Time-Saving TipS For BuSy SenDCoS

enCouraging parTiCipaTion in SporT For all

in SpoRt FoR all

What DoeS having ‘high expectationS’ Really Mean?

TimE-SaviNg TipS FOr SENDCOS

WhaT DoeS having ‘high expeCTaTionS’ really mean?

enCouraging parTiCipaTion in SporT For all

in SpoRt FoR all

TimE-SaviNg TipS FOr SENDCOS

WhaT DoeS having ‘high expeCTaTionS’ really mean?

EDITOR’S LETTER - THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS: Could addressing teachers’ happiness be the key to solving the teacher retention crisis?

6. TIPS FOR THE ECT RE TEACHER TO THRIvE

Strategies for RE ECTs to help them make the most of their time as new teachers

12. WHAT DOES HAvING ‘HIGH EXPECTATIONS’ REALLY MEAN?

An exploration of what having high expectations really means and what that might look like

18. TEACHER RETENTION AND RETURNING TO TEACHING

Why do older teachers leave before retirement and how can school leaders improve their schools to encourage them to stay?

24. TIME-SAvING TIPS FOR BUSY SENDCOS

Strategies for SENDCOs to save them time, so they can focus on what matters most

28. DEvELOPING METACOGNITIvE EvALUATION SkILLS

An exploration of what it means to develop metacognitive skills of evaluation

38. HOW TO INTERPRET THE WRITING MODERATION CRITERIA FOR THE END OF kEY STAGE 2

KS2 writing moderation can be a tricky business. Here are some tips to help make it clearer.

44. ENCOURAGING PARTICIPATION IN SPORT FOR ALL

Why is sport participation so important and how can we encourage it?

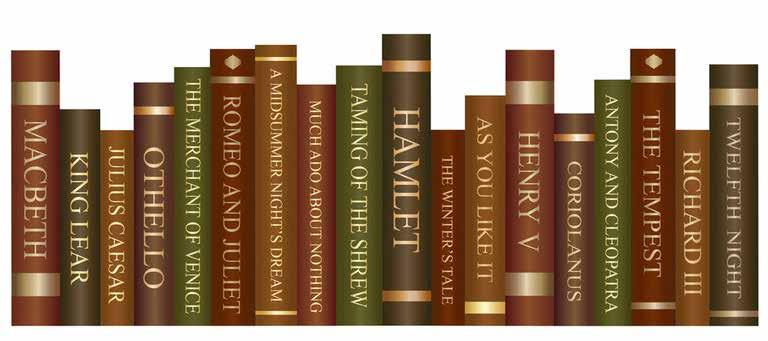

46. WHAT MAkES SHAkESPEARE SO RELEvANT TODAY?

Why students won’t be ‘bard stiff’ when learning about Shakespeare in today’s classroom

32. A PEDAGOGIC IDIOLECT: WORDS FROM THE ENGLISH CLASSROOM

Thoughts on some effective phrasing in English, to encourage higher quality student responses

54. DO PARENTS MAkE BETTER TEACHERS?

A controversial idea, but do parent-teachers really have an edge when teaching children?

56. WHY TUTORS AND MENTORS ARE ONLY EvER ONE APPOINTMENT AWAY FROM BEING SUED

Advice for teachers on how to avoid common legal issues when setting up a side-hustle

60. TIPS FOR MAXIMISING YOUR EARNINGS

Financial advice for teachers, which might just make the difference in the cost of living crisis

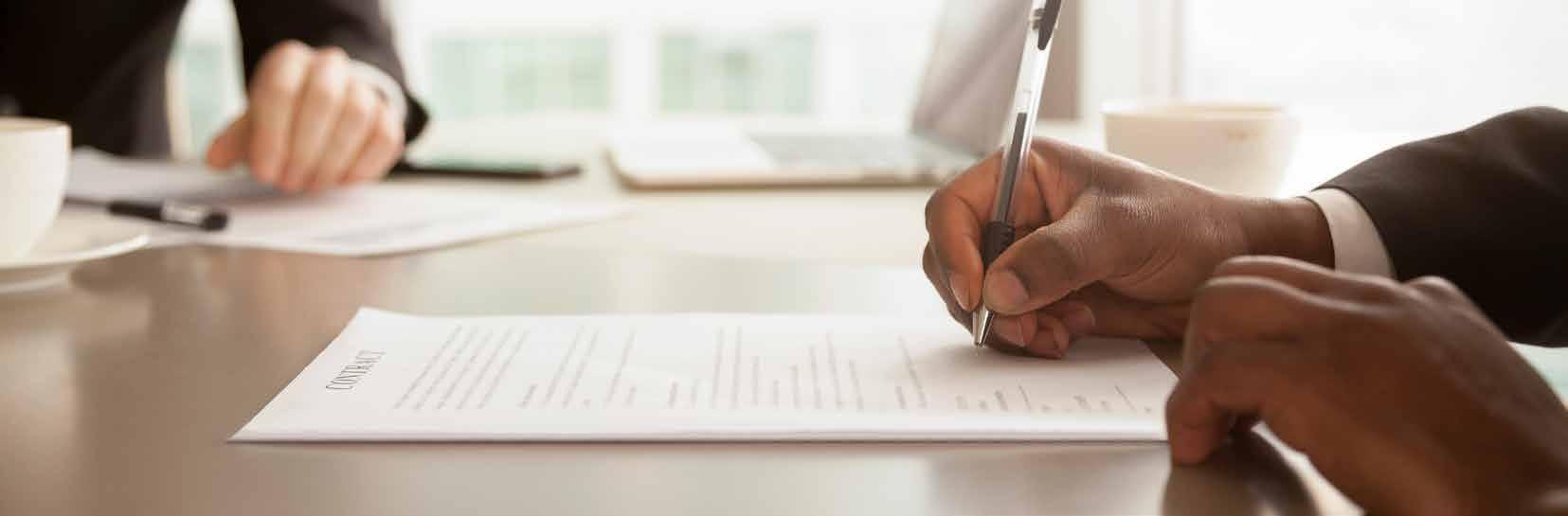

63. COMPUTING POSTER Expanding Computational Thinking

Andy Atherton

@__codexterous

Andrew Atherton is a Teacher of English as well as Director of Research in a secondary school in Berkshire. He regularly publishes blogs about English and English teaching at ‘Codexterous’ and you can follow him on Twitter @__codexterous

Jack Watson

@diaryofateacher1

Jack is a primary school teacher working in Year 6. He knows he’s different but he absolutely loves writing moderation. Don’t worry, he has other hobbies as well. You can also read Jack’s weekly blog, ‘Diary of a Teacher’, on Substack.

Catherine Lester

@catlester7

Catherine is an Executive Director of LEO Academy Trust, previously serving as Headteacher of Cheam Fields Primary Academy. In her current role, she works as a school improvement partner and professional coach, supporting schools in their improvement journey.

@MrAston_RE

Teacher

Ginny Bootman is a former headteacher and now a SENDCO with responsibility for four primary schools, as well as a regular speaker at national SEND conferences. Ginny’s new book Independent Thinking on Being a SENDCO (Independent Thinking Press, 2023) is out now

Hetty Steele

@HettyLSteele

Hetty Steele is a PhD student and Head of Drama at a comprehensive school in Bishop’s Stortford. Hetty also contributes regularly to Litdrive UK and to MTPT Project - a UK charity for parent teachers.

Faheema Vachhiat

@FVachhiat

Faheemah always seeks ways to innovate her teaching. Through her substack, she shares her reflections on teaching and learning, explores the latest trends and best practices and shares strategies for other educators looking to enhance their approaches to curriculum design.

Nathan Burns

@MrMetacognition

Nathan is a Head of Maths, education article writer and the author of “Inspiring Deep Learning with Metacognition”.

