HWRK educational mag azine the online magazine for teachers ISSUE 26 / FREE HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK written by teachers for teachers ALSO INSIDE NavigatiNg today’s ChalleNges i N e du C atio N • Developing a p roblem-Solving m in DS et a S an e C t • Drop the Drop Down Day S • r ethinking eD u C ational a mbition i n t he e ba CC e ra • r e S our C e S t o e nri C h Subje C t k nowle D ge i n e ngli S h l iterature • Four t op t ip S t o m ake i nterview S F or t ea C hing j ob S m ore aCCe SS ible • Five t hing S i ’ve l earnt From Creating t he t imetable

Established in May 2006, we are one of the UK’s most dedicated and ambitious anti-bullying charities. Our award winning work is delivered across the UK and each year, through our work we provide education, training and support to thousands of people.

Through our innovative, interactive workshops and training programmes, we use our experience, energy and passion to focus on awareness, prevention, building empathy and positive peer relationships all of which are crucial in creating a nurturing environment in which young people and adults can thrive. Our Mission is to support individuals, schools, youth and community settings and the workplace through positive and innovative anti-bullying and well-being programmes and to empower individuals to achieve their full potential.

DIFFERENCE MAKING A INSPIRING CHANGE EMPOWERING YOUNG PEOPLE To find out more visit www.bulliesout.com | Email: mail@bulliesout.com

BELIEVE IN A WORLD THAT IS FREE FROM ALL

OF BULLYING BEHAVIOUR.

you would like to support us and help us to continue our lifechanging work, you can:

Volunteer with us

Fundraise for us

Make a donation

Join our Speak Out Campaign

Become a Corporate Partner

WE

TYPES

If

\

\

\

\

\

6. developInG A problemsolvInG mIndset As An ect

Pete Forster discusses the journey of new teachers from reliance to independence, highlighting the importance of problem-solving as a mindset for continuous improvement

10. drop the drop down dAys

Revision days might not be the best use of time, compared with other effective strategies

16. rethInkInG educAtIonAl AmbItIon In the ebAcc erA

Is entering students for the EBacc really the best level of ambition schools should aim for?

HOW CAN NOVICE TEACHERS BECOME CLASSROOM PROBLEM SOLVERS?

edItorIAl: Navigating Today’s Challenges in Education

22. unleAshInG the power oF metAcoGnItIon

Why should you change and hone your practice? Why metacognition and not something else?

28. resources to enrIch subJect knowledGe In enGlIsh lIterAture

Andy Atherton suggests a wide range of materials to enrich the English Literature Curriculum and to support students in their studies.

33. eXplorInG morpholoGy, etymoloGy, And coGnItIve strAteGIes For eFFectIve vocAbulAry InstructIon

Students are taught to analyse texts, deconstruct sentences, and decipher meanings, but how often do they explore the architecture of words?

36. how I teAch bAr chArts to yeAr 4

Top tips on how to teach bar charts in Primary Maths to Year 4

42. Is It tIme to Invest In school clerks And GovernAnce?

Neil Collins calls for fair wages and recognition of governance professionals’ skills and experience

47. Four top tIps to mAke IntervIews For teAchInG Jobs more AccessIble

Here are four ways that UK schools can make school job interviews more inclusive and accessible

50. FIve thInGs I’ve leArnt From creAtInG the tImetAble

Here are some key takeaways for you to consider when writing the timetable for your own school.

55. how cAn senIor leAders support mIddle leAders eFFectIvely?

The skills needed for Middle Leadership need to be taught and supported. Here’s how SLT can approach it.

PEDAGOGY consideration of your planning and the outcomes of your cognitive actions. However, it is no surprise that pinpointing exactly what metacognition is is so di cult. If you are practicing ballet, you have huge, mirrored wall to see what metacognition is invisible. Let us consider the planning of a lesson: learn? What their prior learning? What strategies have worked when teaching this topic previously? What behaviour management strategies as much as they should? Do you need to change the methods shown? Do you need to push students on or take step back? After: How far did students get and lesson? Hopefully this illuminates the metacognitive thoughts going on here. Equally, this scenario should highlight how metacognition occurs continuously. Much of what we are implement, but really tweaking certain aspects to rapidly accelerate the progress of your students. So, this is the what and the why. Now, it is crucial that you understand the nitty gritty of the theory. really believe that the more you and student behaviour, amongst other variables. Firstly, you will need understand The knowledge strand refers to the understanding we have of our own cognition, such as our knowledge levels, our content knowledge, and the approaches which we can take to completing task or problem. The regulation strand references the control and monitoring of our own broken down further. Let us begin with the knowledge strand, which broken into ‘knowledge of self’; ‘knowledge of strategies’; ‘knowledge task’. The knowledge of self an individual’s knowledge of the content required to complete di erent approaches that could be utilised to complete task, as well as strong knowledge of how to use ISSUE 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 03 HWRK MAG AZINE .co. UK // INSIDE THIS ISSUE

P 16 P23 P06 P47 P33 @hwrk_magazine FeAtures pedAGoGy currIculum leAdershIp eXperIence

CONTENTS

Pete Forster discusses the journey of new teachers from reliance to independence, highlighting the importance of providing support and a structured framework for their development, and explores the concept of progressive problem-solving as a mindset for continuous improvement in teaching. By Pete Foster

