International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research (IJLTER)

Vol. 21, No. 10 (October 2022)

Print version: 1694 2493

Online version: 1694-2116

International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research (IJLTER)

Vol. 21, No. 10 (October 2022)

Print version: 1694 2493

Online version: 1694-2116

International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research (IJLTER)

Vol. 21, No. 10

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically those of translation, reprinting, re use of illustrations, broadcasting, reproduction by photocopying machines or similar means, and storage in data banks.

Society for Research and Knowledge ManagementThe International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research is a peer-reviewed open-access journal which has been established for the dissemination of state of the art knowledge in the fields of learning, teaching and educational research.

The main objective of this journal is to provide a platform for educators, teachers, trainers, academicians, scientists and researchers from over the world to present the results of their research activities in the following fields: innovative methodologies in learning, teaching and assessment; multimedia in digital learning; e learning; m learning; e education; knowledge management; infrastructure support for online learning; virtual learning environments; open education; ICT and education; digital classrooms; blended learning; social networks and education; etutoring: learning management systems; educational portals, classroom management issues, educational case studies, etc.

The International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research is indexed in Scopus since 2018. The Journal is also indexed in Google Scholar and CNKI. All articles published in IJLTER are assigned a unique DOI number.

We are very happy to publish this issue of the International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research.

The International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research is a peer reviewed open access journal committed to publishing high quality articles in the field of education. Submissions may include full-length articles, case studies and innovative solutions to problems faced by students, educators and directors of educational organisations. To learn more about this journal, please visit the website http://www.ijlter.org.

We are grateful to the editor in chief, members of the Editorial Board and the reviewers for accepting only high quality articles in this issue. We seize this opportunity to thank them for their great collaboration.

The Editorial Board is composed of renowned people from across the world. Each paper is reviewed by at least two blind reviewers.

We will endeavour to ensure the reputation and quality of this journal with this issue.

Editors of the October 2022 Issue

Digital Leadership of School Heads and Job Satisfaction of Teachers in the Philippines during the Pandemic 1 Jem Cloyd M. Tanucan, Crislee V. Negrido, Grace N. Malaga

Unpacking Determinants of Middle School Children’s Direct Nature Experiences (DNEs): An Island Perspective

................................................................................................................................................................................................. 19

Faruhana Abdullah, Nor Asniza Ishak, Mohammad Zohir Ahmad

A Conceptual Model of Culture Based English Learning Materials in Indonesia 50 Muhammad Lukman Syafii, Ghulam Asrofi Buntoro, Alip Sugianto, Nurohman ., Sutanto

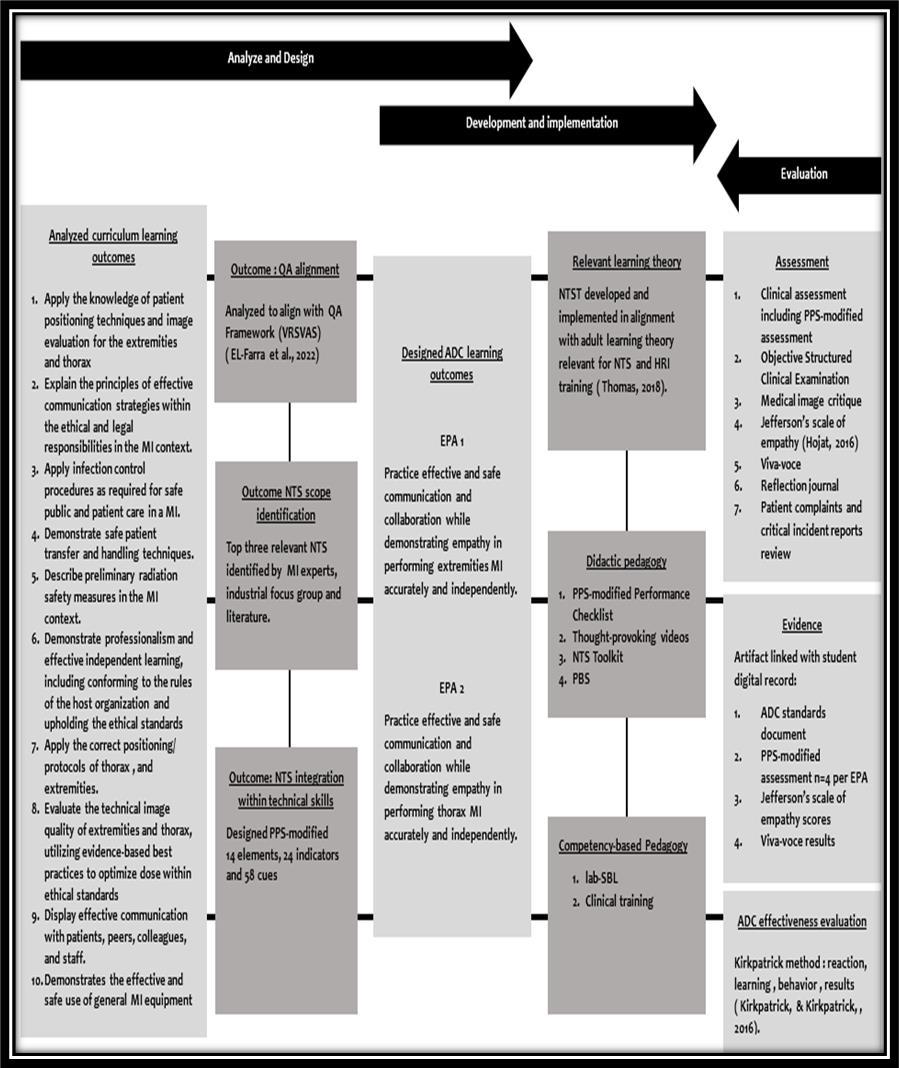

Alternative Digital Credentials: UAE’s First Adopters’ Design, Development, and Implementation Part (1) 64 El Farra Samar

Academic Dishonesty and the Fraud Diamond: A Study on Attitudes of UAE Undergraduate Business Students during the COVID 19 Pandemic 88 Omar Al Serhan, Roudaina Houjeir, Mariam Aldhaheri

Through the Lens of Virtual Students: Challenges and Opportunities 109 Joseph A. Villarama, John Paul E. Santos, Joseph P. Adsuara, Jordan F. Gundran, Marius Engelbert Geoffrey C. Castillo

EFL Pre service Teachers' Online Reading Strategy Use and their Insight into Teaching Reading 139 Anita Fatimatul Laeli, Slamet Setiawan, Syafi'ul Anam

Pre service Teachers Reflection on their Undergraduate Educational Research Experience through Online Instructional Delivery 161 Marchee T. Picardal, Joje Mar P. Sanchez

Validating the Component of E Learning Antecedents, Digital Readiness and Usage Behavior towards E Learning Performance: A Pilot Study 178 Mohamad Aidil Hasim, Juhaini Jabar, Atirah Sufian, Nor Fauziana Ibrahim

Exploring Challenges to Inclusion of Children with Intellectual Disabilities in Early Childhood Development in Mutoko District, Zimbabwe 195 Mercy Ncube, Mabatho Sedibe

Motivational and Perceptual Factors for Choosing Teaching as a Career in Chile: Sex Differences 212 Álvaro González Sanzana, Katherine Acosta García, Jorge Valenzuela Carreño, Jorge Miranda Ossandón, Lidia Valdenegro Fuentes

Exploring Learners’ Experiences of Receiving Formative Written Assessment Feedback in Business Studies as a Subject in South Africa 228 Preya Pillay, Raudina Balele

The Analysis of Natural Science Lesson Plans Integrating the Principles of Transformative Pedagogy 249

Wiets Botes, Emma Barnett

The Impact of Metalanguage on EFL Learners' Grammar Recognition 265 Abuelgasim Sabah Elsaid Mohammed, Abdulaziz B Sanosi

The Implementation of Assistive Technology with a Deaf Student with Autism 280 Asma Alzahrani

Student Perceptions of Covid 19 Induced E Learning in State Universities In Zimbabwe 296 Ashton Mudzingiri, Sanderson Abel, Tafirenyika Mafugu

Exploring Numeracy Skills of Lower Secondary School Students in Mountainous Areas of Northern Vietnam . 309 Thi Ha Cao, Huu Chau Nguyen, Xuan Cuong Dang, Cam Tho Chu, Tuan Anh Le, Thi Thu Huong Le

Innate Mathematical Characteristics and Number Sense Competencies of Junior High School Students 325 Raymundo A. Santos, Leila M. Collantes, Edwin D. Ibañez, Florante P. Ibarra, Jupeth T. Pentang

Exploring the Educational Value of Indo Harry Potter to Design Foreign Language Learning Methods and Techniques 341 Mega Febriani Sya, Novi Anoegrajekti, Ratna Dewanti, Bambang Heri Isnawan

