HWRK educational mag azine the online magazine for teachers ISSUE 27 / FREE HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK written by teachers for teachers ALSO INSIDE What Makes a n e ffective Middle l eader? • They Probably Wouldn’ T b ehave For y ou e i T her • Thinking b ig i n e nglish • b ack To s chool: a dvice For r e T urning Teachers • c P d and Pro T ec T ing Peo P le’s Pie c har T s • h o W To Make i n T ervie W s Work For y ou • u nlocking The Po W er oF sT ories To iMP rove l earning

Established in May 2006, we are one of the UK’s most dedicated and ambitious anti-bullying charities. Our award winning work is delivered across the UK and each year, through our work we provide education, training and support to thousands of people.

Through our innovative, interactive workshops and training programmes, we use our experience, energy and passion to focus on awareness, prevention, building empathy and positive peer relationships all of which are crucial in creating a nurturing environment in which young people and adults can thrive. Our Mission is to support individuals, schools, youth and community settings and the workplace through positive and innovative anti-bullying and well-being programmes and to empower individuals to achieve their full potential.

DIFFERENCE MAKING A INSPIRING CHANGE EMPOWERING YOUNG PEOPLE To find out more visit www.bulliesout.com | Email: mail@bulliesout.com

BELIEVE IN A WORLD THAT IS FREE FROM ALL

OF BULLYING BEHAVIOUR.

you would like to support us and help us to continue our lifechanging work, you can:

Volunteer with us

Fundraise for us

Make a donation

Join our Speak Out Campaign

Become a Corporate Partner

WE

TYPES

If

\

\

\

\

\

HE’S gOT THE WHOlE SCHOOl CalENdar, iN HiS HaNdS…

Unlocking The Power of STorieS To imProve learning

Back To School: advice for reTUrning TeacherS

CONTENTS

EDIToRIAL: The importance of leaving school at school when the summer holiday begins

FEATURES

6. HE’S GoT THE WHoLE SCHooL CALENDAR, IN HIS HANDS The design of the whole school calendar is more than plotting events in a diary

10. CPD AND PRoTECTING PEoPLE’S PIE CHARTS

How do you balance pushing staff to be their best, while taking care of their needs?

16. HoW To MAkE INTERvIEWS WoRk FoR YoU

Tips on nailing the interview process in schools

21. PovERTY, MENTAL HEALTH, AND SCHooLS: A DRoP IN THE oCEAN?

Strategies for using the ‘small moments’ to create a connection with our students

26. THEY PRobAbLY WoULDN’T bEHAvE FoR YoU EITHER

Why do some students only behave for some teachers? (And what can you do about it?)

31. THE JoY oF TEACHING IN bILINGUAL SCHooLS

Why you might want to consider teaching in a bilingual school and how you might prepare for it

CURRICULUM

36. UNLoCkING THE PoWER oF SToRIES To IMPRovE LEARNING

Why does storytelling in the classroom matter so much?

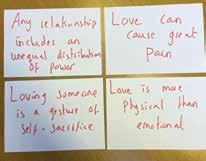

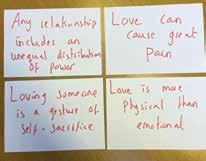

40. THINkING bIG IN ENGLISH

The importance of exploring big questions that span literature, rather than focusing solely on the finer details of a text

44. PLACING ART AT THE HEART oF EDUCATIoN

Why is it so dangerous to leave Art out of the curriculum?

LEADERSHIP

50. WHAT MAkES AN EFFECTIvE MIDDLE LEADER?

Strategies for improving the quality of your middle leadership in school

55. CoMMUNICATIoN FoR LEADERSHIP

How do effective leaders communicate, to make maximum impact?

EXPERIENCE

62. bACk To SCHooL: ADvICE FoR RETURNING TEACHERS

One returning teacher’s advice for going back into the classroom

65. CoMPUTING PoSTEr Algorithm Design - A Step-By-Step Approach

ISSUE 27 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 03 HWRK MAG AZINE .co. UK // INSIDE THIS ISSUE

P 36 P62 P06 P50 P31 @hwrk_magazine

P21

The Joy of Teaching in BilingUal SchoolS

A whole-school calendar is an annual project that needs to be successful; like a curriculum, it is based initially on intent as opposed to reality, but it also carries significant weight; the smooth-running of the institutional machine relies on the clarity and accessibility of the information it shares. By Henry Sauntson

