America’s

Manzanar

WWII Detention Camps With

Ansel

Adams at

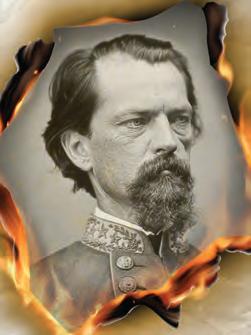

Thomas Jefferson’s Other Expeditions NAACP Warrior Walter White Blues Power B.B. King’s leap from field hand to footlights HISTORYNET.com Winter 2023 AMHP-230100-COVER-DIGITAL.indd 1 9/26/22 3:30 PM

exploring the rugged battlegrounds of a past war, watching a skilled craftsperson at work and hearing riveting stories of the past. Travel back in time and explore the rich history of the Alabama Gulf Coast.

GulfShores.com OrangeBeach.com 888-666-9252 ...like

AMHP-221101-005 Gulf Shores.indd 1 9/22/22 12:13 PM

It’s been more than 100 years since the last Morgan Silver Dollar was struck for circulation. Morgans were the preferred currency of cowboys, ranchers and outlaws and earned a reputation as the coin that helped build the Wild West. Struck in 90% silver from 1878 to 1904, then again in 1921, these silver dollars came to be known by the name of their designer, George T. Morgan. They are one of the most revered, most-collected, vintage U.S. Silver Dollars ever.

Celebrating the 100th Anniversary with Legal-Tender Morgans

Honoring the 100th anniversary of the last year they were minted, the U.S. Mint struck five different versions of the Morgan in 2021, paying tribute to each of the mints that struck the coin. The coins here honor the historic New Orleans Mint, a U.S. Mint branch from 1838–1861 and again from 1879–1909. These coins, featuring an “O” privy mark, a small differentiating mark, were struck in Philadelphia since the New Orleans Mint no longer exists. These beautiful

coins are different than the originals because they’re struck in 99.9% fine silver instead of 90% silver/10% copper, and they were struck using modern technology, serving to enhance the details of the iconic design.

Very Limited. Sold Out at the Mint!

The U.S. Mint limited the production of these gorgeous coins to just 175,000, a ridiculously low number. Not surprisingly, they sold out almost instantly! That means you need to hurry to add these bright, shiny, new legal-tender Morgan Silver Dollars with the New Orleans privy mark, struck in 99.9% PURE Silver, to your collection. Call 1-888-395-3219 to secure yours now. PLUS, you’ll receive a BONUS American Collectors Pack, valued at $25, FREE with your order. Call now. These will not last!

FREE SHIPPING! Limited time only. Standard domestic

only. Not valid

shipping

on previous purchases. GovMint.com® is a retail distributor of coin and currency issues and is not affiliated with the U.S. government. The collectible coin market is unregulated, highly speculative and involves risk. GovMint.com reserves the right to decline to consummate any sale, within its discretion, including due to pricing errors. Prices, facts, figures and populations deemed accurate as of the date of publication but may change significantly over time. All purchases are expressly conditioned upon your acceptance of GovMint.com’s Terms and Conditions (www.govmint.com/terms-conditions or call 1-800-721-0320); to decline, return your purchase pursuant to GovMint.com’s Return Policy. © 2022 GovMint.com. All rights reserved. SPECIAL CALL-IN ONLY OFFER The U.S. Mint Just Struck Morgan Silver Dollars for the First Time in 100 Years! O PRIVY MARK GovMint.com • 1300 Corporate Center Curve, Dept. NSD269-02, Eagan, MN 55121 1-888-395-3219 Offer Code NSD269-02 Please mention this code when you call. Struck in 99.9% Fine Silver! For the First Time EVER! First Legal-Tender Morgans in a Century! VERY LIMITED! Sold Out at the Mint! A+ To learn more, call now. First call, first served! AMHP-221101-013 GovMint 2021 Morgan Silver Dollar.indd 1 9/22/22 12:11 PM

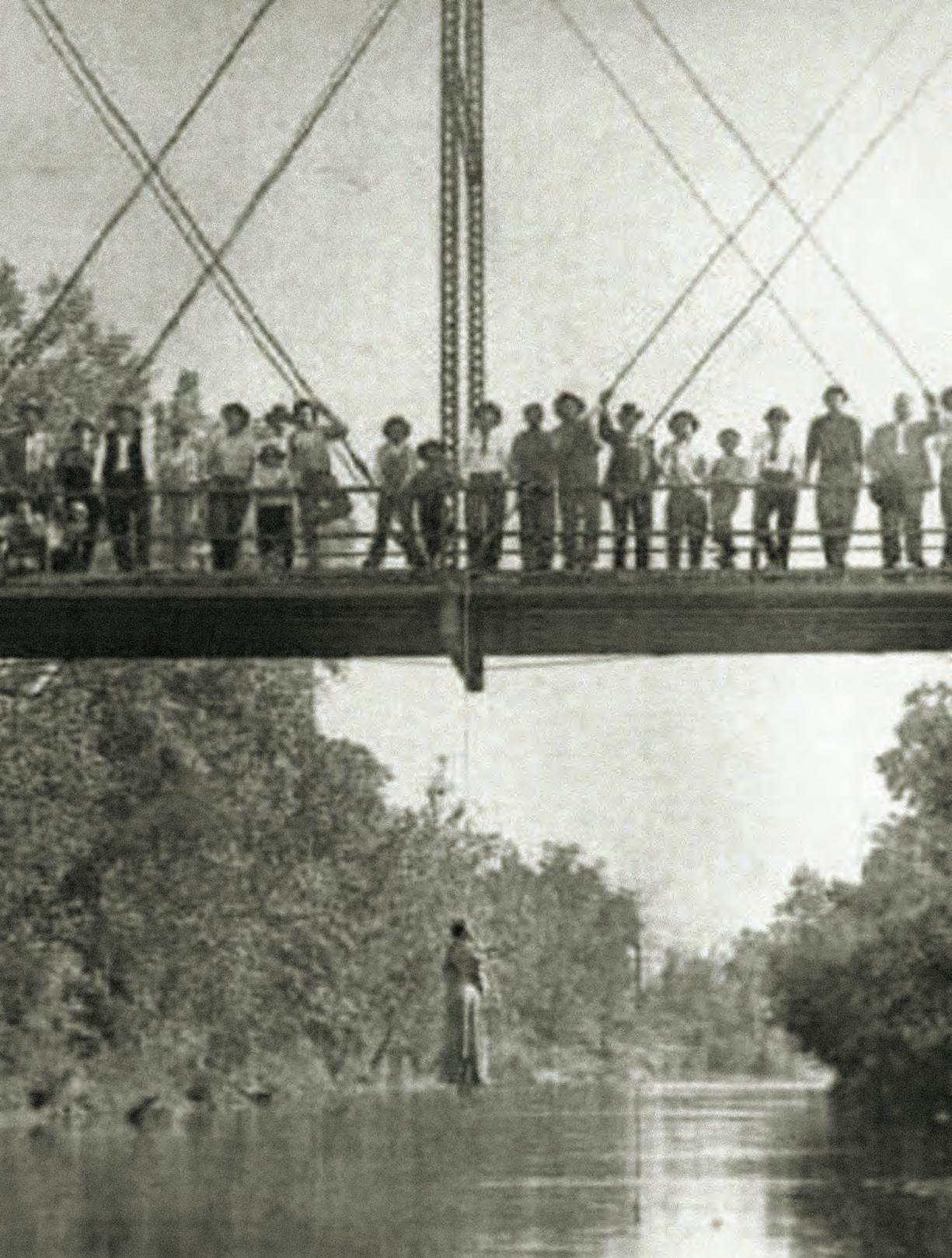

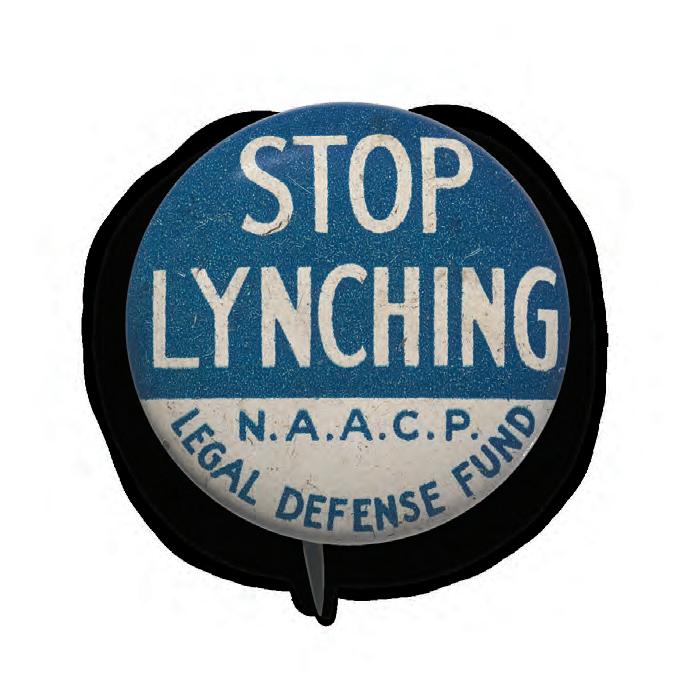

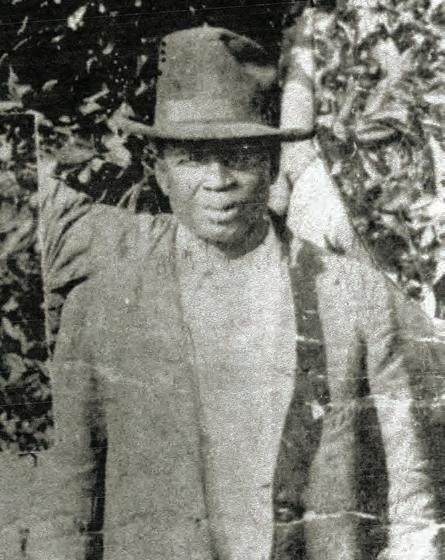

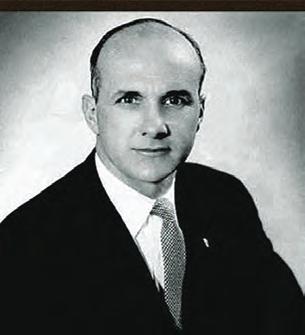

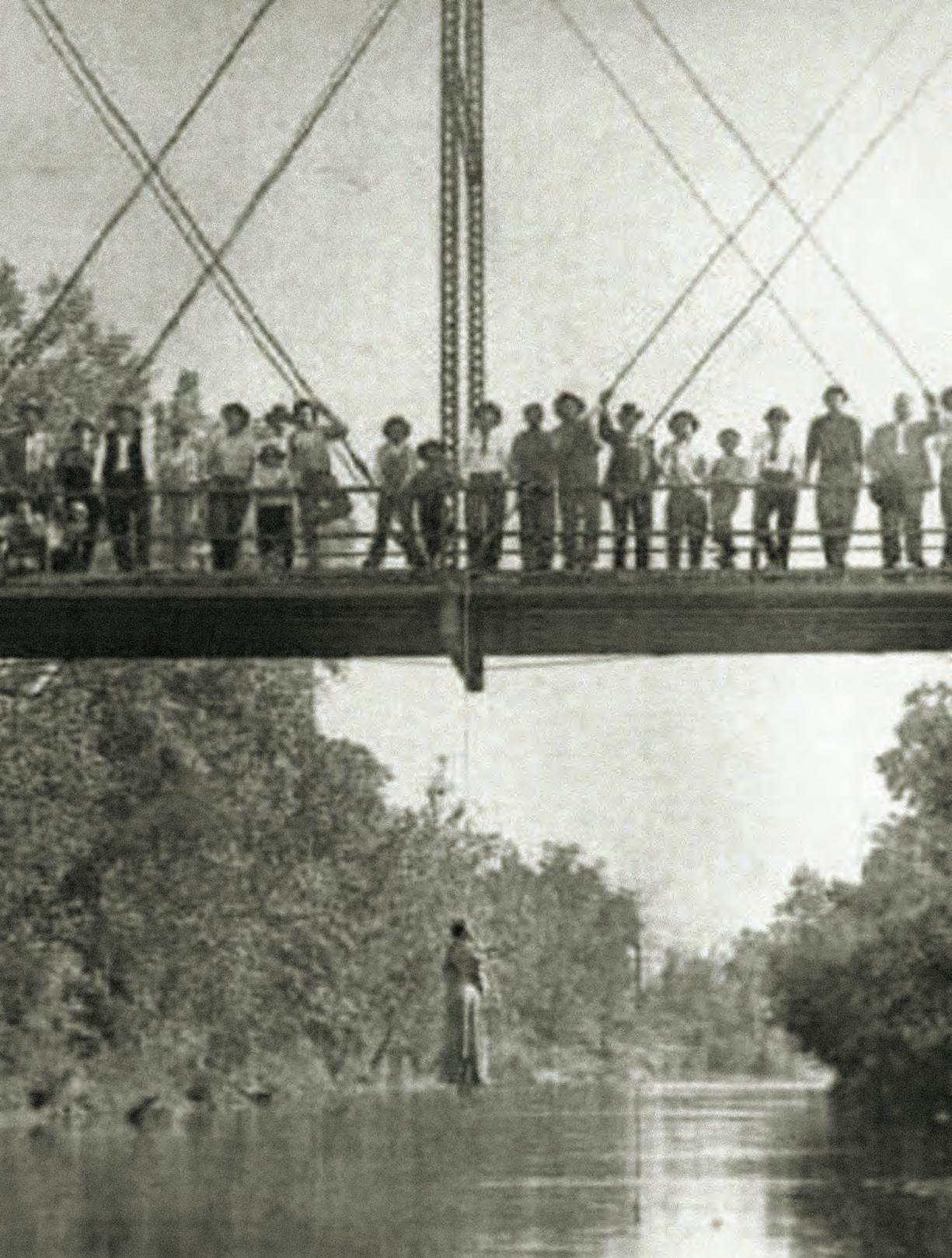

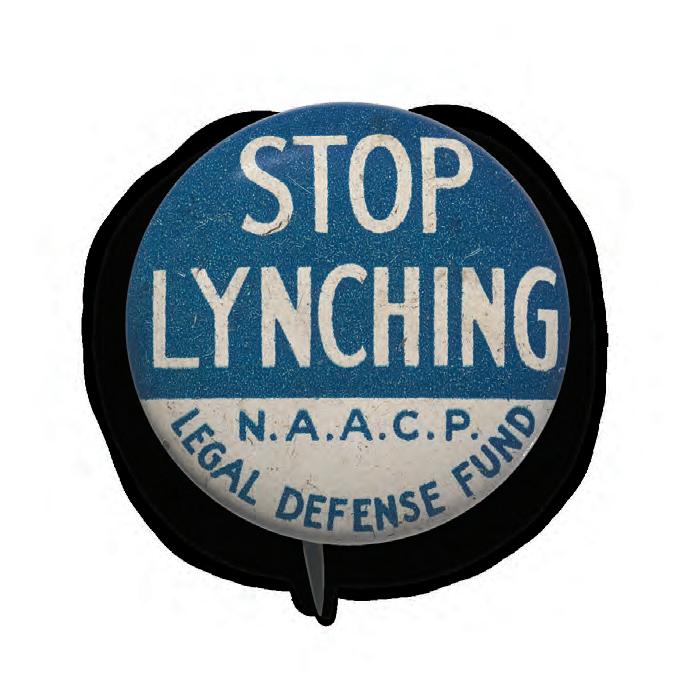

58 Walter White parlayed brash confidence and light skin tone into years of exposing the American plague of lynching.

58 Walter White parlayed brash confidence and light skin tone into years of exposing the American plague of lynching.

AMHP-230100-CONTENTS.indd 2 9/26/22 10:12 AM

Daniel de Visé

By J.

By J.

Zahniser

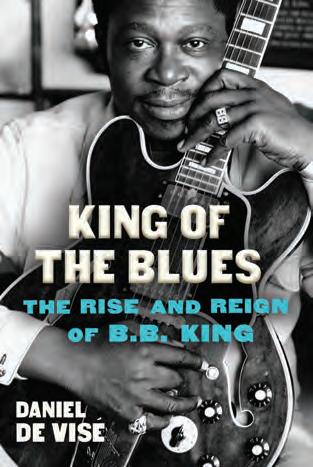

WINTER 2023 3 FEATURES 24 Becoming B.B. Once upon a time a young bluesman put his trust in ambition and was rewarded mightily. By

