HWRK educational mag azine the online magazine for teachers JANUARY 2023 / ISSUE 24 / FREE HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK written by teachers for teachers Creative Writing Strategie S ALSO INSIDE: D E v ELO p IN g Exp E rt ISE t hr O ugh A C OAC h IN g Curr IC u L um Wh A t I’v E L EA r N t Fr O m rECO r DIN g 100 r E pODCAS t S Ar E tEAC h E r S IDE h u S t LES t h E N EW N O rm AL ? E FFEC t I v E C p D D ESI g N F O r tEAC h E r S Wh A t Ex AC t L y I S S C h OOL Cu L tur E ? t h E pOWE r O F S A y IN g “N O ”

Established in May 2006, we are one of the UK’s most dedicated and ambitious anti-bullying charities. Our award winning work is delivered across the UK and each year, through our work we provide education, training and support to thousands of people.

Through our innovative, interactive workshops and training programmes, we use our experience, energy and passion to focus on awareness, prevention, building empathy and positive peer relationships all of which are crucial in creating a nurturing environment in which young people and adults can thrive. Our Mission is to support individuals, schools, youth and community settings and the workplace through positive and innovative anti-bullying and well-being programmes and to empower individuals to achieve their full potential.

DIFFERENCE MAKING A INSPIRING CHANGE EMPOWERING YOUNG PEOPLE To find out more visit www.bulliesout.com | Email: mail@bulliesout.com

BELIEVE IN A WORLD THAT IS FREE FROM ALL

OF BULLYING BEHAVIOUR.

you would like to support us and help us to continue our lifechanging work, you can:

Volunteer with us

Fundraise for us

Make a donation

Join our Speak Out Campaign

Become a Corporate Partner

WE

TYPES

If

\

\

\

\

\

Exploring BEhaviour: unmEt nEEds, Wants or somEthing in BEtWEEn?

CONTENTS

EDITORIAL: THE POwER OF SAYING “NO” Saying “no” more often allows you to say “yes” when it matters most

FEATURES

6. EXPLORING BEHAvIOUR: UNMET NEEDS, wANTS OR SOMETHING IN BETwEEN?

Most behaviour is a form of communication, however, what the behaviour is actually communicating is debatable. But what should we do about it? asks Saira Saeed…

10. HOw TO RETURN TO wORk

A handy eight-step guide to making your return to work from illness work for you

PEDAGOGY

16. DESIGNING kNOwLEDGE ORGANISERS

How to create effective knowledge organisers with a strong rationale behind them

CURRICULUM

24. CREATIvE wRITING AND SELFREGULATION

How can we make a challenging task like creative writing more manageable? Jennifer Webb suggests some strategies to “shrink” it, to help students focus on what matters.

32. HOw I wOULD TEACH CREATIvE wRITING FOR AQA ENGLISH LANGUAGE PAPER 1

Andrew Atherton offers his advice on how to get students started with creative writing when they don’t know how to begin.

37. wHAT I’vE LEARNT FROM RECORDING 100 RE PODCASTS Louisa Smith is the host of The RE Podcast. In this article she shares some of the most interesting things she’s learnt…

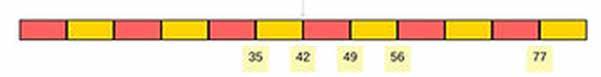

40. TEACHING TIMES TABLES

A winning strategy for teaching times tables

46. wHAT EXACTLY IS SCHOOL CULTURE?

School culture can make or break a teacher. Shannen Doherty sets out what leaders needs to be mindful of when developing culture at their schools.

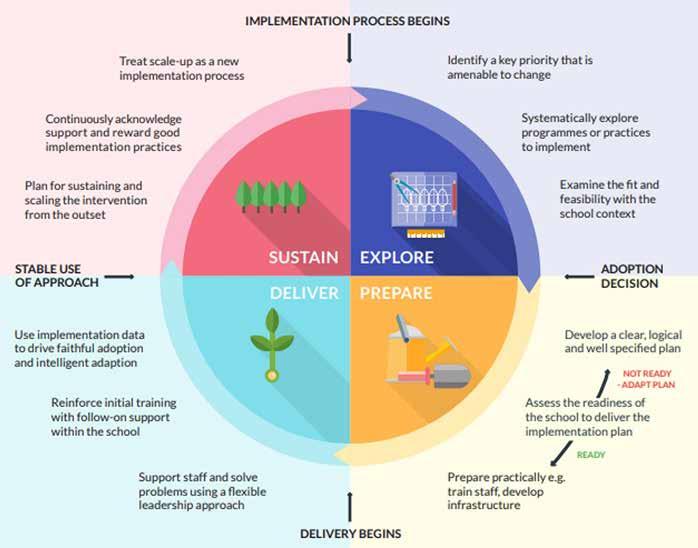

48. EFFECTIvE CPD DESIGN FOR TEACHERS

How can we design high-quality CPD for teachers? Amarbeer Singh Gill offers his suggestions on how to create CPD that is meaningful and effective.

53. DEvELOPING EXPERTISE THROUGH A COACHING CURRICULUM

Sam Gibbs offers suggestions on how to build an effective coaching curriculum to support teacher development.

LEADERSHIP EXPERIENCE

60. ARE TEACHER SIDE HUSTLES THE NEw NORMAL?

More and more teachers are taking on “side hustles” to make ends meet. But is it sustainable?

JANUARY 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 03 HWRK MAG AZINE .co. UK // INSIDE THIS ISSUE

P 06 P53 P24 P40 P37 @hwrk_magazine

@hwrk_magazine 10 // HWRK MAGAZINE // Last August, precisely half way through eating a cheese sandwich, Tabitha had a stroke. This January, She has returned to the classroom for the first time. Cheese sandwiches may or may not be involved (they absolutely are). Here is her handy eight-step guide to making your return to work from illness work for you. By Tabitha McIntosh HOw TO RETuRN TO wORk 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // FEATURE Step One: Accept that you have made life more difficult for your colleagues That thought that keeps you up at night your absence did indeed make life more difficult for everyone else. Supply staff had to be found in very difficult season for be moved around or swapped and duties re-allocated; other people took on your pastoral responsibilities, your mountain of marking, your relentless data deadlines and your bad jokes. You left a hole in the department. had to be worked around and stepped over. Occasionally things fell into it, never to be seen again. And here’s why that’s okay: it’s testament to the fact that you and the job you do are necessary. Step Two: Become your own embarrassingly positive therapist There’s famously cringe-inducing scene in ‘Good Will Hunting’ in which a therapist played by Robin Williams chants ‘It’s not your fault’ at Matt Damon’s tortured, blue-collar genius face until a breakdown and breakthrough of some kind happens and everyone lives happily when say that may be the most Hopeful, positive, fatuously affirming, and, above all, achingly sincere. your fault. That hole in the department into which half your Year 11 folders planning your colleagues had to scramble to complete? Not your fault. for your absence? Not your fault. You’re not weak. You’re not failure. It wasn’t your fault. It’s not your fault. Sincerely. Try telling yourself in an American accent if your usual one is too embarrassed. Step Three: Stay out of your work emails while you’re recovering You’ve been signed off for reason. you’re not fit for physical work, you’re absolutely not fit for intradepartmental emails either. Following Step One means accepting that your absence has made Following Step Two means that you have embraced this and moved beyond the guilt. Looking at your department’s emails will undo all your hard work. It’s one thing to know that you left hole in the resulting chaos happen in real time. You can’t do anything about what the Y9s said to the supply teacher just before the end of Period 5. You are powerless in the even try. Remember: It’s not your fault. your problem. Step Four: Keep the school up to date if you No one expects you to have predictable and convenient progress towards returning to the workplace. But everyone appreciates timeline if one is available. Depending on the reason for your rehabilitation and occupational health professionals who can communicate with the school for you. None of them will send any information that you haven’t seen and agreed to in advance: your privacy absolutely crucial to their work. have found enormously helpful to hand communication over to objective and impartial professionals who aren’t burdened with silly things like anxiety and guilt and the need to make self-deprecating jokes about 1990s Matt Damon films. Step Five: Arrange a phased return to work Congratulations! Everyone wants you back: the school wants you back, the government wants you back, and you sure that you come back and stay back is with a well-thought-through planned return to work shaped by professional input. Your medical treatment will built into it. The school will arrange an occupational health assessment for their own purposes. Programmes like Access while you continue to rehabilitate. The most important thing here is that you don’t trip yourself up with insecurity and misplaced sense of obligation. role you played before you left, you are very likely to bounce back out. You aren’t completely better yet. You aren’t where you were before your absence. And that’s fine. Say it with me: it’s not your fault. Step Six: Arrange to visit the school before your official return date Bostonian an accent you have told yourself that it’s not your fault, the first return to the building is going to bring all that guilt, insecurity and anxiety screaming back to life. It absolutely helps to have gone in and said hello to colleagues. It is also absolutely, brain-meltingly, existentially terrifying. chose to do it at a time when knew the swarming with teenagers and when most of the teaching staff would be in lessons. It might help to have someone meet you at the entrance and walk with you. You may instead choose to stalk, slink or perambulate of your choice. Either way: get in there. It helps. Step Seven: Start shadowing the school day In the final weeks leading up to your return to the classroom, you must begin the Herculean process of adjusting your circadian rhythms, your appetite and your Start going to sleep and waking up at the same time you would for school. Experiment with going out and staying out for the length commute, build that into your experimental work day, but reward yourself with destination more relaxing than Friday afternoon classroom on windy day. One of the milder circles of hell for example. Step Eight: The most difficult step Accept yourself. I’ve been Type One diabetic for two decades and thought had concerned, my erratic blood glucose peaks and troughs were delightful eccentricity akin to coin collecting or weaving one’s own socks (if sock-weaving necessitated the occasional trip to A&E). But having had stroke feels different. It has peeled my thick skin back to the vulnerable nerve endings that are exposed when you first find out that your illness chronic. That your condition is life-limiting. That you are never going to get better. The final step the most difficult because needs you to let go of that idea of ‘better.’ This is you. This is me. And I’m going back exactly as am.