@hwrk_magazine 06 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 27 The core of progress is knowledge of the intended destination – that’s relatively obvious. By starting with the end in mind, the journey can be more flexible, more responsive; it also allows for what Mitchell et al (1989) referred to as ‘pre-mortem’; the use of ‘prospective hindsight’ to identify reasons why project might fail, and thereby putting in steps to prevent this. Teachers may think – why me? I’ll teach my timetable and then I’ll be told what need to do differently if anything crops up. This is not the best approach; schools are not shopping centres full of siloed classrooms, but complex interconnected webs of experience microcosm of life itself. In a shopping centre, one store closes early it has no effect whatsoever on the store next door selling a different product; in school, if one classroom is disrupted for any reason then this causes massive ripples across the whole institution; rooming adjustments, collateral, staff issues, curriculum disruption – Butterfly Effect. In world of tight timetables and slight misalignment between the suggested coverage hours according to their specifications and the realities of teaching this content in classrooms, not minute can be wasted. A carefullyconsidered whole-school calendar makes the process of planning curriculum implementation far easier, as leaders and classroom teachers can anticipate pinchpoints, manage workload and be realistic with expectations, both of staff and the students. Teachers are humans too; they have the same cognitive functions defined by working memory capacity and ability to adapt to change. They too need to optimise their load to ensure their efficiency and The more informed teacher is, the more weight they can place behind their decision-making and their judgments; they can be more confident, and therefore more competent. When teachers know that the calendar has been designed in way that is sensitive and empathetic to the needs of all those invested in, they are happier in their work; competency comes from clarity, and is enhanced by a developed craft that Eno once said, craft is what enables you to be successful when you aren’t feeling inspired. A sensible, empathetic calendar is a mark of strong professional culture in which all individuals can thrive; it is no easy feat to get right. The calendar is the school, on paper (or online); encapsulates everything that will, or should, be happening across the swathe of the Academic year; thereby, as a documentary prediction or anticipation of to-be-enacted events, it must encapsulate the aims and ethos of the school and, perhaps, without being too grandiose, Education doesn’t just qualify students; it socialises them, it subjectifies them in the wider world (Biesta, 2009). Now, if as Biesta argues – the foundation transformation of the person, then that too can be seen as the overriding purpose of the calendar; not in practical terms, but in laying the sequence of opportunities for each individual to access. In Biesta’s view, subjectification is turning students into ‘subjects’, i.e. coming into presence as individuals – independent agents shaping the society they inhabit (Murris & Verbeek, 2014). It is personal quality – the existence of the unique person outside becoming part of existing social orders. When we – or our students –are ‘subjectified’ we make wiser decisions, we take responsibility, we make informed judgments. In essence, the calendar gives us framework in which to make these decisions; the calendar is the social order in which we can subjectify our students. What we want within our calendar is the opportunity to inspire, to be curious, to give all students chance to shine. In some cases it might be what Shimamura called ‘taking trip around unfamiliar terrain’ (Shimamura, 2019) to motivate students and get them to attend, to engage. MAG .co.UK 27 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 07 FEATURE However, beyond the abstract there is also the pragmatic – what does the calendar need to contain? Every school has its own unique deadlines that align with internal policies, funding agreements, articles of association, schemes of delegation and School Improvement Plans (SIP). But they also must pay attention to national factored in. There’s how the Academic year is organised, internal duties and deadlines, school events and meetings; each of these can be broken further down into subcategories, all of which carry implications. It is a highly complex, high-stakes process that needs support and careful consideration. he’S goT The whole School calendar, in hiS handS When you learn the points on a compass in clockwise order, the chances are you heard the phrase ‘Never Eat Shredded Wheat’. But how do you navigate this in a Chinese bilingual school, where most of the students really have never eaten shredded wheat, don’t know what it is, and have a great deal of more pressing linguistic priorities that the points of a compass? The Joy of Teaching in Bilingual SchoolS issue 27 // 31 FEATURE Wellington College International, and one of the great pleasures of this role is visiting our international family of and in India opening in September. recently returned from leading the In both, language learning is priority. But in bilingual school, the seamless which for the students means moving from one language to the other, is utterly extraordinary. Passports first; to attend an international school in China, you have to be foreign But bilingual means exactly that and so much more. The bilingual Huili schools uses Chinese and Western co-teaching approach which we say ‘creates truly immersive bilingual learning environment for pupils. Our teachers, both Chinese and international, work closely together to ensure balanced development in CURRICULUM @hwrk_magazine The primary curriculum is something from different point of Daniel Willingham writes about the power of stories and describes how psychologists argue they are ‘psychologically privileged of the world through narratives. Stories provide structure that helps us organise information, our ability to remember and internalise information. Writing stories is also quintessential part of primary education. Writing narratives, whether real or fictional, is also commonplace in the primary classroom. In fact, the Spoken Language section of the English that children are taught to: “give well-structured descriptions, From the Epic of Gilgamesh to Homer’s Odyssey to the Norse myths of the Vikings, stories have been passed from generation to generation across the world for gods and monsters, and the struggles the human condition, as well as explaining how the and father, whose tight embrace kept the world in eternal darkness, were pushed apart by their children, the gods who craved to be freed. This separation caused Ranginui to cry so intensely that the tears formed the oceans, seas, between Ranginui and Papatuanuku is so strong, however, that despite close to each other: Ranginui, as the sky, watches over and protects One thing that hasn’t changed, however, the centrality of stories to communication, culture, and and increased literacy, storytelling television and films, journalism build relationships, captivate an audience, and inspire others. would argue that everyone of us benefits from acquiring and mastering such skill. which teachers can use to convey the information they want Storytelling is deeply engrained in the essence of being human. It is a powerful tool that has shaped our cultures, facilitated learning, preserved history, fostered social connections, and nurtured our imaginations. unlocking The Power of STorieS To imProve learning c rric M PoverTy, MenTal healTh, and SchoolS: a droP in The ocean? Small moments make a huge difference when it comes to establishing trust and connectedness. We should focus on these if we are to tackle the societal and mental health issues facing our students in schools today. PoverTy, menTal healTh, and SchoolS: a droP in The ocean? FEATURE whaT MakeS an effecTive Middle leader? LEADERSHIP you wish to implement. Self-awareness, and leading by example are the key foundations to building teams. As humans, we are naturally motivated both intrinsically and extrinsically by different factors. Not everyone is in education for the same reason and whilst it may surprise you to begin with, it is important to recognise these differences. For some, money is motivating. For others, desire to help As the Middle Leader, you must consider the diverse factors that motivate your team and use knowledge of these to drive strategic change and development in your To do this, we must ensure that; returned to frequently opportunities for team collaboration and different opinions are considered give your team space, time and autonomy where appropriate 4. The art of delegation team will be laughing when they read have been forced to let go and allow others to grow and develop in areas previously managed. am slowly learning that this must happen for the benefit of myself and my team. As Middle Leader, you cannot and should not do everything. It is important to trust other colleagues 1. For our own workload and mental health 2. For the growth and development of our 3. To empower our teams to take ownership Allowing others to perform tasks and lead changes can lead to more successful outcomes. The feeling of empowerment and ownership can motivate your team which will drive the project/change to a more successful outcome. As humans, we are we are being done to, than done with. The If we allow them responsibility and give them the encouragement and support to lead things themselves, this can often lead to them thriving. 5. Managing Relationships

EXPERIENCE @hwrk_magazine Advice for potential returning teachers Keep your hand in: Whilst working as solicitor, was always looking for opportunities to work with young people, such as leading my law firm’s schools my teaching skills go completely rusty, and it was helpful to have those experiences to draw on at interview. teaching because of my own doubts. As soon as started talking to school leaders, realised how unnecessary that was. Schools are always looking for passionate, and they generally don’t let arbitrary preconceptions around time in or out of the classroom get in the way of hiring good people. The biggest thing that helped me move past my doubts was hearing stories of other people who have returned. now want to give other potential returners that same experience, Teachers Network (on Twitter at @ ReturnTeachers) as space for former teachers thinking about returning to ask questions and to link up with others who Know your motivation: People will inevitably have their own opinions about whether you are doing the right thing. about why you are returning. Personally, returned for community, creativity, and purpose. Whenever am having wobble, check in with myself about whether teaching is providing me with those three things, and the answer is always yes. Get support: The first year back will be rollercoaster, and the change in pace in your working life will likely be shock to the system. It’s really helped me to have family and friends who understand that, and who support me when need most. Similarly, it’s really important to get up to your school how long you’ve been away from the classroom, and advocate for the help you need to find your feet. Advice for schools hiring returning teachers 1. Be open to returning teachers. Qualified teachers who have spent them range of invaluable experiences, perspectives, and soft skills. They have also made conscious decision to return to the profession, with their eyes open to the realities of the job and a clear understanding of ‘what else is out there’, and resilient teachers. At interview, acknowledge the unique journey of the candidate and ask them questions which that they will be bringing back into the 2. Provide tailored support. It’s teacher may feel like a new teacher all over again. Have conversation with them once they’ve accepted the job to agree package of support. This could include them to observe colleagues, offering lesson drop-ins and coaching conversations, or arranging subject-specific CPD. So to any former teachers out there who are weighing up a return to the classroom, say go for it! Find fellow returners, volunteer in schools, and put in the applications. The profession waiting to welcome you back with open arms!

CONTRIBUTORS

WRITTEN BY TEACHERS FOR TEACHERS

Claire Pass

@Claire_Pass

Claire Pass is an AST in English with 21 years’ teaching experience. She holds a Master’s Degree in Education: Leadership and Management. She is also Co-Founder of Dragonfly.

Andrew Atherton @__codexterous

Andrew Atherton is a Teacher of English as well as Director of Research in a secondary school in Berkshire. He regularly publishes blogs about English and English teaching at ‘Codexterous’ and you can follow him on Twitter @__codexterous

Chris Woolf

Chris Woolf is delighted to be the International Director at Wellington College International. Prior to this he was founding Headteacher of a school in north London judged ‘outstanding’ in all categories by Ofsted.

Sam Strickland

@strickomaster

Sam is the Principal of a large all-through school, the organiser of ResearchED Northampton, and author of The Behaviour Manual: An Educator’s Guidebook, published by John Catt (2022)

Jessica Austin-Burdett

@artteachjess

Jessica Austin-Burdett is an Art and Design teacher and leader, with a passion for creativity and interdisciplinary unison, holding a variety of educational positions in diverse inner-city schools over the years.

Marc Hayes @mrmarchayes

Marc is an Assistant Headteacher and Year 6 teacher at Roundhay All-Through School in Leeds. He leads on curriculum development and is passionate about curriculum design, teaching and learning, and school leadership. He blogs at www.marcrhayes.com

Henry Sauntson

@HenrySauntson

Henry Sauntson is a Senior Leader and SCITT Director, based in Peterborough. His enthusiasm and interest lies primarily with teacher education and development, especially in the early career stages. We need to be informed, not led.

Tracey Leese

@MrsqueenLeese

Tracey Leese is an Assistant Headteacher at St Thomas More Catholic Academy in Longton, co-author of Teach

Like a Queen and a passionate advocate for women in leadership

Faheema Vachhiat

@FVachhiat

Faheemah always seeks ways to innovate her teaching. Through her substack, she shares her reflections on teaching and learning, explores the latest trends and best practices and shares strategies for other educators looking to enhance their approaches to curriculum design.