Bridging Culture and Science Education: Implications for Research and Practice 362 Izzah Mardhiya Mohammad Isa, Muhammad Abd Hadi Bunyamin, Fatin Aliah Phang

Information and Communications Technology (ICT) as a Teaching and Learning Tool: A Study of Students’ Readiness and Satisfaction 381 Rozaini Ahmad, Usha Nagasundram, Mohamed Nadzri Mohamed Sharif, Yazilmiwati Yaacob, Malissa Maria Mahmud, Noor Syazwani Ishak, Muhamad Safwan Mohd A’seri, Ismail Ibrahim

Gender Differences in High School Students’ Beliefs about Mathematical Problem Solving .................................. 395 Edgar John Sintema, Thuthukile Jita

Teachers’ Perceived Enacted Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Biology at Selected Secondary Schools in Lusaka 418 Thumah Mapulanga, Gilbert Nshogoza, Ameyaw Yaw

The Influence of Socio Affective Learning and Metacognition Levels on EFL Listening and Speaking Skills in Online Learning 436 Titis Sulistyowati, Januarius Mujianto, Dwi Rukmini, Rudi Hartono

International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research

Vol. 21, No. 10, pp. 1 18, October 2022

https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.21.10.1

Received Au 4, 2022; Revised Oct 8, 2022; Accepted Oct 19, 2022

Cebu Normal University, Cebu City, Philippines

Crislee

V. NegridoTalisay City National High School, Talisay City, Cebu, Philippines

Grace N. Malaga

Cebu Normal University, Cebu City, Philippines

Abstract. This study examines school heads' digital leadership as a predictor of teachers' job satisfaction in the Philippines during the pandemic. A total of 520 public school teachers across the 16 regions of the country answered the validated online survey questionnaires between March and May 2022. With the descriptive predictive research design, descriptive statistics, and regression analysis, the study finds that school heads have a satisfactory level of digital leadership as perceived by their teachers. This finding suggests that Filipino school heads can, at least to a satisfactory level, guide their schools and stakeholders toward digital transformation to remain adaptable and competitive in a rapidly changing digital and social media landscape. Furthermore, Filipino teachers experienced satisfactory job satisfaction during the pandemic, which suggests that they continue to cope with and adapt to the new work and educational changes despite the plethora of challenges and transitions.Finally, thisstudyrevealsthat schoolheads'digital leadership predictsteachers'jobsatisfaction.Whenleadersarecompetenttoleadand model in the digital age, their subordinates become more satisfied with their work. Therefore, training programs for improving school heads' digital leadership are necessary to enhance their teachers' job satisfaction, especially since technology plays a significant part in diverse educational activities.

Keywords: digital leadership; job satisfaction; Philippines; school heads; teachers

* Corresponding author: JemCloydM.Tanucan,tanucanj@cnu.edu.ph

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY NC ND 4.0).

The COVID 19 pandemic has overwhelmed the education system with changes in the teaching and learning process, professional development, communication, and management (Tanucan & Uytico, 2021). The abrupt use and integration of digital tools and platforms, especially in countries with technological gaps, have complicated the teaching and learning process. Nevertheless, learning and work continue amid all the issues and challenges, and everyone in school has to utilize the necessary technologies and other tools for digital communication in their daily activities. Digitalization became the answer to addressing the inability to hold face to face classes effectively and efficiently as well as improving the administration and supervision of schools (Babacan & Dogru, 2022). The role of school heads in this situation is crucial. They must fill in whatever knowledge and skill gaps they may have to be more equipped to achieve digital transformation in schools (Aksal, 2015). They must also take on the mantle of more technologically inclined leadership to help teachers and stakeholders utilize digital tools and other technological platforms in their educational activities (Karakose et al., 2021). Furthermore, they must act as digital leaders to provide the necessary skills and knowledge for a 21st century education to harness digital transformations in schools (Veguilla Martinez et al., 2022). This situation instigated the discussion on digital leadership, especially since education and administrative practices are increasingly technologically integrated.

Digitalization in schools is deliberately becoming the norm (Ainslee, 2018). Among many other efforts towards digitalization, schools' roadmap includes utilizing various online learning platforms, digital textbooks, and digitized administrative activities. This period of transformation lays the foundation for a world where education becomes more accessible and available as long as digital and technological infrastructure and resources are prepared (Tanucan, 2019; Tanucan & Hernani, 2018). With this change comes the concept of digital leadership that can thrive in a digital environment where technology oriented abilities support effective management and teamwork (Abbu & Gopalakrishna, 2021; Bresciani et al., 2021). According to Waldron (2021), digital leadership is a new management approach that supports and propels digital change in organizations to enhance the flexibility, efficiency, and effectiveness of transactions and procedures. This idea corroborates the explanation of De Araujo et al. (2021) that digital leadership is the ability of leaders to develop an insightful vision for the application, adoption, and promotion of technology at work. Likewise, it exhibits the ability of leaders to develop, manage, guide, and apply information and communications technology (ICT) for further improvement of institutions (Chin, 2010). Furthermore, digital leadership can initiate sustainable change (Trenerry et al., 2021) as it is known to be a cross-hierarchical, teamoriented, and suitable type of leadership (Oberer & Erkollar, 2018). Hence, school leaders with digital leadership can guide schools and their stakeholders toward digital transformation to be adaptable and remain competitive in a rapidly changing digital and social media landscape. In this situation, school leaders have to be guided by a set of standards of digital leadership so they can benchmark good practices and develop the essential abilities to harness digital transformation in their respective institutions.

The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) has been conducting international level research on the standardization of technology oriented skills for the successful and long lasting integration of technology in education for various groups (students, educators, coaches, and educational leaders) (ISTE, 2022). The ISTE standards have been acknowledged by various researchers in different nations, as seen in their studies that integrated the concept (e.g., Baek & Sung, 2020; Gomez et al., 2022; Kimm et al., 2020; Vucaj, 2020). More specifically, the latest standards for educational leaders of ISTE involve five areas: Equity and Citizenship Advocate, Visionary Planner, Empowering Leader, Systems Designer, and Connected Learner (ISTE, 2022). These standards serve as a framework for the digital education age, no matter where school heads are on the journey to integrate and promote technology in education. With the standards set for school heads to embrace (Van Wart, 2017), they would be more capable of defining and executing a radical change strategy to harness digital transformation in their institutions rather than simply digitizing their work and operations. Defining the standards for using technology in education would provide teaching and learning that are more creative and successful for the twenty first century (Sam, 2011). It would also help school leaders set expectations for technology use and support rapid cycle evaluation of technology benefits in teaching, learning, and administrative functions (Arinto et al., 2020). However, studies that use the latest ISTE standards to examine school heads' digital leadership are scarce. Thus, one of the objectives of this study is to respond to this matter.

In the Philippines, digitalization has slowly been changing the landscape of the country's education. During the pandemic, education from the primary to tertiary levels employed variousteaching and learning methods that involved technology, which helped ensure the continuity of students' learning and employees' work. In particular, the Department of Education (DepEd) implemented the Learning Continuity Plan (LCP) at the basic education level (DepEd, 2020). The Commission on Higher Education (CHED) also fortified the inherent academic freedom of higher education institutions to adopt the necessary learning strategy to continue education at the tertiary level (CHED, 2020). These initiatives have integrated e learning, distance learning, and other alternative delivery methods into education.

Additionally, the country is beginning to digitalize its educational practices with the launch of numerous initiatives such as DepEd Commons, DepEd TV, DepEd Radio, DepEd Learning Management System, and DepEd Mobile App, among others (Ponti, 2021; Hernando Malipot, 2021). Such initiatives have helped mobilize the utilization of digital platforms and other technologies in classrooms. Likewise, they have been instrumental in supplementing the modular learning adopted by public schools to enhance student learning in various subject areas during the pandemic (Cho et al., 2021; Potane, 2022). Accordingly, the country's education is starting to focus on using ICT through the Digital Rise Program which equips classrooms, teachers, and students with online learning resources (Llego, 2020). Filipinos are among the world's most active Internet and social media users (Baclig, 2022), which are vital components for digital transformation in education.

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

With the country’s efforts toward digitalizing schools, school heads must point the way forward in establishing a digital culture in schools to utilize their digital opportunities fully. Creating a digital culture in schools needs digital resources, such as leaders with developed digital leadership skills, to move it toward its successful implementation (Pendry & Salvatore, 2015). However, this endeavor could be a challenge, particularly in light of the numerous obstacles that prevent the country from fully utilizing and integrating technology in education. Without the necessary digital infrastructure and school leaders with the skills to use and model technology use and integration, schools and their stakeholders could hardly imbibe a culture of innovation and collaboration.