@mrmarchayes

Marc is an Assistant Headteacher and Year 6 teacher at Roundhay All-Through School in Leeds. He leads on curriculum development and is passionate about curriculum design, teaching and learning, and school leadership. He blogs at www.marcrhayes.com

Maz Foucher

@YetAnotherTeach

Maz is a former Assistant Headteacher and the current Devon Regional Representative for the MTPT Project. Following a twenty-year teaching career, she now works as a writer and editor. Maz recently completed an MA in Education Leadership, specifically researching teacher retention.

Eileen Adamson

@YourMoneyCoachx

Eileen Adamson is a PE teacher, host of the Your Money Sorted Teachers’ podcast, ex-host of BBC Clever About Cash podcast and a money coach for other teachers at Your Money Sorted. Eileen offers a wealth of free resources over on her Your Money Sorted website, as well as running various free challenges for teachers, helping them to feel happier, healthier and wealthier.

With 30 years’ combined legal expertise, Kate Bunn and Kirsty Gibbons, of K&K Legal Consulting Ltd, offer legal services to small businesses and entrepreneurs without the constraints of a traditional nine-to-five law firm.

@MrsqueenLeese

Tracey Leese is an Assistant Headteacher at St Thomas More Catholic Academy in Longton, co-author of Teach Like a Queen and a passionate advocate for women in leadership

How are school leaders managing to retain good staff (so far)?

With so much pressure on existing budgets, it’s hard to pay staff more, so how can staff be ‘incentivised’ to stay? I use the term ‘incentivised’ as loosely as possible, to cover both intrinsic and extrinsic motivational strategies. Sometimes there are things school leaders can do/add/ remove that don’t require deep pockets or revolutionising the school as an organisation.

But, sometimes revolutionising is actually the way forward. When the status quo isn’t working, it takes bravery to challenge it and make changes. Sometimes those changes work and sometimes they don’t. But nothing improves by keeping things as they are.

One idea I keep returning to is the notion of happiness. Not job satisfaction, success, or impact. Happiness. It’s vague, subjective and can’t easily be quantified. But perhaps the reason we don’t value it is because we are so used to valuing only the quantifiable.

Do school leaders check for happiness? Should they do so? How could it be done? Will it open a can of worms? Is it worth it?

I think, in this teacher recruitment and retention crisis, we can’t afford to ignore it any longer. It’s time to rip off the plaster. There will be a cost to doing so, but the cost of inaction could be much, much higher.

One way to explore the issue of happiness, before asking colleagues directly yourself, is to consider asking yourself some questions about them first. If you’re honest and thorough, then some of the answers will likely make for uncomfortable reading. But they might just prevent fantastic and often irreplaceable teachers from leaving your school, or worse, leaving the profession.

1. Who among your staff are the happiest?

2. How do you know?

3. What about work makes them happy?

4. Did you contribute to this?

5. Who in your staff are unhappy?

6. How do you know?

7. What about work makes them unhappy?

8. Did you contribute to this?

9. What aspects of staff happiness do you perceive to be outside of your control?

10. What aspects of staff happiness do you perceive to be within your control?

11. What would be the cost (financial and other measures) of five good members of staff leaving?

12. What are you doing to make good staff want to stay?

There are of course many leaders who will be brave enough to ask these questions and they’ll gain valuable insights by doing so. Leaders who act on those insights will likely retain their staff, maintaining a more stable workforce and incur far fewer recruitment costs.

However, there is also the risk that some leaders might just go through the motions, making listening noises, without actually responding positively to what staff are telling them about their lived experience.

What’s the root of the teacher retention problem? Too many teachers are unhappy.

What’s the solution? Increase teachers’ happiness.

How we do that is going to be complex and often very difficult. But it might just begin with asking teachers about their happiness and accepting what they have to say.

Andy McHugh Editor | HWRK MagazineOli Aston argues that early career teachers must take personal responsibility to improve their teaching practice beyond just relying on the formal support systems in place.

I will never underestimate how teaching is such a huge responsibility and privilege. As an Early Career Teacher (ECT) you come to realise this very quickly, even before you have your own classroom, as you complete your training and get to know the role. You develop an appreciation for the job in hand and feel the responsibility you have for shaping young minds and sharing your passion for knowledge. However,

to thrive in your role, I believe you must equip yourself with extra tools and take personal responsibility for improving your practice. Of course, this is as well as utilising the support that your school and the Early Career Framework offers. But, where should you look for those tools?

This is a reflection on my time as an ECT which gives five recommendations for things to focus on as an ECT RE Teacher.

As an RE teacher myself, about to finish their ECT induction years, I’ve reflected on the steps I’ve taken to be personally responsible for improving my teaching practice and the expertise I have drawn upon for my own development. This time of reflection has encouraged me to share with you some practical steps I have taken to develop my subject knowledge and teaching and learning practice as an ECT.

Firstly, it’s important to make the most of the experts you have around you. I work with inspiring and hardworking colleagues and have no doubt that you do too; I will forever be in ore of their dedication to their jobs. Their efforts, experiences and ideas are so worthy of our attention. Those close to you during your induction years are your mentor and Head of Department (HoD). Building positive relationships with every staff member, but especially these two colleagues, is extremely important for the enjoyment of our job, but also for our professional development. When speaking to our mentors and/or HoD, we should aim to build a relationship

of trust through reflecting honestly on our practice. I speak to my HoD and mentor regularly and am extremely fortunate to find confidence in their experience and expertise. I share examples of work, share career ambitions and targets for my classes. A strong sense of self awareness, I believe, demonstrates the ability to be self critical but also to be an honest team player who really is interested in improving and learning. Consider how you invest in the relationships with your colleagues. I’m not suggesting you buy gifts for every meeting but how interested are you in their approaches? How willing are you to trial their ideas, even if we’ve approached it differently before? Schools are full of hardworking and dedicated staff and recognising that we have lots to learn beyond our training from them is really important.

Knowledge is power in the classroom as we know. It is our armoury as a teacher that is always there to protect us, even when the best planned lesson doesn’t go to plan. I decided to begin studying for a Masters at the same time as my ECT induction. Although this won’t be for everyone, consider taking advantage of the opportunities your school has to offer or courses you come across that interest you. For example, is there a teaching and learning forum you could attend, or a course you could complete? Knowing that you don’t know everything leaves space for new knowledge to be acquired. Chester University in the summer offer a number of online lectures for a level students and teachers that cover topics relevant to our teaching in RE. I remember finding the discussions around Judaism extremely useful as it wasn’t a religion I was overly confident with teaching to begin with. I’ve also recently found an enjoyment in learning more about the teaching of RE through listening to a podcast.

Listening to podcasts on topics relevant to your subject enables you to stay up to date with ideas on how to teach and approach contemporary topics. I listen to the RE Podcast during my commute to work. Maybe don’t listen to podcasts on the way back from work as ‘switching off’ is important at the end of the school day. However, listening to this particular podcast developed my awareness of discussions in my discipline and gave me small nuggets of ideas and suggestions that I could use myself. I’ve taken plenty from the discussions of assessment in RE and the worldviews of others from the personal testimonies individuals share. You could even embed some of the debates/ideas in your lessons, especially with sixth formers. Louisa Smith, teacher and creator of the RE Podcast explains what the podcast offers for the ECT RE teacher:

The RE podcast is my easily accessible weekly podcast. As an RE teacher with over 20 years experience of teaching, I explore a variety of subject specific ideas related to religion and worldviews, ethics and philosophy, as well as pedagogy. I chat with people from within a variety of religious and non-religious communities to provide lived experiences to improve subject knowledge and enhance teaching.

Finding opportunities like listening to short and accessible podcasts is easily doable and will develop a wider awareness of your subject.

As well as the aforementioned, it’s important for us to value the extra time we have as an ECT on our timetable. This extra time is a great opportunity to go and observe other teachers around your school or staff in your department, as well as to fulfil the demands of the ECF. Not only will you be guaranteed to learn something during every visit, you will often take ideas that you can put into practice in your own classroom. Go and observe how they implement activities; explore how they use routines in their classroom, promote a safe environment and interact with students and support staff.