CURRICULUM 4. Promote the practice of ‘book dialogue’ Train students to have an ongoing conversation with their exercise book. This means that they are in the habit of writing notes and commentary in the margin of their exercise book as they go along. 5. Insist that the piece of writing isn’t the point – it’s all about the ongoing craft Highlight the idea that they aren’t working on a piece of writing, but themselves as writers The work in their book is their working memory externalised, not a shiny, polished, finished piece. Ensure that each shorter writing task pulls through to thread of skill development. These two steps are critical and inextricably linked to one another. A piece of student writing is NOT perfect, publisher-ready manuscript which should be put on pedestal. The process of writing itself is generative and messy. liken writing to painting or clay modelling students need to see that you have to make mess, make errors, cross out and reflect on your work at intervals in order to craft something effective. A beautiful tidy book is not the endgoal, here. An exercise book is: - A space to work out problems - A space to try out techniques - A space to jot down ideas, externalising them and extending your working memory capacity so that you can build and develop your thinking. - A space to draft, reflect and re-draft To get students thinking like this, we need to change their mindset about their writing. This is what did in this English Book dialogue: - After their first drafted piece of writing, asked students to highlight the sentence they were least happy with and write comment in the margin about why. - I them to do the same for two sentences AND word choice they were unsure about. - During the next draft, ask students to just make any notes about uncertainty or challenges they experience in the margin as they go. model this under the visualiser, and show them, for example, how might highlight margin to show that want to come back to it because I’m not sure it’s the right choice. - Over time, I built this into a consistent part of their writing – students didn’t need to be asked to do this by the end of the unit, because they were doing it automatically. Ongoing craft: Over the course of the unit, was aiming for students to develop one or two really strong pieces of writing. This might have become repetitive or static, had not been about writing short pieces and then tying things together and synthesising their shorter pieces. This is what mean… Writing task 1: A short, literal description of scene as depicted by a photograph they had brought Writing task 2: Taking and transforming it into gothic description by changing specific elements of lighting and temperature. Writing task 3: Looking at a model exposition (the opening ), and then reflecting task 2 and how it might be improved to create more compelling atmosphere. Writing task 4: Students looked at pathetic fallacy as technique, and wrote paragraph using pathetic fallacy. They then found way to combine this with their work from They reflected on things they should keep, things to discard and things they might want to introduce in order to make those two pieces of writing work together. This is just short example of how this might work from one piece to another in continuous thread. This is something which we sustained across the whole unit, so that students could develop ideas from one piece to the next, but also introduce new ideas and experiment with new things. Fundamentally, creative writing requires firm foundation of knowledge, paired with the mindset of someone with over their own work. By giving students excellent explicit instruction in areas of key knowledge, and demonstrating high level models and processes, we provide the base. But this knowledge alone is nothing. Students must take that knowledge and have the confidence to play with language, make choices, change those choices and see themselves as writers. It is so easy for writing instruction where the teacher models and students mimic. However, when we have an open dialogue about choice and self-regulation, our young people actually become writers.

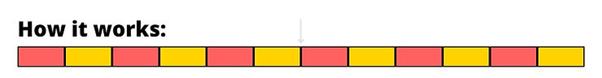

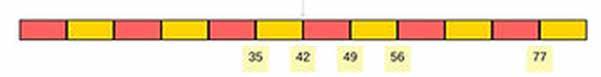

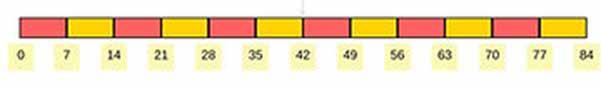

It’s true to say there has been nothing short Career Framework (ECF), which provides teachers in their induction period with statutory entitlement to weekly coaching or mentoring, has contributed to this. Developing expertise through A CoAChing CurriCulum Sam Gibbs explores what is meant by coaching, which can mean different things to different people, while offering suggestions on how to build an effective coaching curriculum to support teacher development. We have seen the production of plethora of rising enthusiasm for instructional coaching. Many schools are keen to utilise its many benefits, to the point where it can sometimes seem like it is taking place in every school. But of course, teacher coaching is nothing the current bandwagon, therefore, we need – like with any promising approach in education to carefully consider the purpose and the implementation. LEADERSHIP dEvEloping ExpErtisE through a CoaChing CurriCulum CURRICULUM By Jon Bee Multiplication times tables are too important to be left to chance. A clear, systematic approach is needed across school in order to support all children to recall times tables facts, both quickly and reliably. Children need to be fluent with multiplication times tables in curriculum. Without fluency and quick recall of multiplication unconnected and confusing. Sounds of ‘I can’t do Maths’ may ring out around our classrooms. Leaving times tables to chance will curriculum. So how might we teach children multiplication facts so that and fluently and to recall them in order to access the curriculum? Enter: the counting stick. Counting sticks are not new to classrooms, but reimagining their The counting stick should be held in the middle to anchor the times tables facts (shown by an arrow in the image below). Jon Bee discusses the pros and cons of using counting sticks to teach multiplication times tables how i woulD teACh multipliCAtion times tAbles tEaChing timEs taBlEs By Louisa Smith idea what was doing, whether it would work and didn’t conceive that 2 years later would still be doing it, and that people would value it. All knew was that, after 20 years in the classroom, wanted my teaching day job. In short, The RE Podcast has changed my life. It has given me purpose, it’s improved my teaching, it’s reinvigorated my passion for education and RE, and it has connected me with so many humbled and privileged. As approach my 100th episode, am naturally reflecting on what has been created and what have learnt. Obviously have learnt how to do podcast, how to edit it and how to promote it! had to learn from scratch! But on personal note, have learnt that am better than people told me was. It feels like this is what was fears and challenges but it uses all my skills am natural communicator, am an extrovert, and am total geek. am also not a details person - I creating the podcast never causes religious Education unnecessarily high expectations, and don’t mind if it’s not perfect. Things just sort of fall together. am really good at time management and organisation but not in way that stifles creativity. past for not being tidy, but think this is key to my success if was too organised, would not be able happy to have an untidy house, am happy to interview someone when haven’t had time to research fully because have developed skills throughout my life to adapt when things don’t quite go to plan. Louisa Smith is the host of The RE Podcast. In this article she shares some of the most interesting things she’s learnt… whAt i’ve leArnt From reCorDing 100 re poDCAsts

i’vE lEarnt from rECording 100 rE podCasts LEADERSHIP senior leader berating staff for booking something the hall on the day he wanted leaders and saying they just don’t care about the job that much …the list could go on. This barely touches comments suggest these people should just put their head down and get on with because might be worse somewhere else outweigh the negative. But that doesn’t positive culture not good enough. No teacher should go to work worried about The negative impact of toxic culture Let’s look at positive culture and invested in, and who want to try things out because they want the best education for their pupils. Positive workplace cultures vision and purpose. Nobody feels unsure about the reaction they’ll get they suggest something new. Ultimately, the culture of school starts and the temperature the current culture in to play in ensuring the culture ticks along, but the leaders are responsible for setting the tone and working with any bad eggs on don’t think I’ll shut up about this until stop hearing wild stories of leaders on power trips who have cultivated negative deliberate choice. Finally, you do find yourself toxic environment, please know that there are

ExaCtly is sChool CulturE? P46

CrEativE Writing and sElf-rEgulation

What

What

CONTRIBUTORS

WRITTEN BY TEACHERS FOR TEACHERS

Saira Saeed

@SafeSENCOSaeed

Saira (better known as Miss Saeed) is an experienced Secondary School practitioner who has been teaching English for the last 17 years. She has also taught PSHE and RE for some of those years. As an accomplished DSL and SENCO, Saira specialises in all things Safeguarding and SEND.

