climate change in practice

Anjali Karol Mohan, Partner, Integrated Design, Bengaluru | anjali@integratedesign.org

Gayathri Muraleedharan, Urban Planner and Researcher, Integrated Design, Bengaluru | gayathri@integratedesign.org

climate change in practice

Anjali Karol Mohan, Partner, Integrated Design, Bengaluru | anjali@integratedesign.org

Gayathri Muraleedharan, Urban Planner and Researcher, Integrated Design, Bengaluru | gayathri@integratedesign.org

The study recognizes informal settlements as important spatial elements and identifies one of their core values - nature and character of “commons”. Various typologies have been studied by taking case studies from South America, Africa and South East Asia to explore and formulate strategies to address their environmental concerns in respect of Climate Change.

change is increasingly acknowledged as one of the greatest threats of the 21st century. As it intersects with the Anthropocene – three quarters of the projected [2050] population living in urban areas, largely in the global South, cities are emerging as epicentres of climate risks and climate action. India is no exception. That these risks are distributed disproportionately with the urban poor bearing the brunt is well evidenced. In response, on one hand, ‘exogenous’ or formal responses are seen in national, state and city scale climate action plans, and on the other, the urban poor are seen to resort to ‘endogenous resilience’ demonstrated through an array of informally-derived coping mechanisms and capacities [Trundle 2020]. However, a lack of interaction between these endogenous initiatives and the exogenous Climate Change efforts is seen. An effective integration of the two can potentially ensure the much needed ‘localisation’ of climate action.

In furthering the exploration of localised solutions to address Climate Change in urban poor areas, Integrated Design [India] in collaboration with Plan Adapt [South Africa], URBAM at Universidad EAFIT [Colombia] and the Gujarat Mahila Housing Trust [India] engaged in a co-creation process that positioned ‘community commons’ or shared spaces within settlements as critical spaces to evolve resilience strategies that can attenuate socio-spatial deprivations.[1] Community commons are critical socioeconomic, ecological, cultural and political spaces that aid everyday living extending from within the household and the community. While the limited availability of private space renders these spaces dynamic and multi-functional, simultaneous Climate Change events –flooding, droughts and heat stress, amongst others - are threatening these spaces, impacting the associated everyday living and livelihoods. By extension, foregrounding these as adaptive [and potentially mitigative] spaces is critical to initiate localised climate action and social justice.

The co-creation started with comprehending the myriad ways in which commons accommodate community and individual living. Primary engagement in the urban poor settlements of Dharwad, Ranchi, and Bengaluru [India] and Medellin [Colombia] was coupled with secondary research [case studies across Africa and South-East Asia] pointed to a diversity in the nature and use of commons, linked closely to the evolution of the settlement. While some settlements have evolved from small squatters, others are traditional habitations/ villages that are subsumed [and densified] as the city creeps in and sprawls out. To illustrate, in Ranchi, the present days slums are 75-100 years old tribal hamlets that embody a wealth of traditional knowledge, especially on stewarding the eco-system that provisions everyday living. In contrast, Moravia in Medellin started as a squatter near the municipal garbage dump. Dharwad and Bengaluru showcased a mixed typology of informal settlements.

