15 minute read

Chapter Three

Chapter Three: Case Studies of Contemporary Sacred Minimalist Interiors

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the levels of contemporary sacred interiors established within the minimalism realm (Vasilski & Nikolic, 2017: 336). This concluding chapter will analyse three precedent studies of sacred interiors as well as the minimalist design elements that have been utilised in the space. This will be undertaken through an analysis of architectural spatial features as well as gathering secondary scholarly sources. The analysis of architectural spatial features will involve an investigation of material choices, lighting strategies and the implementation of scale and the gathering of secondary scholarly sources will analyse published plans and images of the interiors, as well as commentary from the architects and design critics. This analysis of architectural books and articles will utilise the historical and contemporary framework that was discussed in chapters one and two to emphasise how these influences have informed the evolution of minimalism within sacred interiors. The first precedent study will look at the Saint Moritz Church in Germany, designed by John Pawson, to highlight how minimalism within this sacred interior provided a more significant value than merely just aesthetic. The second precedent study will focus on Church of the Light in Japan, designed by

Advertisement

Tadao Ando, to study the notion of how Japanese culture and Zen Buddhism has become

westernised, therefore being utilising a method of implementing and communicating minimalism in an aim to achieve transcendence. The third and final precedent study will examine the Bruder Klaus Field Chapel and will look at how the architect, Peter Zumthor, implemented aspects of minimalism to draw similarities between this chapel and living a monastic life as a hermit. These sacred interiors have been chosen as they are all at different scales and different geographical locations, which emphasises the diversity of minimalism. The case studies were also selected as the architects that completed the works, Pawson, Ando and Zumthor, have been noted for their contribution to the development of minimalism (Bertoni, 2002: 11). This chapter seeks to demonstrate that several architects who substantially contributed to the development of minimalism within contemporary sacred interiors, implemented this aesthetic within this architectural typology to draw parallels between the historical and contemporary influences that were outlined in the previous chapters.

Saint Moritz Church, Augsburg, Germany (2007)

Saint Moritz Church is a Catholic church located in Augsburg Germany and was originally built as a Romanesque basilica in 1019 and was rebuilt over a century later with the influence of Gothic style architecture in 1229. It was once again redeveloped, through a Baroque-style approach in 1714 (Schoof, 2013). British minimalist architect John Pawson (1949-), completed the latest redevelopment of the church in 2007 with the intention to maintain the rich history, whilst restoring the remaining structure that had been destroyed by bombs and fires during World War II (1939-1945). Pawson redesigned the function of the existing form, through a minimalist lens, to best support the liturgy as well as to illustrate