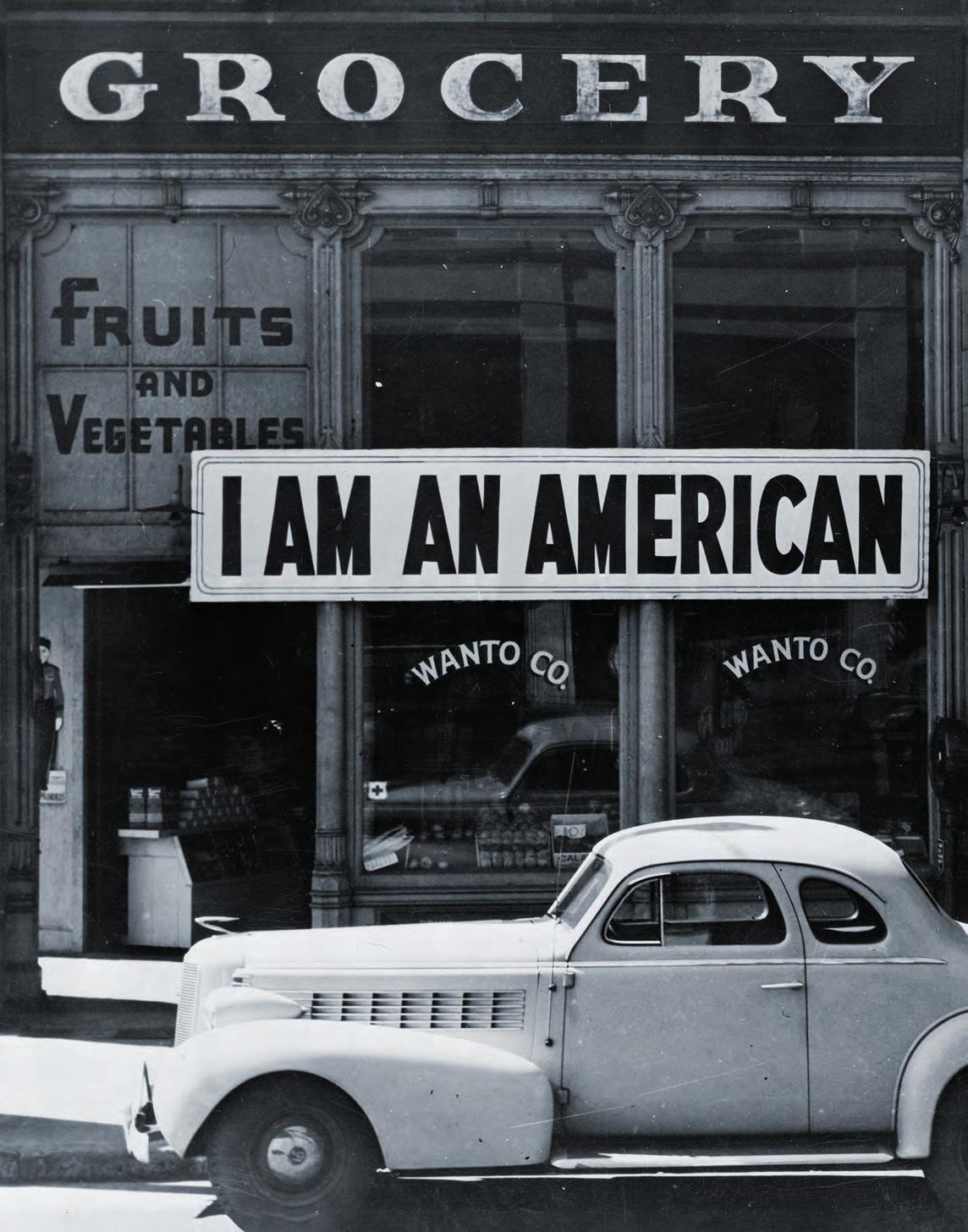

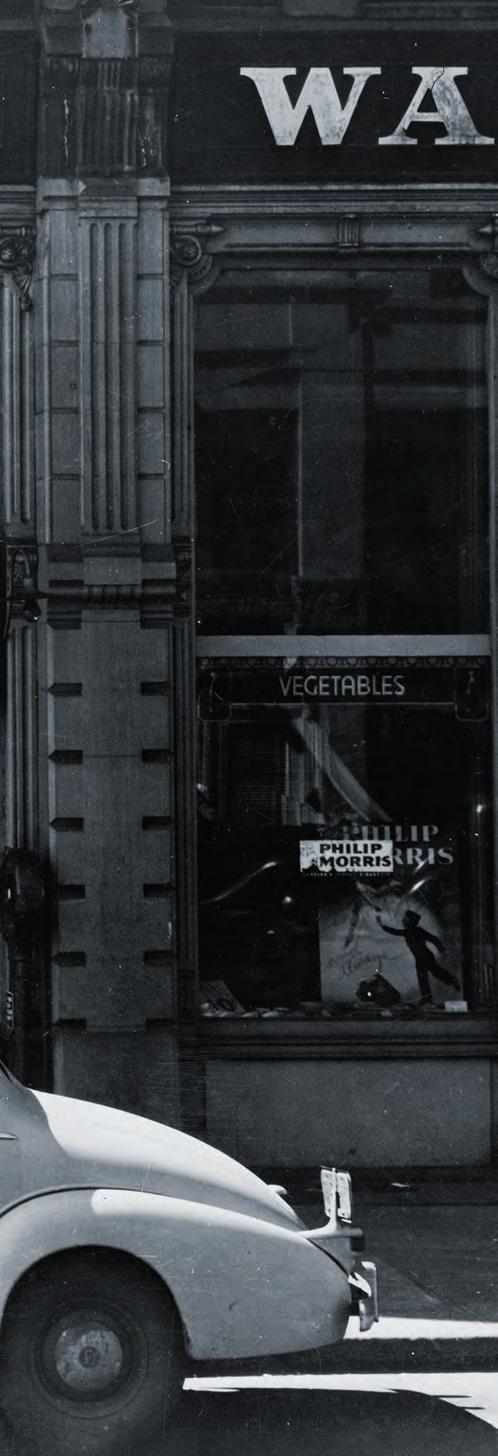

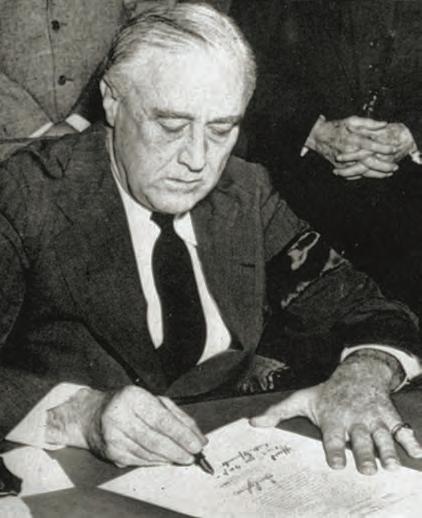

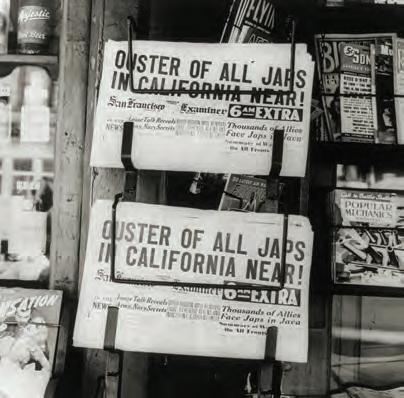

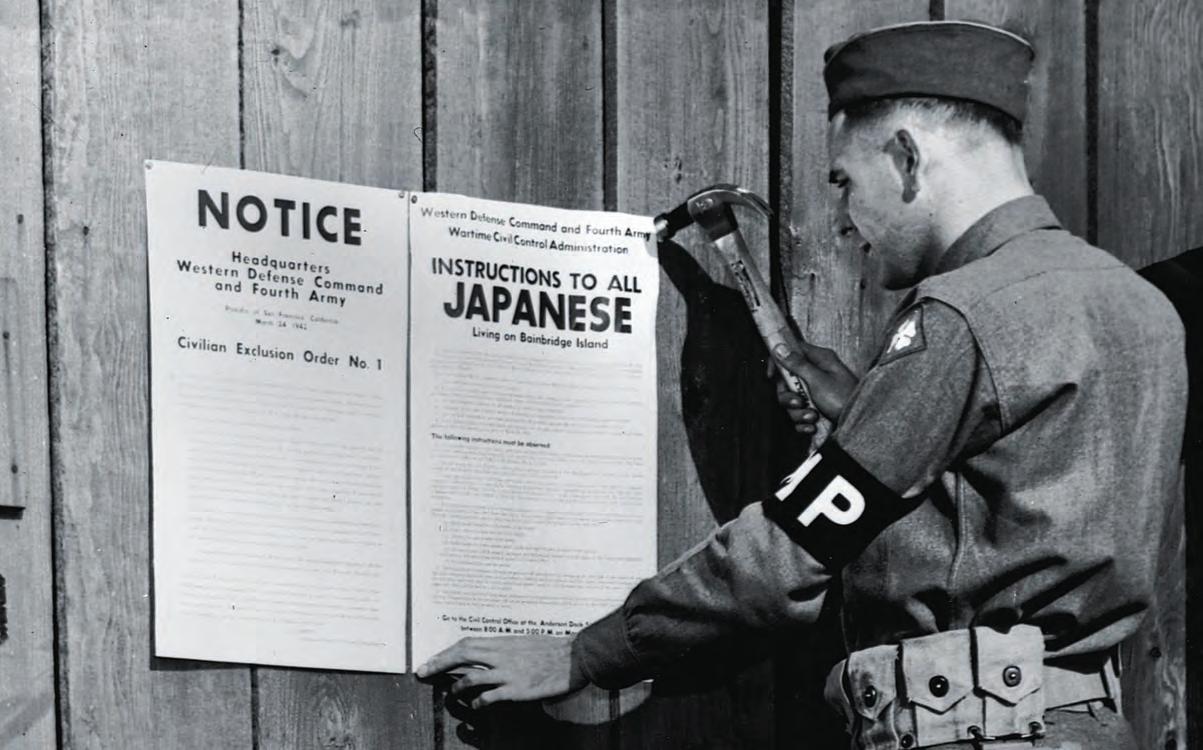

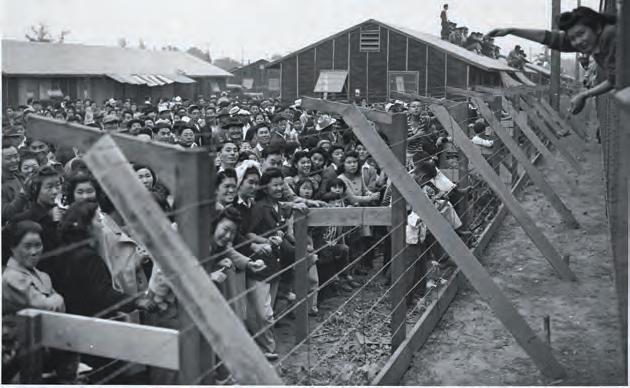

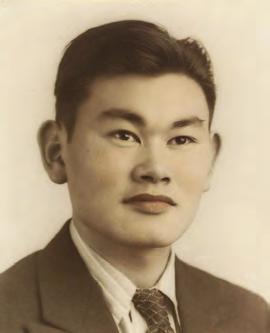

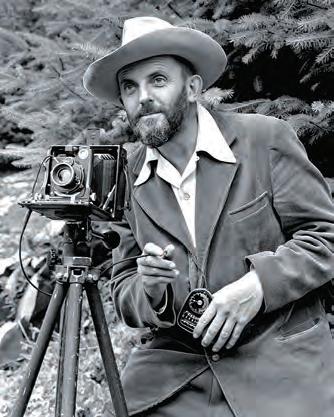

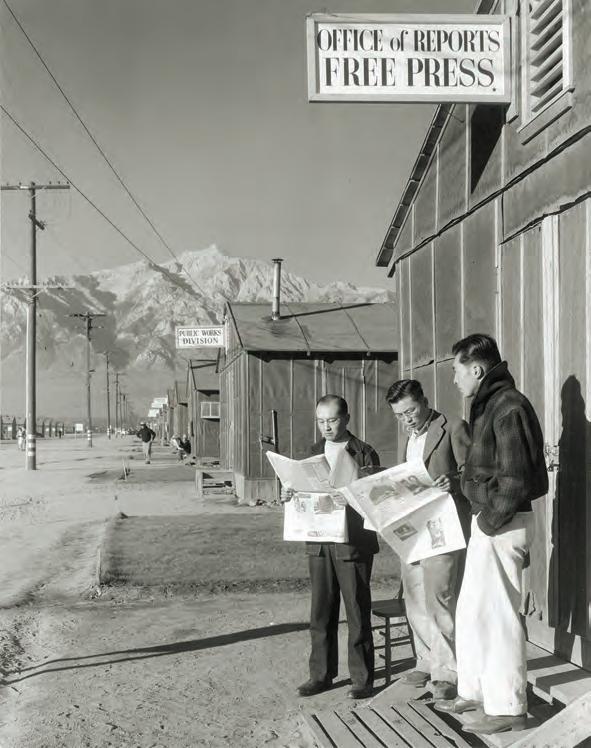

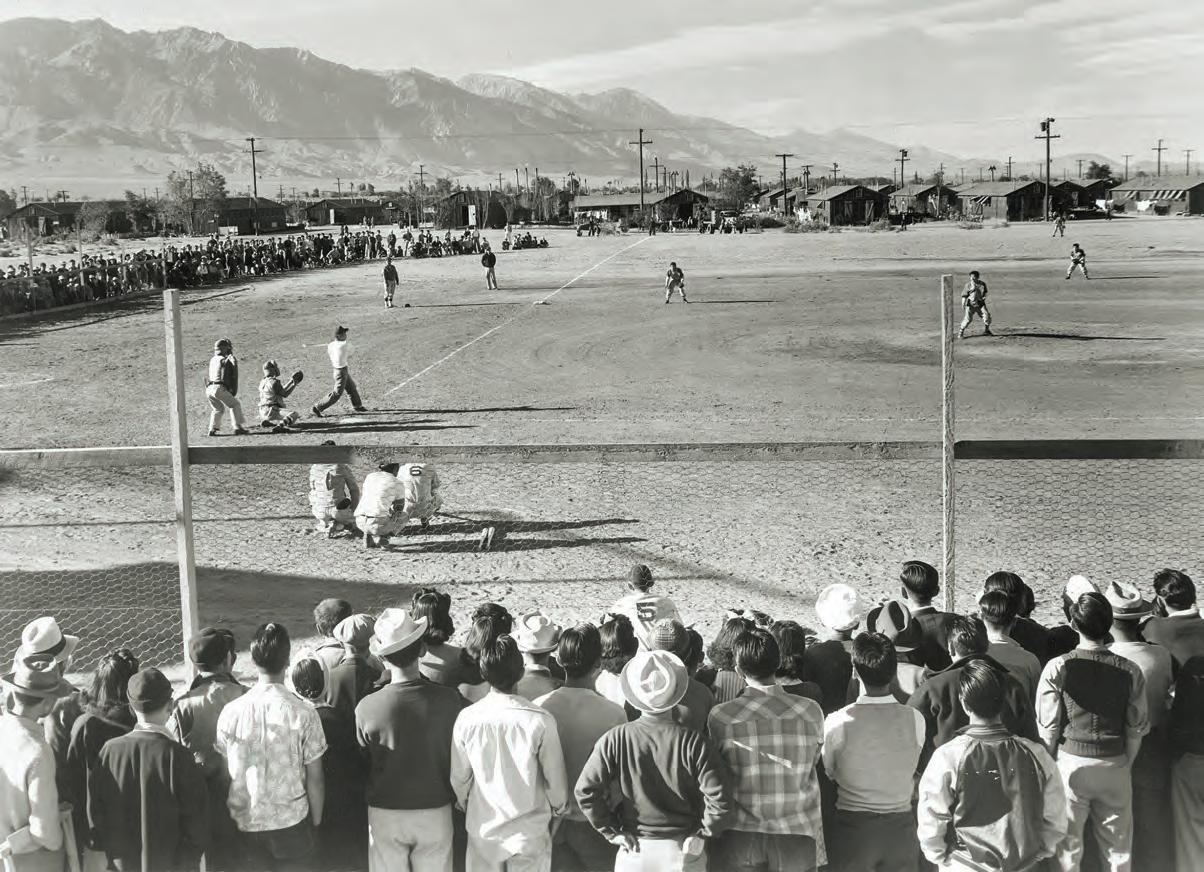

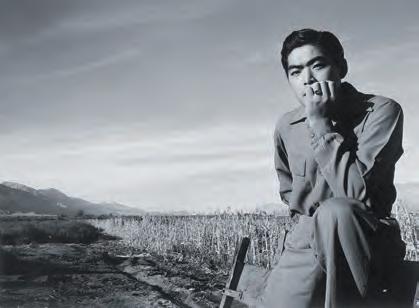

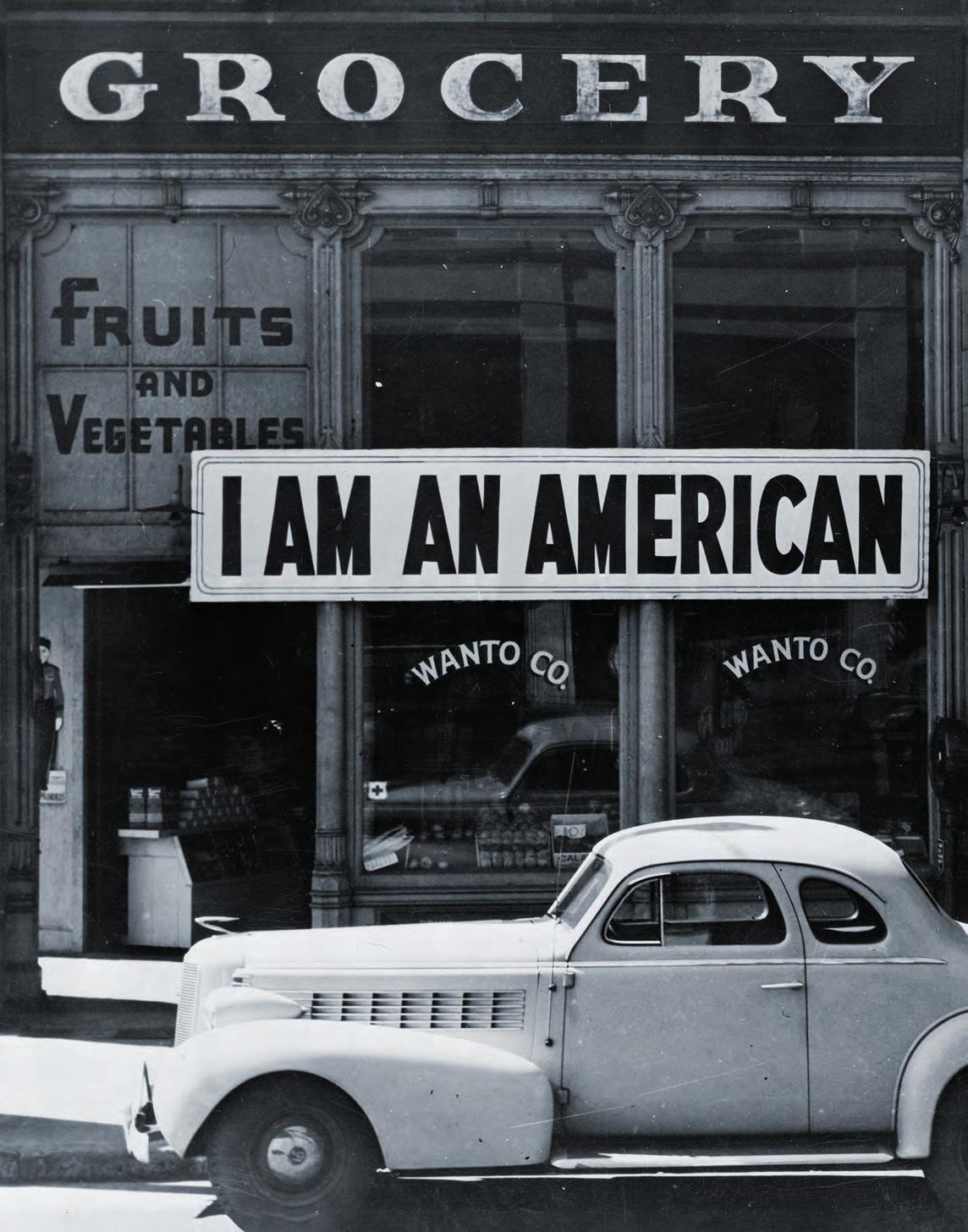

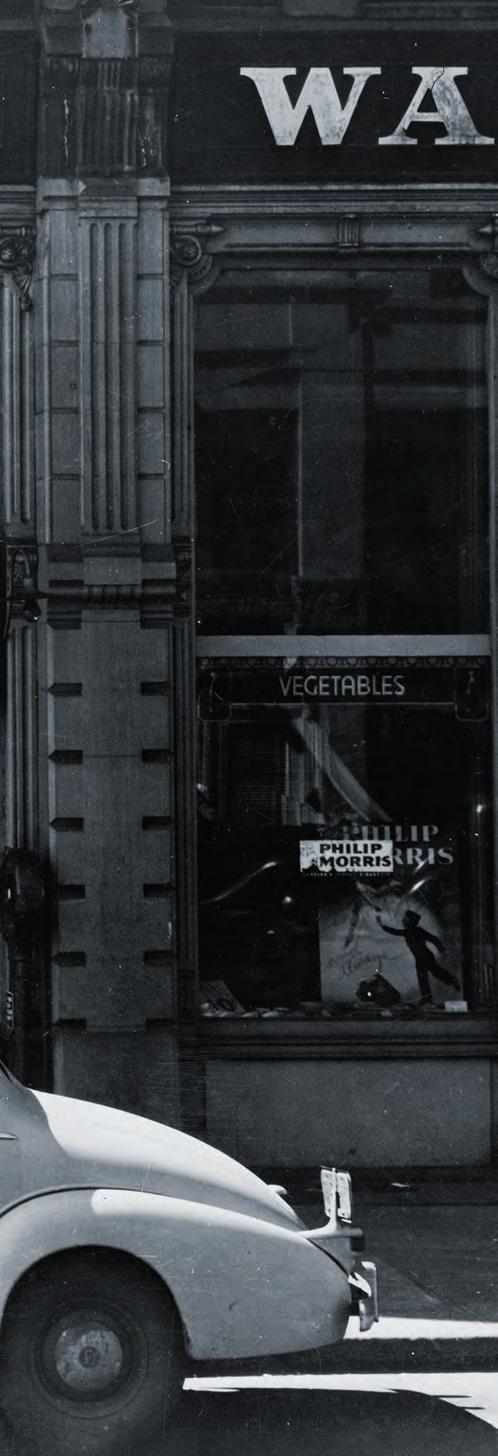

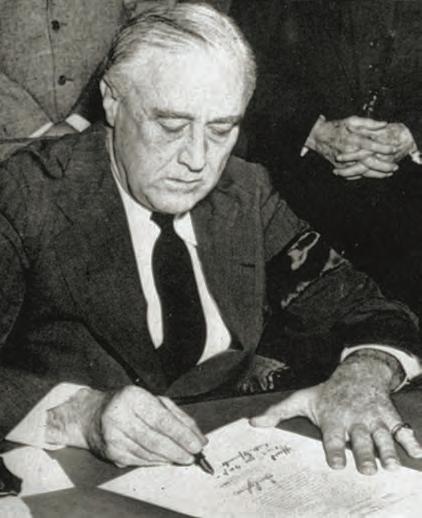

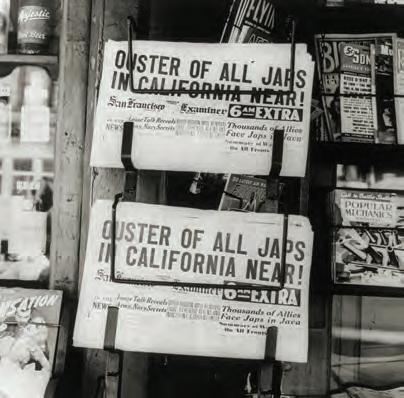

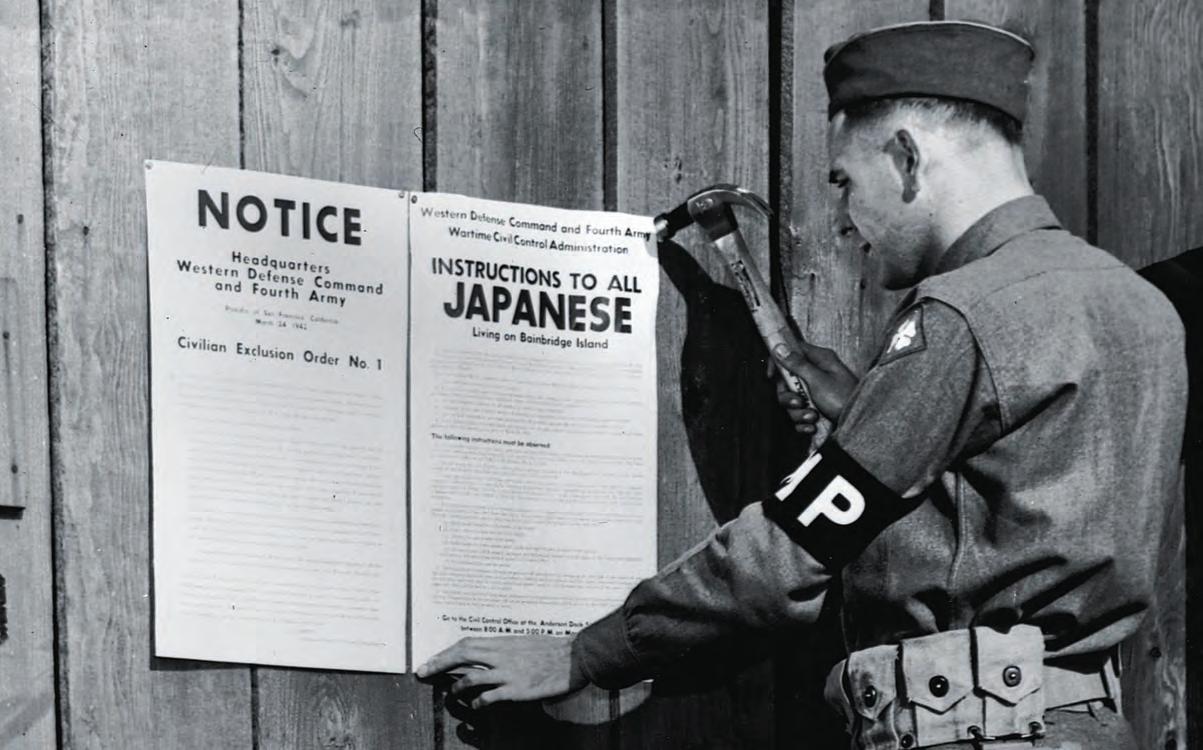

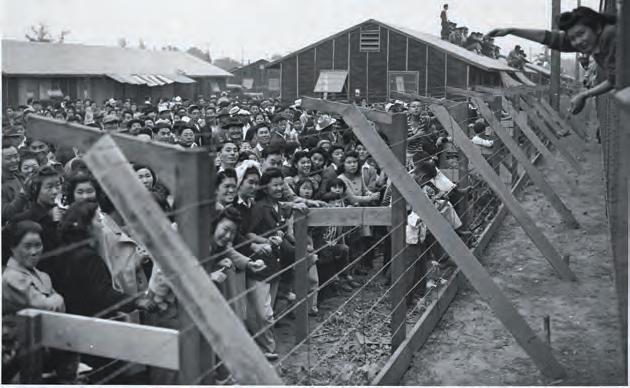

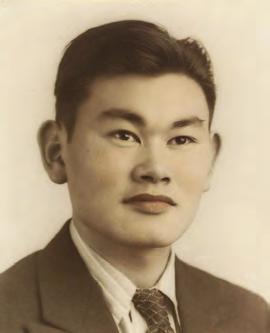

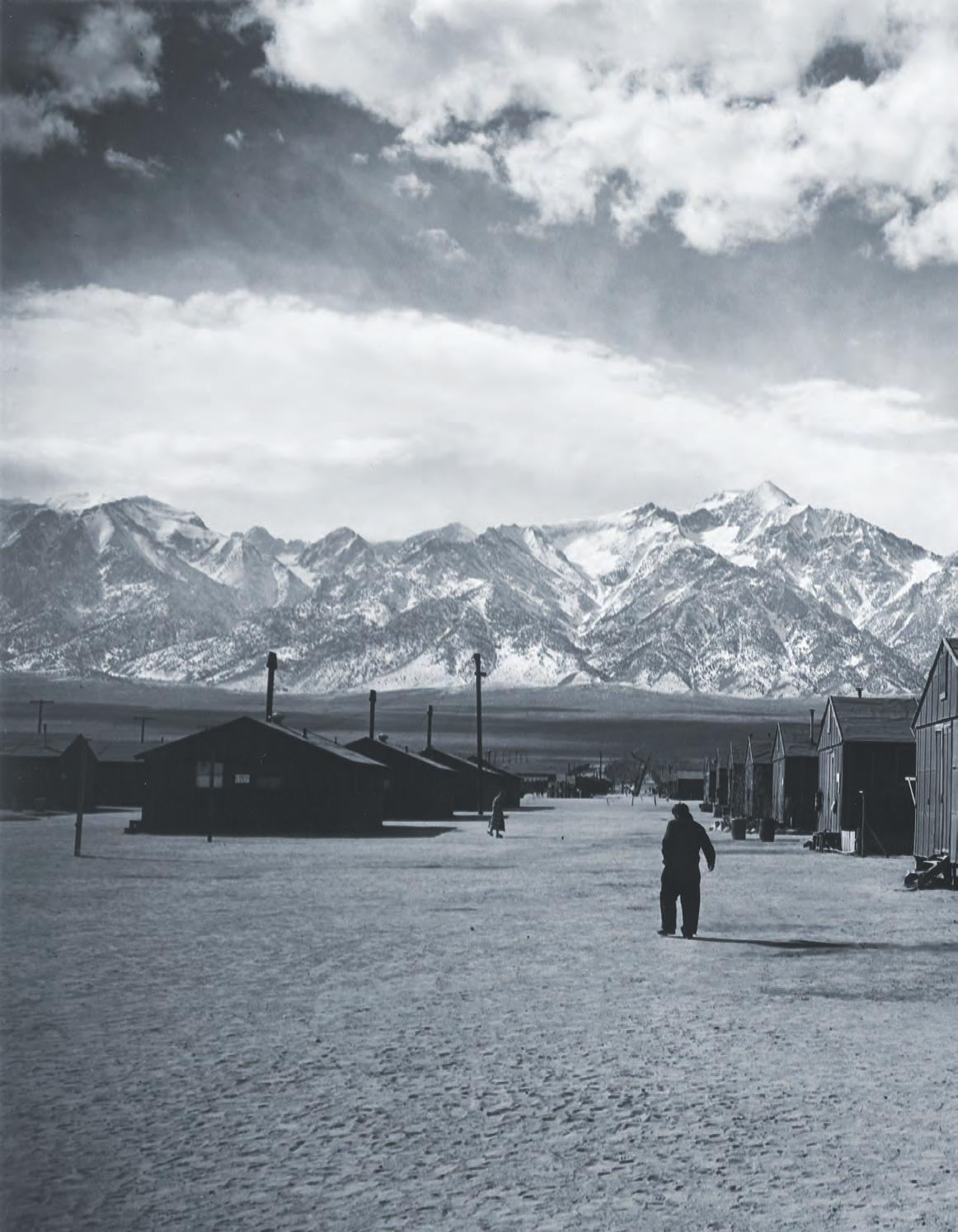

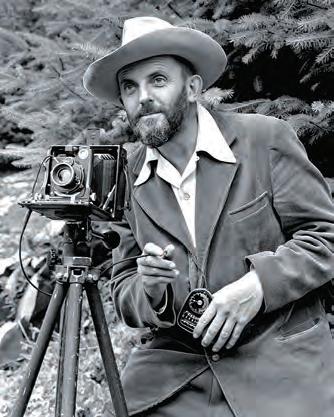

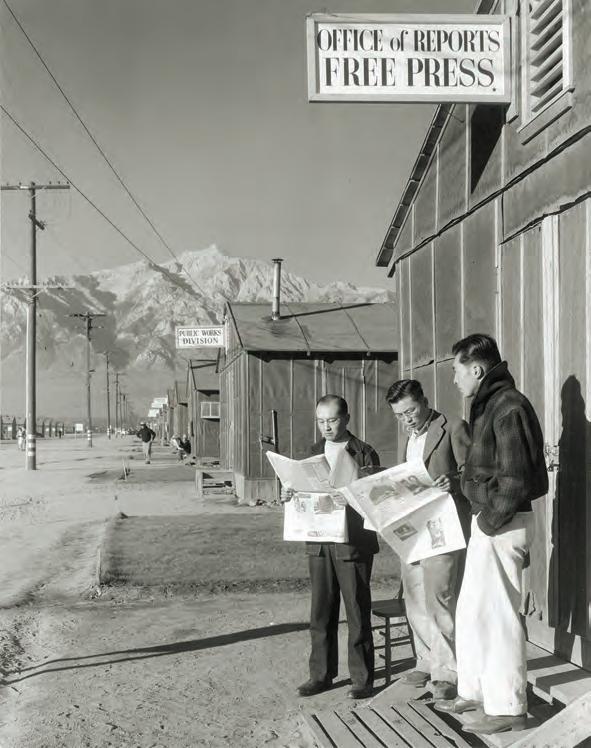

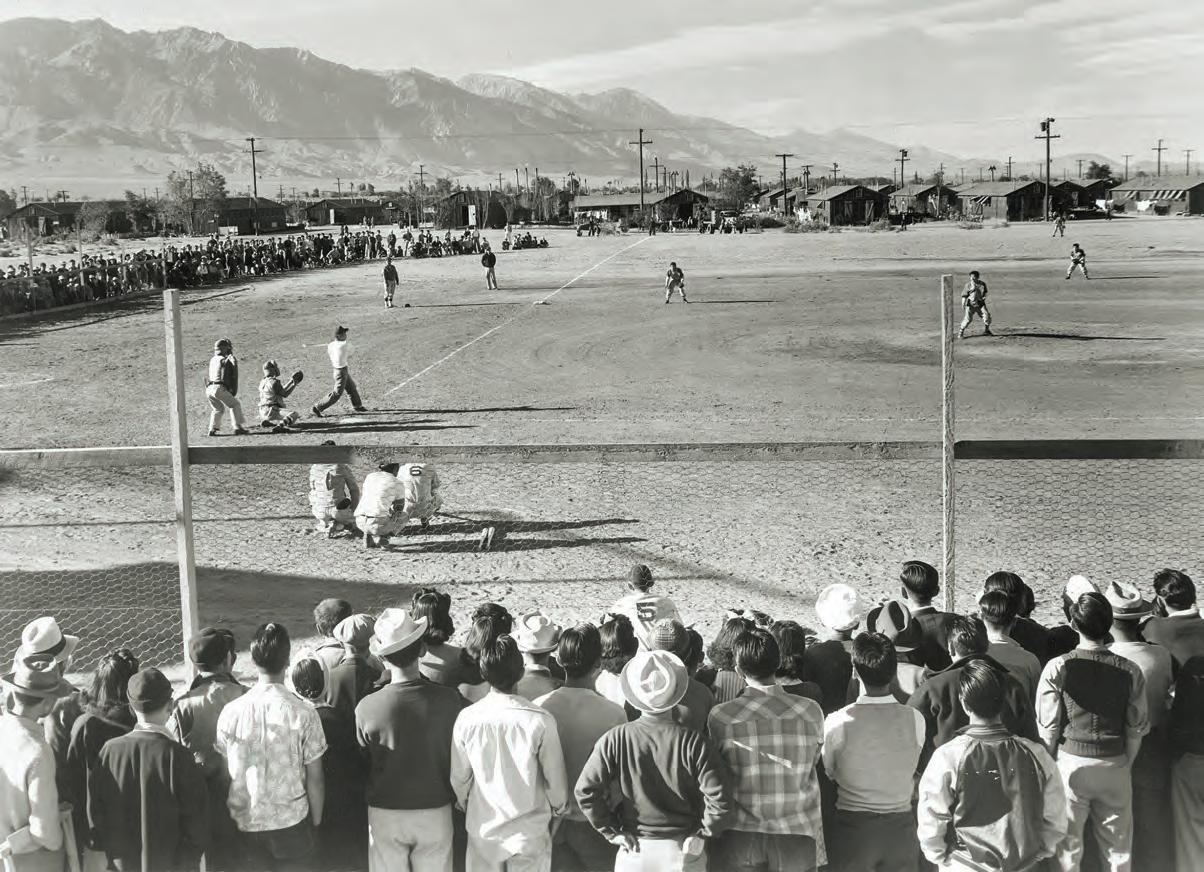

32 Days of Infamy Japan's surprise attack on the U.S. Navy base at Pearl Harbor triggered a profoundly shameful episode.

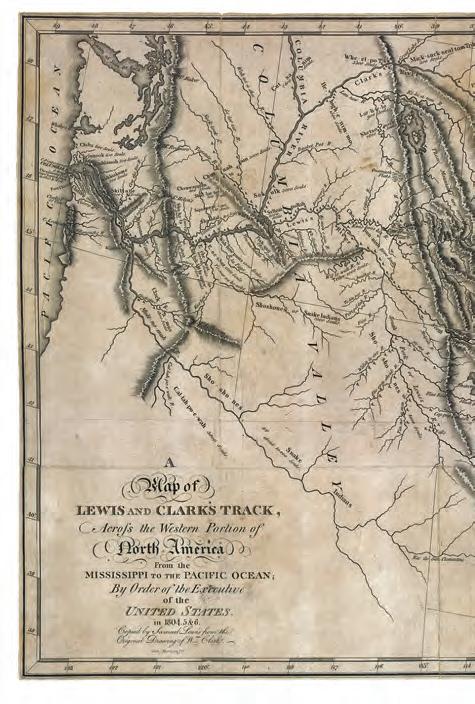

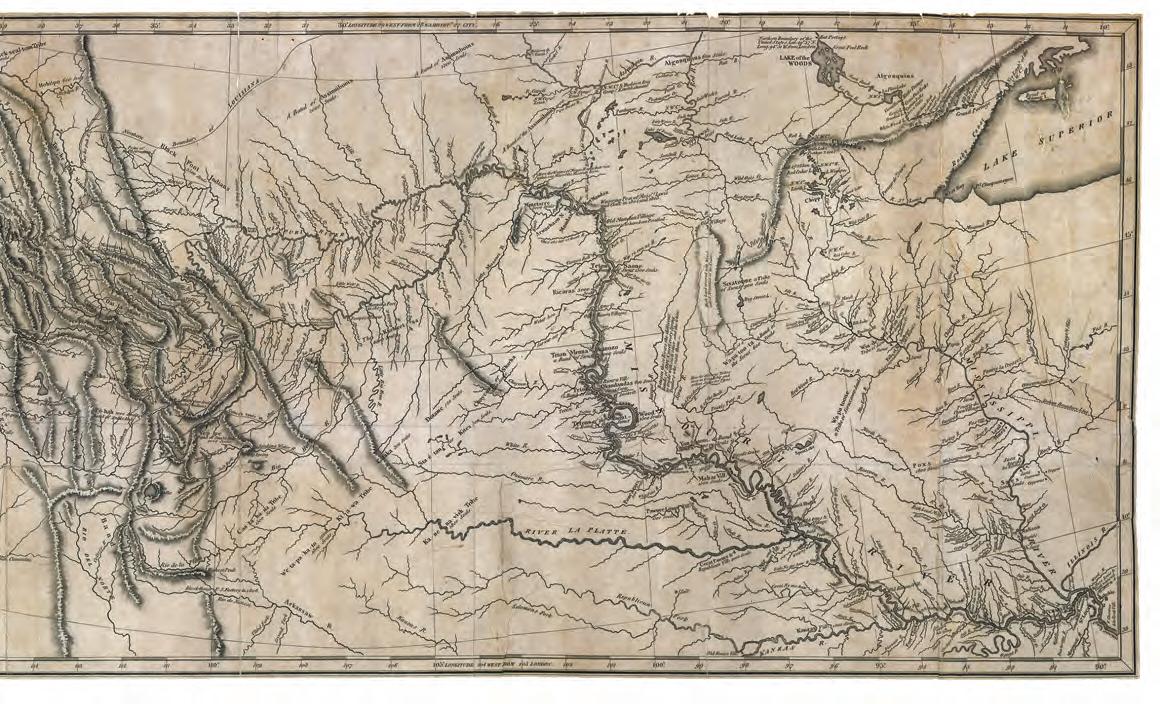

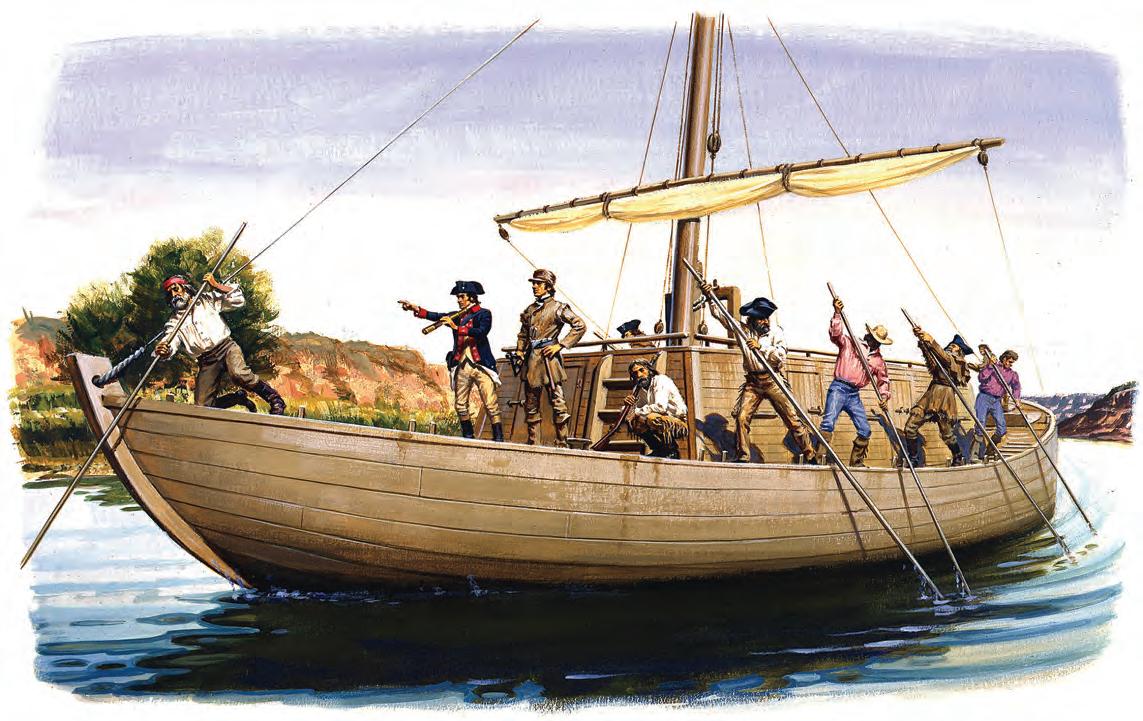

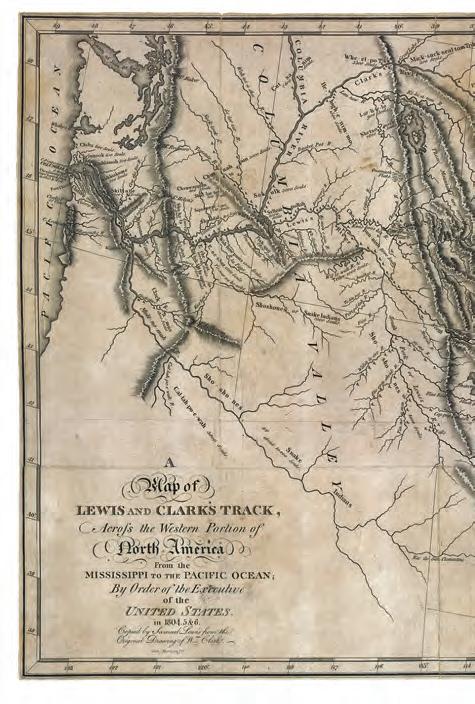

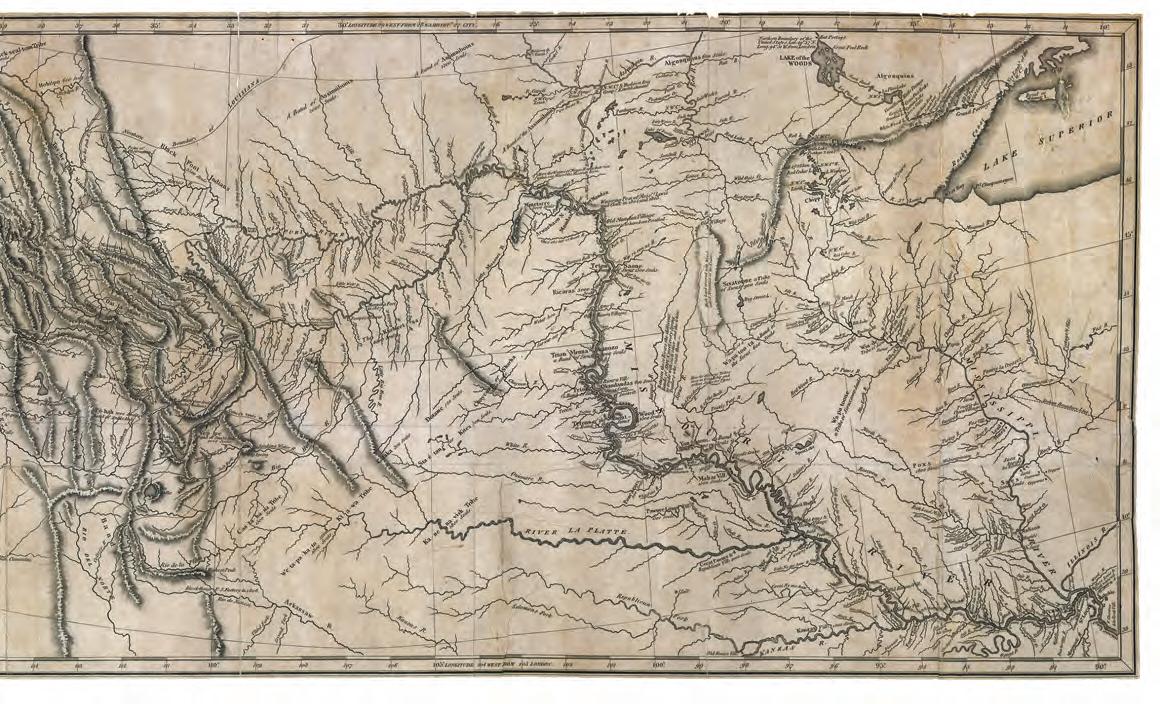

D.

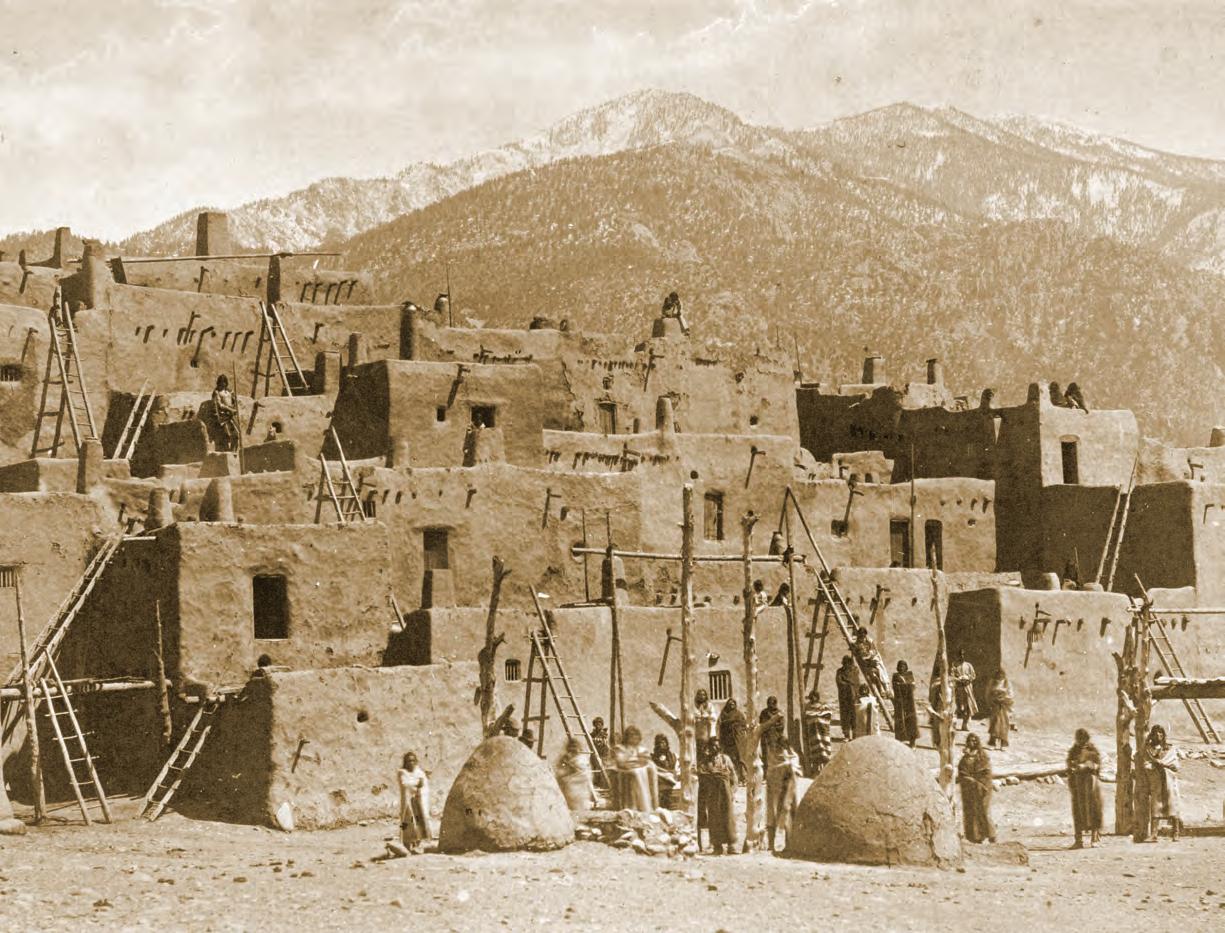

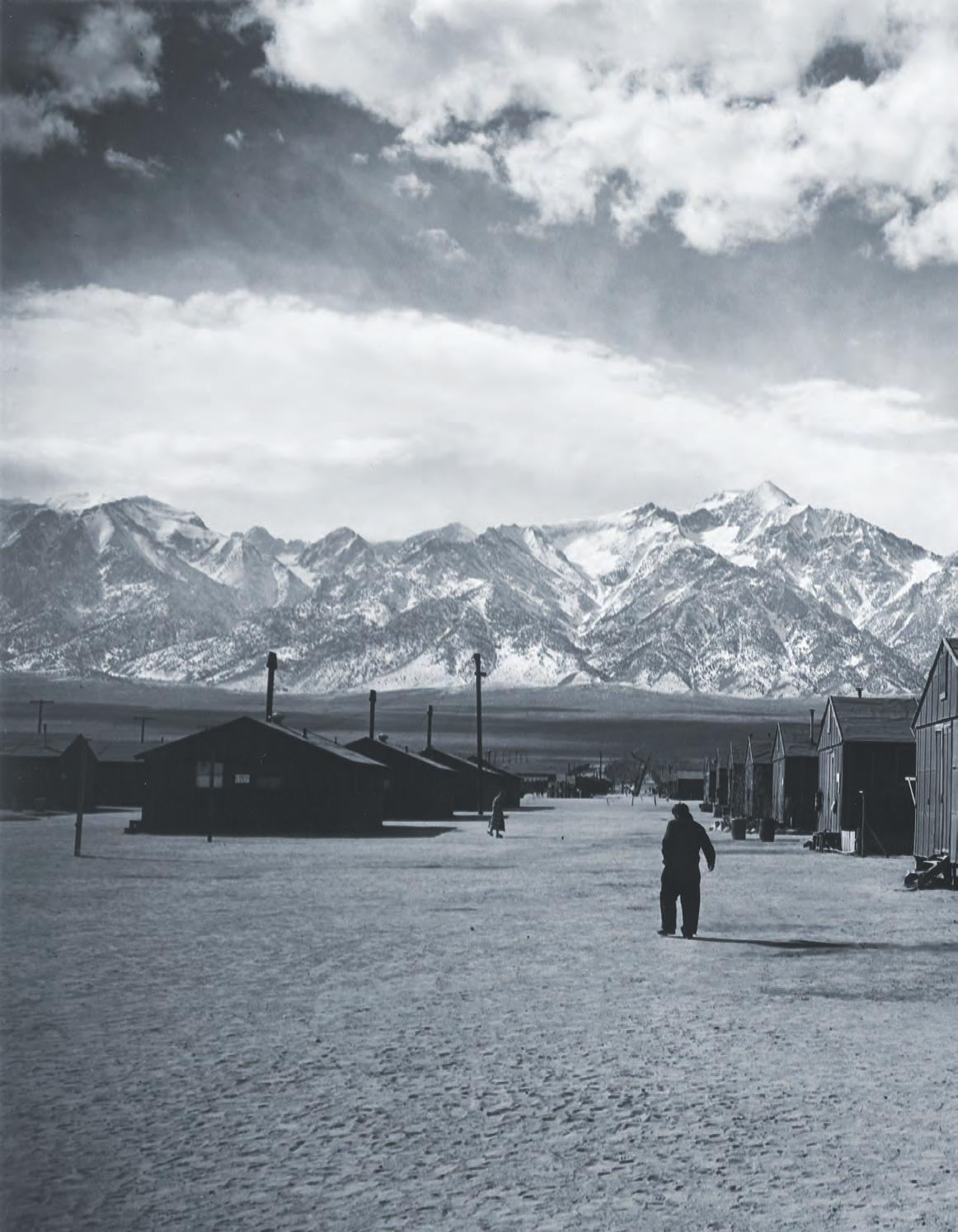

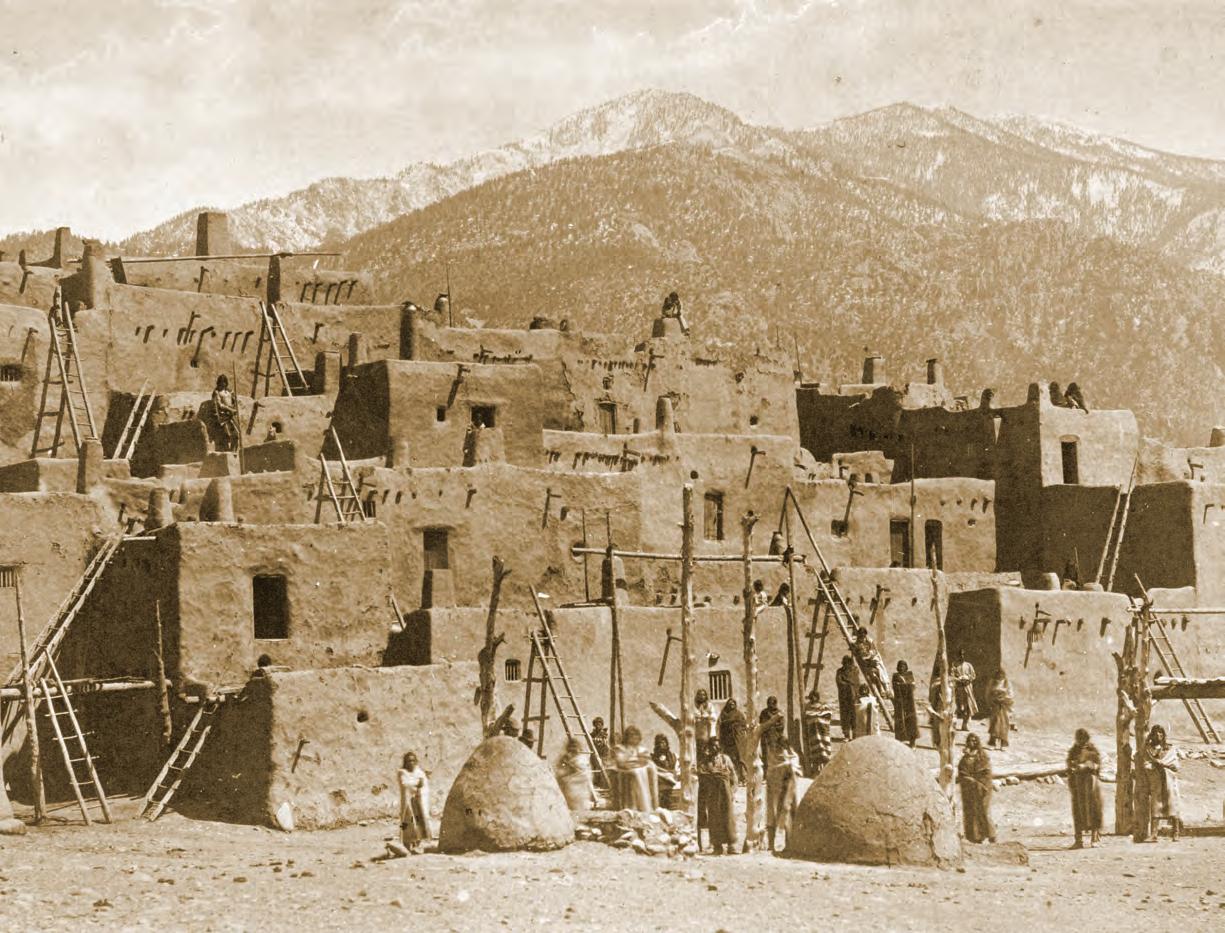

40 Picture Imperfect With photographer Ansel Adams at the Manzanar, California, detention center. By Richard J. Goodrich 50 L ighting Out for the Territory Everyone remembers Lewis and Clark but those worthies had a lot of company when it came to exploring Louisiana. By Mike Coppock 58 White Power R isking his life, NAACP undercover investigator Walter White brought illumination to murderous racist violence. By Peter Carlson Winter 2023 50 14 32 DEPARTMENTS 6 Mosaic History in today’s headlines 12 Contributors 14 A merican Schemers The flimflam man who conned Nazi bigwigs into buying junk. 16 Déjà Vu Temperament and temper help leaders make their cases. 