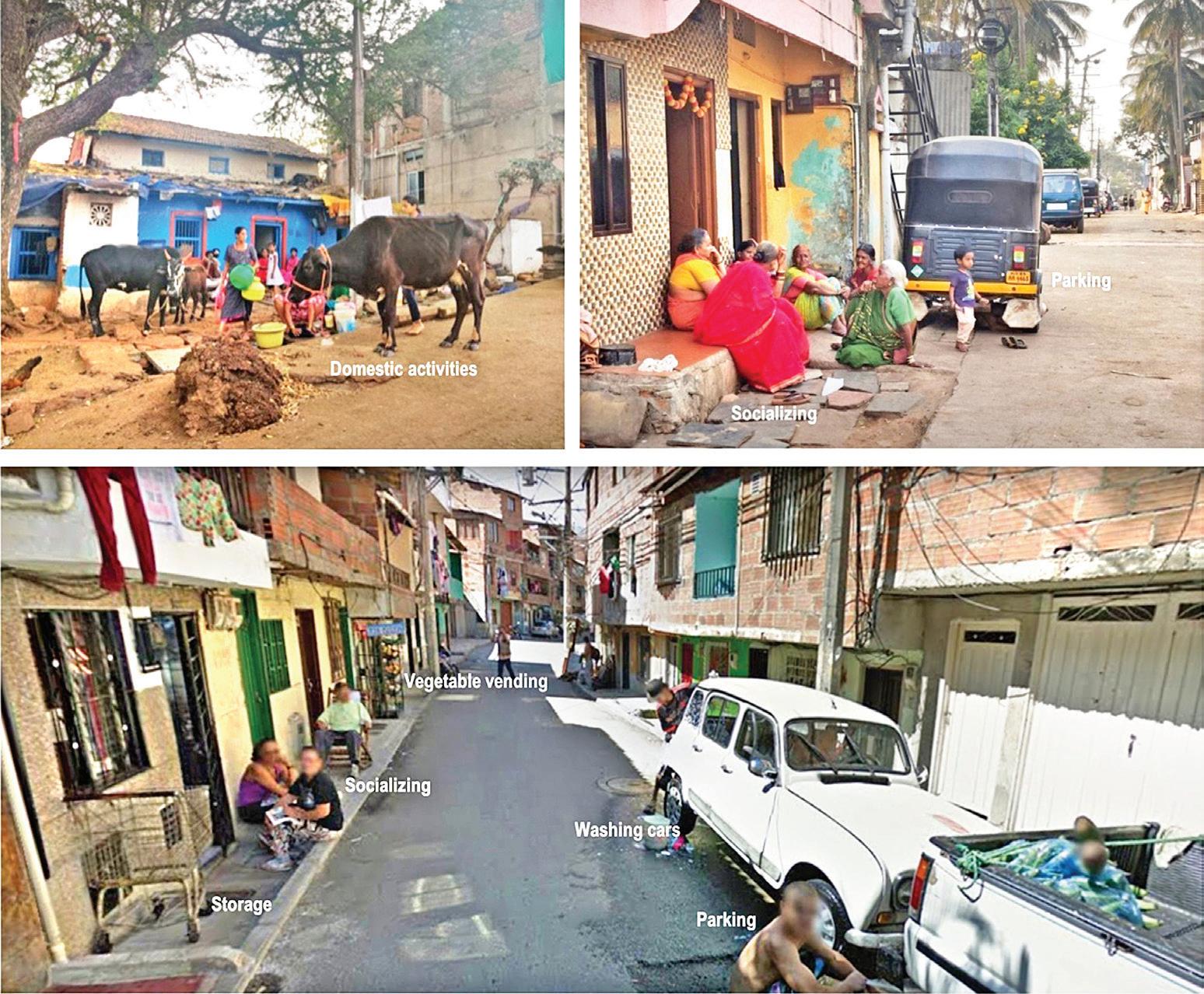

In comprehending the commons, while traditional villages have organically formed common open spaces [like wide street junctions, and shaded areas] in squatter-turnedslums,in the absence of public spaces, streets emerge as critical commons. Across settlements, community commons support livelihoods, social and cultural interactions as well as spill over spaces for daily household chores. While lack of adequate housing renders public spaces into collective commons, in settlements such as Moravia these are planned and managed by the community not only as extensions of their houses but also, as essential places of urban life that require preservation.

Next, the commons were analysed through an inter sectional lens of Climate Change, urbanisation, and informality to arrive at, and foreground the vulnerability experienced, its manifestations and implications on the everyday lives and livelihoods of the urban poor. In addition, given that coping strategies used by informal settlements can potentially emerge as entry points to developing contextually suited and community owned adaptation plans [Jabeen et.al. 2010], a diverse set of coping strategies were observed across different typologies of settlements. These included quick-fix measures like covering household valuables with plastic sheets and storing them on higher racks during floods. Measures to cope with heat stress included temporarily opening up roofs [made of sheets and cloth], sleeping outside their shanties, etc.

OPPOSITE PAGE |

Different activities and types of appropriation in the community commons of Gauli Galli, Dharwad [1] & [2], and Moravia [3]

[4] Streets becoming dynamic, multifunctional spaces, Saraswatipur settlement, Dharwad

