MAY/22 V.67 N.03 $8.95

THE PERFECT BLEND OF ART & SCIENCE

An of ce design that artfully captures the essence of a company is no easy feat –particularly when they specialize in the science of gene editing. MetalWorks™ ceilings and walls offer the design flexibility needed to combine the unexpected. From custom perforations to indoor/outdoor applications to concealed suspension systems, thinking outside the box has never been so inspiring. Learn more about the art and science of metal at armstrongceilings.com/metalworks

METALWORKS TORSION SPRING CUSTOM CEILING & METALWORKS WH1000 CUSTOM WALLS CELLECTIS BIOLOGICS, RALEIGH, NC / CRB GROUP, KANSAS CITY, MO

METALWORKS TORSION SPRING CUSTOM CEILING & METALWORKS WH1000 CUSTOM WALLS CELLECTIS BIOLOGICS, RALEIGH, NC / CRB GROUP, KANSAS CITY, MO

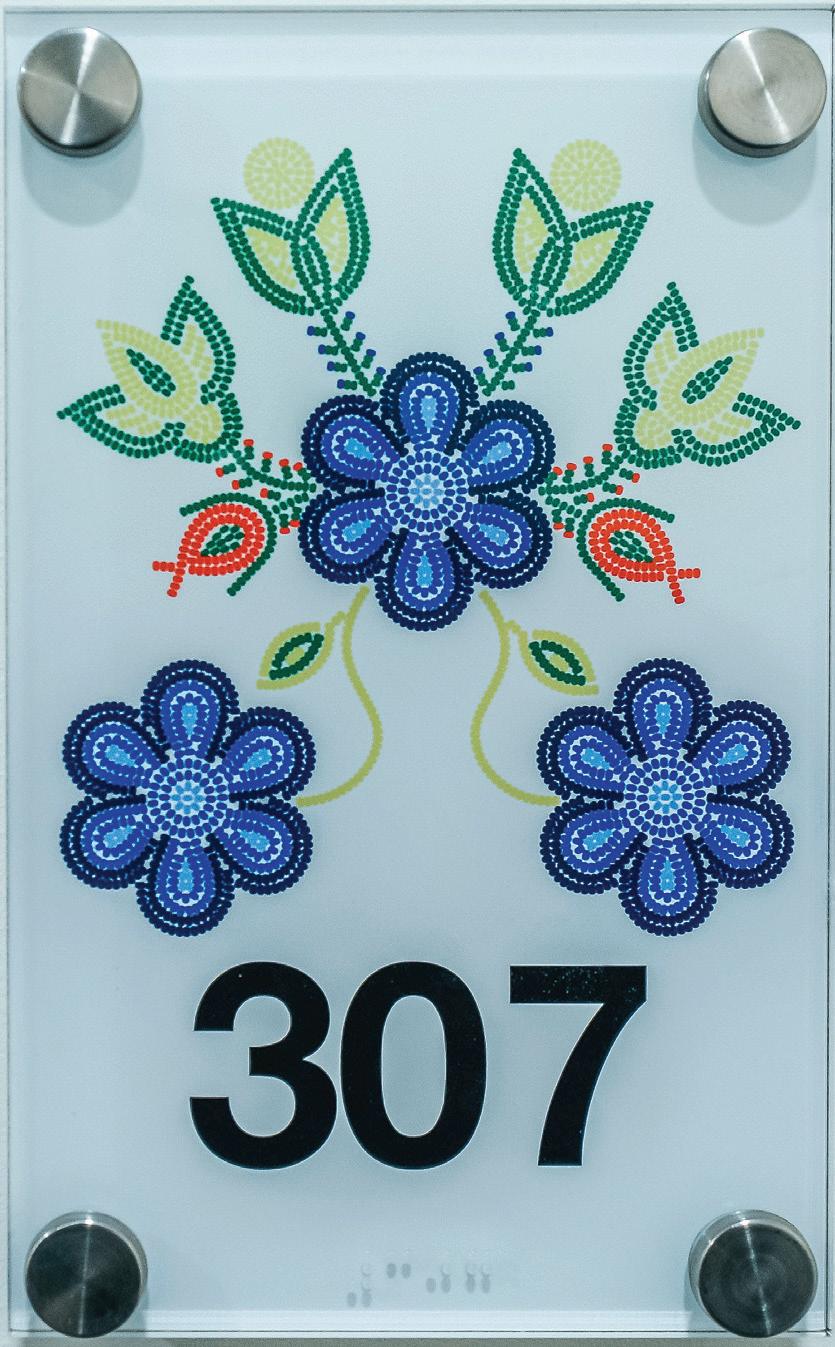

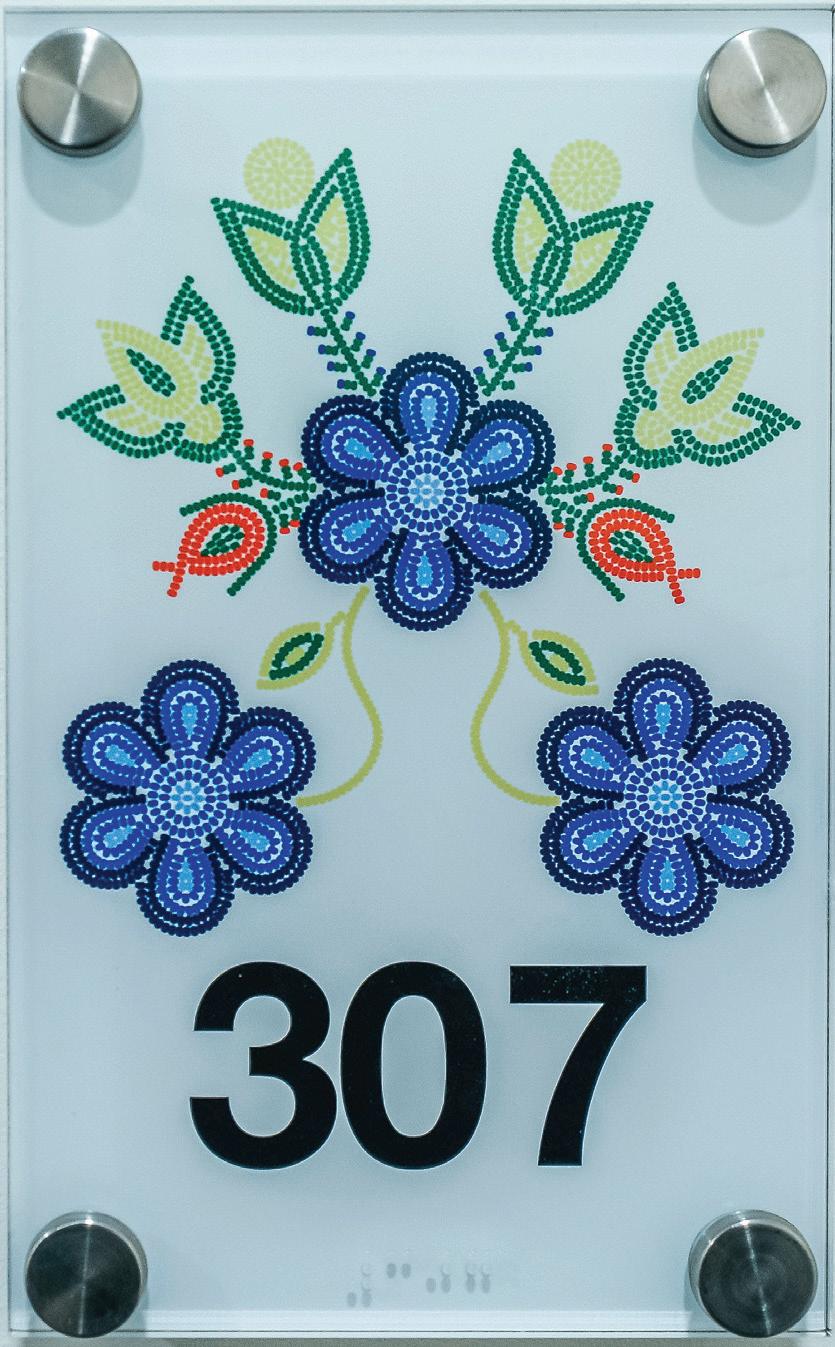

INDIGENOUS DESIGN

04 VIEWPOINT

Guest editor Tiffany Shaw on how architec ture can empower Indigenous communities.

07 NEWS

Canadian Pavilion designers named for Venice Architecture Biennale; winners announced for OAA Awards, OAQ Awards, and National Urban Design Awards.

15 RAIC JOURNAL

Laura Miller on the life and legacy of 2022 RAIC Gold Medallist Jerome Markson.

32 LONGVIEW

The newly opened Malahat Skywalk invites visitors to enjoy soaring views of the sur rounding Nation’s forests and water.

55 INSITES

Educators Shawn Bailey, Honoure Black, and Lancelot Coar on decolonizing the design process with five-Indigenous landbased paradigms.

62 PRACTICE

Kelly Edzerza-Bapty, Dr. David Fortin, Tiffany Shaw, Dr. Patrick Stewart, and Alfred Waugh share insights on working with Indigenous designers and Indigenous procurement requirements.

66 BACKPAGE

Winnipeg’s Rainbow Butterfly pavilion is a site of commemoration and a welcoming place for gentle reconciliation.

Scatliff + Miller + Murray (1, 9); Jason Surkan (2, 14); Gar rett Kendell, King Rose Visuals (3, 12, 13); Verne Reimer Architecture (4, 8); C.Grosset/Nunavut Parks and Special Places (5); VIA Architecture (7); T. Wood/Nunavut Parks and Special Places (10); Des tiny Seymour (11).

03MAY 2022 CANADIAN ARCHITECT COVER IMAGE CREDITS

37 INDIGENOUS DESIGNERS Ten Indigenous designers making their mark from coast to coast to coast. TEXTS Emma Steen, Pamela Young, and Omeasoo Wahpasiw V.66 N.03

THE NATIONAL REVIEW OF DESIGN AND PRACTICE / THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE RAIC / THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE AIA CANADA SOCIETY

48 Tiffany Creyke

VIA

ARCHITECTURE

38 Kelly Edzerza-Bapty

N. RATTE/NUNAVUT PARKS AND SPECIAL PLACES 52 Naomi

Ratte

GARRETT KENDEL, KING ROSE VISUALS 40

Jason Hurd

46

Jason Surkan

THOMAS FRICKE PHOTOGRAPHY JASON SURKAN SCATLIFF + MILLER + MURRAY

44 Rachelle Lemieux and Nicole Luke

42

Destiny Seymour and Mamie Griffith

50 David Thomas 1 2 43 5 76 8 109 11 1312 14

INDIGENOUS DESIGN

There has been a major shift since the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 2015 report, with its 94 calls to action. While we are still in the thick of understanding terms related to reconciliation, conciliation and generational trauma, there are events now in place to help bring greater awareness to the many ways Indigenous people and their communities have been con tinually dismantled. Orange Shirt Day, the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls movement, Starlight tour awareness campaigns, Indigenous Peoples Day, the Six ties Scoop settlement, the First Nations Child Welfare agreement, Day School and Residen tial School testimonials and the continual horror of unmarked gravesites being discov ered around Residential School sites reveal the many attempts to erase Indigenous lan guage, kinships, sovereignty, and access to land and resources. These events remind us about the importance of reshifting our col lective mindset on the inequities Indigenous people face daily in rural and urban spaces, and how we can be seeking solutions, rather than maintaining the status quo that perpetu ates bureaucratic colonial structures.

