SUBS RESCUE

TO THE

HOW AMERICAN CODEBREAKERS ON CORREGIDOR ESCAPED THE JAPANESE

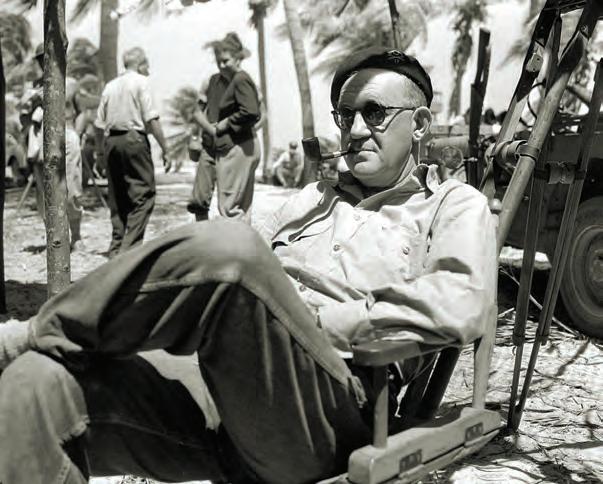

DIRECTOR JOHN FORD AT MIDWAY

GOES TO WAR!DISNEY

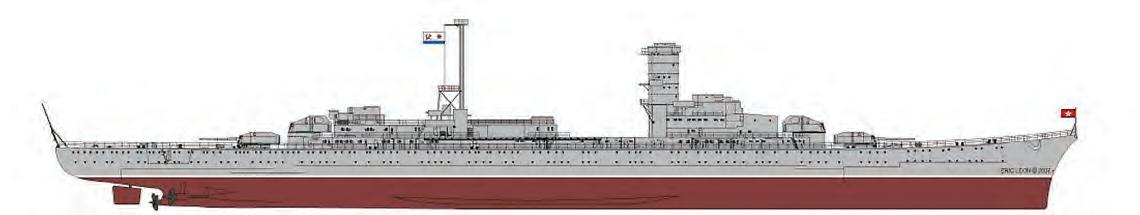

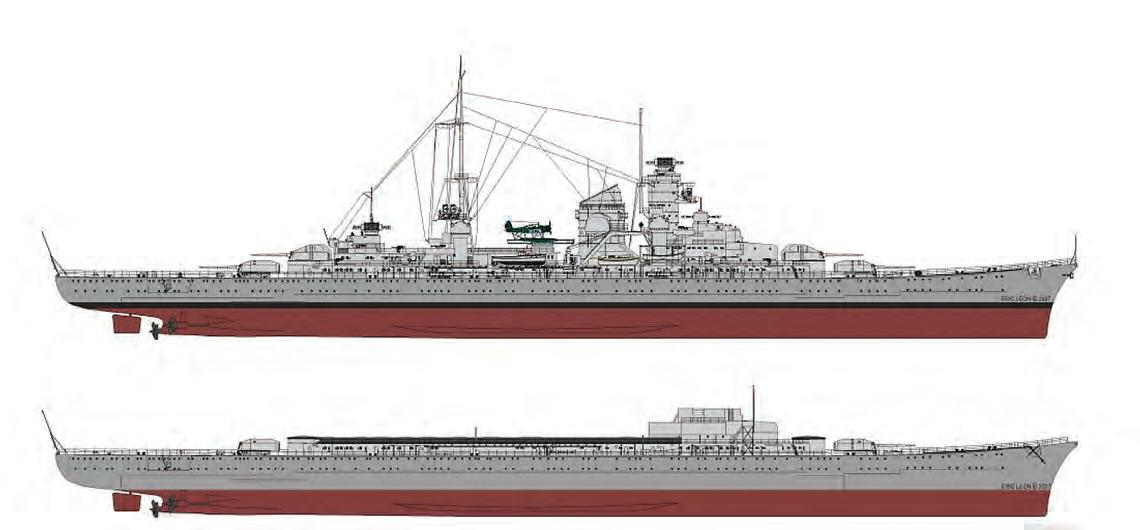

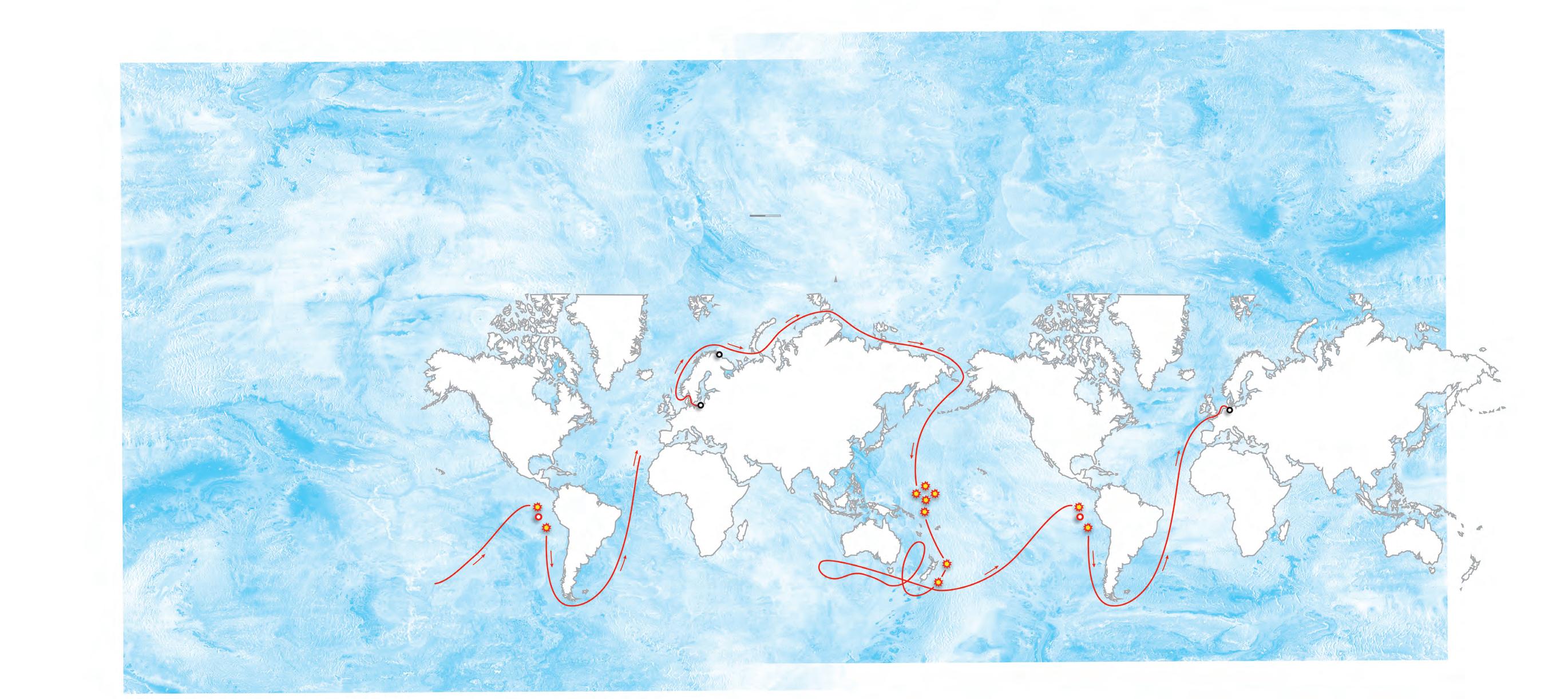

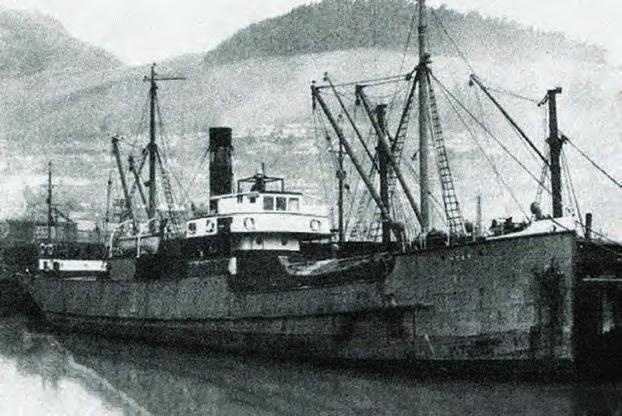

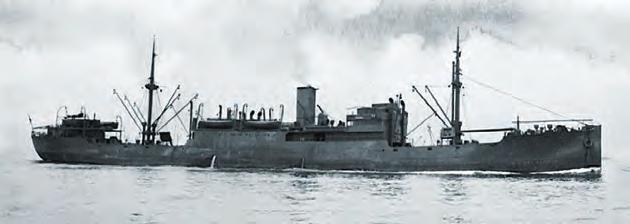

A GERMAN CRUISER RAIDS THE PACIFIC

In the history of timepieces, few moments are more important than the creation of the world’s first Piezo timepiece. First released to the public in 1969, the watch turned the entire industry on its head, ushering in a new era of timekeeping. It’s this legacy that we’re honoring with the Timemaster Watch, available only through Stauer at a price only we can offer.

Prior to Piezo watches, gravity-driven Swiss watches were the standard bearer of precision timekeeping. But all that changed when the first commercially available Piezo watch came onto the market.

The result of ten years of research and development by some of the world’s top engineers, they discovered that when you squeeze a certain type of crystal, it generates a tiny electric current. And, if you pass electricity through the crystal, it vibrates at a precise frequency–exactly 32,768 times each second. When it came on the market, the Piezo watch was the most dependable timepiece available, accurate to 0.2 seconds per day. Today, it’s still considered a spectacular advance in electrical engineering.

“[Piezo timepieces]...it would shake the Swiss watch industry to its very foundations.”

With the Timemaster we’ve set one of the world’s most important mechanical advances inside a decidedly masculine case. A handsome prodigy in rich leather and gold-finished stainless steel. The simplicity of the watch’s case belies an ornately detailed dial, which reflects the prestige of this timepiece.

Call today to secure your own marvel of timekeeping history. Because we work directly with our own craftsman we’re able to offer the Timemaster at a fraction of the price that many Piezo watches cost. But a watch like this doesn’t come along every day. Call today before time runs out and they’re gone. Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Spend some time with this engineering masterpiece for one month. If you’re not convinced you got excellence for less, simply send it back within 30 days for a refund of the item price. But we’re betting this timekeeping pioneer is a keeper.

During World War II, Douglas was home to the primary prisoner of war (POW) camp for Wyoming. There were 17 satellite camps throughout the state.

Construction on the camp took just four months, being completed in May 1943. The first prisoners to arrive at the camp were 412 Italians on Aug. 28, 1943. The federal government paid $23,955 for the land comprising the camp. The total cost for constructing the camp was $1.1 million.

The camp was over a square mile in size and comprised of 180 buildings, which housed up to 2,000 Italian and 3,000 German POWs and 500 army personnel from the spring of 1943 to the

winter of 1946. During the camp’s use it was larger than the town of Douglas. Today, all that remains on the site is the officers club building.

One prisoner at the camp was quoted saying, “We never had it so good.” For many of the prisoners, it was the first time since being drafted that they had clean clothes, a warm bed, good food and health care. Prisoners at the camp ranged from 14 to 80 years old.

The camp was fully self-sufficient with a 150bed hospital, mess halls, kitchens, a motor pool, a cemetery, a newspaper, a bank and a fire department. There was a canine corps that patrolled the compound 24 hours a day.

