16 minute read

Maurizio Saletti

Fuoribordo,

OUTBOARD, mon amour

mon amour

RECUPERARE, RESTAURARE E RIMETTERE IN FUNZIONE I MOTORI ABBANDONATI E DESTINATI ALLA DISCARICA. LA PASSIONE PER I VECCHI FUORIBORDO È ANCHE L’OCCASIONE PER RACCONTARE LA STORIA DELLA NAUTICA RECOVERING, RESTORING AND RETURNING TO WORKING CONDITION ABANDONED ENGINES WHICH WERE TO BE SCRAPPED. THE PASSION FOR OLD OUTBOARDS IS ALSO A CHANCE TO TELL THE STORY OF BOATING FOR PLEASURE by Niccolò Volp i photo by Andrea Musc e o

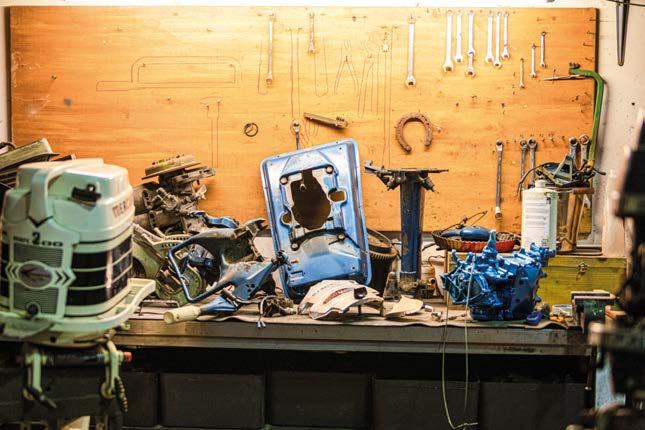

Maurizio, nei primi anni ’70, era un bambino come tanti altri: amava giocare a pallone con gli amici e aveva la passione delle motociclette. Quello che lo differen iava era il contesto. otto la finestra della sua cucina scorreva l’acqua di un canale. Maurizio, infatti, insieme ai genitori, il babbo di iena e la mamma napoletana, viveva a Venezia, nel sestiere Dorsoduro per la precisione. alla finestra non solo vedeva l ac ua, ma poteva salire a bordo di una piccola barca. La prima che ha avuto sotto mano dall’età di dieci anni era motorizzata con un fuoribordo Ducati da 5 cavalli. Ci andava in giro, attraversava anche il Canal Grande e a volte, con gli amici, dopo la scuola, arrivavano sul lato esterno della Giudecca e si mettevano a pescare i cefali. i dice che i vene iani navighino su qualsiasi cosa. Non serve che lo scafo sia particolarmente attraente e ben curato. Basta avere un guscio che galleggi, attaccarci un motore e si inizia a navigare per la laguna. La passione di Maurizio sono i motori, i fuoribordo nello specifico. forse uesta ha molto a che fare con il contesto in cui cresciuto. non solo perch a Venezia, a parte le proprie gambe, l’unico mezzo di trasporto utilizzabile una barca, ma anche perch forse la citt al mondo pi uguale a s stessa nel tempo. A nessuno verrebbe in mente, per fortuna, di abbattere uno dei pala i che si affacciano sui canali per costruirne uno moderno. Conservare, restaurare e lasciare tutto immutato nel tempo è un imperativo che i veneziani hanno ben presente e la bellezza che ne deriva l’hanno sotto gli occhi tutti i giorni. Mettendo insieme questi fattori, il risultato dell’opera di Maurizio è quella di recuperare e restaurare i vecchi motori. non solo uelli, a volte, quando capita, anche le barche. È una passione, non un lavoro. La esercita nel tempo libero, ma lo fa con dedizione e impegno e da parecchi anni. Il primo obiettivo è quello di individuare il relitto. Ci riesce soprattutto grazie alle segnalazioni di amici. Maurizio recupera i motori abbandonati che stanno per finire in discarica. «Io sono un purista, non cambio nulla. Non uso pezzi di ricambio, anche perché spesso non ci sono trattandosi di fuoribordo molto antichi. Sembra paradossale, ma non è così impossibile rimettere in sesto un motore che è rimasto fermo a lungo». La prima operazione, una volta portato nella sua o cina, uella di verificare la compressione. «Se serve li apro, li smonto tutti e intervengo anche su alesaggio e pistoni, ma se la compressione è buona e il motore gira bene non li apro neanche». Poi si passa alla pulizia, alla revisione del carburatore e all’intervento sulla componente elettrica che di solito agisce su una dinamo. Questa è quella più delicata perch soggetta all ossida ione, ma per fortuna questi vecchi motori non sanno nemmeno cosa sia l’elettronica. C’è tanta meccanica, ma questa, appunto, è più facile da restaurare. «I pezzi di ricambio me li procuro, nel senso che smonto tutto quello che mi può servire e spesso da tre motori ne salta fuori almeno uno funzionante». Un atteggiamento assolutamente green che potrebbe rappresentare un esempio di transizione ecologica e che certamente dona valore a oggetti che sono considerati dei rottami.

