Now a documentary filmmaker reveals his murderous crimes against Filipino civilians.

By Zita Ballinger FletcherHiroo Onoda, shown here during World War II, was sent to the Philippines at age 23 and remained in hiding there for 29 years after the war ended, killing many islanders before finally emerging in 1974.

Emelio Viaña went out to farm sweet potatoes with his two sons, Protacio and Diony, both in their early teens, at their farm near Yapusan on the western side of Lubang Island in the Philippines. It was March 8, 1961—the day before his 53rd birthday.

After a morning of hard work, Emelio sat down for a lunch break and was drinking a cup of coffee. Gunshots rang out. The first bullet shattered Emelio’s upper thigh. Another shot struck his young son Diony in the leg. The two boys frantically dragged their father into the shelter of nearby aroma bushes—the large hard thorns were piercing and painful, but their terror was worse.

Bleeding heavily, Emelio couldn’t move. His sons barely managed to drag him away as fast as they could to their small boat and row him to a small fishing port at Tubahin. Still in mortal fear of being shot at as they paddled away, they watched helplessly as their father bled to death in front of their eyes. By the time they reached safety it was too late. Emelio was gone. Amid all the horror there was one sight that Protacio would never forget. While hiding in the thorny bushes he had seen his father’s murderer stalking them. It was a Japanese soldier.

The murder of Emelio Viaña was one in a series of killings that plagued Lubang Island for decades from the end of World War II until the 1970s. All the victims were islanders going about their daily lives who were targeted and assaulted at moments when they were isolated and vulnerable. Their grieving family members have never forgotten them, and their deaths tore wounds in their closeknit community which are still unhealed.

Yet these victims have been forgotten in the world’s collective memory. By contrast, the man responsible for these grisly crimes—which he would later refer to euphemistically as “guerrilla warfare”—became something of a celebrity. His name was Hiroo Onoda.

Onoda shocked the world when, 29 years after World War II ended, he materialized from the wilderness of Lubang Island in 1974 still dressed in his Imperial Japanese Army uniform and formally surrendered. He claimed not to have known that the war had ended—a claim he reinforced with his 1974 autobiography, No Surrender: My Thirty Year War, in which he also claimed to have been conducting a so-called “guerrilla war” on Lubang Island without admitting to the details of what that meant. Returning to Japan as a hero, he died in 2014 and has passed into legend, frequently cast into the role of a “lone samu-

rai” type of character. His story has received renewed attention in recent years—such as in Arthur Harari’s 2021 film, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle, and a fictionalized 2022 novel about him penned by eminent German filmmaker Werner Herzog. Onoda fascinates people.

Meanwhile, in the shadows of Onoda’s dazzling fame stands a host of his silent victims waiting to be noticed. The violence against local people that Onoda barely admitted to in his autobiography has so far done nothing to dim his glamor in popular imagination. The murders committed by Onoda and fellow Japanese stragglers under his leadership on Lubang Island have largely been forgotten and ignored. Until now.

“He committed acts of terror against these people for 30 years. No one has ever asked for their side of the story,” independent documentary filmmaker Mia Stewart told MHQ in an exclusive interview. Mia is Emelio Viaña’s great-niece. With a personal connection to Lubang Island and a dedication to historical research that has seen her gathering testimony from islanders and investigating Onoda for more than 10 years, she seeks to ensure that the voices of Onoda’s victims are finally heard in her documentary, Searching for Onoda. The documentary is in its final stages of production.

“The thing I want to bring out in my documentary is the resilience of the island and the Filipino people as a whole,” said Mia. “That’s something that I want to highlight.”

Onoda claimed to have been a soldier continuing to fight a war. Yet the people he attacked in cold blood were civilians, unarmed and incapable of self-defense. They were not only shot, but also often stabbed and mutilated. It begs the question: was he a soldier…or a serial killer?