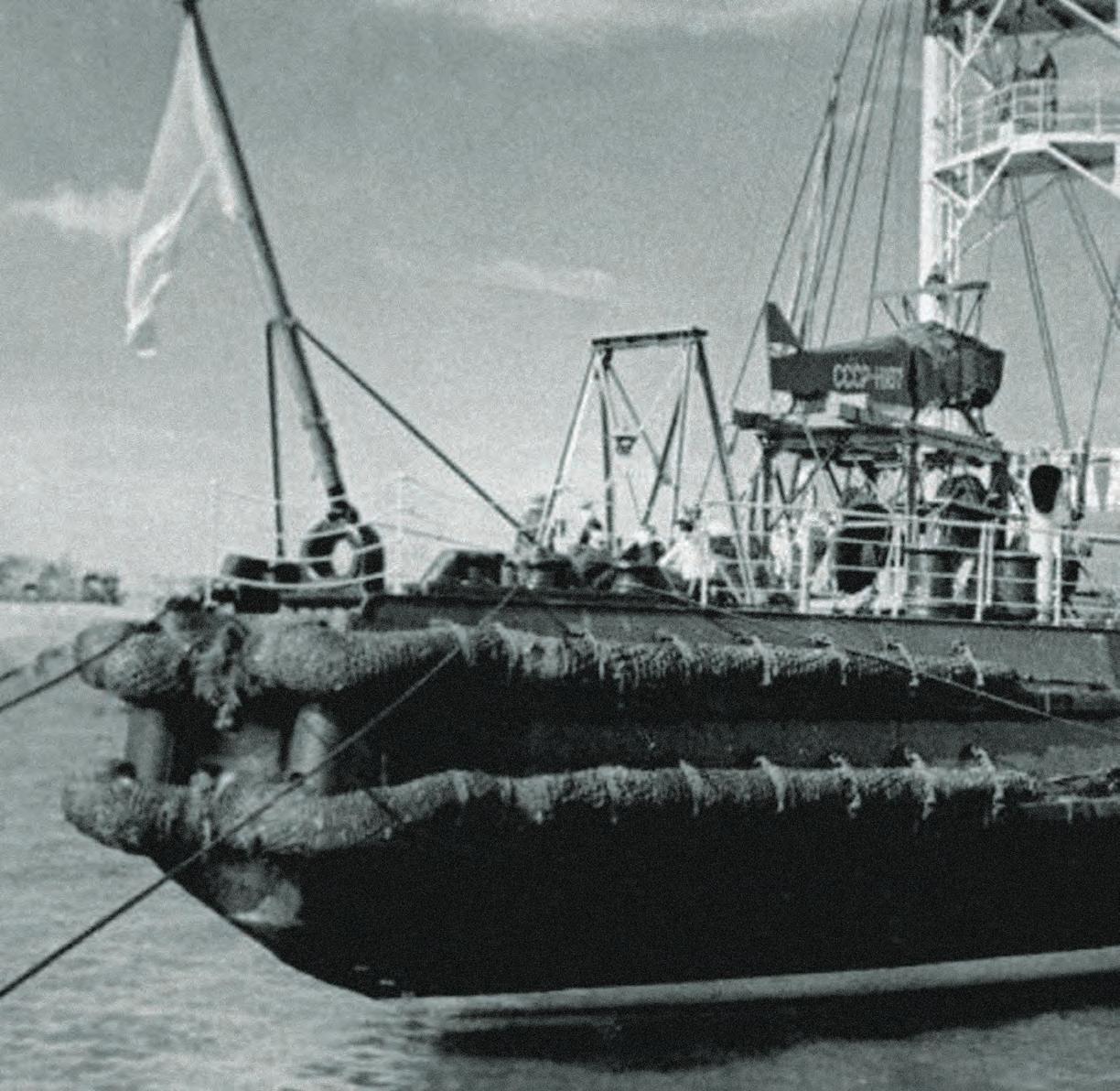

The Soviet icebreaker Stalin gave a helping hand to the German raider Komet as part of a short-lived pact between the two dictatorships.

SUMMER 2023

ENDORSED BY THE NATIONAL WORLD WAR II MUSEUM, INC.

COVER STORY

30 CODEBREAKERS IN PERIL

The men of Station Cast on Corregidor knew too much—so they couldn’t risk falling into Japanese hands JOSEPH CONNOR

38 JOHN FORD AT MIDWAY

The noted director was used to saying “Action!” Now he would experience some for himself TOM HUNTINGTON

46 RAMPAGE IN

After a German raider got stuck in ice, the Soviets helped send it on its way down a trail of destruction STUART D. GOLDMAN

WEAPONS MANUAL

54 DOUBLE TROUBLE

Germany’s 88mm anti-aircraft gun was good for more than just flak PORTFOLIO

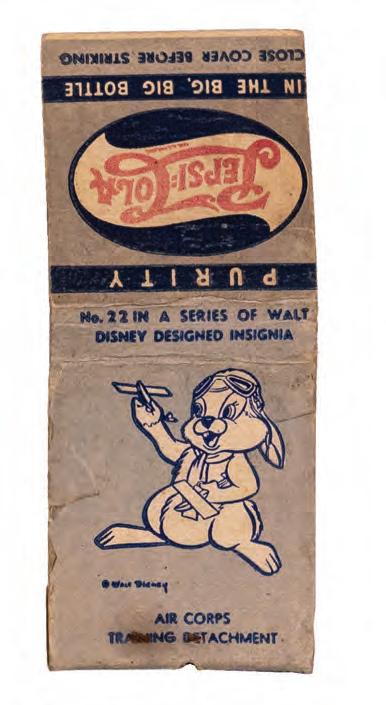

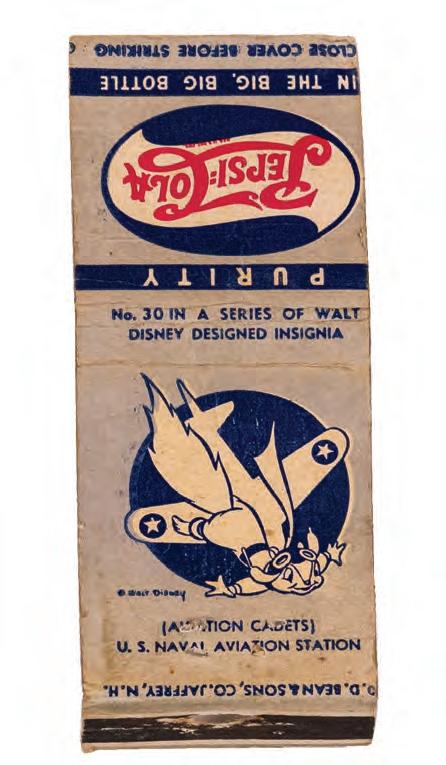

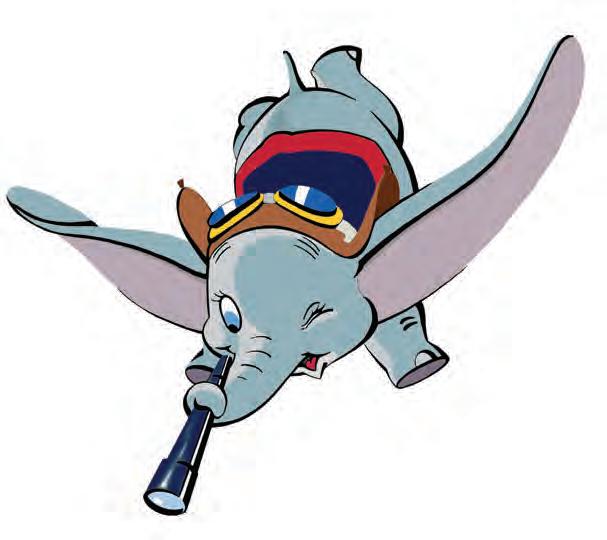

56 DISNEY’S WAR

When the United States entered World War II, the Walt Disney Studios had an animated response

62 BALANCING ACT

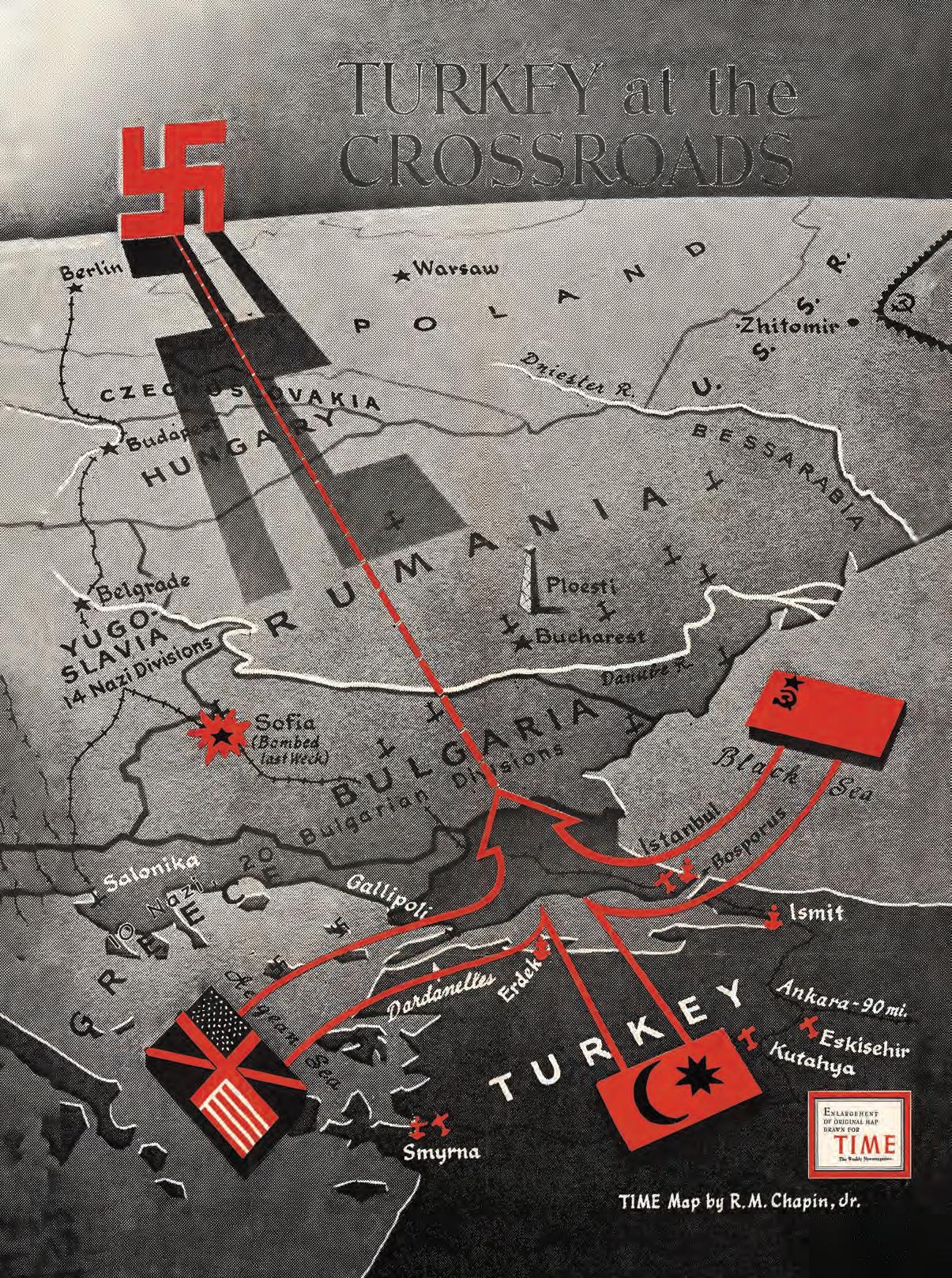

How did Turkey maintain its neutrality for most of the war even though it was surrounded by belligerents? MAC CAREY

