International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research (IJLTER)

Vol. 21, No. 8 (August 2022)

Print version: 1694 2493

Online version: 1694-2116

International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research (IJLTER)

Vol. 21, No. 8 (August 2022)

Print version: 1694 2493

Online version: 1694-2116

International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research (IJLTER)

Vol. 21, No. 8

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically those of translation, reprinting, re use of illustrations, broadcasting, reproduction by photocopying machines or similar means, and storage in data banks.

Society for Research and Knowledge ManagementThe International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research is a peer-reviewed open-access journal which has been established for the dissemination of state of the art knowledge in the fields of learning, teaching and educational research.

The main objective of this journal is to provide a platform for educators, teachers, trainers, academicians, scientists and researchers from over the world to present the results of their research activities in the following fields: innovative methodologies in learning, teaching and assessment; multimedia in digital learning; e learning; m learning; e education; knowledge management; infrastructure support for online learning; virtual learning environments; open education; ICT and education; digital classrooms; blended learning; social networks and education; etutoring: learning management systems; educational portals, classroom management issues, educational case studies, etc.

The International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research is indexed in Scopus since 2018. The Journal is also indexed in Google Scholar and CNKI. All articles published in IJLTER are assigned a unique DOI number.

We are very happy to publish this issue of the International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research.

The International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research is a peer reviewed open access journal committed to publishing high quality articles in the field of education. Submissions may include full-length articles, case studies and innovative solutions to problems faced by students, educators and directors of educational organisations. To learn more about this journal, please visit the website http://www.ijlter.org.

We are grateful to the editor in chief, members of the Editorial Board and the reviewers for accepting only high quality articles in this issue. We seize this opportunity to thank them for their great collaboration.

The Editorial Board is composed of renowned people from across the world. Each paper is reviewed by at least two blind reviewers.

We will endeavour to ensure the reputation and quality of this journal with this issue.

Editors of the August 2022 Issue

Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching in Further Education and Training Phase: Evidence from Entry Level Student Teachers’ Baseline Assessments 1 Folake Modupe Adelabu, Jogymol Kalariparampil Alex

Exploring the Use of Chemistry based Computer Simulations and Animations Instructional Activities to Support Students’ Learning of Science Process Skills 21 Flavia Beichumila, Eugenia Kafanabo, Bernard Bahati

Issues Surrounding Teachers’ Readiness in Implementing the Competency Based ‘O’ Level Geography Syllabus 4022 in Zimbabwe 43

Paul Chanda, Tafirenyika Mafugu

Exploring Headteachers, Teachers and Learners’ Perceptions of Instructional Effectiveness of Distance Trained Teachers

................................................................................................................................................................................. 58

Vincent Mensah Minadzi, Ernest Kofi Davis, Bethel Tawiah Ababio

The Role of Middle Managers in Strategy Execution in two Colleges at a South African Higher Education Institution (HEI) 75 Ntokozo Mngadi, Cecile N. Gerwel Proches

Learners’ Active Engagement in Searching and Designing Learning Materials through a Hands on Instructional Model 92 Esther S. Kibga, Emmanuel Gakuba, John Sentongo

The Development of e Reading to Improve English Reading Ability and Energise Thai Learners’ Self Directed Learning Strategies 109 Pongpatchara Kawinkoonlasate

The Role of Mother’s Education and Early Skills in Language and Literacy Learning Opportunities 129 Dyah Lyesmaya, Bachrudin Musthafa, Dadang Sunendar

Exploring Assessment Techniques that Integrate Soft Skills in Teaching Mathematics in Secondary Schools in Zambia 144 Chileshe Busaka, Septimi Reuben Kitta, Odette Umugiraneza

Generic Competences of University Students from Peru and Cuba 163 Miguel A. Saavedra López, Xiomara M. Calle Ramírez, Karel Llopiz Guerra, Marieta Alvarez Insua, Tania Hernández Nodarse, Julio Cjuno, Andrea Moya, Ronald M. Hernández

Representation of Nature of Science Aspects in Secondary School Physics Curricula in East African Community Countries.............................................................................................................................................................................. 175

Jean Bosco Bugingo, Lakhan Lal Yadav, K.K Mashood

Using Graphic Oral History Texts to Operationalize the TEIL Paradigm and Multimodality in the Malaysian English Language Classroom............................................................................................................................................ 202

Said Ahmed Mustafa Ibrahim, Azlina Abdul Aziz, Nur Ehsan Mohd Said, Hanita Hanim Ismail

Remote Teaching and Learning at a South African University During Covid 19 Lockdown: Moments of Resilience, Agency and Resignation in First Year Students’ Online Discussions 219 Pineteh E. Angu

Enhancing Upper Secondary Learners’ Problem solving Abilities using Problem based Learning in Mathematics 235

Aline Dorimana, Alphonse Uworwabayeho, Gabriel Nizeyimana

The Development of Mobile Applications for Language Learning: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Frameworks 253 Kee Man Chuah, Muhammad Kamarul Kabilan

The Effect of Professional Training on In service Secondary School Physics 'Teachers' Motivation to Use Problem Based Learning 271 Stella Teddy Kanyesigye, Jean Uwamahoro, Imelda Kemeza

Knowledge of Some Evidence Based Practices Utilized for Managing Behavioral Problems in Students with Disabilities and Barriers to Implementation: Educators' Perspectives ........................................................................ 288 Hajar Almutlaq

Exploring Virtual Reality based Teaching Capacities: Focusing on Survival Swimming during COVID 19 ........ 307 Yoo Churl Shin, Chulwoo Kim

Math Anxiety, Math Achievement and Gender Differences among Primary School Children and their Parents from Palestine...................................................................................................................................................................... 326 Nagham Anbar, Lavinia Cheie, Laura Visu Petra

Investigating the Tertiary Level Students’ Practice of Collaborative Learning in English Language Classrooms, and Its Implications at Public Universities and at Arabic Institutions 345 Md Anwar, Md Nurul Ahad, Md. Kamrul Hasan

Navigating the New Covid 19 Normal: The Challenges and Attitudes of Teachers and Students during Online Learning in Qatar 368 Caleb Moyo, Selaelo Maifala

The Classical Test or Item Response Measurement Theory: The Status of the Framework at the Examination Council of Lesotho 384 Musa Adekunle Ayanwale, Julia Chere Masopha, Malebohang Catherine Morena

Addressing the Issues in Democratic Civilian Control in Ukraine through Updating the Refresher Course for Civil Servants

...................................................................................................................................................................... 407 Valentyna I. Bobrytska, Leonid V. Bobrytskyi, Andriy L. Bobrytskyi, Svitlana M. Protska

Supervisory Performance of Cooperative Teachers in Improving the Professional Preparation of Student Teachers 425

Ali Ahmad Al Barakat, Rommel Mahmoud Al Ali, Mu’aweya Mohammad Al Hassan, Omayya M. Al Hassan

International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research

Vol. 21, No. 8, pp. 1 20, August 2022

https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.21.8.1

Received Mar 7, 2022; Revised May 31, 2022; Accepted Jul 17, 2022

Walter Sisulu University, Nelson Mandela Drive, Mthatha, South Africa

Jogymol Kalariparampil Alex

Walter Sisulu University, Nelson Mandela Drive, Mthatha, South Africa

Abstract. This paper investigates entry level student teachers' mathematical knowledge for teaching in the Further Education and Training phase (FET) through Baseline Assessment. The study employed a quantitative research technique. The data collection instrument was a mathematics subject knowledge test (Baseline Assessment) for FET phase student teachers. Purposive and convenient sampling methods were employed in the study. The study enlisted the participation of 222 first year mathematics education student teachers from a rural Higher Education Institution (HEI) specialising in FET phase mathematics teaching.Onehundredandseventy five(175)studentteacherscompleted the Baseline Assessment for all grades in this study (10, 11, and 12). The Baseline Assessment findings were examined using descriptive statistics. The results revealed that student teachers have a moderate knowledge of mathematics topics in the FET phase at the entry level. In addition, an adequate level of understanding for teaching Grades 10 and 12 Patterns, Functions, Algebra, Space and Shape (Geometry), and Functional Relationships. While the elementary level of understanding for teaching grade 10 Measurement, Grade 11 Patterns, Functions, Algebra, and Trigonometry and Grade 12 Space and Shape (Geometry). There is no level of understanding for teaching FET phase Data and Statistics and Probability. The paper suggests that student teachers must develop a comprehensive understanding of the mathematics curriculum with the assistance of teacher educators in HEIs.