Indigenous communities whether in cities or towns, on-reserve, in settlements, within treaties, on unceded land, or in Métis or Inuit Nunangat regions often lack healthy spaces that encourage growth, healing and prosper ity. The built environment and sustainability are key realms of reparations.

In my work as a Métis architect and public art artist, I have seen a staggering under-rep resentation at the decision-making table. Luckily, working alongside my generous col leagues at Reimagine Architects, a firm that has been working with Indigenous commun

ities for over 30 years, has been insightful to the many ways we can always make the circle bigger in regards to community engagement for the betterment of innovative decision making surrounding design, sustainability and procure ment. But there is always more work to do and it has to be explored by more than just a handful in order to make impactful changes to the privileged and protected systems we navigate within. While I have seen Indigenous communities lead strong conversations regard ing autonomy, key decisions are still often made by non-Indigenous participants with lit tle to no contextual knowledge of the Indigen ous environments they work within, and the impact their decisions have on the communities and the land itself. But I see this situation changing as our networks grow and awareness broadens. I am feeling more hopeful each year.

It feels like it would have been impossible to publish this issue of Canadian Architect five years ago. But here we are, with profiles of ten strong, engaging and visionary Indigen ous design professionals, whose work repre sents fresh perspectives on the many ways to achieve successful built projects that focus on supporting Indigenous communities.

As Indigenous and non-Indigenous design ers, it is our task to create buildings and places that weave in the complexities and deep re flective history of the past with new hopes for the future. This issue touches on many facets of this task. How can methods of procurement be positioned to create wealth in local econ omies? How can community engagement allow for direct links to the stewardship of both cul tural practices and land-based teachings? With so many voices involved, how can a con stellation of good ideas and storytelling hold strong and carry itself to the end-conclusion of a built project? The following pages also look at how Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics are bringing collaborative techniques to the classroom, igniting new ways of engaging with Indigenous methodologies that are uni versal, open and exciting.

I believe that these ways of operating can not only help in working with Indigenous com munities. The same principles extend to design work with myriad equity-deserving groups. With the stories in this issue, you are invited to share in learning that will be helpful for design work but moreover, that I hope will benefit all who are affected by the innovative and provocative work that we collectively seek to create.

Tiffany Shaw GUEST EDITOR

VIEWPOINTCANADIAN ARCHITECT 05/22 04

EDITOR ELSA LAM, FRAIC ART DIRECTOR ROY GAIOT CONTRIBUTING EDITORS ANNMARIE ADAMS, FRAIC ODILE HÉNAULT DOUGLAS MACLEOD, NCARB FRAIC ONLINE EDITOR CHRISTIANE BEYA REGIONAL CORRESPONDENTS MONTREAL DAVID THEODORE CALGARY GRAHAM LIVESEY, FRAIC WINNIPEG LISA LANDRUM, MAA, AIA, FRAIC VANCOUVER ADELE WEDER, HON. MRAIC SUSTAINABILITY ADVISOR ANNE LISSETT, ARCHITECT AIBC, LEED BD+C VICE PRESIDENT & SENIOR PUBLISHER STEVE WILSON 416-441-2085 x3 ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER FARIA AHMED 416-441-2085 x5 CUSTOMER SERVICE / PRODUCTION LAURA MOFFATT 416-441-2085 x2 CIRCULATION CIRCULATION@CANADIANARCHITECT.COM PRESIDENT OF IQ BUSINESS MEDIA INC. ALEX PAPANOU HEAD OFFICE 126 OLD SHEPPARD AVE, TORONTO, ON M2J 3L9 TELEPHONE 416-441-2085 E-MAIL info@canadianarchitect.com WEBSITE www.canadianarchitect.com Canadian Architect is published 9 times per year by iQ Business Media Inc. The editors have made every reasonable effort to provide accurate and authoritative information, but they assume no liability for the accuracy or completeness of the text, or its fitness for any particular purpose. Subscription Rates Canada: $54.95 plus applicable taxes for one year; $87.95 plus applicable taxes for two years (HST – #80456 2965 RT0001). Price per single copy: $15.00. USA: $135.95 USD for one year. International: $205.95 USD per year. Single copy for USA: $20.00 USD; International: $30.00 USD. Printed in Canada. All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may not be reproduced either in part or in full without the consent of the copyright owner. From time to time we make our subscription list available to select companies and organizations whose product or service may interest you. If you do not wish your contact information to be made available, please contact us via one of the following methods: Telephone 416-441-2085 x2 E-mail circulation@canadianarchitect.com Mail Circulation, 126 Old Sheppard Ave, Toronto ON M2J 3L9 MEMBER OF THE CANADIAN BUSINESS PRESS MEMBER OF THE ALLIANCE FOR AUDITED MEDIA PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT #43096012 ISSN 1923-3353 (ONLINE) ISSN 0008-2872 (PRINT)

Wall System

PAC-CLAD.COM | INFO@PAC-CLAD.COMIL: 800 PAC CLAD MD: 800 344 1400 TX: 800 441 8661 GA: 800 272 4482 MN: 877 571 2025 AZ: 833 750 1935 Mino-Bimaadiziwin Apartments, Minneapolis Installing contractor: Progressive Building Systems Architect: Cuningham Group Architecture GC: Loeffler Construction & Consulting Photo: Alan Blakely The façade features metal wall panels in a dramatic palette including a custom wood grain finish that ties the building to the tribe’s historic home in a reservation in the woods of Northwest Minnesota. Strength, Beauty, Heritage Metal

Custom Wood Grain, Matte Black Metal Wall System View the case study and videoBone White DURABLE PAC-CLAD COLOUR — Fluropon® 70% PVDF coatings made with Kynar 500® resin, backed with a 30-year warranty against chipping, chalking, peeling and fading.

Strategize for sustainability

“We had a great experience working with the experts from Enbridge Gas and would recommend Savings by Design to anyone looking to improve the energy efficiency of their affordable housing project.”

Wes Richardson, Director of Finance, Youth Services Bureau

While designing their new facility, Youth Services Bureau collaborated with sustainable building experts from the Savings by Design program to optimize energy performance, build better than code, and earn financial incentives.*

* HST is not applicable and will not be added to incentive payments. Terms and conditions apply. Visit enbridgegas.com/SBD-affordable for details. To be eligible for the Savings by Design Affordable Housing program, projects must be located in the former Enbridge Gas Distribution service area. © 2022 Enbridge Gas Inc. All rights reserved. ENB 823 05/2022

— Savings by Design | Affordable Housing Success Story | Ottawa By the numbers 23.0% Projected annual energy savings 30.8% Projected annual natural gas savings 27.9% Projected GHG reduction Youth Services Bureau — Visit enbridgegas.com/SBD-affordable to get the most out of your next project.

PROJECTS

Design chosen for LGBTQ2+ National Monument

The LGBT Purge Fund has unveiled Thunderhead as the winning proposal for the LGBTQ2+ National Monument. The concept was led by a Winnipeg-based team headed by Liz Wreford, Peter Sampson and Taylor LaRocque of Public City Architec ture, with artists Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Millan, and Albert McLeod, Indigen ous and Two-Spirited People subject-matter expert and advisor.

The design draws on the symbolism of a thunderhead cloud to embody the strength, activism and hope of LGBTQ2+ commun ities. Elements of Thunderhead include a sculpture clad in mirrored tile, a pathway through a landscaped park that traces the history of LGBTQ2+ people in Canada, and a healing circle ringed with stones handpicked by Two-Spirit Elders. The monument’s surroundings will allow for large gatherings, performances and places for quiet reflection.

The monument memorializes historic discrimination against LGBTQ2+ people in Canada, including during the LGBT Purge, a widespread campaign during the 1950s to the 1990s led by the Canadian Gov ernment to expel thousands of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender members of the Canadian Armed Forces, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the federal public service.

“We are both proud and honoured to be chosen to create this monument to the resili ency of the LGBTQ2+ community. We look forward to continuing to work with our amaz ing team and community stakeholders in the design of the disco-ball thunderhead. This monument will be a symbol of celebration and a space for reflection, healing, activism and performance for generations to come,” says Liz Wreford of Public City.

Completion of the monument is anticipated for 2025.

Waterfront ReConnect designers selected

The Bentway, in partnership with the City of Toronto, Waterfront BIA, and Toronto Downtown West BIA, has announced the winners of the national Waterfront ReCon nect design competition. The winning designs are: Boom Town at York Street by 5468796 Architecture + Office In Search Of (Winni peg/Toronto); and Pixel Story at Simcoe Street by O2 Planning + Design + Mulvey & Banani Lighting + ENTUITIVE (Calgary/Toronto).

The selected designs will be installed in fall 2022 and will remain in place until that section of the Gardiner Expressway undergoes neces sary repairs in 2025.

Inspired by the ongoing repairs to the Gardiner Expressway and the ubiquitous presence of equipment deployed to inspect and maintain the structure, Boom Town is a theatrical reimagining of the waterfront gateway at York Street, introducing a cast of playful characters that will animate the space with personality and delight.

The design team proposed transforming a trio of boom lifts into “Bent Buddies” named Trekker, Tinker and Trouper charac ters who breathe new life into the intersection and welcome people to the site. “The compe tition’s parameters were very stringent, and understandably so for a temporary installa tion. For a while our ideas fought with these limitations, but in the end, they became a launching point for a simple solution that is memorable, playful and accessible to people of all ages and backgrounds,” says Johanna Hurme of 5468796 Architecture.