20 SCOTUS 101 Invidious as speech may be, it isn't necessarily illegal. 22 Cameo Photographic innovator Robert Cornelius invented the selfie. 66 Reviews 72 A n American Place Taos, New Mexico, was historic when the country was young. ON THE COVER: The whole world came to address him by a euphonious pair of invented initials, but in his scuffling days folks knew him as Riley B. King.CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY; AP PHOTO; GL ARCHIVE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; LOS ANGELES TIMES PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE, LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, CHARLES E. YOUNG RESEARCH LIBRARY, UCLA; BONANZAS; COVER: HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES Bob Dylan's one-off rerecording of his song "Blowin' in the Wind" sold for more than $1.7 million. —see page 10 AMHP-230100-CONTENTS.indd 3 9/26/22 10:12 AM

WINTER

MICHAEL DOLAN EDITOR

SARAH RICHARDSON SENIOR EDITOR

BRIAN WALKER GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR

MELISSA A. WINN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY JON C. BOCK ART DIRECTOR

DANA B. SHOAF MANAGING EDITOR, PRINT MICHAEL Y. PARK MANAGING EDITOR, DIGITAL CLAIRE BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

CORPORATE

KELLY FACER SVP REVENUE

MATT GROSS VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES ROB WILKINS DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING JAMIE ELLIOTT PRODUCTION DIRECTOR

MORTON GREENBERG SVP

TERRY JENKINS

HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

MICHAEL

A. REINSTEIN CHAIRMAN & PUBLISHER

2023 VOL. 57, NO. 4

OPERATIONS

ADVERTISING

Advertising Sales mgreenberg@mco.com