Keywords: Mathematical knowledge; student teachers’ entry level; Baseline Assessments; Further Education and Training

* Corresponding author: FolakeModupeAdelabu,fadelabu@wsu.ac.za

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY NC ND 4.0).

There was much emphasis on the teachers’ content knowledge in mathematics in 2013, according to Julie (2019). The focus on content knowledge was due to the Diagnostic Measures for the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) 2011, which focused mainly on student and mathematics teacher performance in public schools. Based on the test results, Reddy et al. (2016) concluded a need for significant improvement in teachers' content knowledge of classroom mathematics They found that most teachers' lack of mathematical content knowledge is a contributing factor to learners' poor mathematics performance in most South African schools. According to research, several studies in developed countries and developing countries suggest that teachers’ content knowledge for teaching mathematics contributes significantly and is a good predictor of student achievement (Mullens, Murnane and Willett, 1996; Altinok, 2013). (e.g. Norton 2019, Shepherd, 2013) (Monk, 1994; Wayne & Youngs, 2003; Hill, Rowan & Ball, 2005; Rivkin, Hanushek & Kain, 2005). This paper presents the findings of a baseline assessment that investigated the mathematical subject content knowledge of entry level student teachers who are being trained to teach mathematics in the Further Education and Training (FET) phase in South Africa.

The South African educational system is divided into three hierarchical phases: General Education and Training (GET), Further Education and Training (FET), and s Higher Education (HE). The national matriculation examination takes place at the end of Grade 12 to mark the shift from the GET to the FET phase of schooling (DBE, 2011). Secondary school is known as the FET phase, where learners' abilities are improved to prepare them for careers of their choice During this stage, learners lay the groundwork for future success. At the end of the FET phase, learners prepare to transition into university and higher education. According to the DBE (2011), it is expected that all learners will have a sound foundational grasp of the fundamentals that will assist them in choosing courses or study programmes at a higher education institution. Therefore, at this stage, learners concentrate on course selections consistent with their unique professional objectives and goals, whether in Commerce, Humanities, or Sciences

To advance to the HE level for Bachelor’s degree in South Africa, learners must attain at least 40% minimum passes in three or four subjects, including one official home language in the national matriculation and school leaving examination (DBE, 2012). Therefore, the teachers who specialise in the FET phase during the Bachelor of Education degree teach subjects in the FET phase in secondary schools. For example, a student teacher with a degree in FET phase mathematics learns how to teach mathematics to learners in Grades 10 to 12. As a result, the student teacher devotes themselves to mathematics as a subject specialist. The student-teacher concentrates on merging basic mathematics knowledge with efficiently communicating the knowledge to prospective Grades 10 to 12 learners. According to DBE (2011), the link between the Senior Phase and the Higher Education band is FET. Therefore, all learners who complete this phase gain a functional understanding of mathematics, allowing them to make sense of society. FET learners get exposed to various mathematical experiences that provide them with numerous possibilities to build mathematical reasoning and creative skills in

preparation for abstract mathematics in higher education. In this regard, the student teachers for the FET phase need to be prepared for the task and the comprehensive role ahead since studies show that learners' poor performance in mathematics is due to the teachers' poor mathematical content knowledge (Pino Fan, Assis & Castro, 2015; Reddy et al., 2016; Siyepu & Vimbelo, 2021; Verster, 2018). In recent times, there has been increasing attention to investigating knowledge that mathematics teachers should have to execute an adequate control of the learners’ learning. Hence, to quantify the mathematical knowledge content for teaching and understanding level of the student teacher for the FET phase, this paper reports on the Baseline Assessment that investigated the mathematical content knowledge of entry level FET phase student teachers for teaching mathematics in South Africa.

Specifically, it sought an answer to the following questions:

1. What is the mathematical content knowledge of student teachers for teaching FET phase Mathematics through baseline assessment?

2. What is the level of understanding of the entry level student teachers' mathematical content knowledge for teaching FET phase mathematics through baseline assessment?

The theoretical framework that underpins this study is Mathematical Content Knowledge. Mathematical Content Knowledge (MCK) was built on Shulman’s pedagogical content knowledge by Ball and colleagues in 2005. Mathematical Content Knowledge (MCK) is an essential factor to consider when teaching mathematics because it influences teachers' decisions towards teaching and learning mathematics. The entry level mathematics subject knowledge of the student teachers for teaching in the FET phase is crucial because it determines the student achievement in mathematics (Reddy et al., 2016) Jacinto & Jakobsen (2020) argues that several studies highlight that teachers should be able to teach what they know and comprehend. Jakimovik (2013) further supports this, who states that teachers should have the appropriate MCK for effective teaching and learning. (According to Narh Kert (2021), effective mathematics teachers know the mathematics relevant to the grade level and the value of the mathematics courses they teach. Therefore, the authors believe that the quality of FET mathematics teaching depends on teachers' knowledge of the content in the phase.

Deborah Ball and colleagues in Michigan created a test for mathematics teachers' professional expertise aimed at elementary school teachers in the United States (Ball, Hill & Bass, 2005) to assess their MCK for the grades they teach. The test was a multiple choice measure of number and operation, pattern, function, algebra and geometry. This test became a measure and was used to evaluate the MCK of mathematics educators, mathematicians, professional developers, project staff, and classroom teachers. Ball et al. (2005) discovered that teachers lack sound mathematical knowledge and skills. The test results led to the definition of mathematical content knowledge and its two components, Common Content Knowledge (CCK) and Specialised Content Knowledge (SCK) (Ball et al. 2005).

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

These researchers further explained that most of the in service mathematics teachers in the U.S are graduates of a weak system. Therefore, there is a dire need to improve the mathematical knowledge of educators. Ball et al. (2005) state that the system clarifies that these in service teachers learned mathematics with irregularity and insufficient mathematical knowledge, leading to many teachers' weak mathematical knowledge. To improve teachers' MCK, Ball et al. (2005) test approach is embedded in Shulman's (1986, 1987) taxonomy of teacher knowledge.

Shulman makes a theoretical distinction between pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), which is the knowledge of how to make the subject accessible to others, and content knowledge (CK), which is the knowledge of deep comprehension of the domain itself (Shulman 1986). As a result, Shulman (1986, 1987) and Ball et al. (2005) use mathematical subject knowledge to assess teachers’ performance. Both rely on a distinct teaching philosophy that emphasises teachers' capacity to translate content knowledge into pedagogical strategies that help students learn effectively. Jacinto and Jakobsen (2020) state that Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching (MKfT) also provides a long term theoretical foundation and practical ramifications for teacher preparation programs. (. Hence, the theory of MKfT proposed by Ball, Thames, and Phelps (2008) is used in this study.

According to the MK, the following domains are the key focus: common content knowledge (CCK), horizon content knowledge (HCK), specialised content knowledge (SCK), knowledge of content and students (KCS), knowledge of content and teaching (KCT), and knowledge of content and curriculum (KCC) (Jacinto & Jakobsen, 2020).

• The first domain (CCK) refers to mathematical knowledge that is frequently utilised and created in various settings, including outside of formal education. This form of knowledge consists of questions that can be answered by those who know mathematics rather than specialised understandings (Ball et al., 2008).

• CCK is demonstrated by using an algorithm to solve an addition problem.