Pixel Story entices passersby with visual cues showcasing the attractions and experien ces of the waterfront on both sides of the Gardiner, building anticipation for the lake front that lies on the other side of the Simcoe Street intersection, and highlighting the diverse stories that relate to its experiences. “Imagine within the time you’re waiting for the traffic light to change, or you’re riding by in a bus, you could read about someone’s favourite place to walk or see an image of how

this part of the shoreline looked over 100 years ago,” says Grace Yang of O2 Planning + Design. “The design strategies of Pixel Story bring the industrial scale of the Gardiner down to the level of human interaction.” bentway.ca

AWARDS

OAQ award winners announced

The Ordre des architectes du Québec (OAQ ) has unveiled the 14 winners of this year’s Awards of Excellence and Distinctions.

The 2022 Grand Prix d’excellence was awarded to Daoust Lestage Lizotte Stecker for Expérience chute, the redesigned pavilion and walkway at the foot of Montmorency Falls near Quebec City. The People’s Choice award went to the final phase of the CHUM hospital com plex project, including the Amphithéâtre Pierre-Péladeau, which also won an award for the best public institutional building.

Awards of Excellence also went to: Bio dôme Migration, Montreal, by KANVA Architecture in collaboration with NEUF architect(e)s; Montauk Sofa Montréal by Cohlmeyer Architecture; Water Intake, Canal de l’Aqueduc, Montreal, by Smith Vigeant Architectes; Lafond Desjardins Dental Lab oratory, Montreal, by ACDF Architecture; Queen Alix, Montreal, by Blouin Tardif Architectes; Maison Saint-Charles, Montreal, by La Shed Architecture; Maison du Pommi er, Saint-Donat-de-Montcalm, by ACDF Architecture; Bureaux LAUR , Montreal,

CANADIAN ARCHITECT 05/22 07NEWS

canada.ca

ABOVE Thunderhead, a design led by Winnipeg-based Public City Architecture, has been chosen for the LGBTQ2+ National Monument in Ottawa.

by Alain Carle Architecte; EG, Saint-Jérôme, by Jean Verville, archi tecte; Windsor Station Masonry Restoration and Window Replace ment, Montreal, by DMA architectes

Four individual distinctions were also handed out, recognizing exceptional commitment to inclusive, quality architecture in Quebec. The Médaille du Mérite, the OAQ’s highest distinction, was presented to architect and urbanist Renée Daoust. L’ŒUF received the Social Engagement prize, the Emerging Architect prize was awarded to archi tect Jérôme Lapierre, and the Ambassador for Architectural Quality prize, awarded to a non-architect, went to Sophie Lanctôt.

The jury for the 2022 awards was chaired by French architect and studio director at Ateliers Jean Nouvel Didier Brault, and included architects Marie-Odile Marceau (McFarland Marceau Architects), Eric Pelletier (LEMAY – Architecture et design), Étienne Bernier (Étienne Bernier architecture), and writer Kim Thuy as representative of the public. oaq.com

OAA award winners announced

The Ontario Association of Architects (OAA) has announced the winners of its 2022 Design Excellence Awards, as well as the recipi ents of this year’s OAA Service Awards.

Chosen by a jury of design experts who first narrowed 80 eligible submissions into a list of 17 finalists, the projects were judged on cri teria such as creativity, context, sustainability, good design/good busi ness, and legacy.

The award winners are: Buddy Holly Hall of Performing Arts and Sciences (Lubbock, Texas) by Diamond Schmitt Architects (Design Architect), Parkhill (Architect of Record), and MWM Architects (Asso ciate Architect); Centennial College Downsview Campus Centre for Aerospace and Aviation (Toronto, Ontario) by MacLennan Jaunkalns Miller Architects (MJMA) in association with Stantec Architecture; Clearview Public Library, Stayner Branch (Stayner, Ontario) by Lebel & Bouliane; The Springdale Library and Komagata Maru Park (Bramp ton, Ontario) by RDH Architects; Tile House (Toronto, Ontario) by Kohn Shnier Architects; Tom Patterson Theatre (Stratford, Ontario) by Hariri Pontarini Architects; Tommy Thompson Park Entrance Pavil ion (Toronto, Ontario) by DTAH Architects; and University College Revitalization (Toronto, Ontario) by Kohn Shnier Architects in associa tion with ERA Architects.

CANADIAN ARCHITECT 05/22 08 NEWS

ABOVE The OAQ’s 2022 Grand Prix d’Excellence was awarded to Daoust Lestage Lizotte Stecker’s pavilion and walkway at Montmorency Falls.

MAXIME BROUILLET

Smart Density was named winner of the biennial Best Emerging Practice award.

Three service awards were also announced. John van Nostrand will receive the Order of da Vinci for demonstrating exceptional leadership in the profession, education, and in the community. Diarmuid Nash, will receive a Lifetime Design Achievement award, as an architect with a career-long commitment to the promotion and achievement of architectural design excellence. Camille Mitchell will receive the G. Randy Roberts Service Award in recognition of being an OAA member providing extraordinary service to the membership, for ‘behind-thescenes’ dedication and action, as well as employing the skills and the energy to get things done.

The winners will be honoured at the OAA conference, being held in-person in Toronto from May 11-13, 2022.

Winners of National Urban Design Awards announced

The Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC), the Canadian Institute of Planners (CIP), and the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects (CLSA) have announced thirteen projects across Canada as the winners of the 2022 National Urban Design Awards. The awards are a part of a two-tier program held in cooperation with Canadian municipalities.

The following projects have won Awards of Excellence: True North Square (Winnipeg, MB) by Perkins&Will; Saugeen First Nation GZHE-MNIDOO GI-TA-GAAN (Creator’s Garden and Amphithe atre) Master Plan (Southampton, ON), by Indigenous Design Studio / Brook McIlroy and Saugeen First Nation; University of Toronto Scar borough Valley Land Accessible Trail (Toronto, ON) by Schollen & Company, Brown & Company Engineering, Moon-Matz, GeoTerre (Civic Design Award of Excellence); Corner Commons (Toronto, ON) by Perkins&Will with Jane/Finch Community and Family Centre; PARK PARK (Calgary, AB) by Public City Architec ture; Yarmouth Main Street Redevelopment Phase 2 (Yarmouth, NS) by Fathom Studio; and Lakeview Village (Mississauga, ON) by Lake view Community Partners, Sasaki, NAK Design Strategies, Glenn Schnarr & Associates, TYL in, and Urbantech Consulting. A student Award of Excellence went to Mobile Support as Shelter Support Infrastructure (Toronto, ON), by Yongmin Ye, Michelle Li, and Edward Minar Widjaja.

Certificates of Merit were awarded to: Montauk Montréal (Montreal, QC) by Cohlmeyer Architecture; Place Monique-Mercure (Montreal, QC) by Civiliti; CF Toronto Eaton Centre Bridge (Toronto, ON) by WilkinsonEyre (Design Architect) and Zeidler Architecture (Executive Architect); Plaza of Nations (Vancouver, BC) by James KM Cheng Archi tects; and to the student project Filling Pieces Hall’s Lane Creative Studios (Kitchener, ON) by Vincent Chuang and Zihao Wei. raic.org

Three students win RAIC International Prize Scholarships

The RAIC Foundation and the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) have announced the three winners of the 2022 RAIC Inter national Prize Scholarships.

They winners are Lewis Canning (Dalhousie University); Fabio Lima (Université de Montréal); and Jesse Martyn (University of Brit ish Columbia).

Each student has won a $5,000 scholarship, from the RAIC Founda tion, for writing an essay explaining how a work of architecture can be transformative.

53 Armstrong Ave., Unit 1, Georgetown ON L7G 4S1 8 4 4 89 1-8559 c o n t act@anntbollards.com w w w annt .ca Increase Safety & Security With ännT‘s high security K12 bollard, a full-size speeding vehicle is brought to a dead stop.* • Versatile Operation: choose from fixed, removable, semi-automatic or automatic bollards. • A Reliable Sentry: a single 275 K-rated bollard is certified to K/M standards. • Easy to Use: operated by key fob, RFID card, keypad or smart phone. • Blend in: with your urban landscape with brushed stainless steel or powder coated in any RAL colour. * Just one ännT K12 rated bollard will stop a 6,800 kg vehicle moving at 80km/h. ännT distributed by Ontario Bollards, 53 Armstrong Ave., Unit 1, Georgetown ON L7G 4S1 8 4 4 89 1-8559 c o n t act@anntbollards.com w w w annt .ca

oaa.on.ca

The RAIC International Prize Scholarships are presented in con junction with the RAIC International Prize. The RAIC received 75 eligible scholarship entries in both English and French from students enrolled in, or recently graduated from, Canada’s 12 accredited schools of architecture as well as students at the RAIC Centre for Architecture at Athabasca University and the RAIC Syllabus Program.

The jury awarded three Certificates of Merit to the following stu dents: Jerry Chow (Carleton University); Jasmine McRorie (University of Waterloo) and Saba Mirhosseini (University of Manitoba). raic.org

WHAT’S NEW

Architects Against Housing Alienation to represent Canada at 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale

Architects Against Housing Alienation (AAHA) will represent Canada at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, from May 20 to November 26, 2023.

AAHA was selected from among four finalists in a national juried competition. The Canada Council for the Arts, as Commissioner, oversees Canada’s official participation and will contribute $500,000 towards AAHA’s exhibition.

The curatorial collective, newly formed for the Venice Biennale, has a mission to instigate an architectural movement that creates social ly, ecologically, and creatively empowering housing for all. The group includes architects David Fortin, Matthew Soules, and Patrick Stewart, designers Adrian Blackwell and Ali S. Qadeer, architectural historians

ABOVE A new collective called Architects Against Housing Alienation will use Canada’s Venice Architecture Pavilion as the headquarters for a campaign for equitable housing.

Sara Stevens and Tijana Vujosevic, and graphic designer Chris Lee.

The group’s project, Not for Sale!, is an architectural activist cam paign for safe, healthy, and affordable housing.

“Canada is in the midst of a severe and protracted housing crisis, with issues ranging from widespread unaffordability to under-hous ing, precarious housing, and homelessness,” writes the group. “This modern reality, shaped by the extractive logic of speculative

CANADIAN ARCHITECT 05/22 10 NEWS Hiring Made Easy Discover talented, qualified architectural professionals ready to join your team. Get started with our free recruitment services. Revital Abelman 416-649-1710 rabelman@jvstoronto.org 519.787.2910 • Wind • Snow • Exhaust • Odour • Noise • Particulate • Ministry Approvals • CFD A nalysis spollock@theakston.com www.theakston.com

real estate, is founded on the simultaneous colonial dispossession of Indigenous lands and the modern invention of fee-simple property. Real estate speculation is a form of extortion. It converts homes into spatio-financial assets, changing the form, function, and aesthetics of housing to better serve the logics of wealth storage and speculation. The process is violent, resulting in an urban environment that is racist, sexist, and classist at a systemic level. This global phenomenon is nowhere more visible than in Canada, a country whose economy is now dominated by real estate.”