Nikki Sullivan

@Nikki_Sullivan

Nikki is a Deputy Head teacher. With experience in both pastoral and academic senior leadership in the UK and Malaysia, Nikki has led implementation of policy development, CPD, and building a team of Faculty Research Leads.

Rachael Southern

@Rach_TeachAgain

Rachael is Key Stage 3 Progress Lead for English at a comprehensive school in Manchester. Following a nine-year break during which she trained and worked as a solicitor specialising in charities, education, and safeguarding. She is the founder of The Returning Teachers Network (@ReturnTeachers).

Lindsay Galbraith

@MsGHist

Lindsay Galbraith is an educational leader, currently serving as the Assistant vice Principal at Charlton School, Telford. Her passion for teaching and learning ignited a deep commitment to shaping engaging and comprehensive educational experiences for students.

Sharon Leftwich-Lloyd

@leftylloyd

Sharon is Assistant Headteacher at Etone College, Warwickshire. She previously worked as Lead Practitioner at The Polesworth School (Community Academies Trust). Sharon favours a research-led approach to teaching and is a Fellow of The Chartered College of Teaching.

hwrkMAG A zine.co.uk // M ee T T he T e AM

Legal Disclaimer: While precautions have been made to ensure the accuracy of contents in this publication and digital brands neither the editors, publishers not its agents can accept responsibility for damages or injury which may arise therefrom. No part of any of the publication whether in print or digital may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission of the copyright owner. EDITOR Andy McHugh PUBLISHING DIRECTOR Alec Frederick Power DESIGNER Adam Blakemore MANAGING DIRECTORS G Gumbhir, Alec Frederick Power HWRK MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY EDU ONLINE GROUP LTD 1st Floor, GD Offices, 47 Bridgewater Street, Liverpool, L1 0AR E: enquiries@edu-online.co.uk T: 0151 294 6215

Time To Unwind

One of the best pieces of advice I’ve ever been given was by a colleague, years ago.

“It doesn’t matter how hard you work, so long as it feels meaningful and is manageable. What matters much more is how you spend your time when you’re not working. Are you thinking about work? Stop it and go do something else. Are you with people who are talking about work? Go and find some different people.”

You can take her advice as literally or as figuratively as you like, but there’s no denying the wisdom that lies there. If you never truly switch off, you’ll never truly recover enough to go again once the new term restarts. You need to be conscious of taking a genuine break and acting on it with purpose.

Here’s how I do it. Pinch whatever works for you.

1. Get some sunshine and fresh air every day, ideally first thing in the morning. Open your patio doors while you have your morning brew or get outside with the dog. It doesn’t have to involve exercise. Just a quiet sit down outside while the world is still waking up can do wonders for the soul.

2. See family and friends. Too often as teachers, we are so busy during the week and at weekends that we don’t find enough time to meet our nearest and dearest. Invest that time when you canthere’s nothing like other people who know you well, to give you the lift you need after a tough year in school.

3. All work communication is switched off. This means your inbox is paused, work mobile in a locked drawer, and set a date whereby you aren’t allowed to access any of it under any circumstance until that date at the earliest. Even checking an email, or knowing you could check that email can undo all that relaxation that you need if you’re to properly unwind.

4. Do the important thing that you haven’t done yet. There’s nothing worse than getting to the end of the summer holidays and feeling like you’ve wasted it and haven’t done anything worthwhile. This doesn’t mean work, or even anything remotely challenging. It could just mean going for a walk along that footpath that you’ve always wondered about. It could mean trying a slice of that delicious-looking cake in the cafe

around the corner, that you’ve never quite gotten around to. It doesn’t mean painting the bathroom (unless you’re the kind of person that enjoys that sort of thing).

5. Plant something. There’s a real sense of satisfaction and even pride when something you’ve planted begins to grow and flourish. My top tip - make it edible! Or at the very least, something beautiful. You’ll look back on it and enjoy the memory even once it’s gone. Don’t fancy gardening? Start something else instead. A book. Yoga. A fantasy football team. Even a fun side hustle. Something that gets your creative juices flowing and gives you an outlet for your imagination and a real sense of “you’ve earned it”.

But whatever you choose, just take the time you need to get back to doing whatever makes you, you.

Enjoy your hols!

Andy McHugh Editor | HWRK Magazine

ISSUE 27 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 05 HWRK MAG AZINE .co. UK

He’s got tHe WHole scHool calendar, in His Hands…

The core of progress is knowledge of the intended destination – that’s relatively obvious. By starting with the end in mind, the journey can be more flexible, more responsive; it also allows for what Mitchell et al (1989) referred to as a ‘pre-mortem’; the use of ‘prospective hindsight’ to identify reasons why a project might fail, and thereby putting in steps to prevent this.

Teachers may think – why me? I’ll teach my timetable and then I’ll be told what I need to do differently if anything crops up. This is not the best approach; schools are not shopping centres full of siloed classrooms, but complex interconnected webs of experience – a microcosm of life itself. In a shopping centre, if one store closes early it has no effect whatsoever on the store next door selling a different product; in a school, if one classroom is disrupted for any reason then this causes massive ripples across the whole institution; rooming adjustments, collateral, staff issues, curriculum disruption – a Butterfly Effect.

In a world of tight timetables and a slight misalignment between the suggested coverage hours according to their specifications and the realities of teaching this content in classrooms, not a minute can be wasted. A carefullyconsidered whole-school calendar makes the process of planning curriculum implementation far easier, as leaders and

classroom teachers can anticipate pinchpoints, manage workload and be realistic with expectations, both of staff and the students.

Teachers are humans too; they have the same cognitive functions defined by working memory capacity and ability to adapt to change. They too need to optimise their load to ensure their efficiency and therefore their increased effectiveness. The more informed a teacher is, the more weight they can place behind their decision-making and their judgments; they can be more confident, and therefore more competent. When teachers know that the calendar has been designed in a way that is sensitive and empathetic to the needs of all those invested in, they are happier in their work; competency comes from clarity, and is enhanced by a developed craft that makes certain actions automatic. As Brian Eno once said, craft is what enables you to be successful when you aren’t feeling inspired.

A sensible, empathetic calendar is a mark of a strong professional culture in which all individuals can thrive; it is no easy feat to get right.

The calendar is the school, on paper (or online); it encapsulates everything that will, or should, be happening across the swathe of the Academic year; thereby, as a documentary prediction or anticipation of to-be-enacted events, it must encapsulate

the aims and ethos of the school and, perhaps, without being too grandiose, education itself.

Education doesn’t just qualify students; it socialises them, it subjectifies them in the wider world (Biesta, 2009). Now, if – as Biesta argues – the foundation for education is the formation and transformation of the person, then that too can be seen as the overriding purpose of the calendar; not in practical terms, but in laying the sequence of opportunities for each individual to access.

In Biesta’s view, subjectification is turning students into ‘subjects’, i.e. coming into presence as individuals – independent agents shaping the society they inhabit (Murris & Verbeek, 2014). It is a personal quality – the existence of the unique person outside becoming part of existing social orders. When we – or our students –are ‘subjectified’ we make wiser decisions, we take responsibility, we make informed judgments. In essence, the calendar gives us a framework in which to make these decisions; the calendar is the social order in which we can subjectify our students.

What we want within our calendar is the opportunity to inspire, to be curious, to give all students a chance to shine. In some cases it might be what Shimamura called ‘taking a trip around unfamiliar terrain’ (Shimamura, 2019) to motivate students and get them to attend, to engage.

A whole-school calendar is an annual project that needs to be successful; like a curriculum, it is based initially on intent as opposed to reality, but it also carries significant weight; the smooth-running of the institutional machine relies on the clarity and accessibility of the information it shares.