Amarbeer Singh Gill

@SinghAmarbeerG

Amarbeer Singh Gill (or Singh as he’s more commonly known) is a teacher educator for Ambition Institute, former lead practitioner of secondary Maths, and author of Strengthening the Student Toolbox “In Action”. You can read more about his thinking on his blog: www.bit. ly/UnpackingEducation

Jennifer Webb

@FunkyPedagogy

Jennifer Webb is an English teacher, Assistant Principal for Teaching and Learning, and Research Lead at Trinity Academy Cathedral in Wakefield. She is the best-selling author of: How to Teach English Literature: Overcoming Cultural Poverty (2019), Teach Like a Writer (2020) and The Metacognition Handbook (2021). Her new book, Essential Grammar, co-authored with Marcello Giovanelli, will be published by Routledge in June 2023.

Andrew

Atherton

@__codexterous

Andrew Atherton is a Teacher of English as well as Director of Research in a secondary school in Berkshire. He regularly publishes blogs about English and English teaching at ‘Codexterous’ and you can follow him on Twitter @__codexterous

Louisa Smith

@TheREPodcast1

Louisa is a secondary RE teacher with 21 years experience. Head of Life Skills, host of The RE Podcast, Teacher Hug Radio presenter, mum of two. Born in Brighton. Live in West Sussex. Teach in Surrey.

Jon Bee

@mrbeeteach

John Bee is a Primary Deputy Headteacher, Maths leader and Author, based in the North-East of England. He also runs MrBeeTeach.com, a resource website, which is aimed at helping primary-age students to develop their knolwedge and understanding of Maths.

Shannen Doherty

@MissSDoherty

Shannen is a Senior Leader and classroom teacher at a primary school in London. She loves all things Maths and enjoys getting nerdy about teaching and learning. Shannen’s debut book, 100 Ideas for Primary Teachers: Maths, came out in May 2021.

Tabitha McIntosh

@TabitaSurge

Tabitha McIntosh is an English teacher and KS5 subject leader at a Greater London comprehensive. She is also Type 1 diabetic, dangerously over-educated and terminally online

Adam Woodward

@adamjames317

Adam is the Director of Studies at Radnor House School, Sevenoaks. His passions within education lie in curriculum and teacher development as well as his own personal drive to becoming a better practitioner

@samlgibbs1

Sam Gibbs is Trust Lead for Curriculum and Development at The Greater Manchester Education Trust. She is an experienced English teacher, school leader, teacher educator and coach who has worked with schools across the country on teaching and learning, curriculum design and implementation, and instructional coaching. Sam is co-author of The Trouble With English and How to Address It: A Practical Guide to Designing and Delivering a Concept-Led Curriculum (Routledge: 2022).

@sherish_o

Sherish Osman is a Lead Teacher (in charge of research and development), and English teacher at a school in West London, as well as a mother to two boys aged 2 and 5. She is the MTPT Family Friendly Lead at her school, working on making the school more family friendly with their policies for parents. Sherish is also the Design Associate for Litdrive, as well as the Educational Content Creator for Lantana Publishing.

hwrkMAG A zine.co.uk // M ee T T he T e AM

Sherish Osman

Sam Gibbs

Legal Disclaimer: While precautions have been made to ensure the accuracy of contents in this publication and digital brands neither the editors, publishers not its agents can accept responsibility for damages or injury which may arise therefrom. No part of any of the publication whether in print or digital may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission of the copyright owner.

HWRK MAGAZINE

LTD 48-52, Penny Lane, Liverpool, L18 1DG, UK E: enquiries@staffroommedia.co.uk T: 0151 294 6215

EDITOR Andy McHugh PUBLISHING DIRECTOR Alec Frederick Power DESIGNER Adam Blakemore MANAGING DIRECTORS G Gumbhir, Alec Frederick Power

PUBLISHED BY STAFFROOM MEDIA

thE PowEr of Saying “no”

Want something done?

Ask a busy person.

Being “busy” is something I’m known for and to some degree I’m proud of it. Saying “no” doesn’t come naturally to me. I’m not sure why. Perhaps it’s because I don’t want to miss out on the latest thing, or because I don’t want to disappoint someone who has asked for my help. But the problem is that over time it can lead to overwhelm and, crucially, opportunity-cost.

So, to counter this problem, when planning the goals for my department over the coming months, I’m keeping three questions in mind:

(1) what will I keep doing?

(2) what will I adapt?

(3) what will I stop doing?

You might have noticed that I don’t have “What should I start doing?” in my list of questions. This isn’t because it’s unimportant, it’s because it’s a highly problematic question. It’s risky, as “adding more” can take me away from the core priorities of my role, spreading my time too thinly. There is also an underlying and toxic tone of “you’re not doing enough” that accompanies the question and it’s one major reason why many teachers burn out and sadly leave the profession that they should thrive in. But these aren’t actually my primary concerns. What I’m much more

mindful of right now is that if I take on another “thing”, it leaves less time for me to do other “things” that are also valuable, or might even be more valuable.

Now, those of you with your “strategic leadership” hats on might do a quick analysis of which activities provide the most value to you, rank-ordering them and binning the least useful ones. It’s an effective way to begin tackling your needlessly-crippling workload and it frees up your capacity to pursue more worthwhile goals. It’s not enough though.

How can we make time for those activities that bring excellent value, but which we aren’t already aware of?

If I delete my least productive tasks and replace them with more productive ones, this increases my effectiveness, to a point. But If I’m then operating at capacity, I will miss opportunities to do things that I routinely turn down, due to being “too busy” - even if they would provide exceptional value.

How many times have you turned down going to an event, running a club, planning a trip, or organising a guest speaker, because you just don’t have the time? I’d wager you probably did have the time, but instead, it was filled with some other activities that, when you look back on them, weren’t as impactful, or even necessary at all. And we all suffer from this, from Teaching Assistant all the way up to Trust CEO.

This absence of “slack” in the system prevents staff from having adequate thinking time, opportunities to try out things that may or may not work (but are still worth trying) and, yes, to occasionally work with slightly less intensity, between the frequent bouts of ultra-busyness we’ve all unquestionably become accustomed to, so that we can keep “going again” with gusto.

In my opinion, if we’re going to be serious about dealing with the retention crisis in teaching, we need to address this personally, not just systemically. If we don’t individually get our own houses in order, where we can, then what hope do we have that others will too?

So, from this January, why not try saying “no” more often. It seems like a good way to get more done, sustainably and with a positive impact on your own well-being. It’s a start at least.

I’ll still be super-busy, but I’ll also be happy, doing “better” things, sticking to my core purpose more closely and with the capacity to do more when that unmissable opportunity presents itself.

Andy McHugh Editor | HWRK Magazine

Editorial:

JANUARY 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 05 HWRK MAG AZINE .co. UK

Exploring BEhaviour: unmEt nEEds, Wants or somEthing in BEtWEEn?

By Saira Saeed

Having been on Twitter for a year, I have already lost count of the amount of Twitter debates I have read that centre on behaviour. I agree that most behaviour is a form of communication, however, what it is communicating is debatable. The term ‘unmet needs’ is widely used as a tool of criticism for numerous settings nationwide, which is simply unfair. If a student has unmet needs then it cannot and must not be assumed that this is deliberate on the part of the student’s setting. School leaders continue to face a plethora of battles in addition to the ongoing daily rigours of their jobs and sometimes they simply do not have the means, resources, facilities etc required to meet certain student needs.

Moreover, the Cost-of-Living Crisis is impacting schools, their students and their wider communities in drastic and heartbreaking ways. To add to the challenges, the process of either gaining the funds required to meet certain needs or find a more suitable setting for the student in question is time-consuming and emotionally draining for all involved.

This article highlights one particular facet of this challenge; not all poor behaviour in schools is due to a particular need being met/unmet by the school or its leaders. In fact, some of it is due to factors that aren’t fully in anyone’s control, hence can at best be managed and supported.

I intend to explore some of the things poor behaviour could potentially be communicating and then also suggest some strategies that could help. They are by no means ‘silver bullets’ for behaviour, but things to consider and/or try.

To note:

a.) This article is not an exhaustive list but provides ample food for thought.

b.) The case studies are based on true events but for GDPR purposes, key identifying factors have been concealed and (in some cases) events have been paraphrased rather than told verbatim.

@hwrk_magazine 06 // HWRK MAGAZINE // J AN u AR y 2023

Most behaviour is a form of communication, however, what the behaviour is actually communicating is debatable. But what should we do about it? asks Saira Saeed…

1. UnmeT need vs UnmeT WanT

This is arguably the most important factor to consider, as meeting the former usually has some statutory guidance and/or laws underlying them whereas this isn’t always the case for the latter. Notably, this does not mean that the latter is to be dismissed because some student wants are linked to their protected characteristics, thus making them as important as needs (think EDI and the Equality Act of 2010.)

Case study 1: A boy in KS4 started misbehaving as soon as he was moved to my class (lower ability set 4) and he had been moved as he was misbehaving too much in the class above mine (yes, there is lots wrong with this but let’s overlook that for now!) Initially, I tried many things but with no known needs and very little work (he barely wrote anything out of defiance) I was struggling to get him to behave. During a detention, I directly asked him what he wanted. “I want to be in set 2 Miss. I ain’t being rude but this ain’t my set.”