Regional Sales Manager tjenkins@historynet.com DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING NANCY FORMAN / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: SHOP.HISTORYNET.COM or 800-435-0715 American History (ISSN 1076-8866) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC, 901 North Glebe Road, Fifth Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Vienna, VA and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER, send address changes to American History, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900 List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc. 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519, Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001 © 2022 HistoryNet, LLC The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet LLC. PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA Sign up for our FREE weekly e-newsletter at historynet.com/newsletters HISTORYNET VISIT HISTORYNET.COM PLUS! Today in History What happened today, yesterday or any day you care to search. Daily Quiz Test your historical acumen every day! What If? Consider the fallout of historical events had they gone the ‘other’ way. Weapons & Gear The gadgetry of war—new and old, effective and not so effective. Charles Hardin "Buddy" Holly, dead at 22 in 1959, is only one of many entries on the long roster of popular musicians who came to grief while traveling between gigs by airplane. Historynet.com/musicians-who-died Days & Nights the Music Died TRENDING NOW AMHP-230100-MASTONLINE.indd 4 9/26/22 10:20 AM

to the Bone

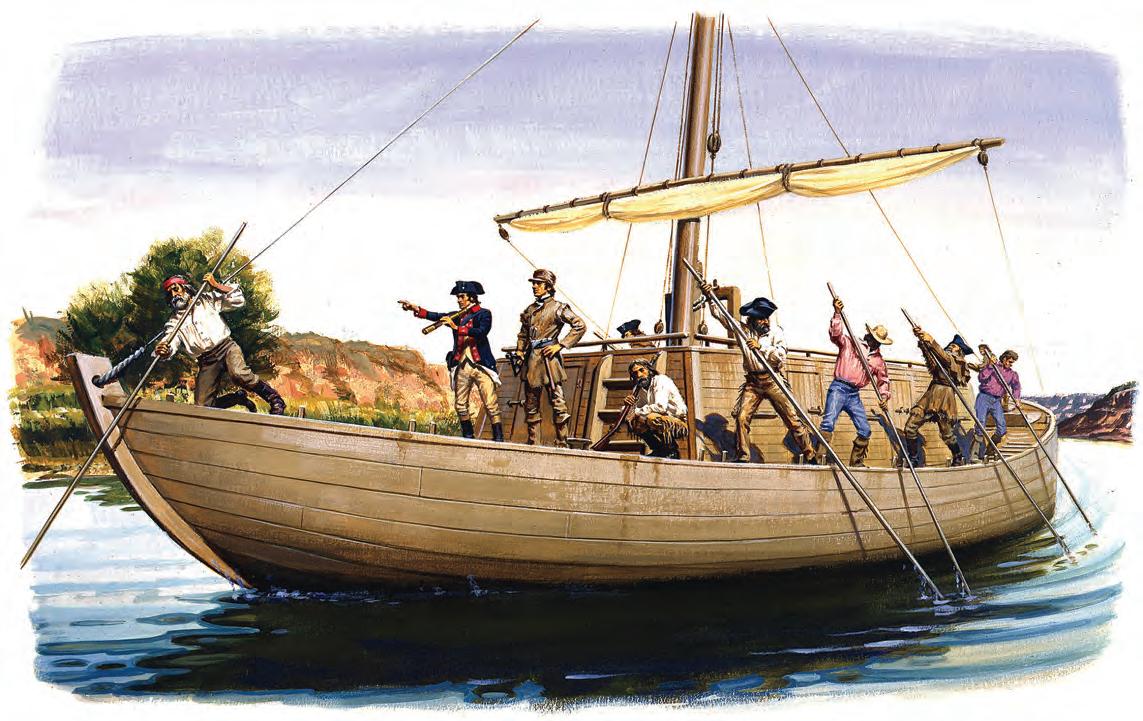

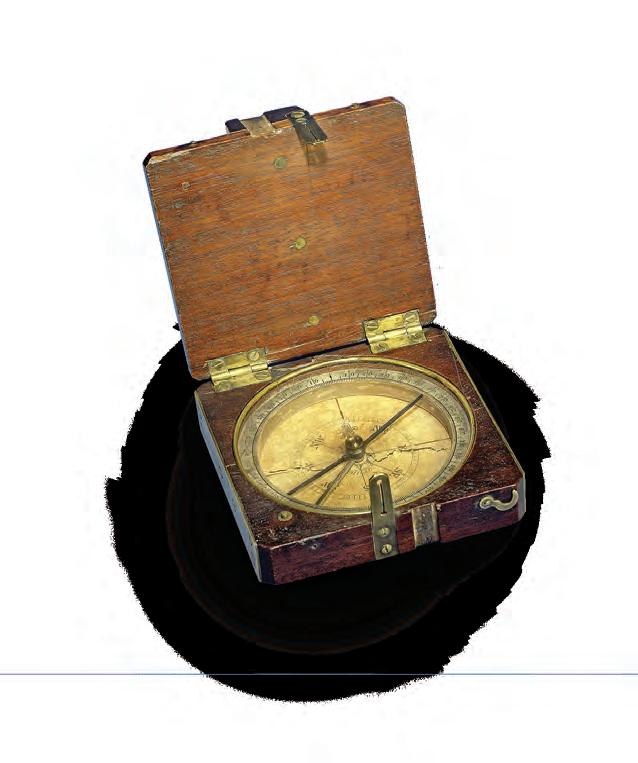

The very best hunting knives possess a perfect balance of form and function. They’re carefully constructed from fine materials, but also have that little something extra to connect the owner with nature.