Architects Against Housing Alienation will transform the Canada Pavilion in the Giardini into a campaign headquarters for equitable housing that rejects this concept of property and the financialized form of architecture that it implies. To address these issues, they will work with interdisciplinary and geographically dispersed teams com prised of activist organizations, advocates for non-alienated housing, and architects. They will collaborate to develop demands and create architectural projects to address housing alienation, presenting bold visions for equitable and deeply affordable housing in Canada. The group’s goal is to mobilize all Canadians to join the call for safer, healthier, and more equitable housing.

“We are thrilled to have been selected to represent Canada at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition, a prestigious international platform that engages critical conversation about contemporary archi tecture,” says the group. “It is crucial that we respond to Canada’s deep housing crisis. Together with Indigenous leaders, activists, advocates, and architects, we will create a campaign for accessible and affordable housing for all.”

canadacouncil.ca

Pritzker Prize awarded to Francis Kéré

Diébédo Francis Kéré, architect, educator and social activist, has been selected as the 2022 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize.

“I am hoping to change the paradigm, push people to dream and undergo risk. It is not because you are rich that you should waste ma terial. It is not because you are poor that you should not try to create quality,” says Kéré. “Everyone deserves quality, everyone deserves lux ury, and everyone deserves comfort. We are interlinked and concerns in climate, democracy and scarcity are concerns for us all.”

Born in Gando, Burkina Faso, and based in Berlin, Germany, the architect known as Francis Kéré empowers and transforms communities through the process of architecture. His work exhibits a commitment to social justice and engagement, and intelligent use of local materials to connect and respond to the natural climate. He often works in marginalized countries laden with constraints and adversity, building contemporary school institutions, health facilities, professional housing, civic buildings and public spaces.

The 2022 Jury Citation states, in part, “He knows, from within, that architecture is not about the object but the objective; not the product, but the process. Francis Kéré’s entire body of work shows us the power of materiality rooted in place. His buildings, for and with communities, are directly of those communities in their making, their materials, their programs and their unique characters.”

The Citation continues, “In a world in crisis, amidst changing values and generations, he reminds us of what has been, and will undoubtedly continue to be a cornerstone of architectural practice: a sense of com munity and narrative quality, which he himself is so able to recount with compassion and pride. In this he provides a narrative in which architec ture can become a source of continued and lasting happiness and joy.”

Significant works include Gando Primary School (2001, Gando, Burkina Faso), the National Park of Mali (2010, Bamako, Mali), Opera

Fire Resistant. Design Consistent.

Fire-Rated Aluminum Window And Door Systems

Aluflam has a complete offering of true extruded aluminum fire-rated vision doors, windows and glazed wall systems, fire-rated for up to 120 minutes. Available in all architectural finishes, our products are almost indistinguishable from non-fire-rated doors and windows. You won’t have to compromise aesthetics to satisfy safety regulations.

Aluflam North America

CANADIAN ARCHITECT 05/22 11

Photo: Mendoza Photography

562-926-9520 aluflam-usa.com

Village (Phase I, 2010, Laongo, Burkina Faso), Centre for Health and Social Welfare (2014, Laongo, Burkina Faso), Lycée Schorge Secondary School (2016, Koudougou, Burkina Faso), The Serpentine Pavilion (2017, London, United Kingdom), Benga Riverside School (2018, Tete, Mozambique), Sarbalé Ke at Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival (2019, California, United States), Xylem at Tippet Rise Art Centre (2019, Montana, United States), Léo Doctors’ Housing (2019, Léo, Burkina Faso), Burkina Institute of Technology (Phase I, 2020, Koudougou, Bur kina Faso), Startup Lions Campus (2021, Turkana, Kenya), and the Na tional Assembly of Burkina Faso (Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, unbuilt).

Kéré established the Kéré Foundation in 1998 to serve the inhabit ants of Gando through the development of projects, partnerships and fundraising, and Kéré Architecture in 2005 in Berlin, Germany. Kéré is a dual citizen of Burkina Faso and Germany. www.pritzkerprize.com

Rise for Architecture releases poll results, launches national survey

Canadians want public spaces that are welcoming for everyone and see room for improvement in how their communities are built.

In an Angus Reid Poll released in April, Canadians are near-unani mous in prioritizing accessibility (96%), aesthetic beauty (92%), and sustainability (90%) in new buildings. They are also widely supportive of new roles which would be responsible for encouraging better design outcomes, such as a Chief Architect or similar title, in both their community (70%) and province (56%).

The online poll, developed by Rise for Architecture in partnership with the Angus Reid Institute, includes viewpoints from a randomized

THAT’S READY WHEN MOTHER NATURE ATTACKS

sample of 1,859 Canadians from the general population polled between January 20-24, 2022.

Rise for Architecture is a national, volunteer-led committee of archi tects, educators, advocates and regulators. Since 2016, the group has been hosting conversations about architecture with professionals, stu dents, and the public. Its findings will culminate in a National Archi tecture Policy for Canada a set of recommendations and actions that governments, professionals, and people involved in the development of our communities can adopt to build a better future for all Canadians.

Three-quarters of the Angus Reid poll’s respondents say culture and heritage should be key considerations in community design. Yet almost three in ten (29%) don’t see themselves and their culture reflected in their community, with visible minorities and Indigenous far less likely than Caucasian Canadians to feel this way. Only 11% of Canadians believe their communities are doing a really good job of protecting the environment.

“Canadians support what we’ve believed all along,” says architect Darryl Condon of HCMA , Chair of the Rise for Architecture commit tee, “that our surroundings shape our future, and the design of our communities has a significant impact on our potential as individuals and as a nation.”

“Canada’s communities are facing unprecedented challenges,” says associate professor Lisa Landrum of the University of Manitoba’s Department of Architecture, and member of the Rise for Architecture committee. “We now have confirmation that Canadians want archi tects to help solve issues like housing affordability, equity and inclusion, and the climate crisis.”

Research shows well-designed buildings create sustainable, socially equitable, and inspiring communities. And yet, the poll found that half of Canadians (51%) say development in their community is poorly planned. Fewer than half (47%) admire the architecture where they live.

NEWSCANADIAN ARCHITECT 05/22 12 THE RACK

Call engineering for specific roof application Patent Pending by Pre-assembled components make assembly a snap! Adapts to work on a variety of roof types Free Samples and Ordering: 860-773-4185 / www.AceClamp.com

ABOVE Kéré Architecture’s concept for a new Burkino Faso National Assembly, proposed after an uprising that destroyed the former facility.

COURTESY KÉRÉ ARCHITECTURE

As a follow-up to the Angus Reid poll, Rise of Architecture has launched an open 12-question survey, directed towards non-architect members of the public. It is encouraging Canadian architects to share the survey with their networks. The survey results will help towards the development of a robust National Architecture Policy for Canada. riseforarchitecture.com

Master’s Program Students Add Indigenous Voices to the CCA’s Collection

Three graduate students, Aamirah Nakhuda, Aidan Qualizza, and Sofia Munera Mora, have published their research undertaken as part of the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s Master’s Students Program. Their project is the second in the three-year thematic series In the Postcolony: Everyday Infrastructures of Design. Building on the Toward Unsettling project conducted by the 2020 Master’s Students Program participants, the research was guided by Rafico Ruiz, Associ ate Director of Research at the CCA , and in virtual conversation with Indigenous and non-Indigenous experts and guests.

Through listening to Indigenous perspectives, the students probed the legal, social, and political impacts of delineating land, offering the story of a three-month investigation into the Saugeen (Bruce) Penin sula as it falls under Treaty 72. As the students began their research into Treaty 72 and the associated land claims, they quickly recognized the lack of primary source material on these subjects. Seeking further information about the intersections of treaty-making and design led to conversations with Indigenous knowledge holders, educators, and designers already at the forefront of these discussions.

The project’s collection of interview transcripts will become the first set of primary sources related to treaties incorporated into the CCA Collection. These interview transcripts and the associated article are intended to serve as primary research resources for students, designers, activists, and historians, as they set out on a path to listening.

The In the Postcolony series is part of a larger effort toward insti tutional acceptance and encouragement of diverse approaches to design within the institution, and within architectural education more broadly. The 2022 Program, to be undertaken in collaboration with community members of the Algonquins of Barriere Lake First Nation as well as with researcher and organizer Shiri Pasternak, will focus on the community’s current initiative to build a multipurpose healing centre on their territory. www.cca.qc.ca

ERRATUM

Our April article previewing new high-rise projects on Vancouver’s Alberni Street omitted the names of the local architects collaborating on several of the developments. The complete architect teams are: Alberni by Kengo Kuma with Merrick Architecture; 1515 Alberni by Buro Ole Scheeren with Francl Architecture; 1700 Alberni by Thom as Heatherwick Architects with IBI Group; and 1684 Alberni by Revery Architecture.

For the latest news, visit www.canadianarchitect.com/news and sign up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.canadianarchitect.com/subscribe.

Make an impression with our distinctive architectural brick

Our unique calcium silicate products perform like natural stone. Our distinctive, long format Architectural Linear Series Brick delivers a modern aesthetic in a weathered, rugged finish. Available in nine designer colours. Inquire today: solutions@arriscraft.com

CANADIAN ARCHITECT 05/22 13

Georgetown Day School |

Gensler Architecture | Architectural Linear Brick Custom Colour |

Photo:

Gensler Architecture

ARCHITECTURAL LINEAR BRICK

Architectural Linear Brick Custom Colour

steeldesignmag.com/subscribe YOUR FREE RESOURCE ON SUBSCRIBE NOW STEEL DESIGN & CONSTRUCTION Steel Design Magazine

is an ArcelorMittal Dofasco

Publication

National Urban Design Awards Roundtable

The RAIC, in partnership with the Canadian Institute of Planners (CIP) and the Canadian Society of Land scape Architects (CSLA), is presenting a virtual Roundtable celebrating the 2022 recipients of the National Urban Design Awards. Taking place on May 26, the event will feature a presentation of the win ning projects, followed by a discussion moderated by Emeka Nnadi, MALA, SALA, CSLA, ASLA, LEED AP, one of the three 2022 jury members.

Célébration des Prix nationaux de design urbain L’IRAC, en partenariat avec l’Institut canadien des urbanistes (ICU) et l’Association des architectes paysagistes du Canada (AAPC), présentera une table ronde virtuelle pour célébrer les lauréats de 2022 des Prix nationaux de design urbain. L’événement se tiendra le 26 mai et comprendra une présentation des projets primés, suivie d’une discussion en direct animée par Emeka Nnadi, MALA, SALA, CSLA, ASLA, LEED AP, l’un des trois membres du jury de 2022.