P22

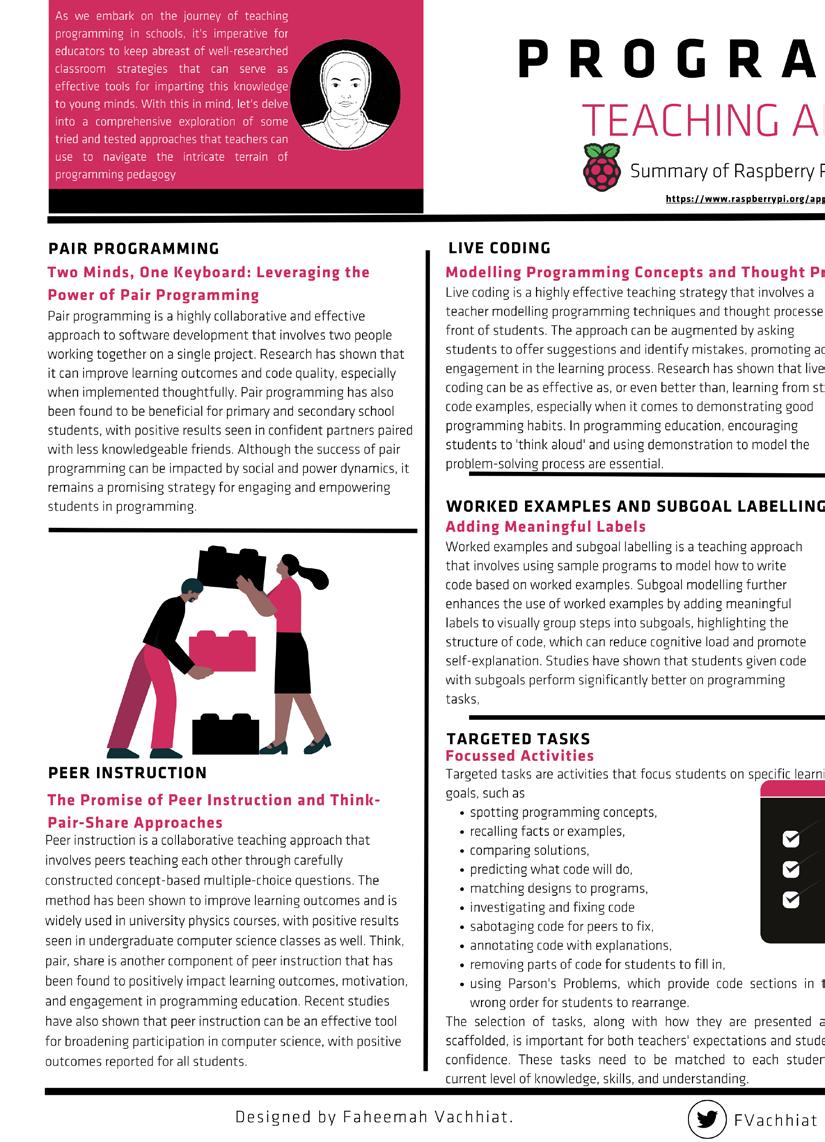

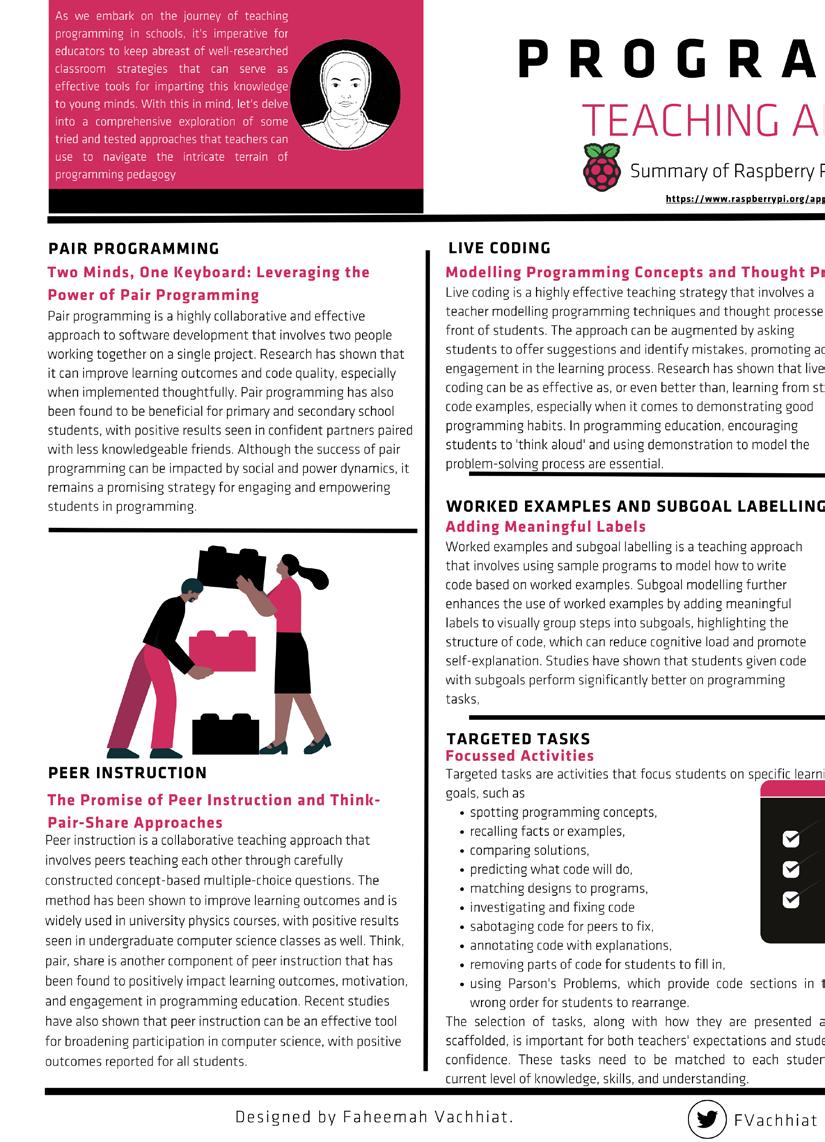

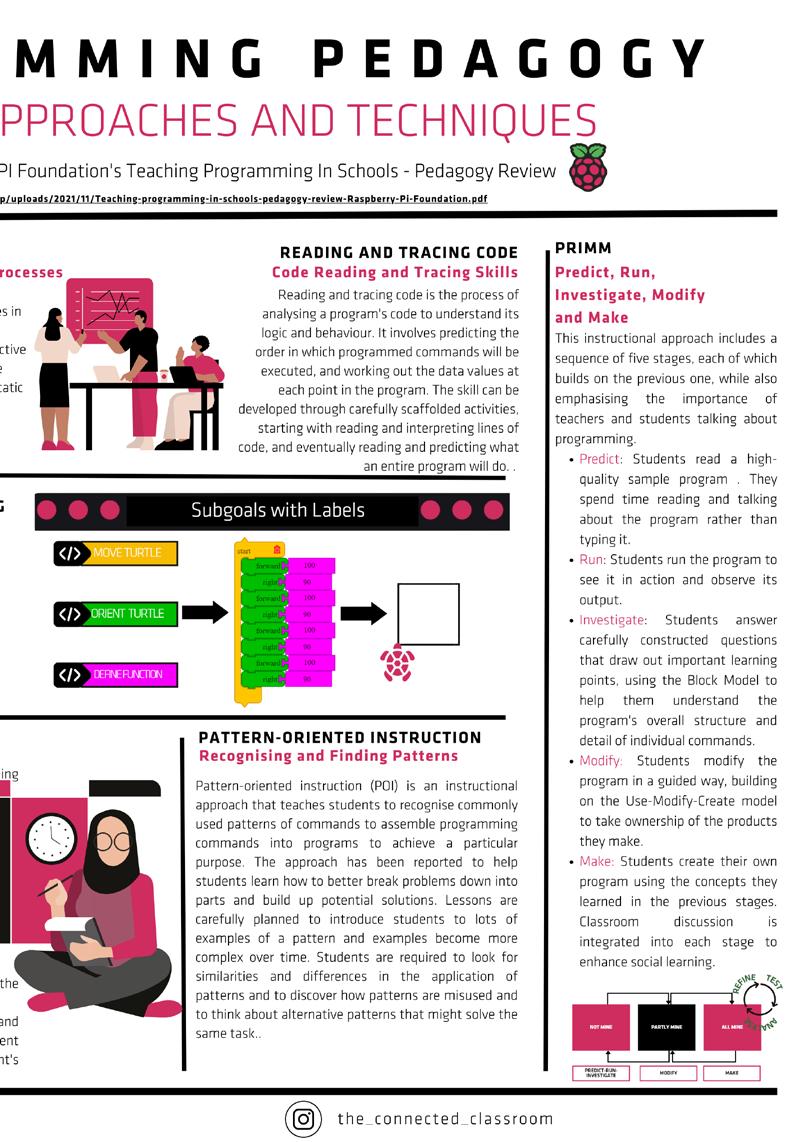

58. computInG poster Programming Pedagogy

How started to become independent as a new teacher had quite a lot to do with being left alone in the classroom. My mentor, James, would go and ‘get something from the cupboard’, briefly at first but later creeping up to ten minutes and much later entire lessons. would white-knuckle until he returned, waiting for the class to implode, waiting for poor or extreme behaviour this particular Year class had never exhibited before. From reliance to independence? to independence, What do new teachers need? is question without single obvious answer. Of course, they need subject knowledge, a good grounding in classroom management and perhaps an understanding of how learning happens. They need time in the classroom, inhabiting that new-found independence. More than all this, they need a structure or scaffold that supports their development step by step. Debates rage as to how directive parts of coaching has become ubiquitous but so have its competing definitions. Directive or not? Dialogic or not? Clear action step or general direction? we owe it to new teachers to be direct about what is important to get right in the classroom. If a new teacher is struggling and we have potential solution, we help no one by withholding it. Less obvious are the ways we hand over responsibility to the new teacher. As teachers, we’re trying to make our role redundant. We’re working to untether students, to wean them off support as they’re problem-solving, essay writing, designing or anything else. It’s not easy to reach these levels of independence. And, counterintuitively, independence is not effectively fostered by just setting lots of open-ended, independent tasks and letting students get on with it. Whilst the route for students from reliance to independence is, if not easy, relatively clear, the same can’t be said for new teachers. Of course, new teacher is a novice teacher. But they are also graduate. Often, they arrive in teaching with experience supplementing and enriching their first steps in the classroom. Easier, for what? Intuitively, we know what new teachers need. Expertise appears to build its foundation on: Large quantities of knowledge: subject, pedagogy, behaviour policy, our students. Process embedded in long-term memory: classroom routines, explanations, questioning techniques. Constraints on mental capacity lessen as we embed more knowledge and process. Unconstrained mental capacity allows us to embed more knowledge or new process. experienced the process described. We arrive in new school and everything from student names to behaviour policy to unfamiliar topics challenges us. Knowledge in one of those areas enables progress in another. We learn names and managing behaviour becomes easier. As knowledge of topic grows, our explanations become clearer. Teaching becomes easier. But what are we freeing up that mental capacity for? Teaching is easier? Great. FEATURE What now? We’ve lessened the demands on our mental capacity but what is expected when those demands are lessened? Some experts on expertise may have the answer. Problem Reduction? present one useful way of conceptualising reached enough automation, enough knowledge to free ourselves from some of the demands of human cognitive architecture. Imagine this moment as fork in the many paths of teacher development. One fork in the path leads us to Problem of the problems we’ve been facing and because of this... Teaching becomes less challenging. Tasks that took long time before take Maybe we’ve grappled with marking policy until we’ve found the way we can follow it quickly and efficiently. Maybe we can use the behaviour policy to remove disruptive student and it’s transformed the atmosphere in our classroom. Maybe we’ve taught ourselves to plan using someone else’s resources and we’re saving so much Of course, these are all good things. A problem with our fork in the road metaphor is that it’s ne to rest in this state for time. Talking one path doesn’t close the other off to us forever. But it’s unlikely we’ll continue to develop if all we do is reduce our problems. Whilst getting easier is probably prerequisite for getting better, our teaching isn’t necessarily getting better as it’s getting easier.