Could it be realistic to aim to do this once a half term? Honestly, I wish I would have done this more but have planned to visit two teachers of a level this term to explore approaches to teaching at this level. Of course, email in advance. Although you will probably be more than welcome to visit teachers around your school, it is good courtesy to give a heads up that you’re interested in popping in. I also like to email or say in person what I took from observing them, showing you valuing their time.

When sitting in any professional development session, I yearn for something that I can take away from the session and apply straightaway in my own teaching. However, it is also good practice to go and find your own research or resource that is new and share this with others. Finding good websites such as RE Online can be great for resources. They have essays on topics relevant to religion and worldviews and even opportunities to enhance subject knowledge and pedagogy through their posts on social media and blogs that various authors contribute to. Another site well worth a visit is The Royal Institute of Philosophy. This year I secured a grant for my school from them to run 10 hours of philosophy activities with an expert in philosophy and some added extras, too. It was to support the teaching and promotion of the love of philosophy in our school. As an ECT, it’s great to get involved in opportunities like these. The Institute also runs competitions, articles, a level guides and masterclasses for FREE. NATRE and the Catholic Education Service have also proven to be invaluable sources of advice and knowledge for teaching RE.

Being an ECT can be hard work; especially when you start a new school with new colleagues, students, policies, etc. However, by taking responsibility for our own practice, as well as making the most out of the experts around us, we can thrive during our induction years. Thriving as an ECT, I believe, involves being proactive about developing your own practice. It involves being honest with our colleagues but most importantly, it involves recognising that the profession we have entered is a lifelong career of a love of learning and that is what we must do.

The term ‘high expectations’ is as commonplace in schools as ‘retrieval practice’ and ‘growth mindset’. I know few, if any, teachers who decidedly have low expectations of pupils. However, I would argue that regular reflection on our expectations of pupils is vital when considering how to improve outcomes for the children we teach. Awareness of what we believe about pupils’ potential achievement, why we believe it, its impact on pupil achievement, and how we might raise our expectations can lead to improvements in our teaching, our own sense of professional self-efficacy, and, of course, outcomes for our pupils.

To understand the effect of teacher expectations and its relation to pupil achievement, we need to start with the pupils themselves. Pupils’ beliefs about their potential for success impact their motivation to commit the necessary resources and behaviours to learn the content we teach them. We have evolved to be wary of allocating our limited

attention to situations where success is unlikely. Such a prediction of failure is enough to lead a pupil to avoid investing their time and energy in a lesson; the repeated experience of failure in a subject can lead to a deep-seated negative belief about their own potential that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of underachievement.

Teachers play a crucial role in shaping pupils’ beliefs. When we have high expectations of what pupils can achieve, we set in motion a virtuous cycle whereby pupils both become and believe they can be more successful. Teacher expectations, too, become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The term ‘high expectations’ is as ubiquitous as it is elusive. Despite the significance of expectancy on achievement, distilling the components of ‘high expectation’ teaching is a challenge. The lack of clarity over what high expectations meant prompted me to study the phenomenon for my final MSc research project.

Teacher expectations can be conceptualised as the beliefs we hold about pupils’ potential achievement. These beliefs are usually based on pupils’ prior attainment but can also be influenced by a range of other factors, such as socioeconomic status and gender.

Our beliefs shape our classroom interactions and approaches. These contribute to our pupils’ self-beliefs and significantly affect the progress they subsequently make. When teachers believe their pupils are capable of more, their pupils often meet these increased expectations.

The famous ‘Pygmalion’ study demonstrated the expectancy effect in action1. Teachers in the experimental group were led to believe their pupils’ had higher potential than those in the control group; these pupils consequently made more progress than those in the other, despite there being a random allocation of pupils between them.

How can just believing in more potential translate to increased achievement?

What we believe about pupils’ potential for achievement shapes our own classroom behaviours, especially our interactions and pedagogical decisions. How we interact with our pupils, the way they are grouped, and the level of work they are set all contribute to how pupils interpret our expectations of them.

Although they are slow to build, conveying higher expectations to our pupils over time positively impacts their achievement and progress; conversely, and alarmingly, transmitting low expectations can swiftly damage children’s perceptions of what they think we expect from them.

The type of behaviours which might cause pupils to infer teachers have low expectations of them are numerous and can often be subconscious decisions. Providing insufficient time for thinking after posing a question, only praising correct answers, and using ability groupings can all contribute to the perception of lower expectations (RubieDavies et al., 2015); when combined with pupils’ anxiety and fear of failure, they limit learning in a profoundly worrying way.

It’s quite common for teachers to behave differently to pupils with different levels of prior attainment. When completing my research project and finding out about the types of teacher behaviours which convey high expectations, this was a sobering reflection point: did I really demonstrate the same high expectations of all pupils regardless of their starting points? I wanted to say yes, but a lingering guilt emanated as I read about how teachers, albeit subconsciously, can differentiate their practice based on their differing expectations.

One study2 found that some teachers respond differently to incorrect answers depending on whether they have high or low expectations of the pupil. The study found that where in response to an error teachers might use language such as ‘You should know this!’ to a child for whom they have low expectations, their responses to similar mistakes for children with high prior attainment usually prompted them to re-teach or re-explain a concept.

Having high expectations does not just mean ‘wanting’ all pupils to do well; having high expectations means truly

‘believing’ in pupils’ potential and demonstrating this belief day-in day-out. Both the beliefs and associated actions are critical in using the expectancy effect to raise achievement.

In many ways, adapting instructional actions to convey high expectations is the easier of these two components. In a 2015 New Zealand study3, Rubie-Davies and others investigated the effect of training teachers to employ what she termed ‘high expectation behaviours’ - strategies and approaches which are commonly used by ‘high expectation teachers’.

Rubie-Davies found that when teachers were trained to incorporate three distinct approaches into their practice both pupil achievement and the teachers’ own expectations increased at statistically

significantly higher rate. These approaches related to learning activities and grouping, cultivating a positive classroom climate, and motivation and goal setting. This was achieved through regular professional development, contrasting previous studies where merely sharing ‘high expectation behaviours’ with teachers had little effect on their practice and their pupils’ achievement.

Crucially, it is important for teachers to be on-board with any such professional development. Where practices are mandated to teachers, it’s likely their intended impact are limited without individual teacher buy-in.

Despite any intervention to improve a culture of high expectations for all pupils, teacher beliefs are notoriously difficult to

change. Our beliefs about teaching and learning are shaped by a whole host of factors, including our own experiences of school. I attended a secondary school where we were in sets for every subject. If you were ‘clever’ you were in Set 1, if you were in Set 7 then, well… you were kept busy. Being educated in such a setting shaped my beliefs about achievement and potential, albeit at a subconscious level.

An important teacher belief is our theory of intelligence. Often conflated with the notion of ‘ability’, intelligence is understood as either an ‘entity’, something which is fixed, or as ‘incremental’, something which can grow.

Our practice is generally informed by whichever theory we hold. Those with an ‘entity’ theory typically see any

‘failing’ as being related to the pupil rather than instruction. For teachers who hold this belief, it is typical to take less responsibility for their pupils’ outcomes and associate pupils’ lower outcomes as being something outside of their sphere of influence. Those teachers with an incremental theory of intelligence conversely consider their own actions as being the definitive cause behind pupils’ achievement.

Interestingly, those who hold an incremental theory of intelligence typically report higher levels of selfefficacy - their belief in their own ability to effectively impact students’ learning and achieve desired educational outcomes. Teacher self-efficacy encompasses a teacher’s confidence in their instructional skills, classroom management, and their

capacity to engage and motivate students. Even more interestingly, a high level of teacher self-efficacy has been linked to increased student achievement, and higher expectations of pupils’ potential achievement.

Self-efficacy is affected by a range of different factors; however, one which is pertinent to expectancy effect is that of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK).