• Horizon content knowledge (HCK) is the knowledge of "how the content being taught fits into and is connected to the larger disciplinary domain." This domain includes knowing the origins and concepts of the subject and how useful it may be to students' learning. HCK allows teachers to "make judgements about the value of particular concepts" raised by students, as well as address "the discipline with integrity, all resources for balancing the core goal of linking students to a large and highly developed area" (Ball et al., 2008: 400; Jacinto & Jakobsen, 2020).

• Specialized Content Knowledge (SCK) is defined as "the mathematical knowledge specific to the teaching profession." It entails an unusual form of mathematical unpacking that is not required in environments other than education. It necessitates knowledge that extends beyond a thorough understanding of the subject matter. Teachers' roles include being able to present mathematical ideas during instruction and responding to students' queries, both of which necessitate mathematical expertise specific to teaching mathematics (Ball et al., 2008: 400; Jacinto & Jakobsen, 2020).

• Knowledge of content and students (KCS) was another sub construct that needed to be redefined because it did not fit the criterion for one dimensionality. For instance, respondents such as teachers, non teachers, and mathematicians used standard mathematical procedures to answer the items designed to reflect KCS, according to cognitive tracing interviews. Furthermore, the use of multiple choice items in KCS measurement was reviewed in favour of open ended questions.

Teachers utilise CCK to plan and teach mathematics concepts, allowing them to evaluate students' answers, respond to concept definitions, and complete a mathematical approach. Therefore, any adult with a well developed CCK but not the knowledge required to educate, such as new student teachers entering Higher Education Institutions (HEI), may have a well developed CCK but lack the necessary knowledge to teach. Hence, this study investigates the mathematical content knowledge of entry level student teachers in the FET phase training phase for teaching mathematics through Baseline Assessment in South Africa.

Educational assessment supports knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs, usually in measurable terms. Assessment is an essential component of a coherent educational experience (Sarka, Lijalem & Shibiru, 2017). According to Sarka et al. (2017), assessment methods considerably influence the breadth and depth of students' learning, that is, the approach to studying and retention, with either a strong influence or a lack thereof. Assessments are used in a variety of ways, which include motivating students and focusing their attention on what is essential, providing feedback on the students' thinking, determining what understandings and ideas that are within the zone of proximal development, and gauging the effectiveness of teaching, including identifying parts of lessons that could be improved. (Patterson, Parrott & Belnap, 2020).

Assessment is a process of collecting, analysing and interpreting information to assist teachers, parents and other stakeholders in making decisions about the progress of learners (DBE, 2011). Therefore, assessment serves a wide range of functions, including permission to progress to the next level, classifying students' performance in ranked order, improving their learning and evaluating the success of a particular technique for improvement (Sarka et al., 2017). Furthermore, the assessment goals include curriculum development, teaching, gathering data to aid decision making, communication with stakeholders, instructional improvement, program support, and motivation (Pattersonet et al., 2020; Sarka et al., 2017; Wilson, 2018)

According to the DBE (2011), there are various types of assessments. These include formative assessment, summative assessment, diagnostic and baseline assessment. Formative assessment is assessing students' progress and knowledge regularly to identify learning needs and adapt teaching accordingly (Wilson, 2018) The Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) (2008) states that teachers who use formative assessment methods and strategies are better equipped to address the requirements of a wide range of students. This can be done by differentiating

and adapting their instruction to enhance students' achievement to achieve more significant equity in their learning outcomes Formative assessment can also be defined as the activity that supports learning by giving information that can be utilised as feedback by teachers and students to evaluate themselves and each other to improve the teaching and learning activities. Therefore, formative assessment is one of the primary core activities in teachers' work (Wilson, 2018).

Summative assessments are used to determine what students have learned at the end of a unit and are used as a measure for promotion purposes. Dolin et al. (2018) state that summative assessment ensures that students have fulfilled the requirements to achieve certification for school completion or admittance into higher education institutions or occupations In addition, when an assessment activity is used to provide a summary of what a student knows, understands, and can do rather than to aid in the modification of the teaching and learning activities in which the student is engaged by providing feedback, it is considered summative (CERI, 2008; Wilson, 2018). Summative assessments are used in education for a variety of reasons. Individual students and their parents discuss progress and receive an overall assessment that includes praise, inspiration, and guidance for what has been accomplished. Summative assessments provide a comprehensive guide to the effectiveness of the students' work, which may be externally standardised ((Dolin et al., 2018; Wilson, 2018). Wilson (2018) agrees that summative assessments assist schools in making the best possible grouping and subject choices for the learners Both a school and a public authority employ summative assessments to inform teachers and the school’s accountability. As a result, a common element of summative assessments is that the results are utilised to guide future decisions.

The initial assessment occurs when a student begins a new learning program. The initial assessment is a comprehensive process in which students start to piece together a picture of an individual's accomplishments, abilities, interests, prior learning experiences, ambitions, and the learning requirements associated with those ambitions. The information from the initial assessment is used to negotiate a program or course (Quality Improvement Agency (QI), 2008). Diagnostic assessment supports the identification of individual learning strengths and weaknesses. It provides learning objectives and the necessary teaching and learning strategies for achievement. This is necessary because many students excel in some areas but struggle in others. Diagnostic evaluation occurs at the start of a learning program and again when required. It has to do with the specialised talents needed for specific tasks. The information acquired from the initial examination is supplemented by diagnostic testing (QIA, 2008).

Baseline assessment commonly used in early childhood education gathers information regarding a child's development or achievement as they transition to a new environment or grade. These assessments are conducted in various ways, ranging from casual observations to standardised examinations. The information gathered from these assessments assists educators in fulfilling the learner's requirements, highlighting their strengths and areas for improvement. All these assessments are helpful in their capacity to assess the learners. Baseline

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

assessments assist schools in understanding the students' requirements. It also aids in determining learners' learning capability and potential and assessing the influence the schools have on learners. Information from baseline assessment facilitates schools in customising planning, teaching, and learning, including determining the most effective resource allocation to track learners’ progress throughout the school year. According to Khuzwayo and Khuzwayo (2020) and Tomlinson (2020), the baseline assessment findings provide information to the teacher regarding the learners’ abilities and knowledge gaps. This evidence assists the teacher in organising learning content, selecting, and matching teaching and learning approaches with the learning needs of individual students or groups of students.

The three assessments (The Initial, Diagnostic, and Baseline assessments) are interrelated in education. The assessments are always administered at the beginning or entry of students into the school, measure the strengths and weaknesses, and deduce places for improvement in a learner. The assessments are embedded in formative assessment.

The baseline assessment (CAMI) utilised in this paper is in accordance with the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) for Further Education and Training in South Africa. The licensed online Computer Aided Mathematics Instruction (CAMI) software is used to program the baseline assessments. CAMI is a high productivity software system that can improve mathematics grades in a minimal amount of time. One of the software's functions is to correct extension work for a more advanced student. CAMI employs the computer as a "Drill and Practice" system rather than a tutoring system because it focuses on knowledge retention (see www.cami.co.za).