DEPARTMENTS

6 FRONT LINES

8 MAIL

10 WORLD WAR II TODAY

20 CONVERSATION

Wally King talks about his experiences flying the P-47 Thunderbolt

24 NEED TO KNOW

26 TRAVEL

The Mediterranean island of Malta still bears traces of war

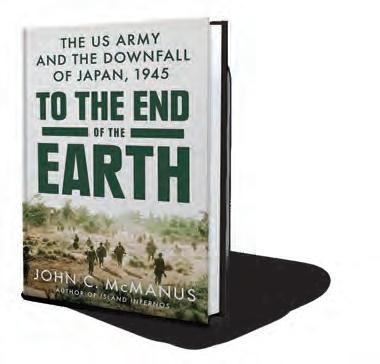

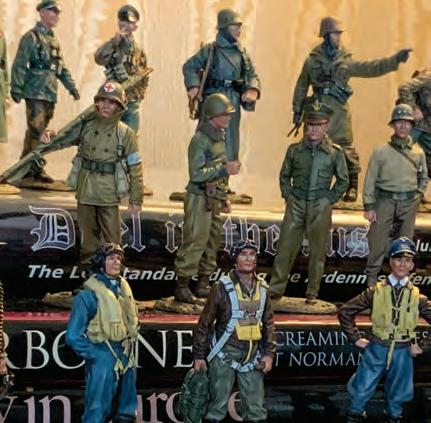

70 REVIEWS

To the End of the Earth, The Collaborators, and more

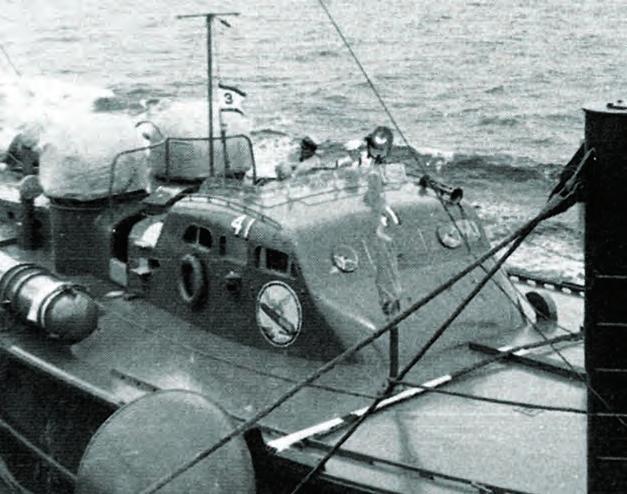

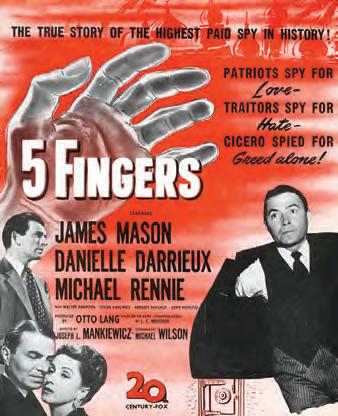

76 BATTLE FILMS

John Ford’s They Were Expendable is a love letter to PT boats

79 CHALLENGE

80 FAMILIAR FACE

Tom Huntington EDITOR

Larry Porges SENIOR EDITOR

Jerry Morelock, Jon Guttman HISTORIANS

David T. Zabecki CHIEF MILITARY HISTORIAN

Paul Wiseman NEWS EDITOR

Brian Walker GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR

Melissa A. Winn DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

Guy Aceto PHOTO EDITOR

Dana B. Shoaf EDITOR IN CHIEF Claire Barrett NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

ADVISORY BOARD

Ed Drea, David Glantz, Keith Huxen, John C. McManus, Williamson Murray

CORPORATE

Kelly Facer SVP REVENUE OPERATIONS

Matt Gross VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES

Rob Wilkins DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING

Jamie Elliott SENIOR DIRECTOR, PRODUCTION

ADVERTISING

Morton Greenberg SVP ADVERTISING SALES MGreenberg@mco.com

Terry Jenkins REGIONAL SALES MANAGER TJenkins@historynet.com

DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING

Nancy Forman / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com

© 2023 HistoryNet, LLC

Subscription Information 800-435-0715 or shop.historynet.com

LIST RENTAL INQUIRIES:

Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc. / 914-925-2406 / belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com

World War II (ISSN 0898-4204) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC, 901 N. Glebe Road, 5th Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Vienna, VA and additional mailing offices. Postmaster: send address changes to World War II, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900 Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519 Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001

The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet, LLC.

PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

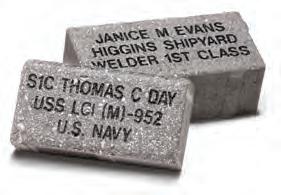

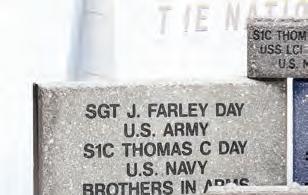

As we near completion of our expansion, exclusive new Victory pavers are now available. Honor your WWII hero’s legacy, and that of other veterans, in the heart of our campus!

BRICK & PAVER TEXT (Please Print Clearly)

Honor your hero with a classic red Victory brick along the sidewalk of our campus.

BRICK & SMALL PAVER TEXT (3 Lines*)

8” x 4”

9” x 4.5”

*18 characters including spaces.

LARGE PAVER TEXT (6 Lines*)

12” x 12”

18” x 12”

*20 characters including spaces

Installation in prominent area of Founders Plaza.

*Includes an image of your paver and 44 page history of WWII.

PLEASE MAKE CHECKS PAYABLE TO THE NATIONAL WWII MUSEUM

tribute items (if applicable). The National WWII Museum’s Road to Victory brick and paver program honors the WWII generation, the American heroes who served during the war, U.S. veterans, veteran organizations, and individuals who exemplify the American spirit. The goal of our program is to celebrate the American spirit while forging a link between the present generation and the generations who fought to secure our nation’s freedom during World War II and other wars and conflicts. Therefore, the Museum reserves the right to deny requests for inscriptions that might be considered offensive or inappropriate to those who sacrificed during the WWII era or other eras, or messages that do not align with the Museum’s mission, which is to tell the story of the American experience in the war that changed the world—why it was fought, how it was won, and what it means today—so that all generations will understand the price of freedom and be inspired by what they learn. HistoryNet

IN COLLEGE , I wanted a solid, practical education, so I majored in…cinema history and criticism. In truth, I guess what I really wanted was a way to watch movies in class.

One thing my teachers stressed in scriptwriting class was that every scene in a screenplay needed some kind of conflict. It could be as simple as two characters disagreeing about something, or it could be British bombers attacking German infrastructure in The Dam Busters . Conflict is essential. So, it’s no wonder that war movies have become such a film staple. In fact, the first movie to win the Academy Award for best picture was Wings, a World War I film.

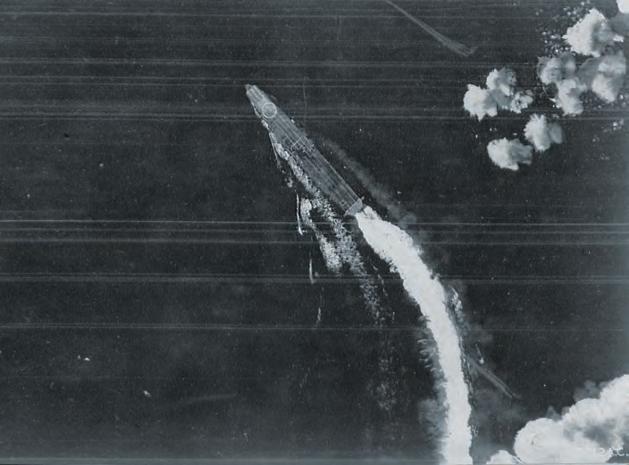

The Second World War has inspired a slew of feature films, and every issue of World War II takes a look at one of them in the “Battle Films” column. Most of the movies we cover there are fictionalized, but one feature article this issue takes a closer look at a real war movie—the Battle of Midway short that director John Ford produced from his experiences on the island when the Japanese

attacked on June 4, 1942.

Ford is best known today for his Westerns, but I find it a little surprising that he didn’t direct more features set in World War II, since he loved the U.S. Navy and was very proud of his war experiences. We look at They Were Expendable, his 1945 adaptation of the Walter Lindsay White book, in this issue’s “Battle Films,” but the only other World War II feature Ford directed was 1955’s Mister Roberts. An adaptation of a successful play, it starred Henry Fonda (see “Familiar Face” on page 80 for more about Fonda’s military career), who was recreating his successful stage role, as well as James Cagney, William Powell, and Jack Lemmon. Mister Roberts is a much-loved movie, but it had a tumultuous production. Shooting started in September 1954 on location at Midway, 12 years after Ford’s experiences there during the war. But the director was drinking heavily, and Fonda was becoming increasingly disenchanted with the way the film was diverging from the play, especially with all the comic relief Ford was creating for Lemmon. When Fonda went to Ford’s room one evening to talk to the director about his concerns, Ford, who had been drinking, got infuriated and slugged him. The incident ended the friendship between the two men. Before long Ford fell ill and needed gallbladder surgery, so director Mervyn LeRoy stepped in to finish the film.

Come to think of it, maybe conflict isn’t always good for a movie, at least when it happens offscreen.

On another note: A lot of readers were fooled by last issue’s “Challenge” (see page 79) because the Hurricane in the image had a two-bladed propeller. While it’s true that the propellers in later versions of the airplane had three blades, early Mk 1 versions like the one in last issue’s photo did indeed have the two-bladed Watts propeller (and the airplanes had fabric-covered wings, too). We always like to keep you guessing! H

5 Countries, 5 Pure Silver Coins!

Travel the globe, without leaving home—with this set of the world’s ve most popular pure silver coins. Newly struck for 2023 in one ounce of ne silver, each coin will arrive in Brilliant Uncirculated (BU) condition. Your excursion includes stops in the United States, Canada, South Africa, China and Great Britain.

Each of these coins is recognized for its breathtaking beauty, and for its stability even in unstable times, since each coin is backed by its government for weight, purity and legal-tender value.

2023 American Silver Eagle: The Silver Eagle is the most popular coin in the world, with its iconic Adolph Weinman Walking Liberty obverse backed by Emily Damstra's Eagle Landing reverse. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the U.S. Mint.

2023 Canada Maple Leaf: A highly sought-after bullion coin since 1988, this 2023 issue includes the FIRST and likely only use of a transitional portrait, of the late Queen Elizabeth II. These are also expected to be the LAST Maple Leafs to bear Her Majesty's effigy. Struck in high-purity

99.99% fine silver at the Royal Canadian Mint.

2023 South African Krugerrand: The Krugerrand continues to be the best-known, most respected numismatic coin brand in the world. 2023 is the Silver Krugerrand's 6th year of issue. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the South African Mint.

2023 China Silver Panda: 2023 is the 40th anniversary of the first silver Panda coin, issued in 1983. China Pandas are noted for their heart-warming one-year-only designs. Struck in 99.9% fine silver at the China Mint.

2023 British Silver Britannia: One of the Royal Mint's flagship coins, this 2023 issue is the FIRST in the Silver Britannia series to carry the portrait of King Charles III, following the passing of Queen Elizabeth II. Struck in 99.9% fine silver.

These coins, with stunningly gorgeous finishes and detailed designs that speak to their country of origin, are sure to hold a treasured place in your collection. Plus, they provide you with a unique way to stock up on precious silver. Here’s a legacy you and your family will cherish. Act now!

You’ll save both time and money on this world coin set with FREE shipping and a BONUS presentation case, plus a new and informative Silver Passport!

BONUS Case!

2023 World Silver 5-Coin Set Regular Price $229 – $199 SAVE $30.00 (over 13%) + FREE SHIPPING

FREE SHIPPING: Standard domestic shipping. Not valid on previous purchases. For fastest service call today toll-free

1-888-201-7070

Offer Code WRD288-05

Please mention this code when you call.

SPECIAL CALL-IN ONLY OFFER

Not sold yet? To learn more, place your phone camera here >>> or visit govmint.com/WRD

GovMint.com® is a retail distributor of coin and currency issues and is not a liated with the U.S. government. e collectible coin market is unregulated, highly speculative and involves risk. GovMint.com reserves the right to decline to consummate any sale, within its discretion, including due to pricing errors. Prices, facts, gures and populations deemed accurate as of the date of publication but may change signi cantly over time. All purchases are expressly conditioned upon your acceptance of GovMint.com’s Terms and Conditions (www.govmint.com/terms-conditions or call 1-800-721-0320); to decline, return your purchase pursuant to GovMint.com’s Return Policy. © 2023 GovMint.com. All rights reserved.