RAIC 2022 Virtual Conference on Architecture Held virtually in June, the conference will feature weekly launches of on-demand continuing educa tion sessions and live broadcasts of special events. In addition, the conference will include a showcase of advocacy initiatives, the return of the RAIC + CCUSA Academic Summit and engage ment for the development of the RAIC Climate Action Plan. Stream topics include The Practice and Business of Architecture, Sustainability, Technology and Construction, and Housing, Plan ning and Urbanism.

Conférence virtuelle sur l’architecture 2022

La conférence comprendra des lancements heb domadaires de séances de formation continue à la demande et des diffusions en direct d’événements spéciaux. Elle présentera égale ment des initiatives de sensibilisation; le Sommet universitaire IRAC + CCÉUA, de retour cette année; ainsi que la mobilisation pour l’élaboration du Plan d’action climatique de l’IRAC. Parmi les volets de la conférence, mentionnons notamment les suivants : pratique et affaires de l’architecture; durabilité, technologie et construc tion; logement, planification et urbanisme et d’autres encore! La Conférence sur l’architecture 2022 de l’IRAC se tiendra en mode virtuel en juin.

RAIC Journal Journal de l’IRAC

Gold Medallist

Jerome Markson (centre) with George Baird (left) and the building contr actor on the con struction site of Chatelaine Design Home ’63, Brama lea, Ontario.

Le médaillé d’or Jerome Markson (au centre) en compagnie de George Baird (à gauche) et de l’entrepreneur, au chantier de Chatelaine Design Home ’63, Brama lea, Ontario (1963).

RAIC Gold Medal: Jerome Markson Médaille d’or de l’IRAC

The RAIC is the leading voice for excellence in the built environment in Canada, demonstrating how design enhances the quality of life, while address ing important issues of society through responsi ble architecture. www.raic.org

L’IRAC est le principal porte-parole en faveur thel’excellence du cadre bâti au Canada. Il demon tre comment la conception améliore la qualité de vie tout en tenant compte d’importants enjeux sociétaux par la voie d’une architecture respon sable. raic.org/fr

Certain works of architecture are so carefully woven into the times, places and cultures within which they are set, they seem to have always been there. Such buildings form the settings for events both ordinary and extraor dinary, shaping not only the ways we engage and remember these events, but also quietly defining how we see ourselves, through shift ing circumstances wrought by time. It can be a valuable lesson to look back at the moments these buildings appeared. What was the vision that brought them into being, that imagined them as something wholly new?

Happily, the RAIC 2022 Gold Medal Jury has done just this, in awarding Jerome Markson its highest honour. Markson has spent his career creating just such works of architec ture: inscribed within their contexts, imbued with a masterful level of craft and character, and conceived foremost as settings for human interaction. His practice of nearly 60 years can only be described as omnivorous, embracing a wide range of building types and programs, from single family homes, to multi-family housing, to housing for the aged, to cultural

Certaines œuvres d’architecture sont si fine ment intégrées aux époques, aux lieux et aux cultures dans lesquels elles s’inscrivent qu’elles semblent avoir toujours été là. Elles offrent un cadre à la tenue de diverses activi tés, ordinaires ou extraordinaires, et définis sent notre façon d’y participer et le souvenir que nous en gardons tout en définissant tranquillement notre perception de nousmêmes au fil du temps et des circonstances. Il y a des enseignements utiles à tirer d’un examen de l’époque à laquelle ces bâtiments sont apparus. Quelle était la vision qui leur a donné vie, qui les a imaginés comme quelque chose de tout à fait nouveau?

C’est ce qu’a fait le jury de la Médaille d’or 2022 de l’IRAC en attribuant sa plus haute distinction à Jerome Markson. Nous ne pou vons que nous en réjouir. Markson a créé ce type d’architecture pendant toute sa carrière : des bâtiments inscrits dans leur contexte, imprégnés d’une maîtrise de la conception et de l’exécution et destinés avant tout aux interactions humaines. Il n’y a qu’un mot pour décrire sa pratique qui s’étend sur près de 60

15 Briefs En bref

Courtesy George Baird

Laura J. Miller Associate Professor, Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design Professeure associée, Faculté Daniels d’architecture, d’architecture du paysage et de design

One of Markson’s earliest houses was the Smith Residence in Woodbridge, Ontario (1955), created for a family with young children. Résidence Smith, à Woodbridge, en Ontario (1955), l’une des pre mières maisons de Markson, créée pour une famille ayant de jeunes enfants.

and religious buildings, to medical and office buildings—even post-office prototypes, and yes, a floating cottage. He created notable buildings of distinction in all these categories, earning over 50 design awards in the course of his career. The longevity of Markson’s practice is a testament to his extraordinary commit ment, dedication, and achievements in archi tecture and urbanism during a period of great change, and speaks to the continuous rele vance of his architecture to diverse audiences inside and outside of the profession.

Through his diverse work, Markson pursued a more open and inclusive expression of modernity, one that moved away from the doctrinaire, object-focussed Modernism widely accepted in the mid-twentieth century when he began his practice. Architecture critic Christopher Hume has observed that Markson is “the rare architect who creates cities while designing buildings.” Indeed, Markson’s buildings are as attentive to the way they reshape their sites and affect the city as they are to providing rich possibilities within newly created spaces.

Early in life, Markson experienced the reso nant complexities the city could present. Born in 1929, he grew up in downtown Toron to between two vibrant immigrant neigh bourhoods, Kensington Market and the Ward (now vanished). His parents, Etta and Charles, were children themselves when they came to Toronto around 1900 as immi grants, from Lithuania and Poland respec tively. The Markson family’s home still sits on the north side of Dundas Street, now facing the lilting portico of the Art Gallery of Ontario. The family lived on two floors above the street-level medical practice of Dr. Charles Markson. More than once, Markson’s father was paid with a chicken from patients who had no money to spare for medical care.

Seeing the struggles of his neighbours in the Depression years made a profound impact on Markson, inculcating a deep sense of obligation to help others, and a desire for greater social inclusivity. A keen observer, Markson also saw the dignity and vitality in more ‘ordinary’ buildings that con stituted the fabric of the city around him— Toronto’s neighbourhoods filled with modest housing types, its mercantile blocks, store fronts, and warehouses.

Enrolling at the University of Toronto in 1948, Markson joined a class that spent its first year at drafting boards set up in a former bomb factory in Ajax, Ontario. Eric Arthur was a forceful presence in the faculty, and his argu ments for recognizing the irreplaceable cul tural value of the city’s heritage buildings res onated with Markson. Markson also discov ered the work of the British Townscape move ment, led by Gordon Cullen, Nicholas Pevsner, and others who argued that the incorporation of new, Modern buildings should be based on spatial relationships and visual sequences cal ibrated in relation to the existing urban con text—counter to the Modernist preference for more singular, object-oriented buildings.

Another profound influence on Markson was Eliel Saarinen, whose pedagogy he encoun tered during a summer program at the Cran brook Academy of Art. Saarinen’s philosophy of “always design[ing] a thing by thinking of it in its next biggest context—a chair in a room, a room in a house, a house in an environ ment, an environment in city plan” struck a chord with Markson. At Cranbrook, Markson also met a talented ceramic artist from Win nipeg, Mayta Silver. They were married fol lowing Markson’s graduation in 1953, and after saving money to travel, embarked to Europe to experience firsthand the buildings Markson had studied in school.

After a more con ventional cottage design had been rejected because this Georgian Bay, ON, site was declared off-lim its for permanent construction, Markson designed this ‘floating cottage’ for Toronto Life pub lisher Michael de Pencier.

Conçu pour l’éditeur du Toronto Life, Michael de Pen cier, ce « chalet flottant » a été construit après qu’il a été interdit d’ériger un bâti ment permanent sur le terrain de la baie Georgi enne sur lequel un chalet plus conventionnel était prévu.