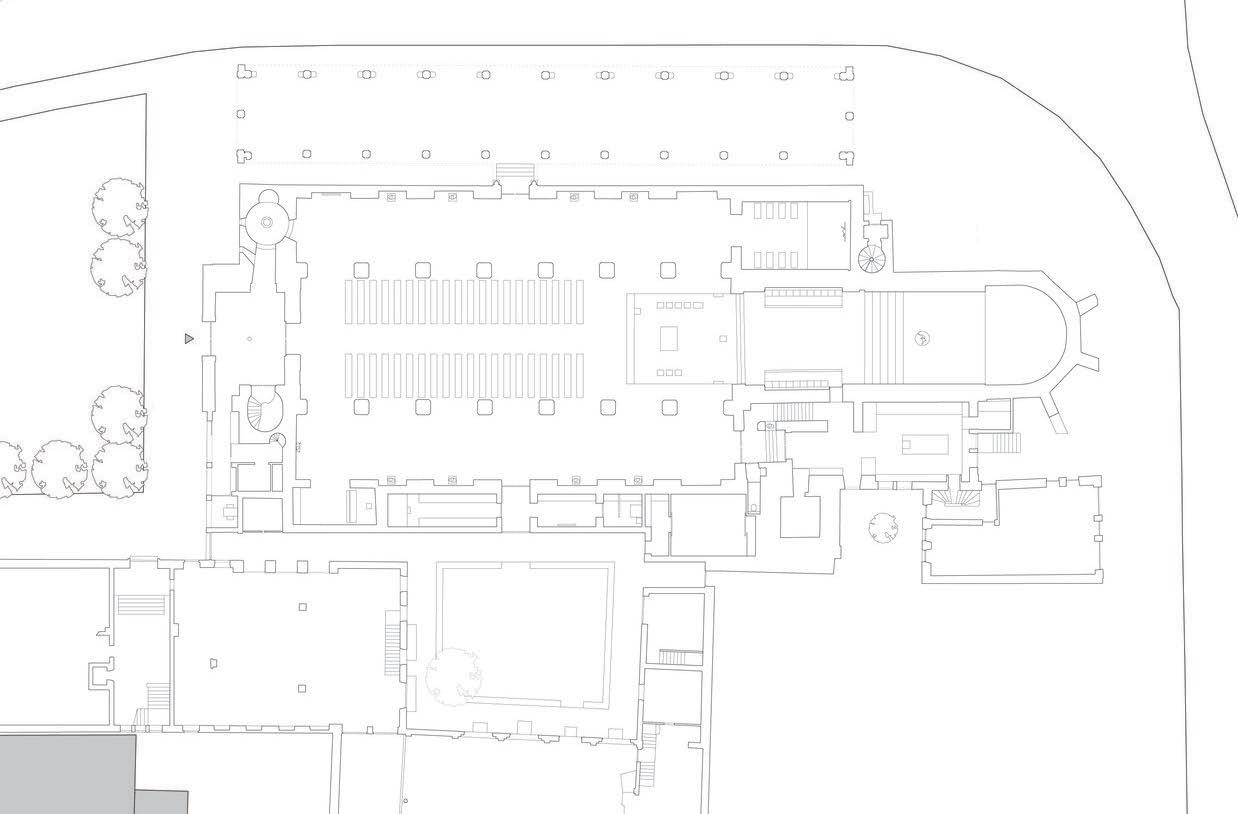

the evolving history of the church, without introducing any clashing components. This emphasises how the implementation of minimalism has the ability to create a space that is free from distraction and as a method of respecting the historical footprint of the church. Whilst the restoration of the church redefined functional elements, Pawson strived to ensure that all redevelopments served a distinct purpose, as being considerate of the historical significance of the sacred interior was at the forefront of all design decisions (Pawson, 2013). The floorplan of the interior, as seen in figure 3.01, and the interior itself, as seen in figure 3.02, is formed of a nave and is defined through its traditional Baroque-style clerestory arches. The church floor is covered in beige Portuguese limestone tiles, which offers a smooth transition to soften the contrast between the dark-stained timber joinery in the choir stalls, as illustrated in figure 3.03. Public seating and the dark-stained joinery, which houses the pipe organ against the white walls, is evident in figure 3.04, which serves to draw attention to the front of the church and contribute to the ethereal atmosphere within the church.

Figure 3.01. Image showing the interior floorplan of the Saint Moritz Church

Figure 3.02. Image showing the interior of Saint Moritz Church, the nave and the Baroque-style clerestory arches

Figure 3.03. Image showing the interior of Saint Moritz Church and the strong contrast between the white walls and dark-stained timber joinery in the church choir.

Figure 3.04. Image showing the interior of Saint Moritz Church and the strong contrast between the white walls and the dark-stained timber joinery which houses the pipe organ

Figure 3.05 Image showing the interior of Saint Moritz Church and the religious symbols that have been placed in the lateral aisle.

Whilst the implementation of minimalism within this church may seem to serve a purely aesthetic purpose, the historical framework provided in chapter one reinstates that parallels can be drawn between monasticism and iconoclasm within the redevelopment of Saint Moritz Church. The white walls, stripped of all ornamentation, serve to conceal the damage that the church had endured, and it is only through the clerestory arches embedded within the interior architecture itself that any form of its Baroque history is revealed. This emphasises Pawson’s implementation of minimalism as an interpretation of monastic traditions, as the renunciation of material aesthetics within the church illustrates the parallels of avoiding distraction to ensure a completely meditative space where one can devote themselves entirely to Christian worship. Pawson claimed that ‘clear simplicity has dimensions to it that go beyond the purely aesthetic’ (Pawson, 1996: 07), which he substantiated within SaintMoritz through lighting and a reduced material palette. The lighting strategy employed within Saint Moritz Church demonstrates a systematic approach, as it was claimed by Etherington, that it filters out direct sunlight and welcomes a ‘haze of diffused luminescence’ (Etherington, 2013). The religious and devotional symbols that have been placed in the lateral aisles, as seen in figure 3.05, in addition to the restraint of religious symbols from the centre aisle revealsparallels betweenthis church and iconoclasm. Whilst this church is operated under Catholicism and therefore cannot be completely void of religious symbols, the influence of modernism can be seen through the implementation of minimalism as Pawson deliberately placed the religious symbols in the side aisles of the church, as a method to void any form of distraction to shift the focus towards worship (Foges, 2014: 160). These modernist traits that have assisted with the interpretation of minimalism within this interior include the open floor plan, white interior walls and the use of timber. Therefore, this emphasises how the architectural design elements that Pawson implemented can be seen as an interpretation of monasticism, iconoclasm and modernism which emphasises how these historic influences have impacted the development of minimalism within sacred interiors. Similarly, the following case study will further reinforce how both historical and contemporary influences have impacted the development of minimalism within sacred interiors.