If you’re on the hunt for a knife that combines impeccable craftsmanship with a sense of wonder, the $79 Huntsman Blade is the trophy you’re looking for.

The blade is full tang, meaning it doesn’t stop at the handle but extends to the length of the grip for the ultimate in strength. The blade is made from 420 surgical steel, famed for its sharpness and its resistance to corrosion.

The handle is made from genuine natural bone, and features decorative wood spacers and a hand-carved motif of two overlapping feathers— a reminder for you to respect and connect with the natural world.

This fusion of substance and style can garner a high price tag out in the marketplace. In fact, we found full tang, stainless steel blades with bone handles in excess of $2,000. Well, that won’t cut it around here. We have mastered the hunt for the best deal, and in turn pass the spoils on to our customers.

But we don’t stop there. While supplies last, we’ll include a pair of $99 8x21 power compact binoculars and a genuine leather sheath FREE when you purchase the Huntsman Blade

Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Feel the knife in your hands, wear it on your hip, inspect the impeccable craftsmanship. If you don’t feel like

a fair deal, send it back within 30 days

a complete

Limited Reserves. A deal like this

last long. We have only 1120

of

let this beauty

for this ad only.

through

fingers. Call

we cut you

for

refund

the item price.

won’t

Huntsman Blades

Don’t

slip

your

today! Stauer… Afford the Extraordinary ® Full tang stainless steel blade with natural bone handle —now ONLY $79! BONUS! Call today and you’ll also receive this genuine leather sheath! Not shown actual size. 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. HUK834-01 Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.comStauer ® *Discount is only for customers who use the offer code versus the listed original Stauer.com price. California residents please call 1-800-333-2045 regarding Proposition 65 regulations before purchasing this product. Rating of A+ Bad

EXCLUSIVE FREE Stauer® 8x21 Compact Binoculars -a $99 valuewith purchase of Huntsman Blade Huntsman Blade $249* Offer Code Price Only $79 + S&P Save $170 1-800-333-2045 Your Insider Offer Code: HUK834-01 You must use the insider offer code to get our special price. •12" overall length; 6 ¹⁄2" stainless steel full tang blade • Genuine bone handle with brass hand guard & bolsters • Includes genuine leather sheath What Stauer Clients Are Saying About Our Knives êêêêê “This knife is beautiful!” — J., La Crescent, MN êêêêê “The feel of this knife is unbelievable...this is an incredibly fine instrument.” — H., Arvada, CO AMHP-221101-011 Stauer Huntsman's Blade.indd 1 9/22/22 12:29 PM

Flood Trashes Historic School

by Sarah Richardson

by Sarah Richardson

Mosaic

Among horrific effects of flooding in Kentucky on July 27-28, 2022, was havoc wreaked upon Hindman Settlement School in Hindman in eastern Kentucky. Troublesome Creek breached its banks, breaking open the facility’s new steel doors and flooding several buildings, some housing the institution’s archive of artifacts, photos, books, and documents. Founded with funds from the Kentucky Women’s Christian Temperance Union by educators May Stone and Katherine Pettit in 1902 as a resource for the “people of the moun tains,” Hindman pioneered in education, community services, and cultural preser vation in central Appalachia. Staff rescued what they could, hanging photos to line-dry and stowing other items in freezers until their condition can be evaluated. The flooding exceeded any previous events, exacerbated by climate change and a mountaintop removal method that has simplified mining but eradicated vegeta tion that slows runoff. To donate to Hindman’s flood relief, visit hindman.org.

During and After the Deluge

A surging creek at the Hindman School complex led to inundation, above, that penetrated and soaked archives and classrooms, inset.

COURTESY OF

LYMAN

ALLYN

ART MUSEUM; AP

PHOTO/MATT ROURKE

COURTESY OF HINDMAN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

AMERICAN HISTORY6 AMHP-230100-MOSAIC.indd 6 9/28/22 4:21 PM

Historic Banjos on Display

Lyman Allyn Art Museum in New London, Connecticut, is exhibiting 50 banjos dating from 1840 to about 1900 from Jim Bollman’s 100-plus banjo collection.

Starting at 13 trading Dinky Toys for an English zither banjo, Bollman became fascinated with the evolution of the instrument, which is related to the banjar, a gourd-bodied West Afrian lute. Enslaved Africans fashioned versions in the New World, and over time its construction changed, resulting in a louder instrument more suited for performances in minstrel shows, and later, country music. “As a collector I love showing off the evolution of the banjo aesthetically by the most skilled makers in the 19th century,” Bollman said. “The best of the early minstrel ante-bellum banjos have a wonderful folk art quality showing the artisanship of the various makers.” Starting in the mid-1800s, small factories handled much banjo manufacturing but visual aesthetics also figured. S.S. Stewart of Philadelphia, the Dobson family of New York and Boston, and other entrepreneurs recast the rough-and-tumble musical tool into a finely finished, often lavishly decorated artifact to grace Victorian parlors and concert halls. Makers enlisted the era’s high style furniture producers to source elaborate marquetry veneers to doll up banjos, boosting prices, attracting women musi cians, and making the banjo respectable. By the 1890s such ateliers as Cole and Fairbanks in Boston were producing exquisite banjos bedizened with engraved shells, carved necks, and intricately worked metal parts, selling for hundreds of dollars. So-called “presentation” banjos, meant only for show, afforded instru ment makers occasions for touting in advertisements honors conferred at fairs and exhibitions. The collection is on view until January 8, 2023. lymanallyn.org

Fancy Picking An instrument from the display shows how far banjo makers could take design.

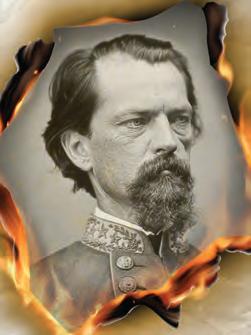

The U.S. Military Academy and U.S. Naval Academy will remove physical references to the Confederacy. A federal commission assigned to identify Confederate symbols at the acade mies reported to Congress in August 2022. The panel urged renaming sites at West Point, including a barracks, a street, and a gate named for Robert E. Lee. Ditto for Naval Academy buildings named for officers who resigned federal commissions to serve the Confederacy, Franklin Buchanan as an admiral and Matthew Maury as a ship procurer. The panel noted that West Point resisted such gestures until 1930-31, when, with “Lost Cause” sentiment high, policy changed. drive.google.com/file/d/19nhxKfBungsgL1d157vjDUdAlk4V-8g8/view

Red Hook Remains

On June 26, 2022, archaeologists at the site of the Battle of Red Bank in National Park, New Jersey, found a human femur. The thighbone upended expectations for the dig, left, accord ing to The New York Times. Excavating a trench at Fort Mercer, where Continental sol diers held off Hessian mercenaries, the team expected to find a midden of 18th century rubbish but uncovered the skulls of 14 Hes sian soldiers bearing graphic reminders of the October 22, 1777, fight. Some 500 Continental soldiers, helped by gunners aboard Pennsyl vania warships on the Delaware River, with stood an assault by more than 2,000 Hessians. The 75-minute battle left 377 Hessian fatali ties but only 14 American dead. The research ers hope analysis of the remains deepens understanding of the battle and perhaps leads to identification of the soldiers whose remains were found.

COURTESY OF LYMAN ALLYN ART MUSEUM; AP PHOTO/MATT ROURKE COURTESY OF HINDMAN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

Confederate Memorials No More WINTER 2023 7 AMHP-230100-MOSAIC.indd 7 9/26/22 10:28 AM

DNA at Assateague

Statuary Update

With two installations, summer 2022 raised the count of women representing U.S. states in the Capitol’s Statuary Hall to 11. On July 13, 2022, a statue of Florid ian Mary McLeod Bethune, left, born in 1875 to parents who had been enslaved, replaced one of Confederate general Edmund Kirby Smith dating to 1922. An educator who founded Daytona Beach’s Bethune-Cookman Uni versity, Bethune was a lifelong advocate for the rights of Blacks and women; her statue is the Hall’s first state-commissioned figure of a Black. On July 27, a statue of Kentucky-born aviator Amelia Earhart replaced one of Kansas abolitionist, judge, and senator John James Ingalls, who coined the Kansas motto “Ad Astra per Aspera” (“To the stars through adversity”). Earhart not only became the first female aviator to fly across the Atlantic but was also the first person to fly solo from mainland Ameri can to Hawaii.

Mammoth Clues

A decade ago, Tim Rowe, a paleontologist with the University of Texas at Austin, got curious about bones on property he owns in New Mexico. Rowe’s interest led to a study. The results found that the bones, above, were from a mammoth butchered by people 37,000 years ago. Distinctive chipping and puncture marks made the case. The conclusion establishes the presence of humans in North America far earlier than conventionally assumed. “What we’ve got is amazing,” said lead author Rowe, a professor at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences. “It’s not a charismatic site with a beautiful skeleton laid out on its side. It’s all busted up. But that’s what the story is.”

GETTY IMAGES; ARCHITECT OF THE CAPITOL; TIMOTHY ROWE/UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS

Cattle genetics are redefining the ancestry of wild horses, above, on Assateague Island in Chesapeake Bay. The animals were thought to descend from English stock from the colonial mainland or Spanish horses loosed from a 16th-century galleon, but no one knew for sure. A researcher analyzing a tooth labeled as being from a cow in a collection of early Caribbean finds realized the tooth had come from a horse on the island of Hispaniola. Comparing that DNA to material from other horse lineages, he found the closest match to be the Assateague herd, supporting the Spanish thesis.

AMERICAN HISTORY8 AMHP-230100-MOSAIC.indd 8 9/26/22 10:29 AM

LIMITED-TIME OFFER—ORDER NOW Uniquely Designed. Exclusively Yours. ©2022 The Bradford Exchange 01-30578-001-BICI B_I_V = Live Area: 7 x 9.75, 1 Page, Installment, Vertical Price Logo Address Job Code Tracking Code Yellow Snipe Shipping Service Signature Mrs. Mr. Ms. Name (Please Print Clearly) Address City State Zip E-mail PRIORITY RESERVATION SEND NO MONEY NOWWhere Passion Becomes Art The Bradford Exchange P.O. Box 806, Morton Grove, IL 60053-0806 Connect with Us! 01-25530-001-E35507 *Plus $16.00 shipping and service. Please allow 4-6 weeks for delivery of your jewelry after we receive your initial deposit. Sales subject to product availability and order acceptance. For Distinguished Service... To Wear with Pride Steadfast in their values, the soldiers of the United States Army—whether active or retired from service—have dedicated their lives to the noble tradition of serving their country and preserving freedom worldwide. Now, you can show your allegiance to the enduring, steadfast spirit of the United States Army like never before, with a new limited-edition jewelry exclusive as distinctive as the soldiers that it salutes. A Singular Achievement in Craftsmanship and Design Our “This We’ll Defend” U.S. Army® Tribute Ring is is individually crafted in solid sterling silver with gleaming 18K gold plating and features the Army emblem in raised relief standing out against a custom-cut genuine black onyx center stone. The contrast of silver and gold is continued in the prongs holding the onyx stone, and in the rope border that surrounds the central emblem as well as the sculpted eagle—a symbol of strength and freedom—on each side. Adding to the meaning and value, the ring is engraved inside the band with: This We’ll Defend and United States Army. Order online at bradfordexchange.com/25530 ®Official Licensed Product of the U.S. Army. By federal law, licensing fees paid to the U.S. Army for use of its trademarks provide support to the Army Trademark Licensing Program, and net licensing revenue is devoted to U.S. Army Morale, Welfare, and Recreation programs. U.S. Army name, trademarks and logos are protected under federal law and used under license by The Bradford Exchange. ©2022 The Bradford Exchange All rights reserved 01-25530-001-BI A Custom Jewelry Exclusive Available Only from The Bradford Exchange Limited-Time Offer...Order Now! A magnificent statement of everything the Army stands for, the “This We’ll Defend” U.S. Army® Tribute Ring comes in a deluxe wood presentation case with a plaque engraved with the same words that are on the ring, and includes a Certificate of Authenticity that attests to the ring’s original design in an edition limited to only 5,000 rings. An exceptional value at $279.99*, you can pay for your ring in 6 easy installments of $46.67. To reserve yours, backed by our unconditional 120 day guarantee, send no money now. Just mail the Priority Reservation. But hurry... this edition is strictly limited! Expertly hand-crafted in solid sterling silver Gleaming with rich 18K gold plating Featuring a custom-cut genuine black onyx center stone Engraved with the motto of the United States Army® YES. Please reserve the “This We’ll Defend” U.S. Army® Tribute Ring for me as described in this announcement in the size indicated. LIMITED-TIME OFFER Reservations will be accepted on a first‑come‑first‑served basis Respond as soon as possible to reserve your ring. SATISFACTION GUARANTEED To assure a proper fit, a ring sizer will be sent to you after your reservation has been accepted. Actual SIze Ring size (If known) ______ U.S. ARMY® TRIBUTE RING AMHP-221101-009 Bradford US Army Men's Dress Defend.indd 1 9/22/22 12:10 PM

The African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund has announced 33 awards totaling $3 million for 2022. Among recipi ents of preservation grants are the South Side Chicago home of Mamie Till, the courageous mother who brought the nation’s atten tion to the lynching of her 14-year-old son Emmett Till in Missis sippi in 1955; the Jackson, Mississippi, home of civil rights activist Medgar Evers in whose driveway Evers was assassinated in 1963; the Queens, New York, home of musical innovator Louis Armstrong; the Great Barrington, Massachusetts, writing cabin of author and activist James Weldon Johnson; and the store at Whitney Plantation in Wallace, Louisiana, where the lives of the enslaved are depicted and commemorated.

Black History Preserved

A new studio recording, left, of Bob Dylan performing his 1962 song “Blowin’ in the Wind” sold for $1,769,508 at Christies in London on July 7, 2022. Dylan performed his song at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village in April 1962 and recorded it that July 9 for his second LP. This release was recorded by producer T-Bone Burnett on Burnett’s Ionic Original label. Only one copy of the recording was made.

AGEFOTOSTOCK/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; RYAN VICTOR/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; JIM WEST/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; COURTESY OF CHRISTIE’S AUCTIONS

TOP BID Unique $1,769,508

Whitney Plantation

Evers

home AMERICAN HISTORY10 AMHP-230100-MOSAIC.indd 10 9/26/22 10:29 AM

On May 18, 1980, the once-slumbering Mount St. Helens erupted in the Pacific Northwest. It was the most impressive display of nature’s power in North America’s recorded history. But even more impressive is what emerged from the chaos... a spectacular new creation born of ancient minerals named Helenite. Its lush, vivid color and amazing story instantly captured the attention of jewelry connoisseurs worldwide. You can now have four carats of the world’s newest stone for an absolutely unbelievable price.

Known as America’s emerald, Helenite makes it possible to give her a stone that’s brighter and has more fire than any emerald without paying the exorbitant price. In fact, this many carats of an emerald that looks this perfect and glows this green would cost you upwards of $80,000. Your more beautiful and much more affordable option features a perfect teardrop of Helenite set in gold-covered sterling silver suspended from a chain accented with even more verdant Helenite.

Limited Reserves. As one of the largest gemstone dealers in the world, we buy more carats of Helenite than anyone, which lets us give you a great price. However, this much gorgeous green for this price won’t last long. Don’t miss out. Helenite is only found in one section of Washington State, so call today!

Romance guaranteed or your money back. Experience the scintillating beauty of the Helenite Teardrop Necklace for 30 days and if she isn’t completely in love with it send it back for a full refund of the item price. You can even keep the stud earrings as our thank you for giving us a try.

Stauer… Afford the Extraordinary . ®

• 4 ¼ ctw of American Helenite and lab-created DiamondAura® • Gold-finished .925 sterling silver settings • 16" chain with 2" extender and lobster clasp Rating of A+ 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. HEN433-01, Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.comStauer ® * Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without your offer code. Helenite Teardrop Necklace (4 ¼ ctw) $299* .....Only $129 +S&P Helenite Stud Earrings (1 ctw) ....................................... $129 +S&P Helenite Set (5 ¼ ctw) $428* ...... Call-in price only $129 +S&P (Set includes necklace and stud earrings) Call now and mention the offer code to receive FREE earrings. 1-800-333-2045 Offer Code HEN433-01 You must use the offer code to get our special price. Uniquely American stone ignites romance Tears From a Volcano Necklace enlarged to show luxurious color EXCLUSIVE FREE Helenite Earrings -a $129 valuewith purchase of Helenite Necklace 4 carats of shimmering Helenite Limited to the first 1600 orders from this ad only “I love these pieces... it just glowed... so beautiful!” — S.S., Salem, OR AMHP-221101-010 Stauer Helenite Teardrop Necklace.indd 1 9/22/22 12:28 PM

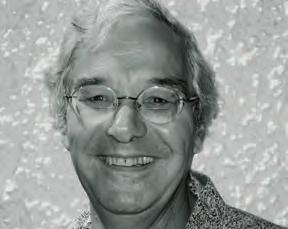

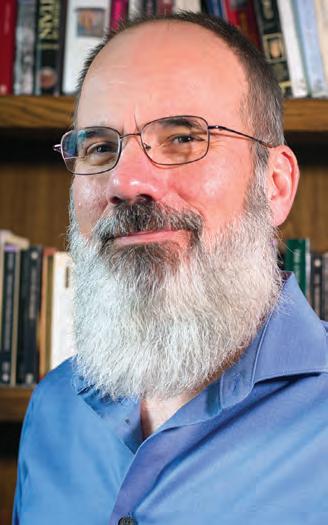

Peter Carlson is a longstanding stalwart of the magazine who besides features such as “White Power” (p. 58) writes American Schemers.

Mike Coppock (“Jefferson’s Other Expeditions,” p. 50) is a regular contributor who most recently delivered “Bear Wars” (June 2022).