NEGLI ANNI ’50 E ’60 SONO NUMEROSE LE AZIENDE ITALIANE CHE SI SONO DEDICATE ALLA PRODUZIONE DI PICCOLI FUORIBORDO: MAC, CRISTIANI, FRANCHI E POI LE PIÙ NOTE DUCATI, PIAGGIO, CARNITI E SELVA. IN THE 1950S AND 60S THERE WERE A LARGE NUMBER OF ITALIAN COMPANIES THAT PRODUCED SMALL OUTBOARDS: MAC, CRISTIANI, FRANCHI AND THEN THE BETTER-KNOWN DUCATI, PIAGGIO, CARNITI AND SELVA.

Passando dalle pazienti mani di Maurizio aletti uesti rottami ac uisiscono una seconda vita. Il restauro che realizza, infatti, non si limita a un maquillage per metterli in mostra, ma li rende nuovamente funzionanti e in grado di navigare. na volta restaurati che fine fanno? «Qualcuno l’ho ceduto a persone che li utilizzano sui laghi o in laguna, ma la maggior parte li ho messi in un museo». Il museo è in un piccolo capannone a pochi chilometri di distanza, nel quale mi conduce. Non è ancora aperto al pubblico, per il momento è solo uno spazio, molto ben allestito, che Maurizio fa visitare ad amici e conoscenti. ui piedistalli ci sono decine di modelli, per me, nella maggior parte dei casi, di marche sconosciute. Il più antico è un Caille del 1916, più o meno lo stesso periodo di Evinrude e quindi uno dei primissimi modelli di fuoribordo. Anche Caille è americano e ha un’elica a passo variabile in grado di fornire addirittura cin ue differenti velocit . Tra i motori d’Oltreoceano ci sono i tanti brand che si sono affermati nel tempo Evinrude, Johnson e Mercury, quasi tutti esemplari degli anni ’50. Maurizio ne ha recuperati anche di italiani, come Carniti e Selva e c perfino un esemplare di Cucciolo, il Ducati da 5 cv, lo stesso modello di fuoribordo che Maurizio usava da bambino. Maurizio mi racconta la storia di altri modelli come Franchi o Cristiani, un motore inventato da un ingegnere di Pavia. La maggior parte risalgono al secondo dopoguerra come Helios, un fuoribordo da 1,5 cavalli che si ispirava all’analogo modello di Johnson fatto però dell’ingegner Vassena. Helios nasce perch fino al c era l’embargo dei prodotti americani e così Vassena si arrangiò rifacendolo. «Secondo me lo ha migliorato perché Helios funzionava meglio di Johnson». Molti fuoribordo nascono da altri settori. Per esempio, il 2 cavalli di Honda deriva dall’impiego come tagliaerba. Altri erano usati per il giardinaggio prima di incontrare l’acqua. La stessa cosa successe per la MAC di Castelfranco Veneto, che fu la prima a utilizzare un motore a pistone rotante che veniva impiegato come decespugliatore. poi ci sono i modelli della Piaggio che interruppe la produzione nel 1966, perch con l alluvione di Firen e la fabbrica fu travolta dall’esondazione dell’Arno e l’azienda non ritenne più vantaggioso riprendere questa produzione. Visitare il museo del fuoribordo allestito da Maurizio aletti come ripercorrere la storia dell’industrializzazione italiana. Ci sono tante aziende, di piccole e medie dimensioni, con molto ingegno e capacità di adattamento e altrettanto spirito imprenditoriale. È una memoria pre iosa che va salvaguardata, perch anche la nostra storia. La passione nel restauro di Maurizio si nutre proprio di questo. È un autodidatta con grande manualità. Quello che ha imparato deriva soprattutto dall’ascolto di chi nei cantieri della laguna veneta ha messo le mani su questi fuoribordo per ripararli. L’auspicio è che presto questo piccolo museo possa essere aperto al pubblico perch , come si dice, sen a memoria non c’è futuro.

At the beginning of the 1970s Maurizio was a child like any other: he liked playing football with his friends, and he really liked motorbikes. What made him stand out from a lot of others were his surroundings. Beneath his kitchen window water ran through a canal. Maurizio lived in Venice, in the Dorsoduro quarter to be precise, together with his grandfather (from iena and his mother, who was from Naples. He could not only see water from

Il museo che ha allestito Saletti ospita decine di modelli restaurati. Il più antico è un Caille del 1916 e i più recenti sono degli anni ’70.