Whether right or wrong, I set him an exam question in my next lesson; in light of his answer corroborating with his claim I successfully utilised it to get him moved to set 2. He genuinely transformed into one of the best behaved and best attaining students in the set he was moved to. Was I meeting a need or a want? A bit of both, I think it would be fair to say.

Case study 2: A girl in KS3 began misbehaving for seemingly no reason and made a point of trying to be the class clown on any given occasion. This threw me, as this was completely out of character for her. I did not waste time in speaking to her and learnt that she was trying to impress a new boy who had joined our school and my class a few weeks earlier. When I asked the girl if her friend was correct, she nodded and apologised.

We then had a talk about many things including priorities and how to impress people without breaking school rules or behaving inappropriately. For those of you wondering, he had a girlfriend at his last school whom he was very loyal to so alas my young student’s efforts had been in vain! An unmet need? No. An unmet want? Absolutely.

2. medical needs

Medical needs are something that I personally feel aren’t given sufficient focus in staff CPD bar the statutory annual Asthma, Allergies, Epilepsy and Diabetes sessions delivered by a team of NHS nurses. This lack of focus serves to worsen medically triggered instances of behaviour, as staff won’t be equipped with the knowledge requisite to prevent these instances from occurring nor the skills to manage them when they do.

Case study 1: A severely asthmatic child in KS3 was on steroid tablets, which caused weight gain, thus impacting his self-esteem. This is turn made him extremely self-conscious, which manifested as sudden bouts of unprovoked anger.

Case study 2: A teen was misbehaving in a seemingly deliberately defiant manner. Upon liaising with her family, it was discovered that she had an eating disorder and was trying to curb her hunger pangs by drinking multiple cans of energy drinks a day, and was also seeking energy bursts via bags of sweets. These were making her extremely hyperactive, thus disruptive in lessons.

In both these case studies, the solution wasn’t straightforward nor quick, but in collaboration with the SENDCO who was also the medical lead, a comprehensive IHCP (Individual Healthcare Plan) was put together to help staff (and the student) manage their behaviour.

3. send

Undiagnosed SEND is a complex area, as it can take a very long time to identify it and subsequently seek out and provide additional support, resources etc that the student needs. In the interim, if staff aren’t aware of what to look for etc, students will suffer (the students displaying poor behaviour and their peers in their lessons.)

Case study 1: A student in KS3 had undiagnosed Speech and Language difficulties, which created multiple barriers to his learning; limited vocabulary, which in turn hindered his ability to articulate what he wanted to say, forgetting what he meant to say and lacking (at times) intelligibility so he knew what he was saying but few others understood. His understandable

frustrations manifested themselves in many ways ranging from low-level disruption to outright refusal to do anything.

This took a lot of work to address, as the student needed substantial external support amongst other things (securing speech and language therapy is no mean feat!) He was also an EAL learner, which added to the challenges faced by him (and my colleagues and I) when trying to develop his communication and interaction skills.

Case study 2: A KS5 student quickly became notorious; rude, running out of lessons, refusing to work, distracting peers amongst other similar behaviours. Upon liaising with her family and other teachers, I learned (in my capacity as SENCO) that they had asked for help from the setting for many years prior to my joining it, as they believed she was Autistic and because they had not been helped, they (and their daughter) had given up on the system.

This case was multi-faceted as it was a result of multiple issues; unidentified SEND, broken down relationships between a family, student and the setting, a student who’s behaviour was out of control and a set of staff who wanted to teach her (she was very bright) but didn’t want her in their lessons, as she was hindering the progress of her peers.

A number of actions took place collaboratively over a period of time but eventually a reduced timetable was put in place for her before she successfully completed her KS5 journey. Sadly, her needs weren’t fully met before she left but the processes for obtaining an Autism diagnosis had been initiated so that they could be in the next stage of her life. This wasn’t an ideal outcome but the best that could be done in light of the legacy attached to it.

4. safegUarding

Safeguarding is a complex area riddled with an increasing number of barriers to detecting potential abuse, neglect and the like. A clear and consistent set of processes including an effective system of information-sharing is required (as per the ‘Keeping Children Safe in Education’ 2022 DfE guidance) in order to ensure that no child ‘slips through the net’ through being misidentified as simply a disruptive student.

HWRK MAG AZINE .co.u K JAN u AR y 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 07 FEATURE

Case study 1: A student in KS4 was seemingly always disengaged in my lessons and rarely handing in homework (with the repeated excuse that she ‘forgot’ or ‘was busy.’) Upon investigation, my colleagues and I learned that she was in fact a young carer with a very sick mother (single parent) and younger siblings whom she was practically mothering. The support she required was beyond my classroom but safe to say, I adapted my approaches when teaching her (leniency with homework deadlines, checking on her regularly in my lessons when circulating my class and so on.)

Case study 2: A KS3 student misbehaved for me repeatedly: defiance, distracting others, being completely disengaged in every lesson etc. I learned, at a Parents’ Evening meeting with his father (who was a single parent) that the student had been abused by his mother for the first half of his life and I – unfortunately – looked VERY similar to his mother. That was it.

The student and I had a very long meeting with his father (the DSL was involved too) but he was eventually removed from my class because he continued to disrupt the learning of the rest of my class and my colleagues and I were also worried that him seeing his mother’s lookalike might be triggering for him (upon reflection, it probably was.) Not everyone will agree with the outcome of this case study but sometimes, the only feasible strategy is what happened with this student.

5. cUlTUral impacT

I could give umpteen case studies here. For instance, in many cultures (especially South East Asian) it is deemed exceptionally rude to make eye contact with an elder who is reprimanding you. It is also no secret that a child being identified as SEND is stigmatised in a number of cultures, hence some families may actively hinder settings from identifying their children as SEND learners and seeking out external support for them. In light of this, I would highly recommend doing your research; reach out to friends, colleagues and community leaders (you could even politely/ sensitively ask questions on social media platforms like Twitter) to learn more about the cultural communities your students are a part of.

suggested strategies:

1. Do not be afraid to ask for help; it is NEVER a sign of weakness/being an incompetent practitioner. I have been teaching for over 17 years and I will still

happily seek out strategies/advice if one of my colleagues has better control of a certain class than I do! Additionally, do not worry if you feel you are the only member of staff struggling with a certain student/class and/or asking for help. I can almost guarantee that you won’t be the only one experiencing this; it is more likely that you are the only staff member seeking help for it.

2. NEVER, EVER take poor behaviour personally. It is upsetting, may make you cry/angry etc (and that is completely valid) but you do not get paid to take it home with you nor to waste energy harbouring ill feelings towards anyone. Moreover, the student/s in question may not even give it a second thought after they have left the school gates, so why should you? Lastly, as covered in this article, the poor behaviour may have been a result of factors that have no malice attached to them at all and may even be a cry for help.

3. This next point feels like a case of grandma and sucking eggs but if you find yourself getting increasingly agitated that student x has an attitude problem, or an issue with teachers of a certain gender, or is just rude because they won’t look at you when being reprimanded then take a step back, breathe and inquire why (this may need to be done later and not at the time of the poor behaviour occurring.)

4. If the poor behaviour is impacting your lesson to the extent where it is stopping

you teach then for that instance, remove the student but do follow it up later. Every school I have ever worked in had a faculty buddy system of some sort whereby colleagues could send a student to a colleague’s classroom as part of a de-escalation process.

5. Information seeking is absolutely paramount and where appropriate and possible, converse with the student directly but if not then do liaise with your HoD, SENCO, DSL, etc as required. Context can be a real eyeopener!

6. Don’t be afraid to reprimand, as required. Yes, a number of the case studies above highlight that some poor behaviour isn’t deliberate but that doesn’t mean you don’t consistently follow your setting’s behaviour policies.

One of the best behaviour policies I have ever seen in a setting was unbelievably simple (yet still humane) but it worked because all staff were empowered and supported in applying it consistently and fairly in their lessons (as well as during duty at unstructured times.)

7. Establish good relationships with parents; they are a knowledgeable and powerful ally! Some of the trickiest students I have ever managed to successfully deal with had parents who supported me and reiterated my expectations at home.

@hwrk_magazine 08 // HWRK MAGAZINE // J AN u AR y 2023

Key consideration point: HQT (the concept formally known as QfT.)

As tempting as it is to list a set of strategies that will solve all behaviour management issues (eg doing X for learners with SEND or doing Y for students who have tough home lives etc), there is no simple quick fix.

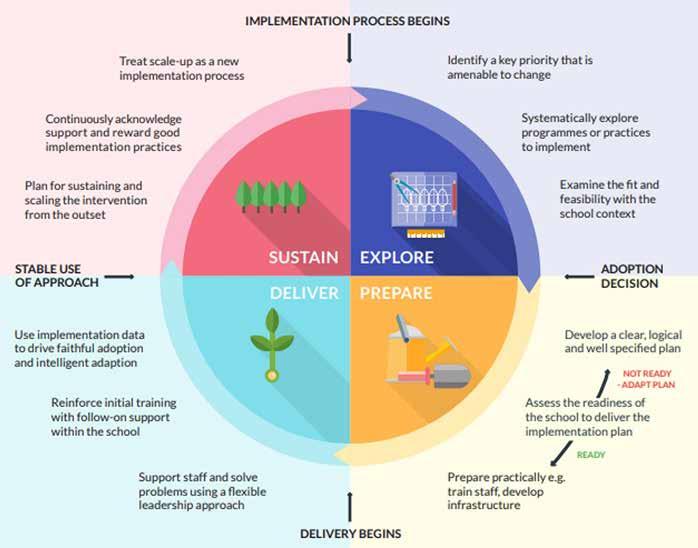

A culture is needed where all of the areas listed above are taken into consideration when planning the intent, implementation and impact of the curriculum.