a problem-Solving minDSet aS an eCt Tracey Leese explores the narrow focus on English Baccalaureate (EBacc) entries as the measure of educational ambition, highlighting the need for a broader perspective that considers diverse student needs, aspirations, and the overall purpose of education. RETHINKING EDUCATIONAL AMBITION IN THE EBACC ERA @hwrk_magazine How do we know if we are ambitious enough for our students? Dolly Parton advocates that we pour ourselves daily cup of ambition, and whilst it’s unlikely that composing, this still ideal life advice from country music’s beloved matriarch. Like Dolly applaud Outside of education ambition is loaded term which synonymous with striving, achieving and succeeding. An empowering (if intangible) concept. Within schools the notion of ambition has come to characterise the current inspectorate framework – as practitioners and leaders we are directed to build and deliver curriculum which broad, balanced and (you guessed it) ambitious. Clearly, the current political agenda and subsequent impact measures position ambition at the heart of school’s intent and impact As an English teacher by trade, recognise the importance of ambition within the curriculum; especially within the inner-city school in which teach. also happen to believe that literature texts act as gateways to other worlds, eras and experiences. Where else will children explore Petrarchan sonnet or Shakespearean tragedy not in school? Of course, this isn’t only true for English – but for all the challenging content we deliver; poverty indices), also believe that ambition transcends curriculum. You will doubtlessly be familiar with the correlation between word and literal poverty and the impact this can have on students accessing their wider curriculum (howsoever well-sequenced or broad) because if children cannot interpret and infer, they simply surely di er according to school context. The EBacc directive seems loaded with assumptions about the FEATURE rethinking eDuCational ambition in the ebaCC era unleaShing the power of metaCognition HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK // // A huge emphasis has been placed on explicit vocabulary instruction in the past few years. It plays a significant part in the 2019 Literacy Guidance Report which highlights what constitutes good practice. People familiar with these conspicuous emergence of two new terms in the vocabulary toolkit: “Morphology” and “Etymology”. Morphology (of which etymological roots are subset), is branch of grammar. As such, suffers from ENGLISH prevailed in British education for decades. But grammar is not about rules and prescription (although there are conventions), is about about trying to resuscitate moribund languages but about understanding modern ones. For over two millennia, the atom was considered the smallest building block of life until scientists discovered the electron, nucleus, and elementary particles. While we’ve made progress in understanding the physical world, many people still perceive words as the ultimate frontier in language. Students are taught to analyse texts, deconstruct sentences, and decipher meanings, but how often do they explore the architecture of words? UNLOCKING THE POWER OF

EXPLORING MORPHOLOGY, ETYMOLOGY, AND COGNITIVE STRATEGIES FOR EFFECTIVE VOCABULARY INSTRUCTION exploring morphology, etymology, anD Cognitive StrategieS for effeCtive voCabulary inStruCtion FOUR TOP TIPS TO MAKE INTERVIEWS FOR TEACHING JOBS MORE ACCESSIBLE Job interviews are artificial high-stress environments that don’t always allow candidates to show their true potential. The nerves, the uncertainty and the feeling of being under scrutiny can sometimes be overwhelming for candidates. There is a better way. Making school job interviews more inclusive and accessible is a moral and strategic imperative. By taking these steps, schools can attract a more diverse range of can-didates and tap into the wealth of talent and expertise that they bring. LEADERSHIP four top tipS to make interviewS for teaChing JobS more aCCeSSible HOW CAN SENIOR LEADERS SUPPORT MIDDLE LEADERS EFFECTIVELY? Middle Leadership is highly complex and requires strategic thinking. Yet many Middle Leaders have not been trained to develop this area of their practice. In this article, Kara Kiernan explains how Senior Leaders might be able to provide more e ective support for Middle Leaders. By Kara Kiernan LEADERSHIP leaDerShip routeS anD preparation

Developing

WORDS:

CONTRIBUTORS

WRITTEN BY TEACHERS FOR TEACHERS

Pete Forster

@pnjfoster

Pete leads secondary teacher development across a multi-academy trust. He’s the author of What do new teachers need to know?

David Voisin

@ukneighbour

Seasoned Head of MFL and linguist in the broader sense. Passionate about language. NPQSL (Literacy)

Nathan Burns

@MrMetacognition

Nathan is a Head of Maths, education article writer and the author of “Inspiring Deep Learning with Metacognition”.

Andrew Atherton

@__codexterous

Andrew Atherton is a Teacher of English as well as Director of Research in a secondary school in Berkshire. He regularly publishes blogs about English and English teaching at ‘Codexterous’ and you can follow him on Twitter @__ codexterous

Tracey Leese

@MrsqueenLeese

Tracey Leese is an Assistant Headteacher at St Thomas More Catholic Academy in Longton, co-author of Teach Like a Queen and a passionate advocate for women in leadership

Henry Sauntson

@HenrySauntson

Shannen Doherty

@MissSDoherty

Shannen is a Senior Leader and classroom teacher at a primary school in London. She loves all things Maths and enjoys getting nerdy about teaching and learning. Shannen’s debut book, 100 Ideas for Primary Teachers: Maths, came out in May 2021.

Emma Cate Stokes

@emmccatt

Emma Cate Stokes is a KS1 teacher and Phase Lead at a coastal school in East Sussex.

Neil Collins

@GovernorHub

Neil Collins is Managing Director and one of the founders of GovernorHub. The organisation supports more than 100,000 governors, trustees and governance professionals. Neil has been a school governor and academy trustee for nearly 20 years and is currently a trustee at a specialist school for young people with autism in Norfolk.

Sam Brown

@_SamBrown_1

Sam is a senior leader at The Fulham Boys School, a secondary school in West London

Kara Kiernan

@karalkiernan

Freelance Educator. Former Head of Junior School & Nursery. School Governor. MEd in Educational Leadership. Founder of http:// thebooktrain.co.uk

Faheema Vachhiat

@FVachhiat

Henry Sauntson is a Senior Leader and SCITT Director, based in Peterborough. His enthusiasm and interest lies primarily with teacher education and development, especially in the early career stages. He has contributed material to a number of journals and spoken at a range of events that celebrate the use of evidence in education; we need to be informed, not led.

Faheemah is an experienced educator with over a decade of teaching experience. With a passion for providing the best possible learning experiences for students, Faheemah is always seeking ways to improve and innovate her teaching practice. Through her substack, she shares her reflections on teaching and learning, explores the latest trends and best practices and shares strategies for other educators looking to enhance their approaches to curriculum design, classroom management, and pedagogy.

hwrkMAG A zine.co.uk // M ee T T he T e AM

Legal Disclaimer: While precautions have been made to ensure the accuracy of contents in this publication and digital brands neither the editors, publishers not its agents can accept responsibility for damages or injury which may arise therefrom. No part of any of the publication whether in print or digital may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission of the copyright owner.

HWRK MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY EDU ONLINE GROUP LTD 1st Floor, GD Offices, 47 Bridgewater Street, Liverpool, L1 0AR E: enquiries@edu-online.co.uk T: 0151 294 6215

EDITOR Andy McHugh

PUBLISHING DIRECTOR Alec Frederick Power DESIGNER Adam Blakemore MANAGING DIRECTORS G Gumbhir,

Alec Frederick Power

NAVIGATING TODAY’S CHALLENGES IN EDUCATION

What are the challenges facing our teachers and school leaders today? And how should we approach them?

Recruitment and retention

With an increasingly demanding educational landscape, recruiting and retaining highly qualified teachers has become a pressing concern. Budget cuts and workload intensification contribute to teacher burnout and lower job satisfaction. To address this, school leaders must emphasise the importance of teacher well-being and provide support systems that promote work-life balance, professional growth, and collaborative learning communities. While money also talks, only by fostering a culture that values teachers and their contributions, will schools di erentiate themselves from “the competition” and attract and retain dedicated educators.

Post-pandemic attendance

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted attendance and academic progress in schools worldwide. Many students have faced learning gaps and socio-emotional challenges due to prolonged remote learning and limited interaction. To address these issues, schools can implement targeted intervention programmes, personalised learning approaches, and additional resources to support students’ academic recovery. Moreover, fostering a sense of belonging, providing emotional support, and cultivating inclusive classroom environments are crucial for students’ holistic well-being.

Behaviour issues

Behavioural challenges hinder the learning environment and impede student progress. The post-pandemic period has brought forth additional emotional and behavioural di culties, requiring educators to be equipped with e ective strategies for managing

student behaviour. By promoting positive behaviour support systems, incorporating restorative practices, and o ering social-emotional learning programmes, schools can create a safe and supportive environment that helps students develop self-regulation skills and make positive choices.

N.B. These strategies are not always successful and even when they are, it’s often down to a complex network of other factors too.

Curriculum matters

An overcrowded curriculum can overwhelm teachers and hinder students’ deep understanding and critical thinking skills. School leaders must advocate for a balanced and streamlined curriculum that prioritises essential knowledge and skills while allowing for flexible teaching approaches. By providing teachers with professional development opportunities focused on curriculum design, instructional strategies, and assessment practices, schools can empower educators to navigate the challenges of a bloated curriculum and create meaningful learning experiences.