AS SOON AS I saw the headline “Rescuing Norway’s Gold” in the Spring 2023 issue, I remembered a book I read as a kid, called Snow Treasure. In the story, four Norwegian children help to get gold bars out of Norway by taking them a few at a time on their sleds down a mountain and past German guards to a hiding place, and from there Norwegian volunteers pick up the gold bars and get them to the ship that will take them to safety. An Internet search identified the author as Marie McSwigan; the book was first published by E.P. Dutton in 1942. The author claimed her book was based on a true story, although most people disagree. As a child I didn’t know whether it was true or not, it was simply a very exciting tale.

I remember another book I picked up in my elementary school library about D-Day—I can’t remember the title, but I never forgot the names of the five beaches. Around the same time, my father got out his collection of newspapers from World War II and went over them with me. He had saved not just front pages but entire papers, and we could see the ads, the funnies, what the weather was like, the radio listings. (My father served in the Marines during the war but did not go overseas; the war ended as he was still training.)

Never underestimate the power of a book, or a newspaper, or a magazine, to spark a lifelong interest in World War II history. I am still reading about it some 60 years later.

Anne Moiseev Springfield, New JerseyI am no gamer. I put away childish things many years ago. I did play the board games D-Day and Gettysburg back when I was a youth. But somehow my youthful brain did not process these pursuits as “fun” and “entertaining.” T his was serious business. Educational even.

Chris Ketcherside, who wrote the recent review in World War II magazine of the Undaunted: Stalingrad board game [Spring 2023], uses the above words to describe the game and then adds: “The city tiles realistically recreate Stalingrad, and it is fun that they can be replaced as the game goes along and the city becomes increasingly damaged.”

No need to point out to the readers of World War II magazine the insensitivity, for lack of a better word, of describing the awfulness of the siege of Stalingrad within the framework of a board game. Wouldn’t it have been better to highlight the possible educational factors involved in a game concerning a battle-to-the-death on both sides and how a twist here or a turn there might have impacted the final result? As I said: even as a kid I respected the D-Day and Gettysburg board games as a means to a better understanding of what the heck was going on. Saying, “It’s only a game” just didn’t sit well with me this time around.

Martin E. Horn South Plainfield, New JerseyWhat a pleasant surprise to open up the Spring 2023 issue and read the letter from the new editor, Tom Huntington [“Front Lines”]. I immediately had flashbacks (good ones!) to my senior year in high school in 1973. While looking through a newsstand, I noticed the eyecatching cover photo of the initial issue of Marshall Cavendish’s History of the Second World War. I was immediately hooked. I purchased a number of issues in the ensuing weeks, including some of the “special issues” mentioned. Unlike Tom, I did not continue to buy all 96 issues. Something called college diverted my interests!

I am not sure what happened to my small collection, but I vividly remember reading each issue cover to cover, a number of times.

Mark R. Lindon Longmont, ColoradoI read “Front Lines” in the Spring 2023 issue and had to laugh at the irony behind the anecdote you shared of your pursuit of collecting issues of History of the Second World War

I have been a longtime reader of World War II, and I, too, purchased binders to keep my print copies neatly organized on my library shelves. I even purchased the CD containing all past issues that I didn’t have but reading them on the computer just didn’t satisfy the way the printed magazine does. Sadly, I decided to let my subscription lapse this year after the decision was made to go to a quarterly schedule. I agree fully with fellow reader Sidney Spezza and the comments he made in his letter to the “Mail” column this issue. The printed magazine is the gem in your custody.

Christopher Carbott, CDR USN (RET) Northville, MichiganI have two comments on the Spring issue. In reference to “Armed Medics” in “Mail”: Based on my service in Korea at the ceasefire on July 27, 1953, the medics I met all carried carbines (updated to M2, automatic or semi-automatic) for their own protection

Jessica Wambach Brown’s feature “Dog Bait on Cat Island” reminded me how, after the ceasefire, I participated in patrols in the DMZ, occasionally with a dog and its trainer. When we were briefed prior to the first patrol we were told to avoid trying to pet the dogs, as they were trained to resist that. As I heard this, I felt a cold, wet nose in the palm of my hand. I folded my arms.

Carl Sardaro Milan, New YorkI have points to make about two of your articles in the Spring 2023 issue of World War II

About the report in “World War II Today” [“Eighty Years Later, WWII Still Causing Damage”], the author describes finding radioactive contamination “far in excess” at an elementary school in suburban St. Louis. Subsequent testing of the site, first by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and secondly an independent St. Charles company, SCI Engineering, which was hired by the school district for independent testing, found that the school building and grounds do not contain higher levels of radioactive materials than

you’d expect to find at any other school.

In an otherwise excellent article on a conversation with author Bruce Henderson [“Conversation”], Mr. Henderson makes the unsubstantiated statement: “With the anti-immigrant sentiment in this country today, we need to be reminded that we all come from somewhere.” We are all entitled to opinions, but I would remind Mr. Henderson that opposition to illegal immigration is not necessarily anti-immigrant as some of the strongest opponents of illegal immigration are themselves legal immigrants.

Drew Klein Ballwin, MissouriAs a reader of your magazine for many years, I must write and tell you what a great job that you are doing.

I enjoyed “Bomber Boys” in the Spring 2023 issue. Looking at all the photos of the A-2 Jackets and the stories behind them made me think of my WWII AAF collection of over 40 years and the 30-plus A-2s that I have. Yes, each jacket is a part of history and does have its own story that goes with it.

Keep up the good work, World War II magazine

John Reid Marietta, GeorgiaIn the Winter 2023 issue of Wo rld War II m agazine on page 13, you have a picture of the “Hollywood Victory Caravan” with 11 Hollywood stars with their hands raised in what would seem to be “V for Victory” signs. During World War II, you will find pictures of world leaders such as Prime Minister Win ston Churchill raising his hand both ways. With two fingers raised and the palm of the hand facing forward, it was “V for Victory.” If the two-fingered gesture had the back of the hand facing forward, it was telling Der Fuhrer “where to go and what he could do to himself.” Five of the actors in the picture of the Victory Caravan have their hands raised in the V-sign with their palms forward while the other six have the backs of their hands facing forward. One can assume which version each actor preferred.

Ted Severe Baltimore, Maryland

Ted Severe Baltimore, Maryland

PLEASE SEND LETTERS TO:

In England, with the two-fingers up and the palm facing inward, the symbol means “Up yours” or “Go eff yourself.” It’s also true that Churchill used the “V for Victory” symbol that way early in the war, until his aides told him the lower classes were giggling at him. So, we don’t think the meaning was universally known in WWII, because we can’t really imagine Winston Churchill intentionally giving the equivalent of a middle finger in public appearances.

worldwar2@historynet.com

Please include your name, address, and daytime telephone number.

@WorldWarIImag

REPORTED AND WRITTEN BY

PAUL WISEMANTHEY DID NOT GET OFF to a dazzling start. Disembarking at Glasgow, Scotland, on February 14, 1945, after nearly two weeks at sea, many of the more than 800 women—nearly all of them Black— were seasick or covered in salt spray. Then a German V-1 buzz bomb hit near the dock and they had to scramble for cover. They were, their commander Major Charity Adams later wrote, “a very unhappy looking lot.”

And that was before they began their daunting task: sorting through a backlog of mail—eventually 17 million pieces of it, includ-

ing airplane hangars full of undelivered Christmas presents. The letters and packages were stuck in England, far from American G.I.s fighting their way through Nazi-occupied Europe and longing to hear from their families and friends back home.

From those decidedly unglamorous beginnings, the 855 women of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion (part of the Wom-

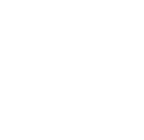

TONY VACCARO, an American infantryman who took stunning but forbidden battlefield photos on a small camera he’d bought as a teenager, died December 28, 2022, at age 100. Vaccaro (center, above) requested assignment as a combat photographer in Europe but was told that at 21 he was too young and should stick to fighting. Army regulations limited photography to the Signal Corps, but Vaccaro kept snapping pictures on his 35-millimeter Argus C3 as the 83rd Infantry Division battled from Normandy to Germany. His photographs provided an up-close view of war unavailable to Signal Corps photographers who carried heavier equipment. After the war, Vaccaro became known for his magazine fashion shoots and celebrity photos.

en’s Army Corps, or WACs) are finally getting their due. In 2019, they were the subject of a documentary film. In 2022, President Joe Biden signed legislation awarding them the Congressional Gold Medal. And now they are receiving the full Hollywood treatment: filmmaker and actor Tyler Perry is writing and directing a film about the battalion’s wartime experiences. Six Triple Eight will feature Kerry Washington (Scandal ) and Oprah Winfrey among the ensemble cast.

It’s a story of perseverance. Inspired by the motto they created—“No Mail, Low Morale”—they developed their own sorting system and plowed through the backlog. A job that was expected to take six months took them three. The 6888th had its own medics, dining hall, support staff, and military police (unarmed but trained in jiu-jitsu).

Along the way, they battled racism and sexism. Adams, only 26 years old, refused to accept Red Cross equipment for a segregated recreational center and urged members of the 6888th not to stay in a segregated Red Cross hotel while they were on leave. When a visiting general threatened to send “a white first lieutenant” to show her how to run the battalion, Adams stood firm: “Over my dead body, sir,” she said. She braced for a court-martial, but the general backed down. Adams was, in fact, promoted to lieutenant colonel—the highest possible rank

for a woman in the WAC—in December 1945.

Coming from segregated America, the women were surprised that they could go wherever they wanted in Birmingham, England. They bowled. They went dancing. They were invited to locals’ homes for dinner. But mostly they worked in eight-hour shifts, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Asked what drew him to making Six Triple Eight , which will air on Netflix when completed, Perry told World War II, “ I had the honor of meeting [6888th veteran] Lena King in April 2022. I was so moved in hearing her story and the emotion she still carries about the people in her life and her experiences with the 6888th over 70 years later…. The spirit of these women wanted us to tell their story.” Perry added, “My hope is that audiences w ill connect with their story and the struggles they faced on many levels.”

THE USS ALBACORE was one the deadliest American submarines in the Pacific—and one of the unluckiest. In the fall of 1943 it was hit twice by friendly fire, once sustaining heavy damage from American bombs. A year later, the 312-foot, Gato -class submarine went missing in the heavily mined Tsugaru Strait off Japan’s Hokkaido island. All 85 men aboard were lost.

Nearly eight decades later, a retired University of Tokyo engineering professor located the wreck of the Albacore 800 feet underwater. Tamaki Ura, who has developed unmanned mini-submarines to scour Japanese water for the wrecks of wartime submarines, raised $15,000 via crowdfunding sources to search for the Albacore

Using documents from the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, Ura zeroed in on the lost sub’s possible location. A survey by one of his mini-subs in October 2022 convinced the U.S. Navy that he’d found the Albacore. Particularly persuasive were images showing modifications known to have been made to the Albacore before her last mission, including an SJ radar dish and mast and a row of vents along the top of the superstructure. Strong currents and heavy vegetation had made the site difficult to study.

“We sincerely thank and congratulate Dr. Ura and his team for their efforts in locating the wreck of Albacore,” said Samuel Cox, a

retired navy rear admiral and director of the Naval History and Heritage Command, when the findings were announced in February. The command has jurisdiction over legally protected American wartime wrecks.

The Albacore, named for a species of tuna, was built in Groton, Connecticut, by the Electric Boat Company and commissioned June 1, 1942. It is considered one of America’s most successful wartime submarines, sinking 10 confirmed Japanese ships and possibly three others. On June 19, 1944, the Albacore torpedoed and sank the 31,000-ton Taiho, Japan’s newest and biggest aircraft carrier, during the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

The Albacore was last seen October 28, 1944, refueling at Midway en route to Japanese waters. On November 7, a Japanese patrol boat reported seeing the explosion of a submerged submarine before bedding, oil, and food supplies rose to the surface.

—French general Charles de Gaulle in a BBC radio broadcast from London on June 18, 1940, as France was falling to Hitler’s Germany

“Has the last word been said? Must we abandon all hope? Is our defeat final and irremediable?