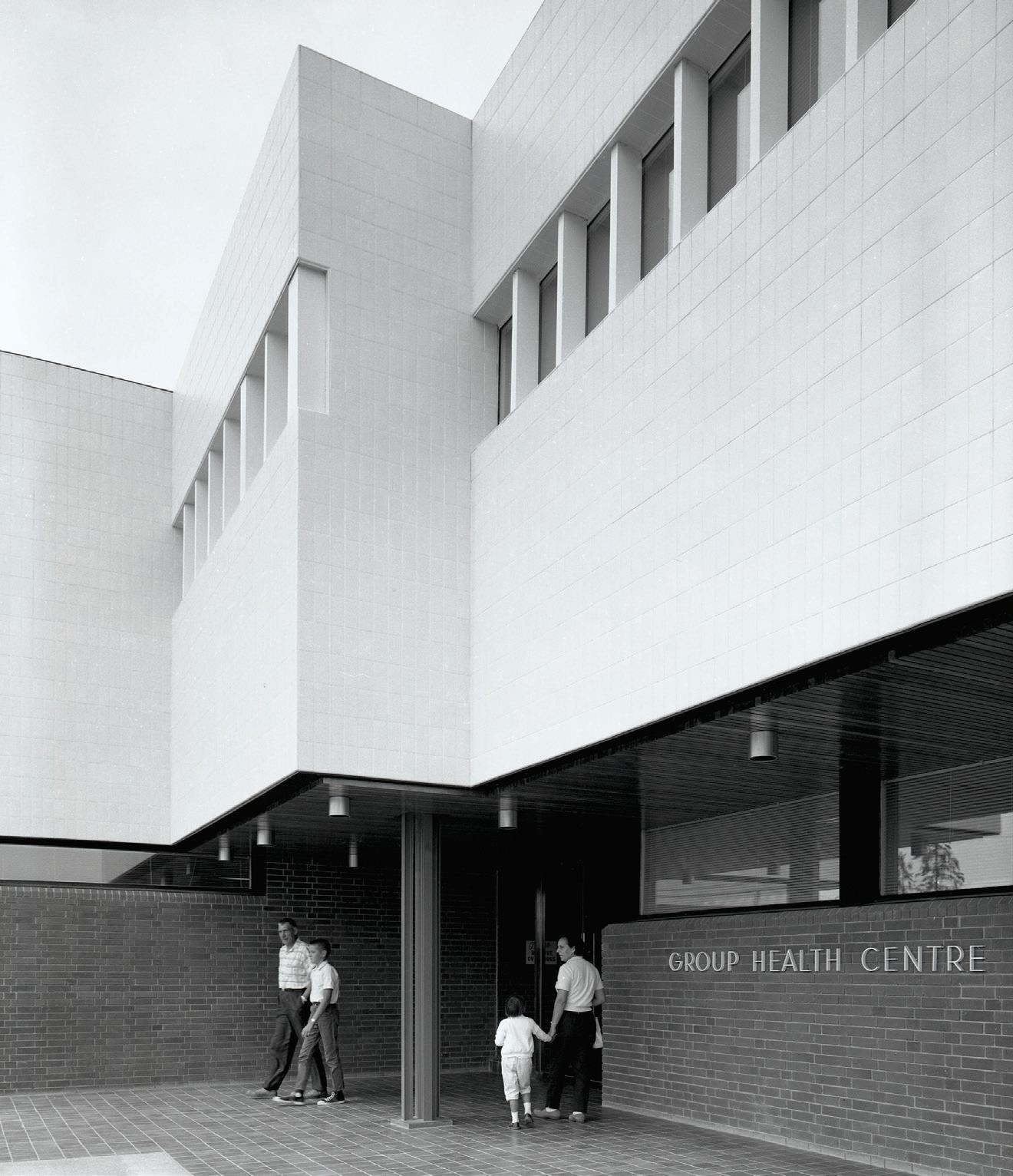

The Marksons returned to Toronto and Jerome opened his office in 1955. It was an exhilarating moment to embark on practicing architecture. Urban planner Macklin Hancock summed up the spirit at that time: “Canada suddenly flowered, it wanted to be modern.” Markson’s architectural and urban works from the 1950s and 1960s, particularly those in Toronto, were created at a time when many were discussing the ideals of a progressive society within the context of post-war prosper ity. Although fewer in number, his buildings outside Toronto, too, gave architectural expression to important social developments and innovations of their time. The emergence of socialized medicine was registered in Mark son’s groundbreaking design for the Sault St. Marie Group Health Centre, demonstrating that a systemic overhaul in the name of great er social equity could also spark a more humane model for spaces of treatment. His thoughtful designs for speculative model homes at Seneca Heights and the density of his Concept 3 stacked townhouses in Brama lea suggested distinct alternatives to the selfsame houses of a rapidly expanding subur bia. Markson’s Elliott Lake Plaza showed that the increasingly ubiquitous strip malls prolif erating throughout Canadian cities could have civic potential. And, in a period of inten sive post-war urbanization and consumer ism, Markson forcefully recalled the impor tance of wilderness in the Canadian imagi nary in such buildings as the Sherman Staff Lodge, hovering at the edge of Lake Temaga mi; the exuberant collection of buildings at Camp Manitou-Wabing; and the improvisa tional rusticity of The Shack, Uxbridge.

Architectural Practice as City-building

The question of not only where social housing for the needy should be built, but how it could better value—and even learn from—the

Peter Varley

RAIC Journal Journal de l’IRAC16

Jerome Markson

ans, omnivore. Il a réalisé des bâtiments de tous types et programmes : résidences unifamiliales, immeubles à logements multi ples, résidences pour personnes âgées, édifices culturels et religieux, établissements de soins de santé et de bureaux—il a même créé des prototypes de bureaux de poste et une maison flottante, eh oui. Il a créé des bâtiments remarquables dans toutes ces catégories et a remporté plus de 50 prix de design. La longévité de cette carrière témoigne de l’extraordinaire engagement de Markson, de sa passion et de ses réalisa tions en architecture et en urbanisme dans une période de grands changements. Elle témoigne aussi de la pertinence avérée de son architecture pour les professionnels du domaine et les profanes.

Dans sa pratique diversifiée, Markson a cher ché à exprimer la modernité d’une manière plus ouverte et inclusive, s’éloignant ainsi du modernisme doctrinaire axé sur l’objet qui était largement reconnu au milieu du

vingtième siècle lorsqu’il est entré dans la profession. Comme l’a fait remarquer le critique d’architecture Christopher Hume, Markson « est ce rare architecte qui crée des villes lorsqu’il conçoit des bâtiments ». En fait, Markson est aussi attentif à la façon dont ses bâtiments remodèlent leur emplacement et modifient la ville qu’aux riches possibilités offertes par les espaces nouvellement créés.

Tôt dans sa vie, Markson a été mis en présence des complexités résonantes que pouvait présenter la ville. Né en 1929, il a grandi au centre-ville de Toronto entre deux quartiers dynamiques d’immigrants, Kens ington Market et The Ward (maintenant dis paru). Ses parents, Etta et Charles, étaient eux-mêmes des enfants lorsqu’ils sont arrivés à Toronto vers 1900, comme immi grants de la Lituanie et de la Pologne. La maison de la famille Markson existe encore, du côté nord de la rue Dundas, en face du portique actuel du Musée des beaux-arts de l’Ontario. La famille occupait les deux étag

Concept 3, a sixstorey, stackedtownhouse com plex in Bramalea (1968), brought a new monumen tality to the sub urban landscape, with its high entry portal and con nections between discrete buildings via pedestrian ways at the ground and fourth levels.

Concept 3, un complexe de maisons en ran gée superposées de six étages à Bramalea (1968) a ajouté une cer taine monumen talité à la banli eue avec son haut portail d’entrée et les voies piétonnes qui relient les différents bâti ments au rez-dechaussée et au quatrième étage.

es supérieurs du bâtiment qui abritait le bureau du Dr Charles Markson au rez-dechaussée. Bien souvent, des patients qui n’avaient pas d’argent pour payer les hono raires du médecin lui donnaient un poulet.

Markson a été profondément touché par les difficultés de ses voisins pendant la Dépres sion. Il en a ressenti une obligation d’aider les autres et un désir d’une plus grande inclusion sociale. Fin observateur, il a égale ment vu la dignité et la vitalité des bâtiments plus « ordinaires » qui constituaient le tissu de la ville qui l’entourait—les quartiers de Toronto aux logements modestes, ses quadrilatères commerciaux, ses devantures de magasins et ses entrepôts.

Inscrit à l’Université de Toronto en 1948, Markson fait partie d’une classe qui passe sa première année sur des planches à des sin installées dans une ancienne usine de bombes à Ajax, en Ontario. Eric Arthur jouait un rôle percutant au sein de la faculté et son plaidoyer sur la reconnaissance de la valeur culturelle irremplaçable des bâtiments pat rimoniaux de la ville a trouvé écho chez Markson. C’est également à cette époque que Markson a découvert le mouvement bri tannique du Townscape, mené par Gordon Cullen, Nicholas Pevsner et d’autres qui soutenaient que l’intégration des nouveaux bâtiments modernes devait reposer sur des relations spatiales et des séquences visuelles harmonisées au contexte urbain existant—ce qui va à l’encontre de la pré férence du modernisme pour des bâtiments plus originaux, orientés vers l’objet.

Markson a également été influencé par Eliel Saarinen dont il a découvert la pédagogie dans le cadre d’un programme d’été à la Cranbrook Academy of Art. La philosophie de Saarinen a touché une corde sensible chez Markson. Il prétendait qu’il fallait toujours penser au prochain contexte élargi d’une chose au moment de la concevoir—une chaise dans une pièce, une pièce dans une maison, une maison dans un quartier, un quartier dans le plan de la ville. C’est aussi à Cranbrook que Markson a rencontré une céramiste tal entueuse de Winnipeg, Mayta Silver. Ils se sont mariés après l’obtention du diplôme de Markson, en 1953, et après avoir économisé pour voyager, ils se sont embarqués pour l’Europe dans l’objectif de voir de près les bâtiments que Markson avait étudiés à l’école.

À leur retour à Toronto, en 1955, Jerome a ouvert son bureau. C’était une époque exal tante pour ouvrir un bureau d’architecte.

L’urbaniste Macklin Hancock a résumé ainsi l’état d’esprit qui régnait à cette époque :

RAIC Journal Journal de l’IRAC 17

Roger

Jowett

existing city was central to Markson’s design of Alexandra Park Social Housing (with Klein & Sears and Webb Zerafa Menkes). This was Markson’s first public housing work and rep resented a radical departure from the sterile paradigm of concrete towers-in-the park. Markson and his collaborators proposed brick, mostly low-rise walk-ups with groundlevel access, laid out as a series of undulating units with wood bay windows and individual entries, interspersed with garden courts configured to preserve heritage trees. All was consistent with the scale, and using the materials of, the surrounding urban housing. It was a humanistic retort to the state of housing for the ‘needy’ that to-date had been erected through massive urban clearance. While the architects’ plans to preserve key buildings within Alexandra Park’s site area (another groundbreaking idea for that era) were rejected, Markson achieved this goal a few years later. His Pembroke Mews Cooperative integrated historic and vernacular structures with new housing—one of the first urban infill projects in Toronto.

Later, Markson designed the critically acclaimed David B. Archer Co-operative Housing as part of the massive redevelop ment of an industrial area south of the St. Lawrence Market. The Co-operative took shape as a combination of townhouses and apartments, with a seven-storey apartment building across from the linear Crombie Park, transitioning in height at abutting side streets to two- and three-storey townhouses. An assortment of intermediate-scale architec tural elements—window surrounds, bay win dows, corner posts, and porches—brought a sense of animation and identity to the red brick street elevations, each developed according to the street typologies they front ed. Built in the still-early years of postmodern

architecture, the Archer Co-operative dem onstrates the syntactical richness possible in the composition of architectural elements integrated into a scalar logic, and their role in creating both urban variety and continuity.

Markson’s nearby Market Square has been recognized and awarded for both its architec ture and the exemplary quality of its urban design. Its sensitive siting and shrewd use of the courtyard typology allow the building to be relatively low-rise yet high-density, and its split massing constructs a visual and pedes trian axis with St. James Cathedral one block to the north. Urban designer Roger du Toit referred to the complex as an “essay in mod ern design.” The modulation of Market Square’s bulky exterior—from the expres sion of its structural frame and recessed infill panels, to the building’s generous win

dows with their elegant, recessed brick jambs, to the distribution of tall glass bays— suggests the forthright efficiency found in nearby industrial loft buildings, yet, in its refinement, Markson’s design stands apart.

The museum designed by Markson for the works of Group of Seven painter Frederick Horsman Varley in Unionville, Ontario, deftly negotiates between a historic city fabric and modern development. Markson placed his Varley Art Gallery slightly off-centre at the juncture of the quaint town centre and a new, wider road, creating an open plaza at the ter minus to historic Main Street, while also mir roring the openness of parking surrounding the town’s nearby hockey rink. Writes critic Christopher Hume: “Markson’s willingness to serve the city, to blend with the urban fab ric, mark him as an architect of rare selfless ness and sensitivity.”

A Deeper Signature: Design, Experi mentation, and Expression

Markson’s choreography of architectural program and site is clearly seen in his singlefamily house designs, a staple of his practice. Markson’s study of the emerging suburbs resulted in a diverse array of houses, each considering how the car engaged the domes tic program, and how a house could better engage its site. The Moses, Smith, and Min den Residences, Seneca Heights Model Homes, and the Chatelaine Design Home ’63, as well as later houses such as the Enkin Residence and the Ravine Residence, are but a few examples of how Markson deftly orchestrated the routine movements of daily life within his rich architectural frameworks.