Acknowledging SEND and Safeguarding in tokenistic CPD sessions for staff, having sporadic curriculum drop-down days for students or inviting parents to tick-box coffee mornings will not suffice. These areas of education need to be threaded through the culture of any given setting in order for that setting’s curriculum to truly to be inclusive.

truly High-Quality Teaching; confident practitioners who feel valued and trusted to deliver a meaningful curriculum in a way that improves the learning experiences for all learners (not just SEND for example.) This in turn will make behaviour easier to manage, as there will be fewer opportunities for students to misbehave and when they do, staff will have ample knowledge and a broad range of strategies they can utilise to manage it.

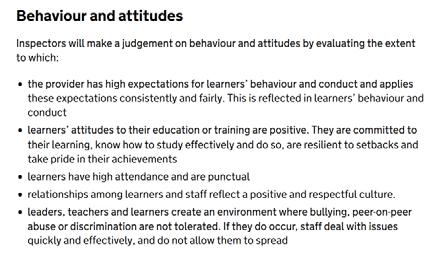

Admittedly, this is easier said than done and requires investment from all involved (teaching staff, support staff, SLT, students and their families) but it can be done. Yes, the status quo has added a plethora of challenges (budgeting and staff retention to name but two) but that does not mean all hope is to be lost. In fact, what Ofsted are looking for is inclusivity and safety for all, which is needed now more than ever before:

Moreover, staff then need to be given adequate CPD to empower them to deliver this inclusive curriculum via www.gov.uk/government/publications/education-inspection-framework/education-inspection-framework

end note

We can all agree that behaviour is complicated. Why? Humans are complicated, especially young ones who aren’t physically, emotionally and mentally developed, hence adequately equipped to deal with this gargantuan challenge we call ‘life.’ There are no quick fixes for every form of poor behaviour that you may encounter during your career in teaching. However, investigating and identifying underlying reasons for behaviour (even if it is a classroom crush!) will place any classroom practitioner in good stead to manage it as best possible without compromising the learning of others in your classrooms.

recommended reading

• Tom Bennett - ‘Running the Room: The Teacher’s Guide to Behaviour.’

• Paul Dix - ‘When the Adults Change, Everything Changes: Seismic shifts in school behaviour’

• Rob Potts - ‘Caring Teacher: How to make a positive difference in the classroom.’

• Andrew Hall - ‘Safeguarding Handbook.’

• Stephen Lane - ‘Beyond Wiping Noses: Building an informed approach to pastoral leadership in schools.’

• Maria O’Neill - ‘Proactive Pastoral Care’

• Samuel Strickland - ‘The Behaviour Manual: An Educator’s Guidebook’

• SAPHNA Eating Disorder Toolkit - https://saphna. co/homepage/toolkits/eating-disorder-toolkit/

• DfE Guidance:

- Safeguarding: https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications/keeping-children-safe-in-education--2 - Medical: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ supporting-pupils-at-school-with-medical-conditions--3

- Looked After Children: https://www.gov.uk/ government/publications/promoting-the-health-andwellbeing-of-looked-after-children--2

HWRK MAG AZINE .co.u K JAN u AR y 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 09

How To ReTuRn To woRk

By Tabitha McIntosh

By Tabitha McIntosh

Last August, precisely half way through eating a cheese sandwich, Tabitha had a stroke. This January, She has returned to the classroom for the first time. Cheese sandwiches may or may not be involved (they absolutely are). Here is her handy eight-step guide to making your return to work from illness work for you.

@hwrk_magazine 10 // HWRK MAGAZINE // J AN u AR y 2023

Step One: Accept that you have made life more difficult for your colleagues

That thought that keeps you up at night is correct. There’s no way around this: your absence did indeed make life more difficult for everyone else. Supply staff had to be found in a very difficult season for recruitment and budgets. Classes had to be moved around or swapped and duties re-allocated; other people took on your pastoral responsibilities, your mountain of marking, your relentless data deadlines and your bad jokes. You left a hole in the department. It had to be worked around and stepped over. Occasionally things fell into it, never to be seen again. And here’s why that’s okay: it’s a testament to the fact that you and the job you do are necessary.

Step Two: Become your own embarrassingly positive therapist

There’s a famously cringe-inducing scene in ‘Good Will Hunting’ in which a therapist played by Robin Williams chants ‘It’s not your fault’ at Matt Damon’s tortured, blue-collar genius face until a breakdown and a breakthrough of some kind happens and everyone lives happily ever after. I’m speaking as an American when I say that it may be the most American scene ever committed to film. Hopeful, positive, fatuously affirming, and, above all, achingly sincere.

You need some of that. Because it’s not your fault. That hole in the department into which half your Year 11 folders have disappeared? Not your fault. The planning your colleagues had to scramble to complete? Not your fault. The reason for your absence? Not your fault. You’re not weak. You’re not a failure. It wasn’t your fault. It’s not your fault. Sincerely. Try telling yourself in an American accent if your usual one is too embarrassed.

Step Three: Stay out of your work emails while you’re recovering

You’ve been signed off for a reason. If you’re not fit for physical work, you’re absolutely not fit for intradepartmental emails either. Following Step One means accepting that your absence has made life more challenging for your colleagues. Following Step Two means that you have

embraced this and moved beyond the guilt. Looking at your department’s emails will undo all your hard work. It’s one thing to know that you left a hole in the department. It’s quite another to read the resulting chaos happen in real time. You can’t do anything about what the Y9s said to the supply teacher just before the end of Period 5. You are powerless in the face of Alex in Year 7s lost blazer. Don’t even try. Remember: It’s not your fault. Or your problem.

Step Four: Keep the school up to date if you can

No one expects you to have predictable and convenient progress towards returning to the workplace. But everyone appreciates a timeline if one is available. Depending on the reason for your absence, you will be seeing medical, rehabilitation and occupational health professionals who can communicate with the school for you. None of them will send any information that you haven’t seen and agreed to in advance: your privacy is absolutely crucial to their work. I have found it enormously helpful to hand communication over to objective and impartial professionals who aren’t burdened with silly things like anxiety and guilt and the need to make self-deprecating jokes about 1990s Matt Damon films.

Step Five: Arrange a phased return to work

Congratulations! Everyone wants you back: the school wants you back, the government wants you back, and you want to be back. The best way to make sure that you come back and stay back is with a well-thought-through planned return to work shaped by professional input. Your medical treatment will have occupational health assessment built into it. The school will arrange an occupational health assessment for their own purposes. Programmes like Access to Work can help with the commute while you continue to rehabilitate. The most important thing here is that you don’t trip yourself up with insecurity and a misplaced sense of obligation. If you try to step back completely into the role you played before you left, you are very likely to bounce back out. You aren’t completely better yet. You aren’t where you were before your absence. And that’s fine. Say it with me: it’s not your fault.

Step Six: Arrange to visit the school before your official return date

No matter how well, how often, or in how Bostonian an accent you have told yourself that it’s not your fault, the first return to the building is going to bring all that guilt, insecurity and anxiety screaming back to life. It absolutely helps to have gone in and said hello to colleagues. It is also absolutely, brain-meltingly, existentially terrifying. I chose to do it at a time when I knew the entrance and playgrounds wouldn’t be swarming with teenagers and when most of the teaching staff would be in lessons. It might help to have someone meet you at the entrance and walk with you. You may instead choose to stalk, slink or perambulate in the otherwise self-conscious manner of your choice. Either way: get in there. It helps.

Step Seven: Start shadowing the school day

In the final weeks leading up to your return to the classroom, you must begin the Herculean process of adjusting your circadian rhythms, your appetite and your bladder. You need to be re-institutionalised. Start going to sleep and waking up at the same time you would for school. Experiment with going out and staying out for the length of your usual school day. If you have a long commute, build that into your experimental work day, but reward yourself with a destination more relaxing than a Friday afternoon classroom on a windy day. One of the milder circles of hell for example.

Step Eight: The most difficult step

Accept yourself. I’ve been a Type One diabetic for two decades and thought I had stopped internalising ableism. As far as I was concerned, my erratic blood glucose peaks and troughs were a delightful eccentricity akin to coin collecting or weaving one’s own socks (if sock-weaving necessitated the occasional trip to A&E). But having had a stroke feels different. It has peeled my thick skin back to the vulnerable nerve endings that are exposed when you first find out that your temporary sickness is permanent. That your illness is chronic. That your condition is life-limiting. That you are never going to get better. The final step is the most difficult because it needs you to let go of that idea of ‘better.’ This is you. This is me. And I’m going back exactly as I am.