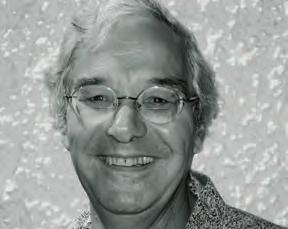

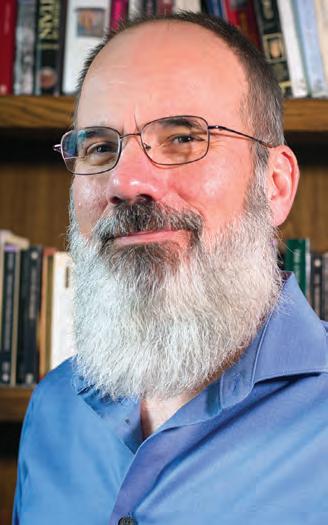

Contributors

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Daniel de Visé has written four books. His latest, King of the Blues: The Rise and Reign of BB King, is excerpted in this issue (“Becoming B.B.,” p. 24). His 2015 book Andy & Don, the source for “Sheriff Tay lor Hires a Deputy” (August 2016)), is in its 11th paperback printing. The Comeback, de Vise’s 2018 profile of Greg Lemond, inspired Congress to award the bicyclist its highest civilian honor, the Congressional Gold Medal.

Former history professor Richard J. Goodrich (“Picture Imperfect,” p. 40) is author of Comet Madness: How the 1910 Return of Halley’s Comet (Almost) Destroyed Civilization. His most recent article was “Slaves at Sea” (February 2022). Find him at richardjgoodrich.com.

J.D. Zahniser (“Days of Infamy,” p. 32) speaks and writes regularly about women’s history; she wrote the 2014 biography Alice Paul: Claim ing Power. Her most recent American History article was “Becoming Jane Crow” (August 2022). She lives in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Read On!

Out of the Picture

Letters

Buffalo’s Great Northern grain elevator stands to the right of the structure shown in the June 2022 issue. Here are a couple of images of the actual building—one show ing damage to an end wall from a December 2021 windstorm and a photo of the elevator and the water front in 1905.

Paul Fronckowiak Buffalo, New York

Paul Fronckowiak Buffalo, New York

The editor regrets his error.

So Long, Uncle Joe!

Thanks for running Albert Schmidt’s “Cold War Chronicle” (June 2022). I particularly enjoyed the passage, “…In the morning Stalin was nowhere to be seen. Had our ado over the statue has tened the de-Stalinization in Stalin’s hometown?” I love the thought, and the interesting format, an article derived from the author’s journal entries and letters to his spouse. If only we could travel in a similar way today and assimilate other cultures.

Byron Loubert Bethesda, Maryland

American History readers wanting to pillory, praise, or query the publication: write to mdolan@historynet.com.

CarlsonGoodrich

Coppock

Zahniser

de Visé

AMERICAN HISTORY12 AMHP-230100-LETTERS.indd 12 9/26/22 10:17 AM

We’re Bringing Flexy Back

a

is cyclical. And there’s a certain wristwatch trend that was huge in the 1960s and then again in the 1980s, and is ready for its third time in the spotlight. We’re talking, of course, about the flexible stretch watch band.

To purchase a vintage 60s or 80s classic flex watch would stretch anyone’s budget, but you can get ahead of the crowd and secure a brand new version for a much lower price.

We’re rolling back the years AND the numbers by pricing the Stauer Flex like this, so you can put some bend in your band without making a dent in your wallet.

The Stauer Flex combines 1960s vintage cool with 1980s boardroom style. The stainless steel flex band ensures minimal fuss and the sleek midnight blue face keeps you on track with date and day subdials.

Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed.

the Stauer Flex for 30 days. If you’re not convinced you got excellence for less, send it back for a refund of the item price. Your satisfaction is our top priority.

Time is running out. As our top selling watch, we can’t guarantee the Flex will stick around long. Don’t overpay to be underwhelmed.

a

Looks

•Precision movement • Stainless steel crown, caseback & bracelet •Date window at 6 o’clock; day window at 10 o’clock • Water resistant to 3 ATM • Stretches to fit wrists up to 8 ½" Stauer… Afford the Extraordinary .® Just like

good wristwatch movement, fashion

Experience

Flex your right to put

precision timepiece on your wrist for just $79. Call today! 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. FMW202-01 Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.com Stauer Flex Men’s Watch $299† Offer Code Price $79 + S&P Save $220 You must use the offer code to get our special price. 1-800-333-2045 Your Offer Code: FMW202-01 Please use this code when you order to receive your discount. Rating of A+ Stauer ® † Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without your offer code. TAKE 74% OFF INSTANTLY! When you use your OFFER CODE êêêêê “The quality of their watches is equal to many that can go for ten times the price or more.” — Jeff from McKinney, TX

The Stauer Flex gives you vintage style with a throwback price of only $79. Flexible Stretch Watch Bracelets in the News: “The bracelets are comfortable, they last forever, and they exhibit just the right balance of simplicity and over-engineering” – Bloomberg.com, 2017 e

of a Classic Flex Band Watch for only $79! AMHP-221101-012 Stauer Flex Men's Watch.indd 1 9/22/22 12:27 PM

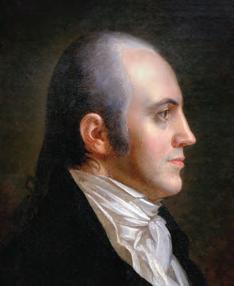

Hoodwinking Hitler

by Peter Carlson

American Schemers

ON FEBRUARY 18, 1937, Freeman Bernstein eased his pudgy 63-yearold body out of the back seat of a rented limousine at the Hollywood home of actress Mae West. Thirty years earlier, Bernstein had been West’s agent, booking her in vaudeville shows. Now he was hawking jew els he’d smuggled from China. A tough customer, West bought some rubies and sapphires but rejected the cheap zircon that Bernstein tried to pass off as a dia mond. Then she autographed a picture for her guest, writing “To Freeman Bernstein, who was my first agent at the age of 10.”

Bernstein took West’s check and the picture and instructed his chauf feur to drive him to the Brown Derby restaurant. On the way officers of the Los Angeles Police Department stopped the limo and arrested Bern stein: He was wanted in New York for swindling the German govern ment out of nearly $150,000 by selling the Nazis a load of what was supposed to be valuable nickel but which turned out to be scrap metal.

“Adolf Hitler was on bended knee begging me to help him get some

nickel,” Bernstein told reporters the next morn ing. “Hitler got just exactly what he paid for in that deal—scrap steel and nickel—and I’ll prove it.”

The tale of an American accused of swindling Hitler made news nationwide and inspired a cringe-worthy Wisconsin State Journal headline: “Jew Denies Gyping Hitler in Junk Deal.”

Actually, Bernstein did bilk Hitler—or at least the Führer’s government—but that wasn’t sur prising. He’d been flimflamming suckers on sev eral continents for decades. Bernstein was a carny, a card sharp, a con man, a shady showbiz promoter, and a racehorse owner so crooked he was banned from tracks in Canada, Mexico, and Austria. But he was charming and persuasive and he convinced countless dupes to invest in his

COURTESY NYC MUNICIPAL ARCHIVES LOS ANGELES TIMES PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE, LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, CHARLES E. YOUNG RESEARCH LIBRARY, UCLA

AMERICAN HISTORY14

Familiar Setting Bernstein, seated, in a New York court in 1938 with lawyer Greg Bautzer to answer charges of kiting checks.

AMHP-230100-SCHEMERS.indd 14 9/26/22 10:35 AM

dubious schemes. “Even when fleecing the gullible, he did it with such infectious high spirits that he believed the marks didn’t really mind,” Walter Shapiro wrote in Hustling Hit ler, his wry 2016 biography of the grifter.

Freeman Bernstein was born in 1873 in Troy, New York, son of Polish immigrants. He quit school after fifth grade and at 13 experi enced the first of many arrests, for stealing $10 from the pocket of a man who’d doffed his clothes to swim in the Hudson River. Bern stein drifted into the carnival business, receiv ing a valuable education in the art of the grift. By the early 1900s, he was a low-rent impresa rio, booking vaudeville acts in the boonies. The troupes he hyped as “The Greatest Aggre gation of Vaudeville Talent Ever Brought Together” consisted mainly of has-beens, wannabes, and goofy novelty acts—a one-legged acrobat, a dwarf comedy team, and “the white man who sings coon songs.”

When a performance failed to draw a crowd, Bernstein would grab the box office receipts and flee on the next train, leaving his performers stiffed and stranded. In 1912, he took a 45-mem ber opera cast to Puerto Rico; when the show failed to attract audiences, he skedaddled. “He’s left stranded troupes all over the world,” the edi tor of Variety, the showbiz newspaper, lamented.

In 1915, inspired by the huge success of the movie Birth of a Nation, Bernstein created a film company, found impressionable investors, and produced two movies, both starring his wife, singer May Ward. When the first, a Revolutionary War drama entitled A Continental Girl, tanked, Bernstein made his second movie steamier. In Virtue, Ward played an innocent farm girl lured into sexual slavery. Bernstein billed the film “the Most Striking, Realistic and Sensational Film Ever Presented.” Alerted, censors in Philadelphia and New York banned Virtue. Bernstein recouped his losses when a mysterious fire incinerated his movie studio, which he’d presciently insured. He showed a Variety reporter the policy, saying, “See, I told you there was money in pictures.”

Ah, so many Freeman Bernstein scams, so lit tle space:

During World War I, he set up carnivals out side army bases and took doughboys’ dough with rigged games.

In 1929, Bernstein—rebranding himself “Roger O’Ryan”—staged a week-long Irish Fair in the Boston Garden, advertising “SOD FROM EVERY COUNTY IN IRELAND…HUNDREDS OF IRISH COLLEENS.” The sod was grown in Massachu setts and the colleens were local showgirls. On the fair’s final day, Bernstein took the money and ran, leaving employees unpaid. “OWNER OF IRISH

FAIR MISSING,” screamed the Boston Her ald’s front page. “COLLEENS CLAMOR FOR WAGES.” Soon, Bernstein—dubbed “Mr. O’Ry anstein” by the Herald—was wanted for fraud.

Big Bogus Deal

Dockside in 1936 at Hamburg, Germany, the notorious “nickel” shipment awaits its purchasers, who dropped $150,000 to acquire a load of Canadian scrap.

Any time cops and creditors closed in, Ber nstein took to the sea, sailing to Europe or Asia, earning cash en route by skinning fellow first-class passengers in high-stakes card games. Upon docking, he’d search for and frequently find rubes dying to be separated from their lucre. “A guy like me should travel,” he wrote in a letter from London. “There are so many saps around, I don’t know which one to tap first.”

Bernstein spent much of the 1930s in China, calling himself “The Jade King” and selling precious stones—and dubious facsimiles—to tourists. Occasionally, he’d smuggle jade into the U.S. by feeding the jewels to Benny, his Sealyham terrier, shortly before he and the pooch strolled through cus toms, retrieving the stones when Benny relieved himself.

Bernstein was in Shanghai in 1934 when he conceived his notorious nick el-to-Nazis scam. He met a German diplomat who said his government was looking to buy large quantities of nickel, needed to make weapons. Bern stein claimed to have a nickel connection in Canada, which produced most of the world’s supply but had barred the metal’s export to Germany. The diplomat suggested Bernstein meet an official at the German embassy in Washington. In 1935, Bernstein visited the fellow, bringing samples of highgrade nickel he’d bought at a shop in Manhattan. Impressed, the bureaucrat dispatched Bernstein and his samples to the Fatherland, where Nazis gave him $1,000 as a down payment on an order of 225 tons.

Setting his trap, Bernstein told his customers that, to avoid the embargo, the shipment would come labeled “scrap metal.” Then he found a crooked Canadian junkman. Together, the pair gathered 225 tons of scrap and a smidgeon of nickel, bribed an inspector to certify that the load was 99 per cent nickel, and shipped it all to Germany, collecting nearly $150,000. It was, biographer Shapiro wrote, “the grandest racket of his career.”

Fearing the inevitable indictment, Bernstein fled to China but when he returned to Los Angeles in 1937 to sell jewels, the cops nabbed him. He spent seven weeks in jail then went free on bail. After years of legal wran gling, the charges were dropped in June 1941.

Seven months later, Bernstein was on his way to meet with a Hollywood producer when he suffered a fatal heart attack.

“When I die,” he’d bragged years earlier, “no matter where I go, you can gamble that I will pick up a little coin on the jump.” H

COURTESY NYC MUNICIPAL ARCHIVES LOS ANGELES TIMES PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE, LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, CHARLES E. YOUNG RESEARCH LIBRARY, UCLA WINTER 2023 15

AMHP-230100-SCHEMERS.indd 15 9/26/22 10:35 AM

Presidential Temper

by Richard Brookhiser

POLITICAL MAVENS were titillated to learn, via the January 6 Com mittee, that when President Donald Trump heard that his own attorney general, Bill Barr, had told the press there had been no widespread fraud in the 2020 election, he threw the meal he was eating at a convenient wall. “There was ketchup dripping down the wall and a shattered porce lain plate on the floor,” former White House aide Cassidy Hutchinson testified. She and a valet grabbed towels to clean up the condiment.

In the annals of temperamental leaders, this is small, er, potatoes: when King Saul was angry, what he threw at David and his own son Jonathan was spears. Americans like to think, however, that our system of elected leaders is the best. The men and women we choose should therefore be better than those ele vated by bloodlines, intrigues, or coups. As the country has grown in military might, however, we don’t want a loose cannon within grabbing range of the nuclear launch codes. This duality renders tales of presi dential temper both scandalous and, in modern times, worrisome.

The stories begin at the beginning. George Washington had a tightly controlled temper—except when he didn’t. One outburst occurred at a cabinet meeting in 1793. Foreign policy had become a domestic political football: should the United States support the French Revolution, or

politely ignore that rumpus? The specific problem for Washington and his advisers was how to han dle unreasonable demands by a French diplomat, Edmond-Charles Genêt. All at the table wanted Genêt recalled, but factions split over whether the administration should lay an account of his provo cations before the public. Secretary of War Henry Knox stirred the pot by producing a satirical description, in a Francophile Philadelphia paper, of Washington being led to the guillotine. Wash ington was not pleased. “The President,” wrote Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson in his journal that night, “was much inflamed, got into one of those passions when he cannot command himself, ran on much on the personal abuse which had been bestowed on him…that by God he had rather be in his grave than in his present situation. That he had rather be on his farm than to be made emperor of the world…He ended in this high tone.” After this eruption there was, Jefferson added,

BETTMANN/GETTY IMAGES

Blooded Brothers Former Secretary of State George Marshall, left, with Columbia University president Dwight Eisenhower in the early 1950s.

Déjà Vu AMERICAN HISTORY16 AMHP-230100-DEJAVU.indd 16 9/28/22 2:46 PM

Order by Dec. 6 and you’ll receive FREE gift announcement cards that you can send out in time for the holidays! LIMITED-TIME HOLIDAY OFFER CHOOSE ANY TWO SUBSCRIPTIONS FOR ONLY $29.95 TWO-FOR-ONE SPECIAL! CALL NOW! 1.800.435.0715 PLEASE MENTION CODE HOLIDAY WHEN ORDERING SCAN HERE! OR VISIT HISTORYNET.COM/HOLIDAY Offer valid through January 8, 2023 * For each MHQ subscription add $15 Vicksburg Chaos Former teacher tastes combat for the first time Elmer Ellsworth A fresh look at his shocking death Plus! Stalled at the Susquehanna Prelude to Gettysburg Gen. John Brown Gordon’s grand plans go up in flames Tulsa Race Riot: What Was Lost Colonel Sanders, One-Man Brand J. Edgar Hoover’s Vault to Fame The Zenger Trial and Free Speech Yosemite The twisted roots of a national treasure HISTORYNET.com JUL 2020 H H HISTORYNET.COM JUDGMENT COMES FOR THE BUTCHER OF BATAAN THE STAR BOXERS WHO FOUGHT A PROXY WAR BETWEEN AMERICA AND GERMANY PATTON’S EDGE THE MEN OF HIS 1ST RANGER BATTALION ENRAGED HIM UNTIL THEY SAVED THE DAY In 1775 the Continental Army needed weapons— and fast World War II’s Can-Do City Witness to the White War ARMS RACE THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MILITARY HISTORY An ammunition dump explodes during the April 1972 battle for An Loc. Defeating Enemy Stereotypes White and Black POWs bonded as cellmates The Green Berets Battles that inspired the book and movie TERROR AT AN LOC 9TH CAVALRY’S HEROIC FIGHT TO RESCUE DOWNED AIRMEN Huey Haven Old Warbirds Are Getting a New Museum HOMEFRONT Sweet success for Sammy Davis Jr. JUNE 2022 HISTORYNET.COM HNET SUB AD_HOLIDAY-2022.indd 1 8/30/22 8:34 AM

“some difficulty in resuming our discussion.”

Andrew Jackson was a fighter, on and off the field. Before he was elected to the White House, he had been shot in a duel in which he killed his man, and was also wounded in an armed brawl in a hotel with his own officers. In 1835, during Jackson’s second term, a would-be assassin fired two pistols at him as he was leaving a congressman’s funeral at the Capitol. Both weapons mis fired, and Jackson clubbed his attacker with a cane—a reasonable response, considering the circumstances. But the president unreasonably told anyone who would listen that the gunman, Richard Lawrence, had been put up to the assault by George Poindexter, a Mississippi senator with whom Jackson was then feuding. Lawrence was in fact a lunatic housepainter who imagined himself to be the legitimate king of England. He had once painted Poindexter’s house, but there was no evidence that the two were in cahoots; a jury found Lawrence insane after only five minutes’ deliberation. Harriet Martineau, an English sociologist who happened to be in Washington at the time, found Jackson’s tirades against Poindexter embarrassing.

“The President’s misconduct on the occasion was the most virulent and protracted,” Martineau wrote. “It was painful to hear a Chief Ruler trying to persuade a foreigner that any of his constituents hated him to the death, and I took the liberty of changing the subject as soon as I could.”

Andrew Johnson became Abraham Lincoln’s running mate, and ulti mately his successor, based on Johnson’s loyalty to the Union despite being a senator from Tennessee. But there was no charity for all in Johnson. In Feb ruary 1861 he had a conversation with Charles Francis Adams, Jr., 25-yearold sprig of the Massachusetts presidential clan, in which Johnson railed at secessionist colleagues. David Yulee of Florida was a “miserable little cuss,” a “contemptible little Jew,” and a “despicable little beggar.” Judah Benjamin of Louisiana was “another Jew….He looks on a country and a government as he would on a suit of old clothes. He sold out the old one; and he would sell out the new if he could in so doing make two or three millions.” Louis Wigfall of Texas—a gentile, for a change—Johnson called “a damned blackguard” and a bankrupt, explaining that “the strongest secessionists never owned the hair of a nigger.” What was remarkable about this splenetic display was not John son’s opinions of these men, who were after all working to destroy the coun try, but that he should express them so vividly to a kid he barely knew.

Ready to Rumble

A young Andrew Jackson, right, looks on at his handiwork after engaging in a duel early in his career as a man of public distemper.

Dwight Eisenhower’s mile-wide smile, his nick name rhyming with like, and his tangled syntax conveyed an air of innocent geniality. But on the eve of Ike’s first run for the presidency journalist Murray Kempton provoked his wrath. Senator William Jenner, Indiana Republican, had called Secretary of Defense George Marshall “a living lie,” holding Marshall responsible for losing China to communism, entangling us in NATO, and every thing else about the world that the isolationist Jen ner disliked. Kempton asked Eisenhower, whose mentor in the Army had been Marshall, what he thought of the charges. “He leaped to his feet and contrived the purpling of his face,” Kempton wrote. “How dare anyone say that about the great est man who walks in America?...He would die for George Marshall. He could barely stand to be in the room with anyone who would utter such a profana tion.” Kempton felt like an enlisted man being reamed as “an example to the rest of the troops.”