Reasons to be optimistic

Amidst the challenges, it’s important to balance lighthearted optimism about the future with realistic expectations. Acknowledging the di culties while nurturing a positive outlook can inspire resilience and perseverance in both teachers and students. By celebrating successes, fostering a growth mindset, and providing ongoing support and encouragement, schools can cultivate an atmosphere of optimism and motivation that fuels student achievement.

In the realm of education, we encounter a tapestry of triumphs and obstacles. By confronting these challenges headon and implementing strategies to

empower teachers and inspire students, schools can cultivate an environment that nurtures growth, resilience, and academic achievement. Through teacher support, personalised learning approaches, e ective behaviour management, and a balanced curriculum, we can navigate the complexities of education and equip students with the skills they need to flourish in an ever-changing world.

Final thoughts…

It’s tempting to focus on becoming more e cient, or speeding towards the next target. But let’s not forget the importance of time and a healthy dose of realism when tackling the hurdles that lie ahead. As the saying doesn’t go, “Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither was a wellprepared lesson plan”.

It’s crucial to acknowledge the limitations of an often crippling workload and instead to embrace a sense of balance. By finding the right equilibrium between ambition and pragmatism, we can create an atmosphere that promotes joy, productivity, and well-being in our educational journey. As we navigate the path forward, let us embrace the challenges as opportunities for growth and transformation, ensuring a bright future for our educators and students alike. Together, with a dash of humour and a firm grasp on reality, we can overcome any hurdle that comes our way and forge a path to educational excellence.

Andy McHugh Editor | HWRK Magazine

ISSUE 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 05 HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK

HOW CAN NOVICE TEACHERS BECOME CLASSROOM PROBLEM SOLVERS?

By Pete Foster

How I started to become independent as a new teacher had quite a lot to do with being left alone in the classroom. My mentor, James, would go and ‘get something from the cupboard’, briefly at first but later creeping up to ten minutes and much later entire lessons. I would white-knuckle it until he returned, waiting for the class to implode, waiting for poor or extreme behaviour this particular Year 8 class had never exhibited before.

From reliance to independence?

As we chart their course from reliance to independence, What do new teachers need? is a question without a single obvious answer. Of course, they need subject knowledge, a good grounding in classroom management and perhaps an understanding of how learning happens. They need time in the classroom, inhabiting that new-found independence. More than all this, they need a structure or scaffold that supports their development step by step.

Debates rage as to how directive parts of that structure should be. Instructional coaching has become ubiquitous but so

have its competing definitions. Directive or not? Dialogic or not? Clear action step or general direction?

It seems obvious – to me at least – that we owe it to new teachers to be direct about what is important to get right in the classroom. If a new teacher is struggling and we have a potential solution, we help no one by withholding it. Less obvious are the ways we hand over responsibility to the new teacher.

As teachers, we’re trying to make our role redundant. We’re working to untether students, to wean them off support as they’re problem-solving, essay writing, designing or anything else. It’s not easy to reach these levels of independence. And, counterintuitively, independence is not effectively fostered by just setting lots of open-ended, independent tasks and letting students get on with it.

Whilst the route for students from reliance to independence is, if not easy, relatively clear, the same can’t be said for new teachers. Of course, a new teacher is a novice teacher. But they are also a graduate. Often, they arrive in teaching with experience supplementing and enriching their first steps in the classroom.

Easier, for what?

Intuitively, we know what new teachers need. Expertise appears to build its foundation on:

• Large quantities of knowledge: subject, pedagogy, behaviour policy, our students.

• Process embedded in long-term memory: classroom routines, explanations, questioning techniques.

Constraints on mental capacity lessen as we embed more knowledge and process. Unconstrained mental capacity allows us to embed more knowledge or new process.

If that all feels a little abstract, we’ve all experienced the process described. We arrive in a new school and everything from student names to behaviour policy to unfamiliar topics challenges us. Knowledge in one of those areas enables progress in another. We learn names and managing behaviour becomes easier. As knowledge of a topic grows, our explanations become clearer. Teaching becomes easier.

But what are we freeing up that mental capacity for? Teaching is easier? Great.

Pete Forster discusses the journey of new teachers from reliance to independence, highlighting the importance of providing support and a structured framework for their development, and explores the concept of progressive problem-solving as a mindset for continuous improvement in teaching.

@hwrk_magazine 06 // HWRK MAGAZINE // IssuE 26

What now? We’ve lessened the demands on our mental capacity but what is expected when those demands are lessened? Some experts on expertise may have the answer.

Problem Reduction?

Carl Bereiter and Marlene Scardamalia present one useful way of conceptualising this moment, the moment when we have reached enough automation, enough knowledge to free ourselves from some of the demands of human cognitive architecture. Imagine this moment as a fork in the many paths of teacher development.

One fork in the path leads us to Problem Reduction:

• We’ve solved some of the problems we’ve been facing and because of this...

• Teaching becomes less challenging.

• Tasks that took a long time before take less time now.

Maybe we’ve grappled with a marking policy until we’ve found the way we can follow it quickly and efficiently. Maybe we can use the behaviour policy to remove a disruptive student and it’s transformed the atmosphere in

our classroom. Maybe we’ve taught ourselves to plan using someone else’s resources and we’re saving so much time.

Of course, these are all good things. A problem with our fork in the road metaphor is that it’s fine to rest in this state for a time. Talking one path doesn’t close the other off to us forever. But it’s unlikely we’ll continue to develop if all we do is reduce our problems. Whilst getting easier is probably a prerequisite for getting better, our teaching isn’t necessarily getting better as it’s getting easier.

HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.uK IssuE 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 07 FEATURE

Or Problem Seeking?

The other fork leads us to Problem Seeking. Now, problems don’t exist in your classroom because you’re a bad teacher. The classroom is a complex environment and in its very nature it offers us problems to solve.

In Surpassing Ourselves, Bereiter and Scardamalia describe how as mental constraints are reduced we can pay attention ‘to other aspects of the problem that previously had to be ignored.’ They use the metaphor of reinvestment because

we can reinvest energy and effort that previously had to be paid elsewhere.

As we develop, we look out for new problems or more complex versions of existing problems. We shouldn’t feel guilty that not everything is perfect in our classroom. But we can look out for ways to continue to solve the problems posed by the classroom.

Entry routines to the classroom have been practised and practised until we’ve reached a level of order we never thought possible. Now we notice that students do come in

well but they don’t start the first task well. We reinvest our attention on their apathy. Or recent energy has been devoted to learning enough about this term’s history topic to explain it. Now that knowledge has improved, we can start to consider how lead effective class discussion, asking the right questions, on that topic.

Bereiter and Scardamalia call this Progressive Problem Solving because we are constantly on the look out for the next problem to solve. That may sound exhausting but this should be an attitude or perspective rather than a constant frenzy.

Progressive Problem Solving for Novice Teachers

To develop a Progressive Problem-Solving mindset, new teachers can ask the following questions:

• What are the most significant problems I’m facing right now? These will be the problems that are most getting in the way of your success. What are the key problems getting in the way of learning right now. Often this is the behaviour of the students or their attitudes.

• How can I break this problem down further? At times, problems like Behaviour loom, making it hard to define what kind of solution we’re looking for. We’re not usually looking for a solution to Behaviour or Planning or Marking. We want students to listen when we’re talking. We want to

plan in a way that encourages student memory. We want to give feedback without taking too much time. Seek to specify, narrow down and define.

• Are there any clear solutions? Sometimes we just need to do that thing we’ve been meaning to do. Sometimes a bit of reading or a quick chat can define a solution quickly.

• Where can I go for support? Often, but not always, this is the mentor. It might be the teacher who knows part of the curriculum really well. It might be the teacher who taught the students you’re struggling with previously.

• What do I need to do first? Once the problem is clear, once support has been sought, first steps can be defined. We trail solutions, searching for one that does what we need it to. Behaviour gets better. Planning becomes more straightforward.

Feedback is high impact and low workload. Viewing your own development through the lens of Progressive Problem Solving is useful because it encourages ownership of the problems you face. Anytime you’re directed to practise and embed a behaviour in a coaching or training session, you’re being offered a way to reduce the constraints on mental capacity further. You’re being offered a tool to solve future problems.

When we just focus on the granular –practising that narrow next step – we can miss the big picture. Our eyes are on the moment so we lose the horizon. Whenever we can, we should look up and, perhaps with the help of others, take a broader view of our development. We should consider how these small steps build into something larger: a set of solutions to the infinite and varied problems of the classroom.

@hwrk_magazine 08 // HWRK MAGAZINE // I ssu E 26

The UK’s Number One School Playground Specialist

With over 25 years’ experience, qualified Outdoor Learning Consultants, and reliable Installation Teams, Pentagon Play o er innovative products and solutions, created to meet the needs of your pupils. All of our schemes and items are designed to encourage learning through play, crafted with the curriculum in mind to support pupils as they learn and grow. No matter the requirements of your development, Pentagon Play can support you in finding the best solution for your space.