The museum that Saletti has set up houses dozens of restored models. The oldest is a Caille from 1916, and the most recent are from the 1970s.

Come nasce il fuoribordo? How was the outboard invented?

Come spesso accade per le invenzioni destinate a cambiare il corso degli eventi, non esiste una sola versione della storia. Per il fuoribordo, gli inventori che si contendono il primato sono almeno due. Cameron Waterman, uno studente di legge di Detroit, nel febbraio 1905 smontò il motore di una motocicletta e ci attaccò un’elica, poi ci aggiunse una barra e un ser atoio di en ina e lo utili sul fiume etroit. onostante il fiume osse pieno di locchi di ghiaccio e uno di questi fece saltare la catena della trasmissione, la prova fu un successo tanto che nel 1906 iniziò la commercializzazione anche attraverso i fratelli Caille. Nel 1922 l’azienda fu rilevata dalla neonata Johnson Motor Company. Waterman non ottenne mai un vero brevetto perché c’era già, nel senso che alla fine dell 800 era stata depositata un in en ione che contemplava una piccola caldaia con un’elica attaccata alla poppa di una barca ed è per questo precedente che, secondo Cameron Waterman, la sua invenzione non fu protetta dal brevetto che aveva richiesto. La seconda versione della storia della nascita del fuoribordo è forse più romantica e ci porta da Ole Evinrude. Il periodo è più o meno lo stesso, per l’esattezza la calda estate del 190 . le il figlio di una amiglia di immigrati norvegesi che viveva in una fattoria vicino al lago Riple , in isconsin, e a e a una fidan ata di nome ess. Dall’altro lato del piccolo lago c’era una gelateria, ma ogni volta che Ole acquistava un cono per Bess e glielo portava con la barca a remi, arrivava sciolto. Fu così che gli venne l’idea di applicare un motore sullo specchio di poppa della piccola barca per fare più in fretta. Tre anni dopo, nel 1909, iniziò la commercializzazione dei primi fuoribordo Evinrude. As is often the case with inventions that are set to change the course of events, there is not just one version of this history. There are at least two inventors who can claim to have invented the outboard. In February 1905 Cameron Waterman, a law student from Detroit, took apart a motorbike engine and attached a propeller to it, before then adding a bar and a petrol tank, and used it on the Detroit River. Despite the fact that the river was full of blocks of ice, one of which knocked the transmission chain o , the trial was s ch a s ccess that in 1906 he started selling the engines, including through the Caille brothers. In 1922 the company was taken over by the newlyformed Johnson Motor Company. Waterman did not ever get a real patent because there was already one, which is to say that at the end of the nineteenth century an application had been made for an invention that included a small boiler with a propeller attached to the stern of a boat. And that, according to Cameron Waterman, was why his invention was not protected by the patent that he had applied for. The second version of the story of the birth of the outboard is perhaps more romantic and takes us to Ole Evinrude. It was more or less at the same time, to e s ecific the hot s mmer of . le came from a family of Norwegian immigrants who lived on a farm close to Lake Ripley in Wisconsin, and he had a girlfriend called Bess. There was an ice cream parlour on the other side of the lake, but every time that Ole bought Bess a cone and took it to her in his rowing boat, it had melted by the time he arrived. And that was how he got the idea of adding an engine to the transom of the small boat to go ic er. hree years later, in , he started to mar et the first Evinrude outboards.

MAURIZIO È UN APPASSIONATO E UN AUTODIDATTA. GIRA PER I CANTIERI E GLI PIACE ASCOLTARE I CONSIGLI DI CHI HA LAVORATO PER UNA VITA RIPARANDO MOTORI. MAURIZIO IS BOTH PASSIONATE AND SELF-TAUGHT. HE GOES AROUND BOATYARDS AND HE LIKES TO LISTEN TO THE ADVICE OF PEOPLE WHO HAVE SPENT THEIR LIVES REPAIRING ENGINES.