The main mathematics topics in the FET phase are Functions; Number Patterns, Sequences, and Series; Finance, growth, and decay; Algebra; Differential Calculus; Probability; Euclidean Geometry and Measurement; Analytical Geometry; Trigonometry; and Statistics. The topics constitute Papers 1 and 2 of the national examinations in South Africa. The weighting of content areas is shown in Table 1 below:

Table 1: The weight of content areas description of FET’s mathematics topics

The weighting of Content Areas

Description Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade 12 Paper 1 (Grades 12: bookwork: maximum 6 marks) Algebra and Equations (and Inequalities) 30 ± 3 45 ± 3 25 ± 3 Patterns and Sequences 15 ± 3 25 ± 3 25 ± 3 Finance and Growth 10 ± 3

Finance, growth, and decay 15 ± 3 15 ± 3 Functions and Graphs 30 ± 3 45 ± 3 35 ± 3 Differential Calculus 35 ± 3 Probability 15 ± 3 20 ± 3 15 ± 3

TOTAL 100 150 150

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

Paper 2: Grade 11 and 12: theorems and /or trigonometric proofs: maximum 12 marks

Description Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade 12

Statistics 15 ± 3 20 ± 3 20 ± 3 Analytical Geometry 15 ± 3 30 ± 3 40 ± 3

Trigonometry 40 ± 3 50 ± 3 40 ± 3 Euclidean Geometry and Measurement 30 ± 3 50 ± 3 50 ± 3

TOTAL 100 150 150 (Source: CAPS Documents, DBE, 2011)

A quantitative research design and methodology were used in this study. The data collection instrument was a mathematics subject knowledge test (Baseline Assessment by CAMI) for FET phase student teachers. The Baseline Assessment was used to assess the entry level student teachers' mathematical content knowledge through online Computer Aided Mathematics Instruction (CAMI) software. The CAMI programme is part of the ongoing research conducted in the Mathematics Education and Research Centre established in rural higher education (HEI) in South Africa. Two hundred and twenty two (222) first year mathematics student teachers specialising in FET phase mathematics teaching participated in the study. This paper included 175 student teachers who completed the Baseline Assessment for all grades (10, 11, and 12). Purposive and convenience samplings were utilised to collect data. Participation in the CAMI Baseline Assessment was done in a controlled environment in an invigilated computer lab for two weeks. The majority of the student teachers enrolled in the FET Teaching Bachelor of Education Course came from rural secondary schools and had not experienced computer assisted learning.

3.2.1 Baseline Assessment through CAMI Computer Aided Mathematics Instruction (CAMI) baseline assessment is an online assessment available in the CAMI EduSuite program (further information is available from www.cami.co.za). The FET baseline assessment consisted of a 60 minute online test with 25 items that student teachers can easily access through internet connectivity CAMI was installed on the lab computers, and all student teachers participating in the FET Mathematics courses were given credentials to log in and access the FET Baseline Test (Grades 10, 11, and 12). After completing the Baseline Assessment, the teacher can access their results The navigation to the FET Baseline Test on the CAMI package is illustrated in the figure below.

After logging into the system, student teachers should go to the Assessment box and click ‘Do assessment’, which will bring up the Baseline and Grades assessments. After that, the student teachers choose Grades 10, 11, and 12 from the Baseline Assessment and complete the test items one by one, as shown in figure 1. Each of the Baseline Assessments for Grades 10, 11, and 12 has 25 items.

The findings of the Baseline Assessment were analyses using descriptive statistics. The frequency distributions were used to establish the mathematical content knowledge and the level of understanding of the contents for teaching mathematics in the FET phase. One way ANOVA was used to establish the variability of the mean performance of the student teachers from grade to grade. Because the program includes the Baseline Assessment, all the questions on each grade are valid. All ethical requirements were completed, and the student teachers participated (Ethical Clearance Number: FEDSRECC001 06 21).

Below are some of the sample items from the CAMI Baseline Assessment.

Figure 2: assessment items no. 9 and 16 (source: www.cami.co.za)

Figure 3: assessment items no. 20 and 25 (source: www.cami.co.za)

According to international benchmarks, 60 per cent was used as the understanding level of mathematical content knowledge in the FET phase in this study. The national codes and descriptions of the percentages that qualify learner performance can be found in Table 2 (DBE, 2011).

Table 2: Codes and percentages for recording and reporting in Grades R-12 performances

Achievement level Achievement description Marks % 7 Outstanding achievement 80 100 6 Meritorious achievement 70 79 5 Substantial achievement 60 69 4 Adequate achievement 50 59 3 Moderate achievement 40 49 2 Elementary achievement 30 39 1 Not achieved 0 29 (Source: DBE, 2011)

According to the benchmarking, "Substantial achievement" was the minimum score for student teachers' subject content knowledge mastery at a specific grade level.

4.1. Baseline assessment of the mathematical content knowledge of student teachers for teaching FET

The mean of the Baseline Assessment in the three grades of the FET phase was determined using a one way single factor ANOVA. The following tables depict the outcome:

Table 3: ANOVA Summary table

Groups Count Sum Average Variance

Grade 10 175 7832 44.75429 113.3588

Grade 11 175 6580 37.6 166.9885

Grade 12 175 5756 32.89143 171.7985

Table 4: One way ANOVA single factor

Source of Variation Sum of Squares Df Mean Squares F P value F crit

Between Groups 12488.11 2 6244.053 41.42947 2E 17 3.012991 Within Groups 78673.37 522 150.7153 Total 91161.48 524

Notes: Df Degreeoffreedom;P value:p<0.05

As shown in Table 3, the mean strengths range from 32.89 for Grade 12 to 44.75 for Grade 10, indicating that the sample means are different. That is to say; the average score is not the same. Table 4 shows that the p value of 2 ×10 17 is less than the significant level of 0.05, implying that the Baseline Assessment mean scores for FET student teachers are not equal. This means that student teachers' average performance in the FET phase varies from grade to grade. The mean percentage scores of student teachers in the FET phase Baseline Assessment are shown in the graph below.

The mean percentage scores of student teachers in the FET phase Baseline Assessment according to the content areas are shown in Figure 4 above. The results revealed that the students' mean percentage in Space and Shape (Geometry) Grade 10 was 59.18%, Patterns, Functions, and Algebra at 50.96%, measurement at 36.48 per cent, data and statistics at 19.13%, and probability at 2.55%. Patterns, Functions, and Algebra (39.59%), Trigonometry (30.35%), and Space and Shape (Geometry) (27.69%) are the average percentage scores of student teachers in Grade 11. The student teachers had the highest mean percentage in Functional Relationships Grade 12 (54.28%), 38.07%percent in Space and Shape (Geometry), 27.60% in Trigonometry, and 22.68% in Patterns, Functions, and Algebra (see Figure 4).

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

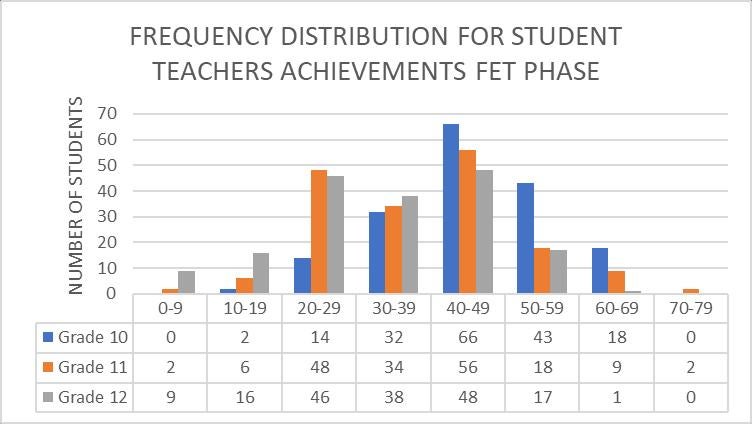

According to the above findings, student teachers scored better in Grade 10 concepts than in Grades 11 and 12 during the FET phase. Patterns, Functions, and Algebra in Grade 12 and Measurement and Space and Shape (Geometry) in Grade 11 were all below average. Students in Grades 11 and 12 should study trigonometry and functional relationships, whereas, in Grade 10, students should study Data Statistics and Probability. The frequency distribution of the student teachers' achievements was analysed to corroborate the study's findings. Figure 5 depicts the frequency distribution of student teacher marks for the FET phase:

Figure 5: Frequency distribution of the student teachers’ achievements in Grades 10, 11, and 12

The percentage marks from the CAMI Baseline Assessment for Grades 10, 11, and 12 for entry level student teachers are shown in different percentiles in Figure 5. As indicated in the graph, most student teachers' achievements for Grades 10, 11, and 12 are within 40% and 49% of each other, corresponding to 66, 56, and 48 in Grades 10, 11, and 12, respectively. For the three FET Grades (10, 11 and 12), the number of student teacher marks above 50% is 61, 29, and 18. The number of student teachers with scores below 30% in Grades 10, 11, and 12 is 16, 56, and 71. In Grades 10, 11, and 12, 32, 34, and 38, student teachers within 30 per cent and 39 per cent, respectively. In Grades 10 and 12, no student teacher receives a score higher than 70%. In Grade 11, just two student teachers receive a score of more than 70%. The signal denotes moderate achievement in Grades 10, 11, and 12.