Only £495

Looking for a freestanding, movable solution for your playground space? Our Pentagon Play Online Shop is the ideal source for all of your educational play needs.

Designed with budgets in mind, create an engaging learning environment for your pupils without the need for a full installation. Resources delivered to your door in just 4-6 weeks!

01625 890 330 (North O ce) | info@pentagonplay | 0117 379 0899 (South O ce)

on

Online Shop

Our Website

Free delivery

100+

products Visit

Range

Mud Kitchen

Essentials

-

mI a ignative & Creati ve Outdoor Classroo sm Sport Active Play Surfacing &Land sc a gnpi inruF ture,Fencing&S t o r ga e

DROP THE DROP-DOWN DAYS

By Henry Sauntson

Henry Sauntson examines the challenges and potential drawbacks of lastminute revision approaches, such as drop-down days and holiday revision sessions, in preparing students for GCSE exams, arguing instead for a more e ective strategy.

Schools are slow-cookers; the lid begins to sweat around March and then rattle in late April as the GCSE-year students reach the end of their stewing. The natural action of all schools, intent on ensuring the best possible results for both the students and their own dashboards, is the last-minute revision approach; what to

do in the ever-lengthening run-up to the GCSE exams in May and June.

All subjects want their students to give them their time, but with every student taking a minimum of 5 GCSEs – and ideally 8 or more – that’s a lot of ways to split a student, and a very thin way to

spread them. A further natural recourse then is of course the maximising of time for subject areas by setting up ‘Holiday Revision’ sessions and ‘Drop-down Days’, where students spend an entire day (either in term time or outside it) working on a particular subject area.

@hwrk_magazine 10 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 26

But what of the collateral disruption?

Every drop-down day for one subject has immediate and very real impact on all other subject; students are missing curriculum portrayal, their routines are disrupted; more cognitive damage is caused than perhaps learning gain is made as students struggle to adjust to the changes in their established and rehearsed timetable patterns.

Then there’s the paradox of the Holiday Revision sessions, with whole days dedicated to specific curriculum subjects –those students who attend these are either motivated enough to revise well anyway and therefore get nothing from it or they are attending merely to use it as a form of justification of having ‘tried their best’ later down the line so don’t actually want to be there; either way the motivations are not intrinsic, and the sessions largely ine ectual. They show willing, but they don’t show impact. Yes, I am generalising, but if we look closer into specific subject areas I am sure we would struggle to show a genuine correlation between attendance at these sessions and improvement in outcomes.

This approach is seemingly counterproductive with the agreed and established principles of e ective learning; spaced practise over a longer period of time, with

content interleaved and regularly revisited to strengthen recall; cramming doesn’t work, yet that is in essence what DropDown and Holiday Revision Days are. So, how do we o -set the issues that this approach has the power to present?

There is little contestation of the evidence behind Spaced Practice, with a number of significant research studies demonstrating its impact; when combined with lowstakes quizzing and regular, purposeful retrieval, students can be supported in developing strong mental representations of concepts, recalling in a range of situations and transferring that knowledge to di erent problems.

In their 2022 paper Pan, Carpenter and Butler posit that ‘successful learning requires building factual knowledge as well as an understanding of how that knowledge can be integrated, utilised and applied in new situations’, with durable knowledge being built by when ‘learners have to repeatedly study and use the information that they are trying to learn’; not only is knowledge regularly recalled and checked but it also a ords the mental break that, in their words, ‘encourages more e ective attention’.

The issue with the Drop-Down Day is that it is just that: a day. A day is a long time to

expect students to pay ‘e ective’ attention and, given that attention is the ‘gateway to cognition’ (Hobbiss), we don’t spend enough time factoring it into our teaching. We can’t just expect students to pay attention over 6 hours because we want them to, no matter how many ‘brain breaks’ we put in. Teachers, too, su er from overload and burnout; these are exhausting days both in the conception and the realisation; to me, they’re just not worth it unless designed with care.

So, what do we do about it? Well, to go back to Pan et al, ‘spacing and retrieval practice can be combined to enhance learning more e ectively than either strategy alone’ – we form the method of ‘successive relearning’. This re-learning involves, as Pan et al put it, ‘an initial session in which learners try to retrieve the information they are learning and then receive feedback to check their accuracy, repeating retrieval practice until they are able to recall all of the information to a predetermined criterion’. No, that criterion is up to you but it needs to be made clear to the students too – motivation comes from knowing your destinations. Each additional ‘relearning’ session is a combination of retrieval and feedback using the same criterion for success but – and it is a big ‘but’ – this long-term learning we strive for is best attained when these sessions are spaced out, not crammed together.

HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK ISSUE 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 11 FEATURE

Any time we set up a learning opportunity or experience for our students we are, consciously or not, promoting its approach as a useful one; we are saying, with DropDown Days, that this is a good way to study. For students to learn successfully they need routines for that learning –the right things to do, using the right resources, at the right time. Routines are at their best when they prioritise consistency over challenge and are used regularly to allow for rehearsal and, in time, automaticity, freeing up cognitive capacity for attention on learning. We must be aware, therefore, of the subconscious impact of school decisions around curriculum on students’ own selfregulation and metacognitive awareness; ‘if the school is making me do this, then it must be a good thing to do’… we have a duty to promote e ective revision strategies and allocation of study time.

Often, too, Drop-Down days and Holiday Revision sessions are led by sta who may, in terms of pedagogical and instructional approach, be unfamiliar to the students; this means we must focus solely on

content and strategy, not relationships. However, relationships are vital – the forming of the attachment by the student to the new teacher and the possibly unfamiliar learning environment will have detrimental e ects on their capacity for attention; di erent students will behave in di erent ways when removed from the routines of their classroom peers, location, teacher approach and beliefs et al. Are these days, therefore, far harder to get right than they are to get wrong?

Equity is another factor; for sessions like these to be beneficial it is also important that they are equitable – not one teacher planning reams of content across a day and another hoping to ‘wing it’ or be ‘responsive’; the planning and preparation must be collaborative, focussed on curriculum content and clearly mapped in terms of what is retrieved and when –along with how feedback is given – during the successive relearning experiences.

In conclusion, such days can have their benefits but only if they are carefully thought through, their purpose clear

and their position in a curriculum made explicit; subjects need to be able to plan their curriculum portrayal in the knowledge that these days are part of it, and then design the days themselves to best reflect the principles of the aforementioned ‘Successive Relearning’; focussed retrieval and feedback activities around previously taught and previously revisited concepts and knowledge, as well as taking into account the need to maximise students’ ability to pay attention to content over a prolonged period of time.

Plenty of notice is needed also to flag up the potential disruption to established behavioural, cognitive and learning routines for students and to consider the impact of the collateral damage within the structure of the timetable. If all of these are factored in at the outset and, in a sense, a ‘pre-mortem’ conducted to identify potential barriers and conflicts before they occur, putting an action in place for each one during the planning phase, then the implementation and hopefully impact of these days will be more positive and purposeful.

@hwrk_magazine 12 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 26

References: Carpenter, S., Pan, S., Butler, A. (2022) The Science of E ective Learning with spacing and retrieval practice; Nature Reviews Psychology; Vol.1; p.496 - 507

RETHINKING

EDUCATIONAL AMBITION IN THE EBACC ERA

By Tracey Leese

By Tracey Leese

How do we know if we are ambitious enough for our students?

Dolly Parton advocates that we pour ourselves a daily cup of ambition, and whilst it’s unlikely that she had the current Ofsted framework in mind when composing, this is still ideal life advice from country music’s beloved matriarch. Like Dolly I applaud ambition in all its forms, as a teacher and school leader I must reference this almost as frequently (though admittedly less eloquently) as Dolly. Ambition is something we’re measured against and something we endeavour to instil in our learners – and yet it’s incredibly hard to quantify.

Outside of education ambition is a loaded term which is synonymous with striving, achieving and succeeding. An empowering (if intangible) concept. Within schools the notion of ambition has come to characterise the current inspectorate framework – as practitioners and leaders we are directed to build and deliver a curriculum which is broad, balanced and (you guessed it) ambitious. Clearly, the current political agenda and subsequent impact measures position ambition at the heart of school’s intent and impact which really does make sense… on paper at least.

As an English teacher by trade, I recognise the importance of ambition within the curriculum; especially within the inner-city school in which I teach. I also happen to believe that literature texts act as gateways to other worlds, eras and experiences. Where else will children explore a Petrarchan sonnet or Shakespearean tragedy if not in school? Of course, this isn’t only true for English – but for all the challenging content we deliver; especially when this content feeds into students’ cultural capital.