HWRK MAG AZINE .co.u K JAN u AR y 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 11 FEATURE

PEDAGOGY

16. Designing Knowledge Organisers

How to create effective knowledge organisers with a strong rationale behind them

hwrkMAG A zine.co.uk JA nu A r Y 2023 // hwrk MAGA zine // 15

Designing Knowle D ge o rganisers

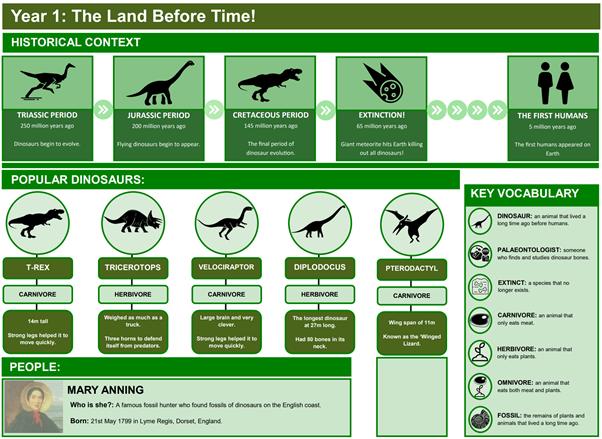

In my previous article, I spoke about the research behind memory and retaining information in relation to the implementation of knowledge organisers within the primary classroom. Below, I move on to explain how I have created knowledge organisers for my school and explain the rationale behind them and the “dos and don’ts”regarding their creation, ensuring that the benefits of them provide children with the perfect platform to retain and retrieve core knowledge around a subject.

By Adam Woodward

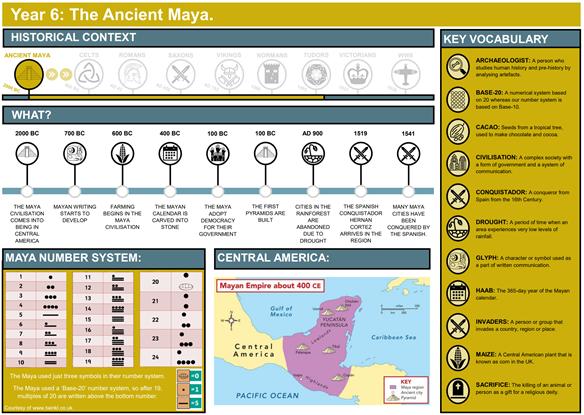

When implementing knowledge organisers as one form of retrieval practice in my school, it was important that teachers did not feel overwhelmed with their introduction. Therefore, I began this process with the Humanities subjects of History and Geography. They are the backbone to the primary curriculum, and this seemed like a logical place to start to be able to develop their implementation as a form of planning for curriculum progression across the school.

An important part of the process when creating knowledge organisers is that it begins and ends with the

class teacher. The first step that is taken is to ask class teachers what the key knowledge is that is included within their unit. These conversations occur in plenty of time before a unit begins and teachers provide this information, including any diagrams, maps or case studies that they want to include.

I spend the time creating these, making sure that links are made with prior units in conjunction with our Humanities lead. The class teacher, in liaison with our Humanities lead, then has the final say on the design for use in their classes.

The focus, during creation needs to revolve around the identification of key elements of knowledge required during a unit. These include (but are not restricted to) the inclusion of key dates, events, people and vocabulary. It is important to make links back to prior learning as part of a progressive curriculum model that builds upon the learning that has taken place in the unit, term or year before.

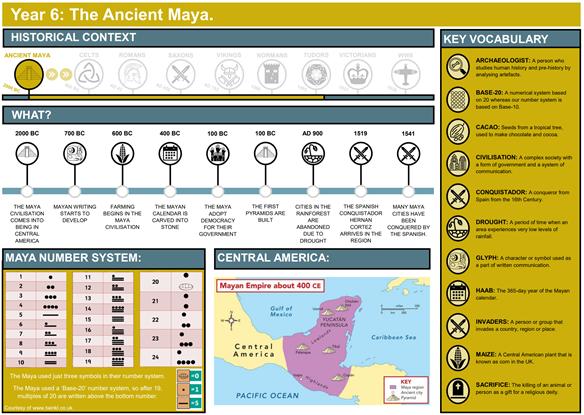

An example of this can be found in our History knowledge organisers where a ‘historical context’ section can be located. This section purposefully links back to periods of history previously covered within the curriculum.

@hwrk_magazine 16 // HWRK MAGAZINE // J AN u AR y 2023 PEDAGOGY

This example clearly shows children where this unit is located in relation to other units covered from the Celts through to the end of World War II. This unit is purposefully placed after our World War II unit for pupils to see the consequences of the war on the population.

In my school, I am responsible for the creation of these. It is a huge task initially, and I am fortunate to be in a position where I have time to be able to do this. I also understand that context is key and not all teachers have this benefit. However, I feel that it is important to ask the question ‘Why not give full autonomy to class teachers?’

There are three reasons why I have taken this task upon myself

1. Workload

Asking teachers to create their own knowledge organisers adds extra work on teachers who work

incredibly hard. With this added expectation, there is a chance that their creation could end up at the bottom of a ‘to do list’ pile and not created to a standard that children would benefit from, therefore making their use and application redundant. By investing the time that I have available in creating these, I can relieve this workload and support class teachers in implementing knowledge organisers, entwined with other forms of retrieval practice, into their curriculum with purpose.

2. ConsistenCy

I can make sure that there is clear progression across the school. One example of this is the use of dual coding within a knowledge organiser. Whenever a key word or vocabulary choice appears, the same icon is used across the school, so children are exposed to and reminded of the context of that word or period of history. If teachers

were responsible for the creation of their own knowledge organisers, there is the chance that different icons could be used in different organisers, thus not forming such a secure schema.

3. Quality Control

I have felt it important that each follows a similar structure, layout and organisation. For children, this breeds confidence as they know what to expect and recognise from knowledge organisers throughout their time in school.

However, as I stated previously, I am in a fortunate position of having the time to be able to create these. For other contexts, and to meet the reasons that I state above, the creation of a school-wide ‘working party’ could ensure that workload, consistency and quality control are all managed across the school.

J AN u AR y 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 17 HWRK MAG AZINE .co.u K PEDAGOGY

Above is an example of a knowledge organiser for a Year 6 History unit. Most importantly is the historical context and where that period of history falls within other units that have been taught. For this example, Year 6 are going ‘back in time’ to a period in world history after covering elements of most of the other periods identified in this section.

Key vocabulary is clearly vital too. I have already mentioned the necessity of dual coding as a key part of the knowledge organisers that I create and this is visible here (as it is within the historical

context too). An example of the importance of dual coding is the icon used to demonstrate the word, ‘Invaders.’ This same image can be seen in other knowledge organisers containing the same word, including the use of it within our Anglo Saxons unit for Year 4. Key vocabulary choices are made to be included here but clearly not exhaustive. There isn’t enough room to include everything and, if I did, it would distract from other key areas of the unit.

With the timeline of key events, it is vital for most historical units to show the progression of a period of

history. Again, note the use of dual coding. Some icons can be identified in both the timeline and vocabulary and this is done purposefully for children to be able to identify links here.

Other important visuals including maps of key areas, and, in this case, an image of the Maya number system, add more visual detail to the unit and vital elements of knowledge for children to use and apply in their learning.

@hwrk_magazine 18 // HWRK MAGAZINE // J AN u AR y 2023

PEDAGOGY

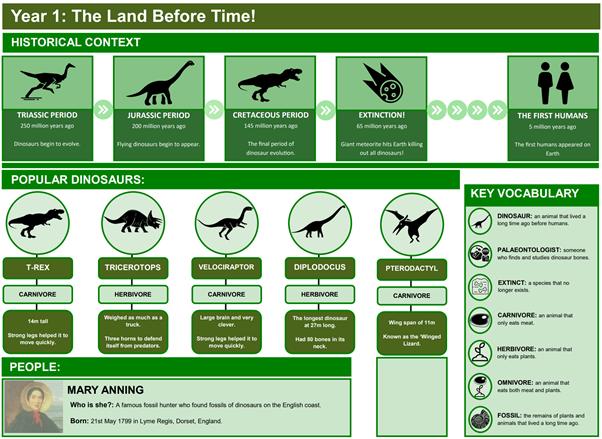

There is a discussion as to whether knowledge organisers are applicable to KS1 children and what they can gain from them. For me, there are many reasons why they have a place in a KS1 classroom as much as they do elsewhere.

Firstly, there is the need for all schools to have high expectations of children, especially those of a younger age. By providing examples for KS1, we are increasing the expectations of how we want children to access their learning. By providing this expectation early on, children also have the opportunity to become familiar with the structure and layout at an early age. There should not be anything on here that won’t

be covered during the unit itself so there is nothing that children won’t eventually become familiar with, regardless of what year they are in. Note the use of high order vocabulary – palaeontologist for example. This is not an oversight. Whilst it is not expected that the children know how to spell the word from memory, what we should expect is for an understanding of what a palaeontologist is and their role within the unit.