It is unlikely that anyone ambitious enough and compelling enough to rise to the top does so with out some degree of temper in his or her makeup. Temper can be the shadow of forcefulness. The question for those who possess a temper is, can they control it, or does it control them? After Washington lost his cool in front of cabinet mem bers, he and they returned to the question of whether to publicize Genêt’s misbehavior, and he decided: not yet. Washington’s critics could imag ine chopping off his head, but he would not be pro voked by a journalistic screed into losing it. Murray Kempton realized even as Eisenhower was bawling him out that the would-be Republican nominee had not criticized Senator Jenner. Ike would defend his idol, but not condemn his idol’s slan derer so long as he needed the slanderer’s support.

Andrew Jackson’s admirers then and since claim that Old Hickory used his wrath as Ike did, for momentary effect. “I never saw him in a passion,” testified Amos Kendall, one of Jackson’s senior cro nies. Kendall must have been out of town in 1835. Andrew Johnson has almost no admirers to stick up for him, and why should he? His impulses, vio lently anti-rebel then equally violently anti-Black, crippled Reconstruction out of the gate.

Once in a while a leader emerges whose veins run with the milk of human kindness. Secular saint Lincoln is one example; another is Ulysses S. Grant who, though he killed thousands in battle, was in peacetime benevolence itself. But most leaders, like most of us, are human, all too human. The good ones don’t leave ketchup on the walls. But it is always wise to clear the table after every course. H

NORTH WIND PICTURE ARCHIVES/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

AMERICAN HISTORY18

Admirers saw Jackson as making tactical use of a display of feigned wrath, not succumbing to a fit of genuine passion.

AMHP-230100-DEJAVU.indd 18 9/28/22 2:47 PM

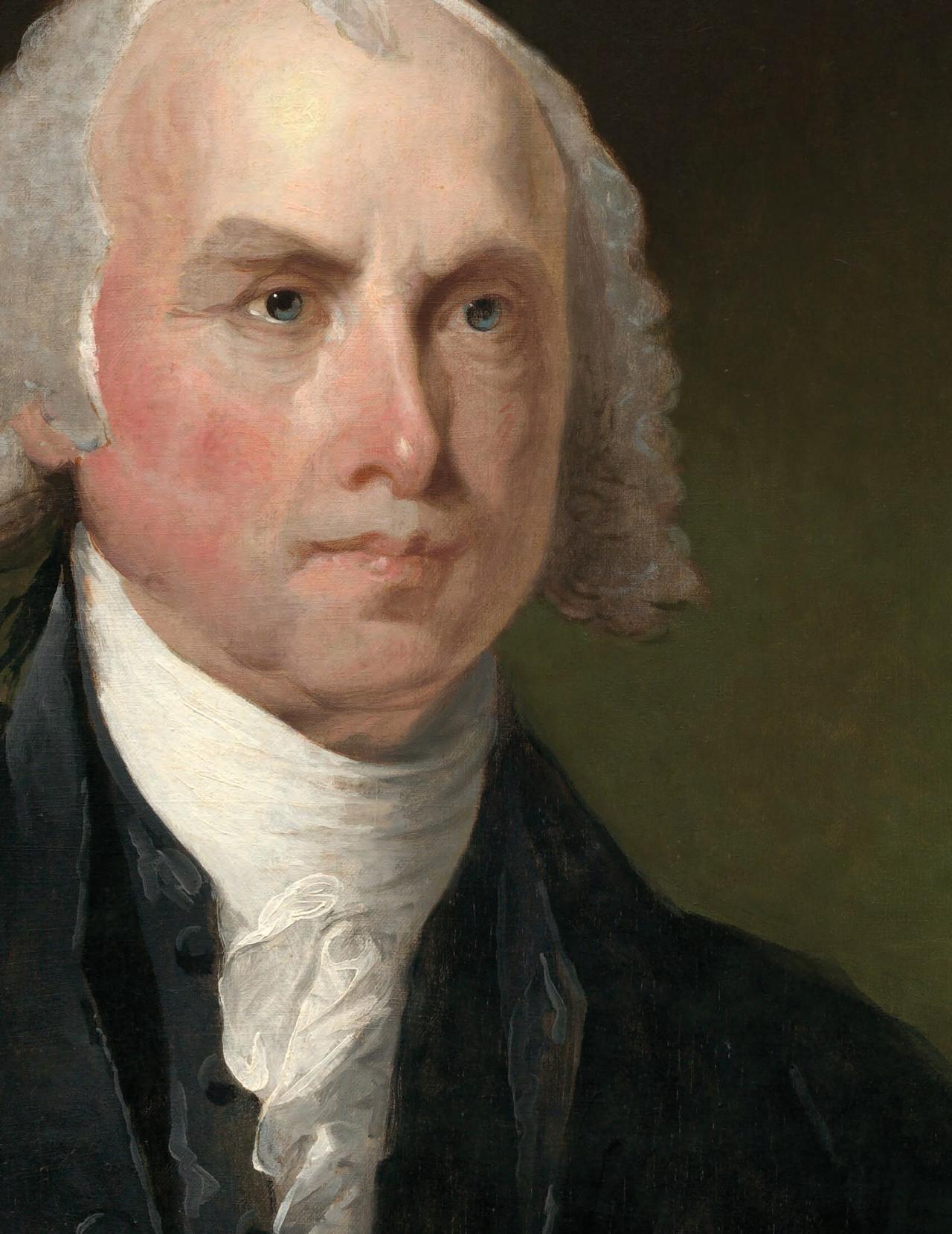

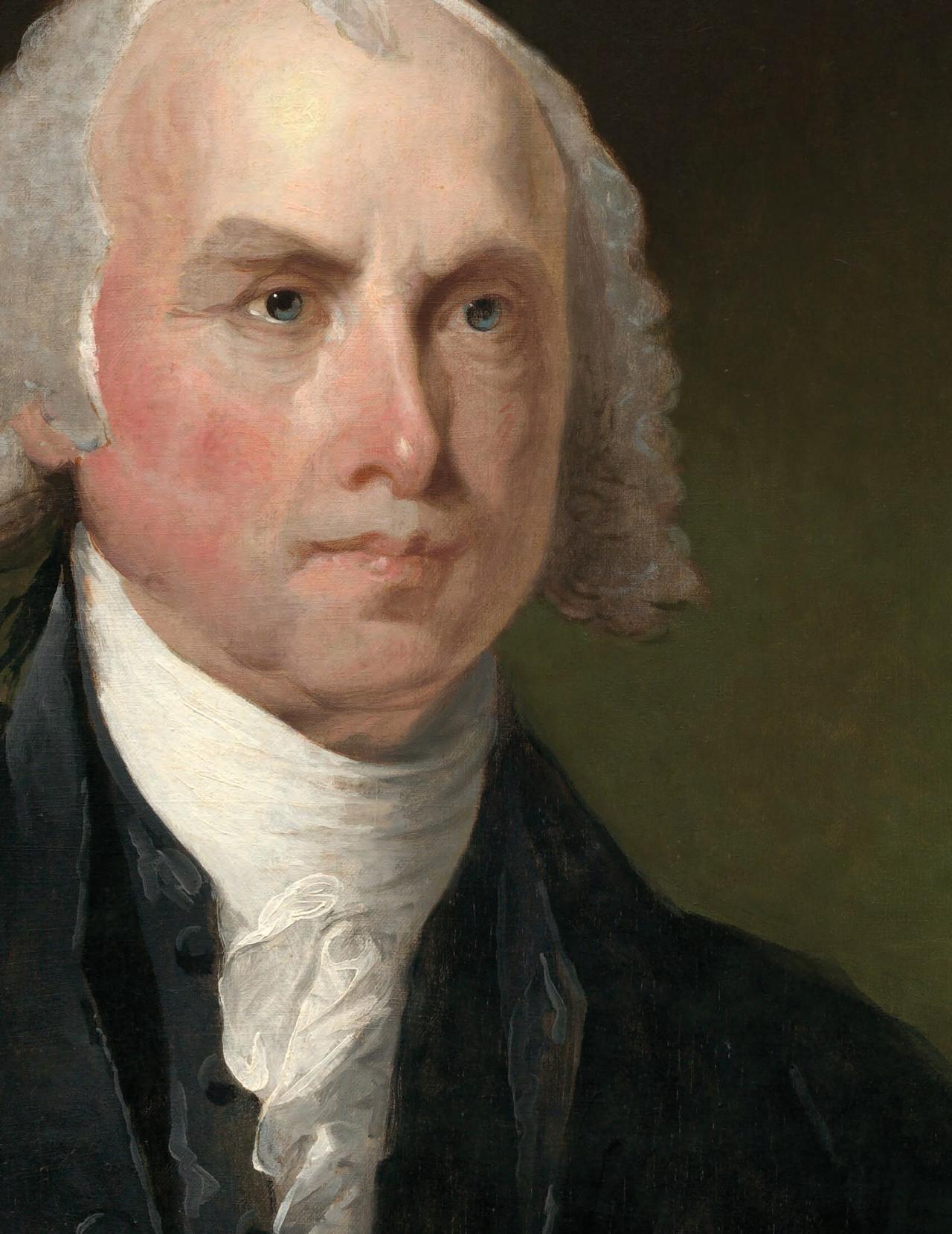

BROOKEVILLE, MARYLAND, BECOMES “U.S. CAPITAL FOR A DAY” WHEN PRESIDENT JAMES MADISON TAKES REFUGE THERE. EARLIER THAT WEEK, BRITISH TROOPS HAD SET FIRE TO WASHINGTON, INCLUDING THE WHITE HOUSE AND CAPITOL BUILDING. MADISON FLED THE CITY, ALONG WITH MEMBERS OF HIS CABINET, AND SPENT THE NIGHT OF THE 26TH AT THE HOME OF BROOKEVILLE POSTMASTER CALEB BENTLEY. THE TOWN STILL CELEBRATES THE EVENT EACH YEAR. TODAY IN HISTORY For more, visit HISTORYNET.COM/TODAY-IN-HISTORY AUGUST 26, 1814 TODAY-MADISON.indd 22 9/28/22 2:51 PM

Embracing Ugliness

by Daniel B. Moskowitz

Scotus 101

Brandenburg v. Ohio 395 U.S. 444 (1969)

Speech advocating illegal conduct is protected under the First Amendment unless the speech is likely to incite “imminent lawless action.”

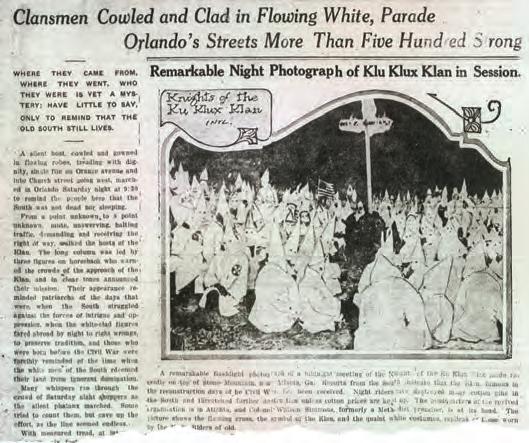

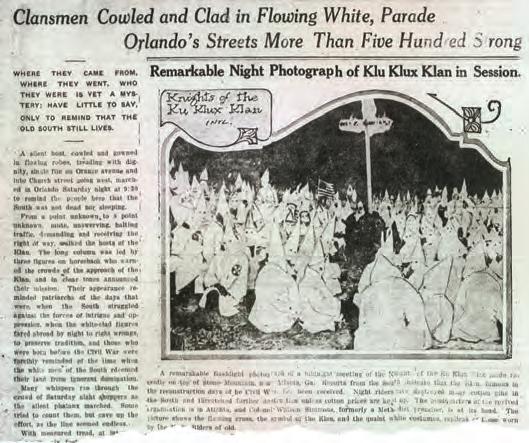

WHAT STARTED OUT AS LITTLE more than a racist publicity stunt ended up being the defin ing Supreme Court decision on the meaning of the Constitutional guarantee of free speech—a ruling far more protective of controversial speech than previous high court holdings. Those prior decisions essentially told courts to balance the harm the contested speech posed against the benefits of unfettered freedom of expression, but now the Justices were “putting the thumb firmly on the scale in favor of the First Amend ment,” explains Katherine Fallow, senior coun sel at Columbia University’s Knight First Amendment Institute.

The case began in the summer of 1964, when Clarence Brandenburg telephoned Cincinnati, Ohio, NBC-TV affiliate WLWT with a tip: Ku Klux Klan members were to rally at a local farm. A reporter and camera crew showed up to cover the event, which was less than a success—no more than a dozen KKK supporters were milling around. The news team went to work anyway. The handful of armed, white-robed men and their burn ing cross made for arresting images and Brandenburg’s speech, even with no real audience, was fiery enough to make that evening’s news. In

offensive terms, the Klan organizer demanded the country expel Jews and Negroes. “If our President, our Congress, our Supreme Court continues to suppress the white, Caucasian race, it’s possible that there might have to be some revengeance taken,” Brandenburg said. “We are marching on Congress on the Fourth, four hundred strong.”

Observing what WLWT aired, local officials found Brandenburg’s screed provocative enough to dust off a 1919 Ohio “criminal syndicalism” law that outlawed advocating “sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform” or assembling or joining any group formed to advo cate such actions. Prosecution of Brandenburg—in a trial that consisted of nothing more than screen ing the footage that WLWT had run—was success ful. The state fined the firebrand $1,000 and sent him to prison for 1-to-10 years.

The Ohio law under which Brandenburg was convicted was almost a carbon copy of other laws

LOS ANGELES EXAMINER/USC LIBRARIES/CORBIS VIA GETTY IMAGES HUM IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

AMERICAN HISTORY20

AMHP-230100-SCOTUS.indd 20 9/26/22 10:37 AM

Hate on the March

In September 1926, with the terror group ascendant, a KKK parade drew 30,000 Klansmen to Washington, DC, in a display of strength.

enacted in the years just after World War I by 21 other midwestern and Western states. Despite civil liberties champions’ claims that such sweeping bans on advocacy of unpopu lar viewpoints eroded First Amendment free speech protections, in four separate cases the U.S. Supreme Court upheld criminal syndicalism statutes. In the most recent of those four Court endorsements, the justices had unanimously upheld the conviction of Charlotte Whitney for helping to found the Com munist Labor Party of California. Whitney’s support for an organization that endorsed violence to achieve social change could be prosecuted, the justices explained in 1929, because the First Amendment does not protect speech “inimical to the public welfare, tending to incite crime, disturb the public peace, or to endanger the foundations of organized government.”

Brandenburg unsurprisingly got no relief when he appealed. Citing the four Supreme Court precedents, an Ohio appellate court upheld his convic tion. The Ohio Supreme Court summarily dismissed the Klan man’s appeal, saying it presented no substantial constitutional question. By the time the Brandenburg case got to the high court in 1969, the Whitney decision was 40 years old, and there had been hints that the men of the high court no longer held the broad view of what speech could be curbed that their antecedents had enunciated. The issue was a hot one, with anti-Vietnam War protests and campus demonstrations dividing the country. So many lawyers repre senting defendants convicted for engaging in such protests had picked up those hints that when the Justices ruled on Brandenburg, the docket included four other free speech cases. All were sent back to lower courts for reconsideration in light of the Brandenburg ruling.

The first hint came in 1957. The high court had earlier green-lit government efforts to prosecute Americans for belonging to the Communist party, holding that such membership could be con strued as a “clear and present danger” to the country.

That decision in hand, the Justice Department moved against more than 100 party members, including Oleta Yates. Voting 6-1, the justices threw out the case against Yates, essentially stopping prosecution of card-carrying Communists. They ruled that the Constitutional guarantee of free speech prevented prosecution for endorsing a doctrine that might be dangerous to the country; in other words, prosecution was permissible only for encouraging specific actions to overthrow the government.

In 1961, the Court underscored its holding in Yates, dismissing the prosecution of John F. Noto, another Communist Party member. In composing his opinion for a unanimous court, Justice John M. Har lan II sounded a bit exasperated that authorities were not heeding the court’s pronouncement in Yates and repeated that the First Amendment protected all speech and advocacy except those posing real and immediate danger.

“We reiterate now, that the more abstract teaching of Communist theory, including the teaching of the moral propriety or even moral necessity for resort to force and violence is not the same as preparing a group for violent action,” Harlan wrote. “There must be some substantial direct or circumstan tial evidence of a call to violence.”

When Brandenburg came before the high court, the outcome was hardly in doubt. In fact, prosecution of the KKK figure was so clearly unconstitu tional that rather than a signed opinion the Court issued a per curiam rul ing. That’s usually a signal that the justices think their conclusion quite noncontroversial, but in this case that status also reflects the fact that there was no single author. Justice Abe Fortas had written the first draft of the Brandenburg decision, then, after financial dealings of his came into ques tion, had resigned. Justice William Brennan edited the final version. The

ruling ’s significance is not simply that it exoner ated Brandenburg, but that it provided a gauge with which to assess the legitimacy of future attempts to stifle inflammatory rhetoric. That yardstick consists of three elements:

H Did the defendant intend his or her words or expressive action to incite violence or other law violations?

H Would those illegal acts be imminent?

H Would the incitement likely be successful?

A government may punish speech only if that speech passes all three tests, the opinion decrees. Any law or local ordinance which punishes expression that does not do so “sweeps within its condemnation speech which our Constitution has immunized from governmental control.”

The third element of the test, Fallow says, means “you look at, not just the text of the speech or the context of the speech itself, but at the con text in which it takes place. How likely would it be to trigger violence?”

The high court confirmed its reliance on the Brandenburg formula in multiple cases, over

Keep Carrying That Card

In a 1957 decision, the justices reversed field, declaring that Oleta Yates, above with attorney Benjamin Dreyfus, was not committing a crime by belonging to the Communist Party.

turning in 1973 conviction of a college student for his shouts at an anti-war rally and in 1982 the conviction of a local NAACP official for warning that those failing to join a boycott of businesses that discriminated against Blacks might face vio lence. That’s still the standard—a standard, Jus tice Ruth Bader Ginsburg once said, that “truly recognizes that free speech means not freedom of thought and speech for those with whom we agree, but freedom of expression for the expres sion we hate.” H

LOS ANGELES EXAMINER/USC LIBRARIES/CORBIS VIA GETTY IMAGES HUM IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES WINTER 2023 21

AMHP-230100-SCOTUS.indd 21 9/26/22 10:37 AM

Picture This

by Sarah Richardson

IN 1839, ROBERT CORNELIUS took the first photographic self-por trait. What in the Philadelphian’s era was an enforced moment of somber motionless reflection, lest blink or breath blur the image being exposed on a chemically treated silver-coated plate, today is casually snapped in a fraction of a second by billions in the form of “selfies.” An innovator in photographic method, Cornelius established a successful portrait studio in Phila delphia at 8th and Market Streets. He soon returned to work at his father ’s lighting and lamp firm, but his brief stint as a photographer opened doors, technical and aesthetic, to a revolution in the new medium. Cornelius also had a career as a metallurgist that traces the rise and fall of innovations in another product involving light: lamps.

Cornelius, born in 1809, was son of Christian Cornelius, a

The Incunabular Selfie Besides advancing the medium on a scientific plane, Robert Cornelius, left, invented what may be the most common photo category ever.

watchmaker’s son turned expert in silver plating who at 13 had emi grated from the Netherlands to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He is said to have started out in Philadelphia in 1827 by melting down the family silver dishes. The company would create brass lamps, chandeliers, and candlesticks, including a springdriven candlestick that cleverly kept a wick and its flame at a con stant level. The elder Cornelius later moved into more elaborate lighting apparatus. His business enabled him to send son Robert to private schools that trained the youth in chemistry, geology, and drawing. In 1831, Robert, 22, started working for his father.

The young man developed a side line in 1839 upon learning how French inventor Louis Daguerre had developed a technique for cap turing images on pieces of sil ver-plated metal.

The earliest photographic images necessarily were Parisian city scapes because the plate needed many minutes to register a sharp exposure on its treated surface; ani mals and passersby moving across the frame appeared as ghostly smudges. Samuel Morse, seeing an early Daguerre image, wrote in April 1839, “…the exquisite minuteness of the delineation cannot be conceived. No painting or engraving ever approached it.” Details of the spectacular pro cess soon reached the United States, where the younger Cornelius may have read about it in the August 1839 issue of the journal of the Philadel phia-based Franklin Institute. He and kindred spirits immediately began experimenting.