According to national codes and descriptions (DBE, 2011), the number of 'not achieved' student teachers in the FET phase Baseline Assessment is 16, 56, and 71 in Grades 10, 11, and 12, respectively as shown in Figure 5 above. In Grades 10, 11, and 12; 32, 34, and 38 of the student teachers have elementary achievement, 66, 56, and 48 have moderate achievement, 43, 18, and 17 have adequate achievement, 18, 9 and 1 have substantial achievement, respectively and just two have meritorious achievement at Grade 11 level. In the FET phase Baseline Assessment, no student teacher achieved the outstanding achievement (80% and above) According to the findings, the student teachers have a moderate level of accomplishment. As a

result, student teachers' entry level mathematical content knowledge in the FET phase is of modest achievement.

4.2. Level of understanding of student teachers’ mathematical content knowledge for teaching FET phase mathematics through baseline assessment Table 5 shows the student teachers' mathematical content knowledge level for teaching the FET phase in each grade according to the content areas.

Table 5: The understanding level of student teachers’ mathematical content knowledge for teaching FET phase mathematics according to content areas

Achievement level Achievement description Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade 12 7 Outstanding achievement 6 Meritorious achievement 5 Substantial achievement 4 Adequate achievement Patterns, Functions, and Algebra; Space and Shape (Geometry)

Functional Relationships 3 Moderate achievement 2 Elementary achievement Measurement Patterns, Functions, and Algebra; Trigonometry

Space and Shape (Geometry)

1 Not achieved Data and statistics; Probability; Trigonometry; Functional Relationships

Data and statistics; Space and Shape (Geometry); Measurement Probability; Functional Relationships

Data and statistics; Measurement; Probability; Patterns, Functions, and Algebra; Trigonometry

The results given in Table 5 show the level ofunderstanding of the student teachers according to the content areas. The findings revealed that student teachers have an adequate level of understanding of Patterns, Functions, Algebra and Space and Shape (Geometry) in Grade 10 and Functional Relationships in Grade 12. Furthermore, the student teachers have an elementary level of understanding of Measurement in Grade 10, Patterns, Functions, and Algebra, Trigonometry in Grade 11, and Space and Shape (Geometry) in Grade 12. The student teachers have no level of understanding of Data and statistics and Probability in any of the grades, that is, Grade 10, 11 and 12. The finding indicated that the level of understanding of the student teachers’ mathematical content knowledge for teaching Grade 10 Patterns, Functions, and Algebra, as well as Space and Shape (Geometry) and Grade 12 Functional Relationships, is adequate level. While the level of understanding of the student teachers’ mathematical content knowledge

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

for teaching Grade 10 Measurement, Grade 11 Patterns, Functions, Algebra, and Trigonometry and Grade 12 Space and Shape (Geometry) is elementary level. In addition, the results revealed that the student teachers did not have sufficient understanding of the mathematical content knowledge for teaching FET phase Data and Statistics and Probability.

The evidence can be drawn from the findings that the entry level student teachers' mathematical knowledge for the FET phase is at the 'moderate level' of achievement. In contrast, the actual level of understanding was not attainable. However, the findings in table 5 revealed an adequate level of understanding of the entry level student teachers’ mathematical content knowledge for teaching grades 10 and 12 Patterns, Functions, and Algebra, Space and Shape (Geometry) Functional Relationships. Elementary level of understanding for teaching Grade 10 Measurement, Grade 11 Patterns, Functions, and Algebra, including Trigonometry and Grade 12 Space and Shape (Geometry) The entry level student teachers do not have adequate mathematical content knowledge for teaching FET phase Data and Statistics and Probability.

The result of the mean percentage from the Baseline Assessment (Figure 4) determined the mathematical content knowledge of the student teachers to be in Grade 10 Space and Shape (Geometry) and Patterns, Functions, and Algebra with (59.18%) and (50.96%) respectively as well as Grade 12 Functional Relationships with (54.28%). Similar results were obtained by Fonseca, Maseko, and Roberts (2018) in their study ‘Students’ mathematical knowledge in a Bachelor of Education (Foundation or intermediate phase) programme’ that there is a good distribution of attainment for the first year students in their pilot test. In contrast, the findings in this study disagree with Alex and Roberts (2019), where low percentage performance and poor mathematical knowledge for teaching were recorded in their research. There is a need to improve entry level first year student teachers’ mathematical content knowledge. The finding also revealed that none of the student teachers achieved the “outstanding achievement", and only two have “meritorious achievement” at Grade 11 level.

The results of the student teachers' level of understanding are in agreement with Reid and Reid (2017). They found that student teachers had difficulty understanding mathematical content knowledge,such as probability and standard algorithms. According to the above researchers, the student teachers performed below the expected standard. As a result, student teachers must have a strong understanding of mathematical concepts and be able to express and explain them in a variety of ways in their future teaching.

According to studies, the primary purpose of a baseline assessment in teaching and learning is to get to know students at the entry level of a new school year (Khuzwayo & Khuzwayo, 2020; Nguare, Hungi & Matisya, 2018; Tiymms, 2013; Tomlinson, 2020). Therefore, the goal of baseline assessment in this study is to assist HEIs teacher educators in developing learning activities inclusive of various learning styles. This would also assist in detecting student teachers' special needs

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

at an early stage so that a remediation program can be implemented (DBE, 2019). Taylor (2021) states that in South Africa, a vicious cycle system problem is evident Due to the negative public perception of teaching, ITE programs cannot attract competent matriculants to study for a teaching qualifications. Most of the students intending to study teaching as a career are often rejected in their first and second choices at the university level. Often universities are forced to recruit a lesser quality of pre service teachers into the programme, which demands a reduction in the rigour of their training. A lower quality or competent teacher is thus deployed into schools, resulting in poor quality teaching, thus lowering the learner performance and the prestige of the teaching profession. Matriculant quality while also lowering the perceived prestige of teaching. Taylor & Robinson (2016) opine that the inability to recruit qualified pre service teachers enhances the cycle of poor quality teaching and learning.

According to Deacon (2016), the entrance requirements for Initial Teacher Education programs are generally lower than most other entry level degree programs. The evidence suggested that the weakest students enter education faculties as a last resort, motivated by a desire to earn a university qualification rather than a desire to make a difference in students' lives. Taylor (2021) supported his claim with data from the Centre for Educational Testing for Access and Placement's National Benchmark Tests (NBTs) (CETAP, 2020). Most university applicants take the NBTs, which require a minimum to gain admission into a particular programme. However, this is not applicable to most Initial Teacher Development Programme. Over 75 000 university applicants took the Academic Literacy (AL) and Quantitative Literacy (QL) examinations, while over 58 000 took the Mathematics Test (MAT) during the 2019 NBT entry cycle. Candidates planning to study Education had the second lowest average score of all applications to all faculties, with only those intending to study Allied Healthcare or Nursing having a lower average (CETAP, 2020). Basic, Intermediate, and Proficient are the three tiers of NBT scores, with applicants in the Basic band defined as: “Test performance reveals serious learning challenges: it is predicted that students will not cope with degree level study without extensive and long term support, perhaps best provided through bridging programmes (i.e., non credit preparatory courses, special skills provision) or FET provision. Institutions admitting students performing at this level need to provide such support themselves.” (CETAP, 2020, p. 18).

Due to the low mathematics achievement of students entering teacher education programs, the goal of creating a deep understanding of mathematics required for teaching should become an essential aspect of the mathematics course design and implementation (Jakimovik, 2013). Furthermore, Jakimovik (2013) claims that the complete lack of a link between mathematics and methods courses is a long standing trend in teacher preparation programs. The only stipulation is that students complete the mathematics course’s exams before enrolling in the methods courses. The mathematics courses are taught by university mathematicians and academics who teach the techniques courses, which place less emphasis on the interaction between subject matter expertise and teaching.