The study by Dotong et al. (2016) identified insufficient financial and infrastructure support, human capital, management support, and behavioral and environmental factors as barriers to using and integrating technology in education. Tanucan et al. (2021) also identified that age is a significant factor for teachers conducting remote digital teaching. Hence, there is a need for substantial training for senior teachers who are not technologically inclined or adept. The Philippines' inadequate digital infrastructure, outdated technology, and slow Internet connectivity (Salac & Kim, 2016; World Bank, 2020), coupled with the traditional mindset of school principals, were significant factors for the lack of technical staff for maintaining computers and computer networks, and providing support for Internet related activities (UNESCO UIS., 2014). This finding corroborates the study by Hero (2020) citing that principals' technological leadership does not influence teachers' technological leadership, implying that principals fell short in modeling and empowering their teachers in integrating technology into their functions. This situation would help explain why only a meager 23 percent of leaders in the Philippines considered themselves influential leaders in the digital era, as indicated in the Global Leadership Forecast 2018 (Development Dimensions International, 2018).

In light of these convoluted concerns, training programs that aim to improve school heads' digital leadership are justified. The problem is that the country's programs to capacitate or improve school leaders, particularly in their digital leadership, vis à vis identified standards such as the ISTE standards for education leaders, have not been deliberately emphasized. The recent study by Arinto et al. (2020) recommended the same idea, emphasizing the need for school leaders in the country to take the lead in setting expectations for technology use and supporting rapid cycle evaluation of technology benefits following a set of standards determined by the national office of education. Failure to do so may adversely impact teachers' job satisfaction, the significant rise in stress and burnout (Zhai & Du, 2020), and the digital divide in the academic community (Talandron Felipe, 2020).

Teachers' job satisfaction plays a crucial role that can affect the completion of various curricula regardless of the learning platform (Li & Yu, 2022). It is also crucial for students' overall learning (Devi & Soni, 2013) and schools' attainment of their objectives and overall growth (Jun, 2015; Sahito & Vaisanen, 2020).

Compared with traditional face to face teaching, teachers' situations become more challenging owing to their complex professional roles, disturbed job satisfaction levels, and lack of digital literacy during the pandemic (Li & Yu, 2022). Recently, several studies have started examining teachers' job satisfaction, with some primarily concerned with the predictors, variables, and degrees of job satisfaction (e.g., Gómez Leal et al., 2022; Hewett & La Paro, 2020; Richards et al., 2019).

However, recent studies have examined digital leadership's role in job satisfaction. Matriadi et al. (2021) found that digital leadership positively and significantly affected employee job satisfaction in an energy company. Srimata et al. (2019) alsofound that school heads' digital leadership components significantly influenced teachers' school climate and engagement, suggesting that teachers experienced a degree of satisfaction in their job. Pasolong et al. (2021) explained digital leadership's role in inspiring employees to innovate and defend their ideas, making them feel satisfied in their jobs The concept of Frederick Hertzberg's two factor theory (also called Motivator Hygiene Theory) also explains the value of satisfaction in the workplace, particularly the role of leadership or management in engendering employee satisfaction (Lee et al., 2022). Other related studies described how employees' perceptions of digital leadership positively and significantly affected their work behavior, giving them more favorable job satisfaction and improved performance (Hamzah et al., 2021; Marbawi et al., 2022; Muniroh et al., 2021). Altogether, the literature points to the idea that digital leadership is a way of supporting employees, including teachers, to appreciate what they have been doing.

The Philippines is already on its way to digitalizing its education practices and operations. However, it needs substantial studies to help educational leaders craft training initiatives that will hone the digital leadership of school heads. To the researchers' knowledge, there is a gap in the literature that examines the level of digital leadership among school heads in the country and its link to teachers' job satisfaction. Hence, this study aimed to examine the digital leadership of school heads as a predictor of the job satisfaction of teachers in the Philippines. The objectives below guided the researchers to achieve the aim mentioned above.

1. Determine the level of digital leadership of school heads; 2. Ascertain the level of job satisfaction among teachers; and 3. Examine the digital leadership of school heads as a predictor of teachers' job satisfaction.

This study followed a descriptive-predictive design as the analysis of the variables relevant to the aim of the study was carried out by employing descriptive and predictive quantitative methods. The study specifically sought to describe school heads' levels of digital leadership and job satisfaction among teachers. Furthermore, it examined the digital leadership of school heads as a predictor of teachers' job satisfaction. The data collection was done between March and May 2022, two years after COVID 19 had been declared a pandemic.

The respondents were the 520 public school teachers across the 16 regions of the Philippines. They were selected based on convenience sampling, as this study employed data collection via online platforms, making it difficult to control the population parameters fully However, this sampling method effectively achieved the study's objectives, as it allowed for the widespread dissemination of the questionnaire during the pandemic when direct contact and social interaction were discouraged. Additionally, theuse of the Internet has significantly increased, making it easier to reach the respondents of this study. The computed sample size using the Raosoft® software for the unknown population was 377 after calculating the 95% confidence interval, a 50% response distribution rate, a 5% margin of error, and 20,000 pre set numbers for the unknown population. However, there was a high turnover in the survey, which led the researchers to prefer 520 respondents as their sample size. Table 1 presents the distribution of respondents from the country's different regions.

Table 1: Distribution of respondents by region

Demographic Variables

Number of Respondents Percent

Region I Ilocos Region 29 5.58

Region II Cagayan Valley 28 5.38

Region III Central Luzon 26 5.00

Region IV A Calabarzon ALABARZON 26 5.00

Region IV B Mimaropa IMAROPA 30 5.77

Region V Bicol Region 28 5.38

Region VI Western Visayas 32 6.15

Region VII Central Visayas 40 7.69

Region VIII Eastern Visayas 29 5.58

Region IX Zamboanga Peninsula 31 5.96

Region X Northern Mindanao 34 6.54

Region XI Davao Region 41 7.88

Region XII Soccks OCCSKSARGEN 31 5.96

Region XIII Caraga Administrative Region 33 6.35

Cordillera Administrative Region 40 7.69

National Capital Region 42 8.08

Total 520 100

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

On the other hand, Table 2 shows the demographic profiles of the respondents. In terms of gender, the distribution of the respondents has a male population comparable to its female counterpart. Moreover, most of them are between 25 to 35 years old, with a bachelor’s degree as their highest educational attainment, and with at least five years of teaching experience.

Table 2: Demographic profiles of respondents Demographic Variables Frequency Percent

Gender

Male 262 50.38 Female 258 49.62

Years of service

1 5 years 208 40.00 6 10 years 210 40.38 10+ years and above 102 19.62

Highest Educational Attainment

Bachelor's degree 335 64.42 Master's degree 120 23.08 Doctoral degree 65 12.5

Age

25 35 years old 208 40.00 36 44 years old 151 29.04 45 54 years old 121 23.27 55 64 years old 40 7.69 n = 520

The data gathering procedure followed five phases: Phase 1: Identification of questionnaires that measure the variables of the study; Phase 2: Validation of the identified questionnaires guided by three education experts; Phase 3: Pilot testing of questionnaires to determine their internal reliability consistency; Phase 4: Implementing the questionnaires through an online survey in a Google Form distributed via social media groups and institutional websites; and Phase 5: Screening of gathered data. In Phase 1, the study used two questionnaires: the ISTE standards for education leaders (ISTE, 2022) to measure school heads' levels of digital leadership; and the Teacher Job Satisfaction Scale of Pepe et al. (2017) to measure teachers' level of job satisfaction. In Phase 2, the identified questionnaires underwent a series of reviews by three education experts to ensure that each item aligns with the intended concepts of the study's variables and the respondents'

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

context and culture. In Phase 3, the computation of the questionnaires' Cronbach's alpha ratings commenced after the pilot testing. A total of 30 respondents, who were public school teachers, were invited to participate in the pilot testing of the questionnaires. The ISTE standards for education leaders' questionnaire achieved a Cronbach's alpha rating of .87, and the Teacher Job Satisfaction Scale had a Cronbach's alpha rating of .86. Both ratings indicate high internal reliability consistency. In Phase 4, the prospective respondents answered the questionnaires distributed online via social media groups and institutional websites. Before answering the questionnaire, the respondents had to read the essential ethical protocols to which the study adhered, which include the purpose of the research, informed consent, and respect for autonomy and confidentiality. The respondents could choose whether to participate in the study or not. In Phase 5, screening of the gathered data commenced by excluding incomplete surveys and those whose responders were not legitimate, regular DepEd teachers. The responses were kept private in a computer file that could only be unlocked using a password.

The SPSS software version 26 (SPSS 26.0 IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) analyzed the data, particularly the descriptive statistics and the regression analysis. The p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

The findings in Table 3 showed that teachers have a satisfactory level of perception regarding the digital leadership of their school heads. Accordingly, all the five areas of digital leadership, such as Equity and Citizenship Advocate, Visionary Planner, Empowering Leader, Systems Designer, and Connected Learner, received a satisfactory rating.