PCK involves understanding not only the subject matter but also how pupils learn the content as well as providing insight into how to adapt instructional strategies, explanations, and examples to suit pupils’ varying needs and levels of understanding. PCK is closely related to teacher self-efficacy in that it forms a critical foundation for teachers’ confidence in their ability to facilitate meaningful learning experiences.

Improving our PCK seems, therefore, a critical way of raising our expectations of our pupils. Developing our understanding of how pupils learn the content we are teaching them can develop our belief that all pupils can be more successful. The insights that PCK brings support teachers to use more effective pedagogy. Not only does this lead pupils to experience more success, but it also provides teachers with a clearer framework of why pupils might have misconceptions as well as supporting teachers to effectively address them.

While a focus on high expectation practices is a good starting point, it is not sufficient. For us to truly come to believe that all our pupils can achieve highly, we must also consider the extent of our PCK. It is the combination of understanding how our pupils learn the desired content as well as adopting effective behaviours and instructional practices that lead our pupils to themselves believe that they can be successful.

REFERENCES:

1. Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom; teacher expectation and pupils’ intellectual development Robert Rosenthal Lenore Jacobson. New York, NY: Holt, Rhinehart and Winston.

2. Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2007). Classroom interactions: Exploring the practices of high- and low- expectation teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 289-306. doi:10.1348/000709906x101601

3. Rubie-Davies, C. M., Peterson, E. R., Sibley, C. G., & Rosenthal, R. (2015). A teacher expectation intervention: Modelling the practices of high expectation teachers. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 40, 72-85. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.03.003

Older women are often made to feel excluded by the current education system. Maz Foucher explores why this might be the case and what could potentially be done about it.

When I first started teaching, I worked alongside teachers from a whole age range - from 21-year-old NQTs to those in their 60s on the verge of retirement. There was always someone older and more experienced to give support and guidance. How then, by the age of 40, did I find myself the oldest member of our full-time teaching staff and the only one with more than 10 years’ experience?

This changing demographic within our staffrooms is indicative of a huge issue within the profession. In 2023, Teach First found that only 35% of female education staff felt that headship was compatible with parenthood. However, this also applies to many full-time roles within education. It has also become incompatible with many of the other aspects of life that women in the 40+ age bracket experience. Often called ‘the squeezed-middle age’, women in their 40s may also be juggling the needs of elderly and ill parents alongside those of young children or teenagers, as well as

tackling their own health issues. In 2022, like many of my colleagues and teacher friends, I concluded that the role I had was no longer sustainable, so I left.

Statistically, one in three teachers leaves within the first five years (Zuccollo, 2022). Additionally, the largest cohort to leave are women in their 30s, often parents of young children (DfE, 2022).

I am highly concerned about a teaching profession which is losing teachers at such an alarming rate so I am working to improve these statistics through several projects I have taken on since leaving, including my Regional Representative role with the MTPT Project.

Through this, I help teacher-parents (primarily mothers) to form supportive networks, to access coaching and CPD and to share advice on how to juggle teaching when you have a young family. However, barely a week goes by without a conversation with an older teacher who has also left the profession: women like

me who are experienced teachers who no longer see where they fit within education.

I initially believed it was a regional issue related to the educational landscape in which I worked. However, I now speak to women all over the UK and I don’t believe it’s limited to the Southwest. It seems that the ever-increasing workload coupled with years of moral stress and secondary trauma are the perfect recipe for a career disaster.

Personally, I had survived the main pinch points for career retention: I made it through my first five years of teaching (and fifteen more) and survived the hectic years of having young children. Logically, at this point women should be ready to thrive within the profession. However, it simply felt like I was at a career dead end with nothing more to give. Like many of the friends and colleagues who had left before me, I could list the things that were wrong but was unsure whether the issue was with me or with the profession.

I opted to take a sabbatical year while I considered this and whether it could be fixed. Within this time, I also studied for an MA in Education Leadership and focused my dissertation research on teacher retention. I decided to speak to those recently qualified primary teachers who were leaving within the first five years of their career. I hoped that comparing my experiences with those of these newer teachers might help me find the key to staying in the profession or at least what I could do to support others.

What I found was startling. The interviews I held with recently qualified teachers were emotional and often upsetting. Despite being at opposite ends of the career ladder, their stories were eerily like mine. They too had struggled with:

• excessive workloads.

• the lack of compassionate support.

• the lack of autonomy.

• accountability and performativity cultures.

• increasing behavioural needs of children.

• ever-increasing requirements for differentiation.

• The lack of resources to support students effectively.

However, whilst I am incredibly grateful to my research participants for sharing their experiences, these were all things that I should have been able to influence for myself within my own working life through my SLT role. These weren’t the final straw that led me, and the experienced teachers I know, to leave teaching.

Many of the other issues that my peers have articulated relate to how older, more-experienced teachers now feel within the profession. Rather than feeling their experience is valued, they are now made to feel guilty for being too expensive, too critical, too much of a threat to younger, less-experienced staff, especially those in leadership.

The current trend which sees people reach headship quicker than ever means

we have leaders with less knowledge and experience of teaching managing systems with high-stakes accountability. The competition caused by the external publication of data leads to often arbitrary links being made between data and teaching approaches. We are attempting to apply superficial actions to complex issues and making causal correlations where there often are none.

Increasingly, we see policies which reduce teaching to a set of instructions, or non-negotiables, to make the intangible (learning) seem tangible. If you have been in teaching long enough, you know that these won’t often be the long-anticipated answer, they are simply different models. What works for one child or class won’t work for everyone. Schools are all different, with different cohorts of children, and the learning of children is determined by so many different external and internal factors that can’t always be measured in the way that it is claimed.

Once you have seen enough of these approaches come and go, you grow tired of it, and this is partly why so many of us are leaving. Where older teachers were once respected for their experience, they now feel like a burden by being the ones to point out the flaws in current policy.

The recommendations I gave in my dissertation about newer teachers are similar then to those that would have supported me to stay. A reduction in workload, an increase in autonomy and more support to deal with the intensification of the teaching day would all of course have been beneficial. However, I still believe that some tangible changes at an HR and leadership level would have helped me, and many of the teachers I speak to, to remain in teaching.

• Firstly, opportunities to work with an older, more-experienced mentor or career-based counsellor would have made a huge difference. Teachers who come to this pressurised point in life and their middle years of their career need the sort of emotional support and guidance that sadly an inexperienced leadership team are unable to give. Having researched reflective supervision, I believe this sort of approach would have helped enormously.

• We also need to normalise and encourage flexi-working, and to have access to this at different points of our lives. The damaging and restrictive idea that teaching or leadership posts can only be full time needs to change. I have seen part-time teaching and leadership done brilliantly, with huge success. In a profession full of such intelligent, creative people, it’s about time we found ways to make this work as it would allow many, more-experienced colleagues to stay.

• We also need to encourage career paths that don’t always head upwards but which allow people to stay in teaching and develop their careers as respected members of the profession without having to go into management roles. Career pathways that head sideways and backwards simply mean that staff have had different priorities at different times. We need to allow people to slow the pace of work when they need to, and to step back up when they are ready. When recruiting, we need to be much more open to this, applying compassion rather that critique, to allow people to take steps in different directions as their circumstances change.

Overall, it is tragic that most of the experienced teachers I have worked with over the years have now left the profession, long before retirement. The skills that experienced teachers bring could be pivotal to reversing the retention issues we now face. Many of us are great teachers who have helped hundreds of children and families and supported countless new teachers to join the profession. We have extensive curriculum knowledge, vast experience of different pedagogical approaches and masses of life experience which we could be using to coach and mentor those newer teachers who are struggling.

By twenty years in, you have come across most things and seen things come and go. My concern is that, when the pendulum swings back to giving teachers more professional autonomy, there will be very few people left who remember what this looks like. Instead of being made to feel like a burden for being too expensive and too critical, experienced teachers should be seen as a force for good. Ultimately, it impacts negatively on the nation’s children when we keep losing experienced, knowledgeable professionals from education.