his window, but he could also access it through it, climbing down to a small boat. The first boat that he helmed, aged ten, was driven by a five horsepower Ducati. He used it to get around, crossing the Grand Canal, and occasionally going to the other side of the Giudecca with friends after school, and fishing for mullet. It is said that the Venetians will use anything to get on the water. You do not need a boat that is especially attractive and well maintained. You ust need a shell that floats, then if you fit an engine onto it, you can start to travel across the lagoon. Maurizio has a passion for engines, especially outboards. And perhaps that passion has a lot to do with where he grew up. And not just because in Venice, the only way of getting around – apart from your legs – is on a boat, but also because it is the city in the world that changes least. Luckily nobody would envisage knocking down one of the palaces that look onto the canals and building a new one. Conservation, restoration, and leaving everything unchanged over time is an imperative that the Venetians are very much aware of, and they enjoy the resulting beauty on a daily basis. If we put these factors together, what has emerged from Maurizio’s passion is the recovery and restoration of old engines. And not just that: sometimes he also works on boats. It is a passion, not a job. He does this in his free time, but he does it with dedication and commitment and has been doing so for a number of years. The first thing is to find the old piece. t is mainly from word of mouth from friends that he can do that. Maurizio then recovers the abandoned engines, which would otherwise have ended up in the dump. «I am a purist, I don’t change anything. I don’t use spare parts, not least because they are often very old outboards and the spares just don’t exist. It might seem paradoxical, but getting an engine that has not been used for a long time back on track isn’t really so impossible». The first thing he does, once he has taken an engine into his workshop, is to check the compression. «If it needs opening, then I do so, and I take everything apart and also work on the bore and pistons. But if the compression is good, and the motor turns over, then I don’t even open it». Then he starts cleaning it, and checking the carburettor, and working on the electrical parts, which normally use a dynamo. That is the most delicate part, because they can be rusty, but luckily these old engines have never heard of electronics. There are a lot of mechanical parts, but they are actually easier to restore. «I get hold of the spare parts, in that I take apart everything that might be useful, and often at least one working engine emerges from three old ones». That is very much a green approach, which could represent an example of ecological transition, and which definitely gives value to ob ects that are seen as junk. Once it has passed through Mauri io aletti s patient hands, this junk acquires a new lease on life. The restoration that he does is not limited to ust a superficial treatment to

MAURIZIO SALETTI STA LAVORANDO AL RESTAURO DELLA BARCA PIÙ ANTICA CHE HA AVUTO PER LE MANI CHE RISALE AL 1910. È UNO SCAFO IN LEGNO CON MOTORE ENTROBORDO. MAURIZIO SALETTI IS WORKING TO RESTORE THE OLDEST BOAT THAT HE HAS HANDLED, WHICH GOES BACK TO 1910. IT IS WOODEN HULLED, AND HAS AN ONBOARD ENGINE.

put it on display, but he actually makes the engines work again, and ready to use on a boat. What happens to them once they are restored, and running again? «A few I’ve given to people who use them on lakes, or on the Venetian lagoon, but most of them I have put in a museum». The museum is in a small warehouse a few kilometres away, which he took me to. It’s not yet open to the public, and for the moment there is just one area, which is very well laid out, which Maurizio shows to friends and acquaintances. There are dozens of models mounted on display, most of which were from brands I had never heard of. The oldest of all is a Caille from 1916, more or less the same era as Evinrude, and thus one of the very first outboards. Caille is also American and has a variable pitch propeller that can deliver as many as five different speeds. Amongst the American engines there are a lot of brands that have become established over time: Evinrude, Johnson and Mercury, with nearly all of them from the 1950s. Maurizio has also recovered some Italian ones, like Carniti and Selva and there is even an example of Cucciolo, a five-horsepower Ducati of the same type that Maurizio used as a boy. He told me the story of other models like Franchi or Cristiani, an engine invented by an engineer from Pavia. Most of the motors go back to the post-war period. Like Helios, which was a 1.5 hp outboard that took inspiration from a similar Johnson model, but was made by the engineer Vassena. Helios came about because until 1945 there was an embargo on American products, and so Vassena solved the issue by remaking the engine. «I think he improved it, because a Helios worked better than a Johnson». Many outboards start life in different sectors. In recent times, for example, the two-horsepower Honda was derived from one used in a lawn mower. Many in small outboards were used in gardening before finding the water. The same thing happened with MAC from Castelfranco Veneto, who were the first to use an engine with rotating pistons that had first been used in a strimmer. And then there are the engines made by Piaggio, who stopped production in 1966 because of the Florence flood, which saw the factory inundated when the Arno broke its banks, and the company decided it was no longer profitable to continue. Visiting the outboard engine museum set up by Maurizio Saletti is like going through the story of Italian industrialisation. There are numerous companies, small and medium sized, with plenty of good ideas, the ability to adapt to circumstances, and impressive entrepreneurial spirit. It is a precious memory that should be guarded, because it is also our history. That is something that feeds the passion that Maurizio deploys in restoration. He is self-taught, and is very dextrous. What he has learnt comes, above all, from listening to the people around the Venice lagoon who have handled the outboards when repairing them. The hope is that this small museum will soon be able to open to the public because, as people say, without memory there is no future.