To those questions I answer—No!”

My brother, Private Joseph Patrick Donnelly, was a member of the 9th Armored Division, 19th Tank Battalion, Headquarters Company. He was killed on November 10, 1944, in Scheidgen, Luxembourg. Unfortunately, most of Joe’s military records were destroyed in the 1973 St. Louis Archives fire. What can you tell us about Joe and his unit?

—Rich Donnelly, Williamstown, New JerseyThe lineage of your brother’s unit, the 19th Tank Battalion, goes back to 1836 and the formation of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment. The 2nd Cavalry saw action in some of the most notable campaigns in U.S. military history, including Gettysburg, Little Big Horn, and the Meuse-Argonne (as America’s only horse-mounted cavalry unit to fight in World War I).

The regiment was assigned to Fort Riley, Kansas, in July 1942. There, the 2nd’s centuryold service as a cavalry unit came to an end and it was redesignated the 2nd Armored Regiment, part of the 9th Armored Division, with its men transitioning from horses to tanks. The newly formed regiment trained at Fort Riley until June 1943. Your brother enlisted in the army on November 12, 1942, so he joined the regiment there.

On October 9, 1943, the 9th’s 3rd Battalion was redesignated the 19th Tank Battalion and, in November 1943, the division moved to Fort Polk, Louisiana, for nine months of maneuvers, training, and testing until deploying overseas. The 9th sailed from New York to Scotland on August 20, 1944, before taking a train south to billet in England. Assigned to the U.S. Ninth Army, the 9th was the first armored division to receive the latest model Sherman M4A3s— with 76mm guns—and new 105mm howitzer assault guns. With these tools in hand, it sailed from England on October 1, 1944, and landed in France two days later. The troops stayed in Ste.-Marie-duMont, Normandy, for ten days while prepping to march east, and the unit history evokes the details of what might have been your brother’s experience: “Nightly movies and broadcasts of the 1944 World Series helped to while away the chilly, rainy days.”

On October 13, the push toward Germany began. The 9th

arrived in central Luxembourg, an active combat zone, on October 19 and remained in reserve for two weeks. On November 3, the 19th Tank Battalion moved to the front at Scheidgen, Luxembourg, an evacuated town, where it shelled German positions in its first wartime action. A week later, on November 10, the 19th took its first casualties. An assault gun platoon moved under cover of fog into firing position. When the fog suddenly lifted and exposed the platoon, a barrage of German artillery found its mark. All six tanks in the platoon were hit, killing three men and injuring six. This is no doubt the battle in which your brother lost his life.

The 9th Armored Division soon found itself at the forefront of the Battle of the Bulge, meeting the initial German thrust on December 16. The 19th Tank Battalion was assigned near Echternach, Luxembourg, with some elements of the battalion farmed out to support other units. On January 3, 1945, after months of intense fighting and 125 battalion casualties during its advance east, the 19th was relieved and its role in the Bulge ended. Fifteen battalion officers and men later received decorations for their actions.

The 19th rejoined the fight in late February 1945 as the U.S. Army advanced into Germany. Fighting intensified throughout March and April in the last-ditch German attempt to stave off defeat. Town-by-town battles against anti-tank guns, sniper fire, mortars, and artillery from retreating Wehrmacht troops resulted in heavy American casualties, but by early May the end of the war was clearly at hand. Germany surrendered on May 8.

The 19th then assumed occupation duty. Stationed in central Germany, the battalion took on outpost duty to help control refugees fleeing west from the Soviets and to pick up any straggling German soldiers. Some battalion members guarded factories, hospitals, and POW work patrols, while others served in camps for displaced persons.

In October 1945, the 9th Armored Division returned to the United States and was inactivated on October 13, its major role in the defeat of Germany complete. Your brother’s name, Joseph Patrick Donnelly, is listed in the unit history among the 52 members of the 19th Tank Battalion who died in those final months of World War II. —Larry

Porges

Porges

Do you have a relative from a World War II unit you’d like to learn more about?

Contact us at worldwar2@historynet.com (with “My Parents’ War” in the subject line) with the following:

—Your relative’s full name, date of birth, and the specific unit in which he or she served

—A high-resolution wartime-era photograph —Copies of any paperwork that may help us determine the particulars of your relative’s service.

Note that we are unable to conduct independent genealogical research.

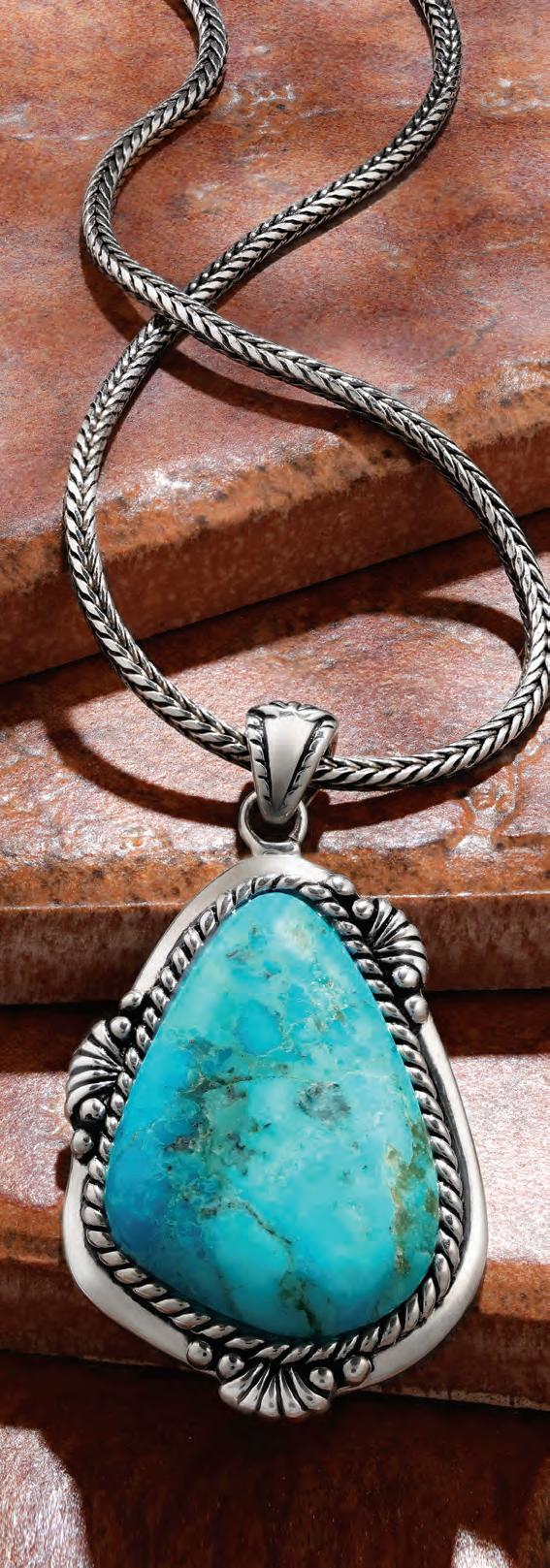

ago, Persians, Tibetans and Mayans considered turquoise a gemstone of the heavens, believing the striking blue stones were sacred pieces of sky. Today, the rarest and most valuable turquoise is found in the American Southwest–– but the future of the blue beauty is unclear. On a recent trip to Tucson, we spoke with fourth generation turquoise traders who explained that less than five percent of turquoise mined worldwide can be set into jewelry and only about twenty mines in the Southwest supply gem-quality turquoise. Once a thriving industry, many Southwest mines have run dry and are now closed.

We found a limited supply of turquoise from Arizona and purchased it for our Sedona Turquoise Collection . Inspired by the work of those ancient craftsmen and designed to showcase the exceptional blue stone, each stabilized vibrant cabochon features a unique, one-of-a-kind matrix surrounded in Bali metalwork. You could drop over $1,200 on a turquoise pendant, or you could secure 26 carats of genuine Arizona turquoise for just $99

Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. If you aren’t completely happy with your purchase, send it back within 30 days for a complete refund of the item price.

The supply of Arizona turquoise is limited, don’t miss your chance to own the Southwest’s brilliant blue treasure. Call today!

Jewelry Specifications:

• Arizona turquoise • Silver-finished settings

Sedona Turquoise Collection

A. Pendant (26 cts) $299 * $99 +s&p Save $200

B. 18" Bali Naga woven sterling silver chain $149 +s&p

C. 1 1/2" Earrings (10 ctw) $299 * $99 +s&p Save $200

Complete Set** $747 * $249 +s&p Save $498

**Complete set includes pendant, chain and earrings.

Call now and mention the offer code to receive your collection. 1-800-333-2045

Offer Code STC788-09

You must use the offer code to get our special price.

*Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without your offer code.

26 carats of genuine Arizona turquoise ONLY $99

A.

B.

A.

B.

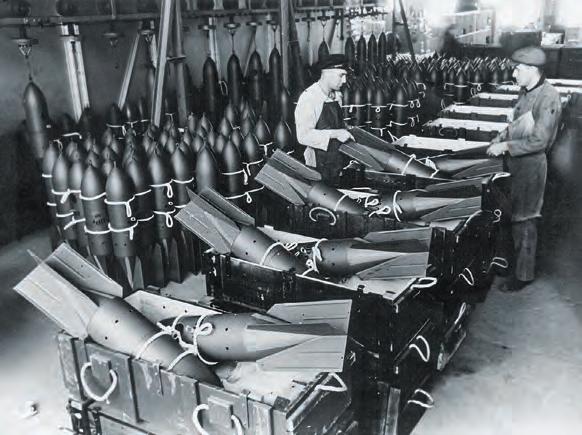

THE SHOOTING STOPPED nearly 80 years ago, but the dying continues in the South Pacific’s Solomon Islands, scene of some of the bloodiest fighting of World War II.

Every year at least 20 islanders are killed or maimed by the detonation of leftover bombs, artillery shells, or other munitions. In January, the United States stepped up efforts to solve the problem, providing $1 million to the demining nonprofit HALO Trust to

locate and document unexploded ordnance left behind by American and Japanese forces.

A survey is considered long overdue. There are no reliable records on where the bombs are most likely to be buried, just anecdotes and old war stories. The munitions are often discovered in the worst way possible—when someone disturbs them and sets them off. In May 2021, for instance, two people were killed by an explosion at a Seventh Day Adventist Church cookout; parishioners had unknowingly started a fire on top of a buried American artillery shell.

Adding to the problem: local fishermen often dig up the munitions and turn them into homemade fishing bombs. One explosion can bring in a catch worth $240—more than a month’s income for the average Solomon Islander, according to reporting by the nonprofit news site Honolulu Civil Beat. Farmers burning vegetation to clear land for crops can also detonate hidden munitions.

The Solomon Islands, an impoverished nation of 900 islands and 700,000 people, gained independence from Britain in 1978, but its government has been too overwhelmed fighting economic woes and political unrest to do much about the problem. And the issue has been something of an afterthought for Japan and the United States. But U.S. officials have recently begun to pay more attention to the Solomons, partly to counter growing Chinese influence in the Pacific.

The Japanese occupied the Solomon Islands in early 1942 and began constructing naval and air bases to defend their invasion of New Guinea and to disrupt Allied supply lines. The Allies counterattacked in August 1942, sending a force led by American Marines onto the Solomons’ Guadalcanal island. Japanese troops were vanquished on Guadalcanal by February 1943 after months of vicious jungle warfare, but fighting continued in the Solomons until the end of the war in August 1945.

American soliders prepare to storm Omaha Beach on D-Day. How did Omaha and the other Normandy beaches get their code names?

Q: I am in my 80s and have read numerous books on World War II—but in all my years I have never seen who came up with the names of the five beaches on D-Day. Can you help?