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

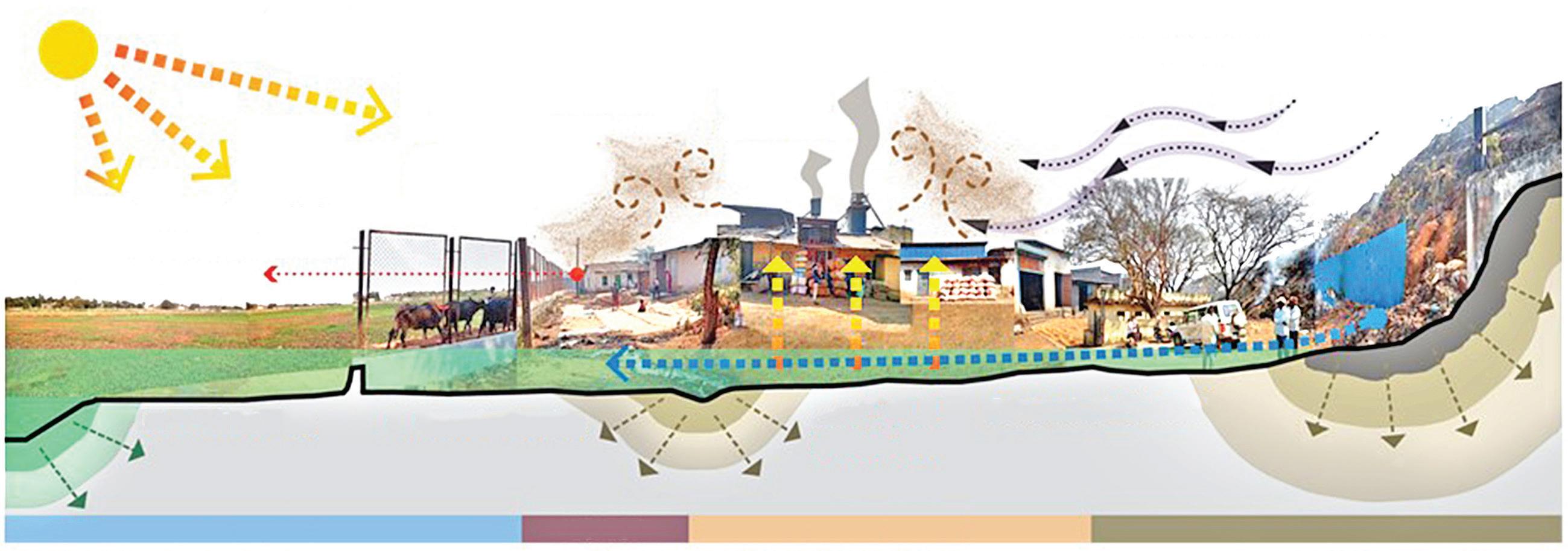

Vulnerabilities are as much triggered by occupational hazards as these are a result of extrinsic conditions such as bad urbanisation. To illustrate the former, people working in the puffed rice units and in black smithy in Dharwad are exposed to extreme heat. While a continuous exposure across generation has increased the tolerance levels, the long-term impacts on health are often dire and not well understood. Workers in the puffed rice industries mentioned that while their bodies are used to the heat, the attendant stress does not allow them to be gainfully employed beyond 45 years of age. An example of the latter is seen in slum redevelopment projects in Dharwad where new roads were laid out at a level higher than the adjoining houses leading to increased flood incidences. Coupled with improper and inadequate drainage and attendant sewage back flow has further exacerbated the vulnerabilities while rendering houses and the common unusable. Similarly, cutting trees to accommodate urbanisation has increased heat related stresses.

Overall, even as these settlements get densified, Climate Change trends projected for the city - increase in temperature by 1.80C and rainfall by 8% in 2021-2050 compared to 1990-2019 - will only exacerbate existing occupational and urbanisation induced vulnerabilities [CSTEP, 2022].

THIS PAGE | [5] Framework for understanding community commons

OPPOSITE PAGE | [6], [7] Houses below the road/ pavement level exacerbating flooding events in Gollar Oni, Dharwad [6], and a flooding event affecting agricultural equipment’s and livestock in Haveripete Dharwad [7]

[8] Shrine and attendant common space in Gauli Galli, Dharwad

“Over the years, many large trees have been cut down in our area. This tree is still standing because of the shrine. Our house doesn’t heat up in summer because of its shade.”