Table 3: Teachers’ level of perception of their school heads’ digital leadership

Digital Leadership of School Heads Min. Max. Mean SD

Equity and Citizenship 1.25 4.00 3.506 0.436

Visionary Planner 1.60 4.00 3.332 0.420

Empowering Leader 1.40 4.00 3.482 0.443

Systems Designer 1.06 4.00 3.266 0.614

Connected Learner 1.00 4.00 3.486 0.437

Total Mean Score 3.41 = Satisfactory

Note: n = 520. Confidence interval; 3.51 4.00: Very satisfactory, 2.51 3.50: Satisfactory, 1.51 2.50: Unsatisfactory, and 1.00 1.50: Very unsatisfactory

On the other hand, the findings in Table 4 showed that teachers have a satisfactory level of job satisfaction, with satisfaction with co workers having the highestmean score (M = 3.775, SD = 0.378) and satisfaction with parents having the lowest mean score (M = 3.075, SD = 0.566).

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

Table 4: Teachers’ level of perception of their school heads’ digital leadership

Job Satisfaction of Teachers Min. Max. Mean SD

Satisfaction with Co workers 2.00 4.00 3.775 0.378

Satisfaction with Students' Behaviors 2.00 4.00 3.627 0.484

Satisfaction with Parents 1.00 4.00 3.075 0.566

Total Mean Score 3.49: Satisfactory

Note: n = 520. Confidence interval; 3.51 4.00: Very satisfactory, 2.51 3.50: Satisfactory, 1.51 2.50: Unsatisfactory, and 1.00 1.50: Very unsatisfactory

Finally, as shown in Table 5, the regression analysis is statistically significant on the grounds that the F ratio = 47.601, R2 = 0.562, ΔR2 = 0.316, p < 0.05. Additionally, the value of R2 is 0.562, demonstrating that this model accounts for 56% of the variance of teachers’ job satisfaction. The regression analysis displayed that all five areas of digital leadership were found to be predictors and have a substantial positive influence on teachers’ job satisfaction. Among these predictors, Systems Designer (SD) (β = 0.243, B = 0.140, SE = 0.026, CI = 0.089 0.191, t-value = 5.398, p < 0.05) was indicated as the strongest predictor, followed by Equity and Citizenship Advocate (ECA) (β = 0.132, B = 0.108, SE = 0.038, CI = 0.032 0.183, t value = 2.798, p < 0.05), Connected Learner (CL) (β = 0.128, B = 0.103, SE = 0.040, CI = 0.025 0.182, t value = 2.601, p < 0.05), Visionary Planner (VP) (β = 0.125, B = 0.106, SE = 0.040, CI = 0.027 – 0.184, t value = 2.655, p < 0.05), and Empowering Leader (EL) (β = .103, B = 0.082, SE = 0.037, CI = 0.010 0.155, t value = 2.223, p < 0.05) respectively.

Table 5: Regression analysis indicating the role of school heads’ digital leadership in predicting teachers’ job satisfaction Model Unstandar dized Coefficients Max.

Standar dized Coefficie nts T Sig

95% Confidence Interval for B ���� ∆���� F Sig.

B SE Β Lower Upper (Consta nt) 1.658 .131 .132 12.645 0.000 1.401 1.916 0.562 0.316 47.601 0.000

ECA .108 .038 .125 2.798 0.005 .032 .183 VP .106 .040 .103 2.655 0.008 .027 .184 EL .082 .037 .243 2.223 0.027 .010 .155 SD .140 .026 .128 5.398 0.000 .089 .191 CL .103 .040 .132 2.601 0.010 .025 .182

Note: n = 520. ECA Equity and Citizenship Advocate; VP Visionary Planner; EL Empowering Leader; SD Systems Designer; and CL Connected Learner

An analysis of the survey showed the digital leadership of school heads and teachers' job satisfaction during the pandemic. It also showed the regression analysis, which examined the school heads' digital leadership as a predictor of teachers' job satisfaction.

The findings in Table 3 indicated that teachers have a satisfactory level of perception about the digital leadership of their school heads. Accordingly, all five digital leadership areas have a satisfactory rating. This finding suggests that school heads in the Philippines can, at least to a satisfactory level, guide their schools and stakeholders toward digital transformation to remain adaptable and competitive in a rapidly changing digital and social media landscape. Since the start of the COVID 19 pandemic, the digitalization of the education sector has become indispensable with the rapid adoption of digital and distant work setups (Tanucan et al., 2021; Tanucan & Uytico, 2021). School heads in this situation have had to fill in whatever knowledge and skill gaps they may have to be better equipped to achieve digital growth in schools (Aksal, 2015). They also have taken on the mantle of a more technologically inclined leadership to help teachers and stakeholders utilize digital tools and other technological platforms (Karakose et al., 2021). Furthermore, they served as digital leaders to their subordinates, providing the necessary skills and knowledge for a 21st century education to harness digital transformations in schools (Veguilla Martinez et al., 2022). However, having a sufficient level of digital leadership would need more enhancement, particularly in light of the numerous obstacles that prevent the country from fully utilizing and integrating technology in education.

The study by Dotong et al. (2016) identified insufficient financial and infrastructure support, human capital, management support, and behavioral and environmental factors as barriers to using and integrating technology in education. Tanucan et al. (2021) also identified that age is a significant factor for teachers’ conducting remote digital teaching. Hence, there is a need for substantial training for senior teachers who are not technologically inclined or adept. The Philippines' inadequate digital infrastructure, outdated technology, and slow Internet connectivity were also significant issues (Salac & Kim, 2016; World Bank, 2020). The traditional mindset of school principals also hampers the full integration of technology in schools as they tend to devalue the role of ICT in education, leading to a lack of technical staff for maintaining computers and computer networks, as well as user support for Internet related activities (UNESCO UIS, 2014).

In light of these convoluted concerns, training programs that aim to improve school heads' digital leadership are justified. The problem is that the country's programs to capacitate or improve school leaders, particularly in their digital leadership vis à vis identified standards such as the ISTE standards for education leaders, have not been deliberately emphasized. The recent study by Arinto et al. (2020) made the same recommendation, emphasizing the need for school leaders in the country to take the lead in setting expectations for technology use and

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

supporting rapid cycle evaluation of technology benefits following a set of standards determined by the national office of education. Failure to do so may adversely impact teachers' job satisfaction, the significant rise in stress and burnout (Zhai & Du, 2020), and the digital divide in the academic community (Talandron Felipe, 2020). Nevertheless, helping school heads strengthen their digital leadership would open up new prospects and opportunities in the education sector while also providing solutions to existing and emerging issues when harnessing digital transformation in schools (Karakose et al., 2021).

The findings in Table 4 showed that teachers have a satisfactory level of job satisfaction, with satisfaction with co workers having the highest score rating and satisfaction with parents having the lowest score rating. This finding implies that teachers in the Philippines are coping and adapting steadily to the new work and education despite the plethora of challenges and changes. Many reasons could contribute to the teachers' satisfaction. One could be the sense of networking and support they receive from their co workers, as indicated in the findings Numerous studies have stressed the value of having support from co workers to combat feelings of isolation, mainly when working remotely (Mulki & Jaramillo, 2011). Sewell and Taskin (2015) also added that regular team communication was necessary to minimize any possible drawbacks of working remotely. In the Philippines, many public school teachers started physically reporting to school after a year of the pandemic, enabling them to work together and socialize.

Another reason could be the various interventions and innovations to address the challenges of the pandemic and to capacitate teachers in using and integrating the necessary technologies and other tools for digital communication in their daily activities. The diverse in service training provided to the teachers on topics such as capability building training, use of technology, and student counseling was vital to respond to the academic challenges and meet several demands, including the socio emotional demands of students and teachers alike (Darling Hammond & Hyler, 2020; Tanucan & Uytico, 2021). The flexible learning options implemented by DepEd and CHED have also been relevant to continuing the education services of schools and universities while considering the health and safety of teachers, students, and other stakeholders (CHED, 2020; DepEd, 2020).

This flexibility in education also considers each student's unique demands, learning preferences, rate of progress, and technology in education, thereby helping the teachers in the process. Moreover, the pandemic relief measures of the Philippine government such as the Bayanihan to Recover as One Act (Bayanihan 2) contributed the lion's share of the money for educational initiatives in the public education sector, freeing up additional funds for the purchase of necessary instructional materials and the construction of pertinent infrastructure. Assistance was also given to teachers and students during the epidemic under the provisions of the Act mentioned above. Notably, the coming together of concerned agencies and individuals, whether from the government or private sector, has been instrumental in the survival of many Filipinos (Canete et al., 2021) and the continuation of education amid and beyond the pandemic (Dayagbil et al., 2021).