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

According to Ma (1999), teachers should possess a Profound Understanding of Fundamental Mathematics (PUFM). This means teachers' mathematical content knowledge should be a thorough understanding of mathematics that has breadth, depth, connectedness, and thoroughness, not on the average level. Jakimovik (2013) maintains that one of the most critical aspects of teaching is understanding what will be taught. In addition, mathematics is one of the fundamental realms of human thought and investigation. Learners need to build intellectual resources for knowing about and actively engaging in mathematics. The above researcher explains that the future teachers must use their mathematical knowledge in conducting classroom discourse in a learning community, mentioning students' educational needs by involving them in genuine mathematics learning, analysing students' productions, examining students' mathematical knowledge and skills in lesson preparation, or in evaluating curriculum materials. Consequently, to provide successful learning for future teachers, educators must establish specialised instructional methodologies in the HEIs.

According to Burghes and Geach (2011), the requirements for being a good mathematics teacher are confidence, competency, commitment and a passion for mathematics at a level much higher than the one being taught. Furthermore, knowledge of the topic tobe taught is a significantfactor in determining thequality of training. Goldsmith, Doerr and Lewis (2014) believe that teacher’s capacity to recognise and analyse student’s thinking also their ability to engage in effective professional conversations are hampered by a lack of mathematical content understanding

In conclusion, to become a FET mathematics teacher, student teachers must be exposed to many mathematical experiences. They should be offered a variety of opportunities to hone their mathematical reasoning and creative abilities in preparation for teaching mathematics in the FET phase. Their low level of mathematical knowledge and understanding may make it difficult for the student teachers to teach the FET phase in the future. To teach in the FET phase, student teachers must have mathematical solid foundational knowledge and understanding. Since FET is the link between the Senior Phase and the Higher Education band, the student teachers should have an appropriate achievement level, namely, adequate, substantial, meritorious, and outstanding achievement level, to link FET learners to the Higher Education band.

Consequently, student teachers will need to improve their ability to teach mathematics effectively and ensure that it is meaningful for learners. They will be able to effectively teach mathematics in the future, even further than their current level of knowledge and ability. Then the mathematics performance of the learners will improve.

This paper showed that the mathematical content knowledge of the student teachers at the entry level is at a moderate level, and the level of understanding was low. Therefore, this paper recommends that with the assistance of teacher

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

educators in HEIs, student teachers must gain a thorough understanding of the mathematics curriculum. Furthermore, the mathematics appropriate to the grade level and mathematical courses that the student teachers are responsible for teaching should be known and well understood. This study also recommends that only those students who have attained substantial achievement in mathematics should be allowed to study FET mathematics at higher education institutions. HEI should consider those students who have applied for teaching as their 1st option rather than their last option as an entry requirement Stricter entry level to FET teaching programmes should be implemented at HEIs, such as good mathematics attainment levels in the matriculation examination. Finally, every university should build into their entry level programme a 'Baseline assessment’ for all students intending to study towards teaching mathematics in the FET phase.

In conclusion, the authors believe that teachers with a low entry level and a low level of understanding will have poor content knowledge of mathematics. As a result, there will be ineffective classroom teaching and poor mathematics performance in secondary schools. Therefore, for learner performance improvement, HEIs and the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) should ensure that student teachers have a solid entry level level of understanding of the mathematics curriculum. Student teachers' entry level should be investigated for all educational system stages, including general education and training, further education and training, and higher education for future studies.

This research is confined to student teachers who enrolled in a FET mathematics teaching programme and came from poor, disadvantaged backgrounds The majority of the student teachers had not experienced computer assisted learning, which may have contributed to their performance in the baseline test.

Alex, J., & Roberts, N. (2019). The need for relevant initial teacher education for primary mathematics: Evidence from the Primary Teacher Education project in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 27th Conference of the Southern African Association for ResearchinMathematics,ScienceandTechnologyEducation (59 72).

Altinok, N. (2013). TheImpactofTeacherKnowledgeonStudentAchievementin14Sub Saharan African Countries. Retrieved from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/ 002258/225832e.pdf

Ball, D. L., Hill, H.C , & Bass, H. (2005). Knowing mathematics for teaching: Who knows mathematics well enough to teach third grade, and how can we decide? American Educator, 29(1), 14 17, 20 22, 43 46. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/65072/Ball_F05.pdf

Ball, D. L., Thames, M. H., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makesitspecial. Journalofteachereducation, 59(5),389 407.https://www.cpre.org/ Behrman, J. R., Ross, D., & Sabot, R. (2008). Improving quality versus increasing the quantity of schooling: Estimates of rates of return from rural Pakistan. Journal of Development Economics, 85, 94 104. https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0304387806001301

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

Burghes, D., & Geach, R. (2011). International comparative study in mathematics training: Recommendations for initial teacher training in England. CfBT Education Trust. https://www.nationalstemcentre.org.uk/res/documents/page/International%2 0comparative%20study%20in%20mathematics%20teacher%20training.pdf/.

Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) 2008. Assessment for Learning Formative Assessment. OECD/CERI International Conference “Learning in the 21st Century: Research, Innovation and Policy 15 16 May 2008

CETAP, (2020). The national benchmark tests. National report: 2019 intake cycle, Centre for Educational Testing for Access and Placement, University of Cape Town. https://nbt.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/NBT%20 National%20Report%202019.pdf.

Deacon, R. (2016). The initial teacher education research project: Final report. Johannesburg: JET Education Services. https://www.admin.jet.org.za

Department of Basic Education. (2011). CurriculumassessmentpolicystatementsGrades10 12Mathematics.

Department of Basic Education. (2012). Curriculum assessment policy statements. http://www.education.gov.za/Curriculum/NCSGradesR12/CAPS/tabid/420/ Default.aspx

Department of Basic Education. (2019). Mathematics Teaching and Learning Framework for South Africa: Teaching and Learning mathematics for understanding. Department Printers: Pretoria RSA. https://www.jet.org.za

Dolin, J., Black, P., Harlen, W., & Tiberghien, A. (2018). Exploring Relations Between Formative and Summative Assessment. In J. Dolin & R. Evans (Éd.), Transforming Assessment (Vol. 4, p. 53 80). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978 3 319 63248 3

Fonseca, K., Maseko, J., & Roberts, N. (2018). Students’ mathematical knowledge in a Bachelor of Education (Foundation or intermediate phase) programme. In Govender,R.&Jonquière,K.(2018)Proceedingsofthe24thAnnualNationalCongress oftheAssociationforMathematicsEducationofSouthAfrica (124 139).

Goldsmith, L., Doerr, H., & Lewis, C. (2014). Mathematics teachers’ learning: A conceptual framework and synthesis of research. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 17, 5 36. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s10857 013 9245 4.pdf

Hill, H. C., Rowan, B., & Ball, D. L. (2005). Effects of Teachers’ Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching on Student Achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 42, 371 406. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3699380.pdf

Jacinto, E. L., & Jakobsen, A. (2020). Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching: How do Primary Student Teachers in Malawi Understand it? African Journal of Research in Mathematics,ScienceandTechnologyEducation, 24(1), 31 40.

Jakimovik, S. (2013). Measures of mathematical knowledge for teaching and university mathematics courses design. u: Kiryakova V.[ur.]. In Complex Analysis and Applications' 13'(Proc. Intern. Conf. Sofia, 2013), Institute of Mathematics and Informatics,BulgarianAcademyofSciences (118 138).

Julie, C. (2019). Assessment of teachers’ mathematical content knowledge through large scale tests: What are the implications for CPD? Caught in the act: reflections on continuing professional development of mathematics teachers in a collaborative partnership, chapter 3, 37 53.