By Henry Sauntson

@hwrk_magazine 06 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 27

However, beyond the abstract there is also the pragmatic – what does the calendar need to contain? Every school has its own unique deadlines that align with internal policies, funding agreements, articles of association, schemes of delegation and School Improvement Plans (SIP). But

they also must pay attention to national issues and deadlines, all of which must be factored in.

There’s how the Academic year is organised, internal duties and deadlines, school events and meetings; each of these

can be broken further down into subcategories, all of which carry implications. It is a highly complex, high-stakes process that needs support and careful consideration.

HWRK MAG AZINE .co. UK ISSUE 27 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 07 FEATURE

Take, for example, the placement of INSET days; it is not just a case of when they should fall, but also what will be covered therein and whether or not that is the appropriate time of year to address those issues and provide that training – what immediate benefit will it be to staff and therefore students? Certain aspects, such as Safeguarding and PREVENT have to be covered annually at the start of the Academic Year in September, but when do you factor in the other days?

An INSET day in school hours is a day when students aren’t at school – is that the best thing? Could a lot of INSET time be rejigged into twilight sessions, or disaggregated across the year in other forms? However, if that is the case, how invested will staff be in sessions that ask them to stay later at school? In essence, how can we best develop our staff within our shared school culture, and when is the optimal time to help that happen? This then has to be aligned to whatever performance management or review structure operates within the setting to ensure that there is authenticity and validation of the process, and staff have the chance to achieve.

When should Open Evenings happen?

Is it a cross-Authority bun-fight where each school wants to get in first to snag the best? Or is a more harmonious and collaborative approach to ensure there are no clashes or conflicts?

Internally, what deadlines are being set, for what, and why? Take, for example, reporting of data; we know from much research and evidence that in terms of assessment there is always a trade-off; assessments set require marking and feedback, both of which take time; data entry requires time as well, and unless the data is purposeful and useful, informing decision-making, is it worth gathering it at all?

There is an ever-present danger that what is measurable isn’t always meaningful, and what is meaningful isn’t always measurable – this must be carefully considered when plotting the deadlines for data entry.

Add to this the need to couple this with reporting to parents and the proximity of these against the reporting deadlines; after all, what we send home in a report is a strong message to our parent communities about what we as schools value; whatever that is, we have to be sure it is accurate, relevant, pertinent, useful – it can’t be outdated. These decisions then, of course, influence the design of curriculum; assessment validates the curriculum and is its servant, not its master, but when working with numerous subject curricula across more than one Key Stage, how true is this as a maxim when looking at wholeschool practice?

There has to be an element of give-andtake, with curriculum design being built

around summative assessment reporting deadlines, otherwise teaching would go on and on ad infinitum. The clarity and accuracy of this calendar also allows curriculum designers and implementers to harness the benefits of interleaved and spaced practice, having a clear understanding of the journey students will take and the milestones they have to reach.

Anything that may impact on the day-today of the standard timetable structure has to be factored in: school photographs; special assemblies; vaccination dates; the dreaded ‘collapsed days’ for revision (see my previous HWRK article Drop The Drop-Down Days) or PSHE; trips and visits; enrichment; Sports Days, and so on – all of these have an impact not just on those involved but, as cited before, the Butterfly effect and ripples into other things.

At its heart, the design of the calendar is a complex, multi-agency process with many tangled factors and inputs; on its surface, it is the document around which school life evolves and revolves, and affects all those within it. It is the ultimate set of predictions and projections – not a complete determinant of what will happen but a strong anticipation of what is most likely. Through the security of the calendar, subjectification can take place; there is shared accountability and individual development, all of which is a pretty desirable outcome in any situation.

@hwrk_magazine 08 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 27

The UK’s Number One School Playground Specialist

With over 25 years’ experience, qualified Outdoor Learning Consultants, and reliable Installation Teams, Pentagon Play o er innovative products and solutions, created to meet the needs of your pupils. All of our schemes and items are designed to encourage learning through play, crafted with the curriculum in mind to support pupils as they learn and grow. No matter the requirements of your development, Pentagon Play can support you in finding the best solution for your space.

Only £495

Looking for a freestanding, movable solution for your playground space? Our Pentagon Play Online Shop is the ideal source for all of your educational play needs.

Designed with budgets in mind, create an engaging learning environment for your pupils without the need for a full installation. Resources delivered to your door in just 4-6 weeks!

01625 890 330 (North O ce) | info@pentagonplay | 0117 379 0899 (South O ce)

on

Online Shop

Our Website

Free delivery

100+

products Visit

Range

Mud Kitchen

Essentials

-

mI a ignative & Creati ve Outdoor Classroo sm Sport Active Play Surfacing &Land sc a gnpi inruF ture,Fencing&S t o r ga e

CPD anD

ProteCting PeoPle’s Pie Charts

“Humans first, professionals second”

“Humans first, professionals second” (Mary Myatt). This quotation, alongside “every teacher needs to improve, not because they are not good enough, but because they can be even better” (Dylan Wiliam), is probably the one I have heard most often throughout my career – and with good reason. As CPD lead, my role and my values link inseparably to these two pearls of wisdom – how do I ensure we are creating the conditions for professional growth whilst respecting the person and their ‘pie chart’?

People’s pie charts are only ever the same size. At different points in our lives, different sections take up more space. And putting staff first means putting people and all of their pie chart first.

As leaders we seek to nurture excitement around professional learning, underpinned by a moral imperative. In our school, we talk about “the Beckfoot buzz” and a determination to enable our professionals to thrive as “lifelong learners and reflective practitioners”. This determination, I believe, needs to come with a caveat, a health-warning, in order to ensure that we do not become overly occupied with supposed signals of engagement over true indications of impact and culture. It can be the seeking of these signals that can lead to circumstances where we lose sight of “humans first”.

CPD curriculum, cohesion and “opportunity costs”

To put people first, we have to recognise the never-ending nature of the job, and subsequently the importance of staff’s entitlement to CPD, within directed time, which supports them in growing in their role. In order to do this, a CPD model needs to be cohesive, not only considering its content as a curriculum (Zoe and Mark Enser), but also considering which forms of CPD work in our setting – what our “rhythm of inputs” (Sarah Cottingham) will be. How can we ensure that CPD becomes ‘part of how we do it here’, as opposed to another plate to spin or ball to juggle?

Vitally, alongside an ever-ongoing consideration of workload, we also need to consider “opportunity cost” (Dylan Wiliam) – stopping doing things or doing them in “a different way that results in even greater benefit for your students”. Schools need leaders who not only do everything they can to minimise workload, but also look to maximise impact from the strongest inputs. Here is where we distinguish between what makes up our core CPD model, and what is part of our extra-curricular ‘opt-in’ offer, accepting that there is not enough time for everything.

Bespoke inside and outside the core model

To enable all staff to develop, a school’s core CPD model should enable the right degree of personalisation, supported by a non-core offer that can be opted into depending on areas of need or interest. Additionally, CPD is pivotal in preparing staff for their next steps, where and when that is the aspiration, and again this needs to be built into the regular rhythm of the school.

This model needs to enable sufficient flexibility to enable bespoke decisions that support our staff, not only in their development, but also in getting home at a decent hour! For example, where staff are undertaking an NPQ, how can we as leaders support them during their assessment window? Let’s pause their coaching cycle for a fortnight to give them time to focus on this development. As our CPD model is strengthened through its longevity, this flexibility is something I know I want to get better at.

We offer a range of ‘extra-curricular’ CPD opportunities for those staff who want to give a bit of their ‘pie chart’ beyond the core model, but we don’t mind if staff don’t come. We don’t see that as a symptom of

How far can teachers be expected to go one step further, ‘be even better’, or be part of the ‘professional culture’ that so many great schools want to adopt? Nikki Sullivan argues for a thoughtful approach…

By Nikki Sullivan

@hwrk_magazine 10 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 27

“Intelligent accountability” and learning to “love uncertainty” (David Didau)

a lack of motivation to develop. It isn’t indicative of how engaged in CPD and a culture of professional learning staff are. It is indicative of what they have on that evening, of what their hobbies are, of their family situation, of how sunny it is outside.