Explanations need to be clear, however, so that children are not overloaded with lots of information. Working memory is limited and so the inclusion of just the vital elements of the unit is important

here. As is the inclusion of dual coding theory, similar to other knowledge organisers. There is a need for more examples of this to be included in younger year groups so that children are able to make more visual links. Therefore, a more visual experience, but one that still has a place and a purpose within the curriculum.

As has already been stated (but cannot be overstated), knowledge organisers support teachers in the classroom when it comes to planning, teaching and assessment. However, children need to be given the opportunity to engage with them.

J AN u AR y 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 19 HWRK MAG AZINE .co.u K PEDAGOGY

*Focus on vocabulary – what do you want children to retain? Make sure that the definition is in child speak as the word in isolation means nothing.

*Share them – make sure that knowledge organisers are not just tucked away and forgotten about. Refer to them regularly and increase their importance through regular retrieval practice.

*Refer to prior learning – as with all retrieval practices, there should be regular opportunities to refer to prior knowledge from units taught across the school. Make sure that children see the links and the purpose for what is being taught. This can be achieved in many forms like links to historical concepts or the effective use of dual coding on a knowledge organiser.

One way of supporting this outside the classroom is by sharing them with parents. The way that we have done that is by sending these to parents via our school bulletin with a pre-amble as to what they are and how they can be used effectively to support the learning of the children. We also state how parents can be supporting the acquiring of key knowledge with their children.

Sharing these at home also promotes revision techniques and independent study as we ask for these to be printed and pinned to the fridge or bedroom wall with the hope that discussion around the dining table can also be had. In a world dominated by screens and digital media, we see this as a great way for families to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of a unit together.

As with anything, the impact of knowledge organisers in the primary classroom is only as successful as how they are used and applied. I have compiled some quick ‘dos and don’ts’ when creating and implementing these to provide a useful guide for their use.

*Ensure consistency – I have made the decision to create all of these for my school, but there isn’t a reason why a working party couldn’t produce something of a similar quality. What is important is that everyone involved in the process is aware of what should be included. *Include an overload of information – keep the information important and key. You cannot include a whole unit’s knowledge on a knowledge organiser so keep it important. If there is too much information, the organiser itself becomes a distraction.

*Think that sticking into books is enough – it is a common downfall of the knowledge organiser. They are stuck in books and forgotten about. Make sure that they are referred to and acknowledged regularly.

*Let children use them in retrieval tasks – for children to get the most from knowledge organisers and to be taking in the information from them, when they are quizzed, by having access to them, children are not remembering key information, but are just copying what has been produced for them. You will only know the impact that a knowledge organiser is having when it is not available for children to use.

*Differentiate them – apart from the obvious workload issue, all children should be able to access a knowledge organiser no matter their ability or SEND need. As the organiser contains all of the key knowledge for the unit, if you differentiate these, you are ultimately depriving some children from access to key knowledge that others would have available to them.

@hwrk_magazine 20 // HWRK MAGAZINE // J AN u AR y 2023 PEDAGOGY

do

t

don’

24. Creative Writing and Self-Regulation

How can we make a challenging task like creative writing more manageable? Jennifer Webb suggests some strategies to “shrink” it, to help students focus on what matters.

32. How I Would Teach Creative Writing For AQA

English Language Paper 1

Andrew Atherton offers his advice on how to get students started with creative writing when they don’t know how to begin.

37. What I’ve Learnt From Recording 100 RE Podcasts

Louisa Smith is the host of The RE Podcast. In this article she shares some of the most interesting things she’s learnt…

40. Teaching Times Tables

A winning strategy for teaching times tables

EXPAND YOUR MIND ONE SUBJECT AT A TIME JANUNARY 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 23 @hwrk_magazine

Creative Writing and Self-regulation

How can we make a challenging task like creative writing more manageable? Jennifer Webb suggests some strategies to “shrink” it, to help students focus on what matters.

By Jennifer Webb

By Jennifer Webb

Self-regulation is an act of awareness – being aware of: what you are doing; how you are doing it; why that is; actively considering how you might do it better, and adjusting your own behaviours accordingly. In The Metacognition Handbook, I defined self-regulation as: ‘the learner’s ability to plan, monitor and evaluate their own learning whilst completing the task itself (…) actively applying metacognitive knowledge in real time.’ (Webb, 2021)

The self-regulating student is the ultimate goal. They:

- know what success looks like

- know their own tendencies and weaknesses

- have a clear sense of what they are going to do

- are able to self-correct at the same time as doing a complex task

- take ownership of their learning and work output

The problem with creative writing:

1. Creative writing is creative. How can students have a ‘clear sense’ of anything when the final product is inherently creative and, as yet, undefined?

2. Writing is an extremely complex set of processes. How can students know enough of their own weaknesses when there are so many potential areas of the craft to work on?

3. ‘Success’ in this arena is, arguably, subjective.

These problems are real. Creative writing is a challenging term. We tend to use it in the English classroom to denote anything which is not a literature essay or piece of functional ‘transactional’ writing, such as an article or an advert. That is, anything which does not have a distinct purpose. This is difficulty because some might argue that ‘creative’ writing is the most purposeful of all – it transcends the

mundane everyday experience and functionality required to exist in the word and is, essentially, art. What could be more meaningful than that?

In my view, the only way to tackle the broad and infinite possibility of ‘creative’ writing is to shrink it so that it is classroom sized. This is not about limiting student ambition or putting a ceiling on their efforts. It is simply about selecting a small focus area and working at that in a conscious, deliberate way.

English teachers teach writing all the time. Writing is a skill we continue to hone, even when we are teaching something which is traditionally considered a ‘reading’ topic. Even when we teach a novel or a poetry unit, students will use writing as a servant strategy to develop their notes and thought processes, and also as a way to express their ideas in more formal academic writing. When teaching any kind of writing, I have a set structure.

CURRICULUM @hwrk_magazine 24 // HWRK MAGAZINE // J AN u AR y 2023

Writing unit principles:

These are the key principles I apply when planning and delivering a writing unit. The examples alongside are from a Gothic writing unit I recently taught to Y7. It was their first explicit writing topic of secondary school.

1. Set intention

Choose a narrow, specific set of knowledge and skill which you will focus on developing during the unit. Ensure that this is something which is borne out of your knowledge of the students and where they are. I usually select:

• 2-3 areas of knowledge and skill which are new

• 1-2 areas of knowledge which are a continuation of a previous unit

• 1-2 things which have been misconceptions which I want to continue to reiterate as we go along

EXAMPLE

Intentions for the unit:

2-3 areas of knowledge and skill which are new

- Exposition (creating atmosphere and setting tone)

- Pathetic fallacy

- Foreshadowing

1-2 areas of knowledge which are a continuation of a previous unit

- Modification and expansion (building on knowledge of word classes, function and clause structure from Y6)

- The Gothic (building on reading unit from September)

1-2 things which have been misconceptions which I want to continue to reiterate as we go along

- Fragmentation

- Concrete/abstract nouns

- Run-on punctuation

2. Live models which springboard CHOICE

Ensure that all modelling is done live under a visualiser, highlighting the skills and knowledge which you are chosen as your intention. Ensure that there is dialogue about what is written, how it is written, what else could be written and which the students prefer…

I modelled live almost every lesson. There were a range of models, from single word choices in single sentences, to longer descriptive pieces. Often there would also be opportunities for me to put student work under the visualiser and model marking and feedback, or model how their writing might be enhanced. By the end of the unit, a handful of students had also been confident enough to come to the visualiser themselves and model a skill for the group.

HWRK MAG AZINE .co.u K J AN u AR y 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 25 English

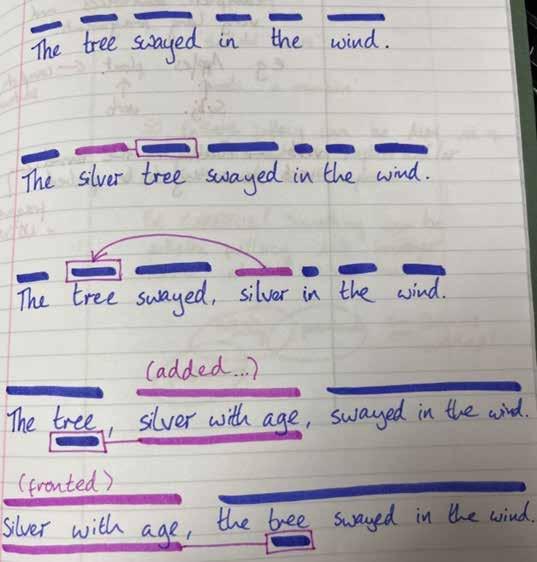

Examples of some models:

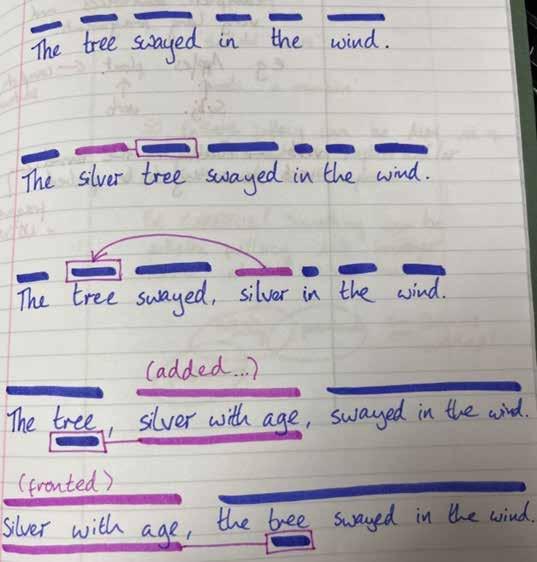

This demonstrates the difference between a descriptive sentence (top), one with a modifier (silver), then with the modifier moved so that it is post-modifying, then with expansion (addition of a phrase: silver with age), then with that phrase moved so that it is fronted.