Khuzwayo, M. E., & Khuzwayo, H. B. (2020). Baseline Assessment in the Elementary Mathematics Classroom: Should it be Optional or Mandatory for Teaching and Learning? InternationalJournalofLearning,TeachingandEducationalResearch, 19(8), 330 349. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.19.8.18

Ma, L. (1999). Knowing and teaching elementary mathematics: Teachers’ understanding of fundamental mathematics in China and the United States. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

Mullens, J. E., Murnane, R. J., & Willett, J. B. (1996). The Contribution of Training and Subject Matter Knowledge to Teaching Effectiveness: A Multilevel Analysis of Longitudinal Evidence from Belize. Comparative Education Review, 40(2), 139 157. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1189048.pdf

Narh Kert, M. (2021). PredictiveValidityofEntry LevelMathematics:MathematicalKnowledge ofStudentTeachersforTeachingBasicSchoolMathematicsinGhana. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

Nguare, M. W., Hungi, N., & Mutisya, M. (2018). Assessing Learning: How can classroom based teachers assess students' competencies inNumeracy. JournalofAssessmentin Education, 26(2), 222 244. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2018.1503156

Patterson, C. L., Parrott, A., & Belnap, J. (June 2020). Strategies for assessing mathematical knowledge for teaching in mathematics content courses. In A. Appova, R. M. Welder, and Z. Feldman, (Eds.), Supporting Mathematics Teacher Educators’ Knowledge and Practices for Teaching Content to Prospective (Grades K 8) Teachers. Special Issue: The Mathematics Enthusiast, (17) 2 & 3, 807 842. Scholar Works: University of Montana. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/tme

Pino Fan, L. R., Assis, A., & Castro, W. F. (2015). Towards a methodology for the characterization of teachers’ didactic mathematical knowledge. EURASIAJournal ofMathematics,ScienceandTechnologyEducation, 11(6), 1429 1456.

Reddy, V., Visser, M., Winnaar, L., Arends, F., Juan, A., Prinsloo, C. & Isdale, K. (2016). TIMSS 2015: Highlights of Mathematics and Science Achievement of Grade 9 South African Learners (Nurturing green shoots). Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council.

Reid, M., & Reid, S. (2017). Learning to be a Math Teacher: What Knowledge is Essential? International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 9(4), 851 872 https://www.generationready.com/white papers/what is effective teaching of mathematics

Rivkin, S. G., Hanushek, E. A., & Kain, J. F. (2005). Teachers, Schools, and Academic Achievement. Econometrica, 73, 417 458. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1468 0262.2005.00584

Sarka, S., Lijalem, T., & Shibiru, T. (2017). Improving Academic Achievement through ContinuousAssessmentMethods:IntheCaseofYearTwoStudentsofAnimaland Range Sciences Department in Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia. Journal of EducationandPractice, 8(4), 1 5. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1133029.pdf

Shepherd, D. L. (2013, June). The impact of teacher subject knowledge on learner performance in South Africa: A within pupil across subject approach. In International Workshop on Applied Economics of Education, Cantanzaro (1 32). http://www.iwaee.org/papers%20sito%202013/Shepherd.pdf

Siyepu, S. W., & Vimbelo, S. W. (2021). Student teachers’ mathematical engagement in learning about the total surface areas of geometrical solids. SouthAfricanJournalof Education,41(2), 1 13. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v41n2a1837

Taylor, N. (2021). The dream of Sisyphus: Mathematics education in South Africa. South African Journal of Childhood Education 11(1), a911. https://doi.org/10.4102/sauce.v11i1.911

Taylor, N., & Robinson, N. (2016). Towards teacher professional knowledge and practise standards in South Africa. Areportcommissionedbythe CentreforDevelopmentand Enterprise. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nick Taylor 23/publication/339592811

Tomlinson,C.A.(2020). Fulfillingthepromiseofthedifferentiatedclassroom:Strategiesandtools for responsive teaching. Alexandria. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

Tymms, P. (2013). Baseline Assessment and Monitoring in Primary schools: Achievement, Attitudes, and Value added indicators. New York: Routledge. https://www.api.taylorfrancis.com

Verster, J. (2018). Experiencesoflearningtobecomeafurthereducationandtrainingmathematics teacher’ case study (Doctoral dissertation, Cape Peninsula University of Technology).

Wayne,A.J.,&Youngs,P.(2003).TeacherCharacteristicsandStudentAchievementGains: A Review. Review of Educational Research, 73, 89 122. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3516044.pdf

Wilson, M. (2018). Making measurement important for education: The crucial role of classroom assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 37(1), 5 20. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/emip.12188

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research

Vol. 21, No. 8, pp. 21 42, August 2022

https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.21.8.2

Received Mar 30, 2022; Revised July 12, 2022; Accepted July 27, 2022

African Centre of Excellence for Innovative Teaching and Learning Mathematics and Science (ACEITLMS), University of Rwanda, College of Education

Eugenia

KafanaboUniversity of Dar es Salaam, School of Education, Tanzania

Bernard BahatiUniversity of Rwanda, College of Education, Rwanda

Abstract. This study aimed at exploring the instructional activities that could support students’ learning of science process skills by using chemistry based computer simulations and animations. A total of 160 students were randomly selected and 20 teachers were purposively selected to participate inthe study. Data were gathered in both qualitative and quantitative formats. This was accomplished through the use of a classroom observation checklist as well as a lesson reflection sheet. The qualitative data were analyzed thematically, while the quantitative data were analyzed using percentages. The key findings from the study indicated that chemistry based computer simulations and animations through instructional activities, particularly formulating hypotheses, planning experiments, identifying variables, developing operational definitions and interpretations, and drawing conclusions, support students in learning science process skills. It was found that during the teaching and learning process, more than 70% of students were able to perform well in the aforementioned types of instructional activities, while 60% performed well in planning experiments. On the other hand, as compared toother instructional activities, planning experiments was least observed among students and teachers Students can be engaged in knowledge construction while learning science process skills through the use of chemistry based computer simulations and animations instructional activities. Therefore, the current study strongly recommends the use of chemistry based computer simulations and animations by teachers to facilitate students’ learning of chemistry concepts in Tanzanian secondary schools.

Keywords: chemistry based computer simulations; instructional activities; science process skills

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY NC ND 4.0).

Thepossibilityof involvingstudents in theacquisition of knowledgeandscientific skills, particularly science process skills (SPSs), has grown in importance in chemistry curricula globally (Aydm, 2013; Bete, 2020). This is owing to the science process skills' alignment with students' learning and application in everyday life. As a result, different countries' chemistry curricula include science process skills in both basic and integrated SPSs. Basic SPSs includes observing, classifying, measuring, calculating, inferring, and communicating. Integrated SPSs include formulating hypotheses, identifying and controlling variables, designing experiments, data recording and interpretation (Abungu et al., 2014; Athuman, 2019; Aydm, 2013). During chemistry teaching and learning, effective instructional strategies that engage students in inquiry activities are essential for the development of science process skills. Therefore, inquiry based approaches to teaching and learning, such as practical work and hands on activities, are critical for engaging students in active learning (Abungu et al., 2014; Irwanto et al., 2018; & Seetee et al., 2016).

Chemistry includes abstract concepts such as chemical kinetics, equilibrium and energetics which students find difficult to learn (Lati et al., 2012). Along the same line, teacher centeredness dominates chemistry teaching and learning in Tanzanian classrooms, with the teacher remaining the primary source of information through the chalk and talk technique. Moreover, inquiry learning tasks such as observations, hypotheses, testing, data collection, interpretations, discourse, and conclusions are similarly restricted in the learning process (Kalolo, 2015; Kinyota, 2020). Consequently, memorization learning persists, and there is little effort to support learners with science process skills (Mkimbili et al., 2018; Kinyota, 2020; Semali & Mehta, 2012). In this regard, inappropriate teaching strategies which rely on teacher centeredness and occasional practical work, shortages of laboratories and teaching aids, as well as large class size, are among the contributing causes (Mkimbili et al., 2018; Semali & Mehta, 2012).