As a secondary practitioner and leader within an inner-city school located in the bottom 10% of deprivation in the UK (according to national poverty indices), I also believe that ambition transcends curriculum. You will doubtlessly be familiar with the correlation between word and literal poverty – and the impact this can have on students accessing their wider curriculum (howsoever well-sequenced or broad) because if children cannot interpret and infer, they simply will not learn. An ambitious curriculum must surely di er according to school context. The EBacc directive seems loaded with assumptions about the purpose of education, some of which will resonate more in some contexts than others.

Tracey Leese explores the narrow focus on English Baccalaureate (EBacc) entries as the measure of educational ambition, highlighting the need for a broader perspective that considers diverse student needs, aspirations, and the overall purpose of education.

@hwrk_magazine 16 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 26

HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK ISSUE 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 17 FEATURE

base on which to draw; curriculum plans, programs of study and statements of intent. Our smoking gun, however was our destination data (Oxbridge and other Russell group universities and those who had left us to read medicine the month before the inspection). Arguably, having students who live within one of the most deprived areas in the country attend the best universities in the country could not illustrate ambition more!

However, the DfE’s definition of ambition is somewhat narrower than ours, because their definition of ambition is (ironically) narrow and rests (almost) solely on English Baccalaureate entries. According to the Department for Education, this is an airtight litmus test for how ambitious a school is. So when this became a talking point within our inspection it’s fair to say that it felt somewhat unjust.

The DfE aim is for 90% of students to be studying towards the EBacc by 2025; meaning that the majority of students would be studying a traditional and academic pathway regardless of SEND

needs, disadvantage or EAL status and career aspiration. I can’t help but wonder…

An EBacc pathway is a hard sell, students do not receive formal recognition for this suite of subjects, nor is it requested specifically by employers or universities (not even Russell Group). As a metric it seems arbitrary as there is no actual benefit for students – only for schools who have to report on the number of students who were entered for the EBacc as part of accountability measures.

But wait – EBacc is a DfE directive, not Ofsted’s – surely there is a case to be made that a school’s ambition can transcend EBacc? Whilst this isn’t an Ofsted directive per se, EBacc entries feed directly into a school’s Quality of Education judgement. In reality this means that schools are forced to measure the ambition of their curriculum based on factors other than their students. It’s completely counterintuitive, if not unjust.

I understand that reporting on EBacc entries prevents schools from narrowing the curriculum (and therefore gaming) – though in reality the Creative Arts and vocational subjects are casualties of

this – subjects in which many students have natural aptitude. For some young people this may be the main area where they accrue most of their success – the resulting self-esteem and motivation is not to be underestimated. Not to mention the collateral damage this does to a school’s overall Progress 8 figure.

It’s also notable that we report on students who are entered for the EBacc – not necessarily who passes. So are we asking schools to enter students who may not be equipped to succeed at GCSE in a second language in order for them to fail? School leaders find themselves in the invidious position of reconciling DfE directives and providing students with the best life chances possible.

So though I would consider myself an advocate for both ambition and aspiration, there surely needs to be some more thought given to what is driving the directive about EBacc and the subsequent impact on the very the very thing at the heart of our education system – the young people in our care. To truly cultivate aspiration in our students, it may be necessary to expand our perspectives and set higher ambitions beyond the confines of the EBacc.

@hwrk_magazine 18 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 26

what for? Or rather – for whom?

An Inspector Called, and we

PEDAGOGY

22. Unleashing The Power Of Metacognition

Why should you change and hone your practice? Why metacognition and not something else?

HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK ISSUE 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 21

UNLEASHING THE POWER OF METACOGNITION

By Nathan Burns

By Nathan Burns

I think that we’ve all got things that we love a little more than others, that are a little unusual. Some people love train spotting. Others love waxing their car. Some love colour-ordering their bookcase. For me, it is metacognition. I’ve shared my love of metacognition previously – blogs, podcasts, and recently my first book (with more in the pipeline). Excitingly, this piece marks the start of a series of articles on metacognition, walking you through from the complex theory and misconceptions, into strategies that you can use and apply directly into your classroom. These pieces, over the coming weeks and months, will hopefully give you insight into the theory and lead to improvements in your own classroom practice.

I’m going to start with the why of metacognition. Why should you change and hone your practice? Why metacognition and not something else?

Firstly, is the EEF. As you’ll be aware, the Educational Endowment Foundation summarise the impacts of dozens of di erent educational interventions. Of all these strategies, metacognition is the one with the greatest positive impact.

If that doesn’t convince you, then perhaps OFSTED will. In their recent summary of what makes high-quality CPD, coverage of metacognition is highlighted. This is important, and not just to tick an OFSTED box, but rather because OFSTED criteria are determined by educational research. If metacognition is an included criterion, it must be worth it!

Besides the EEF and OFSTED, there are of course numerous other studies from the last 50 years which support the positive impacts of metacognitive teaching across all educational stages and subjects, which aren’t hard to find.

So what is metacognition? My favourite definition from the literature is from Flavell (1976):

I am being metacognitive if I notice that I am having more trouble learning A than B; if it strikes me that I should double check C before accepting it as fact.

This definition provides such clarity – emphasising how metacognition is an evaluation of our thinking at all stages. I’ve also endeavoured to formulate my own definition, which is as follows:

The little voice inside your head that constantly evaluates and informs your actions.

The emphasis here is on the constancy of metacognition. This evaluation of cognition is constantly occurring and should also constantly inform future actions.

@hwrk_magazine 22 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 26 PEDAGOGY

The first in a series of enlightening articles exploring metacognition, from its theoretical underpinnings to practical strategies, to enhance classroom practices and empower students’ cognitive development

Metacognition is more than just ‘thinking about thinking’ - a commonly coined phrase of the early noughties. It involves a consideration of your planning and the outcomes of your cognitive actions. However, it is no surprise that pinpointing exactly what metacognition is is so di cult. If you are practicing ballet, you have a huge, mirrored wall to see what you are doing. If you are learning to drive, whacking a kerb, or getting hooted will quickly make you know that you’ve gone wrong. Yet metacognition is invisible. Let us consider the planning of a lesson:

Before: What do students need to learn? What is their prior learning? What strategies have worked when teaching this topic previously? What behaviour management strategies work with this group and these students in particular?

During: Are students understanding as much as they should? Do you need to change the methods shown? Do you need to push students on or take a step back?

After: How far did students get and how do you know? What worked well in the lesson and what would need to improve the next time you teach the topic? What changes are you going to make in your approach to the next lesson?

Hopefully this illuminates the metacognitive thoughts going on here. Equally, this scenario should highlight how metacognition occurs continuously. Much of what we are doing is already metacognitive and this is what makes metacognitive teaching so appealing. It is not a completely new strategy to implement, but really a tweaking of certain aspects to rapidly accelerate the progress of your students.

So, this is the what and the why. Now, it is crucial that you understand the nitty gritty of the theory. I really believe that the more you understand the theory, the better the implementation will be. Strategies are so specific to the situations that you are in – the year groups, subjects, and student behaviour, amongst other variables.

Firstly, you will need to understand the di erence between the two sub-strands of metacognition. The first is knowledge of cognition, and the latter is regulation of cognition. The knowledge strand refers to the understanding we have of our own cognition, such as our knowledge levels, our content knowledge, and the approaches which we can take to completing a task or problem. The regulation strand references the control and monitoring of our own thinking – that is the evaluation of strategies which we use.

In turn, these two strands get broken down further. Let us begin with the knowledge strand, which is broken into ‘knowledge of self’; ‘knowledge of strategies’; ‘knowledge of task’. The knowledge of self is an individual’s knowledge of the content required to complete a task. Does the individual have the information that they need to be able to approach this question? The knowledge of strategies defines the di erent approaches that could be utilised to complete a task, as well as a strong knowledge of how to use

ISSUE 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 23 HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK PEDAGOGY

them (i.e. not just knowing that the use of e.g. a Frayer Model may be helpful, but also knowing how to set it up and use it e ectively). Lastly, knowledge of task refers to the individuals understanding of the specific requirements of the task or problem that they have been given, such as key command words or outcome criteria.

The cognition strand itself is also broken down into three di erent areas, which are planning, monitoring and evaluation. These three areas complement the three areas of knowledge of cognition well, as will now be shown.

Firstly, planning refers to the consideration of how to approach a task, for example, including an evaluation of task criterion, the strategies available to complete a task, and their comparative e ectiveness.

Secondly, monitoring refers to the ongoing evaluation of the progress being made towards the competition of a task. Here, an individual will be reviewing if things are going to plan, if changes need to be made or if they require support to be able to complete the task.

Lastly, evaluation is the consideration of the e ectiveness of the complete task completion and will include reflection such as whether an alternative approach is required next time, gaps in knowledge of content and skills required and whether task criterion were e ectively met. In turn, these evaluations should inform future planning, providing a continuous improvement loop.