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

Nevertheless, much work must be done for the country's education system to remain relevant, flexible, and resilient. A strong parent or stakeholder partnership with schools is crucial to this endeavor. As previously mentioned, this study's finding indicated a lower level of teachers' job satisfaction with parents compared to other job satisfaction constructs. This finding indicates that issues around parent teacher or parent school partnerships exist. According to De Dios (2022), Filipino parents seldom offer support or direction to their children in the remote learning environment because of their low educational background, limited subject knowledge, and low self confidence in the teaching the learning process. Several technological and Internet related constraints and difficulty in managing the work home balance were also the common problems for parents (Palos Simbre, 2021). Further, the lack of preparedness of parents for home based learning is also a significant obstacle. In other countries, parental involvement in remote learning, including interventions to enhance parent teacher communication, was necessary for the success of remote learning (Chen & Rivera Vernazza, 2022; Knopik et al., 2021; Ricker et al., 2021). This shift in education from traditional teaching methods is a complex process that requires mutual communication and cooperation among various stakeholders, including parents (Tocalo, 2022). Hence, including parents' experiences and perspectives in decision making, particularly in digitalizing education, is essential.

The findings in Table 5 show that each area of the school heads' digital leadership significantly predicted teachers' job satisfaction. This finding demonstrates how school heads' ability to guide their schools and stakeholders toward digital transformation to remain adaptable and competitive in a digital and social media landscape could influence teachers' job satisfaction. This finding concurs with the study of Matriadi et al. (2021), which demonstrated how digital leadership positively and significantly influenced employee job satisfaction in an energy company. Likewise, it also conforms to the study of Srimata et al. (2019), which described how school heads' digital leadership components significantly influenced teachers' school climate and engagement, suggesting that teachers experienced a degree of satisfaction in their job. It also corroborates the finding of Pasolong et al. (2021), which explained the role of digital leadership in inspiring employees to innovate and defend their ideas, making them feel satisfied in their job. The finding also supports the concept of Frederick Hertzberg's two factor theory, which explains the value of satisfaction in the workplace, particularly the role of leadership or management in spurring employee satisfaction (Lee et al., 2022). Finally, this study also corroborates related studies that describe how employees' perceptions of digital leadership positively and significantly affect their work behavior, giving them more favorable job satisfaction and improved performance (Hamzah et al., 2021; Marbawi et al., 2022; Muniroh et al., 2021).

Teachers' job satisfaction should be highlighted in decision making as it plays a crucial role that can affect the completion of various curricula regardless of the learning platform (Li & Yu, 2022). It is also crucial for students' overall learning (Devi & Soni, 2013) and schools' attainment of their objectives and overall growth

(Jun, 2015; Sahito & Vaisanen, 2020). School heads in this situation should harness their digital leadership skills to satisfy their teachers at work, especially since educational activities, including administrative functions, involve technology for more efficient and effective operations.

Creating a digital culture needs digital resources that will move towards its successful implementation (Pendry & Salvatore, 2015). Such resources include the leaders who have exhibited qualities of digital leadership. School stakeholders could hardly imbibe a culture of innovation and collaboration without the necessary digital infrastructure and school leaders with the knowledge and skills to use and model technology use and integration. With the rapid move to remote work, organizations must facilitate simplified communication channels between geographically dispersed teams, often in different time zones (Waldron, 2021). The Philippines, being an archipelagic country, will ultimately benefit from having a pool of leaders with digital leadership skills. Moreover, the country is already on its way to digitalizing its education practices and operations by adopting e learning, distance learning, and other alternative methods of delivery (CHED, 2020; DepEd, 2020). Likewise, the country is beginning to digitalize its educational practices with the launch of numerous initiatives such as DepEd Commons, DepEd TV, DepEd Radio, DepEd Learning Management System, and DepEd Mobile App, among others (Ponti, 2021; Hernando Malipot, 2021). These initiatives have been instrumental in supplementing the modular learning adopted by public schools to enhance student learning in various subject areas during the pandemic (Cho et al., 2021; Potane, 2022) Moreover, the country's education is starting to focus on using ICT through the Digital Rise Program, which equips classrooms, teachers, and students with online learning resources (Llego, 2020). Furthermore, Filipinos are among the world's most active Internet and social media users (Baclig, 2022), which is a vital component in the digital transformation of education.

The study revealed that Filipino school heads have a satisfactory level of digital leadership as perceived by their teachers. This finding suggests that school heads can, at least to a satisfactory level, guide their schools and stakeholders toward digital transformation to remain adaptable and competitive in a rapidly changing digital and social media landscape. Furthermore, Filipino teachers have satisfactory job satisfaction during the pandemic, which suggests that they are coping and adapting steadily to the new work and education despite the plethora of challenges and changes. Finally, this study reveals that school heads' digital leadership predicts teachers' job satisfaction. When leaders are competent to lead and model in the digital age, their subordinates will become more satisfied with their work. Therefore, training programs for improving school heads' digital leadership are necessary to enhance their teachers' job satisfaction, especially since technology plays a significant part in diverse educational activities. For future research, examining the socio demographic profiles of school heads and teachers as a predictor of digital leadership may also substantiate the study's findings.

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

Abbu, H. R., & Gopalakrishna, P. (2021). Synergistic effects of market orientation implementation and internalization on firm performance: direct marketing service provider industry. Journal of Business Research, 125, 851 863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.004

Ainslee, J. (2018, April 18). Digitizationofeducationinthe21stcentury. eLearning Industry. Retrieved from https://elearningindustry.com/digitization of education 21st century

Aksal, F. A. (2015). Are headmasters digital leaders in school culture? Education and Science, 40(182), 77 86. https://www.proquest.com/openview/72c100dd3b4de9bf28b97d7c75f954ab/1 ?pq origsite=gscholar&cbl=1056401

Arinto, P. B., Dunuan, L. F., & Sasing M. T. (2020). EdTechEcosystemReport:Philippines United States Agency International Development. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00WKGW.pdf

Babacan, S. & Dogru Yuvarlakbas, S. (2021). Digitalization in education during the COVID 19 pandemic: Emergency distance anatomy education. Surgical and RadiologicAnatomy,44(1), 55 60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276 021 02827 1

Baclig, C. E. (2022, April 29). Social media, internet craze keep PH on top 2 of world list. Inquirer.Net https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1589845/social media internet craze keep ph on top 2 of world list

Baek, E. O., & Sung, Y. H. (2020). Pre service teachers’ perception of technology competencies based on the new ISTE technology standards. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 37(1), 48 64. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2020.1815108

Bresciani, S., Ferraris, A., Romano, M., & Santoro, G. (2021). Digital leadership in digital transformationmanagementforagileorganizations:Acompasstosailthedigitalworld. Emerald Publishing pp. 97 115.

Canete, J., Rocha, I. C., & Dolosa, J. (2022). The Filipino community pantries: A manifestation of the spirituality of 'Alay Kapwa' in the time of the pandemic. Journal of Public Health, 44(2), e295 e296. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab210

Chen, J. J., & Rivera Vernazza, D. E. (2022). Communicating digitally: Building preschool teacher parent partnerships via digital technologies during Covid 19 Early ChildhoodEducationJournal, 1 15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643 022 01366 7

Chin, J. M. (2010). Theoryandapplicationofeducationalleadership. Taipei, TW: Wunan. Cho, Y., Avalos, J., Kawasoe, Y., Johnson, D., & Rodriguez, R. (2021). The impact of the COVID 19 pandemic on low income households in the Philippines. WorldBank https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35260

Darling Hammond, L., & Hyler, M. E. (2020). Preparing educators for the time of COVID and beyond. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 457 465. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1816961

Dayagbil, F.T., Palompon, D.R., Garcia, L.L., & Olvido, M.M.J. (2021). Teaching and learning continuity amid and beyond the pandemic. Frontiers in Education, 6, 678692. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.678692

De Araujo, L. M., Priadana, S., Paramarta, V., & Sunarsi, D. (2021). Digital leadership in business organizations. International Journal of Educational Administration, Management,andLeadership,2(1), 45 56. https://doi.org/10.51629/ijeamal.v2i1.18

De Dios, C. B. O. (2022). Children's home learning during COVID 19 pandemic: The lived experiences of selected Filipino parents on remote learning. Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 1(2), 1 13. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6523232

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

Development Dimensions International. (2018). The Global Leadership Forecast 2018. https://media.ddiworld.com/research/global leadership forecast 2018_ddi_tr.pdf

Devi, D., & Soni, S. (2013). Essentials of job satisfaction in effective teaching. AsianJournal of Multidimensional Research (AJMR), 2(3), 96 102. https://www.indianjournals.com/ijor.aspx?target=ijor:ajmr&volume=2&issue= 3&article=008

Dotong, C. I., De Castro, E. L., Dolot, J. A., & Prenda, M. (2016). Barriers for educational technology integration in contemporary classroom environment. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, Arts and Sciences, 3(2), 13 20. https://www.academia.edu/download/53094207/APJEAS 2016.3.2.03.pdf Gomez,F.C.,Trespalacios,J.,Hsu,Y.C.,&Yang,D.(2022). Exploring teachers’ technology integration self efficacy through the 2017 ISTE Standards. TechTrends,66(2), 159 171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528 021 00639 z