Chemistry based computer simulations and animations are examples of an information and communication technology (ICT) invention that has been explored and used as alternative teaching and learning resources in classrooms globally. Computer simulations are computational models of real orhypothesized situations or natural phenomena that allow users to explore the implications by manipulating or changing parameters within them (Nkemakolam et al., 2018). In addition, animations are dynamic displays of graphics, images, and colors that are used to create certain visual effects over a series of frames (Trindade et al., 2002). Computer simulations and animations include virtual laboratories and visualizations of phenomena. Further, the interactivity feature of computer simulations in involving students in hands on activities has promoted their importance as they are essential for inquiry learning and a learner centered environment in the classroom (Moore et al., 2014; Plass et al., 2012). Based on the significance of ICT, the competence based curriculum in Tanzania recommends the availability and use of ICT, including computer simulations and animations This is to ensure smooth teaching and learning as well as giving learners real world experience in learning (MoEST, 2015; MoEST, 2019).

Despite Tanzania's government's initiatives to integrate ICT into classrooms, little is known about how chemistry content may be presented effectively in an inquiry based setting(Ngeze,2017). ICTuses encompassesspecific instructional strategies that support students in learning science process skills through inquiry learning in the chemistry classroom. This follows the fact that blending proper instructional activities when using computer simulations is an important factor in engaging students in learning chemistry concepts and specific science process skills (Çelik, 2022). The reviewed literature (Beichumila et al., 2022; Çelik, 2022; Moore et al., 2014) advocates the use of computer simulations and animations in chemistry learning to improve students’ acquisition of science process skills.

In the above regard, Çelik (2022) and Sreelekha (2018) emphasize teaching strategies for students to acquire science process skills through computer simulations and animations. In such a learning context, little is known about instructional strategies that support the learning of these integrated science process skills through computer simulations and animations. Therefore, the goal of this study was to investigate the chemistry based computer instructional activities used to engage students in building integrated science process skills during chemistry teaching and learning. The study sought to address the following research question: What are the chemistry based computer simulation and animation instructional activities used to engage students in building integrated science process skills during chemistry teaching and learning?

The interactivity feature of computer simulations and animations has ability to enable students to observe process, events, and activities during learning (Smetana & Bell, 2012). As students interact with computer simulations and animations, they become engaged in the exploration of the world around them through inquiry activities (Moore et al., 2014). In this sense, students get the opportunity to engage in inquiry learning and gather scientific evidence that are important for learning science concepts. Through computer simulations students develop scientific knowledge as well as science process skills (Beichumila et al., 2022; Çelik, 2022; Supriyatman & Sukarino, 2014). However, aspects of inquiry are not the focus in most of the lessons in science classrooms. As a result, instructional strategies as advocated by Yadav and Mishra (2013) in teaching and learning processes are critical towards using any inquiry based approach, including computer simulations and animations to develop science process skills. Students learn less in terms of science process skills by using computer simulations in a teacher centeredformat in which students’ complete recipe type tasks thatrequire them to verify solutions (Çelik, 2022; Smetana & Bell, 2012). Thus, instructional activities for inquiry learning are important.

2.2 The importance of instructional activities and development of science process skills

Instructional activities relate toall activities that support theteaching andlearning process (Akdeniz, 2016). These instructional activities are teaching and learning activities and assessment activities that play a significant role in engaging

students in the construction of knowledge and the acquisition of skills. Instructional activities that engage teachers in explaining or lecturing students while students are passivelisteners donothelpstudents toacquirescience process skills. One way to develop the science process skills among students is to use appropriate instructional activities that engage students in inquiry activities (Bete, 2020; Coil et al., 2010; Irwanto et al., 2018; Seok, 2010). Activating students' background knowledge, offering analogies, asking questions, and encouraging students to use alternative forms of representation are some of the teaching strategies. According to Supriyatman and Sukarino, (2014), teachers can use computer simulations to assist students in predictions to generate inquiry.

Furthermore, Brien and Peter (1994) and Jiang and McComas (2015) advocated the need for instructional activities that integrate well into lessons for inquiry learning. The approach allows students to gain a deeper and broader understanding of science content with real world applications, as well as learning about the scientific inquiry process. This includes developing general investigative skills (such as posing and pursuing open ended questions, synthesizing information, planning and conducting experiments, analyzing, and presenting results). For example, during classroom lessons, students were engaged in tasks such as making observations and inferences, planning experiments, and generating predictions (Abungu et al., 2014., Chebii et al., 2012, Rauf et al. 2013, Saputri, 2021). As a consequence of involving students in these learning activities, they work collaboratively in groups, interact with each other through discussion and carrying out experiments under the guidance of the teacher. In addition, the instructional activities mentioned develop critical thinking skills and learning curiosity among learners (Higgins & Moeed, 2017; Pradana et al., 2020). Thus, in the Tanzanian context it was important to explore instructional activities that support students’ learning of science process skills while using computer simulations and animations to learn chemistry concepts.

This study was framed within social constructivism theory by Vygotsky (1978) whobelieved that knowledge construction is an active process conducted through social interaction among learners themselves, learners and teachers or learners and materials. This indicates that scientific knowledge and skills are socially constructed and verified under social constructivism in science learning. As a result, Onwioduokit (2013) suggested that when students are taught science, they should participate in inquiry activities. This becomes possible when learners are encouraged to learn by doing something as a means of learning instead of only listening (Demirci, 2009). In essence, these instructional activities are essential to enable teachers and learners to interact with computer simulations and animations during teaching and learning.

Vygotsky (1978) explained the role of teachers in using instructional activities and learner centered strategies to enable students to construct knowledge and skills. Therefore, using social constructivism theory, it was believed that it could help to understand instructional activities that engage learners in knowledge construction and learning science process skills as they learn using computer simulations. These are essential learning environments to create a social learning

environment that facilitates students' construction of knowledge and skills that can be applied from a classroom context to real life experiences.

The study was carried out at four secondary schools from the Dodoma and Singida regions of Tanzania's central part. The area was chosen because students perform poorly in science, including chemistry, and there is a shortage of instructional materials (MoEST, 2019, 2020). The selection of schools was based on the availability of computer laboratories and other ICT equipment or tools such as projectors. The assumption was that by using computer laboratories, students could be subjected to the teaching and learning of chemistry using computer simulations as one way to engage learners in hands on activities

The challenging topic of chemical kinetics, equilibrium, and energetics was the focal point of the current study (Beichumila et al., 2022; Lati et al., 2012), which is taught at level three of secondary education in Tanzania (MoEVT, 2010). This served the choice of 160 Form Three students (level 3 of ordinary secondary education), who were rondomly selected to be involved in this study. Furthermore, 20 chemistry teachers were purposely involved in the study based on the criteria that they had prior training in ICT integration in the classroom.

The study employed a mixed method through both quantitative and qualitative approaches to collect data This was done through classroom observations focusing on both teachers' and students' learning activities (Cresswell, 2013; Cresswell & Clark, 2018). In addition, a lesson reflection sheet was used to explore students’ insights on lesson instructional activities. The focus was to explore the instructional activities that could support students’ learning of science process skills by using chemistry based computer simulations and animations. This generated information that helped the research team to explore the instructional strategies that could engage students in learning chemistry concepts using computer simulations and animations The use of both classroom observation and a lesson reflection sheet was considered as triangulation of information (Cohen et al., 2011). The design of the study followed two steps, namely pre intervention and post intervention.

The first four sessions, which were utilized as a pre intervention, focused on the topics of chemical kinetics, equilibrium, and energetics, with conducted one lesson per school being conducted. The four lessons in pre intervention were purposely used to capture an actual picture of instructional activities used by teachers to support students’ learning of science process skills through computer simulations. This was a baseline setting. At this stage a classroom observation checklist was used as a data collection tool. The classroom observation checklist was developed by the researcher from existing literature, for example, Chebii et al. (2012). Classroom observation was chosen as the method since it provides first

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

hand evidence of what the teacher and students perform in class as compared to a questionnaire (Atkinson & Bolt, 2010).