I’m aware that this is quite heavy and can be quite confusing. I urge you to take the time to re-read and potentially summarise these key notes on metacognition. The strategies to be explored in future weeks will reference these areas of metacognitive knowledge and cognition, with each strategy supporting student development in one or more of the subset areas.

To finish o this introduction to metacognition, I’ll briefly consider a few misconceptions. Metacognition is not something new, either as a theory (being traced back at least a century) or as a pedagogical tool in schools (having floated in an out of popularity in di erent guises over the last 50 years). Because of these reasons, plenty of misconceptions have evolved and embedded themselves into common opinions on the

theory. The most concerning of these misconceptions is that metacognition is only for highly attaining students.

Though it is true that metacognition can only begin where cognition is cemented, this does not mean that it needs to be reserved for highly attaining students. It is also true that highly attaining students are more likely to have stronger metacognitive skills, but again, this does not mean that it is only these students who should have their metacognitive abilities strengthened. If a student is weak cognitively, or weaker metacognitively, and is not given the opportunity to develop their metacognition, then they will never actually improve their skills, and so will continue to be metacognitively weak.

This is an extremely negative loop, cemented through the belief that students aren’t able, whereas they actually are. In addition to this misconception are several others I have written about previously, including believing that boys cannot be good metacognitively, focussing on non-SEN students and that metacognition can only be improved in older students. The key point to come away with though is that metacognition is for all.

@hwrk_magazine 24 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 26 PEDAGOGY

28. Resources To Enrich Subject Knowledge In English Literature

Andy Atherton suggests a wide range of materials to enrich the English Literature Curriculum and to support students in their studies.

33. Exploring Morphology, Etymology, and Cognitive Strategies for Effective Vocabulary Instruction

Students are taught to analyse texts, deconstruct sentences, and decipher meanings, but how often do they explore the architecture of words?

36. How I Teach Bar Charts to Year 4

Top tips on how to teach bar charts in Primary Maths to Year 4

EXPAND YOUR MIND ONE SUBJECT AT A TIME issue 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 27 @hwrk_magazine

DEVELOPING SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE IN ENGLISH LITERATURE

By Andy Atherton

When I first started teaching A Level English Literature, an experienced colleague offered me some advice. Over the years, I’ve offered this same advice to countless other colleagues as they embark on their own A Level teaching journey. ‘Just make sure you know the texts inside out’, he said. Sometimes the simplest advice is the best.

It seems to me the last several years have witnessed a revival in the importance of subject knowledge as a key lever of pupil progress. Knowing your texts inside out is not just excellent advice for A Level teachers, it’s excellent advice for everyone.

However, what practical steps might we take to accomplish this? In this article, I’ll outline some of the resources I personally use to develop my own subject knowledge. Whether it’s a text I’m teaching for the first time or one I’ve taught for many years, trying to improve our own knowledge is always time well spent.

Massolit

This is such a superb resource and possibly the one I get most use and benefit from on a week by week

basis. There are so many courses to choose from covering a vast range of texts and literary topics. In recent months, I’ve completed courses on Emily Dickinson, Unseen Poetry, Hamlet and Philip Larkin.

When completing a course, I try to make notes using the Cornell method — a strategy I have shared and modelled with my students — so that I can return to these notes at a later date.

I also really like that the courses tend to be relatively short and each episode in the region of 10 to 20 minutes. This makes it very easy to fit alongside other commitments.

MOOCS

Similar in nature to Massolit, but, broadly speaking, probably more detailed and often pitched academically at a slightly higher level, MOOCs are short online courses that you enrol onto and complete in a designated window of time. They typically require a certain number of hours commitment per week and last anywhere between 4 to 10 weeks. They tend to be comprised of materials to read, podcasts to listen to, and videos to watch.

These courses are offered by universities and university academics and tend to be pitched at high A Level or beginning undergraduate level, making them perfect for someone looking to brush up on or learn about an academic area with which they’re otherwise only slightly familiar.

By far the best MOOC I have ever completed is one offered by Coursera called ModPo, which looks at a broad sweep of modernist and postmodern literature across the twentieth century. It is amazing. As someone with a PhD in exactly that area of study, I cannot tell you the level of quality in this MOOC. It is like getting a 10 week undergraduate course in twentieth century literature for free. I share and promote it with all of my A Level students.

Some excellent sites for MOOCs include:

1. FutureLearn

2. Coursera

3. EdX

4. Stanford Online

5. Harvard Online

6. Udacity

CURRICULUM @hwrk_magazine 28 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 26

Andy Atherton suggests a wide range of materials to enrich the English Literature Curriculum and to support students in their studies.

Podcasts

There are some excellent literarybased podcasts out there, not including listening to books themselves on Audible or similar. With a 30 minute commute to school each day, I have racked up many hours of enjoyable and fascinating literary discussion.

Some of my favourites, all freely available, include:

1. In Our Time

2. Hardcore Literature

3. Backlisted

4. Shakespeare Unlimited

5. Emma Smith’s series of podcasts about Shakespeare for Oxford University

There’s then a great range of podcasts that whilst not directly related to literature, connect really well:

1. The Rest is History

2. Philosophise This

3. You’re Dead to Me

Taking The Rest is History as an example, recent episodes on the history of climate thinking helped me to teach Romanticism; one on the murder of Julius Caesar, perfect for Shakespeare’s play; and a series on Ronald Reagan was really helpful for thinking about the political context underpinning The Handmaid’s Tale.

In Our Time

Deserving of an entry of all its own, In Our Time is simply an incredible resource for subject specific development. With over 800 episodes spanning a massive range of disciplines and topics, there will be something of interest and value for everyone.

In the recent couple of months, for instance, I’ve listened to episodes on Wuthering Heights, The Great Gatsby, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, amongst others.

Given every episode includes experts in whatever topic is being discussed, the conversation is always incredibly stimulating and insightful. One on Emily Dickinson, for instance, included contributions from Fiona Green who is a leading and internationally renowned scholar in the area of American Literature.

Norton Critical Editions

Moving away from podcasts and online lectures, some of the most useful books I buy when trying to develop of my subject knowledge on a particular text or writer is the relevant Norton Critical Edition. In fact, if I am teaching a text for the very first time, I’ll always look to buy one.

As well as the text itself, these editions often include really useful supplementary resources like contemporary reviews, scholarly articles, detailed annotations, relevant historical or social context, and a whole host of other valuable materials. When I first taught Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde a few years ago, for instance, the Norton Critical Edition was invaluable and a lot of the ideas I then taught I first encountered in its introduction or the articles.

It’s worth saying too that these editions are often updated and so it is best to look for the latest one so that the articles are as recent and up to date as possible. However, if price is an issue, you can find earlier editions often incredibly cheaply.

HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK ISSUE 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 29 ENGLISH

New Critical Idiom

This is a series of books that function as a high-level introduction to various topics within literary studies, as well as other disciplines. Rather than focussing on a specific text or writer, these texts often look at broader areas such as literary movement, genre or something like literary form. They are really excellent at condensing a really broad topic into a couple of hundred pages of accessible yet still scholarly prose.

Taking a quick look at their catalogue, for example, I can see books on modernism, Romanticism, comedy, stylistics, literature itself, intertextuality, the gothic, satire, myth, the author, genre, discourse, science fiction, and on and on.

If there was a particular area of literary studies that I wanted to know more about and to get a broad overview of the debates within that area then this would probably be my first call.

Cambridge Companions

Similar in nature to the above, but typically a series of essays rather than a single text and also including text and author specific entries, the Cambridge Companion series are also a really excellent way into an otherwise potentially intimidating area of literary study.

The essays are always written by specialists within that field and tend to be geared towards a high performing A Level or first year undergraduate audience. As such, like New Critical Idiom, you can be guaranteed to really get a sense of the key de-bates and ideas within a specific field, even if it’s not something with which you’re particularly familiar. The two often go really well together too, if, for example, you read the relevant New Critical Idiom for a specific movement or genre and then the text-specific Cambridge Companion.

Subject-specific Organisations

Over the years, I have learned an incredible amount from associations and groups such as NATE (National Association of Teaching English), LATE (London Association for the Teaching of English), The English Association, and EMC (English & Media Centre). A quick browse of their respective websites, reveal a huge amount of subject-specific guidance, both pedagogic and literature-specific.

EMC’s emagazine is always packed full of really interesting subjectspecific articles and they have published loads of really great study guides for various texts and writers. Their Literature Reader, a collection of critical essays, is especially valuable, including a range of topics such as how we define literature, context, modernism, Romanticism, the novel, post-colonialism, dystopia, and many more.

Likewise, NATE’s magazine Teaching English is always wonderful, including a vibrant range of articles written by teachers, academics and others involved in the teaching of English. A recent issue dedicated to the teaching of poetry included lots of practical ideas to try out, but also, for the purposes of this article, signposted lots of interesting new poets and books.