Church of the Light, Ibaraki, Japan (1999)

Ibaraki Kasugaoka Church, most commonly known as Church of the Light, is a Protestant church located in Ibaraki, Japan and was completed in 1999 by Japanese minimalist architect, Tadao Ando (1941-). This church remains one of Ando’s signature architectural projects, as it has been acclaimed for his ability to integrate form with nature and to define space through the utilisation of voids and light (Richardson, 2004: 12-13). This precedent study was chosen as it has strong Japanese influences, which further supports the contemporary influences mentioned in chapter two. The floorplan of this chapel can be seen in figure 3.06. The interior or the church is defined by its minimal lighting strategy and material palette, as these architectural design elements assist in introducing a distinct contrast between light and shadows, therefore establishing a distinct meditative atmosphere (Silloway, 2004). Within the chapel, the most prominent source of light is brought into the space through the cross window which is

formed from a void in the architecture. The light that passes through this window provides an illusion that the density of the concrete appears weightless as the light appears to pierce through the solid mass, as seen in figure 3.07. The controlled injection of light that enters the church is contrasted with the materiality, as the dark timber flooring made from re-purposed scaffolding boards and the reinforced concrete, further supports the darkness and weight of the church, contributing to the contemplative atmosphere.

As discussed in chapter one,aspects of iconoclasm can be seen within Church of the Light as this church establishes itself as being iconoclastic as the only symbol of religious significance is formed from the void in the wall which forms a symbol of a cross. The cross forms a point of focus, which ultimately screens and directs the views to evade any form of distraction from the exterior, positioning the church as an extremely internalised meditative space. The use of reinforced concrete walls, in conjunction with the aesthetic influence of minimalism, illustrates the integration of western culture and Japanese architecture. Whilst this church is situated within Japan, parallels can be seen in the methodology that Ando adopted when integrating notions of Zen Buddhism and aspects of western culture (Stevanovic, 2011: 24). This ultimately perceives Zen Buddhism as merely contributing to the aesthetic value of the church, rather than recognising it as method to gain self-realisation which can heighten the human experience and trigger a deeper emotional and spiritual connection (Stevanovic, 2011: 25). This synthesises how the implementation of minimalism within sacred interiors has been reinterpreted as a physical representation of Zen Buddhism, encouraging users to think through abstraction. This illustrates how the relationship between minimalism and Zen Buddhism has been redefined as a consequence of being a product of the western world and as a means of integrating traditional Japanese architecture and culture (Stevanovic, 2011: 24). Similarly, the following case study will provide further evidence to illustrate how the theoretical framework provided in chapters one and two have assisted in the development of minimalism within sacred interiors.

Figure 3.06. Image showing the interior floorplan of Church of the Light, Ibaraki, Japan (1999) (not to scale)

Figure 3.07. Image showing the interior of Church of the Light, Ibaraki, Japan (1999) and the light entering the church in the shape of a cross, which appears to cut through the concrete.

Bruder Klaus Field Chapel, Mechernich, Germany (2007)

The Bruder Klaus Field Chapel, as seen in figure 3.09, is a Catholic pilgrimage chapel, located in Mechernich, Germany, and was built in 2007. It was designed by Swiss architect Peter Zumthor (1943), who is known for his minimalist aesthetic. The floorplan of this chapel can be seen in figure 3.08. This pilgrimage chapel has been chosen as a case study as the minimalist traits, implemented by Zumthor, can be seen to have strong connections with monasticism, which further supports the theoretical framework that was provided in chapter one. It has been claimed that the most remarkable aspect of the chapel lies within the construction itself (Svevien, 2011). All materials were sourced locally and the chapel itself was constructed by farmers that were local to the community, to honour the Saint Bruder Klaus of the 15th century (Svevien, 2011). The chapel was constructed as a series of processes which firstly involved the gathering of 112 locally sourced pine tree trunks, which were utilised to form a framing structure resembling a wigwam (Pallister, 2015). Architectural writer, Ariana Zilliacus, claimed that whilst there is a ‘stark contrast to the comparatively smooth angular façade’, the chapel, ‘despite its concrete surface and straight edges, does not stand out as brutal’ (Zilliacus, 2016). This ultimately emphasises Zumthor’s intent of establishing the chapel as being a spiritual contemplative space through its ‘composure, durability, presence, and integrity with warmth and sensuousness’ (Svevien, 2011). After the framing structure was completed, individual layers of concrete, which was formed from local sand and gravel, were poured and rammed, 500mm thick to form a total of 24 layers. The verticality of the interior encourages the user to consistently shift their view upwards, emphasising the use of scale to create a sense of being engulfed and immersed within the chapel. The concrete, being held in place by steel tubes, were then removed to reveal small holes which brings natural light into the chapel. Once this had been set, the pine trunks were set ablaze, which left the interior as ‘a hollowed blackened cavity’ , evident in figure 3.10 (Pallister, 2015). The scorched emptiness of the charred walls within the chapel is the only form of materiality used, reinforcing it as extremely minimal, with the addition of the molten lead flooring which completed the chapel. The combination of the two raw materials ultimately contributes to the ‘sombre and reflective feelings that becoming inevitable in one’s encounter’ (Svevien, 2011), therefore situating this chapel as ‘one of the most striking pieces of religious architecture to date’ (Svevien, 2011).