Working in his home with a tin box and lenses meant for opera glasses, in October or November 1839 Cornelius exposed and chemically stabi lized, or fixed, an image of himself on a sil ver-coated plate of his own devising. Recognized as the first photographic portrait, this artifact is remarkable not only for its technical excel lence—due to its creator’s expertise at fashion ing and polishing a fine silver plate—but for the way in which the 30-year-old Cornelius, young and vibrant, seems to be catching himself in the

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Cameo AMERICAN HISTORY22 AMHP-230100-CAMEO-BW.indd 22 9/26/22 9:53 AM

moment, tousled hair, popped shirt collar, and all. Casually positioned in front of the camera, he has used one hand to uncover the lens and then kept still to immortalize himself.

Others were tinkering as well, and newly minted photographers were soon producing what became known as daguerreotypes—images on metal plates about 5”x7” in size set in wood or gilt metal frames. But for an image to be its sharpest, a subject had to be inanimate or able to sit utterly still for five, even ten minutes, produc ing a stiff and unnatural look. Some photogra phers had subjects sit with eyes closed or head gripped by an armature; others dusted subjects’ faces with flour to heighten contrast.

While fellow experimenters were working on contrast, Cornelius was tackling the chemistry of recording light.

His circle included Dr. Paul Goddard, who aided Cornelius in figuring how to dramatically cut exposure time. Photographic plates pro duced images on a thin layer of silver coated with iodine crystals that reacted to light. God dard suggested adding bromine, which reduced exposure time to as little as 30 seconds.

The men shared the discovery with the local scientific society—once they had cornered the local bromine market—and opened a studio in Philadelphia in May 1840. Two large mirrors positioned outside the studio were angled to direct light within, filtered through purple glass to reduce glare.

Customers needn’t be rich. A daguerreotype could be had for $5, a fraction of what a painted portrait cost. Yet photographs seemed not to reduce demand for painted portraits, and paint ers often took daguerreotypes of subjects for ref erence instead of putting customers through hours-long sittings. Rival studios opened.

Perhaps tired of the medium and dismayed by competition, Cornelius closed his studio in 1842. His output is unknown, but a recent survey iden tified 54 Cornelius daguerreotypes in museums and private collections

Philadelphia became a bastion of studio pho tography, by 1849 counting more than 40 studios in the city center, where photographers con verted lofts to studios with reflective white walls and large windows to direct light.

Cornelius returned to the family business, which was thriving by manufacturing large lamps renowned for their brightness, sturdiness, and beauty and often were fueled by whale oil in a reservoir surrounded by prisms to intensify the glow. The 1840s saw the beginning of whal ing’s heyday. Spermaceti, a dense slippery sub stance from a sperm whale’s head, burned bright and long and was one of the prime products of the hunt. Spermaceti eclipsed a succession of

No Blinking!

The first American photograph, depicting Philadelphia’s Central High School, was made in autumn 1839 by Joseph Saxton.

other substances—beeswax, beef tallow, pork lard, colza oil (from rape seed), oil from whale blubber, and camphene, a derivative of turpentine— during 1840-1870 becoming the preferred lamp fuel.

Cornelius patented a type of solar lamp, said to rival the sun for bright ness, that burned lard and salvaged kitchen grease. He was granted more than 20 patents. As gas light gained popularity, the Cornelius company adapted, manufacturing large gas-powered lamps, chandeliers, and osten tatious assemblages known as girandoles, from the Italian for “to turn.”

Christian Cornelius retired in 1851, and Robert Cornelius and relatives carried on. By 1855, the Cornelius company was employing 500 workers in two large factories in Phila delphia. The enterprise is most remembered as the premier manufacturer for grand giran doles marketed worldwide.

Cornelius lamps, installed in state capitols and in the U.S. Senate and three rooms at the White House, were a million-dollar business.

With the discovery in 1859 of petroleum in Titusville, Pennsylvania, much of the market for table lamp fuel shifted to kerosene made from petroleum. According to historical lighting expert Dan Mattausch, one Robert Cornelius patent was for a ker osene table lamp, but a competitor brought out a far cheaper version that won consumers’ favor. In 1877, Cornelius retired, and with him, perhaps, the spark of innovation. The company continued to make showy gas fix tures, sometimes depicting American icons such as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Andrew Jackson, or a generic hunter.

Robert Cornelius left his mark nonetheless. As he put it in 1839, “I made a likeness of myself, and another one of some of my children in the open yard of my dwelling, sunlight bright upon us, and I am fully of the impres sion that I was the first to obtain a likeness of the human face.” H

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WINTER 2023 23

A recent survey of Cornelius images found there to be 54 of them in the collections of private individuals and museums.

AMHP-230100-CAMEO-BW.indd 23 9/26/22 9:53 AM

On the Rise

PHOTO CREDIT

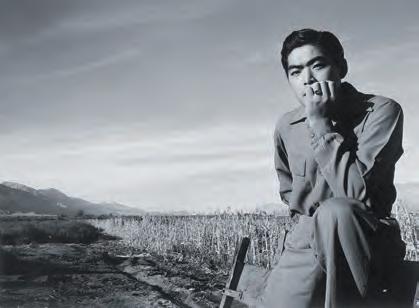

Riley B. King soon after engineering a start to a career that would make him a worldwide star.

AMHP-230100-BB KING-BW.indd 24 9/26/22 10:55 AM

n early 1949, Riley B. King, 23, was living and working as a tractor driver on a plantation outside Indianola, in the Mississippi Delta, where he mostly had grown up. A share cropper’s son determined to pursue a career in music, Riley busked playing the blues on the street and had had a gospel group and, as often as he could, and despite his stutter, chatted up working musicians. At Jones’ Night Spot in Indianola, he had buttonholed Sonny Boy Williamson, famed regionally for his lunchtime radio show, broadcast out of West Memphis, Arkansas. Now Riley was heading to that town, hoping to break into the music business.

RILEY BID FAREWELL to planter Johnson Barrett. “I’ll send for you, soon as I get settled,” he told his wife, Martha. Guitar in hand, he hitched a ride in a Lewis Grocery truck, helping the driver make deliveries in exchange for passage to West Memphis, across the Mississippi from Mem phis, Tennessee. Against the March chill he wore the field jacket he’d got ten during a brief wartime stint in the U.S. Army. His destination was 231 East Broadway, the studios of KWEM, which had launched in 1947 on a pay-to-play system. Local performers could book a time slot by ponying up $15 or $20 or find a sponsor to cover the cost. One of the station’s first stars had been Chester Burnett, a giant of a man from the Mississippi Hill Country who performed as Howlin’ Wolf.

Becoming B.B.

A crucial 48 hours changed a Mississippi-born musician’s life

By Daniel de Visé

By Daniel de Visé

PHOTO CREDIT

WINTER 2023 25

I AMHP-230100-BB KING-BW.indd 25 9/26/22 10:56 AM

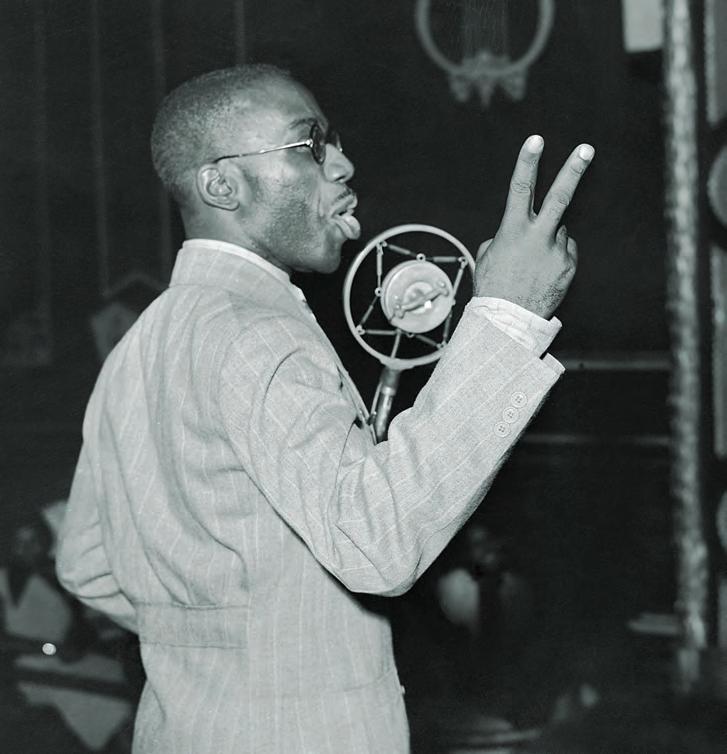

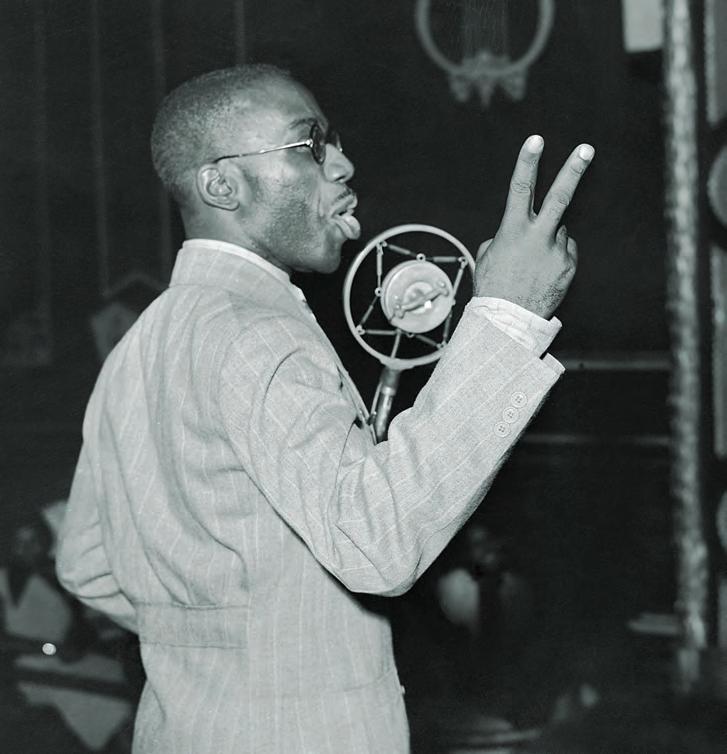

Mentor and Patron

Sonny Boy Williamson II (at mic) during a 1942 show at KFFA in Helena, Arkansas. From left: Joe Willie Wilkins, Dudlow, Williamson, announcer James Curtis, Herb Langston, Willie Love.

Excerpted from KING OF THE BLUES © 2021 by Daniel de Visé. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.

Wolf’s voice, a bone-rattling bass baritone growl, froze listeners in their seats.

KWEM’s other star was Sonny Boy William son. Born Alex Ford around 1912 on a Mississippi plantation, he mastered the harmonica and by the 1930s was traveling around Mississippi and Arkansas and performing with many singers and guitarists, including Robert Johnson.

In 1941, Ford landed on the air at KFFA in Hel ena, Arkansas, playing music and touting baking products on a show, “King Biscuit Time,” named for sponsor King Biscuit Flour. Sponsors suppos edly rechristened Alex Ford "Sonny Boy William son" to exploit the brand of a Chicago musician already recording under that name.

In 1948, Sonny Boy moved to West Memphis and KWEM, arriving shortly after Wolf, a friend he had taught to play harmonica. Sonny Boy’s sponsor was Hadacol, a patent medicine mar keted as a vitamin supplement for the entire fam ily. In truth, the “Wonderful Hadacol Feeling”

was actually inebriation; the stuff was 12 percent alcohol (American Schemers, April 2018).

For years, Riley and the other hands at Bar rett’s plantation had been coming in from the fields at lunchtime to relax listening to Sonny Boy. And there had been that encounter at Jones’ Night Spot. “I felt I knew him,” he recalled. Still, Riley could not explain how he summoned the nerve that Wednesday to walk into KWEM, clutching his guitar and asking for Sonny Boy. He found Williamson in the studio, finishing a num ber with guitarist Robert Lockwood Jr. and pia nist Willie Love. When he had finished playing, Sonny Boy gave his visitor a hard look.

“What do you want?”

Riley took a deep breath and tried his best to remember those warm memories he treasured of Sonny Boy on the radio.

“I…I…I…I wanna sing a song on your program,” Riley B. King stammered.

“You do, huh?”

AMERICAN HISTORY26 COLIN ESCOTT/GETTY IMAGES PREVIOUS SPREAD: MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES; THIS PAGE: MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

AMHP-230100-BB KING-BW.indd 26 9/26/22 10:56 AM

“Yes, sir.”

Sonny Boy and his band members now remembered the night a few years back when a boy with a stutter had peppered them with questions in Indianola.

“Go ahead,” Sonny Boy said. “Lemme hear you.”

Riley swung his guitar around and lit into “Blues at Sunrise,” which had been a hit for Ivory Joe Hunter. “I sang with all the soul I could muster,” he recalled. “My gui tar hit the right notes and I sang in tune.” He waited for Sonny Boy’s verdict.

“What do you call yourself, son?” the radio host asked with a flicker of warmth.

“Riley B. King.”

“All right, Riley B. King,” Sonny Boy said. “You can sing your song at the end of my program. Just be sure you sing as good as you did just now.”

Riley stood by until Sonny Boy gave him a nod. At the microphone he played and sang as well as he ever had. When he was done Sonny Boy took back the mic.

“The boy ain’t bad, but you tell me what you think,” Williamson told his listeners. “Call in if you like him.”

As Sonny Boy was wrapping up, Riley waited. A White man came into the studio and announced that many listeners were calling in to praise Riley’s performance. Then he whispered in Sonny Boy’s ear.

“Shit,” Sonny Boy Williamson said. “I done messed up.”

Riley started to panic, thinking he was some how at fault.

“Lookee here, Riley B. Seems like I dou ble-booked myself,” Sonny Boy explained. “I’m working down ‘round Clarksdale tonight, but I also got me another date at that Sixteenth Street Grill here in West Memphis. You wanna play the Grill for me?”

“Yes, sir,” Riley replied in an instant. He was “thrilled beyond reason,” he recalled. “Giddy and silly and screaming hallelujah inside.” In the space of an hour, he had debuted as a radio blues man and earned his first paying solo gig.

Sonny Boy picked up the telephone and placed a call. “Did you hear the boy who just sang?. . .How did you like him?. . .Well, I’m gonna let him work for you tonight.” He hung up.

“I want you to go down and play for Miss Annie at the Sixteenth Street Grill,” Sonny Boy said, menace in his voice. “And you better play.”

“Yes, sir,” Riley replied.

The club, a block off Broadway in West Mem phis, was variously known as the Square Deal Café, the Sixteenth Street Grill, and Miss Annie’s

No Frills

Place, after owner Annie Jordan. Miss Annie showed Riley around. “The joint was just a couple of rooms,” he recalled. “One up front for music and sandwiches, one in the back for gambling.”

“I got me a jukebox in here,” Annie told Riley. “But I turn it off ‘cause the ladies like to dance to a live man.”

A live man. The words danced in the young musician's head. And sure enough, as showtime approached, a procession of ladies filed into the café, some with escorts, some without. The men retreated to the gambling parlor, leaving their dates up front to dine and dance.

Having no better clothes, Riley took the stage wearing his field jacket. The ladies didn’t seem to mind. “For the first time I played for dancers, played for these ladies who moved so loose and limber that I played better than I’d ever played before,” he recalled. “Might have messed up my musical measures or screwed up a lyric or two, but, baby, the beat was there.”

Riley filled Miss Annie’s Place with the blues, his only accompaniment his Gibson guitar run ning through a tiny amplifier as he sang through a small public address system. He held down the

WINTER 2023 27 COLIN ESCOTT/GETTY IMAGES PREVIOUS SPREAD: MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES; THIS PAGE: MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

He filled Miss Annie's with the blues, his Gibson guitar running through a tiny amplifier as he sang through a small public address system.

The young bluesman made his WDIA debut in a stark setting.

AMHP-230100-BB KING-BW.indd 27 9/26/22 10:56 AM

beat, and the dance floor filled with hot, heaving bodies.

“I want to hire you,” Miss Annie said after wards. “But you can’t help me get business unless you’re on the radio, like Sonny Boy is. If you can get on the radio, I’ll pay you $12 a night and give you room and board.”

“Yes, ma’am," Riley replied. “I will get on the radio.”

The club owner offered to put him up. “That night I couldn’t sleep for the pictures running through my head,” he recalled. He imagined women in various states of undress, “bending over and stretching, grinding and grinning and showing me stuff I ain’t ever seen before.”

The next day, Miss Annie told Riley about WDIA hiring Black deejays like local celebrity Nat D. Williams. On previous forays to Memphis, Riley, with his cousin Bukka White, had played Nat D.’s amateur nights at the Palace. Guitar in hand, Riley caught a bus for Memphis to find WDIA.

WDIA, 1070 AM, HAD COMMENCED operations on Union Ave nue in the summer of 1947. The founders were White men. John Pepper, the businessman, was a scion of an affluent Memphis family; WDIA was named for his daughter Diane. Bert Ferguson, the station manager, was short on cash but long on experience. Eight years earlier, Pepper had brought Ferguson in to run WJPR-AM in Greenville, Mississippi. The two were looking for a niche in the Memphis market, dominated by five stations with ties to national networks and celebrity disk jockeys.

WDIA started out playing country-and-western. When that format failed to attract listeners, the owners tried pop and even classical music. Now they were back to country, airing shows like “Cracker Barrel” and “Hillbilly

AMERICAN HISTORY28 MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES PICTORIAL PRESS LTD./ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; COURTESY OF SPINDEL FAMILY (2)

A King and His Court B.B. King, center rear, with his band and fellow announcer Nat Williams, right.

Bert Ferguson

Christine Cooper

AMHP-230100-BB KING-BW.indd 28 9/26/22 10:56 AM

Party.” Nothing was working. Christine Cooper, Ferguson’s programming director, searched in vain for the right format. Chris Cooper, 23, was a striking woman, taciturn and serious, with soul ful brown eyes and a sharp mind. Ferguson had lured her from an ad agency to become one of the first women in Memphis radio.

In spring 1948, Cooper was wondering if she had made the right choice. WDIA was hovering near bankruptcy, and the owners seemed desper ate. Cooper and Ferguson and two other station employees, to save on hotel bills, had left an industry convention in Nashville early and were driving the 200 miles to Memphis.

Ferguson was at the wheel, with Cooper riding shotgun. As they were rolling past moonlit farm houses on two-lane blacktop roads, Ferguson leaned toward his program director.

“What do you think about programming for Negro people?” he whispered.

Cooper considered. Their competition in Memphis had divvied up the region’s White audi ence. No mainstream station was programming for Blacks, a potential audience as large as the entire White market—“tens of thousands of peo ple with names and faces who had served me at restaurants and ridden on the same bus,” she recalled. Blacks in and around Memphis had their own clubs, their own festivals, and even a newspaper—the Memphis World—but no radio station. Cooper told her boss she loved his idea.

“Would you object to working alongside Negro people at the station?” Ferguson asked, again speaking sotto voce.

No, Cooper replied, she would not.

After that furtive exchange Ferguson dropped the topic. Cooper thought he had lost his nerve or his focus. He was always coming up with new con cepts, sometimes with Pepper. Lately the two had been pushing a tonic they had dreamed up to compete with Hadacol and had gotten so far as to organize a company to sell it. Ferguson had tried to get her to write the ads, but she refused. But Bert had not lost focus on taking WDIA Black. That October he told her he had decided “to go ahead with it.” Chris knew instantly what “it” was.

AFRICAN AMERICAN RADIO had begun in the 1920s with a visionary named Jack Cooper. Born in Memphis in 1888, Cooper made his name reporting for Black newspapers in Chicago, Illi nois. In 1925, on WCAP in Washington, DC, a strong Black market, he launched a variety show. Cooper performed dialect skits; he joked later that he had been “the first four Negroes on radio.” Returning to Chicago, in 1929 he brought out “The All-Negro Hour” on WSBC, patterning this show on African American vaudeville line-ups.

A Different Ax

In a 1949 promotional photo, B.B. holds a Fender Esquire solid-body electric guitar.