The idea of saving time is so important and is always at the forefront of any busy SENDCOs mind. The issue is that we never seem to have enough of it; so here are my top tips to find more time.

It seems a bit direct, doesn’t it? But sometimes we do need to be direct. Ask yourself; is what someone is asking me to do actually part of my job? If you’re unsure, just ask your line managers. And just because they say, “Ginny, you’re so good at filling in forms”, doesn’t mean I want to or should be filling in forms for other people. Just because “Ginny, you’re really good with people”, doesn’t mean I should end up tackling all of the tricky conversations. By nature, SENDCOs are kind and caring individuals who don’t want to offend others. By saying no, you are looking after yourself, which is something that all SENDCOs need to prioritise more often.

We are allowed to be unavailable at times. We truly are. Try it and you will realise that people understand that we are not on call 24/7. I was working with a family recently and had to say that I wasn’t available on a couple of dates and times they suggested and guess what? We just found another suitable time. We often don’t try things for fear of how we will be perceived. Others know that we are human and acknowledge that as a given.

When I’m talking about robust systems, I’m talking about, in the first instance, having a system in place for when teachers are concerned about a child in their class. Rather than teachers coming straight to the SENDCOs and having a hurried and often somewhat incoherent conversation, consider how to make this a more robust system. If you have termly pupil progress meetings, consider this to be a mechanism for discussing children with additional needs and putting systems in place to support them. Some schools even have an electronic system whereby teachers complete forms to identify the areas that they think a child is struggling in. Once again, this is a system that does not rely on ‘incidental’ conversations.

4. Triaging our time. They do this in accident and emergency rooms, so why shouldn’t we adopt it in our working days? Do we need to do something this minute, today, or dare I say it, this week? Everyone is busy, so ask yourself: does this person really want a meeting ‘foisted’ on them today? They probably already have their day mapped out, so we are inadvertently putting a metaphoric ‘spanner in the work’ of their day. If the conversation allows it, why not even push the meeting back to, dare I say it... next week?

5. Map out your days.

I like to try and plan out my time for each day. If I see that my day is back-to-back with meetings, I try not to shoehorn any more tasks ‘to do’ in because I know that they will become ‘haven’t done’, which makes me feel as if I haven’t achieved.

6. Set out timescales.

I think it is important that others know how much time certain tasks take. In the role of a SENDCO, we often just get on with things without others realising how long these tasks actually take. Why not put together a list of your tasks and note down how long each one takes to complete? Or even better, get your headteacher to sit down with you and complete a referral together. Doing this is a real eye-opener for those working in SLT to understand how we are triaging our time and acknowledge that there must be a timescale provided for any task we need to complete.

7. Using a diary.

As SENDCOs, we are so busy and must manage our diaries so carefully to make sure that we’re at the right place, at the right time and with the right people. I am a strong advocate of the electronic diary; it works across all my devices, so I always have it with me. However, I know other SENDCOs who like to have their physical diary with them as a comfort blanket, so it’s just about knowing what works best for you.

Consider how best to have a meeting. I always used to have in-person meetings, but I now realise in this new hybrid

world we live in that virtual meetings can be quite useful. I now give choices for a meeting to be in person, over a video call or a phone call. Giving options brings people together, as they feel valued and can also save us precious time. it’s a win-win situation, in my opinion.

9. The ongoing email debate.

Sending and replying to emails is an ongoing discussion. So, here is my take on it… If we answer emails outside of school hours, then others will think that we are happy to do this. I often hear people say, “But what will people think if I don’t answer emails quickly?”

To this, I say they will understand that you reply at a time which suits you. Try it – you’ll be surprised at how liberating it is.

10. Schedule where you can.

Whilst we are on the topic of emails, let’s consider the use of the ‘schedule send’ facility. If you haven’t used it yet, please do look it up on Google or YouTube. It allows you to write emails in advance, at a time which suits you and then set the time at which you’d like the email to be sent. I like my emails to be received in others’ working hours, so I set mine to go out during the average working day.

11. Set boundaries between ‘work’ and ‘life’.

Whenever I do talks, this always gets a sharp intake of breath from members of the audience, so here goes…

Consider removing school email from your phone. Doing this gives you ownership over your own time and allows you to set a boundary between your work and home life. If you need a middle ground, just turn off email notifications so that they don’t ping up constantly, but you can check it at a time that suits you.

I guess what I’m saying is let’s look at being in more control of our time. Consciously triaging helps us to stop and think about how we are managing our time and consider how it impacts others.

With over 25 years’ experience, qualified Outdoor Learning Consultants, and reliable Installation Teams, Pentagon Play o er innovative products and solutions, created to meet the needs of your pupils. All of our schemes and items are designed to encourage learning through play, crafted with the curriculum in mind to support pupils as they learn and grow. No matter the requirements of your development, Pentagon Play can support you in finding the best solution for your space.

An exploration of what it means to develop metacognitive skills of evaluation

A Pedagogic Idiolect: Words From The English Classroom

Thoughts on some effective phrasing in English, to encourage higher quality student responses

Welcome to the fourth article in this run of metacognitive pieces, which began with an overview of the theory, and continues with another set of strategies, ready to introduce into your classroom.

If you haven’t done so already, read the first article in this series on metacognitive theory. If you don’t understand the theory, then you won’t be in the best position to introduce these strategies into your classroom. And if your understanding is not quite there, then the benefit of the strategies for your students will be reduced.

The aim of this article is to place a focus on the evaluation skills of our students. This is perhaps one area where more focus has been placed than others (for example, monitoring skills, which were covered in the previous article), and so it is likely that you will already have a repertoire of strategies, or whole school expectations, which help to develop student evaluation skills. Having said that, there is always room for improvement, and I’m sure that there will be something in this article that you can take, to improve your own practice and hence the metacognitive evaluation skills of your students.

I would be quite surprised if you had not come across an exam wrapper in some format at some point in your teaching careers. These ‘wrappers’ (I believe so named as they can literally

be wrapped around a booklet) are typically used after an assessment, often a Year 10 or 11 mock assessment. The aim of the wrapper is to evaluate, in depth, every aspect of the assessment, from preparation for the assessment, all the way through different aspects of the assessment, and changes to future assessment preparation.

What so often happens with assessments is that they provide us with some decent data, and allow us to inform our teaching, especially for exam

classes. They also provide some helpful information for students, such as topics that they are strong with and areas that they really need to work on. However, there is so much more than can be gleaned from an assessment, which is what the wrapper helps us do.

To begin, several questions can be asked about an individual’s preparation for an assessment, including how long they revised, what methods they used for revision, and the environment in which they revised (three crucial factors that

we are aware of, but students typically are not, especially the latter two).

The wrapper then homes in on the assessment itself, and is often presented as a table, including columns such as question number, question topic, and then columns including common reasons for losing marks, such as failing to show method, misreading the question and running out of time.

reduced, and so students can really focus in on how to use the alternative strategy and begin to consider the relative benefits (and drawbacks) of that alternative strategy for the given question or task.

This added depth allows students to really pinpoint why they have dropped marks. Though often it is due to not revising or understanding a topic, it helps students identify patterns of lost marks from, for example, not reading the question criteria carefully enough.

Finally, the wrapper goes on to evaluate what the student ought to do for the next assessment. Again, directed questions can be used such as ‘what will you do differently next time’. This section really helps to evaluate the previous two, providing students with an action plan of what they need to do next time.

This is one of my favourite methods – perhaps because I am a teacher of Maths, a subject in which this strategy likely works better than most.

As we will all be aware, there are often multiple ways in which a student can approach a question or task. As we are also aware, there is often one approach, strategy/method which is more efficient that the others. We wish that students would use this one, but they often use methods which are possibly easier to understand or more generalizable across multiple different questions or tasks.

One way in which to force students (nicely) to explore alternative strategies is to get students to repeat a task that they have just completed, but this time with one of those alternative methods.