Most of our teachers aren’t on Twitter, might never have read a whole edu-book from cover to cover, and that’s OK. We strive to seek out what is needed and distil this into our CPD framework. Yes, of course we want our staff to engage and be proactive about their development, but we recognise that this does not mean that all staff will fall into the ‘job as hobby’ camp, and that there are other elements of our roles that take up this time that might have been spent with a good edu-book and a cup of coffee. CPD should be prioritised, protected and impactful – vitally, our core

CPD model should be good enough. And if we want to prioritise staff reading a book with a cup of coffee then the nature of the job means that we need to apportion off the time to make this a reality.

This is why I don’t, and won’t ever, keep a record of how many staff attend optional CPD, e.g. our 15-minute forum programme. I love these sessions. Our staff who present and attend tell me that they love these sessions (thank you Shaun Allison!). But I’m not going to record who attends – this is not indicative of culture. It is something that could change from school to school or over time depending on the age of the team, depending on what else is part of the CPD model – we could not say that an increase in attendance is the consequence of a stronger culture of professional learning.

In a job where the end of the day has a blurry line and the to-do list can be infinite, staff can go home and do things they love with people they love – go for a swim, read a book, pick up their children from school, go to the cinema with friends, or whatever else they enjoy filling their time, their pie chart, with. Or as Emma Kell says, “to splash around and howl with laughter in a swimming pool; to stand on the sidelines of my children’s football matches and whoop and holler whilst 100% there”. In doing so, we are aiming to be leaders who invest “in the wider part of the human being, beyond their work”

(Mary Myatt). This is not something we have ‘nailed on’ but is a huge part of our thinking as we refine our CPD model for next year.

HWRK MAG AZINE .co. UK ISSUE 27 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 11 FEATURE

Better measures of impact

Of course, school leaders need to evaluate the impact of their work. In schools this is never easy because we face issues around correlation and causation, multiple inputs affecting singular outputs, and the intangibility of some of the impact measures we are looking to evaluate. In the second part of this article, I’ll share some thoughts about how we might go about evaluating the impact of CPD and the growth of a culture of professional learning. But for now, I will just close with a few of my favourite moments which you can’t measure.

The passing conversation with the Assistant Head of Sixth Form talking about how they had been recommended ‘Atomic Habits’ by the Head of Sixth Form and you recommend ‘Habits of Success’ in turn.

The AFL for Maths who wants to do a ‘15-minute forum’ because they were inspired by this blog from Tom Sherrington.

The non-teaching Head of Year who wants to come along to their first researchED as part of their new role as Faculty Research Lead.

The Science team who get giddy when Adam Boxer publishes a follow-up blog to a previous blog that had been hugely influential in their faculty teaching and learning policy.

But, importantly, we don’t believe that the staff who don’t read a blog, a book or want to go to researchED are any less dedicated than the staff that do! And walking into the lessons of teachers with all manner of pie charts fills me with equal joy.

To close Part 1…

Emma Kell also states, ““Beware those who preach wellbeing, as I have written many a time, because it’s more than likely because they know what it is to lose a sense of balance and perspective”. I can most definitely relate to this. My researchED talk in September will be looking at all things CPD and how to sensibly evaluate our impact – this article is the start of me delving deeper into reading and thinking around this area. For now, Kelly Tatlock (@socwarrior) and I are striving to refine an impactful CPD model within the regular rhythms of school. CPD is too important to be reliant on good will. And people’s pie charts are too important to be taken for something that should be an enjoyable entitlement.

Bibliography

Allison, S. (2014) Perfect Teacher-Led CPD. United Kingdom: Crown House Publishing.

Boxer, A. (2023). Just 18 minutes of teaching. Available at: https://achemicalorthodoxy.co.uk/2023/05/10/just-18-minutes-of-teaching/ (Accessed: 3 June 2023).

Clear, J. (2018) Atomic Habits: An easy & proven way to build good habits & break bad ones. United Kingdom: Random House. Cottingham, S. (2022) Steplab Summer Conference Session #2: Training instructional coaches. Available at: https://youtu.be/RwOjA5FXF9Y (Accessed: 3 June 2023).

Didau, D. (2020) Intelligent Accountability: Creating the Conditions for Teachers to Thrive. United Kingdom: John Catt Educational Limited. Enser, Z., Enser, M. (2022) Why A CPD Curriculum Matters & How To Build One. Iris Connect. Available at: https://blog.irisconnect.com/uk/cpd-curriculum (Accessed: 3 June 2023).

Enser, M., Enser, Z. (2021) The CPD Curriculum: Creating Conditions for Growth. United Kingdom: Crown House Publishing.

Fletcher-Wood, H. (2021) Habits of Success: Getting Every Student Learning. United Kingdom: Routledge.

Kell, E. (2018) Remember you’re humans first, teachers second. Tes Magazine. Available at: https://www.tes.com/magazine/archive/remember-youre-humans-first-teachers-second (Accessed: 3 June 2023).

Myatt, M. (n.d.) Humans first, professionals second. Available at: https://www.marymyatt.com/blog/humans-first-professionals-second (Accessed: 3 June 2023).

Sherrington, T. (2023) Teaching some vs teaching all. This is where the action for improvement lies. Available at: https://teacherhead.com/2023/05/07/teaching-some-vs-teaching-all-this-is-where-the-actionfor-improvement-lies/ (Accessed: 3 June 2023).

Wiliam, D. (2018) Creating the Schools Our Children Need: Why What We’re Doing Now Won’t Help Much (And What We Can Do Instead). West Palm Beach, Florida: Learning Sciences International.

Wiliam, D. (2019) Teaching not a research-based profession. Tes Magazine. Available at: https://www.tes.com/magazine/archive/dylan-wiliam-teaching-not-research-based-profession (Accessed: 3 June 2023).

Wiliam, D. (2021) [Twitter] 11 March. Available at: https://twitter.com/dylanwiliam/status/1370099308532531200 (Accessed: 3 June 2023).

Wiliam, D. (2021) [Twitter] 12 March. Available at: https://twitter.com/dylanwiliam/status/1370496278493343744 (Accessed: 3 June 2023).

A Chemical Orthodoxy. (2022). Just 4 minutes of teaching. Available at: https://achemicalorthodoxy.co.uk/2022/06/21/just-4-minutes-of-teaching/ (Accessed: 3 June 2023).

@hwrk_magazine 12 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 27

How to… Make IntervIews work for You

a guIde to wInnIng at applYIng for proMotIon (regardless of tHe outcoMe).

Step 1: Knowledge is power

If an external post, prior to application take the time to visit and learn as much about the school as possible. This may comprise looking at the any of the following: Ofsted reports, SIAMS/CSI reports, external data sets, financial benchmarking, the school’s Inspection Data Summary Report (IDSR) as well as any information about the school’s wider trust and governance structure. This will help you to build up an informed and broad picture of the school’s needs enabling you to create a letter which maps your skills and experience to their needs accordingly. If you’re an internal candidate try to look at the school strategically as though you don’t know that the key to improving teaching and learning in the Geography department is actually getting a better photocopier – as an internal candidate avoid minutiae at all costs to allow strategy to prevail.

Step 2: You’ve got to role with it

Applying for leadership is as much about the role as the school and applicants. Whilst you’re mapping your skills and experience against the person spec – if you can, speak with someone (in your school or otherwise) who is already doing the role you are applying for – what leadership behaviours do they exhibit? What are the challenges they have navigated in order to discharge the role effectively? A forensic understanding of the role you’ve applied for will translate to any subsequent interviews and is thus long/medium term win – regardless of the outcome in the short term.