Gómez Leal, R., Holzer, A. A., Bradley, C., Fernández Berrocal, P., & Patti, J. (2022). The relationship between emotional intelligence and leadership in school leaders: A systematic review. Cambridge Journal of Education, 52(1), 1 21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2021.1927987

Hamzah, N. H., Nasir, M. K. M., & Wahab, J. A. (2021). The effects of principals’ digital leadership on teachers’ digital teaching during the COVID 19 pandemic in Malaysia. Journal of Education and ELearning Research, 8(2), 216 221. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2021.82.216.221

Hernando Malipot, M. (2021, September 2). DepEd trains over 550K teachers for SY 2021 2022 through VINSET 2.0. Manila Bulletin. https://mb.com.ph/2021/09/02/deped trains over 550k teachers for sy 2021 2022 through vinset 2 0/

Hero, J. L. (2020). Exploring the principal's technology leadership: Its influence on teachers' technological proficiency International Journal of Academic Pedagogical Research,4(6), 4 10. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED606393

Hewett, B. S., & La Paro, K. M. (2020). Organizational climate: Collegiality and supervisor support in early childhood education programs. EarlyChildhoodEducationJournal, 48(4), 415 427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643 019 01003 w

International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE). (2022). ISTEStandards:Education leaders. https://www.iste.org/standards/iste standards for education leaders Jun, L. Z. (2015). JobsatisfactionandmigrationamongteachersinselectedIslamicprivateschools inSatun,SouthThailand [Master's thesis, Kuala Lumpur: Kulliyyah of Education, International Islamic University Malaysia] http://studentrepo.iium.edu.my/handle/123456789/3934

Karakose, T., Polat, H., & Papadakis, S. (2021). Examining teachers’ perspectives on school principals’ digitalleadershiprolesand technologycapabilitiesduringtheCOVID 19 pandemic. Sustainability,13(23), 13448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313448

Kimm, C. H., Kim, J., Baek, E. O., & Chen, P. (2020). Pre service teachers’ confidence in their ISTE technology competency. JournalofDigitalLearninginTeacherEducation, 36(2), 96 110. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2020.1716896

Knopik, T., Błaszczak, A., Maksymiuk, R., & Oszwa, U. (2021). Parental involvement in remote learning during the COVID 19 pandemic Dominant approaches and their diverse implications. European Journal of Education, 56(4), 623 640. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12474

Lee, B., Lee, C., Choi, I., & Kim, J. (2022). Analyzing determinants of job satisfaction based on two factor theory Sustainability, 14(19), 12557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912557

Li, M., & Yu, Z. (2022). Teachers’ satisfaction, role, and digital literacy during the COVID 19 pandemic Sustainability,14(3), 1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031121

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

Llego, M. A. (2020). Accelerating the DepEd Computerization Program in the light of COVID 19 pandemic, TEACHERPH https://www.teacherph.com/deped computerization program covid 19 pandemic/ Marbawi, M., Hamdiah, H., & Nurmala, N. (2022). Antecedents of competence, digital learning and the influence on teacher performance of senior high school. InternationalJournalofEngineering,ScienceandInformationTechnology,2(1),152 157. http://ijesty.org/index.php/ijesty/article/view/237/178

Matriadi, F., Ikramuddin, I., Adamy, M., & Chalirafi, C. (2021). Implementation of digital leaderships on Pertamina Hulu Energy in Aceh. International Journal of Engineering, Science and Information Technology, 1(2), 125 129. http://www.ijesty.org/index.php/ijesty/article/view/132/110

Mulki, J. P., & Jaramillo, F. (2021). Workplace isolation: Salespeople and supervisors in USA. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(4), 902 923. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.555133

Muniroh, M., Hamidah, H., & Abdullah, T. (2021). Indicator analysis of employee performance based on the effect of digital leadership, digital culture, organizational learning, and innovation (case study of PT. Telkom Digital and Next Business Department) Proceedings of the 5th International Indonesia Naval Technology College STTAL Postgraduate Conference on Maritime Science and Technology,,5(1), 324 334.

Oberer, B., & Erkollar, A. (2018). Leadership 4.0: Digital leaders in the age of industry 4.0. International Journal of Organizational Leadership, 7(4), 404 412. https://doi.org/10.33844/ijol.2018.60332

Palos Simbre, A. (2021). Exploring the experiences of Filipino parents on distance learning during COVID 19 pandemic. ASEAN Journal of Education, 7(2), 25 35. https://aje.dusit.ac.th/upload/file/Flie_journal_pdf_11 04 2022_160442.pdf

Pasolong, H., Nilna, M., & Justina, A. J. (2021). Digital leadership in facing challenges in the era industrial revolution 4.0. Webology, 18, 975 990. http://repository.poliupg.ac.id/id/eprint/1884

Pendry, L. F., & Salvatore, J. (2015). Individual and social benefits of online discussion forums. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 211 220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.067

Pepe, A., Addimando, L., & Veronese, G. (2017). Measuring teacher job satisfaction: Assessing invariance in the teacher job satisfaction scale (TJSS) across six countries. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 13(3), 396 416. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v13i3.1389

Ponti, J. (2021, May 26). The Philippines’ DepEd reveals tech based plans. OpenGov https://opengovasia.com/the philippines deped reveals tech based plans/ Potane, J. D. (2022). Desıgn and utılızatıon of televısıon and radıo lessons amıd COVID 19: Opportunıtıes, challenges and inıtıatıves. InternationalJournalofSocialSciences and Humanities Invention, 9(03), 6862 6873. https://doi.org/10.18535/ijsshi/v9i03.03

Republic of the Philippines Commission on Higher Education. (2020). Guidelinesforthe prevention,controlandmitigationofthespreadofcoronavirusdisease2019(COVID19) in higher education institutions (HEIs) https://ched.gov.ph/wp content/uploads/CHED COVID 19 Advisory No. 6.pdf

Republic of the Philippines. Department of Education (DepEd) (2020). Adoptionofthebasic educationlearningcontinuityplanforSchoolYear20202021inlightoftheCOVID19 public health emergency. https://authdocs.deped.gov.ph/deped order/do_s2020_012 adoption of the be lcp sy 2020 2021/ Richards, K. A. R., Washburn, N. S., & Hemphill, M. A. (2019). Exploring the influence of perceived mattering, role stress, and emotional exhaustion on physical education

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

teacher/coach job satisfaction. EuropeanPhysicalEducationReview,25(2), 389 408. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X17741402

Ricker, G., Belenky, D., & Koziarski, M. (2021). Are parents logged in? The importance of parent involvement in k 12 online learning. Journal of Online Learning Research, 7(2), 185 201. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/219541/

Sahito, Z., & Vaisanen, P. (2020). A literature review on teachers’ job satisfaction in developing countries: Recommendations and solutions for the enhancement of the job. ReviewofEducation,8(1), 3 34. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3159

Salac, R. A., & Kim, Y.S. (2016). A study on the internet connectivity in the Philippines. Asia Pacific Journal of Business Review, 1(1), 67 88. https://doi.org/10.20522/APJBR.2016.1.1.67

Sam, D. (2011). Middleschoolteachers'descriptionsoftheirlevelofcompetencyinthenational educationtechnologystandardsforteachers [Doctoral dissertation, Johnson & Wales University] ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://www.proquest.com/docview/864734626

Sewell, G., & Taskin, L. (2015). Out of sight, out of mind in a new world of work? Autonomy, control, and spatiotemporal scaling in telework. OrganizationStudies, 36(11), 1507 1529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615593587

Srimata, T., Niyamabha, A., Wichitputchraporn, W., Piyapimonsit, C., Prachongchit, S., & Koedsuwan, S. (2019). A causal model of digital leadership and school climates with work engagement as mediator affecting effectiveness of private schools in Bangkok, Thailand. Asian Administration & Management Review, 2(2), 290 297. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3655032

Talandron Felipe, M. M. P. (2020). The digital divide among students and support initiatives in the time of COVID 19. Proceedingsofthe28thInternationalConference on Computers in Education, 2, 42 51. https://apsce.net/icce/icce2020/proceedings/W1 13/W1/ICCE2020 Proceedings Vol2 7.pdf

Tanucan, J.C.M. (2019). Pedagogical praxis of millennial teachers in mainstreamed physical education. International Journal of Advanced Research, 7(1) 54 562. http://dx.doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/8361

Tanucan, J.C.M., & Hernani, M. R. (2018). Physical education curriculum in standard based and competency based education International Journal of Health, Physical Education and Computer Science in Sports, 30(1), 26 33. http://www.ijhpecss.org/International_Journal_30.pdf

Tanucan, J.C.M., Hernani, M. R., & Diano, F. (2021). Filipino physical education teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge on remote digital teaching. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 11(9), 416 423. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijiet.2021.11.9.1544

Tanucan, J.C.M., & Uytico, B. J. (2021). Webinar based capacity building for teachers: “Lifeblood in facing the new normal of education”. Pertanika Journal of Social SciencesandHumanities,29(2), 1035 1053. https://doi.org/10.47836/pjssh.29.2.16