As students have already completed the task once with a method that they are confident with, the difficultly of answering the question should be

Though this may seem as though it will take a lot of time (it will, especially to begin with), the benefits of students being exposed to multiple methods, and forcing them to consider the relative strengths, weaknesses and efficiencies of both, outweighs the time taken.

A PMI grid is a very quick form of evaluation which takes absolutely no planning time whatsoever for you. The PMI grid focusses on a positive, minus and interesting piece of information, and can be used at the end of a lesson, string of lessons or at the end of a topic.

All students need to do is record down one positive, one minus and one interesting piece of information – from their own thinking rather than what their friends say! The caveats on this can be increased by you, as the teacher, too. Rather than getting students to write down any sort of positive, you can instead get them to write down one positive of the method they used, one minus (or as I like to say, negative), and one future consideration.

So this method may not be the most in-depth form of evaluation for students, but, with certain caveats, can force a certain depth of thinking. The beauty of this method is it has very low barriers for entry (not just in terms of your planning, but also in terms of how complicated the method is - I.e. not very – so students can easily access it). Because of this fact, this strategy can be used frequently (even every lesson, should you so wish), and does not take a long time for students to complete, either. It can also be used in conjunction with the previous method very easily, too.

This strategy is often used in primary, but can also be adapted for the secondary classroom, too. The learning diary is self-explanatory –students quite literally keep a log of their learning. However, the focus here, of course, is on the evaluation. This means that you are unlikely to get students to use their learning diaries each lesson, or even each week, but after crucial events in their learning where you want students to carry our significant evaluation and be able to refer to it in future.

One example may be through the evaluation of end of topic tests. These typically, will be every couple of weeks in secondary, especially for the core subjects. Often, students complete these, have them marked, possibly do a little evaluation, and then move on. This means, though, that students do not make future plans or have a record of their previous evaluations.

Rather, in this situation, students could keep little learning diaries that they complete after each of these end of topic tests. Perhaps 5 consistent questions could be posed to students after each test, including topics that need future revision, strategies that need to be worked on, and the links certain topics have with each other?

When students come around to an end of term or year assessment, they have their own, personalised revision book, guiding them in what they need to revise, their difficulties and things that they have successfully done before.

So, that’s it for this metacognitive article. Hopefully a further set of helpful strategies which you will be able to implement into your classroom with ease! In the next strategy article, the focus will be on metacognitive processes – somewhat fiddly, but hugely beneficial!

What is a ‘pedagogic idiolect’ and how might focusing on your own improve your teaching?

As a child, my mother would take her video recorder everywhere: on day trips, family gatherings, birthdays, Christmas, holidays. She had — and still does — a massive stack of these videos, piled like books on a shelf. If bored on a Sunday afternoon, she would take one down and we would watch it together.

Maybe seven or eight, I remember watching these with equal measures of awkward embarrassment and fascination. The same basic insight fuelled both emotions: to see myself as others did, to notice the way I talked, acted, moved; both familiar and strange. I would laugh and recoil; hide my face yet at the same

time affix my eyes to the screen. For many years, I have been a massive advocate of using video recording as part of my professional development. In fact, it is one of the activities that has had the most significant impact on my improvement as a teacher. Yet, even now, watching myself played out on a screen conjures the same two emotions. Embarrassment but also studied fascination. It is, I think, the ability to see oneself at a distance, once removed from the actual remembered experience of doing whatever it might be. This frisson might cause a certain awkwardness — in me anyway — but it is also what makes it so hugely valuable for

getting better in the classroom. We see ourselves as our students do; notice things we would not notice in the moment.

Having watched myself teaching for many hours, it is quickly apparent I speak with what I might call a pedagogic idiolect: certain phrases or habits of speech that I say over and again. These phrases comprise the patter of my pedagogy. In this article, I want to share three of these sayings; things I find myself repeating lesson after lesson. It is a useful test case in the kind of relationship I have to my subject; the way it is presented and embodied to students.

I must ask a variation of this question every single lesson I teach. To my mind, it is one of the most powerful questions English teachers can ask their students; unlocking a deep sense of the inherent multivalency of language.

The conversation might look something like this, using the poem ‘Walking Away’ as an example:

• Teacher: Let’s consider Day-Lewis’ use of the word ‘wrenched’ in the line ‘like a satellite wrenched from its orbit’. What other words could have been used?

• Student A: Maybe pulled

• Student B: Grabbed

• Student C: Tugged

And now, the all-important question: well, why do you think Day-Lewis chose ‘wrenched’ and not, say, ‘pulled’, grabbed’, or ‘tugged’? What’s the difference?

Just by asking this question, we guide students towards a far more precise, detailed and rich appreciation of the connotations and associations of the given word. It works so well, I’ve found, because comparison tends to be easier than trying to evaluate within a vacuum. It is easier to compare the difference

(and therefore possible effects) of ‘wrenched’ in comparison to ‘walked’ than simply asking what the effect of the word is. [As an aside, this is the same reason why comparative judgement is probably a much better way to mark student work than trying to assess a single piece of work in isolation].

By making this question part of my everyday discussion routines — my pedagogic idiolect — it becomes a lot easier to direct and focus analytical attention. It also helps to avoid vague comments like ‘the word makes me want to read on’.

Another way I help student to appreciate the complexity and richness of literary language, is to give it a name. There are certain images or quotations that repay analysis more than others. These are the images that if grappled with and poured over will yield a wealth of ideas. They’re the quotations we signpost, that we teach, that we help our students to remember in the hope they spend precious essayspace discussing them.

Such images go by many names. Power quotations, neon lines and juicy quotations are all ones I’ve used before. However, in recent years I’ve settled on calling them ‘diveable’. There are a few reasons this specific term has made its way into my pedagogic idiolect:

1. It communicates what makes these quotations so useful: they are linguistically ‘deep’, repaying continued digging and exploration.

2. It helps me to differentiate between those that repay such analysis and those that don’t. I talk a lot about ‘shallow’ quotations that students should avoid.

3. It provides a useful way to express the need to keep pushing, saying multiple things about a given image. I encourage my students to ‘keep diving’ or to ‘dig deeper’.

Of course, simply labelling something does not automatically mean students will be able to do it. But, as a conceptual shortcut that signposts and makes explicit the intellectual process I’m hoping to inculcate, I’ve found it to be incredibly helpful.

Shifting from micro to macro, one of the most frequent questions I ask to help students grapple with the thematic landscape of the text is ‘what does it do?’ This has been one of the best and biggest changes I’ve made to my teaching of authorial intent in recent years.

Asking this question stops the text being seen as a container for an author’s personal views, but instead an active agent in its own right. It is capable of actually doing something, both when originally published and when read now. It makes an impact; continues to exert influence long after the author has died.

Asking this question, opens up a whole attendant vocabulary that also forms a fundamental part of my pedagogic idiolect. I talk about the way a text might:

• Challenge

• Warn

• Uphold

• Subvert

• Critique

• Celebrate

• Ridicule

In my teaching of Pride and Prejudice, for instance, I talk about the way the text subverts Regency Period attitudes towards marriage or how it ridicules the pomposity of character like Mr Collins. This opens up an entire way of thinking about the powerful impact a text can have that moves students well beyond the often unhelpful ‘Austen thinks’ or ‘Austen does this because…’

Whenever I teach non-fiction writing, I always encourage students to conclude with a call to action. Their writing should, I say and paraphrasing TS Eliot, end with a bang and not a whimper.

And so here’s my own call to action. If you haven’t already, trying recording yourself teaching. It may be awkward to watch at first, but the rewards are well worth it.

And if you do, listen out for the phrases, snippets and repeated words that comprise your own pedagogic idiolect.

38. How To Interpret The Writing Moderation Criteria For The End Of Key Stage 2

KS2 writing moderation can be a tricky business. Here are some tips to help make it clearer.

44. Encouraging Participation In Sport For All

Why is sport participation so important and how can we encourage it?