Step 3: It’s not (really) a competition

It’s so tempting to invest time learning about the quality of the field. Often the jungle drums of teaching will tell you who you’re up against before you’re

even issued with a visitor’s badge. It’s important to focus on what you bring to the table, rather than your perception of your competitors’ abilities. Do yourself a favour and resist the urge to give too much of your time and energy to learning about the opposition because really and truly it’s for the school to decide who is right for the role (and surely no one can ever live up to their bio on LinkedIn?) It’s extremely likely that due to the nature of the profession, that you will be familiar with at least one of the other candidates – directly or otherwise. As part of our innate teacher humility, we collectively tend to underestimate ourselves and overestimate others. It’s also important to avoid jumping to conclusions if you’re an external applicant regarding internals and vice versa because there are pros and cons to appointing both. It’s also worth remembering that the national recruitment crisis is highly likely to impact on the field of applicants – being part of a strong field is unbeatable CPD (especially if you get the job).

It feels remiss not to preface this guide with the fact that teaching interviews are a uniquely bizarre and arduous process. As someone who has had their fair share of both successful and unsuccessful interviews of this nature, I stand by my claim that promotional interviews are amongst the best CPD available. Take note aspiring school leaders because your new role could be just one (weird) day away…

By Tracey Leese

@hwrk_magazine 16 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 27

HWRK MAG AZINE .co. UK ISSUE 27 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 17 FEATURE

Step 4: You can only be you

Recruitment is a two-way process so during any leadership interview make sure you interview the school too. Not many of us show up to interviews relaxed and unguarded, but it’s important to really be yourself throughout the process – and if it’s not the right fit it’s far better to find out on interview than a term into the post. The more you know about the culture and ethos of the school prior to application the easier it will be to gauge. Some questions to consider: how is the school led? To what extent are staff consulted in the strategic vision of the school? What steps does the school take to mitigate against staff workload? Make sure the values of the school resonate with your own to enable you to lead authentically if appointed (and dodge a bullet if not).

Step 5: Consistency is key

Leadership interviews are designed to assess a range of competencies – from in-tray activities to delivering a lesson or assembly, a sound strategy is to aim for consistency across a range of competencies, rather than absolutely nailing a few. That isn’t to say that you should seek to conceal your strengths, but rather on demonstrating that you’re not just your strengths – and that your overall practice is secure in a range of areas. So when you’re preparing for interview tasks, ensure that you allocate equal preparation time for all, rather than the ones in which you know you will naturally shine.

Step 6: (Net)work it!

My first teaching interview was in as school where I had taught on placement, I was mad keen and didn’t hide it. I didn’t get the job but the head mentioned me to someone else and before I knew it I was gainfully employed. Similarly, some years later the successful candidate and I would both attend the same Subject Leaders’ meetings when we were both subject leaders in our respective school. All of which would have been tres awkward had we not been supportive of each other throughout the day. It goes without saying that teaching is a small world and the very least you can expect from a promotional interview is the opportunity to network and connect with colleagues – which can be a long-term benefit regardless of the outcome on the day. In the era of multi-academy trusts, this has never been more true – you never know where the impression you make will lead.

Step 7: Question Time

Interviews are ace opportunities to fact-find – not just about the school, but about the role, leadership and CPD. So in and amongst the process keep an open mind about any processes or initiatives you can take back to your own school/ trust/practice. Similarly go into the process armed with questions and ask them of the different stake holders you speak with throughout the day – it can be particularly helpful to ask the same question of teaching staff/students and school leaders in order to ascertain perception from a range of stakeholders across the school – you can then use these responses to support your answers in the formal interview. For example “When I asked students about the role of rewards in school, they struggled to articulate how this supports some behaviour for learning – so this is something I would take into account if appointed.”

Step 8: Take note!

Something I have done for every job I have ever applied for is to create a mind map of every previous role I have ever held and how I think this has prepared me for the desired post. Together with an annotated copy of my letter of application, I take this with me on the day and read it through in the inevitable down time between tasks. I would also suggest taking this in to the formal interview as an aide memoir. Though I was once ridiculed by another candidate (who was unsuccessful I hasten to add) this has always served me well in order to ensure that my answers reflect the breadth of my experience.

Overall, my final thoughts mirror my advice to my divorced friends – put yourself out there because you never know where that may lead. Good luck!

@hwrk_magazine 18 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 27

Poverty, Mental HealtH, and ScHoolS: a droP in tHe ocean?

By Claire Pass

By Claire Pass

Small moments make a huge difference when it comes to establishing trust and connectedness. We should focus on these if we are to tackle the societal and mental health issues facing our students in schools today.

hwrkMAG A zine.co.uk issue 27 // hwrk MAGA zine // 21 FEATURE

Around 10 years ago, I was a parenthelper on a library visit with a class of Year 1 children. As a secondary teacher, I watched the process with curiosity – there were some embedded routines in place. The thing that stayed with me most was the process of ‘book-approval’, where each child needed to get the OK from the class teacher before checking out their library book.

It was a seemingly innocuous element, but even then – without the knowledge I have now – I knew I was witnessing something important. Every child in that class felt seen, felt listened to, and felt important during that process. It was a small moment that has influenced both my personal and professional interactions for the best part of a decade.

Now, of course, the research highlights how small moments such as this serve to establish and maintain a climate of trust and connectedness, which are protective factors for mental health and an important part of creating an ethos and environment that promotes good mental health1

Move forward 10 years and the importance of such moments is more significant than ever. However, with the financial crisis showing no signs of abating, and the well-established links between poverty and poor mental health– are such things simply drops in the ocean?

Poverty

All the way back in the pre-Covid world of 2019, a study involving over 28,000 Year 7 and Year 9 pupils across 97 schools found that mental health issues in pupils were much more prevalent than previously believed, with 2 in 5 pupils scoring above the thresholds for emotional disorders, conduct problems or inattention/hyperactivity in the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Those from deprived backgrounds were significantly more likely to experience issues2.

This is underlined by reports indicating that children on the lowest income quintiles are twice as likely to be diagnosed with an emotional disorder3 and 4.5 times more likes to experience serious mental health problems4. These are staggering numbers, with huge implications for equality in our society, and they could be explained by what Mind refers to as the ‘mental health trap’, where mental health negatively impacts on income and relationships, which in turn makes mental health problems more severe and long lasting for those in poverty5

The irony is that at a time when schools are looking to safeguard mental health, the very act of getting children to school is a major household expense, putting more pressure on those already struggling financially. On average, it costs a minimum of £864.87 each year for primary school children and £1,755.97 for secondary school pupils6

Pupil Premium funding is not enough to level the financial playing field when it comes to the cost of school – and there are a lot of demands on this pot of money. Other support on offer is means tested and accessed by only a small proportion of lowincome families.

Many schools try to mitigate costs, for example by fundraising for school trips, providing uniform, or providing resources for homework. There are also schools who wash and dry school uniform, provide free breakfasts, or even offer no-questionsasked ‘grab bags’ of food essentials for parents. The dedication of schools to their communities cannot be questioned – but schools simply cannot do everything. A national approach is needed. In the absence of this, what many see as ‘normal’ school experiences, or rites of passage, are not open to all pupils and ultimately impact on both outcomes and life chances. A consistent national policy is vital if we are to create equity of experience.

The Place of Schools

In this context, when the bigger picture feels outside of our control, it’s tempting to focus on what we can potentially ‘fix’, but we must be careful not to focus on a within-child deficit model. This is different to the library scenario when each child felt ‘seen’. A within-child deficit model concentrates on the problem, not the child.

It’s reminiscent of the cartoon of a koala clinging to a tree stump in a sea of felled trees, while officials stand focused on the koala (rather than the surroundings) and authoritatively state “This young koala has a mental health condition”. Sometimes, people find things difficult because they are in difficult circumstances. It might be tough and uncomfortable to acknowledge these – particularly when we can’t ‘fix’ the issues – but truly ‘seeing’ the child means seeing them in context, and if we are to foster that sense of trust and connectedness so important to mental health, it’s crucial that we do so.