—Robert Palmer, Pass Christian, Mississippi

A: The code names for the Normandy landing beaches are well known, but their exact origins are murky at best. In theory, World War II code names were randomly assigned from existing code books and were frequently changed due to concerns over security or appearance. Hence the three British/Canadian beaches were originally designated after species of fish: Gold, Jelly, and Sword. However, according to legend, no less a personage than Winston Churchill himself objected to the term “Jelly Beach”—he considered it too frivolous for the site where Canadian forces would kill and die, and suggested Juno in its place. (Churchill also objected to early code names for the entire invasion: “Roundup,” “Sledgehammer,” and the melded term “Roundhammer.” Churchill insisted on the more magisterial sounding “Overlord.”) Lesser known is “Band Beach,” proposed in a swampy area east of Sword. Considered for a possible landing, it was eventually deemed unnecessary and unsuitable. Presumably the term came from the bandfish species.

The origin of the American beach names is also uncertain. One anecdote, recorded by British historian Peter Caddick-Adams, recounts that two American soldiers were assigned to perform carpentry work at the headquarters of U.S. general Omar Bradley in London as the invasion plans were being developed. Chatting with the soldiers, Bradley discovered one was from Omaha, Nebraska, and the other from Provo, Utah. Soon, “Omaha” and “Utah” beaches appeared on Bradley’s planning maps to replace the code names “X-Ray” and “Yoke.” CaddickAdams calls this an “intriguing addendum to history, but impossible to verify.”

Regardless of the origins, the names Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword have made the transition from top-secret terms to common geographic usage in ways no other code names ever have.

—John D. Long is the director of education at the National D-Day Memorial Foundation in Bedford, Virginia.

The French port city of Marseille recently marked the 80th anniversary of the wartime roundup of Jews and suspected resistance fighters by German troops and French authorities (top). The January 1943 raids targeted the city’s Old Port district (above) and sent hundreds of Jews to their deaths.

Mayor Benoît Payan told a crowd outside City Hall on January 29, 2023, that Marseille “represented everything the Nazis hated…. It was a cosmopolitan city where people of all backgrounds mingled.” After deporting its residents, the Germans and French police razed an entire section of the district, destroying more than 1,500 buildings.

French Minister of the Interior Gerald Darmanin told the audience the event “gets too little attention in the history books.” A photo exhibit planned for later this year will help keep it in public memory.

Giant Grab Bag of over 200 used US stamps includes obsolete issues as much as 100 years old. Also historic airmails and commemoratives. Each Grab Bag is different and yours is guaranteed to contain at least 200 used stamps. Perfect to start or add to a collection. Strict limit of one Grab Bag per address. Satisfaction guaranteed.

Send $1 for your Grab Bag today and you’ll also receive special collector’s information along with other interesting stamps on approval.

o Yes! Send me the Giant Grab Bag of 200 used US stamps. Enclosed is $1. Strict limit of one. Shipping and guaranteed delivery are FREE. My satisfaction is guaranteed.

4

Quick order at MysticAd.com/5H148

Name ___________________________________________________________________________________________

Address _________________________________________________________________________________________

City/State/Zip ____________________________________________________________________________________

IN THE SPRING OF 1945, Wally King was a young lieutenant flying a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt over Germany. During King’s last combat mission, his plane was hit by flak and he bailed out over enemy territory. He survived the last few weeks of World War II in captivity but was able to return home, raise a family, and start a successful career as a CPA, eventually owning one of the largest accounting firms in Pittsburgh. Today, the 99-year-old veteran serves as a volunteer for the Meals on Wheels program, visiting shut-ins and the infirm near his home in New Wilmington, Pennsylvania. The active almost-centenarian spoke with World War II about his military career.

I turned 18 and graduated high school in 1942 in my hometown in Ohio. I went to the recruiting office and said I wanted to be a pilot. He said, “Let me sign you up and then once you’re in the army, you can ask to go for pilot training.”

Well, I didn’t fall for that. So they told me to go to Cleveland to apply for pilot training. I was called up for active duty in January 1943 and went through basic training.

I trained on P-40s in Tallahassee, Florida. Nice solid airplane, but certainly way behind other aircraft by that time. Then I shipped over to England in 1944 and went to Goxhill airfield on the North Sea to fly the P-51. Probably got about 30 hours in the air there. Then, after D-Day they flew us over to A-1 Airfield behind Utah Beach. I was assigned to the 363rd Fighter Group.

A few days later, the army deactivated the unit because they needed more photo reconnaissance. We could stay with Mustangs that had cameras in their bellies or transfer to fighter groups, which is what we did. I went to Le Mans and joined the 513th Squadron of the 406th Fighter Group in the Ninth Air Force. The operations officer took me out to a P-47 Thunderbolt for a cockpit check and then told me to fly it. The next day I flew my first combat mission.

How did the P-47 compare to the P-51? The Thunderbolt was a totally different airplane than the Mustang. It was much easier to fly. The P-47 was also a better ground-support airplane. It was a very honest fighter that didn’t have any quirky habits and could take a lot of punishment. One time, we hit a German night fighter field. I was flying low and looked over to my wingman, who was going down this concrete runway. I could see this fire on the end of his propeller. He was grinding it on the concrete! About five inches of his blade was gone. I never really had any major damage on the missions that I flew, except for the last one. The P-47 was a durable, tough machine.

You flew 75 missions during the war. What type of action did you experience?

Most of the time, we would fly along the battlefield and look for enemy vehicles. After the Falaise Gap [in mid-August 1944], the Germans were afraid to move because they would get strafed. We rarely saw vehicles on the road. Never saw many tanks. I did see a couple of Tigers, but we didn’t have anything that would damage them. If they were on a hard surface road, we would strafe the back of it and bounce the bullets up underneath to the fuel tanks. I did that once but can’t say it was effective.

Our targets were mostly marshaling yards, rail traffic, road bridges, and just cutting railroad lines. We’d send one plane down and drop bombs to blow the railroad tracks, then send another one a few miles away to do the same thing.

The most memorable mission was when the Ardennes Offensive began [on December 16, 1944]. Our group provided air cover during the Battle of the Bulge. We hadn’t flown for a week or more until the weather cleared a couple of days before Christmas. Our goal was to quiet the flak before air drops of supplies were made around Bastogne. We couldn’t see

anything because of the snow cover, so we bombed, fired rockets, and strafed the woods. Once the C-47 Dakotas pushed out supplies, a whole army of ants appeared out of the white snow. These guys had been dug in and started dragging those supplies into town.

What other missions did you fly?

Our squadron had the undesirable task of beating up flak before a parachute drop on the Rhine River near Wesel in March 1945. When we saw the line of transport planes coming, we went down to make a strafing pass. As I was coming up, the C-47s had already started dropping their people. A paratrooper went right over my wing! I thought, “This is suicide!” It looked like Dante’s Inferno. These C-47s were burning, they had engines out, paratroopers were being dropped in the river, gliders were crashing and, of course, the air was filled with flak. It looked to me like a colossal failure, but it wasn’t. They got pontoon bridges over the river and the tanks went across.

Let’s talk about your last mission, which you were told would be your last.

They called for an eight-plane mission on April 18, 1945. I was leading the second flight. I said to the squadron commander, “This is my 75th mission. Don’t you think it’s time to quit?” He said, “Yeah. This is going to be your last mission.” Little did I know!

The army had reached the Elbe River and crossed over just south of Magdeburg. We were looking for targets of opportunity. On our way home, my wingman spotted a cannon on a railroad car and wanted to go after it. So we buzzed down to take a look.

I was pretty low but I wasn’t strafing. All of a sudden, there was a boom. I knew I had been hit in the engine by flak. Soon, fire was coming over the windshield. I looked down at my feet and saw the armor plate in front of the cockpit was melting. I said, “Time to go,

At the age of 99, King remains a captivating storyteller. Below: During the war, King perches atop his Thunderbolt, which he considered to be a “durable, tough machine.”

Wally!” I was like a cork out of a bottle! The chute opened and I was upside down. I got myself upright and I heard this noise whizzing by. I thought it was bees. It was civilians shooting rifles! I started swaying to make myself a poor target. I drifted over this house

into the backyard. I got down and could see the Elbe River. I thought maybe I could float downstream to an American bridge. I’d gone about 100 yards toward the river when this little boy tripped me. Then these guys showed up with rifles. I just put my hands up and surrendered. They took me into the house where a medic started working on me. I had burns on my face, a broken wrist, and a bad ankle. Then two German soldiers came in. They smashed me across the side with their guns and knocked me off a stool I was sitting on.

“I looked down at my feet and saw the armor plate in front of the cockpit was melting.”

King’s decorations from the war include the Purple Heart, Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Air Medal. He flew 75 missions during the war and came back safely from all of them—except the last one.

They hauled me out into the yard where the civilians started beating me. I’m pretty terrified. I am in the toughest situation of my life and I’ve never even thought about God. Once I said that, the most sublime peace settled over me. I felt God had come to take me home. That sense stayed with me for the two weeks I was a prisoner. Whatever happened to me was going to be all right.

The soldiers took me to a bunker, where this big, burly noncom was going to rearrange my teeth. A German officer just shoved him and started screaming. From what I could get, he was saying, “Would you like our pilots to be treated this way?”

It wasn’t long before a Mercedes staff car pulled up with two Wehrmacht officers. They brought me to a major, who looked like he had just walked off a movie set. There was all this destruction everywhere and he was dressed immaculately. He started asking me questions and I answered name, rank, and serial number. Just then the door banged open and in comes a Luftwaffe major, who was also immaculately dressed. They started shouting at each other. I knew what it was about. The Wehrmacht had no authority to hold American airmen. He was supposed to turn me over to the Luftwaffe.

So the Luftwaffe major took me to a dispensary where a medic starts working on me. He says, “You’re a lucky guy. The people in that village killed a bomber crew yesterday.”

A few days later, we evacuated the building. They took me to a house near the Russian front where other Americans were being treated. I was there for nearly two weeks and had little food. There were several American patients, but most were unconscious. An American captain told me he wanted to take these guys to a bridgehead about 40 miles away because no one was caring for them. Somehow, he found a couple of ambulances with fuel. So off we went with a German doctor and these other German soldiers, who had surrendered since the war was all but over now.

We made it to this castle, which looked like something you’d see at Disneyland. A lady came down and handed us keys to the fruit cellar. She said if the Russians get close, we should destroy all the food. This German officer said, “The Russians are close enough. Let’s eat!” So they made this big meal, which was the first real food I had had in two weeks. Then I found a bed in the castle—the biggest I had ever seen in my life—and went to sleep.

The next day, we headed for the American lines. Because of the German soldiers, we avoided the SS since they would kill these men for surrendering. We left after dark with no lights. American soldiers on a Jeep with a .50-caliber machine gun found us and guided us the rest of the way. We kept stopping so they could drag anti-tank mines off the road. We finally got there and they took me to the medical tent. They cleaned me up and took care of my burns and injuries. The next day, I was flown out with other burn patients to a hospital in France. I was there for about eight weeks. They finally sent me home on a Liberty ship loaded with cargo, tanks, and halftracks.

You went back to Europe last year as part of a Normandy tour. What was that like?

Delta flew us on a charter right to the beachhead—the first commercial airliner ever to land there. I wanted to find A-1, the first airstrip I landed at with the Mustang. I was near Sainte-Mère-Église, behind Utah Beach. My guide and I went to look for the airstrip. It was almost dark and we were about to give up when I spotted this monument. It said this was the site of A-1. I walked up this road that could have been the runway. I felt like I had been there before. It was a strange feeling standing on that spot where I had been 78 years ago.

You talk to groups about your experiences. What do you tell them?

I’m not a rah-rah-boy-we-won-the-war type of guy. I tell them that war is a nasty, dirty, evil business. There is nothing glamorous or glorious about war. I also tell them not all Germans were bad guys. That German doctor risked his own life for the Americans in his care. I wonder how many of those wounded guys would have made it if not for him.

I’m troubled by the fact that the U.S. college students and the high school students know nothing about World War II. Contrast that with France. We visited a school there and they were so engaged. They knew their history and asked intelligent questions. The headmaster asked the last question: “What advice do you have for these students?” I said, “Put down your cell phones and love one another.” H

You can’t always lie down in bed and sleep. Heartburn, cardiac problems, hip or back aches – and dozens of other ailments and worries. Those are the nights you’d give anything for a comfortable chair to sleep in: one that reclines to exactly the right degree, raises your feet and legs just where you want them, supports your head and shoulders properly, and operates at the touch of a button.