Figure 3.08. Image showing the interior floorplan of the Bruder Klaus Field Chapel (Not to scale)

Figure 3.09. Image showing an exterior of the Bruder Klaus Field Chapel, (2007), and where it is situated within the landscape of Mechernich, Germany.

Figure 3.10. Image showing the interior of the Bruder Klaus Field Chapel, (2007) and the final result after the pine tree trunk were set ablaze, which left the interior charred and hollow.

As the churchis located within a remote field and requires the effect of a pilgrimage chapel, fundamental

links can be drawn between the architectural conventions integrated throughout the Bruder Klaus Field Chapel, monasticism and living an ascetic life, which has been implemented through the aesthetic of minimalism. This is seen through the discussion in chapter one, where the notion of the hermit and living an ascetic life, similar to Anthony the Great (251AD-356AD), required one to remove themselves from common life in order to live in complete solitude whilst sacrificing material possessions and all aspects of luxury, in an endeavour to devote life entirely to spiritual work (Goswami, 2006: 1329). This decision of living as a hermit involved the acceptance of living in severe discomfort, travelling extreme distances and living amongst exposed climate elements in order to achieve a higher sense of connectivity with God and also a form of enlightenment through this process and prayer (Goswami, 2006: 1329). During the process of living as an ascetic life, the hermits would travel in solitude to reach a destination, that was exposed to the natural elements, where they could conduct spiritual practices. The requirement of a journey in solitude can be seen to have similarities to the Bruder Klaus Chapel. In addition, Zumthor designed the chapel to exclude any form of plumbing, bathrooms, running water and electricity (Svevien, 2011), in aim to draw parallels with living a monastic life to intensify the emotionalresponse within this chapel. It can be noted that Zumthor implemented this notion of ensuring

that all users in this space must experience a glimpse of a pilgrimage life as a hermit, as the path to this private chapel requires one to travel a far distance, whilst being exposed to the natural elements. Once inside, the oculus which is the main source of light, as seen in figure 3.10, is completely exposed which demonstrates the inability to find refuge and comfort within this private chapel. This emphasises how this private chapel has been interpreted as a representation of minimalism and therefore, emphasises how the theoretical framework provided in the previous chapters have contributed to the evolution of minimalism within sacred interiors.

In conclusion, this chapter discussed three case studies which embodied the theoretical research that was discussed in the previous two chapters. This aided in the understanding of how historical aspects of monasticism, iconoclasm, asceticism, together with contemporary influences such as Japanese culture and Zen Buddhism, can shape the interpretation of minimalism within sacred interiors. The architects detailed in this chapter, John Pawson, Tadao Ando and Peter Zumthor, have all been recognised as pioneers in the articulation of minimalism (Bertoni, 2002: 11). Through the series of precedent studies that were provided and analysed in this chapter, it becomes evident that parallels between contemporary sacred interiors and historical and contemporary influences, as mentioned in chapter one and two, can be drawn together. The first precedent study of the Saint Moritz Church in Germany showcased how John Pawson implemented aspects of monasticism and iconoclasm as a tribute to the church’s history, as well as highlighting Pawson’s intention of illustrating that the power of minimalism stretches far beyond an aesthetic. The second precent study of Tadao Ando’s Church of the Light demonstrated how Japanese culture and Zen Buddhism has been westernised as it has been utilised as a method of communicating minimalism. The third precedent study examined Peter Zumthor’s Bruder Klaus Field Chapel and how it analysed how this minimalist chapel could be interpreted as having significant similarities to monasticism and living as a hermit. Ultimately, this chapter explored three sacred minimalist interiors which drew connections between these case studies and the theoretical research that was discussed in chapters one and two, to emphasise how these influences contributed to the evolution of minimalism within sacred interiors.