Children at play in the humanely scaled pedestrian spaces of Alexan dra Park Social Housing in Toronto (1965), designed by Markson with Klein & Sears and Webb Zerafa Menkes.

Enfants qui jouent dans les espaces piéton niers à échelle humaine du pro jet de logements sociaux du parc Alexandra à Toronto (1965), conçu par Mark son en consor tium avec Klein & Sears et Webb Zerafa Menkes.

View along George Street of the David B. Archer Co-opera tive (1976), part of the massive St. Lawrence Neigh bourhood created in an underused industrial area southeast of Toronto’s down town core.

Vue de la coo pérative David B. Archer (1976) sur la rue George, qui fait partie de l’immense quart ier St. Lawrence créé dans une zone industrielle sous-utilisée au sud-est du centre-ville de Toronto.

RAIC Journal Journal de l’IRAC18

Courtesy of City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 68, File 24, J52R4-14

Fiona Spalding-Smith

« Le Canada a soudainement éclos, il voulait être moderne ». À partir des années 1950 et 1960, les projets d’architecture et d’urbanisme de Markson, particulièrement ceux de Toronto, ont été créés à une époque où l’on discutait beaucoup des idéaux d’une société progressiste dans le contexte de la prospérité d’après-guerre. Bien que moins nombreux, ses bâtiments en dehors de Toron to ont également donné une expression archi tecturale à d’importants projets à caractère social et innovateur de leur époque. Le Group Health Centre de Sault-Sainte-Marie au design avant-gardiste exprimait l’émergence de la médecine socialisée tout en démontrant qu’une réforme systémique au nom d’une plus grande équité sociale pouvait également don ner lieu à la création d’espaces de soins plus humains. Les designs réfléchis de Markson pour des maisons modèles spéculatives à Seneca Heights et la densité de ses maisons en rangée Concept 3 à Bramalea ont proposé des solutions de rechange aux maisons toutes identiques les unes aux autres d’une banlieue en croissance rapide. L’Elliott Lake Plaza a montré que les centres commerciaux liné aires de plus en plus omniprésents dans les villes canadiennes pouvaient avoir un potentiel civique. Et, dans une période d’urbanisation et de consumérisme intensifs d’après-guerre, Markson a rappelé avec force l’importance de la nature dans l’imaginaire des Canadiens par des bâtiments comme le Sherman Staff Lodge, au bout du lac Temagami; la collec tion exubérante de bâtiments du Camp Mani tou-Wabing; et la rusticité improvisée de The Shack, à Uxbridge.

Une architecture qui crée la ville

Lorsque Markson a conçu les logements sociaux d’Alexandra Park (avec Klein et Sears et Webb Zefara Menkès), il n’a pas seulement cherché à déterminer l’emplacement des logements pour les gens dans le besoin, mais aussi à déterminer comment valoriser la ville existante—et même en tirer des leçons. C’était le premier projet de logements publics de Markson et il provoquait une rupture radicale avec le par adigme stérile des tours de béton dans le parc. Markson et ses collaborateurs ont proposé des bâtiments en brique, générale ment de faible hauteur, avec accès au rezde-chaussée, implantés comme une série d’unités ondulées avec des baies vitrées en bois et des entrées individuelles, entrecou pées de cours-jardins configurées pour préserver les arbres patrimoniaux. Le tout était en harmonie avec l’échelle et les maté riaux des logements urbains des environs. Il s’agissait d’une réplique humaniste au prob lème du logement pour les « gens dans le

1 View of Market Square Condo miniums (1980) along Toronto’s Front Street, looking west towards the Goo derham Building and CN Tower.

1 Vue depuis Market Square Condominiums (1980) le long de la rue Front à Toronto, en regardant vers l’ouest en direc tion de l’édifice Gooderham et de la Tour CN.

2 Market Square under construc tion (c. 1983), showing the cru cial relationship with the historic St. James Cathe dral to the north.

2 Market Square en construction (c. 1983), illus trant sa relation cruciale avec la cathédrale historique St. James au nord.

besoin » dont la solution reposait jusqu’alors sur un nettoyage urbain massif. Les plans des architectes visant à préserver les princi paux bâtiments du secteur d’Alexandra Park (une autre idée novatrice pour l’époque) ont été rejetés, mais Markson a tout de même atteint son objectif quelques années plus tard. Dans son projet de coopérative de Pembroke Mews, il a intégré des éléments historiques et vernaculaires aux nouveaux logements—l’un des premiers projets urbains intercalaires de Toronto.

Plus tard, Markson a conçu la coopérative d’habitation David B. Archer, acclamée par la critique, dans le cadre du réaménagement majeur d’une zone industrielle au sud du St. Lawrence Market. La coopérative consistait en une combinaison de maisons en rangée et d’appartements, et comprenait un immeuble d’appartements de sept étages en face du parc linéaire Crombie, puis des maisons en rangée de deux et trois étages dans les rues latérales adjacentes. Une panoplie d’éléments architecturaux d’échelle intermédiaire— encadrements de fenêtres, fenêtres en saillie, poteaux d’angle et porches—créaient une cer taine animation et donnaient une identité aux élévations en brique rouge côté rue, chacune

étant conçue en fonction de la typologie de la rue sur laquelle elle donnait. Construite dans les premières années de l’architecture post moderne, la coopérative Archer démontre qu’il est possible d’exprimer une richesse syn taxique dans la composition d’éléments archi tecturaux intégrés dans une logique scalaire, et leur rôle dans la création de la diversité et de la continuité urbaines.

Le Market Square, situé à proximité, a été reconnu et primé pour son architecture et pour la qualité exemplaire de son design urbain. Par une implantation sensible au site et l’utilisation habile de la typologie de la cour, Markson a conçu un bâtiment d’une hauteur relativement faible et d’une densité pourtant élevée, dont la masse divisée construit un axe visuel et piétonnier avec la cathédrale St. James, située à un pâté de maisons au nord. L’urbaniste Roger du Toit a qualifié le com plexe « d’essai de design moderne ». La modulation de l’extérieur volumineux de Market Square—allant de l’expression de son cadre structurel et de ses panneaux interc alaires en retrait, jusqu’aux fenêtres généreuses du bâtiment avec leurs élégants montants en brique en retrait et à la distribu tion de grandes baies vitrées—rappelle la

RAIC Journal Journal de l’IRAC 19

Office of Jerome Markson

Office of Jerome Markson

1 2

Wood-and-steelframed pedestri an arcades line the entry court of the Cedarvale Community Centre (1964) in Toronto.

Arcades pié tonnes à ossat ure de bois et d’acier qui mar quent la cour d’entrée au cen tre communau taire Cedarvale (1964), à Toronto.

Markson considered each iteration of a par ticular program or typology as a new oppor tunity to test and extend design solutions to the problem at hand. Rather than being con cerned with establishing a signature identity for his work, he consistently sought new orders of program, space, sequence, materi al expression, and form. Markson’s design philosophy gave priority to an open, experi mental process of inquiry and saw construc tion as a critical extension of his process. This, along with his commitment to work for a diverse mix of clients, led to a body of unique and distinct works of architecture.

Inventing a Diverse and Representative Material Idiom

Near the mid-point of Markson’s career, architect and theorist George Baird observed:

“Markson has…pursued a quite individual course within the territory of Canadian archi tecture… [T]here is…in the best of his works a characteristic almost unique in contempo rary Canadian architecture: a subconscious tactile iconography of the materiality of build

ing, a materiality that is, for me, reminiscent of some aspects of the work of Aalto and Le Corbusier. Albeit an elusive characteristic of any contemporary architecture, this is par ticularly important in the Canadian context on account of its extreme rarity here.”

Rather than based in a purely craft tradition, Markson’s architecture uses materials and building elements that communicate viscer ally through experience. Diverse influences— particularly Aalto, Britain’s Townscape move ment, Arthur, and Saarinen—but also, cru cially, encounters with vernacular architec ture both in Canada and in Europe, were instrumental in Markson’s development of a pluralistic, materially oriented approach, one that innately recognizes the intrinsic qualities of the city’s historic fabric.

Markson’s cultural and community works, despite their institutional programs, reflect his commitment to such material exploration. His Cedarvale Community Centre delineates the building’s utilitarian spaces—offices, changing areas—as a dense package of cellu lar rooms. That same utilitarian logic might

have been extended to the collective commu nity assembly space. Instead, Markson fash ioned that space as an amorphous figure, a space at once explicitly about form, but also, at times, formless. The compound curvature of its primary exterior wall and its diffuse light sources contribute to a sense of shifting per ceptual boundaries. The specificity of the wood ceiling and beams within the gathering space counter this ambiguity with a distinctly warm, immediate material presence.

His Regional Headquarters for the Interna tional Woodworkers of America is an essay in wood and brick: a lightly scaled, even delicate post-and-beam structure spans between two sidewalls of brick. Its interior spaces are lined with a textured wood tapestry emphasizing a sense of containment and interiority, strategi cally juxtaposed with views to a ravine, incor porating the larger landscape into the archi tectural ensemble. Other buildings for sites in natural settings also have a loosely expres sive, improvisational quality, attributable to Markson’s choice of wood as a primary struc tural material. The incrementality of wood framing facilitates the minute adjustments that allow a wall to splay out, such as at his early buildings for Camp Manitou-Wabing; a roof to sweep and flare at Cedarvale Commu nity Centre; and a large structure such as the Humber Arboretum to appear as a fragile, tree-like form hovering over the landscape.