Our Perfect Sleep Chair® does all that and more. More than a chair or recliner, it’s designed to provide total comfort. Choose your preferred heat and massage settings, for hours of soothing relaxation. Reading or watching TV? Our chair’s recline technology allows you to pause the chair in an infinite number of settings. And best of all, it features a powerful lift mechanism that tilts the entire chair forward, making it easy to stand. You’ll love the other benefits, too. It helps with correct spinal alignment and promotes back pressure relief, to prevent back and muscle pain. The overstuffed, oversized biscuit style back and unique seat design will cradle you

OVER 100,000 SOLD

OVER 100,000 SOLD

in comfort. Generously filled, wide armrests provide enhanced arm support when sitting or reclining. It even has a battery backup in case of a power outage.

White glove delivery included in shipping charge. Professionals will deliver the chair to the exact spot in your home where you want it, unpack it, inspect it, test it, position it, and even carry the packaging away! You get your choice of Luxurious and Lasting Miralux, Genuine Leather, stain and liquid repellent Duralux with the classic leather look, or plush MicroLux microfiber, all handcrafted in a variety of colors to fit any decor. Call now!

1-888-420-8757

Please mention code

“To you, it’s the perfect lift chair. To me, it’s the best sleep chair I’ve ever had.”

— J. Fitzgerald, VA 3CHAIRS

I CAN VIVIDLY REMEMBER the first few interviews I did with veterans of the Second World War. One was with Wendy Maxwell, who had been a secretary to General Hastings Ismay (later Lord Ismay), military adviser to the British War Cabinet. She’d attended cabinet meetings and all the Allied conferences and had been at Nuremberg, too. It seemed incredible that the very elegant lady sitting opposite me had been a witness to such enormous events and met so many towering figures from history. A few weeks later, I chatted with a Battle of Britain Spitfire pilot, Geoff Wellum, in his local pub. He was terrific, holding his beer in one hand, an ashtray in the other (that’s how long ago it was) and saying, “So, I’m in my Spit, and this Me-109 is bearing down on me…”

Over the next few years I talked to veterans all over the world: Germans, Austrians, South Africans, Australians, French, Indians, Brits, and, of course, Americans. I reckon I’ve visited more than 30 states in my time. It was a huge privilege; these veterans were a living, tactile link to the past and helped me shift from a world that, in my mind’s eye, was monochrome to one of vivid color.

These 300 or so interviews of mine are all preserved, as are tens of thousands of others, so we do have an excellent—although sadly not comprehensive—global archive of veterans’ testimonies, but that greatest generation is now slipping away. It’s sad and makes me feel wistful and yet, as I have been discovering, there are still plenty of untapped voices from the war for the generations that follow to dis-

cover. A couple of years ago I was working on a book about a British tank regiment, and while I had a few interviews with veterans, I discovered it was the letters and diaries of those who served that were the most interesting and valuable. I was struck by their immediacy; after all, they had no idea how the war would play out, or even if they would make it through.

It was also astonishing how their young selves shone off every page. There was one 32-year-old tank commander who wrote the most touching letters back to his wife, full of longing, regret, hopes, and anxiety, but also of humor, too. I really felt I got to know him very well, and in writing about him was putting flesh back onto bones that had long ago been laid to rest. Another was a young officer who turned 21 on the day the Allies liberated Paris, August 25, 1944. He was very clearly a boy-man: old enough to command men and tanks in battle, but still young enough to be dependent on his parents and with a lack of worldliness that was very engaging. I cannot stress enough how upsetting it was to learn that he died less than a month later, on September 23.

I’ve since been doing some work on the Italian campaign and have deliberately decided to use contemporary sources as much as possible. The diaries and letters, written at a precise moment in time and on a particular day, are very moving. These servicemen obsess about letters from home and about aircraft in the skies. The Germans worry endlessly about the future, the fate of Germany, and what will happen to their families and homes back in the Reich. The Americans curse and grumble about the mud and rain but are extraordinarily stoic and phlegmatic. I’m in awe. One set of letters I’ve been reading are by an Australian serving in an Irish battalion who writes heartbreakingly to his wife about his best friend, a fellow officer, dying in his arms. It’s devastating to read, although even more tragic is that he, too, loses his life. And that’s it. The letters end.

I still believe oral histories are of immense value and feel very lucky to have spoken to so many veterans while I still had the chance, but men and women who are long gone from this world have been coming back to life for me in their words from 80 years ago, their young selves bursting from their pens. It has been utterly illuminating. H

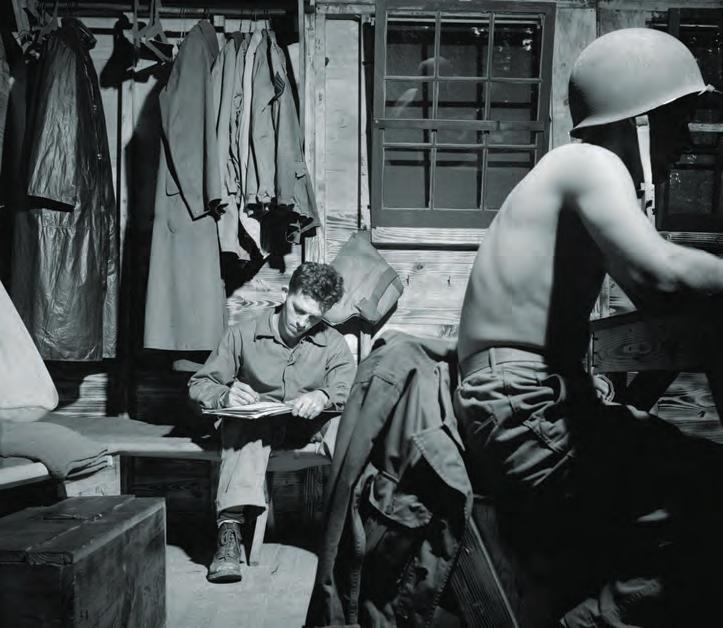

● Easy One Touch Menu

● Large Fonts

200% Zoom

● 100% US Support

● Large Print Keyboard

If you find computers frustrating and confusing, you are not alone. When the Personal Computer was introduced, it was a simple. It has now become a complex Business Computer with thousands of programs for Accounting, Engineering, Databases, etc.

You want something easy, enjoyable, ready to go out of the box with just the programs you need. That’s why we created the Telikin One Touch computer.

Telikin is easy, just take it out of the box, plug it in and connect to the internet. Telikin will let you easily stay connected with friends and family, shop online, find the best prices, get home delivery, have doctor visits, video chat with the grand kids, share pictures, find old friends and more. Telikin One Touch is completely different.

One Touch Interface - A single touch takes you to Email, Web, Video Chat, Contacts, Photos, Games and more.

Large Fonts, 200% Zoom – Easy to see, easy to read.

Secure System – Telikin has never had a virus.

Voice Recognition - No one likes to type. Telikin has Speech to Text. You talk, it types.

Preloaded Software - All programs are pre-loaded and set up. Nothing to download.

100% US based support – Talk to a real person who wants to help

Secure System No Viruses!

Speech to Text You talk, It types!

Great Customer Ratings

This computer is not designed for business. It is designed for you!

" "This s was s a great t investment." "

Ryan M,CopperCanyon, TX

"Thank k you u again n for r making g a computer r for r seniors" "

Megan M,Hilliard, OH

"Telikin n support t is s truly y amazing.”

NickV,Central Point, OR

Call toll freeto find out more!

Mention Code 1224 for intro pricing. 60 Day money back guarantee

844-201-8310

FOR GENERATIONS OF BRITISH SERVICEMEN, the Mediterranean island of Malta came to be known as a place of “yells, bells, and smells,” and for good reason. Street hawkers loudly peddled their wares, and there always seemed to be a local festa somewhere, accompanied by booming fireworks and the ringing of parish church bells. During the often unbearably hot and dusty summers, one routinely encountered herds of shoats (supposedly a sheep-goat hybrid), horse- and donkey-drawn carts, and numerous stray cats and dogs. The mess such creatures left behind worsened after festering in the summer sun, making it a hazardous undertaking to negotiate the island’s narrow streets.

My mother was Maltese. She married my father, who was in the Royal Navy, in 1955. I was born over a year later. My early memories are of 1960s Malta, a very different place from the island today. There was a very noticeable British military presence then, but that had changed by the 1980s. The island had also begun to undergo massive redevelopment, slowly at first, and then with startling rapidity. As in times past, the roads can still be difficult to negotiate, but now it is because of traffic congestion. And while much of the original architecture remains—not least the magnificent Baroque churches—entire streets have been transformed elsewhere, with traditional balconied homes, none of them alike, having been replaced by characterless high-rise apartment blocks. Those who desire the hustle and bustle of the new Malta will not be disappointed. The capital city, Valletta, is always busy and provides an eclectic choice of

tourist sites, shops, restaurants, and bars.

In the early 1800s, after the British ousted a French occupation force, Malta became part of the British Empire. It soon became a popular posting for the armed forces, with Grand Harbour providing a natural deep-water port for the Royal Navy’s warships. In the 20th century, British army battalions were based at various locations around the island, while the Royal Air Force (RAF) maintained a modest presence at Luqa, today’s International Airport, in central Malta.

Being part of the British Empire had its benefits, but it was also not without its perils. When Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, hostilities were initially confined mainly to northern Europe and the Atlantic Ocean. But on June 10, 1940, Italy joined Germany in the war against Britain and France. At dawn the very next day, units of the Italian air force, the Regia Aeronautica, commenced operations against Malta. At the time, Malta’s fighter force consisted of no more than four Gloster Sea Gladiator biplanes, acquired from the Royal Navy by the RAF. These planes and a half-dozen pilots were hastily formed into a Fighter Flight. Opposing them from bases in Sicily was a variety of Italian aircraft of 2a Squadra Aerea, including Fiat CR.42 and Macchi C.200 fighters.

In January 1941, units of the Luftwaffe joined the Italian effort to neutralize Malta as an effective Allied base. As the war continued, Malta received steady reinforcements of British troops, antiaircraft guns, and Hawker Hurricane fighters. The RAF included volun-

teers from South Africa, Rhodesia, and the United States, as well as pilots and aircrews from the air forces of Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. From Malta, fighters and bombers, together with warships and submarines, struck at Axis Mediterranean supply convoys, presenting a very serious threat to Italo-German forces in North Africa.

In March 1942, the first Supermarine Spitfire Mk Vs landed on Malta. These new fighters quickly made their presence felt. In the hands of an experienced pilot, the Spitfire V was a formidable machine, with the speed and maneuverability to take on the latest Messerschmitt Me-109F fighter and the necessary firepower to destroy the Junkers Ju-88 bomber.

Throughout its ordeal, Malta continued to receive supplies by sea, but at heavy cost to the Merchant Navy and escorting warships and their crews. The islanders endured well over 3,000 air alerts. More than 1,500 people lost their lives and many more were injured. Malta held out and emerged undefeated and triumphant following the failure of the final Axis air offensive at the end of October 1942. Britain continued its long military association with the island until withdrawing its remaining units in 1979.

Today, Malta has a number of museums devoted wholly or in part to its role in World War II. The National War Museum is the oldest of these and owes its origins to a group of dedicated enthusiasts who opened an exhibition at Valletta’s Fort St. Elmo in May 1975. This led to the inauguration of the National War Museum in 1979.