48. What Makes Shakespeare So Relevant Today?

Why students won’t be ‘bard stiff’ when learning about Shakespeare in today’s classroom

After a year teaching Year 4 children, I found myself thrust into the minefield of Year 6, where I currently reside.

In that first year, I was thwacked with the holy trinity of primary school moderation: an Ofsted deep dive, SATs and an external writing moderation. Heavy stuff.

Without question, I found the writing moderation the most challenging of the three.

The SATs come at the end of the year and you have the whole year to prepare. Ofsted is horrible but over in a flash. Writing moderation, however,

requires weeks of endless writing, marking and refining for a single, high-stakes moderation event, one that we weren’t expecting.

What I found the most challenging was how inaccessible the language around some of the moderation criteria was. In this article, I am going to dissect one element of it and give examples of how students can both meet and exceed the Expected Standard (EXS) placed at Year 6 with a short paragraph.

(Disclaimer – one paragraph won’t be enough for a student to score EXS writing or above. This is just an example of how it can be done.)

EXS – Use a range of devices to build cohesion within and across paragraphs.

To achieve the expected standard, cohesive writing is required. It’s got to flow.

There is a simple list of strategies I look for in my students’ writing to make this happen.

Helpfully, they are listed in the writing criteria; annoyingly, this is done without context or explanation. (There are other things you can look for but I

believe that, if you are new to Year 6 moderation, this list is a good place to start.)

Here are those four key skills plus their purposes:

1) Pronouns – these help avoid repetition and keep the reader interested;

2) Conjunctions – these create fluidity;

3) Adverbials of time and place – these connect events happening in a chronological order or a single location;

4) Synonyms – once again, these help avoid repetition.

Here’s a paragraph without these skills in use:

The lion was hungry. The lion headed to his wife’s suggestion: the deli. The lion was so hungry that his tummy was rumbling like the engine in his Ferrari. The lion’s tummy ached. Saliva was running down his chin. His wife followed along the high street. His wife was just as desperate for something to eat as the lion.

This reads like a series of sentences written one at a time with no clear plan. Many skills are in use but the

passage lacks cohesion. For this reason, the paragraph wouldn’t meet the EXS criterium, ‘use a range of devices to build cohesion within and across paragraphs’.

Now, here is the same paragraph with those skills there.

The lion was starving so he immediately headed to his wife’s suggestion: the deli. He was so hungry that his tummy was rumbling like the engine in his Ferrari. His stomach ached and saliva was running down his chin. She followed along the high street, swiftly passing their neighbour along the way, because she was just as desperate for something to eat as him.

1) Pronouns – the writer has introduced the lion but referred to him using pronouns (he/his/him) thereafter to avoid repetition.

2) Conjunctions – ‘so’ (the second one), ‘and’ and ‘because’ have all allowed the writer to add further detail to each sentence in a fluid way.

3) Adverbials of time and place –the reader knows where to picture the lion’s saliva. The reader is reminded of where the lion and his wife are (the high street) and informed of when they continue walking (immediately).

4) Synonyms – ‘famished’, ‘hungry’ and ‘desperate for food’ all depict the same idea but with a varied vocabulary (‘tummy’ and ‘stomach’ do the same and allow the writer to use a Year 5/6 spelling word –stomach).

Using the aforementioned skills turns it into a single, cohesive element of the story.

Now, here’s how your students can manipulate them to achieve Greater Depth Standard (GDS) writing…

GDS - Write effectively for a range of purposes and audiences selecting the appropriate form and drawing independently on what they have read as models for their own writing.

I am now going to rewrite this paragraph. This time, I will make and underline modifications that can demonstrate GDS capability:

Despite his disappointing visit to the butcher’s moments earlier, the lion was famished so he immediately headed to his wife’s suggestion: the deli. He was so hungry that his

tummy was rumbling like the engine in his Ferrari. His stomach ached and saliva was streaming down his chin while his mind battled with visions of salami. His wife pursued him along the high street, swiftly passing their neighbour along the way, because she was just as desperate for something to eat as her starving husband.

Here’s what makes this GDS writing:

1) Pronouns – used for the lion throughout to avoid repetition. However, when they walk past a neighbour, it is important to use a noun/proper noun so we know the final clause refers to the lion. Furthermore, using ‘her starving husband’ is better than ‘the lion’ here because it still helps avoid repetition, tying this skill in with synonyms.

2) Conjunctions – we have a sentence that contains three but still maintains flow, sense and cohesion. Shorter clauses help to make sure this sentence isn’t overbearing.

3) Adverbials of time and place – another place adverbial (‘the butcher’s’ has been added to the start, creating a closer link to the previous paragraph. ‘Moments earlier’ tells the reader that they are likely to still be close to the shop; they haven’t travelled between the paragraphs.

4) Synonyms – I have improved words such as ‘starving’, ‘running’ and ‘followed’ with more challenging yet realistic language.

And finally:

5) The most complex element of this writing, which I explain below:

Despite his disappointing visit to the butcher’s moments earlier, the lion was famished so he immediately headed to his wife’s suggestion: the deli.

We’ve started with ‘he’ – doesn’t this create ambiguity instead of clarity? How can the reader be sure who ‘he’ is?

‘Despite his disappointing…’ is a subordinating clause, something that is more commonly found after the main clause. For example:

The lion was famished so, despite his disappointing visit to the butcher’s, he immediately headed to his wife’s suggestion: the deli.

Here, we see a more typical use of ‘noun-pronoun’. Because it works this way around, lifting the subordinating clause and placing it

at the front of the sentence is still appropriate. We start with ‘he’ but we immediately find out who ‘he’ is. Clarity is restored.

What makes these three elements of the text GDS is that the writer has done something that usually wouldn’t work and made it work:

- Repeated a noun without it being repetitive;

- Used multiple conjunctions without the sentence becoming onerous to read;

- Used a pronoun before the noun without it becoming ambiguous.

Furthermore:

- The more challenging vocabulary improves the quality of the writing and, such is the complexity of the words, could provide evidence that the writer has drawn on examples from their reading.

- The writer has also created a direct link between this paragraph and the previous one with a carefully chosen adverbial that they have delivered in the form of a sentence opener. This single clause is packed with skills: conjunction, adverbial of both time and place, sentence opener.

This is the value of reading in primary schools and the impact it can have on writing. Many of these skills children will pick up from what they read.

If you want to explicitly teach them in lessons, they also make increasing sense to the students the more they come across them.

There is a lot going on here, I understand. However, I recommend keeping hold of this article and returning to it when moderating your own students’ writing. I hope it helps you know a little more about what to look for.

As we witness another great year of sporting achievement, educators must look at how we can capitalise on recent successes to inspire schoolchildren to become more active and motivated – especially those who are traditionally discouraged from participating.

Schooling is the process of creating responsible, respectful, and well-rounded individuals who are set up for success. A cornerstone of this should be sports and their potential to foster a culture of sportspersonship and holistic development as well as create healthy habits for pupils.

A lifelong enjoyment of sports and physical activity ought to be available to everyone. We must widen participation and give our pupils the best chance to engage with exercise, in a way that suits their level of ability and commitment. At LEO Academy

Trust we re-shaped our existing sports provision to ensure that our approach is one that effectively supports physical activity at such a formative moment in pupils’ development.

Finding an appropriate P.E. curriculum is a one of the most influential steps, as this not only forms a huge part of life at school for both staff and pupils, but it also sets the tone for how your pupils will engage with sport beyond their childhood.

For us, this has meant a childcentred approach, focusing on driving participation levels for

every child. We want our pupils, regardless of baseline ability levels to feel empowered to take part in sport, whilst also providing them with a challenge, to facilitate skill learning.

A curriculum specifically designed to build pupils’ skills and knowledge will be much longer lasting and impactful than approaching PE as a statutory requirement to fulfil. Resilience, respect, teamwork, and building awareness of exercise’s link to good wellbeing should be prioritised within the primary curriculum, just as the development of hand-eye

coordination, balance and physical fitness are.