Tocalo, A. W. I. (2022). Listening to Filipino parents’ voices during distance learning of their children amidst COVID 19. Education 313, 1 12 https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2022.2100439

Trenerry, B., Chang, S., Wang, Y., Suhaila, Z., Lim, S., Lu, H., & Oh, P. (2021). Preparing workplaces for digital transformation: An integrative review and framework of multi level factors. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 620766 620766. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.620766

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UNESCO UIS). (2014). Information and communication technology(ICT)ineducationinAsia:AcomparativeanalysisofICTintegrationandE readinessinschoolsacrossAsia http://dx.doi.org/10.15220/978 92 9189 148 1 en

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

Van Wart, M., Roman, A., Wang, X., & Liu, C. (2017). Integrating ICT adoption issues into (e)leadership theory. Telematics and Informatics, 34(5), 527 537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.11.003

Veguilla Martinez, N., Corrales, A., Grace, J., & Peters, M. (2022, April). Campus leaders’ use and attitudes towards technology impacted by COVID 19. In Society for InformationTechnology&TeacherEducationInternationalConference (pp. 697 701). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE) http://www.learntechlib.org/p/220815/

Vucaj, I. (2022). Development and initial validation of Digital Age Teaching Scale (DATS) to assess application of ISTE Standards for Educators in K 12 education classrooms. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(2), 226 248. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1840461

Waldron, J. (2021, January 20). Digital leadership: The challenges, skills and technology. Metafresh. https://metasfresh.com/en/2021/01/20/digital leadership the challenges skills and technology/ World Bank (2020). PhilippinesDigitalEconomyReport2020:ABetterNormalUnderCOVID 19: Digitalizing the Philippine Economy Now. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/796871601650398190/pdf/Phil ippines Digital Economy Report 2020 A Better Normal Under COVID 19 Digitalizing the Philippine Economy Now.pdf

Zhai, Y., & Du, X. (2020). Addressing collegiate mental health amid COVID 19 pandemic. PsychiatryResearch,288, 113003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113003

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research

Vol. 21, No. 10, pp. 19 49, October 2022

https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.21.10.2

Received May 31, 2022; Revised Oct 14, 2022; Accepted Oct 19, 2022

Faruhana Abdullah

Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia Maldives National University, Republic of Maldives

Nor Asniza Ishak* Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

Mohammad Zohir Ahmad

Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Malaysia

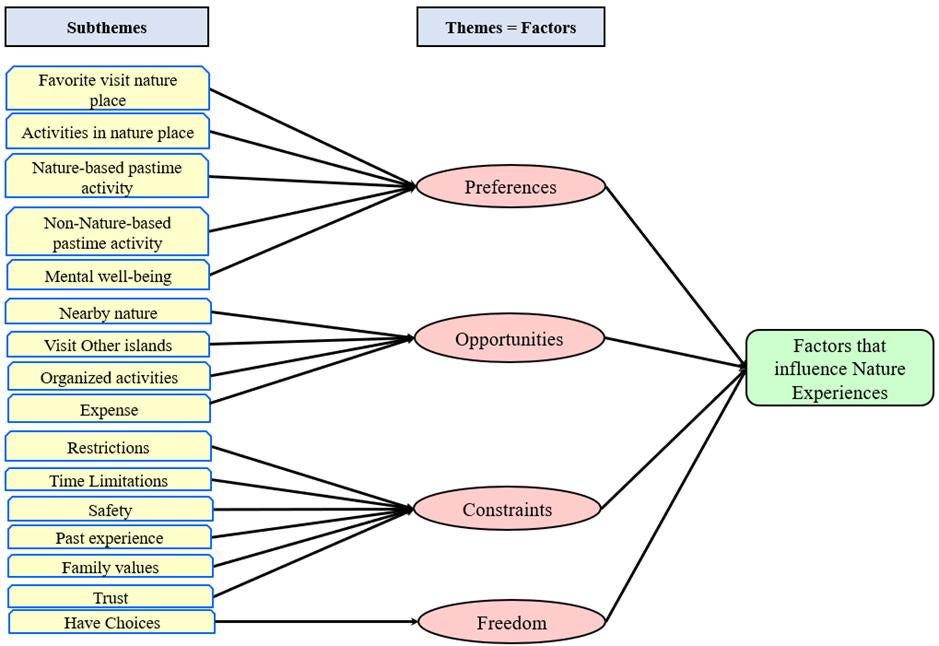

Abstract. This study aimed to explore and understand the contextual factors that influence nature experiences amongst 11 12 year old children in their local island environments of the Maldives. The study adopted a qualitative phenomenological approach using semi structured focus group interviews, held online, with seven groups, one per island environment. A total of 34 children participated in the interviews, with 4 6 children per group, recruited purposively based on inclusion criteria. The interviews were transcribed, and a thematic analysis was carried out. The analysis demonstrated that children’s nature experiences were primarily influenced by preferences, opportunities, constraints, and freedom, of which opportunities have the greatest influence. Similarly, constraints deter the use of available opportunities, regardless of where children live. Females appear to have more constraints on their nature experiences than males. Children must be facilitated with meaningful opportunities for DNEs to overcome constraints and motivate nature engagement. Schools must play a proactive role in facilitating these experiences to foster nature connections to ensure the success of their sustainability targeted curricular objectives. While the subject of DNEs has a wide place in the literature, the lack of studies in the field of education for sustainable development (ESD) increases the importance of this study. The findings can guide the promotion of ESD as a pathway to a sustainable future in the country. Future research should examine barriers to children’s DNEs at the school level.

Keywords: children; contextual factors; direct nature experiences; island environments; Maldives

* Corresponding author: NorAsnizaIshak, asnizaishak@usm.my

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY NC ND 4.0).

A deficit of direct nature experiences (DNEs) and its consequences is the subject of current scholarly concern. DNEs, which involve direct contact or physical, multisensory engagements with natural elements (Beery & Lekies, 2021; Gaston & Soga, 2020) in childhood, are especially pivotal for establishing lasting human nature relationships that underpin several of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Thus, efforts towards attaining sustainability must also focus on reconnecting people with nature (Charles et al., 2018; Ives et al., 2018). In particular, Goal 4 of the SDGs stipulates the necessity of inclusive and quality education for all and the promotion of lifelong learning; Goal 4.7 targets promoting sustainable development (SD) through education for sustainable development (ESD). Thus, “this education and lifelong learning must necessarily be connected to the living earth” (Charles et al., 2018, p. 41).

ESD embraces a transformative approach to teaching and learning that strives to equip learners with the competencies necessary for lifelong sustainable behaviours. Thus, schools in many countries including Germany, Macau, the United States (Müller et al., 2021), Sweden and Japan (Fredriksson et al., 2020) are embracing this approach to education. Promoting ESD is especially crucial for small island states such as the Maldives, which are the most vulnerable to the accelerating climate change crisis. In the Maldives, the National Curriculum Framework (NCF) provides a comprehensive framework for promoting ESD through its key competencies, learning areas, and pedagogical approaches (Di Biase et al., 2021) Particularly relevant to this study is its key competency, Using Sustainable Practices, which aims “to raise awareness to engage in sustainable practices and learn conservation for the future” (National Institute of Education [NIE], 2014, p. 19) It is envisaged that through this key competency, learners will acquire the knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes necessary for taking care of their environment and will be motivated to become future stewards of the natural world. Meanwhile, scholars strongly recommend the improved application of learner centered approaches as a basis for transitioning towards ESD in the Maldives (Di Biase et al., 2021) However, successful ESD also requires revising educational curricula with a view to increasing nature experiences to redress waning human nature relationships (Ives et al., 2018; Selby, 2017). Yet, environmental education in the Maldives lacks experiential learning and a sense of place related to children’s local natural environment (N. Mohamed & Mohamed, 2021)

Historically, rich everyday experiences with abundant natural surroundings have enabled Maldivian children to learn and connect with nature in a myriad of ways. This contextualized, experiential learning laid the groundwork for sustainable practices in the country. In contrast, disturbing trends towards a reduction in DNEs among children are emerging. For example, children learn about nature and its values primarily through schoolbooks that emphasize global knowledge (M. Mohamed, 2012) Generations of children are becoming separated from their traditional island lives, subsequently reducing their nature interactions. Observed unsustainable practices, including abuses of nature by today’s youth (M. Mohamed et al., 2019), suggest a progressive state of decline. Importantly, the frequency of children’s DNEs has been found to differ significantly based on

where they live, with children outside the capital city tending to experience nature more frequently (Abdullah et al., 2022a). While such trends have been attributed to factors such as migration to the capital for better childhood education (M. Mohamed, 2015; M. Mohamed et al., 2019) and differences in available opportunities (Abdullah et al., 2022a), the true determinants of DNEs among Maldivian children remain uncertain. Thus, this study aimed to explore and understand the contextual factors that influence nature experiences amongst 11–12 year old Maldivian children in their local island environments.