In 2021, research by Mind found that whilst the conversation about mental health is opening up, those in poverty

feel excluded from it. This was reinforced by a perception of certain types of mental ill health being ‘acceptable’ but people not wanting to talk about the ‘mental health trap’ of poverty7. In other words, there’s a perception that people are willing to look at the koala but don’t want to look at the felled forest surrounding it, and this consolidates feelings of isolation and shame.

This might explain why so many 11–16-yearolds with a mental health condition were less likely to feel safe either at school or online, and less likely to feel as though they had a friend to turn to8. Considering ways of removing these barriers and fostering connectedness and belonging for these pupils is something that schools can do.

A Systemic Approach

Creating a whole school approach that removes such barriers is part of the remit of a senior mental health lead (SMHL) –one of the elements of the wider systems approach that has been taking shape for quite some time now. It also includes mental health support teams (MHSTs) and educational mental health practitioners (EMHPs), whose role is to bridge the gap between schools and mental health services, ultimately reducing the burden on CAMHS.

There is still a way to go, however, with many SMHLs reporting that they do not have the time or capacity to do their role justice. Also, the University of Birmingham’s ‘Trailblazer’s’ evaluation9, focusing on the first 25 sites for MHSTs and EMHPs, found that there were issues with retention and professional development for EMHPs (for example, in supporting neurodiverse pupils for whom the CBT based techniques might need adapting).

Add to this the somewhat woolly remit of EMHPs supporting those with “mild to moderate” mental health difficulties, with no national consensus about what constitutes a “mild” or a “moderate” difficulty, and the danger is that many pupils still fall through the net.

It’s likely that these approaches are facing such challenges because the proposals for them drew on data from ten years ago10 At that time, the figures suggested that 1 in 10 children would suffer from a mental health condition. However, the NHS report in 2022 highlighted that the number of children aged 7-16 with a probable mental health condition had risen from 1 in 9 in 2017, to more than 1 in 611. There are simply more demands on both schools and services than were ever anticipated.

@hwrk_magazine 22 // hwrk MAGA zine // issue 27

Making the Difference

Despite these challenges, the systems now in place form a major step forward in promoting and protecting the mental health of all pupils. Together with mental health becoming an established element of PSHE curriculums and spotting the signs of mental ill health forming part of schools’ statutory safeguarding duties, mental health has been placed firmly on the agenda in schools. These steps are a significant part in the journey towards ending the ‘mental health trap’ faced by those in poverty.

Even though schools may feel like they are drops in a very large ocean, they do make a significant difference – huge in fact – to the wellbeing of children. The HOW is a tricker question to answer, although there have been some studies in recent years about social and emotional

learning (SEL) that provide some food for thought.

A meta-analysis of 200 SEL Programmes12 reveals that programmes work better when manualised (provide materials and teacher notes for each lesson) and when they focus on what to do rather than what to avoid. Even though they improve wellbeing for those whose wellbeing was initially low, the aim is also to reduce stigma and change the overall ethos of the class. A universal rather than targeted approach is therefore very important.

An important point to note is that the positive effects of such programmes are only short term unless they are maintained – so building a long-term curriculum is crucial. The four-year Healthy Minds experiment pulled these elements together into a curriculum for 11–15-year-olds and was shown to raise life-satisfaction by 10

percentile points and this is a structure that has since been adopted by many schools.

The thing that struck me most about the findings about the difference schools make to wellbeing, is that it’s not just schools that make the difference. Individual teachers do too. A primary school teacher who knows how to support and raise levels of wellbeing has as much impact as a pupil’s parents and improves their life chances – even making them more likely to go to university13

This brings us back to the teacher doing the ‘book approval’ check during the library visit and the significance of this seemingly small interaction. And to answer the question ‘are schools just a drop in the ocean?’ No. If individual teachers are more than a drop in the ocean, schools are so much more.

References:

1. https://www.ncb.org.uk/about-us/media-centre/news-opinion/best-practice-framework-help-schools-promote-social-and

2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7557860/

3. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2017/2017

4. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/explore-mental-health/statistics/poverty-statistics#:~:text=Analysis%20of%20data%20from%20the,considerably%20over%20the%20past%20decade.

5. https://www.mind.org.uk/about-us/our-strategy/working-harder-for-people-facing-poverty/facts-and-figures-about-poverty-and-mental-health/

6. https://cpag.org.uk/cost-of-the-school-day

7. https://www.mind.org.uk/about-us/our-strategy/working-harder-for-people-facing-poverty/facts-and-figures-about-poverty-and-mental-health/

8. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2022-follow-up-to-the-2017-survey

9. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/brace/projects/children-and-young-people’s-mental-health-trailblazer-programme.aspx

10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7557860/

11. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2022-follow-up-to-the-2017-survey

12. Layard and DeNeve (2023) Wellbeing Science and Policy. Cambridge University Press.

13. Layard and DeNeve (2023) Wellbeing Science and Policy. Cambridge University Press.

hwrkMAG A zine.co.uk issue 21 // hwrk MAGA zine // 23

They Probably Wouldn’T behave For you eiTher…

By Sam Strickland

Picture the scene, as an experienced middle leader you walk your subject team corridor and hear a chaotic noise coming from one classroom within your team’s corridor. The class is inevitably taught by an Early Careers Teacher (ECT), who appears to be struggling. There are pupils out of their seats, pupils calling out and pupils simply behaving as they wish. The class looks chaotic and out of control.

You walk in the room, raise your voice to the class, tell them to fall silent and sit in their chairs. As you do so the class follow your every instruction, without hesitation nor argument. You tell the class you will be back in ten minutes to check that they are all on task and doing as they are told by the teacher. Then you stare at the group for a prolonged period before walking out of the room. Internally you are conflicted between a feeling of annoyance, frustration and thinking to yourself ‘why do they behave for me?’ ‘Why can’t the ECT simply get them to behave?’

In this situation the middle leader thinks to themselves that all behaviour is about relationships. If only the ECT invested time, care and dedication to get to know the pupils then surely they would behave for them. Surely the pupils would feel

invested in and cared for. It surely isn’t that hard!

Telling a fellow colleague that behaviour is all about relationships is about as useful, effective and helpful as stating that they behave for me! It is the equivalent of throwing a brick at the ceiling of a glass house, except instead of shattering the glass you are actually shattering your colleague’s confidence and self-esteem. Why? Because the ECT probably has no real concept as to what good teacher-pupil relationships actually look like. In essence, this is the curse of knowledge, where you say something that you know inside out expecting a less experienced colleague to get it because you do.

The reality is that good relationships need a bedrock of rules, routines, systems and processes in place so pupils then know what the boundaries are. Relationships then have the platform that they require to grow and develop. But relationships take time to foster, to flourish, to nurture and to mature. More experienced teachers often make relationships look easy but that is because of a number of key factors. Namely:

• Experienced teachers know what they are doing and have honed their craft.

• More seasoned teachers are highly experienced and have a more developed, honed, rehearsed and nuanced toolkit of strategies at their disposal that only really comes with time, practice and experience.

• They have often worked in a school for a sustained window of time, therefore have developed something of a reputation and rapport that precedes themselves with the pupils.

• They often, though not always, have put in the hard yards with the pupils, having been on school trips or run extracurricular clubs therefore allowing pupils to see them in a more personal and different light.

• They have established systems and routines that the pupils are aware of.

• Through their wider school reputation, pupil word of mouth and pupil folklore the pupils have passed on the wisdom of their experience and knowledge of teacher X that they are ‘safe,’ not a ‘melt,’ take no nonsense or are simply superb. This provides those established teachers with an instant ‘home advantage.’

Is behaviour management all about relationships, or is there something else that makes the difference? Headteacher Sam Strickland explains.