I was more than familiar with the original museum prior to 2015, when it moved from Lower St. Elmo to elsewhere within the fort. Today it covers all eras of Malta’s military history. On a recent visit I sought out several of the museum’s World War II displays, including the George Cross that King George VI awarded to the island on April 15, 1942, at the height of the Battle of Malta. The restored fuselage of the only surviving Malta Gladiator (N5520, known as Faith) is positioned a little too high to be fully appreciated, but a Willys Jeep has a prominent place in a spacious setting. General Dwight

D. Eisenhower used the vehicle when he was in Malta to prepare for Operation Husky—the Allied invasion of Sicily—after which it was presented to Air Vice Marshal Sir Keith Park, Air Officer Commanding (AOC) Malta. The jeep later transported President Franklin D. Roosevelt when he visited the island in December 1943.

Other World War II sites include the Malta at War Museum, the War Headquarters Tunnels, and the Lascaris War Rooms. The Malta at War Museum is in a former wartime police station at Couvre Porte, Birgu (also called Vittoriosa). I visited it for the first time in February 2023 and was pleasantly surprised with Artifacts at the National War Museum (above) recall Malta’s role in the war, when Axis bombs reduced much of the island to rubble (below).

Takali (Ta’ Qali). A main focus has been the restoration and display of historic aircraft. The first such venture was rebuilding a Spitfire Mk IX—a later variant of the Spitfire V flown during the

southwest of the village of Qrendi, on farmland accessible via a lane off Triq ta’ Ħassajeq, shortly before it joins Triq Ħaġar Qim—but do ask the farmer before entering his property. H

Malta is situated in the central Mediterranean Sea. Air Malta provides regular flights from numerous European destinations, and a ferry service runs between the island and Sicily, some 55 miles north. The best time of the year to visit is late spring or summer, although it tends to get quite hot from June to August. Getting around is easy. There are cabs, but Malta’s buses are an inexpensive, reliable, and convenient mode of travel. Most museums are run by either Heritage Malta heritagemalta.mt), a government department, or Fondazzjoni Wirt Artna wirtartna.org), a volunteerbased NGO.

Hotels and tourist accommodation vary considerably. If you’re looking for nightlife, opt for St. Julian’s or St. Paul’s Bay. A quieter time may be had in Mellieha. Xara Palace xarapalace.com.mt) is a converted 17th-century palazzo and the only hotel within the walls of the ancient city of Mdina. Bars and cafés are many and all around, and restaurants cater to every kind of taste—the local cuisine is typically fish, rabbit, or pasta.

Besides the exhibits on display, the National War Museum (heritagemalta. mt/explore) is worth visiting for its location. Fort St. Elmo, overlooking Grand Harbour, was a strongpoint during the Great Siege of 1565, which ended in defeat for invading Ottoman forces.

MAY 6, 1996

FORMER DIRECTOR OF THE CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY WILLIAM COLBY IS FOUND DEAD ON A RIVERBANK IN ROCK POINT, MD. AN AVID OUTDOORSMAN, HE HAD SET OUT ON A SOLO CANOE TRIP NINE DAYS EARLIER. CONSPIRACY THEORIES ABOUND REGARDING THE CAUSE OF HIS DEATH. CLOAK AND DAGGER DAYS BEHIND HIM, COLBY WAS QUOTED AS SAYING “THE COLD WAR IS OVER, AND THE MILITARY THREAT IS NOW FAR LESS, IT’S TIME TO CUT OUR MILITARY BUDGET BY 50 PERCENT AND TO INVEST THAT MONEY IN OUR SCHOOLS, OUR HEALTH CARE, AND OUR ECONOMY.”

For more, visit HISTORYNET.COM/ TODAY-IN-HISTORY

U.S. Navy personnel on Corregidor continued deciphering Japanese messages even as the enemy closed in—and they knew they couldn’t be taken alive

By February 1942, the 74 men of Station Cast on the Philippine island of Corregidor had become some of the most important sailors in the U.S. Navy. These radio operators, linguists, and cryptanalysts were eavesdropping on enemy radio transmissions and had made steady progress deciphering the Japanese naval code. The U.S. military hoped this top-secret project would soon give the United States advance notice of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s plans.

Station Cast’s problem was its location. The Japanese had invaded the Philippines two months earlier and were pushing the American and Filipino defenders back toward a last-ditch stand on the Bataan peninsula on the island of Luzon. Corregidor, a small fortified island in Manila Bay, lay only two miles off Bataan. If Bataan fell, which seemed inevitable, Corregidor would soon follow.

The navy couldn’t let Station Cast’s personnel fall into enemy hands. The Japanese knew what these men were doing and would torture them to

Codebreaking personnel of Station Cast in the tunnels of Corregidor show the strain of knowing the Japanese are approaching. The top-secret work the men did here had to be kept from the enemy, one way or another.

BY THE TIME the United States entered the war in December 1941, the U.S. Navy had made codebreaking a high priority. The Japanese relied heavily on radio signals to send information to their bases and warships across the Pacific, and their communication

ing off to the sides. It was stocked with hightech equipment that included 11 National model RAO shortwave radio receivers, 21 specially built Underwood typewriters to translate Morse code into the Japanese alphabet, various IBM machines that were precursors of modern computers, and direction-finding equipment to determine the origin of enemy radio transmissions. It also housed a so-called Purple machine, which decrypted Japanese diplomatic messages and was one of the fewer than a dozen such machines in existence.

Station Cast was a hush-hush operation, and security was tight. A double iron gate blocked the tunnel’s entrance. Classified documents were stored in a vault protected by a triple-combination lock, and a Marine sentry stood guard at the tunnel entrance 24 hours a day. To disguise the outfit’s true purpose, it was called the Emergency Radio Station, with a cover story that it was merely a back-up communications system for the U.S. Asiatic Fleet.

The station had two components: a general unit, which did the interception work, and a special unit, which analyzed the intercepted messages. The cryptanalysts were a special breed. Their work required a high IQ, an abundance of curiosity, and painstaking attention to detail. They were dedicated to their craft. “I have never seen a more devoted group of workers. Many of us often worked two shifts a day,” said Ensign Laurance L. MacKallor, one of the codebreakers. “The work was too challenging to put down as long as one could keep his eyes open.”

The tunnel protected the men from the frequent bombing raids, but the war hit home in other ways. Lieutenant Rudolph J. Fabian, a cryptanalyst, had stockpiled crates of food for Station Cast, but the army confiscated these rations and put them into the communal pot for the entire Corregidor garrison. After that, said Chief Yeoman John E. “Vince” Chamberlin, Station Cast’s personnel ate only two sparse meals a day, mostly spaghetti and soggy rice. The skimpy fare wasn’t enough for active men in a tropical climate, and all lost weight. In four months, for example, Chief Radioman Sidney A. Burnett dropped 53 pounds, and Chamberlin lost 40. Occasionally, the chow contained meat, and when it did, Radioman James B. Capron Jr. worried that Monkey Point had gotten its name for a reason.

Corregidor was a likely target for a Japanese landing, so all troops, regardless of spe-

cialty or assignment, trained to defend its beaches. This posed a problem for Station Cast, whose arsenal consisted of only two .45-caliber pistols and one .22-caliber rifle, but an enterprising chief petty officer found a sunken barge in shallow water nearby and salvaged several crates of .30-caliber Enfield rifles. The men cleaned these weapons and practiced infantry drills, calling themselves the Monkey Point Militia.

The Japanese blockade isolated Corregidor from the outside world, and the men were on their own. No mail could get through from home, so their only contact with the United States came when they tuned in KGEI, a shortwave radio station in San Francisco. The codebreakers knew that Corregidor was doomed and in January 1942 they began burning sensitive documents, including used carbon paper, and destroyed any equipment they didn’t need for daily operations.

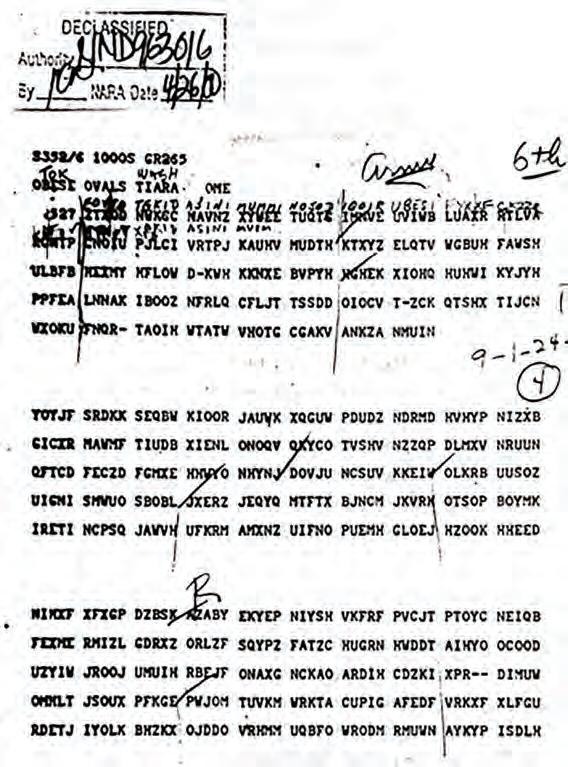

The navy high command pondered Station

Top: American codebreakers put together a machine that helped them crack the Japanese “Purple” diplomatic code. Above: This piece of a Purple machine was taken from the Japanese embassy in Berlin at the end of the war. Background: Encrypted Purple messages looked like random letters. The handwritten notations were to indicate how to adjust the machine’s rotors to break the code.

Cast’s future. It realized it couldn’t let these men fall into Japanese hands. “Their loss would represent a severe setback to our Communication Intelligence activities,” the brass noted on January 23. It recommended evacuation, but that presented daunting problems. Dodging the Japanese blockade to get out of the Philippines would be risky, and the loss of these men would eliminate nearly half of the American codebreakers in the Pacific theater. A mass evacuation was out of the question because, even if it succeeded, it would put Station Cast out of business for weeks as the men traveled to Australia and set up shop there. At this critical juncture in the war the codebreaking activities were essential. “Communication Intelligence organization…is of such importance to successful prosecution of war in Far East that special effort should be made to preserve continuity,” insisted Admiral Ernest J. King, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Fleet and, beginning in March 1942, chief of naval operations.

King ordered the men to be taken out in stages so Station Cast could keep operating on Corregidor for as long as possible. He knew the Japanese would eventually capture the island, but he couldn’t predict how much longer Bataan or Corregidor could hold out. He believed a staged evacuation was worth the risk.

While the high command pondered its options, the codebreakers learned there was a far more drastic plan in play. One evening, Radioman Duane L. Whitlock saw two officers in the tunnel sitting at their desks and cleaning their .45-caliber pistols. He jokingly asked if they were expecting a visit from the Japanese that night, but they didn’t smile. “No, these are for you and the others,” one of them explained. “We have discussed it between us and have decided we will not let a single one of you fall into their hands. When the time comes, we are going to shoot every one of you, then shoot ourselves.” Whitlock knew the officers weren’t kidding around. The general feeling, Radioman Burnett said, was that if “any of us got off the place alive, it would be a miracle.”

THE EVACUATIONS BEGAN on February 5, 1942, at 7:31 p.m., when the submarine USS Seadragon (SS-194) surfaced off the coast of Corregidor. It left 15 minutes later, carrying four officers and 13 enlisted men from Station Cast. The submarine took them to the Netherland East Indies (now Indonesia). From there, they went to Australia to begin setting up a new Station Cast. The evacuation happened unexpectedly and on short notice, leaving the 57 men left behind startled to find their 17 colleagues gone so quickly that they had to leave all their worldly goods behind. Their clothing went into a “lucky bag” for communal use, and Chief Machinist’s Mate J.W. “Pappy” Lowery received their cigarettes for rationing. Station Cast remained in business. The navy had made sure that enough linguists, cryptanalysts, and radiomen stayed behind to do the work.

By March, the Japanese continued to push the Allied defenders farther back on Bataan. The navy high command realized that Bataan and Corregidor could fall at any time. “Evacuate personnel of Radio Intelligence Unit soon as possible…. Take all steps possible to prevent loss of personnel of Radio Intelligence Unit,” Admiral King ordered on March 5.

The evacuation would take time. While they waited, the men continued their daily work, and on March 16 they made a discovery, seemingly routine at the time, that justified King’s insistence on keeping the station open. The cryptanalysts determined that “AF” was