CURRICULUM @hwrk_magazine 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // J AN u AR y 2023

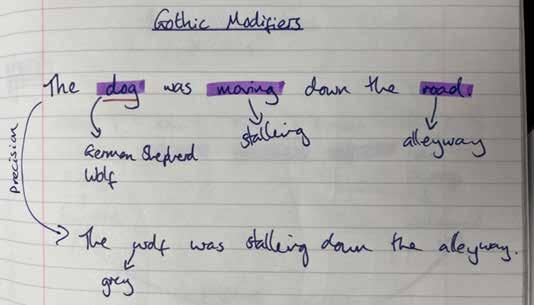

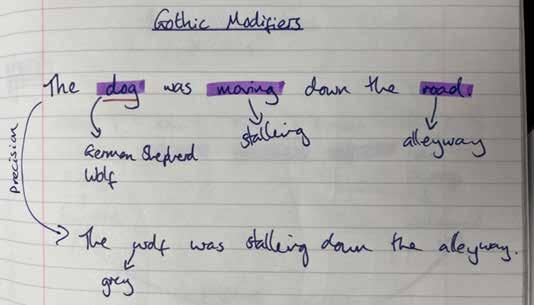

This model shows students how we might write using more precise nouns and verbs – dog becomes wolf; moving becomes stalking; road becomes alleyway.

With each of these models I ask questions like:

- How does this new element change the meaning?

3. Reflection wraps practice

- What would a different choice look like?

- Which one do you prefer?

- Does this capture what we want to say, or is there still something which isn’t right?

All the time, we are stressing the importance of choice in writing.

There are many, many options open to students – there is no right answer here. The only ‘right’ answer is the one which most closely voices what they really want to say. I would highly recommend the work of Myhill and the team at Exeter University to anyone interested in Grammar as Choice Pedagogy: https://education.exeter.ac.uk/ research/centres/writing/grammarteacher-resources/grammaraschoice/

Prompt student reflection before they write, while they write and after they write. Ensure that the reflection is precisely linked to the unit intentions.

I used a four-part frame to scaffold student reflection before, during and after writing. They just take a page I their exercise book and divide it into four.

Comprehension

Students write down what they understand the task to be – e.g. it will be three paragraphs of prose describing a tree in a park. It will use X devices, etc.

Strategy

What is their ‘battle plan’ for this task? This should be a really clear, simple breakdown of what they will do in order. There might also be some reminders here about what they might do to avoid specific errors they tend to make, e.g. checking for capital letters.

Connection

Students reflect on when they have done something like this before – how did it go? What were their errors or areas for development? How will they build on previous successes and learn from previous weaknesses?

Reflection

This is completed AFTER the task has been done and feedback has been given.

How did it go? What were the key successes? What prompted them? What were the key areas for improvement? How might they be tackled in future? Did my ‘strategy’ work? How will it change next time? What questions do I have? What are my priorities moving forward?

This reflection enables students to process all their key understanding before beginning. It then also acts as a prompt during the writing process. When students are first learning to self-regulate, I remind them at intervals during their independent writing, to look back at their reflection plan and ensure that the strategy and key areas of focus are at the forefront of their minds. We also return to it explicitly during the proof reading stage before students hand in.

HWRK MAG AZINE .co.u K J AN u AR y 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 27 English

4. Promote the practice of ‘book dialogue’

Train students to have an ongoing conversation with their exercise book. This means that they are in the habit of writing notes and commentary in the margin of their exercise book as they go along.

5. Insist that the piece of writing isn’t the point – it’s all about the ongoing craft

Highlight the idea that they aren’t working on a piece of writing, but on themselves as writers. The work in their book is their working memory externalised, not a shiny, polished, finished piece. Ensure that each shorter writing task pulls through to the next, and that it is a continuous thread of skill development.

These two steps are critical and inextricably linked to one another. A piece of student writing is NOT a perfect, publisher-ready manuscript which should be put on a pedestal. The process of writing itself is generative and messy. I liken writing to painting or clay modelling –students need to see that you have to make a mess, make errors, cross out and reflect on your work at intervals in order to craft something effective. A beautiful tidy book is not the endgoal, here.

An exercise book is:

- A space to work out problems

- A space to try out techniques

- A space to jot down ideas, externalising them and extending your working memory capacity so that you can build and develop your thinking.

- A space to draft, reflect and re-draft

To get students thinking like this, we need to change their mindset about their writing. This is what I did in this unit.

CURRICULUM @hwrk_magazine 28 // HWRK MAGAZINE // J AN u AR y 2023

Book dialogue:

- After their first drafted piece of writing, I asked students to highlight the sentence they were least happy with and write a comment in the margin about why.

- After their next draft, I asked them to do the same for two sentences AND a word choice they were unsure about.

- During the next draft, I ask students to just make any notes about uncertainty or challenges they experience in the margin as they go. I model this under the visualiser, and show them, for example, how I might highlight a word and make a note in the margin to show that I want to come back to it because I’m not sure it’s the right choice.

- Over time, I built this into a consistent part of their writing – students didn’t need to be asked to do this by the end of the unit, because they were doing it automatically.

Ongoing craft:

Over the course of the unit, I was aiming for students to develop one or two really strong pieces of writing. This might have become repetitive or static, had it not been about writing short pieces and then tying things together and synthesising their shorter pieces. This is what I mean…

Writing task 1: A short, literal description of a scene as depicted by a photograph they had brought in.

Writing task 2: Taking task 1 and transforming it into a gothic description by changing specific elements of lighting and temperature.

Writing task 3: Looking at a model exposition (the opening to Rebecca), and then reflecting on task 2 and how it might be improved to create a more compelling atmosphere.

Writing task 4: Students looked at pathetic fallacy as a technique, and wrote a paragraph using pathetic fallacy. They then found a way to combine this with their work from task 3. They reflected on things they should keep, things to discard and things they might want to introduce in order to make those two pieces of writing work together.

This is just a short example of how this might work from one piece to another in a continuous thread. This is something which we sustained across the whole unit, so that students could develop ideas from one piece to the next, but also introduce new ideas and experiment with new things.

Fundamentally, creative writing requires a firm foundation of knowledge, paired with the mindset of someone with agency over their own work. By giving students excellent explicit instruction in areas of key knowledge, and demonstrating high level models and processes, we provide the base.

But this knowledge alone is nothing. Students must take that knowledge and have the confidence to play with language, make choices, change those choices and see themselves as writers.

It is so easy for writing instruction to become a stale series of exercises where the teacher models and students mimic. However, when we have an open dialogue about choice and self-regulation, our young people actually become writers.

HWRK MAG AZINE .co.u K J AN u AR y 2023 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 29 English

How I would TeacH creaTIve wrITIng For aQa englIsH language PaPer 1

Andrew Atherton offers his advice on how to get students started with creative writing when they don’t know how to begin.

By Andrew Atherton

By Andrew Atherton

A blank piece of paper can be a fearsome thing. Liberating to some, but anxietyinducing to others. Nowhere is this more apparent than with creative writing. I imagine accosting a comedian whilst they’re shopping, a trolley filled with the weekly groceries, and insisting that they tell me a joke. Something splutters out, a half-joke, not really funny, and they limp off, back to the cereal aisle. Being creative on cue is never an easy task, but yet this is what is demanded of our students. ‘You have forty-five minutes’, their GCSE intones, ‘now be creative! Go!’ The clock starts to tick, louder than any clock should.

How can we help our students to crack this? They can’t rely on creativity striking at 9am on a random Friday in May. How do we transform a blank piece of paper from a source of angst to a source of enjoyment? One answer lies in teaching, rehearsing and modelling certain generative structures that students can depend upon, both to shape their response and to plan it.

Such structures not only prime student thinking, giving them a much needed starting point, but they feed forward into the piece of writing. This article outlines one such structure that you can use with your own students, either as something to rehearse or to model.

A Photograph Finish…!

This strategy works best with a question that asks students to respond to an image, an increasingly common style of question. However, even if it doesn’t use this format, students can still utilise this structure. For ease, we’ll imagine the student is presented with some kind of image or photograph.