Conclusion

Taking the time to develop our own subject knowledge is always a worthwhile venture. It leads to richer conversations in the classroom and the ability to immerse our students in the literary hinterland that exists beyond and around the texts we study.

As a final suggestion, here are ten literature-specific books I’ve read over the last year that I thoroughly enjoyed. Happy reading!

1. Adam Nicolson’s The Making of Poetry

2. John Sutherland’s A Little History of Literature

3. John Carey’s A Little History of Poetry

4. Kevin Jackson’s Constellation of Genius: 1922, Modernism and all That Jazz

5. Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination

6. Shakespeare’s Sonnets

7. Robert Hass’ A Little Book on Form: An Exploration into the Formal Imagination of Poetry

8. Don Paterson’s Reading Shakespeare’s Sonnets

9. Carlin Borsheim-Black’s Letting Go of Literary Whiteness

10. Maud Ellmann’s The Nets of Modernism: Henry James, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Sigmund Freud

CURRICULUM @hwrk_magazine 30 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 26

UNLOCKING THE POWER OF WORDS: EXPLORING MORPHOLOGY, ETYMOLOGY, AND COGNITIVE STRATEGIES FOR EFFECTIVE VOCABULARY INSTRUCTION

For over two millennia, the atom was considered the smallest building block of life until scientists discovered the electron, nucleus, and elementary particles. While we’ve made progress in understanding the physical world, many people still perceive words as the ultimate frontier in language. Students are taught to analyse texts, deconstruct sentences, and decipher meanings, but how often do they explore the architecture of words?

By David Voisin

A huge emphasis has been placed on explicit vocabulary instruction in the past few years. It plays a significant part in the 2019 Ofsted framework and the Education Endowment Foundation released a Literacy Guidance Report which highlights what constitutes good practice. People familiar with these

documents will have noticed the conspicuous emergence of two new terms in the vocabulary toolkit: “Morphology” and “Etymology”.

Morphology (of which etymological roots are a subset), is a branch of grammar. As such, it suffers from the same stigmatisation which has

prevailed in British education for decades. But grammar is not about rules and prescription (although there are conventions), it is about meaning and construction. It is not about trying to resuscitate moribund languages but about understanding modern ones.

HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK ISSUE 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 33

ENGLISH

Patterns

MFL teachers are experts at learning and teaching vocabulary because polyglots are constantly exploring the similarities between words across languages. It is about building from what we already know.

It is possible to understand and memorise new words the same way we generate ideas: through associations, and this is where morphology can be extremely useful. Foreign languages are great for discovering patterns. For instance, to wait in Spanish is Esperar. Espérer in French means to hope. Hoping is indeed akin to waiting. Waiting in French is attendre. What do waiters do? They attend to tables! If you like this type of word dominoes, The book “The Etymologicon” from Mark Forsyth is a great read.

On a lexical level, however, many of our learners are ill-equipped to recognise patterns. I had to explain to some KS4 students that the words “imitate” (which they knew) and “inimitable” (which most did not recognise) were connected. The same with “stellar” and “constellation”. This is problematic because what matters is not so much how many new words students acquire but how they get to recognise and memorise them.

To understand how we learn new vocabulary, I believe that we need to look at the basics of cognitive science. Cognitive Load Theory is sometimes reduced to the simplistic notion notion that only a limited amount of information can be processed at once. This is true, but there is a lot more to it. The idea that working memory and long-term memory are two separate blocks may not be entirely helpful because the most interesting aspect of learning is not the transfer from one to the next, but the constant exchange between the two.

Words are not indivisible entities. They can be broken down and linked to other words, either morphologically (in their form) or semantically (through meaning). Of course, the two are not mutually exclusive. The huge advantage this presents is that it allows learners to connect new words to words they already know, a bit like a mental “Velcro”, to borrow E.D. Hirsch’s analogy. It also enables them to understand how these words can relate to others and how they can be modified to generate new meanings or functions within a sentence.

Morphology does not replace reading for vocabulary acquisition but rather complements it, allowing students to be more independent and providing additional clues about meaning when context alone does not suffice. In their book “Bringing Words to Life”, Beck, McKeown and Kucan explain that only certain types of context (directive and occasionally general) are conducive to meaning. For instance, pupils may use context to decipher the meaning of the word “philanthropist” in the sentence “He is a lavish philanthropist, donating generous amounts of his own personal fortune to charities or other noble causes”.

However, students would be none the wiser if they came across the related words “anthropology”, “anthropophagous” “anthropomorphic”, “anthropocentric”, “misanthropy” and this is only half of the etymological roots of “philanthropy”. Context alone is not enough. Every classroom teacher should use affixes (prefixes and suffixes) as well as etymological roots to help students recognise, memorise, analyse and construct words.

The other advantage is that etymological roots are distributed over all three Word Tiers, linking easy words to more academic ones (for instance “quad”, “quadriceps” and “quadruped”). Etymology is

a fantastic tool for learning and understanding. Pupils find it fascinating.

This linguistic reverse-engineering is not just helpful for meaning but also for spelling. For instance, have you ever noticed that the root “pter” at the beginning of “pterodactyl” is also present in “helicopter” (“pter” meaning “wing”)? As for “dactyl”, it means finger and it is featured in “dactylography”. 90% of polysyllabic words in English come from Latin or Greek.

So, should we teach our students hundreds of Greek and Latin roots? No, not at all. What we must do is incite them to be observant and teach them to make connections. We need to have a forensic approach to language.

The chunking down of words for memorisation is the best way to reduce cognitive load; we do it every time we try to memorise a phone number (three sets of three digits is easier to remember than nine individual numbers). For example, the spelling of Wednesday is easier to remember for students once they break it down into Wed-nes-day. The process of ‘chunking’ is at the core of the morphological approach.

Another crucial function of morphology is to ‘navigate’ words along a grammatical spectrum. For instance, the adjective ‘clear’ can be turned into an adverb (clearly), a noun (clarity) or a verb (to clarify).

Pattern identification does not always necessitate a lexical decoupage though. Orthographic associations (via spellings) can be very helpful too. Surprisingly, there are many words in English which are separated by just one letter. Here are a few, just to illustrate: Insidious / invidious, plumber / plunder, insolent / indolent… Because words are best remembered when they are used, it could be judicious to encourage students to come up with

CURRICULUM @hwrk_magazine 34 // HWRK MAGAZINE // ISSUE 26

their own mnemonics (Mnemosyne is the Goddess of memory in Greek Mythology).

Stories

As Daniel T. Willingham points out, people remember words much better when they are articulated within a narrative. We are not just pattern seeking animals, we are also natural storytellers. Anthropologists explain that good raconteurs were endowed with a greater chance to reproduce. We ascribe narratives to our lives to give them meaning and purpose but we also use stories to memorise things better. Teachers should never neglect anecdotes when planning lessons. These are the best way to catch pupils’ attention, make new information stick and illustrate the patternicity of words.

Images

So, we must use patterns and stories to teach vocabulary. But there is a third element. As we have seen, words are not independent entities. They may be linked to other words (synonyms, antonyms, words of similar spellings or semantic fields) but also narratives, emotions. In the brain, words are not in a single location. Conceptually, words are

more of a network distributed over several cognitive areas.

At the heart of the word “imagine” lies the word “image”. Like other diurnal animals, we have a vast visual cortex. A recent arrival on the scale of human evolution, the circuitry of language (and even more recently, reading) had to bolt itself onto pre-existing systems which had helped us thus far navigate the world visually and spatially.

Einstein allegedly claimed to do most of his thinking visually rather than verbally. The English language is replete with abstract visual representations. Metaphors and idiomatic expressions are not simply aesthetic or stylistic tools for language, they bear witness to our fantastic ability to conceptualise abstract thought.

In her book “Mind in Motion: How Action Shapes Thoughts”, Stanford University professor Barbara Tversky argues that our senses of space and motion underlie our capacity for thought. She explains that educators and parents should not underestimate the didactic power of comic strips a in verbal development. I once read that Martin Amis read nothing but

comics as a child until he discovered Jane Austen.

A useful tool in the panoply of teaching strategies is dual-coding, which is predicated on the idea that information is better encoded in the brain when it stems from two types of stimuli. Thus, using images as well as text to support word acquisition is a very efficient strategy. Introduce the word “irascible” in a directive context, along with a picture of Scrooge from Disney’s animated version of “A Christmas Carol” and pupils are more likely to remember it.

Language is about communicating with others. On a cognitive level, language is also about communication: communication between the hippocampus and the visual cortex (episodic memory), or with the prefrontal lobes (semantic memory); communication between the left and the right hemisphere.

To conquer language teaching, we need to have, at the very least, an understanding of how language acquisition and development works. It is not about blindly adhering to educational fads; it is about embracing science and evidence to deliver what is best for our students.

ENGLISH HWRKMAGAZINE.CO.UK ISSUE 26 // HWRK MAGAZINE // 35

HOW I WOULD TEACH BAR CHARTS IN YEAR 4