—Old lady residing in a house near the shrine

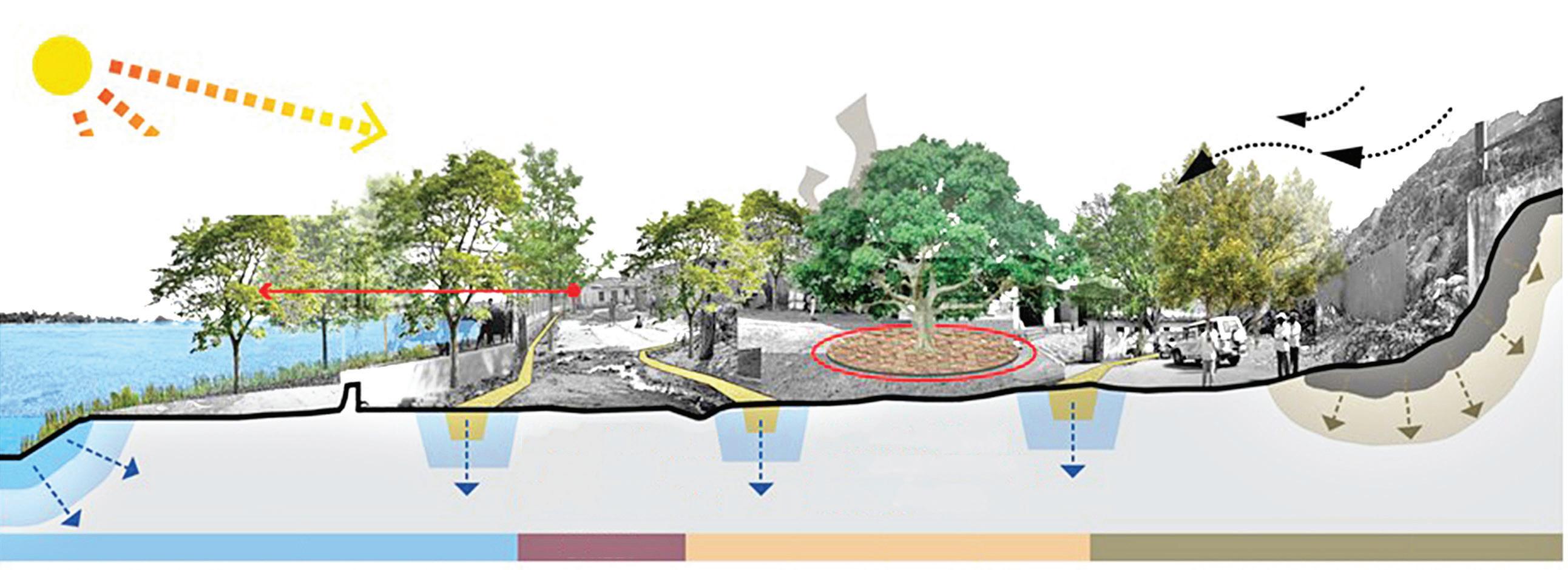

The observations for Moravia are similar. The current high vulnerability to flooding – that tends to increase in a scenario of more frequent torrential rainsis connected to the informal occupation of the creeks and a blockage of natural drainage systems. While this antagonistic relationship between urbanisation and the natural systems has rendered Moravia vulnerable to Climate Change, it also presents an opportunity to create an integrated system of community commons and natural systems to reduce flooding and enhance ecological connectivity at different scales.

climate change in practice |

Community commons identified in Moravia

High risk of flooding

Medium risk of flooding

Low risk of flooding

Built-up

This section illustrates the vulnerabilities and adaptation strategies for two settlements – Churmuri Bhatti, Dharwad [Karnataka], and Moravia, Medellin [Columbia]. The strategies rely on decentralised passive technologies that are easy to implement.

Churumuri Bhatti is a settlement engaged in the production of puffed rice. Currently open spaces are used for drying rice and husk. Sandwiched between a lake and a landfill, people residing and working here are exposed to fumes and leachates [intensified during monsoons] from the landfill. Coupled with inadequate drainage, most residential and industrial waste water floods the common spaces, polluting the lake while impacting the ground water.

[9] Community commons and flooding in Moravia

[10], [11] Concretised drains clogged with solid waste exacerbates flooding incidents inside the settlement. La Bermejala creek in Moravia, Medellin [10], and Haveripete in Dharwad [11]

Moravia was established as an informal settlement in a vacant land close to an abandoned train track and an informal landfill. Opening of another municipal landfill in the city outskirts led to the closure of Moravia’s dump leaving a 30-meter -high garbage mountain that was later occupied by families that arrived to the city either displaced by rural violence or attracted by job opportunities. In 2004, an integral urban project was implemented by the local government and it included the relocation of the families that occupied the hill of trash, the decontamination of this area and its transformation into public space.

Climate change is intensifying the existing urbanisation and informality induced vulnerabilities of the urban poor. While extrinsic [unplanned urbanisation and lack of recognition by the State] and intrinsic [occupational hazards, location on ecologically fragile areas]factors are impacting health and livelihood, Climate Change will exacerbate these impacts. The urban poor are aware of these risks, although, ironically, the global, national and sub national conversations and dialogues around Climate Change and climate actions have not trickled down to these communities that are and will be the most impacted. Thus, the need for community dialogues on climate induced risks and localised action. Community commons can emerge as transformative spaces for community-based and adaptive responses.

OPPOSITE PAGE [15] & THIS PAGE [16]

Transformation of the hill of trash into a public space by the Integral Urban Project

CSTEP. [2022]. District-level changes in climate: Historical climate and Climate Change projections for the southern states of India. [CSTEP-RR-2022- 01]

Jabeen, Huraera, Cassidy Johnson, and Adriana Allen. 2010. ‘Built-in Resilience: Learning from Grassroots Coping Strategies for Climate Variability’. Environment and Urbanization 22 [2]: 415–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247810379937

Trundle, Alexei. 2020. ‘Resilient Cities in a Sea of Islands: Informality and Climate Change in the South Pacific’. Cities 97 [February]: 102496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102496