One such approach we have undertaken with marked success has been combining morning clubs across our schools with sports clubs. Uptake of these morning clubs has been very high and we have noticed that they tend to generate excitement amongst children who are ordinarily reluctant to attend school. With a worrying national trend of unauthorised absences from school showing no signs of decreasing (up to 17.2% in 2022/23 for primary schools), measures such as our morning clubs can encourage and

excite children about coming to school.

Exercise can also encourage children to regulate their emotions; any measure to help our pupils enter the classroom feeling settled, focused and ready to for their day ahead is something we champion. Research suggests that morning exercise has 1 numerous cognitive benefits for children , and our own experience at LEO Academy Trust confirms this thinking; our teachers consistently report a positive effect on behaviour in the classroom. It also has the benefit of granting access to sports clubs to pupils who might be unable

to attend in the afternoons; it is important not to always conflate non-attendance of a sports activity with a lack of interest in attending.

Furthermore, promoting positive role models are fundamental in encouraging schoolchildren to get more active and involved in sport. We have been privileged to give our own pupils the chance to see their sporting heroes in action, such as watching Wimbledon tennis matches and seeing the Lionesses play. Whilst these large-scale events are indeed inspiring, access to role models can be even more inspiring. Through effective sports coaching, partnering with local sports teams

or even championing past pupils who have gone on to achieve in sports at a high level, schools can provide children with role models that can inspire them to achieve.

Improving representation in sport is key to improving participation in sport. Pupils need to see themselves reflected in their role models, be that on the pitches at school or the pitches of the world stage. For girls in particular, celebrating the success of the Lionesses as well as the rugby and cricket teams on a global platform is critical if we are to overcome the stubborn participation gaps in sport.

The World Health Organisation has found the vast majority of teenage girls do not meet the minimum threshold for activity. We also know that girls drop off from playing sport at a much earlier age and in greater numbers than boys. The primary school age window is key to keeping all pupils, especially girls, involved in sport and exercises throughout their lives

Female coaches help young girls to feel more confident as they play sports with their presence helping to dismantle stereotypical tropes around sport and who should be participating. A key element with regard to this has been increasing

our female coaching representation to help ensure that the girls can see themselves reflected in their role models. Our sports coaches are also involved in a wide range of sporting activity outside of school, providing a real-life example of how women can be active into adulthood.

The greater the diversity in sports leadership, the more everyone benefits from different perspectives and styles of instruction. This can only have a positive effect in keeping as many children as possible involved in sports and enjoying their sporting education.

Inspiring schoolchildren also means

ensuring that all pupils, regardless of ability, can access and enjoy sports. This must include providing pupils with SEND physical exercise in a way that suits their level of needs as well as their own interests. The benefits of physical activity for children with SEND are particularly clear – from improving balance and coordination skills, to increasing strength, reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease, and supporting the regulation of energy levels.

A seemingly minor change we have made to our school days is the introduction of ‘movement breaks’ in the classroom. At appropriate

moments, teachers intersperse academic learning with brief bursts of physical activity for their pupils – whether some simple stretches, a quick walk around the school grounds, or even a mini ‘dance party’.

These breaks are beneficial for all (including our teachers), but particularly for neurodiverse pupils. Teachers have noticed an improvement in classroom behaviour and attention since the introduction of these breaks, as pupils are given an appropriate opportunity to channel any excess energy. It also has the added benefit of teaching our pupils how to

deal with moments of agitation, frustration or over-stimulation through the benefits of exercise; a lesson that all children can carry with them throughout their lives.

Every child – regardless of ability level – should be supported to enjoy the benefits of team sports, such as boosting confidence, improving communication skills and building friendships. We have tried to extend these benefits to our SEND pupils by embracing adapted sports such as sitting volleyball.

Our Trust has also been involved with organisations such as the Panathlon Challenge, giving our SEND pupils the chance to try a wide array of sports whilst providing a clear goal of acquiring skills and ensuring that they aren’t excluded from the joys and challenges of competition. A healthy level of competition teaches some childhood’s most fundamental lessons; fairness, focus and the ability to deal with difficult emotions, such as nervousness or disappointment.

It must always be recognised that not all sports will be of interest to all children, and where possible, introducing pupils to a range of sports allows them to choose one that appeals to them, on a level appropriate to their needs and interests.

Whilst it can be tempting as educators to keep our sights set on the highest possible level of achievement, dreaming of a stuffed trophy cabinet, gold medals and World Championships, what matters more is ensuring our pupils can all access the benefits of sports and physical activity. Not only is it an important part of ensuring we have a community of happy and engaged learners, but it is also vital to building healthy futures for our younger generations.

Hetty Steele argues that Shakespeare’s works remain entirely relevant for students today, providing opportunities to explore complex themes around race, power dynamics, religion, and social control.

Last month saw the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s first folio, marking four centuries of the playwright and poet’s influence on the theatre and literature of this country. Almost without exception (baring perhaps international qualifications), every 16-year-old in this country is required to study a Shakespearean play at GCSE. This requirement is met with varying levels of enthusiasm, by students and staff alike, and there are voices that complain of inaccessible language, outdated characters and ‘done’ storylines. However, I argue that these works from 400 years gone by are as important and as relevant today as they ever were. In fact, I argue that they are fantastic vehicles into important 21st century discussions around race and power.

For evidence that Shakespeare can be successfully updated to the needs and interests of the time, we need look no further than the Globe. The Globe are acutely aware of the need to scrutinise the words, themes and content of Shakespeare. So much so, they dedicated their Summer 2023 season to ‘Anti-Racist Shakespeare’, hosting webinars that invited actors, directors, academics, and members of the public to come and discuss the representations of race and social justice in Shakespearean works. The last of these occurs in February 2024 ‘Anti-Racist Shakespeare: Othello’ and considering the play’s prominent place on the English Literature A-Level syllabi around the country this is one to encourage our Year 13s towards. The Globe’s role in the

contextual history of the plays, and its stance in 2023 surrounding issues of race, is a fantastic ‘in’ for conversations with students. The key is to remember the context in which the plays were written – it might be easy to condemn Shakespeare at first glance for stating ‘all the water in the ocean/ Can never turn the swan’s black legs to white’ as though such a pursuit were surely all a living creature could wish for. But Shakespeare was very much a product of the social fabric of the sixteenth century, and we cannot forget that Shakespeare wrote black leaders, clever black lovers, and black, beautiful ‘natives’.

Let’s turn to Othello then, and issues of power. It is impossible to avoid issues of race within the

play: Othello is the only black character and ultimately emerges as a deeply flawed individual. He also receives a host of racial remarks from other characters. At the turn of the sixteenth century Elizabeth I wrote a series of letters complaining that there were too many black people in England: there is no denying racial prejudice existed in this country at the time. However, colour and race in Othello are more complex than the play merely holding

a mirror up to the sixteenth century’s audiences’ prejudices. The act of staging this prejudice was, debatably, a brave theatrical and literary act of its own.

Othello is the protagonist of the play, ultimately flawed but also powerful. His characterisation is more than the colour of his skin, his role as general questions notions of loyalty, betrayal, persuasion and what it means to have and retain power. Othello is

a subtle, nuanced and impressive character and our students analysis of his character can draw parallels with 21st century politics: what will individuals do, and who will they tread on, to obtain power? Is there a strength in being the outsider, and what dos Othello’s refusal to be cowed on intimidated tell us about Shakespeare’s view on the prejudices that were aimed at black people at the time of original performance?

To explore ideas about societal divisions in 2023, you could provide students with production shots where directors have taken risks with the casting of the play. In 1997, director Jude Kelly cast Patrick Stewart in the role of a white Othello with all other cast members played by black actors – images available on Google. Clint Dyer’s 2022 production at The National projected Othello posters from performances past, including Laurence Olivier in blackface, deliberately critiquing previous production decisions. It’s a fascinating way into racial divides that still exist in society today, issues that have never been more prevalent to our students.