@hwrk_magazine 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 27

HWRK MAG AZINE .co. UK ISSUE 27 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 27 FEATURE

So, whilst it is easy to become frustrated that an ECT cannot seemingly control a class the reality is that they often lack the experience, professional yards, toolkit and honing of their craft to do so. They have not yet fully established themselves with the pupils to get them to behave for them or to build those all important and key relationships.

In the absence of watertight school systems a more experienced member of staff seeking to support an ECT would be well served taking the time with this member of staff to consider:

• How their lessons are structured.

• The routines, systems and processes that are in place.

• How they command the room.

• How they uphold and consistently (or otherwise) adhere to the school behaviour policy and approaches.

• To train them explicitly in an array of class management tools.

• To set up a series of lesson observations so they can see how other staff organise and manage their classes to gather ideas.

• Team teach lessons with the ECT to allow them to test, trial and practice key approaches to build up their confidence in their own ability.

• To work with the ECT to consider how they speak to pupils and how they issue instructions.

Above all else, as a more senior member of staff, do keep in mind that if you were stripped of your title/seniority, experience, reputation built up over time and your school based ‘home advantage; then you may well find that the pupils would not behave for you either. Relationships may well be the magical ingredient but they do not just happen.

@hwrk_magazine 28 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 27

The Joy of Teaching in Bilingual SchoolS

By Chris Woolf

When you learn the points on a compass in clockwise order, the chances are you heard the phrase ‘Never Eat Shredded Wheat’. But how do you navigate this in a Chinese bilingual school, where most of the students really have never eaten shredded wheat, don’t know what it is, and have a great deal of more pressing linguistic priorities that the points of a compass?

I’m the International Director at Wellington College International, and one of the great pleasures of this role is visiting our international family of schools: 6 in China, 1 in Thailand, and 1 in India opening in September. I recently returned from leading the reviews of three of our schools in China, international schools and bilingual schools too. I had thought the defining feature of each was the type of passport the students held, but I was wrong.

In both, language learning is a priority. But in a bilingual school, the seamless collaboration between co-teachers, and the constant switch between them, which for the students means moving from one language to the other, is utterly extraordinary.

Passports first; to attend an international school in China, you have to be a foreign passport holder. To attend a bilingual school, you can have a Chinese passport.

But bilingual means exactly that and so much more. The bilingual Huili schools uses a Chinese and Western co-teaching approach which we say ‘creates a truly immersive bilingual learning environment for pupils. Our teachers, both Chinese and international, work closely together to ensure a balanced development in both languages, and more importantly, to master the delivery of multi-subject bilingual learning.’

hwrkMAG A zine.co.uk issue 27 // hwrk MAGA zine // 31

FEATURE

The website would have you believe that ‘pupils respond enthusiastically to this blended approach which emphasises the importance of Chinese history and culture while also cultivating an international mindedness’ and the website would be right. It was amazing to see teachers planning together, and supporting each other in different subject areas. Chinese teachers even support the delivery of English, identify misconceptions, and help students make extraordinary levels of progress.

Pastoral care models thrive in this context too, the English-speaking co-teacher leads the wellbeing lessons for students, and the Chinese co-teacher leads the interaction with parents, which keeps them fully involved in and supportive of their child’s learning.

The team I was with in China included Delinda Wu, Chinese Principal of Beijing International Bilingual Academy and Executive President of Institute of Learning and Research 海嘉国际双语 学校.Her view is that, such is the scope and depth of the programme, ‘in 10 years’ time, this model of learning will have an impact on the world of education in this region’.

Bearing in mind that teachers do not complete a PGCE in bilingual education, and that much of the training is done inhouse, this really is impressive. Teachers reported that they feel “integrated, and rely on each other in a bilingual context.” Students told me that they ‘like the way education is done here’. It is easy to see why. The values of the school are universal; kindness, responsibility, respect, integrity and courage. But the curriculum goes beyond this, with students well on the way to achieving genuine bi-culturalism. They will be equally at home in western or Chinese culture, each enriched by the other, and with a truly global understanding of the influences of both on the world around them.

With lessons in multiple subjects in both languages, they are bringing this to life in imaginative ways. In the Huili School Hangzhou, the Chinese Social Studies curriculum looks at 地球的运 动 or ‘Movement of the earth’ in grade 7. Meanwhile, the English Social Studies programme investigates 资源与能源 or ‘Resources and Energy.’ This course then examines 工业革命 ‘Industrial revolution’, when the Chinese programme focuses on 中国历史:明朝至清朝

‘Chinese history: Ming Dynasty-Qing Dynasty.’ Each course is worthy of

study in their own right, of course, but collectively they are greater still.

If we can see past the sometimes negative headlines about China, teachers will find living and teaching in China extremely rewarding, professionally fulfilling and enormous fun, especially in a bilingual school.

So what should you bear in mind if you are considering stepping into a bilingual school? Flexibility and a willingness to learn are pre-requisites in most schools, but even more so in this context. But beyond that, you might be surprised how much actually looks familiar. Coplanning is normal in most year groups or departments, and this just takes it that bit further. The same is true of team teaching. Lots of schools do this to some degree; a good bilingual school does this really well.

Transitions between teachers need careful consideration to play to each other’s strengths and experiences. Sometimes it is not the native speaker who gives the best explanation of the difficult linguistic concept. The teacher who has had to learn the grammar in the classroom rather than in conversation often breaks the concept down the best for the students to learn themselves. Either way, planning this with a colleague will lead to strong outcomes for the students.

You need to enjoy this close collaboration, and if you do, the shared planning

experience is a real pleasure. It is a great practical approach to providing excellent proactive and purposeful mentoring. You don’t need to be bilingual yourself, but an interest in language and language acquisition, is certainly helpful. Many colleagues do embark on their language learning together, which is a good way to do this, and lots of fun. It models bilingual learning for students, and also helps you pick up on comments students make in the classroom that they don’t think you will understand!

Teaching in a bilingual school helps you distil key words and vital skills in a way you may not have done before, and helps you push new boundaries along with your pioneering students. Displays take on extra meaning, changing them frequently to support the language learning in a new topic is a really important way of helping students learn even more.

Embracing every opportunity is a great way to get the most out of the experience. Supporting learners in your subject with their English will probably teach you lots about your use of language too.

And so back to the compass. How does a bilingual school help students find the right way round a compass? Never Eat Sea Weed. Easy.

With thanks to Dean Clayden of the Institute of Learning, Wellington College China, for the first discussion about compasses!

@hwrk_magazine 32 // hwrk MAGA zine // issue 27

36. Unlocking The Power Of Stories To Improve Learning

Why does storytelling in the classroom matter so much?

40. Thinking Big In English

The importance of exploring big questions that span literature, rather than focusing solely on the finer details of a text

44. Placing Art At The HeART Of Education

Why is it so dangerous to leave Art out of the curriculum?

EXPAND YOUR MIND ONE SUBJECT AT A TIME issue 27 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 35 @hwrk_magazine

Unlocking the Power of StorieS to imProve learning

By Marc Hayes

By Marc Hayes

The primary curriculum is full of wonderful stories. From EYFS to Y6, we share a vast and diverse range of different tales, each one an opportunity to teach our pupils something new about the world or ask them to look at something from a different point of view.

Daniel Willingham writes about the power of stories and describes how psychologists argue they are ‘psychologically privileged1’: our brains are wired to make sense of the world through narratives. Stories provide a structure that helps us organise information, remember details, and comprehend complex ideas. They engage multiple areas of the brain, activating sensory, emotional, and cognitive processes, which enhance our ability to remember and internalise information.

Writing stories is also a quintessential part of primary education. Writing narratives, whether real or fictional, is also commonplace in the primary classroom. In fact, the Spoken Language section of the English National Curriculum requires

that children are taught to: “give well-structured descriptions, explanations and narratives for different purposes, including for expressing feelings”.