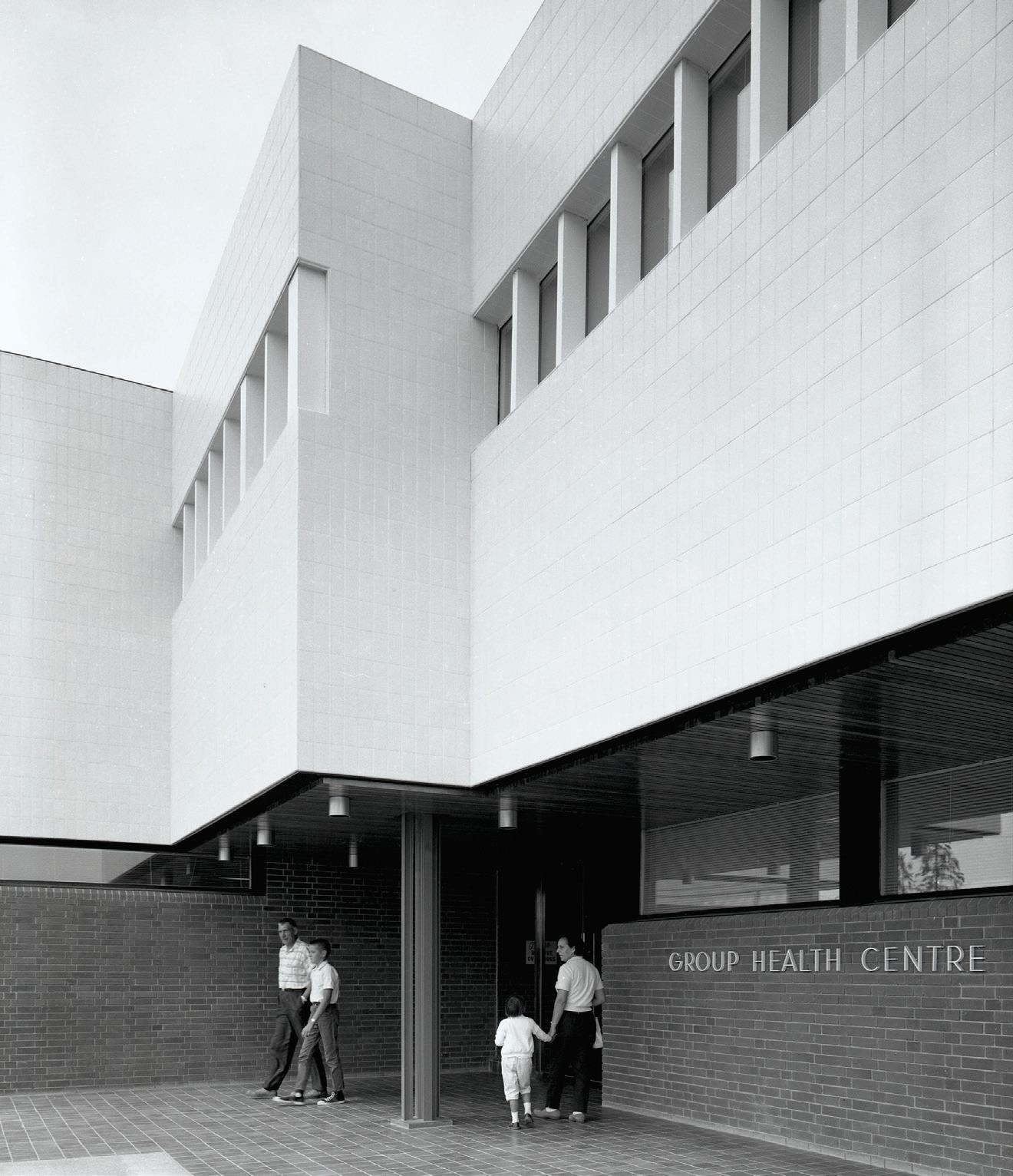

Markson’s understanding that light is not only a medium of architectural expression, but also has the potential to heal, led to his inven tion of a new typology for medical facilities at his Sault Ste. Marie Group Health Centre, built at a time when the prospect of socialized medical care was being hotly debated across Canada. The ubiquity of the hospital atrium today and its current association with retail spaces may obscure what a real innovation Markson’s design was at the time. Markson excised an open core of light from what ordi narily would have been densely packed, func tional floor plates. Architecture critic Hans Elte saw Markson’s innovation quite clearly, and his comments are worth quoting in full:

“Among the agencies of atmosphere is light ... It has played a major part in stimulating this remarkable space, resulting in an atmo sphere of sheer lucidity, which incidentally, no photograph or film could accurately por tray. Its designer has been roused by a love affair with light.

Over many medical institutions both large and small, there still hangs, in a rather remote way, something of the cloud of gloom always present in the ancient ‘maison de

RAIC Journal Journal de l’IRAC20

Photographer

Unknown

franche efficacité des lofts industriels voisins, mais le design de Markson se distingue toutefois par son raffinement.

Le musée conçu par Markson pour abriter les œuvres du peintre Frederick Horsman Varley du Groupe des Sept, à Unionville, en Ontario, négocie habilement entre un tissu urbain historique et un développement mod erne. Markson a érigé son musée Varley légèrement décentré à la jonction du centreville pittoresque et d’une nouvelle route plus large, créant ainsi une place ouverte au bout de la rue Principale historique, tout en rap pelant l’ouverture du stationnement entou rant la patinoire de hockey de la ville. Selon le critique Christopher Hume, la volonté de Markson de servir la ville et d’harmoniser le tissu urbain en fait un architecte très sen sible, d’un rare altruisme.

Une signature qui s’affirme : concep tion, expérimentation et expression

Les designs de maisons individuelles de Markson, un volet incontournable de sa pra tique, illustrent clairement la chorégraphie entre le programme architectural et

l’emplacement. Son étude des banlieues émergentes l’a amené à créer un large éven tail de maisons qui tiennent compte de l’utilisation de la voiture par la famille

et de la meilleure façon d’intégrer la maison à son site. Les résidences Moses, Smith et Minden, les maisons modèles de Seneca Heights et la Chatelaine Design Home ‘63, ainsi que des maisons plus récentes comme la résidence Enkin et la résidence Ravine ne sont que quelques exemples qui illustrent son orchestration habile des mouvements routiniers de la vie quotidienne dans ses riches cadres architecturaux.

Markson considérait que chaque itération d’une typologie ou d’un programme donné était une nouvelle occasion de tester des solutions conceptuelles et de les étendre au problème qui se posait. Plutôt que de chercher à créer une signature à ses projets, il a toujours été à la recherche de nouveaux ordres de programme, d’espace, de séquence, d’expression matérielle et de forme. Sa phi losophie de conception l’amenait à accorder la priorité à un questionnement ouvert et expéri mental et à considérer la construction comme une extension essentielle de cette démarche. Cette philosophie et son engagement à tra vailler pour une clientèle diversifiée ont donné lieu à un ensemble d’œuvres architec turales uniques et distinctes.

Inventer un langage matériel diversifié et représentatif

À l’approche du mi-temps de la carrière de Markson, l’architecte et théoricien George Bair a écrit :

« Markson a... suivi un parcours assez partic ulier sur le territoire de l’architecture cana dienne ... On retrouve ... dans le meilleur de

Entry to Sault Ste. Marie’s Group Health Centre (1962) built for the United Steelwork ers of America, one of the first facilities for socialized medi cine in Canada.

Entrée du Group Health Centre de Sault-SainteMarie (1962) construit pour l’United Steel workers of America, l’une des premières installations de médecine sociale au Canada.

Central stair at the Sault Ste. Marie Group Health Centre (1962), infused with light and fea turing a hanging ceramic artwork installation by Mayta Markson’s collaborative stu dio Five Potters.

Escalier central du Group Health Centre de SaultSainte-Marie (1962), imprégné de lumière et montrant les œuvres d’art en céramique sus pendues de Five Potters, l’atelier collaboratif de Mayta Markson.

RAIC Journal Journal de l’IRAC 21

Roger Jowett

Roger

Jowett

Dieu,’ a place where there was little hope for life, a place where one could go to die rather than to get well.

There is no doubt that it has been the great merit of this architect that he has been able to make a most capable attempt to reverse the symptoms of this phenomenon. Whilst walking through the building, it is manifest that he had a bold flair for the unusual and, a marked perception for the poetical.”

An Architecture of Empathy and Dignity

Markson’s multi-unit housing works were an essential part of his practice. These projects were the fullest expression of Markson’s belief that architecture is not reserved for an elite class of users, but should rather be funda mentally democratic in its ability to frame lived space and its occupants with dignity. He has said, “Why should [Alexandra Park] be differ ent-looking than houses for the more welloff? We are all human beings, for God’s sake.” His close attention to the design of housing units in that project—varied unit types with individual access to the ground, featuring architectural elements such as V-shaped bay windows conceived as “punctuation along the street”—brought a human scale to the hous ing complex, enriching the texture of resi dents’ daily experiences moving through pedestrian pathways throughout the site.

In True Davidson Acres/Metro Home for the Aged, Markson considered how each resi

dent might use and occupy their living space, and their needs for privacy and social connection over time. He created an innova tive unit plan for the rooms, allowing dis crete territories and views to be claimed by each resident. In so doing, he refashioned a space where the extent of engagement became a matter of individual choice, pre serving personal dignity and privacy while offering the potential for sociability. Creating ambiguity in a space precisely shaped, yet open to divergent uses and interpretations by its occupants, reveals the generosity in Markson’s architecture.

Cultivating Architecture as an Inclusive Spatial Setting

Understanding space as an empathic medi um, and architecture as a material and spa tial setting for human interaction and the appearance of the individual, recasts the object-focussed propensity of Modernism into a more inclusive construction. This is reflected in Markson’s photo-documenta tion of a number of his architectural works.

Instead of sterile formal compositions, we see adults, children, families, friends, and sometimes pets—present, and occupied with their comings and goings, their hob bies, their conversations, and their play.

Markson’s images provide insight into how a key aspect of his work was conceptualized: the character of his architectural settings is inseparable from the human characters who would be an integral part of those

Roger Jowett

spaces. “If not for the people who will inhabit it, then who is the architecture for?” Markson has asked.

When recorded, these images must have been arresting, even poignant. Today, some years later, the same photographs are certainly so – the familiar objects and appearances of everyday life, from objects in a household to how people dress, is more distant. Markson’s architectural set tings impart the specificity of an individu al’s experience at a particular point in time; because of this specificity, we can empathize with the shared aspects of that experience today.

Markson’s compassionate, humanistic approach to design ultimately transcended formal preoccupations in favour of a more immediate material and spatial dialogue with its users. A similar concern has been taken up anew within contemporary archi tectural practices, witnessed in the work of architects such as 2021 Pritzker Prize winners Lacaton & Vassal, who position their architecture with respect to the occu pants of their buildings ‘completing’ the architecture in an active way. Decades earlier, Jerome Markson’s compassionate, humanistic approach to design transcend ed formal preoccupations in favour of a more immediate material and spatial dia logue with its users. The continued rele vance of his architectural approach and works is evident.

Markson’s recognition of the essential role that constellations of individuals play as they appear, and are brought together, in the inclusive, collaborative construction of architectural space is at the core of what our most ambitious work as a profession can achieve. Perched as we are at the far edge, hopefully, of a global pandemic, still suffering from loss and social isolation that we have endured, many of us long for a return to the architectural settings of everyday life that Markson envisioned and built—an architecture that situates diverse human experiences in exquisitely com posed and spatially rich settings, enabling participation within a shared social and temporal space.