Regular DNEs, particularly with children’s daily environments, can establish baselines of nature conceptions A lack of positive DNEs or continuous exposure to nature destruction can cause negative shifts in the baselines of accepted nature norms, such as increased tolerance to environmental degradation that can worsen over time or with each generation (Papworth et al., 2009; Soga & Gaston, 2018). Thus, the progressive decline in human nature interactions, or an extinction of experience in many countries, is deeply concerning (Colléony et al., 2020; Gaston & Soga, 2020; Soga & Gaston, 2016). Evidence supporting a decline in DNEs among children includes a reduction in time spent outdoors (Larson et al., 2018; Skar et al., 2016; Soga & Gaston, 2016), less free play in and use of nearby nature places (Gundersen et al., 2016) and reduced frequency of DNEs (Soga et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2014). While this change is not always evident (Muslim et al., 2017), trends in nature experiences often depend on where children live. For instance, children in less urban areas tend to engage in more frequent DNEs than those in urban areas (Abdullah et al., 2022a; Muslim et al., 2019; Soga et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2014) Furthermore, perceived negative trends may be related to the types of experiences rather than their frequency (Larson et al., 2018; Novotný et al., 2021). Concurrent with these debates are calls to increase childhood DNEs as a means to tackle the widening disconnect between people and nature and to ameliorate the ensuing negative effects (Charles et al., 2018) In order to do so meaningfully, it is first necessary to understand what factors influence children’s DNEs.

The main determinants of children’s DNEs are sometimes broadly categorized as opportunities or orientations (Soga et al., 2018; Soga & Gaston, 2016). Opportunities constitute possibilities for interactions with nature in terms of time and space (Soga et al., 2018) that tend to decline with urbanization (Imai et al., 2018; Muslim et al., 2019; Mustapa et al., 2018; Soga et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2014). Urbanization imposed barriers to DNEs include a loss of access to nature due to a depletion of wildlife (Kai et al., 2014), increased distance to nature spaces (Colléony et al., 2020; Soga & Gaston, 2016), logistics of city design and spatial barriers (Kellert et al., 2017). Although cities can typically present more barriers to DNEs (Freeman et al., 2018), some may nevertheless offer ample opportunities for DNEs (Almeida et al., 2018; Charles et al., 2018; Freeman et al., 2018) Such findings demand serious consideration, given the long term impacts of DNEs on learning and future global conservation (Kellert et al., 2017). In fact, the latter may increasingly depend on city dwellers’ connections with nature through interactions with urban species

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

found within city limits, a concept coined as the “Pigeon Paradox” (Dunn et al., 2006 p. 1814)

Opportunities for children to experience nature are often hindered by the restrictions of everyday life, regardless of their natural surroundings. In this regard, parental involvement poses a primary deterrent to children’s DNEs by restricting children’s autonomy of movement ranges, destinations, time spent outdoors, and personal lifestyle (Freeman et al., 2018; Hand et al., 2018) as well as close supervision (Larson et al., 2011). These constraints may be related to traffic and safety concerns (Skar et al., 2016), socio cultural values (Evans et al., 2018; Freeman et al., 2018, 2021; Soga et al., 2018) or both Contrasting findings suggest contextual differences in restraints. For instance, time pressure due to organized activities and increased homework presents major barriers for Norwegian children’s DNEs (Skar et al., 2016), but not for Japanese children (Soga et al., 2018).

Orientations involve feelings or emotions (Soga & Gaston, 2016) that can dictate how opportunities are utilized (Hand et al., 2018; Larson et al., 2018; Soga et al., 2018; Soga & Gaston, 2016). A decline in DNEs among children is sometimes driven by a loss of orientation towards engaging with nature, rather than a loss of opportunities. A loss of orientation reflects a disconnect with nature that decreases motivation (Soga et al., 2018; Soga & Gaston, 2016) or biophilia that discourages engagement with biodiverse spaces (Hand et al., 2017). Notably, the latter view has been contested (Fattorini et al., 2017)

The loss of orientation is often associated with manifestations of modernization, particularly increasingly sedentary lifestyles (Kellert et al., 2017) and substitution of DNEs with digitally mediated engagements (Ballouard et al., 2011; Kellert et al., 2017). Sometimes, children prefer to engage in screen based activities (Larson et al., 2018) or sports (Mustapa et al., 2018) rather than DNEs, even while outdoors Nonetheless, children’s use of screen based media is not always negatively associated with the extent of their DNEs (Soga et al., 2018). Other studies not only support a greater inclination towards indirect and vicarious nature experiences but also show that such experiences contribute more to children’s connectedness to nature (CTN) than DNEs (Mustapa et al., 2019). Additionally, family members’ attitudes, gender differences (Soga et al., 2018), and fear for personal safety, danger, and crime (Adams & Savahl, 2015) can influence children’s orientations towards nature.

Undoubtedly, several contextual factors either impede or promote children’s DNEs. Identifying barriers is important as they often have deep seated origins in children’s daily lives that marginalize DNEs and may be difficult to break down once they are established (Moss, 2012). However, to mitigate the reduction of nature experiences, it is also imperative to identify drivers that motivate children to engage with nature (Soga et al., 2018). In particular, culturally rooted transformations must be identified in order to optimize nature connections (Novotný et al., 2021).

Unpacking the determinants of DNEs is particularly crucial in the Maldives for several reasons. Limited studies suggest emerging negative trends in DNEs and

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

relationships with nature among Maldivians, entwined with transitioning from rural to urban areas and modern lifestyles that conflict with the intrinsic culture of the Maldives (M. Mohamed, 2012, 2015; M. Mohamed et al., 2019) Subsequently, the perceived value of nature is changing from sustainable resources to extractive uses or recreation (M. Mohamed, 2015). Unlike in the past, current nature interactions take a more formal route based on the NCF, aimed at inculcating robust pro conservation competencies from childhood as a step towards attaining SD (NIE, 2014) However, engaging children in stimulating DNEs in formal, non formal, or informal contexts can be particularly challenging considering the ever increasing congestion, societal issues, and human altered environments prevalent on most islands. As already noted, environmental studies in the Maldives lack direct, contextual experiential learning from local nature, which is critical for building children’s nature connections, knowledge, and values associated with local environments (M. Mohamed, 2012; N. Mohamed & Mohamed, 2021) Indeed, children’s DNEs have significant direct effects on their biodiversity knowledge and attitudes, which influence their willingness to conserve biodiversity. These effects can have implications for future biodiversity conservation (Abdullah et al., 2022b). Therefore, identifying the determinants of DNEs among Maldivian children is urgently needed to facilitate impactful DNEs, to bring about effective changes to current practices in an educational context, as well as to harness other benefits of these experiences. This study adds new knowledge to the understudied area of children’s DNEs in the context of small islands, especially the Maldives, which face multiple challenges to SD. In particular, while the subject of DNEs has a wide place in the literature and is an essential requisite for SD and ESD (Charles et al., 2018; Ives et al., 2018; Selby, 2017), the lack of literature from the perspective of children following a curriculum structured around ESD, as in the Maldives, increases the importance of this study. This study identified contextual determinants of DNEs among Maldivian children that are not well documented in literature. This information can contribute to enabling DNEs in nature spaces within everyday use areas through pedagogical shifts and informal means to foster strong connections with nature to achieve the sustainability targeted goals of the Maldivian NCF as well as long term SD.

This study, being part of an in depth study of children’s DNEs in the Maldives, is primarily supported by the modified Experiential Learning Theory (Morris, 2019) and the model of modes of nature experiences and learning in childhood development (Kellert, 2005), both of which emphasize the importance of contexts of experiences in learning and outcomes. In this framework, the island environments where children reside provide the contexts of experiences and are expected to determine how children experience nature. The emphasis on contextually rich experiences is further supported by the philosophy of place based education. Advocates of this philosophy recommend that place based education should form the basis of environmental education, in which children are immersed in personal, real world experiences of the local environment to enable them to truly understand, connect, and engage with local environmental problems for a sustainable future (Di Biase et al., 2021; N. Mohamed & Mohamed, 2021; Ontong & Grange, 2014).

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

This study employed a qualitative phenomenological approach to explore and understand the contextual factors that influence children’s nature experiences among middle school children in their local islands of the Maldives. Children’s nature experiences are often influenced by their natural surroundings and personal circumstances and are subject to personal interpretation (Adams & Savahl, 2015; Freeman et al., 2018) To examine such phenomena, authors recommend using qualitative, open ended approaches to data collection and analysis (Cohen et al., 2018; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). This study used focus group interviews (FGIs) to gather data. FGIs involve a series of carefully planned open ended, face to face interviews with a selected group of participants, aimed at eliciting personal views and opinions on the chosen topic (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018; Krueger & Casey, 2015) and gathering a large amount of rich data within a limited time frame (Krueger & Casey, 2015).